A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Barton St David', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10, ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp122-141 [accessed 23 April 2025].

'Barton St David', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Edited by Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online, accessed April 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp122-141.

"Barton St David". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online. Web. 23 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp122-141.

In this section

BARTON ST DAVID

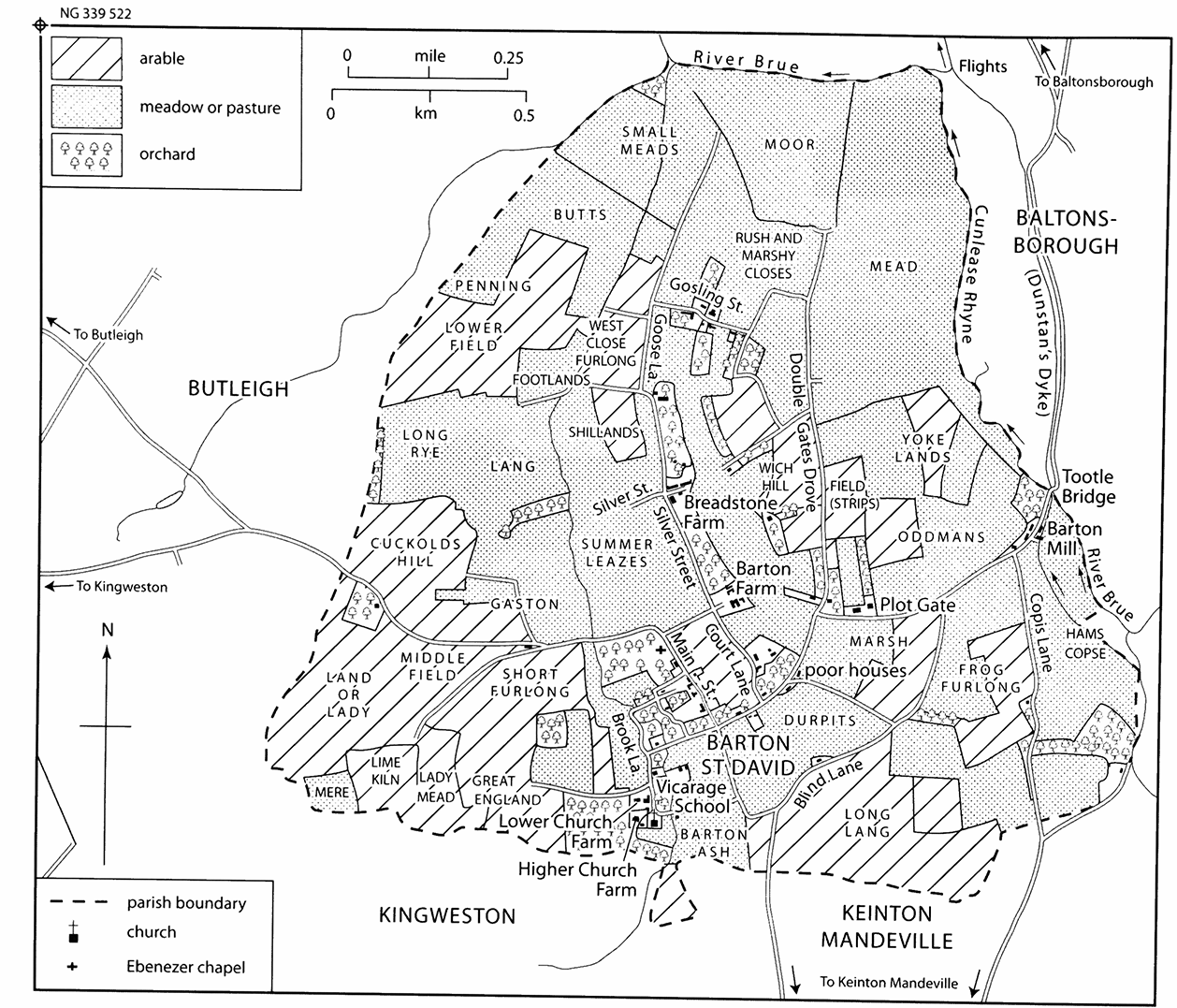

45. Barton St David 1841

The parish in 1841, showing the village on the southern side near the arable land. Several farmsteads had been established among the grasslands, which occupied the low-lying land bounded by the river Brue and Cunlease Rhyne, but had access to arable land, small areas of which remained in 1841.

THE PARISH of Barton St David lies west of the river Brue 7.25 km. (4½ miles) south-east of Street. It was described as low, fruitful, well-wooded and sufficiently watered in the late 18th century. (fn. 1) The parish comprises the eponymous village in the far south, formerly isolated farms to the north at Silver Street and Gosling Street, and the mill by the Brue. Later 20thcentury infill has made the formerly sprawling village appear more nucleated. The parish is compact in shape with gently curving boundaries formed by a millstream and Cunleaze rhyne on the east, the Brue to the north, and small streams on the south and west. (fn. 2) The parish was simply called Barton in the Middle Ages, the name possibly implying an outlying grange, although sometimes Barton by Kingweston. (fn. 3) It was only from the mid 16th century that the addition of Davy or David was used occasionally. (fn. 4) From the later 18th century the form Barton St David came into regular use. (fn. 5) The origins of the suffix are uncertain, as the dedication of the church was originally All Saints. (fn. 6) Barton Ash, recorded in 1511, probably marked the place where Blind Lane crossed into Keinton Mandeville. (fn. 7) A field there was known as Bartons Ash in 1841 and others called Land Mere lay in the south-west corner where Barton, Butleigh and Kingweston parishes met. (fn. 8) The northern half of Mill Hams between the millstream and the Brue was included in Barton parish as was a close of arable in Keinton Mandeville because it had been part of Barton glebe. (fn. 9) The parish was said to measure 945 a. in 1841, (fn. 10) but 988 a. in 1921. (fn. 11) Under the 1982 Yeovil Parishes Order further areas of the former North field at Keinton Mandeville with a few houses were transferred to Barton in exchange for land in the south-east near King a Mill, leaving a parish of 398 ha. (983 a.) in 1991. (fn. 12)

The far north of the parish lies on the alluvium of the Brue valley but most lies on gently sloping ground composed of Lower Lias clay rising to 60 m. (197 ft) in the extreme south west on Cuckolds hill or Cuckhill. (fn. 13) The slope is bisected by the Barton brook which runs from a pond in Kingweston along the west side of the village through Hurtle Pool beside the Butleigh road and into the Brue. (fn. 14) The Cunleaze rhyne may be the old course of the river before Dunstan's Dyke and Baltonsborough Flights were made. Bartonswaysshe, recorded in 1448–9, may have been in West Lydford. (fn. 15)

COMMUNICATIONS

Barton St David lies away from major roads and the village is accessed from Butleigh, Baltonsborough, and the Somerton–Castle Cary road. There are no through routes although a footpath directly linking the roads to Butleigh and Baltonsborough probably marks a cart route between the two villages recorded in the 18th century. Improvements to bridges near Baltonsborough mill led to the abandonment of that route by 1782. (fn. 16) Blind Lane from Tootle Bridge to the Somerton–Castle Cary road was important enough to be presented at the hundred court for its bad state in 1511. (fn. 17) By 1841 the wider lanes had been encroached on for cottages and gardens many of which remain. (fn. 18) The present roads in the parish involve many sharp corners and bends.

In 1686 Tootle or Toothill Bridge was declared to be in Baltonsborough parish because the owners of land there had gated and repaired it. The boundary had been a cross, which formerly stood in the southern side of the bridge. (fn. 19)

POPULATION AND SETTLEMENT

Very little evidence of prehistoric activity has yet been found in the parish apart from a Neolithic greensand axe. In the late 19th century several Roman brass and copper coins were found but the precise location is unknown. (fn. 20)

The former open fields lay either side of the village on land rising up from the Brue valley where the common meadows and moor lay. La Lhupeghete was recorded in 1327 (fn. 21) and Lippgate Street in 1779. (fn. 22) There is no record of a park in the manor and in 1636 the park stile and land near Park field on the boundary probably referred to Butleigh park. (fn. 23) However, a small pasture was called Park Close in 1779 (fn. 24) and since 1861 the southern part of Court Lane from the village to Gosling Street has been known as Park Lane and may be the former Lippgate Street. (fn. 25)

It is very difficult to determine early levels of population as for tax and other purposes Barton also comprised Keinton Mandeville and later Kingweston parishes. Licence was given for a cottage to be built on the waste in 1617 (fn. 26) and there were about 31 houses in the parish c. 1670. (fn. 27) In 1751 the parish was said to be small with few inhabitants (fn. 28) but in the 1780s there were c. 220 people in c. 40 houses, many said to be neat and comfortable. (fn. 29) By 1801 the population was 288 and rose rapidly to 358 in 1821 and more gradually to a peak of 455 in 1841. (fn. 30) In 1821 there were 48 houses and 52 in 1831. (fn. 31)

The central area of the village by the 19th century consisted of a rectangular close of pasture, surrounded by lanes. Main Street, called Borough in 1861 possibly in error, links the three minor roads to Butleigh, Baltonsborough and Keinton Mandeville and had buildings on the west side with back alleys and long plots down to the brook, several of which were not developed. Parallel with Main Street was the lane to the moor in three sections: Park Lane called Court Lane in 1831, (fn. 32) Silver Street, and Gosling Street with side droves and widely-spaced principal farms and cottages, on the east side. The church, former rectory, and the two Church farmhouses, one of which may be medieval, lay together apart from the rest of the village, almost on the boundary with Keinton Mandeville and west of the brook. There is insufficient documentation to show if this unusual pattern reflects landownership or whether the church lies in a primary settlement and the other farms represent expansion of cultivation into the Brue valley in the medieval period. Settlement seems to have expanded east later with cottages built on plots taken out of the East field by 1723 (fn. 33) and known as Plot Gate. (fn. 34)

A string of farms extends north from the present Park Lane between the two former arable fields, notably Breadstone farm in Silver Street and Lower Barton farm in Gosling Street. The name Gosling Street, Goslane in 1672 (fn. 35) and Goose Lane in the 1860s (fn. 36) was also given to the hamlet of a farm and a few cottages. (fn. 37) There were seven houses there in 1861 but only three in 1891, all unoccupied apart from Lower Barton Farm. (fn. 38) Cottages had been built at Barton mill and on roadside waste south of the village by 1841 when there was a house out on the road to Butleigh, now Jarmany Hill. More houses were built there in the later 19th century when the area became known as Jarmany. (fn. 39) During the 20th century new houses have been built at Jarmany and Silver Street.

The population declined gradually from 442 in 1851 to 277 in 1901. Although cottages in rows and yards were recorded in 1871 (fn. 40) and a house at St James Square in 1881, many houses were unoccupied. (fn. 41) Two decayed cottages were recorded in 1892 (fn. 42) and in 1901 there were eleven permanently uninhabited dwellings. (fn. 43) The population fell to 229 by 1921 but four local authority houses had been built by 1927, probably to replace some of the many substandard cottages. (fn. 44) There were 77 houses in 1931 but 82 in 1946. (fn. 45) The population rose to 271 in 1931 and remained fairly stable until the 1970s when it rose from 281 in 1971 to 381 in 1981 as infilling and farmyard conversions provided new homes. By 1991 the resident population was 493, partly owing to boundary changes, but by 2001 the population had reached 528. (fn. 46) Substantial housing development has taken place in the south-west of the village along and between lanes incorporating the church and formerly isolated houses into a continuous built-up area. Bungalows and houses have also been built towards Plot Gate filling in most of the space between that settlement and the main part of the village.

Farmhouses and Cottages

In the village large numbers of 20th-century houses, including large ones near the brook, dominate a few older houses including the 17th-century Rose Cottage, Park Lane, which was remodelled in the 19th century, and Plot Gate Cottage dated 1723 and standing within a small later row at the end of Double Gates drove. Several houses in the village and beyond belonged to farms and some still have farmbuildings, those at Higher Church farm and Breadstone House having been converted into dwellings. Manor House and Lower Church Farm, just north of the church, are the earliest houses, both much rebuilt from the 17th century. East of the church, Higher Church Farmhouse appears to be a mid 17th- or 18th-century building. Its barn is now a dwelling called Mapstone Barn. The former Breadstone Farm, north of the village, which has a handsome symmetrical three-bayed, two-storeyed facade with gabled attics, is said to be dated 1692 and bears the initials of Stephen Slade, his wife and two others, possibly a son and married daughter. It is attached to an extensive range of farmbuildings, which stretch along the side lane to the north. A new Breadstone Farm was built opposite in 1986. The early 18th-century two-room house Withy Lane Farmhouse was extended in later in the century and again at the side, possibly for a store. Home Farm was rebuilt c. 1800. (fn. 47)

46. Breadstone Farm, dated 1692 with the initials of Stephen Slade, his wife and two others, possibly a son and married daughter.

LANDOWNERSHIP

Barton was probably a single estate including at least part of Keinton Mandeville but had been divided in two by 1066 and the Keinton lands separated from it by 1086. In 1066 the larger Barton holding was held by Edwulf but in 1086 Edmund son of Pain held it of the king. The smaller holding held by Alstan in 1066 was held by Norman under Roger de Courcelles in 1086. (fn. 48) The descent of the smaller holding is obscure and the pattern of freeholds in the parish is difficult to unravel. Although many freehold farms date from the late 17th and 18th-century break-up of the main manor, there were others in existence in the early Middle Ages and some were held of manors outside the parish including Butleigh and Sparkford. The lack of manorial and other early material makes it difficult to trace the ownership of most of them but at least one may have resulted from provision for relatives of the owner of the manor. Estates were built up and dispersed again notably by the Taunton and Bush families in the 17th and 18th centuries. By the 19th century landownership consisted of single farms. (fn. 49)

BARTON MANOR

By 1198 Edmund's holding may have come to Pain of Walton (fn. 50) who was involved in litigation with Reginald of Albemarle (fn. 51) and in 1200 with William Briwerre. (fn. 52) A three-way settlement appears to have been made under which Pain and William did homage to Reginald for a fee in Barton, Holcombe and Walton. (fn. 53) Possibly that was an arrangement to divide the fee, as William's son William Briwerre (d. 1233) was recorded as overlord of Walton. (fn. 54) However, in 1303 and 1361–3 Barton manor was held of William de la Zouche, descendant of William Briwerre's niece and co-heir Eve de Braose. (fn. 55) In 1513 it was said to be held of Glastonbury abbey, (fn. 56) possibly because part of the manor was in Whitstone hundred, (fn. 57) in 1515 of the queen as of Bridgwater castle (fn. 58) and in 1587 of the Crown in chief. (fn. 59)

Pain of Walton was alive in 1205 but in 1206 Michael of Walton disputed possession of a tenement in Barton with John Wake (fn. 60) who held the issues of Barton in 1212. (fn. 61) In 1232 Michael son of Pain (fl. 1242), probably the same Michael, secured from John de Meysi a quitclaim to 3½ hides in Barton. (fn. 62) Sir Alan of Walton, who married Julian de Reigny c. 1243, (fn. 63) held Barton from at least 1259. (fn. 64) Sir Alan (d. 1275) (fn. 65) was succeeded at Barton by his son Nicholas (fn. 66) but Alan had settled two tenements on his daughter Julian. She was dead by 1278 when her husband Nicholas of Bridport released the property to Nicholas of Walton. (fn. 67) Nicholas, (fl. 1327) (fn. 68) was succeeded by his son Stephen but his younger son John Mody held a house and lands. John's sons Nicholas and Geoffrey Mody died childless and the property passed to the Wake (fn. 69) and Gerard families but cannot be traced after the mid 16th century. (fn. 70)

Stephen of Walton settled the manor in 1338 (fn. 71) on himself and his second wife Christine for life and then on his son Alan (d. by 1361) and Alan's wife Isabel who died in 1361 holding two parts. Alan's son John came of age in 1363. (fn. 72) John (fl. 1392) (fn. 73) was followed by his widow Edith who in 1406 settled Barton after her life on her son Thomas, who came of age c. 1412, and his wife Joan Russell and settled other lands on Joan. (fn. 74) By 1435 Barton was held by Thomas's son Richard who was succeeded by John possibly before 1480. (fn. 75)

John Walton (d. 1513) settled Barton manor on his son William and William's wife Joan. William (d. c. 1515) left an infant son Robert. (fn. 76) In 1517 Queen Catherine granted Joan custody of Robert and his estates until he came of age. (fn. 77) In 1521 Joan settled land in Barton on her marriage to Thomas Hassage. By 1528 she was the wife of Sir Nicholas Wadham and the Wadhams appear to have been resident and may have built Barton farm. (fn. 78) The same year Robert Walton entered into a settlement of Barton manor and other estates (fn. 79) but when Joan died in 1557 her sons Robert and Richard had died without issue and the heir was her daughter Isabel, wife of Christopher Cheverell. (fn. 80) In 1574 Isabel (d. 1590), then a widow, let the manor for 800 or 850 years to her grandson Robert Cheverell, son of her eldest son Hugh, (fn. 81) and in 1587 she sold it in fee to Robert's son Christopher. (fn. 82) Robert lived at Barton in 1590 and was lord in 1612 but mortgaged his interest. (fn. 83) When Christopher died in 1623 he claimed to hold only an 18a. tenement, presumably because the manor had been settled on his wife Avice. He left infant daughters; Jane (d. 1623), Isabella, and Alice, later called Ann. (fn. 84) His widow Avice married William Bowerman of Brook (IoW), who held the manor in right of his wife in 1637. (fn. 85)

William's son by a former wife, Thomas Bowerman (d. 1677), farmer of the rectory in 1634, married Isabella Cheverell (fn. 86) and may have been resident c. 1664. (fn. 87) Isabella's sister Ann Cheverell married William Sandham of Chichester and unsuccessfully claimed a share of the Barton estate in 1646. (fn. 88) Both Avice and Isabella were dead by 1677 when Isabella's son John Bowerman mortgaged the manor in part to provide for his wife Mary. (fn. 89) John was dead by 1693 when his widow Mary (d. by 1706) and son William held the manor and assigned the term granted to Robert Cheverell to Sir Richard Grobham. The term was assigned by Sir Richard's executor in 1707 to Robert Cambridge of London who assigned it the next day to John Still the younger of Shaftesbury. Not recorded again, it was presumably merged with the freehold. (fn. 90)

In 1706 William Bowerman agreed to sell the entire manor to John Gregory for £4,200 but failed to reveal the existence of mortgages for £1,200 and interest held by Sir Richard Howe, Sir Richard Grobham's executor. John claimed he was pressured to allow the demesne farm to be sold, that leaseholds intended to be sold to tenants had been relet or sold by William who retained the proceeds, that he had been put to great expense travelling to see Bowerman, that tenants had neglected their farms and buildings and felled timber, and that the 'dregs' of the manor would be difficult to sell. (fn. 91) William continued to sell houses and lands to tenants (fn. 92) and the demesne farm was bought by William Howe in 1707. (fn. 93) In 1740 William Bowerman and his wife Margaret sold the rest of the manor to Thomas Keate of Somerton (d. 1748). (fn. 94) However, 'remains of the manor' were also said to have been sold to William Peirs. (fn. 95) Joan Keate c. 1783 (fn. 96) married the Revd Walter (fn. 97) Wightwick who held the lordship in 1788. (fn. 98) Having sold the last small parcels of land c. 1797, (fn. 99) Wightwick sold the lordship in 1806 to Wm Dickinson of Kingweston. In 1825 Dickinson bought Church, now Higher Church, farm (c. 60 a.) from the Welchman family who had inherited it from Richard Phelps (d. 1725). (fn. 100)

Demesne Farm

The demesne farm, known as Bowermans (c. 265 a.), was acquired by William Howe of Somerton (d. c. 1731), for £1,643 in 1707. (fn. 101) William's son John (d. c. 1764) was followed by his widow Margaret who gave it in 1782 to her only surviving son William. In 1796 it was settled on the marriage of William Howe and Matilda Woodville but by 1798 it had been divided into two farms and heavily mortgaged. In 1801 it was sold to John Smith (d. 1808), fourth husband of the dowager Viscountess Dudley and Ward (d. 1810). In 1809 the reversion, on the death of the Hon. Mrs Catherine Leslie and the viscountess, was sold to William Jenkins, owner in 1832. (fn. 102) Most of Jenkins's estate, an amalgamation of three farms known as Barton farm including Callows and other land he bought in 1814–15, was left to his daughter Marianne, wife of Edward Colston (d. 1847). (fn. 103) Her second son William Jenkins Craig Colston divided and sold it in 1866. (fn. 104) The only surviving farmhouse was Barton, later Manor, Farm, which has early 16thcentury fabric and was substantially rebuilt in the early 17th century to provide principal rooms in a west wing with a new entrance and stair, and rooms in the existing two-storeyed entrance porch. It may be the house with nine hearths occupied by Thomas Bowerman in the 1660s, although Thomas had demolished three. (fn. 105) It was extended and altered in the 19th century to provide dairy, cheese room, and store, and is now known as the Manor House. (fn. 106) The manor court was probably held here: the lane from the village to the farm was formerly known as Court Lane (fn. 107) and fields to the east were called Court Barrs. A large building south of the house in Court House Ground was demolished in the later 19th century for new farm buildings. (fn. 108)

The Cotele Manor

The smaller Barton holding, held by Alstan in 1066 and by Norman under Roger de Courcelles in 1086, (fn. 109) may be the fee later in Whitstone hundred which like other Courcelles holding was held of the barony of Curry Malet until 1508 or later. (fn. 110)

In 1303 William Cotele, son and heir of Sir Elias (fl. 1248–91), held a fee in four estates including Barton. (fn. 111) Sir William was dead by 1327 (fn. 112) and his widow Maud died c. 1334. (fn. 113) Elias Cotele (d. c. 1336), possibly William's son, left a daughter Edith, wife of Oliver Dinham, (fn. 114) but by 1346 the fee was held by Sir John de Palton. (fn. 115) Sir John (fl. 1361) had been succeeded by 1374 by his son Sir Robert (d. by 1400) who married Elizabeth Asthorp, Edith Cotele's great-granddaughter and sole surviving heir. (fn. 116)

Elizabeth survived her husband by whom she had at least three sons who died childless: Robert (d. 1400), (fn. 117) Sir William de Palton (d. 1450), (fn. 118) and John (d. before 1450). (fn. 119) Sir William appears to have settled Barton on his second wife Anne (d. 1465) who married Richard Denzell. (fn. 120) In 1500 Sir Richard Pomeroy and his wife Elizabeth (d. 1508), (fn. 121) daughter and heir of Richard Denzell, (fn. 122) settled Barton on their younger son Thomas (d. 1508) whose successors were his elder brother Sir Edward (d. 1538) and Edward's son Sir Thomas (d. 1566). (fn. 123)

Subsequent descent is unclear but both the Jennings and Peirs families later claimed to hold manors of Barton. (fn. 124)

JENNINGS' MANOR OF BARTON AND KEINTON

The origins of the estate are obscure but it may possibly have been former Barton family property. In 1278 Avice, widow of Robert of Barton (d. by 1254), held dower in a carucate of land with her then husband Walter de la Wyle, the inheritance of John of Barton. (fn. 125) In 1282 Robert's brother, also Robert, held a house, a carucate of land, and a sixth of a mill, possibly including the house and 80 a. released to him in 1263 by Sir Martin of Leigh and his wife Alice. (fn. 126) Both estates came into the Backwell family and possibly into the possession of the lords of Keinton Mandeville who had lands in Barton by 1351. (fn. 127)

Marmaduke Jennings (d. 1567) had land in Keinton in 1566, held by Sir William Hody in 1488, (fn. 128) and a capital messuage and lands in Barton, which his son Robert (d. c. 1593) described as Barton David manor in 1580. (fn. 129) Held freely of Sparkford manor in 1630, the manor only covered c. 100 a. with five messuages in Barton and Keinton Mandeville. (fn. 130) Robert's son Marmaduke (d. 1625) was succeeded by his son Robert (d. 1630) and Robert's infant son Marmaduke (d. 1658), whose estate was described as the manor of Barton and Keinton, and perhaps most land lay in the latter. (fn. 131) The elder son Marmaduke (d. 1660 s.p.) left his younger brother Thomas a minor and the estate was held by their mother Elizabeth and her second husband Jonathan Pitt. In 1672 the family estates were settled on the marriage of Thomas (d. c. 1679) and Mary Speke. (fn. 132) Their son Thomas died in 1695 and in 1707 the surviving children, Mary and Elizabeth, released their shares to their mother Mary (d. 1715). (fn. 133) Mary left the estate, described as land in Keinton, in trust for sale and there is no further of record of the manor. (fn. 134)

OTHER ESTATES

Prebend

Robert de Meisy, clerk, gave Barton church to Wells and Bishop Jocelin c. 1215 (fn. 135) and the first recorded prebendary was Nicholas of Walton, possibly a younger brother of the lord of the manor. (fn. 136) Barton was not listed as a prebend in 1291 (fn. 137) but in 1298 the prebend was valued at £8, about three quarters of the value of the church. (fn. 138) By 1319 it was expected from the dean and chapter's jurisdiction, (fn. 139) although they took the income during vacancies. (fn. 140) A pension was due to the prebend from Keinton Mandeville church in the late 14th century. (fn. 141)

By 1535 the prebendary took the whole income of the church as rector and paid the vicar a stipend. (fn. 142) Prebendaries were often pluralists and let the prebend, one such was the king's chaplain George Carew who was licensed to serve abroad in 1547. Lessees of the prebend, who included Christopher Cheverell in 1617 and Thomas Bowerman in 1634, were required to pay £8 to the vicar who also had the house. In 1636 the rectory comprised c. 46 a. arable, 9½ a. meadow, 11 a. pasture and common for ten beasts, a watermill, and all tithes and offerings. (fn. 143) In 1707 land and tithes were valued at only £18 9s. 1d. (fn. 144) but in 1661 a man paid £315 for a lease including 67½ a. of glebe. (fn. 145) In the 18th and 19th centuries lessees, from 1765 the Foster family of Wells, (fn. 146) paid only £5 rent to the prebendary. (fn. 147) In 1836 the gross rent the lessees received for the prebend was £130 of which £45 was spent on the vicar's stipend, land tax on 54 a., and other costs. The tithes, said in the 1780s to be taken in kind, were commuted in 1840 for £170. (fn. 148) In 1852 the reversion was conveyed to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. (fn. 149) In 1870 the lessees surrendered their interest and the tithe rent charge to the Commissioners who obtained an order to sell the remaining land in 1872. (fn. 150)

Peirs Family Estate

Augustine Pyne (d. 1555), as grandson and coheir of Robert Appleton, held 75 a. in Barton of Butleigh manor. (fn. 151) It has been suggested that it was the later Peirs estate (fn. 152) although the overlordship makes that unlikely. Land in Barton belonged to West Bradley manor from 1620 (fn. 153) or earlier. A small freehold called Callows, later part of Lower Barton farm, (fn. 154) owed 1s. quit rent to West Bradley but payment had ceased before 1811. (fn. 155) Most of the Barton land in West Bradley manor formed part of the demesne in 1653 and descended to William Peirs (fn. 156) who in 1729 and 1750 claimed to be lord of a Barton manor. (fn. 157) That lordship was not claimed by his successors.

William Peirs (d. 1764) was followed by his son, also William (d. s.p. 1765), who left his estate in trust for the children of his great-niece Augusta (d. 1766). In 1767 the estate was held by Augusta's husband, Lord Burghersh, later earl of Westmoreland. It passed to Augusta's younger son Thomas Fane (d. 1809) who in 1816 settled four messuages and at least 254 a. on the marriage of his son John Thomas (d. 1833) to Mary Anne Shrimpton Jackson (d. 1836). Their only child Augustus sold off some property. (fn. 158) After he died childless in 1840 his grandmother Anne Fane administered the estate. In 1841 Augustus's great uncle the earl of Westmoreland sold the remaining 217-a. farm to Joseph Motley. (fn. 159) It was later bought by William Dickinson and descended with his Kingweston estate as Home farm (195 a.). (fn. 160) The house was rebuilt c. 1800, with only three bays and two storeys and a Tuscan porch.

In 1756 William Peirs purchased a small estate, which John Semer bought from William Bowerman in 1707. Peirs immediately conveyed it to his daughter Lucy (d. s.p. 1763) who devised it to her niece Frances Bertie (d. s.p. 1771). (fn. 161) Frances left it to her mother Elizabeth, Lady Bertie, who conveyed it to Henry Fane in 1771. Henry secured a release of rights by John Semer who should have inherited part of the land. In 1806 it was sold to Edward Indoe (fn. 162) in whose family it remained until 1882 or later. (fn. 163)

Allambridge Holding and Lower Church Farm

John Allambridge (d. 1590) held two messuages and 180 a. in Barton and Keinton of Barton manor. In 1597 his heir was Stephen son of Thomas Allambridge, a minor (fn. 164) who appears to have died the same year. William Allambridge of Dorset sold 100 a. in 1597 to Alexander Pester and the rest to William Kelway. In 1610 Pester conveyed a third of the property to John Parker who had provided part of the purchase money but it is not clear what became of the rest. (fn. 165) By defaulting on several mortgages the Parker family lost their land and it was mainly acquired by William Jenkins in 1814. (fn. 166)

William Kelway (d. 1612) left a house and lands held of Barton manor, bought from Allambridge, to his son Richard (d. 1637). (fn. 167) John Taunton of West Lydford bought William Kelway's house and 90 a. in 1689 and later. (fn. 168) Other Kelway land was later part of the Peirs family estate. (fn. 169) In 1710 John Taunton also acquired the estate, which Robert Gregory had inherited from his father Robert (d. 1641). (fn. 170) John's successor Thomas Taunton (d. 1767) added a smallholding at Gosling Street to his estate, which was settled in 1741 on his son Samuel (d. 1762) for his marriage to Elizabeth Chapman (d. 1757). Samuel's eldest son Thomas (d. 1828) inherited two farms and bought further land. (fn. 171) He left some land to his grandson William Knight to provide for his other grandchildren but his heir was William Taunton of Worcester whose younger brother, Thomas, was his tenant. (fn. 172) In 1840 William Knight's widow and daughters sold their land to William Taunton. In 1866 William conveyed his estate, including Lower Church farm, to James Wyatt Baker who divided and sold the holding the same year. (fn. 173) The house at Lower Church farm, north-west of the church, has a late medieval core with evidence of an open hall but was largely rebuilt in the mid 17th century to a high standard with a symmetrical threebayed front, Hamstone ovolo-moulded windows, one nine-panel ceiling, and some plasterwork; it was extended later. (fn. 174)

Cudworth Glebe

In 1729 Thomas Curtis of Shepton Mallet and the Governors of Queen Anne's Bounty settled a 30-a. estate, including Roche's tenement, on the incumbent of Cudworth. The farmhouse, stable, and piggery were destroyed by fire in 1876 and not rebuilt as the land was too scattered to let as a holding. The land was divided and sold in 1909. (fn. 175)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

AGRICULTURE

There are few early records of Barton and nothing is known of the management of the medieval estates or how they, and possibly the larger freeholds, derived from the unusually large demesnes in 1086. There appear to have been only two open fields, East and West divided into furlongs, some called Hill, Down, and Hanger reflecting their position on rising ground, parts of which were not inclosed until 1843. (fn. 176) Some pasture lay in paddocks around the village and also probably between the west field and the meadows where later fields were called Butts and Pennings. A second Penning Ground near King a Mill was shared with Keinton Mandeville. (fn. 177)

Estates and farms were built up in the late 17th and 18th centuries, mainly by men who had made their money in trade, only to be divided again in the 19th century after the family moved away or left heirs who did not live in the parish. Land from farms broken up in the later 19th century was probably acquired by owners of adjoining farms and the number of holdings did not increase significantly. (fn. 178) An unusually large number of new farms were created in the 20th century. (fn. 179)

The 11th to the 16th Century

Barton was a divided five-hide estate in the 11th century with land for eight ploughs, although only three were recorded. It was said to have had an additional two hides, which had been added to estates in Keinton Mandeville. The larger estate had 3½ hides of which all except a virgate, held by two villeins and four bordars, was demesne but worked by only one serf. The demesne also comprised 50 a. of meadow, 60 a. of pasture, five beasts, and four pigs. There were six cottars. The smaller estate had one hide in demesne with 24 a. of meadow, 24 a. of pasture, and 18 pigs. A half hide was worked by two villeins and four bordars. The value of the two estates had fallen from £8 to £4 10s., (fn. 180) possibly because of a reduction in arable and population. Expansion of arable followed by reduction in the Middle Ages probably accounts for ridge and furrow in Butts pasture, Small Meads, and Rush Croft meadow on low-lying land in the north of the parish indicating cultivation of what now appears unsuitable ground. (fn. 181) Common pasture was recorded in the later 13th century. (fn. 182)

An estate held by the Marshal family since at least the later 13th century, (fn. 183) included two tofts and two messuages with 155 a. of arable and 13 a. of meadow in 1324 indicating that four tenements had been converted to two. (fn. 184) Nothing is known of the management or composition of the manors. In 1327 a tenement in La Lhupeghete, later Lippgate Street, was held in villeinage. (fn. 185) It may be that some of the many freeholds which included the Marshal family's 200 a., the c. 100 a. bought by the Gilbert family from Joan, wife of William Hannam, in 1447, (fn. 186) a roofless 100-a. tenement in the 1550s, and possibly the later Church farms, may have been former demesne. (fn. 187)

In 1596 a husbandman left his house to a kinsman with orders not to remove the maltmill from the hall. (fn. 188) Pasture for oxen in the common moor was recorded in deeds from 1597 but most pasture was in closes. The East and West fields were open arable and there was a common meadow. (fn. 189) A husbandman had sheep stolen in 1612. (fn. 190) Goslane, later Gosling Street, may have been the lane along which geese were driven to the moors. (fn. 191)

The 17th and 18th Centuries

In 1636 the prebendary and the vicar had arable in the two open fields and beast leazes in Barton moor. The former also had both inclosed and several meadow, divided between west and east furlongs, a close of pasture taken out of the East field, and had exchanged open arable with another landholder. Another close was taken out of the East field, which paid 1s. in lieu of tithe, the two halves of Board meadow were tithed in alternate years, and provision was made for tithing grass mown on summer pastures. Most tithes, including orchard fruit, were paid in kind. (fn. 192) A new cottage was let in 1637 with inclosed arable, later pasture, called Durpits and open arable in 12-a Furlong in West field. The rent included a well-fed goose. (fn. 193) Land had been inclosed out of the West field for pasture by 1653, but the common meadow remained several. Oxen leazes or shutes were recorded in 1653, usually six or more to a tenement, and in 1661 the prebendary was allowed ten rother cattle in Barton moor. (fn. 194)

A 50-a. leasehold had a ruined house in the 1640s and was let to a farmer in Kingweston. (fn. 195) Many parishioners were too poor to pay hearth tax c. 1665; two houses had hearths, which had fallen or been pulled down, and only two had more than two hearths. (fn. 196) In 1667 two men were allowed to build a cottage on the waste. (fn. 197) However, both Higher and Lower Church farms were largely rebuilt at this period and a cart shed, cheeseloft and cider house at the latter date from the same period although those may not have been their original uses. Stephen Slade of Barton bought land in 1679 from Henry Cox and probably built the farm, later known as Breadstone or Broadstone, at Silver Street in 1692. (fn. 198) The farm remained in his family for c. 150 years and John Slade (d. 1782) bought further land. (fn. 199)

By 1672 Barton moor was inclosed and c. 2 a. to 4 a. allotted to leaze holders, (fn. 200) although leazes continued to be recorded in deeds. (fn. 201) By 1683 some allotments were meadow and part of East field was pasture. (fn. 202) Flight close by the river, recorded in 1684, was later said to have been taken out of the common meadow, which was later inclosed and divided by the parallel Lower and Middle Rhynes draining into the Brue. (fn. 203) Englands (15 a.) was described in 1698 as lately inclosed out of the West common field and adjoining a similar inclosure. (fn. 204) A field called King a Mill had been divided by 1710 (fn. 205) and new closes in the field were recorded in 1738. (fn. 206)

A survey of the manor in 1700 listed demesne, cottages, and twenty tenements including the mill and a roofless tenement. (fn. 207) Lang Furlong in West field was recorded in 1701 and Maple Furlong in 1724 (fn. 208) but by 1742 arable there was newly inclosed and arable in the East field was described as lately inclosed in 1704. (fn. 209) Holdings were relatively small and some houses were divided in the 18th century. (fn. 210) However, some families were investing the proceeds from trade in accumulating land by long lease or purchase although their estates were short-lived. John Bush (d. 1731), parchment maker, acquired land in 1692 and 1710 and bought a house and land at King a Mill from the manor in 1707. (fn. 211) His son John married local heiress Hester Goodson but before 1754 they moved to Baltonsborough. They disposed of their Barton land except for a small holding near King a Mill, (fn. 212) which was divided between the six children of Mary Bush (d. 1789), wife of John Dauncy (d. 1827). Between 1828 and 1840 the shares were bought by John Chancellor. (fn. 213) By 1881 the house was unoccupied and the land was probably absorbed into King a Mill farm, farmed from Keinton Mandeville, and a county council smallholding in the 20th century. (fn. 214) At the same period as John Bush was acquiring land so too was John Taunton, a mercer from West Lydford. (fn. 215) His successors gradually accumulated a substantial freehold and leasehold estate in Barton and neighbouring parishes during the 18th century. (fn. 216) They were among the highest land taxpayers and let two farms at rack rent in 1767. (fn. 217)

Common meadow was recorded in 1779 but by 1782 much arable had been inclosed and closes in West field were meadow. (fn. 218) In the 1780s the greater part of the lands were said to be meadow and pasture and the arable produced wheat and beans. (fn. 219) Inclosure probably enabled the creation of new smallholdings such as Withey Lane farm. (fn. 220) Three farms sold in 1798 had fewer that 100 a. and one had no house but two were rackrented. The land was mostly in closes, one farm had been inclosed since 1742. (fn. 221) A ½-a. withy bed was valued at 18s. a year. (fn. 222) Coppice grounds (15 a.) were recorded in 1742 (fn. 223) and the parish was said to be well-wooded in 1836 but this must have been with hedgerow trees, probably the fine elms recorded in 1780s, as no woodland was recorded in 1841 or 1905. (fn. 224)

The 19th and 20th Centuries

From 1809 or earlier the parish employed a molecatcher, and in 1854 agreed to pay him 1d. an acre. (fn. 225) The rack rents of two farms sold in 1809 were described as low but capable of improvement. Another had a good orchard producing 100 hogsheads. (fn. 226) By 1841 a 1½-a. close of glebe meadow had been converted to orchard. (fn. 227) In 1836 the parish was said to be chiefly arable and well cultivated with rich meadow and pasture by the river. A further 27 a. had been inclosed by mutual consent in 1835 leaving only c. 6a in unfenced strips. (fn. 228) However, conversion to grass had already begun and in 1841 arable covered only 269 a. and 540 a. was under grass. (fn. 229) A teasel grower was recorded in 1841, by 1871 one of two growers was unemployed but the other remained in business in 1881. (fn. 230)

The cider cellar, cheese room, and dairy at Higher Church farm may have been added after 1825 by William Dickinson. A threshing barn, engine house, cowstalls, and stables were provided later in the century as the acreage of the farm increased from 55 a. to over 100 a. with the addition of land in Kingweston. Dairies and cheeserooms were provided for other farms during the 19th century and several farms were rebuilt. Lower Church farm was extended to provide a waggon shed, cow house, stable, and threshing barn. (fn. 231) Several other estates in the parish were broken up during the 19th century. Breadstone farm, after the death of John Slade's daughter Elizabeth, separated wife of Thomas Foster, (fn. 232) childless in 1827 and of Richard Haydon (d. 1831), heir to her stepmother Anne (d. c. 1792), was divided and sold in the 1830s. (fn. 233) The largest lot, (c. 35 a.), was bought by Revd Aaron Foster and later settled on Robert Nash and his wife Elizabeth (fl. 1887). (fn. 234) The Taunton family estate was broken after the death of Thomas Taunton in 1828 and finally dispersed by William Taunton in 1866. (fn. 235) Also in 1866 William Jenkins Craig Colston broke up and sold his family's estate, the largest and most valuable in the parish. (fn. 236)

Fragmented ownership meant that in 1841 only three landowners had over 100 a., each a single farm although the largest, Edward Colston's farm (223½ a.), had formerly been three. Only eight other holdings were over 10 a. of which the largest was the 54-a. glebe. (fn. 237) Eleven farmers were listed in 1851 but only eight and a dairymen in 1851. (fn. 238) The reduction may have been partly due to the exchange and reorganization of land in 1843 when the remaining open fields, known as Barton field, north-east of the village, and Barton Lower field in the west of the parish were officially inclosed although the latter was in closes by 1841. (fn. 239)

In 1851 five farms had over 100 a., the largest 260 a., and employed 29 labourers of 60 recorded in the parish, many only young boys. (fn. 240) The number of labourers employed on farms rose to 38 in 1861 when the smallholdings and a dairy each employed two. (fn. 241) The incumbent complained that boys were out early and late bird-scaring and got wet. (fn. 242) In 1870 boys failed to attend school because there was a demand for labour at an early age and their parents were poor. Children were regularly taken out of school for bean planting, apple picking, potato digging, and haymaking and in 1902 were said to be absent every summer for field work. (fn. 243)

Orchard produce was an important crop by the 1860s and a cooper worked in the parish. (fn. 244) In 1841 64 a. of orchard and garden were recorded. Before 1866 a 1.5a. pasture near the church was converted to orchard (fn. 245) and by 1885 paddocks, meadow, and arable had been converted. (fn. 246) In 1935 one farm had several acres of orchard producing market and cider fruit. (fn. 247)

By 1881 a 200-a. farm had been divided and another was worked by a farmer who lived elsewhere. The number of agricultural labourers employed had declined to ten. (fn. 248) Several farms were owner occupied by 1905 when the largest was c. 195 a., most having fewer than 50 a., (fn. 249) and there was only 192½ a. of arable, whereas grass covered 795 a. (fn. 250) In the 1920s the county council acquired land and smallholdings, including that near King a Mill, to become the principal landowner in the parish in 1931. A dairy cottage and new farm buildings were added in 1921 but the rent declined by over 30 per cent between 1921 and 1926. (fn. 251) In 1930 Church, now Higher Church, farm was described as a dairy and cheesemaking farm with stalls for 27 cows and two cattle yards with liquid manure tanks. Arable was about to be laid to grass. (fn. 252) A 74-a. farm sold in 1935 had stalls for 15 cows, three piggeries, and two stone loose houses used for poultry. (fn. 253) Dairy produce was a chief crop (fn. 254) and in the 1930s children were absent from school milking. (fn. 255) In 1939 only one farm, out of ten, had over 150 a. (fn. 256) In 1955 Manor farm (129 a.) was a dairy and grazing farm with concrete cowstalls for 28 and four calving pens. The farm had a quantity of arable but the grass included 12 a. of 'deep milking pasture'. (fn. 257) During the 20th century village farmyards were replaced by Westfield, actually in the east, Tynings and Hill farms in the west, School farm in the south, and Laurel and Witherliegh farms at Plot Gate. (fn. 258) In the later 20th century one farm was derelict and its buildings offered for conversion to dwellings, (fn. 259) and redundant buildings were turned into dwellings or holiday accommodation. However, alpaca were introduced into the neighbourhood.

MILLS

In 1086 two mills were recorded, one each on estates held by Norman and Edmund, the latter paying twice as much as the former. (fn. 260) By the late 13th century one mill was divided into 1/6 and 1/12 shares. (fn. 261) The second mill may have been given to the prebend. In 1636 it was said to have been converted to a fulling mill (fn. 262) and was not recorded again. A new watermill in Keinton Mandeville belonged to the Cheverell's Barton manor in 1589. (fn. 263)

In the 1560s Edward Wadham, presumably as lessee of the main manor's mill, was presented for taking excess toll. (fn. 264) In 1700 the manor, presumably on the site of one of the 1086 mills, was valued at £10 a year (fn. 265) but was probably sold before 1767. By 1794 it was owned and occupied by the Sheat family of millers, bakers and mealmen who held it in 1837. Cottages there by 1841 were probably built for its workers. (fn. 266) In 1851 and 1861 Samuel Wilkins worked Barton flourmill assisted by his son, and four men, two of whom lived in. (fn. 267) The mill employed several people for the rest of the century. (fn. 268) Beside Tootle Bridge in Baltonsborough, it used the same tributary of the Brue that drove King a Mill and West Lydford mills. (fn. 269) It was disused by 1923 and in 1928 was a cottage. (fn. 270) In the late 20th century the early 19thcentury house with the former mill attached to its east side was converted into a guesthouse. There is an arched recess for the wheel and the millstream remains but the mill ponds have been reduced.

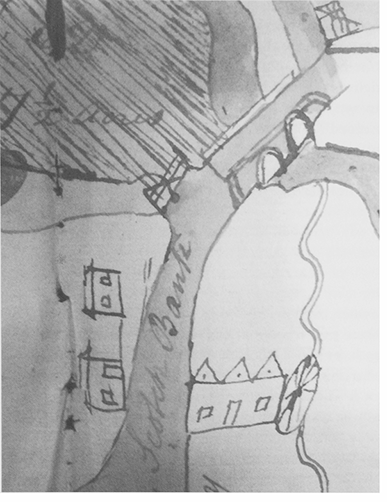

47. Barton Mill, Barton St David, sketched in 1759 on a plan of neighbouring fields when it was a three-gabled building with a large waterwheel. The mill lies near Tootle Bridge on the boundary with Baltonsborough, shown in the drawing, and was worked by the same tributary of the Brue which drove King a Mill and West Lydford mills. The building still has an arched recess for the wheel.

TRADES AND SERVICES

Quarrying

The parish probably had a limekiln (fn. 271) and part of West field was called Rockhill in 1636. (fn. 272) The many masons, stonecutters, and 'quarriers' recorded in the 18th and 19th centuries (fn. 273) probably worked in the Keinton quarries. In 1821 only 42 out of 72 families were employed in agriculture and only 39 out of 61 in 1831. (fn. 274) Many of the others were employed in the quarries. In 1851 19 stone workers were recorded and 22 in 1861. (fn. 275) After a decline to 11 in 1891 there was a sharp increase to 29 stone workers and two apprentices in 1901, out of 76 households. (fn. 276) Thereafter the quarries declined. (fn. 277)

Trades and Crafts

Apart from the usual village craftsmen, a bricklayer made his will in 1652 (fn. 278) and several generations of the Bush family were parchment makers from 1683 or earlier. (fn. 279) The presence of James Gooden, serge maker, in 1724 (fn. 280) and Thomas Lucas, woolcomber, in 1790 suggest a modest involvement in the cloth trade, although the latter's sons left to find work. (fn. 281) In 1841 two women were spinners and five sisters were gloving. (fn. 282) By 1861 there were 18 glovers in the parish (fn. 283) and a child was withdrawn from school for gloving in the 1860s. (fn. 284) Thereafter numbers declined and only one was recorded in 1891. (fn. 285) The women factory workers recorded in the later 19th century were possibly employed in Street (fn. 286) and many shoe binders, shoemakers, and machinists were probably outworkers for Clarks. (fn. 287)

In 1871 there were nine carpenters, one of whom was also a wheelwright, two sawyers, and two coopers (fn. 288) and in 1886 there were two smithies on the main street. (fn. 289) Other occupations recorded were a lace maker in 1891, a shirt maker in 1901, and a watchmaker in 1923. (fn. 290) One man described was a builder, plumber, glazier, decorator, assistant overseer, and parish clerk in 1897. (fn. 291)

Inns and Shops

In 1759 John Hill was accused of selling ale without a licence. (fn. 292) An innkeeper was resident in 1811 (fn. 293) but no public house was recorded in 1841. (fn. 294) The Waggon and Horses was in business by 1845 (fn. 295) and remained open as a beerhouse, with a smithy, (fn. 296) until c. 1891 when it was renamed the Barton inn. (fn. 297) It remains in business in Main Street.

In 1787 a yeoman left a shopkeeping business to his wife. (fn. 298) Two shopkeepers were recorded in 1841 (fn. 299) including John Diment whose shop continued until 1883 or later. (fn. 300) There were four shopkeepers in 1859 (fn. 301) but usually only two, of whom one was the postmaster in 1881. (fn. 302) In 1891 the post office was the only shop but two were in business between 1901 and 1906. (fn. 303) In 1939 there were two shops and a newsagent (fn. 304) but by 1947 only the post office and a newspaper delivery from a house. The post office remained open in 1979 when a village shop was said to be urgently needed (fn. 305) but has since become a private house. There was a farm shop open three days a week. Small rural workshops including a glass business have been built at High Jarmany.

SOCIAL HISTORY

Barton was a parish of several freeholds and no large estate. Although the tithing also covered Keinton Mandeville only six taxpayers were recorded in Barton in 1327 and the names of many contemporary landowners were missing. (fn. 306) Perhaps because of the paucity of taxpayers, by 1558 Kingweston was also included in Barton tithing but only 11 people were taxed, mainly on goods, rising to 17 in 1581 (fn. 307) and 37 in 1641. (fn. 308) Christopher Chapel, a substantial leaseholder, was an ardent Royalist. The charges against him covered nearly a sheet of paper and four soldiers were sent to arrest him. The sequestrator, Edward Curle, spent much time searching moors and fairs for his cattle and horses and guarding the crops he had seized. His fine remained unpaid in 1653 (fn. 309) and he was probably impoverished, as in the 1660s he had a house with only one hearth. In 1664–5 only two of the 20 houses assessed for hearth tax had more than two hearths. (fn. 310) In the 1760s only 16 of 43 holdings were assessed at £1 or more for land tax. (fn. 311)

The later social structure of the village differed slightly from most of its neighbours because of the presence of quarry workers. Most fathers recorded in an early 19th-century parish register were either labourers or stonecutters. (fn. 312) In 1831 61 families lived in 52 houses. (fn. 313) However, a large number of people owned their own homes in 1841 when of 60 landowners 39 were owner occupiers. (fn. 314) Lack of large houses meant that there were few opportunities for domestic service in the 19th century. Only four maidservants were employed in 1841 and in 1851 three were employed on farms and one each at the mill and the vicarage. (fn. 315) Some farms had young resident labourers until 1871 or later. (fn. 316) In 1881 the only resident domestic servants were two women at the vicarage. (fn. 317) However, in 1901 there were six female and two male servants living with their employers and one with her mother. (fn. 318)

Declining population meant that for most of the 19th century there was little overcrowding, although houses were small and in the 1860s only about two thirds were rateable. (fn. 319) In 1901 one third of houses had fewer than five rooms and four had only two. (fn. 320) By 1927 four local authority houses had been built and Langport RDC had 2 a. of land to build more. (fn. 321) Several farms still had one or two cottages in the mid 20th century. (fn. 322)

EMIGRATION

Henry Adams, ancestor of two American presidents, is said to have been born in Barton in the late 16th century, moved to Kingweston by 1622, and emigrated to America in the 1630s with several of his wife's relatives. (fn. 323) In the early 19th century the parish baptism register recorded people 'abroad' and young men sought work in Bristol and London. (fn. 324) Many families emigrated in the later 19th century including members of the Carey family who went to America in 1866 (fn. 325) and the Barbers who moved to Canada. (fn. 326)

EDUCATION

In 1709 Richard Phelps (d. c. 1725), formerly a schoolmaster at Market Dayton, Salop., was licensed to teach English grammar. He seems to have taught until his death, probably at Church Farm, which he bought in 1704. (fn. 327)

Weekly schools for small children were in existence by 1818. (fn. 328) In 1825 20 boys and 20 girls were taught, (fn. 329) although at least one local boy attended school in Babcary. (fn. 330) Three dame schools in 1833 taught 26 children at their parents' expense. A day and Sunday school supported by two ladies taught 40 children with 50 attending only on Sunday, (fn. 331) supported by the prebendary in 1836, (fn. 332) in a room east of the church on land belonging to the Dickinson family. (fn. 333) It was the parochial school in 1847 attended by 43 children daily and on Sunday, 32 children on weekdays, and a further 33 on Sunday only. Twenty pupils were infants. (fn. 334) In 1861 it was an infant school supported by Mrs Dickinson. (fn. 335)

In 1864 there were 65 pupils on the register but grant was withdrawn because too few were presented for examination. Many children absented themselves on Fridays and were taken out of school for home duties, farm work, and employment at an early age. (fn. 336) That year the rector and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners gave glebe land opposite the schoolroom for a new school for children and adults of the poorer classes. (fn. 337) It opened in November with 60 pupils and more were admitted later. However, absences, epidemics, including scarlet fever, which killed two pupils in 1865, and the lack of qualified teachers led to loss of grants and examination failures. Night schools were held on Mondays and Thursdays in 1868. In 1870 few boys attended and children presented a poor appearance due to poverty. There were frequent changes of head teacher, possibly because there was no accommodation; the earlier teachers had been local women. (fn. 338) The younger children were often in the care of two older girls but the vicar and his family visited regularly and one daughter taught singing. In 1887 one parent withdrew a girl to be educated privately because he was unhappy with the school. In 1891 education became free and the children were encouraged to start savings accounts with their school pence. (fn. 339)

In 1896 69 children were registered and the school was enlarged in 1898 to accommodate 79. (fn. 340) Absenteeism continued and the school closed for up to a week for elections or the chrysanthemum show. (fn. 341) There were two classrooms with two teachers in 1903 when there were 55 children on the books and both evening and Sunday schools were held. (fn. 342) The infant gallery was removed c. 1908. Despite absenteeism the school received good reports until 1913 when a deterioration was noted. Lectures on agriculture and poultry keeping were given in the 1900s and the children had school gardens, which they maintained mainly in their own time until the 1930s or later. There were clashes between managers and the head teachers over politics and the treatment of assistant teachers, and frequent changes of staff. (fn. 343)

Attendance fluctuated from 62 in 1905 to 75 in 1908, including 15 from Kingweston, and 48 in 1917. Belgian children were admitted in 1915 and the children collected vegetables for sailors. Absenteeism remained a serious problem mainly due to epidemics but also to attend horse races at Keinton Mandeville. In 1930 admission of children under 5 was discouraged. The state of the school gave cause for concern including the lack of water and the dangerous state of the ceiling. Numbers continued to fall to 33 by 1945, despite the presence of many evacuees, and 18 by 1949 when all but 3 children had chickenpox. Another fall of part of the ceiling caused the children to be transferred to Keinton Mandeville and it was decided to close the school and keep the children at Keinton. (fn. 344)

In 1994 a pre-school had opened at Barton St David with 21 children aged between 2 and 5 in 1998. (fn. 345) It was held on weekday mornings in the old school, now the village hall.

HEALTH AND SOCIAL WELFARE

William Noble (d. 1413), clothier of Salisbury but originally from the area, left 30 pairs of linen garments to be distributed amongst the poor of Barton and Baltonsborough, especially those related to him. (fn. 346)

Many poor children were apprenticed from the 1770s, sometimes three a year. By 1809 the overseers paid poor relief by regular payments or 'as a help'. Some house rent was paid in 1820 and in 1825 six paupers were on the regular calendar. (fn. 347) In 1837 Langport union and the parish vestry ordered the sale of a poorhouse comprising five dwellings in Marsh Lane occupied by paupers since 1809 or earlier. (fn. 348) It was parish property in 1841 (fn. 349) but belonged to John Whittle in 1843 when it was described as four cottages called the poor houses. (fn. 350) Several local people died in Langport workhouse from the 1840s, probably having been transferred from the poor houses. (fn. 351) In 1852 the parish agreed to send two men to the workhouse if they became chargeable but to bring another out and provide him with furniture by subscription. (fn. 352)

Epidemics of measles, influenza, and chickenpox frequently closed the school in the late 19th and early 20th century. There were outbreaks of whooping cough and impetigo and fears about diphtheria against which schoolchildren were inoculated in 1940. (fn. 353) There was no mains water in 1947, but it had been installed by 1972 when Langport RDC bought land north of Gosling Street for a sewage pumping station. (fn. 354)

COMMUNITY LIFE

The Barton club was recorded in 1877 and a clothing club in 1895. (fn. 355) Social events included a November chrysanthemum show in 1895 (fn. 356) and a July carnival between 1927 and 1931. (fn. 357) A new Carnival Trust was set up in 1977 but the carnival had ceased to exist by 1994. (fn. 358) A branch of the WI met in the Congregational chapel from 1943 but was wound up in 1950. (fn. 359) A youth group had to be banned from using the school in 1947 (fn. 360) but dances were held in a wooden hut. (fn. 361) In 1962 a charitable trust was set up to provide a village hall and playing field at the old school (fn. 362) and by 1979 the parish had a cricket club. (fn. 363) The parish runs road races in April, a July carnival, and raft races in the Brue. There are sports teams and scouts.

About 30 men from Barton were said to have served in the First World War (fn. 364) but 42 are recorded on the village war memorial, an obelisk within a garden of remembrance, which also lists 34 people who served in the Second World War. (fn. 365)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Barton tithing was recorded in 1225 and 1243 (fn. 366) but by 1327 it included Keinton Mandeville and from the 16th century Kingweston. (fn. 367) The parishes were assessed separately for land tax. (fn. 368) Part of Barton lay in Croscombe tithing in Whitstone Hundred. Bishop Jocelin (d. 1242) had encouraged suitors to the hundred court from a third of Barton tithing to attend Whitstone court instead of Catsash presumably after the gift to him of Barton church. (fn. 369) Inquiries in 1274, 1276, and 1290 found that suit had been withdrawn for over 40 years. (fn. 370) Despite the complaints the arrangement became permanent and in 1316 a third of Keinton, probably in error for Barton as they formed one tithing, was said to be in Croscombe tithing in Whitstone. (fn. 371) In 1742 part of Barton was described as a fifth of Croscombe tithing. (fn. 372) The lands whose owners paid tax under Whitstone hundred were scattered amongst those who came under Catsash hundred and many people had land in both therefore the split was presumably based on 13thcentury landownership. (fn. 373)

MANORIAL ADMINISTRATION

In 1435 manor tenants owed suit at two courts each year. (fn. 374) Suit of court was still demanded in 1699 (fn. 375) but no court rolls survive. Pound Close was recorded in the centre of the village and two Pennings on either side of the parish in 1841. (fn. 376)

PARISH ADMINISTRATION

The parish had two churchwardens but by 1820 one was chosen by the vestry and one by the minister who also appointed the parish clerk. The clerk and sexton, whose wages were halved that year, were paid by the wardens. In the early 19th century the wardens paid for the killing of sparrows, woodpeckers, and hedgehogs and the repair of paths, a bridge, and the stocks (fn. 377) which were recorded at a village crossroads in 1886. (fn. 378)

A vestry was meeting by 1763 but often only two men signed resolutions although up to five approved the parish accounts. (fn. 379) By 1826 the vestry appointed a hayward, and in 1850 sold the feed of the roads. (fn. 380) The vestry met in church in 1840 but was not chaired by the minister although he took the chair in the early 1840s before it returned to laymen. (fn. 381) By 1845 the annual vestry adjourned to a private house, later the school, to appoint a warden, overseers, and waywardens. In 1846 they appointed a guardian. Additional meetings were held to approve the rate and make a return of men to be constable. In 1850 it was declared illegal to elect wardens at the annual vestry so a second vestry was held. The vestry appointed the sexton and paid for catching moles. In the 1860s the incumbent again chaired the meetings. (fn. 382)

In addition to relieving the poor, (fn. 383) the overseers employed a molecatcher and maintained hatches near the mill in 1809 and 1811. In 1826 the vestry agreed to appoint a select vestry, apparently of three people, who allowed cheap coal to 12 poor people and payments to others. In 1831 a perpetual salaried overseer may have replaced the select vestry and exercised many of the overseers' functions. After 1848 the overseers were responsible for collecting rates and paying fees to the magistrate's clerk, Langport Union, and from 1863 to the Highway board, implying that they may have acted as waywardens. (fn. 384)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

In the 12th century Barton appears to have had a substantial parish church, which was enlarged in the late 13th, possibly to reflect its status as a prebendal church. However, as a prebendal rectory the church was ill served especially from the 15th century and was often without a vicar. During the 18th and early 19th centuries there was often no resident clergyman nor was there a powerful landowner to object to the situation. Unsurprisingly nonconformity gained a hold from the 1770s and throughout most of the 19th century. Only in the mid 19th century was the vicar provided with a house and an independent income enabling him to reside and hold regular services. (fn. 385)

CHURCH

Barton church was dedicated to All Saints in 1279 (fn. 386) and to St David by 1791. (fn. 387) The churchyard cross may be 13thcentury and the figure on it is said to be St David. Although the church was given to Wells c. 1215 (fn. 388) it was served by rectors until 1268 or later. (fn. 389) Thereafter it was regarded as a prebendal rectory with the prebendary or a vicar as incumbent, (fn. 390) the latter regarded as a perpetual curate. (fn. 391) In 1932, under an order of 1930, Barton was united with Kingweston at the next vacancy. (fn. 392) An order of 1977 united the benefice with Keinton Mandeville and Lydford on Fosse. They are now known as the Wheathill Priory Group. (fn. 393)

Advowson

Robert de Meisy gave the advowson with the church to Wells cathedral and bishop Jocelin c. 1215. (fn. 394) The prebendary was patron of the vicarage from 1325 or earlier. (fn. 395) However, in 1556 the bishop collated during a vacancy (fn. 396) and for most of the 18th century no vicar was appointed. (fn. 397) By the late 18th century it was said that after so long a lapse patronage had fallen to the Crown (fn. 398) but the prebendary claimed that as rector and having no vicar he was the incumbent. (fn. 399) From 1810 the prebendary again exercised patronage (fn. 400) and in 1831 it was said that lessees of the prebend might provide someone to serve during a vacancy but only the prebendary could present a vicar. (fn. 401) However, the farmers of the prebend exercised patronage (fn. 402) until the disposal of the prebendal estate in 1872 when patronage was transferred to the bishop of Bath and Wells. (fn. 403) The bishop has the third turn in the united benefice. (fn. 404)

Income and Endowment

The church was granted pasture for oxen in Baltonsborough but in 1268 the rector resigned his claim. (fn. 405) The church was valued at £10 13s. 4d. (fn. 406) and the prebend at £8 in 1298, the difference possibly a vicar's stipend. (fn. 407) However, in 1445 the vicarage was assessed for tax at the value of the rectory. (fn. 408) In 1473–4, during a vacancy in the prebend, a chaplain at Barton was paid £3 3s. 4d. (fn. 409) By 1535 the vicar was paid a stipend of £8 from the prebend but all tithes and offerings went to the prebendary as rector whose gross income was £11 7s. 4d. (fn. 410) The stipend remained the same in 1636 but the vicar had been assigned the house with orchard, two fields, 4 a. of common arable, and two beast leazes. (fn. 411) In 1645 Barton was described as a poor vicarage (fn. 412) and the incumbent was probably paid by Commissioners during the interregnum. (fn. 413)

The vicarage was assessed at £12 c. 1661, presumably including the house and land. (fn. 414) However, from 1756 and probably earlier the vicarage was left vacant in the 18th century sequestration granted to the prebendary (fn. 415) and the vicar's property had been reabsorbed into the rectory by 1841. (fn. 416) Curates were paid £20 by the prebendary or his lessee from the late 18th century (fn. 417) and £40 in 1815. (fn. 418) The vicarage, or perpetual curacy, was augmented between 1778 and 1822 by a total of £900 used to buy land in Keinton Mandeville, (fn. 419) which produced an income of c. £50 in the 1830s. (fn. 420) Further augmentations totalling £400 were made in 1853 and 1865 (fn. 421) to provide a house and land, bought from the rector. Transfers of land and tithe rent charge from the rector to the incumbent were made in 1872 and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners undertook to pay the £30 stipend formerly paid out of the prebend. (fn. 422) By 1897 the vicar had 35 a., partly in Keinton Mandeville, and the living was worth £250 a year. (fn. 423) By 1934 c. 23 a. remained. (fn. 424)

The rectory house was presumably used by the vicar during the Middle Ages and in 1354 the rector of East Lydford was living there in the care of the vicar. (fn. 425) In 1636 it was described as four poles long, probably three bays, with a barn annexed and furnished with a table and bench. (fn. 426) In 1664 it was a two-hearth house but the vicar was too poor to pay the tax. (fn. 427) In 1815 it was very dilapidated and both vicar and curate lived outside the parish. (fn. 428) In 1840 it was under repair and was used as a farmhouse by the undertenant of the lessee of the rectory. (fn. 429) It was confusingly known as the Old Vicarage. (fn. 430)

In 1851 the incumbent was resident, in rented accommodation, (fn. 431) and a subscription was raised to provide a house. A grant was obtained from Queen Anne's Bounty. An order in council proved necessary to ensure that the site, former glebe, was vested in the incumbent and did not benefit the rector therefore work did not begin until 1853. It was built by Alex Higgins to designs by C. E. Giles of Taunton in the south-east of the parish on the road to Keinton Mandeville. Another room, stables, and coachhouse were added in 1854, (fn. 432) and the house was enlarged and refitted in 1866. In 1975 it was described as structurally the worst house in the diocese. (fn. 433) Following the 1977 union of benefices it ceased to be the clergy house and is known as Peacock Hill House.

Pastoral Life

The only recorded rector was Nicholas son of Nicholas in 1268. (fn. 434) Vicars included Richard de Sanford who served West Lydford twice a week in 1350 and Richard Lawrence, coadjutor to the rector of East Lydford who was in his care in 1354. (fn. 435) During the early 15th century the church was served by chaplains, none of whom stayed long (fn. 436) but the plain octagonal font, possibly dates from this period although on a 19th-century base. There were vacancies in the mid 16th century and a curate was recorded c. 1555. (fn. 437) William Ham was resident in 1568 but also served Kingweston. (fn. 438)

The church received gifts of wax, including ½lb. charged on an estate bought by Joan, widow of William Walton, in 1521, (fn. 439) and in 1554 three parishioners were accused of withholding a total of 8 lb. (fn. 440) In 1571–2 it was said that 3s. 4d. had been given for lights in the church, apparently a rent charge on 6 a., and that John Ludwell had given 1½ a. worth 4d. for a priest to pray for all souls. (fn. 441)

In the early 17th century there were said to be no perambulations, no regular monthly sermons, no pewter pot for communion, and an unlearned clerk, although the altar table, the gift of William Kelway, is dated 1613, (fn. 442) and there is an early 17th-century pulpit with cornice and carved panels. (fn. 443) There may have been recusants in the parish in 1606 and 1612. In 1634 the south aisle was ruinous, needing tiling and glazing, but since it belonged to the demesne farm either the lord or his tenants were required to repair it. (fn. 444) The vicar was Thomas Higgins (fl. 1640), instituted 1588, who was also vicar of Frome and held a living in his native Shropshire. (fn. 445) In 1654 Ralph Sprake, a probationer preacher served for three months, (fn. 446) a Mr Horsey served in 1657, (fn. 447) and in 1658 a scandalous minister from East Lydford was paid by the Commissioners to serve Barton. (fn. 448) Richard Smith, ejected rector of Whitestaunton, became vicar in 1662 but was also preacher at Chard. (fn. 449) Joseph Dauncy was licensed to preach and serve the cure in 1701. (fn. 450) The registers date only from 1714. (fn. 451)

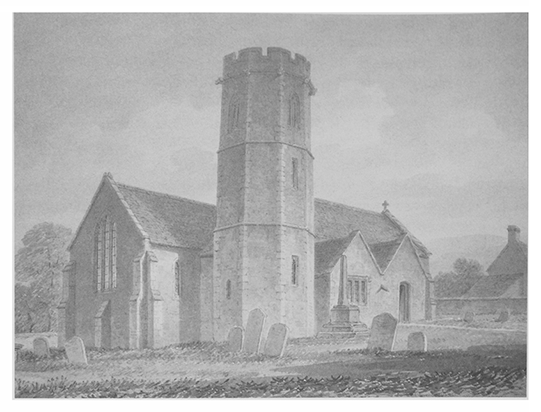

During the 18th and early 19th centuries the parish was served by curates, including relatives of the farmers of the rectory and neighbouring incumbents. (fn. 452) By 1751 the south aisle, probably a transept 18½ ft long by 14½ ft wide, was said to have fallen down and, was demolished but without filling the arch with the 'handsome' window the parish had desired. (fn. 453) In 1764 the vestry agreed to have the church ceiled. The barrel ceilings were plastered on reed. (fn. 454) Deal seats were made for the church in 1772 and in 1774 the church was paved. (fn. 455) There was a gallery, repaired in 1793 and altered in 1809, but it was taken down in 1859. The painting of King David placed above the chancel arch may have been the gallery panel. (fn. 456)

In the late 18th century one service was held on Sunday, alternately morning and afternoon. (fn. 457) Communion was celebrated three times a year. (fn. 458) Edward Foster, prebendary 1809–1826, appointed a vicar in 1810 and thereafter the parish was served by vicars, known as perpetual curates. However, the vicar was a pluralist in 1815 and assigned the vicarage income to a curate who also served two other parishes. One Sunday service was held (fn. 459) increased to two in 1840 when the vicar was resident. In 1843 he lived at Keinton Mandeville but there were two Sunday services and communion was celebrated four times a year. (fn. 460) The tower had been repaired in 1805 and reroofed in 1821 and the church was whitewashed and coloured in 1842 by George Davis of West Lydford. Oak woodwork was cased in elm, which was grained. (fn. 461)

On Census Sunday 1851 66 people attended morning service and 140 in the afternoon. (fn. 462) The church was repewed in 1858 and again in the 1870s (fn. 463) when the chancel was heavily restored (fn. 464) but plans for a south transept, south porch, restoration and reseating produced in 1873 by Thomas Graham Jackson were not carried out. (fn. 465) By 1870 communion was celebrated monthly. (fn. 466) The plate included a paten of 1633, a late 18th-century chalice, and a flagon of 1881–2. (fn. 467) The church had a harmonium by 1866 (fn. 468) and an organ by 1892. An organ blower was employed until an electric blower was installed in 1964. (fn. 469) By 1904 the four 16th and 17th-century bells could not be rung (fn. 470) and the broken 1693 tenor by Thomas Purdue was recast in 1911 when a 5th bell was added to mark the Coronation and the bells hung in a new frame by John Sully of Zinch, Stogumber. (fn. 471) In 1962 the 1591 bell by Robert Wiseman was recast and a 6th bell was added in memory of George and Sarah Plumley. (fn. 472)

48. Barton St David church from the north-east. The drawing by J. Buckler shows the church before restoration. The tower has been restored several times.

A reredos and panelling were installed in the late 1920s by an American descendant of Henry Adams (fn. 473) but have since been removed. Electric lighting was installed in 1948. (fn. 474) In 1950 the altar was enlarged and a credence table installed. (fn. 475) In the early 20th century there was fortnightly communion (fn. 476) and morning and evening service every Sunday. Easter communicants fell from 22 in 1921 to 10 in 1942 but rose after the war to 26 in 1954. From 1975 evensong was held on special occasions and in 1991 there were 25 Easter communicants. (fn. 477) Services were held fortnightly in 2005.

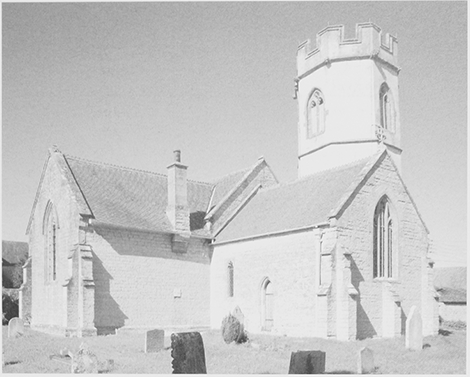

Church Building

The church has an unusual plan of nave and chancel with, adjacent to each other on the north side from west to east, a porch, north transept, and an octangular tower, one of very few in Somerset and the only one in this position and octangular from the base. (fn. 478) It was built of Keinton stone that has weathered badly; the tower has been rendered at least from 1904, and the render was redone in 1956 when the tower was leaning. (fn. 479) The nave may be 12th-century and has a north doorway with lozenge and chevron banding. The north transept and chancel were built in the late 13th century, from which period the east window with cusped rere-arch survives. Perpendicular remodelling contributed the windows and the tower. (fn. 480) A Salisbury clothier left 20s. for work on the church in 1413. (fn. 481) A blocked doorway indicates that there may have been a south porch. The mullioned north window of the shallow north transept is 16th- or 17th-century and may date from work to remedy the disrepair the church was suffering in 1594 and between 1626 and 1634. (fn. 482)

A south transept only was built in 1894 to designs by Edmund Buckle with a grant for 32 additional free seats. (fn. 483) The tower was restored and reroofed in 1908 by Buckle. (fn. 484) In 1969 repair work was done to walls and windows and the nave roof was covered with concrete tiles. (fn. 485) Restoration took place in the 1990s when the transepts were closed off from the nave, the north one as vestry and kitchen, the south one as a meeting room. (fn. 486)

The church is sited south-west of the village near the parish boundary. It is not known when the churchyard was inclosed but bones have been found in the roadside verge north of the church. (fn. 487) The Doulting stone cross in the churchyard may be 13th-century and bears the worn figure of a bishop, said to be St David, under a crocketed canopy. (fn. 488) It was placed on a new base in the 19th century and repaired in 1965. (fn. 489) In 1875 a piece of land was given to enlarge the churchyard eastwards, almost doubling its size. (fn. 490) The churchyard was extended again to the south-east by a further gift in 1947. (fn. 491) An early-18th century chest tomb with arched panels and pilasters is said to commemorate the Bird or Bush family. (fn. 492) Oak gates were installed in the 1960s. (fn. 493)

49. The parish church of All Saints from the south-east, showing the 15th-century north tower, 13th-century chancel and south transept added in 1894.

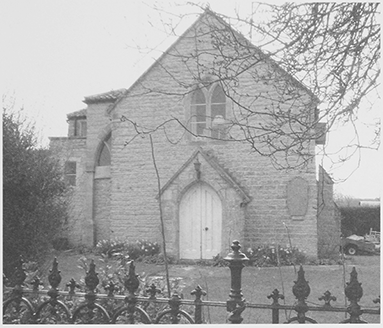

50. (below) Former Ebenezer Independent chapel, Barton St David, built 1804, given a spire in 1871, renovated and extended in 1878 and closed by 1958. Now a house called The Old Chapel.

NONCONFORMITY

Between 1777 and 1805 several children from the parish were baptised by the Revd Richard Herdsman of South Petherton, the first student of the Countess of Huntingdon's college. (fn. 494) Part of a house was licensed for worship in 1789. (fn. 495) Ebenezer Independent chapel, with seating for 200, was licensed in 1804 and vested in Herdsman and another. By 1809 William Reynolds was pastor at Barton. Minister Thomas Greenway was resident in 1841 and a Sabbath school was started in 1842. (fn. 496) The chapel had a burial ground. (fn. 497) In 1851 80 people attended morning service and 70 in the afternoon. (fn. 498) William Kick, minister from 1853 to 1880, revived the cause and the school although non-resident. In 1878 he acquired land for classrooms and renovated the chapel. From 1879 there was an evangelist attached and the chapel served many villages, which later built their own chapels. (fn. 499) In 1885 the evangelist shared a meeting with the Moravians at Southwood, Baltonsborough. (fn. 500) In 1891 the resident preacher's daughter taught at the school. A minister was resident in 1901 (fn. 501) but in 1914 the chapel was served from Street. (fn. 502) By 1958 the chapel had closed and was sold in 1959. (fn. 503) The plain chapel of 1804 with Y-traceried and quatrefoil windows had a small asymmetrical spire added in 1871. (fn. 504) It is now a private house.

Licences were issued for unspecified congregations in 1824 and 1829, the former, possibly Bible Christian. (fn. 505) In 1871 two stonecutters were Methodist preachers and one continued in 1881 assisted by his son. (fn. 506)