A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Broughton Poggs Parish', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp146-173 [accessed 10 May 2025].

'Broughton Poggs Parish', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online, accessed May 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp146-173.

"Broughton Poggs Parish". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online. Web. 10 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp146-173.

In this section

BROUGHTON POGGS PARISH

Until 20th-century boundary changes the small parish of Broughton Poggs (fn. 1) occupied a thin sliver of land between Broadwell, Langford, and the county boundary, stretching for three miles (5 km) from the high downland of the Cotswolds in the north-west to the low-lying village beside Broadwell brook in the south-east. A detached part of the parish at Lemhill (transferred to Lechlade (Glos.) in 1886) lay two miles south-west of the village on low-lying ground by the river Leach. The village itself developed alongside the main Lechlade– Burford road around a small green, which in the early 21st century remained a largely open wooded area. From the 18th century (and possibly earlier) the village effectively merged with neighbouring Filkins, and the two parishes were formally united in 1954.

In the 14th century the parish was sometimes known as Broughton Mauduit (from the medieval lords of the manor), distinguishing it from Broughton near Banbury. (fn. 2) Occasionally it was also called Broughton by Bampton, by Broadwell, or by Burford. (fn. 3) The suffix 'Poggs' or 'Pogis' became established in the early 16th century, probably through association with Stoke Poges in Buckinghamshire, which was in common ownership. (fn. 4) The parish remained predominantly agricultural, and until the 20th century most inhabitants were engaged in farm work: the only building of gentry status is Broughton Hall on the south-western edge of the green, which was adopted as the manor house in the 17th century and subsequently enlarged. (fn. 5) The nearest towns lay 3 miles south-west at Lechlade and 5 miles (8 km) north at Burford.

Parish Boundaries

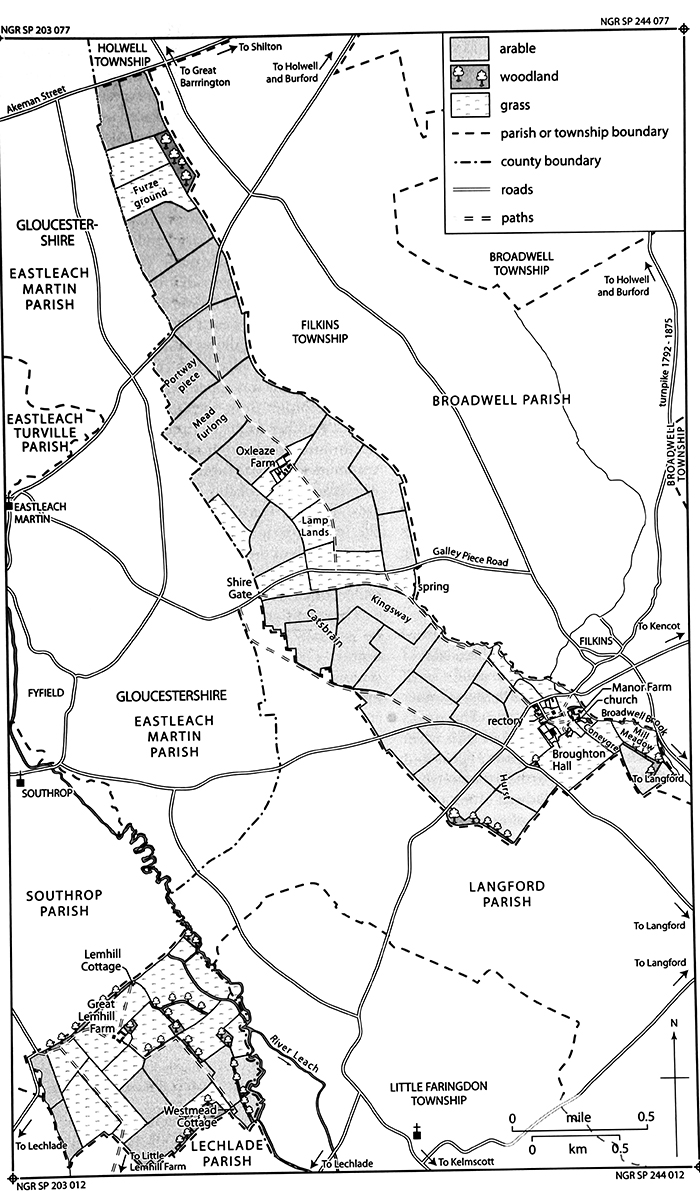

The parish's elongated shape encompassed a variety of agricultural resources, from the open pastures of the higher ground to the meadows beside the brook (Fig. 44). (fn. 6) Presumably that resulted from conscious planning, when Broughton was first separated from the large late Anglo-Saxon estate of Broadwell and Langford before the Norman Conquest. (fn. 7) The parish's (and county's) western boundary with Eastleach Martin (Glos.) was formed mainly by field divisions, its indentations (characteristic of areas of open-field farming) suggesting that the boundary was determined only after the fields were laid out. (fn. 8) The south-western boundary with Langford followed similar features, while the eastern boundary with Filkins ran along Broadwell brook as far as Galley Piece road, after which it again followed field divisions to the short northern boundary with Holwell along the Roman Akeman Street.

The detached part of the parish at Lemhill was the site of an 11th-century mill belonging to Broughton Poggs manor: the place name is a corruption of 'le Mulle', meaning 'the mill'. The detached area is roughly square-shaped, its northern boundary with Southrop (Glos.) and southern boundary with Lechlade following field divisions. The western boundary, also with Lechlade, ran along a stream, while the eastern boundary with Little Faringdon followed the river Leach. (fn. 9)

The ancient parish covered 1,154 a., of which 245 a. lay at Lemhill and 909 a. at Broughton Poggs. (fn. 10) In 1844 Lemhill was transferred to Gloucestershire for civil purposes, and was formally added to Lechlade under the Divided Parishes Acts in 1886. (fn. 11) In 1954 Broughton Poggs was united with Filkins to form a combined civil parish of 2,690 a. (1,088 ha.), which remained unaltered in 2001. (fn. 12) For ecclesiastical purposes the two parishes were united earlier, from 1855 to 1864 and again from 1942. From 1980 both places were merged in new team ministries. (fn. 13)

Landscape

44. Broughton Poggs parish in 1840, showing land use, boundaries, and key buildings.

As with Filkins, the ancient parish sloped southwards from the foothills of the Cotswolds at 140 m. to low-lying meadows by the village at 80 m. (fn. 14) Two streams join to form Broadwell brook just north of the village, and pass under a narrow bridge where a mill (in Filkins parish) was formerly located. (fn. 15) In 1930 and again in 2007 the brook flooded, badly affecting the village. (fn. 16) At Lemhill the ground slopes gently eastwards from Great Lemhill Farm at 85 m. to the river Leach at 80 m. (fn. 17)

Both the village of Broughton Poggs and Great Lemhill Farm lie on the northern edge of extensive areas of sandy limestone gravel of the Second (Summertown–Radley) Terrace. Narrow bands of alluvium along Broadwell brook and the river Leach provided good meadow. The underlying geology of most of the parish, however, is cornbrash and Forest Marble, the clayey limestone soils of which are well suited to the area's traditional Cotswold sheep-and-corn husbandry. (fn. 18) The nature of the soil was reflected in the field name 'Catsbrain', which referred to land consisting of rough clay mixed with stones. (fn. 19) The field name 'Hurst' (south-west of the village) suggests that woodland was once more extensive, before it was cleared to extend the arable. (fn. 20)

Stone and gravel were dug on a relatively small scale in Broughton Poggs from the 19th century, and more extensively at Lemhill in the mid 20th; there the pits were later filled with water. (fn. 21) Sand was also dug at Lemhill in the Middle Ages. (fn. 22) Overhead power-cables cross much of the length of the parish, entering Langford near Shire Gate.

Communications

In the late 18th century the main Lechlade–Burford road (turnpiked in 1792) ran along the northern edge of Broughton Poggs village, which grew up around a small green close to the road's intersection with several other probably early routes at Filkins (Fig. 2). (fn. 23) The road's course may, however, have been altered in 1748, when William Burnaby, then living at Broughton Hall as lord of the manor, received permission to inclose a stretch of highway from the bridge over Broadwell brook to the Langford–Southrop road (a distance of c. 528 m.), and to 'set out one other highway convenient for passengers'. (fn. 24) Possibly the earlier road took a more southerly course, and was diverted in connection with an extension of the grounds of Broughton Hall. No further evidence survives, however, and by the time of the first reliable map in 1767 the road followed its later course. (fn. 25) In the 1960s it was replaced as the trunk route by the new Filkins bypass, constructed west of the village. (fn. 26) The bridge over Broadwell brook must be medieval in origin, but has been rebuilt several times, including in the late 19th century and again in 1925. (fn. 27) The intersecting eastwards road to Kencot and Bampton must also be early, and in 1784 was a 'good carriage road' and 'lately made' (i.e. resurfaced). (fn. 28)

A number of lesser roads cross the parish, including that from Langford to Southrop, and Galley Piece road from Filkins to Eastleach Martin. The latter road was named from a gallows at Shire Gate, to which Broughton Poggs village was connected by footpaths; (fn. 29) one of the paths was apparently known as 'Kingsway', a name recorded from 1712 for an adjoining piece of land. (fn. 30) Another footpath from Galley Piece road runs northwards to the 18th-century Oxleaze Farm, then continues to the road from Holwell to Eastleach Martin. (fn. 31) The latter was probably the 'port way' mentioned in 1563: 'Portway Piece' lay next to it in the 19th century, the 'port' (or town) presumably being Burford. (fn. 32) A short stretch of the Roman Akeman Street (still in use) forms Broughton's northern boundary, although its embankment (or agger) does not survive. (fn. 33)

The condition of the parish's roads was considered to be 'generally bad' in 1839. (fn. 34) Nonetheless in the late 19th century carriers operated from Filkins, (fn. 35) and in 1873 stations on the East Gloucestershire Railway line opened three miles east at Alvescot, and three miles south-west at Lechlade. The line became part of the GWR, and closed in 1962; (fn. 36) local bus services continued through Filkins, however, and in 2010 there were regular services from there to Carterton, Lechlade, and Swindon. Post was delivered from Lechlade and later from Swindon (Wilts.), and from the 1870s the nearest sub post-office was at Filkins. (fn. 37) The village letter box, mentioned from the 1880s, was next to the rectory house. (fn. 38)

Settlement and Population

Early Settlement

Undated prehistoric features have been identified north-west of the village south of Galley Piece road, and at Great Lemhill Farm. (fn. 39) An extensive area of cropmarks south-east of the village, most of it in Langford parish, probably represents scattered Iron-Age occupation, trackways, and agricultural boundaries. The Iron-Age settlement did not continue into the Romano-British period, although a trackway near Broughton Poggs may have been associated with a separate rural settlement in Langford, and from the mid 3rd century AD the area became a focus for funerary activity. (fn. 40) At Lemhill a probable Roman villa lay on alluvium by the river Leach, on the site of later water meadows; stone buildings and occupation evidence of 2nd to 4th-century date have been found. Transport links were provided by the river, and the site may have included a mill. (fn. 41) A minor agricultural settlement of similar date has been found to the south of the villa. (fn. 42)

A late 5th or 6th-century Anglo-Saxon inhumation cemetery was discovered during stone-quarrying about ½ mile north-west of Broughton Poggs (SP 2219 0434). Sixteen skeletons, both male and female, were buried east–west in shallow graves with accompanying grave goods, and were probably formerly covered with mounds. (fn. 43) No other archaeological evidence of Anglo-Saxon occupation has yet been found, but by the mid 11th century there was substantial settlement within the parish. (fn. 44) Almost certainly it was focused on the site of the modern village, whose Anglo-Saxon place name (recorded from 1086) means 'tūn (or settlement) by a brook'. (fn. 45)

Population from 1086

In 1086 there were 31 tenant households on Broughton Poggs manor (probably including Lemhill), headed by 11 villani, 11 lower-status bordars, and 9 slaves. (fn. 46) The number of households remained the same in 1279, suggesting little growth of population: two were located at Lemhill and 29 in Broughton village, the latter headed by 20 unfree customary tenants, two cottars, and seven freeholders. (fn. 47) By 1303, when the population may have peaked, an increase of cottars and freeholders raised the number of households to 39. (fn. 48) In 1306 only 23 landholders were assessed for taxation, falling to 20 in 1316, and 15 in 1327, each presumably representing a household. (fn. 49) The population almost certainly fell further after the Black Death: in 1377 only 30 adults over 14 paid poll tax, and there may have been little more than a dozen households. (fn. 50) In 1428 Broughton reportedly had fewer than ten households, and was thus exempt from the tax on parishes. (fn. 51)

Population probably remained below its early 14th-century peak in 1544 when 13 landholders were taxed, although 43 people were recorded in 1548. (fn. 52) In 1642 the obligatory protestation oath was sworn by 38 men, implying an adult population of around 80; fifteen houses were assessed for hearth tax in 1662 and ten in 1665, and 59 adults were recorded in 1676. (fn. 53) From the 1570s baptisms usually outnumbered burials, although as late as the 1780s there were peaks in the number of people buried at Broughton. (fn. 54) Rectors reported between 15 and 20 houses in the parish during the 18th century, suggesting that there was little increase in population before 1801, when 19 houses were occupied by 103 inhabitants. (fn. 55)

In the 19th century population peaked in 1831 at 158 inhabitants occupying 29 houses, falling to 127 in 1851, then rising to 143 (in 28 houses) in 1881. In 1901, following the onset of agricultural depression, numbers fell further to 107. The fluctuations were most noticeable in the main part of Broughton Poggs parish, where 24 houses were occupied by 121 inhabitants in 1881, and only 88 in 1891. By contrast, from 1851 to 1891 the population of Lemhill's four houses remained about the same. By 1931 Broughton's population had fallen still further, to 47 inhabitants occupying 14 houses. Following an increase to 63 (in 20 houses) in 1951, Broughton Poggs was united with the much larger village of Filkins, their combined population in 2001 standing at 404 inhabitants in 172 houses. (fn. 56)

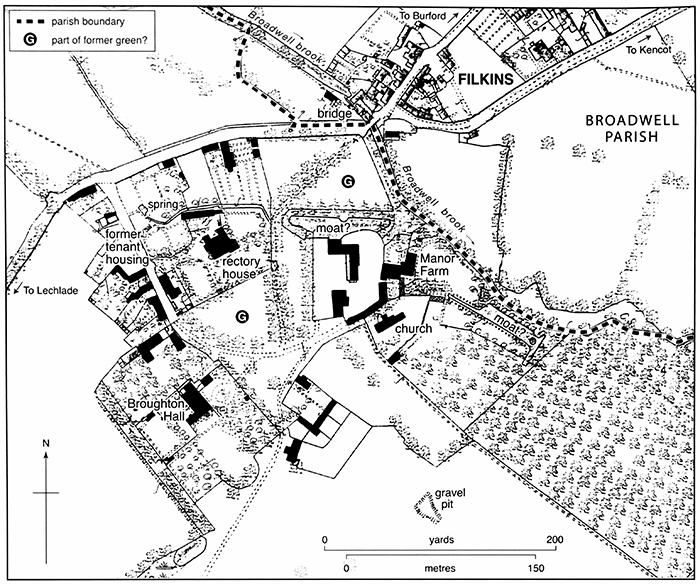

45. Broughton Poggs village in 1881, showing key buildings.

Village Development

The village's position alongside the Lechlade–Burford road and beside Broadwell brook provided its inhabitants with a good water supply and favourable transport links. In the Middle Ages houses were probably arranged around a small green (Fig. 45), situated where the better-draining soils of the gravel terrace intersected the alluvium and water-retaining stonebrash. (fn. 57) The church, established by the early 12th century, stands on the green's south-eastern edge next to Manor Farm, which almost certainly occupies the site of a medieval moated manor house rebuilt as a farmhouse in the 17th century. These buildings are effectively screened off from the rest of the village by walls, dense trees, and the grounds of the former rectory house, an arrangement which may preserve the medieval layout: the rectory house site, too, is almost certainly of medieval origin, and may represent an early encroachment on part of the former green. (fn. 58) Medieval tenant housing was probably mostly situated on the village's north-western edge, (fn. 59) although surviving buildings there are all later, and the possible diversion of the main road in the 1740s (fn. 60) may have obscured the earlier topography. When the parish was mapped in 1839 around 16 cottages lay north and west of the rectory house's grounds, with another (belonging to the rector) on the south side of his garden. Up to 18 families occupied those buildings in 1841, with at least three other households accommodated in a cottage on the green's southern edge. (fn. 61) Two adjoining buildings, described as a 'hovel', may have been parish houses used to shelter the poor. (fn. 62)

46. Former tenant housing along the village street, separated from the church and manorial centre by a former green (see Fig. 45). The arrangement is probably of medieval origin.

The character and layout of the medieval village was altered in the 17th century when Broughton Hall, Manor Farm, the rectory house, and a number of cottages were rebuilt in limestone and stone slate. (fn. 63) The grounds of Broughton Hall, in particular, are apparently a creation of the late 17th to early 19th centuries, (fn. 64) and at least one old cottage standing 'just in front' and representing 'a great nuisance' was removed by the lord of the manor in 1695. (fn. 65) Little new building occurred in the village in the 19th century, though in the early 20th some formerly subdivided cottages were probably converted to single ownership, while some others seem to have been demolished. (fn. 66) After the Second World War, infilling and conversion of farm buildings and outbuildings increased the number of houses in the village to 24 by 2001. (fn. 67) By the late 19th century water was pumped from a spring rising in the village; the pump survived in 2009. (fn. 68)

The only buildings outside the village are the 18th-century Oxleaze Farm, a pair of 19th-century cottages on Galley Piece road (which belonged to the farm), and a late 20th-century factory beside Broadwell brook. (fn. 69) At Lemhill the 17th-century farmhouse, enlarged in the 20th century, survived in 2009. Lemhill Cottage to its north-east and Westmead Cottage by the Leach were demolished in the 20th century. (fn. 70)

MANOR AND ESTATES

Broughton Poggs probably formed part of the large late Anglo-Saxon estate of Broadwell and Langford, from which it was detached before the Norman Conquest. (fn. 71) From the 11th to the 16th century the manor was held by a series of high-status but mostly non-resident lords, originally for a falconry service which was later commuted to a cash payment. (fn. 72) After 1600 the manor was owned by a succession of minor gentry, of whom most lived at Broughton Hall, a house south-west of the church which seems to have been adopted as the manor house in the 17th century, and which was subsequently remodelled and extended. The medieval manor house probably occupied the site of Manor Farm. (fn. 73)

The medieval manor seems to have included most of the parish, save for the glebe (two yardlands before inclosure in 1711), (fn. 74) 8 a. given by John Mauduit (d. 1302) to the dean and chapter of Lincoln cathedral during Henry III's reign, (fn. 75) and the detached part of the parish at Lemhill, which was separated from Broughton Poggs manor in the earlier 13th century and remained a distinct estate. (fn. 76) The parish's northern part, known as Hockstead or Oxleaze farm, was sold off in the early 18th century. (fn. 77)

Broughton Poggs Manor

Descent to 1600

In 1066 Broughton Poggs was held freely by three freemen, and in 1086 (of the king) by Robert son of Murdrac. (fn. 78) The manor descended in Robert's family until 1194, when Ralph Murdac (possibly his great-grandson) forfeited the estate as a rebel. (fn. 79) In 1197 it was restored to Ralph's wife Eve de Grey and her second husband Andrew de Beauchamp, (fn. 80) and before Eve's death c. 1246 passed to her daughter Beatrice Murdac, who married Robert Mauduit. (fn. 81)

Following Beatrice's death after 1250 the manor descended to Sir John Mauduit (d. 1302) of Somerford (Wilts.), her son or grandson. (fn. 82) It then passed (with Somerford) to Sir John's nephew Sir John Mauduit (d. 1347), to his widow Agnes (d. 1369), who married Sir Thomas de Bradeston (d. 1360), Lord Bradeston, and to John and Agnes's grandson Sir William de Moleyns (d. 1381), son of their daughter Gilles. (fn. 83) From William the manor passed to his son Richard (d. 1384) and grandson William de Moleyns (d. 1425), who came of age c. 1398. His son William was killed in 1429 at the siege of Orléans, leaving an infant daughter, Eleanor. She married Sir Robert Hungerford, later Lord Hungerford and Lord Moleyns, who was attainted in 1461 and executed in 1464. (fn. 84)

Broughton Poggs remained with Eleanor (d. after 1487) and her second husband Sir Oliver Maningham (d. 1499), passing to her granddaughter Mary Hungerford, suo jure Baroness Botreaux, who held with her husbands Sir Edward Hastings (d. 1506) and Sir Richard Sacheverell (d. 1534). Mary was succeeded c. 1533 by her son George Hastings (d. 1544), Lord Hastings and later earl of Huntingdon, who in 1537 sold the manor to Thomas Cromwell, later earl of Essex. (fn. 85) On Cromwell's fall in 1540 the manor escheated to the Crown, and in 1541 was granted for her life to Anne of Cleves (d. 1557). (fn. 86) In 1545 the reversion was sold to Sir Thomas Pope (d. 1559) of Wroxton, purchaser of a large estate in Broadwell, from whom the manor passed to his brother John (d. 1583) and nephew William (d. 1631), later earl of Downe. (fn. 87)

Descent from 1600

In 1600 William Pope sold the manor to Henry Alder, possibly a former lessee, who in turn sold it in 1610 to Henry Godfrey. (fn. 88) In 1626 John Godfrey sold it to Arthur Mowse (d. 1644), a London fishmonger, whose grandson Richard sold it in 1661 to Andrew West. (fn. 89) In 1670 the manor was bought by William Goodenough (d. 1673), one of a prominent Broadwell family, from whom it passed to his son William (d. 1732) and grandson William (d. 1768), rector of Broughton Poggs. (fn. 90) Some 490 a. in the parish's northern part (comprising Hockstead or Oxleaze farm) was separated from the manor in 1718, having first been mortgaged probably to help cover inclosure costs. The purchaser was the lord of neighbouring Broadwell, and the land remained part of Broadwell manor thereafter. (fn. 91)

47. Manor Farm from the north in 1964, showing the 17th-century ranges and stair turret (left), the later extension, and the Clock House with bellcote. The church tower is visible behind.

By 1744 the rest of Broughton Poggs manor belonged to Arthur Mohun St Leger (d. 1750), 3rd Viscount Doneraile, who sold it in 1747 to the distinguished naval officer William (from 1754 Sir William) Burnaby (d. 1776). (fn. 92) The manor passed to Sir William's son Sir William Chaloner Burnaby (d. 1794), whose younger son, Crisp Richard Beckingham Burnaby, sold it in 1824 to the Revd Bowen Thickens (d. 1825). (fn. 93) The manor passed to Bowen's cousin George Thickens (d. 1844) and his son John (d. 1845), then to George's brother John Thickens (d. 1863) and his son John, who was declared bankrupt in 1886. In 1888 he sold the manor to Sir William Henry Marling (d. 1919), 2nd baronet, of Stanley Park (Glos.). (fn. 94)

In 1898 Marling conveyed the manor to his younger son Sir Charles Murray Marling (d. 1933), who sold it in 1902 to Robert Gerald Trollope. (fn. 95) Trollope sold the manor before 1907 to John Norman Hardcastle (d. 1948), during whose tenure the lordship seems to have lapsed, and whose executors offered Broughton Hall and a few acres of land for sale in 1950. (fn. 96) The Hall subsequently passed through various hands, and the estate's remains were broken up. (fn. 97)

Manor Houses

Manor Farm

A moated manor house recorded from the 14th century almost certainly occupied the site of Manor Farm, which was rebuilt as a farmhouse in the 17th century. A predecessor may have been built or rebuilt by the Murdacs in the early 12th century, along with the neighbouring church to the south; (fn. 98) Broughton's medieval lords had estates and residences elsewhere, however, and probably stayed in the parish only occasionally. (fn. 99) At other times the premises were presumably occupied by their demesne managers or lessees, and in 1385 a chamber, dovecot, stable, and other buildings were in disrepair. (fn. 100) Two long, narrow, straight ponds to the north and south-east (Fig. 45) are probably the remains of a medieval moat, which survived in the 1540s when it was the scene of an adulterous relationship involving the lessee's wife. (fn. 101) A field called 'Coneygre', next to the village, may mark the site of a medieval rabbit warren. (fn. 102)

The present two-storeyed, L-shaped farmhouse (Fig. 47) dates chiefly from the 17th century, and was extended westwards by two bays in the late 18th or early 19th. (fn. 103) The easternmost roof truss may be a remnant of a 16th-century structure substantially rebuilt for the resident Alders, Godfreys, or Mowses, or after 1670 by their successors the Goodenoughs; (fn. 104) around that time the Goodenoughs moved to Broughton Hall, however, and except for a brief period in the mid 19th century Manor Farm became a tenanted farmhouse. (fn. 105) Compared with the more obviously gentrified Broughton Hall the house retains a vernacular feel, built of coursed limestone rubble with stone-mullioned casement windows under hoodmoulds, and a stone-slated roof. Nonetheless it was one of the largest houses in the village, (fn. 106) and features dressed quoins, ashlar chimney shafts, and bands of decorative dressed stone in its former main entrance front towards the church.

In its late 17th-century form the house probably comprised a three-bay east-west range with a surviving stair turret at the rear, abutting an added north range with a large kitchen fireplace. The former main south door is set within decorative stone and timber surrounds, and originally opened to a through passage. The house's westward extension (fn. 107) was followed by minor alterations, including the insertion c. 1810–20 of an east door with gothic-style tracery, and possibly the conversion of attic rooms for habitation. A detached five-bay accommodation range for farm workers was added on the south-west probably in the 19th century, and in the 20th became a separate dwelling called the Clock House, facing into the former farmyard; (fn. 108) the name derives from a clock set in an elaborate stone gable over the central doorway, formerly surmounted by a bellcote (Fig. 47). Most other surviving farm buildings were converted for domestic use in the late 20th or early 21st century.

Broughton Hall

Broughton Hall, now set in extensive grounds on the village's south-west edge, seems to have been adopted as a manor house during the 17th century, presumably by the Goodenoughs or their immediate predecessors. The house (Plate 7) was successively remodelled and extended, and the name Broughton Hall was established by the 1750s. (fn. 109) The oldest part is the central section of the surviving north-south range, which may have begun as a modest late 16th- or early 17th-century house only one room deep, with a massive central chimneystack and associated newel stair. If so it was extended and aggrandized in the late 17th century by the addition of rooms to the west, creation of an access corridor between the old and new parts, and probably the insertion of a now-lost stair lit by a tall west-facing window. (fn. 110) The builders were almost certainly the Goodenoughs, who by 1694 occupied a 'new or late erected capital messuage' with an adjoining dovehouse, close, garden and orchard. (fn. 111)

Further remodelling followed William Burnaby's acquisition of the manor in the mid 18th century, when a large two-storeyed range was added on the south forming an L-plan. Its regular seven-bayed garden front has a stone-slate hipped roof half concealed behind a coped parapet, and overlooks a large lawn with a stone-built semi-circular ha-ha at the far end. The range's western part contains a large drawing room raised above a cellar, and its eastern part (almost certainly incorporating earlier fabric) a large entrance hall and staircase, which has been renewed. The entrance hall (originally single-storeyed with two floors above) was heated, and an adjoining room in the house's older part received new panelling and a new fireplace around the same time. (fn. 112) Much of the work may have been carried out around 1748, when Burnaby diverted a road through the village perhaps in order to extend the grounds. (fn. 113) A small square gazebo or summer house (attributed to the Lechlade builder Richard Pace) was added to the south-west around 1800. (fn. 114)

Minor 19th-century changes included addition of a canted bay window in the east front, and around 1906 a three-storey stone tower was added on the north as servants' accommodation. A large water tank on top of the tower served the house and surrounding outbuildings. (fn. 115) After the sale of 1950 a part was briefly divided into flats let to USAAF personnel from Brize Norton; the house was subsequently restored to single occupancy, and in the 1960s the ceiling of the entrance hall was removed to accommodate a full-size pipe organ opposite the doorway, placed in front of the altered stairs. Renovations from the 1970s, following the organ's removal, included rebuilding of the staircase, creation of a mezzanine floor over part of the now two-storeyed entrance hall, addition of a new entrance porch supported on Doric columns, and re-roofing of the south range. (fn. 116) In 2011 the Hall, Tower, and former coach house (to the north) were all separately owned and occupied.

Estates at Lemhill

A 3-yardland estate at Lemhill was granted by Beatrice Murdac to her kinsman Robert Murdac before 1250. (fn. 117) Robert's successor Geoffrey Murdac held it of John Mauduit (d. 1302) for the service of mewing a falcon, the same service as John owed the king for Broughton Poggs. (fn. 118) The estate remained with members of the Murdac family (who adopted the surname Lemhill) until the mid 15th century, when it was probably conveyed to trustees. (fn. 119) In 1466 the surviving trustee conveyed it to Sir Richard Harcourt, who granted it to his son William in 1478. (fn. 120) Robert Harcourt of North Aston owned the estate in 1547, when it was leased to Thomas Dawes (or Davies), then Broughton's wealthiest inhabitant; in 1577, however, it was sold to the Fettiplaces of Coln St Aldwyns (Glos.), who also owned Radcot manor. (fn. 121)

By 1840 the estate (c. 243 a. in all) was divided among three farms: 153 a. belonged to Great Lemhill farm (owned by Sir Michael Hicks Beach), 61 a. to Little Lemhill farm (owned by Sir George Shiffner, lord of Radcot), and 29 a. to West Mead (owned by George Thickens, lord of Broughton Poggs). (fn. 122) Probably the division was carried out by the Fettiplaces. In the late 19th century the estate seems to have been reunited, (fn. 123) and in the early 21st century it was owned by George Ponsonby, a nephew of the 6th Baron de Mauley (d. 2002) of Little Faringdon. (fn. 124)

A mill at Lemhill, granted to Eynsham abbey by Ralph Murdac in 1192, was still held by the abbey in the late 15th century. (fn. 125)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until the 20th century most of Broughton's inhabitants were employed in agriculture. From the Middle Ages the traditional sheep-and-corn husbandry characteristic of the Cotswolds was widely practised, although cattle and pigs were also reared on a significant scale. Dairying increased in importance in the late 19th and early 20th centuries during the agricultural depression. The village's open fields were inclosed in the early 18th century, after which the vast majority of inhabitants were reduced to working as wage labourers on two newly created farms.

Few trades and crafts were practised, and two medieval mills failed to survive, probably because of competition from the neighbouring village of Filkins, which from the 18th century developed into a successful local centre for goods and services. In the late 20th century, as agricultural employment declined, Filkins's businesses provided jobs for many local residents, although most worked further afield.

The Agricultural Landscape

Broughton's strip-like shape and its detached portion at Lemhill provided varied agricultural resources (Fig. 44). Rivers and streams produced valuable meadow and pasture, and in the Middle Ages powered two watermills. The downland provided rough grazing for livestock: 18th-century field names there included Oxleaze (meaning 'ox pasture or meadow'), and in the absence of woodland the downs also produced furze and heath for fuel. (fn. 126) From the 16th century small plantations of wood were grown by both lord and tenants, but woodland was never plentiful. The open fields, laid out probably in the 9th or 10th century before the parish boundaries were finally determined, (fn. 127) were subject to piecemeal inclosure from the late Middle Ages, but remained mostly uninclosed until 1711 when remaining common pasture rights were extinguished. Thereafter, despite changes in the balance of arable and pasture and the removal of some hedges, the patchwork of fields created at inclosure remained broadly unchanged in the early 21st century. (fn. 128)

Arable

In 1086 the cultivated area (probably including Lemhill) covered nine ploughlands, although ten were available, which suggests room for expansion. (fn. 129) An increase may have occurred by 1220, when Broughton was assessed for taxation at ten ploughs or ploughlands and paid £1. (fn. 130) By the 17th century (and probably from the Middle Ages) the village's open-field arable lay in two large fields called East and West fields, divided by hedges and headlands, and extending as far north as the downs. (fn. 131) Land in the north of the parish (called the wold in 1381) went in and out of cultivation according to demand: it was ploughed in the early 14th century when population was high but was laid down to fallow after the Black Death. (fn. 132) From the 15th century small areas of arable were inclosed, (fn. 133) and the open fields were probably subject to increasingly complex rotations. In the early 17th century the rector had stocks of wheat, barley, oats, peas, and vetch, and grazed sheep in the fallow. (fn. 134) At that date customary yardlands seem to have included around 36 a. of arable, judging from the size of the glebe. (fn. 135)

After inclosure in 1711 most of the land was divided between two farms. (fn. 136) That closest to the village was around three quarters arable in 1744, and that on the downs more than two thirds in 1802. (fn. 137) Including Lemhill, the parish as a whole remained about two thirds arable in 1840, when there was a standard five-course rotation (or six including sainfoin) of (1) turnips, (2) barley, (3) seeds, (4) wheat, and (5) beans or oats. (fn. 138) During the agricultural depression of the late 19th and early 20th century the proportion of arable fell to less than half of the cultivable area, (fn. 139) and remained low until the 1970s. It was increased again before 1988, when more than two thirds of the available land was cropped. (fn. 140)

Meadow and Pasture

Common meadow, estimated in 1086 at 36 a., probably lay chiefly in the east by Broadwell brook, and along the river Leach in Lemhill. (fn. 141) Only 8 a. of meadow was in demesne in 1303 when it was valued at 20d. an acre, more than six times the value of the arable. (fn. 142) The demesne meadow was increased to 20 a. by 1381, although its value fell temporarily to only 7d. an acre, possibly because of drought; by then it lay in 'various parcels', and was probably inclosed. (fn. 143) By contrast the common meadow probably remained open until inclosure in 1711, certainly at Lemhill, where some 35 a. of common and lot meadow remained at West Mead. (fn. 144) Several 17th-century inhabitants left quantities of hay, (fn. 145) and a tenant in 1700 held 3 a. of meadow presumably in strips. (fn. 146)

Pasture was estimated at 40 a. in 1086, and in 1303 the demesne pasture was worth 5s. a year. (fn. 147) Some pasture was inclosed in the 14th century, and limits were imposed on common pasture rights in the 16th, though common grazing persisted until inclosure. (fn. 148) Thereafter permanent grassland was more plentiful in the north of the parish than the south, where meadow (45 a.) and pasture (31 a.) occupied only a quarter of cultivable land in 1744. (fn. 149) In 1839 around 165 a. of hay were cut, worth 50s. an acre, and a similar amount of pasture was valued at 40s. an acre. (fn. 150) In the late 19th century and still in 1930 around three fifths of available grassland was grazed, compared with two fifths used for hay. (fn. 151) During the Second World War farming practices in the parish diverged: hay and clover were cut more extensively in the north to feed a larger cattle herd, while sheep grazing was more important in the south. (fn. 152) From the late 1960s the acreage under grass in Filkins and Broughton Poggs began to fall. (fn. 153)

Woodland

Woodland was probably scarce at Broughton Poggs throughout the Middle Ages, (fn. 154) and in 1538 Thomas Cromwell (as lord) was informed of a potential shortage of timber. (fn. 155) In the late 16th century tenants were obliged (as in neighbouring Broadwell) to plant oak, ash, or elm trees as a condition of their tenancies, and John King forfeited his holding for felling 11 sapling oaks in a plantation and cutting 21 elms. (fn. 156) Only hedgerow trees were marked on 18th-century maps, although around 20 a. of coppice wood was recorded in the early 19th century, about half of it at Lemhill. The largest plantations lay on the downs in the north of the parish (8 a.), and at Bushyleaze (5 a.) in Lemhill. (fn. 157) Most of those woods remained in the early 21st century, and several more acres were planted in Broughton itself. (fn. 158) In the late 19th and early 20th century a few acres were also given over to orchards, some 9 a. of which remained in 1941. (fn. 159)

Medieval Agriculture

Medieval Tenant Farming

In 1086 the manor's tenants (11 villani and 11 lower-status bordars) shared 7 ploughlands, of which one (later reduced to 3 yardlands) lay probably at Lemhill. (fn. 160) Tenants' rents in 1194 yielded £3 7s. 4d. a year, rising to over £4 by 1279. By then there were also eight free tenants, holding 7 or 8 yardlands in total; another 20 unfree customary tenants, possibly the successors of the Domesday bordars and slaves, held only half a yardland each for cash rent and labour services, and two cottars occupied smallholdings. (fn. 161) The creation of free tenures from customary holdings seems to have been an ongoing process: by 1303 the number of unfree tenants holding half yardlands had fallen to 18, while two others held a quarter yardland each, and the remaining half yardland was held freely by Thomas Baldwin, who had been a serf in 1279. Some new smallholdings (both free and unfree) were also created, suggesting rising population and pressure on resources. Customary tenants' labour services included ploughing and harrowing ½ a. at the winter sowing, working for five days out of every 15 from Midsummer to Michaelmas, and finding two men for two days at harvest. Some of the cottars also worked every Monday from Midsummer to Michaelmas, and for a day during harvest. (fn. 162)

More than two fifths of Broughton's taxpayers in 1306 belonged to families which had held in villeinage in 1279. Individuals' assessed wealth fell mostly within a range of £1–£2, which was already fairly low for the area, (fn. 163) and thereafter Broughton Poggs seems to have suffered a protracted decline in wealth and probably in tenant numbers throughout the 14th century. In 1316, during a period of national agrarian crisis, the median assessment of twenty taxpayers was only £1 4s., and of those at least ten probably subsisted on half yardlands. (fn. 164) Further local disruption accompanied John Mauduit's opposition to the Crown. In 1322 Mauduit was captured at the battle of Boroughbridge, and briefly forfeited Broughton Poggs before being pardoned the following year; (fn. 165) the royal keeper found three holdings abandoned by their tenants and 'derelict for want of maintenance', and he was unable to re-let them. (fn. 166) By 1327 those who survived the crisis had apparently recovered, but the number of taxpayers (and perhaps also of inhabitants) was still lower than earlier, either through death or migration. (fn. 167) Even in the 1380s, rental income remained low. Free tenants in 1381 paid 15s. in all compared with £1 6s. 9d. in 1303, while rents from unfree tenants and tenants at will were worth £4 16s. 8d. compared with £6 10s. 11d. (including the value of labour services) in 1303. The figures suggest a significant fall in tenant numbers, perhaps partly as a result of the Black Death. (fn. 168) In 1385 total rents from tenants were valued at just £4 a year, rising to £5 15s. in 1387. (fn. 169)

Tenant numbers probably remained below their early 14th-century peak in the 1480s. A cottage with its smallholding was left empty, and several tenants allowed buildings to fall into disrepair, presumably because they lay unused on what had once been separate holdings. Former open-field land was inclosed to create private pastures, prompting disputes among tenants. One (Thomas Reeve) was found to have no grazing rights for his sheep in new private closes belonging to his neighbours in 1486, and was fined for allowing his pigs to enter an inclosed field called le Hethynlond before it was opened to common. (fn. 170) Tenants probably followed the traditional Cotswold sheep-and-corn husbandry practised by the lord (see below), although no direct evidence survives.

Medieval Demesne Farming

In 1086 Robert son of Murdrac's manor was assessed at 7 hides less 1 yardland, and its value had increased from £6 in 1066 to £7. Two ploughlands were in demesne, and there were nine servi or slaves; this was a high proportion, and suggests that some of them may have served in capacities other than ploughman, possibly as shepherds. (fn. 171) In 1194 the manor was briefly forfeited to the Crown, and in 1195 it was leased for an annual rent of £3 9d., rising to £6 10s. 9d. in subsequent years. In 1194–5 the demesne produced small amounts of grain and hay for sale, and in 1195–6 it was restocked with oxen, a plough-horse (affrus), and over 100 sheep. (fn. 172)

In 1279 John Mauduit held 3 ploughlands in demesne, probably equivalent to the 140 a. of demesne arable valued at 3d. an acre in 1303. By then grain production predominated: most labour services were directed towards ploughing and harvesting, and there was relatively little demesne meadow and pasture. (fn. 173) Demesne farming may have been abandoned in 1322–3 during Mauduit's opposition to the king: in the first year of the royal keeper's custody no animals were found to graze 140 a. of untilled arable (friscus), and a similar problem was reported the following year when 300 a. were uncultivated. (fn. 174) A grant of free warren was made to Mauduit in 1345, and fish were available from two ponds (possibly the moat surrounding Manor Farm). (fn. 175)

As elsewhere, arable farming declined after the Black Death. In 1381 it was claimed that only 120 a. of demesne arable remained, worth a mere 2d. an acre because it lay on the wold (le wolde) 'in an infertile place', and had mostly been uncultivated since the first outbreak of plague. (fn. 176) The absentee Moleynses probably leased the demesne to tenants, and allowed farm buildings used in traditional sheep-and-corn husbandry to fall into disrepair, including a barn, byre, stable, and sheepcote. (fn. 177) In 1440–1 Anne Moleyns (mother of Eleanor) received dower income from Broughton Poggs, amounting to £2 from John Ball for the lease of the demesne, and £1 11s. 3½d. from the reeve, who presumably collected tenants' rents. (fn. 178) In 1464, when the lord Robert Hungerford was executed, the manor almost certainly included no more than the single ploughland of demesne arable and few acres of meadow mentioned in the late 14th century. (fn. 179) Manor courts held there in the late 15th century suggest close supervision of manorial tenants and income. (fn. 180)

Farming from 1500 to 1800

In 1540, when the manor again escheated to the Crown, the demesne farm was leased to Thomas Limerick for £7 13s. 4d. a year, and rents of £4 9s. 2d. were collected from the free and customary tenants. (fn. 181) The demesne was still leased during the later 16th century, mostly to people who lived in the village; (fn. 182) one lessee sublet the right to graze 100 sheep (out of his allowance of 240) on Broughton's commons, and as elsewhere in the region sheep were probably a common sight. (fn. 183) Two villagers quarrelled in 1596 when a flock entered a field of peas, (fn. 184) and sheep were frequently bequeathed to relatives, although a flock of 100 left by William Thomas (d. 1568) seems to have been exceptional. (fn. 185) Other Elizabethan wills reveal the usual pattern of mixed farming, combining barley and wheat production with cattle, sheep, and pig rearing. (fn. 186) Barley was the dominant crop, Robert Elk (d. 1603), for instance, leaving £20-worth compared with wheat, oats, and malt together worth less than £5. (fn. 187) A few households made cheese, but the main animal products were meat and wool. (fn. 188)

Most land remained uninclosed in the late 16th century, although some tenants had closes in addition to their open-field land. The husbandman Thomas Turner (d. 1620) was fairly typical, occupying a house, two closes, and half a yardland for three lives at the lord's will. Turner may have used one close as a paddock for his horses, and the other for growing timber, of which he had £6-worth at his death; also worth £6 were two plough-beasts and crops ready to be harvested. (fn. 189) Turner was a successor to the half-yardlanders of the Middle Ages, and most other tenants held no more than a yardland, suggesting that the lord had little difficulty filling vacant holdings: Richard Pearson (d. 1596) was probably unusual in having accumulated 1¾ yardlands. Pressure on land is also indicated by court orders forbidding encroachment on the common, and limiting pasture rights to four plough-beasts and two horses per yardland. Bylaws specified when cattle and sheep could graze in particular meadows and pastures, and tenants were obliged to maintain buildings and fences and to plant trees. (fn. 190)

Several of Broughton's 16th-century farming families (including the Allens, Thomases, and Turners) remained in the village during the 17th, although none were particularly prosperous. Two thirds of the inhabitants for whom 17th-century inventories survive left goods valued at less than £50, and of ten houses assessed for hearth tax in 1665 half had only one or two hearths. (fn. 191) The husbandman Andrew Read (d. 1681) was probably characteristic of many of Broughton's yard-landers: assessed on a single hearth, he left some modest pieces of furniture and other household goods in his hall, buttery, and chamber, arable farming equipment, a small flock of sheep, and two pigs fattened for market. (fn. 192) Less typical was Andrew Jeffrey (d. 1686) who held 2½ yardlands and left 92 a. of crops worth £45, a flock of 110 sheep worth £22, cattle worth £15, horses, and pigs. (fn. 193) Robert Fettiplace's inventory of 1634 suggests that farming practices were similar at Lemhill, although he lived in greater comfort than most of his Broughton contemporaries. (fn. 194)

In the early 18th century William Goodenough, as lord of Broughton manor, held 19¾ yardlands in Broughton Poggs. The demesne farm (8½ yardlands) was leased to Nicholas Sanders, while the rest was divided among five or more tenants including Andrew Jeffrey's widow and Richard Allen (d. 1742), head of a long-standing Broughton family. (fn. 195) In 1711 Goodenough and the rector (the only other landowner in the parish) reached agreement to inclose the open fields, transforming the pattern of tenure as well as the landscape. Hockstead (later Oxleaze) farm (490 a.) was created on the downs in the north, while closes in the south of the parish were absorbed into an enlarged Manor farm (346 a.). (fn. 196) Former tenants, who presumably could not afford to take on such sizeable new holdings, were reduced to landless cottagers, and even their houses were gradually sold off: in 1753, for example, the labourer John Radway bought the Allens' former cottage from William Burnaby. (fn. 197) The two new farms were leased to incomers: Thomas Gardner (d. 1814) paid £200 a year for Oxleaze farm in the 1770s, while from 1740 Manor farm was held by William Bush for 21 years at an annual rent of £180, rising to £185 after the first four years. (fn. 198) A five-bay barn with a projecting gabled porch was built in traditional Cotswold style at Manor Farm in the mid to late 18th century, and both farms remained mostly arable. (fn. 199)

Farming in the 19th and 20th Centuries

Oxleaze and Manor farms were leased for much of the 19th century. In 1824 George Beak took a 14-year lease of Oxleaze at £383 a year, and the family remained there until the early 1850s. (fn. 200) In 1840 about three quarters of the farm was arable, and in 1851, when his farming interests extended into neighbouring Filkins, Beak employed 11 men, 5 women, and 7 boys, of whom several lodged in the farmhouse. (fn. 201) His successor Robert Hiett, formerly of Filkins, remained lessee for much of the later 19th century, (fn. 202) while the lessee of Manor farm, John Tombs, also built up his (mostly arable) acreage, farming around 600 a. in 1851 and employing 23 men, 10 women, and 7 boys. (fn. 203) Tombs came from a local family which had leased Great and Little Lemhill farms in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and he himself moved to Great Lemhill after John Thickens (d. 1863), the lord of Broughton manor, took over direct management of Manor farm. In 1861 Thickens farmed 380 a. there with the help of 12 men and 5 boys, (fn. 204) and after his death his son ran the farm until its sale in 1888, when it was again leased out. (fn. 205) Both the Thickenses and their tenants may have contributed to the farmhouse's extension and improvement during the period. (fn. 206)

In 1870 around two thirds of Broughton's cultivable area (including Lemhill) was ploughed. The main crops were wheat, barley, and root vegetables (especially turnips and swedes), with smaller quantities of oats, beans, and peas. Sheep numbered around 850, a few horses and pigs were kept, and cattle were reared on a considerable scale, mostly for beef: the dairy herd comprised only 13 cows. (fn. 207) Dairying increased with the onset of agricultural depression in the late 1870s, the number of dairy cattle increasing to 33 by 1880, and to 40 ten years later. Nevertheless, Broughton's traditional sheep-and-corn husbandry was preserved. Around three fifths of the land was ploughed (with barley as the largest crop), and there were 870 sheep. Alongside the two principal farms, half a dozen villagers held small-holdings or allotments. (fn. 208)

By 1900 the crisis in arable farming had deepened. At Broughton only half the cultivable area was ploughed, with less than three fifths of the arable devoted to barley, wheat, and oats, and most of the remainder planted with fodder crops. The dairy herd continued to expand, though sheep numbers were beginning to decline. (fn. 209) In the early decades of the 20th century the arable acreage was maintained at around 400 a., although there was a renewed emphasis on cereals (especially wheat and barley) at the expense of fodder crops. Sheep numbers fell further to around 450, while the cattle herd remained in excess of 100 animals, mostly for beef. The number of pigs averaged about 45 from the 1880s. (fn. 210) Following his purchase of the manor c. 1907 John Hardcastle installed a bailiff to manage Manor farm, while the lessee of Oxleaze farm (Charles Kynaston) purchased the freehold in the early 1920s. (fn. 211) In 1930 the two farms together employed only 14 workers. (fn. 212)

Sheep-and-corn husbandry, with a significant element of cattle rearing, continued in 1941. At Manor farm more than half the total acreage was given over to cereals, especially oats, which were also sown on ploughed-up pasture. Only 75 a. of permanent grazing remained for nearly 200 sheep and 50 cattle, and another 18 a. were mowed. There were also more than 200 poultry. Hardcastle had clearly invested in the farm: the land was 'well done', and his bailiff was a 'very capable farm manager', assisted by eight farm workers. On Oxleaze farm, by contrast, a 'lack of capital' had resulted in buildings falling into disrepair; Kynaston and his brother were getting old, and with only four workers the farm was understaffed. About a third of the acreage was devoted to cereals, with more than half (presumably mostly on the downs) laid down to grass and clover. The cattle herd numbered 84 and the sheep flock 60, and there were some pigs and poultry. (fn. 213)

During the later 20th century farming in the new civil parish of Filkins and Broughton Poggs followed trends seen elsewhere in the area. Barley's dominance as the principal crop in the 1960s gave way to wheat in the 1980s, and livestock farming went into decline, with sheep and pigs increasingly substituted for cattle, and the number of farm workers continuing to fall. (fn. 214) Oxleaze and Manor farms continued to operate at the end of the century. (fn. 215)

Rural Trades and Industry

Apart from milling, few trades and crafts were documented in Broughton Poggs until the 19th century. For goods and services the inhabitants presumably travelled to nearby towns and villages, including the thriving local centre at Filkins. (fn. 216) Occupational surnames in the late 13th and early 14th centuries included Leatherhose and Weaver, but there is no other evidence of cloth workers in the village until the early 17th century when a tailor was mentioned. (fn. 217) In the 18th century craft workers included a carpenter, dyer, and the Cox family of tailors, and Elizabeth Turner was a pedlar. (fn. 218) In 1821 only two families out of 24 were employed in trade, craft, or manufacture, among them, perhaps, the village carpenter, slater, or tailor mentioned in 1841. (fn. 219) The most notable was William Preston, whose tailoring business expanded and in 1851 employed two assistants. The family continued as village tailors until the mid 1890s. (fn. 220) Masons, seamstresses, and wheelwrights were mentioned occasionally, and Charles Booker worked as a shoemaker from c. 1890 to the early 1930s. (fn. 221)

In the 20th century the village lacked its own shops, pubs, and other amenities, but a range of local trades and services were conveniently located in Filkins. (fn. 222) After the Second World War local manufacturing jobs were created at a factory built alongside Broadwell brook, which in the 1990s supplied components to furniture and bed manufacturers; it closed in the early 21st century. Businesses were also established in workshops at Oxleaze Farm, including (in 1997) a saddlery, a printer, and a metal window company. (fn. 223) Russell Winn, designer of the Winn City Bike electric scooter, lived at Broughton Hall in the 1960s, where he had a workshop in the former coach house. (fn. 224)

Stone quarries in Broughton Poggs in the late 19th century were part of the larger quarrying industry based at Filkins. (fn. 225) Small-scale digging of stone, however, was probably an ancient practice, and was recorded at Broughton in 1605. (fn. 226)

Milling

Two mills together worth 12s. 6d. were recorded in 1086. (fn. 227) One called West Mill, on the river Leach at Lemhill, was granted to Eynsham abbey by Ralph Murdac in 1192, together with an annual gift of wheat (probably a quarter) from Broughton manor 'for making hosts'. (fn. 228) The abbey retained it with 6 a. at Lemhill until the late 15th century. In 1254 it was leased for 15s. a year, falling to 14s. in 1269, 8s. in 1390, and 6s. 8d. in 1470; by then it belonged probably to Sir Richard Harcourt. (fn. 229) The mill may have been abandoned about that time.

The other mill probably stood south of Broughton village on Broadwell brook, possibly on the site later called Mill Meadow. (fn. 230) In 1279 it was leased with 6 a. to a free tenant (Richard Miller) for 12s. 2d. a year, and in 1303 to an unnamed miller for an annual rent of 8s. and two days' work at harvest. (fn. 231) In 1316 Walter at Mill was taxed on the relatively modest sum of 16s., but he left the village before 1322 when the royal keeper of the manor described the mill as 'empty and ruined'. (fn. 232) It probably remained untenanted thereafter, Broughton's inhabitants presumably using one of three or four mills in Filkins and Broadwell. (fn. 233)

SOCIAL HISTORY

Social Structure and the Life of the Community

Until 1700 most inhabitants were modest husbandmen who, in the frequent absence of a resident lord, cooperated in the running of manor and village. Alongside them were a few wealthier families and an ill-documented group of local poor. Inclosure initiated major social change, reducing most villagers to the status of landless cottagers employed on the two large new farms, which were run by prosperous incomers. The resulting hardship led to widespread petty crime amongst impoverished labourers in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the 20th century the decline of agriculture, the break-up of the manor, and the sale of estate cottages to private owners brought about a further transformation, attracting newcomers who shared in the growing affluence of the region. The parish's community life merged increasingly with that of neighbouring Filkins, where most public buildings and local facilities were situated.

The Middle Ages

Most of Broughton's medieval lords held other manors and probably visited the parish only occasionally. A manor house may have been built or rebuilt in the 12th century, and by the 14th was owned (with a dovecot and gardens) by the Mauduits. (fn. 234) Presumably it housed demesne farm managers when not occupied by the lord or his family. John Mauduit (d. 1347) was taxed on goods at Broughton in the early 14th century, but his political and military career must have led to frequent absences, and he was also an active administrator in Wiltshire, where his house at Somerford Mauduit was probably his principal seat. (fn. 235) In the late 14th and 15th centuries the Moleyns family lived mostly at Stoke Poges (Bucks.), and Broughton manor house fell into decay. (fn. 236) The lords' officers were a more permanent presence, collecting rents and holding manor courts throughout the 15th century. (fn. 237)

In the absence of a resident lord, village society must have been dominated by the wealthier tenants. Of those, the wealthiest in the early 14th century were the Murdacs of Lemhill, though their influence in Broughton itself (two miles distant) was probably limited. (fn. 238) Other freeholders rarely stayed in the parish for long. Few of those named in 1279 were listed among 14th-century taxpayers, and as a group they seem to have been no wealthier than their unfree neighbours. The yardlander William Travers, for example, was assessed on goods worth only £1 2s. 6d. (fn. 239) Families of customary tenants proved more stable, and several remained in the village for fifty years or more: examples include the Boywells, Dustlings, Echedays, Gilmans, Goldlocks, and Passavants. All those families held half a yardland, but the Gilmans consistently paid the most in tax, and probably there were clear social and economic distinctions within the village. (fn. 240) In 1285 it was reported that Robert Dustling's house had been burgled, possibly by a local miller. (fn. 241)

Most tenant families were replaced after the Black Death, and by the 1480s a new group of inhabitants dominated proceedings in the manor court. (fn. 242) Some (such as the Bakers, Hillses, Proudfoots, and Reeves) were established in the village by 1417, and the Bakers, Parsonses, and Proudfoots remained there in the mid 16th century. (fn. 243) Richard Reeve (d. 1417) had contacts well beyond the parish, reflected in his bequests to the churches and clergy of Eastleach Martin, Kencot, Langford, and Shilton, to the Carmelite friars of Oxford, and for upkeep of Lechlade and Radcot bridges. (fn. 244) A quarrel between Reeve's widow and two local farmers acting as overseers may reflect more widespread petty disputes, since in 1442 one of them (the husbandman John Proudfoot) failed to appear before the justices to answer a plea of debt. (fn. 245)

1500–1800

Broughton's lords were non-resident throughout the 16th century, their place in village society taken by minor local gentry. (fn. 246) Thomas Limerick, who leased the demesne in 1540, was taxed on goods worth the large sum of £30, and until the 1560s he regularly witnessed villagers' wills. (fn. 247) Relations were not always so harmonious, however: around 1547 he accused a Filkins inhabitant of keeping a bawdy-house, to which the accused angrily retorted that he had seen Limerick's wife 'meddle carnally' with a man by the moat of Manor Farm. (fn. 248) Other resident gentlemen in the late 16th century included Thomas Dawes of Lemhill, Giles Love, and John Stock. (fn. 249)

Most inhabitants were more modest tenant farmers, taxed in 1544 on goods with a median value of £2. (fn. 250) Members of several such families (including the Bakers, Thomases, and Turners) made wills in the period 1550–90, the value of their goods for probate purposes ranging from £3 to £30, with an average of around £15. Such people were probably fairly typical of poorer husbandmen in Elizabethan Oxfordshire, furnishing their homes in moderately comfortable fashion. Katherine Thomas (d. 1575) left a table cloth decorated with blue thread and a pillow-case embroidered with silk, and most families owned some pewter and brass-ware. (fn. 251)

Seventeenth-century lords were more frequently resident, although the Alders, Godfreys, and Mowses appear to have been no wealthier than the minor gentry they replaced. (fn. 252) Repeated sales of the manor led to disputes. In 1620 Henry Alder's daughters complained that they were denied living space in the manor house, in contravention of an arrangement made following the manor's sale ten years before. John Godfrey (then living at the house with his wife and father-in-law) allegedly subjected them to intimidation and violence, and members of the local community were also said to be involved. (fn. 253) When one of Alder's daughters later presented to the parish church, Arthur Mowse claimed that she had no right to the advowson and presented a rival (but unsuccessful) candidate. (fn. 254) The usual petty disputes affected Broughton's tenants too. In 1596 Thomas Pritford quarrelled with Toby King, calling him 'an arrant cuckold maker' and boasting that 'if he had had his pike with him he would have had King's heart's blood'. (fn. 255) In 1611 the rector refused the sacrament to William Turner in a dispute over tithe payment. (fn. 256)

A few of Broughton's 17th-century inhabitants possessed quite considerable wealth. The rector Richard Deakin and his brother-in-law Robert Elk, who shared a house and both died of plague in 1603, left goods valued at £113 and £75 respectively. (fn. 257) The Burdocks, a family of yeoman farmers, were also relatively prosperous, and their house (taxed on four hearths in 1665) was one of the largest in the village, after Manor Farm and Broughton Hall (with eight or nine hearths each). (fn. 258) But such men were not typical. (fn. 259) Eleanor Greenhalf (d. 1682), widow of a former constable, left goods worth only £16, although her will is of interest in demonstrating wide social contacts. Eleanor made bequests to family and friends in Burford, Brize Norton, Longcot (near Faringdon), Drayton (near Abingdon), and Clifton (near Banbury), and she was also related to the local Turner family. (fn. 260) The very poor are less well documented at Broughton in this period, although their existence is indicated by the number of charitable bequests by better-off neighbours. A 'raggwoman' was buried in the parish in 1679. (fn. 261)

From the late 17th century the Goodenoughs (as lords of the manor) had a significant and long-lasting impact, most notably by their probable enlargement of Broughton Hall as a gentry house, and by their Enclosure of the open fields. (fn. 262) Inclosure in particular transformed the village's social structure, widening the gap between rich and poor. The broad social spectrum of relatively wealthy yeomen, more modest husbandmen, and poor smallholders or labourers was replaced by a much more polarized society, in which a new class of landless cottagers whose common rights had been extinguished was employed as wage labour by a few wealthy tenant farmers. Many long-standing families left the village, and few 18th-century inhabitants made wills (in contrast to their predecessors or their contemporaries in neighbouring villages). (fn. 263) Parish officers such as churchwarden were also increasingly drawn from a narrower local élite. (fn. 264) The Burnabys, who succeeded the Goodenoughs as lords of Broughton, aggrandized the Hall and its grounds yet further, apparently diverting the road through the village in the process. (fn. 265) Both families were mostly resident (the naval officer Sir William Burnaby serving as sheriff of the county in 1755), although in the 1780s William Chaloner Burnaby made an unsuccessful attempt to sell the mansion, which was subsequently leased until around 1800. (fn. 266)

Some of Broughton's less prosperous 18th-century inhabitants were both resilient and long-suffering. The widow Dorothy Lock, who rented a house and garden for £2 a year, died in 1764 at the age of about 100, and was described by the parish clerk as a most remarkable woman, noted for her 'great patience and evenness of mind'. William Lock (d. 1777) was evidently less equable, and drowned in a ditch while drunk. His family's fortunes seem to have suffered thereafter, since Thomas (d. 1791) and Mary Lock (d. 1793) were both paupers. (fn. 267) Poverty, disease, and misfortune affected many families. In 1715 Elizabeth Turner's house and her stock of pedlary wares were destroyed by fire, and she was compelled to turn to the parish 'as a real object of poverty'. (fn. 268) In 1765 and 1770 outbreaks of putrid fever swept through almost 'every house in the parish', killing the infant Mary Lock. (fn. 269) Theft was probably widespread and was severely punished. In 1790 Thomas Gardner's servant Martha Selman was sentenced to twelve months' hard labour for stealing from him, while Sir William Burnaby reported a theft from his garden in 1775, and in 1779 two labourers were accused of stealing turnips from a local husbandman, whose goods were later sold 'under distress'. (fn. 270)

The 19th and 20th Centuries

In 1841 two thirds of the parish's households (including those in Lemhill) were directly dependent on farm work, the majority of them as agricultural labourers. (fn. 271) Most inhabitants were not native to the parish: in 1861 only a third of households included an adult member who had been born there. (fn. 272) Nevertheless some labouring families (including the Cotterels, Harmers, and Vellenders) were of long standing, providing social continuity over half a century or more. In the late 19th century agricultural employment declined: by 1901 only 7 out of 22 households worked on the parish's farms, and many villagers left. (fn. 273)

The Filkins stonemason George Swinford (b. 1887) remembered the hardships endured by late 19th-century farm workers. At Oxleaze farm the labourers sometimes went without food, and were compelled to steal swedes or turnips to eat on the journey home. Workers caught stealing were instantly dismissed, and so, too, was a shepherd at Oxleaze whose children inadvertently revealed that he had taken a lamb. Another inhabitant stole cheese and bacon from Manor farm, which he hid in a tomb in the churchyard. (fn. 274) The agricultural depression must have exacerbated labourers' distress, especially as rural wages in Oxfordshire were notoriously low throughout the 19th century. (fn. 275) Poaching and pilfering were 'the only way' to survive even for the young, and though farmers could be severe in punishing such crimes, they were not unsympathetic to the plight of their workers. On Oxleaze farm in the 1890s the bond between master and servant was evident in shared banter about the workhouse. (fn. 276)

Broughton Poggs lacked public houses, and its inhabitants probably frequented those in Filkins. (fn. 277) In other ways, too, the two villages had a shared communal culture in the 19th and early 20th centuries, whether at school and church, or in sports teams, clubs, and societies. (fn. 278) Even so Broughton had some distinctive features. In the 1870s prize fighting was encouraged by the lessee of Broughton Hall, and featured a well-known local labourer. (fn. 279) The Hall was a focus of a number of community events, including celebrations of Queen Victoria's coronation and diamond jubilee, to which residents of Filkins were also invited. In 1856 the lord held a dinner there for fifty poor inhabitants 'with his accustomed liberality', to mark the end of the Crimean War. (fn. 280) Cricket was played in a field in front of the Hall in the early 20th century, until the new owner (John Hardcastle) confiscated the equipment and ended the club. (fn. 281)

The Thickens family, lords of the manor from 1824 to 1888, played a modest role in parish life. Originally from Wales, Revd Bowen Thickens (d. 1825) was briefly Broughton's curate, and had enough wealth to pay £10,000 for the estate. (fn. 282) John Thickens (d. 1863) lived at Broughton Hall in the 1850s, but later moved to Manor Farm. (fn. 283) His son improved the approach to the Hall, planting an avenue of trees; the Oxford Journal was impressed, noting approvingly that the scheme provided employment 'to many who would be otherwise out of work'. (fn. 284) Thereafter the Hall was leased to tenants, including the London businessman David Gaussen. (fn. 285) Later owners and lessees made little impression until J. N. Hardcastle (d. 1948) bought the estate c. 1907. (fn. 286) Swinford called him a 'real old-fashioned customer', and he seems to have kept himself aloof from most of the villagers. (fn. 287) Nevertheless, by breaking up the manorial estate, his impact on local society was comparable to that of the Goodenoughs.

During the 20th century Broughton Poggs was transformed from a poor estate village in which most cottages were rented from the lord of the manor to a desirable residential community of high-quality owner-occupied homes in an affluent area. (fn. 288) Even before the union of the parishes in 1954 community activities were based mostly at Filkins, the larger of the two villages, where the pub, village hall, school (closed in 1981), and other public buildings were located. (fn. 289) The exception was Broughton church, which in 2010 remained a focus of parish life. (fn. 290)

Education

In the 18th century Broughton's rectors catechized children at Lent, and around 1790 one of them taught reading, although an attempt to establish a Sunday school seems to have failed. (fn. 291) Later clergy paid less attention to parishioners' educational needs: in 1815 the rector reported that the parish had too few children to support a school, and that they attended the Sunday school in Filkins. (fn. 292) By 1819 a day school had been established in Broughton and taught 12 children, but as it lacked an endowment the poor were largely excluded. (fn. 293) The school closed before 1831 when many of the children were again educated at Filkins, although a village Sunday school (for boys only) survived. Its master, according to the curate, was 'somewhat objected to', although the curate acknowledged the difficulty of attracting a suitable master or mistress to such a small place. (fn. 294) The Sunday school closed temporarily soon afterwards, but was re-established later in the 1830s, when the rector paid for some children to attend the day school at Filkins. (fn. 295)

By 1853–4 another day school supported by the rector taught 12 pupils, and 12 others (mostly older children) attended the Sunday school. (fn. 296) Both probably closed after Broughton Poggs was united with Filkins parish in 1855, (fn. 297) and after the parishes were once again separated in 1864 Broughton's children continued to attend the Church of England (later National) school in Filkins. (fn. 298) A proposal in 1872 to build an infants' school at Broughton was withdrawn, (fn. 299) and in 1914 the rector taught at Filkins one day a week. (fn. 300) John Avent (rector 1867–1909) briefly resurrected a night school in Broughton, and reestablished the village Sunday school, which was held in the rectory's coach house and had 24 pupils in 1872. (fn. 301) In the 1890s it was taught by the rector's three daughters, and remained well attended in 1914. (fn. 302)

48. Broughton-cum-Filkins school in Filkins village, established by William Hervey of Bradwell Grove in 1837, and formally extended to Broughton Poggs in 1855.

Day-school provision continued at Filkins until the school's closure in 1981. Thereafter primary-age children attended Langford school and older pupils Burford Comprehensive, while some others were educated privately. (fn. 303)

Charities and Poor Relief

From the 16th century a number of local residents left mostly small bequests in cash or grain to Broughton's poor. (fn. 304) A larger gift of £3 from a former rector (John Oliver, d. 1661) was distributed by the churchwardens in 1663, (fn. 305) and a poor-box in the church was mentioned in 1685. (fn. 306) The parish lacked any endowed charities, (fn. 307) and in the 18th century, apart from offertory money distributed by the rector, (fn. 308) the mounting cost of poor relief was funded almost exclusively by a few relatively wealthy ratepayers.

Annual spending on Broughton's poor increased in line with national trends, rising from around £29 in 1776 to £75 in 1783–5, then almost trebling to £220 in 1803. At that date nearly three fifths of the village's population were assisted by the overseers: a high proportion, which was indicative of the poverty endured by many labourers. In all, 55 people (including 31 children) received regular out-relief, and another 4 occasional relief. (fn. 309) Expenditure peaked in 1814 at more than £2 per head of population, a total outlay of £232, when 23 adults were relieved; three inhabitants were also members of a local friendly society, of which nothing more is known. (fn. 310) Annual spending on the poor fell thereafter to around 30s. per head in 1815–19 and 28s. in 1820–5, rising again to 31s. in 1826–9 as Broughton's population increased. It remained at a similar level in the early 1830s, when total expenditure averaged some £237 a year. (fn. 311) In 1831 the rector reported that there was no poorhouse in the parish, although a so-called 'hovel' shown on the tithe map of 1839 may have been used to shelter the indigent or homeless. (fn. 312)

From 1834 formal responsibility for Broughton's poor passed to the new Witney poor-law union. (fn. 313) The rector continued to provide occasional help to those in need, and in 1863 it was reported that a former rector's daughter (then living in Bristol) had for some years paid for the distribution of a piece of beef to every poor person in the parish. (fn. 314) In 1844 the curate William Colston endowed a charity with stock worth £166 13s. 4d., which in 1890 produced an income of £4 11s. 8d.; the money was given to the poor in kind, probably as coal. (fn. 315) The charity continued in 1967, but by then increased affluence meant that it was no longer distributed. In 1976 it was amalgamated with other charities in Filkins. (fn. 316)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

Broughton Poggs had its own church by the early 12th century. By the 13th the benefice was a rectory with its own endowment, though the church did not become fully independent of Langford until at least the Reformation. The living was not well endowed, and from the Middle Ages Broughton's rectors were mostly undistinguished. In the 18th century, however, the church became effectively a private living of the Goodenoughs, who were both patrons and lords of the manor. Successive family members served as rector from 1734 to 1855, when the benefice was merged with that of neighbouring Filkins. Separated in 1864, the two parishes were again combined in 1942, and from 1980 declining church attendance led to their incorporation into ever larger benefices.

Until the arrival of the wealthy Goodenoughs the parish suffered periods of poverty and neglect, and in the 17th century part of the church collapsed. The Reformation caused local disruption, but from the 1550s most inhabitants conformed: neither Protestant Dissent nor Roman Catholicism (despite its strong presence elsewhere in the area) achieved much of a foothold, and no permanent Nonconformist meeting house was established. The Anglican congregation remained small throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, although the church continued to benefit from the patronage of the local élite, especially the Goodenoughs.

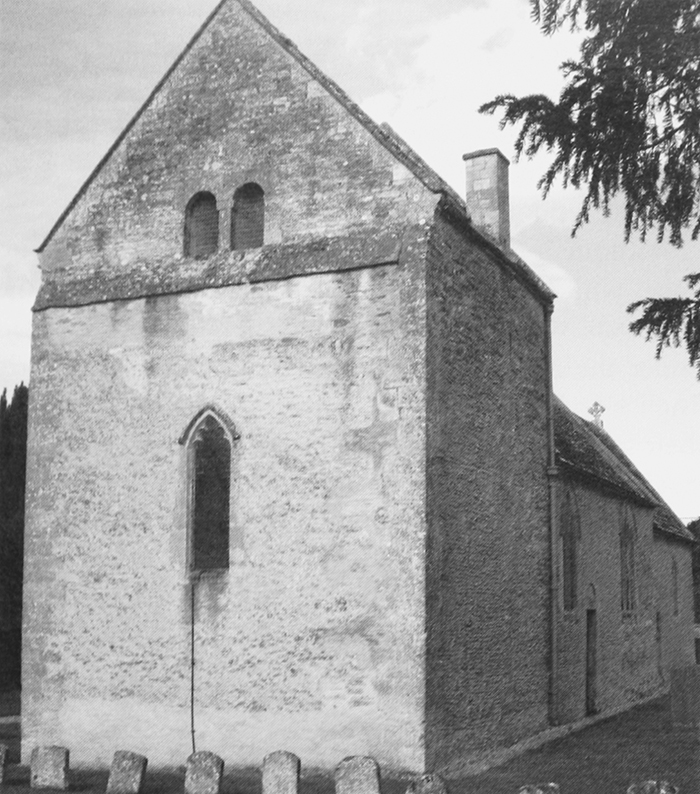

Parochial Organization

In the late 11th century Broughton Poggs was most likely dependent on the important Anglo-Norman church at Langford, the site of a possible pre-Conquest minster. (fn. 317) A church was built at Broughton in the early 12th century and was probably given baptismal rights, since the tub-shaped font appears to be of similar date. (fn. 318) In other respects, however, the church achieved independence only slowly. In 1277 Langford vicarage was endowed with Broughton's grain tithes (later exchanged for those of Grafton), and in 1291 the vicar of Langford received 10s. a year from Broughton church. (fn. 319) The payment continued in 1428, though it had probably ceased a century later. (fn. 320) Broughton seems to have finally acquired burial rights in the early 16th century, perhaps around 1556 when the earliest surviving parish register commences. (fn. 321) Even so most of Broughton's inhabitants were buried at Langford or (less commonly) at Broadwell until the early 17th century, (fn. 322) and in 1664 one of Langford's churchwardens allegedly tried to prohibit further burials at Broughton. (fn. 323) In 1540 Broughton's inhabitants refused their customary contribution towards the repair of Langford's churchyard walls. (fn. 324) The church's dedication to St Peter, which is common in Oxfordshire, is probably of medieval origin, although it was not recorded until the 18th century. (fn. 325)

In 1855 Broughton Poggs was united with Filkins to form the new ecclesiastical parish of Broughton-cum-Filkins, and in 1857 Broughton's church was closed. It re-opened in 1863, and the following year Broughton was separated from Filkins, becoming once again an independent parish. An order reuniting the benefices was agreed in 1921, but did not take effect until 1942. In 1980 the combined benefice was merged with that of Broadwell, Kencot, and Kelmscott, and other parishes were added later to create the large Shill Valley and Broadshire ministry. (fn. 326)

Advowson

The advowson is first recorded in the possession of Robert Mauduit in 1227, and remained with the lord of the manor. (fn. 327) Crown presentations in 1393 and 1432–4 were made during minorities. (fn. 328) Thomas Limerick, who held the demesne in 1540 and presented to the rectory in 1556, was patron during Anne of Cleves's tenure of the manor. (fn. 329) In the 17th century the right of presentation was sometimes sold for particular turns: in 1632 Arthur Mowse granted the patronage to a fellow London fishmonger, while in 1690 the Revd Robert Glyn of Little Rissington (Glos.) presented his son Edward. (fn. 330) In 1638 the advowson was briefly in dispute, when the daughter and son-in-law of Henry Alder, a former lord of the manor, successfully presented their candidate in place of the current lord's nominee. (fn. 331)