An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 3, South west. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1972.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface: History of York and Religious Buildings', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 3, South west(London, 1972), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol3/xxxvii-lx [accessed 26 April 2025].

'Sectional Preface: History of York and Religious Buildings', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 3, South west(London, 1972), British History Online, accessed April 26, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol3/xxxvii-lx.

"Sectional Preface: History of York and Religious Buildings". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 3, South west. (London, 1972), British History Online. Web. 26 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol3/xxxvii-lx.

In this section

SECTIONAL PREFACE

Pre-Roman Settlement

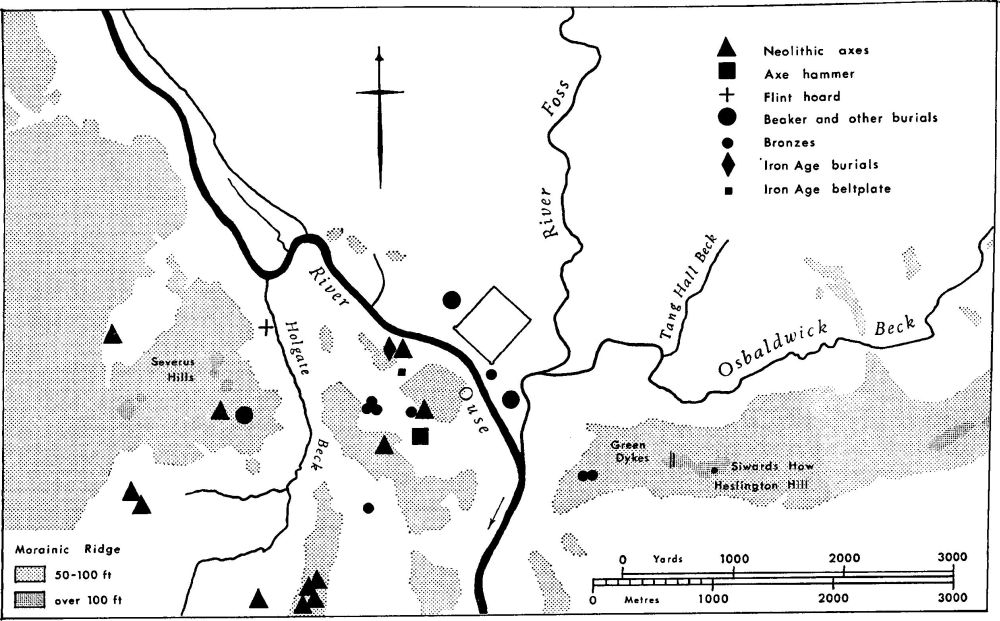

Most pre-Roman finds within the city have been made S.W. of the Ouse and for this reason it is convenient to consider the prehistoric evidence as a whole in this volume.

The importance of the geographical background as it affected Roman settlement has been summarised in York I (p. xxix) and similar factors controlled earlier settlement. The morainic ridge provided a natural causeway across the wide and often marshy Vale of York between, on the E., the chalk wolds which supported one of Britain's most significant prehistoric centres and, on the W., the Pennine foothills and the Dales which penetrated the higher land beyond.

This ridge provides an agriculturally attractive environment of well drained sandy and loamy soils, which in York reaches its greatest width about a mile S.W. of the river. The continuation E. of the river Ouse is narrower and lies S. of the junction with the river Foss. The Roman fortress was sited for tactical reasons on a small isolated block of moraine between the Ouse and Foss. As a result the river crossing has been moved N. from its natural site, and the centre of subsequent settlement lies N.E. rather than S.W. of the river. Significantly the Roman civil settlement remained S.W. of the Ouse and continued to form an important part of the mediaeval and later city. The bulk of the pre-Roman evidence comes from S.W. of the river (see Fig. 4).

There is no Palaeolithic or Mesolithic evidence from the Vale of York, although the area should have been attractive to the hunters and fishers of the latter period. The Neolithic period is mainly represented by axes and concentrations of struck flints with a distribution concentrated on the chalk and sandstone fringes of the Vale and to a lesser extent on the moraines, and absent in the low-lying areas. Within York at least twenty-three axes have been found of which all those with a sufficiently specific provenance come from S.W. of the river (see Table I, p. xxxix). Flint sites occur at Overton and Fulford just outside the city, and a unique hoard from the city was discovered during the erection of the N.E. Railway gasworks (582527) in 1868. The latter comprised at least forty-three implements including seven axes which were found in a compact group deep in the gravel terrace near the junction of Holgate Beck and the Ouse. The regular, sharp flakes and blades, and unused appearance of the finished blades suggest a merchant's hoard, whilst the inclusion of a barb and tang arrowhead could imply a late Neolithic-early Bronze Age context (YAJ, xlii, 131–2). Three finds of Beakers—a fine 'C' Beaker (York Survey 1959, fig. 11a, p. 87; YM, 1000, 1947) found near Bootham before 1842 (Wellbeloved, pl. xv, 15 and YMH 2nd ed. (1854)), and two sherds of 'B' Beaker from West Lodge Gate, probably Acomb Road, Holgate (583514; BM, 1853, 11–15, 18)—suggest late Neolithic burials within the city.

Bronze Age occupation of the Vale is limited to the dry ridges and the river banks. Round barrows occur E. and W. of York but none are proved within the city. The contracted burial in a cist under Clifford's Tower (York I, 69 n.1) need not be later than the early Bronze Age. No Food Vessels or later Bronze Age cinerary urns are known from the city. There is a marked concentration of bronze implements from the city (see Table II, below) although few have a known find spot. Bronzes also come from just outside the city, a looped spearhead from Heslington and a palstave from Bishopthorpe. The almost complete absence of bronze weapons so frequently found on the Trent together with the absence of burials suggests that York had less importance as a centre in the later Bronze Age. The moraine was, however, part of a well defined E.-W. trade route from Irish metal sources to East Yorkshire and the Continent, as demonstrated by the presence of Irish gold ornaments in East Yorkshire and the numerous bronze hoards in the Vale. Stone axe-hammers, usually attributed to the Bronze Age, are less frequent than polished axes but there are four from the city (see Table III, below) and one from Poppleton (YM, 1052, 1948).

Fig. 4. Distribution of Pre-Roman Finds in York.

Iron Age acquaintance with the site of York is implied by the Celtic origin of the name Eburacum (Vol. 1, xxx) and possible settlement on the present Railway Station site is implied by the find of contracted inhumations underlying Roman burials (Vol. 1, 85, area f, (vi)) and of the well known enamelled bronze belt plate in the Yorkshire Museum (YM, 845, 1948; E. T. Leeds, Celtic Ornament (1933), 129; C. Fox, Pattern and Purpose (1958), 119, pl. 52). The latter is dated by Fox to the decade centring on A.D. 70 and the evidence, slight as it is, is consistent with a small agricultural settlement S.W. of the Ouse on the eve of the Roman conquest, its leaders having some share in the wealth that accrued to the Brigantes as a result of their Roman policy. A cross-ridge dyke formerly existed at Green Dykes on the E. side of the river, controlling the E.-W. ridge at its narrowest point and the approach to a river crossing well S. of the Roman and later bridges (YAJ, xli (1966), 587 ff.).

Early History

TABLE I

Neolithic Axes

1. Polished greenstone axe from Viking Road. Private collection.

2. Polished blade and butt end of opaque grey flint, probably parts of one axe, and possibly dumped. Found in a garden inside Micklegate Bar. YM, 1952. 19. 1, 2.

3. Polished greenstone axe, broken. YM, Cook MS., pl. 1, no. 1; 'from the railway diggings before crossing the Ouse-Scarborough Line'. 1847.

4. Polished greenstone axe, broken. YM, Cook MS., pl. 1, no. 7; 'nigh the Railway Bridge, Dringhouses, 1851'.

5. A stone axe from Holgate. Benson, York, 1 (1911), 5.

6. A stone axe from The Mount. Benson, York, 1 (1911), 5.

7. A possible sandstone axe or hammerstone from Dringhouses. YM, 349, 1948.

8. Three polished greenstone axes, found together at Dringhouses 1884. YM, 443–5, 1948. YPS Report (1905), 50, pl. 4, fig. 2.

9. Two polished stone axes from Gale Lane. One now lost. YM, 1948, 10–11.

10. Polished cherty-flint axe, damaged. From York. Hunterian Mus. B.1951. 2594.

11. A polished axe from York. YM, 477, 1948.

12. A polished stone axe from York. YM, 1022, 1948.

13. A polished stone axe from York. YM, 1565, 1948.

14. Hoard of axes, one of which is a polished greenstone and at least six more are polished flint. With these axes were found three arrowheads, nine ovoid spearheads, three scrapers, eleven blades and flakes, and two worked points, all of flint. N.E. Railway Gasworks, 1868. YM, 446–7, 1948; YM, FW 100. 1–18.

TABLE II

Bronzes

1. Found within York

A. Flat axes

1. YM, 1033, 1948. From York.

2. YM, 1183, 1948. From York.

3. ? 'brass celt'. Knavesmire (Stukeley Letters, III, SS, LXXX (1885), 348).

B. Spear

1. YM, 1171, 1948. Looped and damaged; High Ousegate.

C. Socketed axes

1. YM, 1146, 1948. The Mount.

2. BM, WG.2010. York Cemetery.

3. BM, WG.2011. York Cemetery.

4. Sheffield Museum. J.93.507. From York.

5. ? 'bronze celt', L. 33/8 in. YMH (1891), 205. From York.

6. ? Sheffield Museum. J.93.505. 'Bought at York, from W. Cook's Yorkshire Collection.'

D. Palstaves

1. YM, 1132, 1948. Looped. From York.

2. YMH (1891), 204. Not looped. From York.

2. Found 'at or near York'

A. Flat axe

1. YM, 1242, 1948. 'Vale of York.'

2. BM, lost. Near York, decorated with chevrons. Arch. J., XIX, 363.

B. Winged axes

1. BM, 53, 11–15, 10. Near York.

2. BM, 53, 11–15, 11. Near York.

C. Socketed axes

1. BM, 63, 12–24, 1. With waste metal rammed into socket. At or near York.

2. BM, Henderson Gift. At or near York.

3. Bronze Hoards (It seems probable that two groups of finds can be justifiably recorded as hoards.)

1. BM, WG.2010–11 (see above), York Cemetery. It is reasonable to suppose that these were found together.

2. A hoard of many socketed axes, found by George Milford, 1847, during the making of a railway cutting, was formerly in the Mayer Collection, Liverpool Museum; records of one socketed axe survive (M.6996).

TABLE III

Axe-hammers

1. YM, 1020, 1948. Found 1886. L. 4¼ in. Scarcroft Road (? same as Benson, 1 (1911), 5).

2. YM, 1022, 1948. L. 6¼ in. Label reads, 'found with a celt in York', possibly a battle-axe.

3. YM, 1032, 1948. L. 8 in.

4. YM, 1067, 1948. Fragment. L. 15/8 in.

The part of the city covered by this Inventory, regarded in mediaeval times as ultra usam and sometimes described as a suburb, was always subordinate to the area on the N.E. bank of the river. It had developed from the Roman colonia, of which structural remains survived above ground in many places until after the Norman Conquest. This had been a walled town with a built-up area not completely identical with that of the mediaeval period, rising in a series of terraces up slopes steeper than at present; the streets formed a grid parallel to a main road N.W. of Micklegate leading to a bridge opposite the Guildhall; important groups of buildings stood on the sites of Railway Street and of the Old Station (Vol. i, xxxv-ix, 49–58).

Roman occupation continued into the 5th century, as shown by excavations near the church of St. Mary Bishophill Senior, and early Germanic cremation burials on The Mount are thought to be a cemetery of mercenaries rather than of invaders (J. N. L. Myres, Anglo-Saxon Pottery and the Settlement of England (1969), 73 ff.). Severe flooding during the 5th and 6th centuries rendered the riverside areas of the town uninhabitable and probably destroyed the Roman bridge (R. Cramp, Anglian and Viking York (1967), 3; more fully considered by H. G. Ramm in R. M. Butler (ed.), Soldier and Civilian in Roman Yorkshire (1971)). These areas were reoccupied by the 9th century, when metalwork was lost in Tanner Row (Med. Arch., VIII (1964), 214–16), and the main road was deflected from the line Toft Green-Tanner Row to Micklegate, curving E. to the new river crossing on the site of Ouse Bridge.

Archaeological evidence for the Northumbrian period consists of meagre finds scattered widely over the colonia area, sufficient to indicate its continued occupation. Sculptured stones indicate at least two churches, at Bishophill Junior and on the Old Station site. The numerous 10th and 11th-century finds imply that the large and bustling city indicated by documentary sources extended onto the S.W. side of the Ouse over the whole of the later walled area. During the 10th and 11th centuries were built the churches of St. Mary the Old and St. Mary Bishop, both in Bishophill, of which the former may well have replaced a still older church. St. Martin, Micklegate was founded in the 10th or 11th century. This church-building activity indicates sufficient population to justify parochial organisation. The pre-Conquest churches, other than the two on Bishophill, and including Holy Trinity, St. Martin's and probably St. Gregory's, are sited along Micklegate, and the importance of this road linking the Roman road from Tadcaster with the new river crossing was both military and commercial. Its commercial use is indicated by the satellite settlement of Copmanthorpe, a name referring to merchants (EPNS, XXXIII, 227), and by the mention of road transport in 1070–80 (YAJ, XVIII (1905), 413).

North Street, first recorded in c. 1090, and Skeldergate, attested in the 12th century but of Scandinavian origin, follow the Ouse bank and indicate the importance of river-borne commerce to the life of York. Extension of occupation downstream by satellite settlements, as the -thorpe names imply (Clementhorpe, Bustardthorpe, Middlethorpe and Bishopthorpe), was probably also commercial. The archbishop's right to custom from ships berthed at Clementhorpe is specifically mentioned in a document of 1106 (A. F. Leach, Visitations and Memorials of Southwell Minster (1891), 195–6). York on the S.W. side of the Ouse was probably already fortified before 1066 and, although the extent of these defences is unknown, the line of the subsequent Norman ramparts was followed by the later mediaeval defences. The S. extremity of the town was occupied in 1068 or 1069 by a motte and bailey castle, the Old Baile. Most of the mediaeval street names are recorded in the 12th century: this fact and their Scandinavian origin suggests that by 1100 the city's later mediaeval plan was already established.

Domesday Book (VCH, York, 19–24) provides a detailed picture of York both before and after the Norman Conquest, but the statistics are hard to elucidate and the record excludes the property of St. Mary's Abbey. Administratively the city was divided into seven 'shires', of which one was cleared of houses when the two castles were built, and there was a complex division of jurisdiction between the archbishop and the king. The importance of the city as a centre of communications and commerce is implied. The rebellions of 1068 and 1069 followed by the Harrowing of the North resulted in devastation on both sides of the Ouse and one estimate based on Domesday suggests that the population of York was reduced by half as a result. However, the population must eventually have increased as survivors from the ruined villages for miles around made their way to York. It is therefore not surprising to find two more parish churches—All Saints', North Street, and St. John, Ousebridge End—being built in c. 1100, although these too may have had Saxon predecessors, indicating a substantial influx into the sparsely-populated areas N. of Micklegate. A set-back to growth must have been caused by the great fire of 1137 which spread to this side of the river. The fact that the fire could reach Holy Trinity Priory near the top of Micklegate suggests that the street was pretty well built up by that date.

Carved Saxon Stones

About thirty carved stones of Saxon date survive from York S.W. of the Ouse; with one exception they come from the restricted area of the two churches of St. Mary Bishophill and the neighbouring St. Martin's Church in Micklegate. The exception, of unknown original derivation, was found with a mixed cache of stones, including Roman material and a Norman cross base, in the rampart of the city wall by the Railway War Memorial. Part of an elegant and well-cut cross head, it also happens to be the only stone to which a pre-Danish date can be given with any assurance.

Some of the seven stones from Bishophill Junior were also dated by W. G. Collingwood before the Danish invasions. But although none show signs of Danish influence in their decoration, only three have significant ornament. Of these one is a hog-back (3) which must be post-Danish, and another was dated by Kendrick to the 11th century. The third, a fine figured cross (1), could indeed be of 9th-century date but in view of the persistence of Anglian ornament in the other stones and the fact that excavation (by L. P. Wenham, 1961–2) failed to reveal evidence of burials earlier than the 10th century, it is perhaps best to regard all three as 10th century or later.

None of the twenty-one stones from Bishophill Senior can be put before the 10th century. Some are clearly contemporary with the 11th-century church, in particular (3), (18), and (20). Only (19) can be proved demonstrably to precede it, although others certainly did. With the exception of the large crossshaft, the stones were all probably sepulchral; six are grave covers, two certainly hog-back and two flat slabs, whilst a seventh (21) could also be part of a grave cover. Two stones could be either headstones or the bases of cross-shafts and the remainder are all from cross-shafts. A cemetery existed on the site in the 10th century and produced, beside the crosses, a strap end of probably 10th-century date and Scandinavian origin. No evidence was found for burials before the Danish invasions. The finest stone was the cross-shaft represented by (1) and (13), a fine figured shaft originally standing nearly 6 ft. high. It displays a flat linear style of which other examples can be seen at Shelford, Notts., and Leeds, and which represents a barbarisation of the pre-Danish style exemplified at St. Helen's, Auckland. The figures are reminiscent of those at Nunburnholme, but the carver of that cross has begun to move away from the linear treatment that is so marked a feature of this cross. The back of the stone shows a 'dragon' of distinctively Scandinavian type.

Another cross-shaft (2) has the fragment of what may be the nimbus of a figure in the same linear style. The only other stone with animal decoration (10) is part of a grave slab bearing a closely packed design of animals reminiscent of the more famous coped grave slab from St. Denys, Walmgate, and like it showing Scandinavian influence. Except for (21) with its crucifix and (12) which has a debased key pattern, all the other stones have an interlace pattern, usually simple but including in some cases later features such as the ring plait (15), (20) and chain interlace (16). Only (19) has any depth and roundness of relief. This stone also is the only magnesian limestone; (21) is an oolitic limestone; all the other stones from this side of the river are gritstone. With the exception of the hog-backs, the stones are similar in style and quality to those of the same date found recently in York Minster, where, in the S. transept, several graves still retained cover slabs, headstones and footstones in position.

Two stones from St. Martin are both probably from cross-shafts, one with a heavy late scroll showing on the only visible side and the other showing a late and barbarous human figure. Neither need be earlier than the 11th century. (H.G.R.)

Agrarian History

In 1297, arable strips were recorded outside Walmgate Bar in North Field, and no doubt some modified form of open field agriculture existed in other wards. Arable strips survived until 1444 in Bootham and the physical remains of early agriculture, represented by broad plough ridges, are preserved in several parts of the city. By 1546 the city appears to have rationalised its lands into forty-one closes which were leased to tenants, but strips may have survived longer in closes or groups in the hands of private individuals. Within the walls some closes were used for pasture and arable into the 19th century, for example near Walmgate, Bishophill and Peaseholme Green, but most had been built on or converted into gardens and orchards. Outside the walls the city was ringed with fields which often survived into the 20th century, contiguous with the former open fields in Acomb, Heworth and other townships, parts of which are now incorporated into the city.

By 1272 freemen and religious institutions had rights to keep a restricted number of animals, later limited to horses and cattle, and excluding pigs, sheep, and geese. Pastoral activities were always more important to the city than arable, and were carefully organised. Meadowland, or 'ings', usually on low ground, provided winter fodder, often supplemented with hay from lands held in outlying townships. The common pastures were divided into whole-year pasture on the four commons or strays, and half-year pasture, or average, on the closes which were thrown open each year from October to the end of March, representing a survival of similar rights in the former open fields.

The four strays, one for each of the present wards, formerly extended up to 6 miles from the city between the nearby villages with which they shared common grazing, and into the Forest of Galtres. By 1530 it was customary for a freeman to graze his quota of stock on the stray attached to the ward in which he lived, in the care of pasture-masters. Expansion in the city and adjacent townships created friction over grazing rights on the strays, often leading to agreements restricting numbers of animals. Bootham Ward shared its stray with Clifton, Huntington, Rawcliffe and Wigginton; Micklegate Ward with Middlethorpe and Dringhouses; Monk Ward with Heworth and Stockton-on-the-Forest; and Walmgate Ward with Heslington and Fulford. Not until the Parliamentary enclosure acts were passed did the city have exclusive rights to specific areas of stray, which are maintained by the city on behalf of the freemen down to the present time. (J.R.)

ECCLESIASTICAL BUILDINGS

York S.W. of the Ouse formerly comprised seven intramural parishes, of which three extended outside the walls and between them covered most of the suburban area. The extramural parish of St. Clement, which had given its name to Clementhorpe by the time of the Conquest, had become united to that of St. Mary Bishophill Senior for taxation purposes by the early 14th century; the benefices were formally united in 1586, when the small parish of St. Gregory was also merged with that of St. Martin in Micklegate, after a similar long period of effective union for taxation. There are now no monumental remains of the churches of St. Clement and St. Gregory, and St. Mary Bishophill Senior was demolished in 1963 (see Monument (9)). Within the suburban area were two chapels-of-ease, both to the parish of Holy Trinity (formerly St. Nicholas), Micklegate, namely St. James on The Mount, all trace of which has gone, and Dringhouses (see Monument (12)). The rural parish of Acomb was brought within the city boundaries in 1937 (see Monument (11)).

Mediaeval Churches

The churches in S.W. York are not spectacular but are of great interest. Three have towers which are specially noteable: St. Mary Bishophill Junior has a Saxon tower of exceptional size, comparable to that at Barton-on-Humber; St. John the Evangelist has the only 12th-century tower surviving in the City of York; the 15th-century tower and spire at All Saints', North Street, form a remarkable composition, comparable with that at St. Mary's, Castlegate (Plate 11), across the river. Both these last probably derive from the typical Friars' steeple and may be compared with examples like the Franciscan Friary of Christ Church, Coventry. The development of the plans of the parish churches is discussed below; Holy Trinity, having been a priory church, follows a different pattern. The development of masonry in the walling of the churches and the changes in design of window tracery are also outlined in separate sections. Among the fittings, the glass is exceptional both in quality and quantity and is discussed at some length (pp. lii–liv).

Development of the Parish Church Plan

Barwick-in-Elmet (W.R.) and Farlington (N.R.) also had churches of this type.

Rectangular Cell without Structural Chancel. The simplest form of church plan recorded in this volume is the plain rectangular cell. Excavation has shown that the earliest building at St. Mary Bishophill Senior, erected early in the 11th century, was of this type. A similar cell was added soon after the Conquest to the 10th-century tower of St. Mary Bishophill Junior, the interior of which is exceptionally large and probably had had a small eastern arm attached to it, similar to that at Barton-on-Humber. The single cell plan became common after the Conquest and in the early 12th century York churches of this type included St. Martin-cum-Gregory, St. John the Evangelist, and All Saints', North Street. Other churches that were probably of the same type occur in York E. of the Ouse and within a few miles outside the City; they are listed above with their approximate internal dimensions and wall thicknesses.

Addition of Aisles. The next stage in development is usually the provision of an aisle or aisles to the simple cell. In order to enclose the sanctuary, the 12th-century arcade at St. Mary Bishophill Junior starts a few feet from the E. end leaving a length of wall flanking the altar; this was only pierced in modern times. Except in St. Mary Bishophill Senior, where the larger Saxon cell had a 12th-century three-bay N. aisle added, the aisles are of two bays. St. Mary Bishophill Junior had a N. aisle added in the 12th century; the S. aisle is of the 14th century. All Saints', North Street had a S. aisle in the late 12th century; that on the N. followed in the early 13th century. At St. Martin-cum-Gregory N. and S. aisles were added about the same time in the 13th century and at St. John the Evangelist the earlier S. aisle was of the 13th century and the N. aisle of the 14th century. Although later expansion may have enveloped the original cell, it is usually recognised by two-bay arcades inserted in rubble walls rather less than 2 ft. 6 in. thick.

Addition of Chancels. A general development in the 13th century was the extension of the chancel. Where this already existed, an extra bay was often added to the E. Where there was no structural chancel, as in so many early churches in the Vale of York, one was added de novo. At St. Oswald's, Fulford, a simple 12th-century rectangle of good magnesian limestone ashlar was given a late 12th-century chancel of rubble. In S.W. York a fine 13th-century chancel was built at St. Mary Bishophill Senior. Smaller ones were added at St. Mary Bishophill Junior, and probably at St. Martin-cum-Gregory and St. John's.

The addition of a new chancel to a simple rectangle can be identified by the fact that it is almost always of the same width as the original cell; there is rarely a chancel arch.

The Cruciform Plan. Apart from the Priory Church of Holy Trinity, Micklegate, the only example of a cruciform plan in the area surveyed is at All Saints, North Street, where this shape was reached early in the 13th century. The evidence for transepts of this date depends on inference and is set out in the account of the church (p. 3).

Chantry Chapels. From the 14th century onwards town church plans often became complicated through the foundation of chantry chapels in or adjoining both chancel and nave. They often formed added aisles, sometimes on a larger scale than the earlier building; their greater breadth might lead to the widening of adjacent aisles. At All Saints', North Street, Benge's chantry (1324/5), at the N.E. corner, was erected to align with an earlier transept, and in c. 1410 the N. aisle of the nave was widened to the same line; at the same time Adam del Bank's chantry (1410) in the S. aisle led to the same development on that side. At St. Martin-cum-Gregory the rebuilding of the N. aisle of the nave was connected with a chantry founded by Richard Toller in c. 1332. The width of the 14th-century N. aisle at St. John's may also have been due to chantries; that the present N. wall, remodelled c. 1500, represents an earlier one is shown by the survival of a 14th-century Founder's Canopy, now cut into by a later window.

A 14th-century chapel to the N. of the chancel at St. Mary Bishophill Junior looks like a chantry. It is true that none is mentioned in the Survey of 1546 (SS, xci (1892–4), 80–2) but it is well known that these returns were not complete; moreover some chantries had become extinct before 1546. That there was a chantry of St. Katherine in the church of St. Mary Bishophill Junior seems to be clearly established by the detailed list of York clergy and their stipends compiled between 1522 and 1526 (BM, Lansdowne MS. 452, f. 1 et seq.). This names 'dominus Willelmus Richardson cantarista sancte Katerine in ecclesia beate Marie super Bishophill', whose chantry had a clear value of 20s. That this is not a chantry in the church of Bishophill Senior is proved by that church being always called 'ecclesia beate Marie veteris'; in it 'dominus Willelmus Hoperton cantarista sancte Katerine' is named, with a valuation of £3. Both of the Bishophill churches, therefore, had chantries dedicated to St. Katherine, that of Bishophill Junior being the less valuable. At St. Mary Bishophill Senior the Basy chantry of c. 1320, built to the N.E., was the same width as the remodelled N. aisle of late 13th-century date.

Final Form and Position of the Entrance to the Chancel. The process of assimilation of earlier parts of the church into a logical plan was completed by c. 1500. The typical York parish church of that date is an aisled parallelogram.

The nave aisles at All Saints', North Street, were broadened c. 1410 in line with earlier parts of greater projection, and in the middle of the 15th century an extra western bay and a tower and spire, with aisles on either side, were added. The chancel and aisles were remodelled at St. Martin-cum-Gregory after 1425 and the S. aisle of the nave was rebuilt in the mid 15th century. The arcade was rebuilt and the S. aisle widened at St. John's in the late 15th century and the N. aisle was remodelled not long afterwards.

It cannot be assumed that the division between chancel and nave has always remained constant. When the 13th-century chancel was added at St. Mary Bishophill Senior it was larger in area than the original church and later the nave was extended into the W. bay.

The reverse happened at All Saints', North Street. The chancel through much of the Middle Ages was confined to the two E. bays of the church. It is likely that the chancel was extended one bay to the W. after the construction of the W. bay of the nave and the tower c. 1440–50. The chancel had been reduced to the original size before 1670, when Henry Johnston refers to the window of the Nine Orders of Angels as being 'the first south window of the body of the church' (Bodleian, MS. Top. Yorks. C14, f. 96); thus it remained until after 1860.

Walling

Pre-Conquest. When the tower of St. Mary Bishophill Junior was restored in 1908 the foundations were discovered to be of good rubble composed of Roman tile and bricks and broken stones. Otherwise the only footings examined were those of the 11th-century part of St. Mary Bishophill Senior. The footings, in a U-shaped trench, consisted of rubble and soil, with stones pitched in a rough herringbone fashion, without mortar but set in soil and occasionally clay. They narrowed to the width of the wall built on them, from a greater width below, and were wider on the side walls than the end walls. The average depth below ground level was just under 3 ft. (For a more detailed account see H. G. Ramm, 'Excavations at St. Mary Bishophill Senior' (MS. 1966), RCHM archive.) In general the Saxon walls are built of reused Roman material, large pieces of gritstone, saxa quadrata of magnesian limestone, and pieces of brick, very roughly coursed. The inner order of the tower arch at St. Mary Bishophill Junior does not have the characteristic through-stones. The middle section of the tower of St. Mary Bishophill Junior has occasional patches of reused Roman stone placed obliquely.

In general quoins are megalithic; one at the N.E. angle of the nave of St. Mary Bishophill Senior was formed of smaller pieces. The stone of the tower arch at Bishophill Junior may have been quarried by the Saxons; it is tooled in two directions (Plate 20) giving a rough herringbone finish. The ordinary wall thickness is about 2 ft. 4 in.

Norman. The walls of the rectangular churches are all thinner than the usual 3 ft. and are of haphazard material containing reused Roman gritstone and brick and some pieces of magnesian limestone. Only at St. John's was a plinth found, of square section and Saxon in character. The N. aisle wall at St. Mary Bishophill Junior is of 12th-century date and though of rubble is better coursed.

The only ashlar in a parish church is in the tower of St. John's and this is not normal in that some of the stones in the W. wall are markedly oblong and could be reused Roman material. The other walls use the normal square blocks of magnesian limestone and the tower had a plinth of two offsets. None of these walls have buttresses. The Priory Church of Holy Trinity is built of excellent late 12th-century ashlar with fine diagonal axing (Plate 20) with a plain chamfered plinth and a simple pilaster buttress.

13th century. The chancel walls at St. Mary Bishophill Junior are of early 13th-century rubble. The large chancel at St. Mary Bishophill Senior was of similar date and had an external facing of oblong blocks of gritstone, chamfered water-table and plinth, a keeled-roll string course and pilaster buttresses. The E. wall of the chancel at All Saints', North Street, of similar date, is also of squarish blocks with a chamfered plinth and pilaster buttresses with wall arcading internally. The remaining fragment of the N. aisle at Holy Trinity Priory (under the tower) has walls with skins of excellent oblong ashlar with rubble core, and a chamfered plinth; the buttresses were semi-octagonal in plan. Particularly valuable is the close proximity of 12th-century axing and early 13th-century chiselling on the inside of the W. end, where the masonry of the N. aisle wall abuts the pilaster buttress of the aisleless Norman nave; the N. aisle walls exhibit the bold claw tooling found after c. 1200 (Plate 20). The only example of late 13th-century walling was that of the N. nave aisle at St. Mary Bishophill Senior, built of large markedly long pieces of freestone with a chamfered plinth and deep buttresses of two orders with gabled weatherings.

14th century. The practice of building with skins of ashlar and a rubble core now ceases as walls become thinner and ashlar reaches its maximum size in the wall of the N. nave aisle at St. Martin-cum-Gregory, and the E. wall of the S. aisle at All Saints', North Street, contrasting with the E. wall of the chancel, with its earlier small blocks. Claw tooling is finer than that of the 13th century but still of the same type as on the N. arcade of St. John's (Plate 20). Not enough 14th-century buttresses survive to generalise about them; plinths and water-tables are chamfered as before.

15th and early 16th century. Walls are in general of good quality magnesian limestone but the stones are not so large as in the previous century and the tooling, where visible, has a pattern of very small squares; masons' marks are more in evidence. The chancel and aisles of St. Martin-cum-Gregory (after 1425), although very weathered externally, represent work of high quality; the buttresses are narrow and deep, and the plain parapet has a moulded string at the bottom and bold gargoyles; the S. nave aisle (c. 1450) is also of good quality but more robust. Parapets and plinths are moulded and there have been good carved gargoyles. At St. John's the S. aisle wall had deep three-stage buttresses surmounted by pinnacles and a battlemented parapet. Perhaps the finest ashlar is that of the late 15th-century clearstorey of St. Martin-cum-Gregory (c. 1470–80).

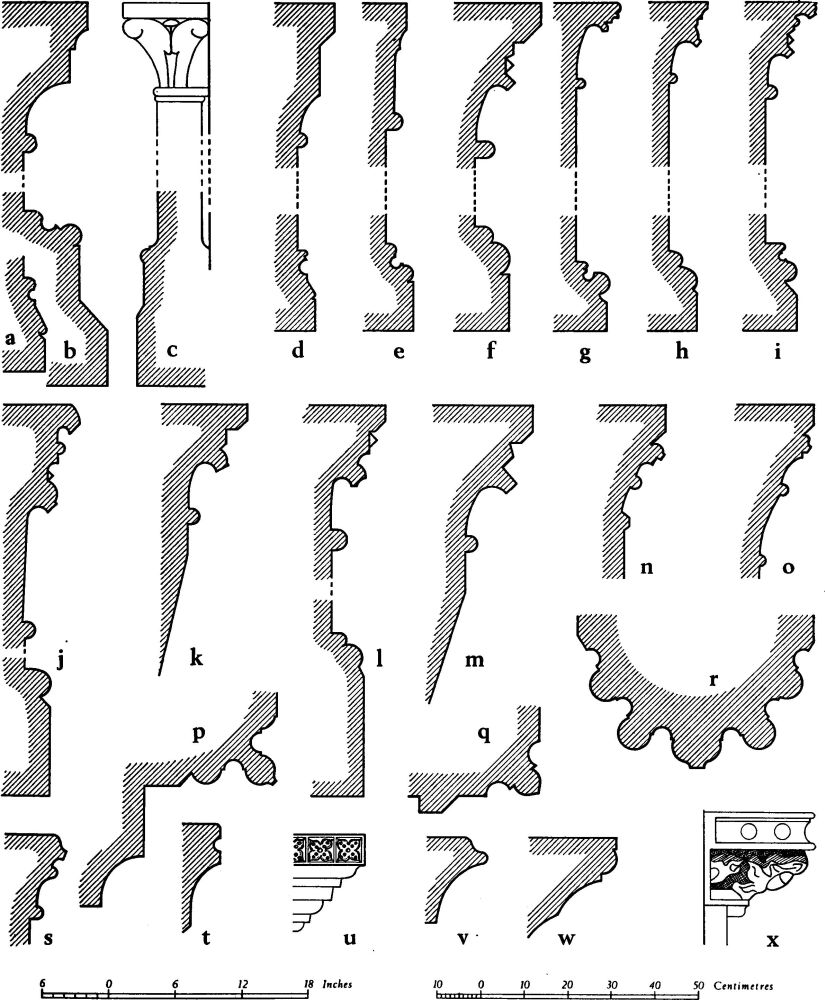

Fig. 5. (opp.) Stone Mouldings.

(5) Holy Trinity

a. Crossing. N.W. pier, minor shaft, c. 1120.

b. Nave. S. arcade, c. 1180.

(9) St. Mary Bishophill Senior

c. S. doorway, E. jamb, c. 1180.

d. N. arcade, 5th pier from E., c. 1180.

(4) All Saints', North Street

e. Nave. S. arcade, 4th pier from E., c. 1190.

f. Nave. N. arcade, 4th pier from E., early 13th century.

g. Chancel. Arcading at S.E. corner, c. 1210.

(5) Holy Trinity

h. Tower. Arcade at triforium level, c. 1230–40.

i. Nave. N. doorway, c. 1220.

(7) St. Martin-cum-Gregory

j. Nave. N. arcade, pier, early 13th century.

k. Nave. N. arcade, E. corbel, early 13th century.

l. Nave. S. arcade, pier, early 13th century.

m. Nave. S. arcade, E. corbel, early 13th century.

n. Chancel. N. arcade, pier, c. 1410.

o. Chancel. S. arcade, pier, c. 1410.

p. Nave. N. aisle. Tomb canopy, c. 1330.

(9) St. Mary Bishophill Senior

q. S. doorway, arch, c. 1180.

(8) St. Mary Bishophill Junior

r. Nave. S. arcade, western archway, early 14th century.

(6) St. John the Evangelist

s. N. arcade, first pier, E. side, late 13th/early 14th-century.

t. N. arcade, second pier from E., corbel of outer order, 14th century.

(7) St. Martin-cum-Gregory

u, v, w. N. and S. chancel aisles.Brackets, 15th century.

x. S. chancel aisle. Corbel under wall post.

Windows

The churches show a sequence of windows covering the whole mediaeval period. The belfry windows at St. Mary Bishophill Junior with turned balusters between the openings illustrate a common pre-Conquest type. A Norman window in the tower of St. John the Evangelist is of interest as it has no provision for glass. Lancets of the 13th century are exemplified at St. Mary Bishophill Junior and (before its demolition) at St. Mary Bishophill Senior. Others occur at Holy Trinity, some elaborated by shafted jambs and dog-tooth enrichment. Early tracery, of the late 13th century or c. 1300, appeared in the nave of St. Mary Bishophill Senior. The E. window at St. John's has modern intersecting tracery reproducing the form of the previous window, of the beginning of the 14th century but with the addition of cusps. At All Saints' there are windows with reticulated tracery of the second quarter of the 14th century, as well as others of the same period; the E. window has rather later flowing tracery of the middle of the century. Straight-sided reticulation was used at the beginning of the 15th century in the S. wall of the nave of St. Mary Bishophill Senior. Typical of the early 15th century are the windows in the chancel aisles of St. Martin-cum-Gregory with gridiron rectilinear tracery in sharply pointed two-centred heads. Broader in proportion and in the best Perpendicular tradition are the windows of c. 1450 in the W. part of All Saints' and in the S. nave aisle of St. Martin-cum-Gregory. Windows at St. John's show a late 15th-century form with rectilinear tracery extending down below the springing of the low four-centred heads.

Church Building after the Reformation

There was little work of note carried out in the 16th century. The 17th century, however, saw extensive rebuilding and additions in three churches. In 1646 a timber-framed structure was placed on top of the remnant of the Norman tower of St. John's, and in 1659 at St. Mary Bishophill Senior a tower of brick was erected over the W. bay of the N. aisle and a roof fitted to the chancel on walls heightened in brick. In 1677 the tower at St. Martin-cum-Gregory was rebuilt in brick with stone dressings and a balustraded parapet (the latter removed 1844–5). In the 18th century St. Mary Bishophill Junior was given new aisle roofs.

A large number of restorations were carried out in the 19th century, the majority by Messrs. J. B. and W. Atkinson. To this period also belong the erection of two new churches, St. Edward's, Dringhouses (1847–9), and St. Paul's, Holgate Road (1850–1), and the rebuilding of a third, St. Stephen's, Acomb (1830–1). St. Edward's, Dringhouses, designed by Messrs. Vickers & Hugall of Pontefract, is a pleasing scholarly exposition of Decorated Gothic. The other two are less successful. St. Paul's, Holgate Road, built by Messrs. J. B. & W. Atkinson in the Early English style, is interesting for its use of cast iron for the piers; St. Stephen's, Acomb, rebuilt by G. T. Andrews ostensibly in the Early English style, shows no real appreciation of mediaeval architecture.

(E.A.G.)

Non-Anglican Religious Buildings

By far the most interesting Roman Catholic building in York is the Bar Convent (13) in Blossom Street. The buildings are remarkably well documented and provide a gazetteer of well-known Roman Catholic architects and craftsmen. The various 18th-century buildings designed by Thomas Atkinson are all of distinction, and among them the chapel, based on a Roman model, is exceptional. The ranges dating from the first half of the 19th century by J. B. & W. Atkinson and by G. T. Andrews, the railway architect, are also noteworthy. The Convent, which has been on this site since 1686 and suffered remarkably little persecution throughout, comprises one of the oldest girls' boarding schools in England.

There were few Nonconformist chapels in the area covered by this volume and little of note survives of the only Primitive Methodist chapel (15), built in c. 1846 on Acomb Green. Albion Chapel (14) was designed for the Wesleyan Methodists by the Rev. John Nelson junior and opened in 1816 to serve the needs of the area, and also to accommodate overflow from New Street Chapel (1805). It cost £6,000 and was to provide 1,600 sittings. It survives though sold in 1856, when it was replaced by the Wesley Chapel, Priory Street, a grandiose red brick building with stone dressings designed by James Simpson of Leeds, who was responsible also for Centenary Chapel, St. Saviourgate (1840). A Wesleyan Chapel in Acomb, now represented by 91–93 Front Street (16), was built in 1821; little of it but the shell remains.

Two noteworthy burial grounds are not attached to ecclesiastical buildings. The Friends' Burial Ground (18) in Bishophill, bought in 1667 and closed in 1885, contains headstones which, after 1818, record members of most of the eminent local Quaker families who contributed so much to social life in York. A burial ground near the railway station (17) was provided during the cholera epidemic of 1832.

Fittings

Bells. Three of the bells in the area covered by this volume are of the 14th century. One at St. John's, Ousebridge, has on it a shield charged with three helmets, which could be the arms of the benefactor or a device used by the maker. The treble at St. Mary Bishophill Junior has a Lombardic inscription also found at Church Fenton, and technical details identical with the later tenor in the same church. A bell at Holy Trinity Priory was made by John Potter (Free 1359) and has the same inscription as that on a bell at West Halton in Lincolnshire (G. Benson, 'York Bellfounders', YPS (1898), 7). The two largest bells at St. John's, Ousebridge, which came from St. Nicholas Hospital, Hull Road, and one of which is dated 1408, have inscriptions in Lombardic capitals and were said by the late H. B. Walters to be the work of John Potter also (MS. list prepared for the Council for the Care of Churches). A third bell from St. Nicholas Hospital and also now at St. John's has a black-letter inscription and is a little later.

The tenor at St. Mary Bishophill Junior is probably by John Hoton of York, who was paid for a bell at the Minster in 1473/4 (Browne, 254); there are similar bells at St. Nicholas, Newcastle (two), and at Heighington and Sedgefield in County Durham (Benson, 'York Bellfounders', AASRP, xxvii, pt. ii (1904), 641). John Hoton was Free as a potter in 1455, and the Rev. J. T. Fowler noted that inscriptions commonly put on bells by John Hoton were used by Nottinghamshire founders between 1450 and 1774 (Benson, YPS, 8; AASRP, 628).

A single bell of the 16th century remains at St. Martin's, the survivor of three given by John Beane and made in 1579 by Robert Mot, famous for his work at the celebrated Whitechapel Foundry, which still exists (Benson, YPS, 11) (Plate 21). The shield charged with a crown between three bells is his mark. He was a very successful founder and over fifty of his bells remain (H. B. Walters, Church Bells of England (1912), 216).

William Oldfield's bells are the most frequent in the 17th century: one of 1627 at All Saints', North Street, one at St. John's of 1633 and one at Acomb of the same date, a bell of 1640 at All Saints', North Street, and an undated one at St. John's are either definitely or probably by him. His favourite inscription is 'Jesus be our Speed' (St. John's and Acomb), but he also uses 'Soli Deo Gloria'. A bell, now recast, at Acomb and of 1660 was the only one by James Smith (Benson, YPS, 12), but the treble at St. Martin's was made by Samuel Smith senior (d. 1709) in 1697 and one dated 1731 at Holy Trinity by Samuel Smith junior (d. 1731), all members of the same firm whose shop was in Toft Green. Their favourite inscription is 'Gloria in altissimis Deo' (also found on the first bell formerly at St. Maurice's).

A fine peal of six made by Pack & Chapman of London in 1770 for St. Mary Bishophill Senior is now at St. Stephen's Church, Acomb. The partnership was formed in 1769 and was very important until the death of Thomas Pack in 1781 (Walters op. cit., 217; J. E. Poppleton in YAJ, xviii, 92).

Bell Frames. Two bell frames of the 17th century remain, one at St. John's of 1646 and another at St. Martin's of 1681 (Plate 21); they were almost certainly made by the same craftsman, Robert Rason ('Rinson') who was paid £17 for work on the St. Martin's bell frame and steeple (Benson in AASRP, xxxi, pt. ii (1912), 614).

Benefactors' Tables. There is a good series of Benefactors' tables and all entries have been fully recorded for the Commission archive, a practice which has proved its value as some have recently been destroyed. A number date from the 18th century and others from the early 19th century. Renewal of the painted entries is often evident, for example one table in All Saints', North Street, made in 1764, was relettered in 1804. The entries on a 19th-century table at Holy Trinity are in imitation black letter with red capitals. In general the tables are of planks with a moulded frame. The one at St. Martin's is surmounted by ball finials (Plate 22), and the framing of one which formerly belonged to St. Mary Bishophill Senior has some architectural pretension (Plate 22).

Brackets. Six large moulded stone brackets, oblong in plan, at St. Martin's are of a kind that occurs more often in secular than in ecclesiastical architecture. Their use is in some doubt. A similar bracket at Norrington Manor, Wilts., still retains spikes on which candles were fixed (see M. Wood, pl. LVII, G. H. for other examples), but at Bolton Castle, Wensleydale, lamp brackets exist alongside such brackets.

Brasses and Indents. A great number of indents remain in the parish churches, particularly in All Saints', North Street, and there were many in St. John's, Ousebridge, before the recent restoration.

Six brasses dating from before 1800 give a representative series. In All Saints', North Street, are two mediaeval oblong plates of practically the same size but not by the same craftsman. One, in memory of Robert Colynson, 1458, and William Stokton, 1471, both husbands of Isabel Stokton (herself commemorated, d. 1503), is in excellent black letter (Plate 36). The other, to Thomas Clerk, 1482, though not quite so well lettered, is perhaps the more interesting because of the signs of the Evangelists on the same stone, three of which remain (Plate 27). A brass to Thomas Askwith, 1609, in the same church has an inscription in capitals on an exceptionally heavy oblong plate and a coat of arms on another shield-shaped plate. It is effective, but the execution is not so professional as that of all the others (Plate 35).

In Holy Trinity, Micklegate, an oblong plate in memory of Alderman [Elias] Micklethwait, 1632, has merely his name in a good script. The only brass with a person represented on it is that of Thomas Atkinson, 1642, in All Saints', North Street; the demi-figure is well drawn but the lettering in capitals is not so competent. The whole is engraved on a large plate with the upper corners cut off which was originally set in the same stone as that of Thomas Clerk, 1482 (Plate 35). An oblong plate in All Saints', North Street, to Charles Towneley, 1712, is in good cursive script (Plate 36).

The few other plates are all of the early 19th century. Two, of 1810 and 1839, are on an interesting tombstone at Acomb to the Hubback family. The brass to Thomas Mosley, 1624, recorded in St. John's in 1904 had vanished by 1950, and another formerly in St. Mary Bishophill Senior, with initials of the Dawson family, c. 1813, has vanished recently.

There are 18th-century Breadshelves at St. Martin-cum-Gregory (Plate 23) and, from St. Mary Bishophill Senior, at St. Clement's, Scarcroft Road (Plate 23); both are designed as entities and have contemporary enrichments. A handsome brass Candelabrum of about 1715 is in St. Martin's (Plate 24), and in the Yorkshire Museum are two enamelled prick Candlesticks discovered under the floor of St. Mary Bishophill Senior (Plate 24). Two pewter candlesticks, given in 1754 to St. Martin-cum-Gregory, are now at Holy Trinity. Chairs, of 17th or early 18th-century date, include one of 'Yorkshire' type, from St. Mary Bishophill Senior (Plate 44), which is noteworthy and probably belonged to the church from the time it was made. Two late 17th-century sanctuary chairs with high backs with cane insets and elaborate enrichment are shown as belonging to All Saints', North Street, in J. B. Morrell, Woodwork in York (1949), Fig. 162, but have not been seen recently. Only one Chest is worth mentioning; this is in Holy Trinity, of wood and leather, and of c. 1600.

Coffin Lids. There is a good series of coffin lids in the area covered by this volume and in particular in All Saints', North Street. In general it would appear that the rougher coffin lid directly placed on a coffin just below floor level was supplanted by deeper burial and a floor slab in the mid 14th century. The floor slab to John Bawtrie (1411) in All Saints', North Street, is important in this respect as it has the type of cross to be expected on a coffin lid. Practically all the lids have a cross on them and in general the crosses are (A) incised, or (B) formed in relief but in a recessed circle. If these two groups can be regarded as different techniques, then the shapes of the crosses provide further classification, which however may have no true chronological significance.

(A) Incised Crosses. Two lids have crosses based on a circle; in All Saints', North Street, (1) has straight arms to the cross and trefoiled ends to the arms all conjoined with a circle, and (7) has petal-shaped cross arms within a circle, and both are probably of the 14th century. In the same church (4) has a cross with fleur-de-lis ends set in an incised circle (Plate 27). All the other lids have crosses with some variant of trefoil at the end of each arm. The round-lobed trefoil is perhaps the earlier, succeeded in the early 14th century by the fleur-de-lis. All Saints', North Street, (9) with straight arms and round-lobed trefoil is 13th century, and St. Mary Bishophill Senior (6) has straight arms and trefoils which have a round lobe but the outer ones are on drooping stalks and are tending towards the fleur-de-lis type.

All Saints', North Street, (5) has straight arms and fleur-de-lis ends but under each fleur-de-lis is a round knop. St. Mary Bishophill Senior (1) has a cross with straight arms and fleur-de-lis ends and the tooling on the lid is of early 14th-century type (Plate 27).

Next come two lids with crosses with curved sides to the arms, fleur-de-lis ends, and voided centres to the crosses. In All Saints', North Street, (2) and the two crosses on (10) are of this form.

The crosses on all these coffin lids have been similar, but two crosses on a lid at Holy Trinity (3) are quite complicated and may be compared with some in Lindsey, Lincolnshire, described as round leaf with cross band between the leaf and the butt, and of 1200–50 (L. Butler, Arch. J., cxxi (1964), fig. 4D). Another similar cross is at South Leverton, Nottinghamshire (L. Butler, 'Mediaeval Cross Slabs in Nottinghamshire', Thoroton Soc. Trans., LVI (1952), plate 1.j.).

(B) Crosses in Relief in a Recessed Circle. In All Saints', North Street, (2), a complicated cross with straight arms and the angles filled in with circles and with all ends trefoiled, is like one from St. Mary Bishophill Senior (3), and as the lobes are of fleur-de-lis type they may be slightly later than All Saints', North Street, (6) which has straight arms each with three ends all with round-lobed leaves; all may be of c. 1300.

South Derbyshire has a semi-relief group of this type as early as c. 1210–40 (Butler, Arch. J., as above, fig. 6A) and a clustered trefoiled head like All Saints', North Street, (3) is found at Belvoir and Eastwell in Leicestershire in c. 1250/80 (ibid., fig. 6D).

Knops on the stems can vary from round (All Saints', North Street, (11)) and oblong (St. Mary Bishophill Senior (1) and All Saints', North Street, (6)) to leaves (All Saints', North Street, (12)), but they have no dating value. All bases are of Calvary type except All Saints', North Street, (3) which only has a fleur-de-lis at the foot of the stem.

Various symbols are found, including two chalices (All Saints', North Street, (2), St. Mary Bishophill Senior (6)), a sword probably for a knight (Holy Trinity (3)), a mace and a sword (All Saints', North Street, (4)), a bow and arrow and sword perhaps for a man-at-arms (All Saints', North Street, (10)), and a cleaver (All Saints', North Street, (7)).

Only two lids have fragments of inscriptions, both in Lombardic capitals. The one at Holy Trinity has H(I)C JACE[T] and one from St. Mary Bishophill Senior (4) has PRIEZ PVR LEALME....

There are two early 19th-century wooden Collecting Shovels from St. Mary Bishophill Senior at St. Clement's, Scarcroft Road. The only early Communion Rails are the oak ones at St. Martin-cum-Gregory (Plate 127) for which Mr. Matthew Butler was paid £8 in 1753. They have the semicircular front feature which is almost peculiar to York. Communion Tables are generally of oak, have turned legs and strong rails, and are of 17th-century date. The one from St. Sampson's, now at St. Mary Bishophill Junior, is perhaps the best as it has carved arabesques on three of the upper rails. The Door (Plate 15) now placed in the north doorway at Holy Trinity is of the 15th century and was found in rubbish at the base of the tower in 1902–5; with its central wicket, it is like one at the Merchant Taylors' Hall.

Fonts and Font Covers. The fonts are hardly worthy of mention, but the four early 18th-century font covers in this area form an interesting group. In general they consist of enriched scrolls conjoined at the top and are of oak, and although the general effect is Jacobean, the carving is of Baroque character. The finest is the one now in Holy Trinity, from St. Saviour's, dated 1717; it differs from the others in having two tiers instead of one, but there is little doubt that the original font cover of 1717 is the top part and that the rest was added in 1794 (Plate 28); the upper part is very much like that at St. Martin's, Coney Street, in the degree of enrichment.

The three other covers are at St. Hilda's, Tang Hall (from St. John's), St. Martin's and St. Mary Bishophill Junior (Plate 28). They all have a dove set above an acorn finial, but whereas those from St. Martin's and St. Mary Bishophill Junior are virtually identical, with urn-forms set on pedestals on the backs of the scrolls, and may be by the same hand, the one from St. John's has richer scrolls like those on the Holy Trinity cover, is more competently carved and has flaming hearts as on the one at St. Martin's, Coney Street; it is identical with one at Bolton Percy (F. Bond, Fonts and Font Covers (Oxford, 1908), 312).

Glass. The glass in the area covered by this volume is exceptional not only in its quantity but also in its dating range: there are examples of all periods from the early 14th century to 1850 and later (Plates 29–31, 98–116, 122–3). The finest body of glass in a York parish church is in All Saints', North Street, where the early 15th-century sequence is probably the best of that period in any parish church in England, (fn. 1) for all the famous groups in other English churches are later. St. Martin-cum-Gregory also contains very good glass and that from St. John's, Micklegate, almost equals it. Much of the glass had remained intact in its mediaeval form until c. 1730, but between 1730 and 1846 the glass in All Saints', North Street, was so moved about or even damaged that thereafter only one window remained intact in its mediaeval position. There is a similar story of movement and destruction in St. Martin-cum-Gregory, and the greater part of the glass formerly in St. John's, Micklegate, is now in the N. transept of York Minster. It is noteworthy that, whereas York churches had retained most of their glass unscathed through the religious and political troubles of the 16th and 17th centuries, they suffered very serious losses during a period of calm and of renewed antiquarian interest. Perhaps the brighter side of this picture is that there is also a record of restoration; many of the fragments too have been saved. The chief 18th-century glass-painter who not only produced new glass but restored the old was William Peckitt.

In the early 19th century William Wailes of Newcastle and Barnett & Son restored glass. J. W. Knowles of York repaired windows in All Saints', North Street, between 1861 and 1877 and in St. Martin-cum-Gregory in 1899; in 1965–7 the windows of All Saints', North Street, were re-arranged and again repaired by the York Minster glaziers O. Lazenby and P. Gibson.

The following account assesses the glass chronologically and gives a list of subjects, but details will be found under the respective church entries. The 14th-century painted glass is of good quality; it includes a quantity of pot metal. The canopies are of Geometrical type, and graphically there is a tendency toward minute detail.

At All Saints', North Street, the glass in the E. window of the N. aisle was originally in the E. window of the chancel and, like the masonry there, may be of c. 1330; the very much restored glass in the E. window in the S. aisle of the same church has similar details. Two lights in the E. window in the nave N. aisle wall at St. Martin-cum-Gregory are from the same shop and as they were almost certainly made for Richard le Toller's chantry of 1332, the date becomes more definite. The centre figure-subject of the E. window of the S. aisle of the chancel in the same church is of similar character and date.

Donors in the E. window of the N. aisle of St. John's, Micklegate, came from windows of c. 1340; apart from the fact that the activities of these donors, Richard and Katherine Briggenhall, John and Joan Randeman and William and Agnes Grafton, suggest this date, Richard le Toller and his wife Isabella founded a chantry here in 1320 as well as in St. Martin's and may have employed the same glazier. Diaper backgrounds and other details of glass from the E. window of the S. aisle, belonging to the Shupton and Briggenhall chantry of 1319–38, appear to be identical with, or very closely related to, parts of the great W. window of York Minster by Robert (? Ketelbarn) and precisely dated to 1339. The St. John's window showed the story of St. John the Baptist.

The E. window of the S. chancel aisle of St. Martin-cum-Gregory has tracery lights, canopies and main panels in the outer lights probably given by Nicholas Fouke whose executors founded a chantry in 1367. If, as seems almost certain, he was the Nicholas Fouke Free in 1309/10 and Lord Mayor in 1340/1, (fn. 2) the window may be of the same date as or slightly later than the previous ones.

The whole character of the glass both in texture and drawing changed in c. 1400. The early 15th-century glass has much less pot metal, much more silver stain and the figures become naturalistic. The canopies are bigger and more architectural, and detail is not only larger in scale but is also given new forms.

Virtually the whole scheme of glazing at All Saints', North Street, as completed by c. 1450 survives: it consists of the 'Prick of Conscience' window of c. 1410 given by Roger and Cecilia Henrison, Abel and Agnes Hesyl and one Wiloby; the 'Corporal Acts' window also probably of c. 1410, the donor being Nicholas Blackburn; and the 'Nine Orders of Angels' window of c. 1410–20. The date of the present glazing in the E. window of the chancel may be narrowed down to 1412–27; it has Nicholas Blackburn senior and his wife Margaret and his son Nicholas Blackburn junior and his wife Margaret as donors. The third N. window was given by Reginald Bawtre after 1429; the second S. window is dated by the donors, James Baguley and Robert Chapman and his wife, to c. 1430–40, and the latest window of the series is the fourth on the S., which may have been made between 1436 and 1451 to commemorate Richard Killingholme and his wives Joan and Margaret.

There is relatively little painted glass of the later 15th century and by far the best is the former E. window of the N. aisle of St. John's given in memory of Sir Richard Yorke after 1498 and now in the Minster, in the W. aisle of the N. transept. Otherwise there are four panels in the second window on the S. side of the chancel at St. Mary Bishophill Junior and two remarkable small panels portraying the betrayal of Christ and David and Goliath, in the third window in the S. aisle of the chancel at St. Martin-cum-Gregory.

A shield of Bishop John Alcock in All Saints', North Street, must be of c. 1500. In the same church some strap work and the initials 'BB', as well as the vanished arms of Archbishop Harsnet, were probably painted in the 17th century by one of the Gyles family, and at St. Stephen's Acomb is a very good achievement-of-arms dated 1663 and probably by Edmund Gyles.

The important 18th-century glass painter, William Peckitt, is well represented and various fragments of this date from All Saints', North Street, include one with his signature. In St. Martin-cum-Gregory the first window in the N. nave aisle was painted by him in memory of two daughters and is dated 1792, and the fourth window in the N. chancel aisle consists of three main lights all from the Peckitt workshop; the outer lights have geometrical patterns and intricate medallions; the centre light is by Mrs. Peckitt in memory of her husband and dated 1796. Two pictures of dogs in Micklegate House dated 1756, are also by Peckitt.

The most important glass-painters at work in the early 19th century were Messrs. Wailes of Newcastle. At All Saints', North Street, they made new glass for the tracery and lower part of the E. window of the chancel and new tracery lights for the E. window of the N. aisle in 1844. Eight windows at St. Edward the Confessor's, at Dringhouses, one signed 'M.W. 1849', were made by the firm, and the E. window there won a first prize in the Great Exhibition of 1851. A window of 1850 by John Joseph Barnet, late of York, in Holy Trinity is very well drawn with crisp patterns in good glass.

The scenes depicted in the glass in York are many and varied. The most remarkable subject is the 'Prick of Conscience' in All Saints', North Street, and the 'Corporal Acts' and the 'Nine Orders of Angels', in the same church are scarcely less noteworthy; all three windows are of the early 15th century; their donors are named above. The only Old Testament subject, the slaying of Goliath by David, is in St. Martin-cum-Gregory (late 15th-century), though other scenes were before 1939 in the same church.

Christ is shown in Gethsemane (All Saints', 14th-century), is betrayed (St. Martin-cum-Gregory, 15th-century), shows himself to St. Thomas (All Saints', after 1429) and is shown crowned and enthroned in the Coronation of the Virgin (St. John's, 15th-century). The story of His life is the subject of the 14th-century glass in the E. window of the N. aisle in All Saints', North Street. The Virgin occurs twice in this same church (14th-century) and is enthroned in glory in St. Mary Bishophill Junior (15th-century). The Trinity is shown also in All Saints', North Street (1412–27), and in St. John's (15th-century). The various saints depicted are listed in the Index, under Glass.

The Mass of St. Gregory in the fourth window of the S. aisle in All Saints', North Street, is of iconographical interest. The concept is probably based on the original Image of Pity in the church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme at Rome (Exeter Diocn. Arch. Soc., xv (1927), 22). The York panel lacks the Arma Christi and other elaborations found in later versions.

There is good heraldic glass at All Saints', North Street (15th to 16th-century), from St. John's, now in the Minster (after 1498) and at Acomb (royal arms dated 1663).

Hatchments never seem to have been very common in York churches and the only one remaining here is to Joshua Crompton (1832) in Holy Trinity.

Images. There is practically no good mediaeval sculpture, and the only interesting feature is a 14th-century corbel in All Saints', North Street, on the W. face of the third N. pier (Plate 18).

All the 15th-century examples are moveable and there is no proof that they belonged to the church in mediaeval times. All Saints', North Street, contains an attractive head and shoulders of a woman in limestone (Plate 39), a Nottingham-type alabaster panel of the Resurrection (Plate 39), and the wooden figure of a priest holding a chalice, all of which may have been bought by the late Rev. Patrick Shaw. A Trinity at Holy Trinity church, Micklegate (Plate 9), when bought in Holland was said to have come from the York priory. An 18th-century wooden figure of King David in All Saints', North Street (Plate 42), possibly belonged to the destroyed reredos and, if so, may have been made by William Etty in 1710.

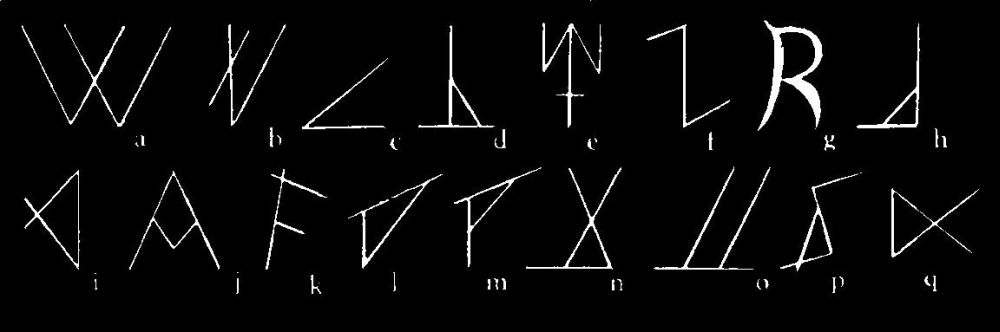

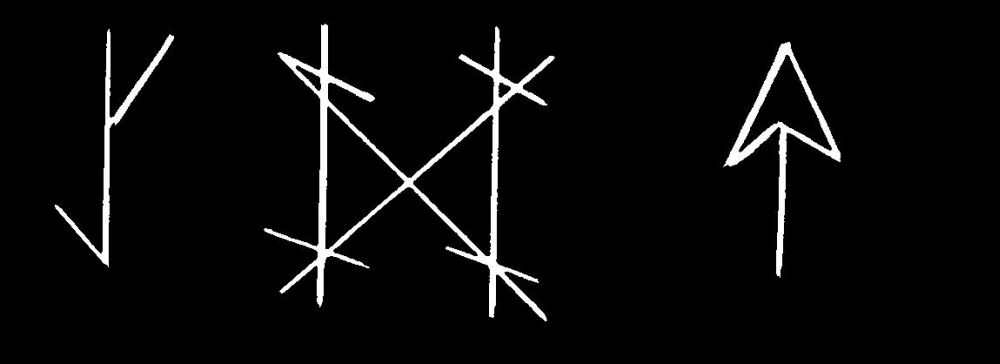

MASONS' MARKS

(See under Inscriptions etc. p. lvi.)

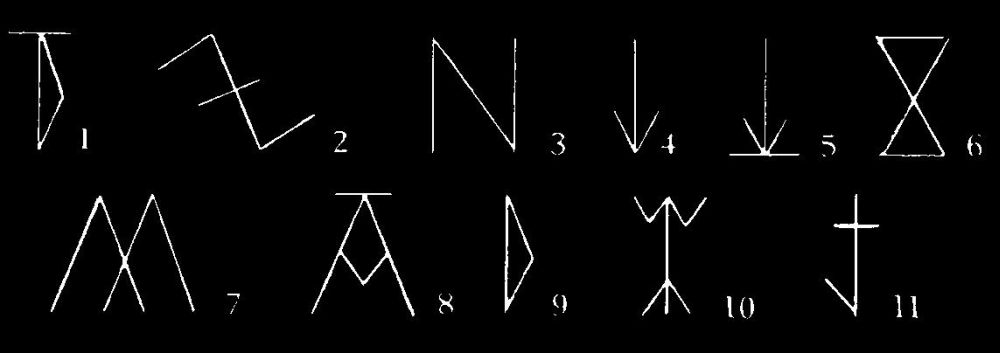

Fig. 6. (4) Church of All Saints, North Street.

a. N. arcade, second arch from E. S. arcade: first pier from E., N. side; second pier, N. side.

b. N. arcade, second arch from E.

c. N. arcade, second arch from E.

d. N. arcade, fifth arch from E., N. chamfer.

e. N. arcade, fifth pier from E., W. side. S. arcade, fifth pier, N. face.

f. S. arcade: first pier from E., N.W. side; second pier, E. side.

g. S. arcade, second pier, S.W. side (probably reused stone).

h. S. arcade, fifth pier, S. face.

i. Tower, N. pier, N. face.

j. Tower, N. pier, N.W. face.

k. Tower: N. pier, E. face, high up; S. pier, N.E. face; S. pier, S.E. face; Tower, S. arch.

l. Tower, N. pier, S. face.

m. Tower, S. pier, N. face.

n. Tower, S. pier, W. face.

o. Tower, S. pier, S.E. face.

p. Tower stair, S. side of doorway.

q. Tower stair, N. side of doorway.

Fig. 7. (5) Church of the Holy Trinity. In porch, in arch in E. wall of tower.

Fig. 8. (7) Church of St. Martin-cum-Gregory.

1. Chancel, N. arcade, W. arch, third stone on E. side. Chancel, S. arcade, W. respond pier.

S. chancel aisle, S. wall, second window from E., W. jamb.

2. Chancel, N. arcade, central pier.

N. chancel aisle, N. wall, W. window, W. jamb (twice).

S. chancel aisle, S. wall, second window from E., W. jamb.

S. chancel aisle, S. wall, third window from E., E. jamb.

S. chancel aisle, S. wall, W. window, E. jamb, fifth stone up.

3. Chancel, S. arcade, central pier.

Chancel, S. arcade, second stone on W. side.

N. chancel aisle, N. wall, E. window, E. jamb.

S. side, archway between chancel aisle and nave aisle, N. respond.

4. Chancel, S. arcade, central pier.

N. chancel aisle, N. wall, W. window, W. jamb.

S. side, archway between chancel aisle and nave aisle, N. respond.

5. Chancel, N. arcade, E. respond.

6. S. chancel aisle, S. wall, second window from E., E. jamb.

S. side, archway between chancel aisle and nave aisle, N. respond.

7. Chancel, S. arcade, W. respond (twice).

Chancel, S. arcade, W. arch, third stone on E. side.

8. Chancel, N. arcade, central pier.

N. chancel aisle, N. wall, third window from E., W. jamb.

9. S. side, archway between chancel aisle and nave aisle, N. respond.

(?) same archway, S. respond.

10. Tower arch, stone adjacent to, but not certainly part of, N. respond.

11. N. aisle, N. wall externally, on a stone next to the W. buttress of the N. chancel aisle.

The Bar Convent in Blossom Street has some exceptional later figures. Three Baroque alabaster statues, of St. Sebastian, St. Michael and St. Margaret (Plate 140), are probably Spanish and came to the Convent in 1805 through the Rev. Anthony Plunkett, who was the last Prior of the Dominican Priory of Bornheim in the Netherlands. They are probably of the early 18th century. Two white marble statues of the Virgin and of St. Joseph were bought in Florence in 1823 specifically for the Convent. Four figures of the Latin Doctors, St. Jerome, St. Augustine, St. Ambrose and St. Gregory (Plate 40), carved in solid oak in a distinctly Italian Baroque style, were once on top of an 18th-century reredos long since removed, and they and a pelican in piety fortunately survived. The St. Gregory is perhaps the best.

Inscriptions etc. Various signatures and scratchings appear on quarries in the windows of St. Martin-cum-Gregory.

There are some interesting masons' marks (Figs. 6–8), of various dates in the 14th and 15th centuries, in All Saints', North Street, and of the early 15th century in the chancel and chancel aisles of St. Martin. In general they are of simple forms and of little use for identification and dating, but one like a two-pronged fork, found on the fifth N. pier at All Saints', North Street, is found on the corresponding pier of the S. arcade, and both are associated with the tower. This latter point is significant, for a similar one is found on the S. pier of the tower of St. Mary's, Castlegate, and on the jamb of the arch to the Howme Chantry at Holy Trinity, Goodramgate (founded before 1396 and certainly built by 1433), and in St. Michael's, Spurriergate, on Perpendicular remodelling.

Two marks on the chancel of St. Martin-cum-Gregory are like ones on the S. pier of St. Mary's, Castlegate, and are also of the first half of the 15th century. St. Martin's, Coney Street, also has marks common to one or other of the above churches, and all can be assigned to the first half of the 15th century.

The only Lectern of note, of desk type, 15th-century, from St. John's (Plate 44) is now at Upper Poppleton.

Lord Mayors' Tables. The finest table of Lord Mayors is that from St. John's, Micklegate, now in York Minster (first entry 1708) (Plate 22); it is the only one to retain sword and mace rests. Tables also survive in All Saints', North Street (first entry 1723), St. Clement's (1704 and 1848) and Holy Trinity (1772); the two in St. Clement's are from St. Mary Bishophill Senior.

Monuments and Floor slabs. The only table tomb is to Sir Richard Yorke (1498) in St. John's, Micklegate. The mediaeval coffin lids provide a good series (see p. li). There are no effigies, mediaeval or later, and the wall monuments, although not of great quality, are nevertheless of interest. A list of signed monuments and tombstones follows this account.

The monuments designed as cartouches form a distinctive, and distinguished, group ranging in date from 1615 to 1766. The earliest to Ann Danby (1615) in Holy Trinity, Micklegate, of freestone with finely carved scrolls, is the only 17th-century one. The large cartouche of 1701 to Andrew Perrott in St. Martincum-Gregory has fine script and is of high quality; the small one below it to his widow, Martha (1721), is relatively crude in comparison. A cartouche to Thomas and Sarah Carter (1708) in the same church, and those to John Etty (1709) in All Saints', North Street, and Elias Pawson (1715) now in St. Clement's, are, like that to Perrott, excellently carved. Of these, the one to John Etty is particularly interesting not only in being the memorial to a very important local carpenter, to whom Grinling Gibbons may have been apprenticed, but because it could have been made by his son, William Etty, who was an equally important craftsman. The freestone cartouche to John Greene (1729) in Holy Trinity is severe compared with the previous ones, which are of white marble, and those to Anne Haynes (1747) and Elizabeth Potter (1766) in St. John's are small and show that the fashion is in decline. A lozenge in a framework (1760) in Holy Trinity is unusual.

Among other monuments noted, those of Henry Pawson (1730) and of Althea Fairfax (1744) from St. Mary Bishophill Senior, now in St. Clement's, have particularly good lettering. Two in Holy Trinity, of 1797 and 1807, are the only ones in the area embodying coloured marble; most are of black and white or veined marble. An extraordinary, and probably unique, design is that with a great charter and seal held up by two books and an urn against a Gothic frame to John and Mary Burton (1771) in Holy Trinity. The memorial to Thomas and Elizabeth Bennett (1825) in St. John's is exceptional in a different way: all the decoration, consisting of a weeping tree framing a sarcophagus fronted by a scroll, is in plaster.

Floor slabs. Numerous floor slabs have been noted, including many since destroyed at St. John's and St. Mary Bishophill Senior. All Saints', North Street, contains mediaeval ones to John Rothum (1390), John Wardalle (1395), John Bawtrie (1411) and Thomas de Kyllyngwyke (15th century). This last has an intricate cross and a good black-letter inscription. The slab in St. Martin-cum-Gregory to Henry Cattall (1460) is interesting because it has a black-letter marginal inscription within which are later inscriptions added to the Peckitt family (famous for their painted glass) and the Rowntree family who married the Peckitt heiress (Plate 36). A slab of 1599 to Joan Stoddart in All Saints', North Street, has rarity value as the only 16th-century one.

Armorial slabs of note (Plate 36) include those to Susanna Beilby (1664) in St. Martin's, Joshua Witton (1674) in All Saints', North Street, Andrew Perrot (1701) in St. Martin's and Frances Bathurst (1724) in the same church. In this context the tombstones with coats of arms of Richard Bealby (1805) and Robert Driffield (1816) at Acomb may be mentioned.

Panels. At the Bar Convent are two sets of 16th-century panels, each consisting of four panels, carved with Biblical subjects and allegorical themes respectively. The first is well carved, the second less competently done. They are both Flemish and in general consist of figures set within classical, round-headed archways. Two early 17th-century panels, dissimilar, are set in the restored, or even made-up, chairs at St. Stephen's church, Acomb; one is carved with Adam and Eve, the other with Hope with dove and anchor (Plate 42).

Plate. (Ref. T. M. Fallow and R. C. Hope, YAJ, viii (1884), 300 et seq.) Nothing of mediaeval date remains, and only two or three pieces dating from before the Civil War survive. Cups. Perhaps the earliest cup (with cover) is one at St. Mary Bishophill Junior of 1570/1 by Robert Beckwith. Another at Acomb is said to be of c. 1570; the shape and decoration are similar to those of the foregoing. A cup at Holy Trinity of 1611/12 (Plate 37), made in London, has a simple bowl and attractive stem with pear-shaped knop. The cup (with cover) at All Saints', North Street, given by Archbishop Samuel Harsnett in 1630, is also like the St. Mary Bishophill Junior one, with a similar deep straight-sided bowl with angular base. Two cups from St. Martin-cum-Gregory (now at Holy Trinity), one of 1636 and the other a copy of 1818 again have bowls like that of the early St. Mary Bishophill Junior one and stems with thin round knops. There are some good patens, other than the covers specifically associated with cups. The best is the one from St. John's (1697) (now at Holy Trinity) which has a round plate with gadrooned lip and a good stem beneath. One from St. Martin-cum-Gregory of 1737, exceptionally elegant with an elaborate deckle-edged rim, and one of 1843 at Holy Trinity are domestic salvers turned to ecclesiastical use. The flagons present an interesting series. Two at St. Martin-cum-Gregory date from 1720–9 and 1740 respectively; each has a rounded body, with curved tapering neck and lid but no thumb-piece. The one of 1739–40 at Holy Trinity is much simpler, with plain straight sides tapering upwards, a shaped lid with thumb-piece and a graceful handle. Most of these were London made. The most impressive one, however, from St. John's and now at Holy Trinity, was made at York in 1790/1; it is very simple and heavy and has a plain straight-sided tapering body, flat lid and distinctive grid-iron thumb-piece (Plate 37). Two flagons of 1781/2 at All Saints', North Street, are elegant, with urn-shaped bodies and well executed inscriptions (Plate 37).

Base Metal. Some of the pewter is noteworthy (Plate 37). Perhaps most remarkable is the flagon from St. John's at Holy Trinity which has incised figures and decoration of c. 1620. Another flagon from St. John's of c. 1725 is of a relatively rare type with bulbous body, tapering neck, lid with acorn knob and thumb-piece.

Pulpits. A pulpit at St. Martin-cum-Gregory, of Jacobean type, was made in 1636 by John Harland; it is like one in All Saints', Pavement. One of 1675 in All Saints', North Street, is enriched but in more orthodox classical style than the foregoing and had figures painted in the panels. It may have been made by John Etty; his friend Henry Gyles, the glass painter, used similar emblematic figures (Plate 38).

Reredos. The only reredos noted is in St. Martin-cum-Gregory and is of 1749–51; the churchwardens were permitted to negotiate for a reredos in 1749 and sold the old one for £2 2s. in 1751. The new one (Plate 127), made by the local joiner Bernard Dickinson, is of oak, of a robust classical design, and still retains the Commandments, Paternoster and Creed; it forms an effective composition with the communion rails (made by Matthew Butler after Dickinson's death) and the steps on which they are set. One in All Saints', North Street, made by John Etty in 1710, remained until 1807.