A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Henley: Town Buildings', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp49-72 [accessed 23 February 2025].

'Henley: Town Buildings', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online, accessed February 23, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp49-72.

"Henley: Town Buildings". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online. Web. 23 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp49-72.

In this section

TOWN BUILDINGS

Medieval Henley was predominantly timber-built, reflecting the widespread availability of timber across the Chilterns. Examples survive throughout the town, some clearly visible, others concealed behind later façades of brick, render, or (in a few instances) 20th-century mock timber-framing. (fn. 1) Stone had to be expensively imported presumably by river, and was generally used only for high-status structures such as the bridge or church, although in 1310 a wealthy merchant owned a stone house near the bridge. (fn. 2) Flint and chalk, both also widely available, were used for cellars and foundations from the Middle Ages. A vaulted and chalk-lined stone cellar beneath the former White Hart may be as early as c. 1300, and some other cellars have substantial flint walls, some of them with quoins or relieving arches in narrow (and therefore probably early) brick. (fn. 3)

Brick was available locally by the early 15th century, and was used on a large scale at nearby Stonor (1416–17) and Ewelme (from 1437). (fn. 4) In Henley, its first known use on a substantial scale was at the White Hart in 1530–1, when some of the outer walls of the courtyard lodging ranges were rebuilt in brick and decorated with blue-brick diaper patterning. (fn. 5) Henley bricklayers were mentioned sporadically from the mid 16th century, (fn. 6) but timber construction continued well into the 17th century. Siberechts' paintings of the 1690s (Plates 3–4) show a town still dominated by traditional timber-framed houses, many of them with multiple gables to the street.

More widespread use of brick came in gradually during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, along with other aspects of London-influenced classical styles. (fn. 7) Stockpiled bricks and a 'brick room' were mentioned in 1668 and 1698 respectively, (fn. 8) and by the early 18th century brick was the preferred material for street façades, giving Henley, along with neighbouring riverside towns such as Marlow, much of its present-day visual character. (fn. 9) Typical of Henley's earlier 18th-century houses is an inventive use of brickwork, incorporating contrasting dressings, burnt headers, combined Flemish and header bonds, and patterning in red and grey (Plate 7); by contrast most later 18th-century buildings are plainer, with façades sometimes rendered and painted. Brick remained the chief material, though in the late 19th and early 20th centuries some notable additions were made in an Old English half-timbered style shared with riverside resorts such as Pangbourne and Streatley, and handled with what has approvingly been described as 'hedonistic license'. (fn. 10)

The pronounced shift in the structure and style of Henley's buildings from around 1700 suggests a natural break, which is adopted in the following account. (fn. 11) The parish church and other religious buildings are discussed separately. (fn. 12)

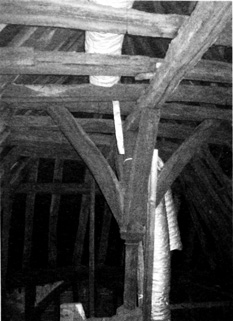

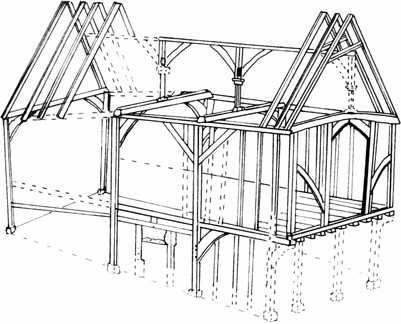

14. 20 Bell Street (the Old Bell). Left: crown post dated to 1325. Right: conjectural reconstruction looking south-east (inferred timbers dotted), with the crown-post visible in the central bay. The building was probably an upper-end cross wing, and its street front (facing right) was most likely jettied.

Building to c. 1700

Houses to 1550

Despite constant rebuilding, remains of medieval houses have been identified across much of the medieval settled area (Fig. 7). The chief exception is Duke Street, which was entirely rebuilt in the 1870s. In several instances only a jettied cross wing remains, the hall and lower end (typically the less prestigious parts) having been demolished, perhaps after passing into separate ownership. (fn. 13) Many other houses have had their street frontages rebuilt, typically during the 18th century to create more fashionable brick façades: sometimes only the front wall was rebuilt, and sometimes the entire front rooms, leaving older timbered ranges to the rear (e.g. 39 Hart Street, Fig 18). Others were rendered over, and have retained their framing virtually intact. (fn. 14) Dendrochronological dating suggests substantial building activity during the 15th century, on the town's edges as well as in the centre, (fn. 15) and parts of two substantial 14th-century houses survive at Market Place and on Bell Street, both close to the central market area. The proportion of firmly dated buildings is, however, still relatively small.

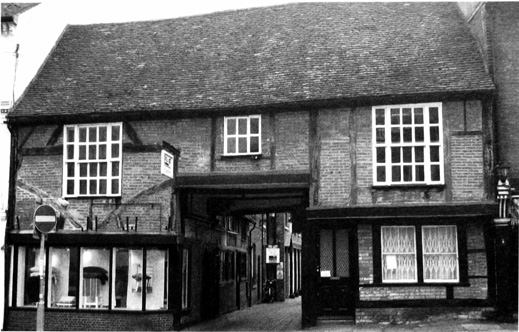

Like several of Henley's other early houses, the Bell Street building (No. 20) contains high-quality detailing, and was probably built for a prosperous merchant. Lying gable-end to the street behind a later façade, it includes three timber-framed bays dendro-dated to 1325, and has a carved crown post to the roof (Fig. 14). A two-centred arched opening in the front wall may have been the rear-arch of an oriel window. Probably it formed the upper cross wing of a substantial house, which had a hall running along the street. (fn. 16) The eastern part of Nos 45/47 Market Place (the Old Broad Gates, Fig. 15) is similar, with a formerly jettied first floor which apparently contained a single large chamber, and which has remains of a crown post. The adjoining carriageway probably began as a conventional cross passage, and retains a two-centred doorway to the cross wing, with good evidence of a second one adjoining. Possibly these gave access to the buttery and pantry. (fn. 17) A former cross wing at No. 22 Hart Street has a blocked and formerly shuttered trefoil-headed window of c. 1400 in the eastern first-floor wall, now abutting No. 24.

A more complete medieval house (part dendro-dated to 1405) survives at Nos 74–78 Bell Street, whose façade masks remains of a two-bay open hall (No. 76) aligned along the street, with a contemporary three-bay cross wing at the upper (north) end. The hall retains a decorated wall post, deep arch braces, and two-tiered cusped wind braces. (fn. 18) Baltic Cottage, at the riverside end of Friday Street, incorporates another open hall, its impressive crown-post roof dendro-dated to 1438. (fn. 19) A concealed, high-quality four-bay range at Nos 93/95 Bell Street is also 15th-century, with heavily moulded timbers and cusped wind braces. The two southern bays have a central arch-braced truss, and despite the lack of sooting may also have been a hall.

15. The Old Broad Gates south of Market Place. The left-hand (eastern) part began as the jettied, gabled cross wing of a medieval house, probably with a hall to its right. It became an inn in the 17th century.

Little evidence survives for halls positioned behind the street front, as occurred widely in larger towns. A tall, hall-like structure behind 82 Bell Street has steeply arched ties and a moulded wall post with a carved fleur de lys, and may be early 15th-century, but its relationship with the front range is unclear. So, too, is that of a similar range behind 77–81 Bell Street (subsequently the Bear Inn), dendro-dated to 1438 and considerably enlarged in 1590. (fn. 20) That has no superfluous decoration, and may have been a commercial structure or kitchen.

Some smaller houses remain on Gravel Hill above the market place, where Nos 9–11 share a common closed truss with smoke blackening on each side. Possibly they formed part of a terrace with the much altered No. 7, built for renting out to small craftsmen. They pre-date a substantial adjoining cross wing at No. 13 (dendro-dated to 1454), (fn. 21) and are probably early 15th-century.

Roofs and Framing (fn. 22)

The crown-post roofs already mentioned (and a fourth at the former White Hart) suggest that this was a common roof-form in 14th and early 15th-century Henley, although the hall at 76 Bell Street has an arch-braced central truss with butt purlins, and there is evidence of a similar roof at 91 Bell Street. The crown post was wasteful of timber, and in Henley seems to have been largely superseded from the mid 15th century by the crown-strut roof, with a central post rising from the tie to the collar of the principal truss, and two side purlins rather than a single collar purlin. The earliest firmly dated examples in Henley are the 1454 cross wing at 13 Gravel Hill and the slightly earlier adjoining halls, (fn. 23) which is consistent with the emergence of similar roof-construction at Hambleden (1443) and Ewelme Almshouses (1430–50). (fn. 24) Others survive at 77–81 Bell Street (the former Bear Inn) and 8–16 New Street (built as two medieval houses), while variants at 61 Bell Street and 44 Hart Street (fn. 25) have curved side braces creating a fan shape, reminiscent of a crown post. All employ good-quality timber framing, and are unlikely to be later than the 15th century.

The town's most typical medieval framing consists of large rectangular panels with arch bracing between posts and plates. Externally visible examples survive at the Chantry House, in the rear ranges of the Bear on Bell Street, and at Nos 16 and 58/78 New Street (Fig. 16); internally, such a structure is almost universal. (fn. 26) The chief exception is the distinctive long tension braces found so far only in early buildings, where they appear to have been used in particularly visible locations such as first-floor cross wings abutting the street. Prominent examples survive at Nos 20 and 61 Bell Street, 22 Hart Street, and the Old Broad Gates, probably none of which are later than c. 1400. The distinctive two-centred arched openings at 20 Bell Street and the Old Broad Gates are of similar date. (fn. 27)

16. Nos 58/78 New Street (Tudor and Anne Boleyn Cottages): a 15th-century jettied house with cross passage, later subdivided. The passage now gives access to cottages built at the rear between the 17th and early 19th centuries.

Decorative framing in three fairly late houses suggests that such display may once have been widespread on the town's better buildings. No. 14/14a Friday Street, probably the parlour wing of a large house of c. 1600 on the edge of the built-up area, has close studding to the front, and similar framing is shown in a 19th-century view of 44–50 Hart Street. No. 7 Market Place may be of similar date, but has small panels to the front with ornamental, small-scale quadrant bracing. (fn. 28)

Houses c. 1550–1700

During the 16th and 17th centuries Henley's buildings were modernized on the usual pattern, by flooring over of halls, insertion of fireplaces, chimneys and new windows, increased use of glass, and reconfiguration of internal rooms. Buildings already described provide examples, although the structural changes are generally impossible to date. A house 'against the high cross' (i.e. near the crossroads) had a chamber over the hall by 1532, when it was divided at the owner's death: the hall, chamber, and a chamber over the kitchen went (with a cellar under the hall) to one son, while 'the parlour next the street', the kitchen, and chambers over the parlour and shop went to another, along with a second cellar under the shop. (fn. 29) Such divisions were common, and sometimes resulted in flying freeholds, whereby the upper floor of one property oversails the lower floor of a house adjoining. (fn. 30) New houses built in traditional timber style included Nos 48–50 Hart Street, an impressive double-jettied house of three storeys on a prime site opposite the church, with a stair tower (Fig. 19) at the rear. (fn. 31)

A national innovation of the 16th century was the lobby entrance plan, in which a central entrance, opening against a chimney stack, gives access to rooms on either side, each heated by a fireplace. An unusually early example may be Ancastle Cottage on Gravel Hill (Fig. 47), which when first built stood above the market place well outside the town. Its jettied front (concealed by later additions) faced westwards towards Badgemore, and probably it was built as a farmhouse. (fn. 32) Within the town itself, a comparable layout was created at Baltic Cottage on Friday Street by the insertion, during the 16th century, of a stack and floor at the centre of the earlier two-bay hall house. Most other lobby entrances in the town are probably early 17th-century, among them 16 West Street and the former Anchor Inn on Friday Street.

Further change arose from the increasing use of coal rather than wood as a domestic fuel, transported presumably along the coast and upstream through London. John Parkes, bargeman, had a chaldron of coals worth £1 in his shop in 1668, (fn. 33) and from the 1680s several householders had 'coal irons' or 'coal iron grates', sometimes listed alongside 'chamber faggots' for those fireplaces which had not been narrowed for coal burning. (fn. 34) In new houses, the general acceptance of coal presumably led to an overall reduction in the size of chimney stacks.

Rooms and furnishings

Despite the structural changes, in many of Henley's houses the hall continued as the main room into the late 17th century. In smaller houses, it was still used for living, eating and cooking: the butcher Henry Cules (d. 1626), for instance, had a kitchen equipped with simple utensils, but his spits and pot hooks were in the hall, with a table, three stools and an old cupboard. (fn. 35) For those with only two rooms (hall and chamber), cooking in the hall remained a necessity. Richard Morris (d. 1640), described as a 'poor man', had no kitchen and only the simplest furnishings, including tongs and dog irons. (fn. 36) Probably he was not unusual, since in 1662 over 13 per cent of householders (31 out of 233) were taxed on one hearth only, and another 49 people on two. (fn. 37) By contrast some larger houses had well-equipped kitchens and outhouses. In 1597 John Thorne 'gentleman', possibly a grocer and fishmonger, had a well-furnished hall fitted with benches and tables, cushions and a pair of flower pots, but cooking and food-preparation vessels were all in the kitchen. (fn. 38)

Parlours seem to have been introduced only gradually. The rectory house (taxed on 6 hearths) had a study and a well-furnished parlour by 1580, (fn. 39) but inventories contain relatively few references until the 1650s, and then primarily amongst the better-off and socially aspiring. (fn. 40) Robert Heybourne (d. 1661), Richard Allen (d. 1663) and Thomas Allen (d. c. 1678) all had parlours, one of them (Heybourne's) furnished with a clock, while Heybourne and Thomas Allen also had studies. All called themselves 'Mr' or 'gentleman', and were probably successful traders or maltsters. (fn. 41) Around the same time traditional halls seem to have declined in importance. The leading maltster Humphrey Newbury (d. 1665) had a parlour but no hall, while the drawing table and leather chairs in the hall of Thomas Flight (d. 1679), another prosperous maltster, suggest that it was a parlour in all but name. (fn. 42)

Use of bed chambers changed less than that of ground-floor rooms, although some were luxuriously furnished. In 1580 the great chamber in the rectory house must have been one of the grandest rooms in the town, with a fireplace, decorative painted cloths, window curtains, and a bed with curtains, feather pillows and a tapestry coverlet. (fn. 43) Some such chambers were probably for guests. Joan Stevens, widow, had a 'guest chamber' in 1581, (fn. 44) while the maltsters Solomon Sewen (d. 1631) and John Grant (d. 1662) both had great chambers more luxuriously furnished than their own private lodging chambers. (fn. 45) Occasionally beds were noted in ground-floor parlours, though as in other towns the practice seems to have died out by the early 18th century. (fn. 46)

Reference to a glazier in 1564 suggests increased demand for window glass, (fn. 47) and though some better houses still had shuttered hall windows in the early 17th century, (fn. 48) both glass and wainscot were commonly listed as movables. Richard Dunt (d. 1589) left all the glass about his house, together with wainscot in the hall, parlour and parlour chamber, and as late as 1630 Solomon Sewen bequeathed his 'glass and wainscot and heirlooms'. (fn. 49) By then both glass and panelling were evidently coming to be seen as standard fixtures, and were rarely mentioned later. Panelling presumably replaced the painted cloths mentioned in some earlier inventories, which most commonly decorated halls, but also chambers and parlours. (fn. 50) The fishmonger Ralph Munday (d. 1604) had several worth at least 19s., (fn. 51) though by the 1620s they were apparently passing out of fashion. A 'painted chamber' mentioned in 1639 points to the domestic wall paintings which must have decorated many of the town's better 16th- and early 17th-century houses. (fn. 52)

Changes in other furnishings followed standard patterns. Beds with testers of painted cloth remained common in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, but seem to have gone out of fashion around the same time as painted cloth hangings. Chairs gradually superseded stools or forms in better-off households, and there is occasional mention of settles. Cupboards were listed throughout, accompanied increasingly by chests of drawers. (fn. 53) The four-bedroom house of the surgeon and grocer Edward Stevens (d. 1663) was fairly typical of those occupied by Henley's more prosperous late 17th-century inhabitants, with its curtained feather beds and court cupboards, its tables, cushions and leather chairs in the hall (furnished effectively as a parlour), its well-equipped kitchen and wash house, its adjoining warehousing and apothecary's shop, and (less common but not unique) his 'study of books'. (fn. 54) By then, looking glasses, pictures and clocks were also becoming more common.

Non-Domestic Building to 1700

Shops around the town's commercial core are documented from the late 13th and early 14th century, many with domestic accommodation above and sometimes behind. (fn. 55) One in 1346 had a frontage of 16½ ft (1 perch) and a depth of 17 ft, with a solar above and a chamber (camera) to the rear. (fn. 56) Such details are rare, however, and no early shopfronts survive. Shops in the Middle Rows may have been smaller. One in 1688 measured only 14 ft by 9 ft., although a butcher's shop nearby had a 'penthouse' and a brick floor. (fn. 57)

Craft processing and (later) malting were carried out in outbuildings on back plots, requiring direct access from the street to the rear. In the early 17th century several houses seem to have had a side passage with first-floor buildings above, an arrangement which can probably be assumed at an earlier date. The fishmonger Ralph Munday's house had a chamber over the entry in 1604, while Christopher Grainger's had a chamber over the gate. (fn. 58) Not all the houses so described were necessarily in the town centre, but many probably were, and the numerous warehouses, malthouses, workshops and slaughterhouses mentioned in 17th-century probate inventories were presumably accessed in this way. (fn. 59) Few identifiable rear-plot outbuildings survive, but an exception is a former malthouse or hop kiln behind 57/59 Market Place (Fig. 27). Built probably in the 17th century as a traditional timber-framed outhouse, possibly a domestic malt kiln, it seems to have been modified later as a hop-drying kiln, perhaps when new maltings were built on levelled ground behind No. 57. (fn. 60)

Inns (fn. 61)

The most substantial remains of an early inn are those of the former White Hart (17–23 Hart Street), which occupies a width of three burgage plots on the north side of the street, and extends their full depth to include two courtyards. The inn existed by 1428–9, and fragments remain of a street-front hall range with smoke-blackened crown posts. Behind, three ranges of 1530–31 face into the first courtyard, each with a formerly continuous passage at first-floor level giving access to lodgings (Fig. 26). Probably there were stables below. The new west range's southern end included a contemporary open hall with a fireplace, whose roof retains deep moulded arch braces to the central truss. (fn. 62)

The former Bear Inn at Nos 77–81 Bell Street is recorded as an inn only from 1666, but contains building of the 15th and 17th centuries. (fn. 63) Four gables face the street, and a carriage entrance beneath the northern bay of 77–79 gives access to the inn yard. The front range of No. 81 appears to be a mid 17th-century addition. A very simply furnished hall was listed in an inventory taken on the death of the landlord John Dolton in 1683, (fn. 64) together with a chamber over the courtyard entry, a parlour with leather chairs and musical instruments, and a 'new chamber', which may be the first-floor front range of No. 81 with its 17th-century window bay. No room can be easily identified with an impressive three-bay chamber in a long range at the rear of 77–79. Carriageways with rooms above survive at some other former inns, among them the King's Arms (32–6 Market Place) and Broad Gates (45/47 Market Place).

Detailed 17th-century probate inventories survive for some other major inns, notably the Catherine Wheel on Hart Street (established by 1499), the Bell at Northfield End (established by c. 1592), and the Red Lion near the bridge (established by the early 17th century), (fn. 65) though as the buildings are so much altered relating them to the standing fabric is not possible. The Catherine Wheel, not yet extended into neighbouring premises, was taxed on 17 hearths and had at least ten bed chambers, most of them furnished as bed-sitting rooms and identified by such names as the Queen's Head, the Swan, or the wainscot room. Other rooms excluded beds, and there was a parlour, shuffle-board room, kitchen and outbuildings. (fn. 66) The Red Lion and the Bell (patronized by Archbishop Laud c. 1633) (fn. 67) also had parlours, wine and beer cellars, kitchens, outhouses, and several named chambers. (fn. 68)

Riverside buildings

From the 14th century there is considerable documentary evidence for granaries along the waterfront. (fn. 69) In 1499 the merchant and innkeeper John Lyde owned riverside 'garners and solers' on the north side of New Street, (fn. 70) and similar storehouses for grain and malt were mentioned frequently throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. (fn. 71)

Siberechts' paintings of the 1690s show ranges of such buildings above and below the bridge. Only two survive: one on the north side of Friday Street extending as far as the waterfront, and the other (dendro-dated to 1548–50) (fn. 72) running northwards from it parallel to the river. One of the paintings (Plate 3) seems to include the latter range, and though the depiction is not entirely accurate (the east-facing gable to the corner block with Friday street is not shown), Siberechts was probably correct in showing the upper floor with small taking-in doors rather than domestic windows. (fn. 73) This part has no evidence of heating or early stairs, and former partitions rising to the roof suggest that it may have been occupied as a series of individual units. The ground floor has been underbuilt in brick, but large openings shown by Siberechts suggest warehouse or business use or the storage and repair of boats and tackle, and there seems to have been a cart entrance beneath the northernmost bay. The Friday Street range is similar in construction, though the prominent corner site may have had some superior function, since it had a large ground-floor room and was jettied with square-laid joists on both façades, with a dragon beam to the angle. (fn. 74) Nearby, Siberechts showed another riverside range, probably on the site of the present Old Rectory: that had four gables towards the river, and projecting oriel windows beneath gablets, similar to those at the former Bear Inn. The oriels suggest an early to mid 17th-century date and possibly a domestic function, at least for the upper floor. (fn. 75)

A painting from the north-east (Plate 4) shows a further line of adjoining buildings downstream of the bridge, running towards New Street. These were two-storeyed and jettied, some with small openings on the upper floor, others with what may be domestic windows: certainly there were bargemen's houses there in the mid 18th century. (fn. 76) In the painting, the ground floors of all of these buildings suggest storage or warehouse functions, some open-fronted with piles of goods stacked up between posts, others enclosed with door openings but no windows.

Such details seem confirmed by the major surviving late-medieval building in the town, the so-called Chantry House (Plates 5–6). (fn. 77) This stands a little way back from the waterside in an area which, from the 15th to 17th centuries, was occupied by granaries, storehouses and malthouses, and though it also faces westwards towards the churchyard it shares many of the characteristics of the buildings shown by Siberechts. Because of a drop in ground level the building is two-storeyed to the west but three-storeyed to the east, where it opens to the river through the yard of the Red Lion Hotel. The top floor seems to have contained four chambers and a landing linked by a river-facing corridor, while the middle floor, entered through a large doorway from the churchyard, contained a large room of unknown (but non-domestic) function, possibly a trading floor. The lower floor was open-fronted towards the river, and probably served for temporary storage of goods for trans-shipment. No firm date has been obtained for the building, but it is likely to be of the later 15th century and was associated with the Elmeses and Devens, who were leading Henley merchants. (fn. 78) From the 16th century it became a school, but the name Chantry House was not coined until the early 20th century, probably following the local historian John Burn's association of the building with 'four priest's chambers in the churchyard' mentioned in 1552. Those seem, however, to have been distinct from the 'schoolhouse' mentioned at the same time, and there is nothing to suggest that the Chantry House had any church connections before its sale for use as a parish room in 1923. (fn. 79)

Building 1700–1850

Higher Class Housing and Inns

1700

ndash; c. 1760 Regular street architecture with classical details, executed in brick, was established in London from the 1630s. When such styles reached Henley is unknown. A house on the west side of Duke Street (demolished in the 1870s) had a richly ornamented façade with pilasters, cornice and frieze, and heavy rustication, executed probably in plaster or wood. (fn. 80) Stylistically it was of the 1680s or perhaps a little later, and given Henley's trade links with London it is unlikely to have been unique. Some of the gables in Siberechts' paintings of the 1690s (Plates 3–4) seem to display the brick-built 'artisan mannerist' style of London in the 1640s–50s, which spread rapidly through the home counties, though such details are small and not necessarily accurate. A further link with London is suggested by a drawing of 1712 for a pair of gabled houses attributed to 'Mr Jennings', possibly Richard Jennings of Badgemore House, who was Wren's master carpenter at St Paul's Cathedral. The houses are small and slightly old-fashioned, however, and unusual in that they have separately hipped roofs running at right angles to the façades. (fn. 81) Certainly nothing like them now exists in Henley.

Nonetheless, by the early 18th century brick was firmly established in the town, (fn. 82) and with it an increasingly prevalent use of London-influenced classical styles. Accurate dating of these 18th-century façades is impossible without documentary or other stylistic evidence, particularly as local conservatism may have perpetuated practices long discarded by London builders. Windows have often been altered, obscuring the dating evidence. Thus sashes with lighter glazing bars or larger panes have often replaced the original heavy bars (which at 1–3 Bell Street survived until the house's demolition c. 1955), (fn. 83) while frames have sometimes been set back from their original position close to the plane of the wall (e.g. at Saragossa House at 13 New Street, a building of c. 1700 stucco-fronted in the 19th century). Even so the brick façades of Henley's 18th and early 19th-century houses show a steady stylistic evolution, within a satisfying overall uniformity of materials, colour and scale.

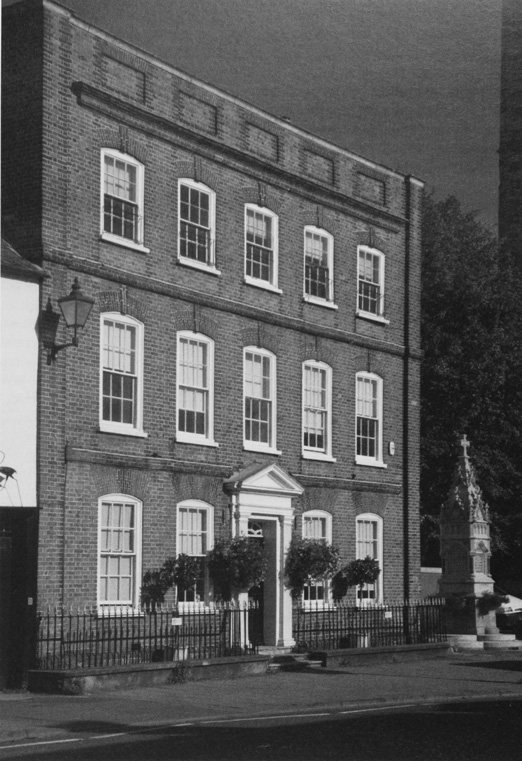

Richer townsmen were presumably the leaders of fashion, (fn. 84) and the earliest surviving houses in the new styles are quite large, typically of five bays, with swept eaves and deep dentil cornices. The Old Rectory on the waterfront (Fig. 41), with a plain seven-bay façade of grey and red brick, bears scratched dates of 1701 and 1715; either is possible, and the house (owned in the later 18th century by the brewer James Brooks before its conversion into a rectory) shows signs of early enlargement. (fn. 85) No. 55 New Street bears a date of 1715 on a rainwater head, and though the head is modern the date is plausible. The almost identical 53 New Street must be contemporary. Broadly similar are the riverside range of the Red Lion Inn (probably part of a rebuilding before 1732), (fn. 86) No. 32 Bell Street, and 17 Market Place; the last has a date of 1749 on a rainwater head, which, if related to the building, indicates how long the formula persisted. No. 86 New Street is similar in character but has a plainer cornice, and may be of c. 1750, while 65 Friday Street and 82–84 Bell Street are smaller, their location in a terrace dictating a pitched roof rather than hips. (fn. 87) Many such houses display typically inventive brickwork. (fn. 88)

The alternative to the deep cornice was a parapet, and though these were probably introduced slightly later and persisted longer, for a while both types co-existed. No. 13 Reading Road may be of c. 1725, and fully exploits the decorative possibilities of the parapet front. The façade is modelled in cut brick, with pilasters, rusticated voussoirs to the windows, and a cornice beneath a parapet with sunk panels (Plate 7). No parallel exists elsewhere in Henley, and given its location away from the town centre it was conceivably built by a bricklayer or brickmaker as an advertisement for his skills. Other houses with parapet fronts are 39 Hart Street (Longlands) (Fig. 17) and Countess Gardens on Bell Street, both possibly of c. 1740, while 37–41 Market Place has a rainwater head dated 1755. A parapeted row at 46–50 Bell Street may be the houses described as 'lately built' in a rental of 1785. (fn. 89)

c. 1760–1850

Henley's later 18th-century houses tend to look plainer, with more muted brickwork and increased use of stucco. Sometimes this may have helped to disguise irregularities resulting from alteration, as at the Bell Inn at Northfield End, where the old timber-framed range was given a symmetrical 15-bay front with a central pediment. The adjoining Denmark House and adjacent row at 92–102 Bell Street, all in a prominent location at the entrance to the town, were refronted around the same time, probably in the 1780s or 1790s when the properties belonged to Strickland Freeman of Fawley Court. (fn. 90)

Equally characteristic of the period are front doors recessed beneath a fanlight under a plain arch of rubbed brick, replacing the decorative surrounds or projecting hoods found in some earlier houses. Examples survive on New Street (Nos 3–5, 31, 39, 50 and 54), at 46 and 63 Bell Street, and at 33 Church Street. Of those, 54 New Street was described in 1834 as 'newly erected', (fn. 91) and may be of c. 1825. Fanlights lighting an entrance passage persisted into the mid 19th century and beyond, as at 54–60 Market Place and 62–66 Market Place.

17. Longlands (39 Hart Street), a typically London-influenced house of c. 1740. Yellowish bricks in the façade were possibly imported from Kent via London, as Chiltern Clay does not produce this colour. (See also Fig. 18.)

Some 18th and early 19th-century houses have a more individual character, even though in scale they sit easily with their neighbours. Nos 31–33 Hart Street have a five-bay brick façade and a hipped roof with dentil cornice: the brickwork is relatively plain, but the façade is framed by pilasters and the window spacing is particularly subtle. No. 20 Market Place, probably of c. 1760, is also five-bayed, its three central bays projecting slightly beneath a pediment (Plate 7). Probably slightly later No. 9 Northfield End acquired a rendered front disguising earlier work, with an unusual line of Venetian windows to the first floor; Northfield House next door, built in 1812 for Richard Ovey, is also rendered, and has shallow segmental window bays rising to a shallow-pitched roof. (fn. 92) A distinguished building of obscure origin is the former Assembly Rooms at 16 Bell Street. Built above a carriage entrance, the rendered façade has a Venetian window at the centre, Ionic pilasters at the angles, and a pediment to the gable. The rear is tile-hung, and evidently timber framed. By the 1790s it was occupied by the auctioneer and cabinet maker James Owthwaite, (fn. 93) and though it cannot have been built much earlier it seems unlikely that it was erected for that purpose. By 1839 it doubled as a functions room, and so continued throughout the 19th century. (fn. 94)

Few buildings can be ascribed specific dates or builders. An exception is the Kenton Theatre and the adjacent 15–17 New Street, built c. 1805 on the site of a former workhouse. The corporation sold the plot on a 99-year building lease in 1792, the purchaser being required to build one or more substantial houses at a cost of least £700 'for the reception of a gentleman or a gentleman's family,' with a 'handsome brick and sash front'. The lease came to Samuel Allnutt, brandy merchant, and Robert Kinner, bargemaster, for whom the existing buildings were erected by the Henley builder William Parker. (fn. 95) Nos 15–17 have a rendered façade with front doors and windows framed beneath sunk, arched panels: a sophisticated design for a pair of small houses. The Kenton Theatre has lost all early internal fittings; a side passage on the west probably gave access to the pit, and the main entrance to a gallery. (fn. 96) Another datable façade is that of 56 New Street (the former Rose and Crown), built probably c. 1812 by the builder, brickmaker and publican John Strange. This appears to be a refronting of an earlier structure, but the brickwork is unusually fine. Strange's father John (d. 1809) was also a builder (and publican of the King's Arms), while the younger John's son W. C. Strange became surveyor to the local board. (fn. 97)

Road improvements under the 1808 Bridge Act (fn. 98) account for the rounded corner of the shop north-east of the crossroads, which with its shallow-pitched slate roof and deep eaves appears to be of that period. A similar building on the south-east corner was demolished in 1893. (fn. 99) Other examples remain at the river end of Hart Street (rebuilt after 1829), (fn. 100) and at the junction of New Street and Thameside, where the rounding involved the partial demolition of a 15th-century house. (fn. 101)

Plan forms and interiors

For the 18th century few inventories exist, and those that do are generally less informative. (fn. 102) An exception is that for the tanner John Bird (d. c. 1780), whose house on Friday Street (now known as Queen Anne Cottage) is an 18th-century remodelling of two earlier houses. The survival of a hall presumably reflected the earlier layout, since furnishing was otherwise fashionable. Bedrooms had matching window curtains and bed hangings, Wilton carpets, and dressing glasses standing on mahogany chests of drawers, while in the parlour were mahogany tables and chairs, pier glasses in carved and gilt frames, mahogany tea caddies on the sideboard, cut-glass decanters, dinner plates, and 'a complete long set of tea china comprising forty two pieces'. The 'back parlour' seems to have been a smaller, more intimate room, with similar furniture but, in addition, a bureau desk, two bird cages (with their birds), jars of pickles, and a sugar loaf. Utensils in the kitchen show that food was prepared there, but there was also a large kitchen range in the hall, along with a table, chairs, a clock in a walnut case, and floorcloth on the floor. Here, it seems, the hall remained the everyday family eating room. Bird's tanning yard and premises adjoined the house. (fn. 103)

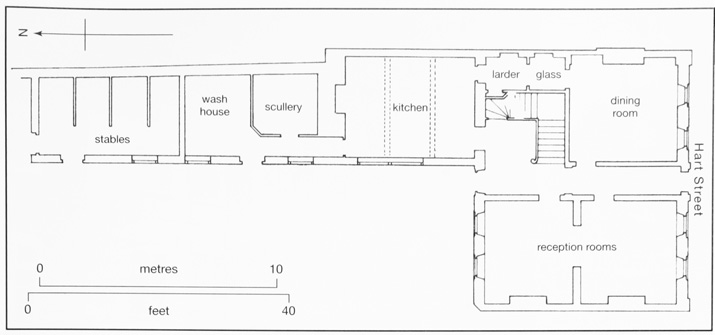

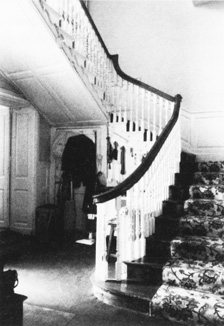

An illuminating contrast can be made with 39 Hart Street (Longlands), one of the largest of Henley's early 18th-century houses. Here the front part was newly built c. 1740, and represents best current practice (Figs 17–19). The plan is square, with three rooms on each floor and a central passage leading to an open-well stair with turned balusters, which occupies the greater part of the fourth quadrant at the rear of the house. A large kitchen with a broad deep fireplace is in the earlier wing to the rear, beyond which are scullery, wash-house and stables. The largest room, in the front of the house, was the dining room, with interconnecting reception rooms on the opposite side of the passage. A cellar is reached by a stair accessible to both dining room and kitchen.

Most house owners must have needed access from the rear to the street, not least to clean out cesspits. Nos 86 Bell Street and 39 New Street have evidence of side passages incorporated within the street elevations, an arrangement which some other houses probably shared.

Lower-Class Housing

As population rose, speculators and rentiers expanded the stock of lower-class housing. In 1786 the (market) gardener Richard Swallow held several tenements 'on the hill', all of which he sublet. One row of five (built of brick, and so probably fairly recent) was leased from the corporation, while four of his other tenements included part of a former malthouse. The rest of the malthouse had been divided into six rooms let to five tenants, of whom four occupied a single room each. (fn. 104) Such overcrowding was probably more widespread than such isolated examples imply. A similar conversion may survive at 20–22 Greys Road, built probably in the late 17th or 18th century as a two-storeyed barn or stable, and adapted as dwellings with the insertion of a central stack and upper floors. (fn. 105)

18. Longlands (39 Hart Street): ground floor plan. (For façade see Fig. 17.)

19. Domestic staircases. Left: 17th-century rear stair turret at 48–50 Hart Street. Centre and right: 18th-century staircases at 39 Hart Street and 20 Market Place, both with elegant turned balusters.

More substantial cottage rows survive on the north side of Friday Street, remodelled from corporation houses and a former malthouse by the Henley carpenter and builder Benjamin Bradshaw between 1737 and 1750. Among them are Nos 17–29 (Fig. 20), a row of three probably 16th-century houses which Bradshaw refronted and divided into six. This may have been partly to remedy subsidence (of which there is physical evidence), but it also maximized rental income and, like Swallow, Bradshaw took a block lease of the rebuilt cottages presumably for subletting. (fn. 106) The corporation's late medieval cottages at 8–16 New Street (Barnaby Cottages) were similarly converted from two tenements into five in the later 18th century, and before 1820 William Parker rebuilt and sublet four other cottages on Friday Street. (fn. 107) Slightly different was the late 18th-century remodelling of 92–102 Bell Street (near the Bell Inn), where a disparate group of timber-framed structures were unified behind a row of smart stuccoed and slated cottages. (fn. 108)

20. Nos 17–29 Friday Street: earlier corporation buildings converted into a cottage row c. 1737–50, probably for artisans or craftsmen. Similar subdivisions are recorded elsewhere in the town.

Cottage rows built in yards behind the street front (fn. 109) have almost all been swept away. One remains behind 58/78 New Street, where the late medieval house fronting the street was divided into two, and a passage made through the middle by way of the original front door (Fig. 16). This leads to two adjoining groups of cottages: one of the 17th and 18th centuries, and the other comprising four much larger double-pile cottages with the date 1823 and the name of the builder John Strange, who lived next door at the Rose and Crown. (fn. 110) Probably these represent the most substantial of such cottages, since later reports describe the 'inferior construction' and insanitary conditions found in the cottage yards of many 19th-century towns. (fn. 111) Some in Paradise Yard were of wood and had only two low rooms, while a cottage behind the Swan public house had two rooms 6-ft square, a single fireplace, and no windows that could be opened. Most yards shared wells, privies, and cesspits, risking water contamination and causing 'abominable' stenches as overcrowding increased. (fn. 112) Even on Friday Street seven cottages shared a single privy. (fn. 113)

The demand for cheap housing also spurred the town's earliest suburban growth. Between 1831 and 1841 the number of houses in Rotherfield Greys parish grew from 228 to 308, probably largely accounted for by cottages in Greys Hill and Newtown. (fn. 114) In 1851 there were 44 occupied houses on Gravel Hill, probably few with more than two bedrooms, and some certainly smaller; nonetheless they were occupied by on average 4.8 people, mainly labouring or pauper tenants. Densities in West Street were slightly lower, but houses there were probably equally small, and out of 126 households, 91 were headed by labourers or paupers. (fn. 115) From the 1870s demolition of insanitary and poor-quality housing removed all but the best of these cottages, and those that remain are only a fraction of the early 19th-century housing stock. Many of those now gone were probably of timber, or of timber behind brick fronts. Examples of 18th-century timber houses survive in Newtown at 273–281 Reading Road, all with weather-boarded fronts.

Building 1850–1914

Rebuilding in the Town Centre

During the later 19th century large-scale building revived, as Henley recovered from the economic doldrums which followed the eclipse of its coaching and river trades. (fn. 116) In the town centre the principal work of the early 1870s was the rebuilding of Duke Street's west side for road widening. Buildings there were a dense mix of residential and commercial, including some twenty cottages in six separate ownerships, a coach maker's works, four shops, various workshops, and a barn. (fn. 117) The road-widening scheme was proposed in 1868, but compulsory purchase and negotiations over compensation delayed construction until 1872–3. Costs estimated at £5,850 eventually rose to £8,674, although the corporation recouped some through sale of the sites and building materials. (fn. 118)

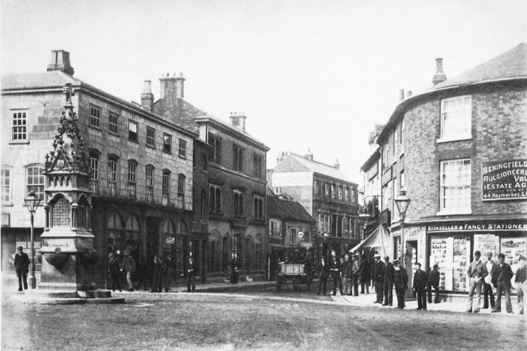

21. The main crossroads c. 1890, looking north towards new commercial buildings on Bell Street. The rounded corner on the right reflects street widening under the 1808 Bridge Act; the drinking fountain was given in 1885.

Site boundaries were re-drawn and the land divided into twelve plots. Purchasers were initially expected to erect a house and shop worth at least £400, presumably to ensure good-quality premises and to maximize the rates; the value was lowered first to £350 and then to £300, however, and stipulations were further relaxed to allow the building of a Wesleyan Methodist chapel and school following representations by neighbouring purchasers and 100 other ratepayers. (fn. 119) Most of the new buildings (built apparently by Charles Clements) (fn. 120) were architecturally undistinguished, comprising commercial premises on the ground floor and residential above. Exceptions were the gothic-style chapel of 1873–4 (Fig. 42), designed by Cattermole and Eade of Ipswich, and the Working Men's Institute of 1874–5, both also built by Clements. The chapel was demolished in 1983, and the Institute (which became a Technical Institute and reading room) in 1967. (fn. 121)

Other parts of the town centre saw more piecemeal rebuilding, particularly in the Market Place, Hart Street and the southern part of Bell Street. Despite Henley's depressed economy in the mid 19th century, new building did not cease. The south-west end of Bell Street, for instance, acquired a substantial stone-faced shop in 1854 for the watchmaker and jeweller William Grayson, while a draper added an ostentatious shop front to a large 18th-century house on the adjoining corner site probably a few years earlier (Fig. 21). (fn. 122) Apart from some modest polychromy to brick façades most town-centre building over the next forty years was utilitarian, but from around 1890 there was an upsurge of new commercial building, reaching its climax probably around 1900. These buildings display little uniformity, but by their sheer exuberance some of them make a powerful contribution.

One, at 17 Bell Street (dated 1887), was built in two phases for the draper W. Simpkins, and is a crude exercise in decorative brickwork in a debased Queen Anne manner, with large plate-glass windows on the first floor. (fn. 123) Some ten years later the junction of Duke Street, Friday Street, Greys Road and Reading Road was widened and redeveloped, with tall new buildings on three of the four corners. The south-eastern corner acquired a large and dull brick post office (now Lloyds bank) in 1895. (fn. 124) But on the north-east corner is a three-storey building of 1899 with large stone-mullioned windows, built for W. G. Burgess, (fn. 125) while on the south-west corner is the Lenthall block of 1896, erected by Charles Clements in a late-medieval style reminiscent of his work at Friar Park and Norman Avenue. (fn. 126) More sober but similar in scale is the building on the corner of Duke Street and Hart Street, built in 1893 as the Henley Restaurant, and occupied from c. 1907 by W. H. Smith's stationers. (fn. 127)

22. The Imperial Hotel on Station Road, built in 1896 to attract visitors arriving through Henley station around Regatta time. Its half-timbered 'Old English' style is common both in Henley and in neighbouring Thames-side towns such as Pangbourne.

These buildings are predominantly of brick, with detail in stone or wood. Others are in a 'distinct and memorable' Old English half-timbered style found in some other Thames-side places. (fn. 128) Most striking is the Imperial Hotel of 1896 and its adjoining row of shops (Fig. 22), built in what was then a prime site opposite the station. The architect was William Theobalds of London, and the builder Hughes of Wokingham. (fn. 129) Similar in character are the present Barclays Bank on Hart Street (designed by W. Campbell Jones and built by Charles Clements), (fn. 130) the National Westminster (formerly London & County) Bank on the north side of Market Place, 40–42 Bell Street (dated 1899), (fn. 131) and the former Duke's Head at 41–3 Duke Street (built 1901). (fn. 132)

Riverside Buildings

Rebuilding of the waterfront reflected the river's transition from commercial waterway to leisure amenity. (fn. 133) An 'elegant' crescent of 13 houses near the bridge was proposed in 1837, (fn. 134) but nothing was done until 1866 when the Henley Building Company erected a block of seven large stuccoed houses (Riverside Terrace) on former wharfs south of Friday Street. (fn. 135) The leading Henley builder Robert Owthwaite erected the adjoining Royal Hotel three years later, in a somewhat utilitarian style; it failed soon after, and in the 1880s (when owned by Greys Brewery) it was 'remodelled at great expense', providing 36 bedrooms. In 1900 its river frontage was rebuilt for Brakspear & Sons by the Reading architect G. W. Webb in a free Old English manner, so arranged that the principal rooms all looked towards the Thames. (fn. 136) By then a further spate of new riverside building was underway. A pair of two-storey boathouses for W. E. Hobbs & Sons were built in 1899, giving onto the river south of Station Road, (fn. 137) and in 1900 the Little White Hart public house (towards New Street) was rebuilt with a striking line of gables, making the most of a prominent location. (fn. 138)

North of New Street, Webb's wharf with it sheds, warehouses and steam mill was replaced from the 1880s with elaborate two-storeyed boathouses and villas (Fig. 39). (fn. 139) A row of five boathouses built for Hobbs & Sons is fairly functional, with low-pitched roofs and ornamental bargeboards. (fn. 140) The adjoining boathouse, built for Sir Frank Crisp, is more striking, with a turret at one angle and a polygonal, heavily glazed saloon opening onto a balcony, which overlooks the river and the rowing course. 'Summer rooms' on the first floor, designed for entertaining, included a dining room, ladies' dressing room, scullery, and kitchen. (fn. 141) Three villas beyond (built by 1897) (fn. 142) are plainer, but have decorative timber-framed gables, and gardens descending to their own private boathouses by the river. The designers are unknown.

New Streets and Suburbs

From the 1870s to c. 1910 Henley was transformed by suburban growth on an unprecedented scale (Fig. 11). Most new housing until the 1890s was predominantly lower-middle class and artisan, with a few isolated villas catering for wealthier incomers. The need for cheap working-class housing was well recognized, (fn. 143) but such cottages as were built were mainly piecemeal replacements for demolished town-centre dwellings. Only towards the end of the century did new working-class terraces along Reading and Harpsden Roads (adjoining middle-class housing on higher ground to the west) start to address the situation. Local building regulations introduced from 1865 helped to enforce minimum standards, at least in theory. (fn. 144)

Among the earliest and most interesting developments is a group of semi-detached, three-bedroom cottages towards the northern end of Hop Gardens, built in 1872–3 on land belonging to Col. Makins of Rotherfield Court, and designed by W. Fawcett of Cambridge. With fronts of flint with brick dressings, casement windows, and shared central chimneys that unify the composition, they are among the most attractive of the town's smaller houses, facing onto three sides of a grassed area held in common by the owners of the twelve cottages, and on which building was prohibited. (fn. 145) Queen Street, leading towards the station from Friday Street, was laid out from 1879 by Robert Owthwaite, (fn. 146) who built three pairs of sizeable semi-detached houses at the south-east end, with attractive brick and tile-hung fronts and decorative sgraffito plasterwork (Plate 8). (fn. 147) Most of the street is lined with relatively uniform terraces of three-bedroom houses, however, some with attics. Those on the west are nearly all by Thomas Hamilton, (fn. 148) a leading Henley builder who lived at No. 22; (fn. 149) that house is slightly larger and double-fronted, with stone carvings over the door. Most have projecting bay windows rising through one or two storeys, although some were added c. 1900 to match what was by then a universal feature of Henley's newer artisan housing. (fn. 150) Albert Road (further west) was built up by Thomas's brother William from 1884, with short but continuous terraces of uniform houses. (fn. 151) William was accused of using poor-quality mortar, not the only occasion on which he was challenged for poor workmanship or for transgressing the corporation's building bylaws. (fn. 152)

Caxton Terrace, a row of three-storey houses on the north side of Station Road, is of 1885–6, (fn. 153) while King's Road and its tributaries were built in the 1890s for artisan tenants, on fields behind Short Hill and Market Place. (fn. 154) Rather different is Norman Avenue, a pleasantly tree-lined street laid out in 1880 not far from the station. Over the next twenty years its north side was built up by Charles Clements with ten superior detached houses in an idiosyncratic medieval style (Plate 8), recalling his work at Friar Park. (fn. 155)

Such new streets quickly established their own social character. In 1901 five out of eight households on Norman Avenue had live-in servants, and residents included two widows of independent means, a grocer running his own business, a timber yard manager, and a female 'writer and journalist'. Rents for these 5-bedroom houses c. 1911 were £50–55 a year. Queen Street was less upmarket, with rents of £18–£26, and occupants who in 1901 included several widows (presumably of Henley tradesmen), and a retired bootmaker, brewer, farmer and revenue officer. Other occupants were a coal merchant, a brewer's traveller, a cabinet maker and a grocer's manager. King's Road, closer to the old working-class area of West Street, comprised smaller 2 and 3-bedroom houses let for £15–22; tenants there included skilled manual workers such as a gas fitter, 9 carpenters and joiners, a railway porter, a tinker, and a drayman. Significant numbers of lodgers (14 in 54 houses) raised average occupancy to 5.5 people per house, suggesting that rents were at the upper limit of what such tenants could afford. (fn. 156)

Distinct from these artisan suburbs were a few larger detached houses in various styles, some of them built for the local well-to-do, and others speculations aimed at middle-class incomers. (fn. 157) Oxford Villas in the Fair Mile, eight semi-detached 5-bedroom villas in loosely Italianate style, were built c. 1860. (fn. 158) South-west of the town, the gothic-style Rotherfield Court (formerly 'Fairfield') was built for the rector T. B. Morrell in 1861, to designs by Henry Woodyer, and was enlarged by Col. Makins after 1872. (fn. 159) Another gothic house, Surrey Lodge, was built at Hop Gardens for Charles Lucey, also in the 1860s. (fn. 160) A house nearby, with ornamental brick chimneys, is built in a tile-hung manner with close similarities to Norman Shaw's work of the early 1880s.

23. Henley from the south-west in 1880, before the development of the St Mark's Estate. Holy Trinity church (built 1847–8) is on the left, and Henley church and the chimney of Brakspears' Brewery on the right. Land in the foreground was built up from the 1890s.

The St Mark's Estate and Reading Road

From the mid 1890s there was a pronounced acceleration of suburban building, much of it south of the town on land only finally inclosed in 1860 (Fig. 11). (fn. 161) The principal landowner there, with 104 a., was Robert Owthwaite, who in 1871 sold his business to his manager John Weyman. (fn. 162) Possibly this land was included in the 90-a. Portobello Estate offered for auction in 1872, which with its 'elevated position' and 'pleasing views' was thought 'capable of ... advantageous subdivision into choice sites for villa residences of the first class'. (fn. 163)

Much of the land failed to sell, but in 1887 14 a. were put up for sale on the 'St Mark's Estate', on rising ground west of Reading Road. St Mark's and St Andrew's Roads were to be made up by the developers, and were described as 'suitable ... for the erection of moderate sized detached houses, summer residences or bungalows'. (fn. 164) Following Owthwaite's death in 1887 more land was sold piecemeal: 224 building plots in three sales in 1893, 256 in 1894, 185 in 1895, and more in 1904. (fn. 165) At first development was slow, but it accelerated c. 1890–1910 as Hamilton Avenue (named by William Hamilton), St Andrew's Road, St Mark's Road and Vicarage Road were gradually built up. St Mark's Road had 21 houses in 1901, and 82 by 1911. (fn. 166) Various builders were involved, among them George and Richard Wilson, who from the 1890s built several houses and villas across the estate. (fn. 167) A pair at 31/33 St Marks Road carries Richard's initials in decorative stonework. Beyond the original streets, Berkshire, Western and Belle Vue Roads were laid out early in the new century, though it was many years before all the vacant plots were taken up.

The estate was primarily aimed at prosperous middle-class townspeople, although the new houses varied considerably in size. In 1898 houses in Vicarage Road included a 9-bedroom villa let at £50 (or £70 with stabling), two semi-detached 4-bedroom villas at £32, two others at £30, and another without a bathroom for £28. In St Andrew's Road an 8-bedroom villa with a tennis court was offered at £60. (fn. 168) Nine out of 14 houses in St Andrew's Road had resident servants by 1901, when household heads included a builder, a coal merchant's manager, a retired farmer, the clerk to the poor law guardians, and the station master. (fn. 169) Sale clauses preventing building of pubs further emphasized the estate's superior tone. (fn. 170) Architecturally the houses show great variety, and though most are unremarkable a few display unusual stone carvings and dressings. One on St Mark's Road (dated 1907) has pantomime characters, while two in St Andrew's Road show hunting scenes, in one of which a man and a boy mistakenly shoot an old woman's cat. The same unknown carver probably created the similar details at 22 Queen Street.

At much the same time William Hamilton built Henley's first large-scale working-class terraces on the lower ground around Reading Road, close to the scatter of cottages and market gardens at Newtown where 'excellent building and access land' had been offered for sale in 1872. (fn. 171) Development focused on the junction of Reading Road and Harpsden Lane (called Harpsden Road from 1899), and on the flat land between there and the railway, conveniently close to Hamilton's building yard. Painted plaques on the façades give the terraces names from Canada and the USA, commemorating Hamilton's recent visit. (fn. 172) Other builders included George Wilson, who built houses on Boston Road, (fn. 173) while Thomas Hamilton developed Park Road and its tributaries (on the eastern side of Reading Road) from c. 1893. (fn. 174) High demand is suggested by a case in 1905, when William Hamilton was reported for allowing a new house to be tenanted before inspection and before proper drainage was installed, in 'gross breach of the bye-laws'. (fn. 175)

Some of the houses have modestly polychromatic façades and ground-floor window bays. Most were built with 2 or 3 bedrooms, though not with bathrooms, despite the provision of mains water to much of the town. (fn. 176) By 1901 the houses around Park Road were virtually a railwaymen's colony, with large numbers of porters, firemen, platelayers and others, many of them young single lodgers. Here they were five minutes' walk from the station, and even closer to the railway line. (fn. 177) Unlike the St Mark's Estate the area acquired a pub (the Three Horseshoes on Reading Road), built by Brakspears' c. 1899 in their favoured Old English style. Attempts to secure full licensing were thwarted by local magistrates until 1930. (fn. 178)

Housing of the Poor

Poverty remained evident in some of the older parts of the town, where overcrowding, inadequate drainage, poor water supplies and poor construction were routinely reported. (fn. 179) Alterations and demolitions under local bylaws, combined with new sewerage and water supply, led to some improvement, (fn. 180) but in 1894 a single standpipe still supplied 16 cottages in Barlow's Yard, (fn. 181) and in 1901 insanitary accommodation remained in Crocker's and Smith's Yards, Horse and Groom Yard in New Street, Greys Brewery Yard, and Black Horse Yard in Friday Street. (fn. 182) Dwellings with four rooms or fewer included nearly half the housing on Greys Road, Friday Street and New Street, over half that on West Street, and all the cottages in Barlow's Yard, the average number of occupants ranging from 3.5 in Greys Hill and Barlow's Yard to 4.3 on Friday Street and West Street. Similarly crowded cottages remained at Newtown and at Northfield End. (fn. 183)

A recurrent problem was the lack of affordable alternative accommodation for families evicted from condemned cottages. (fn. 184) A blacksmith's wife displaced by the rebuilding of Duke Street complained that she and her husband had rented the same cottage for thirty years and would find it hard to get another, (fn. 185) and for impoverished slum dwellers with large families the problem was far greater. (fn. 186) Landlords threatened with closure of their cottages generally undertook the minimum improvements required, and where they were non-resident it was probably more difficult to force them to act. Cramped cottages in Adwell Square off West Street, for instance, were owned by the Birch Reynardsons of Adwell, members of the county élite. (fn. 187)

Provision remained with the private sector. The Henley Building Company was formed in 1864 to provide 'improved dwellings for artisans and the labouring classes' as well as larger houses, and early on acquired plots on Gravel Hill. (fn. 188) The Henley Cottage Improvement Association replaced several 'wretched tenements' on West Street with 17 cottages 'of a very superior class' in 1875–6, built probably by Charles Clements, and went on to acquire 14 cottages in Strange's Row. By 1877 those were 'so much changed as to be scarcely recognizable', (fn. 189) and when the Association was wound up in 1896 it owned 30 cottages in Gravel Hill and West Street. (fn. 190) A stuccoed cottage pair at the top of Gravel Hill, with brick gablets in a rather crude Queen Anne style, is inscribed 'HCIA 1896', and was perhaps built with proceeds of the sale. Even so the Association's cottages were probably beyond the means of most displaced tenants, as were the new brick terraces south of the town.

Landlords and Tenants

Though builders such as Clements, the Hamiltons and the Wilsons frequently offered new houses for sale, (fn. 191) they also retained large numbers, turning some of them into substantial landlords. In 1911 the largest by far was William Hamilton, with 199 houses mostly off Reading and Harpsden Roads (where he had been building since the 1890s), and in a few other recently developed parts of the town. Charles Clements similarly retained the Norman Avenue houses built since the 1880s. Other large-scale landlords included W. D. Mackenzie of Fawley Court (whose 51 properties included 14 in Bell Street), and the brewers W. H. Brakspear & Sons, although most of their 42 properties were pubs. G. W. Turner and the auctioneer and estate agent John Chambers each owned 41 houses, and a scatter of 24 belonged to John Cooper, whose family had for generations been lawyers and town clerks. (fn. 192)

Opportunities for 'the small capitalist' were emphasised repeatedly in advertisements, (fn. 193) though much investment was small-scale. (fn. 194) Some of the smallest investors were women, who in 1911 accounted for 21 per cent of those owning four houses or fewer. By contrast, all those with five or more were men. Steadily rising prices from the 1870s were a further incentive, (fn. 195) though after 1900 demand may have flattened out somewhat. Building plots on the St Mark's Estate were frequently offered with incentives to buy neighbouring plots, on which purchasers might erect a semi-detached pair worth at least £250 each (compared with £300 on a single plot). (fn. 196) Such provisions were generally intended to maintain the value of the area, and might also control who moved in as neighbours.

Rents corresponded broadly to the size and amenities of houses (above), and in the more prosperous suburbs and town-centre streets there were higher numbers of owner-occupiers. Even so, from a sample of 1,080 houses noted in 1911, only 140 were owner-occupied, while the remaining 940 belonged to 173 different owners. (fn. 197) A sale of three houses in York Road in 1912 envisaged giving not only 'small capitalists' but 'working men ... the opportunity of acquiring a freehold cottage,' though in the event these were bought by an established small investor. (fn. 198) It was still almost unknown for artisans of the type living in King's Road to own their own homes.

Building Since 1914

During the 20th century the built character of the town centre and waterfront changed relatively little, reflecting not only increasingly stringent planning legislation, but a growing recognition that Henley's economic wellbeing was inextricably linked with the preservation of its historic character and setting. (fn. 199) Consequently most town-centre building was small-scale and unobtrusive, some of it in neo-vernacular styles established before the First World War. Conversion of earlier buildings (notably Brakspears' Brewery) similarly tended to respect the town's existing character. The chief exceptions are two striking additions of the late 20th century, the Royal Regatta Headquarters of 1986 and the River & Rowing Museum of 1994–8.

Much more new building occurred in the suburbs. Several large detached houses on their own plots were built particularly after the First World War, many of them in the neo-vernacular style dubbed 'Stockbrokers' Tudor' by the cartoonist Osbert Lancaster (who lived in Henley from 1953). (fn. 200) Most were on the town's undeveloped south-west fringes, particularly along Rotherfield Road, where a house of 1912, in brick and tile with white roughcast elevations and leaded casements, has been attributed (apparently without foundation) to Edward Lutyens. (fn. 201) Most suburban growth, however, was to provide council and other working-class housing after the First World War, and ordinary 2- and 3-bedroom family homes in more recent decades.

Town Centre Buildings since 1914

Nineteenth-century rebuilding of the town centre and waterfront meant that changes between the World Wars were mostly small-scale and cosmetic. Some hotels and inns were remodelled to cater for summer visitors: in particular the Catherine Wheel was enlarged and refurbished in 1928, with garaging, additional bathrooms, central heating, a cocktail lounge, and a 'luxurious new ballroom'. (fn. 202) A few pub façades were remodelled in a half-timbered neo-Tudor style, among them the Argyll in the Market Place (rebuilt c. 1919) and the White Hart in Hart Street (1931), while in 1938 the Old White Horse at Northfield End was rebuilt in an attractive Arts-and-Crafts-inspired manner to designs by the Henley-based A. E. Hobbs. (fn. 203) Other examples of 'Old English' remodelling include 49 Duke Street (Tudor House), a medieval building whose front was rebuilt using old timbers in 1936. (fn. 204) A handsome neo-Georgian post office was built on the site of Southfield House in Reading Road in 1922, (fn. 205) replacing that of 1895 opposite. More radical would have been a cinema designed for Hart Street by Verity and Beverley of London in 1933–4, (fn. 206) requiring demolition of 18th-century buildings at No. 18. The scheme was abandoned following public protest, (fn. 207) and instead the existing cinema on Bell Street (renamed the Regal) was rebuilt in 1936–7, to designs by L. T. Hunt. That had less visual impact, but was still unusual for Henley, with its solidly brick façade and Art Deco interior. (fn. 208) Otherwise, the only significant inter-war building is the War Memorial Hospital of 1922–3, designed by Charles Smith & Son of Reading. (fn. 209)

After the Second World War town-centre building was increasingly constrained by conservation considerations, although not without controversy. Buildings on the south side of Market Place were demolished c. 1962 to give access to the new Greys Road car park, (fn. 210) while the Catherine Wheel narrowly escaped demolition in 1961, (fn. 211) and in 1960 a private developer proposed a 25-storey tower block at Paradise Road only 400 yds from the town hall. (fn. 212) The last two schemes prompted strong local campaigns. Equally vociferous was a campaign to save the Regal (demolished 1993), (fn. 213) which was replaced by a new Waitrose store in a bland, neo-vernacular brick-built style typical of 1990s commercial architecture. A similar style had already been used at the nearby Henley Library (1981) with its steep-pitched tiled roof, and at Badgemore School, designed by Oxfordshire County Architects in 1978. (fn. 214) More striking is Perpetual House on Station Road, built for a local investment company in 1993–4 to designs by Broadway Malyan, (fn. 215) and followed in 1998 by Henley College's premises at Deanfield Avenue, a £1.2 million construction of brick and glass. (fn. 216) A noteworthy interior remodelling was that of the re-opened Kenton Theatre, refurbished in 1951 with a surviving proscenium arch by the artist John Piper, and again in 1965 by David Tapp of Maurice Day & Associates. (fn. 217)

More typical of town-centre development was adaptation of existing buildings. In the 1980s Brakspears' former maltings on the north side of New Street were turned into offices and eventually flats (the kiln stacks being replaced with fibreglass replicas), while in 2004, after the brewery's closure, buildings on the southern side became a hotel. (fn. 218) Perpetual House, too, was converted into luxury flats in 2009, following the company's relocation in 2003. (fn. 219) A few architect-designed houses are for the most part discreetly hidden, among them The Walled Garden, which the architect Francis Pollen built for himself in 1959, (fn. 220) and Past Field, designed by Patrick Gwynne in 1960 and extended in 1966. (fn. 221) Gwynne also designed a doctors' surgery with an ingenious circular plan (1968), fitted unobtrusively into a corner of the Townlands Hospital site. (fn. 222)

The two chief additions to the riverside are buildings of national significance. The Royal Regatta Headquarters (Plate 10), adjoining the bridge on the Berkshire bank, was built in 1986 to the designs of Sir Terry Farrell, replacing the Carpenter's Arms. The design echoes that of a classical temple, but uses bright colours and glass to enliven the brick façade, and combines a central clubroom with boathouses below. (fn. 223) The River and Rowing Museum at Mill Meadows, designed by David Chipperfield and built in 1994–8, is more hidden. The award-winning design draws on traditional Oxfordshire barns, on the profile of tents erected for the regatta, and on the material and forms of wooden boats, and was described by the architect as 'closed boxes floating above a glass ground floor.' (fn. 224) Standing on a concrete podium, the building comprises two ranges parallel to the river, with light-filled galleries on the upper floor.

Council and Other Suburban Housing

Lack of affordable housing created the greatest pressure for new building in Henley for much of the 20th century. (fn. 225) From 1919 to c. 1960 much of this need was met by Henley corporation, which built well over 500 council houses west and south of the town to a number of standard designs (see map at Fig. 11). (fn. 226)

The earliest were built in two phases c. 1920–1 and 1925–6, on a 13½ -a. site around Western Avenue and Vicarage Road. These formed part of an ambitious scheme under the 1919 Housing Act for 145 dwellings grouped around a circus, and laid out on garden-city principles. The scheme's most vociferous supporters included the Henley builder and alderman Charles Clements, but the designs themselves (based on Ministry models) were by Henry Hare, architect of Henley's town hall. (fn. 227) Permission to continue building was refused by the Ministry in 1921, and when work resumed in 1925 government subsidies were less generous. The resulting houses (a variant of the Hare plans by the borough surveyor E. A. Pratt) were consequently smaller, cheaper, and (as a further cost-saving device) constructed not of brick but of 'clinker ... cement and roughcast in cement', a method developed by Calway Construction Ltd. The differences are clearly visible around the never-completed circus, where the earlier brick houses are larger and have more generous through passages. Contractors for the later council estate at Mount View (1933–5) were Messrs Hull of Hounslow. The estate's most attractive feature was again its layout, with houses facing onto an open grassy quadrangle, (fn. 228) though the range of accommodation (including one- and two-bedroom houses) was wider than in previous schemes, and probably better suited to local needs.

Many of the Mount View incomers were people displaced by slum clearance around the town centre, which was resumed with the help of newly introduced government subsidies. In 1933 the corporation identified 73 houses for demolition in Greys Hill, Greys Road, Northfield End, Friday Street, and particularly West Street, all areas long identified with poor housing. (fn. 229) Demolition proceeded slowly, but was largely complete by the end of 1937. (fn. 230)

Private building resumed in the early 1920s, (fn. 231) and in 1928 Richard Wilson received permission for 28 new houses in Wilson Avenue, (fn. 232) marking a return to larger-scale private enterprise. The Henley and District Housing Trust was founded in 1929, after a meeting at the Chantry House identified housing as a paramount social need. The corporation's 13½-a. site was not yet fully built up, and before 1933 the Trust erected 28 houses there using central government grants, beginning with ten cottages on Peppard Lane. Probably they were designed by the borough surveyor F. C. Wren, acting in a private capacity. (fn. 233) Other new buildings included single-storey brick almshouses on Western Avenue, built for Henley Municipal Charities c. 1938 in a loosely neo-vernacular style. (fn. 234)

Continued housing pressure after the Second World War was reflected in the Ministry's allocation to Henley of at least 34 'Universal type' prefabs, (fn. 235) and in squatter occupation of abandoned military hutting at Dry Leas, Phyllis Court and elsewhere. (fn. 236) The prefabs (south of Greys Road at The Close) remained in use until 1985, and were replaced by permanent housing. (fn. 237) The hutting was largely unfit for habitation, but in return for rents the corporation provided stoves and sanitation, electricity, and in some cases corrugated-iron roofs. The last huttings were cleared in 1950–6. (fn. 238) Stables, outbuildings, and a forge were also converted to domestic use, and some houses were divided into flats. (fn. 239)

Plans for renewed council-house building were presented at an exhibition in the town hall in June 1945, which attracted 8,000 visitors. (fn. 240) Houses on the post-war Gainsborough estate, designed by the borough surveyor T. L. G. Jefferies, were broadly similar to those of 1920–5, but were smaller and more varied and included a few 2-bedroom flats and bungalows. Unlike the prewar houses they were designed with electric rather than gas lighting, although an intention to provide large numbers of garages was dropped. Lovell & Son of Marlow and Walden of Henley were the principal contractors. On the slightly later Abrahams estate (begun c. 1952) the trend towards smaller houses continued, with half of the 159 dwellings built by Benson Brothers (to designs by E. G. V. Hines of Reading) designated two-bedroom houses and bungalows. Numbers on the corporation waiting list fell from 546 in 1946 to 171 by 1958, and with completion of the Waterman's Estate off Reading Road in 1961 large-scale council-house building effectively ended, to be superseded by private development. (fn. 241) Shortage of affordable housing for small families and young couples remained a serious problem in the late 20th and early 21st century, with private development concentrating mainly on low-density 3–4 bedroom houses aimed at better-off incomers. (fn. 242)

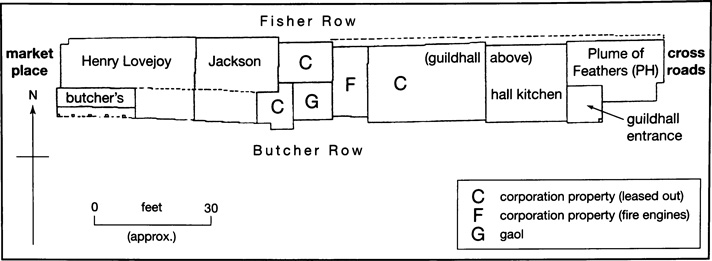

24. The Middle Row in the market place in the late 18th century, showing the guildhall, gaol, and fire engine house. The market house (demolished 1793–4) lay further west, on the site of the later town hall. From an undated 18th-century plan.

Town Hall and Guildhall

The Medieval Guildhall

A guildhall presumably existed by the late 13th century, when the merchant guild was first recorded. (fn. 243) In the early 15th century it stood on the south side of Hart Street a little way east of the crossroads, and included a cellar; (fn. 244) meetings of the warden and commonalty were held there regularly, and new forms or benches were provided in 1419. (fn. 245) Payments in 1479 'for making the guildhall' must have been for repairs only, since in 1487 it was agreed to create a new hall in the Middle Row in the market place. (fn. 246) Thereafter the guildhall remained on the same site until the late 18th century.

In the 1780s and presumably earlier the council chamber occupied the first floor above a hall and kitchen (Fig. 24). On the east the premises abutted the Plume of Feathers inn, (fn. 247) and on the west, corporation property let as houses or shops. A little further along the row, also at ground-level, were a gaol and a space used for the town fire engines. (fn. 248) All or part of the hall was apparently timber-framed, with a jettied upper floor on the north, (fn. 249) and by the 1690s there was a large octagonal lantern with a cupola, surmounted by a gilt orb (Plate 3). The chamber continued to be used for corporation meetings, and both it and the hall were frequently let for other purposes: Nonconformist ministers unsuccessfully petitioned for its use in the 1670s, (fn. 250) and in the 18th century it was regularly used for social events and public meetings, as well as by the Turnpike and Thames Commissioners and other bodies. (fn. 251) In 1753 Lords Macclesfield and Parker requested use of the guildhall and kitchen for a political entertainment. (fn. 252)

The Town Hall of 1796