A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Benson (Including Fifield, Preston, Crownmarsh, Roke)', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp21-68 [accessed 31 January 2025].

'Benson (Including Fifield, Preston, Crownmarsh, Roke)', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online, accessed January 31, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp21-68.

"Benson (Including Fifield, Preston, Crownmarsh, Roke)". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online. Web. 31 January 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp21-68.

In this section

BENSON

The large and thriving village of Benson - by far the most populous settlement in Ewelme hundred - lies in the clay vale close to the River Thames. (fn. 1) Originating as an important royal estate-centre in the mid-to-late Anglo-Saxon period, in the 18th century it became a coaching stop on the London road, with a relatively broad range of trades and a diverse social structure. Until the 20th century it nevertheless remained predominantly agricultural, bordered until 1863 by its large open fields, and governed by the usual rural institutions of manor and parish. Its late 20th-century development was influenced by the establishment of a wartime military airfield which, with RAF Brize Norton, developed into one of Oxfordshire's two main military air stations. The extended airfield now occupies much of the former farmland between Benson and Ewelme.

At approaching 3,000 a. the surrounding ancient parish was large, encompassing the small outlying hamlets of Fifield, Preston Crowmarsh, Rokemarsh, and most of Roke. (fn. 2) All are included in the following account.

PARISH BOUNDARIES

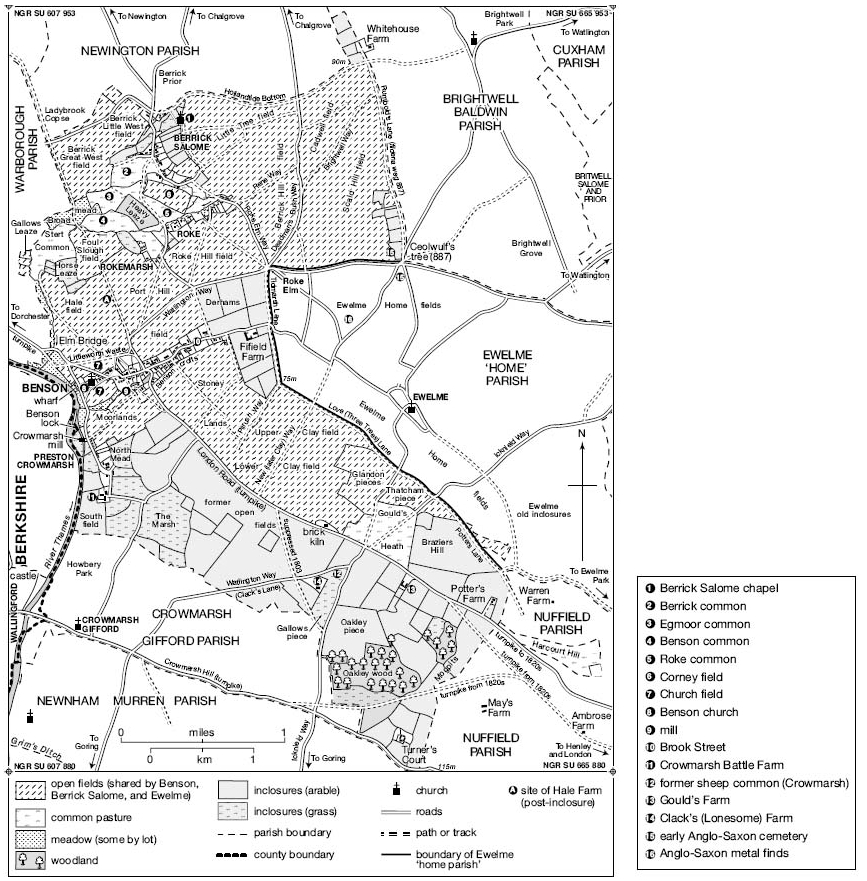

What became Benson parish emerged gradually during the 10th and 11th centuries, as the piecemeal break-up of the Benson royal estate (which extended across the Chilterns) created the later pattern of manors and parishes. (fn. 3) Benson, Ewelme, and Berrick Salome formed separate lordships by 1086, but their earlier interconnection was reflected in a shared open-field system which continued until 1863 (Fig. 4). (fn. 4) Consequently their mutual boundaries were indistinct, definable only by the scattered open-field strips belonging to their respective manors and owing tithe to their respective churches (see Plate 7 and Table 3). (fn. 5) A more clearly defined boundary along Love and Potters Lanes separated a core area of Ewelme known as the 'home parish', an arrangement established by the 18th century and possibly from the Middle Ages. (fn. 6) In the north, the hamlet of Roke became divided amongst all three parishes, reflecting manorial divisions established by the 13th century, while three cottages in Berrick Salome village similarly remained part of Benson. (fn. 7)

Benson's boundaries elsewhere were more clearly defined. On much of the west they followed the 11th-century shire boundary along the Thames, (fn. 8) taking in islands near Benson lock, while the north-west boundary with Warborough (mapped in 1606) divided fields and commons, following in part a straight (and possibly pre-Roman) lane to Ladybrook copse. (fn. 9) Warborough nevertheless remained closely associated with Benson, containing much of the manor's medieval demesne. (fn. 10) The main southern boundary was probably established by 1066 when Crowmarsh Gifford formed a separate estate, and in part follows indentations suggesting that it cuts through formerly shared open fields. (fn. 11) Irregular boundaries in the south-east brought in Oakley wood, the medieval Turner's Court, and a sliver of common pasture at Harcourt or Hartocke Hill, confirmed as belonging to Benson in 1594. (fn. 12) Benson also (like most neighbouring parishes) retained small pieces of detached meadow in Drayton St Leonard. (fn. 13)

An independent manor at Fifield formed a detached part of Dorchester hundred until the 19th century, reflecting its pre-Conquest connection with the bishop of Lincoln's Dorchester estate. (fn. 14) By the early 17th century it included a clearly delineated block of old inclosures totalling 139 a., although as it also contained open-field strips its early boundaries may have been less distinct. For ecclesiastical and civil purposes it belonged to Benson parish throughout, and was counted as part of Ewelme hundred from c.1882. (fn. 15)

Benson's boundaries were rationalized at inclosure in 1863, creating a parish of 2,920 acres. Ten scattered detached areas in the north and north-east (totalling 160 a.) reflected earlier complexities. Changes in 1882 reduced the detached areas to five (total 154 a.), whose removal in 1932 (alongside other alterations) left Benson with 2,748 acres. The projection at Harcourt Hill was transferred to Nuffield at the same time. (fn. 16) The changes left Roke still divided between Benson and Berrick Salome, until in 1992 Rokemarsh and the whole of Roke were transferred to Berrick, and Turners Court to Nuffield. Other rationalizations were made around Oakley wood, Potters Lane, and in the north-west, and in 2011 the parish covered 2,431 a. (984 ha). (fn. 17)

Benson, Ewelme, and Berrick Salome parishes c.1800, showing shared open fields and early inclosures. (See also Fig. 50 and Plate 7.)

LANDSCAPE

Most of the parish (including Benson itself) occupies open and low-lying agricultural land on the Thames floodplain, rising eastwards, in some places quite steeply, from c.45 m. by the river to over 100 m. near Potters Farm, Turners Court, and (within the former shared fields) north-east of Berrick Salome. The geology is mostly gravel rising onto chalk, while a narrow strip of riverside alluvium provided a few small meadows. North of Roke the alluvium spreads further, underlying the large former commons from which Rokemarsh is named. Crowmarsh, by the River Thames, recalls another low-lying common further south, although there the settlement itself rests (like Benson) on riverside gravel.

Until 1863 the rest of the parish was mostly taken up by the shared open fields, with contrasting areas of 17th-century inclosure at Crowmarsh, and of probably medieval inclosure interspersed with woodland on the slightly higher ground in the south-east. Field names reflected the terrain and the soils' varying quality, with hill-names predominating north-east of Berrick, clay-names in the south close to Ewelme, and Moorlands marking a small low-lying field next to Crowmarsh. Streams are plentiful, that from Ewelme (emptying into the Thames through Benson village) now partly culverted, but still flowing open alongside Brook Street. Others crossed the former Roke commons, (fn. 18) and occasional riverside flooding continued in the mid 20th century. (fn. 19)

COMMUNICATIONS

Roads

Until 1932 the main Dorchester-Henley road (turnpiked in 1736) ran through Benson village, continuing eastwards to London, and westwards (via Oxford or Abingdon) to Wales and the Midlands. (fn. 20) Roads north-eastwards link with neighbouring villages and the former market town of Watlington, (fn. 21) while Wallingford, across the river, is accessible via the early river crossing at Shillingford, (fn. 22) and southwards via the medieval bridge from Crowmarsh Gifford. No early river crossings are known at Benson itself, though by the 1760s a ferry ran from just south of Preston Crowmarsh mill, (fn. 23) supplemented in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by others at the lock and near the village. The lock ferry continued until the 1960s, to be replaced in the 1980s by a footbridge across the weir. (fn. 24)

Most of the roads are of medieval or earlier origin, but with some changes in their alignments. The Roman road from Dorchester to Henley may have run a few hundred metres north of its modern and medieval counterpart, skirting Benson's northernmost edge to continue along Love Lane, while the Shillingford crossing (established in the Anglo-Saxon period) was preceded by a Roman ford a little further west. North of Benson, a partly surviving track past Hale Farm and Ladybrook copse may mark another early route connecting with the Roman road from Dorchester to Fleet Marston (Bucks.), and seems to align with the top of the former Henley/London road. (fn. 25) A lost Roman road running down Tidmarsh Lane to Silchester has also been suggested, although the name apparently derives from the local Tidmarsh family rather than from Tidmarsh in Berkshire. (fn. 26) Part of the pre-Roman Icknield Way cuts across the parish's south-eastern edge following the Chiltern scarp, and Rumbold's Lane (running southwards along the Brightwell Baldwin boundary) was a 'fielden way' in 887. (fn. 27) Most other major routes were established by the 17th or 18th centuries, (fn. 28) while yeldenbrigge (now Elm Bridge), where the Henley road crosses the Warborough boundary brook, was mentioned in 1301. (fn. 29)

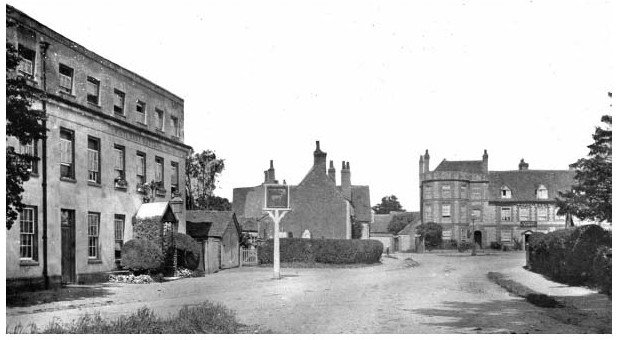

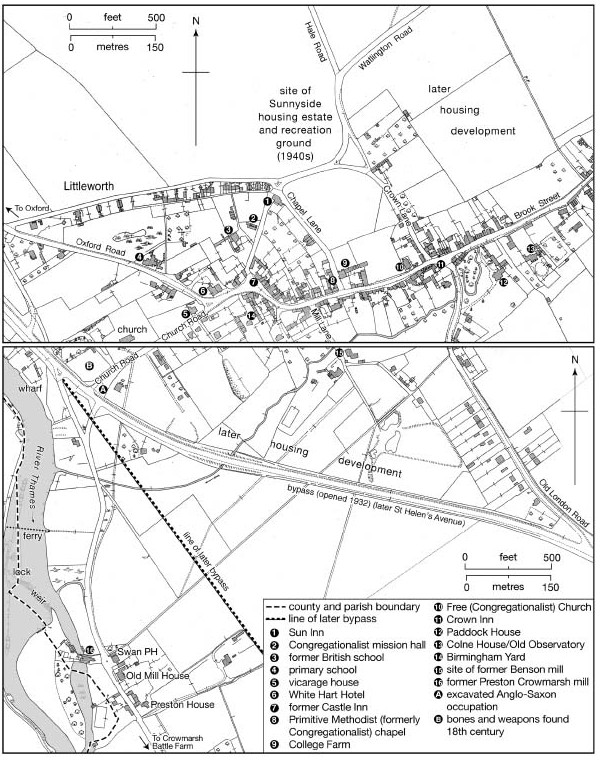

Castle Square in the early 20th century, showing the White Hart (left, with adjacent fire engine shed), and (ahead) the Castle Inn.

Inclosure in 1863 saw suppression of several field tracks and re-routing or straightening of others, (fn. 30) while the Henley turnpike road near Potters Farm was diverted c.1827, linking it with a re-routed turnpike to Wallingford as part of wider road improvements. (fn. 31) The route was disturnpiked in 1873. (fn. 32) A Benson bypass running from near Elm Bridge to the Henley/ London road was opened in 1932 (Fig. 6), and ten years later (when the London road was severed by the airfield) was replaced by a new, more westerly road to Crowmarsh Gifford, connecting with the Henley road along Crowmarsh Hill. (fn. 33) A section bypassing Crowmarsh Gifford village was added in the later 20th century, and as part of the A4074 remained the principal route towards Henley and Reading in 2015. The truncated old London road survives as a minor metalled road, and the 1932 bypass as St Helens Avenue.

Coaching, Carriers, and Post

Commercial coaching between London and Oxford was established by the 1660s, with services running via Stokenchurch or Benson. (fn. 34) Benson's leading inns were being refurbished by c.1700, (fn. 35) and by the mid 18th century the village (midway between Henley and Oxford) was a chief stopping point for connections, refreshments, and changing horses. (fn. 36) Coach-building developed, (fn. 37) and by the 1790s at least eight long-distance services passed through twice daily, together with mail coaches and 'several' daily services from Oxford. (fn. 38) Opening of the GWR's London-Bristol railway line in 1839–41 had immediate repercussions, however, leading by 1850 to 'the entire discontinuance of 30 coaches that formerly changed horses there daily', and causing unemployment in the village. (fn. 39)

A Benson carrier died in 1695, (fn. 40) and for 'many years' until 1775 John Parker of Benson operated stage wagons and carts from Abingdon to London. (fn. 41) London carrier services continued intermittently from the 1840s (when Roke had its own carrier) to 1890s, alongside services to Oxford, Abingdon, and (sometimes) Wallingford and Reading. By the 1920s carriers ran to Wallingford only. Motorized bus services from Oxford and Wallingford were established by 1920, and by 1939 were extended to Henley and Reading. (fn. 42) Even so in 1965 nearly 70 per cent of the working population relied on car travel. (fn. 43)

A post office was established by 1809, with letters delivered in the 1840s through Wallingford. (fn. 44) By 1869 it was also a money-order and government annuity and insurance office and a post office savings bank, and by 1876 a telegraph office. (fn. 45) Sited then near Mill Lane, it moved before 1899 to a site further along High Street, (fn. 46) and in 2010 (following a brief closure) to a pavilion behind the village hall. (fn. 47)

River and Railways

During the earlier Middle Ages Benson may have benefited from a well-documented river trade between the upper Thames and London, its right to salt tolls (recorded from the 1260s) perhaps reflecting a pre-Conquest trade in salt shipped downriver from Bampton. (fn. 48) From the later Middle Ages large-scale commercial navigation this far upstream largely ceased until the Thames's re-opening to Oxford from the 1630s; (fn. 49) by the 18th century, however, barges carrying agricultural and other goods passed regularly through Benson lock, (fn. 50) and a wharf west of the church existed by 1717. (fn. 51) Even so some London imports were still carted overland from Henley in the 1780s, (fn. 52) and in the 1750s Benson's wharf house was decayed and the profits minimal. (fn. 53) By the 1830s the wharf dealt predominantly in coal, and so continued until the mid 1930s, after which it was redeveloped for pleasure traffic. (fn. 54)

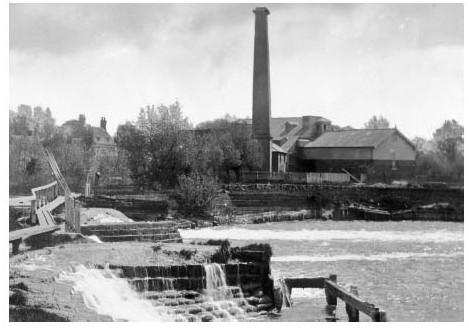

Benson lock, associated with the nearby mill at Preston Crowmarsh, existed presumably from the Middle Ages, and was perhaps the derelict weir associated with a mill c.1375. (fn. 55) From the 1580s both lock and weir were mentioned frequently, and in 1788 the flash lock, with a winch on the Benson bank, was replaced by a gated pound lock on the Berkshire side. Even so neglectful keepers (including millers) caused occasional delays to traffic in the 1790s–1850s. The lock was rebuilt in 1870, when pleasure boats were superseding commercial vessels, and in 1913 the keeper's house was replaced. (fn. 56)

Early railway links left Benson stranded, and plans in the 1860s for a GWR branch to Watlington via Benson were abandoned because of rival schemes. A station at Wallingford (c.3 km from Benson) was opened in 1866, however, and another at Watlington (with a line running eastwards to Princes Risborough) in 1872. In the 1890s an omnibus ran twice daily to Wallingford from Benson's Crown Inn, connecting with London trains, and both lines still transported livestock and agricultural produce in the 1930s, bringing in coal and coke, fertilizer, cattle feed, and road stone. Passenger services ended in the late 1950s, and the stations were closed in 1965 and 1961 respectively (fn. 57) Plans c.1898 for a Didcot-Watlington light railway across part of the parish came to nothing. (fn. 58)

POPULATION

Benson In 1086 Benson manor had 66 recorded tenants, although many probably lived outside the later parish in Warborough, Nuffield, Nettlebed, or Holcombe. (fn. 59) Some of the 135 or so tenants listed in 1279 (excluding institutions) probably also lived elsewhere, including Nettlebed: certainly not all of the numerous freeholders were necessarily resident, although few are expressly known to have held land in other places. (fn. 60) Early 14th-century taxation lists confirm that Benson was amongst the larger villages in the hundred, but not exceptionally so: 24 people paid tax in 1306 and 26 in 1327, compared with 23 in Warborough, 27 in Ewelme, and as many as 80 in Chalgrove. (fn. 61) In 1377, following the Black Death, 206 people aged over 14 paid poll tax in Benson and Nettlebed combined, of whom 150 or more were probably from Benson. If so the village may have had a total population of c.270–325 and c.60–80 houses, although Warborough remained of comparable size, and Chalgrove larger. (fn. 62) Sixteenth-century taxation lists suggest a similar ranking, with 26 Benson householders paying tax in 1524 and 8 in 1581, behind Chalgrove in both years. (fn. 63)

From the late 16th century Benson's population rose in line with national trends, particularly after 1700 as coaching boosted its economy. (fn. 64) Fifty three householders paid hearth tax in 1662, (fn. 65) and 268 'conformists' (probably adult inhabitants) were noted in 1676, making Benson marginally the largest settlement in the hundred. (fn. 66) That position was cemented during the 18th century, which saw the parish's total population (most of it in Benson) rise to 811 in 193 houses by 1801, easily outstripping its closest contender Warborough. By 1831 there were 1,266 people and over 220 houses, and though the demise of coaching and agricultural depression saw a fall to 965 by 1901 (when 27 houses were vacant), small-scale growth returned in the earlier 20th century and accelerated from the 1950s, reflecting the RAF presence and village expansion. By 1931 the parish population was 1,264, rising to 2,274 in 1951, and to 4,603 (in 1,315 households) in 1971. Reductions at RAF Benson contributed to slight falls in the 1970s–80s, but population by 2011 totalled 4,754 (1,620 households). (fn. 67)

Hamlets Benson's hamlets had much smaller populations. The largest (Preston Crowmarsh) had 13 recorded tenants in 1086 and 25 in 1279, (fn. 68) but the Black Death left at least five holdings vacant in the 1350s, (fn. 69) and in 1377 only 40 people aged over 14 paid poll tax. (fn. 70) Seven householders were taxed in 1524, (fn. 71) and in the 1630s there were at least nine houses besides the manor house. (fn. 72) The estate was later reorganized as two inclosed farms, though in the 1840s the hamlet still contained 19 houses accommodating 93 people. (fn. 73) Fifield had up to 19 tenant households in 1279, (fn. 74) but may have been substantially depopulated during the later Middle Ages: a map of 1638 showed only the manor house, although several other houses were still counted as part of Fifield in 1662. (fn. 75) By 1811 the population comprised only the 16 inhabitants of Fifield Manor. (fn. 76)

Tenants at Roke were mentioned frequently from the 13th century, (fn. 77) and the total of six households taxed in 1662 must represent a substantial under-assessment. (fn. 78) By 1841 Roke had 40 houses and neighbouring Rokemarsh 21, accommodating a combined population of 270. Over all, some 462 people (37 per cent of the parish total) then lived in the hamlets or outlying farms. (fn. 79)

SETTLEMENT AND BUILDINGS

Prehistoric to Roman

Finds and occupation evidence fit a general pattern for this part of the Upper Thames valley, which saw intensive activity from the Palaeolithic onwards. (fn. 80) Excavated Neolithic settlement by the river (close to Benson church) was probably occupied by part of a wider pastoralist population responsible for the area's numerous monument complexes, which included a cursus and a possible oval barrow within the modern Benson airfield. The same riverside site saw successive Bronze-Age and Iron-Age settlement subsisting on mixed farming, with comparable occupation further north near the Berrick–Warborough boundary. (fn. 81) Finds suggest similar early settlement around Littleworth, and possibly south of Crowmarsh Battle Farm. (fn. 82)

Roman rural settlement seems to have been widespread, focused on low-status farming communities set within a managed landscape of fields, enclosures, and drainage ditches. A 1st-century site on the modern village's southern edge proved relatively short-lived and saw successive reorganizations, but occupation sites on the Berrick-Warborough boundary continued into the late 4th or early 5th century, and included corn-drying kilns. Further Roman settlement probably lay around the eastern end of modern Brook Street close to an area called Blacklands, (fn. 83) while coin finds and a possible Roman enclosure have been noted on slightly higher ground near Gould's Grove, close to the Roman road. (fn. 84)

The Development of Benson

Anglo-Saxon Benson (fn. 85) Benson village occupies a gravel island by a bend in the Thames, 5 km east of Dorchester and 2.5 km north-east of the 9th-century fortified burh at Wallingford. Written sources suggest that by the late 8th century it formed an important royal estate centre with a significant strategic role in the contested border zone between Mercia and Wessex. Bishop Forthhere of Sherborne may have witnessed a royal grant there between 727 and 736, (fn. 86) and in 779 King Offa of Mercia reportedly recovered Benson from Wessex during a military campaign. (fn. 87) The evidence is not contemporary and may not be wholly reliable, but subsequent land-grants confirm its 9th-and 10th-century status as an important West Saxon royal possession with a large dependent territory. (fn. 88) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle's account of a West Saxon victory at Benson in 571, though probably largely mythic, similarly reflects the area's importance when the Chronicle was being compiled in the late 9th century. (fn. 89) A key factor in Benson's early emergence as a royal centre was presumably its proximity to the former Roman town of Dorchester, where King Cynegils of Wessex was baptized c.635 in the presence of his overlord King Oswald of Northumbria, and which subsequently became the area's chief ecclesiastical focus. (fn. 90)

Archaeology confirms an early-to-mid Anglo-Saxon presence in Benson, with possible foci in the south-west near St Helen's Avenue, and further east around Brook Street. The excavated St Helen's Avenue site (100 m. south of Benson church) revealed 6th-to 8th-century occupation including sunken-featured buildings, and a comparable site may be recalled in the place name Littleworth, for a fringe area on the village's northern edge. (fn. 91) Finds suggested only modest rural settlement, however, and no archaeological confirmation has yet been found for a royal residence or high-status focus, despite recent speculation regarding an excavated feature south of Benson church, (fn. 92) and despite earlier claims for an enclosure (now under housing) between the church and the river, where finds of bones and weapons were reported in the 18th century. (fn. 93) A late Anglo-Saxon royal residence may, however, have lain outside the main estate centre near Newington, where a site called Kingsbury ('king's burh or fortified enclosure') belonged to the royal estate until c.1155, and included a walled curia. (fn. 94) Firm evidence for an early church at Benson is similarly lacking, although in the medieval period Benson claimed residual parochial rights over much of the former royal estate, suggesting a pre-Conquest church of above average status. (fn. 95) Recent work also suggests that Benson's topography may preserve traces of late Anglo-Saxon grid planning, of a type lately proposed for many other sites during the period. (fn. 96) The place name Bensington (gradually shortened to Benson from the 16th century) (fn. 97) means either 'the tūn of Banesa's folk' (suggesting an early established Anglo-Saxon settlement), or, more likely, 'Banesa's tūn'. (fn. 98) If the latter, Banesa's identity and date remain problematic, unless he was an unrecorded royal tenant.

Benson itself was set within a wider landscape shaped by the royal estate, with the putative king's burh and a dependent farm or berewic to the north, the likely hundredal meeting place to the north-east, and a possible trading or tax collection area suggested by coin and metal finds on the edge of Ewelme parish. (fn. 99) To the west, Warborough ('watch hill') may have fulfilled a protective function for the royal centre, (fn. 100) while undated burials reported at Gallows Leaze, on the Warborough–Benson boundary, may reflect an Anglo-Saxon execution cemetery. (fn. 101) Over all, what constituted 'Benson' in the 8th or 9th century probably encompassed a complex extending way beyond the modern village.

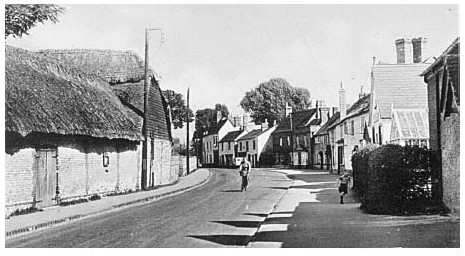

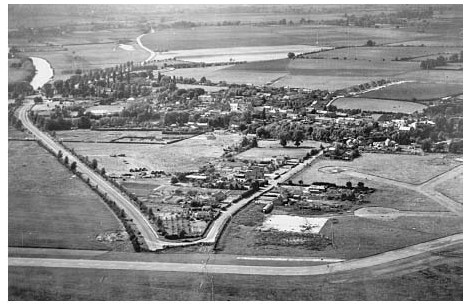

Benson village in 1938, before the airfield's creation.

Medieval and Later Development In 1086 Benson remained the most valuable royal estate in Oxfordshire, (fn. 102) but despite its early importance it failed to develop urban characteristics, overshadowed at first, perhaps, by the important ecclesiastical centre at Dorchester, and from the 9th century by the new royal burh at Wallingford and other emerging market centres. (fn. 103) How late any royal residence was maintained is unknown: no late-Saxon or post-Conquest kings are known to have stayed there, (fn. 104) and from the mid 13th century the manor was frequently held by high-status non-resident lords whose local power-base was Wallingford castle. (fn. 105) A broadening of Benson's main street at what is now Castle Square (where there is a pronounced dog-leg) (fn. 106) may hint at a small pre-or post-Conquest market area, but no market grants are recorded, and by the 13th century Benson was a predominantly agricultural village, albeit with a relatively broad range of crafts. (fn. 107)

Benson High Street in the mid 20th century, looking east. The large barns attached to College Farm (left) were demolished c.1962.

Evidence for Benson's medieval topography (the church apart) is mostly lacking, (fn. 108) but the main elements were established by 1638 when it was partly mapped. (fn. 109) As later, the London road dog-legged through the densely built-up village centre past the White Hart and Red Lion inns, continuing down Mill Lane. An alternative route ran down the later London road a little further east, adopted as the turnpike road in 1736. (fn. 110) Church Way (so called by 1788) (fn. 111) ran westwards past the church to Crowmarsh Lane and the river, while modern Chapel Lane (already partly built on) (fn. 112) ran northwards to the open fields. Late-medieval buildings survive near the parallel Crown Lane (named from an 18th-century inn), on High Street, and possibly near the top of Old London Road, while 16th-century buildings in the village centre include part of the large former farm complex at College Farm. (fn. 113) Brook Street, running alongside the stream from Ewelme, may have also been partly built up in the Middle Ages: Exeter College's farmstead at its eastern end (near Fifield) existed probably by the 1480s, (fn. 114) and in the mid 18th century several houses lined its north side, with a few others south of the brook. Littleworth waste, a strip of land on Benson's northern edge, had cottages on its southern side by 1708, although most existing buildings there are later. (fn. 115) A village pound reportedly stood at Littleworth's eastern end, with the stocks nearby. (fn. 116)

Eighteenth-century rebuilding and refronting altered the village's appearance but not its basic layout, the rising population being apparently accommodated through subdivision, increased infill, and (by the 1840s) the development of a few cottage rows and yards. (fn. 117) The mid-to-late 19th century saw some small-scale new building at Oxford Road (site of the new village schools), Littleworth, and the area in between, but in the 1930s the built-up area remained little expanded, interspersed with several large open spaces (including allotment gardens) in and around the village, and with a few larger houses (chiefly but not exclusively along Brook Street) still occupying their own grounds as in the 1840s. Small-scale expansion along the Old London Road and near Hale Farm began before the Second World War, but only in the 1960s–70s was there substantial growth, with intensive housing development on the village's northern fringe and in the angle between the Old London Road and St Helen's Avenue. The northern development incorporated playing fields and a new school, and a large village hall was opened nearby in 1988. Changes within the older village included demolition of College Farm's street-side barns c.1962 and their replacement by a nondescript row of shops, set back behind a featureless parking area. Later proposals prompted local protests and, eventually, creation of a conservation area in 1995, retaining much of Benson's historic character. The waterfront was developed for recreation from the 1940s, when the former wharf was bought for conversion into a bathing and boating station and Rivermead gardens were laid out by the parish council. By the 1980s there was a cruiser station, marina, and caravan park, largely separated from the village by the busy A4074. (fn. 118)

No. 1 Brook Street, with remains of cruck framing in its east wall. The central datestone commemorates remodelling in 1747.

Twelve street lamps were erected by subscription in 1887 to mark Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, (fn. 119) and piped water and electricity (generated initially at Crowmarsh mill) were available from the 1920s, although many houses remained unconnected until considerably later. Mains drainage followed in the mid 1950s. (fn. 120)

Benson's Built Character (fn. 121)

The village's most distinctive buildings are those reflecting its prosperous coaching era (c.1690–1830), featuring red, glazed, and grey/blue brick (sometimes elaborately patterned), red-tiled roofs, and (sometimes) stone dressings. Timber framing also continued into the 16th and 17th centuries, while many lesser buildings are of poor-quality local stone rubble or clunch (now usually rendered), sometimes combined with brick dressings and flint, and sometimes thatched. The better-quality bricks were almost certainly imported, despite the establishment of a small-scale brickworks at Beggarsbush Hill (by the turnpike road) by the 1780s. (fn. 122)

One of the village's few surviving medieval houses is 1 Brook Street at the bottom of Crown Lane, a small cruck-framed dwelling of relatively primitive construction encased in banded clunch rubble and brick in 1747. The structure retains smoke blackening from an open hearth, and remains of a cross passage. (fn. 123) The slightness of its timbers (replicated in re-used medieval fragments in the loft of 20 Old London Road) has prompted speculation that good building timber was in short supply in medieval Benson; (fn. 124) high-quality local building stone was also largely lacking, however, and many of the villages medieval houses may similarly have been timber-framed. If so their loss presumably reflects large-scale rebuilding during Benson's later periods of prosperity. Sixteenth- and 17th-century timber buildings (all box-framed) include Brook Cottage, and College, Castle, and Brook Farmhouses, of which College Farm (now rendered) passed to Magdalen College, Oxford, with a substantial freehold in 1569–70, (fn. 125) and subsequently acquired a timber-framed parlour and chamber wing. Its large adjacent barns fronted the main street, (fn. 126) and similar farmyards formerly adjoined most other large farmhouses in the village, reflecting the prosperity of Benson's emerging yeoman farmers. (fn. 127)

An Exeter College tenant was required to erect a chimney in 1553, (fn. 128) and chambers over former open halls are documented from the 1580s. (fn. 129) Inserted brick chimneys at 28 High Street and College Farm culminate in diamond-shaped stacks intended for show, while surviving internal decoration includes an early 17th-century painted frieze and false painted graining around the doorway at Brook Farmhouse, superseding the painted cloths mentioned in an unidentified house in 1588. (fn. 130) Up-to-date lobby-entrance plans (grouped around central stacks) were being introduced by the later 17th century, while the former farmhouse at 74–76 Brook Street incorporates end-stacks and a central stair tower facing the road, flanked by outshuts which probably provided cool storage. The house's end walls are of stone rubble, which thenceforth became more common. (fn. 131) Seventeenth-century probate documents point to adoption of parlours and increasingly elaborate furnishings by better-off yeomen and gentry, (fn. 132) of whom some occupied houses taxed in 1662 on between six and eleven hearths. Nevertheless a fifth of householders in the 1660s still had only two hearths, while 38 per cent had only one. (fn. 133)

The partly timber-framed Red Lion inn was successively remodelled from c. 1680–90, beginning with a fashionable brick-and-stone east front, and culminating by 1752 in a gently curving 'brick showpiece' along High Street, featuring sash windows, a parapet, and blue/grey headers with red dressings (Plate 11). The Crown was refronted in brick and stone in 1709, while the King's Arms was adapted from two former cottages before 1727 and remodelled in phases, acquiring a striking semi-circular brick-built corner tower (Fig. 5) which, between 1750 and 1779, prompted its renaming as the Castle Inn. Rounded corners facilitated access to the rear stable yard. (fn. 134) Several private houses acquired similarly fashionable frontages alongside more humble rebuildings in stone and thatch, while in the late 18th and early 19th centuries compact villa-style dwellings in their own grounds were built for aspiring gentleman farmers or tradesmen. Of those, Paddock House south of Brook Street (grey and red brick with a Welsh slate roof) was owned in 1841 by the farmer Edward Shrubb, while Kingsford House and Colne House belonged to the prominent Powell family, coachmakers, innkeepers, and landlords. The latter passed through marriage to the lawyer Henry Corsellis, whose relative Nicholas (a surgeon) occupied another villa off Brook Street. (fn. 135) The final inn refurbishment was that of the White Hart (Fig. 5), remodelled in the 1830s with a grand three-storeyed stuccoed front of eight bays, a delicate ironwork porch, and a (now lost) carved hart facing the street. (fn. 136)

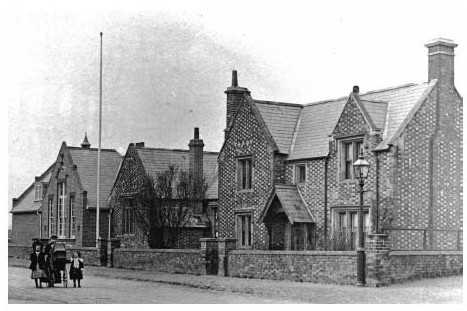

Labourers' accommodation was increased partly by subdivision during the late 18th and 19th centuries, though some small cottage rows were built on High and Brook Streets, and from the 1770s to 1870s Littleworth was built up piecemeal with cottages and cottage terraces, of which several bear initialled datestones and may have been speculative developments. Some are remodellings of earlier buildings, and variously feature stone or clunch, brick, thatch, tile, and Welsh slate. (fn. 137) Additional cottages were created in Birmingham Yard south of Castle Square, adjoining small-scale industrial premises including a wheelwrights' and smithy. (fn. 138) New 19th-century institutional buildings included the National and British schools (1851), new vicarage house (1869–70), and Congregationalist Free Church (1879), all of brick or flint. A timber and corrugated-iron Congregationalist hall was built on Watlington Road before 1903. (fn. 139)

Part of Benson airfield in the late 1940s, showing the 1932 bypass (left) and old London road (right) truncated by the extended runway.

Modest red-brick terraces at 5–11 Brook Street and on Chapel Lane are dated 1905 and 1911, and in the early 20th century the pioneering meteorologist W.H. Dines (d. 1927) built a small (now-demolished) observatory next to Colne House. Otherwise there was little new building until the 1930s, when the parish's first council houses (featuring period designs and 'Tudor' half-timbering) were built near Hale Farm. More standard post-war designs (by Harry Smith of Oxford) followed at Sunnyside, grouped around a new recreation ground. Private development accelerated from the 1960s, with new housing built around St Helen's Avenue from 1958, at Blacklands and Westfield Road from c.1966, and off Brook Street (partly replacing demolished buildings) from 1965 and in the 1970s. Much is in standard 1960s style, though some later designs attempted, with varying success, to echo traditional materials and features. (fn. 140) As elsewhere, some surviving agricultural buildings were converted into houses. (fn. 141)

The Development of RAF Benson (fn. 142)

A grass airfield on farmland between Benson and Ewelme was constructed in 1937–9 as part of the RAF's pre-war expansion programme, equipped at first with four C-type hangars and small domestic and workshop blocks. Bomber squadrons (flying Fairey Battles) moved in briefly from April 1939, followed by the King's Flight and (during 1940–1) by No. 12 Operational Training Unit. The airfield's most crucial wartime contribution, however, was in aerial reconnaissance, heralded by the arrival in 1940 of No. 1 Photographic Reconnaissance Unit. Throughout the war the PRU and its successors (flying Spitfires and Mosquitoes) provided crucial strategic information, processed at the Old Mansion in Cottesmore (in Ewelme parish) before transfer to Danesfield House (Bucks.). Notable successes included location of the Bismarck and Turpitz battleships, identification of V1 and V2 sites at Peenemünde, photographs of the Ruhr dams before and after the Dambusters' raid, and surveying of D-Day landing sites. Extended hard runways were constructed in 1942, providing for heavier aircraft but cutting off the old London road, which Royal Engineers based at Howbery Park replaced with the current road to Crowmarsh Gifford.

The King's Flight (disbanded in 1942) was reformed at Benson in 1946, and in 1953 the newly expanded station (with an additional south runway) (fn. 143) assumed a role within Transport Command, ferrying aircraft across the world. Its transport function was adapted to medium-range operations in 1961, bringing in new Argosy squadrons. Changes from the 1970s maintained a high level of activity, bringing in a succession of squadrons and units including (in 1983) the Andover Training Flight, and in 1992 (on the closure of RAF Abingdon) the Oxford and London University Air Squadrons. From 1990 the station was developed as a major helicopter base, operating Wessexes and (later) Pumas and Merlins: in 2013 it remained a front-line support helicopter base within Joint Helicopter Command, accommodating four helicopter squadrons, several other units, and some 2,000 service personnel and civil servants, alongside a similar number of dependants and civilian staff. The King's (later Queens) Flight remained until 1995, when it was transferred to RAF Northolt. As the station's role expanded so too did its facilities, including the development of a large domestic area (begun by the early 1950s and greatly expanded from the 1970s) east of Green (formerly Clay) Lane near Ewelme, with its own school, church, and recreational facilities set within a fenced compound. (fn. 144) A replica of the Benson Spitfire which photographed the Ruhr dams after the raid was placed outside the station's main gate in 1989. (fn. 145)

Hamlets and Outlying Settlement (fn. 146)

Settlements at Preston Crowmarsh and probably Fifield existed before the Norman Conquest, (fn. 147) and by the 13th century there was settlement at Roke and at some other outlying sites. Preston Crowmarsh, close to the river, developed on the north-western edge of the 'marsh [or common] frequented by crows' from which it and Crowmarsh Gifford are named, its medieval fields extending beyond the common towards Oakley wood. (fn. 148) The apparently interchangeable names Crowmarsh Battle and Prestecromerse (priests' Crowmarsh) were established by c.1300, (fn. 149) reflecting the manor's ownership by Battle abbey (Sussex); both remained in use, but from the 17th century the form Preston Crowmarsh became increasingly common. (fn. 150) The present hamlet comprises Crowmarsh Battle Farm (on the site of the abbey's medieval manor house) and houses further north along Crowmarsh Lane, whose curving line near Lower Farm formerly continued north-eastwards towards Benson. It was apparently truncated during 17th-century inclosure, leaving a sharp angle in the modern road. (fn. 151)

The hamlet's layout was broadly established by 1638 and probably from the Middle Ages, with tenant housing perhaps intentionally separated from the manorial site. (fn. 152) Lower Farm became a significant focus following its sale in 1617, and by the late 18th century included a new farmhouse set back from the lane, with farm buildings and cottages to its south. (fn. 153) Several other cottages were rebuilt or remodelled during the same period, (fn. 154) but there was little infill until the early 20th century when a few houses were built west of the lane to Crowmarsh Battle Farm. (fn. 155) A cluster of houses at the hamlet's northern end lay outside Crowmarsh Battle manor, (fn. 156) but like the nearby mill may occupy medieval sites. They include the former Swan pub (part-dated 1730) (fn. 157) and the 18th-century Old Mill House, while the larger Mill Cottages and Preston House replaced former yards and malthouses in the early 20th century. (fn. 158)

Fifield (meaning 'five hides') formed a separate 5-hide estate before 1066, when there was probably a tenanted house on or near the site of the present Fifield Manor. (fn. 159) Domesday Book mentioned no other tenants, but a parochial chapel probably near Fifield Manor existed in 1163, and by the 1270s there were up to 19 households. (fn. 160) Their location is unclear, though poor-quality earthworks have been noted east of the house. (fn. 161) By 1638 late medieval shrinkage had left Fifield Manor isolated within an island of old inclosures; (fn. 162) early 17th-century deeds still mentioned houses and tofts belonging to its estate, however, and seven houses were taxed under Fifield in 1662. (fn. 163) Possibly those included cottages straggling eastwards over the Ewelme boundary, or lying elsewhere within the parish. (fn. 164) By the 1830s Fifield comprised only Fifield Manor and its surrounding closes, together with a newly built lodge fronting Ewelme road. (fn. 165)

Roke and Rokemarsh developed along a spring line on the southern edge of low-lying commons stretching up to Berrick. (fn. 166) The place name originated as '(le) oak', where habitation was mentioned frequently from the late 13th century. (fn. 167) Possibly the name referred to the later 'Roke Elm' at or near the putative hundredal meeting site, (fn. 168) although that lay some distance south of the modern hamlet. By the 1470s Roke had taken its later linear form, with houses arranged along the southern side of the stream marking the commons edge. (fn. 169) Its regularity suggests a degree of planning, and its division amongst several manors and parishes may indicate an early (and possibly pre-Conquest) origin. (fn. 170) Rokemarsh, a more haphazard cluster of houses to the south-west, may have developed slightly later, though there were buildings there by 1638 and the hamlet was separately noted on 18th-century maps. (fn. 171) Loss of some dwellings during the 20th century was counterbalanced by small-scale rebuilding and infilling, and in 2015 the hamlets' over-all shapes remained little altered. (fn. 172)

A few other outlying sites are recorded from the Middle Ages, some of them possibly survivals from an earlier and more dispersed settlement pattern. The 13th-century bynames 'of Mogpits', 'of Grendon', and 'of Oakley' suggest habitation on the parish's south-eastern edge towards Nuffield and Ewelme, (fn. 173) and substantial inclosed freeholds there called Turner's, Potter's, and Gould's (formerly Goul's or Gull's) were established by the 14th or 15th centuries, probably already with their own farmsteads. (fn. 174) Clack's (formerly Lonesome) Farm was established between 1638 and 1767, superseding a nearby sheephouse. (fn. 175) A brick kiln and adjacent cottages (including a pub) were built on the London road west of Gould's Heath before the 1780s, (fn. 176) and following inclosure in 1863 Hale Farm was built on former open-field land south-west of Rokemarsh. (fn. 177) Outlying 20th-century development included a few houses along the old London road and the Farm Training Colony at Turner's Court, where new housing was built following the school's closure in 1991. (fn. 178)

Buildings in the Hamlets

The hamlets' buildings comprise cottages and a few larger farmhouses constructed of similar materials to those in Benson. Fifield House and Crowmarsh Battle Farm (both former manor houses) are discussed below, together with the outlying Turner's Court. (fn. 179) Otherwise the earliest known domestic building is Russetts at Roke, which incorporates a thatched and cruck-framed structure (possibly a former detached kitchen) dendrodated to 1468, and a storeyed box-framed cross-wing of 1550, the two now linked by a central bay which perhaps replaced an open hall. The box-framing is infilled with painted brick, and the rest encased in stone rubble. (fn. 180) Other larger farmhouses include the probably 17th-century Roke Farm (an L-shaped building combining timber framing, brick, clunch rubble, and a plain-tile roof), while The Cottage in Roke is a smaller dwelling of painted limestone rubble with brick stacks, whose attic storey retains fragments of early 18th-century decorative wall painting and devotional texts, executed in rustic style. (fn. 181) As at Benson, 17th-century inventories show a few leading yeomen occupying wellfurnished houses with parlours, (fn. 182) although in the 1660s few houses were taxed on more than 1 or 2 hearths. (fn. 183)

Among later buildings, Lower Farm in Preston Crowmarsh (rebuilt in the 18th century and remodelled in the 19th) has a rendered front and a hipped slate roof, while the Old Mill House to the north (occupied with the mill by 1841) was remodelled in the late 18th or early 19th century, and has a symmetrical five-bay brick front with banded decoration, 16-pane sash windows, and a moulded timber cornice. (fn. 184) The 19th century saw little new building in either Roke or Preston Crowmarsh, (fn. 185) and 20th-century additions were chiefly confined to small-scale infill in mostly unsympathetic styles. Exceptions include the striking Mill Cottages and Preston House at Preston Crowmarsh's northern end, built by George Faber (later Lord Wittenham) of Howbery Park for his estate workers and bailiff in the early 20th century, (fn. 186) in an idealized vernacular featuring brick and flint dressings, leaded casements, and hipped tiled roofs with decorative brick chimneys. New buildings on the old London road included a thatched 'Keep the Countryside Beautiful' Roadhouse and petrol station built in the 1930s, and the large brick and mock timber-framed London Road Inn at Beggarsbush Hill. Both were demolished in 1942 following (respectively) the airfield's expansion and a fire, although the inn was later rebuilt on a smaller scale. (fn. 187) Surviving agricultural buildings include important farmyard complexes (now converted to other uses) at Crowmarsh Battle Farm and Fifield Manor. (fn. 188)

Russetts at Roke, showing the box-framed cross wing of c.1550 (left), and the cruck-framed structure of c. 1468 (right), perhaps originally a detached kitchen.

MANORS AND ESTATES

Throughout the Middle Ages much of Benson parish belonged to the large royal manor of Benson, which derived from a larger pre-Conquest royal estate. Exceptions were the small independent manors of Fifield and Crowmarsh Battle, created before 1086, while parts of Roke (along with neighbouring Berrick Salome) belonged to Chalgrove manor from the 11th or 12th century. (fn. 189)

Benson manor's predominance was undermined, however, by its substantial number of free tenancies, reflecting its status as ancient royal demesne. (fn. 190) By the 17th century most Benson holdings owed only small quitrents, while several freeholds and leaseholds had developed into substantial subsidiary estates. (fn. 191) Fragmentation was accelerated by the manor's sale to non-resident owners in 1628, and though it continued as a legal entity, claiming quitrents, suit of court, and rights over commons, landownership was dominated by an increasingly complex pattern of freeholds, leaseholds, and subtenancies. By the 1840s there were over a hundred separate owners and, though many were cottagers or other small freeholders, a few leading proprietors had estates of 100 a. or more. In particular the local Newton family owned over 800 a. in all, besides farming the still-separate Crowmarsh Battle estate. Institutional owners included Magdalen and Exeter Colleges, Oxford, with 94 a. and 60 a. respectively, while Lincoln and St John's Colleges owned small parcels attached to neighbouring estates. Christ Church, Oxford, held 17½ a. as appropriated glebe. (fn. 192)

BENSON MANOR

The Manor's Extent

The territory dependent on Benson before the Norman Conquest stretched across the Chilterns to Henley, and may originally have encompassed much of the 4½ Chiltern hundreds. (fn. 193) By the 11th century its fragmentation through piecemeal land grants was well advanced, (fn. 194) though in the 1780s the manor still claimed residual quitrents from Checkendon in Langtree hundred and from Henley and Rotherfield Greys in Binfield hundred, while a perambulation in the 1820s included waste along the length of the Dorchester–Henley road. Within Ewelme hundred, quitrents remained due from Nettlebed, Nuffield, Holcombe (in Newington parish), Warborough, Shillingford, and Roke, and in 1826 jurors alleged that the whole of Nettlebed parish remained within the manors jurisdiction. (fn. 195) Earlier jurors had found the manor so intermixed 'amongst adjacent manors of other lords' that they were unable to 'discern or distinguish [its] certain bounds or limits'. (fn. 196)

The estate's core was nevertheless substantially reduced by the later Middle Ages. In 1086 (when rated at 11¾ hides) it probably still encompassed Benson, Warborough, Shillingford, Nettlebed, part of Nuffield (excluding Gangsdown), and part of Holcombe, together with Henley-on-Thames and Wyfold in Checkendon, while other outliers included ½ hide of waste in 'fern field' (Verneveld), possibly in Swyncombe. (fn. 197) Three hides held by prominent royal servants imply continuing fragmentation, (fn. 198) and Nettlebed, Wyfold, Henley, parts of Shillingford, and Huntercombe in Nuffield were all detached over the following 150 years, alongside numerous smaller-scale grants in various parishes. (fn. 199) In 1279 Henley, Nettlebed, Huntercombe, Wyfold, Preston Crowmarsh, Warborough, Shillingford, and Up Holcombe were still claimed as 'hamlets' and were counted, with Benson itself, as ancient royal demesne. (fn. 200) Most, however, were already effectively independent, and only Warborough and Shillingford (which contained most of the Benson demesne and copyhold land) remained an integral part of the manor into the 16th and 17th centuries, prompting prolonged conflict over manorial rights with other landowners. (fn. 201) In the 19th century the manor retained a 169-a. farm in Warborough and 49 a. in Benson, (fn. 202) along with courts, quitrents, and other manorial rights. Surviving Warborough and Shillingford copyholds were conveyed through the Benson manor court until the 1920s, when the courts and lordship lapsed. (fn. 203)

Ownership to 1628

In the later Anglo-Saxon period direct control seems to have remained with successive kings of Wessex or Mercia, as political authority switched back and forth. Recorded 9th- to 11th-century land grants were made by Æthelred of Mercia (with King Alfred's agreement), Æthelred II, and Queen Ælgifu, (fn. 204) followed by post-Conquest grants by William I, Stephen, and Matilda. (fn. 205)

From the 12th century all or part of the manor was sometimes leased, and from the 13th and 14th centuries it was regularly granted to royal favourites or family members, usually for a limited term. Twelfth-century lessees included Geoffrey de Ivoi (d. 1178), William of Waltham (1189), Richard son of Renfridus (1190), William d'Aubigny, earl of Arundel (1191), and William de Sancte Marie de Ecclesia (1194–6), who mostly paid £57 8s. a year. At other times the manor was run directly through Crown officers. (fn. 206) In 1199 King John granted the manors of Benson and Henley as a knight's fee to the Norman lord Robert de Harcourt, who forfeited his English estates in 1204; (fn. 207) both manors were briefly restored to John de Harcourt in 1217–18, but in 1219 Henry III gave them at pleasure to the alien royal favourite Engelard de Cigogné (Cigony). (fn. 208) He retained them until his death c.1244 when they were given to the king's brother Richard (d. 1272), earl of Cornwall, becoming part of the honor of Wallingford. (fn. 209) Soon afterwards Richard leased the Benson rents and demesne to a group of free tenants for a fixed annual sum, reserving his woods, the lordship, and manorial and hundredal jurisdiction. Their payment was reduced in 1278 after some Warborough lands were given to the chapel of St Nicholas in Wallingford castle, but otherwise the arrangement continued until 143 8. (fn. 210)

Both honor and lordship reverted to the Crown in 1300 following the death of Richards son Edmund, earl of Cornwall. (fn. 211) In 1302 the manor (but not the honor) was granted to Roger Bigod (d. 1306), earl of Norfolk, and in 1309 both were granted to the king's favourite Piers Gaveston (d. 1312), earl of Cornwall. (fn. 212) Queen Isabella held them in dower from 1317–24 and 1326–30, (fn. 213) following which Edward III bestowed them on his younger brother John of Eltham (d. 1336), earl of Cornwall. (fn. 214) The honor was annexed in 1337 to the newly created duchy of Cornwall, which Edward III settled on his son Edward, the Black Prince, and on future heirs to the throne; thereafter until 1540 Benson belonged both to the honor of Wallingford and to the duchy, generally reverting to the king during periods when there was no male heir. (fn. 215) On the Black Princes death in 1376 Benson revenues were settled on his widow Joan as dower, (fn. 216) and on her death in 1385 Benson and Nettlebed manors were granted for life to Richard II's chamber knight Sir John Salisbury (executed 1387). (fn. 217) Henry V's widow Catherine (d. 1437) received Benson and other local properties in dower in 1423, (fn. 218) and in 1488 revenues from Benson and three other manors were granted to a doctor for attendance on Prince Arthur. (fn. 219) Otherwise both manor and honor were administered through local Crown officers. (fn. 220)

In 1540 the honor was separated from the duchy and absorbed into the newly created honor of Ewelme. (fn. 221) Benson remained in royal hands until 1628 when, having formed part of the Prince of Wales's endowment from 1619–25, it was sold as part of an extensive disposal of Crown lands. (fn. 222)

Ownership from 1628

The purchasers in 1628 were a group of leading London citizens acting for the City, (fn. 223) who in 1630 sold Benson to the London merchant and future lord mayor Christopher Clitherow (knighted 1636, d. 1641). Clitherow's son Christopher (as executor) sold the manor in 1651 to his fellow London merchant John Highlord, who the following year sold it to the elder Christopher's son-in-law William Paul (d. 1665), a future bishop of Oxford. James and John Clitherow and Thomas Cory, in whose name courts were held, were trustees only. A fee farm rent of £28 145. 1½d. remained payable to the Crown under the 1628 sale, but like several similar rents was later sold. (fn. 224)

The manor passed successively to Paul's sons Christopher (d. 1671), of the Inner Temple, and James (d. 1693), of Bray (Berks.). (fn. 225) Thereafter it descended with the Pauls' recently acquired manor of Rotherfield Greys, (fn. 226) passing to James's son William (d. 1711) and granddaughter Catherine (d. 1753), who married Sir William Stapleton (d. 1740), Bt, and (later) the Revd Matthew Dutton. (fn. 227) Both manors descended to her and William's son Sir Thomas Stapleton (d. 1781), Bt, and to Thomas's son Thomas (d. 1831), Bt, who became Lord le Despenser. Transactions, however, were sometimes in the name of the elder Thomas's widow Mary (d. 1835), who was succeeded by her and Thomas's unmarried daughters Maria (d. 1858) and Catherine (d. 1863), holding in common. All of the Stapleton owners lived at Rotherfield, although their stewards still held manor courts at Benson. Catherine was followed by Lord le Despenser's son Sir Francis Jarvis Stapleton, Bt, and in 1874 by Francis's son Francis George Stapleton (d. 1899). His nephew Sir Miles Talbot Stapleton was lord in 1926 when the surviving copyholds (all in Warborough) were extinguished. (fn. 228)

FIFIELD MANOR

By 1086 a 5-hide estate at Fifield belonged to the bishop of Lincoln's large Dorchester manor, having presumably been granted to one of his predecessors before the Conquest. The tenants were probably Rainald and Vitalis, who jointly held 5 hides of the bishop at an unspecified location. (fn. 229) By the early 13th century the manor was held as a knight's fee by members of the de Hoyville family, including Richard (d. c.1212), (fn. 230) Geoffrey (fl. 1228), (fn. 231) Sir Hugh (fl. 1260), (fn. 232) and Sir Philip (fl. 1279), who owed scutage and suit at the Dorchester hundred court. (fn. 233) The bishops over-lordship was still mentioned in 1396, (fn. 234) and the estate was called a manor into the 18th century, long after it became a single farm. (fn. 235) Annual quitrents of 29s. 4d. to Benson manor remained due in the 1780s. (fn. 236)

Philips successors included William (fl. 1316–27), Richard (fl. 1346), (fn. 237) and John de Hoyvile, who in 1360 sold the manor to John Bernard of Wooburn (Bucks.). (fn. 238) From 1379 the owner was John James (d. 1396) of Wallingford, a landowner and MP succeeded by his son Robert (d. 1432), sheriff of Oxfordshire and Berkshire. Fifield passed with Boarstall manor (Bucks.) to Roberts daughter Christine Rede (d. 1435) and grandson Sir Edmund Rede (d. 1489), who left it to John Rede, then a minor; it reverted to the main Boarstall line, however, passing before 1560 to the Dynhams as the Redes' descendants through marriage. (fn. 239) They and probably the Redes and Jameses leased the estate (reckoned at some 790 a.) to resident farmers, including (from 1575 to 1685) successive members of the Stampe family. (fn. 240)

The manor was included in the Dynhams' transactions with Alexander Denton (d. 1577) and his son Thomas, who secured it in 1596, and in 1623 sold it to the Abingdon lawyer John Blackmail (d. 1625), owner of Preston Crowmarsh. (fn. 241) Blacknail's daughter Mary married Ralph (later Sir Ralph) Verney of Middle Claydon (Bucks.), who suffered serious losses during the Civil War, and sold most of Fifield in 1662 to the Wallingford maltster Richard Sayer or Sawyer. (fn. 242) Sawyer's grandson sold it in 1708 to Richard Wise (d. 1740) of Benson, gentleman, who moved to Fifield Manor soon after; in 1724, however, he sold the estate to his creditor George Lewin (d. 1743) of London, who later mortgaged it. Wise's son John (then living in Bloomsbury) re-purchased the freehold in 1747, (fn. 243) the house having been briefly occupied by Hatton Tash (d. 1725) presumably as lessee. (fn. 244)

John Wise moved to Fifield after 1754 (fn. 245) and died there in 1776, leaving the estate to his wife Anna (d. 1779) and then to his nephew John Boote of Stonehouse (Glos.). (fn. 246) From 1777 both house and land were let to the Bonners as tenant farmers, while ownership passed to Bootes daughter Frances, who married Edward Harrington of London. In 1818 she sold the estate to Thomas Newton (d. 1842) of Crowmarsh Battle Farm, whose son Robert Aldworth Newton moved to Fifield c.1827. (fn. 247) By 1841 Robert's combined Benson lands, still focused on Fifield Farm, totalled 398 a., excluding 100 a. of leasehold. (fn. 248) Following Robert's death in 1879 the land was leased and the house occupied by his daughter Emma, who continued as tenant after the estate was sold piecemeal in 1900. The occupant in 1939 (Mrs A.G. Wainwright) was still called lady of the manor, but by 1948 the house was held with only 4 acres. (fn. 249)

Fifield House or Manor

Though heavily remodelled in the 18th and 19th centuries, Fifield Manor retains a medieval core. (fn. 250) In its present form it comprises a thick-walled east-west range parallel to the street, with projecting service ranges to the south, and two large courtyards of former farm buildings to the west. The main north front, remodelled by Robert Newton in the earlier 19th century, (fn. 251) has a grand stuccoed façade of eight bays and three storeys, entered through a central colonnaded entrance porch which opens externally onto a balustraded terrace. Tall sash windows light the ground and first-floor rooms, and smaller sashes the upper floor, while the four central bays are marked by brackets under the eaves cornice and by bracketed cornices over the first-floor windows.

The house's western part may have begun as a medieval upper hall accessed from a projecting stair turret at the rear: rooms under the hall were mentioned in 1609, (fn. 252) and the present upper west room retains an early 14th-century traceried window (partly reconstructed), (fn. 253) with evidence of another stair. A medieval private chapel (recalled in the adjacent field-name Chapel close) may have formerly stood beyond the hall or physically within the house, whose westernmost ground-floor room contained a recessed wall painting of the Devil destroyed in the 19th century. (fn. 254) The house's eastern part may have contained a storeyed chamber block with ground-floor service rooms, whose two-centred arched doorways (one of which survives) led to a narrow bay containing a cellar and, probably, more stairs. A detached kitchen beyond survived in the 17th century. (fn. 255) The Ewelme stream flows through the curtilage on the north, but no trace of a moat survives on the other sides.

The main north front of Fifield Manor, remodelled by the prominent farmer Robert Newton.

By 1612 the hall contained wainscoting, glazed windows, and a fireplace. (fn. 256) Remodelling before 1685 saw the ground-floor rooms converted to kitchen, ceiled hall, and parlour, all with chambers above, and in the 1660s the house was taxed on four hearths, implying some upstairs heating. The old detached kitchen stored 'lumber' and had a granary above, other outbuildings including a buttery and milk-house. (fn. 257) Eighteenth-century panelling in the entrance hall and ground-floor west room reflects remodelling probably by the Wises, (fn. 258) who added a rear service wing, while Newton's remodellings included addition of the house's third storey, creation of the new entrance front, insertion in the former hall of an open-well staircase with cast-iron balustrade, and addition of a south-west domestic block parallel to the main range. An ornamental fountain was added at the front in 1849. (fn. 259) Major renovations to the house and gardens were carried out from the 1980s, and a new brick, flint, and timber range was added at the rear in 2000. (fn. 260)

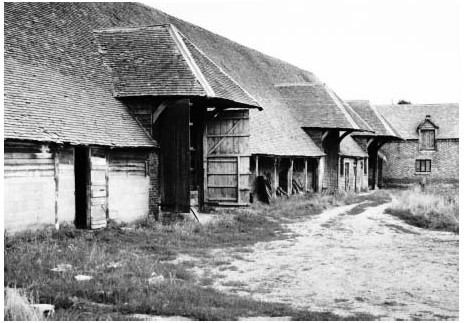

Farm buildings in the 1630s included a dovecot to the south and barns to the west and south-west. (fn. 261) The present clunch-built rectangular dovecot was altered for the Wises in 1767, (fn. 262) its upper part rebuilt in flint, and the interior re-lined in brick. Robert Newton rebuilt the farmyard on an imposing scale in 1825–7, creating a courtyard flanked by cattle sheds, a stable block, and four large brick-built barns with vitrified headers, all closely reminiscent of the layout at the Newtons' Crowmarsh Battle Farm. (fn. 263) The farmyard became separated during the earlier 20th century, and was converted to other uses from the 1990s. (fn. 264)

PRESTON CROWMARSH (CROWMARSH BATTLE) MANOR

A 5-hide estate at Preston Crowmarsh was granted to Harold Godwinson before 1066, rejoining Benson manor on Harold's accession as king. William I gave it to Battle abbey (Sussex), (fn. 265) which retained it until the abbey's dissolution in 1538. (fn. 266) In 1279 the estate included a 240-a. demesne and 9½ tenanted yardlands, perhaps 520 a. in all, and had its own manor court. (fn. 267)

In 1540 the Crown sold the manor to Sir Thomas Pope, who returned it in exchange five years later. (fn. 268) In 1590 it was sold via agents to William Spencer (d. 1609) of Yarnton, (fn. 269) whose heirs sold it in 1617 to Thomas Freeman, lessee of the manor house and farm. Freeman sold it in 1619 to John Blackmail of Abingdon, and it descended with Fifield until 1664 when Sir Ralph Verney sold it to a Clerkenwell brewer, Henry Knight or Brothers. (fn. 270) In 1696 it was bought by Thomas Cowslad of Newbury, whose son William sold it in 1742 (as a manor) to the Southwark brewer Ralph Thrale (d. 1758) with five houses, a dovecot, and 490 acres. (fn. 271) Ownership passed thereafter to Ralphs son Henry (d. 1781) and granddaughter Hester Maria (d. 1857), later Viscountess Keith, followed by her nephew Bertie Mostyn (d. 1876) and daughter Georgina Augusta Osborne Elphinstone (d. 1892). (fn. 272) Under Augustas will the estate was offered for sale in 1893 as a 433-a. farm, (fn. 273) but passed instead to her relative the dowager marchioness of Lansdowne (d. 1895), succeeded by the 5th marquis. He sold it in 1909–10 to the farmer F.P Chamberlain (the tenant since 1894), (fn. 274) whose family still farmed there in 2015. Earlier owners were non-resident, and from the 16th to 19th centuries the manor house, demesne, and later the whole estate were leased to prominent local farmers including the Freemans, Stampes, Symeses, Lovegroves, and (from c.1796) the Newtons. (fn. 275) Manor courts in the 1590s–1610s were held in the Stampes' or Freemans' names. (fn. 276)

A smaller estate focused on Lower Farm (fn. 277) may have originated with Thomas Freeman's sale of 62 a. to Anthony Phelp (alias Janes) of Preston Crowmarsh in 1617. (fn. 278) The Phelps remained at Lower Farm in 1724, (fn. 279) but by the 1780s the estate was owned with Fifield and let to Philip Padbury, until sold to the Newtons c.1799. (fn. 280) They ran it with Crowmarsh Battle farm, and in the early 20th century the land passed to the Chamberlains. (fn. 281)

Manor House (Crowmarsh Battle Farm)

A manorial complex on the site of Crowmarsh Battle Farm may have existed by 1086, and in the 14th century included a hall, great chamber, chapel, bakery, and numerous farm buildings including stables, an oxhouse, and a pigsty. A tile-coped wall with a south gate enclosed the curtilage. (fn. 282) The premises accommodated abbey officers or bailiffs until 1362, when the buildings were presumably let with the demesne. (fn. 283)

The existing two-storeyed farmhouse, rendered save for a clunch-and-brick west front towards the farmyard, reflects successive remodellings from the 17th to 19th centuries, but contains hints of an earlier house. (fn. 284) The roof includes numerous re-used medieval timbers, some of them smoke-blackened, and the large central brick-built stack may have originally been an insertion into a north-south timber-framed open hall. (fn. 285) Remnants of a possible west-east cross passage towards the house's southern end may also hint at a medieval plan. The brick-and-clunch west front was built probably in the late 17th century, perhaps by the tenant Bartholomew Symes, whose initials (with the date 1684) formerly appeared on the adjacent brick-built dovecot. (fn. 286) Sash windows were inserted a few decades later, and the range extended at the north end. The house's current appearance dates primarily from a remodelling c.1820, presumably for the prominent tenant farmer Thomas Newton (d. 1842): the eastern front was substantially rebuilt with new windows and a projecting wing, a new main staircase was inserted, and (then or earlier) the roofs were reconstructed, combining softwood with the re-used timbers. Piecemeal 19th-century additions on the north include a larder, scullery and dairy mentioned in 1893. (fn. 287)

The farmyard lay south-west of the house by the 1620s, flanked by barns and stables and including a predecessor of the present dovecot. (fn. 288) The farm buildings were rebuilt on a grand courtyard plan c.1790–1820 presumably for Newton, the barns and shelter-sheds predominantly timber-framed, and the stables of brick-and-flint, while a timber granary dated 1800 is raised on staddle-stones. All were converted to commercial use c.1998–9. (fn. 289)

TURNER'S COURT MANOR

An inclosed estate near the Benson–Nuffield boundary existed by 1316, when Robert Breton gave Tornorleslonde and Tornorescrofte to William Marshall, lord of Crowmarsh Gifford. (fn. 290) An associated house called Turners Court existed possibly by the 1330s and certainly by the 1550s, (fn. 291) when the estate was usually called a manor. (fn. 292) Ownership passed to the royal administrator John de Alveton (d. 1361), whose goods at Turners were posthumously seized by the Black Prince. (fn. 293) By 1409 the estate belonged to Thomas Chaucer, (fn. 294) and though formerly held of Benson (fn. 295) it became associated until the 17th century with Chaucer's neighbouring manor of Ewelme, passing in 1501 to the Crown, and from 1525–34 to Charles Brandon, duke of Suffolk. (fn. 296) By then it was regularly let to resident yeomen on 21- or 31-year leases at £5 3s. 11d. rent, 16th-century tenants including Richard Dewbury (by 1515), (fn. 297) John Collins (d. 1559), (fn. 298) Stephen Smith (d. 1606), (fn. 299) and Stephen's son Richard. In 1609 it comprised 300 a. of mostly inclosed land in Benson, Nuffield, and Newnham Murren, occupied with the house and farm buildings. (fn. 300)

In 1628 the Crown sold Turner's with Benson manor to representatives of the City of London, (fn. 301) who sold it to John Wise of Nuffield. Richard Wise (owner of Fifield manor) sold it in 1712 to Richard Jennings (d. 1718) of Badgemore near Henley, whose brother William (d. 1732) left it to his sister Margaret Sharpe. Following family disputes she and her son sold it in 1736 to the London brewer William Hucks (d. 1740), who had interests in Wallingford and Ewelme; (fn. 302) the Huckses retained it until 1814 when Robert Hucks (declared a lunatic in 1792) was succeeded by his niece Ann Noyes (d. 1841), who left her Oxfordshire properties to her cousin G.H. Gibbs (d. 1842). (fn. 303) None of the post-1628 owners resided, and both house and land were let to resident farmers including the Hardings, Harfords or Harwards, and Greenwoods. (fn. 304) By 1841 the estate covered c.444 a. in Benson (55 a.), Nuffield (67½ a.), and Newnham Murren, held with 67 a. of additional woodland. (fn. 305)

In 1878 Gibbs's son sold the estate to the resident farmer W.H. Deane, who in 1897 sold it to the farmer William Purves (d. 1906). In 1911 it was bought by the Christian Service Union, which opened the Wallingford Farm Training Colony there the following year. By 1941 the farm covered 850 a., but piecemeal sales followed and in 1993, after the School's closure, the remaining land and buildings were sold. (fn. 306)

Turner's Court itself was in 1628 a Tow old timber building' of four bays, tiled, with an orchard, garden, barns, stables, and malfhouse. (fn. 307) In 1662 it had five hearths, (fn. 308) and in 1706 included a hall, parlour, kitchen, best and maid's chambers, cellars, and outbuildings. (fn. 309) Extensive Farm School buildings were erected to the east and south from 1912 (Fig. 15), but were mostly replaced by upmarket housing in the 1990s. (fn. 310) The much-altered former farmhouse (brick and render with some oak beams and an inglenook fireplace) (fn. 311) was demolished.

MONASTIC AND COLLEGE ESTATES

Several religious houses acquired land in Benson manor during the Middle Ages, though only a few minor holdings (Fifield and the rectory excepted) lay within the parish. (fn. 312) Dorchester abbey held 12 a. there as lessee in 1279, (fn. 313) and a grant to it in 1324 may have included property at Benson or Roke, where the abbey owned 8s. 6d. rents in 1535. (fn. 314) Osney abbey received a 245. prebend in Benson manor from King Stephen c.1140, but exchanged it soon after for land at Warborough and Holcombe (in Newington parish). (fn. 315) Small parcels held by Littlemore priory and Godstow abbey in 1279 were most likely in Brightwell Baldwin and Shillingford, (fn. 316) while weirs or fisheries held by Wallingford priory, the bishop of Lincoln, and Canterbury cathedral priory lay all or partly in the Shillingford–Dorchester stretch of the Thames or in Newington. (fn. 317)

Magdalen College, Oxford, acquired premises in Roke in 1485–9 as part of Chalgrove manor, (fn. 318) and subsequently expanded its holdings. In 1569–70 it acquired an apparently substantial estate from John Marmion of Ewelme, who had inherited from his wife Cecily Slythurst: a 16th-century fine estimated it at over 400 a. including six houses, two tofts, and two dovecots, although the acreages were probably inflated, and not all necessarily lay in Benson. (fn. 319) By the 18th century the holding was focused on College Farm north of High Street, and totalled c.70 a.; (fn. 320) another 34 a. was separately leased, (fn. 321) and in 1833 the colleges combined Benson and Berrick Salome estate covered 312 a. (109 a. in Benson, 193 a. in Berrick, and 10 a. in Ewelme or Warborough). (fn. 322) Another 231 a. was added from the Fifield estate in 1900–1, (fn. 323) but the colleges Benson holdings (including College Farm) were mostly sold to the tenant in 1920–2, and Roke farm (192 a.) in 1986. (fn. 324)

Exeter College, Oxford, acquired a freehold at Benson in 1486 from Robert Bray of Henley, built up piecemeal by the Brays and their ancestors the Meriets. (fn. 325) In 1606 (when it owed quitrent to Benson and Ewelme manors) the estate was reckoned at 63 a., and was focused (as later) on a farmstead on the site of Brookside, at Brook Streets eastern end. (fn. 326) The farm was leased throughout, and sold in 1878. (fn. 327)

RECTORY ESTATE

Between 1140 and 1142 Empress Matilda granted Benson church (with its tithes and a yardland of glebe) to Dorchester abbey, which informally appropriated the revenues. (fn. 328) In 1542 (following the abbeys dissolution) the Crown granted the rectory estate to Oxford cathedral, and in 1546 to its successor, Christ Church College, (fn. 329) which leased it to local gentry and farmers including, for much of the 18th century, the Wises of Fifield, and in the 19th century the Newtons. (fn. 330) The rectorial glebe then comprised only 17½ a., although the great tithes were valued in 1771 at over £630 a year gross. (fn. 331) A 'barn and other houses' mentioned in 1544 (fn. 332) stood probably on the north side of Castle Square, where the estate retained a farmyard, barn, and stabling in the 19th century. (fn. 333)

In 1841–2 Christ Church was awarded an annual rent charge of £1,046 in lieu of great tithes, and at inclosure in 1863 it received allotments totalling c.19 acres, (fn. 334) sold in 1919. (fn. 335) Tithe rents totalling £102 were conveyed to the vicar in 1927. (fn. 336)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Benson remained predominantly agricultural until recent times, though by the 13th century, like some other large vale villages, it also had a relatively wide range of trades and crafts. During the 18th century coaching briefly expanded its non-agricultural trades, although in 1841 nearly half the population (including 155 agricultural labourers) were still directly involved in farming. Lesser activities included small-scale mineral extraction and (briefly) brickmaking and lime-burning. (fn. 337) The village retained a broad range of shops and services in the early 21st century, though by the 1960s most inhabitants worked elsewhere.

THE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE (FIG. 4)

Open Fields

Until inclosure in 1863 Benson's landscape was dominated by the vast open fields shared by Benson, Ewelme, and Berrick Salome, which in 1788 covered c.1,950 a. from Berricks northern boundary down to Goulds Heath. (fn. 338) The fields' medieval extent was greater, including much of the 500-a. manor of Crowmarsh Battle (inclosed in the 17th century) south of the London road. (fn. 339) Probably the fields were created during the early-to-mid 11th century: before Ewelme and Berrick Salomes separation from Benson, but after Berrick Priors detachment c.1017–35, since Berrick Prior had no stake in them. (fn. 340) By 1300 they had apparently reached their full extent. (fn. 341) Warborough's fields were separate by the 12th century, although the concentration there of Benson's medieval demesne points to their earlier intermingling as part of the large Benson estate. (fn. 342)

Some medieval land grants mentioned Berricks west field and Benson's west, east, and south fields, (fn. 343) but by the 15th century the fields were heavily subdivided, (fn. 344) and in the 18th comprised 16 fields of greatly varying size (c.20 a. to 243 a.). Most contained land belonging to all three parishes, although Berricks strips showed some limited concentration in the northern fields, and Ewelme's in the north-east and south-east (Table 3 and Plate 7), perhaps reflecting a planned allocation at an early date. (fn. 345) In addition Ewelme had its own independently organized 'home fields. (fn. 346) In the 18th century a third of the land was theoretically divided between wheat and barley, a third planted with beans, and a third left fallow, although actual rotations were more varied. (fn. 347) Earlier arrangements are unrecorded, but as farmers held land in widely differing combinations of fields (fn. 348) rotation must always have been complex. A few field and furlong names reflected the arable's varying quality, as with Stoney and Clay fields (between Ewelme and the London road), or the smaller Foul Slough and Moorlands fields (both bordering areas of common). (fn. 349) In 1839 the soils were described as a Tight and fertile loam resting on gravel or clay'. (fn. 350)

Preston Crowmarsh's medieval fields may have been separately organized, since they were apparently inclosed independently of the larger field system. (fn. 351) Middle field, Stoneland, and South field were mentioned in 1391–2, (fn. 352) and a map of 1638 suggests that the fields had formerly covered much of the estate's central area. (fn. 353)

Common Pastures and Meadows

Source: Ch. Ch. Arch., T.viii.b.71.

Commons totalling 220 a. were also shared, though custom limited grazing in some to particular settlements. The largest (100 a. combined) lay between Roke and Berrick Salome, divided into Benson, Egmoor, Berrick, and Rowe or Rokemarsh commons. Inhabitants of Benson, Fifield, Roke, Berrick Salome, and Ewelme claimed rights there, while nearby Sterte common (32 a.) was open to Benson and Fifield inhabitants and to some from Roke and Ewelme. Goulds Heath and Harcourt Hill in the south-east (87 a. in all) were reserved for Benson, Fifield, and some Ewelme tenants. (fn. 354) Most farms carried specified rights in particular commons, (fn. 355) and in the 1790s tenants of Fifield farm and Magdalen Colleges Benson farm were each obliged to provide a bull and a boar to service the herd. (fn. 356) Additional grazing was available in Lammas grounds particularly at Berrick, (fn. 357) and all three parishes shared grazing in the arable or 'intercommoning' fields after harvest. (fn. 358) Preston Crowmarsh's medieval tenants had pasture rights in Heycroft and in the marsh near Crowmarsh Battle farm, and could fold sheep in the manors sheep pasture. (fn. 359)