A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Originally published by Oxford University Press for Victoria County History, Oxford, 1981.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Lechlade', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7, ed. N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp106-121 [accessed 9 May 2025].

'Lechlade', in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Edited by N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online, accessed May 9, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp106-121.

"Lechlade". A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 7. Ed. N. M. Herbert (Oxford, 1981), British History Online. Web. 9 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/glos/vol7/pp106-121.

In this section

Lechlade

Lechlade is situated 19 km. east of Cirencester in the Thames-side meadow land on the east boundary of the county. A borough and market town from the early 13th century, it later played some part in the Cotswold wool trade. Its chief function, however, was as a staging-post for goods and passenger traffic, for it stood at the head of the navigable Thames and at the entrance into Gloucestershire of a major road route from London. By the late 17th century large quantities of cheese were being shipped down river from Lechlade and after the opening of the Thames and Severn canal in 1789 the inhabitants also traded in coal. From the late 19th century the river played a new role, attracting visitors to the town for fishing and boating.

The boundaries of the ancient parish, which touched those of the counties of Wiltshire, Berkshire, and Oxfordshire, were mainly on rivers and watercourses, the river Thames supplying much of the south boundary and the Coln and Leach, which meet the Thames in the parish, parts of the other boundaries. South of the town the county and parish boundary diverges from the Thames to follow Murdock ditch, (fn. 1) presumably the original course of the river. A reference to the old Coln in 1627 (fn. 2) suggests that it too has been diverted within the parish. North of the old parish Lemhill, comprising 245 a. with a single farm-house, was a detached part of Broughton Poggs (Oxon.). It was added to Lechlade in 1886, increasing the area of the parish to 3,870 a. (1,566 ha.). (fn. 3) The history of Lemhill is included in this account.

The south part of the parish lies on alluvium and the north part on Oxford Clay with surface deposits of gravel or cornbrash. (fn. 4) The land is low and flat, mainly lying at about 70 m., and meadow land intersected by willow-lined watercourses and drainage channels provides the main feature of the landscape. There has never been much woodland apart from that in small copses and brakes in the north-west part of the parish and that in the park formed around the manor-house, north-east of the town, in the 19th century. In the mid 20th century gravel and sand workings transformed the appearance of the north-east part of the parish.

The crossing of the Thames near its confluence with the Leach has played a major role in the history of Lechlade and probably gave the parish its name; (fn. 5) a piece of land at the crossing was known as the Lade in 1246. (fn. 6) St. John's bridge, built at the crossing by 1228, carried the main road connecting mid Gloucestershire with London. Traffic was channelled into Lechlade and the bridge from Cirencester, from Gloucester by the Welsh way which met the Cirencester road at Fairford, (fn. 7) and from the north part of the Cotswolds by the Droitwich salt-way through Hatherop. (fn. 8) It was presumably to succour sick and poor travellers using the road that the owners of Lechlade manor, Isabel de Mortimer and her second husband Peter FitzHerbert, built the hospital or priory of St. John the Baptist on the north side of the bridge before 1228. (fn. 9) The hospital was dissolved in 1472, and c. 1520 part of the buildings was pulled down and the material used to repair the bridge, (fn. 10) but Leland some years later reported seeing a chapel and large enclosures of stone walls. (fn. 11) There was some effort to preserve the foundations when the site was used for building a parish workhouse in 1763, (fn. 12) but they were disturbed on more than one occasion subsequently. (fn. 13) In 1977 the site was used as a permanent caravan park.

The hospital had responsibility for the repair of St. John's bridge, for which the prior had grants of pontage in 1338, 1341, and 1388. (fn. 14) Later the bridge comprised two large and two small arches and there was a long causeway of more than 20 arches crossing the meadows on the Buscot side of the river. (fn. 15) A gateway to the bridge was built by Peter FitzHerbert in 1228 (fn. 16) and possibly survived as the building on it that was known as Noah's Ark in 1716. (fn. 17) By 1831 the bridge was dilapidated and a dispute over the liability to repair it arose between the county and the occupiers of the former hospital lands. In spite of the seemingly clear historical evidence of the liability of the latter the suit was inconclusive (fn. 18) and the county later accepted responsibility, employing a local builder, Peter Cox, to rebuild the bridge as a single arch. (fn. 19) An ancient right of taking toll from barges passing under the bridge, with which went the obligation of penning back the water to create a 'flash' to enable them to pass, was claimed by the lords of Lechlade manor as owners of the hospital estate. (fn. 20) In the late 17th century and early 18th the right to take toll was disputed by the bargemen and in the time of Sir Thomas Cutler led on one occasion to the bridge being chained up. (fn. 21) In 1791, however, the difficulties of passing the bridge were avoided when the navigation commissioners for the upper Thames by-passed it with a short new cut and a lock. (fn. 22)

The road from Cirencester to St. John's bridge was turnpiked in 1727. (fn. 23) The other main route through the parish, from Burford to Highworth and Swindon, was probably not of much importance until 1792. Under a turnpike Act of that year (fn. 24) a new bridge, (fn. 25) known as Halfpenny bridge from the tolls that were charged to pedestrians until 1839, was built over the Thames south of the town with a new stretch of road leading from it in Inglesham parish. There was formerly a ferry over the river south of the town, (fn. 26) and also a ford, (fn. 27) but it seems that before 1792 most traffic using the route had to go out to St. John's bridge and then follow Lamborne Lane which crossed Buscot parish to Lynt bridge. (fn. 28)

Road transport played an important part in the life of the town, which had several substantial inns. In 1794 an Oxford mail coach passed through the town twice daily and the London coaches from Cirencester passed back and forth three times a week. There was also a considerable traffic of stage-wagons, particularly those carrying cloth from the Stroud region. (fn. 29) Entries in the parish registers reflect the number of vagrants and travelling people, such as strolling players and licensed hawkers, passing through the town. (fn. 30) The easy connexions with London by road and river meant that the capital exerted a particularly strong attraction and numerous examples of natives of Lechlade who left to work in London are recorded. (fn. 31)

The Thames and Severn canal from Stroud to Lechlade was opened in 1789, the junction with the Thames being 1 km. SW. of the town where a circular watchman's house was built. The canal was closed in 1927. (fn. 32) After the opening of the Great Western railway in 1840 Lechlade was served by coaches and carriers from Faringdon Road station near Challow (Berks.). (fn. 33) In 1873 the East Gloucestershire railway from Witney to Fairford was opened (fn. 34) with a station for Lechlade on the Burford road north of the town. The line was closed in 1962. (fn. 35)

The place-name Lechlade probably refers to the vicinity of St. John's bridge, and the possibility that the original settlement was there cannot be entirely discounted, though rendered unlikely by the liability of flooding in the area. It is more likely that the Saxon settlement, first recorded in Domesday Book, (fn. 36) was at the present site on better-drained ground 1 km. NW. of the bridge near a lesser crossing of the Thames and that it was enlarged by Isabel de Mortimer when she founded a borough in the early 13th century. She obtained a grant of a market in 1210 (fn. 37) and c. 1230 Lechlade was referred to as her 'new market town'. (fn. 38) The rents from the burgages produced £3 16s. 8d. by 1275 (fn. 39) and £4 13s. 5½d. by 1326. (fn. 40) Some 40 houses in the town were classed as burgages in the late 16th century. (fn. 41)

The town is based on a reversed L shape formed by High Street, on the main Cirencester–London road, on the south side and Burford Street, probably that called Pipemore Street in 1490, (fn. 42) on the east side; at the angle formed by the two streets are the parish church and the market-place. (fn. 43) Originally, and probably until 1774, the Cirencester road entered the town from the west side by way of the hamlet of Little London, (fn. 44) skirting north of the close called All Court (fn. 45) which was doubtless the site of the capital messuage owned by Peter atte Hall before 1326. (fn. 46) The continuous property boundary at the back of the burgage plots on the north side of High Street may represent an ancient course of the road, aligning with St. John's Street (so called by 1580) (fn. 47) by which it leaves the town on the east. Possibly High Street was created when the borough was founded, causing the main road, having passed Little London, to veer southwards to meet it. Sherborne Street, formerly known alternatively as Pudding Lane, (fn. 48) is a back lane linking High Street and Burford Street, and the only other ancient streets were those which ran southwards from the town to the wharves on the river. Bell Lane, which ran down to the old crossing-point of the river, (fn. 49) was the most important of those until 1792 when Thames Street, leading to the new bridge, became the main road out of the town to Highworth and Swindon. Thames Street probably existed before 1792 as the Red Lion Street mentioned in 1730. (fn. 50) Wharf Lane running southwards from St. John's Street to Old Wharf was presumably built with the wharf in the mid 17th century. (fn. 51)

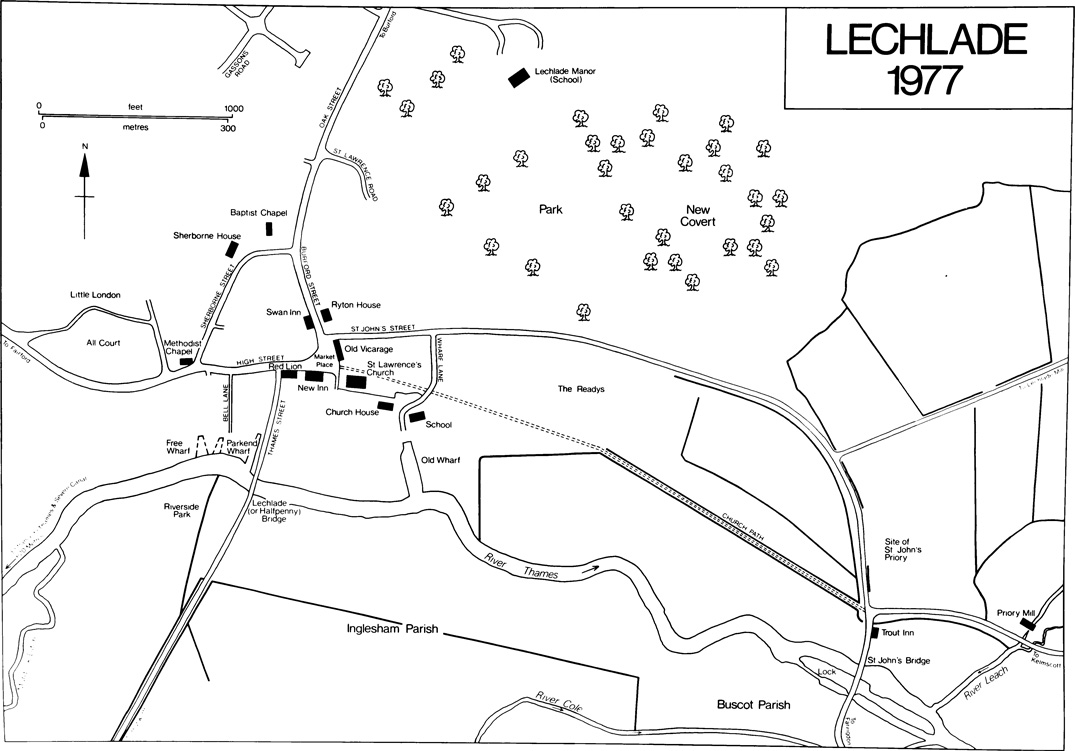

Lechlade 1977

A small house on the east side of Burford Street has a 16th-century carved doorway, which is, however, reset and was presumably brought from a larger house. One or two gabled 17th-century houses survive in the town but most of it was rebuilt in the very late 17th century and in the 18th when the river trade and the growth of road transport brought it modest prosperity. The principal residences of that period include Church House, (fn. 52) on the south side of the churchyard, which was the home of the Ainge family of wharfingers who traded from Old Wharf at the end of the garden; John Ainge settled there in the later 17th century and was followed by his son Richard (fn. 53) (d. 1730) (fn. 54) and by another Richard (d. 1778). (fn. 55) It is a small 17th-century house that was refronted and partly refitted in the early 18th century and extended to east and west in the early 20th. An extensive formal garden laid out in the early 18th century includes a short canal, a brick summer-house, and a gazebo built into the churchyard wall. The gazebo is a feature repeated at other houses in the town, including Grey Gables on Wharf Lane and Sherborne House (fn. 56) which stands at the angle of Sherborne Street. The latter is an early-17th-century house which was remodelled late in that century, being given a principal front of 5 bays with mullioned and transomed windows and a doorway with a segmental pediment. In the 18th century the windows were altered to sashes and there was some internal redecoration. The house is traditionally associated with a branch of the Dutton family of Sherborne, but in the 18th century it was the home of a branch of the prominent Lechlade family of Loder. (fn. 57) Another of the larger residences is Ryton House on the east side of Burford Street; it was rebuilt early in the 18th century by a wealthy mercer, John Ward (d. 1721 or 1722), and from 1755 was the home of Charles Loder (d. 1803). (fn. 58)

There are other small but good-quality 18th-century houses, including some on the south side of High Street which were probably built for wharfingers and maltsters. Other houses reflect the continuing prosperity of the early years of the 19th century when it was said that the appearance of the town was much improved by the work of the local architect and builder Richard Pace. (fn. 59) Examples of his work may include the ogee porches added to Grey Gables and to a house at Downington, and the two-storey semicircular bays on a house in St. John's Street and on the house, apparently Pace's own, (fn. 60) north of the Swan inn in Burford Street. After 1792 a terrace of cottages was built on Thames Street, and such development as there was in the 19th century was mainly in the form of cottages or small houses in the minor streets, including some in St. John's Street, Sherborne Street, and Oak Street (the northern continuation of Burford Street presumably named from the Royal Oak inn). Most of the 20th-century development occurred on the north side of the town around Hambidge Lane, the name given to the old salt-way where it meets the Burford road. The building of the Gassons council estate, south of the lane, had begun by 1933 (fn. 61) and more houses were added to it in the 1960s and 1970s, when a private housing estate was also built north of the lane. Another private estate was being built east of Burford Street on part of the manor-house park in 1977.

There are two small roadside hamlets on the west side of the town. Little London on the old Cirencester road is a small group of cottages, some possibly dating from the 17th century. Downington is a late-17th-century suburb comprising several substantial detached houses of that date. (fn. 62) Butler's Court, beyond Downington, is the only outlying farmstead recorded from medieval times apart from Great Lemhill Farm in the detached part of Broughton Poggs. Ruffords Farm, later called Green Farm, (fn. 63) on the opposite side of the road to Butler's Court was recorded from 1597 when the lord of the manor Edward Dodge left it to his niece Elizabeth Heylyn; (fn. 64) the house was rebuilt in the 19th century.

Most of the outlying farms of the parish date from the dismemberment of the manor estate in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Clayhill (later called Claydon House) on the north side of the Cirencester road, is a substantial 17th-century gabled house, (fn. 65) apparently built by Robert Bathurst (d. 1692), a son of the lord of the manor Sir Edward Bathurst; his family lived there until the 1760s. (fn. 66) The house was remodelled and enlarged in the 19th century by the owner G. A. Robbins (fn. 67) (d. 1887), (fn. 68) and further alterations were made in 1896 when the west front was cased. (fn. 69) Thornhill Farm on the west boundary was built for an estate acquired from the manor by the university of Oxford in 1670. (fn. 70) The farm-house was refronted in the 19th century but may be late-17th-century in origin. Downs Farm, further north, was built on an estate which passed from the manor to the mortgagee John Chaunler in 1707 (fn. 71) and it later descended with Stanford Farm in Southrop. (fn. 72) The farm-house, which was occupied as cottages in the 19th century, (fn. 73) was demolished c. 1961. (fn. 74) Warren's Cross, standing on the south side of the Cirencester road, possibly near the site of a wayside cross mentioned in 1458, (fn. 75) is a small farmhouse built in the early 18th century, before 1724, (fn. 76) and Trouthouse Farm near by is of a similar date. Chipley House, formerly called Little Clayhill (or Claydon) Farm, was probably the new farm-house near Clay hill mentioned in 1764; (fn. 77) it was remodelled and a new wing added in the 19th century. In the 19th century several pairs of farm cottages were built along the Cirencester road for the farms in that area of the parish.

In the east part of the parish Leaze Farm was built, probably in the late 17th century, to serve an estate which had passed to a branch of the Loder family by 1673, (fn. 78) and Paradise Farm near by had been established by 1788, (fn. 79) though apparently rebuilt later. A few small, mostly late, farm-houses in the north part of the parish include Manor Farm (formerly Red Barn Farm), Roughground Farm, and Little Lemhill Farm. (fn. 80)

Fifty-three inhabitants of Lechlade were recorded in 1086. (fn. 81) Fifty-nine were assessed for the subsidy in 1327 (fn. 82) and c. 138 for the poll tax of 1381. (fn. 83) Estimates of c. 200 communicants and 65 households were made in the middle of the 16th century, (fn. 84) of 96 families in 1650, (fn. 85) and of c. 500 inhabitants about 1710. (fn. 86) The prosperous years of the 18th century contributed to a considerable increase in population, though Rudder's figure of 925 in the 1770s (fn. 87) was an over-estimate according to the curate who counted 845 inhabitants in 1789 (fn. 88) In 1801 the parish had 917 inhabitants and there was a gradual rise to 1,373 by 1851. The population then fell slowly to 989 by 1931. New housing development later boosted it to 1,134 by 1961 and 1,689 by 1971. (fn. 89)

In a town with so much passing trade inns naturally played an important role. There were at least 10 innkeepers in the parish at the beginning of the 18th century (fn. 90) and 11 were licensed in 1755. (fn. 91) The Swan in Burford Street is apparently one of the earliest, for an inn of that name was mentioned in 1513. (fn. 92) In 1588 an inn called the George, apparently on the north side of St. John's Street, was mentioned. (fn. 93) The other chief inns were in High Street and included the Red Lion on the south side which was presumably the inn called the Lion in 1592, (fn. 94) the Crown which had opened on the north side by 1696, (fn. 95) and the Bell at the head of Bell Lane which was recorded from 1719. (fn. 96) Shortly before 1754 the large New Inn was built on the south side of the market-place (fn. 97) and apparently became the principal inn of the town. The four inns in High Street were evidently suffering from the decline in coaching in 1856 when their landlords all pursued additional callings. (fn. 98) Nevertheless there were 15 public houses in the parish in 1891 (fn. 99) and the numbers of summer visitors and growth of motor traffic in the 20th century helped to give the older inns of the town a new lease of life; the New Inn, Red Lion, Crown, and Swan all survived in 1977.

By 1692 there was an inn at St. John's bridge named the Baptist's Head (fn. 100) after St. John's hospital. It was part of the manor estate until c. 1800 when it was sold together with the manorial fishing rights in the Thames. Renamed the Trout before 1831, (fn. 101) it became a favourite resort of fishermen and boating parties in the later 19th century and in 1890 included a detached summerhouse for picnics. (fn. 102)

A friendly society, the 'Old Club', was founded at Lechlade in 1766 (fn. 103) and several others functioned in the 19th century. (fn. 104) In 1870 the town had a readingroom supported by subscriptions, (fn. 105) and a working men's club with coffee-house and reading-room was opened in 1880 under the patronage of local gentry but by 1888 was suffering from lack of members. (fn. 106) The Victoria Memorial Hall in Oak Street, apparently built by the lord of the manor to mark the Jubilee of 1897, was given to the town in 1919 (fn. 107) and a recreation ground on the Gassons near by was acquired in 1958. (fn. 108) In 1839 horse-races were run on Town East meadow (fn. 109) and in the 20th century a cricket club, with a pitch in the manorhouse park, was strongly supported. Annual social events in the early 20th century included a flower show, (fn. 110) and a water carnival was held between 1903 and 1936. (fn. 111) In 1977 the Thames with its facilities for boating continued to attract many visitors to the town during the summer months and the south bank (in Inglesham parish) had been made a riverside park with access for cars.

Water was laid on to Lechlade c. 1888 from a works built north of the town by the rural sanitary authority after the wells were found to be contaminated. (fn. 112) The town had a fire-engine by 1845 and from the following year it was housed in the old blind-house (fn. 113) adjoining Ryton House. (fn. 114) A new fire brigade, formed in 1895 and disbanded in 1936, was one of the responsibilities of the Lechlade parish council, an active body which also managed the street-lighting, installed by 1895, and a cemetery, opened north of Downington c. 1913. (fn. 115) Electricity was supplied to the town by the Lechlade Electric Light and Power Co., formed in 1909 and later absorbed by the Wessex Electricity Co., (fn. 116) and gas was laid on by the Swindon Gas Co. in 1937. (fn. 117)

Henry III passed through Lechlade in 1229 and 1258 (fn. 118) and Edward I in 1279 and 1281. (fn. 119) In the Civil War the town, which lay in debatable ground, saw several troop movements (fn. 120) and, in November 1645, a minor skirmish when a small parliamentary force sent to fortify it drove off a royalist attack; (fn. 121) the town was still garrisoned for parliament the following April. (fn. 122) Natives of the town have included Thomas Prence (1600–73) who became governor of Massachusetts, and Thomas Coxeter (1689–1747) who followed literary and antiquarian pursuits. (fn. 123) One of Shelley's poems was inspired by a visit to Lechlade churchyard in 1815. (fn. 124)

Manors and Other Estates

In 1066 the 15-hide manor of LECHLADE was held by Siward, apparently Siward Barn, a great-nephew of Edward the Confessor, who joined the rebellion against the Conqueror in 1071. By 1086 the manor was held by Henry de Ferrers (fn. 125) and it probably descended with Oakham (Rut.) to his son William and to William's con Henry. Henry's son Waukelin de Ferrers (d. 1201) (fn. 126) held Lechlade in 1185 (fn. 127) and later gave it to his son Hugh (fn. 128) (d. 1204). Hugh's heir was apparently his elder brother Henry whose forfeiture of his English estates on the loss of Normandy (fn. 129) led to the Crown taking possession of Lechlade. The Crown granted the manor in 1204 for life to Hugh's sister Isabel, wife of Roger de Mortimer (fn. 130) (d. 1214). (fn. 131) Isabel married secondly Peter FitzHerbert (d. 1235) (fn. 132) and died in 1252. At her death the manor reverted to the Crown (fn. 133) whose right was disputed by Isabel's grandson Roger de Mortimer until 1263 when he abandoned his claim in return for a grant of other property. (fn. 134)

In 1252 Henry III granted the manor to his brother Richard, earl of Cornwall, (fn. 135) (d. 1272), whose son Edmund succeeded and granted it in 1300 to Hailes Abbey to hold for a fee-farm rent of 100 marks. When Edmund's estates passed to the Crown on his death the same year the rent was raised to £100. (fn. 136) Half of the rent was granted to Queen Margaret in 1307 but later there were conflicting grants to her and to Peter Gavaston until the queen's moiety was confirmed with arrears after Gavaston's death. (fn. 137) The rent was later settled on Queen Isabella and her children John and Eleanor. (fn. 138) Hailes Abbey held the manor until 1318 when in exchange for Siddington it granted it to the elder Hugh le Despenser, (fn. 139) who had quittance of the fee-farm rent in 1324. (fn. 140) From that time, except that Geoffrey de Mortimer held it briefly in 1330, (fn. 141) Lechlade manor descended with Barnsley until 1548. (fn. 142)

In 1550 the Crown granted the manor to Denis Toppes and his wife Dorothy. (fn. 143) Denis (d. 1578) was succeeded by his son Thomas (fn. 144) but by 1581 the manor was in the possession of Nicholas and George Rainton, London haberdashers. They sold it that year to two other London tradesmen, Benedict Bartholomew and John Weaver, (fn. 145) but before the sale the Raintons had made acknowledgement of a large debt as a result of which Lechlade was seized by the sheriff in 1587 and granted the following year to their creditor Thomas Riggs to hold until he had recouped his money. Bartholomew and Weaver retained a reversionary right to the manor and sold it in 1588 to Edward Dodge and Peter Houghton (fn. 146) who had a quitclaim from Thomas Toppes in 1591. (fn. 147) Dodge bought out Houghton in 1595 and died, apparently with an unencumbered title to the manor, in 1597. He left it to his nephew Robert Bathurst (fn. 148) (d. 1623), whose eldest son Robert (fn. 149) died a minor in 1627 and was succeeded by his brother Edward. (fn. 150) Edward Bathurst was made a knight and baronet in 1643, (fn. 151) though later under threat of sequestration he claimed that any support he gave to the royalist cause in the war was given under duress. (fn. 152) Sir Edward died in 1674 but made the manor over to his son Laurence before 1668. (fn. 153) Laurence (d. 1670) left the manor to his wife Susanna to hold during the minority of his son Edward. (fn. 154) Edward died under age in 1677 and Susanna, who was married twice more, to Sir John Fettiplace, Bt., and to Sir Thomas Cutler, then held the manor during the minority of Edward's sisters and heirs, Ann and Mary. (fn. 155)

In 1686 Ann and Mary Bathurst married respectively John Greening and George Coxeter, (fn. 156) and they made a partition of the manor in 1690. After the deaths of Ann and John their moiety passed to John's niece Elizabeth Greening, who married Nicholas Harding in 1695. Nicholas died in 1736 and his wife the following year. In 1718 the Hardings had granted the moiety to trustees in preparation for a settlement which had never been enacted. After their deaths Sir Francis Page, the surviving trustee, took possession of the estate, notwithstanding the claim of Richard Burgess, cousin and heir-at-law of Elizabeth. Page devised the estate on his death in 1741 to Sir George Wheate, Bt., who defended his claim against Burgess's heirs. The litigation was finally concluded in 1754 with a judgement that Page had had a just title to the estate and that even if he had not Burgess's claim could not have been substantiated. (fn. 157) Sir George Wheate had died in 1752 and his son and heir Sir George died under age in 1760 to be succeeded by his brother Sir Jacob Wheate. (fn. 158)

The moiety of George and Mary Coxeter was retained by Mary after her husband's death in 1702 (fn. 159) and was heavily mortgaged by 1721 when she made it over to her son Thomas so that he might clear it from incumbrances. After a suit by the mortgagee the estate was contracted to be sold in 1724 to the trustees of the will of Edward Colston, though the actual conveyance to them was not made by Thomas Coxeter until 1741. The estate was divided among various beneficiaries under Colston's will. Sarah Edwards, the daughter of one of them, married John Pullen who acquired the rights of the other beneficiaries and died in 1769. He was succeeded by his son John who sold the moiety to Sir Jacob Wheate in 1775, (fn. 160) thus reuniting the manor.

Sir Jacob died in 1783 leaving the manor heavily mortgaged. In 1794 his trustees, his brother and heir Sir John Thomas Wheate, and the mortgagees agreed on a sale to Samuel Churchill of Deddington (Oxon.). (fn. 161) Churchill sold in 1807 to William Fox, (fn. 162) the founder of the Sunday School Society, who may have sold the manor before his death in 1826. (fn. 163) It passed to George Milward (d. 1838). The manor, to which 348 a. of land was then attached, passed in succession to Milward's son George (d. 1871) and grandson George. (fn. 164) In 1895 it was bought by H. W. Prior-Wandesforde, from whom it passed to James Jones (d. 1910). Jones's trustees offered the estate for sale in 1921. (fn. 165) The manor-house and park were acquired in 1939 by the nuns of St. Clotilde, a Catholic teaching order, who used the house for a girls'boarding school. (fn. 166)

The manor-house of Lechlade was recorded from 1270 and was used by the earls of Cornwall on occasion in the 13th century. (fn. 167) About 1500 the hall of the manor-house was dismantled and moved to Barnsley (fn. 168) but in the late 16th century there was a manor-house at Lechlade, known as the Place. (fn. 169) At the partition of the manor it seems to have been included in the Coxeters' moiety (fn. 170) and so was presumably the house north-east of the town later occupied by the Pullens. (fn. 171) In 1695 the other moiety included a newly-built house, probably built by John Greening, (fn. 172) and that was presumably a house by the river south-west of the town where Sir Jacob Wheate lived in the mid 1770s. (fn. 173) After he reunited the manor Sir Jacob pulled down both houses and built a new one (fn. 174) by the Burford road near the site of the Pullens' house; (fn. 175) a square threestorey building with sash windows, it was extended by lower, flanking wings in the early 19th century. (fn. 176) It was replaced in 1873 by George Milward who built a new house on a site to the north-east and laid out parkland around it. The new house, a substantial mansion in Jacobean style, was designed by J. L. Pearson. (fn. 177) New school buildings were put up adjoining it in the 1970s.

The site and lands of the hospital of St. John at Lechlade were used by its patron Cecily, duchess of York, to endow a chantry in Lechlade church in 1472. (fn. 178) In 1508 the chantry was dissolved and its estate granted to the college of St. Nicholas in Wallingford castle. (fn. 179) In 1572 the estate, sometimes known as the manor of ST. JOHN, was granted by the Crown to Denis Toppes and it descended with Lechlade manor. (fn. 180)

LEMHILL, the detached part of Broughton Poggs north of Lechlade, formed a separate manor held from Broughton manor. It belonged in the 14th century to Robert Murdock, possibly the same who died c. 1369. Murdock was succeeded by his nephew Robert Lemhill. The manor later passed to Robert Lemhill's great-niece Margaret, daughter of John Querndon or Lemhill, and her cousin and heir Henry Spicer of Burford held it in 1437. (fn. 181) Thomas Dawes (d. c. 1554) was a later owner or lessee of the estate (fn. 182) and in 1577 it was sold by John Dynham to George Fettiplace of Coln St. Aldwyns, who died that year. George's widow Cecily held it for life and it passed to his son John (fn. 183) (d. 1636), who was succeeded by his brother Sir Giles Fettiplace. (fn. 184) Sir Giles (d. 1641) was succeeded by his nephew John Fettiplace. (fn. 185) In 1713 Lemhill belonged to Elizabeth and Katherine, daughters and coheirs of Henry Sackville of Bibury, and was awarded to Katherine at a partition of Henry's estates. (fn. 186) Katherine (d. 1760) was succeeded by her great-nephew Estcourt Cresswell who sold the estate to Michael Hicks Beach of Williamstrip in 1806. (fn. 187) Lemhill was sold by the Hicks Beaches in or before 1849 and was later owned by J. T. Tombs (d. by 1888). In 1884 the estate comprised Great Lemhill Farm and 236 a. (fn. 188) In 1977 it was owned by R. Hinton and Sons and farmed in association with their land in Southrop. A former kitchen at Great Lemhill Farm may survive from a late-16th-century house, the rest of which appears to have been demolished and replaced by a new house in the late 17th century. The new house, which had a front to the south-east, was enlarged in the later 19th century when gabled additions were made on the south-west.

The manor later called BUTLER'S COURT was evidently the 4-yardland estate that John de Bellew granted to John Butler in 1304. (fn. 189) Butler or an heir of the same name held it in 1326. (fn. 190) John Twyniho of Cirencester was lord of Butler's Court in 1479 (fn. 191) and died c. 1486. (fn. 192) His heir was Dorothy Moreton and the manor passed to her son Robert Moreton (fn. 193) (d. 1514). Robert's son William (fn. 194) died a minor in 1522 when his heirs were his sisters Dorothy and Elizabeth. (fn. 195) In 1581 Margaret, widow of Thomas Dutton of Sherborne, granted the manor to Thomas Meysey. Meysey's interest passed to William Dutton, who sold the manor to John Gearing, a London grocer, in 1614. Gearing settled it on the marriage of his son John, also a London grocer, in 1627 and the son or another John Gearing sold it in 1660 to Robert Oatridge. Robert was dead by 1680 when a moiety of the estate was assigned to his widow Miriam for life with reversion to her son Robert, who succeeded to the other moiety. (fn. 196) The estate later passed to Anne Oatridge (d. 1722 or 1723) who devised it to a kinsman Henry Oatridge (d. 1758). Henry had settled it on his wife Sarah and devised the reversion to his brother Daniel, whose son Thomas succeeded on Sarah's death c. 1772. Thomas (d. 1789) devised it to his wife Ann with reversion to his brother Simon Oatridge of Doughton, Tetbury. Simon (d. c. 1801) devised the estate to his sister Ann Matthews with reversion to his niece Mary Matthews (fn. 197) who married John Paul Paul (d. 1828) of Highgrove, Tetbury. John's son Walter Matthews Paul sold Butler's Court in 1841 to William Gearing, who had been lessee of the estate since 1806 (fn. 198) and was also owner of the adjoining Trouthouse farm. Gearing died in 1850 leaving the estate to trustees for a sale and it was bought by his daughters Elizabeth (d. 1866) and Ann Gearing and his son-in-law Matthew Edmonds (d. 1871). Elizabeth devised her share for life to her sister Ann, who bought the third share after the death of John, son of Matthew Edmonds, in 1872. Ann died in 1874 and in 1876 her trustees and those of her sister sold the estate to New College, Oxford. (fn. 199) The college later enlarged its estate, adding Green farm in 1969 and another 100 a. in 1970, (fn. 200) and it retained the estate in 1977.

Butler's Court is a substantial mid-17th-century gabled farm-house, which was refronted on the east side early in the 18th century when the rooms behind that front were refitted. In the 19th century additions were made to the north-west but those were much altered when the western end of the house was reconstructed after a fire in 1966. The garden formerly extended southwards to the main road where an early-18th-century gazebo remains.

In 1670 an estate in Lechlade, comprising 221 a., two houses, and rights in the meadows, was bought from Laurence Bathurst by Archbishop Gilbert Sheldon, who settled it on Oxford University for the maintenance of the newly built Sheldonian Theatre. (fn. 201) Most of the estate was later based on Thornhill Farm at the west boundary of the parish. The farm was sold by the University in 1919. (fn. 202) A small estate of c. 40 a. in the east part of the parish, later called Paradise farm, was conveyed by George Hill to Brasenose College, Oxford, in 1675. (fn. 203)

Economic History

Agriculture

In 1086 there were 4 plough-teams and 13 servi on the demesne of Lechlade manor. (fn. 204) In 1275 the demesne land comprised 518 a. of arable, 667 a. of meadow, and a several pasture. (fn. 205) In 1270 a dairy herd, comprising 16 cows, was maintained on the demesne, mainly to produce cheese, and the other livestock included a flock of c. 250 sheep. The extensive demesne meadows were a valuable asset: in 1270 the mowing rights in them were sold for £52, providing a third of all the profits of the manor. The farmservants employed then included 3 ploughmen and 3 drivers of plough-teams, a carter, a shepherd, a cowherd, and a dairyman. (fn. 206) An undated account roll of the same period apparently concerns a year in which demesne farming was resumed after being temporarily abandoned, for all the grain and livestock accounted for had been bought in the course of the year. (fn. 207) By 1326 the demesne arable in hand had been reduced to 304 a., and 88 a. of former demesne were let to tenants; the meadow land was then extended at 596 a. and there were pasture rights for 27 oxen, 57 cows and calves, and 300 sheep. (fn. 208) The whole demesne was let at farm by 1411. (fn. 209) In the early 17th century it was represented by numerous closes and meadows, (fn. 210) most of which were alienated from the manor before the end of that century.

The tenants on the manor in 1086 were 29 villani, 10 bordars, and a Frenchman holding the land of a villanus; they worked 16 plough-teams between them. (fn. 211) In 1275 there were, besides some free tenancies and the burgages in the town, 25 customary yardlands and 7 cottage-tenements. (fn. 212) In 1326 there were some fairly substantial free tenements held from the manor, including John Butler's estate and a two-hide estate formerly belonging to Peter atte Hall but by 1326 divided among a large number of owners. The customary tenants in 1326 were 15 yardlanders, 17 half-yardlanders, 7 mondaymen, and 9 cottagers. They were probably already paying cash instead of working in the winter months in the late 13th century when in one year 706 works valued at ½d. each were sold, (fn. 213) and in 1326, when each yardlander owed 6s. 6d. cash rent, most of their works had apparently been permanently commuted; they no longer worked on a regular weekly basis but owed 42 days in the year on specific tasks, mostly in the hay- and corn-harvests, as well as doing ploughing-service and a few bedrepes. The mondaymen still owed their one day a week and worked in the corn-harvest on Fridays as well and some of the cottagers owed bedrepes. A smith held his land in return for shoeing-service and work on the demesne ploughs. (fn. 214)

There were open fields at Lechlade in 1326 when 218 a. of the demesne arable lay in them. (fn. 215) They were evidently inclosed at a fairly early date, for the only later reference found to them was in 1670 when lands lying by the Fairford road in the west part of the parish were described as former parts of Over and Nether Street fields. (fn. 216) The later evidence of field names suggests that the open fields were small and fairly numerous, scattered across the north and west parts of the parish. (fn. 217)

The meadow land was very extensive, as the value of £7 7s. put on it in 1086 (fn. 218) and the evidence for the demesne given above show. It occupied the whole of the east and south parts of the parish. In the east part between the river and the Kelmscott road lay a large common lot meadow called Town East meadow. (fn. 219) The rights of the lord of the manor in Town East meadow, comprising the first math (or crop of hay) of 90 a. of the lots and the second math and subsequent pasture rights in the whole 200 a. of meadow, were sold before 1673 and became part of the Leaze estate. In 1860 the meadow was inclosed by Henry Parker, owner of the Leaze, who bought out the other holders of lots. (fn. 220) A smaller common meadow called Town Rumsey lay by the parish boundary south-west of the town (fn. 221) and was cultivated as such until at least 1859. (fn. 222) Eighty-two acres of several meadow by the Thames south-east of the town belonged to the hospital of St. John in the Middle Ages; the lord of the manor sold them with other meadow to William Blomer before 1613 (fn. 223) and they remained part of the Hatherop estate until the early 20th century. (fn. 224)

In the north-west part of the parish lay a tract of pasture called the Downs, covering 190 a.; it belonged to the manor until the beginning of the 18th century and had probably once been open to commoning rights of the tenants. (fn. 225) Thorn hill further south, which comprised 91 a. in 1670 when it was alienated from the manor, (fn. 226) may have been another common pasture. (fn. 227)

The later history of agriculture in Lechlade is the individual history of the various freehold farms, including the ancient estates of Lemhill and Butler's Court and those such as Clayhill, the Leaze, Downs farm, and Thornhill farm which were established on land alienated from the manor in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Those farms together with Trouthouse and Little Clayhill farms were the principal farms of the parish in the 1830s though most were of modest size, no more than c. 200 a. There were also a number of smaller farms, mostly under 100 a., including Little Lemhill, Warren's Cross, and Ploughed Ground farm (later called Roughground farm). The manor estate, to which only 348 a. remained, was then kept in hand by George Milward though a separate farm-house had been built for it at Red Barn Farm (later called Manor Farm). (fn. 228) In 1831, when the agricultural workers of the parish outnumbered its tradesmen and shopkeepers, there were 8 farmers employing a total of 97 labourers and 7 employing no labour. (fn. 229) The number of smallholdings became a much more significant feature of the parish in the later 19th century and the early 20th: in 1896 a total of 53 agricultural occupiers was returned (fn. 230) and in 1926 a total of 35, 24 of them having less than 50 a. and 10 having less than 5 a. (fn. 231) In 1976, however, only 7 smallholdings of under 20 ha. (49 a.), most of them worked on a part-time basis, were returned, together with 8 larger farms of between 20 ha. and 200 ha. (494 a.). (fn. 232)

In spite of the extensive meadows arable land predominated over permanent grassland in the 19th century: in 1838 there were 1,810 a. of the former to 1,440 a. of the latter (fn. 233) and the equivalent amounts returned in 1896 (when Lemhill had been added to the parish) were 1,910 to 1,596. The maintenance of the level of arable cultivation to the end of the century may reflect the pattern of holdings in the parish, with small mainly family-run farms being better able to withstand the slump in prices. In the 19th century the farms grew mainly wheat, barley, and roots and raised sheep, of which 2,985 were returned for the parish in 1866. Cheese-making had presumably played a significant role in local farming in the past but in 1866 only a modest number of milk cows, 76 in all, were returned; the increase to 190 by 1896 was probably the result of the growth of a liquid milk trade, made possible by the railway. (fn. 234) In the 20th century dairying remained important and local farming was further diversified by the introduction of more pigs and poultry, returned at 770 and 9,114 respectively in 1926, (fn. 235) and, in the case of several of the smallholdings, by specialisation in market-garden produce. (fn. 236) Sheep-farming declined and no sheep were returned in 1976. Of the full-time farms in 1976 4 specialised in dairying and 3 in pigs and poultry, while another was devoted to general horticulture and another mainly to cereal crops. (fn. 237)

Mills

There were three mills on Lechlade manor in 1086. (fn. 238) One, called Lade mill, was granted by Isabel de Mortimer to St. John's hospital before 1246 (fn. 239) and the other two, later known as West mill and At (or Act) mill, remained part of the manor estate. (fn. 240) West mill was a ruin by 1527 (fn. 241) though there was still at least a dwelling of that name in 1627. (fn. 242) It stood in the meadows south-west of the town (fn. 243) and according to tradition was a windmill. (fn. 244) Act mill on the Leach, later called Lechlade mill, remained part of the manor until at least 1754. (fn. 245) It continued to work until c. 1930. (fn. 246) Lade mill, later called St. John's or Priory mill, stood further down the Leach near the site of the hospital, with which it passed to the manor. (fn. 247) It was alienated from the manor by John Greening in 1694 and continued to work until the beginning of the 20th century. It is probably significant that the owner of Priory mill in 1730 was a Thames barge-master, (fn. 248) for the corn trade on the river doubtless provided the two mills on the Leach with much of their business. At both sites there are fairly substantial mill-houses of the late 18th or early 19th century.

Trade and industry

Lechlade was a borough and market town from the early 13th century and with the advantages of its position at the head of the navigable Thames and on a major road route to London might have been expected to become a significant commercial centre. That it remained small was perhaps due in part to the proximity of another market town at Fairford, only 6.5 km. away. Two inhabitants selling wine, mentioned in 1287, (fn. 249) and the surnames of smith, tanner, and tailor among those assessed for the 1327 subsidy (fn. 250) are among the earliest evidence of trading activity. In 1381 the town had a fairly substantial body of tradesmen and craftsmen, 44 being included in those assessed for the poll tax, among them 3 merchants, 2 mercers, 2 tanners, a draper, a skinner, a weaver, a spicer, and 15 brewers. (fn. 251) Henry Woolmonger was trading in the town in the late 13th century (fn. 252) and the merchants of 1381 were perhaps also involved in the wool trade, for the town stood on one of the chief routes for the carriage of Cotswold wool to London. John Townsend, who died in 1458 leaving legacies totalling over £1,800, was a Lechlade wool-merchant, (fn. 253) and the rebuilding of the parish church in 1470 suggests that the town had a number of fairly wealthy inhabitants at that period. As a local market centre, however, the town appears to have been in decay in the late 15th century, for 5 selds in the borough belonging to the lord of the manor were untenanted in 1490. (fn. 254) In 1608 31 tradesmen, a few more than those engaged in agriculture, were listed. They included 6 weavers, a mercer (one of the Gearing family which was prominent at Lechlade for several centuries), two masons, and a slater. (fn. 255)

Most of the town's commercial activity was later connected with the river trade, said to be its chief support in the early 18th century. (fn. 256) The use of the river for carriage was no doubt ancient, though the mention of a wharf house in 1639 (fn. 257) is the earliest evidence found of such activity and, according to the reminiscences of aged inhabitants recorded in 1719, the main wharves and warehouses were all built in the middle years of the 17th century. They included the Bell and Red Lion wharves, named from inns in High Street and evidently at the complex of wharves and warehouses immediately south of the town later called the free wharf and Parkend wharf, and a wharf occupied by the Ainge family, evidently that later called Old wharf at the end of Wharf Lane. (fn. 258) In 1716 there were also a warehouse and wharf by St. John's bridge, (fn. 259) apparently used as a depot by the London cheesemongers. (fn. 260) Cheese collected from Gloucestershire and the north part of Wiltshire or carried across from the Severn at Tewkesbury was the principal commodity shipped down river, and there was also some trade in corn and malt. (fn. 261) Other wares were brought by road from Gloucester, particularly in wartime when much of the trade down the Severn bound for London was diverted from coasting vessels to that route. (fn. 262) In 1758 Richard Ainge and Robert Anderson, Lechlade wharfingers, announced an arrangement with two Gloucester wharfingers for the conveyance of goods (fn. 263) and the opportunity brought by war is presumably again reflected in the scheme of another Lechlade man in 1781 to operate weekly stage-wagons between Gloucester and his wharf. (fn. 264) Several Thames bargemasters, at least two in 1701 (fn. 265) and three in 1779, (fn. 266) were also based at Lechlade.

The river trade was increased significantly by the opening of the Thames and Severn canal to Lechlade at the end of 1789, though the failure to improve the Thames navigation lessened the opportunities provided by the new waterway. (fn. 267) The first cargo through the canal to Lechlade was Staffordshire coal (fn. 268) and coal was always the main item in the west-to-east trade, the opening of the canal reducing the price in the Lechlade region by about 8s. a ton. Grain was one of the chief items shipped westwards to Brimscombe Port at Stroud (fn. 269) and in 1794 two coal- and corn-merchants and a corn-factor were based at Lechlade. Also trading in the town then was Henry Burden, agent to the London cheesemongers, the trade in cheese retaining its importance. (fn. 270) Parkend wharf, occupied by Richard Gearing and then by William Hill, a Cirencester merchant, at the beginning of the 19th century, (fn. 271) was bought in 1813 by the canal company which built new warehouses and an agent's house. (fn. 272) There were still three coal merchants trading in the town in 1856 but after the building of the railway only one such business, that of the Hicks family, survived and in the early years of the 20th century was the last representative of Lechlade's involvement in the river trade. (fn. 273)

Apart from the wharfingers and the innkeepers who served the road traffic, the principal inhabitants of the town included some fairly substantial shopkeepers, such as mercers and linen-drapers, and a few professional men, represented in 1794 by two surgeons and an attorney. (fn. 274) Malting played a quite significant part in the town's economy in the 18th and 19th centuries (fn. 275) and a small wool trade, probably an offshoot of that of Cirencester, employed a wool-stapler in 1774, a wool-comber in 1789, (fn. 276) and a wool-merchant who went bankrupt in 1821. (fn. 277) A family of rope-makers was recorded between 1773 and 1851, (fn. 278) the trade being perhaps connected with equipping Thames barges. Masons and slaters were fairly numerous and the building trade, though on a small scale, was a regular source of employment in the 19th and 20th centuries. (fn. 279) James Hollingsworth of Lechlade, bankrupted in 1796, was a mason and architect, (fn. 280) as was Richard Pace (d. 1838), who had a considerable local practice. Pace's business was continued by his son Richard (fn. 281) until at least 1856. (fn. 282) There were three other builders apart from the younger Pace in Lechlade in 1851 and it also had 11 masons. (fn. 283) A firm of agricultural implement makers and feed suppliers, established by 1879, and the cattle-dealers, corndealers, seedsman, hurdle-maker, and ploughmaker, recorded during the 19th century, reflect the town's role as a centre for the local farming community. (fn. 284)

From the late 19th century others have found employment in catering for those visiting Lechlade for fishing and boating. There was a boat-hirer by 1897 and two boat-builders in 1935, (fn. 285) and in 1977, when many private launches were berthed at Lechlade, a ship's chandler had premises at Parkend wharf. .Summer visitors also accounted for the several antique shops then open in the town. The building trade and the sand and gravel workings were the main local sources of employment in the mid 20th century (fn. 286) but after the Second World War most of the working population travelled to near-by R.A.F. stations or to factories at Swindon and Witney. (fn. 287)

Market and fairs

In 1210 Roger de Mortimer and Isabel his wife were granted a Tuesday market and an annual fair on St. Lawrence's day (10 August) and the two days following. (fn. 288) In 1234 the hospital of St. John was granted the right to hold a fair at St. John's bridge for 5 days around the Decollation of St. John the Baptist (29 August). (fn. 289) In 1270 the lord of the manor's tolls from the market produced 18s. 6d. (fn. 290) The market was evidently in decline in the later Middle Ages when the reeves' accounts contain no returns for its tolls and, although the charter was confirmed in 1566 and 1664, (fn. 291) the market was later of little significance in the economy of the town. It did little business in the 18th century (fn. 292) and an attempt to revive it in 1775, when the day was changed to Friday and 3 years' toll-free trading offered, (fn. 293) met with little success. In the earlier part of the 19th century it was almost completely disused, (fn. 294) but it was revived in 1873, after the building of the railway, and a firm of auctioneers, Innocent & Son, became the lessees before 1888 and conducted a livestock sale on the last Tuesday of each month. (fn. 295) In 1928 the firm moved the market from the streets of the town to a new sale yard at the railway station, where it continued to be held until 1959. (fn. 296)

The manor fair held at St. Lawrence brought in tolls of 46s. 6d. in 1270 and in another year at the same period 70s. 5d. were received. (fn. 297) Business declined in the later Middle Ages and during the 15 th century only about 4s.–7s. were received in tolls. (fn. 298) The fair was later eclipsed by the success of the other fair, known as the St. John's Bridge fair, which was in the same ownership after 1572. (fn. 299) The closeness of the two fair days was probably the reason why the St. Lawrence fair was continued on the original date after the calendar change of 1752 while the other was moved to 9 September. (fn. 300) The St. Lawrence fair was still held in the late 18th century, when it dealt mainly in horses and cattle, (fn. 301) but it is not recorded later.

St. John's Bridge fair had become a major cheesefair by the late 17th century. (fn. 302) In 1719 various deponents estimated that between 140 and 200 wagon loads of cheese were brought to the fair besides what was carried on horseback, and the lord of the manor needed to set up several pairs of scales at the site for weighing it. Much of the cheese, being destined for the London market, was taken for convenience directly to the wharves and the lord of the manor had to go to law to uphold his right of having scales and levying toll on the cheese sold outside the site. (fn. 303) Interference to the fair by flooding caused it to be moved from the meadow by the bridge to the streets of the town in 1776. (fn. 304) It still dealt then in large quantities of cheese though the volume was declining. (fn. 305) It continued in the 19th century, apparently mainly as a horse-fair, and after the early 1920s was merely a pleasure-fair. (fn. 306)

Local Government

Isabel de Mortimer apparently created a borough within her manor of Lechlade soon after securing the right to a market in 1210. There were tenants holding by burgage tenure c. 1230 when an agreement to regulate the jurisdiction over her 'new market town' was made between Isabel and the abbot of Cirencester, lord of the hundred; the abbot granted her the right to have a tumbril and pillory and allowed her to take the profits of the biannual view of frankpledge, which was to be held in her court at Lechlade in the presence of the abbey's bailiffs. (fn. 307) The working of this arrangement was upset after the earl of Cornwall became lord of the manor; he apparently claimed to hold the view in his own right, but in 1258 he restored to the abbey its rights of jurisdiction. (fn. 308) A further dispute broke out in 1270, however, over the earl's claim to have gallows at Lechlade, a franchise that had formerly been exercised by Peter FitzHerbert, (fn. 309) and the disputes continued under the earl's son. (fn. 310) The arrangements for holding the view continued in the 15th and early 16th centuries, when separate views were held for the borough and for the manor or 'foreign', (fn. 311) a distinction that had apparently been made from the 13th century. (fn. 312) In 1550 the borough was administered by a bailiff and the foreign by a reeve, (fn. 313) though earlier a single annual account for both was rendered. (fn. 314) The view of frankpledge continued to be held in the manor court (fn. 315) and was still being held, though only triennially, in the 1850s. (fn. 316) Only one court roll, for a session of the court baron in 1546, (fn. 317) is known to survive.

Of the records of the parish officers churchwardens' accounts survive for 1567–1677 and from 1795. (fn. 318) The parish had a workhouse by 1735 (fn. 319) and a new one was later built at the site of St. John's hospital, which was leased to the parish officers in 1763. (fn. 320) The workhouse went out of use between 1793 (fn. 321) and 1803. (fn. 322) There was also a pest-house, in the north part of the parish near the Burford road; (fn. 323) it was built after 1744 with charity money given to the parish and was also used as a general poorhouse. (fn. 324) In 1803 the number of paupers on permanent relief was 69 and the number on occasional relief 180, (fn. 325) the latter figure reflecting the volume of travellers and pauper traffic on the main road. By 1813, presumably as a result of deliberate parish policy, the figure for occasional relief was down to 24, while that for permanent relief remained about the same. (fn. 326) In 1835 Lechlade became part of the Berkshire poorlaw union of Faringdon, (fn. 327) an anomaly that was heightened by its inclusion in the Fairford highways district in 1863. (fn. 328) It became part of Faringdon rural district after the implementation of the 1894 Act (fn. 329) and a plan to include it in a proposed Fairford rural district later in the 1890s met with strong local opposition, led by the parish council which was dissatisfied with the work of the highways board. (fn. 330) In 1935 it was transferred from Faringdon to Cirencester rural district, (fn. 331) and in 1974 it became part of the new Cotswold district.

Church

No record of Lechlade church has been found before 1254 though by inference it existed in 1210 when a fair was granted on St. Lawrence's day, its patronal feast. (fn. 332) In 1254 the king granted the advowson of the church to Richard, earl of Cornwall, having recovered it as an adjunct of the manor against the claim of the hospital of St. John at Lechlade. (fn. 333) In 1255, however, at the instance of the earl the king granted the advowson to the hospital. A vicar's portion had already been assigned out of the profits (fn. 334) and the grant was presumably made with the intention that the hospital should appropriate the church. The appropriation was carried out then, or at least by 1305, (fn. 335) and the rectory descended with the hospital estate (fn. 336) until 1670 when Laurence Bathurst devised it to the vicar of Lechlade. (fn. 337) Although from that time endowed with all the profits of the church, the living continued to be called a vicarage.

The grant of 1255 reserved the right of presentation to the vicarage to Richard of Cornwall, his wife Sanchia, and the heirs of their bodies. (fn. 338) Edmund, earl of Cornwall, presented in 1280 (fn. 339) and Hailes Abbey in 1307 (fn. 340) but the claim of the lords of the manor to the advowson was later challenged. In 1341 the hospital, which may have claimed a reversionary right on the failure of Richard's line at Edmund's death, presented and forced the withdrawal of a clerk presented by the Crown by right of the minority of the lord of the manor; (fn. 341) the hospital again successfully presented in 1361. (fn. 342) The Crown made unsuccessful attempts to present in 1391 (fn. 343) and 1404, its candidate conceding on the latter occasion to a clerk presented by the countess of Kent, lady of the manor. (fn. 344) The countess was said to be seised of the advowson at her death in 1411, (fn. 345) and during the 15th century the owners of the manor appear to have exercised it without challenge. (fn. 346)

The Crown retained the advowson in hand when it alienated the manor in 1550 (fn. 347) but included it in the grant of the hospital estate to the lord of the manor in 1572. (fn. 348) Edward Yate and George Raleigh respectively presented at the next two vacancies in 1579 and 1618 under grants for one turn (fn. 349) but from 1645 (fn. 350) the advowson was exercised by the lords of the manor. It was divided at the partition of the manor; the Greenings were patrons in 1689 and the Wheates in 1761 while the alternate right was exercised in 1738 by a Mrs. Purcell and in 1774 by John Moreton of Tackley (Oxon.) who had bought that turn from the Pullens. (fn. 351) Samuel Churchill presented in 1795 but later the advowson was alienated from the manor. The bishop presented in 1806; Edward Leigh Bennet presented himself in 1832; Henry Grace of Lambeth (Surr.) presented in 1843 ; and Henry Carnegie Knox presented himself in 1850. (fn. 352) In the last year the advowson was bought by Emmanuel College, Cambridge, (fn. 353) which remained patron in 1977.

The vicar was given a fairly generous portion of the profits of the church. His portion was valued at £10, the same as that of the rectory, in 1291 (fn. 354) and it included part of the corn and hay tithes as well as the wool tithes and other small tithes. (fn. 355) The gift of the rectory under the will of Laurence Bathurst (d. 1670) (fn. 356) had evidently not been implemented in 1680 when a terrier still credited the vicar, Thomas Davies, with only a portion of the hay and corn tithes (fn. 357) and in 1686 Davies was at law with Sir Thomas Cutler and his wife over the rectory. (fn. 358) The rectory had evidently been confirmed to the vicar by 1705 when he was receiving the full tithes. (fn. 359) By 1680 the vicar had negotiated compositions with some of the landholders, and for all tithe payers there were moduses for cows and lambs. The former lands of St. John's hospital were tithe-free. There was no glebe attached to the living. (fn. 360) In 1838 the vicar was awarded a corn-rent of £710 for his tithes. (fn. 361) The vicarage house, recorded from the 1560s, (fn. 362) stood on the east side of the market-place. (fn. 363) The house remains basically as rebuilt before 1778 (fn. 364) but it was remodelled to the designs of Richard Pace in 1804–5 (fn. 365) and again altered later in the 19th century when a castellated porch was added. In 1952 it was replaced as the vicarage by a house in Sherborne Street. (fn. 366)

The vicarage was valued at £12 13s. 3½d. in 1535 (fn. 367) and at £66 7s. in 1650. (fn. 368) It was worth c. £200 about 1710 when the endowment of the rectory tithes was said to have added over £140 to the value. (fn. 369) Its value had risen to c. £220 by 1738 (fn. 370) and to c. £300 by the 1770s. (fn. 371) In 1856 it was worth £513; (fn. 372) either that was a net value or else the value of the tithe corn-rent had already fallen considerably.

The names of the vicars of Lechlade are known from 1255 (fn. 373) but nothing significant of them until the time of Conrad Nye who promoted the partial rebuilding of the church following his institution in 1468. (fn. 374) That was, however, his second incumbency at Lechlade, assuming him to have been the same Conrad Nye who served from 1446 to 1462. (fn. 375) Adam Russell, the vicar in 1551, was found to be ignorant of the commandments; (fn. 376) he was deprived for being married in 1554. John Golshill, instituted in 1562, (fn. 377) was a pluralist (fn. 378) and neglected quarter sermons. His successor in 1572, John Dormer, (fn. 379) was described as zealous in religion but omitted some of the prescribed readings and employed an illiterate parish clerk in 1576. (fn. 380) He was said to be in trouble with the Commission for Ecclesiastical Causes in 1579 when he resigned, tricked into doing so, it was claimed, by a man who had obtained from him a lease of the vicarage. He was succeeded by Henry Garbett (fn. 381) who was living at Oxford in 1584. (fn. 382) He was still serving the cure as a sick man of 80 in 1618 when William Phipps was licensed to assist him. It was probably also Garbett's infirmity that prompted John Gearing of London, owner of Butler's Court, to found a Sunday lectureship in the church before 1618 but it is not recorded later and may have lapsed on Garbett's death the same year. He was succeeded by Phipps (fn. 383) who held the living until at least 1642. (fn. 384) Thomas Davies, described as a preaching minister, (fn. 385) served as vicar from 1645 until his death in 1689. John Whitmore, vicar 1738–53, held the living with Fenny Compton rectory (Warws.). John Thomas Wheate (later Sir John) served from 1774 until 1795. (fn. 386)

In 1472 a chantry dedicated to St. Mary and served by three chaplains was founded in Lechlade church by Cecily, duchess of York, who endowed it with the possessions of St. John's hospital. At the same time another chantry, dedicated to St. Blaise, was founded by John Twyniho, lord of Butler's Court manor, and was assigned a pension of 10 marks from the hospital estate. (fn. 387) St. Mary's chantry was dissolved in 1508 when the three chaplains granted its possessions to the college of St. Nicholas in Wallingford castle. (fn. 388) St. Blaise's chantry survived until the dissolution of the chantries. (fn. 389) Before 1565, perhaps at the time of the 15th-century alterations to the church, a number of houses and some land were given for the maintenance of the fabric of the church, (fn. 390) and Nicholas Rainton gave a rent-charge of £4 for the same purpose in 1586. Part of the rentcharge came from the church house (fn. 391) in St. John's Street, which was being used as an alehouse in 1635 (fn. 392) and was in ruins by 1677. (fn. 393)

The church of ST. LAWRENCE, which bore that dedication by 1305, (fn. 394) is built of ashlar and comprises a chancel with north vestry and north and south chapels, an aisled and clerestoried nave with north porch, and a west tower with a tall spire. (fn. 395)

The church was wholly rebuilt in the late Middle Ages. In 1470 the vicar Conrad Nye stated that he and the parishioners with other helpers had rebuilt the 'parish church', presumably the nave and aisles, and that with some friends he intended to rebuild the chancel, though responsibility for the latter was shared with Nye by St. John's hospital as rector. (fn. 396) The funds used for Nye's rebuilding probably included £120 left to the church by John Townsend in 1458 (fn. 397) and the north and south chapels, which presumably formed part of the same rebuilding, are likely to have been paid for by the duchess of York and John Twyniho to house the chantries founded in 1472. While the general arrangement of the new building reflects the contemporary fashion for the larger churches in the county much of the detailing is old-fashioned: the window tracery is in a debased early-14th-century style, the window and arcade arches are two-centred, and some of the mouldings could be mistaken for work of a century earlier. Other parts of the church, notably the nave roof and clerestory, the north porch, and the tower and spire, are more characteristically late Perpendicular in style and may be additions of the early 16th century.

A west gallery for the singers was installed in the church in 1740 (fn. 398) and in 1829–30 Richard Pace was employed to provide new pews and side-galleries; (fn. 399) all were replaced at another refitting under Waller & Son in 1882, when the organ, brought from Faringdon church in 1864, was moved from the west gallery to the north chapel. (fn. 400) Screens were installed as a memorial to G. A. Robbins of Clayhill in 1887. (fn. 401)

Among the features of the 15th-century work are the bosses on the chancel roof which include a set of angels carrying implements of the Passion. They were restored and re-painted in 1938. (fn. 402) The bowl of the font is of the 15th century but the ornate pedestal, recorded in the mid 19th century, has been replaced. (fn. 403) A new pulpit provided in 1882 stands on an ancient base which was recovered from the vicarage garden. (fn. 404) The clerestory windows have some fragments of ancient glass. (fn. 405) There is a brass in the south aisle depicting the wool-merchant John Townsend (d. 1458) and his wife, (fn. 406) and another in the north aisle, probably to another wool-merchant. (fn. 407) A carved wall-monument in the chancel to Ann Simons (d. 1769) is by Nicholas Read. (fn. 408) A brass chandelier was given by Richard Ainge in 1730. (fn. 409) There are five old bells: (i) 1742 by Abel Rudhall; (ii) 1802 by James Wells of Aldbourn (Wilts.), (fn. 410) a recasting of a medieval bell; (fn. 411) (iii) 1590 by Joseph Carter of Reading; (fn. 412) (iv) 1635; (v) 1626. (fn. 413) A sanctus bell was cast by John Rudhall in 1796 (fn. 414) and a treble was added when the peal was rehung in 1911. (fn. 415) The plate includes a chalice and paten-cover of 1641 and a pair of chalices with paten-covers of 1727 given by Susanna (née Bathurst), widow of Chancellor Richard Parsons. (fn. 416) The registers survive only from 1686 and there are gaps in the 18th century; (fn. 417) two volumes are said to have been burnt by one of the vicars. (fn. 418)

Nonconformity

By 1676 Lechlade had a small group of Quakers, including a tallow-chandler who died in prison in 1683 after refusing to take oaths. The Quakers sought to register a house for their meetings in 1741 but they are not recorded in the town after the late 18th century. (fn. 419) Houses registered for worship in 1784, 1802, and 1811 may have been for the Baptists, who under the leadership of William Fox, lord of the manor, built a chapel in Sherborne Street in 1817. (fn. 420) The chapel had an evening congregation of 105 in 1851. (fn. 421) In 1848 or 1849 a chapel for Congregationalists was built in the Burford road by the Revd. H. J. Crump but his death soon afterwards left it heavily encumbered and, though it had morning and evening congregations of 35 and 80 in 1851, it passed into the hands of the mortgagees and was closed. It was re-opened in 1867 and attempts made to secure it financially (fn. 422) but it had closed again by 1888. Shortly before 1888 a Wesleyan chapel was built at the west end of High Street. (fn. 423) It and the Baptist chapel remained in use in 1977.

Education

William Turner (d. 1791) was schoolmaster and parish clerk at Lechlade for 50 years and Alexander Gearing (d. 1827) was schoolmaster there for 56 years (fn. 424) but their schools were apparently purely fee-paying as no record of a charity school has been found. In 1818 the town had two fee-paying day-schools with a total of 80 children and a boarding school for children of the wealthier classes. (fn. 425) By 1833 another day-school had opened and there were also church and Baptist Sunday schools, (fn. 426) the former perhaps in existence since c. 1790. (fn. 427) The first parish school was started in cottages in Wharf Lane by the vicar Edward Leigh Bennett a few years after his institution in 1832. (fn. 428) By 1847 the school, then in association with the National Society, was teaching 145 children. (fn. 429) The buildings were extended in 1874 to comprise an infants' section with 65 children and a mixed section of 90; finance was from pence, voluntary contributions, and a small endowment, (fn. 430) part of the proceeds of the Loder family's charities. In 1885 the school was receiving a part of the income of the parish charities (fn. 431) that was assigned to educational purposes by a Scheme of 1882 and that income, constituted as the Lechlade Educational Foundation in 1905, (fn. 432) was used mainly for buying equipment for the school in the 1970s. (fn. 433) The average attendance at the school rose to 195 by 1885 (fn. 434) and 219 by 1911, but declined to 95 by 1936. (fn. 435) In the 1960s there was rapid expansion due to new housing development in the town (fn. 436) and in 1977, when the school was known as St. Lawrence's, attendance was 204. (fn. 437)

Charities for the Poor

An ancient charity known as the Maiden Dole, said to have been given by two maiden sisters, (fn. 438) comprised 5 bushels of wheat and 5 bushels of barley charged on land. The charity lapsed in the late 16th century but was restored by royal order in 1602 together with the arrears of 21 years, (fn. 439) and in 1604 Robert Bathurst charged it on a part of the manor estate. (fn. 440) By the early 19th century its cash value was usually distributed. A gift of £5 for the poor was charged on the manor estate by Edward Dodge (d. 1597) and became known as Dodge's Dole. (fn. 441) A commission for charitable uses c. 1679 directed Dodge's Dole to educating and apprenticing children (fn. 442) but there is no record of it being so used.

Richard Wellman by will dated 1703 gave a rentcharge of 10s. for 10 poor widows at Christmas. Francis Loder by will dated 1720 gave £100 for the poor, which was used with another £30 to buy land in 1737; (fn. 443) Francis's nephew, the Revd. John Loder (d. 1744), left £100 to augment the charity (fn. 444) but the parish used the money to build a pest-house on the land bought with Francis's gift. In 1721 Robert Loder gave 20s. to be distributed in bread each year. Ann Simons (d. 1769) gave £200 which was laid out in stock and the interest later distributed with the proceeds of stock bought with £100 given by Elizabeth Underwood. (fn. 445) Thomas Oatridge of Butler's Court (d. 1789) left a reversionary interest in £200 stock, which fell in to the parish in 1828, for a distribution to the 12 oldest poor inhabitants. (fn. 446) The Revd. John Lifely, owner of Priory mill, gave £100 by will proved 1801 to support an annual sermon and a distribution in bread. (fn. 447) Mrs. S. Powell gave £4 interest from stock in 1807. (fn. 448) Richard Bowles (d. 1804), a former vicar of Lechlade, and his wife Catherine (d. 1814) gave a total of £1,000 stock. (fn. 449) Robert Wace by will proved 1820 gave £500 stock. (fn. 450) Lechlade was one of the parishes which benefited under the will of John Harvey Ollney (d. 1836), receiving £200 for coal and blankets at Christmas. (fn. 451)

Under a Scheme of the Charity Commissioners in 1882 all the above charities, which then brought in a total sum of c. £125 a year, were consolidated, one half of the income directed to local educational purposes and the other half to general relief schemes. (fn. 452) In 1885 the second half of the income was being paid to a provident club, (fn. 453) and in 1977 when it amounted to c. £400 a year it was distributed in coal or cash at Christmas. The Scheme did not include the charity of George Milward (d. 1838) who gave £200 for a distribution among 12 people aged over 65; in 1977 the annual income, c. £15, was distributed in cash at Christmas. (fn. 454)