Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'St John's Church and St John's Square', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp115-141 [accessed 15 April 2025].

'St John's Church and St John's Square', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 15, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp115-141.

"St John's Church and St John's Square". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 15 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp115-141.

In this section

CHAPTER IV. St John's Church and St John's Square

Writing of St John's Square in the 1880s, George Gissing fixed upon its 'number of recesses, of abortive streets, of shadowed alleys', such that 'from no point … can anything like a general view of its totality be obtained'. (fn. 1) A less saturnine eye might have found a picturesque charm in this irregularity, the product of long evolution.

The square originated in the twelfth century as the inner precinct of the priory of St John, English headquarters of the Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem—the Knights Hospitallers. But it was not until long after the final suppression of the Order in England, by Elizabeth I, that the old precinct was distinguished as a 'square'. The earlier name was St John's Court or just St John's, more colloquially St Jones. The name St John's Square appears in a deed of 1712 (fn. 2) and was no doubt coined earlier, but it was not commonly used until the middle of the eighteenth century. Rocque's map (1747) gives the name to the northern part only, and shows the larger southern portion still as St John's Court.

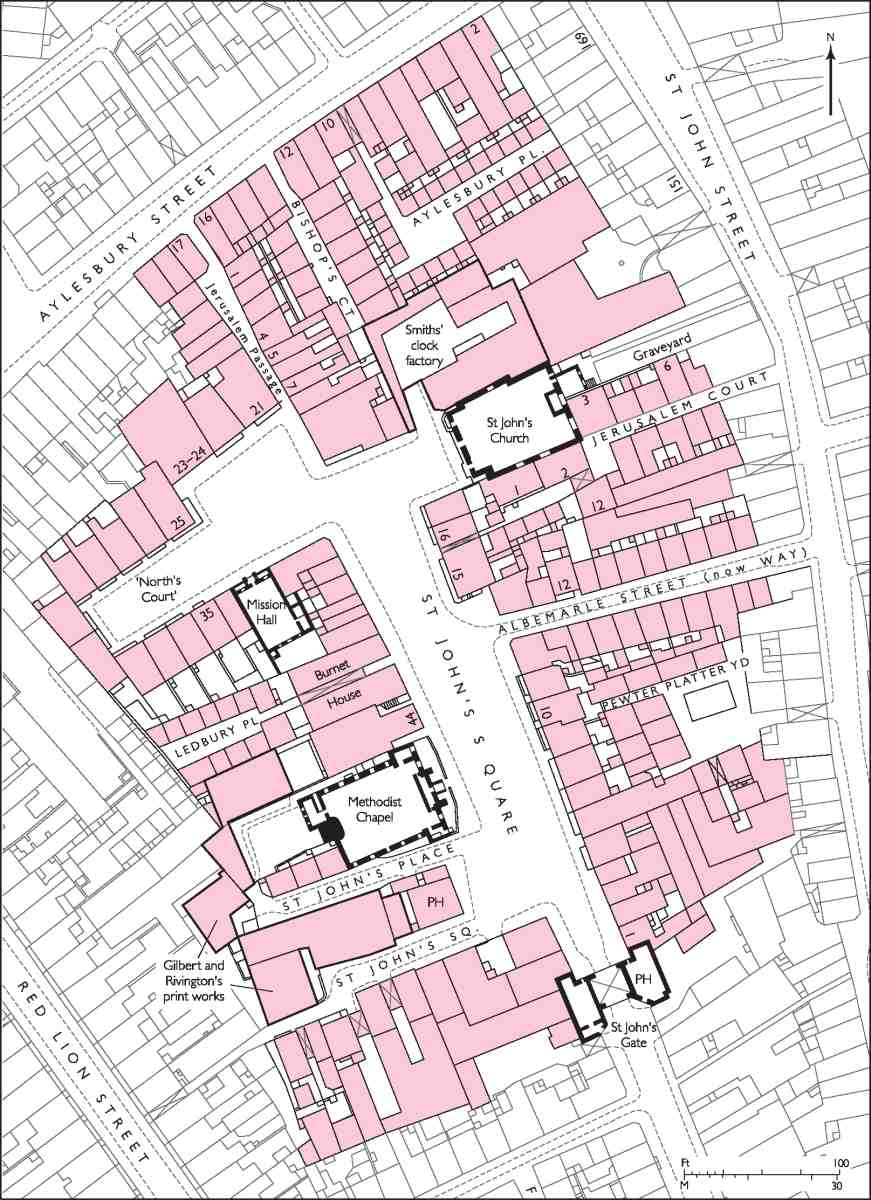

Much longer than wide, the core of the precinct was aligned with its main axis running from north-west to south-east. Jerusalem Passage, narrower than now, and covered, was its northern entry, while St John's Lane made a grander, processional approach from the south. Albemarle Street, until the creation of Clerkenwell Road the only direct link to St John Street, was not laid out until the early eighteenth century. So for many years after the Dissolution the old precinct stayed relatively isolated, a quiet enclave. When Gissing wrote, the square had not long been cut in two by Clerkenwell Road, pushed through by the metropolitan authority with characteristic cost–consciousness and disregard for ancient topography. Since then, redevelopment has been considerable, but the priory gatehouse and (though essentially rebuilt) the priory church convey a vivid sense of the square's monastic origins.

In the present chapter, a brief account of the priory as a whole is followed by a general discussion of how the area has evolved since the initial dissolution of the priory under Henry VIII. St John's Church itself is considered in some detail, but with the main focus on its post-Dissolution story. This is followed by a description of the principal buildings in and around the square; a few buildings in the square south of Clerkenwell Road are dealt with in the next chapter, their story being closely tied up with that of St John's Gate.

Priory of the Order of St John of Jerusalem

An archaeological site of international importance, the Hospitaller priory has been investigated in recent years by the Museum of London Archaeology Service. The account given here is largely a summary of the archaeologists' findings, and the reader is referred to their detailed published report. (fn. 3)

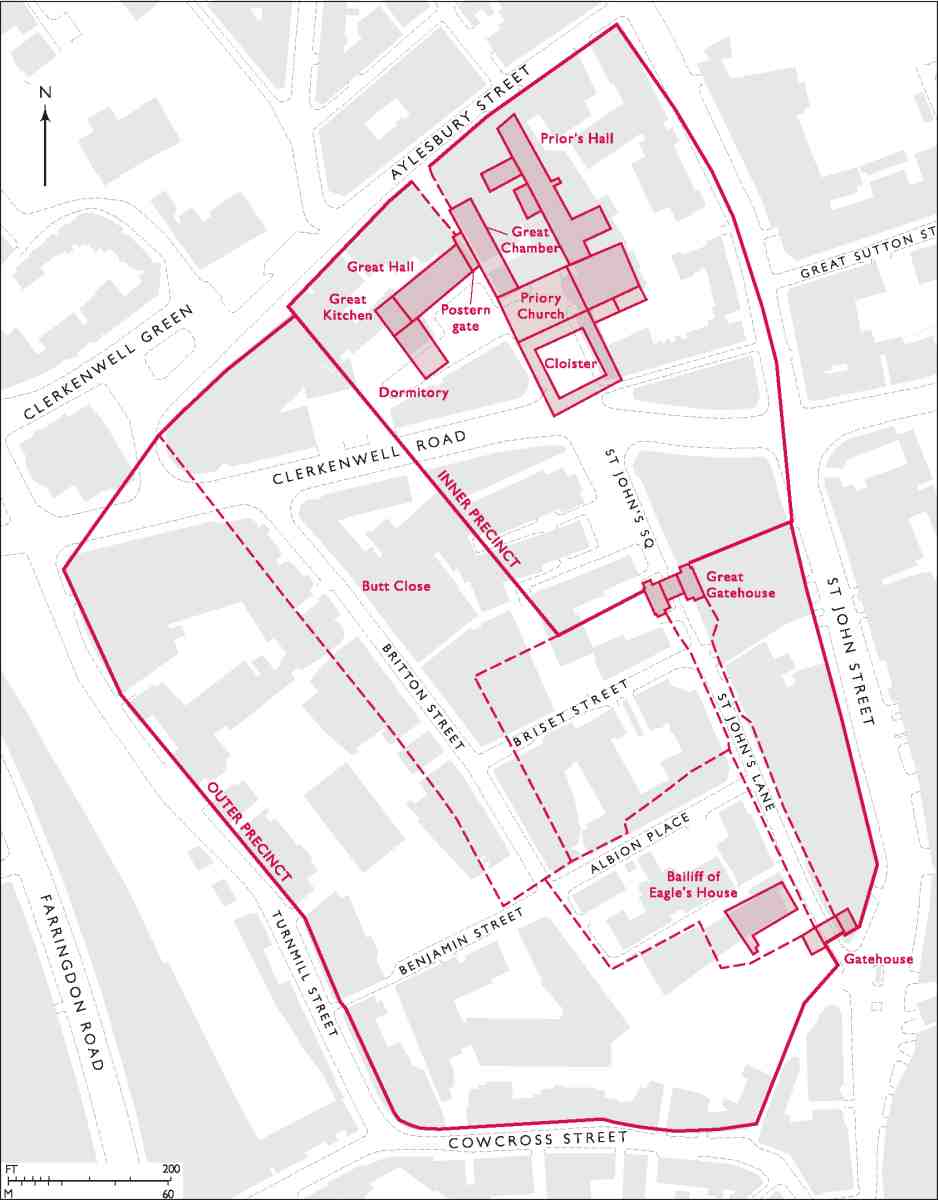

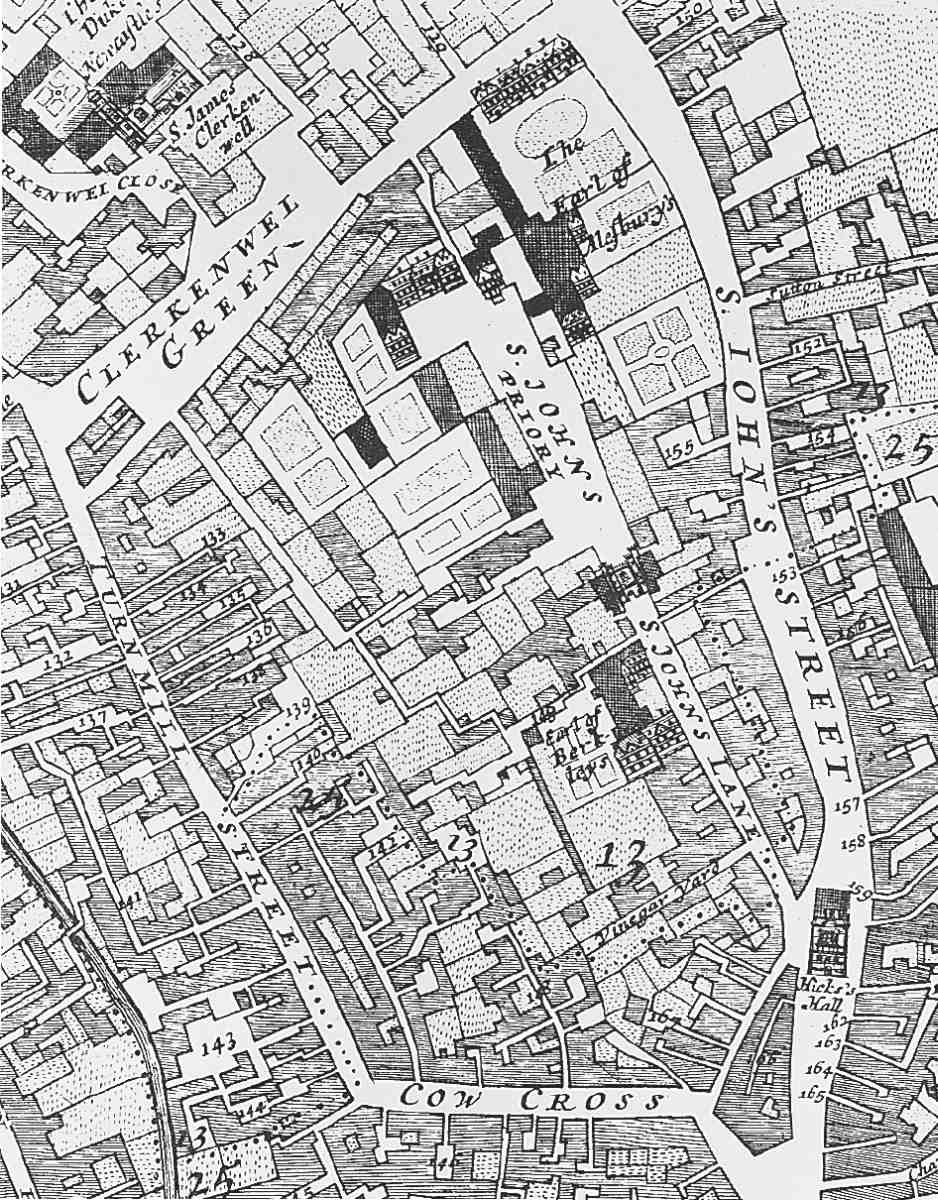

The priory was founded around 1144 on ten acres granted by Jordan de Bricet, lord of Clerkenwell manor. Separated from the Augustinian nunnery of St Mary to the north by a wedge of open ground and the nunnery's private road (now Clerkenwell Green and Aylesbury Street respectively), the site of the priory sloped gently to the west, towards the River Fleet, and to the south, towards the City; the road to Islington (now St John Street) was its eastern boundary (Ill. 129).

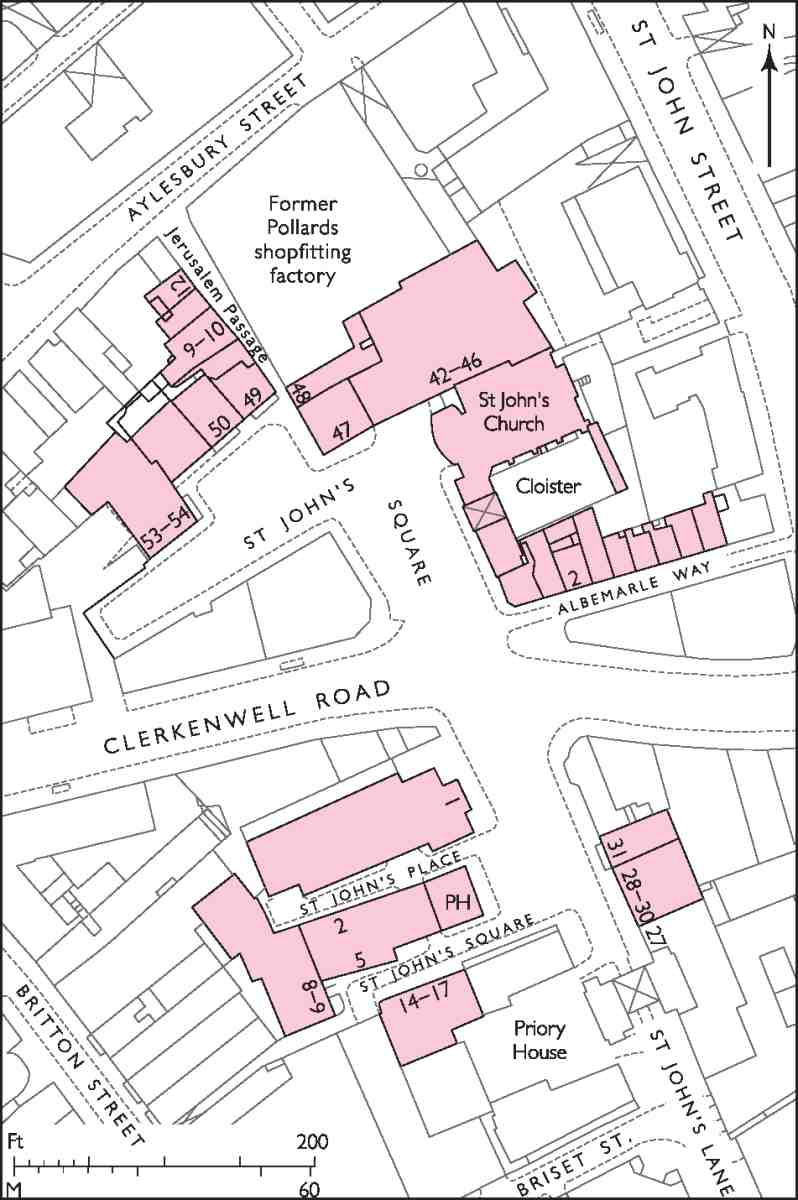

128. St John's Square area

129. St John's priory. The precinct and principal buildings in the early sixteenth century (superimposed on the modern street plan)

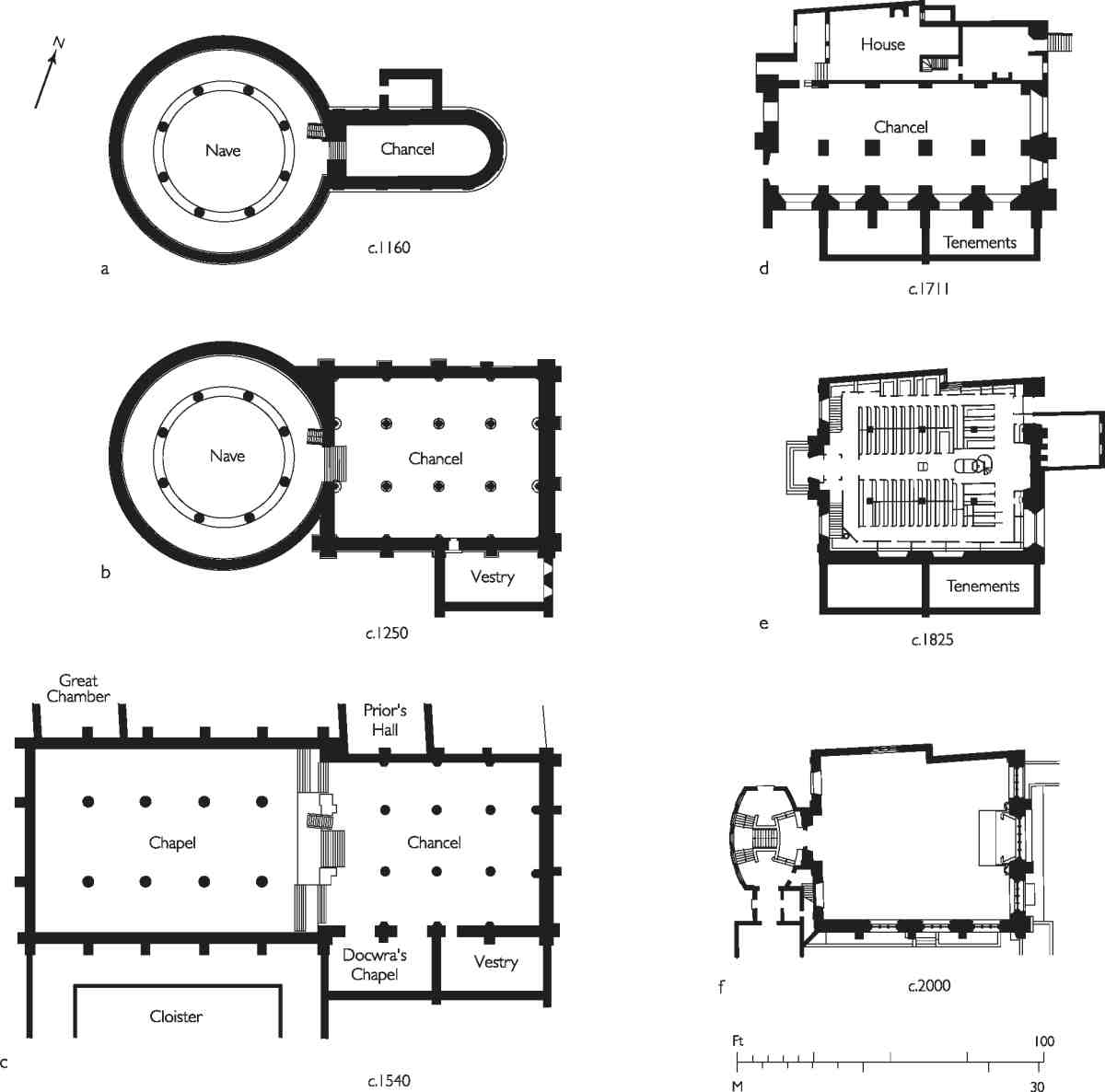

The first permanent structure was the round-naved church of c. 1144–60 (Ill. 147a). Over the next 350 years, as the English branch of the Order became more wealthy, powerful and independent, so the number and size of the buildings grew; and a walled inner precinct, comprising the church, hall and other important buildings (equating to present-day St John's Square), became divided from a more secular outer precinct of houses, gardens and tenements for the Order's chaplains and knights, and their servants and tenants (now St John's Lane, and parts of Turnmill Street, Cowcross Street and St John Street).

130. Former priory from north-west, c. 1577–98, showing (1) Prior's Hall or apartments, (2) Church choir, (3) Great Chamber, (4) Edmund Tilney's mansion, (5) Great Hall

In 1283–4, among various alterations and additions to the church, the nave was rebuilt on a rectangular plan. Further rebuilding at the priory in the late 1300s and early 1400s may have been prompted by damage sustained during the Poll Tax revolt of 1381.

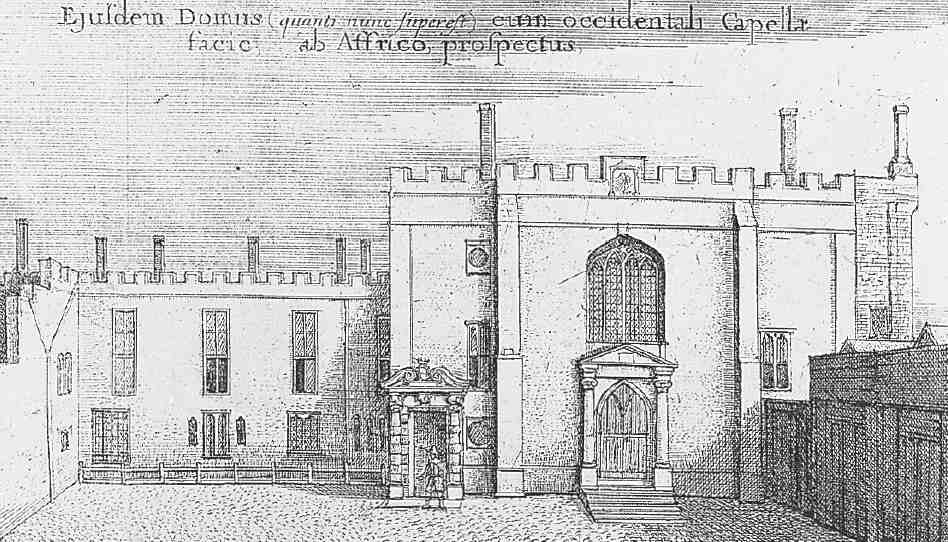

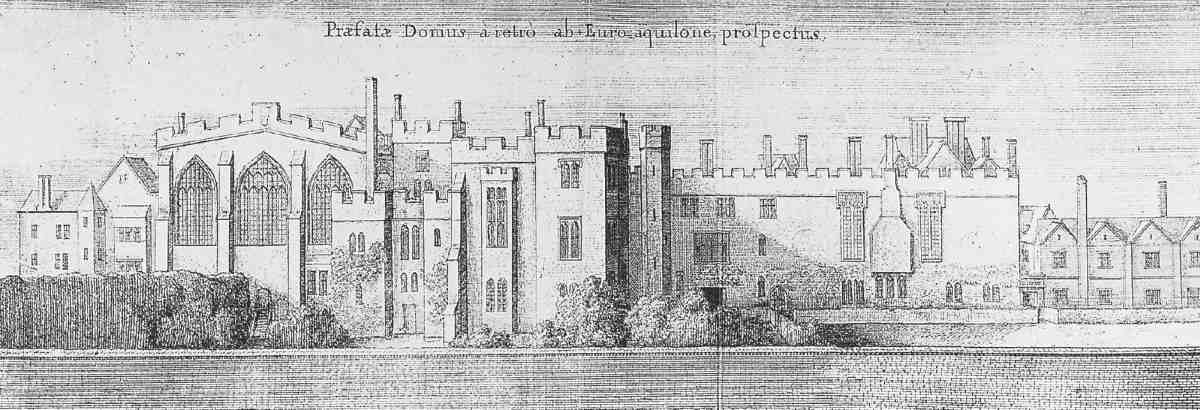

Over a period of sixty years from about 1480 until the Dissolution, the priory's fortunes were at their highest, and substantial building was done under Priors John Kendal (d. 1501) and Thomas Docwra (d. 1527), including the construction of St John's Gate. By the Dissolution, the inner precinct had more the character of a secular palace than a monastic house, though the church was still the dominant presence. To its north and west stood a number of quite grand buildings, mostly stone-faced, like the church, in a late Perpendicular, castellated style (Ills 130–133). Most were state apartments: the Prior and other officers were influential, here and overseas, as diplomats and soldiers, and the priory regularly accommodated royalty, nobility, high-ranking churchmen and senior Hospitallers, with their considerable entourages.

The principal range of apartments was the Prior's Hall or Lodging on the east side of the precinct, north of the church chancel. About 200ft long, it had a two-storey hall at its north end, on the upper floor. Near by was the Great Chamber range, running north from the nave and built alongside and over the 'long entry' to the priory (later Jerusalem Passage). At the south end of the entry was the postern gate. Projecting into the court at the south end of the Great Chamber was the Great Stair, perhaps incorporated in the church bell-tower of c. 1501, thought to have stood at the north-west end of the nave.

131–133. Hollar's views of the former priory, c. 1661: Great Gatehouse, from the north (top left); west front of the church (top right); east front of the church and former Prior's Hall (Ailesbury House)

134. Part of the Great Chamber undercroft at No. 47 St John's Square, in 1995

West of the Great Chamber apartments and postern gate was the Great Hall, on the site now occupied by Nos 49–52 St John's Square, beyond which was the Great Kitchen, and a dormitory and refectory for the Order's yeomen or sergeants-at-arms. In the south-west corner of the inner precinct were stores and workshops, close to the Great Barn and stables in the outer precinct; this corner retained a 'mews' character as late as the nineteenth century. The south-eastern part of the court consisted mostly of gardens.

Excepting the gate and church, the only priory fabric surviving in situ is below ground. Beneath Nos 49–50 St John's Square is a series of chambers, part of the Great Hall undercroft, one with fragments of Reigate-stone window reveals, a doorway and part of the moulding of a four-centred arch. Another has a wall of chalk and greensand chequerwork. (fn. 4) At Nos 47–48 are three tunnelvaulted cellars. The heavy ragstone and chalk blocks which form the lower parts are remnants of the Great Chamber (Ills 134, 166), the upper parts, of soft two-inch red bricks, probably belonging to a post-Dissolution rebuilding.

The Dissolution and its aftermath

St John's was one of the last monastic houses to be dissolved under Henry VIII, in March 1540, and aside from the church, which was reduced to a fraction of its size, the inner precinct survived remarkably intact.

In 1544–5 Henry used St John's for temporary storage of tents, and in 1546 sold the precinct (or part of it) to John Dudley, Viscount Lisle (afterwards Earl of Warwick and Duke of Northumberland). But he evidently maintained a superior interest, keeping part of his wardrobe there and allowing the royal builders to plunder the church and steeple for materials; and on his death in January 1547 he bequeathed the site to his daughter Mary. (fn. 5) Dudley returned his interest in the property to Edward VI in March 1547, and in the following year the young King granted the priory to his sister Mary, in accordance with their father's will. (fn. 6)

Mary made St John's her London residence, but after becoming Queen authorized Cardinal Pole, the papal legate and archbishop of Canterbury, to re-establish the English Order of St John under Prior Sir Thomas Tresham, who received what remained of the priory in 1557–8. (fn. 7) The Hospitallers' return was cut short by her death in 1558, Elizabeth I suppressing the order the following year and confiscating the property.

Post-Dissolution developments, to c. 1680

Elizabeth I's seizure of the priory did not lead to the immediate destruction or fragmentation of the inner precinct. A few buildings were sold or granted to royal officers, but most of the site was given to the Offices of the Tents and Revels for their headquarters, which it remained until c. 1607. (fn. 8) Many of the state apartments became official residences: Sir Henry Seckford, Master of the Tents, lodged in the Prior's Hall, and used the chancel as a store-house; Edmund Tilney, Master of the Revels from 1579, had a house to the north of the Great Hall (Ill. 130). (fn. 9)

The remaining priory buildings were used by the Revels office mostly for making and storing costumes, stage sets and equipment, and rehearsing plays to be performed at Court. The Great Hall undercroft was turned into three 'woorking houses' and a cutting-house. Rehearsals usually took place in the Great Hall or Great Chamber (known as the Revels Chamber), or in the Master's lodgings. Tilney's appointment came at the onset of a new period of 'heightened splendour' in Court entertainments, and preparations for plays at St John's were often elaborate, with musicians and 'cumbrous' props. (fn. 10) The Tents and Revels must have left St John's by May 1607, when the King granted the priory to Martin Freeman, a City fishmonger. (fn. 11)

Freeman sold on the freehold to Sir Thomas Fowler the Elder, of Islington, who by 1608 had sold or let it in several lots. (fn. 12) These were soon broken up by further sales and leases and the buildings modified or replaced. Within a decade or so the old precinct had evolved into a residential quarter of high standing, known as St John's Court.

By far the biggest of the houses at this time was the former Prior's Hall, to which belonged gardens and buildings, including the chancel of the priory church (Ills 130, 133). In 1612 this site was purchased by William Cecil, Lord Burghley, for his London residence; the chancel later became his private chapel. (fn. 13) After 1623, when Cecil succeeded his father as Earl of Exeter, the buildings were known as Exeter House. (fn. 14) He died there in 1640, and the house subsequently descended by marriage to the Bruces, later Earls of Ailesbury, from whom it acquired the name Ailesbury or Aylesbury House. (fn. 15) They were the leading residents of St John's until the 1680s, regularly visited there by, among others, Charles II's natural son the Duke of Monmouth, and the politician Charles Howard, Earl of Carlisle, a former captain of Cromwell's bodyguard. (fn. 16)

It was during the Bruces' residence that Hollar made his views of St John's Court, showing Ailesbury House and the church (Ills 131–133). Like the Cecils, the Bruces used the chancel as a private chapel: by this date it comprised only the central aisle, the remainder, on the ground floor at least, having been converted to domestic use. They retained porters to man the gates at either end of the court, and in 1679–82 Lord Ailesbury erected a new 'great Gateway' to the house, in front of the chapel, topped with two lions (carved by Thomas Cartwright the Elder). (fn. 17)

Of the other priory buildings on the north side of the court, the Great Hall had by the mid-seventeenth century been converted to or rebuilt as two separate houses, on the sites of the present Nos 49–50 and 51–52 St John's Square (Ill. 135). On the Great Chamber site, two new houses were built soon after the departure of the Tents and Revels by William Buggin or Buggins of Lincoln's Inn. By the 1660s these had been made into one house, occupied by Arthur Capell, newly created Earl of Essex. Later residents included Sir Nicholas Crispe, 2nd Bart, and Erasmus Smith, Turkey merchant and educational benefactor. (fn. 18)

135. St John's Court in 1682

136. Bishop Burnet's house, c. 1828

Post-Dissolution redevelopment was concentrated on the west side of the court, where houses were built in the 1610s or 20s by Dame Rebecca Seckford, widow of Sir Henry Seckford. (fn. 19) These were a row of nine or so in the north-west corner, facing Clerkenwell Green (see page 89), and three mansions in grounds within the court itself.

Two of these mansions were acquired from the Seckfords in the 1630s by the Hon. John North, son of the 3rd Baron North, who in the 1670s and 80s lived in one. (fn. 20) The other, which stood to the north, was raised on the stone-vaulted cellar of what had been the priory yeomen's dormitory; this survived the demolition of the house in the 1680s. (fn. 21)

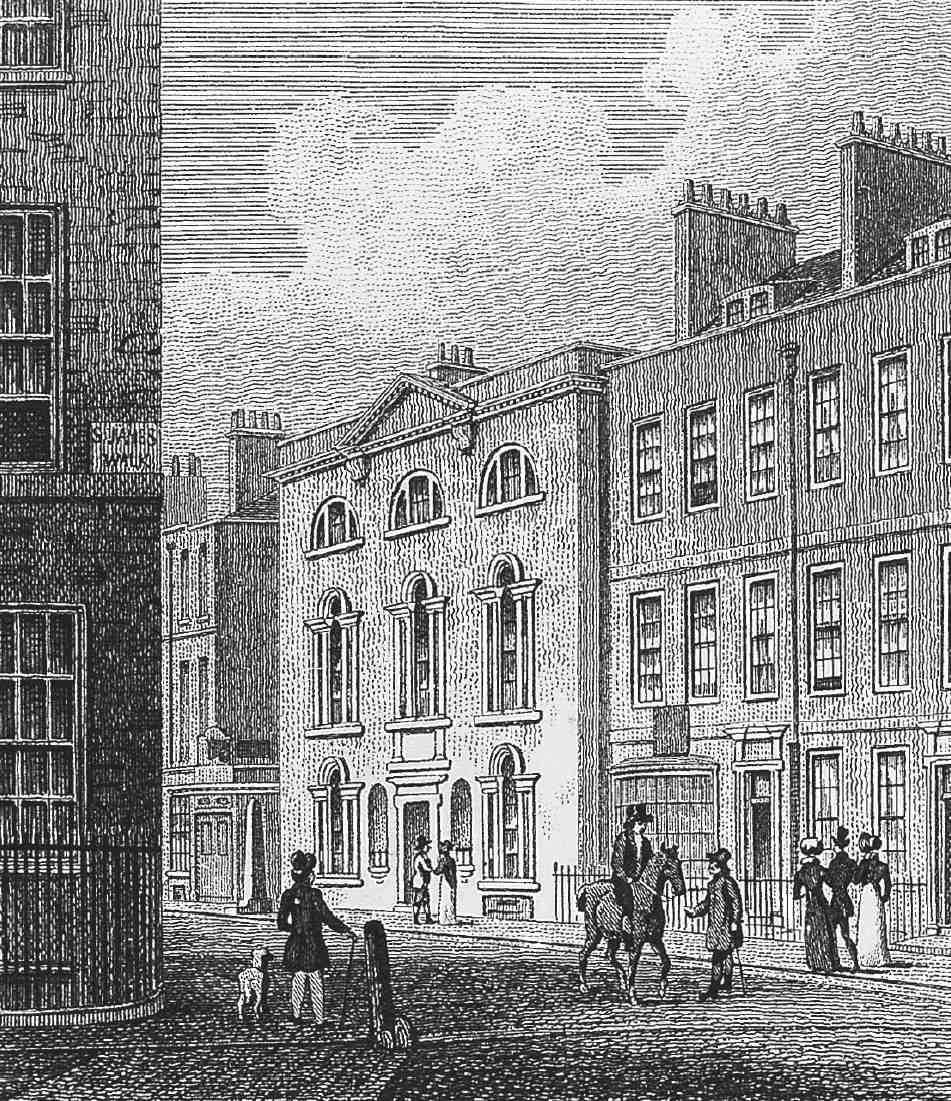

The third mansion, the southernmost, was later called Burnet House, after the historian Gilbert Burnet, Bishop of Salisbury, who inherited it from his wife and lived there in the early 1700s. (fn. 22) In the 1690s it was the residence of Robert Sydney, Viscount Lisle (later Earl of Leicester). By the time the house was recorded in nineteenth-century illustrations (Ill. 136) it had been much reduced in size, parts having been incorporated into a later house adjoining. This house, dating from about 1674, was one of two built on the south side of Burnet House by the then owner, Sir Richard Blake; the other was described as 'new built' in 1683. (fn. 23) By this time, however, St John's Court was losing its appeal for the nobility and gentry, as the West End became increasingly the focus of influence and fashion in London.

Later developments, to c. 1870

Between about 1680 and 1730 most of the mansions of St John's Square were subdivided or pulled down and replaced with terraces of brick houses, producing a much denser pattern of building (Ill. 137).

137. St John's Square area, mid–1870s

Around 1685 John North demolished the northern of his two properties, erecting in its place a court of eleven houses, the Little Square or 'North's Court' (later twelve houses, numbered 25–36 in St John's Square). (fn. 24) By January 1687 the 2nd Earl of Ailesbury had established himself in a new house in Leicester Square, and after his mother's death in 1689 Ailesbury House stood empty. About 1697 a deal to lease the site to a Mr (probably John) Rossington for building 25 'new brick double houses' fell through. But within a few years a sale had been agreed with three businessmen, one of whom, Israel Wilkes, erected a large brick dwelling-house and a distillery covering most of the site. At the same time new terraces were built by his co-purchasers fronting Aylesbury Street and St John Street, on parts of the old gardens. (fn. 25) Jerusalem Court, linking St John's Court with St John Street, was laid out on the southern part of the gardens, south and east of the former Ailesbury Chapel.

138. Jerusalem Passage, east side, in 1906. Foreground: houses of the 1720s at Nos 1–4, shortly before demolition

139 (top right). Nos 15 and 16 St John's Square, of c. 1692, photographed in 1906. Demolished

140. Aylesbury Street, south side in 1906. Houses of c. 1700 on the site of Ailesbury House. Demolished

Fresh impetus to development was provided in the early 1720s by Simon Michell's reconstruction of Ailesbury Chapel as a new parish church. New building continued near the church in the late 1720s and early 30s, and the last remaining part of the Ailesbury House gardens disappeared under a new street of houses, Albemarle Street. Part of the Great Chamber site was also covered by houses, in a court called Bishop's Court and adjoining parts of Aylesbury Street and Jerusalem Passage. The main developers here were two Holborn bricklayers, Moses Westbrook and Edward Cooper. (fn. 26)

Most of the new buildings in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries were variants of characteristic middling sorts of London speculative houses of the period: plain, brick-faced and narrow-fronted, of two or three storeys, usually with two rooms to a floor (Ills 138–140). There were only two large houses: that built by Wilkes as his family home—a squarish, three-storey brick building, with wainscotted rooms and marble chimneypieces, built up against the north wall of the church; and the home and workshop of the furniture-maker Giles Grendey (now No. 47 St John's Square), erected in the 1730s on part of the old Great Chamber site (Ills 141, 166). (fn. 27)

With the nobility gone, their houses were taken by merchants, clergymen and minor gentry, while by and large the new developments were inhabited by tradesmen. In 1717 William Brook or Brooks, a City merchant, acquired Sir Richard Blake's two houses, living in one and letting the other to another merchant, William Tillard, and both men typify the area's new elite. (fn. 28) The broader social shift was exemplified by Israel Wilkes, who in building a large dwelling-house next to the church could be seen as drawing upon the area's old cachet yet at the same time, in setting up his distillery, helping to destroy its remaining attraction. (fn. 29) His house is thought to have been the birthplace in 1725 of the radical politician John Wilkes, second son of Israel Wilkes II; the distillery failed later in the century, mismanaged by the youngest son, Heaton. (fn. 30)

Wilkes's distillery was part of a general pattern of industrialization, which accompanied the redevelopment of the area. As well as distilling and brewing came printing, already well established in St John's Lane. The longest-running printing-house here was set up in the 1750s by James Emonson on the west side of the square, in the former mews area known as Badger Yard. Later run by John Rivington and Deodatus Bye, this was to evolve into Gilbert & Rivington's, which was still here in 1900. (fn. 31)

141. St John's Church and Square from the west, c. 1828. Giles Grendey's house (now No. 47) far left; Israel Wilkes's adjoining the church, behind trees

142. Clerkenwell charity school, Aylesbury Street, c. 1828;

Strickland Holden, architect and builder, 1759–60. The buildings now on this site (Nos 17A, B Aylesbury Street) were built here shortly after the school's demolition in the 1830s Other trades and industries in the eighteenth century included furniture-making (particularly in the 1760s and 70s), and clock- and watchmaking, firmly established by the 1770s. (fn. 32)

St John's Square retained its respectable character into the nineteenth century, with a number of 'gentlemen' residents. (fn. 33) Among several mostly dissenting clergymen residing in and around the square were Edmund Calamy, a Presbyterian minister who lived in North's Court in the 1740s and 50s; Dr Joseph Towers, Presbyterian preacher and biographer, who died at his house in the square in 1799; Dr John Warner, radical Whig parson and scholar (d. 1800); and Dr Adam Clarke (d. 1832), the Wesleyan preacher and writer, whose sons ran a printing-house at No. 44 (one of Sir Richard Blake's houses), where most of his works were printed. (fn. 34)

There were two charitable institutions. The Clerkenwell parochial charity school moved in 1759–60 to a new schoolhouse on Aylesbury Street, designed and built by the carpenter and surveyor Strickland Holden (Ill. 142). (fn. 35) From the mid-1780s until 1806 Finsbury Dispensary, a free dispensary for the poor, was based in one of the old houses in the square. (fn. 36)

During the first half of the nineteenth century the area of the square became yet more densely built up, with rows of smaller houses and tenements replacing some of the old houses and gardens; it also became further industrialized, supporting two large works and a host of craftsmen and artisans in small workshops and converted houses.

On the west side of the square, Burnet House had been split into just two residences by the early 1800s; by the 1850s it had been sub-divided and partitioned into 23 'apartments', occupied by 13 'poor but industrious' families engaged in such activities as shoe-making, box-making and stay-making. A court of small tenements, Ledbury Place, had been built over the back garden, and shops were later erected on the front garden (Ill. 137). (fn. 37) On the northeast side of the square a larger court of small two-roomed tenements, Aylesbury Place, was developed in the 1820s on part of the distillery site. (fn. 38) And in the 1830s the south-western side of the square was redeveloped with new houses, shops and workshops, including a brass foundry. (fn. 39)

By 1850 the remainder of Wilkes's distillery had been razed and a factory constructed there by John Smith & Son, clockmakers, already established locally. Besides Smiths, the chief individual concern was Gilbert & Rivington's printing works, housed in a disjointed group of buildings on the west side of the square, either side of St John's Place.

Redevelopment from c. 1870

In the 1870s the construction of Clerkenwell Road destroyed Burnet House and other old mansions on the west side of the square, and the south side of Albemarle Street, though the route was diverted so as to avoid incurring the heavy cost of acquiring Gilbert & Rivington's works and the adjoining Wesleyan Chapel. The new road opened up the area to larger-scale redevelopment chiefly with factories and warehouses, while the remaining houses became increasingly subdivided and slummy.

143. Jerusalem Court, looking east, c. 1880; remains of Prior Docwra's chapel (with buttress) on left. Demolished

Towards the end of the century industry and commerce took over almost entirely. Such few pockets of mostly overcrowded residential buildings as remained were inhabited not so much by locally employed artisans but by the poor and unskilled who, if they worked, were likely to work elsewhere: typically dock labourers, costermongers, charwomen and fancy flower-makers. Those betteroff had, reputedly, left for the new north London suburbs. (fn. 40)

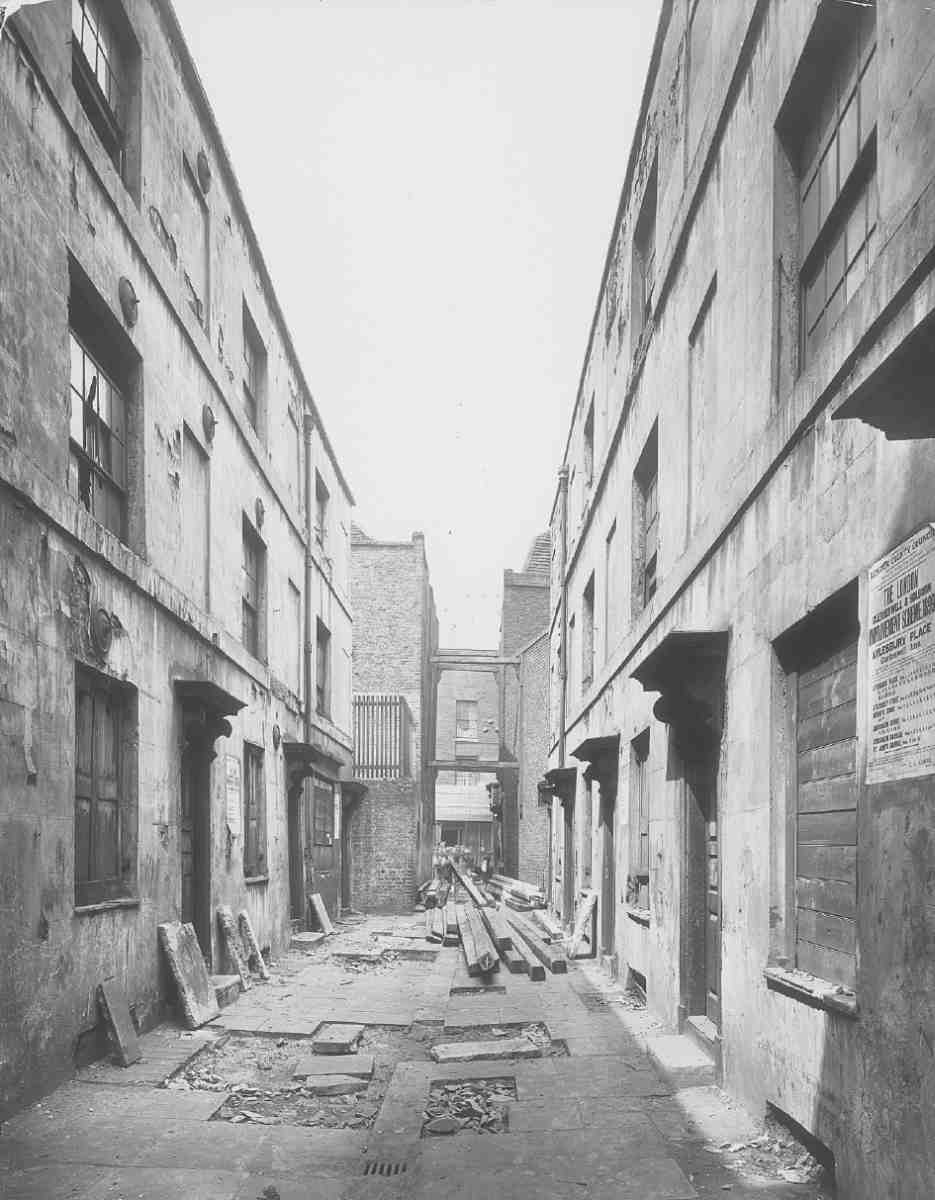

Inevitably, the worst conditions were in confined courts and alleys. Particularly bad was the group north-east of the square, comprising Bishop's Court, Aylesbury Place and Jerusalem Court (Ills 143–145). Population density and infant death-rates here greatly exceeded both the Clerkenwell and London averages. (fn. 41) These were rough and reputedly dangerous addresses: 'you cannot paint it black enough; Savages', was a policeman's comment on Jerusalem Court to Charles Booth's investigator in 1898. (fn. 42)

In Bishop's Court there were eleven eighteenth-century houses, sub-divided into tenements, sometimes as many as five or six to a house. Aylesbury Place can hardly have been other than fairly wretched when it was built in the 1820s. It comprised 29 small houses, ranged around a court with a common tap, each house consisting of two tiny rooms, one above the other, in most cases with a ladder instead of stairs. (fn. 43)

144. Houses of 1726–8 in Bishop's Court, c. 1906. Demolished

145. Two-room houses of the 1820s in Aylesbury Place, in 1899. Demolished

Between 1900 and 1906 the London County Council pulled down all the old houses in the Aylesbury Place area in conjunction with a scheme to widen St John Street at this point by demolishing buildings on the west side (see page 215). The old properties were replaced by commercial buildings and model dwellings. But there remained in the vicinity a population described in 1911 as 'entirely destitute'. (fn. 44)

146. St John's Square, north-east corner, in 2006. St John's Church (right) and Nos 42–46

A subtler influence came with the acquisition of St John's Gate in 1873 by Sir Edmund Lechmere for the new English Order of St John, and the organization's gradual adoption of St John's Church as its private chapel. Not only did the Order restore and re-use these two historic buildings, it also bought up what property it could near by to protect the gatehouse and church and provide for future expansion. In the early 1900s and 1920s several sites were acquired next to the Gate which looked likely to fall to the cold-storage trade, expanding from around Smithfield Market, and so 'ruin the whole neighbourhood of this historic building'. (fn. 45)

Bomb damage, post-war redevelopment, and the general downturn in industry in the 1960s and 70s all left their mark on the square, particularly on the southwestern side, which today is largely taken up with office blocks of the period. The area was still viewed by Greater London Council planners as industrial, but attempts to revitalize crafts and industry locally faced long odds and since the 1980s the trend has been towards offices, design studios and restaurants. There has been a mixture of remodelling and replacement of buildings. At Nos 53–54, a commonplace 1960s office building, originally occupied by Zetters Pools, has recently been enlarged, refurbished and re-clad (by GML Architects); the ground floor is now the Priory restaurant. (fn. 46) Adjoining St John's Church on the Smiths' site, unattractive industrial buildings have been replaced by the glass-fronted offices of the advertising agency McCann-Erickson, built c. 2000 (Ill. 146).

For a long time the central spaces of the square on either side of Clerkenwell Road were given over to carparking. Since 2000 these have been repaved and largely pedestrianized. The scheme, co-sponsored by the City Fringe Partnership (a Greater London Authority initiative) and property developers, was designed by the landscape architects Gross. Max. (fn. 47)

St John's Church

Ravaged by fire during the Blitz of 1941, St John's Church was extensively reconstructed after the war for the Order of St John by the architects Seely & Paget. Behind the rather bland 1950s entrance front a patchwork of fabric remains visible, evidence of an involved constructional history. The building occupies the site of the original round-naved Hospitaller church of the twelfth century. Much enlarged and embellished, this church was largely demolished after the Dissolution, leaving only the chancel, side aisles and crypt. In the 1720s this battered remnant was rebuilt as a second parish church for Clerkenwell, which it remained until 1931, when it was given to the Order for its private services and investitures.

Priory Church

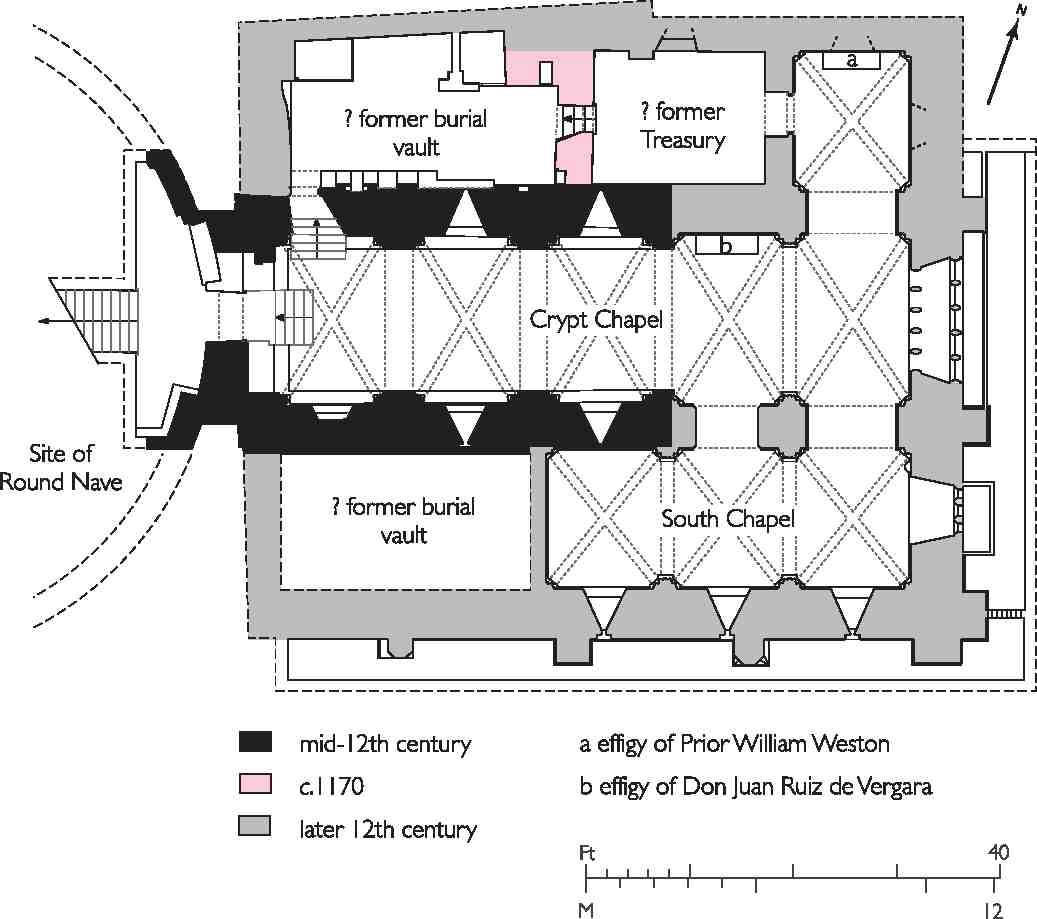

The first Hospitaller church, of c. 1144–c. 1160, comprised a round nave linked to a short and narrow raised chancel over a crypt (Ill. 147a). Such naves, emulating the Byzantine rotunda of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, were characteristic of Hospitaller and Templar churches. With an internal diameter of some 65ft and an external facing of finely dressed stone, the round nave at Clerkenwell was one of the largest and grandest in Britain. (The discovery of parts of the nave in 1900 during work on the crypt enabled its original extent to be determined and the outline marked with granite setts in the forecourt.) (fn. 48) An internal arcade, probably of eight piers, supported a triforium and clerestory. The nave was entered from a doorway to the west or south; to the east were steps leading up to the chancel and down to the crypt. Only ordained Hospitallers were admitted to the chancel, and the narrow opening and variance in floor levels would have left lesser brethren in the nave with a restricted view of any ritual.

147. St John's Church. Ground plans, twelfth century to present day

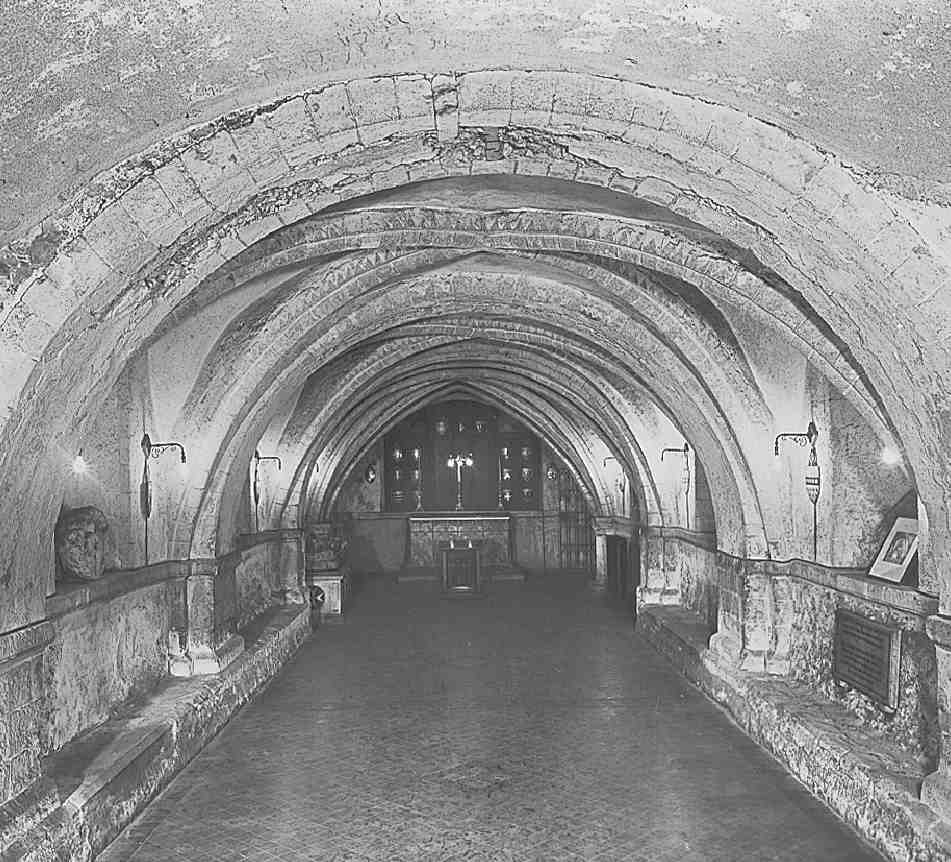

The chancel and crypt, corresponding in size and plan, were three bays long, aisleless, and probably terminated in an apsidal east end. All that remains in place of this first phase of building are the three westernmost bays at the centre of the crypt, part of the present Crypt Chapel (Ills 148, 149). The style is Romanesque, with broad, round transverse arches, segmental ribbed vaults, and splayed window-openings with narrow, round-headed lights. Some arches and ribs bear faint traces of decoration, in the form of chevrons and scallops cut from a layer of plaster and coloured red. A low stone bench runs along these bays, suggesting communal use of the crypt, perhaps as a chapter-house.

148. St John's Church crypt. Plan showing principal phases of construction

149. St John's Church crypt, looking east, in 1937

Towards the end of the twelfth century the priory church was greatly enlarged, reflecting the growing wealth of the English Hospitallers. Extensions were made to three sides of the crypt, and an entirely new aisled chancel erected above (Ill. 147b). These additions appear to have been completed by 1185, when the church was dedicated by Heraclius, Patriarch of Jerusalem, during a mission to the West to enlist help for Henry II (who was also present at the ceremony) in the fight against Saladin. (fn. 49) Records made in the nineteenth century and surviving architectural fragments show that the new work was of high quality, influenced by the latest design in continental Cistercian churches (Ill. 150).

In the crypt this later work is most readily identifiable in the two easternmost bays of the central Crypt Chapel, a chapel on the south side and a smaller north chapel (Ill. 151). The style is Transitional, with pointed transverse arches supported by triple-clustered shafts. The vaulting, too, is richer, with moulded pointed ribs, and the windows are lancets. Two further chambers on the north side, added in the same period, are of simpler construction. One, adjoining the north chapel, has a heavy wagonvault, and may have been a treasury or store. The other (incorporating part of an earlier addition) was probably filled with earth and used for burials. A corresponding chamber on the south side, now sealed, was very likely intended for burials too.

Of subsequent additions and alterations to the priory church almost nothing remains above ground, and details are uncertain. (fn. 50) It is likely that the round nave had been rebuilt on conventional rectangular lines by 1283–4, when Prior William de Hanley erected a memorial cloister to its south. A small vestry was also added to the south of the chancel, probably in the thirteenth century. The chancel was renovated or reconstructed during the late fourteenth or fifteenth century, probably under Prior Botyll (1440–68), when the Perpendicular windows shown by Hollar were installed (Ills 132, 133). Of these, only the large east window retains any original tracery, now heavily restored.

At the time the priory was dissolved in 1540, the church had a 90ft-long nave of three aisles (Ill. 147c). It had also acquired a tall bell-tower at the west end, described by Stow as 'a most curious peece of workemanshippe, graven, gilt, and inameled to the great beautifying of the Cittie, and passing all other that I have seene'. (fn. 51)

Prior Docwra added his own memorial chapel to the south of the chancel, next to the vestry. The vestry was entered from the chancel aisle through a small doorway, rediscovered during rebuilding work in 1903–8, and Docwra's chapel through two openings in the chancel wall, beneath stone-dressed brick relieving arches. Inside the chapel, buttresses against the south chancel wall were reshaped and decorated with chamfer stops, carved with the Prior's badge. (fn. 52)

150, 151. St John's Church. Fragment of late twelfth-century respond capital from chancel, now in Museum of the Order of St John, and (right) the crypt, east end, looking to South Chapel, 2006

Ailesbury Chapel

After the initial dissolution of the priory, the fabric of the church was first despoiled by Henry VIII's surveyor, masons and carpenters for improvements at the royal palace at Whitehall, and then in 1549 by Lord Protector Somerset, who blew up the nave and bell-tower to provide building materials for his new house in the Strand. One stone porch was re-erected at the church of All Hallows, Lombard Street, since demolished. The remains of the chancel, side-chapel and vestry were given a new west front by Cardinal Pole during the priory's brief revival under Queen Mary. (fn. 53)

In the second half of the sixteenth century the old chancel and crypt were used for storage by the Offices of Tents and Revels. By about 1600 local inhabitants were using Docwra's chapel for worship, but not for long, as within a few years the precinct came into private ownership and its dismemberment began. Docwra's chapel and the adjoining vestry had already been blocked off from the chancel and made into rooms or lodgings (probably at the time of the Dissolution, to judge from stone fragments and stained glass bearing Docwra's badge, discovered during building work in 1903–8). They were bought by George Pollard, an usher to James I, in 1606, and survived until the 1880s (see Ill. 143). (fn. 54)

The chancel itself was acquired by William Cecil in 1612 along with the main east range of the priory for his London residence, and in 1623 'restored and reedified' for private worship (the earl was a convert to Catholicism). (fn. 55) It continued to be used as a private chapel by the Bruce family, later Earls of Elgin and Ailesbury, to whom Cecil's house descended, acquiring the name of Ailesbury or Aylesbury Chapel. The ecclesiastical historian Thomas Fuller, writing in the 1650s, considered it one of the best private chapels in England, 'discreetly embracing the mean of decency betwixt the extremes of slovenly profaneness and gaudy superstition'. (fn. 56) By this date the lower part of the side aisles had been walled off. Later the entire north aisle was made into a small house, the lower portion of the south aisle was reclaimed, and the upper portion became a library. This arrangement is shown on an early eighteenth-century sketch plan, which also suggests that Cardinal Pole's west front stood further into the square than the present one, making an extra bay (Ill. 147d). (fn. 57) The chapel's external appearance is known from Hollar's views of the former priory precinct, one of which shows Pole's west front, with a Gothic-style central window and battlements to match the east front (Ills 132, 133). The classical central doorway, and a Baroque doorway with swan-necked pediment and blocked surrounds leading into the north-aisle house, were probably added by the Earls of Ailesbury.

After the Bruce family sold their Clerkenwell estate in 1707 Ailesbury Chapel and a strip of land behind became the property of a local ropemaker, William Pratt, who built two new houses at the east end of the site, fronting St John Street. Pratt let and mortgaged the chapel to Dr John Ker, a Highgate physician, who claimed to have spent 'diverse considerable sums' of money on improvements and himself became the owner. (fn. 58) Ker let the chapel to William Richardson, a Presbyterian preacher, for a meeting-house, and it was ransacked during the anti-dissenting Sacheverell riots of February 1710. (fn. 59)

Before long Richardson was ordained as a Church of England minister, re-opening the chapel for Anglican services, and in December 1711 he proposed its acquisition by the new Commission for Building Fifty New Churches in London, which had identified Clerkenwell as in need of another place of worship. (fn. 60) Some of Richardson's dissenting flock had followed him into the established church and he was now looking for a 'much greater Harvest' in the area, as well as financial support. (fn. 61) The building was inspected by William Dickinson, one of the Commission's surveyors, and re-visited in May 1714 by a high-powered deputation which included Wren and Hawksmoor. But nothing came of the proposal at this time, perhaps because rebuilding would have been required to meet the high architectural standards of the early Commissioners. Services must have come to an end soon after, for in 1716 the chapel was advertised for sale or rent, with the suggestion that some parts of the property—namely the small house on the site of the old north aisle, and the south aisle gallery (formerly Lord Ailesbury's library)—could be adapted for educational use. In 1719 the Welsh School later at Clerkenwell Green was briefly based here.

Parish Church

In October 1721 the lawyer and property developer Simon Michell bought Ailesbury Chapel, with the land and houses at the rear, from John Ker's descendants. His intention was to make it a 'convenient' place of worship for the inhabitants of his new development at Red Lion Street (now Britton Street, see Chapter VI). (fn. 62) Restoring the north and south aisles to the body of the building, he rebuilt the west front and the roof, erected galleries around three sides, installed pews and an organ (by Renatus Harris), and added a small vestry room at the east end. He also cleared two vaults, formerly used for storage, to take burials. Michell then offered to sell the building to the Commission to serve as the church for a new ecclesiastical district to be centred on St John's Square and Red Lion Street. (fn. 63)

Michell had dealt with the Commission before, having provided part of the site in 1713 for Christ Church in Spitalfields, an area where he and Charles Wood were about to embark upon speculative house-building on their estate. (fn. 64) His present offer was one calculated to appeal to the more Whiggish Commissioners appointed since then, who had cut short the costly building programme of their Tory predecessors.

Fearing the loss of parish income it would mean, the vicar and churchwardens of St James's and many of their congregation took great exception to Michell's scheme, insisting that their church was large enough to accommodate Clerkenwell's growing population. In spite of these protests, and some suspicion as to Michell's motives within the Commission, his offer was accepted and a price of £3,000 agreed. He engaged two ministers, an organist, a clerk and pew-openers, and personally managed St John's until its consecration as a parish church on 27 December 1723. (fn. 65)

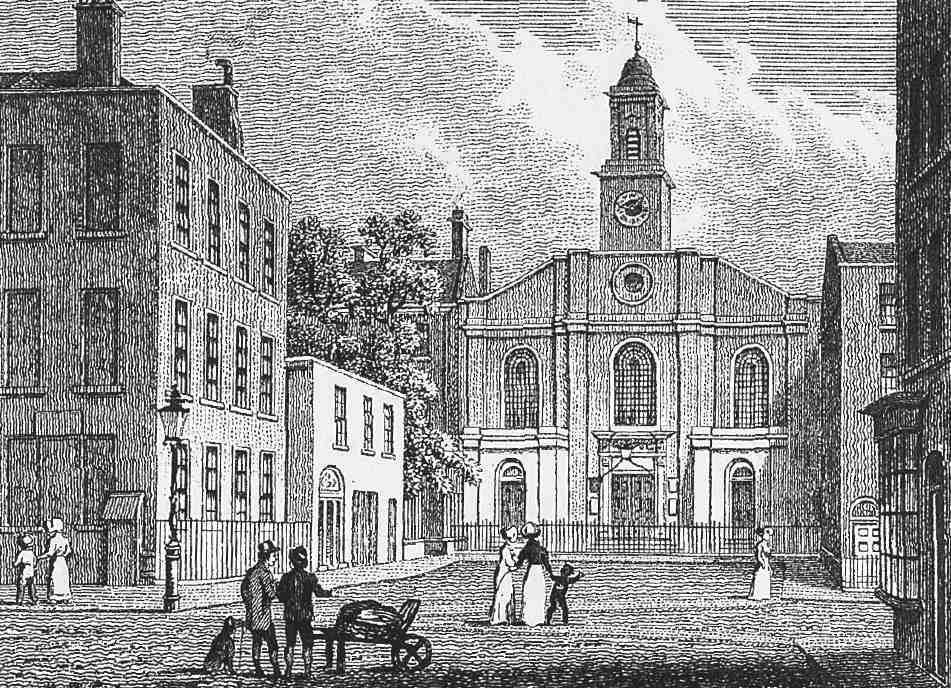

152. St John's Church. Interior looking east in 1899

As reconstructed, St John's was a large oblong box, with galleries on three sides carried on Doric columns, and a coved, panelled ceiling (Ills 147e, 152). In the centre aisle were the minister's reading-desk and pulpit. It reminded later commentators of a chapel-of-ease, or dissenters' meeting-house, and some regretted the disharmony between Michell's robust classical interior and the surviving medieval windows. (fn. 66) The Georgian classicism was continued in a more understated form on the new west front, a three-bay composition of brick, with stone pilasters and dressings and a prominent door-surround of carved wood (Ill. 153). A steeple and portico, requested by parishioners in 1724, were never built, although the existing turret was too low and the bell too small to be heard across the parish. (fn. 67)

The narrow strip of land at the back was made into a churchyard, but the two houses on St John Street intended as a rectory were found to be unsuitable, and one of Michell's new houses on Red Lion Street was bought for that purpose. (fn. 68)

The first substantial modifications to Michell's church were made in 1812–13, when James Carr, surveyor to St James's Church, supervised the stuccoing of the west front and the addition of a clock-turret and cupola (see Ill. 141). (fn. 69) In 1825 J. W. Griffith of St John's Square built two stuccoed porches (serving improved staircases to the galleries). A third porch, to the main entrance, was added by his son and successor, W. P. Griffith, in 1845. (fn. 70)

In 1885–6 these porches (described by the then incumbent, the Rev. William Dawson, as 'hideous') were pulled down and the west front re-instated, under J. Oldrid Scott's supervision, to something like its former state, with exposed brickwork and windows either side of a central entrance. Michell's wooden doorcase, which had survived intact, was embellished with a relief panel in the same material of the three St Johns (Almoner, Evangelist and Baptist), carved by Harry Hems of Exeter. (fn. 71)

153. St John's Church. West front, c. 1800, as rebuilt by Simon Michell in 1721–3

The crypt, long over-filled, was closed following the Burials Act of 1853. (fn. 72) Some clearance took place in 1854, and the remaining coffins were subsequently bricked up in the side vaults. The last human remains were removed to Brookwood Cemetery in 1894. (fn. 73)

St John's remained a parish church until 1931. By then attendances had fallen to such an extent that the Ecclesiastical Commissioners were happy to unite the benefices of St John and St James as a single ecclesiastical parish under St James's Church, and to hand over St John's to the modern Order of St John. (fn. 74)

Grand Priory Church

This change in status was the culmination of a growing connection from the 1870s between the building and the revived Order of St John, which had established itself at St John's Gate. The Order soon began holding services in the church, and contributed towards the cost of the alterations by Scott, who was already working at St John's Gate under the patronage of the Secretary General, Sir Edmund Lechmere. Lechmere had also purchased the advowson of the church (transferred to the Order in 1909), and from 1892 rectors were selected from the Order's chaplains. (fn. 75)

Further work by J. Oldrid Scott, 1889–1908

Following his restoration of the west front, Scott was to make further substantial alterations over the next twenty years. In 1889–90 he saw to the east front, refacing it in red brick and replacing the Georgian glazing of the outer windows with tracery. At the same time he installed benches and choir-stalls of mahogany and walnut in place of Michell's deal box-pews, removed the organ from the west gallery, and gilded and coloured the gallery pillars and the ceiling. The Rev. Dawson bore most of the cost of these works, done as a memorial to a relative. (fn. 76)

In 1900–1 Scott oversaw the restoration of the crypt, fitting up the middle aisle as a chapel, with a tiled floor and a new entrance and steps at the west end. The old way in, an irregular 'hole' in the east wall where a window had once been, approached via steps under the vestry, was bricked up. (fn. 77)

In 1906 the London County Council, as part of the Aylesbury Place Area Improvement Scheme, removed the tenements in Jerusalem Court, abutting the church— unrecognized as the remains, albeit much altered, of Prior Docwra's chapel and the monastic vestry. This revealed the exterior of the south wall as, in Scott's words, 'a most confused mixture' of fabric. Between 1906 and 1908 he refaced the wall, his intention being to 'repair rather than "restore" in the modern application of the word', removing any 'incongruous' additions and making use of stone from demolished houses in the Aylesbury Place area, believed to have been reused from the priory buildings. The Perpendicular tracery of the three large windows on this side is entirely his work, based, he claimed, on traces in the old masonry (Ill. 154). The narrow strip of cleared ground adjoining, formerly part of Jerusalem Place, was then given to St John's by the LCC in exchange for the easternmost portion of the churchyard, required for widening St John Street. (fn. 78)

The last significant alteration before the transfer of the church in 1931 was the installation in 1914 of stained glass in the central east window (see below).

Plans by Frederick Etchells and Ninian Comper

Having taken over the church, the Order of St John launched a 'fabric fund' in the early 1930s to aid its restoration. In 1934 Frederick Etchells, then engaged in designing a headquarters for the Order beside St John's Gate, was appointed advisory architect for the church, and during the next few years oversaw a number of works and produced plans for a re-ordering. (fn. 79)

In May 1941 St John's was hit by incendiary bombs and reduced by fire to a shell. The Georgian interior and fittings were entirely destroyed, but the crypt and enough of the walls and tracery remained to encourage some form of reinstatement, and in January 1943 the veteran Gothicist J. Ninian Comper was asked to prepare a rebuilding scheme. (fn. 80)

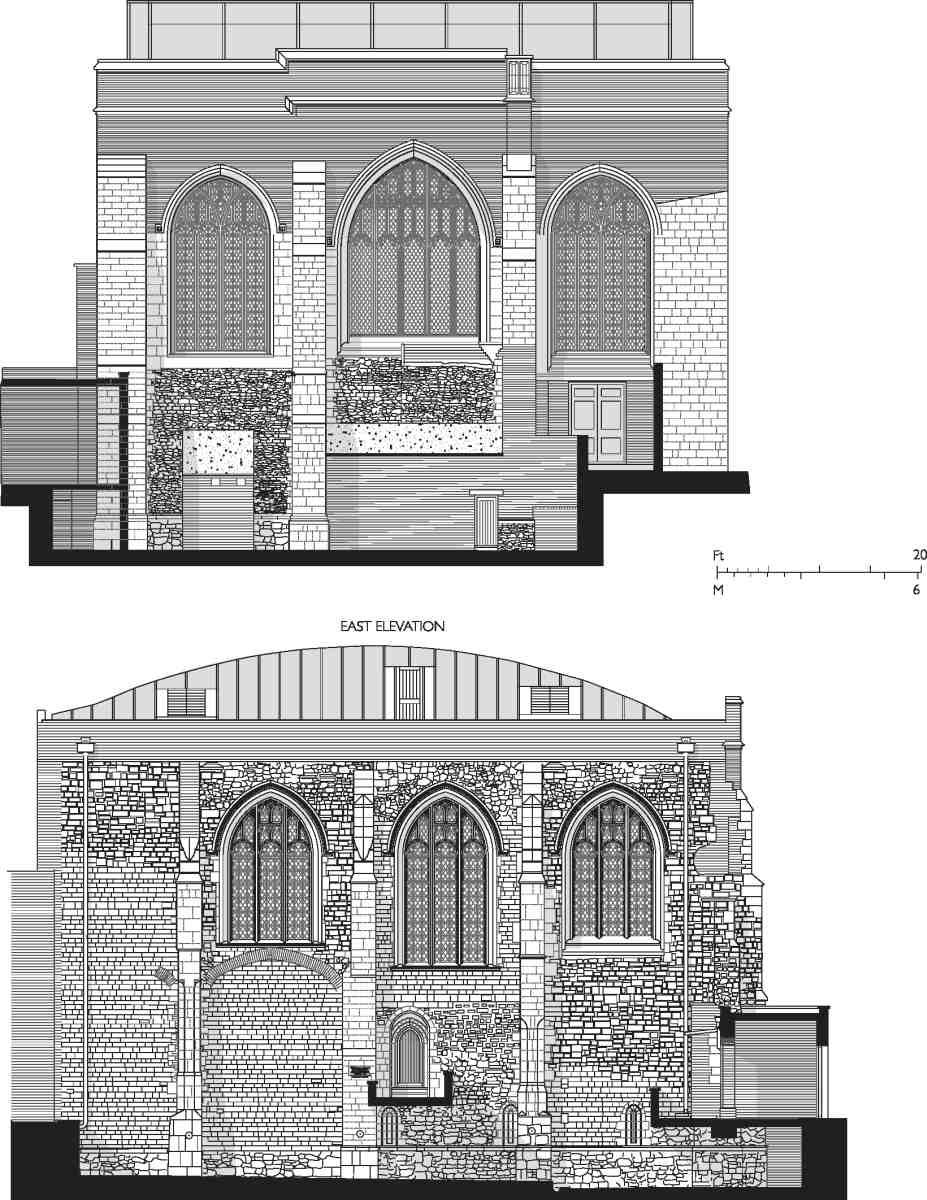

154. St John's Church. East and south elevations in 2004

Comper owed the commission to his patron the 9th Earl of Shaftesbury, a senior officer of the Order and chairman of the Church Committee, with whom he had enjoyed a warm relationship since 1907–8, when he designed a chapel for the earl's Dorset residence at Wimborne St Giles, and began rebuilding the parish church there. (fn. 81) 'Between ourselves', Shaftesbury told him, 'I do not intend to allow any interference on the part of Mr. Etchells', who had taken a 'very disgruntled view'. (fn. 82) Concerned about the probity of the situation, the Chapter-General sought legal advice before agreeing to proceed with Comper's plans. (fn. 83)

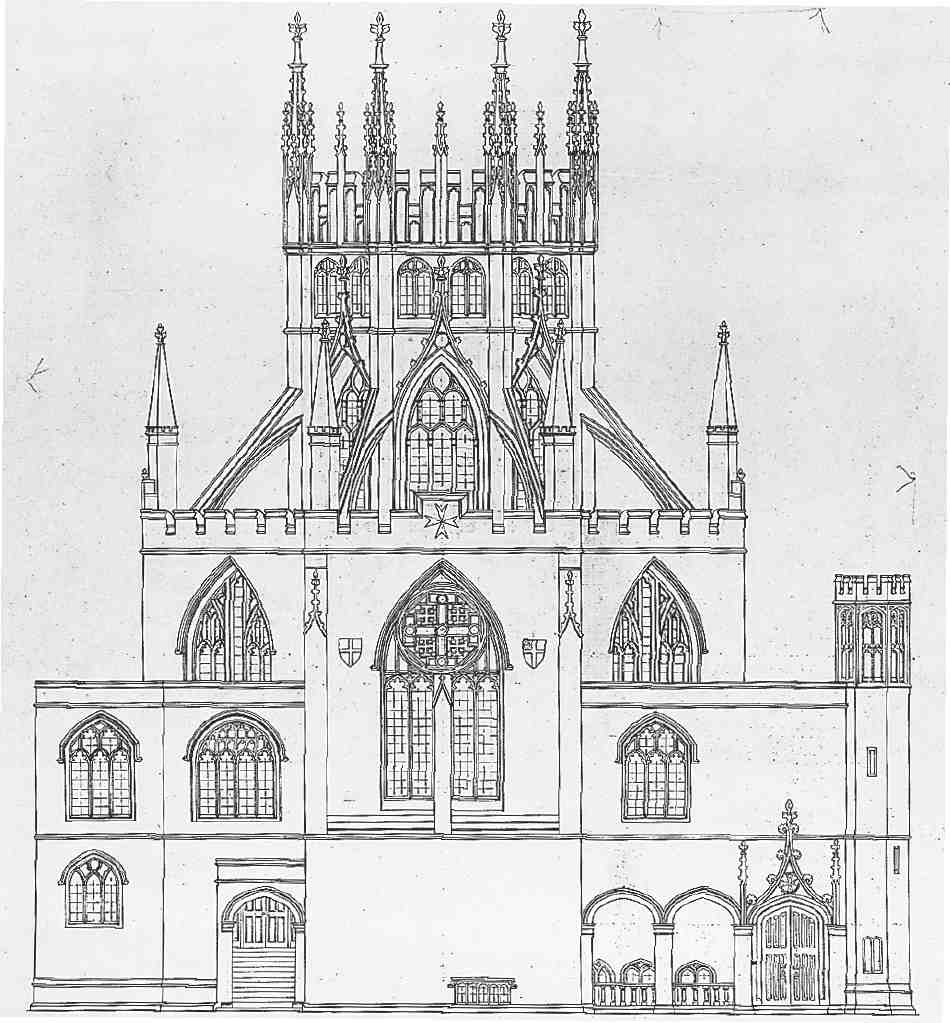

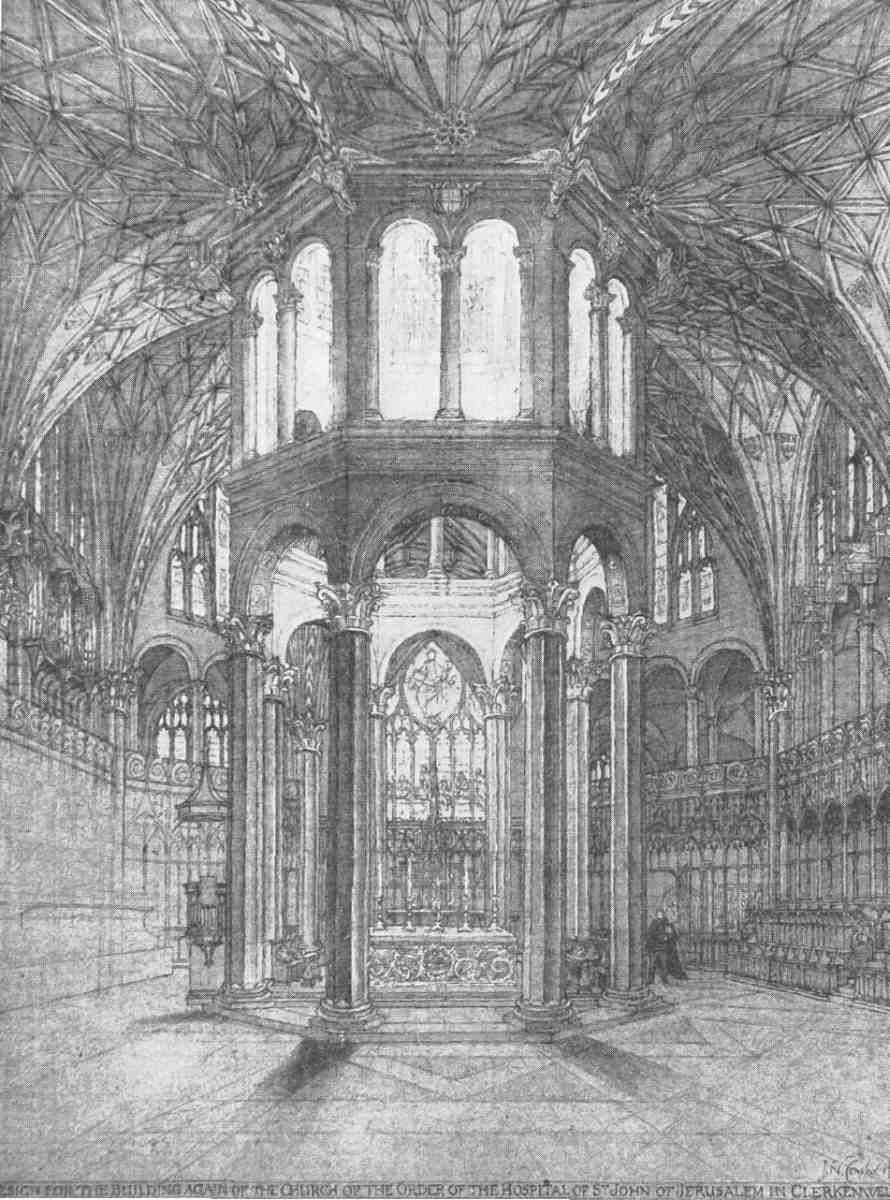

During and after the war, a number of church authorities approached Comper to restore their bomb-damaged buildings, but few were willing or able to adopt the extravagant plans he conceived. At Clerkenwell the story was little different. His proposals for St John's were the most grandiose of all these wartime and post-war schemes (Ills 155, 156). The final design, accepted by the Order's Church Committee in September 1943, attempted to recreate something of the spirit of the original Hospitaller church. Taking the Templar church at Tomar in Portugal as a model, the plan focused on a central octagonal tower with a free-standing altar beneath, the latter a feature increasingly favoured by the Anglo-Catholic Comper. As at Tomar, the altar was encircled by a two-tier colonnade of classical columns. This basic form Comper elaborated with lierne vaults and canopied stalls for a hundred knights, the whole top-lit by a lantern, reminiscent of Ely. He characterized the design as homage to 'pure Greek and Gothic and the example of 16th century England in combining the two'. Galleries or 'Tribunes' on an upper floor would accommodate more knights, and an organ, choir and orchestra; memorial chapels, a vestry, a college for priests and other facilities were to be dispersed around the edges of the site. (fn. 84)

This fantasy was hardly sympathetic to the prevailing national mood of austerity. Within the Order, some feared that such a building in a relatively poor part of London would raise adverse comment, even supposing the money to pay for it—estimated by Comper at £200,000—could be found. (fn. 85) A public appeal raised only £18,000 by July 1951, and Comper was asked to prepare a much more modest proposal, concentrating on the restoration and beautification of the crypt. But in May the architects John Seely (Lord Mottistone) and Paul Paget, recently appointed to restore St John's Gate, had met the new Prior, Lord Wakehurst, to discuss the 'maintenance management and development' of the Order's property, and Paget noted privately that Comper's involvement was unlikely to continue. (fn. 86) Although money was the main consideration, age—Comper was 86 when knighted in 1950— seems also to have influenced the decision. (At one planning meeting Comper was asked if there was anyone in his office able to complete the work should he die. He is said to have picked up his hat and departed with the words: 'Did Michelangelo have an office?') (fn. 87)

This would have been the great finale to Comper's career. The boldness of his designs was perhaps fuelled by the recent regard for his architecture among a younger generation, by John Betjeman in particular; and, though never realized, it has been suggested that they might have had some influence on Sir Frederick Gibberd's Roman Catholic cathedral in Liverpool of the 1960s. (fn. 88)

155, 156. St John's Church. Scheme for rebuilding by J. N. Comper, c. 1943. West front and (below) central arcade and altar

The appointment of Seely & Paget brought matters down to earth. Their friend Lady Doreen Brabourne, a Dame of Grace in the Order (in which Seely was himself a knight), wrote to Paget in July expressing her delight that the 'Johnnies' had finally chosen someone young, go-ahead and human to deal with the problems of rebuilding— adding that the Order had a habit of employing people 'conspicuously lacking' in all three attributes. (fn. 89) In October Shaftesbury met the architects on site, and their proposals, designed by Lord Mottistone, were accepted by the end of November. Shortly afterwards Shaftesbury stood down as chairman of the Church Committee. (fn. 90) In a mollifying letter to Comper, Mottistone contrasted his own 'very modest' plans with the former's 'magnificent' designs, 'conceived when the recovery of the nation's fortunes seemed to be near at hand', Comper offering in response to show him simpler plans he himself had made. (fn. 91)

157. St John's Church. Interior looking east in 2006

Restoration by Seely & Paget, 1951–8

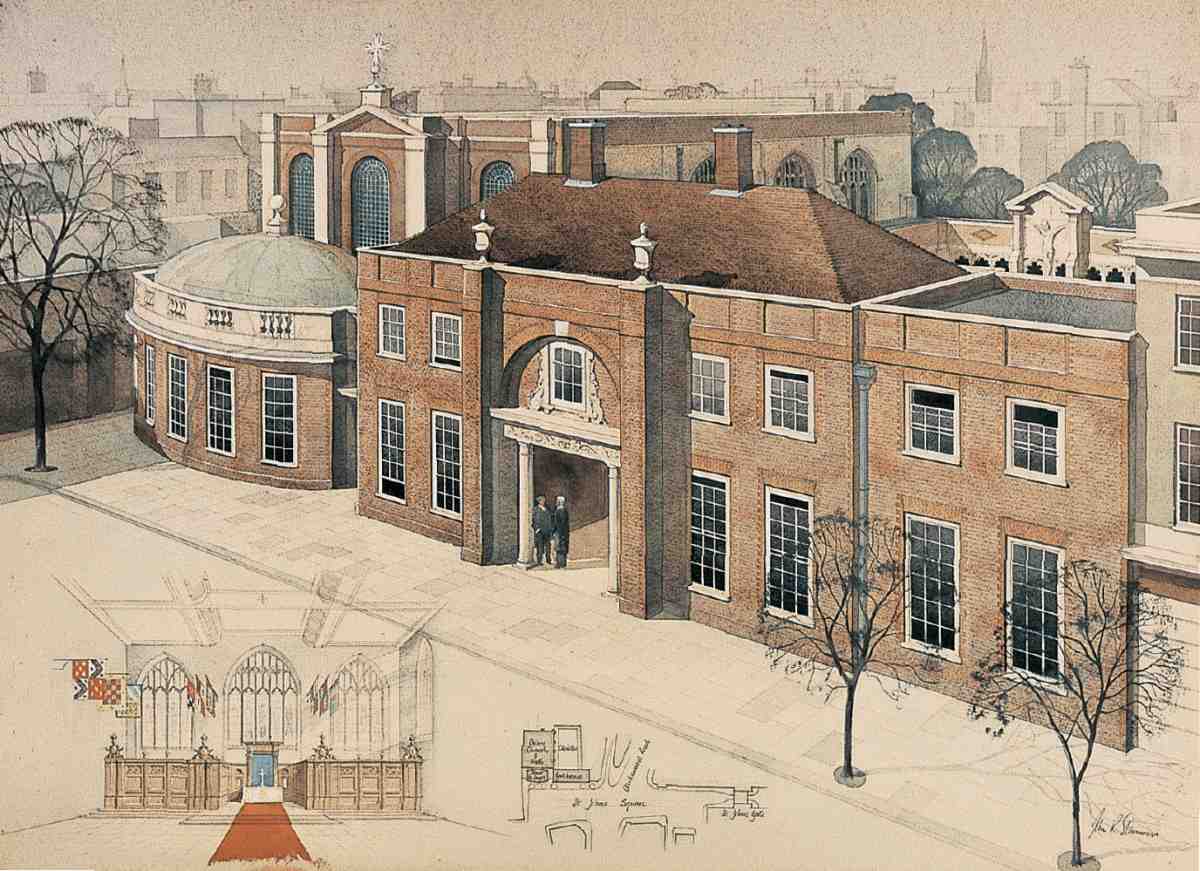

Besides the reinstatement of the church, and minor improvements to the crypt, Seely & Paget's scheme included new buildings and a memorial garden and cloister, adjoining the church on the site of a timber yard and houses (Nos 37 and 40 St John's Square) acquired before the war. (fn. 92) Modest as it was, this programme proved hard enough to finance and some sacrifices had to be made. The works, for which the general contractor was Ward, Paterson Ltd, were completed in October 1958. (fn. 93) On the 17th the church was rededicated by Dr Geoffrey Fisher, Archbishop of Canterbury and Prelate of the Priory Church, and a memorial tablet in the cloister was unveiled by HRH the Duke of Gloucester, Grand Prior of the Order. (fn. 94)

Rebuilt in a basic hall form, the church was designed to be suitable alike for religious services and other meetings and ceremonies (Ill. 157). The simplicity of the architectural space was matched by the clarity of the decorative scheme: exposed stone walls and a plastered, panelled ceiling, all painted white, offset by a black-and-white terrazzo floor, coloured banners, and oak chairs upholstered in red hide. The stained glass, removed for safekeeping in the war, was not reinstalled, plain obscure glass being used instead. 'I think the whiteness of the restored church is ideal for the Order', Mottistone told the Daily Telegraph, 'and I hope stained glass will not be used again'. (fn. 95) The altar, incorporating fragments of carved woodwork from the early eighteenth-century west front, was set beneath a deep canopy with curtains that could be closed for nonreligious occasions. The floor level was lowered to allow bases from the arcade responds of the medieval church to be displayed in situ, on either side of the altar.

158. St John's Church. Rebuilding scheme by Seely & Paget. Perspective view by John R. Stammers

The roof, constructed of laminated timber with a shallow curved profile, was covered in copper.

The new buildings consist of an entrance hall to the church and crypt, with a curved front to the square, and a 'guard-house', screening the memorial cloister from the roadway and containing a robing-room and vestibule on the ground floor, and a caretaker's flat above (Ills 146, 147f, 158). They are faced in purple-grey bricks with dressings of red brick, in a refined if slightly insipid neo-Georgian style, intended to complement Michell's much-restored west front behind. Oval in plan, in allusion to the medieval round nave, the entrance hall incorporates a double-staircase to the crypt. The intended balustraded parapet and shallow dome were omitted, presumably for financial reasons.

From the guard-house, a porticoed archway leads to the cloister garden, designed as a memorial to the members of the Order and its foundations, including the St John's Ambulance Association and Brigade, who lost their lives in the two world wars. The wrought-iron gates were given by the Docwra family. Funds being short, the intended four-sided memorial cloister was reduced to a single cloister-walk, aligned on the entrance gates in St John's Square. On the outer wall is a stone crucifix, by Cecil Thomas. (fn. 96)

Effigy of Prior Weston

The north chapel of the crypt contains the mid-sixteenth-century funeral effigy of Sir William Weston, prior of the English langue of the Order of St John of Jerusalem, who died on the very day in May 1540 that the priory was dissolved. In the tradition of the cadaver tomb, Weston is represented as a hollow-eyed, emaciated corpse, naked on its winding sheet (Ill. 160).

The effigy is only a remnant of the original canopied marble monument (Ill. 159). This was erected shortly after the prior's death in the chancel of old St James's Church, the former nunnery church in Clerkenwell Close, which had enjoyed parochial status for some time. St John's having been seized by the Crown, this was the nearest suitable resting place. (Another Hospitaller official, the auditor Constance Benet, was also buried in the chancel there, in 1577.) (fn. 97)

The monument was broken up in 1788 during the demolition of old St James's, (fn. 98) and the fragments stored with other salvaged material in the garden of Peter Mallett, the furniture-maker, at Newcastle House. (fn. 99) By that date the effigy was already 'much defaced' and its right arm broken off. (fn. 100) The Rev. Sir George Booth, Bart, who lived in St John's Square and was a trustee of the rebuilding committee, bought the pieces and is said to have carried them off to 'Burleigh'—what became of them is not known. (fn. 101) The effigy, however, was left behind and later put in the crypt of the new church, where it was propped against the north wall, alongside another memorial carving, from the tomb of Lady Berkeley. (fn. 102)

In 1882 the effigy was mounted on a new plinth in the north-east corner of the nave, close to its original site in the old church, by Col. Gould Hunter-Weston, a knight of the Order of St John who claimed descent from the prior. Effigy and plinth were removed to their present location in St John's in 1931, when the two parishes were united. (fn. 103) The broken arm was restored in 1943. (fn. 104)

159. Monument to Prior William Weston, probably of the 1540s or 50s, in old St James's Church; watercolour by Schnebbelie, 1787

Effigy of Don Juan Ruiz de Vergara

Also in the crypt is the late sixteenth-century effigy identified as that of a Castilian Knight Hospitaller, Don Juan Ruiz de Vergara, who died at sea fighting the Turks near Marseilles (Ill. 161). Donated in 1915 by Sir Guy Laking, Bart, Keeper of the London Museum and a member of the Order, it had formerly belonged to Valladolid Cathedral. Dating from about 1575–80, the recumbent alabaster figure is attributed to Esteban Jordán, active in Valladolid at that time and later court-sculptor to Philip II. (fn. 105)

Vergara is shown dressed in full plate armour, with the Order's eight-pointed cross on his breastplate and robe. His head rests on two finely carved cushions, which, with the lion and sleeping page at his feet, are characteristic of Spanish funeral effigies of the period. The base, in the form of a tomb-chest decorated with shields, was designed by C. M. O. Scott in 1916, when the effigy was brought to the church. (fn. 106)

160, 161. Monuments in St John's Church crypt, 2006. Prior Weston's effigy, and (below) Don Juan Ruiz de Vergara

Stained glass

The stained glass installed in 1914 in the large east window was given in memory of Col. J. A. Man Stuart, a Knight of Justice of the Order, by his widow. Designed by Archibald K. Nicholson, it contained scenes depicting the original Hospitaller Order's role as protector of pilgrims. The glass was removed for safekeeping during the Second World War, after which some was re-used as part of Seely & Paget's post-war refurbishment of the crypt. (fn. 107)

The east lights in the central Crypt Chapel (see Ill. 151) come from the lower half of Nicholson's window: they depict the Entombment, with, above, the figures of Raymond du Puy (Grand Master of the Order of St John, 1118–60), St John the Baptist and St Ubaldesca (a sister of the Order, canonised for charitable deeds and miracles). To either side is the Tree of Life, with medallions representing some of the eight beatitudes symbolized by the points of the Order's cross. The north chapel windows, formed from the upper lights, contain figures of SS George, Andrew, Patrick and David, and angels holding shields with the arms of the Order and some of its English priors and knights. (fn. 108)

The lancet trio in the east window of the south chapel, depicting Christ, St John the Baptist and St John the Almoner, is by Powell & Sons, and was inserted in 1903–4 by Dr W. A. Jamieson in memory of his wife. (fn. 109) The small individual memorial lancets in the south wall date from 1907, after the demolition of the old buildings adjoining the church on that side.

Other Buildings: St John's Square

The lesser buildings of St John's Square date mostly from the late nineteenth century and the twentieth century. Commercial blocks predominate. On the north side something of the square's semi-domestic Georgian character survives. The following accounts of individual buildings begin with the southern half of the square, in deference to the present numbering. Priory House and No. 27 are described in the context of St John's Gate in Chapter V.

Free-thinking Christians' Meeting-house (demolished)

In 1831–2 a meeting-house was built on the west side of the square, on the site of Sir John North's mansion, for a Unitarian sect called the Free-Thinking Christians, formerly at the Crescent, Jewin Street, in the City. It had a brick and stone façade in the Tudor style, and could seat 300. Internally it was a plain, open hall, in keeping with the sect's eschewal of religious ceremony in favour of moral and spiritual discussion inspired by the New Testament. The last meeting took place in 1871, and thereafter the building was rented by the London District Unitarian Society as a mission-hall. It was demolished c. 1877 for the construction of Clerkenwell Road. (fn. 110)

Wesleyan Chapel (demolished)

Designed by James Wilson of Bath, this Early Decorated–style chapel was built in 1848–9 for a Wesleyan congregation from Wilderness Row. Of brick with Bath-stone dressings, it had a prominent gabled front with a large central window and flanking turrets. Inside, under an open timber roof, was seating for 1,300, including a gallery supported on wooden columns. (fn. 111)

From the 1880s it was run by the London Mission Committee, and in the late 1890s new Gothic-style buildings were added, including Sunday schools, a lecture hall and dispensary, designed by Arthur Wakerley of Leicester. (fn. 112) Extensive modernization was carried out in 1930 in connection with the building's new status of Methodist Central Hall. This included a new entrance block and shops, and internal remodelling. The buildings were wrecked during the Blitz of 1941, and although a temporary church was opened in 1949 plans for rebuilding were finally abandoned in 1957 and the site sold, the proceeds going towards the construction of a new St John's Methodist Church in Amersham. (fn. 113)

162. St John's Square, south-west side in 2006; No. 1 (Gate House), to right

No. 1 (Gate House), an office block, was built in 1962–3 for Arrol Investments Ltd. The architects were Richard Seifert & Partners. The reinforced-concrete frame is exposed, and the elevations are each treated differently, with panels of brick, stove-enamelled steel, exposedaggregate concrete, and, on the east face to the square, glass mosaic and marble (Ill. 162). (fn. 114)

163. No. 5 St John's Square and No. 2 St John's Place in 2006

No. 2, dating from 1964, was designed by Raglan Squire & Partners for the brewers Whitbread & Co. A determinedly modern design, it was nevertheless supposed, by virtue of its red brickwork, to blend in with the surrounding buildings. It comprises a public house, the Bear (originally the Coach and Horses), with offices above. The former name was retained from the old-established tavern on the site, rebuilt in 1898 for Whitbreads to the designs of A. Dixon. (fn. 115)

No. 5, a late expression of Clerkenwell's craft tradition, dating from 1973, was intended to alleviate the shortage of workshops locally. More than half the space was designed for industrial use, with silversmiths particularly in mind, for which reason security as well as natural lighting were given high priority. The building (also numbered 2 in St John's Place) was designed by John Gill Associates for a small property company. Obscurely sited, it stands behind the Bear pub, between two narrow courts (Ill. 163). (fn. 116)

Nos 6–8 (Knight's Court) was built in 1903 or shortly after as warehousing for J. Lyons & Co. It is largely hidden away at the back of No. 5 St John's Square and 2 St John's Place, on part of the Gilbert & Rivington printing-works site. Derelict throughout most of the 1970s, it was later the headquarters of the Samuel Lewis Housing Trust, and was refurbished about 2004 as offices and apartments. (fn. 117)

The office building at Nos 14–17, designed by Raymond J. Cecil & Partners, dates from 1971–2 and replaced warehouses probably of the 1890s. It was altered and refurbished in about 2000 in a development which included a new block adjoining at No. 12 and No. 6 Briset Street. (fn. 118)

Nos 28–30, a speculatively built factory-warehouse of the 1880s, faced in white brick, may have been the work of the architect Herbert D. Appleton (later Searles-Wood), who oversaw extensions to the building in 1891 and 1902. (fn. 119)

No. 31, with a plain neo-Georgian front of three bays, dates from 1960. It replaced an old house, also of three bays, one of a short row probably built in the eighteenth century. (fn. 120)

Nos 36–36A, on the corner of Albemarle Way, is a threestorey house and shop rebuilt by James Brake in 1830—a fairly late instance of domestic-scale development in the area of the square. (fn. 121)

Nos 42–46

In the early 1830s, John Smith and his son John Launcelot Smith began trading in St John's Square, at Nos 2 and 8, the former as a maker of glass shades and clock- and watch-glasses, the latter as an enameller. By 1843 they had joined forces with another son, William, as John Smith & Sons, and had begun to manufacture clocks and clockcases. (fn. 122) In that year the Smiths took a long lease of the cleared site on the north side of the square where Israel Wilkes's house and part of his distillery had stood, and over the next few years erected an extensive factory there, later numbered 42–46 (Ill. 164). (fn. 123)

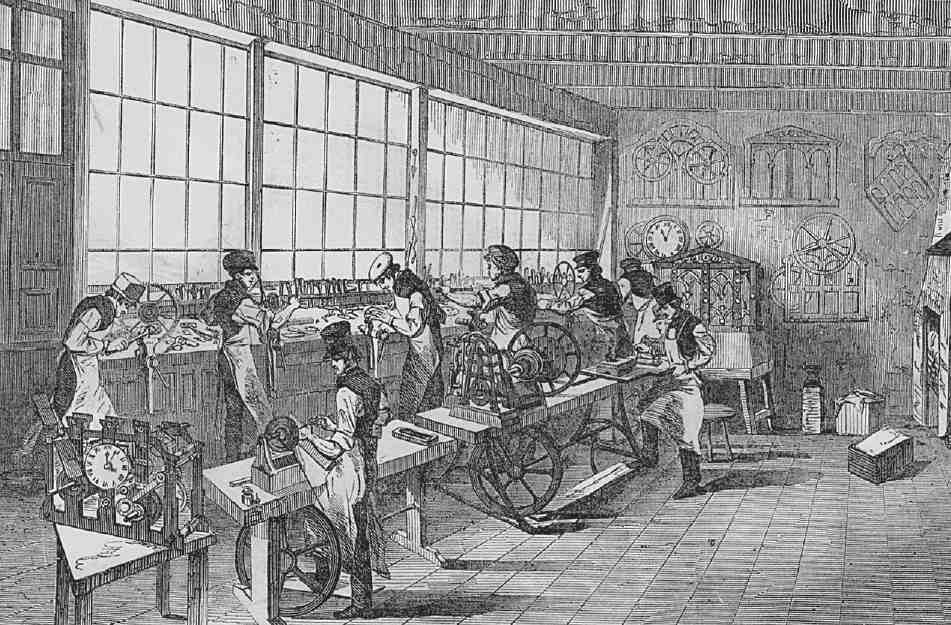

The Smiths' factory—there is no connection with the famous clockmaking firm S. Smith & Sons, later Smiths Industries—was significant as an early example of the centralization of all aspects of clock manufacture, each hitherto the preserve of individual masters employing specialist journeymen. Gun-metal and brass clock parts were cast in a foundry at one end of the yard. There were finishing shops, where rings were turned, wheels cut, dials silvered, and clock-cases made; and a glass-bending shop, with furnaces and an annealing oven. Other specialist workshops dealt with fine and delicate assembly work, bracket clocks and regulators, and the manufacture of turret and church clocks, for which Smiths had a particular reputation (Ill. 165). Logs of mahogany and other woods for cases, brought from the West India Docks, were cut on site into boards and seasoned in the yard. Next to St John's Church, a three-storey building contained offices and showrooms. (fn. 124)

164, 165. Smith & Sons' clock factory, St John's Square. General view, 1880s and (right) turret-clock workshop in 1851. Demolished

In 1859 the company acquired the metal-stockholding business of David George Foster, a relation, at Nos 51–52 St John's Square. A number of specialist firms were acquired in the early twentieth century, and Smiths expanded into other buildings in the vicinity, at No. 47 St John's Square adjoining the main factory, and at Nos 18–19 Aylesbury Street, where a screw and nut store (Aylesbury House) was erected c. 1936. By this date they had stopped producing clocks (reflecting the declining market in specialist hand-made pieces), concentrating instead on metals, tool manufacture and general engineering. By 1949 Smiths held all the buildings on the north side of the square (see Ill. 167), from No. 42 to No. 54, and for a time had a second factory at Archway Road. (fn. 125)

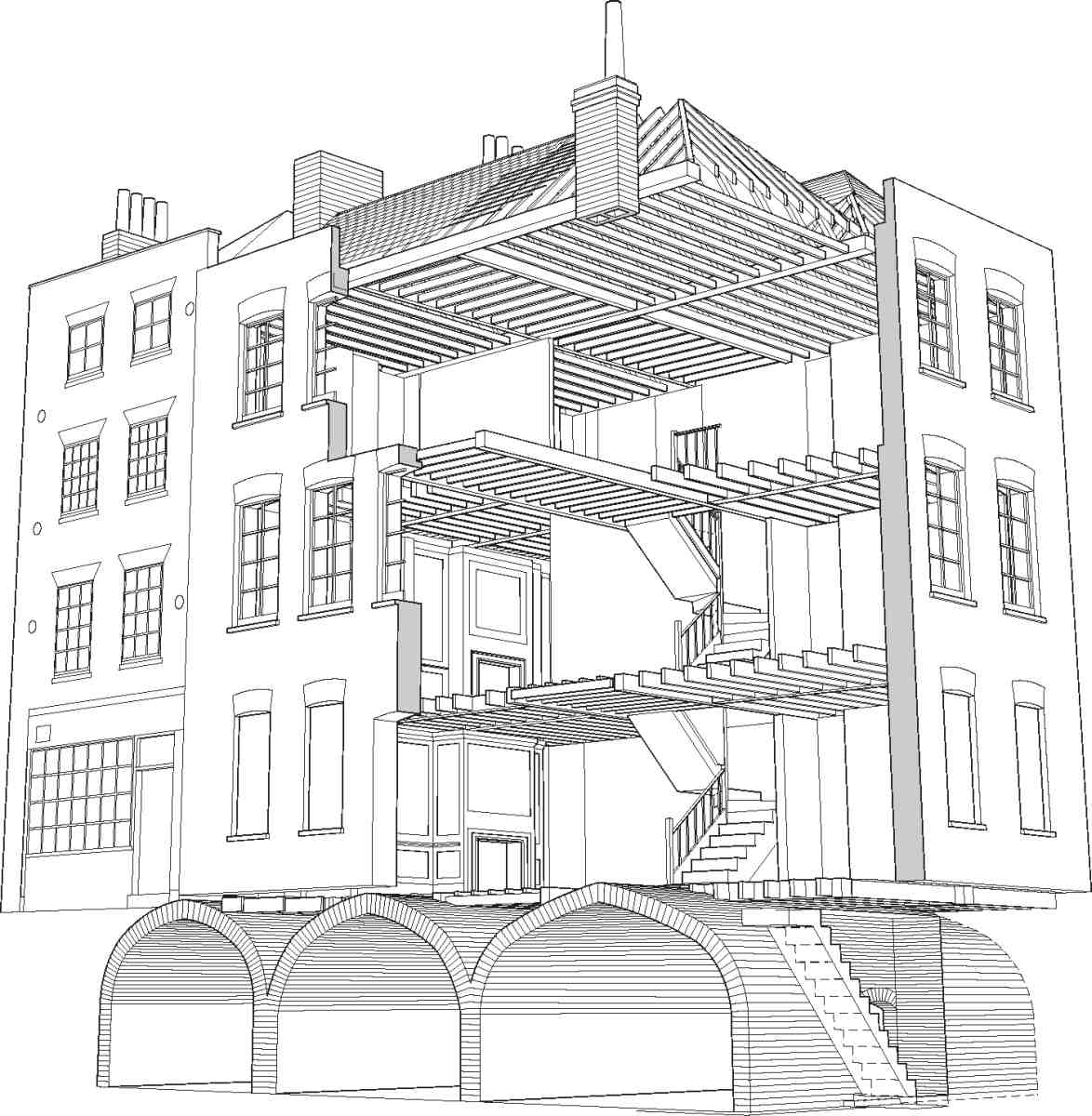

166. Nos 47 and 48 St John's Square in 2004. Cutaway view, showing Georgian houses built over medieval and Tudor vaults

The site of Nos 45–46 was redeveloped in 1938–9 with a two-storey building facing the square. (fn. 126) Badly damaged during the war, the works was largely rebuilt in the 1940s and 50s in the same workaday manner in brick and concrete. (fn. 127) Smiths remained at St John's Square as metal stockholders until c. 1988, when they relocated to Chelmsford. (fn. 128)

In 1999 the buildings were pulled down to make way for the present glass-fronted offices, occupied by the advertising agency McCann-Erickson (Ill. 146). The development was carried out by Meritcape Ltd. (fn. 129)

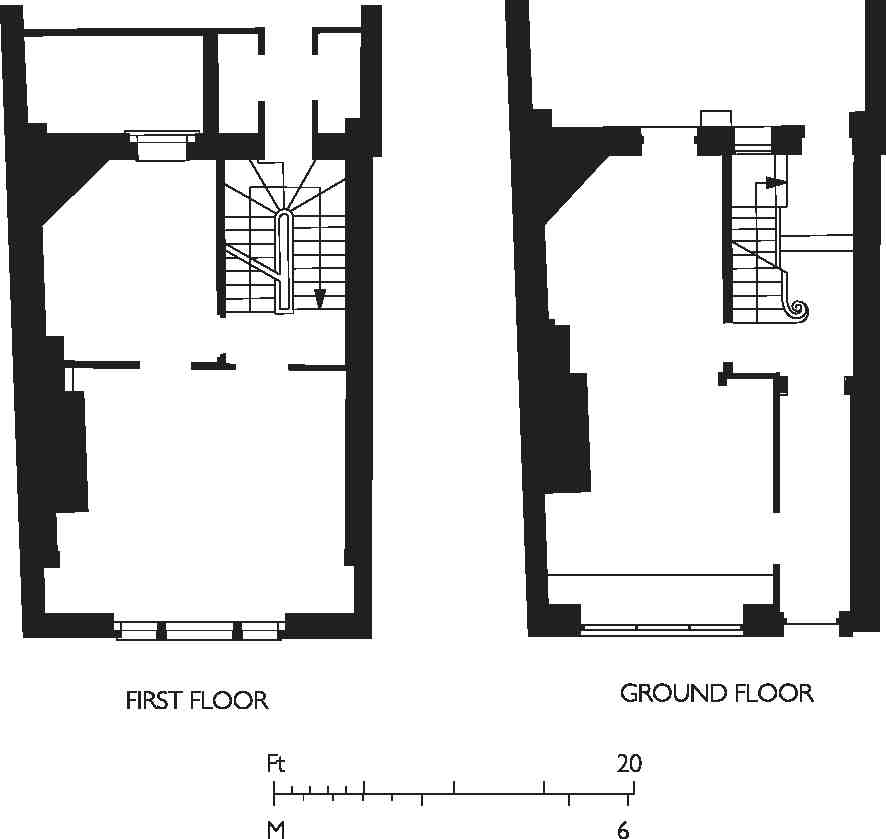

Nos 47 and 48

Behind its outer skin of early twentieth-century brick, No. 47 is recognizably a house of the 1730s, when it was built for Giles Grendey or Grindey, the Gloucestershire-born furniture-maker. It stands at the south end of the site of the Great Chamber of St John's priory, a series of apartments that once took up most of the east side of presentday Jerusalem Passage. Fabric from the Great Chamber and the post-Dissolution house which evolved from it survives in the basement, in the form of stone walls and brick vaults extending northwards under No. 48 (Ills 134, 166).

An important figure in the furniture trade, Grendey supplied chairs and cabinets to the middle-classes and gentry, and produced some elaborate pieces for export to the continent, in particular Spain and Portugal. In the early 1720s he took rooms in the southernmost end of the house on the Great Chamber site as his home and workshop. At this stage he shared the premises—misleadingly referred to at the time as 'Ailesbury House'—with an organ-maker called Briggs on the second-floor, and an upholsterer (presumably upholstering Grendey's chairframes); the vaults beneath the house were let to the Jerusalem Tavern in Jerusalem Passage for storing wine. (fn. 130)

167. Nos 49–52 St John's Square in 1946

In August 1731 fire broke out in Briggs's rooms, destroying the entire house and 'two others backwards' (presumably other parts of the Great Chamber range). (fn. 131) Grendey lost some £1,000-worth of goods, packed for exportation 'against the next Morning', and other valuable items, including an easy chair 'of such rich and curious Workmanship, that he had refus'd 500 Guineas for it, it being intended … as a Present to a German Prince'. (fn. 132) His stock was insured for only £500. (fn. 133)

After the fire the present house was built on the surviving Tudor vaults, presumably to suit Grendey; for, although he was only a lessee (of the Smith-Barry family, the freeholders), he continued in business here as the principal occupant until 1778, when he retired to Palmer's Green. Grendey, who also traded in timber, had a warehouse and yard adjoining the house. (fn. 134) For a time he also had a small shop on the other side of Jerusalem Passage, and with the house rented a stable and coach-house in the south-west corner of the square, where he seems to have had a sawpit. (fn. 135)

A view made in the 1820s shows the house with a plain front of regularly spaced windows (Ill. 141). As now, the west side was blank, with blind windows in all three storeys at its south end, where there was a chimney-stack; the breast has since been removed from the ground floor, to accommodate a shopfront.

The rooms were evidently arranged on either side of a central staircase hall, entered from a door in the middle of the west front. Such a plan is confirmed by partitions and ovolo-moulded panelling on the upper floors, though the layout of the ground floor—an open space since the 1880s—is less certain, the beams and joists in the floor above suggesting greater sub-division. (fn. 136) Box-cornicing and parts of the original floor-frames and roof-timbers survive.

After Grendey's departure, the house became an alehouse, called St John's Tavern, which it remained until the early nineteenth century. (fn. 137) In 1826 it was purchased by William Clare, a feather-bed maker, who lived here, at the same time letting part of the house to the Finsbury Savings Bank, and the vaults to a wine merchant next door at No. 48. The bank remained here until 1841–2, when it moved to purpose-built premises in Sekforde Street. (fn. 138)

Thereafter the house was shared by various independent craftsmen until the mid-1870s. (fn. 139) According to the local architect and antiquarian W. P. Griffith, by 1861 the vaults were in use as Turkish baths and had been cementrendered. The baths appear to have been a commercial failure and short-lived. (fn. 140) From 1875 until c. 1905 the house was the headquarters of Clements, Handley & Co., dealers in jewellers' tools and materials, and clockimporters; by this time a series of shopfronts had been inserted. (fn. 141)

Subsequently John Smith & Sons took a lease of the premises, later acquiring the freehold. (fn. 142) The present stock-brick facing probably dates from 1912, when Smiths carried out structural repairs and alterations to all their buildings on this side of the square, or 1930 when another programme of repairs was undertaken. (fn. 143) At the time of writing (2006) the building is intended to be used as a restaurant and delicatessen. (fn. 144)

No. 48 was the largest of a row of four houses (the others being Nos 5–7 Jerusalem Passage) erected here in 1784 by John Sergeant, a Bermondsey bricklayer, as part of Gabriel Gregory's development (see below). (fn. 145) The others were pulled down as part of the LCC's clearance of the Aylesbury Place area in 1906.

Nos 49–52, and 8 Jerusalem Passage

These houses, of which only the façades are original, are built on the site of the Great Hall of St John's priory. They were built as two pairs, and replaced two houses of postDissolution date, possibly converted from the Great Hall itself. Nos 49–50 and 8 Jerusalem Passage were built in 1780, Nos 51–52 in the early nineteenth century (Ill. 167). Part of the undercroft to the hall remains beneath Nos 49–50.

In 1757 the larger of the two post-Dissolution houses (on the site of Nos 49–50 and 8 Jerusalem Passage) was taken by Benjamin Lamb, a clock- and watchmaker, as his home and workshop. By 1777 he had been joined there by Benjamin Webb, 'maker to His Majesty', and the two men continued in business together until Lamb's death in 1781. (fn. 146) In 1780 Webb's kinsman the Southwark builder Gabriel Gregory built two new houses on the site as part of a redevelopment which involved the demolition of the postern gate and the last remaining fragment of the Great Chamber, and included the construction of houses on the east side of Jerusalem Passage. (fn. 147) Both new houses were occupied by Webb, but he moved to Red Lion Street when Gregory sold them in 1805. (fn. 148)

By 1812 the St John's Square house had become the printing-office of William Lewis, formerly of Paternoster Row, and this it remained until the early 1820s. (fn. 149)

The smaller post-Dissolution house had by 1785–6 been taken by the Finsbury Dispensary, a charitable establishment intended to provide free advice, medicine and food to the 'necessitous' local poor. This moved to St John Street in about 1806, apparently to avoid costly repairs on the renewal of the lease, and the old structure was either pulled down and replaced by two new houses, or repaired and divided. (fn. 150) By 1818 these were occupied by the printer John Foster Dove, who gradually expanded into Lewis's former premises next door, and by 1825 was using all four properties for his dwelling-house, printing-works and offices. (fn. 151) He was the publisher of 'Dove's English Classics', reprints of standard literary works including Izaak Walton's Compleat Angler, and Pope's Poetical Works. (fn. 152) During his occupancy the Gregory buildings were turned into three houses, one of them a small dwelling entered from Jerusalem Passage. (fn. 153) The stuccoed doorcases on the main St John's Square front were probably added at this time (that at No. 50 was moved during the 1980s redevelopment). Interior features at Nos 49–50, recorded before demolition—such as slender stick balusters and reeded chimneypieces—point to some interior remodelling in the early nineteenth century. (fn. 154)

Dove left the square in the early 1830s, and was succeeded at the Gregory houses by Francis Bryant Adams & Sons (formerly of No. 8 St John's Square), makers of clocks and watches, who remained here until the late 1870s. The second pair of houses, on the dispensary site, was pulled down in the early 1830s and rebuilt for David George Foster, ironmonger, who himself occupied the larger of the two new houses (now No. 51); by 1845 he was occupying both. (fn. 155)

Foster's business was acquired in 1859 by the clockmakers Smith & Sons, to whom he was related, his premises becoming their metal and tool warehouse. In the twentieth century Nos 49–50 were also acquired by Smiths. (fn. 156)

Redevelopment as offices and flats, behind the existing façades, was carried out in 1987–8 by Graham Berry Partnership for Clayform Properties plc. (fn. 157)

Jerusalem Passage

Jerusalem Passage (Ills 138, 168) follows the line of the covered 'long entry' to the priory of St John, which was demolished in 1780 together with the postern gate at its south end. No. 11 was probably built in the 1750s, and prior to its modernization in the 1950s still had some eighteenth-century panelling and corner fireplaces in the rear rooms. (fn. 158) No. 12 is of similar or slightly earlier date, and also has been stripped of original fittings. (fn. 159) Nos 9 and 10, faced in red brick with segmental window arches, are somewhat different in character. Though easily mistaken for a double-fronted house, they were built in 1828–9 as a pair, each having an old-fashioned central-stairwell plan; No. 10 (the smaller of the two) perhaps incorporated the remnants of an older building. They have since been largely rebuilt behind the façades. (fn. 160)

168. Jerusalem Passage, looking west from the site of Bishop's Court, 1912

Thomas Britton, the 'musical small-coal man'

From about 1677 an old stable on the east side of Jerusalem Passage, at the Aylesbury Street end, was occupied by Thomas Britton, a small-coal seller, who used the ground floor for storing coal and resided in the hayloft. (fn. 161) No ordinary coalman, Britton was a collector of books and manuscripts on music, science and esoteric subjects, and through Dr Theophilus Garencières of Clerkenwell Close developed an active interest in chemistry. His 'unexpected Genius' brought Britton into contact with collectors and dilettanti, including Roger L'Estrange of Hunstanton, who encouraged him in establishing a musical club.

On Thursdays from 1678 until his death in 1714, enthusiasts climbed the outside stairs to Britton's cramped and low-ceilinged den for concerts at which guest performers included John Banister and Philip Hart and later Handel, J. C. Pepusch and Matthew Dubourg. Britton and L'Estrange often played viol da gamba and bass viol respectively, and other amateurs to take part were the poet John Hughes, the portraitist John Woolaston, and Obadiah Shuttleworth, later organist at the Temple church.

At first the gatherings were small and entrance free, but as word spread, drawing West End society and foreign tourists, Britton charged an annual fee. On occasion recitals took place in a larger room in the adjoining house, so that 'the Company might not stew in Summer-Time like sweaty Dancers at a Buttock-Ball, or like Seamens Wives in a Gravesend Tilt-Boat, when the Fleet lies at Chatham'. (fn. 162)

The building disappeared with the redevelopment of this corner of Jerusalem Passage and Aylesbury Street in 1727. Its site was occupied by the Bull's Head at No. 16A Aylesbury Street, since demolished, and is now marked by a plaque at the rear of the former Pollard's shop-fitting works in St John Street.

Albemarle Way