A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Keinton Mandeville', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10, ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp142-161 [accessed 23 February 2025].

'Keinton Mandeville', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Edited by Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online, accessed February 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp142-161.

"Keinton Mandeville". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online. Web. 23 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp142-161.

In this section

KEINTON MANDEVILLE

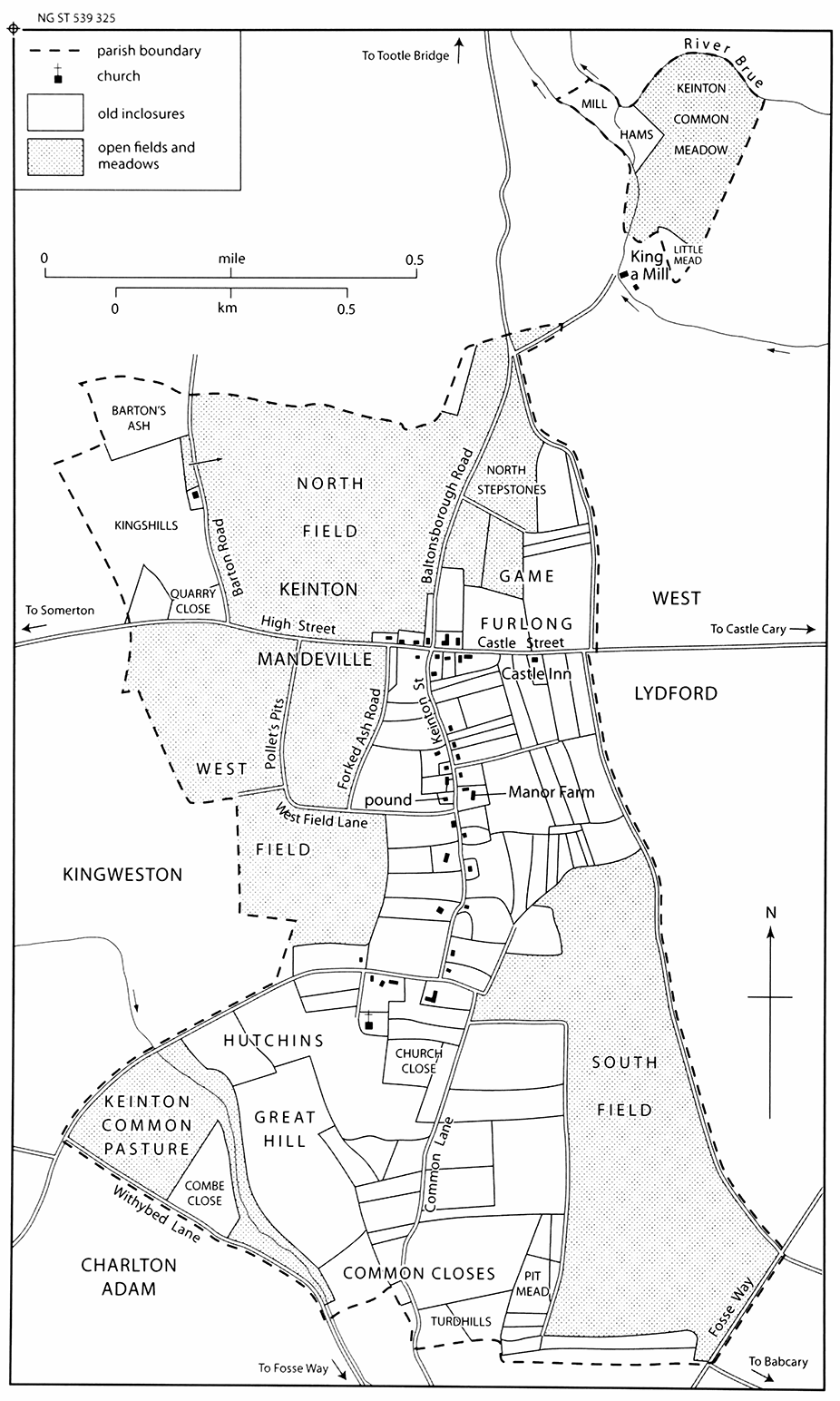

51. Keinton Mandeville 1810

Keinton Mandeville's three great fields survived in 1810 although partly laid to grass. Names like Stepstones and Pollet's Pits indicate the quarrying which soon after was active over large areas of the parish. The previous extent of arable meant that a detached area of the parish was needed by the river Brue to provide meadow.

THE PARISH of Keinton Mandeville, its name implying former royal estate (fn. 1) and its suffix referring to its medieval owners, (fn. 2) lies half way between Somerton and Castle Cary. It occupies a shallow dip between the gentle hill, which separates the parish from the Fosse a mile to the east and Luns hill, King's hill, and Kingweston's parks to the west. To the north there was formerly a detached area on the Brue, which probably arose from an ancient arrangement to provide the parish with meadow. To the south the narrow Keinton Coombe opens out towards the Cary valley near Steart in Babcary. The ancient parish was said to measure 770 a. in 1841 (fn. 3) but 685 a. in 1901. (fn. 4) Under the 1982 Yeovil Parishes Order further areas of the North field with a few houses were transferred to Barton St David in exchange for land in the north-east near King a Mill, linking the detached area with the rest of the parish and leaving Keinton Mandeville with 277 ha. (684 a.) in 1991. (fn. 5) Now roughly rectangular the parish is bounded on the east by Cotton's and Babcary Lanes and on the south-west by Combe and Withybed Lanes. The parish measures 2 km. north to south and between 1 and 1.5 km. east to west.

The village of Keinton lies in the centre of the parish around the T junction formed by High, Castle, and Queen Streets, the first two being part of the Somerton–Castle Cary road, which occupies the highest ground (55 m. (180 ft)) but dips to 50 m. (164 ft) in the centre of the village. From that point Queen Street slopes gently down to 45 m. (148 ft) at the church. The land beyond falls away gently to 25 m. (82 ft) on the southern boundary. The land north of the village drops more steeply to 20 m. (66 ft) on the former boundary at Coombe Hill. (fn. 6) The appearance of the village, and the scars of old quarries, point to its industrial past. The main area of the parish lies entirely on the Lower Lias; the beds of stone lying close to the surface in many places were ideal for paving slabs (fn. 7) and produced ichthyosaurs, one collected by Thomas Hawkins, and other important fossils. (fn. 8)

COMMUNICATIONS

The old village street, Keinton, now Queen Street, probably formed part of a route from the Fosse Way through Charlton Adam to Tootle Bridge on the Brue and thence possibly to Glastonbury. Half a mile north of the church the street crosses the Somerton–Castle Cary road, dividing it into High and Castle Streets, and continues to Coombe Hill recorded in 1619. (fn. 9) The Somerton–Castle Cary road, turnpiked by the Langport, Somerton, and Castle Cary trust in 1753, (fn. 10) helped the development of the quarry industry but caused problems from the later 20th century with the increasing volume of traffic.

The road from the church to Charlton Adam, often known as Combe Lane, was probably the way to La Cumbe recorded in 1299. (fn. 11) Withybed and Common Lanes link it through Broadway with the Roman Fosse Way. (fn. 12) Common Lane was the preferred route to Yeovil in 1925. (fn. 13) Cotton's and Babcary Lanes on the eastern boundary link the Fosse Way with Baltonsborough and beyond, avoiding Keinton village. The Barton road runs from the western end of High Street north to Barton St David. (fn. 14)

A tramway along the south side of the Somerton–Castle Cary road to link the quarries with the railway at Castle Cary, and later also at Evercreech Junction, was proposed by shopkeeper Frank Pitman and quarry owner Charles Matcham, with the support of a group of Bath businessmen. An agreement was drawn up between the Somerton, Keinton Mandeville, Castle Cary and Evercreech Tramway Syndicate Ltd and the Great Western Railway Company in 1892. Under an Act of 1893 work started on laying tracks beside the road in East Lydford parish. However, they made little progress and the scheme was opposed by the county surveyor who realised that it would eventually lead to a full-scale railway on highway land. In 1896 the successor body, the Somersetshire Tramways Company Ltd, published a prospectus but by May 1897 only a small length of track had been laid and the scheme was abandoned. (fn. 15)

The two civil engineers in the parish in 1901 (fn. 16) may have been planning the new railway line between Langport and Castle Cary completed in 1906 by the Great Western Railway. (fn. 17) However, Keinton Mandeville station was built over a mile from the village in East Lydford parish. It opened in 1905 and closed in 1962. (fn. 18) Bus services were introduced in the 1940s and a free service to Somerton was offered in 1985. (fn. 19) Most services have since been withdrawn although there is a service once a week to Street.

SETTLEMENT AND POPULATION

Despite proximity to the Fosse Way, claims of a possible villa site, and extensive quarrying no evidence of Romano-British or earlier settlement has been found. (fn. 20)

Before inclosure in 1810 there were three open fields, reduced in size by that date. The north field lay north of the main road and the west field south of the road extending west from the village street in 1299. (fn. 21) South, formerly east, field occupied the south-west of the parish. Keinton Coombe in the south-east provided the only common pasture. The village developed originally along Keinton Street running north from the church between the fields. (fn. 22) In the later 17th century c. 40 houses were recorded (fn. 23) but by the 1780s the village was described as a straggling L-shaped street of c. 30 houses comprising three farms, two public houses, and cottages. (fn. 24) In 1801 the population was 206. (fn. 25) In 1810 the village still consisted of dispersed buildings mainly along Keinton, later Queen Street, with some development around the crossroads with the Somerton–Castle Cary road at the northern end, and near the church on Charlton Road, later Church and Combe Lanes to the south but the church remained relatively isolated. (fn. 26) Inclosure created new side roads and resulted in the division of laneside fields into plots, which soon acquired cottages, especially between High Street and Westfield Road, later Chistles or School Lane. (fn. 27)

The rapid expansion of the quarry industry in the 19th century led to a rise in population and temporary housing shortages. In 1821 the number of houses had risen to 70 but families to 77. (fn. 28) The population rose substantially in each decade from 261 in 1811 to 586 in 1841 but stabilised at 584 in 1851 and thereafter declined only very gradually to 506 in 1891 before rising again to 530 in 1911. (fn. 29) Houses under construction were recorded on most Census days and from 1871 there were sufficient although some were poor quality such as the Row off High Street, recorded in 1901 as six 3-roomed dwellings. (fn. 30) Those have been demolished but gave their name to Row Lane.

By the early 20th century High and Castle Streets were densely built on both sides with terraced housing giving an urban feel to the village. Here were situated the shops, post office, public houses and one of the chapels. In contrast Queen Street still had undeveloped plots, orchards, and small farmsteads. Houses had spread along Barton Road by 1901, the Baltonsborough road, later Combe Hill, and Cotton's Lane by 1885, many connected with the quarries. (fn. 31)

With the decline in quarrying the population fell from 512 in 1921 to 460 in 1931 and 449 in 1961. (fn. 32) During the 20th century there was further concentration of building along High and Castle Streets, as far as the Kingweston boundary in the west and spilling over that with West Lydford to the east, along the Barton road from 1928, and in the south along Church Street as far as the parish boundary. Some small terraces and cottages were replaced by bungalows and houses and some very large houses have been built at the west end of the village. Infill has taken place along Queen Street and new estates were built between Queen Street and Chistles Lane in the 1980s when Orchard Way, Amberley Close, Irving Road, and Chapel Close were laid out. (fn. 33) Others have followed although a proposal for 21 new houses was rejected in 1998. (fn. 34) Houses continue to be built on plots of orchard and garden land and some have been subdivided. Development has led to a doubling of the population, which rose to 569 by 1971 and 592 in 1981 to 902 residents in 1991 and 949 in 2001. (fn. 35)

Houses

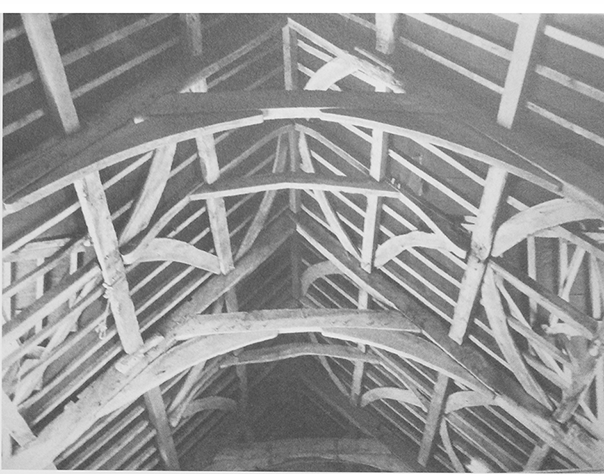

Before the 1660s up to four houses had five or six hearths but more than half the houses taxed had only one or two as did the eleven exempt, and three had fallen down. (fn. 36) Only two buildings of the 17th century or earlier have been identified. Most were lost possibly when the village experienced a decline in the late 17th and 18th centuries. Manor Farmhouse in Queen Street has in its former farmyard a five-bayed late-medieval barn. Its unusual roof has two trusses formed by two jointed crucks and three rows of staggered windbraces. One cruck was replaced in the 20th-century and the barn was converted to a dwelling in the mid 1990s. (fn. 37) The house is later 16th or 17th century, with a contemporary fireplace, two blocked ovolo-moulded 4-light windows, and an 18th-century extension, all possibly affected by the remodelling done by auctioneer Daniel Knight in 1902. (fn. 38) A small 17th-century cottage survives near the church. (fn. 39)

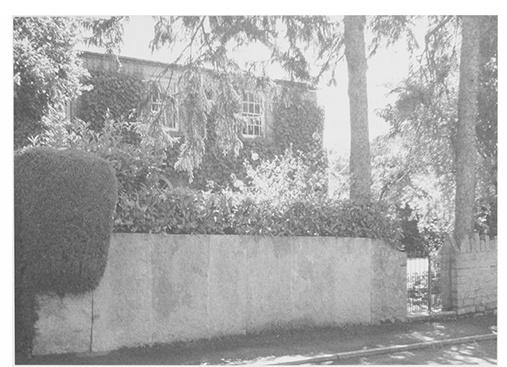

52. Stone fencing round a house at Keinton Mandeville.

In the late 18th century the village houses were 'neat' and 'comfortable' of two storeys and mostly thatched. (fn. 40) They included the Three Old Castles inn in Castle Street and the Homestead, formerly a farmhouse and buildings, in Queen Street, both of which have lost their thatch. In the early 19th century the quarrying industry produced both the demand and the materials for good quality villas and more modest terraced housing, most of the latter being in Castle Street. Queen Street has The Firs, Corner House, Rosedale, and Ivy House, Castle Street Irving House, birthplace of Sir Henry Irving, and its neighbour joined in one long row, Lynlea, and a fine double shopfront attached to the 18th-century Keinton House, possibly a grocer's shop. (fn. 41) At the 18th-century Shield House, Row Lane, off High Street, an internal ground-floor wall is made of two 7-ft high blue lias slabs, known locally as shields. (fn. 42) Many such large slabs, often standing some 4 ft or more above ground level, are still found fencing gardens. The 20th century has seen a great deal of housing development including local authority housing and farm conversions, especially along and off Queen Street which now has little open space.

LANDOWNERSHIP

There are few records for Keinton Mandeville and no dominant estate. The manor appears to have been progressively broken up from an early date.

MANOR

In 1066 there appear to have been two estates at Keinton, one held by two or three thegns, the other, linked with Barton, held by Aelmer. Both by 1086 were held by Mauger de Cartrai of the count of Mortain and presumably thereafter became a single holding. (fn. 43) It was said to be held of the heirs of the count of Mortain in 1275. (fn. 44)

Eustace de Devereux paid for the fee of 'Kinton' in 1203–4 (fn. 45) but shortly afterwards it had passed to the Mandeville family, whose name was associated with that of the parish by the later 13th century. (fn. 46) In 1275 Keinton was held for a fee of the heirs of Mortain (fn. 47) but in 1321 the manor was held of the Mandeville manor of East Coker by knight service and for ½ fee. (fn. 48) Robert de Mandeville, who recovered his ancestors' honor of Marshwood, (Dors.) in 1205, (fn. 49) granted land in Keinton to his uncle William de Mandeville (fn. 50) whose widow Beatrice claimed dower in 4½ virgates there in 1238. (fn. 51) Robert appears to have handed over his estates to his son Geoffrey in 1239, in return for maintenance for himself and his wife Helewise. (fn. 52) In 1242, possibly after Beatrice's death, Geoffrey recovered the land given to William from his son Stephen de Mandeville. He also mortgaged the manor and advowson. (fn. 53)

53. Birthplace of John Henry Brodribb 1838, better known as the actor Henry Irving. Photographed c. 1900, his former home in Castle Street is typical of the severely plain houses built of local stone in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Geoffrey de Mandeville died in 1269 and was followed by his son John (d. 1275). Keinton was in 1275 held of John, who was of unsound mind, by William de Mandeville, presumably his younger brother whose son later claimed he was given the half manor by Geoffrey. John de Mandeville's son, also John, was a minor at his father's death. (fn. 54) John's widow Clemence had the fee in dower in 1276. (fn. 55) The younger John (d. 1313) was still returned as feudal owner of Keinton in 1303, but by that date the fee was held of him by William de la Welde. (fn. 56) By 1346 William had been succeeded by another of the same name, who had died by 1369. (fn. 57) In 1428 the fee was owned by John Welde. (fn. 58) It is not clear what land the family had but they exchanged 30 a. for the same amount with St John's Wells in 1355. (fn. 59)

However, in 1315 and 1331 it was said that William de Mandeville had enfeoffed William de Favelore, of half the manor before 1285. (fn. 60) In 1289 William de Favelore acquired land in Keinton, which belonged to Cecily, then wife of William Attetoneshend. (fn. 61) Favelore's estate was said to have passed to Richard of Compton before 1315. (fn. 62) In 1316 Richard and the prior of St John, Wells were returned as holders of the Keinton fee (fn. 63) and in 1327 they were recorded as taxpayers. (fn. 64) In 1331 Sir William, son of William de Mandeville, tried unsuccessfully to recover the moiety from Richard of Compton. (fn. 65) The descent of the half manor is unclear, the fee was claimed by the Weldes, (fn. 66) and by the 16th century the Wells estate was known as the manor and was the largest and most valuable estate in the parish. (fn. 67)

The estate appears to have passed to the Gerard family who also acquired the advowson. John Gerard of Keinton bought the reversion of the Wake estate in Barton St David and Keinton in 1401 (fn. 68) and was still described as of Keinton in 1407. (fn. 69) He was followed by a namesake (fl. 1443–62) but the family had moved to Sandford Orcas, their principal manor. (fn. 70) Robert Gerard (d. c. 1505) (fn. 71) was succeeded by Robert, son of his deceased son William, who claimed that Robert Eyre, husband of William's widow Elizabeth, detained deeds to Keinton and other estates. (fn. 72) The Gerard estate appears to have been dispersed; the advowson had passed to William Meare by 1554, (fn. 73) possibly with some land, (fn. 74) and most of the estate probably passed to the Cheverels, lords of Barton St David. (fn. 75)

In 1578 Robert Cheverel gave his mother Isabel the farm in Keinton Mandeville with lands, also a watermill with 30a. (fn. 76) This estate descended in the family to the Bowermans who presumably divided and sold it like Barton St David in the early 18th century. (fn. 77) In 1810 the largest holding, apart from the former Wells estate, was 68 a. and there were 40 landowners. (fn. 78)

ESTATE OF ST JOHN'S HOSPITAL, WELLS

St John's hospital, Wells, had an estate in Keinton by 1257, said to have been given by Geoffrey de Mandeville (d. 1269) (fn. 79) and enlarged in 1321 and 1343. (fn. 80) It was presumably half the manor as there was a dispute as to whether the Mandeville heirs or the priors should do suit to the hundred for Keinton. (fn. 81) In 1355 30 a. and rent were exchanged with William Welde for a messuage and 30 a. (fn. 82) and more land was added in 1370. (fn. 83) From 1534 the estate, then described as their manor, was leased by the hospital brethren for forty years to Richard Bramston, vicar choral of Wells and composer, for only 4d. a year. (fn. 84) He probably sublet it. (fn. 85) In 1570 a Crown grantee undertook to break Bramston's lease but his own was surrendered in 1577 and replaced by another for years and a reversionary lease, both at market rents. (fn. 86) A quarry was let separately. (fn. 87) The Crown sold the estate, described as the manor formerly belonging to the hospital at Wells and including quarries and land in East Lydford, in 1610 (fn. 88) to Christopher Sotherton and John Wotton. (fn. 89) In 1650 John Sotherton, probably nephew and executor of Christopher Sotherton (d. c. 1637), (fn. 90) Nicholas Gray, (fn. 91) their wives, and Anne Wotton conveyed the manor to Stephen Phesaunt of London. (fn. 92) William and Mansell Phesaunt in 1708 sold it to Tristram Flower. (fn. 93)

John Foster, vicar of Longbridge Deverill (Wilts.), bought the manor and other lands in the parish including those of the Dauncy family in 1709 for £2,061 to produce an income of £103 as augmentation of his benefice. (fn. 94) By 1766 the estate was known as the Farm or Keinton Farm (fn. 95) and in 1818 as Keinton Farm and Feasants tenement comprising 218 a. in Keinton and 38 a. in East Lydford. (fn. 96) In 1876 the farm, then known as Manor farm and measuring c. 140 a., was put up for sale in lots. (fn. 97) There was no reference to lordship, which was retained by the then vicar of Longbridge Deverill, the Revd. David John Morrice, in 1883 and 1889 while still at Longbridge and between 1894 and 1914 when he lived in Salisbury. (fn. 98) No lord was noted in 1919. (fn. 99)

JENNINGS' MANOR OF BARTON AND KEINTON

The origins of the estate are obscure but the lords of Keinton Mandeville had lands in Barton by 1351. (fn. 100) Marmaduke Jennings (d. 1567) had land in Keinton in 1566, held by Sir William Hody in 1488, (fn. 101) and his descendant and namesake (d. 1658) held what was called the manor of Barton and Keinton, (fn. 102) and later as the manor of Keinton Mandeville with Barton. (fn. 103) It remained in the family until Mary Jennings (d. 1715) left the estate, described as land in Keinton, in trust for sale. (fn. 104) There is no further record of the estate.

OTHER ESTATE

In 1745 the largest holding (over 100 a.) was mortgaged by Marmaduke Coate, owner in 1766. He was followed before 1778 by George Harris (d. c. 1802), who also mortgaged it in 1797, and his wife Rachel Coate. By 1808 the estate had been dispersed between several owners. (fn. 105)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

The large number of small holdings may have delayed inclosure of the arable and it is not clear how early quarrying was managed. By the 19th century agriculture occupied few of the residents and further areas were opened up for quarrying following inclosure in 1810. (fn. 106)

PRE-INCLOSURE AGRICULTURE

The two Domesday estates may together have comprised land for six ploughteams, representing almost the whole of the modern parish; the 30 a. of meadow conform equally accurately with the detached piece of grassland to the north-east between Barton St David and West Lydford. (fn. 107) The demesne stock in 1086 comprised five pigs and 85 sheep on the main holding, which had lost a fifth of its value in the previous twenty years. (fn. 108) Six tenant farms indicated in 1086 (fn. 109) cannot be traced thereafter individually, but one of 20 a. including a dovecote may have become a freehold by 1310 (fn. 110) and was thereafter linked with holdings in Barton St David, Butleigh, and Hinton St George; (fn. 111) and another with Barton, Street, and Littleton in Compton Dundon. (fn. 112) At least five freeholders gave houses and small amounts of land to St John's, Wells in the early 14th century. (fn. 113) In the later 15th century there was a holding of 120 a. in Barton and Keinton, (fn. 114) and in 1551 a holding of 100 a. in Keinton alone, (fn. 115) evidently the former holding of St John's hospital, Wells. (fn. 116) It is possible that the Strickland family of Evershot (Dors.) and later of Yelden (Beds.) farmed the former Wells hospital estate. Richard was indicted for stealing cattle at Keinton in 1563 (fn. 117) and Christopher Strickland let land part of the capital messuage called Keinton farm in 1627. (fn. 118)

Cultivated plots called la Worthe and Langland were recorded in 1249 (fn. 119) and a church lamp was endowed with land called Magdalyn Ruge (fn. 120) but there is no record of the open fields until the early 17th century. Possibly during the Middle Ages cultivation was in three open arable fields, east, (fn. 121) west, and north of the settlement. References to the north field are rare and it was apparently regarded as part of the west field as the two were only separated by a road. (fn. 122) The common Keinton or North meadow lay detached from the parish to the north by the river Brue. (fn. 123) Farm grounds, recorded in 1619, may have belonged to Keinton farm, the former hospital estate, possibly let in small units including beast leazes in Keinton Combe. (fn. 124) A freehold farm with a large farmhouse, pigeon house, mow barton, hopyard, pear and apple trees was divided in two in 1639. The lands comprised closes of pasture and meadow and ½-a. parcels of arable in the east and west fields. One share totalled over 20 a. and had two beast leazes in Keinton Combe. (fn. 125) In 1688 a 6-a. close of pasture was described as 'lately' inclosed from a common field. (fn. 126) The Common plot, presumably at Keinton Combe was recorded in 1745 but land there had also been enclosed. (fn. 127)

In the mid 18th century there were three principal farms: the Farm, the rectory with over 50 a., and a holding of over 100 a. owned by George Harris of Somerton in 1778. (fn. 128) Smaller holdings included that of the Dauncy family, descendants of Joseph Dauncy, rector 1686–1706. Tassell Dauncy, Joseph's grandson, had at least 20 a. by 1752 (fn. 129) and Tassell's son, also Tassell (d. 1796), divided just under 50 a. between his children and grandchildren. Two parts had earlier been separate tenements named Culling's and Symes's. (fn. 130) By 1810 five members of the family shared over 75 a. (fn. 131)

In the 1780s there were still three large common fields, described as mostly in tillage, but the only manure used was dung from the bartons and sheepfolding although the soil was cold wet clay. Wheat, beans, and a few oats, peas, and vetches were grown and local practise was to sow clover in the wheat, feed it in autumn then leave it for cutting twice in the following summer. It was then ploughed in about Christmas when beans followed. The pasture in the parish needed draining and improving. (fn. 132) By 1791 large areas of arable were actually quarries because the blue lias stone lay only two to four feet below the surface. (fn. 133) In 1801 there were only 100 a. under wheat, 18 a. under beans, 14 a. of barley, and 2 a. of potatoes. (fn. 134)

54. Medieval barn at Manor Farm, formerly Keinton Farm. It was probably built by St John's Hospital, Wells, which owned the estate and has been converted into a house.

POST-INCLOSURE AGRICULTURE

An Act of 1804 permitted the inclosure of the arable land; agreement was reached in 1810 to inclose 288 a. of arable in three fields and 14 a. of shared grassland. The Farm now measured 218 a., followed by three farms of between 40 a. and 70 a. and three others with over 25 a. (fn. 135) The Farm included 38 a. in East Lydford and was soon afterwards leased for 8 years. (fn. 136)

In 1821 only six families out of 77 in the parish were said to be involved in agriculture, (fn. 137) much of the arable acreage by that time having been given over to quarrying and subsequently to orchards. In 1840 the rector let most of the glebe with barns and stable to two stonecutters for 50 years for rent and part of the costs of drainage. (fn. 138) In 1841 there were ten farmers, although three were in one household, and a cheese factor could afford two resident servants. Five members of the Stuckey family were growing teasels. (fn. 139) By 1851 Manor farm comprised 247 a. and employed six men. Only two other inhabitants described themselves solely as farmers, one with 120 a., but there were two members of the Culling family who combined dealing in stone with small-scale farming. There were also a dairyman, three cattle dealers, and nine people involved in growing, processing, or selling teasels. (fn. 140) Ten years later there were five farmers, 15 people involved in the teasel business, pig and cattle dealers and a cheese factor at Coombe Hill, but only two farmers were recorded as employing labourers although several female farm labourers were recorded. (fn. 141) In 1871 there were two large farms (250 a. and 120 a.) and two others, four teasel workers, and 24 agricultural labourers but in 1881 one farmer was also a stone merchant and no-one was growing teasels. (fn. 142) When Manor farm was sold in 1876 it comprised c. 78 a. of arable, 6 a. of orchard, 12½ a. of meadow, and 44 a. of pasture scattered throughout the parish. (fn. 143) In 1891 five farmers lived in the village but the family of one worked as labourers and servants and another was an auctioneer. A horsebreaker, a shepherd, and three cattle dealers were recorded. (fn. 144)

In 1901 there were three farms in High, Church and Queen Streets, four cattle dealers, a poultry dealer and a nurseryman. Only eight farm workers were recorded. A traction engine team was resident, but that might have been for quarry rather than agricultural use, and two horse trainers had a resident stable hand. (fn. 145) By 1905 there were only 96 a. of arable and 461 a. of grass. (fn. 146) Three farms were recorded in the early 20th century producing clover, beans, wheat, and orchard produce. (fn. 147) Attempts to increase potato growing in 1916–18 were hampered by lack of allotments. The ground was said to be not much use for food. In 1930 the parish was not considered an agricultural district. Allotments were available by 1942 and there was a working farm in Queen Street. (fn. 148) In the 1970s a large pig farm planned to increase stock from 3,000 to 4,500. Other farms were developed in the late 20th century one of which was provided with cold storage. (fn. 149) New farms were sited on the outskirts of the parish including Newcombe and Southmead farms in the south and Westfield and Coombe Hill farms in the north, on land formerly in Barton St David parish. In 2002 Coombe Hill Farm, a county farm at King a Mill, had only 40 a. (fn. 150)

MILL

The Cheverells, lords of Barton St David, had a watermill with 30 a. in Keinton in 1578. Known as the New mill it was leased in 1589. (fn. 151) It was not recorded again but was presumably on the millstream between King a Mill and Barton mill in the detached part of the parish. (fn. 152) A mill was said to be included in the sale of the former hospital estate in 1610 but there is no record of a mill on the estate. (fn. 153) Millers recorded living in the village in 1871 probably worked at King a Mill or elsewhere (fn. 154) and the road to the mill damaged by an 'engine' in 1896 was probably at King a Mill. (fn. 155)

QUARRYING

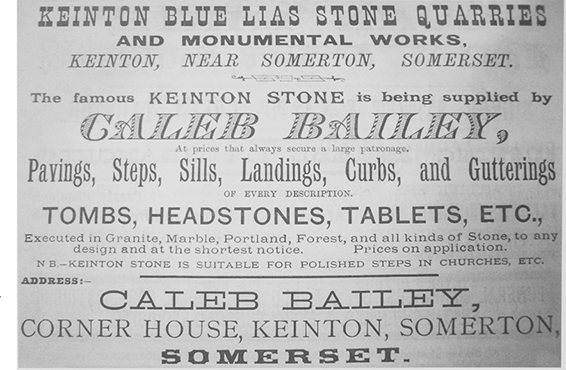

In the later 18th and the 19th century quarrying lias for paving and other building work provided the principal occupation of the inhabitants of Keinton Mandeville. In the 1780s stone was sent 'considerable distances' for internal and external paving and for gravestones (fn. 156) and fifty years later was supplied for a house beyond Salisbury. (fn. 157) In the 1840s stone was supplied to Castle Cary church and many neighbouring villages such as West Lydford have paving and fencing slabs of Keinton stone. (fn. 158) In the 1880s the principal quarry owner supplied stone paving, steps, sills, landings, curbs, and guttering as well as tombs, headstones, and tablets not only in the local lias but also in a wide variety of other stones. (fn. 159)

A reference to a mason at Keinton in 1280 may suggest early use of local stone (fn. 160) but the first record of a quarry is in the mid 16th century. (fn. 161) In 1580 a quarry on the former St John's, Wells estate was let for 21 years to John Harrington (fn. 162) and in 1606 to Sir Thomas Neale for 40 years. (fn. 163) Both presumably sublet it. In 1610 the quarries on that estate were sold with the lands and were valued at £5 9s., slightly more than the rest of the estate. (fn. 164) Pasture call Pits Close and West field arable called Little Quarpits and Great Quar in 1639 indicates old quarries. (fn. 165) There were at least two quarries in the earlier 17th century. (fn. 166) A mason or stonecutter who died in 1696 and appears to have kept an alehouse in his four-roomed home had cash to lend on bonds and a leasehold property. (fn. 167) Field names in and around the village including Harpits, Hallstones, Pit Mead, Quar Close, and North Stepstones, and a lane across the west field called Pollets Pits in 1810 probably relate to earlier quarrying. (fn. 168)

In the later 18th century the largest quarry probably lay to the north of the village, perhaps giving land there the name Stepstones. (fn. 169) The Dauncy family had two quarries in 1789, one by the turnpike road and the other in a common field. (fn. 170) By 1791 extensive quarrying for lias was taking place in the arable fields. The stone lay in layers two to six inches thick and separated by similar thicknesses of earth. The stone could be lifted in slabs up to 15 ft by 30 ft making it ideal for paving. If properly dried after lifting it was frost resistant. Large quantities were sent out of the area, as were gravestones. The stone was so smooth it needed no dressing but would not polish well. (fn. 171)

After inclosure in 1810 many new quarries were developed throughout the parish. (fn. 172) In 1801 40 people were engaged in trade or craft compared with only 18 in agriculture. (fn. 173) By 1802 members of the Harris, Chalker, and Culling families were employed as masons or stone cutters (fn. 174) and by 1831 John Dyke held Keinton quarry of the Revd. G. B. Tuson, successor to his father George and to a Mr. Lucas back to 1806. (fn. 175) In the 1830s at least fifteen families were involved in stone cutting or as masons (fn. 176) but by 1841 there were five stone merchants and 64 stone cutters. (fn. 177) Two members of the Culling family of stone cutters leased nearly 40 a. from the rector in 1840 in the south of the parish. (fn. 178) In 1851 83 men were employed in the stone business, one seventh of the total population: 16 worked for John Harris, master stone cutter, ten for Thomas Culling, eight for William Culling, both stone cutters, and six for Thomas Culling the elder, stone master. John Dyke described himself as headstone cutter. All three Cullings farmed the land not quarried on their holdings. (fn. 179) In 1856 a smallholding was offered for sale with an acre of unquarried stone, probably in the former west field. (fn. 180) In 1876 part of the Longbridge Deverill glebe was sold to a stone cutter presumably to open a quarry. (fn. 181)

55. Keinton Mandeville in 1885, showing the village surrounded on three sides by active quarries and the scars of former quarries.

In 1868 Robert Bailey offered Weston Super Mare Board of Health 3-inch paving slabs delivered at Weston station ready for laying at 6¾d. per ft. He supplied testimonials from several towns including Salisbury, paved with Keinton stone c. 1845, and Frome, which had used Keinton paving since the 1830s. (fn. 182) In 1861 there were two stone merchants, including a woman, and 94 other stone workers. In addition there were specialists; a marble sawyer, a monumental sculptor, and a sculptor employing four men who also had a grocery business. (fn. 183) A similar number were employed in 1871 and 1881 but one merchant employed 45 men, nearly half the total. (fn. 184)

56. Advertisement for Keinton stone goods in 1883. Caleb Bailey was a stone merchant at Keinton Mandeville where at least five families were prominent in the industry. At that period c. 5,000 tones of stone was exported from the parish each year.

By the late 1880s there were two principal quarries, Combe Hill and Keinton quarries, but six people described themselves as quarry owners, presumably of the smaller diggings, most equipped with a crane, recorded along both sides of Queen Street. Twelve people operated as stone merchants. (fn. 185) By the early 1890s there were said to be 14 quarries in the parish whose output, some 5,500 tons, most recently used in Swindon (Wilts.), Winchester, and several Dorset towns, was the principal reason for the promotion of a tramway between Somerton and Castle Cary by among others quarry owner Charles Matcham. By that date the three largest quarries produced 1,500 tons and were owned by Walter Sheppard, (fn. 186) who also operated at Castle Cary. (fn. 187) By that date the distinction between merchants, cutters, quarrymen, masons, and labourers appears clearer and in 1891 there were three apprentice cutters. A total of 104 men worked with stone. (fn. 188) In 1894 Alfred Matcham, a former Keinton stone merchant, sold Sheppard Matcham's quarry, formerly Chaffey's, beside the churchyard with the business goodwill. (fn. 189)

In 1901 numbers employed had risen and over a fifth of the population worked in the stone trade. There were 11 stone merchants and contractors and at least 104 other stone workers including a monumental mason, eight stone carters and hauliers, and three apprentice stone cutters. An additional 31 stone workers lived in Barton St David, which had housed quarry workers since the 18th century. (fn. 190) The families of Bailey, Brooks, Chalker, Cox, and Dyke continued to be involved in the eight quarries apparently at work after the turn of the 20th century. Oliver Chalker, with operations also in Charlton Adam, offered head and tomb stones, landings, steps, sills, kerbing, channelling, sinks, troughs, paving, pitching and building stone. Similar stone articles were offered by Silas Bailey of Westfield House and James Cox, who also had a depot in Yeovil, whereas George Cox was a sculptor and monumental mason offering crosses and tablets. (fn. 191) A firm called Hardstone or Hard Stones had a depot in High Street, which had closed by 1907. (fn. 192) In 1910 United Stone Firm Limited, probably its successor, owned and worked five quarries and limekilns, owned land called Stepstones, and had another 12 a. of land. They also let a quarry. Two other quarries were owner occupied, one was leased, and four more were unoccupied. (fn. 193)

By 1914 the industry had been reduced to three businesses. (fn. 194) The war caused a scarcity of labour with a fifth of the population in the services or doing war work. (fn. 195) The parish council deplored the decline of 'our staple industry' and in 1919 referred to the industry as in the 'lowest possible state'. (fn. 196) Stone cutting continued on a small scale throughout the 1920s and at least two quarrymen were employed in the 1930s, (fn. 197) but by 1939 only the Cox family were in business as quarry owners and sculptors. (fn. 198) Quarry pits were used as refuse tips in the 1930s. (fn. 199) The 'ham hill' quarry was referred to in 1967. (fn. 200) A single quarry, known as Lake View quarry and sited between the school and the village hall, was being worked in 2005, producing what was described as natural walling and stone paving from shallow workings. Old quarries have been converted to orchard or pasture.

TRADE AND CRAFTS

The poor survival of records for the parish do not permit a view of the parish's crafts before the later 18th century when women were said to spin and knit stockings for Glastonbury manufacturers. (fn. 201) A clothworker was recorded in 1700. (fn. 202) Many of the 69 families, out of 77, who were engaged in trade, manufacture or craft in 1821 would have worked in the quarries. (fn. 203)

Sixteen tailors were recorded in 1841, mainly young men living together in groups. With the three dressmakers and three shoemakers they were probably supplying the needs of the wage earners in the quarries. (fn. 204) In 1851 six people were involved in wool preparation, two made gloves, and one mattresses, perhaps employed in either Glastonbury or Street. (fn. 205) A glover, a labourer in a shoe factory, and a mattress maker were recorded in 1861. (fn. 206) By 1871 dressmakers had replaced tailors as the most numerous clothing workers and there were two female glovers. The number of dressmakers peaked at 14 in 1881. (fn. 207)

Painters, plumbers, glaziers, and a cabinetmaker at work in the later 19th century may reflect the expansion and improvement of housing. (fn. 208) Less common tradesmen were a cooper recorded in 1871 and a basketmaker and an upholsterer in 1881. (fn. 209) In 1901 a watchmaker was also a stonecutter and there was a basketmaker. (fn. 210) A saddler was at work in 1923 (fn. 211) and a cycle repairer in 1947 when the only industry, apart from one quarry, was a two-man carpentry business. (fn. 212) A small woodworking business remained in the village in 2005.

Retail ServicesKeinton's position on a major road ensured that one or more public houses could provide three beds and stabling for four horses in 1686. (fn. 213) It is possible that a stonecutter was keeping an alehouse in the 1690s. (fn. 214) The two inns of the 21st century, the Three Old Castles and the Quarry, may be traced back under similar names: the first, south of Castle Street, to 1793, the second, north of High Street, to 1813, and both to the two houses licensed by 1750, one of which was first licensed in 1738. (fn. 215) They had been joined by a third, the Masons Arms on High Street, probably by 1841, but that was last recorded in 1871. (fn. 216) In 1840 two men entered an agreement for the sale of oxen at the Keinton Quarry inn. (fn. 217) Licensees were sometimes also farmers, stonecutters, or general dealers in the 19th century. (fn. 218) Both inns belonged to breweries by 1910. (fn. 219) In the 1930s the Quarry described itself as an hotel and the Three Old Castles offered bed and breakfast, lunches, and teas. (fn. 220)

There are no early records of shops but a linendraper was recorded in 1625 (fn. 221) and a pedlar was selling muslin in the parish in 1796. (fn. 222) Keinton appears to have functioned as an industrial rather than an agricultural economy in the later 19th and early 20th centuries reflected in the urban pattern of shops and services. Most of the stone workers' wages were probably spent in the public houses, shops, and other businesses in the village. By 1830 there was a linendraper and grocer. (fn. 223) By 1841 there were two shops; a grocer and a glass and china dealer. (fn. 224) In 1861 there were four shops including a grocer, draper, and outfitters run by a couple and three staff. Two of the shopkeepers also had resident domestic servants. About 20 men and women were dressmakers, tailors, and shoemakers, and there were five laundresses and four nurses. A photographer and his family were lodging. (fn. 225) By 1881 there were the Corner Shop, a grocer and general dealer, a tailor and woollen draper and a second draper in High Street, and in Castle Street the post office which was also a grocer's shop, a bakery with two assistants, and a general store employing three. (fn. 226) Grocer Frank Pitman was a promoter of the tramway and claimed to import hundreds of tons of groceries through Castle Cary station. (fn. 227) Between 1841 and 1881 a yeast vendor was recorded. (fn. 228) A drapery was named Old Keinton Shop in 1891 when in addition to the PO and bakery, there was a milk seller, a butcher, and five other shops. (fn. 229)

In 1901 there were three grocers with four assistants, two drapers, a post office, a milkman, a butcher, a baker with resident assistant, a lock-up shoe shop, a general haulier, and a life assurance agent. (fn. 230) Even after quarrying declined there were at least five grocers and drapers, two bakers and a butcher, a cycle agent and hauliers. (fn. 231) In 1928 petrol pumps were installed at one of the village shops reflecting Keinton's favourable position on a main road with easy access from adjoining villages. (fn. 232) This position and the closure of shops in neighbouring villages enabled it to retain its position as provider of shops and services for the surrounding area. By 1939 a bootmaker was also dealing in radios and there was also a newsagent and a hairdresser. (fn. 233) In 1947 there were seven shops and several artisans and by 1950 a cycle shop had been added selling electrical goods. There were also two petrol pumps and an undertaker, two banks open on Thursday mornings, and a café. Most of those services were still provided in 1979 when five shops remained open despite the village having easy access to several towns. (fn. 234) One shop closed c. 2000. There were three shops, a hairdresser, and a photographer in business in 2005, but both banking facilities were withdrawn in 1992 and two shops had closed by 2005. (fn. 235)

SOCIAL HISTORY

There is little trace of Keinton Mandeville's preindustrial social structure. By the early 18th century it was a small agricultural parish with no high status residents and only two large farms. (fn. 236) It had been more prosperous as several large houses were recorded in the 1660s and a baronet had a house in the village but already many hearths had been destroyed, three houses had fallen down and three people charged with tax were too poor to pay. (fn. 237) By the late 18th century Keinton was becoming an industrial village. In 1791 there was said to be only one pauper as most of the poor found employment. (fn. 238) During the 19th century the pattern of housing, shops, businesses, public houses, and rival Methodist chapels and schools gave Keinton the appearance of a working-class parish very different from its farming neighbours.

The social structure of the quarry industry is difficult to unravel. Merchants were usually employers but the term stonecutter and mason included both employed and employers and possibly unskilled quarrymen, whereas some masons were sculptors. In 1861 of 71 cutters, seven employed up to 14 workers and two had domestic servants. One mason was also an employer. (fn. 239) By the end of the 19th century there were apprenticeships, although sons would have probably learnt from their fathers, and a distinction was made between quarrymen and quarry labourers. Much quarrying was organised by family businesses such as the three Brooks brothers and two Chalker brothers, merchants and contractors in 1901. (fn. 240)

The large number of workers, probably earning more than agricultural labourers, supported several trades and services including dressmakers, tailors, and shopkeepers. Many of the last employed resident domestic servants and several housemaids were recorded living with their families. (fn. 241) The cash wages earned by the stone workers allowed them to live in fairly good houses, not in the poorer small houses, (fn. 242) and to purchase clothing and household goods. They could afford to patronise a glass and china dealer in 1841, (fn. 243) a watch and clock cleaner in 1871, and an upholsterer in 1881. (fn. 244) The family economy was enhanced by the many wives of stonecutters who had their own businesses including shopkeeping. In at least some cases where a man is entered with two occupations one is that of a wife or child. (fn. 245) Very few in the stone trade had a resident servant from outside the family but many sisters and daughters were employed as servants, often for their own families but sometimes for others. (fn. 246) Amelia Chalker, a marble mason's wife with five children in 1861, gave her occupation as 'slave to the rest of the family'. (fn. 247)

Unlike neighbouring parishes there is little evidence of overcrowding at Keinton. In 1861 there were 134 households in 115 houses and additionally many people took in lodgers (fn. 248) but from 1871 there were as many houses as families. In 1891 of 124 houses only 16 had fewer than five rooms of which only one had fewer than three. (fn. 249) That also contrasts with Barton and West Lydford where a third of houses had fewer than five rooms. (fn. 250) By 1901 houses had probably been divided and, although new houses were being built, 35 houses had fewer than five rooms and six called the Row had only three rooms each. There were still a number of boarders. (fn. 251)

A few widows had lived on their own means in the 19th century (fn. 252) but there was no evidence of gentry in the parish. In the early 20th century a few genteel residences were located in the parish notably Combe Hill House north of the village. (fn. 253) The decline of the quarrying trade which had employed most adult males in the parish until the First World War probably led to some hardship not only for those directly involved but for other trades. Local authority houses were proposed in the 1920s and 21 applications were received but the rural district council agreed to build four. More were built in 1950 and 1958, and housing for the elderly and flats were provided in the 1970s and 1980s. (fn. 254) The existence of a thriving school, two places of worship, several shops and businesses, and two public houses have probably both encouraged and been sustained by the housing development of the late 20th century which led to a doubling of the population. (fn. 255)

EMIGRATION

In 1851 a New York stonecutter was formerly of Keinton Mandeville. (fn. 256) In 1881 two women from the parish were arranging passage to America. (fn. 257) An emigrant to Canada volunteered for service in the First World War. (fn. 258)

EDUCATION

In 1818 there was a day school for 30 children taught by a poor man and supported by the rector. (fn. 259) Wesleyans opened a Sunday school in 1823, which by 1835 had 77 pupils, as compared with 35 pupils at the Church Sunday school. (fn. 260) A schoolmaster was in the parish in 1841. (fn. 261) The Church Sunday school was affiliated to the National Society by 1846 when it had 46 pupils; it was then hoped to open a day school when an efficient master could be found. (fn. 262) By 1851 a master and his daughter taught at the Church school, which had 69 pupils on Sundays. Wesleyans and Bible Christians both had Sunday schools. (fn. 263) In 1861 the National School teachers had four pupils boarding, a couple were teaching at the Wesleyan school which may already have taken day pupils, and a staymaker was a teacher at the Bible Christian chapel. (fn. 264) By 1875 the Wesleyans certainly had a day school (fn. 265) and difficult relations between the two churches probably resulted in the creation of a school board in 1878, which was responsible for a new school for 100 pupils. (fn. 266) However, in 1888 and 1893 the schoolroom was used for Anglican services. (fn. 267) Not all parents found the school adequate as in 1881 six girls from the parish were away at boarding school. (fn. 268) In 1891 a couple taught and resided at the school and two other board school teachers and a pupil teacher lived in the parish. (fn. 269)

The church school, originally a single classroom in Westfield Road, later Chistles Lane, had a second classroom and porch added to designs by J. Day of Glastonbury, possibly in the 1840s. He also designed a three-bedroom teacher's house to the west, which does not appear to have been built. (fn. 270) A new and larger school was built west of the older school to the designs of a Mr. Bowring (fn. 271) in 1902–3 and there were 97 children on the books under four teachers in two rooms, although six teachers were recorded in 1901. (fn. 272) A night school and later cookery and dairying classes continued to be held in the old schoolroom. In the 1920s the school produced a remarkable number of pupils who became teachers and was regarded as a model. Girls from Lovington and Lydford attended the cookery classes and pupils came from Barton, Kingweston, and Babcary. (fn. 273) Attendance fell significantly after seniors were transferred to Ansford but the number of pupils more than doubled between 1985 and 1995 as the general population of the village expanded. (fn. 274) The school building was extended in 1994 (fn. 275) and in 1998–9 there were 161 children on the books aged between 4 and 11 years. (fn. 276) The old National schoolroom, which had been used as a hall, was demolished and houses were built on the site c. 1997. (fn. 277)

Parents' days were held at the school from 1919 and a special meeting was arranged 'to promote cordial relations between teachers, managers, and parents'. (fn. 278) A parent-teacher association had been formed by 1967. (fn. 279) By 1979 there was a pre-school playgroup (fn. 280) and a nursery play school started in 1988. (fn. 281) Stepping Stones was registered for pre-school education in 2000. (fn. 282)

Evening classes were held from 1899 and for some years after the First World War there were choral and orchestral classes. (fn. 283) Evening classes were still being held in 1979. (fn. 284)

WELFARE

The parish officers owned two poorhouses in 1810. One lay south of the main road opposite the later United Methodist chapel. The other adjoined a cottage on the south-west corner of Westfield Road, later Chistles Lane, and Keinton now Queen Street, next to the later school site. (fn. 285) There was said to have been only one pauper c. 1791 (fn. 286) but the annual cost of poor relief to the parish before 1834 was £74. (fn. 287)

The parish council was concerned with health and sanitation. A drinking fountain was repaired in 1895 and concern expressed at unhealthy closets in Castle Street in 1899. From 1911 the council wanted a water supply although a parish meeting rejected the idea in 1912 and in 1922 declared the public wells adequate. Although 20 wells were condemned in 1931 mains water was not provided until 1955 and drainage until 1975. (fn. 288)

There was a doctor in the parish by the 1920s and in 1923 a second who acted as medical officer for the Langport Union. By 1939 there was a dentist available on Wednesday afternoons. (fn. 289) A surgery was kept in the village daily in 1950 and there was a doctor in 1979. (fn. 290) The surgery had transferred from the Old Temperance Hall to the village hall by 1998. It is only open for half an hour in the mornings, served from Castle Cary. (fn. 291) Two nursing homes, Beech Tree and Castle House, opened in the later 20th century. (fn. 292)

COMMUNITY LIFE

As a reflection of Keinton's non-agricultural character there were five friendly societies in the parish in the first half of the 19th century. The Keinton club was formed in 1796 and met at first at the Old Castle inn. (fn. 293) From 1812 until 1831 or later it occupied a house. (fn. 294) A friendly and benefit society was begun in 1830 and a Society of Tradesmen and Others in 1835. Perhaps all three joined in a Union Society, which met at the Quarry inn from 1849. A female friendly society met there from 1852. (fn. 295) The Men's Social Club, which may be the successor to the union society, acquired an army hut after the First World War. The Village Hut, as it was known after the Second War, was used for billiards and darts in 1946. (fn. 296)

A harvest home had been established by the rector by 1876 (fn. 297) and horse racing was held in the parish in 1926. (fn. 298) A Band of Hope committee had been formed by 1906 and held a festival in the village in 1914 and for several years after the war until 1930. (fn. 299) There was a branch of the Mothers' Union in 2002. (fn. 300) In 1979 there was an old age pensioners' club, a branch of the Women's Institute, and a pack of Brownies. (fn. 301) There was a tennis court and playing field. A new village hall west of Chistles Lane opened in 1998. The Sir Henry Irving Club for the over 60s was proposed in 1974 and was in existence in 2005. (fn. 302) The county library supplied books to the school for public borrowing from 1919 until the early 1930s or later and there was still a village branch library in 1947 but by 1979 a mobile library served the community. (fn. 303)

By 1872 the headquarters of the 25th Somerset Volunteer Rifle Corps was based in the village with a commander and a drill sergeant. (fn. 304) Sixteen men volunteered at the Temperance Hall in 1914. Over 80 men from the parish served in the First World War of whom 11 or more (fn. 305) were killed and 20 women did war work out of a population of just over 500. (fn. 306) After the Second World War a branch of the British Legion was established linked with Charlton Mackrell. (fn. 307)

The son of local Methodists, Henry Irving, born John Henry Brodribb in 1838, left the parish at the age of four. He was later noted for his generosity and may have given money for a Methodist chapel. (fn. 308) A singer, Miss Marsh, inspired Thomas Hardy's poem 'The Maid of Keinton Mandeville'. (fn. 309)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

The small size of the parish, the early break-up of the manorial estate, (fn. 310) and the almost complete loss of parochial records preclude a proper study of local government. In 1242–3 it was described as a township, (fn. 311) in 1315–16 as a hamlet; (fn. 312) in 1327 it was assessed with Barton St David (fn. 313) and by 1560 until the mid 18th century with Barton and Kingweston constituted a single tithing. (fn. 314) In the 1620s Keinton had fought to reduce its share to less than one third of the tithing rate (fn. 315) and in 1742 Keinton and Kingweston together bore half the charge of Barton. (fn. 316) As late as 1671 Keinton was described as 'in the same parish' as Barton. (fn. 317)

No manorial records have been found. No courts were held in respect of the former priory estate of St John's, Wells, by the end of the 18th century, (fn. 318) and probably no such rights ever belonged to that holding. A pound west of the village street abutting the west field was recorded between 1639 and 1810. (fn. 319) A manor pound was recorded in the south-west corner of Manor farmyard in 1876. (fn. 320)

Two churchwardens and two sidemen signed the glebe terrier in 1638 (fn. 321) and in 1840 the parish employed as clerk who was paid 50s. a year. (fn. 322) The vestry was meeting in the schoolroom in 1876. (fn. 323) The parish council met in 1894 and elected chairman, vice chairman, treasurer, and waywardens. There were also two overseers and a salaried assistant overseer. The last was called up in 1917 and his wife took over the post. From 1895 the council usually met in the school and concerned itself with a wide range of parish business. The council pressed for a railway station when the new line was proposed in 1900 and wanted a halt in 1928, presumably because Keinton Mandeville station was so far from the village. (fn. 324) The council also tried to bring in mains electricity, street lighting, water, and drainage but the village had to wait until the later 20th century for those services and sewage works. (fn. 325) From 1941 the council met in the hut at Combe Hill, demolished in 1992. (fn. 326)

There was a police constable in the parish from at least 1861 until 1923 and a police station in 1939, (fn. 327) but there was no police presence in 1947. (fn. 328)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

The industrial character of the parish fostered the growth of nonconformity from the early 19th century in the form of various branches of Methodism with their own schools. (fn. 329) The rector complained in 1851 that Dissent abounded in the parish. (fn. 330) There appears to have been animosity between the rector and the leading men of the parish, presumably nonconformists. In 1894 the rector was bottom of the poll for the parish council and the following year he refused to give up the parish documents. In 1910 the parish council thought Sunday post was undesirable. (fn. 331) During the 20th century there was increasing co-operation and the Methodists united at a single chapel from 1950. (fn. 332)

CHURCH

The church is first mentioned in 1242–3, (fn. 333) and the lancets in the chancel suggest a foundation in the earlier 13th century. The parish may originally have been part of Barton St David, since in the late 14th century the rector of Keinton Mandeville was found liable to pay a small sum to the rector of Barton by agreement made at the foundation of Keinton. (fn. 334) The church was dedicated to St Mary Magdalen by the 16th century. (fn. 335) It was a poor living until the 16th century but was augmented (fn. 336) and remained a sole rectory until 1977, when it became a united benefice with Lydford on Fosse. From 1991 it was held also with Barton St David and Kingweston, a benefice that in 2000 was named the Wheathill Priory group. In 2001 Keinton parish was united with Kingweston. (fn. 337)

Advowson

Geoffrey de Mandeville mortgaged the advowson with the manor c. 1242 (fn. 338) and in 1274 William de Mandeville was in dispute with Ralph Albot over the presentation during a vacancy. (fn. 339) The next known owner was Sir Robert Fitz Paine (d. 1315), (fn. 340) who in 1299 secured a quitclaim to the advowson from Robert son and heir of Sir Robert of Wootton who held a small freehold in Keinton in 1275. (fn. 341) The advowson formed part of a fine between the parties in 1302 to settle many estates on Robert Fitz Paine and his wife Isabel (fn. 342) who presented in 1317. Her son, also Robert Fitz Paine, presented between 1339 and 1348. (fn. 343) During the 15th and early 16th centuries patronage belonged to the Gerard family. (fn. 344) However, in 1428 the advowson was in the hands of John Daniell probably as part of a settlement. (fn. 345)

By 1554 it had come to the possession of the Meare or Meyer family of Sherborne (Dors.) and later of Portskewett (Mon.). They kept it, although it was claimed by John Currell in 1566 and held by Walter Bourne in the 1570s, (fn. 346) until Magnus Meyer granted it to Christopher Cheverell in 1620. Cheverell later that year conveyed it to Adam Abraham, a clergyman. (fn. 347) In 1640 William Mullett, the rector, bought it from Abraham and in 1653 it passed to Francis Baynton, who in 1661 presented Mullett's son, also William, to the living. (fn. 348) Mullett presented in 1662 and 1663 but in 1670 conveyed it to Richard Symb or Symbb, a clergyman, who probably in the next year conveyed it to Elizabeth Tassell or Tazwell, who presented in 1671. (fn. 349) In 1686 the patron was Rebecca Dampier, probably the widow of the previous rector, but in 1688 the property, described as lands and tenements, rectory, and advowson, passed to the rector, Joseph Dauncy and his wife Rebecca Dampier, and to James Tazwell of Limington (Som.) and his wife. (fn. 350) In 1727 Dauncy's son also Joseph and rector, together with his own son Tassell, assigned the advowson in trust for William Clarke, rector from 1729, possibly for a turn. In 1743 the Clarkes assigned or mortgaged it to William Provis. Following a royal presentation for lapse or simony in 1754, Provis, the Clarkes and the Dauncys conveyed the advowson in 1755 to Edmund Gapper, appointed to the rectory the previous year. The right thereafter passed to Edmund's brother Abraham and his brother-in-law Richard Southey. Richard presented a second Edmund Gapper in 1778. Patronage remained in the Gapper family until 1810 when it was conveyed to George Stone for the benefit of the new rector, William Hungerford Colston. In 1840 the Colston trustees sold it to Michael Sharp of Runcorn (Ches.) (fn. 351) who was evidently acting for the new rector, Edward Allen. Subsequent rectors became patrons after appointment either by their predecessors or by trustees until after the appointment of A. F. Whitehead in 1892. His grandson retained the patronage, then two shares in five, in 2002. (fn. 352)

Income and Endowment

The living was valued at only £4 in 1291. (fn. 353) In 1535 the value was assessed at £6 13s. 9d. of which tithes accounted for over £5. (fn. 354) It was worth under £40 in the later 17th century when glebe amounted to well over 40 a. (fn. 355) In 1774 the living was augmented by the former rector, Edmund Gapper (d. 1774) (fn. 356) and in the early 1830s was worth £151. (fn. 357) Tithes on newly-inclosed lands were abolished in 1810 and remaining tithes were worth only £110 in 1851 out of a stated income of £180. (fn. 358) In 1931 the living was worth £314 net. (fn. 359) In 1810 there were over 53 a. of glebe in the parish, (fn. 360) and 25a. in Charlton Adam and Barton St David, probably purchased with augmentation money in the later 18th century. The railway reduced the size of the glebe and in 1934 it totalled c. 74 a. (fn. 361)

Rectory house In 1619 there was a small house and farm buildings. The house had a hall and kitchen with chambers above and its adjoining farm buildings by 1640 were a barn, stall, and pigeon house, the latter converted from a stable. (fn. 362) The house, which then adjoined the churchyard, was described c. 1785 as 'one of the worst in the parish'. (fn. 363) In 1815 it was said to be 'a mere cottage' (fn. 364) and in the early 1830s as 'unfit'. (fn. 365) A house was built in 1836 on a new site and enlarged in 1840. (fn. 366) There were extensive farm buildings in 1941 and an apple loft attached to the house approached by an outside stair. (fn. 367) A new rectory house was built in the grounds in 1973 to designs by A. D. R. Caröe, and in 1974 the old rectory was sold. (fn. 368)

Pastoral Care and Parish Life

In 1354 the rector was allowed to serve in the household of Sir John of Clevedon for six months and to let his church. (fn. 369) A stipendiary chaplain, presumably in addition to the rector, served the church in 1450. (fn. 370) There was an endowed light in the church in 1548. (fn. 371) The rector was deprived, probably for being married, in 1554 and in 1557 it was reported that the rood was not restored, (fn. 372) suggesting a reluctance to accept the restored Catholic regime. In the early years of Queen Elizabeth's reign rectors were absent and curates served the parish. (fn. 373) A cup and cover were made in 1575 by the maker of the cup and cover at South Barrow. (fn. 374) Monthly sermons were not preached in 1606 and rectors were reported non resident in 1629 and 1634, (fn. 375) although there was a resident curate in the early 1620s. (fn. 376) The present, much restored, altar table bears the date 1634. In 1639 prayers were neglected by an absentee curate. (fn. 377) At least two members of the Mullett family succeeded each other in the mid 17th century and were followed by two members of the Squibb family. (fn. 378)

Joseph Dauncy, rector 1706–29, cared for at least one mentally ill patient. (fn. 379) The registers begin in 1728 and also from Dauncy's incumbency is the 1719 coat of arms. (fn. 380) In the 1780s there were a singers' gallery, removed in 1903, a communion rail with turned balusters and a pulpit and reading desk of 'fine old panelled wainscot'. Seating was in five pews and backed oak benches. The walls were decorated with texts in 'coarse' painted ovals. (fn. 381) A painting in the church, probably King David with his harp, may have come from the gallery. (fn. 382) About 1780 there were about five communicants (fn. 383) but the rector, who lived in Charlton Adam, preached every week. (fn. 384) William Hungerford Colston, rector from 1810–39, lived at West Lydford, where he was also incumbent, and took services at Keinton alternately at 11 am. and 2 pm. (fn. 385) The parish church was probably increased in size in his time and a paten was given in 1819. (fn. 386) He was also rector of Clapton in Gordano and employed a curate. (fn. 387) By 1840 there were two services each Sunday and the rector was resident. (fn. 388) Shortly afterwards the church was extended and in 1843 a curate was employed. (fn. 389) Congregations in 1851 numbered 25 in the morning and 70 in the afternoon but the rector drew attention to the strength of dissent. (fn. 390)

By 1870 communion was celebrated about six times a year after morning service. (fn. 391) By 1876 services were held at 11 am. and 7 pm., both with what the churchwardens described as long sermons, and communion was celebrated every Sunday at 11 am and twice on feast days. (fn. 392) A surpliced choir had been introduced by 1877. (fn. 393) The communion rail, pulpit and lectern were replaced in the later 19th century, the pulpit in 1878. (fn. 394) In the 1880s and 1890s the board school was used on weekdays as a mission chapel. (fn. 395) The reseating scheme of 1904 reduced the number of sittings in the parish church but the total of 112 was thought to be sufficient for the 50 people who usually attended. The same year the bishop gave an almsdish to the parish. (fn. 396) In the 1920s there were still two services each Sunday and in 1923 there were 30 Easter communicants. The rector gave a new chalice in 1929. In 1953 the number of Easter communicants had risen to 49 and there were normally services three times on Sundays. The same pattern was maintained in 1973 when there were 61 Easter communicants. (fn. 397) A toilet and kitchen were built in 1998 on the north side of the tower in place of a boiler room. (fn. 398) A lych-gate and small car park were made in 2002. By 2005 there was only one Sunday service but a weekday communion service was sometimes held in one of the nursing homes. A short communion service for families was introduced in 2005 and there was an Ark Club for the young. (fn. 399)

57. Keinton Mandeville church in 1834, not long after major building work was completed, including the destruction of the octagonal tower which was probably similar to that of Barton St David.

Church Building

The medieval church, which was 54 ft long but only 18 ft wide, had a simple nave and chancel of the 13th century. Both survive together with a simple font, probably, of the 12th century. The octagonal north tower 11 ft in diameter and 40 ft high with a conical roof, joined to the nave through an arched passage (fn. 400) was demolished in 1834 and replaced by one at the west end of the nave, very plain and considered of a 'rather bad design'. (fn. 401) The medieval tower may have reflected the relationship between Keinton and Barton St David, which still has an octagonal tower. (fn. 402) There are three bells, two of 1788 by William Bilbie of Chew Stoke, the treble of 1824 by Cockey of Frome, although sometimes said to be medieval. They were unsafe for ringing in the later 20th century. (fn. 403)

In 1840 the church was said to be under repair and a grant for additional sittings and enlargement was obtained in 1841 including an extended gallery. (fn. 404) Those sittings were in a new, three-bay north aisle by Petvin and Merrick, builders, which in 1903, initially without faculty, was incorporated into the body of the church by the removal of the arcade and the lowering of the north wall. (fn. 405) The whole building was re-seated in 1904 to a plan by Mr. H. E. Cox of Keinton. (fn. 406)

PROTESTANT NONCONFORMITY

Nonconformity flourished in the 19th century and in 1810 a house was licensed for use by an unspecified congregation. (fn. 407) Several branches of Methodism were represented including the Wesleyans in Queen Street and the Bible Christians, later the United Methodists, in Castle Street. A Primitive Methodist minister was resident in 1910 but had no chapel. (fn. 408) Of the three 19thcentury chapel buildings only the Wesleyan chapel remains in use.

Wesleyan Methodists

A congregation described as Wesleyan and within the Glastonbury circuit met in a private house from 1816 and in 1834 was using a large room in the house of a stonemason. A chapel was built in 1843 at the edge of a quarry in what is now Queen Street and had services twice on Sundays and on Tuesday evenings. (fn. 409) Licences issued in 1844–5 may have been for that chapel. (fn. 410) In 1851 there were adult congregations of 67 in the morning and 122 in the evening. (fn. 411) One of the circuit ministers lived in the village in 1851 and the 1860s. (fn. 412) In 1881 a blacksmith and a stonecutter were Wesleyan preachers. (fn. 413) The chapel was strongly supported by stonecutters although it had pew rents until c. 1903. By 1906 a Sunday school was held in the morning and the afternoon when the chapel had come to be part of the Mid-Somerset Mission. An organ was installed in 1907 and there was a choir. The noted Leigh Road Methodist choir from Street were regular visitors to the chapel in the 1940s. In 1918 there were 39 members, in 1947 there were 42, and in 1965 44 members, including those formerly belonging to Castle Street chapel. A minister was resident in the village between 1938 and 1947. (fn. 414) A baptism register survives for 1939–69 when many people from elsewhere including Weymouth and Torquay, presumably former residents, had their children baptised at Keinton. (fn. 415) By 1974 there were 14 members and members of the former churches at Lydford and Charlton had joined the Keinton church. (fn. 416) During the later 20th century the local preachers' meetings were held at Keinton. (fn. 417) In 2005 a service and Sunday school were held every Sunday morning. There was also a Friday Club for children.

The chapel building Built in 1843, it is a simple gabled box of local stone and Welsh slate over a partial undercroft lit by sash windows. The front of the chapel is blank except for entrance doors in a pointed arch under a datestone. Gothic side windows and wroughtiron railings and lamp brackets are the only embellishment. There is a 20th-century western extension and an east gallery.

Bible Christians

Bible Christians meeting in 1851 traced their origin in the parish to a chapel built and licensed in 1832 in what was later Castle Street, perhaps in succession to premises licensed in 1824. (fn. 418) The afternoon congregation in 1851 numbered 60. (fn. 419) The chapel was extended in 1859 (fn. 420) but was replaced by a new building on the opposite side of the street in 1880–1, (fn. 421) to the cost of which Sir Henry Irving may have contributed. (fn. 422) The old chapel became the Temperance Hall, which was still in use in 1947. (fn. 423) A preacher, absent on Census Day 1881, may have belonged to the Bible Christians and one of their preachers boarded near the chapel in 1891. (fn. 424)

United Methodists

The new Bible Christian chapel in Castel Street became a United Methodist chapel in 1907 and was supported by the stonecutters but later trustees included shopkeepers and a schoolmaster. (fn. 425) The chapel had 26 members in 1947 and two services were held each Sunday. The roof was in a bad state in 1949 and in 1950 a majority of members wanted to approach the Queen Street chapel with a view to union. By June 1950 the Castle Street chapel had closed for worship.