A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Henley: Social and Political History', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp120-159 [accessed 10 May 2025].

'Henley: Social and Political History', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online, accessed May 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp120-159.

"Henley: Social and Political History". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online. Web. 10 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp120-159.

In this section

SOCIAL AND POLITICAL HISTORY

The Middle Ages to the Reformation

Social Structure and Wealth

The quality of some of Henley's surviving medieval houses points to considerable disposable wealth in the town, and a few prosperous and well-connected Henley merchants are identifiable throughout the Middle Ages. Yet despite the importance of the grain trade and the increasing independence of Henley's merchant guild, for much of the period Henley lacked the large and wealthy mercantile élite which dominated some medieval towns. In 1327 only 4 out of 38 taxpayers in Henley (11 per cent) paid 3s. or more, compared with 30 per cent in Abingdon, and over 20 per cent in Reading, Wallingford and Thame. The spread of Henley's other tax payments, from 6d. to 2s. 6d., suggests more modest wealth amongst a significant group of lesser traders, shopkeepers and craftsmen. (fn. 1)

Part of the reason, at least until the Black Death, was the dominance of the Henley grain trade by large-scale London merchants, to the extent where, it has been suggested, Henley 'must have seemed like an up-river London colony ... a place where Londoners met merchants from other Thames-side towns'. (fn. 2) Even so, some Henley men stood out. Most notable was the grain merchant Robert of Shiplake (fl. 1306–33), whose tax payment of 4s. 3d. (with another 4s. from property in Badgemore) set him alongside some of the wealthiest inhabitants of neighbouring towns. Shiplake was also prominent in town affairs, serving four times as warden and appearing as a witness to town charters. Two other exceptionally wealthy traders, Thurstan of Ewelme (fl. 1305–16) and John of Harwell (fl. 1315–58), may have enjoyed similar status. Both witnessed charters, and Harwell (who was also elected warden) endowed a chantry in Henley church. (fn. 3)

The Black Death seems to have broken the London merchants' hold over Henley and brought more Henley traders to the fore, but as earlier only one or two exceptionally wealthy individuals dominated the town at any one time. Thomas Clobber (fl. 1363–1433), involved in the cloth and possibly grain trades, had business interests as far afield as Devon, and from 1384 to 1417 served 17 terms as warden. On the last occasion he must have been in his seventies, making him a venerable figure of at least 90 by his death. (fn. 4) A similar role was fulfilled in the 15th century by the wool merchants John Elmes (d. 1460) and his younger namesake (d. 1491), alongside their fellow merchants John Logge and John Deven. Like Deven the elder Elmes was a newcomer to the town, and had far-flung trading and social links. Some of the wine which he imported through Southampton was presumably for his own use, and probably he enjoyed a lavish lifestyle. Besides serving as warden he became a significant property owner in the town, acquiring rents, three gardens, two granaries and 22 tenements, and like Harwell he founded a chantry in the church, for which he built a side-chapel. His role in local government extended way beyond Henley, and by 1443 was sufficiently onerous for him to obtain a life exemption from serving on assizes, juries and inquisitions, or as bailiff, escheator, coroner, constable, and collector of tenths and fifteenths. (fn. 5) The domestic comfort and display of such townspeople is reflected in their wills. John Deven owned jewels and silver bowls and left money to his servants, while William de Barneville (d. c. 1466) left feather beds and bolsters, silverware, numerous cooking utensils, and clothing including a gown lined with beaver fur. (fn. 6) Presumably these were the sort of people occupying houses like 76 Bell Street, its timber-framed hall embellished with elaborate decorative carving. (fn. 7) Alongside them, the 15th-century wool trade apparently also attracted members of some Oxfordshire and Berkshire gentry families into the town. (fn. 8)

Beneath these dominant individuals, a broader borough élite was represented by the town guild, (fn. 9) which in the 1290s probably included less than a fifth of the adult male population. Members were drawn from a broad spectrum of the town's more prosperous inhabitants, encompassing craftsmen as well as merchants, traders and shopkeepers: among them were tailors, tanners, carpenters and smiths, while a weaver was admitted in 1449. Women were excluded, in contrast to some other towns. A smaller group within the guild exercised particular authority, regularly witnessing town charters, and dominating the most important offices such as bridgeman or warden. Craftsmen, although admitted as burgesses, seem at first to have been excluded from this self-appointed oligarchy, but from the 15th century they too appeared in greater numbers, presumably in response to declining guild membership as the population fell. By c. 1400 town officers included tanners, tailors and a hosteler, and by mid-century there were nearly equal numbers of craftsmen and traders or shopkeepers. (fn. 10)

The wider populace, irrespective of guild membership, was dominated by a significant body of moderately prosperous craftsmen, traders, and retailers, who in the early 14th century may have numbered around 140: in all, some 55 to 70 per cent of the town's adult male householders. Such people extended way beyond the burgess body and the 38 inhabitants wealthy enough to be taxed in 1327, and by comparison are poorly documented. Many, however, appeared as pledgors in the manor court, and several had craft-related bynames such as Baker, Barber, Dyer, Mareschal (or farrier), Smith, and Taylor. (fn. 11) The overall picture seems to have been similar in the early 16th century, when 191 taxpayers were listed. Of those, over a fifth (22 per cent) paid between £2 and £19, and were probably substantial tradesmen and retailers. Another 76 (or 40 per cent) paid £2, most likely representing small craftsmen and husbandmen, while 60 (31 per cent) paid at the wage earners' rate of £1, and were presumably servants or labourers. By comparison, the upper élite remained small. Only 13 (7 per cent) paid over £20, among them the grain merchant and sometime town warden Richard Brockham, the fuller and innkeeper Robert Kenton, the glover John Hogge, and the butcher John Jessop. Of those only Brockham (taxed on goods worth £80) approached the wealth of earlier merchants such as Clobber or Elmes. (fn. 12)

Less visible is the sizable group who fell below the tax threshold, and who appear in the records only sporadically. A late 13th-century guild document known as the Nuns des Gent hints at a significant but relatively transient population of adult sons, servants, apprentices, journeyman, and lodgers, for whose good conduct established Henley householders were required to give pledges. (fn. 13) In 1332–3 a total of 266 named men and 50 named women appeared before the manor court, presumably representing much of the adult male population, (fn. 14) and by the early 16th century it has been estimated that Henley's untaxed poor could have included up to 95 households. If so, the combined body of untaxed poor and £1 wage-earners made up just over half the adult male population by that date, a relatively high proportion. (fn. 15)

Locative surnames suggest that many of the town's inhabitants were drawn from the hinterland described above, which stretched 10 miles or so across the Chilterns, but only 4 miles or so into Berkshire and Buckinghamshire across the Thames. (fn. 16) The significant London trading presence declined sharply after the Black Death, though small-scale immigration from London possibly continued: some mid 14th-century incomers may have been London merchants trying to escape the plague, and the significant number of newcomers admitted to the guild in the late 14th century and the 15th perhaps also included a few from the London area. (fn. 17) Many 15th-century incomers came from elsewhere, however, and were probably connected with the wool and cloth trades. Among them were immigrants from Reading and other Berkshire towns, (fn. 18) while a man from the Low Countries was mentioned in 1436. (fn. 19) Several other late 15th- and early 16th-century inhabitants were of Welsh origin, (fn. 20) and in the 1480s at least two came from Scotland or close to the Scottish border. (fn. 21)

Government and Politics

Though the planned town originated as a royal creation the manor was seldom in royal hands from the late 12th century, and probably the king never made more than passing visits to Henley. (fn. 22) Building work was carried out at the manor house in 1209 following Robert de Harcourt's forfeiture, (fn. 23) and letters patent or close were occasionally dated at Henley into the 14th century, long after the Crown had granted away the manor. (fn. 24) Routine royal inquisitions and sessions of the peace were held in the town from time to time, unsurprising given its accessibility, proximity to London, and importance as a market centre. (fn. 25)

Henley remained a seignorial town throughout the Middle Ages, with authority technically vested in the lord of the manor and exercised through his three-weekly court and annual view of frankpledge. But in reality, from the 13th century the townspeople enjoyed a significant and steadily increasing degree of self-government through the merchant guild, which appointed its own officers and which, by the late 14th century, owned substantial property in the town. Even the manor court, which by the 1380s may have met in the guild hall, was effectively run by leading burgesses, and in the later Middle Ages it seems to have served partly as a small claims court rather than as an instrument of lordly control. (fn. 26)

On the whole relations between Henley's lords and townspeople seem to have remained amicable, a situation no doubt helped by the fact that the lords were mostly non-resident landholders on a large scale, and took little direct interest in town government. An exception may have been John de Moleyns, whose power base was in Buckinghamshire and who, by the time he acquired Henley manor in 1337, was already infamous for lawless thuggery and intimidation. At Henley, as in other manors, he secured confirmation of extensive manorial rights including a gallows, and it has been plausibly suggested that the warden's designation as 'mayor' in 1337–8, which was unique in medieval Henley, represented an assertion of status and defiance by the townspeople. (fn. 27) A later keeper of the manor (following Robert Hungerford's attainder in 1461) may have also been guilty of extortion, for which he received a royal pardon in 1466. (fn. 28) By contrast, there were some striking examples of cooperation. In 1328–9 Hugh d'Audley supported the town's right to exact tolls from London merchants trading through Henley, (fn. 29) and in 1440 a new fair grant was obtained at the joint petition of the lord, the warden (John Elmes), and the 'whole community of the town'. (fn. 30)

Owners of Fillets manor, of whom several lived at Phyllis Court, (fn. 31) presumably had closer dealings with the town. William Wyot, who was also the Moleynses' lessee, was cited in 1419–20 for obstructing a field path and for failing to provide a pillory, cucking stool and gallows. (fn. 32) More positively William Marmion (d. c. 1470) oversaw the will of the wealthy Henley townsman and sometime warden William de Barneville, served on the local commission of the peace, and in 1459 accounted before the guild (with John Deven) for lead for the church. (fn. 33) Thomas Hales was in dispute with the rector over tithes in 1502, and as a merchant of the staple possibly had more in common with his fellow townsmen than with the aristocratic lords of Henley manor. (fn. 34)

The guild's assembly books (extant from 1395) give little insight into town politics. Its regulatory powers and fines may occasionally have prompted hostility, however, and from the 1490s there are hints that its authority was coming under increasing pressure. Two prominent burgesses (one of them an innholder, barge owner and possibly grain merchant) were expelled in 1496 and 1506, and others were cited for opposing the warden. A ruling of 1492 laid down fines for inhabitants who disobeyed the warden's injunctions, while a new oath of admission required burgesses to obey officers' orders and to support the guild's ordinances. Around the same time there seem to have been moves to involve the entire burgess body more closely in town government, reflected in a new (1480) requirement for at least 24 burgesses to ratify grants of town property, and in more detailed recording of the names of those attending. The reasons for the increased tension are unclear, though it has been suggested that the resurgence of the river-borne grain trade and attempts to regulate out-of-market trading may have played a part. So, too, may the belated establishment in 1498 of separate craft guilds for weavers, mercers and tailors, although like Henley's contemporary religious fraternities these were established on the town guild's authority, and seem to have had a limited role.

A more general nervousness about vagrancy, lack of order, and the undermining of established authority is suggested by a series of manucaptions during the 1490s and 1500s, by which townsmen guaranteed the good behaviour of their servants or sons. During the same period several inhabitants (including servants and craftsmen) were bound over to keep the peace, and an exceptional meeting of the warden, burgesses and 'all the inhabitants' in 1532 was called expressly to improve order in the town. Masters and mistresses were to ensure that their servants were home by 8 p.m., illicit games were outlawed, and town officers were to be informed when servants left their master's service. (fn. 35) Hedge-breaking seems to have been a cause of concern in 1535, when the guild ruled that masters of servants found guilty of three such offences should be banished from the town. (fn. 36)

Despite these concerns, there is little evidence for exceptional social or political disorder. In the 1320s Robert of Shiplake and another leading guildsman (John at Greenlane) were implicated in raids on neighbours' property at Bolney, Nettlebed and elsewhere, and in 1400 a Henley man suspected of involvement in Sir Thomas Blount's failed uprising against Henry IV had his property temporarily forfeited. (fn. 37) More seriously, from the 1460s Lollardy became a significant factor in the town as it did across the south-west Chilterns, its growth promoted by London trade links and by the activities of itinerant preachers. A 'false priest' who allegedly incited riot and sedition at Henley in 1453 may have been involved, and ten years later half a dozen Henley townsmen were accused of holding or promoting heretical beliefs. All of them either abjured their beliefs or were acquitted, however, and most seem to have enjoyed normal relations with their neighbours. The religiously radical smith William Ayleward was a burgess and held town property, while John Redhode (accused with him in 1463) went on to serve as constable. (fn. 38)

Otherwise, the occasional recorded instances of violence or disorder were such as might be found in any town. The most serious included thefts from the church and, in 1520, the murder of a priest. (fn. 39) But far more common were fines for illegal gambling or disorderly behaviour, as when a burgess was bound over in 1493 for drunkenly disrupting church services. (fn. 40)

Popular Culture and Social Provision

Much of the evidence for Henley's communal life revolves around the church, with its chantries, fraternities, and seasonal festivities. Two of the most important chantries were run by the guild and had a strong communal element, as did the 15th-century Fraternity of Jesus, whose members included women as well as men. More popular festivities included, by the early 16th century, an Easter Resurrection play and an annual Corpus Christi 'pageant'. (fn. 41)

Other events in the ritual calendar were of a more secular nature, though proceeds were administered by the guild and used sometimes for church purposes. All were variants of the seasonal games found in many late medieval parishes, although in Henley none are recorded before the mid 15th century. Hocktide festivities included a 'wife gathering' at which local men 'captured' local women (or vice versa) and released them on payment of a fine, while a 'king play' at Whitsuntide involved election of a mock king or queen, sometimes with entertainment by a minstrel or a fool. From the 1490s to 1520s there was also a Robin Hood game, recorded around the same time at Thame and Reading. In 1520 the gross profits from all three events were nearly £9, more than half from the Robin Hood game and some 48s. from the wife gathering. (fn. 42) Some of these seasonal games survived into the later stages of the Reformation, with payments made in the mid 1550s for refurbishing morris costumes, repairing the garters of bells, and for a fool and tabor-player at Whitsuntide, while the king game continued in the mid 1560s. Presumably all of them lapsed soon after. (fn. 43)

The guild's close involvement in these festivities suggests that it actively promoted them, and in 1498 it re-established a custom whereby the warden perambulated High Street, Bell Street and New Street over Christmas to 'drink, make merry and visit the houses of his neighbours'. The motive may have partly been to improve relations between the guild and the inhabitants, (fn. 44) though if so it is unclear why Duke and Friday Streets were omitted: possibly they were perceived as too low-status. In contrast, everyday gambling, dicing and cards were frowned on, probably as much for the risk of violence as on moral grounds. In 1422 the guild received 6s. 8d. in fines from dice players and gamblers, and occasionally it bound over named individuals to refrain from allowing dice, cards and other illicit games on their premises. (fn. 45)

Poor relief fell within the guild's remit through its administration of town property, and through the bridgemen's joint role as churchwardens. (fn. 46) Much of the guild's property was for upkeep of the church and bridge, but some surplus was occasionally given to the poor: in 1419 the guild agreed that the residue of funds for a particular obit should be given in alms, (fn. 47) and Easter collections at the church door may have been similarly distributed. (fn. 48) By the mid 15th century some burgesses were making explicit provision for the poor in their wills. In 1443 the smith John at Lee (who served several terms as constable) left the guild three houses on Bell Street, partly to provide coats every year for five poor inhabitants. (fn. 49) Ten years later William Pykard left houses on High Street partly to provide an annual 20d. dole, (fn. 50) while John Deven's widow Joan (d. 1484) provided for 6 qrs of charcoal to be distributed twice a year. (fn. 51) Jane Stonor (d. 1493 x 1494 ), though not endowing a charity, left the exceptionally large sum of 5 marks for distribution to the poor at her funeral and month's mind. (fn. 52) Some such bequests may have reflected local Lollard influence, which elevated almsgiving above obits or oblations to priests. (fn. 53)

An almshouse existed by 1453, when Pykard earmarked part of his bequest for the inmates. John Elmes left 10s. to the 'poor men' there in 1491, and in 1498 the warden paid 4s. for fuel. The building adjoined the hermitage near the bridge, close to St Anne's chapel. It was superseded in the 1530s when Bishop Longland founded a new almshouse nearby, which seems at first to have used the earlier building as well. (fn. 54)

A school master was mentioned in 1419, when the guild appointed him town clerk at 6s. 8d. a year. (fn. 55) Possibly the school had a continuous existence: Bishop Longland (who was born at Henley) attended a 'school of good and sound learning' there in the 1470s or 1480s, giving him a sufficient grounding to go on to Eton, and Henley still had a school in the early 16th century. (fn. 56) By the 1550s it occupied a building in the churchyard, probably the so-called Chantry House. Despite the name, however, the building seems not to have originated as church property, and the arrangement was probably of recent origin. (fn. 57)

Town and Society 1550–1700

Townspeople, Wealth and Social Life

During the century and a half from 1550 Henley remained heavily reliant on river-related trades. Among the most significant developments was the emergence of a prosperous group of maltsters, many of whom also farmed, and who were sometimes involved in trading other goods along the river. By the mid 17th century they included some of the town's wealthiest and most prominent inhabitants, displacing to some degree the grain merchants of the earlier period. Bargemen, though still not especially wealthy, were by 1700 the single largest occupational group, and with the maltsters probably accounted for over a third of the adult male population. The rest comprised the various craftsmen, tradesmen and retailers found in most small towns. (fn. 58)

In overall size and prosperity the town ranked fairly high among Oxfordshire market centres. In 1581 its taxable wealth placed it behind only Oxford, (fn. 59) and in 1665 only Oxford and Abingdon (then Berks.) had more recorded houses. (fn. 60) Individual wealth varied considerably, however. Out of a sample of 170 testators between 1568 and 1709, half left goods worth under £50 and over a fifth under £15. At the opposite extreme, 47 (28 per cent) had goods worth over £100, and 18 (11 per cent) over £300. (fn. 61) The wealthiest by far were the maltster and farmer Thomas Parslow (d. 1679), the maltster and timber merchant Ralph Messenger (d. 1668), and the innkeeper Abraham Goodwin (d. 1666), who each left goods valued at over £1,400. (fn. 62) Equally exceptional were the maltsters Humphrey Newbury and Thomas Flight (d. 1665 and 1679), the mercer Ambrose Freeman (d. 1662), and the innkeeper Richard Stevens (d. 1702), with goods worth between £755 and £972. (fn. 63) Other notably well-off inhabitants included the tanner William Osgood (d. 1668, £467), the timber-merchant George Cranfield (d. 1667, £384), the butcher and farmer John Woodroffe (d. 1675, £299), (fn. 64) and several other maltsters-cum-farmers with goods worth £100–£600. (fn. 65)

Such statistics are slightly misleading in that much of this wealth was wrapped up in stock and business. Over £300 of Parslow's estate, for instance, was in malt, billets and other agricultural produce, with another £620 owed him in debts. Nonetheless the social aspirations of these prosperous traders are clear from their wills and inventories. Messenger had a house of at least seven rooms excluding outbuildings, which was furnished with 'turkey-work' and leather chairs, hangings and rugs, a clock, court cupboards, and feather beds. As was usual in this period his working premises adjoined his domestic accommodation, but this was still an environment framed for polite living. (fn. 66) Several such people made bequests to servants, (fn. 67) and a maltster's house mentioned in 1630 included a maid's and man's chamber. (fn. 68) At a slightly lower level the locksmith Robert Douglas (who also traded in malt, and had goods worth £92) owned good joined furniture, feather beds, curtains, rugs, books, pewter, and numerous cooking utensils. (fn. 69) So, too, did most innkeepers, although again their premises represented stock-in-trade and capital rather than indicators of personal status. The town's numerous bargemen, even the minority who owned or part-owned a barge, were generally of much more modest wealth, with inventories valued at between £6 and £96. Several had moderately well furnished houses of at least 3–4 rooms (sometimes with shops), but many others left no will and, as hired hands, may have been considerably poorer. (fn. 70)

As in the Middle Ages, social status was also expressed through involvement in town government. Membership of the corporation established in 1568 (fn. 71) was dominated by a closely knit élite in which wealthy traders figured large. Parslow, Messenger and Freeman (or his father) all served as warden, in some cases for several terms; so, too, did the farmer and maltster John Hunt (d. 1631 or 1638), the maltster (and possibly grain merchant) Thomas Cleydon (d. 1630), the innkeepers Henry Boler and William Atkins (d. 1665 and 1692), and the prosperous fishmonger William Robinson (d. 1698), who issued a trade token. Many of these people were closely interconnected, often intermarrying, and witnessing or overseeing each other's wills. (fn. 72) Similar people seem to have dominated the wider burgess body, certainly the capital burgesses and chief officers: 34 burgesses listed in 1639 included maltsters, brewers, and at least one each of innkeepers, tallow chandlers, and drapers, of whom several went on to hold town office. (fn. 73) Wealth was apparently not the only criterion, however. Craftsmen, bargemen, bakers, butchers and lesser retailers – even those whose probate inventories suggest that they were fairly prosperous – seem generally not to have featured amongst the town's capital burgesses or office holders, perhaps reflecting a continuation of prejudices noted in the medieval period. (fn. 74) In addition, several prosperous and well connected townsmen in the more 'élite' trades (the timber merchant George Cranfield or the maltster William Elton the younger, for instance) seem to have played no part in town government, perhaps from personal choice. (fn. 75)

By the 17th century, many of the more prosperous maltsters and traders called themselves gentlemen or 'Mr'. The phenomenon has been noted in other towns such as Witney, although there it may have been primarily in retirement. (fn. 76) In Henley, at least 10 per cent of the wills which included a title or trade designation were ostensibly made by 'gentlemen', of whom many were clearly working traders, and similar people were sometimes called gentlemen in other documents. The title may have been partly associated with involvement in town government: wardens and other officers were regularly called 'Mr' in borough records, and many of those so designated in 17th-century hearth taxes had already held town office or soon went on to do so. (fn. 77) Another criterion may have been property ownership, since several prominent traders were also landlords. John Hunt (d. 1631) had houses throughout the town and farmland in Remenham, while Parslow owned Mankorns Farm and a house on Bell Street. (fn. 78) Townsmen's aspirations were further reflected in new educational initiatives. A grammar school was established in 1604, and as early as 1600 the warden John Lewes had a nephew at Oxford University. (fn. 79) Wide horizons are illustrated not only in extensive trading and social connections with London, but in occasional links with places as far afield as Herefordshire, Winchester, Northampton, and Marlborough. (fn. 80)

Against such a background, it is not surprising to find Henley already catering for the prosperous and socially aspiring, a phenomenon which accelerated from the late 17th century with the development of coaching. Inns such as the Bell at Northfield End were well regarded by the 1630s when Archbishop Laud stayed there, and some seem to have acquired bowling greens which were used by better-off townsmen as well as by visiting guests. (fn. 81) In the 1680s the newly extended Bear Inn on Bell Street had a set of musical instruments in the parlour. (fn. 82) Equally symptomatic (and presaging a trend which increased from the 18th century) was the appearance of educated professionals serving the town's better-off inhabitants. (fn. 83) The town's first known attorney (Solomon Sewen) may have been warden in 1681–2, (fn. 84) while the surgeon and apothecary Edward Stevens (d. 1663) occupied a well-furnished house which included a study of books and his surgery instruments, although he also stocked groceries and haberdashery. (fn. 85) A 'musician' was recorded in the town in 1639. (fn. 86)

At the opposite extreme were the 13 per cent of householders taxed on only one hearth, or whose household goods (like those of the labourer Jasper Wellman in 1634) were worth only £1 or £2. (fn. 87) In 1595 an impoverished weaver was said to have persuaded a small boy to steal wood for him from Elmes' wharf overnight, and the corporation records occasionally detail poor-relief payments to particular individuals. (fn. 88) Otherwise, the lowest tiers of Henley society are hinted at only in the town's numerous charitable bequests and in the corporation's operation of the poor law.

Landowners and country gentry

Henley's social élite extended beyond the town to the surrounding countryside. Some local landowners were old-established families such as the Stonors of Stonor Park, who had had close dealings with Henley from the Middle Ages and whose property there included (by the 17th century) Jennings' wharf south of Friday Street. (fn. 89) As an Oxfordshire JP Sir Walter Stonor (d. 1550) played a prominent local role in enforcing the Reformation (in contrast to his strongly recusant descendants), while John Stonor served as JP in the 1680s. (fn. 90) Many other local landowners were newcomers, however, often with a background in trade or the professions. The Drapers, who acquired Park Place in Remenham by 1642, were brewers and merchants with interests in the Thames malt trade, and typified the new commercial wealth which increasingly displaced older landed families along the middle Thames. Probably they commissioned one of the famous views of Henley and the river painted in the 1690s by the Flemish artist Jan Siberechts, who undertook work for London merchants, bankers and financiers as well as for aristocratic patrons. (fn. 91) At Harpsden Court the long-established Forsters were replaced in the 1640s by the lawyer Bartholomew Hall (d. 1677), a close friend of Sir Bulstrode Whitelocke, (fn. 92) while London bankers such as Sir Robert Clayton (d. 1707) acquired other local estates through skilful financial manoeuvering, often involving offers of credit to impecunious landowners. (fn. 93) In Henley itself, owners of Phyllis Court included the London alderman William Masham (d. 1600), who came from a local family and left £100 to the town's poor. (fn. 94) His successor Sir John Meller, whose father-in-law was another prominent London alderman and lord mayor, was living at Phyllis Court in 1622, when violence erupted during a dispute with fellow townsmen over rights of way. (fn. 95)

Of longer term significance was the arrival of the judge and lawyer Sir James Whitelocke at Fawley Court in 1617, and the family's piecemeal acquisition of the Phyllis Court estate and Henley manor. Thenceforth until the 20th century Henley had resident lords who took an interest in town affairs, living first at Phyllis Court and, from 1768, again at Fawley. (fn. 96) Bulstrode Whitelocke's first legal work was for Henley townsmen, and he later served both as counsel for the corporation and as a governor of the Periam school. A bid for parliament in 1640 was warmly supported by 'the town of Henley and the freeholders thereabouts', and his local influence is suggested by an attempt to involve him in promoting a new type of malt kiln in the town. Whitelocke subsequently served as MP for nearby Marlow, and commanded the Parliamentary garrison at Henley during the Civil War. Relations with leading townsmen were sometimes close: in the 1660s he dined several times with the Messengers, and attended formal events such as the warden's feast. (fn. 97)

Festivities and recreation

Henley's traditional seasonal games were suppressed at the Reformation, and thereafter the only regular festivities recorded were exclusive events such as the warden's annual feast in September (held presumably in the guildhall), (fn. 98) or the annual dinners provided for governors of the Periam school. (fn. 99) More popular games are hinted at in the statutes of the grammar school, which forbad pupils to play football, dice, or cards, or to swim or bathe in the river without the master's consent. (fn. 100) Alehouses, though poorly recorded before the 18th century, were presumably a further source of popular recreation. (fn. 101)

Bowls seem to have been popular among Henley's more prosperous social classes. Charles I 'came to bowls' at Henley (probably at Phyllis Court) in 1647, (fn. 102) and several townsmen owned their own sets. (fn. 103) A house with an attached bowling green in 1638 (sited probably off the Fair Mile) seems to have been an inn or tavern frequented by Henley's social élite; goods in the hall included several sets of bowls belonging 'to diverse gentlemen', (fn. 104) and the Broad Gates inn had a bowling green by 1723. (fn. 105) Other inns had shuffleboards and (apparently) chess boards, complete with their 'men'. (fn. 106) Recreational use of the river is reflected in a two-day boat trip to Hampton Court and Windsor in 1648 by the Whitelockes and their friends the Halls of Harpsden Court, along with the families' servants. (fn. 107)

32. Civil War fortifications at Phyllis Court: a drawing of 1786, allegedly based on a lost original discovered during the house's demolition. Both the earthworks and the house (seen from the north) fit the limited documentary evidence, but the details may be fanciful.

Politics, Civil War, and Revolution

During the 16th and 17th centuries Henley's strong London trade links, combined with its position on the fringe of the county and diocese, contributed to a strand of religious and political radicalism which had a marked effect on the town. Lollardy remained important in the area up to the Reformation, and though Henley's late 16th- and early 17th-century clergy mostly conformed, at least two had Puritan (and in one case Presbyterian) tendencies which were shared by some of the townspeople. The town's Civil War role as a Parliamentary stronghold was largely dictated by its strategic position, but chimed with the political sympathies of some leading inhabitants and of Sir Bulstrode Whitelocke, who went on (despite his relatively moderate views) to hold high office under Cromwell. After the Restoration the south-west Chilterns emerged as one of the main focuses of religious Dissent in Oxfordshire, and though the link with Lollardy remains unclear, the involvement of soldiers from Cromwell's disbanded New Model Army raised establishment concerns. (fn. 108) Similar worries were expressed in the 1680s when, amidst fears of whig plots, the town was singled out as being 'too full of men of those principles', providing 'a more convenient hiding place as lying on the edge of the county'. (fn. 109) None of these tendencies were universal within the town, whose inhabitants also included religious and political conservatives. Nonetheless they reflect the extent to which Henley, like neighbouring towns along the middle Thames, remained firmly within London's cultural and political orbit.

Henley's position between London and Oxford made the town strategically important in the Civil War, particularly after Oxford became the Royalist capital in 1642. Control of the river was considered essential: in 1643 the Committee for Safety of the Kingdom instructed the lord mayor of London 'to consider of some speedy way for guarding the river of Thames', and Parliamentarian scouts reported that provisions were sometimes surreptitiously shipped upstream to Henley for conveyance to Oxford by cart or river. (fn. 110) The town's importance was increased by the proximity of Reading and of fortifiable riverside houses such as Greenlands, both of which became Royalist strongholds until seized by Parliament during 1644. (fn. 111) Henley itself saw a skirmish in January 1643, when Royalists approaching up Duke Street were massacred by cannon fire from Parliamentarians who had just arrived in the town, (fn. 112) and in April 1644 barges from Henley were seized and taken into Reading. (fn. 113) Parliament garrisoned and fortified Phyllis Court in March of that year and again the following spring, 'for hindering the great trade and correspondence between Oxford and London, as also for the well being of Reading and Abingdon, the great supplies of corn and wood for London, and its offensiveness by reason of its nearness to the enemy'. It remained a Parliamentarian stronghold until hostilities ended in 1646, when the defences were slighted. (fn. 114) Charles I briefly stayed there as a captive in July 1647, Bulstrode Whitelocke absenting himself to London. (fn. 115)

Long before it was garrisoned, Henley suffered the comings and goings of both sides. Fawley Court was ransacked by Royalists in autumn 1642, and Prince Rupert had forces at Henley in 1642 and 1643, when a Henley shopkeeper was arrested and a man was hanged from a tree at Northfield End. Bulstrode Whitelocke subsequently complained of pillaging and damage by his own side, including the accidental burning of the Bell Inn in 1644 and malicious damage to his woods and land. (fn. 116) Garrisoning brought new woes, including martial law and mutinous behaviour by unpaid soldiers, (fn. 117) while in 1646 a woman who had complained of mounting taxation allegedly had her tongue nailed to a signpost. (fn. 118) The corporation minute books suggest that routine town business continued, (fn. 119) and Henley undoubtedly suffered less than Reading. Nonetheless the economic dislocation must have been serious. In 1645 the town was 'wholly out of trade', (fn. 120) while the damage to Whitelocke's houses, lands and income caused him long-term financial problems. (fn. 121) Henley bridge, like others in the area, suffered serious damage, but was fairly quickly repaired. (fn. 122)

The town's subsequent political and religious history, combined with the presence of so many prosperous tradespeople with London connections, suggests that there was probably a strong bias towards Parliament. Even so political allegiance may have been mixed. After the war several Henley people were fined for having allegedly helped or consorted with Royalists, some of them possibly under duress, (fn. 123) while in 1655 there was an unsuccessful attempt to replace the town clerk John Tyler with a man claimed to be a 'cavalier'. (fn. 124) An 'aged widow' who had reportedly had her back broken at Henley for her loyalty to the king received a royal pension in 1660. (fn. 125) Whitelocke himself was a committed but moderate Parliamentarian who abhorred the war, and spent much of the 1640s and 1650s pressing for compromise. (fn. 126)

The Whitelockes' political views surfaced again during the revolution of 1688, when on 13 December Bulstrode's son Sir William entertained William of Orange and his retinue at Phyllis Court during the prince's progress to London. There the prince met a deputation of peers, bishops and London aldermen headed by the London banker and former lord mayor Sir Robert Clayton. Sir William's son Bulstrode had been killed at Cirencester the previous month, after a party of horse led by the Whitelockes' friend and neighbour Lord Lovelace was intercepted by loyalist militia. The double rainbow in one of Siberechts' later Henley paintings, possibly part-commissioned by Whitelocke, may recall the family's role in the revolution in symbolic form. (fn. 127)

Some townspeople shared the Whitelockes' views. Government suspicions of subversive whiggism in the town were confirmed in 1683, when pistols and swords were found hidden in a bag of meal; the owner was one Flight, whose brother lived in London, and who was perhaps related to the Henley maltster Thomas Flight (d. 1679). Another prominent Whig, probably also a maltster or brewer, was Adam Springall (d. 1707), one of a leading Henley family who served several terms as town warden, and who was on friendly terms with Lovelace. (fn. 128) The strength of radical religious Dissent in late 17th-century Henley suggests that such views may have been common, and the presence of a large barging community perhaps further strengthened the town's whiggish politics. Oxford bargemen were closely associated with whiggism throughout the late 17th century and the 18th, and in 1640 Marlow bargemen strongly supported Sir Bulstrode Whitelocke when he stood for parliament there. (fn. 129)

Corporation records give little insight into more routine town politics, save for occasional opposition to the corporation's authority. (fn. 130) In 1625 William Gravett complained of 'certain busy factious-headed fellows' who had allegedly set themselves against the warden and burgesses, and hoped that his charitable bequest to the town would ensure that they 'can better maintain their authority in future and punish offenders'. (fn. 131) Personal rivalries may have also underlain a complaint in 1631 that some capital burgesses were being elected without progressing through the lower town offices, contrary to precedent. (fn. 132) More colourfully, opposition to poor rates led to the imprisonment of a Henley glover in the town hall in 1643 following an assault on the constables and overseers and 'uncivil speech in the face of the court', during which he allegedly declared that 'he cared not a fart what they could do unto him'. A Henley brazier apologized for similar 'scandalous words' against the corporation a few months later, having accused them of being 'knaves and fools' who 'made rates money and put the overplus in their own purses'. (fn. 133) In both cases the disruption of the Civil War and exceptionally heavy taxes presumably played a part.

Education to 1700

Two endowed schools set up within a few years of each other in the early 17th century catered for differing local needs. The grammar or free school (formally established in 1604) replaced the existing 15th- and 16th-century school, and pursued a predominantly classical curriculum aimed at the sons of local gentry or of Henley's more prosperous merchants and traders. The Periam or Bluecoat school, founded in 1610, prepared the sons of Henley's poorer tradesmen or craftsmen for apprenticeship, concentrating on reading, writing and accounts. (fn. 134) Both were accommodated in the so-called Chantry House between the churchyard and the river, which was used as a school house by the 1550s and which was sold to the warden and corporation in 1578. From the early 17th century the grammar school occupied the top floor and the Periam school the middle one, which opened onto the churchyard. (fn. 135)

The grammar school was under consideration by 1602, when the Rotherfield Peppard farmer Augustine Knapp left £200 to the warden and corporation for the purchase of lands worth £20 a year, to be used within two years as an endowment. Following a 'humble petition' from the inhabitants, the school was founded in 1604 under the auspices of James I, who allowed rents totalling £11 17s. 4d. from confiscated church obits and chantries in Henley to be added to the endowment. (fn. 136) The warden and corporation conveyed the Chantry House to the newly appointed school governors the same year, together with an associated storehouse stretching eastwards towards the river, and, on later evidence, wharfage rights adjoining the Red Lion, for which rents were received in the 17th and 18th centuries. (fn. 137) In 1625 the lawyer William Gravett, then of Lyon's Inn in London, left additional property in New Street and South field in support of the schoolmaster, (fn. 138) and by the 1770s the school's income was over £80, more than half of it (£44 4s.) from Gravett's bequest. (fn. 139)

James I's foundation charter set up a governing body of 13 with power to acquire property, elect successors, and appoint and dismiss the master and usher. The first appointed governors were typical, comprising local gentry such Sir William Knollys and Francis Stonor (of Greys Court and Stonor Park), the rector Abraham Man, and leading Henley townsmen such as John Kenton, Thomas Cleydon and Henry Thackham, of whom most served at least once as town warden. (fn. 140) Statutes were drawn up in 1612, approved by the bishop of Oxford. The master was to hold a university degree, be well versed in Latin and Greek, and hold 'sound' (i.e. Anglican) religious views. The assistant master or usher was to be a competent grammarian and Latinist, preferably with a degree. The latter also taught arithmetic, 'fair' writing in secretary and Roman hands, and accounts 'to those who desire to be instructed in the same', but such practical training was secondary: no pupils were admitted who could not already read competently, and those in the highest form were to converse in Latin. Religious instruction featured prominently, with pupils taught from the authorized catechism and required to attend church 'reverently' on Sundays and feast days. Parents or sponsors paid fees of 4d. a quarter (or 6d. if they lived outside the town or parish), plus an 18d. entrance fee. (fn. 141) All or most of the 17th-century masters appear to have been graduates, and some were local: Alexander Gregory (master in 1623) was the rector's son-in-law. Their effectiveness varied, however. Henry Monday (d. 1682) reportedly spent much of his energy on 'physic' and writing learned books, while in 1700 a successor was dismissed for absence. (fn. 142)

The Bluecoat school, for 20 'poor scholars' from within the town, was founded by Dame Elizabeth Periam (d. 1621), who following her husband's death lived at Greenlands in Hambleden (Bucks.). As a daughter of the lord keeper Sir Nicholas Bacon she belonged to an important political family with a keen interest in education, and went on to found two scholarships at Balliol College, Oxford. (fn. 143) As with the grammar school, religious orthodoxy featured prominently: the master was to take the Oath of Supremacy and could be dismissed for promoting unauthorised doctrine, while pupils were to recite the Creed, Lord's Prayer and Ten Commandments daily, and attend church as a group. In other respects the curriculum differed fundamentally, with 'grammar learning' expressly forbidden in favour of reading, writing, arithmetic, and accounts, so that pupils 'may be fitted to be apprentices'. In this the school had some success, apprenticing at least 120 boys between 1624 and 1659: of those, 47 were apprenticed in Henley or Rotherfield Greys and as many as 38 in London, with a handful going to other towns including Reading, Wallingford, and even Winchester and Ongar. By the time of apprenticeship the majority had been in school for five or more years (from the ages of 9 or 10 to between 14 and 17), which presumably made them attractive to prospective masters. Some may have been genuinely poor, although as several were subsequently apprenticed to their own fathers (including carpenters, a glazier, and a locksmith), they presumably came from relatively solid backgrounds. Nonetheless parents were not expected to contribute to costs, and were helped with maintenance. Every pupil received a new uniform at Easter and a 12d. gift on Childermas Day (28 December), while 20s. a year was allowed for school heating, and another 20s. for paper, pens and ink. Schoolmasters were required to be a childless bachelor or widower, but otherwise no formal qualifications were laid down. Henry Buck (master c. 1627–41) was a local man who supplemented his income as a scribe, while John Tyler (c. 1649–56) apparently also served as town clerk. (fn. 144)

The school's institutional organization was similar to that of the grammar school. A body of governors set up under statutes of 1610 and 1618 comprised the town warden, the rector, and up to 12 or 13 feoffees of the school's lands; the first feoffees included Periam relatives, the rector of Fawley, and local gentry, succeeded later by (amongst others) Bulstrode Whitelocke and William Knollys (d. 1664) of Greys Court. Like the grammar school governors they had power to receive and administer rents, and to appoint and dismiss masters. The initial endowment comprised property worth £60 18s. a year at Remenham and Skirmett, plus profits from a 24-a. wood in Nettlebed. The Remenham land (Bottom House farm) was exchanged c. 1732 for a £100 fee farm from Park Place in Remenham, and by the 1770s the endowments yielded £134, as well as income from £800 South Sea annuities. (fn. 145)

Almshouses, Charities, and Early Poor Relief

From the mid 16th century to the late 17th Henley benefited, like many towns, from charitable bequests by leading townsmen. Most set up bread, clothing or apprenticeship charities, and three separate almshouse foundations together accommodated 22 old people. A few bequests were of money for investment, but the majority comprised gifts of property or rents in the town and elsewhere. Usually these were conveyed to the warden and bridgemen, or sometimes (after 1568) to the corporation, which administered its charitable property alongside the existing 'bridge rents'. For the most part the charities seem to have been well run, though by the early 19th century the bridgemen's joint responsibility for church, bridge, and eleemosynary charities was creating some confusion. The corporation also oversaw the town's more formal duties of poor relief under national legislation, appointing collectors or overseers and apparently auditing accounts. (fn. 146)

Almshouses

The late medieval almshouse was refounded by John Longland (d. 1547), bishop of Lincoln, who was born at Henley. New arrangements were in hand by 1538, and by his will Longland left £10 for the purchase of land as an endowment, both for upkeep of the buildings, and to provide 4d. a week each for three female and five male inmates. All were to hold orthodox religious beliefs and perform specified daily devotions. Like the town's other charities the almshouse was administered by the guild or corporation, to which land in Windsor was conveyed by Longland's executors in 1566, and which by the 1580s annually appointed two almshouse overseers. Charitable bequests by William Barnaby (d. 1587) and Robert Kenton (d. 1584) augmented the inmates' allowances by a total of £4 4s., and by the 1820s the almshouses' total income was £190, mostly from the Windsor property. Another 5 a. in Rotherfield Greys may have also formed part of Longland's endowment. (fn. 147)

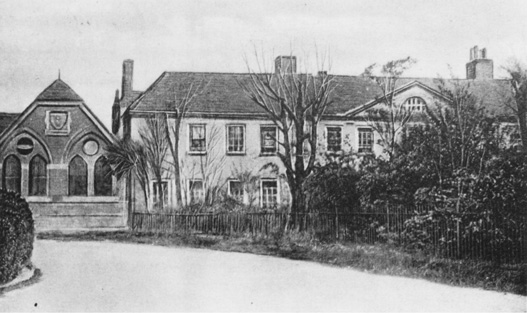

33. The Longland almshouses in 1827, looking north-west towards the church. The buildings were demolished in 1829–30 (partly for road widening), and replaced by almshouses facing into the churchyard.

Until 1829 the premises stood on the south side of Hart Street opposite the church, between the rectory house and the waterfront. (fn. 148) The women were at first accommodated in the 'old house', which adjoined the hermitage near the bridge; possibly it stood on or near the site of the Angel on the Bridge inn, which later formed part of the almshouses' endowment. The five men occupied the 'new house' built close by, apparently on the site of the Hart Street houses given to the guild by William Pykard in 1453 (above). (fn. 149) The almshouses seem to have been remodelled in the 17th century and again in 1723, and by the 1820s were arranged around a courtyard, with a pump in the middle and a carriageway through to Hart Street on the north (Fig. 33). (fn. 150)

The admission of two Henley men to Ewelme Hospital in 1666–70 (supported by town testimonials) suggests that local provision remained inadequate. (fn. 151) An additional almshouse for 10 people was set up in 1665 by the maltster Humphrey Newbury (a victim of the plague), who by his will left £200 and houses on Duke Street, Hart Street and Market Place as an endowment. A plot fronting the churchyard's eastern edge, occupied by a house and malt house, was conveyed to trustees soon after, though the almshouse was not finally erected until 1672. Adjoining it was a separate range for four poor widows, built around 1669 by Ann Messenger (d. 1670), widow of the merchant and sometime town warden Ralph Messenger. A sum of £200 left to trustees by her will was used to buy fee farm rents worth just under £9 a year, and in 1672 another £2 rents were added using a charitable bequest by William Palmer of South Stoke (d. 1598).

The corporation nominated inmates for both sets of almshouses, who were elected by vote. Like the Longland almshouses, the Newbury and Messenger ranges were rebuilt in the earlier 19th century; by then, the inmates' weekly allowance had been supplemented by income from the Longland endowment or from other town charities, in an attempt to make the town's almshouse provision more equitable. (fn. 152)

Poor relief and other charities

Between 1539 and 1664, another 20 charities for the poor were established by prosperous townsmen or by others with Henley connections. Thereafter new endowments fell off sharply as in many towns and villages, with only four more eleemosynary charities set up before 1800. (fn. 153) The trades of many of the founders are unclear, since their wills described them only as 'yeoman' or 'gentlemen'. John Fowl (d. 1544) was probably a fuller, however, William Barnaby (d. 1587) was a draper, and Robert Shard (d. 1663) was an innkeeper, while some others may have been farmers or maltsters, and John Lewes (d. 1600) served as town warden. (fn. 154) Local gentry founding charities included William Masham (d. 1600), the owner of Phyllis Court, and Lady Periam (founder of the Periam school), while Archbishop Laud (d. 1645), born at Reading, remembered Henley in his will along with Wallingford, Wokingham and New Windsor. (fn. 155)

Henley's charities followed a common pattern. Six were for distribution at the town officers' discretion, while four others provided for doles in money or bread on particular days of the year, including Easter, Christmas, New Year's Day, Lady Day and Michaelmas. Another four were clothing charities providing coats, shifts or shirts, in one case specifically for the blind, lame or impotent. Perhaps surprisingly only two charities (excluding the Periam school) funded apprentices: Archbishop Laud's (endowed with a £50 rent charge on land in Eye and Dunsden), and John Hart's (endowed in 1664 with a £9 rent charge in Easington, which was intended to apprentice 2 boys).

Different again were two charities explicitly aimed at setting the poor to work. Abraham Pocock (d. 1596), yeoman, left £10 to buy hemp, flax, wool and yarn to keep the poor in employment, (fn. 156) while Masham left £100 'that [the poor] may learn to live by their honest labour'. (fn. 157) Probably those produced the 'stock' for the poor administered by the corporation in the early 17th century. (fn. 158) In 1651 the corporation used part of Masham's bequest to buy land on the town's western edge, the remaining cost met from £100 given by Richard Jayes of Reading. Thereafter the rent was paid to the overseers and presumably added to the poor rate, until in 1790 the land became the site of a new purpose-built workhouse. (fn. 159)

Alongside the endowed charities, older patterns of ad hoc almsgiving continued. Poor boxes were mentioned throughout, and in 1640 the church contained four. (fn. 160) Occasionally the corporation donated some of its small fines to the poor box, and in 1620 it ruled that fines from outsiders who traded illegally in the town should go to poor Henley people pursuing the same trade. (fn. 161) Churchmen, too, played a part, the intruded rector William Brice reportedly providing broth on Sundays during the 1650s, and generally proving 'very charitable towards the poor of the parish'. (fn. 162) Numerous other inhabitants (amongst them the earlier rector Abraham Man) made one-off gifts in their wills or during their lifetimes, of which some were quite substantial; (fn. 163) among the more unusual was a gift of 6s. 8d. in 1620 by a pregnant gentlewoman, in return for the rector giving her leave to eat meat on Fridays. (fn. 164) Not all charitable giving was for the poor, however. Townsmen continued to make bequests towards bridge repair, among them William Barnaby (d. 1587) and William Gravett (d. 1625), who respectively left endowments of 13s. 4d. and £2. Robert Kenton (d. 1638) left seven houses on New Street for the same purpose. (fn. 165)

The corporation's minute books contain only sporadic references to more formal poor relief, which may (as in the 18th century) have been dealt with primarily through the vestry. (fn. 166) From the 1580s to 1640s the corporation annually elected collectors or overseers of the poor, apparently audited their accounts, and possibly helped set poor rates. (fn. 167) In 1585 grain and cash for the poor were listed in the corporation minute book, (fn. 168) and the corporation occasionally identified individual candidates for relief, to be helped presumably from charities or the rates. (fn. 169) In 1674 the overseers' total income was c. £106, and their expenditure £103; (fn. 170) by contrast the various clothing, bread and money doles probably yielded less than £15–£20, although Laud's apprenticeship charity represented another £50. (fn. 171) More general charitable income was used to help keep poor rates down. (fn. 172)

The 18th-Century Town

During the 18th century the town's social structure remained fundamentally unaltered, notwithstanding the emergence of some prominent bargemasters and wealthy commercial brewers. (fn. 173) Nonetheless the development of coaching, improved roads, and the Chilterns' much admired scenic beauty attracted increasing numbers of gentry, aristocracy and aspiring middle classes to the town and the surrounding area, transforming its social tone, and initiating its transformation into a fashionable social centre as well as an inland port. Local landowners participating in Henley's social and cultural life included successive lords of Henley manor, alongside neighbours such as the Hodges family of Bolney, the Stevenses and Grotes of Badgemore, and Field Marshal Henry Seymour Conway (d. 1795) of Park Place in Remenham, which was earlier a country retreat for the prince of Wales. Conway was a soldier and politician, though many others were incomers with a background in commerce. (fn. 174) The trend continued into the early 19th century, when the 'beauty of [Henley's] situation' was said to have 'induced many private families to construct ornamental houses', and the surrounding hills were 'interspersed with elegant villas'. (fn. 175)

The town itself remained dominated by prosperous tradesmen, brewers, innkeepers, and retailers, supplemented by new specialist suppliers catering for the growing local éite and passing coach trade. The veneer of professionals also increased, so that by the 1790s there were 4 clergy, 5 surgeons or druggists, and 3 lawyers, along with 5 schoolmasters or mistresses employed at a number of private schools and academies. (fn. 176) The town's development into a sophisticated provincial market and social centre was further reflected in its physical transformation, marked by extensive rebuilding in fashionable London styles, and by large-scale public works including the elegant new bridge. (fn. 177)

Henley as a Social Centre

Charity balls and concerts in Henley are mentioned from the 1750s, and by the 1780s subscription assemblies and balls over the winter season (usually from October to January) were well established. Most seem to have been patronised by fashionable local gentry from outside the town, the sort of people who, like the Powyses of Fawley Rectory, often spent the spring season at Bath, and for whom Henley's winter season became part of the social calendar. (fn. 178) The scale of such events is unclear, though an assembly in 1806, described as 'a very good one', had twenty couples, perhaps the number dancing rather than attending over all. (fn. 179) Some events were in the town hall, but many were held in the more upmarket inns, whose remodelling and expansion in the 18th century reflected not only growing trade from coaching, but their increasing association with the social life of the town and surrounding countryside. A charity ball 'for the benefit of M. Vanscor, a dancer at Drury Lane' was held at the Bell Inn in 1777, (fn. 180) and a supper and ball there the same year filled it to capacity, forcing the landlord to take forty private beds in the town. In 1794 it was rebuilt with 'a spacious ballroom, comfortable sleeping rooms [and] four parlours'. A gentleman's club at the equally fashionable Red Lion met regularly by the 1790s. (fn. 181)

By far the grandest social event was a 'gala week' sponsored by Lord Villiers, the tenant of Phyllis Court, in January 1777, and attended by 'so great [i.e. fashionable] a crowd ... [as] you don't often see in the country'. Inns and country houses were filled to capacity, and grand suppers and balls running into the small hours were held both at the Bell and at Fawley Court, where ninety two (including prominent members of the aristocracy) sat down to supper. Musicians included 'the best from Italy', and plays were staged at an improvised theatre at Bolney Court. Ordinary inhabitants were largely excluded, and though one play rehearsal was opened to Hodges' tenants and 'many of the townspeople of Henley', the benefits to the town were largely economic. Never before (wrote Caroline Powys) 'was it so gay or so much money spent there', while 'provisions rose each day immoderately'. (fn. 182) The gala was exceptional, but Powys's diaries also describe a more routine round of balls and dinner parties at local country houses, in which families such as the Grotes and Freemans participated. (fn. 183) The Freemans also owned a pleasure boat with awning and curtains, on which guests enjoyed a 'delightful water party' in 1795. (fn. 184) In addition, coaching brought in a more transient population of gentry and notables. Visitors to the Red Lion reportedly included the lexicographer and wit Samuel Johnson and (in 1788) George III, (fn. 185) who was also a regular visitor to Sambrooke Freeman at Fawley Court. In 1785 the king and his party dropped in unexpectedly on the dowager Sarah Freeman at Henley Park, to the general excitement of the neighbourhood. (fn. 186)

Professional and amateur dramatics (performed by hired or travelling players or by local gentry) were integral to the assembly season, and some performances in the town may have had a more popular audience. In 1765 Foster's Company of Comedians played there for two months in the summer, (fn. 187) and in 1798 the theatre impresarios Sampson Penley and John Jonas staged a season at the Broad Gates inn at Market Place. In 1805 they established a purpose-built theatre on New Street (the future Kenton Theatre), at which Caroline Powys witnessed performances 'as capital ... as any I've seen in London or Bath'. By 1812 (when a bargemen was fined for throwing a quart mug of beer into the pit) its social character had evidently changed, and it closed the following year, having latterly been only 'tolerably well attended a few weeks of the year'. (fn. 188) A slightly earlier theatre at Wargrave (open 1788–92) proved equally popular with local gentry, and possibly with Henley townspeople. (fn. 189)

Occasionally there were more public celebrations. In 1789 the king's recovery was marked by illuminations, a public dinner in the town hall, and distribution of beer to the populace, while the corporation hosted a tea and ball 'for the ladies'. (fn. 190) A state visit in 1814 by the Prince Regent, Czar Alexander I, and the king of Prussia (en route to Oxford) also attracted large crowds. (fn. 191) More regular events included the mayor's annual feast, for which fish was provided by the tenant of the corporation's fishery. (fn. 192) For many inhabitants, however, entertainment presumably revolved around the increasing number of pubs and alehouses, with their skittles, 'five farthings', and ubiquitous card games. Even at such well-appointed inns as the White Hart illegal backroom gambling seems to have been common, sometimes for high stakes. (fn. 193) Organized sport is poorly recorded before the 19th century, though in 1766 a team of Henley 'gentlemen' played cricket against a family side from Rotherfield Peppard, and in later years against Wokingham, Reading and Sonning. (fn. 194)

A final aspect of the area's social life was the scientific interests shared by landowners such as Sambrooke Freeman, Field Marshall Conway, and Thomas Hall of Harpsden, and by Henley's Congregationalist minister Humphrey Gainsborough (d. 1776). Gainsborough, brother of the painter Thomas, was an engineer of note, whose numerous inventions included a tide mill, a condensing steam engine, a refrigerated fish wagon, a drill plough, and timepieces, and who was closely involved in local road and river improvements. Hall (a fellow Congregationalist) may have provided a workshop at Harpsden, and Gainsborough corresponded regularly with Freeman, whom he called his 'good benefactor'. Gainsborough died universally respected, a symptom of the extent to which the Congregationalists were by then an accepted part of Henley society. (fn. 195)

Government and Politics 1700–1800

Though the charter of 1722 revised the mechanics of town government, (fn. 196) the mayor, aldermen and burgesses of the new corporation were drawn from the same leading townsmen as earlier. Members in 1765 included the draper William Newell (as mayor), the attorneys Thomas Newell and Thomas Cooper, the brewers John Blackman and Richard Hayward, the innkeeper Edward Prascey (tenant of the Red Lion), the builders Benjamin and William Bradshaw, and the ironmonger and maltster Thomas Sanders. Membership was similar in 1794, when the mayor was the grocer and tallow chandler John Allen, and members included brewers, grocers, an attorney, a druggist, a saddler, and the sail-cloth and sacking manufacturer James Orme. (fn. 197) No bargemasters appear to have been corporation members, and Nonconformists were excluded from office until repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts in 1828.

As earlier, corporation members called themselves 'Mr' or 'gentleman', and corporation events were attended with some display. The two serjeants at mace appointed under the new charter were each provided with a laced hat, and the charter itself was to be received 'in a public manner', with an entertainment provided by the mayor. (fn. 198) In the 1790s the corporation had its own locked pews in the church, (fn. 199) where they presumably sat in order of rank; numerous other leading townsmen also had private pews, which were numbered and regulated by the churchwardens. (fn. 200) The corporation's influence in the town was enhanced not only by its continuing control of town charities but, after 1722, by its right to hold quarter sessions and a weekly small-claims court. (fn. 201) The vestry (which dealt with poor relief as well as church affairs) included most of the same prominent burgesses and aldermen, and sometimes local gentry. Gislingham Cooper (who acquired Henley manor) attended regularly in the 1720s, while later members included John Raine and Capt. Stevens of Badgemore House. In 1790 Strickland Freeman (then lord of Henley) served on a committee overseeing the new workhouse, while his predecessor Sambrooke Freeman contributed to improvements at the church. (fn. 202)

Relations between the town and lords of Henley manor were not always harmonious, however. In particular there were long-running disputes over Thames fisheries and ownership of the waterfront, which came to a head when the corporation embarked on improvements to landing facilities and embankments. Around 1700 Sir William Whitelocke forced the removal of a campshot built without permission outside the Red Lion, (fn. 203) and from 1786 there was protracted litigation with Strickland Freeman over fishing, riverside encroachments, and loading rights. Freeman sued both the corporation and the owner of the Red Lion and its granaries, Barrett March, and fell out with the bridge commissioners who, in 1787, threatened to cut down stakes demarcating the riverside areas claimed as manorial waste. Armed with the Bridge Act of 1781 (which authorized improvements to the approach roads), the corporation seems to have won its case. (fn. 204) Membership of the bridge commission had already prompted tension with Sambrooke Freeman and other local landowners, who demanded what the townspeople saw as excessive representation: in 1781 the corporation declared that it would prefer 'to have the whole matter dropped, as they certainly think themselves better judges of the interest of the town than neighbouring gentlemen can be'. In the end they accepted 16 external landowners from Fawley, Badgemore, Rotherfield Greys, and further afield, though as the corporation had block membership it retained a small majority. (fn. 205) In such circumstances, town attorneys may have sometimes had divided loyalties. Thomas Cooper (d. 1788) served both as town clerk and as Sambrooke Freeman's manorial steward, while he or his son Thomas was also clerk for the bridge commission. (fn. 206)

Despite Henley's Whig traditions, voting in the contentious 1754 Oxfordshire election was mixed, with only a narrow majority (around 53 per cent of the vote) for the Whig or New Interest candidates. Old Interest (or Tory) supporters included the builder Benjamin Bradshaw, the wharfinger Richard Eylsey, the innkeeper and bargemaster Robert Usher, and Gislingham Cooper, who in 1753 entertained around 180 local gentry, clergy and freeholders at Henley. The New Interest was powerfully represented, however. The 2nd earl of Macclesfield, father of the New Interest candidate Viscount Parker, was high steward of Henley, and two months after Cooper's entertainment staged an even larger treat, at which 800 were said to have been entertained 'in the town hall and at several public houses'. Both New Interest candidates canvassed in Henley on several occasions, and Sambrooke Freeman (who lived outside the county at Fawley Court) became involved in controversial campaigning on their behalf. Several prominent townsmen ultimately voted for the New Interest, among them the brewer John Blackman and the future brewer Richard Hayward. (fn. 207) Lord Macclesfield, whose father had reportedly helped secure the new charter in 1722, (fn. 208) maintained his family's interest in the town beyond the election, serving as governor for the grammar and Periam schools. (fn. 209) Even so an Old Interest club was still holding quarterly meetings at the Bell in 1761. (fn. 210)

The corporation's loyalty to king and constitution was demonstrated in 1792, when, amidst fears of invasion and insurrection, it issued a declaration of support and undertook to suppress 'all seditious and inflammatory publications'. The statement was circulated to every publican, and the constables were instructed to notify the corporation magistrates of unlawful meetings or handbills. (fn. 211) Two years later the corporation voted 50 guineas towards internal defence of the kingdom, though when troops were quartered in Henley in 1796 it nonetheless declared them 'a very great inconvenience', and petitioned the War Office for their removal. (fn. 212) In 1795, when exceptional corn prices prompted fear of bread riots, the corporation was quick to seek the support of local cavalry and militia, though in the event none was needed. Five years later it tempered its response, regulating bread prices and promoting soup kitchens and grain distribution, while simultaneously warning that such initiatives would end 'on the appearance of any tumult or riot'. (fn. 213) The threats were not wholly imaginary, since in March 1800 the mayor received a letter threatening to burn the town if bread prices were not lowered. (fn. 214)

A more routine concern with law and order was reflected in various anti-crime and prosecution societies mentioned from the 1750s, including (in 1757) an annual subscription scheme for prosecution of murderers. (fn. 215) Occasionally the Henley quarter sessions committed felons to Oxford Castle, some of them for corn or sheep stealing rather than domestic burglaries. (fn. 216) Highwaymen remained an occasional threat: post-chaises travelling from Bolney to Henley for the 1777 gala were stopped by highwaymen looking for diamonds, and twenty years later Caroline Powys's husband was robbed four miles outside the town. (fn. 217)

Education 1700–1800

Educational provision was supplemented by several new schools during the 18th century, of which most were unendowed private academies catering for local gentry and for the town's more prosperous inhabitants. A boarding school for young ladies was mentioned in 1782, and a school at Northfield End (run by a clergyman) in 1783. (fn. 218) Ten years later there were three young ladies' boarding schools and another for gentleman, and three other inhabitants were listed as schoolmasters. (fn. 219)

Rather different was the so-called Green or Greencoat School, set up in 1719–20 to clothe and provide basic education for eight poor children (four boys and four girls). In recompense for the children's lost earnings, each parent was to receive an allowance of up to 40s. a year. The founder was the London mercer John Stevens, probably a native of Henley, whose £1,000 bequest was used to buy a £40 rent-charge on New Mills in Rotherfield Peppard; the endowment was supplemented in 1765 from a £100 bequest by Thomas Stevens, one of the trustees. Money in hand was invested in South Sea Annuities, the income used to pay the master and mistress, to provide uniforms, pens, papers, bibles and prayer books, and to pay the parents' allowances. All the pupils learned reading, writing and arithmetic, and the girls learned spinning, knitting and sewing; the number of children benefiting was increased to twelve in 1818. (fn. 220) The establishment of a Sunday school in 1780 may have further benefited rudimentary education for poorer children. (fn. 221)

The grammar and Periam schools continued separately until the 1770s, but with mixed results. The grammar school was largely irrelevant to the town's needs, and suffered from inadequate or neglectful masters: by 1758 only five boys attended, and there was no money for repairs. Numbers at the Periam school were limited by the terms of its foundation, and in 1778 the two were combined by Act of Parliament as the United Charity Schools of Henley. A new body of governors was set up including the rector, mayor, recorder and senior justice of Henley, and the schools were reordered as an upper school (to be taught by a master in holy orders who was versed in classical languages), and a lower school (to be taught reading and arithmetic by a master and usher). Numbers at the upper school were limited to 25 under the age of 14, who had to be able read, write and cast accounts before admittance; the lower school was limited to 60, of whom 20 (designated Lady Periam's boys) received various allowances from the Periam bequest, and could stay until age 16 or 17. Four of the Periam boys were to be apprenticed every year. Quarterly fees (excluding entrance payments) were 1s. 6d. for the upper school, and 6d. for the lower.

Both schools moved probably in 1792 to newly acquired premises on the south side of Hart Street, opposite the church, (fn. 222) with a house provided for the master of the upper school. Despite improvements the links between the schools steadily weakened, and in 1805 the lower school was moved into neighbouring buildings. By 1819 numbers there had fallen to 40, partly through competition from the new National school, though pupils were well taught, and Periam boys were apprenticed 'when their parents could procure them masters'. The upper school had become almost a private academy, teaching 13 boys for annual fees of 4 guineas each. Nine of them were learning Latin and Greek, but none had come up from the lower school as originally envisaged. (fn. 223)

A 'parish library' was bequeathed to the town by the rector Charles Aldrich (d. 1737), who stipulated that neighbouring clergy and anyone paying church rates could borrow books. The library seems to have remained in the rectory house until 1777, when shelves for it were put up in the vestry room in the church. The collection chiefly comprised Greek and Latin classics, books in Hebrew and oriental languages, and theological works, and even in 1813 was 'little if ever used by the inhabitants'. It was finally sold off in the 1940s, having been stored in various places after the vestry was altered in 1883. (fn. 224)

Poor Relief and Workhouses

Controlling poor rates became a dominant theme of town government during the 18th century as the cost of poor relief rose. Total annual expenditure by 1775–6 was over £740, and in 1783–5 an average of £1,000. (fn. 225) This was higher than for most Oxfordshire towns, both as an absolute sum and per head of population, although expenditure also included the rural part of Henley parish. By 1725 and possibly earlier, rate-setting and general policy was overseen by the vestry; the new corporation's role was confined to charity administration and occasional use of its property. Day to day business was jointly managed by the overseers and churchwardens or bridgemen. (fn. 226)