A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Historic Parishes - Lydiard Millicent', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18, ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/186-209 [accessed 3 April 2025].

'Historic Parishes - Lydiard Millicent', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Edited by Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online, accessed April 3, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/186-209.

"Historic Parishes - Lydiard Millicent". A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online. Web. 3 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/186-209.

In this section

LYDIARD MILLICENT

LYDIARD MILLICENT village stands 6 km. west of the centre of Swindon. (fn. 1) The name Millicent was presumably attached c. 1200, when the manor on which the village stood was held by Millicent, widow of William son of Hugh, (fn. 2) and its neighbour Lydiard Tregoze was held by Robert Tregoze. (fn. 3) The parish is long and narrow and adjoins Swindon.

The estate which became Lydiard Millicent manor, and that which became Lydiard Tregoze manor, may have been two halves of an earlier estate called Lydiard. (fn. 4) A church was built at Lydiard Millicent and the manor apparently became its parish. The parish stretches 10 km. from east to west and in places is no more than 500 m. from north to south. Before 20th-century boundary changes it measured 2,339 a. (946 ha.) and contained Lydiard Millicent village, Shaw village, outlying farmsteads, and hamlets called Lydiard Green, Greatfield, Green Hill, Holborn, Nine Elms, and Washpool. The whole parish except the east end lay within the boundary of Braydon forest from 1228; it was disafforested in 1330. (fn. 5) From then the west end was deemed part of the purlieus of the forest and until c. 1630 lay open to the forest and other parts of the purlieus. (fn. 6)

At the east end of the parish 22 a. was transferred to Swindon borough in 1928 (fn. 7) and 759 a., about a third of the parish, was transferred to Swindon in 1980. (fn. 8) In 1984 c. 60 a. at the west end was transferred to Brinkworth, and along its northern boundary there were then several transfers of small areas of land to Lydiard Millicent from Brinkworth and Purton. By those 20thcentury boundary changes Lydiard Millicent was reduced to 1,566 a. (629 ha.). This article is concerned with the area included within the pre-1928 parish boundaries. (fn. 9)

Boundaries

To the north, south and east much of the parish boundary followed watercourses. On the north at the west end it was marked by a lane. Where it was not marked by streams the southern boundary underwent minor revision between 1766 and 1839 and between 1839 and 1885. (fn. 10) In 1928 the eastern boundary was moved westwards to a new course of the river Ray cut c. 1893 and moved away from the Ray further north, (fn. 11) and in 1980 it was moved much further westwards to the Cricklade–Marlborough road. In 1984 the west boundary was moved eastwards to a north–south lane, and the north boundary underwent minor revision. (fn. 12) The area transferred from Lydiard Millicent to Swindon formed the major portion of Shaw and Nine Elms ward, as it existed in 2001 and 2010. (fn. 13)

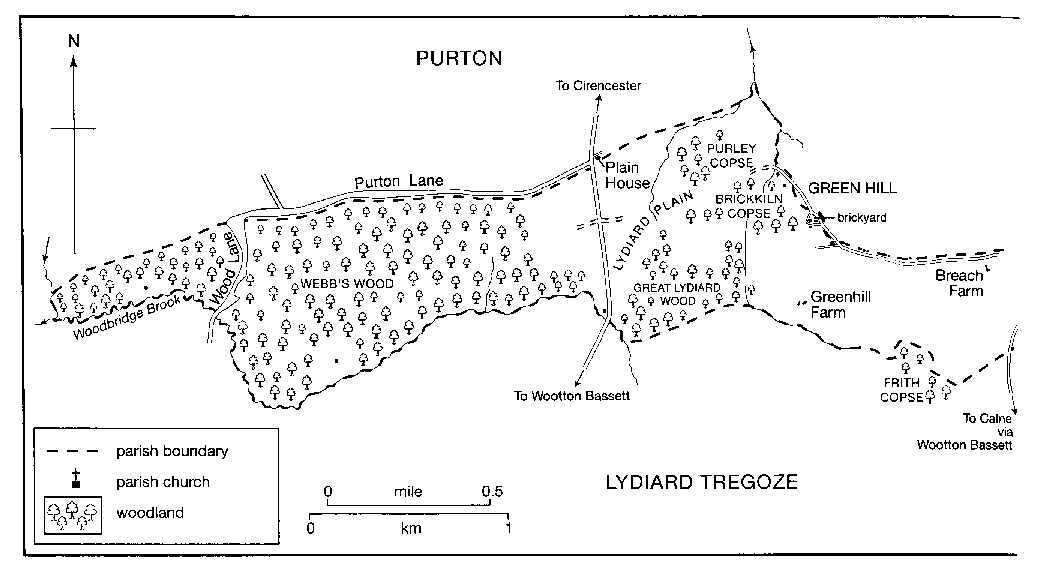

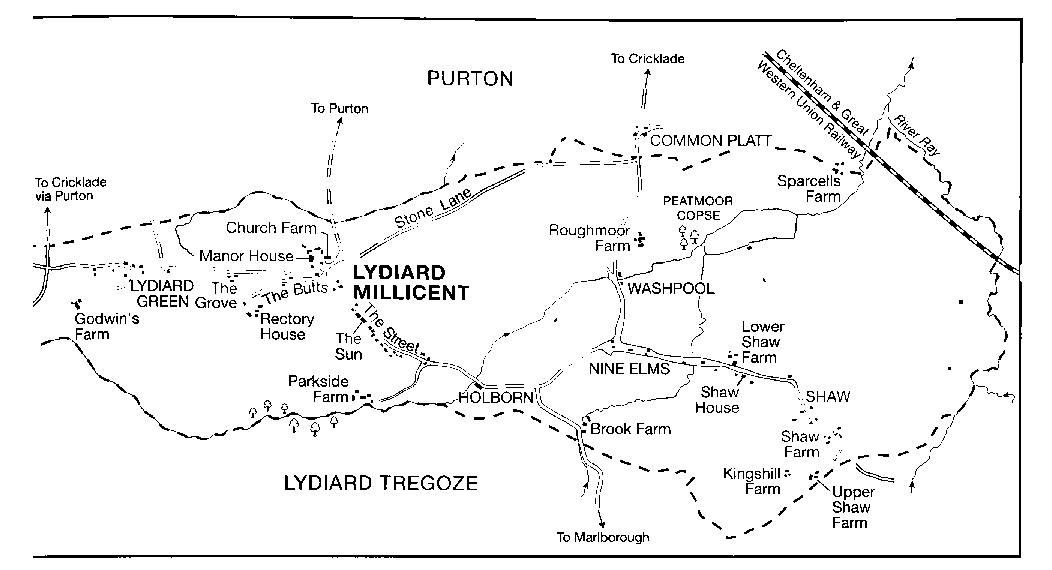

MAP 16. Lydiard Millicent in 1839. In 1980, the eastern third of the parish was transferred to Swindon Borough Council, and has since been subjected to intensive suburban development. The map is spread across two pages because of the shape of the parish.

Landscape

Kimmeridge Clay outcrops at the east end of the parish, Oxford Clay at the west end. Coral-rag limestone outcrops north-east and south-west of Lydiard Millicent village, there is another outcrop of Kimmeridge Clay on high ground at Lydiard Green, and between that and the Oxford Clay the coral-rag continues to outcrop. There is a small area of glacial drift at Lydiard Green, and alluvium has been deposited by the streams. (fn. 14)

An escarpment crosses the parish north–south at Green Hill, and at 145 m. between Green Hill and Greatfield the highest land in the parish is on the plateau east of it. A head stream of the Key rises on the escarpment and flows northwards along its foot. To the east the land is drained by head streams of the Ray, the relief is gentle, and at the east end of the parish beside the Ray the land lies at c. 90 m. The course of the Ray, which marked the parish boundary, was moved eastwards and straightened c. 1893, when a sewage works for Swindon was built on its old east bank. (fn. 15) West of the escarpment the land is nearly flat. The stream which is followed by the parish's south boundary is Woodbridge brook and, like the Ray, leaves the boundary at c. 90 m. A low ridge called Lydiard plain is, at 105 m., part of the watershed of the Thames and the Bristol Avon: the Key and the Ray flow to the Thames, Woodbridge brook to the Avon.

There were open fields on the coral-rag in the centre of the parish. There was mainly meadow and pasture on the clay soils to the east until the 1980s, when the land was built on, and there was extensive woodland on the clay soils to the west. (fn. 16) The Oxford Clay to the west has been used for making bricks and, in small quantities, the limestone of the coral-rag has been quarried. (fn. 17) Beside Woodbridge brook at the west end of the parish 15 ha. of meadow land has been a nature reserve since 1997. (fn. 18)

Communications

Roads

Lydiard Millicent parish, extending far east and

west, was crossed by three locally important

north–south roads. That linking Cricklade, Purton,

Wootton Bassett, and Calne, crossing the high ground

in the centre of the parish, was turnpiked in 1791 and

disturnpiked in 1879; (fn. 19) it remained a busy road in 2010. A

Cricklade–Marlborough road crossed the parish east of

the Cricklade–Calne road. Its importance may have

declined from the 1760s, by when turnpike roads

through other parishes linked Cricklade and

Marlborough, and across the Marlborough downs it was

not tarmacadamed. (fn. 20) The new boundary between

Lydiard Millicent and Swindon adopted in 1980

followed the road, which, south of Lydiard Millicent,

thereafter became part of an urban road system. West of

the Cricklade–Calne road a new and straight road was

built along an existing north–south drove across

Lydiard Plain c. 1826; (fn. 21) it was part of a Cirencester (Glos.)

and Wootton Bassett turnpike road authorized by an

Act of 1810, and it was disturnpiked in 1864. (fn. 22)

The centre of Lydiard Millicent village, where the church stands and the manor house stood, is linked to the north–south roads either side of the village by four lanes. One lane running northwards to the Cricklade–Calne road provides a direct link to Purton; one running south-east to the Cricklade–Marlborough road became, or was an extension of, the village street. At the east end of the parish an east–west lane linked several of the farmsteads of Shaw. At the west end a lane ran east–west along the north boundary of the parish and north–south across the woodland. In 1766 the east–west section was called Purton Lane, the north–south section Wood Lane. (fn. 23) The whole lane, which meets the Cirencester and Wootton Bassett road, was called Wood Lane in the 20th and 21st centuries. (fn. 24)

Railways

A line built by the Cheltenham & Great

Western Union Railway, converging on the GWR at

Swindon, was under construction in 1839 and was

opened north-west and south-east across the north-east

corner of the parish in 1841; the nearest station was at

Purton. The line was transferred to the GWR in 1844,

was for long part of the main route between London

and south and west Wales, (fn. 25) and remained open in 2004;

Purton station was closed in 1964. (fn. 26) The Swindon &

Cheltenham Extension Railway, extending the

Swindon, Marlborough & Andover Railway from

Rushey Platt near Swindon to Cirencester, was built as

a single line north–south across the east end of the

parish and was opened in 1883; the two railways were

merged as the Midland & South Western Junction

Railway in 1884, and the line was extended to

Cheltenham in 1891. Rushey Platt was the nearest

station. (fn. 27) The Rushey Platt to Cheltenham line was built

to pass under the Swindon–Cheltenham line in Lydiard

Millicent parish. It was closed in 1964. (fn. 28)

Population

There were 16 households and nine servi on the estate in 1086. (fn. 29) In 1377 Lydiard Millicent had 72 poll-tax payers and Shaw had 40, (fn. 30) and in 1676 the parish had an adult population of c. 134. (fn. 31) In 1801 the population of the parish numbered 300, which rose to 406 in 1831 and 564 in 1841, when it included 56 labourers temporarily resident while building a railway; the number of permanent inhabitants fell to 491 in 1851. Between 1851 and 1891 the population almost doubled, an increase attributed to the proximity of Swindon: (fn. 32) proximity apparently stimulated dairy farming in Lydiard Millicent and men working in Swindon lived in the parish. (fn. 33) From 912 in 1891 the number of inhabitants fell to 752 by 1921. There was a steady rise thereafter as new housing was built: the population numbered 821 in 1951, 958 in 1961, and 1,224 in 1971. (fn. 34) In 1981, after Shaw had been taken from it, the parish had 1,085 inhabitants, and in 1991, after the boundary changes of 1984, it had 1,203. In 2001 the population numbered 1,598. (fn. 35) The population in 2001 of Shaw and Nine Elms ward, most of which fell within the portion of the parish transferred to Swindon, was 9,608. (fn. 36)

SETTLEMENT

Early Settlement

Apart from a Neolithic greenstone axe found on Lydiard Plain, there is little evidence of prehistoric activity in the parish. (fn. 37) Excavations during the 1980s at various places in advance of the Swindon western expansion discovered an extensive Romano-British ceramic manufacturing industry on and around Shaw Ridge, on land formerly within the two Lydiard parishes. Evidence of kilns, building materials, potsherds and burnt deposits suggest that the industry flourished between 120 and 180 A.D. and supplied coarseware pottery vessels, as well as floor and roof tiles, for the Roman town of Durocornovium (Wanborough) and its hinterland. Although the industry declined abruptly during the late-2nd century, pottery production resumed on a diminished scale c. 300. (fn. 38) Some continuity of settlement in the area may be suggested by the name Lydiard, believed to be of Celtic origin; by the 9th century there was one 10-hide estate, and possibly another smaller estate, within the later parish. (fn. 39)

Lydiard Millicent Village

In the Middle Ages there was a demesne farmstead and c. 15 other farmsteads. (fn. 40) The church was built on a site adjacent to that of the demesne farmstead, and the house at the farmstead was sometimes lived in by the lord of Lydiard Millicent manor and came to be called a manor house. The principal farmstead on a reputed manor called Chadderton's stood nearby, and in the 16th century was also said to be a manor house. (fn. 41) Most of the other farmsteads probably stood beside the street as a settlement which was possibly planned. (fn. 42) If there was a rectory house in the Middle Ages its site is unknown; the 17th-century rectory house presumably stood on the same site c. 300 m. south-west of the church as that standing in 1839. (fn. 43)

The three large houses now standing in the centre of Lydiard Millicent village are Manor House, Church Farm (now called Church Farmhouse), and the Old Rectory. Lydiard Millicent manor house was lived in by some of the lords of the manor from the 16th century or earlier. (fn. 44) It was a large house and in the 18th century had gardens and a small park west of it. (fn. 45) Farm buildings stood north of it, and in the earlier 19th century what was apparently a north wing of the manor house was used as a farmhouse. (fn. 46) The manor house was burned down in 1880. (fn. 47) A new house called the Manor House was built on its site in 1965–6. North of it an 18thcentury barn and an 18th-century dovecot, south-east of it a 19th-century lodge beside the church, and west of it the garden walls all survived in 2004.

The reputed Chadderton's manor house was evidently replaced by Church Farm (now called Church Farmhouse), which was built in the early or mid 17th century and extended later. Two ponds lay south of that house, and the road which leads south-east from the church as the village street ran between the ponds. In 1894 the Purton road was diverted from the west side of the northern pond, where it joined the street, to the east side of the pond and away from Church Farm. (fn. 48) The northern pond became an ornamental lake in the garden of the house; the southern pond dried out or was drained in the mid or later 20th century. (fn. 49) Farming from buildings near Manor House and Church Farm ceased in the 20th century, and in 2004 the church and the two houses stood, slightly apart from the rest of the village, in a quasi park formed by the churchyard and the gardens of the houses.

Lydiard Millicent village has a well preserved centre characterized by large houses set in spacious grounds. That centre contrasts strongly with the Street and the Butts, where there are mediocre and poor quality houses and cottages built from the 18th century to the 20th. It also contrasts with the council houses and private estates built in the village from the 1920s. A few of the isolated farmhouses, a few of the farmhouses built at Shaw, and several houses built in the parish in the 19th century for gentlemen are of good quality. Most of the houses and cottages at Shaw and in the hamlets in the parish, however, are unexceptional, and most of those standing in 2004 were built after 1850; at Shaw, Nine Elms, and Washpool some houses have been embraced by the suburbs of Swindon built since 1980. (fn. 50) At Lydiard Green and Green Hill most houses are detached, at Shaw, Greatfield, and Washpool there are rows of small cottages some of which are singlebayed, and at Greatfield there are four three-bayed villas of the mid or later 19th century.

The predominant building material in the parish was for long limestone rubble. Rendering was commonly applied and the rubble was sometimes dressed with ashlar; buildings were rendered either because the limestone was of poor quality or, in the earlier 19th century, for the sake of fashion. The making of bricks in the parish had become well established by the late 18th century, and soft orange-red bricks, sometimes patterned with vitrified bricks, became widely used in buildings in the parish. Bricks were used especially for fronts, chimney stacks, and dressings of buildings otherwise of stone. In the 20th century new building materials were introduced and council houses were built of concrete blocks.

In 2010 almost all the buildings along the Street, Stone Lane and the lane called the Butts were of 19th or 20th century date, although three houses, 7B the Street, the Sun in the Street, and Priory Cottage in the Butts, have 17th-century fabric. In the early 19th century three small farmsteads stood in the street on sites which had probably been occupied by farmsteads in the Middle Ages. The Paddock, a three-bayed and two-storeyed house of stone with brick dressings, was built in the mid 19th century. It lacked ornamental grounds and was lower in status than the manor house and the rectory house. Most of the other houses built in the 19th century were small, and several cottages, some in pairs and some in short rows, stood at right angles to the Street or the Butts. (fn. 51) In 1839 there were c. 20 cottages and small houses in the Street; four stood on the north-east side at the north-west end, nearly all the others near the middle of the south-west side. (fn. 52) A new house was built on the north-east side in 1851, (fn. 53) and one on the southwest side near the Paddock between 1899 and 1910. (fn. 54) In 2004 several buildings in the Street incorporated 19thcentury fabric.

29. Parish church of All Saints, which marks the centre of medieval village, from the west.

The rectory house south-west of the church was approached by the lane called the Butts. (fn. 55) Priory Cottage, an 18th-century house, and a pair of cottages were the only buildings on the lane in 1839; the rectory house was then used as a farmhouse and there were farm buildings near it. (fn. 56) A red-brick school and schoolhouse was built in the Butts in 1841, (fn. 57) a new rectory house was built off the south side of it in the mid 1850s, (fn. 58) and four cottages stood beside it c. 1900. The old rectory house and most of the farm buildings had been demolished by 1885; (fn. 59) all the other buildings known to have been erected by c. 1900 survived in 2004.

The village expanded in the 20th century and the number of houses in it was greatly increased. Until c. 1960 most of the new houses were built by the rural district council. In 1921–2 the council built six pairs of red brick houses in Stone Lane, (fn. 60) the road running north-east from the village, in a cottage style, with long steep roofs over the outer bays; in 1929 it built two pairs of houses from concrete blocks in Park Lane, off the Street at its south-east end. (fn. 61) In Downs View off Park Lane six council houses were built in 1947 and another six in 1953; (fn. 62) the council built two bungalows and 12 houses in Stone Lane c. 1960 and six bungalows off Stone Lane in Bury Field in 1970; (fn. 63) another six bungalows were built in Bury Fields c. 1995. (fn. 64) In the 1920s and 1930s several private houses and bungalows were built in the village, and from c. 1960 most new houses there were built by private speculators. The Beeches, an estate of 30 bungalows and houses, was built at the west end of the park of the manor house c. 1960, (fn. 65) between c. 1963 and c. 1993 c. 190 houses and bungalows were built in several streets north-east of the Street, (fn. 66) and 22 houses were built in Forge Fields off the south-west side of the Street in the earlier 1990s. (fn. 67) The estates built speculatively before c. 1975 consist mainly of bungalows in a North American style. In those built after c. 1975 the houses were more closely grouped and included some in neo-Georgian style in the Mews and some in Tudor style in Meadow Springs. Also in the later 20th century private houses were built on individual sites in the Street, in the Butts, in Church Place, the road made along the east side of the pond in 1894, and in other parts of the village.

Shaw Village

In the Middle Ages there were c. 12 farmsteads at Shaw, (fn. 68) and they probably all stood in the lane which in two straight sections ran between the parish boundary and an eastern head stream of the Ray. Medieval settlement earthworks along the lane were excavated 1982–4. (fn. 69) Whether or not the settlement was planned, the farmsteads were not closely grouped and the lane, although it was called Shaw street in 1668, (fn. 70) did not become a village street. In 1839 there were only two farmhouses beside the lane, those of Shaw Farm near the south-east end and of what was later called Lower Shaw Farm near the west end, but there were houses, cottages, and farm buildings on four other sites where earlier there may have been farmsteads. There were then 13 houses and cottages beside the lane. (fn. 71) Between 1839 and 1885 a row of eight cottages was built at the lane's elbow and a row of four at its west end; (fn. 72) a house attached to the row at the west end is dated 1876. In the mid 20th century c. 25 houses and bungalows were built along the sides of the west part of the lane.

In 1962 Swindon Borough Council bought Shaw farm, on part of which it had begun to tip refuse in 1961; in 1964 it demolished a pair of cottages near Shaw Farm, and later it demolished the farmhouse and farm buildings. (fn. 73) In the 1980s, after Shaw had been transferred to Swindon, the south-east end of the lane was obliterated and the other buildings standing beside it were demolished. Although Swindon's new buildings approached the back gardens of the houses in it, the west part of the lane was preserved, was given the name Old Shaw Lane, and by 2004 had changed little in appearance since 1980. Lower Shaw Farm stands on the north side of the lane. On the south side Shaw House was built of stone in the later 18th century; it incorporates a brick chimney bearing a re-cut date stone for 1777. At Shaw and in the hamlets of the parish nearly all the houses are 19th- or 20th-century and there is a mixture of house type, with variations at each place.

Swindon's Western Expansion

Suburban development west of Swindon borough boundary, encroaching on Lydiard Tregoze and Lydiard Millicent parishes, was envisaged in planning reports published in 1968 and 1971. (fn. 74) These reports established the principle of creating 'urban villages', each with a mixture of housing types and a neighbourhood centre catering for basic health, educational, social and shopping needs; these in turn were to be supplemented by larger district centres, offering a wider range of service provision to a group of urban villages. (fn. 75) In anticipation that the plans would be implemented, land in both Lydiard parishes was acquired by Swindon borough and private developers, especially during the period 1972–5. (fn. 76) The first three urban villages (Toothill, Freshbrook and Westlea) all lay in areas formerly in Lydiard Tregoze, but a fourth, Shaw in Lydiard Millicent, was envisaged in 1975, and work on this commenced after 1981, by when (in 1980) 759 a. had been transferred from Lydiard Millicent parish to Swindon. (fn. 77) Most housing, industrial and infrastructure development in the area transferred was undertaken within a decade and completed before 1993, although sporadic building, especially in the Hillmead area, has occurred since. (fn. 78)

The built-up area formerly within Lydiard Millicent is characterised by main roads flanked by screening broadleaf trees and intersecting at roundabouts. Constrained within and defined by this network of roads are discrete residential areas, each served by a meandering estate road (Swinley Drive, Ramleaze Drive, Middleleaze Drive, Cartwright Drive), from which branch short culs-de-sac of brick-built detached or semi-detached houses, generally privately owned, with occasional low-rise blocks of flats. There are two neighbourhood centres, Shaw Village Centre at Ramsleaze, and Peatmoor, each of which has a mall of shops (including a small supermarket), a medical centre and a public house, surrounding a car park. At Peatmoor centre is also a school, Peatmoor Community Primary School, and day nursery, while at Ramsleaze is a sheltered housing scheme, George Tweed Gardens, and an interdenominational church, Holy Trinity. (fn. 79) The 'district centre' for the whole of West Swindon, with extensive leisure and shopping facilities and a public library and hotel, lies south of the former parish area, at Westlea.

Although much land formerly within the parish has been used for housing, industrial developments have taken place on estates at Rivermead and Hillmead. The innovative former Renault distribution centre by Sir Norman Foster, built 1981–3 at Rivermead, was acquired by the Chinese government in 2004 for the use of far eastern exporters. (fn. 80) Arclite House at Hillmead is an imaginative cigar-shaped glass construction built 1999–2000 as a call centre overlooking Peatmoor lagoon. (fn. 81) Nationwide Building Society established a major secure computing centre, known as Swindon Technology Centre, at Hillmead c. 1989. (fn. 82) Most buildings on these estates are warehouses or offices, and many are subject to frequent changes of business.

Amenities serving the resident population are located not only at the neighbourhood centres. Primary schools were built north and south of Shaw, at Brook Field and Shaw Ridge, and the Salt Way Centre at Middleleaze provides accommodation for various child support services. The Westlea Campus at Shaw offers further education and training as well as business accommodation. (fn. 83) At Roughmoor in 2010 a place of worship for Jehovah's Witnesses adjoined a small community facility, and there were additional public houses at Middleleaze and Nine Elms. An elaborate, pagoda-style construction with ornamental gateway, adjoining Peatmoor lagoon, closed as a Chinese restaurant in 2008. (fn. 84) A large area east of Mead Way, the site of a former landfill refuse tip, has been reclaimed as amenity land and planted as Shaw Forest Park; and there is a community woodland at Peatmoor adjoining a lake, Peatmoor Lagoon. The entire area in 2010 was served by frequent bus services linking it to Swindon town centre. (fn. 85)

Other Outlying Settlement

Farmsteads

The farmsteads which stood outside

Lydiard Millicent and Shaw villages were probably built

after the open fields and commonable pastures were

inclosed in 1570–1. (fn. 86) In 1839 there were eight such

farmsteads. (fn. 87) Parkside Farm south of Lydiard Millicent

village and adjacent to Lydiard Park (in Lydiard

Tregoze) has the oldest farmhouse in the parish, dating

to the late 16th century. (fn. 88) West of the village the house

called the Grove incorporates part of an 18th-century

farmhouse and marks the site of a farmstead. About

1820 an L-plan block of red brick with stuccoed main

façades and a columned porch was added to the

farmhouse, and a coach house and stables was built; the

house was later extended. Further west Godwin's Farm

and Greenhill (later Koffs) Farm were standing in the

18th century; (fn. 89) the farmhouse at Godwin's was rebuilt

in the 19th century and that at Koffs in 1910. (fn. 90) In the

east of the parish Brook Farm, Upper Shaw Farm, and

Kingshill Farm were built south of Shaw village,

Roughmoor Farm and Sparcells Farm north of it;

Roughmoor Farm was apparently built by 1650 and,

with the possible exception of Kingshill Farm, all were

standing in the 18th century. (fn. 91) Of Sparcells Farm the

farmhouse stood in Purton parish, most of the farm

buildings in Lydiard Millicent; (fn. 92) Kingshill Farm was

small in 1839. (fn. 93) Of those five farmsteads all the farm

buildings and all but two of the farmhouses were

demolished after 1980 to make way for Swindon's new

suburbs. The surviving farmhouses are those of Brook

Farm, rebuilt in the 19th century and used as a

restaurant and public house in 2004, and of Upper

Shaw Farm, apparently rebuilt in the early 20th

century and used as a community centre in 2004.

Between Lydiard Millicent village and the Cricklade–

Marlborough road farm buildings were erected near

an existing cottage between 1839 and 1885. (fn. 94) The

farmstead, West Hill Farm, included a house in 2004.

At the west end of the parish Home Farm was built

west of Wood Lane between 1847 and 1863, (fn. 95) and at the

junction of Wood Lane and the Cirencester and

Wootton Bassett road farm buildings called Plain

Farm were erected between 1839 and 1876 in Lydiard

Millicent parish, beside Plain House, which stands in

Purton parish. (fn. 96)

Hamlets

Six hamlets grew up in the parish,

apparently on waste ground. Lydiard Green was a

hamlet of nine cottages in 1839, which stood beside the

lane linking Lydiard Millicent village to the Cricklade to

Wootton Bassett road. (fn. 97) A Nonconformist chapel was

built there in 1863. In the 20th century larger houses

were built, which in 2004 consisted of the chapel, an

18th-century cottage, c. 10 cottages of the 19th century,

and c. 12 houses of the 20th century.

Greatfield sprang up after 1839 on the west side of the Cricklade to Wootton Bassett road and by 1885 there were several houses, including four three-bayed villas, a pair of cottages, a row of nine cottages, and a beerhouse. (fn. 98) The hamlet grew along a track leading north-west from the road where in 2004 there were disused farm buildings and several small 19th- and 20thcentury cottages and houses. A large bungalow was built c. 1930 and the buildings of a retail garden centre were erected in the later 20th century.

Green Hill straggles for c. 1 km. along the lane marking Lydiard Millicent's boundary with Purton. Most of the buildings stood in Purton parish, (fn. 99) until the boundary changes of 1984 transferred them to Lydiard Millicent. About eight cottages and a brickyard stood in Lydiard Millicent parish in 1839. (fn. 100) A few 19th-century cottages survived in 2004, when most of the houses were 20th-century.

Holborn was the name of a small hamlet, which grew up where the lane linking Lydiard Millicent street to the Cricklade–Marlborough road crossed the western head stream of the Ray. Two cottages stood there in 1839, by 1885 a house had been built nearby, (fn. 101) and four pairs of council houses were built in 1932. (fn. 102) The cottages were demolished by 2004 and three more 20th-century houses had been built.

Nine Elms was the name of the junction where a lane from Shaw street joined the Cricklade–Marlborough road in 1766, (fn. 103) and in the 19th century it was the name of the settlement at the junction and along the lane. (fn. 104) In 1839 there were c. 10 cottages, (fn. 105) more cottages were built later in the 19th century, and a Nonconformist chapel was built at the east end of the lane in 1852. (fn. 106) Shaw Villa, later Elm Grove, a plain classical house with a stuccoed façade, was built north of the lane c. 1850–70, (fn. 107) a stone house was built at the junction in 1873, (fn. 108) and a public house was built in the lane c. 1900. In 2004 the hamlet of Nine Elms, like Old Shaw Lane had changed little in appearance since the later 19th century, despite its proximity to West Swindon.

Washpool grew up about 400 m. north of Nine Elms where the Cricklade–Marlborough road crosses the western head stream of the Ray. There a pool, called Shaw wash pool in 1787, was used for washing sheep. (fn. 109) There were four cottages in 1839, (fn. 110) a row of five cottages was built between 1885 and 1899, (fn. 111) four pairs of council houses were built in 1929, (fn. 112) and a few other 20thcentury houses had been built by 2004, when the cottages on the east side of the road had been absorbed into West Swindon.

Lydiard House

One of three large houses built on

isolated sites in the mid 19th and early 20th centuries,

Lydiard House is an elegant classical villa between

Lydiard Millicent village and Lydiard Green. It was

built in the 1840s and in the Second World War was

used to accommodate prisoners of war. (fn. 113) It is of three

wide bays, is of two storeys, and has a hipped roof; it

has a main front which is rendered, is dressed with

ashlar, and incorporates an Ionic porch. By 1885 a stable

block contemporary with the house had been replaced

by a handsome new coach house and stables built on an

H-plan of squared limestone rubble, the east wing

forming a house. (fn. 114)

Echo Lodge

This was built as a sporting residence

c. 1860 in Wood Lane, at the west end of the parish. (fn. 115) It

is a triple-pile house with a main façade of five bays

and, like the Grove and Lydiard House, is in a plain

classical style with a stuccoed façade.

Selbrook House

Built near Nine Elms c. 1905, (fn. 116) this

is a square three-bayed house, of red brick and with bay

windows, lower in status than the other four houses.

Isolation Hospital

An isolation hospital was built in

1897 by Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural District

Council, on the north side of Stone Lane at the east end

near the parish boundary with Purton. (fn. 117) It was built as

a single stone block with a two-storeyed, gabled centre

and flanking single-storeyed wings. (fn. 118) It was closed for

good in 1930. (fn. 119)

Other Residential Housing

Residential property was

built along Stone Lane in the 19th and 20th centuries:

on the south side there was a cottage by 1839, another

building beside it by 1885, (fn. 120) two pairs of cottages built by

c. 1905, (fn. 121) council houses at the west end near the village,

built in the mid 20th century, and more 20th-century

houses built on individual sites on both sides of the

lane, including some at the east end near the hamlet of

Common Platt in Purton parish. In 2004 several

premises in Stone Lane, including a retail garden

centre, were used for trade.

Residential property was built along Wood Lane, where a cottage was built on the verge in the late 19th century, to which mid 20th-century farm buildings were added, (fn. 122) two pairs of mid 19th century red-brick cottages, (fn. 123) and several mid 20th-century houses and bungalows. Housing was built along the Cirencester and Wootton Bassett road, where a cottage stood on the west side at the south end of Lydiard Plain by 1839, and several more cottages, including a row of five, were built by 1885. (fn. 124) Some of the cottages and some 20th-century houses stood beside the road in 2004.

MANORS AND OTHER ESTATES

In the 10th and 11th centuries, unless Sparcells was then a separate entity, all Lydiard Millicent's land apparently lay as a single estate, later called Lydiard Millicent manor. In the later Middle Ages parts of the manor were evidently demised freely, in the 16th century the copyholds were sold individually, and in the 17th century the manor was further reduced by sale. Some of the former copyholds descended as separate estates, some were accumulated in larger holdings. A holding which had been demised freely by the 13th century was enlarged in the 17th century and was a reputed manor, and land formerly part of Lydiard Millicent manor was accumulated as an estate in Lydiard Millicent by the lord of Lydiard Tregoze manor. Lydiard Millicent manor, the reputed manor, and much of that other estate were sold in portions in the 19th century. In the later 19th and 20th centuries most of the land in Lydiard Millicent was divided into single farms of less than 150 a., the descents of which have not been traced fully in this article. Between 1984 and 2004 the easternmost third of the parish was used as land for building.

LYDIARD MILLICENT MANOR

Eanulf gave a 10-hide estate at Lydiard to the bishop of Winchester, presumably in the late 9th century, and in 900 Denewulf, bishop of Winchester, returned it to Eanulf's grandson Ordlaf in an exchange. (fn. 125) Unless Lydiard Millicent and Lydiard Tregoze were undivided at this date. this 10-hide estate was probably that, also assessed at 10 hides in 1086, later called Lydiard Millicent manor. (fn. 126) It has been suggested that Sparcells in Lydiard Millicent is to be identified with land called Sparsholt, given to King Edward the Elder by Denewulf in another exchange in 900; if so this estate did not survive to be assessed in 1086. (fn. 127) Evidence from the 15th and 16th centuries shows that Lydiard Millicent manor included the farmsteads at Shaw. (fn. 128) By the 13th century land of the manor had been demised freely, (fn. 129) and later the manor shrank further.

In 1066 Lydiard Millicent was held by Godric. Later it was held by William FitzOsbern, earl of Hereford, and was presumably among the many English lands which William I granted to William for his part in the Conquest. William FitzOsbern was succeeded by his son Roger de Breteuil, earl of Hereford, in 1071. Roger rebelled against William I in 1075, his lands were confiscated, and in 1086 Lydiard Millicent was the king's. (fn. 130)

In 1166–7 Lydiard Millicent manor was held by Hugh son of Richard. (fn. 131) It passed to his son William, whose widow Millicent held it as dower in 1199 (fn. 132) and probably in 1222. (fn. 133) William had sons Hugh and Richard, and in 1199 Hugh conveyed the reversion to Richard. (fn. 134) By 1243 the manor had passed to Thomas of Clinton, the grandson of William son of Hugh. (fn. 135) It may have been given by Thomas (d. c. 1277) to his son Thomas (d. by 1264), and in 1264–5 it was taken by the king from the younger Thomas's son Osbert of Clinton (who died without issue) because Osbert was a rebel. Although in 1265–6 the king gave the manor to John of Grimstead, (fn. 136) by 1276 he had returned it to Osbert's heir, his brother John de Clinton (from 1299 Lord Clinton, d. c. 1310). (fn. 137) The manor was held by Lord Clinton's widow Ida (fl. 1322), presumably for her life, (fn. 138) and it passed in turn to his son John, Lord Clinton (d. c. 1335), and grandson John, Lord Clinton (d. 1398). (fn. 139) The third Lord Clinton was succeeded by his grandson William, Lord Clinton, whose feoffees held the manor in 1421–2. (fn. 140)

In 1429 new feoffees conveyed Lydiard Millicent manor to Robert Andrew (d. 1437), (fn. 141) and in 1439 the manor was held for life by Andrew's widow Agnes (d. c. 1442) with remainder to John Basket (d. c. 1452) and his wife Alice. (fn. 142) It passed to Alice (fl. 1466), who c. 1456 married Robert Turges and after 1460 married William Browning. It was held by William Basket in 1477 and 1489, and by 1513 had passed to his son Thomas (d. 1540). It descended to Thomas's son Thomas Basket, (fn. 143) who sold the copyholds individually in the 1560s, (fn. 144) the woodland (in 1569) and the demesne (in 1575) to William Richmond alias Webb. (fn. 145) He held the demesne until his death in 1610 and it descended in the direct line to Giles (fn. 146) (d. 1624), Christopher (fn. 147) (d. by 1667), and Giles Richmond, who all retained the alias Webb. The woodland was sold in 1639, (fn. 148) and what was apparently Roughmoor farm was sold in 1650. (fn. 149) By 1700 the manor, probably consisting of the manor house and no more than c. 200 a., had passed, presumably by inheritance, to Joseph Richmond alias Webb, who in 1714 sold it to John Askew. (fn. 150)

The reduced Lydiard Millicent manor passed from John Askew (knighted in 1719, d. 1739) to his brother Ferdinando (fn. 151) (d. 1783), who devised it to his wife Mary (d. 1804) for life and to his daughter Mary (d. 1822), the wife of Henry Blunt (d. 1811). Mary Blunt devised the estate to trustees of her son Sir Charles Blunt (d. 1838) and of Sir Charles's son W. O. Blunt (d. 1831). In 1838 the estate passed to W. O. Blunt's heir-at-law Sir Charles Blunt Bt (d. 1840), who devised it in trust for sale; (fn. 152) in 1839–40 it consisted of the manor house, a farmstead immediately north of the manor house, a small second farmstead, the Sun public house, c. 25 cottages, and c. 170 a. (fn. 153)

In 1841, what was later called Manor Farm, the manor house, its gardens, the farmstead north of them and c. 30 a. were bought from Blunt's trustees by Revd H. T. Streeten (d. 1849), who devised that estate to his wife Sarah. (fn. 154) About 1871 the estate was bought by Anthony Story-Maskelyne, at whose death in 1879 it passed to his son Edmund StoryMaskelyne (fn. 155) (d. 1921). (fn. 156) Edmund added Godwin's farm and a reduced Church farm to his estate (fn. 157) and in 1913 owned c. 195 a. in Lydiard Millicent. (fn. 158) The manor house was burned down in 1880. (fn. 159) Edmund held the estate until his death, soon after which Manor farm, Church farm, and Godwin's farm were bought by J. J. Webb, the owner in the 1930s. (fn. 160)

In 1841 the executors of Joseph Little owned 48 a. which had belonged to Sir Charles Blunt in 1839, on which Breach barn stood, and which was later called Green Hill allotments. About 1845 the land was acquired by William Lee, and c. 1851 it passed to Charles Lee. In 1880–1 it was acquired, apparently by purchase from Charles Lee's executors, by Jasper Stratton (d. 1913); by 1883 it had been converted to allotments (fn. 161) and c. 1920 it was bought from Stratton's executors by Wiltshire County Council. The council sold the land in portions in the later 20th century, the last portion in 1994. (fn. 162)

Lydiard Millicent Manor House

Large and apparently

rendered, it had three parallel two-storeyed ranges, one

of which was L-plan before it was destroyed by fire in

1880. There was also a north wing which earlier was

apparently used as a farmhouse. Except that of the

wing, which was possibly thatched, the roofs were

apparently stone-slated, and the external features of the

house were 18th- and 19th-century. The house was

entered from the east, (fn. 163) and a single-storeyed 19thcentury lodge stood at a gateway a little east of the

church. In the 18th century high stone walls lined with

red brick were built to enclose gardens west of the

house and to separate them from a farmyard to the

north. A gabled brick dovecot and a barn of stone and

brick were also built in the 18th century and have

survived the demolition of the other farm buildings. (fn. 164) In

1965–6 the site of the manor house was used for a house

which was built of reconstituted stone in a quasitraditional style, incorporated large windows in a latemedieval style, and was called Manor House. (fn. 165)

CHADDERTON'S

Under a licence granted in 1283 Geoffrey of Aspall apparently gave a messuage and 97 a. in Lydiard Millicent to Bradenstoke priory; in 1307 the priory gave that estate to Robert Russell in an exchange. (fn. 166) The estate was later enlarged and became the reputed manor called Chadderton's. (fn. 167) It descended in the Russell family, apparently like Bradfield manor in Hullavington, (fn. 168) and belonged to Thomas Russell in 1412. (fn. 169) By 1452 it had passed to John Russell (d. c. 1469), (fn. 170) whose heir is said to have been John Collingbourne, (fn. 171) and in 1476 it was settled on William Collingbourne (fn. 172) (attainted and executed in 1484). (fn. 173) In 1485 Richard III granted the estate in Lydiard Millicent and other lands to Edmund Chadderton for William's heirs, his daughters Margaret, the wife of George Chadderton, and Joan, the wife of James Lowther. (fn. 174)

By 1489 the estate in Lydiard Millicent had been assigned in tail to Joan (d. 1531, without issue). After Joan's death it was disputed between, on the one side, her nephew and heir Edmund Chadderton (d. 1545) and his son William (d. 1599) and, on the other side, her nephew Thomas Chadderton (d. 1537), to whom she had pretended to demise the reversion, and his son Thomas. The younger Thomas entered on the estate and, probably in 1570, conveyed it to William who, despite continuing dispute, retained it. (fn. 175) In 1583 a third of the estate was settled on George Best (d. 1584) and two thirds on the marriage of George and Edith, the daughter of William Chadderton. George's third passed to his and Edith's son Hatton. (fn. 176) In 1596 Edith, then the wife of John Kibblewhite, conveyed the whole estate to Sir Anthony Ashley, (fn. 177) a conveyance confirmed by Hatton Best in 1605. (fn. 178)

The heir of Sir Anthony Ashley (created a baronet in 1622, d. 1628) was his daughter Anne (d. 1628), the wife of Sir John Cooper Bt (d. 1631), and Anne's was her son Sir Anthony Ashley Cooper (Baron Ashley from 1661, earl of Shaftesbury from 1672, d. 1683), (fn. 179) who bought what was apparently Roughmoor farm from Christopher Richmond alias Webb in 1650. (fn. 180) Chadderton's estate and the farm descended with the title earl of Shaftesbury in the direct line to Anthony Ashley Cooper (d. 1699), Anthony Ashley Cooper (d. 1713), Anthony Ashley Cooper (d. 1771), and Anthony Ashley Cooper (d. 1811), whose heir was his brother Cropley Ashley Cooper, earl of Shaftsbury (d. 1851). (fn. 181) In 1824–5 Lord Shaftesbury sold five farms, Godwin's, Brook, Roughmoor, Sparcells, and what was later called Lower Shaw, a total of c. 516 a.; (fn. 182) in 1839 he owned 413 a. including Church farm, Green Hill farm, and 102 a. of woodland. (fn. 183) The reduced estate descended, again with the title in the direct line, to Anthony Ashley Cooper (d. 1885), Anthony Ashley Cooper (d. 1886), and Anthony Ashley Cooper, earl of Shaftesbury, who offered it for sale in portions in 1892. (fn. 184)

Probably in 1892 Church farm was bought by Edmund Story-Maskelyne. It passed with Manor farm and in the 1930s belonged to J. J. Webb. (fn. 185) Godwin's farm, c. 54 a., was bought by James Kibblewhite in 1825, (fn. 186) and belonged to Anthony Kibblewhite in 1839. (fn. 187) The farmhouse was built in the early 19th century, in a style which is typical of the area. About 1881 the farm was bought from the executors of a Kibblewhite by Edmund Story-Maskelyne. (fn. 188) From then it passed with Manor farm and in the 1930s belonged to J. J. Webb. (fn. 189) In 1824 Brook farm, 119 a., was bought by J. L. Mallett (fn. 190) (d. 1861), and it passed to his son Revd H. F. Mallett, who sold it in 1873–4 to Joses Badcock (d. 1909). (fn. 191) The farmhouse was rebuilt in the later 19th century as a villa-style house of stone with a symmetrical red-brick front. In 1910 it belonged to Elizabeth Akers, (fn. 192) who sold it to A. L. Purkis in 1919. Purkis owned the farm in the early 1930s and probably sold it to Harold Pears, who offered it for sale in 1939. (fn. 193) Probably in 1892 Greenhill (later Koffs) farm, 103 a., and 66 a. of woodland were bought by H. H. Bolton, who owned them until his death in 1943. (fn. 194)

Church Farmhouse

The core of Church Farm is of

the early or mid 17th century, and a north–south range

retains a 17th-century roof and mullioned windows

with hollow chamfers. About 1800 an east–west range,

of two storeys and with a classical three-bayed south

front, was built across the south end of the north–south

range to form an L extending eastwards. A range

extending westwards from the north–south range may

have been converted from a farm building and has

modern mullioned windows.

OTHER ESTATES

Bolingbroke's

Land in Lydiard Millicent may have descended with Lydiard Tregoze manor from the 14th century, and from the mid 15th century 1 yardland there was held with that manor. (fn. 195) In 1615 Sir John St John Bt, the lord of Lydiard Tregoze manor, bought a holding in Lydiard Millicent which had possibly been a copyhold of Lydiard Millicent manor until 1568; (fn. 196) by 1630 he had bought two similar and smaller holdings there, (fn. 197) and in 1639 he bought Clinton's (later Webb's) wood, c. 350 a., from Christopher Richmond alias Webb. (fn. 198) St John's estate in Lydiard Millicent descended in his family with Lydiard Tregoze manor, (fn. 199) and in 1766 Frederick St John, Viscount Bolingbroke, owned c. 800 a. there. (fn. 200) In 1809 George St John, Viscount Bolingbroke, sold 136 a. in Lydiard Millicent, including Shaw farm, 120 a., (fn. 201) and on his death in 1824 his remaining estate there was divided. About 300 a. in the east of the parish, including Parkside farm, 198 a., and 44 a. of East Leaze farm (based in Lydiard Tregoze), passed to his son Henry, Viscount Bolingbroke; c. 400 a. in the west part of the parish, Webb's wood and 43 a. west of, and sharing the name, Lydiard Plain, as devised in trust for sale. (fn. 202) On the death of Henry, Viscount Bolingbroke, in 1851 his land in Lydiard Millicent passed to his son Henry, Viscount Bolingbroke (d. 1899), who devised it to his wife Mary, Viscountess Bolingbroke (d. 1940). In 1930 Mary sold c. 290 a. in portions, the largest of which was Parkside farm, 106 a., (fn. 203) and in 1943 her executors offered 38 a. for sale. (fn. 204)

Shaw Farm

It was sold by Viscount Bolingbroke

with an additional 16 a. to Robert Hughes in 1809, who

in that year sold the farm to T. P. Butt and in 1810 sold

the 16 a. to him. (fn. 205) Butt (d. 1828) bought other lands and

devised the farm, 169 a. in 1839, to his son W. P. C.

Butt (fn. 206) (d. 1848). The younger Butt devised it to his sister

Ann (d. 1884), from 1848 the wife of Revd James Fisher

(d. 1870), and from 1879 the wife of J. H. Sadler, and

Ann devised it to her son J. E. O. Fisher and her

daughters Annie Fisher and Alice Fisher. Alice (d. 1884)

devised her interest to her siblings, who in 1885

partitioned their mother's estate. Shaw farm was

conveyed to Sadler in trust for J. E. O. Fisher, (fn. 207) whose

title evidently passed to Annie (d. 1929). Annie Fisher

devised the farm to Sadler (d. 1929), Sadler devised it to

H. C. Sadler (d. 1933), and that Sadler devised it to his

wife Florence (d. 1947). In 1950 Shaw farm was bought

from Florence's executors by Raymond Simpkins, who

sold it to Swindon corporation in 1962. (fn. 208)

Webb's Wood

In 1828 Isabella, the widow of

George, Viscount Bolingbroke (d. 1824), bought

Webb's wood and the 43 a. west of Lydiard Plain from

her husband's trustees, of whom she was one. In 1847

she sold that estate to Richard Mortimore (d. 1862), a

tanner of Chippenham, (fn. 209) whose heirs, executors, or

trustees sold Webb's wood, c. 360 a., in 1863 to D. S.

White, a timber merchant of Maidstone (Kent).

Mortimore's representatives sold the 43 a. to Gabriel

Goldney, MP, who in 1869 sold it to his son F. H.

Goldney. (fn. 210) White's land, of which the 62 a. west of

Wood Lane had been leased as Home farm by 1873, (fn. 211)

passed c. 1897 to Miss A. White and c. 1900 was probably

sold in portions. The land east of Wood Lane, 298 a.

including Webb's wood, 237 a., belonged to Henry

Longley in 1903 and it apparently descended in the

Longley family until the 1940s or later. In 1910 Home

farm belonged to the executors of C. M. Beak and in

1928 to C. Beak. (fn. 212)

Parkside Farm

In 1930 the farm was bought from

Mary, Viscountess Bolingbroke, by S. E. L. Freegard. (fn. 213)

Its later descent has not been traced. Parkside

farmhouse is the oldest surviving farmhouse in the

parish, dating from the late 16th century. It is a large

house of stone rubble, probably built on an E plan, of

which two thirds, including the west and central wings

survive. The central wing consists of a two-storeyed

gabled porch, and the west wing is three-storeyed and

gabled; both wings retain their original two- and threelight mullioned windows. What was probably a third

of the house, the part east of the porch, was apparently

demolished, and in the 18th century it was replaced by

a service block of one and a half storeys with a hipped

roof. (fn. 214)

Buxton's

In 1825 Sir Robert Buxton Bt, bought Sparcells farm, the farm later called Lower Shaw farm, and Roughmoor farm, a total of 338 a. from Cropley, earl of Shaftesbury. (fn. 215) Sir Robert (d. 1839) was succeeded by his son Sir John Buxton Bt (d. 1842), who was succeeded by his son Sir Robert Buxton Bt. (fn. 216) That Sir Robert sold Sparcells farm in 1864, Roughmoor farm in portions in 1865 and 1870, and Lower Shaw farm c. 1870.

In 1864 Sparcells farm, consisting of farm buildings and 76 a. in Lydiard Millicent and a farmhouse and 42 a. in Purton, was bought by Walter Edwards (d. 1893). Edwards devised the farm to his sons Arthur and Walter as tenants in common, and in 1894 Walter bought Arthur's interest. The younger Walter owned the farm until his death in 1924. (fn. 217) His representatives sold it to R. Paish in 1931. (fn. 218)

In 1865 Sir Robert Buxton sold 19 a. of Roughmoor farm to Revd James Fisher, whose wife owned Shaw farm. The 19 a. was added to Shaw farm. (fn. 219) In 1870 Sir Robert sold the rest of Roughmoor farm, 67 a., to James Hughes, whose mortgagees sold it in 1895 to Mary, the wife of John Haines. On Mary's death in 1918 Roughmoor farm, then 57 a., passed to her daughter Mary Haines, who in that year sold it to S. E. Coles (fn. 220) (d. 1936), the owner in the early 1930s. (fn. 221)

About 1870 Sir Robert Buxton sold Lower Shaw farm, 128 a., to W. T. Young, (fn. 222) whose executors owned it in the early 1930s. (fn. 223) The farmhouse was built in the later 18th century; it bears a date stone possibly for 1787. The house is double-pile and of two storeys and has a stone-slated gambrel roof. It has a principal brick-faced south front of three bays, other outer walls and a spine of stone rubble, and timber-framed partitions between the central staircase hall and the four main rooms on the ground floor. In the early 19th century on the north front a cheeseroom with a loft above it was built at the west end as a north wing, and a walled yard and a bread oven were built at the east end; the yard was built on in the 20th century.

Upper Shaw Farm

The estate may have originated as a small medieval freehold, or as a copyhold of Lydiard Millicent manor, sold by Thomas Basket in the 1560s. (fn. 224) It probably belonged to Henry Oatridge in 1682, (fn. 225) and it belonged to Henry Oatridge (d. 1758), who devised it to his wife Sarah for life. On Sarah's death it passed to Henry's nephew Daniel Oatridge (fn. 226) (d. 1787), who devised it to his wife Mary for life, and on Mary's death in 1806 it passed to Daniel's niece Mary Matthews, the wife of John Paul Paul (d. 1828) of Highgrove (Glos.). The farm passed to Mary Paul's son Walter Matthews Paul, who c. 1830 sold it to the executors of T. P. Butt (fn. 227) (d. 1828). The farm, 91 a. in 1839, passed to Butt's son T. P. W. Butt, a minor until c. 1845, (fn. 228) who sold it to William Plummer in 1870. (fn. 229) It was devised by Plummer (d. 1881) to his sisters Amelia Plummer and Emma Plummer (d. 1890 unmarried), (fn. 230) and on Emma's death it passed to her nephew W. J. P. Kinchin. In 1920 Kinchin sold the farm, then 75 a., to G. H. Cowley, (fn. 231) who in 1930 sold it to W. H. E. Rebbeck. (fn. 232) The farmhouse was largely rebuilt in a simplified, symmetrical, Tudor style in the 1920s or 1930s.

Rectory Estate

Lydiard Millicent church was given to the abbey of Cormeilles (Eure) between 1066 and 1075 by either William FitzOsbern, earl of Hereford, who held Lydiard Millicent and founded the abbey, or his son Roger, earl of Hereford, who also held Lydiard Millicent. The abbey's title was confirmed by the pope in 1168 and by Henry II in 1172. (fn. 233) From the late 12th century to the mid 13th lords of Lydiard Millicent manor tried to deprive the abbey of the church's revenues by presenting candidates for institution as rector, and in 1252 Thomas de Clinton, the lord of the manor, made good his claim to the advowson. The abbey had recovered the advowson by 1259, probably by purchase; it apparently presented no rector (fn. 234) and presumably again took the church's revenues. From 1294 to 1340 the revenues were presumably among the abbey's possessions confiscated by the king when England was at war with France, and in 1340, when the king presented a rector, they became the rector's living. (fn. 235)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

AGRICULTURE

Although there was said to be land for eight ploughteams, there were as many as 10 at Lydiard Millicent in 1086. Nine servi used as many as four teams to farm the demesne, which was assessed at 5¾ hides, 10 villein households and six bordar households farmed their holdings with six teams, and there was 20 a. of meadow. (fn. 236)

In the Middle Ages the agricultural land in Lydiard Millicent parish lay as open fields and common meadows and pastures in the centre, and at the east end, of the parish. It was worked from a demesne farmstead at Lydiard Millicent, from other farmsteads at Lydiard Millicent, most of which may have stood beside the street, and from farmsteads at Shaw which probably stood along two sections of a lane. The men of both places apparently shared a single set of open fields and all the meadows and pastures. (fn. 237) The open fields probably lay north-east of the street in Lydiard Millicent, south-west of the street, and west of the Cricklade and Wootton Bassett road, all on the Coral Rag. Stone field, which may have been bordered or crossed by Stone Lane, and Shaw field evidently lay north-east of the street; (fn. 238) although two fields north-east of the street bore the name Berry in the 19th century, (fn. 239) Bury field possibly lay south-west of it; (fn. 240) Braydon field presumably lay west of the Wootton Bassett road where it would have adjoined the purlieus of Braydon forest. (fn. 241) Of the extensive common pastures Shaw marsh probably lay at the east end of the parish, (fn. 242) and Lydiard marsh (otherwise Hyde marsh) evidently lay beside the stream south-west of the Street where fields were called Hydes in the 19th century; (fn. 243) Sparcells was a common pasture presumably beside the boundary with Purton at the east end of the parish, (fn. 244) and Cow leaze was probably another common pasture. (fn. 245) A common pasture which adjoined Lydiard Tregoze parish to the south was called Bury marsh: (fn. 246) it is not clear whether it was another extensive pasture or whether the name was an alternative to Lydiard marsh. The meadows presumably lay beside the streams at the east end of the parish.

The land at the west end of the parish consisted of woodland and wooded ground in the purlieus of Braydon forest. Both the forest and the purlieus, including those in other parishes, were open to the men of Lydiard Millicent and Shaw, who had customary rights to pasture their cattle there without stint. (fn. 247)

In the mid 13th century the demesne of Lydiard Millicent manor was said to include 200 a. of arable, 20 a. of meadow land, and pasture for 24 oxen and 12 cows. Other holdings were small: 10 freeholds, of which the largest was of 2 yardlands, were assessed at 8½ yardlands, and the holdings of 11 villeins were assessed at 5½ yardlands. (fn. 248) In 1429 and later the demesne was held on lease. (fn. 249) In 1453 four freeholds, which may earlier have been held separately and which became Chadderton's estate, may have been held as a single farm, and five other freeholds, which may still have been held separately, were assessed at 5½ yardlands. At Lydiard Millicent 14 customary tenants then held a total of c. 5½ yardlands; seven of the holdings were Mondaylands, and the largest was of 1 yardland and 1 Mondayland. At Shaw, where three holdings were Mondaylands, eight tenants held c. 4½ yardlands. (fn. 250) In 1489 there were eight freeholds, 11 customary tenants at Lydiard Millicent, and seven customary tenants at Shaw; besides the demesne and Chadderton's the holdings remained small and, although by then a few had been agglutinated, the customary holdings were typically ½ yardland. (fn. 251) If half the freeholds had buildings at Lydiard Millicent it would seem that for much of the Middle Ages there were c. 20 small farmsteads there and c. 12 at Shaw; (fn. 252) later evidence suggests that the demesne farm and the principal farm of Chadderton's each had a farmstead near the church. (fn. 253)

Customary tenure in Lydiard Millicent was apparently ended in the 1560s when the lord of the manor sold the copyholds individually. (fn. 254) Common husbandry was virtually eliminated in 1570–1 when the open fields and commonable pastures were inclosed by private agreement. (fn. 255) So early a comprehensive inclosure of agricultural land was very unusual for a Wiltshire parish, and it apparently set an example for Lydiard Tregoze, where the open fields and most of the commonable pastures were inclosed in the later 1570s. (fn. 256) To amend mistakes small alterations were made to the allotments at Lydiard Millicent in 1576–7. (fn. 257) The closes may have been on average and typically of c. 10 a.; in 1608 a 1-yardland holding included a farmstead and three closes totalling 28 a., and in 1672 the 62 a. of glebe lay in six closes. (fn. 258) Larger closes may have become part of the demesne farm and of Chadderton's. (fn. 259)

Braydon forest was inclosed by the Crown in 1630, (fn. 260) and by c. 1650 the owner of Webb's wood and the owner of Chadderton's had inclosed their lands which, lying at the west end of Lydiard Millicent, were part of the purlieus. (fn. 261) To compensate them for the loss of feeding for their cattle in the purlieus, Lydiard Plain, 40 a. including the wide lane leading to it, was apparently allotted to the other landowners, or to the inhabitants, of Lydiard Millicent and Shaw as a common pasture. How the pasture was used in the 17th and 18th centuries is obscure; it remained grassland and in the 19th and 20th centuries was sometimes leased by the vestry or the parish council. (fn. 262) By 1766 c. 57 a. of Webb's wood, including 42 a. adjoining Lydiard Plain and sharing the name, had been cleared and presumably converted to farmland. (fn. 263)

Between the later 16th and later 18th centuries it is likely that new and dispersed farmsteads were built on land inclosed in 1570–1; the farms in the parish apparently became larger and fewer, and in the earlier 19th century most of the land was worked from outlying farmsteads. In the 17th century the largest farms were probably the principal farm of Chadderton's estate, which may have been of c. 200 a. c. 1600 and was called Church farm in the 19th century, and the demesne of Lydiard Millicent manor, which was called Manor farm in the 19th century. (fn. 264) Upper Shaw farm was of c. 90 a. in 1758. (fn. 265) In 1766 Parkside farm was of c. 150 a. and Shaw farm of c. 112 a.; three farms based in Lydiard Tregoze included land in Lydiard Millicent, Wick farm 46 a., East Leaze farm 40 a., and a farm at Hook 9 a. (fn. 266) About 1790 the farms included Church, 208 a., and Godwin's, 143 a. including 16 a. in Purton; among those at the east end of the parish were Lower Shaw, 137 a., Sparcells, 116 a. including 42 a. in Purton, Roughmoor, 63 a., Brook, 78 a., and one of 59 a. (fn. 267)

There were 556 a. of arable and 1,225 a. of grassland in the parish in 1839. The arable lay mainly on the coralrag on what had almost certainly been the open-field land until 1570–1. East of the Cricklade–Marlborough road there was no more than c. 40 a. of arable at Shaw. Six farms were worked from farmsteads at Shaw, six from farmsteads in the rest of the parish. Brian Bewley, who held Parkside farm (198 a.), Breach barn, and another 144 a., was the farmer with the most land; he held c. 150 a. of arable and apparently had a dairy in which cheese was made. At Lydiard Millicent village Church Farm was held with 194 a., over half of which was arable, Manor Farm was held with 93 a., the Rectory house and adjacent buildings with 85 a., and a farmstead at the south-east end of the street with 24 a.; west of the village Godwin's Farm was held with 59 a. The farms east of the Cricklade–Marlborough road were Shaw, 169 a., Lower Shaw, 127 a., Brook, 119 a., Roughmoor, 94 a., Upper Shaw, 91 a., and Sparcells, the farmstead of which stood on the parish boundary and which included 70 a. at Shaw and c. 42 a. in Purton. Roughmoor farm included 31 a. of arable, Brook farm was entirely grassland, and the other farms were predominantly grassland; all were presumably dairy farms on which cheese was made. By 1839 only c. 120 a. of the former purlieu at the west end of the parish had been converted to agricultural land used in severalty, and 54 a. of that was part of a farm with buildings in Purton parish; a farmyard on the site of Greenhill Farm and c. 50 a. in closes of pasture west of it were part of Brian Bewley's holding. (fn. 268)

In the mid and later 19th century the closeness of Swindon, where the population was growing rapidly, (fn. 269) and the transport of liquid milk by rail probably enabled small dairy farms in Lydiard Millicent to become profitable; cheese making may have ceased. (fn. 270) Also in that period, and presumably for their own profit, landowners leased much land as garden allotments. (fn. 271) In the west part of the parish Greenhill farm was made discrete, (fn. 272) c. 100 a. of woodland was cleared and converted to farmland, and two new farmsteads were built, Home Farm west of Wood Lane, and Plain Farm beside the Cirencester and Wootton Bassett road. (fn. 273) In 1910, by when nearly 10 per cent of the agricultural land lay as allotments and most of the farms had become smaller, there were c. 15 farms based in the parish. Shaw farm, 180 a., was the largest, and only five others, Parkside, Lower Shaw, Brook, Sparcells, and Greenhill, were of over 100 a.; the rest, including Church, were of between 30 a. and 84 a. (fn. 274)

The area devoted to garden allotments fell rapidly after 1910. (fn. 275) Dairy farming continued, (fn. 276) in 1929 there remained c. 15 farms, and by the early 1930s the amount of arable in the parish had been reduced to c. 150 a.; most of the arable lay west of the Cricklade and Wootton Bassett road. Manor farm, 37 a., and Church farm, 69 a., were worked together, and in the west part of the parish a 61-a. farm was worked from Echo Lodge. (fn. 277) Some land was cultivated as smallholdings and as market gardens, presumably to grow produce for sale in Swindon; the number of market gardeners in Lydiard Millicent increased from three in 1911 to 14 in 1939, when there were also two smallholders and three poultry farmers. (fn. 278)

Small dairy farms, smallholdings, market gardens, and poultry farms may have continued in the parish after the Second World War, but in the late 20th century the pattern of agriculture changed. In the 1980s agriculture at Shaw ceased: most of the land there was built on and most of the farmsteads were demolished. By 2004 most of the farmsteads in the reduced Lydiard Millicent parish were no longer used for agriculture and market gardening had ceased. In that year there were dairies at Koffs Farm and Plain Farm and among buildings at Lydiard Green called Lydiard House Farm. Most of the land of the reduced parish was then pasture.

WOODLAND

There was woodland ½ league square at Lydiard Millicent in 1086. (fn. 279) Woodland on the clay at the west end of the parish, called Clinton's wood or Webb's wood, was part of Lydiard Millicent manor. By the 17th century the owner of Chadderton's estate had made good a claim to lordship over 134 a. of waste or wooded ground immediately east of it. (fn. 280) The lord of Lydiard Millicent manor had a huntsman in the early 14th century (fn. 281) and was selling wood from the manor in the mid 15th. (fn. 282) About 1630 Webb's wood was said to cover 387 a., (fn. 283) and it adjoined woodland south of it in Lydiard Tregoze. By 1766 it had been reduced by the grubbing up of 42 a. lying at its east end and west of Lydiard Plain, and by the making of five clearings, 14 a., beside its south boundary. (fn. 284) In one of these, Skinners Ground, structural evidence of a cottage and two pillow mounds of a rabbit warren have been discovered. (fn. 285) In 1839 Webb's wood, which was crossed by Wood Lane, was said to cover 342 a., and Great Lydiard wood, 58 a., Brickkiln copse, 29 a., and Purley copse, 14 a., were also standing in the west part of the parish; the three smaller woods belonged to the owner of Chadderton's and may have survived from woodland standing on the 134 a. c. 1630. (fn. 286)

Between 1839 and 1863 c. 40 a. of Webb's wood west of Wood Lane was grubbed up and converted to farmland. In 1863 the remainder of the wood was bought by a timber merchant, and between then and 1884 the remaining 21 a. of woodland west of Wood Lane, and c. 44 a. elsewhere on the wood's periphery, were also cleared. (fn. 287) In 1880 Echo Lodge was described as a sporting residence, (fn. 288) a description which suggests that Webb's wood was also used for sport in the late 19th century. Also by 1884 much of Great Lydiard wood had been cleared; what remained stood as Cowleaze copse, 13 a., and Plain copse, 7 a. In the 20th century c. 10 a. more of Webb's wood was cleared and c. 7½ a. was replanted with trees. (fn. 289) In 2004 Webb's wood covered c. 200 a.; Brickkiln, Purley, Cowleaze, and Plain copses remained of 25 a., 14 a., 13 a., and 7 a. respectively. (fn. 290)

Two woods mainly in Lydiard Tregoze extended north into Lydiard Millicent parish. South of Greenhill the redrawing of the boundary between 1839 and 1885 transferred 4 a. of Frith copse to Lydiard Millicent, and near Parkside Farm 4 a. of Park copse lay in Lydiard Millicent and was a boundary of Lydiard park. (fn. 291) The 8 a. of woodland remained standing in 2004. Peatmoor copse, 4 a. beside a head stream of the Ray at Shaw, is the only other woodland known to have stood in the centre or east part of the parish. In 1839 willows were grown on part of it. (fn. 292) After the land of Shaw was built on in the 1980s the copse, combined with a lake formed by damming the head stream, was used for recreation.

TRADE AND INDUSTRY

Mills

There was a mill at Lydiard Millicent in

1086, (fn. 293) and in the 13th century there were two mills, (fn. 294) one

of which was a water mill for grinding grain and was

part of a customary holding of Lydiard Millicent

manor. (fn. 295) Its walls and roof were in need of repair in the

1540s. (fn. 296) In 1568 the lord of the manor sold it to the

copyholder; (fn. 297) how long it survived after that is unclear.

It was not standing in the 19th century (fn. 298) and its site is

unknown. The second mill belonged to Bradenstoke

abbey in the late 13th century and early 14th (fn. 299) and was

apparently given to Robert Russell in the exchange of

1307. It evidently descended with what came to be

called Chadderton's estate and in 1586 was described as

a ruined windmill; it may have stood on the high

ground near the site of Breach barn. (fn. 300) There is no

evidence that it was renewed, and it did not exist in the

19th century. (fn. 301)

Stone quarrying

Quarrying took place on the

coral-rag in the east and west of the parish. A stone

quarry which was in use by the mid 17th century may

have been the one near the site of Greenhill Farm. (fn. 302) In

the later 19th century there was a quarry on glebe land

off Stone Lane north of Roughmoor farm, and a quarry

was opened off the Cricklade–Marlborough road

between 1899 and 1922. (fn. 303) The quarry on the glebe had

been closed by 1920, (fn. 304) and the nearby quarry may have

been shortlived.

Brickmaking

A brick kiln at Green Hill was said

c. 1788 to have been erected long before. The kiln fired

clay dug on waste land of Chadderton's estate, (fn. 305) and

presumably burned wood grown at the west end of the

parish. Brick making at the site was carried on by the

Clark family from c. 1870 and ceased c. 1920. (fn. 306) A

brickworks off the west side of Wood Lane was opened

between 1839 and 1863. (fn. 307) It had apparently been closed

by 1884. (fn. 308)

Trades

Until the later 20th century trades in

Lydiard Millicent were typical of those in a rural

parish. (fn. 309) In the earlier 20th century there was a bakery

and a commercial garage in the Street, a bakery at Shaw,

and a slaughterhouse at Lydiard Green. (fn. 310) Especially

from the 1980s the proximity of Swindon may have

stimulated small businesses. A coalyard in the Street

was bought in 1970 and used as a depot by Blackfords

Fuels, a fuel distribution company, and subsequently by

Blackfords Landscaping Services, which moved in 1980

to new premises at Green Hill in Purton parish. In the

late 1990s, when it had 80 employees and 28 lorries, the

business was divided into four independent companies. (fn. 311)

In the early 1980s a market garden at Greatfield was

converted to a retail garden centre; (fn. 312) a second retail

garden centre was open in 2004 in Stone Lane. Also in

2004 motor vehicles were repaired at the garage in the

Street, and several small premises in Stone Lane were

used for trade. Beside a lane running north from

Lydiard Green five buildings for industrial use were

erected c. 1990; (fn. 313) in 2004 the occupants included small

companies which repaired and serviced motor cars. (fn. 314)

By 1901 many men living in Lydiard Millicent parish worked for GWR in Swindon. (fn. 315) In 2004 most of the inhabitants of the reduced parish who were employed worked outside it.

SOCIAL HISTORY

INNS

There were apparently several alehouses in the parish in the 1750s, (fn. 316) there was a public house c. 1790, (fn. 317) and the Bell and the Sun were public houses in the 1820s. (fn. 318) The Bell had apparently been closed by 1848. The Sun, from the 1840s described as an inn, occupied a house on the south-west side of the Street. A beerhouse opened c. 1870 was presumably the Butchers Arms, which was standing on the west side of the Cricklade and Wootton Bassett road in 1885. (fn. 319) The Nine Elms public house was built at Nine Elms c. 1900 (fn. 320) and was later called the Elms hotel. (fn. 321) The Sun, the Butchers Arms, then called Riffs, and the Nine Elms all remained open in 2004. Public houses, including the Village Inn at Ramsleaze, the Brockhurst Farm at Middleleaze, and the Woodlands Edge at Peatmoor, serve the area of modern development transferred from the parish in 1980.

COMMUNITY ACTIVITIES

Lydiard Millicent Industrial and Provident Society existed in the late 19th century. (fn. 322) A clothing club for those with a weekly income of less than £2 was started in the parish in 1911. Members contributed 3d. a week, and money was returned to them yearly. The number of members, 27 in 1911, was highest in the mid 1920s, when there were c. 90. In 1933 the club was closed because it was thought to be no longer serving a useful purpose. (fn. 323)

A public reading room was built of corrugated iron, and stocked with books, by J. H. Sadler of Lydiard House. (fn. 324) It stood near the Sun on the south-west side of the Street, and was apparently erected between 1899 and 1910. (fn. 325) In 1924 Sadler gave it to the parish council, which thereafter met in it and hired it out for educational and social activities. (fn. 326) In 1965 a new hall was built by a voluntary committee, and the parish council sold the old reading room. (fn. 327) The new hall was enlarged in 1974. (fn. 328) A workmen's club at Shaw was open for a few years c. 1900. (fn. 329)

A playing field behind the new housing north-east of the Street was given to the parish council in 1986; a wooden pavilion later erected on it was burned down and in 2002 a new clubhouse was built. In 2004 the field was used for football and cricket. (fn. 330)

Allotments

In 1844 the vestry resolved to provide

garden allotments for the labouring poor of the parish,

and it arranged with 12 owners or occupiers for 14¼ a. to

be converted to ¼-a. or ½-a. allotments. Rules to govern

the use of the allotments were drafted, and the vestry

agreed to pay £2 a year for each acre and to collect rent

from those holding the allotments. Although the vestry

listed 35 men whom it thought qualified to hold an

allotment, (fn. 331) there is no evidence that any garden

allotment was cultivated as a result of the vestry's

resolution.

The provision of allotments was promoted by Revd W. H. E. MacKnight in the period 1852–79, (fn. 332) and by 1873 the philanthropist Anthony Ashley Cooper, earl of Shaftesbury, who owned an estate in the parish, had converted 14 a. of his land to allotments. (fn. 333) In 1883 there was 97 a. of allotments, (fn. 334) from 1895 applications for allotments were dealt with by the parish council, (fn. 335) and there was 175 a. of allotments in 1910. (fn. 336) The reversion of allotment land to farmland apparently began c. 1910 and was apparently completed in the mid 20th century. (fn. 337) The allotments bought by Wiltshire County Council c. 1920 (fn. 338) were being leased in groups as smallholdings or farmland in the 1940s. Of the council's 47 a., 18 a. was leased as a smallholding in 1952. (fn. 339)

EDUCATION

There was no school in the parish in 1783. (fn. 340) In 1819 there were two schools attended by c. 24 children; (fn. 341) both of which had apparently closed by 1835. (fn. 342) A National school consisting of a schoolroom and a teacher's cottage was built on the north-west side of the Butts in 1841; (fn. 343) the schoolroom was heightened, and the cottage enlarged in c. 1858. (fn. 344) Because children from outside the parish were accepted, the number of pupils became too high. In c. 1858 there were as many as 50 pupils from Lydiard Millicent and in 1859 children from outside the parish had to be excluded. (fn. 345) Between 1831 and 1891 the population of the parish more than doubled, (fn. 346) and the school was thrice enlarged: the schoolroom was extended north-eastwards, and a porch was built c. 1866; (fn. 347) in 1870, when the school could accommodate 69 children, average attendance was 61. (fn. 348) A new room for infants was built in 1872, sometimes as many as 136 children attended in 1879, and another new room was built in 1886. (fn. 349) In 1902 the school was attended on average by 115 children, 37 of whom were infants, (fn. 350) and in 1929–30 average attendance was 98. From 1930 Lydiard Millicent children over 11 were sent to school at Purton, and by 1937–8 average attendance at Lydiard Millicent school had fallen to 54. (fn. 351) From 1965 Lydiard Millicent school was attended by children from Lydiard Tregoze, where the school was closed in that year. (fn. 352) New prefabricated classrooms were afterwards placed on the south-east side of Butts Lane, (fn. 353) and in 2004 there were 178 children aged 4–11 on roll at the school. (fn. 354)

A school for the sons of noblemen was held by Revd W. H. E. MacKnight at Purton and from 1852 in the manor house at Lydiard Millicent. The school was closed when MacKnight left the parish in 1879. (fn. 355) A day school and a boarding school, both for young ladies, were held in the parish in the later 1860s. (fn. 356)