A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Henley: Religious History', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp159-183 [accessed 10 May 2025].

'Henley: Religious History', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online, accessed May 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp159-183.

"Henley: Religious History". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online. Web. 10 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp159-183.

In this section

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

A church was founded in Henley presumably at or before the laying out of the planned town. By c. 1200 it had its own rector and endowment, and apparently exercised full parochial rights. By the mid 13th century it was also the centre of the surrounding rural deanery. The benefice remained a rectory, and in the late 20th century was combined with that of Remenham.

Medieval religious life revolved around the institutions and rituals typical of a small trading and market town. By the later Middle Ages the church contained numerous side chapels, lights, and chantries, two of them administered by the town guild, and a separate religious fraternity was established probably in the late 15th century. Popular rituals in the early 16th century included a Resurrection play and Corpus Christi procession, both possibly of relatively recent origin. The late medieval clerical establishment appears to have been large, though not all medieval rectors resided, and some day-to-day pastoral care devolved upon stipendiary chaplains.

Lollardy was recorded in the town from the mid 15th century, associated with an intricate Lollard network focused on the Amersham area of south Buckinghamshire. The town as a whole seems not, however, to have embraced the Reformation with any particular enthusiasm, and with one or two exceptions most late 16th- and early 17th-century rectors held relatively moderate views. The Civil War and Interregnum nevertheless saw both the appointment of a Presbyterian rector and a sustained Parliamentary presence in the town, and by the 1660s the Chilterns as a whole were one of the chief focuses of Nonconformity in the county, attracting former Parliamentary soldiers and ejected radical ministers. An Independent meeting established at Henley remained a permanent feature of the town's religious life, evolving into a respected Congregationalist church supported by traders, farmers, and gentry from both inside and outside the parish. Smaller Quaker, Wesleyan, and Baptist meetings followed, although Nonconformity seems never to have dominated Henley as it did some other Oxfordshire towns. Certainly in the mid 19th century, overall attendance at its two Anglican churches (fn. 1) still exceeded that at the various meeting houses.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries the quality of pastoral care was, by contemporary standards, generally adequate, thanks to moderately conscientious resident rectors and some dynamic Congregationalist pastors. (fn. 2) Tensions over the introduction of High Church practices in the mid 19th century were overcome, and from the 1880s all of Henley's denominations (whether Anglican or Nonconformist) benefited from a reinvigoration of religious life typical of the period, reflected in the establishment of new Baptist and Roman Catholic congregations, and a revival of the ailing Quaker meeting. Religious fortunes during the 20th century were predictably more mixed, though the variety of the town's religious life survived into the early 21st century, when six separate denominations retained places of worship. (fn. 3) No non-Christian religious institutions were established.

Parochial Organization

St Mary's Parish Church

During the late Anglo-Saxon and early Norman periods the Henley area, as part of the royal manor of Benson, seems to have remained subject to Benson church. Local churches were becoming established by the 12th century, and that at Henley may have pre-dated the town's foundation. (fn. 4) No unequivocal evidence survives before c. 1200, however, when Henley church was in the Crown's gift. (fn. 5) As late as 1279 it was claimed (with Warborough and Nettlebed) as a chapelry of Benson, (fn. 6) but by the early 13th century it was effectively independent, with its own endowment, rector, advowson, and (apparently) burial and baptismal rights: a consequence, presumably, of the pastoral requirements of the new town, and perhaps of the church's origins as a Crown foundation. (fn. 7) By then it had also given its name to the surrounding rural deanery, which seems earlier to have been known as the deanery of Chiltern or of Stoke. (fn. 8) The dean's seal, which depicted an angel probably in reference to the Annunciation, (fn. 9) reflected Henley church's dedication to the Virgin, which was recorded from the late 13th century. (fn. 10)

40. Seal matrix of the rural dean of Henley, c. 1200.

Advowson

The advowson was evidently excluded from the Crown's grant of the manor to Robert de Harcourt in 1199, although King John agreed to the presentation of Harcourt's son Aumary, a royal clerk, (fn. 11) and in 1223 Henry III bestowed the right of presentation for that turn on his associate Peter des Roches, bishop of Winchester. (fn. 12) Thereafter the Crown retained the advowson until c. 1244, when Henry III gave it with Henley and Benson manors to his brother Richard, earl of Cornwall. (fn. 13) Richard's son Edmund gave it in exchange in 1287 to the bishop of Rochester, (fn. 14) whose successors remained patrons until 1852 when the advowson was vested in the bishop of Oxford. The bishop of Oxford's successors remained joint patrons of the united benefice of Henley and Remenham in the early 21st century. (fn. 15) Archbishops of Canterbury collated in 1361 and 1405 during vacancies of the see of Rochester, (fn. 16) and lay people presented in 1554 and 1784 following one-off arrangements with the bishop. (fn. 17)

Endowment

Though Henley was among the better-off benefices in the deanery, it was by no means the wealthiest. In 1254 the rectory was valued at £10 a year, the same as Mapledurham and Caversham but less than North Stoke, while in 1291 it was valued at £13 6s. 8d.: less than several churches in neighbouring Aston deanery, and still below North Stoke (over £21) and Caversham (over £16). (fn. 18) In the early 16th century gross income was reckoned at between £21 and £30, from which stipendiaries had to be paid. (fn. 19)

The rector's income came almost entirely from tithes, including full or half tithes from 32 a. of arable and 8 a. of meadow in Rotherfield Greys parish, just south of the town. (fn. 20) Possibly those tithes reflected realignment of the parish boundary at the town's creation, which left the southern side of Friday Street within Rotherfield Greys parish. (fn. 21) In the 17th and 18th centuries the tithes were sometimes leased, (fn. 22) though in the early 19th century the rector still seems to have collected many of them in kind. (fn. 23) The only glebe, other than the rectory house grounds, was an acre of arable in Rotherfield Greys adjoining the Reading road, and an acre or half-acre of former demesne meadow near Phyllis Court, granted before 1296 by Edmund, earl of Cornwall, in recompense for 2 a. of glebe taken into Henley park by his father Richard. (fn. 24) The meadow was disposed of after 1845, and the Rotherfield Greys land in 1885, the proceeds to be invested; (fn. 25) the tithes from Henley were commuted in 1845 for rent charges totalling £482, and those in Rotherfield Greys for rent charges of £18, which in 1849 were transferred to the new church of Holy Trinity on the town's southern edge. (fn. 26) Total income in 1852 was still over £420, but tithe rents were reduced by agricultural depression, and in 1896 net income was little more than £240. (fn. 27)

41. Henley waterfront in 1827, showing (centre) the early 18th-century house acquired as a rectory the previous year; the earlier rectory house lay behind. On the right is the Angel on the Bridge, with (beyond) part of the Red Lion.

Rectory house

An extensive rectory-house curtilage, just south of the church between Hart Street and Friday Street, was established by the 1240s, on land possibly given by the Crown at the town's creation. (fn. 28) A medieval hearth excavated some way south of the Hart Street frontage yielded 13th- and 14th-century pottery and utensils, and presumably marks the site of the early house. (fn. 29) Eastwards, the site was bounded by granaries and other buildings fronting the Thames, while northwards a path led from the rector's hall to a gateway into Hart Street; a south gateway into Friday Street seems to have been established around 1305, when the rector extended the site through piecemeal purchases. The site was bisected by the small stream which formed the later town ditch, and which fed a fishpond near Friday Street's east end. The fishpond was acquired by the rector also in the early 14th century. (fn. 30)

The medieval rectory house appears to have been succeeded by a later building a little to the north-east, which in the 18th and early 19th century included a two-storeyed block opening eastwards towards Thameside, and an abutting two-storeyed range on the west. The house was on two levels, and was probably of at least two builds. Rooms included an entrance hall, pantry, and parlour, four small upper rooms (one 'within the other'), a wine and coal cellar, and kitchen and offices; to the west was a garden, and to the south-west a large tithe barn, stabling, and yards, all entered from Friday Street. (fn. 31)

Repairs were carried out in the 1780s, (fn. 32) but thereafter the house was occupied only by curates. (fn. 33) By 1826 it was considered so inadequate that the rector, James King, bought an adjoining house fronting the river as a private residence, offering to annexe it to the rectory in return for materials from the existing rectory house. The old house was demolished by 1827, and King's house (Fig. 41), with its smart 18th-century river frontage, was formally annexed three years later. (fn. 34) A small garden, stable, and coach house to the south were separately acquired in 1852, following a purchase from the then rector's uncle the Revd Deacon Morrell. (fn. 35) Much of the ancient curtilage was sold in 1925, and c. 1961 the house was divided, its southern part (including the former coach house) being separated from the rectory. (fn. 36) In 1979 the house was sold, to be superseded by a rectory house in Blandy Road and (later) in Hart Street. (fn. 37)

Holy Trinity Church and Chapelry

The district chapelry of Holy Trinity was created in 1849, to serve the largely labouring population of the suburbs developing along Henley's southern edge within Rotherfield Greys parish. (fn. 38) The church, south of Greys Hill (and so outside Henley parish), was consecrated in 1848, with an endowment comprising £1,000 invested in land and stock, £18 tithe rents in Rotherfield Greys (formerly payable to the rector of Henley), £50 a year to be charged on the rectory of Rotherfield Greys, and 2½ a. of glebe bought from Henley corporation, which included the sites of the church and graveyard and of a newly built vicarage house to their south. The benefice was a perpetual curacy to which the rector of Rotherfield Greys had the right of nomination, though the first two nominations were reserved to the bishop; by the later 19th century the incumbent was regularly styled vicar. The cost of establishing the district was met from general subscription supplemented by grants from the Incorporated and Diocesan Church Building Societies, (fn. 39) but in the 1890s endowments and surplice fees together produced net income of less than £55 a year, and the salary of an assistant curate was raised separately by subscription. (fn. 40)

The ecclesiastical district extended northwards to the town ditch, encompassing both sides of Friday Street, suburbs in Rotherfield Greys' eastern part, and a few houses in Rotherfield Peppard. (fn. 41) It remained a separate parish in the early 21st century, with the rector of Rotherfield Greys as patron. (fn. 42)

Religious Life

The Middle Ages

Rectors and clergy

As might be expected of a benefice under Crown and episcopal patronage, Henley attracted several careerists and pluralists, including some university graduates. (fn. 43) Aumary de Harcourt, presented by the Crown c. 1204, was a royal clerk, (fn. 44) while Master Stephen de Lucy, collated in 1224, was perhaps related to the chancellor of Oxford University. (fn. 45) Thomas de Hethe (rector 1327–31) and Master Nicholas North (1337–40) were clerks and commissaries of their patron the bishop of Rochester, who was also Hethe's uncle. (fn. 46) Several other 14th-century rectors had Kentish connections and exchanged benefices frequently, holding Henley only briefly, (fn. 47) while John de Gurmecestr' (1351–6) was a clerk of the Black Prince, who in 1355 presented him to an additional benefice in Cornwall. (fn. 48) Among later rectors, Master Edmund Bekyngham (1405–16) was licensed to study soon after his institution, (fn. 49) and from the 1450s to 1530s most rectors were graduates who held Henley with benefices in other counties. (fn. 50) Some may have resided occasionally, particularly given their Oxford University connections: thus Peter Vasor (rector 1483–1510) was overseer of some local wills between 1499 and 1503, and in 1502 attended a town hearing concerning theft of church plate. (fn. 51) Like his successor Nicholas Metcalfe, however, he chose to be buried at one of his other churches. (fn. 52) Henley's most eminent churchmen included John Longland, a native of the town who appears to have briefly held the rectory before his election as bishop of Lincoln in 1521, (fn. 53) while his successor John Stokesley, rector 1521–30, became bishop of London. (fn. 54)

Henley was not, however, a sufficiently wealthy benefice to attract such figures consistently. In all, only a third of the rectors documented between 1200 and 1530 are known to have been university graduates, and some of the less well-qualified incumbents may have lived permanently at Henley, and in some cases stayed for life. Henry de la More, rector 1247–?82, perhaps belonged to an Oxfordshire family with land at Northmoor, (fn. 55) while John de la Kerson or Kersoner (1291–1311) extended the rectory-house site and, by his will, left small bequests to the churchwardens or bridgemen. (fn. 56) Adam de Elyngton, rector from 1361 until his death in 1405, was the longest serving medieval incumbent, and perhaps the scribe of several local documents, (fn. 57) while William Brightwell (rector 1416–?43) was apparently resident in 1417 and 1421, and was executor to a local woman. (fn. 58) His successor John Say (1443?–1447) was involved in local property transactions, and paid a generous pension to his then aged and blind predecessor. (fn. 59)

Much of the day-to-day pastoral care may nevertheless have devolved on assistant clergy and chantry priests, who appear to have been numerous. (fn. 60) Some of the chaplains and clerks witnessing medieval property transactions (fn. 61) may have assisted at the church, and from the early 15th century several were expressly called parish chaplains: in 1413 one was appointed penitentiary for Henley deanery, while others witnessed local wills and served in varying capacities. (fn. 62) Probably typical was Thomas Shilborne, who, after several years as parish curate and as a proctor for the Fraternity of Jesus, was appointed in 1508 to St Catherine's chantry, though he continued to help with Easter processions and presumably other parish duties. (fn. 63) By then, including chantry priests, there were at least five full-time chaplains besides the rector, and probably numerous clergy in lesser orders: two salaried assistant clerks were mentioned in 1481, and in 1519 holy-water clerks were expected to assist priests both at the altar and when visiting parishioners. (fn. 64) Obits and funerals swelled the numbers of casually employed chaplains: a testator in 1541 provided for five priests and two clerks to celebrate his obit, while Jane Stonor's funeral in 1494 was to be attended by 31 priests. (fn. 65) Four priests' chambers in the churchyard (presumably for chantry priests) were mentioned in 1552, though their association with the so-called Chantry House along the churchyard's east side is probably mistaken. (fn. 66)

Relations between parishioners and clergy seem generally to have been good. In 1502 a tithe dispute between the rector and Thomas Hales of Phyllis Court was referred to the papal courts, (fn. 67) and in 1530 the curate was warned to break off relations with a local woman who allegedly visited his chamber, and whom he had appointed tithe collector. (fn. 68) Otherwise the clergy's regular appearance as witnesses, the laity's numerous religious bequests, and the guild's close involvement in the administration of obits, chantries, and fraternities suggest relatively harmonious relations.

Chantries, guilds, and chapels

By the later Middle Ages the parish church contained at least nine side-altars or lights, including those for five or six large-scale chantries or fraternities. The chapel of the Blessed Virgin, north of the chancel, became effectively the guild chapel for the town's merchant guild, and perhaps for that reason shared the dedication of the parish church. It appears to have been established in or before the early 14th century, a period when the guild was fast increasing its autonomy within the town: a chaplain of the Blessed Virgin was officiating in the 'newly built chapel' in 1311, and several gifts towards its upkeep were made by leading townsmen over the next few years. (fn. 69) A chantry was created in the chapel before 1317, when two townsmen gave the churchwardens and bridgemen money and property towards it; (fn. 70) thereafter the chantry was supported from the town's bridge rents and was overseen by the guild, which appointed priests and fixed their stipends and duties. In 1419 the salary was set at £6 with a suitable chamber, and in the late 15th century the priest was to celebrate mass at 6 a.m. daily. (fn. 71) In the early 16th century the chapel contained a clothed statue of the Virgin, to which a parishioner left a gold ring in 1503. (fn. 72)

A second town chantry, dedicated to St Catherine, seems to have been established a little later. The chapel was mentioned in 1349 when a parishioner left two cottages to support its light, and in 1382 the warden and community obtained royal permission to endow a perpetual chantry there with £14 12s. rent from 115 houses. (fn. 73) Probably that was a formalization of earlier arrangements, since the income comprised the town's existing bridge rents in support of the bridge and church. (fn. 74) Thereafter the town guild administered the chantry alongside that of the Virgin, appointing priests at the same stipend, and occasionally paying for repairs. (fn. 75) The chapel was evidently popular among wealthy parishioners: several requested burial there in the late 15th and early 16th century, while the town's weavers maintained a light before the altar, reflecting the saint's common association with spinners and other craftsmen. (fn. 76) The chapel must have been structurally distinct, since it had its own door and guttering; (fn. 77) possibly it was on the church's south side where a brass featuring St Catherine survived in the 1860s, although the south-east chapel appears not to have been built until the 15th century. (fn. 78) An image of St Catherine was mentioned in 1501, and in the early 16th century a parishioner constructed a small mortuary 'chapel' apparently inside the chantry chapel. (fn. 79)

Other perpetual chantries were founded by leading townsmen. One in the Lady chapel, apparently distinct from the town chantry there, was established in 1338, when the wealthy Henley merchant John of Harwell endowed it with £3-worth of rents on behalf of Ferandus Manioun 'of Spain' and his wife Margaret. (fn. 80) Another chantry, in the newly built chapel of St Leonard on the north side of the church, was established under the will of the wealthy Henley merchant John Elmes (d. 1460), who endowed it with £6 a year from lands in Badgemore and elsewhere. (fn. 81) More common were obits and short-term arrangements such as a one-year chantry endowed in 1466, (fn. 82) and numerous bequests were made in support of particular lights: those in the 15th century included lights of St Nicholas, St Clement, and the Holy Trinity, as well as the rood light and those in the chantry chapels. (fn. 83) The most important were also supported from collections and from general church funds, and by the 1490s the rood lights, said to belong to the 'community of the town', were endowed with land in Church croft or mead. (fn. 84)

A Fraternity of the Altar of Jesus was founded apparently in the late 15th century. Possibly it was focused on the church's south-east chapel, which was built or remodelled around that time. (fn. 85) Arrangements for continuing a weekly mass of Jesus were discussed in 1486, and by the mid 1490s the Fraternity was fully established, with its own plate and vestments, its own income, and two 'proctors' who presented their accounts to the town guild. (fn. 86) Membership seems to have included both men and women, who apparently paid an annual fee, and gifts or bequests were common. (fn. 87) It has been suggested that the Fraternity may have provided a focus for 'foreign' traders moving into the town during the period, (fn. 88) though some at least of its supporters were from old-established families, (fn. 89) and in 1499 Sir Edward Hastings, then lord of the manor, gave 6s. 8d. towards it. General church income was sometimes also diverted, as in 1500 when the Fraternity received 15s. 6d. raised by the annual king game. The same year £2 was spent on painting and gilding an image of Jesus for the altar. (fn. 90) An apparently separate Fraternity of Holy Trinity was mentioned in 1496. (fn. 91)

A freestanding chapel of St Anne, mentioned from 1405, adjoined granaries next to the bridge, with which it was presumably associated. (fn. 92) A hermitage nearby existed by 1496, when the hermit was licensed to collect alms for repair of the chapel and highway, perhaps continuing a long-standing tradition. The arrangement continued in 1529 when another Henley hermit, associated with the Order of St Paul, was licensed by the bishop. (fn. 93)

Popular piety and religious festivals

Popular piety was expressed not only through chantries, fraternities, and lights, but through bequests towards church furnishings and fabric. (fn. 94) Gifts of rents or houses, the origin of the town's bridge rents in support of the bridge and church, were recorded in the late 13th century and the 14th, (fn. 95) and by the 15th century the church appears to have been well provided with plate, books, and vestments. (fn. 96) Less usual gifts included a jewelled collar and coronal given in 1517, to be hired out to local brides in support of the Lady light, (fn. 97) and in 1519 around 26 inhabitants contributed to the cost of a new rood loft. (fn. 98) Among late medieval testators John Deven (d. 1470), fairly typically of wealthier inhabitants, left bequests to six lights and established a 3-year chantry, (fn. 99) while elaborate funeral arrangements were common, prompting detailed rules by the guild concerning the ringing of bells at funerals, trentals, and obits. Ringing of the great bell without the warden's permission was forbidden in 1514. (fn. 100) Leading townsmen were directly involved in running church affairs, both as church officers and as members of the guild. The guild assembly appointed churchwardens and directly oversaw the two town chantries, (fn. 101) while a salaried vestibuler in charge of church goods and a salaried organist mentioned in the early 16th century seem both to have been laymen. (fn. 102)

Churchwardens' and town guild accounts suggest the popular religious festivities common to many small towns, at least from the later Middle Ages. Tenants of a church property in 1466 were to provide a candle before the Easter Sepulchre, and in the early 16th century there was a Resurrection play and procession, followed by collections for the rood light at the church door on Easter Monday. (fn. 103) 'Gear' for the Corpus Christi 'pageant' and procession was mentioned frequently in the 1530s and 1540s, (fn. 104) though not earlier. The proceeds of secular festivities also contributed to church funds. Income from the Whitsuntide 'king game' was put towards upkeep of church bells in 1455 and towards the purchase of a silver thurible in 1502, while in 1499 money from traditional Hocktide games was similarly used to buy church plate. (fn. 105)

The Reformation to the Restoration

Given the number of chantries, the indications of traditional piety, and the apparently large number of assistant clergy in Henley by the early 16th century, the impact of the Reformation must have been marked. Support for the Elmes chantry was withdrawn by the family in the early 1540s (though not necessarily for ideological reasons), and remaining chantries and fraternities were suppressed under government legislation in 1548, when some of the priests received pensions. Land given in support of the rood light was sold in 1549, and by 1552 unspecified church goods, probably including images, jewels, crosses, and cloths, had been sold off and the proceeds used for church and bridge repairs. (fn. 106)

Possibly only a minority of parishioners actively welcomed such changes, although attitudes were probably mixed. Lollards were established in the parish by the 1460s, when five or more were prosecuted for attacking pilgrimages, the sacraments, worship of images, and the papacy. They included the prominent preacher James Willis, a Bristol weaver who moved to London (where he was imprisoned) and later to Henley, where he played an important proselytising role in the area. (fn. 107) Others were Henley burgesses with London trade connections, (fn. 108) involved in town government and associated, as later, with an intricate Lollard network focused on the Amersham area. (fn. 109) The Lollard presence continued in the early 16th century, when several inhabitants, including three women and a cooper, shearman, carpenter, and servant, were prosecuted for reading forbidden books or for expressing heretical views. (fn. 110) Some may have been influential townsmen, (fn. 111) and certainly London trade-links must have helped to transmit Lollard ideas and books. (fn. 112)

Nonetheless such views were not universal in Henley, and were possibly outweighed by adherence to traditional practices. A corndealer and burgess in the 1530s refused to allow five neighbours to meet in his house 'for holding of the Gospel', asserting that he 'had evil will for ... such men of the new learning', (fn. 113) while in 1539 the reformer Miles Coverdale complained that 'beams, irons, and candlesticks' had not yet been removed from the church, 'whereby the simple people believe that they will again be allowed to set up candles to images, and that the old fashion will return'. A stained-glass image of Thomas Becket remained in the Lady chapel, and in the early 1540s parishioners and the town guild continued to hold Corpus Christi processions and to support lights, side chapels, and obits. (fn. 114) The evidence may indicate a genuinely divided town, and perhaps also some inconsistency on the part of individuals, who elsewhere in the region sometimes displayed a surprising mix of Lollard radicalism and traditional piety. (fn. 115) The rector Richard Baldwin, instituted in 1530, must have tolerated the new regime and perhaps encouraged it, since he retained the benefice until 1554 when, a year after the temporary reinstatement of Catholicism, he was deprived. (fn. 116) His successor Edward Smith, presumably a Catholic, resigned on Elizabeth's accession in 1558. (fn. 117)

All of Henley's later rectors accepted the Elizabethan religious settlement, though Thomas Morris or Morrison (1558–63), a former curate, was deprived for non-residence after repeated warnings. (fn. 118) William Barker (rector 1563–81) seems to have had Puritan leanings, which prompted complaints by one of his parishioners; Barker admitted not wearing a surplice, preaching against 'unprofitable' ceremonies, and refusing to church women except in strict accordance with the law, though he denied preaching against the wearing of vestments. (fn. 119) Presumably the authorities considered him reliable, since in 1581 he or his successor was appointed to give Protestant instruction to the Roman Catholic Lady Stonor, who had been confined to nearby Stonor House. (fn. 120) The long-serving Abraham Man (rector 1587–1632), a university graduate like his immediate predecessors, owned commentaries by Calvin and other reformers, (fn. 121) but seems to have avoided religious controversy and to have served the parish conscientiously, witnessing wills, participating in Church court hearings, and overseeing transcription of the parish registers. (fn. 122) Also during his rectorship the great bell was recast and a new frame provided, the cost met by contributions from almost 200 individuals. (fn. 123) Open Catholicism in the parish remained negligible, despite the proximity of Stonor Park. Two yeomen's wives were fined for recusancy in 1613 and 1624 respectively, and in 1634 the husband of one of them was licensed to eat meat on Fridays, suggesting a degree of religious conservatism. (fn. 124) No recusancy was recorded in 1642, however, when all the male inhabitants of Henley and Rotherfield Greys took the protestation oath. (fn. 125)

Man's successor Robert Rainsford (1632–49) seems similarly to have avoided theological extremes. In 1638 Archbishop Laud reported that Henley was the only market town in the diocese to have a lectureship, often seen a symptom of Puritanism, but since Rainsford was 'a discreet man' he was not considered a threat. (fn. 126) Seven years later Rainsford was summoned before the Parliamentary Committee for Plundered Ministers to answer unspecified complaints from the parish, but avoided sequestration and retained the living until his death. (fn. 127) His successor William Brice, apparently a former curate, (fn. 128) had more extreme views and was deprived after the Restoration, retiring to Maidenhead to become a Presbyterian minister. As rector he was reportedly conscientious and charitable, (fn. 129) though relations with his more conservative neighbours may not have been good. In 1654 he served on the Oxfordshire commission investigating 'scandalous' (i.e. non-Puritan) clergy, (fn. 130) and in 1661 refused to vacate the reading pew at Henley to allow a sermon by the rector of neighbouring Fawley. On that occasion he was forcibly removed by the latter's friend and patron William Knollys (of Greys Court), by whom he 'hardly escaped being sent to prison'. (fn. 131) The incompleteness of the parish registers from 1643 to 1653 perhaps reflects more general disruption during the Civil War, although Bulstrode Whitelocke's diaries suggest the routine continuance of church services, and make no mention of religious difficulties. (fn. 132)

The Anglican Church 1660–1820

William Brice's successor resigned after only a few months, (fn. 133) and with the institution of John Cawley (rector 1663–1709) the Anglican Church entered on a period of stability characterised by long incumbencies. (fn. 134) Cawley, though also archdeacon of Lincoln, seems to have resided constantly, perhaps latterly at Henley Park where he was lessee. (fn. 135) His successor Charles Aldrich (rector 1709–37), a nephew of Henry Aldrich, the dean of Christ Church, was also closely involved in town life, regularly attending vestry meetings and bequeathing his extensive collection of books as a parish library. As a chaplain to Frederick, prince of Wales, he probably shared his uncle's High Church Tory views, and with some difficulty established a subscription lectureship to ensure a second Sunday sermon, apparently to offset the perceived threat posed by Henley's new Independent meeting house. (fn. 136)

The lectureship was continued by his successor William Stockwood (rector 1737–84), who was, with Cawley, one of the longest-serving rectors on record, remaining at Henley until his death aged ninety nine. Like Henley's other 18th-century incumbents he served conscientiously by contemporary standards, residing constantly, and employing a curate to assist him; he was, however, castigated by the bishop in 1750 for missing a visitation while serving as a land-tax commissioner, and in 1756 he very publicly fell out with his curate of eight years Henry Hayman, who claimed the support of a majority of parishioners. The bishop accepted that relations were irreparable and that Hayman could not remain. (fn. 137) Stockwood's successor Edward Townshend (rector 1784–1822), the first non-resident rector for 200 years, lived at Bray near Maidenhead (where he was vicar), but installed a full-time curate at Henley rectory house and maintained close links with the town, where he often took services. Although, by his own admission, proud and worldly as a young man, around 1798 he underwent an evangelical conversion, preaching a sermon at Henley church in which he 'candidly and boldly [recanted] his former views ... as to doctrine and practice'. His subsequent zeal and humility, his charity to the poor, and the frequency of his pastoral visits were fondly recalled at his death, though perhaps more in relation to Bray than Henley. (fn. 138) Townshend's curates often stayed for long periods, probably attracted by the remuneration: between the 1760s and 1820 the stipend rose from £30–£40 to £90, supplemented by the rent-free rectory house and by fees and the subscription lectureship (together another £70). (fn. 139) Nevertheless, a curate in the 1790s declared himself 'infirm and weakly' both from illness and 'by the long and repeated exertions in so large a church as Henley', especially with a large family to support. (fn. 140)

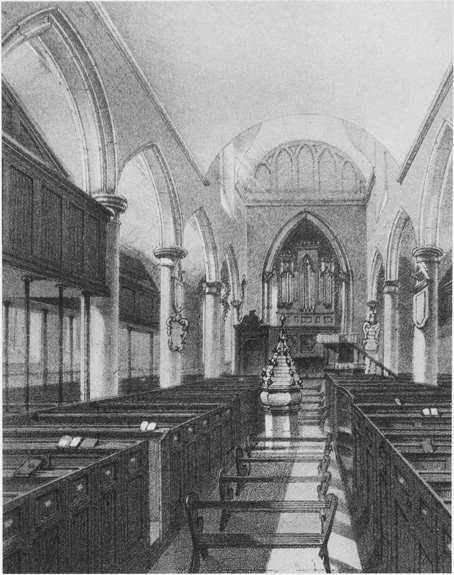

Church provision during the 18th and early 19th century remained typical of the period, with two Sunday services (each with a sermon), morning prayers twice a week and on holy days, and the sacrament administered monthly. (fn. 141) A west singers' gallery was mentioned in 1786, (fn. 142) and a church organ was acquired or replaced around 1804. (fn. 143) Children were catechised at Lent, and a Sunday school supported by subscriptions was opened in 1780. (fn. 144) Church attendance was not recorded before the 19th century, though rectors' visitation returns routinely noted the growth of Dissent, most commonly as a statement of fact rather than as something which might be challenged. Stockwood took pains to continue the afternoon lectureship, specifically citing the proximity of the Independent meeting house, but remained sanguine about payment of dues by local Quakers, whom he thought not worth pursuing for Easter offerings. (fn. 145) His successor Edward Townshend, though a convinced Anglican, seems to have been particularly tolerant, '[loving] all who loved ... Jesus Christ' and allowing 'full rights of conscience to others, whether in or out of the Establishment'. (fn. 146)

Of equal concern was non-attendance through apathy. Townshend lamented in 1802 that 'too many' absented themselves 'upon principles and motives too vague and various to enumerate', and, as the population grew, lack of pew-space was increasingly cited as a contributory factor, (fn. 147) particularly as inhabitants of Henley's southern suburbs (though technically in Rotherfield Greys parish) habitually attended Henley church. (fn. 148) Overcrowding led to erection of new galleries in 1786 and 1820, although as both comprised private seats paid for by subscription they did little to ease the underlying problem, which persisted well into the 19th century. (fn. 149) Numbers of communicants, noted from the early 19th century, rose slightly with the population, from around 40–50 in 1805 to 70 in 1817. (fn. 150)

The routine involvement of the town élite was reflected not only in erection of private pews and galleries, but in repairs and alterations to the church fabric and in occasional gifts of furnishings or plate. A pewter almsdish was given by Richard Jennings of Badgemore in 1711, (fn. 151) and in 1774 Sambrooke Freeman of Fawley Court paid for the setting up a gilt ball on the church tower. (fn. 152) The new organ was supported by a charitable bequest in 1797. (fn. 153) The town corporation, like the guild before it, continued to oversee the churchwardens and the church fabric, agreeing alterations and contracts and, in 1789, voting £100 and another £50 of charitable funds towards more extensive building work, when the church's south side was rebuilt and extended. (fn. 154) Corporation members had their own private pews, for which new locks and keys were provided in 1795. (fn. 155)

Nonconformity 1660–1820

Though Dissent seems never to have dominated Henley as it did some Oxfordshire towns, (fn. 156) in the mid to late 17th century there were nevertheless signs of religious radicalism. Thereafter the Anglican Church faced a marked and continuous Nonconformist presence, particularly among Independents. The presence from 1654 to 1662 of a rector with Presbyterian leanings presumably encouraged local sectaries, (fn. 157) and the town's location on the far edge of the county may also, as suspected in the 1680s, have attracted those keen to avoid the attention of the authorities. (fn. 158) Certainly returns compiled for the bishop in the 1660s suggest that the area around Henley and the Buckinghamshire border was one of three chief focuses of Dissent in the county. Adherents included large numbers of former soldiers and officers from the disbanded Parliamentary army, while promoters included radical former ministers ejected under the Act of Uniformity, at least some of whom came into the area from outside. (fn. 159) Earlier traditions of Lollard Dissent in the area perhaps also contributed, though to what extent is unclear. (fn. 160)

At Henley itself, a conventicle meeting every three weeks in the house of a London vintner was reckoned in 1669 to have 300 members, placing it among the largest meetings in the county. Teachers included the ejected ministers William Farrington, Richard Mayo, and John Brice, son of the ejected rector of Henley. Members, many of them former Parliamentary soldiers, included 'all sorts of sectaries', but were thought to be 'chiefly Presbyterians', and Presbyterians or Independents remained by far the strongest Nonconformist group in Henley thereafter. (fn. 161) A separate Quaker group, with 40–50 members, met at a private house at Northfield End, whose owner was excommunicated for allowing such meetings in 1663 and again in 1678. Nearby cottages were bought as a meeting house in 1672, and continued in use until rebuilt in the late 19th century. (fn. 162) A third, Anabaptist group existed by 1652 when it formed part of the new Berkshire Baptist Association, meeting at Sir Adrian Scrope's house in Lewknor; that group may have disappeared soon after, however, since few Baptists were subsequently reported in the town until the 19th century. (fn. 163) In 1676 the total of 76 Nonconformists reported in Henley was almost certainly an underestimate, even allowing for Dissenters living outside the parish. Nevertheless, figures were substantially higher than for some other parts of Oxfordshire where Dissent is known to have been strong. (fn. 164)

Presbyterians and Independents (Congregationalists) (fn. 165)

By the 1670s the Presbyterian or Independent meeting at Henley was led by Thomas Cole, ejected principal of St Mary Hall, Oxford, and formerly rector of Ewelme. In 1666 Cole established a private academy at nearby Nettlebed, and in 1672 obtained Congregationalist meeting-house licenses for a barn and for two private houses in Henley, one of them his own. (fn. 166) The barn probably occupied the site of the later Congregationalist chapel on the Reading road, just over the parish boundary; (fn. 167) the other house was owned by John Tyler, who during the Interregnum had been temporarily deprived of the office of town clerk apparently because of his political or religious views. (fn. 168) A separate Presbyterian meeting-house licence was obtained the same year by William Cornish, perhaps a relative of the prominent Presbyterian minister Henry Cornish. (fn. 169) An application by Cole to use the town hall was turned down, (fn. 170) although the town authorities may not have been actively hostile: in 1677 the bridgemen and churchwardens were indicted for failing to invoke the Conventicle Act against their neighbours, and in the 1680s they declined to report local conventicles to the bishop. (fn. 171)

Assertions that the meeting's principle adherents were former Parliamentary soldiers (fn. 172) suggest a degree of political radicalism, which seems to have been shared by some early ministers. Around 1674 Cole was succeeded by the radical preacher Jeremiah Marsden (alias Ralphson), who was arrested the following year and imprisoned at Oxford. His successor John Gyles (d. 1683), son of another ejected minister, reportedly preached regularly at Harpsden Wood, where he, too, is alleged to have narrowly escaped arrest. (fn. 173) Presumably such radicalism underlay the Whig extremism of which many in Henley were suspected during the Exclusion Crisis, and to which the town's peripheral position on the county's eastern edge was thought to contribute. (fn. 174) Later pastors had less extreme views, and by the early 18th century the meeting's congregation of 400–500 included 21 'gentlemen', the rest drawn from tradesmen, farmers, and labourers, and including several county voters. The size and status of the congregation guaranteed a reasonable stipend (£40 c. 1690), and in 1719 a purpose-built meeting house superseded the barn on the town's southern edge, just within Rotherfield Greys. The pastor then was John Sills (1718–c. 1740), who reportedly kept 'a respectable boarding house' in Hart Street. (fn. 175)

Throughout the 18th century the Independent meeting continued to thrive. In 1738 the rector claimed that numbers had 'considerably lessened', but admitted that Dissenters still comprised a third of the parish's inhabitants. (fn. 176) Other members were drawn not only from Rotherfield Greys and Harpsden, but from as far as Wallingford, Checkendon, Stoke Row, Twyford, Marlow, and Watlington. (fn. 177) A small increase before 1759 allegedly resulted from members encouraging fellow Dissenters to move into the town as shopkeepers, or forcing their Anglican servants to attend the meeting house, (fn. 178) and in the 1760s and 1770s the rector acknowledged that there were up to 22 Presbyterian or Independent families living within Henley parish. Those he defined as 'chiefly tradesfolk' with no members 'of rank', although outside adherents included gentry such as the Halls of Harpsden Court, while others were prosperous local tradesmen including maltsters, brewers, mercers and grocers. (fn. 179) One, the brewer Peter Sarney, bought cottages north of the meeting house in 1770, which following his death in 1783 were acquired for use as a manse. (fn. 180) Pastors included Samuel Pike (c. 1740–7), who resigned after becoming a Sandemanian, and, most notably, Humphrey Gainsborough (1748–76), brother of the well known painter. An inventor and engineer of note, Gainsborough was deeply involved in town life, and seems to have been universally respected. (fn. 181)

During the late 18th century and early 19th the meeting was beset by temporary splits, the reasons for which are unclear. Nathaniel Scholefield, pastor from 1781, resigned 'at the request of the church' in 1806, suggesting that the existence of a separate meeting in Henley from around 1794 to 1800 was fuelled partly by local divisions. (fn. 182) The strict and energetic pastorate of his successor James Churchill (1807–13) caused further problems, prompting 21 members to secede in 1809 and to set up a separate church; that group continued until c. 1836, meeting at first in premises near the market place owned by the wine merchant Samuel Allnutt, (fn. 183) from 1813 in the recently closed theatre on New Street, (fn. 184) and from 1823 in a newly fitted up chapel nearby. (fn. 185) The main group continued at the earlier meeting house on Reading Road, just over the town and parish boundary. Whatever the nature of the divisions, they seem not to have caused serious long-term damage: in 1805 the rector admitted that Independents remained 'numerous' and that lack of church accommodation was increasing meeting-house attendance, while Churchill's pastorate saw the introduction of Sunday schools, regular evening 'conferences' on religious topics, and quarterly Bible classes for young women, youths, and female servants, combined with vigorous missionary activity in neighbouring villages. A reported fall in numbers before 1820, when there were thought to be around 80 Independents in the town, seems not to have been permanent, and was perhaps exaggerated. (fn. 186) Relations with local Anglicans seem by then to have been reasonably good, particularly during Edward Townshend's rectorship, when Dissenters and church members jointly funded voluntary Sunday schools and a school of industry. Nevertheless, in 1819 safeguards were adopted to ensure that new private galleries in the church could not be appropriated by Nonconformists. (fn. 187)

Friends (Quakers)

The Quaker group reported in the 1660s seems to have originated around 1658, when the prominent Quaker preacher and author Ambrose Rigge and two others 'declared truth' in the market place. (fn. 188) Rigge was pelted with entrails from nearby butchers' stalls, but by 1662 regular meetings were nevertheless being held in a house at Northfield End; early adherents included prosperous hoopmakers, weavers, cordwainers, and maltsters, of whom some had connections with London grocers and cheesemongers. (fn. 189) Two cottages at Northfield End were bought as a meeting house in 1672, and in the mid 19th century had accommodation for 150, including 30 in galleries. The meeting came at first under the auspices of the Warborough Monthly Meeting, until transferred to the Reading Monthly Meeting in 1810. (fn. 190)

Despite early enthusiasm the group remained smaller than the Independent meeting, and throughout the 18th and early 19th century numbers declined slowly but steadily. Ten Quaker families were noted in 1738, 5–6 in the 1760s and 1770s, and only 19–20 individuals around 1820, with no resident teacher; the decline continued during the 19th century, until the religious revival of the 1870s and 1880s. (fn. 191) Nevertheless the meeting continued to attract some prosperous tradesmen and craftsmen, among them the clockmakers Edward and Joseph May who, during the difficult years of the later 18th century, were among its most active supporters. Books were occasionally acquired by subscription or gift, and financial help was offered to Friends for schooling, apprenticeships, clothing, and widows' maintenance. Relations with the Anglican Church seem not to have been especially strained, only one distraint for non-payment of tithes being noted at Henley, in contrast with Turville Heath or Roke. (fn. 192)

Wesleyan Methodists

Wesleyan Methodists were active in the town by the late 1750s, when the rector feared that 'Methodism does and will make the greatest desolation, if the author of it here continues to be encouraged'. (fn. 193) Wesley visited Henley in 1764 but was unimpressed, finding a 'wild, staring congregation ... void both of common sense and common decency', made up presumably of bargemen, labourers, and the poor. Four years later he was more optimistic, reporting better prospects and 'a considerable number of serious people' at an evening meeting, though 'one or two of the baser sort' still 'made some noise' and had to be reproved. (fn. 194) Evidently there was a short-lived meeting house, at which a local butcher and labourer 'misused the preacher' in 1769. (fn. 195) Wesley's hopes were based partly on an unnamed local woman, whom he anticipated would emulate the proselytizing role of Ann Bolton at Witney or of Hannah Ball at High Wycombe; some years later he lamented that she had 'quitted her post', and that 'both she and the Society' had consequently come to nothing. Probably the group's failure owed as much to the continuing local strength of the Independents, which contrasted with the situation in towns such as Witney where the decline of Old Dissent seems to have created new opportunities. (fn. 196)

Despite such setbacks, a small Wesleyan group continued. A room was licensed before 1805, and though the meeting, served probably from Reading, remained relatively small, it overtook the ailing Quakers before 1811, when around 70 Wesleyans were reported compared with only 19 Friends. (fn. 197) A room in a house at Assendon Cross, adjoining Bix on the parish's western edge, was licensed for Wesleyan use in 1822. (fn. 198)

Roman Catholicism

The small scale of Roman Catholic recusancy in the 16th and early 17th century continued throughout the 18th and early 19th, never involving more than four or five families at a time, and rarely any of gentry status. Eight papists were reported in 1676, and two women, both married to Protestants, in 1738. (fn. 199) A Catholic family may have briefly lived at Badgemore in the 18th century, (fn. 200) and in the 1750s and 1760s up to five families had Catholic members, among them one gentlewoman; others included the families of a widowed female glazier and of a widowed pauper. (fn. 201) Two Catholic families in trade and husbandry were noted in the 1790s, and 11 individuals in 1814; there was, however, no place of worship, and no priests in regular attendance. (fn. 202)

The 19th and 20th Centuries

The first half of the 19th century was marked by growing Dissent and, in the 1840s, by increasing dissatisfaction with the Anglican Church, fuelled by non-residence, 'slovenly' services, and the Church's failure to respond to the town's changing needs. From 1793 to 1847 no fewer than 16 Nonconformist meeting-house licenses were granted for premises in the town; (fn. 203) most were, however, for small-scale and impermanent meetings held in private rooms or outbuildings, and in the early 1850s, despite the Church's difficulties, almost a third more people still attended Anglican worship than the town's four Dissenting chapels combined. Independents still accounted for some 85 per cent of recorded Dissenters, with only the Wesleyans otherwise attracting significant numbers: combined attendance at the long-established Quaker meeting at Northfield End and at a more recent Primitive Methodist meeting on Friday Street averaged fewer than 20, compared with up to 500 at the Independent chapel. Up to 970 parishioners in 1851 still attended either Henley parish church or the recently established Holy Trinity church. (fn. 204)

Thereafter, there was a general reinvigoration of religious life among both Anglicans and Nonconformists. The opening (in 1848) of Holy Trinity church to serve the town's southern suburbs was followed by restoration of Henley parish church and by improvements in church services under energetic resident incumbents, while membership of the Congregationalist church remained strong under a series of conscientious pastors, particularly among the town's middle classes. Local Quakers and Baptists also benefited in the 1870s from marked religious revivals, the effects of which were felt well into the 20th century. A purpose-built Baptist chapel was opened in 1879, and a newly built Quaker meeting house in 1894, while the Congregationalist church was rebuilt in 1907. As elsewhere, both church and chapel attendance fell away particularly after the Second World War. Nonetheless, in 2000 the town retained strong United Reformed (or Congregationalist), Baptist, and Roman Catholic communities, while combined membership of Henley parish church and Holy Trinity (as reflected in electoral rolls) was over 300. (fn. 205)

Anglicanism from 1820

The incumbency of James King (rector 1825–52) began with a recognition that, after 50 years, Henley needed a resident rector, which in King's view would 'greatly ... benefit ... the parishioners, and more particularly ... the humble and poorer classes'. Accordingly he bought a smart 18th-century house fronting the river and voluntarily annexed it to the rectory. (fn. 206) Provision in the 1830s nevertheless remained little different from in the late 18th century, (fn. 207) and in 1841 King left Henley for a benefice in Kent, never visiting the town again. (fn. 208)

King's curate F. J. Burlton (1843–52), though 'hardworking' and a 'sound Churchman', proved unable to serve such a populous parish alone, and by 1846, when Bishop Wilberforce demanded that King install an assistant, the town was allegedly 'overrun with Dissent and godlessness'. (fn. 209) Continued pressure led to the provision of three curates by 1848 ('three tails but no head', in the words of a disgruntled parishioner), but few stayed for long, and by 1850 services were allegedly 'worse than ever', marked by 'careless reckless reading, the struggle between the parson, clerk and school children to be the first done, and ... drowsy prosy sermons'. Weekday services were even more pitiful, attended by only a handful of people and 'a few old almshouse women'. (fn. 210) King finally stepped down in 1852 after an exasperated Wilberforce forced him to choose between residence or resignation, to the great relief of some inhabitants. (fn. 211)

Despite such scandals King supported the building of Holy Trinity church as a means of heading off growing Dissent, (fn. 212) and from his departure there was marked improvement under a succession of conscientious resident rectors. King's successor Thomas Baker Morrell, a future coadjutor bishop of Edinburgh, was related to a prominent Oxford family of brewers and lawyers, and already had Henley connections as a nephew of the Revd Deacon Morrell, from whom King had bought the new rectory house. 'Zealous, active, ... and [with] a good private fortune', he quickly made his mark, restoring the church and transforming the parish's religious life during a ten-year incumbency. (fn. 213) Morrell's successors Charles Warner (1863–7), Greville Phillimore (1868–83), and the long-serving J. F. Maul (1883–1915) continued in similar vein, helped usually by two or three curates. Some assistants stayed for long periods, William Chapman (licensed in 1860) remaining for over 20 years. (fn. 214) Phillimore, who belonged to a local landowning family, was himself a former curate, and on his death was commemorated by a drinking fountain set up in the market place. (fn. 215)

Services throughout that period became both more frequent and more decorous. Three Sunday services had been introduced in 1848, reportedly under pressure from Wilberforce, (fn. 216) and from the 1880s there were four, supplemented, as earlier, by weekday prayers and by additional services at Lent and Advent. From 1868 there was a Sunday service and sermon in the new cemetery chapel on the Fair Mile, and another Sunday service and twice weekly 'addresses' were held at the 'iron church', a corrugated-iron mission hall on Gravel Hill. (fn. 217) The accompanying shift towards greater ritual was not, however, universally welcomed. A year after Morrell's arrival an admirer sensed 'a spirit of opposition' to the 'good old reverential church practices' which he was introducing, even the unaccustomed decoration of the altar with flowers at Christmas prompting 'mutterings' from the churchwardens. Another parishioner considered it 'papistical' that school children were required to stand while the clergy and choir entered the church, and withdrew his National-school subscription in retaliation. (fn. 218) Warner nevertheless followed in Morrell's footsteps, introducing a weekly communion office and preaching his sermon as part of it, dressed in his surplice. (fn. 219) Subsequent additions to church furnishings suggest that High-Church tendencies prevailed, with occasional gifts of candlesticks or plate, the acquisition (particularly in the 1880s) of numerous stained-glass windows, and the raising of the sanctuary in the early 1890s, accompanied by installation of new choir stalls and a parclose screen. (fn. 220)

Church attendance was considered adequate by most rectors, even though the 800 parishioners attending morning service in the early 1850s represented less than a quarter of the parish's population. (fn. 221) In the 1860s the building usually 'seemed full', though by then some parishioners habitually attended a neighbouring church: the withdrawal began during Henley church's closure for restoration during 1853–4, and increased, as the rector drily noted, following the 'sudden introduction' of offertory collections a few years later. (fn. 222) Phillimore acknowledged that attendance remained better among the 'higher class', with a disproportionate number of the middle classes drawn to Nonconformity, and attendance among the poor a constant source of concern. Both Morrell and Warner listed drunkenness and the 'miserable' condition of the poor amongst their chief pastoral difficulties, and though Phillimore considered the indigenous poor to be 'not indevout', more recent incomers were judged to be 'careless of ... all sacred duties'. Suggested solutions included establishment of guilds 'carefully adapted to the wants of the district', and 'some system of Sisters of Mercy', which in Phillimore's view was 'indispensable for raising the character of women in all classes of society'; neither suggestion seems to have been implemented, although in 1881 Phillimore noted an apparent increase in the number of younger communicants. (fn. 223) Development of Henley's social scene brought further problems, Maul citing the 'incursion of pleasure seekers during the summer months' as a particular hindrance in 1890. (fn. 224)

Religious education was taken seriously, with regular catechizing at Henley parish church and the iron church, regular children's services, and continuation of the various Sunday schools which, in 1881, had 41 voluntary teachers between them. Even so, there were long-term problems in persuading boys to remain in Sunday school once they left the day school, and in 1878 the Sunday school at the iron church required separate teachers for the 'rougher boys of the parish'. In the 1880s Maul introduced Sunday Bible classes for the 'lads and young men', though attempts from the 1860s to establish adult evening classes were unsuccessful, partly because so many youths left the parish to find employment. (fn. 225)

The new ecclesiastical district of Holy Trinity, established in 1849, (fn. 226) also benefited from long-serving clergy, the first incumbent (W. P. Pinckney) remaining for 40 years, and his successor F. W. Young until 1900. Three Sunday services (with two Sunday sermons) were held throughout Pinckney's time, supplemented by weekday prayers, and the sacrament was celebrated monthly. Most church sittings were free from the outset, although average attendance, reckoned in 1869 at 250, was generally considered inadequate in terms of population. Many inhabitants attended either Henley parish church or the thriving Congregationalist chapel, while conversely those attending Holy Trinity included significant numbers of outsiders: in 1887 non-parishioners made up half the regular communicants, undermining attempts to build up a strong Church community. Attendance improved slightly in the 1860s after installation of better heating and of a new harmonium, but only from the early 1890s did it belatedly reflect the marked population growth of the past few decades, reportedly increasing 'by hundreds' following the church's enlargement in 1890 and other improvements. (fn. 227)

A Sunday school at Holy Trinity had up to 25 pupils in 1851, but during the later 19th century religious education was chiefly through the local infant school, where Pinckney thought his involvement unnecessary. Nevertheless by 1875 the Sunday school had five voluntary teachers, a number increased to 14 a decade later, when there were also weekly bible classes and a mothers' meeting. (fn. 228) A choir of 'singing boys' was mentioned in the 1870s, when seating was adjusted to separate them from the body of the congregation, (fn. 229) and in 1890 women were admitted to the choir as an 'experiment'. (fn. 230)

During the 20th century the town continued to benefit from long incumbencies at both churches, among them those of R. M. Willis at Holy Trinity (1912–44) and A. E. Dams at Henley (1922–46). All 20th-century incumbents resided, those for Henley in houses on Blandy Road and (later) on Hart Street, following sale of the ancient rectory-house site in 1979. (fn. 231) In 1923 Henley parochial church council acquired the Chantry House on the east side of the churchyard as a parish or mission room, and in the early 1960s it briefly owned premises on Queen Street. (fn. 232) Relations with the Congregationalists, sometimes divisive in the late 19th and early 20th century when religious and political affiliations became entangled, (fn. 233) grew steadily closer, and in the late 20th century were marked by close cooperation. In the 1980s Methodists held services in Henley parish church, and in the 1990s the parish ecumenical roll had nearly 150 members. (fn. 234)

As elsewhere, falling attendance prompted parochial reorganization. Henley's ecclesiastical boundaries with Bix and Nettlebed were adjusted in 1953, (fn. 235) and from 1979 the benefice was held with that of neighbouring Remenham, across the river: in 2000 both were served by a single rector based in Henley, and assisted by curates, though the two communities retained their own churchwardens and parochial councils. Holy Trinity remained a separate parish with its own resident vicar and, in 2000, lay minister. Combined membership of all three churches was just under 400, a fall of 30 per cent from the mid 1970s. (fn. 236)

Nonconformity from 1820

Throughout the 19th century the Independents or Congregationalists remained by far the largest Nonconformist group, drawing support from local landowners such as the Fuller-Maitlands of Park Place and from some of the town's leading tradesmen and craftsmen. Other adherents included 'unlearned' tradesmen 'of lowly social standing', of whom several served as prayer leaders. (fn. 237) Average Sunday attendance in 1851 was reckoned at 400–500, with up to 180 attending the Sunday school. A few years later the rector acknowledged that the chapel was both large and well attended, despite the recent opening of the nearby Holy Trinity church. (fn. 238)

Improvements to the chapel and manse were made by the pastor John Nelson Goulty (1815–24), a cousin of Admiral Nelson, and by his American successor Robert Bolton (1824–36), who installed side galleries and in 1829 enlarged the chapel further; the re-opening ceremony was attended by the evangelical preacher Rowland Hill and Congregationalist minister William Jay, who both delivered sermons. James Rowland (pastor 1836–72), son of a Pembrokeshire farmer, oversaw the building of a new British school, and made further improvements including installation of an organ. The combined cost of those initiatives was well over £1,000, reflecting the continued support of Henley's well-to-do middle classes, while the establishment in 1838 of the Henley Congregationalist Benefit Society was presumably aimed at the church's less well-off members. Church discipline during Rowland's long pastorate nevertheless remained strict, with occasional expulsions for Sunday working, drunkenness, gambling, or worse. His successor Joseph Jackson Goadby, from a well-known Midland Baptist family, took up the ministry in 1874 after serving several Baptist pastorates, and quickly became involved in town life, establishing the Liberal Henley Free Press newspaper, founding a footpaths society, and working for local charities. A man of broad interests, he reportedly displayed a common touch in his 'racy talks to working men and popular audiences', which presumably enhanced the Congregationalists' appeal. John Taylor, his successor in 1892, was similarly popular among the town's poor, and was an enthusiastic supporter of the socialistic Brotherhood Movement, co-founding the 'Henley Pleasant Sunday Afternoon Brotherhood' in 1893. (fn. 239)

Fund-raising for a new and larger church was initiated by Taylor's successor Sydney Tucker, who had already successfully renovated the manse (1900), built an infants' school room (1901), and erected a handsome new church hall with space for 300 people (1904). The foundation stone was laid in 1907, and the church, with accommodation for 550, was opened the following year, its imposing appearance a clear statement of the Congregationalists' importance in the town. Benefactors included Frank Crisp of Friar Park, who, though not himself a Congregationalist, paid for the flamboyant south-east tower in memory of a Nonconformist grandfather. The rebuilding was, however, a truly communal venture, with modest contributions not only from working-class members but from a few inhabitants on parish relief. The earlier chapel, on an adjacent site, was demolished in 1909. (fn. 240)

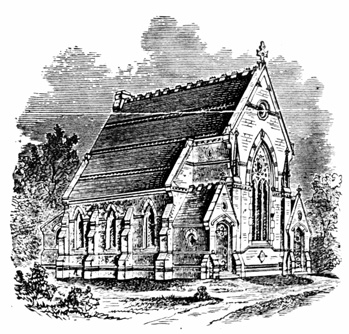

By comparison the Wesleyan group experienced mixed fortunes during the earlier 19th century, presumably due in part to the Congregationalists' continued success. Rooms in Bell Street were licensed in 1847, (fn. 241) and in 1851 a meeting house either there or at the market place had 120 sittings and an average afternoon congregation of 75, served by ministers from Reading. An associated Sunday school was attended by around 20 children. (fn. 242) Only a 'small preaching room' was mentioned in the 1860s, (fn. 243) but in 1874 a purpose-built meeting house was opened on the west side of Duke Street, attractively constructed in Gothic style (Fig. 42). It was enlarged the following year, providing 160 sittings, and a schoolroom was added about the same time. The chapel remained part of the Reading circuit, and was served by a succession of resident ministers, none of whom stayed for long. Nevertheless the congregation remained large enough to justify two Sunday services and an additional weekday meeting well into the 20th century. (fn. 244)

42. The Wesleyan chapel on Duke Street, built in 1873–4.

Baptists mentioned intermittently during the early 19th century were probably Strict or Particular Baptists, and seem never to have formed an especially large group. A short-lived meeting house was mentioned in 1830, (fn. 245) and in 1844 a building in Albion Place, on the north side of West Street, was licensed for Baptist worship, the signatories including a Newtown greengrocer and nurseryman. (fn. 246) Probably it was superseded by a Particular Baptist meeting house on Friday Street mentioned in 1851, which had 14 sittings in a private room or outbuilding; (fn. 247) only 8 or 9 worshippers attended, however, and the meeting house seems to have closed soon after. A more substantial Particular Baptist chapel was opened in 1873 near the top of Gravel Hill, built of red brick, and with accommodation for 150. Called the Hope chapel, it seems never to have had a resident minister, but continued to hold two Sunday services into the 20th century. (fn. 248)

Regular Baptists became established in the early 1870s, when a group rented the Assembly Rooms on Bell Street from Henley Temperance Society for the holding of weekly meetings. Instrumental in the meeting's creation were Frederick Sheppard, then manager for a local paper manufacturer, and the grocer W. T. Lambourne, both warmly encouraged by the minister of King's Road Baptist church in Reading. A church of 21 members was formally constituted in 1876, and the following year a Scot, J. M. Hewson, became first minister, succeeding temporary preachers from Spurgeon's College. A Gothic-style chapel on the south side of Gravel Hill near the market place was completed in 1878 and opened in 1879, the opening ceremony attended by representatives of Regent's Park College; the new building included a schoolroom, and had sittings for 300 people. The well-known Baptist C. H. Spurgeon gave a personal donation of £100, and increasing membership helped to clear the building cost within ten years. Hewson left in 1883, and the period up to the First World War saw a succession of relatively short pastorates: only James Smith (1886–94) and J. G. Wells (1899–1909) stayed for more than five years, followed by three years without a resident pastor. Nevertheless the church continued to thrive, Sunday-school numbers during Hewson's pastorate reportedly reaching 80 or more. A church magazine was started in 1927 following the arrival of T. J. Lewis (pastor 1927–34), and the church was electrified and equipped with a new pipe organ. A deaconess to assist the minister was appointed about the same time. (fn. 249)

Among older-established sects, the Quakers, too, benefited from the religious revivals which characterised the town in the later 19th century. Only 6–7 people were attending the meeting house in 1851, and in 1869 the rector reported only a single Quaker family. (fn. 250) In the 1870s, however, a revival was instigated largely through the efforts of the local grocer Charles Singer, who became a member in 1878 after working at the meeting house with illiterate young men. By 1882 the meeting, with support from Reading, had 'the nature of a mission' and was 'fairly well attended', while separate mission meetings for children attracted up to 120; a Home Mission Committee was formed the same year, and an adult school established soon after acquired 80 members. By 1894 the cottages used as a meeting house since the 17th century were inadequate, and were replaced by a new meeting house with 90 sittings, built on the same site. The meeting continued as a vibrant social and religious focus into the 20th century, with Sunday schools, evening gospel meetings, clubs and trips, an active Band of Hope for Temperance work, and from 1901 a women's adult school, which acquired 75 members. Attendance for worship was around 40–50. (fn. 251)

Roman Catholics, for whom chaplains from Danesfield and Stonor celebrated mass in a house on Bell Street between 1864 and 1867, (fn. 252) also became more firmly established from the 1880s, following the appointment as resident diocesan priest of Father John Northcote Bacchus. In 1888–9 Bacchus oversaw the building near the railway station of a new Roman Catholic church of the Sacred Heart, which doubled as a small schoolroom and had sittings for 100 or more. By 1891 there were prayers or communion twice daily and two Sunday masses, though in 1909, when Father John Hughes succeeded, there were still only 30 parishioners. A new and larger church was built in 1935–6 on Vicarage Road, on a site acquired by Hughes; incorporated were a magnificent east window, reredos, and altar by A. W. Pugin and his son, salvaged from the demolished private chapel at Danesfield (Bucks.). The debt was cleared in 1943, and the church finally consecrated in 1949. An associated school was built on Greys Hill in 1958 and a new parish hall some years later, using proceeds from the sale of the earlier church and school in Station Road. (fn. 253)

Most of those groups continued well into the 20th century, although, like the Anglican Church, several suffered declining attendance. The Particular Baptists' Hope chapel closed in 1923, (fn. 254) and in 1934 falling attendance at the Friends' meeting house led to closure of the Henley Preparative Meeting. The building was let to the Youth Hostel Association, but from the Second World War there was some small recovery, and in 1961 a Preparative Meeting was re-established, still based at the meeting house. It continued, still associated with Reading, in the early 21st century, when the meeting house was refurbished. (fn. 255) The Wesleyan chapel on Duke Street, from 1932 part of the United Methodist Church, closed in the late 1970s after maintenance costs became too heavy, and was demolished in 1983. (fn. 256)

The Congregationalists, by contrast, remained an important part of the town's religious life throughout the 20th century, latterly as part of the United Reformed Church. A new community centre, called the Christ Church Centre, was opened at the church in 2000, catering for local groups and events as well as prayer group meetings and bible classes. In 2005 the church had 149 members and average congregations of 120, a significant proportion of them aged under 18. (fn. 257) The Baptist and Roman Catholic churches also continued, buoyed by the active involvement of their respective communities. The Catholic church was renovated and reordered during 2004–5, partly to accord with current liturgical practice, although proposed alterations to the Pugin altar prompted national controversy and the intervention of the Pugin Society. (fn. 258) The Baptist church and hall underwent major renovation around the same time, aimed partly at providing improved community facilities for the whole town; it, too, attracted a significant number of young people. (fn. 259) Jehovah's Witnesses were established on Marlow Road in the early 21st century. (fn. 260)

Religious Buildings

St Mary's Parish Church

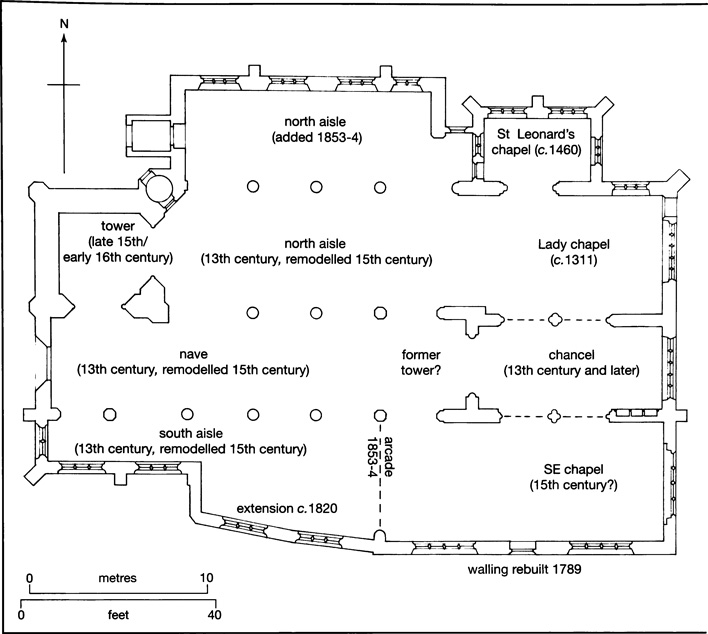

Sited on the north side of Hart Street close to the bridge, St Mary's church is of clearly urban character, with its spacious chancel and aisled nave, its flanking north and south chancel chapels, and its substantial battlemented north-west tower, which may have replaced an earlier tower at the crossing. Though the church was almost certainly established in or before the 12th century, the earliest datable fabric is 13th-century, when there appears to have been considerable rebuilding. Major alterations followed in the 15th and early 16th century (the date of the existing tower), and much of the south side was remodelled or rebuilt in 1789 and c. 1820. The church acquired its final form during a major restoration in 1853–4, which amongst other changes saw the construction of an additional north aisle. (fn. 261) Most of the walling is a mixture of knapped flint and dressed stone; the chief exceptions are the 15th-century stone-built chapel of St Leonard on the north side, and the 18th- and early 19th-century ashlar and stone-and-flint chequer-work on the south, towards Hart Street.

The church to c. 1400

A richly decorated stone doorway of c. 1160–80, which until the 19th century formed the entrance to a nearby house on Hart Street, came possibly from a late 12th-century church of which nothing else obvious remains. (fn. 262) The earliest datable fabric is 13th-century, when the church apparently comprised an aisled nave, a chancel, and probably transepts and a central tower. Survivals from that period almost certainly include the west doorway, which, though heavily restored in the 19th century, is probably of early 13th-century origin. (fn. 263) The central bays of the nave arcade (though heightened in the 15th century) are probably also 13th-century, and a reset window at the west end of the south aisle extension (built c. 1820) may be of similar date. So, too, may the westernmost part of the chancel's north wall, immediately adjoining the chancel arch. Thirteenth-century indulgences granted to Henley church presumably supported some of this work. (fn. 264)

Since bells were mentioned from the 13th or 14th century (fn. 265) the church must have had a tower or belfry. A central tower is suggested by the form of the easternmost bay of the nave, which is longer than the bays to its west, and near square in plan. Before the 19th-century restoration this bay alone had a clerestory, which was interpreted by the architect as part of a lost or unbuilt clerestory along the whole nave; equally, however, it could have survived from the lower tier of a former tower. (fn. 266) The bay's western piers (unlike those in the central part of the nave) are 15th- or early 16th-century, as are the imposts of the chancel arch, indicating a major rebuilding; if a central tower existed it was presumably demolished at that date, having been replaced by the north-west tower. A suggestion that the existing tower was preceded by a freestanding belfry, though not inherently implausible, lacks any firm architectural evidence. (fn. 267)

The Lady chapel which forms the north chancel aisle is almost certainly the 'newly built' chapel of St Mary mentioned in 1311, which became associated with the guild. (fn. 268) Its east window has reticulated tracery, and centred beneath it on the outside is a stone roundel set into the flintwork, which probably bore a consecration cross. An external stone plinth with two orders of mouldings terminates against the line of a former wall between the chapel and chancel, which must have been replaced soon after by the existing arcade: the arcade's detailing is similar to that of the window, which was left slightly off-centre by the wall's demolition. The relationship confirms that the chancel pre-dates the Lady chapel, discounting suggestions (fn. 269) that the chapel may have originated as a remodelling of an earlier (possibly Norman) chancel.

Other 14th-century chantries may have also involved new building, (fn. 270) but no further major additions are known before the 15th century. The chancel's east window is probably early 14th-century, (fn. 271) and the mason Thomas Wolvey was working at Henley church in 1397, while in 1419 over £50 was spent on lead. (fn. 272) A clock was installed before 1410. (fn. 273)

43. St Mary's parish church, showing main phases of development. (Drawing to scale, but not based on detailed measurement.)

Fifteenth- and early 16th-century remodelling