A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Langford Parish: Radcot', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp250-269 [accessed 10 May 2025].

'Langford Parish: Radcot', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online, accessed May 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp250-269.

"Langford Parish: Radcot". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online. Web. 10 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp250-269.

In this section

RADCOT TOWNSHIP

The tiny hamlet of Radcot (fn. 1) lies on the north bank of the river Thames on flat, low-lying ground liable to flood. It now contains only half a dozen houses, including the 17th-century Radcot House; in the earlier Middle Ages it was considerably larger, but probably never contained more than around 35 households. Early settlement was laid out close to an important crossing of the Thames, formerly the boundary between Oxfordshire and Berkshire, where skirmishes were fought in the 12th, 14th, and 17th centuries. A castle, held in 1142 by Matilda's supporters during the civil war with Stephen, was built in the early 12th century within the settled area, but was demolished around 1270–1300, to be replaced by later manorial buildings. A medieval chapel occupied part of the site until the 17th century, when Royalist forces fortified the castle earthworks to defend Radcot Bridge. (fn. 2)

From the Middle Ages Radcot was a trans-shipment point from road to river, providing employment for local people, although until the 20th century most inhabitants worked in agriculture. (fn. 3) The nearest towns lay 2½ miles (4 km) south at Faringdon (formerly Berks.) and 4½ miles (7 km) west at Lechlade (Glos.). Until 19th-century reorganization Radcot remained a chapelry and township of Langford, although for convenience many inhabitants attended church and school in neighbouring Clanfield. (fn. 4)

Boundaries and Landscape

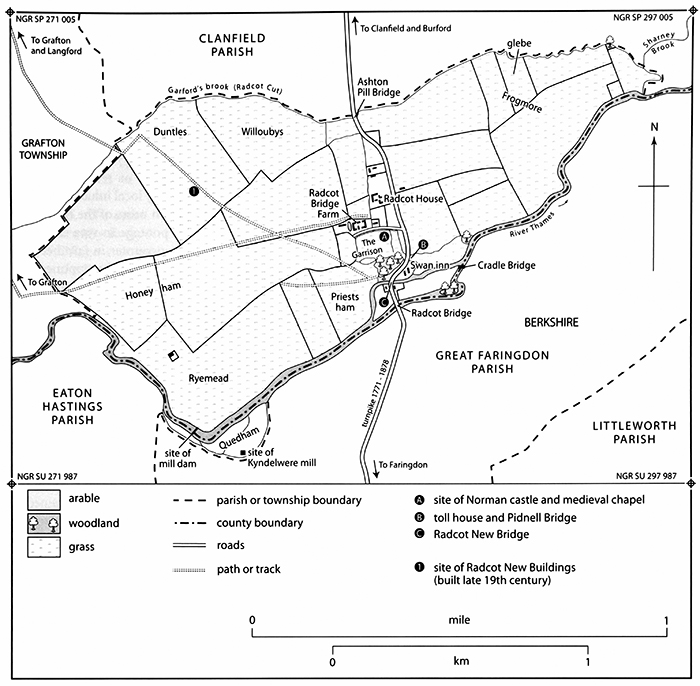

Radcot's boundaries and acreage (441 a.) (fn. 5) must have been established in outline before 1066, when the township formed a distinct territorial unit. By then it was bordered on all sides by neighbouring estates, and although still held with Langford it was separately itemized in Domesday Book. (fn. 6) The southern and western boundaries, following the river Thames, coincided with the shire and hundred boundaries, which were both determined by the early 11th century; there may, however, have been adjustments where a side channel of the river looped around Kyndelwere and Quedham (Fig. 69). (fn. 7) The northern boundary with Clanfield followed 'Garford's brook' (later called Radcot Cut), which was also pre-Conquest in origin, and marked the limit of Bampton minster's parochia. (fn. 8) The short north-western boundary with Grafton must also have existed by 1066, when Grafton was in separate ownership; it may, however, have been adjusted later, and by the 19th century left Garford's brook to follow an irregular field boundary to an embanked drain leading back to the Thames. (fn. 9) Radcot was created a separate civil parish in 1866 and was united with Grafton in 1932. (fn. 10)

The entire township is flat and low-lying at around 69 m. (fn. 11) Riverside alluvium provided extensive (though not necessarily rich) meadows, which were central to Radcot's agricultural economy until modern times. Most of the township, however, including the settlement, lies on river gravels of the First Floodplain terrace, overlying Oxford Clay. (fn. 12) Flooding has long been endemic, and in the Middle Ages was exacerbated by riverine obstructions such as mill dams. (fn. 13) The watery landscape was reflected in medieval field names, which included the elements ēa, hamm, lacu, and mere. (fn. 14) The castle held by Matilda in 1142 was described as 'so surrounded by water and marsh as to be inaccessible', while to the north of the hamlet a series of fishponds was constructed. (fn. 15) Drainage ditches mentioned from the 13th century were extended and improved in the 19th and 20th, although seasonal flooding of meadows remained commonplace, and from time to time more damaging floods occurred, including in 2007. (fn. 16) Over the centuries the river's course was modified by a combination of human intervention and natural events, altering both landscape and land use. (fn. 17) The Thames has also long served as a frontier, and during the Second World War several concrete pillboxes were erected along the Radcot riverbank as part of a defensive line against invasion from the south. (fn. 18)

69. Radcot township c. 1840, showing land use, key buildings, and the site of the Norman castle and medieval chapel. See also Fig. 71.

Apart from hedgerow trees the township lacked woodland, contributing to the landscape's flat and featureless aspect. (fn. 19) Overhead power-cables are prominent: in the mid 20th century they crossed the centre of the township, but were later re-aligned along its south-western edge. (fn. 20) Water-filled pits in the north-east of the township presumably resulted from late 20th-century gravel extraction. (fn. 21)

Communications

Roads, Bridges, and Carriers

The road from Burford to Faringdon, which crossed the Thames at Radcot Bridge, was important from an early date. (fn. 22) A river crossing may have existed at Radcot in the 8th century, although the main route from western Mercia to the south coast is more likely to have crossed the Thames further east at Rushey. (fn. 23) That crossing was probably superseded by one at Radcot in the 11th century, when it connected the two parts of a large and important estate divided by the river, and held consecutively by Earl Harold (d. 1066) and Aelfsige of Faringdon. (fn. 24) Its creation probably involved the construction not only of a new road but of an embanked causeway across the floodplain, most likely linked by timber bridges across the river's various side channels (see Plate 10). (fn. 25) The 11th-century road followed a direct north-south route through Radcot, but was diverted to its present course in two stages in the 12th and 18th centuries. The construction of a Norman castle at the southern end of the hamlet first forced the road to loop around its embankments as shown on 18th-century maps, (fn. 26) and further changes followed the turnpiking of the route in 1771. The stretch through Radcot was already embanked but long subject to floods and sometimes impassable, and in 1779 it was consequently raised above the flood plain and diverted to the east of the settlement. (fn. 27) A toll gate built on the south side of Pidnell Bridge was removed when the road was disturnpiked in 1878. (fn. 28)

A bridleway from Kelmscott, mapped in 1761, joined the main road where it looped around the castle site, creating a T-junction at the settlement's southern end. (fn. 29) By the late 19th century this path was apparently lost, though it may have been partly superseded by a footpath north-westwards to Grafton, which in the early 21st century still joined the former towpath along the Thames at Radcot New Bridge. (fn. 30) The towpath leaves the township at a crossing of the Thames called Cradle Bridge, shown on 19th-century maps. (fn. 31) The eastern end of the Radcot–Kelmscott bridleway, which in 1840 still roughly followed its 18th-century course, was reinstated in the late 20th century, but only as far as the path to Grafton Lock. (fn. 32)

Bridges

From the Middle Ages the Burford– Faringdon road crossed four bridges in Radcot, all of which may have succeeded timber structures established in the 11th century. The oldest surviving is Radcot Bridge, on the former Thames boundary between Oxfordshire and Berkshire; it was first mentioned in 1209, when King John gave protection to Brother Aylwin (possibly of Beaulieu abbey) who had undertaken its repair. (fn. 33) Further repairs or rebuildings were carried out in the 14th century by local inhabitants, who were granted pontage (a toll on users of the bridge) by the king. (fn. 34) The last grant of pontage in 1393 may have followed damage during an encounter in 1387 between Robert de Vere, earl of Oxford, and the opponents of Richard II. (fn. 35) In order to impede de Vere's progress, the earl of Derby's force probably broke the central navigation arch, which was poorly rebuilt and is clearly later than the two outer arches of the surviving 14th-century structure. (fn. 36) An unidentified house called the 'hermitage', mentioned in the 16th and 17th centuries, may recall a medieval bridge hermit licensed to collect alms for bridge repair. (fn. 37)

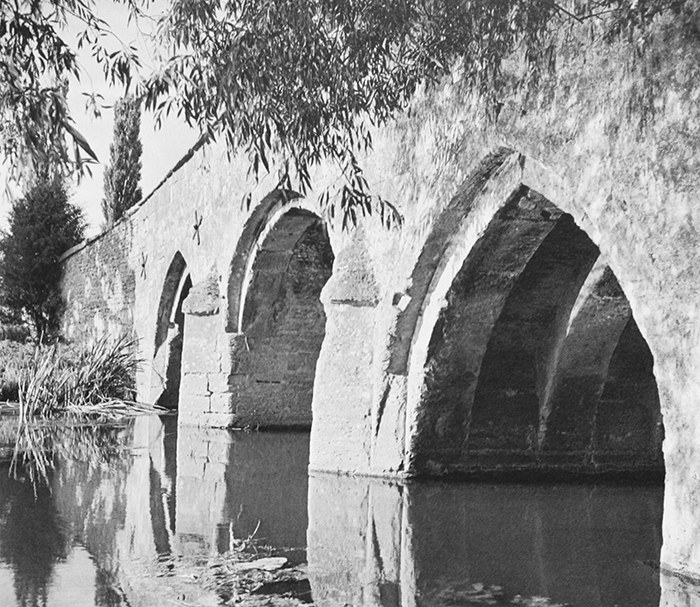

The bridge as it now exists (Figs 70 and 73) has two sharply-pointed outer arches flanking a four-centred central arch, all of limestone ashlar. The coped parapet has a triangular projection over the central arch on the eastern side, which may formerly have contained a statue of the Virgin Mary: according to tradition the statue was destroyed during the Civil War. The western side has a plinth on which a cross may once have stood. (fn. 38)

From Radcot Bridge the road northwards crosses a narrow island to a second channel of the Thames. In 1692, according to Thomas Baskerville, this second stream had 'a bridge with two arches which leads to [the] wyer [weir]'. (fn. 39) Presumably it fell into disrepair and was replaced by 'a crude wooden bridge with one vent', which was removed in 1787 when the channel was widened and a single-arched stone bridge built in its place. (fn. 40) Known as Radcot New Bridge, it was repaired in 1848 and survived in 2011. (fn. 41) In 1871 a local resident complained that both Radcot bridges were inconveniently steep and short, that the road between them lay in a deep dell which sometimes flooded, and that the subsequent right-angled bend caused carts to pitch over. (fn. 42)

70. The 14th-century Radcot Bridge, carrying the Burford-Faringdon road across the Thames. The central arch has been rebuilt, perhaps following damage during a military engagement in 1387.

Near the Swan inn, Pidnell Bridge crossed a third channel of the Thames and was probably first built when the road was diverted in the 12th century. Baskerville described it as having 'four arches but not for great boats to go through', which almost certainly referred to the medieval structure drawn in 1845. (fn. 43) The bridge was owned by the lord of the manor, who replaced it in 1863 with the present structure of brick (later refaced in stone) and iron. (fn. 44) A bridge across Garford's brook, on the boundary with Clanfield, was mentioned in 1395, and was later known as Ashton Pill Bridge. (fn. 45)

Carriers, Railway, and Post

Carriers to Burford, Faringdon and elsewhere passed through Radcot, (fn. 46) but no local carriers are recorded. A railway station was opened at Faringdon in 1864, and one at Black Bourton (called Alvescot station) in 1873, followed in 1907 by one near Langford. (fn. 47) Post was delivered through Faringdon until the early 20th century, when Clanfield assumed responsibility; a letter box was located near Pidnell Bridge from c. 1900. (fn. 48)

River Transport

The Thames was an important artery for trade and communication from an early date. In the 13th century Robert Aleyn of Langford was required to accompany the king's treasure to the sea for one day a year; the obligation was probably of pre-Conquest origin, and suggests a local service to protect royal ships along the river. (fn. 49) Later disputes between lords of Radcot and Beaulieu abbey over shipping rights and weirs point to a significant downstream traffic in grain, loaded near Radcot and possibly shipped as far as London. In 1205 Beaulieu abbey's ships (naves) were granted free passage along the Thames from Faringdon to the sea, a right which Radcot's lords in the 13th and 14th centuries promised not to obstruct. (fn. 50)

The main loading point seems to have been at Kyndelwere, a mill on the Faringdon bank of the Thames a short distance upstream from Radcot Bridge, which apparently marked the upper limit for commercial traffic. (fn. 51) Lords of Radcot constructed a rival 'hard' or landing place on the Radcot bank of the Thames, where a boat carrying wheat and other goods was moored after one of its sailors drowned in 1271. Called 'the Jury's hard', it may also have been the site of a special court concerned with riverine disputes, and was perhaps an attempt by the lord to protect his interests against the abbey along a busy stretch of water. (fn. 52) The lord's establishment of a market and fair in 1272 was probably also inspired by Radcot's position as a trans-shipment point, although it failed to prosper. (fn. 53) Further local disputes revolved around the monks' fishery and sheep-wash at Kyndelwere, whose mill dam adjoined Radcot's riverbank and sometimes flooded neighbouring meadows. (fn. 54)

During the later Middle Ages obstructions on the Thames below Oxford effectively ended large-scale traffic this far upstream, but with the reopening of navigation in the 1630s the trade through Radcot revived. (fn. 55) Stone from Burford and Taynton for building in London and Oxford was shipped down the Thames from Radcot in the 17th and 18th centuries, for which a series of wharfs was constructed. (fn. 56) From the 17th century river traffic from nearby Lechlade also increased, and in 1699 a barge carrying malt from Radcot to Oxford was involved in illicit trading at Bablock Hythe. In 1720 an Oxford bargeman committed an assault at Radcot. (fn. 57)

From 1783 the building of the Thames and Severn canal to Lechlade, opened in 1789, led to improvements in Thames navigation. At Radcot the channel to the north of Radcot Bridge was widened in 1787 and a new bridge constructed, although barges found the archway difficult to negotiate. Coal was a main item in the west-to-east trade, and two coal merchants lived at Radcot in the mid 19th century. (fn. 58) River traffic declined after the building of the railway, and from the late 19th century Radcot became a place for pleasure boating and swimming (Fig. 74). (fn. 59)

Settlement and Population

Early Settlement

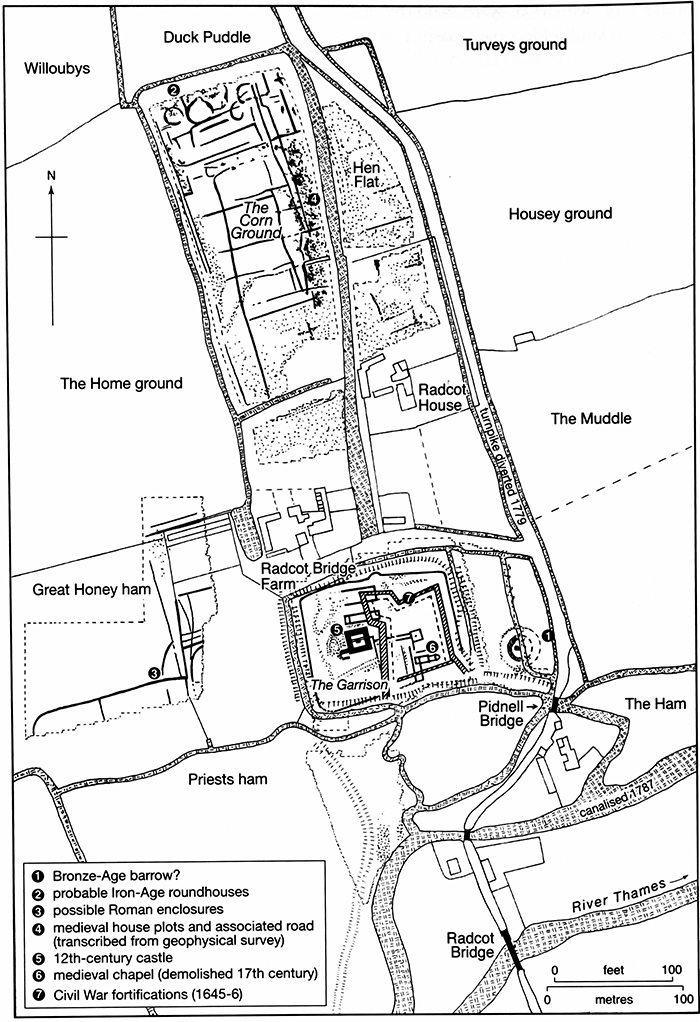

A Neolithic flint axe-head found in the Thames at Radcot Bridge may indicate that the crossing was used before the area was settled, (fn. 60) while undated cropmarks in the north and west of the township probably denote prehistoric settlement and agriculture. A possible Bronze-Age barrow lay to the east of the medieval chapel, and several Iron-Age roundhouses have been found close to the northern edge of the later hamlet (Fig. 71). (fn. 61)

Pottery finds suggest a substantial Romano-British presence at Radcot, but the settlement was apparently abandoned in the post-Roman period until reoccupation in the mid 11th century, when a planned nucleated settlement seems to have been deliberately created. (fn. 62) The place name (reed cot or cottages) suggests a subsidiary settlement dependent on a major estate centre, presumably that at Langford, and even in the 13th century the village was still dominated by smallholding cottars. Its development was presumably also connected with the construction of the major river crossing linking the Langford and Great Faringdon estates, however, which lent it an unusual character throughout the Middle Ages. (fn. 63)

Population from 1086

In 1086 Radcot was held in demesne without recorded tenants, (fn. 64) but by 1279 the village contained around 35 houses, of which 31 were held by unfree cottars. (fn. 65) Seventeen landholders paid tax in 1306, although fewer were noted in 1316 and 1327 when Radcot was taxed with Grafton. (fn. 66)

Thereafter the population declined markedly. Depopulation during the Black Death must have been relatively severe, since in 1377 only 24 adults aged over fourteen paid poll tax. (fn. 67) Two years later only 16 unfree tenants occupied landholdings, and another 15 holdings were vacant. (fn. 68) Population probably fell further during the 15th century, and in 1544 only three taxpayers were mentioned. (fn. 69) Six men swore the obligatory protestation oath in 1642, three houses were assessed for hearth tax in 1662–5, and mid 17th-century parish registers suggest no more than half a dozen resident families. (fn. 70)

Population probably changed little during the 18th century, and in 1801 there were six houses accommodating 31 people. (fn. 71) During the 1820s, as agriculture recovered, numbers rose sharply, reaching 55 (in 13 houses) by 1831; over the next twenty years, however, the population fell back to 36 in eight houses, and following the onset of agricultural depression in the 1870s it declined yet further to only 26 in 1881. A brief increase to 33 by 1891 was followed by further decline, and by 1911 there were only 20 inhabitants and five houses. The number of households was unchanged when Radcot was united with Grafton in 1932. (fn. 72)

Village Topography and Development

The 11th-century village lay within a rectangular enclosure straddling the recently causewayed Burford–Faringdon road (see Fig. 71 and Plate 10). (fn. 73) From the outset its purpose may have been partly defensive, to guard an important river crossing connecting the manors of a single estate, (fn. 74) and in the early 12th century a stone-built castle with a large square keep was erected within the settled area, overlooking the river. Its construction necessitated diversion of the road around its perimeter, and probably some replanning of the settlement to its north, where plots identified by geophysics seem to relate to the redirected roadline. (fn. 75) The castle seems to have been demolished in the late 13th century, and was replaced by domestic manorial buildings (including a three-storey tower house) probably in the same area. Those were themselves abandoned by the early 15th century, and a 'mansion house' mentioned in the 1540s almost certainly occupied a different site: possibly it was a predecessor of Radcot House, to the north. (fn. 76) A 12th-century chapel at the south-eastern corner of the castle site survived until the 1640s, when it was apparently demolished during the construction of Civil War fortifications there. By the 1660s all trace of it seems to have been removed, and the churchyard was in private ownership. (fn. 77)

By then the hamlet was already severely shrunken, and probably comprised no more than half a dozen roadside houses, clustered around the river crossing and castle earthworks and along the Clanfield road. (fn. 78) The largest (Radcot House) was rebuilt probably in the 1660s, very likely following Civil War damage, and the same may be true of some other buildings. (fn. 79) The castle site subsequently became known as 'The Garrison', presumably recalling its use as a minor Royalist encampment during the Civil War. (fn. 80)

In the mid 19th century settlement extended north of Radcot House along the road to Clanfield, but several cottages there were demolished during the agricultural depression. In the late 19th century the conversion of the turnpike keeper's cottage into outbuildings was offset by the building of a farm labourer's house (later called Radcot New Buildings) to the west of the hamlet, among fields owned by Christ Church, Oxford. During the 20th century the settlement pattern remained largely unchanged. (fn. 81)

Castle and Later Manorial Buildings

The castle constructed in the early 12th century was almost certainly built on royal initiative or with royal backing, perhaps by Henry I's local official Hugh of Buckland (d. by 1119), sheriff of Berkshire, or by Hugh's son William, who held Radcot manor. (fn. 82) During the civil wars of King Stephen's reign William supported the Empress Matilda, and presumably held the castle on her behalf until its surrender to Stephen in 1142, following a siege. (fn. 83)

71. Radcot's early topography, showing the excavated 12th-century castle and chapel; medieval house plots and associated road identified by geophysics; and excavated Civil War fortifications. (From a plan by John Blair, incorporating surveys by Abingdon Archaeological Geophysics.)

The castle comprised a square stone keep surrounded by a curtain wall, which also enclosed several ancillary buildings; of those only the chapel has been positively identified, however. A gatehouse in the wall's north side was built of the same stone as the keep, and commanded access to the main road (which was later diverted around the site). The keep's foundations were massive (c. 12 feet thick), and within it a central stone pillar supported an upper storey. Access was probably through a first-floor doorway. Before the siege of 1142 the base of the keep may have been hastily strengthened by a dump of mortared rubble up against its west side. (fn. 84)

The keep seems to have been systematically demolished in the late 13th century, possibly with much of the curtain wall, and its stone was removed for re-use. (fn. 85) A manor house documented in the 14th century probably occupied the same site, although partial excavations in 2007–8 found no firm evidence of later structures and very little late medieval pottery. Manorial buildings mentioned in 1379 included a three-storey chamber-block or tower house 'under one roof', a domestic chapel (distinct from the parochial one), and a barn, byre, and dovecot. All the buildings were clearly still in use, although the value placed on them suggests a degree of dereliction, and they were probably abandoned in the early 15th century when the manor passed at least temporarily to non-resident owners. (fn. 86) Some remains may have been visible in the early 16th century, when the antiquary John Leland commented that at Radcot there 'hathe bene a strong pile, and now a mansion place'. (fn. 87)

72. Radcot House, rebuilt in the mid 17th century incorporating earlier fabric. The west front shown here faced the Faringdon road until its diversion east of the house in 1779.

The 'mansion place' was most likely built to the north of the castle site by the Fettiplaces (who acquired the manor in 1515), and was perhaps a predecessor of the present Radcot House, whose southern part incorporates part of an earlier structure. (fn. 88) Presumably it was damaged or destroyed during the Civil War, along with the chapel and any remains of the medieval tower house. Certainly all trace of the castle must have gone by 1645 when the Civil War defences cut across the middle of the site, re-using the eastern half of the former moat for additional protection. (fn. 89) No traces of any buildings were detected within The Garrison when the earthworks were surveyed in 1912, although the site was said to have once surrounded a 'castellated mansion'. (fn. 90)

Other Buildings

Most of Radcot's houses are constructed of the local limestone rubble characteristic of the area, and in 2011 the majority had stone-slated roofs. The oldest surviving houses are Radcot House and Radcot Bridge Farm, both rebuilt in the mid 17th century by the owners of the township's two principal estates, but probably incorporating earlier remains. Neither, however, served as a manor house, and until the 20th century they were mostly occupied by tenant farmers. (fn. 91)

Radcot House (Fig. 72) is the grander of the two, (fn. 92) and was probably rebuilt during the occupancy of Henry Beck (d. 1670), who was taxed on nine hearths in 1665. (fn. 93) The tall, three-bayed west front (which when built faced the Burford–Faringdon road) (fn. 94) has three steeply-pitched gables, with oval-shaped windows to the attics; the three main floors are each lit by chamfered mullion windows with dripstones. The stonework of the southern bay is of higher quality and superior workmanship than the rest, and may have formed part of the 'mansion place' observed by Leland in the 1540s. (fn. 95) The north bay of the east (formerly rear) front includes a full-height projecting stair-tower. The house is only one room deep, and the position of the original entrance (which would most logically have been placed in the west front's central bay) is uncertain. A new east-facing entrance was created either when the road was diverted in the late 18th century or during a 19th-century re-ordering, and has a shallow porch with embattled parapet and blank shield, inserted into the centre of the two southern bays. Probably at the same time a two-storey lean-to was added in the north-east angle of the stair-tower, squaring up that range, and in the 20th century the house was extended northwards by the incorporation of single-storey outbuildings and the addition of a conservatory.

Radcot Bridge Farm may incorporate the remains of a late 15th-century farmhouse, comprising hall and kitchen separated by a cross passage, and a small outshut which perhaps served as a buttery. (fn. 96) Whether the medieval features are all in situ has been questioned, however. The present house, which was extended northwards in 1726, is of three bays and two storeys with a gable-lit attic, and has a rear range added as a stable or coach house in the 19th century. (fn. 97)

MANOR

In the late Anglo-Saxon period Radcot formed part of the large comital estate focused probably on Langford. (fn. 98) By the 1060s–80s the township was emerging as a separate territorial unit, (fn. 99) and although it was then still held with Langford it subsequently became an independent manor. From the 12th to the 16th century it was held with neighbouring Grafton by mostly resident lords, and in 1614 it was sold to the Fettiplaces of Coln St Aldwyns (Glos.) and became divided. In the late 19th century the manorial rights and some two thirds of the land were bought by Christ Church, Oxford, while the rest remained with a succession of local families.

Descent to 1589

In 1066 Radcot was held by Earl Harold with the rest of Langford, and in 1086 (of the king) by Harold's successor Aelfsige of Faringdon. (fn. 100) In the early 12th century the manor was acquired by the local Buckland family, who from 1130 also leased neighbouring Grafton: possibly it was granted to Hugh of Buckland (d. 1116 x 1119), a powerful local official who served as sheriff of Berkshire and several other counties, and who may have built Radcot castle. (fn. 101) In 1219 it was divided unequally between two of William of Buckland's three daughters. The smaller part was assigned to Hawise of Buckland and her husband John de Bovill, and the greater part to Hawise's sister Maud, wife of William d'Avranches. (fn. 102) Neither sister had surviving heirs, and by 1236 the whole of Radcot was held by the third sister Joan's second husband Simon d'Avranches. (fn. 103) Following Joan's death in 1252 Radcot passed with Grafton to her son John d'Avranches (d. 1257), and to his daughter Elizabeth and her husband Matthew de Besyles, who in 1295 leased Radcot for life to John Wogan (d. 1321/2), justiciar of Ireland. Thereafter Radcot and Grafton descended together until 1589, passing from the Besyles family to the Fettiplaces in 1515. (fn. 104)

Descent from 1589

Radcot was separated from Grafton in 1589, and in 1590 Bessels Fettiplace sold it to Sir Henry Unton (d. 1596), the noted Elizabethan diplomat and soldier. (fn. 105) The manor passed to Sir Henry's sister Cicely, wife of John Wentworth, whose son sold it in 1614 to John Fettiplace (d. 1636), lord of Coln St Aldwyns and owner of Lemhill in Broughton Poggs. (fn. 106) John seems to have sold around 130 a. in the eastern part of the township, (fn. 107) but was succeeded in the rest by his brother Sir Giles Fettiplace (d. 1641), and by Giles's nephew John Fettiplace (d. 1663). (fn. 108) John's son Giles (d. 1702) was succeeded by three daughters, among whom the residual estate was divided, and whose portions were subject to a series of sales and transactions. (fn. 109)

The largest part (with manorial rights) was acquired through his wife by Sir John Bridger (d. 1827) of Coombe in Hamsey (Sussex), whose daughter and heiress Mary married (in 1787) Sir George Shiffner (d. 1842), created a baronet in 1818. (fn. 110) In 1840 Shiffner's estate (which included Radcot Bridge Farm) covered 233 a. on the west side of the Burford–Faringdon road, (fn. 111) which his grandson Sir George Shiffner, 4th baronet, sold in 1867 to J. H. Tombs, a member of a local farming family. (fn. 112) In 1873 the estate was bought by Christ Church, Oxford, which in 1981 sold most of the land to its tenant farmer. (fn. 113) Ryemead (52 a.), another part of Giles Fettiplace's early 18th-century estate, was separately acquired in 1729 by Alexander Ready, whose successors included Thomas Edoe and Christopher Ward. (fn. 114) In 1890 that too was sold to Christ Church, (fn. 115) which retained it in 2011; Christ Church was then, however, preparing to sell the whole of its remaining Grafton and Radcot land. (fn. 116)

The 130 a. or so sold separately in the early 17th century lay mostly east of the Burford–Faringdon road, and included the site of Radcot House. In all it comprised around a third of the medieval manor. In 1621 it was owned by Edward Yate, (fn. 117) and in 1688 it belonged to Edmund Fettiplace, possibly of Kingston Bagpuize (formerly Berks.). (fn. 118) In the late 18th century the estate passed successively to Blandy Shaw, William Kemys, and Thomas Gorges, and in 1802 it was acquired by Pryce Lockhart Gordon, the owner in 1840. (fn. 119) In 1901 it was bought by the lessee, George Adams of Faringdon. (fn. 120) Following the death of Stanley Adams in 1940 the estate was sold to R. N. Willmer of Friars Court in Clanfield; Radcot House was sold shortly afterwards, but the land still belonged to the Willmers in 2009. (fn. 121)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

The Agricultural Landscape

Radcot's low-lying position next to the river Thames and its liability to flood encouraged agricultural specialization. Large parts of the township were ploughed at one time or another, but the vulnerability of crops to flooding and the high demand for grazing promoted the early conversion of tillage to pasture. Open-field strips and common meadows were recorded in the Middle Ages, but piecemeal inclosure by lords or graziers may have begun at a relatively early date. Certainly by the early 19th century the township was fully inclosed (Fig. 69), perhaps following an unrecorded private agreement in the 17th century or earlier. (fn. 122)

As well as providing meadow the river produced fish, and in the Middle Ages it powered a watermill. Woodland was scarce, however, and most households must have purchased firewood or gathered it from hedges. (fn. 123) From the 16th century wool production gradually gave way to cattle rearing and milk production as the main agricultural occupation, until in the late 20th century arable farming re-assumed greater importance.

Arable

In the Middle Ages Radcot's open-field arable was divided into strips or selions of perhaps ½ a.–1 a. each, which were grouped into furlongs and crofts on either side of the Burford–Faringdon road. As at Little Faringdon, some medieval field names (including 'Duntenhull', 'Froggemor', and 'Wilbiescroft') survived into the 19th century. (fn. 124) In the late 14th century 150 selions (perhaps 120 a.) of demesne arable were laid down to grass, and arable cultivation probably declined further in the 16th century following depopulation and the introduction of large numbers of sheep. (fn. 125) The preservation of ridge and furrow, most clearly visible in aerial photographs of the 1950s in fields closest to the hamlet, suggests that about 44 a. of former arable lay to the east of the Burford–Faringdon road and more than 120 a. to the west. (fn. 126)

In the early 19th century no grain tithes were collected in the township, (fn. 127) and in 1840 only 36 a. in the township's north-western corner were ploughed. The figure rose to 75 a. in 1877, but fell again during the agricultural depression: (fn. 128) in 1890 only 14 per cent (63 a.) of the cultivable land was under crop, and in 1901 the estate on the east side of the Burford–Faringdon road was wholly grass. (fn. 129) Arable covered 45 a. in 1930, but in 1940 wheat and barley failed to grow on ploughed-up pasture. (fn. 130) After the Second World War arable farming increased, and much of the ancient ridge and furrow was destroyed. (fn. 131)

Meadow and Pasture

In 1086 Aelfsige of Faringdon held 24 a. of meadow, presumably the area mown that year rather than the total available grassland. (fn. 132) In 1219, when the manor was divided, Maud and William d'Avranches's share included 49 a. and 5 'hams' of meadow, together with rents from other meadows. One was Quedham, which 'the men of Grafton hold', (fn. 133) and which in 1840 covered 2 a. within a D-shaped side channel of the Thames. Although in Berkshire (as confirmed by a jury in 1261), the meadow formed part of Radcot until the 19th century, presumably following the division of the Langford–Faringdon estate in the late 11th century. (fn. 134) In 1378 more than 100 a. of meadow lay in demesne, that on the east side of the Burford–Faringdon road worth 1s. 8d. per acre, and that on the west 1s. 6d., although both fell in value when the land flooded. (fn. 135)

From the 15th century most of the township was permanent pasture, which was owned or occupied by graziers from a wide area, including the Witney clothier Walter Jones (d. 1560) and his descendants. (fn. 136) In 1840 Radcot's meadow and pasture comprised 375 a. worth 5s. an acre; the land was of 'fair average quality', and was chiefly used for the agistment of cattle. (fn. 137) The amount mowed (rather than grazed) varied widely, from about a third in 1890 to three fifths in 1930, falling to around two fifths in the 1960s. (fn. 138)

Medieval Agriculture

Medieval Tenant Farming

Free tenants holding meadow in the early 13th century included Beaulieu abbey, the Knights Hospitallers, and Robert Marsh of Windrush (Glos.). (fn. 139) In 1279 five free tenants paid annual rents totalling 13s. 10d., mostly for small quantities of meadow or arable, while 31 smallholdings, usually a house and an acre or two, were held by unfree cottars for annual rents totalling £3 14s. 8d. and labour services valued at £1 11s. 7d. (fn. 140) In 1306 about half the cottars were liable to pay tax, their assessed wealth ranging from 10s. to more than £6, with a median of £1. This was more than could be raised from their smallholdings alone, suggesting that most supplemented their income through activities other than farming. (fn. 141) Some inhabitants may have found employment maintaining Radcot Bridge, for which pontage was granted to local men including Robert Pulcre and Robert Stephen. (fn. 142) Fishing and fowling may also have been common. Unfree tenants in 1219 included two fishermen and William 'of the bridge' and their families, and perhaps also Miles the fowler and the 'men of Radcot' who held meadow from the Bucklands. (fn. 143)

In 1379, following successive outbreaks of plague, half the smallholdings (each comprising 1 a. of arable and 1 a. of meadow) lay untenanted. Their valuation of 2s. each was less than a third of the 6s. 8d. rent due from those that remained occupied; (fn. 144) nevertheless the abandoned holdings were most likely grazed by sheep, the profits of which may have encouraged further depopulation of the township in the 15th century. (fn. 145) Some families remained on the manor for several generations, including the free Halls and the unfree Elms and Stephens, but presumably they too left after 1400. (fn. 146)

Medieval Demesne Farming

In 1086 Aelfsige of Faringdon held 2 ploughlands in demesne, and no tenants were recorded. The estate was valued at £4, twice the value in 1066. (fn. 147) Following the creation or reintroduction of tenant holdings, Matthew de Besyles retained a ploughland (perhaps 120 a.) in demesne in 1279, which may have been worked by tenant labour services before they were commuted to cash. (fn. 148) In 1295 the entire manor was leased for life, for an annual rent of £9, to John Wogan, justiciar of Ireland. (fn. 149) His assessed wealth in the township was nearly £10 in 1306 but only £8 16s. in 1316, suggesting, perhaps, that demesne profits were adversely affected by the onset of the Great Famine. (fn. 150) Nevertheless Wogan may have been given a preferential lease: in 1318, when it was apparently back in Geoffrey de Besyles's possession, the manor was said to be worth £40 a year. (fn. 151)

By 1378, following the Black Death, Radcot was worth only around £21, of which a third derived from rents and most of the rest from the meadows and fishery. At that time the arable was uncultivated, although the manor's buildings included a barn, byre, and dovecot. (fn. 152) A third of the manor was assigned to Katherine de Besyles in dower, and in 1382, following the death of John de Besyles the younger, the remaining two thirds were leased for £9 6s. 8d. a year. (fn. 153)

Farming from 1500 to 1800

By 1549 much of Radcot's demesne and former tenant land were probably leased to two graziers from Berkshire and another from Buckinghamshire, who kept 1,100 sheep in the township. (fn. 154) Radcot's meadows also attracted outsiders, and in 1618 two inhabitants of Thame leased land from the Fettiplaces for eight years at an annual rent of £40. (fn. 155) Several local families also held meadow in Radcot, amongst them the Broderwicks and Pruneses of Langford and the Clanfield husbandman Christopher Kempster, who leased 19 a. of meadow there, and lived in the township on his death in 1589. (fn. 156)

Other residents included Walter Pyrsonne (d. 1567), who grew small amounts of wheat and barley, grazed sheep worth £13, and kept a few dairy cattle, pigs, and poultry. In total his farming stock and equipment were worth more than £27, or just over half the value of his inventory. (fn. 157) Some families lived in the township for several generations, amongst them a branch of the Maiseys of Grafton. Isaac Maisey (d. 1627) was described as both a yeoman and fisherman, the combination of farming and fishing no doubt following a long tradition. (fn. 158) He owned a boat and net worth £3 and two trunks of fish worth £1, and kept a horse, cattle, and sheep together worth £14. His household made cheese, spun wool, and ground malt, the grain for which may have been grown in two 'hams' by the bridge called 'Maulters'. The risks of farming on a floodplain are nevertheless suggested by a debt of 5s. to an Abingdon man for late-harvested grain, which 'came not in according to the time'. (fn. 159)

The prosperous Penstone family of yeomen, who were related to the Maiseys by marriage, lived at Radcot in the late 17th and 18th centuries, where they engaged in mixed farming but with an emphasis on dairy cattle and sheep. Hugh Penstone (d. 1677) left goods worth more than £260, including cattle, sheep, and pigs worth £75, cheese, bacon, and beef worth £6, hay worth £5, and debts due to him totalling more than £83. (fn. 160) His son Hugh Penstone (d. 1723) was even wealthier, leaving goods valued at almost £700. His crops included wheat, barley, and pulses (of which some was stored in a granary), and £40-worth of hay, which was probably intended to feed the farm's 80 sheep, 20 dairy cows, and other cattle, horses, and pigs. In total his crops and livestock were worth around £230, to which may be added £17-worth of cheese. Much of this produce was probably sold at nearby markets, most likely by Penstone's household servants, who were accommodated in rooms in the house: named rooms included the man's chamber, the cheese chamber, and the garret. (fn. 161) Another Radcot grazier, Joseph Green (d. 1757), held property in neighbouring Faringdon, suggesting that the market there was frequented by the township's farmers. (fn. 162)

The Penstones almost certainly occupied one of two large farms in Radcot, which were probably created when the manor was divided in the 17th century. (fn. 163) Possibly they held Radcot House farm (130 a.) on the east side of the Burford–Faringdon road, but following the death in 1772 of Hugh Penstone, who left cows, sheep, pigs, and grain to his sister Elizabeth, in 1778 the farm was leased to Napthali Wilson for 14 years at an annual rent of £130. (fn. 164) His lease was evidently cut short, and in the late 18th century the farm was held by Robert Killmaster, who paid £23 in land tax. (fn. 165) The larger Radcot Bridge farm (233 a. in 1840) lay to the west of the Burford–Faringdon road, and in the late 18th century was occupied by William Hemming (d. 1801), a 'grazier, farmer, and dairy man' who paid more than £36 in land tax. (fn. 166) Apart from household servants, Radcot's farmers presumably employed labourers from within and outside the township, including, perhaps, Robert Symonds, who was accused of stealing hedgewood in 1776. (fn. 167)

73. Sheep washing at Radcot Bridge in 1885. The projection on the bridge's east side may have formerly supported a statue of the Virgin.

Farming in the 19th and 20th Centuries

In the early 19th century Radcot's farms were leased to a succession of short-term tenants: Hemming was succeeded by the Tuckwells and Pawlings, and Killmaster by the Edoes, Higgons, and Adamses. (fn. 168) Some continuity was provided by the Fairthorns, who occupied Radcot Bridge farm from the late 1830s until its sale in 1867, employing nine labourers in 1851–61. (fn. 169)

In 1873, on the eve of agricultural depression, Christ Church's surveyor confidently asserted that the farm would 'readily let for £600 a year', although soon afterwards it was amalgamated with the college's farm in Grafton and leased to the Akermans. (fn. 170) In 1840 the farm's small arable field was sown with wheat, barley, beans, and turnips, and the same crops occupied more than four fifths of the 57 a. cultivated in 1870. (fn. 171) But the township's main agricultural activity was stock rearing and milk production, and in the late 19th century, unlike at neighbouring Grafton, Radcot's cattle herd was larger than its sheep flock. (fn. 172)

Cattle remained the mainstay of Radcot Bridge farm in 1941, when the tenant was described as an 'average hard working farmer' with a large head of cattle and good milking herd. Less than two fifths of the farm was cultivated, mostly with wheat, oats, and root crops, and the arable suffered from weeds. (fn. 173) After the Second World War an increasing amount of grassland in Radcot and Grafton was ploughed up, presumably following improvements in drainage, although cattle rearing and dairying remained important. (fn. 174)

Market, Fair, and Rural Trades and Industry

Radcot's medieval smallholders almost certainly engaged in occupations to supplement their income from farming, including fishing and activities associated with the road and river trade. (fn. 175) Nicholas of Radcot was a sailor on a local boat carrying wheat and other goods in 1271. (fn. 176) Occupational surnames in the late 13th century included carter, cooper, fowler, hatter, and shoemaker, (fn. 177) and some tenants presumably traded at the weekly Friday market and at the annual fair held on 13–15 September, both of which were established by Matthew de Besyles in 1272. (fn. 178) John Elm was in debt to a Marlborough merchant in 1327–8, and a Northamptonshire skinner, visiting Radcot around the same time, may have attended the market or fair, though no reference to tolls was made in 1378 when both had probably lapsed. (fn. 179) Nonetheless there was probably a good deal of informal passing trade with users of the bridge, many of whom were obliged to pay a toll towards its upkeep. (fn. 180)

From 1500 the hamlet was too small to support the usual rural tradesmen, though in the 17th and 18th centuries labourers were presumably needed to transfer stone and other goods from road to river at the wharfs along the riverbank. (fn. 181) John Wells (d. 1783) was innkeeper at the Swan near Pidnell Bridge, and his family was probably one of only two engaged in trade, craft, or manufacture in 1821. (fn. 182) In 1841 Wells's descendant was both publican and coal merchant, and the turnpike-man also turned to the coal trade in the 1840s. (fn. 183) Two coal merchants continued to live in the hamlet in 1861, but thereafter, apart from the Swan and fishing, the township was almost wholly agricultural. (fn. 184)

Milling

In 1279 Matthew de Besyles owned a watermill, presumably that which was later held by William the miller, a taxpayer in Grafton and Radcot in 1327. (fn. 185) In 1378 it was valued with an adjoining fishery at £1 6s. 8d. (fn. 186) Its site is lost, but probably lay close to one of Radcot's bridges along a channel of the Thames. (fn. 187) The mill was still mentioned in the 15th and early 16th centuries, when it was held by William de Besyles (d. 1515), but was probably demolished soon after. (fn. 188) The medieval mill at Kyndelwere (on the Berkshire bank of the river) lay outside Radcot, and belonged to Beaulieu abbey. (fn. 189)

Fisheries and Weirs

In 1219 two fishermen, Robert and Godwin, were unfree tenants of the manor, and about the same time another Radcot fisherman called Stephen held meadow in neighbouring Grafton. (fn. 190) In 1379 three fishermen leased the demesne fishery (separate from that adjoining the mill) for £3 18s. 8d., a little under a fifth of the manor's total value. (fn. 191) The fishery was probably divided when part of the manorial estate was sold in the early 17th century: (fn. 192) thereafter the Fettiplaces (who owned Radcot Bridge farm) held fishing rights in a half-mile stretch of the Thames from Ryemead to Priests Ham on the west side of Radcot Bridge, (fn. 193) while a fishery on the east side was almost certainly attached to Radcot House farm. (fn. 194) Successive heirs of Giles Fettiplace (d. 1702) were entitled to free fishing in the Thames, although by 1840 ownership of the river was divided between the two principal farms and the innkeeper of the Swan. (fn. 195)

The remains of a series of rectangular fishponds have been identified on the northern edge of the medieval settlement, but nothing is known of their date or ownership. (fn. 196) Richard ad Barram, a cottar in 1279, may have lived by the 'bar' or weir, (fn. 197) possibly Beaulieu abbey's weir at Kyndelwere a little way upstream from Radcot Bridge. Presumably Kyndelwere descended with Faringdon manor after the Dissolution, but it was apparently removed before 1761 when it was not marked on Rocque's county map. (fn. 198) A second weir, mentioned by Baskerville in 1692, lay probably at the confluence of two channels of the Thames to the east of Radcot Bridge; that may have been the weir leased with a house and fishery in 1775, but if so it was presumably removed when the channel was widened in 1787. (fn. 199) A drawing of 'Radcot weir' with a cottage along the riverbank, dated about 1811, may in fact depict Harper's weir in Clanfield. (fn. 200)

SOCIAL HISTORY

Social Structure and the Life of the Community

Though Radcot remained a small and predominantly agricultural community, its location at a trans-shipment point from road to river meant that it was less secluded than some neighbouring villages, and its inhabitants probably enjoyed wide social and economic contacts and opportunities. The availability of valuable meadow and the hamlet's small population, particularly following late medieval contraction, probably also ensured unusually strong social and economic ties with surrounding villages, particularly Clanfield, Grafton, and (to a lesser extent) Langford. The village's strategic position at an important crossing of the river Thames brought less welcome attention in times of conflict, notably in 1142, 1387, and 1645, although in each case the impact upon the local community is unclear.

Until the 17th century Radcot's lords were resident at least occasionally, contributing to community life and especially to the church. Their chief residences, however, usually lay elsewhere. From the 18th century the Swan public house served the growing river traffic and presumably also the township's remaining farm workers, and in the 20th century, as agriculture and commercial river traffic declined, Radcot became a local centre for recreational use of the river.

The Middle Ages

The medieval settlement may originally have housed low-status workers from the estate centre at Langford, possibly including slaves and bordars, whose successors were among the unfree cottars named at Radcot in 1279. (fn. 201) But although all of them were smallholders the cottars were not a homogenous group, and some may have accumulated larger holdings. An example is Robert Stephen, who probably held two houses and 6 a. at a rent of more than 3s. an acre, and whose assessed wealth in 1306 exceeded £6. Others, too, produced a taxable surplus: eleven of Radcot's taxpayers in 1306 (about two thirds of the total) shared surnames with the cottars of 1279, among them the Barrs and Pulcres, who remained in the hamlet in 1327. (fn. 202) Even so many of Radcot's cottars were too poor to pay tax, and in the thirty years following the Black Death about half either died or abandoned their smallholdings, presumably in favour of opportunities elsewhere. (fn. 203) Radcot's location at an important river crossing may even have stimulated inhabitants to leave, by providing access to news from the surrounding countryside and also to potential transport.

The strategic importance of Radcot Bridge encouraged successive lords of the manor to build fortified residences, notably the 12th-century castle held by the Bucklands and the three-storey tower house of Thomas de Besyles (d. 1378). (fn. 204) Severe local disruption must have followed King Stephen's rapid march from Cirencester and sudden capture of Radcot castle in 1142, although the bulk of his army stayed for only a short time before continuing to Oxford. (fn. 205) The encounter in 1387 between Robert de Vere, earl of Oxford, and the opponents of Richard II also appears to have been brief. De Vere arrived at Radcot Bridge from Burford to find the earl of Derby already in possession and the duke of Gloucester in his rear. A brief skirmish was fought in thick fog, in which de Vere's men were routed and de Vere himself fled downstream along the left bank of the Thames. (fn. 206) In 1398 it was reported in Parliament that 'many robberies, thefts, felonies, trespasses, outrages, and riots' occurred at Radcot during the action. (fn. 207)

The Besyles family or their lessees probably lived at Radcot until the 15th century, and maintained a private chapel there, despite holding property in Somerset and Berkshire which included, from the late 14th century, a house at nearby Bessels Leigh. Sherds of elaborately decorated late 13th-century pottery found at Radcot indicate that they lived in some style. (fn. 208) Matthew de Besyles may have been resident in 1279, John Wogan was taxed in the hamlet in the early 14th century, and so too (in 1327) was Geoffrey de Besyles, whose grandson Peter was born there in the 1370s. (fn. 209) The association ended (at least until the early 16th century) with Peter de Besyles's death in 1425 and his widow's remarriage to a Hampshire landowner. (fn. 210) Some social continuity is nevertheless suggested by the preservation of medieval field names. (fn. 211)

After 1500

Following Radcot's depopulation in the 15th century much of its farming was carried on by outsiders, (fn. 212) and the hamlet's few remaining inhabitants must have looked elsewhere for a sense of community and social life. The Fettiplaces' manor house was probably the 'mansion place' mentioned by Leland in the 1540s, when it may have been leased to Thomas Cox, the wealthiest of Radcot's three taxpayers in 1544. (fn. 213) The Coxes were also found at Grafton in the 16th century, and after 1600 Radcot families such as the Clarkes and Maiseys had close ties with Clanfield, Grafton, and Langford. (fn. 214) The Maiseys had many relatives and friends at Grafton, and used both Clanfield and Langford churches for baptisms and burials. (fn. 215)

The Fettiplaces, Radcot's lords until 1702, were occasionally resident in the township, and contributed to community life. Sir Giles (d. 1641) repaired and provided for Radcot's chapel in the 1630s, and his successor John Fettiplace was taxed at Radcot in 1641. Giles Fettiplace (d. 1702) was assessed on four hearths there in 1665, and in the 1690s contributed to parish rates. (fn. 216) Of the three houses documented in the mid 17th century, the largest (with nine hearths) was Radcot House (Fig. 72), which was then occupied by Henry Beck (d. 1670), rector of Eaton Hastings. Beck's family was friendly with the Fettiplaces, and still lived at Radcot in the 1680s. (fn. 217)

During the Civil War Radcot was the nearest Thames crossing to the important Royalist garrison town of Faringdon. (fn. 218) In April 1645 a detachment under Cromwell engaged in indecisive skirmishing at or near Radcot, before crossing the river to briefly lay siege to Faringdon. (fn. 219) The following month a small Parliamentary force was attacked by Royalist troops on the road between Radcot and Clanfield, when two soldiers later buried at Clanfield were probably killed. (fn. 220) In November 1645 the 'fort' at Radcot was held by about 30 Royalist cavalry who attempted unsuccessfully to dislodge Parliamentary troops at Lechlade, and in the ensuing retreat suffered considerable losses 'close under Radcourt wall'. (fn. 221) This was presumably the ditched and embanked fortification whose foundations were excavated in 2008 on the former castle site, and which included a diamond-shaped bastion (for artillery) at its north-west corner (Fig. 71). (fn. 222) In April 1646 Parliament issued orders to 'block up' the Royalist garrison at Radcot, which finally surrendered the following month; (fn. 223) a pewter drinking cup found nearby may have belonged to one of its defenders. (fn. 224) The long-term impact on the hamlet was marked, involving demolition of the medieval chapel (which lay within the fortifications), and probably damage to other houses. The fortifications must have remained prominent for some time, their association with the conflict recalled centuries later in the name 'The Garrison' for the pasture field in which they lay. (fn. 225)

In the late 17th and 18th centuries Radcot was dominated by the three families of Maisey, Penstone, and Wells, who almost certainly occupied the hamlet's two farms and public house. (fn. 226) Like their predecessors they attended church at Clanfield or Langford, and enjoyed family and social ties with nearby places such as Clanfield and Longworth (formerly Berks.). (fn. 227) The Swan inn (first mentioned by name in 1775) was run by John Wells from the 1750s and probably earlier, and was almost certainly intended to serve the growing river traffic. (fn. 228)

74. Pleasure boating at the Swan inn in the earlier 20th century.

The Wellses remained in the township for several generations, and in 1851 were among the 40 per cent of resident adults (18 years and above) born in the hamlet. The remaining adult population came from no more than about ten miles away, mostly from neighbouring parishes such as Bampton, Clanfield, Faringdon, and Langford. (fn. 229) Social structure changed little during the 19th century, with about half a dozen labourers' families (mostly from nearby parts of Oxfordshire, Berkshire, and Wiltshire) working on the hamlet's two main farms. The farmers, too, were mostly local, those coming from further afield including Jesse Chatterton of Radcot House, who was born in Lincolnshire. (fn. 230)

As agriculture declined after the First World War, Radcot's population gradually drifted from the land. Radcot House, leased separately from its farmland from around 1900, was later sold as an exclusive and desirable residence; in 1941 it was owned by a brigadier-general whose wife gave away all the produce of her kitchen garden. (fn. 231) Following the decline in river traffic, the Swan was marketed as a centre for pleasure boating, fishing, and camping (Fig. 74). (fn. 232) A swimming and boating regatta was held at Radcot until the 1930s, and in the early 21st century pleasure boats continued to be moored there. (fn. 233) The Swan remained the hamlet's only public building in 2011, when Radcot's narrow bridges and sharp bends slowed traffic along the busy Faringdon–Witney road.

Education, Charities and Poor Relief

Radcot had no school, and although the hamlet lay in Langford parish, from the 19th century most children (seven in 1871) attended the much closer school at Clanfield, just over a mile away. (fn. 234) The school remained open in 2011.

Radcot's poor were among those remembered by Mary Prunes of Langford (d. 1610), and the township may have benefited from other 17th and 18th-century bequests to Langford parish. (fn. 235) In 1786 an endowed charity established apparently by a member of the Trinder family of Langford was said to have been unpaid for 70 years; (fn. 236) it was mentioned again in 1823, but no separate charities for Radcot appear to have existed, (fn. 237) and the cost of poor relief was met almost entirely from the township's rates.

Annual spending on Radcot's poor fell from around £19 in 1776 to £15 in 1783–5. (fn. 238) In 1803 only three people (including a young child) received regular out-relief, at a total cost of £19: this represented about 10 per cent of the population. (fn. 239) Annual per capita expenditure was lower than for most neighbouring communities, averaging about 12s. in 1813–15, although it rose to 20s. in 1818, a total outlay of more than £30. (fn. 240) Thereafter, as agriculture recovered, annual expenditure fell to a low of 8s. a head in 1822. A further rise to 20s. by 1832 (a total of nearly £56) suggests that the sharp rise in the township's population during the 1820s was made up mostly of poor labourers. (fn. 241) From 1834 formal responsibility for Radcot's poor passed to the new Faringdon poor-law union. (fn. 242)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

Until 1960 Radcot was a chapelry of Langford. A chapel probably existed by the mid 12th century, (fn. 243) and from the Middle Ages until its destruction in the 17th century it was served by vicars of Langford or by chaplains or curates appointed by them, of whom nothing is known. A separate private chapel was maintained by the lord of the manor in the Middle Ages.

Most Radcot inhabitants were baptized and buried at Langford or at the more conveniently located church at Clanfield. Protestant Nonconformity was briefly evident in the hamlet in the late 17th century, but never flourished. After 1960 Radcot was incorporated into ever larger benefices.

Parochial Organization

In the 11th century Radcot was presumably served from the mother church at Langford. (fn. 244) A parochial chapel within the castle's earthworks, close to their south-east corner, was probably established in the 12th century: possibly it was built or rebuilt by the Bucklands after the castle's surrender in 1142, and it was presumably one of the (unnamed) chapels of Langford mentioned in 1163. (fn. 245) Excavation has revealed a three-cell apsidal chapel of typical 12th-century form (Fig. 71). (fn. 246) A chaplain was presumably appointed from that time, either by the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia (as rector of Langford), or by the lord of Radcot, whose grant of the advowson in the mid 13th century suggests pretensions to parochial independence. (fn. 247) If so, the chapel's subservient status was confirmed when Langford vicarage was ordained in 1277. Thereafter, Langford's vicar was to provide a chaplain who was to be presented to the prebendary, and who was to reside at Radcot 'with a suitable clerk'. (fn. 248)

Like the chapel at Little Faringdon, Radcot chapel may have had baptismal rights from its foundation, although Peter de Besyles, born at Radcot in the 1370s, was baptized at Langford. (fn. 249) A tradition that baptisms continued after the chapel's destruction in the 17th century, with the socket for a statue or cross on the central arch of Radcot Bridge serving as a font, lacks any corroborating evidence. (fn. 250) Burial rights were probably reserved to Langford, and Radcot's inhabitants were obliged to maintain Langford's churchyard fence. (fn. 251) The chapel's dedication to St James was mentioned in 1424, when a separate private chapel dedicated to the Virgin existed within the Besyleses' manor house. (fn. 252)

In 1909 the vicar of Langford suggested annexing Radcot to Clanfield ecclesiastical parish, a proposal adopted in 1960 when Radcot became part of a new united benefice of Clanfield with Broadwell. (fn. 253) In 1976 Radcot was detached from Clanfield and added to the benefice of Broadwell with Kencot and Kelmscott. It was reunited with Langford in 1986 as part of an extensive rural benefice, which in 1995 became part of the even larger Shill Valley and Broadshire ministry. (fn. 254)

Advowson, Glebe, and Tithes

In the 13th century the advowson of Radcot chapel was granted to the bishop of Lincoln by John d'Avranches, a descendant (through marriage) of the Bucklands who, as lords of the manor, had probably built the chapel in the 12th century. (fn. 255) The bishop presumably granted it to Langford's rector, the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia, who in turn bestowed it on the vicar of Langford at the vicarage's ordination in 1277. (fn. 256)

The glebe in Radcot belonged to the vicar of Langford, who held 4 a. of meadow in the north-east of the township in 1840. (fn. 257) The small tithes were similarly granted to Langford vicarage in 1277, although the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia (as rector of Langford) retained the grain and hay tithes, which were valued at £100 a year in the early 19th century. (fn. 258) In 1840 Radcot's tithes were commuted to an annual rent-charge of £104, of which the prebendary received £65 10s. and the vicar £38 10s. (fn. 259)

Land called 'le Presteslond' was mentioned in the 14th century, (fn. 260) and may once have formed part of the glebe. It was perhaps the meadow called 'Priests Ham' which belonged to the lord of the manor by the 16th and 17th centuries, and covered 13 a. in 1840. (fn. 261)

Pastoral Care and Religious Life

From 1277 Langford's vicar was required to appoint a resident priest and clerk to Radcot, although it is not known to what extent this obligation was met. The priest was to celebrate mass at least three days a week, according to later evidence on Sunday, Wednesday, and Friday. (fn. 262) Services were presumably being held in 1424 when Peter de Besyles bequeathed £1 in cash, a breviary, and a missal to the chapel; however, he also left a total of £30 for the repair of the Besyleses' private domestic chapel at Radcot, suggesting that the family usually worshipped there. (fn. 263)

A house called the 'Hermitage' was mentioned in the 16th and 17th centuries. (fn. 264) Hermits were often associated with bridges in late medieval England, collecting tolls and undertaking repairs. (fn. 265) No further evidence for a hermit at Radcot has been found, however.

In the 1630s the chapel was repaired by the lord of the manor Sir Giles Fettiplace (d. 1641), who provided a bible and book of common prayer, a set of bells, a surplice, and 'all other things necessary for divine service'. Radcot's inhabitants worshipped there until around 1639 when William Phipps (vicar of Langford 1635–67) failed to provide a chaplain to officiate: one of Langford's churchwardens reported that Phipps 'has not by himself or any sufficient curate maintained divine service in the chapel of Radcot on Sunday, Wednesday, Friday, and other festival days, to the peril of his soul and those of the inhabitants of that chapelry'. (fn. 266) The fortifications subsequently thrown up during the Civil War surrounded the chapel, which may have been intentionally demolished for its stone: certainly it was destroyed around that time, and the footings were very thoroughly robbed. (fn. 267) If so, the fact that it was already closed up perhaps contributed to the decision. Any remains were apparently removed by 1664–5, when the churchyard seems to have been partly appropriated and enclosed by Henry Beck, rector of Eaton Hastings from 1647 to 1670, who was then living at Radcot. (fn. 268)

Thereafter many of Radcot's inhabitants were presumably baptized and buried at Langford church, as some had been from the 16th century and probably earlier. Others used Clanfield church. (fn. 269) Relations with Langford were not always good, and in the 1660s Radcot's inhabitants were refusing to contribute to the repair of Langford's churchyard fence. (fn. 270)

In 1672 Anne Beck (Henry Beck's widowed sister-in-law) was licensed to hold Presbyterian or Congregationalist worship at her house in Radcot. (fn. 271) Another Dissenter, Humphrey Gunter, stayed at Radcot c. 1679–81, having been deprived of his fellowship at Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1660. (fn. 272) Despite the lack of an Anglican chapel Dissent failed to become established, however, and most inhabitants continued to attend Langford church or that of Clanfield, which was acknowledged to be more convenient. (fn. 273) A request by the vicar of Langford in 1860 for a curate to serve Grafton and Radcot seems to have come to nothing, and though a later vicar (Edmond Walters) held occasional Sunday or weekday services in an unlicensed room at Radcot in 1890, the practice was probably discontinued by his successors. (fn. 274)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Manor Courts and Officers

From the 13th century the lord of the manor probably held regular manor courts, which in the 1370s yielded 3s. 4d. a year. (fn. 275) In 1279 Radcot's free tenants owed suit of court every three weeks, an obligation which presumably extended to the manor's cottars; in addition Matthew de Besyles claimed the privilege of infangthief and outfangthief, the right to execute thieves caught red-handed. (fn. 276) In 1320 the gallows were probably located on the boundary between Kelmscott and Grafton, of which the Besyles family were also lords. (fn. 277) Their jurisdiction seems to have extended to settling riverine disputes, for which a special court may have met at 'the Jury's Hard', a landing place on the Radcot bank of the Thames. (fn. 278) The right to hold manor courts presumably passed to the Besyleses' successors, but no further details are known.

Parish Government and Officers

Although it was a chapelry of Langford, from the 14th century Radcot's closest administrative links were with Grafton and Clanfield, with which it was sometimes joined for the collection of taxation. (fn. 279) In the Middle Ages local inhabitants were involved in the repair of Radcot Bridge, (fn. 280) for which Richard Reeve of Broughton Poggs left a bushel of dredge in 1417. (fn. 281) Other bequests included that of John Pape, vicar of Bampton, who left 6s. 8d. to maintain the roads around Radcot and Clanfield in 1499. (fn. 282) Responsibility for the maintenance of Radcot Bridge and Pidnell Bridge lay with the lord of the manor in the 19th century and presumably earlier, although repair of Radcot New Bridge, built by the Thames Commissioners in 1787, was undertaken by the county. (fn. 283)

A constable was mentioned in the 14th century and again in the 17th, and an overseer in the 1640s. (fn. 284) In 1866 Radcot was separated from Langford and became a separate civil parish, succeeded in 1932 by a united civil parish of Grafton and Radcot. (fn. 285) Under the Local Government Act of 1894 Radcot became part of the newly formed Witney rural district, and in 1974 was included in West Oxfordshire district. (fn. 286)