A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Langford Parish: Little Faringdon', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp209-233 [accessed 2 February 2025].

'Langford Parish: Little Faringdon', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online, accessed February 2, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp209-233.

"Langford Parish: Little Faringdon". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online. Web. 2 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp209-233.

In this section

LITTLE FARINGDON TOWNSHIP

The small, limestone-built village of Little Faringdon lies close to the Gloucestershire border on flat, lowlying ground watered by the river Leach. (fn. 1) Until the 20th century most inhabitants were employed in agriculture, the nearest towns lying 1½ miles (2.5 km) south-west at Lechlade (Glos.) and 6½ miles (10.5 km) north at Burford. From the Middle Ages it was in the single ownership of initially distant and then mostly resident lords of the manor, and developed many of the characteristics of a 'closed' village: in the 18th and 19th centuries the squire dominated the economic, social, and religious life of the community, helping to keep the population low and ensuring that few new houses were built. The village's unspoilt and secluded character, and its relatively good-quality buildings, encouraged an influx of wealthy residents in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Little Faringdon was almost certainly named from Great Faringdon (formerly Berks.), with which it had connections by the mid 11th century and possibly earlier. (fn. 2) Until 19th-century reorganization it remained a township and chapelry of Langford, with which relations particularly over church matters were sometimes strained. Like Langford, Little Faringdon was included in the Berkshire hundred of Faringdon from the 13th century to 1844, when it rejoined Bampton hundred in Oxfordshire. It was created a separate ecclesiastical parish in 1864 and a separate civil parish in 1866. (fn. 3)

Boundaries and Landscape

Little Faringdon's boundaries and acreage (1,167 a. or 473 ha.) were determined in outline by the mid 12th century and possibly earlier, when it first became defined as a separate estate. (fn. 4) The western boundary with Lechlade followed that between Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, which was broadly established by the early 11th century. (fn. 5) For part of its length it follows the river Leach, but at a former minor crossing-place the river divides, the boundary following what was probably the river's original course before it was diverted to feed Little Faringdon and Lechlade mills. From near Little Faringdon mill the boundary follows a straight and artificial-looking ditch just west of the river, bringing meadows on the Lechlade side into Little Faringdon township. (fn. 6) The short southern boundary with Kelmscott follows field divisions, while the long eastern and northern boundary with Langford follows Langford brook to the edge of Whitehill, and then field divisions to a pre-inclosure road (later bridleway) to Lemhill, which it follows the short distance to the Leach. (fn. 7) The township's boundaries remained unaltered in 2001. (fn. 8)

The land rises gradually from 74 m. on the Kelmscott boundary to 81 m. around the village, reaching 93 m. at Whitehill on the eastern boundary with Langford. The village occupies an outcrop of sandy limestone gravel of the Third (Wolvercote) Terrace, entirely surrounded by underlying Oxford clay; the clay extends towards the flat, low-lying ground in the south of the township, which lies chiefly on gravels of the Second (Summertown-Radley) Terrace. Pockets of gravel, tufa, and Kellaways Sand lie in the north of the township near Common Barn Farm, while a small outcrop of Third (Wolvercote) Terrace is occupied by the preinclosure Hulse Grounds Farm near Whitehill. (fn. 9) Soils of both gravel and clay were ploughed, as reflected in 19th-century field names such as 'the Sands' and 'Long Clay'. A band of alluvium along the river Leach, and a narrower band along Langford brook, provided meadow and pasture. (fn. 10)

Some 50 a. of partly wooded grounds were laid out around the 17th-century manor house (known later as Langford or Little Faringdon House), and in the 19th century lords of the manor created several woodland plantations, partly for fox-hunting. (fn. 11) In the mid 20th century large-scale gravel extraction transformed the landscape west of the Leach along the Gloucestershire border; the pits were later converted into artificial lakes, and used for recreational fishing. (fn. 12) The river and streams provided the village and farms with a good water supply, but were liable to flood in winter. (fn. 13)

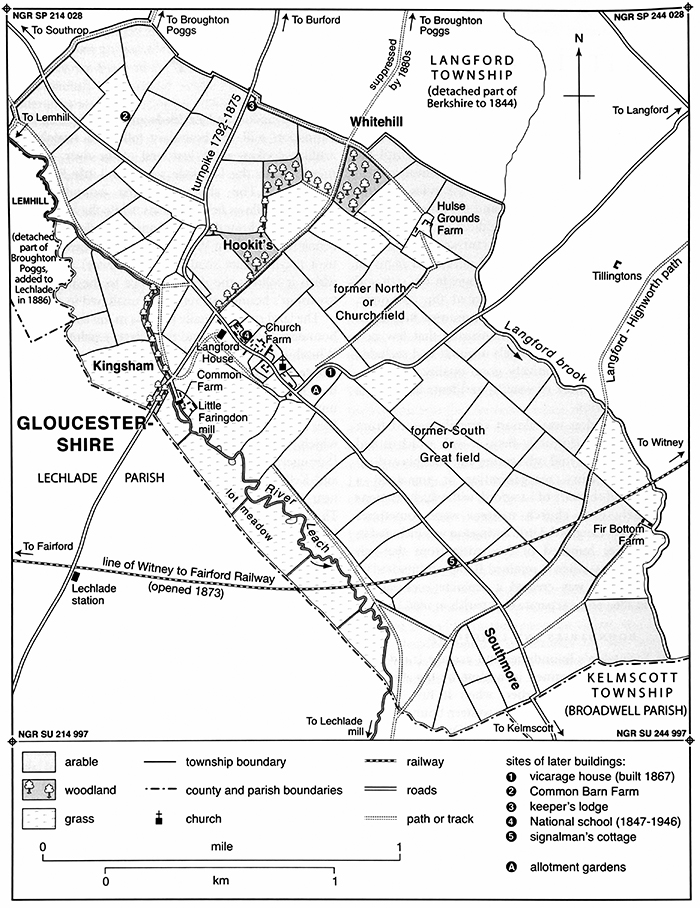

59. Little Faringdon township in 1840, showing land use, boundaries, and some later buildings.

Communications

Roads

The village lies at a former crossroads, where the main Lechlade–Burford road intersected roads to Kelmscott and Broughton Poggs (Figs 2, 59, and 60). The settlement itself developed mainly along the road south-eastwards to Kelmscott. (fn. 14) At inclosure in 1788 that part of the Lechlade–Burford road passing through the township was widened to 50 feet (including verges) because of its 'founderous state'; (fn. 15) it was turnpiked in 1792, and in the 1960s it was diverted to remove a sharp right-angled bend where it skirted the north end of the village. (fn. 16) The turnpike road took traffic from the alternative north-eastwards route to Broughton Poggs and Filkins, which in 1788 was only four feet wide. (fn. 17) That road dwindled further when the turnpike was diverted away from the manor house in the mid 19th century, and by the 1880s its continuation through Langford was stopped. (fn. 18)

The village is thus bypassed by the present Lechlade–Burford road (the A361), and lies on what is now a minor side-road to Kelmscott. Two other roads pass through the township. The road from Langford, mentioned in 1307, (fn. 19) meets the Kelmscott road on the eastern edge of the village, and in 1788 was also made 50 feet wide because of its liability to flood. The road to Southrop (Glos.), made 40 feet wide in 1788, branches from the Lechlade–Burford road. (fn. 20)

No roads or paths were suppressed at inclosure, though an objection (later withdrawn) was made to the road along the township boundary from Lemhill to Broughton Poggs. (fn. 21) Half a dozen public footpaths and bridleways were listed in 1788, of which most survived in the mid 20th century; those subsequently suppressed included part of an ancient footpath from Langford to Highworth (Wilts.), which was diverted along Langford brook and the disused Witney–Fairford railway line. (fn. 22)

Carriers, Rail, and Post

No village-based carriers were recorded, though 18th-century overseers of the poor hired carriers on an ad hoc basis, (fn. 23) and presumably regular traffic passed through the township on the Lechlade–Burford road. Lechlade station, opened in 1873 on the East Gloucestershire Railway from Witney to Fairford, lay less than a mile from Little Faringdon, and the line passed through the township's southern part. A level-crossing and keeper's cottage were built where it crossed the road to Kelmscott. (fn. 24) Following the line's closure in 1962 regular bus services linked the village to Carterton, Lechlade, and Swindon, and continued in 2010. Post was delivered from Lechlade in the 19th century, and from the 1870s a village letter box was located at the junction with the Lechlade–Burford road. (fn. 25)

Settlement and Population

Early Settlement

Evidence of prehistoric settlement is concentrated on the river gravels in the south of the township. Although largely undated, two areas of scheduled cropmarks and similar features nearby include possible remains of Neolithic, Bronze-Age, Iron-Age, and Roman settlement and farming. (fn. 26) Particularly notable is a group of up to 20 round enclosures, most with entrances, bounded on the east by Langford brook. (fn. 27)

No archaeological evidence for Anglo-Saxon settlement has yet been found, and as the Domesday description of Little Faringdon is concealed under other headings nothing is known of the 11th-century population. Given the scale of late Anglo-Saxon settlement elsewhere in the parish it seems unlikely that Little Faringdon was uncolonized, however, and some medieval field names, including 'Hangynde-londe' ('land on a hillside') and 'Lexslade' ('salmon ground'), may be of Anglo-Saxon origin, suggesting both settlement and farming. (fn. 28) The place name 'Faringdon' means 'fern-covered hill', which could conceivably apply to Whitehill north-east of the village. However, the settlement was almost certainly named from Great Faringdon in Berkshire, with which, by the late 11th century, it had close tenurial connections as part of a large composite estate which straddled the river Thames. (fn. 29)

Population from 1086

Some of the tenant households recorded on Langford or Faringdon manors in 1086 may have been at Little Faringdon, but if so their numbers are unknown. (fn. 30) Twelve landholders in the township were taxed in 1327, and 16 in 1332; each presumably represented a household, and since more customary holdings were being created in the late 13th and early 14th century tenant numbers must have been rising. (fn. 31) Poll tax in 1381 was paid by 42 adults aged over 14 (comprising some 17 families or households), (fn. 32) suggesting that depopulation during the Black Death was relatively limited. Even so ruined houses were reported in the 15th century, and though tenants in the 1460s and 1470s obeyed orders to repair buildings, (fn. 33) the continued amalgamation of once separate holdings suggests that population remained below its early 14th-century peak in the 1520s and 1540s, when 14 or 15 taxpayers were recorded including labourers. (fn. 34) In 1662 nineteen households paid hearth tax and three others were excused through poverty, (fn. 35) while in 1716 some 21 landholders (not all necessarily resident) paid land tax. (fn. 36) Baptisms generally exceeded burials in the 17th and 18th centuries, the number of baptisms increasing from an annual average of around 2.5 in the early 18th century to nearly 3.5 at its close. (fn. 37)

In 1801 there were 24 houses and a population of 131, which rose to a peak of 185 (accommodated in 38 houses) in 1851. Thereafter population declined presumably because of agricultural depression, and by 1901 there were only 126 inhabitants and 30 houses, three of them unoccupied. Until the 1950s the population remained fairly stable, but then again began to fall: slowly at first, and then more rapidly, reaching 61 (in 25 houses) in 1971. Stability returned in the late 20th century, and in 2001 there were 63 inhabitants. (fn. 38)

Little Faringdon Village

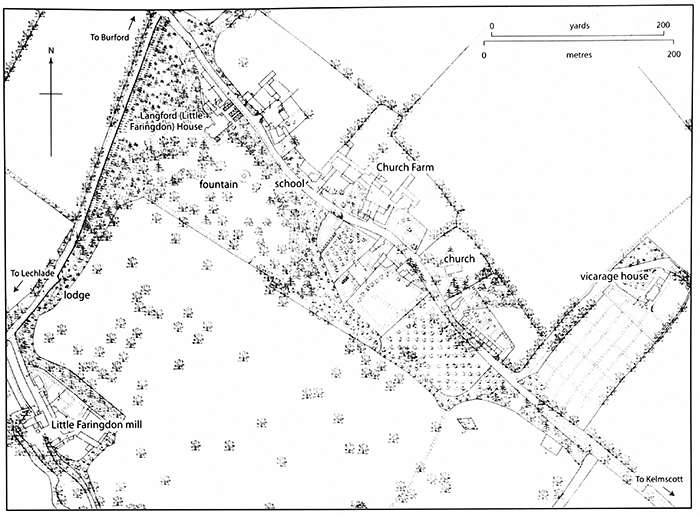

The village (Figs 59–60) developed as a regular row, 500 m. long, on the north side of the Kelmscott road, between the junctions with the Langford and Lechlade–Burford roads. Settlement may have spread out from the 12th-century chapel, (fn. 39) and in 1840 included an early 18th-century farmhouse and several rows of workers' cottages. The post-medieval manor house (Langford or Little Faringdon House) lies at the village's northern end on the southern side of the Kelmscott road, in an area which was exclusively the preserve of the lord of the manor: in 1840 only a few workers' cottages lay nearby, immediately to the south-east. During the 19th century the house was substantially enlarged and partly gothicized, and a long high wall along the street still screens it from the rest of the village. (fn. 40) A vicarage house was built on the east side of the road to Langford in 1867, and in the 20th century another house was built to its south. (fn. 41) Existing houses were restored and extended in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, though little new building took place.

Until the 20th century Little Faringdon remained an estate village: in 1901 eighteen of the 30 houses recorded were workers' cottages owned by Baron de Mauley, and in 1910 almost the entire housing stock was owned by the lord of the manor. (fn. 42) The surviving houses all seem to be post-medieval (16th to 20th-century), and as elsewhere in the area most are of traditional stone and slate. (fn. 43) The small number of more substantial houses lie along the village street north-west of the church, many of them converted from former farm, estate, and public buildings including the 19th-century school. To the south-east are the smaller and more numerous former estate cottages, including a row of eleven between the church and the road to Langford. Built of stone and slate in groups of two or three, the present row (Fig. 61) dates probably from the early 20th century, replacing earlier terraces shown on 19th-century maps. (fn. 44) A few other cottages lie to the west of Church Farm, or within the grounds of Langford House; the latter include the early 19th-century Gardener's Cottage, which in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was occupied by Baron de Mauley's head gardener William Hobbs. (fn. 45) Despite its name the building is a substantial two-storeyed house with twin attic gables and a central porch, built of roughly coursed and dressed limestone rubble with stone quoins and red brick dressings. (fn. 46) Another cottage, vacant in 1901, was demolished soon afterwards, its site incorporated into the grounds of Church Farm. (fn. 47)

Church Farm itself (separated from most of its land in 2004) is the only surviving farmhouse in the centre of the village. Built in the early 18th century at a time of growing prosperity, it is of uncoursed limestone rubble with stone-slated roofs, has two storeys with attics, and before later alterations and additions was L-shaped in plan. Extensive outbuildings suggest a considerable farming operation, and include a mid to late 18th-century barn of five bays, built of stone and slate with a collar and tie-beam roof. (fn. 48)

60. Little Faringdon village in 1876, showing key buildings.

Outlying Sites

From the Middle Ages a watermill occupied the site of the present Little Faringdon mill beside the river Leach, about 400 m. south-west of the manor house. (fn. 49) A medieval ditch and pit found in the field between the mill and manor house may indicate an area of settlement which was later abandoned, (fn. 50) and other evidence of medieval occupation has been recovered closer to the Leach. (fn. 51)

The surviving mill house, which straddles the mill race, was rebuilt in the mid to late 18th century, incorporating parts of an earlier building (Fig. 63). The single-storeyed main range, of stone and slate, has attics lit by gabled eaves dormers, and is linked to the three-storey mill, which includes surviving 19th-century mill-work. (fn. 52) On the river's north bank is a late 16th-century farmhouse (Common Farm) and an early 19th-century cottage, both built in traditional vernacular style. The quality of the building work at Common Farm, particularly the use of ashlar in the mid 18th-century extension, reflects the prosperity enjoyed by a number of Little Faringdon's farmers around that time. (fn. 53)

In the 18th century (but before inclosure in 1788) Hulse Grounds Farm was built in the north-east of the township near Whitehill. The two-storey main range, with gabled cross-wings, originally included a bread oven, while one of the outbuildings was formerly a dairy. (fn. 54) In the early 19th century a labourer's cottage called Fir Bottom Farm (now demolished) was built in an isolated location by Langford brook, while around the 1870s a house called Common Barn Farm was built along the road to Southrop, and later extended. (fn. 55) From the mid 19th century the lord's gamekeeper occupied a lodge alongside the Lechlade–Burford road (later moved to a different site), (fn. 56) and around 1873 a signalman's cottage was built beside the level-crossing on the road to Kelmscott. (fn. 57)

61. Looking north-west along Little Faringdon's main street, with terraces of former estate cottages on the right, and Gardener's Cottage just visible in the distance.

MANOR

In the late Anglo-Saxon period Little Faringdon formed part of a large royal or comital estate which included Langford and Broadwell (Fig. 1), and by the mid 11th century if not earlier it was held with Langford and Great Faringdon. (fn. 58) A separate manor of Little Faringdon was created before 1156, when the Crown is first known to have leased it independently; the arrangement may, however, have had earlier origins, as the Langford estate gradually became fragmented. Like its successor, the 12th-century estate presumably encompassed the whole of Little Faringdon township. (fn. 59)

From 1156 to 1173 the Crown's lessee was Ralph of Worcester (paying £16 10s. a year), (fn. 60) and from 1190 Arnulf de Mandeville (at an annual rent of £5). (fn. 61) The discrepancy in rent may indicate that Ralph's lease included part of Langford as well. Arnulf's interest was probably ended by King John, who in 1203 granted the manor to the community of Cistercians which he established at Great Faringdon. The monks retained Little Faringdon after their move to Beaulieu in the New Forest in 1204, and the manor remained their property until the Dissolution in 1538. (fn. 62) In 1351 it was probably included in their 15-year lease of Great Faringdon to William Wykeham, bishop of Winchester. (fn. 63) Manor courts were held by the 14th century and probably earlier. (fn. 64)

After the Dissolution the manor was leased to Thomas Moores of Great Coxwell (then Berks.), who was a former lessee of Beaulieu's demesne farm and who paid tax in the township in 1540. (fn. 65) Thomas and his son James bought it from the Crown in 1545 for £330. (fn. 66) In 1578 James settled it on his son Thomas with contingent remainders to other family members, (fn. 67) who together sold the manor in 1588 to William Bourchier of Barnsley (Glos.). (fn. 68) From William (d. 1623) the manor passed through the male line (with Barnsley) to Walter (d. 1648), William (d. 1693), and Brereton (d. 1714). (fn. 69) In 1719 Brereton's daughter and heir Martha married Henry Perrott of North Leigh, who was succeeded at his death in 1740 by his daughters Martha (d. 1773) and Cassandra (d. 1778). (fn. 70)

Cassandra Perrott devised the manor to her relative James Musgrave, who inherited a baronetcy on a cousin's death in 1812. (fn. 71) Sir James (d. 1814) was succeeded by his son Sir James (d. 1858), who sold the manor in 1831 to William Vizard (d. 1859), a distinguished lawyer. (fn. 72) Little Faringdon was sold by Vizard's widow and daughters to Charles Frederick Ashley Cooper Ponsonby (d. 1896), 2nd Baron de Mauley of Canford (Dorset), from whom the manor passed to his sons William (d. 1918) and Maurice (d. 1945). They were followed by Maurice's son Hubert (d. 1962) and grandson Gerald, the 6th baron, who died childless in 2002 and was succeeded in the title by his nephew Rupert Charles Ponsonby. (fn. 73) Much of the estate passed with Little Faringdon House (below) to J. Abdy Collins, son of the 6th baron's wife by a previous marriage, and over the following few years was substantially broken up. Nonetheless in 2012 the de Mauleys retained nearly 500 a. in the parish, including Common Barn, Hulse Ground, and Common farms, and part of Church farm. (fn. 74)

Manor House (Little Faringdon House)

The manor house in the 1840s and presumably earlier was Little Faringdon House (known formerly as Langford House) at the village's north-west end. (fn. 75) Set in extensive grounds, it remains distinct from the rest of the village and from the former tenant housing on the road's opposite side. The arrangement may reflect the medieval layout, since Beaulieu abbey presumably maintained premises for its demesne farm either at Langford or at Little Faringdon. (fn. 76) From the mid 16th century to the mid 17th members of the Moores and Bourchier families probably lived at least partly in Little Faringdon, and though the house seems to have been leased for much of the following century and a half, from the 1830s it was substantially enlarged by the resident Vizards and by their successors the Ponsonbys, Barons de Mauley. (fn. 77) After 2002 it passed to the Abdy Collinses, who lived there from 2004 and sold it in 2010. (fn. 78)

The earliest surviving part is a two-bayed fragment of a probably 17th-century house, embedded in the midst of 19th-century additions which together form a T-plan (Figs 60 and 62). (fn. 79) Two-storeyed with attic gables and built of coursed limestone rubble, the 17th-century part seems originally to have extended further north-west (fn. 80) and possibly south and east, while a cellar under the later south-west block retains fragments of a newel stair, and may formerly have belonged to a lost 17th-century service range. (fn. 81) In 1662 the house appears to have been taxed on seven hearths, (fn. 82) and re-used 17th-century panelling in the present entrance hall came presumably from this phase of the building.

Substantial additions and alterations were made around 1830, most likely after William Vizard bought the manor in 1831. A large, square, double-pile residential block was added on the south-west, built of ashlar and embellished with battlemented single- and two-storeyed bay windows (Fig. 62). (fn. 83) A probably contemporary gothic-style conservatory projects south-eastwards, while a single-storeyed skirt around the block's north and west sides, incorporating a battlemented porch, was probably a slightly later addition. (fn. 84) North-west of the 17th-century range, a slightly higher two-bayed service range was added around the same time, its heated ground floor probably incorporating a servants' hall. (fn. 85) Contemporary remodellings of the house's earlier part included addition of a battlemented oriel window and the opening up of the attic rooms, lit by new round-headed casements with gothic detailing. (fn. 86)

62. Little Faringdon (formerly Langford) House from the south-east, showing the battlemented block of c. 1831 (left) and that of 1876 (right). The house's 17th-century core lies behind, abutting 19th-century service ranges.

Further additions were made for the 2nd Baron de Mauley in 1876, (fn. 87) when the south-east front was squared up by the addition of another large twin-gabled block with a battlemented ground-floor bay window, adjoining a new service range running north-eastwards towards the road. The new work was characterized by ball finials on the gables, and incorporated a new main staircase lit by a tall, eastward-facing window filled with coloured glass. Two small single-storey additions to the new service range were made in the early 20th century, (fn. 88) and a small single-storey kitchen with battlements, stone mullions and hoodmoulds was added in the south-east angle c. 2005. A major refurbishment by new owners was underway in 2011.

A long, five-gabled stable range north-west of the house, closing off the premises from the road, was probably added by Vizard in the 1830s, and includes a clock surmounted by a pedimented bellcote decorated with a quatrefoil. Some of its stable boxes remained in 2011. A cottage at the range's north-west end was added before 1876. (fn. 89)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until the 20th century agriculture remained the main source of employment in Little Faringdon. In the Middle Ages most of Beaulieu abbey's customary tenants probably held sufficient land to support their families, although there must have been some smallholders or landless labourers willing to work for wages. From the 16th century wage labourers were more evident, and presumably worked on the lord's farm and on those of local copyholders. Land was consolidated into fewer and larger farms before parliamentary inclosure, when four principal farms remained. From the Middle Ages grain, wool, and dairy produce were the most important products.

A water-powered corn-grist mill operated on the river Leach from the 13th to the 20th century, while another for fulling cloth opened in the late 13th and closed in the late 17th or early 18th century. Apart from milling, few trades and crafts were practised in the township, most residents travelling to neighbouring villages or nearby market towns for their purchases. In the 20th century, as agricultural employment declined, Little Faringdon's population increasingly worked outside the village, although some businesses, including a trout farm on the Leach, continued in the early 21st century.

The Agricultural Landscape

Despite the township's small size, Little Faringdon's varied landscape provided a range of agricultural resources (Fig. 59). The rivers and streams ensured a good water supply, and produced fish and valuable meadow and pasture. Furze was available on the higher ground in the north-east, and in the absence of woodland provided fuel and rough grazing. Small 19th-century plantations of woodland were the exclusive preserve of the lord of the manor. The open fields, laid out perhaps in the 9th or 10th century, were inclosed in 1788, though inclosure of meadow and pasture took place from the 13th century and possibly earlier. In particular an area of old inclosure on Whitehill, called Hulse (i.e. hill) Grounds, bordered a similar area at Tillingtons in Langford, and may have been inclosed from the early Middle Ages. (fn. 90) Farming was mixed as at Langford, combining large-scale grain cultivation with sheep husbandry and cattle-based dairying.

Arable

By the 13th century Little Faringdon's open-field arable lay in two large fields called North and South fields, divided by the road to Langford. North field was the larger of the two, probably extending by the mid 13th century to the township's northern and eastern boundaries. At that date it included 228 a. of demesne, and 9 yardlands held by tenants; in South field the demesne measured 155 a., and there were 7 tenant yardlands. Demesne and tenant land was most likely intermixed. (fn. 91) In 1220 Little Faringdon was assessed for taxation at 12 ploughs or ploughlands (roughly 50 yardlands), and paid £1 4s. 8d. (fn. 92) The arable was almost certainly extended later, and in the late 13th and early 14th centuries Beaulieu abbey created additional customary holdings. (fn. 93)

Some arable was inclosed before the Act of 1788, especially around Whitehill. (fn. 94) Most, however, remained divided between Church (formerly North) and Great (formerly South) fields, (fn. 95) which were presumably subdivided for cropping. By 1840 around 70 per cent of the township was arable, and most farmers followed a four-course rotation of (1) turnips, (2) barley, (3) beans, clover or fallow, and (4) wheat. (fn. 96) Arable still accounted for 60 per cent in the 1870s, but during the agricultural depression of the late 19th and early 20th centuries much land was laid down to grass. (fn. 97) In 1920 around two fifths of the cultivable area was sown with crops, and in 1941, despite wartime demands, only 34 per cent of the recorded farmland was arable. (fn. 98) That trend was reversed after the Second World War, the area devoted to crops rising from 44 per cent in 1960 to about 60 per cent in 1965–75 and 75 per cent in 1988. (fn. 99)

Meadow and Pasture

In the mid 13th century Beaulieu abbey held about 120 a. of meadow and pasture in four closes called Bradmore, Chalkhurst, Kingsham, and Southmore. (fn. 100) Most probably lay along the river Leach, encompassing Kingsham meadow to the south-west of the village, where Beaulieu abbey's customary tenants were obliged to make hay in return for an allowance of flour, salt, and cheese. (fn. 101) Southmore was an area of pasture near the boundaries with Kelmscott and Lechlade, to which Beaulieu's tenants were allowed access to graze their oxen and other cattle in return for ploughing the demesne. (fn. 102) Common or lot meadow was also available along the Leach, including 3 a. belonging to the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia. (fn. 103) In 1233 the prebendary claimed more extensive grazing rights, arguing that before the grant to Beaulieu abbey the parson of Langford had been entitled to pasture his sheep throughout the township. (fn. 104)

Rights of common grazing in meadow and pasture persisted into the 18th century. (fn. 105) In 1788 areas of common pasture, including plots of furze, lay beside Langford brook and next to the Lechlade–Burford and Langford roads. (fn. 106) Field names in the north-east of the township, including Furzen Knowl and West Green, suggest additional areas of former pasture which were cultivated by 1840, when only about a quarter of the township was under grass; the proportion was increased to two fifths in the 1870s, and rose still further during the agricultural depression. (fn. 107) By 1920 around three fifths of the cultivable area was meadow and pasture, while in 1941 about two thirds of the recorded farmland was grass, half of it used for grazing and half for mowing. (fn. 108) In the 1960s the acreage under grass, especially meadow, fell sharply, and in 1988 grass covered less than a fifth of the cultivated area. (fn. 109)

Woodland

Woodland was probably rare in Little Faringdon before the 19th century. (fn. 110) Mention of 49 a. in 1801 may be doubted, since a map of 1828 showed only a 6-a. wood called Hookit's. (fn. 111) The name probably recalls the medieval Hoket family, customary tenants in the 13th and 14th centuries; (fn. 112) if so this shows remarkable continuity in the use of a field name, perhaps because it represented the township's only available woodland.

In 1840 around 21 a. of wood was recorded, most of it in plantations presumably created by William Vizard as coverts for fox-hunting. (fn. 113) Vizard employed a game-keeper who lived in a purpose-built keeper's lodge outside the village, a practice continued by his de Mauley successors. (fn. 114) Further plantations were added by 1877 when woodland covered 32 acres; (fn. 115) most of it lay near Whitehill or in the grounds of Langford House, and increased from 54 a. in 1975 to 66 a. in 1988. The woodland mostly survived in the early 21st century, when the de Mauleys planted another 90–100a. in the same area. (fn. 116)

Medieval Agriculture

Medieval Tenant Farming

In 1269–70 Beaulieu abbey received £2 3s. 4d. in customary rents from Little Faringdon, and a further 6s. 3d. from houses rented annually, possibly by hired workers. (fn. 117) By the late 13th century the abbey's customary tenants included 11 yardlanders and 9 half-yardlanders, who owed the same rents, dues, and labour services as their counterparts in Langford. (fn. 118) The amount of tenant land increased in the following decades, with names such as 'Brokenland' suggesting that some of it was newly cultivated: by the early 14th century 12 tenants held yardlands and 14 held half-yardlands, and in all around 30 tenants paid rents totalling £8 4s. 8d. a year. (fn. 119) Most of the taxpayers named in 1327–32 can be identified among Beaulieu's customary tenants, and like those in Langford their assessed wealth ranged widely, suggesting marked differences in status and prosperity. (fn. 120)

Tenant farming in Little Faringdon probably resembled that practised at Langford, and in 1341 the township was similarly affected by 'exhausted and unsown' arable and high sheep mortality. (fn. 121) In 1346 typical manor court business included an agreement by two tenants over a loan of wheat and barley, the forfeiture by two women of a black ewe each for leyrwite (a fine for illicit fornication), and payments by many tenants for brewing ale. (fn. 122) In the 15th century some tenants took advantage of changing economic and social conditions to abandon their holdings and leave the manor, but others remained willing to hold customary land 'at the will of the lord', to repair dilapidated buildings, and to serve in traditional manorial offices such as hayward (messor). (fn. 123)

Medieval Demesne Farming

In the first decade of its ownership of Little Faringdon, Beaulieu abbey leased its demesne collectively to the villagers. After 1213, however, it took over responsibility for the manor's cultivation, agreeing to share the tithes with the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia. (fn. 124) In 1269–70 the abbey's estate was managed jointly with that of Langford by a reeve; grain production in both townships was strongly commercialized, and the abbey's extensive sheep flock was centrally managed. Dredge accounted for 40 per cent of the seed sown, followed by barley and wheat (about 23 per cent each) and oats (14 per cent). (fn. 125) In 1291 the abbey's lands and rents in the township were valued at £12 16s. 6d., and its crops and stock at £3 18s. 8d. (fn. 126)

By the early 14th century changing cropping strategies had led to the promotion of wheat and barley, which together accounted for some 56 per cent of the seed sown. Next in importance were oats (21 per cent), dredge (15 per cent), and beans (8 per cent). By then the abbey hired many of its workers, including three plough-holders, three plough-drivers, and a carter, while at harvest-time a granger and a cook were also employed. (fn. 127) Demesne farming continued at Little Faringdon until the mid 14th century, when the manor was probably included in a lease to the bishop of Winchester. (fn. 128) A grant of free warren was made to the abbey in 1359. (fn. 129)

The 16th Century to Parliamentary Inclosure

In 1534 the abbey leased the demesne to Thomas Moores of Great Coxwell (then Berks.) for a term of 96 years at an annual rent of £8, which was confirmed by the Crown after the Dissolution. Rents totalling a further £8 were separately collected from ten copyholders and two free tenants. The copyholders held between 1 and 3½ yardlands each, reflecting the amalgamation of what had once been separate holdings; most were held for annual rents of 8s. per yardland. (fn. 130) Fourteen inhabitants were named in the military survey of 1522, and the same number were taxed in 1543, among them eight labourers who were assessed on wages. Presumably the labourers worked on the holdings of their wealthier neighbours. (fn. 131)

The most prosperous inhabitants included the Fisher family, who lived at Little Faringdon from the 16th century to the 18th. Walter Fisher was assessed on £6-worth of goods in 1522 and rented 2½ yardlands in 1540. (fn. 132) His successor Robert Fisher (d. 1574) was a husbandman who left grain and hay worth £10, six oxen worth £12, other cattle worth £4, and pigs and poultry worth almost £2. (fn. 133) In the 17th century the family prospered: John Fisher (d. 1654) had pretensions to gentry status, while Alice Fisher (d. 1687) was taxed on four hearths in 1662, one of the highest assessments in the village. (fn. 134) Until the late 18th century the family regularly filled offices such as overseer of the poor, although it disappeared thereafter. (fn. 135) Among the Fishers' neighbours, Christopher Atterton was less successful. An apparently well-off taxpayer in the late 16th century and holder of 3½ yardlands, he was later obliged to sell his lease in order to repay his debts. (fn. 136)

Prosperous families in the 17th century included the Betts, Fords, Fowlers, and Hearings, members of which all left goods worth over £100. (fn. 137) Debts owed by the husbandman William Ford (d. 1672) show that he bought cloth, shoes, and wood in Burford (where he owned property), grain and pigs in Lechlade, and cloth in Faringdon, and that he had dealings with people in Filkins and Southrop. (fn. 138) In 1662 he was among the two thirds of householders taxed on between two and four hearths, alongside his contemporaries Walter Bett (d. 1682), William Fowler (d. 1669), and William Hearing (d. 1675). Of those taxed on only one hearth, Francis Ford (d. 1679) left possessions worth only £30, while the goods of the blacksmith William Worrall (d. 1667) were worth a mere £27. (fn. 139)

In the 18th century other wealthy inhabitants emerged, among them the yeoman Robert Saunders (d. 1713), who left goods worth more than £300, and his son Robert (d. 1751), a substantial farmer in Gloucestershire who also rented Little Faringdon mill. (fn. 140) The period witnessed a consolidation of farms in Little Faringdon, resulting in a substantial fall in the number of land-tax payers from 21 in 1716 to eight in 1798. (fn. 141) Some families seem to have been adversely affected by the change, and in 1765 Robert Bett and his family were removed by the overseers to Stanford in the Vale (formerly Berks.). (fn. 142)

Despite the changes in tenure, farming remained mixed as in the Middle Ages. The most common winter-sown crop was wheat, while barley was sown in the spring (some of it malted for brewing), and peas and beans were grown for fodder. (fn. 143) Small quantities of hemp may also have been grown, since a number of households owned spinning wheels. (fn. 144) Small dairy herds were commonly kept, although cheese-making was not prominent until after 1650, when stocks of both hard and soft cheese were produced. (fn. 145) Pigs were widely kept, and many households had a store of bacon. (fn. 146) Sheep were initially less ubiquitous, and before 1700 flocks rarely exceeded 50 animals. Robert Saunders (d. 1713) owned a flock of 150 sheep and left wool worth £45, however, reflecting the growing size of farms in the 18th century. (fn. 147) As elsewhere many inhabitants owned ducks, geese and poultry, and some also kept bees. (fn. 148)

Parliamentary Inclosure and Later

Inclosure was carried out under a private Act of 1788, following a petition by the lord of the manor James Musgrave and the vicar of Langford Thomas Clark. (fn. 149) Apart from Musgrave, who received 764 a., awards were made to only two landowners: the vicar received 30 a. for glebe, and the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia was awarded 3 a. of meadow. (fn. 150) Musgrave's lessees in 1788 included Robert and William Godwin, John Lapworth, and William Yells, who together paid more than three quarters of the land tax due in 1798. (fn. 151) All four belonged to established but previously not very prominent local families, which emerged as Little Faringdon's principal tenant farmers during the later 18th century. (fn. 152) William Godwin (d. 1805) occupied Church Farm in the village centre, where his son Thomas Godwin succeeded him and farmed 442 a. in 1840. (fn. 153) Robert Godwin leased Hulse Grounds farm, focused on another early 18th-century farmhouse from which Cornelius Godwin farmed 257 a. in 1840. (fn. 154) Lapworth (d. 1800) and Yells (d. 1850) farmed smaller amounts of land, mostly west of the Lechlade–Burford road. Lapworth may have occupied the late 16th-century Common Farm next to the mill, while Yells farmed land which later belonged to the de Mauleys' Common Barn Farm (built before 1884). (fn. 155)

Further consolidation took place before 1850 when only three principal farms remained, (fn. 156) and by 1910 Church farm (then 618 a.) was leased to the Kelmscott dairy farmer and stock-breeder R. W. Hobbs. Common farm (250 a.) was let to John Roper, and Hulse Grounds farm (99 a.) was held with Whitehill farm (108 a.) in Langford. (fn. 157) By then the township supported a dairy herd of 80 cows and more than 160 other cattle, (fn. 158) reflecting the widespread shift to stock-rearing and milk production encouraged by the late 19th and early 20th-century agricultural depression. Even so, sheep-and-corn husbandry remained important in the township until the eve of the First World War. (fn. 159) Sheep numbers rose from a little over 700 in 1870 to more than 1,100 in 1900, when the principal crops were wheat, oats, barley, and root crops, (fn. 160) and in 1890, when Baron de Mauley leased his small home farm, his livestock included 535 sheep and 40 pigs, compared with only 5 dairy cows and 54 other cattle. (fn. 161) Sheep numbers collapsed after the war, with none remaining in 1930; by contrast cattle numbers increased to over 340, while production of wheat, oats, and barley remained much as earlier. (fn. 162)

Mixed farming with an increased pastoral bias continued in 1941, when tenants occupied four farms owned by the de Mauleys. Church farm (584 a.) was around a third arable, growing mostly wheat and oats, some barley and mixed grains, and fodder crops for a herd of 50 milk cows and 40 other cattle. Common Barn farm (94 a.) had been wholly dairy before the war, but in 1941 the tenant planted a third of the land with oats and fodder crops for the war effort. Hulse Grounds farm (187 a.) was also largely dairy, with only a fifth of its land ploughed; by contrast, Common farm (176 a.) was 50 per cent arable, growing mostly wheat, barley, mixed grains, and oats. All the farms raised poultry, but no sheep were kept. (fn. 163) After the Second World War sheep farming briefly resumed, but during the 1960s numbers of sheep and cattle fell sharply as more land was devoted to barley and wheat. Herds and flocks reappeared in the 1970s, and by 1988 sheep had again replaced cattle as the principal livestock, while wheat was increasingly substituted for barley. The number of farms over 150 a. fell from three in 1960–70 to two thereafter, and some land was sold. (fn. 164)

Rural Trades and Industry

Apart from milling, few trades and crafts are documented in Little Faringdon before the 19th century: presumably inhabitants looked to Lechlade and other towns and villages for goods and services. (fn. 165) Brewers were mentioned in the mid 14th century and a baker in the mid 16th, while William Worrall (d. 1667) was a blacksmith, and Thomas Greenhalf (d. 1777) was a mealman. (fn. 166) In 1821 only one family out of 31 was employed in trade, craft, or manufacture. (fn. 167) A shoemaker lodged with the miller in 1841, and in the 1850s the township supported a grocer and a wheelwright-cum-carpenter, while the miller also served as a maltster, grain dealer and baker. (fn. 168) In the late 19th century a few women worked as laundresses and domestic servants, and other trades in the village included carpenter, cattle dealer, and sewing-machine salesman. (fn. 169)

63. Little Faringdon mill and millpond in 1935, with Common Farm and neighbouring buildings on the left. A mill existed here by the 1260s.

A grocer's shop mentioned in the 1850s was probably taken over in the 1860s by John Godwin, the owner and driver of an agricultural steam engine. (fn. 170) After his death in the late 1880s the business was briefly run by Godwin's widow Sarah, but probably closed soon after. (fn. 171) A village shop was re-opened by Agnes Whiting in the 1930s, but does not survive. (fn. 172)

In the 1970s, following the mill's closure, the gravel and sand workings in Lechlade were extended into Little Faringdon, and much of the former meadow and pasture between the county boundary and the river Leach was quarried. The resulting pits were turned into artificial lakes, and a trout farm was established in 1975. (fn. 173)

Milling

A watermill has occupied the present site beside the river Leach since at least the 1260s, although the surviving buildings date mostly from the 18th century. (fn. 174) In 1269–70 the mill was owned by Beaulieu abbey, which leased it for an annual rent of £1 4d. (fn. 175) Thereafter the abbey may have invested in new buildings, since in the late 13th century Robert Acke paid £2 a year for the watermill and a fulling mill. (fn. 176) All the abbey's tenants in Little Faringdon and Langford were obliged to grind their grain at the mill, and some had to help fetch replacement millstones and repair the millpond. (fn. 177) In 1335 the abbey received £8 for a life-lease of the mills, and an increased annual rent of £2 13s. 4d. (fn. 178)

The mills lay within a ditched inclosure, within which the lessee held the meadow and pasture beside the mill-stream and pond, and kept any fish caught there. (fn. 179) William le Walker (i.e. 'fuller'), who in 1346 claimed a roadside plot belonging to the mill, may have rented the fulling mill, (fn. 180) while William Wolf, the miller in the 15th century, was fined repeatedly in the manor court for the common complaint of charging excessive tolls. (fn. 181)

After the Dissolution Little Faringdon's mills passed with the manor from the Moores family to the Bourchiers. (fn. 182) An attached fishery in the river Leach was mentioned in the late 16th and mid 17th centuries, and was retained by the lord at inclosure in 1788. (fn. 183) By the 18th century only the corn mill remained, leased to various millers including Robert Saunders (d. 1751), Henry Green (d. 1766), and John Tuckwell. The last was probably living there when the mill and mill house were rebuilt in the mid to late 18th century. (fn. 184)

In 1910 the mill was leased by Baron de Mauley to Thomas Lock, (fn. 185) and it continued to operate until the 1960s. The mill-work (replaced in the late 19th century) included three pairs of millstones powered by a metal breastshot wheel, (fn. 186) and was still in working order in 1985, when the mill buildings formed part of the trout farm and fishery. (fn. 187) The business continued in 2009.

SOCIAL HISTORY

Social Structure and the Life of the Community

From the Middle Ages Little Faringdon remained a small, predominantly agricultural community. Long-standing social stability between the 14th and 17th centuries was reflected in the survival of surnames and the long-term residence of leading families, while the preservation of some medieval field names also suggests continuity. After 1700, however, social and economic differences (already evident in the Middle Ages) became steadily more pronounced. Farms were consolidated, and a few leading tenant farmers dominated village life, regularly holding offices such as churchwarden and overseer of the poor. Even so their position was not entirely secure, and in the 19th century some prominent families rejoined the ranks of the relatively low-status agricultural workers who made up most of the population.

From the 16th century the lord of the manor was often resident, and took a close interest in the economic, social, and religious life of the community. The lord's influence may have discouraged the opening of public houses and the use of the school for community activities, of which little evidence survives. Nonconformity also failed to take root, and in many ways Little Faringdon assumed the characteristics of a 'closed' village. The lord still lived in the parish in the early 21st century, (fn. 188) when the much reduced population was mostly made up of wealthy pensioners and professionals.

The Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages most inhabitants were customary tenants of Beaulieu abbey, holding either a yardland or a half yardland. Free tenants, cottars, and other smallholders are not well documented. (fn. 189) Yet despite the relative uniformity of landholdings, assessments for taxation varied widely. In 1332 the yardlanders William Arnold and William Young paid respectively on goods worth £2 16s. and £7 7s., while individuals' assessments sometimes fluctuated markedly from year to year. Thus the yardlander John Hoket was assessed on goods worth £1 3s. in 1327 and £5 15s. in 1332, while the goods of the half-yardlander Andrew Barnard were valued at £3 10s. in 1327, but at £8 five years later. Such variations may indicate rising wealth, temporary changes of fortune, or more deep-seated contrasts in wealth and status within the community, reflecting a range of seasonal, local, and personal factors. Over all, however, the township's early 14th-century taxation returns suggest an inequitable society in which the half-yardlanders paid a disproportionate share of the total, while yardlanders' contributions ranged from a few pence to several shillings. (fn. 190)

In 1381 the poll tax was paid by 17 families or households each sharing a surname, of which around a third were apparently new to the township. The rest were recorded in the village before the Black Death, and a degree of social continuity persisted into the 15th century with surnames such as King, Long, and Young recorded both in 1381 and in the 1460s. (fn. 191) The preservation of some 13th-century field names into the 19th century similarly suggests not only continuity of land use and ownership, but a striking and enduring collective memory. (fn. 192) In part, such cohesion may have been fostered by the long-standing and undivided lordship of Beaulieu abbey. Tenants met regularly at the manor courts, presenting cases, paying tithingpenny, electing each other to offices, supervising the repair of buildings, and enforcing judgements, while courts probably also resolved disputes between inhabitants. (fn. 193) The abbot himself visited the manor on occasion, although after the manor was leased such visits probably became infrequent. (fn. 194)

The abbey's influence may have also contributed to a long-lived antipathy between the inhabitants of Little Faringdon and neighbouring Langford. In 1274 the prebendary of Langford Manor accused the abbot of Beaulieu of instigating an attack on his property, led by some of the abbey's lay brothers and possibly including men from Little Faringdon. (fn. 195) Tensions between the two villages continued in later centuries, particularly in relation to church matters. (fn. 196)

1500–1800

In 1522 more than two fifths of the inhabitants assessed on goods were taxed on sums of less than £2, suggesting a considerable body of wage-earners, while many of the same people were among eight labourers assessed on wages in 1543. Presumably such inhabitants were employed on the holdings of wealthier neighbours such as the Fishers or the Moores family, lords of the manor. (fn. 197)

Such labouring families may not always have been landless, however, since some of the township's leading farmers had evidently taken over holdings from their less prosperous neighbours. Walter Fisher acquired holdings formerly belonging to the medieval Dameanne and Crocker families, while a yardland called 'Barnard' (held by Thomas Moores the younger) had probably belonged to the Barnard family, recorded in Little Faringdon in the 14th century. (fn. 198) More remarkable was the survival of the Kings, another late medieval family which seems to have remained in the village until the 17th century. John King held 2½ yardlands in 1540, while the widow Amy King died in 1627, to be succeeded by her daughter Anne. (fn. 199)

The contrasts in personal wealth evident in the medieval township persisted in the 16th and 17th centuries, but do not seem to have widened significantly. In 1662 most houses in the village were assessed on between one and four hearths, suggesting relatively modest buildings, (fn. 200) and though probate inventories varied widely in value (particularly regarding grain stocks and livestock), to some extent this reflected the agricultural season in which they were taken. Contrasts in the range and standard of household goods and furnishings were less obvious, although contemporaries were no doubt aware of subtle differences in quality and quantity. (fn. 201) Until around 1700 the social continuity of earlier centuries also remained apparent. The Kings provide the most striking example, but several families remained in the village for several generations, and were interrelated by marriage or kinship, overseeing and witnessing each other's wills and serving as churchwarden or sidesman. (fn. 202) By contrast, the 18th century saw some newly emergent families leasing the larger farms, in particular the Godwins, Lapworths, Saunderses, Tuckeys, and Yellses. Many were interrelated, and members of each of them served as churchwarden or overseer of the poor, while a few held property in surrounding parishes. (fn. 203) At the same time some other families fell in the social hierarchy, among them the Fords, Fowlers, and Betts. The latter had been one of the most prominent yeoman families in the 17th century, but in 1765 Robert Bett and his family were removed by the overseers. (fn. 204)

Lords of the manor were mostly resident until the mid 17th century, although from then until the early 19th century the manor house (Little Faringdon House) was usually leased. Thomas Moores and his successors were the village's leading taxpayers in the mid 16th century, (fn. 205) and though the Bourchiers' principal seat was Barnsley in Gloucestershire, family members probably still lived at Little Faringdon until the death of Walter Bourchier in 1648. (fn. 206) Presumably they were responsible for some of the surviving 17th-century work at Little Faringdon House. (fn. 207) By 1662 the manor house seems to have been occupied by Thomas Warwick, whose assessment of seven hearths (five of them then blocked up) was the highest in the village. (fn. 208) Later members of the Bourchier family visited the manor only occasionally, and in the early 18th century the house and part of the estate were probably leased to the Catchmay family. (fn. 209) The Bourchiers' successors the Perrotts and Musgraves similarly lived at Barnsley, although James Musgrave (d. 1814) took a close financial interest in Little Faringdon, petitioning for its inclosure in 1788 and leasing its tithes from Langford rectory in the late 18th century. (fn. 210)

The 19th and 20th Centuries

For much of the 19th and 20th centuries Little Faringdon once again had a resident lord. The manor house was extended and remodelled c. 1830, most likely for the incoming lord William Vizard, who by 1851 was living there with his family and nine servants. (fn. 211) Vizard was a vigorous supporter of the township's schools and chapel and played an important role in promoting the creation of a separate ecclesiastical parish, which was completed after his death in 1859. (fn. 212) His philanthropy was continued by the Ponsonbys (Barons de Mauley), who briefly let the manor house in 1871 but moved back before 1876, when the 2nd Baron further enlarged the building. (fn. 213) In 1891 he and his family employed twelve servants, only one of whom was born in Little Faringdon, and over all his household comprised around a sixth of the population. (fn. 214) When the 2nd Baron died in 1896 village life experienced a temporary but marked hiatus, the manor house lying empty for several years before his successor resumed residency. (fn. 215)

The social continuity of earlier centuries was still evident in 1861, when half the population was native to the township and a further 25 per cent had been born within five miles. (fn. 216) Thereafter village society began to change, so that by 1901 only a quarter of inhabitants had been born in the township, and a fifth within five miles. (fn. 217) The explanation lies probably in agricultural depression and in changing patterns of agricultural employment, which prompted an increasing turnover of families: in 1909 the vicar complained that four or five changes or removals of farm workers every year made it difficult to hold regular evening classes, while in 1929 a school inspector reported that almost all the pupils were recently arrived, following a change in the occupancy of the principal farm. (fn. 218) In a small place, even modest population movements had a considerable impact on local society. Some individual families also experienced a marked change in fortunes. The Godwins, who occupied Church and Hulse Grounds farms in 1841, became much reduced in later decades, working as labourers and shopkeepers. The Lapworths, too, experienced a decline in status. (fn. 219)

Community activities are poorly documented, and there were no public houses, the villagers presumably frequenting those in Lechlade or Langford. (fn. 220) In the early 20th century farmworkers played football at Lechlade with residents of neighbouring villages, much to their employers' disapproval according to the Filkins stone-mason George Swinford, (fn. 221) and a joint Little Faringdon and Kelmscott horticultural society was mentioned in 1928. (fn. 222) No other sports or social clubs are known, and the village school (unlike its counterpart at Langford) seems not to have been a venue for community events. (fn. 223) Following its closure in 1946 the school building was converted into a village hall, and continued as such until at least the 1970s; by 2009 it was a private house, however, (fn. 224) and the church was again the only public building. Occasional social events were held at the manor house and in other private houses in the early 21st century. (fn. 225)

From the 1920s members of the Ponsonby family lived not only in the manor house but also at Common Barn Farm. (fn. 226) The village increasingly attracted wealthy incomers, who moved into the former vicarage house, mill, school, and farmhouses, (fn. 227) and in 2004 Church Farm was sold by the Ponsonbys' successors to the fashion model Kate Moss (b. 1974). (fn. 228) Little Faringdon House was sold a few years later to the founding partner of a private equity firm. (fn. 229) The population as a whole fell by half between 1951 and 1971, reflecting the village's final transformation from a predominantly poor agricultural community into one of wealthy pensioners and professionals working outside the area. (fn. 230)

Education

In the early 19th century and probably before, education in Little Faringdon was mostly provided by the Church. A school established by the lord of the manor in 1847 became an Anglican National and (later) primary school, but declining numbers of pupils led to its closure in 1946. Thereafter primary-age children attended Langford school.

Private, Church, and Sunday Schools

A Sunday school supported by subscription was attended by around 20 children in 1808. (fn. 231) Though apparently short-lived it was re-established in 1814 and again in 1827, and in 1834 it taught 26 children supported by William Vizard, the recently arrived lord of the manor. (fn. 232) Vizard also supported a day school, which in 1834 was attended by 18 children paying 1d. a week; the mistress in 1841 was Sarah Spokes, the wife of one of Vizard's servants. (fn. 233) In 1847 Vizard built a new school and school house in the centre of the village, (fn. 234) which at first remained privately owned, and was funded almost entirely by Vizard and his successor Baron de Mauley. By the later 19th century it was linked to the National Society, and received a parliamentary grant (see below). (fn. 235)

Vizard and de Mauley continued to support the Sunday school, which in 1854 was attended by around 30 children. Those included some older boys who worked during the week, but attendance fell in the late 19th century, and the school closed before 1896. (fn. 236) William Adams (vicar 1864–1901) regularly catechized the village children, and during most of his incumbency held evening classes for working boys and young men. Attendance was irregular, however, and in 1899, 'after repeated trials', he gave up, claiming that house visits were the only effective means of offering guidance and instruction. (fn. 237) His successors held similar classes in the early 20th century, but faced the same difficulties. (fn. 238) Small private schools were established occasionally in the 19th and 20th centuries, but were mostly short-lived. Clara Brownrigg, for example, taught at Common Barn Farm on the Southrop road in the 1910s. (fn. 239)

Little Faringdon National (later Primary) School

The school opened by Vizard in 1847 had accommodation for 56, although on inspection day in 1871 only 23 children attended. (fn. 240) A succession of school mistresses was appointed, including Mary Tester (who was assisted by her niece) and Anna Pike, who was said by the vicar in 1878 to be uncertificated; at the same time the vicar reported that the buildings were privately owned, and that Baron de Mauley was unwilling to respond to government enquiries. (fn. 241) In 1880, however, the school received a parliamentary grant for the first time, and thus became subject to regular inspection. (fn. 242) Standards of accommodation and teaching were generally judged unfavourably until the end of the century, and were not helped by a rapid turnover of teachers, although threats to withhold the grant raised protests from the vicar that some of the criticisms were unfair. (fn. 243) Intermittent improvements were made by Ada Harris (mistress 1893–1903), and in 1902 the buildings were modernized, the cost met by a government grant and by contributions from the National Society, Baron de Mauley, and the vicar. The capacity was 40 children, but average attendance was only 24, and infants and older children continued to be taught in a single room. (fn. 244)

During the early 20th century progress was made despite frequent changes of teacher, and in 1913, though the children were still described as 'very backward', the school was satisfactory. (fn. 245) It remained privately owned, and in 1912 Harriet Mainwaring was forced to resign when she asked to move out of the school house, which incurred the relatively high annual rent of £10. (fn. 246) Improvement continued under her successor Ethel Clarke (mistress 1912–31), assisted by a monitress: the school received several favourable reports, although average attendance often fell below 20. (fn. 247) Having survived a recommendation for closure in 1916 the school was reorganized for juniors and infants in 1932, with older children going to Langford school. (fn. 248) By 1938 only 13 children attended, and though up to 15 evacuees boosted numbers during the Second World War the school was finally closed in 1946, when its six remaining pupils were transferred to Langford. (fn. 249)

Charities and Poor Relief

In the 16th and 17th centuries a few one-off bequests to the poor, mostly in cash, were made by inhabitants of Little Faringdon and Langford, (fn. 250) and the township may have also benefited from bequests to the poor of Langford parish. (fn. 251) Little Faringdon lacked any endowed charities of its own, however, (fn. 252) and in the 18th century the mounting cost of poor relief fell almost entirely on its poor rates, which were levied two or three times a year. In the 1760s annual expenditure by the overseers averaged around £17, although in 1762 the costs of treating an outbreak of smallpox raised expenditure to more than £28. The township also maintained three 'parish houses' which the overseers used to accommodate poor families, and work (especially wool-spinning) was provided for the unemployed. (fn. 253)

In line with national trends, the annual cost of poor relief rose from an average of £25 in the 1770s to about £34 in 1783–5, almost quadrupling to more than £127 in 1803 when it was levied at a rate of just over 2s. 3d. in the pound (see Table 2). At that date 19 people (including 12 children) received regular out-relief, and another seven occasional relief, in all around 20 per cent of the population. (fn. 254) By 1813 expenditure was nearly 20s. per head of population and, though it fell in 1814–17, by 1819 it was 23s., a total outlay of £165. (fn. 255) Thereafter, as agriculture recovered, annual costs fell to an average of 17s. a head in 1820–7, and to 14s. in the late 1820s and early 1830s. (fn. 256)

From 1834 formal responsibility for Little Faringdon's poor passed to the new Faringdon poor-law union, (fn. 257) although few of the township's inhabitants entered the Faringdon workhouse. (fn. 258) In the 1870s church collections included a contribution towards parochial charities, (fn. 259) and coal and clothing clubs were mentioned in 1910. (fn. 260) In the late 19th century Baron de Mauley provided allotments for the 'labouring poor' on 2 a. of land on the east side of the village. The land remained open but neglected in 2009. (fn. 261)

RELIGIOUS HISTORY

Until the 1860s Little Faringdon remained a chapelry of Langford. A chapel existed by the 12th century, the date of the earliest surviving fabric, and from the Middle Ages it was served by vicars of Langford or by chaplains or curates appointed by them. The chapelry had no independent endowment, and its priests are not well documented.

Little Faringdon inhabitants were buried at Langford, and in the 17th century a long-standing disagreement over the township's contributions to the mother church remained unresolved. Protestant Nonconformity may have underlain some of the disputes over church rates, but if so it was short-lived, and a Primitive Methodist group established in the 1820s also faded away after a few decades. The chapelry was separated from Langford in 1864, after more than a decade of negotiation; it retained its independence for less than a century, and from 1960 was incorporated into ever larger benefices.

Parochial Organization

In the late 11th century Little Faringdon was presumably served from the mother church at Langford. (fn. 262) A dependent chapel was established most likely in the 12th century, perhaps in the 1150s when the Little Faringdon estate is first known to have been held separately from Langford. (fn. 263) A chaplain was probably appointed from that date, but no permanent arrangement was made until Langford vicarage was ordained in 1277. Thereafter one of two chaplains assisting the vicar of Langford was to celebrate mass at Little Faringdon on three days a week or more, having first been presented to the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia for approval. (fn. 264) The chapel probably had baptismal rights from its foundation, since the tub-shaped font is of 12th-century date; baptisms were recorded in Langford's parish registers until 1864, however, (fn. 265) and burial rights were not granted until the churchyard's consecration in 1865. (fn. 266) The medieval dedication is unknown, and the present dedication to St Margaret of England was made only in 2000. (fn. 267)

In 1848 the bishop advised making Little Faringdon a separate parish, and asked the Ecclesiastical Commissioners (as Langford's lay impropriators) to endow the new benefice. A vicarage house was to be provided jointly by the Commissioners and the lord of the manor William Vizard, but disagreements over the details led to delays in creating an independent parish until 1864. (fn. 268) From 1930, following falling church attendances, Little Faringdon was held in plurality with Langford, and in 1960 the two benefices were formally reunited. (fn. 269) In 1986 Langford and Little Faringdon were added to a single benefice incorporating Broughton Poggs, Filkins, Broadwell, Kelmscott, and Kencot, which in 1995 became part of the Shill Valley and Broadshire ministry. (fn. 270)

Advowson

In 1848 the bishop suggested that the patronage of the new vicarage was a matter for the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, but that it should be vested in the bishop, to whom the patronage of Langford would belong following the expiry of a lease to Francis Lémann (Langford's vicar 1855–85). (fn. 271) Nevertheless Lémann claimed it following the new parish's creation in 1864, refusing to concede it even when the Ecclesiastical Commissioners offered to augment the income of both Langford and Little Faringdon vicarages in return for its surrender to the bishop. (fn. 272) Presumably agreement was reached, since the bishop presented Little Faringdon's first vicar in 1864 and each subsequent vicar until 1986, when he became a co-patron of the united benefice. (fn. 273)

Glebe and Tithes

Little Faringdon's tithes were given in the 12th century to the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia, as part of the endowment of Langford church. (fn. 274) The small tithes were granted to Langford vicarage on its ordination in 1277, but the prebendary retained the grain and hay tithes, which were leased to James Musgrave in the late 18th century for £74 10s. a year, and were valued at £200 in the early 19th century. (fn. 275) At Little Faringdon's inclosure in 1788 the vicar of Langford was awarded a grain-rent of £19 18s. in lieu of the small tithes, and a further £17 1s. was awarded at commutation in 1840. At the same time the prebendary received a rent charge of £236 4s. for the great tithes. (fn. 276)

Langford's glebe in Little Faringdon similarly belonged to the vicar, who at inclosure in 1788 received 30 a. in lieu of common arable and meadow and a plot of furze in the common pasture. (fn. 277) At Langford's inclosure in 1808 that land was exchanged with the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia for an equivalent area in Langford, and passed later to William Vizard and his successors as lords of Little Faringdon manor. (fn. 278) An acre near Hulse Grounds Farm (later called the Vicar's Acre) was granted to the vicar of Langford under the tithe award of 1840. (fn. 279)

At the creation of the new benefice in 1864, the vicar of Langford's combined annual tithe income of £36 19s. was transferred to the vicar of Little Faringdon, whose gross income was made up to £150 by a grant from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. (fn. 280) Vicar's Acre also passed to the new benefice, (fn. 281) but was leased and later sold to the lord of the manor, who had previously given a separate acre in the village as the site for a new vicarage house. (fn. 282) In the 1930s, when Little Faringdon was held in plurality with Langford, the vicar received a net income of £152 from Little Faringdon, and £300 from Langford. (fn. 283)

64. The entrance front of the former vicarage house, designed by William Butterfield c. 1867 for the recently created parish of Little Faringdon.

Vicarage House

The chaplains and curates serving Little Faringdon were not provided with a house, and many or most may have lived outside the township. In the 1850s William Vizard provided the curate with a rent-free house in the village, but this was withdrawn after Vizard's death in 1859. (fn. 284) Robert Tilbury (curate 1860–2) lodged with the parish clerk in Langford, though in 1863 the vicar of Langford remained hopeful that the lord of the manor might give the house formerly provided by Vizard. (fn. 285) The intention to build a vicarage house, expressed by the bishop in 1848, was still not realized when the first vicar of Little Faringdon was appointed in 1864. (fn. 286)

In 1867 the Ecclesiastical Commissioners contributed £1,400 towards the cost of building a house on land provided by Baron de Mauley, and a further £50 was paid by the Diocesan Church Building Society. Even so the vicar claimed to need more than £1,700 to complete the house (designed by William Butterfield), which was deemed not to be 'unnecessarily large or extravagant'. (fn. 287) A grant of £100 for improvements was made in 1884, and the house was occupied by successive vicars until James Fisher moved to Langford in 1933. (fn. 288) Thereafter it was occupied by private residents until its sale c. 1962. (fn. 289)

Described by Pevsner as displaying 'a design of the utmost austerity', the irregular main range comprises three linked gabled blocks of different shape and height, built of limestone ashlar with ashlar dressings, and with steeply pitched red-tiled roofs (Fig. 64). Its prominent ridge and end stacks prompted a change of name to Tall Chimneys following the vicar's move to Langford, although in 2009 it was called Butterfield House. (fn. 290) The original design included a stable, coach house, and outbuildings; (fn. 291) those were perhaps included in a smaller range to the rear, which in the early 21st century was known as Butterfield Annex. (fn. 292)

Pastoral Care and Religious Life

The Middle Ages to c. 1700

Little Faringdon's 12th-century chapel was remodelled and extended in the early 13th century, possibly under Beaulieu abbey's direction after it acquired Little Faringdon manor in 1203–4. (fn. 293) The abbey's involvement in the chapelry's religious life and its relationship with the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia as rector are not well documented, however, except with regard to the payment of tithes. (fn. 294) Little is known of the chaplains required to be appointed by the vicar of Langford, (fn. 295) although provision of a piscina in the nave (presumably for a side altar) suggests that the church was adequately served for at least some of the period. (fn. 296) The only pre-Reformation priest recorded by name is Robert Wylly, curate in 1526, who received a £5 stipend paid presumably by the vicar. (fn. 297) The chapel's fabric and furnishings suggest investment in the 14th and early 16th centuries, (fn. 298) and in particular Little Faringdon is notable as one of only three Oxfordshire churches which possess surviving pre-Reformation church plate, in this case a silver chalice of c. 1500. The chalice is of unknown origin but high quality, suggesting a wealthy donor such as Beaulieu abbey. (fn. 299)

The Reformation must have caused local disruption, not least given the ending of Beaulieu abbey's involvement in the township. The medieval screen may have been dismantled and re-used for flooring around that time, (fn. 300) although the chalice evidently escaped confiscation. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, Little Faringdon probably followed Langford's acceptance of the Elizabethan religious settlement. (fn. 301) The Moores family, as beneficiaries of the Dissolution, unsurprisingly showed no loyalty to the Catholic faith, (fn. 302) and there is no other suggestion of the lingering Catholicism found elsewhere in the area. (fn. 303)

From the early 17th century Little Faringdon's churchwardens reported on the state of the church and the conduct of its congregation: in 1620, for example, they noted the lack of a stile on the eastern side of the churchyard, while some years earlier they presented James Eagles (d. 1620), a local husbandman, for 'scolding and railing' with Thomas Snotter's wife in the church and churchyard. (fn. 304) In 1662 the chapel was in sufficient repair, but a book of homilies and a surplice were to be provided as soon as possible. Langford's vicar William Phipps (1635–67) evidently took services himself at Little Faringdon, although his recent infirmity and weakness meant that John Moone, Langford's schoolmaster, read prayers in his place. By 1664 Phipps's substitute was Edward Davis (d. 1679), a yeoman and churchwarden at Langford, who may have been related to Langford's vicars of the same name (1692–1730 and 1730–60). (fn. 305) A curate performed the duties at Little Faringdon in 1666. (fn. 306)

During the last years of Phipps's incumbency, Langford's churchwardens complained that the inhabitants of Little Faringdon refused to contribute towards the repair of Langford church and the churchyard mound or fence. (fn. 307) The inhabitants of Little Faringdon countered that for a long time no such contributions had been required or paid, that they met the expenses of their own chapel without any assistance from Langford, and that they paid for burial in Langford churchyard. (fn. 308) In 1664 the case proceeded to the Court of Arches, but the mounting expense rapidly brought both parties to agreement: Little Faringdon's churchwardens agreed to pay £10 towards Langford's costs, and in future to contribute towards the dues of the mother church. (fn. 309) Nonetheless, in 1669 Langford's churchwardens were accused of overcharging Little Faringdon, and agreed that the township should pay only three eighths of Langford's contribution towards the church rate. (fn. 310) Despite this settlement the quarrel persisted into the 18th century, (fn. 311) offering by far the most vivid expression of a possibly long-standing acrimony between the two communities. (fn. 312) Some of the inhabitants who refused to pay church rates at the end of the 17th century may have been additionally motivated by Nonconformist beliefs, but if so their activities are not well documented and may have been short-lived. (fn. 313)

Perhaps as a result of these tensions, although many inhabitants of Little Faringdon requested burial at Langford church few left money towards its repair. An exception was Laurence Hall (d. 1608), who left 1s. to both churches. (fn. 314) In 1677 and 1694 the chancel of Little Faringdon chapel was in decay, although it had been repaired by 1696 presumably at the expense of the prebendary of Langford Ecclesia (or more likely his lessee). (fn. 315) Evidence of neglect and disrepair continued throughout the 18th century, including damage to the porch, roof, and windows. (fn. 316)

1700–1864

Edward Davis the younger served as curate of Little Faringdon before succeeding his father as vicar of Langford in 1730, but it is not clear to what extent the appointment of curates was normal practice in the 18th century. (fn. 317) A silver paten was donated around 1759, possibly by a person with the initials RH, (fn. 318) and though both of the chapel's bells were broken in 1803 they were repaired or replaced in 1805. (fn. 319)

In the early 19th century Langford's vicar James Johnson (1800–25) or his curate performed Sunday afternoon service with a sermon at Little Faringdon, 'at a convenient hour between the services at Langford'. Around 100 people were said to attend. Johnson claimed that Nonconformity was absent from the township, (fn. 320) although Primitive Methodists were active there by 1826, when there were 13 members. (fn. 321) Ten years later a vacant house belonging to the farmer William Yells was licensed for Nonconformist worship: (fn. 322) probably that was the building used by Primitive Methodists in 1851, when their average congregation was 35, almost as many as were then recorded at the Anglican services. Most adherents were probably farm workers, amongst them the building's steward David Lynn. (fn. 323)