A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Historic Parishes - Marston Meysey', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18, ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/210-224 [accessed 3 April 2025].

'Historic Parishes - Marston Meysey', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Edited by Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online, accessed April 3, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/210-224.

"Historic Parishes - Marston Meysey". A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online. Web. 3 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/210-224.

In this section

MARSTON MEYSEY

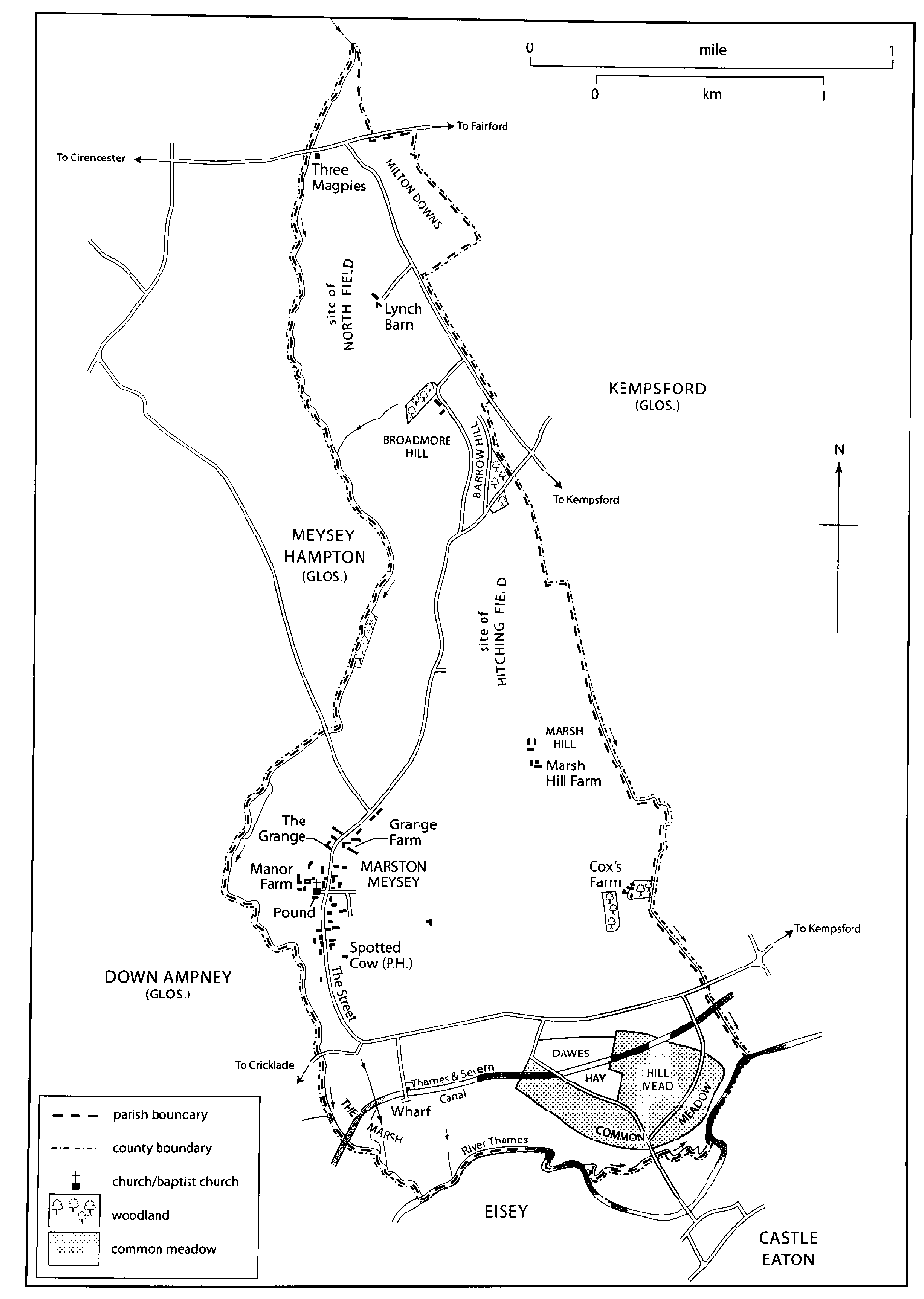

MARSTON MEYSEY village lies 11 km. eastsouth-east of Cirencester (Glos.) and 12 km. north of Swindon. The village street displays a trim, affluent character, which is determined by large stone houses, set at widely spaced intervals in large gardens which were once working farmyards. The parish, the most northerly in Wiltshire, is long and narrow and runs northwards from flat land beside the Upper Thames. (fn. 1) The name is derived from the Old English for settlement associated with a marsh, perhaps implying a specialist function, (fn. 2) to which is affixed the family name of a manorial owner. The de Meysi family held both Marston Meysey and Meysey Hampton (Glos.) until the lands were divided by inheritance in the 13th century. (fn. 3) Marston Meysey, a tithing of Highworth hundred, was regarded as a chapelry of Meysey Hampton, and by 1302 a new chapel had been built for its inhabitants. (fn. 4) Its anomalous status as a chapelry of a Gloucestershire parish whose territory lay wholly within Wiltshire continued until the 19th century. The chapelry covered the same area as Marston Meysey manor and lay in Worcester diocese until 1541 and thereafter in Gloucester diocese. (fn. 5) It had its own churchwardens and relieved its own poor, and functioned intermittently as an independent parish from at least 1648. In the 19th century it became a civil parish. (fn. 6) It is the only Wiltshire parish never to have been part of Salisbury diocese. (fn. 7) In 1990 its northern tip, a 7 ha. triangle of land, became part of Meysey Hampton parish, thus reducing the area of Marston Meysey from 1,334 a. (540 ha.) to 1,317 a. (533 ha.). (fn. 8)

Boundaries

Most of Marston Meysey's boundary follows watercourses. Beyond the long east and west sections lie Gloucestershire parishes, and the stream which forms the western boundary with Meysey Hampton was known as the Shire brook. (fn. 9) The whole west section and the south part of the east section follow head streams of the Thames. The southern boundary follows the Thames itself for most of its length and it may follow an old course of the river for the remainder. A section of the north-east boundary may follow a prehistoric bank and ditches, (fn. 10) and another section follows the road from Kempsford (Glous.). In 1990 the northern boundary was moved south to the Fairford and Cirencester road. (fn. 11)

Landscape

There are outcrops of clay in the centre of the parish and Cornbrash in the far north. Alluvium has been deposited by the Thames and the western head stream, and there are extensive deposits of gravel in most parts of the parish. Most of the parish is flat land lying at c. 80 m. The valley of the western head stream is steep sided; two low rises, Marsh hill and Marston hill, originally named Broadmore hill, lie in the centre of the parish, and the land rises slightly to over 100 m. along the north-eastern boundary. (fn. 12)

Before inclosure open arable fields lay on the gravel in the centre and north of the parish. There was meadow land, some of it used in common, on the alluvium beside the Thames, and there was pasture, some of which was commonable, in most parts of the parish. Very little woodland is known to have existed in the parish. (fn. 13) In c. 1950 the runway of RAF Fairford in Kempsford (Glos.), was extended westwards across the whole width of Marston Meysey parish, divorcing the village from Marston hill and its farms to the north. (fn. 14)

Communications

Roads

Until a change made c. 1950 only two roads

crossed the parish east-west. That at the north end, part

of a route mapped in 1675 from London to St David's via

Gloucester, was named London Way in 1839. (fn. 15) It links

Fairford and Cirencester (both Glos.), was turnpiked

through the parish in 1727, disturnpiked in 1879, and

remained a main road in 2009. (fn. 16) A second east-west road

crosses the south end of the parish, linking Kempsford

and Cricklade, and lanes lead from it to Castle Eaton.

Marston Meysey village is approached from the Cricklade road by a lane running north which forms the village street and then forks, north-west to Meysey Hampton, north-east towards Fairford and Kempsford. The latter, which served Marston Hill and the north of the parish, was truncated when the military airfield was extended c. 1950, and replaced by a new east–west stretch of road accessed from the Meysey Hampton lane. At a cross-roads in Kempsford parish (Glos.), south-east of Marston Hill, the Fairford lane meets a road running north-north-west to the Cirencester road. (fn. 17)

Canals

In 1789 the Thames & Severn Canal was

opened across the south part of the parish. A wharf, a

goods yard and a watchman's cottage, round with

gothic windows, were built south of the village. The

canal carried little traffic from the 1860s and was closed

in 1927. From 1831 the Round House was rented to

tenants, and in 2007 was part of a private house. By 1984

most of the canal passing through Marston Meysey had

been filled in, although there were plans to re-open it as

a leisure facility. (fn. 18)

Population

In 1377 there were 51 poll tax payers. (fn. 19) In 1801 the population was 185. By 1831 it had risen by 30 per cent to 240 and peaked at 245 in 1841, when it included seven gypsies living in tents. In the later 19th and early 20th centuries the number of inhabitants stabilised at around 185. Following a peak of 232 in 1931, the population declined to 166 in 1971. New housing built in the later 20th century halted this decline and the population stood at 172 in 2001. (fn. 20)

SETTLEMENT

Early prehistoric activity is represented in the south, south-east and north of the parish, and west of the village, by ring ditches of probable Bronze Age barrows, by field boundaries and a pottery scatter. (fn. 21) Settlements and related enclosures were established during the Middle Iron Age on the Thames gravels on either side of a former stream course in the south of the parish. (fn. 22) A second area of Iron Age settlement, extending into Fairford parish (Glos.) has been identified in the extreme north of the parish, and pottery scatters may indicate a third area close to or underlying the present village. (fn. 23) A Roman trackway and associated field system lay between Roundhouse Farm and the Thames, and a possible early Saxon sunken hut was excavated in 1993 west of Lady Lamb's copse, but other evidence for Romano-British and Saxon settlement in the parish is meagre. (fn. 24)

Marston Meysey Village

The village of Marston Meysey stands close to its western boundary stream, and north of the road from Kempsford to Cricklade. It has the appearance of a planned medieval settlement ranged along its northsouth street, and augmented at both ends. An earlier focus, however, may have lain further west, near the present Manor House, where the medieval demesne farmstead and the chapel probably stood close together, and where village earthworks have been identified surrounding them. (fn. 25) There may have been c. 20 farmsteads of free and customary tenants in the 14th century, many presumably lining the village street, (fn. 26) and there were 13 there in the early 19th century. (fn. 27) In 1974 the historic core of the village was designated a conservation area. (fn. 28)

Many of the farmhouses, such as the the Grange, Three Wells and Woldstone, date from a major rebuilding which began in the late 16th century and gathered pace in the 17th century, particularly the second half when the Manor farmhouse was rebuilt and Middle House was started. (fn. 29) Building and enlargement went on into the 18th century, notably at Grange farmhouse and in the farmyard at Manor Farm which was provided with handsome new farm buildings. (fn. 30) In the early 19th century development occurred at both ends of the street: at the southern end the Spotted Cow public house, the Croft, and the Old Post Office were built, and north of Grange farm, two cottages were planted on the roadside waste. In the second half of the century a new parish church, a new vicarage (later renamed Bleeke House), a plain school and a house called the Beeches, which was designed in a style similar to the buildings on the Marston Hill estate, gave visual emphasis to the centre of the village. (fn. 31) Some farmhouses, which in the 19th century had been divided into cottages, were later converted into desirable houses; Manor farmhouse was enlarged and repaired in the 1920s and the Grange and Three Wells farmhouses were modernised in the 1930s by architects from Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire respectively. (fn. 32)

Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural District Council built six semi-detached houses on the west side of the street, south of Manor farm in 1922. They were joined by six more at the north end of the street in 1948. On the east side of the street north of the vicarage four council retirement bungalows, completed in 1964, took the place of alms cottages. (fn. 33) In the later 20th century some private housing was built on the farmyards and orchards along the street and farm buildings were converted into homes. Conservation area designation and the lack of mains drainage has constrained further development. (fn. 34)

Outlying Settlement

Until the 20th century there were only two outlying farmsteads in the southern half of the parish; Cox's Farm was apparently built by the 16th century, (fn. 35) and by the early 18th century Marsh Hill farmstead had been built, but was demolished c. 1950 to make way for RAF Fairford runway. (fn. 36) In the north of the parish Broadmore Hill farmstead, which existed in the 18th century, was demolished c. 1885 to make way for Marston Hill House. A separate stable block, gate lodge and cottages were built nearby and the farmyard was relocated northwards to the site occupied by Lynch barn in 1839. There a new farmhouse called Marston Hill Farm and outbuildings were built. More estate cottages were built near Marston Hill house after 1918. In the later 20th century Kencot Hill Farm and an equestrian centre also stood on Marston hill, and there were some dwelling houses converted from field barns and outbuildings. (fn. 37) The Three Magpies public house, notable as the northernmost building in Wiltshire, was apparently purpose built in 1830 on the Cirencester road, as a plain 2½-storeyed stone house with brick dressings and a wing of stables with hayloft, but was a farmhouse by c. 1941. In the south of the parish Blackburr Farm, Roundhouse Farm, and the Second Chance Touring Caravan Park near the Thames were all established in the 20th century. (fn. 38)

MANORS AND ESTATES

MARSTON MEYSEY MANOR

The manor is not named in Domesday Book, and was probably subsumed within the fee of Roger of Montgomery, earl of Shrewsbury, which included neighbouring Meysey Hampton (Glos.) and Castle Eaton. After 1086 it presumably descended, like Penton Mewsey (Hants.) from Turald and his heirs, who held these manors of the earl, to the de Meysey family. (fn. 39) In 1212 the manor, assessed as half a knight's fee, was held by Roger of Meysey and like the manors of Meysey Hampton and Castle Eaton, it descended in his family. (fn. 40) An inheritance dispute arose within the family which was apparently resolved in 1259, when one John of Meysey held Marston Meysey manor. (fn. 41) In 1295 the manor was held by the heirs of Robert of Meysey. (fn. 42) In 1302 John of Meysey, son of Sir John of Meysey, granted the manor to Sir Hugh Despenser, Lord Despenser (earl of Winchester from 1322, executed 1326). (fn. 43) After the fall of the Despenser family in 1326, the manor was confiscated by the Crown. Around that date John of Meysey petitioned the King for restoration of the manor, stating it had been taken from him by force. (fn. 44) Meysey's claim would have been upheld, but documents found in 1331 revealed that he had sold it to Despenser and the Crown retained the manor. (fn. 45) Marston Meysey manor passed with the crown until 1564 and generally formed part of the Queen's dower, (fn. 46) or was granted to other members of the royal family, (fn. 47) or to royal servants. (fn. 48)

In 1564 Elizabeth I granted the manor to the bishop of Salisbury as part of a property exchange. (fn. 49) The bishops leased out the manor until parliament confiscated episcopal property in the Civil War. (fn. 50) In 1648 the trustees of Parliament sold the manor to Robert Jenner (d. 1651), citizen and goldsmith of London. (fn. 51) The Jenner or Gynner family already owned lands in Marston Meysey. (fn. 52) On Robert Jenner's death, the manor passed to Robert Jenner junior. (fn. 53) After the Restoration, it reverted to the bishops of Salisbury, (fn. 54) and in 1856 ownership was transferred to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. (fn. 55) Between 1856 and 1868 the manorial demesne land was sold off and nearly all the copyhold properties were enfranchised. The copyholds were enfranchised mainly as eight farms, of which the largest was 131 a. and the smallest 35 a. (fn. 56) By c. 1900 the Ecclesiastical Commissioners had sold all their property apart from c. 90 a. including Marsh Hill farm, which was sold in the 1920s. (fn. 57)

The demesne of c. 335 a., known as Manor farm, was sold to the lessee John Archer in 1856 (fn. 58) and David Archer later acquired additional parcels of land. The farm became part of the Archers' Castle Eaton estate, which was sold by Major S. F. Alderson Archer in 1925. (fn. 59) John Rickards bought Manor farm, then comprising 215 a. and it became the centre of his estate. He already owned 254 a. in the parish, and leased another 300 a. including Marston Hill farm. (fn. 60) In 1939 Rickards was one of the three principal landowners in the parish, the others being Major Robert Hamilton-Stubber of Marston Hill House and W. H. Maundrell of Grange farm. In the later 20th century the Manor farmhouse was sold off and the lands were purchased by Robert Spackman of Marston Hill farm. (fn. 61)

Manor Farmhouse

Perhaps built anew after the Jenners acquired the manor, in 1669 it contained a parlour, hall, buttery, kitchen and two chambers over hall and buttery. It appears to survive as the L-plan core of the present gabled house, original fabric being preserved on the north front, which has ovolo-moulded mullioned windows. In the later 18th-century the farmyard was renovated and the interior of the house was remodelled, with new main staircase and fireplaces. In 1817 that staircase and a service stair linked ground floor hall, sitting room, parlour, kitchen, pantry and outbuildings with six chambers on the first floor, and two good cheese rooms and a bedroom on the second floor. In 1927 a gabled two-storey north-western wing was added on the site of a 17th-century carthouse to provide a drawing room and accommodation above, and the main south front was much embellished. An early 18thcentury doorcase and medieval hinges on an outside door appear to have been imported, possibly from the demolished chapel. By 1981 the house had been modernised again. The outbuildings, which were extensive by 1817, include two stone barns, one with a dovecote and the other with an attached store, and a granary as the end of a range of animal shelters. (fn. 62) The larger, originally 5-bayed barn has a tie beam dated 1788.

MARSTON HILL ESTATE

31. Parish church of St James, 1874–6 by James Brooks of London, from the south-west with the 18thcentury tomb of John Bleeke in the foreground.

By 1878 the Rev Dr Frederick Bulley (d. 1885), president of Magdalen College, Oxford, had purchased Broadmore Hill farm and adjacent lands from several owners, creating an estate of c. 250 a. in the north of the parish. (fn. 63) On the site of the farm, Bulley and his wife Margaret built Marston Hill House, a fashionable mansion with extensive views, completed the year he died. The Bulleys were influenced by the designs which the Oxford architect William Wilkinson published in his book of English Country Houses in 1870. They employed Waller, Son and Wood of Gloucester as architects to design a neo-Jacobean house, built of rock faced coursed limestone with Bath stone dressings, and with a tiled roof and carved decoration round the entrance doors. The striking feature of the main block of reception rooms is the tall north-western tower, topped with decorative gables and chimneys. A lower service wing extended to the west, and stables and a carriage house were built around a yard further to the north-west; the stables have been converted into flats. (fn. 64) The estate passed to their son Frederick Pocock Bulley, but was sold in 1921 to Major Robert and Lady Mabel Hamilton-Stubber. (fn. 65) From 1952–58 Marston Hill House was used as a school for the children of United States servicemen stationed at RAF Fairford, and in 1960 it was converted into flats. By then the Marston Hill estate was the property of the Spackman family. The stables, the estate cottages and later the mansion were sold off as private housing. Robert Spackman retained the lands and bought those of Manor farm and Grange farm. In the early 21st century Spackman's land in Marston Meysey were part of an estate of over 1000 a. centred on Kempsford (Glos.).

ECONOMIC HISTORY

AGRICULTURE

Arable

The arable lay in three open fields before

inclosure: Lower field; Upper or Hitching field, which

was to the north-east of the village; and North field in

the far north of the parish. In 1669 a nominal 850 a. was

under arable cultivation. In Marston Meysey at this

date a yardland was c. 25 a. Manor farm had 183 a. of

arable land, the equivalent of c. 7½ yardlands. Three

freeholders held c. 113 a., 12 copyholders held c. 500 a. in

holdings of between 25 and 75 a., and four cottagers

held a total of 50 a. (fn. 66) In the later 17th and 18th centuries

piecemeal inclosure of the open fields took place and

the land was divided into smaller parcels. The lands of

Lower field seem to have become the property of

Manor farm and inclosures in Upper field of various

farms. In 1736 the only arable lands still cultivated in

common were in North field, and by 1839 these too had

been inclosed. (fn. 67) Until the inclosure of the common

fields, sheep were pastured there after harvest, in North

field from Michaelmas, 29 September, and in Upper

field from the feast of St Luke, 18 October. (fn. 68)

Pasture

This was concentrated in the southern

half of the parish. In the 17th century Black Gore

belonged to Manor farm and a lease of 24 a. of this

pasture was worth £150 in 1669. (fn. 69) Other pastures in this

area were Dawes Hay and the Marsh. (fn. 70) Just to the northeast of the village and to the south of Upper field was

another area of pasture around Marsh hill. (fn. 71) Nearby 60

a. of Upper field was used as pasture by Manor farm in

1729, and by 1839 rick and cow yards, a barn and

cowshed had been built here. (fn. 72) Lady Croft pastures also

lay near Marsh hill. (fn. 73) In the north of the parish

Broadmore hill was used for hay in 1669, and pastures

on Milton downs belonged to Manor farm in 1839. (fn. 74)

The inclosure of pasture had already begun by the late

17th century and was complete by 1839, when each

parcel was allocated for the use of a particular farm. (fn. 75) In

the 1870s c. 500 a. in the parish was laid down to

pasture. (fn. 76)

Meadow

The meadows lay in the south-east

corner of the parish close to the Thames. (fn. 77) Common

rights in Hill mead, a Lammas meadow, survived until

the later 19th century: the homage met each year to

survey the mere stones, which marked out the

boundaries between parcels of meadow land. After the

first hay crop was cut, animals were allowed to graze

there according to the customary allocations for each

holding. In the early 19th century one cow or horse in

every four could feed on the meadow between 12

August and 12 November, and one sheep in every four

between 12 November and 5 March. From the later

17th century there were injunctions in the court books

against cattle 'without the town mark' grazing in the

meadow. These animals, and others found grazing in

the lanes without a keeper were removed to the village

pound. (fn. 78) There was a market in parcels of meadow,

which were sublet to other tenants and to people

outside the parish. (fn. 79) 30 a. of Thames Mead already

belonged to Manor farm in 1778. (fn. 80) The inclosure of

Hill mead took place in 1864 and was ratified by Act of

Parliament in 1866. A total of 99 a. was divided into 18

lots, allocated to 13 parties. The largest allotments

were 39 a. to John Archer of Manor farm and 21 a. to

William Lane. (fn. 81)

Woodland

The little woodland in the parish was

originally the property of the lord, but by 1654 he had to

give notice to the tenants before cutting down trees on

their holdings. The tenants had the right to trees which

had blown down, they could cut thorns and willows on

their holdings, and could cut hedgerows and take lops

and tops with the consent of the Lord's bailiff. In 1839

Manor farm had 28 a. of woodland in several small

plantations. Furzy wood, the largest area of wood, on

the north-east border with Kempsford, was standing in

1773. (fn. 82) By the 1870s fewer than 10 a. of woodland

remained. (fn. 83)

Farms and Farming

In 1331 the demesne consisted of a farmstead of 244 a., later called Manor farm. It had 210 a. of arable land, 27 a. of meadow and 7 a. of pasture. Most of the land was held by tenants: customary tenants held 18½ yardlands of arable land and there were ten households of cottagers. Other lands were farmed by a small number of free tenants. The customary tenants owed heavy labour duties to the lord of the manor: in addition to paying rent, the yardlanders and cottagers were required to work every other day on the demesne and the cottagers also had to make hay for the lord. (fn. 84)

In 1559 Manor farm comprised 266 a. and over half was pasture and meadow for stock. (fn. 85) In 1817 two thirds of its 335 a. were used for stock rearing and it was described as a 'capital dairy farm'. Substantial outbuildings included two cattle yards, two cowsheds and calf pens. In the farmhouse attic were 'two good cheese rooms'. (fn. 86) In 1925 after restructuring as part of the Castle Eaton estate, it was described as a 'valuable corn and dairy farm'. In the 20th century it was one of the three largest farms in the parish, and in 1941 its 370 a. were part of John Rickard's estate. In the later 20th century the Manor House was sold off. The lands became part of Robert Spackman's estate in Marston Meysey and adjacent parishes, and arable crops were grown to feed turkeys and chickens. (fn. 87)

In the course of the 17th century ten or more farmhouses were built or rebuilt by tenants along the village street, surrounded by yards and outbuildings and three outlying farmsteads, Cox's Farm, Marsh Hill, and Broadmore Hill, were built on areas of pasture. (fn. 88) Some tenants rented more than one copyhold and their farms had between 30 and 100 a. of arable land. (fn. 89) Other branches of the Jenner family, which leased Manor farm c. 1621–1820, acquired other holdings and parcels of land. In 1669 tenants named Jenner held a 2-yardland freehold, and five other copyhold properties, a further 8¼ yardlands in total. Jenners farmed at Marsh Hill and Broadmore Hill farms in the 18th century, (fn. 90) and in the early 19th century William Jenner farmed in the parish. (fn. 91)

Cox's farm was probably based on a medieval freehold property. In 1669 Jeremy Cox, whose family was first recorded in the parish in 1571, held a 2yardland freehold. In 1799 it belonged to Richard King and consisted of c. 90 a. of mainly arable land. In the early 20th century it was a mixed arable and dairy farm of 125 a. In 1971 the house was sold off, and the lands were bought by Sir Anthony Tritton of Grange farm. (fn. 92)

Marsh Hill farm was first recorded in the early 18th century. It was farmed in conjunction with Manor farm by John Jenner (d. 1788). It was farmed by John Trinder in the late 19th century and in 1881 the 51 a. farm was mainly pasture. It is now part of RAF Fairford and the buildings have been demolished. (fn. 93)

During the 18th century the King family leased a 1yardland copyhold and additional lands. The farmhouse is 18 The Street. When the copyhold was enfranchised in 1856, Kings had 46 a. of mainly arable land, which was purchased by John Archer of Manor farm in 1862. (fn. 94) The Bleeke family leased a 1½-yardland copyhold in the later 17th and early 18th centuries. In 1839 Bleekes had 38 a. of copyhold land, mainly pasture. In 1863 the buildings were demolished to make way for the vicarage and its gardens. (fn. 95)

In 1840 Marston Meysey was a community of small farmers. There were 13 tenants with farms of over 20 a. based on the copyhold farmsteads arranged along the village street and on the three outlying sites. Subsequently the small farms were amalgamated into larger units. By 1856, when the enfranchisement of copyholds began, there were seven tenants who between them held 32 copyhold properties, three quarters of which were in the hands of only three men, William Lane, Edward Fletcher Booker and William Jenner Lane. (fn. 96) In 1840 Edward Fletcher Booker farmed 142 a. from 21 The Street, now called Woldstone. (fn. 97) This was the second largest farm after the Manor, and he had recently added Bleeke's lands to the four copyholds he already possessed. In 1856 he rented eight copyholds, and at his death in c. 1877, his lands included the farmstead now called the Grange with 84 a. of land. (fn. 98)

By 1888 the Grange and its lands had been detached from Booker's other lands and amalgamated with a separate holding, now called Grange farm, to create a dairy farm of 146 a. In the 20th century Grange farm was one of the three largest farms in the parish. In 1964, its 318 a. of land were used mainly for dairying. By the early 21st century the house and farm buildings had been sold separately, and the lands produced arable crops as part of Robert Spackman's estate. (fn. 99)

Broadmore Hill farm was first recorded in the later 18th century, and c. 100 a. of arable and pasture were owned by William Jenner Lane in 1840. He also rented 35 a. belonging to another copyhold and by 1856 he was renting six other copyhold properties. (fn. 100) Broadmore Hill farm was bought in 1878 by Dr Bulley, who built a new farmhouse and farmyard further north on the site where Lynch Barn stood in 1839. The new farm, Marston Hill farm, had 255 a. in 1910 when it was leased to John Rickards who farmed over 550 a. in the parish. It was one of the three largest farms in the parish, comprising of 322 a. in 1941, when it belonged to Major Hamilton-Stubber. In the 1950s the land was farmed by Major Tim Northen and by the later 20th century it belonged to the Spackman family and produced arable crops. (fn. 101)

32. The Grange, an L-plan house of the 16th and 17th centuries, one of several large farmhouses in Marston Meysey.

During the 20th century farmland continued to be amalgamated into larger holdings and the remaining farmhouses were sold off as private residences. In the mid 20th century there were seven farms in the parish: in the south, Cox's farm, Blackburr farm, a dairy farm owned by Wiltshire County Council, (fn. 102) and Roundhouse farm, a stock farm where llamas were bred for a time; in the village, Manor farm and Grange farm; and in the north, Marsh Hill farm and Marston Hill farm. By the early 21st century all but the last had ceased to operate as farms. (fn. 103) Since the Middle Ages, farming had always been mixed, but it was almost entirely arable in the early 21st century. Most of the land was farmed as part of the Spackman estate, or by contract farmers based elsewhere. The lands around Marsh hill lost to RAF Fairford, and areas near the Thames to gravel extraction. Only one person living in the village was employed to work on the land, and other residents worked for employers outside the village, although some worked from home. (fn. 104)

Major farmhouses and farmbuildings

The Grange,

on the western side, and Grange farmhouse, on the

eastern, flank the village street at its northern end. The

Grange is one of the oldest and most complex

farmhouses. It was built in the 16th century and the

north-western wing contains original fabric, which may

have been partly timber framed. A south wing and

probably the stair tower were added in the 17th century

and a detached bakehouse or brewhouse was built. Three

Wells, a mid 17th-century house of similar size retains

more of its quite elaborate internal details, as does

Middle House, a larger, later symmetrical house, divided

internally by timber-framed partitions and originally

with gabled attic, raised later to form a third storey.

The main range of the Grange was extended and reroofed late in the century or early in the 18th. About the same date Grange farmhouse was also built, with symmetrical 2-storeyed façade and attic lit by dormers, and the 17th-century Cox's farmhouse was enlarged by a taller south range. In the early 19th century the Grange was gentrified and given sash windows on the east and south, while at Grange farmhouse a long wing incorporating a dairy was added. (fn. 105)

Both the Grange and Grange farmhouse were divided into two cottages before being turned back into single houses in the 20th century. The Grange was converted in 1938 by Kenneth B. Mackenzie, architect of Bibury, who renovated it in 17th-century style, adding a north porch with bathrooms over. (fn. 106) It was just one of several houses to be made into more desirable residences in the interwar period. Manor farmhouse was renovated, as was the 17th-century Cox's farmhouse, where the walls were raised in the 1930s, and at Three Wells John Jefferies and Sons of Cirencester made plans in 1938 to turn the farmyard into a garden. (fn. 107)

Changes continued after the Second World War, especially as farmhouses were sold off. The Grange, which had been occupied by four families during the war, reverted to a single dwelling and was renovated again in 2005. Grange farmhouse was converted back into a single dwelling, with much renovation, after 1964. The stable was converted into a house, and the barn into garages and accommodation. Another barn was built further south in the late 20th century.

Houses and farmyards were often developed in parallel, for example at Manor farm. (fn. 108) At Grange Farm a small barn is probably contemporary with the original farmhouse, and a large stable with hayloft over may have been built about the same time as the domestic additions. At Cox's Farm the buildings represent several phases of change, and include a group of stone outbuildings which were originally thatched, a milking parlour of c. 1930, a bull pen and other 1950s structures. (fn. 109)

GRAVEL EXTRACTION

Gravel working by M. C. Cullimore (Gravers) Ltd, begun since 2006, extended in 2009 over most of the former meadow land in the south-west of the parish between the Thames, the Cricklade road and the caravan park.

SOCIAL HISTORY

Until the late 20th century Marston Meysey was an agricultural community engaged in mixed farming. In the late 13th and early 14th centuries, members of the of Meysey family may have lived on the manor, there were perhaps two or three households of free tenants, and around 30 households of serfs, two thirds of which farmed modest holdings and one third of which were cottagers who survived by labouring for others. (fn. 110) After the manor became the property of the Crown and later of the bishop of Salisbury, there was no resident lord. The earliest surviving part of Manor farmhouse, now called the Manor, was built as a substantial 17thcentury farmhouse, not a gentry residence. Surveys of the manor made in 1669 and 1690 indicate that the Bishop was then regaining his hold on the estate after its confiscation and sale by Parliament. (fn. 111) The 17thcentury rebuilding of many farmsteads in stone suggests increased prosperity in the community. For centuries the social composition of the parish remained very similar.

From the 17th through into the 19th centuries, one or two minor gentry families lived in the parish, for example the Jenners of Manor farm, and James Vaulx (d. 1626), a physician. Between 12 and 20 yeoman families farmed most of the land and there were a small number of cottagers. The medical practice of James Vaulx and his son Francis attracted strangers to the parish for treatment, some of whom died there and were buried at Meysey Hampton. (fn. 112) The wealthiest tenants, notably the Jenners, exercised influence over the rest of the community as parish officers, and as tax collectors and assessors. (fn. 113) The Jenner family is recorded in the area from the early 15th century and more than one branch lived at Marston Meysey. (fn. 114) Their fortunes from c. 1621–1820 were associated with Manor farm, their wealth and status as tenants, and briefly as owners, together with ownership of a 2-yardland freehold, enabled some members of the family to call themselves gentlemen. Others were in trade, like Eleanor Jenner, who was apprenticed to a mantua maker at Marlborough in 1713. Jenners were tenants of several other farms and parcels of land during this period, and although Mary Jenner lost the lease to Manor farm in 1820, the family continued to farm in the parish until the later 19th century. (fn. 115) John Archer of Lus Hill (Castle Eaton), the Jenners' successor as tenant of Manor farm, was remembered in the 1920s as a benevolent employer by his farmworkers. (fn. 116)

Social structure changed in the later 19th century, as farms were amalgamated. The residence of full-time clergymen, such as Revd Frederick Bulley of Marston Hill House, and their families exerted a strong influence on church and community life. The greatest changes took place in the 20th century. Gradually all the farmhouses were detached from their lands and inhabited by professional families employed elsewhere. Council housing and retirement bungalows were built for agricultural workers. As agricultural employment disappeared, population declined and amenities closed, including the school, the post office (in 1984) and the garage. When commuting to work by car became common in the late 20th century, old houses were renovated and some new housing was built. This brought in new families and halted population decline. Residents travel from the village for employment, education, shopping and leisure activities, but they expressed the strength of community feeling when they bought the old school in 2005, so that it could continue to be the community centre. (fn. 117)

EDUCATION

John Kircheval (d. 1725), rector of Meysey Hampton, bequeathed £60 to apprentice poor children or to send them to school. Some of the money endowed a school and the parish vestry paid a school master or mistress 1s. 6d. a week to teach several poor children. (fn. 118) In 1871 the school had room for up to 17 pupils, but was too small. (fn. 119) The vestry commissioned a new National school, designed by the architect of the church, James Brooks. It was built in 1874 and enlarged in 1901–2 by Waller and Sons of Gloucester. (fn. 120) It was supported by Kircheval's charity and there was room for 71 children, although average attendance was under 30. The vicar and his family helped with the teaching, as did Mrs. Bulley of Marston Hill House. She examined the needlework, paid for a new cloakroom and held end-ofterm parties for the children. Educational standards were generally high, but average attendance shrank to 19 and the school was closed in 1924. (fn. 121)

CHARITIES FOR THE POOR

Three rectors of Meysey Hampton, all fellows of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, bequeathed sums of money to be invested for the benefit of Marston Meysey's poor. Richard Samways (rector 1662–69), and Dr John Beale (rector 1688–1712), professor of theology at Oxford, each gave £5. Dr John Kircheval (rector 1712–25), also professor of theology, was the donor of £60 to apprentice poor children or send them to school. In 1776 William Jenner of Meysey Hampton bequeathed £25 to Marston Meysey's poor. The interest paid for bread to be distributed on old Christmas day to the poor who did not receive parish alms. In 1798 the money from all these donors had been invested in annuities by the rector of Meysey Hampton and the churchwardens of Marston Meysey. (fn. 122) By 1813 the £85 from Kirchevall and Jenner had been invested in three small cottages and a building plot in Marston Meysey. In 1834 four cottages were let for a total of £6 18s. John Bleeke (d. 1744), John Jenner (d. 1756), Mary King (d. 1772), and Elizabeth Jenner (d. 1780), bequeathed a total of £25, Henry Lane (d. 1822) bequeathed £25, and William Jenner (d. 1826) £20 to buy bread for the poor. In the 1820s all the money was in the hands of the churchwardens, who paid four per cent interest. In 1823 three apprenticeships were set up at a cost of £44. In 1834 the interest on £151 paid for £4 worth of bread, distributed in winter to the second poor, those not receiving regular poor relief, and occasional apprenticeships. In 1844 Elizabeth Lewis bequeathed £100 to the poor. In 1861 the vicar transferred £255, all the charity money, to the Official Trustees of Charitable Funds, and the cottages were transferred in 1877. (fn. 123) In 1907 the charities owned £277 in annuities and three cottages, as two had been knocked into one. The earlier charities, known as the Eleemosynary Charity of Samway and others provided upkeep of the cottages and interest was reinvested. Dividends were distributed in the name of the Elizabeth Lewis charity, as gifts of small sums of money, food or clothing for the needy. In 1919 the vicar Horace Sketchley bequeathed money for a coal charity. The funds were added to the Elizabeth Lewis charity, and from 1948 the two charities were administered as one. Between 1936 and 1945 the cottages were sold off and Council retirement bungalows were built on the site in 1962. Both charities were defunct by 2000. (fn. 124)

COMMUNITY ACTIVITIES

From the earlier 19th century to the mid 20th century there were two public houses in the parish. At the north end the Three Magpies was built beside the Cirencester road in 1830, and the Spotted Cow was on its present site at the south end of the village by 1840. The Three Magpies was no longer a public house in 1947, but the Old Spotted Cow remained open in 2009. (fn. 125) After the school was closed in 1924, it was used as a village hall. In 2005 residents conducted a successful fundraising campaign and bought it to ensure it would continue to be available for community activities. (fn. 126)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

MANOR

In the Middle Ages the manor court of Marston Meysey exercised authority over the inhabitants. (fn. 127) In 1259 it was decreed that the reeve of the manor and four villeins should do suit of court twice annually at Castle Eaton. (fn. 128) They were also subject to the jurisdiction of the lord of the manor and borough of Fairford (Glos.), who held courts in the village in the 1480s. (fn. 129) The bishops of Salisbury held manorial courts until 1869. The court appointed manorial officers, a bailiff, constable, affeerors, a sheep teller, a hayward and tithingmen, and the jury. During the 17th century the court's main business became the registration of land transactions. Another important activity was control over where animals should graze. The court also issued permits to lop timber, orders to repair drains, walls, and highways, and maintained the village stocks and the pound for stray animals. From 1856 to 1869 its main function was to enrol deeds of enfranchisement of copyhold properties. (fn. 130)

PARISH

By 1680 churchwardens were elected for Marston Meysey, who oversaw public affairs with the principal inhabitants. (fn. 131) By 1813 the principal inhabitants met as a vestry, which elected parish officers, churchwardens, overseers of the poor, overseers of the highways, and a constable, administered the charities, and levied rates to support highway maintenance and poor relief. (fn. 132)

The vestry spent £49 on poor relief in 1775–6 and £66 in the three years to Easter 1785. The low sum of 1s. 9d. was levied as the poor rate of 1802–3, when a total of £71 was spent on the outdoor relief of 30 adults and four children. (fn. 133) In 1813 £183 relieved 21 paupers. Between 1813 and 1834 expenditure was generally between £150 and £200, with unusually high expenditure of £270 in 1818–19 and £260 in 1832. (fn. 134)

In 1835 Marston Meysey joined Cirencester Poor Law Union, and in 1881 it was transferred to the Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Poor Law Union. In 1884 the vestry discussed a return to Cirencester union, as the Wiltshire county rate was far higher than the parish's rateable value. The parish remained in Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural District until 1974, and then North Wiltshire District until 2009. (fn. 135) In 2009 it was transferred to Wiltshire Council. In the early 21st century there were too few inhabitants to qualify for a parish council, but a parish meeting was well attended. (fn. 136)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

PARISH CHURCH

Marston Meysey, a dependent chapelry of the adjacent parish of Meysey Hampton (Glos.), lay in the diocese of Worcester until 1541, and thereafter in the newly created diocese of Gloucester. (fn. 137) There was a chapel at Marston Meysey by 1302, (fn. 138) and in the early 14th century additional clergy were recorded in the parish, whose duties would have included serving the chapel. (fn. 139) The dispute over ownership of the manor during that period affected ecclesiastical affairs. By 1329 the inhabitants of Marston Meysey had withdrawn from their obligations to Meysey Hampton church, and the chapel functioned as their parish church with services on Sundays and festivals. John of Meysey's chaplain, Sir John Ford, performed services for which the chapel was not licensed, including baptisms. The loss of income to Meysey Hampton church provoked its rector to complain to the bishop. The dispute was resolved in 1330 in favour of the rector, although not without resistance from John of Meysey. (fn. 140)

The hamlet's population was too small to fund its obligations to Meysey Hampton church and to maintain its own chapel and services, and the subsequent history of the chapel is one of neglect and periodic revival. By 1548 the chapel was no longer in use and all the inhabitants were obliged to worship at Meysey Hampton church. (fn. 141) In 1648 Parliament granted Marston Meysey full parochial rights in response to a petition from the inhabitants. Robert Jenner (d. 1651), who purchased the manor from Parliament, rebuilt the derelict chapel on its former site. (fn. 142) Following the Restoration, Marston Meysey reverted to its former status as a dependent chapelry. By 1680 the chapel and its yard had been re-absorbed into Manor farmyard, and the bell, font and other furnishings were in the hands of trustees. (fn. 143) In c. 1700 the chapel was described as having been demolished. (fn. 144) In 1714, in consideration of £18 paid for the use of the poor, the chapel, yard and other possessions were given to William Jenner of Manor farm by the other ratepayers. (fn. 145)

In the 1730s the chapel was again restored, after many years in ruins. The inhabitants raised money to repair the building and to endow a curacy, and Queen Anne's Bounty gave additional funds. In 1739 a curate was appointed for Marston Meysey and in 1742 the chapel was reconsecrated and rededicated to St James with full rights. (fn. 146) The consecration deed, the earliest record of the dedication to St James, made Marston Meysey's inhabitants responsible for the upkeep of the chapel and chapel yard. Their failure to do so compounded the deficiencies in the 1730s building work. By 1842 the dilapidated state of the chapel had come to the attention of the lord of the manor, the bishop of Salisbury, who offered to contribute to the cost of rebuilding. The vestry hoped to postpone the expense and started an angry dispute with the diocesan authorities. This was not resolved until 1848, when the chapel was patched up to both sides' satisfaction. (fn. 147) Despite the improvements of the mid 18th century, religious provision remained inadequate as there was no clergy house until 1864. Curates generally lived in adjacent villages and combined their work with other cures. (fn. 148) William Rankin, rector of Meysey Hampton, took on the additional duties of curate of Marston Meysey, thus reuniting the two livings from 1873 to 1882. (fn. 149) Under his incumbency an entirely new church was built, completed in 1876. (fn. 150) In 1924 the diocesan authorities decided to reunite the benefices of Meysey Hampton with Marston Meysey permanently, which came into effect in 1937. (fn. 151) In 1981 Marston Meysey became part of the united benefice of Meysey Hampton with Marston Meysey and Castle Eaton, and in 2005 the diocese was considering plans to incorporate this into a larger team ministry. (fn. 152)

Advowson

In the early 14th century John of Meysey unsuccessfully claimed the advowson, the right to present a priest to serve the chapel on his manor of Marston Meysey. (fn. 153) Robert Jenner (d. 1651), who bought the manor in 1648 revived a claim to the advowson. (fn. 154) However, it was not until 1737 that the curacy of Marston Meysey was endowed as a separate benefice, and the right of presentation granted to the rectors of Meysey Hampton. (fn. 155) By 1937 the advowson had been transferred to the Church Society Trust. (fn. 156)

Value and Property

All income from church property and tithes belonged to the rector of Meysey Hampton until the 18th century. The greater and lesser tithes were worth £90 a year in 1784 when the rector leased them to the Jenner family. (fn. 157) Most of the glebe lands were in Meysey Hampton, but by 1612 these included 2 a. in Hill Mead, Marston Meysey. (fn. 158)

In the 1730s a total of £400, including £200 from John Bleeke, was raised towards endowing a curacy at Marston Meysey. Another £400 was granted from Queen Anne's Bounty to match the funds raised locally. (fn. 159) £200 was spent on rebuilding the chapel and c. 14 a. of land in Meysey Hampton was purchased, producing a rental income of £24 a year towards the curate's salary of £50. (fn. 160) Between 1775 and 1832 Marston Meysey received five further payments of £200 each by lot from Queen Anne's Bounty to augment the living. (fn. 161) The income from the endowment only just covered the curate's salary, making it difficult to pay the church rates charged by the rector of Meysey Hampton, although these ceased to be paid by agreement in 1862. (fn. 162) By 1861 a further £200 had been raised by subscription from benefactors. In 1863 both the trustees of Mrs Pyncombe and the Diocesan Society each gave £100 and the net value of the benefice rose to £77.

In 1863 work began on building a parsonage house, with additional funds from Queen Anne's Bounty. (fn. 163) This was on the site of Bleeke's farmstead, which was transferred from the ownership of the bishop of Salisbury to the governors of Queen Anne's Bounty for this purpose. The architect of this Victorian Gothic building was James P. St Aubyn of London. (fn. 164) In 1869 economy measures were introduced after church rates were abolished: the vicar subsequently paid for washing the surplices and cleaning the church, and churchwardens' expenses at visitations were disallowed. (fn. 165) In 1887 the parish owned 26 a. of land in Cricklade and Meysey Hampton, which produced an annual rental income of £45. The land in Cricklade was sold before 1914, when the 14 a. of pasture in Meysey Hampton was sold, as its rental income had shrunk during the Agricultural Depression to £10 10s. a year. (fn. 166) In 1923 the vicar described Marston Meysey as a poor parish. Most of the net income of £239 came from grants from various ecclesiastical bodies. The benefice's poverty led to its union with Meysey Hampton, which had a net income of £400 at this date. (fn. 167)

RELIGIOUS LIFE

A chalice of 1648, two pattens, one dated 1793, the other 1895, and a silver-mounted baptismal shell of 1916 remain the property of the benefice. (fn. 168) The chalice was presumably supplied by Robert Jenner (a goldsmith) (fn. 169) when he rebuilt the chapel to be a parish church. The church has one bell dated 1741. (fn. 170) The registers date from 1742. (fn. 171)

Clement Headington, who became perpetual curate in 1739, held two services every Sunday. (fn. 172) After his death the chapel was less well served, for example his successor Charles Coxwell (1782–1817) served at least four other parishes and resided in a fifth, although he did employ some deputies. (fn. 173)

The pattern of non-resident clergy was broken by Meyrick Holme (perpetual curate 1839–1873), who lived in lodgings in the village until the vicarage was built in 1863–4 and was able to perform full duties. (fn. 174) Early 19thcentury church wardens and vestry were generally wellorganised and efficient in their running of parish affairs. (fn. 175) However their low-church Anglicanism brought them into conflict with the diocesan authorities. In 1842 the first plans were drawn up for a fashionable new gothic chapel. The communion table was to be moved from the centre to the east end of the chancel, and the pews altered to allow kneeling, thus introducing more ritual into religious worship. The ratepayers signed a petition stating that this would be a return to the superstition of the Middle Ages. They also rejected the enlargement of the church to make room for free seats for the poor. The diocese was keen to make church-going more accessible and the existing chapel could only accommodate about half the population in rented box pews. The plans were rejected partly for financial reasons, as they would have cost far more than the temporary repairs. (fn. 176)

A new church was eventually built and worship became more elaborate and 'High Church' in the later 19th century, probably under the influence of Revd Frederick Bulley of Marston Hill House. He and his wife Margaret gave most of the stained glass windows and liturgical ornaments for the new church, and others were given by the clergy and their families. (fn. 177) In the 1880s mid-week church activities were introduced. In the 1890s and early 1900s the Confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament, an Anglo-Catholic organisation in vogue at the time within the Anglican church, met for extra communion services and in 1895 gave the church a silver paten. (fn. 178) In the later 20th century there were family services, when there were sufficient numbers of children, and despite an overall decline in numbers, religious worship was maintained by a small but active group of inhabitants. (fn. 179)

No Protestant Nonconformity or Roman Catholic public worship is recorded in Marston Meysey.

CHURCH BUILDING

St James Chapel

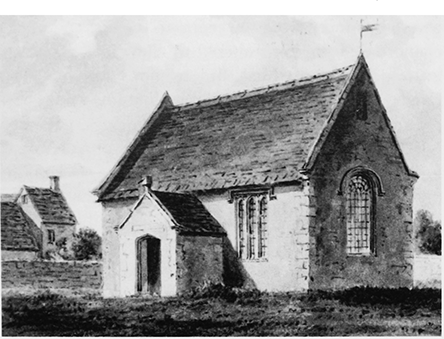

There is now no trace of either the medieval chapel, or of the 1648 chapel built on the same site and with the original materials. (fn. 180) After restoration work was completed in 1742, the chapel was said to be 40 ft. long and 17½ ft. wide and the burial ground 60 by 38 ft. (fn. 181) In 1810 it was depicted as a simple single-cell building with late medieval windows and porch. (fn. 182) The south porch was said to have been re-used as the front porch of Manor farmhouse when this church was dismantled, and probably two of the doors. Another door and panelling were probably re-used at the Grange. (fn. 183) Inside were private box pews, two of which belonged to Manor farm, a gallery which had been added in 1808 to provide extra seating and a reading desk for the minister. (fn. 184) By the 1840s major repairs were needed because of the poor quality of the 18th-century restoration. The roof beams of unseasoned oak sagged under the weight of the stone tiles and thrust out the walls, for which insufficient mortar had been used. The structure was held up by the south porch and heavy buttresses along the north wall. In 1848 the church was re-roofed using pine timbers and the original stone slates. The walls were repaired and raised by a foot and the gallery and the pews were reinstated. The curate Meyrick Holme gave £20 to enlarge the windows and to make them pointed. (fn. 185) The burial ground was enlarged at the same time. (fn. 186)

33. The old church from the south-east c. 1810. Built in 1648 to replace a medieval chapel, this modest building was replaced in 1876.

A new building was proposed in 1874 by William Rankin, rector of Meysey Hampton and curate of Marston Meysey. It was designed by James Brooks of London, one of the most inventive architects then working, and was completed in 1876 at a cost of almost £900, which was raised by public subscription. (fn. 187) It was built on a new site to the north-east of the old church yard to avoid disturbing the graves. The walls of local coursed limestone incorporate material from the previous chapel. (fn. 188) The lines of the church are simple, bold, and characteristic of Brooks. The style is Early English and the nave and chancel are contained under one steeplypitched stone slated roof. The church is lit by lancet windows, the east window being large and of three lights. In the west gable is a sexfoiled circular window and a bell recess and on the south wall a south doorway projecting as a shallow block. Nave and chancel are divided by a low screen with integrated semi-circular pulpit. The nave with wooden barrel vault is plain in contrast to the much more ornate chancel, which is raised and has a stone vault carved with nailhead, and a piscina. The only other decoration is the colour introduced by red and cream banding in the stone screen, and coloured stones in the font. (fn. 189) The altar, lectern and choir stalls were given by the parish of Meysey Hampton and the stained glass windows are by Bagally of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. (fn. 190)

MAP 17. Marston Meysey in 1839. A dependent chapelry of Meysey Hampton (Glos.) until the 19th century, a large proportion of the modern parish now lies under the runways of RAF Fairford.