A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Broadwell Parish: Broadwell', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17, ed. Simon Townley( Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp20-59 [accessed 18 January 2025].

'Broadwell Parish: Broadwell', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Edited by Simon Townley( Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), British History Online, accessed January 18, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp20-59.

"Broadwell Parish: Broadwell". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 17. Ed. Simon Townley(Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2012), , British History Online. Web. 18 January 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol17/pp20-59.

In this section

BROADWELL TOWNSHIP

Broadwell village, which in the early 21st century was a small rural settlement of around fifty houses, (fn. 1) lies some 5 miles (8 km) south of the former market town of Burford, and 7½ miles (12 km) south-west of Witney. The parish's name implies that Broadwell was the primary focus of the late 11th-century estate, and the village retains a medieval parish church of some size and importance, adjoining an abandoned medieval manorial site. (fn. 2) Nevertheless by the late 13th century Filkins was at least as populous, and by the later Middle Ages it had overtaken Broadwell, remaining the larger (and apparently the wealthier) settlement thereafter (see Table 1). (fn. 3) In contrast to Filkins, with its prosperous yeoman and gentry houses, Broadwell has few domestic buildings of note, other than the former vicarage house (now Finial House) and the early 19th-century Manor Farm near the church. The township boundaries between the two settlements were defined at inclosure in 1776, and are described above; otherwise Broadwell's boundaries were those of the ancient parish. (fn. 4)

Communications

In 1320 the king's highway from Lechlade and Langford passed north-eastwards through the lower part of the parish, leading to Kencot and on towards Burford and Witney (Figs 2 and 6). (fn. 5) This was the road along which settlement developed, forming the main street through the village. Several lanes branched south-eastwards into surrounding arable and meadow, among them a 'way' leading to Summerleaze or Summer Leys pasture and to the meadows around Edgerly and Cottesmore. (fn. 6) Possibly that was the later Calcroft Lane, which crosses Broadwell brook at Broadwell mill, and which was described in 1776 as an ancient public road from Broadwell to Clanfield. Other early tracks included Mackige, Mackage, or Maggott's Lane near Lower Farm, and the unidentified Drove Lane. (fn. 7)

Other lanes led northwards and north-westwards towards Filkins, to the Downs and Bradwell Grove, and to Holwell and Burford. King's Lane, leading to Upper Filkins from Broadwell's village street, was so called by 1776, probably from the local King family, who were yeomen in Broadwell in the 16th and 17th centuries. (fn. 8) A lane linking Filkins with Broadwell church was called 'church way' by 1531, but gradually fell out of use after Filkins church was built in 1855–7. (fn. 9) Wood way, mentioned in the 17th century, (fn. 10) was probably an intersecting lane which ran northwards towards Bradwell Grove, meeting the main Lechlade–Burford road north of Filkins. Possibly this was the road from Broadwell to Bradwell Grove mentioned in 1320, but it seems to have fallen out of use at or soon after inclosure, and thereafter Broadwell was linked to Burford only via Filkins or Kencot. (fn. 11) The road through Bradwell Grove to Holwell was made more direct around 1814, with William Hervey's agreement as landowner. (fn. 12) Broadwell's roads were maintained by the manor courts or by parish officers until 1863, when responsibility passed to the Bampton West Highway District Board. (fn. 13)

No village carriers are recorded, but presumably inhabitants used those operating from Kencot and Langford in the 19th century. (fn. 14) The nearest railway station was two miles east at Alvescot, opened in 1873 on the East Gloucestershire line to Fairford (Glos.), and closed in 1962. (fn. 15) Bus services continued thereafter, and in 2010 Broadwell was served by regular daily services to Carterton and Swindon. Post was delivered through Lechlade (Glos.) from the mid 19th century, and a village letter box was provided on the main street near the vicarage house. A sub post-office was opened near Lower Farm in the early 20th century, and until the mid 1930s was run by Emma Young with the village shop. It continued in the 1970s, but was subsequently closed. (fn. 16)

Settlement and Population

Early Settlement

A Neolithic polished flint axe was found near the Shilton parish boundary close to Bradwell Grove, (fn. 17) and linear and circular features south-east of the present village near Broadwell mill suggest prehistoric or later settlement. (fn. 18) In contrast with neighbouring Filkins no archaeological evidence for Roman or early Anglo-Saxon activity is known, but by the late 10th century Broadwell belonged to a large royal and comital estate which included Langford and several neighbouring settlements. Presumably an emerging settlement existed at Broadwell as at other places within the complex, and by the mid 11th century it had become the focus of a substantial independent estate held probably by Aelfgar (d. 1062), earl of Mercia. Domesday Book implies both a large population and a large demesne farm, run in part by a sizeable body of slaves or servi. The form of the settlement is unknown, although it may already have been concentrated along the Langford-Kencot highway, and around the adjoining sites of the medieval manor house and church. (fn. 19)

Population from 1086

In 1086 Broadwell manor contained 74 tenant households in all, including 14 slaves who were probably housed near the demesne farm. Otherwise there is no indication of how many of the tenants lived in Broadwell itself, as opposed to at Filkins, Holwell or Kelmscott. (fn. 20) By 1279 Broadwell village contained 35 tenant households, of which two were headed by freeholders and the rest by unfree villeins or cottagers; since the demesne farms of all three manors were based in Broadwell, the overall population may have been between 150 and 190. (fn. 21) The 20 or so Broadwell land-holders paying tax in the early 14th century probably each represented a household, and there must have been others too poor to pay tax; nevertheless in 1377 only 46 adults aged over fourteen paid poll tax, which even allowing for evasion implies population loss through plague or emigration. (fn. 22)

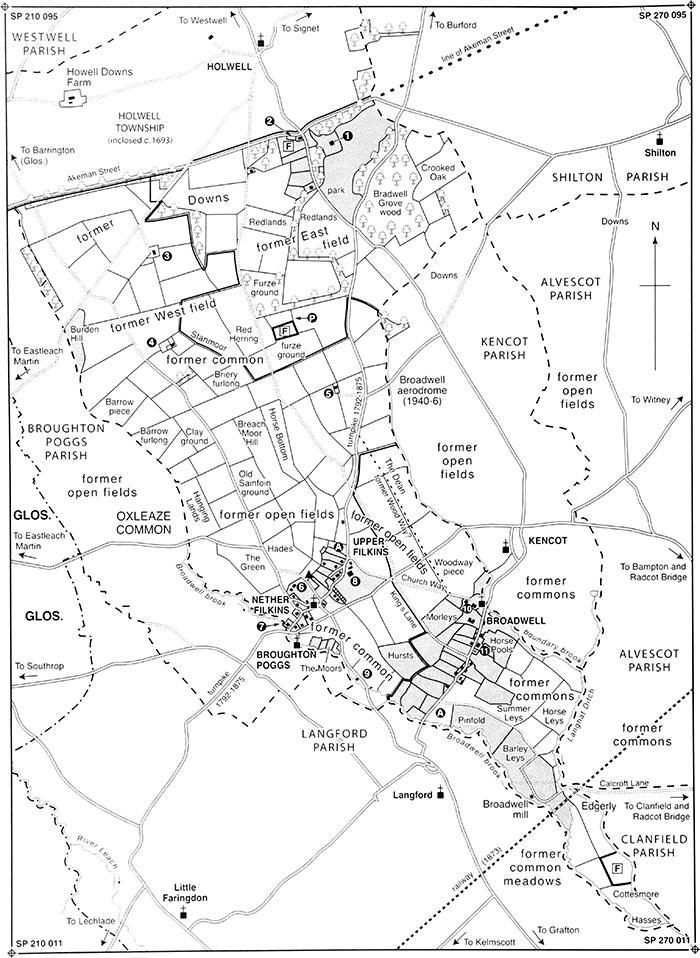

6. Broadwell and Filkins townships c. 1880, showing post-inclosure township boundaries and the approximate location of the former open fields and commons.

Key to Figure 6.

The population had probably not fully recovered by the early 16th century, when around 14 householders regularly paid tax. Long before then Filkins had overtaken Broadwell as the largest settlement in the parish (Table 1). (fn. 23) In 1642 the obligatory protestation oath was taken by 121 adult men in the three villages of Broadwell, Filkins, and Holwell, suggesting a total adult population of 240–50; of those, perhaps 70–75 lived in Broadwell. Thirty one Broadwell landholders were taxed the same year, and in 1662 twenty two houses were assessed for hearth tax. (fn. 24) In 1676, when the combined adult population of Broadwell, Filkins, and Holwell was around 300, the total number of people living in Broadwell was presumably well over a hundred. (fn. 25)

Population seems to have risen only slowly during the 18th century. In 1738 Broadwell probably contained around a quarter of the 136 houses noted in the four hamlets, and by the later 18th century it had 30–40 houses and 200 inhabitants. (fn. 26) During the 19th century its population generally remained around 200, with peaks of 234 in 1811, and 255 (the highest recorded figure) in 1881, when there were 54 households. Presumably because of agricultural depression numbers fell to 202 by 1901 and to 177–90 in the early decades of the 20th century, and during the later 20th century, as agricultural jobs disappeared, the population dwindled further. In 2001 the civil parish had 120 inhabitants accommodated in 54 houses. (fn. 27)

Development of the Village

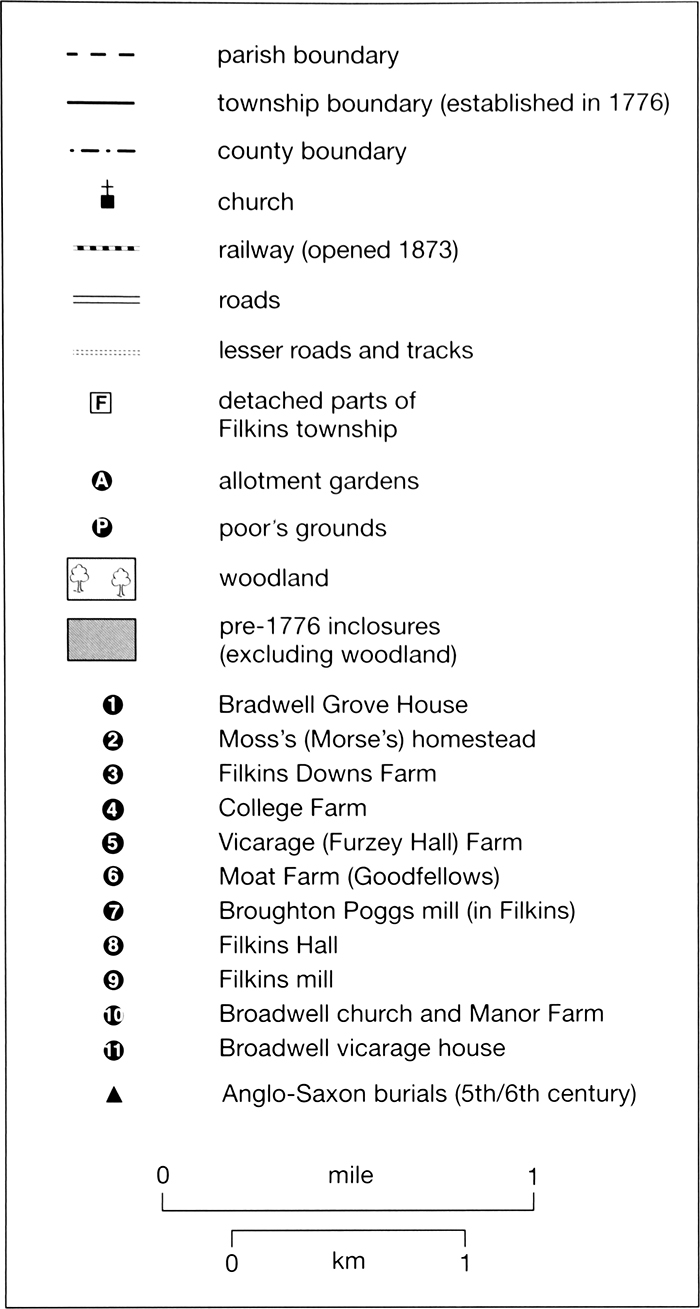

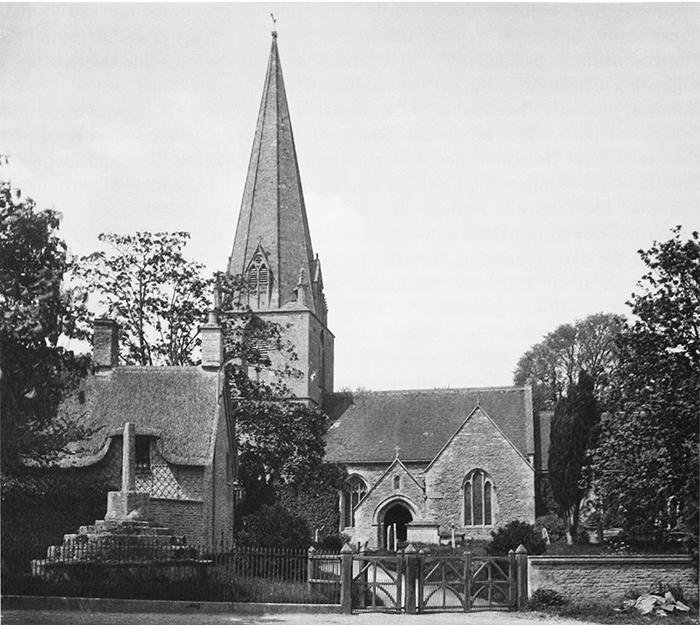

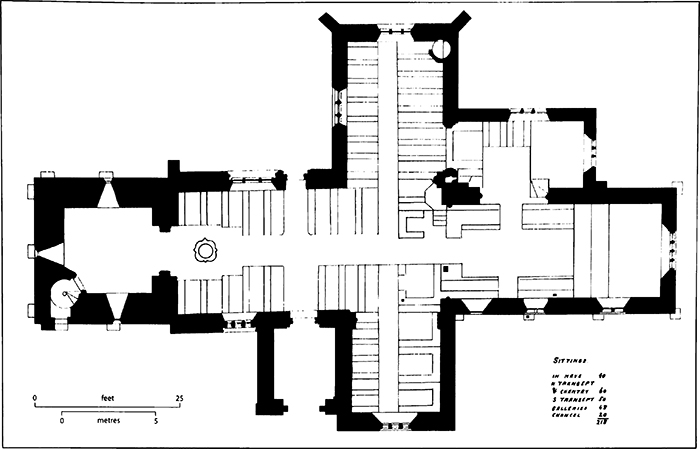

The 'broad stream' to which the place name refers (fn. 28) was almost certainly Broadwell brook, which formed part of the estate and parish boundary, and which from the Middle Ages was powerful enough to drive several corn mills. (fn. 29) Less likely candidates are Langhat ditch and the stream adjoining Broadwell churchyard, which still divides Broadwell from Kencot. The church itself lies at the extreme north-eastern edge of the village, and existed by the mid 12th century. (fn. 30) Some early settlement presumably grew up around there and around the adjacent manor-house site, now partly occupied by Manor Farm: by 1320 the site was divided between two separate Broadwell manors, each of which had neighbouring complexes of farm and domestic buildings there. Abandoned manorial buildings may lie under uneven ground to the north of the church and Manor Farm, with some others under the adjoining vacant field known as 'Burnt Backside' (Fig. 7), where in the 19th century foundations were said to be 'plainly visible' in dry weather. (fn. 31) Medieval embellishments to the church suggest some local prosperity, (fn. 32) and in the 15th century an octagonal cross with five tiers of kneeling places was erected just outside the churchyard (Fig. 13). (fn. 33) Presumably that was the 'high cross' mentioned in 1540, (fn. 34) and it remained a social focus in the 1590s when local women gathered there to gossip about their neighbours. (fn. 35)

7. Broadwell village c. 1883, showing key buildings and the former manorial site.

The present village consists of a ribbon development of cottages and farmsteads spread out along the single village street, a pattern well established by the 18th century (fn. 36) and probably from the Middle Ages. As elsewhere in the area, surviving buildings are of limestone rubble with stone-slated roofs, and date mostly from the 17th and 18th centuries, with a few later alterations and additions. (fn. 37) The cottages are interspersed with a few larger buildings. Finial House (the former vicarage house) is of 16th or 17th-century origin, (fn. 38) while Lower Farm and Broadwell House began as farmhouses probably in the 17th century, before being substantially altered and enlarged over the next two hundred years. The Old Manor, another former farmhouse, was built in the late 18th or early 19th century with a symmetrical three-bayed front, a pedimented door hood, and ashlar dressings. (fn. 39) The only other house of note is Manor Farm (Fig. 9) near the church, built in 1804 by the Lechlade builder Richard Pace for William Hervey of Bradwell Grove, to provide accommodation for Hervey's agent and tenant Joseph Large. (fn. 40) The sole institutional building was the village school built in 1847 (Fig. 11), which in the early 21st century housed a private nursery school. (fn. 41) A war memorial cross was erected in the churchyard c. 1920, commemorating parishioners killed in the First World War. (fn. 42)

8. Broadwell's main street in the mid 20th century, looking north. The gate piers on the left survive from a former manor house reportedly burned down in the 17th or 18th century. The Five Bells pub existed by the mid 18th century.

By the end of the 20th century most cottages had been amalgamated with their neighbours to make larger dwellings, and as elsewhere many farm buildings were turned into houses. Among them was a former malt house, possibly that owned by the local Turner family in the 18th century. (fn. 43) One or two poor-quality cottages were demolished in the 1950s, but there was very little new building to compensate. Electricity was available by 1939, although in 2011 many houses still lacked mains drainage. (fn. 44)

Bradwell Grove and Other Outlying Sites

Until inclosure in 1776 there was virtually no outlying settlement, and only a few outlying farmhouses (mostly in Filkins township) were built thereafter. (fn. 45) A pre-decessor of Broadwell mill, on Broadwell brook near the parish's south-eastern edge, existed by the 1180s and possibly by 1086; (fn. 46) the surrounding area was called Cottesmore (i.e. Cott's marsh) by the late 10th century, when it was held by Aethelmaer (d. 982), ealdorman of Hampshire, but there is no evidence of settlement there, and in the 14th century it was low-lying meadow and pasture. (fn. 47)

Bradwell Grove, a sizeable woodland area in the northern part of the parish, included a house of gentry status by the mid 17th century. (fn. 48) Settlement around the crossroads with Akeman Street may have originated earlier, and in the 1750s included a short-lived pub or inn. (fn. 49) From the early 19th century the newly built Bradwell Grove House became the centre of William Hervey's extensive Bradwell Grove estate, (fn. 50) and over the following decades lodges and a few scattered houses and cottages were built for estate workers (Fig. 10). (fn. 51) Many of those employed at the house or neighbouring farm came from nearby settlements including Holwell, however, and not until the late 20th century was there larger-scale domestic building a little further north along the Burford road. (fn. 52)

Military activity followed during the Second World War. Bradwell Grove Camp was built in estate woods just over the parish boundary in Shilton around 1942, and in the latter part of the war became a large American army camp, its field hospital used to treat casualties flown in to nearby airfields. Broadwell aerodrome, so called despite actually lying in Kencot parish, was also built on estate land, and played a significant role in the build-up to D-day. (fn. 53) In 1944 there were plans to set it aside for afforestation, but the site was later bought for development as a golf course and remained semi-derelict in the early 21st century, when the runways were still visible. (fn. 54)

The field hospital was used after the war as a music school for the Royal Marines, and in 1947 became a hospital for 'mental defectives', under the supervision first of Wiltshire Health Authority and later of the Oxfordshire Area Health Authority. Staffing problems in such an isolated area, combined with the expense of maintaining the old army huts, led to its closure in the late 20th century, when the services were relocated. (fn. 55) By 1998 the site had been transformed into a new housing development called Bradwell Village, whose design, 'in true Cotswolds tradition', was compared with that of the model village of Poundbury in Dorset. The development acquired its own village hall, although inhabitants relied primarily on amenities in Burford and other neighbouring towns. (fn. 56) By then Bradwell Grove woods also contained a caravan park, along with the Cotswold Wildlife Park in the grounds of the 19th-century mansion. (fn. 57)

MANORS AND ESTATES

In the early 11th century the whole of what became Broadwell, Langford, and Broughton Poggs parishes almost certainly belonged to a single royal estate, which was held by prominent earls perhaps ex officio. (fn. 58) The Langford and Broughton Poggs parts were separated before the early 1060s, when Broadwell manor, assessed at 24¼ hides and apparently including most of Broadwell, Filkins, Holwell, and Kelmscott, was held by Aelfgar (d. 1062), earl of Mercia. (fn. 59) The manor appears to have remained largely intact until the 12th century, when piecemeal grants, followed by an early 13th-century partition between coheirs, resulted in all four of Broadwell's townships becoming divided among three large manors for the remainder of the Middle Ages, one of them under secular lordship, and the others owned by Cirencester abbey and the Knights Templar (later the Hospitallers). Two large freeholds in Filkins became reputed manors during the later Middle Ages. (fn. 60)

Sales and grants after the Dissolution produced several new estates and freeholds, of which one (in Holwell) became a reputed manor. From the early 17th century, however, the core of the three medieval manors was reunited under the Hampson family, passing eventually to William Hervey (d. 1863). During the early 19th century Hervey built up an estate of over 2,000 a. centred on Bradwell Grove (in Broadwell), which included the remains of the manors together with several smaller estates, and which extended into surrounding parishes. The Bradwell Grove estate survived in the early 21st century when it was owned by the Heyworth family, though by then much of the former Broadwell parish was in private ownership. (fn. 61)

Broadwell Manors

Descent to c. 1223

By 1086 the 24¼-hide Broadwell manor (including most of Broadwell, Filkins, Holwell, and Kelmscott) was held by Eadgar Aetheling's sister Christina. (fn. 62) Following her brother's rebellion her lands were granted to Ralph de Limesy (d. 1093), who gave land in Filkins to Hertford priory. The rest of the manor passed to his son Ralph (d. c. 1129) and grandson Alan (d. by 1162), who further endowed Hertford priory, and who gave 5 hides in Broadwell to the Knights Templar. (fn. 63) From Alan, the rest of the manor passed presumably to his son Gerard (d. by 1185) and grandson John (d. 1193), who in 1190 owed the king 1 mark for the right to hold Broadwell in preference over Ralph of Worcester. (fn. 64)

John de Limesy's heirs were his sisters Basile and Eleanor, both minors. (fn. 65) A third sister, Amabel, was later alleged to have held the manor for life by force with her first husband Hugh Bardolf (d. 1203), the chief justiciar, and her third husband Robert of Ropsley, constable of Bristol. (fn. 66) Certainly Bardolf was granted custody of John's heirs in 1193, (fn. 67) while in 1212 Ropsley held the Limesy barony in wardship, (fn. 68) and in 1215 custody of Broadwell manor, lately held by Robert of Ropsley, was granted to Thomas Mauduit. (fn. 69) Before 1223 the manor was nevertheless divided between the surviving heirs, half passing to Basile and her husband Hugh d'Oddingseles, and the rest to Eleanor and her husband David de Lindsay. (fn. 70) The two halves descended separately thereafter, becoming regarded as separate manors.

Bradwell Odyngsell Manor (c. 1223–1655)

The d'Oddingseles' half of Broadwell manor, known from the 16th century as Bradwell (or Broadwell) Odyngsell, included land in all four townships. (fn. 71) During the 13th century it was assessed (like the Lindsays' share) at 1 knight's fee, and was held in chief, (fn. 72) although in 1301 Henry de Pinkeny (as lord of the Lindsay part) unsuccessfully claimed overlordship. (fn. 73) The manor was sometimes still assessed at 1 knight's fee in the 14th and earlier 15th century, (fn. 74) but at only one fifth of a fee in 1336 and 1347 and at half a fee in 1404, perhaps following its reduction by late 13th-century land grants. (fn. 75) In the late 16th century it was again alleged to be held of the former Lindsay manor, to which the lord was said to owe suit of court. (fn. 76)

From Hugh d'Oddingseles (d. 1239) the manor passed through the male line to Gerard (d. 1267), Hugh (d. 1305), and Sir John d'Oddingseles (d. 1336). (fn. 77) John was succeeded under an earlier settlement by his widow Emme (d. 1347) and son Sir John, who in 1349 granted the manor to Richard de Hastang for life, and whose lands were briefly seized by the Crown c. 1351. (fn. 78) The younger John died in possession in 1352, to be succeeded by his widow Amice (d. 1361) and son Sir John (d. 1380), (fn. 79) whose lands were briefly seized for felony in 1358; (fn. 80) his son John (later Sir John) came of age c. 1386 and died in 1403, (fn. 81) to be followed by his son Sir Edward, who was of age by 1415. (fn. 82) In 1446 Edward settled most of the manor on his son Gerard and daughter-in-law Margaret, who in 1485 settled the rest on themselves and their heirs. (fn. 83) Thereafter the manor passed apparently through the male line to Edward (fl. 1502–9), Edmund (d. 1523), Edmund (d. 1558), and John, who fell into serious debt and sold his estates piecemeal. (fn. 84)

Most of the manor, with lands in Broadwell, Filkins, and Kelmscott, was conveyed in 1563 to Peter Hyde (who was probably a trustee), and in 1570 to John Thompson (d. 1591), who had already bought a part in 1562–3. (fn. 85) The land in Holwell was sold separately, and remained a distinct estate until the 19th century. (fn. 86) Before 1589 (and possibly by 1585) two thirds of Thompson's lands were seized by the Crown because of his Roman Catholicism, and in 1590 it was alleged that he had let all or part to Sir Laurence Tanfield in order to defraud the Crown. (fn. 87) The seizure was cancelled in 1593 when the Crown restored ownership to John's son Robert (d. 1601), who in 1603 was succeeded by his brother John, another recusant. (fn. 88) In 1627–30 John and his wife Anne sold the manor to Thomas Hampson (d. 1655) of Taplow (Bucks.), whose brother Nicholas had already acquired the other two Broadwell manors. (fn. 89) Following Nicholas's death in 1637 all three manors were effectively reunited as a single estate, with lands in all of the Broadwell townships except for Holwell. (fn. 90)

Bradwell Cirencester Manor (c. 1223–1655)

Following the division of Broadwell manor in the early 13th century (fn. 91) the Lindsays' half, known from the 16th century as Bradwell Cirencester, passed successively from Eleanor de Limesy and her husband David de Lindsay (d. by 1219) to their children David (d.s.p. 1241), Gerard (d.s.p. 1246), and Alice, who married Henry de Pinkeny (d. 1254). (fn. 92) There were, however, complex subdivisions among the family. A ploughland was reportedly given by the younger David to Alice and Henry, who c. 1242 enfeoffed Laurence de Brok, while another ploughland was given to David's relative Richard de Bickerton. Both those holdings were acquired by Peter of Ashridge, who gave them to his brother Jordan; he in turn gave them to Cirencester abbey (Glos.), (fn. 93) which by 1279 held all or most of the Lindsay manor of Robert de Pinkeny (d. 1296), Henry de Pinkeny's grandson. (fn. 94) The manor (assessed at 1 knight's fee) still included lands in Broadwell, Holwell, and Filkins, (fn. 95) and a further ten yardlands in Kelmscott, Filkins, and Holwell (subinfeudated by David de Lindsay to Roland d'Oddingseles) were acquired by the abbey after Roland's death c. 1316. (fn. 96) The Pinkenys' over-lordship continued until 1301, when Robert's brother Henry (d. 1315), Lord Pinkeny, surrendered his lands to the Crown. (fn. 97) A separate knight's fee, reportedly still held by Peter of Ashridge, was mentioned in the early 14th century and again (probably in error) in 1401–2. (fn. 98)

Following Cirencester abbey's dissolution in 1536 the manor passed to the Crown, which in 1542 sold it with the former Hospitallers' manor of Bradwell St John to Sir Thomas Pope (d. 1559) of Wroxton. (fn. 99) He was succeeded by his brother John (d. 1583) and nephew William, later earl of Downe, (fn. 100) who in 1599 sold both manors to Sir Robert Hampson (d. 1607), a citizen and alderman of London; Hampson's family had been lessees of the demesne farm since the early 16th century. (fn. 101) The manors passed from Sir Robert to his elder son Nicholas (d. 1637) and younger son Thomas (d. 1655), purchaser of Bradwell Odyngsell manor; (fn. 102) thereafter all three manors descended together. (fn. 103)

Bradwell St John Manor (c. 1223–1655)

The manor of Bradwell St John, so called from the 16th century, (fn. 104) originated in Alan de Limesy's grant to the Knights Templar in the mid 12th century of five hides in Broadwell, together with the church and rectory estate, and meadow at Cottesmore. (fn. 105) During the 13th century the Templars repeatedly sought warranty for six hides or 13 librates of land against owners of the other manors. (fn. 106) In 1279 they held over 24 yardlands in Broadwell, and another hide was held for 4 marks' rent of Brimpsfield priory (Glos.), whose right is otherwise unrecorded. (fn. 107) Following the Templars' dissolution the manor was seized by Edward II, (fn. 108) who gave it to Hugh le Despenser (d. 1326) with other lands formerly belonging to the Templars' preceptory of Temple Guiting (Glos.). In 1328, after Despenser's fall, Edward III granted the Temple Guiting estates to his clerk Master Pancius de Controne, (fn. 109) who in 1340 granted them to Sir William de Clinton, earl of Huntingdon. (fn. 110) Longstanding claims by the Knights Hospitaller, who counted Bradwell St John among their possessions in 1338, (fn. 111) seem to have been vindicated soon after, and the Hospitallers' preceptory of Quenington (Glos.) retained the manor until the Dissolution. (fn. 112) In 1542 the manor was granted to Sir Thomas Pope, whose nephew sold most of it to the Hampsons in 1599 with Bradwell Cirencester. (fn. 113)

The Reunited Manor and the Bradwell Grove Estate (1655–2011)

Thomas Hampson, a baronet from 1642, died in 1655, and under a settlement of 1650 his combined manors of Bradwell Odyngsell, Bradwell Cirencester, and Bradwell St John passed to his son Sir Thomas Hampson (d. 1670) and grandson Sir Dennis Hampson (d. 1719), both baronets. (fn. 114) By 1673 Dennis was in debt, and in 1696, following numerous mortgages, he appears to have lost control of his property to various creditors. In 1703 they sold the estates to George Hamilton (d. 1737), 6th earl of Orkney, who freed the Broadwell estate from incumbrances only in 1719. (fn. 115) In 1723 Hamilton added lands centred on Bradwell Grove House, which John and Anne Thompson had separately sold to Sir Laurence Tanfield (d. 1626), and which had subsequently passed to Tanfield's grandson Sir Lucius Cary (d. 1643), Viscount Falkland, by sale to William Lenthall (d. 1662), and through the male line to Lenthall's great-grandson John (d. 1763). (fn. 116) Hamilton also acquired the 490-a. Oxleaze farm in Broughton Poggs parish. (fn. 117)

Under his will Hamilton was succeeded by his eldest daughter Anne (d. 1756), styled countess of Orkney. In 1753 she and her husband William O'Brien (d. 1777), 4th earl of Inchiquin, settled their Broadwell lands on their only surviving daughter Mary (d. 1790), a deaf mute who in 1756 became countess of Orkney. Her husband Murrough O'Brien (d. 1808), 5th earl of Inchiquin from 1777 and marquis of Thomond from 1800, acquired a life interest, and from 1776, although the estate was entailed on their children, they gained outright control. (fn. 118) O'Brien fell heavily into debt: in 1765 he was in the Marshalsea debtors' gaol in London, (fn. 119) and he continued to charge his inheritance with various annuities. (fn. 120) In 1777, with the agreement of his wife and daughter, he mortgaged the estate, resulting in litigation to safeguard his grandson's inheritance. (fn. 121) O'Brien, his daughter Mary (d. 1831), countess of Orkney, and her son John Hamilton Fitzmaurice, Viscount Kirkwall, were all parties to the sale of the combined Broadwell manor to William Hervey in 1804. (fn. 122)

Hervey's initial purchase of over 2,300 a. in Broadwell, Filkins, Broughton Poggs, and Kelmscott, thenceforth called the Bradwell Grove estate, was encumbered by O'Brien's debts until 1815. (fn. 123) Hervey greatly increased the estate, buying all of Holwell (some 970 a.) in 1838–9, the Filkins Hall estate in 1849, and other smaller parcels. (fn. 124) He died in 1863 leaving his estate to Henry William Vincent, who was succeeded in 1865 by his daughter Susan Anne, wife of Lt.-Col. John Henry Bagot Lane. (fn. 125) Under Hervey's will the remaining Kelmscott land was sold in 1864, (fn. 126) and in 1871 Lane sold the rest of the Bradwell Grove estate, then 3,690 a. in Broadwell and neighbouring parishes, to William Henry Fox (d. 1920), son of a Yorkshire industrialist and umbrella manufacturer. (fn. 127) In 1875 Fox added the rectory estate in Broadwell and Filkins, (fn. 128) and despite the sale of 170 a. in Filkins in 1914 (fn. 129) the estate totalled 5,114 a. by 1921, when it was sold after Fox's death. (fn. 130) Most, including Bradwell Grove House, was bought by Lt.-Col. Cecil Heyworth-Savage (d. 1949), whose grandson John Heyworth retained some 3,000 a. in 2001. (fn. 131)

Manorial Sites and Manor Houses

Manor houses for all three Broadwell manors existed probably by the late 13th century, when each of the manors included home farms held in demesne. (fn. 132) Houses for Bradwell Odyngsell and Bradwell Cirencester manors adjoined each other close to the church, on what was probably the divided site of an earlier, 11th- or 12th-century manor house. (fn. 133) The site of the Templars' house for Bradwell St John manor is unknown, though a 'capital mansion' called Templars' Farm still existed in the early 17th century, when it was let to local tenants with the demesne farm. (fn. 134) Surviving buildings on the Bradwell Odyngsell site were replaced in 1804 by the existing Broadwell Manor Farm, William Hervey having adopted Bradwell Grove House, in woodland to the north, as his main residence. (fn. 135)

Bradwell Odyngsell and Bradwell Cirencester Manor Houses

In the early 14th century Cirencester abbey's manor house or 'court', presumably comprising agricultural buildings and accommodation for bailiffs or other officials, stood immediately west of the d'Oddingseles' house, their interlinked curtilages and gardens divided by ditches and boundary stones. In 1320 John d'Oddingseles agreed to allow access for repair of the abbey's stables and other buildings. (fn. 136) Medieval evidence for the houses' location is lacking, but their 17th- and 18th-century successors appear to have stood close to the church, partly within a large, now mostly vacant close fronting the village street (Fig. 7). (fn. 137) Presumably the division of the curtilage followed the manor's partition in the early 13th century, suggesting that this was also the site of the earlier manor house. The Limesys had numerous lands elsewhere, however, and are unlikely to have been resident permanently. (fn. 138)

In 1305 the d'Oddingseles' manor house included a garden, dovecot, and fishpond (vivario), (fn. 139) and in 1320 John d'Oddingseles and the abbot reached agreement over rabbit-hunting in the manorial warren. (fn. 140) The house was worth only 2s. a year in 1347 and nothing in 1361, however, and it was dilapidated in 1380, when it still included a hall and chambers, a fishpond, a grange, and other agricultural buildings, also in disrepair. (fn. 141) The family was presumably resident in 1356 when Amice d'Oddingseles, her son John, and others allegedly attacked Cirencester abbey's property in Broadwell, (fn. 142) and in 1358 John dated a grant there, (fn. 143) but subsequent generations apparently lived elsewhere, (fn. 144) and the buildings were probably let. Cirencester abbey's house apparently survived in the 1540s, when the 'site' of its manor was let with buildings, a dovecot, and the demesne to the Hampson family. (fn. 145)

The Thompsons, purchasers of Bradwell Odyngsell in 1570, were mostly resident until c. 1630, (fn. 146) and although the Hampsons' main residence from 1635 was Taplow Court in Buckinghamshire, (fn. 147) several family members continued to live in Broadwell. (fn. 148) In the early 17th century there was evidently still a manor house for each manor, (fn. 149) probably on the adjoining sites by the church; one of them may have been the richly furnished house occupied by Thomas Hampson (d. 1640), lessee of the 'site' of Bradwell Cirencester, which at his death included at least seven bedrooms, a hall and parlour, a study of books, and numerous service rooms and outbuildings. (fn. 150) In 1665 Sir Thomas Hampson (d. 1670) occupied a house taxed on four hearths, possibly the d'Oddingseles' manor house, and his brother George one of nine hearths, the second largest in the parish. (fn. 151) Thereafter the reunited manor seems to have included only one house presumably on the same site, which was let to local gentry or farmers. (fn. 152) The house reportedly burned down in the late 17th or early 18th century, (fn. 153) leaving farm buildings and a surviving pair of 17th-century roadside gate piers, which lead into a large close named Burnt Backside (Figs 7–8). (fn. 154) If so it must have been rebuilt, since manorial deeds continued to mention a manor house with barns and stables. In the late 18th and early 19th century it was let with 300 a. to the farmer Joseph Large, the occupant in 1802. (fn. 155)

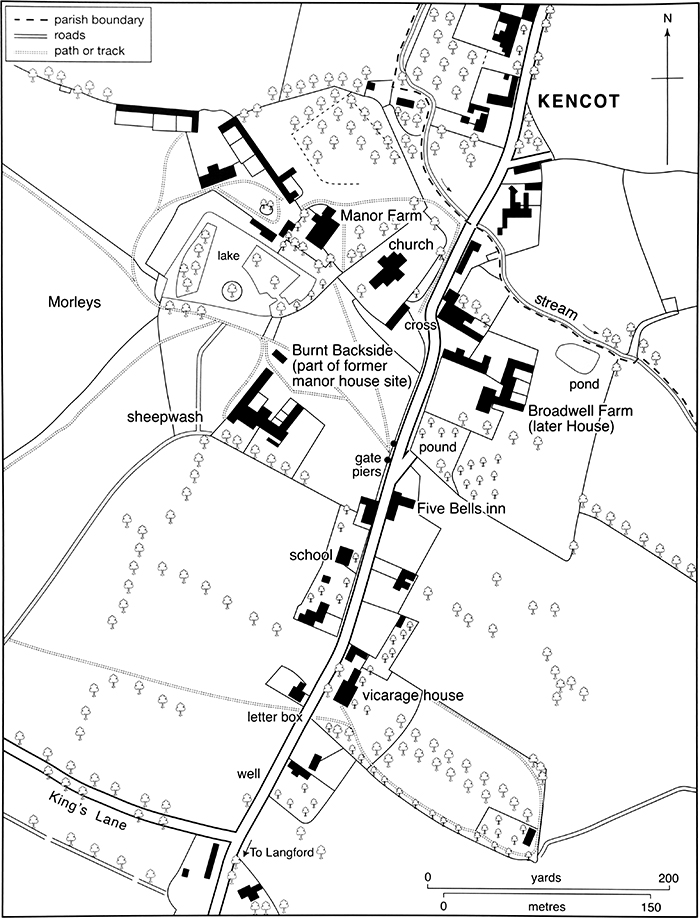

Broadwell Manor Farm

In 1804 Large's house was replaced with Broadwell Manor Farmhouse on the close's north-eastern edge, designed and built for William Hervey by Richard Pace of Lechlade (Glos.). (fn. 156) Built on a square three-bay plan with later extensions at the north-west corner, the house is two-storeyed with attics, and has a hipped, stone-slated roof (Fig. 9). Like the area's other high-quality farmhouses it is constructed of coursed limestone rubble with ashlar dressings; the main west front has a slightly projecting central bay with moulded cornice and shaped pediment, and its central double doors are set within an elegant 20th-century ironwork porch, which replaced an earlier wooden one. In 1921 the house and its farmland were sold to the tenant, thus separating them from the rest of the Bradwell Grove estate. The following year the farm was bought by F. C. Goodenough (d. 1934) of Filkins Hall, whose descendant F. R. Goodenough occupied the house in 2011. (fn. 157)

9. Manor Farm from the south-west, built on part of the earlier manorial curtilage in 1804 for the lord's tenant and agent Joseph Large.

Agricultural buildings, ranged around the edge of Burnt Backside south-west of the farmhouse, include a late 18th- or early 19th-century granary and a 19th-century stable, both of limestone rubble. A stone barn on the close's south-west side, with dressed quoins and a dovecot loft in the porch, may be of 16th- or early 17th-century origin, and was perhaps associated with the Bradwell Cirencester manor house; a 16th- or 17th-century hollow-chamfered stone-mullioned window survives in the porch, set under a Tudor hoodmould. The triple-purlin roof is pegged but has timbers of modest proportions, and is probably 18th- or 19th-century. (fn. 158) Ponds mentioned in 1802 were presumably the large ornamental lake with islands which survives immediately south-west of the present house. The lake existed by 1881, having perhaps been adapted from the medieval fishponds. (fn. 159)

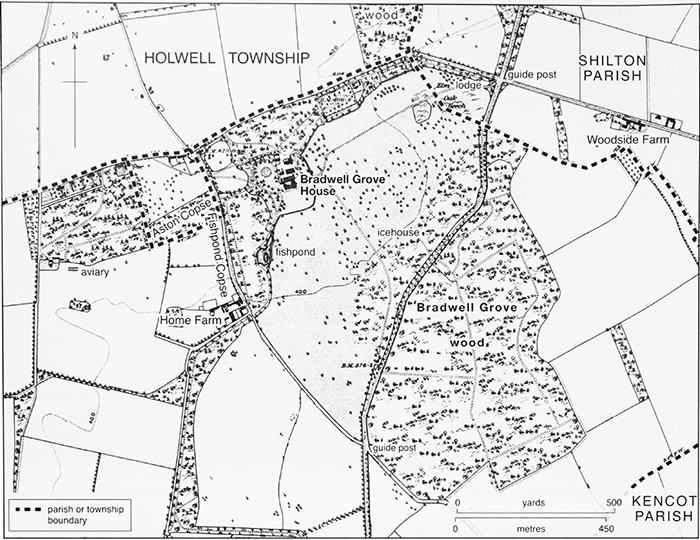

Bradwell Grove House

A small woodland estate at Bradwell Grove was separately owned by the Tanfields and Lenthalls from c. 1630 to 1723, (fn. 160) and by the mid 17th century included a house of gentry status. The occupants (presumably as lessees) were John Huband (d. 1668) and Ann Walford (d. 1681), and though nothing is known of the building it may have been of moderately high quality, judging from Huband's mural monument in Broadwell church with its classical detailing and bracketed scroll pediment. (fn. 161) William Lenthall's widow Catherine Hamilton (d. 1723), countess of Abercorn, may have occasionally occupied the house, (fn. 162) and presumably this was the 'hunting seat' in Bradwell Grove owned by Murrough O'Brien in 1759. (fn. 163) From the 1760s the house was let to tenant farmers, and in 1802 it was described as a mansion house with barns, stables, and out-buildings. (fn. 164) Soon after, William Hervey adopted Bradwell Grove as his principal seat, and in 1804 he rebuilt and probably enlarged the house in gothic style, to designs by William Atkinson. The builder was Richard Pace. (fn. 165)

10. Bradwell Grove House and Bradwell Grove in 1883.

The house (Plate 6) lies in parkland laid out by Hervey, (fn. 166) and is two-storeyed with a U-plan. Long, low and irregular, it is mostly ashlar-built and includes an embattled parapet and pinnacles, while the interior, too, retains simple early 19th-century gothic detailing. A contemporary orangery in matching style survives at the house's south-west corner, towards the garden. The north service wing, at the rear, incorporates part of an 18th-century extension to an earlier house, perhaps that occupied by Huband. (fn. 167) After Hervey's death in 1863 the house was briefly let to various gentry, (fn. 168) followed in the 1870s by W. H. Fox, who in 1891 lived there with his mother and twelve servants. Later occupants included Col. Heyworth-Savage, who moved there after acquiring Fox's estate in 1923. (fn. 169) Minor additions and alterations for Fox and his successors included new bay windows to the south front, (fn. 170) and a keeper's lodge was designed by William Wilkinson in the early 1870s. (fn. 171) Piped water was supplied from a stream at Signet in the earlier 20th century, pumped to a raised tank near the house. (fn. 172)

From the 1950s the house was leased to the Oxford Regional Hospital Board, until in 1970 John Heyworth opened the surrounding parkland to the public as an exotic wildlife park. The house itself was converted into offices and staff flats, and the stables and outbuildings into a reptile house and aquarium. A large cafeteria extension was later built along the house's west side, and in 1989 a garden terrace was constructed along its south front. (fn. 173)

Rectory Estate (College Farm)

Broadwell rectory estate comprised glebe and tithes from all four townships, and throughout the Middle Ages formed part of the Templars' (and later Hospitallers') manor of Bradwell St John. (fn. 174) Fountains abbey (Yorks.) received two thirds of the demesne tithes in the early 13th century, presumably following a grant by one of the Limesys, and in 1313 Edward II ordered keepers of Bradwell St John manor to pay the abbey 60s. a year for tithes and a yardland in Broadwell. (fn. 175) Neither the land nor the payment was mentioned among the abbey's possessions later, however. (fn. 176)

In 1542 the glebe and tithes in Broadwell and Filkins were granted with Bradwell St John manor to Sir Thomas Pope (d. 1559), (fn. 177) who gave them to Trinity College, Oxford, soon after its foundation in 1555. (fn. 178) The estate was let to local gentry including, in the 18th century, owners of Filkins Hall. (fn. 179) In the mid 18th century it appears to have included great tithes, 5 yardlands mostly in Upper Filkins, and another 24 a. bought with two cottages in 1713, although there was evidently some confusion with freehold land belonging to the Filkins Hall estate, which was exacerbated by exchanges of land in the early 18th century. (fn. 180) At inclosure in 1776 Trinity College received 457 a. in Broadwell and Filkins, of which 345 a. was for commuted tithes. (fn. 181) From 1805 the college's lessee was William Hervey of Bradwell Grove, whose successor W. H. Fox bought the freehold in 1875. (fn. 182) Thereafter the land formed part of the Bradwell Grove estate.

College Farm

A farmhouse for the newly inclosed estate was built in 1777–9 on an outlying site in the north of Filkins township. (fn. 183) Its main three-bayed part, built of coursed limestone rubble with brick quoins and window-dressings, has two storeys with attics and a central entrance; at the rear is a former stair projection, and attached at the north-east is a lower two-storey range with a mid 19th-century cottage extension. The house faces into a large square farmyard flanked by ranges of farm buildings, including a 7-bay barn-range built of similar materials, and a stone cart-shed and stabling; most are probably broadly contemporary with the house. (fn. 184)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until recent times Broadwell was a predominantly agricultural village, which until inclosure in 1776 shared an open-field system with Filkins. Post-inclosure farms and estates were also intermixed between the two townships, and in the following account their agricultural history is treated together. (fn. 185)

As well as extensive open fields Broadwell contained substantial woodland around Bradwell Grove, which local lords often exploited directly. Pasture was available on the upland downs, which extended into Holwell and neighbouring parishes, and meadow adjoined the streams in Broadwell's southern part. In the late 16th century the combined manors were reckoned to include around 1,300 a. of arable, 450 a. of pasture, 140 a. of meadow, 110 a. of wood, and 140 a. of furze and heath; the figures are not accurate, but probably give a general indication of the spread of resources. (fn. 186) Medieval demesne farms were focused on Broadwell, and from the 16th and 17th centuries formed the basis of some relatively large leasehold farms there. Filkins, by contrast, was characterized from the Middle Ages by a significant number of freeholds, which perhaps reflected its distance from the manorial centre. Those in turn formed the basis of substantial yeoman farms in the post-medieval period. From the 19th century Broadwell's agricultural development was conditioned in part by the policies of the Bradwell Grove estate, which turned Holwell into an estate village and created local employment for estate workers.

Rural crafts and trades (including commercial malting) were recorded at both Broadwell and Filkins, but were far less significant in Broadwell than in the latter township, with its quarrying and stone masonry and, by the 19th century, its higher concentration of shops. Both villages experienced 20th-century decline, but only in Filkins was this was balanced by the establishment of new craft-based industries in the latter part of the century.

The Agricultural Landscape

Open-Field Arable

By 1086 some 30 ploughlands of arable were cultivated on Broadwell manor, six of them in demesne, and 24 by tenants based in the four townships. (fn. 187) A century later the Templars' manor alone included 20 yardlands (5 ploughlands) in Broadwell, and in 1279 over 90 yardlands (22½ ploughlands) were recorded in Broadwell and Filkins together. (fn. 188) Since yardlands here seem to have measured around 25 a. each, some 2,000 a., more than half the total area of Broadwell and Filkins, may have been under cultivation. (fn. 189)

The townships' shared fields (Fig. 6) were concentrated on the lighter stonebrash soils, and seem to have covered much of the area north and south-east of Filkins, excluding the woodland at Bradwell Grove, the downs in the extreme north, and an area of common in the vicinity of the later College Farm. (fn. 190) In 1347 and 1361 the fields were rotated on a two-course system, (fn. 191) but a three-course rotation was introduced before 1380, perhaps following changes brought about by the Black Death. (fn. 192) The fields' later organization is not entirely clear. Fields and commons belonging to Broadwell and Over Filkins were generally mentioned together, and in the early 18th century still seem to have been divided into two large units called East and West fields. The former lay in the north-east near Bradwell Grove (including the area called Redlands), and the latter further west, including the area around Stanmoor and Red Herring (or Earing Green) Bottom. (fn. 193) Grove field, mentioned in 1599 and 1723, may have been the same as East field. (fn. 194) Nether Filkins's fields and commons were sometimes mentioned separately, (fn. 195) though whether they were ever independently administered is uncertain. An estate described around 1750 was divided among Broadwell Near field (where it included 81 a.), Broadwell Far field (66 a.), and Filkins field (15¾ a.); (fn. 196) by then, however, the earlier arrangements were becoming obscured, as landowners embarked upon exchanges to concentrate their lands in Broadwell, Upper Filkins, or Lower Filkins, presumably in preparation for inclosure. (fn. 197) Whatever the formal disposition of the fields, by the early 18th century there were complex subdivisions for cropping. In 1713, for example, furlongs in East field were variously planted with barley, wheat, and oats, while those in West field were fallow or planted with peas. (fn. 198)

Pasture and Meadow

The townships' commons were concentrated around the two villages and on the downs adjoining Holwell, with a smaller area in the fields north of Filkins. (fn. 199) Those immediately south-east of Broadwell village included Summer Leys (originally a summer pasture), Horse Leys, and Cottelake in or near Cottesmore, where Bradwell Odyngsell and Bradwell Cirencester manors had pasture rights in 1320. (fn. 200) Filkins or Nether Filkins common lay between the villages, and evidently included small greens within Filkins itself: one such was the Gassons, which remained commonable until inclosure. (fn. 201) Further north, a common pasture in the vicinity of College Farm was known as the Marsh and (probably) as Upper Filkins common, and included the area laid out as furze grounds for the poor in 1776. (fn. 202) A 19th-century account claimed that up to 500 cows had formerly been pastured close to Filkins, and that cow keepers' cottages had stood by the bridge and at the Hades, on the village's northern edge. (fn. 203) The downs themselves, extending into Holwell and neighbouring parishes, covered the higher ground towards Akeman Street, (fn. 204) and were an important shared resource used by sheep farmers and others from neighbouring parishes. (fn. 205) In 1320 the lords of Bradwell Odyngsell and Bradwell Cirencester also had sheep folds in the copse (spineto) at Bradwell Grove, and pastures belonging to Bradwell Cirencester and to the Templars lay in the west of the parish at St John's Leys and 'Fishpol'. (fn. 206) Additional pasture was available in the fields after harvest. (fn. 207)

Much of the 185 a. of meadow recorded on Broadwell manor in 1086 probably lay in Kelmscott adjoining the river Thames, where Broadwell Odyngsell manor had demesne meadow until the 19th century. (fn. 208) Another sizeable area lay south-east of Broadwell village between the two boundary streams, in Cottesmore (Cott's marsh) and Edgerly (Ecgheard's island). Presumably this narrow corridor of land was intentionally included in Broadwell manor in the 11th century, in order to increase its access to meadow. (fn. 209) Some of it may have been inclosed demesne: the Templars' manor included meadow at Cottesmore in the 12th century, (fn. 210) while the two other manors had meadow in Edgerly and Hasses (adjoining Clanfield) in the 14th century and later. (fn. 211) Even so at least 95 a. in Edgerly was still common meadow in the 18th century, and there was lot meadow presumably nearby or elsewhere along the boundary streams. (fn. 212)

Elsewhere in the townships there was probably little meadow, and for some smaller farmers it may have remained in short supply. Two 16th-century tenants apparently occupied only 1–2 a. with holdings of up to 2½ yardlands, although that could have been in addition to their allowance in the common meadows. (fn. 213) Some Broadwell and Filkins farmers acquired meadow outside the parish (including at Radcot), (fn. 214) while others retained small parcels in Kelmscott, a pattern which continued following Kelmscott's inclosure in 1798–9. (fn. 215)

Given the relatively scattered nature of the commons and meadows, the carting of hay and droving of animals across the parish must have been commonplace from the Middle Ages until inclosure. Its importance is reflected in an agreement of 1320 between John d'Oddingseles and the abbot of Cirencester, by which right of access was confirmed along the chief roads and lanes linking Broadwell village with the pastures and meadows to the south (as far as Kelmscott), and with the downs, pastures, and woodland in the parish's northern and western parts. (fn. 216)

Early Inclosures

Though much of the medieval common and meadow remained uninclosed until 1776, a few areas were inclosed early on as part of the demesne farms (Fig. 6). In 1347 the Bradwell Odyngsell demesne included 12 a. of inclosed meadow, much of it by the Thames in Kelmscott; the rest (4 a.) lay in Edgerly and Horse Pool and was worth 1s. an acre, (fn. 217) while the manor's inclosed pasture increased from 6½ a. in 1305 to 24 a. (worth 8s.) in 1361. (fn. 218) A Broadwell freeholder seems to have had 18 a. of probably inclosed meadow as early as 1251, (fn. 219) while Goodfellows had 24 a. of inclosed meadow in Nether Filkins in 1479. (fn. 220) Piecemeal inclosure by the abbot of Cirencester and other lords (presumably for sheep farming) continued in the early 16th century, when two 30-a. holdings in Broadwell were reported as recently inclosed and their houses were left derelict. (fn. 221)

By the 1620s Bradwell Odyngsell included around 100 a. of old inclosures, many of them taken from the commons and meadows south-east of the village. Others lay north of the village street, close to the manor house: of those, Morleys and the Hursts were later described as commonable grounds, and were presumably thrown open for grazing at specified times of year. Closes at Burden Hill (in the far north-west) and Hill mead furlong had perhaps been taken from the arable, and the manor's other inclosures still included 18–20 a. of Thames-side meadow in Kelmscott. (fn. 222) Even so some 2,670 a. in Broadwell and Filkins (75 per cent of the total) remained uninclosed on the eve of parliamentary inclosure. (fn. 223)

Woodland

Wood and wood-pasture at Bradwell Grove in the north-east of the parish is recorded from the 14th century, when eight inhabitants were prosecuted for taking timber worth 100s. belonging to the abbot of Cirencester. (fn. 224) Its medieval extent is uncertain, but probably it did not extend west of the Holwell road, where later field names suggest the presence of open-field arable and (further north) of commonable downland (Fig. 6). In 1320 there was also a 'field' (campum) to the east of the 'spinney': possibly that was the tongue of land between the later Bradwell Grove and the parish boundary, although the field name Crooked Oak suggests that the area was wooded at some point. (fn. 225) The woodland was apparently divided between the three principal manors, and was kept in demesne. Bradwell Odyngsell manor included 10 a. in 1305, when profits from sale of underwood totalled 2s. a year; in 1353 the manor had 20 a. of thick wood, although shade from the trees was said to make the pasture worthless, and there were then no profits from underwood. (fn. 226) A part of the woods may have been imparked before 1320, when hunting rights were mentioned in an agreement between John d'Oddingseles and Cirencester abbey. (fn. 227) Coppicing was mentioned from the 16th century, presumably reflecting earlier practice. (fn. 228)

In the later 16th century Bradwell Odyngsell's demesne still included Austin coppice, a 3-a. inclosure south of Akeman Street, (fn. 229) and in 1599 three further coppices at Bradwell Grove were leased by William Pope, the owner of Bradwell Cirencester and Bradwell St John manors, who had an estimated 40 a. of woodland in demesne. (fn. 230) By 1673 the reunited manor included an estimated 100 a. of woodland still kept in hand, which in 1777 produced an annual income of nearly £120, less £10 in woodward's charges and parish tax. (fn. 231) In 1785 the woodland was taxed at £7 8s. 4d. (fn. 232) By then the Bradwell Grove estate included additional woodlands in Shilton and Broughton Poggs, the whole being valued at over £3,211 in 1802. (fn. 233) Trees elsewhere on the Broadwell manors were usually reserved to the lord on leasehold properties, and 16th-century rents habitually included an obligation to plant at least one oak, ash, and elm tree a year, presumably in the hedgerows of closes adjoining tenants' houses. (fn. 234)

By the 18th and 19th centuries Broadwell's landlords were evidently trying to maximize the profitability of their timber resources: fifty trees on the glebe were carefully recorded, (fn. 235) and there was a nursery on Trinity College's lands. (fn. 236) Regular wood sales were held at Broadwell, (fn. 237) and new plantations were made on the Filkins Hall and Bradwell Grove estates. (fn. 238) William Hervey, who acquired the Bradwell Grove estate in 1804, made extensive plantations around the new mansion house and smaller plantations between fields, roughly trebling the amount of woodland: an oration at his funeral in 1863 recalled that 'when he came nearly sixty years ago into this neighbourhood he found it bleak and barren, and he has left it clothed with woods'. (fn. 239) Forestry continued to be important, and in the later 20th century Hervey's successor John Heyworth planted over 300,000 trees, half hardwood and half softwood. In 2002 the estate retained 387 a. of woodland in Broadwell, Filkins, and adjacent parishes, managed by one woodman from a yard near Aston Coppice. (fn. 240)

By the later 18th century Bradwell Grove was a 'hunting seat' of Murrough O'Brien, (fn. 241) who employed gamekeepers and advertised that poachers would be prosecuted. (fn. 242) From then on Broadwell and Filkins were frequently said to be in 'fine sporting country', and hunting and shooting continued throughout the 19th, 20th, and early 21st centuries. (fn. 243)

Tenants and Farming to c. 1540

In 1279 most peasant holdings in Broadwell were yardlands or half yardlands, each yardland probably containing around 25 a. of arable. A few cottagers had smaller holdings of 6 a. (perhaps ¼ yardlands), and a single freeholder (excluding the miller) had 1½ yardlands. Landholding at Filkins was both more complex and more varied, perhaps reflecting its distance from the manorial centres at Broadwell. There 22 out of 36 tenants (over 60 per cent) were freeholders, and holdings ranged from a few acres to 2 yardlands, with one freeholder holding a ploughland. (fn. 244)

All three manors included a large demesne farm centred on Broadwell, each of them reckoned at 2 ploughlands and containing up to 200 a. of arable. Unfree tenants, including those at Filkins, owed light labour services on the demesnes mostly at sowing and harvest times, although some owed only a few days' work throughout the year. (fn. 245) Labour services seem to have been commuted into money rents by 1361, perhaps reflecting difficulties following the Black Death, and by 1381 the d'Oddingseles' demesne arable was reduced to 120 a., 40 a. having lain uncultivated for forty years. (fn. 246) The demesne farms of the two ecclesiastical manors were probably leased out soon after, and certainly by the later Middle Ages. (fn. 247)

The size of the open fields implies the arable-based mixed farming typical of the area, (fn. 248) but as in neighbouring parishes there was also some large-scale sheep rearing, which attracted outsiders and which probably increased from the late 14th and early 15th centuries. In 1347 Reginald Bryan, a clearly prosperous freeholder possibly living near Oxford, had at least 150 sheep, 80 lambs, and 18 oxen in Broadwell parish, where he also grew crops. (fn. 249) Two centuries later three prominent local farmers were taxed on a total of 560 sheep (400 in Broadwell and 160 in Filkins), and six people living outside the parish kept a total of 1,700 on Holwell Downs. (fn. 250) Stints were closely regulated, as elsewhere. In the mid 14th century the d'Oddingseles' 2-carucate demesne carried common rights for 16 oxen and 300 sheep, (fn. 251) while the average stint on the common pastures in the 16th to 18th centuries (perhaps reflecting earlier custom) was around 50 sheep and 8 oxen or horses for each yardland. (fn. 252) By then there was considerable variety, however, presumably following the sale and purchase of pasture rights. (fn. 253) The demesnes included additional inclosed pasture and meadow by the 14th century, and piecemeal inclosure probably for sheep farming continued in the early 16th. (fn. 254) Nothing is known of the townships' arable farming during the Middle Ages, but as in neighbouring parishes it was presumably based on wheat and barley, together with some dredge and oats. (fn. 255)

Farms and Farming c. 1540–1776

From the 16th century, the medieval demesne farms centred on Broadwell continued to form the basis of large leasehold farms. Both the monastic demesnes were being leased at the Dissolution, the Hospitallers' farm (previously let to Steven Bagot) to John Forty and his sons, and Cirencester abbey's to Harry Hampson; in addition a large farm at Holwell was let to the abbey's former bailiff Richard Symons or Symonds, together with a small inclosed estate at Puttes in Alvescot. (fn. 256) John Whiting, who was of comparable wealth, perhaps held the Odyngsell demesne. (fn. 257) After the Pope family acquired the monastic estates in 1542 they continued to lease the demesne farms, the Goodenough family taking over from the Fortys during the later 16th century. (fn. 258)

In Broadwell the demesne farmers were among the most prosperous of a group of around ten leading farming families who were still mostly manorial tenants. Bradwell St John manor had customary tenants only, all living in Broadwell, although Bradwell Cirencester had some free tenants in Filkins and Kelmscott and customary holdings of varying sizes in Over and Nether Filkins, Broadwell, and Holwell. (fn. 259) As earlier, freeholders were concentrated in Filkins, where there was a slightly larger group of prosperous farmers with holdings based on the former medieval freeholds and larger leaseholds. Around 30 landholders in the two townships together were rich enough to pay lay subsidies and parish tax in the 16th and 17th centuries, of whom the majority had 1–2 yardlands. A small handful of yeomen and gentlemen had over 4 yardlands, while conversely some cottagers had less than a yardland. (fn. 260)

Farming at all levels was still mixed, with an important pastoral element. Harry Hampson of Broadwell had around 200 sheep in 1549, as did his contemporary Robert Turner, by far the wealthiest taxpayer in Filkins. (fn. 261) Most tenants farmed on a more modest scale, keeping animals in closes or backsides attached to their homesteads. Many possessed small numbers of sheep, milk cows, and draught animals (both oxen and horses), along with poultry and one or two store pigs for bacon. Most grew barley as their main arable crop, while the wealthier also grew wheat and owned a variety of carts and other agricultural implements. (fn. 262)

During the 16th century the number of yeoman farmsteads in Broadwell and Filkins was roughly equal, but from the 17th century, as the Hampsons consolidated their estates in the parish and became the dominant landowners, lands in Broadwell seem to have been consolidated into larger leasehold units. (fn. 263) Manor, Lower, and Grove farms, leased to major tenants, may have originated around this period, and by 1762 Grove farm included some 289 a. of inclosed arable and pasture, together with 140 a. in the common fields and commons for 300 sheep. (fn. 264) Filkins remained dominated by independent yeomen, of whom some took advantage of an active land market to consolidate substantial holdings, and to lease out smaller parcels of land and houses to other inhabitants. (fn. 265) In the 17th century there was occasional encroachment on the wastes and commons in Filkins to make way for new cottages and inclosures, (fn. 266) and in the 18th and early 19th centuries many buildings were renovated and new ones erected. (fn. 267)

From the early 18th century Filkins was increasingly dominated by the Filkins Hall estate, built up by the Bristol lawyer Thomas Edwards (d. c. 1743) from around 1704, when he first acquired the lease of Trinity College's estate (by then some 6½ yardlands). Edwards and his son-in-law Alexander Ready (later Colston, d. 1775) augmented the leasehold by purchasing lands and common rights in Filkins and surrounding places, and by 1839 the estate totalled nearly 600 acres. (fn. 268) Nevertheless Filkins retained some wealthy freeholding farmers into the 19th century, among them such long-established yeoman families as the Purbricks and Bassetts. (fn. 269) The former were among the wealthiest yeomen in Filkins from the later 16th century, and in the 18th acquired several other holdings (including Maverleys, Burbiges, and Packers) through inheritance and purchase. By 1776 James Purbrick was the wealthiest member of the family, with extensive lands and a homestead on Filkins village street, (fn. 270) possibly that now called Peartree Farmhouse. (fn. 271) The family remained prominent in Filkins's farming and social life throughout the 19th century. (fn. 272) The Bassetts were both farmers and fellmongers in the late 17th and early 18th century, enabling Simon Bassett (d. 1742) to build a new house, possibly the one which his grandson Jonah Bassett (d. 1821) refronted in 1759. (fn. 273)

Parliamentary Inclosure to 1900

In the mid 18th century owners of the Filkins Hall and Broadwell estates began exchanging lands in the common fields, concentrating Broadwell holdings in Broadwell field, and Filkins Hall lands in Upper Filkins. (fn. 274) Alexander Ready (later Colston) of Filkins Hall had already shown himself an 'improving' landlord at Coln Rogers (Glos.), where, after purchasing the manor in 1727, he had acquired most of the copyholds and inclosed the parish by 1746. (fn. 275) In Filkins he inclosed several acres of common land near his house before 1750, prompting his fellow commoners to pull down the wall several times. (fn. 276) Possibly he was already contemplating a full inclosure, although if so his intentions were clearly frustrated.

An Act for inclosing Broadwell and Filkins and for commuting the tithes was finally obtained in 1775, and when inclosure took place in 1776 Murrough O'Brien and the Colstons were the chief beneficiaries. (fn. 277) O'Brien, as lord of the manor, received 1,200 a. mostly in Broadwell, where by 1785 he owned around 77 per cent of the land. He was swift to capitalize on the increased value of his estate, using it to secure further mortgages in 1776 and 1777. Alexander Colston's widow Sophia received 340 a. mostly in Filkins, where she became the single largest landowner. Trinity College, Oxford, owner of the rectory estate, received 457 a. in lieu of tithes and glebe, split between Broadwell and Filkins and run thereafter from the newly-built College Farm north of Filkins village. Owners of the major yeoman freeholds in Filkins also received substantial acreages. James Vincent, gentleman, was allotted c. 130 a., and so too was Ann Brooks for Moat (or Goodfellows) farm. James Purbrick and Jonah Bassett, both described as yeomen, received 119 a. and 65 a. respectively. Out of a total of 17 proprietors named in the inclosure award, the rest received between 12 a. and under an acre as compensation for common rights. (fn. 278)

Inclosure did not universally lead to agricultural improvement. Trinity College had already lost some of its lands to its lessees the Colstons, apparently through poor management, and at inclosure it was allotted some of the poorest farmland in the parish, on the northern edge of the limestone band running through Filkins common. Unlike Sophia Colston and Murrough O'Brien the college failed to invest sufficiently in planting hedges around the newly inclosed fields, causing more expense in the long run. Some of its hedging plants died in the poor soils, and the process was not helped by thefts of plants and fencing, which occurred on some other farms too. (fn. 279) The vicar of Broadwell and his successors were similarly awarded poor-quality land in lieu of tithes, comprising 120 a. of former common pasture. (fn. 280)

A 19th-century inhabitant claimed that before inclosure there were up to 40 small farms in Broadwell and Filkins, (fn. 281) but inclosure reinforced the consolidation of farmland into larger units. In Broadwell, where there were very few owner-occupiers, (fn. 282) the lands still belonging to the manor were leased as three large farms, some parts of which were already inclosed before 1776. Of those, Manor farm was around 300 a. for most of the 19th century, Lower Farm around 240 a., and Grove or Home farm (partly in Filkins and Shilton) was 600 a. in 1802. (fn. 283) Until 1776 the latter was farmed by John Godfrey, the owner of Holwell rectory estate, (fn. 284) who in the late 18th and early 19th century was succeeded by the Ilotts. They were prominent yeomen who owned various properties in Filkins (including three pubs), and in 1802 another of the family was lessee at Lower farm. (fn. 285) Manor Farm was rebuilt in 1804 for William Hervey's agent Joseph Large, a local man and an important sheep breeder, who by 1822 held Manor and Lower farms together; before 1861 he was succeeded by Henry Kleeves, who employed 13 men and 7 boys. (fn. 286) Rather smaller was Vicarage or Furzey Hall farm, made up of land granted to the vicar at inclosure, and lying partly in Filkins. While the vicar was a member of the Colston family it was run as part of the Filkins Hall estate, and in 1839 it totalled 139 acres. (fn. 287) Edgerly farm, based on a 34-a. allotment to Sophia Colston, was increased to 68 a. by 1839 and to twice that by the later 19th century, when it included lands in Clanfield and Alvescot. (fn. 288)

In Filkins landholding remained more complex after inclosure, with over twenty proprietors, and several farmers renting land from more than one owner. (fn. 289) Nevertheless a few large commercial farms emerged. Trinity College's farm, centred on its newly-built farmhouse and barns by 1779, was 400–450 a. in the late 18th and 19th centuries, and in 1861 was farmed by Edward Lord with eight men. (fn. 290) Filkins Down farm, carved from former downland pastures, belonged to the Bradwell Grove estate, and was of similar size; at first it was leased to Thomas Gardner with Hockstead (or Oxleaze) farm in Broughton Poggs, and by 1861 to Henry Glover, who employed nine men and five boys. (fn. 291) Filkins (or Filkins Manor) farm, made up of lands allotted to the Colstons, lay north and south of Filkins Hall, and totalled 194 a. in 1839; it grew to c. 400 a. by the end of the 19th century, and in 1861 was farmed by John Garne with 13 men and six boys. (fn. 292) Moat farm, based on a medieval freehold, (fn. 293) was 140 a., lying along Thrupp Lane to the north of Nether Filkins village. The lessee in 1809 was Robert Purbrick, succeeded by the Wheelers and Glovers. (fn. 294)

In the parish as a whole, 19th-century changes in agriculture were initiated mainly by owners of the Bradwell Grove estate and their agents, to increase efficiency and profitability. Throughout the period, William Hervey and W. H. Fox expanded the estate by leasing and purchasing additional lands: Hervey's original purchase of some 2,000 a. had increased to over 3,600 a. when sold to Fox in 1871, and from 1805 Hervey also held the lease of College farm, which Fox bought in 1875. The Filkins Hall estate was added in 1849, pre-empting a bid by the Chartist Feargus O'Connor. (fn. 295) From the mid 19th century Manor and Lower farms were generally farmed together to make a larger unit, (fn. 296) and by 1831 Grove farm had been taken in hand, to be farmed directly by Hervey under a series of bailiffs. (fn. 297) By 1895 Filkins Down farm was also under direct management. (fn. 298)

Hervey also made improvements to farm buildings. Broadwell Manor and Filkins Down farmhouses were rebuilt to attract a better sort of tenant, (fn. 299) while Filkins Manor Farmhouse was refurbished for Hervey's tenant John Garne, and a new cow-house range was provided to bring dairying operations up to higher standards. (fn. 300) Barns, stables, and cow- and cart sheds were improved on other of the estate's farms, (fn. 301) and in the mid 19th century extensions were possibly made to College farm's buildings. (fn. 302) All Hervey's farms were registered for fire insurance, to guard against both accidents and arson, as he introduced innovations such as steam threshing machines which took jobs from agricultural labourers. (fn. 303) The diminution in size of Manor, Lower, Grove, and Filkins Down farms by 1910 resulted from reorganization of the Bradwell Grove estate, and because Squire Fox had set lands aside for sporting activities. (fn. 304)

Despite such intensification, types of farming remained much the same as earlier. Mixed agriculture continued on all of Broadwell's estate farms and on Downs farm in Filkins, where wheat, barley, and oats were grown, and sheep, cattle, pigs, and poultry reared. Smaller farms in Broadwell followed a similar pattern, although Edgerly farm's rich pasture and meadow (65 per cent of the acreage in 1839) made it more suitable for rearing horses and cattle, (fn. 305) while John Garne of Filkins Manor farm was a noted breeder of Cotswold sheep and Shorthorn cattle in the mid 19th century, and also made cider. (fn. 306) By contrast some other estate farms in 1871 (notably Filkins Down and College farms) were almost entirely arable, although the great agricultural depression encouraged an increased emphasis on pastoral farming later in the century. (fn. 307) Changes in land use also occurred on smaller farms. Peacock farm in Filkins was mainly pasture in the later 18th century, which suited the Bassetts' trade as fellmongers, but by 1901 it also grew crops. (fn. 308) Moat or Goodfellows farm, mainly arable in 1898, was reckoned a good sheep farm by the early 20th century. (fn. 309)

Farms and Farming From 1900

The large estates in Broadwell and Filkins were better able to survive the economic problems which affected agriculture from the late 19th century, and expanded without reference to parish boundaries as smaller farms were bought up. The trend towards centralized operations continued: increased mechanization meant that farms needed less labour, and diversification into other activities helped to subsidize agriculture.

Some Bradwell Grove lands were sold off after the deaths of respective tenants, while others were purchased to make the estate more compact. By c. 1900 the estate included lands not only in Broadwell, Filkins, and Holwell, but in the adjacent parishes of Kencot, Shilton, Upton-and-Signet, Broughton Poggs, and Eastleach (Glos.). It was managed by Fox's steward Thomas Kilbee from the estate office at Bradwell Grove, and at Fox's death in 1921 incorporated 16 farms with a total of over 5,000 acres. The bulk of the estate continued to be managed as a large commercial operation, comprising 3,850 a. in 1949 and 3,000 a. in the early 21st century, (fn. 310) although in the 1940s the estate's Filkins Down, College, and Furzey Hall farms were all leased to tenants. (fn. 311)

In 1917 the banker Frederick Crauford Goodenough bought Filkins Hall and began building up another large estate, adding Manor and Lower farms in Broadwell in 1922. In 1939 the Broadwell land was farmed under a bailiff, Frank Walker. As smaller farmers went bankrupt during the depression of the 1920s and 1930s, Goodenough and his son William added Peartree farm in Filkins and other farms in Langford, Kencot, Alvescot, and Shilton, bringing the estate to 1,204 a. by 1941, when parts were still farmed by tenants. Filkins Hall was sold in 1987, and in the early 21st century Broadwell Manor farm, as the estate was then known, comprised 1,458 a. (590 ha.) in Filkins, Broadwell, Kencot, and Langford. (fn. 312) Another significant estate was built up by Sir Stafford Cripps of Goodfellows in Filkins, who expanded his initial purchase to create the 410-a. Filkins farm, which in 1941 was run by tenants. (fn. 313) The only small independent holding to survive in Broadwell in the early 20th century was Broadwell Mill farm, which in 1920 contained around 40 a. lying partly on the heavy soils of Edgerly. (fn. 314)

In 1914 around 30–50 per cent of the cultivated land in Broadwell and Filkins was under crop, including wheat, barley, and oats. Another 40–50 per cent was permanent pasture, supporting 40–50 sheep per 100 acres and a smaller number of cattle. The remaining cultivated land produced root crops as animal fodder and potatoes for human consumption. (fn. 315) By 1941 over 1,000 a. of the Bradwell Grove estate was successfully run as a single farm with a bias towards livestock, supporting a pedigree herd of Red Poll dairy cattle, sheep which contributed to the fertility of the arable land, and some poultry. Crops were wheat, barley, oats, and root vegetables for animal feed, and forestry remained important. The Goodenoughs' farm, too, was in good condition, having been much improved since its purchase, when some of the land was in a neglected state following the agricultural depression. Around 40 per cent was arable in 1941, with 17 per cent root crops and 44 per cent pasture; livestock comprised over 250 cattle (including a dairy herd) and over 1,000 sheep, together with some pigs. The estate had 17 full-time workers and, as on the Bradwell Grove estate, there were two tractors. Similar agriculture was practised on smaller farms, encompassing dairying, pig- and poultry rearing, and the growing of wheat, oats and fodder crops. Cripps's Filkins farm (let to A. V. Arkell) had a herd of 95 cows including 33 dairy cattle, while at Ivy House in Broadwell the aptly named Charles Bird raised poultry for the war effort. (fn. 316) Moat Farm or Goodfellows, used as a Land-Army hostel in the Second World War, burnt down in 1947, and the garden was cultivated as a market garden. (fn. 317)

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as British agriculture declined, some farmers diversified. On the Bradwell Grove estate outlying lands in Eastleach and Upton-and-Signet were sold off, estate cottages and farmhouses were sold as private dwellings, and the site of the Second World War hospital at Bradwell Grove was sold for redevelopment as Bradwell Village. The prize herd of Red Poll dairy cattle was sold in 1969, and the estate was converted entirely to arable and woodland. In the early 21st century around 2,300 a. of arable and 400 a. of woodland were farmed from the centre of operations at Filkins Down farm by only five employees: three tractor drivers, a woodman, and a cowman who managed a recently acquired herd of Limousin beef cattle. (fn. 318) John Heyworth further diversified in 1970 by opening the Cotswold Wildlife Park, which by 2000 housed some 200 species of exotic animals in the park around Bradwell Grove House and in converted agricultural buildings. The zoo participates in international conservation schemes, and by the early 21st century attracted over 300,000 visitors a year. In contrast with the farming operation it then employed about 50 full-time staff, rising to 100 in the summer season. Adjacent is a caravan site which Heyworth started around the same time, and which is now franchised to the caravan club. (fn. 319)

Broadwell Manor farm remained mixed in the early 21st century, reflecting the variety of soil types. The main crops were then wheat, rye, barley, oilseed rape, beans, and linseed, and there were 185 dairy cows and 300 breeding ewes. The farm was a demonstration farm for LEAF (Linking Environment and Farming), and followed a careful system of crop rotation, taking environmental issues into account. (fn. 320) Broadwell Mill farm, part of the Walker family's land, was farmed from Kencot. (fn. 321) At Filkins farm arable farming continued in the 1960s, though sheep replaced dairy cows; in 1968 the Filkins bypass separated the farmyard from the land, and in 1981, as part of the pattern of economic diversification in the parish, the proceeds from the sale of Filkins Farmhouse financed the conversion of the farm buildings into craft workshops. By 1987 these included the Cotswold Woollen Weavers and other enterprises, employing around 12 full-time and 12 part-time workers. In the early 21st century the farm covered just under 500 a., run as a one-man operation rearing organic beef. (fn. 322)

Rural Trades and Crafts

Throughout its history Broadwell was primarily an agrarian community. (fn. 323) Most inhabitants in the Middle Ages were peasant farmers, though the surnames Miller, Baker, Croc (or potter), Smith, and Chapman suggest that some tenants also practised rural trades and crafts. (fn. 324)

Broadwell usually had a resident blacksmith, (fn. 325) and by the 18th century there were wheelwrights, tailors, (fn. 326) and (at Bradwell Grove) a victualler. (fn. 327) Quarrying, the most important non-agricultural activity from at least the 16th century, was concentrated mostly in Filkins. (fn. 328)

Commercial malting developed from the mid 17th century. (fn. 329) By then the manor-house complex included a kiln house where malt and bacon were matured, and the yeoman John Bartlett (d. 1670) had a malt house. (fn. 330) In the 18th century three generations of the Turner family were maltsters and had a malt house attached to their house; probably they were related to the Turners of Burford, who were maltsters and licensed victuallers during the same period. (fn. 331) Malting continued into the 19th century, when a malt house was said to stand near the church. (fn. 332) In the 18th century prosperous yeoman or gentry families such as the Turners seem to have used their capital to diversify into other industrial activities as well. Henry Willett (d. 1702) apparently had a bell foundry, and may have used church connections to acquire customers. (fn. 333)

In the 19th century Broadwell's occupational structure remained largely unaltered: in 1861 nearly all of the village's 41 households relied primarily on agriculture, while the rest included smiths, wheelwrights, carpenters, tailors, and butchers. (fn. 334) In 1881 a few estate servants had more diverse occupations including those of game-keeper, woodman, coachman, and engine driver for a steam plough, and the community remained much the same in 1910. (fn. 335) With the mechanization of agriculture employment opportunities declined, and with them the population; the process accelerated in the later 20th century, despite the employment created by ventures such as the Cotswold Wildlife Park or Filkins craft workshops. (fn. 336)

Mills and Fisheries

In 1086 there were two mills on Broadwell manor, and by 1279 there were at least four within the parish as a whole. (fn. 337) All of them apparently continued in the 1680s, (fn. 338) and in the 1790s three lay along Broadwell brook.

Broughton Poggs mill, despite its name, stood on the Filkins side of the stream, while Filkins mill lay further south by the Langford road. Broadwell mill stood further south again, adjoining meadows south-east of Broadwell village. All three produced flour until the mid 20th century. (fn. 339)

Broadwell Mill