A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Henley: Urban Economic History', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp78-104 [accessed 9 May 2025].

'Henley: Urban Economic History', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online, accessed May 9, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp78-104.

"Henley: Urban Economic History". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online. Web. 9 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp78-104.

In this section

URBAN ECONOMIC HISTORY

Medieval Trade and Economic Life

Like those of most small towns, Henley's inhabitants were engaged in a range of craft and service occupations. The town provided a market for its inhabitants and hinterland, and for traders from local towns and more distant centres. It also functioned as a trading port, becoming a trans-shipment point for goods transported between London and places beyond the Chilterns, and in particular supplying London with grain and wood. London's influence was most intense between the 1290s and the Black Death, when its population reached its medieval peak and numerous London corn- and fishmongers established a base in Henley. Thereafter the pattern of grain-exporting from Henley altered: Londoners were little involved, and for much of the 15th century Henley was also a wool-exporting centre, trading partly through Southampton. Grain-exporting to London revived in the later 15th century, as London's population began to grow again. Other occupations in Henley changed slightly in response to local farming and purchasing power. Tailors and tanners, for example, were seemingly more numerous by the late 14th and 15th centuries, while carpenters, too, became more numerous in the 15th century.

Economic Life to c. 1350

Trade, occupations, and hinterland

The provision of a large planned market place suggests that Henley's weekly market existed from the town's creation, though it is not recorded until the late 13th century. (fn. 1) A fair was granted between 1199 and 1204, (fn. 2) and a pavage grant in 1205 authorised the levying of tolls, (fn. 3) while the transport of royal plate from Henley to Oxford in 1205, sent presumably to Henley by river, suggests that the town was already used for commercial trans-shipment of goods between the London and Oxford areas. (fn. 4) Otherwise Henley's early economy is obscure until ampler sources become available in the later 13th century.

By 1300 Henley's population included craftsmen, victuallers, labourers, and traders. (fn. 5) About 30 occupations are recorded, a number characteristic of unspecialised English medieval small towns. (fn. 6) Victuallers included bakers, cooks, and fishermen, while craftsmen included workers in metal, wood, leather, and cloth. Metalworkers were mostly smiths, though a bell-founder and goldsmith are also recorded. Woodworkers included coopers, a carpenter, wheeler, and shipwright, while leatherworkers comprised tanners, skinners, shoemakers, glovers, and a saddlemaker. Fullers, dyers, tailors, and a repairer reflect clothworking, and two potters and a tiler were also noted. Traders included spicers, chapmen, a herring man, and a merchant. A small group had transport occupations, including carters, a sumpter (or packhorse-driver), boatmen, and porters, while others (including parkers, a gardener, and a reeve) had rural or administrative occupations perhaps associated with Henley manor.

Henley's hinterland lay mostly in Oxfordshire, extending westwards to the Thames, across the Chilterns to Cuxham (10 miles), and northwards to Chinnor (11 miles). It also encompassed five Buckinghamshire parishes, including Medmenham (3 miles), and land in north-east Berkshire between Remenham and Hurley (4 miles). In all it comprised around 36 parishes covering 142 square miles, encompassing the vale below the Chiltern scarp, and the Hambleden valley. (fn. 7) People from towns and market centres in the Henley region also traded in the town. A manor court roll of 1332–3 mentioned people from Reading, Wallingford, Abingdon, and Aylesbury, together with the market centre of Wargrave (Berks.). (fn. 8)

Grain exports and long-distance trade

From the later 13th century Henley was among the places powerfully affected by London's increasing grain requirements, and became the city's most important inland supply centre. (fn. 9) Between c. 1295 and c. 1350, 24 Londoners (including some important merchants) are known to have been involved in Henley, of whom a dozen were operating there c. 1320. (fn. 10) Many belonged to London's cornmongers' and fishmongers' guilds. One of the earliest in Henley, in the late 1290s, was Adam of Fulham, the first fishmonger to become a London alderman, (fn. 11) while another London trader, Adam Wade (d. 1310), was a substantial cornmonger. (fn. 12) At least eight Londoners held granaries in Henley, and the same number held other tenements: (fn. 13) Robert Adrian's property in 1327 included selds or shops, while Adam Wade had a stone house near the bridge. (fn. 14) At least two such people also owned boats (called shouts). (fn. 15) In addition, Henley's position as London's chief grain supplier influenced the economy of estates within its hinterland and possibly beyond. Over half of Merton College's demesne at Cuxham was sown usually with wheat (the most valuable crop), of which 40–50 per cent was sold, the bulk of it carted across the Chilterns to Henley rather than to the larger centres at Oxford and Wallingford. (fn. 16) Demesnes over a large area may have been similarly affected. (fn. 17)

Other commodities traded through Henley are less well documented. Important exports probably included wood and faggots, (fn. 18) while imports were mostly goods for consumption which were unavailable locally. Herrings were probably important: consignments were shipped via Henley to Oxford and Aylesbury (Bucks.), (fn. 19) and London cornmongers and fishmongers who frequented Henley were involved in the Great Yarmouth herring industry. (fn. 20) Other imports probably included salt, wine and household goods, (fn. 21) while millstones were imported via Henley from overseas. (fn. 22)

Despite Henley's considerable trade with London, only three substantial Henley-based merchants are known in the early 14th century. Robert of Shiplake (fl. 1306–33), (fn. 23) who was several times warden of the town guild and paid the largest amount in the 1327 subsidy, (fn. 24) was probably involved in grain-trading, and in 1308–10 owed rent arrears for two granaries. (fn. 25) Thurstan of Ewelme (fl. 1305–16) owed £60 to a Londoner in 1315, and John of Harwell (fl. 1315–58) similarly owed 100 marks in 1317. (fn. 26) The contrast between the numerous outsiders involved in Henley and the few substantial local men suggests that in the early 14th century Henley functioned more as an entrepôt for outside traders than as an inland centre organising trade in its own right.

Economic Life from the Black Death to c. 1420

The sudden reductions in London's population and food requirements caused by the Black Death (1348–9) must have disrupted supply networks and caused a contraction of London's supply area. At least two Londoners with Henley property died in the pestilence, (fn. 27) and as the capital's population began to grow again in the 1350s–60s, earlier supply networks operated by Londoners were not re-established. Only one Londoner bequeathed property in Henley after the Black Death, (fn. 28) and few Londoners appear in Henley property charters. (fn. 29) This disengagement probably reflected the failure of London's population to regain its pre-plague level, and perhaps the City authorities' dislike of middlemen in an age of rising wages. (fn. 30) The London cornmongers' company, for instance, was excluded from city affairs. (fn. 31) Londoners' involvement in the herring-supply centre of Yarmouth (Norf.) similarly ceased. (fn. 32)

Grain-exporting to London nonetheless continued. After the Black Death some leading Henley men acquired granaries, and presumably began (or more likely expanded) grain-exporting. John of Turville (fl. 1349–68) probably inherited a granary from a Londoner in 1349, (fn. 33) while Richard Jory (fl. 1329–60) acquired two granaries in 1354 and probably another in 1359. (fn. 34) William Wakeman (fl. 1354–81) also acquired a granary in 1357. (fn. 35) William Woodhall (fl. from 1350, d. 1358) appears to have been a Londoner who made Henley his base after the Black Death. (fn. 36) These developments suggest that Henley changed from being a place subjected to an unusual intensity of outside demand to a more conventional small town which exported agricultural produce from its hinterland. Information about grain-exporting in the later 14th century is negligible, but Richard Jory's son Reginald (fl. 1377–1414) probably held a granary and may have exported grain into the early 15th century. (fn. 37) Probably some of Henley's grain-exporters owned boats, but evidence is lacking, and the boats themselves were built probably in London and Southwark. (fn. 38)

Other goods were also traded, with wood probably remaining an important export. In 1355 John Fisher of Henley owed money to the London firewood-monger and shout-owner John of Potenhale (fl. to 1368), for whom he was previously a receiver, (fn. 39) and in 1357 Thomas Huberd of Henley had wood from a Wallingford taverner. That connection, and Huberd's dealings with a London vintner, point also to wine-importing, (fn. 40) and in 1398 Nicholas Wylly (fl. 1383–99) owed money to a London vintner and a London fishmonger. (fn. 41) By the 1390s some Henley men were also involved in cloth trading, among them Thomas Clobber (fl. 1363–1433), John Benyn (possibly the skinner John Bevyl), and John Kemp (fl. 1377–1432). (fn. 42) Henley's role as a trans-shipment centre also continued. In 1395, for example, Canterbury College shipped wine from London to Oxford via Henley, (fn. 43) and in 1410–11 New College similarly transported Purbeck marble for its chapel. (fn. 44)

Nonetheless, apart from those already mentioned, few significant traders were based in Henley in the decades after the Black Death. William Cooper (fl. 1341–81), probably a cooper in the 1330s, held land by the 1350s, and may have become involved in more lucrative activity. (fn. 45) Thomas Clobber was a much richer figure in the late 14th and early 15th century, and in 1391 registered a debt of £180 to the Devon knight William Hasthorp. (fn. 46) Nothing is known of his economic activities apart from cloth trading, however.

Victualling and crafts are poorly documented in the late 14th and early 15th century, with only 15 occupations recorded. (fn. 47) Seven tailors were mentioned between 1395 and 1420, along with three men surnamed Taylor, perhaps indicating increased purchasing power within Henley's hinterland. In the same period there were five tanners, and three men surnamed Tanner. Possibly more cattle were being kept locally, their skins processed in Henley.

The Fifteenth-Century Economy: Contraction, Inns and Wool

From the 1420s–30s Henley's population and much of its economy appear to have contracted. Nonetheless new activities (particularly wool exporting) emerged, while others became more important, partly in response to broader changes. Contraction is suggested by several trends, including average numbers of new burgesses, which in the 1420s–30s fell from four to two a year. (fn. 48) Admissions remained relatively low, with yearly averages of only 1.5 and 1.7 in the 1450s and 1480s. (fn. 49) In the late 1420s and 1430s the bridgemen regularly reported deficits at the annual audit of their accounts, a situation that occurred in only two other years, (fn. 50) while revenues from the manor court also fell from £2 6s. 1d. in 1431–2 to £1 4s. 2d. in 1432–3, and remained at a similar level. (fn. 51) Even so, there was sufficient wealth in Henley to allow some significant domestic rebuilding during the 15th century. (fn. 52) One development which may have benefited the town from mid century was the cessation of navigation upstream to Oxford by larger vessels. Though it had probably become increasingly difficult and uneconomical, navigation that far may have continued into the 1440s, finally ending because of mid 15th-century economic depression. If so, this presumably enhanced Henley's role as a trans-shipment point in the late 15th and 16th centuries. (fn. 53)

26. The courtyard of the former White Hart Inn (recorded from 1428–9), looking south towards Hart Street. The existing lodging ranges were built c. 1530–1, incorporating a hall on the west (or right). The former galleries (now filled in) are timber-framed.

Londoners remained little involved in Henley, though debts owed by Henley traders imply that they still bought commodities in London. (fn. 54) The Stonors of Stonor Park imported goods from London via Henley, especially wine and fish, and in the 1470s–80s regularly engaged the London-based bargemen William and John Somers. (fn. 55) Debt cases in the manor court and other references show continued dealings by Henley men with towns such as Reading, Wallingford, Abingdon, and High Wycombe. (fn. 56) Victualling and craft activities also continued, though references are meagre and only 17 occupations are recorded between 1420 and 1490, probably an under-representation. Tailors remained relatively prominent, with seven mentioned between the 1420s and 1440s, and seven tanners and five cordwainers were recorded from the 1420s to 1450s. Carpenters appear to have increased, with seven recorded between 1420 and 1487. (fn. 57)

Provision of inns expanded in the 15th century. By 1430 there may have been three or more: the White Hart was mentioned in 1428–9, and two hostelers in 1429–30, (fn. 58) while in 1438 hostelers were first mentioned as an occupational group. (fn. 59) By the 1440s there were probably at least five inns: the White Hart, three unnamed hostels implied in 1437–8, (fn. 60) and the King's Head, which was acquired by two merchants by 1443 and so named by 1452. (fn. 61) The unnamed hostels probably included some of four inns operating within the next century. The Bull existed by c. 1478 and possibly the 1430s, (fn. 62) while the Catherine Wheel was mentioned from 1499, (fn. 63) and the George between 1518 and 1526, all of them in the eastern part of High Street. (fn. 64) A Lion inn on New Street was mentioned in 1470. (fn. 65)

Wool trading

The most important 15th-century change was the expansion of Henley's wool trade. The central agent was John Elmes the elder (d. 1460), who became one of the wealthiest inhabitants in Henley's history. Admitted as a burgess in 1417, Elmes was probably an immigrant, as his byname was new to Henley. Possibly he came from Wiltshire, where Elmes was a familiar name in the 14th century. (fn. 66) He was involved in wool trading by the 1440s: in 1443 he owed money to a London wool-packer, (fn. 67) and in 1456 he sold 120 sacks of wool (worth £840) to an Italian merchant. (fn. 68) His sources of wool are unknown, but besides the Chilterns may have included the Berkshire Downs and the Vale of the White Horse, where he had personal connections and land. (fn. 69) Elmes traded through Southampton, where in 1454 he held the large warehouse called the Wool House. (fn. 70) This suggests that he was dealing with Italians who exported directly to the Mediterranean.

Elmes also did business with one of Southampton's leading merchants, the draper Walter Fettiplace (fl. from 1412, d. 1449), (fn. 71) from whom he acquired alum and possibly commodities such as wine, fruit, tin and millstones, which were also sent to Henley. (fn. 72) At Fettiplace's death Elmes owed him £312. (fn. 73) A debt of £200 owed to Elmes by a Reading dyer suggests that Elmes supplied dyestuffs and possibly wool to Reading's cloth industry, (fn. 74) and he also appears to have been engaged in trading along the Thames above Henley and in grain-exporting. In 1441 he was a creditor of an Abingdon merchant, (fn. 75) and in 1449 he disposed of a tenement by the hythe in Oxford. (fn. 76) By 1460 he also held the Antelope inn in Wallingford, and two granaries in Henley. (fn. 77)

Elmes was succeeded in Henley by a namesake who was clearly a relative, but apparently not a son. (fn. 78) Though admitted as burgess only in 1462, (fn. 79) the younger Elmes was probably an established merchant before 1460: in 1451 he contributed to the provision of a large mortgage, (fn. 80) and in 1457 married a daughter of William Browne, the leading wool merchant of Stamford (Lincs.). (fn. 81) He was later a member of the Calais staple. (fn. 82) Apparently he discontinued his predecessor's trading through Southampton, disposing in the mid 1460s of his sole known property there. (fn. 83) Nonetheless he continued to trade with London, since a Londoner owed him 80 marks in 1487. (fn. 84) On his death in 1491 he was succeeded by his son William, a lawyer, who from 1493 had little to do with Henley. (fn. 85)

In the mid 15th century other Henley men were connected with wool trading, and the involvement of gentry families in the town suggests that Henley had become a significant wool centre. In 1449 the leading townsman John Logge (fl. 1433–79) was an executor for a member of the Calais staple, (fn. 86) and John Deven (fl. from 1433, d. 1470), another leading townsman, co-owned the King's Head inn with John Elmes the elder. (fn. 87) Gentry with tenements in Henley included two members of the Fettiplace family, (fn. 88) probably Richard Quatremain (d. 1477) of North Weston and Rycote, (fn. 89) Robert Danvers (d. 1467), an agent of Archbishop Chichele in the 1430s and a landowner in Buckinghamshire from 1456, (fn. 90) and two members of the Loveden family, possibly of Long Crendon (Bucks.). (fn. 91) Their presence coincides with a period when many south Oxfordshire gentry were creating extensive sheep pastures and maintaining large flocks: Richard Quatremain, for example, kept 400 sheep in Great Milton in 1474. (fn. 92) When John Elmes obtained two new fairs for the town in 1440, it seems likely that the fair at Corpus Christi (May or June) was specifically timed to facilitate disposal of sheep and purchase of young stock after sheep-shearing. (fn. 93)

Economic Life c. 1490–1700

For the next two centuries London's changing requirements continued to influence Henley's economy. (fn. 94) Demand for grain and probably wood initially expanded with London's population, and, as earlier, involved some leading Henley men, besides providing work for (e.g.) bargemen and porters. From the later 16th century, as London's population growth accelerated, Henley turned to malting like other Thames-side towns, and from the later 17th century it also exported large quantities of meal. Imports comprised mainly foodstuffs and fuels which were unavailable locally, such as salt, salted fish, wine, sugar, and coal. (fn. 95) In addition, the general increase of population and inland trade in England in the later 16th and early 17th centuries stimulated a broadening of economic activity in Henley. New crafts appeared together with some professional occupations, while a particularly unusual initiative was the brief establishment of a glass manufactory.

Expansion to c. 1600

Grain and barging

An expansion of grain-exporting to London was underway by 1493, when the presence of Londoners in Henley for grain-buying was noted. (fn. 96) Sixteen leading Henley men were listed as corn-buyers in 1517, all but one of whom were burgesses. (fn. 97) Richard Brockham, at the head of the list, was Henley's joint wealthiest man in 1524 with goods assessed at £80, and in 1527 bequeathed a granary, three barges and other property. (fn. 98) Corn-buyers, however, also engaged in other occupations. John Fowl, whose tax assessment equalled Brockham's, was a fuller, while the three next wealthiest men in 1524, all listed as corn-buyers, are known to have been respectively a fuller and innkeeper, a glover, and a butcher. (fn. 99) By the 1560s–70s Henley was again a major source of London's grain: 34 per cent of corn shipments recorded in the Bridgehouse corn book in 1568–73 came from Henley, and from October 1573 to March 1574, 43 per cent of London's corn was allegedly imported from there. (fn. 100)

London's resurgence probably also reinvigorated the export of wood. In the mid 16th century farmers at Marsh Baldon (near Oxford) made a large sale of timber to a Henley merchant, (fn. 101) while John Venner, warden 1558–60, supplied wood to a London woodmonger. (fn. 102) In 1559 London's governors obtained authority to seize wood at Henley and elsewhere after merchants had allegedly restricted supplies. (fn. 103)

The revival in export of bulk goods from Henley must have required an expansion in river transport, which presumably increased employment for bargemen. Probate documents survive for six Henley bargemen between 1563 and 1574, and another two were mentioned; (fn. 104) recorded wealth ranged from c. £6 to c. £79, (fn. 105) the higher amounts being comparable with the wealth of modestly prosperous farmers. (fn. 106) One owned a quarter share in a barge called the Dragon, (fn. 107) which implies participation in a barge-owning partnership, and possibly receipt of a share of profits. Two bargemen in 1587 likewise owned a quarter of a barge each, the two other part-owners including the Henley-based grain-exporter Michael Woolley (d. 1608). (fn. 108) Most bargemen, however, must have been casual labourers, and large-scale barge owners seem to have been rare at Henley during the 16th century. Apart from Brockham and Woolley, the only known 16th-century example was Richard Cutler (d. 1566), who called himself yeoman and made cash bequests totalling £127. He bequeathed a barge called the Sun, half of a barge called the Peter, and a barge under construction, suggesting an expansive economic climate. (fn. 109) Probably many barges were owned by Londoners and men at other riverside towns.

Cloth and other activities

In the late 15th and earlier 16th century Henley also participated in the widespread expansion of clothmaking. Regulations made for 'foreign' weavers in 1498 suggest that weavers were settling in the town and working outside the authority of a trade organization, and between 1509 and 1511 the borough assembly books contain incidental references to six weavers, a relatively large number. (fn. 110) More pertinently, in the 16th century several prominent townsmen were clothmakers. Robert Kenton (d. 1532), who served as constable, bailiff and bridgeman between 1506 and 1516, was a fuller and inn owner, (fn. 111) while the wealthy fuller John Fowl (d. 1544), mentioned above, held various town offices and bequeathed fullers' shears and tenter racks. (fn. 112) Henry Lewen (warden 1548–50 and 1554–6) also bequeathed fulling shears, (fn. 113) while Robert Rawlyns (warden in the 1540s–50s) was a dyer who probably traded dyestuffs. (fn. 114) Resurgence of the grain and cloth trades also stimulated expansion of Henley's inn accommodation. The George may have opened during the early 16th century, and at the White Hart, lodging ranges were built around three sides of the rear courtyard in 1530–1, providing 22 chambers. (fn. 115) The number of inns remained constant (at around six) until the late 16th century. (fn. 116)

Henley's economic activity in the late 16th century is obscure. Grain- and wood-exporting must have remained important, and some leading towsmen were involved. John Parkes (warden 1590–1 and 1600–1) lived next to the corn market at Henley and sold wheat to Londoners, (fn. 117) and some wealthy predecessors with property in and around the town may have done likewise. (fn. 118) John Farmer (warden 1595–6) was a wheat seller and possibly a wood exporter, as he possessed 7 a. in Lambridge Wood. (fn. 119) The occupations of other leading men suggest that distributive and victualling trades were also expanding, enabling a few individuals to become wealthy and acquire property. William Barnaby (warden 1560–2) was a draper who owned at least ten tenements and a shop, (fn. 120) while Thomas Morgan, a capital burgess from 1568 and twice nominee for the wardenship, was possibly the first innholder to become a leading townsman. (fn. 121) Ellis Webb, warden 1587–8, was a vintner. (fn. 122) Most unusually amongst the town élite, Ralph Wilkes (warden 1594–5) was a shoemaker, although he also owned some property. (fn. 123)

Against these buoyant elements in Henley's economy, some business may have been lost as upriver places challenged Henley's primacy as a trans-shipment point. From at least the 1560s Burcot (near Dorchester) and Culham (near Abingdon) were used to trans-ship goods, presumably to Henley's detriment, (fn. 124) and in 1635 the river was re-opened to Oxford and beyond for large barges, following the work of the Oxford-Burcot commission. (fn. 125) The impact on Henley was presumably outweighed in the longer run by increased exports from Henley's hinterland, generated by London's expansion.

Malting and Other River-Borne Trades c. 1570–1700

Malting

From the late 16th to early 19th century malt production for export was a major trade in Henley. Its expansion was part of a wider growth of malting in Thames valley towns from Maidenhead (Berks.) upriver to Abingdon (formerly Berks.), (fn. 126) creating an additional supply area for London. Malting required investment in buildings, labour and heating, but as malt was lighter than unprocessed grain larger loads could be carried. (fn. 127) Henley's participation started possibly in the 1570s, when stables at the Bull inn were allegedly converted into malting rooms, (fn. 128) and in 1587 'Mr Wolley' (probably Michael Woolley, warden 1586–7) owed money to a bargeman for the carriage of 8 quarters of malt. (fn. 129) In the early 1590s John Kenton was supplying malt to Windsor and London. (fn. 130) By the 1630s Henley was a considerable production centre with at least seven maltsters, some of whom had other interests. (fn. 131) In 1677 malting was said to have been Henley's principal trade for many years. (fn. 132)

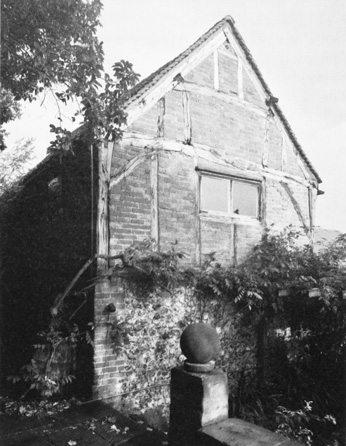

27. Former malthouse or hop-drying kiln behind 57/59 Market Place, apparently inserted into an earlier timber-framed outbuilding which was underbuilt in brick and flint. Kilns on back plots became widespread in Henley from the 17th century.

The increasing importance of malting is reflected in the growing wealth of maltsters. Specialist maltsters in the early 17th century typically left personal estate worth up to £150, including stocks of barley and malt. (fn. 133) The estate of John Morris (d. 1632), for example, was valued at £131 and included 80 quarters of malt and 15 quarters of barley worth £85. In the week before valuation, malt worth £10 had been sent to London. (fn. 134) Maltsters with other occupations or interests were sometimes much wealthier: William Jennings (d. 1634), for instance, who left an estate worth £411, was a maltster and landowner. (fn. 135) By the mid 17th century specialist maltsters had become very wealthy men. William Elton (d. 1674) left an estate valued at £320 which included 110 quarters of malt and debts owing worth £106, while Thomas Flight (d. 1679) made bequests totalling over £615, and Humphrey Newbury (d. 1666) endowed an almshouse. (fn. 136) The wealth of leading maltsters continued to increase. William Toovey (d. 1710) made bequests worth over £1,050, and owned estates at Pishill and Turville (Bucks.). (fn. 137)

A malthouse was first mentioned in 1632, and a malthouse containing a cistern (for soaking barley) in 1637. (fn. 138) In the late 17th century Dr Plot reported that malt kilns in Henley were heated from kitchen fires, which suggests that some maltings followed a plan recorded in the 19th century, i.e. a row comprising a house, kiln, cistern and malthouse. (fn. 139) Heat from bread ovens was also said to be used for drying malt. (fn. 140) Most maltsters in the 17th–18th centuries operated a single malthouse: (fn. 141) Thomas Goodinge (d. 1698) was unusual in owning three, and leased out two of them. (fn. 142) William Toovey (d. 1725) held two malthouses. (fn. 143)

Other exports and bargemen

Alongside malt, Henley continued to export grain and wood. In 1673 its market was 'considerable' for corn, though barley was the main traded grain, with (allegedly) around 300 cart-loads often sold in a day. (fn. 144) Grain exporting probably became a secondary activity, since several leading maltsters had wheat in addition to barley and malt. Thomas Cleydon (d. 1630), who was three times warden of Henley, held malt, wheat, maslin and barley worth £155, (fn. 145) while in 1674 William Elton had 18 quarters of wheat worth £40. (fn. 146)

Wood-exporting remained a principal activity, (fn. 147) though London woodmongers probably controlled much of the trade and bought directly from landowners outside Henley. (fn. 148) Only two or three Henley-based timber merchants are known in the 17th century. One was George Cranfield (d. 1667), who bought widely in the south-west Chilterns, exported through wharfs in several parishes, and left an estate valued at £384. His stock included worked products such as sections of wheels, casks and transoms for windows. (fn. 149) Another was Ralph Messenger (d. 1668), twice warden, who at his death held 'stock wood' worth £225 as well as 220 quarters of malt. (fn. 150) William Waters, a timber merchant with woods in Henley and Rotherfield Greys, died in 1725. (fn. 151)

The export of meal (ground grain) began in the late 17th century, presumably stimulated like other export trades by demand from London. In 1683 pistols and swords were concealed in sacks of meal, and in 1687 the Henley trader Richard Sanders owned 22 sacks. (fn. 152) Probably meal was produced at nearby watermills, (fn. 153) though there was an enclosed horse mill at Henley in 1692. (fn. 154)

A claim in 1673 that Henley's inhabitants were mainly bargemen and watermen was doubtless exaggerated, (fn. 155) but as earlier many bargemen were based in the town. Their wealth was much as in the 16th century, with probate inventories ranging in value from c. £6 to £96. (fn. 156) Some engaged in other activities. Two each kept a shop (one containing cheese and salt, the other coal), (fn. 157) while another was possibly involved in the malt trade, as in 1632 he had £26 of barley being malted, presumably for sale. (fn. 158) The most valuable 17th-century bargeman's estate, that of Nicholas Savage in 1639, included £80 due from loans. (fn. 159)

Barge owning remained rare in Henley before the later 17th century. The bargeman James Guile (d. 1665) had a quarter share worth £11, (fn. 160) and Humphrey Parkes (d. 1658), who was earlier involved in selling malt, owned an entire barge worth £40. (fn. 161) Barges probably continued to be built in or near London. Henley people certainly had contacts with London boat-builders, as several Henley boys were apprenticed to London shipwrights in the years around 1700. (fn. 162)

Crafts and Services c. 1590–1700

The crafts and services recorded earlier remained conspicuous. (fn. 163) Inhabitants provided food, drink and accommodation as bakers, butchers, vintners, and innholders, and there continued to be a small cloth industry employing weavers, shearmen, and dyers. The dyer Daniel Stockwell was warden in 1626–7, (fn. 164) and numerous tailors worked in the town. In leatherwork there were still tanners, shoemakers and glovers, and in metalwork, mainly blacksmiths. Henley also retained building craftsmen, including carpenters and glaziers. Among distributive occupations, mercers were prominent and included several who served as warden, notably Thomas Bryan (warden 1609–10), (fn. 165) William Springall (1612–13), (fn. 166) and Ambrose Freeman the elder (three times warden 1640–62). (fn. 167) Traders accounted for at least half of the 13 men who issued trade tokens in the late 17th century. (fn. 168)

Provision of inns expanded markedly in Henley in the later 16th and 17th centuries, reflecting a national resurgence of inland trade and development of waggon services. (fn. 169) Three (the King's Head, the George and the Bull) ceased trading, (fn. 170) but the Catherine Wheel and White Hart continued alongside several major new establishments, notably the Bell (mentioned from c. 1592), (fn. 171) the Bear (by 1666), the White Horse (by 1693), and the Red Lion near the church (opened by the mid 17th century if not earlier). (fn. 172) Three or four others opened near the market place, among them the Rose and Crown (mentioned from 1658), the Broad Gates (by 1673), the King's Arms (by 1684), and probably the Seven Stars. In the 1680s the Bear had stables, barns, a brewhouse, and malthouses, while in 1716 the Broad Gates was associated with stables, granaries, an orchard, and a hop garden, replaced later by a bowling green. (fn. 173) Coaches probably started to use inns in the later 17th century, though the first known association of coaching with a particular inn dates from 1717. (fn. 174)

In contrast to inns, alehouses are poorly recorded before the 18th century, and most were evidently short-lived. (fn. 175) The licensing of victuallers and tipplers in 1585 provides an idea of their number, listing 13 men and 1 woman. (fn. 176) Two houses that proved long-lasting through occupying advantageous sites were the George on the corner of Duke Street and Market Place (recorded 1625–1730s), and the Brewers' Arms on the waterfront, which existed by the late 17th century and became the Little White Hart in the 18th. (fn. 177)

New Occupations and Activities

During the later 16th and 17th centuries several new occupations became established in Henley, (fn. 178) some of them representing specialist activities for which there was presumably now sufficient local demand. In leatherwork they included collarmaker and saddler, (fn. 179) while new occupations in metalwork and woodworking included pinmaker, locksmith and brazier, (fn. 180) and hoopshaver and hoopmaker. (fn. 181) Other craft activities included bricklaying (reflecting increasing use of brick), rope making (possibly connected with barge traffic), and basket making. (fn. 182)

Commercial brewing also seems to have expanded, presaging a later trend. An innholder in 1570 owed money to a brewer for beer, (fn. 183) and in 1586 Henley corporation permitted Edward Arden, gentleman, to work as a brewer. (fn. 184) In the late 16th and early 17th century three members of the Woodroffe family were brewers, of whom William (d. 1597) left a brewhouse by the waterside, and Ellis (his son) served as warden in 1617–18. (fn. 185) Later brewers included Humphrey Farmer (warden 1639–40), (fn. 186) Adam Springall (d. c. 1644) of the notable Springall family, (fn. 187) and Abraham Carter, who was both brewer and maltster. (fn. 188) George Munday (d. 1666) owned a 'beer house', and William Benwell was renting a brewhouse in 1672. (fn. 189)

From the late 16th century professional occupations also appeared. A few scriveners were noted from the 1580s, including Francis Buck (d. 1631), (fn. 190) who was a burgess in 1585 and town clerk by 1591. (fn. 191) The earliest known attorney was Solomon Sewen (d. 1707), (fn. 192) who was active from the 1660s (fn. 193) and became town clerk in 1691. (fn. 194) Early apothecaries included Thomas Seakes (d. 1621) and Geoffrey White (d. 1625), of whom the latter (active from the 1590s) was also a mercer. (fn. 195) Later examples included the apothecary and surgeon Edward Stevens (d. 1663), who left an estate valued at £395, and Richard Pickering (d. 1680). (fn. 196)

An unusual development in the late 17th century was the foundation of a glass manufactory. (fn. 197) It was started by George Ravenscroft (1632/3–83), a London merchant and manufacturer who in 1674 patented a kind of lead crystal glass, and in October obtained agreement from the London Glass Sellers' Company to establish a glassworks at Henley for a year. His purpose was evidently to work out how to avoid 'crizzling', i.e. the appearance of fine cracks which made the glass grey and opaque. He and his assistants were possibly attracted to Henley by the availability of white sand at Nettlebed and black flints in the Chilterns, and perhaps also by his connection (as a Roman Catholic) with the Stonors, who reportedly provided a site off Bell Street. (fn. 198) Here Ravenscroft could experiment away from competitors, whilst retaining easy communications with London. He reported in June 1676 that he had solved the crizzling problem; the duration and exact location of his glassworks are unknown, however.

Occupations c. 1700

The structure of Henley's economy from 1698–1709 is clearly visible thanks to the recording of occupations of adult men in the parish register (Table 3). (fn. 199) The largest group was barge workers, followed by those (including maltsters) providing food, drink and accommodation. Barge workers and maltsters together, as chief participants in the river trade, comprised over a third of adult males (36 per cent), a concentration comparable with that found in other towns with a specialist economic activity. (fn. 200) The next largest group was labourers (16 per cent).

Over all, Henley had around 58 occupations c. 1700, about twice as many as were recorded in some well-documented small towns 200 years earlier. (fn. 201) Leather, building and cloth still featured strongly, alongside metalworking, distributive trades and professions. More specialist trades included those of edgetoolmaker, pipemaker, trumpeter, and watchmaker. Among miscellaneous occupations, that of 'gardener' may have included a small group of market gardeners, growing hops and other produce in some of the small plots (known later as Hop Gardens) around the town's western edge. (fn. 202)

Economic Life c. 1700–1800

During the 18th century the main elements of Henley's economy remained largely unchanged, though their relative importance altered especially from mid century. Malting and grain-exporting continued, but the rise of two large breweries in the later 18th century, supplying both the town and its area, probably reduced the amount of malt exported to London. The number of Henley-based bargemen evidently declined, perhaps partly because of reduced malt exports; other possible factors were the increasing size of Thames barges, and greater involvement in Henley's river trade by barges from elsewhere. Notable developments in the town were the growth of coaching, which benefited the major inns and their suppliers, and an increase in the range of distributive trades and shops, presumably to meet demand from a wealthier and more fashionable town and local élite.

River-based Trades and Barge Operation

According to observers Henley's staple trades in the 18th century remained malting and the supply of malt, grain, meal and timber to London, while Henley's inhabitants continued to include maltsters and a few mealmen and timber merchants. (fn. 203) The importance of grain-related trades was demonstrated in the 1780s when the innholder Barrett March built new granaries adjoining the Red Lion, (fn. 204) and in 1787 when March (during a dispute) seized numerous sacks of oats, corn, barley and malt from barges. (fn. 205)

By the mid 18th century many malthouses belonged to outsiders or to Henley residents uninvolved in malting. (fn. 206) One on Bell Street was owned by a shopkeeper, (fn. 207) and one on Hart Street (in 1788) by a Nettlebed gentleman. (fn. 208) Maltsters were often short-term lessees, and some combined malting (which was seasonal) with other occupations. Edward May, who occupied a malthouse and other premises by the market place in 1789, was a maltster and patten maker, while one of Henley's largest malthouses, in Greys Road, was acquired probably in 1782 by a man later described as a maltster, tallow chandler, soap boiler, and grocer. (fn. 209) Brewers also rented malthouses in the late 18th century, and, as commercial brewing expanded, increasingly controlled Henley's malting capacity for their own use. (fn. 210) The changes are reflected by a decrease in the number of maltsters' wills, from a highpoint of 14 in 1720–9 to only five in the 1730s, two in the 1750s, and one in the 1760s. (fn. 211) Maltsters also became less important in Henley society. Of 13 listed in the 1790s none became mayor, and only one (Stephen Bacon) was a burgess. (fn. 212) Exceptionally, the Riggs family's malting business was run by a woman (Mary Riggs) from 1754 to 1770, along with family property in Henley, Clifton and Shillingford. (fn. 213)

Depositions about activity at Henley's wharfs in the 1740s–60s suggest that imported commodities (presumably mostly from London) included raw materials for processing, as well as goods for local consumption. (fn. 214) Coal was of considerable importance: deponents recalled seeing sacks unloaded from barges in the 1740s, and loose coal being packed in sacks for distribution by waggon in the 1760s. Fragile consumer goods such as glass and earthenware were transported to Henley in crates, and tallow was imported for tallow-chandlers in the town and further afield (including Benson). Bundles of flax were possibly for spinning by poor women in the town and surrounding area. (fn. 215) Agricultural crops were also imported along the Thames, probably from both directions, and in the 1750s wheat was taken from the riverside at Henley to Temple Mills at Bisham (Berks.) for grinding into meal or flour. Groceries were imported, and in the 1760s beans were landed for sale in the town.

River navigation remained the basis for Henley's involvement in long-distance trade. From the later 17th century barges were increasingly owned and run by men designated as bargemasters, an arrangement probably encouraged by an Act of 1695 which made barge owners responsible for damage to locks caused by bargemen. (fn. 216) Four Henley bargemasters were mentioned in 1699–1703, (fn. 217) and during the 18th and early 19th centuries there were usually around 3–6 based in the town. (fn. 218) Two generations of the Hale, Smith and Usher families were bargemasters in the early 18th century, (fn. 219) and three generations of the Jackson family in the late 18th and early 19th. (fn. 220) By 1812 there were four Henley barge owners running five barges, while the Henley Navigation Company ran two. (fn. 221) In addition, much of Henley's river-borne trade was carried in barges run by outsiders, operating in the 1750s–60s from Abingdon and Reading in Berkshire, and from Marlow and Wooburn in Buckinghamshire. (fn. 222) The overall number of bargemen in Henley appears to have declined, perhaps as a consequence of the tighter organization of barge operations. No bargeman's will is recorded after 1738, (fn. 223) and there were few bargemen in the 1840s. (fn. 224)

Barge sizes also increased. In the 1720s Defoe reported that vessels operating between London and Reading typically carried between 100 and 120 tons, but by 1767 barges carrying 160–180 tons were using the river, and vessels of 170 tons reportedly operated to Wallingford. (fn. 225) The maximum load of Henley-based barges in 1812 was 133 tons. (fn. 226)

Brewing c. 1700–1800

During the earlier 18th century there were several brewers in Henley, who commonly held an inn or public house and were often wealthy. Charles Brigstock (warden in 1716–17 and mayor in 1749–50) was lessee of the Rose and Crown from 1727, (fn. 227) and made bequests totalling over £600, (fn. 228) while Robert Cluett (d. 1744) owned the Black Horse in the market place and property in London. (fn. 229) John Blackman (fl. 1740s–70s) leased a pub on the corner of Market Place and Duke Street, and acquired freehold property. (fn. 230) During the later 18th century, however, two major businesses developed from similarly sized operations, one latterly run by the incomer Robert Brakspear, and the other owned by the Sarneys. (fn. 231) Both were sustained by the acquisition of inns and pubs run by tenants, and by the 1790s, although some independent pubs and inns possibly still brewed their own beer, no other brewing businesses were listed. (fn. 232)

The future Brakspear business (fn. 233) was started in 1722 by William Brooks (d. 1744), with a brewhouse on the west side of Bell Street behind Merton House. (fn. 234) Brooks acquired the Bear and other property, (fn. 235) and in 1750 his son and successor James (d. 1803) bought a second malthouse on the east side of Bell Street (behind Nos 76 and 78). James was apparently the first Henley brewer to acquire inns and pubs both in Henley and outside. In 1768 he went into partnership with his kinsman Richard Hayward, acquiring more public houses soon afterwards; Hayward bought the business in 1772, granting a half-share to a prominent Henley draper probably to obtain capital. (fn. 236) From 1779 he was assisted by his nephew and godson Robert Brakspear, a native of Faringdon who had previously run an inn in Witney. Brakspear acquired Hayward's share following the latter's retirement in 1795 and death in 1797, and in 1803 acquired the remaining investor's share to become sole owner. Like Hayward and their sometime partner Benjamin Moorhouse, Brakspear served several times as mayor. (fn. 237)

The brewery's chief rival was started probably by Benjamin Sarney in the early 18th century. (fn. 238) In 1739 Sarney sold a brewhouse in New Street (later No. 86) to his relative Daniel Sarney (d. 1747), who also bought the White Hart inn; his relative Peter Sarney accumulated properties around the original site, and c. 1775 leased the business to John Shaw and Robert Appleton, who served several terms as mayor. (fn. 239) Ownership passed on Sarney's death in 1783 to his nephew Joseph Benwell who, like Sarney, left its running to the lessees.

During the later 18th century the two businesses became increasingly competitive, expanding their collections of public houses despite mounting competition from other brewers in the region (e.g. Simonds of Reading, founded 1785). By 1812 Brakspear had 34 pubs and inns, three quarters of them held on lease, while Joseph Appleton (Robert Appleton's successor) had at least ten. From the mid 1790s Brakspear produced c. 6,000 barrels a year, and by 1806 he used three malthouses; nonetheless brewing remained under his personal supervision, with a smaller annual output than that of the pre-eminent firms in some other small towns. (fn. 240) In 1812 Brakspear voluntarily amalgamated with his competitor, leasing his properties for 14 years to Benwell, and selling his stock-in-trade to Benwell's tenant. However, he arranged for his younger son William Henry (then a minor) eventually to enter the business. (fn. 241)

Inns, Coaching and Public Houses

Only three new inns are recorded in the 18th century: the Three Tuns on the south side of the market place (opened by 1713–14), the Bull in North Street (by 1744, though possibly much older), and the White Horse at Northfield End (by 1774). (fn. 242) The expansion of coaching, however, provided a major economic stimulus for some older inns. A frequent service to London ran from the White Hart by 1717, and in 1744 a coach was associated with the Bull. (fn. 243) Both the Bell and the Red Lion were remodelled and extended, and became particularly fashionable, catering probably for private carriages as much as stage coaches. (fn. 244) By the early 19th century, when coaching was at its height, the White Hart was the premier coaching inn, and additional facilities for travellers and horses were provided at the Catherine Wheel in Hart Street, and at the Bear and the Bull in Bell Street, as well as at the Red Lion and Bell. (fn. 245) Presumably there was considerable demand for meals, accommodation, and horse feed.

Three other inns (the Bear, Broad Gates, and White Horse and Star) catered for carriers and waggons: in 1789 the landlord of the White Horse and Star planned to provide horses for hauling barges between Marlow and the Kennett, and waggons for carrying trans-shipped goods. (fn. 246) In addition, numerous alehouses opened during the 18th century, many of them (until c. 1770) situated around the Market Place. In 1800 there were c. 11 inns and 27 alehouses, (fn. 247) some of them possibly still brewing their own beer.

Shops, Services and Crafts

During the 18th century the number and range of retailers expanded, presumably reflecting increased local wealth, new patterns of consumption, and probably transient trade brought in by coaching. (fn. 248) From the early 18th century the main traders were grocers (sellers of spices, dried fruits, sugar, coffee, tea, etc.) rather than mercers: (fn. 249) in 1794 there were 16 grocers, along with three drapers, four linen-drapers and three ironmongers. New specialists appeared particularly from mid century, amongst them the brandy merchant Henry Benwell (d. 1777) and bookseller Christopher Edwards (fl. 1784); (fn. 250) two other brandy merchants and two booksellers were listed in 1794. Retail shops probably also became more prominent from the mid 18th century, as several shopkeepers had wills proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, suggesting wealth and social pretension. (fn. 251) Coal merchants included Catherine Eylsey (d. 1783), lessee of Eylsey's wharf, who was succeeded by her brother Thomas Harris (d. 1794). (fn. 252) Two coal merchants were listed in 1794, together with Richard Wigginton, a bargemaster, timber dealer and coal merchant.

Most established crafts and services continued, and a few new ones appeared. Leatherworkers in 1794 included a tanner, a currier, and eight cordwainers, though glove-making possibly declined: only one glover and a breeches-maker and glover were listed in 1794, compared with six glovers c. 1700. There were no observable changes in building, and textiles remained a small element. Tailors, however, remained numerous, with six listed in 1794. An ironfounder, Richard Darby, was active by the 1770s (fn. 253) and still in 1794.

The appearance of new crafts, like new types of retailer, presumably reflected increased wealth and new fashions. A watchmaker, Edward May, worked in Henley from the 1750s, (fn. 254) and there were three watchmakers by 1794, along with two cabinet-makers of whom one was also an upholsterer. In 1786 the peruke maker and hairdresser John Avery had a shop in Bell Street, (fn. 255) and there were two other peruke makers c. 1794. Craftworkers catering for women included, by 1794, a mantua maker and a milliner and staymaker. Providers of professional and similar services in the 1790s included three surgeons, two druggists and three attorneys, while Henley's first bank was started in 1791 by Messrs Hayward, Fisher and Brakspear, presumably funded largely by money from brewing. It operated in association with a London company, and was closed probably in 1798 after Hayward's death. (fn. 256) By 1794 there was also a pawnbroker.

Economic Life c. 1800–1918

In the early 19th century Henley's two specialist activities declined: malting for export became unimportant, and coaching provision at inns shrank rapidly from 1840 when most long-distance coaches were diverted to new railway stations elsewhere. Although the exporting of grain and wood through Henley continued, (fn. 257) and there were modest developments in the early 19th century (introduction of silk-winding, expansion of financial services), Henley reverted to being largely an unspecialized small town providing a range of services and small-scale manufactures for its inhabitants and locality. In 1852 it was observed that Henley had 'no peculiar manufacture', (fn. 258) and the 1840s–50s seem to have been a stagnant period.

From mid century, however, leisure-related activities such as angling, tourism, and competitive rowing became more firmly established, building on initiatives since the 1820s. Such activities stimulated boat-building for leisure purposes, and the promotion of inns as hotels, developments strengthened by the opening of a railway branch line in 1857. The regatta and tourism flourished most strongly in the later 19th and early 20th century, when Henley has been described as a 'resort town', (fn. 259) and during the same period its population and built-up area expanded on an unprecedented scale, generating considerable employment in building work. The arrival of relatively wealthy new residents further stimulated the expansion of services, attracting, for example, branches of several national retailers by 1914.

Trade, Industry and Services to c. 1850

Malting, barging and coaching

Except for production for local brewing, malting declined in the 1820s–30s. In 1813 it was still regarded as a principal 'interest' in Henley, and 12 maltsters (excluding brewers) were listed in 1823–4; (fn. 260) only nine were noted in 1830, however, and four in 1842. (fn. 261) At least eight malthouses went out of use between 1800 and 1840, (fn. 262) and in 1861 it was observed that numerous houses had disused back buildings, (fn. 263) many presumably malthouses. The decline was allegedly caused by London brewers restricting their malt supply area to East Anglia. (fn. 264) In 1896 there was only one working malthouse apart from three used by brewers. (fn. 265) Barge work, too, provided little local employment by 1841, when only three bargemasters and two bargemen were recorded, (fn. 266) although Robert Webb and Sons still ran a weekly barge to Lambeth until the 1880s. (fn. 267) Soon after, the wharf (north of New Street) was redeveloped. (fn. 268)

Henley's economy was further weakened by the abrupt decline of coaching following the opening of the Great Western Railway in 1839–40. Only four long-distance coaches passed daily through Henley in 1842, compared with over 20 in 1830, and by 1863 there were none. (fn. 269) Inhabitants complained in 1848 that diversion of road traffic caused by the railway had reduced trade and increased the burden of supporting the poor, (fn. 270) and in 1853 Bishop Wilberforce described Henley as a 'very poor and decayed place'. (fn. 271) Inns were presumably badly hit. The Red Lion closed (temporarily) in 1849, and by 1841 the Bell had been reduced to a much smaller establishment (the Bell Tap) in part of the building. (fn. 272)

Brewing to c. 1850

During the 19th century beer production in Henley increased and, as malting declined, became Henley's only significant manufacturing industry until the late 19th century. Brakspears' became one of Oxfordshire's best-known brewers, operating for much of the 19th century alongside the rival Greys Brewery. (fn. 273)

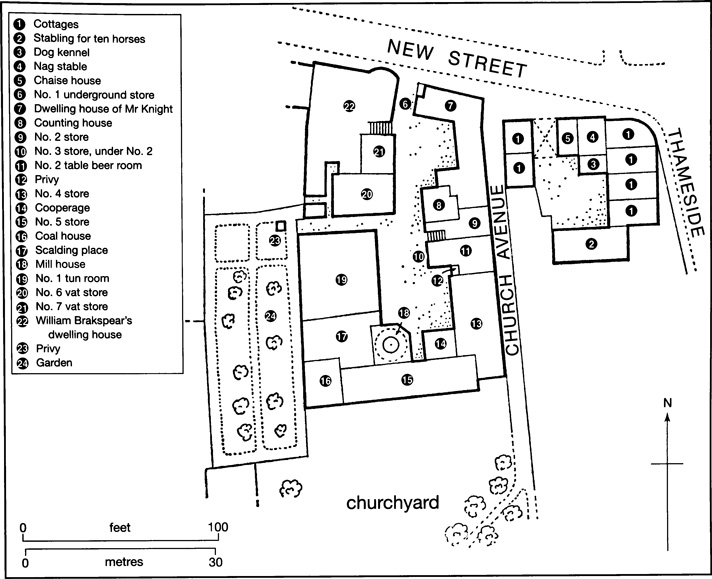

After Robert Brakspear amalgamated with Joseph Benwell's firm in 1812, brewing continued at Benwell's New Street brewery (Fig. 28), and the former Brakspear premises on Bell Street probably closed. In 1825, under the 1812 agreement, William H. Brakspear became a business partner with Joseph Benwell and his younger son Peter Sarney Benwell, and replaced Joseph Appleton as manager, the firm being renamed Joseph Benwell and Co. When Joseph Benwell died in 1830, heavily indebted, Brakspear secured a majority share and the firm became Brakspear and Benwell. Brakspear acquired total control in 1848 when P. S. Benwell died without male heir, though many premises, including the brewery, remained on lease from people connected with the Benwell family. By 1863 the brewery was known as the Henley Brewery (to distinguish it from its rival), and c. 1869 the business was reconstituted as W.H. Brakspear and Sons.

What became Greys Brewery was started on the south side of Friday Street by Thomas Soundy and Henry Byles, importers of coal, coke and London porter, soon after they acquired a malthouse in 1803. (fn. 274) Byles ran the firm, (fn. 275) which specialised in pale ale, and which by 1847 was called Byles and Son. The name Greys Brewery was established by 1852, and by 1867 the business was called T. F. A. Byles & Co. (fn. 276)

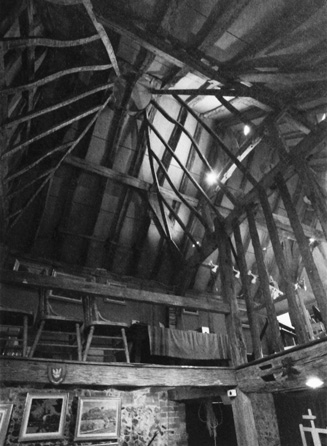

28. Brakspears' Brewery c. 1826. The arrangement is typical of Henley, where most early brewhouses and malt kilns were built on back plots. The brewery expanded along the street front and into premises on the opposite side in the late 19th century.

One or two smaller breweries provided beer for retail customers, and were often run alongside other activities. In the early 19th century the Crown Brewery operated in Market Place (1829–30s), and John Sharp brewed in New Street (c. 1828–36). (fn. 277) The Cannon Brewery was started at the Cannon beerhouse in the upper market place c. 1838, moving later to the North Star (renamed the Cannon Inn) further down the market place. Both brewery and pub were acquired by Simonds' Brewery of Reading in 1871, and the brewery was closed. (fn. 278) William Cobb, a Bell Street corndealer and maltster, also brewed in the 1840s–50s. (fn. 279)

New developments

Financial services expanded modestly, presumably in response to increased demand. In 1830, 11 insurance companies were represented in the town by nine agents, and there was a savings banks (founded 1817) and an office of Simonds' Bank of Reading. (fn. 280) The situation remained similar in the 1850s. (fn. 281) By the 1860s 25 insurance companies were represented by about 22 agents, and an office of the London and County Bank (Reading Branch) had also been started, though both outside banks opened only on Thursdays (market day). (fn. 282)

A further small development in the early 19th century was the introduction of silk-winding. A mill in Bell Lane was started by 1814, run probably by Mr Billings. He was succeeded before 1825 by George Shelton, described later as a 'silk throwster'. (fn. 283) The business used silk imported from London, and was regarded as 'a considerable manufactory'; it remained in Bell Lane, although Shelton lived in New Street by the 1840s. In 1841 there were five other silk workers including two 'throwers', who presumably worked for the business. (fn. 284) Shelton closed the mill in 1856, apparently because the silk supply ceased. (fn. 285) Another silk mill, on the south side of Friday Street, operated briefly c. 1823–6, run by Messrs Barbel and Beuzeville. (fn. 286)

Occupations in 1841 (Tables 4–5

Following the decline of malting and coaching, four long-established occupational groups remained important: providers of food, drink and accommodation, building workers, leatherworkers (principally shoemakers), and those in distributive occupations. Together, these accounted for 39 per cent of male household heads. Individual occupations with large numbers included bakers (12), butchers (13), publicans (17), bricklayers (16), carpenters and similar workers (30), shoemakers (32) and grocers (14). Smaller groups included clothworkers (principally tailors) and metalworkers (including blacksmiths and plumbers). Professionals and officials included a small but significant group of lawyers and doctors. In addition, 125 male household heads (21 per cent of the total) were described as labourers, many of them presumably working in brewing and building. Another 48 (8 per cent) were designated agricultural labourers, working presumably on farms outside the town.

The census suggests that the number of occupations was continuing to increase, recording about 100 occupations for male household heads compared with 58 c. 1700. Many were in specialized crafts or services, including clock making, gun making, and hairdressing. The only numerous craft occupations were cabinetmakers (7), chairmakers (4), papermakers (6), and wheelwrights (7), while numerous service occupations included gardeners (15), carriers (5), and porters (5).

Only a relatively small number of women were heads of households with designated occupations (89 compared with 599 men). Few were engaged in occupations normally held by men, the main exceptions being provision of food and drink (an area in which women had long participated), and teachers. The largest female occupational group was that of laundresses and washerwomen (22), while 12 had clothing-related occupations. Numerous female household members had occupations, the commonest by far being that of servant, which accounted for 215 women and girls. Another 20 were washerwomen, and 15 were dressmakers. (fn. 287)

29. Tom Shepherd's boat building sheds in 1900, adapted from former granaries adjoining the Red Lion (to the left, covered in ivy). The firm was one of several successful boat-building businesses in Henley.

Economic Developments c. 1850–1918

Leisure-related activities

Leisure-related activities developed steadily from the 1830s, with the promotion of fishing, development of the regatta (established in 1839), and a broader encouragement of tourism, all designed to help Henley through its economic difficulties. (fn. 288) By the 1830s boats could be hired at the Angel by Henley bridge, and in 1847 Henley was 'a favourite resort for anglers', with the Red Lion particularly popular during the fishing season. (fn. 289) Tourism and regatta both benefited from the opening of a railway branch line to Henley in 1857, but flourished most vigorously from the 1880s to the First World War, attracting up to 38,000 visitors at regatta time and substantial numbers over the rest of the summer. (fn. 290) The benefits for the town's economy were recognized by 1849, when local traders petitioned for the regatta's continuation. (fn. 291) Nonetheless the tourist trade remained seasonal, and in the 1890s tradesmen complained that casual Sunday visitors often went straight to the river, bringing their own supplies from London and scarcely visiting the town's shops and pubs. (fn. 292)

In the later 19th century tourism and recreational boating prompted rebuilding of the waterfront and the erection of some new hotels, principally the Royal (in 1869) and the Imperial (1896). (fn. 293) Some older inns were promoted as family and commercial hotels, amongst them the Catherine Wheel (by 1853), the re-opened Red Lion (refurbished in 1889), and the Angel on the Bridge, (fn. 294) although as late as 1888 one directory listed only four lodging establishments as hotels. (fn. 295) By c. 1900 an increasing number of inns and pubs were being so promoted: eight hotels were listed in 1897, and 18 in 1908–9. More accommodation may have been provided in pubs and beer houses, of which 20 were listed as inns in 1908–9. (fn. 296)

Boat-building for angling and recreation began as a secondary activity by the mid 1850s, when Edward Johnson of the Angel was both publican and boat-builder. (fn. 297) He possibly maintained both activities until the 1870s, (fn. 298) and in the 1860s James Hooper at the Ship pub (at the wharf north of New Street) was also a boat-builder. (fn. 299) Frederick Johnson was a boat-builder from the mid 1870s to mid 1880s. (fn. 300)

In the 1880s–90s four much more substantial boat-building businesses were established, all of which also hired out boats. One, begun by William Parrott before 1883, continued under Alfred Parrott, and in 1896 was situated at the corner of Friday Street and Thameside; it continued until the Great War. (fn. 301) H. E. Hobbs, publican of the Ship, began boat-building probably c. 1884 after he obtained permission to build a boathouse, and by 1896 his firm had accommodation for 200 boats, including boathouses at the north end of Thameside (Fig. 39). The yard built boats ranging from punts to steam launches, and also stored boats. (fn. 302) A third business was started in 1888 by Thomas Shepherd, who bought the Red Lion and converted two adjoining granaries into a boathouse (Fig. 29). Shepherd constructed boats in partnership with a Mr Dee, specialising in skiffs, but also building and running saloon launches. The firm won awards at international exhibitions, and sold a boat to the Sultan of Turkey. After 1893 Shepherd continued the business alone, building an additional boathouse in 1894 on the Berkshire bank opposite the railway station; the firm survived his death in 1898, and was probably sold to Messrs Hobbs and Sons with the Red Lion in 1918. (fn. 303) The business of Searle and Sons, in Station Road, was started by 1891, and by 1898 had been appointed boat-builders to Queen Victoria and the prince of Wales, building boats and launches. (fn. 304) At least another three inns and two individuals were boat proprietors in the late 1890s. (fn. 305)

Building trades

An important development of the later 19th century was a large increase in building, especially house-building. Recorded builders rose from five in 1874 to twelve in 1888 and 1901. (fn. 306) Some were both developers and contractors, who invested in house-building on their own account as well as working for clients, presumably in Henley and its neighbourhood. Such builders were largely responsible for the southwards extension of Henley from the 1880s, and for large-scale rebuilding in the centre: of particular note were Charles Clements (who served several terms as mayor), the Hamilton and Wilson brothers, and, slightly earlier, Robert Owthwaite. (fn. 307) Some became substantial landlords, and in 1881 Clements employed 100 people. (fn. 308) In 1901 building trades constituted Henley's largest occupational group, including 203 male household heads out of 1,044 (19 per cent). Among them were 51 painters and decorators, 50 carpenters and joiners, 42 bricklayers, and 26 bricklayers' labourers. (fn. 309)

Brewing c. 1850–1918

Brewing remained dominated by W. H. Brakspear and Sons and by the rival Greys Brewery, absorbed by Brakspears' in 1896. W. H. Brakspear continued the expansion begun in the 1830s, when he had bought out a small rival (John Sharp) and begun to acquire more pubs. After Henley's railway was opened he added pubs in and around Wokingham, and in 1865 bought the freehold of the brewery and several pubs from Joseph Benwell's widowed daughter-in-law. A further major purchase followed in 1881. Brakspear improved the brewery's equipment and facilities, increasing output from c. 8,300 barrels in 1835 to 14,300 barrels in 1880, and by his death (aged 80) in 1882 the business owned about 80 pubs. (fn. 310)

Brakspear was succeeded by his sons Archibald and George Edward, who over the next twenty years further expanded the business. (fn. 311) A mineral-water factory was built in 1888, (fn. 312) and in 1896, after forming a limited company to raise capital, they took over Greys Brewery, which since 1872 had been in various ownerships. (fn. 313) The merger created a business with about 150 pubs. Greys Brewery and some pubs were closed, but the New Street brewery was modernized, and in 1899 the Brakspears built a large three-storey malthouse, stables and carthouse opposite. In 1905 the brothers appointed a managing director and withdrew from active involvement.

A few smaller breweries continued. (fn. 314) The Union Brewery in Duke Street operated under several owners from the 1850s to 1870s, (fn. 315) while the Ive brothers started a brewery c. 1883, alongside their wine and spirit business at Market Place. By 1895 they also manufactured mineral water, and the company continued until c. 1915. (fn. 316) Numbers employed in brewing nonetheless remained relatively small: in 1901 only 20 male household heads (2 per cent) were expressly employed in brewing, although by then closure of Greys Brewery had reduced the workforce, and some of the miscellaneous drivers and others listed may have worked for brewers. (fn. 317)

Services, crafts and retail

Work in some service activities expanded in the late 19th century, notably gardening and transport. By 1901 male household heads included 59 gardeners and 20 coachmen, 19 carmen or carters, 8 carriers, and 4 drivers, together with 20 employed on the railway. Others working in service activities included 7 agents and auctioneers, 4 hairdressers, 2 chimney sweeps, and a musician. (fn. 318) Photographers had worked in Henley since the early 1870s when Harry and Tom Marsh opened their business, (fn. 319) and by 1883 there were two photography businesses, rising to five by 1908–9. (fn. 320)

The retailing/distributive sector remained similar to earlier, including (in 1898) 13 grocers, 8 drapers and clothing shops, and an ironmonger. (fn. 321) A distinctive new direction was the opening by 1888 of the first branches of 'multiple' stores, namely the boot- and shoe-retailer Freeman, Hardy and Willis, and the International Tea Company. By 1915 five 'multiples' had Henley branches, including the newsagent W. H. Smith. A further new area of trade was antiques, especially furniture. The antique furniture dealer Arthur Goddard was established by 1897, and by 1915 there were 3 dealers. (fn. 322) By contrast, leatherwork slowly contracted: in 1901 there were only 7 shoemakers, and no tanners or curriers. (fn. 323)

Around 1877 Charles Henry Smith began manufacturing umbrellas and paper bags at premises in Duke Street, moving soon after to Friday Street where he undertook bag making and printing. (fn. 324) Around 1900 the business also manufactured bags at New Mills in Rotherfield Peppard, and continued in Friday Street until c. 1950. (fn. 325) Other new developments reflected technological change and sometimes tourism. (fn. 326) Three cycle agents (one of them a bicycle manufacturer) were noted in 1899, and four cycle-related businesses in 1915. Around 1905 a coach builder in Northfield End provided garage facilities for motor vehicles, (fn. 327) and before 1908 the carriage builders Motts and Betts opened a motor garage, operating as Betts and Son. In 1915 there were three motor engineers. The Henley Sanitary Steam Laundry on Reading Road was started before 1900, (fn. 328) and in 1899 there was a dealer in domestic machinery and a sewing machine agent.

Stuart Turner Engineering

A particularly important addition was the Stuart Turner engineering business, developed in Henley from 1905 by Turner and his successors. Until the 1960s it was the only significant industrial enterprise in Henley apart from Brakspears' Brewery. (fn. 329) Turner, a Scotsman, started making model steam engines in his spare time in Shiplake, where he was employed from 1897 to supervise steam-powered electricity generation at Shiplake Court. In 1905 he created a machine shop for the production of model engines in Henley behind premises in Duke Street, (fn. 330) and from 1906 traded as Stuart Turner Ltd. The firm also made petrol engines for motorcycles. In 1908 Turner moved to premises in Market Place (by the Broad Gates inn) and expanded the product range, which by 1911 included complete motorcycles and electricity generators: in 1914 the firm supplied a generator for Ernest Shackleton's ship Endurance. During the Great War it concentrated on war-related contracts (e.g. petrol engines), increasing the workforce to over 300 men and 100 women, and in 1917 bought the Broad Gates to provide extra space.

Economic Life c. 1918–1960

In the interwar years Henley's economy remained little changed from the Edwardian period. (fn. 331) Provision of food and drink through small outlets remained important, with numerous bakers, butchers, confectioners and fruiterers. Likewise the retail and distributive sector still included grocers, drapers, ironmongers and chemists, although national multiple businesses became more numerous, confirming that Henley was seen as a worthwhile centre for investment. Nine such companies had branches in Henley by 1935, including F. W. Woolworth (opened 1931) and Boots the Chemist. (fn. 332) Financial services also expanded, with four banks in Henley (including the Henley Savings Bank) in 1920, and six in 1928. The Savings Bank merged with the Reading Savings Bank in 1938, and later joined the Trustee Savings Bank. (fn. 333) Amongst traditional crafts, leatherwork remained a small sector: in 1928 there were seven boot- and shoemakers, six boot-repairers, a saddler, a harness-maker, and two leather sellers. (fn. 334) Smithing, however, was provided by businesses with broader activities, such as the engineers R. C. Barnett Ltd.

Tourist accommodation may have contracted slightly after the First World War: the Royal Hotel was converted into flats in the late 1920s, (fn. 335) and fewer hotels were listed in 1928 than in 1908–9. Nonetheless Henley's role as an upmarket resort and social centre continued, and in 1939 there were at least 10 hotels, 7 guest- or boarding houses, and 13 cafés or restaurants. (fn. 336) Facilities for local and recreational motoring and cycling were expanded: in 1928 there were at least 11 such businesses, including 6 motor garages and engineers. Building work was stimulated by large-scale housing schemes, while installation of mains electricity from 1926 presumably created work for electricians. (fn. 337)

Stuart Turner's engineering business continued to thrive despite its founder's retirement in 1920, expanding its product range and gaining new markets. (fn. 338) In 1923 it won a military competition for a generator to power wireless plant, and during the 1930s it developed engines for small boats, and a milking system for cows. From 1936 it sold pumps incorporating a frictionless shaft seal designed by Alec Plint. The firm expanded its foundry in 1925, (fn. 339) and built a new engineering shop in 1931, (fn. 340) followed by an erecting shop in 1936. During the Second World War it suspended model manufacturing, producing generators, petrol engines and pumps for military purposes; thereafter it restarted its models range and increased the output of marine engines.

In the 1950s Henley's increasing population sustained numerous small food and drink outlets and other retail shops. (fn. 341) In 1960 there were 19 grocers and general stores, including a branch of the national grocer Tesco (opened c. 1955), while 19 drapers and outfitters included Facy, a draper's business which became a department store during the 1950s. Other stores included ironmongers and chemists, among them branches of Boots and Timothy Whites. Improved living standards were reflected in the presence of house furnishers, radio and television dealers, antique dealers, and tobacconists, while personal services included a chiropodist, hairdressers, and dry cleaners. Leisure-related businesses included four boat proprietors, of which Hobbs' continued to build boats, and in 1952 a company specializing in the building and maintenance of Bentley cars (Hofmann and Burton) moved to Henley. (fn. 342) Building trades, too, remained strong, with 17 men recorded as builders and decorators. By then, however, the only traditional craftsmen were a basketmaker, two shoemakers, a monumental mason, and two plumbers.

Economic Life From c. 1960

From the 1960s a considerable new business sector developed, encouraged by the creation in 1963 of the Newtown Industrial Estate. (fn. 343) This provided space for light industrial factories, office blocks and warehouses, and was largely occupied by 1977. (fn. 344) Thereafter other small business estates were developed between Reading Road and the Thames. The sites attracted new and relocated businesses operating in national and international markets, some of which were subsidiaries or offices of major British and overseas companies. The main areas of activity were engineering, financial services, computer systems, and other business-related services; there was little industrial production, and though distribution depots were opened, most businesses were run from offices and warehouses rather than factories. Many operated in highly competitive environments, prompting a steady turnover. (fn. 345)

Henley also retained a strong retail sector, which was generally considered sufficient for most local needs. In 1971 its catchment area was thought to include at least 18 nearby parishes containing about 30,000 inhabitants. There were then 156 retail shops in the town, with 27 per cent of floor space given to food retailing, and 43 per cent to clothing, footwear and household goods. Established businesses also sold durable goods, though the town was reckoned to be too small to attract national chain stores selling such items. (fn. 346) Retail suffered from national recession in the early 1990s and again in 2008–9, which left significant numbers of town-centre shops temporarily vacant, and prompted claims in 1993 that Henley was a 'dying town' in need of regeneration. (fn. 347) Recovery followed on both occasions, though a report in 2009 concluded that the town should improve its attractiveness to shoppers and visitors if it was to combat growing competition from Reading and other centres. (fn. 348) Tourism also remained significant. In the late 1970s there were five hotels providing 126 beds, along with guest houses offering bed and breakfast, and in 1977 it was estimated that possibly over 27,000 visitors stayed in the town. (fn. 349) In the early 21st century Henley ranked as an international tourist destination. (fn. 350)

Overall there were some 5,400 jobs in Henley in 1971, with a strong bias to services and retail; 62 per cent were held by townspeople, and 38 per cent by outside commuters. Around 93 per cent of businesses were 'small' (i.e. with under 100 employees), and 70 per cent employed fewer than 10 people. Only 19 firms employed more than 50, although together those accounted for 1,900 jobs. (fn. 351) Some jobs were lost in the recession of the early 1990s, (fn. 352) but in the longer run the town's economy remained successful and continued to expand. By 2007 about 7,500 people were employed in the town: 39 per cent in banking, finance and insurance, 25 per cent in distribution, hotels and restaurants, and 17 per cent in public administration, education and health. Only 4 per cent were employed in manufacturing, Brakspears' having closed in 2002, leaving Stuart Turner as the main manufacturing company. (fn. 353)

Shops and Tradesmen