Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Clerkenwell Green', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp86-114 [accessed 6 May 2025].

'Clerkenwell Green', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed May 6, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp86-114.

"Clerkenwell Green". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 6 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp86-114.

In this section

CHAPTER III. Clerkenwell Green

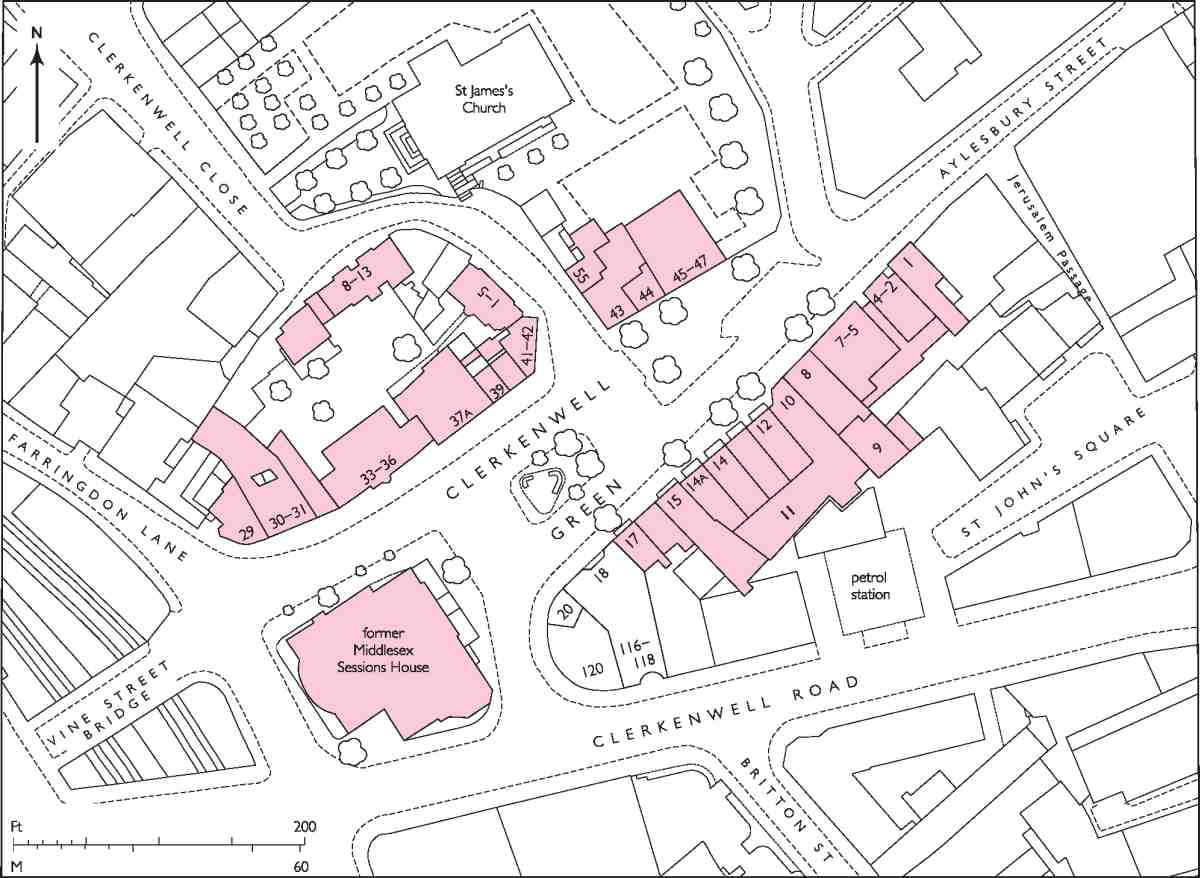

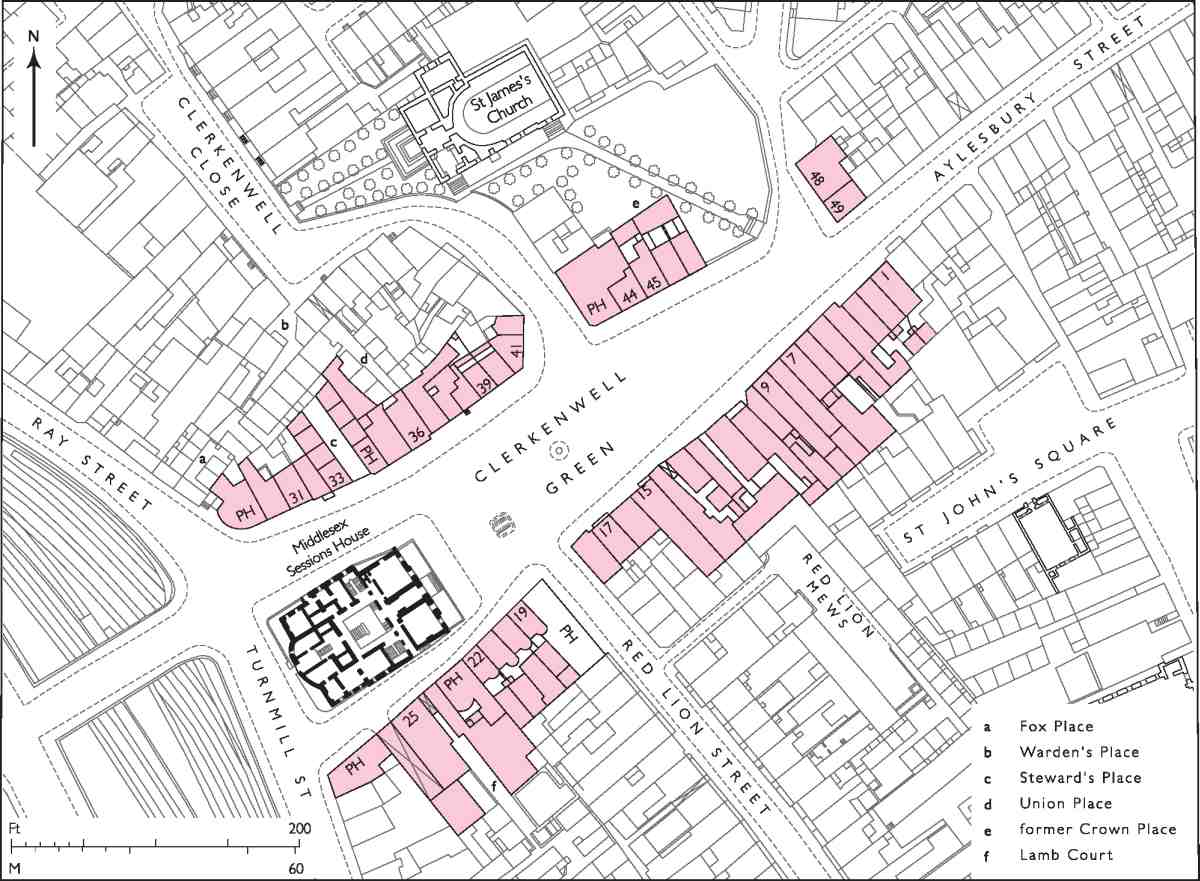

90. Clerkenwell Green

Clerkenwell Green, with the church of St James in the background, presents an image of the quintessential London 'village' (Ill. 92). But though it is widely thought of as the natural and historic centre of Clerkenwell, its origins are not those of a typical English village green. It was not the nucleus of early development, which took the form of ribbons of building extending from Smithfield and Cow Cross, up St John Street and into the Fleet valley along Turnmill Street. On the contrary, the Green seems to have come into separate being in the twelfth century as a sort of buffer between the two new monastic houses whose layout still informs the local street pattern: the Knights Hospitallers' priory of St John, to the south; the Augustinian nunnery of St Mary to the north. It is not known when Clerkenwell Green was first so called, but the name was in established use by the 1580s. (fn. 1)

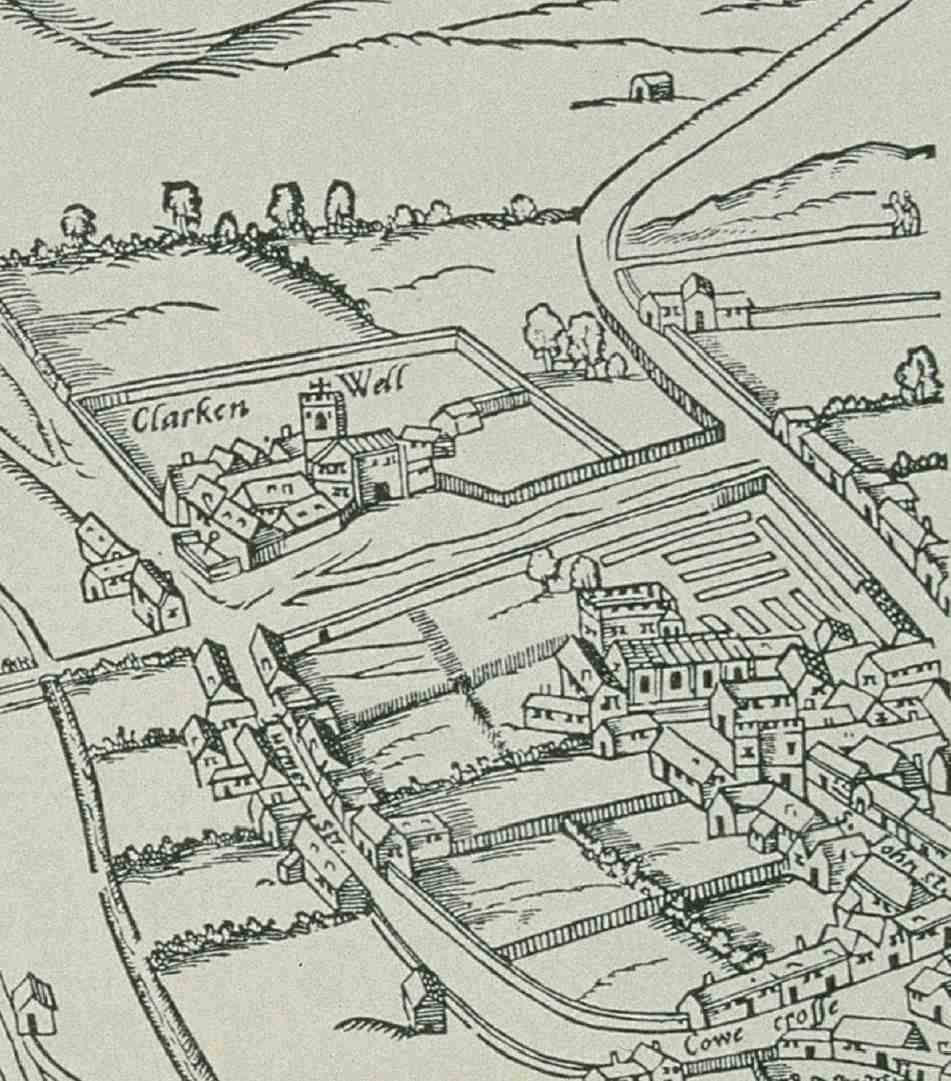

An early depiction suggests no more than the broadening out of a thoroughfare between St John Street and the Fleet, a patch of bare ground between the respective old monastic walls (Ill. 91). But as the former religious houses were redeveloped in the course of the later sixteenth century and after, Clerkenwell Green took on the character of an urban 'place' or square, the new buildings not turned away from it as the old had been, but fronting it.

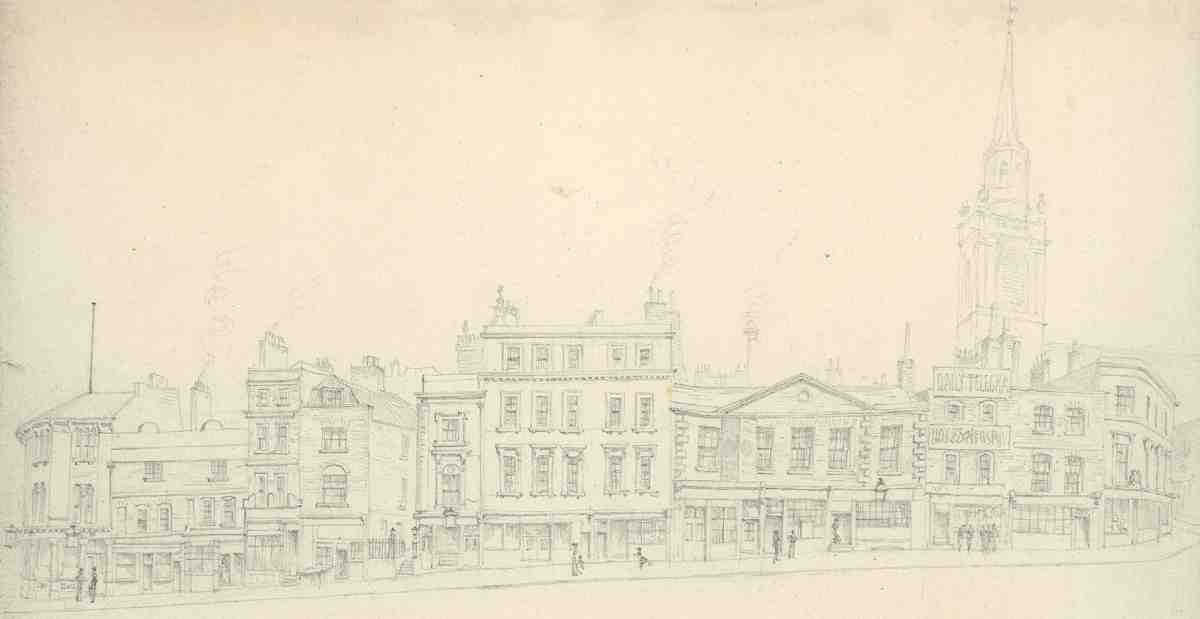

Only with the erection of the Middlesex Sessions House towards the end of the eighteenth century did Clerkenwell Green begin to attract special attention from artists and topographers (Ill. 98). Until then there was neither any building of status or serious architectural pretension, nor any obvious focus to what was a fairly large, but irregular and sloping, open space. The rebuilt parish church, too, with its 'City' air, gave an increased sense of dignity and civic importance to the locale—lack of which hitherto was in some measure behind the creation of the breakaway parish of St John earlier in the century. But there was nothing to follow this lead, and the Green developed and retained a busy, mixed character, far from smart, with much commercial and industrial activity.

The buildings around the Green today are mixed indeed, and reflect a number of influences. In common with other parts of Clerkenwell, the Green evolved in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries into a centre for specialized crafts and manufactures, carried on in houses and small workshops, alongside shops, taverns and other places of refreshment. Late Victorian and Edwardian redevelopment with larger commercial buildings is most apparent on the south side, the consequence of its proximity to the new Clerkenwell Road. The north mostly retains the older scale, the Edwardian bulk of Clerkenwell House at Nos 45–47, overlooking the churchyard, excepted. Some of this north-side streetscape is revival rather than survival, however: the 'early Georgian' front of No. 37A is a 1960s version of the 1730s original, while the group of buildings immediately west, built in the 1980s, occupies what had for many years been a vacant lot.

No. 37A, the Marx Memorial Library, not only commemorates the great political philosopher himself but stands for a long tradition of Radicalism and agitation which found a particular focus at Clerkenwell Green. This phenomenon was closely associated with the artisan population of the surrounding streets, and encouraged by topography, for the Green is a natural meeting-place and forum.

Architecturally, this radical tradition contributed nothing to the appearance of the Green, in contrast to the established order: the former Sessions House, much enlarged in the Victorian period, remains the strongest architectural presence (Ill. 105).

Recent new building on the south side of the Green has been successful in blending with the historic fabric, while supplying an admixture of contemporary style and materials (Ill. 93).

91. Clerkenwell Green and vicinity in the 1560s

92. Clerkenwell Green and St James's Church in 2007

93. Nos 16–20 Clerkenwell Green in 2007

Patterns of change since the Dissolution

St John's priory and St Mary's nunnery were founded in the 1140s on land granted by Jordan de Bricet, lord of Clerkenwell manor. The grants were made through an intermediary, Robert the chaplain, who, for whatever reason, held back four of the nuns' intended fourteen acres, situated between their walls and those of the Hospitallers. These four acres would have included the Green and the nuns' private road into their precinct— present-day Aylesbury Street. But by the 1170s the nuns had apparently obtained possession of all fourteen acres, and throughout the medieval and early Tudor periods the Green, or at least parts of it, remained under their control, the nuns for example holding rights to levy tolls for bringing livestock there during Bartholomew Fair. (fn. 2)

Early development was concentrated within the walls of the two religious foundations, a number of secular houses having been built in the precincts before the Dissolution. After the monastic property was dispersed by the Crown many more houses appeared, during the later 1500s and early 1600s. On the south side, parts of Butt or Butcher's Close, which had belonged to St John's priory, had by the 1570s been walled off and divided into gardens, soon afterwards covered with houses, some facing the Green (Ill. 94). (fn. 3) Further east, towards Jerusalem Passage, Dame Rebecca Seckford put up a row of nine houses around 1610 or 1620 on a plot referred to as 'St John's ground', the site of the priory brewhouse and bakehouse; these, too, faced the Green. (fn. 4)

As well as those in the former monastic precincts, houses were built on plots taken out of the central 'waste' itself. Encroachments continued until the late eighteenth century, greatly altering the size and shape of the Green. (fn. 5) The largest was at the west end, where an island of buildings (future site of the Sessions House) was in existence by 1593. (fn. 6)

From later evidence, this site comprised houses and an inn with various sheds and yards, and was probably typical of the character of the Green generally. There is nothing to support the picture given by the Victorian writer William Pinks of large houses beside the Green in the seventeenth century, abodes of wealth and nobility, comparable with those of Clerkenwell Close, St John's Square and St John's Lane. (fn. 7) Extensive vaults beneath No. 37A and adjoining buildings may conceivably be the remains of such a mansion, but if so it had been demolished by the time of Ogilby & Morgan's survey of 1676.

By this date only four properties on the Green had as many as ten hearths (all were on the eastern part of the south side) and most of the houses at this time were small or medium-sized. (fn. 8) Rebecca Seckford's were among the largest: narrow-fronted, timber-framed houses with plastered or weather-boarded fronts, probably of two rooms to a floor, with central staircases (Ill. 96). (fn. 9) Beyond Garden Alleys (precursor of Britton Street), towards Turnmill Street, the houses on the south side became smaller and meaner. At the western end, beyond the future Sessions House site, near the bottom of the Fleet valley, stood an east-facing row of small houses, later known as Silver Street.

As the range of house-sizes suggests, the seventeenth-century social composition was varied. Towards the end of the century, the proportion of residents in the higher social levels, as indicated by a number of knights, baronets and other 'persons of quality', was clearly falling, to be replaced by artisans and tradesmen, as the area took on the commercial and industrial character which survived until recent times. (fn. 10)

94. Clerkenwell Green in 1676

95. The north side of Clerkenwell Green in the 1870s: Nos 29 (left) to 41–42

96. Early seventeenth-century houses at Nos 8 and 9 Clerkenwell Green, shortly before demolition in the 1860s

Residents in the early 1600s included Francis Thynne (d. 1608), antiquary and herald, cousin to Sir John Thynne of Longleat; (fn. 11) and Sir Ferdinando Gorges (d. 1647), soldier and promoter of American colonization, who was born and lived at his family's home on or near the Green, on the north side. (fn. 12) Dame Elizabeth Bullock, widow of Sir Edward Bullock of Faulkbourne Hall, Essex, was living on the Green in 1644 when her house was attacked by soldiers, who tore the rings from her fingers and shot at her neighbour, Dr Sibbald, vicar of Clerkenwell, as he remonstrated with them from his window. (fn. 13) Izaak Walton lived at the Green from c. 1650 until about 1661, during which time The Compleat Angler was published. (fn. 14)

The eighteenth century saw a certain amount of piecemeal reconstruction, adding further to the variety in size and shape of the buildings (Ill. 95). Small brick houses were erected as early as the 1690s: in 1696 the Vestry accepted the offer of Robert Bellfour to pull down three wooden houses at the west end of the Green, belonging to a parochial charity, and erect two substantial brick ones in their stead on a 51-year lease. (fn. 15) About ten years later three brick houses were built on the south side near the eastern corner with Garden Alleys, and towards Turnmill Street a dozen or so were erected in Lamb Court. (fn. 16) Also on the south side, Simon Michell's development of Red Lion (now Britton) Street during the next two decades prompted further building at the west end of the Green. (fn. 17) On the north side, the erection in 1738 of the Welsh School was accompanied by new building on the adjacent plots, fronting the Green and in Steward's Place (Ill. 97). (fn. 18) These were modest houses, two of them wooden and quite lowly in character; the school itself was the first consciously 'architectural' statement on the Green.

97. Nos 32–33 Clerkenwell Green and Steward's Place, c. 1900. Mostly demolished

The reconstruction of the parish church in the 1790s may well have encouraged some new building which took place about the same time or soon afterwards. This comprised a line of houses and shops on the east side of the Close and continuing along the Green, with the Crown Tavern on the corner. A new house was also built at the corner of St James's Walk and Aylesbury Street (No. 49, on the site of present-day Woodbridge House). (fn. 19)

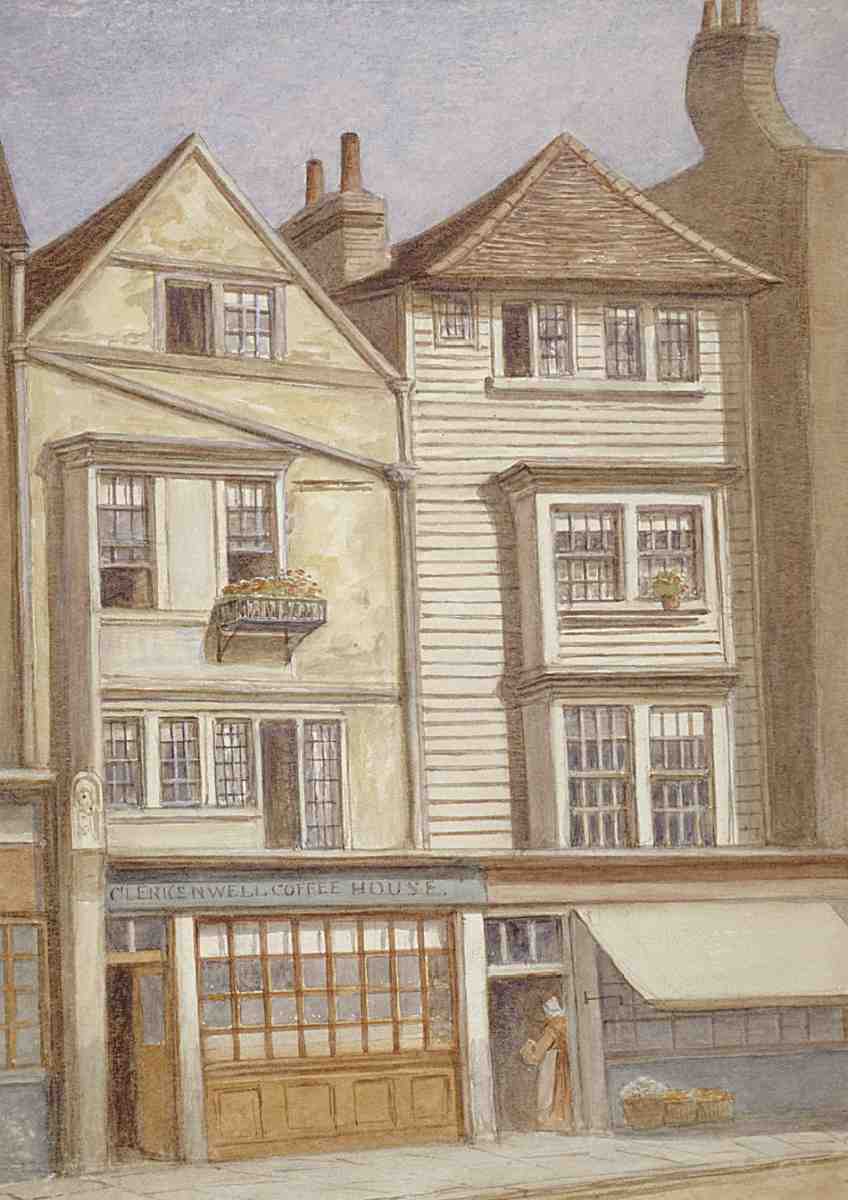

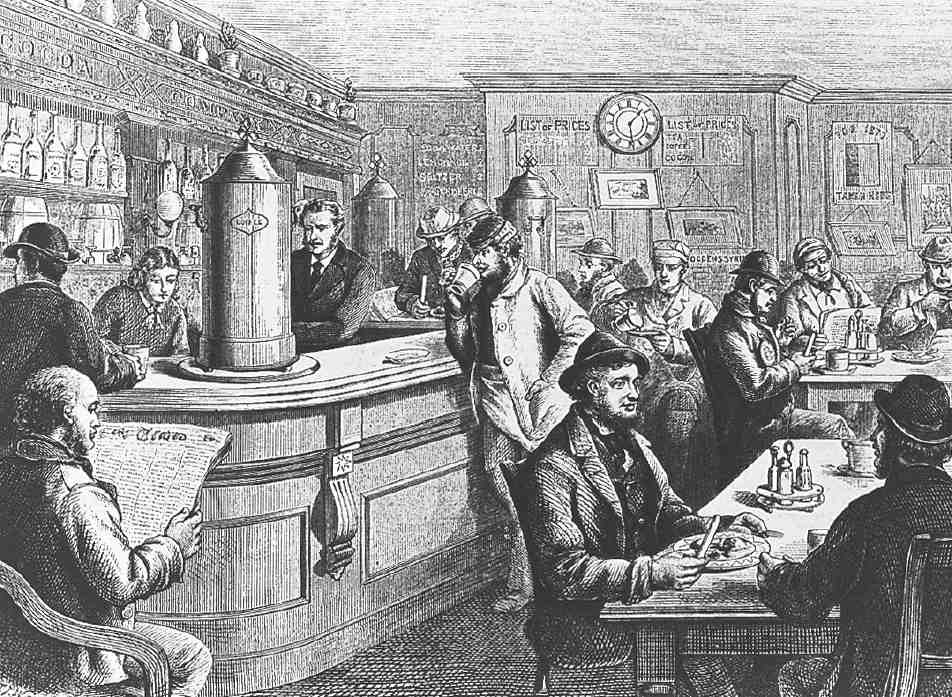

With the exceptions of the Welsh School and the Sessions House, the buildings put up in the eighteenth century were mostly houses and shops, generally of no more than two or three storeys. The Green was above all a place for traffic and trade, shopkeepers making use of the ground in front of their premises to display wares, and street-vendors finding ample space for pitches. (fn. 20) There were numerous inns—the Crown, Northumberland Arms, Fox and French Horn, Queen's Head, Lamb and Flag and Red Lion, as well as the Spencers' Arms and the Magpye in Silver Street, were all in existence by about 1800. (fn. 21) Coffee-houses, too, were a feature, among them Kingston's, probably established in the 1680s in the house later occupied as the Red Lion, and Herbert's, at No. 4 on 'St John's ground', probably established in the early eighteenth century. (fn. 22)

Most residents in the eighteenth century appear to have belonged to the middling and somewhat lower classes, chiefly businessmen such as shopkeepers, small-scale merchants and tradesmen, or skilled artisans of the type who inhabited much of Clerkenwell—typically clockmakers, watchmakers, jewellers, goldsmiths, and cabinet-makers. (fn. 23) Very few styled themselves 'Gentleman'. There were, too, a number of poor inhabitants. Notable individuals living on the Green in this period included Thomas Kitchin, the mapmaker and engraver, at No. 19 on the south side in the 1750s; and the wood engraver John Bewick, who had rooms at No. 7 in the 1780s. (fn. 24)

Glimpses of the Green at the turn of the nineteenth century are offered by reports of fires, which suggest both the prevalence of timber building as well as the mixture of tradespeople and poor living there. In 1799 a pawnbroker's and a grocer's adjoining, near the Sessions House, were completely destroyed. Four years later, a jeweller and goldsmith on the south side, near Turnmill Street, set light to his (largely timber-built) premises while melting gold. His and several adjoining houses, all in poor occupation and also wooden, were destroyed. (fn. 25)

The predominantly entrepreneurial and artisanal character of the Green found its cultural expression in the taverns and coffee-houses, where a lively social and political debating life flourished. Perhaps the best-known was Lunt's Coffee House and Reading Rooms, at No. 7 from 1822 till about 1830. This had a 60ft-long coffee-room, purpose-built, decorated with portraits, maps and casts of antique statues. (fn. 26) The Chartist William Lovett was a regular, coming to hear radical oratory from men such as the secularist Richard Carlile and the deist preacher Robert Taylor. (fn. 27) Lunt moved from there to No. 34, on the north side of the Green, which remained a coffee-house until the 1860s. (fn. 28)

Successive metropolitan improvements in the second half of the nineteenth century left Clerkenwell Green slightly smaller and less secluded than it had been, but it escaped drastic alteration. Excavations for Farringdon Road and the Metropolitan Railway in the 1850s and 60s completely changed the face of the area just to the west, Silver Street, Mutton Lane and the whole west side of Turnmill Street being obliterated. In the 1870s, Clerkenwell Road cut closer, taking away a swathe of buildings on the south side of the Green along with the north ends of Turnmill and Red Lion Streets. Most importantly, the Green was opened up directly to Clerkenwell Road with a prominent sweep of new building at the junction (Ill. 90, and see Ill. 584 on page 405). This gave a small fillip to commercial property development on the Green itself, where speculative warehouses of a 'main road' character appeared at Nos 11–14a in 1878. But the new premises seem to have been slow to take, and were not followed by comparable developments until the early twentieth century. These were a pair of factories or warehouses at Nos 1–2, built in 1904 and now demolished, (fn. 29) and the tall commercial block at Nos 45–47, of 1904–6, also slow to find tenants.

By the turn of the twentieth century the economic character of the Green had changed, many of the erstwhile craftspeople having been supplanted by semi-skilled and unskilled labourers, probably in consequence of mechanization and foreign competition in the clock and other trades. (fn. 30) Socially the Green, like many of the older districts of southern Clerkenwell, had been declining for some time, with a large influx of Irish poor since the 1840s. (fn. 31) A description of the Green in 1871 gives an impression of a bustling, working-class place, raucous with costermongers and the 'Babel of the genuine cockney tongue'. (fn. 32)

98. Clerkenwell Green, looking north-west, with the Sessions House and St James's Church. Extract from Thomas Hornor's Plan of the Parish of Clerkenwell, 1813

Printing and associated trades, although already represented on the Green, became increasingly important from the late nineteenth century. Among the newcomers was a Nonconformist advertising agent and publisher, Samuel Edwin Roberts, who in 1898 took over a printing house at Nos 8–9, set up a few years earlier, chiefly for producing his own religious books and tracts. The firm, later the John Roberts Press, moved to No. 14 in 1921, and was still in existence in the 1980s. (fn. 33) By 1939, of the sixty or so businesses listed in the Post Office Directory, about twenty were associated with the printing trades; by 1946 the number had risen to nearly half.

At No. 35 a cardboard factory was set up in 1866, more than twenty men, women and children working there in 1871. This closed in the early 1880s, and the building was fitted out, probably a few years later, as a workmen's lodging-house. It seems to have been run by the proprietors of a shop at the front of the site, successively a tobacconist's, a general store and coffee-rooms. The lodging-house was still functioning shortly before the First World War, when it was described as a 'barn like' place with 73 beds, some at least of them on the upper floor of the building, ascent to which was by ladder. (fn. 34)

Industrial development continued up to the Second World War, with a four-storey factory begun in 1939 at Nos 33–34, but never finished; the basement was used as an air-raid shelter. (fn. 35) After the war, in which the Green escaped much serious damage, industry declined. In the 1960s the London County Council pursued a plan to demolish the northern side and much of Clerkenwell Close for an extension of the open space, which initiated a lengthy period of planning blight. In 1973 the Green was characterized as a 'shabby muddle of rubbish-strewn vacant sites and derelict buildings'. (fn. 36) However, by then the open-space enlargement scheme had been dropped and the Green designated the borough's first Conservation Area, paving the way for its regeneration. In recent years it has become a favoured location for architectural practices and media companies, in common with much of southern Clerkenwell.

The Green as an open space

Ownership of the open ground since the Dissolution is not entirely clear. As a piece of manorial waste, it was included in a royal grant of 1599 of Clerkenwell manor and other former nunnery holdings to Sir John Spencer of Islington, merchant and one-time Lord Mayor. (fn. 37) After Spencer's death in 1610 the lordship of the manor descended via his daughter Elizabeth to the Compton family, Earls (later Marquesses) of Northampton, who throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries claimed title to the Green, a claim more than once challenged (unsuccessfully) on the grounds that it was anciently part of the King's highway. (fn. 38) How and when the Comptons disposed of it is not known, but by the time Clerkenwell Road was built in the 1870s the Green, as a public thoroughfare, was owned by the Vestry. It was subsequently inherited by the vestry's successor bodies, Finsbury Borough Council (from 1900) and the London Borough of Islington (since 1965). (fn. 39)

99. Clerkenwell Green in the 1870s

The open area was formerly much larger than today and oblong in shape (Ill. 91). For two centuries after the Dissolution, it was encroached on from all sides for building and other purposes, taking on its present triangular form in the late eighteenth century, at the time of the rebuilding of the parish church. The churchyard was then extended southwards and the building line eastward of Clerkenwell Close brought forward for the construction of the new Crown Tavern and adjoining houses and shops (later Nos 43–47, see Ills 98, 99, 126). (fn. 40)

In the 1720s the Earl of Northampton began leasing plots in front of houses on the south side to householders there. Though not built on, these plots were railed off, effectively reducing the open space, and remained so until the mid-nineteenth century. (fn. 41) Also by the 1720s the central green had been further reduced and cut up by paths and roadways. A watch-house, well and pump occupied the centre. (fn. 42) In 1788 a space in front of the Sessions House, some 50–55ft by 85ft, was leased by the Earl to the county magistrates and fenced off to provide an improved approach to the building; for a time there was a whippingpost in the middle of this enclosure. (fn. 43) Rows of trees in front of the houses, shown on Rocque's map and in late eighteenth-century views, had gone by the early 1800s, and with them went any lingering 'rural' impression—the inevitable consequence, as the Clerkenwell chronicler Thomas Cromwell put it, of 'trade and Scotch paving'. (fn. 44)

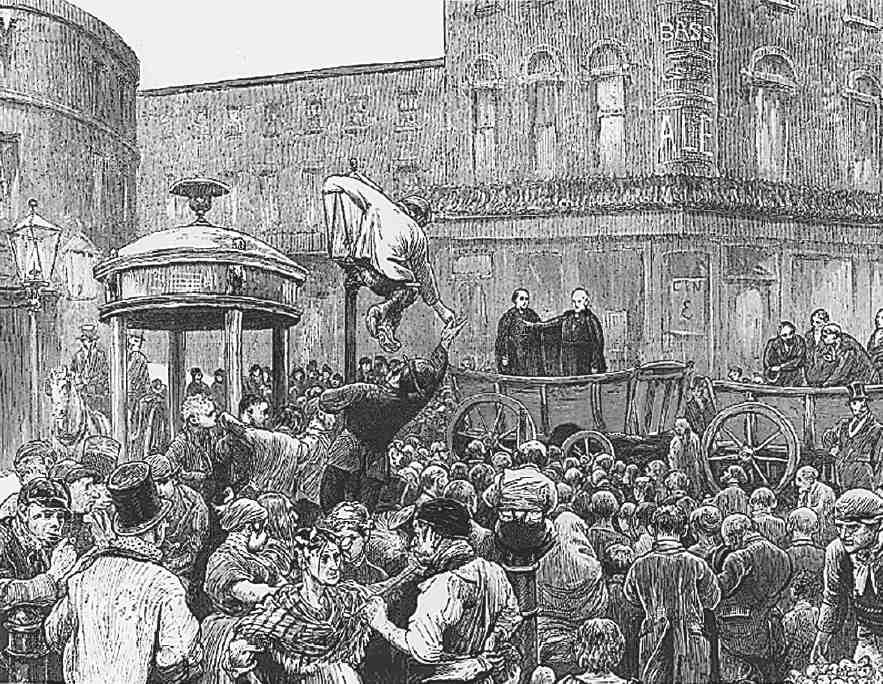

In the mid-nineteenth century the vestry began to improve and regularize the open space of the Green, and by 1900 it had acquired much of its present-day aspect. The watch-house was removed in the 1840s, its place being taken by a round paved area with a lamp, and in 1856 a new well was sunk and a pump erected beside it. (fn. 45) In 1862 the pump was replaced by an ornamental cast-iron drinking-fountain, modelled on the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, which became a focal point for meetings (Ills 100–102). This was the gift of the Good Samaritan Temperance Society, based in Saffron Hill, which raised the money from local subscribers. (fn. 46) Water flowed from an urn enclosed by the columns, and the whole was originally surmounted by a gilded figure, gone by the 1880s. (fn. 47)

For several years after the fountain's installation the vestrymen had further improvement in mind, envisaging the Green as a 'pleasant resort' like those at Islington and Camberwell. (fn. 48) Spurred on by the effect of demolitions for Clerkenwell Road, they decided in 1878 to enclose the central area as a flower garden, with shrubs, paving and seating, incorporating the drinking-fountain in a brick canopy designed to match the Sessions House. Behind this plan for municipal beautification was an apprehension that the Green might be left a deserted backwater by the new road, offering 'greatly increased facilities' for disorder. (In fact, the creation of the road seems to have had no such effect.) (fn. 49) Local inhabitants and groups who used the Green regularly for meetings objected vehemently, and the Metropolitan Board of Works, upon whose sanction and financial assistance the scheme depended, decided against it. (fn. 50)

100. The Green in 1898 showing drinking-fountain and trough in their original positions

101. Reform League procession leaving Clerkenwell Green for Trafalgar Square, February 1867; note 'liberty' caps on some banners

102. Archbishop Manning administering the pledge outside the Crown public house, 1872

103. The Crown and adjoining buildings at Nos 44–45, c. 1900; Lion House (No. 48), far right

Thereafter, improvements were of a piecemeal nature. In the late 1870s the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association provided a horse trough near the fountain (Ill. 100). In 1889 a 'kiosk' convenience of 'artistic appearance' was put up in front of the Sessions House as an experiment by the International Hygienic Society; (fn. 51) it was taken down in 1899, when underground public conveniences for both sexes were constructed, by British Sanitary Works Ltd. Now disused, these occupy the site where the fountain and trough formerly stood, one of two raised areas paved and planted with trees by the Vestry. (fn. 52) The trough and fountain were re-erected at either end of the second, more elongated paved area, in front of Nos 43–47; the fountain had gone by the 1930s. (fn. 53)

After the Second World War most of the buildings on the north side of the Green and in Clerkenwell Close were threatened with demolition by the London County Council's scheme to extend the open space and combine it with an enlarged St James's churchyard. Essentially this would have created one large expanse between St James's Row and the south side of the Green, with the church at its centre. Many of the properties affected were dilapidated or 'obsolescent', and the wider area was felt to be sorely in need of public amenities. Throughout the 1950s and early 60s the LCC acquired and demolished buildings, including Nos 33–36 Clerkenwell Green and 9–13 Clerkenwell Close, and others north of the church, transferring sites to Finsbury Borough Council, which was to lay out and maintain the ground. (fn. 54) The plan was later amalgamated with another to clear the northern end of the Close for an enlargement of the Hugh Myddelton School, and by January 1964 a firm of landscape architects (Richard Sudell & Partners) had prepared plans. (fn. 55)

Several factors combined to sink the open-space scheme, principally the abandonment of the proposed school enlargement, and a well-supported campaign to save the Marx Memorial Library. This raised awareness of the historic value of the neighbouring buildings, leading to the designation of the Green as a Conservation Area and its ultimate rehabilitation. (fn. 56)

The defeat of the LCC scheme has left a legacy of determined local opposition to any further designs on the historic Green, and recent proposals by Islington Council to replace the disused public lavatories with a wine bar have been defeated.

Clerkenwell Green and Radicalism

The association of Clerkenwell Green with political agitation and reform is a long one, reaching back into the second half of the eighteenth century, when local support for John Wilkes led to rioting in the vicinity in the late 1760s. (fn. 57) In the 1790s Clerkenwell was prominent in opposition to the war against France. A branch of the anti-war London Corresponding Society was set up in Jerusalem Passage just off the Green, and a tavern in Mutton Lane, at the west end of the Green, was one of many recruiting stations in London attacked by protesters (though the landlady persuaded the mob to desist). (fn. 58) This radical character was essentially the consequence of the local economy, based on specialized crafts and vulnerable to changes in trading conditions, as evidenced by the crisis in watchmaking when heavy duties were imposed on imported watch-cases in 1798. (fn. 59) The presence, too, of the Sessions House and two county prisons probably helped make the area a rallying-point for radicals and malcontents. But it was not until the nineteenth century that the Green itself emerged as a venue for open-air demonstrations, along with Spa Fields and White Conduit Fields, and not until the 1860s that the Green became almost synonymous with Radicalism. (fn. 60)

In February 1826 Cobbett spoke against the Corn Laws to a large crowd gathered on the Green, (fn. 61) and during the 1830s and 40s Anti-Corn Law and Chartist meetings became regular events. In the 1860s the Reform League, which had particularly strong support in Holborn and Clerkenwell, held mass meetings here. Fenian sympathizers and agitators also met on the Green, both before and after the 'Clerkenwell Explosion' of 1867 (see page 57). Of thirty-six potentially dangerous political meetings held in the capital during 1867–70, reported by the Metropolitan Police to the Prime Minister, twenty took place on the Green. (fn. 62) These drew crowds ranging from one or two hundred to several thousands. Between the 1870s and 1890s, working-class meetings attracted very large numbers (though estimates of 15,000 to 20,000 were probably exaggerations).

Whatever the political thrust of the event, proceedings followed a similar pattern. A wagon or cart was drawn up to serve as a platform or hustings, sometimes in the centre of the Green, sometimes directly and flagrantly in front of the Sessions House. (fn. 63) Just such a meeting, erupting into riot, forms the climax to Demos, Gissing's 'story of English Socialism' (1886). Night-time meetings were torchlit, the speakers usually standing under a lamp-post. At a Franchise Bill meeting organized by local radical clubs in 1884, limelight for the speakers was provided from the roof of the London Patriotic Club at No. 37A. (fn. 64) Sometimes effigies were burnt or strung from a gallows. Day-time gatherings, such as those of the Reform League and the mass unemployed, were often part of a London–wide or national campaign, and after speeches the crowds would march in procession, banners raised, to another venue (Ill. 101). Eleanor Marx Aveling, Karl Marx's daughter, spoke at a gathering of the unemployed on Clerkenwell Green in October 1887, before proceeding with them behind a red flag to Trafalgar Square. (fn. 65) Three weeks later William Morris, having addressed a similar crowd of some 5,000 on the Green, was leading a procession heading for Trafalgar Square when they were attacked by police in what became known as 'Bloody Sunday'. (fn. 66)

During potentially volatile meetings, police reserves were stationed in the Sessions House and nearby houses, in case of disturbance. (fn. 67) Though alarming to the local populace and the authorities, the crowds generally were well behaved, with the exception of some of the 'physical force' Chartists of 1848, who on several nights threw stones and caused damage, inviting a show of strength by troops of cavalry and mounted police. (fn. 68) One ex-policeman later described the Chartists hiding in the houses around the Green, and throwing things at the police as they were chased from room to room. (fn. 69)

Not all gatherings on the Green were of a political

nature. In the 1870s there were regular religious and

Sunday temperance meetings, the latter often presided

over by Archbishop Manning, who on one occasion

'administered the pledge' to a crowd of mostly Irish

migrants from a coalman's cart drawn up in front of the

Crown Tavern (Ill. 102). (fn. 70) As well as the larger meetings,

the Green also seems to have attracted all sorts of soapbox orators and tub-thumpers, in the manner of Speakers'

Corner. Gissing again:

Towards sundown, that modern Agora rang with the voices

of orators, swarmed with listeners, with disputants, with

mockers, with indifferent loungers. The circle closing about

an agnostic lecturer intersected with one gathered for a

prayer-meeting; the roar of an enthusiastic total-abstainer

blended with the shriek of a Radical politician. Innumerable

were the little groups which had broken away from the larger

ones to hold semi-private debate on matters which demanded

calm consideration and the finer intellect. From the doctrine

of the Trinity to the question of cabbage-versus-beef; from

Neo-Malthusianism to the grievance of compulsory vaccination; not a subject which modernism has thrown out to the

multitude but here received its sufficient mauling. (fn. 71)

By the early 1900s working-class aspirations had found alternative expression through the growth of the Labour Party and the advent of universal male suffrage, and though the Green has continued to host public assemblies— such as services for the war dead, trades' union rallies, and most recently May Day demonstrations—it has never been with the frequency or intensity of Victorian times. Since then No. 37A has provided the area's main radical focus, as home to the Twentieth Century Press until the 1920s, and since the mid-1930s to the Marx Memorial Library.

The Buildings

Former Middlesex Sessions House

The Middlesex Sessions House was built in 1779–82 to replace Hicks' Hall in St John Street, where county sessions had been held since 1613. By about 1770 Hicks' Hall had become both too small and structurally unsound, while the site itself, on an island in the roadway, was far from ideal: size apart, the congestion of the street with cattle and sheep being driven to Smithfield made rebuilding on the same spot undesirable. The move to Clerkenwell Green was a matter of contingency rather than planning, but from a later standpoint the building, presiding with magisterial impassivity over a place that has become redolent of demagogy and dissent, could not have been more aptly situated.

The Sessions House of 1779–82

No firm decision as to rebuilding was taken until December 1774, when the magistrates determined that a new site must be found. Heaton Wilkes offered his failing distillery adjoining St John's Church (see page 121), but this eventually proved too expensive. (fn. 72) Newspaper advertisements were placed, and subsequently three apparently suitable sites were offered—one just south-west of St John's Gate, another on the Earl of Northampton's estate opposite Coldbath Fields, the third at the west end of Clerkenwell Green. (fn. 73)

Another and more tempting opportunity then arose: part of the site of Ely House in Holborn, recently purchased by the Crown, which was brought to the justices' attention by (Sir) Robert Taylor, architect of the new Ely House in Dover Street. It was generally felt that this would be 'a most Excellent Situation', and on Taylor's advice a petition was drawn up for presentation to the Prime Minister, Lord North, asking for the Treasury's support. (fn. 74) These efforts did not meet with success, presumably because the ground had already been sold to Charles Cole, who developed Ely Place on the site. (Some negotiations did in fact take place subsequently with Cole, who was willing to buy the Hicks' Hall site if the justices bought some of his ground.) (fn. 75)

The other sites had to be reconsidered. Only one was readily obtainable freehold: that at Clerkenwell Green, an island of old houses, sheds and other buildings (including the Nag's Head tavern), with a frontage of about 70ft. This was selected in December 1777, though not finally cleared and purchased, for £2,000, until February 1779. (fn. 76) Statutory powers to replace Hicks' Hall, borrowing up to £11,000 for the purpose, had been granted a few months previously. (fn. 77)

Thomas Rogers, the county surveyor, put forward plans for the new court-house, but they were rejected, as was his request six months later to take on the job of designing it. Instead, the magistrates decided on a public competition. (fn. 78) But when they examined the eleven entries, it was a design by Rogers that they chose, and he was duly appointed surveyor to their building committee. (fn. 79)

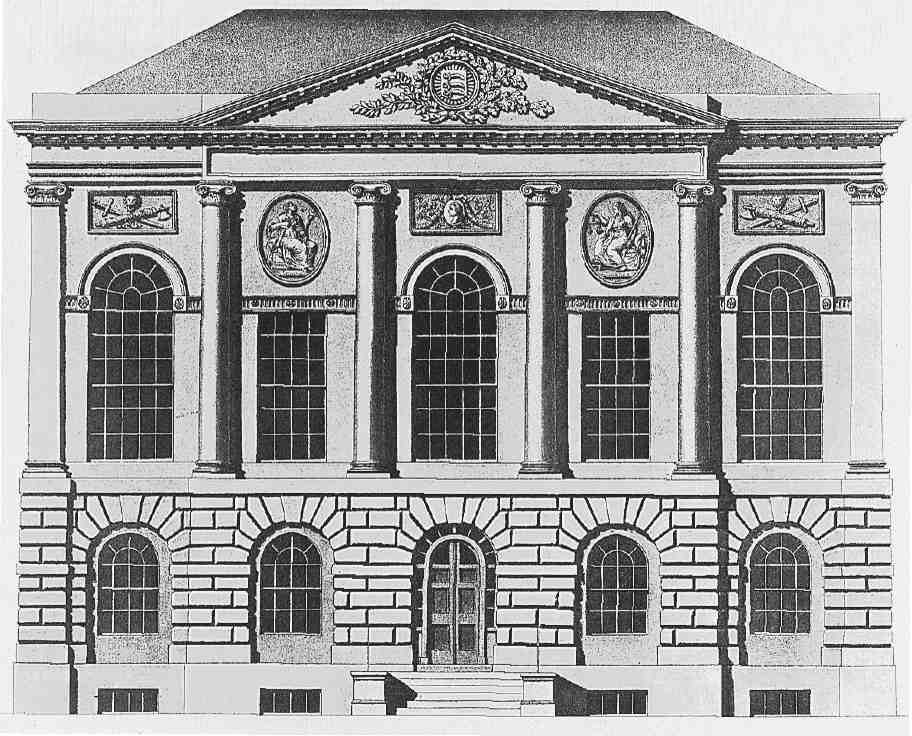

104. Middlesex Sessions House. Front elevation in 1799, with sculptural panels designed by Joseph Nollekens, executed by J. C. F. Rossi

105. Middlesex Sessions House, front elevation in 2006. Thomas Rogers, architect, 1779–82

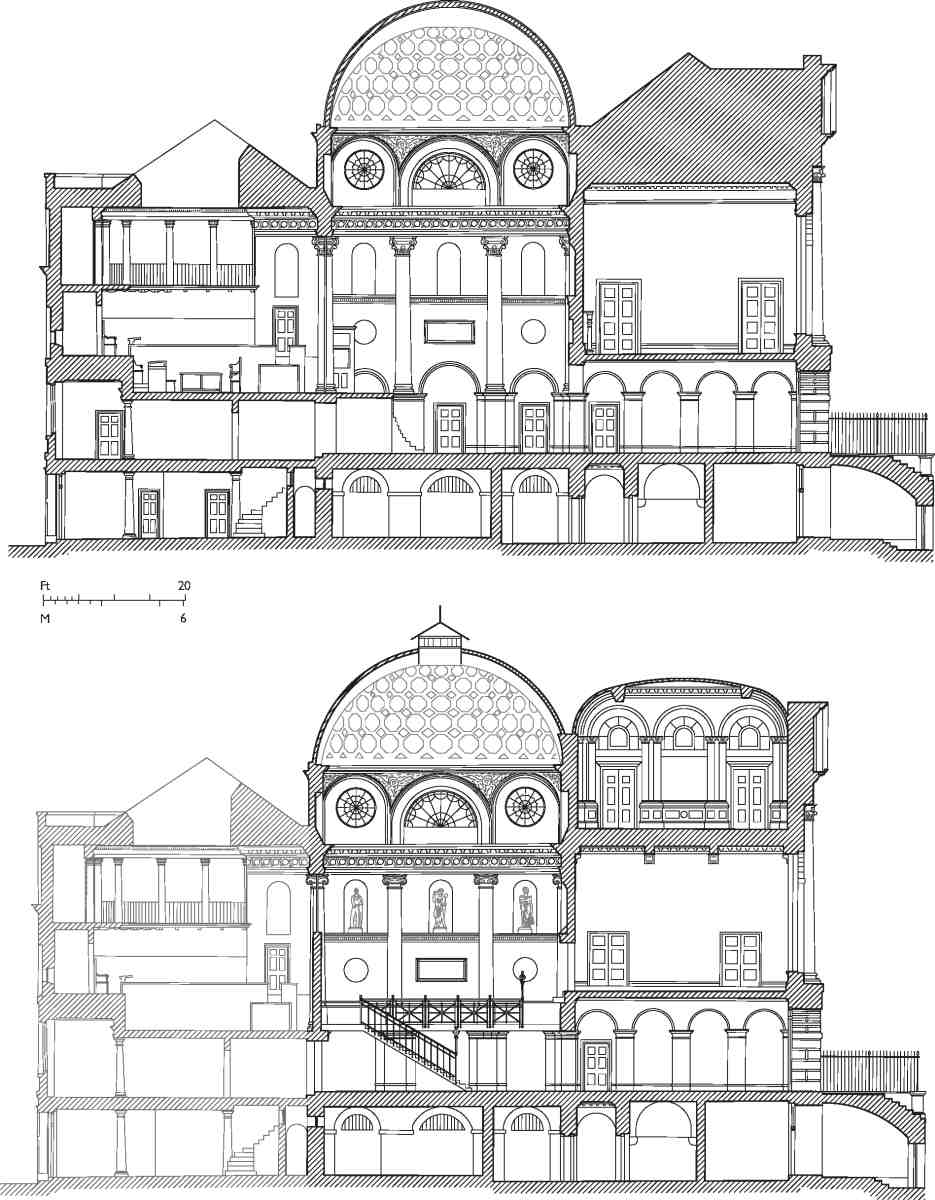

106. Middlesex Sessions House. East—west sections before and after F. H. Pownall's alterations of 1859–60

By the summer of 1779 contracts had been awarded to John Collins (masonry), Thomas Gilbert (bricklaying), John Papworth (plasterwork), William Thompson (painting and glazing), James Tyson (slating), and Joseph Wood (carpentry, plumbing and smithery). (fn. 80) Work then began on the foundations, and in August of that year the first stone was laid with some pomp by the Duke of Northumberland, Lord Lieutenant and Keeper of the Rolls of Middlesex, who had been instrumental in smoothing the enabling Act's passage through Parliament. (fn. 81) During the severe winter of 1779–80 work was suspended and the brickwork covered with straw, and there was a further delay at the time of the Gordon Riots in June 1780, the bricklayer charging an extra sum for 'Time the men was obliged to loose when the Rioters where going about'. (fn. 82) Progress was also held up by frequent alterations made at the magistrates' request, mostly in connection with the acoustics and lighting of the courtroom. The building was eventually ready for occupation in July 1782. (fn. 83) It was known at first as Hicks' Hall or New Hicks' Hall, but this name gradually faded from use.

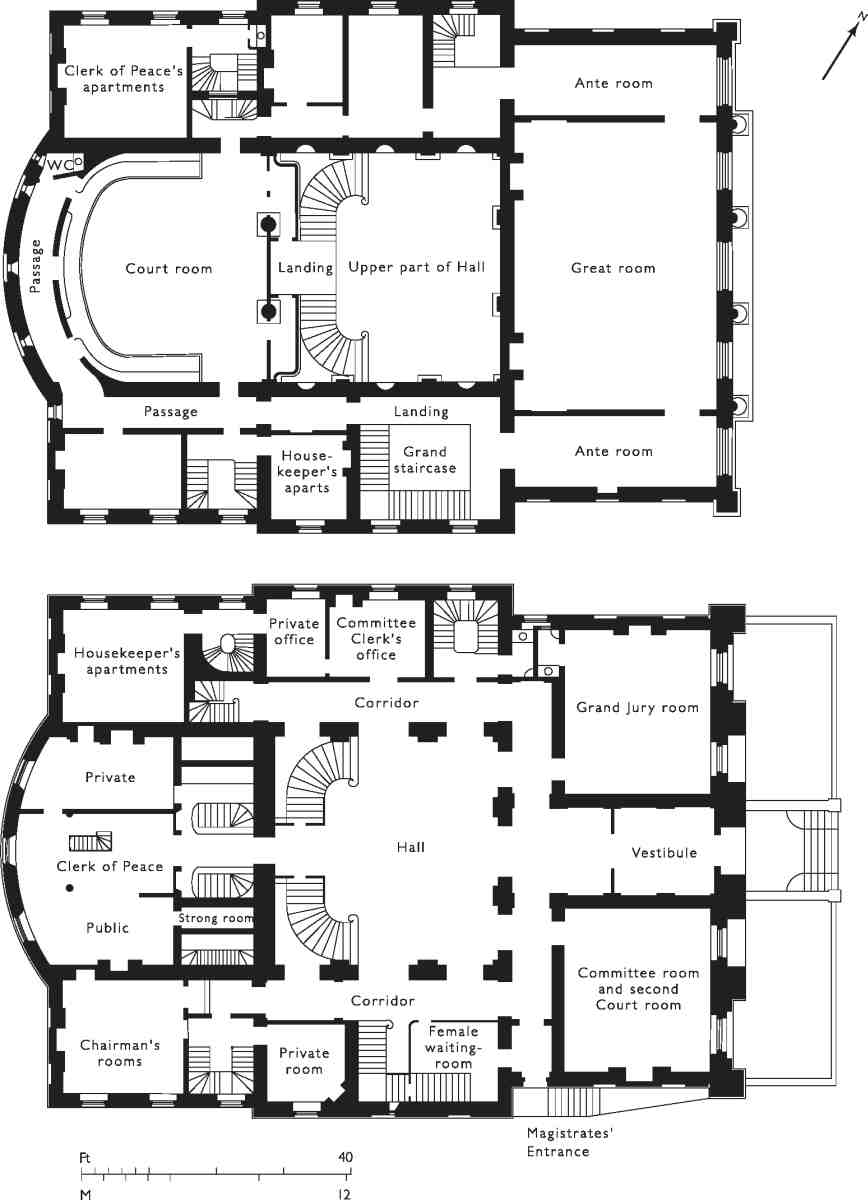

107. Middlesex Sessions House. Ground- and first-floor plans in the 1850s

Architectural ornament was concentrated naturally on the main, east front, overlooking the Green; the sides and rear, facing on to streets of narrow houses, though plainer, had respectable Palladian compositions—a bow at the rear, pediments and regular rows of windows and string courses to the sides. To James Peller Malcolm, the combination of horizontal emphasis and the sloping site gave the building a heavy appearance, as if it were 'sinking into the earth'. (fn. 84)

Apart from a later roof extension, the main elevation is little altered (Ills 104, 105). Its Palladian arrangement of rusticated ground floor, central portico and pediment was shared by many county, shire and town halls erected in England in the late eighteenth century. However, the façade that we see today is not Rogers's winning design (which is unknown), as a number of important modifications were made to it before the building opened.

Firstly, in January 1779, before construction began, the magistrates asked Rogers to prepare three variants of his design for the façade: stone with Doric columns; stone with Doric pilasters; brick with Doric stone columns. They chose the most expensive option—the first—and decided that the remainder of the building should be of brick, with stone dressings. (fn. 85)

By April of the following year, with work well under way, Rogers had re-arranged the elevation once more to incorporate some 'embellishments', added 'under the Direction' of the Duke of Northumberland. (fn. 86) These were five Adamesque panels of symbolic sculpture in relief: figures of Mercy and Justice flanking a profile portrait of George III, festooned with laurel and oak leaves (emblems of the 'Genius of the Country', Strength and Valour), and outer panels of a lion's head above a crossed sword and fasces (for Authority and Punishment). Once again, the magistrates put dignity before economy, choosing Portland rather than artificial stone. (fn. 87) Joseph Nollekens won the contract for the sculptures, at £100, which presumably also included the carved county arms in the pediment. (fn. 88) Though he made the preliminary models, Nollekens was in Harrogate 'taking the waters' when the work was executed in August 1780, and he entrusted the job to the Verona-born sculptor John Baptiste Locatelli. (fn. 89) In the event it was Locatelli's pupil, the 18-year-old John Charles Felix Rossi, who seems to have done the carving, under his master's direction. (fn. 90)

The Duke of Northumberland, an important patron of Robert Adam, was well versed in the arts and sciences, and capable of providing Rogers with detailed instructions, or even a sketch. Whatever his involvement with the reliefs, the introduction of the panels must have greatly affected Rogers's elevational design, especially the arrangement of the first-floor windows which previously may have been taller. It was probably at the same time that Ionic was substituted for Doric, as more befitting the delicate sculptures. Again, this may have been at the behest of the Duke—a man who 'knew unerringly when an architectural order was wrongly applied'. (fn. 91)

Many years later, the originality of Rogers's design was challenged in an anonymous obituary of a fellow competitor, the antiquarian and architect John Carter (d. 1817), written most probably by Carter's friend and executor, the antiquarian Philip Hammersley Leathes. Carter apparently told Leathes that Rogers had simply copied an earlier design of his for a county court, published in the Builder's Magazine about 1774, the plagiarism, coupled with his own rejection, causing him 'singular mortification'. (fn. 92) Later commentators have dismissed or ignored Carter's claim with good reason: his published elevation is a more fanciful, Piranesian concoction, any general similarities between the designs simply reflecting the narrow vocabulary of eighteenth-century public architecture. (fn. 93) Rather, Carter's resentment is probably attributable to his welldocumented cantankerousness: J. C. Buckler, another Carter memorialist, described him as a man who would 'fancy the greatest consequences to have arisen from the most casual and trifling cause'. (fn. 94)

The new Sessions House was arranged around a central hall, rising through the full height of the building to a coffered dome. Intended for circulation and as a gathering place for witnesses and the general public, this was surrounded on three sides by arcades opening on to spacious corridors; on the fourth, above a suite of offices, was the court-room on the first floor (Ills 106, 107). In the hall, plasterwork decorations by John Papworth included a frieze with medallions bearing fasces and Mercury's caduceus, and, in the pendentives to the dome a series of symbolic decorations against a background of oak leaves representing the Crown, including the cockerel (symbol of penitence), the serpent and looking-glass (symbolizing wisdom) and the scales of justice (Ills 108, 109).

The court-room, at the west end, was approached by a sweeping double flight of stairs. Added at the magistrates' request in 1781, at a late stage in the construction, these replaced Rogers's initial much tighter, less majestic pair of 'corkscrew' stairs, which were taken down and their short steps re-used elsewhere as back stairs. (fn. 95) At the top of the staircase a landing led directly into the main body of the court.

Originally, only a screen of two giant Composite columns divided the hall and court, which otherwise intercommunicated freely. (fn. 96) Openness was an essential requirement of court planning before the nineteenth century, such colonnades or screens having been introduced in the mid-eighteenth century to demarcate specific areas, such as the court-room and hall, while at the same time retaining the ancient sense of an 'open court'. (fn. 97) At Clerkenwell the continuation of the hall frieze into the court-room and around its eastern end emphasized the relationship between the two spaces. But once the court was in use the magistrates complained of an echo, and as a temporary measure Rogers enclosed the room with deal boards, separating it from the hall. Though this generally improved the acoustics, it made the court unbearably stuffy, and Rogers eventually devised the cast-iron and glass screen with sliding sashes, shown in Rowlandson's view of c. 1808, a permanent (albeit transparent) barrier between hall and court (Frontispiece); this was completed in March 1783. (fn. 98)

Rogers had allowed for only a few small openings behind the gallery at the top of the court-room, presumably intending that air and borrowed light should come mainly via the hall. This was no doubt in response to the magistrates' complaints about the old court at Hicks' Hall, where the noise from windows opening on to the street made hearing difficult, and often brought business to a halt. (fn. 99) So gloomy was the new court that a committee of justices met before the building opened in 1782 to consider the question of lighting, with the result that an extra window was added in the gallery, and a small skylight above. (fn. 100) Originally, Rogers intended the court-room to be arranged around a large oval table, recalling his earlier scheme for rebuilding Hicks' Hall (page 207), but this may not have been carried out, and was certainly not the arrangement in 1799, when plans of the Sessions House were made for George Richardson's New Vitruvius Britannicus. One aspect of Rogers's plan that did endure was the long semi-circular magistrates' bench running around and above the floor of the court, with a spectators' gallery over, the differing floor levels giving at least one visitor the impression of entering a well (Ill 106, 110). (fn. 101) Wide corridors ran behind both hall and court, communicating with ancillary rooms and staircases for the various individuals involved in court proceedings.

At the front of the building, on the first floor, was the 'Great Room', 64ft long, intended for county meetings and later also used as the magistrates' dining-room (Ills 107, 111). It was approached via a spacious magistrates' staircase in a compartment on the south side of the hall. Beneath the Great Room, to either side of the entrance vestibule, were a public room (to the north, later a grand jury room) and the original justices' dining-parlour (later a committee room), where a Jacobean chimneypiece from the Great Room in Hicks' Hall was installed (see Ill. 262 on page 208). (fn. 102) In the basement were bail docks or cells (under the hall), a room for county records, a grand jury room, kitchen and domestic offices, and a second waiting hall, for visitors to the Clerk of the Indictments. (fn. 103) Apartments for the two resident staff, the Clerk of the Peace and housekeeper, were provided originally in the western corners of the building.

Despite the modifications made during and soon after construction, there remained many shortcomings. The court was still badly ventilated. Vinegar was sprinkled before and after each sitting in an attempt to freshen the air, and in 1785 a ceiling ventilator was fitted. In 1824–5 a steam-powered system for heating and ventilation was installed, the work of the engineer Thomas Tredgold. (fn. 104) To alleviate the gloom in court, in 1819 a large skylight was inserted in the ceiling, and the gallery windows and smaller skylight were filled in. This work was overseen by the architect Samuel Ware. (fn. 105) At a later date the central entrance between the two columns was filled in, and two new side openings made in Rogers's screen, approached from the hall through low timber-and-glass compartments. The hall itself, draughty and cold in winter, was generally unruly, with prosecutors, witnesses, prisoners' friends and the general public milling about together. (fn. 106) Further inconveniences were the cold and the echo in the Great Room, to remedy which in 1788 the ceiling was lowered and partitions put up at either end, making two ante-rooms. (fn. 107)

Alterations and enlargement, 1859–78

108, 109. Middlesex Sessions House. Entrance hall in 1994, and (above) detail of decorative plasterwork by John Papworth in 2007

110. Middlesex Sessions House. The principal court-room in 1914

By the 1830s, such were the continuing problems, particularly with lighting, ventilation and acoustics in court, it was contended that 'no place could have been more improperly constructed for its purpose'. (fn. 108) Increasing legal business had led to the use of the ground-floor committee room as an ad hoc second court-room. In the mid-1840s the magistrates considered demolishing the Sessions House, letting the site for development, and building a more spacious replacement on the county's land in front of the House of Correction at Coldbath Fields. (fn. 109) Clearance carried out for the building of Farringdon Road offered the possibility of extending the site on the west side, and in 1855 Frederick Hyde Pownall, the county surveyor, drew up plans for such a scheme, involving the reconstruction and enlargement of the western half of the building to accommodate a second court-room. (fn. 110) In the event, the price for the land was too high, and Pownall produced a number of more modest plans based on a rearrangement within the existing walls. (fn. 111) The scheme eventually carried out in 1859–60 provided a second court by converting the justices' dining-room on the first floor. The ceiling there was further lowered and a new diningroom built above, with a lead-covered elliptical roof. To soften the visual impact a stone parapet wall was added either side of the pediment (Ills 105, 106). (fn. 112)

111. Former second court-room, originally the magistrates' Great Room, in 2006

112. Middlesex Sessions House, entrance hall, 1914. East end, showing door to second court-room, and statues by Domenico Brucciani, both of 1859–60

In the new court the ceiling was coffered by thick ribs with double guilloche decoration (Ill. 111), the panels incorporating ventilation grilles, part of a new heating system, 'on Messrs. Haden's principle' (G. & J. Haden of Trowbridge). (fn. 113) A dais at the southern end accommodated the justices, who entered via a small stair in the adjoining ante-chamber. (fn. 114) The dining-room above was lit by large semi-circular windows at either end, echoed in the arches which divided the long walls into bays and neatly accommodated the room's curving shoulders.

In the hall, Pownall replaced the double staircase with the present single flight, leading to a wide stone gallery, supported on iron girders, running around the walls to the second court (Ills 106, 109). This was decorated with railings bearing the county arms, and carried ornate gaslights, since replaced by electric facsimiles. (fn. 115) The slender iron columns beneath the gallery seem to have been added shortly afterwards to give extra support, because of the large number of people crowding in and out of court during sessions. (fn. 116) Pownall inserted a glass lantern in the dome to improve the lighting, replaced the Composite capitals to the pilaster order with Ionic ones, and filled the niches in the walls with symbolic classical figures, the work of the plaster-cast maker Domenico Brucciani (Ill. 112). (fn. 117) Pownall had intended to substitute a 'new Partition Wall of an Architectural Character' for the glazed screen, but in the end made do with retaining the upper part above a solid partition with two new doorways to the courtroom. (fn. 118) The arcaded corridors at the sides of the hall were sacrificed to provide more space for offices, leaving only the corridor along the front. These changes were in a heavy Victorian manner, contrasting with Rogers's generally lighter, Adamesque work—exemplified in Pownall's entrance doorway to the new court-room, with its nailhead and foliage plasterwork (Ill. 112).

At the same time as the internal alterations, Pownall refaced the south, west and north fronts with cement and Portland stone dressings. The recent demolition of houses in Silver Street for the construction of Farringdon Road had given these parts of the building a prominence never anticipated by Rogers, and his restrained brick neoClassical façades were out of step with architectural fashion (Ill. 113). (fn. 119) As executed, the new work, though less enriched than suggested by published elevations, was more ponderous and ornate than the old, Pownall adding giant rusticated pilasters to the central bow and Gibbs surrounds to the first-floor windows (Ill. 114). Now much discoloured, the render was intended to simulate Portland stone. Messrs T. & W. T. Piper of Bishopsgate were the contractors for all the works, which cost nearly £14,000. (fn. 120)

The construction of Clerkenwell Road in the mid-1870s gave the magistrates an opportunity to extend the building southwards, in a two-storey wing, again designed by Pownall. Stylistically this matched his earlier refacing work at the rear, with no attempt to line up the floor levels with those of Rogers's main east front, though this time stone was used instead of cement. As well as additional rooms for committees and the Clerk of the Peace, the extension gave the magistrates direct access to the second court and dining-room by way of a new entrance from the Green and a spacious staircase. A magistrates' luncheon room was also provided on the first floor, overlooking the new roadway, with an octagonal timber roof-lantern; the Hicks' Hall fireplace was moved here from the old diningparlour on the ground floor. The work was carried out in 1877–8 by Higgs & Hill. At the same time the two courts in the main block were re-arranged and redecorated. (fn. 121) Also, the reception and release of prisoners—which formerly took place in the open street—was made more secure and private by enclosing a yard with 12ft-high stone walls in the angle at the south-west corner of the building, where prisoners could pass directly from prison van to cells beneath the new extension.

113. West front as completed by Rogers, photographed in 1854 during construction of Farringdon Road

Since 1889

With the creation of the County of London in 1889, much of the Middlesex justices' business was transferred to the new London County Council (LCC). Sessions for London were divided between the former county buildings for Middlesex (at Clerkenwell Green) and Surrey (at Newington, in Southwark), which had been vested in the LCC; those for Middlesex were relocated to Westminster Guildhall. However, by 1910 the LCC had decided to economize by concentrating all London quarter sessions in a new court-house on the Newington site, and to sell the sessions house at Clerkenwell. (fn. 122) Construction of the new building at Newington took place between 1913 and 1920, and in December of that year the last trial was held at Clerkenwell. The Jacobean chimneypiece was moved once more, to Newington, along with memorial stones recording the enlargement of the Sessions House in 1860 and 1878. (fn. 123) The building was eventually sold in 1923 for £26,500—well below its 1912 valuation (£63,625) or the LCC's initial asking price (£35,000)—in view of the expense required to convert it to commercial use. It then seems to have remained empty for nearly a decade. (fn. 124) Some alterations were carried out before it was fully occupied.

114. West front in 1945, showing additions of 1859–60 and single-storey shops on the site of prisoners' entrance

In 1929 the prison van yard was replaced by single-storey shop premises (now demolished, see Ill. 114), and in 1930 the floor of the old court-room was raised several feet and a new first floor inserted. (fn. 125)

In 1931 the building was taken over by Avery, the weighing-machine and scale manufacturers, as headquarters for their 500 or so clerical staff, and was known thereafter as Avery House until the firm's departure in 1973. It then stood empty and deteriorating until 1978, when it was acquired for restoration and conversion to a Masonic conference and social centre, opened in 1979. Now known as the Old Sessions House, it contains lodge and training-rooms, with a restaurant, bar and other social facilities. (fn. 126)

South Side

The numbering sequence begins at the eastern end, where the building line in Aylesbury Street continues with two late twentieth-century developments for office and lightindustrial use: No. 1, a six-storey block of 1986, faced in red brick, designed by Daniel Watney Douglas Young; and Nos 2–4 and 5–7, of plum-coloured brick, by Design 5 Architects, built in two phases, in 1970 and 1974 respectively, with a later attic storey. (fn. 127)

Nos 8 and 9, built in 1997 on the site of a former printing works, were designed by the husband-and-wife practice Paxton Locher Architects. No. 8 is a six-storey office and apartment building, steel-framed and glass fronted. Concealed behind at No. 9 is a small house, originally the architects' own home. Approached via a long passageway through No. 8, and then by a timber bridge spanning an indoor pool, it is planned around an atrium, which forms the principal living area, with galleries above serving as the main bedroom and children's playroom, inter-connected by a glazed bridge. More rooms and a roof-terrace are situated above. The building has no windows, light coming entirely through a retractable roof of stainless steel and high-performance glass. (fn. 128)

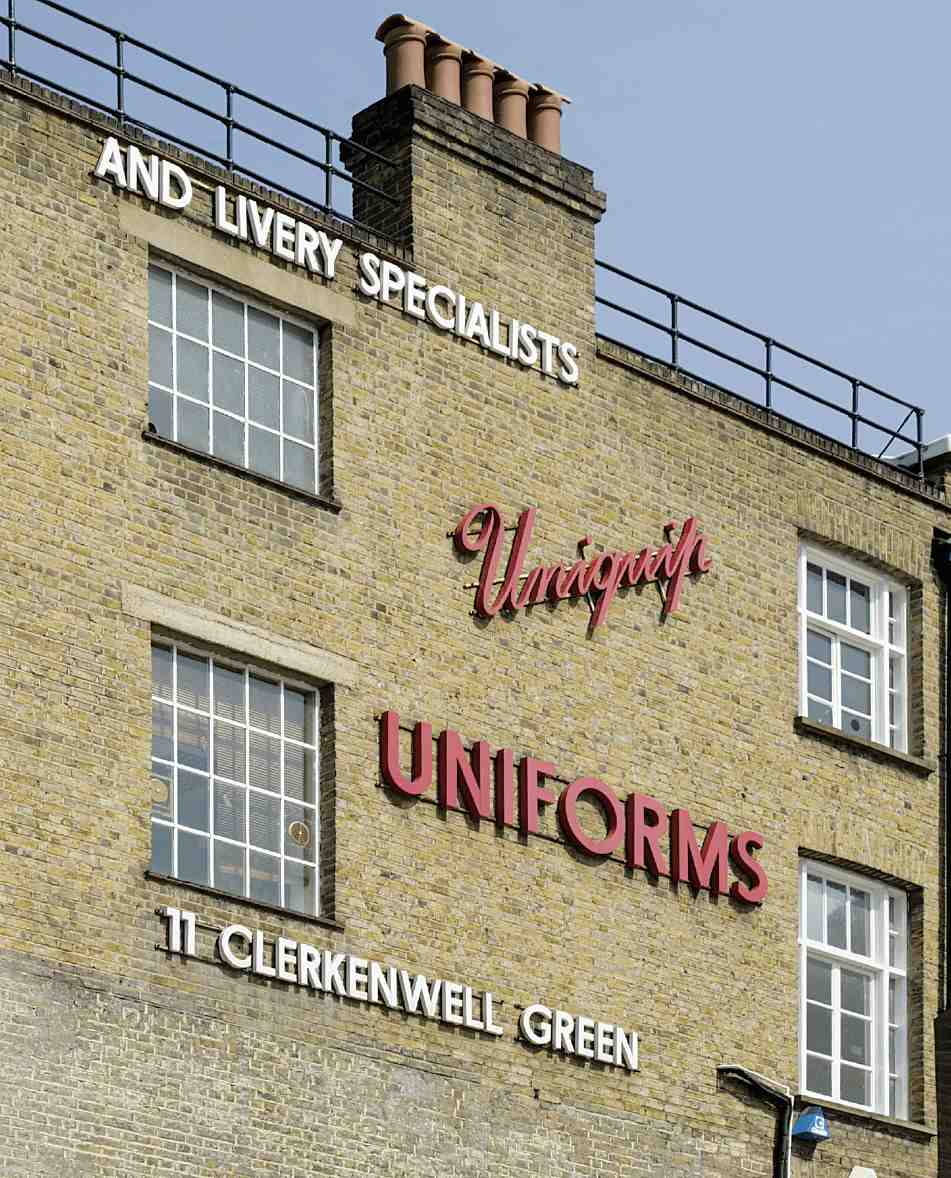

Nos 10–14A. The site was acquired for speculative development by the Holloway builder Thomas Edward Irish Channing, and Nos 11–14A erected in 1878: a row of four warehouses fronting the Green with a fifth (No. 11, since rebuilt) hidden at the back, entered through a narrow passage on the east side of No. 12. (fn. 129) They were briefly known as 'Channing's Buildings'. (fn. 130)

In plan, Nos 12–14A were typical 'terrace-warehouses' of the period, but their external architectural treatment was relatively flamboyant: eclectic in style, with large shaped gables and dormers, the plentiful detailing picked out in red brick, terracotta and stone to relieve the predominantly stock-brick facing (Ill. 115).

The development did not take immediately. The earliest tenants, in 1881–2, were an electro-plate manufacturer and the Venetian Glass Bevelling Co. (at No. 11), and a billiard-table maker (at No. 13); the other buildings remained largely empty until 1888. (fn. 131) From c. 1908 to 1928 the upper floors of No. 14A were occupied by the Peel Institute, the sports and social club associated with the Friends' meeting-house in Peel Court, St John's Lane. (fn. 132) In the mid-1930s a lecture room and smaller meetingroom at No. 14A were used as an annexe to Marx House at No. 37A. (fn. 133)

115. Nos 12–14A Clerkenwell Green in 2007

116. Former Uniquip factory at No. 11 Clerkenwell Green, seen from Clerkenwell Road in 2006

117. Nos 15–17 Clerkenwell Green c. 1940. Demolished

In June 1913 fire destroyed No. 11, then in use as workshops and stores for the Uniform Clothing & Equipment Co. of No. 5, and the present building was completed for them the following year, to designs by Charles V. Stevens & Co. of Westminster. (fn. 134) The demolition of bombdamaged warehouses on Clerkenwell Road has exposed the rear wall, convenient for advertising (Ill. 116).

The site of No. 10, vacant at the time of the 1913 fire, remained so until the erection of the present office-block for Uniform Clothing & Equipment in 1927–8. Designed by Bethel Swannell & Durnford, it originally had a projecting ground-floor shopfront, now replaced. (fn. 135) Uniquip, as the company became, remained at Nos 10–11 until the 1990s, since when the buildings have been converted to offices. (fn. 136)

Nos 15–17. The present Nos 15–17, of 1986 (Ill. 93), replace in pastiche three early eighteenth-century houses. Incorporated into the design are a few meagre fragments of older fabric: a pair of wooden Doric columns from a door-surround, added at No. 15 in the early nineteenth century; and three Ionic capitals from a decorative wooden shopfront of similar date at No. 16. (fn. 137)

The original houses, three storeys high, with attics, were built around 1706 by William Palmer as part of the settlement for his daughter's marriage to Joseph Marshall, a City stationer. (fn. 138) The brick parapet visible in old photographs was probably a later addition, perhaps replacing a projecting wooden eaves cornice; the backs had gables and segmental-headed windows (Ills 117, 118).

Eighteenth-century occupants included some clockand watchmakers, for example William and Thomazon Fitter at No. 17 from the mid-1740s to the mid-1760s, and Joseph Bosley (or Boseley) at No. 16 from c. 1730 till c. 1748. (fn. 139) Rear workshops were later added to all three houses, and by the late nineteenth century they were generally in multi-occupation by craftsmen and manufacturers. (fn. 140)

118. Nos 15–17 Clerkenwell Green. Rear view in 1880, following clearance for Clerkenwell Road.

Although all three houses were acquired compulsorily by the Metropolitan Board of Works for the Clerkenwell Road improvement, in the end they were not needed: J. P. Emslie's view of 1880 shows them shored up beside the adjoining cleared sites to the west (Ill. 118). By the early 1950s, they had been partly demolished, possibly as a result of war damage, leaving only the ground floors standing. (fn. 141) New first floors were added in 1958. (fn. 142)

It was originally intended to retain the listed groundfloor fronts at Nos 15 and 16 as part of the 1980s redevelopment, designed by G. B. Dunseath of Norwich for the developers Hilstone, but they had deteriorated too far. (fn. 143)

No. 18 (formerly 18–19) and No. 20. The sites here were cleared for the making of Clerkenwell Road. For an account of these buildings, see page 406.

North side

No. 29. This former public house was erected in 1866–7. Named the Fox and French Horn, it replaced an earlier inn on the site, known in 1781 as the French Horn, and as the Fox and French Horn by 1796. (fn. 144) The rebuilding was carried out by the licensee Joseph Lambert, who had taken on the lease of the inn and five small cottages behind in Fox Place (now demolished, see Ill. 99). (fn. 145)

The new building, savouring mildly of Venetian Gothic, was one of the first works undertaken by the architectural practice of Walter Augustus Hills and Thomas Wayland Fletcher, a tempestuous partnership which nevertheless endured for twenty years. Hills and Fletcher had both been employed by Poplar District Board of Works as surveyors, and their most important achievement was the board's new offices of 1869–70, on Poplar High Street. Pubs were the mainstay of their business, however, and both men were more or less alcoholics. (fn. 146)

At the time of the rebuilding, Fletcher was still employed by the Poplar Board of Works, and possibly for this reason his name does not appear in the official records. (fn. 147) But he later claimed the design as his own, accusing his 'reptile of a partner', Hills, of taking 'no responsibility' for the work of the practice, other than the levelling. (Apparently the levelling instrument belonged to Hills and he would not lend it to Fletcher.) (fn. 148)

Although still working out his notice at the Board of Works, Fletcher was at pains to keep an eye on the building's progress, rising three mornings a week at 4:45am in order to travel to Clerkenwell Green, and afterwards breakfasting at a local café before making his way to the board's offices in Poplar. (fn. 149)

Since its closure as a pub in the early 1920s, the building has lost various decorative features, among them the Corinthian pilasters originally framing the ground-floor windows (Ills 95, 119).

119. Nos 29–31 Clerkenwell Green in 2006

Nos 30–31 were erected in 1911–12 by Gordon & Sons of Kilburn as a new shop, workshop and dwelling for Henry Bogie Allan, saw manufacturer. (fn. 150) Allan had been in business at No. 33 since 1887. (fn. 151) At the time of the redevelopment, he owned not only the freeholds of Nos 30–31, but also the freehold to No. 32 and a leasehold interest in No. 33 and No. 6 Steward's Place, adjoining. (fn. 152)

120. No. 32 Clerkenwell Green in 1958

The new building at Nos 30–31, with its asymmetrical, architecturally progressive façade and good-quality stone detailing (Ills 119, 120), was designed by Richard Reginald Barnett of Wimbledon, at that time a temporary architectural assistant at the Ministry of Works; he had previously worked under W. E. Riley in the LCC Architect's Department. (fn. 153)

The site—formerly occupied by eighteenth-century houses, shops and workshops—was a long one, stretching back beyond Warden's Place (Ills 90, 99). Above the shop was a showroom and manager's office, with the family's living accommodation on the two upper floors. Behind this front building was the long, single-storey, top-lit main workshop, where the grindstone and forge were situated, and at the back of the site was another workshop, of two storeys. The family also had the use of a second parlour and living-room on the third floor of No. 32. (fn. 154)

Allan died in 1933, but the firm of H. Allan & Sons remained in business here until the late 1970s. (fn. 155) The original shopfront was removed and replaced shortly afterwards as part of an office conversion. (fn. 156)

No. 32, despite having a modern shopfront and attic storey, is still recognizably a house of mid-eighteenth-century origin (Ills 95, 120). It was built about 1756 by Benjamin Ashby, baker, apparently as a speculation, as from c. 1739 until 1771 Ashby's own dwelling and bakery were a few doors along at No. 35 (now demolished). (fn. 157) No. 32 also seems to have been a shop, its early tenants including Thomas Evans, a grocer. (fn. 158) Remodelled as offices and extended at the rear in the early 1980s, it has today an entirely modern interior. (fn. 159)

Nos 33–36 (with Nos 1–5 and 8–13 Clerkenwell Close). This stretch of frontage was formerly occupied by eighteenth-century buildings: two small houses at Nos 33 and 34, erected in the 1730s as part of a court opening off the Green called (after its builder) Steward's Place; and a pair of more substantial houses at Nos 35 and 36 (Ills 95, 97). In 1939 No. 35 was taken down, and at about the same time Steward's Place was demolished to make way for a factory at Nos 33–34, which was never completed. (fn. 160) In the 1950s and early 60s the mostly ruinous buildings here and in the Close were cleared by the London County Council as part of its scheme to throw Clerkenwell Green and St James's churchyard together into a single open space (see above). Though this scheme was abandoned in the late 1960s, the land remained undeveloped until the 1980s, when the Greater London Council finally agreed to its use by Islington Borough Council for new buildings. (fn. 161)

The present workshops, shops, flats and maisonettes on the Green and in the Close were erected in 1984–5 by Islington Council, to designs by the Borough Architect's Department under Christopher Purslow. (fn. 162) The variety of materials and shaped bays were intended specifically to blend with the surviving small-scale eighteenth- and nineteenth-century buildings near by (Ill. 92). In addition to the brick- and cement-faced apartments fronting the two streets, there are gardens, pedestrianized courtyards and walkways in the space between (Ill. 90).

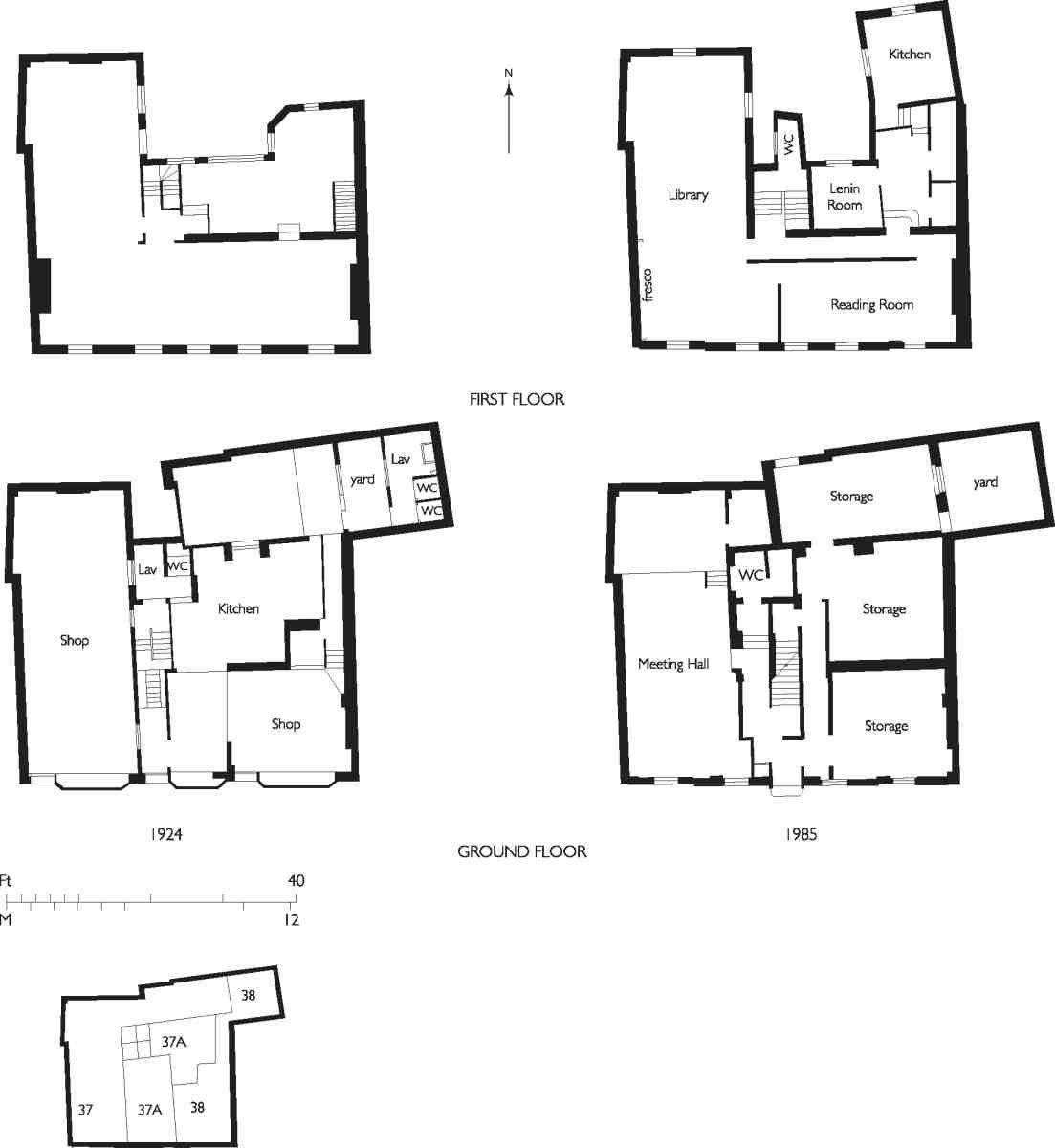

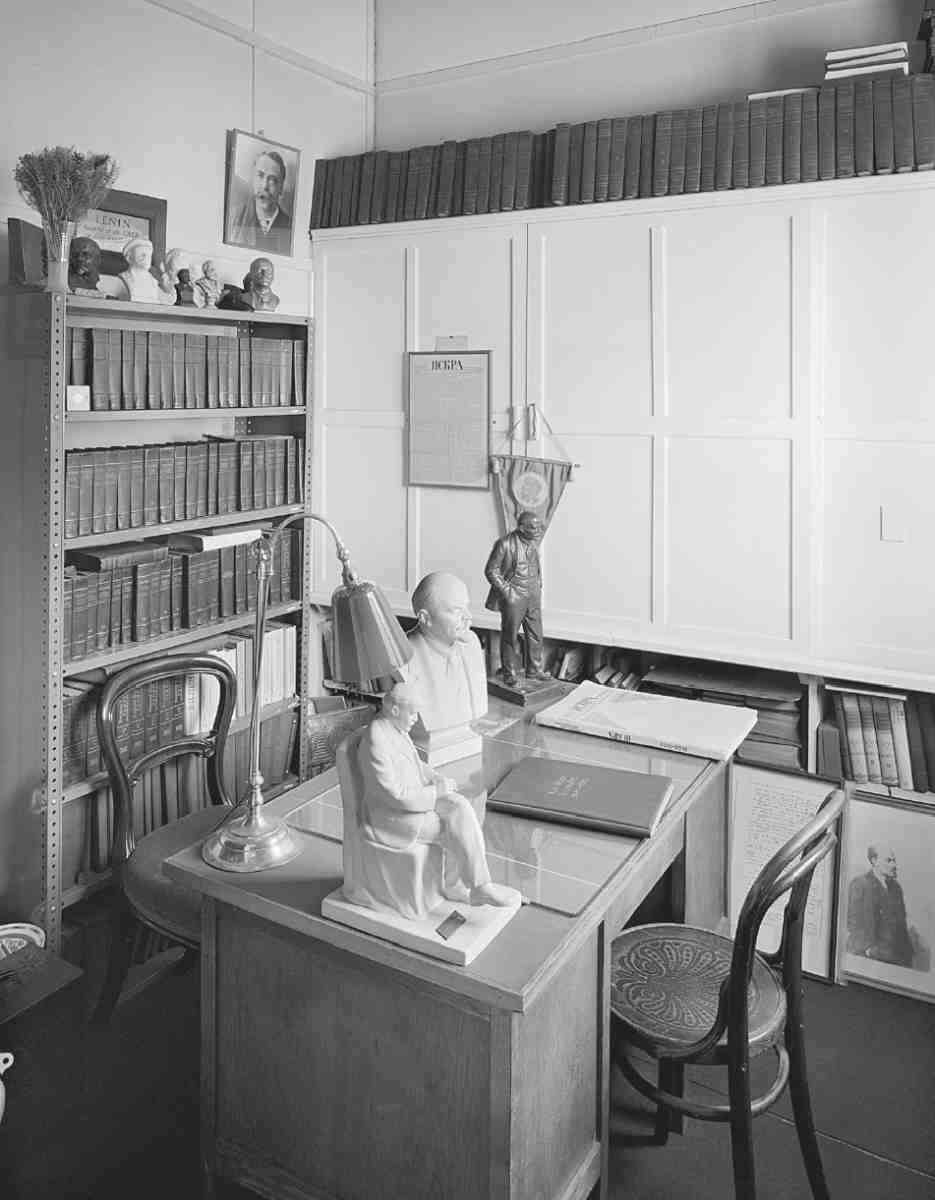

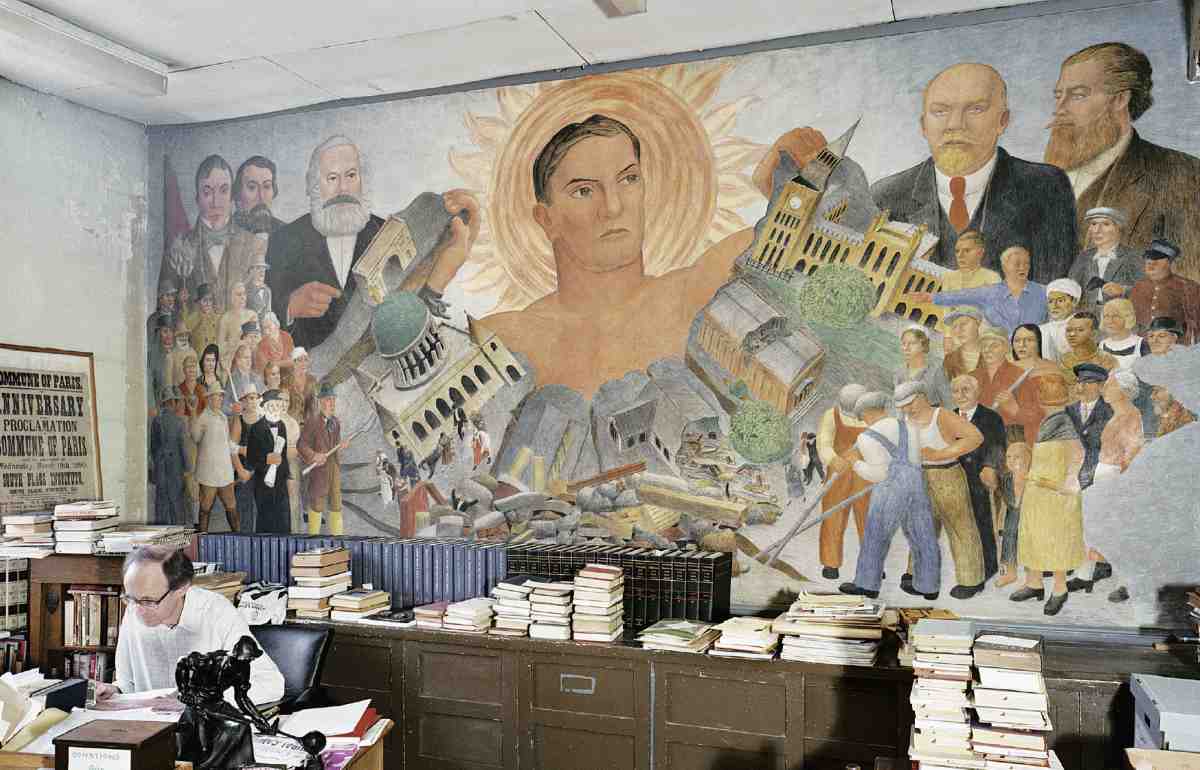

No. 37A, Marx Memorial Library

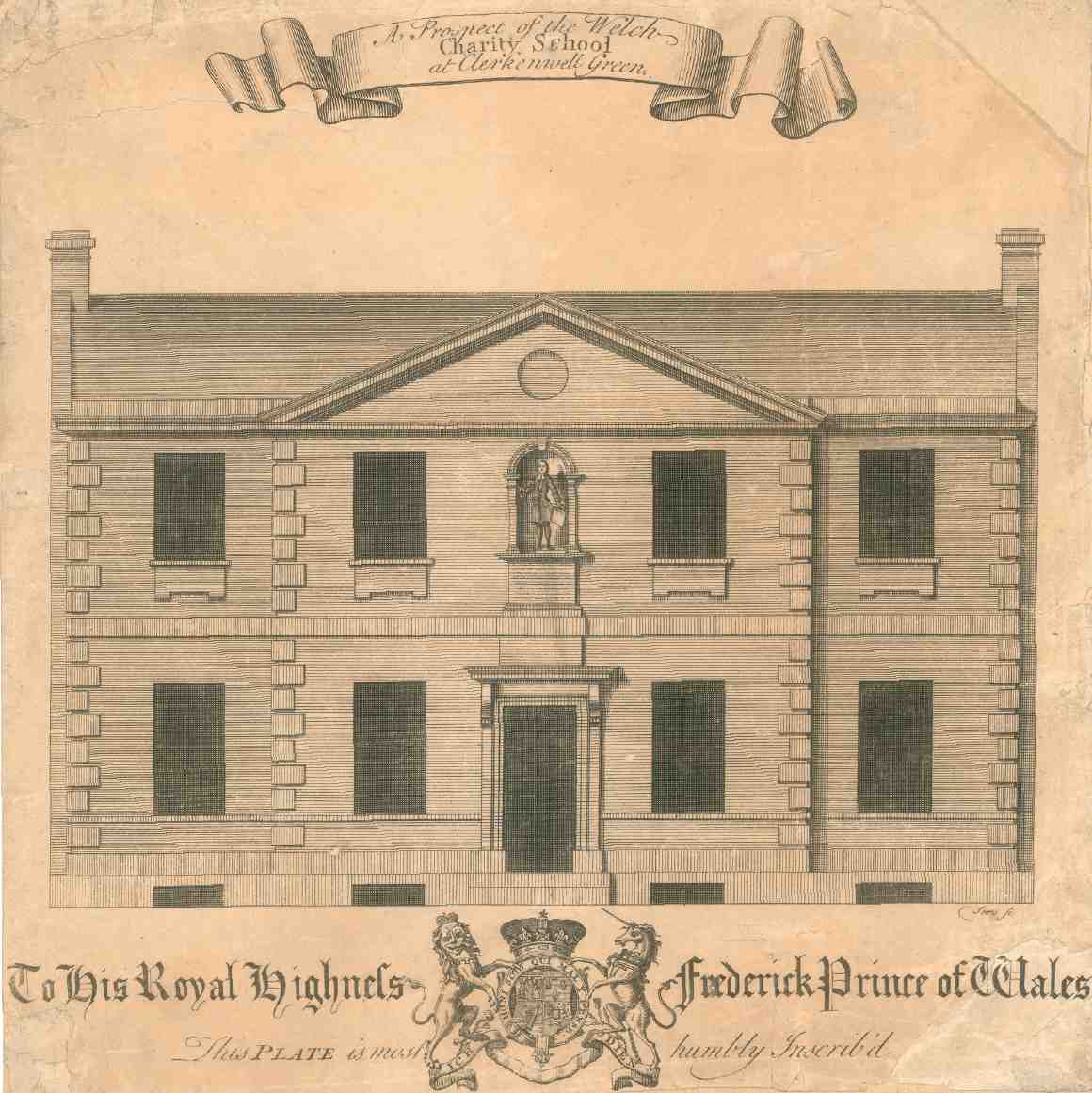

Ostensibly the oldest building on the Green, No. 37A was erected in 1738 as the schoolhouse of the British Charity School, or Welsh School as it was more generally known. In fact, hardly anything of the 1738 structure survives. The stuccoed 'Georgian' façade is a modern quasifacsimile—of the original only the outer quoins can have survived—while the body of the building has undergone successive alterations (Ill. 124). Older than the schoolhouse itself, though of uncertain origin, are the brickvaulted cellars which extend beyond the curtilage of the site (see page 89). If wanting in original fabric, No. 37A is rich in historical associations and has long been connected with radical and left-wing causes. Lenin himself was a regular visitor in the early years of the twentieth century when his Russian-language underground newspaper Iskra was printed here. Today the link with Lenin is recalled in the small room named after him, part of the Marx Memorial Library established here in 1933. He also figures, with other socialist luminaries, in a fresco of Marxist allegory in the library, painted in 1935. (fn. 163)

The Welsh School

Although the building was new in 1738, the Welsh School itself was already twenty years old. It owed its existence to the Most Honourable and Loyal Society of Antient Britons, an association of London Welsh founded at the time of the Jacobite rebellion in 1715. The Society had two principal aims: to safeguard its more prosperous members from imputations of disloyalty—the Principality's allegiance to the Hanoverian succession being by no means solid—and to assist poor children of Welsh parentage born in or near London, initially through apprenticeships. Financed by subscription, and managed by trustees, the school, as first instituted, was nonresidential and only for boys, who in addition to receiving tuition were clothed; later, girls were admitted and boarding introduced. In 1882 it was reconstituted as a girls' high school, now the St David's School for Girls at Ashford, Middlesex. (fn. 164)

The school was first held in a house in 'Sheer Lane'— probably one of two narrow streets near Temple Bar obliterated by the building of the Royal Courts of Justice—but moved in 1719 to the disused Ailesbury Chapel in St John's Square. A year or two earlier the gallery there had been advertised as suitable for use as a schoolroom. (fn. 165) The choice of Clerkenwell does not appear to have any special significance: at this date the Welsh population of London was no more clustered there than in other districts. Turned out for the rebuilding of the chapel, the school moved to nearby Jerusalem Passage by 1724, and may still have been there in 1732 when the master drew attention to the 'ruinous condition of the house where the school is at present kept'. (fn. 166)

In 1736 the trustees decided to build their own schoolhouse (fn. 167) and in March 1738 agreed to take a 61-year lease of a site on Clerkenwell Green belonging to the Bedfordshire baronet Sir Rowland Alston. (fn. 168) Larger than required, this had a long frontage to the Green and extended round the corner into Clerkenwell Close as far as the old (nunnery) gateway, taking in the Three Queens public house there. It also included a detached piece of garden adjoining the parish church. Those parts not needed for the school were later sub-let, raising almost enough income to cover the £25 ground rent. (fn. 169)

In April the trustees invited James Steer, Town Surveyor to the Hand-in-Hand Fire Office, to draw up plans 'according to his own Judgment'. The builder, selected by tender in June, was a Mr Holden, who agreed to erect the school 'according to Mr Steer's Draught' for £332, and to finish it within five months, under a penalty of £50. (fn. 170) Very probably he was the carpenter and surveyor, Strickland Holden, who later both designed and built the Clerkenwell Charity School in Aylesbury Street (page 122).

A carpenter and joiner by training, Steer designed very few buildings, and of just two known to have been built, only the former Welsh School survives. (fn. 171) He published his design for the front elevation with a dedication to the Prince of Wales, who reputedly contributed to the building costs (Ill. 121). It shows a building which differs from its modern counterpart in several telling ways. The front is not stuccoed but brick-faced, with quoins, band-courses and window aprons all of brick, and over the doorway is a niche with a statue of a uniformed schoolboy. This niche may not have been filled until 1770, when the trustees accepted an offer of 'a Boy to be put up in the front of the School House'. (fn. 172)

The plans were not published and have not survived, but it is known that the schoolroom and the trustees' committee room were both on the ground floor, presumably on either side of a front passage or hallway. The schoolroom would have been on the deeper, west side of the building: in 1750 it was furnished with four fixed desks, fourteen benches, frames for hats, a shelf, and the master's writing-desk. (fn. 173) The master himself lived on the first floor—where there were latterly four rooms, after a partition had been erected over the committee room in 1756 and a new room built out over part of the schoolroom in 1759. (fn. 174) The kitchen was in the basement and at the back was a paved yard. The old brick vaults, passing partly under the building and partly under the yard, were let as stores. (fn. 175)

Support for the school came from the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, founded in 1751 primarily to promote the 'Cultivation of the British [i.e. Welsh] Language' and whose members were encouraged to 'use their best Endeavours for supporting the British Charity School on Clerkenwell Green'. The Welsh traveller and naturalist Thomas Pennant, a 'corresponding' member, dedicated his British Zoology to the school and promised it the royalties, though none accrued. In effect the school building became the society's home, being used for meetings and for housing its library and museum, while the schoolmaster was appointed its ex officio librarian and 'perpetual Clerk'. (fn. 176)

121. Welsh School of 1738, published elevation by James Steer, architect

Girls were admitted from 1758, and in 1768 bunks seem to have been fitted up in the basement to accommodate six girl boarders. (fn. 177) But the building was 'not near large enough' to take on more pupils and begin boarding boys as the trustees wished. In 1770–2 a new mixed-sex boarding school was erected in Gray's Inn Lane (now Road), the trustees holding their last meeting in the old building on 7 September 1772. (fn. 178)

Later history, 1778—c. 1932

Shortly before the departure of the Welsh School from Clerkenwell Green, the lease was sold at auction to Roger Meredith, a local cheesemonger, possibly acting on behalf of the upholsterer and cabinet-maker Peter Francis Mallet, since it was to Mallet that the trustees made out the assignment, in October 1772. (fn. 179) Mallet occupied the building until 1776, when he moved to Newcastle House in Clerkenwell Close, the old home of his now bankrupt former partners (see page 36), selling the lease in 1778 to a local businessman and JP, William Blackborough. (fn. 180)

Within a few years the building had been sub-divided, the western two-thirds, later numbered 37, becoming a public house and wine vaults called the Northumberland Arms. First licensed around 1782, it was named in honour of the first Duke, who as Lord Lieutenant of Middlesex had laid the foundation stone of the nearby Sessions House in 1779. In what was probably an allusion to that occasion, the proprietors installed a painting of the ducal arms 'with allegorical representations of Justice, etc.' in the pediment. They also converted the niche above the door into a window. (fn. 181) The building's earliest associations with radical politics relate to the Northumberland Arms. Dr Joseph Towers, the dissenter and constitutional reformer, is said to have been an habitué, and in November 1831 it was the venue for a meeting of the Clerkenwell Political Union in support of the Reform Bill. (fn. 182)

The eastern third of the building, meanwhile, was separately occupied, later becoming No. 38, and was in commercial use certainly by the early years of the nineteenth century. After the pub closed, around 1838, its premises were subdivided and numbered 37 and 37A. At some point (possibly in the 1860s) shopfronts were inserted, surviving until the façade was restored in the 1960s. Of the three separately numbered premises, 37A was the largest, comprising the first floor and part of the ground floor. No. 37 included a single-storey wing extending behind 37A and 38 and over the back yard (Ill. 122). (fn. 183)

In 1872 No. 37A was taken over by the London Patriotic Society. Based in the pubs and coffee-houses of Holborn and Clerkenwell, this had emerged in 1869 out of the ferment for social and political reform, demanding manhood suffrage and the settlement of unemployed workers on the land ('Home Colonisation'). It also had strong republican leanings. (fn. 184) Nos 37 and 38 continued in commercial use, 37 being occupied for many years by a firm of tea-urn makers, 38 remaining as it had long been, a café, and becoming a fried-fish shop in the 1890s. (fn. 185) (A claim, made on the opening of Marx House in 1933, that meetings of the General Council of the First International were held at this café in 1867–8 is without foundation). (fn. 186)

In 1893, the society having moved, No. 37A was taken by the Twentieth Century Press Ltd, recently established to publish Justice, the weekly newspaper of the Social Democratic Federation, and other 'Socialist and advanced literature'. William Morris guaranteed the first year's rent. Under the management of Harry Quelch, editor of Justice, the Press expanded into Nos 37 and 38, taking over the whole building in 1908–9. (fn. 187) Sympathetic to the cause, Quelch allowed the presses to be used for Lenin's Russian Social Democratic newspaper Iskra (Spark), and seventeen issues were printed here in 1902–3.

Occupation as a printing works took its toll on the fabric, shown by a survey made in 1913 (the year of Quelch's death). By then the upper part of the front had been crudely rebuilt, in 1908 or 1909, and retained only the most basic outline of its original pedimented form. Inside, the ground floor was used for a printing shop and office, its timber floor, saturated with oil from the machinery, being partly supported on scaffold poles in the basement. Rough holes had been knocked through the walls for communication and in places the brickwork was exposed. Power for the presses came from a 'very old' Capel Otto gas engine. The first floor, its roof old and lined with matchboard, was used for a printer's shop and office. (fn. 188)

The Press remained here until 1922. From 1924 until 1939 No. 37 was used as the Clerkenwell Waste Paper Works. (fn. 189) The remainder was refurbished in 1924 for Messrs Magnani & Valli as premises for a short-lived Anglo-Italian Club. (fn. 190) After this closed in the late 1920s, Nos 37A and 38 were occupied by Commercial Letters Ltd, facsimile letter printers, followed in the early 1930s by Modern Display Ltd, poster-writers. (fn. 191)

Marx Memorial Library and Workers' School

Fifty years after Marx's death, in 1933, a Marx Commemoration Committee was set up through the Labour Research Department and the Marxist publishers Martin Lawrence Ltd, with the aim of creating a permanent memorial. At a conference held in March at Conway Hall it was decided that the best form this might take would be a library and workers' school. Although it has since been claimed that the idea of a library was suggested by the Nazi book-burnings, this was not then given as a reason; and it was in any case not until May 1933 that the book-bonfires in Germany began. At the time, it was simply noted that there was 'no library at all in Britain where workers could educate themselves in Marxism'. (fn. 192) The choice of the Clerkenwell Green building was much later attributed to Harry Quelch's son, Tom, who had worked here as an apprentice compositor at the time of Lenin's visits, and in 1933 was research officer with the Amalgamated Union of Building Trade Workers. (fn. 193) At an inaugural conference, held in October at the Peel Institute in St John's Lane, Harry Adams of the AUBTW announced that a lease of the premises had been secured and that all necessary building work had been carried out, by direct labour. The freehold of the building was subsequently bought by Noreen Branson of the Labour Research Department and donated on behalf of herself and her husband, the artist Clive Branson. (fn. 194)

122. No. 37A Clerkenwell Green. Ground- and first-floor plans in 1924 and 1985, and block plan in 1884