A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Broadwell Parish: Holwell', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp87-111 [accessed 10 February 2025].

'Broadwell Parish: Holwell', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online, accessed February 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp87-111.

"Broadwell Parish: Holwell". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online. Web. 10 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp87-111.

In this section

HOLWELL TOWNSHIP

The small hamlet of Holwell (fn. 1) lies on downland formerly included in the northern part of Broadwell parish, around 2¾ miles (4.5 km) south-west of Burford and 8 miles (13 km) west of Witney. Throughout its history it has been a small agricultural community, and during the 19th and earlier 20th centuries it became an estate village for the neighbouring Bradwell Grove House. From the Middle Ages and particularly after the Black Death it was by far the smallest of Broadwell's four settlements, and in the later 20th century, as the population shrank further with the decline in agricultural employment, it was increasingly inhabited by professional incomers, with some cottages becoming weekend homes. (fn. 2) Around twenty domestic and farm buildings of traditional stone and slate are clustered around the central pond, church, and small green with war memorial. Some barns and agricultural buildings have been converted to home and office premises, and there are outlying farm buildings at Holwell Downs.

Boundaries and Landscape

From the Middle Ages until the mid 19th century Holwell formed the northern section of Broadwell parish, whose origins are discussed above. (fn. 3) It was nevertheless an independent township with its own fields and parish officers, and a chapel was established there before the late 12th century. From the mid 19th century, like Broadwell's other townships, it was treated as a separate civil parish, and its acreage of 1,063 a. (430 ha.) remained unaltered in 2001. (fn. 4)

On the west the township adjoined the county boundary with Gloucestershire, and on the north and east the parishes of Westwell and Shilton. (fn. 5) By 1840 the boundaries there followed regular field-boundaries; some may, however, have been adjusted in the 1680s, when Henry Trinder, in preparation for inclosure, spent several years 'dividing the greatest lots in the common fields and wastes of Holwell from the fields and wastes of adjacent villages'. (fn. 6) The southern boundary with Broadwell and Filkins followed Akeman Street, certainly from Holwell's inclosure and probably earlier. In 1850 a new ecclesiastical parish was formed which included both the ancient civil parish and some houses at Bradwell Grove, causing occasional confusion. (fn. 7) Even for civil purposes, houses at the Grove and south of Akeman Street were occasionally grouped with Holwell for administrative convenience. (fn. 8)

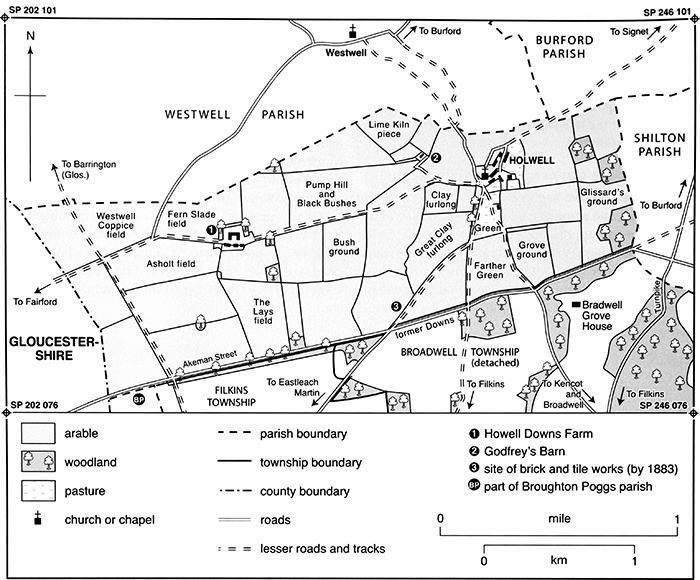

26. Holwell township c. 1840, including some later features.

The hamlet stands on the first ridge of higher ground between the river Thames (some 6 miles to the south) and the river Windrush (2 miles to the north), at around 130 m. above sea level. Along the township's north-east edge the land falls away sharply towards a small boundary stream, but otherwise the terrain is relatively flat and only gently undulating, rising gradually to 155 m. at the township's north-west corner (Fig. 3). (fn. 9) The soil, predominantly stonebrash overlying White Limestone and Forest Marble, is best suited to sheep pasture, owing partly to the intermittent water supply. Nonetheless the township's economy was mixed from the Middle Ages, with extensive arable fields as well as downland pasture and, by the 18th century, a few small plantations of trees. (fn. 10)

Communications

Though now relatively isolated and served only by minor roads, Holwell lies at the intersection of several formerly long-distance routes. (fn. 11) Much of the village lies along a south-west to north-east route now mostly marked by bridle paths, but which formerly led from Eastleach Martin through to Signet and Burford. The metalled road from Westwell, which intersects it by Holwell church, continues south-eastwards to Bradwell Grove and Kencot, crossing the main road from Burford to Filkins and Lechlade. The Burford–Lechlade road was turnpiked in 1792, (fn. 12) and part of the route through Bradwell Grove was diverted and slightly shortened in 1814, with the consent of William Hervey of Bradwell Grove House. (fn. 13) A track westwards from Holwell (past Holwell Downs Farm) began as a through route to Fifield Warren and on into Gloucestershire, linking with routes to Fairford, Eastleach, and Aldsworth, while the Holwell stretch of Akeman Street remained a moderately significant hedged lane in the 18th century. A surviving public bridle way from Holwell to Filkins and Broadwell existed by 1776. (fn. 14)

The nearest railway station (4½ miles south-east at Alvescot) was opened in 1873 on the East Gloucestershire line to Fairford (Glos.). The line later became part of the Great Western Railway, and closed in 1962. (fn. 15) Post was delivered from Burford in the 19th and earlier 20th century, and by 1895 there were collections from Holwell. (fn. 16) No village carriers are recorded.

Settlement and Population

Early Settlement

The remains of what was possibly a Neolithic henge monument are visible on Holwell Downs, together with linear features which may indicate trackways. (fn. 17) The proximity of Akeman Street does not necessarily indicate Roman settlement, and nothing further is known of pre-Anglo-Saxon activity in the township. (fn. 18)

By the early 11th century Holwell was included within the large comital estate focused on Langford or Broadwell. (fn. 19) Given its location on the traditional summer pastures of the downs, it may at first have been only seasonally occupied; even so it seems likely that some of the Broadwell manor tenants recorded in 1086 already lived at Holwell, where a chapel was built before the late 12th century near what was apparently an Anglo-Saxon holy well. By the late 13th century Holwell was a sizeable hamlet with its own open fields, and a social structure which bore no signs of recent colonization. (fn. 20)

Population from 1279

By 1279 there were around 24 households in the hamlet, a total population of perhaps 100–120. Most people listed were unfree villeins, together with three or possibly four households of free tenants. (fn. 21) Around 15 of the more prosperous inhabitants (presumably mostly householders) were taxed in the early 14th century, (fn. 22) but in 1377, following mid 14th-century plagues, only 17 inhabitants over the age of fourteen paid poll tax. Even allowing for evasion and omission, the figure implies that the population had fallen sharply. (fn. 23) Earthworks suggesting deserted buildings and enclosures east of the village street are further evidence of population decline in the later Middle Ages. (fn. 24)

The population remained well below 13th-century levels in the 17th century. In 1641 only nine landholders (at least one of them non-resident) were taxed, (fn. 25) and in the 1660s only seven householders were assessed for hearth tax. In 1665 two of those were too poor to pay, and one house was uninhabited. (fn. 26) By then the Trinder family dominated the hamlet, and in 1693 they inclosed the open fields; inclosure does not seem, however, to have reduced the population further, and in 1759 Holwell contained 10–11 families. (fn. 27) In 1801 there were 14 houses and 70 people, all but six of them employed in agriculture. (fn. 28)

The population peaked in 1851, when 131 people occupied 23 houses. Thereafter numbers gradually dwindled to 47 living in 16 dwellings in 1951. From then on, with the decline in agricultural employment, the population decreased more rapidly, to only 13 households (containing 27 inhabitants) in 1991, and to 17 people ten years later. (fn. 29)

Development of the Village

The earliest evidence for Holwell's topography is its place name, recorded from the early 12th century and meaning 'holy well'. (fn. 30) Presumably this was the deep pond at the village's southern end, next to which a baptismal chapel was built probably in the early-to-mid 12th century. (fn. 31) The existing 19th-century church occupies the same site (Plate 2). The buildings of the present nucleated settlement lie along a single village street running north-east from the pond, which was formerly part of a through-route to Signet and Burford. (fn. 32) Where the Westwell-Broadwell road intersects it by the church is a small open area or former green, now marked by a village war memorial cross erected c. 1920. Possibly this was the area denoted by the medieval surname 'at green' (recorded in the 13th century), (fn. 33) although a larger area south of the village was still called The Green in the 1840s. (fn. 34) Some house plots a little to the east of the modern hamlet were apparently abandoned in the later Middle Ages. (fn. 35)

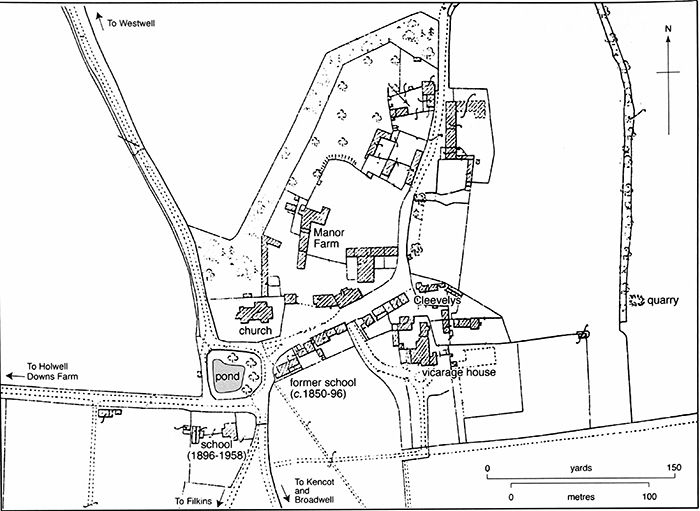

27. Holwell village in 1899, showing key buildings.

By the 17th century the hamlet consisted of the recently built Manor Farm (near the chapel), (fn. 36) a few cottages, and one or two slightly more substantial yeoman houses and farmsteads. Among the latter were houses called Cooke's, George's, and Cleevely's, all named from the families occupying them in the 16th and 17th centuries, (fn. 37) while an unidentified holding called Harecourt had probably once belonged to the Harcourt family. (fn. 38) The name Cleevely's still survives for a late 17th-century cottage on the south side of the village street. (fn. 39) By the time of the first reliable maps in the late 18th century the village's modern layout was well established. (fn. 40) Manor Farm (Fig. 28) remained the most substantial building, encompassing a large adjacent barn and stable-range built along the village street. (fn. 41) Outside the village a rickbarton on Holwell Downs was mentioned in 1606, (fn. 42) and cottages and agricultural buildings at what became Holwell Downs Farm were most likely built in the early 19th century after the Westwell farmers John Pinnell and John Bagnall took over the estate. (fn. 43) A brick and slate farmhouse incorporating an unusual tower block (Fig. 29) was added there in the 1870s, when the resident Maces took on the tenancy. (fn. 44) A now-demolished barn called Godfreys, a little way north-west of the village, seems to have been built in 1725 for the recently inclosed rectory estate. (fn. 45)

Apart from Holwell Downs Farmhouse the surviving vernacular buildings are of local stone and stone slate, built in a Cotswold style typical of the area. (fn. 46) In the 19th century they were joined by a few Victorian institutional buildings, all using traditional materials: the old and new schools (c. 1850 and 1896), the vicarage house (1850), which rivalled Manor Farm in size, and the church, which was heavily remodelled in 1842 and completely rebuilt in 1895. All those additions reflected the influence in the village of William Hervey of Bradwell Grove and his successors. (fn. 47) By the early 20th century there was a village pump, and additional piped water was pumped by windmill from a well near the township's southern boundary. (fn. 48)

Of some 22 houses in the village centre in 1841, fifteen were estate cottages, and in 1910 the housing stock remained much the same. (fn. 49) During the early and mid 19th century, as population increased, former farmhouses such as Cooke's and George's were divided into cottages for agricultural labourers, and some houses were occupied by more than one household, although there was no significant overcrowding. (fn. 50) The 1861 census counted 34 dwellings in Holwell, among them the outlying cottages at Holwell Downs Farm and a ribbon development of cottages along the south side of Akeman Street, technically in Filkins. (fn. 51) The 20th century saw virtually no new building, although during the later 20th and early 21st centuries several farm buildings in the village were converted into houses or business premises, and so too were the former schools. (fn. 52)

MANORS AND ESTATES

In 1086 Holwell formed part of the large manor of Broadwell. On the manor's partition in the early 13th century the township became divided between the manors of Bradwell Odyngsell and Bradwell Cirencester, which were respectively owned by the d'Oddingseles family and (from the late 13th century) by Cirencester abbey. A small lifehold estate held in 1279 by Roland d'Oddingseles (d. 1316) passed to the abbey on Roland's death. (fn. 53)

In the late 16th century most of Holwell became detached from the Broadwell manors, and during the 17th and 18th centuries the local Trinder family and their successors gradually accumulated the various freeholds. From around 1670 their combined estate, eventually comprising the whole township, became known as Holwell manor, although it carried no exercisable manorial rights. In the early 19th century it was acquired by William Hervey of Bradwell Grove, and became part of the large Bradwell Grove estate.

The Creation of Holwell 'Manor'

In 1564 John d'Oddingseles sold his Holwell land to James Moores of Little Faringdon (in Langford parish), together with a chief house which is probably to be identified with Holwell Manor Farm. (fn. 54) In the late 16th century and the 17th the estate was usually reckoned at 22 yardlands, nominally the whole township; from the late 17th century it was said to contain only 11 yardlands, however, the rest comprising separate freeholds. (fn. 55) Possibly those had become separated from the Moores' estate, though it seems more likely that the original claim to the whole township was spurious. (fn. 56)

In 1577 James Moores granted his Holwell lands to his son Thomas, to whom they were confirmed ten years later; various relatives named in interim transactions were probably trustees. In 1611 Thomas's son Farmar and widow Hester, with her husband John Snape, sold it to the London merchant Thomas Harris, who in 1620 (with his wife Mary) mortgaged it to his father Thomas, a London salter. The elder Thomas Harris sold the estate in 1625 to James (later Sir James) Cambell (d. 1642), a prominent London alderman, (fn. 57) who the following year leased it for 99 years to Charles Trinder (d. 1658) of Holwell. The lease was renewed in 1647 after Trinder defaulted on a payment, and again in 1658 by Trinder's widow Jane (d. 1688) for the lives of their sons John (d. c. 1707), Charles (d. 1718), and Henry (d. 1712). (fn. 58) In 1683 Henry and his youngest brother William (d. 1690) bought the reversion of an additional 200-year lease, which Cambell's nephew and heir James Cambell (d. 1659) had granted to trustees in 1653 in order to secure family payments from the estate after his death. (fn. 59)

Most of the Bradwell Cirencester lands in Holwell were granted in 1542 to Sir Thomas Pope, but seem to have been excluded from Sir William Pope's sale of Bradwell Cirencester in 1599. (fn. 60) During the 17th century they, too, were acquired by the Trinders, partly with a view to inclosure. (fn. 61) A 5-yardland holding called Cooke's, after its 17th-century subtenants, was leased by the Popes to Charles Trinder from 1633, and in 1670 trustees for the Pope family sold the freehold to Henry Trinder. (fn. 62) The holding was sold with the title of the manor or reputed manor of Holwell, which passed with the Trinders' combined estate until the 19th century. (fn. 63) A 5-yardland holding called George's, sold by John Snape the younger to Thomas Harris in 1606, had presumably also belonged either to Bradwell Cirencester or to the Moores' estate. Before 1636 it was acquired by Sir Lucius Cary, Viscount Falkland, and passed by sale to Ambrose Sheppard and, in 1637, to Thomas Hampson (d. 1655), lord of Broadwell. William Trinder (d. 1690) bought the reversion from Sir Dennis Hampson in 1685. (fn. 64) The family's Holwell purchases formed part of a wider policy of acquisition within the area. In 1634 Charles Trinder acquired the neighbouring manor of Westwell, and in 1641 he bought that of Eastleach St Martin (Glos.). (fn. 65)

Of the Trinder coheirs, John, who lived at Westwell, (fn. 66) seems to have had no active interest in Holwell after 1658. Both he and his brother Charles were Roman Catholic recusants, (fn. 67) and it was presumably to avoid confiscation that the younger brothers, Henry and William, acted for Charles in legal transactions. Charles and Henry (who were both lawyers) appear to have each had a half interest in the estate, with William merely purchasing and holding land on their behalf, although the complex transactions make the ownership unclear. (fn. 68) Only Charles and Henry seem to have ever lived at Holwell, (fn. 69) and by 1717, following his brothers' deaths, Charles was sole owner. By then the estate comprised a chief house and 11 yardlands (which remained leasehold), the two 5-yardland freeholds, and the manor or reputed manor. (fn. 70)

On Charles's death in 1718 his estates were divided equally between his daughter Eugenia, wife of John Wright of Kelvedon (Essex), and his grandson Charles Boddenham, who in 1721 sold his share to the Wrights. (fn. 71) The estate passed thereafter to Wright's son John (d. 1751) and grandson John (d. 1792), who in 1765 bought Holwell's tithes with an associated yardland, thus becoming owner of the entire township. (fn. 72) His son and successor John (d. 1826) sold the estate in 1804 to Patrick Craufurd Bruce of Taplow and London, who in 1812 sold it to the tenant farmers, John Bagnall and John Pinnell of Westwell. They partitioned it in 1819, and in 1822, following various mortgages, Bagnall sold his half to Pinnell, who in 1828 was succeeded by his sons Thomas and Richard. (fn. 73) They sold it in 1838–9 to William Hervey of Bradwell Grove, who with difficulty secured reversion of the 200-year lease granted by James Cambell in 1653. (fn. 74) Thereafter Holwell formed part of the Bradwell Grove estate. (fn. 75)

28. Holwell Manor Farm from the south-east, showing the probably 16th-century core (left), and the 17th- and 19th-century north-east ranges.

Holwell Manor Farm

Holwell Manor Farm, at the centre of the village north-east of the church, was so called by 1871, (fn. 76) and was probably the house sold by John d'Oddingseles in 1564. Called a 'mansion house' in 1578, (fn. 77) it was occupied by some of the Moores family (fn. 78) and later by the Trinders, in particular Charles (d. 1658) and his wife Jane. (fn. 79) Their sons Charles and Henry also lived there for a time: Charles was taxed on ten hearths at Holwell in the early 1660s before moving to Bourton-on-the-Water (Glos.), (fn. 80) and Henry was 'of Holwell' in 1669. (fn. 81) Charles's will provided for his grandson William Wright to live at Holwell to manage his estate and malting business, (fn. 82) but the Wrights lived chiefly at Kelvedon Hall in Essex, (fn. 83) and from the early 18th century both house and estate were let to local farmers. (fn. 84) In the 1830s John Pinnell's son Thomas occupied the house and farm (then called Home farm), and after Holwell was absorbed into the Bradwell Grove estate he became William Hervey's tenant. (fn. 85) The house continued to be let to tenant farmers for most of the 20th century. (fn. 86)

The present building (Fig. 28) is probably of 16th-century origin, with numerous later additions and alterations. (fn. 87) Built of limestone rubble with stone-slated roofs, it is two-storeyed with attics, and has an irregular L-plan. The earliest part is the central section of the south range, built on a lobby-entrance plan around a large stack. The range has fireplaces with depressed Tudor heads, three-light stone-mullioned windows with hoodmoulds, and a two-light window in the gabled attic. A two-storeyed north-east wing, with a stair turret at the rear, was added at right angles apparently in the early 17th century: a wooden lintel over the north ground-floor fireplace (removed during late 20th-century renovations) reportedly bore the inscription CT 1628, presumably for Charles Trinder. (fn. 88)

A long range of attached outbuildings to the south, single-storeyed with some attics, is probably 17th- and 18th-century, and at its southern end includes a mullioned window apparently in situ. A freestanding barn and stable range was added to the south-east in the 17th or early 18th century, aligned along the village street. (fn. 89) The house's north-east range was extended on the north in the early 19th century, creating a new entrance, and with a service corridor at the rear leading to a large reception room. The range's older parts were given sash windows probably around the same time.

An adjacent 'messuage' or 'tenement' called the 'kite house' was mentioned in the 1570s and 1640s. Possibly it was a former dairy converted into a dwelling, though if so it seems to have gone by 1812. (fn. 90)

Holwell Rectory Estate (Cleevely's Or Godfrey's)

From the 12th century until the Dissolution, rectorial tithes in Holwell belonged to the Knights Templar and to their successors the Hospitallers, as part of Bradwell St John manor. (fn. 91) The tithes were evidently excluded from Henry VIII's sale of Bradwell St John to Sir Thomas Pope in 1542, (fn. 92) and from 1564 they were leased by the Crown for 40s. a year as Holwell 'rectory', the lessee from 1565 being the wealthy Burford merchant Simon Wisdom. (fn. 93) In 1604 James I sold the tithes to Sir Thomas Shirley and others, reserving the 40s. rent to the Crown; the purchasers were evidently agents or trustees, and immediately sold them on to Sir Thomas Denton of Hillesden (Bucks.). Denton sold them in 1607 to William Fisher, a former vicar of Broadwell, and his daughter Elizabeth, and in 1611 the Fishers sold them to William Cleevely of Holwell. He was succeeded in 1623 by his daughter Mary, wife of John Godfrey of Milton-under-Wychwood. (fn. 94) A house, close, and yardland already belonging to the Cleevelys (and formerly part of Bradwell Cirencester manor) descended with the tithes thereafter, but were not strictly part of the rectory estate. (fn. 95) The 40s. rent reserved by the Crown was sold to Godfrey in 1670, and thus extinguished. (fn. 96)

The combined tithes and land (c. 52 a. after inclosure) passed to Godfrey's son William (d. 1713), grandson Thomas (d. 1747), and great-grandson William, who in 1756 sold them to a creditor, Revd Robert Leyborne. He was succeeded by the Taylors of Westwell, his relatives through marriage. In 1765 they sold them to John Wright, owner of the rest of Holwell township, with whose estate they were sold to William Hervey of Bradwell Grove in 1838–9. (fn. 97) In 1840 Hervey was awarded an annual rent-charge of just over £211 in lieu of commuted great tithes, from which he gave £25 (later £50) a year to help support the incumbent after Holwell became a separate parish in 1850. (fn. 98) The remaining tithe-rent was sold as part of the Bradwell Grove estate in 1871. (fn. 99)

Rectory Estate Buildings

An unoccupied house owned by John Godfrey in 1665 (when it was taxed on five hearths) was presumably that formerly owned by the Cleevelys. (fn. 100) By the mid 18th century the combined estate included a house and malthouse (later converted into cottages), with two barns and stables. (fn. 101) All the property appears to have lain south of the village street near the 19th-century vicarage house, which William Hervey built on the site of the malthouse in 1850. In the mid 19th century cottages fronting the street to its north were still counted as part of the rectory estate, (fn. 102) and in the early 21st century one nearby was still known as Cleevelys. (fn. 103) Godfrey's Barn, ¼ mile west of Holwell village, was probably built as a tithe barn by Thomas Godfrey in 1725. (fn. 104)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

The Agricultural Landscape (See Fig. 26)

A defining characteristic of Holwell is the rolling downland west of the village (Fig. 3), which extends into neighbouring parishes and which attracted graziers from an early date. Arable farming remained important through much of its history, however, and has often been dominant, focused until the late 17th century on sizeable open fields around the village, and later on more widely spread closes. Meadow was generally in short supply, reflecting the absence of streams, while woodland, too, seems to have been minimal until the 18th and 19th centuries, when local landowners established a few new plantations as game coverts and for ornamentation. Availability of clay gave rise in the late 19th century to a short-lived brick and tile works, and earlier may have prompted some small-scale pottery making. (fn. 105)

Arable

In 1279 just under 20 yardlands were recorded in the township, suggesting that there were perhaps 400–500 acres of cultivated arable, up to half the total. (fn. 106) By the later 16th century the township was usually reckoned at 22 yardlands, (fn. 107) perhaps reflecting an early expansion of the cultivated area. Until the 1690s the arable was organized as open fields, of which one lay to the south and east of the village in 1578, (fn. 108) where ridge and furrow remained visible on Glissards ground in the mid 20th century. (fn. 109) Another field lay possibly to the south and west, where field names incorporating 'furlong' survived in 1840. (fn. 110) A croft mentioned in 1409 may indicate small-scale inclosure on the outskirts of the village, and further inclosure was recorded by the later 16th century, when the Moores family's Manor farm included five closes and pasture grounds. (fn. 111) The soil, predominantly stonebrash overlying limestone, is stony dry sand or loam, and a band of clay running through the township was reflected in the field names Great and Little Clay furlongs. (fn. 112)

From around 1672 the dominant Trinder family set out to inclose the township. The process was completed by 1693 when much of the former arable was laid out as sheep pasture, (fn. 113) although arable farming continued: during the high farming of the early to late 19th century virtually the whole township was under crop, and the same remained true at the turn of the 21st century. (fn. 114) Crops in the 16th and 17th centuries, as elsewhere in the area, included barley, wheat, peas, and oats, and in 1663 one farmer was manuring part of his fallow, suggesting innovative husbandry. (fn. 115) By 1813 turnips were a significant crop in addition to grain, (fn. 116) and in 1941, under wartime conditions, other root crops were grown, among them potatoes, mangolds, and kale for fodder. (fn. 117) Grain crops remained important throughout, accompanied in the later 20th century by linseed and rape. (fn. 118)

Meadow and Pasture

Holwell had little meadow, as its lands extended along a watershed above the spring-line, and water supply was intermittent according to season. (fn. 119) In 1611 the Moores' 11-yardland farm included only 10 a. of meadow, and in 1756 the rectory estate was said to include 50 a., although the figure was almost certainly inflated for legal purposes. (fn. 120) Given the scale of pastoral farming in the township, Holwell's farmers presumably either bought hay or rented meadows elsewhere, for example at Kelmscott. A prosperous yeoman in 1663 had two stacks of hay worth £8, (fn. 121) and in the early 19th century large-scale operators such as the Pinnells and Bagnalls no doubt benefited from their access to other parishes. (fn. 122)

The shortage of meadow was counterbalanced by abundant pasture on Holwell Downs. (fn. 123) In the later 16th century the Moores family had rights for 660 sheep and 100 rother beasts and horses, both in the commons and downs and in their private closes and pasture grounds. (fn. 124) Tenants, too, had generous common stints. (fn. 125) In 1606 the 5-yardland holding known later as George's had folding for 300 sheep and commons for one team or ten cattle, 'according as the same shall be rated by consent of other commoners and inhabitants', while in 1637 it was claimed to include 100 a. of pasture in addition to common rights. (fn. 126)

The downlands were also heavily used by farmers from outside the township. In 1540 Cirencester abbey's manor of Puttes in nearby Alvescot had the right to pasture sheep there, (fn. 127) and in 1549 some 1,700 sheep grazed at Holwell belonged to persons living outside the county, many of whom were prosperous sheep farmers and wool merchants. (fn. 128) Richard Wenman, an exceptionally wealthy wool stapler from Curbridge near Witney, had a leasehold estate at Holwell in 1534. (fn. 129) Holwell's 'common herdsman' was mentioned in 1623, when he received 10s. a year from Cleevely's charity in addition to his wages. (fn. 130)

Woodland

Though extensive woodland lay nearby at Bradwell Grove, none was recorded in Holwell itself until the early 18th century. In the 1590s Holwell tenants of Broadwell manor were required to plant two oak, ash or elm trees a year as part of their rent, presumably to help provide minimal timber and fuel. (fn. 131) The Wrights, who acquired Holwell in 1719, seem to have developed small plantations, whose acreage grew from 10 a. in 1721 to 20 a. in 1761, and to 30 a. by 1787. (fn. 132) By 1774 they also appointed gamekeepers, (fn. 133) and in 1838 (when it was acquired by William Hervey) the estate included ornamental woods and 'young thriving plantations' said to be 'particularly desirable for preservation of game'. Most lay on the east adjoining Bradwell Grove, and in 1840 totalled some 38 acres. (fn. 134) Thereafter Holwell's coppices were managed as part of the Bradwell Grove estate, and in the later 20th century some new plantations were made in Holwell by John Heyworth. (fn. 135)

Medieval Tenants and Farming

In 1086 Holwell was presumably included in the Domesday description of Broadwell manor. (fn. 136) By 1279 there were at least three freeholds at Holwell: one a sizeable holding of three yardlands which owed suit of court and the exceptionally high rent of 50s., and the others (held for suit of court and 4s.) comprising one yardland each. Another yardland seems to have been freely held of Roland d'Oddingseles for ½d., but was sublet for 13s. 4d. and labour services. (fn. 137) The remaining 19 tenants (fn. 138) were unfree villeins holding of Bradwell Odyngsell or Bradwell Cirencester manors, or of Roland's small lifehold estate. Nine occupied whole yardlands, comprising perhaps 20–25 a. of arable with common pasture; another seven held ½ yardland each, and three (including one cottager) had between 8 a. and 1½ acres. Around two thirds of the unfree holdings owed both money rents and labour services, which (unless they were already commuted) were presumably exacted on the lords' demesne lands in Broadwell and Filkins. Two tenants also owed small renders in wheat or barley, reflecting a general inconsistency in the rents demanded for similar-sized holdings. Tenant farming was presumably mixed as later, although apart from the reference to barley and wheat there is no direct evidence.

Early 14th-century taxation lists suggest that Holwell was among the more prosperous of Broadwell's hamlets, and that its prosperity was increasing. In 1306 the township paid a total of only 24s., but by 1316 and 1327 the amount had risen to 60s. 11d. and 67s. 1d. respectively, second only to Kelmscott in terms of overall taxable wealth and average per capita payments. Possibly that reflected the fact that both places had relatively small populations, and access not only to arable but to extensive commons or meadows, which seem to have attracted outsiders from an early date. Even so Holwell remained a small peasant community, and in broad terms its wealth was comparable with that of most other rural settlements in the area. Among individual tenants there were the usual variations in taxable wealth, which were not always clearly related to the size of families' late 13th-century holdings. Tax payments in 1316 averaged 3s. 9d., with individuals paying between 16d. and 6s. 9d.: the latter sum was owed probably by the tenant of the three-yardland farm. In 1327 fifteen taxpayers paid an average of 4s. 5d., with individual payments ranging from 22d. to 10s. (fn. 139)

The sharp fall in population following the Black Death must have caused major disruption, (fn. 140) but as elsewhere the reduced pressure on resources created new opportunities. Late medieval evidence for Holwell is meagre, but by the early 16th century and probably in the 15th large numbers of sheep were being grazed on Holwell Downs, many of them by prosperous outsiders. (fn. 141) Some local yeomen, too, probably kept small flocks as well as growing crops: two shepherds, for instance, made wills in the later 16th century, of whom one had Burford connections, while the other made gifts of over 30 sheep mostly to his children. (fn. 142) Over all, the pattern of farming c. 1500 was possibly little different from that recorded in the 17th century, when some of the more prosperous yeomen specialized in arable crops such as barley, wheat, peas, and oats, and kept a few cattle, while some others had flocks of 60 or more. (fn. 143)

In the 16th century some tenant farms were still granted as copyholds in the Bradwell manor court, and were held for customary rents and heriots. (fn. 144) Long leaseholds (generally for lives) became the norm during the 17th century, as the Trinders established themselves in the township. (fn. 145) Creation of the large 5-and 11-yardland holdings recorded from the late 16th and early 17th century (fn. 146) may also have begun in the later Middle Ages.

Inclosure and the Trinders, 1600–1700

In the early 17th century the 11-yardland Manor farm seems to have been viewed as an investment opportunity by a succession of largely non-resident gentry and London merchants, culminating in the Trinders' acquisition first of the Manor farm estate, and later of the entire township and of two neighbouring manors. (fn. 147) By the mid 17th century there had been significant consolidation of holdings, resulting in part from the break-up of the Broadwell manors. There were then seven recorded households in Holwell, (fn. 148) one headed by the Trinders (who seem to have directly managed much of their land), and two others headed by William George and Charles Cooke, who each occupied 5-yardland farms. Another house belonged to the owner of the rectory estate, John Godfrey, and three others to tenants or subtenants. (fn. 149) Of those Richard Plowman or Wright (d. 1663) was taxed on only two hearths, but was a substantial mixed farmer who left goods worth over £300, and had land and a second house at Curbridge (near Witney). (fn. 150) Of more modest means was the yeoman Robert Sperrink (d. 1678), a sheep farmer who held a cottage and a quarter yardland from Henry Trinder, and whose goods at his death were worth £43. (fn. 151)

In 1672 Charles and Henry Trinder agreed to make further purchases in Holwell 'to procure an inclosure of the common fields, downs and places ... to profit the owners'; their intention was to plough up the downs and sow them with cereal crops. (fn. 152) The scheme led to prolonged conflict with William Godfrey, whose rectory estate covered only a yardland, but which was rated as six because of the value of the tithes. (fn. 153) Conversion of the downs to arable would have been to his advantage as owner of the grain tithe, which was then worth some £40 a year, but by 1689 the Trinders, in an apparent change of policy, had laid down all their share of the former common fields for sheep pasture, and profits from the grain tithe were consequently negligible. (fn. 154) The same year they bought the rights to all waste and common ground in Holwell from the owner of Broadwell manor, thus depriving Godfrey of the right to pasture and water his animals, which were regularly impounded by the Trinders. (fn. 155)

Godfrey launched a series of court cases, but in 1693 was forced to agree to a private inclosure of Holwell in which his holdings, distributed throughout the common fields, were exchanged for a single piece of land (on which his successors built a barn), and for the right to water his cattle at a pit adjoining the public road. The agreement provided for 400 a. of pasture to be sown with cereal crops for three years, so that Godfrey could have the tithes; thereafter it was intended to sow most of the land with 'sainfoin, great clover, hop clover, ray grass, lucerne, or other seeds of foreign grass' for hay. (fn. 156) Godfrey later asserted that the agreement had not been kept to, but was contradicted by local witnesses and lost his case. (fn. 157)

Farming from 1700

The Trinders' inclosure accelerated the consolidation of holdings, and from the mid 18th century Cooke's and George's were subsumed into Manor farm, which thereafter covered virtually all the township. The tenants in the 1750s–60s (at the commercial rent of £350 a year) were the Hazards, followed before 1770 by the Wells family. (fn. 158) The Godfreys retained their 52 a. (latterly as tenants) until 1765, after which it became part of the main Holwell estate. (fn. 159) There were half a dozen cottages, which in 1761 housed two masons, a maltster, and (presumably) agricultural labourers. (fn. 160) The 20 a. of woodland, described as coppice wood, was kept in hand by the Wrights as non-resident lords and owners. (fn. 161)

29. Holwell Downs Farm, built in the early 1870s alongside earlier cottages and farm buildings.

From c. 1806 Manor farm was let to two gentleman farmers based in Westwell, John Pinnell and John Bagnall, who bought the freehold six years later. (fn. 162) In all they farmed over 2,000 a., their other interests including meadowland in Kelmscott. (fn. 163) Pinnell was described by the agriculturalist Arthur Young as one of the greatest farmers in the county, and at Holwell continued the tradition of mixed sheep-corn husbandry. Arable productivity was increased by planting turnips and sainfoin (which was pared and burnt to produce ash), and by manuring with a mixture of dung and earth or road dirt. Horses and oxen were fed on a mixture of vetch and sainfoin to produce larger quantities of dung, and rather than stabling them Pinnell kept them loose in a yard overnight with sheds for shelter, making them healthier and more efficient. Teams of oxen were preferred to horses, as they could do the same work but were cheaper to keep. Good feeding was seen as a key to profit. Sheep were also kept, fattened on hay and Swedish turnips in April, and left to roam in summer instead of being folded, which gave them more lambs and greater weight. Pinnell favoured a Gloucestershire— Leicestershire crossbreed, valued both for its size and for its wool. (fn. 164)

In 1819 Bagnall and Pinnell formally partitioned their Holwell lands, perhaps consolidating earlier arrangements: Bagnall retained Home or Manor farm to the east, and Pinnell the lands to the west, focused on recently built cottages, barns and granaries at Holwell Downs Farm. (fn. 165) Pinnell bought Bagnall's share three years later, (fn. 166) and by the 1830s his sons Thomas and Richard respectively ran Home farm's 470 a. and Holwell Downs farm's 530 a., Thomas directly, and Richard through a bailiff. (fn. 167) In 1838 they sold Holwell to William Hervey, but continued to farm the land as tenants of the Bradwell Grove estate. (fn. 168) Hervey still owed the Pinnells £3,650 on his death in 1863, which was paid by his executors. (fn. 169)

Thereafter Holwell functioned increasingly as an estate village, (fn. 170) although the majority of unskilled inhabitants probably found work on the two chief farms rather than on the estate itself. In 1841, with the exception of Thomas Pinnell and a shoemaker, all the working inhabitants were agricultural labourers, (fn. 171) including the boys who worked on the farms every school holiday. (fn. 172) Other 19th-century occupations included dressmaking and straw bonnet-making, and in 1861 there were two schoolmistresses. Some of a small number of carters, grooms, shepherds, and domestic gardeners recorded in Holwell from mid century may have been directly employed by the estate or at Bradwell Grove House: a late example was the gardener Norman James (b. 1907), who worked first for Stafford Cripps at Filkins and later for Col. Heyworth-Savage at Bradwell Grove, while some women from the village (including James's wife) were employed at the house in menial domestic work. A much larger group of domestic and estate staff lived at Bradwell Grove itself, which from 1850 was included within Holwell ecclesiastical parish. As well as servants, footmen, and a butler, in the later 19th century they included gardeners, a gamekeeper, grooms, a coachman, a dairymaid, and a woodman. Very few were local, however, and scarcely any came from Holwell. (fn. 173) The Pinnells continued at Holwell until the 1870s, when they were succeeded at Holwell Downs farm by Charles Mace and at Manor farm by the Porters, who were already established at Broadwell. The Porters remained at Manor farm until c. 1920, to be followed by James Hollies and the Sturches. Holwell Downs farm was taken in hand by the Bradwell Grove estate before the 1890s, and again run by a bailiff. (fn. 174)

Farming in the township remained largely arable for much of the 19th century, with some 95 per cent of the land under crop. Some animals and poultry were reared for consumption, and horses were used for heavy work. (fn. 175) Despite a spate of machine-breaking in the area in 1830, (fn. 176) by 1854 Hervey had introduced steamthreshing machines to the farms on his estate, which were covered under his fire insurance policy. (fn. 177) A steamplough was in use in Holwell by 1881. (fn. 178) By 1914 the proportion of arable had fallen to around 70 per cent, presumably in response to the agricultural depression.

Crops still included wheat, barley, and oats, with some swedes and turnips, but the proportion of permanent pasture had risen to around 30 per cent and was grazed mainly by sheep, with some cattle, horses, and pigs. (fn. 179) The 500-a. Manor farm remained mixed, growing cereals and supporting a flock of 500 animals. Farm workers included a carter, four men in charge of the horse-teams used for ploughing, and two shepherds, while hurdles and gates were all made on site by a man living in the village. Petrol-driven tractors began to replace horses after the First World War, reducing agricultural employment. (fn. 180) Many of the villagers grew vegetables and corn on small allotments, and most kept pigs and bees. (fn. 181)

In 1941 the farms continued to be well maintained and managed, with a similar range of crops and timber, although water was scarce and there was still no electricity. (fn. 182) By the early 21st century, however, stock-rearing had ceased, and only wheat, barley, rape and linseed were grown. Along with the woodland plantations, both farms were managed from Filkins Down Farm as part of the Bradwell Grove estate. (fn. 183)

Trade and Industry

Holwell has always been predominantly agricultural, with even standard rural trades such as smithying infrequently recorded. The medieval surname Crocker may imply small-scale pottery-making, though by the 13th and 14th century the name was evidently hereditary. At least one of the family held an entire yardland, and was presumably chiefly dependent on agriculture. (fn. 184)

During the 17th and 18th centuries some of the Green family of cottagers were blacksmiths, masons, or slaters, (fn. 185) and in the late 17th century the Trinders established a commercial malting business, taking advantage of the growing trade in malt along the river Thames from Radcot. The family invested in a new type of stone malt-kiln said to have been recently developed around Burford, increasing production from two quarters of malt a day to six using the same amount of fuel. The business continued in 1718 when Charles Trinder left it to his grandson, (fn. 186) and maltsters were recorded occasionally at Holwell into the 19th century. (fn. 187) By then there may also have been some small-scale brick-making. Lime kiln ground (on the township's northern edge) was mentioned from the early 19th century, (fn. 188) and before 1883 a brick and tile works was built near Akeman Street to supply the needs of the Bradwell Grove estate. The clay was found to be deficient, and the works (incorporating two 100-foot high chimneys) were disused by 1900 and dismantled in the 1920s. (fn. 189) Small-scale quarrying in the township was associated with the industry focused on Filkins. (fn. 190)

A village shop was opened by 1895 but closed in 1926; thereafter groceries and other necessities were brought in by tradesmen from Burford and Lechlade. (fn. 191) A few small non-agricultural businesses moved into the village during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, accommodated in domestic premises or former agricultural buildings. Those in 2011 included a direct marketing company, a tourist company specializing in African and Indian travel, and a bed-and-breakfast guesthouse. (fn. 192)

SOCIAL HISTORY

Holwell seems to have developed relatively little communal life before the 19th century, with no public buildings except for the chapel, no public houses, no recorded village customs, and no known village societies. In part this reflected its small population and, from the 17th century, its domination by a few wealthy farmers and gentry. In religious affairs it remained subordinate until the 1850s to the mother church at Broadwell, and though it had its own fields and apparently its own parish officers, on occasion it was taxed and administered jointly with Westwell. Its common pastures, too, were much used by outsiders from neighbouring communities. (fn. 193) Burford, as the nearest market town, may have provided a significant social focus, and by the 16th century several of Holwell's inhabitants had family or other connections there. In the 19th century some Holwell people belonged to Burford friendly societies. (fn. 194)

From the early 19th century, with its absorption into the large Bradwell Grove estate, Holwell became essentially an estate village. Social life was dominated by the school, the church, and the neighbouring Bradwell Grove mansion house, while the predominantly labouring population was employed either on the tenanted Holwell farms or elsewhere on the estate. The pattern continued largely unaltered until the mid 20th century, when falling agricultural employment and the leasing of Bradwell Grove led to dwindling population and the arrival of a few prosperous outsiders unconnected with agriculture. (fn. 195)

Social Structure and the Life of the Community

The Middle Ages to c. 1838

For much of the Middle Ages Holwell remained closely tied to the manorial centres at Broadwell. Most tenants were villeins who held their land of the two main Broadwell manors, and in the earlier period owed labour services on the Broadwell demesne. (fn. 196) The local chapel, theoretically served three times a week and on church festivals, had baptismal rights and possibly a resident chaplain, and presumably provided a strong communal focus. Broadwell church nevertheless retained a monopoly on burial, while Holwell's tithes were paid to the Hospitallers as owners of Bradwell St John manor. (fn. 197) Burford presumably provided another external focus, while outsiders with interests in Holwell's downlands must have reinforced the village's contacts with a wider world.

Medieval Holwell seems to have had a relatively diverse social structure. In the 1270s the hamlet's peasant yardlanders and half-yardlanders lived alongside tenants subsisting on much smaller holdings, who probably complemented their income by labouring for their better-off neighbours. At the opposite extreme was Thomas Baron, lessee of a substantial 3-yardland freehold which he held with additional villein land in Holwell and Westwell. The pattern continued in the early 14th century when the freehold was held by John Turfrey, possibly the 'John le Freeman' who was Holwell's wealthiest taxpayer in 1316. Among other tenant families there were the usual smaller variations in taxable wealth, which were not always clearly related to the sizes of holding recorded in 1279. John Echeday (whose family held a yardland in villeinage in 1279) paid one of the largest amounts in 1306, rather more than the freeholding Pikston family, while in 1316 and 1327 the Proud foots (recorded as villein half-yardlanders in 1279) were amongst Holwell's most prosperous inhabitants, and were probably employers of labour. By then the township's wealthier taxpayers included a significant number of newcomers, whose payments collectively pushed up its overall taxable wealth. Some may (as later) have been outsiders investing in downland pasture. (fn. 198)

Population collapse during the Black Death, which left only 17 adult inhabitants paying poll tax in 1377, (fn. 199) must have radically altered the village's character, but presumably created opportunities for investment by survivors, incomers, and outsiders. By the 16th century many of those grazing animals on Holwell's downs were farmers or wool merchants from outside the parish, (fn. 200) and some of the large consolidated farms recorded in Holwell from the 17th century probably had their origins in the later Middle Ages. No firm evidence survives before the late 16th and early 17th centuries, however, when social relations in the township were further transformed by its severance from the main Broadwell manors, and by the arrival first of the Moores family and later of the Trinders. Both were ascendant yeoman families on their way to becoming local landowners and gentry. The Moores family had already acquired nearby Little Faringdon manor (of which they were formerly lessees), and were probably responsible for building the earliest parts of Holwell Manor Farm, from which they farmed half the township. The Trinders acquired gentry status and a coat of arms while building up extensive local estates and becoming de facto lords of Holwell, as they bought out the remaining owners in preparation for their inclosure of the township in the 1690s. Charles and Henry Trinder's training as lawyers no doubt facilitated their manoeuvres. (fn. 201)

As a result, 17th-century social relations in Holwell were increasingly dominated by the Trinders as farmers, landowners, employers, and resident gentry. By the 1660s Manor Farm (taxed on ten hearths) was by far the largest house, where the family lived in some comfort with their own servants. (fn. 202) Charles Trinder (d. 1718) witnessed the wills of neighbours and tenants and acted as steward for the lord of Broadwell, Dennis Hampson. (fn. 203) Resident cottagers and smallholders were dependent on the family for their holdings, and there is evidence that the Trinders favoured fellow Roman Catholics as employees and possibly as tenants. Holwell recusants listed in 1695–6 included several Trinder servants, while the Griffin family (which included a Catholic in 1716) rented a cottage holding from the Trinders for many years. (fn. 204)

Even so, in the mid and late 17th century there were some relatively prosperous inhabitants who engaged with the Trinders on more equal terms. The moderately prosperous farmer Richard Plowman alias Wright (d. 1663), whose family owned property in Curbridge and Northmoor, lived in a small but reasonably well furnished house, and his will was witnessed both by Charles Trinder and by another well-off Holwell farmer, Charles Cooke. (fn. 205) The farmer and freeholder William Godfrey (owner of the rectory estate) challenged the Trinders in a long-running and acrimonious dispute over their proposed inclosure, although he ultimately lost his case. (fn. 206) Earlier in the 17th century, the resident yeoman freeholder William Cleevely (d. 1623) felt sufficiently attached to Holwell to endow its chapel and to establish local charities. Cleevely also had wide horizons, with relatives and property in Wiltshire, and connections in Burford, Abingdon, and Witney. (fn. 207)

With Charles Trinder's move to Bourton-on-the-Water and the descent of his estate to the Wrights, Holwell again had non-resident owners. Nonetheless its domination by one or two large resident farmers continued, first under the Hazards and Wellses at Manor Farm, and later under the Bagnalls and Pinnells. (fn. 208) The Hazards' relations with their neighbours were evidently not always good, since in 1761 several inhabitants (including a maltster and his wife, two spinsters, and the owner of the rectory estate John Godfrey) were charged with an assault on one of the family. (fn. 209) During the earlier 19th century the Pinnell and Bagnall families continued to play a prominent role in the community, not only as employers but as tithe owners, churchwardens, and administrators of the village's sole charity for the poor. (fn. 210) In 1841 Thomas Pinnell lived at Manor Farm with his family, two guests, and two female servants, and by the 1860s he employed 13 labourers. (fn. 211) In other respects, too, there was some continuity, the Green family, for instance, remaining as cottage tenants from the 1660s into the early 19th century, and working as blacksmiths, masons, and slaters. (fn. 212)

Social Life from c. 1838

Following its absorption into the Bradwell Grove estate from 1838 Holwell increasingly took on the characteristics of an estate village, reinforced by the proximity of the mansion house built by William Hervey in 1804 (Plate 6). (fn. 213) In 1861 Hervey (who was then deputy lieutenant) occupied the house with eight live-in servants, and at the time of the census had four house-guests including the earl and countess of Rosebery, who brought with them their own valet, page, and lady's maids. Thirty years later W. H. Fox lived there with his mother, a guest, and twelve live-in servants, excluding the numerous estate staff housed elsewhere at Bradwell Grove. (fn. 214)

Both Hervey and Fox took a close and paternalistic interest in Holwell, where each in turn rebuilt the church (which they attended regularly), and established a village school. (fn. 215) Hervey's social position was symbolized by the double-decker pew he erected in the church, from which he looked down on both his household and his tenants, (fn. 216) and at his funeral procession in 1863 his body was escorted by twelve tenant farmers on horseback, followed by relatives and upper servants in coaches, the keeper on horseback, and other mourners. (fn. 217) Excepting Manor Farm the only gentleman's residence in the village itself was Holwell vicarage, built by Hervey in 1850 and occupied by churchmen who owed their preferment to Hervey or his successors. The occupant in 1861 was the vicar Daniel Ward Goddard, who lived there with his young nephew and three servants and served as a local JP. (fn. 218)

During Fox's time (1871–1920) Fox himself, the vicar, and the village schoolmistress controlled all aspects of Holwell's social life, which revolved mostly around the church and school. Fox was habitually referred to as 'Squire Fox' or 'the squire', and children or employees were expected to touch their caps or curtsey on encountering him, the vicar, or the schoolmistress. At church he took note of any absences, and explanations were sought. An inhabitant born in 1907 recalled that:

'Mr Fox and the household staff attended church each Sunday morning. All the staff in uniform wore white gloves. They filled most of the south side of the aisle, employees, foremen etc. on the north side and children in the chancel. They all walked in file from the house on the path ... gravelled and raked each Saturday by the woodman'.

But though strict, Fox was a generous patriarch. Besides rebuilding the church and school he provided a reading room, poor-allotments, and piped water, distributed free milk, dripping, and Christmas gifts to his employees, allowed free collection of wood from the estate, and hosted Christmas festivities. There was no pub, but the village had a communal brewhouse which Fox presumably provided or at least tolerated. After the new school was built in 1896 its predecessor was used as a parish hall for meetings, dances, whist-drives, and rummage sales, and in the earlier 20th century the new school accommodated larger dances, held at one time once a month to a live band. (fn. 219) The community remained tight knit: in the 1860s over 60 per cent of inhabitants had been born in the village, and though by 1901 the proportion was halved, another 42 per cent still came from within ten miles. (fn. 220) Unsurprisingly work at Holwell was considered desirable, and those employed on the farms or estate tended to stay for long periods. (fn. 221)

The first half of the 20th century saw considerable continuity, with Hervey and Fox's roles perpetuated by Col. Heyworth-Savage (d. 1949) as the new owner of Bradwell Grove. As earlier several villagers worked for the estate, which fielded a 'first-class' cricket team enthusiastically supported by Heyworth-Savage: as one inhabitant remembered, 'proficiency in cricket was a good recommendation for a job on the estate'. A village shop opened by 1895 continued until 1926, selling 'cottons, candles, stationery, sweets ... and all the necessities', while medical care was provided by a doctor from Burford. Eleven villagers killed in the First World War were commemorated on a war memorial cross erected outside the church c. 1920, and during the Second World War the village received visits from King George VI and Winston Churchill, who were inspecting troops stationed nearby. The village also took in evacuated schoolchildren from London, who were taught in the old school. (fn. 222)

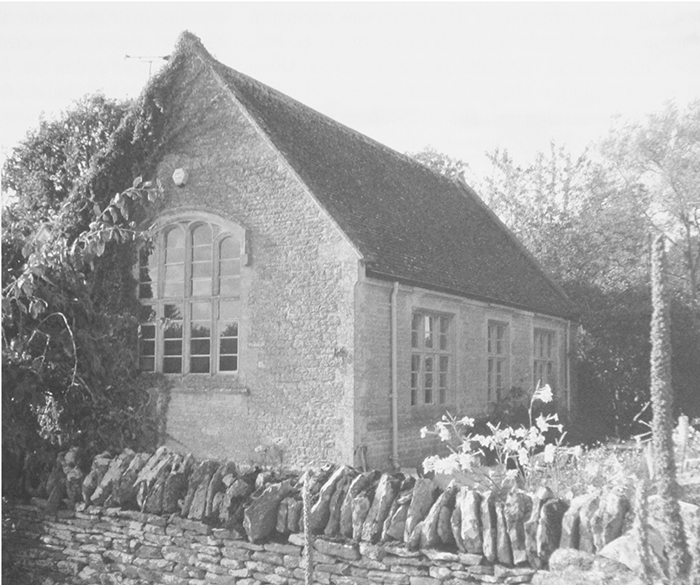

30. The former Holwell National school, built by W. H. Fox in 1896 to designs by W. E. Mills.

During the later 20th century Holwell's character changed markedly. Bradwell Grove ceased to function as a great country house, and the village's population declined sharply as agricultural employment contracted. The school closed in 1958, taking 'most of the life out of the hamlet' according to the vicar, (fn. 223) and an elderly inhabitant in the 1980s described the village as considerably 'quieter' than in his youth. As estate cottages were sold off they were increasingly bought by retired or professional incomers, and as weekend homes: by 1987 there were only 15 full-time residents, joined by others from London at weekends. (fn. 224) In 2011 a converted barn at the village's north end was on the market for approaching £½ million, (fn. 225) while one or two other converted buildings housed small businesses. (fn. 226)

Education

In 1819 it was alleged that all poor children in Broadwell parish were taught to read, (fn. 227) presumably at Sunday or day schools in Broadwell or Filkins, and in 1831 there were said to be 'means of instruction' within reach of Holwell children if their parents wanted it. (fn. 228) A Sunday school supported by subscription was started in Holwell itself in 1826, and by 1835 taught 24 boys and 13 girls. By contrast, a private day school in Holwell had only four boys and six girls, all paid for by their parents. (fn. 229) Presumably it was housed in a cottage, perhaps (as later) on the south side of the village street opposite the chapel. (fn. 230)

Before 1851 William Hervey of Bradwell Grove built a schoolroom onto the schoolmistress's house, and in 1855–6 part-endowed the school with £8 a year. (fn. 231) In 1854 it had an average attendance of 20 children, supported by their pence and by voluntary contributions. It did not receive a government grant. The vicar of the newly established Holwell parish set up evening classes which proved more successful than he had hoped, but for unspecified reasons he was forced to abandon them before 1854. (fn. 232) A few 'lads' were taught on winter evenings in the 1870s. (fn. 233)

In 1871 Holwell school was affiliated to the National Society, confirming its Anglican connections. By then it had accommodation for 29 children, though only 5 boys and 13 girls attended on the day of inspection. (fn. 234) A new building south-west of the church was opened in 1896 on a site given by Hervey's successor W. H. Fox, who employed W. E. Mills as architect and Alfred Groves as builder (Fig. 30). Thirty-seven children attended the opening day, and a week later there were 48 on the roll. As well as providing for village pupils the school admitted children of Bradwell Grove estate-workers from outside Holwell, all of them taught by a head teacher and an assistant. (fn. 235)

Inspectors' reports during the first ten years were complimentary, calling it a 'well-equipped little school', and its tone 'beyond praise'. By 1913 the diocesan inspector considered it one of the best country schools he had ever seen. In 1916 Westwell children were ordered to attend their own school, but 13 of them had returned to Holwell by 1919, except when prevented by floods or snow.

During the 1920s and 1930s the school's success continued, despite numerous changes of staff. In 1932 there were 37 children on the roll aged from 3 to 13, all taught by one unaided teacher. The inspector found a 'lack of natural initiative' amongst the children, but several won scholarships to Burford grammar school and in 1947 all three candidates were successful. In September of that year Holwell school became a primary school, with 21 on the roll; those aged over 11 were transferred to Burford council school. (fn. 236) By 1954 the roll had fallen to 14, (fn. 237) and the school was closed in 1958. (fn. 238) In 2011 the building formed part of a private guesthouse. (fn. 239)

Charities and Poor Relief

Though Holwell's poor received some one-off bequests from local gentry or wealthy yeomen in the 17th century, (fn. 240) only one endowed charity was established. By his will proved in 1623 the prominent Holwell farmer and landowner William Cleevely, who made several charitable bequests in the area, gave an annual £3 rent-charge on his Holwell property, to take effect after the death of his three sisters. Of that, 20s. a year was for the poor, with 10s. for the 'common herd' or herdsman, and the remaining 30s. for church repairs and sermons. (fn. 241) In 1630 Cleevely's son-in-law John Godfrey had to be ordered to maintain the chapel, and the family were still evading their charitable obligations in 1730. (fn. 242) In 1759, however, the vicar reported regular payment of the 20s. for the poor, (fn. 243) and in 1787 Holwell's non-resident owner John Wright still paid the full amount. As there was then no herdsman, the 10s. was given to Burford as directed by Cleevely's will. (fn. 244) In the 1820s Wright's successor John Pinnell paid the 20s. to eight or ten of Holwell's poor on St Thomas's day (29 December), and in 1823 the Charity Commissioners ordered him to include the 10s. formerly earmarked for the herdsman. (fn. 245) By 1871, however, the whole £3 rent-charge had apparently been diverted to church purposes. (fn. 246)

By the late 18th century and presumably earlier the Cleevely income was supplemented by funds raised from the poor rate, which increasingly met the rising cost of poor relief. In the mid 1770s just over £4 a year was raised and spent, very low for the population; (fn. 247) by the mid 1780s this sum had doubled to an average of £9 5s. 2d., (fn. 248) and by 1802–3, in keeping with national trends, it was £70 a year, levied at a rate of 2s. 9d. in the pound. Of this sum £68 was spent on outdoor relief, supporting 12 adults and a child (some 19 per cent of the population) throughout the year, and a further 17 inhabitants occasionally. In all some 24 per cent of the population received relief, though neither overall expenditure nor the parish rate were especially high by local standards (Table 2). (fn. 249) By 1813 the sum required had diminished to £44, of which £34 was spent on the outdoor relief of five permanent and three occasional paupers, (fn. 250) and over succeeding years expenditure fluctuated greatly as in other parishes, from under £30 in 1816 to £95 in 1822, and to £26 by 1834. (fn. 251) In 1831 the poor rate was supplemented by an offertory collected at church three times a year, producing around 4–5s., which was given to the poorest at the time. (fn. 252) No parish workhouse is recorded.

Following the 1834 Poor Law Act responsibility for the township's poor passed to the newly established Witney poor-law union, (fn. 253) though local collection of poor rates and private charitable gifts presumably continued. W. H. Fox (d. 1920) of Bradwell Grove, a generous benefactor to the village, left £1,000 to establish a charity for needy persons living within five miles of Holwell church, (fn. 254) which was subsequently diverted towards upkeep of graves. In 1971, after this use was declared void, the charity was merged with the Burford Nursing Charity as Fox's Holwell and Burford Trust; (fn. 255) it was removed from the Charity Commission register in 1997 because the funds were used up. (fn. 256) The Cleevely £3 rent-charge was redeemed in 1968, when John Heyworth, as owner of the Bradwell Grove estate, paid a capital sum to produce £8 a year. Various proposals were made to merge Holwell's Cleevely charity with those of neighbouring parishes (in particular Westwell's), but in 1973 the decision was postponed. (fn. 257)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

Holwell's medieval chapel remained subject to Broadwell until 1850, when it became an independent parish church as part of a reorganization initiated by the owner of Bradwell Grove. Little is known of medieval pastoral care, and from the 16th century to the 19th the chapel was served mostly by curates, between occasional periods of neglect. During the 17th century the township's religious life was heavily influenced by the dominant Trinder family, who were Roman Catholics and who may have used the chapel for clandestine worship. By the 1680s, however, the chapel was again served from Broadwell, with the occasional help of a Presbyterian minister.

From the 1830s, as Holwell became an estate village to Bradwell Grove, church attendance was increasingly regulated by the local squires William Hervey (d. 1863) and W. H. Fox (d. 1920), who each rebuilt the church. Their influence, combined with the arrival of a resident vicar, seems to have all but eradicated the incipient Dissent of the early 19th century, leading to the closure of a short-lived Baptist chapel.

Parochial Organization

Like the rest of Broadwell parish, in the 10th and early 11th century Holwell was most likely dependent on a minster or other early church at Langford. (fn. 258) A chapel at Holwell was established probably in the early 12th century (the date of its lost medieval font), and by the early 13th century it was served by the vicar of Broadwell or by chaplains whom he appointed. (fn. 259) The chapel had no independent endowment until 1623, when William Cleevely of Holwell left annual rent-charges totalling £5 to support fortnightly sermons there, together with 20s. for two Christmas sermons, and another 10s. towards the building's upkeep. (fn. 260) In the 1690s a vicar of Broadwell unsuccessfully challenged the right of Cleevely's trustees to appoint the preacher, (fn. 261) but by the late 18th century the vicar's successors had apparently acquired full control over the bequest. (fn. 262)

The former medieval font implies that the chapel had baptismal rights from its foundation, although the first recorded baptism was in 1688. By then many inhabitants were baptized and buried in the neighbouring parish of Westwell, and the number increased significantly after the dispute between the vicar and Cleevely's trustees in the 1690s. (fn. 263) The chapel had no burial rights until 1845, despite an assertion in 1850 that baptisms, churchings, marriages, and burials had been performed there 'for many years'. (fn. 264)

In 1850 the chapel became an independent parish church. The chief instigator was William Hervey, and the new parish included both the ancient chapelry or township and the contiguous area of Bradwell Grove, where Hervey had his mansion house. (fn. 265) The living lacked sufficient endowment, and in 1925 it was united with neighbouring Westwell. (fn. 266) In 1979 the joint benefice was united with that of Alvescot, Black Bourton and Shilton, (fn. 267) and in 1995 the whole became part of the Shill Valley and Broadshire ministry. (fn. 268) The dedication to St Mary the Virgin is recorded from the 1870s. (fn. 269)

Advowson and Endowment

The advowson of the newly created parish was bought by William Hervey in 1850 from the vicar of Broadwell. (fn. 270) It passed with his Bradwell Grove estate, first to his heirs, and later to W. H. Fox and Lt-Col. Cecil Heyworth-Savage. (fn. 271) After 1925 the patrons nominated alternately with Christ Church, Oxford, the patron of Westwell, (fn. 272) and the Heyworths retained a share in the patronage of the united benefice in 2000. (fn. 273)

The new parish's endowment comprised the Cleevely rent-charge, a rent-charge of £41 representing Holwell's commuted tithes, and £1 in surplice fees. In addition William Hervey gave a newly built vicarage house and a rent-charge of £25 on the Holwell rectory estate, the latter in response to a £200 grant from Queen Anne's Bounty. (fn. 274) By 1851 annual income was around £80, (fn. 275) which Hervey augmented with a further rent-charge of £25 in 1858. (fn. 276) By 1899 the gross annual value was £96, including £12 from Queen Anne's Bounty; by contrast the benefice of Filkins was worth £185, and Broadwell's £250. (fn. 277) In 1910 W. H. Fox gave a small parcel of land by the vicarage house to provide a right of way, (fn. 278) but in 1913 Holwell remained 'a miserably endowed living', (fn. 279) and in 1917 the Ecclesiastical Commissioners agreed to match a further gift from Fox of £1,000, followed in 1921 by a temporary award of £18 a year and authorization of a table of fees. The Commissioners' award was renewed in 1923, bringing the incumbent's annual income to £98. Having learned that the benefice was ineligible for further grants, the incumbent resigned in 1924 after only a year, and the benefice was united with Westwell. (fn. 280) Compensation for tithe-rent income was agreed in 1939 under the Tithe Act of 1936. (fn. 281)

Vicarage House

The vicarage house built by William Hervey in 1850, in preparation for the creation of the new parish, stands a little way south of the church, on the site of a malthouse and close which formerly belonged to the rectory estate. (fn. 282) Built of local stone and slate in gothic style, it originally had a drawing room, dining room, study, kitchen, and scullery on the ground floor, with five bedrooms and an attic above, a separate stable and coach-house block, and a garden and 1-a. close. (fn. 283) Improvements were carried out in 1913 and 1932, and some buildings were demolished. (fn. 284) From 1924 it became the residence for the newly united benefice of Holwell and Westwell, (fn. 285) but in the later 20th century it was sold, and vicars of the amalgamated benefice lived elsewhere. (fn. 286)

Pastoral Care and Religious Life

The Middle Ages to 1800

The early 13th-century vicarage ordination for Broadwell ruled that services should be held at Holwell chapel three times a week and on festivals. This was less frequently than at Kelmscott, although it was apparently envisaged that both places should have their own chaplain. (fn. 287) William of Holwell (who witnessed a land grant in 1305) and Stephen the chaplain (taxed in 1327 on goods worth c. 37s.) may have served the chapel, (fn. 288) but no formal medieval appointments are known. During a period of neglect in the early 16th century services were withdrawn for at least eight years, (fn. 289) though by the 1520s the vicar employed a curate, John Lucas, who probably served Holwell, and who may have been an Oxford graduate. (fn. 290) From 1623 Cleevely's charity provided a modest stipend for a clerk to preach fortnightly lectures or sermons, (fn. 291) an arrangement which may indicate Puritan leanings. In 1635 William Crane was curate, but in 1642 Holwell seems to have been served by the curate of Westwell. (fn. 292)

Charles Trinder the elder (d. 1658) and his wife Jane (d. 1688), who came to Holwell in 1626, seem to have been Roman Catholic sympathizers if not themselves practising Catholics, judging by the marriage patterns of their children. (fn. 293) By the terms of his will Charles allowed for his two elder sons John and Charles, both known recusants, to inherit his lands, while his younger sons Henry (d. 1712) and William (d. 1690) were respectively educated at Trinity College, Oxford, and apprenticed in London. Such was their family loyalty that the two younger, Anglican sons enabled their brothers to retain their estates. By the 1660s John had placed his Holwell estate in the hands of family trustees: (fn. 294) a Royalist during the Civil War, he was forced to flee in 1689 for remaining loyal to James II after his abdication, and he died at Poitiers (France) before 1707. His brother Charles, to whom the Holwell lands subsequently passed, was also forced to leave England for a time in 1656. (fn. 295) His estates were held on his behalf by his younger brothers and family trustees, thus avoiding recusancy fines until the 1690s. (fn. 296) A series of court cases brought from the 1680s by the local yeoman landowner William Godfrey may have been partly designed to question Charles's title and deprive him of his lands, (fn. 297) much as the Hampson family benefited from the dispossession of the Roman Catholic Thompsons at Broadwell. (fn. 298) If so, the complex family arrangements amongst the Trinder brothers prevented this.

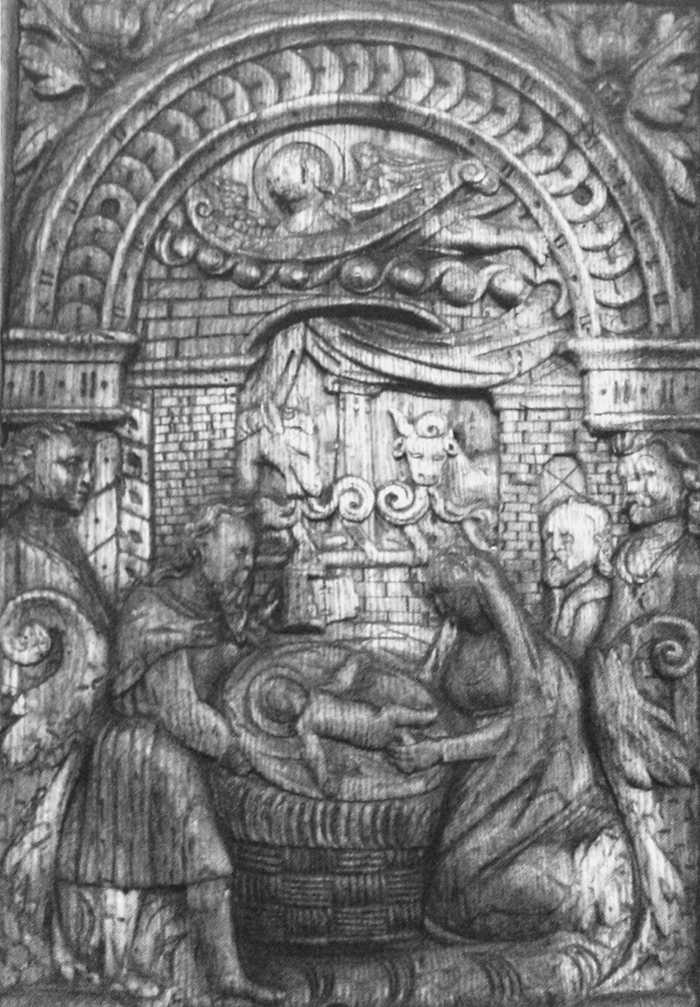

Given the Trinders' dominance within the township, Holwell chapel may occasionally have been used for clandestine Catholic worship. The present building contains a set of finely carved early 17th-century Flemish panels expressing Marian devotion (Fig. 31), which were perhaps brought in by John or Charles Trinder following a period of exile. (fn. 299) In 1687 Charles Trinder bought the manor of Bourton-on-the-Water (Glos.), where he already lived, and where he seems to have maintained a priest; (fn. 300) recusants were recorded in Holwell itself only from 1695, however, perhaps due to clever concealment before that date. Most of those named were Trinder family servants, including Charles's clerk William Cruse; otherwise recusancy in the township may have been minimal, and the last (Widow Griffin) was reported in 1716. (fn. 301) Trinder's daughters married into Roman Catholic families outside the county, and after his death in 1718 the estate passed to non-resident Catholic heirs, the Wrights of Kelvedon (Essex). They remained owners (subject to recusancy fines) until 1804, (fn. 302) but no further Roman Catholicism was recorded.

31. The Nativity: one of three 17th-century Marian panels possibly brought into Holwell church by the Roman Catholic Trinders, and re-used in the 19th-century pulpit.

In the late 1670s and early 1680s the vicar of Broadwell (Thomas Thackham) usually performed the fortnightly services at Holwell, sometimes with sermons and communion. On a number of occasions he allowed a local Presbyterian (Mr Park) to substitute for him, (fn. 303) perhaps in an attempt to combat Catholic sympathies. In 1691–2 the Cleevely trustees nominated the vicar of Shilton (William Chadwell) to deliver the fortnightly sermons, causing conflict with Thackham's successor Henry Whitfield, who disputed their right but lost his case. Whether conflicting religious views lay behind the dispute is not clear, and possibly Whitfield was more concerned about the perceived challenge to his authority and income. (fn. 304) By the mid 18th century the Cleevely money had apparently been appropriated by the vicars of Broadwell, who conducted services at Holwell and Kelmscott on alternate Sundays with communion three times a year, either personally or through stipendiary curates. (fn. 305) The arrangement probably resulted in neglect, since in 1756 the chapel required a new Book of Common Prayer, a surplice, a linen cloth and napkin for communion, and other items. (fn. 306) In 1790 both Holwell and Kelmscott were being served by the curate of Lechlade. (fn. 307)

The 19th and 20th Centuries

William Hervey, who acquired Bradwell Grove in 1804, (fn. 308) made significant improvements to Holwell chapel at his own expense, as it was more convenient for his family and staff to worship there than at the mother church of Broadwell. In 1830 he had the chapel extended to incorporate a double-decker box pew at the west end, where he and his family sat in the upper tier, with the servants below. (fn. 309) But in 1837 the chapel's walls and foundations were unsound and the building damp, (fn. 310) and in 1842 Hervey largely rebuilt it, adding an attached graveyard which was consecrated three years later. The earlier building had seated only 60, whereas its successor increased the number of free seats 'for the benefit of the poorer inhabitants'. (fn. 311) In 1851 there were 120 seats (80 of them free) for a population of 131, although the average congregation numbered only 53. (fn. 312)