A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Easington', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18, ed. Simon Townley( Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp180-191 [accessed 27 November 2024].

'Easington', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Edited by Simon Townley( Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online, accessed November 27, 2024, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp180-191.

"Easington". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Ed. Simon Townley(Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), , British History Online. Web. 27 November 2024. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp180-191.

In this section

EASINGTON

Easington is a tiny ancient parish east of Chalgrove and north of Cuxham, with which it was united in 1932. (fn. 1) The population was never large and declined in the late Middle Ages, with little substantial growth thereafter. By the mid 19th century the settlement comprised just seven houses, six of them clustered around the small medieval church and hidden down a single-track road. The manor belonged during the Middle Ages to the Templars and (later) the Hospitallers, and from the late 16th century was held by a succession of minor gentleman farmers, eventually becoming a single farm.

PARISH BOUNDARIES AND LANDSCAPE

In 1881 the ancient parish covered 235 a., (fn. 2) making it the smallest rural parish in Oxfordshire. (fn. 3) In the 9th century it belonged to the large neighbouring estate of Readanora (or Pyrton), and may have formerly been associated with Benson; it seems, however, to have formed a separate land unit by the late 10th century, (fn. 4) and some of its boundaries (mapped in 1612) (fn. 5) followed features of considerable antiquity. The western boundary with Chalgrove included sharp indentations which presumably followed open-field furlongs, while the straighter northern section cut across fields, and the eastern boundary followed an ancient track. The southern boundary briefly followed the Stadhampton-Thame road, before crossing a stream which in 1605 was called Easington brook. (fn. 6) That diversion, close to Cutt Mill in the north of Cuxham, gave both parishes a share in streamside meadow, and was evidently long-established, since 9th-and 10th-century descriptions of estate boundaries there mentioned a ford ('egsanford') at the point where the road north from Cuxham crossed the stream. (fn. 7) In 1886 the parish took in a 60-a. detached portion of Lewknor to the north, (fn. 8) and in 1932 it was united with Cuxham to form the civil parish of Cuxham with Easington. (fn. 9)

The parish is dominated by the low, flat-topped hill from which Easington ('Esa's hill') takes its name, (fn. 10) which cuts across the parish's middle part, and forms the southern end of a ridge of higher ground stretching north-east through Pyrton to Stoke Talmage. The church and surrounding cluster of houses sit on its north side at 85–95 m., looking towards Warpsgrove and the Haseleys, and from the hilltop just to the south (at 107 m.) there are spectacular views of the Chiltern scarp, which curves north-east towards Lewknor. From the summit the land drops quite steeply towards the Cuxham boundary stream and more gradually towards the parish's northern edge, both at c.8o metres. The geology is almost all Upper Greensand, with streamside alluvium in the south, (fn. 11) and the soil is marl running to heavier clay. (fn. 12) The landscape is dominated by open farmland, with trees restricted mainly to closes, and to small avenues around the settlement and further north.

COMMUNICATIONS

The Thame road, which cuts across the far south of the parish, was mentioned in the 13th century. (fn. 13) The short lane which links it to the settlement formed part of a minor medieval through-route to Warpsgrove and the Haseleys, (fn. 14) but in 1840 was in such a poor state that Easington was said to be all but inaccessible to carriage or loaded waggon. (fn. 15) The section north-west of the settlement disappeared in the later 20th century, but was subsequently reinstated as a bridleway. (fn. 16) Other branch routes, including one north-east to Colder, were downgraded to footpaths in the early 19th century. (fn. 17) Medieval documents also mention a Wallingford road or 'portway' (later often called the 'west way'), the ridgeway, mill way, church way, and 'neyeringweye.' (fn. 18) The Wallingford road seems to have been abandoned after 1468, its course marked apparently by a headland west of the settlement. (fn. 19)

The parish had no carrier or post office, inhabitants presumably using carriers based in Chalgrove or Pyrton. Letters were received through Tetsworth in 1852. (fn. 20)

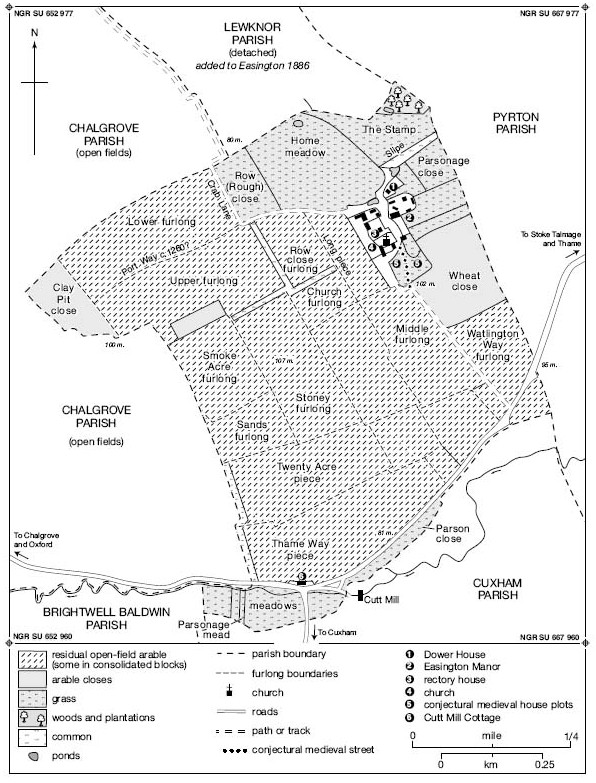

Easington parish c. 1840.

POPULATION

Seven tenant households were recorded in 1086, and 13 in 1279, (fn. 21) the former figure probably excluding estate servants running the demesne plough team, and the latter perhaps excluding some unrecorded subtenants or labourers. (fn. 22) The population showed some resilience to the famine and plagues of the 14th century, since 33 inhabitants aged over 14 were taxed in 1377: almost as many as in Cuxham, where there had been twice the number of tenants in 1279. (fn. 23) Nevertheless by 1428 there were fewer than ten households, (fn. 24) and in the 16th century only 3–5 taxpayers, (fn. 25) while in 1662 just four households paid hearth tax. (fn. 26) In 1676 there were 30 adult inhabitants, (fn. 27) less than half the number in Cuxham, which was itself one of the hundreds smaller villages. By 1738 there were eight households, but in 1768 just two farmhouses and three cottages were occupied, (fn. 28) and in 1801 the population was 31. Numbers fluctuated between 13 and 34 for the rest of the 19th century, and in 1931 there were 20 inhabitants in 5 houses. (fn. 29) In 2012 there were fewer than 10. (fn. 30)

SETTLEMENT AND BUILT CHARACTER

Cropmarks south-west of Easington hamlet indicate a large enclosure of probably late Bronze-Age to mid Iron-Age date, possibly with a contemporary annexe. (fn. 31) Otherwise nothing is known of Iron-Age or Roman activity in the parish, although neighbouring places provide evidence for both. (fn. 32) The place-name element dun suggests an early-to-mid Anglo-Saxon presence, with settlement located somewhere on the side or top of the hill. (fn. 33) The barn-like medieval church (built before 1148) (fn. 34) stands on the gently sloping north side, and the medieval village was probably close by, much like the remaining cluster of buildings in the early 18th century (fn. 35) Possibly the hill's colder north side was chosen in order to maximize arable production on Easington's tiny estate. Several houses must have been abandoned in the late Middle Ages and afterwards, some of them perhaps occupying roadside closes south of the church. (fn. 36) The oldest surviving house (Easington Manor) stands just north-east of the church and dates partly from the 16th century, although it does not necessarily occupy a medieval site. (fn. 37)

Five houses (including Cutt Mill Cottage in the far south of the parish) remained in 2012, when one was empty and one only occasionally occupied. (fn. 38) Buildings immediately around the church comprise a small cluster of brick houses and farm buildings, including a modern metal shed which almost encroaches into the churchyard. A farm labourer's cottage on the south side of the farmyard was extended in 2012. The only substantial dwellings were the brick and roughcast Easington Manor and the nearby Dower House, both described below. (fn. 39)

MANOR

In the 9th century Easington seems to have been part of the bishop of Worcester's adjacent estate of Readanora (or Pyrton), a link reflected in Pyrton's claims to mother-church status in the early 13th century. It was separated from Readanora apparently before the late 10th century, (fn. 40) and in 1086 was held from the king by Robert son of Ralph, a royal servant and tenant-in-chief in Ewelme and elsewhere. (fn. 41) As at Ewelme, the manor passed to the Despenser family probably in the early 12th century; (fn. 42) they granted it to the Seacourts (knights of Abingdon abbey) perhaps on the marriage of William Seacourt and Simon Despenser's sister, (fn. 43) and in 1283 they renounced their rights as overlords. (fn. 44) The Seacourts seem not to have lived in Easington, and c.1200 Robert de Seacourt created a mesne tenancy by selling the manor to his younger son Ralph for 30 marks. (fn. 45) Before 1220 Ralph granted it to the Knights Templar, (fn. 46) who had already acquired a site on which to build a house, and who in the 13th century obtained several smaller holdings from free tenants. (fn. 47)

From c.1240 the Templars' Oxfordshire preceptory was at Sandford, (fn. 48) and Easington was managed from a grange in Warpsgrove to the north. (fn. 49) After the Templars were suppressed in 1308 the king granted their estates to the Hospitallers, who in 1324 gave a ten-year lease of Warpsgrove and Easington to Sir John Stonor and his brother Adam for £18 a year. (fn. 50) By 1338 John held them for life. (fn. 51) The Hospitallers apparently continued their policy of leasing Easington thereafter. William Jordan, who was resident in 1397, was probably a lessee, (fn. 52) and presumably Easington was included in a lease of their Oxfordshire property to William Bedyll of London in the early 16th century (fn. 53)

After the order's dissolution in 1540 its estates fell to the Crown, which in 1564 leased Easington and other lands to Sir Francis Knollys (d. 1596) of Greys Court in tail male. (fn. 54) The Knollyses subsequently purchased Easington outright, and in 1624 Francis's son William, Viscount Wallingford and later earl of Banbury, sold the manor with its lands in Chalgrove, Pyrton and Cuxham to his agent Richard Stevens (c.1562–1644), who had lived in Easington as tenant since 1596 and who was later steward of Benson and Watlington manor courts. (fn. 55) Richard's second son and heir Henry (c.1597–1655) was a servant of the earl of Berkshire, and in 1643 was appointed Charles Is waggon-master-general; (fn. 56) he subsequently became indebted during the Civil War and was fined for delinquency in 1649, (fn. 57) and in 1651 he sold the estate to the London merchant Robert Abdy and his associates for £1,500. They sold it in 1654 to John Hart the younger of Buckingham (and later of Cottisford), whose father John (d. 1664) gave him financial backing and lived at Easington from 1660. (fn. 58)

John Hart the younger died childless in 1665, and the estate passed to his wife Anne and her second husband Edward Andrews of Cottisford. (fn. 59) Before 1739 the Andrews family sold it to Thomas Greenwood (d. 1770), (fn. 60) whose descendants retained it until the 20th century. Most of them (including Thomas) lived and farmed at Easington where they occupied Easington Manor, (fn. 61) and in 1841 the family owned some 93 per cent of the parish (212 a.). (fn. 62) During the First World War John Greenwood sold the farm to Andrew Nixey, (fn. 63) after whose death in 1919 it was bought by Francis Ayres ('Frank') Nixey (d. 1940). He ran the farm in partnership with his sons Frank (of Cuxham) and Albert. Albert took sole possession in 1957, and after his death in 1978 his sons Albert and John farmed it together. John was resident until his death in 2010, when Albert moved to Easington.

Easington Manor (Manor Farm)

The site of the Templars' 12th-century house is unknown, and, as the estate was subsequently run from Warpsgrove, Easington probably lacked a manor house from the 13th century to the 16th, when Richard Stevens adopted and remodelled the house now known as Easington Manor. The present house is a double-depth, two-storeyed building fronted in grey and red brick, (fn. 64) incorporating some early 16th-century random-bond brickwork in the rear wall, and a chimney stack and chamfered cellar beams of similar date. By 1625 a 'new' kitchen and parlour (with buttery) had been added to the hall, as well as a cellar (including a milk house) under the parlour. (fn. 65) Upstairs were chambers and closets. The old (presumably detached) kitchen was still in use, along with a brew house, bake house and malt house, while other outbuildings included a well house, stables, hay house, chaff house, wheat barn, cow house, and pigsties. In 1662 the house had six hearths. (fn. 66)

The resident Greenwoods substantially rebuilt the house in the late 18th and 19th century, introducing sash bay windows and panelled doors as well as a new brew house. The nearby Dower House (to the north) was added probably in the early 19th century and enlarged c.1830, creating a four-bayed rubble-built front with brick dressings, porch, sash windows, and hipped slate roof. (fn. 67)

Manor Farm from the rear (or north-west), showing some 16th-century features to the left.

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Easington's economy has always been based on mixed farming, although in some periods animal husbandry seems to have been more important than in Cuxham to the south. In the Middle Ages land was divided between the demesne (farmed after 1225 from a grange in Warpsgrove), and freeholders and customary tenants. By the 17th and 18th century farming was dominated by one or two resident farmers of whom many had land in adjacent parishes, and from the 19th century most of the parish formed part of a single farm.

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE

In 1841 the hamlet was surrounded by arable fields, with grassland concentrated at the northern and southern ends of the parish. (fn. 68) In the Middle Ages there was a full open-field system, with meadowland allocated partly by lot; (fn. 69) some inclosure took place before 1605, (fn. 70) and by the 19th century, though vestiges of open-field strips survived, much of the land was consolidated in blocks. South, West, Middle and Little fields are named in surviving medieval documents. (fn. 71) Early furlong names related primarily to topographical features including the brook, ditch, port way, ridgeway, and church way, while bury furlong was demesne land; (fn. 72) a few medieval furlong names survived in the 1840s, including church furlong and middle furlong. (fn. 73) Inhabitants enjoyed early intercommoning rights with Lewknor and Warpsgrove, and in the early 17th century there were disputes over tithes from the detached meadow called Lewknor (or Sellinger) mead, to the north. (fn. 74)

FARMS AND FARMING TO c.1840

In 1086 the demesne had one plough, and four villani and three bordars had another. (fn. 75) The manor had risen in value by 155. since 1066 (to £2), perhaps because rents were increased. Only 1½ a. of meadow was mentioned: almost certainly there was more grassland, but possibly it was of little value.

By 1279 the arable comprised just over 10½ yardlands including the Templars' 2-yardland demesne. Much of the tenanted land was held by two leading freemen, John Griffin (with 3 yardlands) and Gilbert Dreu (with 2); of the rest, one yardland was in the lord's hand during a minority, two other free tenants each held ½-yardlands, and one customary tenant had a yardland and a second a ½-yardland. Five cottagers were recorded as holding no land, but may have done so as subtenants. (fn. 76) The Templars farmed Easington from their Warpsgrove grange, and in 1308–11 (when the estate was in Crown hands) demesne produce included wheat, oats, dredge, peas, and beans. There were also several hundred sheep and some cows. (fn. 77) Wallingford was apparently the major early market, (fn. 78) but by the 13th century it seems to have been displaced, (fn. 79) and thereafter produce was sold probably in Henley, Thame or Watlington. (fn. 80)

Little is known about Easington's late-medieval agriculture, but mixed farming continued and, as earlier, some tenants held land in nearby parishes, including Pyrton. (fn. 81) In 1410 one free tenant was struggling to collect rent arrears. (fn. 82) By 1500 most land was held by a few leading tenants: as early as 1523 there was one dominant farmer, (fn. 83) and there were usually only one or two major farmers thereafter. (fn. 84) In the 1620s the main farm was split in two, though in 1660 John Hart the younger leased the whole of it to his father for seven years for £130 a year. (fn. 85) Two or three other inhabitants farmed a few acres in the parish in the 17th century (fn. 86) Mixed farming over this period included the cultivation of wheat, barley, oats, beans and peas, as well as the keeping of sheep, cows, pigs, poultry and bees. (fn. 87) The principal farmers were fairly prosperous, though most of their money was tied up in farming stock including grain and large sheep flocks. Robert Kibbles goods were worth c.£185 in 1678, and Thomas Heybourne's £149 in 1696; (fn. 88) in 1722 Nathaniel Wade's and Henry Franklins inventories were valued at over £704 and £545 respectively, although both men had substantial farming interests in neighbouring Chalgrove. (fn. 89) Another 18th-century farmer, James Treacher, was based at the rectory house, but held land in Golder as well as Easington. (fn. 90) In 1768 there were still two farmhouses, but by 1785 Thomas Greenwood farmed almost the entire parish, and by 1811 Manor Farm was the only farmhouse. (fn. 91)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1840

In 1841 Phyllis Greenwoods tenant John Pusey occupied just over 190 a., and Thomas Greenwood 30 acres. (fn. 92) Ten years later Greenwood was farming 300 a. including land in Great Haseley, and employing 15 labourers. (fn. 93) Easington farm was leased to John Lay in the early 1850s, though Greenwood again occupied it for a time later in the century, when it was reduced to 224 acres. (fn. 94) A report c.1840 claimed that Easington's farmland could bear large crops of wheat and beans with a moderate supply of manure, but that farming had recently been neglected. (fn. 95) Just over 80 per cent of the parish was then arable, (fn. 96) and sheep-corn husbandry continued in the 1880s-90s. (fn. 97)

In 1910 Andrew Nixey farmed 215 a. from Manor Farm, and two outside farmers (including Thomas Hicks of Cutt Mill in Cuxham) had small pasture holdings. (fn. 98) The area of permanent pasture had increased since the end of the 19th century, (fn. 99) and by 1941 the Nixeys' 318-a. farm included 202 a. of grass and 51 a. of clover, its 13 workers tending 89 cattle (including 40 cows in milk), 217 sheep, and poultry. Two years later it was classified grade 'A', although field drainage was only 'fair'; water came from ponds, and there was no electricity supply. (fn. 100) By the 1960s the farm had expanded to 520 a., including land in Chalgrove and Cuxham; it was then mixed, and raised non-pedigree cattle as well as sheep. (fn. 101) In the 1970s it became purely arable, and in 2012, when it formed part of a 1,000-a. holding which included land in Rycote and Tetsworth, it produced rape, linseed and wheat. (fn. 102)

TRADES AND CRAFTS

Easington's small size and relatively remote location prompted little craft activity. Richard the smith (mentioned in 1284) was presumably a blacksmith, (fn. 103) and some medieval inhabitants were involved in small-scale brewing for local consumption. (fn. 104) In the 17th century a tailor and later a shoemaker were resident, but both were evidently also part-time farmers. (fn. 105) In the early 20th century there was a bootmaker at Cutt Mill Cottage, on the main road in the far south of the parish. (fn. 106)

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL CHARACTER AND THE LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

Easington's small medieval population included several freeholders as well as customary tenants, but no medieval lords seem to have resided, and the Templars' and Hospitallers' farming operations were run from neighbouring Warpspgrove. (fn. 107) A leading inhabitant c.1230 was Richard Franklin, described as 'franklin of Easington'. (fn. 108) The range of wealth was fairly typical for the area. In 1316 there were eight taxpayers, of whom the best off (John de Pauta and William Adam) paid 7s. and 5s., and the rest between 8d. and 3s. 9d. Five of the eight families taxed had been established in the parish for at least forty years. (fn. 109) Unsurprisingly, the strongest social links seem to have been with people from surrounding parishes, notably Pyrton, Chalgrove and Cuxham. (fn. 110) A few outsiders were investing in small parcels of land in the parish before 1350: in 1344, for example, John son of John Warrewyk, 'cook', of London, sold three half acres to a local man. (fn. 111)

After the Black Death there was a greater turnover of population, and land and wealth became concentrated in fewer hands. (fn. 112) By 1543 John Fritwell, the principal farmer, was taxed on goods worth £20, and other taxpayers on goods worth £1–£3. (fn. 113) Fritwell (who died the following year) was fairly comfortably off, and owned more than one featherbed; like other 16th- and early 17th-century testators he requested burial at Easington, but family and social links connected him with Watlington, Chalgrove and more distantly Rousham, possibly his place of origin. (fn. 114) Most of those witnessing or overseeing inhabitants' wills in this period were neighbours living in Easington, though inhabitants also had connections in places such as Cuxham, Golder, Watlington, Brightwell Baldwin, Stoke Talmage, Roke, Nuffield, Long Wittenham (Berks.), and, in at least one case, London. (fn. 115) Several small freeholders included members of the Heybourne and Quatremain families. (fn. 116)

From the late 16th century the principal landowners were often resident. Lords such as Richard Stevens (c.1562–1644) and his son Henry had a mix of local and more distant connections: (fn. 117) Richard's family was from Henley, while his wife Anne (nee Edwards) was the daughter of a fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, and a relative of the Edwardses of Chirk Castle (Denbigh). (fn. 118) Though buried in Oxford, Richard lived in Easington (fn. 119) where he probably rebuilt the manor house, (fn. 120) and where his son William was rector in the 1620s. (fn. 121) John Hart the elder lived at Easington in the early 1660s, (fn. 122) but the Andrews family (owners from c.1665 until the early 18th century) were largely non-resident. (fn. 123) In their absence the parish's leading figures were its principal tenant farmers, substantial yeomen such as Thomas Heybourne and (later) Henry Franklin, who acted as sole churchwarden. (fn. 124) Some rectors also resided, but more often the cure was served by clergymen visiting once a week from a nearby town or village. (fn. 125)

The Greenwoods (who bought the estate before 1739) were members of a farming family established originally in Haddenham (Bucks.). (fn. 126) Thomas Greenwood (1709–70) was described at his death as a 'rich gentleman farmer', (fn. 127) and he and his son Thomas (1740–1808) (fn. 128) were successively churchwarden from 1741 to 1807. (fn. 129) Thomas's son, another Thomas (1768–1832), spent his later years in Wallingford (where he was mayor), but was buried in Easington. (fn. 130) His brother and heir John (1776–1858) lived latterly at Easington, as did John's son Thomas (1815–1902). (fn. 131) All employed one or two servants, but did not maintain elaborate households. (fn. 132) Other family members sometimes also lived at Easington, amongst them John Greenwood, who in 1881 was described as a 'Russia merchant'. (fn. 133) John Lay, the Greenwoods' tenant farmer in the mid 19th century, had a bitter and long-running dispute with the resident rector, Isaac Fidler. (fn. 134)

By the 18th century the parish's few other inhabitants were probably mostly short-term residents: in 1768, for example, labourers occupying three farm cottages were described as 'not parishioners'. (fn. 135) In the 1860s the Greenwoods sometimes took their (non-local) maids or servant boys to church, bolstering the tiny congregation, (fn. 136) but in such a small community both short- and longer-term residents presumably looked primarily to neighbouring settlements for social contact. By the 20th century there were just a handful of inhabitants, including the Nixeys (who farmed the entire parish) and a couple of private residents at the Old Rectory and Dower House. (fn. 137) The advent of the motor car presumably strengthened the role of nearby towns as a main social focus, though rural pursuits such as shooting remained important. (fn. 138)

EDUCATION, POOR RELIEF AND CHARITIES

In the 18th and 19th centuries there were generally few if any children to be catechized, (fn. 139) and with provision available in neighbouring Cuxham, Chalgrove and Watlington, no school was established in Easington. (fn. 140) Poor relief costs were also minimal, since few if any poor were allowed to settle. (fn. 141) John Hart the younger (d. 1665) charged numerous charitable bequests on the estate, including £5 to support the apprenticeship of two poor boys from Easington and to maintain a poor widow (fn. 142) The charity was not properly applied in the early 19th century, but continued until the end of the 20th, when remaining funds were given to Cuxham village hall. The payments were resented by the farmer during the difficult farming conditions of the 1920s-30s. (fn. 143)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

Easington's small population had its own church from the Middle Ages, but the living was exceptionally poor and by the Reformation the building was badly neglected. In subsequent centuries inhabitants were unevenly served by usually non-resident rectors, some of them pluralists. The number of services declined in the early 19th century, and in the 1850s the living was united with Cuxham to the south; thereafter the church continued to be used for services, though not always on a regular basis. There is no evidence of Roman Catholic recusancy, and Protestant Dissent found only a very limited footing in the 19th century.

CHURCH ORIGINS AND PAROCHIAL ORGANIZATION

In the later Anglo-Saxon period Easington (as part of the Readanora estate) was apparently dependent on the mother church at Pyrton. (fn. 144) A church was built in Easington before 1148, possibly with its own burial ground and, judging by the Norman tub font, with baptismal rights. (fn. 145) Residual claims by Pyrton were quashed c.1203–6, and thereafter the benefice was a rectory. (fn. 146) A re-dedication to St Mary and St Peter took place in the late 12th or early 13th century, (fn. 147) and the dedication to St Peter continued thereafter.

The parish (only 235 a.) (fn. 148) was united with neighbouring Cuxham under an Order in Council of 1853, implemented in 1864 following the last rectors death. From 1918 the combined parish was held in plurality with Brightwell Baldwin, and in 1985 the benefices were united with Ewelme. (fn. 149)

Advowson, Glebe, and Tithes

An acre of demesne was given to the church by Robert Seacourt at its re-dedication, and in the 19th century the glebe (including the rectory house site) totalled only 6 acres. (fn. 150) The bulk of the church's income consequently came from tithes and offerings, which were also severely limited by the parish's small size and population. Before 1148 William Seacourt and his son Thurstan granted the church to Godstow abbey, (fn. 151) which as patron retained an annual pension of £1 6s. 8d.; as this was the benefice's full value (fn. 152) the abbey presumably paid a small stipend, and in 1273 the rector (Simon) unsuccessfully resisted paying the pension. (fn. 153) It was finally extinguished in 1309 when the nuns gave the advowson to the bishop of Lincoln, (fn. 154) whose successors remained patrons until 1853. Thenceforth patronage of the joint benefice of Cuxham and Easington belonged to Merton College, Oxford. (fn. 155)

The living remained very badly endowed. In 1535 it was valued at £4 12s. 4d., making it the poorest in the hundred apart from Warpsgrove, and in 1754 it was said to be worth £35 18s. net. (fn. 156) In 1808 Thomas Greenwood rented the glebe and tithes for £60, (fn. 157) and in 1841, when the tithes were commuted for £73 14s., the living was valued at £80. (fn. 158)

Rectory House

The medieval rectory house (mentioned in the late 12th or early 13th century) stood next to the church, probably in the same position as its modern successor. (fn. 159) Masonry footings and a medieval pit or well have been excavated in the garden. (fn. 160) In the early 17th century the house had a hall, kitchen, parlour, buttery or cellar, and upstairs chambers and lofts, including an apple loft. Outbuildings included a barn, corn house, and stable. (fn. 161) The house apparently fell into decay, and was replaced or reduced in size in the early 19th century, when it was described as a 'mere cottage'. (fn. 162) It was sold after the last rector's death in 1864, and in 2014 permission was granted for its demolition and replacement. (fn. 163)

PASTORAL CARE AND RELIGIOUS LIFE

The 12th-century church was presumably intended to serve the Seacourts' tenants. Most 13th-century rectors seem to have resided, although in 1294 the rector was blind, and the bishop ordered the rector of Warpsgrove to assist. (fn. 164) Several 14th-century rectors were absent, however, amongst them William Melburn (a clerk of the bishop of Exeter), and William Gunthorp (the king's cofferer and a canon of Southwell); (fn. 165) by then the living was evidently sometimes used as an early or supplementary source of clerical income, and from the 1380s many rectors exchanged it after short incumbencies. (fn. 166) Most medieval rectors (like several of their 16th-century successors) were non-graduates, and some were not in full orders. (fn. 167) By the late Middle Ages absenteeism was causing neglect: in May 1520 the rector was non-resident, and there had been no service since Easter (8 April). (fn. 168) Six years later there was a curate (John Pyke), but he too was a non-graduate, and received a very low stipend of £2. (fn. 169)

Medieval lay involvement is poorly documented, although the church's small size must have created an intimate setting. (fn. 170) Before 1270 Simon the clerk (son of Henry of Easington) gave land to maintain a light, (fn. 171) and the church's rebuilding in the 14th century may have been partly a local initiative, supported possibly by the Templars or their lessee. (fn. 172) Traces of wall painting in the chancel are presumably also medieval. Nevertheless the fabric seems to have been neglected in the late Middle Ages, and by 1520 the entire roof and the chancel were dilapidated, and the churchyard wall had fallen down. (fn. 173) Ten years later the wall still required rebuilding, (fn. 174) and in the early 1550s the church seems to have had few ornaments or vestments. (fn. 175)

From the 16th to the 18th century most rectors were non-resident and often stayed for fewer than ten years. (fn. 176) Many held other benefices or, in the 18th century, worked as schoolmasters in Oxford or Thame. (fn. 177) Some non-residents did the duty themselves, while others provided curates, who often served two or more churches; (fn. 178) several of the pluralists were rectors of neighbouring Cuxham, amongst them Ralph Johnson, John Pratt, and (later) John D'Oyly. (fn. 179) Exceptions to the pattern included the resident Welshman Howell Roberts (rector 1581-1623), a non-graduate judged 'sufficient' in learning, and Thomas Brown (1712–33), who was commemorated by a tablet in the church. (fn. 180) Roberts's close relations with his parishioners are reflected in his witnessing of local wills, (fn. 181) but at other times absenteeism led to outright abuse: in 1703 parishioners complained that the rector John Phillips's whereabouts were unknown, and that he had left his curate William Newlin unpaid for over a year. (fn. 182) Bequests to the church in the 16th and early 17th century were small-scale and of common type, while a few parishioners made gifts to neighbouring churches including Watlington, Chalgrove and Cuxham. (fn. 183)

In 1738 John D'Oyly provided double duty on a Sunday but claimed that he was never required during the rest of the week, when he resided at Merton College or at his family seat in Chiselhampton. (fn. 184) By 1759 the rector Timothy Neve's curate provided only a single duty, though the number of communicants had risen from four to six or ten. (fn. 185) A similar pattern continued in 1808 when the long-serving William Stratford (rector 1773-1819) came from Thame on Sundays, but by then there were only three communicants, (fn. 186) and in 1811 Francis Rowden the younger (of Cuxham) served the cure for a meagre £25 a year, increased to £35 by 1815. (fn. 187) Stratford's successor William Buckle (1819–32), who lived in neighbouring Pyrton, served three churches and held services at Easington only once a fortnight. (fn. 188) Tittle effort seems to have been made to maintain the church fabric, and repairs were ordered by the rural dean in 1759 and 1833. (fn. 189)

A brief effervescence in Church life occurred during the incumbency of Frederick Tee (1832–42), who lived in Thame and was curate of Sydenham. Tee served the cure himself, reintroduced weekly services, and filled the church with people from outlying parts of neighbouring parishes, securing c.20 communicants. (fn. 190) The church's last rector, Isaac Fidler (1842–64), proved unable to maintain this momentum, despite living in the parish and marrying into the Greenwood family. Bishop Wilberforce described him as an active man and former missionary 'of very low origin, who served 'all over the county when wanted'; he seems, however, to have suffered increasing ill health, and by the 1850s was embroiled in a bitter ongoing dispute with the farmer and churchwarden John Lay, whom he accused of Nonconformity, perjury, and theft. (fn. 191) In 1860 Fidler was ordered to follow diocesan rules by providing monthly communion and giving a sermon on sacrament Sundays, but usually only a handful of people took communion, and some services were cancelled because of insufficient numbers or Fidler's gout. In 1861 Lay secured a county court judgement to withhold the parish clerk's salary, probably worsening an already strained atmosphere. (fn. 192)

After Fidler's death and the unification with Cuxham the church experienced mixed fortunes. No services were held in the 1880s and early 1890s, when Easington's few inhabitants attended Cuxham church, (fn. 193) and for a time the building stored agricultural equipment. (fn. 194) Edward Fletcher resumed fortnightly services c.1896, and Thomas Hainsworth (rector of the united benefice 1917–34) provided services at Easington once or twice a month. (fn. 195) Periodic services continued thereafter, though by the late 20th century the incumbent had responsibility for four churches. The building was restored in 1990 after serious storm damage, attracting donations from outside the parish. (fn. 196)

Easington church from the north-east.

CHURCH ARCHITECTURE

Easington church is a small, low barn-like structure, with a simple rectangular plan and no architectural division between nave and chancel. (fn. 197) The chancel's limestone masonry is, however, better dressed and more evenly coursed than that of the nave. The earliest surviving features are 12th-century, including reset zigzag moulding over one of the south windows, and stonework in the reset north doorway, which has a rounded chamfered arch, quatrefoil ornament, and votive crosses. The church appears to have been rebuilt or much altered in the early 14th century, the date of some of the windows, the piscina, and a few floor tiles. The nave's three-bay roof, arch-braced with a collartruss, dates from the mid 15th to early 16th century. (fn. 198)

By the 1520s the building was in a poor state, and there may have been several subsequent phases of repair. (fn. 199) An early 19th-century drawing shows numerous buttresses, a small western bellcote (restored in the 20th century), and an enclosed porch, (fn. 200) since replaced by the present open timber porch. The two larger windows in the south wall are probably Victorian. The canopied pulpit was constructed in 1916 from panels dated 1633, and the 14th-century east window contains reset fragments of contemporary stained glass. Charles Greenwood donated some modern stained glass in 1904. (fn. 201)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Medieval lords of Easington presumably held a manor court, but no records survive, and there is no indication that it continued later: by the 17th century Easington was usually called a 'farm' rather than a manor. (fn. 202) The tithing was represented at the hundred's annual view of frankpledge at Ewelme from the Middle Ages to the early 19th century, when a constable was still sworn there. (fn. 203)

In 1530 there was a single churchwarden, increased to two by the 1550s, (fn. 204) but from the 18th century usually again reduced to one. (fn. 205) Overseers of the poor were mentioned in 1664. (fn. 206) No vestry minutes survive, and in the early 19th century Thomas Greenwood (as owner and principal farmer) held all the parish offices. (fn. 207) In 1834 Easington became part of Thame Poor Law Union, and in 1894 of the new Thame Rural District. (fn. 208) In 1932 the civil parish was united with Cuxham and transferred to Bullingdon Rural District. (fn. 209)