A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Henley: Local Government', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp104-119 [accessed 23 February 2025].

'Henley: Local Government', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online, accessed February 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp104-119.

"Henley: Local Government". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online. Web. 23 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp104-119.

In this section

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

During the Middle Ages Henley was effectively a seignorial borough, though this was an informal arrangement: the town's lords granted no liberties by charter, nor did they provide a portmoot. Nonetheless, by the late 13th century Henley's merchant guild exercised wide authority within the urban area, and by the late 14th century its steward or warden was recognised as warden of the town. Guild members were by then called burgesses.

A royal charter was obtained in 1568, when the guild was reconstituted as a closed corporation. That in turn was modified and given additional powers by a replacement charter in 1722, when, amongst other changes, the title 'warden' was replaced by 'mayor'. Henley was exempted from the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835, and the corporation continued unaffected; in 1864, however, the town adopted a local board, which from 1872 was also the urban sanitary authority. Town government was finally reformed under a royal charter obtained in 1883, which recognised Henley as a municipal borough governed by a town council. The arrangement continued until local government reorganization in 1974, when the town council lost many of its powers but retained its ancient dignities and the office of mayor.

Medieval manorial jurisdiction was complex, reflecting the parish's division among the lordships of Henley (which included the town and Henley park), Benson or Bensington, and Badgemore (which in the later Middle Ages comprised a tithing of Rotherfield Greys manor). Both the Henley manor court and court leet retained some importance into the 19th century, though by then their residual powers were waning. The separate estate of Fillets or Phyllis Court (created in 1340) was usually called a manor, and in 1638 was sold with its courts leet, view of frankpledge, and other manorial rights. (fn. 1) No courts are known to have been held, however.

Vestry government is poorly recorded before the 1720s, when it was concerned primarily with poor relief. Exceptionally, the office of churchwarden was combined from the Middle Ages with that of bridgeman, and remained under guild (and later corporation) control until 1858. A select vestry existed from 1821 to 1835.

Manor Courts and Seignorial Jurisdiction

Henley Courts to 1590

Henley manor was created before 1199, although until 1300 it continued to be held with Benson. (fn. 2) A court is recorded from the late 13th century, (fn. 3) which according to the only surviving 14th-century court roll (1332–3) was a conventional three-weekly court meeting on Tuesdays (and later on Mondays). An annual view of frankpledge was held after a court session in late April, probably because that was the nearest one to hocktide. (fn. 4) During the late 13th and early 14th centuries the court dealt with five broad areas: offences against the court's authority (including contempt, officers' failure to undertake their duties, and false hue and cry); violence and disruption (including bloodshed); inter-personal actions (including debts under 40s. and detention of property or chattels); property transfers; and offences against the assizes of bread and ale. (fn. 5) Debt cases were particularly numerous, accounting for 11 out of 34 items of business in the first session of 1332–3. Over the year, the court produced £4 12s. 9d. in perquisites. At the view of frankpledge in 1333, a jury of 12 men was appointed and cert money of 6s. 8d. was paid. The view also dealt with offences in which physical nuisances were prominent: failure to present brewers and sellers of unsealed ale, making a purpresture or encroachment, obstructing windows, blocking the brook, and raising a hedge. (fn. 6) In 1337 John de Moleyns was granted additional powers in his estates, including return of writs, infangthief, and outfangthief (i.e. jurisdiction over thiefs). (fn. 7) How far he exploited them in Henley is unknown, and receipts in the later 14th century suggest that the court's vigour and authority was diminishing. Annual perquisites in 1381 were only 26s. 8d., and 1384–5 only 13s. 8d. (fn. 8)

A more detailed picture is provided by the court roll of 1419–20, the first of 13 surviving rolls from the 15th century. (fn. 9) As in the 1350s court sessions were on Mondays, with view of frankpledge held that year on 13 May. The court's business was narrower than earlier, with no instances of hue and cry or contempt, and only one case involving violence. In all there were 120 items of business, about a third of the volume in 1332–3, and fines and perquisites produced £2 8s. 3d. At the view the manor's lessee, William Wyot, was ordered to provide a pillory, scolding stool ('schelayngstal') and gallows, suggesting that these instruments of the court's authority had fallen into abeyance. Other business included nuisance cases (e.g. timber in the roadway and a leaking cesspit), debt cases, and deficient bread. In the mid 15th century the amount of business declined, reaching a low point of 51 items in 1455–6. (fn. 10) Probably this reflected economic conditions, as the court had revived by 1499–1500: in that year it handled some 240 items, with debt cases accounting for around 40 per cent. Other prominent matters included essoins (arranged absences), transgressions, and infringements of the assizes of bread and ale. (fn. 11)

The range of business in 1545 (when the first court session dealt with 27 items) remained much the same, although debt cases were more prominent at 59 per cent. From 1547, however, business fell dramatically and remained at a much lower level, consisting chiefly of debt cases and property transfers. Only 4 items were dealt with at a session in September 1547, and only 6 debt cases at one in April 1564. Similarly limited business was conducted at the annual view. On 21 June 1546 the names of the bailiffs, constables, ale tasters, victual tasters, and a park-keeper were listed, and the jury was sworn; the bailiffs, constables and park-keeper reported that all was well, and the tasters were fined for not making prosecutions. By 1564 the view had been moved to October, possibly because this was closer to the burgesses' election day. (fn. 12)

Henley Courts from 1590

For most of the period from 1590 to 1786 the court and view of frankpledge were leased to the town corporation with Henley manor, (fn. 13) although appointment of the manor's steward was reserved to the lord. (fn. 14) Both court and view were apparently suspended during the Civil War and Interregnum, as no sessions are recorded between September 1642 and December 1660. Thereafter, three-weekly sessions continued until 1738, often without business: presumably the establishment of a court of record by the corporation under its 1722 charter drew some of the manor court's business away. After 1738 there were only occasional sessions, mainly to levy or recognize fines for property transfers. The last recorded was in 1808. (fn. 15)

The annual view of frankpledge (or court leet) was held probably throughout the 16th–19th centuries, although records survive for only limited periods. (fn. 16) In the late 1660s it was being used to extract small fines from numerous inhabitants: on 26 October 1666, for example, 76 people were fined for not appearing, and another 150 fines were levied, mostly for encroachments such as posts, gutters, porches, pales, and waterside revetting (campshields). A few people were fined for nuisances, including placing stinking fish in the street to annoy neighbours. (fn. 17) Whether this high volume of activity was typical is unclear, although the corporation clearly valued such fines as a source of income, (fn. 18) and in the 18th century sometimes imposed fines for encroachments at routine corporation meetings rather than in the court or view. (fn. 19)

After Strickland Freeman took back control of the manor in 1786 the court leet was held frequently until 1836, with most meetings between October and December. (fn. 20) The session in October 1786 (held in the Red Lion) appointed a foreman and jury, two chief and two petty constables, and two sealers of leather (although no bailiffs), and fines were imposed for nonattendance and for infringing the waste. In addition, the court asserted the jury's right to inspect weights and measures, which thereafter became one of the court's chief functions. By 1796 the lord had evidently acquired a set of specimen weights and measures, against which inhabitants could (for a fee) check their own equipment. Publicans and other traders were periodically fined and measures destroyed, while in 1826 the court appointed a searcher of weights and measures to undertake examinations, in place of the jury and constables. A related concern was underweight butter sold by farmers and others. In 1816 the court advised the jury to attend the market with the lord's weights, and to seize deficient butter and distribute it to the poor; the matter was raised again in 1820 and 1822.

A further concern was encroachment on the manorial waste, especially the depositing of items on the new embankment adjoining the bridge. (fn. 21) From 1813 it was reported that bargemasters were leaving timber, hurdles and other materials on the embankment and driving in stakes and hooks. In 1822 the court authorized the jury to fine offenders 1s. 6d. per load per week, and the chief constable undertook to give a list of offenders to the jury's foreman each quarter. But it was difficult to assert the court's authority, and in 1826 a prohibition against depositing articles was proving hard to enforce.

The court session in May 1836 elected officers and dealt mainly with encroachments such as windows, posts and railings. Thereafter the court leet was convened only in 1868 and 1881, when it listed quitrents and similar assets, and perambulated the manor.

Relationship with Guild and Corporation

Though technically independent, Henley's manor court and view of frankpledge had close relations with the guild and corporation, and often shared the same officers. Two bailiffs admitted in the manor court in October 1419 were burgesses who had already been elected as bailiffs by the burgess body in September. (fn. 22) The practice may have been established by the late 13th century, (fn. 23) and probably continued into the early 19th. (fn. 24) The two chief constables involved in the view of frankpledge in 1667 and 1670 were similarly corporation appointees, (fn. 25) perhaps reflecting medieval practice. The court stewards in 1352 and 1366 were also leading townsmen (respectively Richard and Thomas Jory, probably brothers), (fn. 26) although that may have been exceptional, since appointment of stewards was generally reserved to the lord even when the manor was leased. From 1545 free suitors, usually including the warden and bridgemen, were recorded at each court session, although it is unclear whether the change in record represented a change in practice. (fn. 27) The arrangement continued until at least the 1660s, although by 1689 the warden and bridgemen no longer appeared among the suitors. (fn. 28)

Townsmen were technically free tenants of the manor, to which they owed quitrent. By the early 14th century property was freely bought and sold in perpetuity. (fn. 29) Nonetheless quitrents were still demanded in the 1880s, (fn. 30) and were rigorously investigated by a court of survey in 1785, in preparation for Strickland Freeman's resumption of direct manorial control. (fn. 31)

Other Manor Courts

Manor courts may have been held for Badgemore between the mid 11th century and 1208, when much of the estate was acquired by members of the Grey family. (fn. 32) In 1279 the Greys had view of frankpledge there, and in the mid 15th century Badgemore comprised a tithing of Rotherfield Greys manor. (fn. 33) Around 1721 the lady of Rotherfield Greys claimed that her tenants in Henley parish (not necessarily in Badgemore) still owed service to her courts leet and baron. (fn. 34)

Bensington manor court retained jurisdiction over Northfield End and manorial waste along the Fair Mile, both of which remained part of Bensington manor. (fn. 35) A tenant of 20 a. at Northfield owed suit to the Bensington court in the early 15th century, (fn. 36) and in the late 18th the lord still levied quitrents there; (fn. 37) in the 1660s Northfield End was separately taxed, (fn. 38) and in the 18th and 19th centuries it was commonly called a 'liberty'. (fn. 39) A constable for Northfield End was still appointed at the Bensington court leet in the mid 19th century, although by then inhabitants were apparently no longer required to attend or do service. (fn. 40) In 1536 'Northfield' tenants also attended the court of the honor of Wallingford, of which Bensington manor was held. (fn. 41)

Town Government

The Guild to 1568

Origins and early organization

By the later 13th century the guild had established an extensive role within Henley, including responsibility for the bridge and church. The guild existed by 1269–70, when it made an annual payment to the lord of 5d. per member; described then as a gilda mercatorum (guild of merchants or traders), (fn. 42) it presumably originated at or soon after the town's foundation as a body of privileged traders. Its responsibility for the bridge may date from the bridge's construction in the late 12th century, although in 1225 custody was granted in Henry III's name to Jordan the Forester, implying royal control. (fn. 43) The guild's responsibility for the church was most likely established in the early-to-mid 13th century, when responsibility for church naves was generally transferred to local communities. (fn. 44) Both responsibilities were reinforced by grants of town rents and property in support of the bridge and church during the late 13th and early 14th centuries. (fn. 45)

In 1296–7 the guild comprised 46 members, probably less than a fifth of the town's adult male population. (fn. 46) According to a fragmentary record of 1296, admission required payment of 1s. or 2s. There were then at least five senior officers: a seneschal or steward (senescallus), two bailiffs (ballivi), and two procurators of the church and bridge (procuratores ecclesie et pontis). The guild also appointed a butler and two candle-bearers, and a common cook was mentioned, suggesting that the guild's coherence was maintained partly through feasting; none of those lesser posts were recorded later, however. The steward and 14 other guildsmen were designated as aldermen, a distinction which also seems to have lapsed soon after. (fn. 47) By 1308 the steward was known as 'warden' (custos), (fn. 48) and from the 1380s he was explicitly described as warden of the town rather than of the guild. (fn. 49) The procurators were sometimes known as 'bridgemen' (pontinarii) by 1337, though their earlier designation continued into the 15th century. (fn. 50)

By 1296 the guild was already regulating the town's wider population. The guild record of that year shows the town divided into five wards (corresponding probably to the main streets), each with two head men. The document itself lists pledgors and 101 pledgees, of whom some were described as servants and pledgors' sons, while others were possibly apprentices and lodgers; presumably the guild was monitoring their residence in the town and ensuring their good behaviour. Night watchmen were also mentioned, their work possibly also organized by ward. In addition the guild held a court on behalf of the so-called 'community of the vill', in which men were fined for transgressions. (fn. 51)

From 1395 the guild's surviving assembly books (records of burgesses' meetings) provide more detail. Members now called themselves burgesses: (fn. 52) in 1381 there were probably around 35 of them, and in the later 15th and earlier 16th century about 30. (fn. 53) Admission normally entailed payment of a fine of 6s. 8d., with lower rates of 1s. 4d. and 2s. 8d. for first and second sons respectively. New burgesses took an oath. (fn. 54) The burgesses met each year to elect the warden, bailiffs and bridgemen, usually on the Friday before Holy Rood Day (14 September). (fn. 55) They also elected two constables, and had possibly done so since the 13th century. (fn. 56)

Officeholders and officers' functions

Although the senior offices were probably ranked in the ascending order of constable, bailiff and bridgeman, and warden, there seems to have been no formal sequence of office-holding. (fn. 57) Nonetheless, each post had a characteristic pattern of tenure which sometimes varied over time. From the early 14th century until 1522 leading townsmen frequently served as steward or warden for several years, though not always consecutively. Robert of Shiplake, Henley's wealthiest taxpayer in 1327, was warden for at least four years between 1306 and 1330, and William Woodhall, a trader with London, for at least two years in the 1350s. (fn. 58) Similarly Thomas Clobber, involved in cloth trading and other substantial business, was warden for a total of 17 years in the late 14th and 15th centuries, (fn. 59) and John Elmes the elder, the wealthy merchant and wool trader, for 16 years in the 1420s–50s. (fn. 60) Wardens between 1496 and 1522 served up to seven years, but thereafter until 1540 only Richard Brockham served more than four, and (Brockham excepted) they were not exceptionally wealthy. (fn. 61) John Arden, warden 1524–5, was the tenth richest person in Henley in 1524, with goods valued at £30. (fn. 62)

Bailiffs in the 15th century commonly served for two consecutive years and sometimes longer, though only four men from 1420 to 1490 served for more than four years. (fn. 63) The post of constable was always held for two consecutive years, which meant that a larger proportion of burgesses held this post than any other: of the 29 burgesses listed in 1492, 14 served as constable. The post of bridgeman was often held for two or three consecutive years in the 15th century, and sometimes for up to five years. Robert Brewster or Cooper, exceptionally, served for a total of 14 years in the 1450s–70s. (fn. 64)

Much of the guild's authority was exercised through its officers. (fn. 65) The warden was the informal head of Henley society, and alongside organizing the burgesses' affairs probably had an informal judicial role within the town. (fn. 66) The bridgemen's main role was presumably to administer the 'bridge rents' and other property vested in them, and to organize maintenance of the bridge and parish church, although some of the latter work was occasionally delegated to other officers. (fn. 67) The bailiffs' work was chiefly concerned with administering the lord's manor court and his rights in the town, but also provided a means whereby the burgesses influenced the operation of the lord's authority. Probably they collected the lord's quitrents, organized the court jury, summoned defendants, and seized goods as distraints or attachments. In 1433–4, for instance, the bailiffs were ordered to make 12 summonses, 57 distraints and 12 attachments, and seized goods including brass pots, dishes, hides, cloth, wine and wax. (fn. 68) Peacekeeping fell to the constables, who in the early 16th century were among the officers present at manucaptions, when townsmen stood surety for their servants' or apprentices' good behaviour. (fn. 69) In the 1530s they also dealt with curfew- and hedge-breakers. (fn. 70)

Lesser officers were appointed as vacancies occurred. A common clerk to assist the officers and burgesses was paid ½ mark a year, and may sometimes have been a minor cleric. (fn. 71) From 1487 Thomas Wagge was required to write documents for the church and bridge estate, and to attend the warden's court. The guild also elected a sub-bailiff to supervise night-time vigils (perhaps the watching of wards), and to ring the bell for the start of the market; in the late 15th century he was paid a mark a year. There was also a bellman, presumably a town crier. (fn. 72) The guild's management of trade was assisted by porters, of whom 2 to 5 were elected in most decades. Until 1444 and possibly later all were burgesses or became burgesses, though from 1473 that generally ceased to be the case. (fn. 73) From at least 1441 the guild also elected usually 2–4 tasters of victuals, although recorded elections are intermittent. (fn. 74)

Temporary posts were created as needed. Church procurators, distinct from the bridgemen, were mentioned sporadically from 1402 to 1428, probably overseeing building work and helping to sustain a richer church ritual. (fn. 75) During the 1430s–40s the burgesses elected wardens of church goods with responsibility for fabric, vestments, and books, (fn. 76) and from the mid 1440s to 1460s men were elected to assist with works on the tower and bells. (fn. 77) In 1494 Thomas Wagge was elected as custodian of the vestry and church ornaments. (fn. 78) Procurators or wardens for the town cross were similarly elected ad hoc in 1433 and 1474, presumably to help deal with significant repairs, (fn. 79) while elections of pig-catchers were recorded in 1453 and 1474, when ordinances were made about free-running pigs. (fn. 80) In the late 14th century and again in the late 15th and early 16th, the burgesses elected 'taxors' for the clerk of the market, possibly to assist the king's clerk of the market or his deputy when he was exercising authority within or near Henley. (fn. 81)

Congregations and councils

Much of the guild's business was conducted at meetings of the guildsmen or burgesses, called (in English) congregations or halls. (fn. 82) Apart from the annual congregation to elect officers, these were occasional and irregular events: between 1395 and 1490 the average number recorded per year (starting with election meetings) was only 2.8, (fn. 83) and in 1482 there is a clear instance of a three-month gap. (fn. 84) Meetings took place on all days except Sunday, with Friday the most popular. (fn. 85) Probably they were called on the warden's initiative, (fn. 86) and burgesses were fined for non-attendance. (fn. 87) The average number of meetings per year rose to 4.7 in the 1490s and to 5.8 in the 1500s, before falling back to 4.2 in the 1510s. Likely causes include increased property grants by the burgesses, demands from the State (especially for military service), and social tensions in the town. (fn. 88)

Election of separate councils was recorded occasionally in the 15th century, though their role and durability are unclear. Twelve men were elected to a warden's council in 1427, but there is no further record of this body: (fn. 89) possibly their election was a short-lived initiative by John Elmes the elder after his first election to the wardenship. In 1464 the guildsmen elected a warden's council of 11 men and a common council of 12 men. (fn. 90) A warden's council was elected again in 1468, and two councils in 1472 and 1493. (fn. 91)

Regulation of the town

The warden and burgesses occasionally issued ordinances regulating behaviour by the town's inhabitants: in 1432, for instance, no one was to leave dung, timber or fuel in the High Street for more than 8 days, on pain of a 40d. fine and confiscation of the materials. (fn. 92) Such infringements were evidently prosecuted by the guild rather than the manor court, since the fines imposed were usually much larger, and were deposited in the burgesses' 'common box'. As there is no evidence for a portmoot, it has been argued from incidental references in the assembly books that there was probably a warden's court which met on an ad hoc basis. (fn. 93) The only record of such an assembly is in 1438, however, when bakers and hostel-keepers made agreements in the presence of the warden and some burgesses. (fn. 94)

The assembly books as a whole show the warden and burgesses dealing with law and order, gaming and keeping of the sabbath, public sanitation, and trading. Burgesses acted as arbitrators, (fn. 95) bound men over to keep the peace, and required townsmen to guarantee good behaviour by their servants or sons, (fn. 96) while an ordinance of 1477 suggests that they sometimes dealt with violent assaults, although some such offenders were prosecuted in the manor court. (fn. 97) Dice- and hazard-players were fined in 1422, and an ordinance of 1451 laid down fines for anyone playing ball or dice during church services on festival and feast days. (fn. 98) Bylaws promoting public health included restrictions on butchering, and ordinances against filth or obstructions in the streets, and loose pigs. (fn. 99) Ordinances regulating the cost of horse loaves were issued in 1438 and 1474, (fn. 100) and in the late 15th and early 16th century, as grain exporting to London revived, the warden and burgesses reasserted their regulation of grain trading. (fn. 101)

1568–1722: Closed Corporation

The new corporation

A proposed confirmation of liberties by Henry VIII in 1525–6 would have considerably extended the town's autonomy, creating an office of mayor, making the mayor and bailiffs JPs for the town, and granting a town coroner and clerk of the market exclusive jurisdiction within the liberty. (fn. 102) For reasons unknown it appears never to have been implemented, (fn. 103) and the established system continued until 1568, when Henley's inhabitants acquired a charter of incorporation from Elizabeth I which formally reconstituted the guild. (fn. 104) This was common in mid 16th-century towns, (fn. 105) but what prompted the action in Henley is unclear. One motive may have been to safeguard the endowment for the bridge and parish church, and to obtain the authority to supplement it at a time of inflation. The chief innovation, however, was to create a permanent, formal hierarchy of burgesses; otherwise the charter mainly gave legal recognition to existing structures and powers, intruding little on jurisdictions such as the manor.

The charter (in Latin) incorporated the 'inhabitants' under the title of the 'warden, bridgemen, burgesses and community [or commonalty]'. Twelve 'better inhabitants' were to be 'chief burgesses and councillors', and to assist the warden and bridgemen. Together they were to elect two bridgemen each year on the Friday before St Matthew (21 September), and on the same day the corporation was to elect a chief burgess as warden. The bridgemen and warden-elect were to be sworn into office the following Friday. When a chief burgess died, the other chief burgesses and commonalty were to elect a replacement. The Church feast to which the election day related was different from that of the medieval guild (Holy Rood day), and was presumably a Protestant alteration.

The corporate body was empowered to hold property, and could plead in court or be impleaded. The charter confirmed the properties given for maintenance of the bridge and almshouses, and licensed the acquisition of lands to a yearly value of 100 marks. The warden, bridgemen and burgesses were authorized to make ordinances for the government of the corporation and of all inhabitants, which could be enforced with fines and imprisonment; the warden was also to be keeper of the town gaol and justice of the peace for the town, with power to inquire into felonies and transgressions. Additionally he was clerk of the market, except during visits by the queen, when he would exercise authority alongside the clerk of the queen's household. The corporation's first warden, bridgemen and chief burgesses were named in the charter.

From 1568 the burgess body comprised the 12 specified chief burgesses (usually called 'capital burgesses'), along with some 24 'secondary burgesses'. (fn. 106) New secondary burgesses were elected as vacancies occurred and, unlike the earlier guildsmen, apparently paid no admission fine. (fn. 107) At the first recorded annual election in 1586 (following a gap in the record), a warden and two bridgemen were elected in accordance with the charter, along with two bailiffs, two constables, and two tithingmen or petty constables; the same set of posts were usually filled annually until the charter was replaced in 1722. Two surveyors of highways were appointed until c. 1647. (fn. 108)

The warden was elected from three nominees, who in 1586 were respectively proposed by the outgoing warden, the other capital burgesses, and the secondary burgesses. (fn. 109) The arrangements were changed in 1587 and again in 1588, when the nominees were to be the oldest capital burgess who had already served longest as warden, the oldest capital burgess who had not yet served, and a nominee of the outgoing warden. (fn. 110) Procedures for election and admission days were laid down in 1586. On election day the burgesses were to attend the outgoing warden at his house, accompany him to divine service, and go to the town hall to make the election; afterwards the new and outgoing warden and the burgesses repaired to the outgoing warden's house for dinner. On the following Friday the burgesses were to process from the outgoing warden's house to the new warden's house and on to divine service, before visiting the town hall for the admission, and returning to the new warden's house. Capital burgesses were to wear robes, and secondary burgesses a gown or cloak. (fn. 111) The warden's equipment was transferred to the new warden usually a week after admission, most items relating to his roles as JP and clerk of the market. An inventory in 1610 included statute books, corporation ordinances, and an order book regarding victuals, along with weights and measures and keys; (fn. 112) a later one (1660) included Dalton's Justice of the Peace, ordinances regarding the sabbath, swearing, blasphemy and adultery, and a black lantern. (fn. 113) In 1641 the warden was to provide food at his house on Thursday evenings for the town lecturer. (fn. 114)

Between the late 16th and early 18th century corporation meetings, still called 'congregations', were held more frequently than the burgesses' meetings of the late Middle Ages, though they remained irregular. The year following the 1586 elections saw 14 meetings, whereas in 1620–1 and 1640–1 there were 7 and 4, and in 1660–1 and 1680–1 there were 11 and 13. Most were on Fridays. (fn. 115) Burgesses were summoned, a bell was rung at 9 a.m., and the burgesses were required to wear gown or cloak according to status. (fn. 116)

The pattern of office-holding in the late 16th and early 17th century remained similar to that in the late medieval period. Numerous burgesses became constable, though not all progressed to more senior positions: thus of 17 constables between 1590 and 1600, only 8 became bailiff or bridgeman (or both), while only 2 became warden. Offices were generally held for short periods, that of constable for one year, and those of bailiff and bridgeman for one or two; wardens served usually for one year. A notable exception was Augustine Springall, who between 1592 and 1622 was constable for 3 years, bailiff for 2, bridgeman for 5, and warden for 2. (fn. 117)

From 1623 (perhaps following difficulty in finding bailiffs) (fn. 118) new arrangements were introduced, creating a narrower body of senior office-holders. Thenceforth most constables served as bailiff the following year, and around half the bailiffs became bridgeman, usually after three to five years. Most bridgemen served for 2 years, and a few eventually became warden. (fn. 119) Additional constables were appointed during the 1640s, presumably reflecting Civil War disruption, (fn. 120) and unusual circumstances following the 1688 revolution may similarly explain the exceptional wardenships of Adam Springall (1690–5) and Thomas Springall (1697–9), neither of whom had previously held town office. (fn. 121)

Ordinances and governance

Much of the corporation's recorded business was long-established routine: the annual election and admission of officers, election of burgesses, checking of officers' accounts, supervision of bridge maintenance and repairs, and granting of leases of corporation property. Other activities and interventions seem to be only sporadically recorded.

No corporation minutes survive for the period 1568–84, but in 1585–6 the corporation made several ordinances promoting economic, social and religious regulation, of which some were probably restatements. Inhabitants were forbidden to make malt for outsiders or 'foreigners', and were to have priority over outsiders in the placing of craftwork; alehouse keepers and other victuallers were to be licensed; and restrictions were laid down for the preparation of meat in Lent, and travel to London on Sundays. (fn. 122) A few more ordinances were made in subsequent years, (fn. 123) and in 1592 the corporation issued a set of 'ordinances and constitutions' applying to everyone in the town, authorized by the justices of assize. (fn. 124) A shorter set concerned with grain was made probably in 1608 in response to a poor harvest, while a more comprehensive set in 1625 supplemented the 1592 ordinances. (fn. 125) All ordinances (together with other orders) were to be read out in the 'common hall' once every three months, notice having been given in church on the previous Sunday. No further set of ordinances appears to have been issued under the 1568 charter, and as late as 1676 it was ordered that the 1592 and 1625 ordinances should be read out to the corporation and other inhabitants. (fn. 126)

On the whole the later ordinances reflected familiar concerns, whilst also responding to current pressures. Those of 1592 restated basic regulations for maintaining order, and confirmed the fines payable for refusing election as a burgess or officer. The ban on malting for strangers was restated, and inhabitants were ordered to pay customary trading tolls and taxes, and to accept any provision of work. Apprentices were to serve at least 7 years, and indentures were to be enrolled with the town clerk, while lodgers of less than 3 years' residence were to be expelled, and new lodgers had to be licensed. The 1625 ordinances were apparently also aimed at current social and economic problems. Practices which allegedly increased grain prices were banned, and tradesmen (with some exceptions) were required to be 'free' of the town. Outsiders who were potentially chargeable to the poor rate were not to be accommodated without licence. Ordinances also ordered that the doors of inns, taverns and similar establishments should be kept closed during divine service, and that carts should not be turned in the street and damage road surfaces. (fn. 127)

Wards, health, and poor

In 1585 the town was divided into 12 wards, each with two supervisors who were to search it every quarter for 'lewd and evil disposed people', and report to the warden. (fn. 128) How vigorously the system was operated is unknown, but probably it was maintained, since in October 1660 it was confirmed with three supervisors per ward. (fn. 129) Presumably that represented a reassertion of the corporation's authority following the monarchy's Restoration. Schedules of wards and wardmen were recorded again in 1665 and 1671, but not thereafter. (fn. 130)

Corporation ordinances continued to deal with nuisances such as the deposit of timber and dung in the street, (fn. 131) while others dealt with fire prevention. (fn. 132) In addition, the corporation attempted to meet public health emergencies. In 1641 it appointed a watchman to attend on infected persons, (fn. 133) and in 1665 forbad inhabitants from receiving people coming by coach from plague-infected London, Westminster or adjacent areas without the warden's licence. Offenders were to be confined to their house for 30 days, and the receiving of goods brought by barge was also banned. A few weeks later the corporation ordered the house of John Hathaway (later recorded as a coach operator) to be shut up. (fn. 134)

The corporation's administration of poor relief and town charities is discussed below. (fn. 135) Until the 1640s it annually elected between two and four collectors or overseers, although responsibility may have passed thereafter to the vestry, since no further elections were noted in the corporation minute books. (fn. 136) Additional officers were sometimes appointed to administer particular charities, in particular the almshouses and, in the earlier 17th century, 'stock' provided to set the poor to work. (fn. 137) In the later 16th and early 17th century the corporation also discouraged immigration into Henley, partly in response to pressure from inhabitants. (fn. 138)

Trade regulation

Ordinances apart, corporation minutes from 1585 to 1722 contain relatively little evidence for involvement in commercial matters. Custom and the ordinances themselves must have provided basic regulation, and the warden probably handled business separately as clerk of the market. Much routine business was possibly not recorded: licensed alehouse keepers and victuallers were listed in the 1580s–90s, for instance (with their sureties), but not usually thereafter. (fn. 139) The minutes more frequently record men who were given freedom to trade in the town, sometimes just in the market. Some were outsiders, and varying fines were charged: a Wargrave glover, for example, paid 10s. (plus 4s. to the poor) for freedom on market day in 1587, while in 1709 Adam Betty paid £3 for freedom as a milliner and linen draper. (fn. 140) The admissions probably represent the granting of licenses either under an ordinance of 1586, which required outsiders to be licensed to show wares in the market, or under one of the 1592 ordinances by which a license was required to engage in a different trade. (fn. 141)

Town Government 1722–1883

The Corporation 1722–1835

Plans to extend the corporation's powers through a new royal charter were under discussion by 1714, and a petition to the Crown was submitted in 1720. (fn. 142) The new charter came into force in October 1722. The reconstituted corporation comprised a mayor, 10 aldermen and 16 burgesses, of whom the mayor was elected annually from amongst the aldermen on the first Tuesday in September. Aldermen and burgesses held office for life, and were respectively chosen from amongst the burgesses and the inhabitants as a whole. All elections were by the entire corporate body. (fn. 143)

Officers still included two bridgemen, elected annually from amongst the burgesses at the same time as the mayor. As earlier they doubled as churchwardens, and received the ancient bridge rents in support of the church and bridge. Other officers included a recorder and a town clerk, both elected for life; the former was an occasional adviser and ex officio JP, while the latter was the corporation's chief legal adviser, the keeper of its muniments, and clerk of the peace. Two sergeants at mace, (fn. 144) appointed by the mayor, received £5 a year plus small fees, and the mayor annually appointed two constables. The final corporation office was the largely honorific one of high steward, who had to be a knight or baron, and was elected by the mayor and corporation for life; his only formal function was a casting vote, not exercised until 1845. Until the mid 19th century the role was filled by successive earls of Macclesfield.

The most important changes, however, were to the corporation's judicial powers. Under the charter the mayor and three other elected aldermen became ex officio magistrates for the town, entitled to hold quarter sessions independently of the county magistrates in cases not affecting life and limb. Sessions were heard before the mayor and recorder or their deputies, the last-serving mayor, and the alderman-justices, with a quorum of three; the mayor was also coroner, and continued his role as keeper of the town gaol and clerk of the market. Alongside the quarter sessions, the charter provided for a weekly court of record to be held on Mondays, with jurisdiction over personal actions for debt or damages not exceeding £10. The quorum was the same as for the quarter sessions, and the mayor could appoint attorneys. Both courts continued into the early 19th century, when the court of record lapsed.

Ordinary corporation meetings (still called congregations) continued in the town hall as earlier, held irregularly but sometimes up to 17 times a year. (fn. 145) Business was much the same as before, encompassing administration of town charities, maintenance and leasing of town and charitable property (usually for 11 years renewable after seven), maintenance of the church, and control of nuisances and stray animals. Until 1781 the corporation retained responsibility for the bridge, and as lessee of the manor it imposed fines or quitrents for encroachments, and administered market tolls; (fn. 146) in 1766 it erected a weighing engine for carts brought to market. (fn. 147) Corporation membership remained broadly similar to earlier, (fn. 148) and from the 1770s the role of town clerk was filled by successive members of the Cooper family of Henley solicitors. (fn. 149)

The mayor was expected to provide an annual public dinner for the corporation and neighbouring gentry, and paid the constables' expenses and the fees for two public sermons. By the 1830s he received a £35 allowance towards such costs at the corporation's discretion, but met the rest from his own pocket. By 1880 the allowance was only £25. (fn. 150)

Bridge and Paving Commissioners

From the 1760s the corporation played a central role in town improvements, including acquisition of the 1781 Henley Bridge Act and its successors. The Acts covered paving, watching, lighting and street improvements as well as rebuilding of the bridge, and established Bridge and Paving Commissions to oversee these works. (fn. 151)

The Bridge Commission, following protracted wrangling between the corporation and local gentry over membership, comprised the entire corporation ex officio (including the high steward and recorder), and 16 local gentlemen including the lord of Henley manor. A further 42 members added by Act of Parliament in 1836 comprised a mix of gentry and prominent townsmen, all of whom were required to meet a £100 property qualification. The commission was empowered to collect bridge tolls, raise loans, and appoint officers as required, including surveyors, toll collectors, and a treasurer; a residue of the corporation's bridge rents was allocated in 1858, following protracted disputes. From the 1780s to the early 19th century the commission oversaw completion not only of the bridge but of the various associated road and waterfront improvement schemes, reinforced by Acts of 1795 and 1808. Thereafter it remained responsible for toll collection and bridge repair until 1873, when the building debt was paid off and responsibility for the bridge reverted to the corporation. (fn. 152) Responsibility passed in 1946 to the Ministry of Transport (for which the corporation acted as agent), and in 1974 to Oxfordshire County Council. (fn. 153) The 1781 Bridge Act also empowered the corporation to raise rates of up to 1s. in the pound for paving and lighting, and a separate Paving Commission was established by summer of that year. Membership seems to have comprised the mayor, aldermen, and burgesses; meetings were monthly, but were sometimes adjourned. The commission engaged lighting and paving contractors, laid down detailed specifications, and appointed two or three watchmen; it also assumed responsibility for keeping streets and drains clear and in good order, including regulating encroachments such as bow windows or projecting shop signs. Penalties for wilful damage (enforceable by the town magistrates) were laid down in the Acts, and in 1809 the commission directed the town beadle and crier to prevent damage to pavements caused by wheelbarrows. In the 1830s it negotiated with the Henley Gas and Coke Company for the laying of pipes through the town. By the 1840s and 1850s it seems to have become more widely concerned with nuisances, drainage and public sanitation, dividing the town into four districts, establishing a sanitary committee, and recommending a general drainage system for the whole town. (fn. 154) From 1865, however, its functions were taken over by the recently constituted local board, and the commission was disbanded. (fn. 155)

The Corporation 1835–83

In 1835 Henley was one of the ancient boroughs unaffected by the Municipal Corporations Act, on the grounds that the corporation seemed popular, was more than adequate for a small community which was not expected to grow, and no longer bore significant responsibility for the bridge. Its chief role was defined as administration of the extensive town charities, which the government commissioners thought 'probably the biggest inducement to persons of wealth and station to serve'. (fn. 156) Despite these claims, the town's exclusion from the Act prompted complaints and public meetings, and over the next fifty years the unreformed corporation became ever more contentious, characterised by a growing body in the town as a moribund, unrepresentative and oligarchic anachronism. (fn. 157) Opposition to the setting of church rates by unelected bridgemen led in 1858 to the separation of the offices of bridgeman and churchwarden, and to the apportionment (following acrimonious wrangling) of the corporation's income in support of the bridge and church among the bridgemen, the new churchwardens, and the Bridge Commissioners. (fn. 158) Around the same time opponents instituted quo warranto proceedings against five corporation members who lived outside the ancient borough boundary, forcing their resignation. Townsmen in favour of reform were reluctant to serve, and by 1857–9 some corporation members were themselves advocating change; the proposals were rejected, however, partly on grounds of cost. (fn. 159) Relations became further strained following the creation in 1864 of the local board, which, though slow to tackle the pressing issues of drainage and water supply, presented itself as the more progressive body, providing a focus for those elements in the town (chiefly prominent tradesmen and builders such as Charles Clements) who were most opposed to the old corporation. (fn. 160)

Despite these difficulties, the corporation continued to administer the charities, almshouses and town hall, (fn. 161) made improvements to the market area and town ditch, (fn. 162) and occasionally appointed an inspector of nuisances or ran soup kitchens; (fn. 163) it also inspected weights and measures, and in 1856 bought up most the market tolls from the lord of the manor. (fn. 164) The town's quarter sessions, long without business, were formally ended c. 1871, but petty sessions continued to 1883, and the town magistrates oversaw liquor licensing, raising tensions with local Temperance supporters. (fn. 165)

The Local Board 1864–83

In 1864 the corporation adopted the 1858 Local Government Act, establishing an elected local board to tackle the town's growing drainage and sanitation problems. The board, which first met in December that year, comprised 12 members including the chairman, of whom a third stood for election every year. (fn. 166) Only five of the initial members were also on the corporation, and although a few townsmen continued to serve on both, those most active on the board were prominent tradesmen who had previously played no formal role in town politics. The board had a clerk, and a salaried surveyor and inspector of nuisances who received £50 a year; meetings were held in the town hall, often several times a month. (fn. 167) On the west and north the local board district extended beyond the ancient borough, giving the board jurisdiction over growing suburban areas, and maximizing its income from rates. (fn. 168)

From its inception the board took over the paving commissioners' responsibility for paving, streets and lighting, as well as for sanitation. (fn. 169) Bylaws (based partly on those for Witney) were issued in 1865, regulating building, sewerage, livestock, slaughter houses, and public health generally. (fn. 170) Occasional recommendations were made by the poor law union medical officer, (fn. 171) and in 1872 the board became urban sanitary authority under the 1872 Public Health Act. Thereafter it appointed a sanitary inspector, and received annual reports from the district medical officer. (fn. 172) The board's failure to provide a municipal water or sewerage system (reflecting ratepayers' reluctance to pay for them) prompted much acrimony; nonetheless the board made substantial progress in improving urban sanitation, and in overseeing the beginnings of large-scale suburban building. (fn. 173) Occasionally its activities brought it into open conflict with the corporation, for example in 1880, when the corporation refused permission to dump scavenging waste on land near Harpsden Lane. (fn. 174)

Burial Board

Henley's churchyard was full by 1865, (fn. 175) and in 1866 the vestry established a joint burial board for Henley and Badgemore. A 4-a. plot at the end of the Fair Mile was bought from Edward Mackenzie of Fawley Court and consecrated in 1868, together with two newly built mortuary chapels, one for Anglicans and the other for Nonconformists. (fn. 176) The scheme was controversial: opponents issued spoof handbills on behalf of the 'Ghost and Goblin Burial Board' (based at 'Body Snatchers' Hall, Bix Hill'), claiming that the land was overpriced, and the cemetery financially unviable. (fn. 177) A 7–a. extension was consecrated in 1932, (fn. 178) and in 1947 the board's remit was extended to include the southern part of the borough. (fn. 179) The board continued until 1952, when its powers were transferred to the town council. (fn. 180)

The Reformed Corporation 1883–1974

The decision in 1882–3 to petition for a new royal charter was prompted by the passage of the Municipal Corporations (Unreformed) Bill, which it was feared might result in Henley losing many of its ancient privileges and being relegated to 'a mere large village'. Supporters and opponents of the old corporation were united in their desire to retain town magistrates, and a popular idea that Henley's corporation predated the Norman Conquest may have also had some influence. (fn. 181) The charter came into force in November 1883, replacing both the corporation and the local board with a new elected town council. (fn. 182) Its jurisdiction was extended to cover the local board district, although Rotherfield Court was excluded following objections by the owner Col. Makins, who claimed that he would not benefit from the corporation's sewerage and road improvement schemes, and paid £1,600 in lieu of rates to remain outside. (fn. 183)

The new council comprised 4 aldermen and 12 councillors including the mayor and deputy mayor. All ratepayers on the burgess roll could vote for the councillors, who in turn elected the aldermen and mayor; those on the roll included single women and widows, but any inhabitants who had recently received poor relief were disqualified. Councillors held office for between one and three years depending on their number of votes, and aldermen for between three and six years, while the mayor was elected annually on 9 November. Neither mayor nor aldermen had to be selected from among existing councillors. Membership as a whole included men who had served on the old corporation or on the local board, along with newcomers not previously involved in either, and both aldermen and councillors frequently served for long periods. The offices of high steward, recorder and bridgemen were abolished, but those of town clerk and surveyor remained, and borough magistrates continued to hold weekly petty sessions and to oversee licensing. The magistrates comprised the mayor, ex-mayor and (in 1896) seven other council members, together with the judge of the county court. (fn. 184)

30. Henley town hall, built on the site of its 18th-century predecessor in 1899–1901 as a memorial to Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee.

Administration of the town charities was transferred to a new board of trustees, (fn. 185) but otherwise the council took over the functions of both the old corporation and the local board. Some early meetings were taken up with wrangling over regalia, (fn. 186) but in 1884 the council issued a comprehensive set of new bylaws, and before 1887 saw through the completion of the town's new sewerage system. (fn. 187) In 1892, despite some ratepayers' misgivings, it secured the borough's extension southwards to Newtown, and acquired responsibility (under the Private Street Works Act) for new suburban roads, while in 1895 it acquired the powers of a parish council, including appointment of overseers and powers under the Burial Act. (fn. 188) In 1904 it secured the right to elect two county councillors rather than one, and in 1905–6 the borough was accordingly divided into north and south wards, each with six town councillors. (fn. 189) A refuse collection van was bought in 1909, when the town was divided into six collection districts. (fn. 190)

Following the First World War the council's largest tasks were provision of council housing and improvements to the sewerage system, (fn. 191) and in 1932 it bought the residual manorial rights (including those over the market) from the lord of the manor. (fn. 192) The borough was further extended the same year. (fn. 193) Business after the Second World War including council-house building and administration, planning applications, and refuse collection, together with traffic regulation and parking, and further sewerage improvements. (fn. 194) Two women were co-opted onto the housing subcommittee in 1919, (fn. 195) and in 1943 the first female councillor was elected, followed by two more in 1946. One (Mrs Jessie Lovell) went on to serve for 18 years, becoming mayor in 1956. (fn. 196)

Town Government Since 1974

Under local government reorganization in 1974 most of the borough council's remaining responsibilities (including planning, housing, refuse collection and leisure) passed to the new South Oxfordshire District Council. (fn. 197) As a successor parish Henley retained a town council, its civic regalia, and some of its property, in particular the town hall and recreation grounds. The council comprised 16 councillors elected every 4 years, from whom a mayor was elected annually; the council's powers, however, were those of an ordinary parish council. In 2008–9 its gross expenditure on services was c. £1.5M, of which c. £704,800 was spent on recreation, sport and tourism, £128,600 on environment and community safety (including the cemetery), £55,500 on community and economic development (including markets), and £10,300 on roads and parking facilities, with £647,100 on corporate management and 'democratic representation'. Income (from charges, rates, investments, and grants) was c. £985,000. Salaried staff in 2010 included a town clerk and a town sergeant, visitor information and park staff, a traffic warden supervisor, and various administrators. (fn. 198)

Town Property

The guild's responsibility for church and bridge prompted numerous gifts of rents and property from the late 13th and early 14th century. Rent arrears listed in 1304–12 imply that the guild already received income from around 50 properties, yielding c. £3 17s. 7d., and following the Black Death it acquired many more as residuary legatee. By 1385, when it belatedly obtained a royal licence for its possessions, it received £14 12s. from 115 houses. Most of its property was granted to townsmen in perpetuity in return for substantial annual quitrents, which by 1470 totalled c. £31. The income was administered by the bridgemen, and became known as the 'bridge rents'. (fn. 199)

Some rents (worth £11 17s. 4d.) were confiscated at the Reformation, but restored in 1604 for the benefit of the grammar school. The rest continued to be received, but became increasingly confused with properties and rents left to the bridgemen for charitable purposes in the 16th and 17th centuries, some of which were also diverted to the church or bridge. In 1854 the bridge rents totalled some £38 12s., including the grammar school's share and £11 8s. 10d. earmarked for specific charities; the rest was combined with surplus from the bridgemen's other charities, and used for church repair. (fn. 200) When the offices of bridgeman and churchwarden were separated in 1858, remaining bridge rents worth £10 15s. 10d. were allocated to the churchwardens. (fn. 201) Some rents were lost in the 18th century when the Middle Rows in Hart Street and Market Place were demolished. (fn. 202)

The guild's only other medieval property appears to have been the guildhall and a fishery in the Thames, held of the manor for 4s. quitrent. (fn. 203) In the 1780s the corporation successfully claimed the fishery against the lord of the manor. (fn. 204) In 1625 William Gravett left the corporation six houses on Friday Street, and in 1626 the warden bought a 4-a. plot in Remenham (called Greencroft); by then the corporation also administered numerous properties as charity trustees, some of them given in support of the bridge. (fn. 205) No further property was acquired until the 1880s, when the reformed corporation opened its Lambridge Wood sewage plant. (fn. 206) The Makins recreation ground was acquired in 1919 and Mill Meadows in 1921, to which the adjoining Marsh Meadows were added in 1968. (fn. 207) From the 1920s the corporation also owned increasing numbers of council houses. (fn. 208)

After 1974 the town council retained only its historic and recreational property and the cemetery. In 2010 it owned the town hall, various allotments and recreation grounds (including Greencroft and Mill Meadows), various car parks, and some riverside moorings, along with the Old Fire Station exhibition centre and a day centre acquired in 1992. (fn. 209)

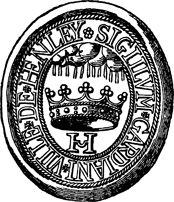

31. Henley town seals. Left: the lion rampant device used in the Middle Ages and from 1664–1883. Right: the device introduced probably in 1568, and re-adopted by the reformed corporation in 1883.

Town Seals and Insignia (fn. 210)

The guild had a seal by the early 14th century, when it was described as the seal 'of the community of Henley'. It was circular, and bore a lion rampant (Fig. 31). (fn. 211) The seal was regularly appended to town leases, and in 1521 was kept with the town's muniments in a coffer with four locks, the keys kept by the warden, the bridgemen, and one other. (fn. 212) The bailiffs may have had their own seal in 1400, and the clerk of the market in 1492. (fn. 213)

The town seal continued in use throughout the Middle Ages, but by 1624 it had been replaced by one bearing a letter H with a ducal coronet, under clouds (or a sunburst) issuing rain (Fig. 31). (fn. 214) Probably that was introduced under the 1568 charter, which authorized the corporation to have its own seal. (fn. 215) In 1664 the corporation acquired a new seal which reverted to the lion rampant device, and which remained in use until 1883; the legend was variously 'Sigillum Communitatis de Henlee', or 'Sigillum Commune Villae de Henlee' ('Seal of the Community of [the Town of] Henley'). (fn. 216) The letter H device was retained for the warden's seal of office, and for corporation trade tokens introduced in 1669. In 1861 there was also a town clerk's seal, with a variant of the lion rampant. (fn. 217)

The new corporation of 1883 intended at first to retain the lion rampant, but upon discovering that the letter H device registered in the 17th century represented the official town arms, and that registering a different device would cost £76, it decided to re-adopt the letter H design. A new oval seal or embossing stamp was copied from the earlier one, with the legend 'Sigillum Gardiani Ville de Henley'. (fn. 218)

A public subscription allowed the town council established in 1974 to acquire a new coat of arms, combining various motifs. The shield, featuring the letter H, ducal coronet, and sunburst, is supported by a lion rampant and by an ox, representing Oxford and Oxfordshire. The crest incorporates a crown (recalling Henley's earlier borough status), a fleur de lys (recalling the dedication of St Mary's church), and two mitres (recalling Bishops Laud and Longland); above the crown are crossed Diamond Challenge sculls recalling rowing and the regatta. Other devices recall the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, the Tudor rose, and St Catherine. The motto is 'Semper Communitas' ('always a community'). (fn. 219)

The silver-gilt mace, acquired after the 1722 charter, is hallmarked London 1722–3. The mayor's silver gilt chain and badge were bought by subscription in 1884 following heated debate within the new corporation, which agreed not to adopt any formal robes. (fn. 220) Portraits of George I and Thomas Parker, earl of Macclesfield, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, were presented in 1725 and 1750 respectively. (fn. 221)

Vestry and Parish Government

Until the 1640s overseers and two surveyors of highways were appointed (like the joint bridgemen and churchwardens) at corporation assemblies, usually around March or April. (fn. 222) Possibly there was a vestry which duplicated or ratified such appointments, although no vestry minutes are known before 1725. By then the vestry was concerned primarily with poor relief, along with other parish matters such as (by the 1730s) repair of the parish fire engines; it routinely regulated the work of the overseers, and of the bridgemen in their capacity as churchwardens. (fn. 223) By the 1790s the overseers were appointed by the town justices, to whom the churchwardens and the previous years' overseers nominated eight or more candidates; (fn. 224) surveyors of highways were no longer mentioned, however. Membership of the vestry overlapped with that of the corporation, but being concerned with matters outside the town it included local landowners as well, together with the rector. (fn. 225) A select vestry to deal with poor relief existed from 1821–35, although in 1823 there were insufficient active members, and the general vestry was asked to elect only those with sufficient time to spare. (fn. 226)

After the transfer of poor relief to Henley union in 1835 the vestry continued to deal with church matters, (fn. 227) and from 1858, when the offices of bridgeman and churchwarden were separated, it appointed churchwardens in the usual way. (fn. 228) In 1866 it was responsible for setting up the new burial board. (fn. 229) Under the 1894 Local Government Act it became a parochial church council concerned exclusively with church affairs, and in that capacity acquired the Chantry House for conversion into a parish room in 1923. (fn. 230)

Policing and Gaols

From the Middle Ages to the 19th century peace-keeping fell primarily on the constables appointed by the manor court and by the guild or corporation. The last two bodies further promoted law and order through their ordinances and fines, in the Middle Ages through sureties for good behaviour, and in the late 13th and 16th–17th centuries through a system of wards. (fn. 231) A cucking stool possibly under the guild's authority was mentioned in 1432, (fn. 232) and the manor court ordered provision or repair of a pillory and cucking stool in 1332–3 and 1667. (fn. 233) A town gaol or lock-up was authorized under the 1568 charter, (fn. 234) and in the 18th century was in the Middle Row, a little west of the guildhall (Fig. 24). In 1796 it was replaced by a 'small dungeon' in the new town hall, used 'for temporary restraint or security'; longer-term prisoners, including those who came before the town magistrates at the petty or quarter sessions, were sent to Oxford. (fn. 235) In the 1850s the county magistrates held fortnightly sessions in Henley, supplementing the separate town magistrates' sessions, and from 1848 a branch of the Berkshire County Court was also held at Henley. (fn. 236)

In 1835 the town's only police were the two constables appointed annually by the mayor or town magistrates, and four others appointed by the manor court. The Paving Commissioners appointed two watchmen under the Bridge Acts, and a superintendent of police was mentioned in 1852. (fn. 237) In 1856 responsibility passed to the new county constabulary, and in 1868 a police station at the bottom of West Street was adapted from two existing houses, to designs by William Wilkinson. (fn. 238) By 1896 there was a superintendent, an inspector, two sergeants, and 14 constables. (fn. 239) In 2001 plans to close the station met strong opposition; (fn. 240) a new station was subsequently opened on Greys Road, though in 2009 its limited opening hours and low staffing remained controversial. (fn. 241)

Medical Provision and Hospitals

A pest house (demolished in 1667) existed by 1653, (fn. 242) and in the late 18th century the vestry occasionally paid for mass smallpox inoculations. (fn. 243) Another pest house was built at the parish workhouse in 1790–1, (fn. 244) and in the 1870s infected persons from the town were sometimes sent there; by then there were increasing calls for an isolation hospital, to help prevent the spread of infection particularly in the town's cramped and insanitary cottage yards. (fn. 245) The local board failed to find suitable premises, but in 1891–2 the Smith Isolation Hospital was built at the end of the Fair Mile at the expense of W. H. Smith (Viscount Hambleden), and opened by his son W. F. D. Smith. The hospital comprised four blocks set in 5 a. of grounds, and could accommodate 14 patients; admittance was free to anyone in Henley rural sanitary district provided they were nominated by a qualified practitioner or by the justices, and there were also paying wards. (fn. 246) Nonetheless in 1904 Henley's medical practitioners complained of difficulties in getting patients transferred. (fn. 247) A cottage hospital on Harpsden Road (just over the municipal boundary) was opened as a War Memorial Hospital in 1923, (fn. 248) and in the 1930s there were proposals for a new mortuary, to supplement those at the War Memorial Hospital and at the former workhouse. (fn. 249)

In 1948 the former workhouse became a general hospital (renamed Townlands) for the newly-created National Health Service. The War Memorial and Smith Hospitals were also transferred to the NHS, and in 1952 the Smith Hospital was converted for the care of child psychiatric patients. (fn. 250) In 1966 it had 46 beds; the War Memorial Hospital had 21, and Townlands 104. (fn. 251) Soon after, the Oxfordshire Regional Hospital Board considered moving surgical services to Reading and closing the War Memorial Hospital, focusing local services and outpatients on Townlands; no decision was reached, but the hospital remained under threat and was finally closed in 1984. The building was converted into sheltered housing, called War Memorial Place. (fn. 252) The Smith Hospital closed c. 1988 and was converted into commercial premises, (fn. 253) and Townlands, too, remained under threat. It was saved following a lively public campaign, and in 2009 there were plans to erect new hospital buildings on the 7-a. site, along with new housing. (fn. 254)

Fire Fighting

A corporation ordinance of 1625 laid down that chimneys must be of brick or stone, and instituted fines of 3s. 4d. for anyone causing a fire through failure to sweep their chimney. In addition, the corporation became responsible for providing ladders, hooks and leather buckets. (fn. 255) By 1739 there was a town fire engine overseen by the vestry, and by 1767 there were two; (fn. 256) in 1771 it was agreed that the overseers should rent a shop under the town hall in which to keep them, and that a pump should be erected nearby, paid for from the poor rate. (fn. 257) In 1765 all the corporation's houses in the town were insured with the Royal Exchange Fire Office, (fn. 258) and in 1790 the Sun Fire Office insured the new workhouse. (fn. 259) Both companies probably maintained their own fire engines in Henley, as later.

In 1856 the corporation investigated the number of fire engines in the town, and who was responsible for their upkeep. Three were reported, one belonging to the Sun Fire Office, one to the Royal Exchange Fire Office, and one to the parish; all were in good order, though who was legally responsible for the parish engine was unknown. (fn. 260) A survey in 1860 found the engines in poorer repair: the parish engine especially was badly constructed, and the corporation recommended acquiring a better one, to be kept in the former lock-up beneath the town hall, and a key made available from the police station. (fn. 261) From 1864 the local board became responsible, and in 1866 repaired the parish and Royal Exchange engines, paying £35 to adapt premises in Northfield End as a depot. (fn. 262) By then the Sun Fire Office engine had presumably fallen out of use.

A volunteer fire brigade was established late in 1866. (fn. 263) By 1870 it had a moveable fire escape, and in 1872 it raised a public subscription to buy a new engine, without any help from the local board. (fn. 264) A new fire station was built in the market place (behind the town hall) in 1880–1, (fn. 265) and in 1892–3 the brigade acquired a steam-powered engine 'of the latest and best design', with help from the borough council. In 1896 it comprised 12 'efficient and enthusiastic and well-drilled' firemen, under the presidency of Archibald Brakspear. (fn. 266) The brigade not only fought fires: in 1910 its engine pumped water from the sewers continuously for 64 hours to alleviate flooding. (fn. 267)

The brigade remained a volunteer service until 1941 when, as elsewhere, it came under the purview of the National Fire Service, and in 1948 responsibility passed to Oxfordshire County Council. Abortive plans for a new fire station were placed before the borough council in 1928, (fn. 268) and a site on West Street was acquired c. 1951, although in the end the new station was not built until c. 1968. (fn. 269) In 2010 it was a retained station, with 12 part-time firefighters living or working within 3 miles. (fn. 270) The old fire station was acquired by the town council c. 1975 as an exhibition space, (fn. 271) and so continued in 2010.