A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Rural Parishes: Rotherfield Greys', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp266-302 [accessed 10 May 2025].

'Rural Parishes: Rotherfield Greys', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online, accessed May 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp266-302.

"Rural Parishes: Rotherfield Greys". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online. Web. 10 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp266-302.

In this section

ROTHERFIELD GREYS

Until 19th and 20th-century boundary changes the ancient parish of Rotherfield Greys stretched for 6 miles (9.6 km) across Binfield hundred, from the Chiltern hills in the west to the Thames in the east. (fn. 1) The parish is mostly rural, although parts of Henley extended into its eastern edge from an early date, and in the 19th and 20th centuries suburban growth there expanded rapidly over former farmland. Otherwise settlement is scattered, comprising isolated farmsteads and widely spaced hamlets set around greens or at road junctions.

Greys Court, the imposing ancestral house of the lord of the manor from the 11th century, occupies a secluded position on rising ground 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Henley. The Greys were landholders on a significant scale, and the house became a major aristocratic seat and a symbol and focus of local power. The western part of the parish, which later became the parish of Highmoor, formed a largely separate community, and from the 15th to the 19th century belonged to the Stonor family. The suffix 'Greys', from the chief medieval owners, was added to the place name from the Middle Ages, distinguishing it from neighbouring Rotherfield Peppard; earlier it was briefly known as Rotherfield Murdac, from a late 12th-century lord. (fn. 2)

Parish Boundaries

The parish's elongated shape encompassed a variety of agricultural resources, from the wood pasture of the Chilterns to the waters of the Thames. (fn. 3) Almost certainly that reflected conscious planning when Rotherfield was separated from the large royal estate of Benson before the Norman Conquest, although on later evidence Rotherfield manor encompassed only the parish's eastern part, as far as Shepherd's Green. (fn. 4) The areas further west (including Highmoor, Witheridge Hill and Padnells) were presumably incorporated into the parish by the 12th or 13th century, as ecclesiastical boundaries crystallized. (fn. 5) In the 19th century the parish's (and county's) eastern boundary followed the river Thames, while that with Henley ran along Friday Street and the town ditch before pursuing a partly undefined course north-westwards through inclosed fields. (fn. 6) Much of the wooded northern boundary, with Bix and Nettlebed, followed stretches of the Iron-Age earthwork known as Grim's Ditch. (fn. 7) The western boundary, with Nuffield, Newnham Murren, and Mongewell, lay along a valley called Stony Bottom, before turning south-eastwards through woodland. The long southern boundary with Rotherfield Peppard passed mainly through fields before following the Henley road to the junction with Mill Lane, which it followed eastwards to the Thames.

In 1879 the ancient parish covered 2,927 a., similar to its estimated acreage in 1844. (fn. 8) Under the Local Government Act of 1894 the part of Rotherfield Greys included in Henley municipal borough became the separate civil parish of Greys (321 a.), which was combined with the rest of Henley civil parish in 1905, leaving 2,606 a. in Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 9) Following further urban growth, in 1932 another 244 a. was transferred to Henley from Rotherfield Greys, which at the same time lost 2 a. to Rotherfield Peppard and gained 148 a. from Mongewell, leaving it with 2,508 acres. In 1952 a new civil parish of Highmoor (1,297 a.) was created from the western part of Rotherfield Greys (1,148 a.) and a small part of Bix (149 a.), while Rotherfield Greys itself was extended northwards into the redundant parish of Badgemore (467 a.) and southwards into Rotherfield Peppard (269 a.), leaving it with 2,096 acres. Minor changes to the boundary around Shepherd's Green left Rotherfield Greys with 2,095 a. (848 ha.) in 2001, and Highmoor with 1,295 a. (524 ha.). (fn. 10)

Landscape

The parish lies chiefly on chalk overlain by extensive patches of river gravel, except in the west where the high ground is capped by a mantle of clay-with-flints. (fn. 11) Chalk was used to improve the soil, dug from pits scattered throughout the parish. (fn. 12) Close to the Thames, the alluvium of the floodplain (at 32 m.) provided a significant area of meadow known as Greys mead, which was partly built on in the 20th century. From there the ground rises to 95 m. at the church and 110 m. at Greys Court, rising still further to 150 m. at Highmoor. (fn. 13) The dry valleys of the parish, known as 'bottoms', provided no water for the inhabitants, who depended for their supplies on ponds and wells until the introduction of mains water in the early 20th century. (fn. 14)

The name Rotherfield means 'open land where cattle graze', suggesting that the parish's greens and commons were already cleared of trees during the Anglo-Saxon period. (fn. 15) The wooded uplands in the west contrasted with the more open farmland further east, as noted in the 16th century by Leland, who observed 'plenty of wood and corn about Henley'. (fn. 16) Two parks called Highmoor extended into the parish in the Middle Ages, (fn. 17) and there was also a medieval park around Greys Court, part of which survived in 2005. (fn. 18)

Communications

Roads

Two parallel roads, both probably of medieval origin, link Rotherfield Greys to the town of Henley: that to the north passes Greys Court, while that to the south leads to the parish church. (fn. 19) The northern road may have formed part of an ancient route from Henley to Swyncombe. (fn. 20) The southern road, which continued (as Mill Lane) to watermills by the Thames, also served as a parish boundary, suggesting that it was well known in the early Middle Ages. A path called Pack and Prime Lane joins the two roads, and was perhaps part of the Henley-Goring road mentioned in 1353. (fn. 21) Other footpaths also lead to Henley, demonstrating the extent of the traffic between Rotherfield Greys and the area's principal market town. (fn. 22)

The various branches of the roads from Henley, which pass through or close to most of the hamlets and farmsteads of Rotherfield Greys, all meet the main north-south road from Nettlebed to Reading, which runs through Highmoor Cross. The only other north-south road is that from Henley to Reading, which cuts across the parish's eastern fringe close to the Thames. Though some considerable distance from Rotherfield's rural settlements, in the 19th century it became a focus for Henley's suburban development, including the market-gardening district known as Newtown. The road was turnpiked in 1768, and disturnpiked in 1881. (fn. 23)

Landscape changes around Greys Court resulted in the removal or realignment of several roads. (fn. 24) In 1741 permission was given to enclose a common highway which passed close by the house and to replace it with another road further away. (fn. 25) Implementation of the change, however, may have been delayed: Jefferys' map of 1767 depicts the original course of the road before its diversion around an enlarged park, while that by Davis (1797) shows the road in its present position. (fn. 26)

Carriers, Post, and Rail

In the early 20th century carriers to Henley or Reading passed through the parish on four, later five, days a week; one resident remembered the weekly shopping trip to be 'a very bumpy ride'. The carriers ceased to operate after 1935, replaced by motorised bus services to Henley, Reading, and Watlington, with which they had been in competition since the 1920s, and which continued in 2009. (fn. 27)

A postal service to Rotherfield Greys was recorded in 1847, and extended to Highmoor a decade later. The main post office for Rotherfield Greys was in Henley; for the inhabitants of Highmoor, that at Nettlebed was closer. A sub-post office opened at Witheridge Hill about 1863, transferred to Highmoor Cross before 1891, and closed in 1964. Another sub-post office, at Greys Green, was first recorded in 1864, but had transferred to Shepherd's Green by 1940. It remained open in 1960 but, like that at Highmoor, was closed later that decade. (fn. 28)

A branch railway line from Twyford to Henley, running north-south between the Reading road and the Thames, was opened in 1857; the railway station was located to the south of Friday Street, within Rotherfield Greys parish. It remained open in 2010. (fn. 29)

Settlement and Population

Early Settlement

Prehistoric hand-axes and other implements have been found in the east of the parish, near the church and New Farm, and in larger numbers at Hernes, close to where a Bronze-Age hammer head and Roman burial urn were also discovered. (fn. 30) Iron-Age coins and a Roman brooch were found in Lambridge Wood, near the Iron-Age boundary bank called Grim's Ditch. (fn. 31) A similar earthwork has also been identified in woodland near Satwell. (fn. 32) No evidence of prehistoric settlement has been found on the higher ground in the west, although there was a Roman pottery kiln in Swan Wood in the 2nd and 3rd century AD. (fn. 33)

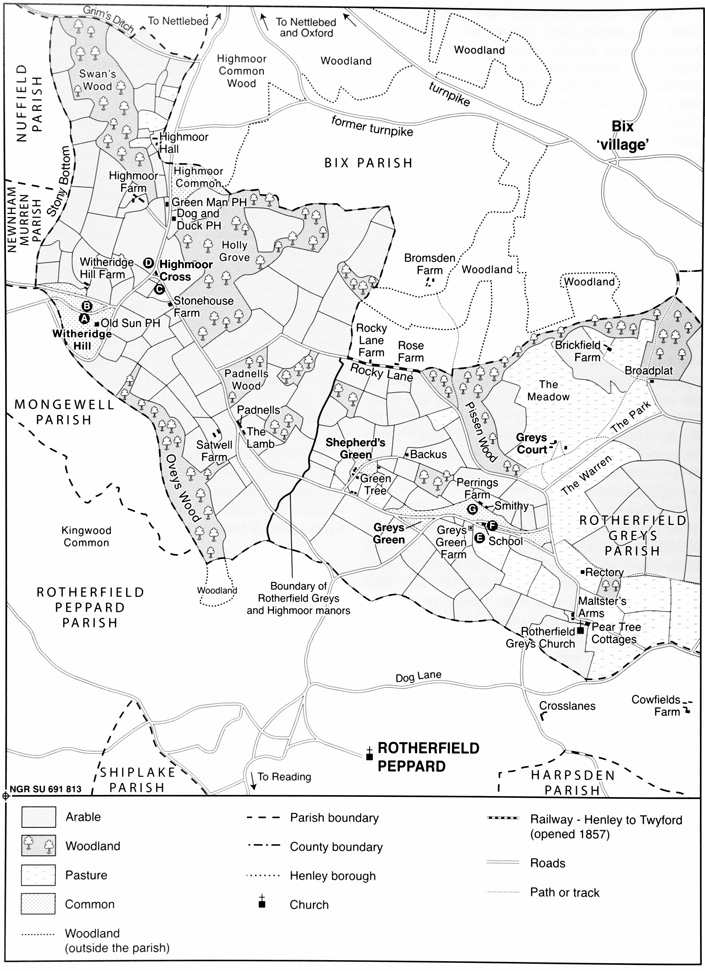

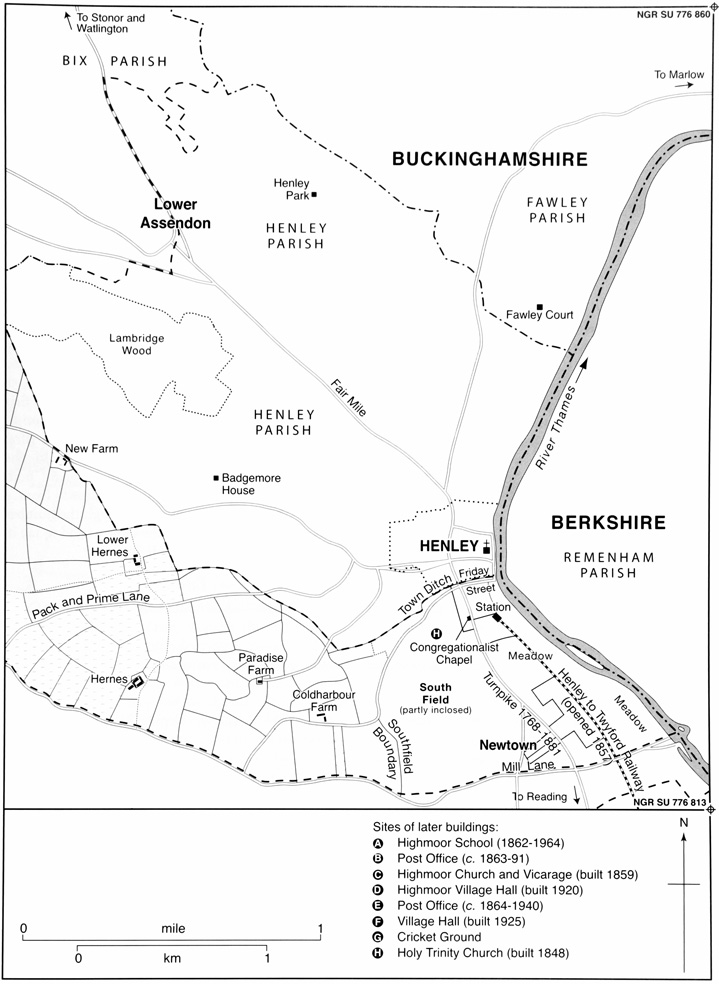

65. Rotherfield Greys parish c. 1840, showing boundaries, land use and some later features.

In Anglo-Saxon times the area's defining characteristic was its open grazing land and wood-pasture. (fn. 34) No archaeological evidence for Anglo-Saxon settlement has yet been found in the parish, though by the 10th or 11th century it seems likely that there were some pockets of scattered and possibly transient habitation, perhaps clustered (as later) around emerging commons and greens, particularly those near crossroads. (fn. 35) The creation of an independent estate at Rotherfield Greys almost certainly pre-dated the Norman Conquest, and suggests that there was probably an early estate centre, possibly with an associated chapel. If so, its likeliest site is that of Greys Court, which from the late 11th century was developed by the Greys as a major aristocratic seat, and remained their primary residence throughout the Middle Ages. (fn. 36)

Population from 1086

In 1086 there were 20 tenant households on Rotherfield Greys manor, headed by 12 villani and 8 lower-status bordars; most, on later evidence, probably lived to the east of Shepherd's Green. (fn. 37) In the western part of the parish at Padnells (an Anglo-Saxon name meaning Peada's nook), a small number of tenants may have been included in Abingdon abbey's manor of Lewknor. (fn. 38) In the following two centuries population at least doubled, although many of the 100 tenants recorded on Rotherfield Greys manor in 1311 (then including Badgemore) were probably non-resident freeholders occupying small amounts of land. Certainly only 10–12 landholders were taxed in the early 14th century, each presumably representing a household, and excluding Friday Street it seems unlikely that there were more than 40 or 50 houses in all. A further four taxpayers were recorded at Padnells. (fn. 39) After the Black Death numbers almost certainly fell: in 1377 poll tax was paid by 61 adults over 14, suggesting a total population of c. 110–135. (fn. 40)

Population probably began to rise in the 16th century: 15 taxpayers were listed in 1523, and 21 in 1543, while from the 1590s baptisms usually outnumbered burials. (fn. 41) In 1642 the obligatory protestation oath was sworn by 106 men, implying an adult population of 212; 57 houses were assessed for hearth tax in 1662 (when burials briefly exceeded baptisms), and 233 adults were recorded in 1676. (fn. 42) Those listed came from all parts of the parish, though it is not possible to determine precisely the population in each of the various settlements.

Seventy two houses were reported in the rural parts of the parish in 1738, together with a further 51 in suburban Henley south of Friday Street; by 1801 the total figure had risen to 151 houses occupied by 164 families, comprising 677 individuals. (fn. 43) Much of the increase was probably a result of Henley's suburban growth. In 1861 about two thirds of the parish's 1,629 inhabitants lived in the suburbs, the population in the rural areas falling from 588 in 1861 to 555 in 1881. Of those, a growing proportion resided in the new ecclesiastical parish of Highmoor, comprising the settlements of Highmoor, Witheridge Hill, and Satwell: the population of Highmoor rose from 283 in 1861 to 305 in 1881, while that in the hamlets and farms of Rotherfield Greys fell from 305 to 250, probably because of greater employment opportunities in the woodlands during the agricultural depression. (fn. 44)

Between 1891 and 1901 the population of the new urban parish of Greys rose from 2,185 to 2,832, while that of Rotherfield Greys and Highmoor fell from 562 to 505. In 1901 there were 654 households in Greys, 58 in Rotherfield Greys, and 65 in Highmoor. In the first half of the 20th century the suburban population of Rotherfield Greys continued to grow, while the rural population remained largely unchanged. In the second half of the century, the population of both Rotherfield Greys and Highmoor declined, from a total of 748 in 1951 to 632 in 2001, though the number of households increased over the same period to 149 in Rotherfield Greys and 122 in Highmoor. (fn. 45)

Medieval and Later Settlement

Despite the establishment of a major seat at Greys Court by the later 11th century, medieval settlement in the parish remained dispersed, comprising widely spaced hamlets and isolated farmsteads: there has never been a village of Rotherfield Greys. Out of seven present-day hamlets in the parish, all but one (Highmoor Cross) probably had a separate identity in the Middle Ages. Each are treated in turn, running from east to west.

Settlement near Rotherfield Greys church

The settlement around the 13th-century parish church lies at a sharp-angled bend on the road to Henley. Pottery of the 12th or early 13th century, found in the churchyard, suggests that the site may have been settled before the earliest church was built. (fn. 46) The church lay about 1,200 yards (1.1 km) south of Greys Court, to which it was formerly connected by a path east of the existing road. (fn. 47) Building at Greys Court began in the late 11th or 12th century if not earlier, and the church was probably deliberately sited in relation to it. (fn. 48) The rectory house lay north of the church in its own grounds, and though recorded only from the 17th century was probably of medieval origin. (fn. 49)

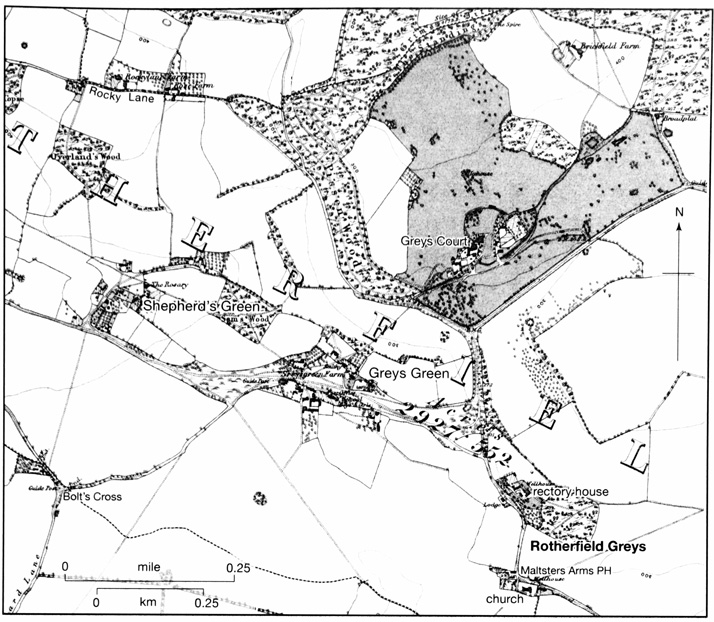

66. Rotherfield Greys c. 1883, showing Greys Court, Greys Green, Shepherd's Green, the parish church, and the rectory house. Such dispersed settlement, focused on commons and early roads, is typical of the area.

In 1844 only nine houses lay near the church, of which 1–2 Pear Tree Cottages date from the early 16th century or possibly earlier. (fn. 50) The Maltsters' Arms public house, which also survives, was recorded as the Broom and Shovel in 1775, but was certainly of older origin. (fn. 51) Another public house closed in the early 20th century. (fn. 52) A well opposite the church porch was opened for the use of the inhabitants in 1818, the well house later serving as a bus shelter. (fn. 53) In the 20th century the hamlet increased substantially in size with the addition of a number of private and council houses. (fn. 54)

Greys Green

The settlement at Greys Green was marked but not named on 18th-century maps. (fn. 55) It developed around an area of common land, called Greys Common in 1635 and Greys Green in 1676, of which more than 20 a. survived in 1844. (fn. 56) Lying roughly equidistant from Greys Court, the parish church, and Shepherd's Green, the hamlet was an important focal point and by the 19th century was the location of a school, cricket pitch, post office, and smithy, and later of the village hall and war memorial (Fig. 67). (fn. 57)

67. Greys Green in 2009, showing the cricket pavilion (built 1983) and former smithy (closed 1981, now a private house). The green and grass verge on either side of the road was declared common land in 1949 and acquired by the National Trust in 1978. Greys Green was designated a conservation area in 1984.

At the beginning of the 20th century the most prominent house was Copse Hill, occupied by a Henley brewer, George Brakspear. (fn. 58) Other large houses were built before the Second World War, especially on the green's south-western edge along the road to Bolt's Cross. (fn. 59) Later development was also limited to individual dwellings. In 1951 an avenue of cherry trees was planted along the road to commemorate the Festival of Britain, and in 1984 the settlement was designated a conservation area. The focus of the present hamlet is the cricket pitch, around which the houses are loosely scattered, many hidden by high walls and thick hedges, and divided by an increasingly busy road. (fn. 60)

Shepherd's Green

The settlement at Shepherd's (formerly Sheepways or Shipways) Green similarly grew up around a small area of common land, much of which still survives (Plate 17). (fn. 61) The surname Shipway was in use in the 16th century, the place was recorded in 1679, and the settlement named on 18th-century maps. (fn. 62) Several houses date from the 17th or 18th century, including Backus on the green's north-eastern edge, which was probably the home of the carpenter John Backhouse (d. 1692). (fn. 63)

The hamlet has a more nucleated appearance than Greys Green, with houses lining either side of a lane leading to the common. Development in the 20th century, including a row of three council houses, blended unobtrusively with the existing housing stock, preserving the hamlet's character. To the west a new road – Satwell Close – was built in the 1920s, to provide access to an exclusive estate of large houses. (fn. 64) The Green Tree public house opened in the 1830s and closed c. 1960 when it was converted into a private residence. (fn. 65) There was also, briefly, a second public house called the Harrow in the late 19th century. (fn. 66)

Satwell

The settlement at Satwell lies at the junction of the Nettlebed–Reading road (the B481) and the road to Henley. The hamlet was probably named after Sotwell (meaning Sutta's spring or stream) in Berkshire: there is no such stream at the Oxfordshire place, but John James (d. 1396) held land in both parishes. (fn. 67) In 1844 the hamlet comprised two farmsteads and six other houses; (fn. 68) the two farms may have been the successors of two estates which included land in Satwell in the Middle Ages. (fn. 69) The settlement was marked on a map of 1725 and named on maps of the later 18th century. (fn. 70)

The parish workhouse was located at Satwell in the mid 18th century. (fn. 71) A pub called The Lamb (which survived in 2006) opened possibly in the early 19th century, and certainly before 1860. (fn. 72) In the early 20th century a number of large houses were built at Satwell, including Satwell's Barton and Satwell Spinneys. Subsequent development was similarly limited to individual dwellings. (fn. 73) Before 1960 the straightening of the Nettlebed–Reading road enabled through-traffic to bypass the hamlet. (fn. 74)

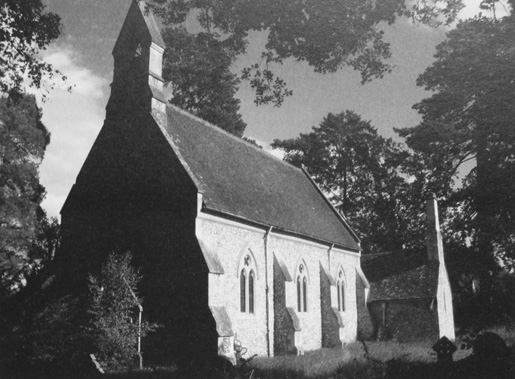

Highmoor Cross

The settlement at Highmoor Cross grew up at the junction of the Nettlebed-Reading road and the road to Witheridge Hill, of which hamlet it may have formed part in the 18th century. (fn. 75) Later Highmoor Cross had a distinct identity. In 1844 its eight houses included Stonehouse Farm and a beerhouse called the Cannon; (fn. 76) that was later replaced by the Woodman (closed in 1984) further down the Nettlebed–Reading road. (fn. 77) St Paul's church was built on the site of the Cannon in 1859, to serve the new ecclesiastical parish of Highmoor. (fn. 78) A well was sunk in 1865, a post office was opened, and in 1920 a village hall was erected by public subscription as a war memorial. (fn. 79) Also in 1920, a row of 12 houses was built by Henley Rural District Council. (fn. 80) In subsequent decades the settlement continued to expand. The sale of glebe land in 1947 allowed housing development to the south-east of the church, and other private and council houses were built at intervals throughout the second half of the 20th century. (fn. 81)

Highmoor

The settlement at Highmoor developed along the edge of Highmoor Common, on the west side of the Nettlebed–Reading road, and was named on 18th-century maps. (fn. 82) In 1844 the settlement comprised about 17 houses, including Highmoor Hall and Highmoor Farm, parts of both of which were built in the 17th century. (fn. 83) Of the two public houses, both of 18th-century origin, only the Dog and Duck survived in 2006. The Green Man closed in the late 1890s or early 1900s and was converted to a private house. (fn. 84) There was some new building in the 20th century, but development was mostly limited to the improvement of existing houses and conversion of farm buildings into residences. (fn. 85)

Witheridge Hill

The settlement at Witheridge Hill grew up around an area of common land on the western edge of Rotherfield Greys parish. Presumably there was settlement in the area by the 1290s, when Ralph of Witheridge (de Wyterugge) was fined at the Bensington manor court. (fn. 86) The name is Anglo-Saxon, meaning 'willow ridge', and was recorded on maps of the 18th century. (fn. 87) In 1844 the hamlet comprised about 19 houses. (fn. 88) A school existed by 1841, and a National school was built overlooking the common in 1862. (fn. 89) There were two public houses: The (Old) Sun, later The Rising Sun, first recorded in 1804, which survived in 2006, and another which closed in the 1850s. (fn. 90) A grocer's shop was opened in the mid 19th century. (fn. 91) A few new houses were built in the 20th century in the southern part of the hamlet, but development was mostly limited to improvement and enlargement of existing buildings. (fn. 92)

The Built Character

The buildings of Rotherfield Greys are similar in character and style to those of neighbouring parishes, the consistent use of timber-framing, brick, and flint, with clay tile and thatch, giving an eclectic mix a harmonious impression. (fn. 93) From the 18th century almost all degrees of building were constructed of brick, made presumably at one of the nearby kilns. Apart from flint (which was often used as infill), building stone was unavailable locally. (fn. 94)

Except for Greys Court and the parish church (both described below), (fn. 95) surviving buildings are all post-medieval. Some of the farmhouses may have been built on the sites of medieval predecessors, but the present buildings date from the 16th century and later. The rectory house, too, originated probably in the Middle Ages, though the existing building was extensively remodelled in the 18th century. (fn. 96) A few cottages survive from the 16th or 17th century, but most of the present housing stock dates from the 18th century and later.

Two notable examples of high-class farmhouses built probably for prosperous yeomen are Hernes (described below) and Lower Hernes. (fn. 97) The latter originated in the mid 16th century as a two-storeyed timber-framed house of two bays (later extended to three). Tree-ring dating suggests a construction date of 1567, when the owner (Sir Francis Knollys) was rebuilding Greys Court. (fn. 98) In the 17th century the house was extended into an L-plan by the addition of a large south wing. The earlier part has a large panelled frame with curved braces and a queen-post roof, and retains an original diamond-mullioned window and some chamfering to internal timbers. The 17th-century range is more sophisticated: the first floor has chamfered beams and joists, and the south face glazed windows with ovolo-moulded mullions. The infilling of the frame (brick in the south wing and brick-and-flint in the north-west) may be original. (fn. 99)

By contrast the state of lower-class rural housing, especially in the west of the parish, caused 19th-century clergy some concern. In 1799 the rector of Rotherfield Greys thought that there were 'too many old houses', and in the 1860s the vicar of Highmoor complained about 'the bad dwellings of the poor' and 'the indecent crowding of the poor in their cottages'. (fn. 100) Many of these were farm workers' estate cottages, usually brick-built and thatched. Most were sold off in the early 20th century, and subjected to an ongoing process of enlargement and improvement.

There appears to have been little speculative building in the 19th century, perhaps because of the control exercised by great landowners such as the Stapletons in the east and the Stonors in the west. Following the sale of their estates in the early 20th century, piecemeal development got underway. Satwell Close, for example, to the west of Shepherd's Green, was built up following the sale of the Greys Court estate in 1922. Other fields auctioned as building sites the same year seem not to have been built on, suggesting limited demand for housing: (fn. 101) a local schoolmaster made a similar observation in 1912, when he purchased a cottage which he let for the very modest sum of £10 a year. But even though property prices were low, cottages were often let to London professionals, foreshadowing later gentrification. (fn. 102) The impact of Henley and perhaps London was also evident at Satwell, where several medium-sized country retreats were built after 1918.

In 1920 Henley Rural District Council built its first council houses in Rotherfield Greys, on land given by the wealthy landowner Sir Paul Makins of Henley. Despite opposition from some councillors the initiative was championed by Harry Burr of Satwell, who was concerned that many agricultural labourers lived in derelict cottages. The four houses were built to a high standard, costing far more than the estimate. (fn. 103) Perhaps as a result, twelve council houses built at Highmoor Cross later in 1920 were in a plainer style. (fn. 104) More council houses were built later in the 20th century, near the church, at Shepherd's Green, and at Highmoor Cross. Private development occurred on a limited scale throughout the parish, cottages were enlarged and improved, and farm buildings and public houses were converted to residences. (fn. 105) Only in the east of the parish was development on a much larger scale, Henley's suburbs extending first over South field and later over farmland to the west. (fn. 106)

MANORS AND ESTATES

Rotherfield Greys was one of several 5-hide estates in the Henley area which were probably detached from the royal manor of Benson before the Norman Conquest, although no Anglo-Saxon holder of Greys was recorded in Domesday Book. (fn. 107) From the 11th to the 20th century the manor was held by a series of high-status and mostly resident lords, including the Greys, Knollyses, and Stapletons, who built and rebuilt the manor house at Greys Court, now in the possession of the National Trust.

The boundaries of Rotherfield Greys manor encompassed only the eastern part of the parish as far as Shepherd's Green (Fig. 65). (fn. 108) In the 13th century a holding called Padnells, belonging to Abingdon abbey, included land in the western part of the parish, which was later acquired by the Stonors of Stonor Park. (fn. 109) In the mid 19th century the Stonors, with 659 a., remained the principal landowners in that area; in the east the Stapletons retained 693 a., their holdings having been much reduced by the sale of part of the manorial estate in the late 17th century. Much of those detached lands were acquired by the Wrights of Crowsley Park in Shiplake, who had 634 a. in Rotherfield Greys in 1844. (fn. 110) A number of sizeable freeholds, among them Hernes and Padnells, were recorded from the Middle Ages.

Rotherfield Greys Manor

Descent to 1503

In 1086 Rotherfield Greys was held by Anketil de Grey of the fee of William FitzOsbern (d. 1071), earl of Hereford. (fn. 111) Anketil held eight other Oxfordshire manors, but Rotherfield Greys was his only possession in the south-east, and important because it lay close to the Thames and the road to London. (fn. 112) By 1242 the overlordship was held with the Isle of Wight by Baldwin (II) de Rivers (d. 1245), earl of Devon, passing with the Isle to the Crown in 1293, (fn. 113) and in 1311 the manor was held of the honor of Aumâle, which remained in the king's hands. The overlordship passed with life grants of the Isle to William Montagu (d. 1397), his son John Montagu (d. 1400), and grandson Thomas Montagu (d. 1428), successive earls of Salisbury, (fn. 114) after which no further references have been found.

In 1242–3 and later the manor was reckoned at 1 knight's fee, (fn. 115) but in the late 13th and 14th centuries the overlordship of the Isle was usually said to include only half the manor of Rotherfield Greys. The other half, at Badgemore, was held of the honor of Derby, and later of the duchy of Lancaster. (fn. 116) Badgemore lay in the neighbouring parish of Henley, and was held with Rotherfield Greys from c. 1240 to the 15th century. (fn. 117)

The mesne tenancy of Rotherfield Greys descended presumably through Anketil's son Richard to his grandson Robert, who held the manor in 1166 and who apparently died childless. (fn. 118) Thereafter the manor passed to Robert's nephew John (d. by 1192), his brother Anketil's son. (fn. 119) John's daughter and heir Eve married the royal judge Ralph Murdac, who was lord in 1192 but whose lands were forfeited in 1194 for rebellion. (fn. 120) Rotherfield Greys was restored to Eve and her second husband, Andrew de Beauchamp, probably before 1200. (fn. 121) Although not without heirs, before 1240 and possibly as early as 1215 Eve gave the manor to her kinsman Walter de Grey, archbishop of York, who settled it on his brother Robert de Grey. (fn. 122) The archbishop nevertheless retained a life interest in the manor and advowson, for which he paid a nominal rent. (fn. 123) On his death in 1255 his heir was his nephew Sir Walter de Grey, son of Robert. (fn. 124) Sir Walter died in 1268 and the manor passed in the direct male line to Sir Robert de Grey (d. 1295), (fn. 125) Sir John (d. 1311), and John, 1st Lord Grey of Rotherfield (d. 1359). (fn. 126) John came of age only in 1321, Edward II meanwhile granting the manor to Thomas Wale for 10 years. (fn. 127)

John, 2nd Lord Grey, succeeded in 1359 and died in 1375, leaving as heir his son Bartholomew, who died the same year. The manor then passed to Bartholomew's brother Robert, who died in 1388 and was succeeded by his daughter Joan, an infant. (fn. 128) Joan married Sir John Deincourt, Lord Deincourt, who had livery of the manor in 1401; (fn. 129) he died in 1406 and his widow in 1408, leaving as heir their infant son William (d. 1422). (fn. 130) His heirs were his sisters Alice, who married William Lovel, Lord Lovel (d. 1455), and Margaret, wife of Sir Ralph Cromwell. (fn. 131) The manor remained divided between them until Margaret died in 1454, leaving Alice as heir; (fn. 132) she subsequently married Sir Ralph Butler, later Lord Sudeley, and held Rotherfield Greys until her death in 1474. (fn. 133)

Alice's heir was her grandson Francis, Lord Lovel, a minor, whose lands were given in custody to John Beaufitz. (fn. 134) Lovel came of age in 1477 when he had licence to enter on the whole of his inheritance. (fn. 135) He fought for Richard III at Bosworth in 1485, fled and was attainted, and his lands escheated to the Crown. (fn. 136) In the same year Henry VII granted Rotherfield Greys, along with other Oxfordshire manors, to his uncle Jasper, duke of Bedford. (fn. 137) On Jasper's death in 1495 the manor passed back into royal hands, and was held by Thomas Kemys of Henley from 1495 to 1501 and by Thomas Hales of Henley from 1501 to 1503. (fn. 138)

Descent from 1503

Rotherfield Greys was granted to Robert Knollys, gentleman usher of the king's chamber, in 1503, and in 1514 Henry VIII settled the manor upon him and his wife Lettice, at an annual rent of a red rose at midsummer. (fn. 139) The grant was renewed and enlarged in 1518. (fn. 140) Robert (d. 1521) and Lettice (d. 1558) were succeeded by their son Francis, reversionary interests granted to the Englefield family in 1524 and 1540 having been surrendered under an agreement of 1545. (fn. 141) Francis Knollys died in 1596, and was succeeded by his second (but eldest surviving) son William, created Baron Knollys of Greys in 1603, Viscount Wallingford in 1616, and earl of Banbury in 1626. (fn. 142) The paternity of two sons born in 1627 and 1631 was disputed, and on Banbury's death (aged about 87) in 1632 the manor passed to his nephew, Robert Knollys, under a licence granted the previous year. (fn. 143) Robert died in 1659 and was succeeded by his son William, MP for Oxfordshire in 1663–4. (fn. 144) Both William (d. 1664) and his son Robert experienced financial difficulties and entered into a number of mortgage agreements, security for which was provided by 1,000-year leases of parts of the estate. (fn. 145) When Robert died in 1679 his heirs were his sisters Katherine, wife of Robert Holdanby, and Lettice, wife of Walter Kennedy; the manor was to be divided between them, subject to clearance of a debt to the Pleydell family, to whom the various mortgages, totalling £7,000, had been assigned. (fn. 146)

In 1682 Robert and Katherine Holdanby sold their share of the manor, and of Robert Knollys's debts, to Thomas Cheyne of Luton for £3,500, thereby initiating the break-up of the manorial estate. (fn. 147) The lordship was not divided and passed in its entirety to Walter and Lettice Kennedy, who took up residence at Greys Court. (fn. 148) In 1688 Lettice (d. 1708), by then a widow, (fn. 149) sold the much reduced manor to James Paul of Braywick (Berks.) and his son William, whose daughter and heir Catherine married Sir William Stapleton, 4th baronet, in 1724, taking Rotherfield Greys as her dowry. (fn. 150) Sir William died in 1740 and was succeeded by his son Thomas (d. 1781), 5th baronet, (fn. 151) and grandson Thomas (d. 1831), who also inherited the title of Lord Le Despenser. (fn. 152)

Thomas's heir was his youngest and only surviving son, Revd Sir Francis Jarvis Stapleton (d. 1874), who was succeeded by his eldest son Francis George (d. 1899), 8th baronet. (fn. 153) His heir and nephew Sir Miles Talbot Stapleton (d. 1977) sold the manor in 1935 to Mrs Valentine Fleming, who in 1937 sold to Sir Felix Brunner (d. 1982), 3rd baronet. (fn. 154) He gave it to the National Trust in 1969, together with Greys Court and the lordship, which brought with it rights over the remaining common land in the parish. (fn. 155) Under the terms of the gift, Sir Felix and Lady Elizabeth Brunner (d. 2003) continued to live at Greys Court. (fn. 156)

Greys Court

Greys Court, which lies roughly in the centre of the ancient parish, was the principal residence of the lords of Rotherfield Greys from the 11th to the 20th century, and has been continuously occupied since its first construction. (fn. 157) Impressive survivals stand on a hillside terrace commanding approaches from the south-east (Figs 68–9; Plate 16). Towards the eastern side of a large platform, defined by an 18th-century ha-ha, a fragmentary but imposing line of curtain walls and towers forms the eastern limits of a fortified manor house, which gave an impression of power and authority beyond its physical strength. In the 15th century the southern part of the house was improved by at least two fashionable ranges, one of which survives in part along the west side. Leland gives a vivid impression of the house as he saw it early in the 16th century, when 'there appear entering into the manor place on the right hand three or four very old towers of stone, a manifest token that it was sometime a castle. There is a very large court built about with timber and spaced with brick, but this is of later work'. (fn. 158) His description suggests that by then either there was little to be seen at the northern end of the complex except the eastern range, or that he failed to penetrate the private, principal court.

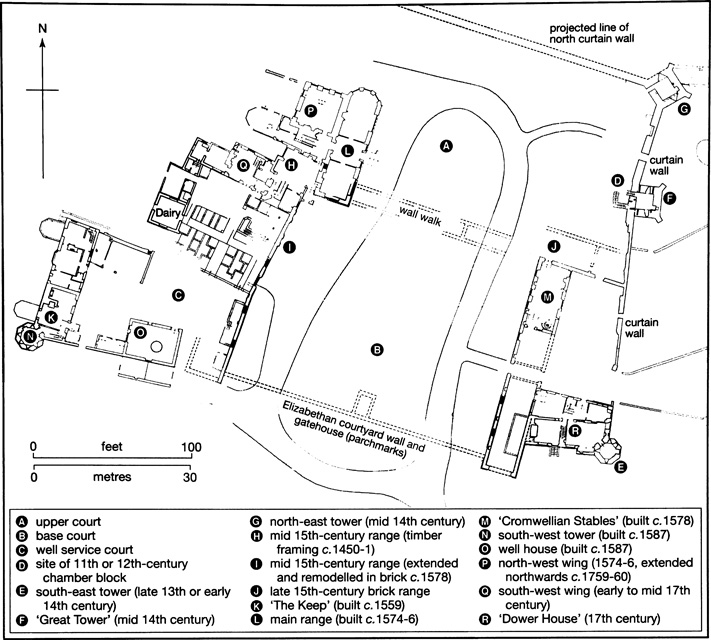

68. Surviving buildings at Greys Court, with approximate dates; adapted (with permission) from plans by English Heritage.

In the 16th century the great courtier and politician Sir Francis Knollys (d. 1596) transformed the medieval remains into a prodigious Elizabethan mansion arranged around two or three courtyards (Fig. 68 A–C). Although only part of the house survives – chiefly a tall gabled block on the western side of the principal court, some of the eastern range of the base court, and the southern and western sides of the service court – the scale of it can be gleaned from records of the late 17th century when, despite depredations in the Civil War, Greys Court had at least 39 hearths. (fn. 159)

The medieval house

When Robert de Grey died in 1295 Greys Court was described as having a curia with curtilage and garden, (fn. 160) almost certainly set within or adjacent to the boundaries of a deer park. (fn. 161) His son, John de Grey (d. 1311), was probably responsible for the construction of the east curtain wall. Its considerable length and height, and the impressive size of the putative precinct, imply that even then Greys Court was arranged on a courtyard plan, the yard or yards enclosed by extensive buildings. (fn. 162)

Robert and John de Grey probably only aggrandized a residence established by the earliest known lord Anketil de Grey, possibly on or near the site of a pre-Conquest estate centre. Part of the late 11th-century building may be traceable on the inner side of the curtain wall (Fig. 68 D) at the point where the 'Great Tower' now projects east. Built of alternate bands of flint and tile to polychromatic effect, this seems to have been the eastern end of a high-status chamber block of rectangular or square plan; the block survived at least into the 14th century, when it was given a new roof with a braced tie-beam truss abutting the east wall. A well shaft, possibly 12th century, lies 90 m. to its south-west within the later well service court, which perhaps already formed part of an extensive curtilage. (fn. 163)

Between about 1250 and 1350 the curtain wall, mainly of knapped and rough flint, was extended north and south from this core, apparently in two separate phases. The southern part ends at an octagonal south-east tower (Fig. 68 E), which may have formed one side of the main gatehouse. (fn. 164) The northern section of wall, which was considerably thicker and probably rendered, incorporated a big square tower (Fig. 68 F; Plate 16) which extended the early chamber block beyond the eastern, outward-facing side of the curtain wall. At the north-east end an angle tower (Fig. 68 G) marked where the curtain wall turned west. That phase may have been associated with the licence to crenellate granted to John de Grey (d. 1359) in 1346, (fn. 165) although the towers, despite small windows and arrow loops, were designed to house chambers and garderobes rather than as primarily defensive structures. The ruined north-east tower is probably the remains of a chamber block of at least four storeys, with a single room on each floor. Where the great hall and the lord's private chambers were located has not been traced, and neither has the position and function of the other buildings within the curtilage. (fn. 166)

After John de Grey's grandson Robert died in 1388, Greys Court was neglected during two successive minorities, so that in 1422 the buildings were 'exceedingly derelict'. (fn. 167) Building began again shortly before Alice Lovel inherited her sister's share of the manor in 1454. (fn. 168) New work included an east-facing, two-storeyed, timber-framed wing along the west side of the base court; its interior, which probably provided accommodation for lesser members of the household, was plain, but its showy jettied façade was designed with expensive close-studding, and brickwork was used for hearths and chimneys. Two complete bays and a large brick chimney survive as part of the existing house (Fig. 68 H), but the range may originally have extended south to six bays or more: its relationship to other ranges in the base court cannot now be determined. (fn. 169)

Later in the 15th century, possibly during Francis Lovel's occupation, a single-storeyed brick range was built, with a low, shallow-pitched roof set behind a crenellated parapet (Fig. 68 J). A fragment of its walling survives at the north end of the so-called 'Cromwellian Stables'. The range's function is unclear, but it divided the base court from the principal court to its north. (fn. 170)

The Elizabethan house

Building was continued by the Knollyses after they acquired the manor in the early 16th century. Sir Francis Knollys undertook three major rebuilding campaigns, and by his death in 1596 the house was arranged around three enclosed courtyards (the principal or upper court, the base court, and the well service court), in the manner of the grandest Elizabethan mansions.

The earliest part of Francis Knollys's work to survive is a short timber-framed range built c. 1559 (Fig. 68 K), which forms the oldest part of the well service court. It has a smoke-blackened roof, may have been a brewhouse, bakehouse or kitchen, and is now known as 'The Keep'. (fn. 171) The most substantial of Knollys's surviving buildings, however, is the tall domestic range on the west side of the principal court (Fig. 68 L; Plate 15). Built some fifteen years after 'The Keep', it presumably replaced medieval accommodation, and incorporated into an L-plan the northern end of the 15th-century west range, which in the present house is a kitchen. The range is two-storeyed with attics, has three wide gabled bays, and is constructed of rendered flint, brick, dressed stone and re-used materials; probably it was intended not as a self-contained house but as fashionable new quarters for Knollys or an important guest. (fn. 172) The principal accommodation was probably on the first floor, lit by mullioned and transomed windows with flattened arched heads; the ground floor may have been blind towards the court. A blocked first-floor doorway in the east wall probably gave access to a wall-walk along the roof of the range between the upper and base courts. (fn. 173)

69. Greys Court from the south in the 18th century, following demolition of many of the medieval buildings. The 'Great Tower' is visible on the right of the upper court, which is separated from the base court by a wall and gateway (later demolished).

Knollys unified most of the base court and made it symmetrical. On its eastern side, in or soon after 1578, he built brick lodgings of one storey and attics lit by dormers. The northern third (now known as the 'Cromwellian Stables') survives intact (Fig. 68 M); the rest of the range is ruined, though its west wall still closes off the courtyard's eastern side. In the 17th century it was linked to the curtain wall by a brick cottage, now known as the 'Dower House'. To correspond with the eastern lodgings, the 15th-century range opposite was extended and refronted in brick and stone (Fig. 68 I); fragments of its front wall form the courtyard's present west side. On the south Knollys enclosed the base court with a wall which created a long south façade, and incorporated a new gatehouse. (fn. 174) That new southern boundary extended westwards to a rendered octagonal tower with pyramidal roof (Fig. 68 N), which was added in or soon after 1587 to mirror the medieval tower at the base court's south-eastern angle. The tower seems to have formed part of a more general refurbishment of the well service court, which included the insertion of a smoke bay within 'The Keep' and the building of the well house. The latter is of two-and-a-half storeys, and contains a contemporary donkey wheel. (fn. 175)

The house since 1600

Over the following decades much of Greys Court suffered damage and decay. Use of the house as a garrison during the Civil War undoubtedly took its toll, although the 39 hearths recorded in 1665 are many more than the 21 or 22 hearths that can be accounted for in the present buildings. (fn. 176) An inventory of 1679 also appears to describe more rooms than now survive. (fn. 177) Substantial demolition probably took place between 1708 and 1724, when the house (following the death of Lettice Kennedy) is likely to have been empty: in June 1722 the antiquary Thomas Hearne was told 'that a great deal of the old buildings at Rotherfield Greys have been pull'd down, and the stones carried to build with at Henley'. (fn. 178) A contemporary illustration (Fig. 69) confirms that the house was probably reduced to more or less its present form around that time. (fn. 179)

Members of the Stapleton family, who lived there almost continuously from 1724 to 1935, made changes to all parts of the site. Sir Thomas Stapleton (d. 1781) added brick crenellations to the medieval 'Great Tower' and south-east tower, and made other attempts to romanticize the buildings. (fn. 180) The surviving main block (Fig. 68 L), which was the family's chief residence, was changed most. In the early 18th century the main reception rooms flanked a central entrance hall, which led to a rear stair; there was a parlour in the north-west wing, and probably service rooms in the south-west wing. In the mid 18th century a two-storeyed ashlar bow window was added to the north front, lighting the drawing room, which was given a fine rococo plasterwork ceiling perhaps to celebrate a Stapleton family wedding in 1765. The north-west wing was extended northwards c. 1759–60 to create a large reception room (now called the 'school room'), whose ceiling was decorated with a plaster wreath. (fn. 181)

The house's appearance remained largely unchanged until Francis Jarvis Stapleton (d. 1874) inherited Greys Court in 1863. The details of his alterations are difficult to determine, but principally concerned the stairs and chimneys. (fn. 182) His son Francis George Stapleton (d. 1899) made more extensive alterations, all subsequently removed. The façades were transformed during the 1880s when bay windows were added to both main reception rooms, and a modest front porch was built apparently in ashlar; a large, single-storeyed billiard room was built onto the north-west wing about the same time. Stapleton's architect is said to have been David Brandon. (fn. 183) The central courtyards had by then been transformed into a garden, with an arrangement of sweeping drives that survived in 2006. (fn. 184)

Between 1935 and 1937 the porch and southern bay window were pulled down by Mrs Fleming, who stripped off the stucco and installed some new windows. It is not clear how far her extensive plans for altering the interior were carried out. (fn. 185) The Brunners' changes to the house early in the next decade left an arrangement with central hall and flanking reception rooms, similar to that which survived in 2006. They demolished the billiard room and eastern bay windows, replacing the latter with mullioned and transomed windows, and altered the windows of the so-called 'school room'. They also made major changes to the inner hall. (fn. 186) Lady Brunner was instrumental in re-landscaping the gardens, commissioning work from the architect Francis Pollen, amongst others. (fn. 187)

In 1982 the National Trust converted the house's south-west wing (abutting the 15th-century range) into a custodian's flat, and in 1984 a conservatory was added to the back of the house, west of the main stair. (fn. 188) Improved standards of accommodation for domestic and estate staff were also achieved in the other ranges, and alterations made to the garden and park. (fn. 189) The exterior and the roof were thoroughly restored in 2006.

Other Estates

Freeholds in Highmoor

A number of sizeable freeholds existed in the Middle Ages in the western part of the parish outside the manor of Rotherfield Greys. In 1284 land granted to Rewley abbey by Edmund, earl of Cornwall, extended into Highmoor. (fn. 190) In the 15th century estates held of the honor of Wallingford included land in Highmoor, (fn. 191) while one of the tenants of the honor, William Stonor (d. 1494), also held land in that part of the parish. (fn. 192)

An estate called Padnells was held of Abingdon abbey as a detached part of the manor of Lewknor. In 1279 the abbey's tenant, Thomas de Padehale, paid an annual rent of 5s. 1d., (fn. 193) and in 1494 William Stonor held 200 a. of land and 100 a. of wood there for 5s. rent. (fn. 194) The Stonors retained the estate after the Dissolution, and still owned a farm called Padnells (at Satwell) in 1815. (fn. 195) This formed part of the 659 a. held by the Stonors in the mid 19th century, which was later referred to as the manor of Highmoor. (fn. 196) Manorial rights over Witheridge Hill common remained in force in 1913, when they were sold by the Stonors' successor Robert Fleming. (fn. 197)

Another estate at Satwell was recorded in the late 14th century, when John James of Wallingford (holding in his wife's right) was granted free warren. (fn. 198) The estate passed by marriage to the Rede family, and in 1438 to the Marmions of Checkendon, who retained it in the mid 16th century. (fn. 199) Later it belonged to the House family, who sold the estate in the late 17th century to Robert Ovey of Henley. (fn. 200)

Freeholds in Rotherfield Greys

Reading abbey held lands and rents in Caversham and Rotherfield Greys in 1291, (fn. 201) and in 1324 Dorchester abbey was granted unspecified land in Rotherfield Greys by Elias Bakun and William de Crek, in return for a chaplain to celebrate daily service. (fn. 202) The rectorial glebe, c. 46 a. from the 17th to mid 19th century, lay mostly in the south and east of the parish. (fn. 203)

The part of the manorial estate sold by Robert and Katherine Holdanby in 1682 remained intact until the late 19th century, and was acquired during the 1680s by Francis Heywood of Oxford (d. 1739), a tenant of the Knollys family in Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 204) He was succeeded, in turn, by his sons Francis (d. 1747) and William (d. 1762), both of Crowsley Park in Shiplake, (fn. 205) after whose death the estate eventually passed to their sister Mary Wright, and subsequently to her nephew John Atkyns Wright (d. 1822) and his wife Mary (d. 1842). (fn. 206) The estate was sold in 1844 to Henry Baskerville, whose son-in-law William Dalziel Mackenzie of Fawley Court acquired the lands in Rotherfield Greys c. 1880. (fn. 207) Part of the estate was sold by Keith Ronald Mackenzie to Richard Ovey of Badgemore in 1890, while the remainder was auctioned in 1906. (fn. 208)

Hernes

A substantial estate focused on the house now called Hernes (formerly Ardens) was of medieval origin. In the early 14th century it was probably owned by the merchant Henry de Ardern, one of the wealthiest taxpayers in the parish, who in 1300 lent money to John de Grey. (fn. 209) The estate seems to have passed to the Quatremain family, which c. 1400 had a yardland held of Rotherfield Greys manor for knight service, and a 'formerly built-up place' called 'Ardernes'. (fn. 210) In the early 17th century, when sold to Thomas Snelling of Kingston upon Thames, the estate comprised a chief house called Great Ardens, 110 a. of land, and 20 a. of wood. (fn. 211) Later owners, mostly non-resident, included members of the Northey, Heywood, and Wright families. (fn. 212) In 1815 the farm, renamed Hernes, measured 241 a.; (fn. 213) it was bought in 1890 by Richard Ovey, owner of the Badgemore estate, (fn. 214) and remained in the Ovey family in 2006.

The timber-framed, L-plan house was built in two distinct phases, and has been enveloped in later alterations. In 1647 a hall, parlour, kitchen, and inner cellar were mentioned, with a chamber over the hall. (fn. 215) The south-western part may be a medieval house, to which a north chimney with diamond stacks was added in brick in the 16th century. The north wall of the range is also of old brick, and the framed south wall has brick infilling. The two-storeyed cross-wing to its north, also 16th-century, is framed separately, and has curved braces and a queen-post roof. The east face of that range has been clad in flint and brick, probably in the early 19th century.

In the mid 19th century the property was improved by the construction of new brick farm buildings round a large farmyard east of the house; some buildings, including a grain barn, were demolished in the 1960s, and others have been converted into industrial units. The improvements included a trackway, and a water system which incorporated a timber tank in a water tower, added to the east side of the house. At the same period a row of rooms, brick built, two-storeyed and with three gables, was added along the north side of the house, and an additional bay built at the south end of the east range. In the early 20th century conversion into a gentleman's residence began with the building of a billiard room and master bedroom at the western end of the west range. Later the drawing room was extended west (squaring up the range), the south façade was remodelled with pebbledash, a porch was added, and an avenue of horse-chestnuts and more permanent oaks was planted as an approach. A conservatory and verandah have been demolished. (fn. 216)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until the 20th century the inhabitants of Rotherfield Greys depended largely on agriculture: only at the parish's eastern edge, which became part of Henley's suburbs, was there a more diverse range of occupations. (fn. 217) Farms were dispersed throughout the parish's settlements and fields from the Middle Ages, and a variety of rural trades and crafts were practised, though evidence of local industries such as brick-making is limited. Some local shops were established by the 18th century, but most residents probably bought goods at the market towns of Henley and Reading. Employment opportunities in the parish declined during the 20th century, and the community was transformed by an influx of retired people and commuters. (fn. 218)

The Agricultural Landscape

The strip-like shape of the ancient parish provided the inhabitants of Rotherfield Greys with a variety of agricultural resources. The Thames produced fish and valuable meadow land. On the high ground in the Chilterns was plentiful wood, while the greens and commons provided the rough grazing reflected in the place name 'rother feld' or 'open land where cattle graze'. Arable and pasture fields and closes were scattered throughout the parish. The earliest depiction of this landscape is in Domesday Book, which suggests that the mixed countryside and mixed farming of later periods was well established by the 11th century. In 1086 Anketil de Grey's 5-hide manor had land for 7 ploughteams, 12 a. of meadow, and woodland 4 furlongs long and as many broad. (fn. 219)

Fields, Crofts, and Arable

Until the early 16th century, the arable belonging to the Greys' manor lay partly in open fields. Four fields were mentioned in 1409, among which the demesne arable was divided. (fn. 220) Communal farming in the later Middle Ages is suggested by occasional references to tenants' yardlands, but it is not known whether the demesne and tenant land were intermixed. Nor is there certainty about the location, extent or organization of the open fields, but presumably they included South field, south of Henley, which remained open until the 19th century. (fn. 221)

The medieval open fields almost certainly adjoined private inclosures or crofts, which were used for both arable and pasture. In 1400, for example, Thomas Quatremain's widow Joan was assigned dower comprising 29 a. of fallow scattered in various named crofts, such as Sheep croft and Crooked croft (by Broad field), located close to the present Hernes. (fn. 222)

Further west, yardlands were also recorded at Padnells in the 13th century, but most of the countryside around Highmoor was probably made up of inclosed crofts cleared piecemeal from the surrounding woodland and wood pasture, which was typical of the upland landscapes of the Oxfordshire Chilterns in the Middle Ages. (fn. 223) Characteristic of the area, including Rotherfield Greys, were strips of woodland called shaws, left as boundaries to crofts after clearing. (fn. 224)

Most of the parish's open fields were apparently swept away in the early 16th century when Robert Knollys inclosed about 245 acres. This presumably represented an attempt to maximize profits on the part of an ambitious new lord, whose tenure of Rotherfield Greys manor was confirmed by the king in 1514. (fn. 225) In 1515 Knollys took possession of a house and 80 a. of arable previously occupied by 10 people, and substituted his bailiff. Another house and 30 a. of arable, formerly supporting 5 people, were sublet to Robert Baret and Thomas Springold, both of whom were prominent taxpayers in Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 226)

Only South field appears to have escaped Knollys's inclosing activities, though consolidation of open-field holdings took place there too. A tenant in 1584 had 3 a. 'lying together in the field called Sowthffelde', and by 1815 the field was a patchwork of small closes and individual strips. (fn. 227) The field presumably remained subject to common crop rotation, and in 1679 common grazing rights there, enjoyed by tenants of the manors of Rotherfield Greys and Harpsden after harvest, were carefully apportioned according to size of holding. (fn. 228) Both South field and the adjoining Greys mead were finally inclosed by Act of Parliament in 1860, the new consolidated plots divided unevenly among 12 landowners according to the size of their former holdings. (fn. 229)

Woodland, Parks, and Pasture

Woodland was scattered throughout the parish, but in the 18th and 19th centuries lay mostly in the north and west: in 1844 about 380 a. were recorded, mostly beech. (fn. 230) The area of woodland was not unchanging, however: throughout the Chilterns between 1600 and 1800 woods were cleared for farming, and some new woods were planted. (fn. 231) A number of 18th-century holdings in Rotherfield Greys included land recently 'grubbed up' and converted from woodland to tillage, though their overall extent is impossible to determine. (fn. 232) Grubbed Hill, recorded in the 1760s, was still arable in the 1870s, lying to the south of Lower Hernes. (fn. 233)

In the Middle Ages great tracts of wood and wood pasture were owned and kept in hand by the principal landowners. John de Grey had 100 a. of wood and 200 a. of pasture in 1375, while in 1494 William Stonor had 100 a. of wood at Padnells. (fn. 234) The woodland was exploited for timber, underwood, and coppicing, and also for hunting and parkland. The Greys were granted free warren in their demesne in 1240 and had a park before 1290, which probably surrounded the house at Greys Court. (fn. 235) Two other parks belonging to Rewley abbey extended into Highmoor. (fn. 236) At Satwell, John James was granted free warren in 1394, bestowing limited hunting rights but not necessarily implying a park. (fn. 237)

Although some large private pastures were kept in hand by lords, there were also areas of common pasture, most notably around the settlements at Greys Green and Shepherd's Green. In 1679 tenants had the right to pasture sheep there according to the size of their holdings, and also alongside the road from Greys Court to Henley at the lord's will. (fn. 238) A lease of a house and 40 a. in 1743 included commons for 60 sheep, and another tenant enjoyed 'common of pasture for all manner of cattle' in 1737. (fn. 239) Grazing rights on Greys Green and Shepherd's Green persisted into the 19th century and later. (fn. 240)

Some common land close to Greys Court was inclosed in 1738 by Sir William Stapleton, who paid compensation to the copyholders. (fn. 241) Tenants, too, were sometimes able to inclose small pieces of common 'for herbage', for which they owed quitrents. (fn. 242) Perrings Farm, which belonged to the Stapletons, was surrounded by wood and common, from which it had probably been carved. Unusually, when recorded in 1815, none of its arable crofts had names, suggesting that they were recent creations. (fn. 243)

Meadow

Lack of water meant that the area of meadow in Rotherfield Greys was largely confined to the Thames frontage in the extreme east of the parish. Only 12 a. were recorded on the Greys' manor in 1086 and 1409, along with several eyots, the small islands in the Thames which lay within the parish boundary. (fn. 244) Presumably this was private meadow, inclosed from the larger common meadow. In 1400 land granted to Thomas Quatremain's widow included arable lying alongside the 'ditch' of Rotherfield mead, similarly suggesting an inclosure, while another ¼ a. lay to the east in the meadow of Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 245) The distinction between private and common meadow persisted. In 1685 a grant of Corderoy's farm (modern Lower Hernes) included 6 a. of meadow in Greys mead, occupied by John Corderoy, and 1½ a. in the common meadow. (fn. 246)

In 1657 the Knollys family's demesne included 40 a. of meadow, perhaps part of the 'Greys great meadow' leased later that century for £50 a year. (fn. 247) A common meadow called Greys mead was recorded in 1679, but with no indication of how it was managed. (fn. 248) However, several references to 'lot mead' in the tithe award suggest that part of the meadow was distributed among the tenants by casting lots. (fn. 249) In 1844 most of the land to the east of the Reading road was meadow, covering about 70 a., with a few additional parcels to the west. (fn. 250) The common meadow, inclosed in 1860, lay to the east of the railway line, directly alongside the Thames. (fn. 251)

Medieval Agriculture

Medieval Demesne Farming

The Greys kept a substantial amount of land in demesne throughout the Middle Ages: two ploughlands (around 240 a.) in 1086, and 300 a. in 1295 and for much of the 14th century. The acreage fell to 260 a. by 1422, (fn. 252) when the remaining 40 a. was probably leased; possibly it included the land, with house and barn, 8 a. of meadow, and a private fishery in the Thames, leased to John Russell in 1462 for 60 years, at a rent of £3 8d. a year. (fn. 253)

In the early 14th century tenant labour-services were used to mow the meadows and harvest crops, but by 1375 these seem to have been commuted to cash payments. (fn. 254) A low valuation of 2d. or 3d. an acre suggests that the arable was not farmed intensively and may not have been kept in good heart, prompting its description as sterile and barren in 1422. (fn. 255) In the 15th century the demesne was probably leased, possibly for short terms: the record of John Russell's 60-year lease survives only because it continued beyond the grant of the manor to Robert Knollys in 1514. (fn. 256) Knollys himself leased some land, but reference to a bailiff in 1515 suggests that part of the demesne was still managed directly. (fn. 257)

The type of farming practised is not well documented, but probably continued the mixed farming recorded in 1194–6, when the demesne was stocked with cattle, pigs, and sheep, and produced grain, hay, and wood for sale. (fn. 258) The nearest market to Rotherfield Greys was Henley, which in the early 14th century supplied many of the Greys' consumption needs, purchased through a purveyor. (fn. 259) Henley was by then an important market for supplying London, especially with grain and wood, and much of the Greys' surplus produce was probably sold there. (fn. 260) Apart from grain, this may have included hay from the demesne meadow (valued at 2s. an acre in 1311), and underwood (worth 6s. 8d. in the same year). (fn. 261)

Woodland management was an important aspect of medieval demesne farming in the Chilterns. John de Grey had 100 a. in 1375, from which the underwood, often used for fencing and fuel, was probably cut and sold every few years after natural regrowth. In 1409 it was worth £2 13s. 4d. 'without causing waste'. (fn. 262) The demesne woods were probably divided into coppices, inclosed by bank and ditch, and cropped on a roughly regular cycle. Landowners might open coppices for pannage or pasture, worth 10s. a year to Robert de Grey in 1295, or sell the right to take underwood and timber, as William Stonor did in 1483. (fn. 263)

A private fishery in the Thames belonged to the Greys. Following the parish boundary mid-stream upriver, the fishery extended the length of the Thames frontage. (fn. 264) Before its lease to John Russell in 1462 it may have supplied the lord's household, particularly at events such as the feast to celebrate the birth of John de Grey in 1300. (fn. 265) The park, too, may have been a source of food as well as hunting. In 1482 Francis Lovel wrote to William Stonor: 'Cousin, I pray you that you will see that my game [i.e. deer] be well kept at Rotherfield'. (fn. 266)

Medieval Tenants and Farming

In 1086, when the manor was valued at £5 as in 1066, 12 villani and 8 bordars shared 5 ploughlands (about 20 yardlands). (fn. 267) The division of holdings into half- or even quarter-yardlands, recorded in 1295, suggests that rising population put pressure on resources. (fn. 268) In 1311 there were 32 unfree tenants on the Greys' manor, each holding half a yardland (perhaps around 12–15 a.), for which they owed cash rents and labour services on the demesne. Total rents rose from almost £5 in 1311 to more than £7 in 1375, probably because labour services were commuted. (fn. 269)

Although none were mentioned in 1086, no fewer than 68 free tenants were recorded in 1311, together paying almost £10 a year in rent. (fn. 270) The merchant Henry de Ardern was probably among them; so, too, was the early 14th-century taxpayer John Aleyn. (fn. 271) Aleyn may have been one of the more substantial freeholders. Only 12 taxpayers were recorded in 1316, their payments ranging from 8d. to 7s. 6d., suggesting that most freeholders (and unfree tenants) either evaded the tax, were taxed elsewhere, or were excused payment through poverty. (fn. 272)

Free tenants sometimes gave their name to holdings, which were bought and sold. Thus Emma Cork, a taxpayer in 1316, may have held 'Corkeslond', 5s. rent from which was sold by John of Satwell to John de Alveton in 1351. (fn. 273) Two witnesses at a proof of age in 1401 also held land by charter (i.e. as freehold). (fn. 274) But for the most part, little is known about the size or location of holdings, and about how and when they were created.

Further west, at Padnells, four cottagers held smallholdings for cash rents in 1279, and two free tenants held half- or quarter-yardland holdings. (fn. 275) Some free tenants of the honor of Wallingford also held land in the west of the parish, among them Willelma widow of John Roches, who had a house and 50 a. of arable, meadow, wood, and pasture in Rotherfield Greys, Bix, and Highmoor. (fn. 276)

Tenant agriculture probably resembled the mixed farming of the lords. John Aleyn's barn, which burnt down in 1386, was presumably intended to store grain. (fn. 277) In the early 16th century one tenant grew wheat, barley, oats, and peas, and kept horses, cattle, and sheep. Likewise, Thomas Springold (d. 1544), who was a tenant of Robert Knollys after inclosure, grew wheat and kept sheep and cattle. (fn. 278) John House (d. 1530), who lived at Ardens, also left sheep and cows in his will. (fn. 279) Manorial tenants presumably had the right, recorded in 1679, to take wood for fuel and repairs, but no medieval evidence survives. (fn. 280)

In the mid 15th century there is some evidence of buildings falling into ruin, an indication that holdings lay vacant or were being amalgamated. (fn. 281) Tofts (i.e. vacant house plots) were also recorded on the estates of Thomas Vyne (d. 1479) and of Humphrey Forster (d. 1488) and his son (d. 1500), which extended across a number of parishes including Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 282) There is, however, no evidence of a significant fall in population, and no settlements in the parish were deserted.

Farming C. 1550–1800

Estate Management

Few details of the management of Rotherfield Greys manor survive before 1650, though presumably the demesne was leased, as it was later. In 1657 the demesne comprised 300 a. of arable, 200 a. of pasture, 100 a. of wood, 40 a. of meadow, and the fishery in the Thames; (fn. 283) a rental of around that date shows that it was leased to a dozen tenants paying a total of £455 in rents. The Knollys family kept in hand the house and 'little park' at Greys Court, and 600 a. of inclosed woodland, which probably extended into the neighbouring parishes of Bix and Henley. (fn. 284) The 'great park' was converted to tillage by Robert Knollys in 1637, and later leased to four tenants. (fn. 285) Many parks and private woods were grubbed up around this time, releasing land for agriculture. (fn. 286) Individual coppices were also leased, among them Ashen shaw and Tapsters coppice, for which Ralph Messenger of Henley paid £330 in 1662 for a lease of 99 years, at a rent of £26 8s. a year. (fn. 287)

The Knollys family's financial difficulties led to the division of the manor in the 1680s. The part sold by Lettice Kennedy in 1688, later inherited by the Stapletons, comprised Greys Court with the park, wood, and farmland immediately surrounding the house; included was 120 a. called Park Wood, two farms of 193 a. and 120 a. leased to tenants, and a number of small closes and coppices. (fn. 288) The Stapletons evidently continued the practice of their predecessors: in 1785 the woods were still in hand and the two farms still tenanted. (fn. 289)

Those parts of the estate furthest from Greys Court, subsequently acquired by Francis Heywood of Oxford, were similarly exploited. In 1761 that estate included five leasehold farms, all of them south of the hamlets of Greys Green and Shepherd's Green, and east of the parish church; some woodland was kept in hand, though other coppices were let with the farms. (fn. 290) Rents for the five farms ranged from £26 to £145 a year in 1762–3, and totalled £435. (fn. 291)

The Stonor family's large estate in the west of the parish was mapped in 1725. Like neighbouring lords, the Stonors appear to have leased the farmland and kept the woods in hand. Two farms were shown, of which Padnells was leased to John Grove in 1719 for 14 years at an annual rent of £60. Grove was also to pay £2 10s. for every marked tree felled in the surrounding woods. (fn. 292)

Tenant Farming

The tenant farmers of the early modern period continued the mixed farming practices of the later Middle Ages. Late 16th-century wills record numerous bequests of wheat, rye, and malt, together with horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, and poultry. (fn. 293) Tax records indicate wide variations in wealth: in 1543, for example, 20 taxpayers were assessed on goods valued between £1 and £20. (fn. 294) Some tenants certainly appear to have prospered. The surviving farmhouses at Hernes and Lower Hernes were built to a high standard in the 16th century, probably reflecting the prosperity gained by supplying the London grain market via Henley. (fn. 295) Investment in the parish's farm buildings continued during the 17th and 18th centuries, though whether the costs were borne by lord or tenant is unclear. (fn. 296)

In the 17th and 18th centuries most of the larger farms in the parish were leased. One of the best documented is Hernes, formerly Ardens, which originated as a medieval freehold held of the Greys. (fn. 297) In the early 17th century the estate comprised a house called Great Ardens (including barn, stable, orchard, and garden), 80 a. of arable, 30 a. of pasture, and 20 a. of wood. (fn. 298) The farm was valued at £30 a year net in 1618, and for much of the 17th century was held by various tenants on 21-year leases at an annual rent of £40. (fn. 299) In the 1760s the farm was leased to Thomas Binfield for an annual rent of £145, and the family remained tenants there until the early 19th century. (fn. 300) Arable farming was prominent, with some livestock: in 1794 Frances Binfield insured two stables, wheat and barley barns, two other barns, a cart-house and waggon-house, and wheat, barley, and hay rickyards. (fn. 301)

A number of families remained in the parish for several generations, although not always without difficulty. In the 16th century members of the House family were (briefly) tenants at Ardens and owneroccupiers of the former Marmion estate at Satwell. (fn. 302) In 1654, when mortgaged for £300 by the yeoman John House and his son, the farm totalled 75 a. and was run from the surviving Satwell farmhouse. (fn. 303) Like other farmers in the parish, the family practised mixed husbandry: on John's death in 1677 his grain was valued at £75 and his cows, horses, sheep, and pigs at a further £62, and there were small amounts of wool and hops. (fn. 304) His inventory was valued at £173, considerably less than the £320 left by Ralph House (d. 1631), and hinting perhaps at financial problems. (fn. 305) In 1686 the farm was mortgaged to Robert Ovey, who subsequently bought and leased it; tenants included Thomas Harris, who in the 1770s had a 7-year lease at £41 a year. (fn. 306) It remained in the possession of the Ovey family in 1815, but was sold shortly afterwards. (fn. 307) The House family stayed in Rotherfield Greys during the 18th century, (fn. 308) and in the early 19th returned to Hernes as tenants, succeeding the Binfields; they left when the Oveys bought the farm in 1890. (fn. 309)

Seventeenth-century wills demonstrate not only the tenant farmers' mixed arable and livestock husbandry, but also less well documented activities such as brewing, cheese and butter-making, and linen, wool, and hemp spinning, the produce from which may have been sold. (fn. 310) Tools for cutting wood, such as axes and billhooks, were often recorded, and some wills reveal the purchase or leasing of woodland: John Backhouse (d. 1692) and his son bought 6 a. called Dryfield coppice, while William Benwell (d. 1669) bequeathed his wife an annual supply of firewood from a wood he had purchased. (fn. 311)

The farms were worked by numerous agricultural labourers, not all of whom were local. In September 1769 Ovey's tenant at Satwell, Thomas Harris, employed a Stokenchurch man at Henley hiring fair, paying him £2 4s. for the year. Samuel Bitmead of Greysgreen Farm hired a native of Rotherfield Greys at the fair in 1790, engaging him for a year at 4s. 6d. a week on condition that he found himself board and lodging. When employed on a Sunday he also received food. Although some labourers remained in employment for a whole year, others stayed for only a few weeks. In 1793 Francis Willis worked at Hernes for about 10 weeks before moving the short distance to neighbouring Lodge Farm, having apparently been hired at the Nettlebed fair rather than at Henley. In the same year John Bannister was hired during the hay harvest 'and lived and lodged with his master but no agreement was made either as to time or sum'. (fn. 312)

Farming in the 19th and 20th Centuries

In 1815 there were 15 farms in Rotherfield Greys, and a number of smaller freeholds. Three farms exceeded 200 a., and four 100 a.; the smallest, Witheridge Hill farm, measured only 27 acres. Two thirds of the farms were held under three principal landowners: the Stapletons of Greys Court, the Wrights of Crowsley Park in Shiplake, and the Stonors of Stonor Park. The Stapleton estate comprised New farm (241 a.) and Brickfield farm (77 a.), both established by 1688, Perrings farm (50 a.), probably created from cleared woodland and inclosed common, and Rose farm (75 a.), which lay partly in Bix. The Wright estate comprised Greysgreen farm (233 a.), Hernes (241 a.), and Lower Hernes (104 a., then called Lodge or Bottom farm), which were an amalgamation of the five farms recorded in 1761. The Stonor estate comprised Highmoor farm (156 a.) and Padnells (58 a.), both mapped in 1725, and Bromsden farm (116 a.), which lay partly in Bix.

Of the remaining farms in 1815, three were owned and occupied by members of the Piercy family: Witheridge Hill farm (27 a.), the neighbouring Stonehouse farm (42 a.), and Coldharbour farm (114 a.), which adjoined South field near Henley. Satwell farm (87 a.) was leased by the Oveys to Samuel Benwell, and Paradise farm (97 a.) was leased by the Hodges family of Bolney Court in Harpsden to William Chipp. (fn. 313)

Between 1815 and 1844 the number of farms fell to 11 as a result of amalgamations. (fn. 314) Further consolidation took place during the later 19th century, perhaps partly as a result of agricultural depression. Thus when the Stonor estate was sold in 1894 Witheridge Hill farm had been added to Highmoor farm, and the combined holding (259 a.) was leased for £100 a year. (fn. 315) By 1910 the Stapletons' New and Brickfield farms (336 a.) were also occupied by a single tenant, and Hernes and Lower Hernes (439 a.) were both owned by the Oveys. But some smaller farms also survived, such as Stonehouse farm (44 a.) and the owner-occupied Satwell farm (101 a.). (fn. 316)

Most farmers still practised mixed agriculture. An insurance ledger of 1782–1806 recorded buildings and stock used in both arable and livestock husbandry, (fn. 317) and in 1801 there were reported to be some 858 a. of arable, 771 a. of permanent grass, and 195 a. of woodland. (fn. 318) By 1844 the arable acreage had increased: the tithe award recorded about 1,740 a. of arable, 500 a. of grass, and 380 a. of wood. (fn. 319) By 1879 the amount of arable had risen again, to 1,875 a., while grass fell to 315 a., and woodland remained the same. (fn. 320) In the late 19th and early 20th century the chief crops were wheat, barley, oats, and root crops (especially turnips and swedes). (fn. 321)