Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Rosebery Avenue', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp109-139 [accessed 15 April 2025].

'Rosebery Avenue', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 15, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp109-139.

"Rosebery Avenue". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 15 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp109-139.

In this section

CHAPTER IV. Rosebery Avenue

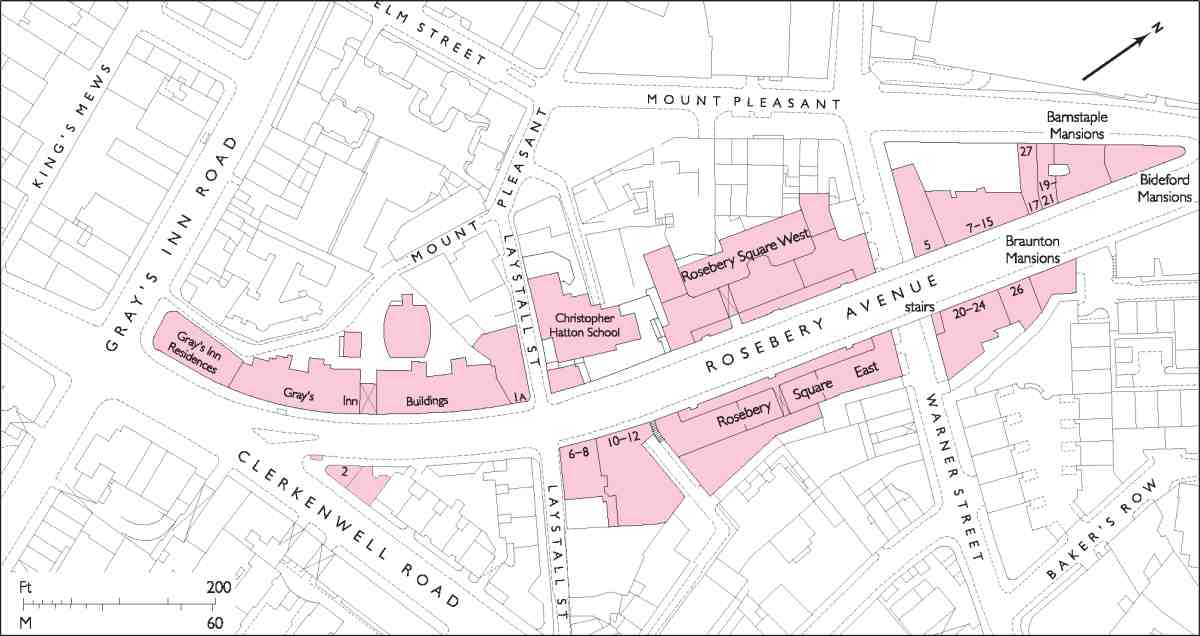

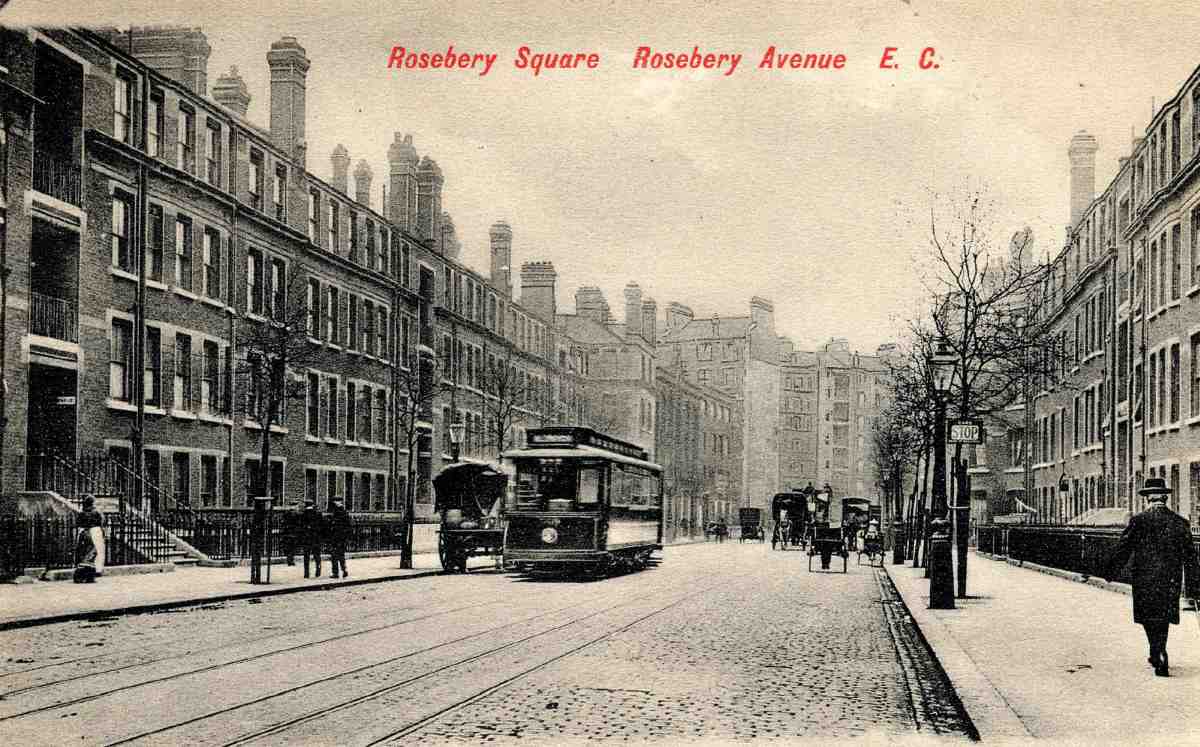

Rosebery Avenue was the second of the two new highways in Clerkenwell planned by the Metropolitan Board of Works (Ills 135, 136). The first was Clerkenwell Road, built in 1874–8. Clearance began in 1887, but little had been constructed by the time of the board's abolition in 1889, and the route was not opened until 1892, by the new London County Council. To the council the road owes both its tree-lined character and its name, honouring the authority's first chairman, the future prime minister Lord Rosebery.

Rosebery Avenue provided a direct route between the Holborn area and the Angel, and must have relieved the narrow and congested St John Street of much traffic north of the Clerkenwell Road-Old Street junction. However, the scheme developed from two separate ideas for new roads, one to replace the steep and awkward way northeast from Gray's Inn Road along Elm Street and Mount Pleasant, the other to connect Exmouth Street (Exmouth Market) with Owen's Row at the north end of St John Street. For various reasons, the roadway and the buildings alongside the south and the north parts of the final route differ respectively in character. Most of the southern section, between Clerkenwell Road and Farringdon Road, is a viaduct, crossing the Fleet Valley and in the process severing Laystall Street and bridging Warner Street (Ill. 141). Its creation involved much demolition of mostly slum property. What survived from among the existing buildings on the line of the road were the present Christopher Hatton Primary School at the south end, and at the north end Clerkenwell Fire Station and a couple of old houses adjoining, part of Cobham Row. But for the greater part, this section of the road was lined by plots of cleared ground, on which rose warehouses, factories and, most of all, blocks of model dwellings.

The longer northern section, north-east of Farringdon Road, required less drastic intervention, particularly at the top end, where New River Head, Sadler's Wells and terraces of mid-century or earlier date escaped destruction. With these smallish houses, the open grounds of New River Head and the new public gardens at Spa Green, this part of the road was and remains much less heavily builtup than the rest. The spaciousness of the streetscape was further enhanced after the Second World War with the redevelopment of the Rydon Crescent area as the Spa Green housing estate (Ill. 117 on page 100).

In this chapter the creation of the road as a whole is discussed, and accounts are given of the individual buildings fronting it, including those at the south end, historically in the parish of St Andrew, Holborn. There are two important excisions: Sadler's Wells and New River Head, the subjects of Chapters V and VI respectively. The stillsurviving houses in Rosebery Avenue predating the road itself are described here, but fuller context for the history of these buildings will be found in the chapters dealing with the adjacent areas (see Ill. 47 on page 52). In Chapter III as well, the earlier history of the area now comprising Spa Fields Gardens is given. The former Finsbury Town Hall, built after the opening of Rosebery Avenue, is described here together with the earlier watch-house and vestry hall on the site.

Character of Rosebery Avenue

For reasons largely accidental, Rosebery Avenue was to acquire a strong municipal character. Take first the role of the London County Council. Not only did the LCC complete and name it (making the roadway to a higher specification than originally intended), but it acquired or erected a series of buildings along it: Laystall Street School, which passed to the LCC with the demise of the School Board for London in 1904; Clerkenwell Fire Station, inherited by the LCC from the Metropolitan Board of Works; and a Weights and Measures Office and a gas-meter testing station, both built in the 1890s by the LCC Public Control Committee, wielder of 'a heterogeneous collection of municipal powers'. (fn. 1) The LCC, too, which had set plane trees along the new road, helping make it one of the more boulevard-like of London streets (Ills 132, 133, 143, 152), was responsible for creating the public gardens at Spa Green, and it was due to the council that the site at the meeting of Rosebery Avenue and Exmouth Street remained an open space instead of being filled with small shops (see page 60). Later, in 1905, the LCC began a tram service along Rosebery Avenue to improve public transport to and from the Angel. (fn. 2)

The local authority, too, had a high profile in Rosebery Avenue, through the presence here of Clerkenwell Vestry Hall, elevated on the abolition of the vestry system in 1900 to be the town hall of the new Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury. The Vestry was also responsible for building public conveniences, in 1899, at the Clerkenwell Road end of Rosebery Avenue and at the Farringdon Road junction. (fn. 3) The Metropolitan Water Board was a third publicauthority presence. Municipalization of the London water-supply in the early 1900s brought New River Head into water-board ownership, and the decision to build head offices on the site gave Rosebery Avenue one of its most prominent buildings.

Housing, though not in municipal ownership, further defined the new Rosebery Avenue as belonging to an age of public improvement. The blocks of model dwellings ranged along the southern section of the road were in large part built because of the statutory requirement for a substantial proportion of the people displaced by the building of the road to be rehoused. In the 1890s Charles Booth's investigators reckoned Rosebery Avenue the 'main factor of improvement' in the district, where crime and vice had been long endemic. This was not simply due to improved social conditions locally but, according to the police, to the departure of some of the rougher elements to the slums of Notting Dale. (fn. 4)

132. Rosebery Avenue in 2007. Looking south from crossing with Farringdon Road. Bideford Mansions right of centre, Mount Pleasant Sorting Office on extreme right

The LCC was never to put up any housing in Rosebery Avenue. After the Second World War, Finsbury Borough Council built the Spa Green Estate between the top of Rosebery Avenue and St John Street (see pages 96–104). It also erected a block of flats in the mid-1950s, Greenwood House, replacing early nineteenth-century houses on what had been the north side of John Street.

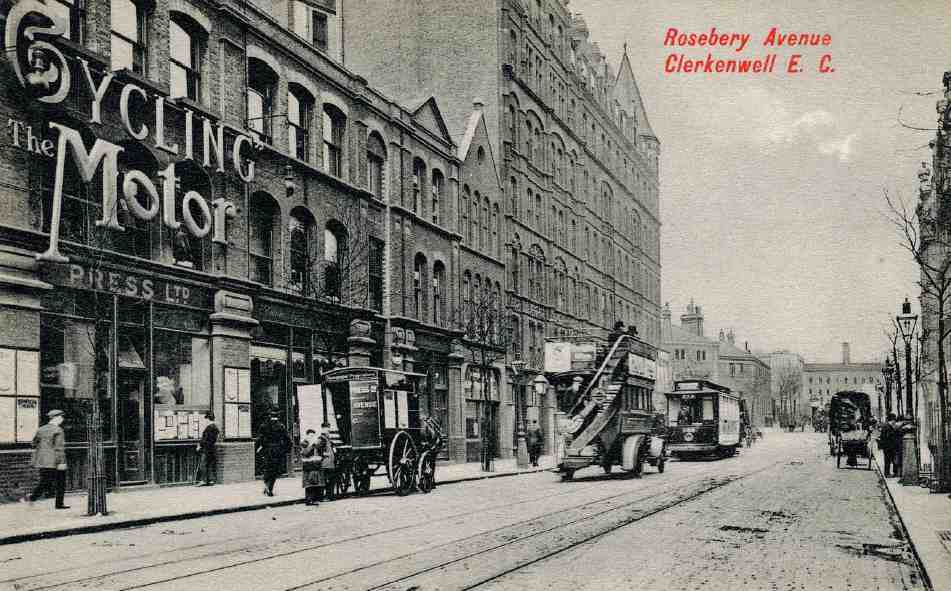

Of the commercial buildings along the new Rosebery Avenue, a number of warehouses or factories were occupied at first by the printing and metal-working industries. A variety of trades and crafts were carried on in smaller premises, such as the early nineteenth-century houses of Green Terrace, on the south side of Rosebery Avenue, including jewellery and instrument-making, and aluminium founding. Nos 111–119 were occupied for many years from 1910 by E. G. Harrop, jeweller and inventor of the expanding watch bracelet, while Nos 72–82 were home for more than 50 years from 1913 to H. Comoy & Co., briar-pipe manufacturers. A number of early businesses were connected with bicycles, and Cycling, the first massmarket illustrated magazine for cyclists, was published by the Temple Press, based for more than 40 years at Nos 7–15 (Ill. 134).

133. Rosebery Avenue in 2007. Looking north from Tysoe Street (extreme right). Centre right, No. 84: Gabriel and Edmeston, architects, 1894–5

Sporadic redevelopment from the 1920s chiefly involved the replacement of old terrace houses with commercial and industrial buildings or public housing. Two important buildings erected in the 1930s were the new Sadler's Wells and the water-board laboratory at New River Head. After the Second World War, there was one major development, the Spa Green Estate, but like much of the wider area, Rosebery Avenue as a whole had become fairly run-down by the 1960s and 70s. With the absorption of the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury into the new London Borough of Islington in 1965, Finsbury Town Hall became redundant, and after dwindling use as a register office was left standing empty. Green Terrace, bomb-damaged in the war, was demolished in 1968–70 and not fully redeveloped for twenty years. The increasingly shabby Gray's Inn Buildings were occupied from the early 1970s until 2003 as a squat, one of London's largest and best organized. (fn. 5)

134. Rosebery Avenue looking north, c. 1910. Left to right: Nos 7–15, premises of Temple Press; Nos 17, 19–21, Barnstaple and Bideford Mansions

While most industrial occupants departed from Rosebery Avenue after the Second World War, several printing and graphics businesses remain. Nos 10–12, for many years the premises of the printers Charles Johnson, and the adjoining warehouse at Nos 6–8, were reconstructed behind the original façades as a single office building in the 1990s, and most of the larger factories and warehouses are now given over to office use. However, perhaps because of the busy nature of the road, there has been little conversion of such buildings to apartments (excepting the offices and laboratory at New River Head).

135. Rosebery Avenue, from Gray's Inn Road to Mount Pleasant

The value of the historic character of the area was recognized in 1992 when Islington Council created the Rosebery Avenue Conservation Area (part of the street had previously been included in the New River Conservation Area, created in 1968). Since that time Rosebery Avenue has enjoyed a period of improved fortune, exemplified by the rebuilding once again of Sadler's Wells, and the conversion of Finsbury Town Hall into a dance school. Nos 45–47 have been remodelled as part of Amnesty International's headquarters (see page 256). At the Holborn end of the road, Gray's Inn Buildings has been reconstructed behind the original façade as public housing, while the adjoining warehouse at No. 1a has recently (2006–7) been converted into a community and children's centre by Camden Council.

Planning the route

The first glimmering of what was to become Rosebery Avenue may be discerned as early as November 1861, when an Improvement Committee was set up by Clerkenwell Vestry to look into the idea of a 'through carriageway' linking Farringdon Road and Goswell Road. This road, intended to follow existing streets as far as possible, was to have run along Exmouth Street and northeast up Garnault Place, Eliza Place, Myddelton Place and Owen's Row. Consideration was given to extending the route beyond Goswell Road into City Road, over the parish bounds into Islington, perhaps with the aim of diverting traffic from the overcrowded intersection at the Angel (a suggestion repeated by the Vestry thirty years later, in connection with the newly finished Rosebery Avenue). But there was no thought, at this date, that the proposed street might extend west of Farringdon Road. (fn. 6)

Part of the intended route followed the line of the New River, and much of the land which would have been required belonged to the New River Company. That body was not, however, prepared to co-operate, anticipating 'considerable interference with the Company's property as well as annoyance by the increased traffic close under the office windows'. (fn. 7) An alternative route slightly to the south, from Exmouth Street to St John Street Road via Myddelton Street (avoiding the offices at New River Head), was considered, but in May 1862 the project was abandoned.

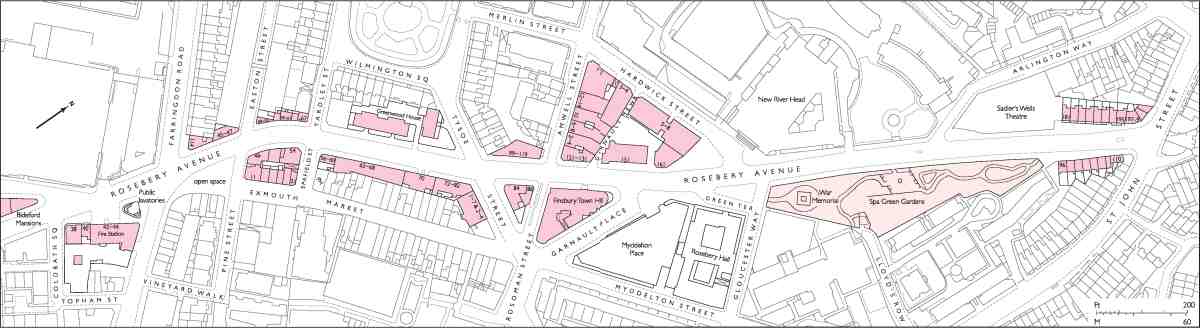

136. Rosebery Avenue, from Mount Pleasant to St John Street

137. 'Banksy' mural on Rosebery Avenue flank of No. 114 Farringdon Road, in 2006

The southern section of Rosebery Avenue originated in 1876 with the recommendation of (Sir) Joseph Bazalgette and George Vulliamy, respectively Engineer and Superintending Architect to the Metropolitan Board of Works, for a new street linking Gray's Inn Road and Farringdon Road, 'passing over Great Warner Street by a bridge'. (fn. 8) This plan was conceived in conjunction with the widening of Gray's Inn Road, part of the idea being that these improvements would destroy much of the slum property east of that street. (fn. 9) As the proposed street was partly carried high on a viaduct, it also afforded the opportunity to build unusually tall blocks of dwellings alongside it. These were intended to accommodate the thousand or so people displaced by the Gray's Inn Road widening (who would be hard to accommodate at that location), as well as the similar number displaced by the building of the new road itself. (fn. 10)

Despite support from the Islington and Clerkenwell Vestries and Holborn District Board of Works, the MBW was unable to get the scheme approved by Parliament. (fn. 11) Vigorous resistance was offered to it by J. Early Cook, a prominent local landlord, who felt so strongly about the loss of his property in Laystall Street, Holborn, and disruption to his 'poor tenants' (his five small houses were home to 50 people) that he had spent 'upwards of 1,000 pounds' opposing the MBW's Bill. (fn. 12) But the crucial objection seems to have been that the new 50ft-wide road would debouch at Farringdon Road into a bottle-neck at Exmouth Street, then only 17ft wide at the end, so that the improvement 'would be an imperfect one'. (fn. 13)

Abandonment of the new street was a disappointment to the local authorities, especially Clerkenwell Vestry, which petitioned the MBW repeatedly over the next five years to resubmit the scheme to Parliament. (fn. 14) The MBW, however, was preoccupied with other major improvements, and it was not until the subject was aired once more, by Holborn District Board, that it finally agreed to include the road in the Metropolitan Street Improvements Bill for 1882–3. (fn. 15) A factor here was the recent relaxation in the laws governing slum clearance, reducing the number of people to be rehoused to 'at least half' of those displaced.

Cook again objected, as did the School Board, which was about to build an extension to Laystall Street School on land now wanted by the MBW. The Marquess of Northampton, through whose land the road was to pass between Farringdon Road and Rosoman Street, protested that he had plans himself to redevelop and widen Exmouth Street, where all the head leases were due to expire within a few years. (fn. 16) These and other objections, coupled with considerations of cost, caused the scheme to be dropped. (fn. 17)

But in 1884 the proposal was back on the table. Now there were six variant routes to choose from. One, first considered in 1877, ran far south of the previous line, via Vine Street and a widened Sekforde Street. Bazalgette counselled against this, as being much longer than the other routes and with a relatively steep incline. The preferred line was very similar to that suggested in 1882–3, shifted slightly south to avoid contentious property. (fn. 18)

The choice for the eastern section was between taking the line of Exmouth Street (and demolishing one or other side) or aligning the road further north, where John Street offered a basis for part of the way. (fn. 19) Though this northern route avoided the valuable commercial properties in Exmouth Street, it worked out more expensive by £35,000. (fn. 20) However, while the Vestry was strongly in support of the new road, it was just as strongly opposed to taking it along Exmouth Street, fearing damage to businesses there and in Myddelton Street. Written objections were made and a deputation of householders came to the offices of the Board. (fn. 21) At first Lord Northampton offered to support the householders in Parliament, but after much horse-trading with the MBW as to the extent of property to be acquired he withdrew his opposition. Residents' objections were not heard, and the scheme was duly given statutory approval as part of the Metropolitan Board of Works (Various Powers) Act, 1885. (fn. 22)

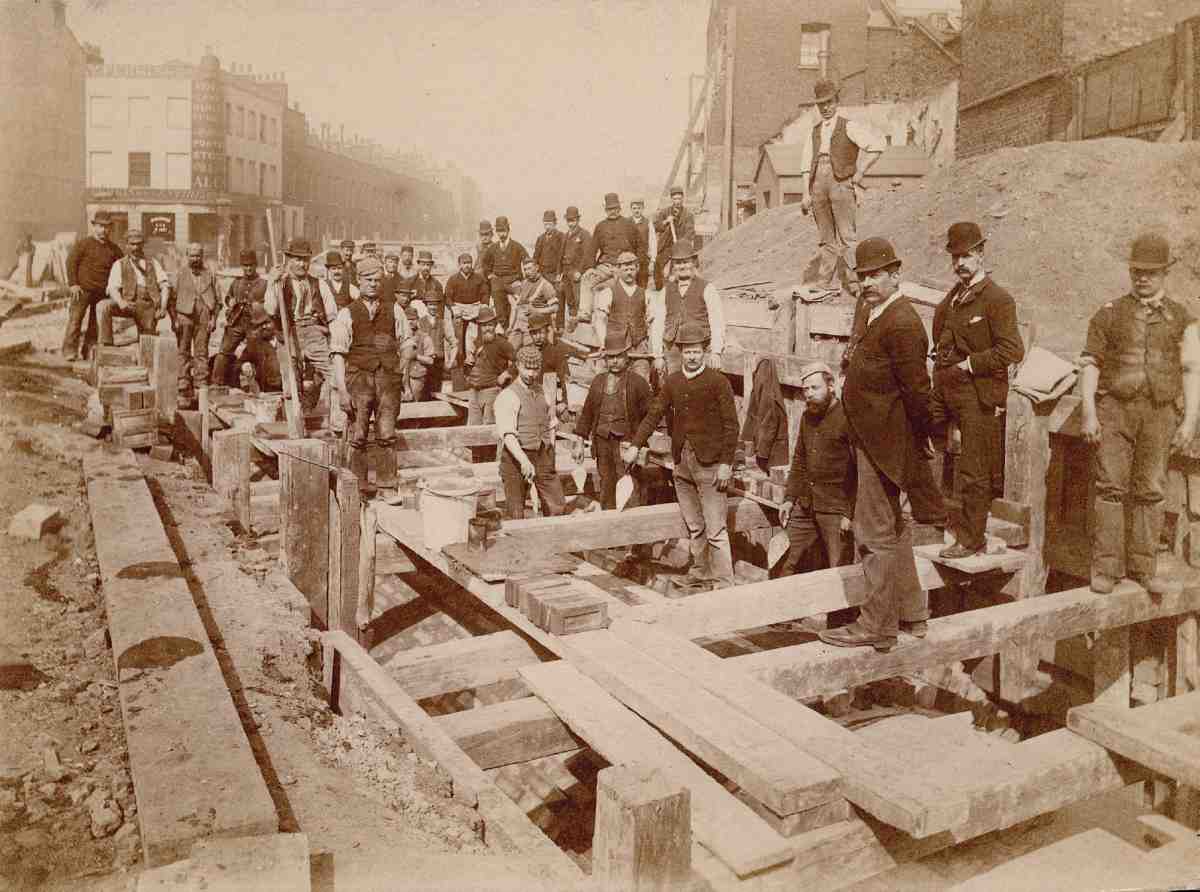

Construction of Rosebery Avenue, 1887–92

At the end of 1886 the MBW began acquiring properties along the route between Clerkenwell Road and Farringdon Road—all of Baynes' Court, Lane's Court, Red Lion Yard and Coldbath Square (including the Cold Bath) were to be destroyed. But control over the order in which sites could be cleared and the street built rested with the Home Secretary, to safeguard the interests of the inhabitants affected. (fn. 23) It was now decreed that two blocks of dwellings to house those displaced must be completed before clearance of the ground for the viaduct between Laystall Street and Coldbath Square might begin. (fn. 24) So the two ends of this section of the road and these dwellings were built together, while the area between was left untouched for the time being.

138. Rosebery Avenue under construction in 1891. Looking north, with Wilmington Arms on corner of Yardley Street, background left. Turner, Son & Evanson, contractors

139. Looking north, with Sadler's Wells Theatre on left, and Nos 177–195 behind. Void for subway in foreground. John Mowlem & Co., contractors

At the south end, John Mowlem & Co. had completed the 300 feet of roadway, sewer and footway between Clerkenwell Road and Laystall Street by the end of 1887, while the north end was finished in February 1888, by the contractor G. G. Rutty. (fn. 25) Meanwhile the Artizans', Labourers' & General Dwellings Co. was erecting Gray's Inn Buildings and, on the site of Coldbath Square, Coldbath Buildings, both groups being completed in the summer of 1888. (fn. 26) Clearance of the intermediate area for the viaduct could now start.

In its last months the MBW had decided to make the road sixty feet wide beyond Farringdon Road, rather than fifty. (fn. 27) The new London County Council, installed early in 1889, now took a similar decision regarding the southern section, something the Vestry had much earlier demanded. However, it was too late to widen the Clerkenwell Road end by more than three feet, as Gray's Inn Buildings had already been erected on one side, and the ground on the opposite corner disposed of. (fn. 28)

The contractor for building the viaduct and bridge across Warner Street was James Dickson of St Albans, whose tender was accepted at the end of July 1889. On the same day the decision was taken to plant trees alongside the road, and the name Rosebery Avenue was settled in honour of the LCC's first chairman. Almost exactly a year later, in a public ceremony on 21 July 1890, Lord Rosebery declared the new highway open. (fn. 29)

Clearance for the rest of the route depended on the completion of two further blocks of dwellings (Rosebery Square Buildings), on either side of the viaduct. Together with the earlier dwellings these fulfilled the LCC's rehousing obligations.

North of Farringdon Road up to Garnault Place, several streets were to be bisected by the road, chiefly on the Northampton estate. Here, complex leasehold interests prolonged the process of acquisition. Anticipating delay, the MBW had applied to Parliament for two years extra time, and in October 1890 the LCC found itself having to seek another extension. Road-building in this sector was carried out by the firm of Turner, Son & Evanson, who, having underbid to get the contract, went bankrupt (Ill. 138). By contrast, the northernmost leg of the route, from Garnault Place to St John Street, involved very little clearance. Taking this into account, the Home Secretary authorized work to begin here in January 1891, six months before Rosebery Square Buildings were ready. This section of road, built by Mowlems, was completed and handed over to the Vestry that December (Ill. 139). (fn. 30)

At a late stage, the Vestry raised with the LCC the idea of protracting the road further to the north, along Owen's Row and Colebrooke Row into Essex Road, in order to relieve traffic at the Angel. However, the council was not prepared to adopt this, and since the Vestry was unwilling to contribute towards it as a 'local' improvement, the proposal foundered. (fn. 31)

On 9 July 1892 the new road was formally opened. Lord Rosebery had resigned as chairman of the council some days before, and the task of officiating fell to the vicechairman, John Hutton, who, three days later, was elected in succession to the earl. (fn. 32)

Viaduct, roadway and subway

The creation of the southern part of Rosebery Avenue came at a time of much change within the Engineer's Department of the MBW as it settled in to the LCC regime. Most important was the resignation of Sir Joseph Bazalgette in the board's last days, and the appointment of his son Edward as Acting Engineer 'for existing contracts'. (fn. 33) It seems that Edward Bazalgette retained his position until the appointment of a permanent Chief Engineer in July 1889.

140. Warner Street Bridge, Rosebery Avenue, in 2007

Edward Bazalgette, who had had particular responsibility for bridges, was almost certainly responsible for drawing up, or at least supervising, the designs and specifications for the viaduct and bridge. the contract drawings for which are dated 19 June. (fn. 34) Responsibility for the design and specification of the road itself is less clear. The LCC lost two Chief Engineers through death and ill health in a short space of time before Alexander Binnie was appointed early in 1890. Probably the work was entrusted to experienced subalterns within the Engineer's Department.

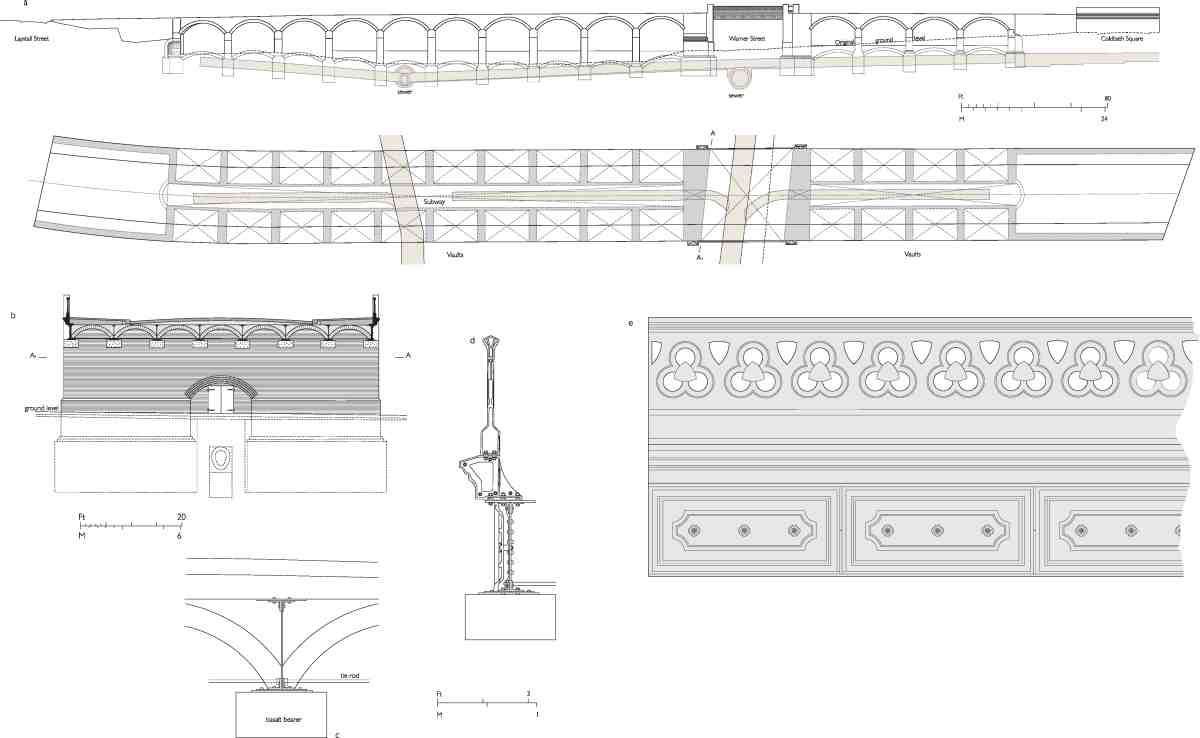

The viaduct consists of fourteen broad, shallow-arched brick vaults carried on cross-walls, with a central subway (fn. a) for pipes and cables, interrupted by the bridge over Warner Street (Ills 140, 141). This gives two rows of spacious vaults, used for storage and garaging. The subway, which resumes beyond Warner Street and continues to St John Street, is ventilated by a series of gratings in the centre of the roadway. Although the viaduct subway was planned by the MBW, the Farringdon Road to St John Street extension, which called for special excavation and added £12,000 to the cost of the works, was only decided on in December 1890. (fn. 35)

The walls of the viaduct carrying Warner Street Bridge are faced in white perforated brick. The bridge itself is built of white-brick jack-arches on riveted compound girders, with decorative side panels and parapets of cast iron, made by Westwood, Baillie & Co. and bearing the date 1890.

Pedestrian access between Rosebery Avenue and Warner Street is provided by stone steps incorporated into the western end of Nos 20–26 Rosebery Avenue, built in the early 1890s. At the other end of the viaduct, between Rosebery Square and Nos 10–12 Rosebery Avenue, narrower steps built in 1890 lead down to Vine Hill (formerly Vine Street). (fn. 36)

As originally finished, Rosebery Avenue was paved in macadam as far as Farringdon Road, and in wood from there to St John Street. The wood paving does not seem to have been a success, however, at least as far as the stretch laid by Turner, Son & Evanson went, for within three years the Vestry had to spend £3,000 on repairs. (fn. 37)

141. Rosebery Avenue, viaduct and Warner Street Bridge. Plan and elevation/section (a); cross-section through bridge, with entrance to subway in centre (b); detail of bridge construction (c); and section and elevation of side of bridge (d, e)

The buildings

Three diverse developer-architects, James Hartnoll, F. J. Chambers and Lewis Solomon, were prominent in the creation of Rosebery Avenue. Their buildings are considered below, in the context of the development of the street generally, and the efforts of the London County Council to ensure a high standard of construction. This discussion is followed by an account of Finsbury Town Hall and its predecessors, and, in topographical order, a select gazetteer of the other buildings in Rosebery Avenue. Finally, a brief account is given of Spa Green Gardens.

Development of the clearance sites, 1887–1905

Building up the cleared ground alongside Rosebery Avenue was a protracted business, beginning at the Clerkenwell Road end in 1887, before the roadway itself had been laid. Development of the viaduct section, dominated as it was by the artisans' dwellings required to be built before further clearances could be made, was largely complete by 1898. A couple of sites beside Laystall Street, however, remained vacant until warehouses were erected at Nos 1a and 6–8 in 1903–4. (fn. 38)

In the early stages the Council had little difficulty in disposing of plots, perhaps because the sites along the viaduct gave the opportunity of raising tall buildings on relatively unencumbered sites. Of thirteen lots offered on lease at an auction in March 1891, eleven were taken at the sale and the other two soon afterwards. (fn. 39)

Development east of Farringdon Road was altogether more problematic, nearly stalling in the mid-1890s and not finally brought to completion until 1905. In the first place, while the LCC was determined to see the best use made of its building plots it failed to make them sufficiently appealing to prospective developers, offering leases of only eighty years. While this had been acceptable along the viaduct, more was required to attract interest beyond Farringdon Road. In June 1892 seventeen plots east of Garnault Place were put up for auction on these terms. Not one was sold. The developer James Hartnoll expressed an interest in them, but wanted the freeholds. (fn. 40)

A second factor was LCC bureaucracy. As the council came to realize in 1893, reflecting on why its recent land auctions had failed to attract bidders, it had gained a reputation for delay in approving plans and granting leases, 'and for undue and unnecessary strictness in enforcing conditions against its tenants', with the result that interest was low, unless the plots in question were 'exceptionally tempting'. (fn. 41)

142. Nos 2–4 Rosebery Avenue in 1945. Shops built by James Hartnoll, developer, 1889–90. Behind, Cavendish Mansions, Clerkenwell Road

While the LCC remained strict in overseeing development on its ground, it now offered leases of up to 99 years and, on especially hard-to-let plots, allowed buyers a fiveyear option on the freehold, at a minimum of 25 years' purchase (that is, for at least 25 times the annual ground rent). (fn. 42) Tempted by these improved terms, Hartnoll again showed interest in the plots that had failed to sell in July 1892, plus a site at the junction with St John Street. He was unsuccessful, however: a better price than his was sought for the junction site, while the other plots were taken by the Parks Department for enlarging Spa Green Gardens. Undiscouraged, in November he made an offer for the freehold of all the other vacant plots between Farringdon Road and Garnault Place, at 10s 6d per square foot—a total of £16,750. This was a remarkable bid and would have seen Rosebery Avenue dominated by a single developer to an extraordinary degree, but the Corporate Property Committee turned him down, against the recommendation of the Valuer. (fn. 43)

By 1895 the LCC was becoming increasingly concerned at its failure to dispose of the remaining plots, now blaming the supposed deterrent effect of the blocks of model dwellings. (fn. 44) In fact, these buildings had not obviously put off developers in the western section of the road, where the dwellings actually were. It seems more likely that developers were deterred by so many odd-shaped and shallow plots, the consequence of increasing the roadwidth to sixty feet. Shores set against many of the adjacent buildings were also felt to be a disincentive, and efforts were made to remove them where possible. (fn. 45)

One of the most awkward little sites was next to No. 114 Farringdon Road, a house which had been acquired for the improvement and was now dilapidated. In 1896 the council developed the plot itself, by direct labour, as a shop, throwing the existing front parlour at No. 114 into a new extension on the Rosebery Avenue side, and making various alterations, including removal of the bay windows. (fn. 46) Shops were the only possible building use for the other very small plots, and these were built up over the next few years by F. J. Chambers with a series of little ironfronted buildings, which did not meet the usual Building Act requirements and were tolerated as 'temporary' structures only. Another such plot, at the west end of Exmouth Street, Chambers lost to the Vestry, who wanted it for an open space, which it remains (see page 60). (fn. 47)

More trouble was given by a series of larger, though still rather irregular, sites on which a building agreement was made in October 1896 with a developer called Henry Roffey. (fn. 48) This was for a long lease with a three-year option on the freeholds. For over two years Roffey wrangled with the council over whether the buildings were to be temporary or permanent, and whether it was possible to conform with the Building Acts on the constricted sites. The Vestry was upset by the 'insignificant elevational appearance' of the proposed buildings, but as the LCC's Architect Thomas Blashill explained, it was simply not realistic to expect expensive or imposing buildings on such limited sites. Roffey's architect Frank Swift eventually produced a set of designs (for two-storey buildings comprising shops with flats above) which satisfied Blashill. But it finally became clear that Roffey was never going to build anything. He gave up on four of the six plots and although Swift designed a factory for the remaining two this also came to nothing. (fn. 49) The sites were eventually filled by substantial buildings (Ills 165, 169).

Architectural character

Rosebery Avenue developed a mixed architectural appearance, to which subsequent redevelopments have added more variety. The strong municipal presence here has been noted, and the various municipal buildings are among the more sophisticated in the street. Of these, the new town hall (1893–4, enlarged 1897–9), which came into being on the eve of local government reorganization, perfectly matched the mood of metropolitan civic optimism. The work of a little-known architect, William Charles EvansVaughan, it was designed in the contemporary free style infused with hints of Flemish Renaissance and, in the later part, Baroque (Ills 152, 153, 159).

Aston Webb, the assessor of the design competition, expressed the belief that this 'good English' design 'no doubt would attract more good building' in Rosebery Avenue. (fn. 50) At first it seemed as if his optimism would be vindicated. In 1894, on a smaller site almost adjacent to the town hall, the London & South Western Bank built new premises to designs by Edward Gabriel (Ill. 133). One of the few buildings in Rosebery Avenue to attract the attention of the architectural press, the bank complemented the Baroque elements of its larger neighbour.

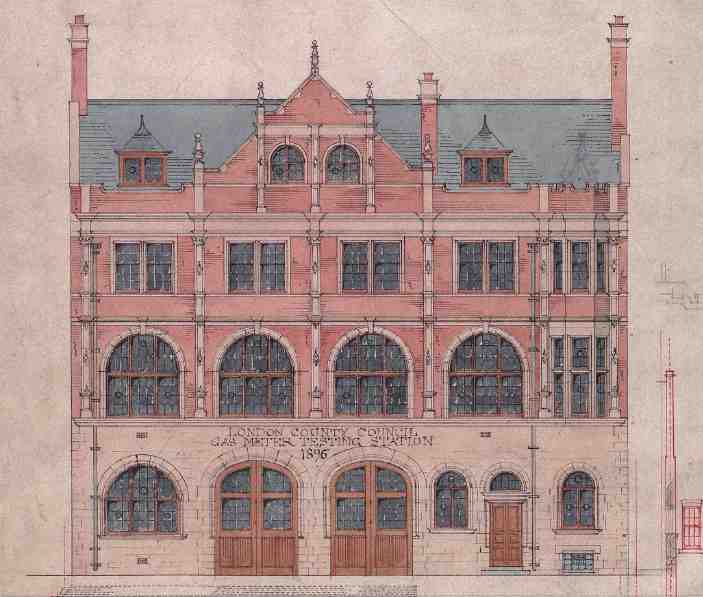

The LCC's two outposts at Nos 5 and 70 were naturally less decorative than the bank or the town hall, in keeping with their relatively unglamorous functions, but maintained the council's high standards of architectural design (Ills 167, 170). In particular, the gas-meter testing station at No. 70, with its massive arched doors and windows in pink sandstone, has a strong presence in the street.

Apart from the rebuilding of Clerkenwell Fire Station, no more buildings of any architectural pretension were to be built in Rosebery Avenue until the Metropolitan Water Board headquarters at New River Head, begun during the First World War. Representative of the lesser ambition of the buildings that went up in the later 1890s and early 1900s were those built at the very top of the north side, at the junction with St John Street. Although most of this end of Rosebery Avenue consisted of terraces predating the road, this corner plot had been cleared to widen the junction, and here in 1895–6 an architect-developer called H. Hardwicke Langston put up four shops with apartments over, which step round the corner into St John Street. In a no-nonsense manner, of brick with a few stone dressings and a pinched stone balustrade to the roof, they could have been built at any time between 1850 and 1920. (fn. 51)

The work of James Hartnoll

The figure who was to play the biggest part in the building up of Rosebery Avenue was James Hartnoll, a joiner turned architect and developer who was, in his own words, 'exceptionally experienced in the successful planning, erection and maintenance of Model Dwellings, as well as being the largest individual owner of this class of property in London'. (fn. 52) Hartnoll, who died at 46 in 1900, made his fortune in the 1880s and 90s building model dwellings and mansion flats on the clearance ground left over from public improvement schemes. He was undeterred by the statutory requirements and restrictive conditions which often made them unattractive to philanthropic societies and other developers. (fn. 53) Charles Booth thought some of Hartnoll's work among the best of the 'modern' blocks, which he regarded as a 'great advance', visually, on older dwellings. (fn. 54) In that each flat had its own WC and scullery, they were also an advance in terms of accommodation on those of the Artizans', Labourers' & General Dwellings Co.

Although best known for his austere model dwellings, in tandem with them Hartnoll sometimes also built more sophisticated mansion flats for the middle classes, using sites bought on the open market, where he was not faced with restrictions as to flat size. His biggest development of this type took place on the Gray's Inn Road improvement in 1888–90, slightly before his Rosebery Square Buildings in Rosebery Avenue. Here, alongside the model dwellings of Holsworthy Square in Elm Street, he built several smarter blocks of flats fronting Gray's Inn Road itself.

Likewise, Hartnoll followed Rosebery Square Buildings in 1891–3 with Barnstaple, Bideford and Braunton Mansions at the north end of the viaduct. Like his mansion blocks elsewhere, these are tall lively buildings in red brick, with stepped gables, stone dressings and carved panels, a manner derived from Norman Shaw's Franco-Flemish designs of the 1880s, though perhaps with a more Germanic flavour.

The extent to which Hartnoll was an architect as much as he was a developer is perhaps masked by the fact that he had no formal architectural training or qualification, and never featured in the architectural press. Although he had given up the practice by the time he was working in Rosebery Avenue, he customarily styled himself 'architect' on earlier drawings, including those for Cavendish Mansions and a warehouse in Clerkenwell Road. (Drawings submitted to the LCC for his Bideford Mansions in Rosebery Avenue are signed 'WJE'.) (fn. 55) The stylistic consistency of his buildings strongly suggests that he himself was at least in a broad sense the sole designer in his extensive business.

143. Rosebery Avenue looking south, with Rosebery Square East (left) and West (right), c. 1910

144. Rosebery Square West, northern flank seen from Warner Street in 2007, with bridge behind

Rosebery Square East and West

Hartnoll's first involvement in Rosebery Avenue was with the small triangular plot east of the junction with Clerkenwell Road, where in 1889–90 he built a couple of shops (Nos 2–4, now occupied as one), entered from Clerkenwell Road (Ill. 142). (fn. 56) These adjoin Cavendish Mansions, which Hartnoll had built for the businessman Samuel Toye on one of the Clerkenwell Road clearance sites in 1880–1. But it was the purchase in April 1890, for £16,300, of two sites on either side of the viaduct, reserved for housing, which launched him as a major player in the Rosebery Avenue development. (fn. 57)

145, 146. Braunton Mansions, Rosebery Avenue. Details of window and doorway, 2007.

147. Barnstaple (left) and Bideford Mansions, Rosebery Avenue, front elevation. James Hartnoll, developer, 1892

The LCC disliked Hartnoll's initial proposal, aimed as it was at a higher class of resident than the legislation called for; individuals within the council were unhappy with what they thought was the poor standard of some of his buildings. However, such feelings were tempered by expediency, and his revised plans were accepted that summer. (fn. 58) Once construction was under way, Hartnoll was reported to be using old bricks and concrete made from defective materials, and the council took the step of employing on-site a full-time watchman 'accustomed to building operations'. The new dwellings, called Rosebery Square Buildings, were ready for occupation at the end of July 1891. (fn. 59)

Both blocks are long and narrow, the main, central section of each façade set back from the road behind a railed area, creating something of the effect of a square (Ill. 143). These areas light the two basement levels, which were designed for business use, and give access to the vaults beneath the roadway (Ill. 144). The larger western plot allowed for additional accommodation in rear wings; there is also a single-storey wing at the south end of Rosebery Square East, alongside Vine Street. When opened, the dwellings comprised 143 flats: 83 in the northern block, and 60 in the eastern. (fn. 60) The apartments were of one, two and three rooms, each with its own copper, dresser and coal-box. (fn. 61)

The four-storey stock-brick elevations to Rosebery Avenue are simple, but monotony is avoided by the use of shallow bay-windows, galleried stairwells and pitched slate roofs.

In September 1940 much of the north end of the west block was destroyed by a high explosive bomb; this part was rebuilt in 1948, with four fewer apartments than before. (fn. 62) The buildings continued to be administered by the Hartnoll estate until 1978 when, with seven other Hartnoll properties in the area, they were acquired by Camden Council and the St Pancras Housing Association. A modernization scheme, designed by Peter Mishcon & Associates, was carried out between 1987 and 1992, when the dwellings were renamed Rosebery Square East and West. (fn. 63)

Barnstaple, Bideford and Braunton Mansions

Hartnoll bought the ground for these buildings at auction in March 1891, when the LCC had offered fifteen plots on the western part of Rosebery Avenue, mostly on 80-year leases. (fn. 64) He tried to get the council to sell him the freeholds for less than their market value, promising to accommodate here 348 of those displaced by the improvement. (fn. 65) There was a clear understanding that this meant model dwellings, yet what he built the following year was obviously not aimed at the same class of tenant as Rosebery Square. The flats in Braunton Mansions were three-bedroomed, and all three blocks were expensively finished with sculptural decoration and ornamental plaster ceilings (Ills 145, 146). In the end the LCC was only prepared to let him have the freehold of Barnstaple Mansions, where the flats were small enough to be considered as aimed at the labouring classes. (fn. 66)

Bideford Mansions (Ills 147, and 37 on page 44) included a two-storey shop (unusually well preserved, with the original enclosed matchboard-panelled staircase).

Hartnoll's final work in Rosebery Avenue, in 1897–8, was a warehouse with shops adjoining Barnstaple Mansions, at Nos 19–21 Rosebery Avenue and 25 Mount Pleasant (see Ill. 134). (fn. 67)

Developments by F. J. Chambers, Lewis Solomon and others

The second major figure in the development of Rosebery Avenue was the architect Frank Job Chambers, who had trained under his father, Francis Chambers, and whose partner he became. In a long career, F. J. Chambers went in for considerable building development on his own account in London and Kent, and the buildings he both designed and developed in Rosebery Avenue suggest a canny businessman with little interest in making an architectural splash for its own sake. (fn. 68)

His first buildings in Rosebery Avenue were Nos 20–26 on the east side and 7–15 opposite, the former as architect for the contractors and developers H. & E. Kelly, the latter his own speculation. Both blocks were built by Holland & Hannen in 1891–3. They make a striking contrast: the Kellys' warehouses eye-catching, with polychromatic brick façades; Chambers's own building utilitarian to the point of spartan (Ills 134, 166). (fn. 69) Plain too was the adjoining shop and warehouse he built in 1893–5 at No. 17 (and No. 27 Mount Pleasant). (fn. 70) But the warehouse he built a few years later in 1896–7 on the long, shallow site at Nos 62–68 (see below) is again boldly polychromatic, with broad bands of red and stock brick (Ill. 164). The difference here may be accounted for by the fact that the duller buildings were leasehold, the other freehold.

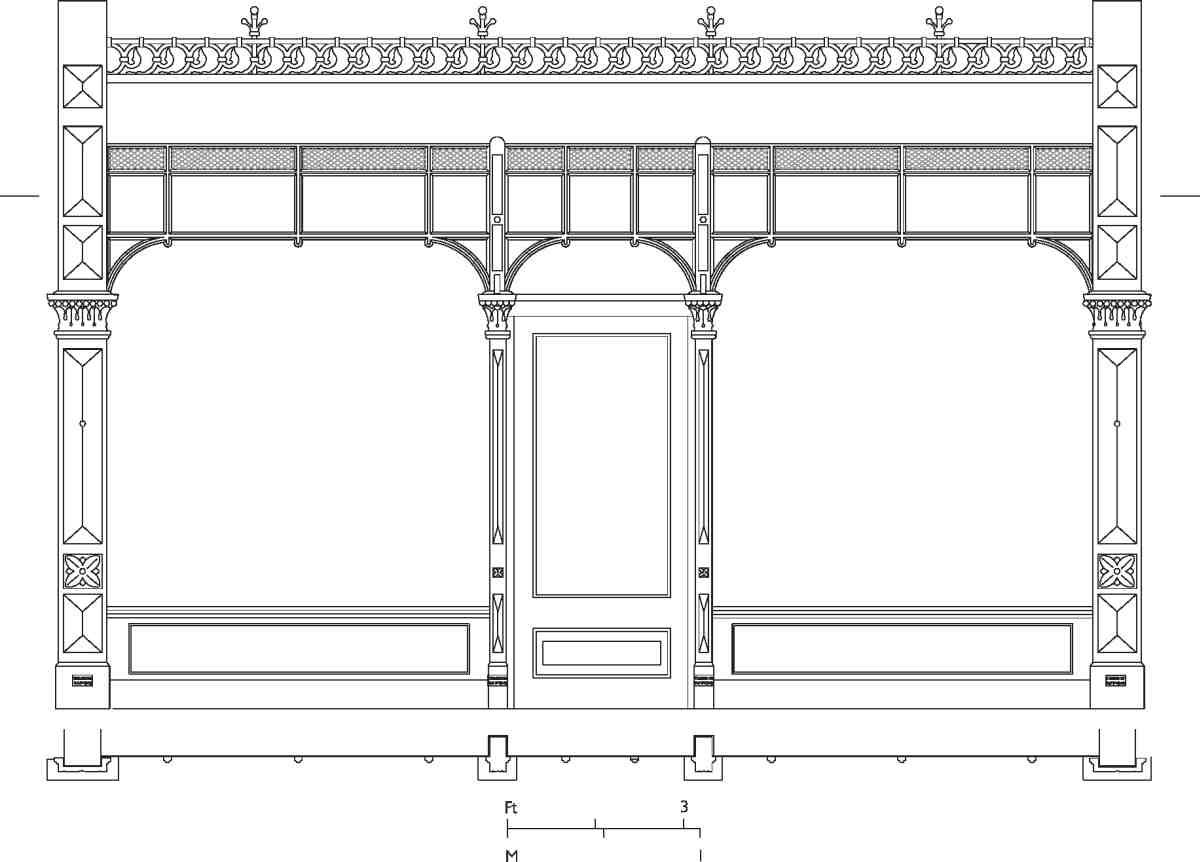

Chambers's patent iron-fronted shops

In 1896 Chambers took on lease, with an option on the freeholds, all the available clearance plots between Easton Street and Yardley Street, and, on the south side of the road, the entire frontage between No. 70 and Pine Street, backing on to the houses in Exmouth Street. (fn. 71) He bought the freeholds the following year, putting up single-storey shops on those plots too shallow to accommodate anything more ambitious. Chambers's shops have cast-iron fronts, of a pattern he himself had patented in 1885–6 with just such very shallow sites in mind, avoiding what he termed 'the sacrifice for constructive purposes hitherto necessary in erecting shops of this nature': the front walls when backed with timber were only three inches thick (Ills 148, 149). (fn. 72) The shops here were, moreover, intended only to be 'cheap and temporary' and 'might be made moveable'. (fn. 73) Chambers undertook to erect 'substantial' buildings in their stead after 21 years, (fn. 74) but this undertaking was not enforced, and excepting those between Pine Street and Spafield Street, redeveloped in the late 1920s, the shops survive (Nos 49–67 and 56–60). (fn. 75) The iron shops on either side of the road were known collectively, until the renumbering of Rosebery Avenue at the end of 1899, as The Façade, and Chambers's drawings show this name incorporated into the ironwork parapet. (fn. b)

The third architect-developer to play an important part in the building up of Rosebery Avenue was Lewis Solomon. Based, like Chambers, in the City, Solomon was public-school educated and had made an architectural 'grand tour' of the Continent. (fn. 76) He is principally remembered today as the architect of a number of synagogues. (fn. 77) Despite this background, his buildings in Rosebery Avenue rival Chambers's for their cost-conscious and utilitarian absence of architectural show. He designed a number of warehouses or factories on the west side of Rosebery Avenue: at Nos 45–47, on the corner of Easton Street, and 121–159, east of Amwell Street. On the east side of the road he was responsible for another warehouse, at Nos 72–82, the final Rosebery Avenue clearance site to be built up. Whether Solomon himself had any involvement in all these developments beyond his role as architect is not known, but he certainly had a financial interest in Nos 133–159 (where the main developer was a Major Ernest Carrington Arnold) and he was the owner of Nos 72–82 by the time of the First World War. (fn. 78) Of the other buildings he designed, Nos 45–47 and 121–131 were for the Clerkenwell builder and developer William Reason. (fn. 79)

In the 1920s Solomon's firm— by then probably run largely by his son Digby—oversaw the redevelopment of the ground behind Nos 121–159, fronting Amwell Street and Hardwick Street.

148. Nos 56–60 Rosebery Avenue, with iron shop front by F. J. Chambers, in 2007

149. Nos 49–67 Rosebery Avenue, typical iron shop front, 1896. F. J. Chambers, architect and patentee

150. No. 151 Rosebery Avenue in 2007. Troughton McAslan, architects, 1989–91

Nos 72–82

The site, one of those given up by Henry Roffey in 1898, was let to a developer named Lamplough, who went bankrupt before he could build anything. (fn. 80) The present building, originally of three storeys, was designed by Lewis Solomon as a warehouse and completed in 1905 (Ill. 169). (fn. 81) Two further storeys were added, in 1998 and 2000. (fn. 82) It has doorcases with sweeping curved consoles, a motif used by Solomon in his contemporary Shacklewell Lane Synagogue.

Hardwick Street—Amwell Street Triangle

Three factories or warehouses (all now demolished) were built in 1900–2 on the frontage between Amwell Street and Hardwick Street, comprising Nos 133–147, 149–153 and 155–159 Rosebery Avenue. Designed, and partly financed, by Lewis Solomon, they were occupied for many years by engineering and metal-plating companies. The ground behind, with early nineteenth-century houses, and stabling in Garnault Mews, was redeveloped after the widening of Hardwick Street in 1923 with light-industrial buildings. All these were designed by Lewis Solomon & Son. (fn. 83)

First was the four-storey stock-brick block at Nos 3–4 Hardwick Street, erected in 1924–5 as premises for Grauer & Weil Ltd, electro-plating outfitters. The subsequent buildings, varying in size, were faced in red brick but otherwise similar in their stripped-down neo-Georgian manner. The large blocks at Nos 5–8 Hardwick Street and No. 161 Rosebery Avenue were built in 1926 and 1928 for E. J. L. Delfosse of Pentonville Road, and occupied by his screw-making concern the Ormond Engineering Co. Ltd. The comparably scaled corner block at Nos 1–2 Hardwick Street followed in 1929–30. (fn. 84) Along Amwell Street the buildings step down to three storeys. Nos 2–4 Amwell Street (1927) comprise a symmetrically fronted three-bay block, first occupied by Henry Ward & Co., billposters, previously at No. 131 Rosebery Avenue. The mirrored pair of three-storey factories at Nos 6–10 Amwell Street was built in 1929, the first occupants being Henry Carlsberg & Son, surgical instrument makers, and the White Electrical Instrument Co. Ltd. The similar factory at Nos 12–14, built for Delfosse in 1930, was initially occupied by the British Blue Spot Co. Ltd, radio manufacturers. (fn. 85)

The Rosebery Avenue buildings were demolished in the 1980s and succeeded by the present High- Tech offices of 1989–91 (No. 151). A development by London Merchant Securities, this was designed by Troughton McAslan (project architect Jonathan Parr). As part of the scheme the adjoining 1920s factory buildings at No. 161 Rosebery Avenue and 5–8 Hardwick Street were refurbished for light industrial use. The new building has a glass-fronted central section, of column and slab construction, flanked by staircase towers faced in grey masonry panels; the top floor is a double-height studio space with a curved steel roof (Ill. 150). At the time of writing (2007), the offices of the Architectural Press were located here. (fn. 86)

Finsbury Town Hall

The building usually known as Finsbury Town Hall was erected as Clerkenwell Vestry Hall in 1894–5, on cleared ground alongside the new Rosebery Avenue, adjoining the existing Vestry hall. In the late 1890s it was extended over the old Vestry hall site to cover the whole triangular block between Garnault Place and Rosoman Street. From 1900 it was the town hall of the new Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury. With two large rooms for public hire, the building was also used for dances and political meetings and, between 1899 and 1908, as the London base of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

On the absorption of Finsbury into the new London Borough of Islington in 1965, the town hall lost its central purpose and after many years of decline as municipal offices was eventually restored as a dance school and community centre in 2005–6.

Clerkenwell Vestry Hall (demolished)

The first Clerkenwell Vestry Hall originated as Spa Fields watch-house, built in 1813–14 for the local Commissioners for Paving, Watching, Lighting and Cleansing the Streets. The watch-house, replacing one in Ray Street, was built on ground belonging to the New River Company, at the junction of Garnault Place and (Upper) Rosoman Street. It appears to have been designed by the company's surveyor, W. C. Mylne. (fn. 87)

Spa Fields watch-house was a two-storey rectangular building, 40 ft by 24 ft, with the entrance on the long side fronting Rosoman Street. It comprised 'an unusually large and lofty room in which the constable of the night receives his charges', and two cells for male and female prisoners. On the first floor was the Commissioners' boardroom. The entrance front was symmetrical, with a central door and two segment-headed windows on the ground floor and three straight-headed windows on the first. The elevations were finished in rusticated stucco, and the whole was surmounted by a stone parapet.

Enclosed by a high wall, the site included a greenyard for holding stray cattle, later used as a stoneyard, and there was also a stone-faced brick watch-box.

In 1825–6, as the business of the Commissioners increased (by this time there were more than a hundred parish staff, including 77 watchmen), the building was extended with an annexe to the north, in Rosoman Street, containing a public office, a committee room and accommodation for various officers.

With the founding of the Metropolitan Police in 1829 the watch-house proper became a district police station, replaced in the early 1840s by the new station in Bagnigge Wells (now King's Cross) Road (see page 308). (fn. 88)

The local government reorganization under the Metropolis Management Act of 1855 saw some of the Commissioners' powers taken over by the Vestry, which in 1856 decided to make the watch-house its meeting hall. The old building was given a bow-fronted addition towards the apex of Rosoman Street and Garnault Place, allowing the boardroom to be extended. This was the work of the architect W. P. Griffith. The boardroom, now 47 ft long, was decorated with a grained and varnished oak dado, papier-mâché ceiling roses, four feet in diameter, concealing ventilators, and two polished marble fireplaces. Raised seating was fitted all round the room apart from the bowed end, enclosing a T-shaped mahogany table. (fn. 89) On the entrance front, the existing windows and new windows to the first floor, including the large window to the bowed end, were embellished with pedimented stucco surrounds, and over the bow was set a pedimented panel inscribed 'Vestry Hall', with the date 1857 (Ill. 151). With some difficulty Griffith persuaded the economy-minded vestrymen to have the corresponding windows on the other side of the building ornamented to match. At the New River Company's request, the wall of the stoneyard was rebuilt further back from Garnault Place, with a railing in front 'to prevent the public from using the wall as a urinal which was now the case to a great extent'. (fn. 90)

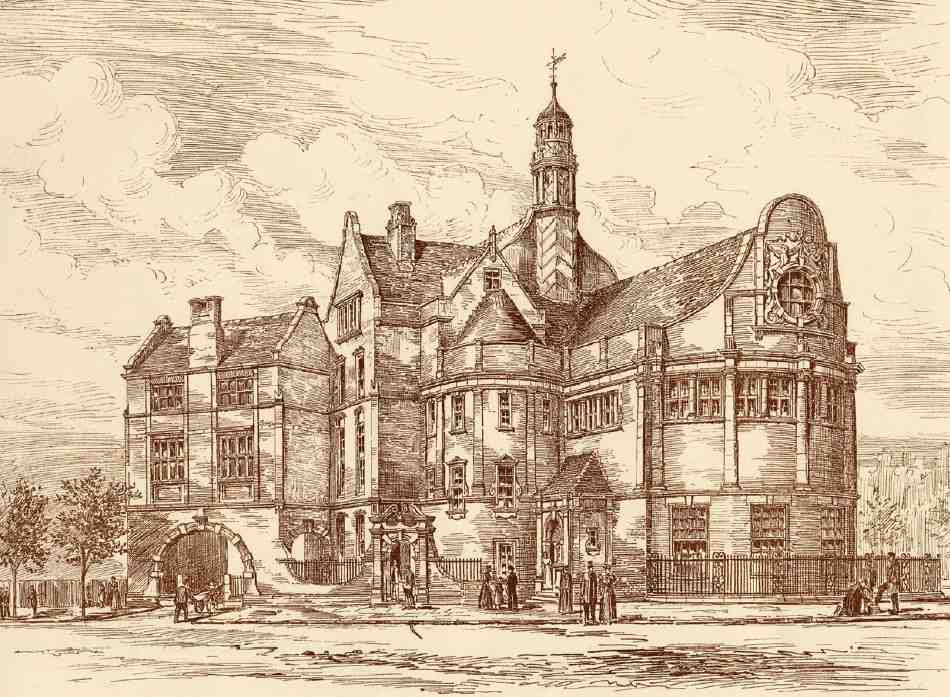

151. Clerkenwell Vestry Hall, looking north-east, c. 1890. W. C. Mylne, architect, 1813–14, with embellishments and bow-fronted end by W. P. Griffith, 1857. Demolished

A ratepayers' gallery was installed in the boardroom in the late 1870s, (fn. 91) by which time the building had become glaringly inadequate. There was only one meeting-room and visitors to the Vestry or Committees had to wait on the stairs. (fn. 92) Occasional outbreaks of fisticuffs between vestrymen, reported with relish by the press, were sometimes attributed to the inadequacy of their accommodation, and it was described some years later as 'the smallest and worst Vestry Hall in London'. (fn. 93) Consideration was given in 1884 to the possibility of enlargement, but nothing was done in view of the nearness of the projected new street (Rosebery Avenue). In 1886, however, a special committee was set up to look into rebuilding; one argument in favour of this was the chance it offered to provide a hall for public meetings and entertainments 'of which the Parish, containing nearly 70,000 inhabitants, is at present destitute'. (fn. 94) A possible new site, that of the future Northampton Institute in St John Street, proved too expensive at 30s a square foot, and the New River Company's offer of 12s a square foot for the existing site was accepted in 1887.

There the matter stood for five years, while Rosebery Avenue was built. In 1892 the London County Council's price of £6,210 for the freehold of adjacent ground fronting the new road was accepted. (fn. 95) The sale was completed the following year, with the aid of a loan from the LCC. There was some opposition among ratepayers to the proposed new building, partly on grounds of cost, partly in view of likely further reform of London government; however, a proposal to postpone matters until this larger matter had been resolved was unavailing, and the Vestry determined to go ahead with a new building.

Design and planning

At the suggestion of John Macvicar Anderson, president of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Aston Webb— then chiefly known as the designer of the Victoria Law Courts in Birmingham (1885–91)— was appointed to assess a limited competition for designs. The Vestry had originally intended a dual-purpose hall-cum-boardroom on the first floor, together with committee rooms, but on Webb's advice decided to make a separate large hall and boardroom a requirement, even if it meant having committee rooms on the ground floor.

152. Finsbury Town Hall, view looking south along Rosebery Avenue around time of completion, 1895. Garnault Place to left

153. Finsbury Town Hall, architect's perspective showing front to Garnault Place, 1894

Of thirteen individual architects or partnerships invited to submit designs in July 1893, eleven complied (two, Lewis Solomon and Mark Judge, declining due to pressure of work). Among them were Charles Bell, W. Charles Evans, F. R. Farrow, E. J. Harrison, Lewis H. Isaacs, John Johnston, Karslake & Mortimer, A. Saxon Snell, G. H. Fellowes Prynne, and Walker & Rüntz. How this list was compiled is a matter for conjecture, but Saxon Snell, a well-known designer of public buildings, including the Holborn Union Offices of 1885–6 (see volume xlvi), and Isaacs, architect of the first Holborn Town Hall in 1878–80, were natural choices. Others were local or had local connections, through other architects or vestrymen, or LCC members; Johnston was an inveterate architectural competitor.

Webb, who said that he 'never saw a fairer competition', (fn. 96) recommended the design of the relatively unknown W. Charles Evans, who, by the time the results were announced in November, had changed his name to Evans-Vaughan. Interested parties among the vestrymen attempted to have the result overturned in favour of either Snell, who won the second premium, or Harrison, who won the third. They were unsuccessful.

The building contract was awarded to Charles Dearing of Islington, on his tender of £14,724 13s. The foundation stone was laid on 14 July 1894 and the building was opened a year later to the day by Lord Rosebery, the first chairman of the LCC.

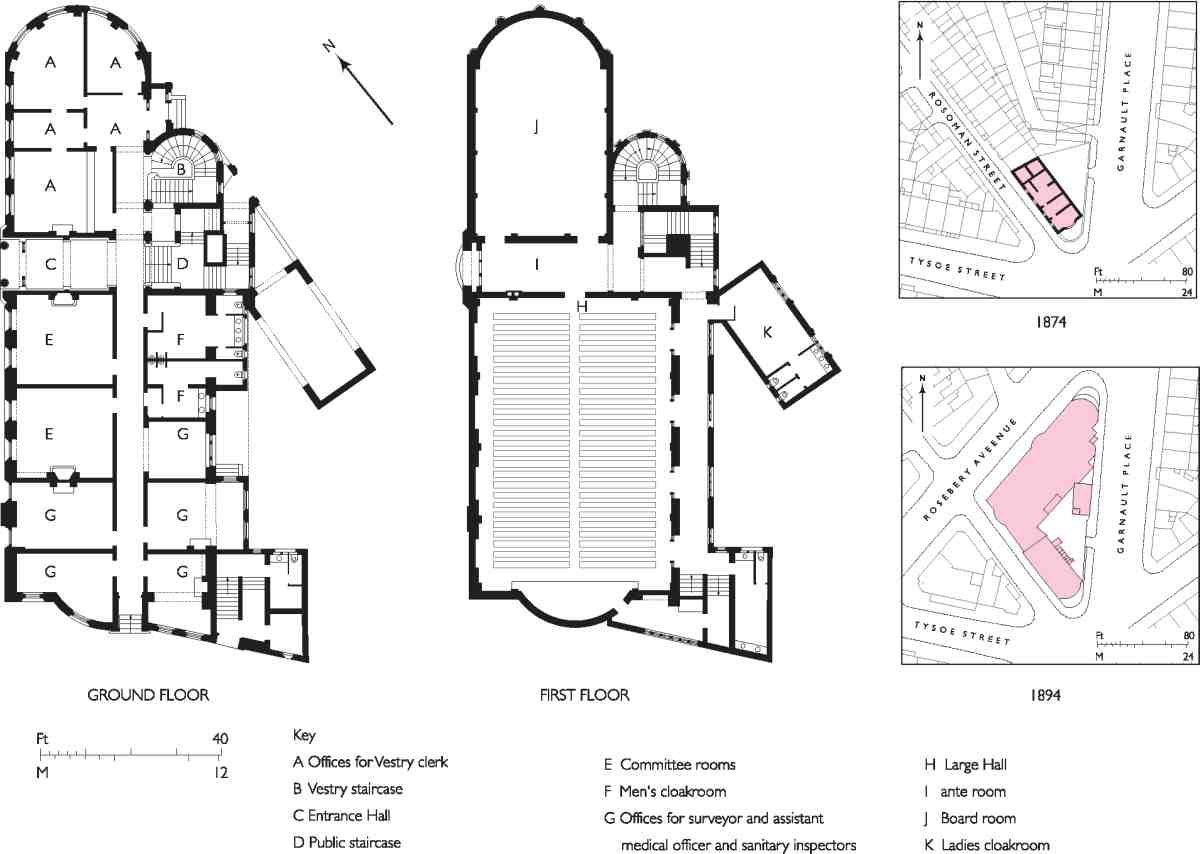

154. Finsbury Town Hall, ground and first-floor plans of main building (1894–5) and site plans of Vestry Hall in 1874 (top) and 1894 (bottom)

Evans-Vaughan's name had been put forward initially by the vice-chairman of the special committee, Joseph Walton, a watch-case manufacturer, and there are other indications that he may have had local connections. (fn. 97) During the 1880s, as plain W. C. Evans, he had designed the Bridge House Farm estate in Brockley, south-east London—a substantial development of houses and a school—all in a flamboyant eclectic style of mixed brick and stone. His other works had included the equally eclectic Welsh church in Falmouth Road, Southwark, still extant. (fn. 98)

A key to his stylistic manner may have been his six years as illustrator for the architectural journal Building World, whose art editor was J. P. Seddon. Along with another leading Goth, James Brooks, Seddon had supported his application for a fellowship of the RIBA in 1887. These artistic architectural circles contrast with the utilitarian projects listed in Evans-Vaughan's obituary, which focused on his final projects for a steam laundry and a sewerage system. (fn. 99)

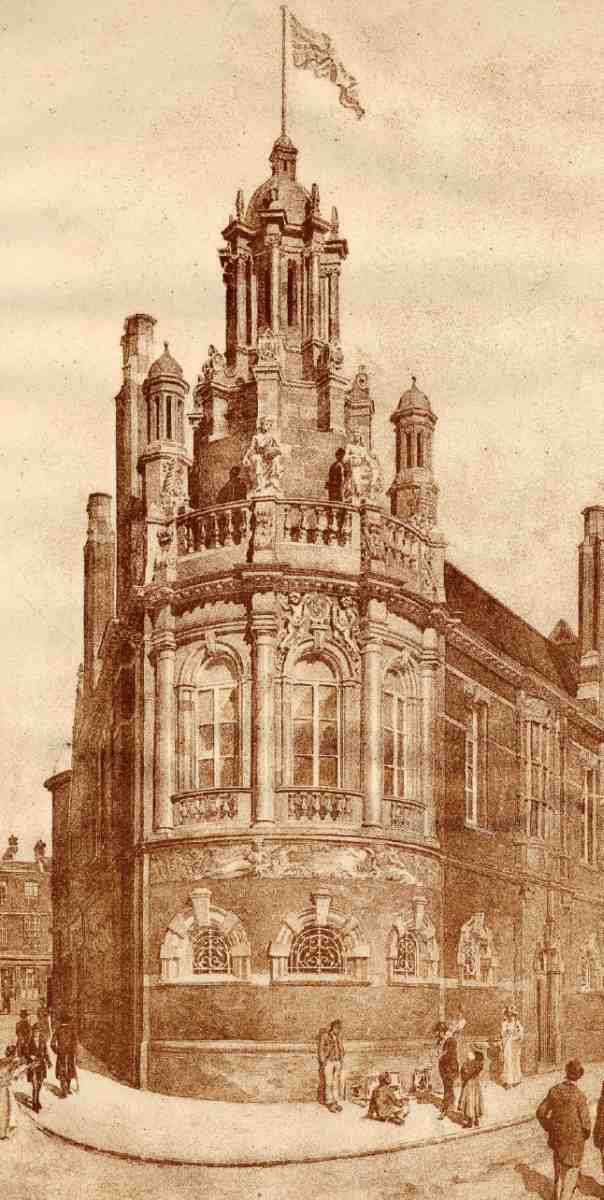

Architecturally, Evans-Vaughan's building was more refined than his earlier work, though just as promiscuous, mixing Tudor, Renaissance and Baroque elements, in keeping with the fashionable 'free-style' of the 1890s. Faced in red Ibstock brick with Ancaster stone dressings, it offered an especially varied and picturesque aspect to Garnault Place, with the curving ends of the staff staircase and boardroom set against the high gable of the Large Hall (Ills 152, 153). Appropriately the Rosebery Avenue elevation is the most imposing. The curving end of the boardroom is marked out externally by five engaged Ionic columns, and the Large Hall by four shallow bowed mullion-and-transom windows.

Possibly Evans-Vaughan was influenced in his design by E. W. Mountford's Northampton Institute near by on St John Street, a building in similar style and materials that also featured a large shaped gable behind an acute corner, as its design was published just before the Vestry Hall competition was announced (see Survey of London, volume xlvi). (fn. 100) Moreover, when Evans-Vaughan was invited to join the vestrymen on visits to new vestry halls at St Martin's-in-the Fields and Battersea to see how they were furnished, he declined to go to the latter as he had already been there. Since Battersea Vestry Hall was also designed by Mountford, Evans-Vaughan may have been taking an interest in his work.

The plan of the new building was much determined by the shape of the site, an irregular quadrilateral with its longest side to Rosebery Avenue (Ill. 154). Evans-Vaughan placed the boardroom and public hall on the first floor, aligned with the main road, and ranged the ground-floor rooms along a corridor parallel to the road. An analyst's laboratory and fume chamber were safely tucked away on the third floor at the top of the main staircase, while the basement was devoted to a strong room, coal and storage. The twin functions of public hall and local authority offices and the need at times to keep the two separate resulted in five entrances, with a sixth way-in from Garnault Place, through a three-storey gatehouse, giving access only to the stoneyard.

155. Finsbury Town Hall, Large Hall in 1993

Evans-Vaughan was also commissioned to design the interior decoration. The ground-floor corridor and the staircases between ground and first floor were lined to dado level with glazed tiles (Ills 156, 158), and there were marble columns in the corridor; the ceilings had elaborate Tudor-style plasterwork, and the floors were laid with composite stone mosaic. (fn. 101) In the Large Hall was a flattened barrel-vaulted ceiling, divided into panels heavily decorated with plaster strapwork, volutes and consoles. At the west end, housing a dais, was an alcove decorated with painted strapwork (since obliterated), with two plaster figures representing Music and Poetry reclining above its semi-circular arch (Ill. 155). The top-lit boardroom, with a gallery for ratepayers at one end, was ornamented with detached Ionic columns around the walls.

The new building was lit by both gas and the new mains electricity, and the electric lamps in the Large Hall, which survive, take the form of sprays of foliage, distinctly Art Nouveau in style, with light-bulb 'flowers', held aloft by winged female figures (Ill. 157). The branches were supplied by Vaughan & Brown of Kirby Street, Hatton Garden, and the figures were modelled by Jackson & Co. (fn. 102) In the ceilings of the boardroom and Large Hall were square and circular ventilators, through which exhausted air was fed out into a flue contained in the turret at the east gable of the Large Hall. (fn. 103) This system was evidently not very effective as it was replaced in 1900 with one by E. Stephens & Co.

Walnut furniture to Evans-Vaughan's designs was supplied for the boardroom, along with bentwood chairs for the Large Hall, committee rooms and offices, by Hampton & Sons. Thwaites & Reed supplied the clock over the main entrance, while Grimshaw & Baxter supplied the boardroom and Large Hall clocks.

Enlargement 1897–9, and later changes

The possibility of extending Clerkenwell Vestry Hall was under consideration even before the final bills were settled. The new building had curtailed the storage space available to the works committee, and, moreover, it was clearly only a matter of time before London's government would be reformed and the Vestry evidently wanted any new body to be based in its fine new building. In 1896 Evans-Vaughan was consulted. He thought it would be possible for about £4,500 to put up an extension in the same style, with a basement, and the ground floor left open as a yard; the upper floors could be let until required by the new authority. (fn. 104) The plans he subsequently produced replaced the old Vestry Hall in just this manner, with a large rectangular room on the first floor, the Minor Hall (Ill. 162), in the position of the old Vestry Hall's boardroom, and a stoneyard on the ground floor. Along Garnault Place he added a two-storey range containing a kitchen and offices, ground-floor storage space (open on its inner side to the stoneyard) and another staircase, giving access to the Minor Hall.

156. Finsbury Town Hall, main stair in 1993

In fact this design was in the same style only up to a point. Although he used the same materials of red brick and stone, with rubbed red-brick dressings and a red engineering-brick plinth, and gave the Garnault Place front a shallow bow window similar to those of the Large Hall, the rounded corner to Rosoman Street and Garnault Place was more Baroque in manner (Ill. 159).

157. Winged figure in Large Hall holding electroliers, 1993

158. Finsbury Town Hall, entrance hall c. 1920

159. Finsbury Town Hall, southern extension showing front towards Garnault Place in 2005

160 (far left). Finsbury Town Hall, architect's perspective of southern extension by C. Evans-Vaughan, 1898

161. Finsbury Town Hall, main front to Rosebery Avenue in 2007

The corner has three tall round-headed windows, the centre one decorated with carved putti supporting a cartouche with a portrait in profile of Queen Victoria. EvansVaughan's original design featured an ornate stone cupola over the curved corner, which the Vestry decided not to build until the parish was transformed into a metropolitan borough (Ill. 160): in the event, it was never built. Instead, recumbent female figures representing Peace and Plenty were carved in relief beneath the broken pediment, together with a stone band, between the ground- and firstfloor windows. These were felt by the Town Hall Committee to 'add very much to the architectural appearance' of the extension. (fn. 105)

B. E. Nightingale's tender of £5,394 for building the extension was accepted in June 1897. Work was finally completed by direct labour, following difficulties with Nightingale's plasterers, at the beginning of 1899. Interior decoration was again specified by Evans-Vaughan, who suggested fixing 'artists' paintings' in eight panels to the Minor Hall ceiling, but this was thought too expensive and he came up instead with a cheaper scheme of plaster cartouches, highlighted with gilding, on a wide coving above a strapwork frieze (Ill. 162). A robust cast-iron and glass canopy, with the name 'Finsbury Town Hall' in black and white glass, was built forward of the main entrance on Rosebery Avenue, replacing the original, slighter iron and canvas structure (Ill. 161). (fn. 106)

By this time the London Government Bill of 1899 had been enacted and from 1 November 1900 the new Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury met in the enlarged building, further decorations being carried out in readiness by Campbell, Smith & Co. Evans-Vaughan had died that May from typhoid fever, and the final works were supervised by A. G. Langdon.

As the new authority administered a larger area and wielded greater powers than had the Vestry, alterations were immediately needed to accommodate more staff. Among the changes, completed in 1901, the ground floor of the extension was mostly converted to offices, reducing the stoneyard to a triangular lightwell. The alterations made little difference externally, as the existing arched openings with metal grilles were easily changed into windows, with lowered sills.

There followed a succession of ad hoc alterations to improve circulation and adapt to changing requirements for office space. In 1920 the inadequacy of the accommodation led to the now grand old man Sir Aston Webb being called on again, and on his recommendation Austen Hall, architect of the new Metropolitan Water Board offices, was asked to make a report. He was dismayed at the state of the building, in particular the inadequate lavatories, the nine separate entrances, and the lack of connection between the original and later parts—which meant that if a visitor entered by the main entrance the only way to reach the Medical Officer of Health was through the Borough Surveyor's office. Hall rejected the council's suggestion for building an additional floor of offices over the council chamber, favouring rearrangement and building above existing lavatories. His proposals were soon abandoned, probably on grounds of cost. (fn. 107)

As Finsbury Council's work grew, particularly with regard to slum clearance and public housing provision, the need for more accommodation became pressing, and in the late 1920s the warehouse opposite the town hall at Nos 121–131 Rosebery Avenue was fitted up as an annexe for the Public Health and Works departments. This work was designed in consultation with the Borough Surveyor by the architect E. C. P. Monson, who was much involved in Finsbury's public housing programme at this time. Monson was also responsible for associated alterations to the town hall itself. As part of this work he added a corridor, parallel to Rosoman Street and joining up with Evans-Vaughan's main corridor, making for the first time a proper ground-floor link between the original town hall and the extension. The most significant external alterations were the filling in of the old stoneyard entrance in Garnault Place, the opening of a new entrance to what remained of the yard, and the installation of an iron escape staircase. The original design and materials were closely followed.

162. Finsbury Town Hall, Minor Hall in the 1920s

Internally, a drastic decorative change was made with the fitting of hardwood panelling in the Members' Room (the former Committee Room to the right of the main entrance) and in several corridors and vestibules, covering up the then unfashionable tiled dadoes and marble columns.

Garnault Place Control Centre

In 1939 Finsbury Borough Council received government permission to construct a two-storey bunker beneath Garnault Place, with access from the basement of the town hall. Designed by Tecton and built by 'cut and cover', this was completed in late 1940 and comprised, on the upper floor, two large air-raid shelters for male and female staff at the town hall, and on the lower a Control Centre for the borough, containing a control room, signals room and messengers' room. It was unusually strong for a council shelter of this type, with external concrete walls 6 ft 6 in thick.

Disused after the war, the bunker was returned to use from 1952 to 1965 as a local control centre in case of nuclear attack. Later it was used for civil-defence training and thereafter as storage. At the time of writing (2006) the bunker is disused and subject to flooding. (fn. 108)

Since 1965

When in 1965 the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury was replaced by the much larger London Borough of Islington, the existing Islington Town Hall in Upper Street became the new authority's headquarters. Finsbury Town Hall provided accommodation for various council departments, including the Housing District Office and the Area Repair Team, and it was used as a register office for civil weddings until 2003. Among comparatively recent alterations was the addition of a wheelchair ramp with a lime-green metal and glass canopy on Garnault Place (Ill. 159).

As early as 1970 suggestions were made that the building be turned into an arts centre on the model of Battersea Town Hall, re-opened in 1974 as Battersea Arts Centre. (fn. 109) Many proposals were mooted along these lines over the following 35 years—including, in 1994, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, a scheme for a Georgian cultural and business centre. (fn. 110) Meanwhile the building deteriorated. In 1987 it was pronounced 'a modest municipal ruin', and in 1989 large-scale functions in the council chamber and Large Hall had to cease on safety grounds. (fn. 111)

A report commissioned in 1995 by Islington Council examined possible courses of action, including an arrangement whereby the building would be used partly for community purposes and partly by an arts organisation, or as a museum, exhibition space and local history library. One reason for the failure to settle the building's future appears to have been local antipathy to Islington Council. (fn. 112)

Unpopular proposals to sell the building to Berkeley Homes in 2002, to be turned into luxury flats with a private gym and café-bar, fell through. This scheme was succeeded in 2005 by that of the Urdang Academy, a dance school based in Covent Garden, to redevelop the building as dance studios, with a fitness centre and cafeteria. (fn. 113) The school moved in late in 2006 and public access was provided soon afterwards for open classes in dance, keep-fit and martial arts. The most radical structural intervention was the creation of two large studios on the ground floor, obliterating the western part of the original corridor and involving the removal of the 1920s panelling and the fireplace of the Marriage Room (the former Members' Room) to the room opposite. The remnant of the old stoneyard was glazed over, and the former ratepayers' gallery separated from the former council chamber (now another studio) by an obscure-glass screen. Plans for a restaurant had yet to materialize at the time of writing, but the Large Hall can be transformed into a party venue, known as 'Clerkenwell Vestry'. (fn. 114)

Other Buildings: Gray's Inn Buildings

Along with their now demolished counterparts Coldbath Buildings (see page 27), Gray's Inn Buildings were the first buildings to go up in Rosebery Avenue, in 1887–8. Erected by the Artizans', Labourers' & General Dwellings Co., the two groups of model dwellings could together accommodate just over 1,000 people. (fn. 115)

163. Gray's Inn Buildings, Rosebery Avenue, in 2007. F. T. Pilkington, architect, for Artizans', Labourers' & General Dwellings Company, 1887

The four blocks of Gray's Inn Buildings display (as did the two blocks comprising Coldbath Buildings) the eccentricities of style evident in all the dwellings designed for the company by their architect, F. T. Pilkington (Ill. 163). The plain brick façades are enlivened with tall, swooping consoles to the ground floor and moulded decoration in the form of over-scaled swags and grotesque classical heads, executed in light-red reconstituted stone. Unlike those built by James Hartnoll, these flats were 'associated', having shared WCs and sculleries, which made them both unpopular and difficult to adapt as tenants' expectations rose. (fn. 116)

More flats, with eight shops, were built by the company on the corner of Gray's Inn Road adjoining Gray's Inn Buildings in 1888–9, again to Pilkington's designs. (fn. 117) The name, Gray's Inn Residences, suggests that this was originally for a middle-class rather than artisanal clientele.

Christopher Hatton Primary School

The oldest part of the building was erected in 1876 for the London School Board as Laystall Street School, intended for 500 children. It was extended to more than double the capacity in 1885–6, the extension being raised on arches because of a drop in the ground level; the space beneath was adapted as a covered playground. A new schoolkeeper's house, replacing an old house originally retained for that purpose, was built at the same time. This was enlarged in 1894, when the playground was extended with a piece of land alongside the new Rosebery Avenue. (fn. 118)

The school, which had become known as Rosebery Avenue School, was reorganized as Rosebery Avenue Primary School in 1949 and in 1951 renamed after Elizabeth I's chancellor Sir Christopher Hatton (of Ely House, near Hatton Garden). By the late 1960s the roll had fallen to little over 200, and the school was eventually closed in 1969. (fn. 119) The building was used for other purposes including teacher-training until reopened as a local authority primary school in 1996. (fn. 120)

Both the original building and the extension are by the School Board's architect E. R. Robson. The shaped gables fronting Laystall Street are characteristic of his early work for the board, while the later wing, of four storeys with a roof-top playground, is in the plainer, rectilinear style favoured by that date.

No. 5, former Weights and Measures Office

Responsibility for the testing of weights and measures was transferred from the police to the London County Council in 1889. (fn. 121) No. 25 Mount Pleasant was used temporarily, but larger and more robust premises were called for, the old house being so badly affected by the heavy work that it had to be demolished. The new premises, known as the North Central Weights and Measures Office, were designed by the Works and Improvements Branch of the LCC's Architect's Department and built in 1892–3, by Co-operative Builders Ltd of Brixton. (fn. 122) A sober, Germanic-style building, faced in red brick and pinkish sandstone, it has a narrow gabled frontage to Rosebery Avenue (Ill. 167). The large five-storey extension along Warner Street, on the sites of Nos 40 and 41 Mount Pleasant was added in 1898–9 by the LCC Works Department, again to the designs of the LCC's architects. (fn. 123) This originally incorporated two decorative tablets from the front of the original No. 41, one of which survives in the present loading-bay, a later extension. (fn. 124)

In 1928 the building was acquired by the Temple Press and connected internally to their premises at Nos 7–15 Rosebery Avenue. The shopfront was reconstructed for Office Cleaning Services in the early 1960s, with a mosaic decoration, since removed, depicting a jaunty workman with a ladder and pail; the architect was Leslie Norton. (fn. 125)

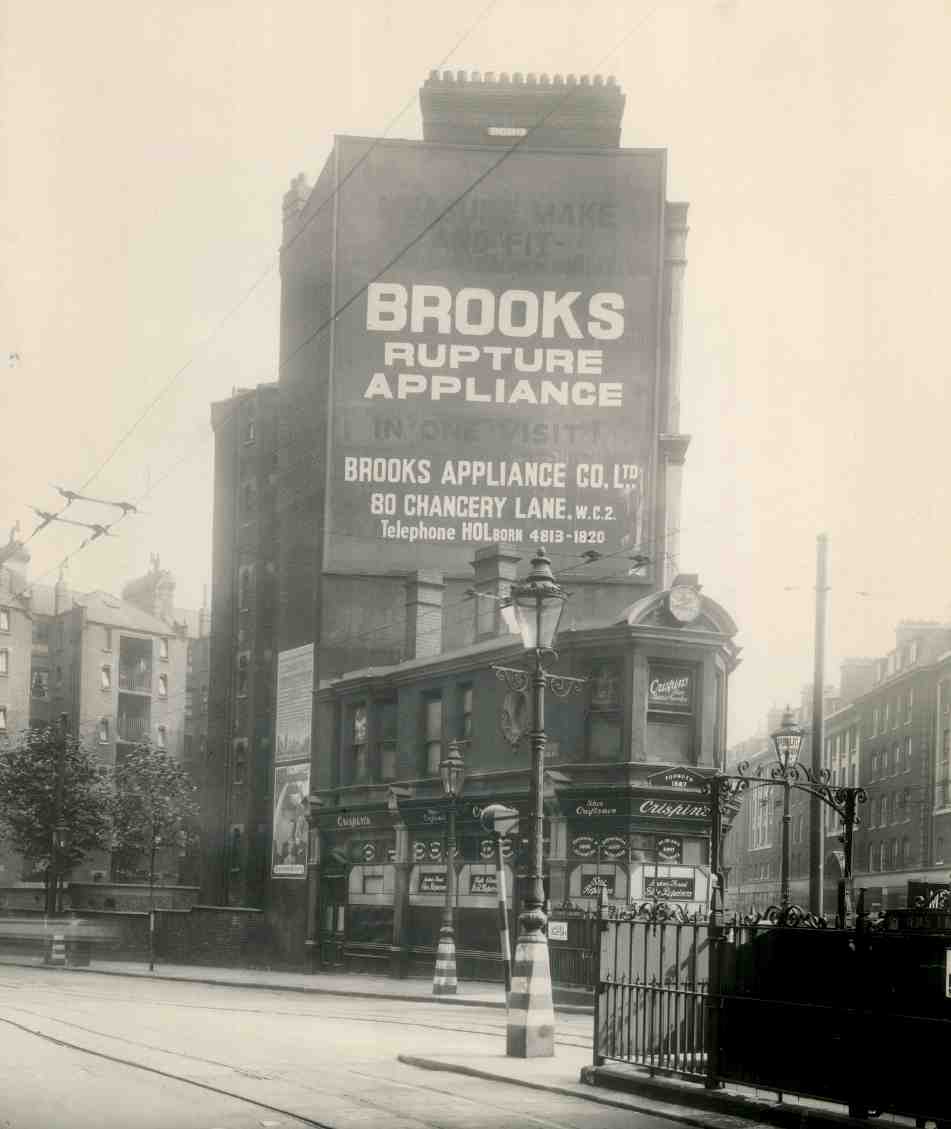

No. 69, Wilmington Arms

The original public house of this name was built here, on what was then the corner of John Street, in 1818–19 (see Chapter X). It was part of a development undertaken by Isaac Woodroffe, gentleman, of Surrey, extending further along both street frontages. These buildings survived the subsumption of John Street into the new Rosebery Avenue (Ill. 138), but the pub was rebuilt in 1927–8, a new long lease having been obtained by Watney, Combe, Reid & Co. in 1920, taking in the site of the house to the east and two adjoining in Yardley Street. The architect was G. G. Macfarlane, and E. A. Roome & Co. of Hackney were the builders. The neo-Georgian red-brick building carries a small stone panel with a stag in relief, representing Watney's origins at the Stag Brewery, Pimlico. (fn. 126)

Nos 99–119

This factory and shop, on the corner of Amwell Street, was designed by an obscure architect, F. Henden Winder, for a local developer, John Milroy, and erected in 1900–2. Winder had to deal with a fairly awkward site, the west end being a narrow wedge-shape, producing a rugged building of some sophistication, with an ogee cupola to the corner and dramatically recessed windows to the second floor (Ill. 165). (fn. 127)

Nos 181–195

These houses, called St John's Terrace, were erected in 1853–4 by George Payne, builder, of Wharf Road, King's Cross, on lease from Mary Ann Lloyd Browne (née Lloyd Baker) (see page 267). No. 177, which completed the original row of ten, was demolished for the rebuilding of Sadler's Wells in the 1930s, No. 179 for the next rebuilding in the late 1990s. (fn. 128) The ground-floor and basement fronts are stuccoed, with a continuous band-course at cornice level; the upper storeys brick-faced, with stucco dressings (Ill. 139).

Nos 6–8

This site, on the corner of Laystall Street, was formerly occupied by the Red Lion public house and not originally scheduled for the Rosebery Avenue clearance, presumably because it would have been expensive to acquire. By March 1890, however, its value had evidently fallen as customers were put off by the surrounding building sites, and the landlord claimed to be destitute: 'a sad illustration of how individuals may suffer by street improvements'. (fn. 129) The plot remained undeveloped until 1903–4 when a warehouse and factory, a plain building mostly of red brick, was erected for W. F. Revill of Hampton Hill. (fn. 130) It has been rebuilt internally, along with Nos 10–12.

Nos 10–12

Except for the shops at Nos 2–4, this was the first commercial building erected in Rosebery Avenue. The site, auctioned by the London County Council in July 1890, was bought by T. N. Debenham and built up the same year with a three-storey warehouse, to which a four-storey extension along Vine Street was added the following year. The architect was T. Chatfeild Clarke. (fn. 131) It is built of red brick, each of the five bays to Rosebery Avenue rising to round-headed lunettes with blind tracery, the centre bay with a crow-stepped, scrolled gable. The building was let to Charles Johnson & Co. in 1891, the first in a succession of printer occupants. (fn. 132) In recent years the whole building, along with Nos 6–8, has been reconstructed behind the original façades, and an attic floor added (Ill. 168).

164. Nos 62–68 in 2007. F. J. Chambers, architect, 1896

165. Nos 99–119 in 2007. F. Henden Winder, architect, 1900–2

Rosebery Avenue

166. Nos 20–26 in 2007. F. J. Chambers, architect, 1891–3