A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Chalgrove', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp122-157 [accessed 31 January 2025].

'Chalgrove', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online, accessed January 31, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp122-157.

"Chalgrove". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online. Web. 31 January 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp122-157.

In this section

CHALGROVE

Chalgrove occupies the flat clays and gravels between the Thame valley and the Chiltern scarp, c.5.6 km north-west of Watlington and 15.3 km south-east of Oxford. (fn. 1) The village developed along a narrow stream-valley south of the Oxford-Watlington road, and became one of the hundreds more populous settlements, growing substantially in the 1960s when new building quadrupled the number of households. An outlying hamlet at Rofford shrank considerably in the later Middle Ages, but remained the centre of a separate liberty until the 19th century. By then the parish was usually administered as a whole, and in 2013 Rofford comprised just two houses.

The parish was predominantly agricultural until the 20th century, its large open fields remaining mostly uninclosed until 1843. (fn. 2) From the 15th century it was largely owned by Magdalen College, Oxford, which sold its estate in 1942. The following year a military airfield was built over former farmland, its huts and barracks providing temporary post-war accommodation pending larger-scale house-building, and in 1946 the Martin-Baker Aircraft Co. (manufacturing aircraft ejector-seats) took over the airfield itself. A late 20th-century industrial estate provided further employment, although by then most inhabitants worked elsewhere. (fn. 3)

PARISH BOUNDARIES

The ancient parish (2,385 a.) comprised the manors of Chalgrove and Rofford, whose boundaries (with those of neighbouring estates) were probably established before 1066. (fn. 4) The northern boundary along Haseley brook was mentioned in 1002, while the western boundary with Newington was apparently established soon afterwards. (fn. 5) The western boundary with Ascott (in Great Milton parish) followed that of the hundred, (fn. 6) diverting westwards along Chalgrove brook to include an area of meadow, while the indented eastern boundary with Easington followed open-field furlongs as far as detached meadow belonging to Lewknor, (fn. 7) continuing in a more or less straight line to take in Chalgrove common. The southern boundary with Cadwell (in Brightwell Baldwin) is probably also pre-Conquest. (fn. 8)

The liberty, tithing, or township of Rofford covered 363 a. in the parish's north-western corner, bordering southwards on the Oxford-Watlington road. (fn. 9) On its north side an isolated dwelling called Lower Rofford lay in a detached part of Wheatfield parish (481/2 a.), which probably originated in the 12th or 13th century when the lord of Wheatfield held Rofford manor. (fn. 10) The Wheatfield land was added to Chalgrove parish in 1886, bringing the total area to 2,433 acres. (fn. 11) In 1932 the parish was united with Warpsgrove but lost 12 a. to Stadhampton, leaving it with 2,756 a. (1,115 ha.) in 2013. (fn. 12)

LANDSCAPE

Chalgrove lies chiefly on gravels of the Second (Summertown-Radley) Terrace, with areas of underlying Gault Clay in the village, and in the north-east and south-west. (fn. 13) The red, gravelly soil is easily worked, and with sufficient rainfall produces large yields, whereas the heavier clays are better suited to grass. (fn. 14) Chalgrove village occupies a slight dip, above which rises the squat church tower, and generally the relief is undramatic, falling gently north-westwards from c.75 m. on the boundary with Brightwell Baldwin to 70 m. at Chalgrove airfield and 58 m. at Rofford (by Haseley brook). Only at the Easington boundary does the ground climb higher towards 'Esa's hill' (107 m.). (fn. 15)

The parish is watered by tributaries of the river Thame, its plentiful marsh and meadow reflected in medieval field names incorporating the elements eg, lag, mœd, and mersc. (fn. 16) Chalgrove brook flows south of the village, passing near the church and formerly powering several mills, including that at Mill Lane. (fn. 17) A separate channel (controlled by a sluice gate) runs along High Streets north side, and until the 20th century houses there flooded regularly (fn. 18) Continued flooding of surrounding fields prompted flood alleviation schemes in 1981–4 and formation of a Chalgrove Flood Alleviation Group in 2008. (fn. 19) Woodland was largely confined to hedgerow trees, contributing to the landscapes flat and featureless aspect. (fn. 20) The large plain north of the village was the scene of a Civil War battle in 1643, (fn. 21) and from 1943 the military airfield covered some 700 a. of the same level ground (Fig. 120). (fn. 22) Water supply was mostly from wells and streams until mains water arrived in 1950. (fn. 23)

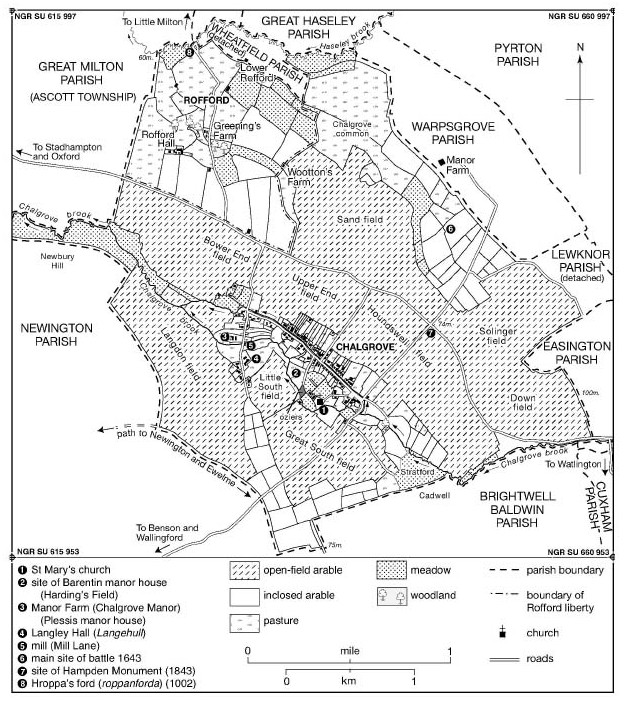

Chalgrove parish c.1840, before inclosure.

COMMUNICATIONS

Until its diversion in 1943 the main Oxford-Watlington road ran north-east of Chalgrove village, connecting with roads to Rofford and Warpsgrove, and intersecting the road to Benson and Wallingford which runs close to Chalgrove church. (fn. 24) Probably it was of pre-Conquest origin, and may have been the 'broad way' mentioned in the Middle Ages. (fn. 25) In the 1770s it was frequently impassable especially in winter, and the parish surveyors were ordered to repair it. (fn. 26) The Rofford road (in poor condition in 1688) (fn. 27) continued to Little Milton, crossing Haseley brook at Roppanforda (Hroppa's ford), which was mentioned in 1002 and where a bridge was broken in 1285. (fn. 28) Lesser lanes mentioned in the Middle Ages included mill way ('mulewei'), 'Medecroftlane', and 'Wauscherdeswey'. (fn. 29)

At inclosure in 1843 the Watlington, Rofford, Warpsgrove, and Wallingford roads were confirmed as public highways, (fn. 30) but in 1943 creation of the airfield stopped up the first two, with Watlington traffic diverted along Chalgrove village street. A bypass (the modern B480) was built in 1966–7, running between village and airfield. (fn. 31) Several footpaths south of the village were also confirmed at inclosure, although residential development from the 1960s caused some diversions. (fn. 32)

A carrier (Ralph Upshaw) died in 1704, (fn. 33) and two carriers were mentioned in 1841, (fn. 34) one of them running to Thame, Wallingford, and Oxford. The business continued in the 1860s, but from c.1900 was gradually reduced to twice-weekly visits to Wallingford. (fn. 35) Motor buses ran to Wallingford and Thame on market days by 1924, with a daily service to Watlington started soon afterwards. (fn. 36) Weekly buses to Wallingford and Thame continued in 1990, (fn. 37) and hourly services to Oxford in 2013.

Post was delivered through Wallingford or Tetsworth in the 19th century. A sub-post office on Chalgrove High Street was run in 1851 by the carriers daughter, (fn. 38) and in 1899 (when run by the farmer Frederick Mander) it was a money-order office and savings bank. (fn. 39) Telegraph facilities were briefly added c.1911, (fn. 40) and the post office remained open in 2015.

SETTLEMENT AND POPULATION

Prehistoric to Anglo-Saxon Settlement

Neolithic activity is suggested by finds of polished stone axes, (fn. 41) but the earliest settlement evidence is a Bronze-Age roundhouse with associated pottery and flint scatters south-east of the modern village. (fn. 42) Iron-Age finds include a gold coin and a few pottery sherds, (fn. 43) while more striking is the discovery of two Roman coinhoards and a 2nd-century cornelian intaglio personifying rustic prosperity. (fn. 44) Cropmarks and pottery finds indicate extensive Romano-British settlement, some of it west of the modern village. (fn. 45)

Chalgrove's Anglo-Saxon place name may refer to chalk- or limestone pits, highlighting a relatively rare resource in the lowland clay vale. (fn. 46) Later Anglo-Saxon settlement was most likely concentrated on the modern villages southern edge close to Chalgrove brook, around the site of the church and nearby Harding's Field. Pottery sherds and two 9th-century strap ends were found in the vicinity, and there are residual earthworks. (fn. 47) By the mid 11th century a sizeable Chalgrove estate (probably still focused on that area) supported a substantial population and a striking concentration of watermills along Chalgrove brook, while a separate settlement had developed at Rofford (Hroppa's ford) by Haseley brook. Recorded Anglo-Saxon field names suggest both open-field cultivation and clearance of land for tillage. (fn. 48)

Population from 1086

By 1086 there were at least 52 tenant households in the parish, 42 at Chalgrove and 10 at Rofford. (fn. 49) By 1279 the number of households had more than doubled to 110, with growth focused exclusively on Chalgrove: there 99 tenants (52 of them free) held land from one or both of the two main manors, while Rofford had only 8 villeins and 3 free tenants. (fn. 50) Total population may have approached 500, and further expansion probably followed in the early 14th century, when the number of taxpayers rose from at least 63 in 1306 to 80 in 1327. (fn. 51)

Fourteenth-century plague reduced population particularly at Rofford, where in 1377 only six households (including 13 inhabitants aged over 14) paid poll tax. Chalgrove had 185 taxpayers in 74 households, suggesting a total parish population of perhaps 450. (fn. 52) By the 16th century population was apparently growing again, despite occasional epidemics including (in 1557–9) a nation-wide outbreak probably of influenza. (fn. 53) Sixty houses were assessed for hearth tax at Chalgrove in 1662 and four at Rofford, (fn. 54) and in 1676 there were an estimated 260 adults in the parish. (fn. 55)

In the 18th century the surplus of baptisms over burials gradually increased, (fn. 56) the estimated number of houses rising from 60 in 1738 to 80 by 1790. (fn. 57) By 1801 Chalgrove's 117 occupied houses accommodated 509 people, and Rofford's two a population of nine. (fn. 58) The 1830s saw a significant increase, the 19th-century population peaking in 1841 at 668 in 136 houses at Chalgrove, and 23 in 5 houses at Rofford. Thereafter numbers declined steadily to 359 people in 90 houses in 1921, with notable falls in the 1840S-50S and 1880S-90S. Nissen huts at Chalgrove airfield (used as temporary housing after the Second World War) accounted for a rise to 910 (in 231 dwellings) in 1951, while residential development in the 1960s increased the population from 652 (188 houses) in 1961 to 2,433 (730 houses) in 1971. Further building swelled the population to 2,909 (1,089 houses) in 2001, and 2,830 in 2011. (fn. 59)

Medieval and Later Settlement

A predecessor of Chalgrove church existed apparently by the late 11th century, (fn. 60) and excavation has revealed late 12th- and early 13th-century occupation of the neighbouring manorial site at present-day Harding's Field. The medieval village developed some distance to the north and west, along High Street and Mill Lane: High Street itself may follow a former headland in the open fields, since curving croft boundaries on its north side suggest that they were laid out on openfield strips. Some of those changes may have followed from the manors division in 1233 and the creation of an additional manorial complex on Mill Lane, which provided a secondary focus and perhaps involved some reorganization of tenant housing. The chronology of the shift is uncertain, however, and other factors (including general population increase) may have played a part. (fn. 61) By the mid 14th century the village was divided into three 'ends' called Langehull (from a significant freehold estate at Mill Lane), Bour or Bower end, and East end, implying some gaps in the over-all settlement pattern. (fn. 62) The name 'bour' suggests an area of lower-status tenants, (fn. 63) and in the 15th century each end was secured by gates, (fn. 64) presumably to control livestock. The moated manorial complex at Harding's Field, expanded during the 13th and 14th centuries, was abandoned by c.1500, but the moated Mill Lane complex is marked by present-day Chalgrove Manor, opposite a medieval mill site on the lane's eastern side. (fn. 65)

Apart from some infilling between the 'ends' the picture was probably little changed by the 18th century, when the village contained 60–80 households. (fn. 66) High Street remained its principal focus, extending for a kilometre from its junction with Mill Lane to the Warpsgrove road, with a small green at its centre where the village stocks and a stone cross formerly stood. (fn. 67) Some houses were later removed, notably along Frogmore Lane, and the rapid increase in the number of households by 1841 must have been largely achieved by subdivision. (fn. 68) As population declined in the late 19th and early 20th centuries several older cottages were demolished, and a row of council houses was built on Monument Road (1928–30). Otherwise the shape of the village remained largely unchanged until after the Second World War. (fn. 69)

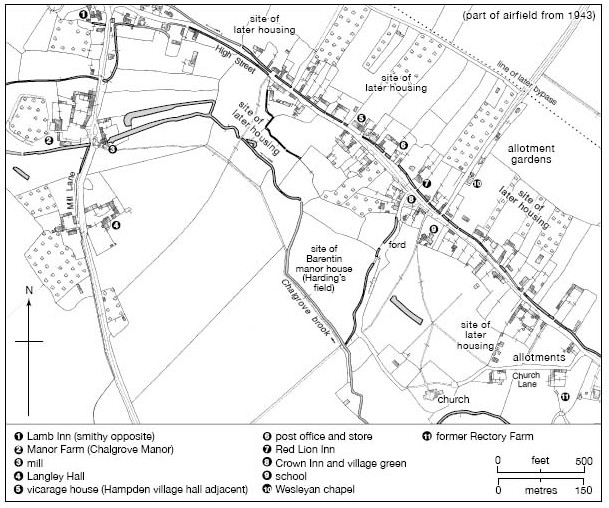

Chalgrove village in 1919, showing some later additions.

From 1948 abandoned Nissen huts at Chalgrove airfield attracted large numbers of incomers, creating a sizeable 'squatter colony' which was eventually adopted as temporary housing by Bullingdon Rural District Council. A school (housed in similar accommodation) was provided in 1950, and the site, known as the Hampden Estate, was only finally cleared in 1958. (fn. 70) Some families moved to new council houses on Chalgroves north-western edge, and in the 1960s development spread eastwards along both sides of High Street, serviced by new residential roads, shops, and other amenities. (fn. 71) Further expansion was limited by the new bypass to the north, the brook to the south, and roads to the west and east, but the whole of that area was infilled by the end of the 20th century (fn. 72) Development elsewhere focused on Warpsgrove Lane, where a light industrial estate, depot, and poultry farm were constructed east of the airfields surviving buildings, on the site of the Hampden Estate. The road to Berrick Salome and Benson also acquired additional dwellings. (fn. 73)

The medieval village at Rofford probably comprised no more than a dozen households c.1300, and after the Black Death gradually declined to the three or four isolated houses marked on 18th- and 19th-century maps, including Rofford Farm, Rofford Hall, and (in the detached part of Wheatfield) Lower Rofford. (fn. 74) The site of the deserted village was bulldozed in 1959, when pottery of the 12th century onwards was found. (fn. 75)

Chalgrove village green and war memorial in 2015. (See also Fig. 37.)

THE BUILT CHARACTER

Chalgrove is notable for its stock of timber-framed and thatched cottages, (fn. 76) of which some are of late medieval origin. (fn. 77) Crucks survive at 68–70 Mill Lane (originally a small two-bay cottage on the villages western fringe), the Red Lion on High Street (its medieval plan obscured by a major 17th-century remodelling), and Apple Tree Cottage, while Brook Cottage (113 High Street) incorporates a former two-bay open hall. As elsewhere upper floors and chimney stacks were inserted in the late 16th or early 17th century, with some Chalgrove buildings showing signs of a transitional phase. No. 1 The Green, built probably on a traditional open-hall plan in the late 16th century, seems to have been modernized only a decade or two later, while 159 High Street was apparently started on traditional lines in the early 17th century, but was given a chimney, lobby entry, and upper floor during construction. (fn. 78) Despite such improvements over 70 per cent of those paying hearth tax in 1662 were still assessed on only one or two hearths, suggesting modest one- or two-storeyed dwellings of two or three bays. (fn. 79) Church Cottage may have been typical, with its three-bay plan with attics, chamfered ogee-stopped beams, and ridge stack. It was extended one bay eastwards in the 19th century, probably acquiring its Flemish-bonded brick front at the same time. (fn. 80)

Unlike neighbouring Great Haseley or Little Milton, Chalgrove lacked building stone, and timber-framing continued into the later 17th century (fn. 81) A high-quality example (built c.1610 probably for a prosperous yeoman) is the present-day Lamb Inn, a lobby-entry house with moulded beams, at least three heated rooms, and a well-lit upper floor. (fn. 82) Jinnetts, on the villages western edge, may have been one of the last timber-framed cottages to be built, probably c.1690. Its timbers of light scantling include a central timber-framed partition with carpenters marks, rising to a closed truss with straight windbraces, (fn. 83) and like other houses in the village it was later extended, modernized, and improved rather than replaced. Brick chimney stacks are widespread, and brick fronts were sometimes added as at Church Cottage, (fn. 84) though more commonly brick was used as infill, preserving the visible timber framing. (fn. 85) Some new building in red and grey brick appeared by the 19th century, the village post office bearing the date 1869 in patterned brickwork in its gable wall.

Few of the villages 17th- and 18th-century houses display social pretension, the most notable exception being the former vicarage house (rebuilt in 1702 and remodelled in 1885). (fn. 86) Rofford Hall, too, is an impressive double-pile farmhouse of 18th-century date, built of uncoursed limestone rubble with brick quoins, dressings, and a parapet. The symmetrical three-bay front is lit by eight-over-eight sash windows, and the central door has a decorative fanlight. (fn. 87) Otherwise the absence of grand houses reflects the relatively modest status of most inhabitants, (fn. 88) combined, perhaps, with landlords' unwillingness to pay for expensive rebuilding. In 1910 Magdalen College, Oxford, the single largest landowner, controlled around a third of the housing stock. (fn. 89) Absentee lordship may nevertheless have provided opportunities for squatters and labourers to build cottages on the waste. (fn. 90) A possible example is John Hampden Cottage, a tiny two-roomed dwelling built on the village's southern edge in the late 17th century, with a single gable-end stack. (fn. 91)

By the mid 20th century Chalgrove presented an attractive mix of timber-framed cottages and brick and tiled Victorian houses, but in the 1960s the pressing need for new housing led to intensive infilling along High Street, with new access roads leading to additional housing behind. Several older properties were demolished. Following a survey in 1966 further expansion was discouraged, and in the 1970s Chalgrove twice won the county's 'Best Kept Village' competition. (fn. 92) In 2015 it remained well cared for, though architecturally its numerous 20th-century buildings were unremarkable.

MANORS AND ESTATES

In 1086 Chalgrove manor was assessed at 10 hides and the smaller Rofford manor at 3 hides. (fn. 93) The former, repeatedly divided by the Crown to reward royal supporters, was partitioned in 1233 between the Barentin and Plessis families, creating two separate manors, and in the 1480s Barentin's and a third of the Plessis manor (called Argentein's) were acquired by Magdalen College, Oxford. Another third (called St Clares) was given to Lincoln College, Oxford, in 1507, while the remaining portion (Ellesfield's), including the present-day Chalgrove Manor, descended from 1594 with an ancient freehold centred on Langley Hall. Magdalen's estate was sold in 1942 when it covered 1,104 a., and Lincoln's (212 a.) in 1950–1. The Langley (formerly Langehull) estate then covered 185 a., the parish's remaining land being divided among numerous freeholders. (fn. 94) From the Middle Ages to the 20th century Chalgrove manor also included Gangsdown (in Nuffield) and Berrick Salome, which were in the same ownership by 1086. (fn. 95)

Rofford remained an independent manor until the 20th century, although by 1925 the liberty as a whole was divided amongst three separate estates totalling 570 acres. (fn. 96) Chalgrove airfield, constructed in 1943, took in 700 a. from several farms and estates, (fn. 97) and remained in state ownership in 2015.

CHALGROVE MANOR

Descent to 1233

In 1066 Chalgrove was held freely by Thorkil, and in 1086 (as part of the honor of Wallingford) by Miles Crispin (d. 1107), who also held Berrick Salome and Gangsdown. (fn. 98) During the earlier 12th century it was probably held by members of the Boterel family as constables of Wallingford castle, passing in 1154 to Peter Boterel (d. 1165). (fn. 99) Thereafter it escheated to the Crown, which periodically assigned parts to royal servants. (fn. 100) Around 1190 Prince John granted it to Hugh de Malaunay (d. 1221) as 2 knight's fees, including Gangsdown, Berrick, and Rycote (in Great Haseley). (fn. 101) It reverted to the Crown c.1210 (fn. 102) but was restored in 1212, (fn. 103) and passed briefly to Malaunay's son Peter. (fn. 104) Another 25 librates were held in 1212 by Thomas Keret. (fn. 105)

In 1224 the Crown granted half the manor to Hugh Despenser and half to Hugh de Plessis, Drew Barentin, and Nicholas Boterel. (fn. 106) It was re-granted to Peter de Malaunay in 1226 and to Theobald Crespin in 1228, (fn. 107) but returned to the Crown in 1229 when the entire manor was divided amongst Hugh de Plessis, John de Plessis, and Drew Barentin. (fn. 108) Hugh's third was given on his death in 1231 to William de Huntercombe, (fn. 109) who was deprived in 1233. The same year the whole was partitioned between John de Plessis and Drew Barentin, (fn. 110) creating two separate manors each reckoned at a knights fee. (fn. 111)

The Divided Manors, 1233–C.1600

Barentin's Manor Drew Barentin (d. 1264 or 1265) (fn. 112) was succeeded by his son (or possibly nephew) William Barentin (d. 1290 or 1291). (fn. 113) The manor then passed in the direct male line to Drew (d. 1329), Thomas (d. c.1364), Thomas (d. 1400), Reynold (d. 1441), Drew (d. 1453), and John Barentin (d. 1474). (fn. 114) John's son John was beset by financial difficulties, and in 1485 sold the manor to Thomas Danvers on behalf of William Waynflete, bishop of Winchester, who used it to endow Magdalen College, Oxford. (fn. 115)

Plessis's and Related Manors John de Plessis (d. 1263), 7th earl of Warwick, was succeeded by his son Hugh, (fn. 116) who in 1279 gave the manor to his daughter Margaret. She married the royal justice Sir William de Bereford (d. 1326), (fn. 117) lord of neighbouring Brightwell Baldwin, and was succeeded by their son Edmund de Bereford (d. 1354) and by Edmund's illegitimate son Sir John (d. c.1356). (fn. 118) Following John's death the manor was divided among Edmund's three sisters Agnes, Margaret, and Joan, and John's illegitimate brother Baldwin (d. 1405). (fn. 119)

Agnes (d. 1375) married John Argentein, their share passing to their son John (d. 1382) and to John's illegitimate son William (d. 1419). (fn. 120) He was succeeded by his grandson John Argentein (d. 1420) (fn. 121) and granddaughters Joan and Elizabeth, the latter inheriting her sister's portion in 1429. (fn. 122) In 1455 Elizabeth's son John Alington sold the manor to Richard Quatremain and others, who in 1459 sold it to John Barentin (d. 1474). (fn. 123) In 1483 it passed to Richard Harcourt (d. 1486), whose grandson Miles sold it in 1487–8 to Thomas Danvers on behalf of Magdalen College. (fn. 124)

Margaret's share (known later as St Clare's) passed from her and her husband James Audley to their sons William (d. 1365) and Thomas (d. 1372), then to Thomas's son James (who died young) and daughter Elizabeth. Later it was held by Philip St Clare (d. 1408), the elder James's great-grandson. (fn. 125) Philip's son John (d. 1418), a minor, was succeeded by his brother Thomas St Clare (d. 1435) and by Thomas's three daughters, (fn. 126) the share passing by marriage to Richard Harcourt. In 1496 Miles Harcourt sold it to Edmund Hampden of Woodstock, who in 1506 sold it to the bishop of Lincoln, and the following year it was given to Lincoln College, Oxford. (fn. 127)

Joan's share passed from her and her husband Gilbert de Ellesfield to William de Ellesfield (d. 1398), (fn. 128) who also held Baldwin de Bereford's portion. (fn. 129) Their combined estate, which on later evidence included the Plessis manor house, passed to Williams daughter and granddaughter, half being held by Joan wife of Thomas Loundres, and half by Joan wife of John Hore. (fn. 130) The two parts seem, however, to have been reunited by John's son Gilbert Hore (d. 1453), (fn. 131) and presumably descended to Gilberts son John (d. 1471) and granddaughter Edith, who married Rowland Pudsey. (fn. 132) The manor remained in the Pudsey family until 1594 when it was sold to Benedict Winchcombe of Noke. (fn. 133) Thereafter it descended with Winchcombe's Langehull or Langley estate, passing to the Halls and in the 18th century to the Blounts. (fn. 134)

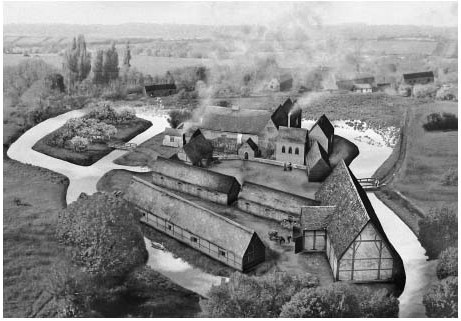

Reconstruction (based on excavated remains) of Barentin's manor house in the late 14th century, looking north. Hall and cross wing lie north of the main courtyard, with an adjoining three-bay chapel and kitchen to their right, and farm buildings in the foreground.

The Manors from 1600

Magdalen College retained the united Barentin's and Argentein's manors until the 20th century, and from the 19th extended its holdings. (fn. 135) In 1900 it bought the Langley estate and Chalgrove Manor farm (the former Ellesfield portion) from the executors of G.R. Blount, (fn. 136) and in 1901 added the former rectory estate (Houndswell farm, 78 a.). (fn. 137) Langley and some other property was sold in 1922, (fn. 138) and in 1942 the college's remaining estate (still 1,104 a.) was sold to former tenants including S.C. Franklin (d. 1948) and PH. Fleming, who bought Manor farm. (fn. 139) Franklin's estate (728 a.) was sold in 1949 to R.N. Richmond-Watson of Brightwell Baldwin, (fn. 140) while Manor farm passed in 1970 to Roy Brown. In 1977 he sold the house (Chalgrove Manor) to Paul and Rachel Jacques, who bought the lordship from Magdalen College in 1995. (fn. 141) Lincoln College sold its estate to the Air Ministry and others in 1950–1, construction of Chalgrove airfield in 1943 having already taken up parts of both the Lincoln and former Magdalen estates. (fn. 142)

Chalgrove Manor Houses

Barentin's (Harding's Field) (fn. 143) Until the manor's partition in 1233 there was only one manor house, situated north-west of the church in present-day Harding's Field. Excavation revealed traces of late 12th- or early 13th-century buildings, associated possibly with Hugh de Malaunay and assigned later to the Despenser and Huntercombe shares of the manor. Drew Barentin constructed a more extensive moated complex probably c.1255, which included a three-bay stone-built hall, a bakehouse or brewhouse, and a dovecot. Re-used voussoirs from a high-quality 12th-century doorway came possibly from the earlier buildings. (fn. 144) In the early 14th century (when Chalgrove was the Barentins' principal mainland seat) the house was remodelled and extended to provide additional services and accommodation, creating an L-plan. Other domestic buildings (possibly including a detached kitchen and bread oven) occupied the north side of a central courtyard, to the south of which lay a large stable block and barn. The house was further extended in the late 14th century by the probable addition of a chapel and new kitchen, while new buildings on the courtyards south side may have included a cattle byre and cart house. In the mid 15 th century the Barentins moved to Haseley Court (in Little Haseley) and abandoned the Chalgrove house, which was probably largely demolished in the 1480s.

Chalgrove Manor (Plessis's) from the south-east, showing the central hall (c.1488), north cross wing (mid 15th-century), and south wing (c.1505).

Chalgrove Manor (Plessis's) The existing Chalgrove Manor off Mill Lane occupies the site of the Plessis-Bereford manor house. (fn. 145) John de Plessis probably began building there c.1240 when he received 30 tree trunks from the king, (fn. 146) with further grants following in the 1240s–50s. By 1336 the site, surrounded by a moat, covered over an acre, encompassing a hall, byre, stable, three barns, and a granary (fn. 147) Probable survivals include a 13th-century oak screen and a stone window-mullion re-used in the present house, unless they were imported from the Barentin site or elsewhere. (fn. 148) Certainly the house appears to have been at least partly stone-built. (fn. 149)

From the mid 15th century the house was replaced in stages, creating a timber-framed successor comprising a hall, two jettied and gabled cross-wings, and a two-storeyed porch. (fn. 150) The north wing (tree-ring dated to 1444–68) was built first, presumably by the Hores or a lessee, and has a braced collar-beam roof, finely moulded beams, and expensive close-studding. Probably it served as a parlour with a solar (or chapel) above. The hall (built c.1488) was originally open to a five-bay arched collar-beam roof of exceptional quality, associated possibly with the Oxford master mason William Orchard, (fn. 151) and was lit by a large oriel window. The south wing was added in similarly lavish style c.1503–5, and the north-wing parlour became a buttery. During the 16th century the house and services were extended to the rear and the hall was ceiled over, brick chimneys replacing its former open hearth and louvre, while the south wing's roof was raised to create an attic room. A 16th-century timber-framed gatehouse (part of a continuous line of buildings fronting the street) survived until the 1970s.

The houses 16th- and 17th-century occupants are not known, but in 1662 it was probably one of several taxed on six hearths, occupied by members of the White, Child, Quatremain, and Wiggin families. Such lessees were perhaps responsible for painted panels of c.1680 in the south wing, and for other 17th-century improvements. (fn. 152) Later modifications included removal of the porch, and in the 19th century the east-facing front was rendered and new windows inserted. The houses present appearance reflects work since 1977 by Paul and Rachel Jacques, who removed the render and restored the timber framing and fenestration. Restoration of the north and south fronts revealed evidence of 15th- and 16th-century garderobes, while the west-facing rear wall, largely of red and blue Victorian brick, overlooks a 16 ft-deep well. (fn. 153)

ROFFORD MANOR

In 1086 Rofford was held of the king by Saswold, and was pledged to Robert d'Oilly. (fn. 154) By the late 12th century it belonged to Robert of Wheatfield, whose widow Isabella received dower there in 1196, (fn. 155) and whose brother Henry of Wheatfield (d. 1226) later held it of the d'Oilly barony as ½ knight's fee. (fn. 156) Henry was succeeded by his son Elias (lord in 1243) and grandson Henry (d. by 1264), (fn. 157) whose son Elias sold two thirds and reversion of the remaining third to John de St Valery in 1275. (fn. 158) John's son Richard was lord in 1279 but sold the reversion to Hugh Despenser in 1309, when the life tenant was Philip de Hoyville. (fn. 159)

Hoyville's wife Mary was taxed there in 1327, (fn. 160) but in 1316 Rofford was held with Chalgrove by Drew Barentin and William de Bereford. (fn. 161) By 1346 Oliver de Bohun held it of Hugh Plessis (d. 1350), (fn. 162) succeeded by Hugh Plessis (d. 1363) and by Margaret de Warbelton (d. 1365), who held it of the d'Oilly fee with reversion to the Despensers. (fn. 163) Instead the manor reverted to the Crown, and in 1367 was granted to the king's yeoman John of Beverley. (fn. 164) In 1377 it was bought by John James (d. 1396) of Wallingford, (fn. 165) whose son Robert sold it in 1408 to his brother-in-law Reynold Barentin (d. 1441) of Chalgrove. (fn. 166) Thomas Danvers acquired it with Chalgrove in 1485 and, following an abortive sale to Magdalen College, (fn. 167) sold it in 1498 to Henry Colet (d. 1505). From him it passed to William Barentin (d. 1549) of Little Haseley (fn. 168)

In 1540 Barentin sold Rofford to John Frost. (fn. 169) It seems later to have been acquired by Sir Christopher Hatton, passing with Warpsgrove to the Molynses and Simeons and (probably) to Sir Robert Dormer in 1631. (fn. 170) Thereafter the descent is unclear, but by the early 18th century the owner was Anthony Collett of Bourton-on-the-Water (Glos.), and in 1753 the manor was sold by Daniel Holworthy to Charles Greenwood. (fn. 171) He sold it in 1799 (with c.210 a.) to Nathaniel Ludbrook, who in 1802 sold to the graziers Christopher and Thomas Reeves. (fn. 172) William Cox of Dorchester followed in 1840, and at inclosure in 1843 owned 326 acres. (fn. 173) His successor Thomas Cox mortgaged the estate, (fn. 174) which in 1868 was sold to C.R. Powys; following additions he held 393 a. in the liberty's eastern part and in adjoining Chalgrove, (fn. 175) other landowners in 1910 including the Revd Hilgrove Cox (147 a.) and Great Haseley's Tayler-Blackall charity (28 a.). (fn. 176) Powys's tenant C.H. Rowles bought the manor in 1915, and was succeeded by B.C. Rowles before 1943, when most of the land was requisitioned (and later purchased) for Chalgrove airfield. (fn. 177) In 2013 the principal remaining landowner was Jeremy Mogford.

Rofford Manor House

An undocumented manor house possibly existed in the Middle Ages. The present Rofford Manor is, however, a late 17th-century farmhouse extended c.1730–40, (fn. 178) and known formerly as Greenings. (fn. 179) By 1738 it belonged to the Colletts, (fn. 180) who may have installed its early 18th-century moulded fireplaces, elaborate panelling, and other fittings. It descended with the estate until 1957 when the Air Ministry sold it to W.E. Hazell of Little Haseley, (fn. 181) but by the early 1980s it was largely derelict until bought by Jeremy Mogford, a managing director, and his wife Hilary. They restored it and created a celebrated garden. (fn. 182) The house itself is of coursed limestone rubble with ashlar quoins, a gabled tiled roof, and a main front of four irregular bays, its two storeys and attics lit by 18th- and 19th-century casements and sashes. (fn. 183)

OTHER ESTATES

Large numbers of freeholds developed between the 11th and 13th centuries, some arising, perhaps, from the Crowns repeated divisions of Chalgrove manor over the period. The most important included the Langehull and Quatremain estates, though many were less stable and cannot be traced beyond the Middle Ages. Part of the Langehull estate was held from Wallingford priory, the parish's largest ecclesiastical landholder, while smaller holdings belonged to the Knights Templar and the Hospital of St John the Baptist in Oxford. (fn. 184) Several other freeholds continued beyond the Middle Ages, (fn. 185) and at inclosure in 1843 c.30 landowners were allotted a total of 620 acres. (fn. 186) The rectory estate (held by Thame abbey from 1319 and later by Christ Church, Oxford) then comprised c.60 acres. (fn. 187)

The Langehull (later Langley) Estate (fn. 188)

Adam de Langehull was a prominent freeholder by the early 13th century, when he granted land to the Knights Templar, (fn. 189) and in 1279 his descendant Thomas son of John de Langehull held 2 yardlands from William Barentin and 6 from the prior of Wallingford, besides having his own tenants. (fn. 190) In 1327 Robert de Langehull was Chalgrove's fifth highest taxpayer (paying 7s. 8d.), while Simon de Langehull served with the Black Prince in Gascony in 1356. Thomas de Langehull paid poll tax in 1377. (fn. 191)

The Wallingford priory land was subsequently held by Edward Woodward (d. 1496) and his son Thomas, who retained it in 1536 when it was called Bossynges Place alias Langhulles. (fn. 192) It passed later to Henry Bradshaw (d. 1553) of Noke, chief baron of the Exchequer, to Bradshaw's son-in-law Thomas Winchcombe (owner in 1568–71), and by 1576 to Thomas's son Benedict (d. 1623), who added the Ellesfields' share of the Plessis manor and was succeeded by his sister Mary Hall. By 1571 the estate was called Langhull manor. (fn. 193) Ownership remained with the Halls until at least the 1680s, (fn. 194) although for much of the 17th century both house and land were let to the Quatremains. (fn. 195) The Halls' Noke estates were largely sold in 1707, (fn. 196) and by 1774 'Langley Hull' belonged to Joseph Blount, esquire, (fn. 197) remaining in the Blount family until bought by Magdalen College (with Chalgrove Manor farm) in 1900. (fn. 198) The estate was sold in 1922 to the tenant George Nixey, whose family retained most of it in the early 21st century (fn. 199)

Mansion House (Langley Hall) The Langehulls' house (at Mill Lane) was rebuilt in the 16th century, and largely demolished in 1980. (fn. 200) The 16th-century house included several elaborately decorated rooms, among them a hall, great parlour, gallery, chapel chamber, and spice loft, and in 1662 it was probably taxed on seven hearths, the highest assessment in the village. (fn. 201) It was later remodelled with a stuccoed Georgian façade of four bays, retaining two mullioned windows at the side and an original chimney with two diamond-shaped brick shafts. (fn. 202) A 17th-century brick-built lodge was erected possibly by the Quatremains, while surviving outbuildings include an 18th-century barn with a queen-strut roof. (fn. 203)

Langley Hall (demolished 1980) in 1955, from the west. The chimney formed part of the 16th-century house, which was refronted in the 18th century.

Quatremain Estate

In 1163–78 William Quatremain was granted two hides in Chalgrove by his relative Gilbert Foliot (lord of Cuxham), to be held as ¼ knights fee. (fn. 204) The holding was divided in 1203, when half was granted to Hugh de Pageham and half to the Quatremains: by 1279 both parts were held as 1/8 knights fee, the Quatremain's part under Geoffrey of Lewknor, who held from Merton College, Oxford, as Foliot's successor. Merton remained overlord until 1517, when it transferred its rights to Magdalen College, (fn. 205) and in 1321 the Quatremains' share comprised a chief house, 4 yardlands (84 a.), 6 a. of meadow, 14 a. of pasture, and 95. rent. (fn. 206) William Forthey (d. 1487), who married the Quatremain heiress, performed homage for the estate in 1485, (fn. 207) presumably ending the family connection. Nonetheless the Quatremains remained a prominent and exceptionally wealthy family in the parish until the 18th century (fn. 208)

Rectory Estate

Chalgrove's valuable rectory estate was given to Thame abbey in 1319, (fn. 209) passing in 1542 (after the abbeys suppression) to Oxford cathedral, and in 1546 to Christ Church, Oxford. (fn. 210) The size of the medieval glebe is uncertain: in 1341 only £4 13s. 4d. income came from glebe and small tithes (compared with £20 from great tithes), (fn. 211) and the estates 60–70 a. extent in the 18th century may partly represent later acquisitions. Shares in the tithes belonged to Bec abbey (£3 6s. 8d. in 1291) and Wallingford castle (£2), both following 11th-century grants by Miles Crispin (d. 1107); (fn. 212) some of the Bec tithes belonged by 1428 to John (d. 1435), duke of Bedford, (fn. 213) and by 1476 all had passed to St Georges Chapel, Windsor. (fn. 214) Thame abbey latterly leased its rectory estate, in 1495 to the vicar, (fn. 215) and in 1534 (for 41 years) to Roger Quatremain. (fn. 216) A few additional acres of glebe lay in Berrick Salome, with whose tithes they passed to the vicar of Chalgrove in the later Middle Ages. (fn. 217)

Christ Church continued to lease both land and tithes, in 1554 for 41 years at £14 annually, and in the 17th century for three lives or 21 years. Lessees were to repair the chancel, give a fat wether or 135. 4d. at audit, and pay part of the rent in wheat and malt. An agreement over division of the parish's tithes was reached with the dean and canons of Windsor in 1561. (fn. 218) In 1771 the rectory lands covered an estimated 60 a. in the open fields, valued at £35 17s. a year, while the tithes were worth £232. The lessee in 1799 (at £80 a year) was John Hatt, based at Rectory (later Houndswell) Farm off Church Lane.

Following an abortive sale in 1803 Christ Church continued to issue 21-year leases, and in 1813 the farm (then 68½ a.) had a rental value of £120. Some buildings were in disrepair, and the tenant considered the tithes over-valued at £635. (fn. 219) The tithes were commuted in 1841, when Christ Church was awarded an annual rent charge of £435, and St Georges Chapel, Windsor, £170 for the former Bec tithes; (fn. 220) the glebe was exchanged at inclosure two years later for three allotments totalling 59 acres. The land (but not the tithe-rent) was sold in 1877, (fn. 221) passing in 1901 (as Houndswell farm) to Magdalen College, which sold it with the manor in 1942. (fn. 222) The farmhouse was demolished in the early 20th century (fn. 223)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

The parish remained predominantly agricultural until the 20th century, combining sheep-and-corn husbandry with cattle rearing and dairying. Rofford was inclosed by c.1600 and divided among three or four farms, although its agriculture remained little different from elsewhere in the parish. Chalgrove, by contrast, was uninclosed until 1843, supporting numerous small-scale farmers and cottagers who benefited from common grazing rights. Parliamentary inclosure promoted no immediate consolidation of landholdings there, and only after the Second World War were some large and increasingly mechanized cereal farms created.

The village also supported the usual range of crafts and trades, and from the 1960s residential development encouraged further expansion of shops and businesses, while the Martin-Baker Aircraft Co. occupied Chalgrove airfield from 1946. Watermills were established by 1086, the last of them closing in the 1960s.

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE (FIG. 31)

Open fields probably covered much of the parish by the mid 11th century, as suggested by Anglo-Saxon furlong names, (fn. 224) indentations (probably derived from open-field furlongs) along the Easington parish boundary, and the total of 18 ploughteams recorded in 1086. (fn. 225) By the 14th century Chalgrove had nine fields grouped into three 'seasons', which were probably cultivated on a three-course rotation of winter- and spring-sown crops and fallow; (fn. 226) in the 19th century they covered 1,764 acres. Three (Langley or Langdon, Great South, and Little South) lay south of the village, with three more (Bower End, Upper End, and Houndswell) along the village's northern edge. The others (Down, Solinger, and Sand) bordered Easington and Chalgrove common. (fn. 227) All those fields were inclosed by Act of Parliament in 1843, long after Rofford's private inclosure in the 17th century or earlier. (fn. 228) In 1841 (when arable covered two thirds of the parish) the largely gravel soils produced good wheat land', and the proportion of arable rose to three quarters by 1870. Following the agricultural depression it fell to less than half by 1930, however, recovering its former primacy after the Second World War. (fn. 229)

Streams provided extensive meadow, (fn. 230) organized from the Middle Ages both in common and in private closes. (fn. 231) Additional meadow lay in the detached part of Lewknor on the parish's eastern border, where Chalgrove's inhabitants were accused of illegally grazing cattle in 1237; (fn. 232) common rights there were still claimed in the 17th century, and c.14 a. were included in Chalgrove's 19th-century inclosure and tithe awards. (fn. 233) Common pasture was available in Chalgrove common (112 a.), (fn. 234) and also in the fallows; the manor court resisted overgrazing, however, (fn. 235) and medieval tenants were sometimes fined for trespassing in private pastures. (fn. 236) Old inclosures were variously grazed or ploughed, (fn. 237) but though the area under grass increased considerably in the early 20th century it was rarely of good quality, and was ploughed up as soon as arable farming's prospects improved. (fn. 238)

The parish was unwooded in 1086, and some manorial woods mentioned in the 14th century may have lain in Gangsdown (in Nuffield). In 1336 the Plessis manor produced 400 faggots and ½ a. of underwood a year, and in 1329 a tenant trespassed in Barentin's wood. Magdalen College received 185. from wood sales in 1504–5. (fn. 239) Building timber had to be purchased elsewhere: 32 cartloads were brought from Shipston-on-Stour (Warws.) via Woodstock in 1453–4, (fn. 240) and in later centuries locally produced timber remained scarce. (fn. 241) In 1671 Thomas Wootton's Rofford holding included timber trees 'wasted and rotten about the grounds', (fn. 242) and only hedgerow trees were marked on 18th-century maps. Fewer than 8 a. of woodland remained in 1841, (fn. 243) increased to 45 a. in a few small copses by 1988. (fn. 244)

MEDIEVAL TENANT AND DEMESNE FARMING

In 1086 Chalgrove manor contained land for 12 plough-teams, meadow 3 furlongs square, and 60 a. of pasture, and yielded £12 including tenants' rents. The smaller Rofford manor comprised 5 ploughlands, 5 a. of meadow, and 16 a. of pasture, and was worth £3. Both manors had increased in value and were largely arable-based, Chalgrove's 13 ploughteams suggesting a recent expansion of the cultivated area. Its 4-ploughland demesne farm was run partly by servi, while Rofford's demesne was 2 ploughlands; the two places together also had 12 teams worked by 43 tenants (30 villani and 13 bordars). (fn. 245) Arable farming continued to provide much of Chalgrove's income in the late 12th century, (fn. 246) and in 1212 the king received more than £9 from grain sales, besides £20 paid by the manors lessee. (fn. 247) The same year 200 a. were sown with wheat, 10 a. with beans, 14 a. with barley, and 215½ a. with oats. The ploughs were worked by oxen (50 were bought in 1195, enough for 6¼ eight-ox ploughteams), and cattle and pigs were also reared. (fn. 248)

In 1233 Chalgrove's demesne and tenant land was divided between two owners, (fn. 249) and in 1279 both the Barentin and Plessis demesnes included c.312 a. of arable, 30 a. of meadow, and 30 a. of pasture. On both manors villeins holding yardlands and half-yardlands owed cash rents and labour services including ploughing, harrowing, weeding, reaping, mowing, carrying, and threshing, although free tenants and cottars owed few if any labour services. Rofford's two-hide demesne (c.200 a.) was leased, and tenants' labour services there were commuted, with yardlanders paying 185. rent compared with 55. at Chalgrove. (fn. 250) The Plessis demesne was still worth £32 in 1336, four times the nominal value of the tenants' rents and services; fields were sown on a complex three-course rotation, and harvested crops stored in three barns and a granary. (fn. 251) The parish's agriculture evidently produced a large taxable surplus, its payment of £15 4s. 6d. in 1334 being the highest in the hundred. (fn. 252)

Tenants' livestock included horses, oxen, cows, pigs, sheep, and geese; some were grazed illegally in the lord's meadow and corn in 1340–1, and one half-yardlander gave a mare for heriot. (fn. 253) Trespass by livestock continued after the Black Death, suggesting continued pressure on grazing; as land became more readily available such cases became less frequent, however, and by the 15th century the manor court's chief concern was neglect of unused buildings and of ditches. Falling land values enabled tenants to accumulate larger holdings, and rents rose as labour services were commuted: in 1424 a half-yardlander paid 125. a year and owed one day's service at harvest-time, while in 1433 William Gregory paid an annual rent of 165. 8d. for 1¼ yardlands and a 3-a. croft. (fn. 254) Mixed farming continued, with the arable acreage apparently undiminished c.1380. (fn. 255)

In 1458–9 John Barentin leased his Chalgrove demesne for £15 2s. 11d. a year, receiving rents of more than £25 from his free and customary tenants and cottagers. Rofford's demesne was leased to Richard Coleman (with tenants' rents) for £11 a year, rising to £12 in 1462–3. (fn. 256) Profits later fell: by 1488–9 Magdalen College received only £11 3s. 4d. from the Barentin demesne, then leased in parcels with some uncultivated parts left unlet, while rent for the Argentein demesne (let to William Wiggin) fell from £3 6s. 8d. to £3. The college also encountered difficulties in collecting tenants' rents, and in the 1490s built a pinfold for impounding defaulters' animals. Nevertheless its Chalgrove estate remained profitable, prompting the college to invest in repair of tenants' buildings and, in 1490–1, construction of a new five-bay barn. (fn. 257)

FARMS AND FARMING 1500–1800

In the early 16th century Magdalen's Chalgrove income rose from c.£35 in 1497–8 to £39 in 1524–5, while rent arrears fell from over £66 to c.£28. (fn. 258) In 1520 all but 26½ a. of its 239-a. Barentin demesne were let at 6d. an acre to a total of 16 tenants, holding plots of between ½ a. and 56 a. each. Lessees included members of the Burnham, Cave, Child, Quatremain, Simms, and Wiggin families, who featured also among the manor's copyholders, occupying open-field yardlands with parcels of meadow and pasture. (fn. 259) Most grew wheat and barley (some of it malted for brewing), kept cattle and sheep, (fn. 260) and were moderately prosperous, (fn. 261) while debts mentioned in 1566 suggest that markets included not only Watlington but Oxford, Reading, and Henley- on- Thames. (fn. 262)

Sheep-and-corn husbandry and dairying continued into the 17th century, most obviously among the parish's wealthier farmers. (fn. 263) Wheat and barley remained the principal cereals, with beans, peas, and hay providing fodder. Farmyard dung (mostly from cattle and pigs) was used for manuring, while oxen were generally supplanted by horses for ploughs and carts. Sheep were presumably folded on the arable (hurdles were sometimes mentioned), and the larger flocks produced marketable quantities of wool; cows supported butter- and cheese-making, although herds (including bulls and younger animals) generally numbered no more than thirty. Pigs provided bacon, while poultry included ducks, geese, hens, and turkeys. Farm servants and labourers were widely employed: William Child (d. 1630) owed wages for ploughing and weeding, and also hired a molecatcher.

In 1678 Magdalen's copyhold rents totalled £35 105. 9d., while three leaseholders paid £12 17s. 11d. and eight freeholders £1 3s. 11½d. The college's total rent-roll of c.£49 remained unchanged between the late 16th and mid 18th century (fn. 264) Amongst Magdalen's tenants, John Sedgley, a barber and wigmaker, held a mixture of copyhold, freehold, and leasehold land, but was bankrupted in 1762; his copyholds were held for three lives, and his college leaseholds for 20-year terms renewable every seven years. His estate (which included 64 a. of freehold) was sublet, although valuations of that and other farms suggest that rack-renting remained uncommon. (fn. 265)

The open fields were cultivated probably on a four-course rotation of wheat, barley, pulses, and fallow, (fn. 266) with apples grown in orchards and crops such as hemp cultivated possibly in gardens. (fn. 267) Holdings were generally scattered across three or four fields, in which tenants enjoyed common grazing rights, and often they included parcels of meadow and inclosed pasture. (fn. 268) The commons were stinted: each yardlander was entitled to graze 4 cattle or horses and 40 sheep, and subletting was restricted to two cow commons per cottager. Cattle were grazed on the harvested fields until 1 November, while sheep were admitted to the wheat field a week after harvest, to the barley and pulse fields on 1 November, and to other named fields on 30 November, remaining there until 25 March. Four fieldsmen were appointed to enforce the orders. (fn. 269)

Rofford's inclosure (complete by c.1600) permitted greater flexibility, though its farming was probably similar to Chalgrove's. Both Greenings and Wootton's farms (in the east of the township) included arable, meadow, and pasture closes, their names suggesting cereal and legume cultivation as well as cattle and sheep grazing. (fn. 270) Proposals to inclose Chalgrove's fields in the 1770s and 1790s were not pursued, (fn. 271) and holdings remained both dispersed and often quite small: (fn. 272) those on Langley manor ranged from 110 a. to 1 a., with most under 10 acres, while open-field land in 1774 (still held in ½-a. strips) was worth a modest 11s.-14s. an acre compared with 305. for nearby inclosed ground. (fn. 273) The agricultural improver Arthur Young dismissed the entire parish in few words: 'Clay; sad roads, and bad husbandry: all open.' (fn. 274)

FARMS AND FARMING SINCE 1800

Young's judgement was confirmed in 1841 by the tithe commissioner, who observed that the open fields were 'let in small farms under college leases and [are] consequently very badly farmed'. (fn. 275) Nineteen farmers were resident in Chalgrove and two in Rofford, (fn. 276) of whom eight held over 100 a., and seven 41–90 acres. Some holdings were owner-occupied or held from a single proprietor, but others were a complex mix of freehold, copyhold, and leasehold. Gabriel Billing occupied 127 a. in 12 parcels from 4 different landowners, while James Honey's 83-a. College farm included Magdalen copyholds sublet by Henry Adeane. (fn. 277)

Inclosure was carried out under a private Act of 1843 promoted by Magdalen and Lincoln colleges and Mary Blount of Langley, (fn. 278) with land distributed among 56 owners and occupiers. Of those, 28 landholders received less than 10 a., and only 6 more than 100 a., out of 1,764 a. allotted. (fn. 279) Inclosure had no immediate impact on either farm size or tenancies: no new outlying farms were built, and many of the parish's established farming families remained in 1851, when eight farmers (including two in Rofford) held more than 100 a., and six farms covered 27–82 acres. In all around 2,100 a. were worked by 16 farmers employing 122 labourers. (fn. 280) The pattern was largely unchanged in 1870–1, when Richard Hatt held 470 a., and five other Chalgrove farmers 142–236 acres. Another six farms covered 20–100 a., and there were six smallholdings. (fn. 281)

At that date Chalgrove remained three quarters arable. Wheat, barley, and oats were the main crops, occupying 55 per cent of the cultivated area, while fodder crops covered 34 per cent, and 11 per cent (142 a.) was fallow. Meadow and pasture (393 a.) supported 70 horses, 67 dairy or younger cattle, 1,960 sheep, and 186 pigs. Similar practices prevailed at Rofford, where two thirds was cropped and a third was grass. (fn. 282) Thereafter late 19th-century agricultural depression reduced the proportion of arable to little more than half, as tillage was converted to pasture: by 1900, 1,000 a. of grass supported an enlarged herd of 277 cattle, 126 horses and foals, and 1,476 sheep. The remaining arable was increasingly dominated by cereal production, sometimes using steam ploughs and other machinery, although sheep were probably still folded. (fn. 283)

Despite the depression, Magdalen initially maintained or even increased its rental income from Chalgrove, collecting more than £1,000 in 1900. (fn. 284) Rents increased still further in the early 1900s and after the First World War, rising on the larger farms from c.21s. an acre in 1911 to 295. in 1922. (fn. 285) Farm sizes still varied: in 1920 nine farms exceeded 100 a. and six covered 20–100 a., and there were eight smallholdings as well as 13 a. of allotments (provided by the parish council). (fn. 286) By the 1930s several farmers could no longer afford Magdalen's rack rents, and were granted allowances. The college's surveyor reported that one farmer was hard working but 'rather beaten by circumstances', and that his rent was too high; another had laid down land to grass, though none of it was 'really good' and a rent reduction 'can hardly be resisted'. Buildings were converted to milk sheds as dairying increased, though one such was condemned as insanitary, and the college was sometimes reluctant to bear improvement costs. (fn. 287)

Chalgrove village street in 1904, looking east towards the green and Crown public house.

Despite the shift towards dairying several farms remained predominantly arable in 1941, growing wheat, barley, oats, and fodder crops, and stocking cattle, sheep, and pigs. (fn. 288) On S.C. Franklins estate (bought from Magdalen College in 1942 and truncated by construction of the airfield the following year), most remaining grass was ploughed up in the later 1940s, and graindrying plants were installed. (fn. 289) By 1960 arable covered almost 70 per cent of the parish's farmland, producing chiefly barley and wheat, while increasing mechanization encouraged larger enterprises, with two cereal farms covering more than 1,000 a. each by 1970. In 1988 a large pig and poultry farm stocked over 6,600 pigs, and there was a smaller cattle and sheep-rearing farm. (fn. 290)

TRADES, CRAFTS, AND RETAILING

Like some other vale settlements Chalgrove had a relatively wide range of crafts and trades. Jordan the weaver was mentioned c.1230–40, (fn. 291) and other medieval occupational surnames included Cook, Ironmonger, Tailor, Skinner (Pellipar'), and Thatcher, while carpenters were employed on Magdalen Colleges manor in the 1480s-90s. (fn. 292) Robert the smith held half a yardland on Barentins manor in 1279, making ironwork for two ploughs for his labour service, (fn. 293) and the family continued as tenants of the village forge into the early 16th century (fn. 294) Brewing was apparently widespread: 43 fines for breaking the assize of ale were paid in 1296–7, and in the I5th-i6th centuries (when production was generally on a larger scale) three or four brewers were named in Chalgrove, and one in Rofford. (fn. 295)

As elsewhere crafts were sometimes practised alongside farming, William Payse (d. 1598) leaving carpenters tools to his son, and wheat, barley, and cattle to other relatives. (fn. 296) Edmund Hambledon (d. 1617) was a weaver, and other 17th-century inhabitants kept spinning wheels, although cloth-making remained small-scale. (fn. 297) Both Chalgrove and Rofford continued to support blacksmiths, carpenters, tailors, and wheelwrights, (fn. 298) while less common occupations included bricklayer, joiner, tiler, and maltster, (fn. 299) with malting possibly increasing during the 18th century (fn. 300) Nonetheless numbers employed outside agriculture remained small, reportedly comprising only 10 people out of a population of 518 in 1801. (fn. 301) Probably those included the grocer and baker John Skeat, the shopkeeper John Cross, and village publicans John Herbert and Edward Peedle. (fn. 302)

Occupations in 1841 included those of baker, blacksmith, butcher, carpenter, clockmaker, cooper, cordwainer, grocer, harness maker, mason, publican, sawyer, shoemaker, tailor, and wheelwright, and ten years later several women were employed as dressmakers, lacemakers, and laundresses. (fn. 303) Even so, as population fell employment became increasingly limited to farm work. (fn. 304) A small brickworks at nearby Lonesome Farm (in Newington parish), opened in 1927, may have provided occasional work, and in 1949 (when renamed the Chalgrove Brick Co.) employed up to a dozen men. Thereafter production fell, and the works closed in 1954. (fn. 305)

A cycle repair business opened in the 1920s and a petrol station in 1954, but in 1966, following closure of two of the villages pubs and of a long-standing grocers (formerly Baileys), only the petrol station, post office, and three other pubs remained, employing twelve full-time staff. (fn. 306) Thereafter housing development attracted new businesses, beginning with a parade of four shops opened on High Street in 1967. (fn. 307) A particular success was the Monument Industrial Park on Warpsgrove Lane, which provided business units, offices, and warehouses to c.8o firms, employing more than 500 people in 2013. (fn. 308) Rather different was the Martin-Baker Aircraft Co., based at Denham (Bucks.), which in 1946 began using Chalgrove airfield to test its aircraft ejector-seats, of which it was the country's only manufacturer. Despite local opposition, in 1963 the government offered the airfield to the company on a long lease on the grounds that its work was 'essential for defence purposes', and it remained in Chalgrove in 2015. (fn. 309)

MILLING

In 1086 Chalgrove manor included five mills worth £3 a year, (fn. 310) sited probably on Chalgrove brook. Almost certainly they exceeded the manor's own needs, and perhaps served neighbouring communities. Several millers were mentioned in the early 13th century, (fn. 311) and three or four mills continued in 1279, including one on each of the two main manors and another leased jointly (fn. 312) The mill's tithes were given by Miles Crispin to Bec abbey, which c.1250 leased them to the rector for life for 135. 4d. a year. (fn. 313)

The Plessis manor still had two watermills in 1336 (let for £3 13s. 4d. a year), but later only one. (fn. 314) Probably that was the mill let by the Audleys for 5s. a year in 1377, which is perhaps to be identified with Stratford mill on the Brightwell Baldwin boundary (fn. 315) The Barentin manor included Trylle and Church mills, let respectively in 1451 to two Wallingford butchers and a miller (for 375. a year), and to Thomas Algar. (fn. 316) By 1490 one was empty and possibly abandoned, although Magdalen College may have repaired the other in 1492–4. (fn. 317) In the 1520s the college owned one watermill and a horse mill (let for £3 135. 4d.), (fn. 318) and from the late 16th century it let its remaining watermill (on Mill Lane) for £20 a year to successive members of the Gillman family (fn. 319)

Henry Gillman (assessed on two hearths in 1662) may have built the surviving timber-framed miller's house, which was probably extended and infilled with brick in the 18th century (fn. 320) Later millers included William Carter, Thomas Young, William Knight, and Richard Smith, the occupant in 1871 when the mill itself was rebuilt in brick, with a weatherboarded extension housing an iron overshot wheel. (fn. 321) In 1900 the lessee Henry Nixey still paid £20 a year, and in 1942 Frederick Nixey bought the freehold for £775; (fn. 322) by 1955 the mill was powered by electricity, but ceased operating in the 1960s. (fn. 323) In the 1990s new owners extended the house and restored the mill machinery (fn. 324)

SOCIAL HISTORY

SOCIAL CHARACTER AND THE LIFE OF THE COMMUNITY

The Middle Ages

Chalgrove and Rofford remained distinct communities throughout the medieval period, notwithstanding that some Rofford inhabitants held land in Chalgrove. (fn. 325) Rofford's failure to expand after 1086 was untypical, and the Black Death exacerbated the gap, making it more vulnerable to inclosure by non-resident lords. By the 16th century it may already have been divided amongst three or four largely inclosed farms. (fn. 326)

By contrast Chalgrove's population more than doubled between the late 11th and late 13th centuries, much of the increase generated by creation of freeholds: 52 free tenants occupied land at Chalgrove in 1279, whereas none was mentioned in 1086. Their presence had a long-term impact, creating a complex and constantly changing tenurial pattern. Some (including William Quatremain) had their own subtenants, (fn. 327) while regular sales, leases, and exchanges allowed outsiders to acquire Chalgrove holdings. (fn. 328) Other newcomers acquired land through marriage, amongst them Thomas Curtis of Birmingham and Thomas Page of Dorchester, who in the 1330s married into the Maynard and Blackbird families. (fn. 329) Some land purchases before 1290 may have been financed by Jewish money-lending. (fn. 330)

The number of unfree customary tenants apparently changed very little between 1086 and 1279, when 39 villeins (mostly yardlanders and half-yardlanders) and 8 cottars were the likely successors to the 23 villani, 10 bordarii, and 9 servi recorded in Domesday Book. (fn. 331) The division of Chalgrove manor in 1233 saw the customary holdings almost equally divided between the Barentin and Plessis manors, with few customary tenants holding land from both, (fn. 332) while Chalgrove's separate 'ends' may have helped to preserve social as well as physical divisions within the village, with tenants at the 'bour end' generally occupying smaller holdings. (fn. 333) Nevertheless the vill remained united for tax purposes, and the whole community cooperated in open-field farming. (fn. 334)

Lords of Chalgrove's two main manors maintained substantial houses (at opposite ends of the village) from the 13th century, but were probably often away on royal service. Both Drew Barentin and John de Plessis were regularly employed by the king in the 1230s-60s, and received royal gifts including timber (from Bernwood forest) for their Chalgrove building works. (fn. 335) In the 1240s the king allowed them to levy tallage at Chalgrove, provoking disputes with tenants, confiscation of livestock, and court hearings, (fn. 336) while in 1293 an attempt to impound cattle led to an assault on one of the lord William de Bereford's servants. In 1340 Thomas Barentin faced encroachments on his demesne by inhabitants and outsiders including John Stonor and the abbot of Osney, (fn. 337) although such incidents were probably untypical. The Barentins and Berefords were of similar wealth and social standing, though from the 1320s it was the Barentins who maintained the closest local links, particularly with Chalgrove church. (fn. 338) The Berefords apparently developed stronger ties with their nearby manor of Brightwell Baldwin. (fn. 339)

Tax assessments reflect wide social and economic stratification. In 1306 the lords of Barentin's and Plessis's manors were among only seven occupiers (11 per cent) paying more than 3s., while 20 people (32 per cent) paid between 13d. and 3s. Amongst them were John Botte, possibly a half-yardlander mentioned in 1279, and the freeholders John Quatremain and John Brian. Another 36 inhabitants (57 per cent) paid 12d. or less, the cottar Robert Whiting contributing only the 4d. minimum. Several families (both free and unfree) remained present both in 1279 and 1327, although others were undoubtedly newcomers. (fn. 340) Pressure on resources, particularly amongst poorer inhabitants, is reflected in royal and manorial court records, which suggest widespread illegal grazing and trespasses by livestock. Other efforts at social control included a prohibition against visiting inns at night, which an unnamed innkeeper swore to support. (fn. 341)

The Black Deaths immediate impact on Chalgrove seems to have been relatively limited judging from court rolls of 1348 and 1352, which recorded routine business including election of harvest overseers. (fn. 342) By the early 15th century, however, the effects of long-term population decline were evident, including abandoned buildings, larger landholdings (often transferred outside the family), (fn. 343) and increased migration. At least two villeins left the manor in the 1370s, (fn. 344) while others fought in the French wars. (fn. 345) Newcomers were presumably attracted by the easier terms available, an entry fine of two capons for a yardland in 1434 contrasting starkly with the 5 marks (£3 6s. 8d.) charged for half a yardland (in eight instalments) in 1340. (fn. 346) Nevertheless several families remained in the parish for more than a century after 1377. (fn. 347)

The Barentins continued as resident lords until the 1440s, Thomas Barentin (d. 1400) serving as sheriff and MP, and enjoying friendly relations with Oxfordshire gentry such as Sir Ralph Stonor and John James of Wallingford, the lord of Rofford. The family's fortunes were transformed in 1415 when Reynold Barentin inherited Haseley and numerous other estates from his uncle Drew, a London goldsmith. After Reynolds son Drew (d. 1453) moved to Haseley Court the family gradually withdrew from Chalgrove, although they continued to be buried in the church until 1474. (fn. 348) Late-medieval lords of the Plessis manor (divided into three in 1356) may have never resided and latterly leased their estates, (fn. 349) while Rofford, too, belonged to absentee landowners. With the subsequent sales to Magdalen and Lincoln colleges, social leadership devolved presumably upon the parish's more important farmers. (fn. 350)

1500–1800

In the early 16th century Chalgrove's cottagers, smallholders, and larger-scale farmers occupied a wide variety of free, copyhold, and leasehold tenancies displaying little regularity, and occasionally combining open-field strips with some small private closes. (fn. 351) Tax assessments suggest a broad range of prosperity, with few markedly wealthy inhabitants. In 1523 a dozen people (43 per cent) paid between 4d. and 12d., 8 (28.5 per cent) paid 18d. to 3s., and 8 others (including several members of the Quatremain and Wiggin families) paid 45. or more. Twenty years later 25 inhabitants were assessed on goods worth £1-£2,11 on goods worth £3-£4, and only 5 (12 per cent) on goods worth £6-£20. (fn. 352)

On both occasions the parish's highest taxpayer was Roger Quatremain (d. 1549), whose family were prominent in Chalgrove from the Middle Ages to the 18th century, and whose goods at death were worth £94 6s. 8d. His widow Alice (d. 1559) owned silver spoons, pewter dishes stamped with a maker's mark, and a painted cloth above her bed, and as befitted their status both were buried in the church's middle aisle. (fn. 353) Most other inhabitants were far less wealthy, the median value of goods itemized in wills for the period 1531–59 totalling only £13 8s. 8d. (fn. 354) Fairly typical were members of the long-standing Burnham, Cave, Child, Simms, and Wiggin families, (fn. 355) who like the Quatremains were interconnected by marriage and friendship, left money to the church and poor or for mending roads, and had links with the nearby market town of Watlington. (fn. 356) Church court records point also to the petty disputes typical of most close-knit rural communities. (fn. 357) A similar picture prevailed in the later 16th century, when Ralph Quatremain (d. 1594) left £180-worth of agricultural stock and a little under £40-worth of household goods in his hall, parlour, buttery, three chambers, milkhouse, and brewhouse. (fn. 358) Few others' goods were worth more than £100, however, and a weaver with only a hall and chamber left possessions worth under £4. (fn. 359)

The more transient population included servants, labourers, and (in 1545) an itinerant miller, (fn. 360) with servants (several of whom lived in) being occasionally remembered in employers' wills. (fn. 361) Beggars and vagabonds (amongst them a 'poor wandering old man and a 'travelling boy') were mentioned intermittently, (fn. 362) perhaps reflecting the village's proximity to the Oxford-Watlington road, which presumably brought more welcome trade to the village's craftsmen and shopkeepers. An alehouse was kept by William Slatter (d. 1660), and slightly later ones were probably run by Thomas Taylor and Walter Haines. (fn. 363)

During the Civil War the parish was the scene of a violent battle. (fn. 364) On 17 June 1643 Parliamentary forces from Thame were repulsed at Islip near Oxford, prompting a Royalist counter-attack against Chinnor. Returning to Oxford the following day, Prince Ruperts cavalry routed pursuing Parliamentary forces in closes near Warpsgrove, numerous Parliamentarian casualties including John Hampden, who was mortally wounded and died later at Thame. More routine Civil War disruption included demands for grain and supplies: Royalist troops camped around Wheatley pillaged food from the surrounding countryside in 1643, and in 1644 grain was taken from the parish for the Royalist garrison at Oxford. (fn. 365) A monument to Hampden was unveiled on the 200th anniversary of the battle by George Grenville, Baron Nugent, and was later enlarged by addition of an obelisk. A brick pedestal faced with stone has a roundel of Hampden on one side, and inscriptions (including donors) on the others. (fn. 366)

The 17th century saw social continuity in the parish, the long-standing families of Burnham, Cave, Child, Quatremain, Simms, and Wiggin featuring prominently in the hearth tax of 1662, when 24 householders (40 per cent) still had one hearth only. Another 19 (32 per cent) paid on two hearths, and 9 (15 per cent) on three or four, with only 8 (13 per cent) paying on five or more. Of those Robert Quatremain (d. 1681) was assessed on seven hearths probably at Langley Hall, though several other family members occupied much smaller houses. (fn. 367) Wealthy newcomers included the Hobbses and their friends the Adeanes of Watlington - related by marriage to the Wiggins and to the vicar Francis Markham (1656–68) (fn. 368) - but during the 18th century most of the parish's longest-standing families departed, including the Burnhams, Childs, and Quatremains. (fn. 369) The Adeanes, too, went elsewhere, leaving the parish (according to the vicar in 1790) with 'no person of opulence'. (fn. 370) New families rising to prominence included the Collinses, Kings, and Whites, though landholding in Chalgrove remained too fragmented to allow any individual or group to dominate. (fn. 371)

Chalgrove's lords made relatively little impression, although in 1685 the Halls (owners of Manor farm and the Langehull estate) disputed Richard Child's erection of a new pew in the church's north aisle. (fn. 372) Magdalen and Lincoln Colleges' more distant lordship may have fostered an independent spirit, reflected in sometimes difficult relations with vicars. Both George Villiers (vicar 1723–48) and Paulo Tookie (1758–83) complained that the church's charitable estate had been 'misapplied for many years', and Tookie's attempts at reform led allegedly to 'odium and abuse'. (fn. 373)

By the 1750s the village had four or five licensed pubs or inns, and two remained in 1800. (fn. 374) Other entertainment included the Whitsun feast, combining communal merrymaking with maypole dancing and a court of misrule, (fn. 375) while an August feast was mentioned in the 1720s. (fn. 376) As in most rural communities occasional crime and disorder were endemic. An alehouse keeper was banned from keeping an alehouse (possibly the Wheatsheaf) in 1708, (fn. 377) and in 1687 a labourer was accused of sheep stealing. (fn. 378) Later cases of theft, fraud, extortion, or violence included accusations in the 1720s against the schoolmaster John Trumble, (fn. 379) while in 1761 a gypsy and ratcatcher stripped and robbed a girl in Chalgrove's fields. (fn. 380) More routine offences included swearing and withholding of wages. (fn. 381) Strangers and vagrants continued to seek shelter and sustenance, although the parish repeatedly removed non-residents under the settlement laws. (fn. 382)

Since 1800

Chalgrove's feast (or 'wissenail') was last held c.1805, though the reasons for its demise are unclear. Possibly rising Nonconformity brought it into disrepute, prompting removal of the maypole into the rafters of an old barn. (fn. 383) In other respects Chalgrove's social character changed only slowly before inclosure in 1843. Poverty and crime remained prevalent, with several incidences of violence, theft, and poaching. (fn. 384) Even the farmers were mostly poor according to the vicar in 1838, with 'scarce a halfpenny to spare', and in 1841 few inhabitants were employed outside agriculture or its related trades. (fn. 385) In 1840 a Friendly Society was established for workers aged 14–45, meeting at the Red Lion as one of four pubs then operating in the village. Its annual club dinner was held at Whitsun, perhaps recalling the former wissenail. (fn. 386)

Chalgrove Temperance Band c.1906.

Inclosure ended common grazing, depriving cottagers of part of their livelihood. (fn. 387) The loss may explain an increase in the number of recorded paupers from 13 in 1841 to 43 in 1851, during a time of over-all population decline. (fn. 388) Presumably the larger farmers benefited from inclosure, although the vicar complained in 1857 of their great parsimony', and bemoaned the 'want of a resident family of the highest order'. (fn. 389) Farm workers were hired at local fairs, which may have involved local merriment; certainly the vicar disliked the Whitsun meeting of the Friendly Society (whose membership rose from 71 in 1855 to a peak of 106 in 1865), and disapproved of a late-summer fair marking the church's patronal festival. (fn. 390) Villagers also gathered on Mid-Lent Sunday at a former clay-pit or hollow, traditionally the burial site of those killed in the Civil War battle, where they indulged in games, drinking, and fighting. (fn. 391)

In 1861 72 per cent of inhabitants were still native to the parish, with only 10 per cent born outside the county. (fn. 392) Poverty and poor housing may have encouraged some to leave, (fn. 393) while others looked to agricultural trade unionism, inviting Fabian Society speakers to the Red Lion. (fn. 394) The rise in trade union support may have adversely affected the Friendly Society, which was last mentioned in 1880 with 99 members; though re-formed in 1892, it was finally dissolved (with 74 members) in 1913. (fn. 395) Late 19th-century agricultural depression prompted further out-migration, reducing the proportion of parish-born inhabitants to 62 per cent by 1901. (fn. 396) By then there were five pubs and beerhouses including the Mousetrap on the Oxford-Watlington road, and it was perhaps to challenge their influence that the vicar J.H. Swinstead (1902–12) raised funds for a village hall, named in memory of John Hampden and opened in 1906. (fn. 397)