A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Rural Parishes: Harpsden', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp231-265 [accessed 10 May 2025].

'Rural Parishes: Harpsden', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online, accessed May 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp231-265.

"Rural Parishes: Harpsden". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online. Web. 10 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp231-265.

In this section

HARPSDEN

Harpsden is a Rural parish just south of Henley, stretching from the Thames in the east to higher wooded ground 3¾ miles (6 km) west, and including the largely deserted settlement of Bolney. (fn. 1) The 20th century saw a limited amount of development in the south-east close to Shiplake, but most of the parish remains sparsely populated, with isolated farms and houses spread along the Harpsden valley and on the plateaux above. A former manor house called Harpsden Court, the church, the old school and a village hall are all located in the valley, but there is no village of Harpsden as such. The parish's dispersed settlement pattern and location seem to have discouraged a strong sense of community in most periods, with many locals developing important external ties with people in Henley and neighbouring parishes. Until the end of the 19th century Harpsden supported a farming population, but it has subsequently been subject to ongoing gentrification.

Parish Boundaries

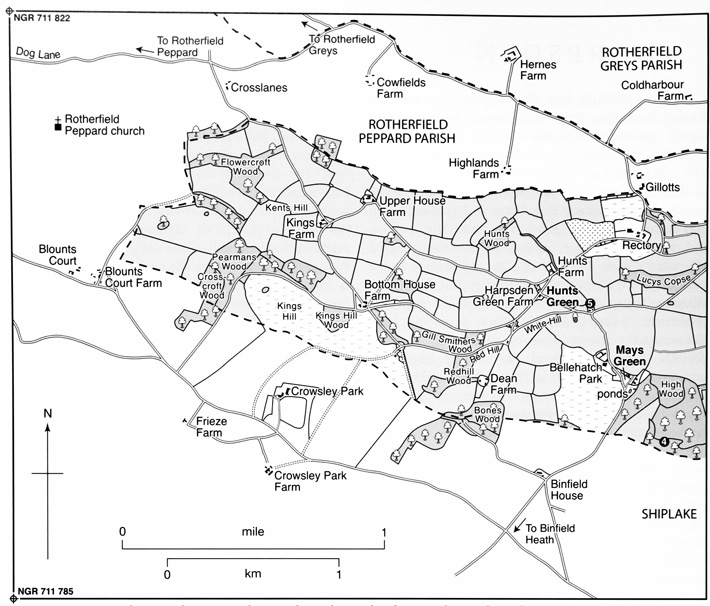

In 1879 the ancient parish measured 2,021 a., similar to its estimated acreage in 1842. (fn. 2) The parish's (and county's) eastern boundary followed the midstream of the river Thames for just under a mile, bringing in several small islands, while the long northern boundary with Rotherfield Peppard ran through fields and then along field boundaries as far as Flowercroft wood. In the west and south-west, the boundary with Rotherfield Peppard and Shiplake was largely undefined, including where it approached and crossed the northern part of Crowsley park and land to the east. (fn. 3) The remainder of the southern boundary with Shiplake followed the edge of High Wood before cutting across fields and following short stretches of field and woodland boundaries to the Thames. (fn. 4) An estate map of 1586 (Plate 12) and the record of a procession in 1672 suggest similar boundaries. (fn. 5)

In the Middle Ages the area comprised the two separate parishes of Harpsden and Bolney, which were amalgamated in the 15th century. (fn. 6) Almost certainly their boundaries derived from those of two late Anglo-Saxon estates recorded in 1086: the Harpsden estate lay to the north, and Bolney to the south, both apparently extending from the Thames to the higher ground in the west. The internal division between them presumably followed the southern boundary of the Harpsden estate as mapped in the late 16th century. (fn. 7) It has been speculated that both estates (with Lashbrook) may once, like neighbouring land units, have stretched further west to the hundred boundary on the Chiltern ridge-line; (fn. 8) there is insufficient evidence to substantiate this, although Harpsden men probably had common rights in Wyfold on the Checkendon–Rotherfield Peppard boundary. (fn. 9)

The historic parish was subject to only minor boundary changes in the 20th century. In 1932 Harpsden lost 1 a. to Henley-on-Thames and gained 4 a. from Rotherfield Peppard. In 1952, 152 a. around Highlands Farm in the north were incorporated from Peppard and 6 a. lost to Shiplake in the south. (fn. 10)

Landscape

Harpsden is located at the foot of the Chiltern dip slope, where the dry Harpsden valley meets the terraces of the middle Thames. The place name refers to the valley or dene, the first element (hearp) possibly describing its curved shape. (fn. 11) The terrain slopes down gently from west to east: the highest point, in Crosscroft Wood, is around 90 m., the lowest, on the flat Thames floodplain, less than 35 m. The chalk geology is exposed on the valley sides, but elsewhere is covered by drift deposits, mainly gravel. On the spur of high ground partly occupied by Harpsden Wood there is clayey gravel, and there are patches of alluvium near the river. (fn. 12) The eastern part of the parish contains several small streams fed by springs emerging near Harpsden Court, and the grassland near the Thames is liable to flooding. (fn. 13)

Most of the parish comprises arable and pasture closes, generally larger in the east and smaller in the west (where some were probably created by assarting). (fn. 14) Woodland, covering 15 per cent of the parish in the 1840s, (fn. 15) is concentrated on steeper valley sides and on poorer soils on plateau tops, mainly in the south and west. Some of the most productive soils are located on the gravels in the east of the parish and on areas of well-drained higher ground, while parts of the valley have rather thin, stony soil, shaded by wooded slopes. (fn. 16)

57. Harpsden parish c. 1840, showing boundaries, land use and some later features.

Communications

The main west-east route through the parish is the road running through the Harpsden valley from Rotherfield Peppard in the west to a point just east of Harpsden church, where it veers north towards Henley. This road and a smaller lane continuing east towards Sheephouse Farm both join the main Henley–Reading road, which passes north-south through the parish's eastern end. (fn. 17) Various small lanes and tracks lead to isolated farms and neighbouring parishes.

The basic road pattern was similar in the 16th century, (fn. 18) and probably much earlier. The Harpsden valley in particular is likely to have been a very early communication route. In the Roman period it would have formed a natural way for inhabitants of sites at Harpsden Wood and High Wood to travel to and from the main Silchester–St Albans (Verulamium) road east of the river, either via a crossing at Henley or perhaps one closer to hand. (fn. 19) Certainly by the Anglo-Saxon period there was a landing place on the river at Bolney ('bullocks' hythe'), probably located at or near Beggar's Hole opposite the mouth of the Hennerton Backwater. The valley would also have linked Rotherfield (meaning 'cattle pasture') to the Thames, and may have formed part of a longer-distance route to Oxford and beyond along Knightsbridge Lane. (fn. 20) In this context an early north-south road to Henley also seems likely, and such a road almost certainly pre-dated the development of the town itself. (fn. 21)

The early landing place at Bolney probably declined in importance in the Middle Ages, especially as Henley grew into a major market and trans-shipment point from the 13th century. Nonetheless, there remained a rope-ferry across the river at Beggar's Hole in 1775, where the towpath switched from the Oxfordshire to the Berkshire bank. A house built for the ferryman in the late 1830s replaced an earlier shelter, but was in disrepair by 1868 and has since disappeared. A ferry boat operated into the 20th century. (fn. 22)

Changes were made to some branch routes in fairly recent periods. In the west of the parish Kings Farm Lane, which degenerates into an unmetalled track, was until the 19th century apparently a more significant alternative route to Rotherfield Peppard (via Dog Lane). (fn. 23) Further east, a road going south past the cemetery through Harpsden Wood to Shiplake was constructed at the beginning of the 20th century, as part of the Bolney Syndicate's building development plans. (fn. 24) Earlier tracks through the wood passed in a south-westerly and southerly direction. (fn. 25)

A daily carrier service to Henley and Reading mentioned in 1887 was still running in 1939 (except on Wednesdays), and by the 1920s the Reading-Henley bus service passed through the east of the parish. (fn. 26) A bus service through the village itself was started in 1935, but was subsequently discontinued because of under-use. (fn. 27) Letters were delivered from Henley in the 19th century, (fn. 28) and a sub-post office was established in a cottage next to the school c. 1900; it closed during the First World War but re-opened in 1933, continuing in a new location until after the Second World War. (fn. 29) Post-boxes were scattered around the parish. (fn. 30)

The inclusion of a small railway station on the Henley branch line at nearby Shiplake provided an important new transport link in 1857. The presence of the station had a strong impact on subsequent development in the south-east of the parish. (fn. 31)

Population

In 1086 14 tenants and four slaves were recorded on the Harpsden estate and 13 tenants and three slaves at Bolney. (fn. 32) The figures suggest a population of at least c. 160–80, (fn. 33) one of the highest in the area, although this is difficult to reconcile with what is known of the population in subsequent periods. As later, habitation was probably spread across the parish in scattered farmsteads and hamlets, but there must have been a larger population on the Bolney estate than later. (fn. 34)

Growth in the 12th and 13th centuries seems to have been very limited, and particularly in Bolney population may actually have declined. In 1306 there were only 11 taxpayers in Harpsden vill, and as few as eight in 1316 and 1327. (fn. 35) On Bolney manor a mere six tenants were recorded in 1322, and three taxpayers in 1327. (fn. 36) After the Black Death the poll tax of 1377 was levied on 41 individuals over 14 years of age, suggesting a total population of c. 75–90, perhaps less than half that of the late 11th century; only nine of them were assessed in Bolney, compared with 32 in Harpsden. (fn. 37) Even allowing for a heavy death toll from successive bouts of plague, these figures suggest little or no expansion after 1086. Perhaps the settlements here, like some others by the Thames, had already reached their full potential by the late 11th century, (fn. 38) and certainly further agrarian development seems to have been limited, despite the proximity of Henley. (fn. 39)

Population remained low, and probably fell further in the 15th century: in 1428 Harpsden was apparently one of three parishes in Henley deanery with fewer than 10 households. (fn. 40) Thirty-two adult males were listed in 1642, and 22 houses were assessed for hearth tax in 1662. (fn. 41) In 1676 there appear to have been about 80 adult inhabitants. (fn. 42) The birth rate generally exceeded the death rate in the late 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in the first half of the 17th century, but overall growth seems to have been slow, with only small numbers of baptisms and burials and, presumably, considerable emigration. (fn. 43) Rectors reported around 30 families in the 18th century. (fn. 44)

The number of baptisms increased from the 1770s, (fn. 45) but the population was still only 173 in 1801. It reached 238 by 1831, but further growth was limited and uneven: numbers fell slightly by 1851 (to 215), rose sharply to 261 ten years later, but then dropped, perhaps because of agricultural changes, from 260 in 1871 to only 226 in 1881. Levels of immigration and emigration seem to have been fairly high after 1841, and probably earlier. By 1901 there had been a small increase, with 256 people living in 51 houses, and rather more substantial growth followed in the early 20th century: by 1921 the population rose to 431 (104 households), reflecting house building on land sold for development by the Bolney Syndicate. Later growth was limited by lack of further substantial house-building, and in 2001 there was a population of 512 (191 households). (fn. 46)

Settlement

Modern settlement in Harpsden is located mainly in the far south-east near Shiplake, and along the road through Harpsden Bottom; in other parts of the parish there are only a few isolated farms and houses. (fn. 47) The overall pattern was apparently similar from the 16th to 19th centuries and probably in the late Middle Ages, with the important exception of the south-east: there, Bolney Court was virtually the only house before riverside villas and suburban homes began to appear in the 1900s. (fn. 48) Early medieval settlement may have been rather different, however, with a greater focus on the Bolney area than in any subsequent period before 1900.

Early Settlement

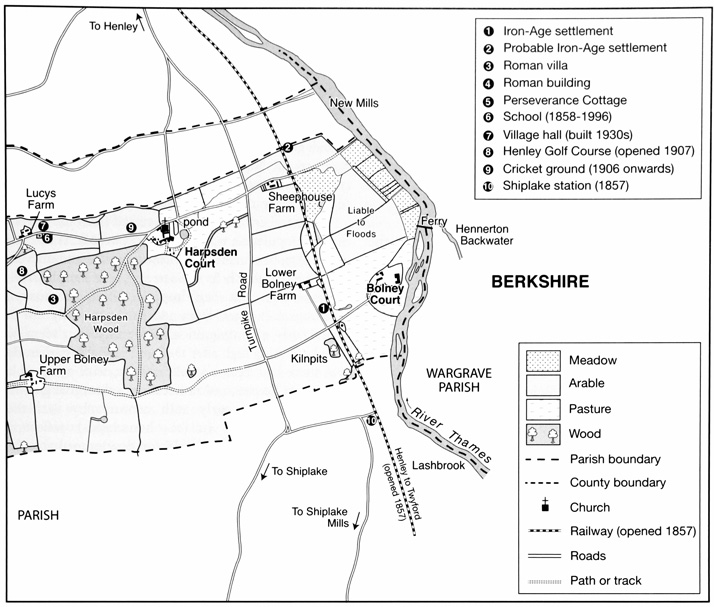

Neighbouring areas show signs of considerable Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, and Bronze-Age activity, and a number of Mesolithic flints have been found in Harpsden High Wood. (fn. 49) By the Iron Age (c. 700 BC to 50 AD) there is evidence of permanent settlement in the east, close to the river. On the parish boundary at the northern end of the floodplain, crop marks near Sheephouse Farm show a rectangular ditched enclosure, and possibly another enclosure to the north. (fn. 50) Excavations just over half a mile south near Lower Bolney Farm suggest a second settlement which was in use c. 400–100 BC, and which was perhaps abandoned because of flooding and alluvial deposition. (fn. 51) The Sheephouse Farm site may have been of similar date. Further south-west a hoard of 17 Gallo-Belgic coins (mostly minted c. 60 BC) were found in Harpsden Wood. (fn. 52)

Romano-British finds have been concentrated on the higher ground in and to the south of Harpsden Wood. A 90 m. x 60 m. site on the southern edge of High Wood appears to include the remains of a building (not certainly a villa) which shows evidence of occupation into the 4th century. (fn. 53) Half a mile north-east was a large winged corridor villa (60 m. long and 12 m. wide) near Harpsden Wood House, apparently occupied in the 3rd to earlier 4th centuries. This complex has not been fully excavated, but included a bath house; only low-status pottery was found, and no tessellated paving. (fn. 54) The antiquary Robert Plot reported that Roman coins were found near a small 'circumvallation' (rampart) in a wood south-west of Harpsden church, (fn. 55) but what connection (if any) this feature had with either site is unclear. Romano-British pottery and other materials have also been found near Mays Green, in the Harpsden valley, and close to Lower Bolney Farm. (fn. 56)

There is as yet no archaeological evidence for early Anglo-Saxon settlement in the parish, though there have been finds in Shiplake and other places nearby. (fn. 57) Given its fairly substantial Domesday population, Harpsden must have shared in the widespread intensification of farming (and presumably growth of settlement) in the 9th to 11th centuries. (fn. 58) The hythe at Bolney may have provided an early focus for settlement, and the establishment of the Harpsden and Bolney estates before the mid 11th century must have involved the creation of two separate estate centres, almost certainly on the sites occupied by the later manor houses at Harpsden Court and Bolney Court. (fn. 59)

Medieval and Later Settlement

Little is known about early medieval settlement in the parish, but Domesday population figures for both Harpsden and Bolney suggest that it was rather denser than later. (fn. 60) Bolney, with only two or three isolated farms after the Middle Ages, was apparently a more fully populated estate in the late 11th century, with only slightly fewer tenants than Harpsden; it had its own church (by Bolney Court near the river) until the mid 15th century. Given the location of the two manor houses and churches and the possible presence of common fields in the east of the parish, (fn. 61) it seems likely that a substantial amount of settlement was concentrated on the river gravels below the spring line, with scattered settlement in the Harpsden valley and elsewhere. (fn. 62) The probable economic and demographic decline of the Bolney estate suggests a reduction in settlement in the east and south of the parish during the Middle Ages, perhaps leaving a pattern similar to that in the more heavily wooded west.

By the late Middle Ages, settlement must have been everywhere very thinly spread. (fn. 63) The pattern of settlement in the parish's northern half was presumably similar to that shown on an estate map of 1586 (Plate 12): isolated farms at Upper House and Bottom House in the west; three more at Hunts Green in the Harpsden valley (the only area which might be called a hamlet); the rectory house; a farm at Lucys with a smallholding on the other side of the road; and Harpsden Court with its attendant farm. (fn. 64) Less is known about settlement in the southern (Bolney) part of the parish, but it seems likely that in the 16th century, as later, there were only a handful of scattered farmsteads: one at Bellehatch, one further east at Upper Bolney, and Bolney Court and its farm by the river.

Succeeding centuries brought only limited growth. A few cottages were built on strips of roadside waste in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, (fn. 65) including the surviving Perseverance Cottage at the junction north of Mays Green. (fn. 66) In the second half of the 17th century new farmhouses appeared at Sheephouse in the north-east of the parish, (fn. 67) and (probably) at Kings Farm in the north-west. (fn. 68) A number of labourers' cottages were erected in the 18th and earlier 19th centuries, (fn. 69) but even in the 1830s there were only 42 dwellings in the parish, some of them sub-divisions of single cottages. (fn. 70) In the second half of the 19th century a few new brick cottages and houses were built, mainly clustered around the school in the Harpsden valley; some other areas of settlement actually contracted, however, amongst them Hunts Green further west, which dwindled to a single farm. (fn. 71)

Twentieth-Century Development

The first decade and a half of the 20th century saw small-scale development by a group of businessmen, the Bolney Syndicate, who sold off building plots on land formerly belonging to the Bolney and Harpsden estate. (fn. 72) Around 20 mainly large new houses were built in three areas: in and to the south-east of Harpsden Wood, where the Syndicate constructed a new road; further east by the river south of Bolney Court; and in the Harpsden valley, mostly in a group north-west of Lucys Farm. (fn. 73) In most of the parish there was very little subsequent development. The exception was the far south-east, where new suburban houses continued to spill over from Shiplake along Northfield Avenue before the Second World War, (fn. 74) and later onto former nursery land to the east and across the railway line behind Bolney Road. (fn. 75)

The Built Environment

Harpsden, like neighbouring parishes, contains a variety of buildings of many periods, sizes and styles. (fn. 76) Sixteenth- to 19th-century farmhouses and country residences are thinly scattered throughout the parish. A few cottages and smaller houses of similar date are located mainly in a handful of loose groups in the Harpsden valley and at Mays Green near Bellehatch. Large modern houses in substantial gardens and more modest suburban homes are overwhelmingly concentrated around Harpsden Wood and the extreme east and south-east of the parish, close to Shiplake and the river. (fn. 77) The only surviving medieval buildings are the parish church, Harpsden Court and Hunts Farm, although some other farms and houses perhaps replaced medieval predecessors. (fn. 78)

The bulk of the present housing stock dates from the 20th century. A spurt of building before the First World War increased the number of houses from 55 in 1901 to 102 in 1921, and subsequent construction took the figure to 214 in 2001. (fn. 79) This growth was, however, very modest compared with that in neighbouring Greys and Peppard, and was brought about solely by speculative builders and private individuals. No council houses were built in Harpsden.

Country Residences and Farmhouses

The parish contains three surviving pre-20th-century gentlemen's residences: Harpsden Court, Bellehatch, and the former rectory (now the Old Rectory). (fn. 80) Otherwise the more substantial buildings erected before 1900 are all farmhouses. The earliest surviving is Hunts Farm (Fig. 58), the last remaining of three farmsteads shown at Hunts Green in Harpsden Bottom on a map of 1586 (Plate 12). The only extant cruck-framed house in the parish, it was built as a two-bay building probably in the 15th or early 16th century, and was enlarged with a two-bay box-framed eastern extension around the end of the 16th century, when it was held with 78 acres. The brick and flint frontage was presumably built when the house was altered to provide two separate labourers' dwellings in the later 19th century. (fn. 81)

Two other farmhouses, Bottom House and Upper House, date from the 16th century. Both are boxframed, perhaps replacing earlier cruck-framed houses similar to Hunts Farm. Bottom House (later called Old Place) was probably originally a two-bay hall house; an unusually fine roll-moulded spine beam in the hall reflects the resources of the tenant farmer, whose 133-a. farm was the largest on the Harpsden estate in 1586. (fn. 82) The house was much improved and extended in the 17th and perhaps early 18th centuries by the Pearman family, who ran a large holding which also included Upper House farm. Bottom House was extended in mock-Tudor style in the 20th century, while Upper House was encased and extended in brick in the 19th century, so that the original two-bay building and its three-bay early 17th-century timber-framed extension are all but invisible from the outside. (fn. 83) Other farmhouses are mainly 18th-century and later, although, apart from the late 17th-century Sheephouse and Kings and the late 20th-century bungalow at Perseverance Farm, they all replaced earlier buildings.

58. Hunts Farm at Hunts Green, a cruck-framed farmhouse of 15th or 16th-century origin. The brick and flint front dates probably from its conversion into labourers' cottages in the 19th century.

In the 17th and 18th centuries the expansion of crop production led to the construction, replacement and extension of many barns and other farm outbuildings. (fn. 84) The surviving 17th-century barns are mainly three-bay timber-framed structures on brick and flint plinths, including examples at Hunts Green, Upper House Farm, and Harpsden Court. Further barns, many of them larger five-bay buildings, were built in the following century at Lucys, Sheephouse, Upper Bolney, Hunts Farm, Kings, and Lower Bolney (where one of the two barns is date-marked 1750). A small granary on staddle stones at Upper House Farm also appears to date from this period. Later work on farm buildings was mainly confined to the extension and alteration of barns and outbuildings to provide facilities for cows and horses in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, although a granary was built at Bottom House in the earlier 19th century. (fn. 85)

Cottages

The earliest surviving cottage, on the crossroads at Perseverance Hill, is a timber-framed house of the early-to-mid 17th century, extended over the following 200 years. (fn. 86) Other cottages, mainly brick-built and dating from the 18th and 19th centuries, are located in Harpsden Bottom and in a group of six around Mays Green. One of the earliest is Old Rectory Cottage, built perhaps in the early 18th century on a narrow strip of land over the road from the rectory. Several of these cottages were apparently occupied by families involved at least part-time in craftwork, and Perseverance Cottage was used as a beer house in the late 19th century. (fn. 87)

Twentieth-Century Housing

Modern houses in Harpsden can be divided into three main types: grand detached residences in large grounds, suburban houses, and converted barns and outbuildings. Many of the larger houses were built before the First World War, including Harpsden Wood House (1908), Penbryn (1908–9), and Cray (before 1913). (fn. 88) These houses were handsomely equipped, and many included servants' quarters. A number were provided with separate lodges, of which some have been converted to substantial houses in their own right. One such is Harpsden Wood Lodge, formerly attached to Harpsden Wood House.

Probably the largest house of this period is Thames-Side Court, around which, in the late 20th century, Swiss financier Urs Schwarzenbach carried out extensive landscaping, including a model railway and an ornamental lake east of Lower Bolney Farm. (fn. 89) But perhaps the most interesting is the White House (1908), created by interior designer and architect George Walton for one of his major patrons, George Davison, head of European sales for Kodak. An innovative and unconventional house built on land formerly belonging to Bolney Court, this house-boat-style building with unusual curving balconies provided the wealthy Davisons with an ideal riverside summer residence at which to entertain the glamorous Henley set. (fn. 90)

Among the more unusual later residences was a long, low courtyard house called Cray Clearing, designed by Francis Pollen for his parents in 1963, but much altered after Pollen's death in 1987; it was eventually demolished in 1995. (fn. 91) Alongside the building of new houses and the often costly improvement and updating of existing ones, (fn. 92) the later part of the 20th century also saw the widespread conversion of barns and other farm outbuildings to domestic use, a development encouraged throughout the Chilterns by stringent planning regulations limiting new building. (fn. 93)

MANORS AND OTHER ESTATES

Eleventh-century Harpsden was divided between two estates: Bolney, an 8-hide holding stretching across the parish's southern part, and Harpsden, a 5-hide unit more typical of the area. (fn. 94) The larger number of hides accorded to Bolney is difficult to account for, since both estates were regarded as single knight's fees by the 12th century, and Harpsden manor comprised c. 1,020 a. in 1586 and probably in the Middle Ages; (fn. 95) of that, around 831 a. lay in Harpsden parish, 158 a. in Rotherfield Peppard, and 31 a. in Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 96) The two estates remained in separate hands until the mid 17th century, when Bolney manor (excluding Bolney Court and a small residual estate) was bought by the Hall family, owners of Harpsden. In the 1850s the reverse occurred when the Harpsden estate was bought by the Hodges family of Bolney Court. The combined estate was sold and broken up at the turn of the 20th century.

Harpsden Manor to 1650

In 1086 Harpsden, along with Eaton (Berks.) and a share of Harlington (Middx.), was held by an Anglo-Saxon called Alfred, who held from Miles Crispin. (fn. 97) Miles had apparently acquired these estates as part of his share of the lands of Wigod of Wallingford, the important king's thegn whose holdings formed the basis of the later honor of Wallingford. (fn. 98) Alfred was dead before c. 1106–8, when his son Roger granted tithes from Eaton to Abingdon abbey; (fn. 99) Roger died between the early 1140s and 1166. (fn. 100) A Roger son of Alfred who served on a jury as a knight of the honor in 1184 may have been a relative, (fn. 101) but by 1196 all three estates were held by Ralph of Harpsden. (fn. 102) The overlordship remained with the lords of Wallingford honor in 1501, (fn. 103) but was acquired by the Stonors before 1618, when Harpsden manor was held from their manor of Rotherfield Peppard in free socage for a £4 annual quitrent. (fn. 104)

The Harpsden family retained Harpsden, apparently their main residence, (fn. 105) until the mid 15th century, (fn. 106) despite forfeitures and legal challenges in the 1390s and early 1400s. (fn. 107) After the death of Sir John de Harpsden in 1438 (fn. 108) his widow Elizabeth married Sir Richard Lestrange, (fn. 109) and in 1444 the couple sold the manor to Humphrey Forster or Foster (d. 1488), later MP for Oxfordshire, for 500 marks (£333 6s. 8d.). (fn. 110)

From the early 16th century the Forsters lived mainly at Aldermaston (Berks.), where Humphrey's grandson Sir George (d. 1533) had acquired a substantial estate through marriage to Elizabeth de la Mare. (fn. 111) Rebuilding at Harpsden Court in the later 16th century suggests a plan to reside there more regularly, (fn. 112) but in the 1640s the Royalist Sir Humphrey Forster (c. 1595–1663) sold his Harpsden estate, apparently to repay debts on building work at Aldermaston and to provide for his younger children. Part was conveyed to Henry Gooding (or Goodwin) of Harpsden in 1642, and four years later Forster sold the manor and demesne lands to Sir Bartholomew Hall (d. 1677) for £5,000. In 1648 Hall bought Gooding's share for £1,750. (fn. 113)

Bolney Manor to 1650

In 1086 Bolney was held at farm from the king by Gilbert de Breteuil, having been held freely by three thegns before the Conquest. (fn. 114) Domesday Book, which lists the manor under Lewknor hundred, states that it formerly belonged to the fee of William FitzOsbern, earl of Hereford (d. 1071), whose son Roger forfeited his lands through rebellion in 1075. Gilbert, who was sheriff of Berkshire in the 1090s, has traditionally been identified as a follower of Earl William with origins in the FitzOsbern honor of Breteuil, (fn. 115) but he could in fact have come from any of the numerous Brettevilles in Normandy. (fn. 116)

Overlordship of Bolney may subsequently have been granted to Walter Giffard, 1st earl of Buckingham (d. 1102), who held land along the Thames from Caversham to Henley, and whose descendant and heir William Marshall was overlord in 1220. (fn. 117) After the division of the Marshall inheritance in 1245, the overlordship passed by marriage to William de Valence. (fn. 118) By the late 14th and early 15th century the overlordship was associated with the manor of Cassington (Oxon.), held by the Montagu earls of Salisbury. (fn. 119) The Columber family obtained a mesne lordship before 1242–3. (fn. 120)

The manor seems to have been held by William of Suleham in 1104, when he granted tithes in Bolney to Abingdon abbey. (fn. 121) William, who perhaps held Bolney through marriage, seems ultimately to have been succeeded by two daughters, possibly following the death without issue of his wife's sons by a previous marriage. (fn. 122) One daughter apparently married Robert son of Alan, who held three fees of the honor of Wallingford in 1166, (fn. 123) and who was succeeded by Ranulf son of Alan (or Ranulf Aleyn) in the early 13th century. (fn. 124) The other presumably married Maenfel of Bolney, (fn. 125) who was succeeded by his son Nicholas. Nicholas was dead by 1217, (fn. 126) when his share was divided between his daughters Alice and Margery, who respectively married Reginald of Whitchurch and Alan of Farnham. (fn. 127)

Reginald held a knight's fee in Bolney in 1235–6, and in 1237 he and Alice acquired Margery and Alan's rights in Bolney and Harpsden. (fn. 128) In 1242 they seem to have acquired most of the rest, when Ranulf Aleyn's son Walter of Bolney confirmed 3½ hides in Bolney and half the advowson to them and to Alan and Margery, retaining only half a hide. (fn. 129) By 1255, however, the re-united manor seems to have passed back to Margery and Alan, (fn. 130) presumably because Alice and Reginald had died without direct heirs.

The manor passed subsequently to Margery's daughter Juliana, who married John Elsfield, (fn. 131) and by 1312 Bolney was held by his son, Sir Gilbert Elsfield. (fn. 132) The Elsfields retained land in Bolney until at least 1401–2, (fn. 133) but the manor was acquired by Sir Hugh Segrave between 1363 and 1381. (fn. 134) In 1382 Sir Hugh sold it to Sir William Drayton, (fn. 135) whose son Richard sold it in 1460 to the Henley merchant John Elmes the elder. (fn. 136) Elmes, who died the same year, also acquired lands nearby, including in Lashbrook (Shiplake). (fn. 137)

Elizabeth Elmes of Henley, widow (presumably John's relict), held the manor in 1471, (fn. 138) and in 1508 it was in the hands of Anne Elmes, widow. (fn. 139) After her death Bolney remained with the Elmses until the mid 17th century, apparently passing to a branch of the family originally from Great Lilford (Northants.). (fn. 140) From the 1640s Humphrey Elmes (a gentleman of the privy chamber) and his son sold the manor piecemeal, (fn. 141) partly because of heavy delinquency fines imposed for supporting the king during the Civil War. (fn. 142)

The Combined Estate, c. 1650–1855

The Elmes family's sale involved a complex series of transactions beginning in 1641 and involving James Vickers, a London merchant tailor, Richard Andrews and Richard Lloyd, London girdlers, and, by 1663, Francis Warner and Henry Hall (1637–1700). (fn. 143) Through these arrangements Hall, whose father Sir Bartholomew already owned the Harpsden estate, obtained the manorial rights and the larger part of the Bolney estate (Upper Bolney), comprising c. 400 a.; the acquisition cost him £3,150. (fn. 144) On his father's death in 1677 he obtained Harpsden manor as well, giving him ownership of most of the parish. (fn. 145)

On Henry's death without children in 1700 his estate passed to his younger brother Bartholomew Hall of Barkham (c. 1639–1717). Bartholomew was succeeded by his son and heir Henry (of Stepney), who died in 1742 less than a month before his only surviving child Henry Warner Hall; the estate then passed to Henry's younger brother Bartholomew (d. 1747), and to Bartholomew's son Thomas (1720–93). Thomas's son Thomas died in 1824, and in 1855 his heirs sold the 1,456-a. estate (including manorial rights and 1,208 acres in Harpsden) to John Fowden Hodges of Bolney Court. (fn. 146)

The Bolney Court Estate c. 1650–1855

The Hall family's mid 17th-century acquisitions from the Elmeses excluded Bolney Court and c. 175 a. surrounding it. This residual Bolney estate, including parkland around the house and Lower Bolney farm, was bought by Richard Lloyd (d. 1659), whose cousin and executor Francis Warner bought out Lloyd's heirs. (fn. 147) The Warner family (which became related to the Halls by marriage in the early 18th century) leased and then sold the estate to Anthony Hodges (d. 1757), who owned slave plantations in the West Indies, and who purchased a considerable amount of property around Henley. (fn. 148) Hodges, who was resident by 1746, was succeeded by his son Anthony, high sheriff of Oxfordshire in 1759, who moved to St Kitts (in the West Indies) two years before his death in 1781. (fn. 149) Anthony's son, another Anthony, was mainly absent, and gained notoriety for allegedly prostituting his wife Anna Sophia (née Aston), whom he later divorced, to the prince of Wales and others. (fn. 150)

In 1799 Anthony died without (acknowledged) male children, and the entailed estate was inherited by his uncle Jeremiah Hodges (d. 1804). He sold the family's plantation on St Kitts to raise the mortgage which the first Anthony Hodges had taken out on their Oxfordshire and Berkshire property, which was worth c. £1,500 a year. (fn. 151) In 1813, after the early death of Jeremiah's son William, high sheriff of Oxfordshire in 1807, (fn. 152) the estate passed to William's brother-in-law, trustee and creditor Charles Green. It was recovered by William's younger brother Frederick Hodges of Henley in 1827, but remained heavily mortgaged. (fn. 153) After Frederick's death in 1843 the estate went to his nephew John Fowden Hodson (born 1815), eldest surviving son of Frederick's sister Sarah and her husband James Hodson, MP, of Holland Grove (Lancs.). On inheriting his uncle's estate John changed his name to Hodges. (fn. 154)

59. Guests at the wedding of Henry Hodges (elder son of J. F. Hodges of Bolney Court) and Eleanor Palairet, 8 August 1867. The photograph was taken at Harpsden Court, which the Palairets were leasing from the Hodges family. J. F. Hodges is on the back row (standing), sixth from right; his younger son John is seated (front right).

Manors from 1855

John Fowden Hodges's inheritance of his uncle's Bolney lands and subsequent purchase of the Harpsden estate in 1855 made him the major landowner in the parish. (fn. 155) He sold part of Bottom House farm to the Baskervilles of Crowsley Park in 1856, and Upper House, Hunts and other land in the west to Edward Mackenzie of Fawley Court in 1864, (fn. 156) but retained 1,465 a. in 1873. (fn. 157) The Hodges' new-found landed dominance was relatively short-lived, however, since John's sons Henry (d. 1907) and John (d. 1924) sold the estate piecemeal a few years after their father's death in 1894. (fn. 158)

The major purchasers from the Hodges' combined Harpsden and Bolney estates were James Rawlins and Emil Theodor, two London property developers, who acquired the manorial lordship along with Bolney Court, Upper and Lower Bolney farms and Harpsden Wood. (fn. 159) In 1906 they formed a syndicate called Bolney Estates Ltd with four local businessmen, and sold 75 a. for the construction of the Henley Golf Course. (fn. 160) The syndicate sold off the rest of its land in the parish piecemeal, retaining 575 a. in 1910 and disposing of the last of it only in the 1920s. (fn. 161)

Manor Houses

Harpsden Court

Harpsden Court, next to Harpsden church, was the residence of the lords of Harpsden manor from the Middle Ages to the mid 19th century. Now a private home, which lost its remaining farmland in 1975, (fn. 162) this small- to medium-sized country house represents the vestiges of a much larger complex, and incorporates elements from many periods. (fn. 163) Embedded in the middle of what is now the main range are remains of a thick-walled, tower-like medieval structure, which probably included a first-floor solar, and may have been fortified; architectural details suggest a late 12th- or 13th-century date. Possibly it was attached to a hall, of which no trace now remains. In the early 16th century the house was a 'large manor place with double courts', implying a collection of medieval buildings around upper and lower courtyards. (fn. 164) Traces of that arrangement survived in 1586.

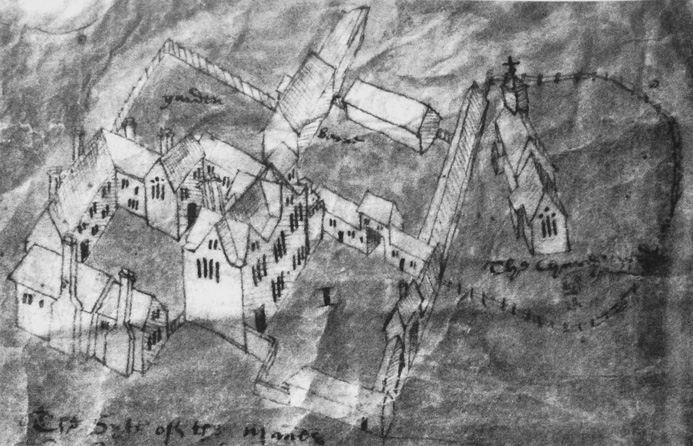

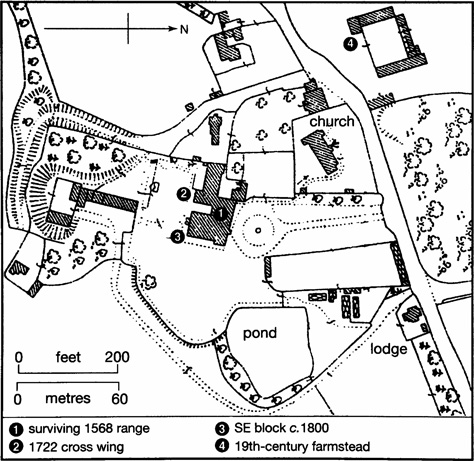

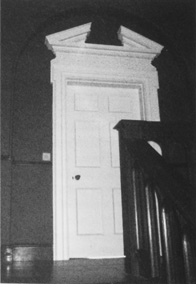

60. Harpsden Court. Top: John Blagrave's drawing of 1586 (north to the right), showing the church, the gabled range of 1568, and associated buildings. Above: surviving buildings in 1925. Top right: blocked lancet window, probably of a former solar. Bottom right: first-floor doorway to the domed music room. (See also Plates 12–13.)

Some rebuilding took place c. 1568, (fn. 165) when the tower-like building was incorporated into a two-storeyed, multi-gabled domestic range, very similar in size and appearance to that built at nearby Greys Court in the 1570s (Plate 15). A drawing of 1586 (Fig. 60) shows it with a substantial set of earlier buildings around a rear (south) courtyard; a smaller front courtyard had a gatehouse (set further back from the main road than the present gateway), and a farmyard was attached on the west. A detached dovecot stood over the road to the north. (fn. 166)

Harpsden Court was much altered by the Hall family thereafter. (fn. 167) Fourteen hearths were taxed in 1665, (fn. 168) and the 1568 range was extended in 1722 (fn. 169) when a gabled cross wing containing a new kitchen was added on the west. Further changes were made from the 1740s, including the construction of a walled kitchen garden to the north-east in 1744, (fn. 170) and the addition of a stuccoed Gothic frontage to the main domestic range, perhaps by Thomas Hall (1720–93) after 1747 (Plate 13). (fn. 171) Around 1800 two sides of a remaining courtyard (probably that at the rear) were demolished, (fn. 172) and a south-east block was added to the main range to provide up-to-date living accommodation. The importance of this extension was reflected in the (temporary) removal of the main entrance to the south of the house by the 1840s. A low service wing projecting westwards from the 1722 cross wing was added before 1842. (fn. 173)

After the Halls sold the estate in 1855 the farmyard and most of the agricultural buildings were replaced by a new home farm and barns over the road, (fn. 174) though the location of a now converted barn west of the church (date-marked 1689) suggests earlier changes to the farmyard shown in 1586. (fn. 175) Further additions and alterations were made in the later 19th and 20th centuries, mainly inside and at the rear of the house. (fn. 176) The two-storey front porch replaced a smaller predecessor, and is roughly contemporary with the stone entrance gateway and front wall at the end of the drive, erected by Leonard Noble in 1907. (fn. 177)

The house's interior contains a mixture of surviving early decorative work and eclectic Arts-and-Crafts additions. Much original late 16th-century panelling apparently remains in place, though in the hall and elsewhere on the ground floor many panels and other decorative features seem to be re-used pieces, resulting from early 20th-century work. The shallow-domed plaster ceiling of the highly decorated mid 18th-century music room (on the first floor) may have been designed by Thomas Hall's close friend, the Henley Congregationalist minister and engineer Humphrey Gainsborough (1718–1776). (fn. 178) Other features include an Edwardian servants' bell system and a 20th-century lift.

Bolney Court

The medieval manor house of Bolney was situated on an area of gravel by the Thames, its large site apparently surrounded by an artificial moat to prevent flooding. (fn. 179) The house had presumably been largely rebuilt or replaced before 1786, when the 'mansion house' at Bolney was described as brick, tiled and stuccoed, except for a small part of the eastern front which was lath and plaster. (fn. 180) This house, perhaps constructed by the Warners or by Anthony Hodges (d. 1757) and latterly known as Bolney Court, was largely uninhabited after 1813, and its ruin was demolished and replaced with a new mansion by John Fowden Hodges in 1852. (fn. 181)

This costly replacement house (Fig. 61) was a free-stone structure standing on arches, with a surrounding terrace and classical entrance portico. Its two floors included a library, smoking room, double staircase and 17 bedrooms. The house and accompanying walled kitchen gardens, stable-block and boathouse were approached by a tree-lined drive through a surrounding 70-a. park. (fn. 182) This in turn was replaced by a large Arts-and-Crafts house of brick and mock timber-framing (Plate 14), built for the merchant banker J. B. Gray between 1908 and 1911 to designs by the Scottish architect William Flockhart. (fn. 183) The house was modernized and reroofed in the 1990s, and in 2004 was sold with two lodges and 11 a. of garden for £7.5 million. (fn. 184) Part of the old stable block and other apparently 18th-century buildings to the north of the house survive as a separate residence called The Garden House. (fn. 185)

61. Bolney Court: the mansion house built by J. F. Hodges in 1852 and demolished c. 1908, on the site of the medieval manor house. From a sale catalogue of 1901.

Other Estates

A freehold called Bellehatch, in the south, was bought by the Towers family before 1567. (fn. 186) It had perhaps been separated from Bolney manor in the later Middle Ages, and may be identifiable with a half fee at 'Bolehicch' held by Joan, one of the two female heirs of William Elsfield (d. 1398), in 1401–2. (fn. 187) In the late 16th century the Towerses mortgaged the land to the Elmes family, and apparently sold it before 1663. (fn. 188) In the late 18th and early 19th century it was owned by resident families including the Alloways and Hanscombs, and c. 1831 it was acquired by Vincent Vaughan (d. c. 1840), apparently through his wife Mary; in 1842 it comprised 122 a. (fn. 189) Trustees of the Vaughan family retained it until c. 1915, when it was bought by Cecil Norton, a Liberal politician who became Lord Rathcreedan in 1916. (fn. 190) The estate was sold by his son in 1976 and split up. (fn. 191)

Part of the main house on the estate, Bellehatch Park, appears to be an early 19th-century country residence, with a Doric-style glazed central porch on the five-bay south-west front. The house's northern part, however, is considerably older, incorporating remains of a two-storeyed, probably late 16th- or early 17th-century farmhouse belonging to the Towers family (Fig. 62). (fn. 192) The brick coach house to the north was converted into a private residence called Bellehatch Farm in the late 1970s.

Several estates in neighbouring parishes incorporated lands in the west of Harpden from an early date. The lords of Crowsley (Shiplake) bought woodland and crofts from the Harpsdens, Elsfields and others as early as the 14th century. (fn. 193) The Crowsley Park estate sold 55 a. in Harpsden (Kings farm) to Thomas Piercy in 1802, and in 1842 retained 118 a. in the parish. (fn. 194) In the mid 1850s Henry Baskerville added part of Bottom House farm to the estate and recovered Kings and another 8 a. from the Piercys. (fn. 195) When part of the estate was sold in 1927, its Harpsden component comprised a 272-a. block west of Hunts Green, split into several lots. (fn. 196) The manor of Blount's Court in Rotherfield Peppard included land in the far west of the parish in the 17th century, of which 41 a. was sold by the Stonors to Henry Benwell the elder and Thomas Rolls in the 1680s. (fn. 197) The estate still included 81 a. in Harpsden in 1842, of which most was later sold to the Baskervilles. (fn. 198)

62. Bellehatch from the south-east, showing the timber-framed back wing. The house belonged to a sizeable freehold established by the 1560s, and possibly by the early 15th century.

The rectory estate comprised 102 a. in 1842 and probably by the 16th century, (fn. 199) concentrated around the rectory house and on a hill to the south. In 1857 c. 40 a. furthest from the house (the former Bolney glebe) was exchanged with J. F. Hodges for 35 a. closer by. (fn. 200) Some 63 a. was sold to Hodges in 1877, and a further small area to K. R. Mackenzie in 1907; the remaining 34 a. was sold with the rectory house in 1922. (fn. 201)

Some substantial but short-lived estates were created in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the later 19th century Edward Mackenzie of Fawley bought 360 a. in the west including Hunts and Upper House farms, mainly from the Hodges family. (fn. 202) In 1919 K. R. Mackenzie sold these lands to George Shorland, (fn. 203) a local farmer and land speculator, who made further acquisitions from the Bolney Syndicate and the Crowsley estate, including Lower Bolney, Upper Bolney, Sheephouse, Upper House, and Kings farms. The resulting 600-a. estate was sold piecemeal after Shorland's death in 1938. (fn. 204)

A smaller holding was created in the 20th century when the Phillimores of Coppid Hall, Binfield Heath (Shiplake), bought High Wood, part of Harpsden Wood, and farmland in the west of the parish. In the 1990s local financial support and a bequest helped the Woodland Trust to acquire the bulk of Harpsden Wood. (fn. 205)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

The varied geology and topography of the parish encouraged human exploitation from an early period. Iron-Age settlers on the floodplain were apparently engaged in grazing, woodland management and flax processing, (fn. 206) and the place-name Bolney suggests a continuing association with cattle in this part of the parish in the Anglo-Saxon period. The higher land around Harpsden Wood and High Wood seem to have supported at least one villa farm in the Roman period. (fn. 207)

From the late Anglo-Saxon period to the 20th century Harpsden's economy was dominated by mixed farming, with some diversification into wood production and fishing. Henley provided a nearby outlet for the marketing of cereals and other produce from the 13th century, but the town's presence does not seem to have encouraged significant agrarian development until the 16th century or later. (fn. 208) Craft activities and retailing were of very limited importance, presumably because of Henley's proximity. Agricultural and other employment declined in the mid to later 20th century as Harpsden became a wealthy dormitory community. (fn. 209)

Medieval Agriculture

The Structure of Farming

In 1086 the Bolney estate was said to have land for seven ploughs and was valued at £8; the Harpsden estate, with land for six ploughs, was worth only £5. (fn. 210) The disparity in value between the two estates had widened since the Conquest, when Harpsden had been worth £6. The reason is unknown, but did not straightforwardly relate to the amount of land being tilled or the availability of manpower: in 1086 both estates had six ploughs in operation, and Harpsden had 18 men compared to Bolney's 16. The organization of farming on the two estates seems to have been very similar, with the majority of land in tenant hands. Both manors had two demesne ploughs run by slaves (four at Harpsden and three at Bolney), and four other ploughs in the hands of tenants (12 villani and two lower-status bordars at Harpsden, and 11 villani and two bordars at Bolney).

The Domesday figures suggest that Bolney and Harpsden were among the more valuable manors in the immediate area, though this is difficult to reconcile with later medieval evidence. Neither estate appears to have developed very substantially, and Bolney manor in particular seems to have declined. Population levels, which were relatively high in the 11th century, seem to have increased little in Harpsden, and in Bolney may even have fallen. (fn. 211) In the 1250s the churches of Harpsden and Bolney were amongst the poorest in Henley deanery, suggesting that limited farming profits in these small parishes produced low tithe income. (fn. 212)

Harpsden manor seems to have emerged as the more valuable estate by the 14th century and probably earlier. In 1322 the Bolney estate was worth only £5 3s. 4d., (fn. 213) whereas in 1438 Harpsden was given a fairly high estimated value of £20 a year. (fn. 214) In part this was probably because Harpsden manor had grown in size while the Bolney estate had contracted. (fn. 215) But more fundamentally, the area which formed the core of the Harpsden estate seems to have had higher agricultural potential: in 1334, for instance, the inhabitants of Harpsden vill paid over one and a half times more tax than those of Bolney. (fn. 216) This contrast became even more marked after the Black Death, when the more numerous inhabitants of Harpsden paid three times as much tax as those of Bolney. (fn. 217)

In 1322 Bolney manor included 200 a. of demesne arable, presumably in poor condition since it was valued at only 2d. per acre. The manor house, located by the river, had what was probably a fairly large garden (worth 10s.), as well as 14 a. of meadow worth 2s. per acre, and inclosed pasture worth 4s. Presumably the Harpsden demesne was of similar size or larger. Bolney manor had just six tenants (four free and two unfree), paying rents totalling 18s. 8d. for an unspecified amount of land; the labour services of the unfree were worth a further 2s. 8d. (fn. 218) The probably more numerous tenants of Harpsden manor presumably also held by a mixture of free and customary tenancies. (fn. 219)

There is no direct evidence for how farmland was organized, but as elsewhere in the area it was probably divided between open fields and closes. The presence of open fields is suggested by the mention of yardlands as well as crofts: (fn. 220) possibly they were located mainly on the flatter land in the centre and east of the parish, though some of the large post-medieval fields there may already have been inclosed demesne fields by 1300. (fn. 221) Further west, many of the smaller, irregularly-shaped and thickly-hedged fields probably had their origins in closes created by woodland clearance, which apparently began before the 14th century and continued after the Middle Ages. (fn. 222)

The 14th and 15th centuries were a period of economic reorientation in Harpsden, as elsewhere. A tax inquest of 1341 reported economic problems, (fn. 223) and the population seems to have been at a low ebb in the 15th century. (fn. 224) By 1488 the value of Harpsden manor had apparently fallen to 10 marks (£6 6s. 8d.), considerably less than 50 years earlier. (fn. 225) These circumstances may well have encouraged the amalgamation of holdings by landowners and the more successful among the reduced number of tenants, creating larger units which formed the basis of many of the farms known from the 16th century. It seems likely, for example, that John Irland of Bolney, 'farmer', mentioned in 1433, was a demesne lessee, holding a large block of land. (fn. 226) Similarly, by the 16th century two thirds of the glebe comprised a single 60-a. holding worth £3 a year, which the rector converted to pasture in 1515. (fn. 227)

Land Use

Domesday indicates substantial arable cultivation in the later 11th century, while 28 a. of meadow provided hay for animals. (fn. 228) Meadow and grassland were presumably concentrated by the river as later. (fn. 229) There were probably large (unrecorded) areas of rough pasture and woodland, including Harpsden Wood and woods in the west and south, while the Thames must have provided fish and fowl. (fn. 230)

There is little evidence for land use in the 12th or 13th centuries, but arable farming certainly continued, and possibly expanded slightly through assarting, for instance around Hunts Green. (fn. 231) In 1326–7 corn from Gilbert Elsfield's lands at Elsfield and Bolney was valued at £20. (fn. 232) The contraction in population after the Black Death probably led to some reduction of arable and an increase in grazing, perhaps particularly on the demesne and glebe. (fn. 233)

The 16th to 18th Centuries

The Structure of Farming

By the 16th century farmland was held in inclosed fields divided into separate farms, most but not all of which included coppiced woodland as well. In 1586 Harpsden manor comprised c. 520 a. of demesne and woods, and a further 498 a. let to tenants. (fn. 234) The demesne, in the hands of a lessee, (fn. 235) formed a large block around the manor house, stretching from Harpsden Wood and Drawback Hill to the river, and including some land in Rotherfield Peppard and Rotherfield Greys to the north. The tenant land, in and around the valley to the west, was divided between seven farmers: William Wynch (136 a.); William Pearman (116 a.); Richard Symons (98 a.); John Wydmere (78 a.); Richard Nutkyn (32 a.); John Payse (31 a.); and Humphrey Symons (8 a.). Tenants' lands were generally arranged in compact blocks, and despite subsequent alterations in size and boundaries are recognizable as the cores of later farms: Wynch's as Bottom House farm, Pearman's as Upper House (then called Searles), Richard Symons' as Lucys, Wydmere and Payse's as Hunts, and Nutkyn's as the southern part of Harpsden Green farm. (fn. 236)

At Bolney the Elmes family seem to have also kept a sizeable block of land in hand in the 16th century, much of it probably around the manor house. Possibly it comprised up to half their estate, the rest of which seems to have been leased to one or two farmers: the Rockolds, for instance, held a large and valuable farm probably from the Elmeses. (fn. 237) The substantial rectory estate was similarly mainly let to a tenant. (fn. 238)

In the early to mid 17th century the part of Harpsden manor previously kept in hand was divided up and leased out, gradually coalescing into units known later as Harpsden farm, Sheephouse farm (partly in Rotherfield Peppard), and Greys farm (in Rotherfield Greys). (fn. 239) By the later 17th century the Bolney estate farmland in the south of the parish seems also to have been permanently divided into the large Upper Bolney farm and the smaller Lower Bolney farm. (fn. 240) As a result of these changes, many farmers in the later 17th and early 18th centuries leased holdings of over 100 a., among them the Pearmans, who held both Upper House and Bottom House farms. (fn. 241) Farm sizes seem to have increased further by the later 18th century, partly through continued assarting, but also because several tenants now leased more than one farm. (fn. 242) By 1788 there were 17 farms in Harpsden, including Blount's Court and Crowsley farms based in adjacent parishes. Edward Green held Upper Bolney farm (287 a.), the largest single farm in the parish; Thomas Piercy rented Harpsden Green, Sheephouse, Lower Bolney and the glebe farms (284 a. in all), while Daniel Piercy held Harpsden and Lucys farms (223 a.). James Hussey held Upper House farm (110 a.) and Blunster Grounds (31 a.), and John Butler Bottom House farm (110 a.), with a further 11 a. of his own. There were also one or two owner-occupiers, including Edward Allaway at Bellehatch farm (122 a.) and Matthew Chipps at Harpsden Green (33 a.). (fn. 243)

The 17th and 18th centuries were a time of prosperity both for the Halls of Harpsden Court (the main landowners) and the major tenants. (fn. 244) By the beginning of the 18th century the Harpsden estate was worth the sizeable sum of £950 a year, (fn. 245) and some of the more successful farmers were able to invest in improvements and extensions to their homes. (fn. 246) This growth was underpinned mainly by increasing productivity in cereal farming, especially in the second half of the 18th century. (fn. 247) Tenants also benefited from security of tenure and moderate rents: in the 17th and 18th centuries some farms were held by short commercial leases, but copyholds and long leaseholds for lives remained more common, for which tenants paid entry fines, heriots and nominal rents. (fn. 248)

The only vestige of communal organization was the management of grazing on greens and verges, and of grassland by the Thames. (fn. 249) Most meadow was still common in the late 16th century, except for one or two small inclosed pieces such as 'Winche meade' (5 a.), held by the lords of Harpsden. (fn. 250) In 1617 each 30-a. yardland in Bolney was allegedly entitled to 1½ a. in Shiplake meadow. (fn. 251) Sizeable areas of common meadow in 1788 included Harpsden meadow (16 a.) and Shiplake meadow, in which land was allotted in strips to the tenants of particular farms. (fn. 252)

Land Use

Sixteenth- and 17th-century tenant farming seems to have been based around sheep-corn husbandry, often supplemented by woodland exploitation. (fn. 253) Grain and sheep were the two most frequent bequests in wills, although little is known about the size of sheep flocks before the mid 17th century. Barley and barley malt were typically the most valuable single items, but farmers also grew wheat, rye, oats, hemp, peas, and vetches. Pigs were kept in higher than average numbers for a Chiltern parish, and most farmers also had some cattle for meat, cheese and milk, but there are no signs of large-scale dairying or cattle-breeding. (fn. 254) Farming on the two demesnes was probably similar, although given the large amount of grass in the east of the parish it seems likely that grazing was carried out on a larger scale than on the tenant farms. (fn. 255)

The later 17th and 18th centuries saw a considerable increase in cereal production, reflected by the building of new and bigger barns and separate granaries. (fn. 256) Larger crop yields seem to have been achieved through the expansion of arable by woodland clearance and cultivation of 'newly-broken ground', (fn. 257) while improved farming techniques included the introduction of new fodder crops and grasses. The number of sheep kept by tenants probably increased in the second half of the 17th century, with flocks of c. 50–220 animals. (fn. 258)

A survey of 1788 suggests that almost 80 per cent of the parish was under arable (including fallow and fodder crops), with only small areas of permanent pasture (66 a.) and meadow (73 a.); woodland covered an estimated 228 a. (13 per cent). (fn. 259) The main crop was wheat (just under 300 a.), followed by barley (over 270 a.), turnips (over 160 a.), oats (over 120 a.), and clover (over 100 a.), with lesser areas of grass, rye grass, peas, and vetches. Around 165 a. were planted with seeds (mainly grass), and 75 a. was fallow. The fodder, meadows and pastures supported around 1,070 sheep, many of them on Lucys, Sheephouse, Lower Bolney and Upper Bolney farms. Cattle herds, pastured in Bolney park and elsewhere, were apparently much smaller, and there were only 20 cows in milk. (fn. 260)

The 19th and 20th Centuries

The Structure of Farming

In the early 19th century the Halls of Harpsden Court appear to have considerably (and sometimes dramatically) increased rents, and more regularly adopted shorter leases, no doubt in response to increased profits from arable production on tenant farms during the Napoleonic wars. (fn. 261) Sheephouse farm, on gravelly loam close to Henley, provides an extreme example: here rent increased slightly from £140 a year in 1795 to £180 in 1801, but in 1811 the new tenant agreed to pay £500 a year for the same 153-a. farm, with vastly increased fines for bringing new land into cultivation. (fn. 262) This represented rent of 65s. an acre, at a time when the Oxfordshire average was estimated at 22s. 10d. (fn. 263)

The more substantial tenants seem to have prospered nonetheless, apparently weathering the post-Napoleonic depression: in 1825, for instance, rent for Upper Bolney farm (c. 300 a.) was increased from 22s. to 28s. an acre. (fn. 264) By the mid 1830s rents on the Harpsden Court estate seem to have fallen, (fn. 265) but in 1851 the estate was nonetheless described as 'very superior sound turnip and barley land', with long-standing tenants from among 'the higher class of agriculturalists, except on one or two smallholdings'. (fn. 266)

In 1842 most farmland was held from the Harpsden Court estate by a small group of farmers, of whom many held more than one farm. (fn. 267) William Workman leased a very large holding comprising Upper Bolney farm (301 a.) and Sheephouse farm (122 a.), (fn. 268) while Charles Sarney held Harpsden farm (109 a.) and Lucys (98 a.), Thomas Frewin Upper House (96 a.) and Bottom House (106 a.), and William Andrews Harpsden Green (52 a.) and Hunts (99 a.). Other sizeable farms included Lower Bolney (or Bolney Court) farm (174 a.), held by Charles Bullock, and the glebe farm, partly let to John Sedgwick. As earlier some farms were based in other parishes, and a handful of smaller holdings included the arable part of the Bellehatch estate, divided between James Beard (36 a. run from Dean Farm) and Richard Bullock (32 a.).

The pattern of tenure changed dramatically in the later 19th century. By 1861 John Fowden Hodges had taken over most of the farms on the Harpsden estate (acquired in 1855), and in 1881 he ran 1,150 a. directly, employing two bailiffs, 32 men and nine boys. (fn. 269) The motivation for his takeover is uncertain, but its timing, during a period of agricultural boom and high farming, suggests an interest in profits rather than difficulty in finding tenants. In 1873 the gross estimated rental value of his land was £2,195. (fn. 270)

The sale of the Hodges' estate in the very different circumstances of the late 1890s and early 1900s led to the break-up of this huge farm, though George Shorland rented large parts of it soon after, creating, for a time, a large farming concern of his own. From c. 1907 until the early 1920s he ran (and latterly owned much of) a holding which came to incorporate Upper and Lower Bolney, Upper House, Kings, Hunts and Sheephouse farms, comprising 848 a. in 1912. (fn. 271) The more typical farming units, however, both then and for the rest of the 20th century, were a group of c. 14–18 small and medium-sized holdings, most of them under 150 a. and a good number under 50 a., run by a mixture of tenants and owner-occupiers. (fn. 272)

By the early 1940s the quality of farming in Harpsden was mixed. Bellehatch park (87 a.) had a good dairy herd and was run by a capable foreman, but many other farms had for some time suffered from lack of capital or poor management by inexperienced, elderly or part-time farmers. (fn. 273) Several farms (including Bellehatch and Lower Bolney) ceased to function in the later 20th century, and by 1988 eight of the fourteen remaining holdings were run by part-time farmers, many apparently small producers. (fn. 274) In 2007 Lucys farm, run by a couple nearing retirement, was the only (small) dairy farm in the parish, while a beef unit run in sheds at Perseverance Farm was struggling to make ends meet. (fn. 275)

Land Use

From the 1830s to 1870s between 1,200 and 1,400 a. of land in Harpsden (c. 65–75 per cent of the parish) was arable. (fn. 276) In the 1860s wheat, barley and oats were grown in roughly equal proportions, with smaller areas of peas and beans; a substantial acreage was also used for turnips, swedes, sainfoin and clover. (fn. 277) Around 250–350 a. (13–17 per cent of the parish) was permanent grass for hay and grazing. Much of this was located in parkland, fields and 'capital meadows' close to the river, with a further 63 a. in Crowsley park in the west. Fodder crops and grassland supported large numbers of sheep (1,593 in 1866 and 2,034 in 1869), (fn. 278) and several men and boys were employed as shepherds. (fn. 279) Pig-keeping was also important, but cattle herds were small.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a major shift towards dairy farming. (fn. 280) In 1869 108 cows were kept in the parish (58 of them producing milk), but by 1896 there were 336 including 205 in milk. (fn. 281) The change was at first even more pronounced than in most neighbouring parishes, and led to considerable investment in dairies, and alteration of barns and outbuildings to include troughs, cow-stalls and drainage passages. (fn. 282) By the 1920s one or two farms seem to have specialized in poultry-keeping, notably Kings Farm. (fn. 283)

The increasing emphasis on dairying was accompanied by a reduction in arable and sheep numbers (to only 537 animals in 1896), and by a big expansion of the area under permanent grass: from 409 a. in 1885 to 1,021 a. in 1907. (fn. 284) Most farms remained largely under permanent grass into the mid 20th century. (fn. 285) In 1906–8 a 105–a. golf course was created in the middle of the parish, mainly on land belonging to Upper Bolney farm; it was initially still used for sheep grazing (to crop the fairways), and 20 a. was ploughed up during the First World War. Thereafter it largely went out of agricultural use, apart from a period as a cattle pasture during the Second World War. (fn. 286)

In the later 20th century the proportion of arable was increased as elsewhere across lowland England, especially for barley and fodder crops. The total area of farmland was declining, however, and in 1967 only 950 a. in the parish remained in active use, compared with 1,434 a. in 1896 and 1,133 a. in 1957. Beef cattle became more important than dairy cows, and other livestock continued to be kept, but from the 1920s there were few if any sheep. (fn. 287)

Woodland Exploitation

Timber was a valuable resource for building work and farm repairs, used both within the parish and in nearby Henley; (fn. 288) c. 1700 that on the Harpsden Court estate was worth around £400–£500. (fn. 289) The town was also a major market and trans-shipment point for fuel wood, (fn. 290) and a sizeable area of woodland in the parish (including over 100 a. on the Harpsden estate in 1586) was managed as coppice in the 16th century and probably earlier. (fn. 291)

From the 16th to 18th centuries landowners apparently managed some coppices directly and leased out others. The tenants were mainly local farmers, (fn. 292) but larger areas were sometimes let to specialist craftsmen, like the Shiplake hoop-maker who took on Highwood and Windmillfield coppices (36 a.) in 1665. (fn. 293) Leases were for variable periods, often 21 years, with cutting-cycles of seven to nine years. (fn. 294) At the beginning of the 18th century the Harpsden Court estate included the large Harpsden and Bolney coppice, worth £70 a year, and five other smaller coppices were let to tenants, bringing in a further £29; four of the tenants had paid entry fines of between 19s. and £12. (fn. 295) In the late 18th century the wood cut from an acre had an average sale value of c. £8. (fn. 296)

The extent of coppiced woodland apparently decreased during the 18th century, partly through woodland clearance, (fn. 297) but also in response to reduced demand for firewood. (fn. 298) By the 1790s there was reckoned to be only c. 30 a. of coppice woodland under 20 years of age on the Hall estate and the glebe, (fn. 299) and the 42 a. of coppice in 1842 represented only 14 per cent of the total wooded area. (fn. 300)

Thereafter woodland remained valuable for beech and oak timber (which was occasionally sold), (fn. 301) for game-keeping, and for its aesthetic appeal to potential purchasers of country estates and houses. (fn. 302) But there is no evidence in Harpsden of systematic management of timber to supply the furniture trade, or of local bodgers working in the woods.

Non-Agricultural Activities

Fishing

The Thames presumably provided fish from the earliest times, and in 1322 Bolney manor had a private fishery worth 6s. 8d. a year. (fn. 303) The continued importance of fishing is suggested by the presence of a weir in the Bolney backwaters in 1585 and by later leases of fishing rights; (fn. 304) in the 17th and 18th centuries a few men were apparently occupied as fishermen on a full-time basis. (fn. 305) The river probably also provided a licit or illicit source of wildfowl. (fn. 306)

Rural crafts and industry

In the 19th century and probably earlier, involvement in crafts and industries seems to have been much more limited in Harpsden than in other rural parishes in Binfield hundred. (fn. 307) There is little medieval evidence, although some people (mainly women) brewed and sold ale. (fn. 308) A basket-maker and a bricklayer were mentioned in the 1610s, (fn. 309) and in the 18th century and perhaps earlier craft activities were carried out in a few cottages in the Harpsden valley. (fn. 310) The name Kilnpits Wood may indicate a former kiln site or a pit for digging materials in the far south-east of the parish. (fn. 311) A blacksmith was operating in 1785, (fn. 312) and for a time in the mid 19th century there were smithies at Dean Farm and Lucys Farm, the latter briefly re-established in the early 20th century. (fn. 313) In the 19th and early 20th century a handful of people were involved in carpentry, dress-making and shoe-making, (fn. 314) and as late as the 1980s an inhabitant made traditional besom-brooms in a small workshop. (fn. 315)

Retailing and other businesses

Locals seem to have done most of their shopping in Henley, (fn. 316) though a beer house in Perseverance Cottage from c. 1860 to the late 1880s evidently sold a few items. (fn. 317) A small shop was run from the sub-post office in the early 20th century, and a short-lived village store opened in the 1960s. (fn. 318) A plant nursery was established on the Reading road in the early 20th century, (fn. 319) and in the 1920s several other small businesses included a boat-hire and boat-building firm at the Bolney Boat House, where a wireless dealer also set up shop. There were also several small building and decorating firms. (fn. 320) In the later 20th century the nursery was succeeded by a Wyvale garden centre, and a handful of other small businesses were established elsewhere in the parish. (fn. 321)

SOCIAL HISTORY

Before the 20th century the population was overwhelmingly agricultural. Dispersed settlement based around isolated farmsteads probably discouraged a close sense of community, and many locals were apparently drawn towards the life of settlements outside the parish, especially Henley and Shiplake. In the Middle Ages religious loyalties were divided between two separate parishes, while in the post-medieval period the single remaining church was distant from those living outside the Harpsden valley. Mainly resident landlords probably exerted some social influence, but the Hall family's Nonconformity limited the integration of church and manor. (fn. 322) In the early 20th century the area near the school became more of a centre for social life; by then, however, the character of the population was already starting to be transformed by suburban growth and an influx of wealthy commuters and retired people.

Social Structure before 1800

Resident Gentry and Clergy

For most of the Middle Ages the lords of Harpsden manor seem to have lived in the parish, while the lords of Bolney were likewise either resident or frequent visitors. (fn. 323) The Harpsdens, Elsfields and Forsters were all wealthy gentry families, who were often involved in local government and enjoyed close links with neighbours such as the Stonors, to whom the Forsters became related by marriage in the early 15th century. (fn. 324) The mercantile Elmes family who acquired Bolney manor in the mid 15th century were of rather more modest social standing, but they too had ties with the Stonors and others. (fn. 325)

For most of the 16th and earlier 17th century the Elmes family were the only resident gentry. (fn. 326) In 1525 Humphrey Elmes was the joint-fourth highest taxpayer in Binfield and Langtree hundreds, and with Sir Walter Stonor of Blount's Court one of only two resident gentlemen. (fn. 327) By the later 16th century, however, the Elmeses seem to have been in financial difficulties, (fn. 328) and after they sold their Bolney estate in the mid 17th century the Hall family assumed their position as the main resident landowners. Bartholomew Hall (d. 1677) was a senior Middle Temple lawyer and a friend of Bulstrode Whitelocke of Fawley and Phyllis Courts. His son and heir Henry (1637–1700), who continued the family's legal tradition, became high sheriff of Oxfordshire in 1671, and later family members lived in some style at Harpsden Court as country gentlemen. (fn. 329)

From the 1660s to 1740s Bolney was the residence of the London alderman Francis Warner and his descendants. (fn. 330) The Hodges family, who followed them, seem to have kept slaves from the family's West Indies plantation as servants at the house. (fn. 331) The notorious Anthony Hodges (d. 1799), who succeeded his father in 1781, lived mainly elsewhere, and from 1787 Bolney Court was leased to various well-to-do tenants, including Dame Elizabeth Taylor and Josias Jackson, both formerly resident in London. (fn. 332)

From the amalgamation of the Harpsden and Bolney benefices in the mid 15th century most rectors, too, seem to have been resident, living in some comfort at the rectory in the Harpsden valley. The combined living was a good one with a large glebe, and by the later 17th century a number of rectors seem to have been from wealthy and well-connected backgrounds. Hugh Boham (rector 1662–87) bequeathed the huge sum of £6,000 to his two daughters, (fn. 333) of whom one married Thomas Lamplugh (a son of the bishop of Exeter) in Harpsden church in 1686. (fn. 334) Miles Stapleton (1690–1731), who was perhaps responsible for rebuilding the rectory, was described by the antiquary Thomas Hearne as 'very rich', and amassed an impressive book collection. (fn. 335) Thomas Leigh (1731–64) was a younger son of a well-established family and married well, (fn. 336) while Edward Ernle (rector 1764–87) inherited his brother's baronetcy in 1771. (fn. 337)

The Farming Community

The great majority of the population were tenant farmers and labourers. During the Middle Ages there were already some social distinctions among them, reflected in free and unfree tenure and above all in the size of their holdings. William of Harpsden, the lord of Harpsden manor, paid 8s. 8d. tax on his moveable possessions in 1306, while two other men paid 3s. and 2s. 11d. respectively. Another eight people in Harpsden vill paid between 4d. and 16d., (fn. 338) with others probably too poor to be assessed. By the 16th century the gap between a few better-off tenants and the rest of the population may have increased. In 1524 John and William Rockold paid £26 13s. 4d. and £18 respectively, while four others paid between £6 and £10, and another six between £1 and £3 6s. 8d. Eight of these men were assessed on goods and four (presumably labourers) on wages. (fn. 339) Mid and later 16th-century assessments imply a possibly narrower range of wealth, but a clearly discernible one nonetheless. (fn. 340)

Seventeenth-century probate records suggest a group of around half a dozen yeoman farmers living in modest prosperity. (fn. 341) Most left moveable goods (chiefly crops, animals and farming equipment) worth between £150 and £300, (fn. 342) which was fairly typical for the area. One or two were very comfortably off, notably Henry Champion, whose possessions were valued at over £623 in 1684 (mostly in farming stock). (fn. 343) Absentee farm tenants included the Henley maltster Solomon Sewen (d. 1631), (fn. 344) but most farmers lived in the parish, (fn. 345) and the more successful seem to have rebuilt, extended or improved their houses in the 17th and 18th centuries, (fn. 346) while some, like Champion, kept one or two domestic servants. In 1785 three members of the Piercy family occupied holdings which together accounted for 54 per cent of the parish's total land tax assessment. (fn. 347)

Below the leading yeoman families were a small number of husbandmen of more modest means, who left goods worth between £10 and £100. (fn. 348) A handful of fishermen and small-scale craftsmen fell into a similar category. (fn. 349) At the bottom of the social scale were those labourers and others too poor to make wills, the kind of people who received handouts at Anthony Elmes's funeral in 1574, and whom Richard Lucy had in mind when he left a £10 charitable bequest in the 1670s. (fn. 350) Their numbers probably increased with the intensification of farming in the 18th century. Many labouring families apparently had no holdings of their own, and were perhaps fairly short-term residents.

Social Structure in the 19th Century