A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Originally published by Oxford University Press for Victoria County History, Oxford, 1981.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Kempsford', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7, ed. N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp96-105 [accessed 9 May 2025].

'Kempsford', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Edited by N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online, accessed May 9, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp96-105.

"Kempsford". A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Ed. N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online. Web. 9 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp96-105.

In this section

Kempsford

Kempsford, which includes the hamlets of Whelford, Horcott, and Dunfield, occupies a tract of low-lying land by the river Thames 15 km. ESE. of Cirencester. The parish includes 2,009 ha. (4,963 a.) (fn. 1) and has its boundaries for the most part on watercourses. The river Coln provides parts of the north-east boundary, though a greater length of the river is within that boundary. The south boundary with Wiltshire is on the Thames and the west boundary, also the county boundary, is marked by the watercourse formerly called the county ditch. (fn. 2)

The land is formed mainly by Oxford Clay with tracts of alluvium bordering the Thames and Coln and deposits of gravel, extensively worked in the mid 20th century, near Horcott and east of Whelford. (fn. 3) Most of the parish lies very flat at around 80 m., so that even the small hillock called Brazen Church hill (possibly from land once owned by Bradenstoke Priory) (fn. 4) forms a landmark. Towards the north there is a gentle rise to c. 90 m. at Furzey hill and Horcott hill. Woodland is limited to a few small copses, though an ancient wood once existed at Dudgrove in the south-east part of the parish. (fn. 5) The dominant feature of the landscape for many centuries was the large area of common meadow land lying by the Thames and Coln. The meadows and the open fields, which occupied the centre of the parish, were inclosed in 1801. (fn. 6) The parish was drained by a network of ditches and 'carries', some part of which was probably in existence in 1133 when the black dyke was mentioned. (fn. 7) In later centuries the system, which was employed each winter to direct floodwater onto the meadows, (fn. 8) centred on the Grand Drain, running the width of the parish from Furzey hill across to the Coln. Some additions to the system were made in 1802 following the inclosure. (fn. 9) The Thames and Severn canal, crossing the south part of the parish, was opened in 1789 and closed in 1927; there was an agent's house and warehouse where it met the main village street. (fn. 10)

In 1976 Kempsford was dominated by the airfield of R.A.F. Fairford with its main runway extending for some 3.7 km. across the centre of the parish. The original airfield was opened in 1944 for use by transport aircraft, which took troops to the D-day and Arnhem operations. After the war it was used intermittently by the R.A.F. until 1950 when it was taken over by the United States Air Force and much enlarged for use as a bomber base; a large staff operated the base during its tenure by the U.S.A.F., accounting presumably for all of the 790 people not in private households enumerated in the 1961 census. Handed back to the R.A.F. in 1964, the base then served a variety of functions but in the early 1970s was for defence purposes maintained only as a reserve airfield; it became widely known at that period, however, from its use by the British Aircraft Corporation for testing the Concorde supersonic airliner. In 1976 B.A.C. employed c. 300 people at the airfield and there was a smaller number of R.A.F. personnel and employees. (fn. 11)

Kempsford village is named from a ford across the Thames, entered at the point where the moated manor-house was built and left further upstream opposite the church. (fn. 12) In the year 800 the earldorman of the Hwicce and his men crossed there and fought a battle with the men of Wiltshire (fn. 13) and it was presumably anciently a recognized crossingpoint on a route from Fairford and Lechlade towards the Roman road near Cricklade. The ford does not figure to any extent in the later records of Kempsford and all traces of a track connecting with it on the Castle Eaton bank have disappeared. It was apparently a difficult ford to negotiate and flooding of the surrounding land may also have limited its use. (fn. 14) The shape of Kempsford village shows that the Cirencester–Highworth road (fn. 15) was a more significant factor in its development. That road, which in the west part of the parish has been severed by the airfield, crossed the Thames at Hannington bridge c. 1.5 km. downstream of the village. A bridge had been built there by 1439, Kempsford and Hannington being responsible for repairing their respective halves. The bridge was rebuilt in 1647 after being destroyed during the fighting in the Civil War, and it was again rebuilt, as three stone arches, in 1841. (fn. 16)

From the manor-house and church at the ford Kempsford village developed along the Cirencester road to form a long street of loosely grouped dwellings, a small green on the south side of the street apparently providing a focal point. The stocks stood at the green until c. 1880 (fn. 17) and in the early 18th century a stone cross stood in the road there; (fn. 18) the cross, from which only the base and part of the shaft survive, was later moved to the corner near Reevey Farm (fn. 19) and in 1890 was moved again to the new churchyard opposite the church. (fn. 20) Opposite the green stood the church house, which was rebuilt after a fire in 1791. (fn. 21) In the early 17th century the houses at Kempsford were said to be mostly built of mud walling and thatch. (fn. 22) Most were rebuilt of stone in the course of the 18th century, and there is some evidence of building on new sites in the village in the early part of that century. (fn. 23) Tuckwell's Farm and Middle Farm are small stone farm-houses of the 18th century and most of the older cottages that survive are from that period. Council houses were built on the street in the 1920s and later, and in the 1960s and early 1970s its appearance was much altered by the removal of some of the old cottages and the addition of new houses for people working in Swindon. (fn. 24) Reevey Farm, west of the village, was named from a late-17th-century tenant; (fn. 25) the original small house (fn. 26) survives, standing on what was possibly the old course of the Cirencester road, but it was replaced as the farm-house by a larger house built east of it in the mid 19th century. To the north-west is the small hamlet called Dunfield, which comprised 8 houses c. 1710. (fn. 27) Dunfield House there dates from the late 17th century as does the older part of Poplar House, which was enlarged and remodelled in 1817. (fn. 28)

Whelford hamlet takes its name from the crossing of the river Coln by the road from Lechlade to Kempsford. A mill had been built beside the ford by the beginning of the 12th century (fn. 29) and a bridge had probably been built by 1283. (fn. 30) A new two-arch bridge was built in 1851. (fn. 31) The hamlet, which comprised 20 houses by the early 18th century, (fn. 32) forms a loose collection of farm-houses and cottages lying west of the crossing. Whelford Little Farm and College Farm and a few cottages date from the 17th century and a greater number of houses were added in the early 19th. A chapel of ease and a school were built in the mid 19th century.

Horcott in the north of the parish takes its name from a dwelling in a muddy place (fn. 33) and the first record of it also concerns a mill on the Coln in the early 12th century, (fn. 34) perhaps standing by another minor crossing. The hamlet contained 7 houses c. 1710 (fn. 35) and comprised a small compact group of farm-houses close to the river at the place that was called Horcott Street in 1801. (fn. 36) A 17th-century cottage survives there together with Horcott Farm and Horcott House, small farm-houses of the 18th century; both farm-houses were given new Tudorstyle windows in the 19th century and Horcott House was enlarged by extensions to the rear. There was some later development to the northwest on the Whelford–Fairford road. A row of labourers' cottages was built on the north-east side close to the parish boundary in the early 19th century and in the middle of that century the Catholic church, presbytery, and school, forming a Gothic group further south, were built. In the mid 20th century Horcott was much enlarged by council and private housing built at various dates on the south-west side of the road.

There are two outlying farmsteads. Dudgrove Farm was built in 1692 (fn. 37) in the meadows in the south-east part of the parish and the south range of the house survives from that period, though the windows have been renewed. Later additions at the rear included a long cheese-barn, which was converted and taken into the house in the mid 20th century. (fn. 38) Furzey Hill Farm in the north-west corner of the parish, a substantial farm-house with mullioned and transomed windows, was built in the early 18th century, probably c. 1708. (fn. 39)

In 1086 62 inhabitants of Kempsford were recorded. (fn. 40) Seventy-four people were assessed for the subsidy in 1327 (fn. 41) and 157 for the poll-tax in 1381. (fn. 42) There were said to be c. 240 communicants in 1551 (fn. 43) and 24 households in 1563; (fn. 44) the latter figure looks too small to be accurate. The population was estimated at 60 families in 1650 (fn. 45) and c. 340 inhabitants in 66 houses c. 1710, (fn. 46) and the early part of the 18th century apparently saw a considerable expansion, with a figure of 100 houses given in 1743. (fn. 47) There were said to be 493 inhabitants in 104 houses c. 1775 (fn. 48) and 656 people were enumerated in 1801. The population then rose steadily to 1,007 in 1861 but fell during the later 19th century to 711 in 1901 and fluctuated in the early 20th century. In 1951 there were 860 in private households, and new building had raised that figure to 1,333 by 1971. (fn. 49)

Two innholders were recorded in the parish in 1755. (fn. 50) In 1856 the George on the south side of the street was apparently the only inn in Kempsford village (fn. 51) but by 1891 there were also the Axe and Compasses at the west end and the Cross Tree (fn. 52) near the green; (fn. 53) the last closed in the 1940s but the other two remained in 1976. The Queen's Head inn opened at the south end of Whelford in the earlier 19th century, before 1844, and was demolished during the extensions to the airfield in 1950. (fn. 54) The Carrier's Arms at Horcott had opened by 1891. (fn. 55) A friendly society met at the George in Kempsford in 1866 (fn. 56) and reading-rooms had been opened in the village by 1879. (fn. 57) A village hall was built on the south side of the street in 1932. (fn. 58)

Edward I made at least four visits to Kempsford in the course of his reign, the last in 1305 (fn. 59) when his nephew Henry of Lancaster held the manor. The ownership of Kempsford by the earls of Lancaster in the early 14th century has given rise to a number of local legends, including some fanciful attempts to connect Kempsford with John of Gaunt and his family, (fn. 60) though Gaunt himself never owned the manor. A more tangible connexion with a great family was that with the Thynnes of Longleat, who had a residence at Kempsford in the 17th century.

Manor and Other Estates

The estate later called the manor of KEMPSFORD was held by Osgod from Earl Harold before the Conquest. In 1086, assessed at 21 hides, it was held by Ernulf of Hesdin, (fn. 61) who was succeeded before 1096 by Patrick de Chaworth, evidently his son-in-law. (fn. 62) The manor, which was the head of a reputed barony comprising a group of manors mainly in Wiltshire, (fn. 63) was retained by Patrick until at least 1133. (fn. 64) It then apparently passed to his son Patrick and to Patrick's son Pain, (fn. 65) also called Pain de Mundubleil, who had succeeded by 1155. (fn. 66) Pain's brother Hugh may have had an interest in Kempsford manor but Pain's son Patrick de Chaworth (fl. 1199) later succeeded. (fn. 67) Patrick was succeeded by Pain de Chaworth, who retained the manor in 1236 and was succeeded before 1243 by his son Patrick. (fn. 68) In 1254 Patrick redeemed an annuity of £7 granted out of the manor by his father to Tironneau Abbey (Sarthe) in 1236. (fn. 69) Patrick died c. 1258 and the manor passed to his son Pain (fn. 70) (d. c. 1279) and then to Pain's brother Patrick (fn. 71) (d. c. 1283), who left an infant daughter, Maud, as his heir. (fn. 72) Rents in the manor were granted in dower to Isabel, widow of the last Patrick. (fn. 73)

The manor passed to Henry of Lancaster, (fn. 74) later earl of Lancaster, on his marriage to Maud de Chaworth before 1297. Henry (d. 1345) was succeeded by his son Henry, created duke of Lancaster in 1351. (fn. 75) In 1355 the duke granted the manor, together with the neighbouring manors of Inglesham and Hannington (both Wilts.) to the hospital of the Annunciation at Leicester (called the Newark), which he elevated into a collegiate church. (fn. 76) The college, which had grants of free warren and protection in the manor in 1356 and 1361 respectively, (fn. 77) held the manor until its suppression in 1548. (fn. 78)

In 1549 the manor was granted to Sir John Thynne (fn. 79) (d. 1580) and it passed to his son John, (fn. 80) whose son Sir Thomas was lord in 1608. (fn. 81) Sir Thomas (d. 1639) was succeeded at Kempsford by his son by his second marriage, Henry Frederick Thynne, (fn. 82) who was made a baronet in 1641 and suffered heavy sequestration fines after the Civil War. (fn. 83) From Sir Henry (d. 1680) the manor passed to his son Sir Thomas, (fn. 84) who was created Viscount Weymouth in 1682, in which year he succeeded to Longleat House and the main family estates. Viscount Weymouth (d. 1714) was succeeded in his estates and title by his great-nephew Thomas (fn. 85) (d. 1751), who gave Kempsford to his second son, Henry Frederick Thynne. Henry sold it in 1767 to Gabriel Hanger, Lord Coleraine (fn. 86) (d. 1773), whose widow Elizabeth apparently held it until her death in 1780. (fn. 87) It passed in turn to his three sons and successors to the title, John (d. 1794), William (d. 1814), and George (d. 1824). George, Lord Coleraine, a former companion of the Prince Regent, used the manor in his dealings with his creditors, who included his nephew and successor at Kempsford, Arthur Vansittart of Shottesbrook (Berks.). (fn. 88)

Arthur Vansittart sold part of the estate, comprising Manor and Dudgrove farms, to his brother Robert (d. 1838). The rest passed at his death in 1829 to his son Arthur. (fn. 89) The younger Arthur sold it in 1841 to Sir Gilbert East, Bt., who bought in the other part of the estate in 1844. Sir Gilbert (d. 1866) was succeeded by his son Sir Gilbert Augustus Clayton East, who sold the estate, comprising 8 farms and 3,085 a., to William Carey Faulkner in 1871. William (d. 1883) left his estates to his three sons, John, James, and Thomas, who made a division of them in 1889 when John's share included the manor and most of the land and James's included Dudgrove farm. (fn. 90) John Faulkner held his estate until his death in 1941 (fn. 91) and his trustees offered it for sale in 1953, when it comprised 2,320 a. (fn. 92) The estate was then split up, several of the tenants buying their farms. (fn. 93)

The belief that there was a castle at Kempsford, recorded in the late 18th century, (fn. 94) probably derived merely from the existence of a large moated manorhouse and from Kempsford's status as the head of a reputed barony. In an extent of 1258 only a manorhouse, with a hall, kitchen, gatehouse, and other rooms, was recorded on the manor. (fn. 95) It evidently stood close to the river south of the church where part of the moat, recorded in 1801, (fn. 96) could still be seen in 1976. In the early 16th century the site of the manor included buildings in an inner and outer court, the former presumably those within the moat. The buildings of the inner court were known as the provost's lodgings from their use by the official of Leicester college who administered the manor, and they were reserved to the college in a lease of 1532. (fn. 97) In the late 16th century the manorhouse was the home of Francis Thynne, second son of Sir John Thynne. (fn. 98) Part of it may have still been standing in 1705 when the buildings of the home farm included one called the porter's lodge. (fn. 99)

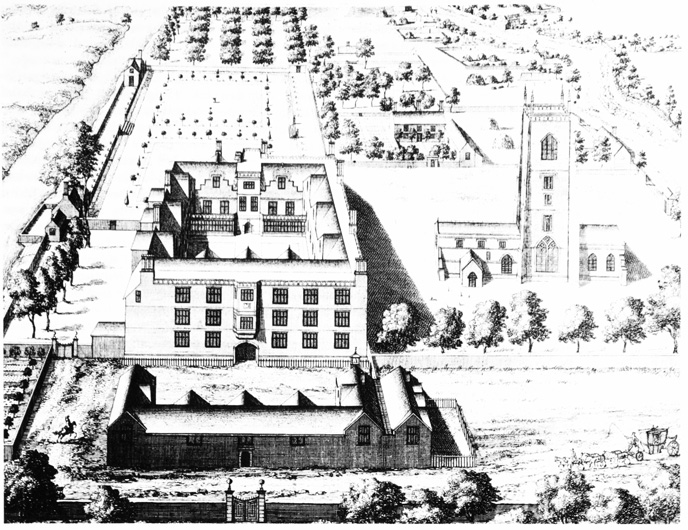

Sir Thomas Thynne built a large new manorhouse at Kempsford between the church and the river, apparently completing it only shortly before his death in 1639. (fn. 100) Sir Henry Frederick Thynne was assessed on 44 hearths at Kempsford in 1672. (fn. 101) The house was ranged around a courtyard and had a walled garden, (fn. 102) known as the provost's garden, (fn. 103) on the north and a terrace walk beside the river. The terrace, which survived in 1976 together with the ruins of one of the summer-houses that stood at each end, acquired the name Lady Maud's Walk in the 19th century from a supposed connexion with the daughter of Henry, duke of Lancaster. (fn. 104) Of the farm buildings which stood south of the house in the early 18th century two barns and a building which became the back range of Manor Farm still survived in 1976. Kempsford was the chief residence of Sir Henry Frederick Thynne (fn. 105) but the house was probably used only occasionally by the family after 1682. In the 1770s it stood uninhabited and ruinous (fn. 106) and it was demolished before 1784, (fn. 107) some of the materials supposedly going to build Buscot Park (Berks.). (fn. 108) An 18th-century house south of the village street later became known as the Manor House (fn. 109) but in 1846 Sir Gilbert East built Manor Farm as the new manor-house, adding to an older building a new front range in the revived 17th-century style. (fn. 110) John Faulkner lived at Benbow House and later at Dunfield House. (fn. 111)

Gloucester Abbey, which was granted Kempsford church by Ernulf of Hesdin, also received various lands at Kempsford by gift of the first Patrick de Chaworth and his wife Maud, including ½ hide, 1 yardland, and a mill at Horcott. (fn. 112) At the Dissolution most of the land was administered with Coln St. Aldwyns manor (fn. 113) and remained part of that manor after it was granted to the dean and chapter of Gloucester in 1541. (fn. 114) In 1649 it was a part of the demesne of Coln St. Aldwyns manor, (fn. 115) but later most of it formed a copyhold based on College Farm at Whelford. After the inclosure College farm comprised 99 a. while another 15 a. were leased separately with a cottage at Horcott. (fn. 116) In 1857 the Ecclesiastical Commissioners sold College farm to Richard Iles, (fn. 117) and Augustine Iles sold it in 1923 to the lord of the manor, John Faulkner. (fn. 118)

The rectory estate, leased from Gloucester Abbey in the early 16th century, comprised the parsonage barn, the tithes of corn and hay, and 3 a. of land assigned in composition for the tithes of a meadow. (fn. 119) It was granted in 1541 to the bishop of Gloucester. (fn. 120) The bishop granted an 89-year lease to the Crown before 1585 (fn. 121) but in 1646 the lessee was the lord of the manor, Sir Henry Frederick Thynne, who was required to grant the rectory as an augmentation of the living of Cirencester. (fn. 122) Viscount Weymouth was the lessee c. 1710, when the rectory was said to be worth £100. (fn. 123) In 1723 it was leased for lives to Algernon Seymour, Lord Percy, and William Greville, Lord Brooke. Their interest was acquired before 1743 by Viscount Weymouth, and his eldest son Thomas, later marquess of Bath (d. 1796), and Thomas's son and heir Thomas succeeded as lessees. (fn. 124) At inclosure in 1801, when the rectory was valued at £236 net, (fn. 125) the marquess was awarded 318 a. based on Furzey Hill Farm for it. He sold the lease the same year to John Hewer of Maiseyhampton. (fn. 126) It was bought from the Hewer family in 1838 by Col. William Pearce of Cheltenham, who bought the freehold from the bishop in 1854 and sold the estate to Edward Fletcher Booker in 1860. Booker and his mortgagees sold it in 1868 to Richard Rickards, (fn. 127) whose family owned and farmed Furzey Hill until the mid 20th century. (fn. 128)

Bradenstoke Priory (Wilts.) in 1258 (fn. 129) and Lacock Abbey (Wilts.) in 1315 (fn. 130) owned lands in Kempsford. Those lands were evidently the parcels of meadow which continued to descend with Hatherop after the Dissolution; they had presumably become attached to Hatherop in the late 11th and early 12th centuries when it was in the same ownership as Kempsford. (fn. 131)

Economic History

In 1086 Kempsford manor had 6 teams in demesne and employed 14 servi. There was a sheepfold on the manor, the flock being apparently valued principally as a means of producing cheese. (fn. 132) In 1258 the demesne of the manor comprised 832½ a. of arable, 156½ a. of meadow, a pasture sufficient to support 24 oxen, and a grove with pasture for 40 cows; (fn. 133) the last was presumably Dudgrove, where the manor sheep-house stood in 1517. Most of the demesne land was leased during the 16th century to the Hitchman family, (fn. 134) which held 14 yardlands in 1587. (fn. 135)

The tenants in 1086 were 38 villani, 9 bordars, and a radknight, with 18 teams between them. (fn. 136) In 1258 there were 37 yardlands held in villeinage; their value to the lord was then realized mainly in cash rents and aids and from each was owed only 5 days' labour in the year. There were also 66 cottagers, owing rent and 2 days' reaping each, and a number of free tenants. (fn. 137)

All or most of the tenant land was copyhold until 1673 when Sir Henry Frederick Thynne apparently ended that form of tenure on the manor. (fn. 138) Later the tenant holdings, which numbered more than 60 in 1710, were mostly held on leases for lives owing heriots and reliefs; quite a high number were held by non-parishioners, possibly attracted by the valuable meadow rights attached to the holdings, while among the Kempsford holders the families of Pope, Jenner, Iles, and Packer were prominent. (fn. 139) Three larger farms on the estate were held on short leases for years in the 18th century: (fn. 140) they were the home farm, which probably had its farm-house at the old site of the manor, Dudgrove farm in the south-east part of the parish, (fn. 141) which was apparently established in the late 17th century, (fn. 142) and Furzey Hill farm, established in the early 18th century on rough grazing land in the north-west corner of the parish. (fn. 143)

Kempsford: The manor-house and church in the early 18th century with the river thames on the left

The tenants in Kempsford village had their arable in Town field, lying immediately north of the village street, in Upper Moor field, lying beyond Town field, and in Upper and Lower Ham fields, lying east of the village between the Thames and the Grand Drain. Dunfield field lay north of the hamlet of that name and Honey field lay east of Furzey hill. Whelford had a great field and a little field, both lying north of the hamlet, and West Horcott field lay west of Horcott. (fn. 144) A rotation of two crops and a fallow was apparently the practice in most of the parish until inclosure (fn. 145) but at Dunfield a part of the open fields, called a hitching, was cultivated every year in the late 17th century and until 1727, when it was included again in the usual rotation. (fn. 146)

The rich meadow land of the manor by the Thames and Coln was valued at £9 in 1086 (fn. 147) and in later centuries occupied more than 1,000 a., most of it common meadow held on the lot system. The largest common meadow, Kempsford meadow, occupied the south-east corner of the parish; Whelford meadow and Bowmoor lay between the Coln and the north-east boundary; and there were several smaller meadows, including one at Dunfield. (fn. 148) The practice of 'drowning' the meadows, flooding them in winter to warm the land and bring on early grass, was recorded from 1707, when the costs of the operation were shared among the occupiers. (fn. 149) The owners of several upland estates in the neighbourhood owned and used parcels of meadow in Kempsford in connexion with their estates. In 1267 one of Gloucester Abbey's tenants at Coln St. Aldwyns had the duty of carrying hay from Kempsford, (fn. 150) and meadow land at Kempsford belonging to the abbey remained attached in later centuries to its manors of Coln, Aldsworth, (fn. 151) and Eastleach Martin. (fn. 152) Other parcels of meadow were attached to the manors of Hatherop and Southrop, (fn. 153) which had both at different times been in the same ownership as Kempsford.

The parish once had a large common pasture called the Moors, lying between the Grand Drain and the Kempsford–Whelford road. It was inclosed by private agreement in the later 17th century, before 1677, and divided into small closes which were assigned to the various tenements on the manor. (fn. 154) There remained the common pasture rights in the open fields and meadows: in 1682 the stint was 20 sheep, 7 beasts, and 2 horses to the yardland in the fields and 4 beasts to the yardland in the meadows. (fn. 155) In 1587 a total of 5,447 sheep and 884 cattle was kept in the parish; the largest flock of sheep, numbering 460, was kept by James Dolle in Whelford while Robert Hitchman, the farmer of the demesne, had 390. (fn. 156)

Inclosure by Act of Parliament in 1801 dealt with 2,224 a. of open field and common meadow as well as re-allotting some old inclosures that were inconveniently situated for the farm-houses to which they were attached. The bulk of the allotments was assigned to Lord Coleraine or his lifetenants but whereas he had previously owned almost all the parish, the small estate of the dean and chapter being the main exception, several substantial freeholds were created as a result of the inclosure. Two of them were those given for the tithes of the rectory and vicarage respectively while the sale of a considerable acreage to meet the expenses of the inclosure enabled several people to acquire estates, in particular Mary Jenner, Thomas Pope of Whelford, and Thomas Packer Butt who became owner of Reevey farm. (fn. 157)

Following the inclosure several large farms were formed. Two on the manor estate covered 653 a. and 628 a. respectively in 1815. (fn. 158) The estate had a total of 8 farms in 1870, the largest being Dudgrove farm with 767 a. and Manor farm with 607 a.; the others were two at Whelford with 472 a. and 200 a. respectively, two at Horcott with 310 a. and 227 a. respectively, Dunfield farm with 297 a., and Tuckwell's farm in Kempsford village with 96 a. (fn. 159) There were altogether c. 22 separate holdings in the parish in the 19th century, (fn. 160) Furzey Hill farm, comprising 317 a. in 1860, being the largest outside the manor estate. (fn. 161) In 1926, however, as many as 31 separate holdings were returned, of which 9 were of over 150 a. and 7 of 50–150 a. (fn. 162) The smaller holdings had mostly gone by 1976 when a total of 15 farms was returned, 7 of them of over 100 ha. (247 a.). (fn. 163)

Arable land predominated over grassland in the 19th century in spite of the extensive meadow land: in 1866 2,835 a., cropped mainly with wheat, barley, turnips, beans, and grass-seeds, were returned compared with 1,545 a. of permanent grassland. (fn. 164) The decline in arable farming in the later 19th century was not so marked as in the upland parishes of the neighbourhood with only wheat suffering a severe reduction in acreage. (fn. 165) The rich meadow land naturally made cattleraising and dairying a significant part of local farming. Cheese-production was no doubt also encouraged by the proximity of Lechlade with its facilities for marketing cheese and shipping it to London; Cobbett in 1826 noted one Kempsford farm with a dairy herd of 60–80 and a cheese-loft containing many hundreds of cheeses. (fn. 166) In 1866 a total of 624 cattle, including 165 milk cows, was returned on the farms of the parish (fn. 167) and in the earlier 20th century even more farms appear to have concentrated on beef and dairy cattle; 828, including 257 milk cows, were returned in 1926. (fn. 168) Sheep were still pastured in large numbers in 1866 when 2,583 were returned, (fn. 169) but none were returned in 1976. In 1976 the amount of arable returned was up again to the mid-19th-century level, for although much of the old arable had been lost to the airfield most of the old meadow land was then under the plough; the arable was then almost entirely under wheat and barley. Dairying had declined to some extent in recent years, though 4 of the main farms still specialized in that branch, while 3 were mainly devoted to cereals, 2 mainly to cattle-raising, 1 to poultry, and 1 to mixed farming. (fn. 170)

Four mills were recorded on Kempsford manor in 1086. (fn. 171) One at Horcott was granted to Gloucester Abbey by the first Patrick de Chaworth, who also gave the abbey the tithes from two at Whelford. (fn. 172) The abbey's Horcott mill was again recorded in 1225 (fn. 173) and may have been working in 1556; (fn. 174) no later record of it has been found (fn. 175) but a side-channel of the Coln survives at Horcott, presumably the mill-leat. The two Whelford mills were again recorded on the manor estate in 1258 (fn. 176) and in 1532, when there were two mills under one roof. (fn. 177) .They were presumably at the site of Whelford mill, on the Coln north of the hamlet. In 1710 Whelford mill was worked in conjunction with a malt-house. (fn. 178) By 1732 the tenant was John Edmonds, (fn. 179) whose family continued as millers there until the Second World War. (fn. 180) The buildings were remodelled and extended in the mid 20th century to form a substantial residence. A derelict windmill standing by the Thames in Kempsford parish was depicted in an undated print; (fn. 181) no other record of it has been found but it is thought to have stood in the meadows downstream of Hannington bridge. (fn. 182)

In 1243 Patrick de Chaworth had a grant of a Tuesday market and an annual fair at the Nativity of the Virgin on his manor of Kempsford, (fn. 183) and in 1267 his son had a grant of a Friday market and a fair at St. Bartholomew. (fn. 184) The alteration of the dates may reflect conflict with markets held at Lechlade and Fairford, though the new market day would still have conflicted with one of the Fairford markets. It seems unlikely that the market and fair ever prospered in such close proximity to the two towns; nothing about their later fortunes has been found.

Henry the walker who was drowned in one of the mill-ponds before 1287 (fn. 185) was probably plying his trade there. In 1327 2 fishermen were recorded in the parish, (fn. 186) presumably lessees or employees under the manor, which enjoyed rights in both the Thames and Coln. (fn. 187) Three tailors and a weaver were the only tradesmen listed in 1608 (fn. 188) and later references found are all to the usual village craftsmen. In 1831 27 families in the parish were supported by trade compared with 142 supported by agriculture. (fn. 189) In the 19th century the traditional craftsmen were joined by a number of shopkeepers and by others–in 1856 a timber-merchant, a coalmerchant, and a corn-dealer–whose business was probably connected with the canal trade (fn. 190) but the numbers engaged in trade were not large in proportion to the total population and the parish presumably looked to the neighbouring market towns for some of its needs.

Local Government

By an arrangement which was apparently in force by 1258 (fn. 191) view of frankpledge was held at Kempsford twice a year before the bailiffs of the abbot of Cirencester, lord of the hundred. The bailiffs were dined at the lord of the manor's expense and at one of the views took 5s. and any goods of fugitives and felons; the remaining profits went to the lord of the manor. (fn. 192) The lord of the manor's court exercised view of frankpledge in the post-medieval period. Rolls of the court survive for some years in the 14th century (fn. 193) and for most years between 1568 and 1646, (fn. 194) and there are draft rolls and court papers for 1682–1735. The court appointed a constable, a tithingman for Kempsford, whose bailiwick also included Dunfield, and a tithingman for Whelford with Horcott. Haywards were appointed for the same two divisions as the tithingmen and in their regulation of common rights were assisted by tellers; from 1692 a parish wonter (mole-catcher) was also appointed. In the 1630s the court still heard occasional pleas of debt and trespass but from the late 17th century it dealt only with agricultural and estate matters, including the upkeep of the system of drainage. It was also at particular pains to enforce the statutory labour on the roads and in 1682 the parish surveyors were apparently appointed in the court. (fn. 195) The court continued to be held until 1851. (fn. 196)

The old church house was used as a poorhouse in the 18th century. (fn. 197) In 1772 the vestry introduced the roundsman system for pauper girls and it adopted the Speenhamland plan in 1795. A parish surgeon was retained from 1797. (fn. 198) In the early 19th century expenditure on relief was generally high, sometimes higher than in the two neighbouring towns; 57 people were on permanent relief in 1803 and 72 in 1813. (fn. 199) By 1833 a deputy overseer was being retained and in that year employment was encouraged by the offer of a bonus of 2s. to employers for each man taken on at 7s. a week. (fn. 200) The parish became part of the Cirencester union in 1836 (fn. 201) and was later in Cirencester rural district, (fn. 202) becoming part of Cotswold district in 1974.

Churches

Kempsford had a church by the late 11th century when Ernulf of Hesdin granted it with the tithes and the land of the priest to Gloucester Abbey; the tithes were confirmed to the abbey by Patrick de Chaworth and his wife Maud. (fn. 203) A vicarage had been ordained in the church by 1198 (fn. 204) and the living has remained a vicarage. It was united with Castle Eaton (Wilts.) in 1974. (fn. 205) The advowson of the vicarage, retained by Gloucester Abbey until the Dissolution, was granted in 1541 to the bishop of Gloucester, (fn. 206) who remained patron in 1976. In 1422 the living was described as the vicarage of Whelford and Kempsford (fn. 207) and the rectory estate was later usually called the rectory of Kempsford and Whelford, (fn. 208) but no evidence of an ancient church or chapel at Whelford has been found.

In 1291 the living was valued at £14 13s. 4d. while Gloucester Abbey's rectory estate, held in commendam by Walter of Barton, was valued at £7 6s. 8d. The abbey also received a payment of 4 marks (fn. 209) out of the vicarage, granted to it c. 1197, (fn. 210) presumably because the original portion settled on the vicar was thought over-generous. The payment continued to be made by the vicar to the lessees of the rectory after the Dissolution. (fn. 211)

In 1677 the vicar's glebe comprised 41 a. in the open fields, 34 a. of pasture and meadow, and 9 'yards' of lot meadow. He then received all the small tithes of the parish and the corn and hay tithes of certain lands, (fn. 212) the latter granted in part as compensation for his loss of small tithes by the inclosure of the Moors. Lands known as the demesne meadows but including a large part of the common and lot meadows were claimed to be tithe free at the time of the inclosure in 1801, a claim not accepted by the vicar. (fn. 213) The lord of the manor usually paid a composition for the tithes of the home farm and some of the other larger farms on his estate. (fn. 214) The tithes were commuted for land at the inclosure, giving the vicar a total estate of 522 a. (fn. 215) The vicarage house, standing north of the church, includes a range built c. 1664; (fn. 216) additions were made on the north of that range in the 18th century, and c. 1856 there was a general remodelling of the house. (fn. 217)

The vicarage was valued at £19 clear in 1535 (fn. 218) and at £80 in 1650. (fn. 219) It was said to be worth £100 at the beginning of the 18th century (fn. 220) and £220 in 1750, when the profits included a rent-charge of £20 given by Lord Weymouth in 1709. (fn. 221) In 1856 it was worth £604 (fn. 222) but declined in value in the later 19th century and was worth only £160 in 1910; (fn. 223) in 1901 it was said to be held at a loss. (fn. 224)

Humphrey Gallimore, instituted to Kempsford vicarage in 1538, was dispensed for plurality in 1550, (fn. 225) and in 1559 leased the vicarage to Sir John Thynne, who was to make provision for serving the cure; (fn. 226) in 1563 it was served by the rector of Bagendon. (fn. 227) Gallimore was apparently in danger of losing the benefice in 1564, when it was said in his support that he was a 'favourer of true religion' who had formerly enjoyed the patronage of Bishop Latimer. In 1569 he was declared contumacious and barred from entering the church and in 1572 he was ejected for not subscribing to the Articles. (fn. 228) In 1639 the bishop, Godfrey Goodman, presented himself to the vicarage. He was succeeded in 1643 by Edward Hitchman (fn. 229) who remained vicar until his death in 1672, when he also held a prebend of Wells cathedral. (fn. 230) William Price, vicar 1761–98, (fn. 231) was living at Epsom (Surr.) in 1784 when Kempsford was served by a curate who lived at Fairford. (fn. 232) Thomas Huntingford, vicar 1810–55, held the living with the vicarage of Dormington (Herefs.) from 1826 and with the rectory of Weston under Penyard (Herefs.) from 1831. (fn. 233) His successor, James Russell Woodford, later bishop of Ely, (fn. 234) introduced daily services and weekly communions. (fn. 235)

The parish church of ST. MARY (fn. 236) is built predominantly of ashlar and has a chancel with south chapel, a tall central tower, and clerestoried nave with north and south porches.

Most of the Norman nave survives and it retains its north and south doorways and four original windows. The present chancel was built in the 13th century and the existence of a central tower by that time can be inferred. A south porch, used as a vestry from 1855, (fn. 237) was added in the 13th century. Early in the 14th century new windows were put into the west wall of the nave and the north wall of the chancel. In the 15th century there was a major reconstruction when a clerestory and new roof were added to the nave, new windows were put into the east end of its side walls, and the tower was rebuilt. The massive tower has a lofty, vaulted lower stage and very large windows in its north and south walls. (fn. 238) Although the north porch incorporates an earlier ogee-headed recess it too was probably an addition of the 15th century. The church was restored in 1858 under G. E. Street when a south chapel was added to the chancel and the nave was reseated. (fn. 239) A west gallery was removed in 1866 (fn. 240) and some further restoration was carried out in the 1880s. (fn. 241)

Few of the early furnishings or fittings survive. The stone pulpit, made in 1862, was designed by G. E. Street as were the choir-stalls. A new font was made in 1868, (fn. 242) replacing an old octagonal one. (fn. 243) Three of the stained glass windows were painted by the curate H. F. St. John, (fn. 244) who with Vernon Benbow was also responsible for painting the bosses and heraldic shields of the tower vault in 1862. (fn. 245) A 15th-century canopied tomb with the effigy of a priest survives in the chancel (fn. 246) together with a brass to Walter Hitchman (d. 1521), (fn. 247) who was lessee of the manorial demesne and of the rectory and possibly also a wool-merchant. (fn. 248) The church had a peal of 6 bells by the early 18th century (fn. 249) and in the late 19th century they were as follows: (i) 1739, by Henry Bagley; (ii) 1700, by Abraham Rudhall; (iii and iv) 1678, stamped with the arms of Sir Henry Frederick Thynne and his wife; (v) 1846, by C. & G. Mears; (vi) 1830, by John Rudhall. (fn. 250) The plate includes a chalice and paten cover of 1660, (fn. 251) presumably those given by Sir Henry Frederick Thynne and his wife, who also gave two silver flagons. (fn. 252) The churchyard contains a number of carved chest-tombs to members of the Iles and other 18th-century tenant families, and on the south side of the church is a group in a uniform style to members of the Arkell family, prominent farmers in the 19th century. The parish registers survive from 1573. (fn. 253)

At Whelford, where services were held in a granary from 1860, a chapel of ease, dedicated to ST. ANNE, was built and consecrated in 1864. Designed by G. E. Street, (fn. 254) it comprised nave with bellcot and apsidal chancel. A south transept was added in 1898. (fn. 255)

Roman Catholicism

A small Roman Catholic church was built at Horcott in 1845 (fn. 256) to take the place of the chapel that had formerly been in use at Hatherop Castle. (fn. 257) The Horcott church had an average congregation of 60 in 1851. (fn. 258) In 1976 it served a parish which included Lechlade, Fairford, and eleven surrounding villages. (fn. 259)

Protestant Nonconformity

Five Anabaptists were recorded at Kempsford in 1735. (fn. 260) Baptists registered a house at Whelford in 1799 and a group attached to the Fairford chapel was meeting in the parish in 1836. (fn. 261) A Baptist mission hall was built in 1879. (fn. 262) Independents registered a chapel at Whelford in 1820, (fn. 263) and there was a village station attached to the Congregational church at Fairford in 1858. (fn. 264) Other meeting-places recorded in the 1840s included a chapel at Horcott, belonging to John Kent, registered in 1841, and a house at Dunfield, registered for use by Primitive Methodists in 1844. (fn. 265)

Education

In 1693 Lord Weymouth was paying a schoolmaster £5 a year to teach children at Kempsford, (fn. 266) and a building called the school house, though possibly not then used for that purpose, was mentioned in 1706. (fn. 267) In 1709 Lord Weymouth settled £10 a year, payable out of estates in Ross-on-Wye and Weobley (both Herefs.), to pay a schoolmaster. (fn. 268) The master recorded at Kempsford in 1715 (fn. 269) was presumably employed by the charity, which in 1735 was teaching poor children to read free of charge and to write for a payment of 2d. a week, while the children from wealthier families paid 1d. for reading and 4d. for writing. (fn. 270) In 1750 a new building for the school, paid for by a subscription among the inhabitants, was put up on the south side of the village street on land given by Lord Weymouth. (fn. 271) In 1787 the school was said to be supported by Lord Coleraine, (fn. 272) who was presumably meeting the costs not covered by the endowment and pence.

By 1818 60–70 children, all the poor children of the parish, were attending the charity school, and a Sunday school supported by the vicar Thomas Huntingford had been started in a cottage adjoining the vicarage. (fn. 273) A new school building was built in 1855 adjoining the old one. In 1869 the school, called Kempsford C. of E. school, was supported by voluntary contributions, pence, and the endowment and had an average attendance of 80. (fn. 274) The average attendance remained at much the same figure in 1904; (fn. 275) it fell during the next 20 years but then recovered and was 81 again in 1936. (fn. 276) In 1976 there were 89 children on the roll. (fn. 277)

A church school for infants had been started at Whelford by 1867 when it taught c. 25 children and was supported by voluntary contributions and pence. (fn. 278) It was held in a cottage until 1874 when a new building was provided. (fn. 279) The attendance rose to 50 by 1885, when older children were also taken, (fn. 280) but fell to 20 by 1904 (fn. 281) and remained at c. 25 during the earlier 20th century. (fn. 282) By 1949 only 11 children remained on the register and the school was closed. (fn. 283) A Roman Catholic school was built at Horcott in 1852 and in 1885 had an average attendance of 36. (fn. 284) It was apparently closed in 1888. (fn. 285)

Charities for the Poor

John Hampson Jones by will proved 1892 gave £1,000 for the poor, and £1,000 stock was given in memory of William Battersby in 1926. In the mid 1970s the income from the two charities, c. £120, was distributed in cash among the old-age pensioners of the parish. (fn. 286)