Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Northampton Square area: South and north of Northampton Square', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp322-335 [accessed 15 April 2025].

'Northampton Square area: South and north of Northampton Square', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 15, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp322-335.

"Northampton Square area: South and north of Northampton Square". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 15 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp322-335.

In this section

South of Northampton Square

Compton Street

Compton Street was laid out and its nearly eighty small house plots were all built up after the lease of Woods Close to William Pym in 1686. A stone on a house at the west end of the road, on the north side, was recorded in 1898 as bearing the inscription 'Rufford's Buildings/ 1688', (fn. 1) referring to Nicholas Rufford, an Islington brickmaker, who put up other sets of 'Rufford's Buildings' in Islington in 1685 and 1688. (fn. 2) Other brick houses on the south side of Compton Street were being insured in 1699. (fn. 3) As first leases ran down there was sporadic rebuilding in the mideighteenth century. In the 1770s, when the Charterhouse estate to the south was being redeveloped, a number of houses on Compton Street were replaced or substantially improved, and Northampton Court was built off the south side. (fn. 4) There is no surviving trace of these first- and second-phase buildings, neither here nor on the other early roads in the vicinity, Agdon Street and Cyrus Street. There was some further rebuilding along Compton Street early in the campaign of improvement on Woods Close that began in 1791 (see Nos 64–77). Here there were none of the problems that arose from water pipes further north.

Compton Street in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was crowded, busy and a fairly rough address, with much domestic industry increasingly overshadowed by purpose-built establishments including a soap works (1827), a printing-ink factory (c. 1830), iron and brass foundries and a timber yard (see Ill. 391 on page 285). Off the street rows of small houses were built in Northumberland Place (1776) and Compton Passage (Caroline Buildings, 1818–20). Population was very dense by the mid-nineteenth century, 701 people being recorded here in the 1851 census, 62 more in Northumberland Place and another 81 in Compton Passage. Large-scale redevelopment took place from the 1870s, with the building of model dwellings (Compton Buildings), a board school and, in the early twentieth century, new factories. Overall population fell as a result, and even the older buildings were less densely occupied by the 1890s. (fn. 5) It was described before the First World War as 'a long, dull street of small tenement houses … haunted in the dinner-hour and after-work times by groups of factory girls, all feathers and freedom'. (fn. 6)

Today, the north side of Compton Street is entirely occupied by public housing (see Percival Street Estate, below). On the south side the chief buildings of interest are a row of mostly late Georgian shop-houses, and the former board school. Accounts of these follow a résumé of the other buildings on this side of the street.

The bulky blocks at Nos 37–42, east of the school playground, were built as a factory for R. H. Filmer & Co., folding-box makers, on the former timber yard. The eastern part (Nos 37–40) was built in 1926–7 by the Pitcher Construction Co., and the remainder in 1933–4 by A. J. King Ltd. The three-storey building at Nos 35–36 was built before 1946, when it was occupied by Frederick Willing & Co. Ltd, metal merchants. (fn. 7)

The site of Nos 54–56 was occupied by an iron and brass foundry in the nineteenth century, the products of which included bedsteads. The present building was built in 1931–3, by Allen Fairhead & Sons Ltd of Enfield, as a glass works for Pugh Brothers Ltd, plate-glass merchants. The steel-framed front block, faced in red brick, has a tall lower storey for handling large sheets of glass, with outer vehicle entrances and a surprisingly grand classical doorway to the centre, where an attic storey gives additional emphasis. Conversion in 2005–6 by Tasou Associates, architects, for the developers London & Regional, involved enlargement at attic level for two flats and a penthouse over commercial units, along with infill to the rear for four houses with a courtyard. (fn. 8)

Nos 57–60 are part of a residential development, extending to Dallington Street (see page 292), carried out in 2003–5 by the developers CYZ Ltd and GML Architects. (fn. 9)

No. 63 is a former electricity sub-station, built about 1938. (fn. 10)

No. 64, the former Harrow public house (established here by the 1760s), is a rebuilding of 1904–5 for Watney Combe Reid & Co. A three-storey, red-brick building, it was designed by J. P. Ensor and built by S. Goodhall & Son of Stoke Newington. It had closed by the late 1980s, the upper storeys being converted to bedsits in 1993–4. (fn. 11)

Nos 65–77

On the south side of Compton Street, adjoining the Well public house at No. 180 St John Street, stand Nos 71–77, all built in 1797–8 (Ill. 443). Confined to narrow (13–14ft) plots originally built up in the late seventeenth century, they are reminders of how small many of Clerkenwell's early buildings were (though the houses here are considerably larger than those that stood in many courts and alleys, now entirely gone). Nos 71–74 were leased to John Thompson, a Holborn carpenter, Nos 75–77 to John Lumb, a Lambeth mason. These takes were separately and somewhat differently built, but it seems likely that the two men were operating together, along with Thomas Younger, a Holborn bricklayer, probably building in a work-for-work consortium. (fn. 12)

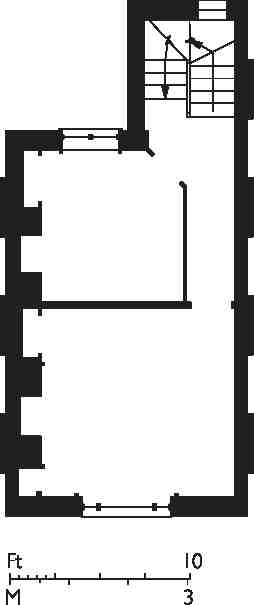

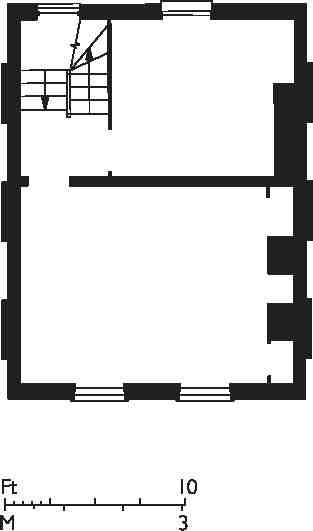

Six of the seven shop-houses have single-window fronts, No. 77 being the exception. The broad northfacing windows may have been designed with domestic industry in mind, whether watchmaking or otherwise. Thompson and Lumb made the most of the narrow plots, giving each house three full storeys and area-lit basements to accommodate eight rooms. Unusually, the staircases were in projecting rear wings (Ills 444, 445), the plots being too narrow to accommodate what was becoming the standard house-plan in London north of the Thames, whereby the back rooms would have been impossibly narrow. So the twin-newel staircases were set back into the small yards. Central-staircase layouts were widespread in narrow-fronted shop-houses in earlier decades. That they were not used here is suggestive of the powerful drive towards standardization in London house-building in the 1790s. Against this, and a further curiosity, are the strikingly tall and narrow staircase windows of Nos 71–74, and some back-room mullioned casement windows. Internally the eccentric layout meant that the upper-storey back rooms were entered by offset doors at the head of poorly lit passages to the front rooms. This arrangement survives in No. 72 with plain panelling, including upper-storey partitions and two-panel doors. At Nos 75 and 76 early nineteenth-century additions enlarged the back rooms alongside the stair wings. Single-storey wash-houses were also added, further reducing the size of the yards. No. 73 retains an early nineteenth-century shopfront. Nos 70 and 71 were both re-fronted in the mid-1970s.

443. Nos 64–73 Compton Street in 2004

Nos 68A, 69 and 70 were rebuilt in 1814–15, the lease going to Thomas Clapton, a Clerkenwell builder. Here there are wider 18ft two-window fronts, and the houses are conventionally laid out, with staircases in the main block, which is only slightly deeper than that of Nos 71–77. Unlike the earlier buildings this group always had privies at the backs of the gardens. (fn. 13) The next group to the east, the four taller and deeper properties at Nos 65–68, was redeveloped in 1871 by George Smith and William Everett, both builders, when the lease from an earlier rebuilding of 1772–3 expired. The shopfronts at Nos 75 and 76 were also replaced in 1871, by Edward Smith. (fn. 14)

444. No. 72 Compton Street, reconstructed first-floor plan

445. Nos 72–74 Compton Street, view of the backs, 2004. The stack shared by Nos 71 and 72 still has pots for all 16 flues, indicating that the shops in this row were heated

The row of shops at Nos 65–77 Compton Street is at least as old as its buildings. After its redevelopment in 1797–8 Robert Mayhew, a butcher, had No. 77. In the 1820s occupants of the row included Job Knott, a chandler or grocer, at No. 76, and John Durnford, a gold and silver beater, at No. 70. In 1841 the census found 82 people residing in the ten properties at Nos 68A–77. Knott, his wife Johanna, and his shop shared No. 76 with Edward Wallis, a silversmith, his wife Sarah, and six children, three adult lodgers and a charwoman. Miss Jane Brown, a hairdresser and perfumer, was at No. 75, with William Hill, another silversmith and his family. Mrs Charlotte Johnson, a butcher, occupied No. 74, and No. 72 was the Star and Garter beer house. The pattern of later occupation is set out in the following list. (fn. 15)

SS Peter & Paul Roman Catholic Primary School, Compton Street

Compton Street School, now SS Peter & Paul Roman Catholic Primary School, was built by the School Board for London in 1880–1 to the designs of E. R. Robson. The contractors were Wall Brothers of Kentish Town and the building, intended for 1,400 children, cost £12,447. (fn. 16) Additional land was acquired and the school-keeper's house, fronting Compton Street to the west of the main building, was erected in 1885–6 on a separate contract, by W. Johnson of Wandsworth Common. (fn. 17)

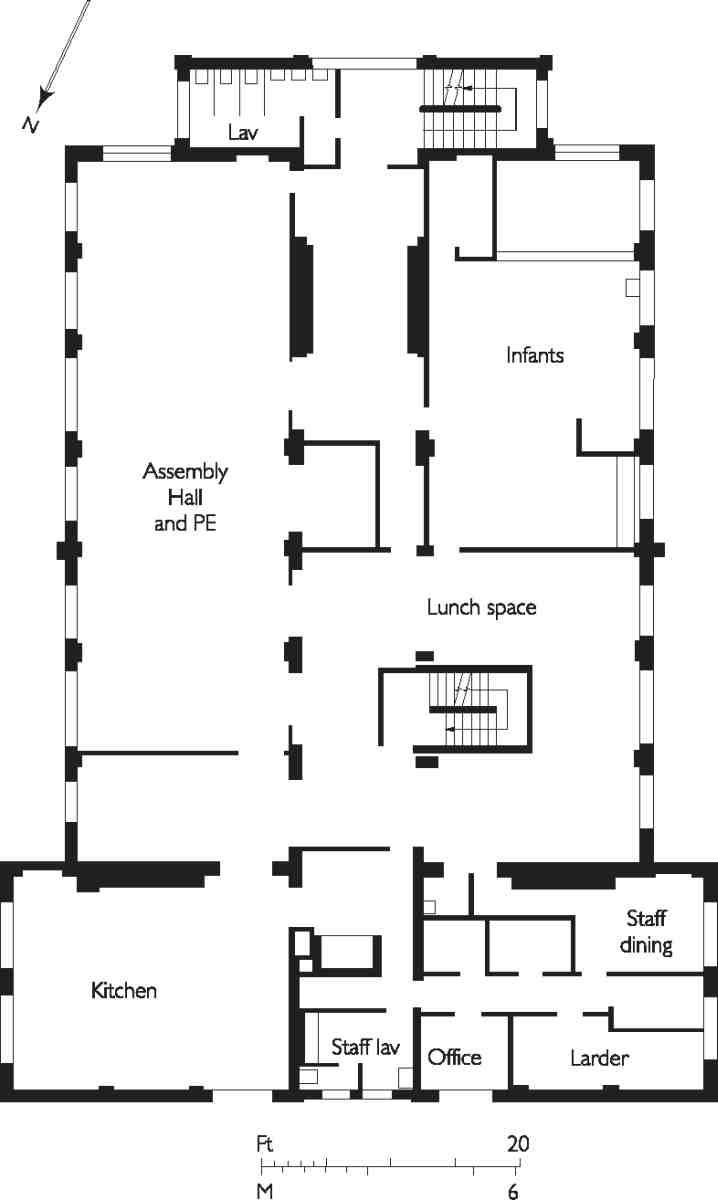

The school's original external appearance is very little altered (Ill. 446). A typical 'three-decker', it is built of stock brick with red-brick dressings, the main ornamental features being unusually shaped gables geometrically decorated with bands of red brick. The original plan was based on a central corridor at right angles to the street, with classrooms to either side, two larger schoolrooms alongside the street, and staircases in a wing at the other end of the building. By the late 1930s complete rebuilding was considered, but this was not carried out owing to the falling school-roll (only 563 pupils in 1938) and the hemmed-in nature of the site. (fn. 18)

In 1967 the Plowden Report on primary education focused attention on the special problems of schools in deprived, typically inner-city areas. One of its suggestions was the remodelling of old schools—opening up the buildings to bring an end to the isolation of individual classes and to create new spatial arrangements suitable for progressive teaching and use by the wider community. It was in direct response to Plowden that the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) and the Architectural Association, with the financial support of the Goldsmiths' Company, set up a competition to transform Compton Street Primary School. This aimed to challenge almost the entire character of the existing building—its scale, layout, floor levels and circulation space, together with the dingy playgrounds and outdoor WCs. (fn. 19)

446. SS Peter & Paul Roman Catholic Primary School, Compton Street, in 1997

447. SS Peter & Paul Roman Catholic Primary School, Compton Street, first-floor plan as remodelled in 1968–71

Of 82 entries, the first prize went to John Dennys and Nigel Farrington of Cassidy, Farrington & Dennys, architects. Their modernization scheme, completed in 1971, remains largely intact. The overall aim was to break down the rigidity of the interior (Ill. 447). This was achieved by removing partition walls, doing away with the corridors where practicable, and by creating mezzanines, which the great ceiling heights (a requirement in rooms designed to be lit by coal-gas) made possible. On the Compton Street front, the ground-floor mezzanine enabled staff rooms and kitchens to be placed over stores and other ancillary rooms, providing a buffer from street noise for the rest of the school. On the same level, a library along the line of the central corridor was given a balcony overlooking ground-floor teaching areas. Amid a first-floor dining area rose a glazed main staircase; lavatories replaced a rear staircase. In general, relatively loosely defined 'zones' and 'spaces' replaced formal and self-contained classrooms. The accommodation was designed for a total of 310 children, less than a quarter of the Victorian complement. In the playgrounds, there was new planting and bright paint.

A few years after the renovation, declining pupil numbers led to the closure of the school by the ILEA. In 1978 the building was taken over by the combined Roman Catholic primaries of St Catherine at Herbal Hill and SS Peter & Paul in Amwell Street. (fn. 20)

Percival Street Estate

This housing estate (known until recently as the Percival Estate) occupies all the land between Compton Street and Percival Street. This area was first wholly built up in 1804–10, when what are now Agdon Street and Cyrus Street were supplemented by the insertion of Little Northampton Street, Prince's Street, Queen—now Malta—Street, and Smith—now Tompion—Street (Ills 410, 414). Redevelopment began in the 1870s, with Compton Buildings, between Compton Street and Cyrus Street, which were replaced by The Triangle in the 1970s. Finsbury Borough Council built Cyrus House to the west in 1933–4, but it was the London County Council that took on the rest of the area to the north and west, providing new housing blocks through the post-war decades (see Ill. 286 on page 219).

Compton Buildings (demolished)

The site on the north side of Compton Street that is now The Triangle and the playground to its west was previously occupied by model dwellings of the 1870s, put up as redevelopment where leases had expired. Known as Compton Buildings, they were erected by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Co., which was given advantageous terms by the 3rd Marquess of Northampton. First, in 1871, the company cleared the latter-day playground site for two relatively small blocks, each of 24 flats, facing Compton Street and King (now Cyrus) Street. They followed the company's standard in-house design, with open staircases and landing access, and were erected by its usual builder, Matthew Allen of Finsbury. (fn. 21)

The remaining two-acre site, with a long frontage to Goswell Road and 'consisting of shops, sheds, barns, cattle lairs, and courts of the worst description', as well as a soap works, was acquired in 1874. (fn. 22) Up to this time the company had not used outside architects, but now decided to hold an open competition for designs, to see whether existing patterns could be improved upon. The assessors (Charles Barry junior, George Godwin and Alfred Waterhouse) selected a design by Henry Macauley, of Kingston-on-Thames; Banister Fletcher was runner-up. They felt, however, that 'no very striking and original treatment' had been produced, and blamed the five-storey limit imposed by the competition rules for producing very high densities. The company pronounced all the plans too expensive to construct if the accommodation was to be affordable to the working classes. Feeling that the superiority of its own designs had been proven, the company prepared a scheme for four blocks of six and seven storeys, to provide 275 flats. Nevertheless the result was a dense and bulky complex. It was built in 1876–7 in the plain form that had emerged after the Artizans' Dwellings Act of 1868 and become typical of the company's projects (Ill. 448). G. W. Gilham of Finsbury Circus was the builder. (fn. 23) Designed for 1,860 occupants in total, the 323 flats of Compton Buildings were listed in the 1891 census as housing 1,594 people. (fn. 24) The leases expired in 1970, and redevelopment ensued, the small early blocks being the last to be demolished, in 1981. (fn. 25)

The Triangle

448. Compton Buildings, Goswell Road, c. 1910

Their successor, the Triangle, was built for Islington Borough Council to designs by Clifford Culpin & Partners, the Compton Street and Cyrus Street blocks in 1970–3, the Goswell Road block in 1976. Davard Construction Ltd were the contractors. With fewer than half the number of dwellings in Compton Buildings, the brown-brick complex consists of 130 one- and twobedroom flats in six-storey cluster blocks, incorporating shops, like its predecessor, but this time arrayed around a landscaped central open courtyard raised over garages (Ill. 449). This courtyard is entered from Cyrus Street under a monumentally framed high-level bridge linking fourth floor access decks. The south and east outward-facing elevations are articulated by a greater geometrical interplay of flush glazing with balconies, both deeply inset and projecting. Where not provided with balconies or terraces the flats have gardens. (fn. 26)

Cyrus House

To the west stands Cyrus House, one of Finsbury Borough Council's earliest housing projects (Ill. 450). In 1929, in negotiations about its wider plans for industrial redevelopment, the Northampton Estate offered the council a preferential rate on this site for new housing. Progress was enabled by changes in the subsidy regime in 1930. The five-storey block of forty largely two- and three-bedroom flats was built in 1933–4 to unswervingly traditional designs by E. C. P. Monson, closely following the precedent of the Margaret Street redevelopment (see Survey of London, volume xlvii), with Monson involved from the first in 1929. The contractors were Gee, Walker & Slater Ltd. (fn. 27) The entrance elevation was along Malta Street, which was extended to Compton Street as part of this project (Malta Street has since been truncated and the southern portion incorporated into Compton Street). It is boldly detailed, with a two-storey arch leading to an inner courtyard from which staircases rise to give balcony access to the flats, in keeping with LCC practice but uncharacteristic of Monson.

Tompion House and Earnshaw House

449. The Triangle, internal courtyard in 1997

The Northampton Estate's Percival Street Improvement Scheme was modified in 1937 when the LCC declared a clearance area south of Percival Street. To the west the estate still intended redevelopment for industry, but it gave up the triangle east of Malta Street and north of Cyrus Street for the LCC to re-house most of the 500 or so who would be displaced, also undertaking to re-house others on Northampton land in Canonbury. Designs for the LCC's new blocks were prepared by Messrs Joseph, architects, in 1938, and demolition began in 1939. (fn. 28) Further work was held up by the war and the flats were not built until 1946–9, erasing the south end of Tompion Street. W. H. Gaze & Sons Ltd were the builders of the two six-storey blocks. They were named after Thomas Tompion, the great clockmaker, and Thomas Earnshaw, the watch and chronometer maker; neither actually lived or worked in Clerkenwell, though Earnshaw had addresses near by in Holborn and St Pancras. (fn. 29) The much larger Tompion House, which has eighty of the ninety one- to four-bedroom flats, has starkly stripped-down Queen Anne elevations in red brick (Ill. 451). Entrances face inwards to a somewhat less severe court. Tompion Community Hall, adjoining Earnshaw House, was part of the development. Its 'special feature' was a communal laundry below the main hall with electric washing and drying machines, later converted to a small hall and offices. The building is currently (2007) being redeveloped with a new community centre and flats above, taking in also the site of No. 44 Percival Street (Piercy Connor Architects). (fn. 30)

Shakespeare's Head public house

The first Shakespeare's Head public house of c. 1808, always so called, stood on the south side of Percival Street, on its east corner with what is now Tompion Street. (fn. 31) Its replacement, built some way eastward to make room for Earnshaw House, was designed in 1937 by Sidney C. Clark and built in 1939 for Charrington & Co. by T. G. Waterman Ltd. (fn. 32) With its mildly surprising suburban flourish of a crow-step gable, it survives as LMNT restaurant (Ill. 452).

Grimthorpe House

In the changed conditions after the Second World War the Northampton Estate was obliged to abandon its existing plans for redevelopment. The LCC took on the now largely cleared westerly block south of Percival Street in 1947–8 through compulsory purchase. The available land, on the north and west sides of S. Ramsey & Co.'s large nineteenth-century wire-working factory at Compton Yard and Globe Yard, the lease of which did not expire until 1954, dictated an L-shaped development. The Valuer's Department, which, in the early post-war years, controlled the LCC's housing design, and generally adhered to traditional patterns, accepted Modernist designs prepared by John Partridge (later of Howell, Killick, Partridge & Amis) and admired by Leslie Martin, later to become the council's superintending architect. The scheme was approved in early 1949, and construction of the eight-storey blocks of 128 one- to five-room flats, by A. E. Symes Ltd, followed in 1950–2 (Ills 454, 455). A playground and communal garden were part of the original layout.

The dramatic change of architectural approach after Tompion House reflects the ascendancy of Modernism within the LCC during 1949 in the build-up to the displacement of the Valuer's Department and the establishment in 1950 of the Housing Division within the Architect's Department. There are echoes of Tecton's Finsbury housing in these blocks (see Survey of London, volume xlvii), but their reinforced-concrete structure—in part a reflection of steel shortages—and hand-made stock facing bricks were more directly influenced by Churchill Gardens, Westminster, of 1947–52. The bold glazed staircase and lift towers to Percival Street are very like those used by Powell & Moya in the first phase of that project; they derive ultimately from Rotterdam's Bergpolder flats of 1932–4. The longer range to Agdon Street was more conservative, with balcony access. Figurative sculpture on the model was not part of Partridge's design, but an afterthought, perhaps added by a more senior architect to help the otherwise purely Modernist project through committee, and probably never a serious intention. The block was named after Lord Grimthorpe, long-serving president of the British Horological Institute (see page 311). It was substantially refurbished by Islington Council in 1984–5. (fn. 33)

450. Cyrus House, Cyrus Street, in 2006

451. Tompion House, Cyrus Street, view from south in 1997

452. Former Shakespeare's Head public house, Percival Street, in 2006

453. Harold Laski House, Percival Street, in 1997; Brunswick Court in background

Crayle House

Crayle House was built in 1959–60 on the site of Ramsey's factory, to designs prepared by the LCC Architect's Department in 1957. Stewart & Partners Ltd were the builders. It was probably named after Richard and William Crayle, seventeenth-century London watchmakers. The balcony-access building, altered by Islington Council in 1983–4, originally comprised twenty maisonettes in two tiers across four storeys above two ground-floor flats for elderly tenants; the ground floor was then open except at the south end. It has a reinforced-concrete frame with panels of pre-cast concrete, tile and yellow stock brick. (fn. 34)

Partridge Court

Between Grimthorpe House and Crayle House, completing the estate, is Partridge Court, apparently named after an old Clerkenwell family. This was added by the GLC in 1976–7, to designs prepared in 1972 by Renton Howard Wood Levin Partners, architects, with Ove Arup & Partners, engineers. Initially the contractors were Courtney & Fairbairn Ltd, but they went into liquidation and were succeeded by Burlingway Construction. The five-storey block has thirteen flats and maisonettes, with housing for the elderly at lower levels. Behind brick cladding there is a reinforced-concrete frame, though the upper storey is of load-bearing brick. (fn. 35)

454, 455. Grimthorpe House. LCC Architect's Department (John Partridge, job architect), 1949–52. Model for Percival Street elevation, 1950, and (below) view from the north-west in 1952

Brunswick Estate

The Brunswick Estate extends from Percival Street to Wyclif Street and the backs of houses in Northampton Square and Sebastian Street. This area takes in the site of the eighteenth-century Skin Market, which was redeveloped in 1816–21 with small houses on a group of streets, renamed Brunswick Close in 1873. From 1923 the Northampton Estate planned clearance, as did Finsbury Borough Council from 1929. After delays and war the new housing was built by the council between 1949 and 1962. The estate consists of Brunswick Close, one of London's earliest high-rise schemes, and two low-rise blocks, Harold Laski House and Mulberry Court.

Harold Laski House

This block of 24 two- and three-bedroom flats was built for Finsbury Borough Council in 1949–52, and named after Harold Laski, the socialist political theorist who died in 1950. It was designed by George Hebson, the borough engineer. The minimally neo-Georgian red brick was intended to harmonize with the LCC's recently completed Tompion House on the other side of Percival Street (Ill. 453). Hebson's traditional approach contains no hint of his employer's dalliance with Berthold Lubetkin. (fn. 36)

Brunswick Close

Heavy bomb-damage resulted in the clearance of the whole Brunswick Close site between Tompion Street and the shops and houses of St John Street. Twelve Uni-Seco prefabs went up, and from 1946 the LCC intended building a replacement for Compton Street School here. However, Finsbury Council was determined to use the whole site for housing. In 1952, when the Northampton Estate applied to build a block of flats on this side of Percival Street, perhaps aiming simply to maximize compensation, the Ministry of Housing and Local Government ruled in favour of the borough on the grounds of acute housing needs, and the compulsory purchase of land that had not already been acquired ensued. The site of the Martyrs' Memorial Church to the north (see above) was a late addition in 1955. (fn. 37)

Joseph Emberton was appointed architect for this scheme in 1952, not so much on the strength of his pioneering Modernism of the 1930s, as because, succeeding Tecton, he was already working on and committed to Finsbury's housing programme. Michael Cliffe, Leader of the Council and known locally as Mr Housing, later recalled: 'We discovered that he had the same keen interest and enthusiasm as ourselves with revolutionary ideas on how housing could best be provided on the limited sites available in the borough'. (fn. 38) After Emberton's death in 1956 his assistant Carl Ludwig Philipp Franck completed the project as principal of the firm Emberton, Franck & Tardrew. Franck had come to England from Berlin in 1937 and found work with Tecton. He worked for Finsbury Borough Council during the war, and for Tecton again in 1945–8; he joined Emberton in 1953, in which year the plans for Brunswick Close were presented, and signed revisions to these plans in 1954. (fn. 39)

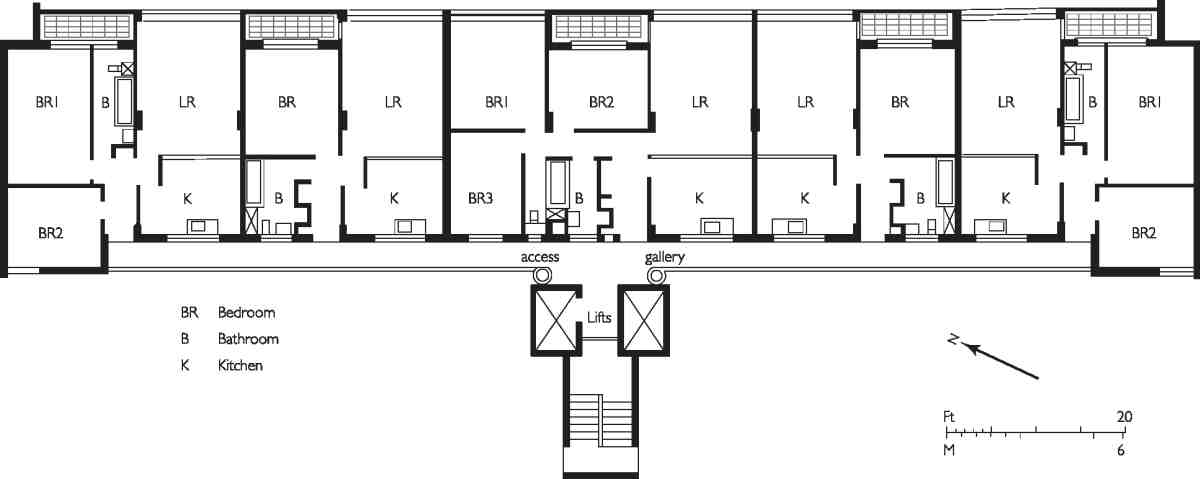

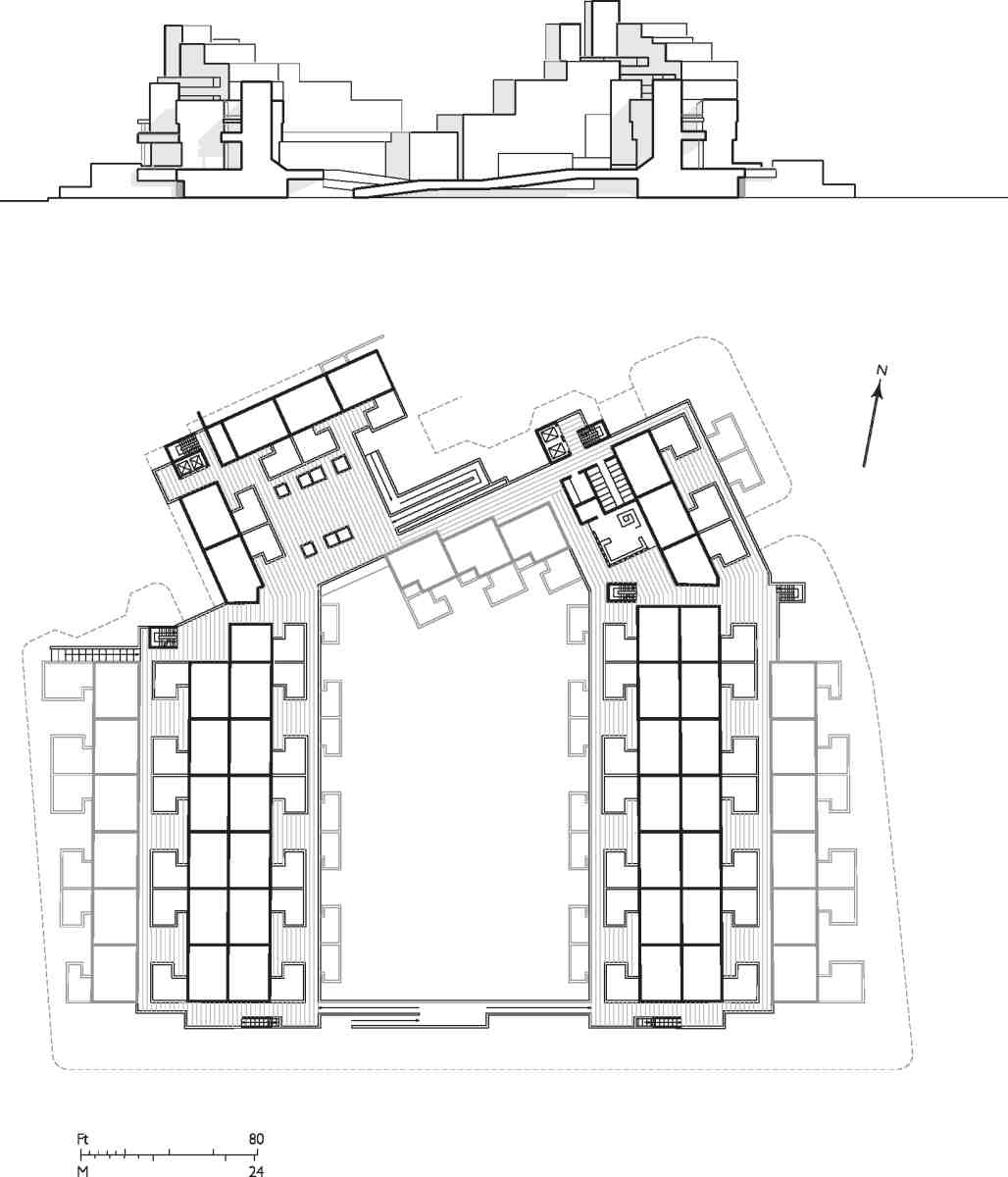

The complex of 207 flats was built in 1956–8 by Y. J. Lovell & Son Ltd, who had already built the Stafford Cripps Estate on Old Street with Finsbury and Emberton. Wyclif Court's name is a gesture to the memory of the Martyrs' Memorial Church that it replaced. Emberton Court was named after the deceased architect. The development comprised three massive slab blocks (Ills 456–458), each of 64 flats and 14 storeys, a bold height in the early 1950s. Emberton's brief was to ensure maximum densities (200 persons per acre), in keeping with the County of London Plan. He believed in building high, to allow space between the blocks. The slabs are staggered from north-west to south-east, in the manner that had come to be known as Zeilenbau following German precedents, for maximum light and open ground to the south and west; use of the Percival Street frontage for a playground had been settled in 1951. Two single-storey link ranges were designed to provide flats for the elderly with small front gardens, a layout that, through the linkage, aimed to avoid an 'old people's colony'. (fn. 40) Commercial units were being displaced, so the inclusion of a parade of ten shops on St John Street was agreed in 1954. Space to the north-east was given over to garages and parking.

456. Brunswick Close. Emberton, Franck & Tardrew, architects, 1953–8. High-level perspective drawing by Joseph Emberton

Felix J. Samuely & Partners, consulting engineers, helped Franck to devise a reinforced-concrete structure that moved away from the limitations of a box frame, using load-bearing end walls and solid four-inch floor slabs linked by columns rather than cross-walls. This construction, and the use of a climbing crane, enabled completion seven months ahead of schedule. The absence of crosswalls allowed novel flexibility in the planning; partition walls included doors to allow the ingenious, if impractical, possibility of an eventual transfer of bedrooms from central to adjoining flats, to meet variable demand. Franck and Samuely & Partners refined these constructional and planning innovations in later projects for Finsbury (see Survey of London, volume xlvii). Interiors were made lighter through part-glazed panels between the livingrooms and the fitted kitchens, which were large enough for dining-tables. The monotonous grid of the frame was externally expressed, with stock-brick wall panels alternating with balconies fronted with fluted concrete, producing an effect not unlike that of the chequerboard designs for the Spa Green Estate (Ill. 458). Central lift towers on the east sides buttressed the main slabs. Highlevel escape staircases from the access balconies met regulations governing means of escape from buildings higher than firemen's ladders, and also provided some formal, even sculptural relief. (fn. 41)

A refurbishment scheme of 1979, by Hutchinson & Partners, was pared back to replacement of the heating and refuse-chute systems in 1980–2. But in 1999–2000 Islington Council removed the external staircases and reclad the blocks, giving them new blue balcony fronts and double glazing. Security was improved, in part through the closure at ground level of what had been open central passages, a feature typical of Finsbury housing. (fn. 42)

457. Brunswick Close. Plan of typical floor in Brunswick Court

Mulberry Court

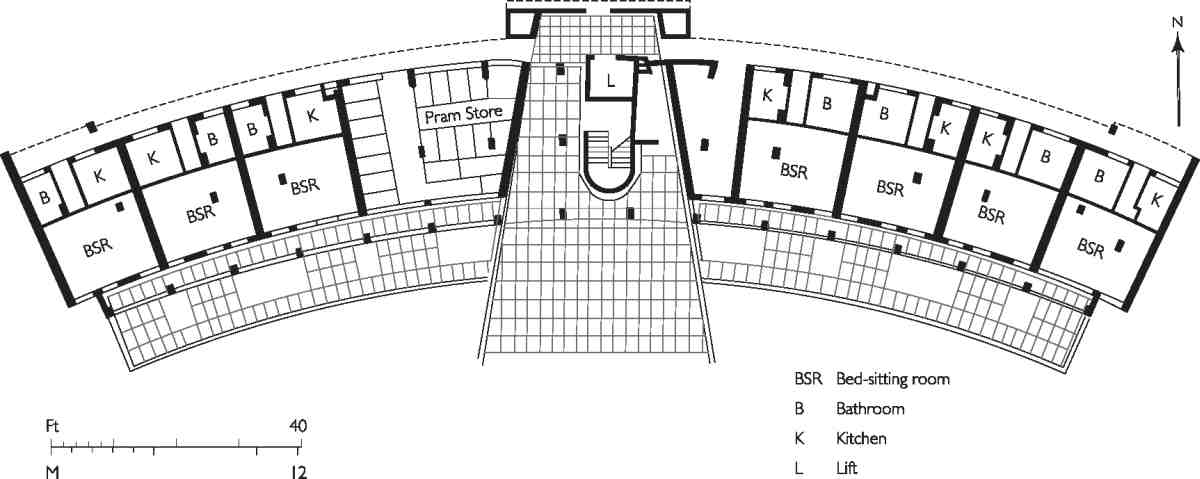

Mulberry Court, which takes its name from Mulberry (formerly Berry) Place, was an addition of 1959–62, later than the rest of the estate because Finsbury's acquisition of land on the east side of Tompion Street was delayed by the difficulties of moving businesses. Once again the architects were Emberton, Franck & Tardrew, and the builders Y. J. Lovell & Son. The lesser height and 'gentle curve' of this six-storey block of 37 flats were intended to provide a transition between the tall slab blocks and the much lower, and distinctly old-fashioned, Harold Laski House. Mulberry Court follows the slab blocks in its construction and general features, but it transcends Emberton's unforgiving formalism and more closely reflects Franck's grounding with Tecton (Ills 459, 460). Here the fluted balcony fronts survive. These pre-cast elements were intended as a decorative solution to rainwater streaking. The roof, with an aerofoil, was designed as a sun terrace and the forecourt as a recreation area. (fn. 43)

458. Brunswick Close. Brunswick Court from south-west in 1998, before refurbishment

459. Mulberry Court, Brunswick Estate. North front in 2007. Emberton, Franck & Tardrew, architects, 1959–62

460. Mulberry Court, ground-floor plan

North of Northampton Square: Spencer Street and Wynyatt Street

Spencer Street was laid out in 1808 and within a decade was lined with about sixty mostly three-storey houses (Ill. 458). Writing in the 1820s, Thomas Cromwell thought it 'one of the widest and handsomest' streets north of London. The houses have gone, and it is now an incoherent, even desolate, place. Its width relates to Cockerell's unrealized aspirations for this to be part of a major through road (see page 297), another relic of which is the alignment with what is now Moreland Street, laid out on a tongue of land east of Goswell Road belonging to the Northampton estate. A proposed semi-circus at the junction with St John Street was abandoned, but the plan gave rise to what remains an open space at that point.

Among the street's first residents was William Vidler, a Universalist minister and Unitarian preacher. The architect Ebenezer Perry, surveyor to the Charterhouse, lived here in the 1840s. The population, as registered by successive censuses, rose from 397 in 1841 to 590 in 1881, indicating growing sub-division. Mixed nineteenth-century occupancy included watchmaking and other commerce, some of which continued until the 1960s. (fn. 44) Nos 44–47, on the south-east corner with Upper Smith Street, were rebuilt in 1925–6 as a factory. This was Ascot House, a three-storey building of reinforced concrete, with largely glass elevations, first occupied by a firm making suspenders and garters. In general, however, the original building fabric survived until the Second World War. (fn. 45)

In 1944 the west end of the street was hit by a flying bomb, and the rest has been redeveloped, as part of the City University on the south side, and as the Earlstoke Estate on the north side.

461. Spencer Street, north side, c. 1970. Demolished

Wynyatt Street (north side)

Wynyatt Street was the first new street to be laid out after the Northampton Estate initiated development of Woods Close in the early 1790s. The north side was building from 1797, by which time the street had been named. (fn. 46) This was the northern edge of the field, and free of the water pipes that complicated development further south. The street was laid out along the property boundary, parallel to Rawstorne Street, the earlier houses of which no doubt influenced the scale of those here; anything larger would have had no local precedent. By 1808 there were 'two long ranges of small but neat houses'. (fn. 47) Of nearly seventy houses thirteen survive, including some of the first to be built (Ills 462, 463).

Nos 1–10, of which Nos 3–9 survive, were developed by Thomas Woollcott in 1797–1802; Nos 1–8 were up by 1799, No. 9 in 1800–1. These were modest fourth-rate houses with 16ft fronts; only No. 9 was given garrets and an open basement area. No. 11 was built in 1800–1 by Joseph Locker, a Clerkenwell carpenter, who intended to build more, but the house was not immediately taken, and Richard Vaughan built No. 12 in 1803, with garrets. The plots of Nos 13–17 were taken by Woollcott in 1803, by the end of which year Nos 13 and 14 had been built. The others, probably re-assigned to more than one builder, were first occupied in 1807–8. They survive and have eight rooms each, in three full storeys with area-lit basements. No. 18, of the garret type, was built in 1803 by William North, a Cripplegate carpenter. While progress evidently slowed around 1804, the fact that the slightly later houses are a bit larger may reflect the impact of the laying out of Northampton Square and other streets to the south, which would have at least appeared to improve the marketability of the area. (fn. 48)

462. Wynyatt Street, north side in 1973

At No. 17, the largest of the surviving houses, the oddity of a single top-storey window, which has been enlarged, combines with breaks in the construction of the staircase and its partitions to suggest that it may have been given its third full storey as an afterthought at some point in 1805–7, perhaps following the example of Nos 15 and 16, which were going up at the same time (Ills 463, 464). Inside, this house retains plain panelled partitions and other early nineteenth-century joinery.

463. Nos 1–18 Wynyatt Street, north side, in 2006

Early occupants of Wynyatt Street included watch- and watch-case makers, carvers, silversmiths and jewellers. In the 1820s No. 17 was occupied by a goldsmith, William Poole, who had a heated workshop that occupied much of the back garden. In 1840 a brass-worker, Frederick Morgan, moved in, and within a year his family was sharing the house with that of William Barnes, a clockcase maker, and another tenant, Naomi Knott. Subdivision and density increased through later decades. In 1861 the census recorded 577 residents in the street, in 1881 the figure was 702. (fn. 49)

464. No. 17 Wynyatt Street, first-floor plan

Nos 19–24 Wynyatt Street were badly damaged during the Second World War. Finsbury Borough Council redeveloped the site in 1956–7 as a plain brick three-storey block of twelve flats, designed by George Hebson, borough engineer, and built by James Webb & Son Ltd of St John Street. (fn. 50) Similar, but smaller-scale, redevelopment occurred at Nos 10 and 13–14. Nos 1 and 2, which had been a small engineering works, were rebuilt in 1986–7 as offices for Pegram Walters Associates, market researchers, in a pastiche development designed by Axis Partnership, architects. (fn. 51)

465, 466. Earlstoke Estate in 2006. General view looking north, with Moorgreen House to left; and (below) detail of typical 'street'

Southwood Court

In 1946 Finsbury Borough Council began buying up sites all along Spencer Street, and recommended that Tecton be appointed to prepare designs for new housing here. Delay was caused by London County Council plans for a new road, and it was 1951 before there was any advance, and then only on the much smaller triangle to the west, a bombsite. Normally, George Hebson, the borough engineer, would have undertaken a development of this scale, but he was understaffed, so Searle & Searle were appointed (John Casey acting as job architect). Hebson recommended 'a traditional brick scheme', in view of steel shortages. Skinner, Bailey & Lubetkin, as Tecton had become, protested that they had already prepared sketches treating the site as an extension of Spa Green, and that they took the approach to other architects as a 'vote of censure' on themselves. This was to no avail, perhaps because the Searle & Searle scheme placed great emphasis on economy, keeping to load-bearing brick construction, and eliminating 'all unnecessary features'. Construction by Henry Kent Ltd in 1953–5, which included floors and flat roofs of pre-cast reinforced-concrete beams, was, however, beset with difficulties. Thereafter Finsbury avoided developments of this 'traditional' nature. (fn. 52)

467. Earlstoke Estate, schematic plan at deck-street or roof-street level and Spencer Street elevation. Maisonettes are indicated by solid lines, walkways hatched

The building is named after Julius Salter Elias, Viscount Southwood, the newspaper magnate and chairman of Odhams Press, who had been educated locally at St Thomas's, Goswell Road, and who died in 1946. A fourstorey block of 48 two- and three-bedroom flats, it is basically L-shaped, with an open forecourt facing Wynyatt Street. It gives little to Spencer Street.

Earlstoke Estate

Finsbury's post-war notions of redeveloping the site between the eastern ends of Spencer Street and Wynyatt Street came to nothing, though the area remained earmarked for clearance. (fn. 53) It fell to the Greater London Council to complete the work, which erased Goswell Terrace and the last of early Spencer Street. In 1969 Renton Howard Wood Associates were employed to design what was initially known as the Wynyatt Street Estate. Gerald Levin took the lead, and in 1970 became a partner of what was thenceforth the Renton Howard Wood Levin Partnership. Building work began in 1972 and was completed in 1976. An intricate yet orderly and subtly grouped complex (Ills 465–467), it reflects the influence of Darbourne and Darke, architects at Lillington Gardens, Westminster, who in 1966 moved on to design the Marquess Estate on Northampton land in Canonbury for Islington Council.

The Earlstoke Estate comprises 137 dwellings, 42 twoperson flats and 95 four- to six-person maisonettes, predominantly back-to-back. High density (160 persons per acre) was reconciled with the predominance of larger (family) units in a low- and medium-rise development, divided as Moorgreen House and Midway House. The latter steps up in ziggurat fashion to nine storeys to the north near Manningford Close, which replaced the bisected east end of Wynyatt Street. There are loadbearing brick walls with reinforced-concrete floor slabs and a podium over garages. Ramps and corner stairwells rise to access decks or walkways on the third and fifth levels, intended to encourage neighbourliness, and to minimize expenditure on lifts. The brown brick and the internal streets aimed to preserve the area's earlier scale and intimate ambience. At the same time open space was introduced, with private gardens and enclosed patios, and a large landscaped 'central amenity area' towards Spencer Street. There has always been a shop on Goswell Road, and an old people's clubroom has become a community hall. (fn. 54)