A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2010.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Castle Cary - Economic History ', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10, ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp32-52 [accessed 23 April 2025].

'Castle Cary - Economic History ', in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Edited by Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online, accessed April 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp32-52.

"Castle Cary - Economic History ". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 10. Ed. Mary Siraut (Woodbridge, 2010), British History Online. Web. 23 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol10/pp32-52.

In this section

ECONOMIC HISTORY

THE PARISH was primarily agricultural until the 19th century. A few medieval yeomen clearly prospered, such as the tenant of Lower Cockhill farm, and there were substantial farmers in the 16th century but little evidence of trade or manufacture. (fn. 1) In the 1641 subsidy Castle Cary paid little more than Sparkford despite having about four times the population. (fn. 2) As late as 1742 Castle Cary paid less tax than neighbouring North Cadbury. (fn. 3) Only with the development of the horsehair industry in the 19th century did Castle Cary provide any large-scale alternative employment.

AGRICULTURE

Few early records survive for Castle Cary and little is known of its agricultural organization. Medieval expansion of cultivation in the west of the parish, into the marshes and woodland, was complete before the 17th century when there were several outlying arable fields. (fn. 4) The Cary valley was originally marshy and would have hampered cultivation of large areas in the west of the parish. Cockhill marsh, recorded in 1424, (fn. 5) Thorney marsh, meadow by 1672, (fn. 6) and Cary moor may have been drained in the 16th and 17th centuries. (fn. 7) Woodland or scrub in the south-west was probably cleared in the Middle Ages for fields known as Lawn and Great and Little Thorn. (fn. 8) Oak timber and other wood were recorded until the mid 14th century, (fn. 9) but by the later 17th century most had gone. Tenants were required to plant trees and forbidden to lop maiden elms (fn. 10) but despite William Player's plantings in the 1690s there was no woodland by the late 18th century. (fn. 11)

Little is known of medieval field patterns but each settlement appears to have had its own arable fields. It has been suggested that North Cary may overlie part of a former open field. (fn. 12) South Town common field, against the boundary with North Cadbury, was probably the Cary South field recorded in 1659 and 1684. (fn. 13) Clanville, formerly Clanfeld, (fn. 14) may have encroached on an open field and Twincome was a small common field there in the 1680s. Great and Little Dimmer common fields survived as remnants in the late 18th century (fn. 15) and a few strips in Little Dimmer or Dimmer Plain, survived into the 19th century. (fn. 16) North and South Thorn fields were recorded in 1682. (fn. 17) Common meadows bordered the marshes but there are few records of common pasture and Hutchins Common, south of Cary Park, was arable in 1808 producing wheat and barley. (fn. 18)

Parks had been created by the 14th century. On the main manor, Home or Cary park, recorded in 1351, occupied most of the hillside south and east of the Castle site. (fn. 19) In the far west, near Alford, Dimmer park may have been laid out in the Middle Ages and occupied gently sloping land between Dimmer field and the Alford boundary. By the mid 17th century Summerleaze and Sleights adjoining Alford were probably carved out of the former Dimmer park. (fn. 20) It is likely that inclosure and improvement in the 17th century led to arable being laid to grass to increase the availability of good pasture. (fn. 21)

The Middle Ages

Cary manor had land for 20 ploughs in 1086 but 23 were recorded of which six, worked by six serfs, were on the 8-hide demesne. The remaining 17 ploughs were worked by 23 villeins and 20 bordars who had seven hides. Those figures conceal the settlement pattern, which may have consisted of several hamlets and farmsteads. Demesne livestock comprised two riding horses, 16 beasts, 20 pigs, and 117 sheep. Eight swineherds paid 50 pigs a year presumably drawn from the woodland measuring one league by half a league. The name Swineherd was recorded in 1327. No pasture was mentioned but there was 100 a. of meadow. Clearly arable land accounted for most of the cultivated land in the parish. The estate had increased in value from £15 to £16. (fn. 22)

The demesne continued to cover about half the manor. Its extensive arable probably accounts for the substantial building whose foundations were excavated on the manor site, probably a 13th-century barn, which was replaced in the late 13th or early 14th century. (fn. 23) In 1351 Cary manor, with Ansford, had 1,000 a. of arable in the fields of which one third was left fallow each year. Tenants owed customary ploughing. There may have been a shortage of grass. The several meadow (60 a.) was worth 1s. an acre although only occupied from 2 February to 24 June, presumably it was grazed outside those dates, and Home park in Castle Cary was worth nothing because it was overstocked with wild animals and had not even beech nuts or acorns for pigs. (fn. 24) The Lovels had clearly regarded the park as a hunting ground rather than profitable grazing. Fallow, red, and roe deer antlers and bones were found on the site of the manor house, together with bones of dogs and a ferret. Pillow mounds for rabbits lie in the former outer castle bailey. (fn. 25) The park was said in 1569 to be a mile in circumference. (fn. 26)

By 1401 the non-resident lords derived most of their income of nearly £128 from tenants' rents, the advowson of Ansford, and knights' fees. In 1409 and 1503 rents totalled £80 but the manor by then covered only 890 a. (fn. 27) By c. 1646 rents had increased to nearly £117 and there was no demesne. (fn. 28)

The 16th and 17th Centuries

Arable continued to predominate, and indeed an estate at Thorn was almost entirely arable in 1538. There appears to have been a continuing shortage of pasture; (fn. 29) while there were dairy cows in the parish in 1530, (fn. 30) in 1536 tithes of wool and lambs amounted to only £2. (fn. 31) Although by 1520 oxen were kept in the Home park, it remained a hunting ground (fn. 32) and in 1595 men from as far as Wells were accused of breaking in at night and hunting the deer. (fn. 33) Deer were bred and cherished there at least until 1633. (fn. 34) In 1638 the park was let for £5 a year to the farmers of the rectory. (fn. 35) It was evidently in the hands of a keeper who in 1663 was accused of negligence in allowing 200 rabbits to be stolen. (fn. 36) The park (180 a.) may have had a small lodge giving its name to Lodge Hill. Its bank and wall were recorded opposite the church, probably on the line of the present road called The Park. (fn. 37)

By the later 17th century the arable fields were largely inclosed although small remnants survived at Twincome near Clanville, South Town on the North Cadbury boundary, and at Dimmer fields. (fn. 38) The marshes were inclosed and presumably drained by the same time. (fn. 39) Although this was possibly by agreement, in 1632 a tenant living at Evercreech claimed he had not sold or given up his right to pasture on 200 a. of Cary moor, alleging that without common he could not provide pasture for his plough beasts. (fn. 40) Hockmead and Addlemead, by the marshes, were shared by several tenants in 1682 (fn. 41) and the only surviving common meadow appears to have been Duck moor, on the boundary with North Barrow, recorded in 1773. (fn. 42) Dimmer Park had been reduced to 12 a. by 1656 and the remainder was in closes by 1824. (fn. 43)

In 1671 over half the £134 annual income of Cary manor (fn. 44) came from copyhold rents and arrears totalled over £88. (fn. 45) The two largest farms at Thorn still had no houses, presumably being held with other holdings, and copyholds had been amalgamated resulting in nine recorded tofts. The largest copyhold was an 82-a. farm at Clanville and 57 holdings were between 3 and 20 a., but tenants may have held more than one and freeholders like Edmund Gregory of Thorn also took copies and leases of adjoining land. The largest farms in the parish were a 240-a. freehold at Thorn and Foxcombe (200 a.). (fn. 46) In the mid 17th century Foxcombe had been divided (fn. 47) but it was later a single farm and in 1722 was let for £80 a year. (fn. 48)

William Player contracted to sell the demesne with other farms to tenants in 1682 and had secured half his share of the price of the manor before completing the purchase. He was left with 99 a. of poor land, whereabouts not stated, and in the autumn of 1684 he enclosed 50 a. of it and sowed a third with French grass. He bought a further 40 a. of poor quality land and in 1686 another 200 a., presumably to make similar improvements. He kept the unsold part of Cary farm in hand and planted it with wood and withies. (fn. 49) William's son Thomas had crops and livestock at several places including Thorn where he had 25 cattle including bulls, milch cows, and calves and 13½ loads of hay. (fn. 50)

The 18th and early 19th Centuries

The break-up of the manor from the late 17th century had led to the development of a few large farms and many small freeholds including single fields. Although open in the late 18th century, by 1808 Home park was divided into large fields as part of Manor farm. (fn. 51) In 1810 only six farms were over 100 a. and a further six between 50 a. and 100 a. Rectory lands were divided amongst the manor tenants. (fn. 52) In 1811 only 29 out of 281 families were employed in agriculture. (fn. 53)

Former manorial lands at Dimmer (fn. 54) had by the 18th century become freehold including Dimmer farm, whose new owners rebuilt the house and a barn. (fn. 55) Other lands there became Gould's (228 a.) and Baker's (48 a.) farms by 1839. (fn. 56) The house at Gould's, later Higher Dimmer Farm, was built in 1601 by John Cary, whose family were major tenants of the manor, but was rebuilt in the early 19th century. (fn. 57) At Clanville the two main farms were owned for long periods by branches of the Russ family. (fn. 58) By the late 18th century remaining manor land was rack-rented. (fn. 59)

A greater variety of produce was being produced and land had been opened up for grazing; in 1719 there was a sheepfold at Sheppards Cross. (fn. 60) In the 1780s agriculture was thought to be well attended to at Castle Cary with blue marl being used as manure, presumably on the light sandy loam. The lower land was heavy clay. The main crops were wheat, beans, and potatoes, but turnips, barley, peas, clover, and flax were also grown. Grass and orchard now covered some former arable land. Large orchards produced 1,500 hogsheads of cider. (fn. 61) By 1745 the parish contained 'one of the finest Nurseries in that Part of the County', which was then offering more than 3,000 apple trees up to five years old, both cider and keeping varieties; (fn. 62) cider orchards were recorded in 1808. (fn. 63) A nurseryman remained in business in the 1790s and during the 19th century, (fn. 64) probably at Townsend where Johnson and Co had a 2-a. nursery with glasshouses in 1902, which was still partly in use a century later. (fn. 65) Market gardening was important in the 18th and early 19th centuries and there were 12 such enterprises by 1840. (fn. 66) In 1773 a farmer took 30 a. of uncultivated ground to sublet at a greatly enhanced rent for potatoes. The growers cleared the land, produced c. 3,600 sacks worth £900, and left the ground fit for wheat. (fn. 67) Potato ground was worth up to £5 an acre compared with 15s for arable and 25s for pasture. 'Ship' potatoes were grown and sold in 1784 at £19 for 100 sacks (fn. 68) and in 1798 fertile soil produced 160 240-lb. sacks to the acre, worth a total of £40. (fn. 69)

In 1801 the parish produced only 143 a. of wheat, 77 a. of potatoes, 70½ a. of barley, 29 a. of turnips or rape, 24¼ a. of peas, 17 a. of oats, and 10½ a. of beans. (fn. 70) Presumably the rest of the parish was laid to grass like Foxcombe farm, which in 1806 had only 30 a. of arable, including a potato garden, the remaining 156 a. comprising grass and orchard. The tenant was allowed only 6 a. of wheat in the last year of his 9-year lease (fn. 71) and was reluctant to drain the two thirds of the estate which could have been improved. (fn. 72) Flax was grown in the parish until the mid 19th century. (fn. 73) By the early 19th century withy beds were recorded (fn. 74) and spear grass was harvested from the Park Pond in 1810 and let, with reed and willows, in 1826. (fn. 75) In 1820 a child's clothes caught fire in a 'bird keeping field' (fn. 76) and in 1834 an arsonist destroyed a clover rick, the produce of 12 a. in the south of the parish. (fn. 77)

Mid 19th Century until c. 2000

In 1839 of 2,560 a. only 514 a. was arable and 196 a. orchard; the rest was grassland. Most farms remained small; 43 had between 5 and 20 a. Some farms had been enlarged including Manor farm, from 162 a. in 1810 to 203 a., and Gould's farm (228 a.), (fn. 78) created by the amalgamation of holdings including Dimmer and France farms in the late 18th century. (fn. 79) The largest landowner, Sir Richard Colt Hoare, held only 386 a. (fn. 80) Rents rose by up to 50 per cent at this period and some fields in the former park were enlarged by removing the ancient boundary. (fn. 81) By 1851 fewer smallholdings were recorded. By the end of that decade farms were employing fewer labourers. (fn. 82) A threshing machine was let out by a local ironmonger in the 1850s and in 1906 by a proprietor at Bailey Hill. (fn. 83) In the 1870s more farm amalgamation resulted in nine with over 100 a. in 1881. (fn. 84) By 1905 the dominance of dairying meant arable had shrunk to 234 a. and 2,146 a. was grass. (fn. 85) Potatoes remained important and in 1917 the parish council bought a potato sprayer. (fn. 86) In 1922 the parish produced wheat, barley, oats, beans, hay, potatoes, turnips, and mangolds but corn did badly in wet seasons. (fn. 87)

Boys were employed milking, keeping sheep, bird scaring, picking apples and potatoes, and weeding in the late 1860s. Women and girls preferred factory work. Few cottagers had gardens but the Revd F. W. Gray let 37 a. of good land to the poor. (fn. 88) George Wyndham Gray, tenant of Manor farm in the 1870s, was a scientific farmer who had studied at Cirencester College, carried out drainage, and supported the rights of agricultural labourers. A National Agricultural Labourers Union meeting was held on Manor farm in 1875 addressed by George Mitchell (d. 1900) who returned in 1882 with Joseph Arch (d. 1919) to address a meeting in the Market Place. (fn. 89)

18. Former cheese store in South Street, it was built by Mackies c. 1900, cheese factors, on the site of a mid 19th-century horsehair factory, some of whose back buildings survived until c. 2000.

By the late 1860s the parish was known as a cheese district and dairying was to be as dominant in agriculture in the modern era as arable had been in the Middle Ages. This change probably began with the increase in grassland after the break-up of the manor and there were dairies at Clanville and Dimmer by 1851. Cheese factor James Mackie (d. 1909) started making cheese in the late 1850s, having come to Castle Cary from Scotland as a draper in 1853. He acquired premises in South Cary opposite the Congregational chapel, probably the former Mathews' factory. James Mackie and Sons, a limited company by 1923, built a new store c. 1900 on the site and remained in business until 1939 or later. (fn. 90) Two cheese dealers were recorded in 1891 and four dairy workers. (fn. 91) The Gould farm at Dimmer and the Penny farm at Clanville were dairy farms in 1899. (fn. 92) There were several dairies and dairy farmers, one producing butter and another with a herd of dairy shorthorns, two cheese factors, and pig and cattle dealers in 1906. (fn. 93) In 1920 Somerset County Council purchased farms around Dimmer and Thorn for division into dairy smallholdings of between 20 a. and 45 a. with new houses and cattle buildings. (fn. 94) They produced milk, pigs, and poultry. Most were sold in the 1980s and a 68-a holding with Frank's or France House was sold in 2002. (fn. 95)

Turnbills at South Cary was a new 8½-a. dairy holding with 14 cowstalls in 1923. (fn. 96) Longmans Farms Limited, established in the 1930s and still in business, ran dairy farms in Galhampton, at Foxcombe with two cattle yards in 1930 and a new milking parlour in 1981, at North Leaze, bought in 1930 and producing cheese in 1981, and later Manor farm, Castle Cary, noted for cheesemaking in the 1950s and with a new dairy unit built in 1977–8. (fn. 97) There were two dairy farms at Clanville with piggeries in 1936. An annual bull show and sale was held at Castle Cary from 1900 until 1938 and in 1950 there was an artificial insemination centre at Higher Flax mills. (fn. 98) A former factory near Florida House was converted into a milking parlour after the Second World War. (fn. 99) The 54a. farm near Galhampton, called Sportsman's Folly, later Lodge, had accommodation for 27 cows in 1939 (fn. 100) and by the 1960s was noted for pedigree Ayrshire cattle and an intensive outdoor poultry business using moveable arks. (fn. 101)

A new factory at Torbay in 1900 produced pasteurised butter. (fn. 102) It was taken over by Applin and Barrett before 1910 but closed later. (fn. 103) There were two dairies in 1939, one of which registered as a commercial dairy in 1950. (fn. 104) In 1981 there were a cheese packer and a supplier of cheese and yoghurt cultures. (fn. 105)

Farms were amalgamated from the 1980s and by 1997 there were only six working farms in the parish, described as mixed livestock farms, and by 2002 only three. Cider was made on eight farms in the 1930s but none in the late 20th century. (fn. 106) Maize was an important crop at the end of the 20th century and vegetables were grown. Several farms in the parish provided serviced or self catering accommodation to visitors in 2000 and at least two former dairy farms combined tourism with rearing beef cattle.

TRADE AND INDUSTRY

CORN MILLS

The river Cary and its tributaries supported several mills in Castle Cary. The sites of the early mills are unknown and since the late 17th century the course of the Cary has been greatly altered to serve the needs of the mills at Torbay. Two branches of the river were amalgamated presumably to increase power. (fn. 107) Three mills paid 34s. in 1086, (fn. 108) and in 1269 there were mills called Clanfeld and Wymund, (fn. 109) the latter probably named after Wymund of the mill (fl. 1280) who had succeeded his father Robert of the mill c. 1254. (fn. 110) There were enough mills to support Drogo the Millward in 1327. (fn. 111) In 1426, in addition to the two named mills, there were two mills in the court garden, probably under one roof, and the lower mills, possibly on the site of the 19th-century Lower Mill. (fn. 112) The court garden mills may have been those let to a Bruton clothier in 1640. Manor tenants could have corn ground there for a reasonable toll, the millers might draw the hatches in the Park Pond provided they did not injure the fish, and the lord would maintain the pond and watercourses and agreed not to set up any new grist mill during the term. They may have been the Cary Mills recorded in 1687. (fn. 113)

By the 18th century milling was concentrated in the Torbay area west of the town, where mills known by the early 19th century as Higher and Lower, (fn. 114) were situated. Originally flour mills with two sets of stones each, one had been rebuilt before 1745 with a bolting mill and a bakehouse and was described as the 'best of the kind that were ever erected'. It ground 100 bushels of wheat a day but bankrupted the Bristol builders. (fn. 115) William Pew, maltster, whose family later owned Lower and Higher mills, had one of his mills, bought from John Barrow in 1756, attacked in 1757. Wheat, malt, and beans were stolen on the grounds that flour was being adulterated. The substance found by the rioters was later proved to be powdered alabaster for cementing the French millstones. (fn. 116)

The Higher mill was let in 1810 to linen manufacturers with its water and cogwheels but no stones and was thereafter a factory. The Lower mill was let to them in 1826 (fn. 117) but the corn mill on the site continued in use as a water, later steam, flour mill, kept by the Eason family during the 19th century. (fn. 118) John Eason (d. 1901) emigrated to America in 1853 and owned mills in Columbus, Pennsylvania. (fn. 119) A waterwheel and fittings for a flour mill offered for sale in 1857 (fn. 120) probably belonged to Lower mill, which remained in business until 1912 or later. (fn. 121) It was offered for sale in 1919 and by 1921 was a dwelling. (fn. 122)

By 1808 a corn mill and house, later known as Millbrook and acquired by the Donne family, had been erected east of Higher mill. It remained in use until c. 1840 (fn. 123) and may have been replaced by the water grist mill built near the Britannia inn c. 1845 (fn. 124) whose owner, Charles Moody, reconstructed Park Pond to provide water power. (fn. 125) The mill was recorded until 1898 when it was occupied by Poole's mineral water business and in 1906 by a grocer and corn dealer. (fn. 126)

TEXTILES

It has been said that the 14th-century cloth called cary or carimaury was made in Castle Cary (fn. 127) but the only recorded clothworkers were a tucker in 1327 (fn. 128) and a weaver in 1435. (fn. 129) It was prosperous in 1327 when in addition to the lord there were 47 small taxpayers in Castle Cary and Ansford but only four or five with occupational names. (fn. 130) In 1334 the two parishes were taxed on £135 in moveable wealth, possibly reflecting a woollen trade that later declined. (fn. 131) In 1524 a glover was recorded and in the later 16th century two clothmen but most taxpayers were yeomen or husbandmen. (fn. 132) One prosperous family, the Cary or A'Cary family, were involved in the cloth trade and in 1581 of 42 subsidy payers in Castle Cary and Ansford two of the three highest taxed were members of the Cary family. (fn. 133) Possibly the assault on a stocking maker in 1623 by the Kirton family, farmers of the manor, may be seen as an attempt to retain the feudal agricultural character of the area. The Kirtons were accused of conspiring to destroy him and his substantial trade but William Kirton in a petition against his conviction claimed Holland was only a poor labouring man. (fn. 134)

A North Cadbury clothier moved to Castle Cary before 1678, (fn. 135) there was a clothworker at South Cary in 1686, (fn. 136) and in 1695 a worsted comber had previously worked for an Evercreech sergemaker. (fn. 137) Local sergemakers, woolcombers, clothiers, hosiers, and stockingmakers were recorded in the 18th century and Defoe described Cary as a principal clothing town making Spanish medley, (fn. 138) but a cloth fair had decayed by the 1730s. (fn. 139) John White, a sergemaker who went bankrupt in 1740, was suspected of fraud because he had manufactured and sold £700 of serge every year and took 16s. a week from his workers for looms and victuals, yet lived like a labourer and drank only water. His father was said to have bought two houses, presumably weaving shops, which produced less than a quarter of the son's output. (fn. 140) Woollen machinery was shown at an inn in South Cary in 1773. (fn. 141)

Horsehair Industry

The success of the horsehair industry in Castle Cary was at least partly due to the availability of the hair. Horses used for farming and transport were bred around Galhampton and Sparkford where several horse dealers and breakers were recorded in the mid 19th century. (fn. 142) The availability of labour familiar with textile work, underemployed with the decline of the stocking industry, (fn. 143) and a plentiful supply of water from the river and springs for water and later steam power, encouraged the development of several linen, sacking, twine, and horsehair factories in the 19th century.

Matthews' Factory Thomas Matthews, a girthwebb manufacturer who moved from Yetminster (Dors.) to South Cary between 1813 and 1815, kept a shop opposite the later Chapel Yard but also employed people weaving horsehair at home. He built a workshop making twine from crimped horsehair and probably used linen and woollen yarn for webbing. (fn. 144) Humphrey Bidgood of Haselbury was said to be Mathews's first horsehair weaver having learnt the trade in Salisbury. He walked to Cary to deliver his work and collect warp and hair before joining John Boyd in his new business in 1837. (fn. 145) In 1828 Mathews acquired the former silk house at Florida for the manufacture of twine, girthwebb, and hair seating. He owned many cottages possibly occupied by his homeworkers and rebuilt several in Woodcock Street, including the Barracks, demolished after his death. (fn. 146) There were 26 people weaving hair in 1831. (fn. 147) Matthews and his son, flax spinners and horsehair weavers, rebuilt the Florida factory in yellow stone, first a three-storey, nine bayed building using the ground floor for hair drawing and bag weaving, the first floor for horse hair seating weaving, and the top floor for starching the warp and later a two-storey building of five bays with central loading door. There was a twine walk in the yard. The yarn for both twine and warp was spun at the factory in Evercreech bought by Matthews in 1838. (fn. 148)

By 1851 Matthews' business was smaller than Boyd's but continued to produce hair seating until 1861 when Thomas Matthews was 73. (fn. 149) Thomas and his wife died in 1863 but their son Thomas the younger is said to have carried on the business in South Cary where he built new premises in 1865. (fn. 150) By 1877 the Florida site had been acquired by John Stephens Donne for his new house, Florida Place, later House. The main factory building was retained by Donne in 1896 but from 1904 to 1910 was used as a Drill Hall for the boys brigade (fn. 151) and was converted to agricultural, and later residential, use in the 20th century. (fn. 152)

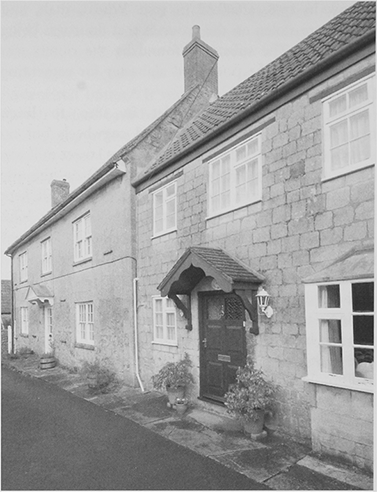

19. Chapel Yard, formerly Golden Lion Yard, South Cary. In these cottages John Boyd began his horsehair business in 1837. The yard takes its present name from the former Congregational Chapel built in 1816.

Boyd's Factory in the 19th century John Boyd is said to have started his horsehair business in a cottage in the Congregational chapel yard in 1837 (fn. 153) although only in his early 20s, the son of a merchant at Cumnock, Ayrshire who came to England as a travelling draper. By 1840 24 women and children and 2 men were weaving haircloth and in 1841 there were about 30 hair weavers of both sexes and three starchers, two black starchers, and a dyer, probably employed by Matthews and Boyd. (fn. 154) In 1851 Boyd, who also continued his drapery business, employed 34 children, 30 women, and 9 men, probably in their own homes (fn. 155) and the same year built his new factory, often known as the Ansford factory, behind Ochiltree House, (fn. 156) in what is now Upper High Street. (fn. 157) As there was no major source of water at the new factory Boyd bought part of the Lower mill site in 1853 for washing hair. The company had a dyehouse there in 1863. (fn. 158)

20. Boyd's 1870s power looms still working at Higher Flax Mills producing horsehair cloth. The power source is now electricity. The horsetails lie in a trough of water and each hair is pulled out by a mechanical picker and taken through the warp. It is a slow process and a paper apron protects the valuable finished cloth from dirt or damage during its long period on the loom.

In 1859 it was said that great numbers of the poor were employed in factories. (fn. 159) In 1871 153 horsehair workers were recorded although Boyd claimed to employ 190, mostly children. (fn. 160) By this date he had taken over the Quaperlake silk mill in Bruton for preparing horsehair for seating weaving. (fn. 161) In 1877 Boyd's installed 50 power looms, invented in 1872 by William Henderson, (fn. 162) in a new brick factory with glass roofs to the north of the 1851 buildings, (fn. 163) but c. 200 handlooms were still widely used in the early 20th century, some possibly in workers' homes. (fn. 164) A small horsehair factory east of the Methodist chapel in Upper High Street in the 1880s may have been an annexe to Boyd's and was not recorded again. (fn. 165) In 1883 Boyd's became a limited company and all property except family dwellings was sold to the company. (fn. 166) John Boyd, who was also registrar, ensign of the volunteer corps, and president of several local organizations, died in 1890. (fn. 167)

Boyd's Factory in the 20th century In 1901 there were c. 130 horsehair workers in Castle Cary and Ansford, mostly employed by Boyd's but some by White's. (fn. 168) The horse tail hair, then from Siberia and China, was washed and disinfected, sorted into colours and lengths, soaked, combed, and dyed before being woven on a black linen warp to produce the lustrous sateen fabric which was the firm's main product. Large numbers of little girls were formerly employed picking and sorting because it was delicate work but following the restrictions on child labour more machinery was installed including a mechanical picker. Hair was also woven on handlooms into tailors' padding cloth known as crinoline, traditionally with a white or lavender cotton warp. (fn. 169) Hair was also used for toothbrushes, hair brushes, wigs, sieves, fishing lines, military plumes, and some musical instruments. Large quantities were curled for stuffing sometimes mixed with cow and hog hairs, which were also used to produce coarse cloths such as those used in cider making. (fn. 170) The ability of horsehair to maintain its shape in heat led to its widespread use for blinds especially on trains. (fn. 171)

In 1905 Boyd's occupied the Ansford factory and new warehouse on their High Street site and the washing yard in Mill Lane. (fn. 172) In 1929 the company was accused of contaminating the sewage works and neighbouring land with black dye. (fn. 173) Part of the Ansford factory was commandeered as a government food store during the Second World War but the company kept 40 employees at work in 1943. A period of slump followed and in 1947 the company employed only c. 41 people making railway blinds, paddings, and stuffing, mainly for export. Washing machines called devils were used to tear the hair and mix it with cow and pig hair before twisting, steeping, and baking to create crimped stuffing. The waste was used as manure and the dust to deter slugs. (fn. 174)

In 1956 Boyd's left the Ansford factory and rented a two-storey building at Higher Flax mills taking 45 of their 150 looms. The company amalgamated with Donne's c. 1977 as T S Donne and John Boyd and Co. Ltd. and bought fourteen early 20th-century American looms which made lightweight cloth with dry hair. (fn. 175) Since 1984 the business has been run by John Boyd Textiles Limited using 30 of the original 1870s looms, (fn. 176) although powered by electric motors, and occupying further buildings at Higher Flax mills. In 2001 it was the only business of its kind in Britain and the only horsehair factory in Europe using powered looms. The company produces sateen, damask, and repp in many colours rather than the traditional black and with cotton rather than linen warp, although silk and linen are sometimes used. In 1993 a 1930s silk warping machine was purchased and dobbies of the same period were used to create patterned fabrics. The length of hair, taken from the tails of live horses imported from China, limits fabric width to c. 2 ft. Short and waste hair is sprayed with latex for stuffing or used to make plaster. Since 1994 dyeing has been carried out on site. Black hair is dyed a uniform black, grey and brown hair is left in its natural state, and white hair is normally bleached and dyed a variety of colours. Natural white hair is the most valuable. Individual hairs are drawn across the loom from alternate bundles of wet hair to compensate for the variation in thickness between the tip and end of each hair. In 2000 fabric was produced at an average rate of 3 yards a day per loom and cost between £90 and £300 a metre. It was used mainly for re-covering antique chairs and other quality upholstery but also for handbags and screens. Over three quarters of the finished cloth was exported. (fn. 177)

The Ansford factory containing 24,000 square feet was bought by Avalon leatherboard in 1960 and occupied until 1992. In 1994 Ochiltree House was reconverted from offices for residential use (fn. 178) and the newer factory buildings were used until 2001 by BM Instruments, transducer and switch manufacturers for the automotive industry. (fn. 179) The 1851 building consisting of a 3-storey, 13-bay mill with linked two-storey, 5-bay office block all of local stone with a Welsh slate roof was intended for residential use in 2001.

White's Factory In 1870 James White, who had been foreman at Boyd's, opened a hair-seating factory at the Bailey Hill premises formerly used by Donnes and before them by Thomas Matthews. By 1881 James and his son John employed 39 hands. (fn. 180) After 1883 Whites rebuilt the factory and expanded the site by acquiring and demolishing cottages. (fn. 181) By 1896 they had two factories at Bailey Hill and a new warehouse. (fn. 182) They remained in business until 1926 manufacturing sateen hair seating and brush makers' drafts. (fn. 183) One building, presumably the 'new' warehouse with an arched entrance to the street, survives and was being converted for residential use. The factory buildings, probably used for making hair cord or twine, as there is no sign of a power source, and including one of two storeys and five bays built in stages, were dilapidated.

Other Textiles

Stockings In 1624 William Holland, a worsted stocking maker, said he had worked in the parish for 12 years making over £700 a year and setting poor people to work combing, spinning, making yarn, and knitting stockings. After a serious assault and stabbing in 1623 inflicted by William Kirton and his sons Daniel and Edward, who were later convicted, Holland gave up his trade and moved to London. His workers were said to be impoverished. (fn. 184)

The Burge family of clothiers, hosiers, and stockingmakers was in business throughout the 18th century although one was bankrupt in 1741 and another, also described as a dealer and chapman, in 1808–9. (fn. 185) The latter's property included land at Torbay and a large house with workshops in South Cary described as suitable for a linen or stocking business. (fn. 186) Another member of the family had a house in High Street in 1839 with a long extension to the rear, which may formerly have been workshops. (fn. 187) Seth Burge (d. c. 1752), also a maltster, insured premises worth £400 in 1749 and William Burge, stockingmaker, buildings worth £300 in 1751. (fn. 188) William (d. 1778) left property and £5,000 to his children and his implements to his youngest son. One of his grandsons became a barrister. (fn. 189) Edward Russ was a hosier in 1748 and Daniel White, another prosperous stockingmaker, died c. 1765. (fn. 190) In the 1780s most of the poor were said to be employed in the manufacture of knitted stockings and the poor of North Cadbury were spinning and knitting for Castle Cary hosiers. (fn. 191) Many of the 280 people engaged in trade and manufacture in 1801 were probably engaged in the stocking and linen trades. (fn. 192) The stocking trade declined in the 19th century although a hosier was appointed tithingman in 1813. (fn. 193)

Silk In 1800 a newly-erected building 100 ft long was intended for manufacturing silk. It was probably the silk house at Florida recorded in 1803 and 1810 and occupied by Richard Francis and then by James Hoddinot, (fn. 194) who had a silk mill in Evercreech. (fn. 195) In 1828 Thomas Matthews, linman of Castle Cary acquired it and also bought the Evercreech mill but discontinued silk making. (fn. 196)

Linen and Hemp Linenweavers were recorded in 1726 and 1728, (fn. 197) in 1768 Humphrey Cox of Castle Cary was tried at Taunton for receiving stolen yarn, (fn. 198) and in 1770 flax workers using the 'Court House' caused a fire. They may have been preparing the flax for a flax-spinning mill said to have stood near the Horse Pond. (fn. 199) William Pew, maltster and possibly son of Richard Pew, linenweaver in 1728, was also a linen manufacturer in 1759 and turned his property in Woodcock Street into a linen factory. (fn. 200) His son-in-law William Aishford and Edward Burge were dowlais and tick manufacturers in the 1790s. (fn. 201) In 1810 Aishford held the Lower Torbay millpond and probably bought part of the property of bankrupt stockingmaker, John Burge. In 1819 Daniel Aishford had a yarn barton, probably at Clanville, and flax was grown in the parish. (fn. 202) John Watts bought Pew's factory, described in 1810 as weaving shops, but in 1818 Thomas Matthews acquired it and divided it into 11 dwellings, known as the Barracks, for handloom weavers. (fn. 203)

In 1810 John Watts and Caleb Barrett the younger of Corton Denham leased Higher mill as linen manufacturers and co-partners to produce sailcloth. By 1820 Barrett was the sole proprietor of the business, although John Watts owned Higher mill, known as Watts' factory in 1830. In 1826 Barrett also acquired the Lower mill, ownership of which was also vested in John Watts before 1839. In 1840 Watts offered for sale the two water-powered flax spinning factories previously flour mills. (fn. 204)

In 1820 Charles Donne occupied a new factory, west of the Lower mill at Torbay, belonging to Robert Penny and moved his linen weaving business from Ansford. (fn. 205) He had intended to form a flax and tow spinning partnership with William Aishford in 1813 but the plan did not take effect. (fn. 206) In 1834 his son Charles was a sailcloth manufacturer and both Donnes were in business in 1839. (fn. 207) They held a house on the corner of Bailey Hill and Woodcock Street, later a small haircloth factory, and the Torbay factory where the elder Charles made twine and rope assisted by his son Edwin and where the younger Charles's sailcloth was bleached. Another son Thomas Salisbury Donne was probably in charge of dyeing. (fn. 208) In 1842 the Torbay factory was partly destroyed by fire having been built out of coppice poles instead of rafters and it was said Donne intended to rebuild in the same manner. (fn. 209) Charles Donne senior (d. 1855) retired in the 1840s and was succeeded at Torbay by Albin Close, originally a saddler, who in 1845 manufactured twine, rope, shoe thread, and sacks. (fn. 210) Thomas Salisbury Donne took over the flax business at Higher mill, which he owned by 1846, having probably purchased it from John Watts. (fn. 211) Donne built a new water wheel in 1844. He originally described himself as a girthwebb manufacturer but by 1850, when his sons had joined him, as a flax and tow spinner and shoe thread and twine manufacturer. (fn. 212) In 1841 two twine spinners, a ropemaker, 22 flax dressers, spinners, and warpers, and a sailcloth weaver were recorded. (fn. 213) Two sackweavers were recorded in 1851 and four with a netweaver in 1861. (fn. 214)

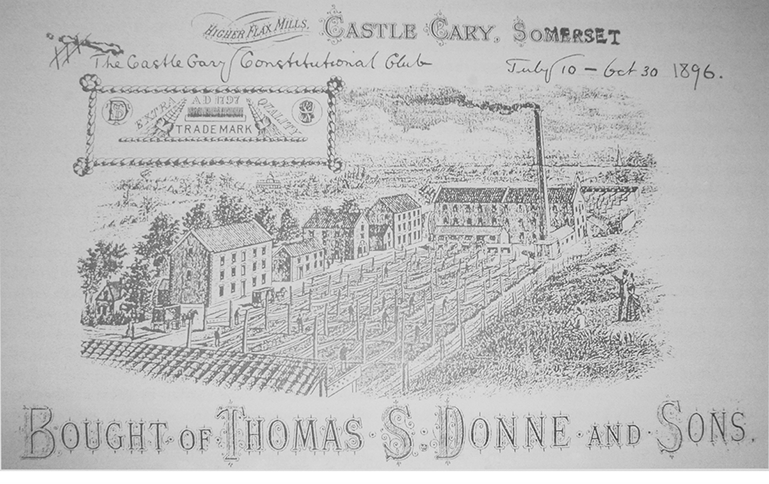

21. Donne's billhead used 1896, showing Higher Flax Mills probably c. 1880, with sets of open ropewalks, the chimney and waterwheel. Rope and twine were produced by spinning fibres into yarn or strands along the rope walk and then laying the strands together from bobbins. The strands were passed through eyes on the hurdles in the rope walk and finally twisted together using a wheel.

By 1851 Albin Close, flax and hemp spinner, had been joined by his son Edward (d. 1855). (fn. 215) They suffered several fires including the burning down of a building in 1853 (fn. 216) then in 1857 an overheated bearing started a fire, which caused £2,000 worth of damage and put more than 50 people out of work. The flax, tow, and twine spinning factory, powered by steam and water, the waterwheel, and flour mill fittings offered for sale or lease that year was probably Close's, however, Albin Close occupied the Torbay factory until he died in 1863. (fn. 217) His son emigrated to Los Angeles (fn. 218) and by 1866 the factory was operated by G. A. Burn as a flax mill. Before 1872 it was taken over by Thomas Salisbury Donne to house one of Thomas Coles's scutching machines. (fn. 219) The tow factory at Torbay was disused by 1885, probably because the extensive building at Higher Flax mills in the 1870s rendered it superfluous, and in 1896 it was occupied by a builder. In 1899 it was bought for £806 by a Mr. Carver who built a new butter factory on the site. (fn. 220) The Torbay area was the site of a trading estate by the late 20th century with new warehouses north of the road. (fn. 221)

Linen manufacturers Thomas Salisbury Donne (d. 1862) and his sons Thomas and Henry had a resident factory overlooker at Higher Flax mills whose sons were employed as engine driver and engineer. (fn. 222) There were c. 40 flax workers in 1861 but only 22 in 1871 and 56 twine workers, as Donnes ceased weaving to concentrate on spinning. In 1871 Thomas Salisbury Donne the younger (d. 1890) said he employed 152 hands. (fn. 223) He installed steam engines, in use until the 1960s, and built the largest of the three-storey buildings on the Higher Flax mills site, 11 bays long, in 1870. (fn. 224) He was probably responsible for the warehouses built at various dates in the later 19th century and an octagonal chimney, since demolished. All the buildings are of local stone with brick dressings under Roman tile roofs and have floors supported by cast iron columns accessed by timber-cased stairs. (fn. 225) Two ponds supplied water for the boilers but one was filled in c. 1970. The younger Thomas's sons, William (d. 1883) and John Stephens Donne (d. 1908), had taken over by 1881. By 1885 substantial ropewalks had been constructed at Higher Flax mills both sides of the main 1870 block and by 1896 the company had new warehouses. (fn. 226) In 1891 there were 19 flax workers and 51 twine workers in the parish, falling to 12 flax and 37 twine workers by 1901. (fn. 227)

22. Higher Flax Mills, in December 1946, showing part of Donne's ropewalk covered in for weaving upholstery webbing and still painted with wartime camouflage.

By the late 19th century Donnes bought in ready processed flax and hemp and the substantial increase in warehousing with their additional designation as merchants implies they were trading in materials as well as utilising them in their mill. In the 1890s Thomas S. Donne and Sons were flax and tow spinners, twine manufacturers, hemp and flax merchants, and manufacturers of hair seating warps, shoe threads, seaming and roping twines, sash lines, box cords, and diaper webs. (fn. 228) In 1926 they became a limited company. (fn. 229) Most of their early 20th-century business was the production of thread, twine, rope, and materials for upholstery and bedding. An unusual item made in the 1930s was the Somerset chair woven from flax cording laid over a basketwork frame. (fn. 230) During the Second World War, despite losing part of the site to a government food store, they produced webbing for gas masks, camouflage nets, twines, ropes, and cordage. The factory was bombed unsuccessfully. One ropewalk was converted into a weaving shed for upholstery webbing and in 1948 a twine-polishing machine was introduced. (fn. 231) The company had c. 80 employees in 1947, (fn. 232) their 150th year, (fn. 233) but used only part of their site and in 1956 rented out a two-storey building to Boyd's and the 1870 three-storey mill to Avalon Leatherboard. (fn. 234) Later other parts of the site were let to small businesses, which in 2001 included a small printing firm. New machinery and electric power were installed from the 1950s but demand for Donne's products fell. They amalgamated with Boyd's c. 1977 but continued to use part of the site until 1983 as T S Donne and Sons to manufacture webbing, two new looms having been acquired in 1980 to replace 20 old ones, and garden netting. Webbing and twine production ceased in the 1980s but manufacturing of some products continued under the name of the Don Cord Company until 1992 when the machinery was scrapped. (fn. 235)

Related Industries

In 1865 and 1872 a chemist and mineral water manufacturer, Thomas Coles (d. 1877), produced artificial manures at a flax scutching mills and was said to have built premises near Clanville. (fn. 236) The scutching machine, for separating linen fibre from the lint waste, was made and patented in 1870 by local engineer William Henderson (d. 1899) who built powered looms for Boyd. (fn. 237) The new machine was in use at Torbay in 1875, (fn. 238) probably supplying processed fibre to Donnes.

Tailoring Factory workers, earning higher wages than labourers, may have encouraged the tailoring and dressmaking trades. There were 14 tailors in 1871 and 32 dressmakers including Susan Cooper of Woodville House who employed a resident dressmaker, milliner, and apprentice. (fn. 239) In 1881 a tailor in South Cary had eight employees and six sewing machines. (fn. 240) The tailoring firm of Churchhouse, established c. 1820, continued in business until 1964. (fn. 241)

23. Higher Flax Mills, photographed in December 1946, showing a woman weaving webbing on a power loom. Several strips could be woven on a single loom each with its own shuttle. The woman is replacing an empty pirn, the removable section on which yarn is wound, in one of the shuttles and several full ones can be seen on the loom.

OTHER INDUSTRY

Footwear

After 1956 Avalon Leatherboard employed 15 men and 11 women at Higher Flax mills making insole strips. After buying Boyd's Ansford factory in 1960 Avalon used the Higher Flax mills building for making backers and shanks for footwear. However, the building was cramped and in 1964 a ropewalk was converted for making insoles and the old mill was abandoned. The premises were sold to Strode Components in 1967. (fn. 242)

Avalon Leatherboard refurbished Boyd's former Ansford factory after 1960 to produce insoles and from 1964 thermoplastic stiffeners. In 1967 the factory was bought by Strode Components, a subsidiary of C. and J. Clark, who erected the large Crendon building in the 1970s for a proposed move of Clark's Maple factory from Street. (fn. 243) In 1981 a last-making plant was installed but in 1992 the whole business returned to Street and all production in Castle Cary ceased. (fn. 244)

Brickmaking

Brickyard Orchard opposite the Horse Pond may have been an early site. (fn. 245) A brick kiln was operating in 1810 (fn. 246) and in 1814 its owner offered for sale a new cottage with a ten-year old brick and tile yard. (fn. 247) That was probably William Creed's brickyard in Mill Lane by 1839. (fn. 248) By 1861 it was a large brick and tile manufactory run by Charles Moody (d. 1870) and employing at least two tilemakers. (fn. 249) In 1896 clay from the sewages works site was burnt for brick. (fn. 250) The Mill Lane works closed shortly before 1910 and was taken over by the gas company and a coachbuilder. (fn. 251)

Other Trades and Crafts

Most crafts and trades were related to agriculture. Between the 17th and 19th centuries a slaughterhouse, tanners, parchment makers, a currier, a coach harness maker, and saddlers were recorded. (fn. 252) A skin house near the Horse Pond, demolished at the end of the 19th century, was said to have been for inspecting and sealing leather, but was possibly part of a tannery. (fn. 253) Two glovers were recorded in 1851 rising to five in 1881 but only one in 1891. (fn. 254) Soapboilers and tallow chandlers were men of means, one chandler described himself as a gentleman but desired six of his workmen to carry his coffin and Charles Moody was a man with several businesses in the 1840s. (fn. 255) Mealmen and maltsters were prosperous men some of whom were also involved in the stocking and linen trades but one went bankrupt and died in Ilchester gaol. (fn. 256) A malthouse near the old Angel inn was converted to a stable before 1808, (fn. 257) and another in South Cary was kept by Robert Penny whose grandson and namesake built the house and factory at Torbay c. 1819. (fn. 258) The last recorded maltster was Martha Francis (d. c. 1852). (fn. 259)

Smiths and building workers were at work in Castle Cary for centuries. In 1558–9 iron and grindstones were being imported through Bridgwater possibly to supply the blademill recorded in 1629 (fn. 260) and there was a family of edgetoolmakers in the later 17th century. (fn. 261) A Mr. Foot in the 1820s made pattens, rakes, and mousetraps, repaired umbrellas and metal items, including teakettles, which he cleaned and delivered. (fn. 262) Tinplate workers were recorded during the 19th and early 20th centuries, four in 1891. (fn. 263) A forge sited in Lower Woodcock Street until the later 20th century produced the churchyard gates. (fn. 264) A glazier was recorded in 1693 and in 1694 two families of London glassmakers were in the parish presumably looking for work. In 1772 a local glazier was fined for 79 profane oaths. (fn. 265) Painters were recorded in the 18th century, one of whom worked in West Pennard church and another, William or Painter Clark (d. c. 1791), was also a schoolmaster, steward of the manor, auctioneer, and valuer. (fn. 266)

Timber throwers recorded in 1881 and a timber carter and three sawmill workers in 1891 were probably connected with the sawmill in Ansford. (fn. 267) A timber sale was held in 1887 and a Castle Cary timber merchant contracted to buy the 21 oak and elm trees on the Dinder prebend estate in 1910. (fn. 268) Basketmakers recorded from 1822 until the early 20th century probably used local materials. (fn. 269) Rake makers used wood from Penselwood and local ash for the tines. Many rakes were dispatched from Castle Cary station. (fn. 270) The trade, latterly dominated by the Clothiers, ceased c. 1950 when the family became builders. (fn. 271)

In 1881 a builder employed 40 hands. (fn. 272) Charles Thomas and Sons Ltd., builders and wheelwrights, begun by Charles Thomas (d. 1909) a former railway worker, later expanded to included plumbers and sanitary engineers, decorators, and undertakers and employed 60 men in 1946. The main business was sold in 1966 but the firm continued undertaking until 1977 or later. (fn. 273) The Clothier family have been builders for 50 years and were responsible for the Churchfields development at Ansford. (fn. 274) Stone fireplaces were made in Castle Cary in the later 20th century. (fn. 275)

A cabinetmaker was in business in the 1790s. (fn. 276) Upholsterers, of both sexes, grew in number alongside the horsehair business, which produced curled hair for stuffing as well as fabrics. There were two upholsterers in 1840 but six and a quiltmaker in 1891 when there were also seven cabinetmakers, two polishers, and a wood carver. (fn. 277) The principal cabinet-making firm was Charles Pither and Son which began at Bailey Hill in 1877 with a workshop, and later a glass and china shop. John Pither invented a method of locking sets of drawers simultaneously. By 1907 the business had moved to a large site opposite the market place including shops and workshops for cabinet making and upholstery. They offered a complete home furnishing and removals business with their own covered waggons. By 1914 they had two shops and a showroom and by 1947 employed c. 40 people. (fn. 278) There were branches at Crewkerne, Wells, and Yeovil. In 1951 the premises were put up for sale including the Emporium with two floors of showrooms, upholstery workshop, mattress repair shop, and storerooms. Thereafter the business was based at Crewkerne. (fn. 279)

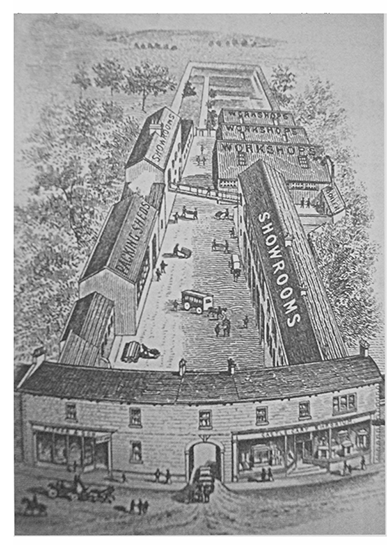

24. Part of a 1911 billhead for C. Pither and Son, cabinetmakers of Castle Cary showing a bird's eye view of premises, which included a rear showroom linked by an overbridge.

Coach building began in Castle Cary c. 1850 with two men, increasing to five in 1861. (fn. 280) By 1871 there were two businesses notably William Bellringer of Fore Street who employed seven trimmers, painters, and wheelers. (fn. 281) Bellringer remained in business in 1901 (fn. 282) but c. 1906 John Squibb started coach making on the former brickyard site. (fn. 283) Squibb's coach and motor works employed 20 people in 1936 and remained in business until 1986 (fn. 284) when the site was acquired for housing. From c. 1884 Gosney's Ivanhoe Cycle Works built and repaired bicycles, which were sold in Scotland and overseas. (fn. 285)

Coles, Andrews, and Co. was producing British wines, soda, and aerated waters by 1866. (fn. 286) In 1891 there were two aerated water manufacturers including the Pooles who ran their business from 1882 until 1906 or later in a former corn mill near the Britannia inn and kept a coffee tavern in 1894. (fn. 287)

Cary Concrete was established in Torbay Road in 1957 and Centaur Services veterinary suppliers moved there from South Street before 1981 when BM Instruments of Wells took over their premises before moving to Boyd's former site. (fn. 288) The Torbay industrial site north of the road houses several other businesses and a large veterinary practice. Other later 20th and early 21st-century businesses included brass product manufacturers, a furniture workshop, providers of survey equipment, and cement casters. Craftspeople included a flutemaker. There was said to be little unemployment. (fn. 289) Despite business closures the town provided employment for c. 1,200 people in 1998, although only two organizations employed more than 100, and had a Chamber of Commerce. (fn. 290)

RETAIL TRADES AND SERVICES

Markets and Fairs

Castle Cary market had a chequered history and despite repeated efforts it was never a success. There may been a corn market in the 13th century. (fn. 291) A market worth 12s. in 1351 (fn. 292) had lapsed before 1468 when John, Baron Zouche obtained a charter for a Thursday market and annual 3-day fairs at the feasts of Saints Philip and James (1 May) and St Margaret (20 July). (fn. 293) By 1610 the market had lapsed again but a cattle fair of unknown date was still held. In 1614, following an inquiry, Edward Seymour, earl of Hertford, was granted a weekly Tuesday market and one annual fair on the Thursday before Palm Sunday with a pie powder court. (fn. 294) In 1633 the market was said to be 'hardly of the middle size', but rent of 10s. and 2lb of pepper was charged in 1649–50. (fn. 295)

In the later 17th and early 18th century the main commodity was sheep. (fn. 296) In 1671 the market house, first recorded in 1670 but said to have been built in 1616, (fn. 297) fairs, and markets were farmed for one year at £20 but the market house and fairs were only valued at 10s. in 1682, possibly because they had failed again. (fn. 298) In 1684 William Player bought them (fn. 299) and in 1687 a list of charges from 2d. to 1s. 4d. for sheep pens, butchers, braziers, cappers, glovers, cutlers, pedlars, bakers, shoemakers, linenweavers, goldsmiths, turners, and the pigward, probably during fairs only, may have been an attempt to revive trade. There were reduced rates for pedlars standing at the cross, possibly that recorded c. 1785, on the second fair day and for beersellers who exposed ivy. (fn. 300)

Castle Cary was described as a market town in 1707 although the market was 'paltry' and the fair on 1 May was as much for entertainment as stock sales including a procession of milkmaids. An April fair was held in 1718 (fn. 301) and c. 1736 Strachey recorded fairs on the Tuesday before Palm Sunday, Mayday, Whit Tuesday for sheep, and 17 September for cloth but the market was decayed with no corn and little flesh. (fn. 302) In 1759 Rachel Ettrick let the market for 14 years, with all utensils but no mention of the market house, to a carpenter for £16, a practice that continued until 1801 or later. (fn. 303) By the 1780s the market had been long discontinued although there were occasional winter sales for corn, sheep, and cattle. (fn. 304) Only three fairs were held by 1767 the September cloth fair having ceased. (fn. 305) The Galhampton wagon of cheese and other produce, robbed in 1774, was probably attending a fair. (fn. 306) In the 1780s the fairs were for cattle, sheep, and pedlary. (fn. 307)

Before 1713 livestock sales had moved to a site known as the sheep market (fn. 308) off High Street in front of the later nursery. It was built on before 1790 and in 1809 and 1846 cottages, other buildings, and an orchard were described as in the sheep market. (fn. 309) In 1809 600 cattle were sold at markets, probably again held in the market place. (fn. 310) In 1831 there were seven cattle markets annually and three fairs but by 1839 the cattle market was held fortnightly and the September fair had been revived for sheep. (fn. 311) The maypole was said to have been erected outside the Angel for the last time at a May fair c. 1835. (fn. 312)

In 1844 the market was changed to alternate Mondays, with 50 people attending an associated dinner, but by 1852 it had returned to Tuesdays and a newly formed agricultural society awarded prizes for bulls, cows, and cheese. (fn. 313) An annual August cattle and cheese show was held from 1883 or earlier until 1906 when it amalgamated with those for Bruton and Wincanton. (fn. 314) The fairs continued with street stalls streets selling cloth, toys, ornaments, and gingerbread but the May fair, held until 1905 or later, sold sheep in pens in the street and other stock on Bailey Hill. (fn. 315) During the early 20th century travelling fairs and circuses used Squibbs' Paddock, since the 1950s the Millbrook gardens car park, sometimes called the Fair field. (fn. 316)

In 1867 the market was licensed to sell store cattle, sold fortnightly until 1899 or later, possibly alternating with a repository sale but very few animals were offered for sale. Typhoid among local pigs in 1879–80 led to cessation of pig sales. (fn. 317) Sheep and pigs were again sold on Bailey Hill by the 1900s but winter cattle sales were abandoned in 1911 due to foot and mouth disease. (fn. 318) In 1912–13, under an order from the Board of Agriculture, a new market for cattle and sheep on Mondays was built west of Lower Woodcock Street but no cattle were brought in for several years. The new yard, with a covered sale ring, was leased by the rural district council to successive firms of auctioneers and managed by the Castle Cary parochial committee. Despite the addition of a new cattle sale area on neighbouring land before 1920 and returning to alternate Tuesdays in 1928 the market was not a success (fn. 319) and it was suspended in 1940. (fn. 320) The auction yard was commandeered by the military in 1942 and the annual bull show, held since c. 1900, transferred to Sparkford. (fn. 321) The market licence was withdrawn in 1949 (fn. 322) and the site was used later for a telephone exchange. (fn. 323)

The Market House Company became a limited company in 1912 and between 1918 and 1937 the parish council acquired 46 shares. (fn. 324) Attempts to revive the market failed and the company was liquidated in 1993 with assets of £33,000. The holders of 88 shares, about a third of the total, could not be traced. The town council set up a market committee and opened a small market on Tuesdays and Saturdays in 1994 but by 1998 there were only three stalls on Tuesdays and two on Saturdays. (fn. 325) An annual street market was held on Bailey Hill in June from 1980 by the Chamber of Commerce. (fn. 326)

Market House The old market house, a rectangular building possibly facing north-west, (fn. 327) had been converted to dwellings by c. 1785 when its roof pillars stood in front of the houses and were painted green. (fn. 328) They and the south-west part of the building had gone by 1807, when a house had been built adjoining the former market house on the north and an enclosed courtyard to the west. (fn. 329) A lease of parcels of the market place was disputed but a garden was enclosed to the rear of the house by 1839. (fn. 330) In 1853 the Castle Cary Market House Company was formed to build a market house for corn, cheese, butter, meat, vegetables, and other produce with provision for assembly and reading rooms in the belief that the new railway would boost trade. The new market house was built in 1855 to designs by F. C. Penrose, an unusual commission for the recently appointed Surveyor of the Fabric of St Paul's Cathedral. (fn. 331) The design of the stone building is peculiar, apparently dictated by the very particular requirements for mixed use and the triangular site. The main range is open on the ground floor. Above corn was stored in a low mezzanine with rows of enclosed bins, and above that lay the assembly room with open timbered roof and adjacent music gallery and refreshment room. This accommodation was managed on the elevation by a giant Gothic arcade with blind arches to the mezzanine pierced by alternating round and triangular windows, and mullioned windows above; the effect was picturesque and perhaps Flemish in inspiration. A west wing cranked to the north-east and projecting from that a single-storeyed butchers' shambles formed the east side of a triangular courtyard with a ramp to the mezzanine. The rear wing housed a reading room and at its north end were rooms for the resident female caretaker. The ground floor colonnade had been enclosed by 1887 with wrought iron railings and gates. (fn. 332)

The new market hall was not a success and at c. £3,000 the building cost more than had been estimated. By the 1880s the corn floor was let as a furniture store and by 1900 the ground floor was used to store agricultural implements and blank tombstones. (fn. 333) Nevertheless, by 1896 it was said to have been of great service as a social and administrative venue. Known as the Town Hall from its completion, it was used by the vestry, parish officers, poor law and utility officials, parish council, education committee, police, registrar, local societies, theatre companies, cinema promoters, and, since the late 1970s a museum and information centre. It was purchased in 1991 by South Somerset District Council. (fn. 334)

Transport

The Pilot coach between Bristol and Bath and Poole served Castle Cary from 1824 and other coach services began in 1834 and 1837. (fn. 335) In 1839 there were carriers to Bath, Bristol, London, and Weymouth. (fn. 336) In 1840 a daily coach service between Taunton and London called at Castle Cary as did services between Bristol and Weymouth and Bath and Lyme Regis, which ran on alternate days. Carriers like Whitmash ran at least weekly to Bath, Bristol, London, Weymouth, Wincanton, and Yeovil. (fn. 337) By 1850 there were daily omnibuses from the Britannia to Bristol and Sherborne. (fn. 338)

The Somerset and Dorset Railway, which bypassed the parish entirely, had an office at the George. Castle Cary station, in Ansford, was served by buses and an office at the Angel Inn in 1883. (fn. 339) In 1851 one railway labourer was recorded (fn. 340) but in 1861 a railway driver and 39 labourers, excavators, and gangers were in the parish. (fn. 341) In 1871 besides workers at a railway saw mill in Ansford, there were platelayers and packers and in 1891 a station master, two signalmen, a railway haulier, and a bus driver. (fn. 342)

Several recorded weighbridges were connected with the delivery of coal and hay. Robert Clarke erected one in 1804 and in 1863 there were two in the High Street. (fn. 343) The Angel and White Hart inns had them. A weighbridge of 1843 was built in, or later moved to, the market place and remained in private ownership in 1910. (fn. 344)

Inns and Public Houses

Castle Cary supported many public houses whose numbers fluctuated partly with attempts to control them. Innkeepers and winesellers were recorded from the later 16th century, (fn. 345) although the authorities made unsuccessful attempts to close at least one public house in the mid 17th century. (fn. 346) In 1686 inns could provide beds for 29 guests and stabling for 54 horses (fn. 347) and in 1687 there were three inns and eleven alesellers or brewers. (fn. 348) Only one or two licences were issued in the early 18th century but numbers increased to nine in 1753, (fn. 349) despite a petition to the justices in 1744 by the vicar and churchwardens for no more than five as there were too many little alehouses where the poor wasted their money. (fn. 350) Three unlicensed premises were reported in 1758 (fn. 351) and licenses were reduced to three by the early 19th century. (fn. 352) However, from the 1830s until the early 20th century there were at least 10 public houses. In 1905 several licences were referred to Quarter Sessions. (fn. 353) Five public houses remained open in 2001, but there were other licensed premises.

25. The George, Market Place, Castle Cary. This inn, so-named in 1686, had a large assembly hall behind, which was destroyed along with much of the premises in 1845.

The most important inns were the Angel, recorded from 1620, (fn. 354) and the George, named in 1686. (fn. 355) The latter may have hosted the manor court as a suspected thief was interrogated in a great chamber there in 1715 (fn. 356) and the lord of the manor owned the furniture of a chamber including a desk appraised in 1729. (fn. 357) Election dinners, vestry meetings, and auctions were held at both inns in the later 18th century, when the George was the excise office. (fn. 358) Both inns were 'tolerable' c. 1780. (fn. 359) The Angel was sold in 1786 with stables, cellar, and brewhouse (fn. 360) and again in 1794 but closed c. 1799 when the lease expired (fn. 361) and became a private house called the Old Angel. (fn. 362) The Angel name was transferred in 1800 to the Catherine Wheel, open by 1707 on the corner of Woodcock Street and Market Place in 1707, and rebuilt, probably between 1802 and 1805 when no licence was issued. (fn. 363) It remained open, despite having its licence referred in 1905, until the 1950s when it was converted into shops. (fn. 364) The George had nine bedrooms, two kitchens, and stabling for nearly 100 horses in 1842. (fn. 365)

Alehouses were often short-lived, like the Three Cups open during the Interregnum, (fn. 366) the Shoulder of Mutton open in 1703, (fn. 367) and the Phoenix recorded in 1718 and 1748, (fn. 368) whose frontage was occupied by six houses and shops in 1808 extending north from the Horse Pond. (fn. 369) The Britannia, probably built and opened shortly before 1768, (fn. 370) kept for most of the 19th century by the Andrews family, (fn. 371) was the main local staging post for coaches, carriers and omnibus services. (fn. 372) As the Horsepond, since 1992, (fn. 373) it remains open. North of the Britannia, the White Hart, also still in business, had opened by 1859, (fn. 374) possibly the beerhouse in Fore Street recorded in 1850, (fn. 375) and was largely rebuilt or refronted in the 1870s. (fn. 376) The Fox and Hounds, in High Street by 1859 (fn. 377) and said to have succeeded the True Lovers Knot open in 1838 and 1842 on the corner of Horner's Yard, south of High Street, (fn. 378) remained open until 1909 when it sold an average of 40 barrels of beer a year. Renewal of its licence was refused and it became a shop. (fn. 379)

Beerhouses included the Half Moon, which had a club in the 1840s, (fn. 380) the Pretty Leg, Mill Lane, also open in the 1840s, (fn. 381) the White Horse in the 1860s, the Live and Let Live in Market Place, which lost its licence in 1911, and those in Ansford Lane and Cumnock Road known only by their keepers' names. (fn. 382) In 1872 a builder opened the Heart (fn. 383) and Compasses in Mill Lane. (fn. 384) By 1894 it was kept by the Squibb family who had a coach building business opposite. (fn. 385) It was granted a full licence in 1953, (fn. 386) changed its name to the Two Swans c. 1997 and remains open.

Public houses at South Cary included the Royal Oak furnished with furniture, pewter, and brewing vessels belonging to the lord of the manor in 1729. (fn. 387) It closed before 1785 when the ballroom, opened in 1779, was converted into a Sunday school and the rest into tenements known as the Old Royal Oak in 1810. (fn. 388) The Golden Lion opened c. 1805 (fn. 389) with its own brewhouse but was a private house by 1816 when Zion chapel opened in its garden off Golden Lion, later Chapel, Yard. (fn. 390) In the mid 19th century Philip Talbot kept the Baytree beerhouse at the southern end of South Cary, (fn. 391) Edward Oram had a beerhouse on the corner of South Cary Lane (fn. 392) and the Mitre, (fn. 393) said to have been built by Robert Gibbons in 1831, was probably the beerhouse in Gibbons Row opposite the church. It remained open until 1905. (fn. 394) The Alma beerhouse was built on the Baytree site before 1859 and belonged to Oakhill Brewery in 1896. (fn. 395) Granted a full licence in 1953 (fn. 396) and still open, it was renamed the Clarence after 1973, and the Countryman c. 1981. (fn. 397)

Outlying beerhouses, included the Wheatsheaf, Smallway lane, near Galhampton, open between c. 1840 and 1925 when renewal of its licence was refused, (fn. 398) the Royal Oak on the Somerton road at Clanville between 1851 and 1872 (fn. 399) and the Royal Marine, probably at Blackworthy in Clanville, recorded between 1845 and 1881. (fn. 400)

Before 1878 a redundant bank on Bailey Hill became a Temperance Hotel and remained in business until 1931 or later. (fn. 401) The Pooles, mineral water manufacturers, kept the Rising Sun Coffee Tavern in Fore Street from 1879 until 1897 or later. (fn. 402)

Shops and Services

John Weche, mercer, died c. 1579 and by 1630 the Cozens family and later the Russes were mercers. Both families remained in the business in the 18th century. (fn. 403) Members of the Francis family were mercers in 1647 and 1793. (fn. 404) A shop was recorded in 1682. (fn. 405) Shopkeepers in the later 18th century included London mercer Richard Gardner who went bankrupt in 1791, (fn. 406) a confectioner, a grocer, a watchmaker, two linen drapers, and a silversmith. At the same date there were an attorney, a barber, an apothecary, a surgeon, an auctioneer, two land surveyors, a dancing master, a carrier, and a post and excise office, indicating that Castle Cary was a local centre for shops and services. (fn. 407)

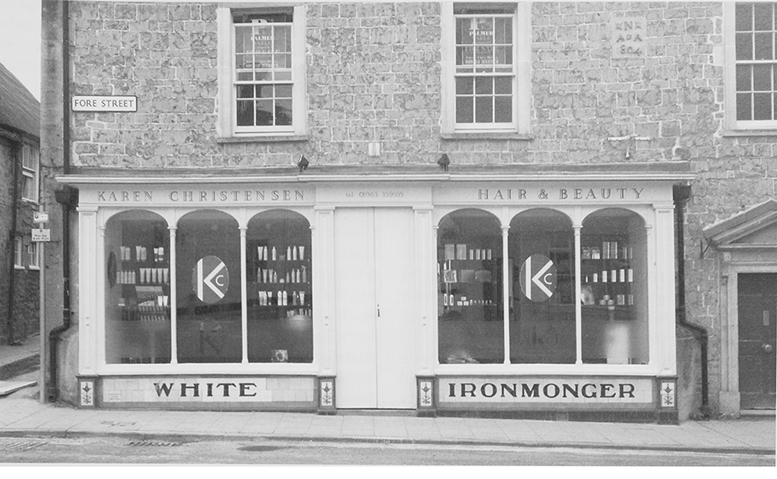

26. Castle Cary, Fore Street. The former White's ironmongers, one of many late 19th-century shopfronts in Castle Cary. The shop was built in 1804. The tiling bears the name of C. Thomas and Sons, builders of Castle Cary who presumably reconstructed the frontage for White's.

Antony Nancolas, shopkeeper by 1791, was the son of a Falmouth clockmaker who came to Castle Cary. He traded in cheese, sold drapery and general goods, and built a new shop in Fore Street in 1804. (fn. 408) In 1823 another shopkeeper described himself as a linen and woollen draper, haberdasher, ironmonger, grocer and tea dealer, sold patent medicines, gunpowder, and shot, and arranged funerals. (fn. 409) In 1836 the proprietor of a printing office, licensed in 1827, had a library and sold perfume, toys, fancy goods, paperhangings, musical instruments, and by 1839 teas from East India House. (fn. 410) In 1839 there were over 20 shops including a bookseller, a fishmonger, and a chemist. There were also two watchmakers, an umbrella maker, two saddlers, four solicitors and two surgeons. (fn. 411) In 1841 there were also a hairdresser and three nurses. (fn. 412)

Many shops combined retail and manufacturing functions. In 1850 the printer was a bookseller and stationer and a furnishing ironmonger, worked in zinc and copper plate, sold oils, colours, and leather and let out threshing machines. There were two printers at work at that period but only one by the end of the century. (fn. 413) Printing has continued in the town. By 1859 among 26 recorded shops were a glass and china dealer, and services included coal merchants, brewers, clockmakers, and nurserymen. (fn. 414) A colour man was recorded in 1865. (fn. 415) The number of shops continued to increase, many with resident staff and in 1871 six young drapers from Scotland shared a house in South Cary, continuing a tradition begun in the 1830s and 1840s by John Boyd and William McKerrow, both from Ayrshire. There were also a photographer, a French polisher, three chimney sweeps, and 15 laundresses. (fn. 416) A piano repairer was recorded in 1872, (fn. 417) a jeweller and a toy dealer in 1881 (fn. 418) and a cycle factor in 1891. (fn. 419) Watchmakers continued in business into the early 20th century including one who was also an optician. (fn. 420) By 1901 there were a few lock-up shops in Fore Street but the larger stores still had resident assistants and the bank manager lived at the bank. (fn. 421)

Wason, later Wosson, Barret (d. 1930) kept a large grocery store and cured ham from his own slaughterhouse and made sausages as well as smoking food for other people. The business started c. 1880 in succession to a well-established confectioner and expanded before 1896 into a row of three premises in Fore Street. His son went bankrupt in 1939. (fn. 422) Martin's grocers began c. 1875 in South Cary and in the 1890s opened a shop near the market place expanding in 1917 into the neighbouring premises where they remain in business. Martin's and Pither's had branches in South Cary in the early 20th century. (fn. 423) During the 19th century shops and businesses were also located in Upper High Street, (fn. 424) mainly residential by the later 20th century, and spread into New, later Station, Road, notably Otton's house furnishers, begun in 1908 and later also wireless dealers. (fn. 425) New shops and showrooms were built on the corner of Station Road and Lower Woodcock Street in 1934. (fn. 426) In the later 20th century those outlying premises were converted to residential use and shops were concentrated in the central area.

In 1947 there were c. 25 shops, seven hairdressers, six car repairers and several other business and professional services. (fn. 427) By 1973 there were 43 shops employing c. 100 full and part time staff in over 16,000 square feet of retail space. There were also 22 services including banks, hotels, hairdressers, an estate agent, and a garage. (fn. 428) Some shops had closed by 1981 and there were several antique shops but a wide range of stores remained. Several still operate behind 19thcentury shopfronts. In 2001 the town provided a wide range of shops and services to the parish and a small rural hinterland. (fn. 429)

Banks and Post Offices

The East Somerset Savings Bank, established in 1818, had its main office at Castle Cary (fn. 430) but declined and eventually closed in 1889 because of competition from the Post Office Savings Bank, established 1861. (fn. 431) By 1839 a branch of Stuckey's Bank, probably in Woodcock Street, was managed by Thomas Matthews. It closed before 1852 (fn. 432) but reopened before 1856 and later moved into the building in High Street, largely rebuilt in 1891, which still bears its name. In 1910 it became part of Parr's Bank (fn. 433) and was in 2001 a branch of the National Westminster Bank. A branch of the Wiltshire and Dorset bank was open between 1886 and 1892. (fn. 434) By 1931 there was a branch of Barclay's Bank, (fn. 435) which remains in business.

In 1828 the Castle Cary receiving office was converted into a sub post office. (fn. 436) By 1842 it had moved from Woodcock Street to High Street, following the transportation of James Edwards, postmaster, for theft, (fn. 437) and by 1850 was in Fore Street. (fn. 438) In 1871 it was in an ironmonger's shop in High Street and employed a telegraphist, (fn. 439) messenger, two letter carriers, and postboy, and provided banking facilities for 92 customers. (fn. 440) In 1882 it moved into its present premises, an 18th–century house on Bailey Hill, with two resident clerks in 1891. The proprietor was also an estate agent, auctioneer, bailiff and the 1891 census enumerator. His daughter was a telegraphist. (fn. 441)