Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Pentonville: Introduction', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp322-338 [accessed 15 April 2025].

'Pentonville: Introduction', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 15, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp322-338.

"Pentonville: Introduction". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 15 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp322-338.

In this section

Chapter XIII. Pentonville: Introduction

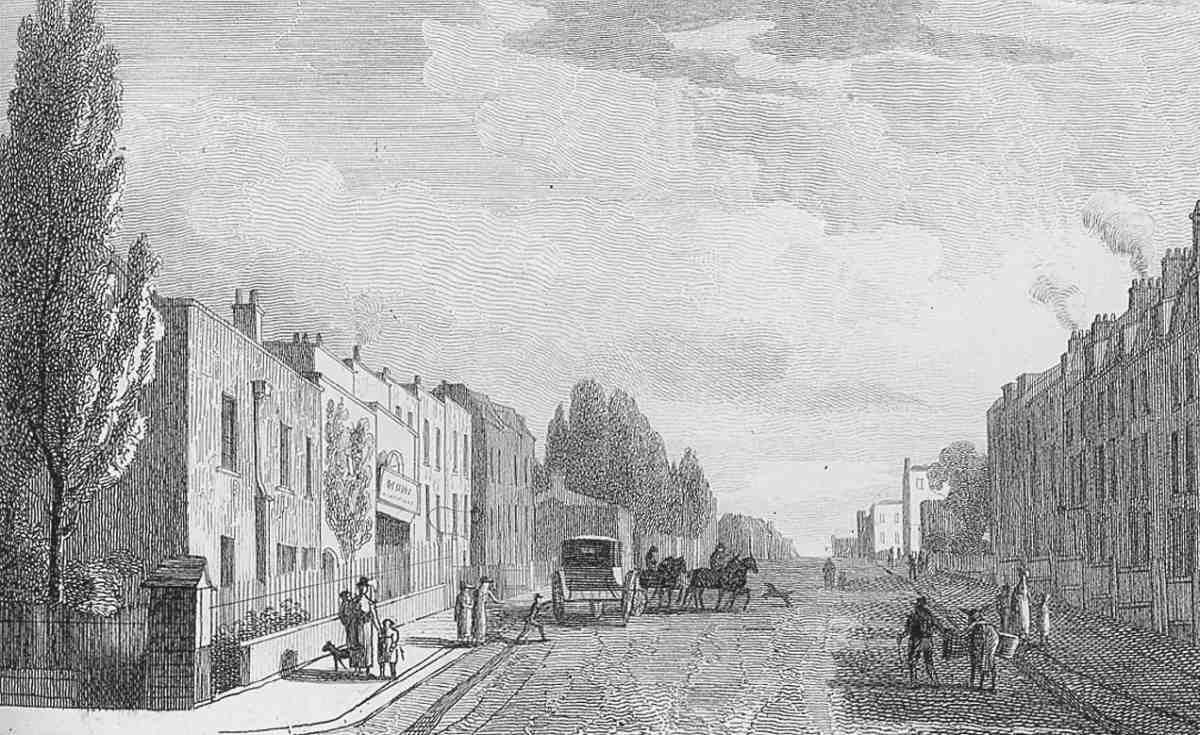

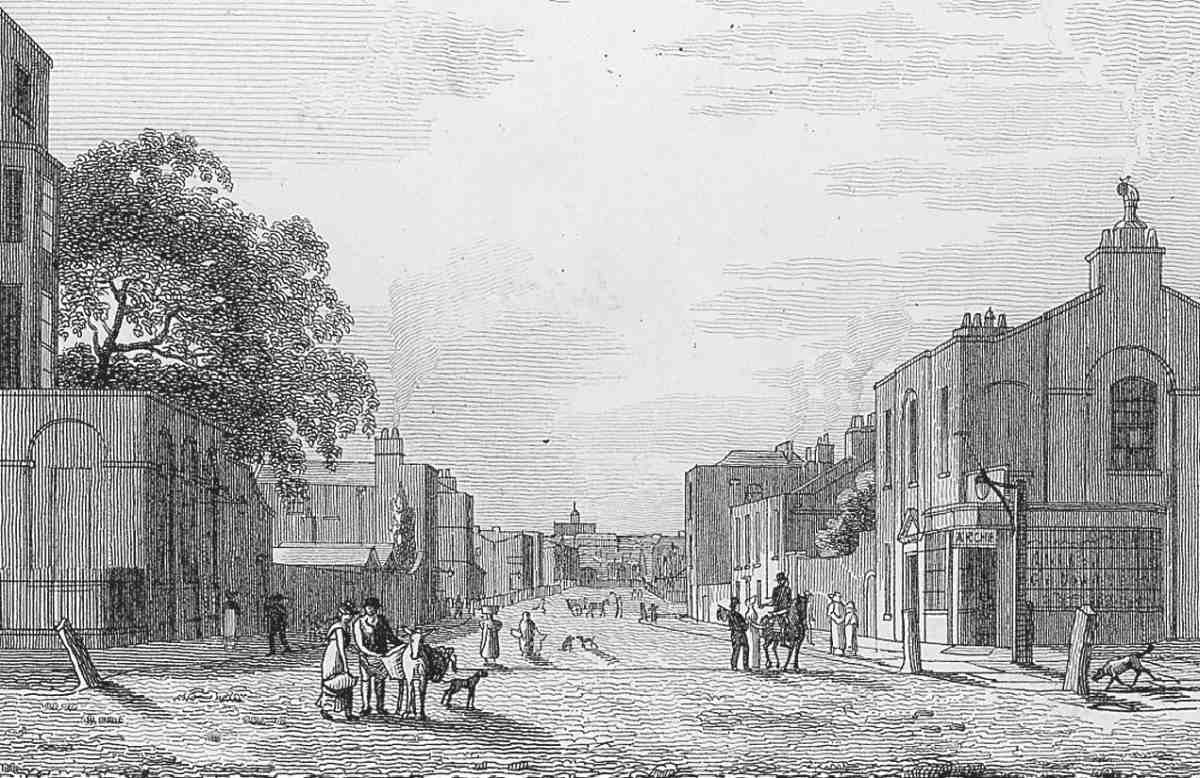

420–422. Early views of Pentonville. Top: New (Pentonville) Road, looking west. Penton Street on the right, Pentonville Chapel in the distance. On the left, houses in Queen's Row. Middle: John (later Risinghill) Street, looking east. Bottom: Collier Street, looking east. Hermes Hill House is on the horizon

The name of Pentonville has fallen resoundingly and, it would seem, irretrievably from favour. Pentonville was perhaps the first new town or suburb in England to have the French suffix that became so widespread in the nineteenth century, especially in North America—though not in London. In its early days the name carried very different connotations from those it later acquired. The misnomer Pentonville Prison—the prison is in fact some distance to the north, on Caledonian Road—no doubt had a part in tarnishing its reputation. Indeed, the word could hardly have been more subtly appropriate to a prison, with its suggestion of pent-upness and penitence, its echoes of evil and bastille.

The name Pentonville seems to have been coined about 1787 to describe the suburb that had been evolving slowly over the previous twenty or so years on the estate of Henry Penton, MP, of Winchester. (fn. a) Its choice, in the Francophilic years before 1789, was perhaps a one-upping response to Somers Town, nearly adjacent to the west and begun in earnest in 1786. A name was certainly needed, for Penton's land was in an ambiguous location—mostly in the northern division of the parish of St James, Clerkenwell, called Islington; partly in the parish of St Mary, Islington. But while it did include a small area identifiable as a section of the roadside settlement of Islington itself—part of Islington High Street and what is now Liverpool Road—Pentonville was essentially something separate and distinct. It stood on the high ground well to the north of old Clerkenwell, facing the city across the fields and reservoirs of the New River Company, with the thirty-year-old New Road, hitherto a lonely bypass, forming its main highway.

Pentonville was built amidst arcadian surroundings. White Conduit Fields and Copenhagen Fields to the north were among Londoners' traditional recreation grounds. On the Penton estate itself there were bowling greens and places of resort. Penton Street, the first street to be laid out in the new suburb, followed the line of an old footpath that led past the bowling greens to the White Conduit House and on to Hampstead and Highgate (Ill. 423).

By the time that extensive building took place on the New River Company and other estates to the south, in the early decades of the nineteenth century, Pentonville had long been a favoured abode for 'gentlemen and affluent tradesmen'. (fn. 2) It is not surprising, therefore, that these emerging districts were ready to adopt its name, in preference to Clerkenwell, with its increasingly industrial connotations, or else some new and untried designation. When in 1835 Charles Dickens, calling at George Cruikshank's house in Amwell Street and finding him out, 'strolled about Pentonville, thinking the air did my head good' and looked at houses in the new streets, he was not referring to the Penton estate, where the streets were fifty or more years old.

Until well into the twentieth century it was quite usual for localities as far south as Lloyd Baker Street and River Street to be regarded as part of Pentonville, and, on the north side of Pentonville Road, parts of the parish of Islington also came to be known as Pentonville. But in later years, with continued social and demographic change, Pentonville receded to something like its original extent— essentially the area alongside Pentonville Road, between the loosely defined, inter-parochial districts of King's Cross and the Angel, its heartland the densely inhabited area on the north side of the road as far as the boundary with the parish of Islington (Ill. 426).

Pentonville's comfortable, even fashionable, reputation faded during the first half of Queen Victoria's reign, for several reasons. The building-over of the picturesque fields to the north, the encroachment of building and later of industry from the south and west, the advent of King's Cross Station, increased traffic on Pentonville Road, and the lure of new suburbs further out combined to undermine its attractions fundamentally. Along Pentonville Road, former private houses became business premises, sometimes of a professional nature but more often than not for some craft or manufacturing activity. On the side streets, private residences large and small became boarding houses, lodgings, tenements, and in some streets shops. Where gentility survived, it was increasingly shabby. Mr Micawber, with his Pentonville lodgings, was no doubt typical of many early Victorian residents.

By the late nineteenth century, the area around and to the north of Pentonville Road was firmly established as a busy urban quarter with a multitude of productive activities, often highly specialized, in warrens of converted houses, sheds and workshops. Physically and socially, there was much squalor. A popular novel of 1891, set in 1877, describes a stroll from King's Cross 'up the dreary slope of Pentonville as far as the noisy draggled, and vilemouthed Angel'. (fn. 3) The predominantly working-class population was made up in large part of unskilled workmen and their families—railwaymen, porters, carmen, labourers—with an increasingly high proportion of foreign émigrés: Russians, Poles, Germans and Italians. Despite the appearance of a number of substantial new buildings across the district—factories, schools, model dwellings— the greater part of the late eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century fabric remained: from double-fronted merchants' houses with bow windows, Coade-stone decorations and good-sized gardens, to tiny workmen's cottages in blind alleys.

423. The western bowling green at Dobney's, looking south, c. 1730. The footpath on the left is on the line of present-day Penton Street

There was a certain amount of piecemeal rebuilding of houses, particularly in Risinghill, Rodney and Collier Streets, specifically to meet the demand for good-class traditional lodgings. According to George Baxter, a surveyor who oversaw the maintenance and rebuilding of a number of houses in this part of Pentonville during the 1880s and 90s, the tenants were mostly men employed in the nearby rail depots and goods yards, who greatly valued lodgings near their workplace. The small flats, typically one to a floor and let on weekly tenancies, offered just the degree of comfort, convenience and privacy required by respectable working families, without the 'barrack-like' look of model dwellings, their open entrances and draughty staircases and corridors. (fn. 4)

Around 1900 Pentonville experienced a sharp downturn in its economic fortunes and social status. Improved public transport, allowing those who could afford it to move away, and foreign competition in watchmaking and other manufactures were among the causes. A horse-tram service had operated on Pentonville Road since 1883, but the real revolution came when the London County Council's subsidized electric tram service opened in July 1907. (fn. 5) One of Pentonville's most characteristic establishments, the private lodging-house or tenement house, often one of several run by the same lessee, ceased to be economic. Falling demand, increased repair costs, improved sanitary requirements, and high ground-rents set in more promising times were all contributory factors. At the same time, slum clearance in central London had generated an influx of low-class, transient tenants. This reduced hitherto reasonably respectable parts of the district to disorderly slums.

By the First World War much of Pentonville was badly in need of improvement or outright redevelopment. The Penton Estate, the main landowner, had long encouraged the piecemeal refurbishment and replacement of old houses and shops, and from 1898 T. H. Watson, the estate surveyor, had pursued an improvement scheme in White Lion Street. After 1921 his successors Gunton & Gunton oversaw renewal with more vigour, and the results are still noticeable today, particularly in refrontings and rebuildings along Chapel Market and Pentonville Road. But ultimately the Estate was unable to prevent the economic collapse of the principal residential part of the district it nominally controlled.

The 1920s had seen some housing built by Finsbury Borough Council, but it was the Busaco Street scheme, designed by Tecton in 1937 and eventually expanded as the Priory Green Estate, which heralded large-scale redevelopment. Delayed but catalysed by the Second World War, municipal reconstruction transformed swathes of Pentonville throughout the third quarter of the twentieth century (Ill. 427).

In common with much of Clerkenwell, Pentonville lost most of its industry in the 1960s and 70s, though as late as the 1990s it was still possible to find small specialist activities such as metal-spinning carried out in obscure workshops, and at least one large commercial operation, Macready's steel stockholding, remained. In the early twenty-first century this is no longer the case, and the dingy relics of Pentonville's industrial past have almost completely vanished. Pentonville is much regenerated. There are diverse reasons. Office development became important in Pentonville from the 1970s following a change in planning policy by Islington Council, and the abandonment soon after of the Greater London Council's plans for improvements freed the Angel area from years of blight. The property booms of the late 1980s and late 1990s led to a number of new developments, and the refurbishment of old business premises as flats, studios and offices. Too much of the old building fabric had disappeared for Pentonville to experience the same kind of gentrification that had spread south from Islington and also become established south of Pentonville Road. However, other kinds of change have taken place—new residential building around White Lion Street, conversions and new buildings for student accommodation, and the sale of council houses.

Old Pentonville may be regarded as a lost suburb of London, for the remains of the first-generation buildings are few. They are largely confined to Chapel Market and the east side of Penton Street. Saving the rather younger terraces of Northdown Street, nothing of the once decent residential streets further west remains but the pattern of the roads themselves, and that not in its entirety.

The Penton Estate, 1710–1951

From its earliest days until the dispersal of the Penton estate in 1951, the leading influence on the development and character of Pentonville came from the Penton family and their agents. Though Pentonville grew beyond the confines of their land, the original suburb was almost entirely developed on building agreements and leases granted by successive Pentons. None of them seems ever to have resided in Pentonville, but their association with the area was far from merely a business one. Members of the family were interred in the vaults at Pentonville Chapel, where at first they rented a pew. (fn. 6) By the late nineteenth century, the social decline of Pentonville encouraged a still closer relationship with the district, but ultimately the complexities of the leasehold system and the scale of new investment needed defeated the family's attempts to manage the estate effectively.

The Penton family and descent of the estate

The estate was acquired in 1710 by Henry Penton (I) of Lincoln's Inn, a bachelor then aged about seventy, from an Islington family named Wood. A Sir Robert Wood had once lived on the estate in a 'great edifice', which stood on what eventually became the north-east corner of White Lion Street and Islington High Street, and part of which, turned into shops, was still standing in the early nineteenth century. (fn. 7) Sir Robert was the son of Roger Wood of Islington, sergeant-at-arms, and was a royal pensioner under James I and Charles I. (fn. 8) Part of the estate was mortgaged by his nephew's widow, Mary Wood, in 1695. Three years later her elder son Roger took out a new mortgage of the whole freehold part for £3,300 (including £1,000 to pay off the earlier loan). This mortgage passed through several hands before it was acquired in 1707, with the smaller copyhold ground at the east end of the estate as further security, by Henry Penton, for £4,400. (fn. 9)

Roger Wood died owing several thousands of pounds in addition to the mortgage sum. Mary Wood borrowed £350 from Penton to pay off some of this debt, and finally she and her younger son Robert sold their interest in the estate to him. The total consideration, including the existing mortgage and loan, was £8,930. (fn. 10)

The estate in 1710 consisted of more than 87 contiguous acres stretching from Maiden Lane (modern-day York Way) to Islington High Street, mostly in Clerkenwell parish but partly in Islington, and twelve further north in Islington, called Vale Royal (later corrupted to Belle Isle). All the land had formerly belonged to monastic foundations. Most was part of the Commandery Mantells formerly owned by the priory of St John of Jerusalem, and 42 acres were still known by that name. Another eighteen had become the Hanging Mantells. The main piece of Islington land, 23 acres along the east side of Maiden Lane, was called Charterhouse Closes, having once belonged to the Charterhouse, while Vale Royal was once part of the estate of Vale Royal abbey in Cheshire. (fn. 11) Towards the eastern end of the estate were the Prospect House and its bowling greens, a popular place of resort. Further east, along Islington High Street, were various copyhold tenements, including the White Lion inn and the former house of Sir Robert Wood, together with at least four acres of copyhold pasture, all this customary property being held of the manor of St John of Jerusalem. (fn. 12)

Henry Penton came of a Winchester family, and was a younger brother of Godson Penton, a woollen merchant who became mayor of the city. (fn. 13) Another brother was Stephen Penton (1639–1706), who became principal of St Edmund Hall, Oxford. As well as Winchester, the Pentons had close links with Princes Risborough, where they had held property since the sixteenth century. In 1686 Henry acquired a leasehold estate in South London, in the parish of St Mary Newington, consisting of Walworth manor house and surrounding fields, and at some point also obtained property in Stanford, Norfolk. (fn. 14)

In 1715, Henry Penton died leaving his estates to his nephew John Penton, instructing that he should be buried in the parish church of St James's, Clerkenwell, where he was commemorated by a mural monument, now in the rebuilt church. After John Penton's death in 1724, the estate passed to his son Henry Penton (1705–62)— referred to here as Henry II, although John also had a brother Henry who died in 1728. Henry Penton II became MP for Winchester and in 1761 obtained the lucrative position of Purveyor of All His Majesty's Mail.

The founder of Pentonville was Henry's son, Henry Penton III (1736–1812). He became a Lord of the Admiralty, and this naval connection was marked by the naming of a new street after Admiral Rodney. His first wife, Ann, was a daughter of John Knowler or Knowles of the Inner Temple. She was still alive in the 1780s, when he began living with his wife's maid Catherine Judd of Stratford-on-Avon, setting her up in a new house in Piccadilly. Property in Penton Street was used to secure an independent annuity for her. (fn. 15) Catherine, whom he married in 1808, was the mother of his heir, Henry Penton IV (1790–1835); after Penton's death she remarried, becoming Mrs Richard Earle Welby. Her new husband was a relative of Catherine Welby of Islington (c. 1772–1833), the mother of A. W. N. Pugin.

Henry Penton IV, also MP for Winchester, married Mary Pritchard, daughter of Charles Pritchard of Grosvenor Square, in 1814, and their son Henry Penton V was born a few years later. Subsequently, Henry spent much of his time in France, and took a French wife. They emigrated to Canada, where he died.

Henry Penton V (1817–1882), who became a colonel in the 3rd Royal Westminster Militia, and Hon. Colonel of the Finsbury Rifles, married Maria Langley of Brittas Castle, Tipperary. Colonel Penton's eldest surviving son and heir was Frederick Thomas Penton (1851–1929). Educated at Harrow and Oxford, Frederick Penton was commissioned into the Dragoon Guards, becoming captain. He married Caroline Stewart of Ards, Co. Donegal, a grand-daughter of the 2nd Earl of Norbury. Captain Penton served in the Egyptian War of 1882, and in 1886–92 represented Finsbury in Parliament as a Conservative, his slogan 'A Clerkenwell Man for Clerkenwell Men'. (fn. 16) He was appointed Deputy-Lieutenant of Middlesex and High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire, and succeeded his father as Hon. Colonel of the Finsbury Rifles.

With Captain Penton's death in 1929, the estate passed to his son Henry Alexander (Harry) Penton. Harry Penton, a racehorse-owner, lived in Paris, where he seems to have married a Frenchwoman; they had two daughters. He assigned his life interest in the estate to trustees, who included his younger brother Cyril Frederick Penton (1886–1960). Cyril, educated at Eton and Cambridge, trained as a barrister and held various legal appointments in the Civil Service. He appears to have been the last Penton to be involved in the running of the estate, and presumably oversaw its dispersal in 1951.

Estate management

Early development of the estate was carried out conventionally on building leases granted to builders and other speculators or investors. In some cases, formal building agreements preceded the granting of leases, but in others a lease seems to have been made out before any building work was necessarily under way, and this incautious practice continued until the 1890s, when stricter procedures were adopted at the recommendation of the agent, James Gibson. (fn. 17) Decisions on the granting of leases and other matters were arrived at through the co-operation of at least four parties: the current owner, his lawyers, his steward or agent, and an estate surveyor. Later, when the estate was subject to a succession of settlements, trustees might also be involved.

Henry Penton III worked closely with an agent or steward, Thomas Collier, whose salary rose in stages from £20 in 1774 to £60 from 1803, presumably reflecting the increasing amount of estate business transacted by him. (fn. 18) During Penton's absences abroad, this included acting as his attorney in the execution of deeds. He was succeeded by William Vokes in 1814.

From the 1880s there was an estate office at No. 19 (later 45) Penton Street, where Gibson, who had run a school there, resided. By the early twentieth century this had reading and recreation rooms, presumably for tenants, where billiards, bagatelle, chess and dominoes might be played. Day-to-day management, including rent collection, arranging for minor repairs, dealing with tenants and finding new tenants, was carried out here by Gibson, who met Colonel and then Captain Penton regularly to report. Important matters, including renewals and new leases, were referred by him to the estate solicitors, Lee & Pemberton, who in turn referred them to Captain Penton. Penton's brother-in-law George Stewart was a partner in the firm, and they corresponded directly about the management of the estate. Gibson remained agent until 1908, when he was replaced by William Croot, who died in post in 1934, by which time Captain Penton had died and the estate was in considerable decline.

There must from the start have been at least occasional need for the services of a professional surveyor or architect. Who filled this role in the early days of Pentonville is not known, though surviving estate records show payment to a Mr Watson for measuring part of the estate boundary in 1780, and the architect James Carr of Finsbury makes an appearance in the accounts the following year. Watson was very likely Joseph Burges Watson, the father of John Burges Watson, who was the estate surveyor for forty years from about 1840. John's son Thomas Henry Watson, who was designing buildings on the estate by 1876, took over from him. Latterly in partnership with his son A. M. Watson and then with Norman Thorp, Thomas retired in 1912. He was succeeded by William E. Clifton of E. N. Clifton & Son, on whose retirement about 1921 the young Edward Noel Clifton took over. He became a partner in the firm Gunton & Gunton, who oversaw substantial interwar renewal on the estate. (fn. 19)

The role of the Penton family

Evidence for the part played by successive Pentons in the running of the estate is lacking until the late nineteenth century, when both Colonel Penton and his son Captain Penton clearly took active, interested and increasingly paternalistic roles in deciding questions of management. Captain Penton and his wife Caroline were much concerned with the social, moral and religious well-being of local people, and it was presumably this link with the area that prompted him to stand in Finsbury as an MP. He paid for the prosecution of brothel-keepers in White Lion Street in the 1890s, funded the rebuilding of the All Saints' Mission there, and in the First World War saw to it that the mission hall, which people were using as an airraid shelter, was protected against blast damage. He was opposed to nonconformity: writing to his brother-in-law the estate solicitor in 1911 about a proposed hall in Islington High Street, he expressed concern about what might happen should the venture fail and the lessee have to dispose of it: 'I don't wish the hall to be taken by some Mormon or other Non-conformist sect! which might very likely be its destiny in the future'. (fn. 20)

Because of underleasing, the family's control over the management of properties might be at several removes, and Pentonville was far from being a 'feudal' estate. This began to change somewhat towards the First World War, when an increasing number of houses had to be taken in hand from failing lessees and directly managed. In 1935–6, with the new Housing Act as a spur, Cyril Penton raised the possibility of bringing some of the worst tenement houses on the estate up to modern standards, and Gunton & Gunton met the borough surveyor and medical officer to look at a selection of properties in Pentonville. It was a disappointing exercise, the council officials being quite definite that the houses were too old to justify the expenditure that would be needed. It also became clear that Busaco Street, a cul-de-sac, and Warren Street, both especially bad streets, were considered fundamentally undesirable. Nevertheless, Penton pressed on with his plan to bring in specialist surveyors—Irene T. Barclay and Evelyn E. Perry—to produce a feasibility study on reconditioning. Quite what level of work he had in mind is not clear, for he had already expressed concern that Busaco Street and Warren Street would need sanitary and hot-water facilities—surely the most basic of requirements—as well as structural work to improve natural lighting. Barclay & Perry's report was another disappointment, for it rejected the idea of reconditioning altogether in favour of something more radical. Cyril Penton's initiative fizzled out.

After the war, the Penton Estate continued for a few years, but the decline of the area and the public housing drive were against it. In 1951 the estate was put up for auction, a few weeks before the Thornhill estate adjoining in Islington. A number of unsold properties were subsequently held by a private company called the Cockington Trust Ltd, and later by the Chapel Property Holding Co. Ltd until the mid-1960s, and seem to have been disposed of piecemeal to the local authority or private buyers. (fn. 21)

The Area before large-scale development

Before the dissolution of the monasteries, this northernmost part of the parish of Clerkenwell belonged to the Knights Hospitallers' priory of St John of Jerusalem, whose main precinct was in the area now comprising St John's Square. The land was almost certainly used chiefly for grazing, for which, with its natural springs, ponds and lush, south-facing slopes it was ideally suited. In the eighteenth century, if not earlier, parts of the ground were fenced off into 'layers', where cattle destined for Smithfield were held for fattening after their trek from distant farms; a number of inns on Islington High Street catered to drovers and other travellers to and from London. But the ground was also dug for clay or brick earth and gravel, certainly by the 1680s and perhaps much further back. (fn. 22) This was an important and lucrative activity, requiring careful control if the land was not to be simply exploited and ruined. Under his 1767 lease of the White Lion inn and adjoining meadow and cattle layers, Joseph Barron undertook to fill up and level the existing gravel, ballast and sand pits, and faced penalties for digging pits himself, or for breaking up any ground for gardening or arable crops. He also undertook to 'spread 50 loads of good rotten dung on the Mantles', any part of which was liable to be let by Penton for digging brick earth or for building. (fn. 23)

A third phenomenon, coming into focus during the seventeenth century, was the growth of this area as a place of popular resort, for bowling, eating, drinking and entertainments. One of the early establishments in the vicinity catering to pleasure-seekers was just over the border into Islington: the White Conduit House, said to have been opened in 1649. (fn. 24) This stood close to a medieval conduit house from where spring water was supplied to the Charterhouse through a buried pipeline.

The Prospect House and Busby's Folly

Gerard's Herball of 1597 mentions a 'bouling place under a few old shrubby okes' in a field near Islington, possibly an early reference to the Prospect House site. (fn. 25) So called for obvious reasons, the Prospect House stood just south of what is now White Lion Street, roughly on the site of the Claremont United Reformed Church. It was a large property, with carriage access from Islington High Street through the yard of the White Lion inn. There was certainly a bowling green at the Prospect House by the 1630s, a second by the 1660s and a third by 1698. (fn. 26)

The identification of Busby's Folly remains mysterious. Its name evidently comes from the landlord of the White Lion in the 1660s and 1670s, Christopher Busbee. But though Busby's is usually said to have become the Belvidere, the tavern on the corner of Penton Street, this seems to be based on no more than an assumption by Thomas Cromwell. (fn. 27) It cannot be identified with any certainty in deeds relating to the Penton estate or in surviving ratebooks and tax returns. Busby's also seems to have been confused with the Prospect House, for the engraving of 'Busby's Folly' published in Pinks's Clerkenwell almost certainly shows the Prospect House itself (Ill. 424). A possible explanation is that Busby's Folly was the 'Bowl house' on the Penton estate destroyed when one of the bowling greens was curtailed to let the New Road pass by the New River Company's Upper Pond. This structure was replaced at the expense of the road trustees (see page 341), but nothing more is known of it.

Arthur D'Aubigny or Dobney took on the Prospect House and its bowling greens around 1720. His wife, Ann, succeeded him and 'Dobney's', as it became known, con tinued up to 1760. By this time the White Conduit House had become a fashionable resort in the hands of Robert Bartholomew. William Johnson 'fresh planned and laid out' (fn. 28) the Prospect House premises in 1767, using the eastern green as an amphitheatre for equestrian performances, and, two years later, for exhibiting the skeleton of a whale. Showmanship did not save the venture from failure, and the house had brief use as a school before the establishment re-opened by 1772 as the Jubilee Tea Gardens, with booths or 'tea boxes' painted inside with scenes from Shakespeare. This was short-lived and, once White Lion Street had been formed, the house was adapted in 1780 as a discussion and lecture room. The grounds were gradually built over and the Prospect House was demolished c. 1820.

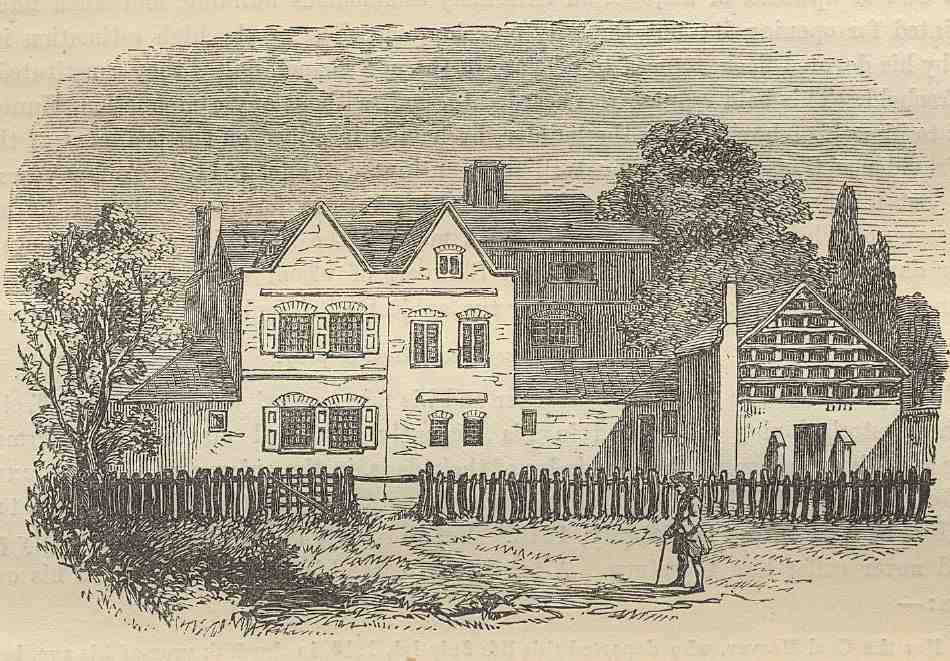

424. 'Busby's Folly'. An eighteenth-century view, published in Pinks's History of Clerkenwell, probably showing the north front of the Prospect House

The third bowling green was probably the site developed by John Pennie in 1768 with a tavern on the western corner of Pentonville Road and Penton Street, called Penny's Folly perhaps in conscious echo of Busby's Folly but soon renamed the Belvidere. A green was maintained and there was also a tea garden and a 'Bunn House'. Rebuilt in the 1870s, the establishment survived as a public house, now a restaurant.

Brickfields

Several well-known brickmakers were involved in brick earth extraction on the Penton estate shortly before its development as a suburb got under way, including Edward Gray and Thomas Bird. Only one, John Weston, became involved in large-scale development there. Gray seems to have taken out a building agreement in 1777, but no leases of houses appear to have been made out to him or his nominees.

The standard rent was £6 per acre for three and a quarter years, and £4 thereafter; some leases also required large additional payments for each acre actually broken up. It was usual for lessees to be required to fill in their pits, and the brickmakers had to respect the requirements of the Act authorizing the New Road by keeping kilns and sheds 50 ft from the roadside. Penton retained a right to let the ground for building, on paying compensation at a rate of £4 10s an acre.

Bird, a builder and bricklayer, and William Lloyd, a plasterer and builder, both of St Marylebone, took nineyear leases on several acres each in 1760. Three years later, Bird leased the Vale Royal for 20 years, and Gray, of St George, Hanover Square, took a total of 33 acres on nineand 21-year leases. In addition to the standard rent, Gray had to pay £145 annually for each acre of ground excavated: eight by 1774, when a new lease was negotiated. He subsequently acquired Bird's Vale Royal lease.

By the late 1760s development of the estate was taking off, and Weston was able to get a 61-year lease of four acres at the west end of the estate, largely for brick earth but also including a new house on the corner of Maiden Lane and the New Road. Other lessees of brickfields included Thomas Wise, who took three and a quarter acres for seven years in 1770, and William Slade, who leased three and a half acres in 1777 for 21 years. (fn. 29)

The Creation of Pentonville, 1764 to C. 1806

Pentonville was developed over many years from the mid-1760s, and areas remained unbuilt on until the early years of Queen Victoria's reign. But 1806–7 marks a watershed in the making of the suburb, for it was then that Henry Penton III sold off the freehold of the as yet largely undeveloped western end of the estate. This western area grew up along different lines, poorer and urban rather than suburban. Pentonville in its original form was a predominantly middle-class residential district.

When building began in the 1760s, the Penton estate was hardly virgin territory to be laid out to any masterplan that might be devised. Much of its future shape was already determined. Most obviously, there was the line of the New Road, providing a great length of valuable frontage, and subject to a statutory requirement for the building line to keep 50 ft from the road edge. At the eastern end were old inns and shops along the west side of Islington High Street, a bustling commercial area which inevitably had an influence on the character of new development. Some constraint was probably posed by the existence of several large brickfields, whose lessees required compensation should any of the ground be required for building development. There were further factors: the existence of the Prospect House and the bowling greens, the fine views over London, and, immediately adjoining the estate, the White Conduit House and White Conduit Fields, prospering places of resort. Although these were before long to disappear under streets and houses, they were in themselves attractions which influenced the kind of suburb Pentonville was meant to be: a distinct 'ville', separated by open land from the edge of the metropolis.

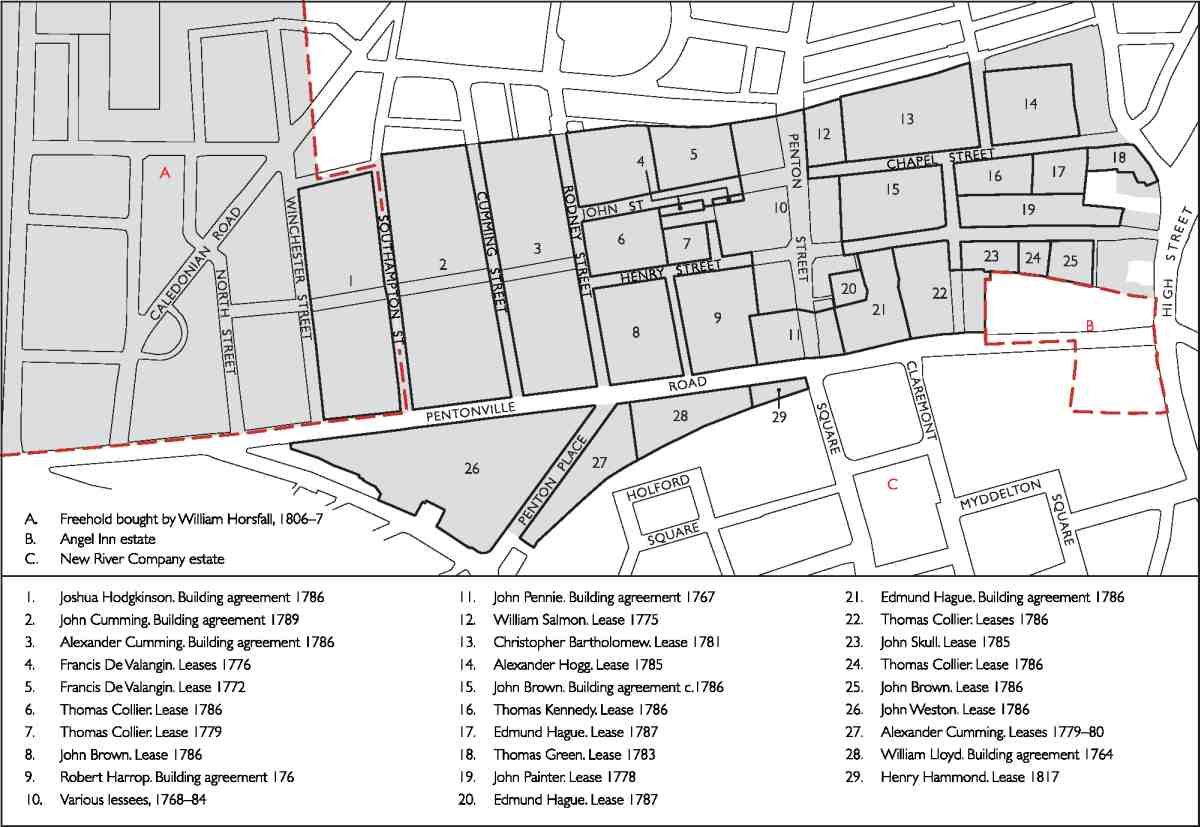

425. Pentonville showing development pattern of Penton estate, 1767–1817

The sequence and process of development

The creation of Pentonville may be said to have begun in February 1764, with the making of the first building agreement between Henry Penton and a would-be developer (Ill. 425). This was William Lloyd, one of the brick-field tenants, who undertook to build at least five houses on about an acre of ground fronting the south side of the New Road, the site today of Nos 91–123 Pentonville Road. The total ground rent was £10. That this was to be a good-quality development was implicit in the long term of the promised leases—120 years. Although the intervening years saw a London-wide building boom, it was not until about 1769 that anything was actually built, and Lloyd himself, if indeed he had any further part in the development, took no leases. The builder seems to have been William Meymott, a Bermondsey carpenter (later 'surveyor'), who acquired the benefit of Lloyd's agreement and took the ground on several leases from Penton in March 1770. Houses had been erected by then, though none was as yet occupied, in what was at first called Prospect Row and re-designated Queen's Row about 1773.

Other early development was concentrated at the centre of the estate, in and around Penton Street, and along the New Road. There were no further agreements for 120-year leases and 99 years became usual. However, a lease granted to Sir Charles Whitworth and John Prujean for a large house on the New Road in 1775 provided for an extra 21-year term after the 99 years were up. (The house seems not to have been built, and the lease was cancelled, perhaps because of Whitworth's death in 1778.) (fn. 30) When John Pennie took out his building agreement for what became the Belvidere in 1767 it provided for 99-year leases. Though his ground was about the same size as Lloyd's, the rent was £58 16s. Two men who took out building agreements in 1768 for houses in Penton Street, adjoining Pennie's development, only obtained 63-year leases. (fn. 31)

Throughout the 1770s development was fragmentary and scattered. In 1769 Robert Harrop undertook to begin what became King's Row, on the north side of the New Road opposite Queen's Row, but little was achieved. Like Queen's Row, this began with a more informal name: Happy Man Row. The embryonic suburb was becoming more dignified. Away to the north Francis de Valangin built himself the substantial Hermes Hill House in 1772–4. Several other lessees filled out Penton Street, building along the west side in the 1770s, and the east side from 1778 up to 1786. These small undertakings included several good-sized double-fronted houses. Mount Place, on what is now the west side of Liverpool Road, also went up gradually from 1771.

426. Pentonville, c. 1874. The broken red line denotes the boundary of the parish of St James, Clerkenwell

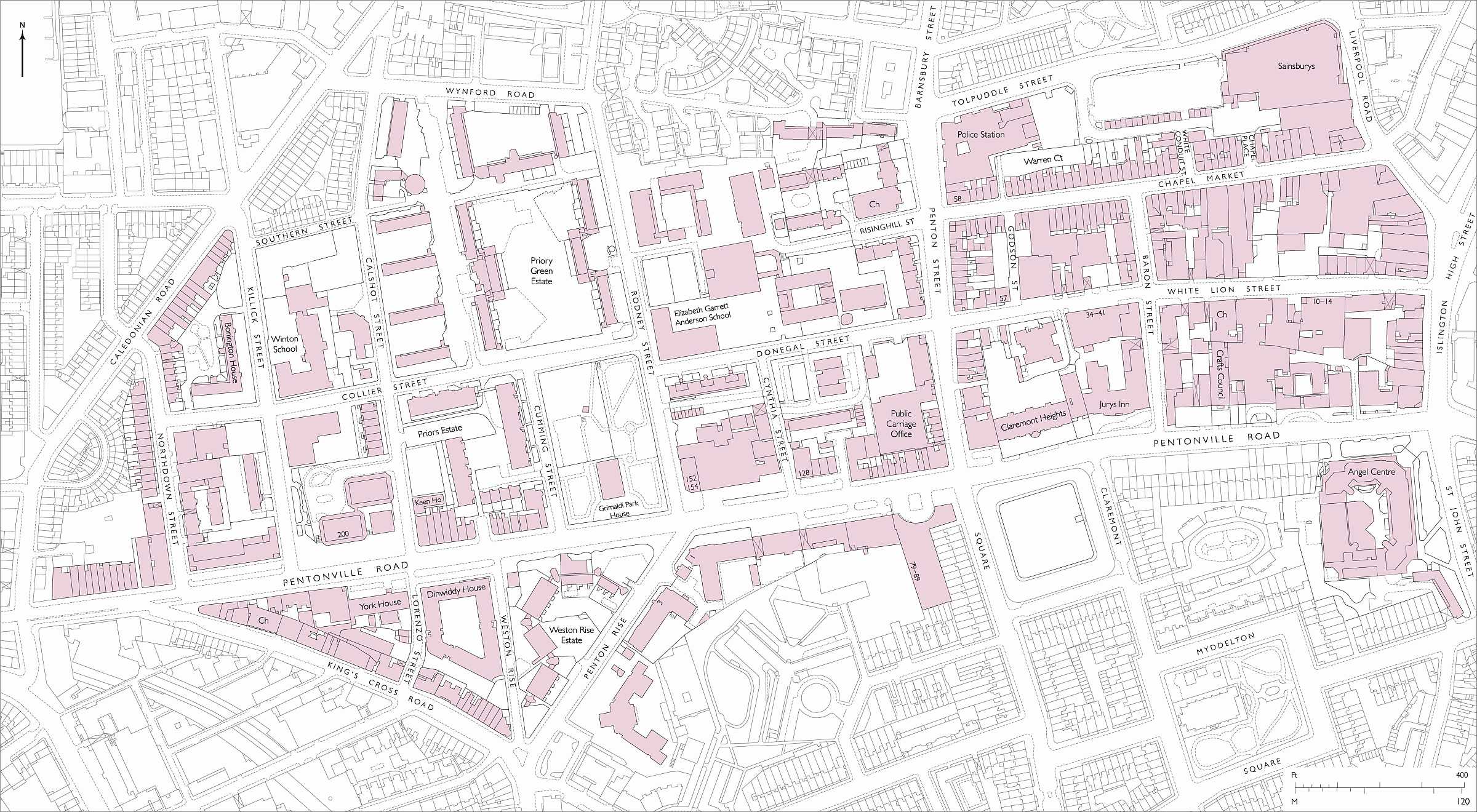

427. Present-day Pentonville, showing the buildings covered in Chapters XIV—XVII and part of Chapter XII

The first wholly new streets led off either side of Penton Street parallel to the New Road, forming a regular grid that had probably been conceived by 1772 when de Valangin's plot fronting John Street was leased. This layout is of interest as an early example of an orthogonally planned suburb, but its regularity may reflect lack of imagination rather than aesthetic sophistication. The surviving estate records give no definite clue to its authorship, though the payment to James Carr of Finsbury in July 1781 of £19 8s 6d 'for drawing a plan for Building' shows the involvement of this architect at a still early stage in Pentonville's development. (fn. 32) Penton Place (now Penton Rise) was laid out west of Queen's Row in 1776–7, on a diagonal parallel to the estate boundary, to maximize frontages. Very little was built along any of the new streets before 1779, and development was still within a framework of relatively small parcels, granted to numerous undertakers from a mix of building-trade and other backgrounds. Several were taken by Collier, others by John Brown, a Holborn bricklayer. Two of the largest, on the north side of Chapel Street (now Chapel Market), went to Christopher Bartholomew, proprietor of the Angel Inn and the White Conduit House, and Alexander Hogg, a successful, elderly City publisher. The first White Lion Street lease was granted to John Painter, a Clerkenwell auctioneer, in 1778, and others followed in the 1780s, when Henry Street and Hermes Street were also being developed. Houses along John Street and Ann (Cynthia) Street were built in the late 1780s, as was Winchester Place, on the north side of the New Road, where the bowling greens had been.

Alexander Cumming, an eminent Scottish clockmaker long settled in London, was one of the most important undertakers. He took the land on the south-east side of Penton Place in 1779 and built a large villa for himself at the northern corner by 1787. By then development had extended further west as Pleasant Row had been built along the New Road's north side, to either side of where Winchester (Killick) Street was to be formed. Most of the western hinterlands were divided up in 1786, in much larger parcels with new streets that had a new geometrical logic. Evenly sized blocks were formed between north—south routes, Rodney Street, Cumming Street, Southampton (Calshot) Street and Winchester Street, all bisected by Collier Street, which aligned with neither John Street nor Henry Street.

Cumming and his brother John took two of four large western parcels. The others went to Joshua Hodgkinson, also active in Somers Town, and John Weston, the brickmaker who also had a presence on the triangle south of the New Road between Penton Place and what became King's Cross Road. Building began forthwith, and included Pentonville Chapel, later St James's Church, at the New Road end of Alexander Cumming's plot; and Cumming House, a villa in the corresponding position on his brother John's plot. A great deal more was done before the outbreak of war in 1793, though much ground north of Collier Street remained open. On Weston Rise, newly formed, building continued up to 1795. York Street was developed in the mid- to late 1790s; Rhodes Buildings, a court off its west side, was built a quarter of a century later. Meanwhile, in the north-eastern sector, Chapel Street was being built from 1789 to 1795, White Conduit Street following in 1795–6.

The stretching of finances that came with wartime inflation was, no doubt, a factor behind the appearance of courts, densely built with diminutive houses to maximise returns; several were formed off Chapel Street and White Lion Street around 1800.

A vivid impression of the new Pentonville is conveyed by the series of drawings made by A. C. Pugin in the early nineteenth century (Ills 420–22). It is apparent that Pentonville's charms were many but that architectural pretension or sophistication was not one of them. The elevated setting, wide and rationally planned streets, and the varied scale of the houses made it a healthy, pleasant and convenient place. The plain brick streets were broadly regular, if not strikingly so, with random variations in heights and plot widths, as still witnessed by the north side of Chapel Market and the east side of Penton Street, the only places where an impression can still be gained of the original housing. Fronts were mostly undecorated and houses were generally laid out two rooms deep in the standard rear-staircase terrace form, though with some variants, from the old-fashioned angle chimneystacks in the back rooms of some smaller houses, to double-fronted one-room-deep plans, as at Nos 50–56 Penton Street. The bigger houses, of which there were once a good number, often had bowed back elevations to make the most of the view—'the uninterrupted prospect over White Conduit Gardens to that charming scene encompassed by Highgate, Hampstead, Caen Wood, etc', as an advertisement for a house in Chapel Street in 1790 has it. (fn. 33) The last such bow survives at No. 19 Chapel Market.

Later development to C. 1850

During inauspicious times for property development Henry Penton III converted a building agreement of 1802 with William Horsfall, a builder, to an outright transfer in 1806–7, Horsfall then acquiring the freehold of the western portions of Penton's estate in both Clerkenwell and Islington parishes. At first little happened. Horsfall focused on the implications for his property of the formation of the Regent's Canal, planned from 1810, and cut in 1818–20, disappearing into the Islington Tunnel where it underlies the north-eastern corner of Clerkenwell. Following an approach from Horsfall in 1815, the canal company formed Horsfall (later Battlebridge) Basin, which was in use from 1822, opening up the area to industrial development. (fn. 34)

Elsewhere, on Penton land, the filling of gaps had continued through the remaining war years and into the 1820s. More courts were formed behind Islington High Street and in 1810–12 Wellington (later Busaco) Street was squeezed in between the gardens of houses north of Collier Street in Cumming and Southampton (Calshot) Streets.

Off the Penton estate, development of the frontages to the New Road east of Baron Street, and on the south side immediately opposite, had been held up by contested ownership of the Angel Inn estate. With this resolved in 1817, Angel Place and Claremont Place were built in 1818–22. Most of the Angel Inn estate lay, with the White Conduit House, separately to the north, in the parish of Islington. One of the beneficiaries of the 1817 agreement there was George Thornhill, who also owned much adjoining land. He already had a scheme for development, but it was 1823 before he began to grant building leases for houses on the northward extension of Southampton Street and on what was eventually to become Wynford Road. (fn. 35)

Another building slump during the late 1820s and 1830s delayed building on the last few vacant plots. These were filled with houses of modest scale in the 1840s, as at Warren Street, north of Chapel Street. Just west of the parish boundary Caledonian Road had been laid out in 1826, with capital from Thornhill, but North (now Northdown) Street was still mostly undeveloped until 1839, when the surprisingly grandiose Greek-Revival terrace on the west side of the street was built. It was probably designed by Horsfall's architect son-in-law, Robert McWilliam. The humbler east side and an even lowlier court, North Place, followed in the mid-1840s, when, beyond the parish boundary, Keystone Crescent and Balfe Street were also being built. The developers did not know that King's Cross Station would open in 1850, bringing change that rippled across Pentonville.

Social Character and Change

Pentonville underwent two distinct transformations before the Second World War. The first, which followed the spread of the name across much of northern Clerkenwell, occurred in the mid-nineteenth century, and saw an early reputation as a place for fun and relaxation, as much as for healthy out-of-town living, ruined by urban expansion and industrialization. In this process of spoliation, Pentonville was in the same position as any of the country villages swallowed up by London in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The second was a sharp deterioration in social character in the early years of the twentieth century.

As late as the 1890s it was possible to find residents such as Napoleon Price, of a well-established Old Bond Street firm of manufacturing perfumers, in Cumming Street, the sort of tradesman who had first been attracted there. (fn. 36) But by that time Pentonville (in the narrow sense of the Penton estate and some adjacent parts) had long ceased to be a middle-class district. The Penton estate wall, which cut off Rodney and Cumming Streets from the neighbourhood to the north (see page 414) was gone, or on the point of going. But despite problems of poverty, crime and prostitution the area had clung to a sort of respectability. This now came under threat from a culture of rowdiness, improvidence and public drunkenness.

The early social character of Pentonville was in modern terms predominantly middle-class, though like most London districts it was never homogeneous. Of a number of well-known figures who lived here—Mary Wollstonecraft, Thomas Carlyle, Charles Lamb, and John Stuart Mill's father James Mill—all were temporary lodgers or soon moved on. Less well known, a number of publishers and artists made their homes across the district, notably in and around Chapel Street. The building of small houses in courts from the 1790s onwards would have brought a higher proportion of small tradesmen and labourers into the area, and institutional use took root in 1806 with the establishment of the London Female Penitentiary in Cumming House. In the 1840s another reformatory for prostitutes took over what had been an academy for young gentlemen at No. 57 White Lion Street.

Such conversions, the filling up of the last remnants of open ground, and the loss of open fields on all sides, would have been cause for regret, but they did not simply obliterate the original ambience. As late as 1859, George Augustus Sala pronounced of Pentonville: 'It won't be suburban much longer'. (fn. 37) The subdivision of houses began to spread, and by the 1860s and 70s there were a number of brothels in White Lion Street (one next door to the reformatory) and others in places further west, including Penton Street and Wellington (Busaco) Street. (fn. 38) Improving interventions in that period included the building of St Silas's Church in Penton Street, the opening of All Saints' Mission in White Lion Street, and two board schools. Model dwellings and tenement blocks replaced some houses from the 1860s to the 1890s. But decline was not precipitous and many of the larger houses continued to be respectably occupied. In the off-street courts, bad sanitary conditions were probably endemic from an early date. Pentonville did not receive the same level of journalistic attention as, for instance, the slums of Turnmill Street, though open cesspools in White Conduit Street, and reliance on water from a polluted well in Union Court off Chapel Street, were brought to public notice in the late 1850s. (fn. 39)

The nadir was reached around 1900. Of St James's, Pentonville, Booth's surveyor concluded in 1898 that 'there is every indication that this is a thoroughly benighted parish'. About half of the women who married in the church were said to be pregnant at the time, and the western parts of Pentonville Road were very rough and widely known to be frequented by prostitutes, the proximity of King's Cross Station being sufficient explanation. (fn. 40)

Improved public transport enabled those who could afford it to move away, leaving only the poorest behind. As a young man working at the Claremont Mission in White Lion Street in 1907–9, Fenner Brockway was moved: 'The poverty of the surrounding slum made my socialism a passion. Most men were workless or only working three days a week; there was no unemployment benefit. Hungry children had no free meals at school. Most women were doing sweated home work in their vermin-infested rooms, making artificial flowers and cardboard boxes or putting the pricks in toothbrushes. I visited a smelly room where three women lived, slept and worked'. (fn. 41)

A Penton Estate tenant complained in 1908 that the

weekly loss of 15s a week on two houses in Warren Street

acquired eight years earlier was 'bringing disaster upon

me':

Since … the numerous County Council & other buildings

sprang up some years ago, people took advantage of the superior sanitary & other good arrangements of these dwellings &

a large number of private houses became deserted, and I,

in common with other property owners, began to suffer

terribly … (fn. 42)

Henry Vincent, a shopkeeper in Penton Street, was the lessee of a number of houses locally, including a lodginghouse on the south side of Pentonville Road with coffeerooms on the ground-floor. He had, according to the Penton Estate surveyor, T. H. Watson, in 1908, 'done fairly well' with the house until about five years before, when demand for his lodgings began to dwindle. Vincent himself was in no doubt as to the cause: 'it is not worth one half the Rent it was 5 years ago, the Rowton-House has ruin it for Lodger's & the Electric Tram's have took the Trade from the shop'. (fn. 43)

Complaints of this sort became common. Businesses of all sorts were closing too. In 1908 a timber yard in Penton Street closed down 'in consequence of all the trade having gone from the district'. (fn. 44) Increasingly, too, local landlords and residents voiced complaints about the behaviour of the weekly tenants who were increasingly replacing steady, long-term monthly and yearly tenants.

In 1913 'a most respectable tenant' gave up a flat on Risinghill Street after a week, 'unable to get any rest on account of the rows, fights and filthy language caused by the residents in the tenement houses opposite'. (fn. 45) A year later similar conduct was reported in Warren Street, where the 'windows in the house is nearly all out and broken and ornamented with bits of sacks'. (fn. 46) Such conditions also pertained on the Penton Estate property on the south side of Pentonville Road.

Cumming Street, 'once the pride of Finsbury', was described in 1911 as 'more like a fair than an English street', with slovenly women and children lounging on the doorsteps and a rowdy clientele at the George the Fourth pub: 'All day long men women and children sit and lay outside the house. At night there is generally a street organ until past eleven o'clock, while boys, girls and drunken men and women dance and sing as loud as they can'. (fn. 47)

Unruliness found a new outlet after the outbreak of war, with attacks on German baker's shops at No. 2 Collier Street and No. 30 Penton Street, the latter at least being 'entirely smashed up'. (fn. 48)

Redevelopment

Physically, social and economic changes were manifested in the appearance of new buildings and the dilapidation of old ones. On the Penton estate model dwellings were built from the early 1870s, but they were never very widespread. Thomas Flight, the head of a vast empire of rental properties, built some in Hermes Street, and after his death the Sanitary Dwellings Co. Ltd (which his old architect, Banister Fletcher, helped set up) built more in John Street and Rodney Street. The grocer F. C. Frye was responsible for Frye's Buildings on Islington High Street in 1881–3, and, after the London Female Penitentiary moved in 1884, Alfred Attneave, another tradesman, laid out Affleck Street on the site and lined it with tenement blocks in the late 1880s. The last to be built were by the East End Dwellings Co., in 1894–5. One of their two blocks, Pollard House in Northdown Street, is the only example left on the north side of Pentonville Road.

A consequence of the social deterioration of the early 1900s was that some properties now ended up in the hands of the Penton Estate to manage directly. Even in comparatively good streets, it was often impossible for lessees to make houses pay without rent reductions and waivers of dilapidations, while the influx of disreputable tenants drove out remaining respectable people. Busaco Street, however, was an out-and-out slum. The leasehold of most of it belonged before the First World War to a woman who lived in the street, and whose husband managed it 'to best possible advantage' while generating little money. The houses were dark, cramped and insanitary. In 1913 one house had been empty for five years following a suicide, and no-one could be induced to live there, even rent-free. The issue of Dangerous Structures notices by the London County Council finally put the couple out of business, and the properties were recovered from the mortgagees by the Estate. Bringing them up to a fit standard was impossibly expensive, as Cyril Penton discovered in the 1930s. (fn. 49)

Redevelopment thus became confined to the shopping and business streets. New commercial buildings had begun to appear on White Lion Street in the 1890s. Pentonville Road had seen enormously varied late nineteenth-century conversions, but large-scale commercial rebuilding there only really began in 1911, when Lilley & Skinner built premises between Calshot Street and Killick Street. Their warehouse extension of 1935–6, designed by Sir Owen Williams, was Pentonville's most remarkable commercial building. Other Pentonville Road commercial premises of the 1920s and 1930s, mostly designed by Lewis Solomon or Herbert Wright, were typically redbrick, invariably prosaic buildings for the making of, among other things, radio components, watch-cases and briar pipes. Wright was also mainly responsible for the similarly banal architecture of a different kind of interwar redevelopment on Chapel Street. This broadly maintained the existing scale, in keeping with the requirements of lessees—typically small tradespeople in what had become a thriving shopping and market street. Another departure that foreshadowed future efforts was Finsbury Borough Council's first public housing ventures, at the north-east and north-west corners of Pentonville, in Grimaldi House and Mandeville Houses of 1926–8.

428. Pentonville from the air in 2002, looking north-east. Left foreground, junction of King's Cross Road and Pentonville Road. Priory Green Estate in centre; Weston Rise Estate far right

Pentonville remained one of London's poorer districts, but there was no large-scale rehousing before the war. That put a temporary stop to what was to become the Priory Green Estate, on the site of Busaco Street. Bombs cleared more ground to either side, with the worst damage around Risinghill Street and on the west side of Killick Street, where a V1 landed, and western Pentonville was primed for wholesale renewal. Housing was the order of the day and it arrived with éclat in Tecton's imperious Priory Green blocks of 1948–58 (Ill. 428). Other architects of note, Joseph Emberton at Stuart Mill House in 1949–50, C. L. P. Franck at the O. M. Richards Estate of 1962–5, and Howell, Killick, Partridge & Amis, at the Weston Rise Estate, built for the Greater London Council in 1965–8, kept up Modernist ideals. The Priors and Wynford estates of the early 1970s rounded off the years of housing renewal in architecturally humbler forms.

The baton was handed on again in the 1970s, as office development succeeded housing as the seat of building activity in Pentonville, along its eponymous road. The two bulky towers of King's Cross House, begun in 1973, made a big impact, in both planning and visual terms, and transformations at the top of the hill began in 1978 with the go-ahead for the Angel Centre. St James's Church was rebuilt as offices in 1988–90, and other commercial buildings were converted to office use as old industries withered away. Since 1997 initiative has been handed back to private housing, with blocks for students on Penton Rise and at the converted King's Cross House, and other residential buildings in White Lion Street. In 1999 Pentonville's extensive public housing was transferred to the control of the Peabody Housing Trust.