A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Ansford', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10, ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp85-100 [accessed 23 April 2025].

'Ansford', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Edited by Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online, accessed April 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp85-100.

"Ansford". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online. Web. 23 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp85-100.

In this section

ANSFORD

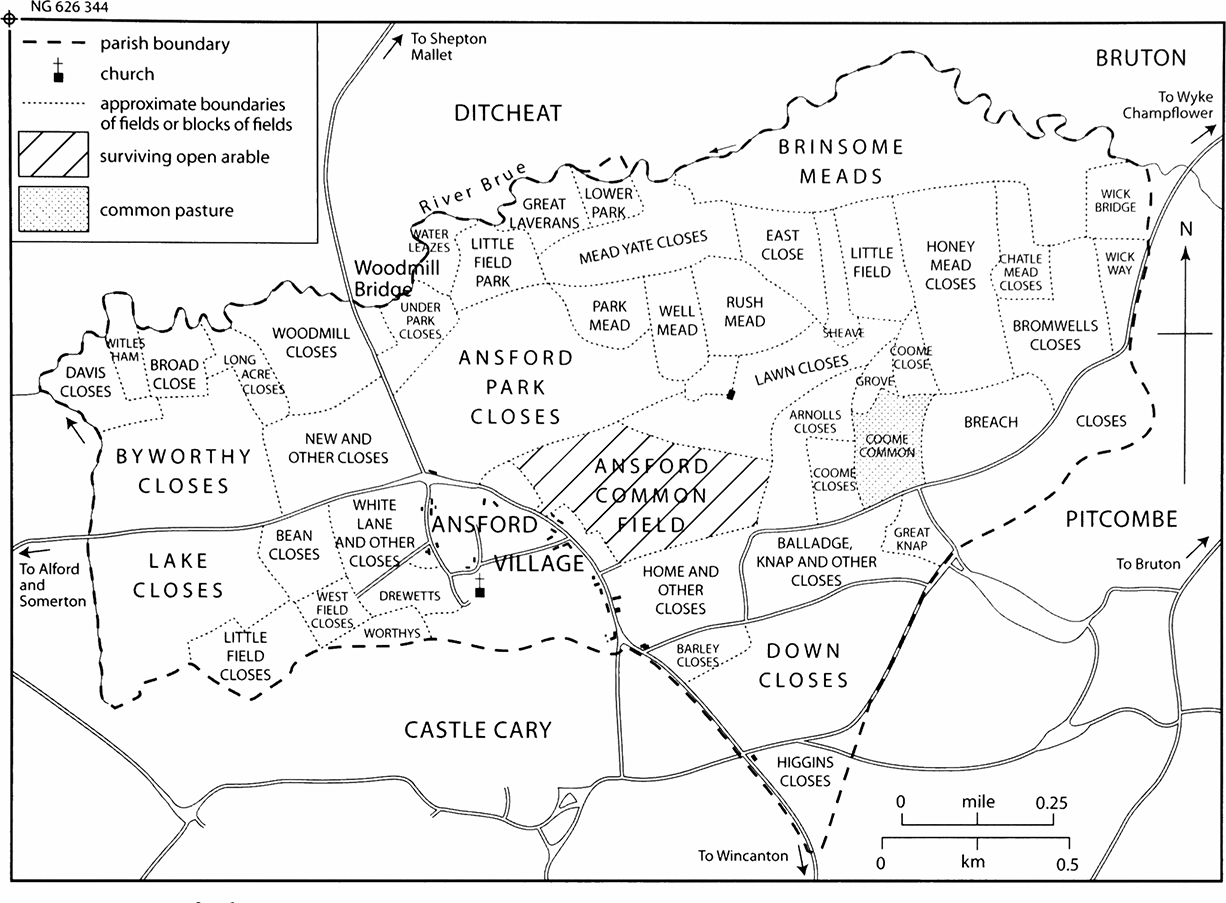

35. Ansford c. 1684

The parish c. 1684, showing that although very closely tied to Castle Cary it had its own common fields and park, which had been largely inclosed by the 1680s.

THE PARISH and village of Ansford lie south of the river Brue and east of a tributary through Clanville, the only natural boundaries, on the steep northern slope of Ridge Hill. (fn. 1) Ansford was noted for its fine views extending over 30 miles westwards but is now associated with the diarist Parson Woodforde. (fn. 2) The parish takes its name, formerly Almsford or Almundesford, from a ford crossing the Brue, possibly on the site of Woodmill Bridge. (fn. 3) The village, in the south of the parish, is practically a suburb of Castle Cary. The ancient parish, roughly rectangular with a triangular southern extension between Castle Cary and Pitcombe, measured 2 km. from north to south at its deepest and 3 km. from east to west, and covered 844 a. The transfer of Clanville hamlet from Castle Cary in 1982 resulted in a civil parish of 340 ha. (919 a.). (fn. 4)

River and stream run over river gravel. The rising ground is composed of bands of Lower Lias clay, Middle Lias silt and clay, and Upper Lias sand following the contours north-west to south-east. The Lower Lias slopes steeply from 50 m. (150 ft) to 95 m. (312 ft) but the rest more gently to 120 m. (394 ft) in the east on the Pitcombe boundary. (fn. 5)

COMMUNICATIONS

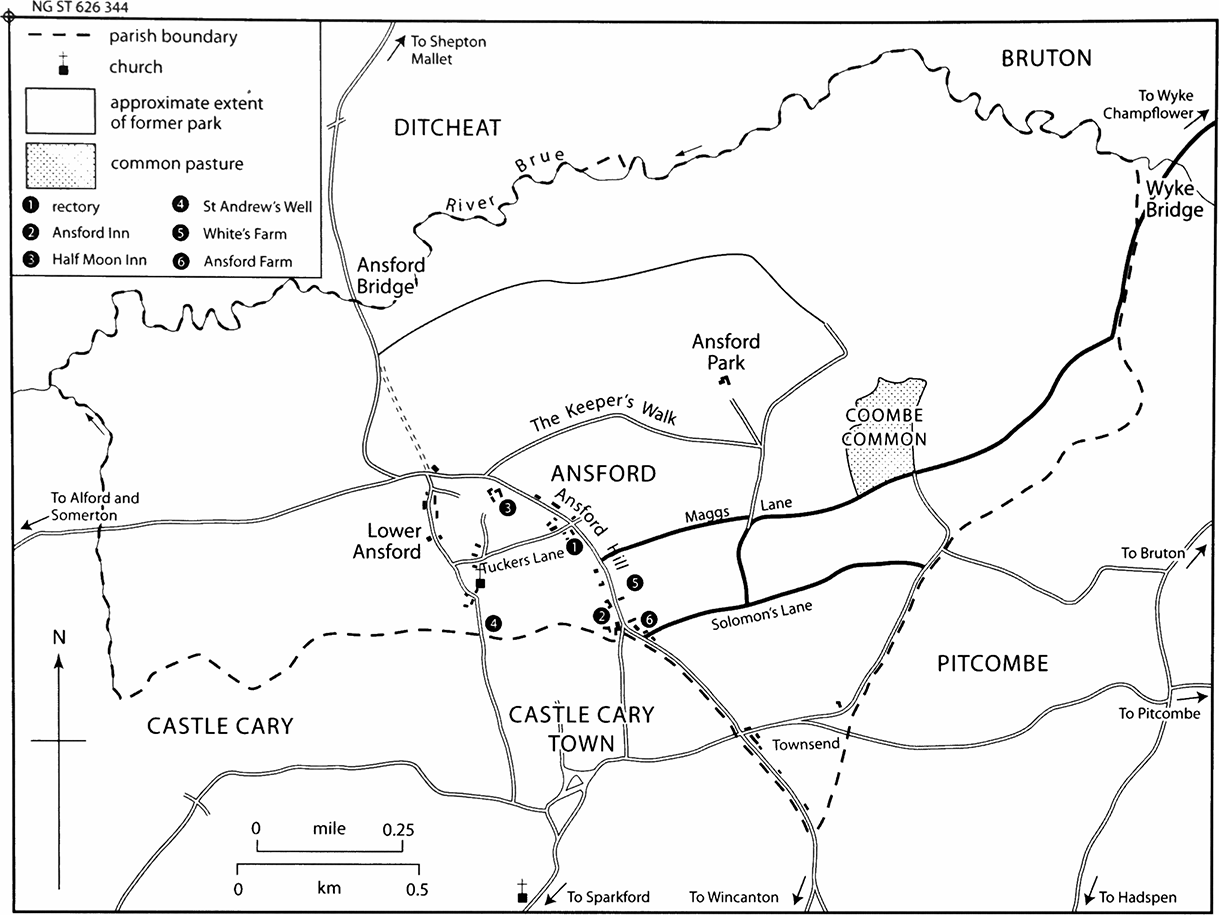

36. Ansford 1838

The parish in 1838 showing that the village footprint had changed little since the 1680s, partly because of the steep drop from village to river, though several large houses had been built at the southern end of the village.

Ansford lies at the hub of several roads and lanes and is crossed by a major railway route. Two major routes converge towards the western end of the parish, probably due to the river crossing and the steep terrain further east. The road from Somerton, established by 1675 and known as Ansford Street in 1715, was turnpiked in 1753 by the Langport, Somerton, and Castle Cary trust. (fn. 6) The road from the north, part of the route from Bristol to Dorchester and Weymouth by the late 17th century, was carried over the Brue by the great stone arch of Woodmill Bridge, which fell in 1696 and was replaced by two arches. (fn. 7) Ansford Bridge, a new single-arched bridge very slightly further east, was built by John Stone in 1823–5 to a plain design by Charles Wainwright. (fn. 8) It was paid for by the county and the Shepton Mallet turnpike trust, (fn. 9) which turnpiked the Bristol road as far south as the Ansford inn and from thence it was turnpiked by the Sherborne trust. (fn. 10) A new turnpike gate was built at the junction with the Somerton road. (fn. 11) The road, which was also the local route to Wincanton, was known by 1765 as Ansford Hill. (fn. 12) North of Ansford it was in poor repair in 1794 and was diverted, probably in the 1820s, in a curve through Butwell field to the west of the existing road, which remained as a footpath. The turnpike gate was removed north of the parish to Ditcheat although still called the Butwell gate. (fn. 13) The new route was also abandoned after the construction of the railway and replaced by New, now Station, Road cut in 1853–4 to link Woodcock Street, Castle Cary and the railway station in Ansford parish. The line of adjoining roads was modified in 1856. (fn. 14) Under an Act of 1857 New Road was turnpiked by the Langport, Somerton, and Castle Cary trust. (fn. 15)

It is possible that in the Middle Ages the road from the north ran through Lower Ansford by the church to Castle Cary but the southern section is now a footpath. (fn. 16) The route to Bruton was through Solomon's Lane in 1675 (fn. 17) and crossed the Brue over Wyke Bridge but in 1793 the Bruton trust turnpiked a road further south from Townsend, Castle Cary. Both roads suffered severe encroachment. (fn. 18) Maggs Lane south of Ansford Park was laid out in the 18th century probably for access to the park farm and Coombe common. (fn. 19) Encroachment by cottages in the 18th century led to a diversion of the east end of Tuckers (fn. 20) Lane, from Ansford Hill to the church, through the rectory grounds but in 1792 the diversion was stopped up and the old lane enlarged, repaired and routed directly past the church to Lower Ansford. (fn. 21)

In 1780 the thrice weekly coach service between Bath and Weymouth called at the Ansford inn. (fn. 22) A coach service from Bristol to Poole called the Pilot began in 1824 and served Ansford. (fn. 23) Two men slept in barges on Census night 1851 but there is no record of the Brue at Ansford being navigable. (fn. 24)

The Wiltshire, Somerset, and Weymouth railway opened between Frome and Yeovil in 1856 with a station in Ansford, later renamed Castle Cary. (fn. 25) In 1904–6 the Great Western Railway built a new line to Langport adapting the existing station and improving facilities. (fn. 26) The Taunton service was withdrawn in 1962 and the line to Yeovil was singled in 1968. However, from 1974 some London trains stopped and a large car park was laid out to encourage commuters from a wide area to travel by rail. Part of the original stone building survives and new buildings were erected c. 1980. (fn. 27) In 2002 seven express trains stopped in each direction on week days in addition to the Bristol to Weymouth services via Yeovil.

SETTLEMENT, POPULATION AND BUILDINGS

Two possible Romano-British settlements have been found: one east of the church where there is evidence of Neolithic and Bronze-Age activity and another possibly west of Ansford Bridge, the site of an early river crossing. (fn. 28) Ansford was first named in 1086 as a small estate with nine farmers or smallholders and three serfs working the demesne lands (fn. 29) who presumably lived along the two north–south village streets, which occupy an area between the land most suitable for arable and the steep slope down to the Brue. Arable was divided between north field, beyond the park, east field, to the south and still arable in the 19th century, and west field. The common meadow was at Brunesham or Brewham by the Brue, and Karemor or Westmor, probably the later Lake adjoining Clanville. (fn. 30)

The church, first recorded in 1219, is at Lower Ansford on a street, which may then have formed part of a route from the ford to Castle Cary. Lower Ansford street and Ansford Hill, probably the Over Ansford recorded in 1462, (fn. 31) formed the village until the mid 19th century. The only dwellings outside the village were in the south of the parish at Townsend, locally in Castle Cary, and the lodge in the park. Ansford park covered c. 110 a. (fn. 32) and seems to have been created from woodland before 1351 by the Lovels. In 1682 the park (103 a.) was still surrounded by a pale 15 ft wide but had been improved for agriculture. (fn. 33) It may have prevented settlement north and east of Ansford Hill.

In the mid 19th century there was development around the railway station (fn. 34) and c. 18 houses were built between 1931 and 1947. (fn. 35) However at Lower Ansford four derelict cottages were used as apple stores and another pair were demolished in the 1960s. (fn. 36) Housing development in the 20th century extended west along Station Road and east along Maggs Lane, with extensive local authority housing in the south-east since 1925. The land between Ansford Hill and the church is covered with late 20th-century housing, notably the controversial Churchfields development, which removed the last remaining open space in the centre of the village and, despite preserving a small open area south of the church, turned Ansford and Castle Cary into a single built-up area. (fn. 37)

Population

In 1428 Ansford had fewer than 100 inhabitants. (fn. 38) In the 1780s there were only c. 30 houses (fn. 39) but by 1801 the population was 237, rising from 244 in 1811 to 300 in 1821 and apart from a fall to 269 in 1851, remained stable until 1931. (fn. 40) Railway workers were in the parish by 1851 and in 1861 there were three railway cottages and 15 railway employees in Ansford while 40 workers boarded in Castle Cary, presumably completing work on the line. In 1871 the stationmaster boarded at the Railway Hotel but later had a house in Cumnock Terrace, Castle Cary. (fn. 41) In 1891, apart from the stationmaster there were 19 railway employees in the two parishes. (fn. 42) The population increased from 305 in 1931 to 653 in 1971, 784 in 1981, and 982 in 1991, due to new housing and the transfer of Clanville to Ansford in 1982. (fn. 43) In 2001 the population was 1,019. (fn. 44)

Buildings

The most prominent houses lie at the south end of Ansford Hill close to Castle Cary and to the west in Lower Ansford and were built in the 18th and 19th centuries of Cary stone with thatched or pantiled roofs, when Ansford was the favoured home of Castle Cary's professional class. (fn. 45) The former rectory (Old Parsonage) is earliest, built in the 17th century with three bays, a cross-wing and wooden ovolo-moulded mullioned windows. Glebe Cottage further north may also have belonged to the church and be on the site of Cote House, included in a terrier of 1606. (fn. 46) Other houses have been rebuilt in plain classical style on the sites of earlier houses. At Lower Ansford Farm a house, known in the 18th century as Lower House, in 1883 as Old Ansford House, and in 1885 as Manor House, (fn. 47) stood there from the 17th century when it was owned by the Collins. It was rebuilt between 1826 and 1838, but in 1908 when it stood ruined was still 17th-century in style. (fn. 48) Two of the classical-fronted houses built close to Castle Cary also took the place of earlier buildings and hug the line of the road: Ansford House replaced before 1791 an L-plan house of the late 17th-century or earlier, (fn. 49) and Ansford Lodge was much rebuilt in 1881. (fn. 50) Of that group largest and most polite in style is the mid 18th-century Hillcrest; its Gothick stables and coachhouse may have been added when the house became the rectory in 1823, and were altered in the 20th century for school and later office use. (fn. 51)

Scattered cottages and villas of the 16th to the 19th century lie to the north and at Lower Ansford, where there are two 18th-century houses, one bearing the date W/SI/1746. Twentieth-century housing has spread along the main streets and across the former orchards and pastures between them. Ansford Hill has several cottage rows, the most interesting being the late 18thcentury row used by Donne to house weavers in the early 19th century. In the mid 19th century four upper windows were larger than the rest, perhaps an adaptation to industrial use. (fn. 52)

The chief inns were built and enlarged in the 18th and 19th centuries. At the Ansford inn a low twostoreyed house was enlarged or partly rebuilt, and later was given a western stable wing and Regency embellishments. The former Half Moon inn, probably built soon after 1772 when its freehold was purchased from the manor, has a façade of expensive red brick, and an attached cottage, perhaps a rebuilding of the original alehouse. (fn. 53)

One or two 18th-century barns survive in the village. Two of the major farmsteads were transformed in the 19th century. Ansford Farmhouse on Ansford Hill retained its small 17th-century core the style of which was imitated when the house was enlarged in 1869, and farmbuildings were added in 1872. Ansford Park Farm was completely rebuilt in 1880 as a plain three-bay, twostorey house under a slate roof, and has a lower rear extension of 1903. Farm workers' cottages were built at the north end of Ansford Hill in 1903 and at Ansford Park Farm in 1899. (fn. 54)

LANDOWNERSHIP

There were two small freeholds in the 13th century (fn. 55) and unspecified land was held by the FitzJames family from the late 14th century (fn. 56) but most of the parish lay in Ansford manor until the 1680s. From that date manor land was progressively sold and by the 1790s 22 proprietors paid land tax. (fn. 57) By 1838 the manor was reduced to 12½ a. and there were 40 landowners excluding the church and the parish. (fn. 58)

ANSFORD MANOR

In 1066 Ketel held Almundesford, and in 1086 Wulfric held it under Walter of Douai. (fn. 59) By the 1280s the terre (fn. 60) tenancy had been extinguished and thereafter Ansford was held by the Lovels with Castle Cary. (fn. 61) In 1280 it was said that a Richard Lovel had given land in Ansford to St Andrew's chapel at Marsh, Wincanton, last recorded in 1326. The land probably reverted to the manor. (fn. 62) In 1684 Ansford was sold with Castle Cary to Anthony Ettrick, his son William, and his son-law William Player. (fn. 63) In 1703, following Anthony's death, Ettrick and Player divided their estate with Player taking Ansford although they continued as joint lords. (fn. 64) The manor was said to have been settled in trust for Ellen, widow of William Player's son Arthur (d. 1728) (fn. 65) but most Ansford land was held by William Ettrick and Ann Powell. (fn. 66) The Revd William Digby purchased Ansford manor from the heirs to Ellen Player's trustees in 1762. In 1763 he settled it in trust on Stephen Fox, earl of Ilchester, and Lord Digby who in 1764 secured a conveyance from a trustee. Those conveyances were later referred to as 'purported'. (fn. 67) In 1768 William Digby levied a fine on the manor with the earl, whose brother Henry, Lord Holland (d. 1774) was tenant of the demesne and leased William Ettrick's chief rents in 1768. (fn. 68) In 1770 and 1771 the earl, joining Lord Digby, William Digby, Lord Holland, and Charles James Fox as parties, sold the manor to Benjamin and Francis Collins of Salisbury. After Benjamin died in 1784 the land was sold and the lordship put up for sale in 1785. (fn. 69) In 1786 what was described as an undivided moiety of the manor was sold to Sir Richard Colt Hoare (fn. 70) who held Ann Powell's moiety, bought by Henry Hoare in 1782 from her executor Charles Wray. (fn. 71) The manor, with only 12½ a. in 1838, (fn. 72) descended in the Hoare family. (fn. 73)

Manor House and Park

The demesne, including a mansion and park, was let to the Kirton family, possibly by the mid 16th century. There is no record of a manor house and the owners were non-resident. Nothing is known of the park except that it was stocked with wild animals by 1351 (fn. 74) and that in the early 16th century William Haward, parker, had a lodge in the park and received an annual stipend of £2. William claimed that he and his family had been driven out of the lodge by a large number of people under the command of Sir Anthony Willoughby, son of William's landlord. (fn. 75) Thereafter the park was occupied by the Kirton family and the lodge was probably the house occupied by Lettice (d. 1620), widow of Edward Kirton. She was followed under the terms of her son James's will by his nephew Edward Kirton (d. c. 1655), son of Daniel (fn. 76) but the house was occupied by another nephew, James Kirton, son of William, and in 1639 by James's estranged wife Joan. In 1645 James, a Royalist captain, was said to be 'distracted' and was let out of prison. His estate was had his estate sequestrated before 1653 but may have been restored as he was buried at Ansford in 1668. (fn. 77) Thereafter house and park were occupied by farmers and were bought by Nathaniel Webb (d. 1782) before 1766. (fn. 78) Webb's son, also Nathaniel (d. 1816) mortgaged the estate and after his death it was sold to Samuel Pretor of Sherborne who had bought land in Ansford in 1796–7. Samuel's grandson and heir Samuel Gill (d. 1877) took the name Pretor (fn. 79) and probably purchased Ansford, later Manor, farm in 1866. (fn. 80) Samuel's son, also Samuel, died in 1907. (fn. 81) His trustees sold one farm and divided the rest for sale in 1912. (fn. 82) The house and farmstead were rebuilt in 1880. (fn. 83)

OTHER ESTATES

The sale of manor lands from the late 17th century gave rise to several freeholds notably that of James Collins (d. 1727), mainly at Lower Ansford, which he left to his second wife Hester (d. 1738). The property later came to Jane, wife of the rector Samuel Woodforde, and her half sister Martha, wife of Dr Richard Clarke. (fn. 84) In 1771 Ann Powell sold Ansford rectory with church, churchyard, house, glebe, and tithes to Thomas Woodforde (d. 1800), Samuel's brother. (fn. 85) By 1838 seven members of the Woodforde family owned 52 a. between them including the former rectory house and grounds, which they regarded as a family home and in 1823 exchanged with the then rector for another house in the village. Two members of the Clarke family jointly held 51 a. (fn. 86)

In 1766 10 a. of land in Ansford belonged to Redlynch chapel, Bruton, probably bought with a grant from Queen Anne's Bounty in 1733. (fn. 87) It was sold c. 1918 to John Clothier. (fn. 88)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

AGRICULTURE

In 1086 Ansford had six ploughlands and gelded for five hides of which three were in demesne worked by two ploughteams and three serfs. Five villeins and four bordars worked the rest with five ploughteams. Demesne livestock comprised a horse, 9 beasts, 11 pigs, and 60 sheep. There were 20 a. of meadow, 20 a. of pasture, and a wood 4 furlongs long and 1½ furlongs wide. The value of the estate had fallen from £4 to £3. A mill, possibly near the ford, paid 7s. 6d. in 1086 but no mill was recorded thereafter. (fn. 89) Ansford may be Aldemaneford where the king's sergeant bought Christmas provisions in 1252. (fn. 90) Nothing is known of medieval farming but two 13th-century freeholds were recorded, one comprising 5 messuages, 56 a. of arable, and small parcels of meadow and wood. (fn. 91) There appear to have been three arable fields and two common meadows. (fn. 92) By 1249 a wood called Otelescumb, adjoining the east field, was in the care of Richard Lovel's forester. (fn. 93) A tenant held 1 a. there in 1280 (fn. 94) but it was partly cleared before 1351 to create Ansford park. (fn. 95)

The 16th to the 18th Century

By the mid 16th century the fields were partly enclosed and land called Broche had been converted to pasture. (fn. 96) In 1535 great tithes were worth £4 and wool and lamb tithe only 10s. (fn. 97) Bovewood, later Bowood, common field recorded in 1590 and 1606, was later known as Ansford Field. (fn. 98) In 1606 Brewham was common meadow by the Brue where at breach the rector could pasture 13 beasts. Most glebe was in closes and a small parcel was newly enclosed following an exchange of a 'scraddle' of land. The Down in the east field encroached into the highway. (fn. 99) By 1613 a close of rectory meadow had been converted to arable but of 68 a., 20 a. was pasture and 20 a. was furze. (fn. 100)

In 1633 Edward Kirton claimed to have drained closes in the park and cleared them of briars but that his tenant had neglected to keep the land trenched and free from scrub and took out at least 30 loads of firewood. (fn. 101) In 1661 a man was accused of breaking into the herbage of the Three Closes. (fn. 102) In the 1660s the Down was pasture and an attempt to grow oats in a small close there produced a poor crop. Other land which in the early 17th century was used to grow maslin, although weeds and rushes had to be mowed off, was enclosed in the 1660s and used as pasture for plough beasts, rother cattle and sheep. Brimsham was enclosed meadow. (fn. 103) In the 1680s Ansford Common Field survived as a very large close east of the village and there were fragments of West field between the village and the area called Lake. (fn. 104) A hopyard was recorded in 1682. (fn. 105)

In 1585 John Fossey alias White left seven cows, calves, bullocks, a colt and sheep, and at least two wains. (fn. 106) In 1610 a Wincanton butcher bought stock at Ansford. (fn. 107) In 1671 hurdles were stolen and during the 1670s a father and son were accused of stealing hay and beans grown in the moor to feed their horses and pigs. (fn. 108)

In 1682 one copyholder held three holdings including the toft of a house. Ten had no land or fewer than 5 a. and seven had between 10½ a. and 74½ a. Seven leaseholders held between 4½ a. and 24 a., possibly overland. (fn. 109) Freeholder John Cary's heirs had two houses and 65 a., probably an amalgamation of medieval freeholds. (fn. 110)

During the 18th century holdings were divided and sold such as the freehold house and four closes which Edward Murrow divided between his nine grandchildren in 1732. (fn. 111) Former manor land was sold, sometimes in single closes but in 1776 49 a. of meadow was offered for sale. (fn. 112) Wealthy farmers took advantage of those dispersals. Before 1766 Robert White created Ansford farm, which had passed with additional land to Sophia White by 1832. (fn. 113) James Clarke bought land to add to his Lower Ansford farm, created earlier by the Collins family, (fn. 114) which in 1789 included a 9-a. orchard, two closes, and a meadow. In 1792 his trustees planted a quickthorn hedge at a field called Shear and Go and apple trees. (fn. 115) In 1789 the parish was mainly pasture but closes called Ansford Field, Barley Close, and Marlpits produced wheat, beans, oats, and potatoes in rotation. Potatoes were the dominant crop and peas were grown on 3½ a. The largest farms were 128 a. and 69 a., only nine others were over 20 a., ten had between 10 a. and 20 a., and thirteen were under 10 a. The farmer of 128 a. produced cabbage plants in 1791 and 6 a. of flax in 1792. A late 18th-century tenant of a parcel of glebe was required to put manure worth a guinea on the land annually. (fn. 116)

The 19th and 20th Centuries

Only 155 a. of arable was recorded in 1801 of which 102 a. produced potatoes. There were 36 a. of wheat, 12 a. of barley, 4 a. of turnips or rape, and 1 a. of peas. (fn. 117) The common at Coombe (11 a.) had been inclosed before 1762. The manor court ordered the inclosure to be removed, claimed Coombe for the lord and commoners, and regularly presented the occupier as having no right there until 1813, (fn. 118) but it had been sold by Thomas Andrews to the Revd Thomas Woodforde in 1807. (fn. 119) Possibly as his gift, it passed before 1819 to the parish officers. In 1838 Hoare claimed the fee as lord of the manor, subject to the rights of commoners who allowed the officers to let it at rack rent to reduce the poor rate. (fn. 120) The overseers rented it out until 1890 or later. (fn. 121) By 1813 the former park, known as Old Park, was part of Ansford Park farm (171½ a.) but was still surrounded by the pale known as Keeper's Walk, (fn. 122) whose southern sections survived in 1838. (fn. 123)

The 1823 the exchange of rectory houses made special mention of the fruit trees, mainly apples, but also medlar, mulberry, and quince. (fn. 124) In 1838 there was over 151 a. of arable, mainly in the east, producing abundant potato crops. (fn. 125) The former park (110 a.) was tithe free in return for the shear of 4 a. commuted to 6s. 5¾d. Grass covered 460 a. including Lake, pasture along the south-west boundary stream. Large orchards surrounded the village but no woodland was recorded. Only two farms were over 100 a., including the largest, Ansford Park (163 a.), two others over 50 a., five between 20 a. and 50 a., twelve with 10 a. to 20 a., and nearly 20 holdings with less than 10 a. Landowning was equally fragmented: Samuel Pretor owned 293 a. including the two largest farms, Sophia White had almost 110 a., the glebe totalled 60 a. but was divided between several tenants, and eleven others owned more than 10 a. (fn. 126)

By 1851 four farms had over 100 a. including Ansford Park (262 a.) and employed 21 labourers. Three small holdings and a dairywoman were also recorded. (fn. 127) In 1866 Ansford farm covered 102 a. of dairy and grazing land and in 1877 Ansford Park farm had 171 a. but both were bisected by the railway, which had taken part of their land. Ansford Farm house was rebuilt in 1869 and in 1872 the farm had housing for 27 cows and six horses, a piggery, and underground tanks for water and manure. The house and farm buildings at Ansford Park were rebuilt in 1880. (fn. 128) The Pretor family reorganized its farms after acquiring the White estate. By 1871 Ansford farm was known as Higher Ansford and by the 1880s as Manor farm. It was enlarged at the expense of Ansford Park farm. (fn. 129) Another Pretor farm was named Ansford farm and was sold to the tenant, Albert Mullins, before 1910. (fn. 130) In 1881 three farms of between 150 a. and 200 a. employed 14 labourers, a dairy had two resident workers, and three small holdings employed no outside help. There was also a threshing machine proprietor and by 1891 a market gardener. (fn. 131)

Dairying and pig rearing predominated. In 1879 a farmer lost 15 pigs to typhoid fever. (fn. 132) In 1881 a herd of 44 dairy cows at the Mullins's Ansford farm supplied whey to fatten pigs bought in from local farmers, milk, both fresh and sour, up to 20 lb. of butter weekly, and 285 cheeses each weighing c. 25 lb. The herd, including 12 young cattle and a bull, was valued at £600. In 1881 an auction at the farm comprised 70 pedigree short horn cattle, 60 sheep, 5 horses, pigs, and cider-making equipment. In the early months of 1889 41 calves were sold and in 1890 cheese was sold to Mackies of Castle Cary. In 1905 cattle and horses were bought in, several from Hornblotton but two from Potters Bar cost over £58. (fn. 133)

37. Flax spinners' cottages on Ansford Hill, built in the late 18th century. They formerly had large upper windows to light the work of flax workers employed by Charles Donne. The nearest house was given to Castle Cary museum in the 1970s by David Mullins in memory of his wife Frances.

In 1896 there had been little change in the number of farms. (fn. 134) In 1905 only 13 a. of arable was recorded and 611 a. of grass. (fn. 135) In 1903 a bailiff's house and labourers' cottages were built for Ansford Park farm and the farmhouse and buildings extended to provide a 28-ft cheeseroom and accommodation for 41 cows. There were stables, piggeries, and a cider house. (fn. 136) It was the only farm with over 100 a. in 1910 (fn. 137) and when offered for sale in 1912 it was a compact dairy or grazing farm of 118 a. Ansford or Manor dairy farm measured c. 180 a., having been assigned land formerly part of Park farm, and had two cheese rooms and cheesemaking equipment. (fn. 138) In 1922 arable produced wheat, barley, oats, beans, turnips, and mangolds (fn. 139) but in 1939 the parish was predominantly pasture with three farms, none over 150 a., a smallholding, dairy, and nurseries. (fn. 140) Cider was made at Lower Ansford farm in the 1930s using an electric hydraulic press and some was bottled. (fn. 141) In 1947 a milk processing depot near the railway station, established by C. and G. Prideaux in 1910, employed 12 people but closed before 1957. The brick chimney survives and in 2002 the site was occupied by a company producing fire surrounds. Between 1939 and 1957 there was a dairy at Hillcrest farm, a new farm created between the village and the railway. (fn. 142) A nursery remained in 1980. (fn. 143)

INDUSTRY AND CRAFTS

In 1555 a man left his wife a spinning wheel and a length of cloth. (fn. 144) A tailor was recorded in 1691 (fn. 145) and a clothier between 1682 and 1692. (fn. 146) A mason was allowed to build a house in 1631. (fn. 147) Ansford's position on a major road may account for the carriers recorded from the 17th century. (fn. 148) Two millwrights were recorded in 1671 (fn. 149) and a sawyer in 1785. (fn. 150)

In 1801 54 people were engaged in trade and manufacture. Only 25 of 54 families were engaged in agriculture in 1821 and 24 were engaged in crafts and manufacture, probably in the new textile industries. (fn. 151) Charles Donne began his sailcloth business in the 1790s, employing weavers in Ansford working about six looms. He was described as a flax dresser and planned a flax and tow spinning partnership in 1813 but continued on his own. Samuel Powell, was also a flax dresser between 1815 and 1818. Three adjoining cottages on Ansford Hill were used by weavers in 1816 and in 1819 an 8-year old boy began working for Donne in Ansford. (fn. 152) In 1820 Donne occupied a new factory in Castle Cary and moved the business there although some workers probably continued weaving at Ansford. (fn. 153) Five weavers of both sexes were recorded in 1841 and three female handloom weavers in 1851. (fn. 154) Eighteen hair-seating weavers and four twine workers in 1871 probably worked in Castle Cary. (fn. 155) Some elderly women worked as knitters, possibly a remnant of the old stocking industry run by Benjamin Collins in 1771. (fn. 156)

38. The former Ansford inn, a centre of social life in the 18th and early 19th centuries and a stop on several coach routes, had a large ballroom and coach house from which chaises could be hired.

In 1841 there were three glovers, three carpenters, a smith, a cooper, a mason, and currier, and a grinder. (fn. 157) A tinplate worker and a gas fitter lived in the parish in 1871 and a spar maker and a rake maker were recorded in 1901. (fn. 158)

Timber merchant Jonathan Cruse built a sawmill near the station in the 1870s and another on land he purchased in 1885 on the Ansford side of the Clanville stream. (fn. 159) In 1881 a sawyer, two machine sawyers, a boxmaker, and a timber merchant were recorded and four strangers in Castle Cary were working at the railway saw mill. (fn. 160) In 1891 seven sawmill workers were recorded including an engine driver with four others living in Castle Cary. (fn. 161) In the early 20th century the business, called Cruse and Gass, was run by David Gass, also known by his pseudonym Daniel Grainger. (fn. 162) It supplied fencing and tinplate boxes and employed c. 20 people in 1947. (fn. 163) In the later 20th century the firm made pallets, packing cases, and crates for food and drink and for export under the Castle mark at the Clanville site. (fn. 164) In the 1980s century there were also a joinery and building firm, a tyre business, and a bookseller. (fn. 165)

RETAIL TRADES AND SERVICES

Public Houses

The inn in 1611 (fn. 166) was probably the George recorded in 1619 and kept by the Cary family. (fn. 167) In 1629 a parishioner drinking in an alehouse refused to attend church. (fn. 168) The Ansford inn, recorded 1711, (fn. 169) was probably the George renamed and stood on the main road near the Castle Cary boundary. (fn. 170) In 1729 it had a hall, a great parlour furnished with an oval table and upholstered chairs, a kitchen, eight bedchambers, a new cellar, a brewhouse, and a stable. (fn. 171) In 1788 it was sold by Francis Wheeler from Bristol who had fitted it out in a 'genteel manner' and supplied post chaises. (fn. 172) In 1830 the antiquary Revd John Skinner stayed there. (fn. 173) The inn then had a 1st-floor ballroom 37 ft by 20 ft, underground cellars, and coachhouse. (fn. 174) In 1851 there were four resident servants but posting had ceased by 1853. In 1861 it was occupied by a farmer (fn. 175) and in 1896 by a seedsman. (fn. 176) The licence was given up in 1879. (fn. 177) The coach house was converted into a cowshed. From 1925 Pithers of Castle Cary used it for furniture storage. By 1951 the stairs to the second floor had been removed and there were ten lock-up garages in the stableyard. (fn. 178) It has since been restored as apartments.

From 1742 there was a second licensed house, probably the Half Moon recorded in 1769 (fn. 179) and sold with 27 a. in 1772 to the tenant William Hurt who probably rebuilt it. (fn. 180) An inquest was held there in 1844. (fn. 181) It had a large yard, with stables and coachhouse, used by coal carriers until the coming of the railway. The yard was converted to cottages before 1880 and by 1891 there were c. 5 dwellings. (fn. 182) The Half Moon remained an alehouse, despite having its licence referred in 1905, (fn. 183) until c. 1957 when the property was divided and sold. There was said to have been illegal cockfighting in the cellars in the 1950s. (fn. 184) After being derelict for a time it became a licensed guest house. (fn. 185)

The Waggon and Horses on the Wincanton road, locally at Townsend, Castle Cary, was opened before 1851 in an older building. It was kept in the 1860s by the huntsman of the Blackmore Vale Hounds. (fn. 186) It was in business in 2000. The Railway Hotel, open in 1861, (fn. 187) was built on surplus land sold by the railway company in 1859 and renamed the Great Western Hotel by 1872. (fn. 188) Sold in 1875, (fn. 189) it reverted to its old name but was destroyed by bombing in 1942. (fn. 190)

Shops and Services

An apothecary and a land surveyor were recorded in the 18th century and another drew maps for the Pitcombe estate in 1810. The growth of Castle Cary from this date resulted in a greater variety of employment and occupation for parishioners. (fn. 191) Many women were employed as dressmakers and laundresses and some as nurses and charwomen. Professional men in Ansford drew their clients mainly from Castle Cary which provided shops and services. There were coal hauliers and weighers and in 1861 six carters were staying at the Half Moon inn. (fn. 192) There was a coal merchant at the station by the later 19th century, (fn. 193) a coal carman was recorded in 1901, (fn. 194) and a haulage company was based in the parish in 1980. (fn. 195)

A shopkeeper was recorded in 1841 (fn. 196) but none thereafter until 1947 when there was a general shop. It closed before 1970. In 1980 travelling shops visited and there was a garage but there were no services and no bus. (fn. 197)

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL STRUCTURE

Ansford's social and economic history was closely bound up with that of Castle Cary. The owners of the manor, and apparently the larger freeholders, were absent before the 17th century (fn. 198) but there was a lodge in the park occupied by a parker in the early 16th century. The dominant local families in the 17th century were the Carys and the Kirtons, conservative gentry families who supported Charles I. (fn. 199) The breakup and sale of the manor lands from the 1680s (fn. 200) led to the rise of professional families like the Collins's who invested in houses and lands in Ansford. Nicholas Collins (d. 1725) was a clothier with little land in 1682 (fn. 201) but James Collins (d. 1727) was a wealthy man who left £1,200 to his elder daughter Jane, wife of the rector Samuel Woodforde. (fn. 202) For over a century thereafter the Woodfordes and the Clarkes were the principal families intermarrying with each other and minor local landowners such as the Whites and the Dawes of Ditcheat. (fn. 203) The Woodfordes, now known as the family of diarist James Woodforde, were clergymen serving Ansford and Castle Cary from the later 18th century. They became local landowners by marriage and purchase. The Revd Samuel Woodforde was steward of the manor, which probably helped his brother Thomas to buy the rectory. (fn. 204) The Woodfordes regarded the rectory house as a family home and did not give it up on Samuel's death in 1771. His son James lived there until 1773 and then James's sister Jane with her husband John Pounsett occupied it until given notice in 1774 by the Revd Francis Woodforde. (fn. 205) In 1823 Francis obtained the house from the rector and as the Old Parsonage it remained in the hands of the family until the early 20th century. (fn. 206)

James Woodforde, the diarist, served as a curate in Somerset from 1763 to 1773, latterly for his father Revd Samuel at Ansford and Castle Cary, Thomas Wickham at Castle Cary and John Dalton at Ansford (1771–3), before obtaining the living of Weston in Norfolk. He expected to succeed his father and blamed his uncle Thomas for securing the living for John Dalton because Dalton would resign it when Francis Woodforde, Thomas's son, was ready to take it. (fn. 207)

More than half the residents in 1801 were neither engaged in trade nor agriculture. (fn. 208) The number of genteel houses, unusual in such a small village, made it a favoured home for professional and business men from Castle Cary, including Francis and John White, hair seating manufacturers, and Wosson Barret, grocer. (fn. 209) Other residents were William Speed, a gentleman serving on HMS St George in 1800, the Revd Richard Warner, antiquary, at Ansford House in the 1830s, and Edward Pritchard, a retired artist, living at Ansford Lodge in 1901. (fn. 210)

Men from Ansford were in Newfoundland in the early 18th century. William Tucker died there c. 1714 but a cordwainer had returned by 1722. (fn. 211) A man of black African origin from Jamaica baptised in 1732 was presumably a servant. (fn. 212)

EDUCATION

In 1606 two men taught without licence but in 1678 a man was licensed to keep a grammar school. (fn. 213) In the early 18th century James Woodforde was said to have attended a school kept by Martha Morris, later wife and victim of Reginald Tucker. There was a school in 1775 (fn. 214) but none in 1819. (fn. 215)

In 1835 two Sunday schools taught 15 girls and 8 boys and two dame schools taught 15 girls and 15 boys. (fn. 216) One Sunday school applied for union with the National Society in 1837 (fn. 217) and was the only school recorded in 1847, with 33 pupils. (fn. 218) In 1843 the children were taught reading and the catechism in church at the rector's expense. (fn. 219) In 1851 Maria Coleman, a labourer's wife, was the schoolmistress and was still teaching in 1881, but in 1861 three schoolmistresses and a school assistant were recorded. (fn. 220)

A National school with one classroom opened in 1890 north of the church (fn. 221) and c. 40 children transferred from Castle Cary. (fn. 222) From 1891 the school received half the income of Mary Woodforde's charity. (fn. 223) In 1903 there were two teachers and 51 children. The infants learnt embroidery and mat weaving and an evening school was kept. Average attendance was 39, falling to 26 in 1925, and 16 in 1935. From 1930 only juniors attended. It closed in 1967 and the 36 children transferred to Castle Cary. (fn. 224) The building became a dwelling called Old School House. (fn. 225)

A secondary modern school at Ansford was planned in 1931 to serve the Castle Cary area. (fn. 226) It was built in 1940 in Maggs Lane and had 109 pupils in 1941, rising to 335 in 1951, 456 in 1965, 598 in 1985, and 610 in 1998 when there were 34 teachers and 33 other staff. By 2002 there were c. 700 pupils. In 1994 Ansford Community School began exchanges with Mufulira school, Zambia. (fn. 227)

Hillcrest school started in a flat in the former Ansford inn c. 1953 with 16 children aged 4 to 8. In 1958 the Rectory and its outbuildings were acquired. A swimming pool was opened in 1966 and an octagonal hall in 1973. In 1974 Hillcrest taught 125 children up to 12. It was part of King's School, Bruton in the late 1980s but closed c. 1991 and the site was earmarked for residential development. (fn. 228)

CHARITIES FOR THE POOR

Cary Creed's gift of £10 to the poor charged on Lovington manor in 1775 had ceased by 1824 (fn. 229) as had the gift from his son the same year. (fn. 230) The Revd Thomas Woodforde, by deed of 1808, gave money to relieve Ansford rates but the fund had been spent by 1998 when the charity was de-registered. (fn. 231)

HEALTH

In 1682 an Ansford man was licensed to practice surgery. (fn. 232) The Clarke family were doctors in the 18th century, (fn. 233) two surgeons lived in the parish in 1841, (fn. 234) and a physician in 1851, (fn. 235) but they served Castle Cary.

In 1758 the proprietor of the Ansford inn gave notice to travellers that smallpox inoculation had ceased. (fn. 236) However, in 1767 Dr Richard Clarke moved his smallpox inoculation hospital from Castle Cary to new premises adjoining his house at Lower Ansford in which he also kept patients. It closed after his death in 1774 (fn. 237) but the Old Hospital building was maintained by the family until 1807 or later. (fn. 238) In 1890 an inoculation record was found under wallpaper in the house. (fn. 239)

COMMUNITY LIFE

James Woodforde's diaries illustrate mid 18th-century social life for his own circle, mainly clerical and professional families. There was bear baiting and cock fighting, election dinners, and a masquerade ball with nine musicians at the Ansford inn in 1767. (fn. 240) Balls and social events were held there until the opening of the new Market House at Castle Cary. (fn. 241) The Ansford club feast was held in May in 1865. (fn. 242)

In 1905 a dinner was held at the Railway Hotel to celebrate the opening of the railway to Charlton Mackrell. The station, which sold c. 1,000 tickets on the opening day, (fn. 243) was bombed and machine gunned on 3 September 1942 killing three signalmen and injuring ten other people. The engine shed, parcels office, signal box, the Railway Hotel and a train were destroyed and the milk factory and three railway cottages were damaged. (fn. 244) The Queen and the duke of Edinburgh travelled to the station in 1966 on their way to the Royal Bath and West show. (fn. 245)

There has been an Ansford football club since 1933, known as the Rovers. (fn. 246) In 1980 there were tennis courts and a swimming pool at the secondary school. (fn. 247) The Caryford Community Hall association was formed in 1986 for Ansford and Castle Cary and in 1994 the Caryford Hall, designed by local architect Nigel Begg, opened near the school. (fn. 248)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Ansford tithing was recorded in 1225 (fn. 249) and answered to the hundred court in 1564 (fn. 250) but was often considered to be part of Castle Cary tithing or Caryland (fn. 251) although separated for land tax. (fn. 252) The north-east corner of the parish, east of Park Lane, was considered part of Honeywick and Hadspen tithing in Bruton hundred in the late 18th century. (fn. 253) The manor was administered as part of Castle Cary manor, which appointed the Ansford tithingman but one copy of court roll for Ansford survives for 1658. (fn. 254) In 1653 a joint registrar was appointed for the two parishes. (fn. 255)

PARISH ADMINISTRATION

There were two churchwardens c. 1600. (fn. 256) In the early 19th century the parish was governed by a vestry of c. 10, reduced later, which paid a tithingman, a sexton and the clerk. The churchwardens, one of whom was chosen by the rector, paid vermin bounties and in 1817 stopped up a footpath across the churchyard. (fn. 257) There are no records of poor law administration before 1836 when the overseers paid to replace bread for the poor stolen from the church. They received the rent for Coombe Common and for a cottage, possibly a former poorhouse, until 1890 or later. (fn. 258) The highway surveyors employed labourers to repair drains and scrape the roads in the 1830s. (fn. 259)

There was a police cottage in 1947 but for most services the parish relied on Castle Cary. It had its own council, despite schemes to unite the two parishes and secure a more progressive council. (fn. 260)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

CHURCH

There was a church at Ansford by 1219 (fn. 261) and it was dedicated to St Andrew by 1253. (fn. 262) It remained a sole rectory, although held with Castle Cary from 1959 (fn. 263) until 1970 when it was united with that vicarage under an order of 1964. (fn. 264)

Advowson

The advowson was held with the manor from 1219, although sometimes let (fn. 265) or held by mortgagees. In 1771 Ann Powell sold Ansford rectory with church, churchyard, house, glebe, and tithes to Thomas Woodforde (d. 1800), brother of the Revd Samuel Woodforde and in 1776 it was decided that, although not mentioned, the advowson had passed to Thomas in 1771. (fn. 266) Thomas's son Francis left it to his son Francis and son-in-law Thomas Fooks in trust for sale. In 1838 it was sold to the rector, George Chamberlaine, also Francis's son-in-law. (fn. 267) Thereafter it was held by incumbents or their relatives, including the Colby family. (fn. 268) Aline Spence-Colby of Tarsop House, Herefordshire gave it to the bishop of Bath and Wells in 1959. (fn. 269)

Income and Property

In 1253 Richard Lovel admitted giving the church 8 a. of arable and 5 a. of meadow but having disseised the rector. (fn. 270) In 1291 the church was valued at £4. (fn. 271) In 1535 the glebe was worth £2 and tithes and offerings £6. (fn. 272) In 1606 tithes on 4 a. were paid to Castle Cary. The glebe, 68 a. with a cottage, was described as poor in 1613, when the cut of hay on 4 a. was said to have been given to the rector long before to free Ansford park from tithe. (fn. 273) By 1838 the hay cut had become a modus worth less than 6s. 6d. (fn. 274) The living was valued at £70 c. 1666 (fn. 275) and £362 in 1831 when there was 60 a. of glebe. (fn. 276) The tithes were commuted for over £215 in 1838. (fn. 277) In 1853 some glebe was sold for building the railway and the money invested in £208 consols. In 1918 54 a. of glebe were offered for sale and raised nearly £3,400. Remaining plots and cottages were sold in 1921 and 1944. (fn. 278)

In 1606 the house had a barn, stable, barton, garden, and orchard. (fn. 279) The Woodfordes regarded it as a family home and John Dalton, rector 1771–3, lived on his estate at Shanks in Cucklington. (fn. 280) In 1815 the house was considered too small and in 1823 was conveyed to Francis Woodforde in exchange for the nearby house of his father, Thomas Woodforde, which became the clergy house. (fn. 281) In 1827 the rector was resident, as were his successors. (fn. 282) After 1958 the rector lived in Castle Cary and the house became Hillcrest private school. (fn. 283)

39. Old Parsonage, on the corner of Tuckers Lane, was given in 1823 to the Woodforde family in exchange for another house and was for a time the home of the clerical diarist James Woodforde.

Pastoral Care and Parish Life to 1700

In 1297 the living was held by Maurice Lovel, presumably a relative of the patron. (fn. 284) In 1348–9 the parish had five rectors, implying the plague may have been endemic at Ansford. (fn. 285) John Lawrence, rector 1530–5, was probably the first graduate to hold the living and he had a curate. (fn. 286) An image of St Peter stood in the chancel in 1503 when Richard Pyn asked to be buried in front of it. Pyn gave a cow to sustain lights before the rood and to pay for an obit, and money for linen for the high altar. Richard Cooper made a further gift of 26s. 8d. to maintain a priest, before 1548. (fn. 287) The registers date from 1554. (fn. 288) Responsibility for maintaining churchyard boundary was shared between parishioners but by 1557 the churchyard was described as in decay. (fn. 289)

During the early 1560s the rector was non resident and his successor, although resident, was presented in 1568 for not preaching or reading homilies. (fn. 290) Even so church acquired two Elizabethan chalices. (fn. 291) John Fenton, rector from 1594, (fn. 292) was a pluralist who in 1606 was said to be maintaining an illiterate clerk and failing to instruct the youth of the parish. By then the church, although it was said to have been repaired and 'beautified', was evidently not well maintained. One of the wardens had sold a chest and carried away a load of stones without the consent of the parish; he had allowed a seat to block the pulpit, which had neither cloth nor cushion, and the minster had no suitable seat. (fn. 293) The present 17th-century pulpit appears to be later and bear the rough inscription EM 1685. In 1634 the seats were said to be neither boarded nor planked under foot. (fn. 294)

William Charlton (d. 1620), was also incumbent of Shepton Mallet. (fn. 295) The failure of Daniel and Edward Kirton to take communion in 1623 probably results from their conviction for assault but Robert Dawe did not receive Easter communion in 1626 and later Kirtons were recusant. (fn. 296) It is not clear what happened during the Interregnum but a new rector Joseph Barker (d. 1677) was appointed in 1660 and became prebendary of Barton St David in 1661 but failed to obtain the subdeanery for which the king had recommended him. (fn. 297) John Creed, vicar of Castle Cary, acted as his curate at Ansford. (fn. 298)

40. The parish church of St Andrew from the south-east. All but the 15th-century tower dates from a rebuilding on a larger scale in the 1860s.

Pastoral Care and Parish Life: the 18th to the 20th Century

Three Woodfordes held the living between 1721 and 1836 and Francis's son-in-law George Chamberlain was rector from 1836 to 1858. (fn. 299) Most also served Castle Cary. (fn. 300) During the incumbency of Samuel Woodforde, before the Hardwicke Marriage Act of 1754, Ansford was a popular church for marriages, mostly of non-parishioners and presumably clandestine. (fn. 301) The Revd Francis Woodforde, rector 1773–1832, was non-resident by 1790 and served neighbouring parishes as a salaried curate. (fn. 302) There was only one Sunday service in 1815. (fn. 303) In 1827 Francis was resident and two Sunday services were held alternately morning and evening, although he was also incumbent of Hornblotton and Weston Bampfylde. He resigned in 1832 and presented his son Thomas, also incumbent of Pointington and South Barrow. (fn. 304)

In the 1780s the church described as small, neat, and Gothic, had a pinnacled, west tower and 28 new panelled deal pews painted cream, as were the singers' gallery, pulpit, carved with cherubs' wings, and communion table and rails. The chancel roof had been ceiled between the ribs. (fn. 305) Repairs were carried out in 1815, 1818, and 1835, when iron gates were installed in the churchyard. (fn. 306) The nave roof was coved, there was carved timber in the chancel roof and screen, chancel and tower arches were pointed, the latter partly obscured by a small gallery, there were a large east window and a square-headed, two-light south window east of the south porch. (fn. 307)

Communion was celebrated four times a year in 1843 (fn. 308) and the pewter paten was replaced by a silver one given in memory of George Chamberlaine, rector 1836–54, a silver pyx was bought in 1933, (fn. 309) and a ciborium in 1947. (fn. 310) In 1851 35 people attended morning service on Census Sunday and 120 came in the afternoon. There were 16 Sunday-school children. There were only 100 seats, none of them free, and there was a non-resident curate. (fn. 311) The Revd Robert Colby, who presided over the rebuilding of the church and was resident, with several servants, including a butler, also employed a non-resident curate. (fn. 312) In 1876 celebrations of communion had increased to six. (fn. 313) By 1888 the Sunday school had ceased and there was no organ. (fn. 314) Under Lewis Colby Price, rector 1888–1926, the church became Anglo-Catholic in tradition. In 1889 the rector gave an organ, built by Harry Ivey of Newton Abbot in 1860 for the earls of Devon. It was overhauled in 1923 and 1977. (fn. 315) In the 1920s there were services morning and evening but an additional morning service was dropped in 1926. There were 106 Easter communicants in 1933 when a silver pyx was bought, and services were described as low or sung mass. (fn. 316) The Revd Mervyn Basil Bazell, rector 1933–47, established a choir for 30 men and boys, which was reduced by the 1950s and had ceased by the 1970s. (fn. 317) A ciborium was acquired in 1947.

The four (fn. 318) bells could not be rung for most of the 20th century, (fn. 319) but in 1992 they were rehung in a new steel frame (fn. 320) with two new ones. The treble and second bells were cast at Whitechapel in 1991, the third, St Katherine, is a medieval Bristol bell, the fourth is by Robert Austen (1661), and the fifth is by William Knight (1747). The tenor by Robert Austen (c. 1625) has the Bristol arms and may be a recast medieval bell. (fn. 321) The new peal was first rung on 31 July 1993 with 5,040 changes. (fn. 322) By the later 20th century matins and evensong were held monthly. Average attendance at Sunday Eucharist was 35–65 with 75 Easter communicants in 1993. (fn. 323) There was one Anglican service each Sunday in 2002.

Church Building

The medieval church of St Andrew was small and had a chancel and nave with Perpendicular windows, a south porch, and an embattled west tower of the 15thcentury. (fn. 324) The tower and tub font are all that survives after Victorian rebuilding in mainly 13th-century style.

In 1859 the vestry declared the church dangerous and too small. (fn. 325) A faculty was obtained in 1860 to demolish all but the west tower. The new church, built of Cary stone (fn. 326) by E. O. Thomas of Castle Cary to designs by C. E. Giles, was to have an extra 1,000 sq. ft on the north with an aisle, vestry and heating chamber, new furniture, and a heating system. The old building was demolished in 1861 and the new one opened in 1862 (fn. 327) with carved flower and ribbon decoration in the chancel by John Seymour of Taunton, Minton tiles around the altar, and windows given by the Woodfordes. (fn. 328) In the 1960s flooring problems resulted in the removal of the pews (fn. 329) and chairs were in use in 2002.

The churchyard had new walls and gates in 1893 and the cross was restored in 1904 but only a small fragment of the medieval shaft survives. (fn. 330)

Other Buildings

Church Institute This was an iron building by Ginger, Lee, and Co. of Manchester erected near the rectory house in 1909. (fn. 331) By 1935 it was too small and an extension was needed. (fn. 332) It only accommodated 80 in 1947 and later went out of use. (fn. 333)

St Andrew's Well Reputedly a holy well which cured eye complaints, it was recorded south of the church in 1885 but only a small marshy area marked the site. (fn. 334)

ROMAN CATHOLICISM

Since the departure of the nuns from Castle Cary in 1996 Roman Catholic mass has been celebrated in Ansford parish church, served from Wincanton. (fn. 335)

PROTESTANT NONCONFORMITY

In 1699 and 1706 houses were licensed for worship by unspecified congregations and in 1832 a building was similarly licensed. (fn. 336) Quakers were said to have met at the Ansford inn in 1766. (fn. 337)