A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Castle Cary - Social History ', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10, ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp53-61 [accessed 23 April 2025].

'Castle Cary - Social History ', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Edited by Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online, accessed April 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp53-61.

"Castle Cary - Social History ". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online. Web. 23 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp53-61.

In this section

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL STRUCTURE

The parish was probably dominated by the manor and its resident lords during the Middle Ages and then by farmers of the manor until the mid 17th century. (fn. 1) There was little evidence of town life or business. (fn. 2) However, from the later 18th century a small town developed with a varied community of business, clerical, and professional families whose aspirations to gentility ensured a rich and varied social life, (fn. 3) the building of several fine houses, and the establishment of institutions such as the market house, private schools, and political clubs. Although the land tax assessment did not change between 1766 and 1832 the number of people paying in North Cary doubled. (fn. 4) By 1839 there were 133 private landowners in the parish. (fn. 5)

By 1821 167 families were occupied in manufacture, trade, or crafts, 158 in agriculture, and eight in neither. (fn. 6) The growth of manufacturing employment during the 19th century created a large working class with a resulting increase in the number of alehouses and the establishment of clubs and friendly societies, reading rooms, and brass bands. (fn. 7) In 1871 c. 350 workers, many of them children, were employed in the factories and others worked in shops and workshops or on the railway. (fn. 8) Before the building of new workers' housing in the later 19th century there was great pressure on the existing housing stock. Two properties on the junction of Woodcock and Lower Woodcock Streets, including a former weaving factory, had been subdivided between six landlords and c. 37 dwellings by 1839. (fn. 9) Most workers lived in rented accommodation and many businessmen were cottage landlords. Although conditions had improved by 1901, almost half the houses in the parish had fewer than five rooms and there were still back courts. (fn. 10) By contrast many successful professional and business families aspired to fine houses on the outskirts of the town or at Ansford. (fn. 11)

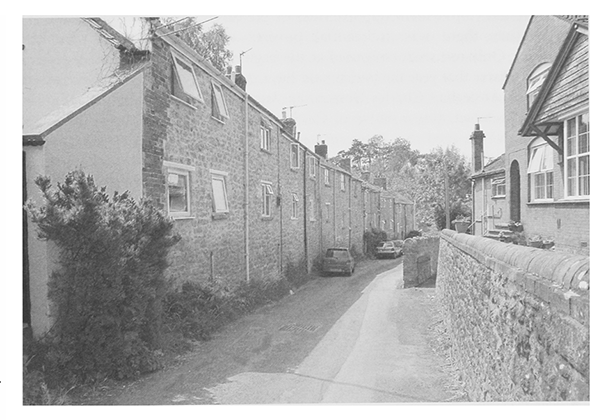

27. Bridgewater Buildings were built in the mid 19thcentury with other terraces of workers' housing west of the town near the textile factories. They were condemned a century later as unfit for habitation but have survived. Unusually they were built with their backs to the lane.

The horsehair industry was a major employer of female labour, especially young girls, often at the expense of their education. (fn. 12) They earned more in the factories than in agriculture, which was left to the boys who did the milking and weeding which was done by women in other parishes. (fn. 13) The clothing trade also employed many women and a successful milliner had two resident staff, an apprentice, and a servant in 1871. Women also kept or assisted in shops and the post office employed female telegraphists and clerks. (fn. 14) There were surprisingly few domestic servants. Professional men and the clergy kept several servants in the mid 19th century but manufacturers were slow to follow suit. John Boyd usually had only one servant even though in 1851 he had four of his staff and an apprentice living with his family. (fn. 15) Thomas Salisbury Donne's daughter acted as housekeeper assisted by two servants in 1861 (fn. 16) and even after the move to the new Florida House the family only had two resident servants. In 1901 a prosperous tailor, a grocer, two private schools, and several innkeepers kept a servant. (fn. 17)

During the later 20th century Castle Cary's role as a centre for the surrounding area was reinforced despite the decline in manufacturing and the rise in commuting because it was seen as an attractive place to live and shop. Its position has been enhanced by its attraction for tourists staying in the neighbourhood in both serviced and self-catering accommodation and visiting the shops, public houses and cafes, museum, and information centre.

MIGRATION

The first emigrant may have been Gabriel Ludlow, baptised in Castle Cary in 1663, who landed in America in 1694. (fn. 18) William Clarke went to Jamaica in the 1790s but in 1814 decided to return to England and was lost with the ship. (fn. 19)

Despite the employment opportunities of the early 19th century there was substantial poverty and migration. (fn. 20) Only one man emigrated at the beginning of 1841 (fn. 21) but later that year the parish paid for a man to emigrate to Australia. (fn. 22) Charles Norton, an Australian artist and architect, was a native of Castle Cary who emigrated in 1842 aged 16. (fn. 23) Between 1849 and 1854 at least 11 adults, all literate and aged 19 to 25, with 5 children, went to Australia. The men were labourers but among the women were a weaver, a dairymaid, and a straw bonnet maker. (fn. 24) In 1849 a local man who found gold in America returned to marry and persuaded four of his siblings to go gold prospecting with him. (fn. 25) In the 1850s several members of the Clothier family and others emigrated to New Zealand. (fn. 26) Between 1872 and 1896 it was said 300 members of the Good Templars Lodge had left the area. Watchmaker James Hill went to America c. 1878 and miller Robert Eason (d. 1897) left in 1881 to join his uncle John Eason in Pennsylvania. In the late 19th century many emigrated to Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, America, Canada, and India and at least one other man had gone to the Californian gold mines. (fn. 27)

There was also immigration, especially from Scotland, which provided such leading inhabitants as John Boyd and William McKerrow from Ayrshire in the 1830s and 1840s and cheese factor James Mackie in 1853 (fn. 28) who all arrived as travelling drapers like the six young men from Scotland who shared a house in South Cary in 1871, and later William Macmillan. A Germanborn photographer worked in the town in 1871. (fn. 29)

EDUCATION

Before the National School

Two schoolmistresses were recorded in 1666 and in 1678 a man was licensed to teach a grammar school. (fn. 30) A day school was held in a room over the market house in the 1740s and a boarding school was kept between 1763 and 1775 by John Tidcombe who took boys for £10 a year. (fn. 31) A subscription Sunday school for the poor was established in 1785 to teach 40 boys and 40 girls to read and write. Two men taught the boys in a schoolroom and two women taught girls at home. The school was held between 8 and 12 a.m. and 2 and 7.30 p.m. and the children were taken to school twice. Any child over 7 found on the street could be put in the roundhouse. The subscribers paid for gifts of prayer books and clothing for the children. In 1786 there were 79 boys and 59 girls but the schoolroom, a former public house in South Cary, was sold in 1794. (fn. 32)

In 1818 the only recorded school (fn. 33) was a church Sunday school with 50 boys and 60 girls (fn. 34) but a schoolroom was mentioned in 1820. (fn. 35) The Sunday school had 72 boys and 80 girls in 1825, (fn. 36) possibly including Ansford children, but in 1833 only 95 children attended. The Wesleyan Methodist Sunday school taught 29 boys and 21 girls in 1833, 6 boys and 18 girls attended the Independent Sunday school and 11 day schools taught 59 boys and 75 girls at their parents' expense. One school had 50 children and another 10 infants. (fn. 37) There was a British day school for boys at Zion Chapel from the late 1830s, originally kept by the minister, which closed c. 1856. (fn. 38)

28. Castle Cary primary school. The National school of 1840 had teacher's accommodation added above it in 1844. The extension to (right) was completed in 1876.

In 1840 Sunday school girls were taught in church between services, (fn. 39) but the boys were taught by James Edwards at his house in Florida to which he added a large schoolroom where he kept a boys' commercial boarding and day school. In 1842 the Sunday school moved to the new National School premises. (fn. 40) A second school was built in Florida before 1850 by Richard John Meade, vicar 1845–80, to prepare infants for the National School, where they moved temporarily in 1868–9 during the illness of their mistress. (fn. 41) In 1869 it was placed under government inspection and in 1872 it was said the schoolroom, 30 ft by 15 ft, should have no more than 57 occupants, including infants under 3. In 1874–5 the school closed because of an outbreak of scarlet fever and was used as a cottage hospital. The infant school reopened in 1875 in the Zion Sunday schoolroom before moving to the National School site in July 1876. (fn. 42) The old school was used as an armoury by the 1890s, for cookery classes in the 1920s, and later became an institute, probably for adult classes. Known as Florida Hall, it was taken over by Pithers as a furniture store from 1942 until 1951. (fn. 43) It was used as changing rooms by the Rugby Club until 1982 and later converted into a dwelling. (fn. 44)

National School

Two of the ten teachers recorded in 1841 apparently taught at the new National school, which had separate classrooms for boys and girls. (fn. 45) In 1844 teacher's accommodation designed by Abraham Bryant was built above the school. (fn. 46) In 1846 the boy's school had 50 pupils who attended daily and on Sundays, a further 29 who did not attend on Sundays, and 54 who attended on Sundays only. In the girl's school the figures were 45, 24, and 77 respectively. During the winter an evening school taught 15 boys and 5 girls. (fn. 47) From 1853 until 1891 the National School received money given by Mary Woodforde for the infant school but during the 20th century the money was used for the Sunday school and had been exhausted by 1998. Another charity, later the Old National School foundation, was established in 1874 to ensure the continuation of the Sunday school and the instruction of the poor. (fn. 48) The evening school continued and 40 children attended in 1865. (fn. 49) Numbers dropped when new dame schools opened in the early 1860s but the 1867 Factory Act led to an influx of child workers who attended school for half the day and were said to be very backward. By 1870 there were 151 children of whom 33 were half-timers but in 1872 there were 295 children on the books including 129 infants. (fn. 50)

The school was enlarged in 1876 to accommodate 250 children and 150 infants from Castle Cary and Ansford, but average attendance in 1883 was 170 and 80 respectively. In 1886 there were only 96 girls on the books compared with 164 boys and 146 infants. The teacher removed the names of girls who worked in the factories and ceased to attend and complained that school attendance was not enforced as only half the girls remaining on the register attended regularly. By 1888 the authorities had taken action and attendance improved. (fn. 51)

In 1889, following financial difficulties, a school board, with five members, was formed and took over the National school. Evening continuation classes including art, nursing, and cookery were held in the 1890s and the Sunday school and temperance society also used the buildings. (fn. 52) In 1903 average attendance was 275, falling to 204 in 1925. From 1941 the school took juniors only and in 1955 there were 169 children. Numbers fluctuated thereafter rising to a peak of 245 in 1975. There were an estimated 198 on the register in 2001. (fn. 53)

National School Building A National school, started in 1839, moved into new premises built by Robert Francis in 1840. (fn. 54) It had a single-storeyed pedimented central block with flanking wings and separate rooms for boys and girls. An upper floor supported on cast iron columns was inserted into the schoolrooms in 1844 to provide teacher's accommodation designed by Abraham Bryant, (fn. 55) but by 1848 the building was out of repair. A new single-storeyed and gabled school for 220 children south of the existing building was planned in 1873 and completed in 1876 to designs by Henry Hall. In 1903 there were 13 teachers and 363 children on the books accommodated in five classrooms subdivided by partitions. Prefabricated and mobile classrooms have been used on the site since 1968. (fn. 56) The premises were enlarged and modernised c. 1996. (fn. 57)

Private Schools

William Paul, a Congregational minister, kept his boys' boarding school in South Cary, described as an English, Classical, and Mathematical Academy, from the 1790s probably until 1836 when he died. In 1791 he charged twelve guineas a year and for a further two guineas a clergyman would teach Latin and Greek. Mathematics, shorthand ('brachygraphy'), merchants' accounts, music, and dancing were also extra. In 1794 he advertised for a second-hand printing press for his Academy. Frederick Smith continued the school until 1843 or later, possibly assisted by William Paige, retired Congregational minister. The school had 18 boys in 1833 when three other boarding schools taught 31 boys and 11 girls. (fn. 58) Thomas Lamb failed to agree terms to take over from Smith and opened a school opposite the Methodist chapel whose schoolroom he rented in 1844, probably in succession to James Stockman who held day and evening schools there in 1841. (fn. 59) Lamb closed his school in 1845 and the Revd Robert Sharman opened a replacement only to give it up in 1846 to sell potions. (fn. 60)

The Misses Armitage kept a ladies boarding school in 1806, possibly in succession to Miss Mogg's school recorded in 1796, and offered lessons in English grammar, French, drawing, music and dancing. They moved to Langport in 1810. (fn. 61) In the 1840s there were short-lived boarding and day schools in Bailey Hill, High Street, Fore Street, and Chapel Yard, South Cary. James Edwards kept a boys' school at Florida but had to leave the country and in 1849–50 John Aaron Lander kept a medial school there. (fn. 62)

In 1851 John Webb (fn. 63) taught English, Latin, Greek, and mathematics and his wife Mary taught English, French, Italian, and music, but they had only one resident pupil. Mary Anne and Charlotte Burge kept a school in High Street and Mary Longman (d. 1866) and her daughter taught English, French, and music and had three girls boarding. (fn. 64) Anne Longman continued the girls' school at Park Villa until the 1880s and her brother Stephen (d. 1885), a retired Catholic priest, taught boys. (fn. 65) Emily Bishop's ladies seminary was open by 1859, although the boarders included young boys in 1861. (fn. 66) It was probably continued in South Cary by Frances Read who was succeeded by the Beake family. The school moved from South Cary House to Weymouth before 1891. (fn. 67)

Between 1858 and 1865 James Grosvenor, Congregational minister, kept a boys' boarding school at South Cary, possibly a revival of William Paul's academy. (fn. 68) After closing for a while it was re-opened before 1881 for both sexes and by 1891 in addition to female boarders taught nearly 100 day boys. (fn. 69) The school was given up c. 1893 because of competition from Sexey's school in Bruton and the Grosvenors emigrated to California but returned in 1895 (fn. 70) and revived the school for girls. By 1901 the Grosvenors occupied one house with a French and German teacher and two female pupils while their daughter occupied the house next door with a music teacher and two more female boarders. (fn. 71) In 1905, when they also taught small boys, there were c. 20 pupils. (fn. 72) Mrs Grosvenor, followed by her daughter Marianne with Ethel Roberts, continued the girls' school at Southend house and later at Scotland House, former home of the Mackies, until 1948 or later. (fn. 73) Known in the 1890s as the Girls' School Home, it prepared pupils for Trinity College and London College of Music and offered lessons in painting in oils and watercolours, arithmetic, bookkeeping, and Latin. A vicar choral of Wells gave singing and violin lessons. (fn. 74) In the late 1920s young boys were again taught and the school had c. 30 pupils. (fn. 75)

A private infant school was recorded between 1851 and 1872, (fn. 76) a day school in Fore Street and a boys' school at Bailey Hill between 1871 and 1881, and a dame school in Knights Yard off Market Place in 1881. (fn. 77) Between 1894 and 1905 a ladies boarding collegiate school was kept by Emma Maidment in the Old Bank House, High Street. (fn. 78) In 1906 there was a preparatory school at Cumnock Terrace, possibly in succession to one kept there in the 1880s by the Congregational minister. (fn. 79)

In addition to evening classes at the Board school there was a women's adult school and a men's school at the Boyd Institute in the late 19th and early 20th century, based on bible studies. (fn. 80)

HEALTH AND SOCIAL WELFARE

Charities for the Poor

Between 1602 and 1935 at least 13 people gave money to endow charities but not all succeeded. The gifts of Ralph Francis (d. 1624), John Russ (d. 1682), Richard Cozens (1716), and Cary Creed and his son Cary (1775) failed. (fn. 81) The bequests of John Francis (d. 1602) and David Llewellyn, surgeon (d. 1605), were used to build the roundhouse in 1779. Attempts to get the parish to cover the loss of charity funds were unsuccessful. (fn. 82) The income from charity endowments was mainly distributed in bread, groceries and coal until the 1960s, in one case restricted to members of Zion Congregational chapel and probably lost after the chapel closed. Medical and nursing charities created by subscription and generous gifts in the early 20th century were used to pay hospital, nursing and sanatorium fees for the poor. The advent of the National Health and other welfare services and the high inflation of the later 20th century rendered most charities ineffective and they were wound up or amalgamated under a relief in need scheme. (fn. 83)

The successful charities included the Castle Cary Bread Charities founded by John Lewis in 1707 and Edward Russ in 1724 with rent charges. The funds were used for an annual sermon and a Good Friday bread distribution. Up to 72 people received loaves in the early 20th century but distribution had ceased by 1960. (fn. 84) Marianne Fennell (d. 1856) left £500, which supplied up to 85 poor people with essentials until the 1960s and a further £500 from Louisa and Lucy Gifford 1905–6 originally benefited 66 recipients. (fn. 85) William Donne's Christmas gift of 2s. 6d. to each poor person begun in 1935 probably failed through inflation. (fn. 86)

Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee convalescent fund was established by subscription and in the late 20th century made donations to convalescent and British Legion homes. Lucy Gifford (d. 1909) provided over £1,423 for a parish nurse, probably to continue the service paid for by Frances Meade in the 1890s. A sister was employed until 1952 or later. (fn. 87)

Almshouses

John Boyd built ten Jubilee Cottages in Ansford Road for horsehair workers or those who had lived in Castle Cary for 20 years. The endowment of £2,750 stock in John Boyd and Co. was augmented by Richard Corner in 1902 with £212 in annuities to provide groceries, coal, and medical attendance for the residents. By 1941 the cottages were uninhabited but were occupied again by 1950. Very little of the income was spent on them and by 1978 only half were occupied and there was no indoor sanitation. They were demolished shortly afterwards and a block of flats called Hanover Court was built on the gardens. In 1978 the charity funds were combined as the Jubilee Cottages Charity for the elderly, poor, or infirm inhabitants of Castle Cary. (fn. 88)

John Iles Barnes (d. 1913) gave land in Ansford Lane to house two or three poor persons. In 1924 two houses were built but as no endowment was provided the occupants paid rents, £14 6s. in 1950, out of which repairs had to be met. In 1978 the cottages, which had no bathrooms, were still occupied. (fn. 89) Permission for demolition was given on several occasions in the 1980s and they were boarded up awaiting redevelopment until 1992 and were then demolished. Under a Scheme of 1995 the charity is known as the Castle Cary Parish Charity. (fn. 90)

The Meade almshouses in Church Street, also known as Swiss Cottages because of their half timbered design, were built on the site of a pound and derelict cottages by Frances Catherine Meade (d. 1903), eldest daughter of Richard Meade, vicar of Castle Cary, for four aged women or nurses, preferably members of the Church of England. The property was sold under an order of 1967, the money to be used for the wants and welfare of members of the Church of England in Castle Cary. (fn. 91)

Health

Doctors and surgeons have served Castle Cary since at least the 16th century and there was a doctors' surgery on Bailey Hill for much of the 19th century. (fn. 92) Dr. Richard Clarke had a smallpox inoculation hospital at Castle Cary by 1761, which later transferred to Ansford. (fn. 93) In 1874–5 there was a temporary scarlet fever hospital at Florida but an attempt in 1887 to establish a permanent hospital beside the Jubilee almshouses failed and a convalescent charity was substituted. (fn. 94) There are several residential care homes in the parish including Cary Brook local authority home near the church for 36 residents who moved into the building in 1973. (fn. 95) There is a health centre nearby.

COMMUNITY LIFE

The town sometimes had a radical reputation, three men were hanged in the town after the Monmouth rebellion in 1685, (fn. 96) there were celebrations in 1769 when Wilkes was released (fn. 97) and in 1794 Benjamin Bull of Castle Cary was sentenced to a year's imprisonment for distributing copies of the 'Rights of Man'. (fn. 98) The passing of the Reform Bill in 1832 was marked with bell ringing, a procession, a distribution of beef to 1,200 householders, the provision of free beer, and a dinner for 120 of the 'more respectable inhabitants' in a booth in the park. (fn. 99)

However there were large celebrations for royal events such as George III's Coronation, which was marked with bonfires and illuminations. (fn. 100) A large dinner in the park celebrated the peace in 1814 and a festival with free drink in 1830 when William IV was crowned. (fn. 101) In 1898 a Peace conference was addressed by Henry Hobhouse MP and local clergy. (fn. 102) Ernest Jardine, the Unionist MP for East Somerset, was presented with much valuable silver plate following a Unionist fete at Florida House in 1911. (fn. 103) A large bonfire was built for Edward VII's Coronation in 1902 and in 1919 a subscription was opened to celebrate that of George V. (fn. 104) Queen Elizabeth II's coronation was celebrated with teas, sports, fireworks, and the distribution of commemorative mugs and tea canisters. (fn. 105) The Princess Royal visited in 1993. (fn. 106)

The town also experienced tragedy. Two people from Castle Cary died in the Titanic in 1912 but three others survived. (fn. 107) During the two world wars 61 lives were lost. (fn. 108)

Friendly Societies

Three friendly societies were founded in 1794, a Castle Cary Friendly society which met at the George and was still in existence in 1856 and two Societies of Tradesmen which met at the Angel and the George respectively until 1837 or later. (fn. 109) The Angel club held its last walk in 1847 and a Half Moon club was dissolved about the same time. (fn. 110) In 1834 the Britons was founded at the Britannia inn with 145 members. It became the United Britons in 1836 and was renewed every seven years. It was the only club, which still walked in 1896 when there were also the True Britons, a Friendly Benefit Society, and a Girls Friendly Society. (fn. 111) The Friendly Benefit Society was founded in 1862 by Canon Meade as the existing societies did not provide sick pay. (fn. 112) A Friendly Society was still in existence in 1905 but the United Britons held their last club day in 1904. (fn. 113)

Other Societies

The first temperance meeting was held at the old Wesleyan chapel in 1837. (fn. 114) A Good Templar Lodge was instituted at Castle Cary in 1872 and in 1885 the first Temperance festival was held. (fn. 115) In 1853 there was a reading room with up to 200 books in a house near the National school, possibly the room recorded in 1872. (fn. 116) The Young Men's Society, established by William Macmillan in 1867, (fn. 117) had a reading room in the Market House but a dispute in 1895 led the Society to move to new premises beside the Liberal club in Woodcock Street. It was disbanded c. 1910 when the church provided similar facilities. (fn. 118) There was a circulating library, probably kept by James Bulgin, in 1802. (fn. 119) In the late 20th century a small branch of the county library was opened on Bailey Hill. The Living History group, which publishes information on Castle Cary, was formed in 1996. A branch of the Women's Institute was established in 1922 and was instrumental in putting on plays at the Market House. From 1949 it has been a joint branch with Ansford. A Castle Cary flower show has been held regularly since 1949. (fn. 120)

Boyd Institute Founded by the Liberal Association in 1885. (fn. 121) The building in Woodcock Street was refurbished and reopened in 1907 as the Liberal Club with reading and games rooms. (fn. 122) The Association purchased the adjoining Constitutional Club for expansion after the latter moved to new premises in 1911. The club provided two billiard rooms, reading room, and card room. (fn. 123) In the later 20th century the lower part was converted into a wine bar (fn. 124) and in 2001 it was occupied by a restaurant and a wine shop.

Castle Cary Constitutional or Conservative Club Established in 1896 when premises were built on the corner of Bailey Hill and Woodcock Street adjoining the Liberal club which later bought the freehold but continued to let the premises to the Conservatives. In 1911 Thomas Donne gave a site near Higher Flax mills for a new clubhouse, built by Pollards of Bridgwater, with billiard and reading rooms, skittle alley, bowling green, and tennis courts. (fn. 125) The club remained in use in 2001.

Volunteers In 1707 local magistrates ordered a recruiting sergeant to leave the town (fn. 126) but volunteer corps were raised locally in the late 18th and early 19th century. In 1794 Castle Cary provided the first troop of Somerset yeomanry whose cavalry kept order during local food riots in 1795. In 1797 c. 50 volunteers formed an infantry company. (fn. 127) A volunteer rifle corps was founded in 1860 with a resident drill instructor and in 1908 it became part of the Territorial Army. The corps had their headquarters and armoury in the old infant school in the 1890s and in 1900 used a building on John Donne's estate at Florida.

Drill Hall Built in 1913 near the school by the War Office at a cost of £3,000. Apart from the hall the building comprised rifle range, armoury and stores, canteen, recreation room, first-floor lecture room and officers' quarters, and a house for the staff sergeant. It was also used for dances in the early 20th century and in 1914 was the venue for a Bruton and Castle Cary musical festival. In 2001 it was used by the Territorial Army, Air Training Corps, and army cadets. (fn. 128)

Newspapers

A newspaper called The Thunderer appeared at irregular intervals between 1889 and 1895, one copy named The Annual. (fn. 129) The Castle Cary Visitor, a monthly, was published between January 1896 and December 1915. (fn. 130) It was founded by William Macmillan (d. 1911), managing director of Boyd's, whose death from cancer led his son Douglas to found the Society for the Prevention and Relief of Cancer in 1912. (fn. 131)

Entertainment

A minstrel caused a brawl playing on a Sunday in 1625. (fn. 132) In 1770 a troupe of entertainers described as mountebanks, ropedancers, tumblers, quack doctors and 'andrews' drew large crowds for up to six hours when they set up a stage in the street and in the market place playing French horns and other large and noisy instruments. (fn. 133) A new ballroom was opened at the Royal Oak, South Cary, in 1779 with a concert given by players from Bath followed by a ball. (fn. 134)

The Castle Cary brass band, formed with six players in 1860, was later known as the Excelsior Band. It was refounded as a Temperance Band in 1893 but from 1897 was known as the Town Band and was still in existence in 1928. (fn. 135) The volunteers also maintained a band, which broke up in 1885 after taking part in election celebrations. It was revived as a bugle band in 1887 and was probably the Castle Cary Military Band recorded in 1897. (fn. 136) The Castle Cary Choral Society, founded in 1882, was in existence until c. 1939. The Jolly Waggoners Concert Party, which also ceased c. 1939, was founded by members of the Congregational chapel under their organist David Gass (d. 1950) who as Daniel Grainger presented dialect plays and talks for radio. (fn. 137) The Castle Cary Choir, with c. 50 members, was formed in 1965. (fn. 138)

In 1766 The Provoked Husband and other plays were staged at the Court House and in 1770 and 1773 travelling players performed Shakespeare including Hamlet and Richard III, and The Beggars Opera. (fn. 139) In 1783 Mr Kent's theatrical company visited and in 1786 that of Mr Baker. (fn. 140) Plays were later performed in a large assembly hall behind the George, which was destroyed in the 1845 fire and not rebuilt. Taylor's Company of actors performed in the early 19th century and Tom Rogers' Company in 1855 and 1871. (fn. 141) Mummers visited houses at Christmas during the 19th century but the tradition had died by 1900. (fn. 142) Equestrian circuses performed in the 1840s and 1850s. (fn. 143) A late 19th-century reading group formed itself into the Castle Cary Literary Society in 1904 and staged costumed performances including Shakespeare's Much Ado about Nothing in 1914, often in the Vicarage grounds. (fn. 144) By 1901 the Market House had secured a drama licence, by 1909 a stage and in 1927 the old corn stores were turned into dressing rooms. (fn. 145) Shakespeare and dialect plays were performed and travelling repertory companies visited. (fn. 146) The Castle Cary players gave performances in the later 20th century, mainly pantomime, and were joined from the 1970s by the Cary Amateur Theatrical Society. (fn. 147)

Mobile cinema shows visited the town and in 1923 the Market House obtained a cinema licence. The first floor was turned into a cinema and the old band room was converted into a projection room. (fn. 148) In 1939 the Magnet Theatre Talkie Company presented films there. In 1951 there were performances daily except Sundays but the cinema had closed by the 1980s. (fn. 149)

In 1947 the council bought a site near the White Hart for a parish hall but it was never built and after letting the land to a bus company the council sold it in 1959. (fn. 150) From the 1980s Castle Cary shared the Caryford Hall with Ansford. (fn. 151) In 2001 Castle Cary maintained several social organizations, an annual carnival, which was first held in 1919 but has had a continuous history since 1977, and a motoring cavalcade begun in the 1980s. (fn. 152)

Sport

Fives was played in the churchyard in 1768 and other 18th-century activities included cockfighting, cudgel playing, and sword fighting at public houses. (fn. 153) Women were encouraged to take part in cudgel playing and races. (fn. 154) In the early 19th century there was a racecourse at Dimmer. (fn. 155) A foot race was held outside the Royal Oak in 1859. (fn. 156) The first Castle Cary Horse Show and Gymkhana was held in 1947. (fn. 157)

The Castle Cary and Ansford Cricket Club, founded in 1837, (fn. 158) had folded by 1840 when the Hadspen club was started. In 1859 the Castle Cary Cricket Club was formed although its headquarters were at Hadspen until 1870 when it acquired a field at South Cary where a pavilion was built in 1881. (fn. 159) In 1900 five members were in the England team, which defeated France in an Olympic match. (fn. 160) The rugby club was begun in 1888, disbanded in 1938, and revived in 1952. A cycle club was started in 1905, a golf club in 1913 with a course on Lodge Hill, and a football club in 1945, although there had been one in the 1920s said to have begun in 1894. (fn. 161) A tennis club ceased in 1996 when its courts at the Constitutional Club were converted into car parking. (fn. 162)

The Jubilee Playing Field, established before 1900, was redesigned in 1947 as the Donald Pither Memorial Field with a new pavilion, football and cricket pitches, one grass and two hard tennis courts, bowling green, car park, seats, and flower garden. (fn. 163) Part of the children's area was compulsorily purchased for housing in 1978. (fn. 164) The workers at Higher Flax Mills had a bowling green and used one of the ponds as a swimming pool. A bowling club, founded in 1984, planned a new green north of Florida Street and opened a clubhouse in 1987. (fn. 165)

Impact of War

A man from Castle Cary served as purser's steward on HMS Polyphemus and was at the battle of Trafalgar. (fn. 166) During the First World War Belgian refugees were housed in Scotland House, South Cary. A women's rifle club was formed in 1914, 20 women qualified as Red Cross nurses, and a workroom produced large quantities of garments, bandages, kitbags, and sandbags. By December 1915 213 men had joined up, over 12 per cent of the population, and a further 50 were turned down. By 1918 330 had served of whom 45 died. (fn. 167)

From 1940 to 1943 a brigade of guards was based at Florida House, black American soldiers were camped on Millbrook north of the church, and American nurses were billeted in Florida House, where Nissen huts and a brick dining hall were built in the grounds. Red Cross nurses were stationed at the adjacent Hollies. (fn. 168) There was some bombing and at least two British planes crashed locally. A large ammunition depot was constructed south-west of Dimmer comprising over 20 storage units each consisting of four semi-circular iron and concrete huts with steel doors on deep foundations and enclosed by brick and concrete blast walls, circular water tanks, accommodation, and other buildings. Sometimes known as Alford camp, it was served by a railway track from the main line in Alford. (fn. 169) Most of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps huts were blown up c. 1976, (fn. 170) but seven survived in 1997. After the war the site was a vehicle breaker's yard and a Wincanton Rural District council refuse dump. In 1989 Somerset County Council bought Alford Well farm in Alford and part of Church farm, Lovington to enlarge the site for a controversial waste tip and recycling centre. A visitor centre and a gas generation scheme were begun in 1998 and in 2002 the site was known as Carymoor Environmental Centre with education facilities, wildlife projects and buildings constructed using traditional oak carpentry and recycled materials. (fn. 171)