Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Penton Street and Chapel Market area', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp373-404 [accessed 15 April 2025].

'Penton Street and Chapel Market area', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 15, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp373-404.

"Penton Street and Chapel Market area". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 15 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp373-404.

In this section

CHAPTER XV. Penton Street and Chapel Market Area

As the new suburb of Pentonville took shape in the last third of the eighteenth century, the areas east and west of Penton Street emerged along slightly different lines. This divergence of character became more pronounced during the nineteenth century and continues to the present day (Ills 426, 427). Eastern Pentonville became a commercial district, partly industrial but with shops and a street market drawing people from a wide catchment. The larger area to the west was more solidly residential, its shops few and industry mostly confined to the New Road (Pentonville Road). Pentonville's chapel of ease was built there, and the larger houses and gardens were concentrated there, including some substantial villas in grounds.

There were several reasons for this. The area that became eastern Pentonville already had a distinct identity before large-scale development occurred, as a place for leisure and refreshment. It backed on to the inns and taverns of Islington High Street, and had bowling greens and drinking-places dating back to the seventeenth century at least. Penton Street itself grew out of a muchused footpath from Coldbath Fields and Merlin's Cave, past Dobney's tea-gardens to the White Conduit House in Islington, four of the best-known attractions locally. So when the New Road linked it with the old high street it was natural that building should be concentrated in the space between, rather than on the more extensive brickfields and pastures further west. The popular, pleasureseeking ambience was naturally fertile ground for shop- and tavern-keeping and houses there appealed to minor tradespeople. In the western zone, there was a clear attempt to secure a quieter, more spacious and genteel atmosphere.

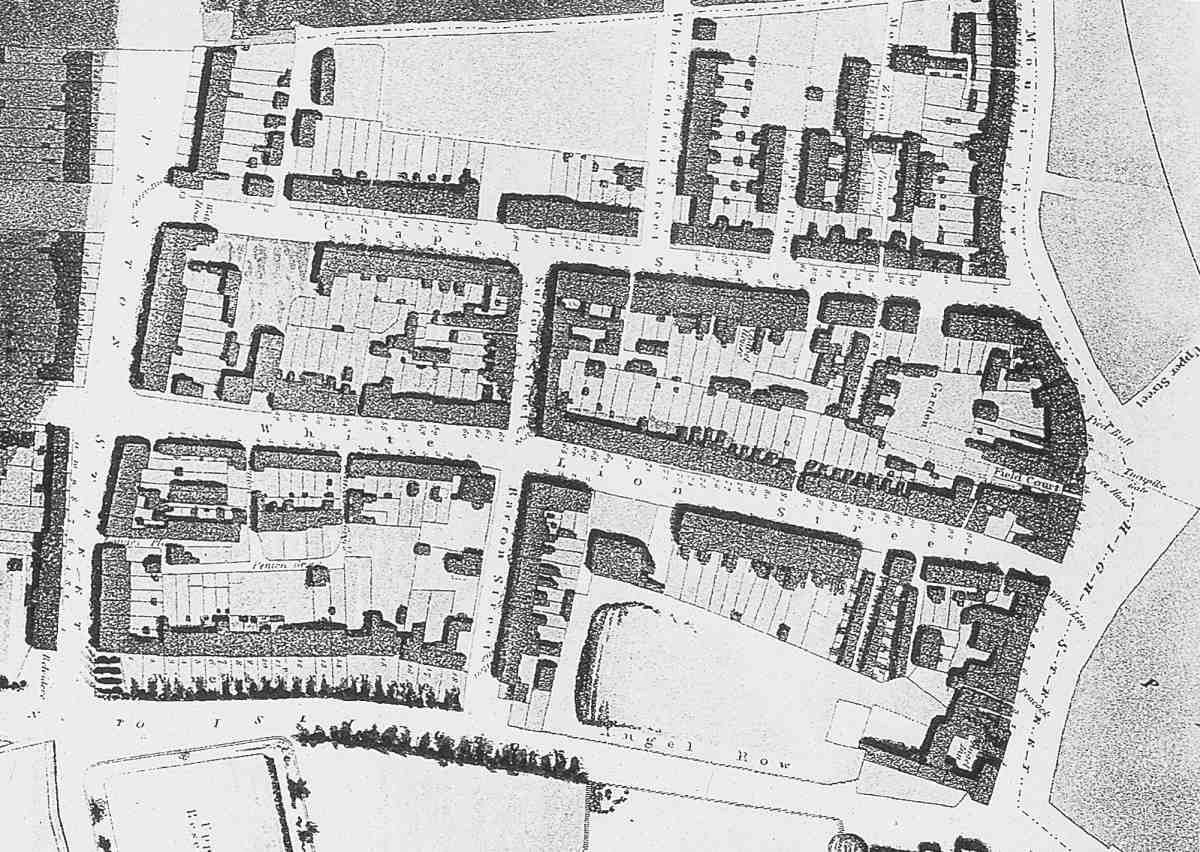

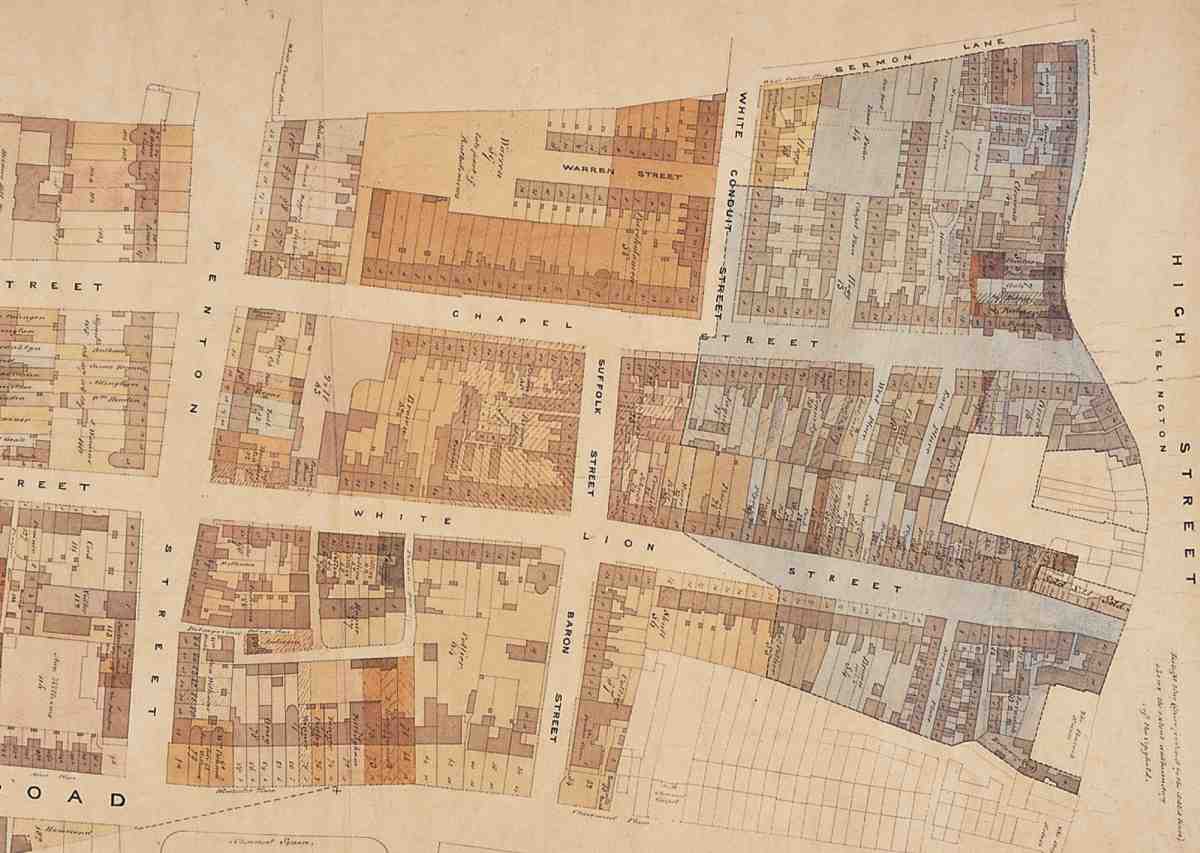

Penton Street gained its first terraces in the 1770s, and by the end of the century the new grid of streets to the east—present-day White Lion Street, Chapel Market and Baron Street—was almost fully built up with plain brick terraces (Ills 481, 482). A handful stood out as superior dwellings, and the area was home to a number of artists and publishers, as well as to a boys' academy in one of the larger houses.

480. Penton Street, looking south in 2007

Commercial use spread gradually westwards from the High Street, and shopkeepers and street traders gradually colonized Chapel Street, which had been essentially residential. The later decades of the nineteenth century saw a decline into poverty and overcrowding, in response to which schools and mission halls were built. As population declined in the twentieth century widespread commercial redevelopment followed, with a shift up in scale after the break-up of the Penton estate in 1951. Chapel Market has kept its shops and stalls and long-established workingclass character. In other streets change is more apparent. The northern fringe was brutally sanitized in the 1980s for a supermarket, car park and police station, while White Lion Street and Baron Street continue to undergo extensive redevelopment, mostly of nondescript post-war commercial buildings. Penton Street retains some of its original late Georgian houses alongside new residential buildings.

481. Eastern Pentonville, excerpt from Thomas Hornor's Plan of the Parish of Clerkenwell, 1813

This account of eastern Pentonville, roughly following the chronology of first development, opens with Penton Street, moving on from there to White Lion Street and Baron Street, to the Chapel Market area and so to Tolpuddle Street, which marks the northern limit of the district.

Penton Street

A scheme for making the path to the White Conduit House across Henry Penton's land into a regular street had been conceived by late 1767. Penton Street was the first street to be laid out as part of what was to become Pentonville, and its name—not adopted till about 1775— conveys its primacy. Building took place between about 1768 and 1786 along its frontages, which were punctuated in due course by two cross streets on either side: Henry (now Donegal) Street and John (now Risinghill) Street on the west; White Lion Street and Chapel Street (now Market) to the east. The present numbering, in odd (west side) and even sequences, dates from 1892 and is used throughout this account.

Penton Street today is a busy through-route leading on to the narrower Barnsbury Road, which continues its line northwards into Islington (Ill. 480). But that continuation dates only from the 1820s. Until then, the road stopped abruptly at a gate leading to White Conduit House and Fields, beyond which the footpath meandered on northwestwards to Highgate. Despite the metropolitan nature of the new houses, the original scenic effect must have been charmingly countrified. The roadway broadens towards the top end, an informality of planning perhaps contrived to create an amenable space in front of White Conduit House, just beyond the last houses on the east side, or perhaps perpetuating an existing arrangement. This broadening was formerly more pronounced in effect, as the original building line on the east side north of Chapel Street was set well back behind gardens (Ills 481, 482).

For some time after it was laid out, Penton Street

retained its half-urban, half-rural air. Thomas Cromwell,

the historian of Clerkenwell, who may have been brought

up in the first decade of the nineteenth century at No. 38,

one of the surviving houses on the east side, (fn. 1) described

Penton Street in 1828 as the 'High Street' of Pentonville:

particularly on Sundays, when, in fine weather, it is thronged

with citizens, hastening to or returning from the fields which

commence a little beyond its northern extremity. The street

is of considerable but unequal width, and by no means regularly built; though it contains several very good houses, particularly at the upper end, which, till within these ten years,

was in immediate contiguity to rural objects, and commanded

a very pleasing and extensive prospect. (fn. 2)

482. Eastern Pentonville, excerpt from Penton Estate map of 1840–1

Looking back from the 1860s, the lawyer John Hodgkin remembered that through his childhood up to 1814 'Everything north of Penton Street was true country, with dairy farms and a few single houses or cottages between it and the fine horizon line'. (fn. 3) At the same remove, Pinks pictured early Penton Street as 'a kind of northern Belgravia'. (fn. 4) If that was exaggerated, it confirms memory of the street's lost charms and amenities. While the White Conduit House stood at the north end, the south was flanked by Dobney's tea gardens and bowling greens, and the Belvidere and its bowling green and bun-house. There were two sizeable pubs besides: the Salmon and Compasses on the east side, still extant, and the Queen's Arms, since rebuilt and renamed, on the west.

The formation of Penton Street started when John Pennie, a paper-hanging manufacturer, took out a building agreement with Henry Penton in October 1767 for ground opposite the New River Company's Upper Pond, facing the New (now Pentonville) Road. Pennie undertook to form a 4ft-wide footway alongside the new 40 ft street, paved with good Purbeck stones or squares and six inches higher than the coachway, which was to be gravelled. The agreement provided for the granting of 99-year leases. Pennie's ground, extending along both sides of Penton Street, probably corresponded to one of the old bowling greens and may have included the site of Busby's Folly (see page 327). Pennie is listed in the ratebooks from 1768 to 1770, across the road at what becomes briefly 'Penny's Folly' and then 'Belvidera House'—the Belvidere pub. (fn. 5)

The first two definitely new houses in the street occur in the ratebook for 1770. These stood on the west side a little north of the Belvidere, around the entrance to the present-day Public Carriage Office. Building agreements for the plots, which had 15 ft frontages, were taken out by Joseph Ayres, carpenter, and Henry Powell, glass-cutter, both of Clerkenwell. Leases for 63 years were granted in March 1769, and Powell and Ayres swapped their houses with one another shortly afterwards. (fn. 6)

In 1774 the two houses were rated with a couple of others under the name Folly Row. Two more then listed as 'Over the Way' may have been in Penton Street, while four more houses appear as being in 'White Conduit Row'. These last probably occupied the west side north of John Street, where St Silas's Church and the flats to its north now stand. The building leases along this side, apart from Ayres' and Powell's houses, all date from between 1771 and 1779, whereas those on the east side date from between 1778 and 1786, suggesting that the western frontage was largely built up before the eastern was begun.

Along the west side only two original houses are left, Nos 7 and 9, both in vestigial form. Opposite, much more of the original fabric survives in the shape of two substantial terraces, Nos 18–30, south of White Lion Street, and 32–56, between White Lion Street and Chapel Market, together with a fragment of the next terrace north, Nos 58–60. Most of these now have shops incorporated within the ground storey or built out over their front gardens and are of standard mid-Georgian type, three storeys high above ground and two windows wide. But a clue to the semi-rural, or hilltop suburban, character of early Penton Street is afforded by Nos 50–56. Here behind the accretive shops on the former front gardens appear double-fronted houses, five windows in width with the central window left blank. Both date from about 1784–5. They are not as large as the frontage suggests, being only one room deep, a layout that seems to indicate a desire to make the most of views, air and light. A row of earlier houses on the west side, on the site of the Public Carriage Office, were similarly shallow, and also presumably designed to maximize light and views; these earlier houses were smaller, with side entrances and almost certainly just one room on each floor. Three big houses further north also on that side had bow windows at the back, looking over the fields.

Abutting the north side of Nos 54–56 is a former fireengine house (No. 99 Chapel Market). Flanking the other side of that street is the Salmon and Compasses (No. 58). This large pub is named after William Salmon, carpenter, the original taker in 1775 of the whole block north of Chapel Street. It is essentially the original building, though enlarged and stuccoed.

Two other early hostelries survive in site and general purpose, if not in name or fabric, on the west side. At the north corner of Henry (Donegal) Street, and numbered in that street until 1892, stood the Queen's Arms, on the site of the present Chapel Bar, No. 29 Penton Street. Further south, the Belvidere next to the corner with the New Road is now numbered 96–98 Pentonville Road and functions as a restaurant (see page 352).

483. St Silas's clergy house, No. 74 Penton Street, front elevation. William White, architect, 1896–7. Demolished

By the early Victorian period Penton Street had become a street of shops and tradesmen's premises with a couple of schools and relatively few private residences. (fn. 7) That consistency was challenged in the early 1860s by the replacement of houses at the north corner of John (Risinghill) Street with first a temporary and then a permanent church, eventually consecrated as St Silas's. Its aggressive promoter, the Rev. Anthony Courtenay, offended local sensibilities by playing up for fund-raising purposes the depravity of a street in which he counted three gin palaces, a Mormon college, a dancing academy where politics was debated on Sunday evenings, and sundry houses of 'ill fame'. (fn. 8) By 1867 the new parish was using No. 23 (later No. 51), the second house north from the church, as a school. After purpose-built schools had been built in 1869 in Vittoria Place, Islington, it became St Silas's vicarage, with the benefit of alterations designed by Habershon & Brock. (fn. 9) In 1896–7 a clergy house and church hall were built opposite, at No. 74, backing on to Warren (later Grant) Street. Built by Dove Brothers, they were designed by William White, the architect of alterations to St Silas's itself (Ill. 483). (fn. 10) Both vicarage and hall have since been demolished.

Though less seedy than Courtenay made out, and ultimately keeping up a better tone than the streets to its west, Victorian Penton Street did not maintain its early character. Shops were built over front gardens from 1852. In 1875 the Belvidere was reconstructed and its remaining gardens were soon built over, with shops (Nos 1–5) appearing along the frontage here, probably in 1877–8. (fn. 11) Behind, manufacturing concerns of varying duration and size tucked in, culminating in the advent of the Gloy Manufacturing Co., the well-known glue-makers.

North of these premises, the first of several institutional halls had appeared by 1867. Known initially as Penton Hall, it was first used as a Wesleyan chapel but soon underwent alteration. (fn. 12) By 1880 it was a volunteers' drill hall. It was eventually rebuilt on a larger scale with its main frontage to Donegal Street. The whole corner site was in military use during the Second World War. Afterwards it was cleared for the Metropolitan Police's Public Carriage Office, which since 1966 has occupied the whole of the west side between No. 9 and Donegal Street. On the opposite side, a Conservative Club arose briefly in 1887 on the site taken ten years later by St Silas's Hall. (fn. 13)

Today the two frontages of Penton Street differ appreciably. The west side north of the carriage office is marked by various types of social housing, punctuated by the raw ragstone bulk of St Silas's with its small garden in front. The east side retains the Georgian houses mentioned above, but has more recent buildings at the north and south ends. They are of low aesthetic value, the big Islington Police Station of 1990–2, with its main front to Tolpuddle Street, in particular evincing an architecture of dispiriting banality.

Residents have included: Joseph Grimaldi, clown, at what is now No. 44 in 1799–1800; John Hodgkin, grammarian and calligrapher, from about 1798 at a house on the site of No. 35, where his sons—the physician Thomas Hodgkin, who identified Hodgkin's Disease, and John Hodgkin, barrister and Quaker minister—were probably both born; Stanley Giffard, editor of The Standard, in the house on the site of No. 31, where his son Hardinge Stanley Giffard, later Lord Halsbury, lord chancellor, was born in 1823; and Lemuel Francis Abbott, portrait painter, who died insane at an unknown house in Penton Street in 1802. (fn. 14)

West side

Of the original houses, Nos 7 and 9, much altered and stuccoed over, are the only ones left. They belong to the subsidiary houses north of the Belvidere leased to Ann Williams, widow of Henry Williams, in 1784. (fn. 15) No. 9 has been heightened. The later houses at Nos 1–5 are discussed together with the former Belvidere, Nos 96–98 Pentonville Road, in Chapter XIV.

No. 29, the Chapel Bar, at the corner of Donegal Street, is the successor to the old Queen's Arms. The present building, of brick with a projecting and rendered lower storey for the bar, dates from 1932–3. (fn. 16) It changed its name to the Chapel Bar in 2000, when the landlord commissioned a ceiling painting by Bob Venables in parody of the Sistine Chapel scene of God bringing Adam to life, showing the handing over of a pint of Guinness. Recycled Gothic church fittings remain, but the painting has gone. (fn. 17)

Social housing

Nos 31–45, and 1–4 Risinghill Street were built in 1976–7 for Islington Borough Council to designs by John Melvin & Partners (job architects, Peter Messenger and Angus McLeish). The builders were G. E. Wallis & Sons. They were earmarked for couples without children and planned as a pilot tenants' co-operative scheme, whereby residents would be drawn into helping manage the block. The internal arrangement consists of small flats, arranged two per floor over three storeys.

Melvin was required to design a building that would fit in with the surrounding terraces. The raked brick elevations, the doors and round fanlights, the party walls visible above the parapets, and the front garden set behind fencing all take their tone from that context, while the projections and recessions and the gable end at the corner with Risinghill Street add variety. (fn. 18) A plaque on the Risinghill Street front commemorates the former presence of the Penton Estate office on this site.

Hayward House (Nos 49–51) is a four-storey block of flats immediately north of St Silas's Church, built in 1980–2 by Dove Brothers to the designs of Caroe & Martin. Brick-fronted with bay windows, it includes a vicarage for St Silas's along with sheltered housing for the New Islington and Hackney Housing Association. (fn. 19) The flats replaced two houses badly damaged during the war, of which the more northerly had been St Silas's vicarage since 1871.

Harvest Lodge (Nos 53–55). The Penton Estate had intended in 1936 to sell the two houses formerly here to the Islington and Finsbury Housing Association once the leases had expired in 1943, but the war-damage they sustained changed these plans. (fn. 20) The present plain brick, four-storey block of flats was built in 1961–2, perhaps privately, by Day (Contractors) Ltd. (fn. 21)

St Katharine's House (Nos 1–15 Eckford Street) stands at the corner of Penton Street and the eastern stub of what had been Wynford Road until that street was cut off to its west by the large Half Moon Estate (not covered in this volume). The previous houses on this site had addresses in Penton Street. As an inscription on the side of these five-storey flats explains, they were built in 1934–5 for the Islington and Finsbury Housing Association by A. T. Rowley to the designs of Hendry & Schooling. Laying the foundation stone, Princess Helena Victoria paid tribute to those who lived in the 'dreadful conditions' of 'their poorer friends in London'. (fn. 22) The flats were refurbished and a lift was added by the Livingstone Design Group in 1987–8. (fn. 23)

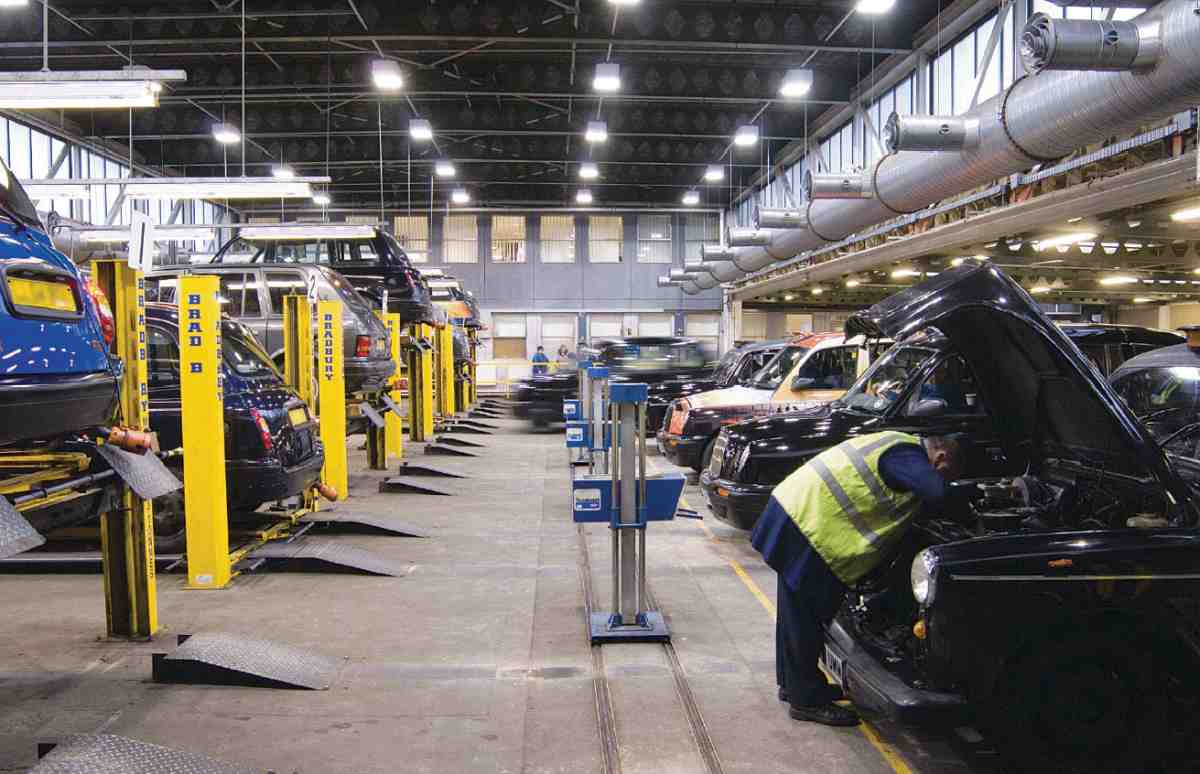

No. 15, Public Carriage Office and Police Buildings

The Public Carriage Office and Police Buildings were built for the Metropolitan Police in 1964–6 under the auspices of its architect and surveyor's department. They accommodate several activities, the best-known being the licensing of Hackney cab drivers and the inspection of their vehicles. This function is carried out by the Public Carriage Office, which since July 2000 has been a branch of Transport for London, part of the Greater London Authority.

484, 485. Public Carriage Office, Penton Street, in 2006. Metropolitan Police Architect and Surveyor's Department, 1964–6. View from Donegal Street and interior showing inspection floor

Before the opening of these buildings, the Public Carriage Office had been based in Lambeth Road, along with the Metropolitan Police Lost Property Office and one of four vehicle-testing stations. It had been decided some years earlier that these should be replaced on a single site in the King's Cross area, together with a pound for illegally parked cars.

The premises consist of an L-shaped range of three and four storeys, mostly given over to offices, an open yard entered from Donegal Street with a car-pound beneath, and a covered yard for vehicle inspection to the south. The strong relief of the pre-cast concrete panels on the street fronts gives the complex a marked 1960s character (Ills 484, 485).

The new buildings were designed by the Metropolitan Police architect and surveyor's department headed by J. Innes Elliott (Peter Silsby, senior architect in charge; job architect, D. J. Hogarth). The main contractor was Walter Lawrence & Son Ltd, and the pre-cast concrete storeyheight cladding units, detailed by the structural engineers W. V. Zinn & Associates, were made by Girlings FerroConcrete Co. The underlying framed structure is of reinforced concrete, with internal walls of brick or block. Prefabrication was used to speed up construction, which took place between November 1964 and September 1966. Aesthetic considerations restricted the use of the faceted cladding to the upper floors, the ground-floor facings being of a black rustic brick. (fn. 24)

St Silas's Church

This Victorian ragstone church had a turbulent early history. Started in 1860 to the designs of S. S. Teulon, it was stopped and partly demolished by the Clerkenwell Vestry for contravening the building line in Penton Street. A fresh architect, E. P. Loftus Brock, built a reduced version of Teulon's plan with new elevations in 1862–3. The chancel was added by William White about 1884.

The prime mover in the founding of St Silas's was the Rev. Anthony Lefroy Courtenay, DD, a Low Churchman of Irish descent, fair means and some aristocratic connections. Dr. Courtenay, as he was generally called, possessed more zeal than judgement and a penchant for litigation. In the 1850s, according to Pinks, 'a fixed dislike to what is called "High Church" principles had taken root in the northern suburbs'. (fn. 25) That gave Courtenay an opening. Early in that decade he had been appointed curate of St James's, Pentonville, then a dependency of Clerkenwell parish church. Soon a Clerkenwell Church Extension Trust sprang up, with the aim of enlarging St James's and securing its own district. The district was obtained, but entailed Courtenay paying compensation to Clerkenwell's incumbent, W. E. L. Faulkner. Meanwhile the idea of enlargement turned into a plan for an additional church and school. (fn. 26)

When Faulkner died in 1856, Courtenay declared himself perpetual curate of Pentonville and entitled to its income. Litigation followed between him and the chapel trustees after he gave the clerk and sexton notice to quit, 'laying hands' on the latter. The issue of his incumbency of the chapel never came to court. Instead he pressed forward with his plans for a new church in Penton Street, claiming that people would not attend St James's 'on account of the graveyard around it, the peculiar shape of the pews, and the noise arising from the busy thoroughfare in which it stands'. (fn. 27) The events of 1856 had led to the dissolution of the original committee, with Courtenay unable to get his hands on the money it had raised and accusing the parish of allowing the poor to be 'plundered of very large bequests'. (fn. 28) Nevertheless early in 1858 a site had been chosen at the corner of Penton Street and John (Risinghill) Street, and drawn out by Thomas C. Lewis, a minor architect who later found fame as an organ-builder. A year later it was conveyed to Courtenay. He paid £1,000 to the Penton trustees for the freehold, and £1,300 to a Staffordshire coaldealer for the end of the leasehold interest. (fn. 29)

In April 1859 Courtenay told the Ecclesiastical Commissioners that he would start building a church for 1,500 people as soon as he could raise the money for a first payment, and solicited a grant, claiming 'growing interest in behalf of the services of the Church, on the part of those classes which have been too long estranged from them'. (fn. 30) Soon he reverted to a temporary church for 500, wherewith to counter Penton Street's rival attractions. Courtenay's allegations about the neighbourhood, repeated 'in circulars soliciting the aid of persons living in different parts of the country', aroused hostility to his plans among respectable locals. (fn. 31)

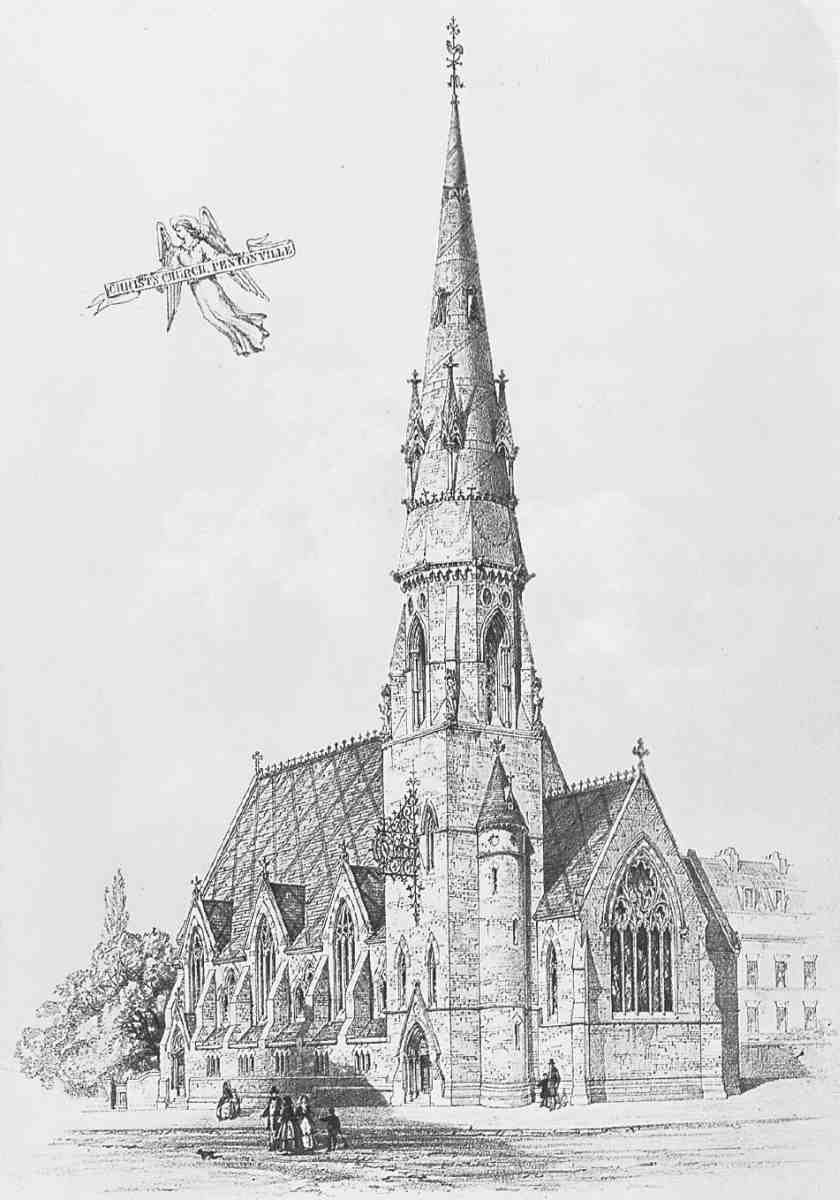

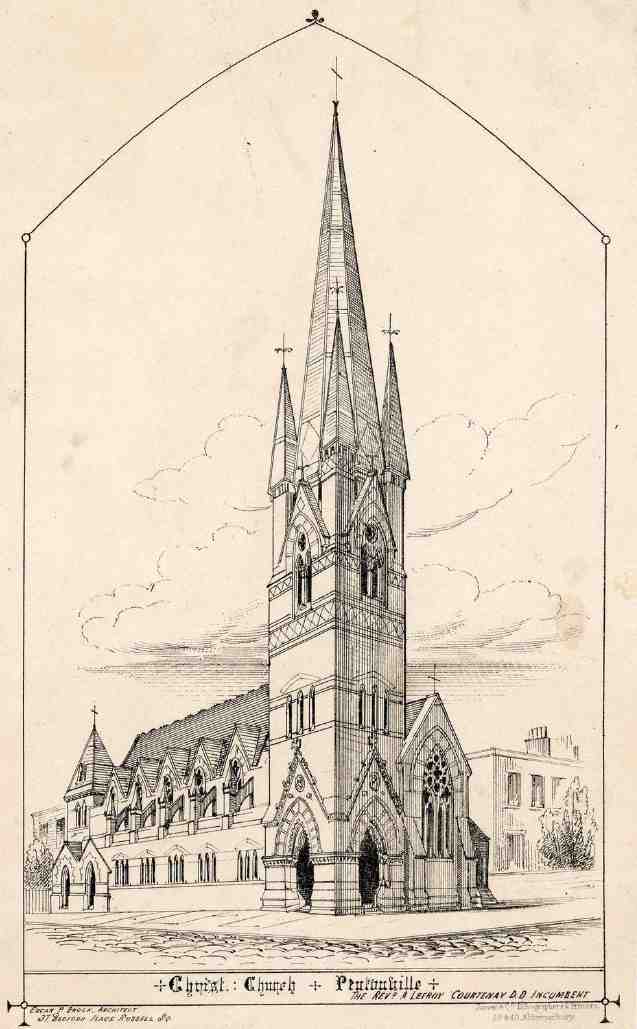

Once the site was cleared, the temporary church was built by Dove Brothers to the designs of the architects Lander & Bedells in six weeks. It was of timber clad in galvanized iron, and largely toplit. (fn. 32) Directly it opened in April 1860, Courtenay pressed on with the permanent church. S. S. Teulon was now his choice of architect and quickly produced a design. No plan survives, but there is a perspective identifying the church for the first time as 'Christ's Church, Pentonville' (Ill. 489). (fn. 33) The arrangement of the nave was peculiar, combining passage aisles with galleries on three sides carried by iron columns. In the clerestory, tall gabled windows thrusting into the roof alternated with lower ones, a touch condemned by The Ecclesiologist as 'whimsical'. There was to be a commanding south-east tower with an octagonal belfry stage tapering to a circular spire. (fn. 34)

A foundation stone was laid in July 1860 and the builders Child, Son, & Martin began work. (fn. 35) Then Teulon and Courtenay ran into trouble. The chancel had been set out well forward of the building line in Penton Street, Courtenay having assumed he was erecting a 'privileged building' and could lay it out as he wished. (fn. 36) That gave his opponents on the Vestry their chance. With the walls some 5 ft above ground, the Surveyor to the Vestry about the end of 1860 took down 'so much of the church as projected beyond the line of frontage'. (fn. 37) Courtenay once more took to law, drawing in the Ecclesiastical Commissioners with him, and lost. (fn. 38) Simultaneously he pursued Dove Brothers for redress in respect of poor materials and workmanship in the temporary church, taking the case as far as the House of Lords. According to Pinks, over and above the suit against the Vestry, Courtenay 'brought actions against the builder of the first portion of the church for using bad materials, and then against the architect of the temporary church for misdirection, as well as against the builder of the temporary church, on the same grounds as against the builder of the permanent church'. (fn. 39) Appealing once again for funds, he alleged that his amputated chancel, 'opposed in the Court of Chancery by an adverse party', would have allowed 200 additional sittings for the poor. (fn. 40)

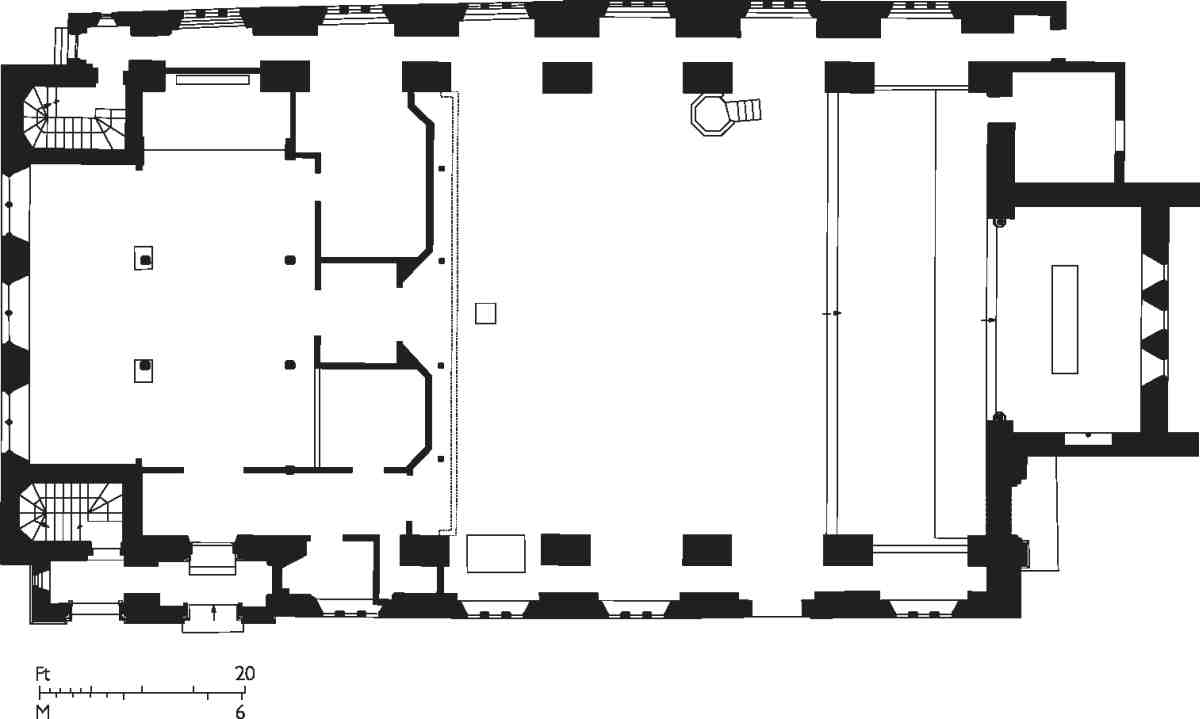

Teulon having been dismissed but seemingly not sued, in August 1862 the church's irrepressible promoter came up with a fresh architect, the 24-year-old Edgar P. Brock (later known as E. P. Loftus Brock) and a revised design. Brock naturally used the existing foundations and kept the basic plan-form of Teulon's building, with passage aisles and a proposed south-east tower. The body of the church was replanned for a congregation of under a thousand; only a western gallery was erected, but the foundations for Teulon's iron columns were left in place and corbels inserted in the walls in case side galleries should be needed. (fn. 41) The triple lancets of the aisles and the repeated buttresses above them are also legacies of the Teulon design. Otherwise Brock restyled the elevations. The nave and aisles were completed by the builders Manley & Rogers in 1862–3. (fn. 42) Brock furnished his own design for the tower and a much-shortened chancel (Ill. 490), but these could not be afforded. (fn. 43)

486, 487. St Silas's Church. Interior in 1975, looking north and (right) west

488. View from the south-west in 1965

489 (left). 'Christ's Church, Pentonville', perspective by S. S. Teulon, 1860

490. Design for completing church by E. P. Loftus Brock, 1862. Tower unexecuted

Brock's completed nave and aisles were reported on by Thomas C. Lewis, apparently acting for the Bishop of London. He found the church 'very notable for its inconvenience of plan a large amount of room being lost in useless alleys not one of them being sufficiently wide for the exit of a large congregation'. (fn. 44) A fresh difficulty now arose. When Courtenay applied for consecration, he asked for the patronage to be vested in his name and for the pew rents to be charged with £2,200 which he had personally spent to get it finished. Disputes on such issues and on the district to be assigned postponed the consecration. (fn. 45) In the interim Christ Church was opened by licence, while the Bishop proved sympathetic enough to support grants and appeals for liquidating the debt on the fabric.

Not until Courtenay had retreated back to St James's, Pentonville, and a 'missionary curate', the Rev. Joseph Wilkinson, had been installed did the consecration take place in July 1867. At that point the church acquired a new identity as St Silas's, and a district taken partly from All Saints', Islington as well as St James's, Pentonville. (fn. 46) Debt on the fabric still remained in 1869, when Courtenay explained that though he had always intended the church to be free, Wilkinson had retained pew rents, and therefore a grant from the Incorporated Church Building Society could not be collected. (fn. 47) Brock's tower and spire were never built. Eventually a short chancel with a plain triplet of lancets at the east end was added to William White's design. It had been planned in 1882 but seems to have been built only in 1884. (fn. 48)

Though not at first sight an alluring church, St Silas's as rescued by Brock retains vestiges of the big-boned energy associated with Teulon's architecture (Ill. 488). The exterior is faced in squared uncoursed ragstone, set off by plentiful flush brickwork in arches, tympana, stringcourses and plinths as well as at the top of the minimal south-west turret over one of the gallery staircases. Twin porches at that end of the south front originally gave separate access to the floor and the west gallery. A further entrance to the church was arranged at the east end of the south aisle, where a timber canopy stood in for the lack of a tower. The upper stages of the aisles, buttresses and the clerestory depart from Teulon's design, the clerestory windows being expressed as a row of gables. The flatfronted west end reflects the church's breadth, and contains a crude rose window (perhaps simplified after war damage) within an arch over three plate-traceried windows. The incomplete east end as left in 1863 must have looked even cruder, with a lean-to vestry against the east wall.

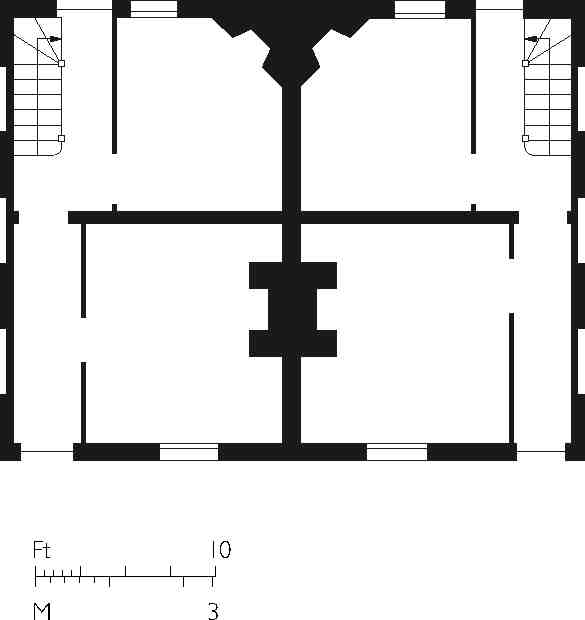

Internally the church, though much altered, retains its peculiar plan whereby a broad auditorial space is combined with narrow passages divided from the nave by high, featureless arches (Ills 486, 487, 491). How side galleries might have fitted around these arches is puzzling. The west gallery is very deep, and now filled in underneath. All these features have been much simplified over the years, leaving only the obtrusive paired trusses of the wide roof as testaments to Brock's taste.

491. St Silas's Church, plan in 2006

The lack of later embellishment to St Silas's fabric followed on from the parish's poverty. A litany of reports over the first forty years of the twentieth century paint a picture of dense population, social distress and low morale. (fn. 49) Restorations took place in 1907 and 1927, probably without major internal changes. During this period St Silas's grew inexorably more Anglo-Catholic in tone and décor. A reredos incorporating a copy of Leonardo's Last Supper was installed over the main altar in memory of Captain Frederick Penton in 1931, but subsequently removed. The present reredos, in vibrantly coloured mosaic offsetting the blankness of the rest of the church, was installed to the designs of Michael Coles in 1994. The organ, moved from the west gallery to the chancel in 1884, was shifted back again in the 1930s and the choir stalls were taken away at the same time; the pews in the nave disappeared after 1975. The present organ and case came from St Thomas's, Kingly Street, after that West End church closed in the 1960s. The pulpit is Victorian, but not original to the church. The quaint font, seemingly of concrete, was given in memory of the Rev. Tiverton Preedy and therefore probably came from the mission church where he mainly served, All Saints in White Lion Street near by, following its closure in the 1950s. (fn. 50)

In anticipation of that event the architects LlewellynSmith & Waters created a transverse chapel under the west gallery to incorporate the handsome reredos and some other fittings from All Saints. (fn. 51) The reredos, the most rewarding of the fittings in St Silas's, is described with the account of All Saints' Mission (see page 390). It now sits in a niche behind a rolling shutter, as the rest of the space under the gallery was converted into a hall and rooms in 1980–1. The whole western end of the church has indeed been several times reconfigured. (fn. 52)

Externally, the one notable feature is the war memorial cross in the garden at the east end, erected at an unusually early date, 1917, with figures by Arthur Walker. (fn. 53) Iron railings round the church were removed during the Second World War, when the fabric suffered chiefly from blast, though its environs were more seriously damaged.

East side

South of the former entry to Dobney's Court and Penton Grove, none of the original houses now remain. The southernmost were demolished for the construction of Nos 90–92 Pentonville Road before the Second World War. No. 10, completely or largely rebuilt about 2000, is in the rawest neo-Georgian idiom. The old house, which had lost its whole second storey and had had its brickwork painted, was a hardware shop of character in the decades before its closure in 1999 (Ill. 492). Nos 12–16 were demolished in 1980, and their sites are now occupied by No. 12, a brickfaced block of flats with three main storeys and a projecting centre, built for Furlong Homes about 1996. (fn. 54)

North of this, the original houses survive. Nos 18–30 are essentially of the late 1770s and early 1780s. The first lessee of Nos 28 and 30 in 1778 was David Crossweller, carpenter. The ground for Nos 18–26 was taken by Thomas Anderson, but the one known lease, for No. 26 in 1783, was made to John Millington of Battle Bridge, carpenter. Crossweller's houses went with four others in White Lion Street, while Anderson's take included one in White Lion Street and others in Dobney's Place and Penton Grove. (fn. 55) All these houses now have shops, and have been much altered; until 1994 No. 18 was an old-fashioned baker's, Restorick's, with a bakehouse wing to the rear; No. 22, with a painted front, has lower storey-heights than the other houses (Ill. 493).

492. G. J. Chapman's hardware shop at No. 10 Penton Street, in 1994. Demolished

Nos 32–56 constitute the most interesting run of Georgian houses in the street. They divide into three groups: Nos 32–38, north of White Lion Street, where the houses come forward to the pavements; Nos 40–48, conventional houses of two windows' width with later shops in front; and at the northern end, the two double-fronted houses, numbered 50–52 and 54–56 because of the paired shops which also protrude here.

Nos 32–38 appear all to be due to Charles Douglas of St Clement Danes, carpenter. The house at the corner of White Lion Street, now divided and numbered 32–34, was in the process of construction by him when he was granted a lease in 1783. It was refronted and possibly rebuilt in the nineteenth century. Nos 36 and 38 are much better preserved, being the only Georgian houses in the street to have avoided shopfronts. They look rather later than the 1780s, but this may be due to the lengthened firstfloor windows and the doorcase at No. 38, both probably early nineteenth-century alterations. (fn. 56)

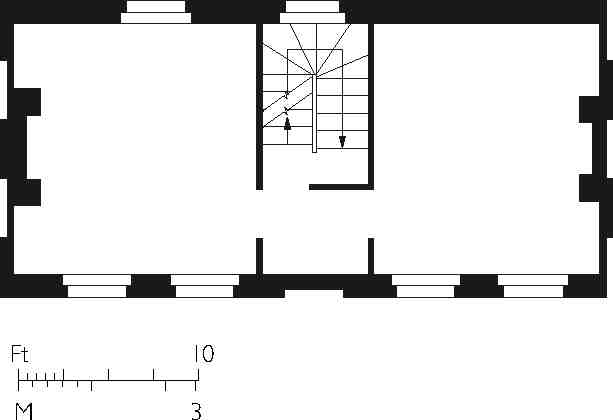

493. Nos 18–22 Penton Street (right to left) in 1994

Nos 40–48 belong to a parcel of ground taken by John Tubb, of Queen's Row in the New Road near by. Tubb, previously a shoemaker of Marshall Street, (fn. 57) was now 'gentleman', having evidently advanced himself through building speculation. The leases identified for these houses date from 1781 and 1784; they are mostly to Tubb, but one demises No. 46 to John May Evans, bricklayer, of Christ Church, Middlesex. (fn. 58) Tubb's ground also included the sites of Nos 50–52 and 54–56. That is confirmed by the continuous building line and storey heights, as well as by a lease of 1784 assigning both houses with Tubb's consent to John Eaton, carpenter, of Monkwell Street, City. (fn. 59) It is likely that, in the usual way, the whole group from No. 40 to No. 56 was built in informal partnership between Tubb, Evans and Eaton. The interest of the plan-form of these two houses, combining 35ft five-window frontages with one-room depths where the plots were no constraint, has already been mentioned (Ills 494, 495).

494. Nos 50–52 Penton Street, reconstructed first-floor plan

495. Nos 46–56 Penton Street in 2007. Houses of c. 1784

No. 58, the Salmon and Compasses, was built by William Salmon, carpenter, of Blue Anchor Alley, Bunhill Row, under a lease granted to him in 1775. This covered a block stretching north from the corner of Chapel Street to the parish boundary. By 1780 the houses that became Nos 58–74 had been built up, but Salmon was dead and new leases were granted with the consent of his executor, Joshua Cook, silversmith, of the same address. (fn. 60) The pub presumably remained with the Salmon family. It alone protruded forward to the road, the other buildings being set back behind good front gardens. Probably the first building completed on the east side of Penton Street, it was first rated in 1775, along with two cottages at the back, later known as Butler's Place, then as Nos 1A and 2A Chapel Market. It appears on Hornor's map as the Compasses, but the fuller name seems also to have been in early use.

The present stuccoed appearance is no doubt due to early Victorian embellishment. By 1855 the whole of the first floor was used as a 'concert room', extended in the next year over the back yard, with the loss of a bow window, allowing a further 100 people to pack in. The decorations and fittings were 'of a solid character', and the exterior too was given a solid-looking treatment with pilasters and a low pediment. The present ground-floor extension to Penton Street dates from 1874. Further alterations were made in 1893, perhaps including the insertion of iron columns in lieu of partitions on the ground floor. (fn. 61)

No. 60 is an unprepossessing survival, its featureless cemented front set back behind a bookmaker's shop that occupies its former front garden. In carcase it is one of the houses leased with the consent of Salmon's executor to John Stevens of Highgate, gentleman, in 1780. (fn. 62)

The remainder of the east side is now occupied by the flank of the Islington Police Station (see under Tolpuddle Street, below).

White Lion Street

White Lion Street is named after the former White Lion inn on Islington High Street, discussed more fully in Chapter XVII. The northern bays of this hostelry were replaced by the east end of the road when it was formed in the late 1770s. From 1898 the road was widened at this end on its south side, and the rest of the old inn of 1714 was then rebuilt as a narrow public house. This survives as offices and a bank at Nos 23–25 Islington High Street. On its north flank rampant-lion relief panels from 1714 and 1898 face White Lion Street, the lions inappropriately painted yellow (see Ills 587, 588 on page 499).

White Lion Row, as it was first called, was densely developed with more than ninety houses, all but a few going up between 1778 and 1795 (Ills 481, 482). Leaseend renewal a century later fed into piecemeal redevelopment in the decades around 1900, for a number of religious or educational buildings, as well as for commerce. The latter shifted from shops and mostly small-scale manufacturing to industrial depots and warehouses in the 1960s. Purpose-built offices arrived in the 1980s and another wave of redevelopment in the years from around 2000 continues to be focused on offices, alongside some new flats. The consequence is a street of considerable architectural diversity, though with few individual buildings of note.

As well as diminishing the White Lion inn, the new street cut across the northern parts of Dobney's bowling greens (see Chapter XIII). To their east the substantial seventeenth-century Prospect House, which had come to be known as Old Dobney's, found itself on the south side of the road, on the site now occupied by the Claremont United Reformed Church. Set back from the road and probably with its main front to the south, it was converted for use as a discussion and lecture room in 1780, and leased to John Skull, gentleman, of Islington, in 1785. It was demolished sometime around 1820. (fn. 63)

Development began with the lease in 1778, for 99 years, to John Painter of a large plot on the north side of the road towards the east end. Painter, a Clerkenwell auctioneer, and Richard Plimpton, a local stockbroker, subdivided the ground and in 1779 the first nine houses were being built. Their frontage was not fully built until 1780–3, after Painter had become bankrupt. (fn. 64) Most of the rest of the numerous house plots on the street were built on in the 1780s, the 'row' becoming a 'street' in 1789. Small groups on the north side were completed in the early 1790s. Other long leases also tended to anticipate building work, suggesting fairly loose estate management. There were numerous developers, the most ambitious being John Brown, a Holborn bricklayer, who took out building agreements or leases in 1786–7. Thomas Collier, Henry Penton's steward, who like Brown was building elsewhere on the estate, took a block of house-plots here in 1786. Gaps filled up with lower-grade housing, as with Seabrook Place and White Lion Buildings on the south side towards the east end, built up in 1807–8. The last piece of frontage to be filled in was at Nos 24–29, following the demolition of the old Prospect House c. 1820. (fn. 65)

White Lion Street had a flat if not quite uniform appearance, with plain three-storey brick houses of eight rooms, generally with 16–17ft fronts and built with basement areas. No. 72 is now the only representative left. Unusually, Nos 13–29 had front gardens, while Nos 24–29 were built with first-floor blind arcading. (fn. 66)

Penton Grove

The narrow loop of road called Penton Grove, now reduced to an L-shaped alley at the side and rear of the White Lion Youth Centre, was laid out on the site of one of the bowling greens belonging to the Prospect House (Dobney's). A narrow court off the west side was called Dobney's Place, and a broader arm, with another narrow court, called Dobney's Court, connected it to Penton Street. Penton Grove was built up with houses in the late 1780s, following a lease of 1787 to Edmund Hague, painter. Much of the south side was occupied by the garden of a house in Winchester Place in the New Road. The north side was redeveloped for the building of Penton Grove board school in the 1870s (later expanded as White Lion Street School), and on the south side W. L. Kellaway built houses in 1884. (fn. 67) Most of Penton Grove was cleared in 1990. The eastern part survives, with a shop (Nos 5 and 6) at the end, behind some ornamental iron gates of the 1990s. (fn. 68)

Social character in the nineteenth century

Around 1800 White Lion Street retained some gentility, with John Hugh Griffith of the Bank of England in a big house on the south-west corner with Baron Street, William Till running an academy for young gentlemen at No. 57, and other residents described simply as gentlemen. John Coote, an eminent bookseller and publisher, lived here up to his death in 1808, and around 1820 B. R. Baker sold prints from No. 77. By this time Benjamin Harman, a mathematical-instrument maker, was at No. 88 and there were shops on both sides of the road, a butcher's shop doubling around this time as a Methodist Sunday school. In the 1840s Lady Anne Hamilton, a former ladyin-waiting to Princess Caroline, spent her last years in the street. (fn. 69)

An 1841 directory lists only twenty-two commercial premises on White Lion Street, mostly on the north side, highly various and probably indicating something less than the full spread of commercial use. Only about a third of the houses were subdivided, and a population of 768 in 106 properties in the census of that year does not suggest poor living conditions. By the end of the decade sixty-six premises were listed in the directories, and the former academy at No. 57 had become a reformatory for prostitutes. In 1873 there were said to be five brothels in the street. During the rest of the century a wide spectrum of commercial uses spread. There were a number of builders, amongst them the firm of E. Wayland, established in 1787. A scion of this dynasty was Edward James Wayland, born at No. 18 in 1888 and later a distinguished geologist and prehistorian. By 1891 the houses were somewhat fewer, but the recorded population had grown to 942. With around ten people and a shop in each house, and overcrowding in the courts off the south side, it was now a poor neighbourhood and said to be 'infested with disorderly houses'. (fn. 70)

From 1898 to 1930 the Penton Estate, through its surveyor T. H. Watson, undertook clearance of the south side east of Baron Street (Nos 1–29) for road widening. As leases fell in, houses were replaced with purely commercial premises. (fn. 71)

Individual Buildings

No. 57

The principal survival from the original development of the street, No. 57 is an imposing building of 1787–8 with a pedimented porch on Tuscan columns (Ills 496, 497). Built as a school, it has an engaging subsequent history of institutional use, having been for many years a reformatory for prostitutes and in the late twentieth century a free school.

The building was presumably specially commissioned by William Till, the Clerkenwell schoolmaster who took it on lease at the direction of the developer-bricklayer John Brown. The site had a 60 ft frontage and was 195 ft deep. (fn. 72) Till's boarding school for 'young gentlemen', some of whom were able to have separate bedrooms, became known as Prospect House Academy. In later years, if not from the beginning, the house had wide windows to the rear, now much remade, as befits institutional use. It appears also to have had a rooftop belvedere, in keeping with its name, though this was obviously chosen in reference to the old Prospect House near by. By 1808 there was another large building, set back to the east and lower, probably a classroom; the ground to the rear was open to Chapel Street. (fn. 73)

496. No. 57 White Lion Street in 2007

497. White Lion Free School and white lion, in 1975

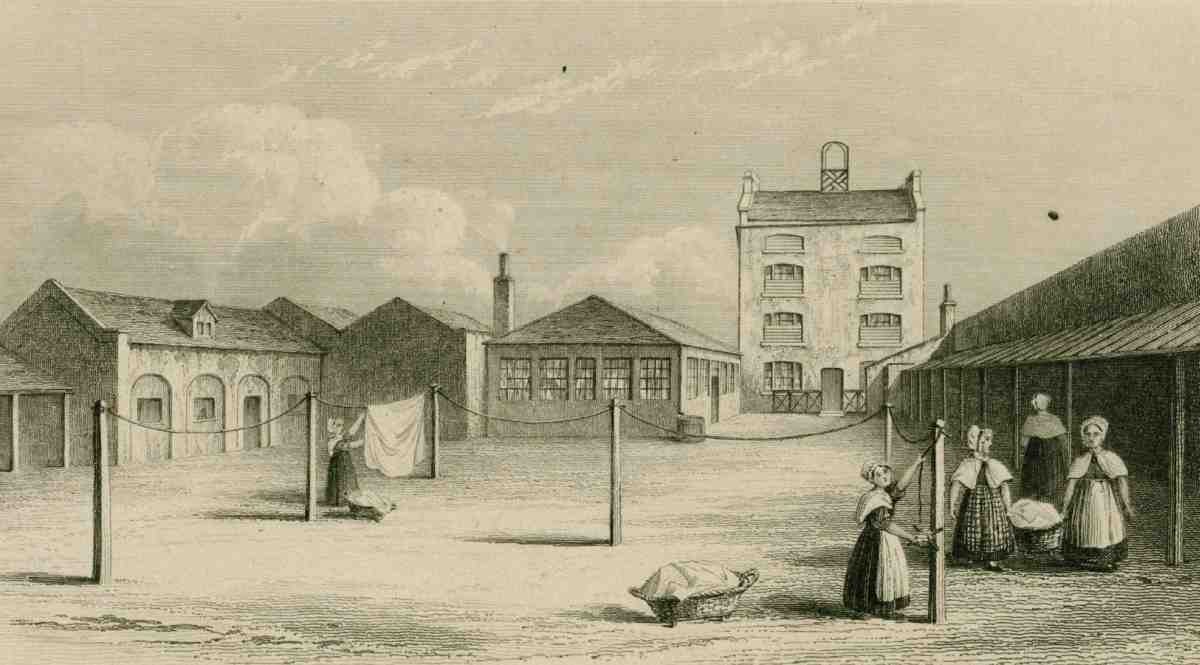

Around 1844 No. 57 became a Probationary House for the London Female Mission. Later known as the Home for Penitent Females, this charitable refuge and reformatory for young prostitutes was the second such institution locally, the London Female Penitentiary on the New Road having then been open for more than thirty years. Further buildings went up along the sides of the yard, the site now having a breadth of 90 ft, in which the residents worked as laundresses (Ill. 499). Up to sixty were admitted at a time, rent free, and there was a rapid turnover. (fn. 74)

In 1880, with the lease soon to expire and concern about the area's declining reputation probably spreading, Colonel Penton decided emphatically that he no longer wanted the reformatory on his estate. New leases were negotiated in 1883–4 with William Lemon Kellaway, a builder, who cleared the ancillary buildings and ran Godson Street through the east side of the former yard, lining it with four-storey houses. The street is named after a forebear of the Pentons. (fn. 75) No. 57 stayed in Kellaway's hands, at least until he went bankrupt in 1890. By the 1920s it had become a registered lodging house, and in 1947 it passed into council ownership and was divided into flats. (fn. 76)

498. No. 57 White Lion Street, ground-floor plan in the 1870s

Institutional use returned in 1972 when an experimental libertarian school was established at No. 57 to provide 'alternative education', free of formal structures and compulsion (Ill. 497). By 1978 the White Lion Free School had more than seventy pupils and was hailed as a great success, with sufficient support to allow it to take in local children at no charge. There was a basement theatre and playroom, a ground-floor kitchen and communal dining room, and rooms for learning above. The clearance of the Godson Street houses meant ground to the rear could be used once again as a playground. One of the best-known and longest-lasting free schools in Britain, from 1982 the White Lion Free School continued under the wing of the Inner London Education Authority until it was forced to close in 1990. (fn. 77) After brief use as a homeless persons' reception centre and serious fire damage c. 1992, the building was converted to flats in 1996–8, retaining the original stair position on the east side. This was done for the Peabody Trust, by the Peabody Design Group (Colin Black, architect). (fn. 78) The former playground on the west side of Godson Street has become an open yard, used to store barrows from Chapel Market.

499. Yard of Probationary House of the London Female Mission (established 1844), seen from Chapel Street, showing the back of No. 57 White Lion Street. Mid-nineteenth century view

Claremont United Reformed Church, Nos 24–27

In 1902, after the London Congregational Union acquired Claremont Chapel on Pentonville Road (see page 349), plans were hatched for the formation of a settlement on the lines of Toynbee Hall, to have 'a rather important Entrance Hall or Vestibule as a means of approach from White Lion Street'. (fn. 79) This scheme soon grew to encompass a complete new building in place of Nos 24–27 White Lion Street for the LCU's Central Mission. It was realized in 1906, as the Claremont Institute (Ill. 500). The architect was Alfred Conder, who also designed the twobay extension on the west side, built in 1910, once the site of No. 27 had become available.

The Queen Anne façade is balanced rather than symmetrical, and has a concrete parapet with a pierced circle–pattern, behind which is a roof garden. Entrance is through a recessed porch with wrought-iron gates beneath a pediment. The Institute provided club rooms for men, including rooms for billiards and music, refreshment bars, a crèche, dispensary, private bathrooms (the district having no municipal baths), kitchens and living accommodation. Fenner Brockway was an early mission-worker and resident. After the old chapel to the south was given up in the 1960s a lecture room was converted for worship. This now houses the successor congregations of both the Claremont and Islington (Upper Street) United Reformed churches, and the rest of the building continues as a social centre, known as the Claremont Project. (fn. 80)

500. Claremont United Reformed Church, Nos 24–27 White Lion Street, in 2007

White Lion Street Centre

The arresting street front of this former board school dates from 1899–1900. Behind it, facing the abridged remnant of Penton Grove, most of an earlier school of 1874–5 survives.

The School Board for London first investigated building a school between the two arms of Penton Grove in October 1872. Since the original site and design proved too small for the government Education Department's requirements for elementary schools, the board enlarged its plans and bought additional property. As a result the school and its playgrounds came to occupy the entire block between White Lion Street and the loop of Penton Grove, with the building set at the south end away from the busier street. A house towards White Lion Street was left as a caretaker's residence. John Grover, who had tendered successfully to build the first design, undertook the work in 1874–5. (fn. 81)

Penton Grove School, as it was first called, was typical in size and genre of the schools designed by E. R. Robson during his first years as the board's architect. The original design, for which his drawings survive (Ill. 501), had been for 524 places; the final version was for 604. (fn. 82) In both, the accommodation was on three storeys: infants were housed on the ground, girls in the middle and boys on top, each level being planned with a large schoolroom and classrooms to one side. Elevationally a plain brick early Queen Anne style was adopted, with many windows paired up and no hint of a shaped gable.

By the 1890s the accommodation was deemed intolerably outmoded and inconvenient. To remedy this and add 360 more places, the site was extended to the west, leading to the obliteration of the western of the two arms linking Penton Grove with White Lion Street. In part on the ground thus gained, a conspicuous block linked to the northern end of the old school was added in 1899–1900 by E. Lawrance & Sons, to the designs of Robson's successor, T. J. Bailey. This brought the school forward to White Lion Street, which name it now took. (fn. 83)

The additions consisted of two stacks of classrooms in the form of pyramidally capped towers, flanking a central block containing staff rooms and staircases (Ill. 502). Between this and the old school came a link-block comprising an assembly hall on each floor for the separate departments, and a rooftop playground for the girls (Ill. 503). The towers convey the beefy inventiveness of later School Board architecture, with orange-red brick dressings, Wrenaissance-style circular windows wrapping round three sides of the top stages, and a spirited cartouche to relieve the eastern tower's blank face. A schoolkeeper's house with shaped gables, added in their lee in 1901, completes the ensemble. (fn. 84)

The school, latterly known as Penton Primary, closed about 1971, the name and pupils transferring to Ritchie Street, Islington. The buildings were converted into a youth centre in 1973. (fn. 85)

501. Penton Grove School, elevations by E. R. Robson, c. 1873

502. Former White Lion Street School from the north-east in 2007. T. J. Bailey, architect, 1899–1900, with earlier building by E. R. Robson at rear (left) and schoolkeeper's house of 1901 (right)

503. Girls on roof of White Lion Street School in 1912

No. 71

This former Sunday school was built in 1896–7 and run in connection with Mount Zion Baptist Chapel on Chadwell Street (see page 212). Set behind tall area railings, it has a sheer brick front dominated by stone mullion–and-transom four-light windows. Gothic tracery appears in the fanlights over the entrance doors. The building comprises a main hall, rising through basement, groundand first-floor levels, with two floors of ancillary and living-rooms above, and a lantern-roofed ground-floor hall forming a rear extension, latterly thrown open to the main hall. There are galleries with cast-iron decorative balustrading. From 1967 into the 1990s the building was used for Pentecostalist worship latterly under the name First Born Church of the Living God. (fn. 86)

All Saints' Mission, Nos 90–92 (demolished)

A small mission room was opened behind the frontage at No. 90 in 1877. (fn. 87) The initiative probably came from the London Diocesan Home Mission, whose remit was to supply missionary clergy to overcrowded areas with a view to forming new parishes. The district to be served by the mission was defined as portions of St Silas's and St Mark's parishes. By 1886 it had advanced to the status of St Stephen's Mission Church. A belfry was then added, (fn. 88) but according to Clerkenwell's church historian, R. K. Boucher, the building had been a disused stable or cowshed, and 'no expense had been incurred in decoration'. (fn. 89) In 1888 the venture attracted the patronage of the fashionable All Saints, Margaret Street, and the name changed to All Saints Mission. Although the West Enders' involvement lasted only until 1897, their Anglo-Catholic legacy proved decisive on the mission's churchmanship. (fn. 90)

A colourful phase now began with the advent of the first resident priest, the Rev. Tiverton Preedy, who transferred from St Clement's, City Road. This muscular clergyman's first ministry had been in Yorkshire, where he effectively founded Barnsley Football Club. (fn. 91) Preedy proved equal to the demands of the district, charming the local costermongers and their boys with his robustness and reputedly press-ganging youths into attending services for fear of his fists. Boxing and wrestling clubs were fundamental to the mission, which drew fashionable support. (fn. 92) The Penton family was also encouraging and generous. 'The Church which only holds 110 is crowded out', Preedy could report in 1899: 'Very many more of our 5,000 people could be reached, but for lack of room'. (fn. 93)

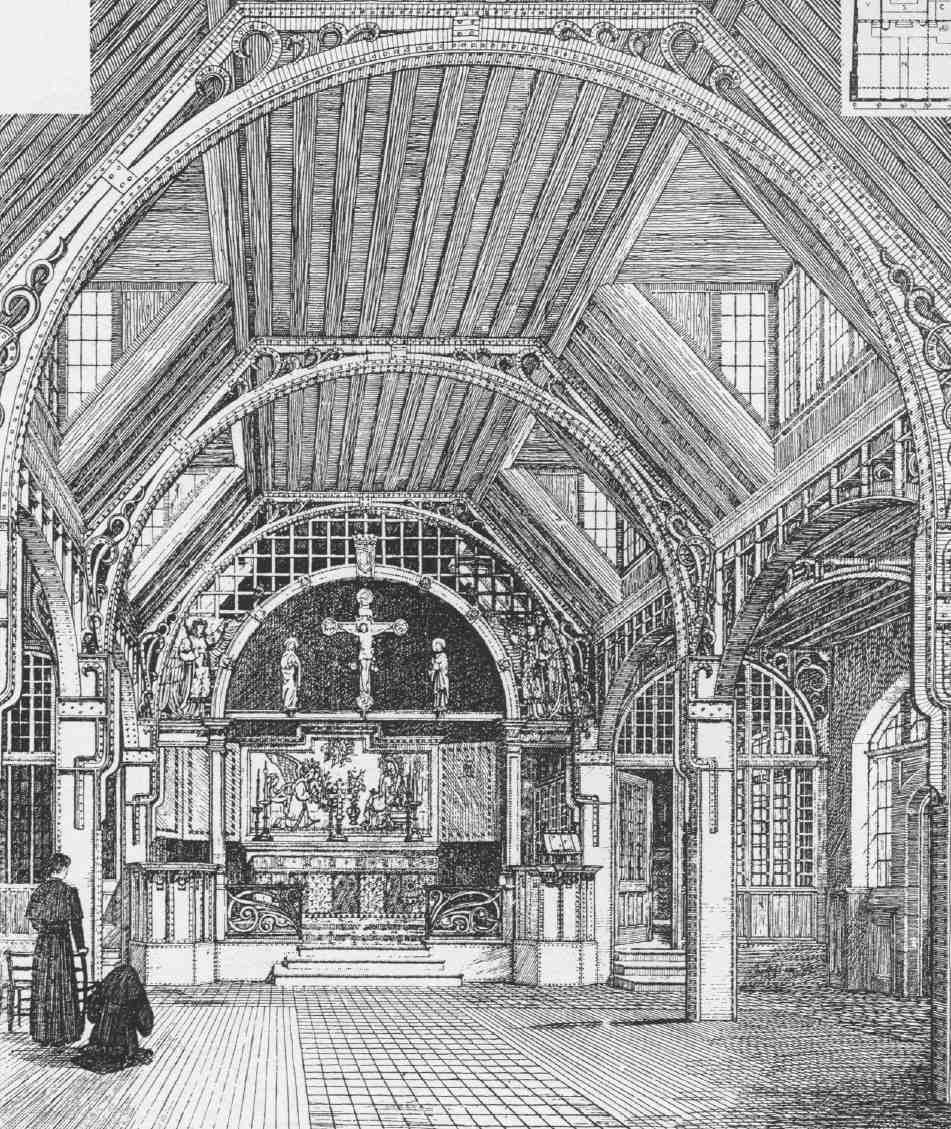

Preedy's energy made it possible to rebuild in 1901–2, to the designs of R. A. Briggs, with Campbell, Smith & Co. as builders. Captain Penton gave the freehold and £1,000 towards the building costs, while a prominent supporter, Lady Jeune (later Lady St Helier), laid the foundation stone. (fn. 94) Still hidden from the street at the back of the plot, the new red-brick mission consisted of a church resting on a 15ft-high basement gymnasium. The church interior, planned to seat 250, was bold. Steel stanchions in the gym below carried up into the church and became the basis of a nave arcade and cross-arches, also in open steel and embellished in the spandrels by wrought-iron ribbonwork. All the steelwork was painted 'dead black', but it was intended to colour and gild the wrought interstices. A chancel screen, rood and pair of ambos, all of wrought iron, were anticipated at the time of opening but may not have materialized. (fn. 95)

Geoffry Lucas's perspective of Briggs's interior also shows a broad figurative reredos with wings, not executed (Ill. 504). Instead, a fine painted reredos was installed about 1912 by the gift of several donors, comprising an old-master Deposition scene flanked by smaller saints in an Arts-and-Crafts style painted by Thomas Noyes Lewis. Inscriptions suggest that the main painting may have been given by the widow of Lord Edward Spencer-Churchill (d.1911), son of the 6th Duke of Marlborough. Of unknown provenance, it has been identified as a hitherto unnoticed seventeenth- or eighteenth-century copy of a painting by Rubens and his workshop, which exists in several versions. The earliest, painted for a church in Lier in 1628, is now in the Hermitage at St Petersburg. (fn. 96) The reredos is now housed in St Silas's Church (see under Penton Street, page 380).

504. All Saints' Mission, White Lion Street. Perspective by Geoffry Lucas of original design for mission church interior by R. A. Briggs, architect, 1901

505. All Saints' Mission, White Lion Street, in 1961, showing front range of 1926–7. Demolished

The mission continued to expand under Preedy's aegis. Around 1910–12 a hall and other additions were made. (fn. 97) In 1926–7 all the frontage buildings at Nos 90–92 were rebuilt by Holland & Hannen Ltd in a plain brick idiom, with a centrepiece in faience or reconstituted stone over the entrance to the church and gym (Ill. 505). (fn. 98) The purposes of this front building were partly educational, partly residential, accommodating the 'missioner' and assistant clergy. (fn. 99) After Preedy's death in 1928 the mission lost its élan. It was united with St Silas's parish in 1936 and closed in the mid-1950s. Demolition took place around 1961. (fn. 100)

Other Buildings

No. 9 is an office block on the site formerly occupied by the north end of the Angel Cinema (see pages 453–4). It was built in 1986–7, when speculative offices were beginning to spread around the Angel, along with industrial units to the rear on much of the rest of the cinema site. The development was by Rank City Wall Ltd, with Anthony P. G. Borley, architect, and McLaughlin & Harvey Ltd, contractors. Among the occupants is the Chartered Institute of Housing. (fn. 101)

Nos 10–14 was built in 1928 by G. Cooper for Lawson's Ltd, drapers and clothiers, to the designs of Montagu Evans. Replacement windows detract from the elegance of the long, low front, a neo-Classical composition with Portland-stone pilasters. The two steel-framed shop floors were originally top-lit, with a central elliptical well. In the post-war decades the building housed BICC Ltd (British Insulated Callender's Cables). It has since been adapted for office use. In 2006 planning permission was secured by Powderworth Ltd for demolition and replacement with a five- and six-storey building, designed by Thomas Nugent Architects for commercial and office use with flats above. (fn. 102)

Nos 15–18 is a five-storey block of 2006–7, built for the Community Housing Group with Islington Council, to combine shared-ownership apartments, key-worker flats and general-needs dwellings with commercial units. It was designed by JCMT Architects, and built by Kingsbury Construction Co. Ltd. It replaces a three-storey neoGeorgian building of 1927 that housed Watkins & Watson, engineers who specialized in organ-blowing apparatus and hydraulic engines. (fn. 103)

Nos 19–23. The old houses here were acquired in 1920 by G. Betjemann & Sons as an extension to their works in Pentonville Road. They subsequently built a cabinet factory on the gardens of Nos 21 and 23. In 1952 the Medici Society, which took over Betjemanns' premises after the firm was wound up, planned to build a warehouse over the whole site of Nos 19–23. This was eventually built about 1960, to the designs of Lewis Solomon, and since the society's departure in 1999 has been partly converted to offices. (fn. 104)

Nos 28–29. This former warehouse, converted to office use in 1970, was built on the site of C. J. Grimes' scrapmetal yard in 1960–1, to the designs of W. C. & R. D. Kain. Vibrated Concrete Construction Ltd were the contractors. (fn. 105)

Nos 34–41. A long, low warehouse of 1970–1, this was designed by John K. Greed for the steel stockholders Macready's Metal Co. Ltd. This firm, which had extensive premises in Pentonville Road and Penton Place, had occupied a site on the west side of Baron Street since the 1920s. (fn. 106) In 1985 the artist Judy Chicago's monumental installation, The Dinner Party, was exhibited here. A triangular table (each side 48 ft long) set with places for 39 great women and standing on a porcelain floor inscribed with the names of 999 further famous women, it now resides at New York's Brooklyn Museum of Art. (fn. 107) The warehouse, long occupied by the Wholesale Lighting & Electrical Co., has been acquired by Noble House Group Ltd, developers. In early 2007 there are plans for redevelopment of the site, to designs by Progetti Architects, for a six-storey 'apart-hotel' or block of serviced short-stay apartments, with ground-floor commercial units. (fn. 108)

Nos 52 and 53 are stock-brick two-bedroom houses, built in 1996–7 as part of the Claremont Heights development in Pentonville Road. (fn. 109)

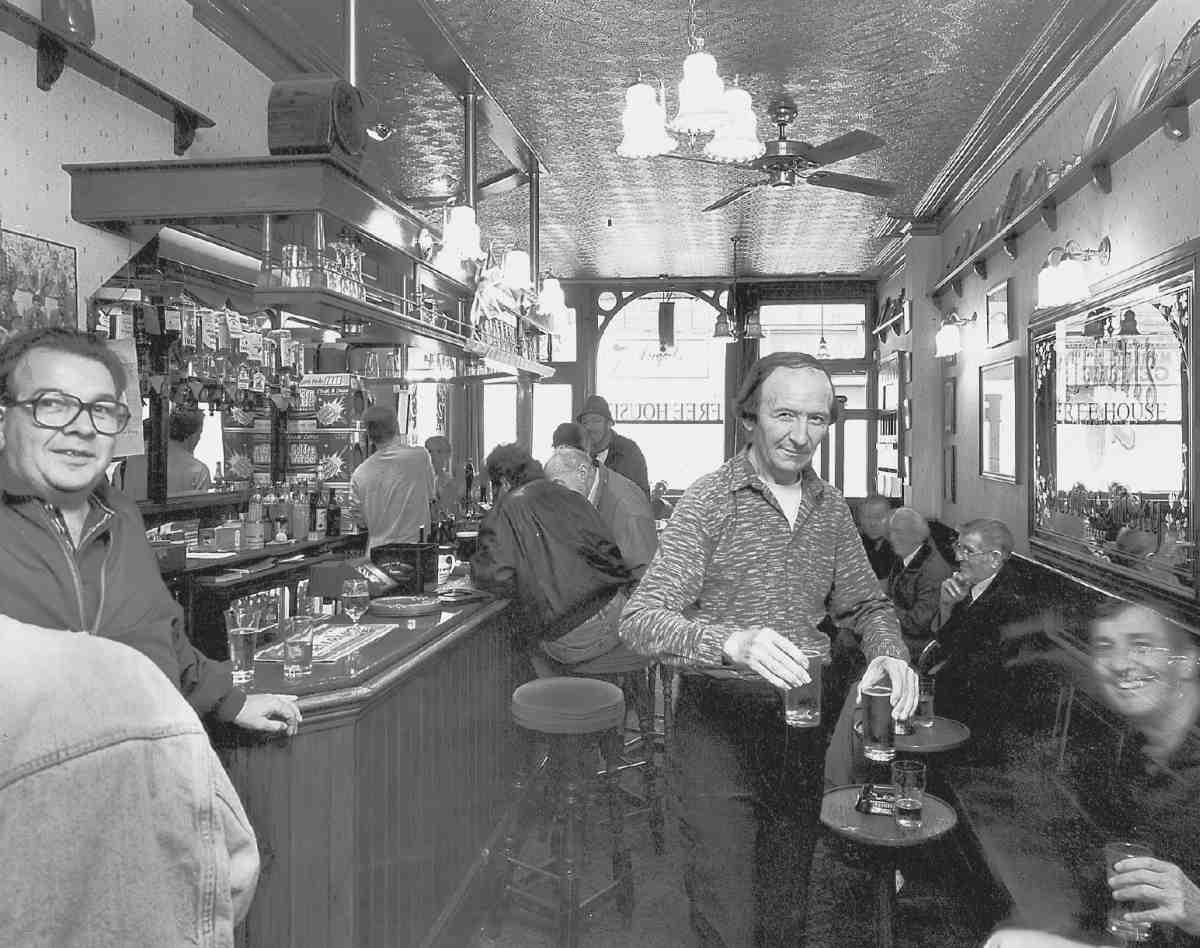

Nos 55 and 56, the Lord Wolseley. No. 55, previously a china warehouse, became a beer-house in the 1860s and was later named the Sir Garnet Wolseley and then the Lord Wolseley after the popular military hero. The present pub dates from c. 1903, and has been extended to incorporate the once separate and seemingly midnineteenth century house adjoining. (fn. 110)

Nos 58–62 is a block of eighteen flats with ground-floor commercial space, built for the Aitch Group to designs by KKM Architects in 2003–4, with No. 8 Godson Street, a similar block of eight flats and offices. (fn. 111)

Nos 63–64. These flats and a clothing factory behind were built by Mattock Brothers in 1923, to the designs of Herbert A. Wright, ubiquitous in Pentonville. The client was a costumier with premises adjoining in Chapel Street (Chapel Market). (fn. 112)

Nos 65–70. A tyre depot and garage, this was built for B. Parrish by Patman & Fotheringham in 1960–2, with Nos 21–29 Baron Street, to the designs of Brown and Brown Architects. The site has been acquired for development by Noble House Group Ltd. (fn. 113)

No. 72 is a remnant of the original development, one of a row of houses built about 1788 by John Brown, bricklayer. There was a baker's shop here from at least 1841 into the 1970s. (fn. 114) White paint on the brickwork no doubt veils some rebuilding, and the property has been extended along Baron Street.

506. Nos 95–101 White Lion Street in 2007, with Eritrean flag at No. 96 (Eritrean Embassy). Geoffrey Reid Associates, architects, 1986–8

No. 73, formerly the Three Johns, stands on a corner site first developed on a lease of 1781 to John Painter. The public house here was known as the Three Johns by 1849, though the name may be a reference to the three Johns who assigned the lease in 1781 to Joshua Johnston, sword furbisher and scabbard-maker—the bankrupt Painter and his assignees, John Bond and John Pricklow. The pub was rebuilt in 1899–1901 for Watney Combe Reid & Co. Ltd. (fn. 115) It is now a restaurant, and the original name has been transmuted to J (fn. 3) or Jay Cubed.

Nos 74–77 and Bradley Close. In 1929 Bradley's Buildings, a little court off Chapel Street, was redeveloped with workshops and warehouses by Commercial Structures Ltd, for Luigi Manze the eel-and-pie shop proprietor (see No. 74 Chapel Market, below). Further redevelopment was carried out for Manze in 1937–8, when the present five-storey factory or warehouse at Nos 74–77 White Lion Street was built, together with the threestorey range to the rear on the west side of Bradley's Buildings, now Bradley Close. Early main occupants of the front range were Kapp & Peterson Ltd, tobacco-pipe manufacturers. (fn. 116) All these buildings are now used as offices.

Nos 78–79. This four-storey warehouse, now made into offices, was built in 1959–60 for Hillwood Properties Ltd and first occupied by a food products company, W. H. Schwartz & Sons Ltd. The architects were Herbert Wright & Tidmarsh. (fn. 117)

Pride Court, at Nos 80–82, is a speculative office building of 1989–94 by Ford Sellar and Morris Developments, its lengthy genesis due to the fact that the owner went into liquidation in 1991. The original design responsibility for the building fell to Architech, but that firm was replaced in 1991 by the Comprehensive Design Group. (fn. 118)

No. 94 was built in 1988–9 for Frederick Barrie Ltd, to the designs of Anthony P. G. Borley, as a warehouse, showroom and office extension of the former Sainsbury's supermarket at Nos 54–55 Chapel Market. It is occupied by the Child Poverty Action Group. (fn. 119)

Nos 95–101 replace a warehouse built for a firm of opticians, G. Culver Ltd, in 1892–3. Plans for industrial redevelopment were abandoned only in 1982, and the present building, a terrace of office units, with archway access to a commercial yard behind, was built in 1986–8. The developers were Plynlimon Estates & Properties Ltd, with Capitol Property Developments Ltd, employing Geoffrey Reid Associates, architects, and Ashby & Horner Ltd, contractors. Architecturally, it represents an early outing for neo-Georgian postmodernism (Ill. 506). No. 96 is now the Embassy of Eritrea. (fn. 120)

Baron Street

Baron Street is named after Joseph Barron, landlord of the White Lion inn during the late eighteenth century, the ground hereabouts, formerly belonging to the inn and used for lodging cattle, being known as Barron's Layers. A large double-fronted house with a southfacing bow and a substantial garden stood on the site of Nos 13–17 from 1787 into the second half of the twentieth century, though the garden was largely built over by the 1890s. Built by Thomas Bell, a Bloomsbury carpenter, this property was leased to and first occupied by John Hugh Griffith, a servant of the Bank of England (fn. 121) It was perhaps here that J. Launcelot Smith, head of the clockmakers J. Smith & Sons, lived until his death in 1864. (fn. 122) The other side of the road, leased to Thomas Collier, was more humbly built up in 1787–93, as was the north half of the street, which was known as Suffolk Street until 1908, and off which ran courts with even smaller houses. Much of Suffolk Street was redeveloped in the late nineteenth century when the first leases expired. (fn. 123)

Nos 2–10. Now called Face House, this was built as a warehouse in 1968 to the designs of W. C. Kain. (fn. 124)

Nos 12–20. Originally a warehouse and garage, with upper-floor offices, this was built in 1968–70 for the legal firm Lewis Silkin & Partners. The architects were Iskip & Wilczynski. (fn. 125)

Nos 22 and 24. are a pair of shophouses, perhaps rebuilt c. 1878, at the time of lease renewal.

Nos 26–30. This block of shops and offices was built in 1939 for Luigi Manze by Mattock Brothers, as part of his redevelopment of Bradley's Buildings (above), replacing the early nineteenth-century cottages of Suffolk Place or Court. (fn. 126)

Nos 13–17. Abutting the return flank of the Jurys Inn hotel on Pentonville Road, this facetiously neo-modernist five-storey block of flats and shops was built in 2002–3 for Try Homes, to designs by Nigel Clark Architects (Christopher Moore, project architect). (fn. 127)

No. 19 is a shophouse, probably of the late 1880s, its windows later enlarged.

Nos 21–29, and 1–7 Baron Close. A block of flats and shops, this was built for B. Parrish in 1960–2, to the designs of Brown and Brown Architects, Patman & Fotheringham being the builders. (fn. 128)

Nos 31 and 33 are a pair of one-bay houses, perhaps a redevelopment of c. 1878, that retains its Victorian shopfront with two canted bays. The improbably worded facia board of William Yearley, 'street trader and wholesaler of groceries' pastiches a genuine old facia visible for many years, announcing 'Wm Yearley, groceries & canned goods'. Long semi-derelict, the houses were used as a store by Chapel Market traders until refurbishment in 1999. A mansard floor and new stair-tower were added, and the whole was converted to residential use over offices.

Chapel Market

Of all the streets in Pentonville, only Chapel Market can fairly claim to have retained its historical character essentially intact through the upheavals of twentieth-century redevelopment (Ills 426, 427). Much of that character derives from the famous street market, the importance of which was acknowledged in the change of name from Chapel Street in 1936. More derives from its status as a general shopping street. Neither market nor shops date back to the early history of the street, which was largely built up in the 1790s and was at first almost entirely residential, its mostly three- or four-storeyed houses set behind small forecourts (Ills 481, 482). It was well into the second half of the nineteenth century before shopping really took hold, reaching its full extent only in the 1880s and 90s.

At this time, Chapel Street was a commercial artery in a district of spreading poverty and squalor. A house in the street itself was singled out in 1885 'as a fair illustration of many of the dwellings of the poor, not only in Clerkenwell but throughout London'. This was No. 13, where 36 people lived, a single wc shared between them. By the time these conditions were published the house was one of a row that had been leased to the architect E. P. Loftus Brock, who undertook extensive improvement and modernization. (fn. 129)

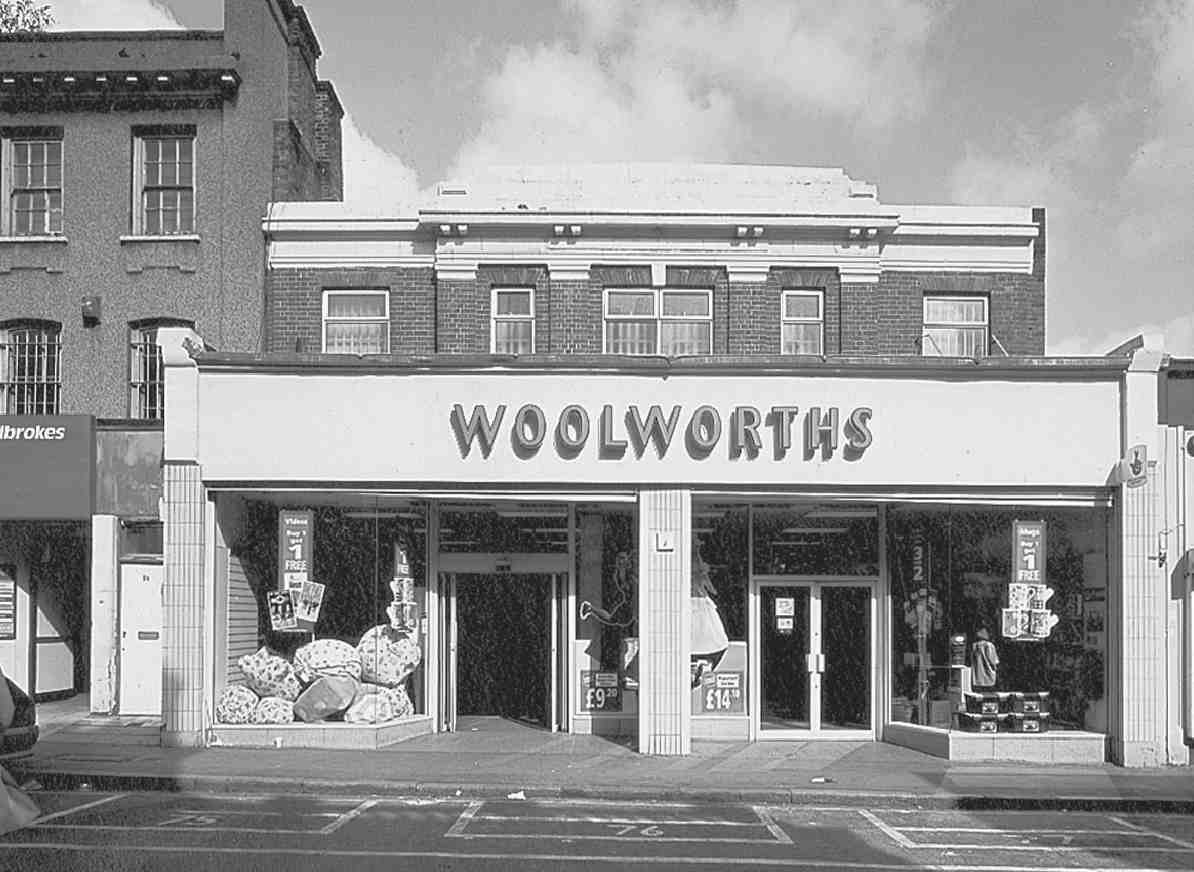

Architecturally, the metamorphosis from residential to shopping is chiefly apparent in the extensions built over the old forecourts. Apart from that, the scale and form of most of the original development has been preserved, despite much rebuilding or refronting of individual houses, particularly in the 1920s and 30s. In matters of detail, these rebuildings range from the crude and spare to the ornate, and even sophisticated. Towards the east end of the street and the busy shopping area around Islington High Street some of the narrow house-plots were amalgamated when chain-store branches were built in the 1950s and 60s. The greatest concentration of original houses is on the north side of the street towards the west end.

The anomaly of Chapel Market is that while there is a market there never was a chapel, or at least never one of any significance. Chapel Street was so called as early as 1781, long before a single building had been erected. (fn. 130) That the street itself was in contemplation some years earlier is shown by the 1775 building lease of the Salmon and Compasses on the corner with Penton Street, which refers to an intended street on the south side of the new pub. (fn. 131) The name was presumably chosen in anticipation of the building of a chapel of ease on a site 'near Penton Street', authorized by the Clerkenwell Paving Act of 1777. That chapel was ultimately built some way west of Penton Street, on the north side of the New Road, eventually becoming the church of St James, Pentonville (see page 355). A clue to the originally intended site may lie in the naming of Chapel Place, a dead-end turning on the north side of Chapel Market towards Liverpool Road. A large plot at the top of Chapel Place, extending to Sermon Lane (now subsumed in Tolpuddle Street) was perhaps the place (Ill. 482), but around 1795 there intruded a row of cottages called Mount Sion (see below). That name, however, as that of Sermon Lane, more likely refers to open-air preaching on White Conduit Fields than to a one-time intention to build the chapel of ease here.

Directly opposite Chapel Place, No. 62 Chapel Market was a public house throughout the nineteenth century and until its demolition in the 1960s, always known as the Chapel House, and shown as such on Hornor's survey of 1808. The rating assessment for 1794 shows the site occupied by a house (No. 62) rated at £20 and a 'Chapel' at £6 here, perhaps a small place of refreshment called The Chapel rather than a place of worship (which would not normally be subject to rates). The site of the 'Chapel' was evidently later annexed by No. 62, which had a wider than usual frontage.

None of the early buildings of Chapel Street survive in entirely original form, owing to rebuilding in whole or part and the creation of projecting ground-floor shops. But many of the plots and the scale of building remain the same, and a number of houses do retain substantial amounts of early fabric. There is considerable variation in scale, both in plot widths and heights, as is evident in the best-preserved run of old houses on the north side at Nos 12–19. From early twentieth-century redevelopment No. 11 stands out as a good early Georgian imitation— much too early to fit a street of the 1790s, but betterdesigned and executed than other rebuildings near by. On the south side there is a long line of dullish 1920s rebuilding to the west. Overall, the south side is the less interesting architecturally, though some plain widefronted post-war blocks have the virtue of preserving the height of building in the street generally.

507. Nos 15–19 Chapel Market (left to right) in 2007

Building development, c. 1789–c. 1818

508. Nos 17–19 Chapel Market (right to left) backs in 1998

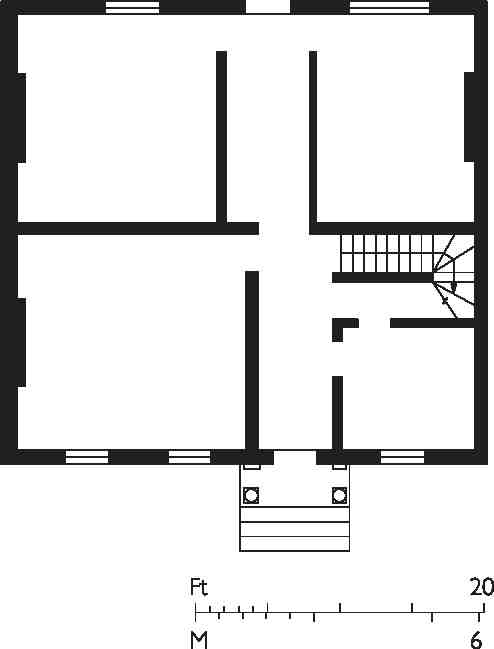

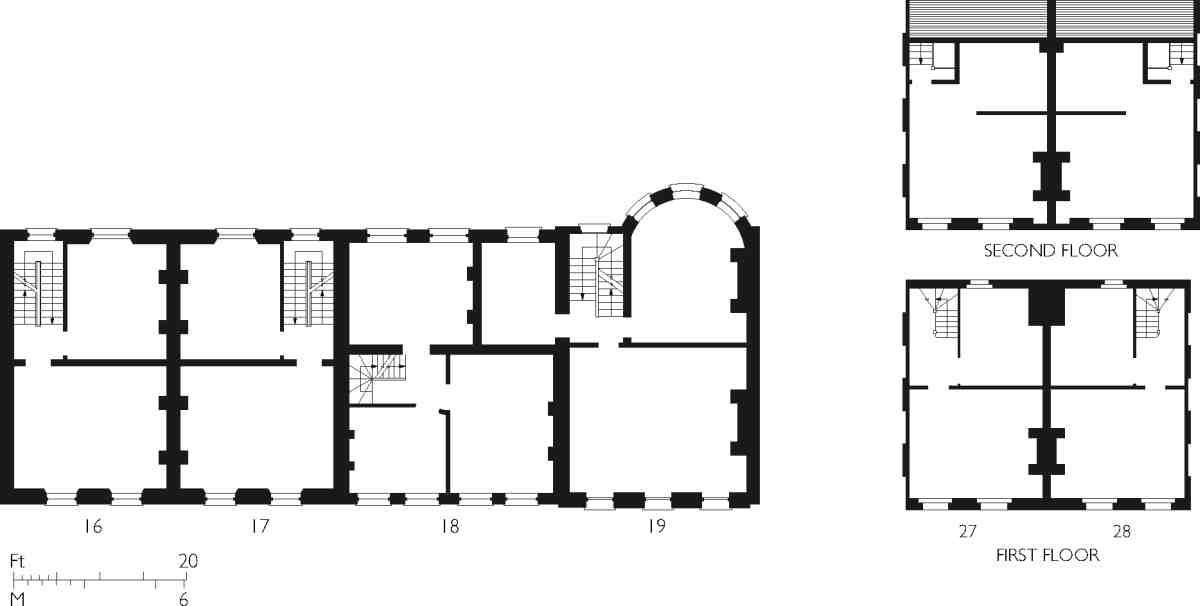

509. Chapel Market houses. First-floor plan of Nos 16–19, and upper-storey plans of Nos 27 and 28, as built

Chapel Street was built up from about 1789, the first surviving rating assessment being for 1790, when 21 properties were occupied, four houses were empty and sixteen were in building. In 1792–3 the ratebooks list 49 occupied properties, one of them a warehouse, plus eleven empty and eighteen in building. By 1795–6 building was tailing off, with rates paid on 65 properties, leaving nine empty and ten still under construction. When these last houses had been completed, the street was almost entirely built up. The principal developers, nominally working under the eye of Thomas Collier, Henry Penton's steward, were: on the north side, Christopher Bartholomew, gentleman, a prominent local property-owner and proprietor of the Angel Inn and White Conduit House; Alexander Hogg, a bookseller of Paternoster Row; on the south side, Thomas Kennedy of Great Queen Street, gentleman, and John Brown, bricklayer. Edmund Hague, a painter who took on a large section of the south side of the street, went bankrupt about 1790. One of Hague's assignees was Joshua Hodgkinson, who was at this time also involved with development along what later became King's Cross Road as well as at the west end of Pentonville. Among others involved were William Walsham, a bricklayer who took up residence at No. 26 Chapel Street; Edward Pewtner, a Charterhouse Lane bricklayer; James Clappe, carpenter; and Charles Douglas, a carpenter also active in Penton Street and Penton Place. (fn. 132)

510. Nos 4–8 Chapel Market (right to left), backs in 2007

Bartholomew's 99-year lease in 1781 took in the sites of Nos 3–25. (fn. 133) A few houses were up by 1790, and all but Nos 15–18 by 1795. That gap, perhaps left for a roadway that was abandoned, was filled by 1811. Most of these houses (Nos 3, 5, 6 and 12–24) survive to a greater or lesser extent. Nos 5 and 6 are a pair of 1792–3, retaining their original form behind shop additions. Typical of the area's smaller houses, they have two-bay 15 ft fronts of three storeys, with the upper storey as garrets to the back, in steeply pitched tiled gambrel roofs, hipped on No. 5 (Ill. 510). The narrow back rooms were heated from angle fireplaces, an old-fashioned feature in the 1790s, used here, no doubt, to avoid loss of room width. (fn. 134)

Nos 12–14 of 1793–4 are rather bigger, with three-bay 18 ft fronts, and three full storeys under slated mansard attics. No. 15 of c. 1803 is yet taller, with considerably greater storey heights (Ill. 507). There was perhaps a raised ground floor here; the shop projection (the last on the street) was not added until 1922. Nos 16 and 17, a mirrored infill pair of 1811 (Ill. 509), are similar but with the attics rebuilt as a full fourth storey, perhaps in 1908, when the shop projection was built. By 1813 George Robinson, the eminent bookseller, was living at No. 16, a measure of Pentonville's early success in establishing itself as a respectable professional address. (fn. 135)