A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Langford Parish: Langford', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/175-208 [accessed 10 May 2025].

'Langford Parish: Langford', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online, accessed May 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/175-208.

"Langford Parish: Langford". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online. Web. 10 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/175-208.

In this section

LANGFORD PARISH

Until 19th-century reorganization Langford parish included the contiguous townships of Langford, Little Faringdon, Grafton, and Radcot. (fn. 1) As with Broadwell, the parish's unusual size reflected its derivation from a large late Anglo-Saxon estate, and in Langford's case medieval tenurial links resulted in the townships of Langford and Little Faringdon becoming (from the 13th century) detached parts of the Berkshire hundred of Faringdon. Only in 1844 were they transferred back to Bampton hundred in Oxfordshire, to which Grafton and Radcot had belonged throughout. (fn. 2)

The villages, built mainly of local limestone, were predominantly agricultural, but from the Middle Ages each developed a distinctive character. Langford, with its renowned Anglo-Norman church, was the most populous and most diverse, and in the absence of a resident lord developed many of the characteristics of an open village. By the 19th century it possessed two Nonconformist chapels, numerous farmhouses and cottages, and several shops, schools, public houses, and friendly societies. Little Faringdon, by contrast, was dominated by its 19th and 20th-century lords, who took a close interest in the lives of its inhabitants and preserved its rural seclusion. Grafton was the most isolated settlement, built on the margins of a large common inclosed only in 1846, and dependent for most local services on neighbouring places. Radcot, on the other hand, developed close to an important crossing of the Thames, and though it suffered considerable depopulation in the later Middle Ages (shrinking to a hamlet of only half a dozen houses), its position ensured that it remained a notable trans-shipment point from road to river. Its strategic location also lent it a sometimes unwelcome role in the national power struggles of the 12th, 14th, and 17th centuries.

Parish and County Boundaries

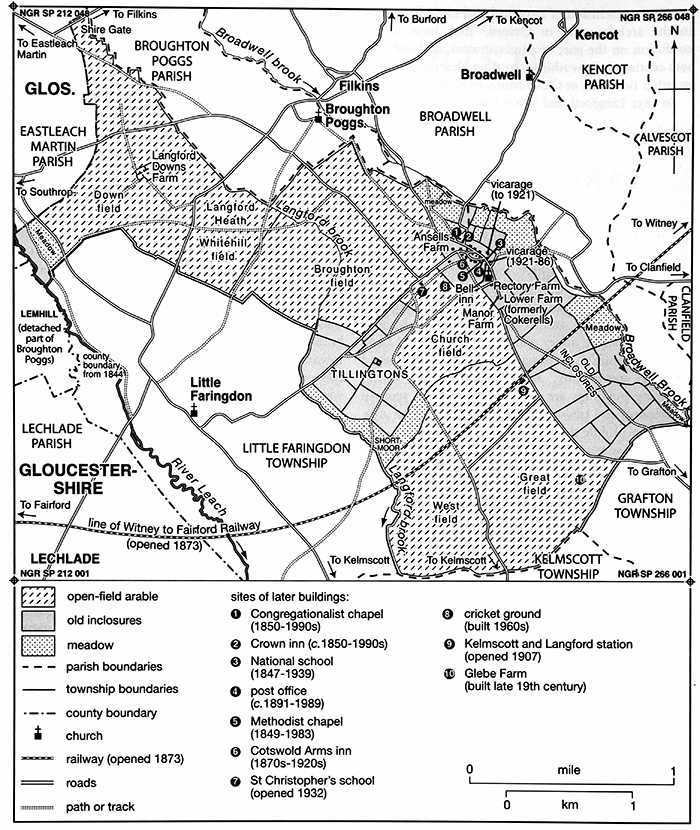

The ancient parish (Fig. 1) covered 4,350 a., comprising the townships of Langford (2,117 a.), Little Faringdon (1,167 a.), Grafton (625 a.), and Radcot (441 a.). (fn. 3) Its elongated shape encompassed a wide range of agricultural resources, from the Cotswold downlands on the Gloucestershire border to the flat meadowlands by the rivers Thames and Leach (Fig. 3 and Plate 1). As with neighbouring parishes, that diversity almost certainly reflected conscious planning when the Langford estate was created during the 11th century, carved probably from a larger unit which included neighbouring Broadwell. (fn. 4)

The parish's southern and western boundaries (fn. 5) coincided with those of Berkshire and Gloucestershire, which were determined in outline by the early 11th century, and clearly reflected earlier divisions. For long stretches they followed the rivers Thames and Leach. (fn. 6) The boundaries with Kelmscott, Clanfield, Broadwell, and Broughton Poggs must have also been broadly established by the mid 11th century, when all those places formed separate territorial units, (fn. 7) although some stretches may have been subject to minor adjustments later on. This was especially true of the northern and south-western boundaries with Broughton Poggs and Kelmscott, which in the 19th century followed field boundaries which were perhaps of relatively recent origin. By contrast, the 19th-century eastern boundary mostly followed small streams flowing into the Thames, and was probably little altered from the Middle Ages.

In 1086 Langford was still included in Oxfordshire. (fn. 8) However, King John's grant to Beaulieu abbey in 1203 of an estate centred on Great Faringdon, including Little Faringdon and 'whatever the king had' in Langford, resulted in the incorporation of both townships into Berkshire and their administrative separation from Grafton and Radcot. (fn. 9) Langford and Little Faringdon's detachment from Oxfordshire was confirmed in 1313 when the lord of Bampton conceded that Beaulieu's tenants no longer owed suit to Bampton hundred court. (fn. 10) Presumably that confirmed a long-standing arrangement, because in 1279 neither township was included in the Bampton hundred roll enquiries, with the minor exception of the land in Langford held by Matthew de Besyles of Radcot. (fn. 11) The unusual division of a single parish between two counties, and the continuing inclusion of Langford and Little Faringdon in the archdeaconry of Oxford, (fn. 12) may have caused confusion on the part of administrators, and until the 19th century the townships were often described as lying in either Berkshire or Oxfordshire, or both. (fn. 13)

In 1832 Langford and Little Faringdon were transferred from Berkshire to Oxfordshire for parliamentary purposes, and in 1844 for civil purposes, when they rejoined Bampton hundred. In 1866 the ancient parish was divided into four civil parishes with the same boundaries as the former townships. (fn. 14) The ecclesiastical parish was divided slightly earlier, in 1864. (fn. 15)

LANGFORD TOWNSHIP

The limestone-built village of Langford lies on the edge of the Cotswolds, on flat, low-lying ground north of the river Thames. Its fine church, incorporating a late 11th-century tower and reset Anglo-Saxon figure sculptures, reflects its early importance as the centre of a large late Anglo-Saxon estate, and its later medieval landowners included Beaulieu abbey and Lincoln cathedral. (fn. 16) Until the 20th century it remained a moderately sized farming community, however, and most other surviving buildings are 17th or 18th-century yeoman farmhouses and labourers' cottages typical of the area. From the Middle Ages it lacked a resident lord, and developed some of the characteristics of an 'open' village: Nonconformist chapels were built in the 19th century and a range of rural crafts developed, although the village failed to expand. (fn. 17) The nearest towns were Lechlade (Glos.) some 3 miles to the south-west, Faringdon (formerly Berks.) 5½ miles south-east, and Burford (Oxon.) 6 miles to the north.

During the 20th century Langford's 'unspoilt' character began to attract a new class of prosperous commuters, for whom many of its better-quality houses were restored as desirable residences. Even so, compared with some neighbouring Cotswold villages the community remained socially mixed in the early 21st century, with council housing making up almost a quarter of the local housing stock. (fn. 18)

Township Boundaries and Landscape

The township (Fig. 51) covered 2,117 a. (856 ha.), its boundaries having presumably crystallized during the 11th and early 12th centuries as neighbouring estates were hived off and became separate manors. (fn. 19) The eastern boundary with Broadwell follows Broadwell brook, where the 'long ford' from which Langford took its name was probably located. (fn. 20) That to the south, bordering Grafton and Kelmscott, runs along field boundaries and ditches. The western boundary with Little Faringdon follows Langford brook and field boundaries to the river Leach, which separates the township from Southrop (Glos.) and from Lemhill, a formerly detached part of Broughton Poggs. The north-western boundary with Eastleach Martin (Glos.) and the north-eastern one with Broughton Poggs follow what appear to be former open-field boundaries, suggesting that the boundary there was determined only after the open fields were laid out. (fn. 21) In 1866 the township became a separate civil parish, and its ancient boundaries remained unaltered in 2001. (fn. 22)

The flat, low-lying ground in the south of the township lies chiefly on gravels of the Second (Summertown-Radley) Terrace, and rises imperceptibly from 74 m. on the Grafton boundary to 78 m. in the village. South-west of there are some small areas of Third (Wolvercote) Terrace and underlying Oxford Clay. (fn. 23) The varied soils were reflected in 17th-century furlong-names such as 'Clay furlong', 'Sandy furlong', and 'Redland', while names such as 'Marsh furlong', 'Fulpitts', and 'Gripe' reflected the need for drainage. (fn. 24) Ditches were dug for that purpose from the Middle Ages, a man drowning in one of them in the 13th century. (fn. 25) Broadwell brook itself has long been liable to flood, and as late as 2007 parts of the village were affected. (fn. 26) Further north, the downs rise to 93 m. at Whitehill on the Little Faringdon boundary, and to 100 m. at Shire Gate on the Gloucestershire border. There, the underlying geology is mostly Cornbrash. (fn. 27)

51. Langford township c. 1800, showing pre-inclosure fields and some later buildings.

Narrow bands of alluvium along the streams provided good meadow, while the township's lack of woodland contributed to a perception of the landscape (largely approved of in the 20th century) as a 'featureless plain'. (fn. 28) Stone and gravel for road-mending and other local uses were dug from small scattered pits before the mid 20th century, (fn. 29) and larger quantities were extracted during the Second World War, particularly in the far west of the township. The resulting pits were later turned into artificial lakes, and used for recreational fishing. (fn. 30) The relative monotony of the landscape is now broken by prominent overhead power-cables, which cross the length of the township and pass south-west of the village. (fn. 31)

Communications

Roads

Langford village lies at a multiple crossroads (Figs 2 and 51). The road south-westwards to Little Faringdon was mentioned in 1307, though it was probably straightened at inclosure in 1808. (fn. 32) From this, another pre-inclosure road branches off to Broughton Poggs and Southrop (Glos.), crossing the main Lechlade-Burford road (the present A361). (fn. 33) The roads north-eastwards to Broadwell and north-westwards to Filkins are both also of medieval or earlier origin. (fn. 34) The Filkins road continues south-eastwards to Grafton, (fn. 35) and it was along this route that settlement in Langford mainly developed. A back lane in the present centre of the village created a loop, which may formerly have bounded a green used for grazing and the protection of livestock, before it was infilled with houses. (fn. 36) The road to Kelmscott, mentioned in 1320, branches off midway along the road from Langford to Grafton. (fn. 37)

No roads or paths were suppressed at inclosure, when a dozen bridleways and footpaths were listed. Most remained in use in the early 21st century, converging on the village from all directions. (fn. 38) The names of some of them, including 'Lychewey', 'Crokers Lane', and 'Westway', are recorded from the Middle Ages. (fn. 39)

Carriers, Rail, and Post

Carriers to Burford, Cirencester, Faringdon, and Witney were mentioned from the 1860s to 1890s, and in the early 20th century there was a short-lived service to Lechlade and Witney. (fn. 40) Presumably the carriers lost business to the railway: stations were opened at Alvescot and Lechlade in 1873, both of them three miles away on the East Gloucestershire line from Witney to Fairford, and in 1907 a closer station called Kelmscott and Langford was built about half a mile south of the village. A siding for loading and unloading cattle and farm machinery was added there in 1928, by which time the line formed part of the Great Western Railway. It closed in 1962, (fn. 41) but local bus services continued. A weekly service to Swindon was mentioned in 1962 and later became more frequent, (fn. 42) and in 2010 there were regular buses to Carterton, Lechlade, and beyond. Post was delivered from Lechlade in the 19th century, and a sub post-office was opened in the village before 1891. It closed in 1989. (fn. 43)

Settlement and Population

Early Settlement

Evidence of prehistoric settlement, trackways, and agricultural boundaries has been found across much of Langford, although much of it is undated. (fn. 44) A possible Neolithic henge lies in the south-east of the township (SP 2600 0153), and a causewayed enclosure in the south-west (SP 245009), while Bronze-Age ring ditches have been identified on the downs (SP 215029). (fn. 45) Significant Iron-Age settlement complexes were situated both on the downs and on low-lying ground in the south, where 34 separate roundhouses have been identified (SP 252010). That site continued to be occupied into Roman times, although the settlement on the downs was abandoned. (fn. 46) Evidence of Romano-British occupation has also been found to the east and north-west of the village. (fn. 47)

The extent to which Langford remained inhabited in the post-Roman period is uncertain, although the minor place name Tillington (meaning the farm of Tilli's people) suggests Anglo-Saxon settlement in an area adjoining the parish's western boundary (Fig. 51). Possibly this was one of several dispersed farmsteads in the township before the development of the village and open fields in the 9th century or later, (fn. 48) and an early-inclosed pasture farm continued there into modern times. (fn. 49) By the 11th century, however, the bulk of the substantial population recorded in Domesday Book was most likely concentrated in and around the site of the modern village of Langford (discussed below).

Population from 1086

In 1086 there were 37 tenant households on Langford manor, headed by 21 villani, 4 lower-status bordars, and 12 slaves (servi). The slaves were presumably located near the demesne farms, but otherwise there is no indication of the pattern of settlement, and some of the tenants may have lived at Little Faringdon (which then still belonged to Langford manor) rather than in Langford itself. (fn. 50) Eighteen landholders in Langford alone were taxed in 1322, 21 in 1327, and 28 in 1332, (fn. 51) most of them probably representing a household. In addition there must have been an unknown number of inhabitants who fell below the tax threshold, and the figures suggest that the township's population was rising.

Depopulation during the Black Death seems to have been relatively limited, since the 1381 poll tax was paid by 86 adults aged over 14 (grouped in about 42 families). (fn. 52) Ruined houses were reported in the late 15th century, implying that population remained below its early 14th-century peak; nevertheless the profits of sheep farming may have brought some local prosperity. (fn. 53) Up to 30 taxpayers, including labourers and servants, were named in the 1520s and 1540s, (fn. 54) and 59 people were recorded in 1548, (fn. 55) while from the 1560s baptisms (for the whole parish) consistently out-numbered burials. (fn. 56) In Langford itself 46 houses were assessed for hearth tax in 1662, including 15 whose occupiers were too poor to pay. (fn. 57) Thirty five land-holders paid land tax in 1716, though not all were necessarily resident. (fn. 58)

By 1801 Langford had 79 inhabited houses and a population of 356, which rose to a peak of 453 (in 103 houses) in 1851. The trend was reversed following the onset of agricultural depression in the 1870s, with population falling sharply to 297 (in 72 houses) by 1901. A partial recovery to 333 followed over the next decade, but thereafter numbers remained under 300 until the 1950s. By 1961 the population was 349 in 107 houses, though it fell again to 275 (in 115 houses) by 1991. In 2001 there were 327 inhabitants, and a total of 138 households. (fn. 59)

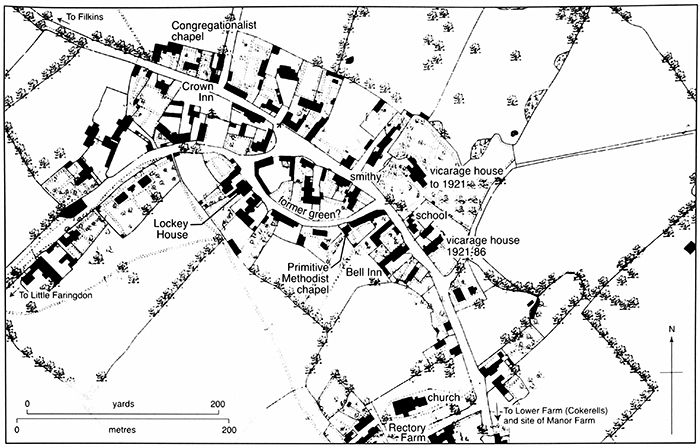

The Development of Langford Village

Langford grew up at an intersection of early routes, and its place name (meaning 'long ford') refers probably to a crossing of Broadwell brook ('broad stream'). (fn. 60) Though first recorded in 1086 the name is Anglo-Saxon, and the village probably had its origins in the 9th or 10th century, when nucleated settlements generally formed. (fn. 61) The early core may have developed close to the parish church, which was built (or possibly rebuilt) in the later 11th century; the rectory, manor house, and a 12th-century farmstead later called Cokerells were all located there, and archaeology has revealed medieval settlement (later abandoned) to the north and east of the church. (fn. 62) The centre of the present village lies about 200 m. north of the church, where the roads from Broadwell and Little Faringdon meet the Filkins-Grafton road; settlement there is grouped around a probable medieval green, which was subsequently infilled (Fig. 52). Similar extension or reorganization of settlement, leaving the original village core isolated, has been noted at other places in Oxfordshire, (fn. 63) although at Langford it is unclear when the change took place or whether it was a planned development.

The physical separation of the southern end from the rest of the village was reinforced in the late 19th century, when a number of houses (including some near the church) were demolished as population fell. (fn. 64) Nevertheless Langford retained a compact appearance, which was only slightly diminished by the building along the Little Faringdon road of a school (in 1932) and of council housing (in the late 1940s). (fn. 65) In the late 20th century some previously undeveloped land was built on, including along the Broadwell road, but most new housing resulted either from the infilling of existing plots or the conversion of former farm buildings to residential use. A cross (Plate 3) was erected at the junction of the Grafton and Little Faringdon roads to commemorate parishioners killed in the First World War, while the village hall (built c. 1923) occupied a vacant plot along the Filkins road. (fn. 66) Water supply, previously from wells or surface springs, was improved in the 1890s by the sinking of an artesian well and provision of a standpipe; (fn. 67) electricity was available from the 1930s, and mains water after the Second World War. (fn. 68)

52. Langford village c. 1880, showing key buildings.

Outlying Sites

Tillingtons was an old-inclosed pasture farm by the 16th century, and in 1808 included a farmhouse (now derelict) some ¾ mile south-west of the village. (fn. 69) Since the place name suggests origins before the Norman Conquest, this may be an example of an isolated farmstead which survived the late Anglo-Saxon development of the village and open fields. (fn. 70)

Apart from the medieval mills (of which no trace remains), (fn. 71) all of Langford's other outlying sites are post-medieval. A farmhouse at Langford Downs was built around the time of inclosure in 1808, while Glebe Farm (near the Grafton boundary) was built in the late 19th century on land allotted to the vicar in lieu of tithes. (fn. 72) In the 20th century a house called The Bungalow was built along the road to Eastleach Martin in the far north of the township, and in 1940 another was built in the far west along the road to Southrop. (fn. 73)

The Built Character

Langford has a largely homogenous built character. Cottages and houses of 17th- to 20th-century date, constructed of local limestone and stone slate, cluster in the village centre (Plate 3), with smaller outliers near the church and school and a few isolated farmhouses further afield. Many feature the stone mullions and hoodmoulds typical of the area, while others have casements under simple wooden lintels, and the majority (with some notable exceptions) have uncoursed walling. (fn. 74) Much of the stone and slate is probably from local quarries; its distinctive grey colour is characteristic of the Cotswolds, and lends the village much of its attractiveness and appeal. (fn. 75) Nevertheless the uniformity of the building materials masks a variety of styles and structures, and is to some extent a product of 20th-century improvement and planning regulations: previous generations used a wider range of often cheaper materials, including timber, thatch, and corrugated iron. An example is the sub post-office, which was partly rebuilt in a stone-and-slate 'Cotswold vernacular' style in 1932. (fn. 76)

53. Lockey House, owned in the 18th century by a prosperous family of tobacconists who became lessees of the manor prebend.

Surviving domestic buildings appear to be post-medieval, (fn. 77) though some farmhouses had medieval predecessors. Lower Farm (or Cokerells) and Rectory Farm are both recorded from the Middle Ages, while Manor Farm (demolished in the 19th century) occupied a medieval site. (fn. 78) Several more modest farmhouses and cottages survive from the 17th century, but most of the present housing stock is 18th-century and later, built chiefly by prosperous yeoman farmers. (fn. 79) Some houses have descriptive names such as Greystones, but many are named after former owners (Ansell, Lockey, Pember), or from their former use (The Old Bakery, The Forge). Blenheim Cottage was presumably named after the early 18th-century battle, although its datestone of 1755 suggests that it may have been rebuilt or remodelled. (fn. 80) The Bell Inn, Langford's oldest and only surviving public house, began as a nondescript mid 17th-century dwelling, which was remodelled and extended in the late 18th century and again in the 19th. Two-storeyed, it is of whitewashed uncoursed lime-stone rubble with a Welsh-slate roof, and has 19th-century casements under wooden lintels. (fn. 81)

At the beginning of the 19th century there were 80 houses in the township, rising to 109 (including six unoccupied) in 1851. (fn. 82) Many of these new dwellings were probably created by subdivision: by 1901 the number of houses had fallen back to 83, of which 11 were uninhabited. (fn. 83) At that time the Ecclesiastical Commissioners (as lord of the manor) owned around 18 cottages, of which several were old and in need of repair; most were maintained, but a few were pulled down. (fn. 84) From the 1920s and especially from the 1950s the Commissioners sold off much of their housing stock to tenants and other private purchasers, a policy which continued in the 1990s. (fn. 85)

The Commissioners also sold land to Witney Rural District Council for house building. An 11-a. area near the school was sold in 1946, and an estate of 33 council houses was subsequently built on part of the site. (fn. 86) Private development followed in the late 20th century, and was chiefly responsible for an increase in the number of dwellings to 138 in 2001. (fn. 87) Like the council housing, most new houses were built of stone and stone slate to mock-vernacular designs, in order to blend in with the village's existing housing stock.

Public Buildings

In the late 19th century Thomas Banting of Filkins reported that a large thatched timber building once stood between the church and the Bell Inn. Demolished during his father's lifetime, it 'used to be a gaol and town hall where the judge used to try prisoners'. (fn. 88) This was perhaps the structure shown on the inclosure map of 1808, and described by another observer as forming part of the northern boundary of the churchyard. According to this account it was a 'large quadrangular building, containing a noble room, lighted by a gothic window of stone, richly ornamented by a cross, and a label supported by two angels, of very elegant workmanship'. Already mostly dismantled for its materials, the building was partly surrounded by a moat, and may have been of medieval origin. (fn. 89)

The National school, built of re-used materials in 1846–7 in traditional Cotswold style, comprised two classrooms and a small two-storey house for the teacher (only 18 ft by 12 ft). (fn. 90) Extended in 1896 by the addition of a galvanized iron classroom, and later rebuilt after protests from educational authorities, the school was sold in 1939 and converted into a house (Plate 15). (fn. 91) In 1972 it was bought by the fashion designer and Queen's dresser Sir Hardy Amies (d. 2003), who employed local craftsmen ('men who understand how to build in stone') to extend it and convert former farm buildings to residential use. (fn. 92) A new school was built in 1932 by the Oxford architect Harry Smith, using local stone donated by Sir Stafford Cripps of Filkins; the village blacksmith provided the wrought ironwork. (fn. 93)

The railway station, which does not survive, was formed from two standard Great Western Railway pagodas, clad in corrugated iron and erected end to end. (fn. 94) The village hall on the Filkins road, built c. 1923 with financial assistance from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, was refurbished in 2000 when a stone façade was added. (fn. 95)

MANORS AND ESTATES

In the late Anglo-Saxon period Langford (including Little Faringdon, Grafton, and Radcot) formed part of a large comital estate which also included Broadwell (Fig. 1). (fn. 96) Broadwell (with its constituent townships) and Grafton were separated before the Norman Conquest, leaving a reduced Langford estate which probably comprised the later townships of Langford and Little Faringdon. In 1066 that estate was held by Earl (later King) Harold, together with Great Faringdon and other property in west Oxfordshire. (fn. 97)

The estate was further subdivided by the king in the late 11th and early 12th century, (fn. 98) creating an independent manor of Little Faringdon and, within Langford township, three separate estates, of which two were granted to Lincoln cathedral c. 1139–46 and used to endow prebends. One (called Langford Manor) included the lordship, while the other (Langford Ecclesia) comprised Langford rectory estate. A small lay estate called Cokerells was also held of the dean and chapter. The rest of Langford remained with the Crown until the early 13th century, when it was granted to Beaulieu abbey (Hants), whose estate was divided into numerous independent freeholds after the Dissolution. All three of the Lincoln cathedral estates and much of the former Beaulieu estate were acquired in the 19th and 20th centuries by the Ecclesiastical (later Church) Commissioners, who in 2008 remained the largest landowner.

Langford Manor

In 1086 Aelfsige of Faringdon held Langford (with Little Faringdon) at farm from the king, together with other properties formerly belonging to Earl Harold. (fn. 99) Thereafter the estate was divided: Little Faringdon became a separate manor from 1156 and possibly earlier, (fn. 100) while under Henry I (1100–35) a part of Langford was held by Ailric, possibly a relative of Aelfsige of Faringdon, and later by Roger (d. 1139), bishop of Salisbury. (fn. 101) This land was granted to Lincoln cathedral probably by King Stephen in 1139–46, and around 1150 Robert de Chesney (d. 1166), bishop of Lincoln, used it to endow a cathedral prebend, later called Langford Manor or Langford Lay Fee. (fn. 102)

The prebend belonged to Lincoln cathedral until 1650 and again from 1660 to 1844, when it was vested in the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. The prebendary, a canon of the cathedral, was lord of the manor and held an estate of about 538 a. before inclosure and 588 a. thereafter, although few if any of the prebendaries visited the parish more than occasionally. (fn. 103) In 1650, following the abolition of cathedral foundations during the Interregnum, the prebend was briefly held by Francis Pigott, a London lawyer. (fn. 104) The Ecclesiastical Commissioners sold part of the land in 1848 to Richard Frampton, owner of Langford Downs farm, but in 2008 their successors the Church Commissioners still retained most of it together with the lordship. (fn. 105)

Manor House (Manor Farm)

A manor house existed in the Middle Ages, at which the prebendary of Langford Manor was lavishly entertained on his occasional visits to the village. (fn. 106) Probably it occupied the site of the now-demolished Manor Farm south of the church, which in more recent times was occupied by the lessee of the manor prebend. In 1650 it was a stone-built house of twelve bays with a tiled roof, and included a hall, parlour, kitchen, buttery, dairyhouse, malthouse, and nine chambers; (fn. 107) in 1662 it was the largest house in the village, taxed on 11 hearths. (fn. 108) The prebendary's lessee Richard Broderwick (d. 1681) lived there in some comfort, occupying at least a dozen furnished rooms. (fn. 109) By 1845 the house and outbuildings were 'rather out of repair', (fn. 110) and although they were probably still standing in the 1860s when William Craddock leased the farm from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, they had been demolished by 1880, when the farmland was incorporated into Lower farm. The site was used for outbuildings. (fn. 111)

Other Estates

Langford Ecclesia Prebend (Rectory Estate)

The church of Langford, with its lands and tithes, was granted by King Stephen as a prebend to Lincoln cathedral in 1139–46, and was confirmed by Henry II in 1155–8. (fn. 112) The prebend comprised the rectory of Langford parish church, with great tithes in Langford, Little Faringdon and Radcot, some hay tithes in Grafton and Radcot, and around 120 a. of glebe with meadow and pasture rights. (fn. 113) The estate belonged to Lincoln cathedral until its temporary suppression in 1650, when it was briefly sold to speculators; (fn. 114) the cathedral recovered the estate at the Restoration in 1660.

In 1846 the prebendary gave up his interest to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners in return for a life annuity of £260, (fn. 115) and in 1848 the estate (453 a. after inclosure) was divided between the Commissioners and the lessee William Vizard (d. 1859). The former received 291 a. and most of the buildings, while Vizard was awarded compensation of £6,500 and the remaining 162 a. as freehold. (fn. 116) Following the prebendary's death in 1866 the Commissioners obtained outright ownership of their share of the estate, which was merged with the lands of Langford Manor prebend and remained with the Church Commissioners in 2008. (fn. 117) Vizard's share passed with Little Faringdon manor to the 2nd Baron de Mauley, whose successors sold most of it to the Church Commissioners in 1970. (fn. 118)

Rectory Farm

Rectory Farm (Fig. 54) lies south of the church, and probably occupies the site of the medieval rectory house said to be in ruins in 1540. (fn. 119) From the 16th century and probably earlier it was occupied by the prebendary's lessee, who was obliged to maintain it. (fn. 120) In 1650 it was of ten bays and included a hall, parlour, kitchen, buttery, and six chambers, and in 1662 it was taxed on eight hearths. (fn. 121) Outbuildings included a five-bay brewhouse and bakehouse, a fourbay malthouse, three barns (one built of stone and tile), a dovecot, a stable, and a two-storeyed gatehouse. (fn. 122) The gatehouse no longer survives, but the present house and dovecot are both of 17th-century date. The house is H-shaped in plan, built of uncoursed limestone rubble with a stone slate roof, and has two storeys with gablelit attics. On the north front the windows are mostly 18th- or 19th-century sashes and casements with dripstones, and during the 19th and 20th centuries the house was subject to other alterations and additions. (fn. 123) The cost of repairs and improvements was shared by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and their tenants. The Kirby family, who look over the lease in 1948, continued as occupiers in the early 21st century. (fn. 124)

54. Rectory Farm from the churchyard, looking south. The house and associated rectory estate formed a prebend belonging to Lincoln cathedral, which leased both to local tenants.

Cokerells

Before Bishop Robert de Chesney endowed the prebend of Langford Manor he granted an estate to his man, Robert son of Fulk. About 1150 the chapter of Lincoln confirmed the grant of a house, half a hide of arable, 20 a. of 'in-land', 8 a. of meadow, and common pasture in Langford, to be held of the dean and chapter for an annual rent of 1s. (fn. 125) Robert was succeeded by his brother Geoffrey c. 1152, but in 1183–4 the estate was granted to Simon of Arden, saving the dower of Robert's widow Reinburga. (fn. 126) Reinburga may have remarried, because in 1198 she and Nicholas de Forholt attempted unsuccessfully to prevent Simon of Arden's daughter Juliana from inheriting the property. (fn. 127)

In the early 14th century the house was held with three yardlands by John de Bourne, whose annual rent of 1s. was granted in 1303 by the dean and chapter of Lincoln to Michael Meldon. (fn. 128) In 1349 the estate was held by Thomas de Bourne, chaplain, and Alice, widow of John Cokerell (perhaps Thomas's sister). (fn. 129) Their successors were probably John Cokerell and his wife Amice, who paid 5s. poll tax in 1381. (fn. 130) By 1421, when it was called 'Cockerelles', the estate belonged to Thomas Cokerell and his wife Alice. (fn. 131) It was inherited in the mid 15th century by Margaret wife of William Bond, who sold it in 1459 to Richard Harcourt. (fn. 132) The estate passed to Thomas Ricards or Fermor of Witney, son of a Langford wool merchant, whose service to the dean and chapter of Lincoln was not known at his death in 1485. (fn. 133)

In 1522 Cokerells was sold by William Porter to the bishop and dean of Chichester, and was granted to the dean and chapter as part of a prebendal endowment. (fn. 134) The estate (67½ a.) remained their property until 1854, when it was sold to the Ecclesiastical (later Church) Commissioners; they remained the owners in 2008. (fn. 135)

Lower Farm (Cokerells)

Lower Farm dates from the early 17th century, and probably succeeded the 12th-century house. In 1662 it may have been occupied by Thomas Broderwick (d. 1677), who was taxed on four hearths and whose furnished rooms included a hall, kitchen, buttery, dairy, and four chambers. (fn. 136) The present L-shaped house was remodelled in the 18th century, and has two storeys with attic dormers; it is built of uncoursed and roughly coursed limestone rubble with a stone slate roof. The interior includes 17th- and 18th-century panelling, and the attic has a tiebeam roof. (fn. 137) The house (with 5 a. of land) was sold by the Church Commissioners in the late 20th century. (fn. 138)

Beaulieu Abbey Estate

In 1203 King John granted more than 800 a. in Langford to his newly founded abbey of Great Faringdon, which was transferred to Beaulieu (Hants) the following year. Beaulieu abbey retained the estate with the adjoining manor of Little Faringdon until its Dissolution in 1538. (fn. 139)

In 1547 the abbey's lands in Langford were granted (with its separate manor of Great Faringdon) to Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, on whose fall in 1549 they reverted to the Crown. (fn. 140) Part of the estate later passed to Toby Pleydell (d. 1583), whose son John sold it in 1590 to Sir Henry Unton; he sold it the same year to Gabriel Bush. (fn. 141) At inclosure in 1808 the Bush family was one of a number of freeholders whose lands probably derived from Beaulieu abbey's estate, although their descent cannot always be traced. (fn. 142) Several freeholds, including that of the Bushes, were later bought by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, and remained the property of the Church Commissioners in 2008. (fn. 143)

Other former Beaulieu freeholds included John Blomer's house and 3 yardlands, called 'Barens' in 1551; this land was inherited by William Blomer (d. 1613) of Hatherop (Glos.), and passed with Hatherop manor to the Webbs of Canford (Dorset), whose descendants, the Barons de Mauley, later held Little Faringdon manor. (fn. 144) A freehold owned by John Webb in 1808 was later combined with those of Simon Ansell and Richard Lockey to create Ansells farm, which was owned in the early 20th century by Ernest Liddiard of Grafton. (fn. 145) Another freehold in 1808 belonged to John Short; that was sold by the Tombs family in 1901, and was later bought by Charles Edmonds of Fairford, the owner in 1942. (fn. 146) Most of Short's farm and Ansells farm were purchased by the Church Commissioners in 1970, and remained their property in 2008. (fn. 147) Another large freehold in 1808 was Langford Downs farm (c. 380 a.), acquired in 1875 by Trinity College, Oxford, and sold to the lessee Charles Wakefield in 1920. It was bought by the Church Commissioners in 1956. (fn. 148)

Lesser Estates

Land held by William of Buckland in 1212 had most likely been granted by the king in the 12th century, and was probably the tenanted estate of three yardlands and two smallholdings which Matthew de Besyles owned in 1279 as part of his manor of Radcot. (fn. 149) It descended with Radcot manor until 1614 when it was sold by John Wentworth to Richard Turner, one of an established family of Langford yeomen. (fn. 150)

In the mid 13th century Robert Aleyn, described as 'half-free' (semiliber), held ten yardlands from Beaulieu abbey, for service which included travelling at his own expense for one day a year with the king's treasure to the sea. (fn. 151) This estate may have originated in a royal grant to a 'riding-man' before the Norman Conquest, although it is perhaps more likely that before c. 1200 goods destined for the sea were loaded onto boats at Radcot and transported along the river Thames. (fn. 152) In the late 13th century Aleyn's holding belonged to Michael Meldon of Cassington as part of a larger estate, which included land held of Langford Manor prebend; it was partly inclosed, and probably run as a sheep farm. (fn. 153) The estate passed c. 1321 to Michael's son William Meldon, who paid Beaulieu abbey an annual rent of 10s. 2d. (fn. 154) Probably it was divided into three freeholds mentioned in 1551, totalling 9½ yardlands and held for a similar rent; one was called 'Molendies', possibly a corruption of Meldon's name. (fn. 155)

The vicar of Langford's glebe comprised 2 yardlands in 1650 and possibly earlier. At inclosure in 1808, 102 a. were allotted for glebe; the estate was sold in 1919. (fn. 156)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until the 20th century most of Langford's inhabitants were employed in agriculture, either on the large estates of non-resident landowners or on the smaller farms of local freeholders and lessees. Grain, wool, and dairy produce were the most important products. From the 15th century medieval customary tenancies were converted into leaseholds and copyholds, which were held both by prosperous yeomen and more modest husbandmen. Inclosure in 1808 led to the consolidation of land into larger farms, many of which turned from arable to dairying during the late 19th-century agricultural depression. A variety of rural trades and crafts developed to service the local community, and there were several retailers of food and drink. In the 20th century, as agricultural employment declined, Langford's population increasingly worked outside the village, and local shops and services closed.

The Agricultural Landscape

The strip-like shape of Langford township provided its inhabitants with varied agricultural resources (Fig. 51). Rivers and streams produced valuable meadow and pasture, and in the Middle Ages powered two watermills. On the downland in the north was furze and heath which, in the absence of woodland, provided fuel and rough grazing. On the flat, low-lying ground in the centre and south, open fields were laid out probably in the 9th or 10th century. (fn. 157) The fields were formally inclosed in 1808, though piecemeal inclosure of meadow and pasture took place from the 13th century and possibly earlier. (fn. 158) The inclosed area known as Tillingtons to the south-west of the village may survive from before the development of the open fields, while the probable green in the centre of the village perhaps originated as an enclosure for grazing before being infilled with houses. (fn. 159) Farming was mixed from the Middle Ages, combining large-scale cultivation of grain with sheep husbandry and cattle-based dairying.

Arable

In 1086 only 10 ploughlands of arable were cultivated at Langford (possibly including Little Faringdon), although as 15 ploughlands were available there was probably room for expansion. (fn. 160) Beaulieu abbey seems to have extended the arable area in the 13th century, agreeing to pay tithe to the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia from half of its newly cultivated demesne ground. (fn. 161) By the 17th century parts of the downs were also cultivated, the arable extending as far north and west as the roads to Eastleach Martin and Southrop, although some areas of rough grazing, described as barren heath in 1650, remained unploughed. To the south the arable reached the boundary hedges of Grafton and Kelmscott, while in the east an arable headland lay next to the 'long ford', possibly that from which Langford was named. (fn. 162)

In the 17th century and probably from the Middle Ages, Langford's open-field arable lay in two large fields called North and South fields, divided by the road to Little Faringdon. (fn. 163) A two-course rotation was probably practised early on in order to maximize the fallow, though more complex rotations may have been introduced following the fields' subdivision in (most likely) the 17th or 18th century. (fn. 164) By inclosure in 1808, when the open fields covered some 70 per cent of the township, North field had been divided into three: Broughton field (368 a.), Langford Heath and Whitehill field (99 a.), and Down field (312 a.). South field had similarly been divided into Church (134 a.), Great (334 a.), and West fields (212 a.). Another 150 a. of arable lay in old inclosures. (fn. 165)

Almost three quarters of the township remained arable in 1877, but during the agricultural depression of the late 19th and early 20th centuries much land was laid down to grass, especially in areas where drainage was poor. (fn. 166) That trend was reversed after the Second World War, and in 1965 about 60 per cent of the available farmland was under crop. (fn. 167)

Pasture

Only 5 a. of pasture were recorded in 1086, but presumably that was demesne and excluded the down, furze, and heath in the north of the township. (fn. 168) Rights of common grazing were defined following the endowment of Langford Manor prebend c. 1150: before then the bishop of Lincoln's man was entitled to undefined common pasture rights, but afterwards his brother was limited to 5 a. of furze and grazing in the lord's pasture. (fn. 169) In 1244 restrictions were similarly placed on Beaulieu abbey's tenants: common pasture for their plough-beasts after harvest was limited to two thirds of the area (mostly in the east of the township) for which they owed a plough-duty called grass acre (gresacre). The remaining third was for the exclusive use of the prebendary, and may have been inclosed. (fn. 170) In 1249 the prebendary of Langford Manor agreed to open his demesne pasture to the rector, who could graze a minimum of 42 cattle and 240 sheep with their young, or half the number of animals the prebendary himself grazed; the rector was to be compensated if any pasture was sold. (fn. 171)

The rector's grazing rights continued in the 17th century, (fn. 172) but by then much of the pasture belonging to the manor prebend was inclosed, lying mainly in the east of the township and at Tillingtons. The prebendary's tenants could graze 6 cattle, 2 horses, and 30 sheep for each yardland held (about 28 a.), both in the fallow field and in the remaining commons, principally Langford Heath in the north and Shortmoor in the west. (fn. 173) Many tenants held parcels of furze on Whitehill or Langford Heath, either as inclosed plots or as shares in the common or lot furze. (fn. 174)

By the early 19th century the area of permanent pasture was much reduced, and it declined further after inclosure. (fn. 175) In 1877 only 450 a. of grass remained, though that figure increased sharply during the agricultural depression. Short's farm, for example, was less than a fifth pasture in 1901, but in 1941 almost two thirds of its acreage was grass, even though some had been ploughed up for the war effort. (fn. 176)

Meadow

Common meadow, estimated in 1086 at 40 a., probably lay chiefly in the east by Broadwell brook, although there may have been smaller parcels in the west along Langford brook and the river Leach. (fn. 177) Most meadow was inclosed from the 13th century: in 1650 more than 50 a. belonging to the manor prebend lay in closes, some with characteristic wetland names such as Over and Nether Eye (OE ēg), a common name for meadow in the area. (fn. 178) Smaller amounts of common or lot meadow survived until inclosure in 1808. (fn. 179)

Although the manor prebend was said to have an abundance of meadow in the early 14th century, Langford's meadows were valuable, worth up to 16s. an acre in 1650 (more than four times the value of arable). (fn. 180) In the 17th century and later, tenants were sometimes limited to taking only the first crop of a meadow or as much as could be mown with a specified number of sweeps (or swaths) of a scythe. (fn. 181) Some freeholders held meadow outside the township, including in Radcot where it was relatively plentiful. (fn. 182) In the 19th century meadow was less likely to be ploughed up than pasture, and in 1877 it still occupied 15 per cent of the acreage (compared with 12 per cent pasture) on the farm of the former manor prebend. (fn. 183) In the early 20th century about a quarter of Langford's farmland was given over to haymaking, but that figure fell after the Second World War. (fn. 184)

Woodland

No woodland was recorded in Langford in 1086, and it remained rare. Trees were felled without permission in 1346, (fn. 185) and in 1650 the manor prebend's surveyor reported 836 small trees of oak, ash and elm, with another 426 in two closes belonging to the church prebend. (fn. 186) By the 17th century tenants were sometimes obliged to plant trees, and timber might be excluded from a lease; presumably most households purchased their supplies of firewood or gathered it from hedgerows. (fn. 187)

In 1801 only 1½ a. of woodland were reported in the township, rising to 5½ a. in 1877. (fn. 188) Most lay along the Little Faringdon road and near the western boundary with Lemhill, though hedgerow trees were more widely scattered. (fn. 189) Small stands of trees were often valuable. When the glebe was sold in 1919, the standing timber was worth £160. (fn. 190)

Medieval Agriculture

Medieval Tenant Farming

Three of Langford's medieval estates had free and customary tenants: the manor prebend, Beaulieu abbey's estate, and Matthew de Besyles' land. The church prebend and Cokerells were wholly demesne. (fn. 191) Most tenants probably grew a combination of wheat, barley and oats, and kept significant numbers of sheep and cows. Some freeholders were engaged in the large-scale production of wool. (fn. 192)

In 1086 tenants on the 15-hide manor of Langford (probably including Little Faringdon) numbered 21 villani, four lower-status bordars, and twelve slaves, and the estate was valued at £18 as in 1066. Of the ten ploughlands (40 yardlands) in cultivation, five were in demesne and five were shared among the tenants, suggesting that most villani held a yardland. (fn. 193) There seems to have been little fragmentation of tenant holdings in the following two centuries, and some accumulation. On Beaulieu abbey's estate in the early 14th century, twelve customary tenants held yardlands and another held ½ yardland; the yardlanders paid annual rents of 5s., owed various servile dues, and performed extensive seasonal labour services, including ploughing, harrowing, weeding, harvesting, threshing, winnowing, and haymaking. Most yardlanders also held a smallholding (nine were listed) for an additional rent of 1s. 4d. Probably such holdings had once belonged to cottars, the successors of the Domesday bordars and slaves; if so, their descendants had presumably become landless wage labourers working on the demesne and on tenants' yardlands. In all, Beaulieu received £4 14s. 9d. in annual rents from Langford. (fn. 194)

Tenants of the manor prebend similarly owed labour services on the lord's demesne. (fn. 195) Another of their customary obligations was to watch over the harvest at night: on one occasion in 1274 a gang associated with Beaulieu abbey attacked them 'with banners outspread', causing damage and stealing property estimated at £20. (fn. 196) As a group they seem to have been less prosperous than some of their neighbours: in 1322 they were assessed on average moveable wealth per head of only 13s., compared with 23s. for Beaulieu abbey tenants and others. In 1327 and 1332 per capita wealth was considerably higher (averaging 52s. and 71s. respectively), although by then Langford seems to have been an increasingly stratified community. The assessed wealth of Beaulieu abbey's yardlanders in 1332 ranged from under £2 to £6, while remaining taxpayers (assessed on goods worth up to £9) may have included some otherwise undocumented freeholders. (fn. 197) The township's overall assessment was reduced in 1341, when, it was claimed, the fields lay 'exhausted and unsown' and sheep mortality was high. (fn. 198)

The abbey's (mostly customary) tenants included the half-free Robert Aleyn, whose exceptionally large holding of ten yardlands was acquired by Michael Meldon in the late 13th century. (fn. 199) Around the same time Meldon successfully claimed other land held freely of Beaulieu abbey, (fn. 200) and in 1309 he rented 8 a. of meadow to the west of the Langford-Broadwell road from the manor prebend. (fn. 201) Meldon inclosed some meadow, for which he was given retrospective permission by Beaulieu abbey, and in 1307 he was allowed by the king to annex and inclose a plot of waste lying between his house and the road to Little Faringdon. (fn. 202) Meldon has rightly been called a 'persistent and enterprising outsider' who was able to carve a farm of an essentially modern type out of a medieval open-field village, and whose business was almost certainly sheep rearing. (fn. 203) Like his successor Henry Ricards (d. 1467), who may have held part of his estate, Meldon was probably a woolman; his estate was subsequently fragmented, however, and is perhaps to be identified with three freeholds belonging to Beaulieu abbey in the 16th century. (fn. 204)

Otherwise there is little direct evidence for the scale and scope of medieval tenant farming. In 1269–70 Beaulieu abbey sold 20d. worth of pannage for pigs, and larger amounts of pasture and stubble, indicating that local tenants had animals to graze. Only 3d. was raised in tolls on animal sales outside Faringdon market, however, charged at the rate of 2d. per horse, 1d. for an ox or cow, and nothing for sheep and pigs. (fn. 205) In the 1340s Beaulieu's tenants regularly brewed ale, illegally grazed cattle, horses and sheep in the abbey's demesne pasture, and were negligent in performing labour services. In the 15th century, by contrast, tenants were most often fined for not maintaining watercourses and for failure to maintain houses, suggesting some depopulation after the Black Death. (fn. 206) The abbey was obliged to negotiate with tenants in order to fill holdings: in 1461 a yardland was leased for the relatively long term of 40 years, the tenant promising in return to be resident, to repair buildings, and to perform customary services, conditions which, by implication, may have been frequently ignored. (fn. 207) Local tenant prosperity, perhaps based on sheep farming, is suggested by 15th-century remodelling of the church. (fn. 208)

Medieval Demesne Farming

The extent to which Langford's medieval demesnes were managed directly or leased is unclear. A single account of 1269–70 survives for Beaulieu abbey's estate, when a reeve managed it jointly with the Little Faringdon demesne. (fn. 209) Langford may similarly have been included in Beaulieu's lease of Great (and probably Little) Faringdon to the bishop of Winchester in 1351. (fn. 210) A single reference survives, too, to the lease of the church prebend, to two men for four years from Easter 1299. (fn. 211) Most demesnes probably employed hired workers: the church prebend and Cokerells had no tenants to work the land, and even Beaulieu abbey hired labour for threshing, winnowing, weeding, and haymaking. (fn. 212)

In the 13th century Beaulieu combined grain production with sheep farming: in 1269–70 the harvest comprised wheat (30 per cent), barley (25 per cent), and dredge (45 per cent). Most of the wheat was sold, together with 50 per cent of the barley and 70 per cent of the dredge, indicating that production was strongly commercialized. (fn. 213) The grain was probably sold at the abbey's own market at Faringdon, where it fetched nearly £42 (about 75 per cent of total receipts in 1269–70). Other sales included straw and hay and some livestock. Beaulieu maintained a team of 12 oxen and a few horses and cows, but its extensive sheep flock was managed centrally, and it is not known how many sheep were regularly pastured in Langford. (fn. 214)

A sheepcote belonging to the manor prebend stood in the pasture near Broadwell brook in 1244, (fn. 215) and in 1253–4 (despite a valuation of only £15) the prebend was leased to Roger de Alfredesfeld for an annual rent of £53 6s. 8d., along with half the court profits, and grain and stock received on the death of the prebendary's predecessor. If the prebendary visited Langford the lessee was to provide hay for 24 horses for eight days, together with litter, and fuel for brewing, baking and cooking; he was also to purchase a fat goose, a hen and two chickens, eight pigeons, wheat, 20 quarters of barley, and oats. (fn. 216) In the late 13th century the prebendary employed a hayward (messor), who apprehended two local men stealing grain from the prebend's granary. (fn. 217) Valuations of the prebend rose to £35 c. 1274 and to £40 in 1291 and 1406, falling to £16 in 1487, then rising again to £18 in 1522 and £20 in 1526–35. (fn. 218) A grant of free warren (to snare small game) was made to the prebendary in 1347. (fn. 219)

The 16th Century to Parliamentary Inclosure

From the 16th century Langford's ecclesiastical landowners continued to lease their demesnes, often to wealthy yeomen, although the township also supported many more modest farmers, craftsmen, and labourers. (fn. 220) Around 30 inhabitants were named in the military survey of 1522, and a similar number were taxed in 1543; of those, 14 were labourers and servants assessed on wages, who presumably worked on the farms of their better-off neighbours. (fn. 221) Among the wealthiest farming families were the Broderwicks, who leased the manor prebend from the early 16th century to the early 18th for a fixed annual rent of only £24 6s., despite an estate valuation in 1650 of over £195. (fn. 222) John Broderwick (d. 1550), who also leased Cokerells from the dean and chapter of Chichester, made bequests of 240 sheep and 26 cattle, and left a farm to each of his two sons. (fn. 223) The family wintered their sheep in Langford, but in summer grazed them on the downs at Eastleach, Holwell, and elsewhere in the Cotswolds. (fn. 224)

55. Walter Prunes, d. 1594, and his wife Mary, d. 1610, as depicted on their memorial in Langford church. Prunes was a wealthy sheep farmer and lessee of the rectory estate.

Other leading taxpayers included Walter Prunes (d. 1594), who leased the prebend of Langford Ecclesia, and who also pastured cattle and sheep in the Cotswolds. (fn. 225) Prunes's annual rent of £20 remained unchanged throughout this period, and charges of £4 13s. 4d. to Lincoln cathedral and 4s. to the prebendary of Langford Manor were similarly fixed. In the 16th century both prebends were leased for terms of between 30 and 50 years, and from 1600 they were usually leased for three lives. (fn. 226) By then the pasture farm called Tillingtons (c. 138 a.) was divided between the two prebends: Prunes pastured cattle, sheep and horses there, although Francis Broderwick (d. 1635) converted part of it to tillage, an indication of the increasing importance of grain production in Langford in the 17th century. (fn. 227)

More than 700 a. of the former Beaulieu abbey estate was leased by the Crown in 1551 to three free tenants and seven copyholders. Most held amalgamations of what had once been separate holdings, reflecting late medieval depopulation. The size of the 16th-century holdings ranged from around 30 a. to 100 a., mostly arable distributed in the two open fields, with smaller amounts of inclosed pasture and lot meadow. Copy-holders held for terms of lives, paying annual rents of 6s. 8d. per yardland; several of them also paid 2d.–6d. for tithingpenny (certum), and one owed suit of court. (fn. 228) A number of copyholders were among the least wealthy of those taxpayers assessed on goods in the 1540s. (fn. 229)

Prosperous yeoman families were recorded through-out the 17th and early 18th century, some of them (such as the Broderwicks, Bushes, Stubbses, and Wheelers) leaving goods worth over £100. William Bush (d. 1702) left 94 a. of unharvested grain worth £84 12s., while in 1724 Simon Stubbs's house and land were alone worth £200. (fn. 230) Several such families were taxed in 1662 on above the parish average of three hearths, and members of the Bush and Howse families, together with the lessees of the two prebends, were among a fifth taxed on five hearths or more, suggesting substantial houses. By contrast 12 inhabitants (more than a third) paid on one hearth only, and 15 were exonerated through poverty. (fn. 231) During the 18th century there was some consolidation of both freehold and leasehold, leading to the emergence by 1800 of seven or eight principal farmers each paying land tax of between £5 and £20. By then some farms were rented from several owners. (fn. 232)

Farming remained mixed as in the Middle Ages. The most common winter-sown crop was wheat, while in the spring still larger quantities of barley were sown, some of it malted for brewing. Beans and peas were grown for fodder. (fn. 233) A few 17th and 18th-century farmers grew small quantities of oats and hemp, and in some cases kept linen wheels. (fn. 234) Flocks of up to 90 sheep were commonly kept, often alongside smaller numbers of pigs and poultry, while dairy herds provided milk for widespread cheese-making. (fn. 235) John Howse (d. 1667), who held a yardland, left grain worth over £15, hay worth £5, 40 sheep worth £6, 5 cows worth £7, 6 pigs worth £2, and cheese worth £1. (fn. 236) Several inhabitants owned bees, ducks, and geese, and many left bacon or (less commonly) beef. (fn. 237)

Parliamentary Inclosure and Later

Inclosure was carried out under a private Act of 1808 promoted by the prebendaries and their lessees. (fn. 238) Land was distributed among some 16 owners and 7 occupiers, of whom 5 (most of them freeholders) received 10 a. or less in exchange for commons or small amounts of land. Among leading farmers, the lessee of the church prebend received 450 a., Richard Wells and William Young of Langford Downs farm 380 a., mostly for freehold land, and Simon Ansell 130 a. as freeholder and lessee. Four other farmers each received 90–100 a. Apart from Langford Downs farm, newly built amidst its fields, the chief farms continued to be run from existing homesteads in the village. The largest, including old inclosures, were Rectory farm (450 a.), Langford Downs farm (380 a.), Ansells farm (375 a.), Manor farm (200 a.), and Short's farm (100 a.). (fn. 239) An allotment of 4a. to the poor was divided into around 40 plots, and in the 19th century was leased to villagers. (fn. 240) By 1908–14 up to nine allotment-holders held 15 a. in all, (fn. 241) and, though some of the land was later sold for council housing, the original poor ground continued as allotment gardens in the early 21st century. (fn. 242)

From the mid 19th century landholding was reorganized following the acquisition of several estates in the township by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. (fn. 243) South of the Little Faringdon road, the Commissioners consolidated land formerly belonging to the two prebends, Cokerells, and several freeholds into two farms called Lower farm and Rectory farm (respectively 518 a. and 434 a. in 1877). (fn. 244) The remaining land in that area belonged to the glebe (77 a.) and a Kelmscott estate (99 a.). (fn. 245) Some consolidation also took place in the north of the township: by 1910 Langford Downs farm was enlarged to 424 a., and the freeholds formerly belonging to Simon Ansell and Richard Lockey were consolidated into Ansells farm (176 a., also called Cooks or Lockeys farm). Short's or Upper farm (114 a.) survived intact. (fn. 246)

The agricultural depression of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was a difficult period for Langford's farmers. William Reading, who took over Rectory farm in 1875, negotiated a reduction in his annual rent in 1881 from £770 to £600, while in 1899 he paid only £340 10s. By 1922 the farm's rent was £406 10s., rising to £600 in 1948 when Sydney Reading, William's son, was replaced as tenant by his nephew. (fn. 247) The Readings turned increasingly to dairy farming during the depression, despite complaints that the cows were milked in inadequate and insanitary conditions. The Ecclesiastical Commissioners responded by investing substantial sums in the maintenance of existing buildings and the erection of new ones, so that by 1941 both farm and farmer were described as excellent. (fn. 248)

Other farmers may have been less capable than the Readings, or less able to invest in capital expenditure than the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. The tenancy of Lower farm, which also turned to dairying in the late 19th century, changed hands several times during the Readings' occupation of Rectory farm. (fn. 249) The mostly arable Ansells farm was sold in 1878, 1899, and again after 1910, and the farm buildings were in need of much attention in 1941 when leased to Sydney Reading. (fn. 250) Short's farm, also largely arable, was sold in 1901, after which a dairy herd was introduced. (fn. 251) During the 1880s the overall acreage devoted to grass surpassed that planted with crops, and the number of milk cows more than doubled to 114. (fn. 252) Nevertheless arable farming remained prominent in 1914, when the chief crops were wheat and barley (21 per cent each), swedes and turnips (11 per cent), oats (8 per cent), and mangolds (3 per cent). The shift to dairying probably contributed to the marked decline in sheep numbers. (fn. 253)

Mixed farming with an increased pastoral bias continued in 1941, when Rectory and Ansells (705 a.), Short's (114 a.), and Glebe farms (98 a.) were each 35–45 per cent arable. Only on the higher ground in the north of the township was the traditional Cotswold sheep-and-corn husbandry preserved: Langford Downs farm (413 a.) was 72 per cent arable and had a flock of over 400 sheep. The chief crops were still wheat, barley, and oats, together with root crops. All the farms had dairy herds, most raised pigs and poultry, and Rectory farm, exceptionally, maintained a flock of comparable size to that on Langford Downs farm. (fn. 254) In the second half of the 20th century the number of farms fell, partly because the Church Commissioners purchased land to enlarge the existing Rectory and Lower farms (respectively 793 a. and 630 a. in 2008). (fn. 255) In the 1960s and 1970s barley replaced wheat as the principal crop, 488 a. of barley being sown in 1965 compared with 110 a. of wheat. Sheep farming declined still further, while dairying became more prominent. (fn. 256)

Rural Trades and Industry

The usual trades and crafts were practised in Langford from the Middle Ages, often alongside agriculture. One of Beaulieu abbey's yardlanders in the 13th century was a smith whose service included mending ploughs, and in 1346 several tenants combined farming with brewing ale, possibly for sale. (fn. 257) Occupational surnames in the 13th and 14th centuries included Fisher, Roper, Smith, and Tailor, while Cakebread, Fleshmonger, Garlic, and Hose suggest involvement in the preparation and sale of food and clothes. (fn. 258) A tailor mentioned in 1592 had only £2-worth of goods, not enough to be taxed, (fn. 259) and village craftsmen in the 17th and 18th centuries, including blacksmiths, carpenters, joiners, shoemakers, tailors, wheelwrights, and weavers, were not particularly prosperous. (fn. 260) Several tradesmen farmed, among them a baker, a butcher, and the wheelwright Thomas Turner (d. 1668), who grew wheat, barley and peas, raised cows and pigs, and made cheese. (fn. 261) John Bond (d. 1783), a grocer, leased his freehold and leasehold land to neighbouring farmers, while in the mid 18th century a prosperous local family of tobacconists, the Lockeys, acquired the lease of the manor prebend. (fn. 262)

In 1821 there were said to be 15 families out of 63 employed in trade, craft, or manufacture, (fn. 263) and in 1851, besides the common rural trades, there were two sawyers, a harness maker, ironmonger, slater, and stonemason. In all, tradespeople represented some 18 per cent of householders. (fn. 264) The Taylor family of coal merchants was mentioned from the 1860s to 1910s, a few women worked as dressmakers and laundresses, and some publicans were bricklayers, carpenters, or drapers. (fn. 265) The overall proportion of tradespeople nevertheless changed very little during the 19th century, and in 1901 still comprised only about 22 per cent of householders. (fn. 266) In the 1930s a baker, blacksmith, carpenter, coal merchant, and fried-fish dealer were based in the village, (fn. 267) and in 1947 a builder was trying to develop a builder's yard. (fn. 268) In the 1970s a specialist joinery and cabinet-making business employed up to 20 local people, and there was a crane-hire depot south of Lower farm. (fn. 269)

Milling

Two mills together worth £1 were recorded in 1086. (fn. 270) One continued in 1451, and probably lay along the river Leach bordering Lemhill, where there was a weir. (fn. 271) The other may have been on Broadwell brook, near Broadwell mill and the meadow at Cottesmore: (fn. 272) in 1244 the house of Bartholomew, miller of Cottesmore, lay between the village and the prebendary of Langford Manor's sheepcote. (fn. 273) This was perhaps the 'mill house' leased by the prebendary of Langford Manor in 1665, but no mill equipment was then mentioned. (fn. 274) In the Middle Ages Beaulieu abbey's tenants were required to grind their corn at Little Faringdon mill. (fn. 275)

Quarrying

Before the mid 20th century gravel extraction was relatively small-scale: from the 1880s, for example, the Ecclesiastical Commissioners took gravel from a pit to the south of Lower Farm for mending local roads. (fn. 276) Larger pits were dug during the Second World War, presumably for the war effort, but unlike in Lechlade no commercial extraction seems to have been attempted, and the pits were later filled with water. (fn. 277) In 2008 controversial plans to extract gravel on Church Commissioners' land were under discussion. (fn. 278)

Shops

In the 17th and 18th centuries several craftsmen owned workshops from which goods were presumably sold; one included a shopboard or counter. (fn. 279) Two shopkeepers lived in the village in the 1840s, presumably selling general supplies, and there was a separate bakery. (fn. 280) In the 1850s (and possibly earlier) publicans also acted as victuallers, while a butcher's shop was opened and a higgler was mentioned. (fn. 281) Thereafter until the early 20th century the village supported a baker's, butcher's, and two grocer's shops, of which one became a sub post-office. Another shop, mentioned in the 1860s, was short-lived, and an established tailor's also closed. (fn. 282) One of the remaining shops closed during the First World War, and by the mid 1920s only the sub post-office and bakery survived; both were owned by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, who paid for repairs. (fn. 283) A village shop and post office continued in 1976, but closed thereafter. (fn. 284)

SOCIAL HISTORY

Social Structure and the Life of The Community

From the Middle Ages Langford remained a small, predominantly agricultural community. In the absence of a resident lord the settlement developed some of the characteristics of an 'open' village, which may have contributed to sporadic outbursts of strife among leading farmers and their tenants. In the Middle Ages there were signs of conflict between tenants of Beaulieu abbey and those of the manor prebend, while after the Reformation competition for pre-eminence was expressed in the pretensions to gentry status of the lessees of the cathedral prebends, in their rising standards of living, and in their burial arrangements and bequests to church and poor. At a slightly lower social level, half a dozen or more yeoman families (some of them long-established in the village) displayed similar aspirations. The spread of Nonconformity during the 19th century added further to village tensions, a problem apparently exacerbated by the Anglican clergy, who accused the township's landowners and farmers (not entirely fairly) of showing little concern for the moral or material welfare of their workers.

Below this village élite, the vast majority of inhabitants were relatively low-status agricultural workers and craftsmen. Friendly societies were established in the 19th century, and for many inhabitants community life probably revolved around the village's public houses. Nonetheless, Langford seems not to have developed the distinctive 'labouring-class' culture evident at nearby Filkins, and despite the township's 'open' characteristics there was no pronounced influx of poor families, with population falling markedly in the later 19th century. In the 20th century, like most neighbouring Cotswold villages, Langford attracted a growing number of wealthy residents, radically changing its social character. Even so the community remained socially mixed in 2001, when almost a quarter of houses were still rented from the local authority. (fn. 285)

The Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages most inhabitants were tenants of either Beaulieu abbey or the manor prebend, and the two groups may have formed distinct communities. In 1322 the village's taxpayers were divided: the wealthier part included tenants of Beaulieu abbey, while the poorer part was listed under the name of the prebendary Peter of Savoy (1292–1308). The continued use of Savoy's name suggests that the tax collectors adopted an existing administrative division, although the practice lapsed in 1327. (fn. 286) The division of Langford's society into two possibly rival groups is also suggested by an attack on the village in 1274. A gang of more than 30 men, led, it seems, by some lay brothers of Beaulieu abbey, rampaged through the village, apparently targeting the men and goods of the prebendary of Langford Manor. (fn. 287) The incident may have been sparked by a poor harvest, although it perhaps also reflected long-term antagonism between the tenants of abbot and prebendary, which may have arisen following the prebendary's restriction of the abbey's pasture rights in the 13th century. (fn. 288) A theft of the prebendary's grain was reported in 1284, (fn. 289) and the abbey's few surviving 14th and 15th-century court rolls report several cases of trespass, assault, and raising the hue and cry. (fn. 290)

Such tensions were perhaps exacerbated by the lack of a resident lord. The prebendary of Langford Manor was an infrequent visitor, despite generous provision for his hospitality, while Beaulieu abbey administered its Langford estate from neighbouring Little Faringdon. (fn. 291) Another factor may have been the wide disparity in wealth reflected in medieval tax assessments, even among Beaulieu's yardlanders. (fn. 292) As later, leadership in the village presumably devolved upon half a dozen or more principal farmers, including, perhaps, the six taxpayers assessed on goods worth more than £5 in 1332. (fn. 293) Prominent sheep farmers and woolmen such as Michael Meldon in the late 13th century or Henry Ricards in the 15th must have been especially dominant, and in the later 15th century Ricards contributed to a remodelling of the church, an expression not only of personal devotion but of social standing. (fn. 294)

1500–1800

Langford remained a clearly stratified society throughout the early modern period. (fn. 295) In the 16th and 17th centuries the wealthiest families were the Broderwicks, Pruneses and (later) the Copleys, lessees respectively of Langford Manor and Langford Ecclesia prebends. (fn. 296) Richard Broderwick (d. 1681) was taxed on eleven hearths in 1662, the highest assessment in the village, and left goods valued at over £200, including £46-worth of silver plate. At least three other members of the Broderwick family lived in the village in 1662, although their occupation of houses taxed on between one and four hearths was more typical of the majority of Langford's yeoman farmers. (fn. 297) Several generations of such families, including the Bushes, Days, Faulkners, Howses, Nortons, Stubbses, Trinders, and Turners, remained in the village throughout the period, overseeing and witnessing each other's wills, and occupying parish offices such as churchwarden and overseer of the poor. (fn. 298)

Langford's prosperous yeoman farmers of the 17th and 18th centuries built most of the surviving farmhouses in the present centre of the village. (fn. 299) A notable example is the house owned by the Bush family from the 17th century to the 19th, and adopted as a vicarage house from 1921 to 1986. Built of uncoursed limestone rubble, the three-bay main range was extended in 1652 by Walter Bush (d. 1670), who was taxed on six hearths in 1662, and whose furnished rooms included a hall, parlour, kitchen, buttery, dairy, three chambers, and garrets. The south front, of two storeys with attics, has four irregular gables with mullioned and transomed windows under hoodmoulds. Grotesque heads set into the front and rear of the building are probably re-used 15th-century gargoyles. (fn. 300) Other 17th-century farmhouses of similar type include Short's Farmhouse (later called Threeways), which is of three bays and two storeys with attics, and built of uncoursed limestone rubble with a stone-slated roof (Plate 3). Its datestone (H/RK/1655) suggests that it was probably built by Richard Howse (d. 1670), who was taxed on five hearths in 1662. (fn. 301)

The building and remodelling of houses and cottages in the 17th and 18th centuries no doubt provided many of Langford's inhabitants with additional rooms and greater comfort. In 1662 nearly two thirds of those paying hearth tax were assessed on only one or two hearths, and half as many again were exonerated through poverty. (fn. 302) Edward Davis (d. 1679) may have been typical of those taxed on two hearths, occupying a hall and buttery with a chamber over each, and a presumably separate dairy house. (fn. 303) Many other 17th-and 18th-century inventories list only a limited number of rooms, such as the hall, buttery and chamber occupied by William Howse (d. 1685), who was excused payment on a single hearth in 1662. (fn. 304) By contrast, the grand appearance of Lockey House (Fig. 53) suggests owners with pretension: its central doorway is flanked by a pair of sash windows in moulded stone surrounds, with five similar windows to the first floor. Although built in the 17th century, a datestone of 1719 suggests that it was remodelled for the tobacconist and Quaker John Lockey (d. 1754). (fn. 305) Many 18th-century features survive, despite its conversion in the 1870s into the Cotswold Arms public house. (fn. 306)

Langford's wealthier inhabitants presumably employed the township's landless labourers and servants. In 1522 about three fifths of those assessed on goods were taxed on sums of less than £2: a high proportion, which suggests considerable dependence on income from wages. (fn. 307) In 1543 the minimum tax of 4d. on wages was paid by 14 labourers and servants, and similar people may have been among the 15 inhabitants too poor to pay hearth tax in 1662. (fn. 308) One such was John Higgs, most likely the son of a labourer who died in 1623 leaving goods worth £33, including some modest pieces of furniture and a few cattle, sheep, and pigs. (fn. 309) Servants were sometimes remembered in the wills of their employers, including the unusual case of Elizabeth Burbridge, who was left part of the house and land leased by Stephen Trinder (d. 1761). (fn. 310) On her own death in 1794 Elizabeth left grain and cattle to John Trinder, whom she employed to farm her land. (fn. 311) By contrast Richard Broderwick's servant Thomas Taylor (d. 1640) owned only a chest of clothes worth £1, while cash and debts owed him totalled £14 11s. (fn. 312)

The poorest members of village society received assistance from the overseers, among them two orphans housed and clothed at the parish's expense during the 1730s. (fn. 313) Occasional help was given to travellers and other outsiders passing through the village, including Irish Protestants driven from their homes in the 1630s and 1640s, and families whose houses had burnt down. (fn. 314) Few such people settled in Langford, and overseers occasionally paid for the removal of labourers under the settlement laws, while in 1672 a group of 18 'pretended gypsies' was driven away. (fn. 315) Even so, by the end of the 18th century the cost of Langford's poor relief was almost 75 per cent higher than the average for the area, although the rate of 2s. 3d. in the pound in 1803 was (like per capita costs) relatively low. (fn. 316)

Social tensions within the village élite were expressed in the 17th century in disputes over church seating, (fn. 317) and in 1704 Richard Turner was fined 10s. for abusing the lord of the manor (presumably meaning the lessee of the manor prebend) in court. (fn. 318) During this period the churchwardens acted as guardians of public morality, presenting inhabitants for non-attendance at church, for sexual relations outside marriage, and for failure to pay church rates. (fn. 319) The church was a focus for community life: a church ale was held at Whitsun, (fn. 320) and considerable sums were spent on the church bells, which were rung to commemorate events such as the fifth of November. (fn. 321) Many wealthier inhabitants requested burial within the church, sometimes specifically in the chancel or close to a spouse. (fn. 322)

The 19th and 20th Centuries