Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sadler's Wells', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp140-164 [accessed 23 April 2025].

'Sadler's Wells', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp140-164.

"Sadler's Wells". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 23 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp140-164.

In this section

- CHAPTER V. Sadler's Wells

- The origins of Sadler's Wells, 1664–84

- Sadler's Music House, 1684–99

- Building and rebuilding by Thomas Rosoman, 1746–9 and 1764

- Under new management, 1771–c.1802

- The aquatic theatre, 1804–1824

- Sadler's Wells in decline, c. 1818–43

- Samuel Phelps and after, 1843–75

- Skating Rink and Winter Garden, 1876–8

- Reconstruction by C. J. Phipps, 1878–9

- From theatre to music-hall, 1881–1914

- Sadler's Wells as a cinema, 1896–1915

- Closure and dereliction, 1915–23

- Lilian Baylis and the rebuilding of Sadler's Wells

- Alterations and improvements, 1930s–70s

- The present building

CHAPTER V. Sadler's Wells

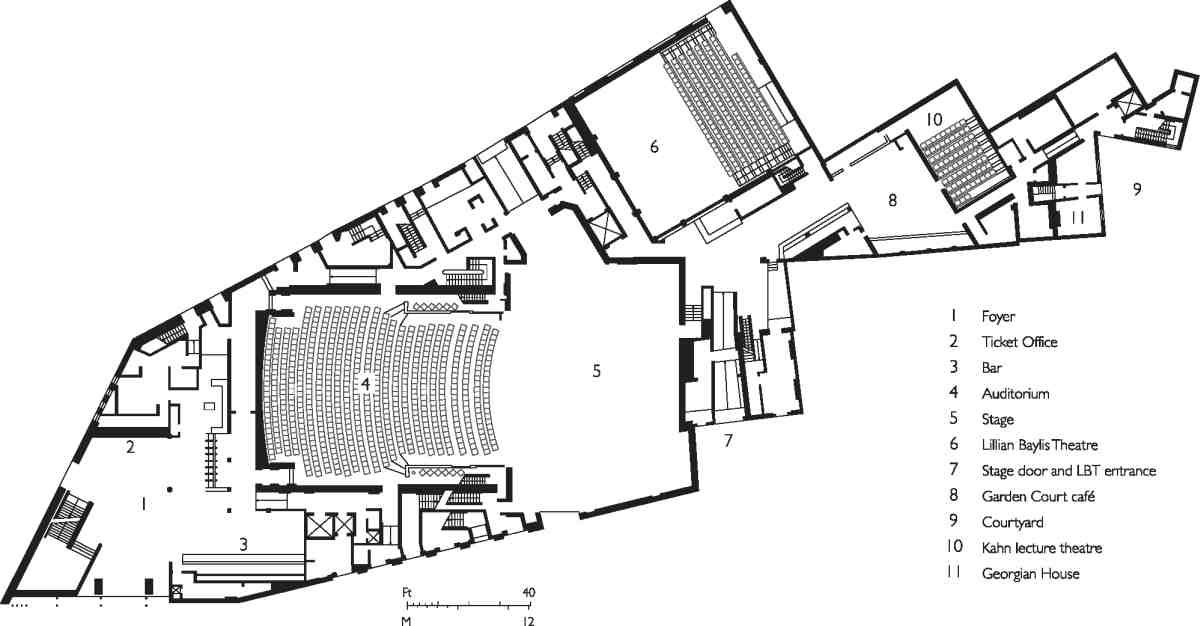

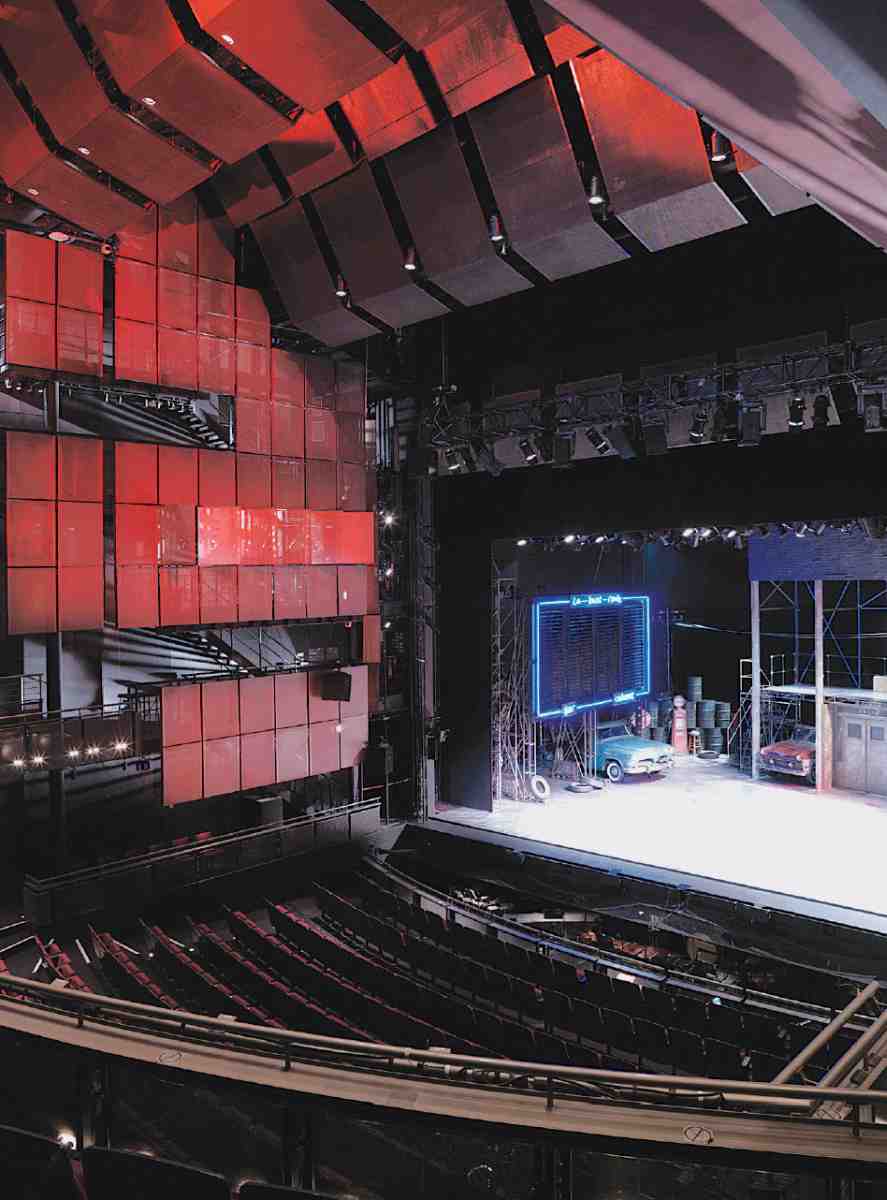

177. Sadler's Wells Theatre, view in 2007. RHWL with Nicholas Hare, architects, 1996–8

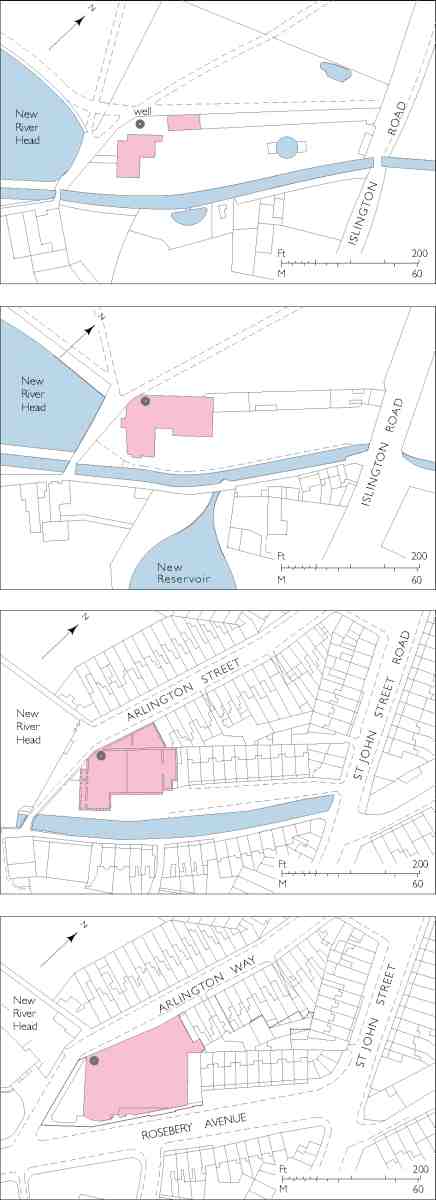

Sadler's Wells is the last survivor of the various spas, wells and places of entertainment scattered about the northern slopes of Clerkenwell from the late seventeenth century (see Ill. 2, page 3). Like the London Spaw and the Cold Bath, it was founded on the tonic properties of chalybeate water, but from an early stage was associated as much or more with alcohol and music, and later plays. The present building, opened in 1998 and finally completed in 2001, is the sixth theatre to have occupied the site. Despite its resolutely up-to-date appearance, it incorporates a small auditorium of ten years earlier (the Lilian Baylis Theatre), as well as parts of the main auditorium walls and steelwork of the previous main theatre, opened in 1931. In thus absorbing and adapting elements into their new building, the architects were following a long-established pattern of accretion. The 1931 theatre itself made some use of the existing walls, and successive reconstructions over the centuries have preserved something of the layout of the former buildings, and probably some actual fabric (Ill. 178).

That Sadler's Wells has survived at all is remarkable. Over more than three centuries it has lost more money than it has made, and on several occasions has come near to permanent closure and redevelopment, surviving periods as a skating-rink and a warehouse, and one of prolonged dereliction. As Anthony Thorncroft observed in 1996, 'Sadler's Wells has had more last-minute rescues than Clara Bow'. (fn. 1)

This chapter addresses Sadler's Wells' obscure and often misrepresented origins, and the evolution of the buildings that have occupied the site up to the present day. Its theatrical history has been dealt with extensively elsewhere, notably in Dennis Arundell's The Story of Sadler's Wells 1683–1977, and only sufficient to set the buildings in their context is given here. Among new discoveries related are details concerning the original Sadler and his 'musick house', the existence of a wooden playhouse erected by Thomas Rosoman many years prior to his rebuilding of 1764, and a late Victorian scheme for redevelopment drawn up by the architect A. H. Mackmurdo. Throughout 'north' may be taken to mean the north-west (opposite prompt, stage right) side of the theatre.

The origins of Sadler's Wells, 1664–84

Despite Sadler's Wells' fame and long history, its origins, and more particularly the identity of the eponymous founder, have long remained unclear. Lack of information has resulted in much speculation about both Sadler and the early history of the theatre buildings. Often Sadler is referred to as 'Richard'; elsewhere he appears as 'Thomas' or, more chummily, 'Dick'. He was, however, definitely Edward, as is proven by the Chancery Court proceedings brought by him against John Langley, a City merchant, in September 1684, a case which throws light on the early ownership of the site. (fn. 2)

Edward Sadler, a vintner, had taken a 35-year lease of the site of what was to become Sadler's Wells in 1671 from the Earl and Countess of Clarendon, whose Clerkenwell property, including Sadler's Wells, was eventually to become the Lloyd Baker estate. Comprising one acre, it was partly on Draw Bridge Field and partly on the Commandery Mantells, on the north side of the New River as it neared New River Head (see Ill. 97, page 86). In his complaint Edward Sadler says that after taking the lease he built a brick boundary wall around the property and, more significantly, a 'great brick messuage', evidently the building, close to the New River Company's Water House, on which he was required to pay tax on nine hearths in 1674–5. (fn. 3)

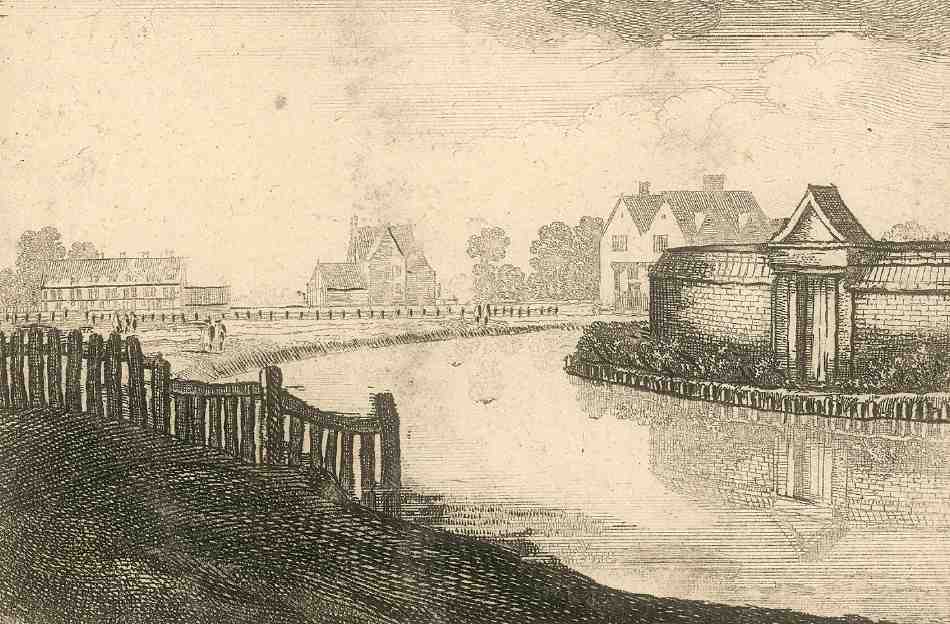

Sadler's connection with the area seems to have gone back earlier. In 1664–5 an Edward Sadler had successfully applied 'to be admitted to Continew and Dwe[ll]' at the Water House, which suggests that he was acting as the New River Company's resident supervisor. (fn. 4) He appears as a ratepayer at the Water House between 1666 and 1671, and for some years also at a neighbouring house described as Fowles's house. In the 1677 Clerkenwell 'census' he is listed as a victualler—like many of his neighbours in this long-established area of resort—and he is shown in various records at a neighbouring property (presumably the great brick messuage he had built) between 1679 and 1693–4; thereafter the evidence is patchy. (fn. 5) A Hollar print of 1665 (Ill. 179) depicts the western end of Sadler's site, its boundaries apparently marked by low posts, which appears to be empty save for a hut. (fn. 6)

In his Chancery complaint, Sadler describes how, after he had built the great brick messuage, he and others discovered 'a Spring or Well of Minerall Waters ariseing in the said premises which is of extraordinary Medicinall Vertue' and how he had 'made very considerable gaine thereby, and by offering Drink and other provisions usually sold in a publique house'. No date is given for the discovery, but it was certainly made after about 1674, when hearth tax was first charged on the house, and probably not long before 1684, the year of the complaint.

Sadler claimed that Langley, one of his customers, had wanted to buy the business and premises, along with another property 'near adjoining' on which there was also a house, which Sadler held on a seven-year lease from Jonathan Miles, taken out the previous month. Langley, Sadler asserted, offered him a £600 fine and £300 annual rent for the residue of his lease, but despite having drawn up an agreement the previous month, had thus far paid only five shillings. In addition Langley had allegedly been telling Sadler's customers that the business was now his and had caused Sadler to be arrested, for reasons that remain obscure but which involved a £2,000 security agreed by both parties.

178. Sadler's Wells Theatre, plans showing evolution of site and buildings in (from top) 1741, 1807, 1874 and 1938—the outline of the 1996–8 theatre is shown in black

Langley, in his reply dated 3 November 1684, denied that he had been stalling. He claimed that he had already spent £300—presumably on Miles's leasehold, the future Islington Spa or New Tunbridge Wells—employing workmen 'to sink wells to separate the Springs, to set upp Basons, to make gravell walks and to dig draynes … and to set up an Iron Balcony upon Columes the length of the end of the house belonging to the said ground'. A year later, in an advertisement in the London Gazette, Langley reappeared as the proprietor of the 'Islington Wells' announcing that they were open for business, and complaining how he had 'been represented by divers of his malitious adversaries to be a person of no estate or reputation, nor able to discharge his debts'. (fn. 7)

Although the result of the case is not recorded, a possible outcome is that Sadler retained his principal acre of land and brick house—Sadler's Wells—and sold Langley the apparently smaller property that he had leased from Jonathan Miles.

Late in 1684 or early in 1685 the chemist Robert Boyle tested mineral waters from three different wells at Islington. (fn. 8) Two—one in a cellar, the other 'in the vault with steps'—had apparently been discovered very recently, although whether these were on Sadler's land, north of the New River, or Langley's, south of it, is not clear. An anonymous tract with the confusing title Sadlers New Tunbridge Wells near Islington: How They were Found Out, attributable on internal evidence to 1684, appears to have come out before Boyle's visit as these two wells were so recently discovered that, it relates, 'their Vertues is not yet known'. The other well tested by Boyle is described by him as being 'from the musick house'. That term is used both in the tract cited above and in another better-known tract definitely of 1684, which has become for most subsequent writers the principal contemporary source of information about the wells' discovery. (fn. 9) The name Sadler's Wells, rather than Sadler's Well, might suggest that there was more than one well on the site north of the New River, but could derive from the fact that Sadler once owned both sites—New Tunbridge Wells and Sadler's Wells.

The second pamphlet, A True and Exact Account of Sadler's Well, was written by Thomas Guidott, a physician with literary pretensions and an established interest in the medicinal benefits of spa waters. It suggests that Sadler's well was discovered the previous year, 1683. Guidott is the source of the apparently erroneous belief that Sadler was a surveyor of the highways. He also suggested that Sadler's well was one of those recorded by Stow as having been in use in the Middle Ages, but insofar as any of these can be located, they appear to have been further south. Both tracts agree that the well, with a stone cover and decayed oak supports, was found in the garden of Sadler's 'musick house' when men in his employment were digging for gravel there (an established activity in this area), and that Sadler used the water to make beer before the benefits of the unadulterated water were recognized in the winter of 1683. Thereafter, so Guidott claimed, 500 or 600 people a day were resorting to Sadler's to take the waters.

Sadler's Music House, 1684–99

Sadler's acre of ground was more than three times as long east to west as it was deep, and stretched from the Outer Pond at New River Head to the Islington road (now St John Street) in the east. The west side tapered to align with a field path running south-west to north-east, the line of the modern Arlington Way. The music house stood near the west end of this property, while the well itself is described by Guidott as in its garden, and in the anonymous tract as in Sadler's 'Back-side'. That might accord with the location of the well that survives today in the basement of the modern theatre, which would have been near the northern boundary of Sadler's land, between the music house and the brick boundary wall. It was probably under the small roofed structure visible between the music house and the boundary wall in the earliest datable view of Sadler's Wells, of 1730, by Bernard Lens (Ill. 180). The whole of the long narrow site stretching eastwards from the music house and well was laid out as gardens with many trees. The entrance to Sadler's grounds and the music house was through a gate on the west side, roughly where the Arlington Way entrance into the foyer of the theatre is today (see Ill. 97, page 86); there was possibly another gate in the boundary wall near the well itself.

It is difficult to form a definitive picture of the early building or buildings on the site. Both 1684 tracts indicate that the music house was already in existence in 1683, and therefore not built to take advantage of the newly discovered wells. Most accounts of the music house have assumed that it was a purpose-built wooden concert room. But the earliest images appear to show a building that is at least partly of brick (Ills 180, 181). The probability is that the great brick messuage referred to by Sadler and the music house were one and the same. Sadler described his messuage as a 'publique house', but 'musick house' in his day seems to have connoted just that—a pub with musical entertainment as an extra attraction. (fn. 10) Nevertheless, neither Sadler nor Langley mentions a room in either of Sadler's messuages designed specifically for musical performances, perhaps preferring not to draw attention to this type of entertainment for fear of alerting the licensing authorities. Ned Ward in the Weekly Comedy of 24 May 1699 and Garbott in the 1720s (see below) describe a show-room or play-room which may have been a separate structure, or more likely a brick or wooden extension to Sadler's original brick messuage, as maps and plans always show a single building on the site.

179. Looking south-east from the Outer Pond, New River Head, in 1665. Sadler's Wells site is marked by posts in middle distance. Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar

Although the diarist John Evelyn visited in 1686 he did not record anything of what Sadler's Wells was like. A more informative early source is François Colsoni's Le Guide de Londres Pour Les Étrangers, published in 1693. Colsoni describes visiting Islington where there are 'two pretty houses' (that is to say, Sadler's Wells and New Tunbridge Wells) 'where one can go in the mornings to drink excellent mineral waters'. (fn. 11) Entrance to each cost threepence, for which the visitor could taste the waters, walk in the gardens and hear a concert of violins. This modest entry fee gives a flavour of the low ambitions of Sadler's Wells, as central London concert rooms at the time charged 2s 6d, and even suburban music houses at Richmond, Lambeth and Hampstead charged a shilling; only Epsom Wells—which did not charge women at all for entry—seems to have been comparable to Sadler's Wells. (fn. 12) At Sadler's Wells, Colsoni describes the additional attractions of dancing, English billiards, Royal Oak (a game of chance), and lotteries (that year Edward Sadler was listed as the proprietor of a lottery in the 1693–4 Four Shillings in the Pound Aid). (fn. 13) The fact that Sadler ran a lottery is consistent with the character of his other entertainments.

In a more satirical and therefore perhaps less accurate vein, Richard Ames and Ned Ward both wrote verses describing visits to Sadler's Wells and New Tunbridge Wells in 1691 and 1699 respectively. Both get comic mileage out of the socially diverse company and, especially, these venues' reputations as haunts of prostitutes and the dissolute, but also convey information about the buildings. In Ames's Islington-Wells it is hard to determine which of his descriptions apply to Sadler's Wells or New Tunbridge Wells as, being almost adjoining, they effectively constituted a single pleasure-seeker's destination. (fn. 14) Ned Ward's Walk to Islington is at once more informative and more scurrilous and colourful. He is the first to describe the inside of Sadler's Wells and its music room. Visiting New Tunbridge Wells and finding themselves in need of food and drink, he and his (newly made) female friend 'turn into Sadler's for sake of the Organ'. They are conducted upstairs to the gallery adjoining the organ 'Where lovers o'er cheesecakes were Scraping and Humming'. From the gallery, which appears from this and other early accounts to have been socially a marginally superior area, they look over into the pit where a huge throng is being entertained by a succession of low-grade singers, fiddlers and an 11-year-old sword dancer. The gallery is painted with allegorical scenes of a lubricious nature, featuring among others Apollo, Europa and Neptune. (fn. 15)

180. Edward Sadler's music house (left) and New River Head (centre) from north-west. Drawing by Bernard Lens, 1730

181. Music house from the north, 1731

182. Sadler's Wells, west front c. 1743, showing extension by Francis Forcer. Engraving by Thomas Kitchin from sheet-music of A New Song on Sadler's Wells

Noticeably absent from Ward's account is the taking of the waters. These appear to have dried up between May 1693 when the waters were advertised in the London Gazette, and an announcement in the Post-boy of June 1697 which stated that 'Sadler's excellent Steel Waters at Islington, having been obstructed for some years past, are now opened and currant again'; newspaper advertisements for the waters continued till 1700 but they had clearly been eclipsed by this time by the other entertainments on offer. In July 1697 an 'extraordinary consort of vocal and instrumental musick' lasting two hours was advertised. (fn. 16) Sadler himself appears to have died in 1699, (fn. 17) and the building is referred to as 'Miles's musick house' from that year, although the name Sadler's Wells persisted. (fn. 18)

The Miles in question was James Miles, a glover who died in 1724 (perhaps a relative of Jonathan Miles, Sadler's landlord in 1684 at what became New Tunbridge Wells). During Miles's stewardship of Sadler's Wells it retained its reputation for low-grade entertainment—a man eating a live cockerel was one 'turn'—and rowdy, even violent behaviour. It was described as a 'nursery of debauchery' in 1711, and the next year a man named Ingram Thwaits was killed in the gallery (the trial record calls it a 'box', suggesting the gallery was at this date divided laterally). (fn. 19) In 1714 Miles was running the Gun Musick-Booth, one of the many such booths at Bartholomew Fair, which offered a similar mix of wine, music, tumblers and ladder dancers to Sadler's Wells. (fn. 20)

During his proprietorship it is said that Miles 'improved and beautified' the music house. (fn. 21) Until the late 1720s or early 1730s Sadler's Wells seems to have consisted of the great brick messuage built by Sadler—that is, a two storey brick building, square or possibly cruciform in plan (including the projecting gallery and boxes), with additional wooden, possibly short-lived structures such as the 'brewhouse' and 'appurtenances' mentioned in Sadler's deposition of 1684. (fn. 22)

Miles renewed the lease for five years in 1719 (the earliest surviving lease), paying £70 a year to the Lloyd family (freeholders of the site until 1883). (fn. 23) When he died in 1724 his will made no mention of Sadler's Wells, so it seems likely that he had already passed it on to his sonin-law, Francis Forcer. Trained as a barrister, Forcer appears in the ratebooks for the area by 1724 and renewed the lease for 21 years with the Lloyds in 1730. (fn. 24) Some accounts state that his father, a composer of the same name, owned the Wells immediately after Sadler, but there is no contemporary evidence for this. (fn. 25) Judging from incremental rises in his rent between 1730 and 1733, it seems that it was in this period that Forcer made the first major additions to Sadler's Wells, especially as it was from 1732 that he began to insure the building, apparently for the first time. (fn. 26)

It is almost certainly Forcer's enlarged Sadler's Wells that can be seen in one of the headpieces of The Universal Harmony, or the Gentlemen and Ladies Social Companion, a collection of sheet music published in 1743 (Ill. 182). This shows a two-storey building of two ranges, the larger one with seven bays facing the Outer Pond at New River Head, the smaller one running along the northern boundary of the site. Of the seven windows along the main front only the three on the right or south end are sashes, suggesting that part was an addition, possibly 'for the purpose of habitation'. (fn. 27) That is supported by the description of the property as 'Sadler's Wells and the dwelling house' in Forcer's insurance policy for 1732. (fn. 28) The entry in the register suggests that Sadler's Wells—specifically noted as a brick building—consisted of one building roughly 50 ft by 33 ft, probably the main seventeenth-century block, including Forcer's new domestic addition in its southern end; another, 33 ft by 12 ft, which was probably the adjoining new or rebuilt north range running along or near the north boundary; and a third structure, 20 ft by 9 ft, probably the ancillary building to the north east, already on the site and shown in a print of 1731 (Ill. 181).

A New River survey, dated to 1741, is broadly consistent with this analysis (Ill. 178). It shows a circular pond to the east with avenues of trees and attached rectangular areas either side, possibly paving. It seems likely that it was in this early 1730s remodelling that Forcer added the pedimented gate inscribed 'Sadler's Wells' shown in the 1743 print and in Hogarth's Evening of 1738. Hogarth's print, not intended as a reliable topographical record, shows only the gate and part of the south end of Sadler's Wells.

Further enlargement is suggested by another survey of the New River made in 1743 (see Ills 97, 239, pages 86, 187), which indicates that by then the enlarged Wells occupied the full north—south depth of the site. Forcer had by then apparently added a small structure on to the south side of the dwelling house and other ancillary buildings stretching along the northern boundary.

Forcer was living at Sadler's Wells when he died in April 1743. His will directed that his interest in the Wells be sold after his death to pay off his mortgage on another property, and in December of that year his widow Catherine assigned the lease to John Warren, merchant, of Clerkenwell. (fn. 29) It was under Warren's brief period of management that the Grand Jury of Middlesex censured Sadler's Wells and a number of other theatres and gaming houses as 'places kept apart for the encouragement of luxury, extravagance, idleness, and other wicked illegal purposes', and temporarily closed it down. (fn. 30)

Building and rebuilding by Thomas Rosoman, 1746–9 and 1764

It has long been believed that Sadler's Wells Theatre was 'an old wooden building', dating back to Sadler's day, when it was rebuilt in brick by Thomas Rosoman in 1764. But this is incorrect. It is clear from insurance records that what Rosoman actually rebuilt in 1764 was a wooden theatre he himself had erected in 1748–9. It appears, too, that Rosoman's wooden theatre may have been a much-reduced version of a decidedly ambitious building projected for the site—how seriously it is impossible to say—for which some intriguing pictorial evidence survives.

Vintner, actor, and former manager of the New Wells near by, Rosoman, and his associate Peter Hough, a tumbler, took a 21-year lease of Sadler's Wells from Christmas 1745. (fn. 31) Their lease gives some idea of the proliferation of buildings on the site by this date, listing, along with the main building, a brewhouse, storehouse, stables, granary, sheds and outhouses. This impression of a diverse collection of buildings is confirmed by the description of the property when Rosoman insured it in April 1748. (fn. 32) At that time the value of the buildings was put at £700, as compared to £400 in 1739. The domestic part of the property was evidently a handsome house, described as being of two storeys with garrets, and containing seven rooms, five wainscotted and two half-wainscotted, with four Portland-stone chimneypieces. What is not clear is how far the buildings were the result of work by Forcer or earlier owners, or by Rosoman himself. Something that does certainly seem to have been new in 1748 was a series of 'Drinking rooms, 2 storey', described in later policies as 'drinking boxes'.

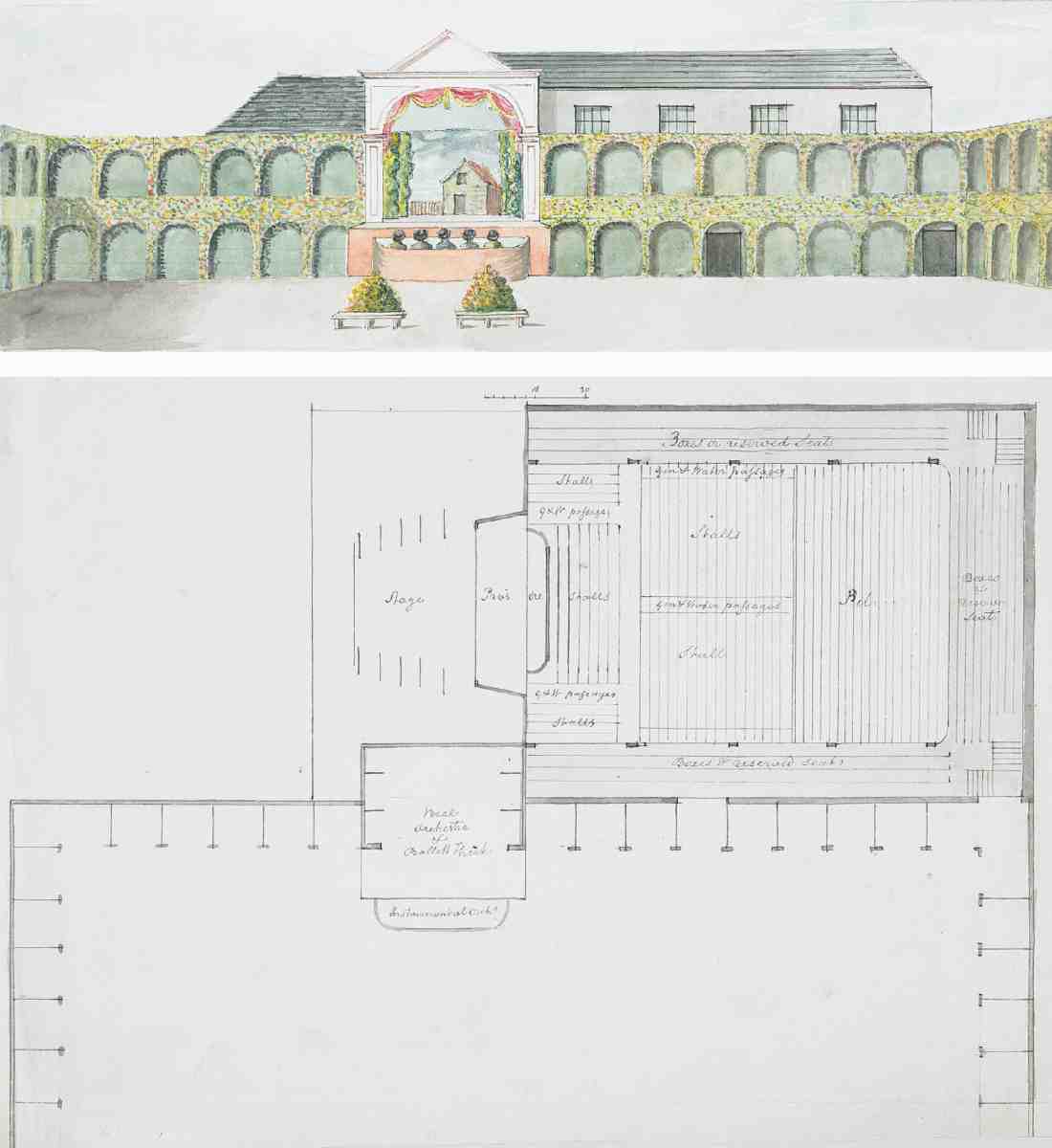

With these drinking boxes there appears to be a link with the plan and elevation of an unnamed eighteenth-century theatre, almost certainly Sadler's Wells, copied in the nineteenth century from earlier drawings now presumed lost (Ill. 183). (fn. 33) The buildings shown consist of a large galleried theatre adjoining a three-sided, cloister-like structure lined with two storeys of open-fronted alcoves or boxes, likely to have been south-facing; the means of access to the upper level of boxes is not indicated. A secondary stage, fronted by an orchestra pit and open to the courtyard, is placed asymmetrically on the long side of the 'cloister' and backs against the stage of the main theatre. If this scheme does indeed relate to Rosoman's tenure of Sadler's Wells, it suggests that he was seeking to emulate the great pleasure gardens of Vauxhall and Ranelagh which acquired private boxes of the type shown during the 1730s or 40s. (fn. 34)

183. Drawings for a theatre, thought to be an unexecuted scheme for Thomas Rosoman's Sadler's Wells, c. 1745–50. View of court with outside stage, drinking- boxes within arches, and theatre behind; and plan

When Rosoman renewed his insurance in 1749 and had the site resurveyed, the collection of buildings included a new playhouse of 2,080 sq.ft. The property was insured for £1,200:£600 for brick buildings and £600 for timber. Given that the year before only £100 had been allowed for timber building and the amount for brick was the same, it is almost certain that this new playhouse was largely or wholly of timber. (fn. 35) Measuring just 52 ft by 40 ft, it was less than half the size of the theatre in the putative Sadler's Wells drawing, though comparable with the surviving 1780s theatre at Richmond in North Yorkshire.

The exact location of this timber playhouse, which survived only fifteen years, is unknown, but it was probably built on to the back of the original music house, running east-north-east. If the plan showing the theatre and the drinking boxes may be taken as a guide, most of the seating would have been on benches, with stalls fronting the ground floor of the auditorium, an open pit behind, and a gallery above round three sides, perhaps with private boxes at the lower level. Rosoman's advertisements for the period indicate that entry to the boxes (where according to the plan seats might be reserved) was 2s 6d, which included a pint of wine, but to the pit and gallery only one shilling. (fn. 36) Conditions were cramped, the benches accessible only from narrow walkways, described evocatively on the plan as 'gin and water passages'. The entertainment on stage was apparently seen as an adjunct to the main event of an evening's drinking. Rosoman introduced seats with ledged shelves behind to accommodate wine bottles and glasses. (fn. 37)

The theatre appears to have remained in this structural form until 1764 when the press announced that 'Sadler's Wells is now rebuilt, and confidently enlarged'. (fn. 38) The rebuilding was accomplished, it was said at the time, in seven weeks. A figure of £4,225 was mentioned, but given that Rosoman insured the new theatre and dwelling house only for £2,000 this may have been a generous 'talking up'. (fn. 39) Thomas Lloyd, on behalf of the freeholder, his brother, the Rev. John Lloyd, was unimpressed with the quality of the work, and rejected Rosoman's claim that he had spent 'a large sum' on rebuilding: 'nor do I look on the place one bit the better for the owner for it … it was understood you intended to build a Palace equivalent in some degree to the fortune you have acquired there'. Lloyd estimated that fortune at £40,000 and claimed that the terms of Rosoman's recent lease, involving a fine of only £250 (as opposed to the £500 originally sought), were 'extremely moderate' and that his brother could have had '£1,000 for such a lease'. (fn. 40)

The new theatre, at 109 ft by 52 ft 6 in, covered more than twice the area of Rosoman's wooden building, and seems to have occupied the sites of both this and Sadler's original music-house. (fn. 41) It was orientated, like every theatre on the site since, with the side of the auditorium and stage more or less parallel with the northern boundary of the site. Although no image survives of the original interior, a later description states: 'At this time the sides of the house were occupied by two tiers of Galleries, which were of equal price, and communicated with each other, so that the occupants might ascend or descend at their pleasure. They were flat with one long seat fixed to the wall, besides moveable benches'. (fn. 42) A projecting staircase bay at the front of the theatre giving access to the gallery features in all the surviving images, but may not have been part of the original building, as the insurance policy does not list the gallery stairs separately until later. (fn. 43) Possibly this separate entrance was added to divide the rougher elements using the gallery from the more genteel occupants of the boxes.

Rosoman also rebuilt the domestic quarters to the south as a four-bay house of two storeys and garrets, with a pedimented entrance adjoining the theatre (Ill. 184). To the side was a canted two-storey bay with a balustrade, and another pedimented doorway. The proportions suggest that Rosoman, not a man to spend money unnecessarily, might have substantially remodelled rather than wholly rebuilt the existing house of the 1730s, reusing existing fabric where possible. Most of the new portions of the rebuilt house, apart from the south-west corner, appear to have been at the rear, as the new house was deeper than the old. One report also mentions the use of 'old materials' in building the new theatre. (fn. 44)

Outside, Rosoman put up a brick wall, with iron railings and gates, from the north-west corner of the theatre to the south-west corner of the site, along what is now Arlington Way. (fn. 45) He also added iron chains and lamps along the southern boundary. (fn. 46)

Under new management, 1771–c.1802

184. Sadler's Wells, west front, c. 1791, as rebuilt by Thomas Rosoman, 1764

The new theatre was clearly a good investment for Rosoman. In October 1771 he sold his interest in it for £9,500, and when he died in 1782 left a reputed £40,000. (fn. 47) The purchaser of the lease, backed by City bankers, was Thomas King, the Covent Garden actor and sometime manager, who had assumed some role in the management of the Wells from 1769. (fn. 48) Despite his connection with the legitimate theatre, King did little to alter Rosoman's winning formula of entertainments. However, he did apparently aspire to alter the tone. In September 1771 he announced misleadingly that 'This is the last week of the company Performing for Wine'. (fn. 49) This caused such consternation among regulars, who inferred that wine would no longer be served, that King had to write to the newspapers before the following season to clarify— wine would be available. What he had actually meant was that the buying of drink would no longer be the requirement for admission. But insofar as the purchase of a 3s ticket now entitled the holder to a pint of Port, Lisbon, 'mountain' or punch, there was not a whole lot of difference. (fn. 50) Raising the tone did little for takings, according to King himself who complained in 1775 that the rise in social class of the clientele had damaged the business compared to when Sadler's Wells had been 'frequented by the meaner sort of people only'. (fn. 51)

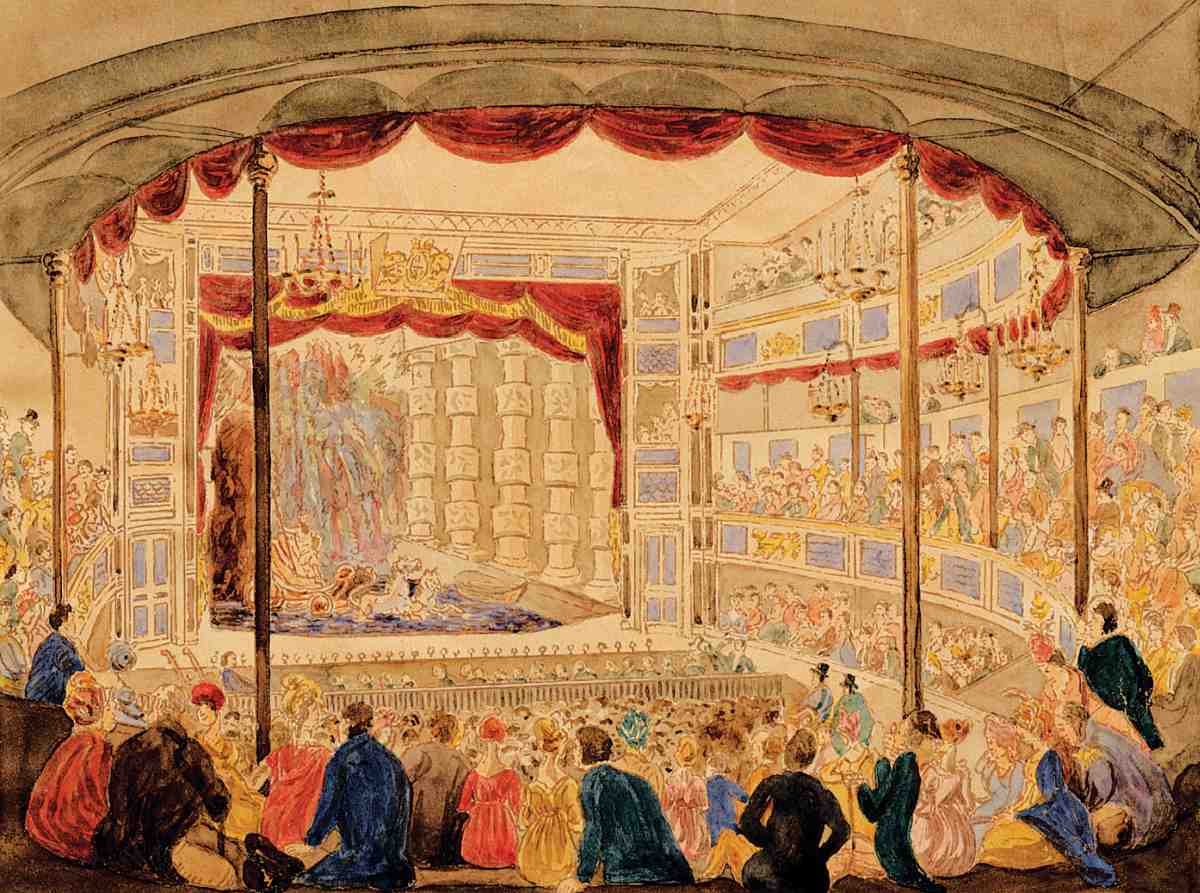

185. Sadler's Wells Theatre, auditorium in 1807, with water scene from The Ocean Fiend or the Infant's Peril

When the theatre reopened in Easter 1772 it had been 'altered and beautified'. The only alterations specifically recorded were a new coach house, stables and scene house (probably the tall lean-to visible in later prints), all timberbuilt, adjoining the back of the theatre towards St John Street. (fn. 52) Following further redecoration a few years later, the auditorium had a 'very pleasing appearance; the colours are milk white, pale green and a beautiful pink', which produce 'a cool, delicate effect'. (fn. 53) In 1776 King got permission from the New River Company to put up a low wall and iron railing along the walk opposite his house and the Wells. This, he claimed, was 'not only an ornament' but would 'prevent the rabble from assembly there, throwing in their dogs etc'. (fn. 54) Around this time also a row of poplars was planted along the southern boundary, beside the New River; later they became 'so lofty as to be easily recognized by voyagers from Margate as they came up the Thames' (Ill. 187). (fn. 55) By a further minor alteration, a footbridge over the New River was widened for the carriage trade in June 1780 and rebuilt in brick. (fn. 56)

Substantial alterations were made to Sadler's Wells in 1778 when the 'whole of the inside of the House was taken down and materially improved. The ceiling of the auditorium was raised, allowing improved ventilation and sightlines. (fn. 57) Then in 1787, perhaps in connection with a failed parliamentary bill to license the theatre, further changes were made to the auditorium. The slips (part of the pit, the front part of which we would now call the stalls) were made a continuation of the ground-floor boxes—' 'tis said, to exclude ladies of a volatile description'. (fn. 58)

This altered interior appears in a small print of 1794, the basis of the coloured view reproduced as the frontispiece to this volume. Depicting a typical Sadler's Wells entertainment of a rope-walker on stage, it shows the auditorium in some detail. There is effectively no division between the stage and the pit, allowing the acrobats and their equipment to extend beyond the proscenium arch, perhaps in the manner of the old show-room of Sadler's time. There are a few benches at the rear of the auditorium— the pit— and at the sides what were presumably the new boxes replacing the disreputable slips, railed off with thin balustrading, presumably of iron. This balustrading is also a feature of the first-floor boxes and the open gallery above. There is a stage box on the right side of the proscenium at private-box level (with a mildly suggestive classical statue below).

From 1792 the leaseholder of Sadler's Wells was Richard Hughes, who had managed a number of provincial theatres. He and his partner William Siddons, husband of the famous Sarah, oversaw the continuing improvement in the theatre's social acceptability, welcoming 'a long et cetera of rank and fashion' in their first season as managers. (fn. 59) It was they who successively engaged the brothers Tom and Charles Dibdin as writers in the 1790s, Charles also being manager from 1799. Charles Dibdin produced a mass of popular entertainments— musical bagatelles, historical ballets, comic songs and pantomimes over the next twenty years. But the presentations for which he was best remembered and which had the biggest impact on the physical form of Sadler's Wells were the aquatic dramas.

Dibdin had worked previously for Philip Astley at his Amphitheatre of Arts and Sciences in Lambeth, devising trick scenery for stage illusions and this skill helped reshape Sadler's Wells. By 1801 it was in Dibdin's opinion 'the dirtiest and most antique Theatre in London'. (fn. 60) Siddons had to ask his landlord for a reduction in rent when the lease was renewed in 1802, on the grounds that the business had lost money every year between 1795 and 1801. (fn. 61)

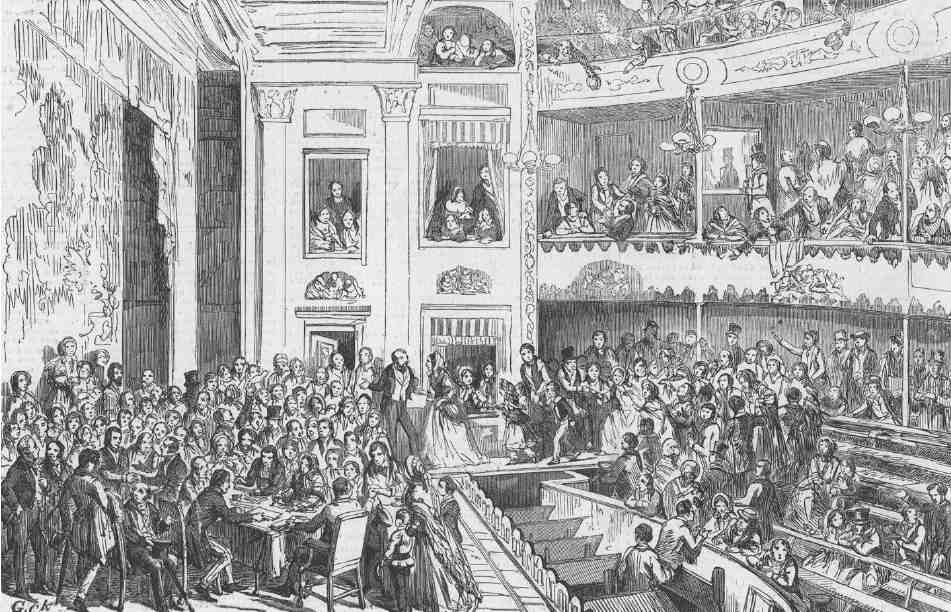

Over the winter of 1801–2 the interior of Sadler's Wells was reconstructed at a cost of about £1,500 by the specialist theatre architect Rudolphe Cabanel. (fn. 62) He had rebuilt a number of theatre interiors, including the Royal Circus in Lambeth, but was presumably known to Dibdin from Astley's where he had devised stage machinery. (fn. 63) By January 1802 Richard Wroughton, who had taken over from King as manager in the late 1770s and still owned a stake in the theatre, was writing to the landlord that 'the Place is completely gutted and a very pretty, handsome Theatre will soon be ready'. (fn. 64) The main alteration was the creation of a semi-circular circle and galleries on the lines of the reconstructions of Drury Lane and Covent Garden in the 1790s, (fn. 65) which gave a more fashionable aspect and better sightlines, also aided by the slender cast-iron columns supporting the circle and galleries, an early example of their use (Ill. 185). The proscenium ends of the gallery and circle had spacious boxes either side, although the dress circle was now no longer composed of boxes, while the gallery was as deep as the circle. Boxes are often referred to in advertisements, but are out of view in most illustrations. Probably these were relatively large boxes (not private boxes intended for one party), located side by side along the back of the auditorium, and considered superior to the undivided pit in front. (fn. 66) Beyond the auditorium little had changed, and there were no proper means of escape, as was demonstrated in 1807, when eighteen people were trampled to death during a false fire alarm. (fn. 67)

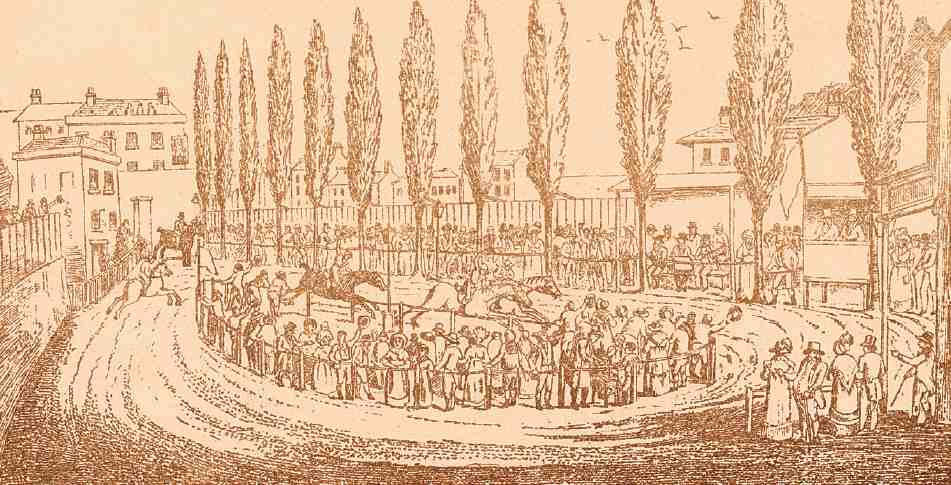

186. Sadler's Wells racecourse, 1806. View looking east away from theatre

187. Sadler's Wells looking north-west across New River, 1813

During the 1802 season Hughes and Dibdin introduced pony races, which were held from time to time over the next quarter-century (Ill. 186). After a short prelude by Dibdin, large doors at the back of the theatre were opened through the scene house to the yard behind, the yard and stage forming the racecourse. The ponies were supplied by I'ons' livery stable in Islington. (fn. 68)

The aquatic theatre, 1804–1824

By 1805 an extra two-storey scene room had been added, along with a covered way (sometimes referred to as 'the piazza') along the south side of the theatre, between the yard and the entrance to box and pit by the manager's house (Ill. 187). Additional sheds and stables had also been put up. But the most important of Dibdin's improvements was the installation in 1804 of under-stage equipment making possible spectacular dramas culminating in a final scene performed on water.

This was not London's first aquatic theatre. In the years around 1700 Henry Winstanley, designer of the first Eddystone lighthouse, and later his widow Elizabeth, had run a theatre in Piccadilly which combined water effects and fireworks. (fn. 69) What Dibdin and Hughes put on, however, was more ambitious than anything attempted before. Dibdin recalled how they executed the alterations in absolute secrecy: We first ripped up the whole of the stage and removed all traps and cellar work, in all future pantomimes, I was obliged to model my mechanical effects so as to enable the machinists to work the pantomime tricks without any assistance from below which created both for them and me no small perplexity'. (fn. 70)

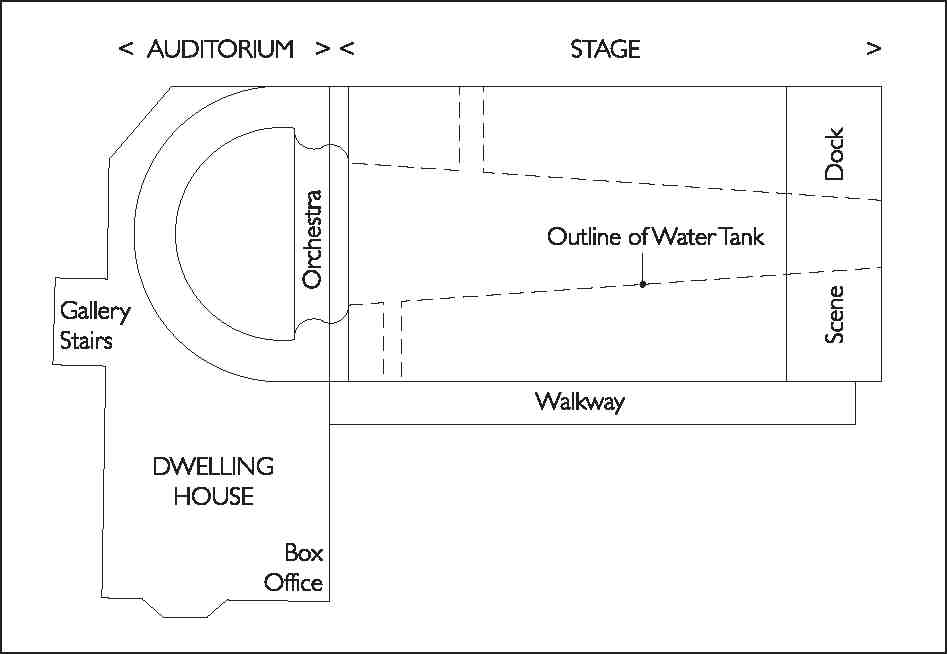

The vast metal tank, 'made like a brewing vat', (fn. 71) perhaps of rivetted copper, ran the full depth of the stage and some way beyond, under the scene house (Ill. 188). It was 90 ft long and 24 ft across at its widest (presumably at stage front), tapering to just 10 ft at the far end, and about 3 ft deep. It rested on dwarf walls in the cellar 2 ft 4 in high and wide and 2 ft 4 in apart, and contained bearers onto which the stage could be lowered. There were two branches, extending to the side walls of the stage, one about halfway down on the north side, the other nearer the stage end. The tank was originally filled from the New River by means of what Dibdin called an 'archimedean wheel'; later the New River Company was paid £30 per year to fill it from the main, and on one occasion the water was cut off because the bill had not been paid. In 1808 an additional tank was added in the flies to create waterfall effects about 15 ft wide. (fn. 72) These alterations, the proprietors claimed, cost £1,000. (fn. 73)

188. Aquatic theatre, Sadler's Wells, diagrammatic plan based on reconstruction by Allan S. Jackson

189. Arlington Street looking south, c. 1875, with Sadler's Wells scene dock to left

Between 1804 and 1824, 36 aqua-dramas were staged, almost all up to 1819 written or co-written by Charles Dibdin. (fn. 74) Until 1823, when alterations were made by a Mr Copping to the stage-lifting mechanism which allowed it to rise in a matter of seconds, the audience had to endure an interlude of up to forty minutes as the stage was removed to reveal the water-tanks for the final scenes. (fn. 75) The watery dénouement typically showed a piece of land bordering a body of water— 'Castle on a Lake with a Water Fall', 'Gibralter by the Mediterranian'— and featured ships in full sail (Dibdin employed shipwrights and riggers from Woolwich dockyard to make correct scale-model ships), sea creatures, all propelled around by small boys clad in duffle coats. (fn. 76) Fireworks and other fiery effects— such as burning castles and volcanoes— were popular as they reflected well on the water, and lit up the dim recesses at the back of the stage. (fn. 77) All this heralded a fresh period of prosperity for Sadler's Wells, stoked by the popularity of Joseph Grimaldi, who 'transformed the clown from a rustic booby into the star of metropolitan pantomime'. (fn. 78)

Sadler's Wells in decline, c. 1818–43

Well before the last aquatic shows were held, the theatre was doing badly. The managers claimed to have lost £3,000 in the 1818 season alone, and by the mid-1820s, with Dibdin departed and Grimaldi retired, Sadler's Wells was firmly set on a decline that lasted until Samuel Phelps's arrival in 1843. (fn. 79) A succession of managers made a number of alterations to attract the public, as well as the usual periodic redecoration. Pony races were revived in 1822 with platforms over the orchestra so that the ponies could pass into and round the pit, and in 1826 they were held just in the yard, with boards erected around the perimeter to prevent free viewing. (fn. 80) This revival may have been connected with the building at this time of livery stables just north of the yard, with a building that survives as No. 381 St John Street, now the Sadler's Wells education centre and known as the 'Georgian House' (see Survey of London, volume xlvi).

In the years following the renewal of the lease in 1819, the theatre was given a new roof and the outside walls were stuccoed, perhaps to update its 'old-fashioned, unpretending appearance'. (fn. 81) Over the winter of 1821–2 alterations converted the circle into a series of boxes. Six further boxes were created at the proscenium ends of the gallery, while two more stage boxes were added each side, and the pit and gallery were enlarged. (fn. 82) The theatre was also 'embellished and decorated in a superior style of elegance and splendour … the prevailing colour is a soft and delicate pink'. (fn. 83) The panels on the fronts of the boxes were decorated with gilt lattice work and silvered scallops. The walls of the lobbies were 'relieved with emblematic devices', while the proscenium and stage doors were painted white with gilt beading. Above came 'a fanciful grouping in bronze of the lyre, cornucopia, and other symbolic figures'. The slim iron pillars supporting the boxes were gilded and cut-glass lustres projected from their capitals. The drop curtain was painted with a scene by Thomas Greenwood; it was predominantly blue, as was the 'imitative drapery' of the boxes. (fn. 84)

Probably in 1824, the New River Company leased to T. J. Lloyd Baker the triangular plot of land between the north flank of the theatre and the newly created Arlington Street. Here the Sadler's Wells management built a scene dock and dressing rooms (Ill. 189)— artistes had traditionally been obliged to change beneath the stage, the women in a makeshift 'canvas compartment' nailed to the underside. (fn. 85) Next year, the London Wine Co. having taken a stake in the business, the dwelling house was converted into box office, wine room, saloon and coffee house—a development deprecated by the Lloyd Bakers as one that might interfere with the business of the Sir Hugh Myddelton's Head, on the other side of the New River, of which they were also the freeholders. (fn. 86) It was some time later that a large covered porch of light construction, four columns wide and two deep, surmounted by a sign board towards St John Street, with the name 'Sadler's Wells', was added behind, presumably to shelter those attending the box office or entering the box and pit door (Ill. 190). The covered way of c. 1804 seems to have been removed when this was built.

190. Sadler's Wells looking west from St John Street Road, c. 1830. New River on left

The 1820s saw intense building activity on the land around Sadler's Wells, and development of part or all of the theatre site for housing and other purposes was mooted many times over the next century and a half. The first proposal seems to have been in 1823 when William Lloyd Baker's solicitor, Augustus Warren, suggested that if the theatre were pulled down, the site, and the triangular plot belonging to the New River Company alongside Arlington Street, could be used for building houses. (fn. 87) In 1826 Richard Hughes junior, the lessee, wrote to Lloyd Baker offering to build ten tenements on the north side of the theatre yard to raise revenue, but the offer was not taken up as the proposed rent was too small. (fn. 88)

In 1828 John Booth, the Lloyd Baker surveyor, or his son William Joseph Booth, drew up a more radical plan to demolish the theatre, and Dibdin's old house at the St John Street end of the yard. In their place were to be built two terraces, one of twelve houses fronting Arlington Street and one of nineteen fronting the New River, the latter reached by a private carriage road along the riverside from St John Street. (fn. 89) Nevertheless, the Booths advised that the theatre was still the most profitable use of the site for the Lloyd Bakers, and nothing was done. In 1830 W. C. Mylne, surveyor to the New River Company, advised the Lloyd Bakers that the best thing for both estates would be demolition of the theatre and redevelopment of the whole site with housing, for building houses alongside the theatre would 'only increase the number of lodging houses and Brothels which cover your Tunbridge Wells property'. As an alternative he suggested that the theatre could be let as a riding school or panorama and 'these itinerant Theatrical corps' compelled 'to quit the spot forever … as it is, nothing could be worse'. (fn. 90)

Thereafter the Wells lurched from one failure to another, as prices and standards gradually sank lower and lower. Superficial changes were made, the saloon being redecorated as a Chinese pavilion in the early 1830s, and the auditorium 'ornamented with emblematical and classical devices'. (fn. 91)

Samuel Phelps and after, 1843–75

An upturn came in 1843, when a new partnership took over, coinciding with the new Theatres Act which allowed the licensing of minor theatres for regular drama. The partner-managers were Thomas Longdon Greenwood, son of the scene-painter and the third generation of Greenwoods at Sadler's Wells, and the actor Samuel Phelps. Over the next nineteen years they produced more than a hundred plays. Their notable success was their Shakespeare seasons, all the more surprising given the distance of the Wells from the educated West End elite, and the type of entertainments which had hitherto prevailed. The management took a stern line with the louche Sadler's Wells crowd, expelling 'friers of fish, vendors of oysters and other costermongers' from around the doors, and beersellers and squalling babies—even the foulmouthed—from inside the theatre. (fn. 92) Under Phelps, Sadler's Wells became a training ground for the West End. (fn. 93)

The Phelps era was less significant architecturally than theatrically. In 1846 a new entrance portico of five roundheaded arches was erected across the front of what had been the manager's house. A separate entrance for the boxes was provided and some benches were abolished in favour of extra boxes. (fn. 94) The front of the first-floor circle appears to have been opened up into a dress circle. (fn. 95)

In 1849 an extension was built on the site of the longdemolished covered way along the south side of the theatre, possibly as a corridor and ancillary rooms. It was designed by Richard Tress, architect and surveyor, and may have been part of a larger scheme of alterations. (fn. 96) This structure, with its stuccoed decoration of blind pilasters, survived up to the rebuilding of 1930.

A 60-year lease was granted in 1851 to Jane Dixon, Jane Bennett and her husband John Hooper, but the site was already being eroded by development. The previous year the house that Dibdin had occupied at the end of the yard, north of the gates on St John Street, was demolished and four houses were built in its place, by John Horden. (fn. 97) Then in 1853–4 two sites were hived off and let to George Payne for building St John's Terrace, immediately east of the theatre (see page 133). (fn. 98)

191. Total abstainers' meeting, Sadler's Wells Theatre, drawn by George Cruikshank, 1854

After 1862 'the hand of decay seemed to be impressed on the house'. (fn. 99) Although Phelps was still a great draw, his partner Greenwood had retired and he himself was on the point of withdrawing from the management of the theatre. The Lloyd Baker family offered the freehold for sale that year, and the particulars give an idea of the accommodation at that time. At ground level the pit could take a thousand people. The dress circle held 150, with an upper circle of boxes at the rear seating another 150. Above that was a more steeply sloping gallery seating between 800 and 1,000. There were six private boxes, four on the dress circle level and two level with the stage (Ill. 191). Over the 'ample and lofty' stage were upper and lower flies and a carpenter's shop. In the two-storey extension of 1849 were a green room and a cloakroom, with ladies' dressing rooms and wardrobe above. On the other side of the stage, in the extension of 1824 was a scene room, while the original dressing room adjoining was now just for men. There were also 'two refreshment rooms and a good box office'. (fn. 100)

The building failed to sell and there followed a return to more mixed programmes with light drama and melodrama as well as Shakespeare, under a series of managers. The theatre was also used for religious meetings in 1866. (fn. 101) Final closure took place in 1875, when the fixtures and fittings were auctioned. It was reported that 'we are going to lose the oldest theatre in London … the theatre is now going to be turned into baths and washhouses'. (fn. 102) The building reputedly was used as a pickle factory for a brief period, but by 1876 it had been acquired to cash in on the craze for roller-skating. (fn. 103)

Skating Rink and Winter Garden, 1876–8

In February 1876 Ernest George Fellowe, who had recently taken a 21-year lease on the property, and William Snell Chenhall, a contractor, registered the Sadlers Wells Skating Rink and Winter Garden Ltd. By an agreement of May 1876 Chenhall proposed to lease the building to the new company for various monthly instalments and allotments of shares. Plans for a skating rink and refreshment rooms, prepared by another shareholder, the architect John Warrington Morris, had been agreed and in July Fellowe applied for a music licence. (fn. 104) He proposed to use the great central hall of the theatre as a concert room accommodating 3,000 people, and the premises variously for 'Sunday services and public meetings … lectures … fancy fairs and bazaars, exhibitions of works of art, athletic sports, wrestling and skating matches, flower shows, prize dog and cat shows, industrial exhibitions and also swimming baths during the summer months'. (fn. 105)

If this diverse array of entertainments suggests an element of bet-hedging on the part of the proprietors about roller-skating, they nevertheless proceeded with internal construction works. The stage was removed and this area together with the pit and the boxes at the back of the auditorium was excavated to 'a considerable depth below the former level'. The back of the stage was opened up and the area behind, presumably including the original scene room and 40 ft of the yard towards St John Street, enclosed within the theatre to create a total skating area of 10,000 sq ft. (fn. 106)

By March 1877 the roller-skating boom was over. No fewer than 49 skating rink companies were registered in 1876; next year there were three and in 1878 none. (fn. 107) So the lessees decided to rebuild the interior—allegedly paying £12,000—and reopen Sadler's Wells as a theatre with Samuel Phelps as its leading tragedian. But Phelps never returned, dying shortly afterwards, while the building failed to secure a licence. (fn. 108) In 1878 the skating rink company was wound up and the theatre taken over by Henry Irving's former partner at the Lyceum, Mrs S. F. Bateman. (fn. 109)

Reconstruction by C. J. Phipps, 1878–9

Despite all the works of the previous two years, Mrs Bateman again reconstructed the interior in 1878–9. One reason may have been the new Metropolis Management Act which required the Metropolitan Board of Works to ensure that theatres were safe in the event of fire, and to compel owners to remedy structural defects. (fn. 110) Her experience at a prestigious West End theatre may also have left Mrs Bateman dissatisfied with the facilities and patched appearance of her acquisition. Her architect was C. J. Phipps, architect of choice to the theatrical establishment, as renowned as J. W. Morris was obscure. However, he was probably employed for his thorough understanding of the practical requirements of theatre, rather than architectural brio. (fn. 111)

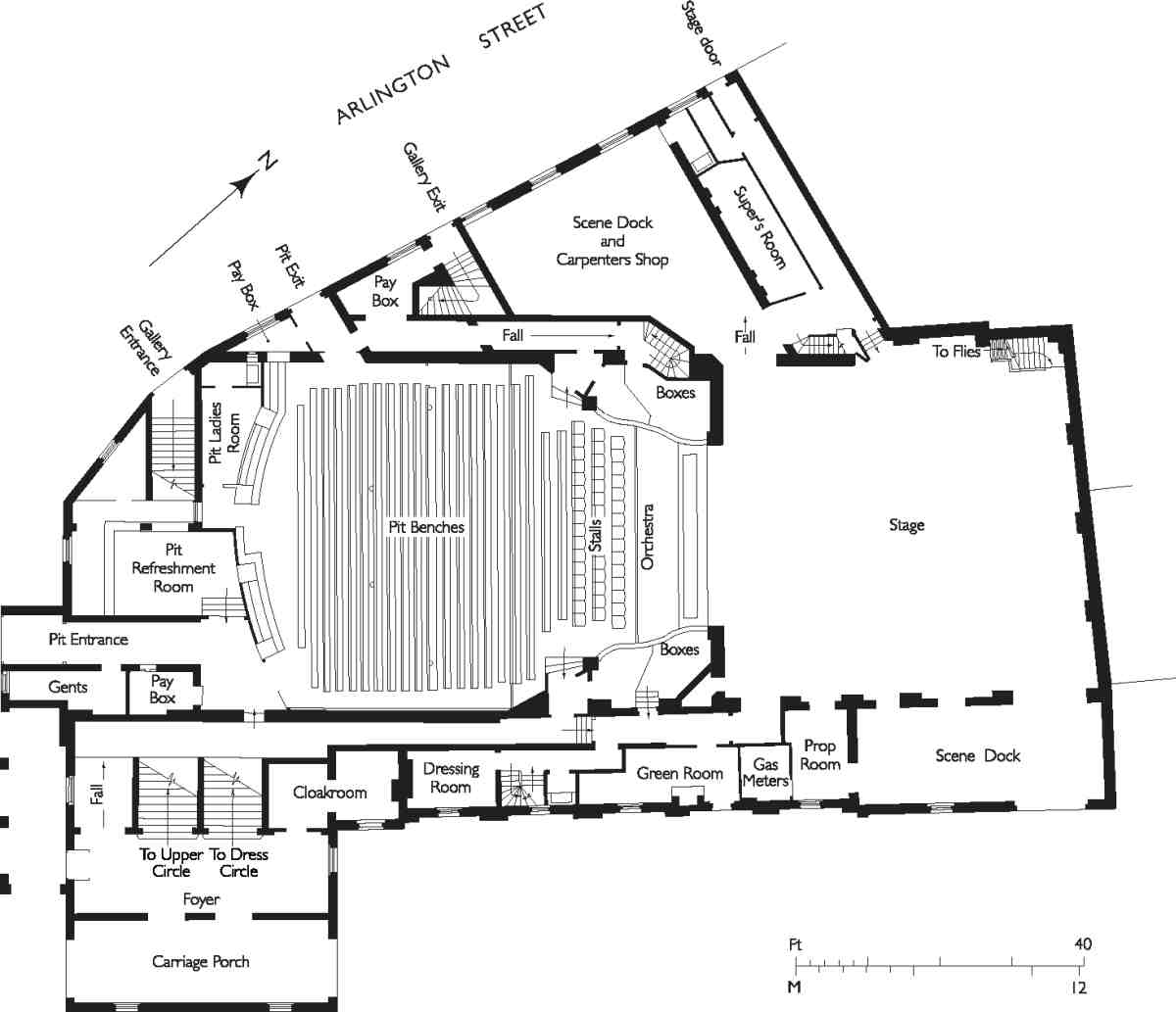

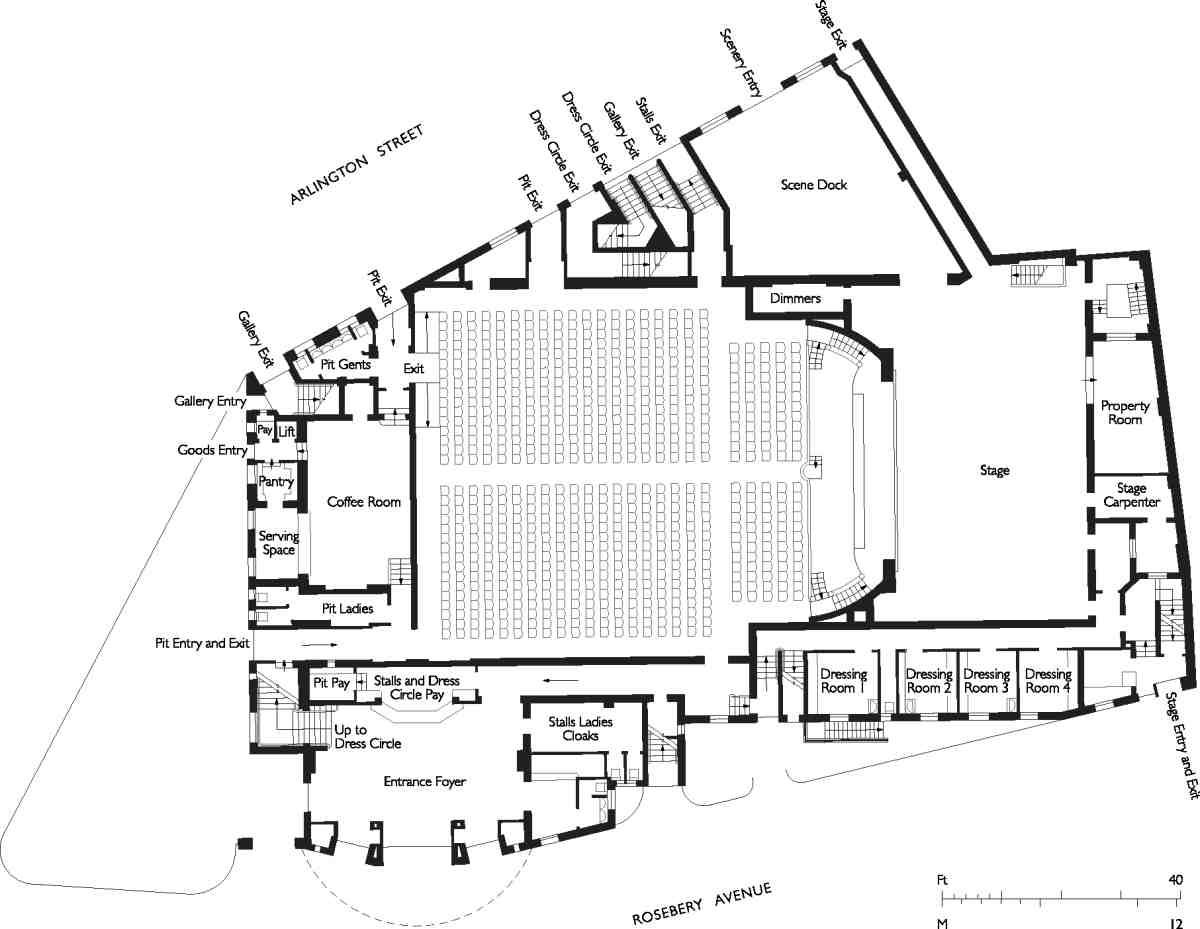

It is debatable whether Phipps's Sadler's Wells counts as a new theatre. Although it was said that he 'removed the whole of the interior of the building, including the inner walls and other structural portions … as well as parts of the main outer walls', plans of 1883 show that substantial parts were retained. (fn. 112) These included the 1824 scene dock and dressing rooms on the Arlington Street front, and parts of many external walls, including those of the auditorium.

Fire-safety measures were greatly improved (Ill. 192). There were now two staircases accessible from the huge gallery—one rebuilt inside the original gallery stair tower on the main front, the other giving access to Arlington Street. Both were built of mass concrete by the specialist firm Charles Drake & Co. There were three exits from the pit as well as two from the stage, with outward-opening double doors. Hydrants were provided on the circle level, stage and up in the flies. (fn. 113)

192. Sadler's Wells Theatre, ground plan as rebuilt by C. J. Phipps, architect, 1878–9

Phipps entirely rebuilt the auditorium, with a stronger horseshoe profile for the front of the dress circle and family circle (on one level) and the gallery above. These were built considerably forward of the previous circle and gallery fronts and the theatre's capacity consequently increased. A pair of opulent private boxes terminated either end of the dress circle, with more modest pit boxes below each. He raised the roof over the auditorium by 15 ft, thereby improving the ventilation, and over the stage to a height of 50 ft, allowing an ample iron equipment grid. One effect of the raised auditorium roof was to improve sightlines by sharper raking of all levels. Three new rows of stalls at the stage side of the pit were fitted with 'Phipps's patent chairs'; this was a socially superior area to the pit, but the pit benches did at least now have backs. The fronts of the circle and boxes were bellied in profile and enriched, while those of the gallery were flatter. Fluted and gilded Corinthian columns supported the circle and gallery, with larger ones flanking the private boxes, decorated with satin hangings (Ill. 193). Over the boxes, were two large lunettes painted with 'figure subjects representing the arts' and on the ceiling was an oval 'with Renaissance ornament on a cream ground'. (fn. 114) In honour of the theatre's long history the act drop featured a fanciful representation of 'Sadler's Wells 1779' by John O'Connor, principal scene-painter at the Haymarket Theatre from 1863 to 1878. (fn. 115)

193. Sadler's Wells Theatre, auditorium in 1879 as reconstructed by C. J. Phipps, with act drop painted by John O'Connor

From theatre to music-hall, 1881–1914

Mrs Bateman died in 1881 and with her the hopes of a Phelps-style revival. Despite her improvements, in the 1880s 'the Saturday night gallery contained the most villainous, desperate, hatchet-faced assembly of ruffians to be found in all London'. (fn. 116)

In 1883 the freehold of Sadler's Wells left the Lloyd Baker family when it was bought by Edmund Temple Godman of Longborough, Gloucestershire. (fn. 117) Only minor alterations were made for the next ten years. (fn. 118) In 1890–3 the lessees Harry Adolphus Freeman and Charles Wilmot, of the Grand Theatre Islington, applied unsuccessfully for a music-hall licence. (fn. 119) This was opposed each year by the Vestry and the London County Council representative for Clerkenwell, F. A. Ford, along with local clergymen and ratepayers, on the grounds that the LCC had decided not to capitalize on the Deacon's music hall site opposite cleared for the building of Rosebery Avenue, and so should not permit a music hall just across the road. Wilmot and Freeman claimed in 1891 that if the licence were granted they would spend £6,000, if not more, 'in making a second Alhambra of it'. (fn. 120)

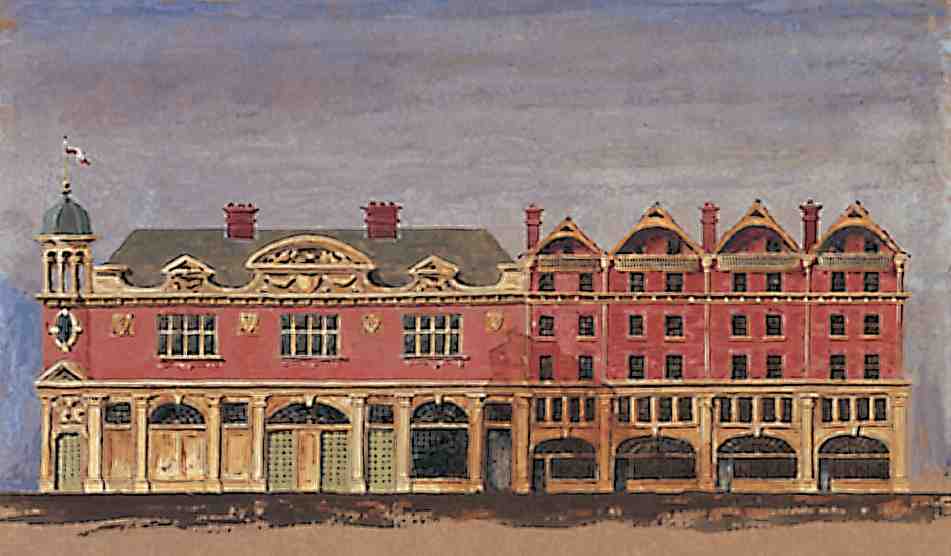

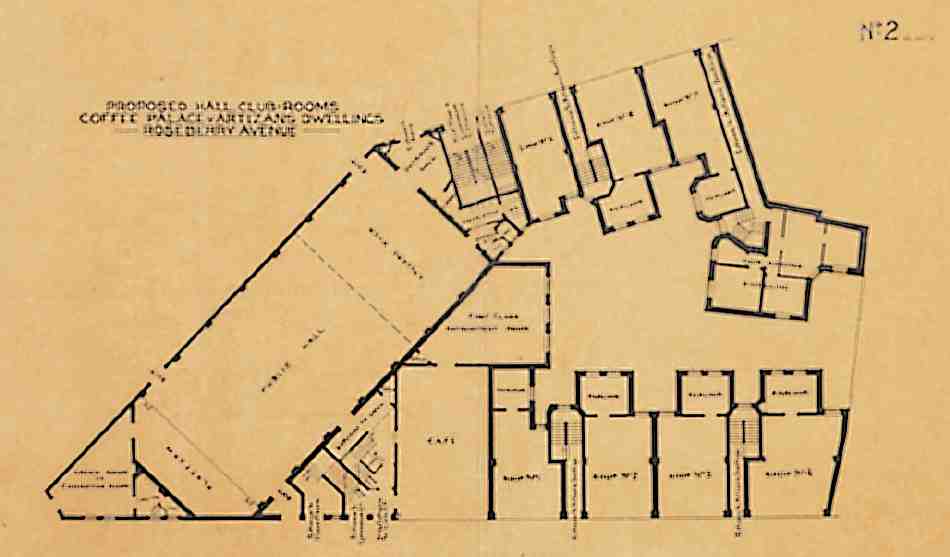

It was during this period that a scheme was drawn up by the architect A. H. Mackmurdo for redeveloping the site as a 'Hall, Club-Rooms, Coffee Palace and Artizans Dwellings (Ills 194, 195). (fn. 121) The address of the building given on the drawing is Roseberry (sic) Avenue, placing the date after July 1890, when Rosebery Avenue got its name. The inclusion of socially improving facilities such as club rooms and a reading room, as well as model dwellings, and the abstaining tone of 'coffee palace', suggest an attempt to win over the Vestry and LCC (the latter much concerned during its early years with the moral reform of Londoners' entertainments). One model for the coffee palace may have been the Royal Victoria Coffee Music Hall—the Old Vic—established in 1880 by Emma Cons to 'purify' working-class recreation. An alderman, Cons sat on the LCC Theatres Committee during its first term. (fn. 122) A room on the ground floor designated 'green room or committee room' suggests that the proprietors hoped that the 'public hall' might double as a theatre. Mackmurdo's jaunty design features many pediments and decorative festoons as well as a favourite motif of his at the date, an open belvedere with a cupola.

The Mackmurdo scheme, which was never presented to the LCC, was probably commissioned by Wilmot and Freeman, who in 1893 sublet the theatre to George Belmont, a flamboyant theatrical personality known as 'Barnum's Beauty'. Lack of a music-hall licence did not stop Belmont from putting on an array of variety acts over the next ten years, including Marie Lloyd, interspersed with 'regular' drama to give a pretence that Sadler's Wells was not a music hall. (fn. 123)

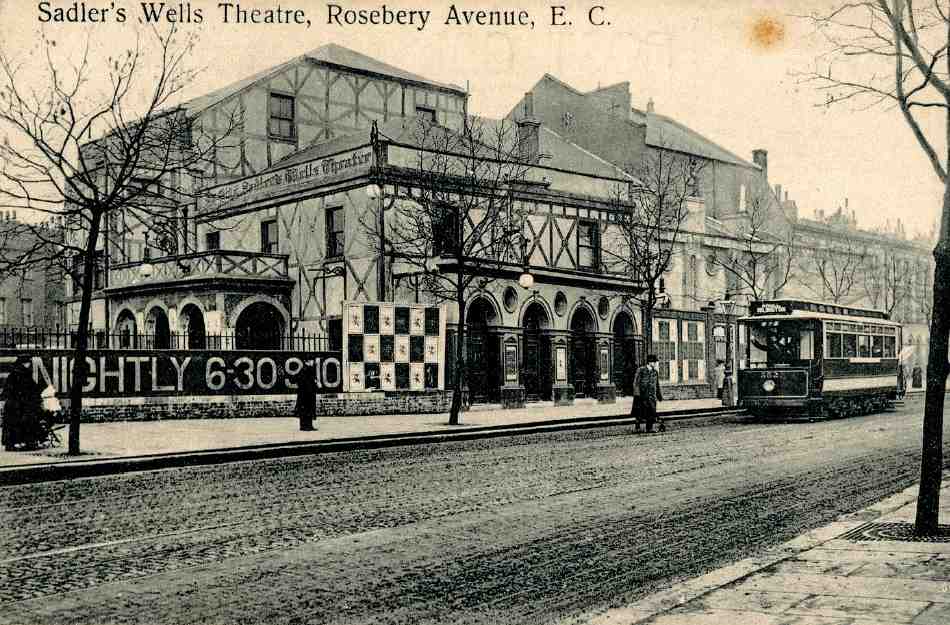

Physical changes to the theatre between then and 1902 were minor and mostly concerned with safety and sanitary requirements. Almost all were undertaken by the theatre architect Bertie Crewe, of Crewe & Sprague. His most visible alteration was a new portico in 1894, aligned to the newly completed Rosebery Avenue (Ill. 196). This consisted of four double doors, three leading into the lobby behind the 1879 carriage porch, one into an office. Built into the divisions between the three entrance doors were two small box offices and two attendants' rooms. (fn. 124) At some time between 1894 and 1900, an enclosed yard was created along the Rosebery Avenue front by means of a high brick wall running along the southern boundary of the site. (fn. 125)

By April 1900 the freehold of Sadler's Wells belonged to Charles and Charlotte Wilmot, who probably acquired it on the death of Godman in 1894. (fn. 126) From November 1902, when George Belmont left, to 1911 the theatre was let to the Music Hall Proprietary Corporation, part of Frank MacNaghten's Vaudeville Circuit, a variety empire based in Sheffield. (fn. 127) It is a measure of how lucrative this type of entertainment was that MacNaghten (who continued Belmont's practice of two programmes each evening) was prepared to give up the Lord Chamberlain's theatrical licence as well as that for selling alcohol in order to secure one for music and dancing, which he obtained in 1903. After a brief period (1910–14) reverting to a theatrical licence, a new music-hall licence was taken out. (fn. 128)

194, 195. Unexecuted scheme for redeveloping Sadler's Wells Theatre. Elevation and plan by A. H. Mackmurdo, architect, c. 1891

Sadler's Wells as a cinema, 1896–1915

An interesting aspect of Sadler's Wells' history in the twenty years before its closure in 1915 is its part-use as a cinema, for which it was licensed under the 1909 Cinematograph Act, possibly as early as 1909 and certainly by November 1914.

Until about 1910 films were generally just one more act in a music-hall programme. One of the earliest film shows in Britain took place here in December 1896, using a Theatrograph projector, devised by the pioneering film producer and inventor R. W. Paul, a local man. (fn. 129) Further 'cinematograph exhibitions' were put on in 1900, by the Edisonograph Co. The word 'exhibition' indicates the transient nature of early cinemas, which did not require permanent installation of equipment. At the end of 1900 George Belmont built a temporary shed at Sadler's Wells 'to contain an engine … used in connection with the cinematograph exhibition'. The first permanent alteration for the showing of films was the creation of a 'biograph box', a very small projection room with a flue, created within the gentleman's lavatory on the dress-circle level. In 1913 a larger and more salubrious two-storey chamber was made, to the designs of J. B. Whittaker, above the back of the gallery, partly protruding through the roof, with a lobby, generator room, winding room and operating box. (fn. 130) Tip-up seats replaced the wooden pit benches a year later. (fn. 131)

When the drama critic S. R. Littlewood visited in February 1914 to check on rumours that Sadler's Wells was now a cinema he was appalled at its state: 'Poor wounded old playhouse! Here it stands even now, shabby and disconsolate, its once familiar frontage half hidden with glaring posters'. Although it showed films on a Sunday, during the week Sadler's Wells still operated as a theatre, packed with 'pale eager-eyed little "flappers", whistling errand boys and chuckling old greybeards' who enjoyed the staple fare of 'cowboy melodramas'. Littlewood's colourful piece ended with prophetic words. 'Does it not seem, then, that here is an unrivalled opportunity for some of these noble philanthropists who are continually dinning into our ears the need for people's theatres, to step in and begin the actual work at Sadler's Wells?' (fn. 132)

Closure and dereliction, 1915–23

Briefly in 1914, it looked as though Littlewood's stinging words would be acted upon, as the leaseholder—Frank MacNaghten's sometime manager Frederic Baugh, who had taken over the lease in 1911—offered to accept only £1,500 for his share of the business if £4,000 was forthcoming to found such a people's theatre, a proposal supported by the Islington Gazette and a roster of theatrical worthies from Shaw to Pinero and Seymour Hicks. (fn. 133)

This all came to nothing as war took hold. The theatre closed in 1915 and was even recorded as 'pulled down' in 1917. (fn. 134) In September 1918 R. A. Beaton of Croydon claimed he was negotiating a long lease and enquired what work would be needed to secure a theatrical licence. (fn. 135) Nothing transpired, and in 1919 serious damage was done by intruders. (fn. 136) Shortly afterwards the theatre was acquired by Ernest C. Rolls, owner of the Kennington Theatre, later a theatrical manager in Australia and 'an entrepreneur with a chequered history of expensive productions, bankruptcy, a prison sentence for voyeurism and court appearances for tax evasion'. (fn. 137)

Rolls submitted two sets of plans to the LCC: the first by Bertie Crewe proposed only minor changes. The second set, by the architect Stanley Harry Burdwood, was more ambitious. It included a two-storey extension covering the triangular yard between the theatre and the corner of Arlington Street and Rosebery Avenue. This was to contain a restaurant, top-lit by an iron and glass lantern and overlooked by a four-sided balcony. Rolls also apparently planned to make capital out of the well (though probably more as an attraction than a source of health-giving water, which had long since dried up), as the plans included 'grotto & well'—just a staircase leading down from the tearoom (the former pit bar) to a small basement room containing the well. (fn. 138)

196. Sadler's Wells Theatre in 1910, showing portico designed by Bertie Crewe, architect, 1894

In the event the only alterations carried out were the removal of the 1846 portico, the division of the Rosebery Avenue yard, the alteration of the entrance portico and lobby to a wide central opening flanked by two narrower ones, the addition of a pediment to the top of the saloon over the entrance, a balustrade to the top of this and the 1849 extension on the south of the auditorium, and a new plain two-storey block housing cloakrooms to the right of the main entrance. The outside of the building was given a mildly Baroque treatment and rendered, the upper parts finished to resemble stonework, replacing the remains of the fake timber-framing which had been painted on about twenty years earlier (Ill. 196). The work, carried out by F. G. Minter of Putney, was completed in July 1921. (fn. 139)

Despite this cosmetic makeover, the theatre did not reopen, but now fell into dereliction. In 1923 the Evening News reported that the poet and theatrical manager Ardeen Foster was giving small cash prizes to the best 'house' built by local children—'the little housewives of Sadler's Wells'—inside the ruins of the theatre (Ill. 197). (fn. 140) The days of Sadler's Wells appeared to be numbered.

Lilian Baylis and the rebuilding of Sadler's Wells

In November 1924 Reginald Rowe, a governor of the Old Vic, was on the look-out, at the suggestion of its manager Lilian Baylis, for a second home for the theatre. At the same time 'an enthusiast' (almost certainly Rowe himself) came across the 'ghost' of Sadler's Wells and was appalled by what he saw (Ill. 198): 'In the roof were huge rents. The walls were crumbling. None of the windows had a pane of glass. A high advertisement hoarding covered the heaps of rubble … which had fallen from the decaying members'. The property was for sale, and the hoarding recommended the site as suitable for 'offices or a factory'. (fn. 141) An option to purchase was secured. (fn. 142)

Lilian Baylis—known always as 'The Lady'—had been running the Old Vic since 1899. Designed as the Royal Coburg by Rudolphe Cabanel, who had also reconstructed the inside of Sadler's Wells, this had been taken over in 1880 by Baylis's aunt Emma Cons as a temperance variety theatre. While Cons was alive Baylis continued as before but from 1912 she began, like Phelps at the Wells, to reinvent the Old Vic as both a people's theatre and a venue for Shakespeare. Alternating Shakespearean with more lucrative operatic productions, and keeping a tight budgetary control, Baylis succeeded in making her policy pay, even with seats costing between 6d and 6s, and by the mid-1920s was attracting West End stars such as John Gielgud and Edith Evans. (fn. 143)

By March 1925 an appeal for £60,000, under a committee chaired by the Duke of Devonshire, had been set up. (fn. 144) Its aim was to buy the freehold of Sadler's Wells, 'reconstruct the interior, and save it, with its historic traditions, for the Nation', as well as establishing a charity to run it in conjunction with the Old Vic as 'an "Old Vic" for North London'. Baylis, aware of the value of publicity, was photographed inside the derelict theatre with Sir Squire Bancroft, a pioneer of the 1860s theatre revival, and Sir Arthur Pinero, a local 'boy' whose Trelawney of the Wells had celebrated that same revival and a little-disguised Sadler's Wells itself.

Later that year, with money coming in slowly and the expiry of the option to purchase looming, the Carnegie United Kingdom Trust bought Sadler's Wells for £14,200, to allow the appeal committee time to raise funds. (fn. 145) Shortly afterwards Frank Matcham & Co. were appointed as architects. Reconstruction plans by the senior partner, F. G. M. Chancellor, were approved in principle by the LCC in July 1926. (fn. 146)

The financial position remained so poor that in June 1927 J. M. Mitchell, chairman of the Carnegie Trust, asked the LCC if they might be allowed to open the theatre with only the ground floor completed: 'the building could be made watertight and suitable for concerts, lectures, etc, with the ground floor and the stage completed, but no galleries', and with no sprinkler system or heating and ventilation systems installed, as it was felt fundraising would be easier if a start had been made on the building. The Theatres Section was surprisingly sympathetic to this proposal. Although Chancellor had devised a scheme for doing this that would have cost only £18,600 it was not carried out. (fn. 147)

197. 'The little housewives of Sadler's Wells': children in the derelict foyer, c. 1923

198. Sadler's Wells auditorium in ruins, c. 1923–4

199. Sadler's Wells Theatre, ground plan as rebuilt in 1930–1. F. G. M. Chancellor of Frank Matcham & Co., architect

After prolonged fund-raising, the new theatre was eventually built in 1930. Donors included the City Parochial Foundation, the Borough of Finsbury and five other north London boroughs. In keeping with the democratic aspirations for the new theatre, individuals of modest means also subscribed, it was said, for individual bricks, while the builder (Frederick Minter) allowed the Trust time to settle his bill. (fn. 148) The completed building opened with a production of Twelfth Night, appropriately on 6 January 1931, with Ralph Richardson as Sir Toby Belch and John Gielgud as Malvolio.

The new Sadler's Wells followed the footprint of its predecessor to some degree (Ills 192, 199). The ghost of Rosoman's 1764 building, specifically the relationship between the manager's house fronting Rosebery Avenue and the theatre with the stage at the east end, persisted. On the ground floor was an entrance foyer (on the site of the old lobby/wine rooms/manager's house), above which, in the place of the old saloon, was the Sadler's Wells Room, intended as a display space celebrating the history of the Wells. The main staircase to the dress circle led off from the left of the foyer. A coffee room occupied the space of the former pit bar. As before, a stalls corridor led from the foyer eastwards, along the south of the auditorium, but only as far as a secondary staircase to the dress circle. Beyond that, self-contained with its own staircase, was a two-storey block on the south side of the stage and orchestra, housing dressing rooms and a chorus room. The stage and scene docks were designed to fit the scenery of the Old Vic so that productions could be transferable. (fn. 149) Behind the stage, much shallower than its predecessors, were the property and carpenters' rooms. A scene dock on the north side of the auditorium occupied the site of the scene dock extension of 1824. The rest of the triangular site was taken up with two staircases, as before, and a pit exit into Arlington Street. (fn. 150)

The 1,700-seat auditorium featured a dress circle and gallery cantilevered out on steel girders, but no boxes; the gallery extended backwards beyond the line of the rear of the pit and dress circle (Ill. 201). In the pit and stalls the arrangement of seats in straight rows was considered oldfashioned. (fn. 151) Also provided in the theatre, above the coffee room, was a cinema projection room. (fn. 152)

The Architect and Building News deplored the fact that the building retained 'some of the historic ruins', and blamed sentiment for this 'anti-functional' blunder. However, economics were a more likely cause. The owners needed to eke out their funds and one way to do this was to make use of the existing structure. To what degree they did so is uncertain. Certainly the auditorium was built using existing walls at least up to gallery height on the north and east sides. Since Phipps in 1879 and Cabanel in 1801 both built within the existing structure these were, in part, Rosoman's walls of 1764.

200. Sadler's Wells Theatre, Rosebery Avenue front in January 1931, shortly before reopening

201. Sadler's Wells Theatre, auditorium in 1993

Chancellor's first designs of July 1926 had suggested 'architectural decoration on walls' in the auditorium, but this was not executed. (fn. 153) For economy's sake the décor was minimal and 'undistracting', with the walls toned a light buff in flat water paint, 'picked out here and there with discreetly gilded features, the woodwork being a silvergrey oak'. The escape stairs were left unplastered. (fn. 154) In the auditorium, it was hoped that the 'necessary warmth and colour' would be provided by a carpet of mauve and vermilion'. (fn. 155) Over the proscenium a scene from A Midsummer Night's Dream was executed in relief plaster 'tinted like old ivory', by Hermon Cawthra and above that the arms of the borough of Finsbury. The only fashionably art deco note was provided by the glass and steel electrolier in the centre of the coffered ceiling. It was not just the architectural press that expressed reservations about the new theatre. John Gielgud later said 'how we all detested Sadler's Wells when it opened first. The auditorium looked like a denuded wedding-cake and the acoustics were dreadful'. (fn. 156)

Externally the building was in the polite, light neoGeorgian fashion of the inter-war repertory theatres, in contrast to the blowzy style with which Matcham's firm had made its name (Ill. 200). Purple-brick planes were penetrated by rows of unmoulded window openings, over a rusticated-stucco ground floor. Decoration was confined to a relief-carved stone panel by Cawthra depicting 'women drawing water from the well' and stylized masks of comedy and tragedy over the entrance (all reused inside the present building). (fn. 157)

Alterations and improvements, 1930s–70s

The new Sadler's Wells began life shakily, with a large building debt and less than packed houses. Productions were originally intended to be alternating opera and drama as at the Old Vic, but the first ballet production came in May 1931. The dancer and choreographer Ninette de Valois, who had been working at the Old Vic, harboured ambitions to extend her teaching and found a ballet school at the Wells, a development supported by Lilian Baylis. For the first few years ballet and drama alternated at both Sadler's Wells and the Old Vic, but from 1935 Sadler's Wells took over as a ballet stage, and the Old Vic as a sole drama stage.

A first token of improved fortunes came with the decision in the summer of 1937 to build an extension on the north side of the theatre, principally for a scene dock and rehearsal space, on the site of Nos 32–34 Arlington Street. Stanley Hall & Easton and Robertson, architects of the water-testing laboratory then under construction at New River Head, were commissioned to produce the design. (fn. 158)

Following Baylis's death in November 1937, the project grew. A fund was launched to raise £40,000 for a memorial in the form of proper facilities for ballet; as it was, the ballet school had to use the largest of the refreshment rooms for daily training. (fn. 159) This further extension included a deepening of the stage, the addition of a large ballet room and property rooms behind (entailing the demolition of No. 177 Rosebery Avenue), the rearrangement of rooms on the street frontage to the south of the stage, and a new floor of offices and dressing rooms above for the use of ballet productions (Ill. 202). The project was expanded still further in March 1938, during the course of building, with the addition of an extra floor, containing a dressing room and office, on the block adjoining the entrance. (fn. 160) It has been claimed that these alterations and additions saw the destruction of the last of Rosoman's theatre but parts of the north wall, at least, survived. (fn. 161)

202. Fund-raising flyer for extensions to Sadler's Wells, c. 1937. Axonometric view taken from the north

In contrast, the death in 1945 of Sir Reginald Rowe, who with Lilian Baylis had been instrumental in saving Sadler's Wells, was occasioned by nothing more substantial than a memorial plaque. Carved by Esmond Burton, this took the form of a portrait in relief, and was unveiled in January 1952 on the main staircase. (It was reinstalled within the present theatre.) (fn. 162)

Throughout the twentieth century Sadler's Wells was hampered by the fact that having incubated successful enterprises, these moved elsewhere—usually to find better accommodation. The Sadler's Wells ballet developed in the 1930s only to move in 1946 to Covent Garden to become the Royal Ballet; de Valois then founded the Sadler's Wells Ballet touring company, also based at the Royal Opera House but performing at Sadler's Wells during its London seasons.