A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Langford Parish: Grafton', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp233-249 [accessed 2 February 2025].

'Langford Parish: Grafton', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online, accessed February 2, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp233-249.

"Langford Parish: Grafton". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online. Web. 2 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp233-249.

In this section

GRAFTON TOWNSHIP

Grafton is a tiny secluded hamlet situated on flat, low-lying land north of the river Thames. (fn. 1) Comprising around fifteen houses, its size is little different from in the Middle Ages. Settlement developed along the west bank of a small brook, and until 19th-century inclosure the limestone-built farmhouses and cottages faced onto a large common or green. Most inhabitants were employed in agriculture, and until the 20th century worked on small mixed farms belonging to absentee lords or to freeholders who generally lived in the hamlet.

Few communal facilities were established, inhabitants travelling to neighbouring villages and towns to attend church, school, market, and other activities. The nearest towns lay 3½ miles (5.5 km) west at Lechlade (Glos.) and 3¾ miles (6 km) south at Faringdon (formerly Berks.). Until 19th-century reorganization Grafton remained a township of Langford some 1¾ miles or 3 km away, although the neighbouring villages of Clanfield and Radcot were closer. It became a separate civil parish in 1866, and was united with Radcot in 1932.

Boundaries and Landscape

Grafton's boundaries and acreage (625 a.) were probably determined in outline before the Norman Conquest, when the manor was separated from neighbouring estates. (fn. 2) When mapped in the 19th century the boundaries mostly followed streams and ditches leading to the Thames (which formed a short stretch of the southern boundary), (fn. 3) though their precise course probably resulted from post-medieval water management and drainage. The north-western boundary with Langford followed Grafton hedge, a markedly straight division between Grafton's and Langford's open fields, (fn. 4) while the western boundary with Kelmscott most likely followed a former road mentioned in 1320, which separated the townships' pastures. (fn. 5) The south-eastern boundary with Radcot followed a watercourse and irregular field boundaries, while the eastern boundary with Clanfield and the short northern boundary with Broadwell both followed streams. Grafton hedge and many of the other field boundaries were ditched by the 1840s, though the stretch near Little Clanfield mill seems not to have been ditched until later. (fn. 6) In 1932 Grafton was united with Radcot to create the new civil parish of Grafton and Radcot (1,066 a.), but the boundaries of both parishes were otherwise unchanged. They remained unaltered in 2001. (fn. 7)

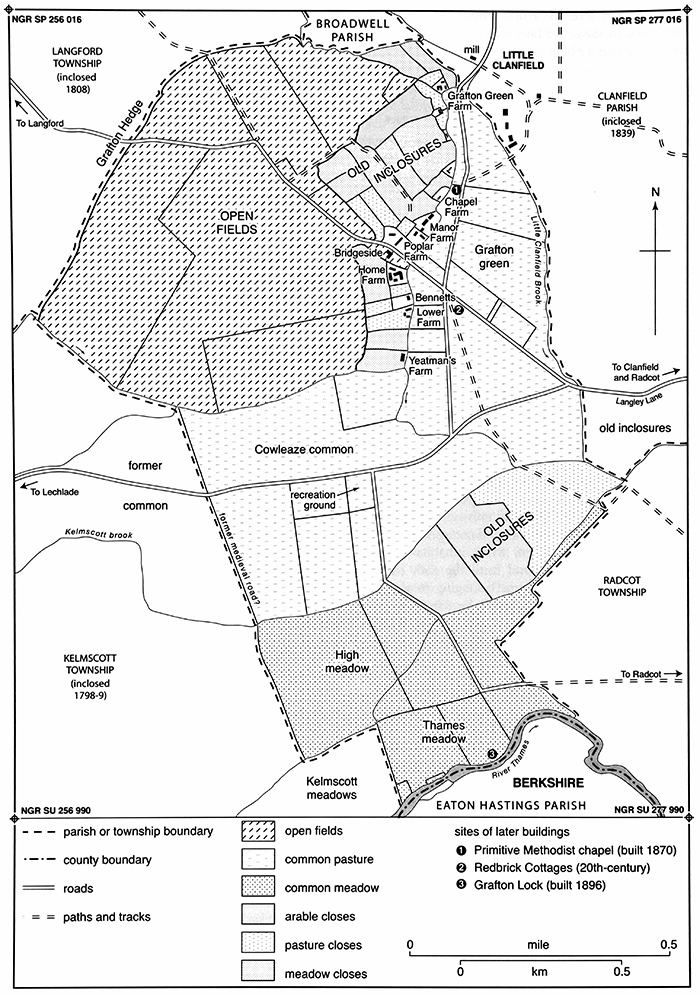

66. Grafton township in the early 1840s, showing open fields and old inclosures.

Most of Grafton township, including the hamlet, lay on river gravels of the First Floodplain terrace, though in the north-west a narrow band of Oxford Clay underlies the former open fields. (fn. 8) The soil is mostly a gravelly loam, though much of it was better suited to pasture (or 'leaze') than to arable. (fn. 9) The ground rises imperceptibly from 68 m. near the river to 74 m. in the north; along the Thames the meadow was very productive, though low-lying and liable to flood. The various streams also flooded, as in 1698 (when Grafton's inhabitants failed to maintain the banks), and in 2007. (fn. 10) Overhead power-cables pass the hamlet to the south-west, clearly visible in the flat landscape.

The place name suggests the presence of managed woodland or coppice (OE grāf), which may have been a prominent feature in the Anglo-Saxon period: if so it presumably formed a contrast with the more open landscape immediately to the east, which is recalled by the neighbouring place name of Clanfield ('clean field'). (fn. 11) Later, apart from hedgerow trees, Grafton lacked any woodland, although in the 19th century several orchards were attached to houses in the hamlet. (fn. 12)

Communications

Eighteenth-century maps show only two roads in the township, both meeting on its eastern boundary with Clanfield. (fn. 13) Of those the main west–east route ran from Lechlade (Glos.) to the road crossing Radcot Bridge; it may have had Roman origins, and was almost certainly used in the Middle Ages. (fn. 14) The road north-westwards to Langford was mentioned in the 13th century. (fn. 15) Another west–east route from Kelmscott to Radcot was shown as a bridleway on Rocque's map of 1761, crossing the southern part of the township. Its course may be marked by an earthwork near Grafton Lock. (fn. 16)

Other paths presumably gave field access or crossed the common, (fn. 17) but the modern network was not laid out until inclosure in 1846 when the Lechlade and Langford roads were confirmed as public carriage roads (Figs 2 and 66). Two public bridle roads were authorized from Little Clanfield mill past the hamlet to the Lechlade road, and from there southwards to the river. Other survivals include three public footpaths to Langford and Little Clanfield, of which one was extended in the later 19th century. (fn. 18) Footpaths to Radcot and around Grafton hamlet were suppressed in the late 20th century. (fn. 19)

Several footbridges, including Bryant's, Cowleaze, High Mead, and Pawling's, crossed streams and ditches in the township. (fn. 20) The nearest Thames crossing was at Radcot, however, supplemented by the 18th century by a footbridge at Hart's weir in Kelmscott. (fn. 21) A weir and flashlock existed at Grafton Lock from the 18th century and possibly earlier, and were replaced in 1896 (Plate 11). The lock-house was considered one of the remotest on the river, and was especially difficult of access in winter or during floods. (fn. 22)

Carriers operated from nearby Clanfield and Langford. (fn. 23) The nearest station (from 1907) was also near Langford on the GWR line, which closed in 1962. (fn. 24) Post was delivered through Faringdon or Lechlade until the early 20th century, when Clanfield assumed responsibility: the hamlet was one of the 'lone places' to which postmen had to walk. A letter box was located on the Langford road from c. 1910. (fn. 25)

Settlement and Population

Early Settlement

Undated cropmarks north-west and south of the modern hamlet relate probably to the Neolithic period and Bronze Age, and suggest seasonal settlement and shifting agriculture by small groups on the gravel terraces. (fn. 26) Human and animal remains found at Grafton Lock, with pottery of Bronze-Age or early Iron-Age date, also indicate probable use of the river, (fn. 27) and the area may have been occupied into Roman times. (fn. 28)

The place name Grafton (grāf- or grove tūn) suggests both mid or late Anglo-Saxon settlement, and association with an area of managed woodland. Presumably the settlement began as a riverside outlier of the large Langford-Broadwell estate, and possibly it specialized in the supply and transport of coppice poles for fuel: like several other grāf-tūns it lies close to early saltways, and it has been suggested that such places formed part of an early distribution network supplying the saltpans at Droitwich (Worcs.). If so, it may have also supplied fuel along the river and elsewhere in the area, either from its own coppices or from the woodland at Bradwell Grove. (fn. 29) Whatever the case no later evidence for such specialization has been found, and by 1066 Grafton was the nucleus of a small independent estate with a dozen low-status households, focused probably in the vicinity of the later hamlet. (fn. 30)

Population from 1086

In 1086 there were twelve tenant households on Grafton manor, headed by one villanus, ten lower-status bordars, and one slave. (fn. 31) By 1279 the number of tenants had increased to 18, comprising eight unfree smallholders and ten freeholders, though not all of them were necessarily resident. (fn. 32) Only 16 landholders paid tax in 1306, and perhaps fewer in 1316 and 1327, when Grafton was taxed with Radcot. (fn. 33) However, poll tax in 1377 was paid by 44 adults aged over fourteen, suggesting relatively limited depopulation following the Black Death. (fn. 34)

During the 15th and early 16th centuries Grafton's population may have fallen sharply, perhaps partly as a result of inclosure for sheep farming. (fn. 35) Only five taxpayers were mentioned in 1524 (fn. 36) and three in 1544, rising to five c. 1600 and six in 1622. (fn. 37) Endemic plague may have kept the population low, an outbreak at Grafton in September 1594 probably killing six people. (fn. 38) Sixteen houses were mentioned in 1627, and 19 men (sharing nine surnames) swore the obligatory protestation oath in 1642. Around 12–14 houses were assessed for hearth tax in 1662–5, and mid-17th century parish registers suggest no more than 15 resident families. (fn. 39)

Population probably changed little during the 18th century, and in 1801 there were 15 houses accommodating 66 people. Numbers rose to 80 (in 18 houses) in 1861, then fell during the agricultural depression to 70 (in 14 houses) by 1901. After a period of stability Grafton's population fell to only 54 in 1931, shortly before the parish was united with Radcot. The combined parish's population fell from 67 (in 23 houses) in 1951 to 41 (in 15 houses) in 1981, and in 2001 the two hamlets had 42 inhabitants. (fn. 40)

Topography and Development

Grafton developed as a regular linear settlement on the west bank of a small brook, extending 800 m. (½ mile) from Little Clanfield in the north to the boundary ditch of the township's arable and pasture in the south (Fig. 66). On their eastern side the farmhouses and cottages faced onto a large green, while to the west lay the township's open arable fields. (fn. 41) The hamlet's present form suggests that it was deliberately planned or replanned, possibly by the Bucklands in the late 12th or early 13th century: elsewhere in the county, villages extending along the margins of commons or greens have been interpreted as the product of a relatively late extension or reorganization of settlement. (fn. 42) If so, reorganization at Grafton may have coincided with the entry into the manor of a number of free tenants, who in 1279 held most of the land, supplementing a population which in the late 11th century had been made up largely of smallholding bordars. (fn. 43) Earlier, Grafton may have been occupied only seasonally by workers based at the estate centre at Langford.

The hamlet's surviving farmhouses and cottages date mostly from the 18th century. (fn. 44) Stone and stone slate, probably from local quarries, were the most commonly used building materials, though from the 19th century brick was increasingly used for dressings and chimney stacks when houses were altered, and corrugated iron was sometimes used to roof outbuildings. (fn. 45) Home Farm, which was occupied by John Watts (d. 1843) and his son William when it was remodelled and extended, has a mid 17th-century core of three bays and two storeys, with gabled dormers to the attic. (fn. 46) Other farmhouses, including Lower and Poplar Farms, are of similar character; a datestone of 1763 commemorates Lower Farm's rebuilding by Daniel Tayler, and the house was further extended in the 19th century. (fn. 47) But despite such improvements (which continued in the 20th century) Grafton's buildings form a remarkably homogenous group, and none stands out as being particularly grand or pretentious.

67. Poplar Farm, just north of the Langford road. The building is typical of the unpretentious rubble-built farmhouses and cottages which characterize the hamlet.

No new building followed inclosure in 1846, when there were around sixteen inhabited dwellings. (fn. 48) Some cottages at the north end of the hamlet were demolished probably in the 1870s when the number of houses fell to fourteen, though at the same time a pair of cottages and a small Primitive Methodist chapel were built on the opposite side of the brook. (fn. 49) Another pair of brick-built cottages was added on land owned by Christ Church, Oxford, in the early 20th century, while the later part of the century saw the demolition of Grafton Green Farm and the conversion of the Methodist chapel to private use. (fn. 50) The only isolated buildings in the township are the lock-keeper's house on the Thames (Plate 11) and Homeleaze Farm, the latter built in the early 21st century on the road to Langford. (fn. 51)

MANOR AND ESTATES

In the late Anglo-Saxon period Grafton almost certainly formed part of the large multiple estate focused probably on Langford. (fn. 52) A separate manor of Grafton, encompassing the whole of the later township, was created before the Norman Conquest, its Anglo-Saxon holders having the right to 'go where they wished'. (fn. 53) This right to enter the service of another lord suggests that they were thegns, (fn. 54) although none were identified by name. From the 12th century to the 19th the manor was held by non-resident lay lords, most of whom lived nearby in the upper Thames valley, and no manor house was built. (fn. 55) In the early 18th century several freehold farms were created, and in 1840 the lord owned only about a third of the land. (fn. 56) In 1867 the manor was bought by Christ Church, Oxford, the owner in 2011.

Grafton Manor

Descent to 1589

In 1086 Grafton was held by William, count of Évreux, who granted the manor to Noyon priory in Normandy. (fn. 57) The overlordship remained with the priory until 1415, when it was confiscated by Henry V and granted to the Carthusian monastery at Sheen (Surrey). (fn. 58) At the Dissolution the overlordship reverted to the Crown, and in 1617 Grafton was said to be held of the king as of the prior of Sheen. (fn. 59)

In 1130 Grafton was leased to William of Buckland. (fn. 60) A part, possibly including the demesne, may have been separately let to Robert of Inglesham, whose successors claimed in 1198 to hold Grafton manor 'at farm' from Noyon priory. (fn. 61) No separate leases were mentioned later, however, and William of Buckland's right in the manor passed probably to his grandson William (d. c. 1216), among whose three daughters it was divided in 1219. (fn. 62) The greater part was probably assigned to Hawise of Buckland (d. 1226) and her husband John de Bovill, who were succeeded by Hawise's elder sisters Joan (widow of Robert de Ferrers) and Maud (wife of William d'Avranches). (fn. 63) Joan later married Simon d'Avranches, and on her death in 1252 her portion passed to their son John (d. 1257). (fn. 64) He was succeeded by three daughters, whose wardship and marriages were granted by the king to his retainer Emery de Besyles. (fn. 65) One daughter, Elizabeth d'Avranches, probably married Emery's nephew Matthew de Besyles, who by 1279, either through death or agreement, also held the shares of Elizabeth's sisters and of Maud de Crevecoeur (d. 1263), daughter of Maud and William d'Avranches. (fn. 66)

Following the deaths of Matthew de Besyles in 1296 and Elizabeth in 1315, Grafton manor passed in the direct male line to Sir Geoffrey de Besyles (d. 1339), Sir Thomas (d. 1378), and John (d. c. 1382 aged about 20), whose own son John died in infancy later the same year. (fn. 67) John was succeeded by Sir Thomas's younger son Peter de Besyles (d. 1425), whose widow Margery (d. 1484) held the manor with her second husband William Warbelton (d. 1469) of Sherfield (Hants). (fn. 68) Margery was succeeded, in contravention of Peter de Besyles's will, by her grandson William de Besyles (d. 1515), son of her and Peter's illegitimate son Thomas. (fn. 69) The manor subsequently passed to William's daughter Elizabeth, widow of Richard Fettiplace, to her son John Fettiplace (d. 1524), and to his son Edmund Fettiplace (d. 1540). (fn. 70) Edmund was succeeded by his son John Fettiplace (d. 1580), a minor, and by John's son Bessels. (fn. 71)

Descent from 1589

In 1589 Bessels Fettiplace (d. 1609) and his son Richard sold the manor to Francis Broderwick, lessee of Langford Manor prebend, and Thomas Fettiplace (d. 1617) of Fernham (formerly Berks.). (fn. 72) In 1593 Thomas acquired the manor outright, possibly in exchange with Broderwick for the redemption of a mortgage. (fn. 73) Thomas Fettiplace was succeeded by his son Thomas, who sold the manor in 1627 to Sir Robert Pye (d. 1662), lord of Great Faringdon. (fn. 74) Pye was succeeded by his son Sir Robert (d. 1701), a Parliamentarian army officer during the Civil War, (fn. 75) whose son Edmund Pye (d. 1705) fell into debt. (fn. 76)

Edmund's widow Anne later married William Rider of Middlesex, who redeemed the mortgage on the manor. Most of it was sold in 1718 (with the consent of Edmund's son Henry Pye) to Mary Marner of Southwark and her son-in-law Richard Abell, (fn. 77) passing to Richard's daughter Mary, who married John Wainewright (d. 1760), and to their three children John (d. 1792), Robert (d. 1800), and Mary, the wife of Reader Watts (d. 1787). (fn. 78) In the early 19th century the manor was divided between Robert son of Robert Wainewright (d. 1841) and Reader son of Mary Watts, though manorial rights seem to have remained with Wainewright, who was succeeded by his brother Arnold (d. 1855). (fn. 79) In 1867 Arnold's widow sold the manor to Christ Church, Oxford, which retained it in 2011; it was then, however, preparing to sell all of its remaining Grafton and Radcot land. (fn. 80)

Lesser Estates

From the Middle Ages some land in Grafton belonged to the Knights Hospitallers' preceptory of Clanfield, with which it passed to Quenington preceptory (Glos.) in the 15th century, and, following the Dissolution, to John Edmonds of Deddington and his 17th and 18th-century successors. No later reference has been found. (fn. 81) In 1540 Edmund Fettiplace acquired land from one of Quenington's tenants in Grafton, which was presumably added to the main manor. (fn. 82)

In 1718 William and Anne Rider sold half a dozen freehold farms in the township to local yeoman families, including the Coxes, Sindreys, and Yeatmans. (fn. 83) Despite some consolidation several freeholds survived until the 20th century, and in 1910 Christ Church still owned only about half the township's land. (fn. 84)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until the 20th century most of Grafton's inhabitants were employed in agriculture, and few trades and crafts were practised. From the Middle Ages the township's chief characteristic was its extensive commons and meadows, which were only finally inclosed in 1846, and in which inhabitants shared carefully regulated rights, supplementing their strips in the arable fields. As in some neighbouring places, the meadow and pasture seems also to have attracted outsiders.

From the 17th century, following the creation of twelve new leasehold farms, a group of prosperous yeoman families emerged, of whom some subsequently became freeholders. During the 19th and 20th centuries the number of farms gradually fell as landholdings were consolidated, although most farms remained relatively small. Grain, cheese, and wool were the most important products until the early 20th century, when dairying rose to prominence.

The Agricultural Landscape

Despite its small size, Grafton's landscape provided its inhabitants with a variety of agricultural resources (Fig. 66). On the higher ground to the north-west lay the hamlet's open-field arable, which remained uninclosed until 1846. To the south and east an extensive and similarly uninclosed area of common provided permanent pasture for cattle, sheep and horses, though from the 18th century (and probably before) animal numbers were restricted by manorial custom. The brook along which the hamlet developed watered numerous small closes of meadow, while in the south of the township by the river Thames was a larger area of productive but low-lying common and lot meadow. Grafton largely lacked woodland, (fn. 85) trees growing mostly along stream and ditch banks and in small groves within the hamlet. Elms, an excellent fuel if well dried, were mentioned from the 16th century. (fn. 86) In 1627, when the manor was sold to Sir Robert Pye, it was reckoned to include 200 a. of arable, 200 a. of pasture, 120 a. of meadow, 100 a. of furze and heath, and 10 a. of wood, together with 16 houses and gardens and a dovecot. (fn. 87)

Arable

In 1086 the count of Évreux's 2-hide manor had land for three ploughteams, of which two were held by tenants and one was in demesne. (fn. 88) In the 18th century and probably from the Middle Ages around 220 a. of arable lay to the north-west of the hamlet, divided by the road to Langford into two open fields called Hill and Lower fields. (fn. 89) Probably they were subdivided for cropping: this was certainly so in the 17th century, when a Grafton yeoman left arable in each of four 'fields'. (fn. 90) The furlongs extended to the parish boundary and to adjoining inclosures, with possible medieval names including 'Sallows', 'Broadwell Hurst', and 'Picked Mead'. (fn. 91) In 1840 there was a four-course rotation of fallow, wheat, beans, and barley, (fn. 92) and at inclosure in 1846 there were five fields called Cowleaze, Farther, Hill, Home, and Road fields. (fn. 93) Yardlands seem to have included c. 30 a. of arable in the 16th century, and presumably earlier. (fn. 94)

In 1507 William de Besyles inclosed around 20 a. of arable, presumably the block of old inclosures between the hamlet and the open fields, (fn. 95) and by the early 19th century there was another block of old inclosure near the Radcot boundary, taken probably from the meadow or pasture. Many of the new closes were probably converted to sheep pasture, though at least one of the hamlet's closes (the 5-a. Corn Close) was arable in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and so, too, was 25 a. of old inclosure in the south. Even so, in 1840 some two thirds of the old-inclosed area was under grass. (fn. 96)

Following parliamentary inclosure the township's overall proportion of arable increased, and by 1877 totalled some 370 a., about three fifths of the land available. (fn. 97) The proportion fell during the agricultural depression of the 1880s onwards: by 1930 only 129 a. (about a fifth of the township) were under crop, (fn. 98) though some grass was ploughed up during the Second World War, raising the arable area to more than a third. By 1965 more than half of Grafton and Radcot parish was under crop, and by 1988 the proportion had risen to two thirds. (fn. 99)

Meadow and Pasture

Common meadow, estimated in 1086 at 63 a., lay chiefly in the south by the river Thames. (fn. 100) In the 18th century it included High Meadow (75 a.), where tenants held plots subject to common rights, and a smaller area of nearby lot meadow (18 a.). (fn. 101) By then there were also 47 a. of inclosed meadow alongside the brook near the hamlet, which was held in small parcels by the manor's tenants. (fn. 102) An area of detached meadow lay south of the Thames at Quedham (Fig. 69), which belonged to Radcot manor and township, but which by 1219 was leased to the 'men of Grafton' for 21s. a year. It remained part of Grafton's lot meadow in the 18th century, when it was reckoned at 20 acres. (fn. 103) In the Middle Ages much of Grafton's meadow was probably divided into strips which were bought and sold like arable strips in the open fields: c. 1230 one such strip called 'Tyntelake' was sold by Ralph of Lechlade for the considerable sum of 11 marks (£7 6s. 8d.). (fn. 104) In the late 14th century Grafton's meadow was worth around 18–20d. an acre, compared with 4d. an acre for arable. (fn. 105)

In 1840 meadow covered about a fifth of the township, (fn. 106) and at inclosure 93 a. were divided into parcels and allotted to four of the township's principal landowners. (fn. 107) Meadow remained a characteristic feature of Grafton's farms during the agricultural depression of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Lower Farm (70 a.) was two-thirds meadow in 1890, while meadow accounted for nearly half of the 46-a. Chapel farm in 1911. (fn. 108)

Common pasture a league in length and breadth was recorded in 1086, (fn. 109) and as in the 18th and 19th centuries probably covered some 208 a. south and east of the hamlet. By 1706 a brook divided it into Cowleaze Common (115 a.) and Grafton Green (93 a.). (fn. 110) Around 1800 the grazing was described as very good for horses, cows, and sheep, and tenants were allowed to pasture a specified number of animals in summer and winter according to the terms of their lease. Common pasture rights were also enjoyed on the arable after harvest and during fallow. (fn. 111) The commons were inclosed with the fields and meadows in 1846 and allotted to individual landowners, (fn. 112) and thereafter the area of meadow and pasture was reduced, covering only 230 a. in 1877. (fn. 113) From the 1880s, as arable farming declined, the hay meadows and permanent pasture again increased in size, covering about three fifths of the available farmland in 1890 and four fifths in 1930. (fn. 114) In 1941 the area of grass on individual farms ranged from just over half to around four fifths, although increasing amounts were ploughed up both during and after the war. (fn. 115)

Medieval Agriculture

Medieval Tenant Farming

In 1086 most of the manor's tenants were smallholders, numbering ten bordars, one villanus, and one slave, and the estate was valued at £2 as in 1066. Of the three ploughlands (or 12 yardlands) in cultivation, two were shared among the tenants, suggesting that most bordars held less than a yardland and possibly only ½ yardland. (fn. 116) The bordars' successors in 1279 were most likely the eight unfree tenants each holding a house and 5 a., for which they paid annual rents of 2s. 10d. and owed labour services worth 6s. ¼d. Ten freeholders were also listed, of whom one held a yardland and another ½ yardland; the remainder held 1–10 a. for annual rents ranging from 3d. to 4s. an acre. (fn. 117) Such free tenants were recorded in the township only from the early 13th century, (fn. 118) and their appearance may have coincided with a planned reorganization of Grafton village and perhaps of local farming practice in an era of agrarian expansion. (fn. 119) In the early 14th century Michael Meldon, the acquisitive Langford sheep farmer, was taxed at Grafton, having perhaps bought land there in order to graze his flocks on the township's common pastures. (fn. 120) Robert Marsh of Windrush (Glos.) was probably another non-resident freeholder making use of Grafton's commons. (fn. 121)

In 1306 perhaps half the unfree tenants were above the tax threshold, their assessed wealth falling between £2 and £3 10s. (fn. 122) Inhabitants of both Grafton and Radcot, who together paid £4 6s. 6d. to the twentieth of 1327, had their assessment for the ninth of 1341 reduced to £4, most likely because of crop failure and animal disease. (fn. 123) The Black Death may have had a relatively limited impact on population, and the arable continued to be ploughed, as indicated by the theft of an ox in 1373. (fn. 124) Nevertheless the sown acreage probably fell in the 15th century, and in the early 16th some arable was inclosed by the lord, most likely for sheep farming. (fn. 125) Many families probably moved away, though some others (such as the Carpenters) were recorded at Grafton from the early 14th century to the mid 16th. (fn. 126) Medieval tenants probably also exploited the river, streams, and commons for pasture, fuel, food, and a variety of other natural resources, although no specific evidence survives. (fn. 127)

Medieval Demesne Farming

In 1086 the count of Évreux held a ploughland in demesne, which was worked by at least one slave. (fn. 128) Whether his successor Noyon priory maintained the demesne farm is unknown, and in 1130 it leased the manor for £3 a year to William of Buckland. The demesne may have been sublet or separately leased, since Robert of Inglesham reportedly paid the priory £33 6s. 8d. a year for the 'farm' of its Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire manors including Grafton, and in 1198, when prices were rising, the priory paid Robert's successors £9 13s. 4d. to recover its estate. By then the priory seems to have had only a nominal overlordship, however, and no further dealings with Grafton are recorded. (fn. 129)

Direct ownership remained with the non-resident Bucklands and their successors, none of whom seem to have kept any land in demesne. In 1279 Matthew de Besyles' income from the manor comprised only £2 14s. 5d. annual rents from freeholders, and £3 10s. 10d. from unfree tenants. (fn. 130) Quenington preceptory, too, seems to have leased out all its Grafton property. (fn. 131)

The 16th Century to Parliamentary Inclosure

In 1507 William de Besyles took 50 a. of arable land into demesne, inclosed 20 a., and demolished two houses, thereby displacing six people from the manor. (fn. 132) His intention was probably to create additional sheep pastures, and in 1549 his successor John Fettiplace grazed 100 sheep in the township. (fn. 133) The small number of 16th-century taxpayers probably indicates an over-all decline in tenant numbers, (fn. 134) although the township continued to support smallholding labourers such as Thomas Johnson (d. 1565), who kept a few cattle, pigs and poultry, made cheese, and spun linen. (fn. 135)

Some tenants almost certainly experienced difficulties, among them the Humfrey family. In the early 16th century the copyholder John Humfrey paid Quenington preceptory rent of 25s. 4d. for a house, close, and yardland, of which 15¾d. went to the lord of Radcot for 1½ a. of attached meadow in Quedham. In 1511 Humfrey was ordered to repair the house, for which he later received three elms from the preceptory's steward, but on his death in 1519 the building was 'almost ruinous both in timber and thatch'. Humfrey's successor, who sublet the property, paid £2 to Quenington for a life lease, and an ox worth 9s. as heriot. (fn. 136) In 1540 Edmund Fettiplace may have acquired the holding from the preceptory's tenant in exchange for land at Clanfield; it was then described as a house, 30 a. of arable (i.e. a yardland), 10 a. of meadow, 2 a. of wood, and common pasture for 60 sheep. (fn. 137)

In the early 17th century the manor was divided into twelve unequal parts or 'farmerships', which were leased to tenants for three lives. Each included a house and close in the hamlet, land in the open fields, and pasture rights in the commons, though some of them were later combined or divided. (fn. 138) Hugh Francis (d. 1620) held one for an annual rent of £3 6s. 8d. and a heriot of £1; (fn. 139) Robert Maisey paid £6 a year for another (called Carpenter's), which later comprised 14 a. of arable and a close of meadow, common pasture for 2 sheep in Grafton Green and for 2 horses, 5 cattle, and 10 sheep in the open fields, and herbage in a coppice of elms. (fn. 140) Later lords continued to lease the farmerships for three lives at varying rents of up to £12 10s. a year, (fn. 141) presumably supplemented by large entry fines, since these rents were way below the holdings' true value. Alice Broad's house, close, and commons, for instance, for which she paid £1 a year, were valued at £30 on her death in 1689. (fn. 142)

In 1718, before the manor's sale to Mary Marner, William and Anne Rider sold six of the farmerships as freeholds, retaining the other six as leaseholds. The freehold rents then totalled £39 7s. a year, and the leasehold rents £34 10s. (fn. 143) The underlying pattern of farmerships remained visible in 1840, despite some consolidation of holdings. (fn. 144) Robert Wainewright (d. 1800) held two freeholds and Henry Bennett (d. 1818) two others, for example, while Sarah Pawling (d. 1809) combined two leaseholds. (fn. 145) Nine farmhouses then remained at Grafton, though only Manor farm (186 a.) and Home farm (141 a.) exceeded 100 acres. Three other farms covered 46–78 a., while the rest included less than 20 a. each within the township. (fn. 146)

A number of families who lived in the hamlet in the 16th century remained there for several generations. Amongst them were the Coxes, who first leased and later bought a farmership, and who finally left the township in the 18th century; (fn. 147) John Cox (d. 1608) left goods worth more than £95, and other yeoman families, including the Clarks, Fords, Francises, Keebles, and Maiseys, were similarly prosperous in the 17th century. (fn. 148) Most were taxed in 1665 on two to four hearths, the hamlet lacking any larger houses. (fn. 149) In the 18th century other families (some of them newcomers) rose to prominence, including the Mays, Pawlings, Taylers, and Yeatmans. With the Wainewrights, those families remained the principal landowners and tenants on the eve of inclosure. (fn. 150)

From the 16th century (and probably in the Middle Ages) farming was mixed. Thomas Francis (d. 1598) grew barley and wheat, kept horses, dairy cattle, and sheep, and made butter and cheese. (fn. 151) Similar practices were followed in the 17th century, when most inhabitants owned stocks of grain, hay, and wood, a horse or two, a few cows, pigs, and poultry, a small flock of sheep, some bacon, cheese, and malt, and sometimes bees and hemp. (fn. 152) John Maisey (d. 1689) was fairly typical, leaving 16 a. of sown crops worth £9 10s., hay, straw, and wood worth £2 10s., four horses worth £3 10s., five cows worth £8, 52 sheep worth £12, bacon and cheese worth nearly £2, bees in the garden, and dung to spread on his land. (fn. 153) Farming was probably little different in 1840 when its scale was described as 'low'. Sheep were grazed on the commons and folded on the arable, which was chiefly sown with wheat, beans, and barley. Potatoes were also grown, some of them for marketing in nearby towns, and cheese-making was common. (fn. 154)

Parliamentary Inclosure and Later

Inclosure was carried out under a private Act of 1843 promoted by the lord of the manor and three other landowners. (fn. 155) By the award of 1846, land was distributed among six principal proprietors. The lord of the manor Arnold Wainewright (d. 1855) owned three farms – Manor (166 a.), Bridgeside (68 a.), and Grafton Green (24 a.) – which were leased to tenants. (fn. 156) Home farm (68 a.), which William Ward bought from the Yeatmans c. 1805, was also leased, and so too was Bennetts (7 a.), which Ward purchased in 1825. (fn. 157) The other four farms were most likely owner-occupied: Poplar farm (146 a.) by William May, Chapel farm (47 a.) by the Watts family, Lower farm (18 a.) by the Pawlings, and Yeatman's (80 a.) by Edward Wheeler. (fn. 158)

Some reorganization of landholdings followed inclosure. Bridgeside was merged with Manor farm (234 a. combined) before its sale in 1867 to Christ Church, Oxford, and was leased to the Akerman family from c. 1850 to the early 1930s. (fn. 159) In 1861 the Akermans farmed 340 a. in all and employed 10 men and 4 boys, while William and John Watts farmed 180 a. from what became Chapel Farm. (fn. 160) Bennetts was added to Home farm (afterwards 87 a.), which was mortgaged by Ward's heirs to the Faringdon ironmonger John Anns (d. 1879); the Anns family let the farm, before selling it in 1940 to the Willmers of Clanfield. (fn. 161) A flurry of further sales took place during the agricultural depression of the late 19th century. In 1890 Christ Church bought Lower farm from the Pawlings, which was later merged with Grafton Green farm, while the Anns family purchased Chapel farm from John Watts in 1894. (fn. 162) Poplar and Yeatman's farms, both owned by William May, were separated and sold following his death in 1895. (fn. 163) In the early 20th century six working farms remained in Grafton – Manor, Home, Lower, Chapel, Poplar, and Yeatman's – all of which were leased, and only two of which exceeded 100 acres. (fn. 164)

From the 1870s about half the township's arable was sown with wheat and barley, a quarter with fodder crops (oats and legumes), and a quarter with root crops, especially turnips and swedes, although the acreage fell during the agricultural depression. Sheep were kept in considerable numbers until the 1920s, after which they all but disappeared; in 1941 the tenant of Manor farm reported that 'a return is to be made to arable sheep', suggesting that their chief role was to manure the fields and that they declined in line with the sown acreage. (fn. 165) As on other farms in the area, dairying increased in importance from the 1890s, and in 1941 the tenants of Manor, Lower, and Yeatman's farms were all described as mainly dairy and poultry farmers. Nevertheless, the three farms remained 35–45 per cent arable. (fn. 166)

Manor, Home, Lower, and Yeatman's farms continued after the Second World War, some of them extending into neighbouring parishes. Barley was the chief crop, though increasing amounts of wheat were sown in the 1980s. Pigs were kept until the late 1960s, after which cattle was the only stock; sheep were not reintroduced. Dairy and cattle farming were the main enterprise until the late 1970s when cereals regained their former dominance. (fn. 167)

Rural Trades and Industry

Grafton's medieval smallholders probably supplemented their farming income through other activities, in particular those associated with the commons and river. (fn. 168) However, the township remained predominantly agricultural. Occupational names other than Carpenter were uncommon in the Middle Ages, and few tradesmen were recorded later except for the tailor Zachary Hall (d. 1656) and the butcher Henry Bennett (d. 1818), both of whom also farmed. (fn. 169) In the early 19th century no families were employed in trade, craft, or manufacture, (fn. 170) though from the 1840s James Pawling ran a grocer's shop, which was taken over by the Watts family c. 1870 before closing in the 1880s. (fn. 171) One mid 19th-century farmer also worked as a farrier, while a labourer's wife was a dressmaker. (fn. 172) Other local skills may have included carpentry. (fn. 173) For most goods and services Grafton's inhabitants presumably travelled to neighbouring towns and villages.

Grafton Lock (Plate 11)

In the 18th and 19th centuries the weir and flashlock at Grafton were owned by the Harts of Eaton Hastings (formerly Berks.), whose attendance there was probably irregular. (fn. 174) Early keepers of the pound lock, which opened in 1896, may also have lived outside the township. (fn. 175) By 1910, however, river users admired the well-tended lock-garden, and thereafter the house was probably continuously occupied by a succession of keepers until the early 21st century. (fn. 176) In the 1950s the lock house was considered one of the remotest on the river, and electricity was installed only in the early 1960s. (fn. 177) Some lock-keepers may also have fished, although in 1898 permission to install eel-traps was refused. (fn. 178)

SOCIAL HISTORY

Social Structure and the Life of the Community

From the Middle Ages Grafton remained a small, predominantly agricultural community. Medieval freeholders were attracted to the township by its extensive commons and were perhaps encouraged to settle by the non-resident lords of the manor. Some families lived there for several generations, though social stability may have been disrupted in the 15th and 16th centuries by small-scale inclosure and an increasing emphasis on sheep grazing. In the 17th century the arrival of new families was again promoted by the lord's decision to lease and later sell portions of the manor as 'farmerships', (fn. 179) and until the onset of agricultural depression in the 1880s Grafton was dominated by a small group of resident yeoman farmers and their workers, many of whom were native to the township. Few formal communal institutions were established in the hamlet, and links with neighbouring communities, especially Radcot and Langford, were probably strong. In the 20th century, despite a gradual drift from the land, farming remained a significant element in Grafton's economy and society.

The Middle Ages

In 1086 most inhabitants were smallholding bordars, suggesting that before the Norman Conquest the settlement may have housed low-status workers associated with the estate centre at Langford. (fn. 180) Unfree smallholders continued to live in the hamlet in the 13th century, but in addition a number of freeholders were perhaps encouraged to settle by the availability of extensive commons in an era of agrarian expansion. (fn. 181) Surviving tax returns suggest that some tenants amassed considerable wealth. Michael Meldon, the Langford sheep farmer, was assessed on goods worth £3 10s. in 1306 and £8 in 1316. (fn. 182) Most others were worth less, though some smallholders also produced a taxable surplus: at least four of Grafton's taxpayers in 1306 (a quarter of the total) shared surnames with the unfree tenants of 1279, including the Hores and Woolways, who remained in the hamlet in 1327. (fn. 183) In 1285 the king's justices heard that Walter Hore died from injuries inflicted by another unfree tenant Robert Melody while working in the fields, though whether this reflected social tensions or was merely an isolated incident is unclear. (fn. 184) Members of the Carpenter and Norton families still lived at Grafton in 1379, following the Black Death, but the economic and social changes of the postplague period probably led to population decline as tenants were compelled or chose to leave. (fn. 185)

None of Grafton's medieval lords lived in the hamlet, and no manor house was built. All of them were resident in the upper Thames valley, however, and may have visited the manor from time to time. The Bucklands' chief residence was at Buckland (formerly Berks.), about five miles east of Grafton, and the family also built a castle at neighbouring Radcot. (fn. 186) One of them may have replanned the settlement at Grafton in the late 12th or early 13th century, when lords generally were taking a greater interest in managing their estates at a time of rising prices. (fn. 187) The Besyles family, too, maintained a manor house at Radcot, and may have lived there for much of the 14th century. Thereafter they moved to Bessels Leigh around twelve miles away. (fn. 188)

The close administrative links between Grafton and Radcot, (fn. 189) which their shared lordship probably encouraged, may have extended to social relations. Some tenants certainly held land in both townships, (fn. 190) and the 'men of Grafton' collectively leased Quedham meadow in Radcot. (fn. 191) Grafton's inhabitants probably also attended Radcot's chapel, market, and mill, a journey of little over a mile; though larger, the villages of Clanfield and Langford were slightly more distant. (fn. 192)

1500–1800

In the early 16th century Grafton was one of many places affected by inclosure and the displacement of local residents, (fn. 193) which must have considerably heightened tensions between the lord and his tenants. Population almost certainly declined, and many inhabitants may have stayed in the hamlet for only a few years. (fn. 194) The Fettiplaces, lords of the manor from 1515, lived some twenty miles from Grafton at Bessels Leigh and East Shefford (Berks.), (fn. 195) and probably used the manor primarily for sheep grazing. (fn. 196) In their absence, leadership of Grafton's small community fell on the more prosperous resident farmers. Leading families in the later 16th century included the Coxes (who also held land at Radcot), the Clarks (of whom some died in an outbreak of plague in 1594), and the Maiseys. (fn. 197) All three families remained in the hamlet in the 17th century, and were among a group of about a dozen yeoman farmers leasing the recently created 'farmerships'. (fn. 198) The Maiseys were particularly numerous: six members of the family swore the obligatory protestation oath in 1642, and with other local people witnessed many of their neighbour's wills and inventories. (fn. 199) John Maisey (d. 1689) leased land from the lord of the manor and two other local landowners (the Keebles and Trinders), but his dealings extended to many other local villages, as indicated by debts owed to people in Alvescot, Bampton, Chimney, Kelmscott, and Langford. (fn. 200)

Many of Grafton's 17th-century inhabitants enjoyed moderate prosperity. In 1665 the hamlet's twelve houses were assessed on between one and four hearths, suggesting relatively modest buildings, (fn. 201) while the median value of thirty surviving inventories was only around £60. Even so, a few individuals possessed considerably greater wealth. John Symes (d. 1670) occupied a house with four hearths (one of only two in the hamlet), and left an estate worth the unusually large sum of £745 10s., including £120-worth of sown crops, room furnishings worth more than £50, and a set of pewter worth more than £4. He was clearly a successful farmer who lived in some comfort, though the value of his inventory was inflated by the inclusion of two leases in Grafton and Langford worth £210. (fn. 202) By contrast Robert Broad (d. 1667), who had only one hearth, lived more frugally, leaving goods worth around £13 of which many were described as old and poor. (fn. 203) Some other inhabitants neither paid taxes nor made wills, and were presumably even less well off. Examples include the Jones family of labourers in the 1690s–1700s, two farm workers in dispute with a shoemaker from Highworth (Wilts.) in 1691, and the two sons of 'some outsider' born in 1637–8. (fn. 204)

Grafton was apparently little affected by the Civil War, despite its ownership by a Parliamentarian family (the Pyes of Faringdon) and its proximity to fighting at Radcot. (fn. 205) Like their predecessors, the Pyes were absentee landlords: Sir Robert (d. 1662) made no mention of the township in his will, and his son, too, seems to have paid the manor scant attention. (fn. 206) Their successors the Wainewrights were also non-resident, working in London as Chancery clerks. (fn. 207) Nevertheless they took careful oversight of the estate, commissioning a series of rentals and surveys during the 18th century. (fn. 208) Once again leadership in the township devolved upon half a dozen or more yeoman families including the Mays, Savorys, Sindreys, and Yeatmans, of whom some aspired to gentry status; such people occupied local offices, gave money to the poor, voted in elections, and purchased land in Grafton and elsewhere. (fn. 209) Many were newcomers who had bought or leased one of the Grafton farmerships, and consequently had wide connections. The Pawlings, for example, came from Shellingford (formerly Berks.) about six miles away, while the Savorys were a Gloucestershire family from Bibury and Fairford, around 7–10 miles from Grafton. (fn. 210)

The 19th and 20th Centuries

Little social change seems to have followed inclosure in 1846 or the sale of the manor to Christ Church, Oxford, in 1867. Population remained relatively stable, and in 1851 more than half the inhabitants had been born in the township, while most others were from nearby places such as Clanfield, Filkins, and Langford. (fn. 211) Opportunities were limited, however, and many younger people may have moved away to marry or to find alternative employment; William Tayler (d. 1892) of Grafton Green Farm, for instance, left the hamlet to enter service in London. (fn. 212) Social stability remained strong in 1871 when over half the population was still native to the township, although many of the domestic servants who were increasingly employed by local farmers came from outside the immediate area. (fn. 213) Change was more evident by 1891 when only a quarter of people had been born in the hamlet, (fn. 214) and during the following decade the community was transformed, with many long-standing inhabitants presumably leaving because of agricultural depression. In 1901 only a tenth of inhabitants had been born in Grafton, the rest coming from the Wychwood area, the Vale of the White Horse, and other places in Oxfordshire, Berkshire, and elsewhere. (fn. 215)

Community activities are not well documented. A 2½-a. recreation ground on Cowleaze Common was granted to the churchwardens and overseers before inclosure 'as a place of exercise' for the inhabitants, (fn. 216) but no village hall or public houses were opened, and inhabitants presumably relied on facilities in Radcot, Langford, or Clanfield. (fn. 217) They probably also attended parish events at Langford, such as the jubilee celebrations held there in 1887. (fn. 218) Harvest suppers were held at Grafton into the 20th century, and were remembered by a former resident to be 'the one time when the whole of the farming community really got together for a good time'. (fn. 219) But as the number of farms fell the population gradually drifted from the land, (fn. 220) and Grafton's farmhouses were converted into desirable private residences. From the 1960s villagers increasingly worked in professional occupations outside the township, although a significant farming element remained. (fn. 221)

Education, Charities and Poor Relief

No school was established at Grafton, and from the 19th century most children (13 in 1871) attended Langford school some 1¾ miles away. The school remained open in 2011. (fn. 222)

Grafton's poor were among those remembered by Mary Prunes (d. 1610) of Langford, and the township may have benefited from other 17th and 18th-century bequests to Langford parish. (fn. 223) Francis Broderwick (d. 1635), lessee of Langford Manor prebend, leased one of Grafton's farmerships from Sir Robert Pye, and left 3s. 4d. to the township's poor. (fn. 224) Among Grafton's resident families, those of Maisey, Prince, Savory, Sindrey, Symes, and Yeatman left one-off sums to the poor ranging from 5s. to £1. (fn. 225) Their bequests, however, often extended beyond the township, indicating the range of their social and family networks. (fn. 226) Grafton lacked any endowed charities, and by the late 18th century the cost of poor relief was met almost entirely from the township's rates.

Annual spending on the poor was around £26 in the 1770s and 1780s, rising in line with national trends to more than £46 in 1803 (see Table 2). Nine people (including 2 young children) were then receiving regular out-relief, about 14 per cent of the population, (fn. 227) and the number rose to twelve in 1813 when annual expenditure was £104, or 30s. per head of population. In 1814–17 spending fell, but increased still further in 1819–21 to around 35s. per head, a relatively high figure for the area, representing a total outlay of more than £140 a year. (fn. 228) Thereafter, as agriculture recovered and population declined, expenditure fell to around £96 in 1824–5. Further fluctuations saw a peak of £130 in 1826–8, followed by a fall to £80 (22s. per head) in 1831. (fn. 229) From 1834, formal responsibility for Grafton's poor passed to the new Faringdon poor-law union. (fn. 230)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

Parochial Organization and Tithes

From the Middle Ages Grafton was served from the parish church at Langford. (fn. 231) Unlike the neighbouring chapelries of Little Faringdon and Radcot it had no dependent chapel, probably because Grafton's non-resident medieval lords saw no need to build one. (fn. 232) The rector collected all the township's tithes until 1277, when the small tithes were given to Langford vicarage, and from the later Middle Ages the vicar received Grafton's grain tithes as well. Over all, Grafton's tithes probably made up most of the vicarage's annual value of £60 in 1650, and in 1840 the tithes were commuted for an annual rent-charge of £115. Grafton's hay tithes remained with the rector, and in the early 19th century, when they were collected from 100 a. of meadow, they were worth £22 10s. a year or 4s. 6d. per acre. They were commuted in 1840 for an annual rent-charge of £29. (fn. 233)

In 1960 that part of the township south of the Lechlade road was transferred to Clanfield ecclesiastical parish, along with Radcot. The rest (including Grafton village) remained part of Langford parish, with which it was incorporated into ever larger benefices in the late 20th century. (fn. 234)

Pastoral Care and Religious Life

In the Middle Ages Grafton's inhabitants may have attended Radcot chapel, which probably had baptismal (though not burial) rights. (fn. 235) By the 16th century, however, many were baptized and buried at Langford, where some (particularly in the 17th century) specifically requested burial. (fn. 236) Among them were Richard Cox (d. 1638) and Henry Keeble (d. 1649), who each left 3s. 4d. to the church, while Agnes Cox (d. 1614) asked to be buried in the church near her husband. (fn. 237) Others apparently attended Clanfield church, where Richard May (d. 1649) asked to be buried, although he also left 10s. to the church at Langford. (fn. 238)

Grafton's church rates in the 17th century varied from 4d. to 2s. per yardland and were levied once or twice a year. (fn. 239) In 1664 Grafton's inhabitants collectively refused to contribute to the repair of Langford's churchyard fence, (fn. 240) as part of a wider dispute which was settled in 1669, when it was agreed that the township should pay only three eighths of Langford's contribution. (fn. 241) Difficulties in collecting money persisted into the 18th century: in 1723 the churchwardens presented Sarah Joys 'for not paying the minister his dues', while in 1732 Aaron Pawling was two years in arrears. (fn. 242) Part of the reason may have been attendance at other churches. Pawling (said to be 'of Little Clanfield') may have attended Clanfield church, and the same may have been true of some other villagers presented for refusing to 'come to prayers and services'. (fn. 243)

Despite these tensions, several Grafton men served as churchwardens for Langford in the 17th and 18th century. Of those Thomas Prince (d. 1623) left 6s. 8d. to Langford church, and a piece of gold worth 11s. for 'some good man to preach at my burial'. (fn. 244) In the early 17th century Grafton's inhabitants were drawn into a dispute over seating in Langford church, although a seat 'erected by Grafton men, who have since enjoyed the same' does not appear to have been particularly contentious. (fn. 245) Thomas Sindrey (d. 1686) of Grafton erected a seat near the chancel for himself and his family. (fn. 246)

Grafton experienced little if any early Dissent or Roman Catholic recusancy. (fn. 247) As in Langford, however, Primitive Methodism spread to the township in the early 1840s when there were up to 14 adherents, many of them agricultural labourers. (fn. 248) Early meetings probably took place at the Watts family's Chapel Farm, where Mr Watts or a travelling preacher often delivered the sermon; a purpose-built chapel (Fig. 68) was erected opposite in 1870. (fn. 249) In the early 20th century the chapel's trustees were drawn from a wide area including Black Bourton, Faringdon, Filkins, Kelmscott, Langford, and Elsfield near Oxford, where two members of the Watts family then lived. (fn. 250)

68. The much altered former Primitive Methodist chapel at Chapel Farm, built in 1870 and closed c. 1950. Primitive Methodism was established in Grafton from the 1840s.

Francis Lémann (vicar of Langford 1855–85) was generally unperturbed by the level of Dissent in the parish, and did not mention Grafton's chapel in his visitation returns, although he requested a curate to cover all three townships. (fn. 251) His successor Edmond Walters (1885–92), by contrast, blamed Nonconformists for 'a considerable amount of schism', and perhaps in response held regular services in an unlicensed room at Grafton. (fn. 252) Constantine Wodehouse (vicar 1892–1910) held monthly evensong with a sermon in Grafton's 'mission room', although the services may have ceased before his retirement and were not resumed. (fn. 253) Despite these initiatives Primitive Methodism in the township remained vibrant, and in 1915 there were three resident preachers and 20 members, one of the largest groups in the circuit. (fn. 254) Thereafter support seems to have dwindled, perhaps as key families moved away. Membership shrank from 6 in 1931 to 3 in 1947, and soon after the chapel was converted to private use. (fn. 255) In the 20th century, as earlier, most inhabitants attended the churches at Langford or Clanfield, at least for baptisms, marriages, and burials. (fn. 256)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Manor Courts and Officers

Manor courts for Grafton were presumably held from the Middle Ages, although as some lords held neighbouring manors the courts may sometimes have met outside the township. Tenants in the 13th and 14th centuries perhaps attended the Besyleses' court at Radcot, while in the earlier 17th century they may have attended Sir Robert Pye's Great Faringdon manor court. (fn. 257) By the early 18th century they expressly owed suit to Grafton manor court, and were to 'keep any orders ordained'; in 1718 the new lords were entitled to invoke existing 'remedies' at the court in the event of 'non-performance of tenant's duties', (fn. 258) and suit of court remained an obligation throughout the 18th century. (fn. 259) In 1852 Arnold Wainewright was said to hold a court leet at the 'manor house', presumably Manor Farm, which he was then leasing to William Akerman. (fn. 260) Grafton had two constables in 1377 (fn. 261) and at least one in 1642, elected presumably in the manor court, (fn. 262) while William May, the owner of Poplar farm, was constable in 1853. (fn. 263)

Tenants of the Knights Hospitallers' Grafton estate attended the court baron and view of frankpledge held at Clanfield. (fn. 264) In the 16th century they elected a tithingman at the Friars Court view and manor court in Clanfield, who paid 1d. in certainty money. (fn. 265) The township continued to be represented there in the 17th and 18th centuries. (fn. 266)

Parish Government and Officers

Grafton remained part of Oxfordshire despite being a township of Langford, and from the 14th century it was often taxed with Radcot, Clanfield, or Kelmscott. (fn. 267) It seems never to have appointed its own churchwardens, although from the 17th century a number of villagers (elected presumably by Langford vestry) served as churchwarden at Langford. (fn. 268) By the 17th century it did, however, appoint its own overseer and seems to have administered its own poor relief, (fn. 269) and in the 19th century the overseer held ½ a. of land adjoining the Langford road, which presumably supplemented the poor rates. (fn. 270) The township's recreation ground, established before inclosure, was intended to benefit the whole parish, and was consequently put under the control of Langford's parish officers, although Grafton's overseer may also have shared responsibility. (fn. 271) The office continued in the 19th century after the establishment of Faringdon poor-law union, when the township contributed some two fifths of the parish vestry rate levied for 'repair of the church and ... other expenses'. Presumably such matters were also handled by the overseer, as Grafton's only parish officer. (fn. 272)

From 1866 Grafton became a separate civil parish until its unification with Radcot in 1932, (fn. 273) and under the 1894 Local Government Act it became part of the newly formed Witney rural district, entitled to elect one district councillor jointly with Radcot. (fn. 274) From 1974 it was included in West Oxfordshire district. (fn. 275)