Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Northampton Square area: Introduction', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp294-304 [accessed 6 May 2025].

'Northampton Square area: Introduction', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed May 6, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp294-304.

"Northampton Square area: Introduction". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 6 May 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp294-304.

In this section

CHAPTER XI. Northampton Square Area

410. Northampton Square area

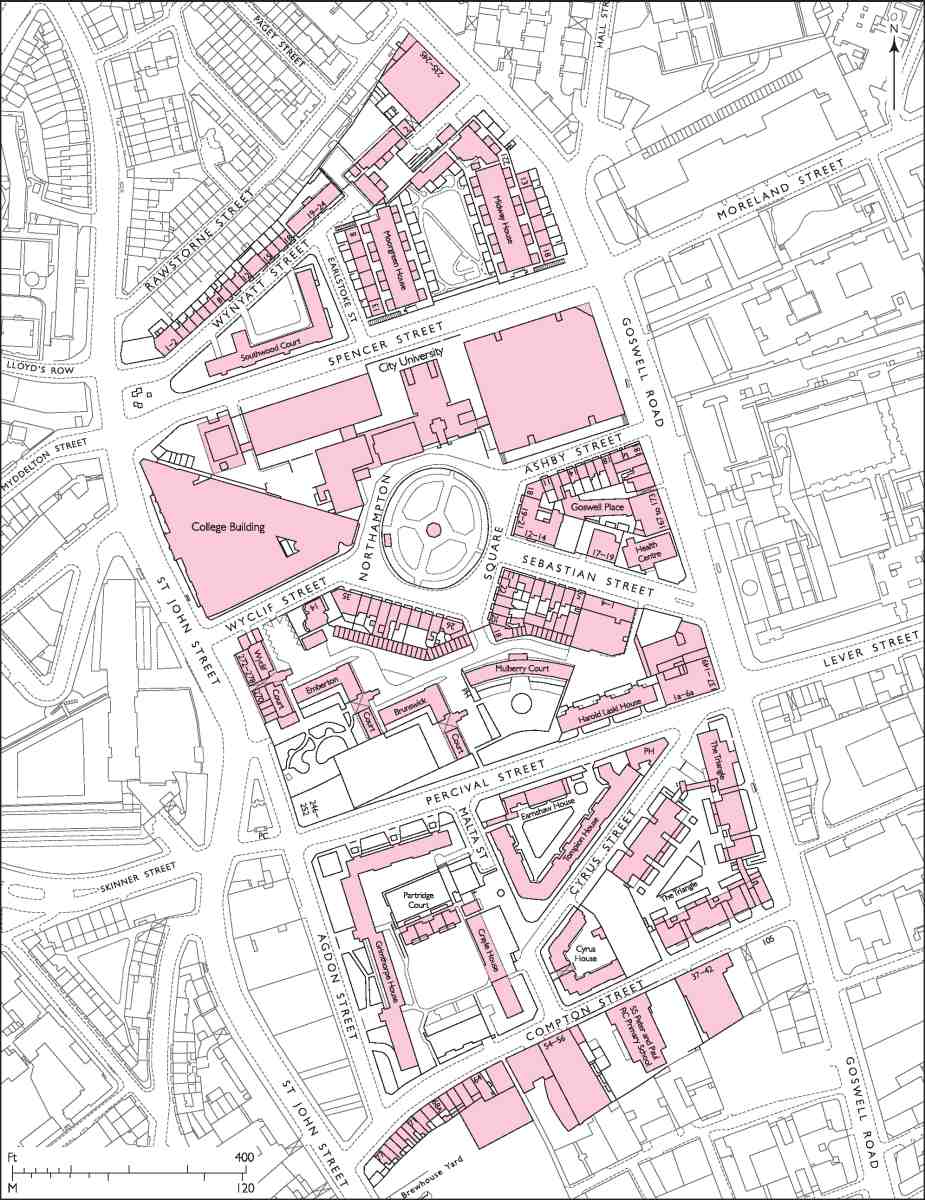

Centring on Northampton Square, the large and diverse area described in this chapter extends north from Compton Street to Wynyatt Street, and is bounded on the east and west by Goswell Road and St John Street (Ill. 410). It was, historically, known as Woods Close and belonged from the end of the sixteenth century until the middle of the twentieth to the Earls, later Marquesses, of Northampton—the eastern of the two Northampton landholdings in Clerkenwell.

Before its systematic development in the early years of the nineteenth century, the ground was mostly pastoral. But it was far from idyllic, lying as it did on the margin of London and alongside a main droving road to Smithfield. It contained, besides a few houses of lowly character, a lunatic asylum and a sale-ground for sheepskins, while across the ground ran the water mains of the New River Company, beside which nightsoil was deposited. (fn. 1)

The new streets and houses attracted inhabitants from among those engaged in the metal-working industries, chiefly clock- and watchmaking, already established in Clerkenwell. Indifference or laxity on the part of the estate management allowed the insertion of small houses in courts, and slum conditions flourished. In the 1880s overcrowding and poor living conditions on the Northampton estate were the subject of scrutiny by the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes, and although some amelioration resulted it was not until the twentieth century that drastic measures were taken. From the 1930s to the 1970s, Finsbury Borough Council, the London County Council and their successors redeveloped large parts of the area with public housing, some prosaic, some inspired.

Despite much twentieth-century reconstruction, some of the late Georgian houses survive, particularly in Northampton Square. A large part of the square was, however, sacrificed for the expansion of the former Northampton Institute as the City University in the 1960s. This institution was originally conceived to serve the needs of the local manufacturing industries, now entirely vanished.

Besides the older houses and the public housing the extensive buildings of the university are the largest presence. There are also some early twentieth-century industrial buildings, and a former Board School, remodelled as an exemplar of the new thinking embodied in the Plowden Report of 1967. Among several demolished buildings described is the Smithfield Martyrs' Memorial Church, a specimen of the High Victorian style which formed a striking architectural ensemble with the neighbouring Northampton Institute (Ill. 433).

The account begins with a chronological overview of the development of Woods Close, and includes some background to the management of the Northampton estate in Clerkenwell generally. The subsequent arrangement is topographical, starting with a discussion of Northampton Square and its immediate surrounds, including the City University campus and part of Goswell Road. This is followed by an account of Compton Street, whose original development dates back to the late seventeenth century, the remainder following a broadly north—south arrangement, dealing with the various public housing projects and concluding with the history of Spencer and Wynyatt Streets. Buildings fronting St John Street, in the block on the west side of Agdon Street, are described in Chapter VIII.

Origins of the Northampton estate

To the north of the built-up area of medieval Clerkenwell, the lands of St Mary's nunnery included two large fields, some distance apart, each of about 29 acres, probably arable and later, by the sixteenth century, pasture. One of these, lying between what are now St John Street and Goswell Road, was known as Farncroft or Fernfield, then by 1590 as Wood (later Woods) Close. The other, known as Hyelie (hilly) Field or Lilliefield (later Northampton or Spa Field), lay to the west, closer to the nunnery itself (see Survey of London, volume xlvii). (fn. 2)

After the Dissolution these fields were leased out by the Crown. In 1599 they were sold outright to Sir John Spencer, along with the manor of Clerkenwell, and other land further north in Islington and beyond. Spencer was a merchant who had been a pioneer in the Levant trade and Lord Mayor in 1594–5. He already owned Crosby Hall in the City and an estate at Canonbury, where he preferred to live. Against his wishes, his only surviving child, Elizabeth, married William, 2nd Lord Compton, later the 1st Earl of Northampton, also in 1599. Spencer died in 1610 ostensibly intestate, though Compton may have suppressed his will. Elizabeth inherited his properties and in 1632 they passed to her son, Spencer Compton, the 2nd Earl of Northampton. From him they descended to subsequent earls and, later, marquesses as parts of the Northampton settled estates. The two Clerkenwell fields together thus formed what came to be known locally as the Northampton estate. (fn. 3) (fn. a)

Northampton House (demolished)

Soon after the Restoration, certainly by 1666, James Compton, 3rd Earl of Northampton, built himself a fashionably Dutch-looking brick lodge on Woods Close (Ill. 411). Set back from St John Street at the end of a drive, it was on the site now occupied by the former vicarage to the Martyrs' Memorial Church, No. 14 Wyclif Street. Usually called Northampton House, but also known as the 'manor house', it was a secondary London residence for the earl and not long used by the family; the 4th Earl abandoned it by c. 1700, in favour of Bloomsbury Square.

Unfashionably located in a fairly isolated spot on the periphery of London, it was then adapted for use as a 'mad house' by Dr James Newton. He and his son, also James, both botanists as well as physicians, laid out the grounds as a botanic garden while managing the asylum up to 1750. The institution later came under the control of Dr John Monro, physician to Bethlem and Bridewell hospitals. His son, Dr Thomas Monro, who was a patron of many watercolourists, admitted the landscape artist John Robert Cozens, who died there in 1797. With development of the surrounding field under way in 1802, the establishment closed and the building was 'substantially' refurbished by Thomas Woollcott, who in 1804 took a long lease of the house and its remaining grounds to the west and south. From 1817 it was a ladies' boarding school, then in the 1850s the 'Manor House School' for boys. The property was acquired in the 1870s for the building of the Martyrs' Memorial Church, the house itself being demolished in 1874 to make way for the vicarage. (fn. 4)

Development of Woods Close, 1686–c. 1790

In 1686 the whole of Woods Close was leased to William Pym, gentleman, of Clerkenwell. His lease ran for 62 years, and gave him liberty to make bricks and build houses. Development of a humble character ensued along newly formed roads at the south end of the field (Ill. 412). By 1688 houses were being built along Compton Street, where there were nearly eighty small plots. A north—south road, spanning the bend in St John Street, was at first simply called Woods Close and then, by the 1770s, Northampton Street; it was renamed Agdon Street in 1939 (after a farm on the Northampton estate near Compton Wynyates). Another road, running eastwards at a diagonal, became known as King Street and was renamed Cyrus Street (perhaps after the Persian king) in 1880. One or both of these routes are said to have originated as a path for the arrival of James I into London in 1603. They may not, however, have been formed as streets until after 1700. About sixty small houses were built on the street called Woods Close, but development on King Street appears to have fizzled out by 1720, frontages remaining largely open through the eighteenth century, with a mid-century ropewalk occupying much of the south side. No buildings of this period survive. (fn. 5)

411. Northampton House, c. 1850. Looking east along what is now Wyclif Street towards Northampton Square

Much of the site now occupied by the Brunswick Close tower blocks was a sheepskin market in the eighteenth century. Charles and Richard Hore were granted letters patent to hold this market 'for the buying and selling of raw and undressed skins of sheep and lamb' in 1707, probably by way of a reward for Charles's role in exposing fraud in naval provisioning in 1703. South of Northampton House, on a plot previously known as the Vinegar Ground (and coincidentally just across St John Street from land owned by the Skinners' Company), the Skin Market was an irregular open quadrangle lined by sheds, running about 100 yards back from its St John Street entrance. It was wound up c. 1815, by which time the site was surrounded by houses and ripe for redevelopment. (fn. 6)

412. Woods Close. Extract from Rocque's map, 1747

Another early route, like King Street, ran diagonally across the otherwise open field north of Northampton House and the Skin Market. It survives in part as Sebastian Street, and more of its line endures as the break between the new and old buildings of the City University. This line was the route of the New River Company's major wooden water main from New River Head towards the City; the water company leased the pipe's bed and the fields on either side. By the 1740s the south side of the path along which the water main ran was home to a public house, the Lord Cobham, on St John Street (Ill. 412). Later decades saw the building of a few two- or three room houses along the frontage behind the pub on what came to be called Taylor's Row.

The Goswell Road frontage as far north as the water main had been built up by 1784 and there was also humble redevelopment along and off Compton Street after 1770, including Northumberland Court (later Northampton Place), fourteen meanly compressed houses of 1776, on what is now a school playground. The seventeen similarly squeezed houses of Northampton Court, just south of the Skin Market, were put up in 1775–8. By 1790 Taylor's Court had been built behind the Lord Cobham, and rebuilding on the west side of Northampton (Agdon) Street was underway. (fn. 7)

Planning and development from 1791

The last decades of the eighteenth century were not good years for the Northampton Estate. Extravagant spending by the 8th Earl, Spencer Compton, became ruinous after a contested election in 1768. He left England for good in 1774, took up voluntary exile in Switzerland, and put his affairs in the hands of trustees, led by his banker and brother-in-law, Henry Drummond (c. 1730–95). Another trustee was Thomas Walley Partington, whose law firm collected the Estate's London rents. He was appointed to look after the London property, which had obvious potential for improving the family finances. This stewardship was increasingly delegated to a junior partner, Edward Boodle (1751–1828). The firm drew on its substantial experience in an equivalent role on the Grosvenor estate in Mayfair, which, from 1785, was also held in trust (Drummond being one of the trustees). There a programme of lease renewal took off in 1789 (see Survey of London, volume xxxix). Around 1790 two nephews of Drummond also became active in the affairs of the Northampton Estate. They were Charles Compton (1760–1828), a man of letters and the heir apparent, and his cousin Spencer Perceval (1762–1812), a lawyer and aspiring politician. Charles Compton's father-in-law, Joshua Smith, a wealthy timber merchant and MP who Drummond had introduced to Compton, was involved as well. (fn. 8) In April 1796 Compton succeeded as the 9th Earl, and was rarely in London thereafter, but he continued to have an active involvement in the affairs of his London estate, meeting Boodle about a dispute with the New River Company as late as September 1799 (see below). (fn. 9) Perceval, Compton's 'man', followed him as MP for Northampton, and his ministerial career began in 1798. (As premier, Perceval returned the favour, securing him a marquessate, though this was only seen through after Perceval's assassination.)

In May 1791 Boodle, who two months earlier had succeeded Partington as the earl's senior London solicitor, met Samuel Pepys Cockerell to give him instructions for a survey of Woods Close, where the New River Company's lease of land around its water main was due to expire in March 1795. Boodle's new authority may have been the catalyst for this initiative on behalf of the Northampton trustees. Cockerell, as district surveyor for the parish of St George, Hanover Square, would have been well known to Boodle, who was also based there. Within a year Cockerell had prepared a 'plan for improvement of the Woods Close Estate'. This included an east—west road along the line of Spencer Street that was to have continued westwards across New River Company land and the western part of the Northampton estate as far as the Fleet valley (presentday Farringdon Road). Land was advertised, and offers began to come in. But another year on, when Boodle, Perceval and Drummond met to receive a report from Cockerell, there had been little progress. (fn. 10)

Driven by the need to restore the Compton family finances, the Estate was thus aiming to take the lead in the northwards spread of built-up Clerkenwell—Pentonville and the Brewer's estate, away to the north, were at this point more extensions of Islington than of London. Within sixty years this growth was to see the whole parish covered in houses. But through the first twenty-five of those years development was essentially confined to Woods Close.

In turning to Cockerell the Northampton trustees were employing an architect of high reputation who was already similarly engaged as surveyor to the Foundling Estate in Bloomsbury. For the latter he had planned various classes of houses, duly separated and respectable throughout, but diverse enough to attract investors. 'Principal features' (squares) were to be of sufficient presence as to draw speculators to the lesser parts, but not so extensive as to invite over-reach and failure. He also urged that outer or marginal developments should be modified to blend with neighbouring properties. (fn. 11) Cockerell followed the same principles on both halves of the Northampton estate in Clerkenwell, in each case introducing a central square and allowing the development to fade at the margins to humble housing.

None of this could be achieved at once. To the outbreak of war and the related building slump in 1793 were added other problems. In May 1794 Boodle and Cockerell attended the New River Company board to present their plans, a delicate matter as these involved the company quitting or re-negotiating its tenancy, while at the same time co-operating in the linkage of the separate Northampton properties. There was no getting round Robert Mylne, the company's Surveyor and a notoriously pugnacious antagonist, who 'took pains to damp Mr Cockerell's project of forming a line of communication between the two ends of the Town'. (fn. 12) So the company was simply given notice to quit Woods Close. Boodle and Cockerell took possession in March 1795, meeting Mylne on site several times, and gaining agreement to the burial of water pipes, for the continuing presence of which Boodle sought, without success, to double the rent. Boodle and Cockerell again attended the board in December 1795, this time with Lord Compton and Joshua Smith (Drummond had since died). The company was refusing either to pay for or immediately remove its pipes and litigation loomed. In the face of these difficulties Cockerell prepared a new plan in January 1796. Despite undertaking to do so he did not refer this to Mylne, though they did together survey the water pipes on the Northampton estate in 1798. (fn. 13)

In 1797 Boodle and Cockerell oversaw small-scale development at either end of the ground, where no pipes ran, rebuilding along Compton Street and forming Wynyatt Street (named after Compton Wynyates, the Northamptons' house in Warwickshire) along the northern boundary. A threat in 1799 to remove unilaterally the New River Company pipes unless the higher rent was paid led the company cynically to offer to remove its own pipes, even though 'the Detriment to the Supply of London may be so obviously seen'. The Northampton interest caved in, accepting the old rent, and agreeing that Mylne and Cockerell together should agree a plan for altering the mains consequent on the laying out of new streets. (fn. 14) It was probably at this point that the square at the centre of the development was reset on a diagonal alignment to reconcile it with the continuing presence of the water main along what was to become Charles Street. This roadway was built over the pipes, with basements at what had been ground level, producing at its west end a hazardous disjunction with the older and lower houses of Taylor's Row. (fn. 15)

In June that year Boodle met Samuel Danford, a Clerkenwell bricklayer and builder, who in 1784 had built up part of the estate fronting Goswell Road south of the water main (the site of Nos 137–157), and had done more building on King (Cyrus) Street in 1792. Danford had worked with Boodle and Cockerell from at least 1796, when they discussed plans for building in Canonbury. (fn. 16) Cockerell had learned, through working with James Burton on the Foundling Hospital estate, the value of a single strong contractor to drive through development, (fn. 17) and clearly hoped that Danford would play that role. Danford eventually agreed, in 1802, to take on just the south-east quarter of the intended development. (fn. 18)

Boodle and Cockerell had also met two more of Clerkenwell's leading tradesman entrepreneurs, Thomas Woollcott and Thomas Carpenter (see below), and Colonel William Tatham, who was projecting a canal across north London that would have run below the New River Company's pipes. (fn. 19) The canal came to nothing and the idea of a road to link the Northampton fields via the New River Company's Waterhouse Field was revived in 1804, but with the pipe-rent issue unresolved had no chance of success. The breadth of Spencer Street is the legacy of Cockerell's ambition. (fn. 20) While the New River Company's obstructiveness was certainly a factor in delaying development on the Northampton estate, blame cannot be laid entirely at that door. Boodle was busy elsewhere and not, in any case, notably energetic; regarding his work for the Grosvenor Estate, John Hailstone commented in 1808 that it is 'impossible to drive him beyond his easy amble'. (fn. 21) Nor was Cockerell, who also had much else to attend to, ever very closely engaged. On the Foundling Hospital estate he was criticized for inadequate supervision, leading him to resign that surveyorship in 1808.

None the less, all the major new roads of the Woods Close development had been laid out by the end of 1804, and there was vigorous progress with houses through that first decade of the century, years during which the building cycle was generally on an upward curve. Cockerell had simply divided the ground north of King Street into quarters, with the diagonally set Northampton Square at the centre. Ashby Street (named after Castle Ashby, the earl's Northamptonshire seat) ran east—west and Smith Street (after his wife Maria, née Smith) ran north—south. Across this grid Charles Street (after the earl himself) ran from north-west to south-east, above the water main. Perceval Street (after Spencer Perceval) cut across the southern quarters in eastward continuation of Corporation Row, and Spencer Street through the northern quarters. Cockerell intended a half-circus where Spencer Street, Charles Street and Wynyatt Street converged at St John Street, but this was never realized as anything more than a large open junction, where a pump surmounted by a lamp was erected by the parish in 1821. Thomas Cromwell commented on this layout in the 1820s, finding that it was 'built on a regular plan, and with an openness, and general appearance, that reflect honour on the spirit of [the] projectors'. (fn. 22) Such favourable opinions were not to last.

The southern sectors, except around the Skin Market and Northampton House, were developed first. By 1808 the area between King Street and Perceval Street had been largely built up with about sixty small houses, principally through William Dempsey, a bricklayer of Northampton Street, who divided up his ground between Northampton Street and Smith Street by laying out Queen Street, Prince's Street and Lower Northampton Street, on which there was a large cooperage. Once the square was laid out it may, as Cockerell foresaw, have helped pull the more marginal development up in scale, as on Wynyatt Street, where the original small houses were followed by somewhat bigger ones a little later. Northampton Square, where building began in 1805, Perceval Street and Charles Street, all lined with good-sized houses, were substantially complete in 1810. Two courts were built off Goswell Road in 1808–11: Goswell Place, with just six small houses, and Goswell Terrace, with about thirty. (fn. 23) Building in Spencer Street was begun in 1808, but there was a hiatus after 1812, and this street of about sixty houses was not completed until 1816, when the building trade picked up again. The Skin Market site was densely built over in 1816–21 with about sixty considerably smaller houses, on Market Place and Street, Brunswick Place and Street, and Portland Place. In 1820 Thomas Hughes, a Perceval Street bricklayer who had built the north-east side of the square, created Spencer Place, a mazy warren off Goswell Road south of Spencer Street, comprising about thirty diminutive houses—some of only two rooms and about 10ft by 12ft. At the rear was a small Nonconformist chapel, used by a Baptist congregation before it was removed in 1869. (fn. 24)

Thomas Woollcott had the largest role, being active across much of the area north of Perceval Street as well as on Compton Street. He built some 135 houses, ranging from larger ones in the square to small dwellings in the later courts. Like the other main developers he was a member of Clerkenwell Vestry, where he was active from 1798; he also served as a churchwarden. In 1801 he was described as a carpenter, and in 1806 as a timber merchant, in partnership with Richard Woollcott, in St John Street. For a time, up to his death c. 1819, he appears to have lived at Northampton House, which he refurbished c. 1802–4. He was probably the father of the architect George Woolcot (see Survey of London, volume xlvii).

Samuel Danford, who was based on Goswell Road and who had been elected a trustee of the parish church of St James during its rebuilding, emerged as the second largest operator on the estate, being responsible for 63 houses under his 1802 agreement. These included the south-east side of the square, present-day Ashby Street, and what is now Sebastian Street, on the south side of which, in Berry Place, was a brewery, on which Danford paid the rates.

Cockerell controlled architectural design in so far as he provided the overall layout plan, typical elevations and lease specifications, as he had done on the Foundling Hospital estate. There was evidently fairly firm control of elevational uniformity, but little concern about regularity behind the fronts. Even the bigger houses were outwardly very plain and straightforwardly designed, as on Spencer Street and Goswell Road. Northampton Square, where Cockerell introduced blind arcading and cornices, was the main exception. There was considerable variation in the sizes of the houses. The early fringes of the Woods Close development, both south and north, were modestly built, fourth-rate houses fitting in with what was already there. The set-piece square and its adjoining streets were much more ambitious, though even the better streets did not rise above third rate. There were no great pretensions—even in the square second-rate houses were not specified.

In the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Northampton Estate had given leases of varying lengths, from 21 to 99 years. Once Boodle and Cockerell were in control in the 1790s there was greater consistency. Woods Close leases ran for terms of 75 years, or slightly less, calibrated so as to fall in with adjacent leases. There were the usual conditions as to keeping buildings in good repair, and standard prohibitions against noxious trades, not just in the square, but beyond. Other trades, already well established around Compton Street, were not expressly prohibited in new leases, and some sites were given over to manufacturing from the outset, like Danford's brewery.

Leases were frequently given in advance of completion, or even commencement, of building work. This was a cause of later problems. When Hughes took on the block between Northampton Square and Spencer Street in 1807 his lease specified that the buildings along the street fronts should be no less than third rate, and that elevations should conform with houses already built, also specifying materials and finishes and requiring inspection by Cockerell. Significantly, in relation to later infill or court development, it was also expressly stated that no other buildings, outhouses excepted, should be built behind these houses. (fn. 25) Typically, the main developers subassigned to numerous small and largely now anonymous builders, who simply ignored these covenants, and faced no enforcement. Control was much looser than it was to be on the New River Company estate after 1810, where leases were not given until after the completion of building works.

By 1820 back building, sanctioned or otherwise, had filled the available ground with mean houses. Together with the earlier courts this left the area very densely built up—excepting the oasis of Northampton Square, where a number of houses were unoccupied for several years. Speculators, evidently disappointed in their initial expectations, were quick to modify supply and provide accommodation for the large numbers of low-paid workers needed by local industries. In the years up to 1820 Boodle and Cockerell's attention on the Northampton estate was focused on the development of the western portion (Northampton or Spa Field). The imputation that the estate managers took their eyes off what was happening on Woods Close has to allow for the fact that this kind of poor court development was widespread in London in these years. Yet the estate did fail to impose its own covenants to enforce a higher standard. When in the 1880s the Northampton Estate agent, H. T. Boodle, claimed that these courts had 'been crammed by speculative builders into spots never contemplated by the freeholders for human dwellings' he was being economical with the truth. (fn. 26)

Social conditions in the nineteenth century

Across the Woods Close development artisan occupancy and subdivision quickly became the rule, even in the bigger houses and on Northampton Square. The area was soon an established centre of the clock, watch and jewellery trades, which had migrated northwards from older-developed parts of Clerkenwell. In the early 1840s about two thirds of the properties on Perceval Street were at least partly occupied by people in the metal trades, principally aspects of watchmaking. Declining trade led many of the masters or employer-tradesmen to move away, their places being taken by larger numbers of poorer people, many of these having been displaced by clearances in the City and for street improvements. By 1870 the population could be characterized as 'mostly of the working classes and many very poor'. (fn. 27) Crowded though it had become, this was far from being London's worst district; in 1884 its people were said to be the 'better class of the very poor'. (fn. 28)

As leases ran down, groups of lesser houses were let to middlemen or house farmers, alternatively known as 'house knackers' or 'house jobbers'. (fn. 29) These unscrupulous slum landlords, like the original developers, were often vestrymen; Decimus Alfred Ball was perhaps the largest such landlord in the Woods Close area. Where they were not already divided, the houses—even the smallest—were split into tenements to maximize rental income. Repair covenants were ignored, and not enforced. In such a densely built-up place the combination of falling employment and increasing population, exacerbated by rackrenting and slack management, was disastrous. Classic slum conditions developed, with families of six or seven living in single rooms, a family to a room being more common than not. The numbers living on certain of the larger streets increased significantly, but some of the worst conditions had for some time been north and south of the west part of Percival Street (invariably so misspelled from c. 1870), on Queen Street and Little Northampton Street, and on the short streets, collectively renamed Brunswick Close in 1873, that had been formed around the former Skin Market. Further north, Spencer Place was also bad. Goswell Place, though redeveloped, is the only surviving reminder in the area of the confined nature of these courts; its nine two-room houses (five of them divided) were recorded as the homes of 73 people in the 1861 Census.

Advised by his agent, Henry Trelawny Boodle, the 3rd Marquess of Northampton (1816–77) made a notable attempt to deal with the estate's poor housing in the 1870s, when some of the earlier leases fell in. The central and eastern parts of the triangular site between Compton Street and Cyrus Street (now the site of the Triangle) were cleared and redeveloped in two phases in 1871–2 and 1874–7 with Compton Buildings, built by the philanthropic Improved Industrial Dwellings Co., which was granted a ground rent significantly below the normal market rate. But this just displaced poverty, as few of those who had previously lived on the site could afford to live in the new buildings, where most dwellings comprised at least three rooms. Besides which, many regarded model dwellings as 'a sort of prison; they look upon themselves as being watched'. (fn. 30)

Around 1880 a sharp depression in local specialist trades coincided with gradually accumulating population pressures and the tail ends of leases. In a wider climate of concern about poor housing, catalysed by The Bitter Cry of Outcast London, published in 1883, a Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes was appointed. Critical opinion tended to deprecate the leasehold system, advocating leasehold enfranchisement and the breaking up of London's great landed estates. One of the Commissioners was W. T. M. Torrens, the Liberal MP for Finsbury and a longstanding campaigner for better working-class housing, through whose sponsorship an Act of 1868 had established the principle of compulsory purchase by local authorities for the purpose of housing improvement. The Northampton estate, its conditions having gained notoriety, was selected as a leading case study.

In November 1883 H. T. Boodle toured the Clerkenwell estate with Lord William Compton (1851–1913), the second son of the 4th Marquess of Northampton. Compton was shocked by what he saw and initiated improvements even before the Commission sat. He later became a Liberal, then a Radical-Liberal MP, then a Progressive and the first Chairman of the London County Council's Housing of the Working Classes Committee. In 1897, his older brother having died, he became the 5th Marquess. He is commemorated by a plaque mounted in 1914 on the Northampton Square elevation of the Northampton Institute, now the City University's College Building.

413. Northampton Square area, mid-1890s

The Commission's report blamed the local authority for Clerkenwell's slums more than it did the Estate, but it did show that the property had been inadequately supervised. The investigation had already provoked a change of direction, the clearance and redevelopment approach of the 1870s being discredited. Under cross-examination Boodle had argued that the building of more model dwellings was the best means of accommodating, and supervising, the estate's poor. But others disagreed. The Rev. Benjamin Sharp, vicar of St Peter's Church, declared: 'I cannot see the necessity for pulling down these fine streets of houses when they might be repaired and made suitable. The people do not want to be driven out of them'. (fn. 31) In fact, Compton had already turned to Octavia Hill for help with alternative approaches. She strongly opposed clearances and advocated direct management of slum properties, to get round the problems of lessees. Her model of active supervision was applied on the Northampton estate through the employment of a Miss Wyld, one of her 'lady visitors', or trained housing workers, to educate poor tenants, collect rents, and report to Boodle on defects and the enforcement of repairing covenants. (fn. 32)

414. Compton Street—Percival Street area, mid-1890s

In a further positive step, in 1885 the Estate gave the public such open spaces as there were, the hitherto neglected gardens at Northampton and Wilmington Squares. Antagonisms with the Vestry were buried and these spaces were transferred to its care in 1887. Small playgrounds followed in 1891, on plots near Smith Street that had been given to the Vestry and asphalted. (fn. 33) Spencer Place, perhaps the worst of the courts, was cleared and opened out as a cart- and van-builder's yard in 1892 (Ill. 413). (fn. 34) Even the notorious house-farming vestrymen had been made to improve their ways, but lease-end dilapidation and insecurity continued, vexing relations with the Vestry, particularly in relation to the western part of the estate. (fn. 35) Lord Compton's desire for improvements of larger scope led in the 1890s to the founding of the Northampton Institute for the education of young adults on a cleared site between St John Street and Northampton Square. As marquess he severed the Boodle connection and, responding to local requests, moved the estate office to Northampton Square. Charles Booth's investigators testified to what appears to have been a general change for the better. Some small masters in the metal trades continued in the Woods Close area, the population of which as a whole was said in 1898 to be 'entirely working class, but nearly all respectable'. (fn. 36)

Redevelopment since 1900

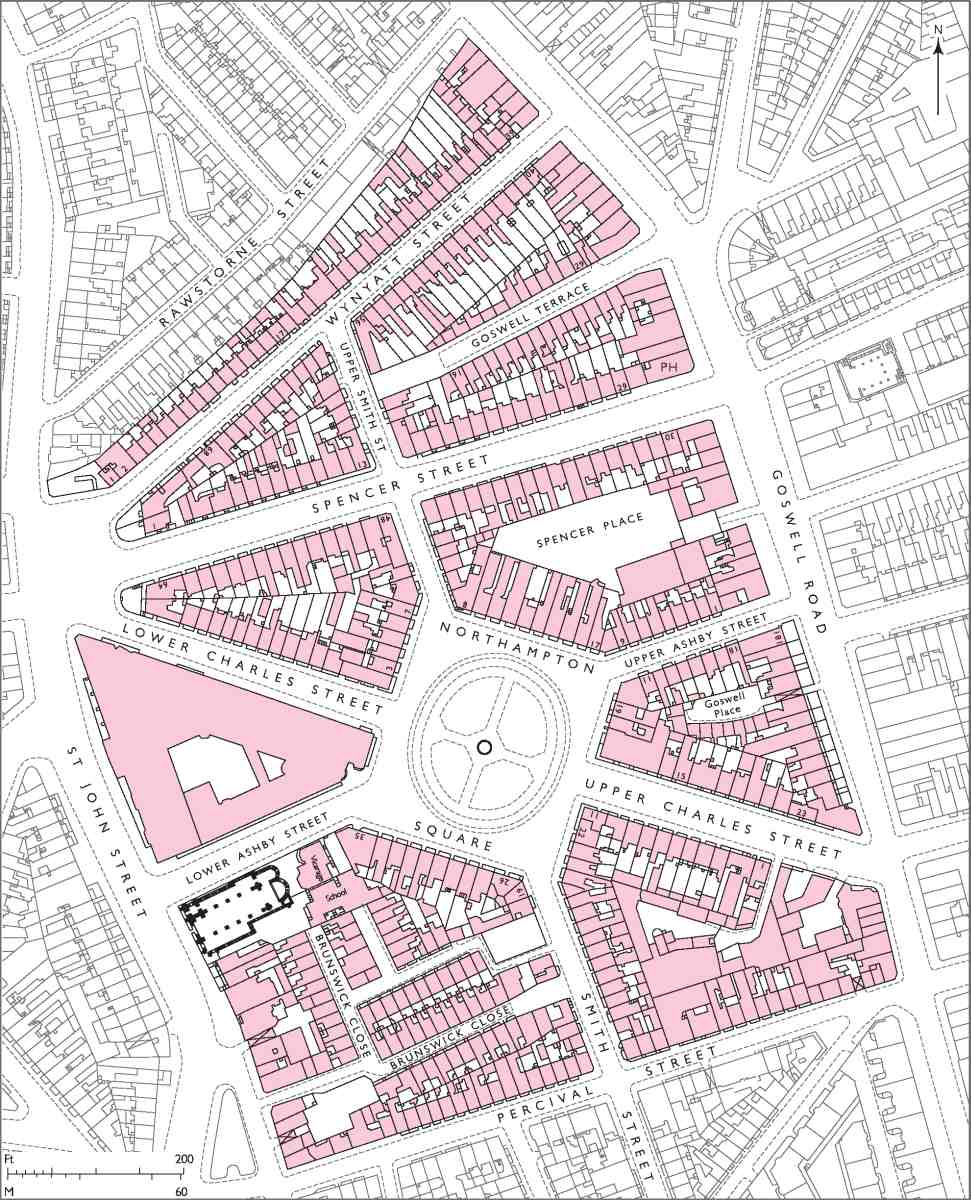

Comparison of maps from the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twenty-first shows a transformation from great density to much more spacious planning (Ills 410, 413, 414). Well into the twentieth century the buildings were simultaneously domestic and industrial, with no intrinsic distinction between houses and workshops. The area was still overcrowded with many very poor people, and clearance and redevelopment came once again into view. The leading interests—Finsbury Borough Council, the London County Council and the Northampton Estate—each saw the need for improvement through new housing and industrial premises, but their priorities differed. The municipal authorities gradually gained the upper hand, and from the 1930s to the 1970s old houses were replaced by flats in tall blocks with open spaces intervening. (fn. 37) This brought diverse groups of buildings that speak tellingly of more widely changing approaches to public housing.

At the beginning of the century Finsbury as a whole lacked vacant sites suitable for new housing, and some of its worst existing housing was on the Northampton estate. The reform-minded 5th Marquess did plan to build maisonette flats (around Margaret Street, see Survey of London, volume xlvii) before his death in 1913, but this was found to be too expensive after the war. The 6th Marquess, with P. F. Storey as his agent and surveyor, devised other plans, and was in any case discouraged from getting involved in housing, Whitehall's view being that the area should be commercial rather than residential. (fn. 38) The Northampton Estate's Percival Street Improvement Scheme of 1923–4, which nominally covered the entire area up to Northampton Square, proposed new development to extend Clerkenwell's industrial district north from the Charterhouse estate to Percival Street, a shift that had begun before the war on the widened Goswell Road. The borough council was offered some south-easterly sites for housing, at half their pre-war value, but even then it could not afford to build as it wished. The Estate's scheme was amended in 1929, and again in 1933 and 1937–8, but progress was prevented by an undertaking to the local authorities that there would be no 'dehousing' so long as housing shortages persisted. While the scheme held, up to the late 1940s, there was some piecemeal industrial rebuilding, factories and warehouses going up on Compton Street, between St John Street and Agdon Street (see Chapter VIII), on Goswell Road and even on Sebastian Street and Spencer Street.

Despite new subsidies that enabled borough councils to undertake slum-clearance developments, progress with new housing was slow given the difficulty of re-housing displaced people. Following the redevelopment of Margaret Street, Finsbury Borough Council—now under a Tory (Ratepayers) administration—did manage to build Cyrus House in 1933–4. However, it was not the borough council but the newly interventionist Labour-controlled LCC that took on the site north of Cyrus Street, as part of an arrangement to enable the Northampton Estate to proceed with industrial redevelopment further west. Clearance began before 1939, but apart from the reconstruction of the Shakespeare's Head public house on a new site building did not. (fn. 39)

The Luftwaffe cleared more space, in the Brunswick Close area and on the block between Spencer Street and Wynyatt Street, and prefabs were erected. In 1946 the Northampton Estate revived its scheme for flatted workshops, factories, warehouses and showrooms on the north sides of Percival Street and Spencer Street. This was blocked by the LCC as, amid acute shortages, the sites were wanted for housing. (fn. 40) The LCC saw through its prewar plans for the triangle north of Cyrus Street, with the Valuer's Department responsible for the building of Tompion House and Earnshaw House in 1946–9. It also compulsorily purchased the site to the west in 1947–8. The break-up of the Northampton estate continued with the sale of 14 acres to Rawlstock Investments Ltd in 1948, and the sale at auction in 1949 of much of the rest of the Clerkenwell property, followed by further local-authority compulsory purchases in the 1950s. (fn. 41) The Brewers' Company, having acquired No. 247 Goswell Road in 1923, bought Nos 235–245 in 1958, to add to its adjoining estate. (fn. 42)

In 1946 Finsbury was set to appoint Tecton as architects for an extension of Spa Green along Spencer Street (see Survey of London, volume xlvii). But the firm was subsequently sidelined, and so had no direct impact on this part of the borough. It was the LCC that brought Modernism to the area in 1949–52, in the shape of Grimthorpe House, in what had been named the Percival Street Estate. Despite this and the continuing work of Tecton's successors elsewhere in the borough, Modernism appears to have made no positive impression on George Hebson, Finsbury's Engineer, who was responsible for the wholly traditional Harold Laski House on Percival Street in these same years. Finsbury's Southwood Court of 1953–5, between Spencer Street and Wynyatt Street, was comparably unadventurous.

This cannot be said of the Brunswick Close Estate of 1953–8, built for Finsbury to designs by the established Modernist Joseph Emberton, who had earlier taken on work elsewhere in the borough, stepping into the gap left by the demise of Tecton and its successors. When completed, these three slabs were among London's tallest blocks of flats. They reflect desires to combine high densities with open space, as well as changes in the subsidy regime. Mulberry Court, added in 1959–62, can be understood as a gesture to mixed development and, through its architect, Emberton's successor C. L. P. Franck, as a manifestation of a more humane and inventive approach, harking back to Tecton.

Southwood Court apart, it was only in the late 1960s that redevelopment spread north of Northampton Square, with the clearance of substantial terraces from places that had never suffered the densities of streets further south. The north side of Northampton Square and south side of Spencer Street were completely redeveloped for the City University in 1966–74, the bulk of the new building and the obliteration of approach roads making the square seem particularly enclosed. In 1969–76 the Greater London Council built the 'streets-in-the-sky' Earlstoke Estate on the north side of Spencer Street, and in the same period Islington Council replaced Compton Buildings with the Triangle. These low-rise, high-density developments were necessarily plain, so as to meet minimum (Parker Morris) space standards within the limitations of centrally imposed budget ceilings. The GLC estates were transferred to Islington in 1981–2.

The area's prolonged reconfiguration through public building thus came to an end. Here the late twentieth century's subjection of the public sphere to the laws of the market has produced little more than a lap of waves from more dramatic 'regeneration' in southern Clerkenwell and in Islington. The displacement of industrial and commercial premises has continued in favour of further housing, of new kinds. One of the district's few remaining industrial buildings, Nos 2–4 Sebastian Street, saw an early loft conversion in 1987–9, and gentrification of many of the remaining early nineteenth-century houses ensued in the 1990s. Since then, in 2004–6, there has even been a revival of high-density court dwellings in a development on the south side of Compton Street, but aimed at a higher social level than that addressed by courts in the past.