A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Ewelme Hundred: An Overview', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp1-20 [accessed 19 April 2025].

'Ewelme Hundred: An Overview', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online, accessed April 19, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp1-20.

"Ewelme Hundred: An Overview". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 18. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2016), British History Online. Web. 19 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol18/pp1-20.

In this section

EWELME HUNDRED: AN OVERVIEW

The fourteen rural parishes covered in this volume occupy a varied landscape in south-east Oxfordshire, (fn. 1) straddling both the clay vale beneath the Chiltern scarp, with its nucleated villages and (historically) large open fields, and the contrasting Chiltern uplands with their dispersed settlement, early inclosure, and extensive wood-pasture. Despite those contrasts close ties across the area have been a recurrent theme, reinforced by long-established routeways, economic interdependence, and (in the early Middle Ages) by the unifying influence of a large royal estate focused on Benson, which extended across the Chilterns. The estates fragmentation between the 9th and 13th centuries created the modern parish structure, while the area's inclusion within a single administrative hundred (known initially as Benson hundred) reflects Benson's early importance. The name Ewelme hundred became established from the 13th century. (fn. 2)

The nearest towns lay outside the area included here, at Dorchester, Wallingford, (fn. 3) Watlington, and Thame, with both Oxford and Henley (and more distantly London) exerting important influences. Benson (and to a lesser extent Nettlebed) emerged as coaching stops in the 17th–18th centuries, but otherwise the parishes remained predominantly agricultural until the 20th century, save for the usual rural trades and crafts, and a significant pottery and brickmaking industry around Nettlebed. The chief modern development has been the growth of a military airfield at Benson, established just before the Second World War and subsequently expanded into one of Oxfordshire's two main RAF stations. A wartime airfield at Chalgrove survives as a self-contained industrial site.

The uplands in particular have long been noted for their scenic charm, (fn. 4) protected since 1964 by inclusion in the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. (fn. 5) The attractiveness of the landscape is complemented by a variety of buildings in timber, brick, chalk clunch, and flint, of which the 15th-century brick-built almshouse complex at Ewelme, co-founded by Chaucer's granddaughter Alice de la Pole, is particularly notable. Sizeable post-medieval mansion houses (some now demolished) were built at Rycote, Newington, Britwell Prior, Great and Little Haseley, Swyncombe, and Brightwell Baldwin, while a more recent addition is Nuffield Place, remodelled in 1933 for the pioneering Oxford car manufacturer William Morris (Lord Nuffield), and transferred to the National Trust in 2011.

LANDSCAPE

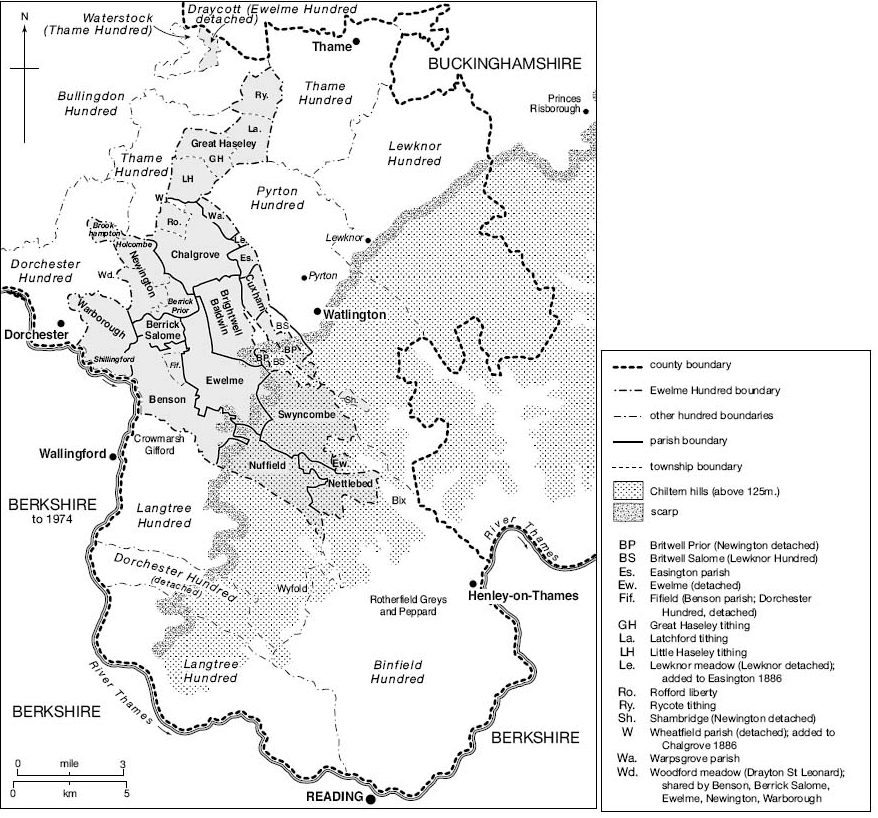

The Chiltern Hills cut across Ewelme hundred in a south-westerly direction, dividing it into two contrasting zones (Figs 1 and 2). On the west, parishes from Warborough to Great Haseley lie below the Chiltern scarp, occupying an open, flat, and (further north) gently undulating landscape of few sharp contrasts, watered by the Rivers Thames and Thame or their tributaries. Benson and Ewelme parishes straddle the two zones, their eastern parts extending into the Chiltern foothills, while Swyncombe, Nuffield, and Nettlebed lie entirely in the uplands. The latter are characterized by a typical Chiltern landscape of deep-etched dry valleys and of dispersed and often secluded settlement, set amidst woodland, wood-pasture, and irregular hedged closes. Such contrasts echo the geology, the lowland parishes resting mostly on gravel, clay, alluvium, or greensand, and the uplands on chalk, their higher parts capped extensively by clay-with-flints. (fn. 6) On the higher or more undulating ground valley-related place names such as Huntercombe, Swyncombe, Gangsdown, and Holcombe predominate, while at the foot of the scarp a series of stream-related names (including Ewelme, Brightwell, Britwell, and Cadwell) trace out the spring-line. (fn. 7) Water supply on the uplands themselves came chiefly from wells, scattered ponds, and cisterns, leaving meadow generally in short supply. High ground in Nettlebed and Nuffield also attracted windmills, with others on more gently rising ground at Great Haseley and Rycote. In the vale, watermills were predictably more common. (fn. 8)

The apparent lack of intensive Iron-Age or Roman settlement in the three upland parishes suggests that the contrast between the open, more heavily populated vale, and the wooded, more sparsely settled hills is long-established. (fn. 9) Even in the 16th century the term 'Chiltern' still denoted a distinctive upland zone, (fn. 10) which c.1916 was described as 'marked off' from the rest of the county 'with considerable definiteness'. (fn. 11) Nevertheless the two have probably always been closely connected. The Roman road from Dorchester to the Henley river-crossing traversed the hills, (fn. 12) while charter references to a 10th-century fildena wudu weg ('open-country wood-way') suggest Anglo-Saxon transhumance routes linking the upland wood-pastures with the lowland 'fielden' areas. (fn. 13) Equally, the density of wood-cover has never been static. Lowland place names such as Haseley (hazel wood or wood-pasture) suggest more extensive woodland in the vale in the Anglo-Saxon period, (fn. 14) while field names such as grubbings' point to partial woodland clearance for cultivation in the uplands. (fn. 15) Other woods were reorganized as medieval deer parks (established in all three upland parishes), while some new 19th-century plantations in both vale and upland were similarly created as game coverts. (fn. 16)

Ewelme Hundred c.1865, showing boundaries and relief.

Open fields were emerging in the vale by the 10th or 11th centuries, (fn. 17) and survived in many parishes until the 19th, despite some early inclosure at Rycote, Latchford, Rofford, Newington, Easington, and Preston Crowmarsh, and in the Chiltern foothills in Benson and Ewelme parishes. By contrast, open fields in the uplands were generally small, ill-recorded, and fully inclosed by the 13th–15th centuries. Sizeable commons (including greens) were found in both zones, although Swyncombe was unusual amongst upland parishes in retaining large swathes of open chalk downland. Post-medieval landscaping of parkland was mostly confined to lowland country houses at Brightwell Baldwin, Britwell Prior, and Rycote, although large houses in their own grounds developed also on the Chilterns, as at Joyce Grove or Soundess in Nettlebed. (fn. 18)

Former pits or quarries remained widespread in the 19th century, (fn. 19) dug at various times for extraction of chalk, flint, or gravel, of building stone (as at Great Haseley) or clay (for brick- or tile making), and of lime or marl (partly for fertilizer). Others are reflected in medieval names such as Mogpits (in Benson), or the place name Chalgrove (possibly 'chalk- or lime-pit'), while chalk-pit way (cealc seapes weg) was mentioned in 996. (fn. 20) Commercial gravel workings (now used for waste processing) remain south-east of Ewelme. (fn. 21)

COMMUNICATIONS

Roads

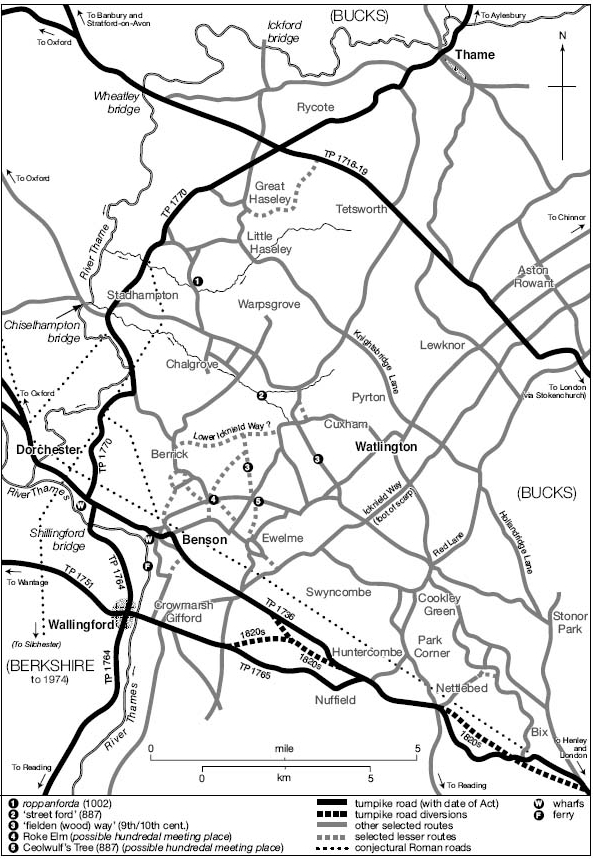

Several major roads cross the area from north-west to south-east, traversing the Chilterns and linking vale and upland (Fig. 3). (fn. 22) Most important are the Oxford-Henley road (part of a route from the West Country to London), which formerly passed through Dorchester and Benson villages, and the more northerly Oxford-London road through Tetsworth, which crosses Haseley parish and is now partly followed by the M40 motorway. The Dorchester-Henley route is of Roman or earlier origin, and both roads remained important from the Anglo-Saxon period onwards. (fn. 23) A roughly parallel route runs from Oxford through Stadhampton, Cuxham, and Watlington, intersecting the ancient Knightsbridge and Hollandridge Lanes. Those last two formed part of an Anglo-Saxon route from Assendon (near Henley) through Pyrton to Oxford, running possibly along the 'broad army path' crossing Little Haseley's northern boundary in 1002, and perhaps continuing to Worcestershire. (fn. 24)

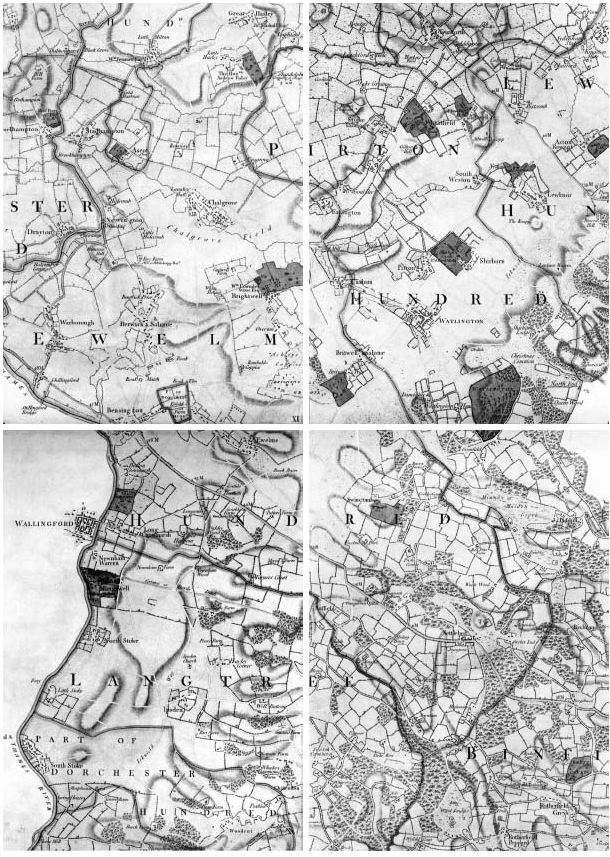

Landscape and settlement in 1797, showing a clear contrast between the Chiltern uplands (bottom right), and the villages and open fields below the Chiltern scarp. The London road through Benson and Nettlebed cuts across the map.

Communications in Ewelme Hundred c.1800, showing major roads and turnpikes and some earlier features.

Major north-south routes include the Thame-Wallingford road through Newington and Warborough, crossing the Thames at Shillingford. Some sections may roughly follow the Roman road from Fleet Marston (Bucks.) to Dorchester and Silchester, the Roman river crossing shifting to its present more easterly position probably when Wallingford's 9th-century burh was established. A medieval bridge at Shillingford was superseded by a ferry from the 15th century and by new bridges in 1764 and 1826–7, the alternative approach to Wallingford being through Crowmarsh Gifford and over Wallingford's medieval bridge. (fn. 25) Roads through Chalgrove, Brightwell Baldwin, and Watlington ran parallel to the ancient Icknield Way, which in the Middle Ages remained an important long-distance route along the foot of the Chiltern scarp, and formed occasional stretches of parish boundary. (fn. 26) Further east, Red Lane and its continuation through Cookley Green and Nuffield may have formed part of a prehistoric or Anglo-Saxon ridgeway, (fn. 27) while the Watlington-Nettlebed road formed part of a through route to Reading by the 13th century. (fn. 28) The Lower Icknield Way, a Romanized prehistoric route on lower ground, ran probably through Cuxham, Brightwell Baldwin, and Hollandtide Bottom (north of Berrick Salome), (fn. 29) a 'street ford' identified on Chalgrove brook (a little way to the north) suggesting either a branch or an intersecting north-south route. Medieval field names suggest a further Roman road running north-south through Newington and Ewelme parishes, some stretches of which remain in use. (fn. 30)

A dense network of lesser routes linked the hundreds villages and scattered upland settlements from the early Middle Ages, allowing villages such as Cuxham and Great Haseley to transport grain across the hills to Henley, and thence by river to London. (fn. 31) Routes mentioned in Anglo-Saxon charters include the present-day Rumbold's and Turners Green Lanes (bordering Brightwell Baldwin and Cuxham), while the ford from which Rofford is named was mentioned in 1002. (fn. 32) Routes converging on the possible hundredal meeting place at Roke Elm or Ceolwulf's tree were presumably also ancient. (fn. 33)

Eighteenth-century improvements saw turnpiking of the northerly London road in 1719, the Oxford-Henley road in 1736, the Thame-Wallingford road in 1764–70, and the Nuffield-Wallingford road in 1765, with an improved link from that to the Henley road laid out c.1819–27. (fn. 34) The improvements facilitated but did not initiate the large-scale development of coaching, which on the Dorchester-Henley road was established by the 1660s, and from which Nettlebed and particularly Benson benefited considerably until coachings demise in the 1840s. Nettlebed also became a significant early postal centre. (fn. 35) Nineteenth-century inclosures affected numerous lesser routes but largely preserved the major roads, until development of Benson and Chalgrove airfields during the Second World War severed the Dorchester-Henley road and roads north of Chalgrove village. Both were ultimately replaced by bypasses, substantially altering the Henley route past Benson. The M40 motorway was built in the 1970s, crossing Haseley parish between Great Haseley and Rycote. (fn. 36)

River and Rail

The Thames was an important transport corridor throughout the early Middle Ages, and Benson's possession of salt rights may reflect involvement in a well documented river trade stretching from Radcot to London. (fn. 37) From the late 13th century vale villages such as Cuxham habitually sent their grain across the Chilterns by road, however, avoiding the rivers long southerly loop, and by the later Middle Ages large-scale commercial navigation as far as Wallingford and Benson had largely ceased, as demand upstream fell and the river became increasingly obstructed. (fn. 38) Following the rivers reopening to Oxford and beyond from the 1630s wharfs were constructed at Shillingford and Benson, remaining in use until the early 20th century for grain, timber, malt, and coal. (fn. 39) Shillingford wharf included a malthouse in 1848, and timber from Great Haseley was possibly shipped via Shillingford in 1823. (fn. 40) Overland trade with Henley continued in the 18th century, however, (fn. 41) and by the mid 19th century the wharfs' chief use was apparently import of coal.

Early railways largely bypassed the area, and though a branch to Wallingford was opened in 1866 and a separate branch to Watlington (from Princes Risborough) in 1872, schemes to join the two via Benson never reached fruition. Both lines were used for export of livestock and agricultural produce (including milk), and for import of raw materials, (fn. 42) while some Nettlebed farmers probably used Henley station (opened 1857). (fn. 43) Nevertheless some Chiltern farms remained handicapped by the relative inaccessibility of local markets in the early 20th century. (fn. 44) Passenger services through Wallingford and Watlington ended in the late 1950s, and the stations closed in 1965 and 1961 respectively. (fn. 45) Abortive plans included schemes for a Ewelme-Watlington railway (1881) and a Didcot-Watlington light railway (1898), crossing Benson and several nearby parishes and with a link to Wallingford. (fn. 46)

SETTLEMENT

Prehistoric to Roman Settlement

Prehistoric activity across the area is well attested, with a particular focus on the important (and now largely destroyed) Neolithic and Bronze-Age monument complexes around Dorchester, close to the Thames-Thame confluence. Mesolithic and Neolithic tools have also been found in the upland parishes, with Mesolithic flintworking sites in Nettlebed probably seasonally occupied by hunter-gatherers. Later settlement was chiefly on the lower ground and river gravels, with Bronze-Age and Iron-Age sites identified in Warborough, Berrick Salome, Chalgrove, and Haseley parishes, alongside isolated finds elsewhere. The late Iron Age saw development of a large enclosed oppidum at Dyke Hills near Dorchester, probably providing a regional focus, while the South Oxfordshire Grims Ditch, a probable late Iron-Age tribal boundary running eastwards from the Thames, extends into Nuffield and Nettlebed. A dyke along the northern edge of Swyncombe Downs is undated. (fn. 47)

In the Roman period Dorchester became a walled town, (fn. 48) and Roman rural settlement in the vale parishes was apparently widespread, focused on low-status farmsteads. No villas are known, despite two possible candidates noted in Warborough. (fn. 49) Third-century coin hoards found in Ewelme and Swyncombe parishes (fn. 50) probably reflect traffic along the road from Dorchester across the Chilterns, while a possible votive figurine found at Ewelme has prompted suggestions of a small shrine associated with nearby springs. (fn. 51)

Anglo-Saxon Settlement and Territorial Organization

Burials near Dorchester (recently re-dated) suggest that Anglo-Saxon cultural practices were supplanting sub-Roman ones in the area by the AD 450s, (fn. 52) notwithstanding suggestions that a British enclave on parts of the Chiltern uplands may have continued into the 6th century. (fn. 53) Within Ewelme hundred, 5th- or 6th-century Anglo-Saxon settlement is known at Benson, Rycote, and possibly Warborough, (fn. 54) while a poorly recorded cemetery on the Ewelme/Brightwell Baldwin boundary has yielded Anglo-Saxon grave goods of similar date. (fn. 55) Some of the area's numerous stream- and valley- or hill-related place names probably also reflect relatively early colonization, at least in the lowlands. (fn. 56)

By the late 6th century most of the area was subject to the Gewisse, a dominant tribal grouping from which later West Saxon kings claimed descent. Probably their local power base was near the former Roman town of Dorchester, where King Cynegils of the Gewisse was baptized c.635, and which he gave to St Birinus as an episcopal seat, establishing it as the areas dominant ecclesiastical focus. Whether nearby Benson was already a royal centre (chosen presumably for its proximity to Dorchester) is unclear: Cynegils (accompanied by his overlord King Oswald of Northumbria) must have been lodged in the vicinity, but no high-status residential site at Benson has yet been discovered, (fn. 57) and the earliest written evidence is of uncertain reliability. By the late 8th century, however, when King Offa of Mercia reportedly seized it from Wessex, Benson was emerging as a valuable and strategically important royal possession, with both an extensive dependent territory and (possibly) an outlying royal residence at Kingsbury, in Newington parish. (fn. 58) From the 9th century its territory was reduced by piecemeal grants, but at the Conquest it still stretched across the Chilterns to Henley, and it has been plausibly suggested that it may have once comprised much of the 4½ Chiltern hundreds (Ewelme, Pyrton, Lewknor, Binfield, and Langtree) whose 'soke' (or jurisdiction) remained attached to Benson manor beyond the Middle Ages. (fn. 59) If so, this vast royal territory of some 500 hides was presumably linked to Benson through renders of corn and livestock, the vestiges of which may be visible in the £30 'corn rent' (annona) still payable to Benson manor in 1086. (fn. 60)

Mid- and late Anglo-Saxon settlement took shape within the emerging royal estate. Berrick (just north of Benson) began as an outlying farm or berewic, while 8th- and 9th-century coin and metal finds between Benson and Ewelme (close to the earlier cemetery) point to trading or other activity probably associated with Benson as an estate centre, or with a nearby hundredal meeting place. (fn. 61) Warborough ('watch hill') may be named from a look-out post overseeing Benson, while the names Haseley and Warpsgrove (further north) imply areas of specialized woodland. (fn. 62) The scale of early upland settlement is unclear: place names (probably early) suggest a relatively uncultivated landscape of rough wood pasture, (fn. 63) which was probably initially exploited by lowland settlements needing upland resources. Certainly both Nettlebed and Huntercombe remained attached to Benson relatively late, and several other lowland places retained upland outliers beyond the Middle Ages. (fn. 64) Nevertheless by the mid 11th century there were small independent agricultural communities at Gangsdown (in Nuffield), and probably in Swyncombe and Nettlebed. The Benson estates subsequent fragmentation also affected lowland settlement, with Newington (the new tun) probably reflecting reorganization by Canterbury cathedral priory after it received an extensive estate there in the early 11th century. Late Anglo-Saxon 'hide farms' may have existed at Ewelme and Brightwell Baldwin. (fn. 65)

Benson's centrality was undermined by foundation of the fortified royal burh at Wallingford in (probably) the late 9th century, the area assigned for the burh's fortification and upkeep (through garrisoning and other services) extending almost certainly into Benson's territory. Residual connections continued in 1086, when six Ewelme hundred manors included property in Wallingford, and several others formed part of the emerging honor, a complex of estates extending into several counties, but with a concentration in south-east Oxfordshire. (fn. 66) Why Wallingford was chosen over Benson as a burghal site is not entirely clear, although the reasons were probably strategic. Either way Wallingford's emergence may have contributed to Benson's failure to develop urban characteristics, despite its continuance as an exceptionally valuable royal estate centre into the Norman period. (fn. 67) The creation of Oxfordshire c.1007 involved further re-alignment, bringing Benson and its dependencies within the new shire despite their Wallingford connections, but leaving Wallingford itself in Berkshire. (fn. 68) By 1086 the later hundredal groupings were also firmly established, Benson's jurisdiction over the 4½ Chiltern hundreds reflecting its continued but waning significance. (fn. 69)

Medieval and Later Settlement

Fragmentation of Benson's royal estate continued into the 13th century, (fn. 70) creating the later pattern of manors and parishes and, in many cases, perpetuating lowland-Chiltern links designed to give access to woodland. Newington and Ewelme retained detached upland outliers until 1932, some of Newington's extending beyond Ewelme hundred into Bix and Pishill. (fn. 71) Several parishes similarly shared detached riverside meadow in Drayton St Leonard (in Dorchester hundred). (fn. 72) Fragmentation also caused some pre-existing settlements to become divided between different estates and parishes, (fn. 73) producing some highly complex shared field systems and intercommoning. (fn. 74)

In the vale, nucleated villages set amidst open fields were the norm by the 13th century, some of them showing signs of planning. At Great Haseley tenant housing extends from the lordly nucleus of church and manor house along the village street, part of which was probably widened for a market in 1228, while at Chalgrove (where the present High Street may have been laid out along an open-field headland) separate manor sites created rival nuclei, giving rise to separate 'ends'. (fn. 75) Several other settlements were grouped around greens, along roads and road junctions, or alongside commons, (fn. 76) with some (like Cuxham) showing evidence of social 'zoning', the larger villein plots kept separate from humbler cottage holdings. (fn. 77) Village sizes varied considerably (Table 1), and the larger lowland parishes all contained outlying hamlets, although some small wics or worths mentioned in the 10th century had disappeared by the 13th. (fn. 78) Settlement on the Chilterns was much more dispersed, with the partial exception of Nettlebed where the Dorchester-Henley road provided a possibly early focus. Small upland clusters of houses were generally grouped around greens or commons, while more isolated medieval farms included the aptly named Hayden (later Hidden) Farm in Nuffield. Additional areas of peripheral dispersed settlement existed in the Chiltern foothills in Benson and Ewelme parishes, while two outlying farms in Newington probably began as medieval freeholds. (fn. 79)

Late-medieval population decline led to uneven settlement shrinkage, most strikingly at Warpsgrove which, by 1453, was all but deserted. Fifield and Cadwell (in Benson and Brightwell Baldwin parishes) became essentially single farms by the 16th century, and several villages (including Cuxham) saw long-term abandonment of house plots. Nonetheless some settlements proved more resilient than others, presumably by attracting incomers. Some upland parishes may have seen disproportionate population loss and perhaps some shifts in settlement, although the precise form of settlement shrinkage there is harder to determine. (fn. 80)

Depopulation was exacerbated by late-medieval and 16th-century inclosure, particularly at Rycote and Latchford in Great Haseley parish, while in the 16th-17th centuries the building of mansion houses at Soundess (in Nettlebed) and Swyncombe may have involved clearance of tenant housing. Subsequent inclosure of greens at Newington and Berrick Prior (in the 17th and early 19th century) led to further house losses, although by then rising population was fuelling incipient infill and fringe development across the area. (fn. 81) A handful of outlying farms were established in the vale in the 16th to 18th century, and one or two more followed parliamentary inclosures. (fn. 82)

Modern development has been relatively limited. The largest areas of new housing appeared in Benson, Chalgrove, Warborough, and Shillingford after the Second World War, but most other villages witnessed less extensive infill and fringe expansion, and new housing in the upland parishes largely preserved their dispersed character. The largest landscape changes were the development of Chalgrove and especially Benson airfields, the latter now accompanied by an extensive fenced compound (near Ewelme) for service personnel. Huntercombe golf course was established on Nuffield common in 1901, while Huntercombe Place became a Second World War internment camp and later a young offenders' institution. Despite such developments many settlements remain small and secluded, even in the vale. (fn. 83)

| Table 1 Population 1086–1901 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place | Tenants 1086 (including servi) (fn. 84) | Free and unfree tenants 1279 (fn. 85) | Poll Taxpayers 1377 (fn. 86) | Taxpayers 1524 (fn. 87) | Houses assessed 1662 (fn. 88) | 'Conformists' (probably adult inhabitants) 1676 (fn. 89) | Population 1801 (no. of houses in brackets) (fn. 90) | Population 1851 (no. of houses in brackets) (fn. 90) | Population 1901 (no. of houses in brackets) (fn. 90) |

| Benson | 66 (fn. 91) | 135 (fn. 92) | 206 (fn. 93) | 26 | 53 | 268 (parish) | 811 (193) | 1219 (272) | 965 (281) |

| Preston Crowmarsh | 13 | 25 | 40 | 7 | 7 | with above | with above | with Benson | with above |

| Fifield | 2 (fn. 94) | 19 (fn. 95) | - | - | 11 (fn. 96) | with above | with above | 2(12) | with above |

| Roke | - | unknown | - | - | 6 | with above | with above | with Benson | with above |

| Berrick Salome | 20 | 21 | 59 (fn. 97) | see Brightwell | 16 | 80 | 143 (30) | 152(36) | 103 (27) |

| Brightwell Baldwin | 22 | 80 (fn. 98) | 104 | 30 incl. Berrick Salome | 32 | 207 [sic] | 237 (38) | 294(57) | 187(51) |

| Cadwell | 1 (fn. 99) | 7 | 13 | with above | 1 | with above | with above | with above | with above |

| Chalgrove | 42 | 99 | 185 | 28 | 60 | 260 | 509 (120) | 600(139) | 387 (97) |

| Rofford | 10 | 11 | 13 | with above | 4 | with above | 9 (5) | 16(4) | with above |

| Cuxham | 15 | 23 | 38 | )17 | 19 | 66 | 144 (28) | 172(37) | 130(38) |

| Easington | 7 | 13 | 33 | ) with Cuxham | 4 | 30 | 31 (5) | 18(6) | 26(6) |

| Ewelme | 46 | 83 (fn. 100) | 84 | 17 | 38 | 150 | 490 (89) | 673(161) | 473 (136) |

| Gt Haseley | 33 | 48 | 71 | 27 | 35 | 269 (parish) | 393 (81) | 558(118) | 551 (145) |

| Lt. Haseley | 12 | 24 | 44 | 25 | 20 | with above | 165 (24) | 122 (26) | with above |

| Latchford | with Gt Haseley | 26 | 34 | 5 | 10 | with above | 35 (7) (fn. 101) | 39 (9) (fn. 102) | with above |

| Rycote | 4 | 39 (fn. 103) | 90 (fn. 103) | 7 | 8 | with above | 15 (3) | 31(5) | with above |

| Nettlebed | with Benson | with Benson | with Benson | 39 (fn. 104) | 32 (fn. 105) | 152 | 501 (99) | 754(150) | 544 (144) |

| Newington | 39 (fn. 106) | 15 | 43 | 28 (parish) | 2 | no return | 195 (29) (fn. 107) | 408 (93) (fn. 107) | 264 (81) (fn. 107) |

| Berrick Prior | with above | 21 | 47 (fn. 108) | with above | 18 | no return | with Newington | with Newington | with Newington |

| Britwell Prior | with above | 15 | 4 | 3 | no return | 52 (6) | 46(8) | 60(16) | |

| Brookhampton | with above | 14 | 21 | with above | 5 | no return | with Newington | with Newington | with Newington |

| Holcombe | with Benson | 11 | 31 | with above | 7 (fn. 109) | no return | with Newington | with Newington | with Newington |

| Nuffield | part with Benson | part with Benson? | - | 16 | 52 (parish) | 139 (29) | 251 (47) | 203 (43) | |

| Gangsdown | 7 | 17 | 11 | with Swyncombe | with above? | with above | with above | with above | with above |

| Huntercombe | with Benson | 21 | 20 | with Swyncombe | with above | with above | with above | with above | with above |

| Swyncombe | none listed | 21 | 16 | 26 (Incl. part of Nuffield) | 13 | 90 | 285 (54) | 428 (82) | 342 (84) |

| Warborough | with Benson | 60 | 152 | 21 | 31 | 230 (parish) | 535(121) | 729(161) | 585(161) |

| Shillingford | with Benson | 17 | with above | with above | with above | with above | with above | with above | with above |

| Warpsgrove | 6 | 12 | 12 | - | - | no return | 25(6) | 30(6) | 30(6) |

ECONOMY

Agriculture

From the Middle Ages until the 20th century the areas economy was based primarily on arable-based mixed farming, with sheep important for wool and manuring, and dairying gaining in importance from the 16th century. In general that was true of both vale and uplands, although on the latter the arable was farmed in private closes rather than open fields, and woodland and wood-pasture provided an important additional element, the woods themselves kept mostly in hand for underwood, coppicing, and timber sales. Lack of meadow and open-field grazing seems not to have seriously handicapped upland stock-rearing, which benefited from more extensive grassland than some lowland parishes, while careful husbandry was capable of producing fair upland crop yields at least in the post-medieval period. (fn. 110) Nevertheless poor soils, small scattered populations, and (probably) more difficult access to markets rendered the Chiltern uplands amongst the poorest areas in the county in 1334 (measured by taxable wealth per acre), by contrast with the slightly richer farmlands of the vale. (fn. 111)

Medieval demesne farming in the vale was characterized by intensive arable cultivation, which generally provided the largest profits despite some sizeable sheep flocks. Crops included wheat, barley, oats, and rye. Upland arable farming in the mid 11th century was much less intensive, and despite some subsequent expansion most demesnes there seem to have generated only modest profits in the 13th-14th centuries, an experience perhaps shared by tenants. (fn. 112) Wallingford provided an important early market for both zones, but was superseded from the late 13th century by other markets including Watlington, Thame, and especially Henley, through which produce was exported to London. (fn. 113) Local markets or fairs at Great Haseley, Nuffield, and Swyncombe all ultimately failed, despite some initial modest profits at Swyncombe. (fn. 114) Wood sales (including firewood) raised additional modest sums for lords, some of it sold within the immediate area and some probably shipped to London. (fn. 115) Even so some building and other timber was imported from outside, both from across the Chilterns and from places such as Reading, Woodstock, Abingdon, and Shipston-on-Stour (Warws.). (fn. 116)

Late medieval contraction and population decline prompted the usual responses in both vale and upland: demesnes were leased, larger holdings were accumulated, and in some places pastoral farming was expanded, although the scale and chronology of the changes varied, and arable remained important in the Chilterns as in the vale. Thereafter farming was dominated throughout the 16th and 17th centuries by moderately prosperous yeomen who benefited from expanding markets, selling principally wheat and barley (much of it for malting) through Abingdon, Oxford, Wallingford, Watlington, Reading, Henley, and London, and generally combining their cereal-growing with sheep-rearing and (increasingly) dairying. Woods, comprising a mixture of coppices, underwood, and standards, were still generally kept in hand by landowners: at Nettlebed the Stonors made regular wood sales in the late 17th and 18th century, while beech poles and faggots were sold from Newingtons Shambridge woods in the 1770s, together with some ash, oak (including bark), and elm. (fn. 117) Some upland rents per acre remained relatively low for the region in the 18th century, with soils unable to sustain wheat crops more than every few years. (fn. 118) Nevertheless careful manuring and new fertilizers improved yields, while conversely some lowland parishes, still wedded to open-field agriculture, suffered from over-cultivation and lack of investment. (fn. 119)

Sheep-corn farming focused on larger units continued in the 1850–60s, which saw the hundreds last parliamentary inclosures. (fn. 120) Thereafter the national agricultural depression prompted a partial shift towards dairying, partly using the railway. Even so a belief in the traditional balance of corn, sheep, and cattle remained strong in the early 20th century, when the agriculturally productive area from Benson and Ewelme to Little Haseley was said to illustrate 'the achievements as well as the possibilities of English agriculture'. Results on the uplands were 'better than [Chiltern farmers] think', despite a sharp fall in sheep numbers, with good crop yields around Nettlebed (improved partly by regular chalking), and milk production geared partly to the Reading market. (fn. 121) Railways also facilitated some late 19th-century watercress production, particularly at Ewelme. (fn. 122) The later 20th century saw a general return to arable on increasingly large mechanized farms, although dairying, pig-breeding, poultry-raising, and sheep-farming continued.

Trade, Crafts, and Industry

Though agriculture remained predominant until the 20th century, most larger parishes supported rural crafts and some a wider range of services, alongside Nettlebed's early pottery, tile, and brick industry, some small-scale quarrying, widespread domestic brewing, and (from the 17th century) some malting, combined in the 18th century with Benson's coaching, innkeeping, and coach-building. Medieval crafts and trades were apparently concentrated in larger lowland villages such as Benson, Chalgrove, and the Haseleys, all of them on or near major routes, and containing significant numbers of freeholders. Occupational surnames (besides smith, carpenter, baker, and butcher) included weaver, dyer, tailor, cobbler, ironmonger, skinner, potter, chandler, soaper, and barber, while Cuxham briefly possessed a fulling mill, and the occasional merchant or trader was noted in Benson, Ewelme, Warborough, and Shillingford (by the Thames river crossing). Smaller hamlets and upland parishes had very few non-agricultural occupations, save for Nettlebed where widespread brewing presumably served traffic along the Oxford-Henley road. The Nettlebed tile and brick industry (substantially confined to the parish) was established by the mid 14th century, while other upland surnames suggest charcoal burning. (fn. 123)

The range of trades expanded during the 17th and 18th centuries, (fn. 124) with grocers and other retailers appearing in Nettlebed and some larger vale villages, particularly but not exclusively on turnpike routes. In Benson (as in Nettlebed) the expansion was partly related to the development of coaching, which saw some Benson innkeepers setting up as coach-masters, and some harness-makers or wheelwrights expanding into coach building. Malt was mentioned from the 17th century, although large-scale commercial malthouses were apparently confined to places within close reach of the Benson and Shillingford wharfs. Shillingford had a brewery in the 19th century, and innkeepers elsewhere mostly brewed their own beer until external breweries moved in from around the 1880s. (fn. 125) The wharfs also attracted coal dealers. Wood-related workers in the uplands in the 19th century included sawyers and (in Swyncombe) a few female chair-makers, while Nettlebed's brick- and pottery-making industry expanded considerably in the 19th century, accompanied by sporadic small-scale brickmaking in several other parishes between the 18th and 20th centuries. The Nettlebed site closed in 1938, presumably through outside competition.

Most larger villages retained a range of shops and services until the Second World War, but as car ownership increased many closed and traditional crafts declined, leaving Benson as the main service centre. Small industrial estates were established at Great Haseley and Chalgrove, whose former airfield accommodated the Martin-Baker Aircraft Co. from 1946, while gravel extraction continued in several parishes. From mid-century commuting gradually became predominant, new incomers working in Oxford, Wallingford, Reading, London, or the atomic research laboratories at Harwell and Culham. (fn. 126) The uplands acquired no new industry, although Huntercombe retained its golf course, prison, and a nursing home.

SOCIETY

Medieval to 1600

Despite Benson's decline as a royal centre, the Crown exerted a strong local influence throughout the medieval period. Benson and its outliers remained royal property until 1627–8, while from 1501 Ewelme became the site of an occasional royal residence and (in 1540) the centre of a new royal honor, briefly succeeding Wallingford castle as the region's favoured royal retreat. Crown estates were used to reward royal officers, kinsmen, and favourites from before the Norman Conquest until the later Middle Ages: several recipients were important magnates in their own right, although many held for only short periods, and probably had limited local impact. Benson itself was frequented by lesser royal officials into the 14th or 15th centuries, some of them associated with administration of the honor of Wallingford, while Ewelme's elevation attracted high-status courtiers and royal servants throughout the 16th century (fn. 127)

Amongst resident medieval lords, a substantial number were involved in county administration and royal service, forming an intricate social network interconnected by marriage. Some were lesser knightly families focused (like the Rycotes of Rycote) on a single manor, and supplementing their income through lucrative offices. Others included upcoming landowners such as John James (d. 1396) of Wallingford, who cultivated links with the Black Princes circle, and served repeatedly as MP. On a different level were the Chaucers and de la Poles of Ewelme or, in the 16th century, Sir John Williams at Rycote, all of them national players forging a power-base in the Thames valley, within easy reach of Woodstock, Oxford, Windsor, and London. Many (though not all) such lords maintained local residences, and some (like Thomas Chaucer and Williams) created parks. Several other manors were owned by ecclesiastical or other institutions, some (like Dorchester and Osney abbeys or Merton College, Oxford) fairly local, others (Canterbury cathedral priory, St Georges Chapel, Windsor, and Bec abbey) more distant, although still exercising authority through local officers. A few ecclesiastical lords were succeeded by laymen at the Reformation, and others by Oxford colleges, while Magdalen and Lincoln Colleges acquired substantial estates through purchase. (fn. 128)

The bulk of the medieval population in both vale and Chilterns comprised a mix of free and unfree tenants, most of the latter holding a yardland or less during the 13th century. Benson, as ancient royal demesne, had (for Oxfordshire) an exceptional concentration of free sokemen, who enjoyed legal privileges but occupied very varied holdings. Elsewhere the proportion of freeholds varied considerably, with significant numbers recorded (alongside villein holdings) in Chalgrove, Ewelme, Latchford (in Great Haseley), and Holcombe (in Newington). (fn. 129) Some had apparently been created since 1086, while a few at Swyncombe may reflect medieval assarting. Nevertheless villeinage was as widespread in the Chilterns as in the vale, albeit within a more dispersed settlement pattern which must (like varying village sizes) have profoundly affected inhabitants' daily experience. (fn. 130) Judging from surnames some of the larger lowland villages included a few incomers from surrounding (and occasionally more distant) counties by the 13th-14th centuries, although migration between vale and upland seems (with the possible exception of Nettlebed) to have been limited. (fn. 131) Local and longer distance mobility increased in the later Middle Ages, with some 16th-century migrants coming from Wales. (fn. 132) The later medieval period also saw the emergence of larger tenants and freeholders in both zones, although even in the 13th century many parishes had complex tenurial structures involving much subletting.

Competition over agricultural resources (especially grazing) emerges from local court rolls, and perhaps lay behind some of the occasional raids on lords' property by local gangs. (fn. 133) Social tensions were heightened in some parishes by late medieval and 16th-century inclosure, the targeting of Sir John Williams during the failed Oxfordshire uprising of 1549 almost certainly reflecting, at least in part, his recent imparkment of Rycote. (fn. 134) On a smaller scale, a resident landholder's attempts to inclose parts of Nettlebed common in the late 16th century led to fence-breaking and impounding of sheep. (fn. 135)

Society since 1600

By the 17th and 18th centuries most parishes were dominated by moderately prosperous yeoman farmers, who as elsewhere enjoyed increasing levels of domestic comfort, and often monopolized parish offices. In addition some important country seats were occupied at least sporadically by resident lords or gentleman lessees, amongst them the short-lived Ewelme Park in Swyncombe (built before 1649 for the earl of Berkshire), or Rycote House (home in the 18th century to the earls of Abingdon). Some such places developed a largely 'closed' character, notably Rycote with its inclosed park and depleted population, or Brightwell Baldwin, which under the Carletons and Lowndes Stones was increasingly dominated by the newly created Brightwell estate. By contrast such places as Benson, Warborough, Chalgrove, and Great Haseley emerged as vibrant 'open villages with strong outside links, a high degree of independence, and (at least by the 19th century) marked religious Nonconformity. Benson's role as a coaching stop introduced a further element, prompting some fashionable remodelling and attracting a few prosperous incomers. Most upland parishes displayed similar independence, particularly Nettlebed with its crafts and brick industry and roadside inns.

Beneath the gentry and better-off farmers was a much larger and poorer population of smallholders, labourers, and servants, supplemented by less visible numbers of travellers, itinerant traders, and gypsies. Charitable bequests, unevenly spread across the parishes, met only a tiny fraction of poor-relief costs by the later 18th century, and amounts raised by parish rates (as measured by expenditure per head of population) were high compared with many parts of Oxfordshire. (fn. 136) Even so expenditure varied considerably between places, not always reflecting obvious distinctions between closed and open parishes or between upland and lowland (Table 2).

Farming in most lowland parishes continued until the 19th century within a highly traditional open-field framework, reliant on custom and cooperation. Conflict with modernizing farmers promoting inclosure was especially marked around Benson, the strongest opposition coming from fellow farmers and landowners, while in 1830 the area was also caught up in Swing Riots and machine-breaking. (fn. 137) Inclosure cemented the larger farmers' dominance and turned the bulk of the population into landless agricultural labourers, until large-scale decline in agricultural employment after the First World War. At the same time the areas social life, long focused on village pubs and traditional parish festivities, became more varied, encompassing clubs, Friendly Societies, and organized sports which were often supported by local clergy or gentry, not least in the uplands, where pubs and commons provided social foci. In several vale and Chiltern parishes resident gentry exercised an old-fashioned paternalistic role well into the 20th century, amongst them incomers like the Scottish financier Robert Fleming (d. 1933) at Nettlebed. (fn. 138)

Gentrification began in some parishes in the late 19th century, gaining momentum from the 1920s–30s as weekenders (including some from London) sought cottages for renovation, and accelerating from the 1970s thanks to new motorway links. Nonetheless the area remained socially mixed, with many places acquiring council housing in the 1940s–60s. (fn. 139) In 2011 c.19 per cent of inhabitants worked in higher managerial or professional jobs, slightly above the regional average; nonetheless some parishes retained over ten per cent social housing, and employment in agriculture or forestry still averaged some four per cent. Non-white ethnic minorities remained minimal. (fn. 140)

RELIGIOUS LIFE

From the 7th century the dominant religious focus in the area was Dorchester, successively the site of an episcopal seat, a collegiate minster, and an Augustinian abbey. (fn. 141) A separate minster at Pyrton, owned by the bishopric of Worcester, had jurisdiction over Easington and (probably) Brightwell Baldwin and Cuxham by the 880s, (fn. 142) and though hard evidence is lacking, a church at Benson seems to have similarly assumed responsibility for Benson's royal estate, its jurisdiction extending eastwards across the Chilterns. Vestiges of such an arrangement continued in the 13th century when Warborough, Nettlebed, and Henley were claimed as chapelries, although Benson church itself was given to Dorchester abbey in the 1140s and its status downgraded to that of chapel. (fn. 143)

The parish structure was firmly established by c.1200, reflecting the widespread foundation of local churches on newly created estates in (probably) the 11th and 12th centuries. (fn. 144) Resulting parishes varied considerably in size, the smallest (Easington) comprising only 235 a., while Great Haseley church served a multi-township parish of over 3,000 acres. Outlying medieval chapels, some of them short-lived and of uncertain status, existed at Rycote, Latchford, Little Haseley, Brookhampton, Berrick Prior, and Fifield, while another at Britwell Prior survived until 1865. Benson, Warborough, and Nettlebed remained chapelries of Dorchester until the Reformation, subsequently becoming perpetual curacies within the peculiar of Dorchester, while Berrick Salome remained a chapelry of Chalgrove, reflecting early manorial connections. Newington parish formed a peculiar belonging to the archbishop of Canterbury, similarly reflecting Canterbury cathedral's lordship. (fn. 145)

Church incomes in 1291 ranged from c.£4–£28, (fn. 146) attracting very different sorts of incumbent, while five parishes were appropriated to religious houses, (fn. 147) with vicarages endowed at Chalgrove and Nuffield. All three upland parishes were poorly endowed, though not exceptionally so, and their small churches (like many in the vale) attracted occasional investment from prominent laymen. Some worshippers in more dispersed areas attended from outside the parish, amongst them the English family (from Newnham Murren) at Nuffield. Lights, side chapels, and chantries were noted even in some smaller churches, and at Swyncombe the 'offering place to St Botolph', apparently a freestanding building, survived into the early 17th century (fn. 148)

The Reformation seems to have been outwardly accepted in many parishes, (fn. 149) although opposition by gentry, clergy, or parishioners is evident in Brightwell Baldwin, Newington, the Haseleys, and Warborough, and was manifested in the 1549 Oxfordshire uprising. (fn. 150) Recusant gentry families were resident in several parishes during the 17th century, (fn. 151) and at Britwell Prior the Simeons and Welds maintained a Catholic mission and chapel until 1796, accommodating a community of Clare nuns until 1813. Protestant Dissenters, notably Quakers and (later) Baptists, became firmly established from the 1660s, focused on Warborough, Benson, and Roke, while at Nettlebed the ejected Independent minister Thomas Cole established a short-lived academy in 1666. As with Catholicism, such activities formed part of a wider concentration in the south Oxfordshire and Chiltern area. (fn. 152) Further Dissent developed from c.1800, with Wesleyans, Primitive Methodists, and Congregationalists established in several vale and Chiltern parishes, often into the 20th century. (fn. 153) Sporadic Anglican neglect was mostly replaced in the 19th century by energetic reforming clergymen, but no new Anglican churches were built despite some abortive plans, (fn. 154) and parochial organization remained unaltered until the creation of some large team ministries in the later 20th century. No non-Christian groups became established. (fn. 155)

Note: sums given are those specifically spent on the poor rather than total sums raised.

THE BUILT CHARACTER

The area's most characteristic buildings, in both vale and uplands, are relatively modest vernacular structures of timber, chalk clunch, or brick, roofed usually in clay tile and sometimes in thatch - materials all widely available. Locally quarried limestone rubble features around Great Haseley and Cuxham, and flint particularly (though not exclusively) on the uplands. (fn. 156) Grander buildings are mostly confined to manor and other gentry houses, some medieval but most later. Others include former inns in Benson and Nettlebed, where coaching prompted some 18th-century refronting in fashionable brick-built or stuccoed styles.

Timber-framing (now chiefly infilled in brick) survives in most parishes, and was almost certainly commoner in the Middle Ages, before buildings were replaced (or in many cases encased) in brick or rubble. (fn. 157) Many use elm rather than oak, some of it of very poor quality, suggesting that good building timber was not always easily available to ordinary peasants or smallholders. (fn. 158) House sizes, too, seem generally to have been quite small: a survey of 1609 suggests that while three-bay and larger houses were not uncommon in the vale, single-storeyed one- and two-bay houses comprised over half the housing stock, and in 1665 nearly 56 per cent of houses were still taxed on fewer than three hearths. (fn. 159) The area lies on the cusp of the western cruck tradition and the eastern box-frame tradition, (fn. 160) and furnishes examples of both. One of the earliest cruck frames (dendro-dated to 1414) survives at Crocker End in Nettlebed (No. 18), where a small three-bay house acquired a box-framed cross-wing in 1441. Similar enlargement probably characterized many houses in the later Middle Ages, while others (like a late 15th-century four-bay house in Warborough with a hall, two service rooms, and solar) (fn. 161) were probably built anew by prosperous tenants on amalgamated holdings. At Russetts in Roke, a detached cruck-framed kitchen of c.1468 and a box-framed chamber-block of c.1550 were apparently brought together in a subsequent remodelling, forming a single dwelling. (fn. 162) Modernization through insertion of chimneys and flooring of halls was under way by the 1550s, (fn. 163) probably accompanied by encasing in rubble, and by the 17th century prosperous yeoman farmers were erecting some larger houses in timber, brick, or clunch, sometimes with lobby entries and often with parlours. Even so significant numbers of open-hall dwellings apparently survived in the earlier 17th century (fn. 164) Some large farm complexes, including barns, granaries, and shelter sheds, survive from the 18th and 19th centuries. (fn. 165)

Early manor houses include Chalgrove Manor, a substantial 15th- and 16th-century timber-framed house on a moated site, while Haseley Court (though remodelled later) contains remnants of the Barentins' 14th- and 15th-century stone-built house. The grandest medieval dwelling was almost certainly the de la Poles' mid 15th-century moated manor house at Ewelme, subsequently adopted as a royal residence but mostly demolished c.1612. Like the associated almshouses and school it incorporated some of the earliest (and finest) medieval brickwork in the county, probably partly reflecting the family's Hull and East Anglian connections. (fn. 166) Comparable in scale was the great Tudor mansion at Rycote, built probably by the courtier Sir John Williams (also in brick), but mostly burned down in 1745. In both cases bricks may have been made on site. (fn. 167) Some other manor-house complexes are known through excavation, (fn. 168) and Great Haseley retains a formerly ten-bayed and partially cruck-framed demesne barn of 1313, repaired in the 1480s–90s. (fn. 169) Seventeenth-or 18th-century mansion houses (many of them stone-built) (fn. 170) include Newington House, Great Haseley Manor, Britwell House, and the bulk of Haseley Court, while lost examples existed at Ewelme Park (one of the largest in the county), Swyncombe, and Brightwell Park. The latter's parkland was landscaped possibly by Humphry Repton, while Capability Brown worked at Rycote. Clergy houses varied greatly in size and prestige, the largest including those at Great Haseley (which incorporates some heavily remodelled 15th-century fabric), Ewelme (with a brick-built 18th-century frontage overlooking the valley), and Cuxham (rebuilt in Regency style in 1823). (fn. 171)

The 19th and early 20th centuries saw new chapels and schools, some rebuilt clergy houses, new labourers' accommodation particularly in Benson, and some new country houses in eclectic styles, notably Joyce Grove (1904–5) in Nettlebed, Ewelme Down House (1905), and Nuffield Place (1914, remodelled 1933). (fn. 172) New council and private housing built in the 1940S–90S was mostly of standard design, with occasional attempts at mock 'vernacular' styles, and from the 1980s several former farm buildings were converted to domestic or other uses. Conservation areas were created in Warborough, Shillingford, Ewelme, and Cuxham in 1978, followed by several more over the next seventeen years. (fn. 173)

The area's churches range from small, aisleless flint- or rubble-built structures at Swyncombe and Easington (the former with an eastern apse) through to larger-scale buildings at Great Haseley, Chalgrove, Ewelme, and Newington, characterized by aisles and side chapels, west towers, and (at Newington) a steeple. Chalgrove's chancel includes early 14th-century wall paintings commissioned probably by the Barentins as lords of the manor, and in general all the larger vale churches achieved their present form piecemeal, reflecting local and often lordly patronage, and in some cases adoption of aisles as private or mortuary chapels. Berrick Salome's small chapel acquired an unusual timber-framed tower (probably a community initiative) c.1429, and Ewelme church, substantially remodelled by the de la Poles in the 1430s–70s, displays East Anglian influences unusual for the area. Benson's tower was replaced by a classical-gothic structure in the 1760s–80s, but few other churches saw significant post-medieval additions until the Victorian period, when varied restorations included an almost complete rebuilding of Nettlebed church, and the transformation of Berrick Salome chapel with external barge boards and fish-scale tiles. (fn. 174)

GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION

Hundredal, Honorial and Manorial Government

Benson hundred was established by 1086, when it belonged, with the other four 'Chiltern hundreds', to the Benson royal estate. By then it was already designated (and remained) a 'half hundred', although Domesday Book rated its later constituents at 121½ above hides in all, comprising an area of some 25,096 acres. (fn. 175) The name Ewelme hundred was substituted piecemeal from the 123os, (fn. 176) reflecting Benson's decline as a royal and administrative centre and, almost certainly, the location of the ancient hundredal meeting place within what was by then the separate lordship and parish of Ewelme. (fn. 177)

Domesday Book identified only one or two places as lying within the hundred, but by 1279 it contained all of the 14 parishes and their constituent hamlets included in the 19th century, together with the detached hamlets of Draycott and Wyfold (Fig. 1). (fn. 178) Of those, Draycott (a hamlet of Ickford parish in Buckinghamshire) was included probably through its early connection with the honor of Wallingford, (fn. 179) and remained part of the hundred until its transfer to neighbouring Waterstock in 1886. (fn. 180) Wyfold (subsequently part of Checkendon parish in Langtree hundred) was included as former ancient demesne attached to Benson manor, (fn. 181) and was still counted as part of Ewelme hundred in the 17th century, though apparently not in the 19th. (fn. 182) The rest of the hundred formed a largely compact block save for the projecting tongue of Great Haseley parish, whose inclusion may reflect its relatively late connection with Benson manor. By contrast places to its west and east (included in Thame and Pyrton hundreds) were alienated long before the Norman Conquest to the churches of Dorchester, Lincoln, or Worcester. (fn. 183)

The hundredal meeting place is not recorded, but two likely candidates occupy rising ground between Benson and Ewelme (Figs 4 and 50). One, known by the 16th century (from a prominent tree) as the Roke Elm, was still clearly marked on 18th and 19th-century maps, and until parliamentary inclosure stood at the intersection of six major routes and of the boundaries of Benson, Fifield, and Ewelme. (fn. 184) At 72 m., it commands wide views over the vale towards the Iron-Age hillfort at Wittenham Clumps. An alternative is an equally prominent (and slightly higher) road intersection 1,300 m. to the east, where the boundaries of Benson, Ewelme, and Brightwell Baldwin meet near a 9th-century 'field way' and a contemporary landmark called Ceolwulf's tree. The latter site lies close to an early-to-mid Anglo-Saxon cemetery, just north of a field where coin and metalwork finds suggest an 8th- to 9th-century trading or meeting point. (fn. 185)

Jurisdiction over the 4½ hundreds descended with Benson manor throughout the Middle Ages, becoming bound up with administration of the honor of Wallingford (to which Benson belonged from c.1244) and its successor the honor of Ewelme. (fn. 186) By the late 13th century, tenants of manors still reckoned as ancient royal demesne or belonging to the honor were exempt from attendance at the hundred court, owing suit instead either at the Benson court and view of frankpledge, or at those for the honor. (fn. 187) For the rest, three-weekly (or more commonly monthly) hundred courts continued in the 15 th century, when they were attended by tithingmen from fees in Ewelme, Brightwell Baldwin, Cadwell, Little Haseley, and Little Rycote. The courts seem to have been combined with those for Langtree hundred, which presumably explains the presence of tithingmen from Checkendon, Little Stoke, and Mongewell. Business included pleas of debt, instances of hue and cry, enforcement of the assizes of bread and ale, and defaults, but the courts appear to have rapidly declined after the later 15 th century (fn. 188)

The hundreds annual views of frankpledge were subsumed by the 15th century in those for the honor, which were held at various fixed locations and dealt with adjacent groups of places. Those in Ewelme hundred (Benson's views apart) (fn. 189) met at Ewelme, Chalgrove, and Great Haseley, and were attended by tithingmen from c.25 places in all, who paid certainty money and reported misdemeanours. (fn. 190) The arrangement survived both the honors reconfiguration as the honor of Ewelme in 1540 and the sale of Benson manor in 1628, when the Crown retained its honorial and hundredal jurisdiction. (fn. 191) Early 18th-century views (held by stewards or deputy-stewards of the honor) were attended by tithingmen and constables from the same groups of places as earlier, who were elected by the court, and whose presentments dealt with upkeep of ditches, roads, and commons. (fn. 192)

In 1817 the Crown sold the honor first to Jacob Bosanquet and in 1821 to the earl of Macclesfield, (fn. 193) who revived the moribund views and the payment of quitrents and certainty money, then heavily in arrears. Despite opposition and non-compliance the Ewelme, Chalgrove, and Haseley views continued until 1847, electing tithingmen, constables, and haywards, receiving payments, and very occasionally ruling on minor local matters such as pounds, ditches, lanes, and stocks. (fn. 194) Thereafter they apparently lapsed, their legal basis having been undermined by the Summary Jurisdiction Act of 1848. (fn. 195) Separate Crown views for Benson manor and its members continued in the 17th century (fn. 196) and were resurrected by the lord of Benson in the 1770s, attended by officers from Warborough, Shillingford, Nettlebed, and Northfield End in Henley. Those views lapsed c.1842, though Benson's courts baron continued to 1922. (fn. 197)

Parish and Civil Government

Parish and vestry government developed on the usual pattern from the 16th century, gradually superseding the role of local manor courts despite the late continuance of open-field agriculture in parts of the vale. Some townships in the larger parishes had their own officers, and were occasionally rated separately for poor relief. Rationalization of parish boundaries was carried out piecemeal from the 1860s, radically altering the civil boundaries around Benson, Newington, Haseley, and Chalgrove, although the three upland parishes remained substantially unchanged. New parish councils or meetings were established under the 1894 Local Government Act, and continued in 2015. (fn. 198)

The hundred was split in 1834 amongst Thame, Wallingford, and Henley Poor Law Unions, Chalgrove and Haseley parishes falling to Thame, and the three upland parishes (with Brightwell Baldwin and some others) to Henley. In 1894 the Thame and Henley unions were succeeded by Thame and Henley Rural Districts, and the Oxfordshire part of the Wallingford union by Crowmarsh Rural District. All but the three upland parishes were transferred to the new Bullingdon Rural District in 1932, and the entire former hundred to South Oxfordshire District in 1974. (fn. 199) For ecclesiastical purposes the hundred was divided (peculiars excepted) amongst Cuddesdon, Aston, and Henley deaneries, with some modern changes. (fn. 200)