A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Broadwell Parish: Kelmscott', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp111-145 [accessed 10 May 2025].

'Broadwell Parish: Kelmscott', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online, accessed May 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp111-145.

"Broadwell Parish: Kelmscott". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online. Web. 10 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp111-145.

In this section

KELMSCOTT TOWNSHIP

Now widely known for its association with the designer, writer, and socialist William Morris (d. 1896), Kelmscott (fn. 1) remains a small and secluded hamlet, sharing much in common with its more obscure neighbours on the Oxfordshire-Gloucestershire border. The village lies just north of the river Thames in what was, until 1974, the county's extreme south-west corner. The market town of Faringdon (formerly in Berkshire) lies 3 miles (5 km) to the south across the river, while that of Lechlade lies 2¼ miles (3.5 km) to the west in Gloucestershire.

The village has always been predominantly agricultural, and contains several high-quality 17th- and 18th-century farmhouses. Most were built by prosperous yeoman farmers in the attractive, stone-built Cotswold style typical of the area. Among them, close to the river, is Kelmscott Manor, which originated as a moderately sized late 16th- or early 17th-century farmhouse long before Morris rented it as a summer home from 1871. (fn. 2) The only medieval building is the church, established as a chapel of Broadwell in the 12th century or earlier, and relatively unscathed by Victorian restoration. The riverside landscape, like that of the neighbouring hamlets of Grafton and Radcot, is predominantly flat and featureless, although now broken up by hedgerows and trees. Morris's friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti thought it 'the most uninspiring I ever stayed in', though to Morris himself, with more idealized views of rural life, Kelmscott was a 'beautiful grey little hamlet' unspoiled by industrialization. (fn. 3) Morris's influence continued throughout the 20th century, first in the erection of a number of Vernacular Revival buildings by his widow and daughter, and later in the development of Kelmscott Manor as a shrine to his life and work. (fn. 4)

Boundaries and Landscape

From the Middle Ages until the mid 19th century Kelmscott was a detached township and chapelry of Broadwell parish, reflecting pre-Conquest arrangements which are described above. In the early 11th century it belonged to a large comital estate which may have included not only Broadwell, Filkins, and Holwell, but nearby Langford with its dependent settlements, and it remained part of the reduced manor of Broadwell until the 16th century or later. (fn. 5) From the late 19th century it was usually counted a separate civil parish, although for ecclesiastical purposes it remained attached to Broadwell until 1960, when it was combined first with Clanfield and later with other neighbouring parishes. Its acreage, 1,037 a. in 1881, remained unaltered in 2001. (fn. 6)

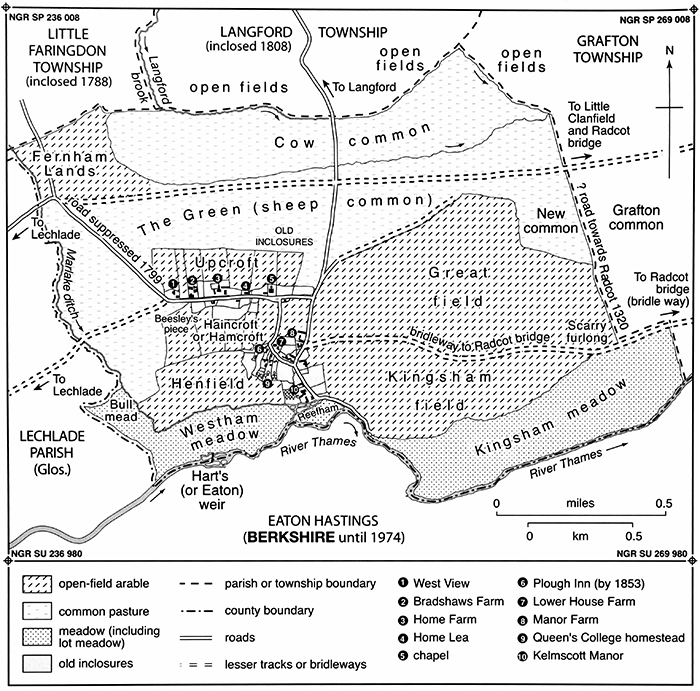

The township's boundaries (Figs 1 and 33) were established in outline by the mid 11th century, when Kelmscott was first defined as a detached part of the large Broadwell estate. (fn. 7) The southern and western boundaries were those of the shire and hundred, (fn. 8) and followed the river Thames and a small tributary of the river Leach called Marlake Ditch. A small detour in the south-west brought an additional parcel of meadow into Kelmscott, and was established by the mid 18th century and possibly by 1066. The north-eastern and eastern boundaries are markedly straight, and in the mid 18th century were marked by watercourses and hedges dividing Kelmscott's and Grafton's fields, commons, and meadows. (fn. 9) Nonetheless they are probably medieval in origin, since in 1320 the eastern boundary followed a north-south way (now lost) from a stream called 'Lake' towards Radcot, which divided Kelmscott's and Grafton's pastures. The road ran on past Radcot's gallows (furcas), which presumably stood on or near the boundary, and from which Kelmscott's Gallow or Galloway field was evidently named. (fn. 10) Elsewhere the township's boundaries followed small watercourses, and were apparently unaltered at inclosure in 1799.

33. Kelmscott township in 1798, showing open fields and commons. (See also Fig. 39.)

The entire township is flat and low-lying, rising from around 68 m. on the eastern boundary to only 71 m. in the village's northern part. (fn. 11) Riverside alluvium provided rich and extensive meadows which were central to Kelmscott's agricultural economy until modern times. Most of the township, including the village, lies on river gravels of the First and Second Floodplain terraces, overlying Oxford Clay; Kelmscott Manor, at the village's southern end, stands on the extreme southern edge of the gravel, close to the former meadows. (fn. 12) Flooding, both of agricultural land and occasionally of the village's southern part, has long been endemic. The name 'at flood', attached to a house in the early 14th century, may have denoted only its proximity to the river, (fn. 13) but field ditches were mentioned in the 16th century, (fn. 14) and extensive new drainage channels were thought necessary at inclosure, including a stank to prevent drain water flowing through the village. (fn. 15) Despite extensive improvements to upper Thames drainage in the late 19th century seasonal flooding of meadows remained commonplace, and there was more serious flooding of the village in 1893, 1903, 1915, and 1947. (fn. 16) Flood-water came close to Kelmscott Manor and the Plough Inn in the winter of 2000, and the village was further affected by the floods of 2007.

Communications

Though no through-routes now run through the village, early roads connected it with important routes outside the township (Fig. 2). The 'royal highway' from Broadwell and Langford to Kelmscott was mentioned in 1320, (fn. 17) and the road southwards from Little Faringdon is presumably also of medieval origin. (fn. 18) The same may be true of the main west-east route north of the village, which links Lechlade (Glos.) with the road to Radcot Bridge, although in the 18th century it seems to have been only a relatively minor track traversing the common. Until inclosure a branch-road ran south-eastwards to the village's western edge, and may once have continued to the present-day road to the river past the Plough Inn and Kelmscott Manor, which is on the same alignment (Figs 33 and 35). (fn. 19) Lesser routes mentioned in 1320, besides that apparently running along the township's eastern boundary, included tracks to riverside meadows, among them an 'ancient' way called Thamesway. (fn. 20) A bridleway from Kelmscott village to Radcot, running through Kelmscott's fields and neighbouring meadows, existed by the mid 18th century, (fn. 21) and a footbridge crossed the Thames at Hart's weir in the late 18th century and possibly from the Middle Ages. (fn. 22)

At inclosure in 1799 the Lechlade road was upgraded as a carriageway 40 feet wide (including verges), along with the intersecting roads to Langford and Little Faringdon. The connecting road from the west end of Kelmscott's main village street was realigned to run north-south, and a few smaller paths and private roads were laid out or confirmed (Fig. 39). (fn. 23) During the 20th century the poor repair of many of Kelmscott's roads and footpaths caused occasional local concern, particularly as the volume of heavy traffic on the Lechlade road increased from the 1970s. The parish meeting pressed frequently for improved public transport from the 1940s, though with limited success. (fn. 24)

River transport was locally important by the 13th century, when there was commercial traffic between Radcot and London. Large-scale navigation as far as Kelmscott seems unlikely, however, and in contrast to Radcot there is no evidence of a landing place or of commercial traders. (fn. 25) From the 17th century, with the reopening of the upper Thames beyond Oxford, river traffic increased, (fn. 26) and it has been suggested that the placing of Kelmscott Manor's farm buildings close to a small backwater may have been intended to take advantage of the river. (fn. 27) Even so most river-borne produce from Kelmscott probably went via Radcot wharf. The flashlock at Hart's weir (a little way south-west of Kelmscott village) was in poor repair in the late 18th century, and in 1883 the weir collapsed. It was rebuilt within twelve months, but there was still only a flashlock in 1914, and in winter small pleasure boats could scarcely fit under the bridge. (fn. 28)

By then river links had been superseded by the railway. Stations were opened at Challow, Witney, and Faringdon in 1840, 1861, and 1864 respectively, and a much nearer one at Lechlade (on the GWR's Witney-Fairford branch) in 1873. (fn. 29) Kelmscott and Langford station was opened 1½ miles north of Kelmscott village in 1907, and continued until the line's closure in 1962. Its isolation and (until 1928) its lack of goods facilities made it of limited use, however, and local dairy farmers continued to transport milk from Lechlade. (fn. 30) Post was delivered through Lechlade from the early 19th century, and in 1908 the parish meeting pressed for Sunday deliveries. A village post and (later) telephone office opened before 1911, re-opened in the 1920s, and closed in the late 20th century. (fn. 31) No village carriers are recorded, though in the early 1870s a carrier delivered parcels from Faringdon station for what Rossetti considered the exorbitant sum of 6s. 6d. per journey. (fn. 32)

Settlement and Population

Early Settlement

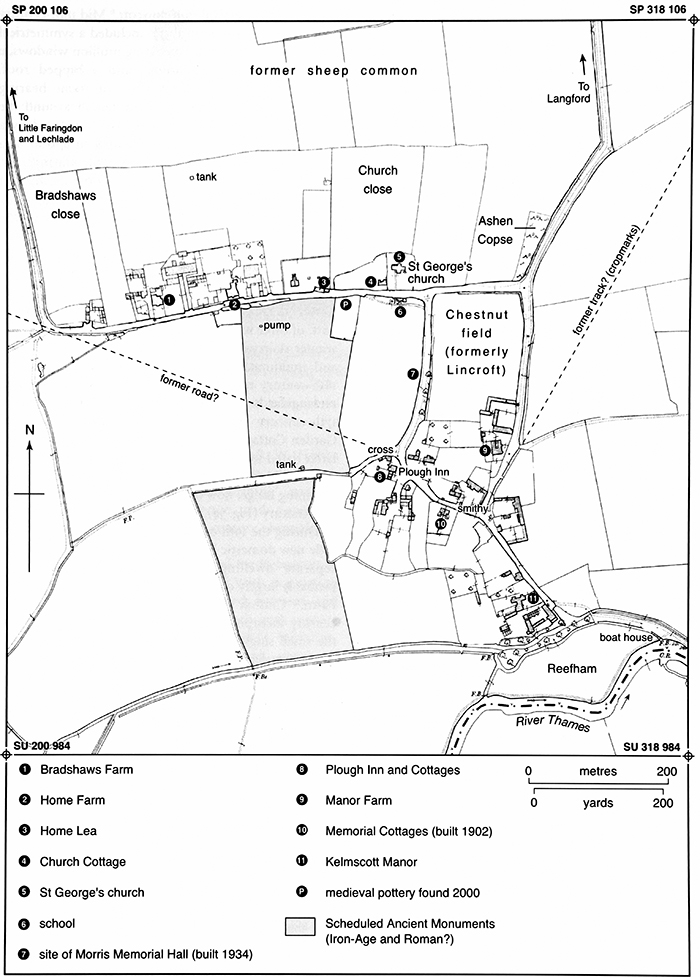

Kelmscott lies amidst a dense concentration of cropmarks along the edge of the gravel terraces, which together suggest extensive Iron-Age and Roman settlement in the area. Traces of paddocks and enclosures imply pastoral farming with seasonal grazing on the Thames floodplain, and possibly there was some small-scale crop-growing. Within the parish clusters of largely undated cropmarks survive immediately west, south, and east of the modern village, ranging probably from prehistory to the Roman period. A rectangular enclosure immediately south of the village may be of Iron-Age date, and traces remain of several undated early trackways, some of them apparently related to parts of the existing road system (Fig. 35). (fn. 33) Roman coins were found near Kelmscott church in 2000, unearthed apparently from a cable-trench in the churchyard. (fn. 34)

No archaeological evidence of Anglo-Saxon settlement has yet been discovered, and from the late Roman period the Kelmscott area (though probably exploited for grazing and hay) may have remained unoccupied for several centuries. (fn. 35) The Anglo-Saxon place name (meaning Coenhelm's cott) suggests settlement by the mid or late Anglo-Saxon period, however, associated presumably with the large emerging estate focused on Langford. (fn. 36) By 1086 Kelmscott was established as an outlier of the recently created Broadwell manor, and it seems likely that some of the 60 tenant households recorded on the estate lay within the later township. (fn. 37) A chapel existed by the late 12th century and possibly by the late 11th, and by the 1270s Kelmscott was an established village of approaching 30 houses, surrounded (as later) by its own open fields and commons. (fn. 38)

Population from 1279

In 1279 the village contained around 28 households, a total population of perhaps 130, of whom most (22 households) were unfree villeins or cottagers. (fn. 39) Between 18 and 23 people, most of them probably householders, were taxed in the early 14th century. (fn. 40) During the 14th century the population fell: only 41 people over fourteen years of age paid poll tax in 1377, (fn. 41) suggesting marked (though not catastrophic) depopulation through plague, and the population had probably not recovered significantly by the 16th century, when only 12 or 13 taxpayers (each presumably prominent householders) were noted in 1544. (fn. 42) Probably such depopulation contributed to the emergence of the prosperous yeoman farmers who dominated the township thereafter, and who from the 16th century benefited from the gradual break-up of Broadwell manor. (fn. 43) In 1642 and 1676 the total adult population appears to have numbered around 60–65, and 16 households were taxed in 1662, probably an underassessment. (fn. 44) During the succeeding century and a half the population seems to have risen only slowly: in 1759 there were reckoned to be 18 families in Kelmscott, and in 1793 around 20 houses, accommodating a total population of 100. (fn. 45) In 1801 there were 27 houses accommodating 132 people. (fn. 46)

34. The Plough Inn and nearby medieval cross base in the late 19th or early 20th century. The thatched cottages were demolished c. 1950, and replaced by a now-vanished tennis court.

Between 1801 and 1821 the population fell to 118: possibly that reflected labourers' difficulties following inclosure in 1799, although the overall number of families and households actually rose slightly to 30. During the 1820s and 1830s the decline was reversed, the population reaching 179 by 1841; by then over 80 per cent of householders were agricultural wage-earners employed on the four main farms, a pattern established apparently by the late 18th century and probably accentuated by inclosure. During the mid 19th century the population again fell steadily to only 101 in 1881, but recovered to 164 (accommodated in 32 houses) by 1901. Such recovery was untypical for the period, and almost certainly reflected the expansion of the Hobbs family's labour-intensive dairying business: in 1891 over 70 per cent of the population came from outside the township, compared with only 45 per cent in 1851. (fn. 47) A small decline before 1921 was followed by a more rapid fall from 152 to 114 during the 1920s, and although the population reached 136 in 1951 following small-scale building of new housing, thereafter it fell steadily to only 82 in 1981. (fn. 48) In the early 1960s there was said to be no demand for new houses, and some younger inhabitants were moving away. (fn. 49) A small increase to 95 by 1991 and to 101 by 2001, following further small-scale building, presumably reflected the village's attractiveness to commuters, over half of its households then owning two or more cars, and most working elsewhere. (fn. 50)

Development of the Village

The earliest surviving building is the church at the modern village's northern end, built possibly in the late 11th century and certainly by c. 1200. (fn. 51) Presumably this was an early focus of settlement: the church's south doorway opens to the main east-west street, and 14th-and 15th-century pottery has been found nearby. (fn. 52) Houses west of the church are 17th-century and later, (fn. 53) but the plots are probably medieval and may represent a planned extension of the village between the 11th and 13th centuries, perhaps associated with the building of the chapel.

Medieval settlement is also documented further south. The medieval surnames 'at flood' and 'at water' imply settlement near the river, (fn. 54) and a freeholder's house mentioned from the 1290s to 1340s stood north of Reefham, presumably near Kelmscott Manor. (fn. 55) Another house, mentioned from 1302, lay probably near the modern Plough Inn. (fn. 56) Long, sinuous tenement boundaries just south of the Plough (mapped in 1798) (fn. 57) may indicate that they were taken from the adjoining arable, presumably during the 12th or 13th century when the population was still rising, and close by is the weathered base of a 14th- or 15th-century preaching cross (Fig. 34), at what may once have been a significant road junction. (fn. 58) The road past Manor Farm, a little further east, seems to relate to earlier cropmarks, suggesting that part of its alignment is of considerable antiquity, (fn. 59) and that too may have been settled in the medieval period, although existing buildings are no earlier than the 17th century. (fn. 60) Late medieval population decline presumably thinned out the density of settlement: by the 1760s the village's north and south parts were largely separate, (fn. 61) although the area between them may once have been more fully built up.

From the 18th century the village's layout changed very little. Early 20th-century additions in Vernacular Revival style, built under the auspices of Morris's widow and daughter, essentially preserved its character, (fn. 62) and by the early 20th century Kelmscott was already being promoted as a 'charming old world village' and 'picturesque hamlet', (fn. 63) building on its association with Morris, and on his idealized representation of it in his utopian novel News from Nowhere (1890). Development during the mid and late 20th century was largely confined to small-scale building in traditional styles and materials, no doubt partly influenced by such attitudes as well as by stagnant or falling population. During the 1960s and 1970s the parish pressed for new bungalows suitable for old and retired people, but only in the 1980s was there small-scale new housing development near the Plough Inn. (fn. 64) In 1991 there were 34 households, little different from the township's average since 1801, and in 1995 further development was proscribed by the creation of a conservation area. (fn. 65) Electricity was available by 1939, but there was still no mains water in the 1960s, and no mains sewerage in the late 1980s. (fn. 66)

During the Second World War a small grass airfield at Kelmscott (opened in 1942) served as a relief landing ground for RAF Watchfield. At first it was used for beam-approach training, and was equipped with corrugated-iron Nissen huts and a 'Blister' hangar. Before the Normandy landings practice parachute-drops were made there, and according to locals it was not uncommon for parachutists to miss the site and land 'in fields and trees for miles around'. (fn. 67) Concrete pillboxes, part of a chain designed to stop German invaders from crossing the Thames, survive just north of the river, and in 1995 were included in the new conservation area; (fn. 68) nothing remains of the airfield, however. In 1958–9 controversy erupted over the siting of a navigation beacon for the military airbase at Fairford (Glos.), which the Air Ministry wished to erect near Kelmscott Manor. The proposal was modified following local enquiries, and interventions by the William Morris Society and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. (fn. 69)

The Built Character

Most existing domestic buildings in Kelmscott are of the 17th century and later, built of rough-coursed limestone rubble with stone-slated roofs, and accompanied by a small group of 20th-century buildings in Vernacular Revival style. (fn. 70) Several high-quality farmhouses, many of which display progressive tendencies for their date, reflect Kelmscott's domination, from the 16th century, by a small group of prosperous yeoman farmers: in 1662 six houses (38 per cent), all belonging to prominent yeomen, were taxed on three or four hearths, while the rest were taxed on one or two hearths only. (fn. 71) By far the grandest house is the so-called Kelmscott Manor (described below) at the village's southern end, built in the late 16th or early 17th century by one of the prominent Turner family, extended around 1666, and occupied by the Morrises from 1871 to 1938. (fn. 72)

35. Kelmscott village c. 1920, showing key buildings.

Other larger houses include Lower House Farm, an L-shaped building of two storeys and attics dating probably from the late 17th century. Its symmetrical five-bayed front has a moulded wooden eaves cornice broken by a large central gable, cross-mullioned windows, and a central doorway in a moulded stone surround, surmounted by a flat hood with carved scroll brackets. In the 19th century and probably earlier it was divided into three labourers' cottages for nearby Manor Farm, but was later restored to single occupancy. (fn. 73) Home Farm (Fig. 40), in the village's northern part, is a house of comparable size, whose rear range is probably 17th-century or earlier. It was remodelled in the mid 18th century perhaps for one of the Turner family, which owned it by the 1790s. The symmetrical main front (originally rendered) has a slightly projecting central bay surmounted by an open pediment with a blind lunette, while the flanking bays have Venetian windows on the ground floor. A central recessed door with radiating fanlight opens into a stone-flagged entrance hall. (fn. 74)

Bradshaws Farm to the west was built for another family of prosperous yeoman freeholders in the late 17th century, perhaps incorporating fragments of an earlier house. (fn. 75) The earliest parts are rubble-built with stone mullion and transom windows, and internal fittings (including an impressive dog-leg staircase) are consistent with a date of c. 1670–90, a few decades after the Bradshaws' arrival in Kelmscott. (fn. 76) Mid 18th-century remodelling (possibly in 1757) (fn. 77) included a symmetrical refronting in ashlar, incorporating mullion windows, a pedimented central doorway, and a hipped roof. Substantial adjacent barns (one of them bearing Edward Bradshaw's initials) were rebuilt around the same time, (fn. 78) although the house itself is fronted by a large garden, and was clearly intended to appear as a domestic dwelling quite separate from its farmyards. (fn. 79) An unusual gothic porch with an ogee head, half blocking the earlier doorcase, was probably added by the Bradshaws or their immediate successors in the early 19th century. (fn. 80)

More vernacular in style is Home Lea near the church, a late 17th-century house of uncoursed lime-stone rubble extended in 1767 for the farmer Thomas Carter (d. 1794) and his wife Mary. The older (western) part, of three bays, has integral endstacks with flanking winder staircases leading from first-floor to attic level, and mullioned windows with dripstones; the lower, 18th-century range has an endstack with a projecting rectangular bread oven at its base. (fn. 81) Smaller houses of 17th-century origin include 2–3 Manor Cottages, Garden Cottage, Jobs Close, and Plough Cottages, the latter dated 1690 and built probably by John and Mary Turner, perhaps as labourers' accommodation. An adjoining range, now the Plough Inn, was added in the 18th century (Fig. 34). (fn. 82)

During the 19th century there appears to have been little new domestic building, the increase from 27 to 36 separate dwellings between 1801 and 1851 being probably largely due to subdivision, as at Lower House Farm. (fn. 83) Church Cottage was rebuilt in the early 19th century incorporating parts of an earlier house, (fn. 84) and the small single-storeyed school nearby, the only new institutional building, was built around 1872. (fn. 85) A few thatched cottages and farm buildings survived in the late 19th and early 20th century: in 1871 Rossetti commented that most farm buildings were 'of the thatched squatted order', while in 1896 William Morris expressed relief that the leading farmer R. W. Hobbs had re-roofed his buildings with thatch rather than corrugated iron, and admitted 'bribing' another landowner to do the same. (fn. 86) Brick, too, made a sporadic appearance from the later 19th century, brought in presumably by rail. (fn. 87)

36. The Morris Memorial Cottages, built in 1902 to designs by Philip Webb. The carving under the central gable (right) shows Morris reclining in nearby meadows.

In 1919 the parish meeting pressed for Kelmscott to be included in local housing plans. (fn. 88) With population falling there was presumably little need, however, and what new building there was in the early 20th century was almost all on the Morris family's initiative, reflecting William Morris's idealized views of vernacular architecture, traditional crafts, and rural life. In 1902 Morris's widow Jane commissioned Philip Webb to build a pair of cottages in her husband's memory, on a plot north of Kelmscott Manor which she bought for the purpose; Webb was a friend and associate of Morris, and had designed Morris's tombstone in Kelmscott churchyard. The cottages (Fig. 36), built of traditional materials in Vernacular Revival style, are of two storeys with attic; a stone plaque on the front, carved by George Jack from a design by Webb, shows Morris reclining in nearby meadows with his hat and satchel. In 1914 William's daughter May Morris commissioned two further cottages on an adjacent site, designed in similar style by the Arts and Crafts architect Ernest Gimson (d. 1919), who erected a limestone-plank fence at the nearby roadside. Soon after, May commissioned Gimson to design a village hall in Morris's memory, and following a public appeal the building was finally erected in 1934 to coincide with Morris's centenary, on a site given by Lord Faringdon of Buscot. The hall, L-shaped and single-storeyed with a cellar and attic in the north range, is in similar vernacular style, with a pegged timber roof covered in stone slate, and a fence of limestone slabs. (fn. 89)

Development during the mid and late 20th century was largely confined to further small-scale building in traditional styles and materials. Small cottages were erected near Home Lea and the school in the 1930s and 1940s, and in 1950 a range of four council houses north of the Plough Inn was erected in a neovernacular, stone-built style by the Filkins mason Joe Swinford, partly re-using materials from three demolished thatched cottages nearby. The architect was Stanley Roth. (fn. 90)

MANORS AND ESTATES

In 1086 Kelmscott formed part of the large estate centred on Broadwell. (fn. 91) On the manor's division in the early 13th century most of the township passed to the d'Oddingseles family, and remained part of their manor of Bradwell Odyngsell throughout the Middle Ages. Another 6½ yardlands (including 4 yardlands in demesne) belonged in the 1270s to Roland d'Oddingseles (d. 1316), who held them for life for an annual render of a pair of gloves. (fn. 92) That land belonged to what became Bradwell Cirencester manor, and on Roland's death reverted to Cirencester abbey (Glos.). (fn. 93) A third Broadwell manor (Bradwell St John) included a meadow in Kelmscott in 1498. (fn. 94)

Bradwell Odyngsell and Bradwell Cirencester manors retained holdings in Kelmscott in the late 16th and early 17th century, (fn. 95) but by the late 18th century most had been sold or otherwise enfranchised. Long before then Kelmscott was dominated by resident and non-resident freeholders including prominent local farmers, and at inclosure in 1799 the owner of Bradwell Grove, though still called lord of the reputed 'manor' of Kelmscott, was awarded only 53½ a. of meadow in the township. (fn. 96) In 1864 the meadow was sold with the 'lordship' to the resident farmer James Turner (d. 1870), the owner of a freehold centred on what was then called Lower House, but which subsequently became known as Kelmscott Manor. (fn. 97) The Turners and their successors were still occasionally called lords of Kelmscott in the late 19th and early 20th century, (fn. 98) but never exercised any manorial rights. Kelmscott Manor itself was leased to William Morris from 1871 and sold to his widow Jane in 1913. Later land purchases resulted in most of the township becoming divided by the late 20th century among the Society of Antiquaries (which acquired Kelmscott Manor), the Church Commissioners, and the National Trust. (fn. 99)

The Turners and Kelmscott Manor

The early descent of the Turners' Kelmscott Manor freehold is obscure, as various branches of the family lived and farmed in the township between the 16th and 19th centuries. (fn. 100) Thomas Turner (d. 1611) and his widow Ann (d. 1620) have been suggested as possible owners, largely on the grounds that Thomas's probate inventory describes a house of roughly comparable size, and that the house's earliest parts appear to be early 17th-century. (fn. 101) The house could equally have formed part of the estate of Richard Turner (d. 1600), however, a prosperous Kelmscott yeoman whose lands in Kelmscott and Filkins passed to his widow Ann and infant son Thomas (d. 1663), and to Thomas's son Thomas (d. 1682). (fn. 102) The elder Thomas lived at Hall Place in Filkins, (fn. 103) but his son, who was granted a coat of arms in 1665, is the first of the family to be unequivocally associated with Kelmscott Manor, which he extended probably in 1666. (fn. 104) By the early 18th century the house and estate totalled 4 yardlands, which was held with other freehold and leasehold estates including a manor in Suffolk. (fn. 105)

Thomas (d. 1682) was succeeded by his eldest son Thomas (d. 1709), who mortgaged the estate and left it to his sons Thomas, Charles, and George in trust to be sold. (fn. 106) They presumably paid off the debts, and on Thomas and Charles's deaths in 1730 their shares passed to George (d. 1734). He left it in trust for his unmarried sister Arabella (d. 1736) with provision for his widow Penelope, and established contingent remainders to members of the Hammersley family and to the sons of his cousin John Turner (d. 1763). (fn. 107) The Hammersleys' interest continued until 1775, (fn. 108) but none of them seem to have lived in Kelmscott, and probably the house and land continued to be occupied by members of the Turner family. (fn. 109) By the 1770s some of the Turners were, however, in financial difficulties. In 1772 John Turner's son John (d. 1779) was imprisoned for debt, and though the Kelmscott estate was briefly recovered by his son, in 1784 John's brother James (d. 1799), together with the mortgagees, sold it to James's brother-in-law John Beesley, of Charney in Berkshire. (fn. 110) James and his son Charles (d. 1833) continued as Beesley's tenants until 1816, when Charles recovered the freehold from Beesley's son. By then the estate (80 a. after inclosure) was combined with a small freehold of 36 a. centred on Home Farm. (fn. 111)

From the 1830s Charles's son James enlarged the estate, acquiring the manorial title in 1864, and by 1867 farming some 478 a. as freeholder and lessee. (fn. 112) James died in 1870 and his widow Elizabeth in 1883, when ownership passed to their nephew Charles Hobbs (d. 1893) of Meysey Hampton (Glos.), also a working farmer. Having no need for the house he let it to Morris in 1871, and from 1873 handed management of the Kelmscott estate to his son R. W. Hobbs (d. 1920), who farmed it from Home and Bradshaws Farms. (fn. 113) On Charles's death the freehold estate, 205 a. in Kelmscott and 70 a. in Lechlade (Glos.), was divided among eight children, of whom R. W. Hobbs bought out the others in 1895 with a loan from Morris. (fn. 114)

In 1905, following financial difficulties, R. W. Hobbs sold Home Farm and most of his land to the Ecclesiastical (later Church) Commissioners, but continued as their tenant. (fn. 115) Kelmscott Manor, which he retained with a few small parcels, was sold in 1913 with a barn, cottage, and 9 a. to Morris's widow Jane, who had remained there as tenant; in 1899 she had already bought part of nearby Crooks Close, on which the Morris Memorial Cottages were built in 1902. (fn. 116) In 1935 William and Jane's daughter May Morris bought another four cottages and some farm buildings from a private landowner. (fn. 117) May died in 1938 leaving Kelmscott Manor to Oxford University, subject to detailed stipulations concerning public access and preservation of its contents, and with wholly inadequate provision for its upkeep. Following numerous difficulties the university proved unwilling to maintain 'a museum piece ... of no conceivable value to its academic life', and in 1962 the house and its land passed to the Society of Antiquaries of London, the residuary legatees under May Morris's will. (fn. 118) In 1967 the Society bought the barns, yard, and an adjacent close from the Church Commissioners, (fn. 119) and remained the owner in 2011.

Kelmscott Manor: Occupancy

In origin an ordinary yeoman farmhouse, Kelmscott Manor stands at the village's southern end near the river Thames. It or a predecessor may have been occupied by Richard or Thomas Turner (d. 1600 and 1611) and their widows, or by the other family members recorded in Kelmscott in the early 17th century. (fn. 120) Thomas Turner (d. 1682) certainly lived there by the early 1660s, before his father's death, (fn. 121) and thereafter the house was continuously occupied by his successors until at least the 1730s. (fn. 122) Before George Turner's death the house was temporarily divided, much of the service end being let to a yeoman tenant (Thomas Ford), and the rest reserved for George's sister, widow, and heirs, who were required to live there for at least six months a year or forfeit the inheritance. (fn. 123) The Fords may have remained until 1775, (fn. 124) but occupation of the rest of the house during that period is unclear: the Hammersleys retained a life interest but were non-resident, (fn. 125) while George's residuary legatee John Turner (d. 1763) and his family had other farmhouses in Kelmscott. (fn. 126) Even so it seems likely that Turner family members continued to farm the land, and to occupy some at least of the buildings: in 1775, when the estate was offered for sale, the farm was leased to James Turner (d. 1799), and the house was said to be in hand. (fn. 127) James and his son Charles probably occupied the house and its farm buildings thereafter, although they also owned and occupied Home Farm. (fn. 128) Charles's son James (d. 1870) farmed from Kelmscott Manor from the 1830s. (fn. 129)

William Morris rented the house from 1871, at first with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and later with his publisher F. S. Ellis. The Morrises and their co-lessees used the house as a second home, visiting mainly in the summers. After Morris's death in 1896 his widow Jane made Kelmscott her main home, buying the freehold in 1913 for her daughters Jenny (d. 1935) and May (d. 1938). After Jane's death in 1914 they continued to divide their time between Kelmscott and London, but in 1923 May settled at Kelmscott permanently, latterly sharing the house with her companion Mary Lobb. (fn. 130)

May's will provided for Oxford University to let the house as a rest home for artists, writers, and academics, with preference given to the Rector of Exeter College, the Slade Professor of Fine Art, Keepers of the Ashmolean Museum, and Bodley's Librarian. None wished to occupy the house, which from 1939 was let successively to a schoolmaster and artist, to the poet John Betjeman (who sublet it), and to the Morris scholar Dr D. C. Wren. (fn. 131) Stipulations that the house should be preserved as it had been during Morris's lifetime and that the public should be given access caused friction with tenants, (fn. 132) and after the house passed to the Society of Antiquaries the southern part was turned into custodian's accommodation, while the rooms associated with Morris, on the north side, were made accessible to visitors through a new north entrance made in 1966. (fn. 133) The arrangement continued in 2011.

Kelmscott Manor: The House

The earliest parts of Kelmscott Manor (Fig. 37 and Plates 8–9) comprised a traditional U-plan farmhouse with a hall at the centre, entered from a screens passage at the southern end, and flanked on the south by a projecting two-roomed service end (which included a heated kitchen), and on the north by a projecting two-roomed high end (of which one room was heated). (fn. 134) From the outset the house was two-storeyed with gabled attics, and like most other buildings in the area it is of uncoursed limestone rubble (formerly lime-washed) (fn. 135) with stone-slated roofs. Entry may originally have been from the west, between the projecting wings, but by the 1660s the main entrance faced eastwards towards the road. A late 16th-century origin has been suggested, based partly on a scratched date on a mullion, which has been questionably interpreted as 1571. The staircase and fireplaces imply an early 17th-century date, however, perhaps adding weight to the suggestion that Thomas Turner (d. 1611) was the builder. (fn. 136)

Thomas Turner (d. 1682) remodelled the north end around 1666, when he acquired an adjoining strip of land lying probably on the house's north side, abutting eastwards on the road. (fn. 137) A new multi-gabled parlour block was added at the house's north-east corner, projecting forwards and forming a cross wing; the scale of the new work was larger than the old, incorporating higher ceilings, applied classical motifs in the form of some small pedimented windows, and high-quality fireplaces which featured Turner's newly acquired coat of arms (Plate 9). (fn. 138) A sophisticated joisting technique between the ground and first floors allowed use of timbers shorter than the space to be spanned, and may have been derived from recent Oxford examples. (fn. 139) Additional work included rebuilding the chimney stacks in a diamond-set pattern and heightening the attic gables, although the conventionally placed staircase in the north-west wing probably remains from the earlier house. Rooms in 1734 included the great (presumably north-east parlour) and chamber above, a 'flock-worked' room probably in the north-west wing, and a study of books, perhaps in one of two small northwards projections or closets. The principal bedroom was over the hall, and the service end (let to Thomas Ford) comprised the kitchen, a maids' chamber with garrets above, a second chamber, and various outbuildings. (fn. 140) Panelling in the north-east parlour is 18th-century, perhaps installed by George Turner, and 17th-century Flemish tapestries in the north-east chamber (Plate 9) may have been brought in around the same time: they are cut to fit the room, and so were not commissioned new. (fn. 141) In the 1780s the house (described as 'genteel') still contained two large parlours, a hall, and a kitchen, with six first-floor chambers and five attic rooms, all elegantly furnished. (fn. 142) A single-storeyed south-west service wing, at an oblique angle to the main range, was built in the late 18th or early 19th century, perhaps replacing the dairy, brewhouse, and butteries mentioned in 1734.

37. E. H. New's bird's-eye view of Kelmscott Manor c. 1890, looking north-west. The twin-gabled hall-range of c. 1600 is in the centre, with Thomas Turner's added parlour range to its right.

The Turners' 19th-century changes were minor, including insertion of small iron grates and conversion of the south-west chamber into a cheese room. (fn. 143) The Morrises, too, carried out few structural alterations, although William redecorated, and in 1895–6 had stone-flagged or solid wood-block floors laid in all the ground-floor rooms, partly re-using flags found under the dining room (the former hall). (fn. 144) Ceramic tiles in the splays of some 17th-century fireplaces have been attributed to Charles Marks of London, and two castiron Art-Nouveau fireplaces upstairs were probably inserted c. 1890. (fn. 145) May Morris intended the house to remain a memorial to her father, and her bequest to Oxford University included furniture, paintings, tapestries, and embroideries associated with Morris and with the family's Pre-Raphaelite and Arts-and-Crafts circle, in particular Rossetti and Philip Webb. Some items had been at Kelmscott during Morris's period, although many others were imported later. (fn. 146)

By 1961–2 the house was in serious disrepair, and over the next few years the Society of Antiquaries undertook a major renovation, overseen by Donald Insall, Peter Locke, and the then custodian A. R. Dufty. The work became a model of late 20th-century building conservation, carried out so far as possible according to Morris's precepts as laid out in the manifesto of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. Following the structural work many of the public rooms were redecorated with Morris wallpapers, some from rolls discovered in the house, while the tapestries and fabrics were cleaned or replaced. (fn. 147)

The main farmyard lies south of the house, flanked by two large stone-built barns and a tall stone dovecot, all roughly contemporary with the 1660s work. The westernmost barn is now a tea room. In the 19th century the farmyard's south side was closed by a byre, and there was a rickyard further west; a granary was added by Charles Turner in the early 19th century. (fn. 148) A stone-built privy with a pyramidal roof, adjoining a garden wall at the back of the house, may be late 18th-or early 19th-century. (fn. 149) In 1993 the Antiquaries initiated a major restoration of the gardens, informed by their use and layout during Morris's tenure. The contractors were the landscape architects Colvin & Moggridge. (fn. 150)

Other Estates

Church Commissioners' (formerly Chichester Cathedral) Estate

A holding of 1½ yardlands, comprising a cottage, close, and 18½ a., was acquired in 1522 by Robert Sherburne, bishop of Chichester, who the same year granted it to Chichester cathedral with land in Langford. (fn. 151) The estate totalled 25 a. after inclosure in 1799, and in the late 18th and early 19th century was let or sublet to local gentry or farmers, including members of the Turner family. (fn. 152) In the mid 19th century it was vested in the Ecclesiastical (later Church) Commissioners, who added to it before 1879 when they held 80 a. in Kelmscott. (fn. 153) In 1905 the Commissioners bought Home farm from R. W. Hobbs, and Bradshaws or Kelmscott farm from trustees for George Milward, and around 1912 they owned 418 a. (let mostly to Hobbs) and 12 cottages. Another 86 a. were bought from the Hobbses' partner Vaisey Davis in 1935, and the Commissioners remained one of two chief landowners in Kelmscott in the early 21st century. (fn. 154)

A house or homestall for the Chichester cathedral estate seems to have stood south of the village street opposite Home Farm, with which it was occupied by the lessee in the early 19th century. The buildings were demolished in the late 19th or early 20th century. (fn. 155)

Manor Farm Estate

A freehold centred on Manor Farm was owned in the late 18th century by the farmer John Edmonds (d. 1809), who in 1767 bought two houses, rectorial tithes, and over 100 a. from James (d. 1799) and Elizabeth Turner. (fn. 156) The estate may formerly have belonged to James's grandfather John Turner (d. 1706) and his wife Mary: their initials appear on Plough Cottages (now part of the Plough Inn), which subsequently formed part of the Edmonds estate. (fn. 157) At inclosure in 1799 Edmonds received 150 a. for his freehold land and 158 a. for the tithes, together with 40 a. for a separate leasehold. (fn. 158)

Around 1821 Edmonds's successor William Edmonds sold the farm to George Milward (d. 1838), lord of nearby Lechlade (Glos.). In addition Milward acquired Bradshaws farm (c. 120 a.) from the Bradshaw family, making him the largest landowner in Kelmscott besides the Turners. (fn. 159) In 1898 trustees for Milward's heirs sold Manor farm (then 314 a.) and a few cottages to Sir Alexander Henderson (d. 1934) of Buscot Park (then Berks.), who in 1916 was created 1st Baron Faringdon; his grandson A. G. Henderson (d. 1977), 2nd Lord Faringdon, sold it in 1948 to Ernest Cook, from whom it passed with the Buscot Park estate in 1956 to the National Trust. (fn. 160) The Trust retained both estates in the early 21st century.

Manor Farm

Manor Farm was so called by 1898, presumably from its recent connection with Lechlade manor. (fn. 161) The house was substantially rebuilt and extended around 1700, perhaps for John and Mary Turner, and displays progressive features for its date. (fn. 162) The symmetrical south front (Fig. 38), with a hipped roof and endstacks, is of five bays, and has a pedimented central entrance and ovolo-moulded cross-mullioned windows. The walling is mostly coursed limestone rubble, but includes two ashlar bands on each floor and ashlar quoins around the windows and at the corners. Early 18th-century fittings in the eastern ground-floor room include panelling, a dentilled wooden cornice, and fluted pilasters to either side of the 19th-century fireplace, while the western room retains an Adam-style fireplace surround. A north-eastern back range, single-storeyed and with agricultural buildings at its northern end, may be of 17th-century origin, although the full-height north-west range is possibly contemporary with or slightly later than the main range. Stone-built agricultural buildings to the north, south-west, and south-east (across the road) include two 18th-century barns and an early 18th-century square dovecot, with a stone-slated roof and a pyramidal-capped louvre. (fn. 163)

38. Manor Farm from the south-east, with the early 18th-century stone dovecot to its left.

The Edmondses farmed the land themselves but mostly lived elsewhere, and in 1799 the house was let to a tenant. (fn. 164) Resident farmers in the 19th and 20th centuries included John Wells Brain in the 1850s and 1860s, Alfred Mace in the 1890s, and later the Eavises, (fn. 165) and the building remained a farmhouse in 2011. It was partly refenestrated during the 19th and 20th centuries, and a two-storeyed addition between the rear ranges was also added in the 20th century.

Queen's College Estate

The Queen's College, Oxford, acquired a holding at Kelmscott around 1526, given by Sir William Fettiplace and his wife Elizabeth as part of a larger estate centred on Letcombe Basset (formerly Berks.). (fn. 166) The Kelmscott holding included a yardland which had apparently been sold by Roland d'Oddingseles c. 1302, and which was acquired in the 15th century by Elizabeth's grandfather Thomas Walrond. (fn. 167) In the 16th and 18th centuries the college's Kelmscott estate totalled 2 yardlands comprising some 40 a., and 62 a. were awarded at inclosure in 1799. (fn. 168) Until the 19th century the college seems to have let the whole of its Letcombe estate to the Fettiplaces, who sublet the Kelmscott part to local farmers including the Davises, Turners, and Edmondses. (fn. 169) The Kelmscott land was sold in 1920. (fn. 170)

A homestead was mentioned from the 16th century, standing at the village's southern edge south of the Plough Inn. Probably that was the site of a house called Snow's Place or Goulds in the 14th and 15th centuries, which was mentioned in the college's early deeds. In 1722 the site included barns and outhouses, an orchard, and a garden; a house or cottage remained in 1920, but was subsequently demolished. (fn. 171)

Rectorial Tithes

Rectorial tithes in Kelmscott, as elsewhere in Broadwell parish, belonged until the Dissolution to the Knights Hospitallers as part of their manor of Bradwell St John. (fn. 172) In 1553 the Crown sold rectorial rights in Kelmscott, all or mostly comprising tithes, to Sir Anthony Hungerford, whose heirs sold them in 1638 to Thomas Turner (d. 1663). He left them to his younger son John (d. 1667/8), whose great grandson James sold them to John Edmonds in 1767. (fn. 173) At inclosure in 1799 Edmonds received 158 a. in lieu of great tithes, and thereafter the land formed part of his Manor Farm estate; (fn. 174) buildings known as 'parsonage farm' lay just across the road from Manor Farm in 1798. (fn. 175) Edmonds' successor George Milward was called lay impropriator in the mid 19th century. (fn. 176)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until the 20th century farming was the principal occupation of Kelmscott's inhabitants. Sheep-and-corn husbandry was probably most common, although the township's rich meadowland encouraged the grazing of both sheep and cattle. From the 16th century several prosperous yeoman families emerged, holding extensive farms as freeholders and leaseholders, and employing local labourers and servants. Parliamentary inclosure in 1798–9 consolidated their position, reducing the remaining smallholders and commoners to the position of wage labourers. In the 19th century the arable acreage increased until the agricultural depression of the 1870s compelled Kelmscott's farmers to diversify into dairying and livestock breeding, some of them (particularly the Hobbs family) on a large commercial scale. Mixed farming with a pastoral bias continued during the 20th century.

The Agricultural Landscape

Kelmscott's riverside location was ideal for the creation of high-quality meadowland, which remained important to its agricultural economy into modern times (see Fig. 33). (fn. 177) Open grassland, too, was in good supply: much of the township's northern part was common pasture from the Middle Ages until 1799, and supported substantial numbers of sheep, cattle, and horses. Between the meadows and the pasture, lying mostly on the river gravels, was an extensive area of open-field arable, which was most likely established by the 11th century, and which until the 1790s comprised several named fields and crofts clustered around the village. (fn. 178) Wood and fuel was possibly available from hedgerows before inclosure, (fn. 179) although much probably had to be brought in from outside. In 1611 the prosperous yeoman Thomas Turner had 15 loads of firewood worth £4 10s., while furze worth 4s. belonging to a labourer in 1582 had presumably been cut on the common or near the river. (fn. 180)

Open-Field Arable

Before inclosure Kelmscott's open-field arable comprised some 476 a. (46 per cent of the township), with 400 a. of common pasture (38 per cent), and 170 a. of meadow (16 per cent). The largest common fields were Great and Kingsham fields, which abutted each other on the township's eastern side and together covered over 300 acres. The smaller Haincroft, Henfield, Upcroft, and Long Croft (or Lincroft) were clustered around the village, while Fernham, which covered 59 a., adjoined the north-west boundary, detached from the rest of the arable. (fn. 181)

Home and Galloway fields, mentioned in 1573 with Fernham, Henfield, and Kingsham, were apparently predecessors of Great field, (fn. 182) and the overall pattern was almost certainly established before the early 14th century, when arable in Lake furlong (later in Home field) was mentioned. (fn. 183) The 'croft' field names suggest that some of the open-field arable around the hamlet may have been taken from medieval closes, but by the 16th century all seem to have been fully integrated into the common fields. (fn. 184)

Kelmscott's soil, a deep loam overlying gravel, was judged in the early 20th century to be 'unequal and inferior' to some in the area, but supported a variety of cereals, legumes, and root-crops. (fn. 185) The 16th-century names Beanlands and Stonyland suggest varying quality, and the name Lincroft implies that flax may have been grown in the Middle Ages. (fn. 186) Nothing is known of medieval crop rotations, though on the eve of inclosure there appears to have been a standard fourcourse rotation of fallow, wheat, beans, and barley. (fn. 187)

Pasture and Meadow

The 'pasture of the men of Kelmscott' was mentioned in 1320, (fn. 188) and then as later probably occupied a broad arc of land from Bull mead in the south-west to Langford brook in the north-east. By the 18th century it was divided into an outer cow common and an inner common called the green, presumably the 'sheep green' mentioned in 1722. (fn. 189) Additional pasture rights in some meadows were agreed in 1320 between the lords of Bradwell Odyngsell and Bradwell Cirencester manors, who confirmed grazing there from mowing time until the feast of the Purification (2 February), (fn. 190) and presumably there was some regulated grazing in the arable fields after harvest. Filkins inhabitants seem to have also had some limited pasture rights in Kelmscott, perhaps for the town bull, since at inclosure they collectively received ¼ a. (called 'Filkins bull') in compensation. (fn. 191) In 1573 the Queen's College's 2-yardland estate carried common rights for 80 sheep, 14 cows, and 4 horses. (fn. 192)

The township's meadows flanked the open fields' southern edge along the northern bank of the Thames, and presumably accounted for much of the 185 a. of meadow recorded on Broadwell manor in 1086. (fn. 193) Kingsham (c. 115 a.) in the south-east and Westham (c. 50 a.) in the south-west were mentioned from 1320, when the lords of Bradwell Odyngsell and Bradwell Cirencester manors shared rights there and agreed access for their servants and waggons, rotating some of their rights from year to year. (fn. 194) Some of the meadow was probably already inclosed demesne, and a few other small inclosed parcels or hams were mentioned from the Middle Ages. (fn. 195) Some was common meadow, however, and in Westham some strips were apparently still allocated by lot in the 18th century. (fn. 196)

The desirability of Kelmscott's meadowland is suggested by numerous purchases made by outsiders. Small parcels in Littleham and Reefham changed hands repeatedly between 1296 and 1364, (fn. 197) and in 1498–9 one of the non-resident Harcourt family held another meadow for 13s. 4d. a year. (fn. 198) Some tenants' shares were apparently much smaller, however, (fn. 199) and by the 17th and 18th centuries most larger farmers probably supplemented their common mowing rights with privately owned meadow. (fn. 200) In the early 19th century a leading Kelmscott farmer praised the quality of local hay, commenting that he had bought no cattle cake for many years and that his prize animals ate nothing else. (fn. 201) Persistent flooding, still common in the 20th century, (fn. 202) may nevertheless have reduced their value, and perhaps that of Kelmscott's other agricultural land.

Fisheries and Weirs

Fish provided an important supplementary resource from the Middle Ages, for both lords and tenants. The lord of Broadwell owned a fishery at Kelmscott by 1086, and his successors retained it until at least the 17th century, (fn. 203) occasionally letting it to local inhabitants. (fn. 204) A Kelmscott husbandman owned a boat and a flue-net in 1632, and in the late 19th century the river was still said to be well stocked with pike and crayfish. (fn. 205) The fishery may have become detached from Broadwell manor by 1784, when the Turner family's Kelmscott holding included a fishery and fishpond. (fn. 206)

Hart's or Eaton weir, which straddled the Thames ½ mile south-west of Kelmscott village, was probably also of medieval origin, and by 1754 was owned with an attached fishery by the local Hart family. An attached house lay just south of the river in Eaton Hastings (formerly Berks.). (fn. 207) Osier beds in Kelmscott (presumably near the weir) were also owned by the Harts in the 1790s, and until 1837 the family owned a small meadow nearby. (fn. 208)

Medieval Tenants and Farming

The Domesday entry for Broadwell did not distinguish between the estate's separate settlements, and nothing is known of agrarian organization in 11th-century Kelmscott. (fn. 209) By 1279, however, the township was divided in the usual way into around 22 yardland holdings, (fn. 210) each, on later evidence, comprising some 17–18 a. of open-field arable, with around 2 a. of common meadow and (in the 16th century) pasture rights for 40 sheep, 7 cows, and 2 horses. (fn. 211)

Fifteen yardlands were occupied by unfree villeins in 1279, each of whom held an entire yardland. Of those, 13 held directly of the d'Oddingseles' Broadwell manor for rents of 3s. 9d. each and labour services valued at 6s. 3d. a year; the other two were tenants of Hugh d'Oddingseles's kinsman Roland, and owed much larger rents (13s. 4d. each) but lighter services. Another seven tenants were cottagers, occupying between 1 a. and 8 a. each for varying money rents. Only 7 yardlands and a few odd acres were occupied by free tenants. Roland d'Oddingseles held 4 yardlands apparently in demesne, while John of Greenbarrow held and sublet 2 houses and 2 yardlands, and another tenant held a house and yardland jointly under Roland and Hugh d'Oddingseles. The last two holdings were unchanged in 1305, although the recorded rents were by then slightly lower. Henry in Angulo, free tenant of another yardland in 1305, came from a family which had earlier held in villeinage. (fn. 212)

Early 14th-century tax assessments show considerable disparities in the wealth of individual tenants, which was not entirely related to size or status of holdings. (fn. 213) Occupiers in 1306 were taxed on moveable goods worth between 12s. and just under £7, and in 1316 on between 26s. and just under £6. Many of the higher payments came from tenants whose yardlands had been held in villeinage in 1279 and 1305, (fn. 214) while Walter Staleworth, assessed in 1327 on goods worth over £14, was related to a family of 13th-century cottagers. (fn. 215) John Crock, tenant of a free yardland, was assessed on £3 in 1306 and on £4 17s. in 1316. The township's total assessed wealth exceeded £70 both in 1316 and 1327, and average assessments per person, 68s. in 1306, 63s. in 1316, and 79s. in 1327, suggest that Kelmscott was among the more prosperous rural settlements in the area.

From the mid 14th century outbreaks of plague reduced Kelmscott's population, though less markedly than in some neighbouring places. Its fortunes during the later Middle Ages are obscure, although extensive remodelling and beautification of the chapel, combined with its acquisition of burial rights in 1430, suggest prosperity amongst some at least of the township's inhabitants. (fn. 216) As elsewhere, the fall in population probably precipitated consolidation of holdings and the emergence of some of the dominant farming families recorded from the 16th century, when piecemeal sale of manorial lands reinforced the process. (fn. 217)

No direct evidence survives for the type of farming carried out in medieval Kelmscott, but presumably it followed a similar pattern to that on local demesne farms, combining cereal-based arable production with sheep rearing and probably some dairying. Pastoral farming (some of it possibly by outsiders) may have been particularly significant given the size of the township's commons and meadows, (fn. 218) and as elsewhere it probably increased in the later Middle Ages. Fishing (both legal and illegal) was probably also important. In 1305 the manorial fishery was let to John at Water with a villein yardland for 28s. a year, and a villein family surnamed Fisher was recorded in the late 13th and early 14th century. (fn. 219)

Farmers and Farming c. 1520–1798

By the early 16th century some of the prosperous yeoman families which dominated Kelmscott for the next few hundred years were beginning to emerge. In particular the prominent Turner family were established in the township by the 1520s, (fn. 220) their growing wealth evidenced by the lay subsidy of 1544, to which Elizabeth Turner (d. 1558) paid almost half of the total raised from 12–13 Kelmscott taxpayers. (fn. 221) By the 1570s three out of eight taxpayers in Kelmscott were members of the Turner family, and together owned nearly half the township's assessed moveable wealth. (fn. 222) The largest taxpayer, Andrew Turner, left goods worth £169 at his death in 1594, (fn. 223) compared with only £10–£30 left by many Kelmscott farmers in the period. (fn. 224)

Such prosperity probably allowed the family to take advantage of the gradual break-up of the Broadwell manors during the 16th and early 17th centuries. At his death in 1600 Richard Turner had a house and 1½ yardlands in Kelmscott as a tenant of Bradwell Cirencester manor, the lingering residue of manorial custom reflected in the relief of a horse which his son Thomas owed for entry into the holding. (fn. 225) Three years later the new owner of Broadwell manor sold to William Turner, in perpetuity, a house, garden, and 84 a. in Kelmscott and Broadwell, including pasture and meadow, (fn. 226) and several other Kelmscott freeholders seem to have acquired parcels of former manorial land around the same time. (fn. 227) By the mid 17th century the later pattern was well established, with landholding and farming in the township dominated by a handful of prosperous yeoman families such as the Bradshaws, Grains, and Symeses, of whom several remained for several generations. (fn. 228) By then the Turners of Kelmscott Manor owned and farmed at least 70 a. with commons for 20 cows and 96 sheep, (fn. 229) while in 1714 the Bradshaws owned a farm of 'pretty considerable yearly value'. (fn. 230)

Further consolidation followed during the 18th century, long before parliamentary inclosure in 1798–9. In 1767 John Edmonds (d. 1809), a leading farmer based in Gloucestershire, bought 130 a. centred on Manor Farm, (fn. 231) and by 1785 he was the second-largest land-tax payer in Kelmscott, assessed at £13 or one quarter of the total paid. Edward Bradshaw (predominantly a freeholder) paid £9 11s. 8d. and James Turner £9, although the largest farm was that of Thomas Carter (£17), an amalgamation of leaseholds held under various nonresident landowners, and run from Home Lea near the chapel. Following Carter's death in 1794 much of his leasehold land was acquired by Edmonds and others, leaving Kelmscott divided among three chief farms. (fn. 232) Such expansion did not come without risk, however. In the 1770s several of the Turners suffered serious financial crises, culminating in imprisonment for debt and the temporary loss of their freehold to a relative, under whom they continued as lessees. (fn. 233)

Sixteenth- and 17th-century wills and probate inventories point to the mixed sheep-corn farming typical of the area. Scythes, ploughs, harrows, harnesses, and other instruments of arable farming were itemized, together with livestock including sheep, cattle, pigs, poultry, and horses. A testator in 1546 bequeathed nearly 40 sheep, (fn. 234) while the wealthy yeoman Francis Symes (d. 1631) left 80 sheep and lambs, 10 cattle, 4 horses, and a few pigs, together with wheat, barley and malt worth £25, and 50s.-worth of hay. (fn. 235) Lambs with ewes were accommodated in cots and stalls, (fn. 236) and some wool was sold direct to weavers in Witney and presumably other cloth-manufacturing centres. (fn. 237) William Turner (d. 1626) had a dairy house fitted with troughs, a tub, a churn, and a cheese-press and rack, and his possession of a malt mill, cistern, and drinking barrels may indicate small-scale brewing. (fn. 238) Bullocks, heifers, sheep, and small quantities of wheat and barley were frequently left to younger sons and daughters, and several Kelmscott testators left quantities of hemp. (fn. 239) Several large, stone-built 17th- and 18th-century barns (some with pigeon roosting boxes) point to significant investment in arable and probably pastoral farming, while Kelmscott Manor and Manor Farm each acquired large stone dovecots. (fn. 240) Even landless labourers sometimes kept a few livestock, pastured presumably on the commons where they could also cut furze. (fn. 241)

Parliamentary Inclosure 1798–9

Some small-scale, piecemeal inclosure was carried out by freeholders before parliamentary inclosure in 1798–9. In 1735 Edward Turner owned 4½ a. of newly inclosed land called Haggots croft, taken apparently from the open fields, (fn. 242) while Beesley's piece (9 a.), mentioned in 1798, seems to have been a consolidated block of open-field arable immediately south of the village. (fn. 243) Except for a few small closes adjoining the houses and some small plots of meadow there was, however, virtually no other inclosed land before 1799, when most arable was still held in small scattered strips of 1 a. or less. (fn. 244)

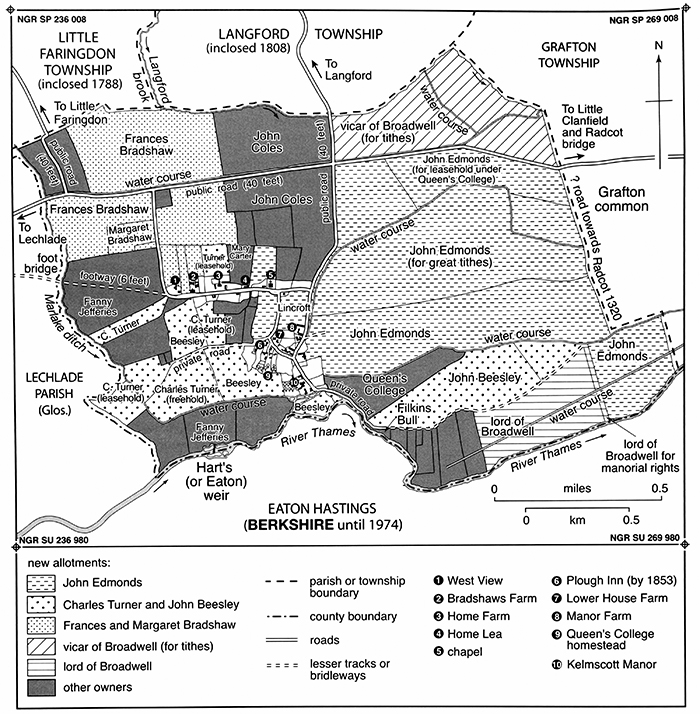

39. Kelmscott township after inclosure in 1798–9, showing new roads and allotments and principal landholders. (See also Fig. 33.)

An Act for Kelmscott's inclosure was obtained by the chief landowners and farmers in 1798, and a professional land surveyor, William Church of Longcot (then Berks.), was appointed. The inclosure was accompanied by extensive laying of new roads and drains, financed partly by the sale of two parcels totalling some 15 a., and the farmers John Edmonds and Edward Bradshaw were appointed as surveyors of the carriage roads. Five new water courses were laid to improve drainage, each of them 6 or 8 feet in width. Their future maintenance was charged to the land-holders through whose allotments they ran. (fn. 245)

The allocation of newly inclosed land, totalling some 970 a., reflected the ascendancy of the chief farming families and of a few non-resident landowners (Fig. 39). The absentee lord of Broadwell manor received 53½ a. in the south-east for his residual rights, but the largest allocation was 347 a. to John Edmonds as freeholder and lessee. This represented 35 per cent of the land allotted, and comprised the whole of the former Great and Kingsham fields and adjacent meadows. Frances Bradshaw received 118 a. north-west of the village in the former common pasture, and Charles Turner (d. 1833) a total of 142 a., including 80 a. rented with Kelmscott Manor from his cousin John Beesley. (fn. 246) The vicar of Broadwell received 79 a. of glebe in lieu of tithes, the remaining land being mostly allotted to non-resident proprietors including John Coles (79 a.), Fanny Jeffries (47 a.), and Francis Grain (12 a.), who let it to local farmers. Five people receiving 2 a. or less may have been cottagers, and so too may one or two others who paid under 5s. land tax. There seem, however, to have been no other resident smallholders, and by the 1840s there were apparently none. (fn. 247)

Inclosure was reckoned by the early 19th century to have increased Kelmscott's arable by 50 a., and John Edmonds, reflecting the conventional view of large commercial farmers, asserted that it had increased both arable and pastoral productivity and had doubled rents, which he claimed were 'paid with more ease'. (fn. 248) His own farming methods, reported with approval by the agriculturalist Arthur Young, included rotations of turnips, beans, wheat, and oats or vetches, with some sainfoin; on former common pasture he burnt off the grass, planted two successive turnip crops which were grazed with sheep, then planted rye grass, hops, or honeysuckle clover. Other improvements included erection of model stalls for livestock, and selective breeding of Cotswold sheep. (fn. 249)

The effects of inclosure on labourers and cottagers were less beneficial, and the decline in Kelmscott's population between 1801 and the 1820s may reflect a gradual exodus following loss of common rights. (fn. 250) Even so the number of families supported by agriculture rose from 26 to 28, (fn. 251) and Kelmscott remained a predominantly agricultural community. Out of 35 households in 1841, 27 (77 per cent) were headed by agricultural labourers, and the proportion remained similar in 1861 and 1881, when the only householders not supported from agriculture were the publican, a housekeeper at Kelmscott Manor, a widow on poor relief, and a domestic groom. In 1851 the chief farms employed a total of 37 labourers and in 1861 a total of 45, suggesting that continuing population decline was not entirely due to agricultural under-employment. (fn. 252)

Farms and Farming From 1800

The Edmondses, Bradshaws, and Turners remained the chief farmers until the 1820s, when Albert Edmonds briefly took over Bradshaws farm, although by then the family had sold its freehold land. (fn. 253) In the 1830s the Edmondses moved elsewhere, and throughout the mid 19th century there were four farms of between 200 and 400 a., centred on Manor and Home Farms, Bradshaws, and Kelmscott Manor. By then Charles and James Turner, the only freeholders, farmed some 550 a. between them, and in 1864 James crowned several decades of expansionism with the purchase of 53½ a. and the manorial title. (fn. 254) From 1873 the combined Turner holdings were farmed from Bradshaws and (later) Home Farms by James's great-nephew R. W. Hobbs (d. 1920), first as lessee and, from 1895 to 1905, as owner, the land having been purchased with a loan from his tenant William Morris. By 1881 Hobbs farmed 600 a. and employed 30 labourers; his estate had a gross annual value of £440, although of that more than half was consumed by overheads. (fn. 255) Thereafter Kelmscott remained divided between the Hobbs farm and Manor farm, the latter let successively to the Brains, Simpsons, Maces, and Eavises. (fn. 256)

The increasing emphasis on arable farming noted after inclosure continued until the 1870s, when Kelmscott was over 80 per cent arable. (fn. 257) In the late 19th and early 20th century, however, R. W. Hobbs and his sons built up a substantial farming enterprise which concentrated on dairying and speciality breeds, including horses and a flock of Oxford Down sheep. The principal output of the flock was shearling rams and ram lambs, of which 300 were sold annually, mainly at Oxford, Cirencester, and Northampton, but also as far afield as Kelso (Roxburghshire) and Edinburgh. Despite the considerable sums invested in their stud, the Hobbses seem not to have profited from this aspect of their stock-breeding, their greatest successes being with their herd of Dairy Short Horn cows, which won numerous awards before the First World War. Bulls and heifers were sold for overseas export, cows were sold domestically, and milk was sold for the London market, fifty of the least productive milk cows being sold off annually. The quality of the calves and heifers was maintained through a special diet of cream substitute, bran, crushed oats, and linseed cake. Pioneers of industrialized milk production, the Hobbses built a dairy and bottling plant at Kelmscott in 1900, their innovative production techniques including tuberculosis-testing of livestock and the refrigeration and sealed bottling of milk, which was transported to London by rail, and distributed from their own outlet at 20 Connaught Street. (fn. 258)

40. Home Farm in 1905, with (left to right) Mrs R. W. (Helen Louisa) Hobbs, d. 1919; her sister Maud Heath; Robert Hobbs, d. 1967; and Henry Hobbs.

In 1905 Hobbs sold most of his land, but continued as a tenant farmer. (fn. 259) By 1916 he farmed 2,300 a., much of it in neighbouring parishes and all but 4 a. of it leasehold. From the turn of the century the emphasis shifted from milk production to cattle breeding, three fifths of the family's income by 1914 coming from sale of stock; by then they had 506 cows, 1,667 sheep, and 117 horses. The partnership continued to pioneer industrialized, capital-intensive farming: by the First World War annual expenditure on cattle feed was £4,000–£5,000, and £100 was spent on super-phosphates, while high wages and much-valued training attracted labour. A commentator in 1916 remarked on the business's consciousness of product-development and cultivation of overseas markets, concluding that there were 'several farms in other parts of the county where the management is highly efficient, but none on which it has been so strictly and formally adhered to'. (fn. 260) Following R. W. Hobbs's death in 1920 his son Robert (d. 1967) succeeded, dissolving the family business and forming a partnership with his brother-in-law Vaisey Davis. (fn. 261)

Notwithstanding the Hobbses' initiatives, in 1916 Kelmscott as a whole remained fairly evenly divided between arable and pasture, the chief crops being wheat and oats (25 per cent each) and turnips (10 per cent). The Hobbses had over 400 a. under wheat and barley, besides oats, beans, and fodder crops. (fn. 262) Mixed farming with a pastoral bias continued in 1941, by which time arable had further declined to 41 per cent: of 605 a. on the Hobbs–Davis farm, 22 per cent was under wheat, 27 per cent under mixed corn, and 10 per cent under barley, with 17 per cent under sainfoin, and 12 per cent under oats. Peas, turnips, swedes, mangolds, kale, and vetches were planted for stock feed, while small crops of sugar beet, potatoes, carrots, maize, and pears were also grown. The dairying tradition continued with a herd of 201 cows and 56 bulls, and there was a substantial flock of 354 sheep and lambs. Manor farm practised similar agriculture, growing wheat, oats, barley, sainfoin, and fodder crops, maintaining a herd of 73 dairy cows, and, like Hobbs and Davis, keeping poultry. Both farms were well managed, though Eavis at Manor farm was 'handicapped by a bad landlord', and buildings were in 'a very bad condition'. The Hobbs farm continued to be labour-intensive, employing 27 full-time workers compared with Eavis's six, though both farms were thoroughly mechanized and used chemical fertilizers. (fn. 263) Following the Second World War Roland Maughan succeeded Davis as Hobbs's partner at Home farm, and in 1969 sold the milking herd to concentrate on pigs, cereals, and potatoes. Manor farm's Shorthorn herd was sold in 1953, and a later Friesian herd in 1981. (fn. 264)

41. The Hobbs family's milk-bottling plant at Home Farm, from a publicity brochure published c. 1914.

Rural Trades and Crafts

A villein surnamed 'smith' in 1279 may have been a blacksmith, (fn. 265) but from the Middle Ages even the usual rural trades were infrequently documented in Kelmscott. (fn. 266) One of the Cockbill family of Filkins was established by the 1840s as a wheelwright, carpenter, and beer retailer at the Plough Inn, and in the 1850s there was a basket- or sieve-maker. A smithy near Manor Cottages was recorded from the 1890s to 1920s, housed in a single-storeyed rubble-built shed which still survives. (fn. 267) During the late 19th and early 20th century some wives or daughters of agricultural labourers worked as dressmakers, and in 1871 one was a laundress. Several other women were domestic servants, working mostly in the households of the principal farmers: in 1891 there were ten such, including a nurse, cook, governess, and general servant all employed by R. W. Hobbs. Only one of them had been born locally. A grocer's shop existed by 1841, and from the 1860s the Cockbills ran another one at the Plough. In the 1890s a former shopkeeper and agricultural labourer became a coal dealer presumably using the railway, and another coal dealer continued in the 1920s.

Most traditional trades seem to have disappeared during the 1920s. By the mid 1930s there was only a recently established cabinet-maker, and in the early 1960s Kelmscott still offered only dwindling agricultural employment, a chief cause of its falling population. (fn. 268) A shop adjoining the Plough continued to sell groceries until the late 20th century, but by 1990 there was no shop or post office, and except for a few farm workers almost all the population were commuters working elsewhere. (fn. 269)

SOCIAL HISTORY

During the earlier Middle Ages Kelmscott housed a middling-sized peasant community similar to many others in the area, closely linked to the manorial centres at Broadwell. Between the 15th and 17th centuries, however, population decline and the sale of manorial lands fundamentally altered its character, creating a prosperous group of yeoman freeholders of whom the Turners, who built Kelmscott Manor, were pre-eminent. The pattern persisted into the 18th and 19th centuries when, after inclosure, the village became primarily a community of agricultural labourers employed on the two or three large commercial farms. The village's social life is poorly recorded before the 19th century, when it finally acquired a pub and school. Earlier the only communal building was the Anglican chapel, with no Nonconformity emerging to provide an alternative focus.

From 1871 the occasional presence of William Morris added a new dimension, though the family's impact on the village was muted until the early 20th century, when Morris's widow and daughter became more actively involved and added several new buildings. Under the terms of May Morris's will Kelmscott Manor became a shrine to her father's life and work, culminating in its opening to the public in the 1960s by the Society of Antiquaries. Even so Kelmscott has largely retained its secluded character, following its transition (like most neighbouring places) into a small community of well-off commuters, with a couple of still functioning farms.

Social Structure and the Life of the Community

The Middle Ages

Like Broadwell's other townships Kelmscott originated within a complex pre-Conquest estate. (fn. 270) As it was not separately described in Domesday Book nothing is known of its 11th-century social structure, though if, as has been suggested, Kelmscott chapel originated in the late 11th rather than the late 12th century, that would imply a sizeable population. (fn. 271) By the 13th century Kelmscott supported a heavily manorialized peasant community, in which the vast majority of inhabitants held their land of the non-resident d'Oddingseles family for rents and labour services. Of those, 15 occupied yardlands in villeinage, while another seven occupied small cottage holdings, and probably supplemented their income by labouring for some of their better-off neighbours. There was a wide range of individual prosperity, with some evidence in the early 14th century of upwards social mobility, and over all, taxation records suggest that Kelmscott was among the more prosperous rural communities in the area. (fn. 272)

The main exception to this landholding pattern was a ploughland (probably around 80 a.) held in demesne by the lord's kinsman Roland d'Oddingseles (d. 1316), who possibly lived in Kelmscott and had a few tenants of his own. After his death his holdings were absorbed into Bradwell Cirencester manor and possibly broken up, but during his lifetime he may have been a dominant local figure, and it is possible that he paid for some of the extensive late 13th-century building work carried out in Kelmscott church. (fn. 273) It has been suggested that his ploughland holding could have been of early and possibly Anglo-Saxon origin, representing a hide unit of a type now widely recognized elsewhere. (fn. 274) There is, however, no supporting evidence, and his life-hold property in Kelmscott and elsewhere may equally have arisen from a recent family settlement.