Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Spa Green to Skinner Street', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp84-108 [accessed 15 April 2025].

'Spa Green to Skinner Street', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 15, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp84-108.

"Spa Green to Skinner Street". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 15 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp84-108.

In this section

CHAPTER III. Spa Green to Skinner Street

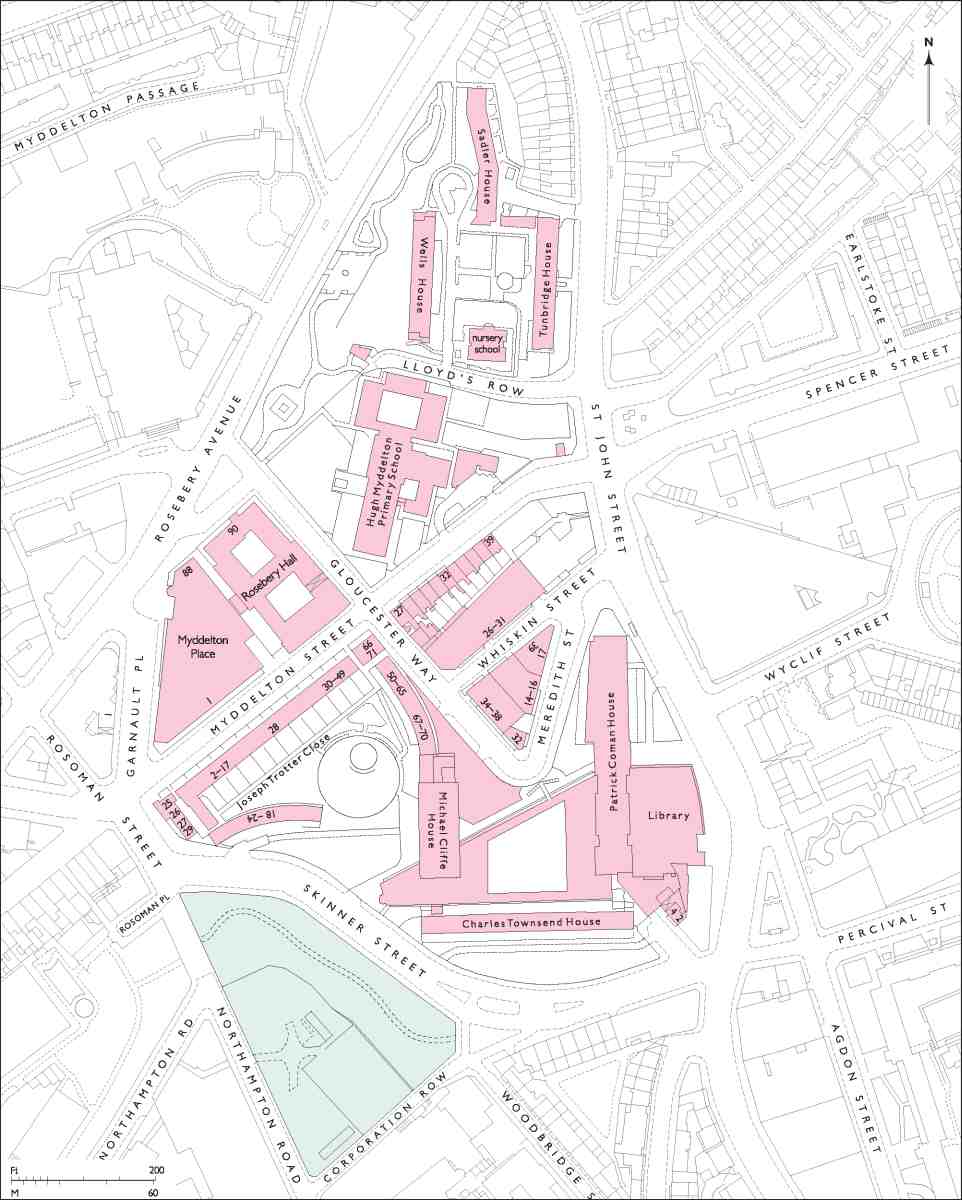

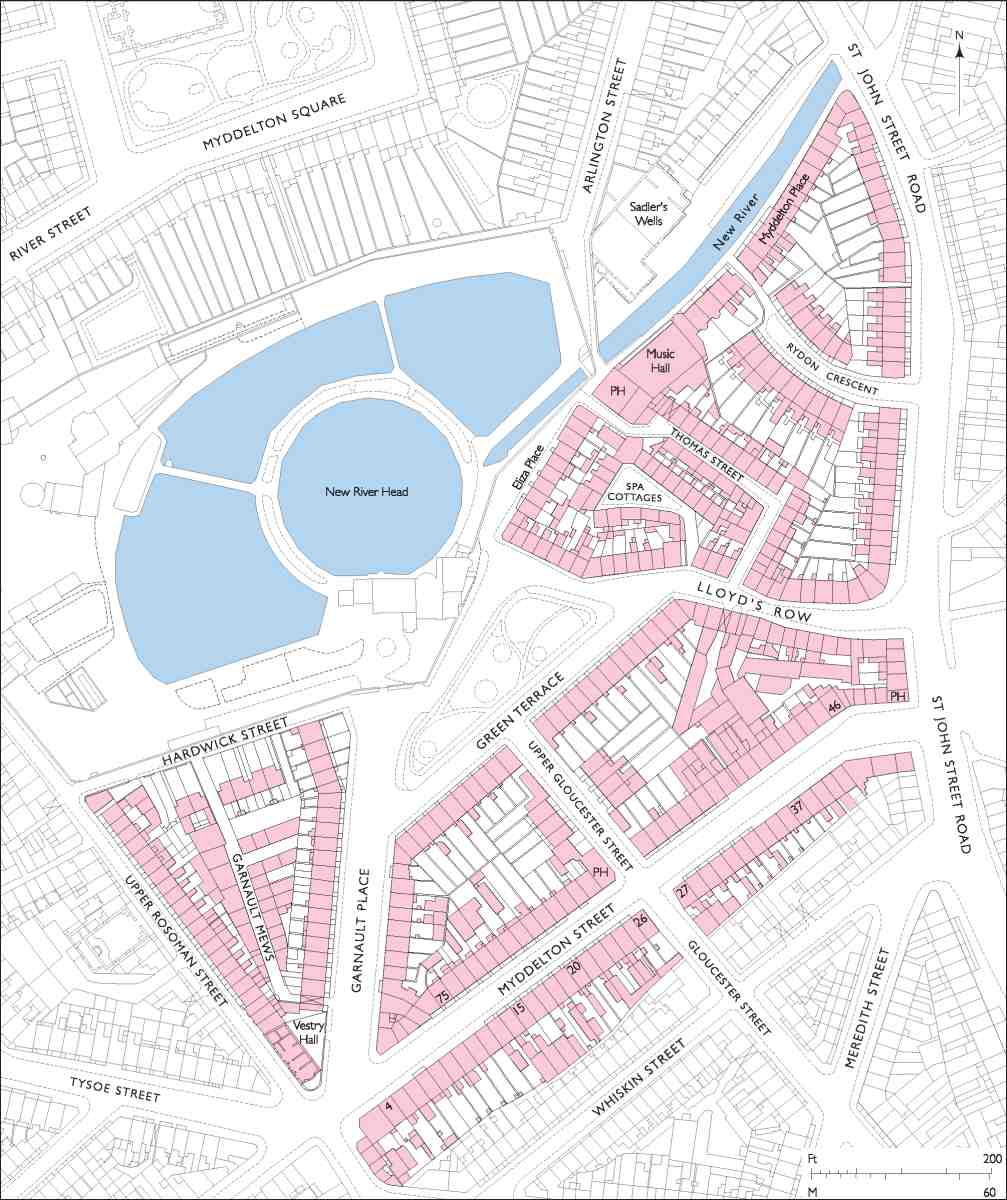

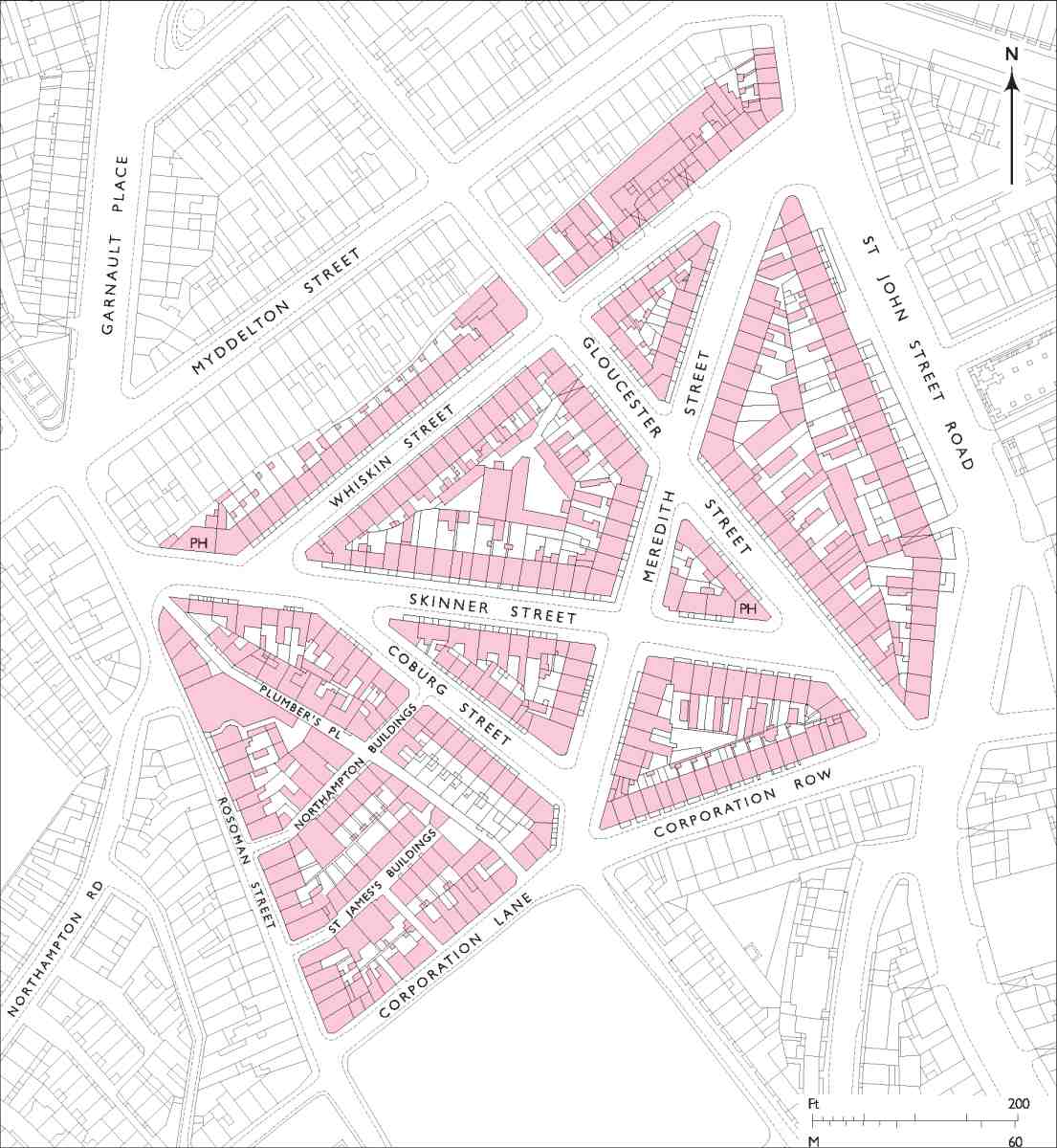

95. Spa Green to Skinner Street area

East and north-east of Rosoman Street and Northampton Road the pattern of building laid down in the nineteenth century has been much reorganized since the Second World War (Ills 95, 101, 107). This area is largely defined by Rosebery Avenue and St John Street as they head north and converge, and its southern limit is the line of Corporation Row and Skinner Street. It contains two major public housing estates. The first, Finsbury Borough Council's Spa Green Estate of 1946–9, designed by Berthold Lubetkin, was a seminal monument in the transfer to Britain of Modernist architectural principles applied to the ideals of public housing. The much larger Finsbury Estate was Finsbury's final big housing project, and largely executed after its absorption into the new London Borough of Islington in 1965. It replaced a development belonging to the Skinners' Company, a network of little streets intersecting at odd angles and densely built up with small houses in the early nineteenth century. Much of this had been rebuilt before the war with model dwellings, warehouses and factories, and a few scraps of industrial redevelopment remain, in and around Whiskin Street. It also included the original Finsbury Library, for many years the only library in the Borough of Finsbury, and the first in Britain to allow borrowers to pick their choice of books directly off the shelves. The Skinners' Company was the principal landowner here before the war, but there were three others: the Lloyd Baker family, the New River Company, and the Marquess of Northampton, each of whose holdings were small fragments of extensive Clerkenwell estates. A few former New River Company houses of the 1820s, mostly much rebuilt, survive on the south side of Myddelton Street. The north side of the street is taken up with Hugh Myddelton Primary School, a student-hostel complex called Rosebery Hall, and Myddelton Place, a speculative block occupied by government agencies—late twentieth-century buildings of varying quality and collectively dissonant appearance.

New Tunbridge Wells or Islington Spa

The spa from which Spa Green takes its name was near the site of Wells House on the Spa Green Estate. There a spring of chalybeate water was discovered, probably in 1684. This was soon after the unearthing of Sadler's Wells, just across the New River. All was then Lloyd family land. Robert Boyle vouched for the medicinal efficacy of the water and its similarity to that of Tunbridge Wells, in Kent, famous since the early seventeenth century, but only built up in the 1660s and 1670s. (fn. 1)

So began New Tunbridge Wells, whose early proprietorship was entangled with that of Sadler's Wells (see Chapter V). In August 1684 Edward Sadler himself took a seven-year lease from Jonathan Miles of the newly discovered spring and a house then on the site, possibly that occupied since the 1660s by William Young, a gardener and victualler. But Sadler then became embroiled in a dispute over ownership of this and Sadler's Wells with John Langley, a City merchant, who in November 1684 claimed to have spent £300 sinking wells, making basins and gravel walks, and erecting an iron balcony on columns on one or both sites. Langley emerged in 1685 as the proprietor of 'Islington Wells', the southern or New Tunbridge Wells site, this alternative designation reflecting the relative proximity at this date of Islington as compared to Clerkenwell. (fn. 2)

Henceforth known interchangeably as New Tunbridge

Wells or Islington Spa, the resort was laid out with

gardens—walks in lime arbours around a central railed

basin. By 1692 'Cooper and Lee' were the proprietors,

with John Eaton, who also held a public house elsewhere

called the Half Moon, paying rates on Young's house. The

establishment offered coffee, dancing and gambling, for a

cut-price entrance fee of threepence. It was thus anything

but exclusive, and was well attended by a varied and picturesque crowd that included fops, sharps and prostitutes:

The Jilts with their Cullies by this time were Prancing

Within a large Shed, built on purpose for Dancing;

Which stunk so of Sweat, Pocky Breaths, and Perfume,

That my Mistress and I soon avoided the Room. (fn. 3)

96. New Tunbridge Wells in 1735, showing the balustraded well and buildings to its north

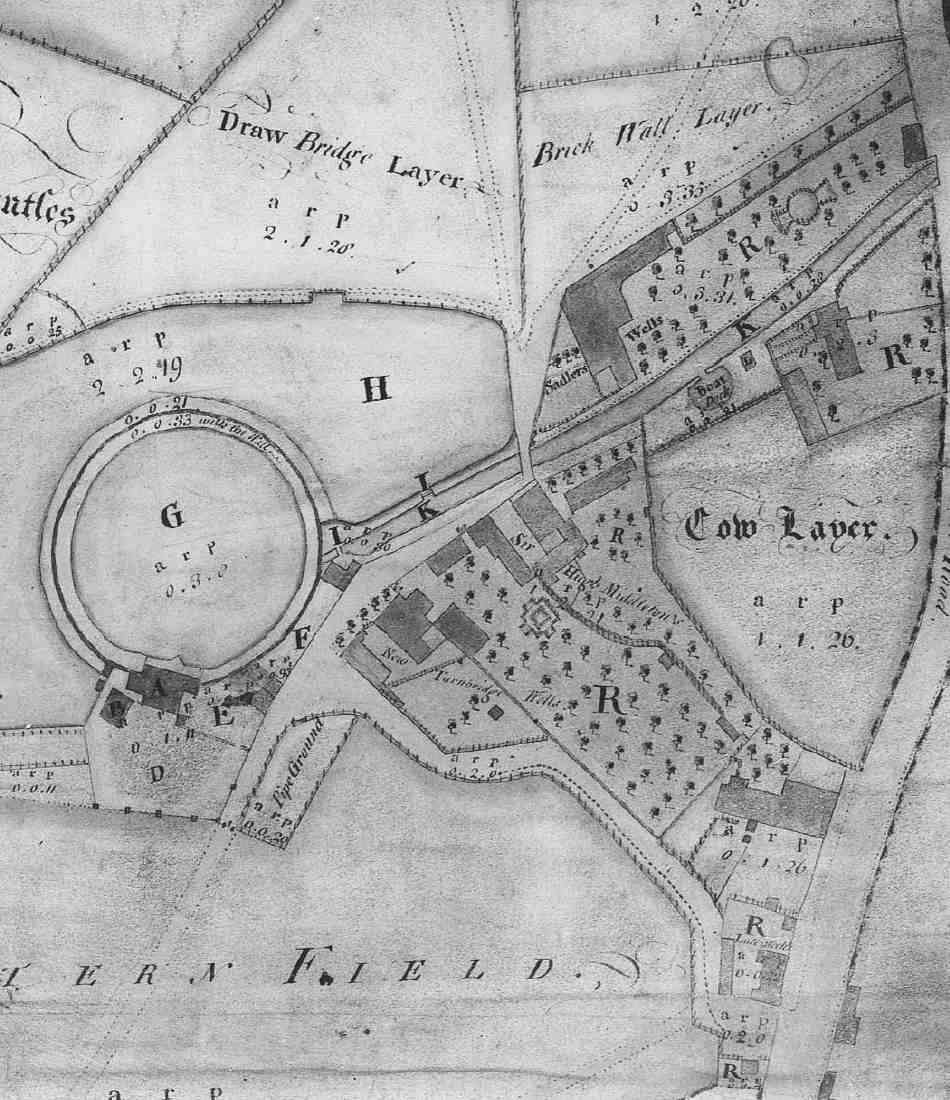

In 1712 New Tunbridge Wells was leased to William Young for 21 years, a term repeated in subsequent eighteenth-century leases, suggesting the existence of a lease of 1691. Young's house was then described as being of brick with four rooms on each floor, with an adjoining brewhouse. There was also a 40ft-long timber and brick structure, most likely built around 1691, which comprised a Coffee House over a Dancing Room, Lottery Room and Hazard Room (for gaming with dice). The upper floor was later referred to as the 'long room'. These buildings were disposed along the north or entrance side of the site, near the New River (Ills 97, 98), with the house and brewhouse to the west and the long building to the east, extending back towards the well itself. (fn. 4)

97. New Tunbridge Wells or Islington Spa area in 1743

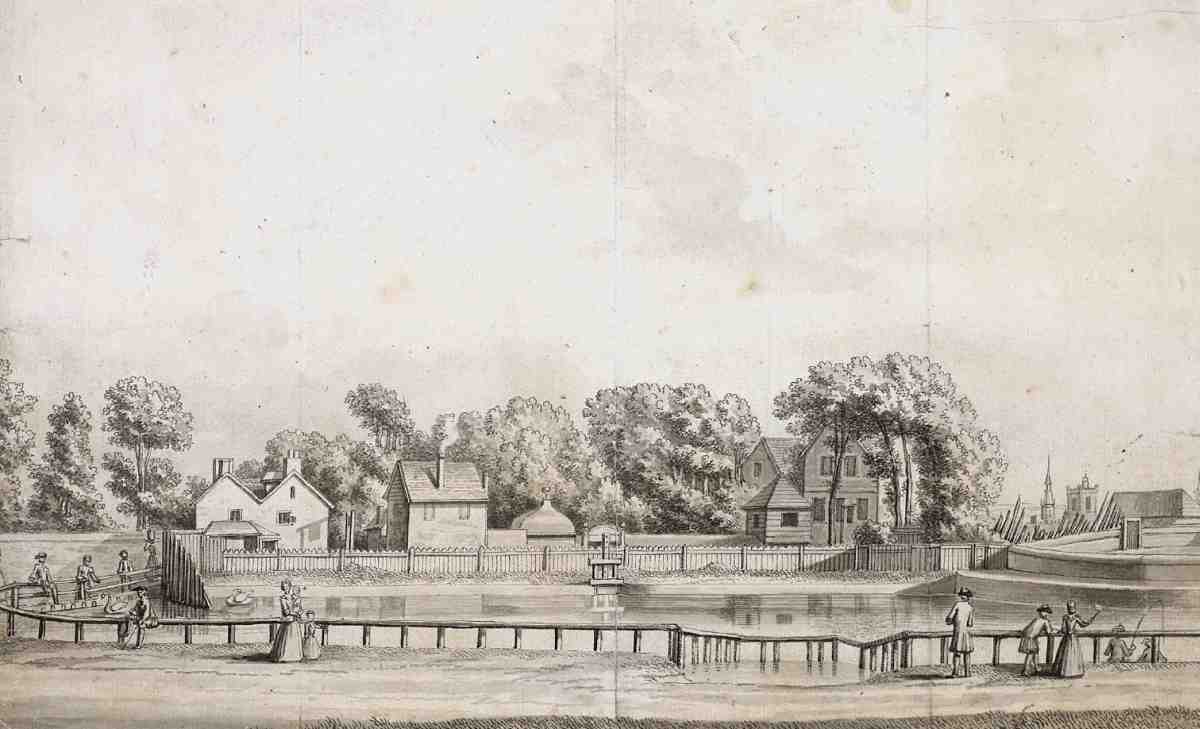

98. New Tunbridge Wells (right) and Sir Hugh Myddelton's Head tavern (left) seen from across the Outer Pond at New River Head, 1730

After the death of Young's widow, Hannah, the lease

was assigned in 1726 to Robert Dowley, a City merchant

tailor. By 1732, when he was given a new lease, Dowley

had spent more than £250 on improvements, parallel to

those then being made by Francis Forcer at Sadler's

Wells. (fn. 5) The premises now included lodgings, breakfasting

rooms and an archway entrance with the establishment's

name in an enriched cartouche. The mainly timber buildings were grouped haphazardly in front of the main

attraction, the balustraded well (Ill. 96). (fn. 6) Now and, briefly,

much more fashionable, the ambience remained informal,

and characterized by an affected 'rusticity' or dressing

down (dishabille). In May-June 1733 Dowley's spa,

managed by a Mr and Mrs Reason, enjoyed royal patronage by the nubile young Princesses Anne, Amelia and

Caroline, the last two attending almost daily. Other

celebrity patrons during this peak of success included

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Beau Nash. Around

those who were slumming were vast crowds of lesser

mortals. The clientele was exceptionally mixed, and there

was still disreputability:

What strange confus'd Variety is there;

The Lord, the Knight, the Cit, the Rich, the Poor,

The gentle Lady, and the brazen Whore;

All Sorts together jumbled crowd each Walk. (fn. 7)

By 1770 the proprietor was Henry Holland, of Assembly House, Walton Bridge, Surrey. As a place of resort, dependent on entertainment and 'company' as much or more than on curative properties, the spa was again experiencing strong competition from Sadler's Wells, lately rebuilt by Thomas Rosoman, as well as the new Pantheon in Spa Fields. Holland took a new lease in 1771, but, despite thorough renovation of the 'tea garden' in 1774–5, could not attract a higher class of visitor than 'publicans and tradesmen'. His cause was perhaps not aided by The Spleen: or, Islington Spa, a farce by George Colman the Elder, performed at Drury Lane in 1776 and satirizing the low respectability of a hypochondriac shopkeeper. Holland was bankrupted and in 1778 John Howard, gentleman, of Holborn, took over. He provided a bowling green near St John Street, a 'Minor Vauxhall' and astronomical lectures with an orrery. (fn. 8)

There were further attempts at revival, culminating in 1806–8 when a Mr Forrester, previously the prompter at Sadler's Wells, fitted out the gardens 'in a stile of superior elegance'. But the Lloyd Baker family was well aware that there was money to be made from building on the land. In 1810 a new lease, this time for 99 years, was granted to Samuel Bingham, who set about developing the peripheral parts of the site (see below). The entrance to the surviving Spa Gardens was moved round from the New River side to the south to face Spa Road (later Lloyd's Row) with a house for the proprietor: Spa House, a stuccoed building standing taller than the other new houses (Ill. 100). Bingham gave up any thought of reviving music and dancing in 1815, but persisted with the gardens. These were evidently not a success, and the spa was again re-opened in 1826, purely as such, under a Mr Hardy and a surgeon named Molloy, with the well now enclosed in a grotto. The last of the long room was demolished in 1840, when Spa Cottages were built over the remaining gardens. (fn. 9) Into the twentieth century the well and grotto work survived in a cellar, in what had long since become 'an obscure nook, amidst a poverty-stricken and squallid [sic] rookery'. (fn. 10)

Other places of resort

Prominent in early views of this area is a large timber-built tavern with a twin-gabled front, the Sir Hugh Myddelton's Head (Ill. 98). This stood on the south side of the New River near its terminus, by a bridge that linked paths connecting Clerkenwell and Islington (Ills 97, 99).

99. New Tunbridge Wells or Islington Spa area in 1807

100. Junction of Lloyd's Row and Green Terrace (right) in early twentieth century. In centre, entrance to Spa Cottages, formerly site of Islington Spa or New Tunbridge Wells, with proprietor's house to left

101. Myddelton Street and area to north, c. 1874

It is said to have been built in 1614, the year following the opening of the 'river' after whose chief promoter it is named. Hogarth's Evening (1738) shows it busy and smoke-filled. Advantageously situated between Sadler's Wells and New Tunbridge Wells, the tavern's regulars included, at different epochs, Thomas Rosoman and his associates, a group portrait of whom hung over the bar in the nineteenth century, and the ubiquitous Grimaldi the clown. (fn. 11)

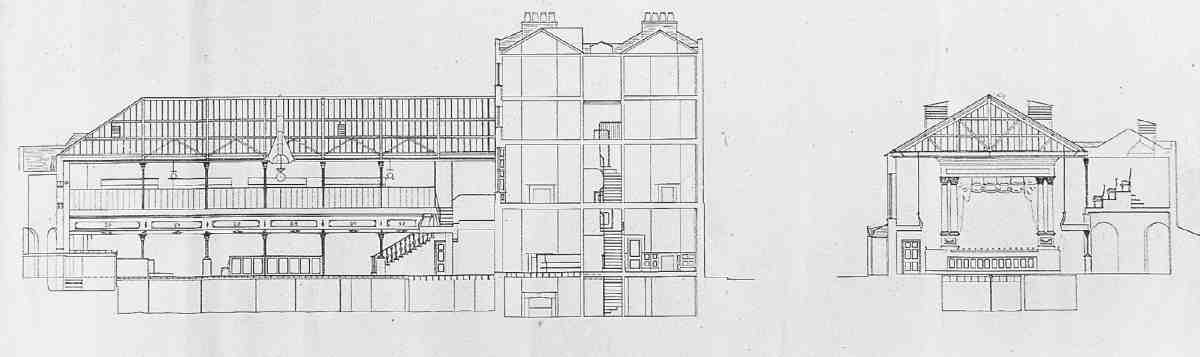

102. Sir Hugh Myddelton's Head and Deacon's Music Hall, section drawn in 1883. Long section of hall, with pub (fronting Thomas Street) to right; and cross-section of hall. Demolished

The Myddelton's Head was rebuilt in 1830–2, when a new lease was granted to Edward Wells, victualler. This was a three-by-three-bay stuccoed brick building with its front to Charlotte (eventually Sadler) Street. (fn. 12) In or soon after 1860, after the Metropolitan Board of Works refused to permit him to build cottages in the garden, a new proprietor, James Deacon, built a public room that became a music hall, adjoining and communicating with the pub, and extending north-east along Myddelton Place, directly opposite the entrance to Sadler's Wells (Ills 101, 102). Deacon's Music Hall was about 75 ft by 52 ft, and could accommodate some 700 people on the ground floor, nearly half of these seated in stalls. Balconies on three sides, the fronts of which were suspended from the tie beams by iron rods, provided space for another 300 or more. The link to the pub was blocked up and other alterations were made in 1884, under the supervision of James George Buckle, architect, to comply with safety legislation following a report by George Vulliamy for the MBW. In 1891 the pub and the music hall were demolished, along with most of the rest of Myddelton Place, for the formation of Rosebery Avenue and Spa Green Gardens. (fn. 13)

Along the south side of the New River to the east there was in the eighteenth century a small boat dock and 'Bullock's Cistern', in front of a large plot of New River Company land used as a cow lair or layer, that is a place for drovers to overnight cattle (Ill. 97). Further along towards the Islington road (St John Street) junction were two humble eating establishments. One of these, which came to be known as the Farthing Pye House, was a brick building, new in the 1740s. It was crowded on Sunday mornings 'with young Fellows, and their Sweethearts, who are drinking Tea and Coffee, telling stories, repeating love songs and broken scraps of low comedy'. (fn. 14) Nearer the corner was Spencer's Breakfasting House, 'a small wooden hut with benches outside', perhaps established in the 1720s by Allen Spencer. (fn. 15)

Away at the south-west corner of Cistern or Water House Field, on New River Company ground below what is now the west end of Joseph Trotter Close, there was a rectangular pond, probably formed c. 1760 for the English Grotto (Ill. 56). This establishment was the creation of one Jackson, who advertised a 'Grand Grotto Garden and Gold and Silver Fish Repository', charging 6d for admission. There was a timber-built water mill and an 'enchanted fountain' with which fireworks were combined to generate 'a beautiful rainbow'. (fn. 16)

The English Grotto was short lived. In 1769 the site was taken by Isaac Mainwaring, a saw manufacturer, who adapted or remade the pond to power two water wheels, one of which linked to a large brick workshop put up in 1777 by Thomas Crawford and briefly used as a silk mill. Crawford, a warehouseman of Honey Lane in the City, also had land just to the south from 1769, assigned to him by Robert Sinclair, a yarn manufacturer of Elder Street, Spitalfields. Crawford's enterprise was an early and rare attempt to relocate London's silk industry from the domestic workshops of Spitalfields, where the 1760s and 70s saw bitter confrontations about means of production and rates of pay. Robert Mylne, the New River Company surveyor, fell out with the tenants and the company took the pond back in 1781, using it as a water-supply reservoir for another thirty years. Remains of the grotto survived throughout the nineteenth century. (fn. 17)

Estate development from 1810: Spa Green Area, 1810–62

The triangle of land to the north of Cistern Field and the crooked route that was known as Spa Road at the beginning of the nineteenth century was divided between the Lloyd Baker family and the New River Company (Ill. 99). The former held two large plots on which almost all the then existing buildings stood, the latter the intervening ground that had been a cow lair and garden until 1805 when it was used for what came to be known as the St John Street Reservoir, an oval pond formed by greatly enlarging the boat dock, to improve water supply to eastern parts of the City. Near St John Street to the south there was an associated circular cistern house. (fn. 18)

Development of the New Tunbridge Wells site with about sixty houses was the first major speculative housebuilding venture on the Lloyd Baker estate, coming a decade before building on the main part fronting Bagnigge Wells (King's Cross) Road. The antiquity of the spa meant that the site was not crossed with the New River Company's water pipes, unlike much of the rest of the locality, where this was a factor that delayed development. Building here followed on from plans prepared for the Lloyd Bakers by Henry Leroux in 1806–8. Leroux was the son of the developer Jacob Leroux and a speculating surveyor who was also working more ambitiously on the Northampton estate in Canonbury, building the first parts of Compton Terrace and instigating Canonbury Square, from 1803 until his bankruptcy in 1809. Leroux's scheme for houses across the whole New Tunbridge Wells site was rejected, William Lloyd Baker feeling that it 'cuts the ground into sad fritters'. (fn. 19)

Samuel Bingham undertook a less ambitious scheme after the grant of his long lease in 1810 (see above). (fn. 20) He was advised by W. C. Mylne, the New River Company's surveyor, who was also beginning to supervise building work on Myddelton Street. Spa Road was renamed Lloyd's Row by 1812, when plans were settled and building had begun. This involved Thomas King of Wynyatt Street, builder, and John Crunnis and John Jones, carpenters. However, in 1815 Bingham complained that he was unable to let his ground, and so had been forced to build himself. Thereafter, as was generally the case, the pace of development picked up. By 1824 Lloyd's Row was fronted by eighteen three-storey houses with 15–16 ft fronts (Ill. 100). Charlotte Street (renamed Thomas Street by 1840 and Sadler Street in 1910) was begun in 1811 and within a decade lined on both sides with thirty small houses. A terrace of larger houses with 16 ft frontages and basement areas facing New River Head was built in 1817–21 and called Eliza Place (Ill. 101). (fn. 21) The New River Company contributed to the making of what had become Myddelton Place, overseeing the erection of four houses to the north of the Myddelton's Head and opposite Sadler's Wells. These were built in 1819–21 by Richard Saywell, the New River Company collector also involved in building Claremont Terrace in the New (Pentonville) Road. That nearest the pub, with a bow window at the back, was for Saywell's own occupation. (fn. 22)

The final failure of the spa led in 1840 to the building of Spa Cottages, eighteen small houses laid out as a court on what had been the last remnant of the spa gardens. This the Lloyd Baker Estate deplored but could do nothing to prevent, as Bingham's lease of 1810 included no covenant against infill. The houses, it alleged, were built as 'slightly as possible' with many old materials. From the start they were densely occupied, with some subdivision, inhabitants in 1841 including ten watchmakers among a mixture of tradespeople and labourers. The somewhat larger houses of Thomas Street were comparably occupied, with 26 people in No. 10. (fn. 23)

In 1857 the St John Street reservoir was filled in, following the ban on open reservoirs imposed by the Metropolis Water Act of 1852. Development of the site was entrusted to Henry Rydon, the developer of Highbury New Park who had been active as a builder in Islington since 1847, with Charles Hambridge as surveyor in the 1850s. In 1859–62 Rydon laid out Rydon Crescent, with fifteen houses. He also built houses to the north in Myddelton Place (later Nos 88–92 Rosebery Avenue), and houses with shops on the north side of Lloyd's Row, at the St John Street end. (For adjacent buildings at Nos 96–110 Rosebery Avenue, see Chapter IV, and for Nos 313–371 St John Street volume xlvi). (fn. 24) Rydon Crescent also saw early multiple occupancy and had an average of nearly nine people in each house in 1871. By 1891 Spa Cottages and Thomas Street had become less densely occupied. There were then numerous artificial flower makers, and many fewer watchmakers. (fn. 25)

Myddelton Street and The New River Estate, 1811–62

Myddelton Street has lost the uniformity engendered by the plain early nineteenth-century terraces with which it was first built up (Ills 101, 103–5), although one row survives. This was the first development of houses anywhere on the New River estate, along what had been a footpath linking the London Spa to St John Street, on plots, unimpeded by water pipes, backing on to the New River's overflow ditch or 'mud shoot' beside the Water House or Cistern Field. This was the estate's southern boundary, and by 1810 the land was flanked east and west by builtup parts of the Northampton estate, though the field belonging to the Skinners' Company to the south still remained open.

103. Myddelton Street from west around 1906. Garnault Place to left. Demolished

104. Nos 1–26 Myddelton Street (right to left) in 1963. Demolished

105. Nos 27–37 Myddelton Street (right to left) in 1963

This first new street, named after the company's founder, was staked out in 1811. W. C. Mylne, having recently succeeded his father Robert as surveyor to the company, was responsible for layout and architectural design. A building agreement of 1812 with Abraham Richardson, whose work did not come up to measure, was replaced by another in 1814, with Henry Hammond, a glass-cutter and dealer of Holborn. Hammond undertook to build thirty-two houses on the south side, of which fifteen had been built, largely through sub-leasing, by the time of his bankruptcy in 1817 (see page 196). His remaining plots were passed on in 1819 and developed by 1824. The surviving houses at Nos 27–37 were built in 1822–4. John Harvey of Gray's Inn Lane, carpenter, who had built and occupied No. 17 in 1815, was responsible for Nos 27–29 along with a cottage to the rear of No. 27 that has been rebuilt as a workshop (now No. 42 Gloucester Way). Charles Wilmot, a builder who sometimes styled himself surveyor, and others built Nos 30–33. John Ramsay's Nos 34–37 were 'finished in a very indifferent way' according to Mylne. (fn. 26) These houses had 16–17 ft fronts, three storeys and basements, standard two-room plans, and flat fronts relieved only by first-floor balconies, lacking the arcading and rusticated stucco that were elsewhere becoming standard on the New River estate. Early occupants appear to have been tradespeople, and there were always back workshops and some shops, one of which was at No. 27, where there is still a nineteenth-century shopfront. In the 1860s Samuel Davenport, historical and topographical engraver, lived at No. 38. Nos 38–42 were sold to the Northampton Institute in 1908 and redeveloped (see Survey of London volume xlvi). Nos 1–26 were later replaced by Joseph Trotter Close. Nos 28–37 were largely rebuilt c.1978 as flats for Islington Council. Calder Ashby & Co. were the architects for this work, which retained some early decorative elements, such as the quarter-column door surround with acorn guttae at No. 33. No. 27, a printing works in the twentieth century, is the least altered survival. (fn. 27)

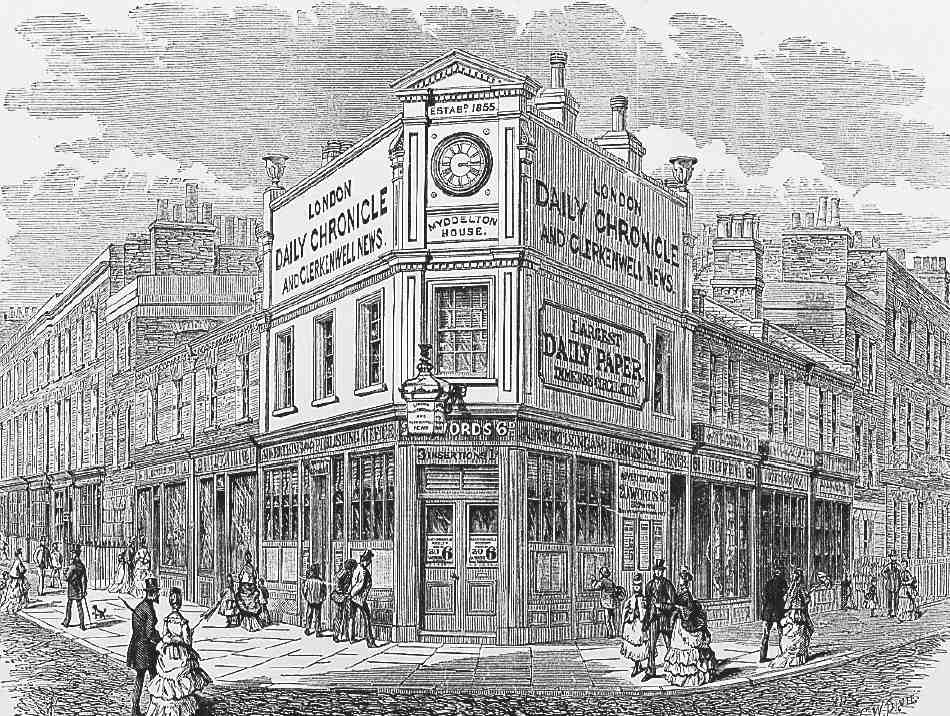

106. Myddelton House, corner of Garnault Place and Myddelton Street. George Low, architect, 1858–62

By 1820 the New River Company had replaced its crossfield pipes enabling wider development. On the north side of Myddelton Street a double-fronted villa, set back from and across the angle of the junction with Garnault Place, was built with adjoining houses in 1821–2 by and for Charles Wilmot. In 1823–7 James Stalley, a St John Street shoemaker, working with John Scott (see page 196), developed the rest of this side of the street with thirty houses (Nos 46–75), some with shops, along with the west side of Upper Gloucester Street (Gloucester Way from 1936). In 1858–62 the villa was concealed behind Myddelton House, the offices of the Clerkenwell News, on the Garnault Place corner, and flanking two-storey shops, built on the villa's front garden to plans by George Low, architect, for H. B. Garling, a retired architect, acting here as the leaseholder and a developer (Ills 103, 106). Nos 64–77 Myddelton Street were subsequently given an Italianate palace front, perhaps in 1912–14. The site was cleared in 1972. (fn. 28)

The New River Company had leased the triangular corner plot across Garnault Place and opposite No. 1 Myddelton Street to the parish for its watch-house, built in 1814. (fn. 29) Garnault Place, named after Samuel Garnault (d. 1827), the New River Company's treasurer at the beginning of the nineteenth century, was laid out thereafter as 'a broad and handsome ascent' (fn. 30) to Mylne's residence in the Water House at New River Head, mirroring Tysoe Street's route to Wilmington Square. There was to have been a circus at the junction. (fn. 31) The new street was built up in 1823–6, Charles Wilmot being the main developer. Grimaldi the clown lived at No. 23 in 1829–32. Green Terrace was principally developed by James Stalley in 1824–7. This 'neat row' (fn. 32) of twenty-three typical New River estate houses faced railed open ground, the Spa Green, that served as a buffer to New River Head. It is said to have been named after John Grene, Clerk to the New River Company in the late seventeenth century, but may have taken its name from the green itself. Along the south side of Lloyd's Row Nos 20–28 were built in 1823–6, all with shops, by Stalley and William Smith, a builder living nearby at Eliza Place. The land between Lloyd's Row and Myddelton Street was rapidly given over to commercial uses; in 1841 a large floorcloth factory here burnt down. (fn. 33)

To the west, the triangular site bounded by Upper Rosoman Street (part of Amwell Street since 1936), Hardwick Street and Garnault Place was built up in 1819–26, with Garnault Mews running through the centre. The houses facing Upper Rosoman Street, relatively small with 15 ft fronts, were built in 1819–22, mostly by Thomas Marsh. The slightly larger Garnault Place houses followed in 1823–6. (fn. 34) Facing Hardwick Street and the Outer Pond at New River Head, behind deep front gardens, three small pedimented three-bay pairs of 'semi-detached' villas were built in 1822–4 by Joseph Astey (Ill. 101). (fn. 35) This was the only early development on the New River estate in which Mylne flirted with the distinctive architectural vocabulary that was beginning to be deployed on the Lloyd Baker estate to the west. This triangle was bisected by Rosebery Avenue in the 1890s, creating two smaller triangular islands, on the southern of which Finsbury Town Hall was built. (For this and the later history of the triangle now bounded by Hardwick Street, Amwell Street and Rosebery Avenue see Chapter IV.)

Skinners' Company Estate

Part of the land belonging to St Mary's nunnery, the eight acres comprising the future Skinners' Company estate became the freehold of the Crown after the Dissolution, and by 1553 had become known as Clarke's Close, having been granted to James Greenwood and Durston Clarke, gentlemen of Market Harborough. (fn. 36) By the early seventeenth century Clarke's Close had been acquired by John Meredith, sometime Master of the Skinners' Company, and resident of the parish of St Bartholomew-the-Less, West Smithfield. Meredith died childless in 1633, leaving the ground, then a field of pasture, to the company in trust for charitable purposes, chiefly the support of aged freemen of the company and unbeneficed clergymen. (fn. 37)

Building development, 1818–34

In common with much of the open ground south of New River Head, Clarke's Close was used for laying wooden water-supply pipes, and in 1754 the New River Company took a 61-year lease of the field to facilitate their management. (fn. 38) It was the expiry of this lease, together with the introduction of iron pipes, which freed the ground for development. Building on Clarke's Close was under consideration in June 1815, and in December 1816 William Jupp, the Skinners' surveyor, began preparing a scheme. By early February 1817 he had produced plans and elevations for the intended buildings and had assessed the depth of brick-earth on the site, which varied from one to four feet. (fn. 39)

A first attempt at letting failed, but the ground was readvertised early in 1818, attracting six tenders, one of them from James Whiskin of Ashby Street, just across St John Street, with whom a building agreement was made. Whiskin undertook to take the land on a 70-year lease from Lady Day 1818, at a rental rising incrementally to £525 per year after nine years. He was to lay out the estate according to Jupp's plan, making sewers, paving the new streets and building at least 40 third-rate houses in the first two years, and not less than 20 in each succeeding year until the estate was fully developed (Ill. 107). Within each range, buildings were to be of uniform elevation (Ills 108, 109). (fn. 40)

A plumber by trade, Whiskin was already well on his way to becoming a prominent figure in local affairs and a substantial businessman. He was a vestryman from 1815, a JP from 1835, became Deputy Lieutenant for Tower Hamlets in 1846, and acquired railway and insurance directorships. At his death he was described as 'a builder of eminence'. (fn. 41) The epithet, however, was hardly justified by the development carried out by Whiskin and his subtenants and nominees on the Skinners' estate, at least in the early years.

Building got off to a slow start, with ground for only seven houses let by March 1819, for which Whiskin blamed the longer building leases available on the nearby Northampton and New River Company estates. The company's refusal to allow longer terms may well have been an important factor in the trouble which brought the development to a halt in 1824. (fn. 42)

Evidence of shoddy work came to light during the annual view of the estate that year, and an investigative committee was appointed. Significant deviations from the building plan were also found, and in places fourth-rate houses had been built instead of third. (This resulted in more houses being built than had been intended, as it happened producing a higher total ground rent than agreed.) Specifications had been ignored and inferior materials used, with cavalier disregard for elevational uniformity from house to house. (fn. 43)

The young Charles Barry, brought in to make an assessment, found the buildings 'generally ill-calculated to last for the term of years', with instances of 'extreme badness' of construction; he found Jupp himself culpably negligent. (fn. 44)

107. Skinner Street area c.1874

Jupp's defence was essentially that the buildings were up to the standard of the neighbouring speculative estates, and that builders at the lower end of the market were difficult to control: too strict an enforcement of specifications would result in plots not being taken up. (fn. 45) Complaining that Barry's report had been 'drawn up rather in a spirit to aggravate the case than to bring the subject fully & fairly before the committee', he eventually admitted that his anxiety to get the ground covered led him to accept things he would not otherwise have allowed. In November 1824 Jupp resigned, to be replaced by the architect and surveyor George Moore. Barry was among the unsuccessful candidates for the post. (fn. 46) On the ground, only limited remedial action was taken and no systematic rebuilding. Building picked up again in 1825, and continued until the estate was fully built-up in 1834. (fn. 47)

A lack of uniformity to the building was in part a consequence of fragmented development, a high proportion of plots being sub-leased singly, or in small batches. Even had greater control been exercised, there would have been some variations given the layout of the streets, which produced many acute angles and awkward plot shapes. Most houses, however, were standard productions of three floors over basements, two-windows wide with side passages and dog-leg staircases. A small proportion, mostly on the shallower plots and built towards the end of the development period, were double-fronted.

108. Whiskin Street, south side west of Gloucester Way, in 1959: Nos 47–58 (left to right), built 1822–4. Demolished

Always a predominantly working-class area, the Skinners' estate was occupied in the nineteenth century to a large extent by people engaged in the characteristic trades of Clerkenwell, including the making of watches, clocks, jewellery, scientific and surgical instruments, and furniture. The 1841 Census records the presence of John Purdy, a notable hydrographer, in Gloucester Street, and William Plant, an artist specialising in enamels, in Meredith Street. The Skinners' Arms at the corner of Coburg and Meredith Streets, built in 1821, is said to have once been a haunt of George Cruikshank, Pierce Egan and others. (fn. 48)

The estate after c. 1890

On the expiry of the original leases in 1888, the company took over direct management of most of the estate, appointing its own rent collector; 21-year leases were granted of some properties, but houses and tenements were generally let quarterly or weekly.

In 1890–2 the entire block bounded by Skinner Street, Coburg Street, Corporation Row and Rosoman Street (belonging partly to the Skinners' Company and partly to the Northampton Estate), was redeveloped by the Artizans', Labourers' & General Dwellings Co. with fiveand six-storey dwellings. Called Northampton Buildings, these were designed by the company's architect, F. T. Pilkington (Ill. 110). (fn. 49)

109. Gloucester Way, west side, looking south to junction with Meredith Street in 1959: Nos 13–23 (left to right), mostly of 1820s. Demolished

Some redevelopment was carried out by the Skinners' Company itself on a small scale, of which one building survives, No. 32 Gloucester Way. This tenement house, built in 1894 by Howell J. Williams, was presumably designed by the company's surveyor, William Campbell Jones. (fn. 50)

More redevelopment, mostly for industrial and commercial premises, followed the expiry of the 21-year leases in 1909. The People's Picture Playhouse Ltd put up a cinema in 1912–13 at the junction of Skinner Street and Goode (hitherto Coburg) Street. This had rusticated elevations, with a flourish at the apex of the site in the shape of a dome and semi-circular portico, collapsible gates being mounted between the columns. It accommodated 800 people. The architect was F. Danby Smith. It was later called the Globe Picture House and, in its last years, the Rio Cinema, closing in 1955. (fn. 51)

In St John Street, Nos 293–299 and houses on the north side of Whiskin Street were acquired in 1907 for the building of an annexe to the Northampton Institute, and Nos 231–243 were redeveloped in 1909 for industry. Also on the north side of Whiskin Street, the present Nos 26–31 were built in two phases, in 1913 and 1920, for Spauldings, vulcanized-fibre manufacturers. The architect, of the first phase at least (on the corner with Gloucester Way), was F. T. W. Goldsmith. (fn. 52) The triangular block opposite was largely redeveloped in 1930–1 with factories by Victor Kerr, architect, for Commercial Structures Ltd (Nos 34–38 Gloucester Way, 14–16 Meredith Street and 39 Whiskin Street). (fn. 53)

Northampton Buildings were sold to the Greater London Council in the 1960s and demolished in the late 1970s. The site was left open as an extension to Spa Fields Gardens (see Chapter II), incorporating an adventure playground to the south, sunk in what had been basements. In 2007 a children's playground was created to the north for Islington Council and EC1 New Deal for Communities. It was designed by Parklife Ltd. (fn. 54) Plans for further re-landscaping have still to be implemented.

110. Northampton Buildings, view along Rosoman Street from south in 1971. F. T. Pilkington, architect, 1890–2. Demolished

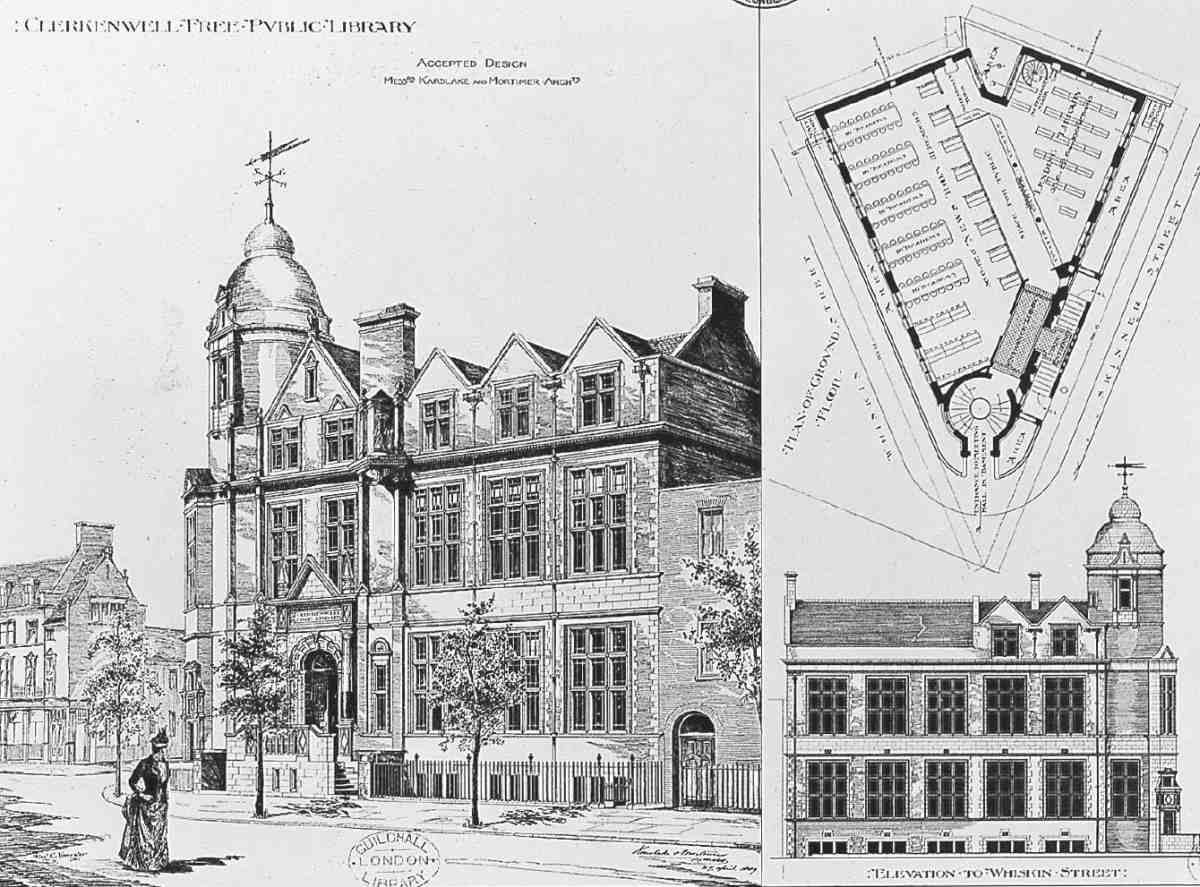

111. Clerkenwell Free Library, Skinner Street, perspective, plan and elevation

Finsbury Public Library, Skinner Street (demolished)

Clerkenwell Free Library (from 1900 Finsbury Public Library) was built in 1890, and four years later became the first public library in Britain to adopt the open-access system already general in the USA. It was demolished in 1967 for the Finsbury Estate development (fn. 55) and replaced by the present Finsbury Library in St John Street.

In 1887 the Vestry voted to establish a library under the Public Libraries Acts, which allowed money to be borrowed on the rates for the purpose, and in 1888 temporary premises were opened in Tysoe Street. (fn. 56) An approach to the Skinners' Company, which was clearing some of the worst property on its newly reverted estate, led to the offer of a site at the junction of Skinner and Whiskin Streets, at a low ground rent. (fn. 57) A limited competition for the design was won by the architects Karslake & Mortimer. (fn. 58) The foundation stone was laid in March 1890 by the Master of the Skinners' Company, and the new library, built at a cost of £6,323 by McCormick & Sons of Canonbury, was opened by the Lord Mayor of London on 10 October. (fn. 59) At least two substantial private donations were received: £600 from the Penton family, owners of much of Pentonville, and £300 (together with more than a thousand books) from Robert Major Holborn of Highbury, a wealthy tea-merchant and bibliophile. (The gift had originally been intended for Islington, which despite his efforts did not adopt the Libraries Acts until 1904.) (fn. 60)

112. Finsbury Public Library, Skinner Street, after 1900

Faced in red brick and Ruabon terracotta, with a domed staircase tower on the street corner, the new building was in a loose Elizabethan style, and comprised three floors over a basement containing a meeting-room and stores (Ills 111, 112). On the ground floor was the lending library, with shelving for 20,000 volumes, and a newspaperreading room with seating for more than 100. On the first floor was the reference library and reading-room, above which were administrative and staff rooms. (fn. 61)

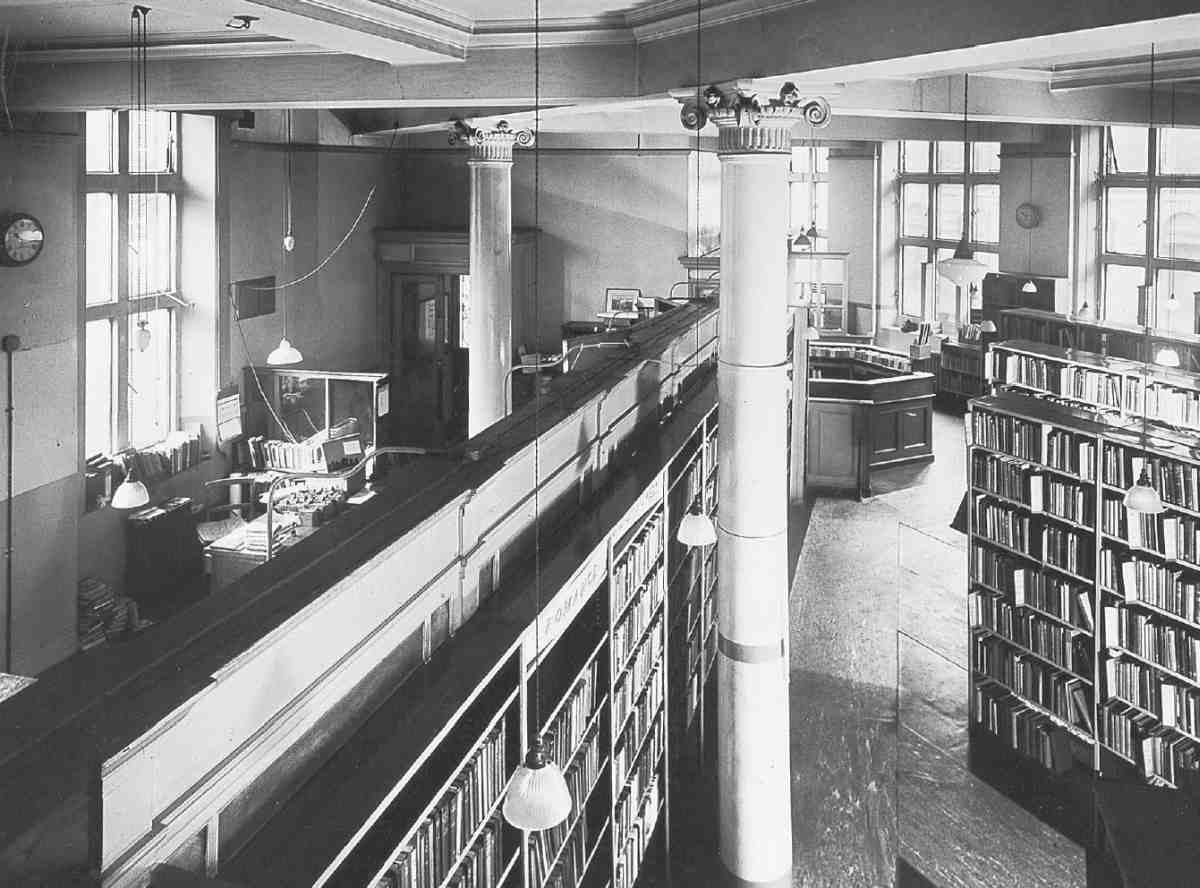

113. Finsbury Public Library, Skinner Street, interior in 1954

The first librarian was James Duff Brown, previously at the Mitchell Library in Glasgow. It was following Brown's attendance at the 1893 International Congress of Librarians in Chicago that the library was rearranged on open-access lines, doing away with the need to queue with requests for books to borrow, the invariable system in use in British libraries. The changeover was effected in 1894, and involved the removal of the counter and Cotgreave Indicator (displaying details of lending stock) separating the books from the public area. The rows of stacks were rearranged in a radial pattern to suit the wedge-shaped room, where they were overseen by staff enclosed in a new pentagonal island counter (Ill. 113). (fn. 62)

Brown's period of office also saw two further innovations. In 1898 the basement was fitted up as a children's library, the first in the country, and he also introduced the practice of holding exhibitions of art—including Old Master works—in the reference section. (fn. 63)

Public housing: Spa Green Estate

Spa Green is the smaller of the two heroic housing estates planned for Finsbury Council on the eve of the Second World War and executed just after it by Tecton, the architectural firm led by Berthold Lubetkin. Though conceived after its bigger counterpart, Priory Green, it was built in amended form slightly earlier (1946–50), much to its advantage.

The first name for this clearance and rehousing scheme was Sadler Street, after an L-shaped thoroughfare, formerly Thomas Street, at its core. The original, very restricted site comprised a rough quadrilateral bounded on the west by the strip of the original Spa Green Gardens next to Rosebery Avenue (page 139), on the east by the backs of houses in St John Street, on the north likewise by backs in Rydon Crescent, and on the south by Lloyd's Row (Ill. 114). This pocket of poor housing had not been on the list of priority areas for slum clearance drawn up by Finsbury Council in 1931. It reached their agenda only in July 1936, when the council's Medical Officer of Health, Nicholas Dunscombe, suggested that insanitary, dilapidated and constricted properties in Sadler Street, Spa Cottages and Lloyd's Row might be declared unfit. Finsbury's Labour administration, with Harold Riley as chairman of the Housing Committee, was keen just then to act. So the scheme passed expeditiously. (fn. 64)

The London County Council having agreed that the borough should take the lead in redevelopment, this nucleus was acquired by negotiated sale. In September 1937 the south side of Rydon Crescent, less than a century old, was added. (fn. 65) Here opposition to compulsory purchase forced a public enquiry. Afterwards, the architect who successfully represented the council, T. Alwyn Lloyd, intimated that he would waive his fee if selected for future work. If Lloyd had his eye on the Sadler Street scheme, his hopes were dashed. In July 1938 Tecton were appointed as architects, well after they had been engaged for Busaco Street, later Priory Green (page 423). (fn. 66)

Evidence for the pre-war designs for the Sadler Street scheme is confined to a single sheet of plans from the office of Ove Arup. (fn. 67) It shows a thin slab of what must be multistorey flats, some 290 ft long but without the breaks and recessions of the Busaco Street scheme, and with just two lifts. At right-angles run two parallel walk-up blocks, each about 100 ft long. The site boundaries suggest that the slab was to run approximately north-south on Zeilenbau lines, while the shorter blocks would have butted close up against the backs of houses in St John Street. Perhaps because of the tight site, the LCC refused permission for the erection of flats at Sadler Street in April 1939. (fn. 68) The scheme made some further progress before the war caused its postponement, but cannot have been as near implementation as Busaco Street.

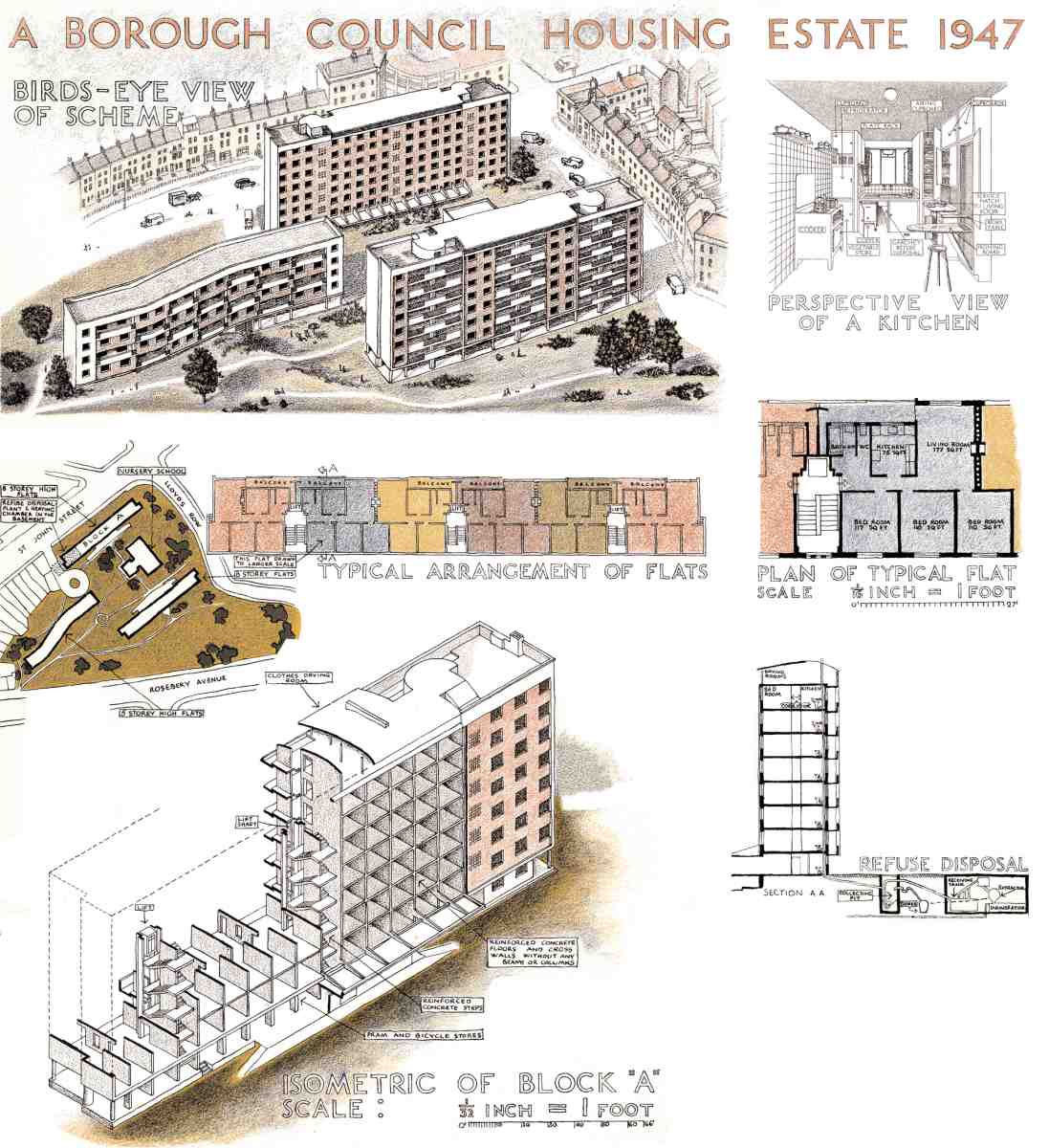

Attempts to restart the two schemes in 1940 were unavailing. But war damage on both sides of Rydon Crescent as well as Sadler Street itself prompted some demolitions and opened the way to the project's expansion, once post-war planning started in earnest. On the basis of a hint from Harold Riley followed by data furnished by the borough engineer, Tecton now drew up a 'New (1943) Sadler Street Scheme', with the brief that open spaces should be maintained and extended, that the eastern edge of the estate should respect the designation of St John Street as a traffic artery under the County of London Plan, and that the enlarged site could be developed in phases. (fn. 69) The project the architects presented in November 1943 covered a triangle of 3.9 acres, taking in the west side of St John Street all the way from Lloyd's Row to the junction with Rosebery Avenue (Ill. 115).

Writing from his Gloucestershire farm, Lubetkin furnished a full description of this, the earlier of the two revised housing schemes proposed by Tecton for Finsbury. Now there were to be four eight-storey blocks, in parallel but overlapping so as to offer an 'imposing façade' to Rosebery Avenue (where Spa Green Gardens was to be enlarged), and two subsidiary blocks. Towards the south 'an airy and open forecourt' faced Lloyd's Row, laid out as gardens and playgrounds for children. About 168 flats in all were included, at a density higher than the County of London Plan prescribed, though lower than in the pre-war scheme. The accommodation in the tall blocks held to the standards specified for Busaco Street in 1938, with staircase and lift access only, and private balconies and Garchey waste disposal in all the flats. (fn. 70)

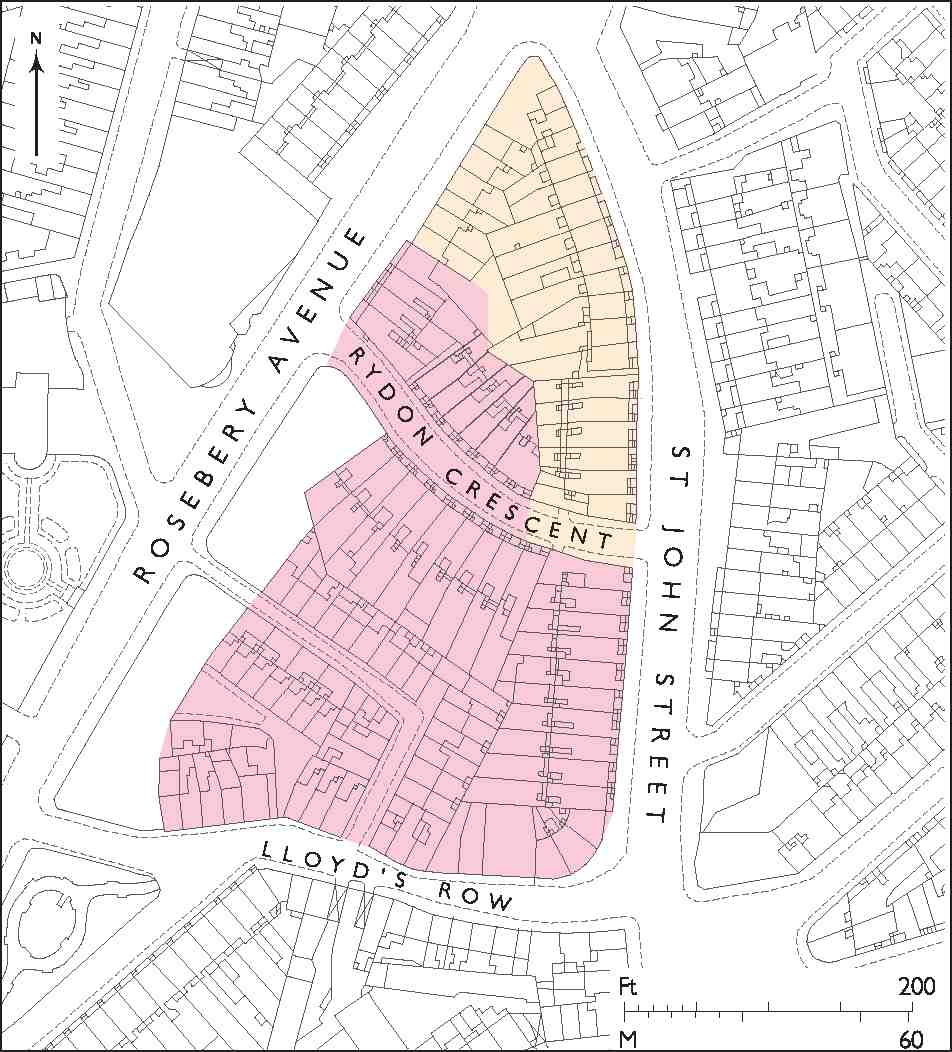

114, 115. Sadler Street clearance area, plans showing changes in site. Left: original clearance area of 1936 (green), with area added in 1937 (purple) and block plan of Tecton's pre-war Sadler Street housing scheme superimposed. Right: area for final Tecton scheme of 1946 (pink) with extra area intended to be included in 1943 (orange)

The November 1943 report also entered fully into construction. At this stage Lubetkin and Arup were contemplating solid external walls built with sliding shuttering, so as to offer 'an unobstructed carrying floor area spanning between the outside walls, and providing opportunities for free sub-division'. In view of anticipated post-war shortages, Lubetkin hoped for 'a maximum utilisation of plastics … Plastics are manufactured from coal, and it is therefore safe to assume that supplies will be readily available in the country, especially in view of the enormous war-time expansion of the plastic industry'. Interior fittings were to be thoroughly industrialized. 'The whole block, consisting of the kitchen, bathroom and living-room equipment will be rigidly standardised, prefabricated, and sent to the site in parts, to be assembled by unskilled labour. The whole of the plumbing and heating equipment will be treated in the same way'. (fn. 71)

This scheme was cautiously welcomed by Finsbury Council, and Tecton were confirmed as architects in February 1944. Delays followed, while intricate negotiations dragged on over their contract and scale of fees, and Lubetkin tussled with the Town Clerk, John Fishwick. (fn. 72) For his part Fishwick represented Sadler Street, by now ahead of Busaco Street, to the council as giving Finsbury 'a flying start'. He had wished, he said, to justify a high fee level on the grounds that the two revised schemes would be 'superior to normal municipal dwellings' yet no costlier to build or maintain. But the architects had fought shy of a contract enshrining such a clause, since 'they cannot undertake to produce something which may on examination prove impracticable'. (fn. 73)

An agreement having finally been signed, in December 1944 Tecton brought to the council a revised design in which the estate began to resemble what was built. The northern horn of the site, where Rosebery Avenue and St John Street converge, was now spared. The blocks shrank to four in number: two slabs of eight storeys, a block to their north reduced to four or five storeys so as not to overshadow the reprieved Nos 335–371 St John Street, and a low block of old people's flats at the south end of the space, later omitted. (fn. 74) There were now 136 flats in all. In the next months this scheme picked its path through the thickets of the council's turbulent politics, as Riley fell from power and a more pragmatic Housing Committee under Dr Katial took charge. A stormy campaign by Riley's supporters protested against the paring-down of Sadler Street. After some reductions, notably in bedrooms, the slight lengthening of the blocks and the squeezing of the space between them, the scheme was approved in May. (fn. 75)

Modifications continued. In November 1945 the northern block (Sadler House) received its serpentine twist, while the low block of flats was adjusted. (fn. 76) Then in February 1946 the LCC asked Finsbury to squeeze a nursery school into the scheme. While not averse to doing so, Tecton objected that the site suggested would reduce the low block and cut into the courtyard. They preferred to incorporate the nursery into the base of one of the slabs. For the time being the issue was postponed and in the event the low block was never built. (fn. 77) In 1970–1 a nursery school was inserted roughly where the LCC had suggested, at the Lloyd's Row end of the open space (see Hugh Myddelton Primary School, below). Also in 1946, Tecton were reserved by Finsbury as architects for a potential eastward continuation to Spa Green, on the north side of Spencer Street beyond St John Street. That too came to nothing. Nevertheless Tecton's successors Skinner, Bailey & Lubetkin complained to the council when they were passed over in 1951 for the Spencer Street site (see Survey of London, volume xlvi), claiming that they had 'produced preliminary sketches showing treatment of the site as an extension of Spa Green'. (fn. 78)

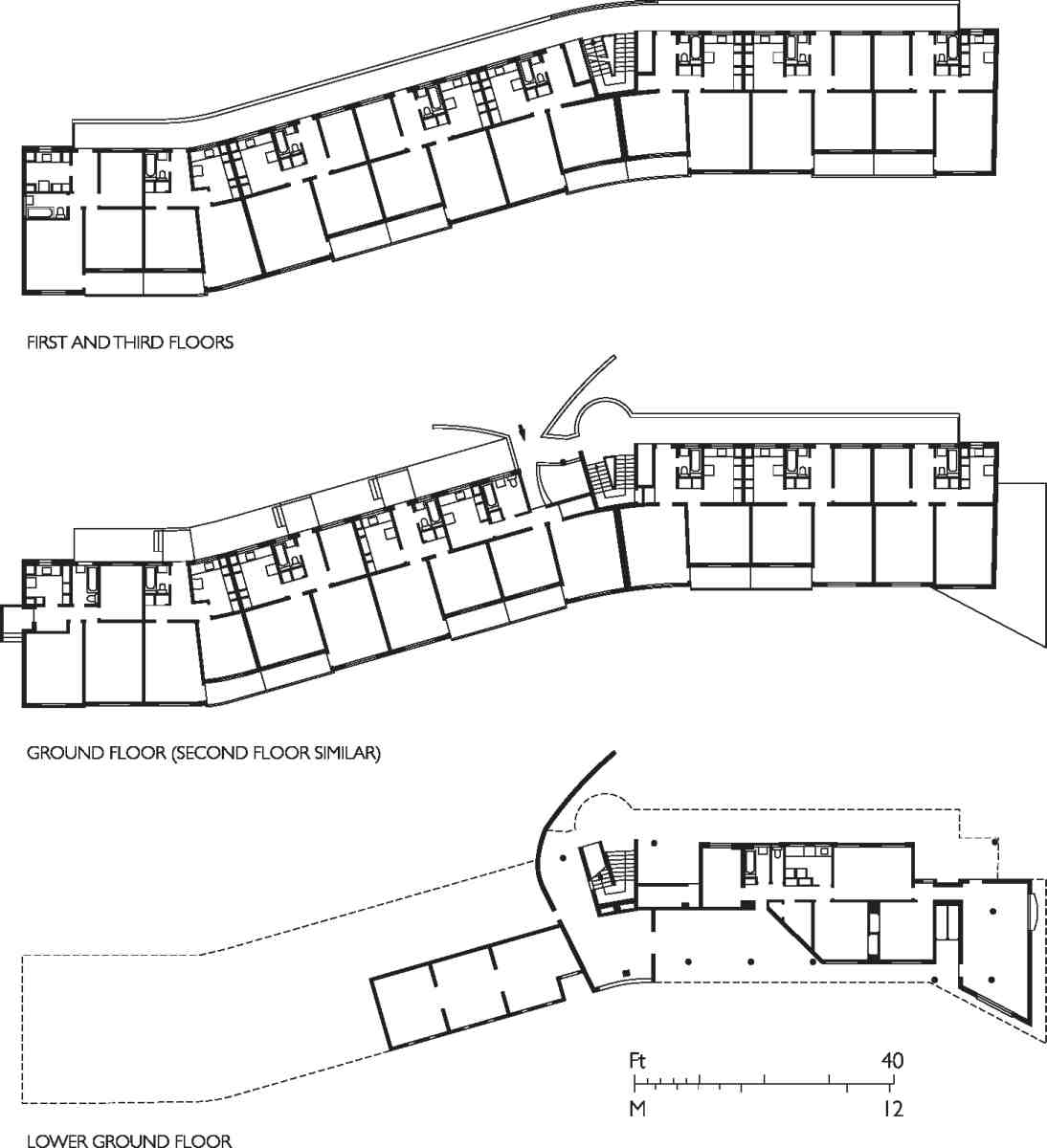

116. Spa Green Estate. Sadler House, plans

Under the new name of the Rosebery Avenue Housing Scheme, the estate went to tender in Spring 1946. The builders William Moss & Sons Ltd won the contract with tenders close to the architects' estimate of £230,000. Doubtless on Arup's advice, his pre-war employer J. L. Kier became the nominated subcontractor for the reinforced-concrete structure, as he had been for Finsbury Health Centre. (fn. 79) Since public housing was then still under his department's aegis, it was the Minister of Health, Aneurin Bevan, who laid the estate's foundation stone on 26 July 1946, choosing this among many such invitations because it 'has so many novel features, I wish to give it every encouragement'. (fn. 80) Instead of a key, Bevan was given a silver and copper model of one of the slabs. (fn. 81)

117. Spa Green Estate, aerial view in 1952. Tunbridge House and Nos 335–371 St John Street in foreground, Sadler House centre right, and Wells House behind. Beyond Rosebery Avenue, Sadler's Wells Theatre (right) and buildings of New River Head (top)

Post-war labour and materials shortages plus the severe

winter of early 1947 hampered progress on the contract.

That March, in an incident typical of those hand-tomouth times,

the Town Clerk reported action taken by him upon the

Council's behalf to support the request to the Ministry of

Fuel and Power for the temporary resumption, during the

period of the recent electricity power cut, of the supply of

electric current to Wembley Pressings, Ltd., for the completion of sufficient shuttering to enable reinforced concrete

work to proceed upon the Rosebery Avenue Housing Site.

At the same meeting the architects asked the council to subsidise a visit to France, where they heard that measures had been taken to obviate the 'disturbing effects of noise' and vibration arising from the action of their cherished Garchey system of waste disposal. They did not however ask for the costs of going on to the Zurich Building Centre, to investigate 'floor finishes and plywood substitutes for door and cupboard construction'. (fn. 82) The high slabs, Wells and Tunbridge Houses, were completed early in 1949; the northern block, Sadler House, crept on into 1950. Rechristened Spa Green, the new estate was formally opened by Herbert Morrison, the deputy prime minister, on 29 April 1949. (fn. 83)

With the completion of Sadler House the estate was finished (Ills 117, 118). There were 126 flats in all. Eight storeys in height, Wells and Tunbridge Houses constitute the core of the development (Ill. 120). (fn. 84) Some 190 ft long by 30 ft deep, they are set in parallel without breaks or projections across an open space 160 ft wide. In plan they essentially mirror one another. The bedrooms of the 46 flats in each block all face inwards towards the quiet open court, while the living rooms with their private balconies and the kitchens, bathrooms and WCs look outwards. Eating was designed to take place in the living-rooms, linked via deep hatches to the kitchens. The latter mostly exceeded 'Existenzminimum' size and enjoyed gas coppers for washing, as well as the costly Garchey units beneath the sink—their first use in London, 'allowed by the Minister of Health as a special case'. (fn. 85) Flats were equipped with background central heating topped up by gas and electric fires. Three staircases and lifts give access to the upper floors in each block.

118. Illustrations of the Spa Green Estate from Margaret and Alexander Potter's Houses, 1948

Externally, absolute symmetry is avoided by varying the two boldly ramped porches towards the court, which give the project one of its crisp, constructivist accents (Ill. 121). They are among the few features which altered their form from a model of the estate made in 1946, when they would have replicated one another. Facing Spa Green Gardens, the west front of Wells House also has a smaller porch of its own, with seats fetchingly attached on each side. Different storage arrangements also obtained on the original ground floor of the two blocks, Wells House having more space for prams, while Tunbridge House accommodated more bicycles. Topping off the centres of the twin blocks are canopies roofing the former drying areas, 'sculpture of social utility' in John Allan's words, their aerodynamic profile worked out by Tecton with the scientist Hyman Levy to induce 'airflow ripple for extra drying efficiency'. (fn. 86) These canopies too are not identical, and likewise evolved during 1946. It is likely that Lubetkin thought of the Spa Green roofscape as a less extravagant response to the excrescences on top of Le Corbusier's first Unité d'Habitation at Marseilles, contemporary in construction but well publicized before completion.

119. Sadler House, west front looking south in 2004

120. View of Spa Green from the west, c. 1950. Wells House in front, Sadler House to left, Tunbridge House behind

121. Wells House, western porch in 1950

The long sides of the slabs were intensely studied for greater human effect. Both elevations are set within defining frames of concrete panelled with faience tiles. Towards the courts, the infill consists of brickwork punctuated by square openings for the Crittall steel window frames, and rarer groups of small cells lighting the staircases. On the other sides, the recesses of the private balconies and the alternation of open iron grilles with concrete balcony fronts interact with the tiers of brickwork in panels to create a pattern of sophisticated abstraction—the first of the chequered rhythms typical of Lubetkin's later architecture. The original colour scheme was intricate: redbrown for the main brickwork surfaces, but dark blue on the recessed ground storey; egg-shell cream for the tiling and columns; Indian red for such exposed concrete features as tank housings; dark grey for the window frames and balcony grilles; and a 'deep slate-coloured cement paint' on the fronts of the recessed balconies. (fn. 87)

122. Box frame of Tunbridge House in erection, c. 1947

The structural system, worked out by Ove Arup and his colleague Peter Dunican in consultation with Lubetkin and the concrete contractor J. L. Kier, was not the first 'box frame' but marked that method's first large-scale trial. Instead of a skeletal frame, the structure consisted of continuous concrete floors and internal cross walls (Ill. 122). The long fronts were left void and walls were then applied as cladding. The system eliminated scaffolding and allowed the complete freedom of elevational treatment, unhampered by structural members, sought by Tecton. It also avoided internal projections and downstands, meant that few internal walls had to be added and allowed fair acoustic insulation between the flats. Special shuttering was required, a Danish patented design of Z-shaped laminated steel sheets in six-foot spans, used for both floors and walls.

Sadler House, the four-storey block north of the two high slabs, followed the same manner of construction and elevation, but all its flats were reached by east-facing balconies, originally served by a single internal staircase (Ills 116, 119, 123). The double twist in the plan, a showy contrivance to fit the building into the curtailed site, evinced little comment. The main access to the block was from a remnant of Rydon Crescent running off St John Street. At the south end of Sadler House a low caretaker's flat with a bay window offering ample view of the open space juts manneristically forwards through pilotis. To its east, a small building formerly housed the boiler house and refuse destructor.

123. Sadler House, east front in 1950

Spa Green was Britain's first completed housing scheme to meet the high aspirations of national reconstruction. Though it had suffered cuts, it escaped the stringent economies which were to damage Priory Green; and as the first post-war project completed by Tecton (Skinner & Lubetkin from 1948) it attracted widespread attention. The estate was noticed for reasons of aesthetics, process and sociology alike. Amid a generally admiring reception, Nikolaus Pevsner's verdict stood out for its severity. 'The buildings are placed in any old direction, and what might have become a visual centre of Finsbury is nothing but baffling and irritating. Yet the flats as such have certainly a good deal of visual kick', he added, instancing the contrast between the porches and the highly coloured walls behind them, 'fascinating in the slightly dubious way in which the ephemeral and therefore legitimately high-pitched effects of exhibition stands fascinate us'. For everyday architecture, Pevsner preferred nearby Myddelton Square. (fn. 88)

124. Sadler House, east front in 2004, showing lift-shaft added by Hutchinson and Partners, architects, 1987

Since its completion, the history of Spa Green has been quite benign. Strict conditions were imposed upon the early tenants, and complaints about crime seem not to have been widespread before the late 1970s. By then the concrete and tiling required attention, and the Garchey waste disposal system was causing complaints of foul smells, 'bubbling back' and poor maintenance. A report of 1978 by Peter Bell & Partners, architects, for Islington Borough Council recommended extensive remedial works both here and at Priory Green. These, along with partial central heating, rewiring and a new external colour scheme were carried out in 1981–2. (fn. 89) Fresh landscaping and security gating took place under the local architects Hutchinson & Partners in 1987, when a circular lift-shaft with metal trellises attached, described by the Architects' Journal as a 'discreet piece of tacked-on Tecton', was added to the back of Sadler House (Ill. 124). (fn. 90)

The effects of 'right to buy' policies were palpable at Spa Green by the 1990s, some new residents being drawn to the estate because of its architecture. A Spa Green Management Group was established in 1996, and the decision to list the estate two years later confirmed the sense of fresh pride. (fn. 91) In 2005 a third of the flats had been sold, many (according to The Guardian) 'to Lubetkin enthusiasts, such as architects, designers and academics'. (fn. 92) The mixture of tenure complicated financial arrangements for the full refurbishment of the whole estate undertaken on behalf of Islington Council by Homes for Islington in 2006–7. This scheme, in progress at the time of writing, consisted of an external restoration of the fabric in accordance with listed building management guidelines compiled with English Heritage's help, and an upgrading of kitchens and bathrooms in all the flats still in council tenure, retaining all the surviving original sinks and Garchey systems. The architect for the scheme was Paul Tobin on behalf of Homes for Islington; the main contractors were Apollo London Ltd. (fn. 93)

Finsbury Estate

In the 1940s plans by both the London County Council and Finsbury Borough Council designated the Skinners' Company estate for redevelopment with high-density housing. Proposals by the company for mixed commercial and residential development were thus frustrated, and in 1954 the estate was sold to the Onyx Property Investment Co., for £70,550. Four years later Onyx was able to sell it on to the borough council for £170,822. (fn. 94) It was redeveloped in 1964–8 as the Finsbury Estate. Designed by Emberton, Franck & Tardrew, architects, and built by Tersons for £2,524,980, this was the last of the major housing developments initiated by Finsbury Borough Council before it was subsumed into the new London Borough of Islington in 1965. It was among the taller and more costly local-authority housing projects of its time.

125. Finsbury Estate. Michael Cliffe House from the east in 1968

126. Michael Cliffe House, entrance in 2006

Following much work elsewhere in Finsbury, as at the Brunswick Close Estate of 1954–8 (see Survey of London, volume xlvi), Emberton, Franck & Tardrew (Franck & Deeks from 1963) were appointed architects for this development in 1961. Carl Ludwig Phillipp Franck's scheme was for a wholly pedestrianized estate of 468 homes with a density of 200 persons per acre. It included a 24-storey tower, an underground car park, a public house (Finsbury Council at first refused to allow any pubs, though there were several on the old streets, resulting in threatened legal action from the London Brewers' Council) and a central borough library. The whole was designed, in large measure through high rise, to provide as much open space as possible, the existing street layout largely being destroyed. The council began winding down tenancies in 1963, most of the site was cleared during 1964, and building began in May 1965, soon after the abolition of Finsbury Council. Skinner Street was widened and diverted southwards along the line of Goode Street and Corporation Row. (fn. 95) The name Clarke's Close—anachronistically preserved over the years by the Skinners' Company— had been abandoned in 1963, when the planned development became known as the Finsbury Estate. (fn. 96) Its buildings were named after prominent former members of the old council: Michael Cliffe (d.1964), Chairman of Housing through the 1950s; Patrick Coman, the first Labour leader in 1928; Charles Townsend, a Labour member in 1913–31; and Joseph Trotter (d. 1967), housing chairman in the early 1960s.

127. Finsbury Estate. Nos 18–24 Joseph Trotter Close, looking east to Michael Cliffe House in 2006

As completed, the mixed-development estate comprised 451 homes in four irregularly grouped blocks: Michael Cliffe House, a central 24-storey tower (reduced from 25 storeys following LCC objections) with one- to three-bedroom flats; Patrick Coman House, a nine-storey slab along St John Street with two- and three-bedroom flats, and ground-floor bedsits for the elderly; Joseph Trotter Close, four-storey ranges along Myddelton Street and Gloucester Way, and a single-storey range to Skinner Street, the last two with curved profiles, where the accom modation included four-bedroom maisonettes for larger families and some bedsits; and Charles Townsend House, a single four-storey range to the south, mostly comprising bedsits and one-bedroom flats. The two taller blocks are oriented precisely north-south, disregarding streetpattern to give the long window elevations east and west aspects. Finsbury Library faces St John Street at the front of Patrick Coman House, and the public house (the Royal Mail) is on the corner of Myddelton Street and Gloucester Way. Two intermediate spaces were laid out as playgrounds, that to the west with a paddling pool and other equipment for young children, the other a fenced area for ball games, above the two-storey car park (Ills 125–7).

In his work for Finsbury, Franck had worked closely with consulting engineers Felix J. Samuely & Partners, from the Brunswick Close Estate on through the Pleydell (Galway Street) Estate, the O. M. Richards Estate in Pentonville (see page 421) and King Square to refine an innovative approach to reinforced-concrete construction. In pursuit of flexible planning, this moved on from the conventional box frame to what came to be known as the Finsbury Method and was applied to ever-taller towers. The system called for large-scale prefabrication, and the logistics of this required a negotiated contract so that the builder could be involved at an early stage in the planning. The Finsbury Estate's taller blocks use load-bearing end walls and solid floor slabs stiffened by structural columns rather than cross walls; staircases and lifts double as loadbearing cores. The four-storey blocks are of load-bearing brick construction on the same principle. All components, save the floor slabs which were cast in situ, were built up from prefabricated sections. The absence of cross walls allowed light internal partitions that could be moved, allowing the layout and size of flats to be altered. The grids of the frame were externally expressed, with pebble-dash wall panels and fluted precast-concrete balcony fronts, producing an effect that has its aesthetic origins in the chequerboard designs for Spa Green, with which Franck had been involved, and which influenced his earlier towers east of Goswell Road. Michael Cliffe House and Patrick Coman House have pilotis and open centres at ground level, characteristic of the wider group, the former with a curved canopy that has a red mosaic soffit. The shaped roofscape is another echo of Spa Green, but here not for drying areas; a large boiler house stands atop the tower. Materials and elevational treatment aside, colour schemes throughout the estate were designed to match those of the sister estates. (fn. 97)

Replacement of the Finsbury Estate's metal-frame windows and other alterations and repairs were carried out over several years up to 2008, the work being carried out by Apollo London Ltd for Homes for Islington, the Arms Length Management Organisation that is associated with Islington Council. (fn. 98)

Finsbury Library, conceived as a cultural centre and book headquarters for the whole Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury, was reduced to branch status with the creation of the London Borough of Islington, by which time plans were too advanced for major changes. The plan is consequently on a more ambitious scale than the average branch library, with a lecture hall among various ancillary rooms. The convex front to St John Street is like an elongated version of the Finsbury Health Centre, with added colour. Free-standing pilotis clad in blue glass mosaic carry a projecting upper storey defined by a frame in faience, within which broad strips of black mosaic alternate with windows over aggregate panels. An oversailing roof drops from front to back. Mosaics in further vivid hues continue on the underside of the entrance canopy and the walls of the outer foyer. Within the spacious main library is a shallow, toplit barrel vault (Ills 128, 129). The plaque commemorating the library's opening by the Minister of Power, Richard Marsh, in March 1967, refers specifically to C. L. Franck as its architect. (fn. 99)

128. Finsbury Library, view from north in 1994

129. Finsbury Library enquiry desk, 1967, with staff members and the architect, C. L. P. Franck, standing at right

Other buildings

In the area between Lloyd's Row and Garnault Place the early nineteenth-century houses largely survived wartime bombing and were not cleared until the late 1960s and 1970s (see Ill. 117). The present buildings south-west of Gloucester Way, although they have Rosebery Avenue numbers at their north ends, belong essentially to Myddelton Street, Gloucester Way and Garnault Place and are therefore dealt with here.

Hugh Myddelton Primary School

The block south of Lloyd's Row that included Nos 46–63 Myddelton Street and the eastern half of Green Terrace was cleared in 1968 for Hugh Myddelton Primary School, which moved here from Bowling Green Lane. Standing between, and almost linking, the Spa Green and Finsbury housing estates, this school for 500 children was built by the Inner London Education Authority and opened in 1971. The architect was Julian Sofaer, the builders E. J. Lacy & Co. Ltd of Brent. Planned by the London County Council from as early as 1959, the school was designed in 1965–6. Sofaer had been appointed on the strength of earlier school projects undertaken for the LCC in which he refined methods of maximizing natural light, starting with his work for Yorke, Rosenberg & Mardall in 1949 at Susan Lawrence School on the Lansbury Estate in Poplar. At Hugh Myddelton he simply introduced a central light well along the main building's spine, flanking which the upper classrooms are cantilevered, permitting clerestorey lighting to the lower classrooms (Ill. 130). The school's proportions were carefully and geometrically worked up from a golden-section base, expressed in brown brick with reinforced-concrete floors and flat roofs. Sofaer rejected system building and prefabrication, keeping faith with his own earlier approaches and Scandinavian influences. The date of design as opposed to construction is also reflected in the fact that the classrooms are cellular rather than open plan; a more open approach to school planning was strongly encouraged by the Plowden Report of 1967. To the north is a single-storey infants' block, and to the east are a dining hall, kitchen and school-keeper's house. Across Lloyd's Row there is a single-room nursery that was part of the 1960s project, harking back to plans of 1946 for the Spa Green Estate (see above). (fn. 100)

130. Hugh Myddelton Primary School from the south-west in 1994. Spa Green Estate in background

Rosebery Hall

The first portion of this students' hostel, numbered 90 in Rosebery Avenue, was built for the London School of Economics in 1971–4, to the designs of J. R. Burden of Cusdin, Burden & Howitt. (fn. 101) This consists of an L-shaped block faced in red brick facing Green Terrace and Gloucester Way, with recessed vertical strips comprising windows separated by grey-painted brickwork panels, and banded by brick soldier courses.

131. Myddelton Street looking south-west from Gloucester Way in 2005. Annexe of Rosebery Hall in foreground; Myddelton Place (No. 1 Myddelton Street) behind

A large annexe extending to Myddelton Street was built in 1992–3, extending the original L-shape into two linked quadrangles. (fn. 102) Designed by MacCormac Jamieson Pritchard it strongly resembles their contemporary student residences in Oxford—the Bowra Building at Wadham College and the Garden Quadrangle at St John's, completed in 1992 and 1993 respectively. It varies between four and seven storeys, with a symmetrical front to Myddelton Street and pavilion towers at the corners of the composition; the lower range along Myddelton Street houses basement conference rooms, lit by a glass-brick screen. Where the 1970s building is reticent to the point of dullness, the annexe is a strong rectilinear composition in orange-red facing bricks with concrete dressings, the metal-framed windows grouped in twos and threes (Ill. 131). (fn. 103)

Myddelton Place

A speculative office development, this was built in 1990–2 for London Merchant Securities. The architects were John Gill Associates. Triangular on plan, it rises bulkily through five loosely historicist storeys. A simulated Bathstone 'rusticated' lower section supports brick-faced upper walls broken up by sharply projecting oriels—a design deemed 'execrable' by one critic. (fn. 104) The building now houses the National Archives' Family Records Centre, at No. 1 Myddelton Street (Ill. 131), and, fronting Garnault Place, an Asylum and Immigration Tribunal Hearing Centre (Taylor House, named after Lord Chief Justice Peter Taylor, Baron Taylor of Gosforth, who died in 1997). (fn. 105)