An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 3, South west. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1972.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'City of York, South-West of the Ouse', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 3, South west(London, 1972), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol3/xxix-xxxvi [accessed 24 April 2025].

'City of York, South-West of the Ouse', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 3, South west(London, 1972), British History Online, accessed April 24, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol3/xxix-xxxvi.

"City of York, South-West of the Ouse". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 3, South west. (London, 1972), British History Online. Web. 24 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol3/xxix-xxxvi.

CITY OF YORK SOUTH-WEST OF THE OUSE

The area described in this volume comprises the part of the walled city S.W. of the Ouse, both the ancient suburb outside Micklegate Bar and Clementhorpe, which have always been part of the liberty of the city, Holgate, which was included in the city in 1884, and a ring of outer villages, Middlethorpe, Dringhouses and Acomb, included in 1937.

The walled part of the city, of 60 acres, extends some 800 yds. along the river bank northward from the natural gully which separated the city from Clementhorpe; it has a maximum width of 500 yds. and is divided into two unequal parts by Micklegate, which links the main S.W. gate, Micklegate Bar, and Ouse Bridge. It includes part of the morainic ridge (Bishophill and Micklegate Hill) with slopes to the river.

The outer villages, now suburbs, were formally separated from the city and inner suburbs by their own fields and by the large open spaces of the Knavesmire, Hob Moor, and Bishopfields, over which the citizens had rights and of which the first two still survive.

Roman monuments and the city defences have been described in the Inventories York I and II respectively.

AUTHORITIES

The sources for the history and dating of York buildings are extremely diverse. For the period between the Norman Conquest and the reign of Henry VIII much information has been gleaned from the study of title-deeds, of which many are in print in published monastic cartularies and in two series produced by the Yorkshire Archaeological Society (Early Yorkshire Charters, and Yorkshire Deeds). There is unpublished material of the same kind in the York City Archives and among the muniments of the Dean and Chapter. From the 14th century onwards these are supplemented by the evidence of wills (Borthwick Institute and York Minster Library). For the churches, and particularly for the building of chantry chapels, there is much miscellaneous material in the calendared Chancery enrolments supplemented by original documents in York collections.

Since the 16th century a long series of antiquaries, local and national, has collected an immense body of material, much of it published. Short notes on the principal antiquarians and historians who have worked on York are appended (pp. xxx–xxxi). Their written work is sometimes supplemented by plans and drawings from their own hands, and also by the output of a number of artists and surveyors (see pp. xxxii–xxxiv). The evidence provided by the series of plans of the city is of considerable importance, though York is not so fortunate as to have any early plan showing details of individual properties, comparable to that of Cambridge by John Hamond engraved in 1592 (see pp. xxxiv–xxxvi).

For the history of houses the most important sources, apart from a few surviving series of early titledeeds in the possession of the present owners, are the Registers of Deeds and the Parish Rate Books. The volumes of Deeds registered before the Lord Mayor (YCA, E.93–E.98), covering the period 1719–1866 (few after 1832), include a high proportion of the conveyances and mortgages of real estate within the City and Ainsty though the system was not, as in each of the three Ridings, compulsory. Occasionally the text of successive deeds at a short interval affords proof of a precise date of building. This is often confirmed by changes of assessment in the Parish Rates, where these survive. In the part of York S.W. of the Ouse there are continuous assessments for Holy Trinity, Micklegate, from 1774, from 1798 for St. Martin-cum-Gregory (both in the Borthwick Institute); for St. John the Evangelist only from 1837 (York City Library); for St. Mary Bishophill Senior a broken series from the mid 18th century (St. Clement's Rectory); for All Saints', North Street, fragments; for Bishophill Junior nothing.

Mention must also be made of the rich stores of contemporary information on York houses of the Georgian and Victorian periods, and on their owners and occupiers, to be found in the local newspapers. The extant files of the York journals (from 1728) are at the York City Library, where are detailed indexes extending from the earliest issues until after 1850, and in progress for later dates.

Antiquaries and Historians of York

Roger Dodsworth (1585–1654), the earliest and most diligent of the great Yorkshire antiquaries, compiled 160 volumes in MS. before the outbreak of the Civil War; these are preserved in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Several of them are of particular importance as containing detailed accounts of church monuments in the city of York c. 1620, notably the complementary MSS. Dodsworth 157 and 161. The work of Dodsworth is for the most part accurate, and his errors are largely due to the illegibility of inscriptions and the decayed state of monuments and stained glass.

Sir Thomas Widdrington (c. 1600–64), recorder of York, compiled the first narrative history of the city, not published until the end of the 19th century (Analecta Eboracensia, ed. C. Caine (1897)). Widdrington made extensive use of the original records of the Corporation, but his work needs to be used with caution.

Sir William Dugdale (1605–86) took copious notes of Yorkshire heraldry in 1641 and again in 1666 and caused a fully illustrated and indexed compendium of these, together with material taken from the earlier heralds' visitations and the notes of Dodsworth, to be compiled. This is known as the 'Book of Yorkshire Arms' and is preserved at the College of Arms.

Matthew Hutton, D.D. (1639–1711), made extremely accurate church notes in various parts of England and also copied extensively from records not now extant. His extracts from the Chapter Act Books and other registers of York Minster are in the British Museum (Harleian MSS. 6950–85, 7519–21; especially 6984 of 1661), but a volume of church notes largely from York is in the Minster Library (another holograph copy is BM, Lansdowne MS. 919).

Nathaniel Johnston, M.D. (1627–1705), of Pontefract, made very extensive collections for the history of Yorkshire, now mostly in the Bodleian Library, Oxford (MSS. Top. Yorks. c. 13–45) and in the Public Libraries of Leeds (Bacon Frank MSS.) and Sheffield (Bacon Frank MSS. 1–13). At least four volumes of collected plans and drawings (Bernard, Cat. MSS. Angliae (1697), II, p. 101, nos. 3861, 3863–5) have been lost but two, containing many drawings by Nathaniel's younger brother Henry Johnston (c. 1640–1723), survive (Bodleian, MSS. Top. Yorks. c. 13, 14).

James Torre (1649–99), made extremely detailed collections on York Minster, with plans and sketches, and for the churches of the county and diocese. He used, and made abstracts from, many registers now lost (see York Minster Library, L.1.2 etc.) and collected 'testamentary burials' for the Minster and churches from the registers of York Wills. His work, though occasionally inaccurate, is of the utmost importance for the state of fabrics and monuments in c. 1687–91. Among his other work is 'The Antiquities of York City collected out of the Papers of Christopher Hildyard Esq.', with further detailed notes on churches (MS. in York City Library, Y.942.74–4259).

Henry Keepe (1652–88), the author of Monumenta Westmonasteriensia (1682), also made substantial collections in 1680 for a history and description of the city of York, Monumenta Eboracensia. What survives is preserved in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge (MS. 0.4.33), and includes a detailed perambulation in which Keepe was guided by 'Mr. Andrew Davye [1630–82] an antient native here, a great lover of this his birthplace and not a little verst in Antiquities...'.

Thomas Gent (1693–1778), the eccentric printer, settled in York in 1724 and published his History of the Famous City of York in 1730; substantial addenda are included in his later History of the Loyal Town of Rippon (1733). Though Gent's methods were slapdash and his woodcut illustrations crude, he preserved much valuable information on York churches, and especially their stained glass, not recorded elsewhere.

Francis Drake, F.R.S., F.S.A. (1696–1771), settled in York in 1718 and became city surgeon in 1727; after several years of painstaking research he published Eboracum in 1736. This has ever since remained the standard work on the city, though superseded on many points of detail. Drake's notes of corrections and additions are included in his own interleaved copy (York City Library).

Thomas Beckwith, F.S.A. (c. 1730–86), a herald painter, made substantial collections for a revised edition of Drake's Eboracum. These include full transcripts of monumental inscriptions in many of the parish churches, from 1736 brought down to 1782, and corrections to Drake, by pages (YAS MSS., especially M.69). Letters by Beckwith on local archaeology are preserved in the collections of John Charles Brooke (College of Arms, e.g. MS. 17B).

William Hargrove (1788–1862), a York newspaper proprietor, was a keen topographer and in 1818 published a History and Description of the Ancient City of York. His work is usually accurate and his descriptions are from first-hand observation. Hargrove's New Guide for Strangers and Residents in the City of York (1838), illustrated with many woodcuts, is of great importance for the state of York immediately before the coming of the railway.

Robert Davies, F.S.A. (1793–1875), Town Clerk of York 1827–48, was a scholarly antiquary deeply versed in the records of the city. His precise knowledge of many of the individual houses in the streets, brought together for a series of lectures delivered from 1854, was published posthumously by his widow and his nephew, R. H. Skaife, as Walks through the City of York (1880).

Robert Hardisty Skaife (1830–1916), nephew of Robert Davies, was a scholar of scrupulous accuracy and editor of many texts of importance for Yorkshire. In 1864 he published a large Plan of Roman, Mediaeval, & Modern York, compiled from all available sources. He also completed but did not publish a very large biographical and genealogical compilation, 'Civic Officials of York' (York City Library, three vols.), including every freeman of York who served the office of Chamberlain. This includes much information on the builders and inhabitants of houses as well as on individual architects and craftsmen of York.

George Benson, A.R.I.B.A. (1856–1935), was a careful observer of local antiquities and incorporated many of his discoveries in his three-volume account of York from its origin to 1925 (1911, 1919, 1925, reprint 1968). Among many other works he published The Bells of the Ancient Churches of York (1885) and an article on 'The Plans of York' (AASRP, xxxviii, ii (1927), 331–52).

William Arthur Evelyn, M.A., M.D. (1860–1935), settled in York in 1891 and built up a very large collection of plans, prints, drawings, watercolours and oil paintings of all periods illustrative of the city. The whole collection was acquired for York (City Art Gallery; plans kept in City Library). Evelyn also sponsored a large collection of photographs, including copies of material in public and private collections (now the property of YAYAS, but deposited in York City Library).

The Rev. Angelo Raine, M.A. (1877–1962), honorary archivist to the Corporation, published a detailed topographical survey Mediaeval York (1955), based upon original records and, to some extent, upon extracts from wills and other York documents made by his father, the Rev. James Raine, D.C.L. (1830–96).

Artists and Surveyors of York

John Speed (1552–1629) was apparently the first to produce a plan of York from original survey. It was engraved in 1610, and another version appeared in the sixth, and last, volume of the Civitates Orbis Terrarum of Braun and Hogenberg, published in 1618 (not, as often stated, in 1574, the date of the first volume). Speed's survey was accurately triangulated, and though engraved on a small scale is surprisingly precise in details which can be checked.

Samuel Parsons (fl. 1618–39) was a surveyor of national repute, for he worked in Middlesex, Essex and Shropshire as well as at York. In 1624 he did the fieldwork for a plan of the Manor of Dringhouses, drawn out in 1629 (York City Library). This is the earliest surviving large-scale plan of any part of York or its near neighbourhood, and is of notable accuracy (Plate 4).

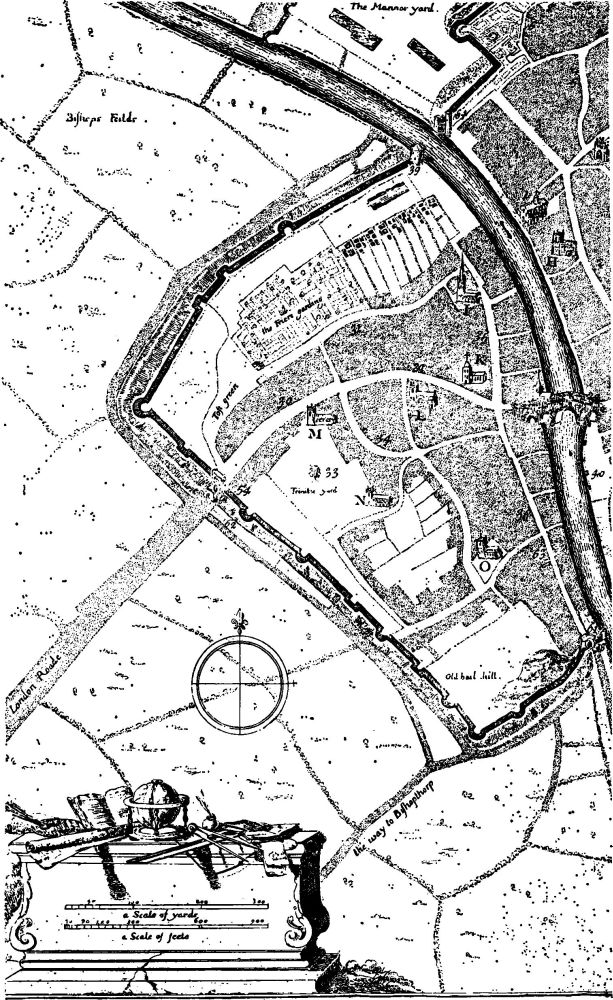

Benedict Horsley (c. 1627–fl. 1702) belonged to a noted York family of herald painters. He took up the freedom as a painter stainer in 1648 and served as Chamberlain in 1688. In 1694 he surveyed the city and published the work as an engraved plan in 1697 (Fig. 2). In 1702 the Corporation ordered him to be paid £15 'for surveying the City and for drawing severall Mapps and Planns therunto relateing', but these are not known to survive.

Henry Johnston (c. 1640–1723), younger brother of Dr. Nathaniel Johnston, made an extensive antiquarian tour in Yorkshire in 1669–70, the results surviving as two large MS. volumes (Bodleian, MS. Top. Yorks. c.13, 14). Johnston, who was later employed by Sir William Dugdale, was mainly interested in heraldry, but he also made drawings of houses and monuments and of a few stained-glass windows of outstanding interest (Plate 101). A prospect of York from the S.W. by him was formerly in the Boyne Collection (vol. x, 12) but has been lost since 1900.

James Archer (fl. 1671–90), a military engineer, drew out a large and detailed plan of the city c. 1682. The drawing survives (now in York City Library) and is the earliest original survey of the whole city with some pretensions to accuracy. It shows the castle, walls and moats in rather precise detail, but it is inaccurate in some respects and indicates built-up areas conventionally. See also York II, Appendix.

Francis Place (1647–1728), a topographical draughtsman of great brilliance, produced the earliest of the large series of detailed prospects and sketches of York and its buildings. He was the close friend of William Lodge (below) and there is some evidence that the two men exchanged sketches of the city for working up into detailed engravings. Place's distant view of York from Middlethorpe (Plate 198) includes most of the area covered by this Inventory.

Gregory King (1648–1712), a heraldic artist, was a boy of 17 when he accompanied Sir William Dugdale on his Visitation of 1665–6. King's rather crude prospects of the city (bound into the MS. 'Book of Yorkshire Arms', see p. xxx above) are of some importance as the earliest surviving general views of York.

William Lodge (1649–89), an amateur artist and engraver and friend of Francis Place (above), drew and engraved several views in York, notably the S.W. prospect from The Mount engraved c. 1678 as 'The Ancient and Loyall Citty of York'. This is based in part upon Lodge's own drawing (Leeds Public Library, Graingerised Thoresby, III, opp. p. 56) but also upon a prospect attributed to Place (R. E. G. Tyler in Leeds Art Calendar, no. 62 (1968), 14) and upon another version now in London (Society of Antiquaries, vol. marked '1750'; Plate 2). All these original drawings by Lodge and by Place show the old spire of St. Martin, Micklegate, taken down in July 1677; Lodge's engraving shows the new tower with classical balustrade.

John Cossins (fl. 1725–48) produced an engraved survey plan of York, to be dated upon internal evidence to c. 1727, and a revised edition of it in 1748. Though showing little independence of Horsley as a survey, Cossins's plate is of interest for the sixteen surrounding views of private houses in the city, of which four lay S.W. of the Ouse (Figs. 22, 23, 49, 56). These are the earliest details of individual house fronts in York, and show the reigning style of 1720–5.

John Haynes (c. 1705–fl. 1751) took up the freedom of York as a sadler in 1728 but engaged also in engraving and land surveying: in 1740 he advertised (York Courant, 9 Sep.) that 'Saddlers that have Occasion to have their Leather printed . . . may have it done . . . by John Haynes, Engraver, and CopperPlate-Printer, in the Minster Yard, York. He likewise surveys Land, and draws Perspective Views of Gentlemen's Seats ...'. He engraved for Gent and Drake, and in 1744 produced a large map of Antiquities on the Wolds in the Malton area, and also an exquisite MS. plan of Newburgh Park (NRCRO, Northallerton, ZDV (vi)). By 1751 he had probably left York, as he then published an engraved survey of the Chelsea Botanic Garden. Haynes's S.W. Prospect of York, published in 1731, though rather crude, shows many buildings in detail (Plate 2).

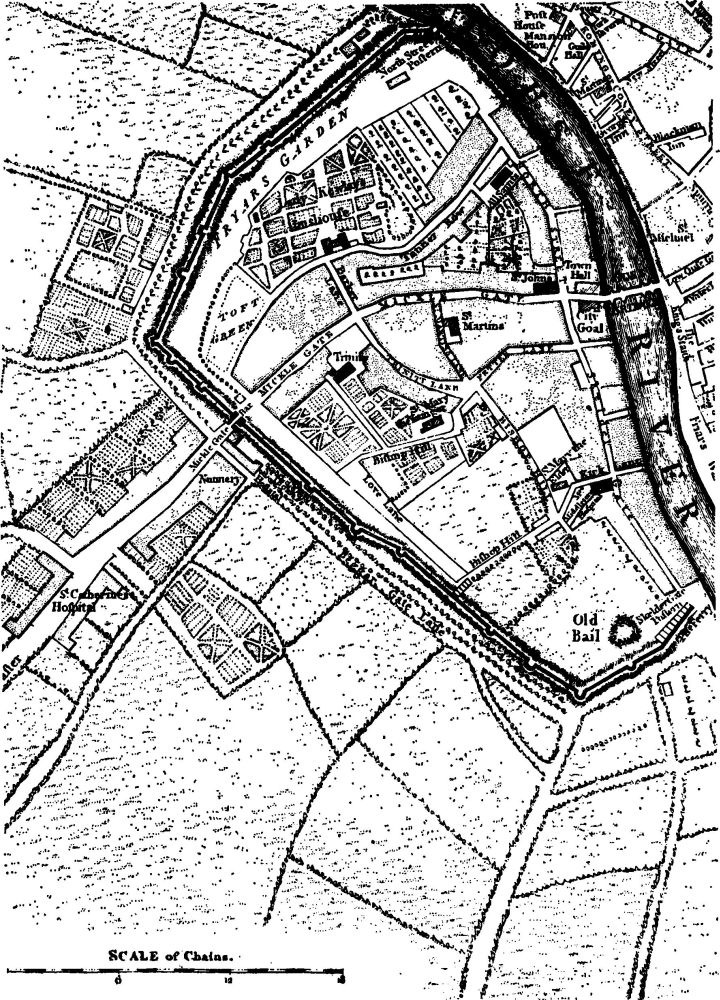

Thomas Jefferys (fl. 1735–94), a surveyor of national reputation, produced his Atlas of Yorkshire in 1772 and included a plan of York (Fig. 3). Jefferys' work is independent of earlier surveys and reasonably accurate.

Edward Abbot (fl. 1774–6), a painter, stayed with Thomas Beckwith (see above) when in 1774 he wrote a 'History of the Cathedral Church of York' (BM, Stowe MS. 884). He also, in 1774 and 1776, made many small watercolour views of churches and other buildings in and around York (Wakefield Museum, Gott Collection; there are photographs of most of the York items in the Evelyn Photographic Collection deposited in the York City Library). Abbot's work was probably meant to illustrate Beckwith's proposed enlargement of Drake's Eboracum.

Francis White (fl. 1770–1801), a surveyor of great accuracy, published in 1785 a good plan of York with a map of the whole of the Ainsty on the same sheet. The map is said to be 'from a Reduction of the Plans of the Townships', implying that White had made a large-scale cadastral survey of every township in the Ainsty. Nothing of White's original work is known to survive.

Joseph Halfpenny (1748–1811), son of Thomas Halfpenny, the Archbishop's gardener at Bishopthorpe, was apprenticed to a house-painter and later acted as clerk of works to John Carr. He was a fine draughtsman and engraver and published a series of detailed views in York as Fragmenta Vetusta in 1807.

John Lund junior (c. 1750–98), one of a family of York surveyors settled in Bootham, produced for the Corporation in 1772 the surviving plans of the four Strays (YCA, d, Vv). They were based on earlier surveys, but indicate the existence of rights of half-year common over enclosed lands around York, and show the extent of the built-up area in the suburbs (Plate 5).

Peter Atkinson junior (1776–1843), the well known architect, was also City Steward and in 1810–13 produced survey plans of all the Corporation properties in the York area (YCA, M.10 A-D).

Henry Cave (1779–1836), a prolific draughtsman and engraver, came of a York family of whitesmiths and engravers. Many of his original drawings survive (York City Art Gallery and elsewhere), as well as his copperplates for Picturesque Buildings of York, published in 1810 (T. P. Cooper, The Caves of York (1934)).

George Nicholson (1787–1878), a topographical artist of great accuracy, produced a large series of sketches of individual buildings c. 1825–30. Some of these are in the Evelyn Collection (York City Art Gallery), but others are now known only from photographs (Evelyn Photographic Collection).

Alfred Smith (fl. 1819–1834) was a land surveyor of Little Preston near Leeds, whose engraved plan of York in 1822 was published in Edward Baines, History, Directory and Gazetteer of the County of York (1822–3). Smith's plan was the first to show detail of property boundaries throughout the city; it is generally of remarkable accuracy for its small scale.

Nathaniel Whittock (fl. 1828–1860), an excellent draughtsman, produced many views in York and in 1858 a large bird's-eye view from the S.W. So far as the viewpoint permits, this gives precise details of the street elevations of all the buildings shown on the Micklegate side of the city (Plate 8). A revised edition of the view was issued c. 1860.

Robert Cooper (fl. 1830–42), a first-class land surveyor, produced in 1831 a map of York and the Ainsty, published the next year. This must have been reduced from a large-scale plan now lost, since individual buildings are marked with great accuracy. Cooper also produced plans of York and other boroughs in connection with Parliamentary Reform.

Plans of York

It has been suggested that a coloured view of a city of the early 15th century in a manuscript of the Brut (BM, Harleian MS. 1808, f. 45v.) represents York (R. A. Skelton and P. D. A. Harvey in Journal of the Society of Archivists, III, no. 9 (April 1969), 496), but if so no strictly topographical features other than the river and walls can be recognised.

The earliest true plan of the city seems to be that on two large skins of parchment, now separated, in the Public Record Office (MPB 49, 51), found among miscellanea of the Exchequer. Though somewhat damaged, the detail can be made out and the wording is legible (Fig. 1). The date is subsequent to the dissolution of St. Mary's Abbey and its renaming as the King's Manor, but on palaeographical grounds the map is not likely to be much later than the middle of the 16th century. It seems possible that it may be the plan referred to on 12 August 1541, when the Corporation 'paid to the armet (hermit) of the Kyngs Manour at York for drawing of the platt of the sanctuary' a sum of 9s. (YCR, iv, 63). In the centre of the city an area is very precisely marked out in red, including three parish churches, Thursday Market and the houses fronting on certain adjacent streets. This area could well be that designated to take the place of rights of sanctuary formerly existing within the precinct of St. Mary's Abbey. The plan is diagrammatic in that the Ouse is shown as a straight line from N. to S. and the streets are set out at right angles. The main interest of the plan historically lies in the naming of the streets and lanes and of other features.

John Speed's plan, 1610, published on his map of the W. Riding, shows the individual buildings in bird's-eye view. Apart from ribbon development along the main streets leading out from the city bars, there is little building outside the walls. Groups of windmills are shown in the surrounding countryside and correspond to known sites. The detail is precise and accurately surveyed.

James Archer's plan, c. 1682, shows the city defences including The Mount, a Civil War fortification on the Tadcaster Road, in great detail. Plot boundaries are shown but are rationalized into straight-sided units, and houses are shown conventionally. The suburbs were destroyed during the Civil War, so that Archer's plan shows their recovery, but their extent is not noticeably greater than in Speed's time. Though reasonably correct for the defences, the street plan suffers from serious errors.

Benedict Horsley's plan (Fig. 2), surveyed in 1694 and published in 1697, shows street frontages with considerable accuracy, but as the streets are shown dark against a light background outside the city walls, buildings in the suburbs are not differentiated from the fields. Individual churches and important structures are correctly shown in bird's-eye view. Considerable development is visible within the walls in the Bishophill, Hungate and Walmgate areas, and outside along Gillygate.

John Cossins's plan, c. 1727, follows Horsley's shading convention but extends it beyond the city walls. In addition to perspective drawings of churches on the plan itself, Cossins shows larger elevations of gentlemen's houses along the margins, an important innovation. The plan is in general cruder than Horsley's.

Fig. 2. From Horsley's plan of York, 1694.

Fig. 3. From Jeffery's plan of York, 1772.

Francis Drake's plan, 1736, follows Horsley closely, especially in the use of conventions, the portrayal of The Mount earthwork, and the enriched cartouche containing the scale, which now contains an elevation of the Mansion House. The new features shown include the Wigginton Road, the Long Walk and Blue Bridge, the new prison, and the Assembly Rooms; the sites of St. George's church and the chapel of St. Saviourgate are marked as vacant plots.

Peter Chassereau, 1750, shows little outside the city walls, but where fields appear they are shown in great detail. The Bishophill area, in opposition to Horsley's map and all its derivatives even after 1750, is now shown vacant. The development of the Monkgate area is clearly visible. The castle gatehouse has vanished. Chassereau shows all the churches in plan and, while following Horsley's stippling convention, shows the open areas within blocks.

Thomas Jefferys's plan, 1772 (Fig. 3), is similar to that of Chassereau but extends further to the south. Buildings not shown by Chassereau include St. Catherine's Hospital and the Nunnery (Bar Convent) in Blossom Street, the Town Hall and 'City Gaol'.

John Lund junior, 1772, produced four plans to show the pastures surrounding the city, providing information on the villages near York. The Micklegate Ward Stray plan (Plate 5) parallels that of the Manor of Dringhouses, produced by Samuel Parsons in 1624–9, and shows details of the new racecourse. Bootham Bar appears to have acquired a Classical pediment.

Ann Ward's plan in her edition of Drake's Eboracum, 1785, is Drake's plan almost unaltered, but it marks recent road widening, especially the formation of St. Helen's Square, King's Square, and the inclusion of St. Crux churchyard in Pavement. This is an exceedingly early example of the use of a plan for morphological purposes.

Francis White's plan, 1785, shows houses less accurately and churches more accurately than Chassereau. New development is indicated on the N.E. side of Thief Lane near the junction with Blossom Street. The Map of the Ainsty, to which it forms an inset, shows the layout of open fields in the villages, many not yet enclosed.

Alfred Smith's plan, 1822, shows the outline of individual buildings and plots. The castle moat has been filled in by an esplanade, but the gate to Castlegate is shown as still extant. This is a most important plan, showing York just before the great changes in the net of streets.

Robert Cooper's plan, 1832, although on a small scale, shows individual buildings as well as the street plan. Only the old part of the city to N.E. of the river is blocked-in solidly.

Bellerby's plan, 1847, is based on the 1822 Smith plan and is probably the same plate, altered to show new buildings. The railway has penetrated the city walls, with the station replacing the House of Correction at Toft Green. The wall has been pierced by the sweep of St. Leonard's Place. In the grounds of St. Mary's Abbey appears the new Yorkshire Museum.

Nathaniel Whittock's plan, 1858, is of considerable interest as a panoramic plan of the whole city Plate 8). It includes precise detail of the street elevations of the time and provides a unique record.

(J.H.H.)