A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Broadwell Parish: Filkins', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp59-87 [accessed 10 May 2025].

'Broadwell Parish: Filkins', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online, accessed May 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp59-87.

"Broadwell Parish: Filkins". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online. Web. 10 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp59-87.

In this section

FILKINS TOWNSHIP

The large and thriving village of Filkins, (fn. 1) with its concentration of high-quality stone-built cottages and farmhouses, lies near the county's western edge around 3 miles (5 km) from the Gloucestershire market town of Lechlade. Burford lies 5 miles (8 km) to the north, and the modern town of Carterton 3 miles to the north-east. By the 14th century Filkins was, and remained, the largest settlement in Broadwell parish, and in the 19th century it became the centre of a separate civil parish. In the 1950s it was united with the adjoining village of Broughton Poggs with which it effectively formed a single settlement, and by 2001 the combined parish contained over 170 households, most of them in Filkins. (fn. 2)

The village was largely agricultural until the 20th century, but from an early date contained an unusually high proportion of rural tradesmen and craftsmen. Quarrying and stone masonry in particular remained important. In the 19th and early 20th centuries its shops and services still served the surrounding area, and in 2011 a few small rural businesses offered local employment, although by then most residents worked outside the parish in neighbouring towns. (fn. 3) From the 1920s Filkins was home to the socialist politician Sir Stafford Cripps (1889–1952), who took a profound interest in village life, providing new facilities and promoting several major building projects in traditional vernacular style; in this he worked closely with the local mason George Swinford (1887–1987), whose memoirs, like those of the 19th-century farmer Thomas Banting (d. c. 1900), reflect a strong community spirit. The Swinford Museum, started in a cottage in 1931 and reopened in 1951, houses Swinford's local collections. (fn. 4) Another notable resident was the garden designer Brenda Colvin (d. 1981). (fn. 5)

Boundaries and Landscape

Filkins remained part of the large parish of Broadwell until the late 19th century. The two places shared an open-field system, and Filkins's independent boundaries (described above) seem to have been established only at inclosure in 1776 (Fig. 6). In other respects the township was independent much earlier, appointing its own parish officers and raising its own poor rates, and from the 1880s it was usually regarded as a civil parish. In 1881 it totalled 1,834 a., reduced to 1,781 a. in 1886 following changes under the Divided Parishes Acts. In 1954 it was united with Broughton Poggs to form a combined civil parish of 2,690 a. (1,088 ha.), which remained unaltered in 2001. (fn. 6) For ecclesiastical purposes Filkins was separated from Broadwell in 1855 (when it first acquired a church), to be united with Broughton Poggs from 1855 until 1864, and again from 1942. From 1980 both places were merged in new team ministries. (fn. 7)

The township's northern part extended up to Filkins downs, which lie among the first foothills of the Cotswolds at 135 metres. From there the land falls gradually to around 90 m. near the village, which borders Broadwell brook surrounded by former grazing land. Between the downs and the village lay Broadwell's and Filkins's large open fields, bisected by a band of poorer soil which provided additional common pasture (Fig. 6). The soil is mainly stonebrash on an inferior oolite, with pockets of clay around the village. (fn. 8)

Communications

Filkins developed at the intersection of several important early routes (Figs 2 and 6), among them the north–south road from Burford to Lechlade and Cirencester, and that from Barrington (Glos.) to Langford and the river crossing at Radcot. Both roads were almost certainly established by the late Anglo-Saxon period and possibly earlier. An intersecting road running north-eastwards to Kencot connected with an early route to Witney, which may be of Roman origin and which in the 16th century was known as Street Way. (fn. 9)

By the 18th century the village included several licensed houses along the Burford–Lechlade road, (fn. 10) and traffic almost certainly increased after the road was turnpiked in 1792. (fn. 11) The route remained a trunk road in the 1960s, when the Filkins bypass was built west of the village to divert traffic away from the village centre. (fn. 12) Within the village itself, a short stretch was redirected south of the church in the later 19th century, becoming known as New Road. (fn. 13)

Several lesser tracks and bridle ways linked Filkins with outlying farms and neighbouring villages. (fn. 14) Church Way and Kings's Lane (running from Filkins to Broadwell) are described above, (fn. 15) and bridle ways to Filkins mill and from Filkins to Holwell were mentioned at inclosure in 1776. The latter skirted the western edge of the poor allotments and furze grounds, and survived as a bridle way in the early 21st century. (fn. 16) Port Way, mentioned in 1546, was probably the road from Eastleach Martin to Burford, which cut across Filkins's north-western edge. (fn. 17) Several lanes were named from prominent local farming families whose property they presumably adjoined, among them Purbricks and Cooks Lanes (in 1776), Rouses (formerly Thrupp) Lane, and Hazell's Lane and Kemp's Lane. (fn. 18)

The nearest railway station was at Alvescot 2½ miles away, opened in 1873 on the East Gloucestershire line to Fairford (Glos.). The line became part of the Great Western Railway, and was closed in 1962. (fn. 19) Local carrier services to Burford, Faringdon, and Witney operated from the late 19th century, and one village carrier continued until the Second World War. Bus services continued thereafter, and in 2010 Filkins was served by regular daily buses to Carterton and Swindon. By the 1840s post was delivered from Lechlade (Glos.), and before 1877 a sub post-office was opened at Filkins; it changed premises several times, and in 2011 was in the Village Centre off Rouses Lane. (fn. 20)

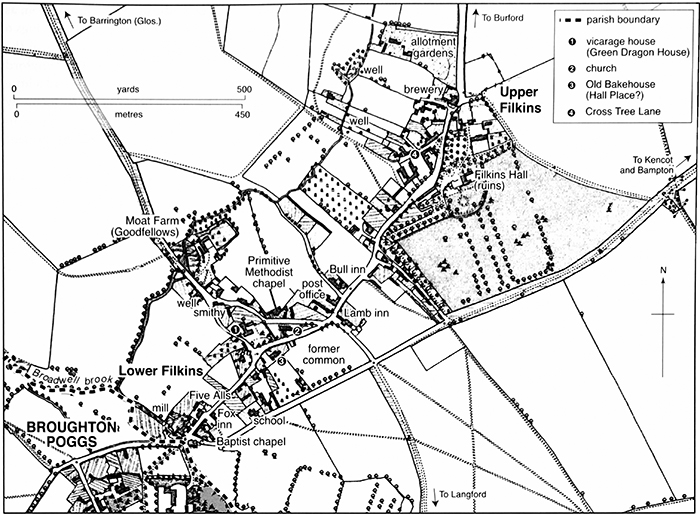

15. Filkins village in 1883, showing key buildings.

Settlement and Population

Early Settlement

An undated cropmark may indicate a prehistoric ring ditch in the township's northern part, close to land formerly known as Barrow piece. (fn. 21) Early (5th or 6th-century) Anglo-Saxon settlement is attested by a small pagan cemetery excavated in 1855, on the northern edge of the modern village: around fifteen graves were uncovered, containing grave goods including weapons, beads, and brooches. (fn. 22) The Anglo-Saxon place name (recorded from the 12th century) refers possibly to the territory or 'people' of a man named *Filica, who was perhaps a local lord or chieftain. (fn. 23) Nothing is known of the form or extent of early or mid Anglo-Saxon settlement in the township, however.

By the early 11th century Filkins formed part of the large comital estate which included Langford, Broadwell, and neighbouring places, (fn. 24) and by then there was almost certainly settlement on or including the site of the present village. An outlying mill existed by the 1160s, and by the later 13th century the village was emerging as the largest of Broadwell parish's settlements. (fn. 25) Medieval pottery fragments of the 12th and 13th century were found in Lower Filkins in 1914, during the building of the Carter Institute. (fn. 26)

Population from 1086

Some of the 74 tenant households recorded on Broadwell manor in 1086 were probably in Filkins, although their number is unknown. (fn. 27) By 1279 the village included at least 36 households, slightly more than at Broadwell, suggesting a population of between 140 and 180 people; around 14 households were headed by unfree peasants, but 22 by freeholders, an unusual preponderance for the area. (fn. 28) The number of taxpayers (representing better-off householders) fell from 27 in 1316 to 19 in 1327, implying falling population or economic difficulty, and in 1377 only 57 adults aged over fourteen paid the poll tax. The figure suggests further population loss from mid-century plagues, although Filkins remained the largest of Broadwell's townships (Table 1). (fn. 29)

The population may have remained below 13th-century levels in 1524, when there were only 11 taxpayers. Twenty years later there were between 18 and 20, however, heralding the emergence of a group of prosperous yeoman freeholders who dominated the village for much of the 17th and 18th centuries. (fn. 30) By the mid 17th century the village probably contained up to 47 per cent of the parish's total population, and in 1662 some 31 households were assessed for hearth tax, implying a total population of at least 130. (fn. 31) Thereafter the number of houses and inhabitants rose sharply. By 1759 there were an estimated 80 families in Filkins township, and by the 1790s between 90 and 100, a total population of well over 400. (fn. 32) In 1801 there were 91 houses and 454 inhabitants, more than twice the population of Broadwell, and significantly more than any other neighbouring village. (fn. 33)

Population growth continued until 1861 when there were 641 inhabitants, but during the agricultural depression large numbers left: by 1901 there were only 388 people and 111 inhabited houses, with another 14 lying vacant. During the 20th century the population generally remained around 400, with peaks of 420 in 1911 and of 482 (including Broughton Poggs) in 1961. In 2001 the combined population of the two villages was 404, accommodated in 172 houses. (fn. 34)

Development of the Village

Filkins's location at the intersection of several early routes (fn. 35) presumably conditioned its topography, and by the 14th century there were already two 'ends' known as Nether (or Lower) and Over (or Upper) Filkins (Figs 6 and 15). The former adjoined Broughton Poggs near the intersection of the Barrington, Lechlade, and Langford roads, while the latter lay along the Burford road a little to the north-east. (fn. 36) The street between them formerly looped just north of the 19th-century church close to Green Dragon House, but was diverted to its present course in the 1850s–70s. (fn. 37)

The space between the village street and the west–east road to Kencot was occupied by a large green or common, which was partly inclosed in 1776 but remained largely unbuilt on in the early 21st century. At its north-east end are the grounds of Filkins Hall, established by the 18th century and taken probably from the common. (fn. 38) Hall Place, the house for another major freehold, may have stood at the common's north-west corner fronting the village street, and was possibly of medieval origin. (fn. 39) On Nether Filkins's northern fringe, Moat Farm or Goodfellows Court originated before the late 15th century as a substantial moated house, the centre of a large freehold which became a reputed manor. (fn. 40)

During the 17th century, as population increased, the settled area may have been enlarged. Some new cottages encroached on the lord's waste, and by the 18th century settlement along the village street between Nether and Over Filkins was fairly continuous. (fn. 41) The only outlying medieval site appears to have been Filkins mill south of the village, which was established by the mid 12th century. (fn. 42) Inclosure in 1776 led to the building of several new outlying farmhouses, however, most notably College Farm (built for Trinity College, Oxford, in 1777–9), and Filkins Down Farm a little further north. (fn. 43)

In the village itself several high-quality farmhouses were built or rebuilt during the 17th century, using the local stone which also provided the area's characteristic limestone plank-fencing and dry-stone walling (Fig. 5). (fn. 44) Stone-slate roofing was presumably also common, although at least some buildings were formerly thatched. (fn. 45) Further rebuilding and refronting followed during the 18th and 19th centuries, much of it by prosperous resident yeomen and farmers. (fn. 46) Gentry houses included Filkins Hall (Fig. 20), remodelled by Thomas Edwards around 1730–40, (fn. 47) while the five-bayed front of Green Dragon House seems to have been built by a lessee in the mid 18th century, when it was probably licensed as the Green Dragon inn. The building was further remodelled by the Colston family in the early 19th century, before being adopted as the vicarage house in 1864 (Fig. 23). (fn. 48) A school and church, both in Nether Filkins, were built in 1837 and 1855–7 respectively, while small Nonconformist chapels were erected in 1832 and 1853, and a substantial stone-built village hall (the Carter Institute) in 1914. (fn. 49) Yet despite such improvements, much of the village's poorer housing remained inadequate. Labourers' cottages at the Cross Tree, owned by the prosperous farmer John Garne, were remembered by the stonemason George Swinford as 'terrible places' and 'very bad slums', and two cottages nearby were used earlier as a parish workhouse. (fn. 50)

16. The village bowling green provided by Sir Stafford Cripps in 1936, with the new Village Centre behind. The complex included a doctor's surgery, children's playground, and open-air swimming pool.

During the 1920s and 1930s the village was transformed through the initiatives of Sir Stafford Cripps, who settled at Goodfellows in 1920, and from around 1929 embarked on major building projects to improve local facilities and accommodation, including new council houses (1929–30), a Village Centre with doctor's surgery, public baths and recreational facilities (1935–6), and improved water supply. Cripps insisted that the new buildings should be of stone and stylistically in keeping with local vernacular traditions, meeting the difference in cost for the council housing, re-opening quarries on his own land to provide many of the materials, and working closely with the Filkins mason George Swinford. As a result, by 1944 Filkins was being hailed as 'a modernized village' and 'an illustration of contemporary village planning', while the council houses, designed by Cripps's architect Percy Morley Horder, were the first social housing to be listed for their architectural merit (Plate 4). Under Cripps's influence a later group of council houses (completed in 1938) were erected in similar style, to designs by Stanley Roth. (fn. 51)

During the later 20th century many of the older houses and cottages were renovated for middle-class incomers, although like neighbouring Langford the village retained some social housing. (fn. 52) Small-scale building and remodelling continued, despite the constraints imposed by the creation of a conservation area in 1986. (fn. 53) Filkins Hall (rebuilt c. 1912) was converted into ten flats or apartments in 1987, and another seven houses were created in its grounds, some of them newly built and others converted from outbuildings. Other new housing was built on open areas along the main street or on the edge of the common, including a nine-unit complex called Jubilee Mews (completed in 2002) which incorporated the former Lamb Inn. (fn. 54) Like most other new building in the village it employed Cotswold stone in an attempt to blend in, an approach reflected even in the nearby bus shelter with its stone walling and hipped stone-slate roof. Agricultural buildings, too, were converted to new uses, most notably a large 18th-century barn in Upper Filkins taken over in 1982 by the Cotswold Woollen Weavers, next to a stone yard which remained open in 2011. (fn. 55) Such developments reflected both the village's vibrancy and its continued desirability as a residential centre, still larger than most surrounding villages, and served by a range of facilities including a community post office and regular bus services. (fn. 56)

MANORS AND ESTATES

Like the rest of Broadwell parish, Filkins was included from the Middle Ages within the three chief Broadwell manors. (fn. 57) From an early date there were several substantial freeholds, however, of which two became reputed manors, while medieval grants created a few small ecclesiastical estates. A large estate centred on Filkins Hall was built up piecemeal from the early 18th century.

Goodfellows Manor

Lands owned in 1454 by John Goodfellow of Filkins were called Goodfellows manor by 1479, when they were settled for life on another John Goodfellow (probably his son), and from Goodfellow's death on John Twynho of Cirencester (Glos.). Twynho died in 1485, leaving his daughter Dorothy Morton as heir. By then the reputed manor included two houses, 300 a. of land, and 25 a. of meadow in Nether Filkins, all held of William Byrll for unknown service. (fn. 58)

No further references have been found until 1612, when the estate (by then 220 a.) was held for their lives by Thomas Woodward, his wife Dorothy, and their daughter Frances and son-in-law Robert Martin. (fn. 59) The Woodwards were gentleman landholders in Filkins by the 1570s, (fn. 60) and had possibly owned Goodfellows for some decades. Thomas (d. 1612) may have been succeeded by his son Thomas (d. 1642), (fn. 61) but c. 1660 Ambrose Sheppard of Lindford (Suff.) conveyed a 1,000-year lease of the manor or farm of Goodfellows to William Gatson, whose executors were sued for non-payment in 1667. (fn. 62) By inclosure in 1776 the estate was owned by Ann Brooks of Witney, spinster, who leased it to the Purbricks. (fn. 63)

In 1809, when Goodfellows manor was advertised for sale, it comprised a house, outbuildings, and some 140 acres. (fn. 64) Sir William Erle, Lord Chief Justice of Common Pleas, bought it from the Valentine family in 1862, and in 1880 devised it to the Revd Henry W. P. Richards and his wife, apparently as part of a marriage settlement. (fn. 65) By 1898 (when it was sold again) the estate was called Moat farm, (fn. 66) and by 1908 it was owned and occupied by Capt. C. J. Wahab. (fn. 67) None of Wahab's 18th- or 19th-century predecessors seem to have actually lived there, however, and both house and estate were usually let to tenant farmers, most notably the Purbricks and (in the later 19th century) the Glovers. (fn. 68)

In 1920 Goodfellows was bought by Stafford (later Sir Stafford) Cripps (d. 1952), who added several other farms around 1928–30. (fn. 69) By 1941 the combined estate was known as Filkins farm and totalled 410 a., all of it (except the house) let to tenants. The Cripps family retained the land in 2002, although the site of the then-demolished house was owned by the Morley family. (fn. 70)

Goodfellows Place (Moat Farm)

Moat Farm or Goodfellows (Fig. 17) was almost entirely burnt down in 1947, but lay north-west of Filkins village on an ancient moated site. Presumably that was the location of the 'court' mentioned in 1479. (fn. 71) Moulded stone of possibly 14th-century date was found during building work in the 1930s, (fn. 72) but the house as it then existed seems to have dated chiefly from the 16th and 17th centuries, and was said to include masons' marks found on contemporary work at Burford Priory. Two-storeyed and built of stone and stone slate, the house and its adjoining stable range formed an L-plan, which was turned into a T when a new south-west wing containing an oak-panelled library was added for Cripps in the 1930s. The architect for the new wing was P. R. Morley Horder, and the builder George Swinford. Other changes included re-roofing of the house's older part, repairs to the dovecot, addition of a new cart shed, and the creation of a 'charming' garden. (fn. 73)

17. Goodfellows or Moat Farm after its renovation and extension in the 1930s. The building burned down in 1947.

During the Second World War the house accommodated evacuees from Bristol, and was later used as a Land Army hostel. A small part of the north end survived the fire of 1947, and was later made into a cottage. (fn. 74)

Filkins or Nether Filkins Manor

A house and ploughland held of Bradwell Odyngsell manor for 1d. annual rent became known by the early 16th century as the manor of Filkins or Nether Filkins. (fn. 75) In 1279 the owner was Ralph de Vernay, (fn. 76) but in 1313 Florence, widow of Philip de Vernay, quitclaimed all her husband's lands and tenants in Filkins to Sir John Mauduit (d. 1347) of Somerford (Wilts.). (fn. 77) Mauduit was lord of the neighbouring manor of Broughton Poggs, with which the Filkins estate descended until the 16th century; the 1d. rent was still recorded in 1369, but not later. (fn. 78)

In 1537 George Hastings (d. 1544), earl of Huntingdon, sold the 'manor' of Filkins to Thomas Cromwell, (fn. 79) who was later created earl of Essex. In 1541, after Cromwell's fall, it was granted to Anne of Cleves (d. 1557) for life, (fn. 80) and in 1557 the Crown sold the reversion to Sir Thomas Pope, purchaser of two of the principal Broadwell manors. Thereafter the estate was apparently merged with Pope's other Broadwell and Filkins lands. (fn. 81)

Hall Place

An estate centred on a house called Hall Place was mentioned from 1600, having presumably developed from one of Filkins's substantial medieval freeholds. In 1601 it totalled 7 yardlands (around 175 a.) with appurtenances in Nether Filkins, Kelmscott, and Broadwell. (fn. 82) Possibly it was of early origin, since a family surnamed 'at Hall' (de Aula) witnessed local documents and served as jurors at Filkins from the early 14th century. (fn. 83)

18. The Old Bakehouse on Filkins's main street, perhaps to be identified with Hall Place. The central gable bears a datestone of 1626.

By the early 17th century the estate was owned by the prominent Turner family of Filkins and Kelmscott, and Hall Place may have been the substantial house with hall and parlour occupied in 1559 by Thomas Turner of Filkins, who left household goods worth over £64. (fn. 84) In 1600 Richard Turner, then living at Kelmscott, left his 'capital messuage, seat, or farm' called Hall Place to his widow Ann and infant son Thomas (d. 1663), who as an adult seems to have settled there: he was certainly living at Filkins in 1662 when he was taxed on five hearths, his son Thomas having been installed at what became Kelmscott Manor. (fn. 85) Hall Place seems to have passed to the elder Thomas's younger son John, (fn. 86) who was drowned in 1667/8, (fn. 87) and thereafter it probably reverted to the Turners of Kelmscott Manor. By 1717 it was owned by Henry Turner (d. c. 1732), a younger son of Thomas Turner (d. 1709) of Kelmscott. (fn. 88)

In that year Henry settled the estate on his wife Martha Geering as jointure, and on his death it passed to Martha and her second husband Henry Whitfield, vicar of Broadwell. He probably lived at Hall Place at least occasionally, although as an army chaplain he was often abroad with his regiment. (fn. 89) After Whitfield's death in 1762 the house was let, and in 1770 it was sold with the 'freehold manor' and farm and two cottages. (fn. 90) The estate has not been traced further and was perhaps broken up.

Hall Place itself is unidentified, but was perhaps the large stone-built house on the main street now known as the Old Bakehouse (Fig. 18). The large central gable bears a datestone inscribed T/TA 1626, perhaps for Thomas Turner (d. 1663) and his wife Ann (née Deane). (fn. 91) The house is of coursed limestone rubble with dressed quoins and stone-slated roofs; the central bay retains a gabled stair turret to the rear and a large fireplace with a four-centred stone arch, but the building has been much altered. New windows were inserted in the late 18th or early 19th century, and the interior was modernized in the later 20th century, removing many internal features. (fn. 92) In the late 19th and early 20th century the Clark family ran a shop and village bakehouse there. (fn. 93)

The Filkins Hall Estate

A large estate centred on what became Filkins Hall was built up piecemeal during the 18th century by the Edwards family and their relatives the Colstons, Bristol lawyers and gentry who settled in Filkins. (fn. 94) In 1704 the lawyer Thomas Edwards (d. c. 1743) became lessee of the rectory estate, (fn. 95) and around the same time he acquired an estate and chief house (apparently Filkins Hall) in Upper Filkins from Thomas Coningsby, Lord Coningsby. Edwards added freehold land acquired from various yeoman families, but his estate became heavily encumbered and a part was sold to his son-in-law Alexander Ready (d. 1775), another Bristol lawyer who had married Edwards's youngest daughter Sophia. Ready continued to expand the estate, changing his surname to Colston in order to inherit from his wife's maternal ancestor, the Bristol philanthropist Edward Colston. (fn. 96) At inclosure in 1776 Sophia owned over 340 a. in Filkins and Broadwell, excluding her lease of the 425-a. rectory farm; (fn. 97) she died in 1790, to be succeeded by her grandson Edward Francis Colston (d. 1825), and his son of the same name (d. 1847). (fn. 98)

After the Colstons left Filkins around 1828 the house was let to tenants, notably the lawyer William Vizard, who in 1831 became lord of Little Faringdon. (fn. 99) The family made several failed attempts to sell the estate, in 1839, 1841, and 1842; by then it comprised Filkins Hall, Filkins farm, Edgerly farm, and land in adjacent parishes, in all some 600 acres. (fn. 100) Prospective purchasers included the Chartist MP Feargus O'Connor, who in 1847 had converted an estate at nearby Minster Lovell into a colony of smallholders. Local gentry were said to be unhappy at the prospect of similar developments in Filkins, and persuaded William Hervey of Bradwell Grove to buy instead. O'Connor claimed £500 compensation, (fn. 101) but in 1849 the estate was nonetheless absorbed into Hervey's Bradwell Grove estate. (fn. 102) The local farmer and antiquary Thomas Banting regretted the lost opportunity, contrasting O'Connor's philanthropic motives with Hervey's drive for profit. (fn. 103)

Before 1869 the Hall and part of the estate were acquired by Captain J. C. Campbell, RN, of Ardpatrick (Scotland). He leased the house to Charles Smith, an estate agent who was living there when it burnt down in 1876. (fn. 104) W. H. Fox of Bradwell Grove sold much of his remaining Filkins land in 1914, (fn. 105) and the rebuilt Hall and parts of its estate were bought in 1917 by the banker Frederick Crauford Goodenough (1866–1934), one of a family established in the area as substantial yeomen and (later) as gentry since at least the 16th century. Goodenough added Manor and Lower farms in Broadwell in 1922, and Peartree farm in Filkins around the same time. (fn. 106) His son Sir William Goodenough (1899–1951), another banker, succeeded, and in 2004 the combined estate, by then run from Broadwell Manor Farm, was owned by F. R. Goodenough, Filkins Hall itself having been sold in 1987. (fn. 107)

Filkins Hall

The house acquired by Thomas Edwards in the early 18th century was evidently a predecessor of Filkins Hall, which was largely rebuilt after the fire of 1876. An iron fire-back with Edwards's initials and the date 1716 was found in the Hall after the fire, and was refitted in the restored building. (fn. 108) The main body of the house appears to have been remodelled by Edwards c. 1730–40 as a square double-pile, retaining part of the earlier building, and in 1819 the mansion, 'although not elevated', commanded 'a fine prospect'. (fn. 109) A service wing was added around 1845, and photographs of the hall taken after the fire show the remains of a handsome if unexceptional Georgian mansion (Fig. 20). (fn. 110)

First-floor rooms were panelled, and there was a large entrance hall with a polished mahogany staircase. (fn. 111) A pair of surviving gate piers on the north side of the Kencot road date from the early to mid 18th century, and are therefore roughly contemporary with the house. (fn. 112) Surviving outbuildings include a stone dovecot of the late 18th or early 19th century, which was originally a square two-storey building with a gable to each side and an oval gable-opening to the south; lean-to extensions have been added to left and right, together with a rear extension and alterations to windows and doors. The stone-built stable block, rebuilt for Edward Colston by Richard Pace of Lechlade, has a datestone inscribed E/C/N 1810, with a dolphin (the Colstons' family emblem) depicted underneath. The building is symmetrical, with a slightly projecting central bay, a central arched carriage-opening, and a shaped gable and belfry. The flanking two-storey stable wings are of three bays each. (fn. 113)

Colonel F. B. de Sales la Terrière, who began the restoration of Burford Priory, bought Filkins Hall in 1912 and rebuilt it in Jacobean style, incorporating some original walling and the mid 19th-century service wing. The builder was Mr Groves, and one of the masons George Swinford. Wrought-iron gates dating from c. 1912 were intended as the start of a driveway leading to the house and to an artificial lake, but neither lake nor drive were ever constructed. (fn. 114) The Goodenoughs lived there from 1917, (fn. 115) but in 1987 sold the Hall to developers. Thereafter the main part was converted into ten apartments and the stable block into three houses. (fn. 116)

Lesser Ecclesiastical Estates

Hertford priory, a cell of the Benedictine abbey of St Albans, was given lands in Filkins by its founder Ralph de Limesy (d. 1093), who was lord of Broadwell. Ralph's wife Hadewise added dower land formerly belonging to Nigel of Broadwell, and their son Alan (d. by 1162) gave or confirmed half a hide and demesne tithes. Alan's granddaughter Amabel (fl. 1200) reportedly bequeathed 5s. rent. (fn. 117) In 1241 the priory claimed a hide in Filkins against the Limesys' successors, (fn. 118) and in 1279 its estate totalled seven yardlands. (fn. 119) The priory was dissolved in 1536, and in 1538 its lands were granted to Anthony Denny and his intended wife Joan Champernoun. (fn. 120) The estate has not been traced further.

Between 1234 and 1241 Hugh de Clifford gave land in Nether Filkins (later described as a yardland) to Abingdon abbey, (fn. 121) which retained it until the Dissolution. A cottage and land formerly belonging to the abbey were sold in 1544 to Thomas Denton, sewer of the king's chamber, (fn. 122) and are presumably to be identified with a cottage in Nether Filkins later known as 'Abingdon'. That was acquired by Thomas Edwards of Filkins Hall, and in 1849 by William Hervey; by then, however, it was held with only 5 a. and common rights. (fn. 123)

Eynsham abbey was given half a hide in Filkins by Ralph Murdac, lord of Broughton Poggs, in 1173–4. The abbey retained a 6s. rent in 1291 and 1390, but neither land nor rent were recorded by the 16th century. (fn. 124)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Agriculture

Until inclosure in 1776 Filkins shared an open-field system with Broadwell. Post-inclosure farms and estates were also intermixed between the two townships, and Filkins's agricultural history is accordingly treated above with that of Broadwell. Broughton Poggs and Filkins mills (both in Filkins township) are also discussed above. (fn. 125)

Trades and Crafts

Though Filkins was a predominantly agricultural community it seems, from an early date, to have had more craftsmen and tradesmen than Broadwell, which in the Middle Ages was dominated by the large agricultural demesnes. Medieval surname evidence suggests the presence of millers, bakers, coopers, ironmongers, and chapmen, (fn. 126) and in the 17th century a butcher and a tailor were mentioned. (fn. 127) From the later 17th century, as Filkins expanded, there seems to have been greater diversity of occupation. Craftsmen included blacksmiths, wheelwrights, carpenters, a siever or sieve maker, cordwainers, and tailors, (fn. 128) while tradesmen included the clothier Thomas Wastie (d. 1667), two fellmongers (both members of the Bassett family), the shopkeeper Robert Richin (d. 1741), and a draper who sold up in 1799. (fn. 129) By the mid 18th century there were also several publicans or innkeepers. (fn. 130) As at Broadwell, Holwell, Burford, and Brize Norton there were significant amounts of malting: maltsters included members of milling families such as the Galloways and Hamlyns, and at any one time there seem to have been at least two or three malthouses. (fn. 131) One at Goodfellows Farm was 'new-erected' in 1809, and others survived in the late 20th century, converted into cottages. (fn. 132) A small brewery at Peartree Farmhouse on the village's northern edge was run in the later 19th century by John Clark, licensee of the Fox, but closed in the 1880s. The family combined its pub and brewing activities with a coal and haulage business. (fn. 133)

The concentration of crafts and trades in 18th-century Filkins led to its emergence by the 19th century as a local centre for goods, trades, and services, probably helped by the turnpiking of the main road through the village in 1792. (fn. 134) Out of 147 households in 1861, around 51 per cent derived their income from agriculture, 10 per cent from quarrying and masonry, 13 per cent from crafts, and 6 per cent from trade and services. In 1876 there was a baker who also sold coal, three grocers (two of them also drapers), and two beer retailers, as well as several licensed publicans. Henry Dring combined his role as innkeeper with that of farrier or vet, and several small traders dealt in agricultural commodities, among them Peter Hall, pig dealer, John Castle, cattle dealer, and Thomas Stevens, miller and mealman. John Williams, a plumber in 1847, expanded into painting and decorating before 1869.

Manufacturers included shoemakers and tin and copper smiths, and by 1847 there was a machine maker, while many women worked as dressmakers and needlewomen. Charles Smith of Filkins Hall was an estate or land agent, and by the 1880s there were several other professionals including a schoolmaster, a policeman, and an inland revenue officer. Transport employed increasing numbers. In 1861 Thomas Clack was a road contractor, and in 1881 there were two carters and an engine driver. One of the Robbins family was a coach builder in 1881, and another had a cycle shop in the early 20th century. (fn. 135) Jim Farmer followed his uncle Jesse as village carrier and continued throughout the Second World War, when private motor vehicles were requisitioned for war work. (fn. 136)

Filkins continued to serve the surrounding area in the early 20th century. Varied facilities (including a doctor's surgery) were opened in 1935 in the new Village Centre built by Sir Stafford Cripps, who initiated that and other building and sanitation projects partly to provide local employment during the economic depression of the late 1920s and 1930s. (fn. 137) In 1939 Filkins was served by four shops including a baker's, grocer's, and cycle agent's, and it retained a doctor, post office, and blacksmith. (fn. 138)

As agricultural employment declined in the later 20th century some local farms diversified. (fn. 139) Light industrial and craft workshops were established at Oxleaze Farm in Broughton Poggs, creating local jobs, (fn. 140) and in Filkins a traditional woollen mill selling its own products (Cotswold Woollen Weavers) was opened in 1982 in a converted 18th-century barn at Cross Tree Yard. (fn. 141) In 2011 the mill adjoined a variety of craft workshops and a stonemason's yard. Further local employment was provided at Minola Smoked Products, a smoked-meats factory based in Filkins from 1984 until 2000, when it moved to larger premises in Wales, taking some of its staff. (fn. 142) During the decade 1987–97 the total number of jobs in the civil parish of Filkins and Broughton Poggs accordingly increased. Of those residents in employment in 1987, 42 (or 25 per cent) worked in the parish, and 61 (or 46 per cent) within 25 miles; ten years later, 62 (or 36 per cent) had jobs within the parish, and 61 (36 per cent) within 25 miles. The number employed in agriculture remained unaltered at 13, and though craft and stonemasonry jobs fell from 20 to 18, the number employed in manufacturing rose from 16 to 102. In 1987 there was a new animal feeds factory, and by 1997 Peter Cook International plc (closed by 2009) was manufacturing components for furniture and beds. (fn. 143) Many other inhabitants worked at nearby RAF Brize Norton, or in the towns of Carterton and Swindon; even so, in the early 21st century Filkins was judged unusual for the high number of inhabitants who worked within the village in commercial (rather than farming) jobs. (fn. 144)

Quarrying and Stone Masonry

Quarrying of limestone deposits in Broadwell, Filkins, and Holwell is recorded from the 16th century, and was almost certainly carried out in the Middle Ages. Some quarries, notably on the Forest Marble west of Filkins village, produced good, durable, general-purpose building stone, and others produced large high-quality slates which, unlike Stonesfield slate, did not have to be frost-split and could be used as dug, both for roofing and as plank fencing. Numerous other sites produced less durable building stone, flooring stone, or stone for road mending, although quarrying in the parish never became a large-scale commercial enterprise, due partly to the lack of easy transport. (fn. 145)

The right to dig materials from the wastes and commons belonged to the manors, and was sometimes leased with other property. (fn. 146) In the late 16th century the Hewlett family held a slate quarry on Broadwell common by copyhold, (fn. 147) and some commoners dug small pits for their own needs, although those without rights were fined for illegal digging. Parish officers organized digging for materials to mend the highway, though some pits were recorded as hazards because of their proximity to the roads. (fn. 148) During the 17th and 18th centuries there were several families of slaters, (fn. 149) among them the Mosses of Bradwell Grove, (fn. 150) the Simpsons, (fn. 151) and the Farmers, who continued as masons at Filkins until around 1900. (fn. 152) Other masons were recorded at Holwell, Filkins, and Broadwell. (fn. 153)

Some of the stone and slate was presumably used in local building work, of which there was a great deal during the 18th and early 19th centuries as wealthier yeomen and gentry remodelled their houses and erected new farm buildings. (fn. 154) At inclosure in 1776 Trinity College, Oxford, as owner of the rectory estate, was allotted lands in Filkins with good stone deposits including a 'great quarry', from which came materials both for the college's new farmstead, and for stone planking in the new fields. (fn. 155) Other large-scale building projects, probably partly using local stone, included work at Filkins Hall and at Broadwell and Holwell churches, as well as the erection of Bradwell Grove House and Broadwell Manor Farm in the early 19th century. (fn. 156)

Before inclosure, stone and slates were quarried in various parts of the parish. In Holwell, there were pits east of the village near the Burford road. (fn. 157) Hampsteads pits lay near Broadwell's and Filkins's West field, (fn. 158) and in Filkins there was a public quarry in Townsend furlong, through which the Broadwell–Burford road passed. (fn. 159) The 'great quarry' on College farm was let in the 1780s to John Farmer for around 4½ guineas a year, and at a nearby 'small quarry' (in Barrow piece) the tenant allowed digging at the rate of 7s. 6d. per thousand stones or slates. (fn. 160) Plank-stones were widely available, (fn. 161) and field names suggest that small-scale quarrying continued on many post-inclosure farms in Broadwell, Bradwell Grove, Filkins, and Holwell. (fn. 162) During the Napoleonic wars French prisoners reportedly helped work some Filkins quarries, (fn. 163) and activity continued throughout the 19th century, when masons, quarrymen, and slaters were concentrated in the village. James Purbrick, a slate and stone merchant, lived there in the 1840s, and in 1881 the mason and quarryman Robert Farmer employed 15 men and boys. (fn. 164)

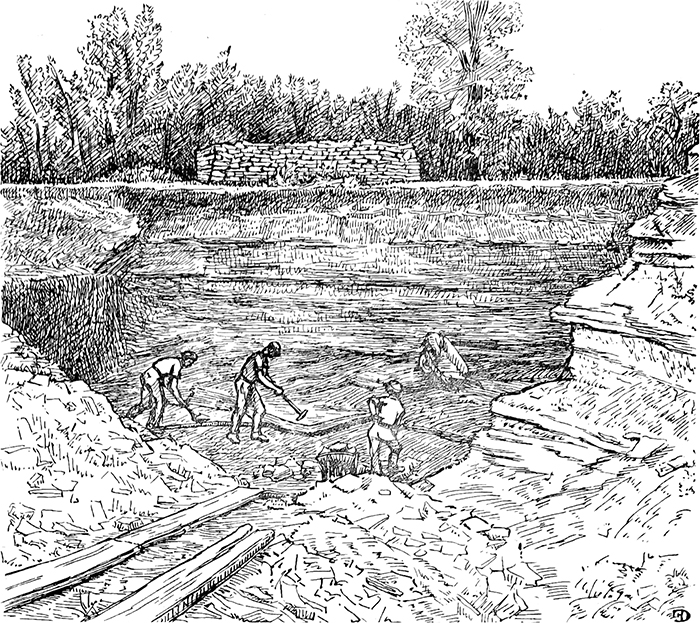

19. Quarrying at Filkins in 1948, from a series of drawings by Freda Derrick.

In the later 19th century the Swinford family migrated from Gloucestershire to work for the Farmers, and married into the family, continuing the industry into the 20th century. George Swinford (1887–1987), a master mason who at one time had 31 men under him, began work in 1900, chopping stones for work on the Bradwell Grove estate by Alfred Groves and Son of Milton-under-Wychwood. In later life he described the main quarries still worked in the early 20th century, which seem to have run in a band roughly west–east across the parish, concentrated around the lands of Oxleaze farm in Broughton Poggs, College farm, Filkins farm, and Broadwell Manor farm. The best stone (Forest Marble) came from Longround and Horsebottom quarries around ¼ mile north-west of Filkins village, where several acres of old workings were re-opened after Sir Stafford Cripps bought Manor Farm in 1928. Between 1929 and 1957, besides road-stones, some 190,000 slates, 11,000 cubic yards of building stone, and 160 tons of paving stone were dug by hand; some of it was sold, but most was used for local building work. Other quarries produced less durable stone but were easier to work, while the White Hill quarries on College farm produced stone flooring. (fn. 165) Throughout that period local landowners initiated a new wave of building projects, of which many were overseen by Swinford: Cripps in particular, as well as extending his own house at Goodfellows, instigated extensive new building in the village and provided the stone for Langford school. (fn. 166) At Kelmscott, the Morris Memorial Cottages, the Memorial Hall, and new council houses were similarly built using local craftsmen and materials. (fn. 167)

After the Second World War building work declined, and though the Swinfords trained apprentices all of them left to earn higher wages in nearby factories or US airbases. (fn. 168) In 1981, however, after John Cripps encouraged the revival of traditional craft skills, Seymour Aitkin of Lechlade re-opened Horsebottom quarries on Cripps's land. Machine-dug slates from there were used to re-roof the great court of Trinity College, Cambridge, (fn. 169) and buildings on the Bradwell Grove estate were re-roofed using stone slate from Rectory farm. (fn. 170) In 1985 the stonemasons D. Collett and Sons moved to Filkins from Burford, establishing premises at Cross Tree Yard, (fn. 171) and in 2011 the Filkins Stone Company had a large stone yard there adjoining the Filkins Workshops and the Cotswold Woollen Weavers.

SOCIAL HISTORY

Medieval Village Society

The hamlets of Nether and Upper Filkins developed at some distance from the centre of lordly control at Broadwell, where the demesne lands and the three manorial sites lay. Perhaps partly as a result, by the 12th and 13th centuries a rather different type of community was emerging from that at Broadwell, characterized by larger numbers of freeholders and by a more complex pattern of landholding. In contrast to Broadwell there were a few small independent estates owned by ecclesiastical lords and others, and in 1279, out of 36 households in Filkins, 22 (over 61 per cent) were headed by freeholders, an unusually large proportion for the area. At the top of the social hierarchy were three landholders with their own subtenants: Ralph de Vernay, who held four yardlands of Hugh d'Oddingseles, Ralph of Filkins, who held Hertford priory's seven-yardland estate, and Roland d'Oddingseles, who held a yardland in his own right. Another 19 households were headed by lesser freeholders including subtenants of the above, and four were headed by women, probably widows. Land tenure was complex, with five tenants holding land from more than one landlord, two holding unfree land in addition to their freeholds, and others holding land in Broughton Poggs or other neighbouring settlements. On Abingdon abbey's small estate all the tenants were freeholders, although their status had been subject to dispute. Acreages varied widely: five freeholders held between 1½ and 2½ yardlands, six held half a yardland, and seven had only between 4 and 13 acres. Alongside these freeholders lived 14 or 15 villein families and cottars, who held their lands of Bradwell Odyngsell and Bradwell Cirencester manors on similar terms to their Broadwell neighbours, and owed labour services on the Broadwell demesnes. The size of their holdings again varied considerably, from a few acres to 2 yardlands. (fn. 172)

Early 14th-century subsidies (assessed on the value of moveable goods) confirm the presence of some moderately prosperous peasant farmers and freeholders, and though none of the individual payments came close to those for the large Broadwell demesne farms, over all Filkins consistently emerged as the slightly wealthier settlement, and had a larger number of taxpayers. (fn. 173) There was, however, no consistent correlation with the size or legal status of holdings recorded earlier. Robert of Quenington, one of the wealthier inhabitants in 1316 when he was assessed on £3, belonged to a freeholding family which in 1279 held one yardland, whereas the Poitevins, who were of comparable wealth, had earlier held in villeinage. (fn. 174) Possibly this reflected shifting individual fortunes and an active land market, and after the Black Death some larger freeholds probably emerged. By the later 15th century one of them (Goodfellows) was being claimed as an independent manor, suggesting an assertion of independence against external lordly control. (fn. 175)

In other respects links with Broadwell probably remained strong. Manorial tenants were still required to attend the manor courts held presumably at the manor houses in Broadwell, while a shared field system must have necessitated strong cooperation in agrarian affairs. Religious life, too, remained focused on Broadwell church, which Filkins inhabitants were required to attend, and for whose upkeep they presumably shared responsibility. (fn. 176)

Yeomen and Gentry, 1500–1800

The presence of independent freeholding yeomen characterized Filkins well beyond the Middle Ages, in sharp contrast to Broadwell, where the medieval demesnes continued as large leasehold farms and where successive lords of the manor resided for much of the 16th and 17th centuries. (fn. 177) Sixteenth-century subsidies suggest that Filkins was still only moderately wealthier over all, although some prosperous individuals were taxed on relatively large sums. Around a dozen inhabitants in the 1540s paid on goods worth between £3 and £8, while Robert Turner paid on £20-worth, placing him on a level with the large demesne farmers in Broadwell. (fn. 178) A later branch of the family acquired gentry status, (fn. 179) and from the 17th century yeoman families such as the Bassetts, Burnetts, Farmers, Hamlyns, and Purbricks seem to have accumulated substantial holdings, often rebuilding their houses, and leasing out smaller parcels to other inhabitants. (fn. 180) By the mid 18th century twelve Filkins freeholders were wealthy enough to vote, and in the 1780s the tenurial structure remained distinctive. Farmers frequently held their land from several owners, while leading yeomen such as the Purbricks combined freehold and leasehold. (fn. 181)

The wills and inventories of Filkins's better-off farmers show increasing levels of domestic comfort, reflected in large quantities of wooden furniture, metal cookware, and occasional luxury items such as the girdle with silver studs which Robert King left to his daughter Eleanor in 1555. (fn. 182) In the 1660s one of the Turner family occupied a house taxed on five hearths, the largest in the township, (fn. 183) and though far more householders were taxed on only one or two hearths (pushing the average below that for Broadwell), not all of them were necessarily poor. Nicholas Saunders and Thomas Godwin were both taxed on one or two hearths, but in 1670 each of them paid church tax on around 7 yardlands, and when Godwin died in 1699 his estate was worth over £455. (fn. 184) Rebuilding and improvement of houses and farm buildings seems to have continued throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, producing by the 19th a significant number of high-status farmhouses with fashionable symmetrical fronts, sash windows, and ashlar façades or detailing. (fn. 185)

In consequence, Filkins seems to have become not only larger than Broadwell but also more fashionable. Several of Broadwell's 18th- and early 19th-century vicars chose to live there, often on their own property, and at least one of them had his own chaise, which around 1750 was involved in a traffic accident injuring his wife. (fn. 186) The village's appeal was further enhanced in the 18th century by the arrival of the Edwardses and their relatives the Colstons, who between them built up the large Filkins Hall estate; both families came originally from Bristol, where they had made their money as lawyers and (in the case of the Colstons) from the slave trade. (fn. 187) Their Filkins estate formed the basis for a fashionable lifestyle: family monuments in Broadwell church were carved by sculptors from London, and a later family member (Marianne Colston) published a journal of her foreign travels. (fn. 188) Their influence was increased by their ownership of the advowson and by the fact that several of the family became vicars of Broadwell, while Alexander Colston (d. 1775) served as justice of the peace. In the early 18th century the family helped supplement the vicar's meagre income, and Alexander Colston, 'ever [ready] to relieve the distressed', was said to have died 'revered and respected', although his inclosure of part of the common around 1750 caused considerable local resentment. (fn. 189) The family eventually sold their Filkins property in 1849 and moved to Roundway Park (Wilts.), having lived beyond their means for some time. (fn. 190)

Village Society Since 1800

After inclosure ended ancient common rights and consolidated the larger commercial farms, polarization between rich and poor in Filkins seems to have become more pronounced. From the late 18th century some of the grander houses were owned and leased separately from their lands by gentlemen, professionals, and retired army officers, presumably attracted by the fine sporting country and (earlier) by the proximity of Burford with its fashionable races, (fn. 191) while an increasing number of tradespeople, including tailors and shopkeepers, existed to service the middle classes of the neighbourhood. (fn. 192)

By contrast, some of the smaller tenant farmers migrated to America to seek new opportunities, while poverty among landless labourers was reflected in mounting poor rates. (fn. 193) Living conditions for the poorest cottagers did not improve until the early 20th century, (fn. 194) and in Filkins and its neighbour Broughton Poggs the 'rough element' remained a feature throughout the 19th century, indulging in drunkenness, prize fighting, and the disruption of Nonconformist religious meetings. (fn. 195) Nevertheless the success of Nonconformity in Filkins, in part encouraged by the village's distance from the mother church and by a strong working-class culture, provided a counter-balancing, 'civilizing' influence. The building of Baptist and Primitive Methodist chapels in 1832 and 1853 prompted the foundation of an Anglican church in 1855–7, (fn. 196) and pubs and churches dominated social life throughout the later 19th and early 20th centuries, when most inhabitants were labourers and artisans, with a minority of well-to-do farmers and incomers living in the larger houses. (fn. 197) Some agricultural labourers supplemented their wages by taking up seasonal work elsewhere: as late as 1912 a group of Filkins men habitually went to London to help with the haymaking, returning to Filkins in time for the harvest, and then moving on to Northleach where the harvest was brought in later. (fn. 198)

20. Filkins Hall after the fire of May 1876. The building remained a ruin until its rebuilding in Jacobean style from c. 1912.

During the later 20th century, as agricultural employment shrank, families which had lived in the village for several generations moved away to take up jobs in Carterton, Swindon, or further afield, and from the 1970s Filkins attracted a new generation of incomers. (fn. 199) In 2001 the proportions of retirees, managers, and professionals were all slightly above the county average, and as in the area generally there were virtually no ethnic minorities. (fn. 200) Other incomers included entrepreneurial craftspeople embracing rural life: potters, cane weavers, furniture restorers, a firm of landscape architects, the proprietors of a picture gallery, and the founders of the Cotswold Woollen Weavers, all attracted by the rural Cotswold setting and by the village's good facilities and easy accessibility. (fn. 201) Nevertheless the village remained socially mixed, with some remaining social housing, and several people on low incomes, including some older residents. (fn. 202)

The Life of the Community

Communal life in Filkins is poorly recorded before the late 18th and early 19th century. By then there were several public houses serving passing trade along the Lechlade–Burford turnpike, and providing a local social focus. The Rose and Crown in Upper Filkins existed possibly by the early 1700s, (fn. 203) and by the mid 18th century there were three licensed houses: the Five Alls and the Green Dragon, both in Lower Filkins, and the Bull in Upper Filkins. (fn. 204) The Green Dragon (closed around 1786) is probably to be identified with the surviving Green Dragon House (Fig. 23), which lay closer to the main road before its rerouting in the 1850s–70s, and which seems to have been extended and refronted by the licensee William Wornell in the mid 18th century. (fn. 205) The building shows no obvious signs of its former use, however, and despite its grand five-bay façade was probably never more than an ordinary roadside inn or pub. (fn. 206) During the earlier 19th century the Bull was joined in Upper Filkins by the Lamb Inn, once the property of the maltster John Hamlyn, (fn. 207) while the Fox Inn in Lower Filkins opened before 1847 and closed by the 1890s, becoming a builder's yard. (fn. 208)

The public houses were sites of village entertainment. A pigeon-shooting contest was held at the Bull in 1778, (fn. 209) while the Lamb had an adjoining area called the Gassons or Garstuns, used for bull-baiting, rabbit-coursing, and (later) for football and quoits. (fn. 210) In addition the pubs hosted holiday fairs, the Five Alls advertising a roasted 'prime fat sheep' and other amusements on the Whitsun holiday in 1859. (fn. 211) The annual Filkins feast was held at the Bull or on the Gassons at the Lamb Inn: an ox-roast and bull-baiting formed part of the entertainment until the early 1800s, but by 1866 had been superseded by stalls and swing-boats. The feast was probably celebrated at Michaelmas until adoption of the Gregorian Calendar in 1752, after which it moved to the Sunday and Monday following 11 October. (fn. 212)

In the later 19th century many small farmers, agricultural workers, and artisans expressed a shared identity through religious affiliation at church or chapel, (fn. 213) or through other elements of communal culture. Filkins was famous for its morris men, who were active mainly between Easter week and the Filkins feast in October, travelling with their musicians for up to thirty miles around. (fn. 214) Local Primitive Methodists formed a Filkins Temperance Band around 1895, which performed at flower shows and garden parties as well as at camp meetings, (fn. 215) and in the early 20th century there was a Langford and Filkins band, whose brass- and reed-players performed an 'up-to-date repertoire'. (fn. 216) By the later 19th century Filkins had its own cricket and football teams, and an annual flower show was begun after the First World War. (fn. 217)

Another important aspect of working-class life was membership of friendly societies, of which more than one operated in Filkins, open to all families who could afford to belong. The Filkins branch of the local 'Red, White and Blue club', founded in 1879, served also as a men's social club, with a room at the Lamb Inn and (later) at the Bull; the club held an annual fête and dinner on Whit Tuesday to which the local MP was sometimes invited, and members received financial help with sickness and funeral expenses. (fn. 218) In 1872 several Filkins men also joined the Labourers' Union (based in Leamington), after attending a meeting at the Bull which dwelt on farm labourers' grievances. (fn. 219) The vibrancy of Filkins's working-class life is further reflected in the memoirs of Thomas Banting (1814–c. 1900) and George Swinford (1887–1997), who came respectively from a family of blacksmiths and small farmers and from a family of local masons. Both not only documented the social changes they saw around them, but took a profound interest in the history and archaeology of the area. Swinford knew Banting as a boy, and may have been inspired by his example to write about his life and about the village community. (fn. 220)

Long-established farming families such as the Purbricks remained prominent in local life. In the early 19th century James Purbrick's brothers William and Robert were successively tenants of Moat farm and other lands, (fn. 221) while William owned the cottages used as a workhouse, and served as overseer of the poor. (fn. 222) In the mid 19th century another family member was miller at Filkins Mill, (fn. 223) and Eliza Purbrick was mistress at Broadwell parish school. (fn. 224)

Local landowners, though aloof, contributed generously to their tenants' welfare. William Hervey of Bradwell Grove established a school and church in Filkins, (fn. 225) while his successor Squire Fox assigned land for allotments for the poor, and in 1899 set up a men's reading room. (fn. 226) The Smiths of Filkins Hall also contributed generously towards the new church (including the acquisition of Green Dragon House for use as a vicarage), while around 1918 Captain Campbell gave land for a cemetery. (fn. 227) F. C. Goodenough, a later owner of Filkins Hall, gave land for a war memorial in 1919, and his son William contributed towards a bus shelter, a new parsonage house (in 1950), and the laying of a new mains sewer (in 1953). (fn. 228) Amelia Carter (d. 1905), a local philanthropist born at Kencot, left funds for a village hall and reading room with space for 150 people, which was completed in 1914. (fn. 229)

Nevertheless there was an assumption that working people should keep to their place. In the 1840s local landowners combined to prevent the Chartist Feargus O'Connor from buying the Filkins Hall estate, apparently fearing the establishment of a smallholding colony along the lines of nearby Charterville, (fn. 230) while the mason George Swinford later recalled that in his youth (the 1890s) 'the upper classes did not discuss things with us'. (fn. 231) In the late 19th and early 20th century W. H. Fox of Bradwell Grove, a strong Conservative, habitually transported men in his employment to the polling station by horse and wagon, though on at least one occasion Swinford's father (as a Liberal) refused, apparently with impunity. (fn. 232) The arrival of a resident rector in the 1850s was claimed to have swiftly improved the villagers' 'morals and manners', and a policeman was expected to stamp out Sunday games and 'loitering' both by village youths and 'those of riper years'. (fn. 233) Earlier forms of social control included the village stocks, which stood on the village's northern edge near the site of the later Primitive Methodist chapel. (fn. 234)

Into this community came Sir Stafford Cripps (1889–1952), the Christian Socialist and Labour politician, who bought Goodfellows in 1920 and who, with his wife Isobel, put his socialism into action in the village. Cripps embarked on a series of major public works which he subsidized from his own resources, in particular donating building stone from quarries on his land. With the rural district council he built new council houses in 1929 to replace sub-standard cottages, and in 1931 provided a cottage to be used as a museum for local artefacts and exhibits; in 1932 he provided stone for a new primary school at Langford, and in 1935 improved the village water supply, as well as building the new Village Centre with its doctor's surgery and public baths. In 1936 an outdoor swimming pool, children's playground, and bowling green were added to the complex to foster health through recreation, and more council houses were built soon after. In George Swinford, Cripps found an extremely able foreman; Swinford, in turn, acted rather like a village head-man, entertaining visiting national and international politicians such as Clement Attlee, George Lansbury, Herbert Morrison, and Pandit Nehru at the cottage which Cripps had given him. (fn. 235)

Swinford's memoirs, while celebrating the collective endeavour and mutual support of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, also lament social change and the perceived decline of the traditional village community after the Second World War. Nevertheless, in the 1980s the memoirs' editors emphasized the continuing vibrancy of Filkins's communal life. The Womens' Institute, originally founded in 1919, lapsed from 1931 to 1947, but had around 30 members when it celebrated the jubilee of its revival in 1997; it continued to play an important role in village life, collecting data on Filkins and Broughton Poggs for the BBC's Domesday Survey in 1987, which was updated and published for the branch's jubilee ten years later. Other groups included a bowls club, a football club, a hand-bell ringers group, and an over-sixties club, while the village hall and other amenities created by Cripps and Swinford continued to host a variety of activities. Retired people formed the backbone of community life, while the church and Methodist chapel, the Five Alls (the one remaining pub), and another dozen or so clubs and societies created social opportunities for residents working outside the village. (fn. 236) The Filkins morris-dancing tradition was perpetuated by a side from Dartington (Devon), which in the 1980s reconstructed the Filkins steps and incorporated them into their Cotswold repertoire. (fn. 237)

21. The opening of the new Village Centre, 28 December 1935. Left to right: George Swinford, George Lansbury, Sir Stafford Cripps, and Joe Swinford (George's father).

Education

Classes taught by the vicar of Broadwell in the late 17th and early 18th century may have catered for some Filkins children, and a separate Sunday school was established in the village by 1802. (fn. 238) That or a successor continued in 1815, when its 60 pupils (30 boys and 30 girls) included some from the neighbouring parish of Broughton Poggs. In 1831 it was said to be well taught, using books provided by the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge. (fn. 239) Two small day schools in Broadwell parish in the early 19th century may have also been in Filkins, (fn. 240) and by 1835 another (opened in Filkins in 1832) had 30 boys and 20 girls, supported by subscriptions and children's pence. A second Filkins school taught 6 boys and 19 girls, all paid for by their parents. The Sunday school still taught 15 boys and 35 girls, while a Baptist Sunday school started in 1832 had 35 boys and 25 girls: in all, therefore, there was day provision for 75 children, and Sunday school instruction for over 100. (fn. 241) By 1854 there were also two dame schools for infants, one run by an Anglican and the other by a Primitive Methodist. (fn. 242)

In 1837 William Hervey of Bradwell Grove established a school at Filkins, by then the most populous village in the parish, and later added schools at Broadwell and Holwell. In 1855, when he conveyed the freehold to trustees, the school (Fig. 48) was said to be Church of England, although it was not yet in union with the National Society: it was probably officially affiliated by the 1860s, and certainly by the 1890s. In 1856 Hervey endowed the three schools with stock worth £1,100, producing £33 a year of which Filkins's share was £17. The school came under government inspection in 1857 and thenceforth received an annual grant, (fn. 243) although Hervey was still personally insuring the premises against fire in 1863. (fn. 244) In 1866, when the schoolroom was inadequately lit and ventilated, there were 109 children on the roll, (fn. 245) though the following year there was said to be space for only 79. Accommodation was increased to 90 by 1871, and to 106 by 1875–6; numbers varied, however, with an average attendance of only 56 in 1875–6. Total income that year was around £101, slightly less than expenditure. (fn. 246) By 1866 there was also a night school with 19 pupils, and evening classes were still being held in 1884. (fn. 247)

In 1885 Filkins school had 84 pupils, whose knowledge was said to be excellent despite many of them being poor and badly fed. In 1889 they received 'thoroughly good instruction', and the roll reached 100 in 1896. In 1902 a new window improved lighting in the schoolroom, and in 1911 wash basins were installed for the first time. In 1906 a difference of opinion with the vicar and interference by a school manager led to the schoolmaster's resignation after 15 years' service, and in 1908 he was succeeded by Frederick Dawson, who continued there until 1935. During Dawson's tenure the school became more outward looking: Filkins children took part in country dancing at Kelmscott from around 1914 and in cookery classes at Kencot in 1916, while its first scholarship to Witney grammar school was won also in 1914. In 1918 the school participated in a government scheme to pick blackberries for the war effort, sending off more than 470 lbs within a fortnight, and in 1920 a school library was opened, for use of which children paid 1d. a month to promote their sense of responsibility. Provision of board games during the dinner hour aroused an interest in chess. Pupils also benefited from the generosity of Mrs Goodenough, who provided half a pint of milk daily for each child from 1928 until 1936, when the government introduced school milk-provision. In 1928 five children were awarded scholarships to Witney grammar school, and in 1927 general elementary science was added to the curriculum. By 1932 there were 13 candidates for the scholarship examination. (fn. 248)

The same year Filkins school became a junior school with aided status, and the seniors were transferred to the newly opened Langford school. (fn. 249) The roll at Filkins remained around 38–49 throughout the 1940s and 1950s, and in 1958 the inspector judged it a vigorous and happy school, which had enjoyed the unusual advantage of 22 years' service from a dedicated headmistress and a long tradition of good students. (fn. 250) By 1962 the school had acquired controlled status and had a roll of 42, but in 1981 it was closed, children thereafter attending schools in neighbouring towns and villages. In 1985 several attended Langford primary school or Burford comprehensive, and in 1997 some were attending Alvescot primary school. The Filkins school buildings were occupied in 1987 by a private nursery school, which had moved there from Alvescot; (fn. 251) another private nursery continued there in 2008, when it had 32 children and a staff of six. (fn. 252)

Charities and Poor Relief

As in Broadwell, most charity in the 16th and 17th centuries came from donations to a poor box presumably in Broadwell church, (fn. 253) and from one-off doles of food or money left by wealthy yeomen or gentry for distribution around the time of their funeral. Thomas Woodward the elder, a gentleman of Nether Filkins, left ¼ bushel of barley to the poor in 1613, and in 1624 Simon Goodenough, yeoman, left 12d. each to eight named individuals in Filkins. (fn. 254) By the 18th century such gifts were supplemented by offertory money and by the ad hoc charity of gentry such as the Colstons of Filkins Hall; (fn. 255) the only endowed charity before the 20th century, however, was the poor's furze ground awarded at inclosure in 1776, half the income from which belonged to Filkins. By the 19th century the rent funded a coal charity. (fn. 256)

Otherwise, poor relief came entirely from parish rates. Filkins had an overseer by the 17th century, (fn. 257) who presumably (as later) raised a separate rate for the township. Like Broadwell's overseers those for Filkins were vigilant, refusing, for instance, to reimburse the overseers of St Peter le Bailey in Oxford for a militia substitute for a Filkins man in 1798. (fn. 258) Poor rates nevertheless rose sharply from the later 18th century. In the mid 1770s more than £58 was paid, but ten years later that had almost doubled to over £100 a year, (fn. 259) and in 1802–3 Filkins raised £655 at a rate of 9s. 5d. in the pound, compared with only £209 (at 3s.) in Broadwell. Of that, £208 was spent on outdoor relief and £417 on a newly-established workhouse (see below). Some 14 per cent of Filkins's inhabitants, 31 adults and 33 children, were then on permanent out relief, with another 8 per cent (39 people) in the workhouse, and 9 per cent (43 people) on occasional relief – in all, one third of the population. (fn. 260) In 1813 Filkins spent £565 on the poor, and in 1814 over £530, while in 1818–20 expenditure again reached over £500. Thereafter it fluctuated from around £350 to £450 until 1834. (fn. 261)

22. The door to the former village lock-up (foreground), with the Swinford Museum, opened in 1931, beyond.

Various innovations were tried to remedy the problems of poverty. In the early 19th century the overseers rented several properties including a pigeon house, presumably to raise income or (in the case of cottages) as accommodation for the poor. The workhouse was set up around 1802 in two rented cottages at the Cross Tree, and was administered by the overseers under the supervision of the vestry. Linen table-cloths were woven there, wool was spun and washed, and women took in laundry. The poor were also sent out to dig stones and mend roads, and roundsmen were mentioned periodically. (fn. 262) Occasional epidemics among the poor included typhoid, scarlet fever, and smallpox; (fn. 263) a pest house was established at an unknown date in fields west of Filkins village, a little way from the Eastleach road, but was pulled down probably in the early 20th century, and its stones reused for farm buildings. (fn. 264) A surviving village lock-up near Rouses Lane, where the constable confined the drunk and disorderly, is said to have remained in use until around 1840. (fn. 265)

After 1834 responsibility for poor relief passed to the new Witney poor-law union, with its own union workhouse. (fn. 266) Conditions in Filkins's workhouse were locally believed to have influenced the introduction of the New Poor Law, after Lord Brougham (d. 1868), then Lord Chancellor, paid a visit c. 1831–2 while staying with William Vizard at Filkins Hall, and found a man dying there in basic conditions. (fn. 267) Later initiatives included friendly societies such as the Red, White and Blue Club, which paid benefits and funeral expenses to its members and remained active throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. (fn. 268) A nursing association provided nurses for subscribers and their families, and offered differential rates for labourers (who paid 2s.), small farmers and tradespeople (4s.), and others (no fixed amount). Its committee was composed entirely of women, and like the Red, White and Blue Club it drew members from several local villages. (fn. 269) Allotments were available by 1910, rented from Captain Campbell (the owner of Filkins Hall) by Filkins parish council. (fn. 270)

The Kencot-born philanthropist Amelia Carter (d. 1905) left a coal charity for Filkins, together with funds to establish a village institute and reading room and £15 a year towards its upkeep. The Institute was built in 1914, and by 1967 the repair fund provided income of £250 a year, with another £16 for the coal charity. By 1921 the Carter charity was overseen by Filkins vestry, and in 1947 the trustees of the coal charity and of the poor's allotment agreed to distribute their funds as one, some 50 or 60 people receiving 10s. 6d. each. By 1972 around 25 people each received £2, and in 1976 a scheme was sealed to amalgamate those charities with one at Broughton Poggs. (fn. 271) In the early 21st century the combined charity distributed around £250–£350 a year. (fn. 272)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

From the Middle Ages until 1855 Filkins was served from Broadwell church, though by the mid 17th century and possibly earlier many inhabitants attended the much nearer church at Broughton Poggs. After a church was built at Filkins in 1855–7 a new parish of Broughton-cum-Filkins was created, and Filkins finally became an independent parish in 1864, served by a perpetual curate or vicar. The church's inadequate endowment sometimes made it difficult to find an incumbent, and Filkins's clergy grappled unsuccessfully with strong competition from Nonconformists, in particular the Baptists and Primitive Methodists who became established in the village from (respectively) the late 18th and early 19th century. Adoption of High Church worship in the church during the late 19th century increased attendance, but led to even greater religious polarization. As elsewhere, adherence to organized religion declined during the 20th century despite the involvement of leading inhabitants such as Sir Stafford Cripps, who actively supported both church and chapel. The Baptist (later Congre-gationalist) chapel closed before 1929, but both the parish church and the Methodist chapel remained active in the early 21st century.

Parochial Organization

A church at Filkins was under consideration by 1852, (fn. 273) and work began in 1855 on land given by William Hervey of Bradwell Grove. The building was consecrated in 1857. (fn. 274) Filkins ecclesiastical district was separated from Broadwell in 1855, and united with Broughton Poggs to form the new ecclesiastical parish of Broughton-cum-Filkins, with Filkins church as the parish church. The church had burial and baptismal rights from its foundation, and the benefice (like that of Broughton Poggs before it) was a rectory. (fn. 275)

In 1864 Filkins was separated from Broughton Poggs, and became an independent parish and perpetual curacy. (fn. 276) By the 1870s the incumbent was usually styled vicar. (fn. 277) The living was never adequately endowed, and in 1942, under an Order in Council of 1921, the two benefices were reunited. (fn. 278) In 1980 both were merged with that of Broadwell, Kencot, and Kelmscott, the vicar of the new united benefice residing at Filkins. (fn. 279) The benefices of Langford and Little Faringdon were added in 1984, (fn. 280) and from 1995 the united benefice formed part of the even larger ministry of Shill Valley and Broadshire. (fn. 281)

23. Filkins vicarage house (Green Dragon House) in the mid 20th century. The building was acquired at the creation of Filkins parish in 1864, having earlier been a private residence and possibly an inn (the Green Dragon).

Advowson and Endowment

The advowson of the new parish of Broughton-cum-Filkins was acquired in 1855 by T. W. Goodlake, who resigned as vicar of Broadwell to become rector of the new parish. He appears to have sold it around the time that he resigned Filkins in 1861, (fn. 282) and from 1864 to 1942 the patronage belonged to successive bishops of Oxford. (fn. 283) From then until 1980 the bishop presented alternately with the Goodenough family (as patrons of Broughton Poggs), and the bishop remained a copatron of the united benefice until 1995. (fn. 284)

The new parish was endowed in 1855 with Broughton Poggs rectory estate and with £30 a year from Broadwell vicarage, including land in Lechlade (Glos.) bought in 1722 to augment Broadwell's living. Trinity College, Oxford, gave £50 before 1858, which was invested in 3 per cent bank annuities. (fn. 285) When the parish was divided in 1864 Broughton Poggs retained part of the glebe, leaving Filkins with only 6 acres; (fn. 286) the living was then worth only £29 a year, but was augmented by a £100 grant from the Diocesan Society. (fn. 287) By 1866 fundraising and other grants had increased the income to over £63 a year, of which £22 10s. came from land rents, £32 from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, and £1 8s. from Queen Anne's Bounty. Another £2 12s. came from house rents, apparently in London. Between 1868 and 1885 the Ecclesiastical Commissioners further augmented the living to match private donations, parish fundraising, and grants from the Oxford Poor Benefice Association, (fn. 288) and by 1899 the living was worth over £185 gross, including £12 from glebe, £100 from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, and £72 from Queen Anne's Bounty. (fn. 289) The Commissioners made temporary grants in 1920 and 1924, pending the union with Broughton Poggs. (fn. 290) The houses in London were sold in 1952. (fn. 291)

Vicarage House