Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Rawstorne Street to the Angel', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp336-357 [accessed 18 April 2025].

'Rawstorne Street to the Angel', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 18, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp336-357.

"Rawstorne Street to the Angel". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 18 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp336-357.

In this section

- CHAPTER XII. Rawstorne Street to the Angel

- Dame Alice Owen and the Brewers' Company estate

- Development of the Brewers' estate

- Individual streets and buildings

- Dame Alice Owen's School and Almshouses

- St John Street

- Goswell Road (west side)

- Rawstorne Street

- Rawstorne Place

- Friend, Paget and Hermit Streets

- Owen's Row

- Owen Street

CHAPTER XII. Rawstorne Street to the Angel

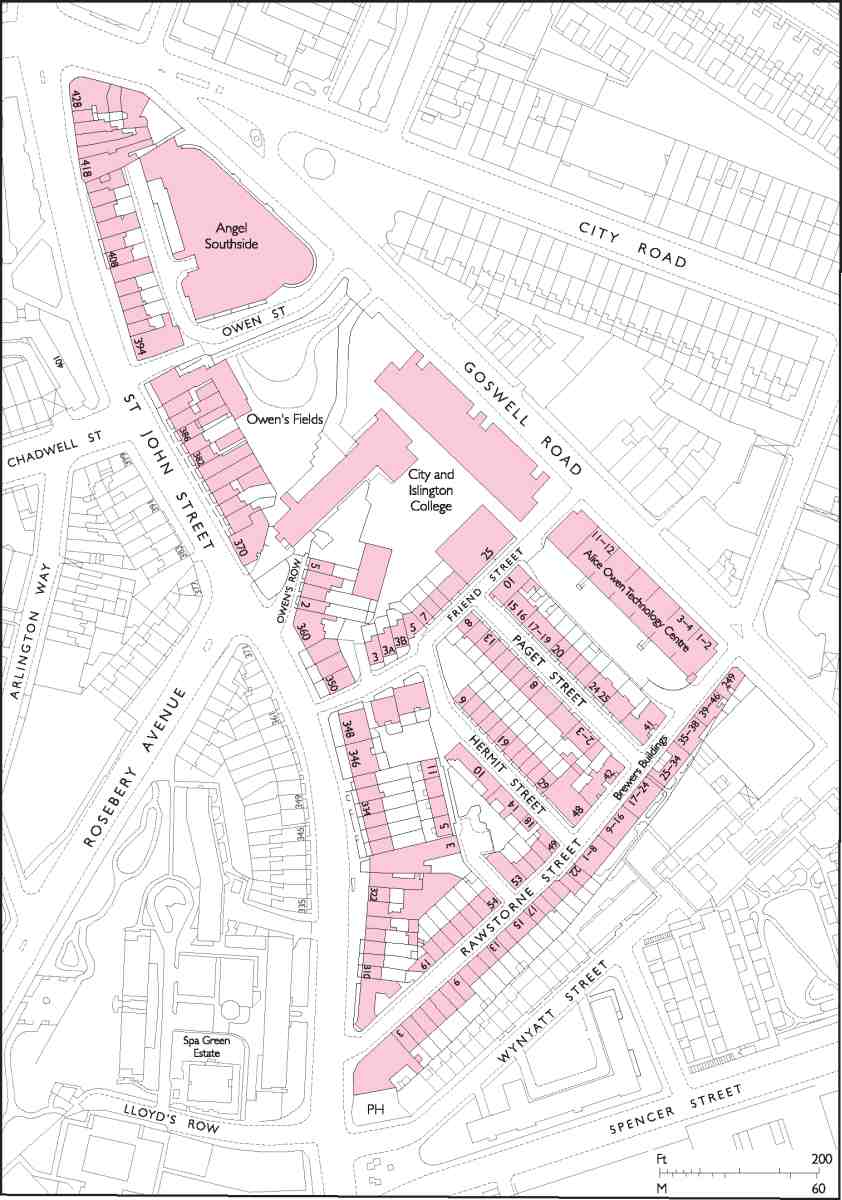

468. Rawstorne Street area. Houses on the west side of St John Street are covered in Chapter VIII

This chapter describes the northern ends of St John Street and Goswell Road, and the small triangular area defined by their convergence towards the Angel (Ill. 468). The two main roads here present a sharp architectural contrast: St John Street lined with attractive late eighteenth-century and later houses, late Victorian pubs or former pubs; Goswell Road almost entirely redeveloped since the 1970s, with industrial units and more recent apartments and a sixth-form college. The space between the roads has a distinct character of its own. Its quiet, narrow streets are lined with small terraces of the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, and later buildings including some late twentieth-century housing, sympathetic in scale and style, and a range of Victorian block-dwellings with a fine architectural façade. North of Friend Street a small public garden called Owen's Fields sets off the sixth-form college in Goswell Road and a former secondary school of the early 1960s.

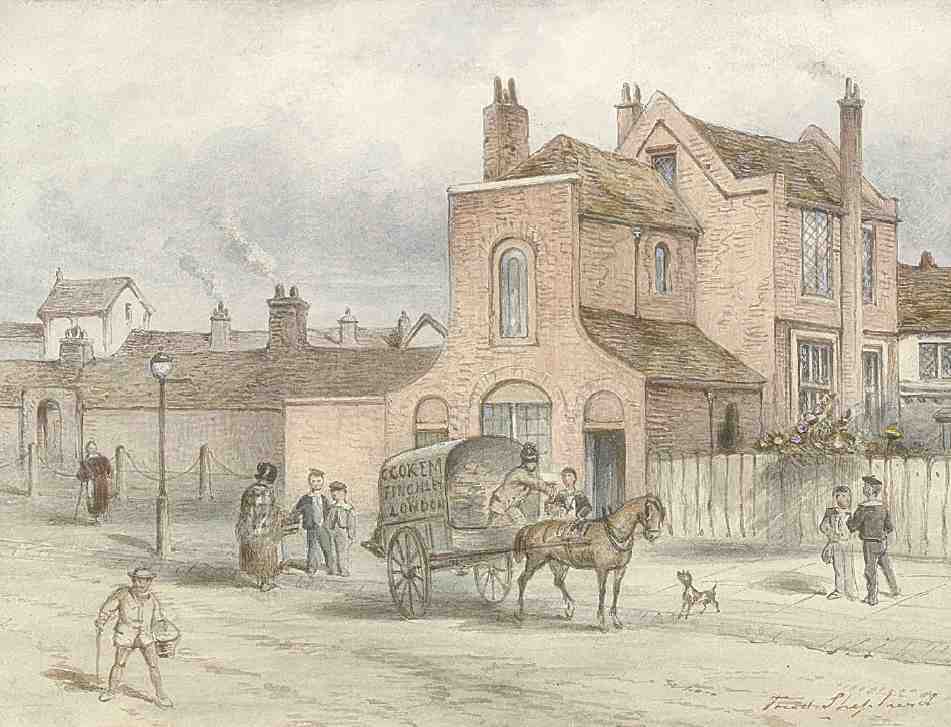

The earliest development, perhaps as early as the late Middle Ages, was along St John Street in the vicinity of the Old Red Lion public house, traditionally said to date from 1415. A hermitage, occupied by Robert Baker, a monk of the Order of St Paul, was set up in 1511 by the Knights Hospitallers, whose priory lay some way to the south-west in what is now St John's Square (see Chapter IV). (fn. 1) Until the dissolution of the priory in 1540, this whole wedge of land, extending as far south as Woods Close, later part of the Northampton estate, was a single field, known as Woodsmansfold or Woodman Field, and later Hermitage Field. The names Sheepcroft and Lambcroft are also recorded. (fn. 2) This field was divided in or by 1545, in which year all but the very apex was granted to Lord Chancellor Wriothesley. (fn. 3) Tenements were later built along St John Street, shown on a map of about 1590 as four buildings including the 'Armitage' itself (Ill. 469).

Early in the seventeenth century what had been Wriothesley's land was purchased by Alice Owen for a charitable foundation, passing from her in trust to the Worshipful Company of Brewers. The company still owns considerable property here through the Dame Alice Owen Foundation, under which the same firm of chartered surveyors, Daniel Watney, has been regularly employed since at least the 1960s to manage, improve and rebuild portions of the estate.

The main roads south of the Angel intersection are, for convenience, referred to throughout this chapter by their present-day names. Historically, St John Street extended from Smithfield only as far as the junction with Skinner Street and Percival Street. Beyond this the road was generally known as the Islington road until it became St John Street Road in 1818. (fn. 4) It was renumbered as part of St John Street in 1905. The northern part of Goswell Road has also been known by various names, including Islington Road, or the Back Road to Islington. It seems to have been more widely known in the eighteenth century as Goswell Street Road, the southern part—from just north of Old Street to Aldersgate Street—being Goswell Street. Both parts of the road subsequently became Goswell Road during the early nineteenth century. This name was used by the Clerkenwell historian Thomas Cromwell in 1827, while Lockie's Topography of London in 1813 still gave the old names.

Dame Alice Owen and the Brewers' Company estate

Alice Owen was born in 1547, a daughter of Thomas Wilkes, an Islington landowner. The story (related by Stow in the second edition of his Survey of London) goes that as a young woman Alice was walking with her maid in or near Hermitage Field, and stopped to watch a cow being milked. She asked to try her hand at milking, and on getting up again narrowly escaped death when a stray arrow from nearby butts pierced her hat. She vowed that if she lived 'to be a lady', she would build something on that spot to commemorate her deliverance. Three wealthy husbands later, she was reminded of her promise by the old servant who had been with her that day. (fn. 5)

Her last husband was Thomas Owen, Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, who died in 1598. In 1608 she obtained a royal patent and acquired Hermitage Field, building almshouses to the south of the Old Red Lion for ten poor aged widows the following year. A second patent, of 1610, authorized construction of a chapel and school as well. She made over the property, together with ground known as Charterhouse Closes (on the north side of modern-day Pentonville Road) to the Brewers' Company, which took over the administration of the charity on her death in 1613. Money for the endowment of the foundation was invested by Alice Owen's executor in the purchase of a farm in Orsett, Essex.

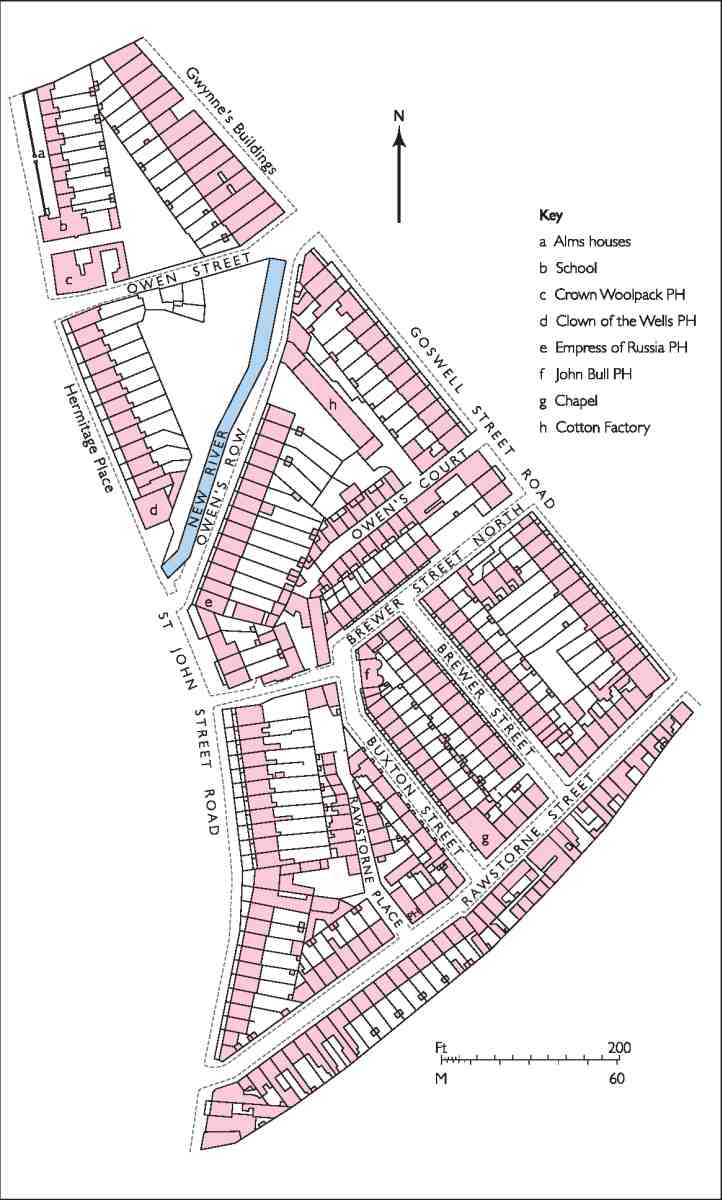

It was at about the time of her death that the New River from Amwell was cut across the estate on its way to New River Head and subsequently most of the ground on either side of the river was let on a succession of leases to the New River Company. The remainder, essentially the area north of what is now Owen Street, comprised two sites: that of the almshouses and school, and a larger site belonging to the Crown and Woolpack inn, backing on to Goswell Road.

469. South end of Islington High Street and junction of present-day St John Street and Goswell Road. Extract from a map of c. 1590, showing the 'Armitage'

Although development of the estate was not actively pursued by the Brewers' Company until the late eighteenth century, some building was carried out earlier. In the early eighteenth century a pie shop adjoined the brewhouse belonging to the Crown and Woolpack, (fn. 6) and to the south there were several tenements along St John Street facing Sadler's Wells, old and ruinous by the 1740s when they were repaired or rebuilt. (fn. 7) South of these, on the north side of the New River and directly opposite the back gates of Sadler's Wells, another hostelry was in existence by the 1750s. This was called the Turk's Head before being renamed successively after the King of France, the Queen of Hungary, the King of Prussia and the Empress of Russia, then becoming the Clown of the Wells in honour of Grimaldi. (fn. 8) An advertisement of 1755 announced the opening of a 'long room' at what was then the Queen of Hungary's Head, boasting of the 'most pleasing prospect, commanding Epping Forest, etc', and offering coffee, tea and hot loaves daily. (fn. 9) Besides this long room, there were also a skittle ground, gardens and summerhouses. (fn. 10)

The first piece of unequivocally suburban rather than semi-rural development took place in the mid-1760s with the building of a row of houses (Gwynne's Buildings) in Goswell Road. This was a time of renewed activity in the building trades, following the end of the Seven Years' War. It was also just a few years after the opening of the New Road (present-day Marylebone, Euston and Pentonville Roads), and the first steps to build alongside on Henry Penton's land, west of Islington High Street, were taking place. Like the soon-to-be suburb of Pentonville, the Brewers' estate developed as an outgrowth of the village of Islington, a tract of countryside separating it from the metropolis proper until well into the nineteenth century.

Systematic development of Hermitage Field became possible once the New River Company's lease expired in 1771. Much of the ground was built up with houses from then until the 1790s, chiefly in St John Street, alongside the New River in Owen's Row, and in Rawstorne Street, while a large site away from the main-road frontages was taken for a Quaker school and almshouse. A small amount of industrial development took place at this time, including a cotton factory off Owen's Row, built in 1791. Other non-residential buildings such as workshops, stores and stabling were also built at the rear of the terraces in St John Street, of which one survives (The Barn, No. 1 Rawstorne Place).

House-building continued in the early nineteenth century, along St John Street (in Hermitage Place) and, to a greater extent, Goswell Road, while the Quakers' ground was completely redeveloped with new streets of artisans' houses in the late 1820s and early 1830s (present-day Hermit, Paget and Friend Streets). Further redevelopment of the estate took place in the late 1830s and early 1840s with the demolition of Alice Owen's almshouses and school and their replacement by new buildings on either side of Owen Street.

By the mid-century the estate was crammed with the industrious poor, many of them engaged in printing and allied trades, metal-working, jewellery and clock and watch manufacture. (fn. 11) Nearly all the houses were in multioccupation. Owen's Row, however, retained a somewhat superior status, and even in the lean years at the end of the century the estate as a whole seems to have kept up a generally respectable front, without the rough and criminal elements found in parts of Pentonville or some of the darker courts and alleys in southern Clerkenwell. (fn. 12) But it was a backwater. When in 1904 the Brewers' Company sought to let a prominent site on the corner of St John Street and Rawstorne Street for building, no one was interested. (fn. 13) Following this failure, in 1908 a report on the estate was commissioned from the surveyors Alfred Savill & Sons, which drew a picture of a declining neighbourhood, from which much trade had departed in recent years and where the class of tenant had deteriorated. Tenants lived 'from hand to mouth' and all took in lodgers. Many houses, worn out and continually in need of repair, were let on short leases or stood empty. There had been some improvement to the south, where houses in Goswell Road had been replaced with warehouses, but this was unlikely to spread northwards for the foreseeable future and demand for vacant land hereabouts was 'extremely limited'. (fn. 14) Much of the area remained run-down in appearance as late as the 1970s.

A consequence of this long-term blight was that industry and commerce did much less here to destroy the old pattern of building than, for instance, on the Charterhouse estate north of Clerkenwell Road, where small houses increasingly gave way to factories and warehouses from the 1860s. In 1923 an industrial building was erected at Nos 281–283 Goswell Road, (fn. 15) and the 1930s finally saw the corner site in St John Street offered for building in 1904 redeveloped, with a factory. The largest commercial development here, however, was a late one: the Alice Owen Technology Centre in Goswell Road, of 1981–2, industrial units which replaced old shops. With this and subsequent (all non-industrial) developments, the west side of Goswell Road north of Rawstorne Street has changed out of all recognition.

Half the south side of Rawstorne Street is now occupied by tenements built by the Brewers' Company in the 1870s and 80s. Further blocks, now demolished, were built elsewhere on the estate about 1885: Hermitage Buildings, in what is now Friend Street, and Rawstorne Buildings, on either side of Rawstorne Place. (fn. 16) Dame Alice Owen's Girls' School was rebuilt in the 1960s following war damage, the reconstruction effectively destroying Owen's Row as a street. Among recent new buildings the largest is the City and Islington College sixth-form centre in Goswell Road.

Block dwellings and other later buildings notwithstanding, a good deal of the old housing survives now rehabilitated, having been acquired by the London Borough of Islington in 1974, following the departure of Dame Alice Owen's School to Potters Bar.

Development of the Brewers' estate

Gwynne's Buildings

In 1765 a row of fifteen houses was built facing Goswell Road at the north end of the Brewers' estate, on what had been gardens and a bowling green belonging to the Crown and Woolpack in St John Street. This was Gwynne's Buildings, the work of a consortium of builders led by Edward Gwynne, painter and glazier of Covent Garden. (fn. 17) Gwynne, who himself had an underlease from the lessee of the Crown and Woolpack, William Howard, a mason, granted leases of individual houses to the others. These included a bricklayer, John Hatred of St Giles-in-theFields, the rest being carpenters, a stonemason and a plumber. (fn. 18)

The houses, on 17 ft frontages, had small gardens front and back. The original lease having expired, in 1827 the row was let by the Brewers' Company to William Elliott, who proceeded to build shops over the front gardens, going bankrupt the following year. One front garden remained in 1832 (Ill. 471). (fn. 19) Latterly numbered 317–345 Goswell Road, most of Gwynne's Buildings survived until the 1990s (Ill. 470). The site is now occupied by Angel Southside (see below).

470. Nos 331–345 Goswell Road in 1993. Houses of 1765 (formerly Gwynne's Buildings), with later shop additions. Demolished

471. Brewers' Company estate in 1832

Development by Thomas Rawstorne and others, 1771–1817

The first suggestion that the Brewers' field might be built over was made in 1769, when Thomas Spencer, probably the proprietor of a 'breakfasting hut' at Spa Green near Sadler's Wells, applied for a building lease, offering a rent of £50 a year. (fn. 20) He was no doubt aware that the New River Company's lease of the ground was coming to an end, and perhaps that the company would not be seeking another term. Digging was carried out in 1771 to find whether the land would yield brick-earth, and later in the year some six acres, described as 'Hermitage or Fern Fields', was advertised for letting on a building lease. (fn. 21) As well as new proposals from Spencer, an offer was made by Thomas Rawstorne, an ironmonger of St Martin-in-the-Fields recently involved in a development at Brompton, (fn. 22) to lay out £10,000 in building at least thirty houses within twelve years. This proposal was taken up. An offer to stand security for him from Henry Holland, proprietor of the Islington Spa near Sadler's Wells, was made but then withdrawn. Instead, Rawstorne got the backing of William Usher, a Leadenhall Market poulterer, and Joseph Pocock, a Chiswick brickmaker.

Rawstorne's building agreement with the Brewers' Company, made in September 1773, allowed for no peppercorn term, but required payment of 'field' rent at £30 a year for seven years, after which the 99-year buildinglease term would start and a ground rent of £120 would become payable. The seven years were later made eight, in view of a legal delay that had occurred. In addition, Rawstorne agreed to pay £650 for the estimated five acres of brick-earth on the site. Of this £130 was paid up-front, but subsequently Rawstorne was late in making payments, both for brick-earth and rent, and more than once had to be threatened with an injunction, or a stay on the brick clamps, before he paid.

It was not intended that the whole of the ground taken by Rawstorne would be built up, the agreement providing for all or most of the backland between the main roads to be left open and let to Rawstorne at a field rent of £16. This was to change. Initially, the development was concentrated in St John Street and alongside the New River, where Owen's Row was built and Rawstorne ran into some trouble with the Brewers' Company for skimping on the construction of the basement walls. In financial difficulties by 1777, he became bankrupt in 1781, and development came to a halt for some years, apart from the building of a school and almshouse by the Society of Friends. Rawstorne resumed building in 1789, now usually describing himself as a builder or brickmaker rather than an ironmonger. Between then and 1792 building continued south along St John Street, and down a new street crossing the south end of the estate, named after the builder himself.

Money for the development was raised on mortgage from Bysshe Shelley, grandfather of the poet. (fn. 23) John Leader, Esq., of Tottenham Street, Tottenham Court Road, was also involved financially, and some of the houses were built in his name or leased to him by Rawstorne's direction. He also paid for some specific work, notably the filling-in of pits dug for brick-earth. Particular craftsmen engaged in the building work who took leases themselves were Thomas Chandler of Clerkenwell, carpenter, William Collins, bricklayer, of Hermes Street in Pentonville, and Job Hoare, carpenter, of Great Castle Street, St Marylebone.

South of Gwynne's Buildings, development along Goswell Road proceeded slowly. The frontage here was 'not so desirable for speculation' as that on St John Street, the ground having been heavily dug for brick-earth and so requiring a considerable outlay on foundations. In 1791 the Brewers granted a building lease to Leader, stipulating that the houses here should have elevations 'as in Gwynnes Buildings'. Ten years later Leader requested an extension period, blaming the 'very high price of building materials' for his delay in covering the ground. (fn. 24) It is likely that the actual building, completed by 1810, was carried out for him in whole or part by Rawstorne. The new houses were in two terraces, Alfred Place at the south, with deep plots backing on to the Quakers' grounds, and Owen's Place to the north, in part backing on to the cotton factory off Owen's Row (Ill. 471).

In St John Street development picked up again as the last of the Goswell Road houses were being completed. North of the Clown public house, a few old tenements including a brewhouse were pulled down in 1804–5, leaving vacant the frontage as far as the Crown and Woolpack. This was after Rawstorne's death. A proposal by W. C. Mylne of the New River Company to build here was turned down, and in 1810 an agreement was entered into with John Eades for building houses on the site on 61-year leases. Working to plans prepared by the Brewers' surveyor Samuel Page, Eades rebuilt the Clown and built one house to the north in 1810–11, and the rest of the row, which was called Hermitage Place, was completed over the next six years. Most of this row survives (Nos 372–390 St John Street, Ill. 482). Eades was to have gone on to build houses along the north bank of the New River, but died before he could do so and it remained undeveloped.

The Quaker school and its redevelopment

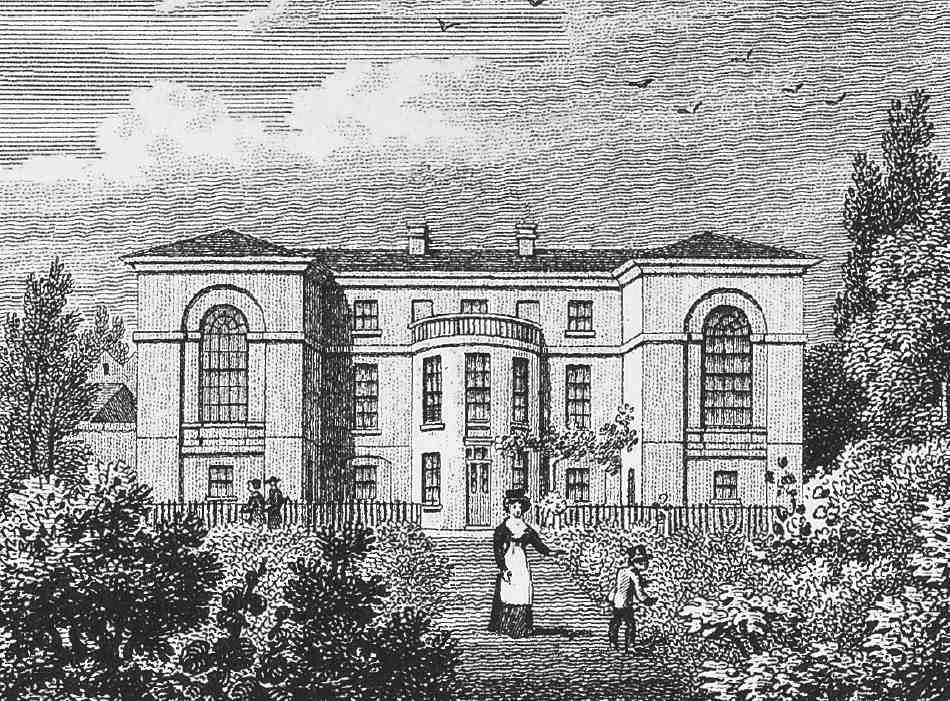

472. Quaker School, south front, c. 1828.

In 1783, two years after Rawstorne had become bankrupt, the undeveloped ground behind St John Street and Goswell Road came to the attention of members of the Society of Friends as a possible site for a school and almshouse (or 'workhouse') to replace their old buildings in Corporation Row (see page 54). A deal was eventually struck for the lease of a 1½-acre plot for two consecutive terms totalling 148 years, the first 84½ years at a rent of £16, and the remainder at £50. (fn. 25) This site was part of the ground which was to have remained undeveloped; the rest was now given over to building as well and it was presumably at this time that the line of what was to become Rawstorne Street was set out, the Quaker school grounds occupying a large portion of the frontage on its north side.

473. Extract from Thomas Hornor's manuscript survey of Clerkenwell, c. 1808, showing the Quaker School and workhouse site. The large building labelled Friends Workhouse is actually the Quaker or Friends' School; the workhouse or almshouse is the smaller building to the north

The new school, built at a cost of £5,500, was to all external appearance a large country or suburban villa. Facing south over semi-formal gardens, it was screened by a brick wall and trees running along the perimeter of the site (Ills 472, 473). It was almost certainly the work of the Quaker carpenter and architect John Bevans, who designed a number of meeting-houses and a Quaker-run lunatic asylum in York, the Retreat, completed in 1796. Bevans was closely involved in the negotations for the site from the Brewers' Company, and acted as a trustee for the Friends in the lease. (fn. 26)

Children from the old 'workhouse' were brought to the school in December 1786. The 'Ancient Friends' went to Plaistow, but in 1792 they were brought back to Clerkenwell, to a new building for 24 inmates just to the north of the school. This arrangement continued until 1823, when accommodation for the almspeople was found elsewhere, and a rural site for a new school was sought. In November 1825 the school transferred to a large house and grounds in Croydon.

Meanwhile, the Society of Friends applied to the Brewers' Company for permission to pull down the school and almshouse and let the ground on building leases. (fn. 27) The exact planning of this development was no doubt the subject of negotation between the Friends' surveyor, William Jupp the younger, and W. F. Pocock, surveyor to the Brewers' Company, who signed the specifications and elevations for the houses in July 1826. Though it was entirely the Friends' development, the street names were chosen in honour of the company. Buxton Street appears to have commemorated a member of the Quaker brewing family who had been Master of the Brewers' Company.

Building work was apparently in progress in 1827 'on the east side', presumably meaning in Brewer (now Paget) Street. (fn. 28) In the same year permission was given for the erection of a chapel instead of three houses, duly erected the following year, in Rawstorne Street.

Several 70-year building leases were granted by the Friends in April 1829 and June 1830, but by 1832 it was clear that something—very likely connected with the building slump of the late 1820s—had gone wrong with the development. Legal action for forfeiture of the lease was threatened, many of the new houses having been 'left in an unfinished state and allowed to fall into a state of dilapidation'. (fn. 29) Other houses had been sufficiently complete for them to be inhabited in 1831–2, though a number of the original occupants seem to have departed quite quickly. (fn. 30) The matter was not settled until about 1835, the Friends undertaking to pay compensation and to repair the houses forthwith; this work seems to have been carried out by Edward Robert Butler, who had an interest in properties on the estate as a mortgagee.

Redeveloped, the Quaker ground comprised three new streets: Brewer Street, Brewer Street North and Buxton Street, now Paget, Friend and Hermit Streets; the present names were assigned by the London County Council in 1936–7. Brewer Street North was an extension of the former entrance road to the Quaker school from Goswell Road; as Friend Street today it includes at the west end a former court off St John Street. Almost the whole was built up with small terrace-houses of three floors over basements, two rooms deep with side-passage entrances.

Apart from the building of the chapel, the only significant departure from the original plan was in the design of the houses on the west side of Buxton Street, where the plots were too shallow for two-room deep terrace-houses with back yards. Instead, there were to have been three pairs of semi-detached houses on this strip, with a doublefronted house at the south end fronting Rawstorne Street. These houses would have taken up the full depth of the plots and had yards or gardens at the side. In the event, the more conventional solution of a terrace of one-room deep houses, double-fronted with central entrances, was adopted.

In Brewer Street North, at the north-west corner of the ground, was the John Bull public house, now demolished, a wide-fronted house with two semi-circular bays at the rear (Ill. 471).

Individual streets and buildings

Dame Alice Owen's School and Almshouses

Nothing remains of the original almshouses or (apart from the gate piers) their successors, which were pulled down in 1879 when a system of out-pensions replaced residential accommodation. The school began as a very small affair, but expanded greatly in the nineteenth century in response to the growth of Clerkenwell and Islington. (fn. 31) The original building was replaced in 1840, and its successor underwent several enlargements during the rest of the century. A new girls' school, built in the 1880s, was destroyed in the Second World War and rebuilt. The site was given up in the 1970s and the former boys' school later demolished. All that remains of the school buildings today are the former girls' school, the rear wing of an ancillary building of 1904, and part of a plain stock-brick range dating from between the wars, now occupied by the Islington and Finsbury Youth Club.

On her death in 1613, Dame Alice was interred in the parish church at Islington, where a monument was erected with sculptured figures of herself and her children and grandchildren. With the rebuilding of the church in the early 1750s the damaged or decayed monument was replaced with a more modest one by the Brewers' Company. Some of the child figures, however, were saved by the schoolmaster and set up in a niche in front of the schoolroom. They were transferred to the new schoolhouse built in 1840, and eventually put on show in the new wing built in the 1890s, near a new statue of Dame Alice herself (see below).

Among the many notable former pupils of the school are: Joss Ackland, actor; William Alfred and Gilbert Foyle, booksellers; Dame Beryl Grey, ballerina; Andrew Rothstein, Marxist historian; Jessica Tandy, actress, and the members of the pop group Spandau Ballet.

474. Dame Alice Owen's School (right) and Almshouses in 1840

The original buildings

The almshouses of 1609 stood towards the top end of St John Street to the south of the Old Red Lion, set back from the road behind a shallow forecourt, enclosed in 1788 by a wall and gate with steps down, this part of the road being raised above the general ground level. Built of 'rough stone', (fn. 32) with mullioned windows, they were arranged as mirrored pairs in a single row, each house comprising one room, a closet at the back and a garden (Ill. 471).

The schoolhouse was built at the south end of the almshouses some time between 1610 and 1612, probably opening in 1613. It contained rooms upstairs for the master's residence, the ground floor comprising a single schoolroom fifty feet by twenty, where free instruction was provided for 30 boys. Of these just six came from Clerkenwell, and the rest from Islington—an indication of the relative populousness of the two parishes at that time; fee-paying pupils were also accepted. The building was extended in the 1640s, when the original small porch was enlarged as an entrance hall and a room built over it for the master's use. Latterly this acquired a brick frontispiece with a sweeping flat-topped gable (Ill. 474).

Rebuilding by George Tattersall, 1839–40

475. Dame Alice Owen's School as rebuilt by George Tattersall, architect, 1839–40

With the growth of Clerkenwell and Islington the question of expanding the school was raised, but this had to wait until a ruling by Chancery as to whether revenues intended for the almshouses (deriving from the now very lucrative Clerkenwell property) might be diverted to the school (whose endowment property in Essex provided meagre returns). A site for a larger building for both the school and the almshouses was chosen in 1825—ground at the back of the Crown and Woolpack, where the lease was shortly to expire. From 1826 W. F. Pocock, surveyor to the Brewers' Company, drew up a number of schemes for the buildings, which were to front the New River. In 1830 Chancery ruled that 40 per cent of the combined trust income should go to the school instead of just that from the Essex property. A 'final' scheme was prepared by Pocock in 1838, for a school to accommodate between 100 and 120 boys, with a master's house of six rooms, to cost between £1,200 and £1,400. His own estimate, however, far exceeded these limits, at £2,000, and when tenders were invited they came in far in excess even of that and he was dismissed.

In his place the company appointed Murray, Tattersall & Murray, and it was George Tattersall who designed the new school. William Cubitt won the contract with a tender price a little under £2,000. Work began the same year and the school was ready by the summer of 1840. The building, conventionally for a charitable institution, was in the Elizabethan style, executed in red brick with stone copings and mullions (Ill. 475). Tattersall also designed new almshouses in the same style. Work on these began in 1840, Cubitt again being the contractor. All that remains of them are the ogee-topped stone gate-piers originally in Owen Street, which were moved to Goswell Road in 1963 and now mark the entrance there to the City and Islington College sixth-form centre.

Enlargement of the school

Following the Schools Enquiry Commission in 1864–8 and the subsequent Endowed Schools Acts of 1869–74, Dame Alice Owen's School was compelled to reform. As regards the development of the properties on the Brewers' estate, the chief results of this process were the abolition and demolition of the almshouses, the enlargement of the existing school building and the building of a girls' school. From a small charitable institution for young children, the school was to be transformed into a large, fee-paying high school, with 300 boys and 300 girls.

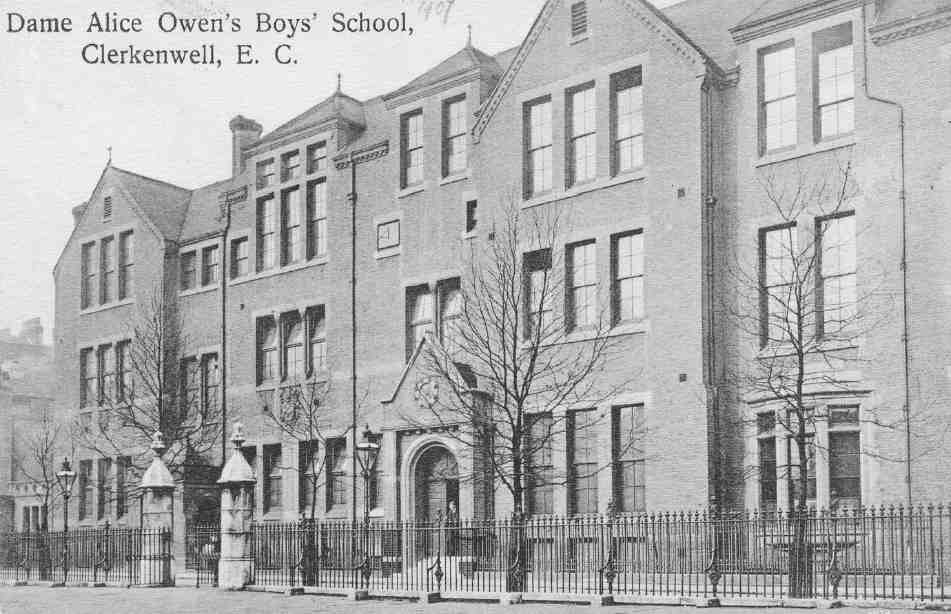

This took some years. With the demolition of the almshouses in 1879, the site was laid out as a playground, and two 'sheds' erected, one a basic shelter and the other fitted up as a gymnasium and fives court. In 1886 the girls' school was built, on the site of Nos 14–16 Owen's Row. It was designed by E. H. Martineau, surveyor to the Brewers' Company (Ill. 476). The boy's school, meanwhile, which had been extended with new classrooms built on at the rear in 1846 and 1860, was considerably altered in 1879–81, when the front portion was rebuilt on a much larger scale. This too was probably the work of Martineau (Ill. 477). In 1895–6 it was again enlarged, by the addition of a gabled east wing at an angle to the main block. The new wing contained a library, fitted up in oak, and on the first floor an art room and science laboratories.

476. Dame Alice Owen's Girls' School, Owen's Row, in early 1900s. E. H. Martineau, architect, 1886. Demolished

477. Dame Alice Owen's Boys' School, Owen Street, main front in 1907. E. H. Martineau, architect, 1879–81. In the foreground are the gate piers, now in Goswell Road, of the demolished almshouses of 1840. Demolished

Funds were raised for a memorial to Alice Owen, which resulted in the commissioning of a statue from George Frampton. Unveiled in 1897 (having been exhibited at the Royal Academy that year), this was installed in the oakpanelled entrance hall to the boys' school (Ill. 478), and is now displayed in Dame Alice Owen's School in Potters Bar, along with the figures from Alice Owen's original monument in St Mary's, Islington. It is a life-size figure in bronze, with a marble head and ruff and hands of alabaster; the inscription on the plinth replicates part of that on the original church memorial.

478. Dame Alice Owen's Boys' School, entrance hall in 1898, with George Frampton's statue of Dame Alice. At the back are weepers from her funerary monument in St Mary's Church, Islington, and decorations in the form of pomegranate trees, the device of her paternal family (Wilkes). Demolished

Enlargement of the school continued with the erection in 1904 of a building at what became No. 392 St John Street, on the corner of Owen Street, comprising a luncheon room and, then or later, rooms for art, woodwork and metalwork. It was demolished for redevelopment about 2002, apart from the rear wing. In 1927 the final important alteration to the boys' school was made, when an assembly hall was perched over the succession of classrooms projecting from the rear of the main range. On each side the hall slightly oversailed the line of this wing, and while on one side a 'cloister' walk was thus created, on the other the entire wall was rebuilt eighteen inches further out.

During the Second World War the schools were evacuated. The girls' school was almost entirely destroyed by bombing in 1940; when the pupils returned in 1945, temporary huts were put up and other makeshift accommodation was obtained near by. Shortly after the war, the junior department was closed and the school became a Voluntary Aided Grammar School. A new school building to replace the bombed one was completed in 1963. But with the restrictions of the site, and the decline in the number of pupils in inner London, it became necessary to relocate. In 1973 the girls' and boys' departments were merged, moving to Potters Bar by stages between then and 1976. The post-war school building now forms part of City and Islington College.

The post-war building

Plans for a new girls' school and science block were prepared in 1955, undergoing several revisions before work began in May 1960. The project involved the destruction of some of the remaining houses in Owen's Row: Nos 11–13 had gone already by 1946, and 6–10 were pulled down about 1959.

Designed by H. A. J. Darlow, of Daniel Watney, Eiloart, Inman & Nunn, the new building was officially opened on 29 October 1963. (fn. 33) Comprising five storeys over a basement, it is constructed of reinforced concrete, with glass curtain walling (Ill. 479). In its original use, the basement contained changing-rooms and music rooms, the ground floor an assembly hall, cloakroom and dining-rooms, the first floor staff, art and craft rooms, and the second a library, classrooms and laboratories. The other floors were taken up by more laboratories and classrooms.

The main stairs were ornamented in 1962 by a mural of broken-tile mosaic, designed by Antony Hollaway, depicting the story of the school as the 'Tree of Knowledge'. In 1966 a sculpture of a winged figure, representing freedom through education, was placed on the north external wall. This was designed and executed by John McCarthy.

479. Former Dame Alice Owen Girls' School and Science Block (now City & Islington College, Centre for Applied Sciences), in 2004

Some time after the removal of the school to Potters Bar, the building was taken by the City University for its optics department, which it remained until c. 2001, since when it has become the Applied Sciences centre of City and Islington College, whose new sixth-form centre is adjacent in Goswell Road (see below). Major alterations were undertaken to update the building about 2003–4 to the designs of Gollifer Langston, architects. (fn. 34)

Owen's Fields, the small public garden occupying the site of the former school playground, was formally opened in 1997. (fn. 35)

St John Street

Nos 296–300. This was built in 1935–6 as a factory for Hodges & Co., surgical-instrument makers, to designs by F. E. Tudor, architect to the Brewers' Company. (fn. 36)

Nos 302–308, St John's Mansions. Originally comprising eighteen self-contained flats, this block was built in 1906–7 by George Edward Chamberlain, a Finsbury contractor, as his own development. His architect was Arthur Kent. The external stair-tower, replacing the original internal stairs, dates from its refurbishment in 1989 for single homeless people under a community housing scheme. (fn. 37)

Nos 310–326. The houses here date from the second phase of Thomas Rawstorne's involvement with the Brewers' Company estate, following his bankruptcy (Ill. 480). Rawstorne himself seems to have been the builder, working for or in association with John Leader. The row was built from north to south in two phases during 1789–92, together with four houses on the site of St John's Mansions, and another on the south corner of Rawstorne Street. Leader claimed to have spent upwards of £1,000 on the five houses at Nos 318–326 in 1789; Nos 310–316 seem to have followed in 1792, after a hiatus accounted for by Leader's time spent filling up ponds elsewhere on the estate where brick-earth had been dug out. (fn. 38) Nos 316–324 now have shops on the ground floor, while at No. 322 a modestly pretty fanlight survives. Most of the houses have Victorian cast-iron balcony railings on the first-floor windows.

480. Nos 310–336 St John Street (right to left) in 1978

No. 326 is larger than the other houses, occupying a broader plot, at the bend in the road, and being built on a raised basement. The plot originally extended back into Rawstorne Place, where workshops or other outbuildings were built in a yard (see The Barn, below), possibly in 1801–2 when the ratable value of the property was raised substantially. The first occupant was Francis Gillyatt, a man of unknown occupation who had previously occupied premises at the north end of St John Street towards the Angel. He remained at No. 326 until 1803 or 1804. (fn. 39)

Nos 328–338 (Ill. 480). No. 328 was built by Thomas Rawstorne in 1780, probably with No. 330. (fn. 40) Rawstorne had completed Nos 332–338, and four houses to the north now demolished, in 1775, when he leased them to a Clerkenwell paper-maker, John Taylor. (fn. 41) The original doorcases were probably all similar to those in Owen's Row; two such survived at Nos 344 and 346 until these houses were demolished in the 1960s (Ill. 481).

Nos 346–354. These plain brick flats and maisonettes were built for the Dame Alice Owen Foundation by McLaughlin & Harvey to the designs of Daniel Watney, Eiloart, Inman & Nunn in 1981–3. They consist of two small blocks linked to others behind in Friend Street: Nos 346–348 with Nos 2–4 Friend Street, and on the opposite corner, Nos 350–354 with Nos 1A–5 Friend Street. (fn. 42)

481. Nos 340–348 St John Street in 1946. All demolished

No. 360 (see Ill. 270 on page 211). This was originally two houses, No. 1 Owen's Row, built by Thomas Rawstorne about 1774, and the adjoining house fronting St John Street, built by Thomas Chandler, carpenter, about the same time. (fn. 43) No. 1 Owen's Row, a somewhat larger house than the others, became the Empress of Russia public house, taking this name from the public house on the opposite side of the New River, which had become the Clown of the Wells. At some point the adjoining house was annexed. The fronts were evidently faced with stucco in the mid-nineteenth century, possibly in 1871 when a short 'building lease' was granted to Whitbreads, and another floor added. (fn. 44) By 1913 the whole first floor had been opened up as a club-room. (fn. 45) The building ceased to be a public house in the 1990s and is now a fashionable fish restaurant, with flats above.

482. Nos 372–390 St John Street, formerly Hermitage Place, in 2007

No. 370 (see Ill. 268 on page 211). The former New Clown public house, this was rebuilt for Whitbreads in 1900. (fn. 46) It is a spirited composition in a red-brick, Queen Anne style, with a crowning shaped gable and sharp broken pediments over the end entrances, which also include branches of bay in relief and iron guards. Taken over after the Second World War as classrooms by Dame Alice Owen's School, it was refitted in the 1990s as a gastro-pub, the Café Med (now Mediterranean Kitchen).

Nos 372–390 (Ill. 482). This row of four-storey houses was built by John Eades between 1811 and 1817 as Hermitage Place (see above).

No. 394. The former Crown and Woolpack public house, this was rebuilt in 1827 for the publican, John Kemp, to a plan and elevation prepared by the Brewers' Company surveyor, W. F. Pocock (Ill. 483). It was in its original form probably as plain as the adjoining house and shop, No. 396, of 1831, built under the same building agreement and again to Pocock's drawing. (fn. 47) The Italianate compo decorations were possibly applied among 'sundry alterations' made in 1865. (fn. 48) A room here was reputedly used by Lenin and fellow revolutionaries in the early 1900s. (fn. 49)

483. Nos 394–416 St John Street in 2007

Nos 398–416 were built on the site of Alice Owen's almshouses and school, demolished in 1840–1 after a new school had been erected facing Owen Street (Ill. 483). The old school was taken down first, and two houses (Nos 398 and 400) built on the site in 1840 by Thomas Matthews; they are very plain four-storey houses, with camberarched windows. (fn. 50) The almshouse site was let to William Griffiths, builder and surveyor of Edgware Road, who was to have built seven houses. These he completed in 1842, leaving enough room to squeeze in another adjoining the Old Red Lion the following year. No. 404 was leased to Griffiths in 1842, the remainder to him or his nominee William Henry Boulton, artificial florist, in 1845. (fn. 51) The design was probably Griffiths' own, his building agreement only requiring that plans and elevations be approved by the Brewers' new surveyor, George Tattersall. (fn. 52)

Nos 402–416 have the stuccoed window surrounds of the 1840s and probably originally all had stuccoed ground floors as well. The whole run of houses from No. 394 to No. 416 were refurbished c. 2005 as St John's Row by Grove Manor Homes (Groveworld Ltd), the architects being Andrews Sherlock & Partners. The development comprises shops and apartments, with one complete house. No. 392 was rebuilt as part of the same redevelopment, becoming No. 6 Owen Street (see below). (fn. 53)

No. 418, Old Red Lion. The Old Red Lion is said to date back to 1415, and surviving deeds show that there was a building on the site certainly since 1596. The name Red Lion appears to have been in use in the 1630s, but about a century later the inn was known as the Welsh Harp, the former name returning to use later in the eighteenth century and subsequently acquiring the prefix 'Old'. (fn. 54) Hogarth's 'Evening', depicting the Sir Hugh Myddelton inn and Sadler's Wells, shows an inn in the distance which may be the Red Lion. This 'small old brick house', as it was described early in the nineteenth century, had by 1840 been re-fronted or remodelled so as to present 'an elegant façade, in the Elizabethan style of architecture', which bore the legend 'established 1415'. (fn. 55)

484. Old Red Lion, No. 418 St John Street in 2007

Among a number of literary and other associations, the most significant concerns Tom Paine, who is said to have lodged at the Old Red Lion and may have written at least part of The Rights of Man there. (fn. 56)

The present building, by the architects Eedle & Myers for the publicans, Charles Dickerson and John North, dates from 1898–1900 (Ills 269 and 486). It was built by Charles Dearing & Son of Islington. (fn. 57) The building has a coarse but vigorous front, with three red lions at first-floor level holding shields. Although altered internally, it retains some of its original mahogany and cut-glass 'snob' screens, which divided the public bar from the saloon (Ill. 484). On the first floor, the former billiard-room has been used as a theatre since 1979.

485. No. 420 St John Street, plan

486. Nos 418–424 St John Street (right to left) in 2007

Nos 420–422. These two houses appear to have been converted from the middle one of three wide-fronted houses, the southernmost of which was the Old Red Lion, shown on Horwood's map of 1792–3 and more precisely on Thomas Hornor's survey of 1808. The original date of building is uncertain, probably not later than the early eighteenth century, and both houses have been refronted and extensively altered (Ills 485, 486). (fn. 58)

No. 424, in 'Ruskinian' Italianate style, was built after the construction of the adjoining Bank Buildings in the early 1880s (the flank of which carries the outline of the roof of the earlier house on the site)—probably about 1884, when the freehold changed hands (Ill. 486). (fn. 59)

Nos 426–428 St John Street (part of Bank Buildings) are described with Nos 355–363 Goswell Road below.

Goswell Road (west side)

No. 249. Built in 1885, shortly after the completion of the adjoining model dwellings in Rawstorne Street, this is a plain stock-brick house and shop, enlivened with red-brick banding and a date-stone with the pomegranate-tree badge of Alice Owen's paternal family.

Alice Owen Technology Centre (Ill. 487). A development replacing the old houses and shops at Nos 251–279, this complex of light industrial units was planned by the Brewers' Company by agreement with Islington Borough Council in 1977–8 and carried out in 1981–2. The surveyor-architects were Daniel Watney, Eiloart, Inman & Nunn, and the builders McLaughlin & Harvey. (fn. 60) The architecture is more formal than is usual for this type of development, with a long brick front broken into seven bays by piers, and with strips of windows at the ends and in the centre. A monopitch roof drops the levels from four storeys at the front to two facing the yard at the back.

487. Alice Owen Technology Centre, Goswell Road, in 2007. Daniel Watney, Eiloart, Inman & Nunn, architects, 1981–2

City and Islington College sixth-form centre (Nos 281–309). Seen to best advantage from the south-east (Ill. 488) this sleek block was designed in its essentials by van Heyningen & Haward, architects, and built under a design-and-build contract by Norwest Holst in 2002–3. It was officially opened in January 2004. The original brief for the commission, won in competition by van Heyningen & Haward in 1999 following the collapse of a hotel and residential scheme for the site by the architects Chassay & Last for the developers Groveworld, was for a full Further Education College, but this was later reduced to a sixthform centre. This called for a different treatment of the interior arrangements, with more emphasis on separate classrooms instead of publicly accessible open-plan spaces. Externally, glazed stair towers were provided instead of an open stair in an atrium at the front of the building, to give the more controlled access appropriate to a sixth-form college. (fn. 61)

The six-storey building has a concrete frame and fully glazed façades, the staircase towers at the ends being particularly open to view. The aim was to make the building a round-the-clock advertisement for the college, and encourage its integration into the local community. (fn. 62) For the adjacent science department of the college, see Dame Alice Owen's School, above.

488. City & Islington College sixth-form centre, Goswell Road, 2007; van Heyningen & Haward, architects, 2002–3

489. Angel Southside development. Looking east along Owen Street towards Goswell Road, 2007

Nos 323–345, Angel Southside (with Nos 1–5 Owen Street). These apartments and town-houses, with a fitness centre and swimming-pool, were built in 2001–2, replacing the houses and shops formerly called Gwynne's Buildings, and the former Dame Alice Owen's Boys' School. The Dame Alice Owen Foundation had intended to redevelop the sites itself, but their plans for offices were turned down in 1993. They were then sold to the property company Groveworld, on whose behalf Chassay & Last, architects, obtained permission for a housing scheme in 1999. When this came to be built, Chapman Taylor acted as 'implementation architects' on behalf of Groveworld. (fn. 63) As part of the development, Owen Street was extended northwards along the rear of the block as a service road, the west end of the street being cut off to through traffic. Character is given to the brick-clad block by a round, glass-walled penthouse on the Owen Street corner, and by gull-winged projections towards Goswell Road, clad in timber and copper.

490. No. 353 Goswell Road and (right) part of Bank Buildings (Nos 355–363 Goswell Road), 2007

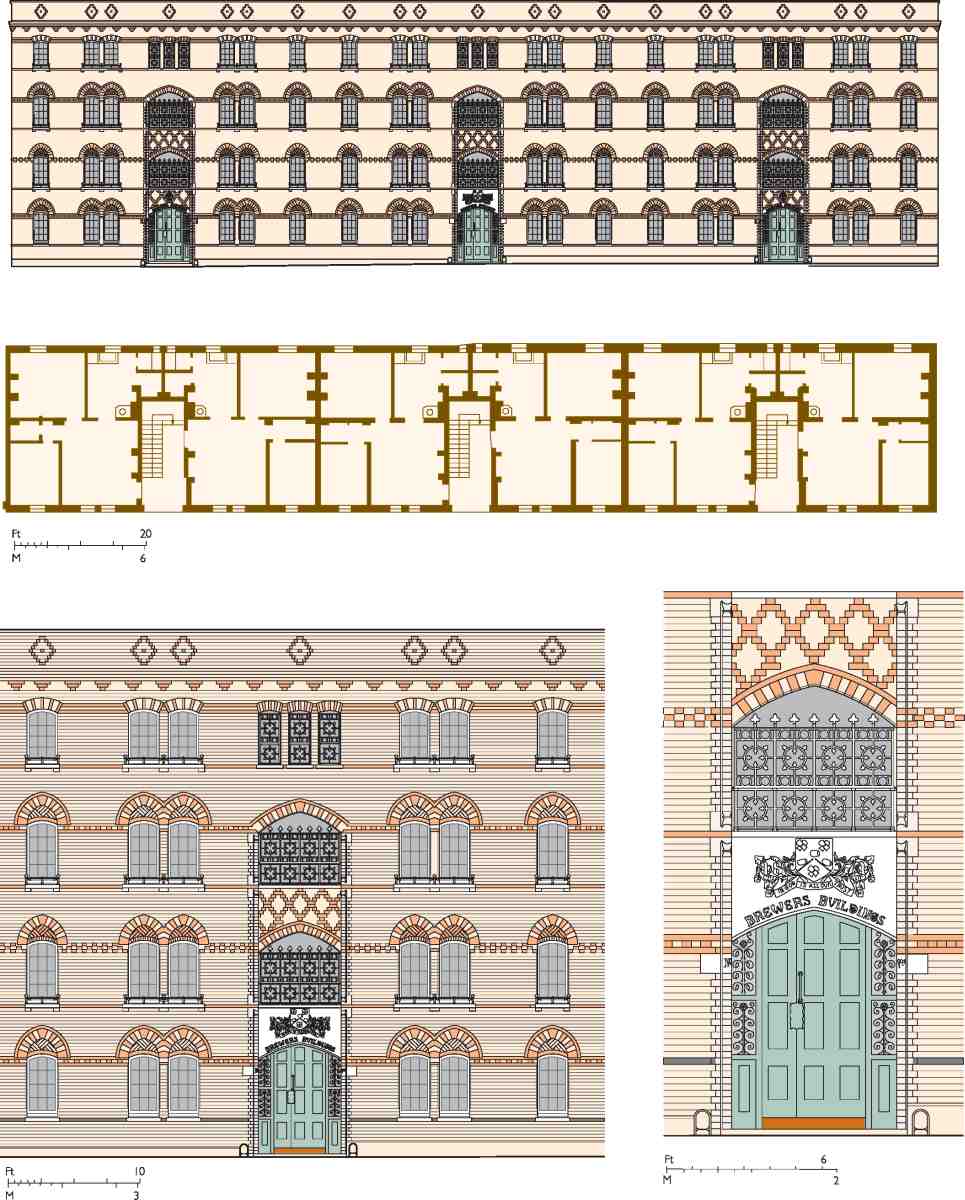

Nos 353–363 Goswell Road and 426–428 St John Street. Redevelopment of this site, at the junction of Goswell Road, City Road and St John Street, was carried out in 1880–1 following road-widening by the Metropolitan Board of Works. This improvement scheme had originated in 1872 with Clerkenwell Vestry, but it was several years before the MBW could be persuaded that it would be of London-wide and not merely local benefit, and so within its remit. The buildings on the corner were demolished, and the building line, irregular and jutting out into the junction, was set back to the present smooth curve. (fn. 64)

In January 1880 the builders Dove Brothers successfully tendered for developing the cleared ground on lease, and in March an elevation by the architects F. & H. Francis was approved. This design was probably drawn up not for Doves but for the actual developer, Michael MacSheehan, to whom Doves now wished to assign their building agreement. (fn. 65)

491. Bank Buildings, Nos 355–363 Goswell Road and 426–428 St John Street, in 2007

The new buildings were erected in 1880–1 by Merritt & Ashby and named Bank Buildings, the principal corner premises (Nos 361–363) having been taken as a branch of the National Bank; the remainder was let as shops with chambers above. (fn. 66) MacSheehan, to whom leases were granted by the MBW in September 1881, (fn. 67) was a developer and speculator in a fairly large way, and the National Bank were his own bankers. A house agent, chiefly involved with deals concerning houses in carcase, he was responsible for a number of substantial warehouse developments, including part of the MBW clearance land in Clerkenwell Road, where he had also employed Merritt & Ashby (see page 391). A referee described him then as 'a shrewd hard bargainer but perfectly fair dealing'. (fn. 68)

Though unadventurous in design, Bank Buildings are sufficiently imposing for the prominent site (Ill. 491), and the conventional Italianate front of yellow brick and stone or composition is lifted somewhat by the treatment of the ground floor, with a mixture of polished marbles and granite. A clashing note is sounded by the offices at the south-west end of the range, No. 355 Goswell Road, where the red Gothic front has clearly strayed in from the adjoining building, No. 353 (Ill. 490).

Not part of the MBW clearance site, No. 353 was rebuilt shortly after the improvement was completed, its frontage re-aligned to follow more elegantly the new building line to the north. The old shop on the site was sold in July 1882 to three associates, Thomas Boney, John Scott and William Sheppard Hoare, who rebuilt it in 1882–3 as offices for their business ventures—the New Imperial Permanent Benefit Building Society, the Freehold & Leasehold Investment Co. and the Cavendish Permanent Building Society. (fn. 69) The building is executed in red brick, red sandstone and polished red granite, with a shallow oriel masking the curve of the frontage. It was designed by the architects and surveyors R. L. Curtis & Son of Blomfield Street, City, and built by G. S. Williams & Son of Islington. (fn. 70)

The Gothic treatment and strong colour are in the idiom of Alfred Waterhouse's insurance and bank buildings, evidently one that the owners valued in their line of business. The various finance and investment companies took over the adjoining and hitherto unconnected shop at No. 355 about 1906, and it was presumably then that the Gothic front there was inserted, to carry on the 'corporate' style. (fn. 71)

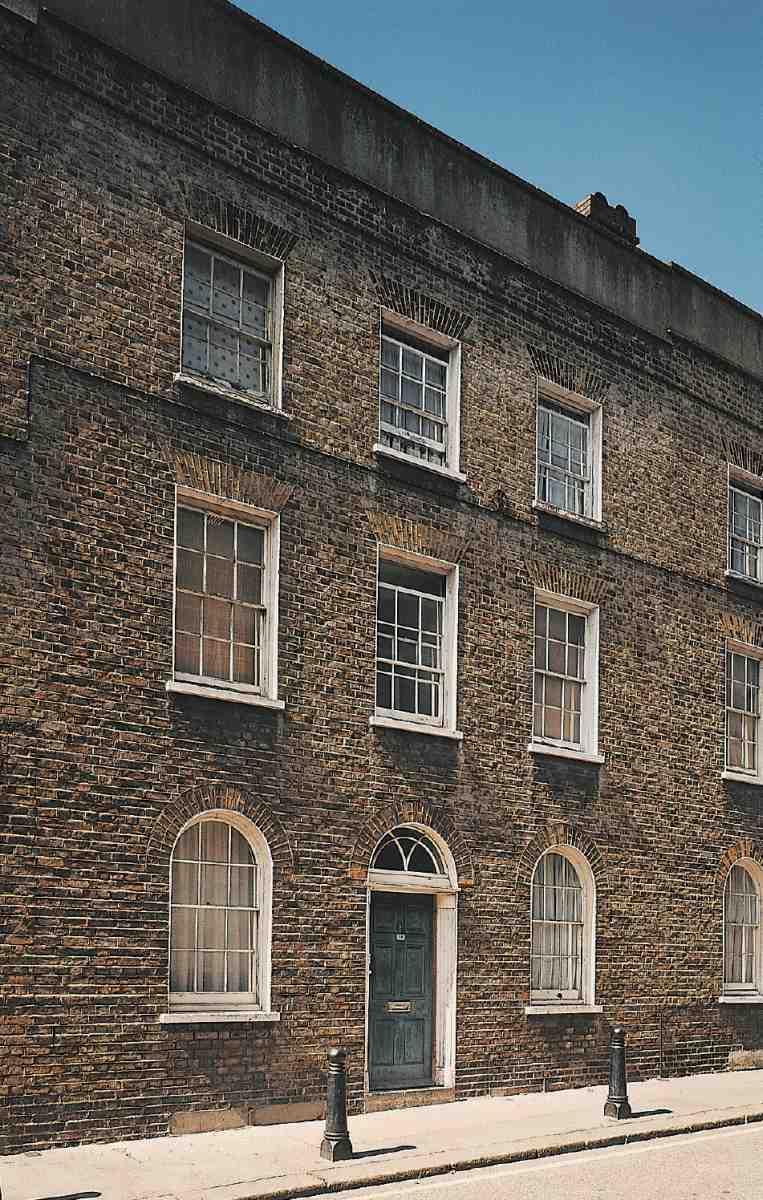

Rawstorne Street

At its western end, Rawstorne Street is a well-preserved remnant of lower-class eighteenth-century London, its tall but dour houses lacking the domestic grace conventionally associated with the Georgian era (Ill. 492). It was laid out in 1789 by Thomas Rawstorne, who built some fifty houses here, of which Nos 3–19 on the south side and Nos 51–61 on the north side survive, with some rebuilding. Flat-fronted and without basements, the houses confront the pavement unremittingly on both sides. The windows are well recessed within cambered heads. These were the best houses in the street: towards the east end, where the plots were shallower, the houses were smaller and meaner, and included a court of small tenements, called Bridge Place. These were all replaced in the late nineteenth century with the present model dwellings (Brewers Buildings), described below, along with other buildings in the street.

492. Rawstorne Street, looking east in 1978

Nos 41 and 42, either side of Paget Street, are two contextual blocks of brick flats, built c. 1978–9 for Islington Borough Council to designs by its Architectural Department, as part of a council initiative in the late 1970s to improve housing in the area (Ill. 493). (fn. 72)

493. No. 48 Rawstorne Street in 2007. No. 42 on right

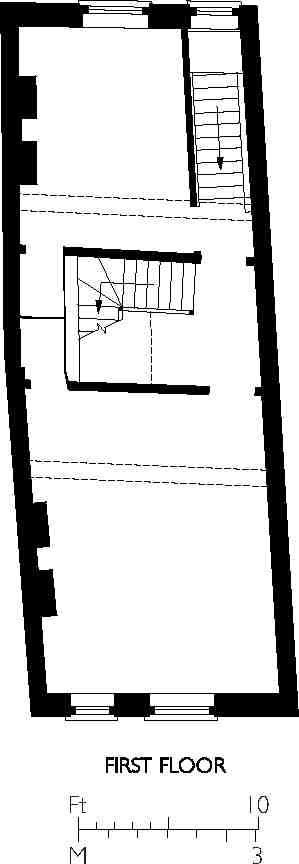

494. Nos 1–24 Brewers Buildings, Rawstorne Street. Elevation, plan and details. E. H. Martineau, architect, 1871–2

No. 48 was built in 1828 as a chapel, probably for the congregation of Calvinistic Methodists from Chadwell Street which had been meeting for some while past in the former Quaker school. It was closed and up for sale in 1837. From 1855 it was used as a National School, which it remained until c. 1890. The Salvation Army were here briefly at the turn of the century. The building has since been variously occupied, among other things as a printing works and a clothing factory, and has now been converted to offices (Ill. 493). (fn. 73)

495. Nos 25–34 (left) and 1–24 Brewers Buildings, Rawstorne Street, looking west in 2004

No. 53, the former King's Arms public house, was rebuilt in 1900 for Watney Combe Reid & Co. (fn. 74) The upper floors were converted to flats by Daniel Watney, Eiloart, Inman & Nunn in 1960. After some years of use as a classroom by Dame Alice Owen's Girls' School, the ground floor became offices. It was eventually taken over by Patel Taylor, architects, who in 2003 built a new office extension at the back facing Rawstorne Place. (fn. 75)

Brewers Buildings. With a number of the original leases shortly due to expire, thought was given to redevelopment, and early in 1871 the Brewers' Company decided to build a 'model lodging house' on the estate. E. H. Martineau, who had been the company's surveyor since 1868, drew up plans for such a building in Rawstorne Street. (fn. 76)

Before settling on the plans, members of the company visited a number of model dwellings, and the works of Henry Darbishire, such as Columbia Square, Bethnal Green (1859–62) and Peabody Buildings, Spitalfields (1864) seem to have influenced the design, if only in stylistic terms. (fn. 77) In general, earlier model dwellings were planned around courtyards, but the site here was too narrow for that. The street façade is beautifully executed in a brick Gothic style, mixing stocks with yellow and red dressings (Ills 494, 495). Numbers for the flats are picturesquely inscribed in the stonework on either side of the entrances. But internally, the flats were fairly cramped and under-lit.

Work on what was to be the first of three contiguous blocks was begun in the autumn of 1871 by the builders William Cubitt & Co., on their tender of £5,923 (subsequently reduced by £142 when Green Moor stone was substituted for Hopton Wood stone). (fn. 78) The block (Nos 1–24 Brewers Buildings) was finished in 1872. Each tenement on the four storeys comprised two bedrooms and a living-room and had its own WC, scullery with copper, cottage cooking-range, and larder. The building was flatroofed, providing a drying place for laundry. The correspondent of Clerkenwell News fancied this as 'a pleasant lounging retreat' and a place where 'the working man, if he be fond of astronomy' could 'contemplate the heavens, and at the same time enjoy his pipe'. (fn. 79) The second block (Nos 25–34) was built in 1876–7. This time the builder was Ebenezer Lawrance: the company had hoped to employ Cubitt again, but Lawrance won the contract through the competitive tendering insisted upon by the Charity Commissioners. (fn. 80) Finally, Nos 35–46 were constructed by B. E. Nightingale of Albert Embankment in 1882–3. (fn. 81)

Rawstorne Place

496. The Barn, No. 1 Rawstorne Place, in 1993

Rawstorne Place appears to have been built up with small houses, workshops and stables in the 1790s and early 1800s. (fn. 82) During part of the early nineteenth century a private theatre existed here, at which the actor Samuel Phelps, later the manager of Sadler's Wells, made his debut and performed regularly from the early 1820s until 1826. His friend the playwright Douglas Jerrold also took part. Surviving playbills printed for the theatre go up to at least 1832, and the theatre may have continued into the 1840s. (fn. 83)

No. 1, The Barn. This is a curiosity of uncertain origin, probably built about 1801–2 for Francis Gillyatt in connection with his house at No. 326 St John Street. (fn. 84) It was perhaps some sort of workshop (Gillyatt's outbuildings here included a brewhouse), or accommodation for horses or cows. While the upper floor or floors may have been used for storage of grain or hay, it is unlikely to have been a barn in conventional parlance, and it does not seem to predate the building of the houses around it in St John Street and Rawstorne Street. A brick and timber building of two and half storeys, with some timber framing and a slated mansard roof, it has been often and much altered for a succession of industrial or other uses. In its original form, it appears to have been open on the ground floor on the north side, with a row of timber posts, and was possibly largely or wholly of timber at that time; the roof was most likely tiled originally. (fn. 85) After years of dilapidation (Ill. 496) it was restored in 2001 by Bennetts Associates, architects, and incorporated into a small office complex for the practice.

Nos 5–11 comprise a simple brick terrace of two-storey houses built in 1980–1 for Islington Borough Council to designs by its Architectural Department, with A. King of Stoke Newington as builder. The open space opposite belongs with the scheme. (fn. 86)

Friend, Paget and Hermit Streets

Of the original houses here, built between 1827 and about 1832, many survive, although settlement and other structural failure led to much reconstruction from the late nineteenth century. Three storeys high over basements, the houses mostly have, in their original form, conventional two-room deep plans and plain stock-brick fronts, many with a plat band between ground and first floor (Ill. 497). Where complete rebuilding has taken place it has been on the same scale, if not necessarily in anything like the original style. Several houses have been re-fronted in whole or part, and in some instances where houses have been thrown together to make flats, front doors have been replaced with windows. These organic changes over many years have produced a pleasantly varied and informal effect.

497. Paget Street, looking south to Brewers Buildings in 1959

To some extent, the evolution of these streets is the result of the slightly unusual pattern of land-ownership and management here and the conscientious management of the head lessee. As described above, the streets were built up on 70-year leases from the Society of Friends, whose tenure was itself leasehold and gave the Society some 40-odd years' possession of the properties after the falling-in of the building leases. This led to a careful programme by the Friends of repair, rebuilding or remodelling so as to generate a good rental income and avoid costly reparations at the expiry of their lease. In this they were apparently successful, tenancies being much sought after, and this enclave appears to have escaped some of the blight that affected the Brewers' estate generally in the early twentieth century. Later in the century, the area has benefited from the equally enlightened management of the local housing authority.

At the south end of Paget Street, the old houses were replaced by the Society of Friends with tenement houses in the 1890s. Nos 24–27 were rebuilt as two such houses in 1897, and Nos 2–5 as two more in 1899–1900. (fn. 87) These were designed by the Friends' surveyors, Edward Saunders & Son. Built of red brick in contrast to the yellow-grey stocks of the original houses, they show the Queen Anne Revival style adapted effectively to a humble class of building (Ill. 498). At the north end, Nos 15–16 and 17–19 have been converted into two tenement houses and re-fronted if not more extensively rebuilt.

Hermit Street survives largely as built, with houses on the east side similar in plan to those in Paget Street. On the west side, the original one-room deep, double-fronted houses have been partly rebuilt and converted into two blocks of flats or tenements (now Nos 10 and 14, Ill. 499).

498. Nos 24–25 Paget Street in 2007

499. No. 14 Hermit Street in 2004

On the north side of Friend Street, a few of the old houses remain. No. 25 is a recent small block of flats, brick-clad and angular, with some of the currently fashionable planes of terracotta-tile panels. Replacing buildings formerly belonging to Dame Alice Owen's School, it was built in 2003–4 to the designs of the surveyor-architects Daniel Watney, with Bilfinger Berger UK Ltd as project managers. (fn. 88) On the south side, No. 10 has been extended and considerably rebuilt. At the west end on each side are flats and maisonettes built in the early 1980s (see Nos 346–354 St John Street above).

The present Nos 3, 3A and 3B Friend Street occupy the site of Finsbury Dispensary, and before that a cowshed and slaughterhouse. Seeking a building lease in 1869, the secretary of the dispensary suggested that it might benefit the Brewers' Company 'to get some sort of superior building' erected on the estate. (fn. 89) The Brewers had supported this charitable institution, founded in 1780 and previously based for a time in Woodbridge House, Woodbridge Street, for some years and gave £50 to the building fund. Costing over £2,500 to build, with nothing whatever 'laid out in useless decorations', the new building was of two storeys, tall, with a gabled corner entrance. (fn. 90) It was designed by a little-known architect, Reginald E. Worsley. (fn. 91) The dispensary was still operating in the 1930s, when King Leopold III of Belgium was its patron, visiting in November 1937. (fn. 92) The building, now demolished and replaced by housing, was used from 1950 by Dame Alice Owen's Girls' School.

500. Nos 3–5 Friend Street in 2007. Daniel Watney, Eiloart, Inman & Nunn, architects, 1981–3

Owen's Row

Only a stub remains of the original line of houses, laid out by Thomas Rawstorne about 1773 along the east bank of the New River between Goswell Road and St John Street (Ills 501, 502). Building began at the St John Street end, where four houses appear to have been completed by 1774 and eight the following year. These were all sublet by Rawstorne to the cabinet-maker William Gates, who supplied furniture to the royal family in the 1770s and 80s. (fn. 93) Gates' houses, numbered 1 to 8 from the west, were joined by two more in the early 1790s, No. 9 being occupied in 1793, No. 10 complete but unoccupied in 1794. Four more houses were built about 1800 and occupied by 1805, completing the terrace. North of No. 14, a factory had been built in 1791. It was originally described as a cotton manufactory, the first ratepayer there being John Hall, probably identifiable as a City cotton merchant of that name with premises in Lawrence Pountney Lane. (fn. 94) By 1804 it was a lace factory, in the ownership of Joseph Beardmore and William Dawson. Dawson was living at No. 14, the large garden of which allowed light into the west side of the long factory building (Ill. 471). (fn. 95) Owen's Court, a narrow street of 19 small houses off Goswell Road at the south end of the lace factory, seems to have been developed by Beardmore about 1805, perhaps for his workpeople. (fn. 96)

501. Nos 2–5 Owen's Row, looking west, in 2004

502. Nos 3–9 Owen's Row in 1946

Owen's Row only became a proper street with the conversion of the open New River running alongside into an enclosed watercourse in 1862, when railings were erected by Dame Alice Owen's School to mark the boundary of the school grounds opposite the houses. (fn. 97)

Of the original houses only Nos 1–5 survive, No. 1 as part of the former Empress of Russia public house, No. 360 St John Street (see above). The whole row appears to have been originally of three storeys over basements, with mansard attics, Nos 3–5 being raised much later to four full storeys. The present doorcases appear to have been heavily restored or entirely remade.

Past residents of Owen's Row include the Rev. John Villette, chaplain to Newgate Prison and author of the Annals of Newgate. He lived at No. 7 from 1789 until his death in the 1790s. (fn. 98)

Owen Street

Owen Street was formed to connect St John Street and Goswell Road in the 1820s on the expiry of the lease of the Crown and Woolpack and the ground behind, including Gwynne's Buildings. This was in preparation for the intended rebuilding of Dame Alice Owen's almshouses and school here, which was delayed until the late 1830s. (fn. 99)

Both sides of the street have again been redeveloped. The south side, with four large plane trees presumably planted soon after the demolition of the 1840 almshouses, runs alongside Owen's Fields (Ill. 489). No. 6 Owen Street, on the corner of St John Street, replaces No. 392 St John Street, a red-brick neo-Georgian building of 1904, erected for Dame Alice Owen's School principally as a luncheon room. Comprising 'live/work units' and flats, the new building was designed to match the former Crown and Woolpack on the opposite corner of Owen's Row. It was completed in 2007 as part of the St John's Row development (Nos 394–416 St John Street) by the developers Groveworld. The architects were Andrews Sherlock & Partners. At the rear, an annexe to the 1904 building was retained and converted to flats as part of the development, becoming No. 7 Owen Street. (fn. 100) For Nos 1–5 on the north side, see Angel Southside, Goswell Road (above).