A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Kingweston', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10, ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp162-176 [accessed 23 April 2025].

'Kingweston', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Edited by Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online, accessed April 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp162-176.

"Kingweston". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online. Web. 23 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp162-176.

In this section

KINGWESTON

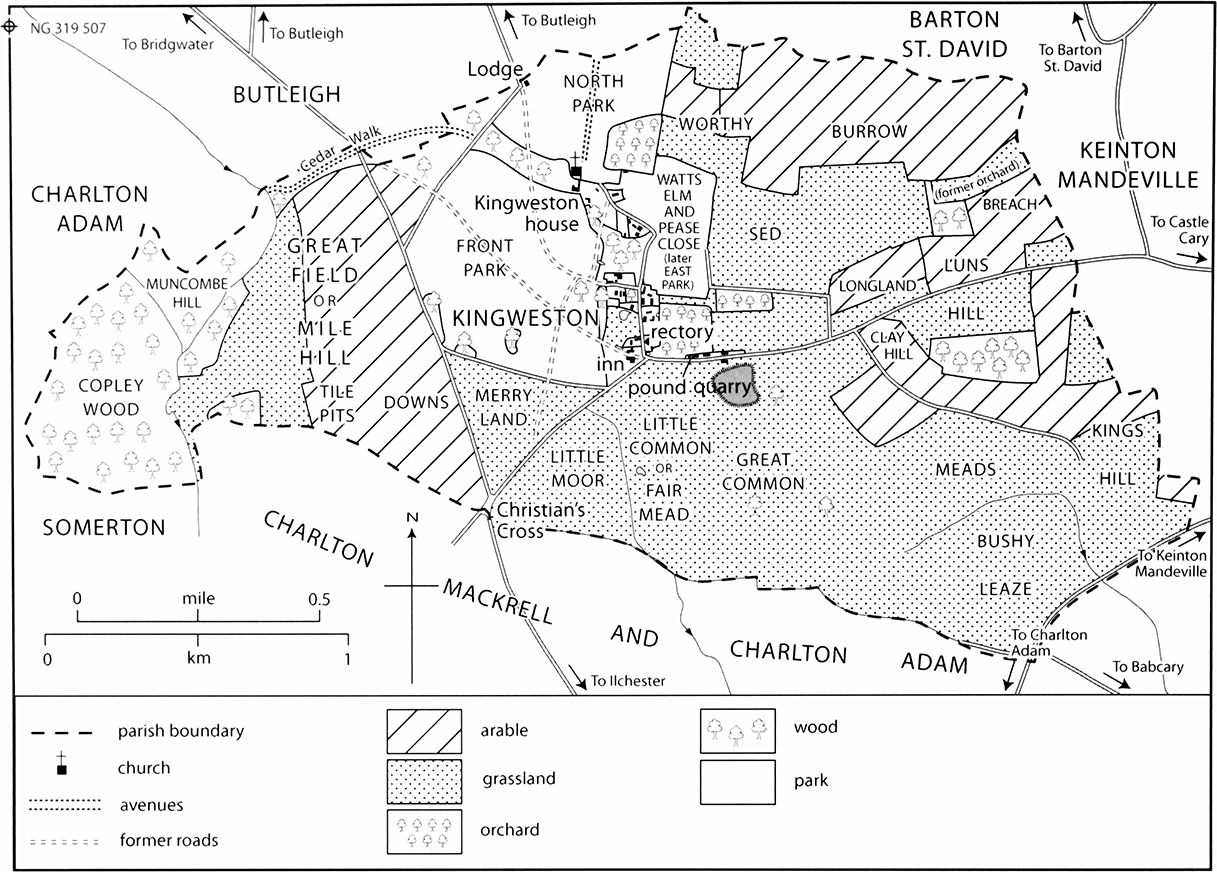

58. Kingweston 1839

The parish in 1839, showing the great alterations to the roads and fields wrought in creating their parks by the Dickinsons who also planted the woods and avenues of trees.

THE irregularly-shaped parish lies largely on the gentle eastern slope of a wooded ridge, which runs south-east from Street. The eponymous village lies in the centre of the parish whose boundary extends to the edge of both Barton St David and Keinton Mandeville villages and follows no natural features. The parish measures 4.5 km. east to west at its widest and 2 km. north to south on the east side but only 1 km. on the west. (fn. 1) In 1839 the parish measured 1,151 a. but in 1887 the incorporation of a detached share of Copley wood belonging to Charlton Adam increased the acreage to 1,243 a. (504 ha.). (fn. 2)

Most of the parish lies on an area of Lower Lias clay and limestone falling from 80 m. (262 ft) on the western boundary to 33 m. (108 ft) on the east where the slope divides at Luns Hill (59 m. (193 ft)). The steep wooded slopes in the south-west, part of the ridge, which forms the watershed between the Brue valley and King's Sedgemoor, are composed of Rhaetic clay rising to 100 m. (328 ft) on the boundary. There, a narrow valley of Keuper marl runs southwards into Somerton parish. (fn. 3) Copley Wood is part of a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest in the care of English Nature. (fn. 4)

COMMUNICATIONS

The ridge road to Ilchester, probably of Roman origin and known by the 18th century as the market road to Somerton, (fn. 5) traversed the parish on the west crossing the Somerton road at Christian's Cross. (fn. 6) A road, established by 1675, (fn. 7) branched off the ridgeway on the north-west boundary to join the Castle Cary–Somerton road at the Kingweston inn. (fn. 8) Both roads were turnpiked by the Langport, Somerton, and Castle Cary trust in 1778 and 1753 respectively. (fn. 9)

Before the late 18th century the village street ran north out of the Somerton road, turned west below the church and continued as the road to Butleigh. It was crossed by a street running south from the church. The new road built by Caleb Dickinson in 1764 may have been from the village street to the church but in 1779 a new road at Merrylands was recorded, possibly an alteration of the road south from the church between the two turnpikes, later abandoned. (fn. 10) His son William's enlargement of the parkland led him to close and divert several roads. In 1788 he was permitted to divert the Butleigh road at the parish boundary along a new route south-west to the ridgeway, finished and banked in 1799 at his expense. (fn. 11) Gates closed parts of the village street, the street south from the church to the Somerton road was closed, and the lane over the fields east of the church to Keinton Mandeville was possibly abandoned at the same time. (fn. 12) In 1803 277 yards of new road across the park, possibly linked the village street with the lane into Copley wood but was abandoned after 1821. The former road from the church to Christian's Cross was turfed. (fn. 13) In 1821 the turnpike from the ridgeway to the Somerton–Castle Cary road was stopped up and a new road built further south, partly completed by 1822. (fn. 14) By 1834 the parish was maintaining the new roads including the extension of the village street to the church. (fn. 15)

In 1891 a tramway was proposed from Somerton to Castle Cary and through Kingweston with a branch through the village to Butleigh using one of the former roads but it was never built. (fn. 16)

POPULATION AND SETTLEMENT

Francis Dickinson's claim that a Roman villa stood in the east of his park is unsubstantiated but there is evidence for Roman and medieval settlement in part of Copley wood anciently in Charlton Adam parish and possibly related to the Copley demesne estate attached to St Cleers manor, Somerton. (fn. 17)

Kingweston takes its name from Cyneweard, presumably an early Anglo-Saxon owner. (fn. 18) The early settlement was probably on the site of the present village sloping gently south from the church and manor house towards the common and hemmed in on either side by the common arable. The lack of early sources and the laying out of extensive parkland and plantations in the 18th century make it difficult to envisage the earlier field pattern. The relatively flat land to the south of the village was common pasture, the part nearest the village street was also known as Fair Mead. Meadow seems to have been scarce and by the early 19th century was confined to a small area beside a stream in the south-east. The north of the parish, high ground sloping gently eastwards, provided two open arable fields and two demesne arable fields. Most arable had been converted to parkland and pasture by the 19th century. (fn. 19)

There was a severe fire in 1665, extent unknown; (fn. 20) the earliest surviving houses date from the 18th century although that may owe more to the Dickinsons. (fn. 21) A map of 1782 shows houses on the present village street, established by 1675 and later called High Street, extending east along the turnpike road, later known as Lower Street, and either side of the street south of the church. The last was closed in 1788 and its buildings removed for the park. (fn. 22) In the 1780s there were five farms and c. 16 two-storey thatched cottages, forming a street. Kingweston was described as 'one of the neatest villages in the county'. (fn. 23)

In 1801 the population was 90; it rose to 111 in 1811 and 128 in 1841. Although the number of recorded houses remained constant, cottages lost in extending the park had been replaced by dividing or extending others. In 1839 three houses contained nine dwellings. (fn. 24) Additional houses were built, including at least two in 1847, east of the church and were later known as East and North Park. The parkland on the east and the grounds beside the south drive to Kingweston House still separate the area around the church from the main village street where the farmsteads lie. (fn. 25)

The population rose more steeply to 149 in 1851 and 172 in 1861 (fn. 26) and in the 1860s a row of three large cottages was built each with three rooms above and below, a vestibule inside the entrance with stairs, landing, which the agent considered wasted space, one heated bedroom, and a boiler. (fn. 27) By 1871 there were 30 houses but by 1891 several houses were uninhabited and the large households at Kingweston House and the rectory accounted for more than a quarter of the population of 121. (fn. 28) The population declined steadily to 99 in 1911. There were 28 houses in 1931 and 1947 and many cottages continued to be held by Bennett and Company as the unsold part of the Dickinson estate. (fn. 29) No houses were built in the 1970s but in 1980 some buildings were being converted. (fn. 30) The numbers of residents fell to 72 (fn. 31) in 1981 and 1991. (fn. 32)

LANDOWNERSHIP

MANOR

In 1066 Kingweston was held by Wulfeva, who may have been a substantial landowner. (fn. 33) By 1086 she had been succeeded by Ida of Lorraine, second wife of Count Eustace II of Boulogne (d. 1093), who held the manor of the king. (fn. 34) Ida was probably followed by Count Eustace III (d. 1125) who appears to have settled it on his wife Mary Canmore (d. 1115), daughter of Malcolm III of Scotland. In 1114 Mary gave Kingweston to Bermondsey priory, abbey from 1399, where she was later buried. Count Eustace and their daughter Maud, wife of (King) Stephen confirmed the grant. (fn. 35) By 1251 the manor was held by the priory chamberlain. (fn. 36) Bermondsey held it until the Dissolution although it was briefly taken in hand by the king between 1403 and 1410 in a dispute over church services at Preston Plucknett, another Bermondsey manor. (fn. 37) James Tutt and Nicholas Hame acquired it from the king in 1545 and the same year sold it to Sir Thomas Moyle, speaker of the House of Commons. (fn. 38) However, in 1557 it was granted in error with Preston to Thomas White and his wife Agnes for services against the conspiracy of Henry Dudley. (fn. 39)

After the death of Sir Thomas Moyle in 1560, (fn. 40) one third of the manor passed to his daughter Catherine, wife of Sir Thomas Finch (d. 1563) and two thirds to Thomas Kempe, son of his deceased daughter Amy. (fn. 41) In 1576 Thomas Kempe with his wife Dorothy and Catherine with her husband Nicholas St Leger sold the whole to Matthew Smyth. (fn. 42) Mathew (d. 1583) was succeeded by his son Hugh, a minor, who in 1627 settled Kingweston on the marriage of his son Thomas and Florence Poulett. (fn. 43) The Poulett family held the estate in trust for Thomas (d. 1641), his son Sir Hugh and younger children. In 1666 it was settled on Sir Hugh and his wife Anne [Ashburnam]. (fn. 44) Sir Hugh mortgaged it in 1675 and in 1723 his son Sir John Smyth released it to Edmund Bower of Somerton. Edmund (d. 1728) settled the manor on his second wife Rachel. In her will of 1729 Rachel left it to her son William Swadlin. The will was not proved but in 1740 Jane, daughter and heir of Edmund and wife of the Revd. Joseph Horler, released her claims to Swadlin to enable him to sell Kingweston to Caleb Dickinson in 1741. (fn. 45)

Caleb Dickinson (fn. 46) (d. 1783) was followed in the direct male line by William (d. 1806) and William (d. 1837), whose second (fn. 47) son Francis (d. 1890) was succeeded by his son William (d. 1914). (fn. 48) William (d. 1964), son of the last, sold most of the estate in 1922 and 1930 and let the house in 1946. His son was killed in 1941 and he was succeeded by his daughter Everilda Joyce, wife of Roger Burden. The family moved into the former rectory house, renamed the Dower House. (fn. 49)

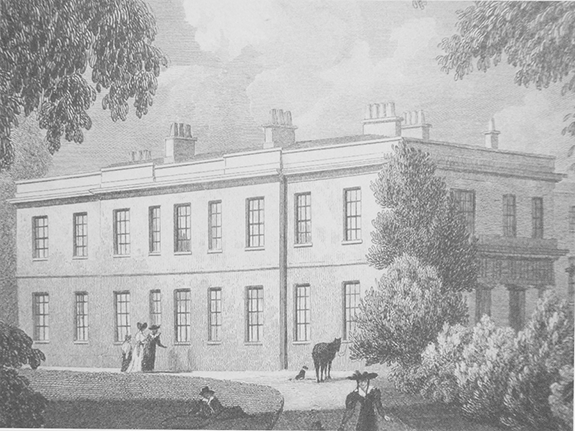

Kingweston House

The capital messuage was let with the demesne in 1559. (fn. 50) It was not occupied by the owners although Caleb Dickinson visited Kingweston for a few days each year. The house was repaired in 1742, in 1743 it was roofed with Cornish slate and a new kitchen was built in 1764. (fn. 51) Other outbuildings were put up in 1765 (one of the ranges of the gothick stables and coachhouse court bears that date) and in 1772 a barn, probably that with gothick details south-east of the mansion. (fn. 52) In 1778 in a codicil to his will Caleb declared that he had spent a lot of money on the Kingweston estate and that he wanted the house to be the family seat and residence of his son. (fn. 53) William at first refurbished the house with paint and wainscoted the parlour chamber but by October 1783 he had plans for a new house drawn by Henry Holland the younger. He appears to have shown them to John Acland who recommended making the main rooms much larger, a minimum of 32 ft for the dining room, and removing the great barn. (fn. 54) William's new work was built between 1785 and 1788 by Samuel Heal of Bridgwater. It seems to have comprised a pedimented south range of 7 or 9 bays: Portland stone was purchased for a tympanum, presumably for the pediment, which was removed after 1824, (fn. 55) and main staircase. An apparently older range survived at its east end and a hipped roof range of six bays with dormers at right angles to the west, with lower buildings north of that. The older parts may have included Caleb's kitchen, which was still standing in February when the stone floor was lifted for laying in the new cellars, and the old servants' hall was converted apparently into a dairy. Alterations to service areas in 1788 included raising chimney heights. By July 1786 the new range was roofed, sash windows were delivered in the autumn, and by December plastering was under way although the main staircase was unfinished. Progress was also made on outbuildings and in the grounds. (fn. 56) In 1799 Dickinson was taxed on 84 windows. (fn. 57) After 1824 (fn. 58) the house was remodelled and partly rebuilt in a more severe neoclassical style, probably to designs by William Wilkins who moved the entrance to the east end of the south range and added a Greek Doric portico. The older eastern work was demolished and a long northeast wing of two and a half storeys was added then or later to form the east side of an internal service court. The long east entrance front faces the 18th-century stable court. The west range was remodelled or rebuilt to match, its large central rooms marked by a canted bay. The 18th-century west entrance hall with staircase hall on axis remains but the interior has been given some Greek decoration. (fn. 59)

59. Kingweston House was built between 1785 and 1788 under the supervision of Samuel Heal of Bridgwater for William Dickinson, possibly adapting plans by Henry Holland. It was altered and enlarged in 1828 by the architect William Wilkins.

In 1788 a London seedsman provided an estimate for supplying thousands of balm of Gilead, beech, birch. Scotch and silver fir, two varieties of spruce, Spanish chestnut, and Weymouth pine, presumably for planting round Kingweston house. (fn. 60) In 1807 John Veitch planted 19½ a. with nearly 30,000 ash, beech, horse chestnut, larch, oak, Scots fir, Spanish chestnut, sycamore, and thorn. Following some failures Veitch planned another planting of 16,000 mixed trees. (fn. 61) A plantation of walnuts had been established by 1812. (fn. 62) By 1839 parkland extended north, west and south of the house, known as North and Front Parks, a thatched lodge on a cruciform plan had been built at the northwest gate, and there was an ice house of 1802 in shrubbery east of the house. (fn. 63) Around the drives, beyond Front Park, and on the hill to the south-west there were extensive plantations. An avenue of elm trees running due north of the house across the North Park had been planted probably in the mid 18th century and a 5-a. cedar walk along the north-west boundary. (fn. 64) Parkland to the east had been created by removing hedges in 1779. (fn. 65) There were concerns over elm disease in 1935 and in 1936 20 cedar were bought to fill gaps in the cedar walk. (fn. 66)

The house was requisitioned during the Second World War as a searchlight headquarters. (fn. 67) William Dickinson (d. 1964) let the house from 1946 to Millfield School, Street. It was given to the school in 1991 and is a boarding house. (fn. 68)

OTHER ESTATES

A freehold consisting of a messuage, 32 a., and 5s. rent was said to have been granted by Bermondsey priory to Walter of Kynwardeston. It passed to Alice le Parker and by 1330 to William of Charlton and Edith Pipard. (fn. 69) In 1347 the estate, described in 1350 as a messuage and 65 a., was given by William of Charlton to Bermondsey and presumably absorbed into the manor. (fn. 70)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

AGRICULTURE

In 1086 Kingweston was taxed at five hides and had land for eight ploughs but only seven were recorded; two in the 2¾-hide demesne worked by six serfs and five with the rest of the land worked by eight villeins and eight bordars. The demesne included 25 a. of meadow, 22 a. of pasture, and woodland one furlong by three, supporting 12 cattle and 12 pigs. (fn. 71) There seems little difference between the number of households recorded in 1086 and in the 19th century. (fn. 72)

The 13th to the 17th Century

Holdings of half a virgate and 11 a. were recorded in the 13th century (fn. 73) and in 1291 the manor was valued at only £10. (fn. 74) One man paid 3s. tax in 1316 but six of the nine recorded taxpayers only paid 6d. (fn. 75) In 1330 there were two holdings of over 30 a. (fn. 76) The wool collectors in 1342 demanded a much larger amount of wool than from neighbouring parishes. (fn. 77) In 1536 over half the rector's income was from corn tithe (£6) but he also received £1 10s. 2d. from wool and lambs. Meanwhile the manor was farmed out and the rental was only £5 3s. 4d. (fn. 78)

A farmer who died in 1555 left two oxen and two cows to each of his five daughters and his inventory was worth £210. (fn. 79) A woman who died in 1558 left a wain, 2 a. of wheat, and 1 a. of oats and a heifer, possibly to her daughter, and many sheep and calves to be distributed amongst various children. (fn. 80) A wealthy farmer leased the capital messuage in 1559 with 224 a. in large closes, 107 a. in the east and west fields, 21 a. of sheep pasture in the west field and common for 24 affers. The enclosed arable was at Copley in the south-west, probably the Downs arable recorded in 1839, and the Burrows in the north. (fn. 81) The lessee's namesake held the same estate in the 1590s when he was described as a gentleman. (fn. 82) Other holdings in 1598 were smaller but five tenants had amalgamated two or more including one woman who had four totalling 130 a. There were two landless cottages, one being a new smithy, but 15 tenants held 23½ tenements, excluding the demesne farm, averaging 32 a. Tenants had pasture for 213 rother beasts in the common. (fn. 83) However, the manor rental was only £15 in 1611. (fn. 84)

The 17th and 18th Centuries

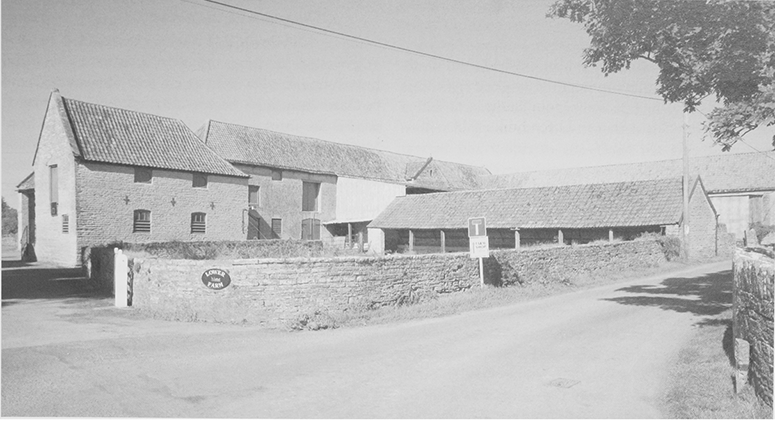

60. Lower Farm, one of several farms in Kingweston given new buildings after 1780.

The rector had common for 18 beasts and could put 70 sheep in leazes in the winter and both cattle and sheep on the herbage of the fields like the manor tenants. He also had a pigeon house, herbage of the churchyard and tithe of corn, hay, and sheep although Stock mead paid a modus of 2d. an acre. His meadow and pasture were in closes but apart from a small close his arable lay open in the east and west fields until 1638 or later. By 1638, however, the stint of stock on the Common had been reduced and the rector's share was only 13½ beasts. (fn. 85)

In 1634 the Admiralty saltpetre maker complained that the owners of four pigeon houses in Kingweston had laid the manure on the land or sold it depriving him of the materials he needed. (fn. 86) One of the offending owners, whose mother had amalgamated three customary holdings in 1598 and who had bought a reversionary lease of the capital messuage, described himself as a gentleman in 1647 and owned land in Moorlinch. (fn. 87) His may have been the circular dovecot in the later Home farm yard. (fn. 88) Another gentleman mortgaged his farm and was unable to repay the debt in the 1650s. Among his goods were a yoke of oxen, hay, wheat, beans, 43 lb. of butter, cheese, beef and veal. (fn. 89)

In 1641 there were complaints that bounds in the open fields had been ploughed out but the Common and meadows had been fenced and tenants had to maintain the fencing. Two moor reeves were responsible for the common and could impound the cattle of tenants not contributing to repair of the great length of fencing and the gates. (fn. 90)

A survey of 1683 shows major changes from 1598. Although much arable was still open land, some holdings were fully inclosed. After one tenant died some of the lands on her holding were exchanged with other tenants presumably for inclosure. Of 16 recorded tenants five held on lease and there was more disparity in size of tenements with three landless cottages and at least six holdings under 20 a. compared with only three in 1598. Two lessees and one copyholder had amalgamated three tenements each. (fn. 91) The demesne farm (c. 350 a.) had been mortgaged by Sir Hugh Smyth in 1675. (fn. 92)

The bounds in the arable fields were said to have been ploughed up in the 1720s (fn. 93) and the common may have been divided into fields at the same time. In 1756 common grazing was available on Bushy Leaze, an enclosed area in the south-east under the care of the moor reeves, although tenants had to be ordered to drive cattle through the gates and not over the hedges and charges for impounding cattle had greatly increased, from 1d. to 3d. for residents, 7d. for others. (fn. 94) Local people violently resisted attempts to distrain a man's oxen and cattle in 1730. (fn. 95)

Caleb Dickinson spent over £10,600 purchasing and maintaining the manor between 1740 and 1746. He bought French grass seed in 1740 and in 1744 paid for shearing 536 sheep and 246 lambs, although some were kept outside the parish, and 220 sheep were sold at Somerton fair. (fn. 96) Hedges were grubbed out for parkland and tree planting was planned. (fn. 97) A plantation near Copley is called Caleb's Plantation. (fn. 98) In 1756 tenants were ordered neither to lop maiden trees nor to sell wood out of the manor. A tenant who was required to plant eight trees annually was warned that failure would mean forfeiting his tenement. (fn. 99) The demesne orchards cropped well in 1748 producing ten hogsheads of cider, (fn. 100) and in 1757 enough teasels were grown to require seven days labour packing them for market. The estate had its own limekiln and in 1760 a marlpit was sunk and marl and soap ashes were used on the land. Sheep, pigs, cows, hens, and turkeys were kept and clover seed was sown. (fn. 101) As the Dickinsons were not resident at this period the bailiff was probably producing for the market to increase the estate income. (fn. 102)

By 1779 major improvements included the building of new waggon houses, great and little barns, wring house, stable, and stall and burning French earth. Between 1779 and 1783 nearly £350 more was spent on improvement than was received from rent. (fn. 103) In the 1780s there were five farms in the parish but most land was demesne and still mainly arable producing wheat, barley, turnips, vetches and a few beans. Productivity ranged from 22 bu. an acre for wheat to 36 bu. for barley and the soil was stone brash only a foot deep. However, not much marl was used and lime husbandry was said to be little understood, in fact the lime produced appears to have been used for building work. In 1783 five members of the Reynolds family produced a total of 155 a. of wheat, 41½ a. barley, 29 a. beans, 7 a. oats, and 8 a. peas, at least one having rented extra acreage to grow corn. (fn. 104) In the 1790s French grass, clover and hop seed were sown, 32 a. of hay were mown on Little Common and the park was extended out from the house by moving roads, grubbing out hedges and levelling banks. (fn. 105) In the 1780s there was a 15-a. coppice (fn. 106) and in 1785 600 ft of oak was felled. (fn. 107)

Several farms were given new buildings after 1780, including farmyards for Lower farm and the inn and the houses at Home and Lower, now Middle, farms were improved. The inn, which became Lower Farmhouse, was provided with a very large barn with paved threshing floor in 1781, (fn. 108) and with tall lofted ranges for stabling and coaches. The rental increased from £512 in 1794 to £681 in 1800 with the rack renting of the farms including one of 465 a. Remaining common appears to have been divided between the farms. (fn. 109)

The 19th to the 21st Century

William Dickinson the younger succeeded in 1807 and began a programme of major agricultural improvements. He sold oxen and appears to have replaced them with horses, although both were being used in the 1840s, and bought a flock of 170 sheep from Seavington. (fn. 110) He redeemed the land tax on the whole parish. (fn. 111) He spent part of 1812 travelling around England studying agriculture and saw Coke of Norfolk. He experimented with mangolds, producing the best crop on land which was green manured, grew vetches and agreed to open a second marlpit. He walked his land planning changes such as draining and noting failures such as too close planting of potatoes and not putting sheep in the water meadows to eat out the old grass. (fn. 112) In 1813 he bought a portable threshing machine, a seed drill, six ploughs, horse collars and harness, and large quantities of seed including over 19 cwt from Thomas Gibbs of Piccadilly comprising several sorts of grass, clover and Portugal corn. The grass was harrowed and rolled and the clover was rolled to improve rooting to be fed by ewes and lambs. Land for barley was double ploughed and trial plantings were made of potatoes. In the summer he sold cows and bought bulls, cows and heifers including prize animals presumably to found a better herd. He spent £460 buying ewes and hiring a ram. (fn. 113)

By 1830 the farms comprised the home farm (564 a. of which 387 a. was in Kingweston and mostly pasture), two other farms with over 200 a. (about half of each in the parish), one farm with 83 a. and one with less than 20 a. A large number of arable and pasture fields had been combined to former larger units and further amalgamations were planned. A quantity of arable had been converted to pasture, including land where Dickinson had grown vetches and clover in 1812. Some conversion had been badly done and it was recommended that those areas and some rough pasture be ploughed up and cropped before being laid to grass. A lot of land required tree removal and draining, including a former quarry. Some land had been planted as orchard and further plantations made. (fn. 114) By 1830 15 a. of wood had been planted on the home farm and a few years later an area of former rough pasture on another farm had been planted. (fn. 115) By 1839 there were 130 a. of wood including plantations around the house. (fn. 116)

By 1836 the home farm was part of the demesne farmed by Francis Dickinson and comprised pasture and plantation but most of the other farms had large quantities of arable. (fn. 117) In 1839 there were 718 a. of grass and 303 a. of arable. Francis Dickinson held grounds, parkland, and woods totalling 137 a. and an enlarged home farm comprising 467 a. within the parish, a farmhouse with attached house for the under bailiff and large farmyards both sides of the village street. Of the five other farms two were under 50 a. and the others were 93 a. with the inn, 119 a., and 173 a. (fn. 118) By 1843 a resident land agent, John Grey, ran the estate. The home farm produced surplus grain, bacon, vetches, winter beans, clover seed, oxen and sheep, the last sold at Smithfield. Coal and oil cake were purchased. In 1849 Lytes Cary was supplied with 20 Devon, 14 shorthorn and 19 Hereford steers from Kingweston. (fn. 119)

John Gray ran 640 a., including 366 a. of arable, for Dickinson. He practiced complex forms of crop rotation according to the soil type but always including several crops of wheat. On the lighter land he also produced oats, clover, vetches, beans, and turnips, the last manured with 20 loads of dung, 2 cwt of superphosphate of lime, and 140 bu. of ash and rotted manure on each acre. On some land peas were planted in winter for harvesting in June and sainfoin was grown to stand up to four years. On the heavy land he grew clover, vetches, mustard for ploughing in, rape, and orange mangolds. The rape was treated with superphosphate but the mangolds were grown in holes filled with manure by women who would be followed by children setting the seed. The team of labourers using a horse to carry the manure sowed 3½ a. a day at a cost of 12s. but produced nearly a ton of mangolds per acre in a year when the swede crop failed. Of 800 Devon sheep, bought as lambs, folded on the arable and fed on turnips in the field, 600 were kept over winter on roots. Gray also kept 10 dairy cows and 50 oxen and steers bought at 2 years old and stalled in winter on one cwt of roots a day besides oil cake and chaff. His 14 horses were never put to grass but fed on oats, beans, bran and chaff costing 9s. a week each. A horse-drawn engine was used to cut all the farm hay and straw, which was consumed in the yard. (fn. 120)

Besides the inn, two farms were recorded in 1851 each with c. 230 a. The three farmers claimed to employ a total of 25 labourers but only 15 were recorded in the parish. There is no record of labour on the home farm although a shepherd, six garden workers, and two gamekeepers were probably employed by Francis Dickinson. (fn. 121) By 1861 one farmer was also a cattle dealer with 350 a. and the inn had closed to become solely a farmhouse. Again the amount of labour employed exceeded the recorded resident labourers. (fn. 122) Boys, employed for bird scaring, worked twelve hours a day from the age of 11 or 12, although in 1867 it was done by an old man who was more dependable. Mr Gray paid them 1s. more than other farmers. Men had 9s. and cider, which they refused to give up for cash. Carters received an extra 1s. Women seldom worked outside but planted beans, made hay, and picked apples. Cottagers grew potatoes and beans for their pigs. (fn. 123) In 1881, with the departure of the land agent and presumably the letting out of the home farm, there were three farms (325 a., 407 a., and 580 a.) employing a total of 37 labourers, more than twice those resident. (fn. 124) That remained the pattern into the 20th century. (fn. 125)

Planting and timber sales continued (fn. 126) and by 1905 there were 260 a. of wood, also 770 a. of grass and 460 a. of arable (fn. 127) A lease of 1912 required a further 53 a. of arable to be laid to permanent pasture. (fn. 128) Farms had reduced in size by 1905 when there were four. (fn. 129) The estate was then being managed by Bennets of Bruton and Bennets continued as landlords of cottage property until the 1960s or later. (fn. 130) By 1906 rents were used to pay mortgage debts and legacies. (fn. 131) During the First World War tractors were brought in to plough pasture for corn. (fn. 132) With the break-up of the estate some tenants bought their own farms. Two farms remained in the same families for most of the 20th century but by 1991 one farmhouse was being converted into a guest house. (fn. 133) In 2000 the parish produced cereals and temporary and permanent grass for dairying and stock rearing. (fn. 134) New farm buildings have been provided around the village, which is dominated by its working farms.

QUARRYING

A quarry close was recorded in 1683 (fn. 135) and a mason in 1716. (fn. 136) An arable field was called Tilepits in the early 19th century. (fn. 137) A limekiln recorded in 1759 seems to have been used to provide lime for the house for which a limeburner was paid 5 gns a quarter in 1781. (fn. 138) A quarry by Langland gate, used for building Kingweston House, was drowned in the winter of 1783. (fn. 139) In 1800 over 1,500 ft of stone was dug in East close and Great Common. (fn. 140) By 1830 a former quarry in agricultural use needed fencing and draining. (fn. 141) In 1839 a small quarry on Great Common remained open and supplied stone in 1844 and in 1850 for the school. (fn. 142) One or two masons were recorded during the mid 19th century. (fn. 143) Quarry workers recorded in 1891 and 1901 may have worked in Keinton quarry. (fn. 144) A 2-a. quarry, recorded in 1902, (fn. 145) was disused by 1929. (fn. 146)

CRAFTS

A new smithy was recorded in 1598, possibly the one next to the pound in 1839, which was rebuilt between 1797 and 1800 at a cost of £85. (fn. 147) A linman was recorded in 1768 (fn. 148) but a weaving loom recorded in 1784 appears to have been provided to employ a poor boy. (fn. 149) In 1801 eight people were engaged in trade or craft but only 3 in 1811 when unusually women made up only 44 per cent of the population. Only 16 out of 25 families were occupied in agriculture in 1831. (fn. 150)

In 1867 girls were said to earn good wages gloving and often started under the age of 11. (fn. 151) A bootmaker was in business by 1872 (fn. 152) and in 1881 two men described themselves as boot manufacturers and had a resident apprentice. (fn. 153) In 1901 the blacksmith was also a hot water engineer (fn. 154) and in 1906 the thatcher was also a hurdlemaker. (fn. 155)

RETAIL TRADES AND SERVICES

An alehouse keeper's wife had her purse stolen in 1678. (fn. 156) That was probably the licensed premises recorded throughout the 18th century, (fn. 157) built or extended in 1751 and provided with signs in 1752 and 1754. (fn. 158) It was rebuilt in the 1780s and provided with coach house, chaise house, stables and farm buildings as despite its position on a turnpike road the innkeeper needed to supplement his income by farming. (fn. 159) It was known as the Kingweston inn but only held a beer licence. (fn. 160) William Dickinson spent £53 building a brewhouse there in 1800 and £142 extending the inn in 1801. (fn. 161) The innholder in 1811 was bankrupt owing nearly £250 to a London wine merchant as well as many other debts, however he survived as innkeeper. (fn. 162) The inn was held with 93 a. in 1839, (fn. 163) employed three servants in 1841, (fn. 164) and was last recorded in 1859. (fn. 165)

In 1889 a sub post office was kept at the smithy. (fn. 166) A shopkeeper was recorded in 1891 (fn. 167) but none later. By 1947 there were neither shops nor services except the post office, which in 1980 sold confectionary and tobacco. (fn. 168) By 2004 there was only a small farm shop.

SOCIAL HISTORY

Kingweston is a small agricultural parish and during the Middle Ages was probably dominated by the bailiff and tenants of Bermondsey. A 13th-century bailiff was accused of acting without permission of the prior. (fn. 169) Between the 16th and 18th centuries the Reynolds family were the largest farming family and William acted as agent for Caleb Dickinson who lived in Bristol. (fn. 170) From the mid 18th century the parish was dominated by the Dickinson family. In 1839 Francis Dickinson owned the whole parish apart from the 30-a. glebe and he leased most of that. (fn. 171)

There was relatively little overcrowding, There was a house for every family in 1801 and 1821, (fn. 172) although in 1831 there were only 21 houses for 25 families (fn. 173) and in 1839 one house was divided into three dwellings and another seems to have been replaced by four cottages. (fn. 174) By 1867 additional cottages had been built and were let for £4 a year although the agent said more were needed and some workers came from Charlton. (fn. 175) By 1891 there were seven uninhabited houses and only six with fewer than five rooms but in 1901 there were 15 such houses of which nine had only three rooms. Most of the smallest cottages were near the church and there were none in the main village street. (fn. 176)

William Dickinson paid tax for six female and five male servants including his gamekeeper in 1787. (fn. 177) Servant girls and boys were employed on farms in the mid 19th century and even a labouring family had a resident servant in 1841. Two or more servants each were kept by the rector and by the land agent and between three and ten at Kingweston House depending on whether or not the family was in residence. A cattle dealer had a governess and three resident servants in 1861. Possibly owing to the employment of servants females formed 59 per cent of the population from 1861 to 1901. (fn. 178) However, by the 1890s the Dickinsons were no longer permanent residents, the carriages were given up and the gardens no longer kept to the same standard. It was said that in 1874 over £341 a year was spent on the garden and nine men and a boy were employed but by 1896 less that £200 was spent, and the staff had been reduced to six. (fn. 179) However in 1901 the Fitzgerolds, tenants of Kingweston House kept eight indoor servants, five gardeners, two lodgekeepers, a coachman and two gamekeepers. (fn. 180)

The rector's son was a farmer in America in 1891 (fn. 181) and at least one man emigrated to Canada in 1919. (fn. 182)

EDUCATION

In 1818 there was a day school for little children but the poor attended a neighbouring parish Sunday school. (fn. 183) In 1825 20 boys and 10 girls attended school (fn. 184) probably the Sunday school which taught six boys and six girls in 1835 when an infant school taught six children at their parents' expense. (fn. 185) In 1846 there was a parochial day and Sunday school, probably provided by Francis Dickinson who paid for work on it in 1844 and 1850. It was described as a good little school worthy of a better room. It taught six boys and 17 girls during the week and on Sunday, a further two boys and three girls on weekdays only and a further four boys and two girls on Sundays. (fn. 186) The school, described as a National school in 1859, (fn. 187) was well-attended in 1867 although the rector said there were insufficient funds to procure proper teachers. He thought every boy of 11 should be able to read, write, and spell and have a knowledge of arithmetic and scripture. (fn. 188) Two teachers were recorded in 1871, one a former cook, but in 1881 the schoolmistress was 20 and a 14 yearold boy was a pupil teacher. (fn. 189) The school was supported by Francis Dickinson (fn. 190) but had closed by 1889 when the children attended Barton St David school. (fn. 191) Later used as a parish room, (fn. 192) it is a small two-storeyed building with probably modern timber windows with arched lights; it was converted into a private residence c. 1980. (fn. 193)

John Gray, the land agent, had three agricultural pupils, boys between 18 and 25, boarding with him in 1871. (fn. 194)

COMMUNITY LIFE

The rector and two residents were royalists including John Hutton who sat in the county court. (fn. 195) The parish revel or wake was the scene of political argument and assault in 1653 between men from neighbouring parishes. It utilised a booth and stage in 1781 and was held on the 21 September. (fn. 196) A cockfight in 1731 attracted men from Butleigh and Barton St David. (fn. 197) The Kingweston club recorded in 1754 (fn. 198) and meeting at the inn in 1780–1, (fn. 199) was presumably a friendly society. An election dinner was held in 1812 for up to 400 people who consumed large quantities of drink at William Dickinson's expense. (fn. 200)

Thirteen local men served in the First World War, five having joined up before December 1914, and the gardens of Kingweston House supplied weekly hampers of vegetables. (fn. 201) There were outbreaks of influenza in November 1918 and February 1919. (fn. 202)

There was a Mothers' Union in 1947 and a cricket club begun c. 1950, (fn. 203) although cricket had been played in 1901, (fn. 204) but both had ceased by 1980 when the only social facility was a playing field. (fn. 205) The Kingweston Golf Club, established in 1982 in association with Millfield School, has its course in the former parkland of Kingweston House. (fn. 206)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Although a separate tithing in 1327, in the 16th and 17th centuries Kingweston formed a single tithing with Keinton Mandeville and Barton St David which led to friction over rating. (fn. 207) In 1767 Kingweston was assessed separately for land tax. (fn. 208)

MANORIAL ADMINISTRATION

There was a hayward in 1242. (fn. 209) Courts were held in the 1530s (fn. 210) and court books survive for 1641, 1650 and 1676–83 but by then courts were held no more frequently than once a year and were concerned with tenancies and maintenance. A bailiff was sworn at the 1641 court and two moor reeves were appointed annually. (fn. 211) Mr. Coward was accused of keeping courts without warrant c. 1646. (fn. 212) Annual courts were still held in the 18th century but except for 1756 no records of their business survive. They then met at the inn. Moor reeves, tithingman and hayward were recorded. (fn. 213) A cage, a pillory and a pound were out of repair in 1641. (fn. 214) The stocks needed repair in 1756. (fn. 215) There was a pound north of the former common in 1839, probably that for which a gate was provided in 1781. (fn. 216)

PARISH ADMINISTRATION

Few parish records survive. In 1613 the churchwardens were assisted by sidesmen (fn. 217) but in the 18th and 19th centuries many church and parish expenses were met by the Dickinsons from painting the royal arms in 1751 and thatching the poorhouse in 1768 to rebuilding the church in the 1850s. (fn. 218) The waywardens also appear to have been supervised by the manor court in the mid 18th century (fn. 219) and by the early 19th there was only one. (fn. 220)

The overseers paid £1 a year rent from 1759 or earlier for a poorhouse. (fn. 221) It seems to have been given up by 1839. (fn. 222) The parish also held a stock on which it was taxed in 1767. (fn. 223) In the 1780s a 'small water engine' at the church may have been a parish fire engine. (fn. 224) A vestry of three farmers meeting by 1834, met at the inn in 1840. The parish paid the clerk £3 10s. a year. (fn. 225) The vestry was succeeded by a parochial church council but there was no parish council. (fn. 226)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

Kingweston from the 13th century was an independent parish with its own rector. It was not a wealthy living and was usually left in the care of curates. The lack of substantial freeholders and independent artisans meant that there was little recusancy or nonconformity. Although Caleb Dickinson was a committed Quaker, his descendants adhered to the Church of England, (fn. 227) and Francis Dickinson rebuilt the church according to the high Anglican tradition.

CHURCH

A rector was recorded in 1242–3 (fn. 228) and the church was dedicated to All Saints by 1532. (fn. 229) Kingweston remained a sole rectory until 1932 when it was united with Barton St David under an order of 1930. (fn. 230) Under an order of 1977 the benefice was united with Keinton Mandeville and Lydford on Fosse. They are now known as the Wheathill Priory Group. (fn. 231)

Advowson

The advowson was held by Bermondsey priory, later abbey, from 1114. After the Dissolution the advowson continued to pass with the manor (fn. 232) and since the union of benefices Everilda Joyce Burden, daughter of William Dickinson (d. 1964), has held the right to present at the fifth turn. (fn. 233)

Income and Property

In 1291 the church was valued at £4 1s. (fn. 234) In 1440 and 1468 it was exempt from tax for poverty. (fn. 235) In 1497 a neighbouring rector left furnishings, books, oxen, and plough gear to the rector of Kingweston. (fn. 236) By 1535 the rectory was worth £10 17s. 8d. gross (fn. 237) but £50 c. 1666, (fn. 238) and £41 14s. 2d. net in 1707. (fn. 239) It was farmed out to the lord of the manor for £50 in 1779 and £120 in 1833 (fn. 240) when the average gross income was £140. (fn. 241) The income was augmented by the interest of £31 surplus from the 1801 redemption of land tax on the rectory. (fn. 242)

In 1535 predial tithes were worth £6, wool and lamb tithes £1 10s. 2d. and personal tithes £1 14s. 8d. (fn. 243) In 1707 tithes were worth £20 and Easter offerings £7 5s. (fn. 244) Caleb Dickinson rented the tithes in 1779. (fn. 245) In the 1780s they were said have been exonerated by William Dickinson who paid the equivalent sum to the incumbent, (fn. 246) but were commuted for a rent charge of £156 in 1839. (fn. 247)

In 1243 the rector was in dispute with the prior of Bermondsey over a house and half a virgate belonging to the church. (fn. 248) A commission was to inquire into the defects of the rectory in 1410 on behalf of the rector. (fn. 249) The glebe was worth £1 12s. 8d. in 1535 (fn. 250) but £16 a year in 1707. (fn. 251) It measured 29½ a. in 1839 when it was parcelled out to tenants. (fn. 252) In 1851 the barn was used for services. (fn. 253) Part of the glebe was sold with the house, c. 15 a. was sold in 1959 and c. 8 a. remained in 1974. (fn. 254)

The house was burnt down c. 1606 but had been rebuilt by 1613 although it lacked internal doors, window glass and other fittings. (fn. 255) The house and outbuildings were in disrepair in 1650 having been occupied by the rector's daughter and her husband. (fn. 256) The pigeon house was repaired in 1740. (fn. 257) In 1783 the rector found the house out of repair and slept at the inn. (fn. 258) The house was repaired before 1815 but the rector considered it unfit for his family and in 1827 the resident curate did not live in the glebe house. (fn. 259) In 1833 the rector let it with the glebe to William Dickinson (fn. 260) probably for rebuilding and by 1839 the new house, a small classical villa, was occupied by the curate. (fn. 261) The rectors were resident for most of the later 19th century and in 1881 had a gardener in a separate dwelling. (fn. 262) In 1896 the house had the usual accommodation as well as a coach house and stable and several farm buildings, which in 1903 it was proposed to demolish to enlarge the garden (fn. 263) but the barn was retained. (fn. 264) The union with Barton St David rendered the house redundant. (fn. 265) In 1933 it was sold to William Dickinson who let it but in 1945 it became the family home and was known as the Dower House. (fn. 266)

Pastoral Care and Parish Life

Henry, the first recorded rector, was in dispute with Bermondsey priory in 1242. (fn. 267) In 1295 John Russell clerk of Kingweston was accused with a local woman of murdering her husband. (fn. 268) In 1315 Robert de Alewy was presented to the living although there was no vacancy. Simon the incumbent resigned the following year but Robert took a year's study leave. (fn. 269) His successor in 1319 was only an acolyte and Nicholas of Somerton, instituted before 1337 was absent in the service of the abbot of Muchelney. (fn. 270) During the early 15th century there were frequent resignations and exchanges of the living; there were three incumbents in each of the years 1413, 1416 and 1421. (fn. 271) This may have been due to the poverty of the living (fn. 272) although in the 1530s the rectory income was more than twice that from the manor. (fn. 273) Kingweston was probably the site of Sir Hugh Pawlet's defeat of the Cornish and Devon rebels in 1549 after they had been pursued from Exeter. Henry Lyte remembered as a boy watching the skirmish in Kingweston's leaze. (fn. 274)

In 1554 the rector, Ralph Laws was deprived for marriage (fn. 275) but had returned by 1562 when he was a pluralist and did not preach although resident. (fn. 276) His successor left the parish in the care of curates. (fn. 277) In 1623, under Paul Godwin instituted 1619 but also vicar of Netherbury, Dorset, the parish had a curate who was only a deacon and a clerk under age. (fn. 278) Although the rector was sometimes resident in the late 1620s he employed ministers one of whom practised physic and surgery. (fn. 279) In 1646 he was accused of deserting Netherbury and was sequestered from Kingweston as a delinquent, idle, and scandalous minister who left his curate, John Backer, in want. (fn. 280) Thereafter the parish was regularly in the charge of a curate (fn. 281) and the registers only date from 1653, 1660 for marriages. (fn. 282) During the 16th and early 17th century the church building seems to have been in poor condition. By the 1590s the chancel windows were in a poor state, (fn. 283) and in 1612 the south wall was rebuilt with a plain porch and the nave roof perhaps raised. The tower was ruinous and it would take two years to repair. (fn. 284) It was evidently rebuilt as in the mid 19th century it was reported that the early 17th-century tower had no foundations. (fn. 285) It housed a peal of three bells and there was a clock. (fn. 286)

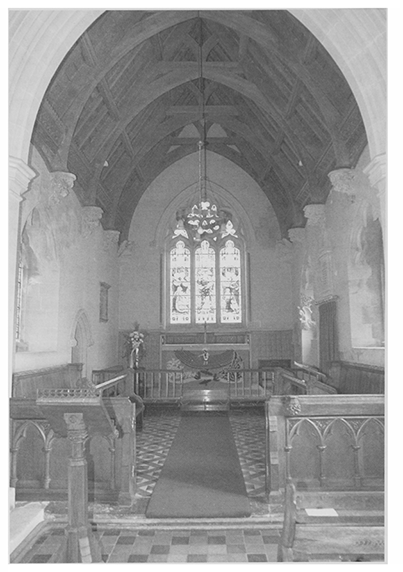

61. Kingweston church, the chancel looking east. It was rebuilt in 1855 to designs by C.E. Giles in an Early English style and ornamented in high church tradition.

By the late 18th century the building was in good repair. It was 68 ft by 22 ft, dry, clean and paved and had whitewashed ceilings with brown ribs, three doors and a singers' gallery, a mixture of pews and old benches, a stone font, a 1634 table inclosed with rails, and an ancient chair, which was said to have belonged to Abbot Richard Whiting and been bought by Mr Dickinson from a Mr More of Greinton; the chair was later removed from the church. (fn. 287) The Dickinsons rented the rectory from Richard Collinson, rector 1770–1811, and employed a minister. (fn. 288) In 1785 the curate had a speech impediment and the minister from Glastonbury was not liked so the vicar of Somerton was employed. (fn. 289) The next rector, Antony Pyne, instituted 1811, also held Pitney where he lived because he considered the house unfit for him. One service was held alternately morning and afternoon in 1815. (fn. 290) His successor Charles Henry Pulsford, 1819–29, was a canon of Wells and non-resident but employed a curate solely to serve Kingweston. (fn. 291) Edward Harbin, instituted 1829, was rector of East Lydford and his successor James Hooper let the rectory in 1833 to William Dickinson but his curate resided and held two Sunday services. (fn. 292) There were only five or six communicants in 1843. (fn. 293) From the mid 19th century rectors were resident. (fn. 294)

In 1850 a new church was planned by the rector and Francis Dickinson (fn. 295) at the latter's expense. The rector thought a bell turret would suffice and wanted a site away from Kingweston House. That would enable the old church to be used until the new one opened and remain as a Dickinson mausoleum. (fn. 296) However, a specification drawn up in 1850 was for demolition and rebuilding, salvaging materials where possible. Kingweston stone would be supplemented by Portland and most of the timber would be English oak. (fn. 297) Designs were submitted in June by Henry Woodyer of Guildford (fn. 298) but by 1851 C. E. Giles of Taunton had been appointed architect and declared that the church could not be restored. He produced several designs in blue lias and Doulting stone with spire and north aisle to cost over £1,000. (fn. 299) A faculty was obtained for removal of all furniture, total demolition, and extension of the site north and west. Although permission was not granted until July demolition began in April 1851 preserving the Dickinson vault. (fn. 300) By July the site was described as desolate and dismal and no decision had been reached on the design or siting of a tower. (fn. 301) By 1854 the church was ready to be fitted out. (fn. 302) The old plate was said to have been replaced c. 1852 by a chalice and a paten of medieval design dated 1845 but a flagon of 1812 was retained. (fn. 303) The five bells by Taylor are dated 1854, (fn. 304) The church was completed, consecrated and opened in July 1855. (fn. 305)

Meanwhile the rectory barn was licensed for divine service and later for marriages. (fn. 306) On Census Sunday 1851 attendance was 40 in the morning and 50 in the afternoon with 18 Sunday school children at each service but 15 members of the Dickinson household were absent. (fn. 307) The rector resisted Francis Dickinson's desire to segregate men from women and children in the new church, (fn. 308) evidence of high churchmanship. Two Sunday services, with daily services in Advent and Lent, were held in the 1890s when 30 or more took Easter communion rising to 37 in 1919, but sometimes there was no congregation at early service. (fn. 309) After a brief attempt to hold three Sunday services in the 1920s, services were reduced to one by 1938 with evensong once a fortnight and later less often although in 1946 community hymn singing was tried instead. Choral communion was held in the late 1940s and there were over 50 Easter communicants. A threepiece private communion set was given in 1955. A new organ by George Osmond of Taunton was installed in 1950 at a cost of £850 and refurbished in 2005. Numbers of Easter communicants fell to c. 24 from the 1960s. (fn. 310) By 2004 services were held twice a month.

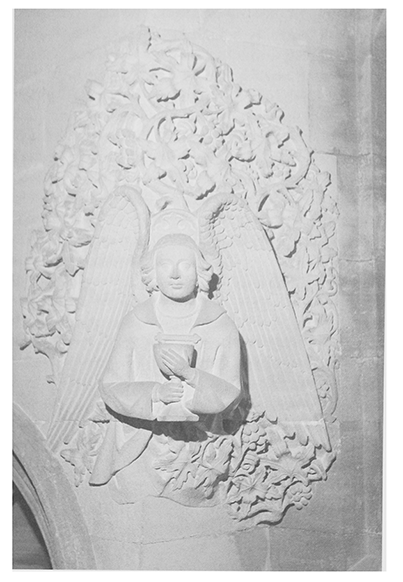

62. Kingweston church, carving in chancel of angel with chalice, probably by Davis of Taunton.

Church Building

In 1850 the medieval church had a chancel with choir door, nave with north aisle or transept and side altar belonging to the Dickinsons, porch and west embattled tower 45 ft high. The building had 12thcentury fabric, including a south door and a font, which were reused in the new building in 1851–4. A commission to inquire into the defects of the chancel in 1410 on behalf of the rector (fn. 311) may have resulted in a remodelling with square-headed windows. The new church of lias and Doulting stone is late 13th-century in style and stands at the highest point of the village, making a picturesque composition with Kingweston House. It has a chancel, nave with north-east vestry, and a tower over the south porch; the spire rises high and sharp over a tall, gabled bell stage. Inside the chancel has elaborate carving, probably by Davis of Taunton, and lavish furnishings include the marble and alabaster reredos and altar, incised stone slabs to cover the Dickinson vault, panelled tower door, and pulpit. (fn. 312) Old memorials were replaced by brasses in the chancel floor. Most windows date from the early 20th century and are memorials. Those on the south side of the chancel are by Clayton and Bell. (fn. 313) A 16th-century painting of the Magi was given by Major Dickinson in 1944 when a credence table was also given. (fn. 314) Seat cushions commemorate George V's jubilee. Cracking of the structure has been blamed either on settlement or the result of nine bombs dropping nearby during the Second World War. (fn. 315)

The churchyard was extended in 1855 (fn. 316) and the lych gate was installed in 1937 for George V's jubilee. (fn. 317) The 14th-century cross erected in the churchyard on a new base and with a new top as a First World War memorial was in the churchyard in 1846. (fn. 318)

PROTESTANT NONCONFORMITY

Although he made generous benefactions to the Society of Friends in Bristol, including the school at Quaker Friars, Caleb Dickinson did not establish a meeting in Kingweston. In 1828 a building occupied by James Cannon was licensed for worship but there is no other record of nonconformity. (fn. 319)