A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Rural Parishes: Bix', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp196-230 [accessed 23 February 2025].

'Rural Parishes: Bix', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online, accessed February 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp196-230.

"Rural Parishes: Bix". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online. Web. 23 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp196-230.

In this section

RURAL PARISHES

Bix

Bix is a Rural parish characterized by a typical Chilterns landscape of woodland and steep valleys, small common- and road-side hamlets, and isolated farms. (fn. 1) Despite its proximity to Henley, the presence of a major through road, and some 20th-century development, much of the parish remains inaccessible and remote. In the Middle Ages the area comprised two main manors, Bix Brand and Bix Gibwyn, each with its own church and parish; a smaller estate called Bromsden (Brun's Hill) lay in the south-west. The manors were absorbed into the Stonor estate in the 14th century, and the parishes united in the 15th. By the 18th century settlement was focused in the south-east, near Bix Common and in the Assendon valley, and in the 19th century the hamlet by the common became generally known as Bix 'village'. (fn. 2) The medieval settlement pattern seems to have been more complex and dispersed. (fn. 3) For most of its history the parish supported a farming population, but from the end of the 19th century there was a gradual increase in wealthier residents in non-agricultural employment.

Parish Boundaries

In 1878 the ancient parish measured 3,078 a., much the same as its estimated acreage in 1840. (fn. 4) The parish was much larger and more elongated than its modern counterpart: its northern arm, which formed the tip of Binfield hundred, stretched up into the hills as far as Redpits on the edge of the Chiltern ridge, near Park Corner in Swyncombe. (fn. 5) Its middle part was almost severed in two by a large incursion from neighbouring Nettlebed, which left only a thin tongue of land within the parish north of Bix Bottom. The boundaries were complex, following a particularly convoluted course in the north-west, where even in the 19th century several sections were marked as undefined. (fn. 6) Estate maps of 1725 and 1788 suggest that the 18th-century parish boundaries were similar, at least in those areas shown. (fn. 7)

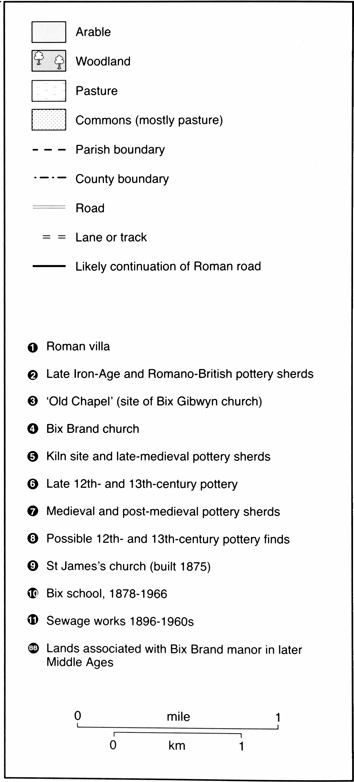

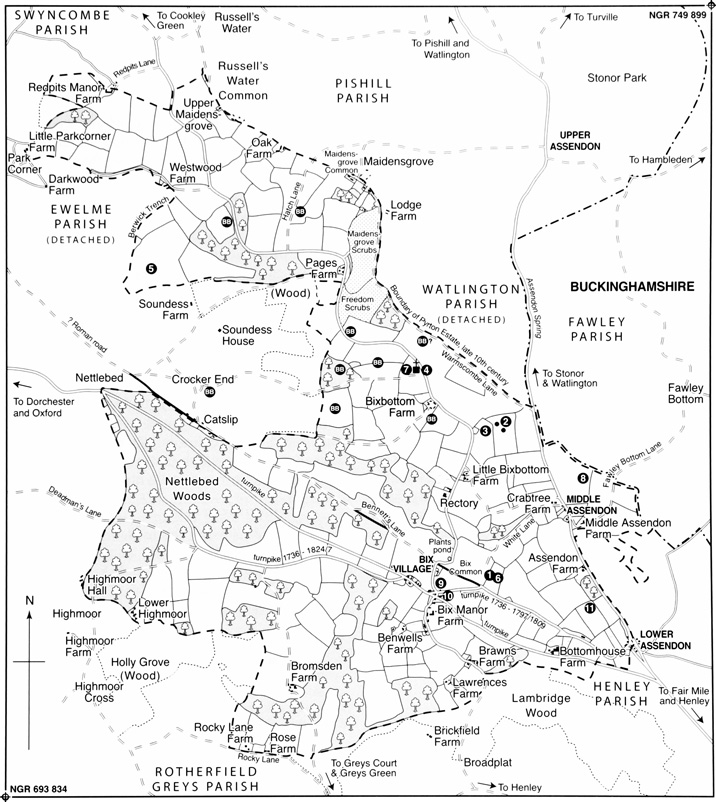

50. Bix parish c. 1840, showing boundaries, land use and some later features.

The 18th- and 19th-century parish comprised two amalgamated medieval parishes, whose boundaries, in turn, were almost certainly derived from those of two late Anglo-Saxon estates at Bix recorded in 1086. Some sections of the 19th-century parish bounds were certainly of considerable antiquity. A short stretch of the eastern boundary coincided with that of the shire, (fn. 8) while the western boundary with Swyncombe, Nettlebed and a detached portion of Ewelme followed that of Binfield hundred, established almost certainly before the Norman Conquest. On the same side a short stretch at Catslip, near Nettlebed village, followed part of the former Roman road from Dorchester. (fn. 9) The remainder of the parish's eastern boundary, adjoining Pishill and Warmscombe, probably divided the large Bensington estate (to which Bix belonged) from the neighbouring estate of 'Readanora' by the mid Anglo-Saxon period, and in the 10th century the Warmscombe Lane section formed part of the bounds of the Pyrton estate. (fn. 10) Much of the southern parish boundary followed Grim's Ditch, which separated Bix from the neighbouring estate of Rotherfield Greys probably by 1086. (fn. 11)

The internal boundaries of the medieval parishes and manors cannot be precisely reconstructed. Nonetheless, it seems that Bix Brand lay north of Bix Gibwyn, as early county maps suggest, (fn. 12) and in the 12th century a lord of Bix Brand was once said to be of 'Bixest', suggesting that he lived in the (north-) eastern part of Bix. (fn. 13) Fields and woods associated with Bix Brand manor in the later Middle Ages appear to have been mainly in Bix Bottom (where the now ruined medieval church of Bix Brand is located), and in the northern arm of the parish, while Bix Gibwyn manor included land in Bix Bottom and further south and south-east (Fig. 50). (fn. 14) This distribution of land may explain the odd shape of the ancient parish, with the lands of Bix Brand stretching up the dip slope from the centre east, and those of the more southerly Bix Gibwyn extending up into the Nettlebed Woods in the west.

The boundaries of the ancient parish were greatly altered in the 20th century. Bix acquired 124 a. from Ewelme in 1931–2, extending its area to 3,203 acres. In 1952 it lost 149 a. to Highmoor, 349 a. to Nettlebed and 868 a. to Swyncombe, acquiring 661 a. from Badgemore. These changes reduced the overall area to 2,498 acres. Nettlebed Woods and the whole northern arm from Freedom Wood northwards were removed from the parish, and an area in the south-east was added, including Henley Park. This shift in focus resulted in the parish being renamed Bix and Assendon in 1986. A further small reduction left it with 987 ha. (c. 2,438 a.) in 1991. (fn. 15)

Landscape

Bix lies on the dip slope of the Chiltern hills, with the dry Bix Bottom and Assendon valleys cutting down through the eastern part of the parish towards Henley (Plates 1–2). (fn. 16) The relief is very uneven, particularly in the north. The highest point is around 190 m. (near Redpits), and the lowest 53 m. (at the bottom of the Assendon valley). The geology is complex, and includes exposed chalk in parts of the north and centre of the parish and Coombe deposits on the narrow valley floors. There are large areas of clay-with-flints in the west, gravel deposits north-east of Bromsden and around Bix 'village', Reading Beds in the south, and a smaller area of sandy clays in the south-west. (fn. 17) Soils are varied, but mainly stony, light and acidic. (fn. 18)

As across most of the upland Chilterns, there are no surface rivers or streams, and water has historically been in short supply. Until the 20th century, domestic and farm water was largely provided by ponds, tanks and deep wells, (fn. 19) and there was at least one common pond in the Middle Ages. (fn. 20) The Assendon valley is periodically flooded by the 'Assendon Spring', which rises near Stonor, but this probably never provided a regular stream. (fn. 21)

The modern parish is well wooded, particularly on the clay soils of the west. (fn. 22) Although woodland has probably always been extensive, its area fluctuated over the centuries, with considerable medieval and later clearance in the south-west and in the north. (fn. 23) By 1840 woodland covered a quarter of the parish, and in the late 19th century it was increased by plantation on former farmland north of Pages Farm (close to a former rifle range much used during the Second World War). (fn. 24) In the 1960s 300 a. around Freedom Wood was clear-felled, but was later partially replanted. (fn. 25)

Despite the substantial woodland, the landscape was at least partly open by the Roman and Anglo-Saxon periods. (fn. 26) In the Middle Ages some farmland was probably organized in small common fields, but private closes predominated by the 15th century. (fn. 27) In most periods permanent pasture and open common were fairly limited, and meadow in particular seems always to have been in short supply due to lack of streams, with only 3 a. belonging to each main manor in 1086. (fn. 28)

Communications

The chief roads through the modern parish are the Henley–Oxford road (now the A4130), which cuts east–west through Bix 'village', and the more minor south–north road running from the Fair Mile up the Assendon valley to Stonor, through Lower and Middle Assendon. (fn. 29) Both of these roads (despite some re-routing) are of considerable antiquity and importance, although until the 19th century the road pattern was both denser and more complex, reflecting the parish's dispersed settlement and scattered agricultural resources.

51. The main Oxford-Henley road through Bix 'village', before its conversion to dual carriageway in 1937. The road widening necessitated demolition of the Fox pub (by the roadside on the right). The former toll house is just visible beyond the brow of the hill.

The main east-west route is almost certainly of Roman or earlier origin, (fn. 30) though its modern course is the result of late 18th- and 19th-century improvements. The Roman road ran north of the present road, up Bix Hill, across the later Bix Common, and on past Catslip to Nettlebed along the line of Bennett's Lane (now a bridleway). That this route was still important in the Anglo-Saxon period is suggested by the fact that the stretch near Nettlebed formed part of the parish boundary; much later, Bennett's Lane was called a 'king's highway' when repaired in the mid 18th century. (fn. 31)

From the Middle Ages, however, the main east-west route seems to have taken a more southerly course from Bix Common along the line of a surviving bridleway, which followed valley contours to Highmoor Trench and then northwards to Nettlebed through Nettlebed Woods. In the 17th century this road was called the 'upper highway from Nettlebed to Henley' and the 'London road'. (fn. 32) This was the route turnpiked in 1736, confirming its status as one of the chief roads from London to Gloucester and beyond. (fn. 33) A toll gate was set up in Bix 'village' in 1772 and the toll house survives as a private house. (fn. 34)

The road was diverted to its modern course in two stages: firstly from the Fair Mile to Bix 'village', where a more southerly 'new road' replaced the ancient Bix Hill route between 1797 and 1809, (fn. 35) and secondly between Bix 'village' and Nettlebed, where a more direct route uphill was constructed between 1824 and 1827, when permission was given to block up Bennett's Lane. (fn. 36) Although the turnpike trust was abolished in 1873, the continuing importance of this road was underlined in 1937 when the section up the steep hill between the Fair Mile and Bix 'village' became a dual carriageway. (fn. 37) This involved the demolition of several buildings, including the original Fox pub. (fn. 38)

The south-north road up the Assendon valley was apparently also of early importance as a route to Oxford and beyond. (fn. 39) The stretch from the Fair Mile to the Assendons was called the 'Assendon Way' in the 15th and 16th centuries, (fn. 40) and the 'lower highway' in 1602. (fn. 41) In the early 19th century, a turnpike gate at the end of the Fair Mile levied tolls on the road through the Assendons. (fn. 42)

A second south-north route through Bix Bottom, now a minor road stopping near Pages Farm, (fn. 43) appears to have once been more significant. In 1392 and 1480 it was a 'royal highway', (fn. 44) and in the 18th and early 19th century it continued to Cookley Green, (fn. 45) linking with roads to Ewelme, Watlington and Nettlebed, and more locally to Crocker End, Soundess, Maidensgrove, Westwood and Redpits. The fact that it ran past the site of both of Bix's medieval churches, presumably focal points of settlement, also suggests its early importance. (fn. 46) It remained the chief access to the one surviving church until the later 19th century, but its significance as a through route towards Oxford was apparently declining by the later Middle Ages when vegetation encroached on the stretch beyond, both reflecting and reinforcing shifts in settlement. (fn. 47)

A similar fate befell the road running south from Bix Common into Greys (past Bix Manor Farm) and thence to Henley, which it has been suggested formed part of an ancient route to Henley from the Chilterns ridgeway at Park Corner (Swyncombe). (fn. 48) Though still of some importance in the 19th century, thereafter it declined to a minor access road.

Transport and Post Office

From c. 1887–95 a carrier to Henley operated on Thursdays; by 1915 a daily service had been established, although it was not mentioned later. (fn. 49) Earlier Bix may have been served by carriers from neighbouring parishes such as Nettlebed and Pishill. (fn. 50) For public transport, Bix 'village' benefited considerably from its position on the main Oxford–Henley road. Numerous stage coaches running through Henley by the late 18th century must have stopped at the Bix turnpike, (fn. 51) and by 1924 the Oxford–Henley bus passed through four days a week. Four years later this service was operating daily, and a daily Cheltenham–London bus also passed through. During the Second World War the increase in local population and movement put considerable strain on transport, and in 1940 a more frequent bus service was 'an absolute necessity'. (fn. 52) By the early 1950s various bus companies ran fairly regular services. (fn. 53)

Mail was delivered from Henley in the 19th century. (fn. 54) By the later 1870s there was a sub-post office in Bix 'village' (for many years in the old toll house), and a post box in Middle Assendon. (fn. 55) In 1931 the post office was also a telephone office, but closed by the early 1970s. (fn. 56) From the early 20th century until the early 1960s there was also a sub-post office in Lower Assendon; (fn. 57) this was replaced by one at 3 Fawley Bottom Lane in Middle Assendon, which closed after 1988. (fn. 58)

Population

Seventeen peasant households were recorded in Bix in 1086, 11 (including one slave) on the later Bix Brand estate, and six at what became Bix Gibwyn; there were also two (and possibly three) manorial centres, and perhaps some unrecorded free tenants. (fn. 59) The figures imply a total population of around 85–100. (fn. 60) The inhabitants presumably lived, as later, in dispersed settlements, although there was probably a greater concentration of population in Bix Bottom than in subsequent periods. (fn. 61)

Evidence for the 12th and 13th century is scanty, but signs of assarting in the more wooded west suggest that Bix experienced the population growth which occurred in the Chilterns as in the rest of England. However, any such growth seems to have stalled before the 1340s, by which time a substantial amount of land had gone out of cultivation in Bix Brand. (fn. 62) After the Black Death, the population was perhaps about the same as in the late 11th century: the 1377 poll tax was levied on 45 individuals over 14 years of age, suggesting a total population of around 80–100. (fn. 63)

Population was slow to recover and may have fallen further in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. From 1390 to 1414 the Bix Brand tithing comprised between six and eight men, (fn. 64) and in 1428 there were said to be fewer than ten households in Bix Brand. (fn. 65) There seems to have been modest growth by the later 17th century, when the 1665 hearth tax listed 14 households in Bix Gibwyn and eight in Minigrove (apparently including Bix Brand), while the Compton Census of 1676 suggests an adult population of around 126. (fn. 66) In the early 18th century there were c. 50 houses, perhaps rising to 60 or 70 later in the century. (fn. 67) By then most houses were in the south of the parish, reflecting a shift in population which apparently began in the later Middle Ages. (fn. 68)

The census enumerated 303 individuals in 1801. The population had increased substantially to 427 in 1841, but 10 years later had dropped to 367, apparently because several large families had moved to Henley and elsewhere. Numbers rose once again into the early 1870s (426), but declined in the 1880s and 1890s, falling to 360 in 1901, an effect, no doubt, of agricultural recession. There was some increase by 1911, and then very rapid growth between 1931 and 1951, when the population almost doubled from 439 to 812, probably partly due to war-time immigration. (fn. 69) Boundary changes in 1952 left the reduced parish with a population of 487, rising to 529 ten years later, and to 696 by 1971. By 2001, however, the number of residents had dropped to 531, presumably because rapidly rising house prices tended to increase the proportion of wealthier older people living in small households. (fn. 70)

Settlement

Modern settlement is focused on Bix 'village' and on the peripheral hamlets of Lower and Middle Assendon (both strung along the road to Stonor in the Assendon valley), with numerous isolated farmhouses and cottages of which many lie near the parish boundaries. Earlier settlement was apparently characterized by a larger number of small centres, although evidence is fragmentary until the 18th century, the date of the earliest surviving estate maps. The location of both of Bix's medieval churches in Bix Bottom, near the narrow neck of the parish, suggests an additional likely focus of early settlement, apparently largely abandoned by the 17th or 18th century; the medieval estate at Bromsden implies another. (fn. 71) Much of the later growth of Bix 'village' and Lower Assendon seems to have resulted from the increasing volume of traffic along the Henley–Nettlebed road from the 18th century.

Settlement to the 11th Century

A number of Palaeolithic and Mesolithic finds have been made on the peripheries of the parish, notably near Nettlebed and Russell's Water. (fn. 72) The first signs of permanent habitation come from the Iron Age and Roman periods. In a steep field in Bix Bottom called Giles's Hill, the laying of a gas pipeline led to the discovery of ditches and pits containing charcoal, burnt flints and late Iron-Age and Roman pottery fragments. (fn. 73) Further Roman pottery of the mid 3rd to 4th century has been found in two cottage gardens in the valley bottom, together with part of a stone building probably of similar date. These finds suggest settlement over a long period, but of unknown and possibly varied character. (fn. 74) Half a mile south, a small 3rd- and 4th-century corridor villa (26 m. long and 13 m. wide), perhaps built on top of an earlier building, was located to the east of Bix Common, close to the Roman road. (fn. 75)

Evidence for Anglo-Saxon settlement is thin, but 10th-century charter bounds suggest that the local landscape was closely organized and, presumably, occupied. (fn. 76) At present the only archaeological finds from within the parish come from the Roman villa site: a post-Roman flint platform (with no associated artefacts), and two later Anglo-Saxon shallow burials. (fn. 77)

The establishment of the Bix Brand, Bix Gibwyn and (probably) Bromsden estates before the mid 11th century presumably involved the creation of separate estate centres. (fn. 78) Bromsden may have had a centre somewhere near Bromsden Farm, and though the locations of the Brand and Gibwyn manor houses are unknown, (fn. 79) probably they lay near the associated medieval churches, which were almost certainly established by late Anglo-Saxon or Norman lords of the respective estates. Bix Brand church survives as a ruin in Bix Bottom, a mile north of the present 'village', while the demolished church of Bix Gibwyn stood c. 700 m. to the south-east, at what was probably the northern end of its parish. Archaeological investigation has confirmed its location in an oval-shaped former glebe field labelled 'Old Chapel' on a map of 1725, where Roman remains were also discovered. (fn. 80)

Medieval and Later Settlement

The medieval settlement pattern was presumably one of small dispersed hamlets and isolated farmsteads. How late the putative settlement or estate centres in Bix Bottom continued is unclear. Small amounts of medieval pottery have been found at the sites of Bix Brand and Bix Gibwyn churches, and reportedly further south. (fn. 81) But the manor houses apparently fell into decay in the late Middle Ages (in 1388 there were no buildings at all at Bix Brand), (fn. 82) and the surviving medieval church was probably isolated by the 16th or 17th century.

The smaller estate at Bromsden may have included several resident households in the Middle Ages, despite apparently having no tenants in 1086. (fn. 83) Two landholders in Bromsden besides the Brands were mentioned in the early 13th century, at least one with a resident tenant, (fn. 84) and a harvest overseer, bailiff and estate servants were mentioned in 1336–7. (fn. 85) By the 16th century, however, Bromsden seems to have become a single farm, as part of a wider reorganization and amalgamation of holdings across the parish during the 14th to 16th centuries, which must have affected settlement. (fn. 86)

The hamlet near the present Bix 'village', south-west of Bix Common and close to the Henley road, was well established by the 17th century, (fn. 87) and was probably of medieval origin. A dense scatter of late 12th- and early 13th- century pottery found in a field off the old Bix Hill road, (fn. 88) close to the Roman villa site, may mark the site of an abandoned farmstead near this hamlet. On the eastern fringe of the parish, Nether Assendon was mentioned in 1409, (fn. 89) distinguishing it from Upper Assendon (later Stonor), and by the 17th and 18th centuries Middle and Lower Assendon had distinct identities. The latter, often called Assendon Cross from the 17th to 19th centuries, (fn. 90) straddled the parish boundary with Henley, while Middle Assendon was almost wholly in Bix. (fn. 91)

Other areas of settlement by the 16th and 17th centuries, possibly also medieval in origin, included a small group of cottages at Minigrove (later Maidensgrove) in the north, partly in Pishill, (fn. 92) and part of the hamlet of Highmoor in the south-west, which was mainly in Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 93) By the 16th century there were peripheral farmhouses at Redpits, Pages and Rocky Lane, and by the 17th century two in Bix Bottom (Valley Farm and Little Bix Bottom) and another on Rocky Lane (Rose Farm). (fn. 94)

Development from the 18th Century

In the 18th and early 19th century much of Bix 'village' was strung along the lane towards Greys. (fn. 95) Buildings here included Bix Manor, Benwells Farm and Lawrences Farm, all 17th-century farmhouses, and Brawns, an early 18th-century gentleman's residence. (fn. 96) Further north, on the main road, were a handful of cottages, the Fox pub (probably set up after the road was turnpiked), and, from the later 18th century, a toll house. (fn. 97) There was also a cottage on the north-western edge of the Bix Common. (fn. 98) By 1841, 33 of the parish's 85 households (almost 40 per cent) were living in this loose collection of farms and cottages. (fn. 99)

In the 1870s the pre-eminence of the 'village' was accentuated by the building of a church on the western edge of Bix Common and a school and teacher's house nearby. (fn. 100) For a time at the end of the 19th century two cottages close to the main road were used as beer houses. (fn. 101) A handful of large houses were built close to Bix Common before 1914, (fn. 102) followed by eight council houses in 1927 and ten more in 1947–8. (fn. 103) When the Fox was demolished in 1936 Brakspear's Brewery built a large new Fox pub over the road, designed to attract motorists and families as well as drinkers. (fn. 104) In the 1960s, a number of other private houses were built around the west and north of Bix Common and on the upper part of the old Bix Hill road. (fn. 105)

In the early 18th century the Assendon hamlets each comprised little more than a handful of farms and cottages. In Middle Assendon, buildings included Middle Assendon Farm (15th- or 16th-century), Webbs Farm (perhaps c. 1600), and the early 18th-century Crabtree Farm. (fn. 106) Further south was the later 17th-century Assendon Farm (now Home Farm). At the top of the Fair Mile, Assendon Cross comprised a little group of 17th-century farmhouses, including the Golden Ball (later an alehouse). In the 18th and early 19th centuries several labourers' cottages were added around a small patch of waste near the Golden Ball, belonging to Benson manor. (fn. 107)

52. Bix 'village' in 2007, looking north from Bix Manor Farm (centre) to St James's church (built 1875) and Bix Common, across the Henley–Oxford road. Concentration of settlement in this area dates chiefly from the 18th and 19th centuries; medieval settlement was considerably more dispersed.

These little hamlets came to be amply provided with alehouses. A tenement called The Royal Oak in Middle Assendon was mentioned in 1702; possibly it was an earlier incarnation of The Rainbow, a beer house in operation by the mid 19th century. (fn. 108) By the 1730s, the Golden Ball in Lower Assendon was servicing traffic along the turnpike road. (fn. 109) The Rainbow and Golden Ball were still trading in 2010. Two other pubs, the Assendon (or Red) Cross and the Travellers' Rest, were in the part of Lower Assendon formerly included in Henley. (fn. 110)

Both hamlets remained very small in 1841, with 12 households in Lower Assendon (including the lower part of Bix Hill) and only eight in Middle Assendon. There was slight growth in the later 19th century, when a saw mill was established in Middle Assendon, and Bix Hill House and a few more cottages were built up the Bix Hill road, (fn. 111) but they were still small settlements in the earlier 20th century. (fn. 112) Development could hardly have been encouraged by the presence of a sewage works between Middle and Lower Assendon, which Henley Corporation established in 1896, and which remained in use until the early 1960s. (fn. 113)

The 20th century saw more substantial growth, particularly in Middle Assendon. Several large houses were built in the inter-war period; in the late 1940s or early 1950s eight council houses were put up at 'Valley Cottages'; and in the early 1960s twelve bungalows were built at 'The Green'. By the mid 1960s half a dozen houses had been built on White Lane, (fn. 114) and in 1967–8, after the closure of the saw mill, 16 new homes were built around two existing houses in Mill Close. (fn. 115)

53. Brawns, one of Bix's few 'polite' residences, from the south-west in 1969. In the mid 18th century it was occupied by an East India Company captain.

One or two other outlying areas also saw some development in the 19th and 20th centuries. At Catslip, partly in Nettlebed, a small collection of houses and cottages was built on the Bix side of the parish boundary in the 19th and earlier 20th centuries, including six council houses in the mid 1920s. (fn. 116) By 1971 the parish as a whole contained 230 separate dwellings, a number which remained fairly stable thereafter. (fn. 117)

The Built Character

The buildings in Bix are varied, creating no strong overall impression. (fn. 118) Middle Assendon and parts of Bix 'village' have an increasingly suburban feel thanks to 20th-century development, while outlying areas are characterized by isolated and secluded farmhouses and cottages. Buildings vary in size and date: mainly 17th-and 18th-century farms and cottages are interspersed with nondescript 19th- and 20th-century houses, including some council houses and a handful of grander residences. A few of the modern houses appeared in the first two decades of the 20th century, (fn. 119) but most date from the 1920s to the late 1960s. (fn. 120) The later 20th century also saw the conversion of farm buildings to domestic use.

Most of the older buildings were originally fairly modest. (fn. 121) Bix has only three pre-20th-century houses which might be thought of as 'gentlemen's residences' rather than farmhouses: the former rectory house (later Bix Hall), (fn. 122) Brawns, and Assendon Lodge. Even these had attached or nearby farmyards in earlier periods. Brawns is a red brick, early 18th-century, architect-designed gentleman's residence. (fn. 123) It was offered for lease or sale in 1761 and 1776, having been occupied by a Captain Brawne (or Braund), who had gone abroad with the East India Company. (fn. 124) The brick-and-flint Assendon Lodge was apparently built by the Stonors on part of the Middle Assendon farm site. Constructed in the mid 19th century, it may originally have been plainer, and has later alterations. (fn. 125)

In addition to these residences, two surviving farmhouses stand out as being larger and better built than the others. Rocky Lane Farm, on the parish's southern boundary, is a well-constructed, symmetrically-fronted, late 16th- or early 17th-century flint and brick building, with a cellar. (fn. 126) It seems to have been held as a freehold property before being acquired by the Greys Court estate after 1840. (fn. 127) Redpits 'manor and farm' was recorded in the 16th century, and the core of the present building (Fig. 54) appears to be the timber-framed house shown on a map of 1694–9. (fn. 128) It was then the seat of a gentleman farmer's freehold estate, and comprised a two- or three-storey, timber-framed house, with dormers and a gabled cross-wing, an adjacent walled garden, and a very large farmyard.

The rest of the farmhouses were originally small, most probably with only three hearths. (fn. 129) The two earliest are late timber-framed hall-houses: Middle Assendon Farm, probably 15th- or early 16th-century, and Pages Farm (Bix Bottom), perhaps early to mid 16th-century. (fn. 130) The majority date from the 17th century, which seems to have marked the earlier part of a period of relative agrarian prosperity. (fn. 131) A few are 18th-century, including Bromsden (presumably replacing an earlier building) (fn. 132) and Westwood; (fn. 133) and one or two others are 19th-century.

Many farmhouses have been subject to substantial piecemeal extension. With some this occurred fairly early on: additions were made in the 16th and 17th century at Middle Assendon Farm, (fn. 134) and in the 18th and 19th century at Little Bix Bottom Farm and Home Farm, Middle Assendon, reflecting the fruits of successful farming operations. The Stonors added large new wings at Bromsden and Bix Manor in the 19th century, in the former case perhaps as part of a short-lived scheme to provide domestic accommodation for Lord Camoys's butler, and in the latter possibly to help attract a better tenant. (fn. 135) But in many instances substantial extensions came only with the conversion of farmhouses to purely domestic buildings in the later 20th century, as at Pages Farm, Brawns, Redpits, and Rocky Lane. (fn. 136) Work on the last two was particularly lavish, including the conversion of Redpits' farmyard into a garden and the construction of a set of replica 'Cotswold' barns at Rocky Lane.

A number of other 17th- and 18th- century houses also survive, mainly around Bix 'village' and the Assendons. Some of these may have originated as farmhouses, but were apparently later detached from their farms or smallholdings and used as labourers' accommodation or for other purposes. Seventeenth-century examples include the timber-framed Pilgrim Cottage (re-converted from two cottages in the early 20th century), Handy Water Cottage, and the Golden Ball in Lower Assendon. (fn. 137) Other slightly later buildings, typically brick or brick and flint, seem to have been designed to house the growing number of farm labourers, like Vine Cottage in Middle Assendon, the well-built mid- to late-18th-century flint row at the top of Fawley Bottom Lane in Middle Assendon, (fn. 138) several cottages near the Golden Ball, and examples by Bix Manor, south of the main road. Many of these buildings were extended in the 19th and 20th centuries.

A handful of rather grander residences were added around the turn of the 20th century: the very large Orchard Dene, Lower Assendon (converted into flats in the earlier 20th century); (fn. 139) Cross Leys (1904) on the old Bix Hill road (demolished and replaced in the late 20th century); (fn. 140) and the new rectory house (1912), north of Bix Common. (fn. 141) A few of the inter-war and mid to later 20th-century houses are also substantial, including one or two in the Assendons and north of the common. (fn. 142) The lavishly-built new Fox pub (1936) was a grand 'roadhouse' with three bars, built in the 'Chilterns vernacular' style favoured by Brakspears' in the 1930s. (fn. 143) Many of the farmhouses were renovated and extended in the second half of the 20th century, a reflection (like the smattering of swimming pools which appeared by the 1980s) of spreading 'gentrification'. (fn. 144)

MANORS AND OTHER ESTATES

Bix seems to have been one of the places separated from the extensive royal estate of Bensington in the late Anglo-Saxon period. (fn. 145) At first it may have formed a single 5-hide holding, but if so it was divided into two estates of 2½ hides before 1066. (fn. 146) Both manors continued for much of the Middle Ages, and by the 13th century were distinguished by the family names of their holders, Gibwyn and Brand. (fn. 147) A third and smaller medieval estate was that of Bromsden in the south-west. (fn. 148)

The expansion of the Stonor estate in the later Middle Ages greatly altered the pattern of landholding in Bix. (fn. 149) The Stonors, based at nearby Stonor in Pyrton parish, had land in Bix from at least the 13th century, and from the late 14th, despite some grants to Dorchester abbey, they held both the main manors, together with Bromsden. In the 18th and 19th century they owned around half the land in the parish, comprising c. 1,500 a. south of Freedom Wood; (fn. 150) some of their land in the south was sold in the 17th century to the Benwells, and some former Bix Brand land in the north before 1725. (fn. 151) A major sale in 1894 finally ended their landholding dominance. (fn. 152) Much of the rest of the parish belonged at various dates to neighbouring estates. (fn. 153)

Some of the earlier lords seem to have been resident, including members of the Bix, Brand and Abingdon families. (fn. 154) Both manorial sites were apparently in decay by the late 14th century, however, (fn. 155) and the Stonors and most other later landowners were based in adjacent parishes rather than Bix itself until the 20th century.

Bix Gibwyn Manor

In 1086 the estate later known as Bix Gibwyn was held by Hugh Bolbec, who held of Walter Giffard (d. 1102). (fn. 156) Giffard's overlordship continued until 1245 when it fell to the Crown, having passed first to Giffard's son Walter (d. 1164) and subsequently, with his other possessions, to the FitzHerberts and Marshalls, earls of Pembroke. (fn. 157) The mesne lordship remained with the Bolbecs until c. 1175, passing through marriage to the de Veres, earls of Oxford. (fn. 158)

The Bolbecs granted the manor to tenants before 1166, when Ralph Gibwyn, with Gilbert Brekespere, held two knights' fees of Walter Bolbec. (fn. 159) Ralph was alive in 1184, but before 1213 was succeeded by his son Geoffrey, a judge under Henry III, and probably a graduate in holy orders. (fn. 160) Two senior Exchequer officials, said to be holding the fees in the 1220s and again in 1242–3, were probably trustees for Geoffrey, who seems to have become insane towards the end of his life. (fn. 161) Geoffrey died in possession in 1235, having spent his last years at Osney abbey; (fn. 162) his heirs were Robert Lisle and Robert Brian, probably relatives through marriage. (fn. 163)

By 1242–3 Giles Lisle (Robert Lisle's heir) and Robert Brian held the nearby Gibwyn manor of Marsh Gibbon (Bucks.), (fn. 164) and by 1254–5 Bix Gibwyn also, by then valued at only one knight's fee. (fn. 165) Both families sold their portions of the manor in 1314, the Lisles to Richard Damory, (fn. 166) and the Brians to John (later Sir John) Stonor (d. 1354); (fn. 167) by then the Lisle share was sublet to two men. (fn. 168) Thereafter the manor descended in two parts until the mid 14th century, when it was reunited by the Stonors and became absorbed into their other local holdings. (fn. 169)

Bix Brand Manor

In 1086 the estate which came to be known as Bix Brand was held of the king by a royal servant called Hervey, who also held an estate at Ibstone (partly in Bucks.) to the north, and had appropriated the profits of half a hide of waste in 'Verneveld', an area associated with the royal manor of Bensington. (fn. 170) By the 13th century Bix Brand was held as half a knight's fee of the honor of Wallingford; (fn. 171) possibly it became attached to the honor along with other nearby lands following Robert d'Oilly's death c. 1092. (fn. 172)

Nothing further is known until 1166, when the estate appears to have been the half fee held by one Hugh son of Osbert. (fn. 173) Hugh seems to have been the Hugh of 'Bixest' (presumably East Bix) who gave land in South Stoke to Eynsham abbey before 1196. (fn. 174) Peter of Bix, Hugh's son, was lord in 1196–1212, (fn. 175) but dead by c. 1220. (fn. 176) His successor, another Hugh, was dead by 1223, (fn. 177) leaving a daughter, Emma, who soon afterwards married Robert Brand. (fn. 178) Robert died between 1258 and 1261, when his daughter Christiana quitclaimed two thirds of Bix and other manors to Maurice Berkeley, in return for his help in recovering possession of them. (fn. 179) Christiana may have been in dispute with her brother John, who was already married but still a minor. (fn. 180) John was probably in effective possession, and Christiana's efforts evidently came to nothing since John held the half fee in Bix as well as Robert's lands at Bensington in 1275–6. (fn. 181) In 1300 Bix was held by Maud Brand, almost certainly John's widow. (fn. 182)

In 1316 Bix Brand seems to have been held by Margaret, wife of Nicholas of Abingdon, the largest taxpayer in Bix in 1306; (fn. 183) possibly she was John and Maud's heir. By 1340 the manor had passed to John Thedemersh (d. after 1346) and his wife Maud (of Abingdon), apparently Nicholas and Margaret's heir. (fn. 184) Maud died before 1362, having granted the manor from after her death to Thomas of St Omer, one of the Black Prince's retainers. The manor was initially taken into the Black Prince's hands (as overlord), but two thirds was released to Thomas's widow and daughter (Alice Hoo) in 1365. (fn. 185)

Before 1373 the manor was apparently acquired by Thomas Waryn, who that year confirmed it to Walter Huwet. (fn. 186) The property conveyed included lands and rents in Bix, Goring and Bensington, (fn. 187) among them a chief house and two ploughlands (presumably demesne), and 78 a. of wood. (fn. 188) Huwet's widow Ameta seems to have granted the manor in 1377 to Edward III's notorious mistress Alice Perrers (d. 1400). (fn. 189) Alice forfeited her properties the same year, but in 1380 Bix and other estates were confirmed to her husband William Windsor, Bix to be held by him during the lives of Ameta Huwet and others. (fn. 190) William died in 1384, (fn. 191) and before 1390 the manor was acquired by the Stonors, (fn. 192) already owners of Bix Gibwyn, Bromsden and other lands; it remained part of the Stonors' combined Bix estate thereafter. (fn. 193)

Bromsden Manor

Bromsden manor or farm lay in the parish's south-west corner, its lands partly in Rotherfield Greys. (fn. 194) Bromsden was probably the hide of land held from the king's soke of Bensington in 1086 by a royal servant called William. (fn. 195) It was apparently acquired before 1236 by the lords of Bix Brand, who still held it in 1279; (fn. 196) the Stonors also had lands there by 1224–5, however, when Richard of Bromsden, in a dispute over half a yardland, claimed that Richard Stonor (d. 1225) was his lord. (fn. 197) In 1314 John Stonor (d. 1354) acquired free warren over demesne lands in Bromsden as well as in Bix Gibwyn and Bix Brand, (fn. 198) and the estate was certainly in Stonor hands by 1334, when (as on some later occasions) it was called a 'manor'. (fn. 199) In 1388 it was described as a ploughland held of Bix Gibwyn manor, (fn. 200) although in 1394 and 1415 it was associated with Bix Brand, and was held of the honor of Wallingford. (fn. 201) In the 16th century the Stonors leased the manor to the Rowse family, who sublet it. (fn. 202) By the 17th century it was usually called a farm, and remained part of the Stonors' estate thereafter, leased to various tenants. (fn. 203)

The Combined Stonor Estate

Following the acquisition of Bix Gibwyn and Bix Brand the combined Stonor estates in Bix, including Bromsden and other pieces of land acquired earlier, (fn. 204) were administered as part of the family's general holdings in the area. (fn. 205) Some land was sold before 1725, (fn. 206) but the majority of the Bix estate descended with the family's other property through the main line until the late 19th century. (fn. 207)

In 1894 the Stonors sold much of the outlying part of their estate, including some 780 a. in Bix. (fn. 208) The main properties involved were Bromsden and Merrimoles farms (598 a., partly in Rotherfield Greys), carrying with them manorial and sporting rights in Bix; Bix Manor farm (143 a.); and Benwells farm (28 a.). The major purchaser of the Bix land was H. H. Gardiner, who, as part of his purchase of the Stonors' Nettlebed estate, acquired the manorial rights along with Bromsden and Merrimoles.

In 1903 the Nettlebed estate was bought by Scottish financier Robert Fleming (d. 1933), who became lord of the manors of Bix, Bromsden and Nettlebed. (fn. 209) Fleming sold part of the estate, but the Bix lands passed briefly to his son and then to his grandson (Robert) Peter Fleming (d. 1971). Peter Fleming bought further land in the south of the parish, including Bix Manor farm in the late 1950s, (fn. 210) and in 2009 his estate remained in the possession of his daughters Kate Grimond and Lucy Williams, who both lived locally.

Further Stonor lands and woods were sold in the earlier 20th century, including Bix Bottom farm (215 a.). (fn. 211) In 1931 the main Stonor properties in Bix were Crabtree farm (108 a.), Middle Assendon farm (53 a.), and Little Bixbottom farm (71 a.), the latter (re-) acquired in the later 19th century. (fn. 212) Middle Assendon and Little Bixbottom farms were sold before 1952, and Crabtree farm shortly afterwards. (fn. 213)

Other Estates

In the late 13th and early 14th century Dorchester abbey built up a sizeable estate in Bix. In 1275 it received permission to appropriate the small rectory estate of Bix Brand, and in 1285 seems to have won a case against Maud Brand over her dower share in this, comprising a third of a house and of 7 acres. (fn. 214) Probably the rectory estate was the abbey's only land in Bix in 1291, when its possessions there were worth just 1s. 8d.; (fn. 215) in 1316–17, however, it acquired over 200 a. and several houses in and around Bix by exchange with John Stonor and others. (fn. 216) The abbey seems to have alienated its Bix lands before the Dissolution, although part of its estate may have been added to the glebe. (fn. 217) That remained with the church until the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when it was sold and broken up. (fn. 218)

A significant remaining acreage belonged at various dates to neighbouring estates. The lords of Rotherfield Greys, Fawley (Bucks.) and Phyllis Court owned land in the south of the parish in the Middle Ages, although its extent in that period cannot be determined. (fn. 219) The Greys' land, amounting to c. 195 a. in the 19th century, was sold in 1922 along with Lawrences farm (acquired in 1901) and Rocky Lane farm, both of which were partly in Rotherfield Greys parish. (fn. 220)

Much of the northern arm of the parish, including Redpits farm (partly in Swyncombe), woodland around Westwood Manor Farm, and land in Minigrove, belonged until 1627 to Ewelme manor. (fn. 221) In the 16th century Redpits itself was occasionally called a 'manor' (fn. 222) (centred presumably on Redpits Manor), and afterwards it formed a freehold estate of c. 293 a., including 119 a. in Bix. (fn. 223) By the early 18th century Redpits, along with other land in the north and west, had become part of the reputed manor of Soundess, centred on Soundess House in Nettlebed, which included land in Bix in the early 17th century. (fn. 224) Most of the Soundess estate was subsequently bought by Sambrooke Freeman (d. 1782) of Fawley Court, (fn. 225) and the MacKenzies (as the Freemans' successors) owned 882 a. in the parish in 1903. (fn. 226) Redpits, however, was retained by trustees of the Taverner Wallis estate until sold to George Grote in 1785. After Grote's death in 1830 his son sold the farm to the tenant, Thomas Cottrell. (fn. 227)

54. Redpits Manor in 1969. Though the estate was a reputed manor in the 16th century, Redpits remained a working farmhouse until the later 20th, when its farmyard was converted into a garden.

Other land in the north was associated with the reputed manor of Minigrove, which was established by the 16th century and possibly included Berrick Trench near Westwood Farm. (fn. 228) The estate apparently included woodland which had belonged to the prior of Canterbury's manor of Newington in the Middle Ages. (fn. 229) In the 18th century its lord claimed ownership of land in the north of Bix against the Freemans, who claimed it as part of Soundess; (fn. 230) in the 19th century the estate included c. 90 a. around Maidensgrove Scrubs and Freedom Wood. (fn. 231)

In the mid 1920s A. A. Dale acquired an 844-a. estate in Bix through purchase of land from the Mackenzies. In 1931 he owned the 215-a. Bix Bottom farm, 60 a. of Manor farm, 54 a. formerly part of Soundess farm, and 515 a. of woodland. (fn. 232) This land, all north of the Oxford road, was sold soon after, much of it to F.M. Bond in the mid 1930s to create the Halfridge estate. That in turn was sold in the late 1960s and early 1970s, partly to the new Warburg nature reserve, which acquired 253 a. north of Pages Farm in 1967–8, (fn. 233) and partly to Maj. Gen. Lord Alvingham, who bought land in Bix Bottom and west of Bix Common in 1968–9. Alvingham's purchases included Bix Hall (the former rectory house), where he lived in 2010. (fn. 234)

ECONOMIC HISTORY

Until the 20th century, the economy of the parish was overwhelmingly based on mixed farming and woodland exploitation, with limited local industry, craft production and retailing. Much of the land was fairly poor, but farming problems were partly counterbalanced by good access to markets, including Henley. (fn. 235) Agricultural employment declined from c. 1880, thanks to farming depression, dairying and mechanization. Towards the end of the 19th century a significant number of jobs were provided by the saw mill established in Middle Assendon, but the period from the mid 20th century was one of economic stagnation: local businesses shut down as Bix increasingly became a dormitory area.

Medieval Agriculture

The Structure of Farming

In 1066 and 1086 the two Bix manors were valued at £3 each, and in 1086 both were said to have land for seven ploughs. (fn. 236) Bix Brand was apparently more intensively exploited in 1086, with six ploughs in operation compared to four in Bix Gibwyn. The majority of farmland was then in tenant hands: only one of the six ploughs at Bix Brand was in demesne (run by a slave), while the other five were held by eight villani and two lower-status bordars. At Bix Gibwyn two ploughs were in demesne, and two used by six villani. On the small Domesday estate probably identifiable with Bromsden there was a ploughland and 4 a. meadow, although apparently no tenants on a holding which had declined in value from 20s. before the Conquest to 12s. 6d. in 1086. (fn. 237)

Little further evidence is available until the 14th century, when much of Bix had become part of the Stonor estate. (fn. 238) In 1388 the Stonor demesne in Bix comprised 60 a. of arable in Bix Gibwyn (two thirds of which lay fallow), and 100 a. in Bix Brand (including 40 a. fallow). A ploughland at Bromsden was leased to Thomas Egham for 4 marks a year. (fn. 239) The Stonors continued some limited direct farming at Stonor in the 15th century, but seem to have leased out most or all of their outlying lands in Bix. (fn. 240)

Stonor tenants held differing amounts of land by various tenures. In the late 14th and early 15th century some in Bix Brand occupied cottages, crofts, or quarter, half and whole yardlands. Some held freely by charter, while other tenancies were customary or at will. Customary tenants owed suit of court and paid small entry fines, but there is no evidence of labour services, and the demesne seems to have relied on hired workers. (fn. 241)

How farmland was physically organized is uncertain, but as in neighbouring parishes there were probably some small open fields in the valleys and on flatter ground. (fn. 242) Communal organization is implied by mention of yardlands, and some sort of common field system seems to have survived on Bix Common in the late 17th century. (fn. 243) Nonetheless, private closes predominated by the late Middle Ages. (fn. 244) Some had doubtless been cleared from woodland, like 'Stokelpaths' croft mentioned in 1314, (fn. 245) or the area called 'Manymolds' (the modern Merrimoles) in the west. (fn. 246) But other inclosures were probably created from former areas of open field in the later 14th and 15th century, when economic problems and the leasing of demesne apparently led to a substantial reorganization.

The first clear sign of later medieval economic change is a low tax-assessment for Bix Brand in 1341, justified by a claim that the larger part of the parish was uncultivated because of the poverty of the parishioners. (fn. 247) The obstruction of stretches of road north of Bix Bottom by trees and undergrowth in the late 14th and early 15th centuries suggests reduced population and activity, (fn. 248) while rent arrears and reductions, unlet holdings, and vacant tenements also point to difficulties. (fn. 249) Bromsden was leased for only £1 in 1417–18, 33s. 4d. less than in 1388, although over the same period assized rents from Bix Brand apparently rose slightly from £2 19s. 4d. to £3 11s. 3d. (fn. 250) As late as 1476 Bromsden was still being leased for only 38s. (fn. 251)

Such circumstances apparently encouraged the consolidation of holdings by remaining tenants and incomers. (fn. 252) Stonor court rolls show individuals acquiring multiple holdings, the dereliction and dismantling of unwanted houses, and the conversion of homes into barns or pigsties. (fn. 253) The larger units so created probably represented the first stages in the formation of some of the farms shown on an estate map of 1725, including 'William Benwell's Farm', 'Bix Farm', and 'John Rowles's Farm' (Middle Assendon). (fn. 254) Court rolls from neighbouring Fawley (Bucks.) suggest that similar processes were taking place on other estates with lands in Bix, (fn. 255) and it is probably significant that Bix's earliest surviving farmhouses date from the late 15th or early 16th centuries. (fn. 256)

Land Use

Mixed farming was no doubt practised from the earliest periods, supplemented by woodland exploitation. Domesday Book indicates substantial arable cultivation in Bix in the later 11th century, and indications of assarting suggest that arable probably expanded in the 12th and 13th century, though by how much is impossible to determine. Since two thirds of Bix Gibwyn's demesne arable was fallow in 1388 there was presumably a three-course crop rotation, which may have operated on demesne and tenant lands across the parish. (fn. 257)

Demesne arable in both manors, likely to contain some of the best land in the parish, was valued at 4d. per acre in 1388. This was a fairly modest sum, but still double the valuation of the demesne at Stonor. (fn. 258) Crops included wheat, barley, oats, and pulses, (fn. 259) and mixed corn (probably wheat and rye) was grown at Bromsden. (fn. 260) In 1336–7 Stonor demesne produce seems to have been entirely used for the household and to feed farm servants, (fn. 261) but in 1381–2 the estate sold 42 qrs and 5 bu. of barley and malted barley, some of it to Alice Cooper of Henley, presumably a brewster. (fn. 262) Tenants must have sold some of their harvest to pay their rent, with Henley and perhaps Watlington the main markets.

The 14th century provides the first evidence of animal husbandry. In 1336–7 the Stonors kept sheep in Bix and sheep and cattle at Bromsden. (fn. 263) The number of animals is unknown, but Stonor flocks elsewhere were not especially large, and there is little to suggest that either Sir John Stonor I (d. 1354) or Sir John II (d. 1361) were involved in large-scale wool production. (fn. 264) The grazing provided by permanent pasture was probably supplemented by the large area of fallow or disused arable. (fn. 265) Given the scarcity of meadowland, (fn. 266) winter hay was possibly brought in from Henley or elsewhere.

In 1383 Thomas d'Oilly, lord of Pishill Napper, (fn. 267) was grazing 200 sheep on the Stonor estate, and in the same year a dozen tenants paid a total of £1 7s. for use of pastures and woods in Bix Brand and Bromsden. (fn. 268) Between them these men kept a total of 415 sheep (and smaller numbers of cows, pigs and horses), but their individual flocks were fairly modest – 20 to 60 sheep rather than the flocks of 100 or more animals which were kept by some tenant farmers in the southern Chilterns at this time. (fn. 269)

Little is known about farming in the parish in the 15th and early 16th century, but probably arable cultivation continued to be combined with sheep rearing and wood production. (fn. 270) Whether sheep flocks grew as much in this period as in neighbouring Pyrton is uncertain; two or three more substantial yeomen may have kept larger flocks by 1500, but most tenants were poor and the Stonors themselves do not seem to have kept large numbers of sheep on their estates. (fn. 271)

The 16th to 18th Centuries

The Structure of Farming

In this period farmland was divided amongst a fairly large number of farms, many only partly in Bix. The 16th and 17th centuries probably saw the continuation of the gradual consolidation of holdings which began in the late Middle Ages, though the organization of farming before the late 17th century is poorly documented. By the 1790s there were some 19 farms with land in the parish. (fn. 272) Thirteen were occupied by 'yeomen' or 'spinsters', and six by 'labourers'. The yeomen and women were no doubt all tenant farmers; some of the labourers seem to have been tenants of small farms, like those at Lawrences and Benwells, but one or two others were more likely servants on larger farms kept in hand, like those at Westwood and Middle Assendon. (fn. 273) At that time around a third of the farms were probably 200 a. or more, a similar proportion under 100 acres, and the rest somewhere in between; (fn. 274) smaller units had probably been more common earlier.

A number of houses and pieces of land were still held on long leases for several lives until the 1740s, the tenants paying nominal rents and substantial entry fines. (fn. 275) But the larger tenant farms on the Stonor estate in Bix were held on fairly short-term commercial leases before 1700. (fn. 276) Bromsden (320 a., including 116 a. in Rotherfield Greys) was leased to Robert Higley for £86 4s. a year in 1705; Bix farm (264 a.) was leased for £58 7s. 6d. a year in 1698; and in 1708 the farm in Middle Assendon that would soon be called John Rowles's farm (186 a.) was leased for £50 a year to Thomas Garter. (fn. 277) These were low rents: at about 5s. per acre they were half the contemporary south Midlands average. (fn. 278) This presumably reflected the limited productivity of the land as well as the large size of the farms.

Nevertheless, this period was one of agricultural growth in the parish, as elsewhere in the area. (fn. 279) The area of farmland was increased through woodland clearance, notably around Bromsden in the south of the parish. (fn. 280) This, together with the adoption of improved farming techniques, resulted in a substantial increase in crop production, reflected in the rector's enlarged tithe income and an increase in rents during the 18th century. (fn. 281)

Leading tenants with large farms were fairly comfortably off, (fn. 282) their incomes in some cases augmented by involvement in exploitation of the large areas of local woodland. (fn. 283) Some of their disposable cash was spent on the building or rebuilding of their homes in the 17th century and on the construction of bigger barns in the 18th. (fn. 284) But individuals' and families' fortunes fluctuated and farm tenancies sometimes changed hands frequently: several farmers went bankrupt in the late 18th century. (fn. 285)

Land Use

Farmers continued to practice mixed husbandry. Henry Benwell's inventory of September 1697 shows £68-worth of corn on his 205-a. farm in the south of the parish, of which c. 90 a. was leased from the Stonors and c. 115 a. was freehold; his £100 ready money and £50 debts owing probably reflected recent harvest sales. His sheep were worth £21 (representing perhaps 90 animals), his hay £11, and he had six cows worth £18, pigs worth £5, and £40 of billets. (fn. 286) Most of Benwell's farmland seems to have been used for cereals, so that he, like other farmers, presumably grazed his sheep and other animals on the fallow fields and commons. Fodder crops such as clover and turnips were not widely used until the 18th century.

Late 18th-century insurance documents show that the great majority of barns were used for either wheat or barley. (fn. 287) Most farmers probably also produced oats (important for horse feed) and rye, but few had dedicated barns for these crops. Oat growing was probably concentrated on the poorer, hillier ground in parts of the north-west and south-west, notably at Redpits and Bromsden. (fn. 288) At John Bowler's farm of Redpits in April 1613 there were 110 a. of crops, including 39 a. of oats, 26 a. of barley, 25 a. of wheat, 14 a. of rye and 6 a. of peas and vetches, together worth £154. (fn. 289) His wheat crop was worth about £2 an acre, barley £1 10s., rye £1 8s., and oats, vetches and peas £1.

The size of sheep flocks varied. In the 1590s John Mosden had some 237 sheep at Redpits, worth £59 5s., (fn. 290) and in the same decade at least one local was employed full-time as a shepherd. (fn. 291) In the 17th century some farmers had flocks of 100 or more, (fn. 292) and John Bowler had 257. (fn. 293) But flocks of 20 or 30 were more common, with smaller farmers and some labourers keeping only a handful. (fn. 294) These animals continued to provide wool (fn. 295) and meat, as well as being a source of fertilizer. (fn. 296) Most farmers also kept a few cows, pigs and poultry.

Surveys of the glebe in 1602 and later provide the first documentary evidence for the area called Bix Common, which seems by then to have been divided by banks and boundary trees into plots owned by the main landowners, rather than being common waste of the manor. (fn. 297) In 1697 it was referred to as 'the common field called Bix Common', (fn. 298) and the terriers suggest that the land was arable. It may be that in this period, as later, this poor land was cultivated for three years and then used as pasture for seven. (fn. 299)

The 19th and 20th Centuries

The Structure of Farming

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries most farms in the parish (of which there were now c. 13–15) continued to be let to tenants. However, the proportion of farms kept in hand by non-resident landowners and run by stewards seems to have been somewhat higher by the 1850s than earlier. In 1841 only two of the 13 farms listed were in hand, compared with five 10 years later; overall, around a third of farms seem to have been kept in hand between 1851 and 1901. (fn. 300) Rents had increased substantially since c. 1700, though they remained modest: in the 1840s Fawley Court leased Middle Assendon farm (87 a.) for £60 a year on a 21-year lease and Bottomhouse farm (107 a.) for £100 a year for 14 years, (fn. 301) while in the 1850s the Stonors leased Bromsden farm (287 a.) for £214 a year, Bix Bottom farm (247 a.) for £197 a year, and Bix farm (176 a.) for £143. (fn. 302)

55. The Busher family outside Bix Bottom Farm, 1903. The family appears to have lived there only briefly, reflecting a rapid turnover of tenancies in Bix in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The agricultural depression of the late 19th and early 20th century had severe effects in the parish. By the 1890s some farm rents on the Stonor estate had been drastically reduced: Bromsden (291 a. plus woodland) was let for £90 a year, and Bix Manor farm (143 a.) for £50 a year, though Benwells (28 a.) and Merrimoles (77 a. plus woodland) still commanded £40 and £56 a year respectively, presumably reflecting greater demand for small farms. (fn. 303) Despite low rents tenants seem to have been difficult to find, and some went bankrupt. (fn. 304) In 1896 several farms were unoccupied, (fn. 305) and by the early 20th century some were run by part-time farmers, the smaller ones being described as 'hobby' farms. (fn. 306) In 1901 Rocky Lane Farm was occupied by an auctioneer and estate agent, and Manor Farm by a blacksmith. (fn. 307) In the late 1920s the Fawley Court estate manager, in response to complaints from the rector about late payment of tithe money, claimed 'terrible recession on all agricultural estates', with rents low and irregularly paid. (fn. 308)

As a consequence, many landowners seem to have focused more on game-rearing than farming, perhaps taking advantage of the 'gentrification' of the area. (fn. 309) Pages Farm, for instance, was used to house game keepers, (fn. 310) and a pheasant breeding farm was set up at Bix Underwood, associated with Bix Manor Farm. (fn. 311) There was considerable reduction in agricultural employment as a result. Between 1841 and 1871 around 60 per cent of heads of households worked in farming, and in 1881 around 54 per cent; by 1891 the proportion was 40 per cent, and in 1901 only 30 per cent. (fn. 312) This trend continued and no doubt accelerated after 1945, so that by the later 20th century only a tiny proportion of the local population worked on the land.

The large brick-lined water-tank near Bix Manor Farm, at the top of the hill from Henley, represents one of the few substantial investments in agriculture in the period. It was constructed between 1897 and 1912, presumably by the Flemings after they acquired the Nettlebed estate in 1903. (fn. 313) The tank was probably mainly intended to provide water for the steam-ploughs, traction engines and threshing machines which had been used in the parish since the 1880s. (fn. 314)

An enquiry in 1941 produced a mixed verdict on farming in the parish. (fn. 315) Some farms were singled out for praise, among them F. M. Bond's Valley farm (498 a.), where good corn crops were grown and a good dairy herd maintained; the Stonor's Middle Assendon farm (152 a.), where the tenant was efficiently producing milk and had good winter crops; and Lawrences farm (49 a.), an arable farm run on sound lines by the Frouds. Others required liming, or suffered from lack of capital or over-attention to sporting interests. Redpits and Westwood were run by agricultural engineers who were only part-time farmers. Most of the land in the parish was 'fair', with much of the 'bad' land concentrated in Middle Assendon. (fn. 316) Low agricultural rents presumably reflected environmental limitations as well as the state of farming. (fn. 317)

By the mid to later 20th century many farmhouses had been sold off, and, despite the persistence of some smaller holdings, most agricultural land was managed by landowners or their tenants from a few farm and estate depots. (fn. 318) The bulk of the farmland in the south of the parish was managed by the Nettlebed Estate, and from the early 1990s most of Bix Bottom was leased from Lord Alvingham by the Hunts, substantial tenant farmers based at Upper Assendon Farm in Stonor, with a further holding at Lewknor. (fn. 319)

Land Use

In 1840 around 70 per cent of land in the parish was arable, 26 per cent wood and only 2 per cent permanent grass. (fn. 320) Figures for 1878 were similar, with most permanent grassland confined to orchards and small closes. (fn. 321) In the 1850s Stonor tenants were obliged not to sow more than a quarter of their land with wheat, or to use individual fields for wheat more than one year in four. White straw crops could be grown for no more than two years in succession, and specified amounts of land had to be under grass, clover, turnips or fallow. (fn. 322) Around 1,500 sheep were kept in the 1860s and 1870s, along with modest numbers of cattle and pigs. (fn. 323)

In the late 19th century Bix farmers followed the trend towards larger dairy herds, (fn. 324) responding to increased urban demand for milk and depressed corn prices. (fn. 325) The area under arable was greatly reduced and fewer sheep were kept. (fn. 326) By the 1890s there were c. 700 a. of permanent grassland and a further 200 a. of temporary grasses. (fn. 327) In 1930 there was 856 a. permanent grass, (fn. 328) and the only large areas of arable were in the eastern part of Bix Bottom, north-west of the common, and south of the main road. (fn. 329) The main crops in the later 19th and earlier 20th century were wheat, barley, oats, and turnips, the latter three grown mostly for fodder. Oats had displaced wheat as the main cereal crop by the 1880s. (fn. 330)

In the early 20th century local dairy herds were producing substantial amounts of milk: Cousins's herd at Manor farm provided c. 275–290 gallons a week in the 1920s and early 1930s. Much of the milk was sold locally, (fn. 331) but quantities from the larger producers were bought by dairies in Reading. (fn. 332) Cows and calves were regularly sold at Henley market. (fn. 333) In 1941 there were 132 cows on Bond's Valley Farm, almost 100 on Nettlebed Estate lands around Bromsden, and 61 at Cousins's Manor farm (including Benwells). (fn. 334) On other farms herds were more modest, between 20 and 50 animals. Sheep rearing had virtually ceased in the 1920s, (fn. 335) but by 1941 significant numbers of sheep (and pigs) were kept at Valley farm and Bromsden. (fn. 336) A few smaller farms apparently specialized in poultry, (fn. 337) and one or two had market gardening sidelines, selling fruit and vegetables in Bix and Henley. (fn. 338)

Mixed farming continued to predominate in the mid 20th century and after. In the 1960s barley was the favourite cereal crop because of government subsidies, its suitability (alongside oats) as animal feed, and to a lesser extent because some could be sold to local breweries. At that time most farmers kept a variety of animals, including beef and dairy cattle, sheep, pigs, and poultry. (fn. 339) By the 1980s the most important crop was wheat, followed by barley and other fodder crops for cattle and sheep. In 1988 61 per cent of available land was used for crops rather than permanent grass, compared to 46 per cent in 1941. (fn. 340) Dairy production ceased in the late 20th century, except on the Nettlebed Estate: there 120 cows were kept for milking in 2006, despite the abandonment of an ambitious mechanized dairy unit established in the late 1960s. (fn. 341)

Woodland Exploitation

Extensive areas of woodland in the parish were long used for wood-gathering, grazing and pig pannaging. (fn. 342) In the Middle Ages and later many woods were inclosed as coppices-with-standards, to produce wood for fuel and a variety of other purposes. Coppices, which included oak and ash as well as beech, were mainly owned by landlords, who generally leased them out, but a few belonged to local farmers. From c. 1800 changing market conditions led to the replacement of coppice with high beech forest producing timber. (fn. 343) In all periods there were sizeable 'common woods' where tenants could find fuel and limited forage for their animals, though here as elsewhere landowners reserved the timber to themselves. (fn. 344)

Domesday Book mentioned only 12 a. of woodland (silvae) on each Bix manor; (fn. 345) since there was almost certainly far more woodland at that time, (fn. 346) this presumably represented some nominal estimate of the area of managed wood. A survey of 1388 suggests that the main woodland products were firewood and other small wood (like the 'crop' of Bix Brand wood), but large areas of wood seem not to have been very systematically managed in this period. (fn. 347) By the 15th century there is evidence of fairly regular wood sales from the Stonor estate, with wood from Bix often worth £5–7 or more. (fn. 348) Sixteenth-century and later documents show detailed arrangements over the leasing of areas of wood for coppicing, with cycles of seven years or longer. (fn. 349) Charcoal burners were recorded from the early 17th century. (fn. 350)

Wood produced in Bix was used both locally and further afield. Local demand was bolstered by the requirements of the Nettlebed pottery and tile-making industry, and firewood was also taken to Oxford and places in the south Oxfordshire clay vale. (fn. 351) But from the later Middle Ages until the 18th century the largest demand came from London, and great quantities of wood were shipped down the Thames via Henley wharf. (fn. 352) In the late 17th and early 18th century the Stonors and some other owners of woodland made frequent and large sales of water-wood billets, oak billets, bastard billets and bavins. (fn. 353)

In the Middle Ages larger pieces of timber were perhaps mainly used for demesne and tenant building requirements, which may be why Robert Newmer was paid 5s. for carting timber from Bromsden to Bix in 1424–5. (fn. 354) Whole trees were occasionally sold, as in the later 15th century when 100 great beeches were sold 'by Bromsden hedge', along with 40 other trees at Bromsden and 20 from elsewhere; the buyers included locals and men from Henley. (fn. 355) In the late 16th and 17th century timber from woods in the far north-west belonging to the royal manor of Ewelme was much used for the navy, and was sold for making houses, barrels and boards. (fn. 356) A timber dealer lived in Lower Assendon in 1751, part of whose stock had been purchased from the Fawley Court estate. (fn. 357)

In the 19th and early 20th centuries income came mainly from 40- to 70-year-old beech trees (or 'poles') cut according to a selection system, (fn. 358) and several timber merchants lived in the parish in the later 19th century. (fn. 359) Some timber was used locally for fuel and fencing, and at the Frouds' saw mill in Middle Assendon, established in the 1860s: in the early 1910s the mill consumed many hundreds of trees each year from the Fawley Court estate, mostly from woods in Bix. (fn. 360) Another source of demand was the furniture-making industry of High Wycombe, Stokenchurch and Chinnor. From the late 19th century the furniture factories relied increasingly on cheap foreign imports, but in the early 20th they continued to buy some timber from Bix and elsewhere in the Chilterns. (fn. 361)

In the inter-war years the timber market probably shrank in size and became more local in character. (fn. 362) By the later 1940s the saw mill in the Nettlebed Estate woods, which employed 14 men, sold planks, posts, bean rods and faggots to householders from Bix, Rotherfield Greys, Henley, and elsewhere. A good deal of timber had been compulsorily felled in the Second World War, and forestry operations were run down, (fn. 363) but the mill still operated in 2009. The Frouds' saw mill remained open until the 1960s, though the scale of its operations declined considerably earlier. (fn. 364)

Non-Agricultural Pursuits

Rural Industry

The only significant local industry before the mid 19th century was brick, tile and pottery making. Nettlebed was a major production centre from the 14th century, and there were lesser sites around the peripheries of Bix, including near Russell's Water. (fn. 365) At least one kiln seems to have been located in Bix parish (north-east of Nettlebed) by the 15th century. (fn. 366) One John le Tiler was resident in Bix Brand in 1341, (fn. 367) Nicholas Tiler held a house, ½ yardland and 6 a. there in 1390, (fn. 368) and in the early 15th century Thomas Tiler was involved in cutting wood, perhaps to fuel a kiln. (fn. 369) In 1720 Edward Deane of Minigrove in Bix described himself as 'brickmaker'. (fn. 370) Nonetheless Bix was on the periphery of this local industry, which provided only limited employment in the parish (mainly for bricklayers) before its decline in the early 20th century. (fn. 371)

In the 1860s James Froud took over the wheelwright's and carpentry shop in Middle Assendon where he had served his apprenticeship, giving rise to a considerable local business. (fn. 372) By the later 1860s he had set up a saw mill for cutting brush backs and veneers, probably mainly for the London market, (fn. 373) and made vent pegs and bungs for beer barrels. He also undertook building work and wheelwrighting, and acquired a portable threshing plant with which he visited surrounding farms; later he used traction engines for agricultural work and timber hauling, and a chalk pit was opened opposite Assendon Farm (later Home Farm) with kilns for making lime. (fn. 374) After Froud's death in 1891 the business was continued by his sons until the early 1930s, when the saw mill was taken over by Richard Ovey, the chalk pit sold, and the agricultural, wheelwright and carpentry business given up. In the late 1870s the Frouds employed around 30 men and boys, rising to over 60 by 1894, and 80 by 1916; workers came from Bix and surrounding areas, including Henley and Stonor. (fn. 375) In the late 1950s the saw mill still employed around 18 men, but closed in 1966.

Crafts

Robert le Smith of Bix was involved in a debt case in Henley in 1332–3. (fn. 376) In 1704 a blacksmith's shop in Middle Assendon was leased by the Stonors to Thomas Coles, (fn. 377) whose family were long associated both with the business and with the adjacent Rainbow pub; the smithy was still operating in 1928. (fn. 378) The wheelwright's shop acquired by James Froud in Middle Assendon was established by the 18th century, and in the mid 19th century a farmer and the publican at the Golden Ball were part-time wheelwrights. (fn. 379) In 1701 a wheelwright was accused of having built a workshop on the common without authorization. (fn. 380)

A range of other crafts was recorded in the parish from the late 18th to early 20th centuries, and although such employment remained small-scale it seems to have expanded somewhat after the early 19th century. The more common crafts included shoe-making, tailoring, glove-making, carpentry, and bricklaying (the latter especially around Minigrove), and to a lesser extent chair turning. Women were involved in many such activities, as well as in domestic service and, later, char-work. (fn. 381)

Retailing and Other Businesses

Ale was produced on a small scale in the later Middle Ages. (fn. 382) Some was presumably sold, but it seems unlikely that anything other than basic commodities were then available in the parish. The Stonors seem to have purchased food and other necessaries mainly at Henley, Watlington and Reading, and shipped luxuries upriver from London to Henley wharf. (fn. 383) In 1668 a recently deceased gentleman farmer, Robert Farmer, owed £5 to a shopkeeper in Reading, £2 10s. to another Reading man, and £2 for wares from the Henley mercer Ambrose Freeman; another £8 was owed to Margaret Dean of Bix, perhaps for goods. (fn. 384)

In the 19th and early 20th centuries a few men retailed beer, dairy produce and groceries, although often only part-time. (fn. 385) There was a grocer's shop and bakery on the Oxford road in Bix 'village' from the mid 19th century, associated with the sub-post office, which closed in the early 1970s; (fn. 386) a shop in Lower Assendon was mentioned in the mid 19th century. (fn. 387) A shop set up in Mill Close in Middle Assendon in the late 1960s soon shut through lack of business. (fn. 388) By 1980 the only local food retail was provided by the weekly visits of a greengrocer and of a Grimsby fishmonger, who stopped at the Golden Ball and the Rainbow on his way back from London. (fn. 389) Bix Manor became a conference and events venue in the late 1980s, and was still functioning in 2009. (fn. 390) Sundials and sculptures were then being made to order in two workshops, (fn. 391) and a plant nursery operated in Lower Assendon.

SOCIAL HISTORY

The pattern of small hamlets and isolated farmsteads scattered among steep valleys and woods created a rather loose-knit society within Bix. The settlements in Bix Bottom, Lower and Middle Assendon, and what became known as Bix 'village' have long formed separate little communities, and many of the peripheral farmhouses and cottages are more closely linked with hamlets in neighbouring parishes. The church does not seem to have provided a particularly strong focus, and from the 14th to early 20th centuries major landowners were generally non-resident. (fn. 392) High illegitimacy rates in the mid 18th century may indicate a lack of strong social cohesion and supervision. (fn. 393) In the 20th century, the transformation of what was previously a farming area into a dormitory parish for commuters and rich retired people did little to weave social threads more tightly.

The leading figures within the parish were for a long time the more substantial tenant farmers and the rectors. The farmers were the major employers and probably exercised some influence through office-holding in local manorial and parish government. (fn. 394) The rectors were resident for long periods and, despite generally poor church-attendance, several of them seem to have been prominent in local society. Landowners living in neighbouring parishes exercised a secondary level of influence, notably the Stonors (in Pyrton), until the 20th century when a number of new landowners came to live within the parish. (fn. 395) In the late 19th to earlier 20th century, the Frouds became the major local employers, and this large family in its various branches owned or occupied a number of houses, farms and local businesses. (fn. 396)

Social Structure before 1800