A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Historic Parishes - Leigh', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18, ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/171-185 [accessed 6 April 2025].

'Historic Parishes - Leigh', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Edited by Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online, accessed April 6, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/171-185.

"Historic Parishes - Leigh". A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online. Web. 6 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/171-185.

In this section

LEIGH

LEIGH is an area of scattered settlement which lies c. 3.5 km. south-west of Cricklade and c. 2 km. south-east of Ashton Keynes. (fn. 1) It was a township and chapelry of Ashton Keynes parish and in 1884 it became a separate civil parish. The Leigh (pronounced 'Lie'), is a name derived from the Anglo-Saxon 'leah', a clearing in a wood. (fn. 2) Leigh was part of Ashton Keynes manor until 1548, when land worked from farmsteads at Leigh was detached from Ashton Keynes manor and held as the manor of Leigh. (fn. 3) The men of Leigh subsequently levied their own rates, appointed their own overseers, and relieved their own poor. (fn. 4)

Some farmsteads at Leigh included land in Ashton Keynes, (fn. 5) on which rates were paid to Leigh. After Leigh was inclosed in 1767, 16 a. of land in Ashton Keynes, on which rates were paid to Leigh, lay as four islands within Ashton Keynes parish, and when Ashton Keynes was inclosed in 1778 Leigh was awarded c. 120 a. of allotments lying in the south-east corner of Ashton Keynes near the boundary with Leigh. (fn. 6) In 1841 Leigh covered c. 1,350 a., (fn. 7) and in 1884, after minor land exchanges with Ashton Keynes, 1,461 a. (fn. 8) Of the 120 a. or so allotted in 1778 to those paying rates to Leigh, 34 a. was transferred from Leigh parish to Ashton Keynes in 1984. (fn. 9) In 1971 the area of the parish was c. 1460 a. (591 ha.). In 1984 small parcels of land on the boundary were transferred from Leigh to Ashton Keynes and c. 741 a.(c. 300 ha.), south of Malmesbury Road were transferred from Cricklade to Leigh: in 1991 Leigh was c. 2216 a. (897 ha.). (fn. 10)

Boundaries

Leigh is separated from Ashton Keynes to the north by the Thames and the Swill brook: it is cut off from Ashton Keynes by winter flooding along this boundary. Sections of the northern boundary now divert from these watercourses to incorporate field boundaries. Derry brook, a tributary of the Thames, formerly known as Sambourne lake forms the western boundary with Minety, and Bourne lake stream forms the eastern boundary with Cricklade. In 1630 the boundary of Braydon forest lay along Leigh marsh between the waste of Leigh manor, which was outside the forest, and the waste, formerly Peverills, within it. (fn. 11) The southern parish boundary mainly followed the south side of the Cricklade to Malmesbury road until 1984, in a couple of places following an older course of the road. (fn. 12)

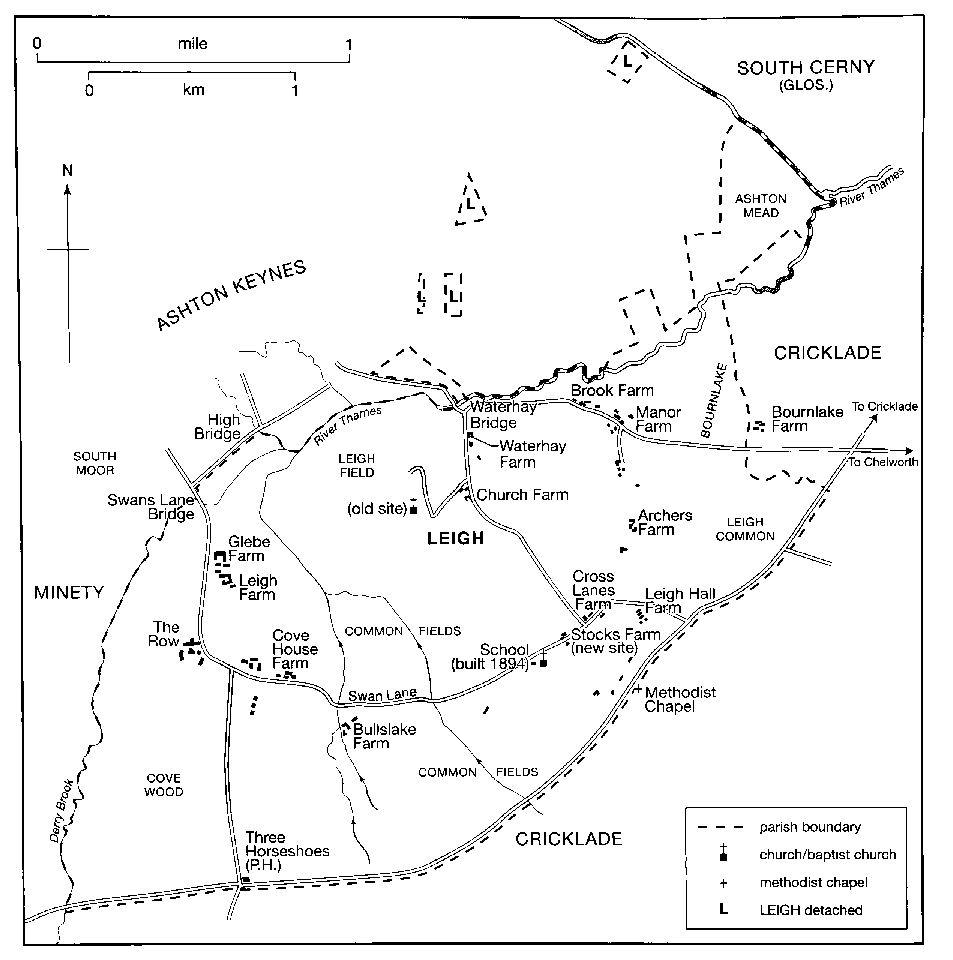

MAP 15. Leigh in 1875. A township and chapelry of Ashton Keynes, it became a parish in 1884. Due to regular flooding, most farmsteads lie along an arc which follows the 85 m. contour, a line traced by Swan Lane.

Landscape

The parish is flat and lies at c. 83 m. in the north and east, rising to c. 94 m. in the south. (fn. 13) The soil is mainly clay, although the beds of the Thames in the north have left gravel deposits and there are three more small gravel deposits scattered throughout the parish. (fn. 14)

Communications

25. Aerial photograph of Leigh, looking west and showing extensive ridge and furrow, some of which appears to be medieval. In the centre are the 19th-century church and former village school, the focus for 20thcentury development.

The main Cricklade to Malmesbury road travels eastwest across the south of the parish. (fn. 15) Another road travels across the west of the parish, linking Leigh with Wootton Bassett to the south and Ashton Keynes and Cirencester to the north: it becomes known as Ashton Road after it joins Swan Lane. Swan Lane runs in a semi-circle through the centre of the parish in an eastwest direction. In the east, a road travelling north west from the Cricklade to Malmesbury road joins Swan Lane at a junction by Crosslanes Farm and turns north to Ashton Keynes across a bridge over the river Thames: Swan Lane continues as a track, which once connected several farms with an east-west road, which bisects the NE corner of Leigh connecting Ashton Keynes with Chelworth. (fn. 16) The Malmesbury road, called Forest Lane before 1831, (fn. 17) was turnpiked in 1755–6 and improved between 1778 and 1810; it was disturnpiked in 1876. (fn. 18) A toll house at Leigh was disused by 1864. (fn. 19)

Population

In 1377 there were 87 poll-tax payers. (fn. 20) In 1523 there were 31 households, but only one was wealthy enough to be taxed. (fn. 21) Four archers were mustered in 1539, (fn. 22) and 10 households were taxed in 1576. (fn. 23) In the 19th century the population increased steadily from 174 in 1801 to 291 in 1901. After a small decrease to 264 in 1911, the population increased steadily to 304 in 1951. (fn. 24) After a peak of 341 in 1971, the population declined to 283 in 1991. (fn. 25)

SETTLEMENT

Because Leigh's farmland has not been exploited for gravel extraction little archaeological evidence of prehistoric, Roman or Saxon activity in the parish has been discovered. The ring ditch of a probable Bronze Age barrow has been identified by aerial photography south-west of Knapp Farm, and a fieldname, Great Oldbury, east of Manor Farm, may denote the site of another. (fn. 26) Leigh is not mentioned in Domesday Book, but some of the households recorded under Ashton Keynes may have lived there. (fn. 27) Tenants of Adam of Purton were living there by 1244, (fn. 28) and the chapel (later church) at Waterhay was built around that time. (fn. 29) Most farmsteads occupy slightly elevated positions above the 85 m contour, ranged in an arc from Brook farm in the east to Glebe farm in the west, and date mainly from the 16th and 17th centuries. (fn. 30) The old church was situated within this arc, at a distance from existing buildings. Some farmsteads may have disappeared: earthworks suggest a complex of closes in the crook of Ashton Road opposite Grove Farm, and a fieldname, Black Piece, on a slight knoll to which several footpaths lead east of Upper Waterhay Farm, may also denote occupation.

Since the late 18th century Waterhay Farm, dating from the 16th century, (fn. 31) and Church Farm, now called Upper Waterhay Farm, (fn. 32) have been the only complexes of buildings near the old church. (fn. 33) The arc of farmsteads begins with Brook Farm and Manor Farm in the north east, connected by a track bearing south west to Archers Farm and Crosslanes Farm, which stands at the crossroads with Swan Lane. The line continues west along Swan Lane with Stocks, Brookside, Knapp, Home and Cove House farms, Grove Farm on the corner where Swan Lane becomes Ashton Road, and Leigh and Glebe farms on Ashton Road. Leigh Hall and Butts Lake farmsteads stand between Swan Lane and Malmesbury Road.

Intermittent settlement had occurred along Forest lane, the Malmesbury road, before 1769, (fn. 34) and a row of houses called the Woodrow in 1671 may refer to buildings in this area. (fn. 35) Ribbon development along Malmesbury Road from the early 19th century included single-storey squatters' houses, which have since been demolished or replaced by more substantial buildings. (fn. 36)

In 1894 a red brick school and schoolmaster's house were built on Swan Lane and in 1896 the medieval church was relocated to the site east of the school. These buildings provided a focus for early 20thcentury development, which took place at the southern end of the parish. Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural District Council built most of the 20thcentury housing in the parish, starting with six houses built on Malmesbury Road in the 1920s. In 1929 there were 40 houses on Malmesbury Road, 10 on Swan Lane and five on Ashton Road. (fn. 37) In 1931 the parish council recorded that over 30 houses had recently been demolished but only 14 had been built. The council applied to build more houses because of unhealthy overcrowding. (fn. 38) Before 1950 the council purchased ½ a. of the Poor's Platt on which four houses were built. (fn. 39) From 1954 more houses were built at Hillside off Swan Lane and on Malmesbury Road to house families living at Blakehill camp. (fn. 40) In the early 1960s travellers began to set up caravan sites for themselves, including the Bourne Lake Caravan Park. (fn. 41)

MANORS AND OTHER ESTATES

Leigh was part of Ashton Keynes manor, probably identifiable as the estate given by King Alfred (d. 899) to Ælfthryth, his youngest daughter, and which in 1066 belonged to Cranborne abbey (Dorset); in 1102 ownership was transferred to Tewkesbury abbey (Glos.). (fn. 42) The manor passed to the Crown after the dissolution of Tewkesbury abbey. (fn. 43) In 1548 Edward VI granted away the land of Leigh as a separate manor, which was briefly reunited with Ashton Keynes in the early 17th century under the ownership of Sir John Hungerford. In 1623 Hungerford sold Ashton Keynes but retained Leigh as part of a larger estate centred on Down Ampney (Glos.), which included lands once belonging to Great Chelworth manor, Cricklade parish. (fn. 44) What remained of Leigh manor in 1803 was put up for sale in lots, after which the manorial title descended with a much reduced estate.

LEIGH MANOR

In 1548 Edward VI granted the land of c. 40 customary tenants of Ashton Keynes to William Sharington (d. 1553), as the manor of Leigh. In 1549 Sharington was convicted of fraud during his vice-treasurership of Bristol mint: although most of his estates were restored to him in 1550, (fn. 45) Leigh was not apparently among them and remained Crown property until the early 17th century. (fn. 46) Sir Anthony Hungerford (d. 1558), became lessee under the Crown of the manor of Ashton Keynes with Leigh in 1538, (fn. 47) and in 1598 Robert Jaye sold various properties in Leigh to Sir John Hungerford (d. 1635). (fn. 48) In c. 1612 Sir John Hungerford bought the manor of Leigh. (fn. 49) He sold the manor of Ashton Keynes in 1623 but retained Leigh and it descended, like Latton manor, in the Hungerford, Dunch, Craggs and Eliot families, (fn. 50) until 1803 when the then owner, Lord Eliot (Edward Craggs Eliot, d. 1804), put it up for sale in lots. (fn. 51) In 1803 Leigh manor was said to be coextensive with the township and it consisted of c. 828 a. including lands in Chelworth, (in Cricklade parish). (fn. 52)

The lordship of the manor of Leigh was purchased from John Eliot, Lord Eliot (d.1823), with Knapp farm, c. 122 a., by Robert Nicholas in 1806, who conveyed it to his brother John Nicholas in an exchange of lands in 1808. (fn. 53) At John Nicholas' death in 1836 his estate was divided between his children. (fn. 54) The lordship of Leigh was sold with Waterhay farm in c. 1855 to Harry Vane, (fn. 55) (from 1864 Harry Vane Powlett, duke of Cleveland). (fn. 56) Thereafter the property descended with the lordship of Ashton Keynes manor to his grandson Arthur William Henry Hay (from 1900 Hay Drummond), (fn. 57) from whom the lordship of the manor was purchased by A. W. Bowley in 1917; (fn. 58) his grandson, Mr A. K. Bowley, retained it in 2001. (fn. 59)

Waterhay Farm

This farm, of c. 143 a., was

purchased by Mr Richards in 1917; (fn. 60) and by c. 1920 had

been acquired by George Brown (d. c. 1945). (fn. 61) By 1956

ownership had passed to the Rumming family; (fn. 62) the

owners in 1996 were Richard and Jane Rumming.

Knapp Farm

This farm, which incorporated Butts

Lake farm, was sold in 1867 by John Nicholas' son

Edward Richmond Nicholas and daughters Jane, wife

of John Roles Fishlake and Frances, wife of Robert

Moulton Atkinson, to Richard Mullings. (fn. 63) It remained

in the Mullings family until at least 1913. (fn. 64) In about 1919

ownership passed to Mr F. W. Baker. (fn. 65) By 1929, when

Knapp farm was of 120 a., the owner was F. R. Read. (fn. 66)

In the 1940s Knapp farm was let to Horace Howse, who

later owned it, and the farmhouse was demolished and

rebuilt on a new site in the 1950s. (fn. 67) The owner in 1963–4

was the Honourable Victor Saumarez. (fn. 68)

OTHER ESTATES

Maskelyne/Jenkinson Estate

The Maskeyne family owned an estate in Leigh by 1780, (fn. 69) which included a moiety of the manor, Manor and Brook farms and other lands. (fn. 70) In 1805 Lord Eliot sold lands which became known as Archers farm to William Maskelyne (d. c. 1809), whose estate of 627 a. in Leigh and neighbouring parishes was inherited by his son Richard. (fn. 71) Richard was later described as a spendthrift who dissipated a fine fortune and ruined his family; (fn. 72) his whole estate was apparently sold in 1827 to Robert Jenkinson, earl of Liverpool. (fn. 73) On Lord Liverpool's death in 1828 the estate passed with the earldom to his half-brother Charles Cecil Cope Jenkinson, and at his death in 1851 to his cousin Sir Charles Jenkinson Bt (d. 1855). (fn. 74) It then passed with the baronetcy to Sir Charles' nephew Sir George Samuel Jenkinson (d. 1892), (fn. 75) and to Sir George's son, Sir George Banks Jenkinson, (fn. 76) who put it up for sale in 1894 as an estate of c. 603 a. lying in Leigh, Ashton Keynes and Cricklade. (fn. 77) The three farms in Leigh, c. 450 a., remained unsold at Sir George's death in 1915 and passed to his grandson and heir, Anthony Banks Jenkinson, then a minor. (fn. 78) Archers farm, c. 105 a. in 1913, was apparently purchased by Mrs C. J. Freeth, and sold in 1943 to Richard Norbury, who sold it in 1948 to Squadron Leader D. Shawe, (fn. 79) who sold it in 1956 to Gwynedd Braby, (fn. 80) who sold it in 1961 to W. E. T. Slatter, whose widow sold Archer's farm in 1969. (fn. 81) Manor farm, c. 185 a. in 1913, was acquired by A. J. Freeth before 1920. (fn. 82) In 1969 members of the Freeth family sold the right to extract gravel from the land to Roger Constant & Co. but still owned the farm in 2008. (fn. 83) Brook farm, c. 127 a. in 1913, was acquired before 1920 by Ernest Ellison, the owner until 1945 or later; (fn. 84) by 1942 all but 12 a. of its land was being farmed with that of Manor farm, (fn. 85) and by 1951 the farmhouse was owned by Brigadier T. K. Merrett, the owner in 1964. (fn. 86)

Cove House Estate (Leigh)

The estate originated in the 16th century, when Henry Cove held a 2-yardland holding and two tenements called Coves and Woodwards. (fn. 87) Cove, his wife Dorothy, and their son Thomas repeatedly mortgaged the estate, (fn. 88) and apparently sold it to Thomas Foxe, whose widow Osweld married Robert Cresswell, who purchased the estate from John, Hugh and Roger Foxe and Anthony Cove. Cresswell conveyed the estate to his brother Richard Cresswell and it passed to Richard's son John Cresswell. (fn. 89) Because of John's Royalist affiliations in the Civil War, the estate was seized in 1649. (fn. 90) Its descent is unclear from then until 1772, when the owner Richard Hippisley Coxe sold it to Richard Kinneir (d. 1812), (fn. 91) a surgeon of Cricklade. The entailed estate passed to his son Richard and grandson Richard (d. 1874), another surgeon. Richard Kinneir conveyed his estate to trustees to sell in 1864, when it was of c. 243 a. including Cove House and Cross Lanes farms and other lands in Leigh, Cricklade and South Cerney (Glos.). (fn. 92)

In 1871 Cove House farm was purchased by Thomas Porter Jose, (fn. 93) who apparently sold it to Hubert Cowley by 1895, (fn. 94) who sold it in 1900 to William Clapton, who by 1910 had sold it to Rowland Read (fn. 95) (d. 1922). (fn. 96) In 1939, Frank Rowland Read, the owner, (fn. 97) sold it as a farm of c. 152 a. (fn. 98) In 1942, as a farm of c. 186 a. it was let to Reuben Howse, (fn. 99) who subsequently owned it until at least 1964. (fn. 100) In c. 1974 Cove House farm was purchased by Doreen Kemp and her husband; Mrs Kemp sold it in 1989. (fn. 101)

Cross Lanes farm, c. 22 a. was part of the Cove House estate in 1864. (fn. 102) It was apparently sold to George Brain (d. c. 1890), whose executors sold it to James Curtis and it was still owned by the Curtis family in 1964. (fn. 103)

Cove House

The farmstead stands on a site which

may have been occupied since the middle ages: the

present house contains features which date to the 16th

and 17th centuries and it was considerably improved in

the 19th century. (fn. 104) In 1866 it was described as a fivebedroom former mansion with c. 87 a. (fn. 105) Cove House

was empty in 1915, (fn. 106) and was requisitioned by the War

Department during the Second World War. (fn. 107)

Great Chelworth Manor (Cricklade parish)

This manor once included c. 141 a. of land in Leigh, laid out as Leigh Hall and Stocks farms, and Butts Lake farm which was later amalgamated with Knapp farm. (fn. 108) By 1803 the land was owned by Lord Eliot, who sold Leigh Hall farm to William Large, (fn. 109) c. 37 a. in 1841. (fn. 110) It passed to Charles Large in c. 1825, to his widow Leah, and to their son William, whose widow sold it to Edward Brown before 1905, who was leasing it in 1910 to Norman Barclay Bevan. (fn. 111) Capt Eric W. Patterson acquired Leigh Hall farm between 1913 and 1920 and still owned it in 1945. (fn. 112) By 1955 it belonged to E. J. Hiett, the owner in 1964. (fn. 113) Leigh Hall, a Georgian house with earlier origins, was modernised in the early 1980s. (fn. 114)

26. Cove House, a fine 16thcentury farmhouse, improved in the 19th century.

Stocks farm, which had also presumably been sold by Lord Eliot, was purchased by Charles Stevens from William Champernowne and William Chapperlin in 1826, (fn. 115) it was c. 53 a. in 1841. (fn. 116) Ownership remained with the Stevens family until 1914, when it was sold as a farm of 83 a. (fn. 117) In 1927 Stocks farm was owned by George Brown, (fn. 118) and in 1964 by W. G. Brown. (fn. 119)

Church (Upper Waterhay) and Home Farms

Both were apparently purchased from Lord Eliot by James Fielder Croome in 1803. (fn. 120) Church or Upper Waterhay farm was sold to Henry Reynolds by 1805, (fn. 121) who in 1826 sold it to William Large, who owned it in 1841 as a farm of c. 87 a. (fn. 122) The farm was sold to William Plummer between 1840 and 1845, (fn. 123) and passed to E. H. D. Plummer, who sold it in 1899 as a farm of c. 93 a. to Revd M. J. Milling, vicar of Ashton Keynes. (fn. 124) Between 1913 and 1920 Milling sold the farm to E. J. Ponting, the owner in 1964. (fn. 125) Subsequent owners included Mr and Mrs Cox and Mr and Mrs Dickinson. (fn. 126)

Home farm was sold by Croome to Thomas Lydiard in 1835, (fn. 127) who went bankrupt in 1842. (fn. 128) By 1845 the farm had passed, presumably by sale, to Joseph Mullings. (fn. 129) Between 1913 and 1927 the Mullings family sold Home farm to E. J. Manners, (fn. 130) and he or another E. J. Manners owned it in 1964. (fn. 131)

Leigh and Peacey (Grove) Farms

Joseph Large bought farmland from Lord Eliot in 1803, which he sold to Henry Hulbert between 1813 and 1817. (fn. 132) In 1826 it was divided: (fn. 133) that lying west of Swan Lane was cultivated from the Row, a group of buildings west of Swan Lane, and was later amalgamated with Peacey or Grove farm, (fn. 134) which belonged to Joseph Hulbert in 1841. (fn. 135) In 1862 Hulbert sold it to Richard Hodgson, who in 1875 sold it to Henry Freeth. (fn. 136) Freeth's executors owned it in 1913 as Peacey farm, c. 82 a. In 1920 the owner was Thomas Curtis, (fn. 137) who sold it to the occupier Rowland Read, from whom it passed to John Read before 1942. (fn. 138) In 1956 Peacey (Grove) farm was owned by H. W. Barrow. (fn. 139)

Leigh farm belonged to the Hulbert family until 1853, when it was sold to John Cook. (fn. 140) Cook sold it to Thomas Peter Jose in 1872. (fn. 141) By 1910 Jose had apparently sold it to Rowland Read, (fn. 142) (d. 1922), and by 1927 ownership had passed to A. F. Seymour. (fn. 143) Leigh farm was 65 a. in 1942, when it was still owned by Seymour, (fn. 144) and C. E. Seymour owned it in 1964. (fn. 145)

Glebe Farm

Hitherto owned by the vicar of Ashton Keynes. (fn. 146) it was sold c. 1920 to Harry Smith, (fn. 147) whose family owned it as Glebe farm in 1964. (fn. 148) The owner in 1993 was A. J. Freeth, who then put it up for sale as a farm of c. 67 a. (fn. 149) The owner of the farmhouse in 1995 was Mr M. Bowness. (fn. 150)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

AGRICULTURE

In 1086 the estate called Ashton apparently included the land which became Leigh parish, and some tenants of the estate may have had farmsteads there. (fn. 151) Although throughout its history the land was used predominantly for pastoral farming, Leigh apparently had its own open fields, as ridge and furrow markings are still visible around the remains of Leigh and on either side of Swan Lane. (fn. 152) Leigh field lay to the north of the old church, (fn. 153) and was farmed collectively until c. 1767. (fn. 154)

Before Inclosure

In 1548 the land granted as Leigh

manor had 20 customary tenants and five free tenants,

one of whom also held a customary holding. That

tenant farmed 2 yardlands, nine tenants farmed 1

yardland each, 8 farmed ½ yardland, 2 farmed ¼

yardland, and a dozen or so rented only a few acres or a

toft. Tallage, perhaps a euphemism for entry fines or

heriots, was paid by 11 tenants, and three cocks and 12

hens were also given as rents. The tenant of the

demesne farm of Ashton Keynes manor held two

parcels of land in Leigh for which he paid 21s. rent. (fn. 155)

In 1681 there were eight free tenants and 20 copyholders. None of the free tenants held more than a few closes of land; of the copyholders, there were five yardlanders, three half-yardlanders, and two quarteryardlanders, of whom all but one were liable to pay heriot either as money or in kind, (fn. 156) but no evidence of the customary tenants providing labour services for the lord of the manor has been found. In 1723 the largest copyhold farm was 51 a., and most copyholders farmed between seven and 16 a. (fn. 157) In 1767 only 54 a. of the land was farmed as arable. (fn. 158)

In the Middle Ages the men of Leigh had extensive feeding rights in Braydon forest: before inclosure intercommoning allowed animals to roam across the common pastures of Leigh, Minety, Ashton Keynes, Chelworth (in Cricklade parish), and the uninclosed land of Braydon forest south-west of Chelworth. (fn. 159) Sir John Hungerford claimed in 1629 that these rights had been allotted them by the swanimote courts and that they included pasture at all seasons for all animals except sheep and pigs in the waste and demesne wood of the forest, the feeding of sheep and pigs in the wastes and marshes outside the covert of the forest, the feeding of cattle at will and pleasure in the winter, and the right to drive horses and cattle into the demesne woods and wastes to feed there. (fn. 160) To compensate them for the loss of those rights after the disafforestation of Braydon c. 1630, 25 a. was allotted to the poor of Leigh. (fn. 161) That land was apparently retained by Hungerford and formed part of the estate of the earl of Liverpool, in 1841. (fn. 162)

The custom of intercommoning continued until the 18th century. Leigh, or Bourne Lake common lay in the east, adjacent to Chelworth and Cricklade commons. (fn. 163) South moor, a common pasture in the south west of Ashton Keynes was open to Leigh. (fn. 164) However, cattle found trespassing on Leigh grounds within Ashton Keynes manor were impounded by the residents of Leigh in their pound on the common mead. (fn. 165) What in 1996 was Waterhay farm was the Pound house in 1773. (fn. 166) Intercommoning by the men of Ashton Keynes was further restricted in 1767 when Leigh manor was inclosed. (fn. 167) At that date Leigh or Bourne Lake common, 172 a., Cove Wood common, 255 a., Ashton or Common Mead, 155 a., Swan Lane End, 18 a., Little Moor, 10 a., and Common Field, 54 a. were all apparently common pastures in Leigh. (fn. 168)

Much of Leigh's pasture and meadow land had evidently been inclosed by 1681. (fn. 169) In 1767 the remaining common land, 629 a., was inclosed, of which 54 a. was arable and the rest pasture. Inclosure restricted intercommoning by the inhabitants of Ashton Keynes, (fn. 170) and the practice had ceased by 1780.

Farms and Farming after Inclosure

In 1803 the land

of Leigh lay mainly as seven farms, of c. 50–150 a.,

divided into many small fields and closes for livestock. (fn. 171)

At that date Leigh farm was run with Grove farm, and

in 1813 Leigh farm covered c. 245 a. of which c. 126 a. was

laid to arable. (fn. 172) Knapp farm covered c. 143 a. in 1846, 90

a. in Leigh and 53 a. in Great Chelworth, Cricklade,

when it was said to be 'much out of condition' and

'much out of repair'. (fn. 173)

In 1839 Leigh had c. 1,202 a. meadow or pasture, c. 127 a. arable and only 1 a. woodland; none of the seven larger farms had more than 125 a. and most of the farms and holdings were less than 100 a.; a few smallholders farmed less than 15 a. and there were around 20 cottages with gardens, of which five were owned by the parish and presumably let to the poor. (fn. 174)

The pattern of small pastoral farms remained the same throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. (fn. 175) In 1861 Church farm, or Upper Waterhay farm, had a newly-erected dairy and cheeseroom. (fn. 176) In 1895 there were 17 farmers, one of whom was also a cattle dealer. (fn. 177) By 1927 five farms had grown larger and had over 150 a., Waterhay, Stocks, Manor, Cove House and Glebe farms. (fn. 178) Waterhay farm was a dairy farm of c. 147 a. with only 4 a. of arable in 1913, with lands lying either side of the Ashton Keynes to Cricklade road and also north of the Thames in Ashton Keynes. It was then part of the estate of Cove House in Ashton Keynes, (fn. 179) which by 1917 was known as the Ashton Keynes estate. (fn. 180) In 1941–2 the largest farms were Manor farm with Brook farm, then farmed as one unit of 326 a., Glebe farm, 218 a., Waterhay farm, 208 a., and Archers farm, c. 127 a. Most had little or no arable, except Glebe farm, of which almost half was cultivated as arable. (fn. 181) Cattle and poultry rearing were the main agricultural activities on all farms and smallholdings; in addition, there were small flocks of sheep on Leigh and Manor farms, and on the latter the farmer also kept 25 pigs. The pigs were presumably processed at the slaughterhouse and bacon factory built beside Malmesbury Road in the 1920s and 1930s. (fn. 182) Although agriculture declined in the later 20th century, there were still dairy cattle on Manor farm and beef cattle at Waterhay farm and several other farmers worked part-time on their land to raise cattle and sheep.

WOODLAND

In 1086 a wood on the estate called Ashton was one league long and half a league wide; it lay south of the Thames in the area later called Leigh, (fn. 183) which was then part of Braydon forest. Some of the wastes of Braydon forest at Cove had been cleared for agriculture by the later 13th century and the wood belonging to the lord of the manor which stood there in 1300 had been disafforested by 1330. (fn. 184) In 1548 Cove wood still contained many mature oaks and elms, mostly coppiced, out of which the farmer of the demesne of Ashton Keynes was entitled to over 212 loads of wood and timber yearly, worth £29 3s. 4d. (fn. 185) In 1628, lands in Leigh were decreed to be outside the bounds of Braydon forest. (fn. 186) All the woodland had been grubbed up by 1769 when the area called Cove Wood common (fn. 187) covered c. 265 a. (fn. 188) There were apparently no later plantations and there was no woodland at Leigh in 2001. (fn. 189)

TRADE AND INDUSTRY

Mills

The site of a windmill is believed to lie adjacent

to Windmill Cottage on Malmesbury Road near the

eastern parish boundary. (fn. 190)

Gravel Extraction

This was controlled by the

manor court, which sent officers to inspect gravel pits

in 1682 and 1683, (fn. 191) and censored digging by the

Thames at Little Moor near Waterhay Bridge in 1788

and 1792. (fn. 192) In 1970 planning permission to extract

sand and gravel from a 48 a. site at Brook and Manor

farms was initially refused, but granted soon

afterwards. (fn. 193)

Other Industries

The Cricklade Bacon Factory

built on Malmesbury Road in 1923 was destroyed by

fire in 1927, when its owners, the Skuse brothers,

were arrested on suspicion of arson. (fn. 194) The site was

probably redeveloped, as J. H. Skuse owned a

slaughterhouse on Malmesbury Road in 1932. (fn. 195)

Skuse had plans for another bacon factory in 1938. (fn. 196)

In the 1980s Glebe farm was run as an outdoor pig

unit and sold direct and wholesale from a farm shop

on the site. (fn. 197)

At various times in the later 19th century food and other supplies were sold by a butcher, baker, grocer, greengrocer, a draper and a marine store dealer. (fn. 198) In 1941 there was a garage and shop on Malmesbury Road. (fn. 199) A shop, post office and general store stood on Malmesbury Road in 1964 and 1975, (fn. 200) in 1989 there was a butcher's shop and the village was visited by mobile food shops between 1964 and 1989, but by 1991 there was no shop in the village and the mobile shops no longer called.

In 1866 a female messenger carried letters from Ashton Keynes Post Office and the Ashton Keynes letter carrier collected outgoing mail as he passed through the parish. (fn. 201) Mains water was supplied to properties on Malmesbury Road in the 1920s, (fn. 202) and in 1975 a sewage works was located at Waterhay off the Ashton Keynes to Chelworth road. (fn. 203)

SOCIAL HISTORY

Before Leigh became a civil parish in 1866, its independence had already grown out of its physical separation from Ashton Keynes by the Thames, and the separation of Leigh from Ashton Keynes manor in 1548. (fn. 204) Leigh's population was small and sparsely scattered, which restricted social life. However, some residents felt strong loyalties: when William Howes died in 1683, he succeeded his father as 'parish clerk' and their combined service at Leigh totalled nearly 100 years. (fn. 205) To celebrate Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897, there was a tea for all inhabitants followed by 'rustic sports' and a bonfire, and Lady Jenkinson donated 84 Jubilee mugs as gifts for the children. (fn. 206)

The parish council first put forward plans to build a village hall in 1954. Financial difficulties could not be overcome, so in 1968 it was decided to renovate the existing recreation hut, located near the Methodist chapel on Malmesbury Road; the hut burnt down in the late 1970s. (fn. 207) In 1975 residents had the use of a public playing field at Hillside and a private playing field belonging to a farmer. (fn. 208) In 1989 there was also a children's play area. (fn. 209) A longstanding concern of the parish council was the lack of affordable housing, (fn. 210) combined with very limited local employment and an inadequate bus service, which together were forcing young people to move away from the village. In 1989 the council commented 'the village is slowly dying'. (fn. 211)

Inns

In 1841 no. 5, Malmesbury Road was an

inn called the Three Cups. The Three Horseshoes had

opened by 1848 on the north side of Malmesbury

Road. (fn. 212) In 1920 it was run by Stroud Brewery, (fn. 213) but was

closed c. 1960. The Foresters' Arms had opened by 1881

and was still in business in 2007. (fn. 214)

EDUCATION

There was no school at Leigh until the 19th century, but children could attend schools at Ashton Keynes or Cricklade. (fn. 215) In 1819 Leigh had a day school with 24 pupils, although this had closed by 1835. (fn. 216) There was a Sunday school in 1851 and during the winter children attended Sunday school at Ashton Keynes. (fn. 217) A National school was built at Ashton Keynes in 1871 with contributions from the inhabitants of Leigh; children from Leigh attended and a night school was also held there four evenings a week. (fn. 218)

In 1893 Wiltshire County Council ordered Leigh parish council to build a school for 55 children. J. Mullings donated a site next to the proposed location of the new church, help with the building costs was provided by Revd Milling as an interestfree loan and the new National school opened in 1894. (fn. 219) In 1906 it had space for 86 children and average attendance was 65. (fn. 220) Average attendance was 48 between 1906 and 1938, (fn. 221) and peaked at 75 in 1934. (fn. 222) Numbers fell in the later 20th century, averaging around 35, and there was continuing discussion of closure and transfer of pupils to Ashton Keynes. (fn. 223) From 1973 the children attended secondary school in Purton. (fn. 224) Although the number of pupils began to rise in the 1980s and the number enrolled was 73 in 2000, (fn. 225) in 2004 Leigh Church of England Primary School was closed and the pupils transferred to Ashton Keynes. (fn. 226)

CHARITIES

By royal charter of Charles I, the poor of Leigh were allotted 25 a. to compensate them for rights of common pasture in Braydon forest, which they lost when it was disafforested in 1628. At inclosure in 1767 an allotment of 20 a. was made in lieu of that land. (fn. 227) This pasture, later called Poor Platt, was leased out by the churchwardens. (fn. 228) Each spring they distributed the income to the second poor, residents of Leigh who were not in receipt of regular parish relief. (fn. 229) The numbers assisted varied considerably from year to year: (fn. 230) in 1816 the income was £24; in 1834 14 people received between £1 5s. and £2, (fn. 231) and in 1840 47 people received between 14s. and £1 15s. (fn. 232) In 1905 single adults received 11s. and married couples £1 2s. and another 2s. 6d. for each child aged under 14. (fn. 233) Between 1902 and 1930 between 24 and 90 adults and children received assistance each year. (fn. 234) In the 1940s Poor Platt was let out as allotments, (fn. 235) and was then purchased by the Rural District Council for new council housing. (fn. 236) In 2000–01 the income of Leigh Second Poor Charity was £1,102. (fn. 237)

Before 1786 an unknown donor gave the interest of £15 to the poor of Leigh who were not receiving poor relief. (fn. 238) That charity produced 15s. in 1816, (fn. 239) but had seemingly been lost by 1834. (fn. 240)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Forest law operated in Leigh while it was part of the royal forest of Braydon. (fn. 241) The inhabitants were summoned to attend the perambulation of Braydon in the mid 13th century, (fn. 242) and Leigh was one of the townships subject to the forest court c. 1595–1623. (fn. 243)

MANOR

The men of Leigh were subject to the manor courts of Ashton Keynes until 1548, after which Leigh developed separate courts. Two surveys of Leigh manor were made, one in 1681 and another in 1687. (fn. 244) From 1680 to 1712 Hungerford Dunch held courts leet and baron with view of frankpledge. (fn. 245) In 1754 the steward apparently held four courts at Leigh and entertainment was provided for the tenants. (fn. 246) At the view of Frankpledge jurors and the homage were sworn, and a hayward, a tithingman, assessors and a constable were elected annually. The hayward and the tithingman probably served for several years; as in Ashton Keynes, the obligation to serve as tithingman was attached to certain tenures and female tenants had to provide a man to serve in their place. In 1684 and 1700 the tithingman swore his oath before a JP. (fn. 247) Property transactions were the main business, also maintenance of watercourses, bridges, gates, and mounds, regulation of agricultural resources, including the common arable field by the Thames, Leigh field, grazing on the lanes and wastes and gravel extraction. (fn. 248) In 1838 new stocks were ordered to replace the ones which had been destroyed, and the pound was out of repair. (fn. 249) The courts leet and baron continued to transact a significant amount of business in the 19th century, (fn. 250) but no record of manorial courts held after 1857 has been found.

PARISH

Leigh functioned as an autonomous parish long before it was granted civil parish status in 1866. (fn. 251) From the 16th century or earlier Leigh appointed its own churchwardens. (fn. 252) A parish clerk, two overseers of the highway, and two overseers of the poor were also appointed each year and Leigh levied its own poor and highway rates. (fn. 253) No churchwardens' or overseers' accounts are known to survive, although it is known that the chapelwardens' attempt to levy a special rate in 1814 to reimburse themselves for repairs to the chapel was defeated by Ashton Keynes vestry. (fn. 254)

Leigh was still part of Ashton Keynes parish in 1835 when it became part of Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Poor Law Union. (fn. 255) In 1866 Leigh was granted civil parish status. (fn. 256) It belonged to Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural District from 1872, (fn. 257) and North Wiltshire District from 1974 to 2009. (fn. 258) A parish council met regularly from 1850, but other than provision for the poor, (fn. 259) little business was recorded until 1894. Thereafter its main concerns were housing provision, resistance to the installation of a mains water supply on grounds of cost from 1918 to 1925, attempts to build a new village hall from 1954 to 1968, (fn. 260) and reduced local employment and amenities in the later 20th century. (fn. 261)

Leigh levied its own poor rates from the 17th century, (fn. 262) although there was a dispute between the overseers of Leigh and Ashton Keynes in 1786 over the rating liability of Leigh's former common land north of the Thames. (fn. 263) In 1716 c. £65 was spent on poor relief; between 1783 and 1785 an average of £85 9s. 1d. was spent, and in 1803, when 27 adults, six children under 5, and 11 children aged between 5 and 14 were relieved permanently and 29 poor received occasional relief, £319 14s. 5½d. was spent on poor relief and £4 4s. 6½d. was spent on materials for employing them. (fn. 264) Money spent on poor relief decreased from £530 in 1813 to £245 in 1815 and numbers of those permanently relieved declined from 39 to 34, while parishioners relieved occasionally increased from four to seven. (fn. 265) Expenditure rose again to £648 6s. in 1819 before dropping to £443 14s. in 1820. Between 1820 and 1834 the amount spent in most years was between £410 and £449, although expenditure reached a high of £684 in 1831, fell to £441 14s. in 1833, and rose again to £524 18s. in 1834. (fn. 266)

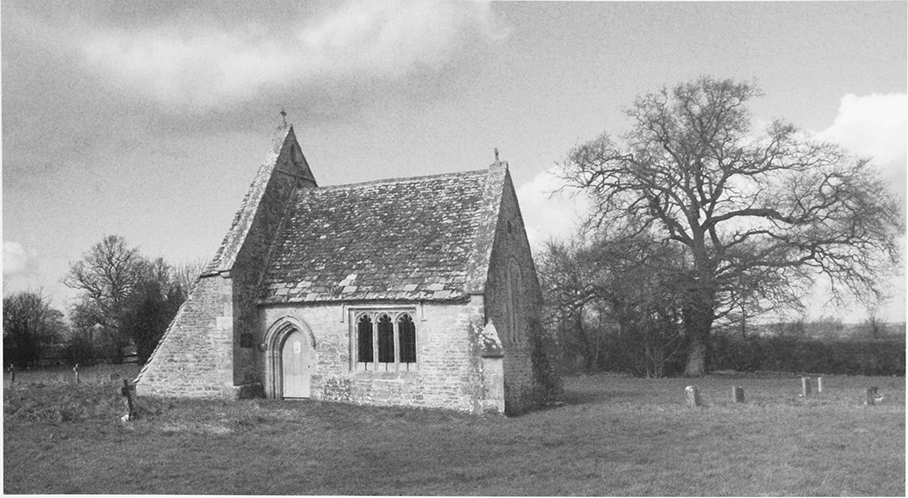

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

Leigh was a dependent chapelry of Ashton Keynes. (fn. 267) The community had its own church at Waterhay by the mid 13th century, (fn. 268) known to been dedicated to All Saints by 1848. (fn. 269) The inhabitants of Leigh had rights of baptism and marriage in their church, (fn. 270) but no right of burial until 1865. (fn. 271) Floods made it inaccessible in wet weather, thus in 1896 much of the church was dismantled and moved to a new site on Swan Lane. (fn. 272) The old chancel, buttressed by the eastern portions of the nave walls, was left behind to serve as a mortuary chapel for the graveyard. Approached across fields this medieval architectural fragment stands alone in its churchyard, an evocative sight in what is now a nature reserve. (fn. 273) In 1987 the benefice of Ashton Keynes with Leigh was amalgamated with Minety to form the united benefice of Ashton Keynes, Leigh and Minety. (fn. 274) In 2007 Leigh became part of the benefice of Ashton Keynes, Cricklade and Latton.

27. The chancel of the former parish church, which was retained as a mortuary chapel when the church was moved in 1896.

RELIGIOUS LIFE

In the Middle Ages the vicar of Ashton Keynes provided services at Leigh, (fn. 275) and in the 16th century he employed a curate for this purpose. (fn. 276) From the 16th century or earlier Leigh appointed its own chapel wardens, (fn. 277) who frequently served for more than one year; (fn. 278) Mr Maskelyne served as chapel warden for a number of years in the early 19th century. (fn. 279) In 1553 there were four bells hanging in the church, presumably including that cast in Bristol foundry c. 1450 which was among those moved to the new church in the 1890s. (fn. 280) By then too the chapel had a 6-oz. chalice and a further 1½ oz. of silver plate, the latter removed by Edward VI's commissioners. (fn. 281) Under this local regime, which by 1671 comprised two churchwardens and two sidesmen, (fn. 282) important work was carried out in the early 17th century, when the nave panelling was refixed and a new wooden gothic-style roof with carved figures was made dated 1638, probably re-using earlier components. (fn. 283) A new bell was also cast by Henry Neale in 1627. (fn. 284)

Substantial renovations were also carried out in the early 18th century: (fn. 285) the church was repaved, plastered and redecorated, a gallery was built in 1717, the chancel was rebuilt in 1720, and in c. 1726 wooden panels bearing religious quotations were mounted on the chancel walls. (fn. 286) The three-decker pulpit, which remains in the chapel, and the font both date from around the 18th century. (fn. 287) A new bell was cast by Abraham Rudhall of Gloucester in 1729. (fn. 288) The tower was repaired in 1736 and again in 1757, and there were more repairs to the church in 1784. (fn. 289) In 1744 the old chalice was replaced by one of unusual design, hallmarked for 1596. (fn. 290) Other 18th-century plate included a paten of 1723 and a pewter flagon of 1776, all part of the church's holdings in 1891. (fn. 291)

28. Interior of the chancel of the former parish, showing wall paintings of the early 18th century.

Families rented space and built private pews, like Somerset Hinton in 1714; extra seating was added in the gallery built in 1717; and more pews were built in 1814. (fn. 292) By 1835 the church had c. 200 seats, (fn. 293) of which 120 were rented in 1851 and 72 were free. (fn. 294)

In 1783 the curate held one service with a sermon each Sunday, which was poorly attended, although no Roman Catholics or Nonconformists were reported. (fn. 295) In 1787 the vicar of Ashton Keynes with Leigh lived at Cricklade. He held services at Leigh every Sunday and communion there three times a year. (fn. 296) In the early 19th century one parishioner refused to pay the chapel rate complaining that there had been no service for 14 months. (fn. 297) A curate served from 1825 except for short periods between 1828–33 and 1833–66. (fn. 298) On Census Sunday in 1851, 35 people attended the single afternoon service at Leigh, about the average; when evening services were held they were usually attended by around 80 worshippers. (fn. 299) Revd M. J. T. Milling, who became vicar in 1884, (fn. 300) oversaw and contributed to the building of Leigh school in 1893–4 (fn. 301) and was instrumental in arranging the controversial scheme to move the nave of Leigh church to a new site, 1896–8; he gave money towards the cost of the work and hunted out and restored the 13th-century font to the church. (fn. 302) The three bells, dating from c. 1450, 1627, and 1729 were also moved to the new church. (fn. 303) Regular services were held throughout the 20th century. In 2007 services were held at Leigh on three out of four Sundays. (fn. 304)

A Quaker family lived at Leigh in the late 17thcentury. (fn. 305) Premises were licenced for Nonconformist worship in 1823 and in 1837. (fn. 306) Brinkworth circuit Primitive Methodists first held an open air mission at Gospel Oak in 1834, 'when the parish was noted for its thieves'. (fn. 307) By 1851 a congregation of 100 people attended the afternoon service and 120 the evening service held in a chapel built in 1849. (fn. 308) A new chapel was built the south side of Malmesbury Road in 1867 and refurbished in 1950 and 1992. It was closed c. 2003 and converted for living accommodation in 2008. (fn. 309)

ALL SAINTS' CHURCH

The nave of the medieval chapel was probably built in the mid 13th century. (fn. 310) The chancel was added in the later 13th century, (fn. 311) and still stands on its original site. The church was remodelled in the 15th century, when a porch and a timber west tower were added, and the east bay of the nave was panelled in oak. (fn. 312)

New Church

By the later 19th century most of the parishioners lived along Swan Lane c. 1 km. to the south. Consequently the location of the church was inconvenient and it was almost inaccessible in wet weather. In 1892 the church was said to be in a 'sad state of dilapidation and unfitness'. (fn. 313) There were various plans: originally to repair the church on the existing site, and later to build a new one on a new site, (fn. 314) but it was eventually decided to move the existing church, except the chancel, to a new site on the south side of Swan Lane, donated in 1895. Permission was granted in 1896, the work begun immediately and was completed in 1898. (fn. 315) The architect was C. E. Ponting, and great care was taken to re-erect the 13th-century nave walls, the porch with original doorway and roof, and the tower exactly as they were, along with a new, larger chancel. (fn. 316) The font from the old church was recovered and restored: part of it had been used as a cattle trough and then a cheese press at an inn in Ashton Keynes and the other part were used to support the tower. (fn. 317) In the late 20th century a new heating system was installed and other amenities added. (fn. 318)

In 1920 a war memorial, which commemorated six Leigh parishioners, was erected in the new churchyard. (fn. 319)

Old Chancel Mortuary Chapel and Churchyard

Before 1869 Leigh burials took place in the Leigh section of Ashton Keynes churchyard, south of the pathway. In 1865 Leigh was granted a burial licence and burials subsequently took place in Leigh churchyard, which measured c. ½ a. in 1671. (fn. 320) After the church was moved, the medieval chancel became a mortuary chapel for the old churchyard. The chancel has a 13th-century east window and priests' door and a 15th-century south window and piscina. It is now buttressed on the west by the remains of the medieval naves south and north walls; the roof dates from c. 1800. Inside, the walls are decorated with seven 18th-century biblical texts and a communion table, gothic altar rail and matching lectern are perhaps part of the 18thcentury three-decker pulpit. In 1898 a new bell was hung in the old chancel. (fn. 321) Repairs to the roof and windows were carried out in 1975–6. (fn. 322) In 1976 the chapel was declared redundant and handed over in 1978 to the Redundant Churches Commission (since 1994 the Churches Conservation Trust), which has since been responsible for its upkeep. (fn. 323) The commission restored the roof in 1980, (fn. 324) the wall paintings in 1983, and carried out further work in 2007. Services are held in the chapel on the fourth Sunday in July each year. (fn. 325)

The parish register survives from 1682 and includes details of Leigh burials at Ashton Keynes. (fn. 326)