A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Alford', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10, ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp75-84 [accessed 23 April 2025].

'Alford', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Edited by Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online, accessed April 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp75-84.

"Alford". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online. Web. 23 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp75-84.

In this section

ALFORD

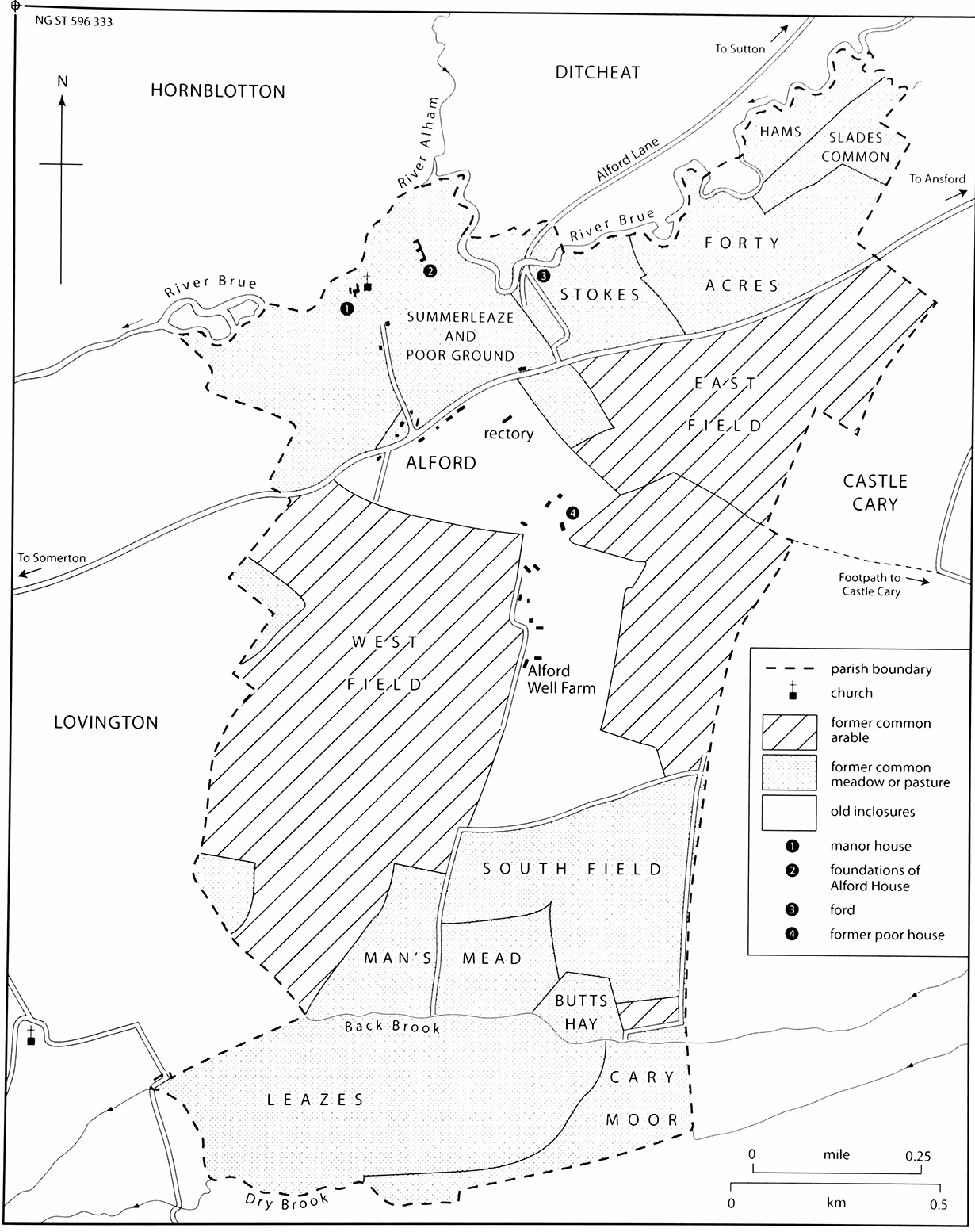

33. Alford 1830

This map shows the original field patterns; farmsteads surrounded by closes between them, and church and manor house by the river Brue.

ALFORD, formerly noted for its medicinal waters, (fn. 1) is a small parish and village 3.5 km. (2 miles) west of Castle Cary between the river Brue to the north and the Dry or Cary brook to the south. The course of the Brue is well-wooded and the rest of the parish is a patchwork of fields cut through from north-east to south-west by the Castle Cary to Somerton road and the London–Penzance rail line, the latter cutting off from the village cottages between the former open fields whose ridge and furrow can still be seen in the pasture fields either side of the railway. The name Alford, formerly Aldedeford (fn. 2) then Alludeford, (fn. 3) indicates a river crossing, possibly Stakesford. (fn. 4) The parish is roughly rectangular measuring 2 km. from north to south and 1.5 km. from east to west and covering 292 ha. (721 a.). (fn. 5) Lower Lias clay occupies the centre of the parish between valley gravel in the north and south-west and alluvium in the south, site of the former common meadow and pasture. The land is fairly level rising from 30 m. (98 ft) north and south to only 36 m. (118 ft) in the east. (fn. 6)

COMMUNICATIONS

The main route through the parish, linking Castle Cary and Somerton, was established by 1675 and turnpiked in 1753. (fn. 7) Alford Lane from Alhampton to the north-east crossed the Brue by Stakesford. (fn. 8) Footbridges now cross the river notably that carrying the way to the former Hornblotton mill to the west. (fn. 9)

Alford halt was opened in 1905 (fn. 10) on a line completed in 1906 by the Great Western Railway between Langport and Castle Cary. (fn. 11) The halt was served by six trains each way daily in 1947 but closed in 1962. (fn. 12) A siding from the main line east of the halt was built to serve the army camp at Dimmer in 1940 but was dismantled in 1959. (fn. 13)

SETTLEMENT AND POPULATION

There is evidence of Iron-Age occupation by the Back brook in the south. (fn. 14) The medieval church and manor house lay near the Brue in the north. The village grew up beside the main road but by the later 17th century a straggling line of dwellings had been built on a strip of land running south from that road between the two medieval open fields towards the meadows and pastures. Some of those houses were lost when the railway was built. (fn. 15)

The population was 99 in 1801 and 96 in 1811 but rose to 136 people in 1821 and fell to 90 in 1841. Apart from a rise to 125 in 1871, partly due to an increase in the Thring household, the figure remained stable at c. 100. (fn. 16) Buildings encroaching on the main road were removed probably in the late 19th century but new houses were built in the 1920s and 1930s. (fn. 17) In the later 20th century bungalows were added and large houses subdivided but the population fell to 81 in 1971 and 68 in 1991. (fn. 18)

There were 16 houses in the parish c. 1665, seven of them with 3 hearths (fn. 19) and 20 in the 1780s. (fn. 20) In 1845 the parish's four farmhouses and 15 cottages, one with a smithy attached, were all but one built of stone with thatched roofs. They included a 16th-century cottage with hollow-moulded mullioned windows and jointed crucks converted to a lodge for Alford House c. 1900, and Parsonage Farmhouse which until 1833 had been the rectory house, and has an arch-braced collar roof with windbraces. Two houses, built in the 17th century, have windows with ovolo mullions. One of them, Alford Farmhouse distinguished by walls chequered in Lias and Cary stone, was much rebuilt in the 19th century when a pair of estate cottages with picturesque timber porches was built in the village. (fn. 21) In 1849 Parsonage farm had a thatched barn, stable, and cider cellar integral with the house. Those buildings have been replaced but a late 16th-century cruck barn survives near the road. In the late 19th century Alford farm had the most extensive farmbuildings, many of which survive. (fn. 22)

LANDOWNERSHIP

ALFORD MANOR

In 1066 Alford was held by Godric and in 1086 by Ansger of the count of Mortain. (fn. 23) By 1234 overlordship had passed to the de Mohun family (fn. 24) who, with their successors the Luttrells, held it as part of the honor of Dunster until 1520 or later. (fn. 25) However, in 1322 it was said to be held of Walter de Romsey. (fn. 26) In the later 13th century it was one fee or two little fees, sometimes described as of Mortain, but by the early 15th century it was a half fee. (fn. 27)

The terre tenancy may have been held by Jocelin of Alford in 1194 (fn. 28) but by 1234 Simon de Ralegh held it for two fees. (fn. 29) Before his death c. 1284 Simon inherited Nettlecombe and Alford descended with that manor to his son John (d. by 1293), to Sir Simon (d. c. 1304), (fn. 30) and Sir Simon's son John (d. 1340). (fn. 31) In 1332 two thirds of Alford was seized by the Crown and was farmed by John of Landymore. (fn. 32) John de Ralegh recovered the manor in 1327 and his son John (d. 1372), settled Alford in 1367 on himself and his wife Ismania for life and on their younger son Simon. (fn. 33) In 1393 the reversion on Ismania's death was settled on Simon's elder brother John and his wife Eleanor. (fn. 34) John died childless c. 1403 when Ismania and her third husband Sir Lawrence de Berkerolles leased Alford to John's brother Simon de Ralegh (d. 1440). (fn. 35) Simon died childless and under a settlement of 1427 Alford passed to his widow Joan or to trustees. (fn. 36)

Before 1442 under pressure from the lawyer William Dodesham Joan was said to have sold Alford, or allowed the trustees to sell, to John FitzJames. In 1442 John's father James FitzJames was either tenant or trustee, but Joan de Ralegh exercised the advowson. After her death in 1455 Simon's nephew and heir Thomas Whalesborough tried to recover Alford. (fn. 37) In 1472 Thomas secured a quitclaim from Joan's heir, her great niece Alice Knyffe, wife of Richard Bulstrode, and again tried to recover the manor. He petitioned the Chancellor a third time c. 1480 without success. (fn. 38)

John FitzJames (d. 1476) of Redlynch was succeeded by his son John (d. 1510), (fn. 39) and grandson Sir John (d. c. 1542), Chief Justice of the King's Bench. Sir John was succeeded by his cousin Nicholas FitzJames (d. 1520). Sir James, son of Nicholas, sold Alford c. 1566 to William Rosewell (d. 1566), Solicitor General, who settled it on his infant children. (fn. 40) William's son Parry died in 1573, a minor in the Queen's ward, and was succeeded by his brother William (d. 1593) and by William's infant son (Sir) Henry. (fn. 41) In 1634 Henry and his wife Mary conveyed the manor to Simon Court, who before 1639 sold it to Sir Robert Gorges of Redlynch. (fn. 42)

On Gorges' death in 1648 the manor passed to his mortgagee, Henry Symes of Poundisford, who in 1652 conveyed it to John Dodderidge of Bremridge (Devon), described as lord in 1653. Dodderidge left it to his brother-in-law Thomas Dacres for conveyance to his two daughters and the son of a third. The shares fragmented still further in the next generation, (fn. 43) but by 1699 one third, which had belonged to his grandson, John Martin, was in the hands of John Pyle of Exeter. (fn. 44) In 1716 John's widow Joan sold to Walter Harvey of Abbot's Leigh who continued to live on the estate as its manager after he had conveyed it to Thomas Freke (d. 1731), a Bristol merchant. The estate passed in succession to Freke's son Thomas (d. 1769), a lunatic, and his daughter Frances (d. 1780), wife of John Willes. Frances's son John Freke Willes (d. 1799) left it to his cousin the Revd William Shippen Willes of Cirencester, Glos. (fn. 45)

The third share of Dodderidge's daughter Elizabeth Crossing probably passed after 1672 to the owners of the other shares. The share of Dodderidge's grandson John Lovering the younger came in succession to the Acland and Barbor families and in 1805 George Barbor let the land to the Revd Willes and sold the lordship to Joseph Pitt of Cirencester. (fn. 46) The same year Willes sold his estate to Pitt who became sole lord of the manor and landowner. (fn. 47)

34. Alford's parish church of All Saints from the south, with the manor house built on a new site to the east in the 19th century.

In 1807 (fn. 48) Pitt sold Alford to John Thring (d. 1830) who was succeeded by his son the Revd John Gale Dalton Thring (d. 1874), his grandson Theodore (d. 1891), and his great grandson John Huntley Thring (d. 1928). (fn. 49) The last sold the estate piecemeal in 1906–7 to pay his debts, but not the lordship. (fn. 50) Alford house was sold in 1907 to Admiral Philip Tillard (d. 1933) (fn. 51) and it was the home of the Balmain family. (fn. 52) Admiral George Thring, nephew of J.H. Thring, bought it with 150 a. in 1945 and was owner in 2002. (fn. 53)

Manor House

The medieval manor house stood close to the church. The owners were not usually resident and the squires' chamber alone was recorded with outbuildings and garden in 1306–7 (fn. 54) and a hall in 1322. (fn. 55) The joint owners let the house in 1669 (fn. 56) and it was let with 100 a. in 1766. (fn. 57) That house, probably rebuilt in the 17th century and extended in the 18th, stood very close to the west end of the church. In 1833 it appears to have been T-plan and in 1845 had at least two wings, which formed an L. (fn. 58) A fragment of the house, converted to a cottage, survived until a fire in 1941. (fn. 59) New stables were built east of the church, probably by John Thring soon after 1807, and fields were cleared for a 100 a. park and plantations. (fn. 60) They became the setting for a larger house to the northeast of the old one. Alford House, designed in an oldfashioned late Georgian Gothic style, was begun in 1838, (fn. 61) and was remodelled in Northern Renaissance style in 1877 reputedly by F. C. Penrose, architect of Castle Cary market house. It was divided into several dwellings in the late 20th century. (fn. 62)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

AGRICULTURE

In 1086 Alford was taxed at 5 hides and had land for 5 ploughs but only 3 were recorded; one in the 2¾-hide demesne worked by 3 serfs and two with the rest of the land worked by 7 villeins, 4 bordars, and 4 cottars. The demesne had 50 a. of meadow and 20 pigs. A mill was recorded and one tenant owed eight blooms of iron. The value of the estate had fallen from £5 to £4. (fn. 63) Population and arable seem high compared with the 19th-century parish of c. 700 a. and c. 100 people. (fn. 64)

In 1306–7 one third of the manor, held in dower, included an oxshed, half a granary and one third of a dovecot. Over 130 a. of arable lay in East and West lands, and in areas called Blackland, Thorngar, perhaps cleared from scrub, and Myddelmor and Estmore. There was c. 20 a. of meadow and 53 a. of inclosed pasture. La Wynard, where geese were grazed, may have been a former vineyard. Lupeyete and the Dych suggest a former park and were still recorded in the 17th century, the former in the west arable field. (fn. 65) Two thirds of the manor, described in 1322, included a barn and oxshed, 53 a. of arable, 30 a. of meadow, and summer and winter pasture. (fn. 66)

There were 12 free tenants in Alford in the early 14th century, one of whom paid rent in iron as successor to the Domesday tenant. Most of them held houses or small plots but two had had 9 a. each and one held by knight service at Knolton. (fn. 67) A further freehold, formerly belonging to Sabina de la Strete, seems to have been absorbed. There were eighteen customary tenants of whom most were half-virgaters owing the usual services. One smallholder paid rent in geese, and some had an allowance of cheese after haymaking; another leased 14 a., possibly demesne arable, and could put 24 ewes on the fallow fields in summer in summer, although he also owed minimal services. Free pannage in Baltonsborough wood indicates that there was no woodland locally. (fn. 68)

The 16th to the 18th Century

Cattle and sheep were mentioned in 16th-century wills and in 1554 a Bruton man's smallholding in Alford included six rother beasts. (fn. 69) Marl was used and withies were grown. (fn. 70) Common pasture for oxen and bullocks at Bushy or Alford Leaze and Longthorne, both in the south of the parish, were by agreement divided and hedged c. 1667 (fn. 71) but common meadow for sheep and horses was still retained in the early 18th century. Stock was still folded on the arable fields, for manure and possibly because of a shortage of pasture, although an island of moors and leazes between the Back and Cary brooks provided common pasture. (fn. 72)

In 1669 two farms were let in consideration of rebuilding the farmstead. (fn. 73) A yeoman who died c. 1690 left corn worth £80 and cattle and sheep worth £66. (fn. 74) By 1710 two holdings had been combined into one and in 1716 there were 27 holdings including parcels of land and three landless cottages. The largest farm was 57 a. and only 14 had more than 20 a., but some tenants had more than one holding and one held several, totalling 92 a. Some capon rents were recorded. (fn. 75) In 1746 repairs were needed and trenching and ditch digging was in progress. (fn. 76) By 1786 amalgamations had resulted in six farms, one with two dwellings and c. 167 a. and two others with over 100 a., and a small holding consisting almost entirely of open arable. Small fields in the north and south of the parish had been combined into larger ones. About c. 160 a. of arable still lay open although a new inclosure of 27 a. was recorded and several closes lay within the open fields. (fn. 77) The two-field system of planting on cold wet clay probably restricted cropping, and of 109 a. of crops recorded in 1801 half was wheat and half barley. However, there were said to be many fine orchards. (fn. 78)

The 19th to the 21st Century

In 1805 an Act was passed to inclose 260 a. of arable, the total probably including old inclosures, by then the sole property of the lord of the manor who redeemed the land tax. After exchanges the estate was divided into seven farms of between 27 a. and 184 a., including the capital messuage and the glebe. (fn. 79) Improvements thereafter included new barns and other buildings and further farm amalgamations. By 1808 there were four farms with between 123 a. and 165 a. and several landless cottages, each usually occupied by one family. (fn. 80) A lease of a 161-a. farm in 1812 required the tenant to maintain and weed the new quick thorn hedges and in addition to the £580 rent to provide the landlord with straw and timber and to breed a puppy if required. An allowance of £10 might be made for trenching, liming, and marling but one third of the manure was to be used on the pasture. One farm in 1817 had roughly equal amounts of pasture and arable but on another only a quarter of the land was arable and the total in the parish was 248 a. The rental of Alford including tithes was over £2,100. (fn. 81)

Farming remained unchanged and in 1839 there were 406 a. of grass and 247 a. of arable, (fn. 82) producing good wheat, beans, oats and clover. (fn. 83) The land was said to be excellent for dairying and a four-field crop rotation including roots was practised on the arable. (fn. 84) Of the four farmsteads c. 1849, three had cowsheds, one new, one had a timber staddle barn, and Parsonage farm had a cider cellar. (fn. 85) There were 13 labouring families in 1841, some of whom took in other labourers as lodgers. (fn. 86) In 1851 the largest farm with 300 a. employed eight labourers, another with 180 a. employed five, and two with 70 a. and 81 a. employed one each. (fn. 87) By 1861 the two larger farms covered 228 a. and 212 a. and the four farms employed a total of 24 labourers, a considerable increase. A dairy had a resident worker and a dairymaid lived on one of the farms. (fn. 88) In 1864 the four farms produced rents and tithe totalling £624. Nearly £30 was spent draining the cheeseproducing Alford farm. A considerable sum had been spent on building work, probably at Parsonage farm. (fn. 89) Between 1866 (fn. 90) and 1871 the number of farms was reduced to three, of between 160 a. and 240 a., employing 20 labourers. (fn. 91) The pattern continued in 1881 although fewer labourers were employed and all three farms were described as corn and dairy in 1883. (fn. 92) Alford and Parsonage farms had horse engines for threshing but gradually the arable was laid to pasture and they became obsolete. A cheeseroom and dairy were added to Alford Farm and Parsonage Farmhouse had a rear wing containing a dairy and a cheeseroom and by c. 1907 also had five piggeries, a whey tank, a mangold shed, a rickyard, and cowsheds. (fn. 93) In 1901 one farmer was a hay and straw merchant and two cowmen were recorded. (fn. 94)

By 1905 there were 588 a. of grass and only 33 a. of arable. (fn. 95) When the Thring estate was broken up Alford and Parsonage farms were sold to the tenants for over £23,000 but Alford Well farm was sold separately to Col. Henry Ridley in 1908. (fn. 96) In 1931–2 Alford Well farm comprised 227 a., all pasture apart from the orchards, and was a cheese-making farm containing a dairy and a cheeseroom in the farmhouse, stalls for 32 cows, three calving houses, three piggeries, stabling for four horses, engine houses, and three workers' cottages. There was c. 25 a. of cover recently planted on Mansmead with larch and fir for foxhunting and let to the Blackmore Vale Hunt. (fn. 97) In 1939 two farms were over 150 a. (fn. 98) Alford Well farm became a private house in the later 20th century and the land was purchased by Somerset County Council to add to their Dimmer refuse site. (fn. 99)

MILL

A mill was recorded only in 1086 (fn. 100) and 1610 (fn. 101) but there was a millway in the east field in 1306 and 1668. (fn. 102) A timber frame was said to have been found in the Brue in the 19th century (fn. 103) but by that date a path from the village to Hornblotton mill indicates that the latter mill had been used for some time. (fn. 104)

CRAFTS AND RETAIL TRADES

A tanner was recorded in 1646. (fn. 105) A weaver in the late 17th century and a sergeweaver in the mid 18th century leased small farms and in the 1690s a cordwainer was also a yeoman indicating that non-agricultural work was parttime. (fn. 106) The shop recorded in 1681 was possibly a smithy or wheelwright's shop. (fn. 107) In 1685 a tobacco pipe maker leased the site of a cottage. (fn. 108) A yarn barton beside the Brue was a nursery and orchard by 1838. (fn. 109) In 1831 only one family was engaged in trade (fn. 110) but a gardener and blacksmith were recorded in 1841. (fn. 111) The tile moulder, brickmaker, and bricklayer recorded between 1851 and 1881 may have been working at Alford House although it is built of stone. The charwoman, dressmaker, and cordwainer probably worked mainly for the Thrings. (fn. 112) A mat maker was recorded in 1927 and 1935. (fn. 113)

There was a grocer in 1851 (fn. 114) and a shopkeeper in 1859. In 1861 there was also a post office but from 1866 it was combined with the shop. (fn. 115) In 1871 the shopkeeper also took in lodgers and in 1881 and 1901 worked as a labourer. (fn. 116) The post office shop remained open until 1939 (fn. 117) but had closed by 1947. Thereafter the parish relied on four mobile shops. (fn. 118)

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL STRUCTURE

Alford was always a small agricultural community and the landlords were not usually resident. After buying the manor and advowson in 1807 the Thring family dominated the community until the early 20th century and most residents worked on the farms or in domestic service with Alford House the major employer. (fn. 119) In 1841, 13 domestic servants were employed in five houses. All the farms had one or two indoor servants in 1851 and there were five resident servants and at least five others, including gamekeeper and gardener, working for the Thrings. (fn. 120) In 1861 eleven servants lived in Alford House but only one was born in Somerset. Two married servants occupied cottages and two others lived with their families. (fn. 121) Alford House was occupied by a caretaker in 1891 but in 1901 there were seven servants living in and at least thirteen, including six grooms, living out. Major Sherston at the Cottage had four female servants. (fn. 122)

There was inadequate housing and serious overcrowding: 136 people lived in 17 dwellings in 1821 and 137 people in 15 houses in 1831. (fn. 123) In 1891 one cottage had two rooms, one of which was occupied by a family of seven teenagers and adults, three cottages had only three rooms. (fn. 124) In 1901 the labourer who kept the fourroomed post office, despite having two adult daughters and a grandson, lodged one of the Alford House grooms. (fn. 125)

EDUCATION

In 1662 the rector was licensed to teach a grammar school and John Gregory was licensed to teach reading, writing, casting accounts and ciphering. (fn. 126) There was no free school in 1666 but Gregory's school continued, (fn. 127) and he was licensed to practice surgery in 1676. (fn. 128)

There was no day school in 1818 but 10–14 children attended a Sunday school, said to provide all the education the poor required, but parents did not enforce regular attendance. (fn. 129) The Sunday school had 21 pupils in 1825 (fn. 130) and 38 in 1835, paid for mainly by the rector (fn. 131) although for several years from 1836 the churchwarden contributed 10s. a year. (fn. 132) There was no school at Alford thereafter children being taught probably at Hornblotton c. 1847 (fn. 133) and later at Lovington school (fn. 134) where the schoolmistress recorded in 1851 probably taught. (fn. 135)

CHARITY

John Fraunceis by will dated 1578 gave 1s. to six named poor men of Alford. (fn. 136) By wills both dated 1703, Edward Gregory and Emmanuel Francis each gave £10 for a total distribution of £1 to the poor each year. (fn. 137) In 1803 the money was let out at 5 per cent. In 1805 the borrower left the parish having sold his property to John Thring to whom he paid £13 arrears in 1819 for distribution. (fn. 138) By 1869, however, the charities were lost. (fn. 139)

ALFORD WELL

In 1670 the well north of Alford Well Farm was found to be impregnated with alum and have purgative properties, purportedly after pigeons were seen flocking to the water. (fn. 140) A farm lease in 1673 excluded the well and spring except water for the tenants' use. (fn. 141) Guidot published the water's properties in 1676. It attracted many visitors and lodgings were fitted up. (fn. 142) By 1692 its value had waned as it was included in the farm lease, the landlord reserving the right to take water until c. 1703. (fn. 143) Celia Fiennes c. 1700 wrote that people no longer came to the well but sent for the water to make beer. By the 1730s it was disused. (fn. 144) A farm lease in 1752 did not mention the well. (fn. 145) By the 1780s it was in a locked shed. (fn. 146) A meal house was built on the site in 1912 and the well was concreted over. (fn. 147)

COMMUNITY LIFE

An inn recorded from 1738, presumably on the main street, may have had bear baiting in 1759, (fn. 148) and was known in 1788 as the Alford Inn. (fn. 149) By 1805 it had closed and was a farmhouse, possibly on the main street. (fn. 150)

In the 1860s a museum was built to house an ichthyosaurus discovered at Alford. The building was later converted to cottages including a post office. (fn. 151) John Gale Dalton Thring provided the village with two pumps. (fn. 152) A reading or lecture room on the site of the Quaker burial ground belonged to Alford House in 1879 and in 1896 may have been the assembly rooms where dancing was held. It was given to the parish in 1925 and used as a Sunday schoolroom and church hall until 1947 or later. (fn. 153) It was sold and became a house known as the Old Reading Room. (fn. 154) The Thrings organized social events such as entertaining the volunteer corps in 1896 and Earl Roberts, a relative, in 1901. (fn. 155)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

MANORIAL ADMINISTRATION

Alford formed a tithing with Lovington. (fn. 156) No manorial records survive but tenants owed suit of court until the early 19th century. (fn. 157) A pound was in use in 1698. (fn. 158) In 1703 the tenant of Alford Well farm was the manor bailiff, collecting rents and heriots and paying them to the Acland's court at Curry Rivel, implying that courts were not then held at Alford. (fn. 159)

PARISH ADMINISTRATION

In 1606 there were two wardens (fn. 160) but only one by the mid 18th century. (fn. 161) In 1703 the wardens and overseers leased a decayed cottage, undertaking to rebuild it within one year; (fn. 162) it was probably the poor house recorded in 1808 half way between the village and Alford Well farm. (fn. 163)

A police constable boarded in 1891 and was in charge of a police station at Alford in 1897. (fn. 164)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

CHURCH

Roger the priest was recorded at Alford in the mid 12th century and later Alford was represented at the Cary chapter. (fn. 165) The church was dedicated to All Saints by 1545. (fn. 166) It remained a sole rectory until consolidated with Hornblotton under an Act in 1836. (fn. 167) In 1977 the benefice was united with those of Babcary, Lovington, and North with South Barrow to form the Six Pilgrims. (fn. 168)

Advowson

The advowson was held with the manor, although from the 16th century it was frequently let and the queen and others presented during minorities. When the ownership was fragmented the advowson was usually let for individual turns but in 1771 the Willes family presented. (fn. 169) The Thrings held the advowson from 1807 (fn. 170) until c. 1950 when it passed to the Diocesan Board of Finance which holds the second turn in the united benefice. (fn. 171)

Income and Property

The church was valued at £5 in 1291 (fn. 172) and 1428 (fn. 173) but paid only 7d. tax in 1441 and in the 1460s was exempt for poverty. (fn. 174) The glebe was worth £2 10s. in 1535 when tithes and offerings were valued at £7 10s. (fn. 175) In 1606 the glebe measured over 42 a. including the churchyard besides six beast leazes in the common. (fn. 176) By the later 18th century some tithes were paid by composition, the rest in kind. (fn. 177) Most glebe was in the open fields and in 1805 the rector wished to exchange and improve his holding. Only c. 4 a. were exchanged but the rector was given an orchard north of the main road by Joseph Pitt. (fn. 178) The glebe was variously said to be c. 39 a. (fn. 179) or 45 a. (fn. 180) probably due to the differences in measurement between surveyors complained of by the lord of the manor. In 1817 the glebe was let and was worth c. £70. Tithes were valued at £217. (fn. 181) In 1839 the glebe measured c. 41 a. and the tithes were commuted for a charge of £140. (fn. 182) Exchanges in 1853 and 1875 (fn. 183) reduced the glebe to 27 a. (fn. 184) and in 1905 land was sold to the Great Western Railway for £128. (fn. 185) By 1907 very little glebe of the united benefice was in Alford. (fn. 186)

Rectory houses A house, recorded in 1606, had in 1623 an 'out' kitchen, barn, stall, and stable. Later a wainhouse and kitchen garden were mentioned. (fn. 187) In 1815 the incumbent, John Gale Dalton Thring, lived in Alford House and considered the rectory house unfit for his household. It was let to a farmer and was thereafter known as Parsonage or Vicarage Farm. (fn. 188) Under the 1836 Act the rectory house was to be in Hornblotton (fn. 189) and was probably the glebe house recorded in the 1840s. (fn. 190) However, in 1875 a small house on the main street was acquired by exchange and was called the Parsonage by 1885, (fn. 191) although also the Cottage. (fn. 192) It was upgraded by the addition of an attic storey and rear wings. (fn. 193) It was probably occupied by curates (fn. 194) while the rector lived at Hornblotton, and in 1897 by John Huntley Thring when Alford House was let. Arthur Burnet Burney, rector 1921–35, lived there and it became the rectory house. (fn. 195) After 1977 the rector lived at North Barrow and the rectory was a private house known as the Old Rectory. (fn. 196)

Pastoral Care and Parish Life

In 1333 Henry Peres, rector 1329–50, was licensed to serve his patron, Lady Joan de Ralegh, for a year. (fn. 197) John Pym, instituted in 1453, was not in holy orders; he was ordained acolyte the following year and deacon and priest in 1455. There was a parish chaplain in 1450 (fn. 198) and a curate c. 1530. (fn. 199)

A gift of frumenty to the church in 1543 may have been for a church feast. (fn. 200) During the 1550s attempts were made to recover money and a missal. (fn. 201) In 1568 there were no sermons and only one homily a month. There were no works of Erasmus and in 1594 no book of common prayer. (fn. 202) The parish has a communion cup and cover, dated 1574, by Richard Orange of Sherborne. (fn. 203) Rectors were resident, but failed to preach. (fn. 204) Henry Maundsell was presented for failing to make perambulation in 1606 when the church lacked a large bible and a pewter pot for communion. (fn. 205) His successor Guy Clinton (d. 1650) was ejected c. 1646 for reading the book of common prayer, being insufficient in ministry, and scandalous in life. His son, also Guy, a royalist supported in arms by his father, was involved in a fracas at Bruton. However, Clinton was living in Alford when he died and R. Howes was not recorded as minister until 1650. (fn. 206) Although Thomas Earle, 1661–70, said there was no nonconformity in 1666, several local people became Quakers during his incumbency. (fn. 207) The registers survive only from 1758. (fn. 208)

By the 1780s there was a wainscoted gallery for the singers. (fn. 209) During most of the 19th century the benefice was held by members of the Thring family who owned the manor and advowson. Under them, and usually at their expense, porch and nave were ceiled in 1813, the church was whitewashed in 1823, (fn. 210) and 'throughly' repaired in 1848–9. (fn. 211) Iron rails and gates from Bristol were erected in 1813, (fn. 212) the latter replaced in oak in the 1960s. (fn. 213) John Gale Dalton Thring, patron and rector 1808–58, held one service on Sundays in 1815 and two in 1827. His youngest son John served as curate in 1851 and 1871. (fn. 214) Elizabeth Thring gave a small flagon and paten at Christmas 1824. (fn. 215) Another son Godfrey succeeded as rector in 1858 and held two Sunday services and celebrated communion three times a year, increasing to six in 1870 and fourteen in 1876. (fn. 216) He was also a prebendary and a hymn writer, invented a stile, restored Alford church, and rebuilt Hornblotton. (fn. 217) There is 19th-century memorial glass to the Thrings in the south chancel windows. (fn. 218) The number of seats was reduced to 80 after 1878. (fn. 219) In 1898 the altar was raised and a super altar added. (fn. 220) By the 1970s the 1620 bell by Robert Austen and the 1753 bell by Thomas Bilbie could not be rung and the remaining bell, cast by Thomas Purdue in 1673, could only be chimed. (fn. 221)

Church Building

The churchyard cross is late 13th-century but the entire church appears to have been rebuilt in the later 15th century and was sympathetically restored, the chancel refitted and the nave roof replaced in 1877–8 by Thomas Graham Jackson. (fn. 222) The interior may have been quite fine. The original roofs to porch and chancel have carved bosses, and the chancel roof angels and heads as well. There remained in the 1780s stained glass windows of c. 1500, including the arms of the FitzJames family and their wives; by the mid 19th century only fragments remained; (fn. 223) some glass may have been removed during work on the windows in 1803 (fn. 224) and was acquired by William Woodforde (d. 1844). Medieval glass, probably from Norfolk, was introduced in the 19th century and was rearranged to fill three lights of a north window c. 1935. It includes St Katherine, the Evangelists, St Margaret, St Mary Magdalene, angels and canopies, probably from the 15th century and a pair of lions thought to be older. (fn. 225) The fragmentary 15th-century roodscreen may be the remains of one in poor condition in the 1780s, (fn. 226) or an introduction, and the pulpit has been assembled of elaborately carved panels, one dated 1625.

The churchyard cross stands on four octagonal steps. After the 1780s it had a finial and calvary added, but those were said to have come off in 1869 to be replaced by a cross. (fn. 227) There were many headstones in the 1780s (fn. 228) but the churchyard was cleared of most gravestones except those of the Thrings in the 1950s. (fn. 229)

NONCONFORMITY

Quakers

In 1657 and 1662 two local men, Samuel Clothier and John Cary, were imprisoned, first for non-payment of tithe and then for attending a Quaker conventicle at East Lydford. Clothier remained in Ilchester gaol until he died in 1670. All those who attended his burial at Alford, including relatives and non-Quakers, were fined. Nine Alford people were among those of many parishes fined for attending an illegal conventicle on the highway in 1670. (fn. 230) Another Samuel Clothier was distrained for tithe in 1690. (fn. 231) The house of John Cary, possibly a son of the man imprisoned in 1662, was licensed for worship in 1706 (fn. 232) and appears to have had a burial ground attached. The Quaker cause had ended by 1718 when the burial ground was let. (fn. 233) It was remembered in the early 19th century when two stones remained visible although no one had been buried there in living memory. (fn. 234)