A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Cuxham', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp158-179 [accessed 19 April 2025].

'Cuxham', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online, accessed April 19, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp158-179.

"Cuxham". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online. Web. 19 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp158-179.

In this section

CUXHAM

Cuxham is a small rural parish at the foot of the Chilterns, c.2 km north-west of Watlington. (fn. 1) The village lies along the Chalgrove-Watlington road, which runs through the middle of the parish, while an isolated former mill stands by a stream close to the northern boundary. The village contracted in the late Middle Ages, and remains small despite some modern house-building.

Until the 20th century the parish was dominated by Merton College, Oxford (as lord and major landowner), by a few leading tenant farmers, and by the rector. The latter was almost invariably a current or former college fellow, and was a sizeable Cuxham landholder. Small freeholders were mostly replaced by villeins in the 13th century, and from then until the 19th century most inhabitants were customary college tenants, many of whom occupied only modest holdings. Fertile soils supported prosperous arable farming, the main beneficiaries of which were the college and its larger, often long-standing lessees. Besides links with surrounding parishes there was a close connection with Henley-on-Thames, which from the Middle Ages was the main market for the sale of grain.

PARISH BOUNDARIES AND LANDSCAPE

In 1877 the ancient parish comprised 492 a., much the same as the measured acreage in 1767. (fn. 2) An estate described in a charter of 995 probably broadly equated to the later parish, (fn. 3) and a reference to 'the boundary of the Cuxham folk' in a charter of c.887 suggests that Cuxham emerged as a clearly defined unit relatively early, during the first phase of the creation of small local estates in the 9th century. (fn. 4) Its boundaries seem to pre-date the creation of open fields, since only in the far north-west do they follow the tell-tale right-angle corners of arable furlongs, (fn. 5) here possibly related to an early 'hide farm' in neighbouring Brightwell Baldwin. (fn. 6) Most of the western boundary follows a track called Hyde Lane and (in the south) Turner's Green Lane, which leads south through Britwell Prior. (fn. 7) The route was described as a 'fildena weg' (or 'fielden way') in 995, and was one of several similarly named local tracks which connected vale dwellers with Chiltern wood-pastures to the south. (fn. 8) The northern boundary (with Easington) cuts across a stream and surrounding meadowland before joining the Thame road, while the southern boundary follows a disused lane called Burrough Way in 1767, which branched off Turner's Green Lane towards the Watlington road. (fn. 9) The eastern boundary follows that of the hundred, possibly another early routeway In 1932 the parish was united with Easington to form the civil parish of Cuxham with Easington. (fn. 10)

The parish is characterized by an undulating landscape of large fields, small brooks, and meadows. A stream (called the 'Merlebrok' in the 16th century) (fn. 11) enters between two low hills in the south-east, turning north to join the stream which flows past Cutt Mill. The village lies in the narrow valley between the hills, and before the stream was culverted in the later 19th century it often flooded the main street. (fn. 12) The parish's rounded hillocks foreshorten horizons from the valley floor, but there are no dramatic differences in relief. The lowest areas by the streams are c.80 m. above sea level, while the highest points in the extreme east and south reach 108–115 m.

Alluvium near the streams supports meadow and pasture, though before modern drainage much of the land there was marshy. (fn. 13) The parish's three open fields (inclosed in the mid 19th century) occupied the slightly higher ground, where greensand, marl, chalk and gravel support a 'rather heavy, but useful' loam. (fn. 14) Little woodland has existed since the Middle Ages, with trees restricted to hedgerows, closes in the village, and the banks of streams. (fn. 15) In the late Anglo-Saxon period there was some woodland on the higher ground in the south, however, and the estate probably included a separate detached portion of woodland in the Chilterns. (fn. 16)

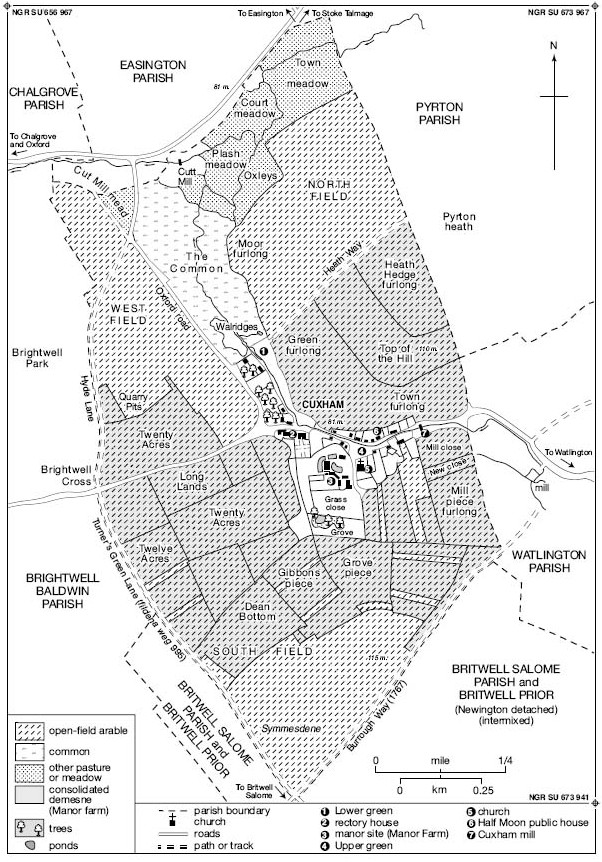

Cuxham in 1767, from a contemporary estate map.

COMMUNICATIONS

The road through the village (the modern B480) links Cuxham to Watlington and (via Stadhampton and Cowley) to Oxford, and was labeled the 'Oxford road' on a map of 1767. (fn. 17) In the far north of the parish it joins a road running north-eastwards past Cutt Mill towards Thame, while at the village's western end it meets the road from Brightwell Baldwin, which follows the course of the Lower Icknield Way. (fn. 18)

Other early routes survive partly as bridleways or footpaths, (fn. 19) though in some cases their courses were altered at inclosure or later. In the 18th and 19th century a track led across the fields north of the village, one fork heading towards Easington, and the other (doubtless a grazing route) leading to Pyrton heath. At that time the lane past the church, which today stops just south of Manor Farm, continued cross-country towards Britwell Salome. (fn. 20) Other early north-west to south-east routes form part of the parish boundary, (fn. 21) running roughly parallel to Knightsbridge Lane in neighbouring Pyrton, which in the Anglo-Saxon period linked the Henley area to royal centres near Oxford. (fn. 22)

The village did not have its own carrier, although Watlington services ran to Oxford, Abingdon, Thame, Reading, and London from the early 19th century. (fn. 23) The parish was also close to the main London road through Lewknor, and by 1830 a coach which met the London road at Stokenchurch could be boarded at the Red Lion in Watlington. (fn. 24) The Watlington to Princes Risborough branch railway opened in 1872 but was closed to passengers in 1957, making Cuxham considerably less accessible other than by motor car: (fn. 25) bus services to Oxford, Wallingford, Watlington, Henley and Reading were established in the 20th century, but were never frequent. A post office was opened in Watlington by 1823, and a sub-post office in Cuxham by 1847. (fn. 26) The latter changed location several times before its closure in 1970, when it was in the Half Moon pub. (fn. 27)

POPULATION

In 1086 the recorded population comprised eleven tenants and four servi, (fn. 28) implying c.15 households or 70 people. The real total was probably higher: the men running Cuxham's three mills were not mentioned, and there may have been unrecorded freemen and servants. (fn. 29) The parish was already intensively exploited, with apparently little potential for further arable expansion; (fn. 30) nonetheless there seems to have been additional population growth in succeeding centuries. By 1279 there were 23 tenants, many of whom had their own labourers, in addition to demesne servants and the rector's household. (fn. 31) By the late 1340s the adult population probably exceeded 110. (fn. 32) The Black Death (which arrived in early 1349) had a dramatic short-term effect: all twelve villeins died that year, and four of the eight cottagers by 1352, when 9 of the parish's 13 half yardlands lay vacant. (fn. 33) Some limited recovery followed, although in 1377 the adult population was still only 38, (fn. 34) about a third of the pre-plague level.

The 15th century probably saw further reversals, since several houses were abandoned. (fn. 35) Rentals record c.12–16 tenants, several of them non-resident, (fn. 36) and growth remained slow, with 15 taxpayers recorded in 1543, (fn. 37) and only 19 households assessed for hearth tax in 1662. (fn. 38) In 1676 the adult population was c.66, (fn. 39) and in 1738 there were said to be 24 houses, (fn. 40) while 128 people in 28 households were inoculated against smallpox in 1772–3. (fn. 41) Numbers rose from 144 in 1801 to 222 in 1841, accommodated in 43 houses; thereafter a sharp drop to 172 by 1851 was followed by a more gradual decline to 104 in 1921, rising to 129 in 1931 and to 183 (including Easington) by 1961. The later trend was generally downwards, especially in the 1960s and 1980s, and in 2011 the combined population (occupying 61 houses) was only 135. (fn. 42)

Cuxham village in 1796, looking south over the village stream to Cuxham church. Cottages in the foreground were replaced by the school (now the village hall) in 1848, while Manor Farm's curtilage lies behind the stocks on the right.

SETTLEMENT

No evidence of Prehistoric activity is known, although archaeological investigation has been limited. Sherds of Roman pottery, including Samian ware, were found close to the spring south of Manor Farm in the 1930s, apparently associated with remains of a wall and fragments of roof tile. (fn. 43) The character and extent of Roman settlement remains uncertain, although this part of the Thames valley was densely settled throughout the Iron-Age and Roman periods. Mention of 'Cuda's tumulus' in the charter of 995 suggests an early Anglo-Saxon burial mound, associated possibly with the memory of a kinsman of Ceawlin of Wessex (d. c.593). (fn. 44) A settled farming population seems to have been established before the late 9th century, (fn. 45) and the 'hamm' element of the place name Cuxham ('Cuc's river meadow') may reflect even earlier colonization, before c.730. (fn. 46)

Settlement probably became concentrated close to the present village in the late Anglo-Saxon period, although the regular roadside house plots documented in the 13th century may not have been created until as late as the 12th. (fn. 47) An outlying farmstead or 'wic' located on the parish's south-eastern boundary in 995 was not mentioned later. (fn. 48) Medieval settlement was probably initially clustered on the south side of the village street around the manor house and church and close to the stream, (fn. 49) but as population expanded in the 12th and 13th centuries cottage holdings were apparently built on the north side of the street, in the lane which led south between the church and manor house, and on poor land north of the rectory house (these last converted to half-yardland holdings in 1290–3). (fn. 50)

The village shrank considerably in the late Middle Ages. (fn. 51) Two homesteads in its north-western arm were abandoned in 1349 and three others in the late 15th century, while at least six cottages south of the church and further east were abandoned before 1388. (fn. 52) The tenement belonging to the Oldman family, just east of the rectory house, was an empty house plot (or 'toft') by the 1480s, (fn. 53) and another cottage (Burdens) was 'very ruinous' in 1513. (fn. 54) Post-medieval development was limited, and most of the abandoned tenements remained pasture closes in 1767. (fn. 55)

The village expanded little thereafter. A few new houses were built in the late 18th and 19th century, but others were demolished, (fn. 56) and in 1901 there were the same number of houses (38) as in 1831. (fn. 57) The most significant 20th-century additions were a row of six council houses ('Mill View') built at the village's eastern end in 1926, and eight (the 'Gregory Estate') added to the western end after the Second World War (four in 1951 and four in 1960). (fn. 58)

THE BUILT CHARACTER

Cuxham retains a mix of medieval to early 19th-century vernacular buildings and modern housing. The earliest surviving structure is the church, and the one piece of 'polite' architecture the early 19th-century rectory. (fn. 59) Older houses are interspersed with modern council houses, bungalows, and suburban houses of standard design, creating a lack of visual unity. Nevertheless most buildings feature red brick and tile, and many older houses are built of (or encased in) limestone rubble, which was quarried in the parish. (fn. 60) A number of houses are painted white, sometimes over render, and the stream running along the street's south side (Fig. 44) is marked off by white railings. Some houses still have thatched roofs, but the proportion is lower than in the early 1970s. (fn. 61)

The oldest houses include Yew Tree Cottage, an originally two-bay box-frame house of c.1500–30, whose open hall was floored over c.1600. College Farm and Wheelwrights are similar houses of probably later 16th-century date, both floored from the start, while Brook Cottage and The Thatch probably also pre-date 1600. (fn. 62) College Farm was long occupied by members of the Crooke family, and in 1602 included a hall, lower chamber, upper chamber, and servants' chamber; (fn. 63) it was altered probably in the late 18th century, when occupied by a subtenant of the rector, and from the 1930s to 1970s it accommodated the cowman and other labourers from Manor farm. (fn. 64) Seventeenth-century houses include Middle Farm, the Half Moon (Fig. 44), and Old Rectory Cottage (which has some re-used medieval timbers). Middle Farm, on the south side of the street, is a two-storey L-shaped house partly rebuilt in 1967; its western range was originally timber framed, but the framing has been replaced almost entirely by coursed rubble. The eastern wing was probably added in the later 17th century by the Cousin or Johnson families. (fn. 65) Roger's Hill Farmhouse (Glenroy), Rose House (Orchard Cottage), Rose Cottage, and Stone Cottage all date from the 18th century. (fn. 66)

Cuxham's two surviving former mills occupy the sites of medieval predecessors, (fn. 67) but their fabric dates primarily from the 18th and 19th centuries. Cutt Mill, in the north of the parish, is a three-storey 18th- and early 19th-century mill with attached domestic accommodation and white-painted, weather-boarded ancillary buildings. The mill machinery was in remarkably complete condition until the early 1980s when the interior was remodelled. (fn. 68) Cuxham Mill, at the village's eastern end, is a substantially mid 18th-century two-storey brick building, though the chalk-rubble rear block may be earlier. An iron overshot wheel is preserved inside. (fn. 69)

MANOR

By the 9th century Cuxham belonged to the bishop of Worcester's extensive Readanora estate, which included nearby Pyrton and which may have once formed part of Benson's early territory. (fn. 70) It remained in the bishop's hands in 887, but was granted to the bishop of Dorchester probably in the later 10th century. (fn. 71) Thereafter it passed to a succession of mostly minor landholders until the late 13th century, when Walter de Merton bought it for his new foundation (later Merton College) in Oxford. The college retained the bulk of the estate in 2015, following more than seven centuries of unbroken possession.

Cuxham from the air, looking south-west towards the church (1) and the adjacent manorial site at Manor Farm (2). Remains of rectangular fishponds are visible centre right (3), just west of the filled-in moat.

Descent

In 995 the bishop of Dorchester granted 5 mansae at Cuxham to his servant Æelfstan. (fn. 72) By 1066 the 5-hide estate belonged to Wigod of Wallingford, whose lands were acquired by Miles Crispin before 1086 as part of the honor of Wallingford. The overlordship remained with the lords of the honor until Richard of Cornwall (d. 1272) surrendered the right. (fn. 73) The Domesday tenant, Alured, is possibly identifiable with Wigod's nephew of the same name, (fn. 74) and by 1166 the manor was held by the Foliots, of whom some seem to have lived in Cuxham. (fn. 75) Walter Foliot, lord from c.1190 to c.1233, (fn. 76) was sheriff of Oxfordshire in 1225. (fn. 77)

Before 1235–6 the manor passed to Ralph Chenduit (d. 1243), who had married Foliot's daughter and heir Joan. (fn. 78) Ralph's son Stephen, a close companion of Richard of Cornwall, became heavily indebted to Jewish creditors, and in 1268 sold the manor and advowson to Walter de Merton (d. 1277). (fn. 79) Walter used Cuxham and other properties to endow the house of scholars he had founded in 1264, which soon after settled in Oxford; (fn. 80) the grant of Cuxham (in 1271) incorporated life annuities of £38 15s. shared between Walter and his relatives. (fn. 81) Merton College remained in possession of the manor thereafter, though from the later Middle Ages it was leased rather than kept in hand. (fn. 82) In 1910 and still in 2012 the college owned 429 a. in Cuxham, comprising the whole of the parish apart from some land in the north; village housing, however, was sold off piecemeal during the 19th and 20th centuries. (fn. 83) In the 12th century the manor also included two hides in Chalgrove, and though the land there was subinfeudated the college retained an interest in part until 1517. (fn. 84)

Manor House (Manor Farm)

A manorial complex on the site of Manor Farm was mentioned in 1244, and probably had much earlier origins. (fn. 85) Air photographs suggest that the domestic buildings, including the lord's room and a hall, stood within a small spring-fed moat, to the west of which were two rectangular fishponds. The stone-built lord's room, a solar-like chamber located most likely above a dairy and cellar, was fitted out to accommodate fellows and college guests, and probably (after the Black Death) the college bailiff; by contrast the sparsely furnished timber-framed hall seems to have been used mainly for demesne workers' meals. The farm buildings lay on the eastern side of the moat around a yard. (fn. 86) The whole complex was enclosed within a large walled garden which produced leeks, onions, beans, hemp, apples, pears, cherries, nuts and vines. By the 14th century the ancillary buildings included a gatehouse, kitchen, bakehouse, barns, byres, stable, carthouse, granary, hayhouse and pigsty; two dovecots stood in the northern part of the garden, and a malt oven in the south. The majority of those buildings were built or reconstructed between 1294 and 1330, when many thatched roofs were upgraded to tiles. The most important addition was a probably 5-bayed wheat barn, built in the 1320s to replace one of the two older barns. The second barn (probably the old wheat barn) was extended in 1335–6, when it was used for oats and other crops. (fn. 87)

From the late Middle Ages Merton and its lessees shared responsibility for maintaining the buildings, (fn. 88) extensive repairs in 1419–20 including work on the hall, 'high chamber' (presumably the lord's room), and great chamber'. (fn. 89) An inventory of 1530 mentioned the hall, high chamber, kitchen, and brewhouse. (fn. 90) In the 16th and 17th centuries the house was large enough to accommodate college members fleeing outbreaks of plague in Oxford; (fn. 91) probably it was remodelled during this period by the Gregorys (as lessees), and by 1662 it had 12 hearths. (fn. 92) A map of 1767 shows a house with an irregular but broadly L-shaped plan, (fn. 93) while a more regular plan was depicted from the 1840s, presumably reflecting further rebuilding. (fn. 94) The house was badly damaged by fire c.1900, and a steep-gabled, four-bay brick and stone frontage was added to surviving parts of the rear. (fn. 95) In the later 20th century two old thatched barns were demolished and the remains of the moat partly filled in. (fn. 96)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Cuxham's economy has always been based on agriculture. From the Middle Ages its mixed farming was strongly biased towards grain production, with farmers benefiting from access to the London market via the Thames at Henley, and from the presence of nearby towns such as Abingdon and Thame. The farmland was primarily divided between Merton College (whose demesne was leased out from 1359), the rector (who was a substantial occupier), and customary tenants with smaller holdings. The demesne was consolidated into blocks in the 13th century, but the tenant land remained in strips scattered across the three open fields until inclosure in 1846–8. Two medieval mills remained important assets, though craft and retail activity was limited.

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE (FIG. 41)

From the Middle Ages to the early 19th century the village was surrounded by its open fields, with inclosures (mostly of medieval origin) restricted to the edge of the settlement and to the low-lying areas of grassland beside the streams. There were a few small copses and orchards in the village, but otherwise trees were found only singly or in small groups around the village and on the edge of the fields and streams. (fn. 97) The open-field system documented after 1200 was probably laid out in the 11th or early 12th century: parts of the fields in the south and east of the parish were still wooded in 995, but had apparently been cleared by 1086. (fn. 98) In the 13th century and later there were three fields, each of 120–130 a.; during the Middle Ages they were usually identified by their proximity to Pyrton, Brightwell and Britwell respectively, but in the 16th century their names changed to North field, West field and South field. (fn. 99) Field boundaries and furlong layout apparently altered little from the 15th century (and probably earlier) until inclosure, although one furlong was transferred from the south to the west field before 1614. (fn. 100)

Grassland totalled 107 a. in 1767, much of it (61 a.) held in closes. (fn. 101) Town meadow (13 a.) in the far north-east corner of the parish was lot meadow in the later Middle Ages, but by 1614 its strips were permanently attached to particular holdings. (fn. 102) The only significant piece of common pasture, called 'the common in 1677 and earlier 'the moor', covered 29 a., having been slightly enlarged in the late Middle Ages by the incorporation of abandoned tenements in the north-west of the village. (fn. 103) In addition there were two small greens, Tower Green (3 a.) in the same area, and Upper Green (1 a.) next to the church. The amount of pasture in the 13th century was apparently smaller. (fn. 104)

MEDIEVAL TENANT AND DEMESNE FARMING

Cuxham's mixed farming can be traced back to the Anglo-Saxon period, when, as later, stream-side meadow provided fodder for plough beasts and other livestock. The chalk and fertile greensand of the lower ground was probably the main arable area, but the presence of a 'wudu wic' (or 'farmstead by the wood') on the south-eastern boundary in 995 shows that farming was already encroaching onto the gravel-topped hills where early woodland was concentrated, some of it probably in the two valleys called 'Symmysdene' and 'Hecchelesdene'. (fn. 105) Domesday recorded no woodland in Cuxham, but five ploughs were in use on land sufficient for four, suggesting an expansion of arable since 1066. Two ploughs belonged to the lord and were run by four slaves or servi, while the other three were held by tenants. Intensive cereal production is suggested by the presence of three mills on what was a small (5-hide) estate. (fn. 106)

Little is known of farming in the 12th century, but the survival of the Merton archives makes this one of the best-documented small manors in England after 1200, and especially in the period of direct management by the college (1271–1359). (fn. 107) Like Merton's other manors Cuxham was run as an individual unit, though sheep farming may have been centrally organized for a time. (fn. 108) The warden and fellows administered the manor personally, making regular visits and supervising the harvest. (fn. 109) The college enjoyed the services of several long-serving reeves chosen from among the more substantial tenants, including Robert Benet (1288–1311) and Robert Oldman (1311–49). (fn. 110) These men managed the demesne in return for remission of rent and other perquisites. (fn. 111) Six to nine workers (or famuli) provided the main demesne labour force, their efforts supplemented by the heavy labour service of the villeins (worth £6-£7 a year) and casual hired labour. (fn. 112)

The Cuxham demesne was highly productive, though it is difficult to put a precise value on its output. By the late 13th century c.269 a. were sown with seed each year: 87½ a. in the north field, 88¼ in the south field, and 93¼ in the west field. (fn. 113) Half of that area was sown with wheat, which was the main cash crop; oats (the next most important) were used mainly for fodder, while dredge, barley, peas, beans, and vetch were grown in smaller quantities. (fn. 114) Around 70 sheep (more after 1310) produced both wool and milk, augmenting that produced by a dozen cows, while c.20 pigs were kept as well as poultry, and the dovecot produced 500–1,500 young doves for the college table. (fn. 115) Gross income in the first half of the 14th century was c.£60 a year, including rents and profits of court (c.£5), but not the produce delivered to the college or consumed on the manor. Income from cereals totalled five to eight times that from livestock, wool and cheese, while net profit, including the value of food consumed by the fellows, averaged just over £40. (fn. 116)

This was a large sum for an estate of under 500 a., and was achieved by high yields. Those in turn reflected careful management, high labour inputs, and good soils, combined with excellent market networks. Efficiency was probably increased by Ralph Chenduit's consolidation of his demesne land in blocks around the village in 1227–43, (fn. 117) and in the later 13th century Merton College increased labour, raised rents, and probably enlarged the demesne, (fn. 118) followed in the early 14th century by investment in new and improved farm buildings. (fn. 119) Cuxham was part of a prosperous mixed farming region, and nearby Thames-side towns provided good outlets for agricultural produce. (fn. 120) Wallingford was important in the 11th and 12th centuries, and from the 13th century Henley became the main market for Cuxham's wheat. Much produce was also bought and sold in Cuxham and surrounding villages and in the small neighbouring town of Watlington, which had a chartered market from 1252. Abingdon and Thame supplied livestock and other items. (fn. 121)

The manors focus on cereal cultivation nevertheless brought certain limitations and inconveniences. In 1279 the demesne included only 11 a. of meadow and 9 a. of pasture (compared with 44 a. in 1767), (fn. 122) and lack of grassland precluded any substantial stock-raising. Hay for plough oxen and horses had to be bought in nearby Thame-side vills to supplement customary grazing rights in neighbouring Pyrton, while timber and firewood was imported from the college's manor of Ibstone (acquired by Walter Foliot in 1202–3), or purchased in the Chilterns, Reading, or elsewhere. (fn. 123) Limited manuring and intensive farming using a three-course rotation of spring corn, winter corn and fallow may have also led to some decline in soil fertility by the early 14th century. Yields seem to have fallen after 1300 despite continued high labour inputs and a slight increase in the planting of legumes, although they remained very high by contemporary standards. (fn. 124)

Tenant farming was smaller in scale but broadly similar in type. (fn. 125) Half-yardlanders, of whom there were 13 by 1293, farmed 12-a. holdings scattered across the three fields, growing wheat, rye, and vetch (rather than oats), and a little barley. In 1304 most had one or more plough horses, a cow, and a pig or two, though few of them owned sheep. Peasant farmers also imported hay for animal feed, John Lacheford of Cuxham being killed in 1378 while loading his cart with hay in Wheatfield. In the late 13th and early 14th century the Green family, by then amongst the very few remaining free tenants, (fn. 126) farmed on a somewhat larger scale, and kept 50 or more sheep; cottagers, by contrast, generally had no open-field land, and were restricted to growing cereals on their crofts and keeping poultry. Nothing is known of the yields achieved by tenant farmers, but it cannot be assumed that they were lower than those on the demesne, and the most successful were evidently quite prosperous. In 1349 the reeve Robert Oldman owned a wide range of farming implements, 67 sheep, and 35 pounds of wool, as well as malt, maslin, five horses, an ox, and a few cows and pigs. (fn. 127) All of Cuxham's villeins were required to perform two days' labour service a week, but their rents were modest, and they were aided by family members and hired labourers. (fn. 128)

The Black Death brought swift and long-term changes to both demesne and tenant farming. Merton College seems to have found it hard to find a reliable reeve or bailiff to manage the demesne after 1349, and as labour services virtually ceased more labour had to be hired. (fn. 129) Profits fell to £10 13s. in 1354–5, and from 1359 the manor was leased to a farmer. (fn. 130) The rector, William Elham, took it for seven years from 1361 for £20 a year, (fn. 131) but later farmers paid varying (and often slightly lower) amounts depending partly on what was included in the lease. (fn. 132) From the late 14th century small parts of the demesne were separately leased to tenants, and in 1441 the amount was increased to 100 a., let for £3 6s. 8d. rent. None of these measures prevented the college's income from Cuxham being much reduced. (fn. 133)

Depopulation, demesne leasing, and reduced rents allowed some tenants to increase the size of their holdings. The Greens acquired additional land at least for a time, and in 1377 the rector William Elham rented three half-yardlands which he sublet. (fn. 134) In 1466 eight tenants held over 8½ yardlands between them, including two yardlands of demesne which were perhaps additional to that leased out long term. Four others, however, still had only cottage holdings without open-field land. The leading tenants were Thomas Freeman and John Parson, who held two yardlands each, and Joan Clement, who had 1¾ yardlands and several closes. (fn. 135) By 1484 William Parson held 4½ out of 9¼ yardlands, and he retained this holding of probably over 100 a. in 1504, when his son held another 1½ yardlands. (fn. 136) Parson lived in the village, but may have sublet some of his land. Arable farming remained central (fn. 137) but may have been less intensive than earlier, and possibly grazing became more significant. Demesne farmers such as John Gregory (1479–1506) (fn. 138) seem to have also had some involvement in the Chiltern timber trade, helped by Merton College's ownership of Ibstone. (fn. 139)

FARMS AND FARMING 1500–1800

Post-medieval farming continued within a customary open-field system, (fn. 140) though as earlier Merton College's Manor farm comprised large blocks of land rather than scattered strips like the other holdings. By the 1760s it had recovered c.50 a. of the 100 a. previously let to tenants, and its 265 a. (including 218 a. of arable) comprised almost 60 per cent of the parish's agricultural land. The rector's 97-a. glebe and leasehold estate (part of which was later called College farm) made up over 20 per cent, with nine copyholds and two small freeholds accounting for the rest, although none of them individually exceeded 20 acres. (fn. 141) Subletting was common, and many inhabitants held additional small parcels of freehold or leasehold land in Cuxham and neighbouring parishes. (fn. 142) Throughout the period land became concentrated in fewer hands, so that by the 1730s there were only four farmhouses. (fn. 143)

In 1535 the college received £8 from the farmer of the demesne (Agnes Gregory) and £8 14s. 6d. from its other tenants, net profit totalling £15 12s. 6d. (fn. 144) Then as in the early 18th century agricultural affairs were organized at least partly in the manor court: (fn. 145) a three-course rotation was adhered to, and a third of the land was still left fallow each year, (fn. 146) with little of the hitching of fallow land practiced in some nearby parishes. (fn. 147) Inventories (mainly 17th-century) suggest predominantly smallscale farming within this strong customary framework. (fn. 148) The value of yeomen's and husbandmen's goods was generally rather low (mostly under £100), and as elsewhere wealth was tied up mainly in farming stock. Wheat was the main crop, followed by barley, beans, peas, and pulses; there is no evidence that oats were grown, and hardly any rye, (fn. 149) while most farmers kept just a handful of cows and sheep. (fn. 150) Henley and Thame (both places where Thomas Gregory owed wheat in 1530) (fn. 151) were probably the main markets for grain, while labourers were hired possibly in Watlington, which had an annual hiring fair by the 18th century. (fn. 152)

The Gregorys remained as demesne farmers until the 1680s, (fn. 153) though from the early 17th century they sublet all or part of the farm to the Clark family and others. (fn. 154) Later lessees and co-lessees included the Inner Temple lawyer Henry Stevens, John Edwards (rector 1693-1718), Robert Eyres (a Middlesex woodmonger), and Gislingham Cooper of Henley, followed by the Merton College fellow John Stevens and the London civil lawyer Henry Stevens. (fn. 155) Almost all of them were non-resident, and by the early 18th century Manor farm was apparently split between several undertenants. (fn. 156) Merton College granted 21-year leases for £5 6s. 8d. a year and a corn rent, with entry fines (usually over £60 in the 17th century) paid every seven years or so. (fn. 157) College officials still held court in person until 1670, and made occasional supervisory visits. (fn. 158)

The 18th century brought increased prosperity to the parish's three or four principal farmers, partly because rents remained low while demand for produce increased. In 1761 the rector's estate, leased for many years to the Neale family, was let for £67 a year (10–125. per acre), while its produce was worth £220 or over three years' rent. (fn. 159) Around the same time the valuation of land on Manor farm (farmed as one holding by 1785) was said to be 'very easy'. (fn. 160) Agricultural profits were invested in extensions to houses and the construction of new farm buildings, such as the granaries at Manor Farm and Yew Tree Cottage and the barn at Middle Farm. (fn. 161) Mixed farming continued to be cereal-led, with 84 per cent of the parish's farmland arable in 1767, and only 16 per cent pasture. (fn. 162)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1800

In 1800 the principal landholders were Thomas Jackson (subtenant of Manor farm), the rector, and a dozen smaller occupiers, of whom most held only a few acres. (fn. 163) The Manor farm lease was acquired in 1808 by Paul Blackall (d. 1811), a substantial farmer in neighbouring Pyrton; (fn. 164) his son William later sublet it to Charles Saunders, who also took on the rectory estate. (fn. 165) In 1814 Manor farm comprised 218 a. of arable and 43 a. of meadow and pasture, and was valued at £452 a year; £703 was paid to renew the lease, (fn. 166) although agricultural difficulties led to reductions soon after. By 1821 the fine was £693, and by 1828 (when the farm's annual value was put at only £278) it had fallen to £346. (fn. 167) By the 1830s Blackall was in financial trouble, and sold his interest to Thomas Ensworth; Ensworth renewed the lease for 21 years in 1835, paying a fine of £366. (fn. 168) The rector's glebe and two leaseholds (97 a.) were held in 1828 by John Hicks, the college's tenant at Cutt Mill; (fn. 169) by then the only other agriculturalists on any scale were Isaac Smith, John Crake, James Brown, and William Rogers, whose 10–30-a. holdings comprised a mix of copyhold, leasehold and freehold, much of it sublet. (fn. 170)

Merton College seems to have taken little interest in agriculture during this period. Farm buildings and cottages were kept in poor repair by small tenants with scattered holdings, (fn. 171) and the rector and some other tenants had generous leases. (fn. 172) From 1830 Manor farm was split up and sublet to several occupiers, and by 1843 its land was reportedly in 'very indifferent condition', (fn. 173) although the parish as a whole was said (in 1840) to bear 'very heavy crops'. (fn. 174) The only significant investment seems to have been a threshing machine installed in an extension to the wheat barn at Manor Farm before 1828, (fn. 175) most likely by William Blackall, who ran the farm himself in the 1820s. (fn. 176) Nevertheless, and despite the college's lack of attention, in 1842 the lessee of Manor farm paid a slightly higher entry fine of £434. (fn. 177) A four-course rotation was followed, with wheat the most important cereal crop. (fn. 178)

Considerable changes took place over the next ten years, under the direction of the college's energetic agent John Dale. Holdings were surveyed and repairs carried out, Manor farm was once again occupied by a single tenant (Joseph Gale) paying a rack rent, and the college instigated inclosure in 1846–8. (fn. 179) This facilitated the consolidation and enlargement of farms, although the location of Manor farm's land in blocks around the village meant that other holdings were generally more distant from the settlement. (fn. 180) Merton was able to increase its rental income by taking back the rector's leasehold land, buying up the copyholds (which Dale thought had 'pauperized' the parish), and introducing more commercial rents. (fn. 181)

By 1861 there were four dominant farmers, some of them with land in nearby parishes. Joshua Smith of Manor farm ran 270 a. with nine men and three boys, while William Hicks (150 a.) ran Cutt Mill, John Carey (sub-post master at College farm) farmed 112 a., and Thomas Tappin 47 acres. (fn. 182) Farming was by then based on sheep-corn husbandry, with only a small number of cows. (fn. 183) In 1888 Manor farm was described as an excellent corn-growing farm, though it was not well suited to keeping sheep over winter, and given the very low price of cereals its annual rental value was greatly reduced' to only £400 (or £300 if the tenant paid the tithe rent). (fn. 184) Agriculture and allied occupations remained the main source of local employment throughout the century, followed by domestic service in the homes of the leading farmers and at the rectory house. (fn. 185)

In 1910 Manor farm (275 a.) and College farm (97 a.) were run by William and Thomas Moffatt. There were also four small occupiers: Thomas Hicks of Cutt Mill (with 41 a.), and Frederick Stevens, David Tappin (the sub-post master) and Robert Gale, all with fewer than 15 acres. (fn. 186) Francis (or 'Frank') Nixey, who had recently bought neighbouring Easington farm, took over Manor farm in 1928, and by 1931 his family also held College farm. (fn. 187) After his death in 1940 his sons (and business partners) Albert and Frank continued to farm together until 1957, when their holding comprised 1,700 a. in Cuxham, Easington, Warborough, Tetsworth, Waterstock and Clare Hill. (fn. 188) Frank remained in Cuxham until his death in 1975, and his son Nicholas continued the business in 2012, farming 900 a. in Cuxham, Waterstock, Great Milton and Clare. The rent for Manor farm rose steadily from £281 to over £670 in 1958, £1,440 in 1963, and £1,970 in 1972, partly reflecting increases in acreage, and partly improvements paid for by Merton College, including new cowsheds, barns, electric lighting, and water supply. From 1973 Manor and College farms were leased together as a single 431-a. holding for £3,500, the college providing a new Dutch barn, implement shed, and cattle yard at Manor farm. (fn. 189)

The Half Moon c.1900, the village stream to the right, and a beer delivery cart (G. Bruce Clarke of Wallingford, wine and spirit merchants) outside.

The area of permanent pasture increased from the end of the 19th century, but farming remained mixed. In the early 20th century the chief commercial crops were wheat and barley and beans and roots were grown for fodder. Alfred Hoar ran a cattle-dealing business from Glenroy. (fn. 190) In 1939 some 44 a. was ploughed up for the war effort, (fn. 191) and in 1941 the combined Manor and College farms included 89 a. of wheat, 32 a. of oats, and 61½ a. of other crops (mainly for animal feed), together with 206½ a. of permanent grass. Nine workers (later reduced to four) tended 93 cattle (including 54 cows in milk), 148 sheep, 14 pigs, and 204 chickens. The holding included a steam engine, two threshing machines, and a tractor, but horses were still used for ploughing. (fn. 192) The main markets for cereals and livestock were Thame, Reading and Oxford, (fn. 193) and until 1961 Watlington station was used to export cattle and sugar beet and to bring in fertilizer; in the 1920s milk also went by rail to London. (fn. 194) The Nixeys' dairy herd comprised c.70 cows in 1973, and Frank's daughter Marygold bred horses and ponies, mainly for export to wealthy clients. (fn. 195) In the early 1960s the Tappin family of Middle Farm (who still ran the village post office) had a smaller dairy herd, (fn. 196) but from 1966 the Nixeys were the only farmers based in the parish. Thereafter further drainage was carried out, milk cows were replaced by beef cattle, and the arable acreage was increased (for wheat, barley and peas). In 2012 cattle and cereals were sold at Thame, which was the only nearby livestock market and had a branch of the grain merchants Glencore Grain. (fn. 197)

MILLS, CRAFTS, AND RETAILING

Domesday Book mentioned three watermills. One was almost certainly on the site of Cutt Mill in the far north of the parish, and another at Cuxham Mill, in the east of the village. (fn. 198) The location of the third mill, which had disappeared before the 13th century, is unknown. Cutt Mill belonged from the 1270s to Merton College, while Cuxham Mill was given by Robert Foliot to Wallingford priory, and was subsequently owned by the Stonors and others before Merton bought it in 1807. (fn. 199) A waterdriven fulling mill built by Merton in 1312 was rented usually for 135. 4d. a year up to 1349, but by then it was run down, and it was demolished shortly afterwards. (fn. 200)

During the Middle Ages both the corn mills were much improved, bringing in rents of over £2 a year, and for a time Cutt Mill was run by the reeve Robert Oldman and his son. (fn. 201) Rents fell after the Black Death. (fn. 202) Post-medieval millers, like their predecessors, were often part-time farmers, and frequently held property in adjacent parishes. (fn. 203) In the 1830s Cutt Mill was leased for £53 a year compared with Cuxham Mill's £31 10s., (fn. 204) but in the 1890s it ceased to operate, followed by Cuxham Mill in the 1930s. (fn. 205)

Medieval villagers were engaged in brewing, and there was a tailor and probably a carpenter. (fn. 206) Craftsmen were also brought in as required from neighbouring villages and sometimes further afield. (fn. 207) A smithy was established at the former Oldman tenement ('Revesplace') by 1354 and possibly before the Black Death; (fn. 208) it apparently continued there in 1401, but was abandoned before 1484. (fn. 209) A new forge was mentioned c.1525 and a blacksmiths shop in 1631, (fn. 210) and by the late 18th century the smithy stood on the north side of the village street. It remained there until its closure during the First World War, having been run by the Newell family for over a century. (fn. 211) Other craft and retail trades (often pursued by part-time practitioners) were represented at various times, amongst them shoe-making, tailoring, carpentry, food and ale retailing, thatching, hurdle-making, and (in the later 19th century) dress making. (fn. 212)

The Half Moon pub (Fig. 44), its sign taken probably from the Gregory family crest, was in operation by the mid 18th century, (fn. 213) and remained open in 2015. The much-altered building is probably of 17th-century origin, and was originally timber framed; a late 18th- or 19th-century rubble structure at its east end is used as a beer cellar, complete with wooden barrel-ramp. (fn. 214)

SOCIAL HISTORY

Until the 20th century Cuxham supported a small, predominantly agricultural community. (fn. 215) By the later Middle Ages village society was already dominated by a few leading farmers and by the rector or his curate, while the influence of Merton College, the major landowner from 1271, was felt through its manor courts and visiting officials. The rectors were almost invariably former college fellows, and often had close personal relations with wealthier farmers such as the demesne lessees or their subtenants, with whom they shared wider social horizons than many of their neighbours.

From the late 19th century fewer villagers made their living from farming, and by the mid 20th most worked outside the parish. Combined with falling church attendance and the decline of local crafts and retailing, such factors contributed by the early 21st century to a loosening of social cohesion typical of many small rural communities.

SOCIAL CHARACTER AND THE LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

The Middle Ages

Village society was stratified from an early date by personal status, wealth, and landholding, but the character and extent of social differences changed over time. In 1086 seven villani had the largest holdings, and were the senior unfree tenants; four bordars had smaller holdings, and four slaves or servi worked the demesne in return for board and lodging. (fn. 216) There may already have been some resident freemen, but if so they are not recorded. By the early 13th century there were at least nine free tenants including the rector, though not all of them lived in the village, and some (like Ascelin of Pyrton) were substantial men with land in several parishes. (fn. 217) Half a dozen half-yardlanders, the successors of the Domesday villani, owed heavy labour services, but in good years perhaps enjoyed a modest prosperity. There were also a number of cottagers, who were poor but had fewer obligations. Their small tenements were created probably in the 12th or early 13th century, and were mainly on the north side of the street, opposite the villein farmsteads, manor house, church and rectory house, and on the southern and western edges of the settlement. (fn. 218) The estate workers or famuli, whose first members may have been heirs of the Domesday servi, lived apparently as a separate household within the manor house complex. (fn. 219)

Changes in the mid to later 13th century reflected the strengthening position of the Chenduits and Merton College as manorial lords. (fn. 220) Most of the free tenants were bought out and their lands added to the demesne or converted to villein holdings. In 1279 there were only three free tenants, and by 1297 just two: the Green family and the prior of Wallingford's miller at Cuxham Mill. (fn. 221) By contrast the number of half-yardlanders rose from six to thirteen between 1276 and 1293, (fn. 222) and cottagers, too, probably increased in number: 13 were recorded in 1279, and others may have included unrecorded subtenants of the Greens, (fn. 223) who were by this time the wealthiest people in the village. In 1295 Robert Green was assessed on goods worth £4 13s. 4d. compared with a village norm of c.30–40s., and he and his son John built up an estate of small holdings scattered across eight parishes. (fn. 224) John's son, another John, was a bailiff of Sir John Stonor in the 1340s. (fn. 225) The villeins' individual circumstances changed frequently, but the Heycroft family (who lived north of the rectory house) and the reeves Robert Benet and Robert Oldman were notably well off, and individuals from all three families acquired free land outside Cuxham in 1315. (fn. 226) Only one cottager, Simon Gardiner, was ever prosperous enough to be taxed (in 1304). (fn. 227)

Leading villeins dominated manorial offices, and doubtless influenced agricultural decision-making. (fn. 228) They were also employers of labour, (fn. 229) giving them a degree of power over their neighbours. Like other halfyardlanders they lived in timber-framed houses with two or more rooms and separate barns, but their houses often had additional chambers or outbuildings. (fn. 230) Even so there was no great gulf between the village's richer and poorer tenant farmers. In 1349 Robert Oldman owned better clothes and furnishings than fellow villager Thomas Aumoner, but both men's wealth was tied up mainly in agricultural equipment and produce. (fn. 231) Even the poorest had some advantages: the cottagers possibly lived in smaller houses, but the lord contributed to repairs, (fn. 232) and while the famuli had little income or autonomy they were at least sure of being fed. (fn. 233) There were also occasional examples of upward mobility: in the early 1290s, for instance, five cottagers took on newly created half-yardlands, and in the early 14th century some demesne servants obtained cottages and land. (fn. 234) Robert Oldman was himself a younger son of a villein and acquired his half-yardland through marriage, (fn. 235) while the younger son of the prior of Wallingford's miller became a professional local clerk, bringing him independence and a good livelihood. (fn. 236)

Some families were long-established before the Black Death, although outsiders also moved in. Villein holdings were passed down by hereditary succession, while most cottage tenements were held for terms of lives, reinforcing social stability. Merton College remained keen to maximize its rents, but tenants were given help in hard times through remittances of rent or loans of grain, and lord-tenant relations seem generally to have been good, despite tensions in 1327–9 over the services owed by some cottagers. Villagers had regular contact with inhabitants of surrounding settlements and market towns, and the leading free tenants and villeins had wider networks, the latter travelling far afield on the lord's business. Nevertheless the parish church and the festivities of the agricultural year probably provided the chief focus for social activity, and surnames drawn from topographical features within the village suggest strong associations at a very local level. The Greens took their name apparently from Lower Green in the north-west of the village, where they seem to have lived, while Richard Bovechurch lived on rising ground above the church. Robert in le Hume's house stood on a bend (or 'turn') in the road. (fn. 237)

The period after 1350 was one of considerable discontinuity. In the decade after the Black Death there was a rapid turnover of tenants and famuli, (fn. 238) and though tenants stayed longer thereafter only one family recorded in 1466 (the Parsons) was still present in 1504. (fn. 239) The Greens were amongst those who moved away in the 15th century, apparently to Henley, and in 1415 their holding was bought by William Walden of Shirburn, whose descendants the Halls remained in the parish in the 16th century. (fn. 240) The reduced population was probably increasingly dominated by a few leading figures, notably the demesne farmer, the rector, and (in the later 15th century) members of the Parson family, (fn. 241) while men such as Walden expressed their social standing through fine possessions (including silverware), and by investment in the ritual furnishings of the parish church. (fn. 242) Social tensions possibly increased as the interests of major tenants and small copyholders and labourers diverged, but the court rolls contain few indications of the ongoing disputes or violence found in some other places during this period. (fn. 243) An exception is the case of the early 16th-century rector William Ireland, who seems to have been an unusually divisive character. (fn. 244)

1500–1800

For much of this period village life was dominated by the Gregory family (Merton College's demesne lessees and rent collectors since 1479) and by the rectors, who were often resident. The rectors maintained close relations with Merton, holding land from the college, advising on the leasing of the demesne, and assisting with valuations. (fn. 245) This link between landowner and parson doubtless helped to reinforce the authority of both, and possibly allowed William Ireland to remain in post in the early 16th century despite the accusations levelled against him, which led to a royal judicial investigation in 1511. Rectors often enjoyed close relations with the Gregorys, with whom they were neighbours and approximate social equals, (fn. 246) and like their medieval predecessors they maintained links with fellow clergymen in Watlington and nearby parishes. (fn. 247) There were also occasional neighbourly quarrels, however, such as the 18th-century disputes over flooding of the rectory house and grounds by the manor fishponds. (fn. 248)

John Gregory (d. 1506) is commemorated with his family by a brass in the church, and came apparently from the north of England. (fn. 249) His descendants lived mainly in Cuxham, obtaining several properties in Oxfordshire and elsewhere through purchase, lease, and marriage. (fn. 250) Edmund Gregory (d. 1583) was taxed in 1543 on goods worth £10 - not a very large sum, but double that of the next highest taxpayer William Wagge, and five to ten times more than most villagers. (fn. 251) By the 17th century, when the family secured a coat of arms, (fn. 252) some of its members were notably well off, amongst them Roger Gregory (d. 1663), a brother of the demesne lessee Edmund (who lived latterly in Britwell Salome). (fn. 253) Roger's bequests included £705 in cash (£10 of which went to the poor), as well as Cuxham Mill and land in Buscot. (fn. 254) The family was ruined in the late 17th century by the extravagance of Edmund's son Edmund, a university friend of the antiquary Anthony Wood. Edmund married a 15-year-old Cholsey heiress in 1657 and was high sheriff in 1680, but debt forced him to sell almost all his property in 1683. (fn. 255) Later demesne lessees were mostly non-resident, though their subtenants still numbered among the parish's leading farmers, of whom there were just four in 1738. (fn. 256) Two of them, Joseph Stevens and Thomas Jackson, were between them churchwardens for much of the 18th century. (fn. 257)

Probate evidence suggests that the other villagers, of whom most were small-scale customary tenants and labourers, had most frequent contact with inhabitants of Watlington and of neighbouring parishes such as Brightwell Baldwin, Britwell Salome, Chalgrove, and Easington. (fn. 258) More distant connections were not uncommon, but probably less regular. Some families in the 16th to 18th centuries stayed for several generations, amongst them the Broadways, Crookes and Fritwells, but otherwise the parish registers suggest a regular turnover of population, particularly among the poor. (fn. 259) Some local traditions survived into the 18th century, including a feast associated with the Holy Cross, (fn. 260) but discontinuity is suggested by changes to most field names. (fn. 261)

Since 1800

At the beginning of the 19th century Cuxham's small population comprised mostly small-scale farmers and agricultural labourers. The occupiers of Manor Farm were by far the biggest farmers and employed the largest number of workers, though in 1830 the holding was temporarily divided up. (fn. 262) Most of the population came from Oxfordshire, and several large labouring families were closely related. (fn. 263) By the second half of the century a more significant minority of adult inhabitants came from outside the county, including Manor Farm tenants such as Joshua Smith (Warwickshire), Robert Palmer (Norfolk), and William Moffatt (Lincolnshire). (fn. 264) The number of people in non-agricultural employment also increased slightly, including servants from Brightwell Park who were housed for some years in Brightwell Villas (erected 1874). (fn. 265)

By the early 20th century there was a handful of residents living on private means, (fn. 266) but the population remained socially mixed, and in the second half of the century many inhabitants commuted to Oxford and other local towns. (fn. 267) Social activities in such a small village were limited: the Cuxham and Easington Women's Institute (formed in 1947) was suspended twenty years later, (fn. 268) and in the early 1970s children had little to amuse them, although a youth club had recently been set up and there was a discotheque and film club in Watlington. (fn. 269) Property prices rose greatly thereafter, and by 2001 almost 60 per cent of working residents were managers or professionals. (fn. 270) A mother and toddler group set up in 1975 closed in 2005, (fn. 271) but in 2012 the village hall (the old school), which had been extended in the 1960S-70S and re-roofed c.2000, (fn. 272) was well used, and a cricket club was based on land belonging to Manor Farm. Community events included a weekly yoga class, annual village walk, barn dances, and bonfire night celebrations. (fn. 273)

EDUCATION

In 1808 it was claimed that attempts to set up a school had failed over the previous thirty years because no teacher could be found in such a small village, and because children were sent to labour so early. (fn. 274) In 1818 the 'poorer classes' were nevertheless said to desire a means of educating their children, and a Sunday school established by the rector Francis Rowden in 1825 had 37 pupils in 1833. (fn. 275) In 1848 Rowden secured £50 from Merton College towards building a day school for 3 5 pupils on the site of two cottages north of the church; (fn. 276) the school was affiliated to the Church of England's National Society, but was funded by private contributions including £5 a year from the college, raised to £20 in 1853. (fn. 277) Later it received a government grant. (fn. 278) In 1854 there were 22 day pupils, and 28 attended the Sunday school. (fn. 279)

By the 1870s many older children went to Watlington Board School, (fn. 280) and average attendance at Cuxham declined from 25 in 1883 to 8–15 in 1887–1903. (fn. 281) Despite little subsequent increase, in 1911 the school was extended to become a two-room mixed elementary school for 42 pupils. (fn. 282) Low pupil numbers, difficulty in securing a permanent teacher, and the building's dilapidated state led to its closure in 1923, despite opposition from the managers. (fn. 283) Thereafter all village children went to Watlington school, those under nine by bus and the older children by bicycle. (fn. 284)

POOR RELIEF AND CHARITIES

A 'church house tenement' mentioned in the 15th century was possibly maintained for the poor, (fn. 285) and in 1768 the parish owned a cottage from which the churchwardens formerly received 20s. a year, but which the current occupant (who was poor) held rent free. (fn. 286) Some villagers made modest bequests to the poor, and in 1627 William Hamildon left money to three named inhabitants including two widows. (fn. 287) There were, however, no endowed parish charities.

In 1776, 305. out of £55 14s. 4d. raised by the poor rate was spent on housing. (fn. 288) A row of six cottages was built on waste near the church in the early 19th century, and was used for the poor until 1850. (fn. 289) As elsewhere poor rates rose considerably in the late 18th and early 19th century, reaching £257 5s. in 1818; costs fell by the 1820s, (fn. 290) but poor relief remained a problem after 1834, when Cuxham joined the new Henley Poor Law Union. (fn. 291) In 1843 Merton College's agent reported continual complaints about the burden of parish rates and a surplus of labourers, (fn. 292) ascribing the difficulties to an excessive number of lifehold tenants with large families chargeable to the parish. Rates were reduced after inclosure in 1846–8. (fn. 293) A cottage used for the parish clerk and later the sexton was sold in 1978. (fn. 294)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

From the Middle Ages to the 19th century Cuxham's rectors were for the most part dominant local figures, closely connected with Merton College, and often representing its secular interests within the parish. (fn. 295) In its religious life, however, Cuxham seems to have experienced no great controversies or enthusiasms. A general attitude of conservatism was often complemented by relative apathy and, in the 18th and 19th century, by low church attendance among a poorly educated farming population. The religious conservatism of some mid 16th-century incumbents prompted no lasting Catholic sympathies, and Protestant Nonconformity, too, found little footing. After 1918 the progressive merging of local benefices contributed to a further decline in church attendance.

CHURCH ORIGINS AND PAROCHIAL ORGANIZATION

In the Anglo-Saxon period Cuxham may have been dependent on a mother church at Benson or (later) at Pyrton, (fn. 296) but there is no evidence of a link with either after the Conquest. A local church may have been built at Cuxham in the late Anglo-Saxon period, when it first became an independent estate: the present building (which dates apparently from the 12th century) stands next to the manor house, an arrangement typical of many small proprietary churches of the 10th century and later. By the 13 th century the church was fully independent, (fn. 297) and its small parish survived until 1853 when it was united for ecclesiastical purposes with neighbouring Easington, included (like Cuxham) in Aston deanery. From 1918 the combined parish (comprising 727 a.) was held in plurality with Brightwell Baldwin, and in 1985 the two benefices were united with Ewelme. (fn. 298) The dedication to the Holy Rood is medieval. (fn. 299)

Advowson, Glebe, and Tithes

In the early 13th century the advowson belonged to the lord of the manor, (fn. 300) with which it passed to Merton College in 1271. The college presented Cuxham's rectors thereafter, becoming sole patron of the united benefice of Cuxham and Easington in 1853, (fn. 301) and (after 20th-century reorganizations) sharing the advowson with the patrons of the churches with which Cuxham was held in plurality and union. (fn. 302)

The church was poor, though from the late Middle Ages the rector's income was supplemented by tenure of additional farmland belonging to the college. (fn. 303) In 1254 its annual value was estimated at £4 13s. 4d., and in 1291 at £5 6s. 8d; (fn. 304) both figures may have been underestimates, however, since in the early 14th century the tithes (excluding profits from the glebe) were worth £8–10, (fn. 305) and in 1535 the value was said to be £9 105. 5½d. (fn. 306) Thereafter the tithes were usually leased, (fn. 307) though in 1715 the living was still worth less than £70 a year. (fn. 308) From 1718 to 1852 incumbents bolstered their low income by holding the Merton living of Ibstone in plurality, though in 1754 the net value of the two was only £120, including £70 from Cuxham. (fn. 309) Fortunately Cuxham's rectors in this period were men of independent means. In 1848 Cuxham's tithes were commuted for an annual rent charge of £192, (fn. 310) though this sum was apparently not collected in full: in 1895 the combined rent charge of Cuxham and Easington was £265, but the average income only £190. (fn. 311) Fifteen years later the gross value of the rent charge was just £165, and the net value of the living (including glebe land) £172. (fn. 312) In 1934 the net value was £295. (fn. 313)

Cuxham rectory house (rebuilt 1823) from the south.

The glebe in the 17th century and probably in the Middle Ages included closes around the house, 30 customary acres of arable (probably 1¼ yardlands), and an acre of meadow. (fn. 314) It remained much the same size (26 a.) in 1910. (fn. 315)

Rectory House

The rectory house has occupied its present site from the Middle Ages. (fn. 316) The homestead included fishponds in the 13th century and by 1504 a dovecot; (fn. 317) in 1614 the house itself comprised a hall, parlour, bakehouse, buttery, and milkhouse, plus upper chambers and a detached kitchen. Two ranges of outbuildings included a barley barn with hay house and stable, and a cow house, wheat barn, corn loft, and cool house. (fn. 318) By 1662 the house had seven hearths, and the long-serving rector Leonard Yate had added wainscot to the parlour and hall. (fn. 319) A gatehouse was mentioned in 1685, when the house and barley barn were both said to have five bays, and the wheat barn seven. (fn. 320) John Edwards (d. 1718) subsequently 'repaired' the parsonage, which had been considerably enlarged before 1756 when it had twelve bays. (fn. 321)

In 1823 Francis Rowden the younger rebuilt the house in Regency style, with a slate roof and Doric-style porch. (fn. 322) The building is double-depth and of five bays, with a flagstone floor, four-panelled doors, marble fireplace, and moulded cornices. A timber-framed barn (dated 1750) was rebuilt as a coach house and stable in 1824, reconstructed in rubble and brick and attached to a high perimeter wall. (fn. 323) After the rector moved to Brightwell Baldwin in 1918 the house was leased and eventually sold. (fn. 324)

PASTORAL CARE AND RELIGIOUS LIFE

The Middle Ages

The first recorded rector is Walter Foliot (a namesake and relative of the lord of the manor), who held the living in the 1220s-30s. Nothing is known of his successors until Merton College acquired the manor in 1271. Adam of Watlington (rector 1298–1322), a former college fellow, was probably resident, but later rectors until 1351 must have been largely absent. Two (John Wantage and Robert Tring) were college wardens, and the third (Walter Burton) was a pluralist clerk to the bishop of Bath and Wells. Chaplains serving the cure in their absence included Adam and Richard, both of whom were called 'of Cuxham'; Richard (and probably Adam too) was a non-graduate. William Elham (d. 1387), fellow and second bursar of Merton, became rector in 1351 and seems to have resided, acting probably as a representative for the college in a period of labour difficulties. Ten years later he became lessee of the manor, and towards the end of his life was assisted by a curate, William Laurence, who lived apparently in the rectory house. (fn. 325)

Subsequent medieval rectors, most of them former college fellows, seem to have lived mainly in Cuxham, and William Motherby (1401–1409 or later) and Richard Colyns (1438–74) were also lessees of the manor. (fn. 326) William Colyns, a 'husbandman' who was lessee in the 1460s-70s, was probably Richard's relative, and acted as his executor. (fn. 327) The pluralist Thomas Lee (1474-1502) may, unusually, have lived elsewhere, (fn. 328) though his pluralist successor William Ireland (1502–37) mostly resided, and in 1530 witnessed Thomas Gregory's will. (fn. 329) Ireland was, however, a quarrelsome man who may have been given the living as a way of removing him from college. (fn. 330) At Cuxham he was accused of numerous transgressions, including (in 1511) ravishing his servant Joan Baker, in 1512 putting his own mark on college land, and (in 1520) keeping a mistress, failing to maintain the rectory house, and cutting down trees around the churchyard. (fn. 331)

Religious life before the 1270s may have been dominated by resident lords, (fn. 332) though from the later 13th century there was probably greater scope for involvement by parishioners. An inhabitant of relatively high status was presumably buried in the stone coffin dug up in the churchyard in 1817, (fn. 333) and 14th-century work on the nave may have been at least partly paid for by local people. (fn. 334) By the late Middle Ages the church was dedicated to the holy cross (or holy rood), (fn. 335) and in 1427 William Walden made a bequest to repair the lights around the crucifix, (fn. 336) located presumably on the high altar mentioned in 1530. (fn. 337) Lights associated with the blessed Mary and St Nicholas were probably on side altars. The level of spiritual and financial investment made by individual parishioners no doubt varied, and the church itself may have suffered periods of relative neglect. In 1520 one parishioner withheld two lamps from the church, several others owed tithes, and thanks to the rector's negligence the chancel was in poor repair. (fn. 338) Ten years later the incumbent William Ireland had still failed to repair the chancel paving. (fn. 339)

The Reformation to 1823

Most rectors continued to be presented by Merton College or its representatives, the great majority being college fellows or graduates. The period 1537–64 was characterized by mainly short incumbencies, mostly of resident rectors who died in post. (fn. 340) Many seem to have had little appetite for religious change. The will of Robert Turner (d. 1549), curate to Richard Bower (1540–53), was conservatively worded and included bequests for masses, (fn. 341) while Humphrey Burneford (1553–8), a former chaplain of the university and principal of St Alban Hall, was instituted in Edward VI's final weeks, but remained in post throughout Mary's reign. (fn. 342) His will of 1557 specified prayers and generous bequests to the poor at the commemoration of his death. (fn. 343) Burneford's successor William Smith resigned in 1559 because he could not accept the Elizabethan settlement, (fn. 344) and his replacement Ralph Johnson (1559–63) was a former Augustinian canon, although his will followed Protestant formulae. (fn. 345) Parishioners' views are largely unknown, although in 1552–3 the churchwardens witnessed the removal of church goods and presumably the rood screen, (fn. 346) apparently without resistance, and none of the few surviving laypeople's wills of the late 1550s or 1580s contain Catholic preambles. (fn. 347)

Johnson's successors John Pratt (1563–77) and Bartholomew Bushel (1577–82) were apparently non-resident, and hired curates who included the Welshman Howell Roberts, a future rector of Easington. (fn. 348) Pratt was a successful pluralist who claimed in 1578 to have been dispossessed of the living, which he was still trying to recover ten years later. (fn. 349) Bushel's successor Robert Wirrall, presented in 1583, was apparently a non-graduate, but was judged sufficient' in learning. (fn. 350) Seventeenth- and 18th-century incumbents were both long-serving and generally resident. Leonard Yate (1608–62), Cuxham's longest-serving rector, was a bibliophile whose varied collection included the works of Thomas More and the popular anti-Catholic satire The Beehive of the Romish Church, (fn. 351) and he continued to sign the register until his death aged about 92. By then, however, the church fabric was probably badly neglected. The great bell' was recast during Robert Cripps' incumbency (1663–93), (fn. 352) and c.1685 Cripps and the churchwardens were forced to rebuild the church which had 'fallen into such decay that the parishioners durst not come into it'. (fn. 353) Several subsequent rectors had assistant curates in their later years, amongst them William Marten (rector 1718–43), who gave a silver almsplate in 1737, (fn. 354) and John D'Oyly (rector 1743–73), who in 1759 became 4th baronet of Chiselhampton. (fn. 355)

There is little indication of any marked religious enthusiasm among villagers in this period, and Nonconformity found few adherents. In 1676 no papists were reported, and there were only three Protestant Dissenters; (fn. 356) of those, one was probably Richard Hollyman, who was evicted that year from Cuxham mill for his Quaker beliefs. (fn. 357) Later there were usually said to be no Nonconformists of any kind. (fn. 358) D'Oyly was described as 'very well' qualified in 1745, (fn. 359) but by 1759 there were some signs of neglect, and orders were issued to remove rubbish from the corners of the church, to whitewash the porch, and to provide a new surplice. (fn. 360)

In 1774 the living was taken by 50-year-old Francis Rowden, a former postmaster at Merton College (through D'Oyly's patronage), and from 1785 a prebendary of Salisbury cathedral. (fn. 361) Rowden was a man of some means who leased the tithes at a lower than commercial rate, (fn. 362) and occupied the rectory for 48 years until his death aged 98 in 1822. (fn. 363) In his later years he was assisted by curates including his younger son Francis, who received a small stipend of £50 and shared the rectory house with his father. (fn. 364) The double Sunday service established by 1738 was continued, (fn. 365) but Rowden's increasing age and infirmity may have led to some neglect. By 1799 the number of absenters 'of meaner condition had increased, (fn. 366) and in 1801–2 the archdeacon ordered provision of a bible and prayer book and repairs to the church, including display of the Creed, Lord's Prayer, and Commandments. (fn. 367)

Since 1823

Francis Rowden the younger (rector 1823–52) seems to have initiated a modest revival of Church life. Bishop Wilberforce thought him a 'very respectable clerk, very attentive in [the] parish', (fn. 368) and during his long incumbency he provided two Sunday sermons, distributed religious tracts to the poor, and started a Sunday school, as well as persuading Merton College to set up a day school. (fn. 369) Even so there was no increase in the number of communicants (which had long stood at c.15), and in 1854 Rowden's successor John Piggott (1853–91) reported an average congregation of 50–70, which he felt did not bear a fair proportion to the population of c.160. He ascribed non-attendance to 'habits of neglect and indifference long indulged on the part of several heads of families'. (fn. 370) The number of Dissenters had also increased since the 1830s (when none were reported), reaching a peak of 12 in 1866, (fn. 371) and though this fell to four or five by 1878 (fn. 372) absenteeism remained a greater problem. By 1875 over half the adult population failed to attend thanks to what Piggott described as 'a spirit of insubordination and disaffection towards employers and clergy', allegedly stirred up by inflammatory speeches and publications of the National Agricultural Labourers' Union, which had been formed three years earlier. (fn. 373) In 1890 Piggott blamed a further fall in attendance on the decrease in population and 'the intrusion of Salvationists at service time', while no churchwardens could be found because of an unwillingness to take responsibility for fire insurance. (fn. 374)

Later rectors such as Edward Fletcher (1893–1902) were evidently High Church Anglicans, (fn. 375) but it is unclear whether this approach was popular among parishioners. Certainly church attendance remained at modest levels, Thomas Hainsworth (1917–34) having only 5–10 regular communicants. (fn. 376) By then Cuxham lacked a permanent Anglican presence: Hainsworth and his successors lived at Brightwell Baldwin and subsequently at Ewelme, and by the 1980s services were rotated amongst the four churches of Cuxham, Easington, Brightwell Baldwin, and Ewelme. In 2012 regular church services were attended by only half a dozen people, but there was a larger congregation of c.40 (including some outsiders) at united benefice services and major festivals. (fn. 377)

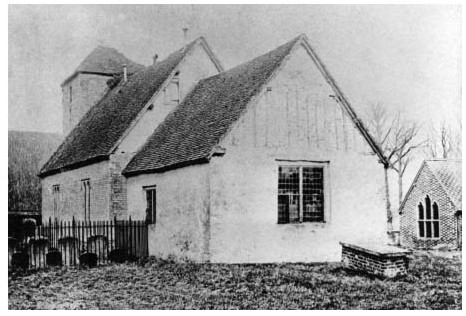

Cuxham church before the chancel's rebuilding in 1895, with the school just visible on the right.

CHURCH ARCHITECTURE

Cuxham church (Figs 42 and 46) is a middling-sized medieval structure substantially rebuilt in the late 17th century and much altered in the 19th. In its present form it comprises a squat west tower, two-bay nave, and rebuilt chancel with north vestry, its older walling composed chiefly of coursed chalk rubble. (fn. 378) The earliest features date apparently from the 12th century, and include the round-arched west doorway with sculpted capitals, the ground-floor window openings of the tower, and the plain tub font in the nave. The windows in the nave's north wall are early 14th-century, but those in the south are probably 17th-century replacements. A Jacobean pulpit survives reset on a late 19th-century base.

The church was largely rebuilt c.1685, (fn. 379) though part of the roof may have been recycled. Drawings of 1806–22 show a small plain church with a low chancel, a nave, and a west tower. (fn. 380) Restoration work was apparently carried out in 1850, (fn. 381) and in 1895 the rector Edward Fletcher commissioned the Anglo-Catholic Oxford architect Clapton Rolfe to rebuild the chancel in Gothic style, complete with piscina and sedilia. (fn. 382) The work, which cost c.£400, was paid for by donations, including £100 from Merton College. Oak panelling fitted on the south side of the nave in 1925 was recycled from a screen by Sir Christopher Wren removed from Merton College chapel in 1851. (fn. 383) The pews are partly Victorian, but may include some 17th-century woodwork. The church contains a memorial to the Gregory family, and brass plaques in memory of four village men killed in the First World War and four in the Second. Electric lighting was installed in 1947 and heating in 1968, and the roof was repaired in 1992. (fn. 384)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

MANOR COURTS AND OFFICERS

In the Middle Ages the lords of Cuxham had a manor court without leet jurisdiction, (fn. 385) the tithing group owing attendance at the honor of Wallingford's view of frankpledge at Chalgrove. (fn. 386) The earliest surviving court roll dates from 1279, and a long series of extant records from 1294 to 1885 is broken by relatively few gaps. (fn. 387) Until the early 18th century (and especially until the 1680s) the manor court dealt with a wide range of business including the regulation of agricultural affairs, but afterwards it was almost solely concerned with customary tenancy transfers. (fn. 388) Latterly it convened when tenancies required renewal, or otherwise every seven years. (fn. 389) Representation at the Chalgrove view continued until 1847, when a constable and tithingmen were still appointed there. (fn. 390)

PARISH GOVERNMENT AND OFFICERS

For a long time the manor court probably organized all functions of parish government, especially as manor, vill and parish were coterminous. (fn. 391) In the Middle Ages the reeve was assisted by a constable (mentioned in 1346), a hayward (who received a grain stipend from 1315), and a butcher (who certified the deaths of demesne livestock). (fn. 392) Churchwardens were mentioned in 1427, (fn. 393) but were at least partly under manorial control: as late as 1620 the manor court ordered the constable and churchwardens to carry out repairs to the gate at the village's western end, (fn. 394) although by then the vestry presumably oversaw parochial functions such as poor relief. Overseers of the poor were mentioned in the 18th century (fn. 395) and a parish clerk in the 19th, (fn. 396) but no parish officers' accounts survive from before 1852. (fn. 397) Village stocks near the church were depicted on an engraving of 1796 (Fig. 42).