Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Pentonville Road', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp339-372 [accessed 15 April 2025].

'Pentonville Road', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 15, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp339-372.

"Pentonville Road". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 15 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp339-372.

In this section

- CHAPTER XIV. Pentonville Road

- North side: Islington High Street to Baron Street

- Baron Street to Penton Street

- Penton Street to Rodney Street

- Rodney Street to Calshot Street

- Calshot Street to Northdown Street

- West of Northdown Street

- South side: St John Street to Claremont Square

- Claremont Square to Penton Rise

- Penton Rise to King's Cross Road

CHAPTER XIV. Pentonville Road

Pentonville Road was created as the eastern third of the New Road from Paddington, opened in 1756 to divert livestock drovers from the West End and Holborn on their way to Smithfield. Pentonville did not then exist. The road from Battle Bridge (the future King's Cross) passed by fields and bowling greens before reaching the Angel Inn, where Islington High Street gave way to the still-rural road (now the upper half of St John Street) running south towards Smithfield and the City. By the time this part of the New Road received its present name, in 1857, Pentonville was a long-established suburb. Pentonville Road itself, developed as a good-class residential address from the 1770s to the 1820s, was filling with shops and lodging-houses, its population becoming poorer and more numerous. The fields south of Pentonville had been completely built up for many years and, while the livestock market at Smithfield had yet to close, Pentonville Road was no longer a mere bypass but an integral part of the northern metropolis.

The road today has no defining characteristic, beyond the heavy traffic thundering up and down 'Pentonville Hill', as the descent from Claremont Square towards King's Cross was known before the New Road was formally renamed. At the east end enough late Georgian houses survive to evoke something of its former suburban character. Elsewhere, a very few scraps of the original development are left, together with some Victorian shops and dwellings. Only towards the junction of King's Cross Road is it still recognizably the place detailed by John O'Connor in his well-known sunset view of St Pancras Station (Ill. 429).

429. 'From Pentonville Road looking West: Evening', by John O'Connor, 1884. On the right is St James's, Pentonville, on the left are Penton Place (now Penton Rise) and the shops of the former Lower Queen's Row. The view appears to be taken from the roof of Dunn & Hewett's cocoa factory (right foreground)

Industrial and commercial buildings, often on a larger scale, replaced many of the original houses from the later nineteenth century. Many of these have themselves been demolished or, if not, converted to new uses. Redevelopment from the late twentieth century, much of it on a fairly large scale too, has moved from offices in the 1970s and 80s to apartment blocks in recent years— especially in the form of student hostels (see Ill. 428, page 337).

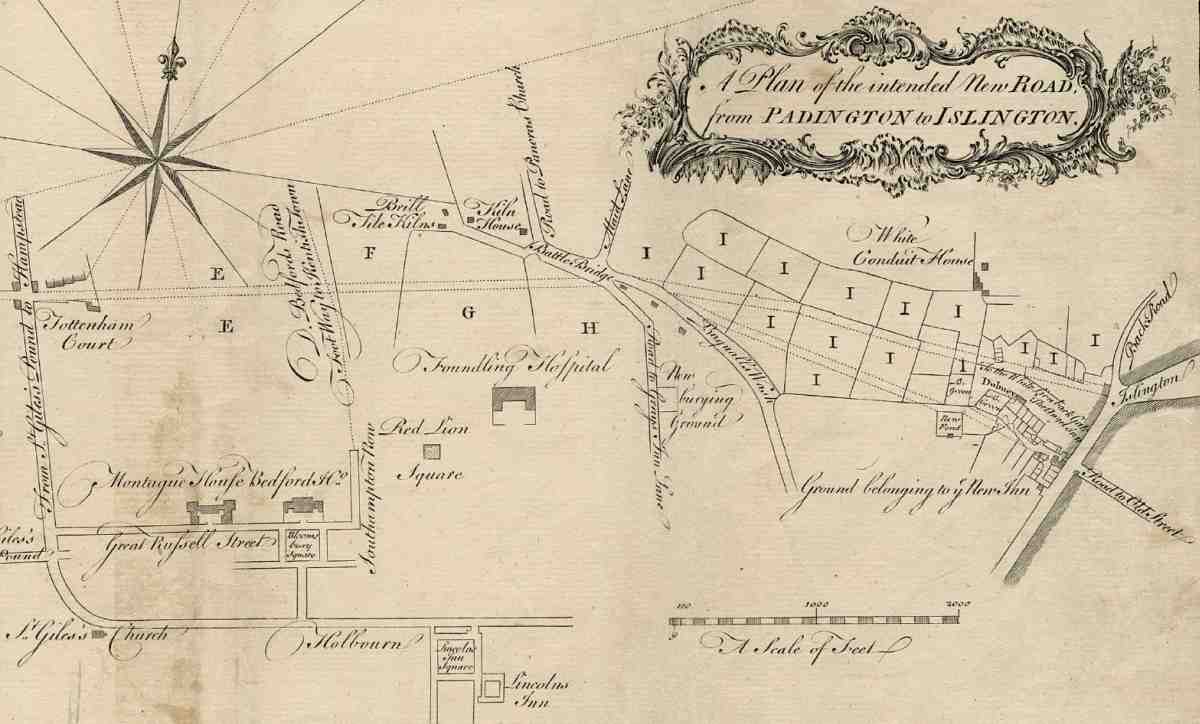

430. The New Road. Extract from a map of 1755, showing the proposed route from Tottenham Court to Islington High Street, with alternative lines east of Battle Bridge. Land owned by Henry Penton labelled 'I'

The present chapter recounts the development of Pentonville Road generally, and describes particular buildings roughly as far west as the parish boundary of St James, Clerkenwell (see Ills 426–7). The short section of the south side west of King's Cross Road, and the buildings west of No. 270 on the north side, including the whole frontage from Caledonian Road to York Way, are therefore not included.

Planning and construction

At the time of its creation in 1756, and for long after, the New Road was unparalleled in London as a piece of largescale road-planning. (fn. 1) The precursor of later bypasses and ring-roads, it retained a separate identity until 1857. By then, as building development had taken place, it had become divided into an unwieldy series of Rows, Terraces and Places, all of which were abolished in 1857 when the Metropolitan Board of Works renamed and renumbered it in three parts as the Marylebone, Euston and Pentonville Roads. (fn. 2)

The New Road was planned to start from the junction of the Harrow and Edgware Roads in Paddington, leading north-east more or less in a straight line to Tottenham Court and thence to Battle Bridge. Finally, with a turn to the south-east, it was to cut through fields belonging to Henry Penton MP, ending near the Angel, Islington. This last stretch had two possible routes: one through the middle of Penton's estate, between the bowling greens there and White Conduit Fields to the north, to join the south end of Upper Street near the junction with what is now Liverpool Road; the other mostly keeping to the south side of his estate, past the New River Company's upper reservoir, and on to the Angel itself (Ill. 430). Penton held 'very great Objections' to the former route as 'detrimental' to his property, but none to the latter, which was the one eventually selected. (fn. 3) The prospect of lucrative future building development was presumably not in Penton's mind, for he thus gave up an outstanding opportunity to maximize his frontages to the new road.

A broad, relatively straight thoroughfare such as this, it was argued, would connect with all the main roads leading south into London, and would provide a direct link between the western and eastern extremities of the metropolis. Gentlemen and men of business could then travel quickly by carriage between City and suburbs without being 'jolted three miles over the stones, or perhaps detained three hours by a stop in some narrow street'. (fn. 4) The road would also help deal with the additional traffic expected to follow the proposed new bridge at Blackfriars (built in the 1760s). In times of emergency, troops would be able to cross London unhindered without entering the centre. But above all it was as a way of taking the twice-weekly flood of sheep and cattle bound for Smithfield away from Oxford Street and the narrow, winding route further east that the New Road was built. That is why it stopped at the Angel, where the Islington road and St John Street provided a direct way south to the market, rather than going on into the City.

The promoters were landowners, farmers, merchants and tradesmen living in and around London—'gentlemen of the greatest eminence and property'. (fn. 5) Though the twenty-five individuals who petitioned Parliament for an enabling Act are not known, some prominent figures can be identified, mostly from among the trustees of the St Marylebone and Islington Turnpike trusts, the two existing bodies that were given the responsibility of constructing and maintaining the road. They included Hammond Crosse, of the Bedfordshire and Clerkenwell brewing family; Richard Whishaw, a Lincoln's Inn attorney and Secretary to the Committee of Gentlemen Practitioners; and George Errington, a landowner in Middlesex and Essex and later High Sheriff of London. (fn. 6) Throughout the committee stage in Parliament the petitioners' interests were represented by an agent, William Godfrey—perhaps William Godfrey of Paddington Green (d. 1766), who had estates in Middlesex and Essex. (fn. 7) Crosse, Whishaw, Errington, Godfrey and Charles Dingley were all on the special committee of twenty-one Islington turnpike trustees set up in May 1756 to manage the making of the road between Tottenham Court and the Angel. (fn. 8)

The 'great projector' (fn. 9) Dingley (d. 1769) is generally credited with the leading role. He and his brother and partner Robert, an architect and philanthropist, had made their fortunes years before, trading with Russia and Persia. (fn. 10) In his evidence to the Parliamentary committee in February 1756, Dingley predicted that the road would be 'one of the most profitable Undertakings he ever knew', offering to put up £1,000 to pay for toll-houses. (fn. 11) He was also behind the creation of City Road in 1761, which carried the New Road on into the City, and projected two more, ultimately unexecuted, roads—an extension of the City Road to the Mansion House, and another linking the New Road with Camden Town. (fn. 12)

When the plan was before Parliament it met opposition from landowners along the proposed route and some of the Islington turnpike trustees, who argued that the existing roads were adequate. The Duke of Bedford protested that dust from the road would affect his land immediately east of Tottenham Court, inconveniencing his tenants, while any roadside building would block the view from his residence, Bedford House—prompting Horace Walpole to remark that the Duke rarely came to town and anyway was 'too shortsighted to see the prospect'. (fn. 13) Wider opinion was supportive. The Gentleman's Magazine stressed the primacy of public over private interests, asserting that 'streets and roads are to inland trade what seas are to foreign', every new road being a 'kind of new mine that encreases the wealth of the community'. (fn. 14)

The Act was passed in May 1756 and the two turnpike commissions immediately set about marking out the route. (fn. 15) In the Clerkenwell section, several surveyors were involved. A preliminary survey and plans had been provided by Edward Cullen, who was paid six guineas in August 1755. (fn. 16) Paul Jollage, surveyor, was paid five guineas for his 'trouble' in planning the road, and a land surveyor named Marsh provided plans and property information for both the Islington and Marylebone trustees. (fn. 17) Labourers working on the road were supervised by the Islington trust's surveyors William Thomas and James Inglish. (fn. 18)

Construction was largely confined to the removal of hedges and banks to make a sufficiently level surface, the digging of ditches, and the erection of fences, gates and toll-houses—mostly from old ships' timbers. As the road was to be used particularly by drovers, the enabling Act forbade the paving of the surface, which was left as turf. However, the pot-holes caused by heavy rain and workmen's carts had to be filled with gravel or ballast, and this was eventually extended over the whole surface. (fn. 19) As early as 13 September 1756 coaches, carriages and horsemen were passing daily in 'great numbers' over the road from Islington to Battle Bridge, and the whole route was opened four days later. (fn. 20)

Compensation had to be paid to landowners and leaseholders, not just for the 40 ft width of the road itself, but for another 10 ft each side for ditches and fencing. An important clause in the Act, never wholly obeyed, forbade building within 50 ft of the road, to admit enough sun and air to keep it dry, and to stop dust from inconveniencing residents. (fn. 21) Henry Penton gave up part of the western bowling green and the 'Bowl house' there, in return for a larger building, with a room over, designed and built by Woodhouse Coker, the turnpike trustees' carpenter. Robert Bartholomew, landlord of the Angel, whose sheep pens stood on the route, asked for money towards replacements; and the New River Company was given £150 towards building a brick wall on the north and west sides of its Upper Pond reservoir. (fn. 22)

Early development

It was some years before building development took off along the New Road east of Battle Bridge. Until then, the ground on either side remained in use chiefly for grazing. The opening of the road must have increased the demand hereabouts for sheep and cattle lairs (or layers), where animals were kept for fattening before going on to market. Parts of the ground, including the Penton estate, continued to be dug for gravel and clay for making bricks and tiles, an activity which went back in this area to the seventeenth century at least. (fn. 23) The road was, at first, rather too far from the built-up area to attract builders, and in any case its opening coincided with bad harvests, the onset of the Seven Years War, tight credit and a downturn in house-building. (fn. 24) But by the late 1760s the picture was changing, and leasehold development was taking off along the New Road.

Building on the Penton-owned frontages was slow. Henry Penton III (d. 1812), who oversaw the development of Pentonville, inherited the estate from his father in 1762. His first attempt at leasehold development seems to have been in 1764, when a St Marylebone plasterer, William Lloyd, agreed to build houses on the south side of the road west of the reservoir. (fn. 25) This proved a false start, but in 1767 the Belvidere tavern was built on the north side, on the corner of the new Penton Street (see page 351). (fn. 26)

Houses near by, on both sides, in King's Row and Queen's Row followed from the late 1760s. By the late 1780s development had spread some way east and west of this nucleus. On the north side, Pleasant Row and Pleasant Place, west of Southampton (now Calshot) Street, went up about 1783–7. (fn. 27) The late 1780s saw the building of Pentonville Chapel and a large detached residence, Cumming House, and houses in Cumming Place. (fn. 28) East of Penton Street, Winchester Place and the Penton Arms on the corner of Baron Street were built in the late 1780s. On the south side, the triangle bounded by Penton Place (now Penton Rise) and Hamilton Row (now part of King's Cross Road) was mostly built up in the late 1780s and 90s, after some earlier building on the east side of Penton Place (see Ill. 528 on page 406).

431. The New Road, looking east past the turnpike gate at the junction with Penton Rise, 1786. On the left are houses in King's Row, on the right part of Queen's Row

The last part to be developed was to the east, on the New River Company's estate and land formerly belonging to the Angel inn. The frontages here were filled with houses from about 1818 until the mid- 1820s: Angel Terrace and Claremont Terrace on the south side, Angel Place and Claremont Place, together with Claremont Chapel, on the north.

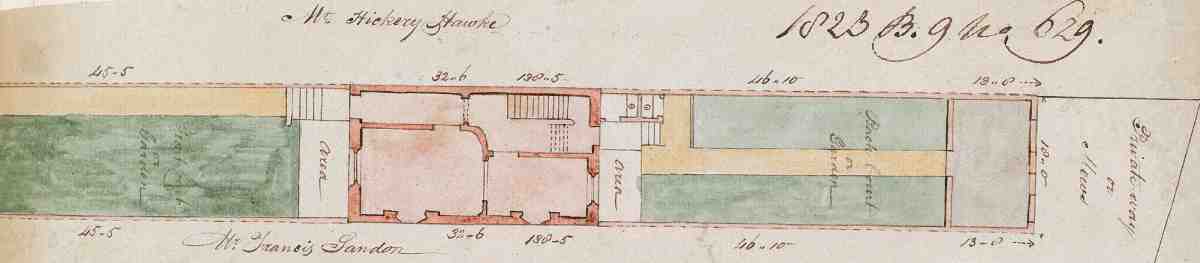

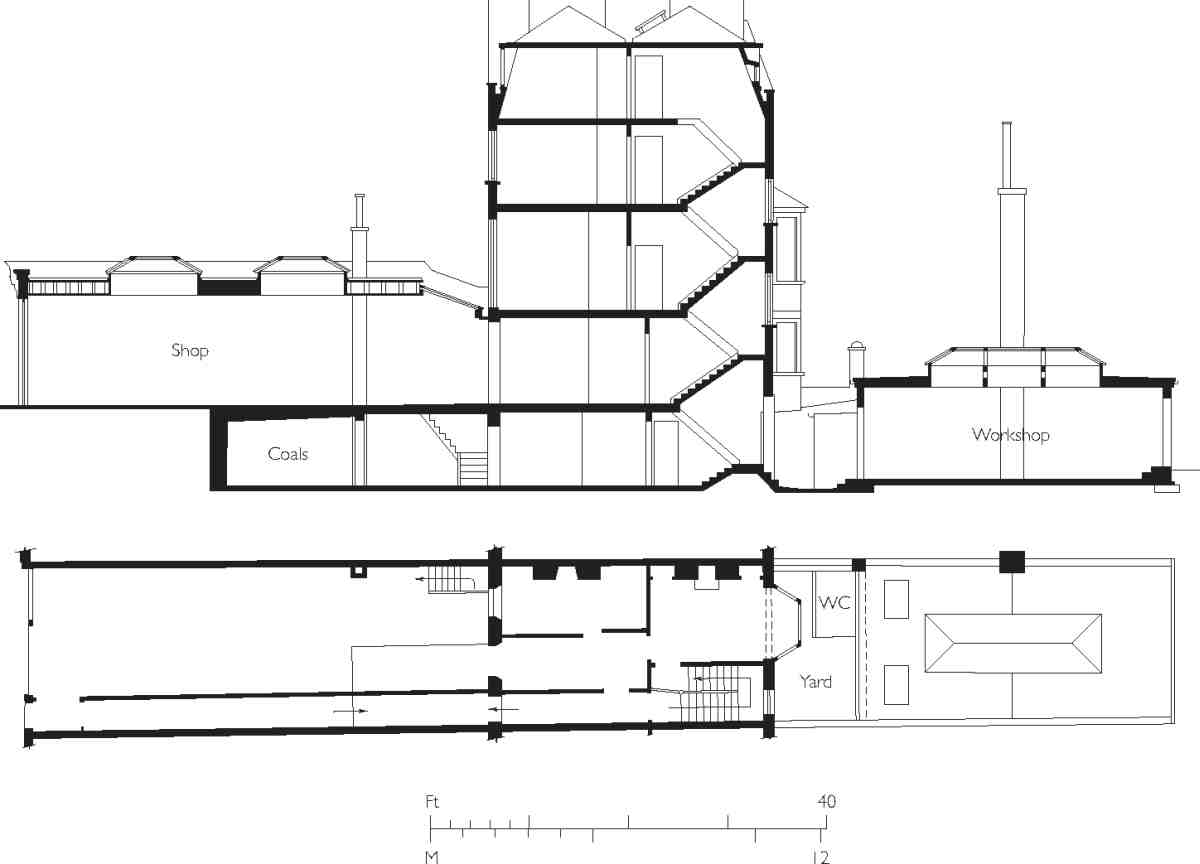

Though differing to a certain extent in size and layout, nearly all this first-generation building consisted of goodclass private houses. Most were three storeys high, with two-bay frontages, though there were exceptions, notably some four-storey houses in Winchester Place, Claremont Terrace and Claremont Place (Ills 431–4, 439, 445). There were at least two houses of only two storeys (Nos 62 and 64). Nearly all had conventional side-passage plans, with two rooms to a floor (Ill. 435). On the north side, many of the houses were raised above the level of the roadway, on semi-basements or basement vaults, and consequently any shops later built out in front usually had steps up at the back.

Why some houses at the west end of Pentonville Road were allowed to be built hard up against the roadway, as at Batchelor Place and Pleasant Place, rather than 50 ft back as required by the New Road Act, is not known. However, none of these early incursions were on the Penton, New River Company or Angel estates. The turnpike trustees' minutes are silent on the matter, so a blind eye may have been turned. By the 1820s some parts of the New Road in and around Battle Bridge had been exempted from the 50ft rule, perhaps retrospectively. (fn. 29)

Changing character

For more than half a century after it was built up, the New Road between Battle Bridge and the Angel was solidly residential and apparently respectable, the address typically of gentlemen and merchants. There were self-styled 'Esquires' in some of the best houses, such as those in Winchester Place and Claremont Place, into the 1860s. (fn. 30) But within a few years of Queen Victoria's accession several houses had become business premises. There were a number of professional occupants, particularly surgeons and physicians, but more often than not some craft or manufacturing activity was being carried on. Directories of the 1840s list an engraver, a chain-maker, two chronometer-makers, a zinc worker, cabinet-makers, printers, and bookbinders. By this date there were also a fair number of shopkeepers and general tradesmen. (fn. 31)

Pentonville Road houses. All demolished

432. Nos 177–183 (formerly part of Clarence Place) in 1964. Part of a development of the 1780s and 90s by John Weston, brickmaker

433. Nos 124 and 126 in 1963. Built as part of King's Row, 1770s and 80s

434. No. 56 in 1953. Built as part of Winchester Place, 1786–90

435. No. 9 Claremont Place (later No. 28 Pentonville Road), as built 1822–3. Demolished

Architecturally, this increasing commercialization was manifested in shops, mostly single-storey extensions to houses. But the earliest instance, Athol Place, was a row of two-storey houses with shops, built about 1839 on part of the gardens belonging to the Belvidere. Within a few years more shops had been built on the south side, in Lower Queen's Row, and in front of houses on the north side, in Cumming Place and King's Row (the latter as a continuation of Athol Place). More than half the houses west of Penton Street and Claremont Square had lost their front gardens to shops by the 1870s.

The new Metropolitan Board of Works was at first stringent in refusing forecourt shops, on the grounds that they projected beyond the existing building line, turning down several applications in 1856 and 1857. (fn. 32) The district surveyor, Robert Sibley, who lived in Pentonville Road, told the Board he was unsure if these structures could be classed as projections, and on at least two occasions magistrates dismissed cases he had brought against owners, on the grounds that the shops were buildings in their own right, or additions to buildings, and not projections. (fn. 33) In neither case was mention made of the 50 ft rule, which had been reaffirmed by the Metropolis Turnpike Road Act of 1826. (fn. 34)

Subsequently, in the 1860s–80s applications to build shop-additions were generally allowed by the board. But in 1887 they were refused at the former Winchester Place opposite Claremont Square (Nos 56–92), perhaps on account of its superior architectural character or setting, as effectively the fourth side of Claremont Square. (fn. 35) Nor would the New River Company permit them on its own Pentonville Road frontage. By 1900 only a few houses on the Penton frontage still kept their gardens, including Winchester Place. On the north side of the road east of the Penton estate Nos 14–44 never acquired shops, but some later had workshops built over the rear gardens, as with Betjemann & Sons' works at Nos 34–42.

436. No. 178 Pentonville Road in the 1930s. Section showing characteristic arrangement of house with later shop and workshop additions to front and rear

As well as shops, rear workshops became common in the mid-to-late nineteenth century, as the character of the road became increasingly industrial, in many instances leaving the old houses sandwiched between long, low structures (Ill. 9). In some cases two, three or more adjoining hybrid house—workshops of this sort were acquired and thrown together to form an extensive factory, as at Dunn & Hewett's cocoa factory, at Nos 130–138.

437, 438. Pentonville Road pubs: Lord Vernon Arms, No. 188 (left), rebuilt 1901; Crown, No. 128a, rebuilt 1873 –4. Both demolished

During the 1870s and 80s more and more premises were given over to light manufactures of various sorts, including musical instruments, furniture, jewellery, and artificial flowers. Several photographic studios were also established. From the outset there had been a number of taverns, and by this period there were numerous coffeeshops and dining-rooms, no doubt to a great extent catering to workers in the many factories and other establishments. (fn. 36)

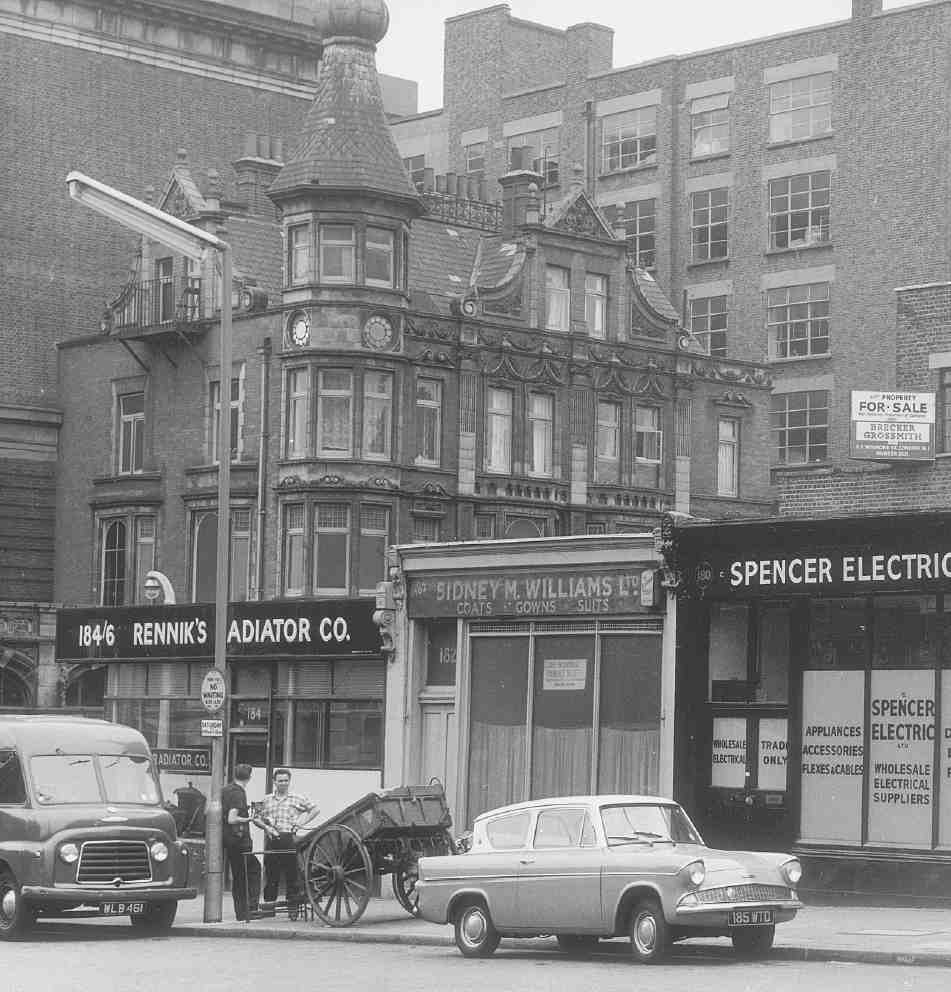

Most of the public houses in Pentonville Road were rebuilt in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Though none were of the scale and elaboration seen in better-heeled areas, there were some quirky designs, such as the Crown at No. 128a (1873–4), with an obelisk-like clock-tower on the corner (Ill. 438). (fn. 37) Another early rebuilding was the Italianate-style Belvidere (1875–6, see page 352). The Welsh Bull at No. 120 was enlarged in 1881 and remodelled internally in the early 1890s (see page 354). Later rebuildings along the north side of the road included the Lord Vernon Arms of 1901 (No. 180, later 188), another showy design with a clock-turret (Ill. 437), and the King George IV of the late 1890s (No. 156), a plainer building with bay windows on the long front to Cumming Street. (fn. 38) Of those mentioned, only the Belvidere and Welsh Bull survive, neither of them now as pubs.

Though there was already much poverty in the area, Pentonville Road received a sharp jolt in the early 1900s, one of the chief factors being the introduction of trams, which brought about an unprecedented degree of mobility among the working-classes. Better shops and better lodgings were easily found elsewhere. Writing to the London County Council in 1908, H. C. Braun, proprietor of an experimental engineering works at Nos 236 and 238, claimed that some 60 per cent of local shops had closed. His claim is supported by the records made four or five years later by Inland Revenue valuers. Many of the forecourt shops were dilapidated, devalued and untenanted. (fn. 39) Braun himself planned (unsuccessfully) to build bigger premises, which he hoped would make a 'good entrance' at the road's west end and help it recover from its 'bankrupt' condition: only redevelopment with large factories could save Pentonville Road from becoming 'a scandal and disgrace to London'. (fn. 40)

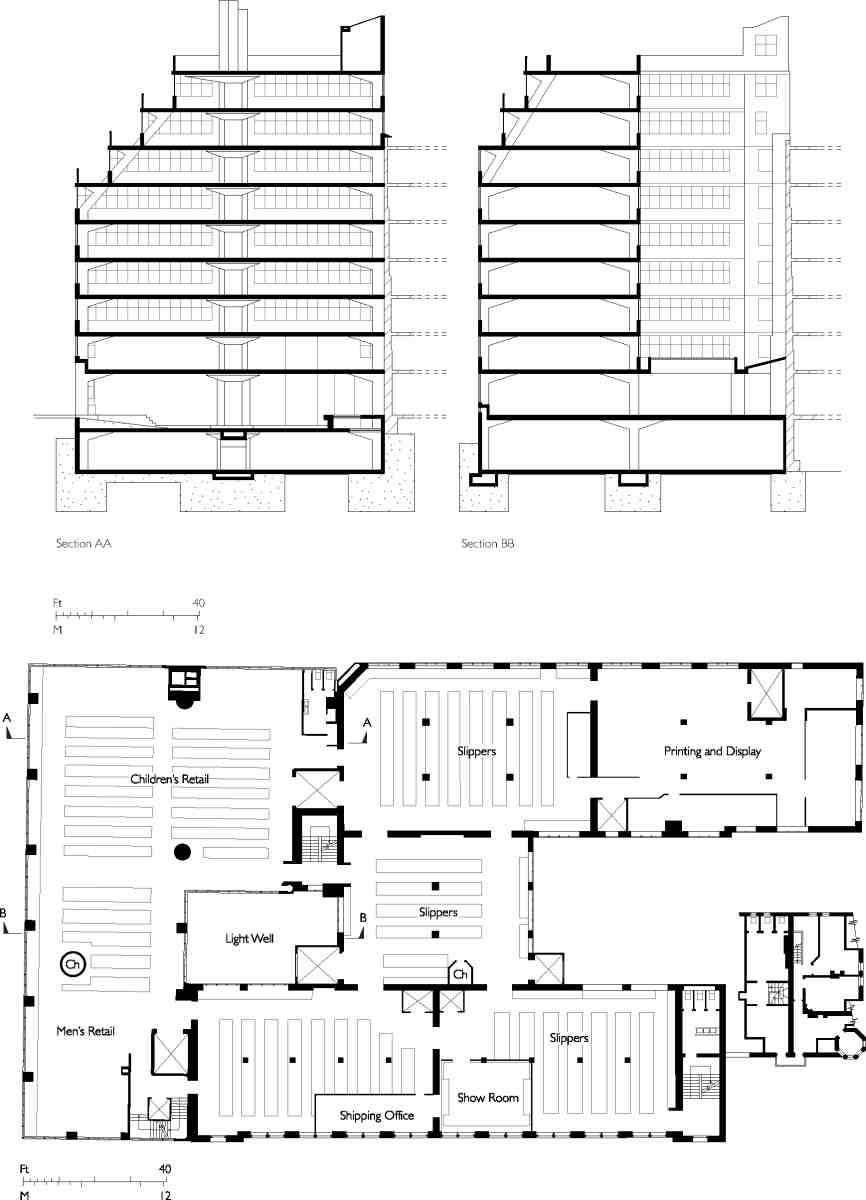

So it proved. Pentonville Road in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century saw redevelopment with a number of large warehouses and factories, and a general decline in the resident population. One of the largest developments was the depot built for the shoe company Lilley & Skinner. The Ormond Engineering Co., based in Holford Mews, built the large factory-warehouse at Nos 91–99 in the late 1930s, and another at No. 189 in the 1950s. Dunn & Hewett expanded their premises. There were also new workshops on a smaller scale, in speculative blocks of the 1930s and, more modestly, in the conversion of houses and shops for manufacturing of all kinds. Makers of weighing machines, electric lamps, toy-eyes, amusement machines, rubber jointings, toilet brushes, band saws, tin boxes, typewriters, motor radiators, billiard tables, Christmas crackers and toffee—all could be found on Pentonville Road in the 1930s and 40s. (fn. 41)

After the Second World War, bomb damage and general obsolescence left parts of the road badly in need of renewal. By the 1950s and 60s, municipal housing developments were transforming the Pentonville hinterland to the north, but Pentonville Road itself was reserved for business use, apart from the triangle between Penton Rise and Weston Rise, where the Weston Rise Estate was built in the mid-to-late 1960s (see page 319).

The road maintained its mixed but predominantly industrial character until the depression years of the 1970s, mostly through the efforts of local planners. The London County Council had been trying after the war to prevent industrial expansion in central London, but by the 1960s Finsbury Borough Council was doing all it could to retain light industry, rejecting proposals in 1962 for offices on a bomb-damaged site at Nos 210–234, which remained vacant for several years, when a scheme for warehousing was accepted. (fn. 42) This policy continued under Islington Council, Finsbury's successor.

By the 1970s it was unworkable, and with so much of the road in decay the pressure to allow offices became irresistible. The Sterling Land Co. was given the go-ahead for two large office towers, King's Cross House, begun in 1973. Islington councillors subsequently expressed regret at having endorsed such an architecturally monstrous scheme. At the other end of the road property had been blighted since the war by LCC and then Greater London Council plans to widen the Angel intersection. This scheme was shelved in 1975, and in 1978 Islington Council permitted London Merchant Securities to build the Angel Centre offices on the corner of St John Street.

In general, however, Islington continued to resist officebuilding, even though refusals were likely to be overturned on appeal, as at Nos 207–221 in 1979–a time when the GLC was favouring office developments near major railway stations; and again at the Angel in the 1980s, where initial attempts to prevent London Merchant Securities building offices on the north side of the road failed. (fn. 43) The developers' vision of Pentonville Road as a 'golden mile' of office blocks ultimately faded. Since the early 1990s the main redevelopments here have been for residential buildings in one form or another including private flats and a hotel. West of Penton Rise there is now a concentration of student apartments, including the former office-towers of King's Cross House.

North side: Islington High Street to Baron Street

Apart from a small portion belonging to the Penton estate at the corner of Baron Street, the frontage here was part of the land belonging historically with the Angel. The story of the old coaching inn itself and the surviving former public house of 1899 (No. 2 Pentonville Road) is given in Chapter XVII.

439. Nos 34–44 Pentonville Road (right to left), formerly part of Claremont Place, in 2007

The Penton ground was built up in the late eighteenth century, but development of the Angel property did not take place until later. It was probably held up by a protracted Chancery suit, settled in 1817 with the division of the ground between several claimants. On this north side of the road the Angel and some 350 ft of frontage went to the Rev. William Coxe, historian and Archdeacon of Wiltshire, his family and associates. The remaining 200 ft of frontage to the west went to William Dyke Whitmarsh of New Sarum, Wiltshire; Martha Young (widow of William Young, the original plaintiff), and one Sarah Foster. (fn. 44)

All soon set about letting their ground for building. (fn. 45) Angel Place (later Nos 2–12 Pentonville Road), a short row of houses adjoining the Angel inn, was built c. 1818–21, Claremont Chapel in 1818 and half of Claremont Place (later Nos 30–44) c.1819. The remainder of Claremont Place (later Nos 14–28) followed over the next six years or so. (fn. 46) (Older houses on the Penton estate west of the chapel were also at one time numbered in Claremont Place.) (fn. 47)

These houses, mostly of four storeys over basements, may have been designed by the architect and surveyor Henry Rhodes, who is known to have acted professionally for the Coxe family elsewhere, and was a party to the conveyance of the Angel estate. (fn. 48) Private stabling, a rarity along Pentonville Road, was provided for Claremont Place in Angel Mews; a stable-yard behind Angel Place was reserved for the use of the inn. Builders and first lessees included Charles Douglas, gentleman, of Chapel Street (Chapel Market); Matthew Elwall of St Giles-withoutCripplegate, painter and glazer; and John Reynolds, painter, of City Road. Many seem to have been involved at the same time with Thomas Richard Read in building Claremont Terrace opposite. (fn. 49)

Of the original houses, a few remain in what was Claremont Place (Ill. 439). Nos 42 and 44 in particular, with their long front gardens and curving steps up to the raised ground floors, preserve an impression of the road's sometime character. Claremont Chapel adjoining was externally embellished later in the century.

440. Former workshops of G. Betjemann & Sons at the rear of Nos 34–42 Pentonville Road; former Claremont Chapel and part of Claremont United Reformed Church buildings, White Lion Street, at right

Early occupants were mostly gentlemen, clerics or men of business. (fn. 50) They included, in the early 1820s, Thomas Arrowsmith, proprietor of John Bull, and Richard Barlow, a bill-broker. (fn. 51) From the outset not all of the houses were in single occupation, rooms or floors being offered to 'highly respectable' lodgers. (fn. 52)

Angel Place was partly in commercial or industrial use by the early 1840s. The business of Alfred Syer, builder's ironmonger and glass-merchant, remained from about 1853 until the 1960s, at one time occupying several houses. (fn. 53) Many coal-hole and manhole covers in the vicinity carry his name. Claremont Place remained largely residential well into the 1870s, though by the 1860s jewellers and other craftsmen were living and working here, including, from 1859, G. Betjemann & Sons, makers of dressing-cases and other specialist cabinetwork, at No. 36.

This well-known firm, established in the 1830s in Upper Ashby Street off Northampton Square, developed a range of luxury goods in metal and wood meeting the requirements of the very top end of the market. One of its most successful products, patented in 1881, was a decanter-holder called the Tantalus, designed to prevent pilfering by means of a lockable bar over the stoppers. The firm acquired a greater, posthumous, fame through (Sir) John Betjeman, great-grandson of the founder, who disliked and despised the business and, having refused to take on the mantle of fourth-generation boss, closed it down in 1945. By that time the firm occupied Nos 34–44, and had covered the back gardens with workshops (Ills 439, 440), recalled by Betjeman in Summoned by Bells. At the front, an alteration made by Betjemanns was the creation in 1927 of the curved in-and-out driveway at Nos 34–40, with iron gates under overthrows with lamps. Herbert Wright acted as architect. The gates and the front railings have now gone. (fn. 54)

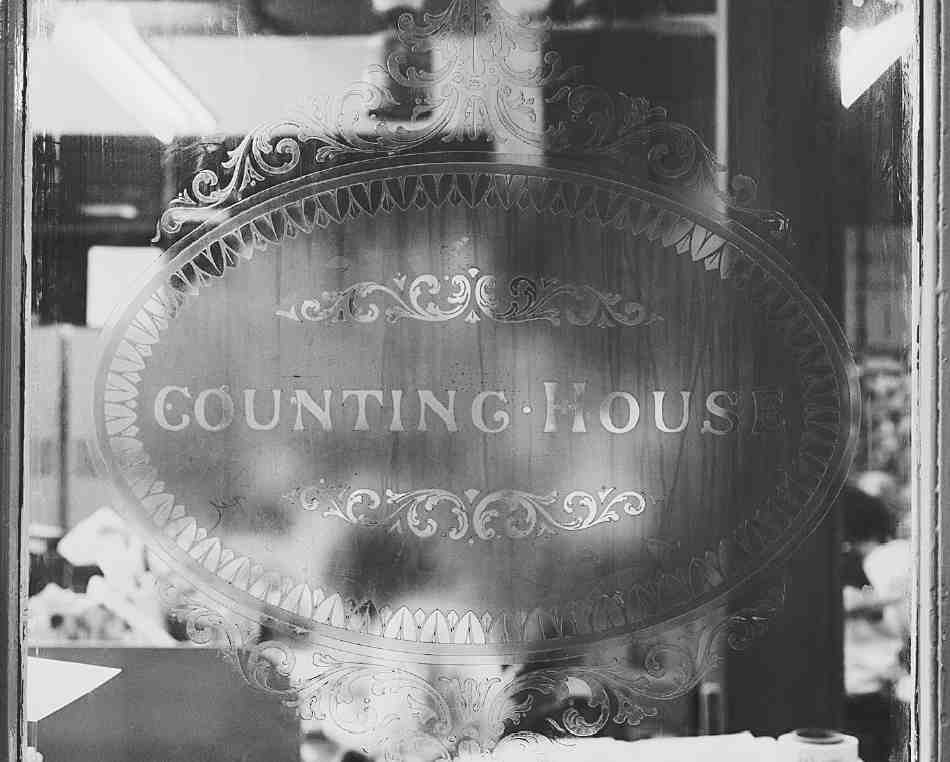

After Betjemanns went into liquidation, Nos 34–42 were taken over as the head office of the fine-art publishers the Medici Society, who remained until 1999. (fn. 55) Relics of the buildings' past were still evident in the early 1990s, including etched glass in the doors to the old showroom and counting-house (Ill. 441). The buildings are unoccupied at the time of writing (2007).

Nos 20–32, Angel House, was built in 1934 by Ansel Blaustein of Angel Estates, Pentonville Road, father of the property developers Cyril and Leonard Blaustein or Blausten. The architect was Leonard Blaustein, and the builders were named as Leonards Ltd. (fn. 56) A six-storey block, faced in red brick with a stone cornice, it comprised shops and workshops with dwellings above. Many of the workshops were converted to offices and self-contained flats in the mid-1980s. (fn. 57)

The two dark-glazed office blocks on the east side of Angel House were built in the 1980s by London Merchant Securities, the developers of the Angel Centre opposite. All three were designed by Elsom, Pack & Roberts (now EPR Architects). (fn. 58) Nos 2–12, built in 1985–7, was first occupied by the life assurance company Aetna UK Ltd. No. 14 followed in 1988–9, after an appeal against the refusal of Islington Council to allow a tall office building on the site, then occupied by three listed houses. At the appeal, the Department of Environment Inspector, disagreeing with the council, cited the increasing popularity of the Angel area for offices, and predicted that in years to come the old houses, if retained, would seem out of place, 'preserved out of misplaced sentiment'. (fn. 59) The new building was let in 1990 to British Rail's Freight Division. (fn. 60)

441. Nos 34–42 Pentonville Road: detail of door to former counting-house of G. Betjemann & Sons, in 1996

West of the former Claremont Chapel, Nos 46–52 is a 1990s office redevelopment in pastiche Georgian style. Previously the site had been occupied by dwelling-houses with, at Nos 46 and 48, a yard with a coach-building works and livery stables, built around 1820 by William Argent. (fn. 61) More than a century later, Henry Argent was trading here as a house agent and valuer. (fn. 62) The yard is now named Freeman Mews, after Albert Freeman, a horse-dealer who took over most of the property in the 1920s.

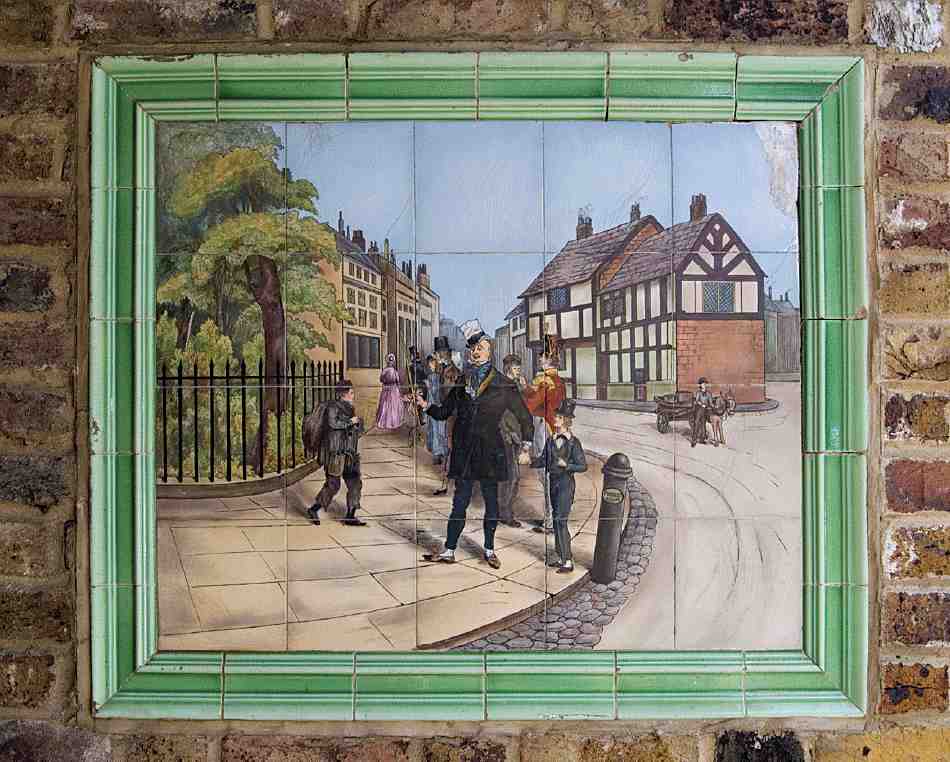

442. Tile panel picture, 1920s, from Freeman's stables, Nos 46–48 Pentonville Road (demolished), re-erected in Freeman Mews

Set in the walls of the new passageway to Freeman Mews is a series of coloured tile-pictures from the earlier buildings, showing hunting and other old-time scenes, including one or two probably of characters from Dickens in the Clerkenwell area (Ill. 442). These were presumably made for Freeman, whose name appears on a facia-board in one of the pictures. (fn. 63) The small factory-workshop at the back of the yard was built for Freeman in 1936 to the design of Herbert Wright. (fn. 64)

On the corner of Baron Street, No. 54 was built about 1789 as the Penton Arms public house. Much altered and extended, it has been called in recent years the Pint Pot and is now the Castle. The architects Finch Hill & Paraire did some work here in 1862, and in the early 1890s the long ground-floor extension was refitted by John Cox Dear, architect, with a series of small private bars or booths and a larger saloon bar at the north end. The chimney stack dividing the front of the main building dates from Dear's remodelling, and was built to provide a fireplace in the saloon. (fn. 65)

No. 44A, former Claremont Chapel

Claremont Chapel was one of several Independent or Congregationalist chapels built in London and the provinces by Thomas Wilson of Highbury, a former silk mercer and ribbon manufacturer, who was also active in the founding of the University of London and the London Missionary Society. During the early 1800s he was busily engaged in chapel-building in the emerging suburbs, to cater for London's expanding population, and funded two other chapels on the New Road—at Tonbridge Place in Marylebone, and at the Paddington end, in Homer Place. (fn. 66)

Wilson had acquired the freehold of a two-acre site on the New Road in Pentonville in 1818 from Martha Young and her family, for about £700, before laying out nearly £6,000 in building the chapel on part of it. The remainder of the site was let for development as Argent's livery stables (above). Included in these costs was £203 17s 8d to a Mr Wallen 'for surveying', almost certainly a reference to William Wallen (d. 1853), a surveyor then based in Finsbury, who is known to have designed two Nonconformist chapels of the early 1820s at Newbury in Berkshire and Newark, Nottinghamshire. Wallen's substantial fee perhaps included the design of the chapel and other work to do with its construction. (fn. 67)

Claremont Chapel, which took its name from the Surrey residence of the recently deceased Princess Charlotte Augusta, was opened for worship in October 1819. Various prominent Congregationalist ministers attended the first service, including Thomas Lewis of the Union Chapel, Islington, John Morison of the Union Chapel in Sloane Street, Chelsea, Thomas Raffles of Liverpool, and John Leifchild, the latter two preaching on the day. However, it was not till March 1820 that an Independent congregation was established here, and October 1822 before a resident pastor was appointed—the Rev. John Blackburn, formerly of Finchingfield, Essex. (fn. 68)

443. Claremont Chapel, c. 1828. William Wallen, architect, 1818–19

Wilson's chapels were designed on functional lines to hold large congregations, and Claremont in its original form was externally spare of detail, except for an Ionic entrance portico (Ill. 443). But it was wellproportioned, and given additional gravitas by standing slightly higher than the road, behind neo-Classical iron gate-piers and railings. The interior, which could hold 1,500 worshippers, attracted attention for the arrangement of the gallery, which ran continuously around all four walls on thin iron columns, forming an oval well. There were also 'light and elegant' upper galleries for Sunday school children. (fn. 69)

444. Former Claremont Chapel, No. 44a Pentonville Road, in 2007

Various alterations and repairs were made during the 1840s, and in 1847 a Sunday school was added at the rear. (fn. 70) Sash windows of wood and cast-iron were installed in the galleries in 1853–4, under the supervision of Henry Owen, a surveyor of Great Marlborough Street, who went on to re-glaze most of the building. In 1854–5 Owen improved the approach to the chapel by adding a stuccoed balustraded terrace either side of the entrance steps (Ill. 444). (fn. 71)

Externally, the building's present appearance owes much to alterations made in 1860, for which money was raised at a three-day bazaar, held at Myddelton Hall, Islington, under the patronage of the contractor Sir (Samuel) Morton Peto and his wife. (fn. 72) The formerly plain brick façade was stuccoed over and enriched with Classical details. Inside, the gallery—inconvenient to those who sat behind the minister—was reduced to three sides. (fn. 73) Some, if not all of these alterations were the work of an architect referred to at the time as 'Mr Tarry'—perhaps John Tarring, a London architect who specialized in Nonconformist chapels. (fn. 74)

Poorly attended and short of funds by the 1890s, the chapel was sold to the London Congregational Union for use as a Mission Station for the increasingly distressed Pentonville district, closing in 1899. It was altered in 1902 for a new role as the Union's Central London Mission. The upper galleries were removed and the chapel became Claremont Hall, part of a mission institute developed over the next few years to the north, on White Lion Street (see page 387). (fn. 75) It was probably then that the side entrances were given their round-headed doorways with open pediments on consoles.

By the early 1960s Claremont Hall had been let by the mission for commercial use. It has since been sub-let to the Crafts Council, re-opening in 1991 after conversion to a white-walled exhibition space (designed by Barry Mazur), with a library and offices above. (fn. 76) In 2006 the Crafts Council closed the gallery to concentrate on 'developing national initiatives with partner organizations'. The building was refurbished over the next two years and now provides an improved research library and resource centre. (fn. 77)

Baron Street to Penton Street

This part of the road was built up with terrace-houses in the late 1780s under the name Winchester Place, and these survived essentially intact until the 1930s (Ill. 445). By then they had long ceased to be private residences, and were mostly in commercial use, ranging from artistic lampshade manufacture at one end (No. 58) to marble masonry at the other (Nos 88–94). None were shops. An application had been made in 1887 to build over the forecourts with shops, as elsewhere in the road, but was refused by the Metropolitan Board of Works. (fn. 78) Some redevelopment occurred in the late 1930s, with light-industrial premises at Nos 90–92 and 86–88, and continued after the war. The last remaining houses were demolished in the 1990s.

Winchester Place (demolished)

Winchester Place was built in 1786–90 on the southern part of the site of Dobney's bowling green (page 327), taking its name from the home town of the Pentons. (fn. 79) The houses here became Nos 56–92 Pentonville Road; No. 94 was originally numbered in Penton Street and was not strictly part of Winchester Place; the site is now subsumed in Nos 90–92.

It was not a uniform development. On the corner of Penton Street, the sites of Nos 90–94 were a portion of the ground covered by John Pennie's building agreement of 1767, most of which was taken up by the Belvidere on the west side of Penton Street, and the south end of Penton Street itself. A pair of three-storey houses, later Nos 90 and 92, was erected, their relatively broad fronts compensating for the shallowness of the plots, restricted by the gardens of houses in Penton Street. They were later thrown into one with the house at the corner of Penton Street, probably by Henry Webb Wilkins & Son, who were here from the 1860s and built showrooms in front (Ill. 446). This firm specialized in marble for statuary and other purposes, describing themselves in the early twentieth century as marble merchants, general and monumental masons, sculptors, table-top manufacturers, shopfitters and interior decorators in marble and tiles. (fn. 80)

445. Nos 62–70 Pentonville Road (formerly part of Winchester Place), in 1938. Demolished

The main part of Winchester Place, a terrace of twelve houses (later Nos 66–88) overlooking the New River Company's reservoir, was built on ground taken by Edmund Hague, painter and builder, by a building agreement of March 1786; this also took in the Penton Grove site later occupied by White Lion Street School. As befitted the site, 'presumed the most eligible Part of the Penton Estate', Hague's terrace was conceived in terms of some pretension, and the design was probably that shown by the architect Aaron Henry Hurst at the Royal Academy in 1788. (fn. 81) Hague, who was also developing in Chapel Street (Market), went bankrupt about 1789, and it was presumably on account of this that the original scheme was abandoned. Three plots at the east end of the ground, with 20 ft frontages, were let at Hague's direction to the bricklayer Joshua Hodgkinson in February 1787 and built up in the next couple of years, the first two (Nos 66 and 68) apparently as the end 'pavilion' of an unrealized grand terrace, with high, partly balustraded parapets. (fn. 82) The third house (No. 70) was enlarged by the addition of an entrance bay at the side, on extra ground, with Venetian windows. Two or all three were leased to George Fillingham, a St John Street hop-merchant, the largest one becoming his own residence. (fn. 83) Meanwhile the remainder of the terrace was built up on plots with frontages of about 16 ft; these narrower houses were of different design, with lower floor-heights. Five of the nine plots were leased to Francis Abercromby Gray, a surveyor, of Wells Street, Cripplegate, and two others to Edward Tanner, a carpenter of Grub Street in the City, who was involved in the building of Fillingham's house. (fn. 84)

The east end of the terrace was built on ground leased by Henry Penton's steward Thomas Collier in January 1786. The houses were again irregular: narrower, threestorey houses at the Baron Street corner (later 56–60), shorter, broader houses at Nos 62 and 64, the last being Collier's own residence. (fn. 85) He might have been the landlord who had the misfortune to let the house next door (No. 62) to Thomas Cooke, who became notorious as a grasping miser. Cooke, a retired papermaker and sugar-baker, who turned the garden over to cabbages and spent nothing on repairs or decorations, lived there fifteen years before eventually being ejected. (fn. 86)

446. Nos 90–94 Pentonville Road, Wilkins' marble works, at the corner with Penton Street, c. 1930. Demolished

Besides Collier, early occupants of Winchester Place included another player in the development of the estate, Henry Penton's lawyer, William Wightman of Lyon's Inn, also Charles Cross, an apothecary, and Henry Batley, a druggist. (fn. 87)

Business use of the houses in Winchester Place began to predominate over residential during the 1850s. Occupations of people working here included bookbinder, professor of music, artificial florist, feather maker, aquatint engraver (Augustus William Reeve), writing master, and net and marquee maker. No. 11 Winchester Place (later No. 72 Pentonville Road) was occupied for several years in the 1850s by the architect E. C. Robins. (fn. 88)

By the 1890s private residents were no longer listed here in the Post Office Directory, and several of the houses (at first No. 74 and subsequently Nos 66, 70, 72 and 80 also) were used as 'Stainer's Homes for Deaf and Dumb Children'. This institution, which also had homes in Paddington Green and Camberwell Green, was run by the Rev. Dr William Stainer, brother of the composer Sir John Stainer. Nos 70–74 were subsequently a remand home of the Metropolitan Asylums Board, later becoming London County Council offices in connection with education and children's care services. (fn. 89)

Illustration 445 shows Nos 66–68 with the signboard of the Cartonite & Arborite Syndicate Ltd, cabinet makers (but latterly 'postal tube makers'), which occupied the premises for many years from 1906. (fn. 90)

Present buildings

Two old houses at Nos 66–68 were refronted and otherwise altered about 1952, but not completely rebuilt, as one building for commercial use; Wright & Tidmarsh were the architects. (fn. 91) This partial survival excepted, the lastremaining houses of Winchester Place were replaced in 1997–8 by a 220-room hotel, the Jurys Inn (Nos 56–64). Built for the Jurys (now Jurys Doyle) Hotel Group (UK) Ltd, this is one of a number in Britain and Ireland designed for this chain by the Consarc Design Group of Belfast and Dublin. (fn. 92) The façade, in stock brick and render, has a central feature of semi-circular steel balconies.

The large site now occupied by Claremont Heights (Nos 70–88) was formerly covered with warehousing built in the 1950s for Henry Righton & Co. Ltd, metal merchants. (fn. 93) Cleared in 1990, it was used as a car park and redeveloped in 1996–7 as private apartments. These were built for Furlong Homes plc to designs by Hazan, Smith & Partners (Ill. 447). In addition to the main six-storey block facing Pentonville Road, two smaller blocks stand in landscaped grounds on the sites of Nos 12–16 Penton Street and 51–53 White Lion Street. All are faced predominantly in stock brick. (fn. 94)

Nos 90–92 was erected in 1936–7 for Brixton Estates Ltd to designs by Lewis Solomon & Son. It seems to have been intended from the start for occupation by the briarpipe makers H. Comoy & Co. Ltd, also at Rosebery Avenue. (fn. 95) Two more bays added in 1938–9 at Nos 86–88 have been demolished. (fn. 96) Occupied for many years by Comoys, the building is now used as offices. It is of five storeys, faced in red brick, and retains its original metal windows.

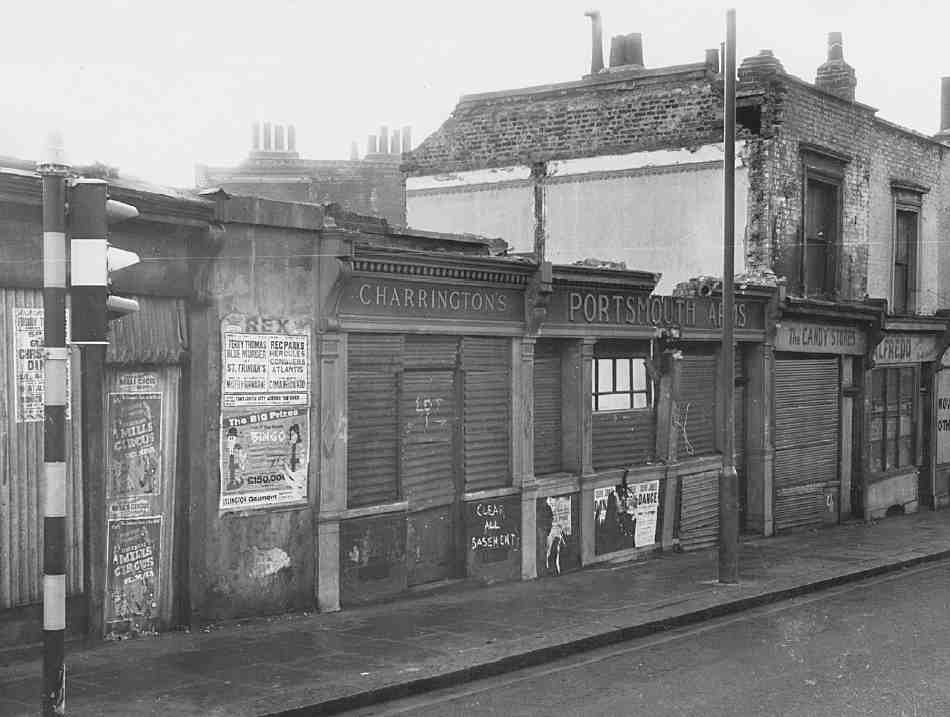

Penton Street to Rodney Street

From Penton Street to Rodney Street the nature of the buildings still shows quite clearly the effects of Pentonville's decline as a residential suburb. For much of the way the building line has been pushed forward to the pavement edge, with thoroughly urban two-storey shop premises. The former Belvidere public house, rebuilt in the 1870s, conveys no memories of the old Belvidere with its bun-house and tea-garden, and the racket-ground where City men came for outdoor exercise. The shops were built over part of the garden about 1839, and where the building line moves back again, towards Rodney Street, the buildings are mostly modern and industrial in character. Hermes Street, which once offered a glimpse of Hermes Hill and the White Conduit Fields beyond, is now a short cul-de-sac giving access to public housing of the twentieth century.

The Belvidere, built in the 1760s, was one of the earliest developments in the creation of Pentonville, and one that perpetuated the resort character which the hitherto rural district had enjoyed for generations. West of the Belvidere tea-garden, the frontage to the New Road was built up with smallish terrace-houses from about 1770. (fn. 97) These were at first known as Happy Man Row, from a tavern called the Happy Man, and renamed King's Row in 1774 (see Ill. 528 on page 406). The Happy Man was later the Crown, this name being in use by 1795; Hornor's map (1808) shows it as a coffee-house. Dickens sets a short scene there in 'Miss Evans and the Eagle', in Sketches by Boz. (fn. 98)

447. Claremont Heights, Nos 70–88 Pentonville Road, 2007

Development of this part of the road was carried out over a good many years, and under several building agreements or leases. Between the Belvidere and Cynthia (then Ann) Street the ground was part of a large plot initially taken on a building agreement of July 1769 by Robert Harrop, merchant, of Coventry Street, St James's, and later of Paris. Four houses, including the Happy Man, were put up more or less at once, (fn. 99) but no further building took place until about 1786, when Harrop's executor, Charles Harrop, gentleman, of Hammersmith, at last surrendered the 1769 articles so that leases could be granted. Dr De Valangin of Hermes Hill took a lease of a deep plot on the west corner of Cynthia Street in 1776. A decade later the remainder of the block between Cynthia Street and Rodney Street, extending north to Donegal (then Henry) Street, was acquired on lease by the bricklayer John Brown of Holborn and built up. (fn. 100)

448. Nos 96–98 Pentonville Road (former Belvidere public house), 2007. W. E. Williams, architect, 1875–6

Nos 96–98, the former Belvidere, and 1–5 Penton Street

The large Italianate public house on the corner of Penton Street, in recent years called the Finca, was erected in 1875–6 as the Belvidere, replacing the earlier tavern of that name on the site. It was designed by the architect W. E. Williams and built by Robert Marr and is constructed of white brick with sparing stone or cement dressings (Ill. 448). Nos 1, 3 and 5 Penton Street, in similar style, were built in 1877 as part of the same development. (fn. 101)

The first Belvidere was built about 1768, and was for a time known as the Penny Folly or Penny's Folly, after its builder, and probably first proprietor, John Pennie, a paper-hanging maker of St James's, Westminster. It was called the Belvidere (or Belvidera House, as it briefly appears in the rate books), from about 1774. (fn. 102) That Penny's Folly was the same place as the earlier Busby's Folly seems to have been a wrong assumption. (fn. 103) Pennie's site, however, clearly existed as an entity before 1768, as a bowling green (see Ill. 423, page 324), with the footpath to White Conduit Fields passing through. The building was set back some way from the front of the present pub, facing the new Penton Street, and had a tea-garden and bowling green at the rear with a long frontage to Pentonville Road and a fine view over the metropolis. Adjoining the tavern on the north, in Penton Street, was the 'Bunn House'. (fn. 104)

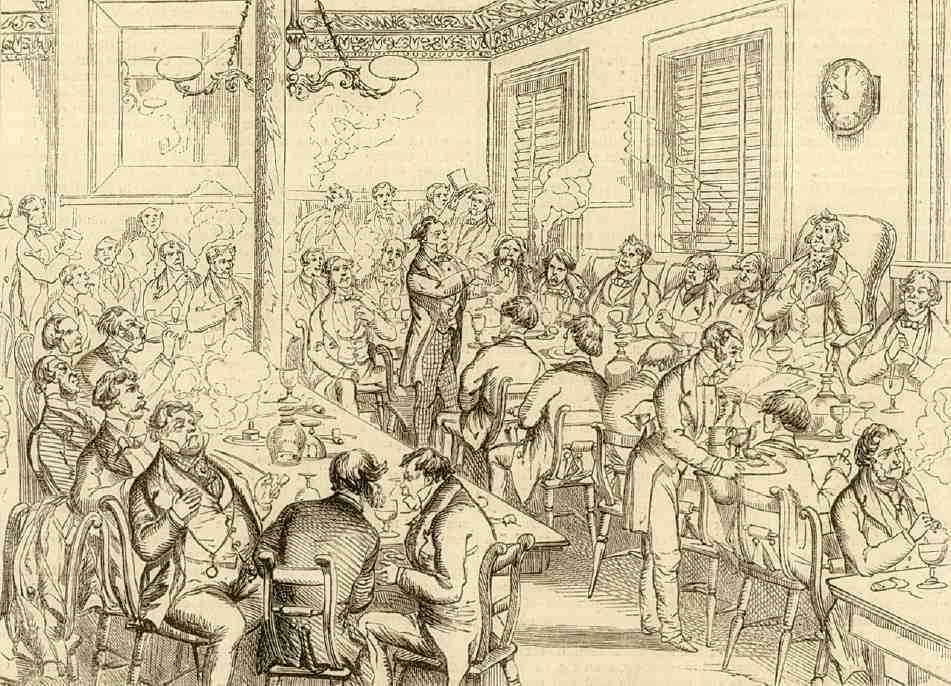

Early entertainments recorded at Penny's Folly include the antics of Mr Zucker's performing horse. (fn. 105) As the Belvidere, the establishment became more than locally well–known for two activities besides drinking: rackets, played in a court in the garden, and Saturday-night discussion meetings, where political subjects were aired, held with free admission in an upstairs room. The clientele in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is said to have included some notable figures, particularly writers and actors, among them Hazlitt, a keen rackets watcher; Grimaldi the clown; the illustrator Isaac Robert Cruikshank; and George III's favourite actor, the comedian John Quick. The British Horological Institute was founded here in 1858. (fn. 106) G. A. Sala distinguished the Belvidere clubroom from the general run of political meeting rooms by its 'eminently respectable aspect', and he contrasted the radical views of the speakers with their tamely conformist appearance. The convivial scene was illustrated in his Twice Round the Clock in 1859 (Ill. 450). (fn. 107)

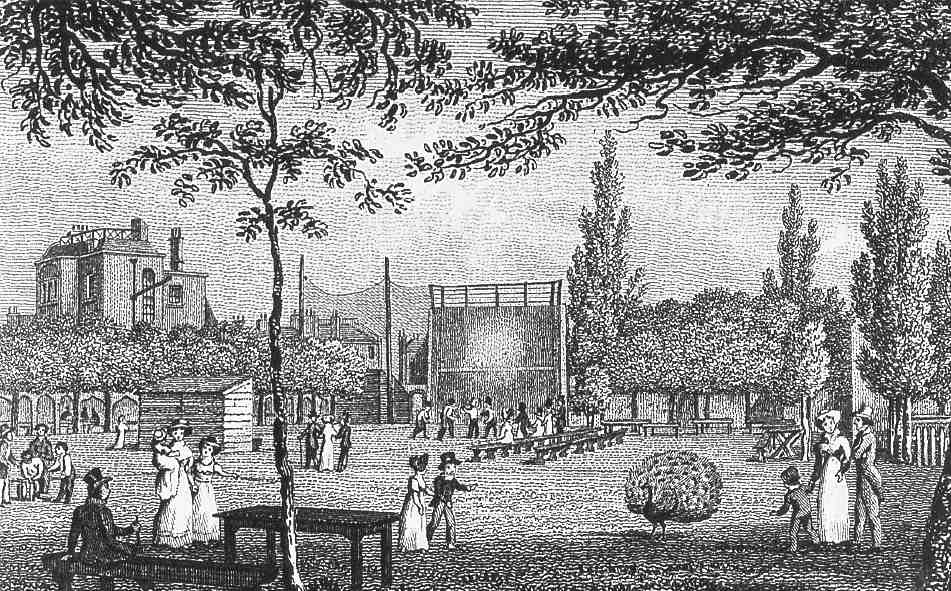

A rackets court was built at the Belvidere in 1820; before that the game had been played 'in much more primitive style', together with Dutch quoits and skittles. The court, which attracted some top players, was surrounded at a safe distance on three sides with open refreshment boxes for spectators (Ill. 449). There was also, by 1856, an American bowling alley and, inside the pub, 'one of the largest and finest' billiard saloons in London, and a private billiard room too. (fn. 108)

449. Gardens and rackets court at the Belvidere, c. 1828

Though sports at the Belvidere were flourishing at this time, the available space had earlier been greatly curtailed with the building of Athol Place along the front of the garden. The reduced garden did not long survive the rebuilding of the pub in the 1870s. In 1880 the lessee put forward proposals for building over it a substantial block of model dwellings, to cost £10,000 and offer accommodation for sixty families. T. H. Watson, the Penton Estate surveyor, was enthusiastic but the scheme fell through. (fn. 109) The garden was subsequently occupied by a piano factory, and later the Gloy glue works; another industrial activity here, in the late nineteenth century, was the manufacture of extractor fans by the Blackman Air Propeller Co. (fn. 110) It now forms part of the Public Carriage Office site in Penton Street.

Nos 100–154 Pentonville Road

450. Saturday-night discussion meeting at the Belvidere, 1858

The row of eight shops immediately west of the Belvidere at Nos 100–114 was built in about 1839 as Athol Place (see Ill. 451), and occupies part of the old tea-garden. Early occupants included an optician, a bookbinder, a furrier and a window-blind maker, a tobacconist and a bootmaker. A ninth house, No. 98 (formerly No. 1 Athol Place), originally a pastrycook's, was incorporated into the Belvidere in the 1860s. (fn. 111) The developer of Athol Place is not known, but the name's Scottish derivation suggests that the Belvidere's landlord at the time, Hugh McDiarmid, might have been involved. (fn. 112)

451. Nos 100–120 Pentonville Road (right to left), in 2007; former Athol Place, now Nos 100–114, far right

452, 453. Nos 116–118 Pentonville Road, 2007. Courtyard (right), with No. 116a (a house of the 1780s) to the rear, and former workshop in front; (left) interior of workshop, and manager's office

The houses typically comprised a ground-floor shop and parlour with living-rooms or stores above, and a small back yard. The style of the houses at the east end of the row—faced in stucco with moulded window surrounds— probably dates from the reconstruction of the upper floor fronts in the early 1880s. (fn. 113)

Though externally similar, the four adjoining shops at Nos 114a–118 date from 30 years later (Ill. 451), having been erected in front of the two old houses at the east end of the former King's Row in 1869 by an Islington builder, John Sharman. (fn. 114) Early occupants included a jeweller, an artificial florist and a haberdasher.

Today most of Sharman's shops form part of an organic agglomeration of buildings at Nos 116–120 (and continuing round the corner at 1–2½ Hermes Street)—old houses, mid-Victorian shops, small warehouses and later additions, currently occupied by the publishers Kogan Page Ltd and a rare survival locally of such accretive premises.

Today the oldest fabric is a bay-fronted late-1780s house at the rear of the site, until recently numbered 116A (Ill. 453). This was one of the former gentleman's residences of King's Row, set well back from the later building line, now much rebuilt and altered but still with a few original features. Until recently another old house stood further forward immediately to the west (No. 118A), but this has been demolished and rebuilt in facsimile. Both houses may have been designed by the architect Aaron Hurst, the first lessee. (fn. 115)

In 1872 Sharman built a workshop for the artificialflower makers in the yard, directly in front of the old house, mostly of one storey and glass-roofed but with a narrow first-floor extension along one side. The baywindowed rooms of the house, overlooking the workshop floor, made ideal managers' offices (Ill. 452). (fn. 116) These buildings were later used by a piano manufacturer, and the London Sewing Machine Co. Ltd, and in about 1899 were taken over by the Salvation Army as barracks and a mission hall, which they remained until after the war, reverting then to commercial use. (fn. 117)

No. 120 was built as a beerhouse in 1851 on the garden of No. 1 Hermes Street, and was called the Welsh Bull by 1866. It was originally of one storey only, the first floor being added in 1881 for the brewers Truman, Hanbury & Buxton (Ill. 451). The ground floor was remodelled in 1893 by the architect W. G. Shoebridge. In this typical late Victorian refitting the old bar parlour and tap-room disappeared and a large bar counter was installed, with subdivisions to make four bars of varying size and a jugand-bottle counter. The main entrance lobby, opening on to the public bars, was on the corner, with a faiencecovered iron column at the angle. The beerhouse closed in 1911, a renewal of the licence having been refused. It was subsequently occupied by a firm making tin boxes. (fn. 118)

On the west corner with Cynthia Street, the two knocked-about old houses at Nos 130–134, now minus their single-storey shop-additions, were formerly part of the extensive cocoa factory of Dunn & Hewett. Daniel Dunn, maker of soluble chocolate and coffee essence, one of the first commercial occupants in King's Row, was based at No. 9 (later No. 136 Pentonville Road) from about 1833. In the 1850s he went into partnership with Charles Hewett, and in the 1870s the firm, who described themselves as the inventors of soluble chocolate and cocoa, took over No. 138 as well. The premises were enlarged and partially rebuilt in the 1880s and 90s, when an extension at Nos 6–10 Cynthia Street (see pages 421–2) was built, to provide more space for chocolate-making, packing and storage. (fn. 119) By about 1907 there was also a tea-room at No. 140 for the girls working in the factory, and apparently for members of the public too. (fn. 120) Dunn & Hewett's factory closed about 1930, and was subsequently sub-divided and let to various enterprises, including firms making Christmas crackers and radios. (fn. 121)

The red-brick factory at the corner with Rodney Street, at Nos 152–154, was built in 1936 for the Ealing Radiator Co. Ltd (later E. R. Engineering), which made car radiators (Ill. 454). It was designed by W. E. Gladstone Hull, architect, of Wembley Park. (fn. 122) Originally the rear buildings and the return along Rodney Street were only of one storey. A first floor extension in matching style was added in 1952 to designs by John K. Greed of Richmond. Greed also designed the low metal-framed building alongside at Nos 136–150 (now a service garage), erected in 1962–3 as a warehouse extension for Macready's Metal Co. Ltd (based across the road at Nos 131–135), who had recently taken over both sites. (fn. 123)

454. Nos 152–154 Pentonville Road. Car-radiator factory of 1936; W. E. Gladstone Hull, architect

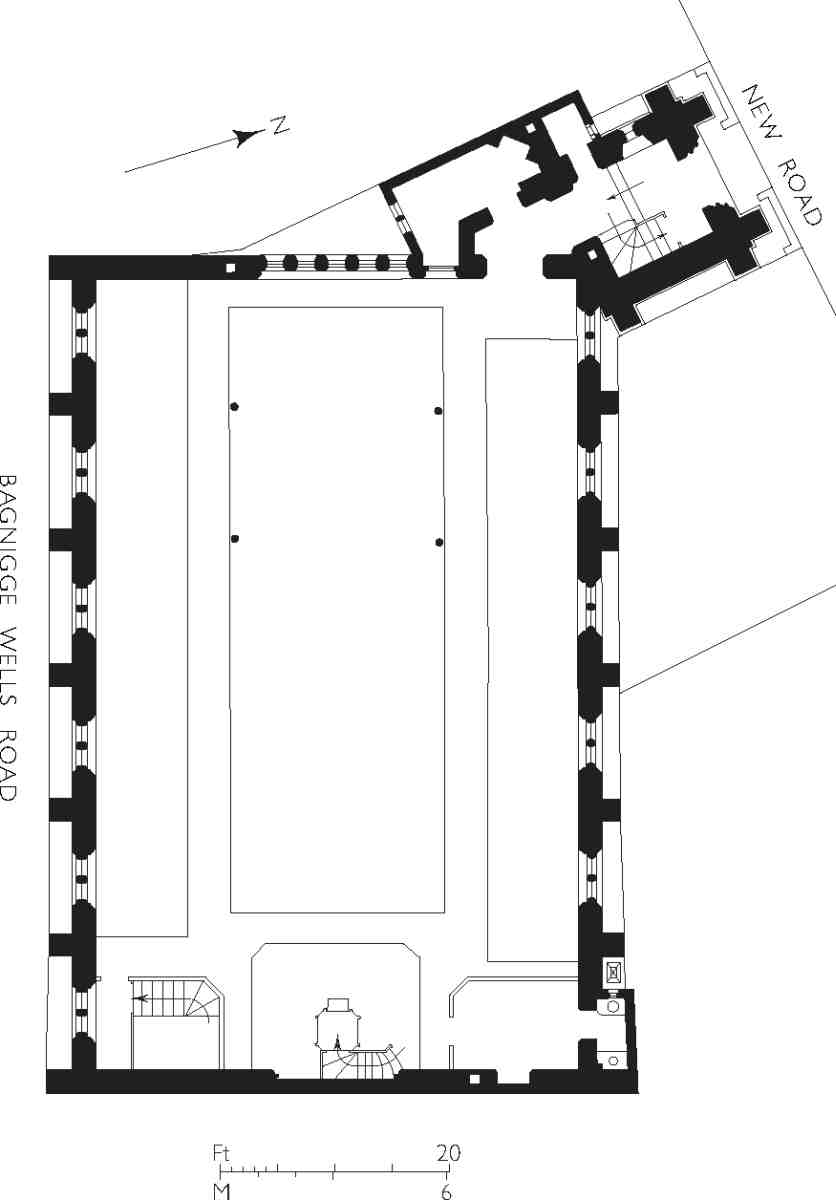

Rodney Street to Calshot Street

The two oblong blocks between Rodney Street and Calshot (originally Southampton) Street, extending north to the Penton estate boundary, were the subjects of building agreements in 1786 and 1789 respectively between Henry Penton and the brothers Alexander and John Cumming. Alexander's take was mostly built up with terrace-houses, some of the largest in Pentonville, but he gave up the New Road frontage for the building of the long-awaited Pentonville chapel of ease, later St James's, Pentonville. John's ground, too, was built up with terracehouses, but he reserved the prime site for his own detached residence, Cumming House. Facing the New Road, this stood in a large garden extending to Collier Street, and was flanked at a little distance by short terraces of goodclass houses, the ensemble taking the name Cumming Place. (fn. 124)

Structurally, little of the original development survives along Pentonville Road, nothing whatsoever beyond. But the pattern set down along the main road frontage in the 1780s and 90s persists: almost unchanged on the east side of Cumming Street—where the church, destroyed in the 1980s after a tortured history, was rebuilt in loose facsimile as offices—and still recognizably on the west, where a few old houses, with some rebuilding, survive behind later shops (Nos 176–182).

The front gardens or forecourts of Cumming Place disappeared by degrees. By the 1870s a few had been built over, including that on the corner of Cumming Street, where there was a single-storey extension used as a public house, the King George IV. Similar extensions for shop use were to cover all the terrace-house gardens before many years were past; at the four houses adjoining the King George IV, these shops were independent structures, alleys giving access to the fronts of the houses behind. Cumming House, much extended and no longer detached, was in institutional use. Within a few years it had been demolished for a large development of shops and model dwellings on either side of a new street, Affleck Street, a fragment of which development survives in the form of Nos 166–174 Pentonville Road. Affleck Street was reduced to a stump by the creation of the Priors Estate in the 1970s (see page 431). East of Affleck Street there remains a degraded row of single-storey shops, the old houses behind now long gone. On the corner of Cumming Street, at No. 156, the King George IV survives in the form of a ground-floor bar in a new terracotta- and aluminium-faced apartment block designed by Alison Brooks Architects (ABA) for Woodlands Estates, completed in 2005–6. (fn. 125)

St James's, Pentonville (demolished)

Pentonville Chapel, later St James's Church, was the centrepiece of the suburb of Pentonville. Built in 1787–8, it became a familiar if isolated landmark on Pentonville Road, conspicuous in the foreground of John O'Connor's view of St Pancras (Ill. 429). Towards the end of its life, Ian Nairn enjoyed the 'splendid, racy rhythm' of its main window, and found its yellow bricks 'among the mellowest and duskiest in London'. (fn. 126) Ecclesiastically the chapel enjoyed little fortune. It was declared redundant in 1978, damaged by fire, and pulled down in 1984. Its replacement, Grimaldi Park House, pastiches the chapel front but contains no shred of the old fabric.

New churches or chapels were viewed as crucial components in major Georgian schemes of urban development, and Pentonville's promoters did their best to provide one. In 1777 Henry Penton persuaded the Clerkenwell Commissioners for Paving to allow in their local improvements Bill provision for a chapel of ease to serve the residents of his estate. A site 'near Penton Street' was proposed, and preparations for building followed. The venture was scuppered by the vicar of Clerkenwell, William Sellon, who was required to approve the scheme but declined to underwrite the minister's salary. Since neither the commissioners nor the churchwardens were prepared to give the bond that Sellon demanded, the matter dropped. (fn. 127)

Ten years later, with the building-up of Pentonville advanced, work began on a chapel funded by subscribers, fronting what was then the New Road. The new initiative was doubtless in large part due to Alexander Cumming, the Scottish-born watchmaker and inventor who was a prime mover in Pentonville's early development, since the chapel was erected on the front of the block of land taken by Cumming from Penton under his building agreement of January 1786 (see above). (fn. 128) This was almost certainly not the site originally intended, which seems to have been in Chapel Market (then Chapel Street). The first intention appears to have been to flank the chapel with 'handsome houses, as wings to the edifice'. (fn. 129) According to James Malcolm there were to have been just two houses, which would have been on a large scale, given the size of the plots. (fn. 130) No such flanking houses were erected, and the side elevations of the chapel as built in 1787–8 were regularly fenestrated as for an open site. Directly behind the chapel, a narrow graveyard extended back between the gardens in Rodney and Cumming Streets as far as Collier Street, where two 'commodious' gate lodges made up a residence for the chapel clerk (Ill. 531). Extra land on either side of this strip was leased to Cumming at the end of 1788, allowing for the graveyard to be enlarged. On New Year's Day 1789 he was granted a perpetually renewable 21-year lease of the chapel and enhanced graveyard, along with two fellow trustees, Penton's steward Thomas Collier, and Abraham Rhodes, clerk to the Vestry and the Paving Board. (fn. 131) This unusual leasehold status continued for most of the chapel's ecclesiastical life.

It was evidently intended that the chapel should conform to the Church of England. During its construction, its acquisition by the parish was discussed at a meeting between the subscribers and the Commissioners of Paving. Once again Sellon appears to have been obstructive, with the result that it opened as technically a dissenting chapel, with attendance restricted to paying seat-holders. The first minister, Joel Abraham Knight, had been a preacher at the Countess of Huntingdon's Spa Fields Chapel, another foundation that brushed with Sellon (see page 57). (fn. 132) In 1790, however, a Bill was successfully brought forward which inserted an obligation to purchase Pentonville Chapel into permission to raise additional funds for rebuilding the parish church. (fn. 133) The renewable lease having thus been acquired by the parish, the chapel and burying ground were consecrated on 8 June 1791. (fn. 134)

455. St James's Church, Pentonville. View from south-east, c.1900

Pentonville Chapel was the work of a young architect, Aaron Henry Hurst, also one of the subscribers and a participant in designing and developing houses hereabouts. Set back from the road behind gates and a semicircular drive, in plan and outline it conformed to the typical Georgian preaching-box, brick-built and squarish, with round-arched windows and doorways echoed by relieving arches (Ill. 455). Externally, ornamentation was confined to the Pentonville Road front, where a flat, pedimented centrepiece in Adamesque taste, made up of Portland stone with Coade stone ornaments, was surmounted by an open-sided timber cupola, later described as a 'baby belfry'. (fn. 135) A clock obtruded in the pediment's centre, leaving the cupola above hollow-looking, though it contained a bell. There were subsidiary porches at the north end of each side.

456, 457. St James's Church, Pentonville. Interior in 1925, (left) looking north to chancel and (right) looking south (to liturgical west end)

The interior was plain, with a flat plaster ceiling and galleries carried on Ionic pillars (Ills 456, 457). A semicircular apse at the north end formed a sanctuary, framed by an arch and Ionic pilasters and flanked by vestries. It contained an altar table surmounted by inscriptions of the Lord's Prayer, the Decalogue and the Creed, and over them a painting by John Frearson, an amateur who specialized in scriptural scenes, showing Christ raising Jairus's daughter ('in West's feeble manner' according to Walford), donated by one of the subscribers, Samuel Walker, at the time of the chapel's opening. In front of the iron altar-rails stood a square pulpit, later joined by a Coade stone font in the form of a pedestal and vase decorated with fruit and flowers. Both the font and the altar painting seem to have survived until the church's closure, though the painting had been removed to the south aisle. (fn. 136) Beneath the chapel were well-ventilated vaults, where Hurst was interred on his premature death in 1799, as was Henry Penton in 1812. Notable early interments in the burial ground included R. P. Bonington, the landscape painter (1827, later removed to Kensal Green), the younger Charles Dibdin, theatre-manager and writer (1833), and Joseph Grimaldi the clown (1838). (fn. a)

Pentonville Chapel cannot have been well built. Hurst found dry rot in the vaults in 1797, and there was recurrent trouble with the roof. After Hurst's death, the maintenance of the chapel fell largely to the supervision of James Carr, the architect of the parish church, to whose designs extra galleries for schoolchildren were added to the chapel in 1811. He was succeeded as surveyor to the chapel by William Lovell in 1816. Gas was laid on in 1821. (fn. 138) The later nineteenth-century history of the chapel was enlivened by the antics of the Rev. A. L. Courtenay, who procured a definite district for it in 1854, when the name St James's, Pentonville—current at least thirty years before—became official. Courtenay decamped to his new foundation of Christ Church (later St Silas), Penton Street, in part because he disliked St James's, but then returned (page 379). In 1874 The Builder noted that the church's history 'has been for many years one of incessant litigation and disagreement'. (fn. 139) That year also saw an abortive proposal to install a mortuary for Clerkenwell either in the vaults or in the burial ground. (fn. 140) Burials had ceased in 1853, and the burial ground was neglected for many years. By the 1890s it was, allegedly, so frequented by prostitutes that 'some sixty or seventy' of them might be there by day or night, and in 1896–7 it was taken over by the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association and laid out as a garden, with the tombstones set against the church walls. (fn. 141)

Intermittent anxieties about the structure, perhaps due to the downhill slippage of the clay subsoil and the decay of the original oak and fir foundation raft, came to a head in 1919, when in view of its overhanging north and west walls a dangerous structure notice was served. A flurry of reports followed. The incumbent, Robert Foulkes, appealed for outside funds, stating that 'there is hardly any church feeling or sympathy for the church in the parish'. (fn. 142) Caroe and Passmore, the architects on behalf of the main grantors, the London Diocesan Fund, suggested putting steel tie-rods across the building at gallery level. That was opposed by the diocesan surveyor, C. Wontner Smith, who thought the construction of the Northern Line beneath might be partly to blame, and more forcibly by Foulkes, who in 1920–1 persistently tried to prevent Dove Brothers from proceeding with the work, stating 'I shall never allow anyone to put the rods through the church'. (fn. 143) Nevertheless Foulkes was keen to have the church restored, publishing pamphlets to warn the people of Clerkenwell that if it were demolished the endowment which Henry Penton had dedicated to the chapel might revert to his heirs. Some repairs were eventually carried out, but St James's continued to deteriorate. Following the partial collapse of the ceiling it was temporarily shut in 1925, services continuing in the church hall in Collier Street. Formal closure followed in 1928.

458. St James's Church, Pentonville, in 1963

St James's would almost certainly have been demolished and its benefice absorbed into neighbouring districts but for the intervention of the Rev. Percy Warrington, vicar of Monkton Combe near Bath. In 1929 Warrington offered to pay towards the repairs if the patronage were vested in his name. He was rebuffed, but in 1931 induced an Oxford architect, R. Fielding Dodd, to study the problem. The following year he employed another architect, T. Murray Ashford of Birmingham. It was on a technical programme agreed with Ashford by Caroe and Passmore, acting for the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, that St James's was recast in 1932–3 and reopened. The main contractors for this work were Coles Brothers of Peasedown St John near Bath, who came close to liquidation, since costs doubled and it turned out that Warrington's finances were muddled; much of the remedial work had to be paid for out of grants. For their part, Caroe and Passmore found the Coles' work 'generally unsatisfactory' and 'not dealt with in an economical manner'. (fn. 144)

Ashford's drastic policy with St James's involved the entire demolition of the side walls from gallery level upwards and the nave's reduction to a narrow vessel sustained by hidden steelwork. The church thus lost its side galleries and assumed the section of a Gothic building with low aisles, to the detriment of its dignity (Ill. 458). Ashford returned the cornice and pilasters of the front pediment by one bay round the sides, 'thus overcoming the weakness of the old design', he claimed. (fn. 145) Fittings were installed into the recast church by Jolly & Son of Bath.

459. Grimaldi Park House, Pentonville Road, in 2007. Allies & Morrison, architects, 1990

Still neither the parochial nor the structural problems of the building were solved. Following at least two further bouts of reinforcement, the church was described in 1977 as 'a constant source of anxiety and expense during the whole of the twentieth century'. (fn. 146) Next year St James's was again closed. This time there was to be no reprieve. Various proposals were entertained for reusing portions of the church, but its structural difficulties and the fact that since the 1930s it had become 'something of an architectural fraud' told against it. (fn. 147) The fulminations of 'Piloti' in Private Eye against the 'disgraceful and disgusting condition' of a fabric desecrated by fires and squatters were of no avail, and in 1984 it was demolished. (fn. 148)

By that time the last act for St James's had been prepared. In 1983 Islington Council recommended a plan originating with Cornerstone Ltd and endorsed by the Church Commissioners 'for a complete reconstruction of the building to its original 1787 external design for offices'—in other words, a replica. In the event the site was sold on. Not until 1990 did the 'strange and puzzling new building' known as Grimaldi Park House arise on the site to Allies & Morrison's designs. (fn. 149) Working with Kyle Stewart Special Works, these reputable architects took some care with the rebuilding on behalf of Scott Howard Furniture Ltd, recreating the pre-1932 façade in simplified style and providing offices behind and to the sides in the best Ibstock bricks (Ill. 459). Over the upper-floor window on the front is a keystone representing Grimaldi, while in a post-modern touch abrupt traces of stone cornice bands appear on the flanks.

Most of the burial ground passed into the ownership of Islington Council in 1968, the open space around the church following on later. The whole block bounded by Pentonville Road, Cumming Street, Collier Street and Rodney Street having been designated as open space after the Second World War, the remaining houses on the east side of Cumming Street and west side of Rodney Street were demolished. The resulting open ground behind Grimaldi Park House now consists of an indecisively landscaped park, known at first as St James Garden, later as Joseph Grimaldi Park. A playground area to the west is divided from gardens on the east by the single patched survivor of the two north—south walls which originally separated the graveyard on both sides from the back gardens of houses on the flanking streets. Largely illegible gravestones line some of its walls and fences, Grimaldi alone having a railed place of honour by the north-east corner of Grimaldi Park House, though this was not the original place of his burial.

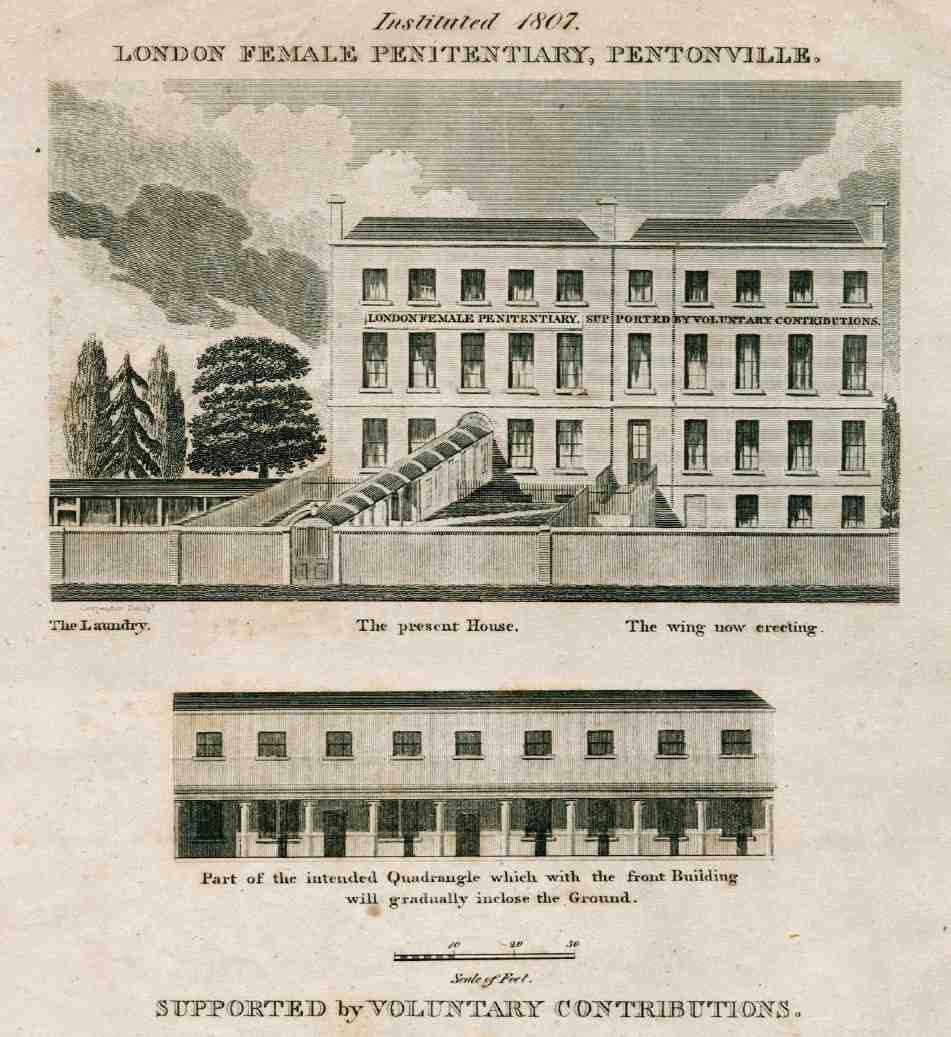

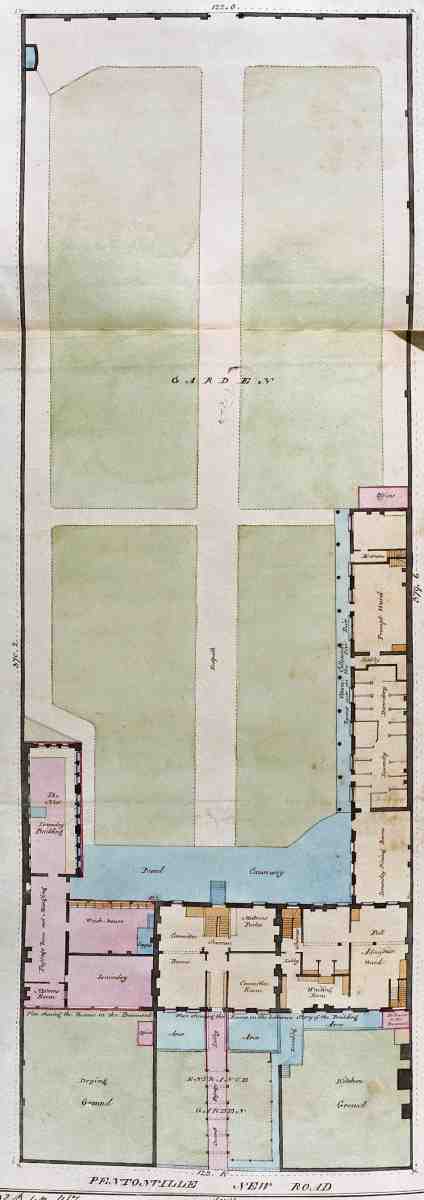

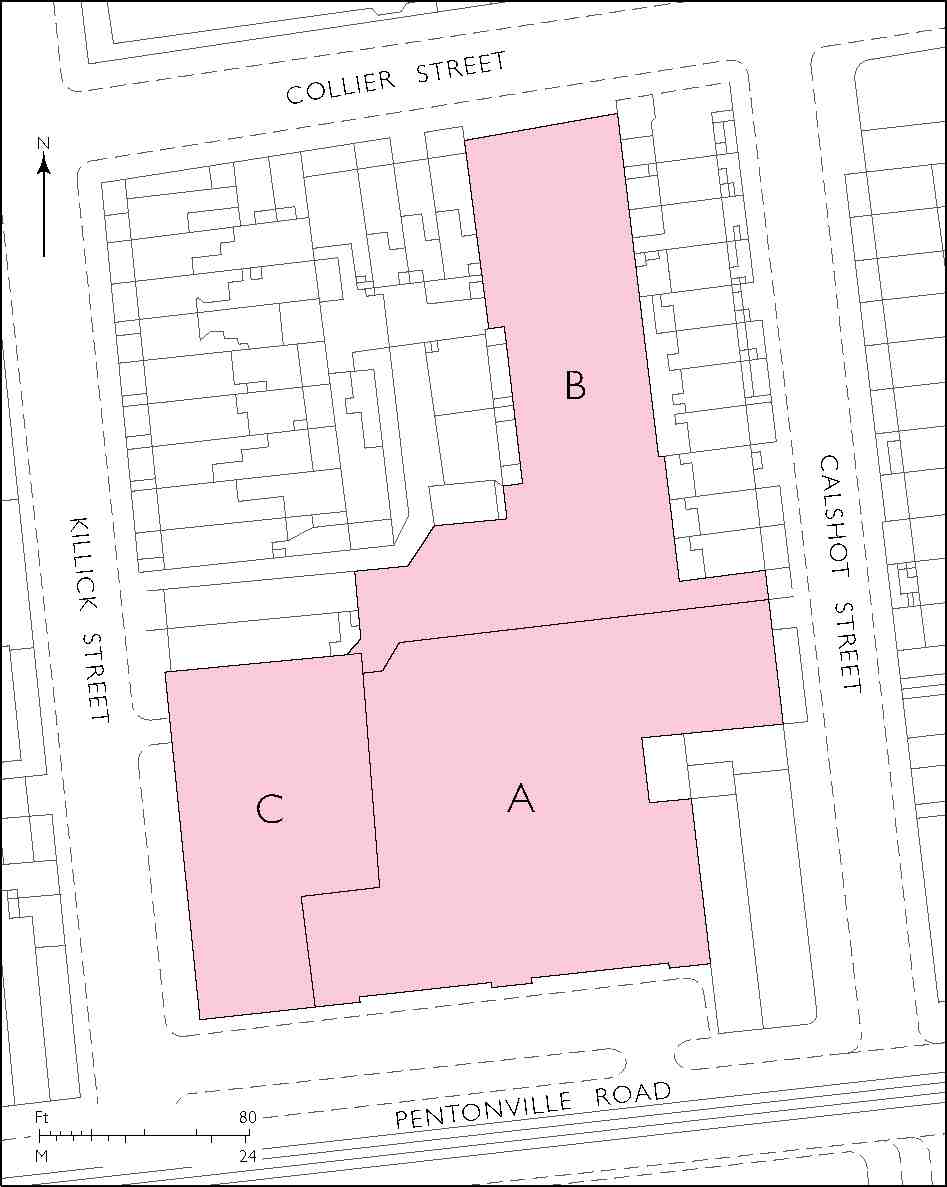

London Female Penitentiary (demolished)

Not long after John Cumming's death in 1796, Cumming House became a Roman Catholic girls' seminary. This institution originated with a community of nuns who came to England in 1792 from the Abbaye des Prés near Douai. After staying briefly in Hammersmith, at what later became Sacred Heart Convent, they moved to Cumming House, where a day and boarding school was set up under the direction of Madame Florence Vittu. This closed in 1806, and in the following year the house took on a new institutional guise, as the London Female Penitentiary, or Female Penitentiary Asylum. (fn. 150)

This charitable refuge and reformatory for prostitutes was based at Cumming House (later numbered 166 Pentonville Road) from soon after its foundation in 1807 until 1884, when it moved to Stoke Newington. It was the earlier and larger of two such reformatories in nineteenth-century Pentonville, the other being the Home for Penitent Females in White Lion Street, opened in the 1840s (see page 386). During the institution's occupation the original house was greatly enlarged, enabling a hundred women to undergo its regime of 'mild discipline, useful instruction, and the ordinances of religion'. (fn. 151) Although not the first establishment of the kind, this was one of the most important and well-known, attracting the patronage of the Prince Regent and the active support of leading philanthropists including William Wilberforce, who became its president in 1823. (fn. 152)

The Penitentiary grew out of a scheme outlined by an anonymous contributor to the Evangelical Magazine of December 1804. This was to help prostitutes who wanted to give up their way of life by opening refuges in quiet out-of-town locations, and was intended to be on 'a more popular and general plan' than existing institutions (such as the Magdalen Hospital in Blackfriars Road). Women and girls would apply directly for admission in response to advertisements, and their supervision would be largely in the hands of respectable London ladies. A feature probably inspired by existing practice at the Magdalen was that they would be segregated according to social background, so that they could receive appropriate training for work. (fn. 153)

After further airing of the subject in the magazine's pages, a general meeting was held at the New London Tavern in the City on 1 January 1807, when the 'London Female Penitentiary' was inaugurated. Behind the new venture were a number of prominent evangelicals variously involved with the London Missionary Society, the Religious Tract Society, and the British and Foreign Bible Society, including George Burder, editor of the Evangelical Magazine, and Adam Clarke, the Wesleyan divine. There was also a strong City element. Subsequently, two distinguished medical officers were appointed: George Pinckard, founder of the Bloomsbury Dispensary, and William Blair, surgeon to the Bloomsbury Dispensary, a Methodist and a supporter of the British and Foreign Bible Society. (fn. 154)

Before long a number of 'chiefly very young persons' were being looked after by the society, and after much searching for a suitable home 'in an airy and healthy situation' Cumming House was found, and a long rent-free lease purchased. Following alterations, including the construction of an attic dormitory, the Penitentiary opened in 1808, on the first anniversary of the inaugural meeting. (fn. 155)