An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 4, Outside the City Walls East of the Ouse. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1975.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 4, Outside the City Walls East of the Ouse( London, 1975), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol4/xxxvii-lvi [accessed 27 November 2024].

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 4, Outside the City Walls East of the Ouse( London, 1975), British History Online, accessed November 27, 2024, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol4/xxxvii-lvi.

"Sectional Preface". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 4, Outside the City Walls East of the Ouse. (London, 1975), , British History Online. Web. 27 November 2024. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol4/xxxvii-lvi.

In this section

Sectional Preface

The Mediaeval Suburbs

The present City of York includes considerable areas that have been absorbed since 1880 but in the mediaeval period the City boundaries already lay mostly well outside the City walls and enclosed extensive areas of pasture, gardens and orchards. Only between the river and Bootham was the City boundary defined by the City walls, leaving St. Mary's Abbey and the S.W. side of Bootham in the North Riding. Surviving stones marking the mediaeval boundaries are at the end of Burton Stone Lane, near Yearsley Bridge on the Huntington Road close to Rowntree's factory, and opposite the barracks in the Fulford Road (monuments 32–34).

St. Mary's Abbey stands on a site previously occupied by the palace of Earl Siward, who governed York and Northumbria from 1041 to 1055, and the church he built dedicated to St. Olaf, represented by the existing St. Olave's. On the southern side of the town and within the mediaeval boundary the church of St. Andrew, Fishergate, is recorded in Domesday Book, and All Saints, Fishergate, was in existence before the end of the 11th century when it was granted to Whitby Abbey. St. Helen's, Fishergate, was also in existence before 1100; it stood on a site crossed by the modern Winterscale Street. Early grants of land and buildings confirm the existence of dwellings by the middle of the 12th century in Bootham, Fishergate, Gillygate and Marygate. In Bootham building was confined to sites opposite the abbey walls or further to the N.W., and here in the late 12th century the Constable of Richmond had a lodging. There were also houses opposite the abbey walls in Marygate. The husgable roll of c. 1282 records 19 tofts in Bootham (YCA, c60). An agreement of 1354 between the City and the abbey confirmed that the abbey should maintain a ditch between the precinct wall and the street of Bootham provided that no buildings were erected there (CPR 1354–8, 84–6). At the end of the 13th century a complaint was made that the paving of Bootham was all broken up and the street was foul with the stench of pigsties and obstructed by loose pigs. At the City boundary close to the Burton Stone stood the Hospital and Chapel of St. Mary Magdalene, from which Burton Stone Lane derived its earlier name of Chapel Lane.

In Gillygate dwellings were probably confined to the S.E. side of the street but the church of St. Giles stood on the N.W. side. References to the street of St. Giles in the 12th century imply the existence of the church at that time, though the earliest direct reference to it is in a will of 1393. Beyond Gillygate was an open space called the Horsefair, extending beyond the junction of the Wigginton Road and Haxby Road. Adjoining the Horsefair were several religious houses: the Carmelites had their first house here before moving to Hungate in 1295; the Hospital of St. Mary, founded in 1314, stood at the S.W. corner of the Horsefair and two other hospitals dedicated to St. Anthony and St. Anne respectively probably lay along its N.W. side. St. Mary's Hospital later became St. Peter's School and was burnt down in 1644. St. Anthony's Hospital is mentioned in 1401, and was still 'lately founded' in 1420. Excavation by the York Archaeological Trust in 1972, on the site of Union Terrace, revealed a 12th-century building, enlarged c. 1200, which may have been a church, possibly used by the Carmelites, and other later buildings, interpreted as the remains of St. Mary's Hospital.

Lord Mayor's Walk was Goose Lane and undeveloped except perhaps in the immediate vicinity of St. Maurice's church. Between the Horsefair and Monkgate lay Paynelathes Crofts, later known as The Groves, an area of small enclosures belonging to St. Mary's Abbey.

Surviving remains of St. Maurice's church include an arch of mid 12th-century date and its existence argues for some suburban development in Monkgate by that time; the name Monkgate appears in the form Munccagate in 1080. In c. 1282 the husgable rolls record 50 tofts under the heading of Monkgate (YCA, c60) including two occupied by millers. Near Monk Bridge stood the hospital of St. Loy established in the 14th century in a house already standing; a little higher up the Foss were the mills of St. Mary's Abbey, perhaps opposite the N. end of Grove Terrace.

From Monkbridge the road to Heworth lies across heavy clayland which up to the middle of the 12th century was included in the Forest of Galtres. Heworth village itself lay outside the mediaeval boundaries of the City, although the ecclesiastical boundaries of the three City parishes of which Heworth formed part extended beyond the City boundary, to include the whole township.

At Layerthorpe there was a small settlement E. of the Foss probably in existence by the late 12th century, served by a small church dedicated to St. Mary. In the 15th century one of the great bells for the Minster was cast here.

Outside Walmgate Bar the City extended as far as Green Dykes Lane and included, in addition to the 12th-century church of St. Lawrence, churches dedicated to St. Edward, St. Michael and St. Nicholas. St. Edward's, on the N. side of Lawrence Street, is first mentioned in the 14th century; it was taken down in the reign of Edward VI. St. Michael's is supposed to have stood between St. Lawrence's and Walmgate Bar and was united with St. Lawrence's in 1365. St. Nicholas's was a larger building, of 12th-century date, from which the 12th-century doorways now at St. Margaret's and St. Denys's in Walmgate are both said to have come. The last remains of the church were removed in 1736; the surviving remains were sketched in 1718 (Evelyn Collection No. 539) and included a nave, large chancel, and substantial 13th-century W. tower. Associated with the church was the largest of York's four leper hospitals. No documents relating to private houses in Lawrence Street of a date earlier than the 14th century have been noticed.

Outside Fishergate Bar, on the site of the Cattle Market, stood the church of All Saints. This may have been a pre-Conquest foundation as already stated; its foundations were discovered in the early 19th century, and a rough plan published in the New Guide (p. 38) suggests an aisled church with an apsidal sanctuary. St. Andrew's church and priory lay to the W. of Fishergate; the pre-Conquest church was given to the Gilbertine Canons in 1202. A little further S. St. Helen's church stood to the E. of Fishergate; it was a small church built before 1100 when it was granted to Holy Trinity Priory. St. Helen's Hospital, Fishergate, must have stood nearby but its site is not known. Also outside Fishergate Bar was a chapel dedicated to St. Catherine. Houses and tofts in Fishergate figure in a number of 12th-century documents, but it is not clear how many of these lay outside the walls.

The Suburbs in the 17th century and later

All the suburbs described above were badly damaged or destroyed in the siege of 1644 but their appearance in the early 17th century was recorded by John Speed whose map of York was published in 1610. Ribbon development of continuous rows of houses is shown along the N.E. side of Bootham and on the S.W. side beyond the abbey walls, continuing a little way down Marygate with some further houses nearer the river. Houses in Gillygate are almost all on the S.E. side. A few houses stand between St. Maurice's church and Lord Mayor's Walk, representing the mediaeval Newbiggin, (fn. 1) and both sides of Monkgate are built up. Houses continue a short distance into St. Maurice's Road and a few more appear in Jewbury. Layerthorpe is represented by less than a dozen houses; a road running S. leads to a larger house, presumably the house which gave its name to Hall Fields and Hall Fields Road. St. Mary's church is not shown. Lawrence Street is built up past St. Lawrence's church and then a few isolated houses lead to St. Nicholas's church. In the whole Fishergate area only one house is shown, possibly representing a remnant of All Saints' church, and three windmills. Archer's plan of c. 1680 indicates that houses had been built in Bootham, backing onto the abbey wall, and shows more houses in Marygate than Speed's plan. In Monkgate however the houses do not extend so far towards Monk Bridge as formerly. No new development is shown on the S. side of the City.

Not until after 1760 was there any significant increase in the population above the 17th-century level of about 12,000. The census of 1801 gives a population of over 16,000, an increase of one third but there was sufficient space within the walls and the existing suburban areas to accommodate this growth. During the first half of the 19th century the population was more than doubled. Baines's map of 1822 shows new development at Bootham Row and some extension of building in Marygate. New houses appear on the N. side of Lord Mayor's Walk and on the S. side adjoining Monkgate. Continuing eastwards, buildings are shown in St. Maurice's Road, then called Barker Hill, but little appears at Layerthorpe. Only the beginning of Lawrence Street is shown and some long buildings to the S. of Fishergate must represent the glassworks founded there before the end of the 18th century.

By 1851 the population of the City had risen to 36,000 and after 1820 the building of new houses proceeded rapidly, as is shown in the Inventory. The City boundaries were not extended until 1884 when Clifton, Heworth and an area around the Fulford Road were included, followed by further extension to the N.E. in 1893 and 1934.

Ecclesiastical

St. Mary's Abbey

Sources. Three mediaeval documents compiled by the monks of the abbey survive to the present day, and all three have been published. The Chronicle of St. Mary's Abbey, in the Bodleian Library (Surtees Society, vol. cxlviii, 1934), includes an account of the founding of the abbey, and covers the years 1258 to 1325 except for a gap from 1284 to 1292 and part of 1293; it contains details of the great rebuilding of the church under Abbot Simon de Warwick at the end of the 13th century and of the building of the walls a little earlier, but little about the construction of the other monastic buildings. The Anonimalle Chronicle (V. H. Galbraith ed., Manchester 1927) covers the years 1333 to 1381 but has only four entries relating to the Abbey; these include an account of the fire in 1377. The Ordinale and Customary, in the library of St. John's College, Cambridge (Henry Bradshaw Society, vols. lxxiii, lxxv, lxxxiv) records the usage for the celebration of the Divine Office throughout the year. It was drawn up between 1390 and 1398 and contains many references to the church and other buildings of the abbey from which it is possible to deduce the uses made of the various parts of the abbey church and of the various buildings whose foundations have been uncovered by excavation.

Excavations carried out in the early 19th century are described and illustrated by the Rev. C. Wellbeloved in his Account of the ancient and present state of the Abbey of St. Mary, York, and of the discoveries made in the recent excavations (1829), which forms Vetusta Monumenta, vol. v.

The Abbey. The 11th-century archbishop of York, Thomas of Bayeux, objected to the foundation of the monastery so close to the Minster and laid claim to St. Olave's himself. The king however supported the monks and gave the archbishop another church in lieu. This was the first of a number of differences that arose between abbots and archbishops as the abbots rose to a position of great importance. The abbey became extremely wealthy and the abbot was one of the only two in the N. of England to have the privilege of pontificalia and a seat in Parliament. It was one of only four Benedictine Abbeys in the province of York, second only to Durham and much more important than Selby or Whitby.

The original foundation of the abbey was the result of a heroic and adventurous undertaking by three monks who came from Gloucestershire to Whitby to revive monasticism in the N. of England, but St. Mary's quickly became very traditional and settled in its ways with the result that in 1132 a party of monks from St. Mary's, dissatisfied with the discipline of the house, seceded to seek a stricter life; they established Fountains Abbey and were received into the Cistercian Order. St. Mary's was not exempt from visitation by the archbishop and the records of these visitations show that in spite of the great wealth of the abbey it was heavily in debt in the early 14th century. In the early 14th century Edward II, when involved in war with Scotland, moved the government from London to York and the Chancery was accommodated in the abbey.

Among the more important members of the community were John Gaytrick, who in the middle of the 14th century translated the Catechism into English verse, the so-called Layfolks Catechism issued by Archbishop Thoresbury (EETS, cxviii, ed. T. A. Simmons and H. E. Nelloth (1901)), and Thomas Spofford, abbot 1404–21, Bishop of Hereford 1422–48, who went to the Council of Constance and helped to organise the reform of German Benedictines.

Lists of monks total 33 in 1258, 48 in 1285 and 50 in 1539. There were eight dependent cells, including Wetherall and St. Bees in Cumberland.

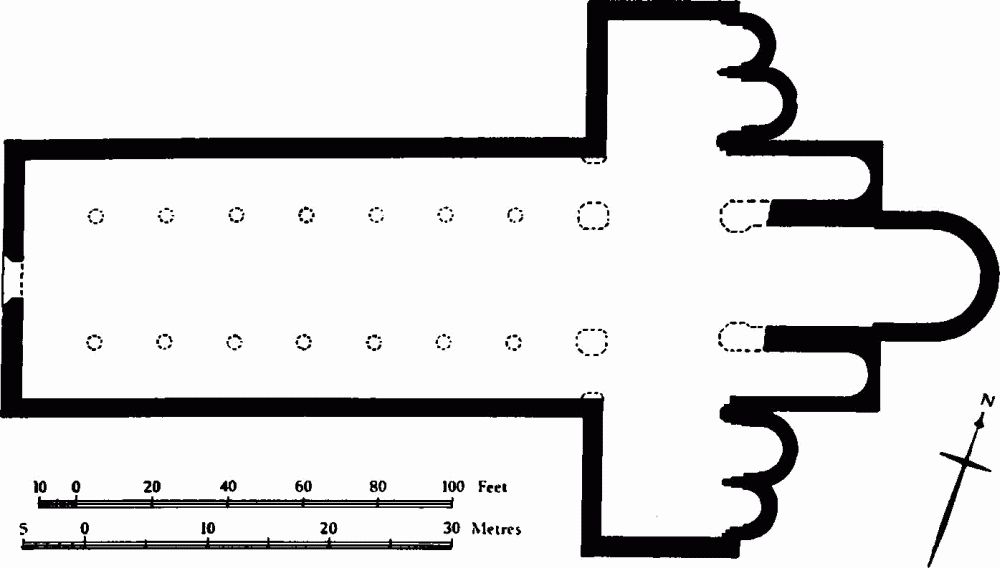

The First Abbey Church. Of the abbey church begun in 1089 very little now remains visible but the general lines of its plan are known from excavation; it was a cruciform building with a short aisled presbytery, transepts with eastern chapels set in echelon, and an aisled nave. At the E. end were seven parallel apses. The choir aisles ended in apses finished square externally; the transept chapels completed the seven apses, progressively receding from the centre.

Fig. 7. (4) St. Mary's Abbey. Plan of Norman church.

The plan with parallel apses of varying projection occurs at about half of the known Benedictine abbeys of the late 11th century, the others having had an eastern ambulatory with radiating chapels. The parallel apse plan was first used in England at the Confessor's church at Westminster and then at Canterbury. It was not however confined to Benedictine churches as it was also used at the secular cathedrals of Lincoln and Old Sarum. These churches were begun between 1070 and 1080; all except St. Mary's had one transeptal apse each side. The only other English churches with two apses to each transept, making seven apses in all, were St. Albans, begun 1077–88, Binham Priory, a little later but before 1100, and Glastonbury after 1100. The short eastern arm of St. Mary's is similar to that of Lanfranc's church at Canterbury, but was only about half the length of the eastern arm of St. Albans which was of four bays giving a length of nearly 100 ft. Like St. Albans, St. Mary's seems to have had the presbytery separated from the aisles by solid walls. There were also solid walls between presbytery and aisles at Shaftesbury (RCHM Dorset, iv (1972), 60).

The fragments of the early church that remain in situ are mostly of dark-coloured gritstone, and fragments of a moulded cornice of the same stone are reused in the base of the W. wall of the present nave. The most likely source of this gritstone is at Bramley Fall on the river Aire near Leeds, whence the stone could easily be brought to York by water, but there is no evidence to suggest that any quantity of this stone was brought to York after the Roman period until the 17th century. The use of gritstone in any large quantity in mediaeval buildings in York is confined to the Saxon and early Norman periods and the stone is generally of Roman origin reused; gritstone at the abbey is certainly of Roman origin.

Surviving carved architectural fragments of the later 12th century, probably from the church and the chapter house, show that work of the highest quality was done here at that date, work which is remarkably like some of the work carried out in the Minster for Archbishop Roger after 1170 and also paralleled in Durham, in Selby Abbey and at Lincoln both in the Cathedral and in the domestic buildings. Particular features are the expansion of the chevron pattern by the alternation of straight sections between the angles of the chevron to give a chain link effect and the enclosing of roll mouldings within a trellis network of small rolls. Capitals carved with a formalised acanthus leaf are of excellent workmanship and form part of a series of capitals in the museum illustrating a wide variety of 11th and 12th-century caps.

The Second Church. The rebuilding of the abbey church in 1270–94 was carried out in a period which covers the finishing of the Angel Choir at Lincoln and the beginning of the new nave at York Minster, and probably also the building of the Chapter House at Southwell, which was closely connected with York. Stylistically it provides an interesting link between the 'Early English' of the 13th century, and the 'Decorated' of the 14th.

The Chapter House. The present vestibule occupies the full width of the E. range, and the Chapter House formed a rectangular projection E. of the range. The building of polygonal chapter houses outside the range was necessitated by their shape; for a rectangular one to be wholly outside the range was exceptional but this cannot have been the original arrangement. In the early 12th century the chapter house must have occupied the space of the vestibule and the remains of its E. wall can be seen under the entrance to the later chapter house. This entrance is of the late 12th century and must give the date of the building of the new chapter house, still rectangular but lying outside the range. The only remains of the new building found in the excavations of 1827–8 were 'the lowest portion of the foundations, built of grit-stone' (Wellbeloved) and later plans showing a triple E. window must be regarded as imaginative. An understanding of the character of the chapter house depends on consideration of a series of stone sculptures which are discussed below; the plan suggests that it was covered by a barrel vault divided by transverse arches into five bays.

The Abbot's Lodging is described under The King's Manor, Monument (11).

Other Claustral Buildings. The remains of the claustral buildings are scanty. The plan of the principal buildings has been recovered by excavation and reading the records of excavation with the surviving mediaeval documents it is possible to arrive at a fairly clear picture of the layout. The surviving remains and the buildings that have disappeared are described together in the Inventory.

The Precinct Walls. The Gatehouse and the Precinct Walls are described in York II, The Defences, and the description given there is repeated in this Inventory. The wall with its towers forms the most extensive surviving monument of ecclesiastical defences in England.

Sculpture. I. In the Yorkshire Museum are thirteen life-size figures or parts of figures which form one of the most important series of English sculptures that have survived from the Middle Ages (plates i, 30–37). Seven of these figures were discovered in 1834 buried in the S. aisle of the abbey church under a layer of 13th-century window tracery set in mortar that was described as being the same as 16th-century mortar in the King's Manor. When found these seven figures, which include those in the best state of preservation, were painted in colour but little or no trace of colour now survives. Three figures were recovered from other parts of York where they had stood in exposed situations and had deteriorated badly. Two figures, purchased in 1954, came from Cawood. (fn. 2) The last figure is more fragmentary and its history is not known. The similarity of the last six to the first seven makes it likely that all the figures belonged to one sequence. Two of the figures represent Moses and St. John the Baptist; eight with bare feet and holding books are probably Apostles, but could also include Prophets. The others are too damaged to give any indication of their identity. All the figures show certain marked characteristics in treatment: the bodies are heavy, the heads are disproportionately large and the figures are apparently standing balanced on both feet although the drapery, falling straight over one leg and looped in folds over the other, is designed for figures with one leg straight and one flexed. The drapery is held up in one hand or looped over one forearm with a characteristic little swirl. The disposition of the drapery, originally invented to help in the representation of jointed limbs in varying positions, is here used on stiff immobile figures purely as a linear pattern without appreciation of its real purpose. The figures have vestigial columns emerging from their shoulders, but they are not true column-figures such as flank the doorways of many French cathedrals, where the figures are attached to full-height columns.

The figures are Romanesque in their proportions and in their heavy drapery falling to lively little pleats around the feet, but the Romanesque mannerisms are much less noticeable than in the comparable figures of the Portico de la Gloria at Santiago de Compostela of 1188. A new feeling of classicism in the York figures must place them later than the Compostela figures but they have not the simplicity and freedom from the Romanesque that was achieved at Laon c. 1190 and at Chartres, more strikingly, by c. 1210. The drapery looped over one leg and falling freely over the other has a longer history in other arts but first appears in French sculpture at Mantes c. 1175 and occurs commonly during the next thirty years, especially at Sens. One other detail affecting the date of the figures must be noticed: Moses is represented holding both the Tablet of the Law and the Brazen Serpent. This occurs in French sculpture only between 1170 and 1215. It seems clear therefore that the York figures cannot be much later than 1200. (See W. Sauerländer, 'Sens and York' in the Journal of the British Archaeological Association, xxii (1958), 54.)

It has been assumed that this series of figures flanked a great doorway to the abbey. The numerous French portals of the 12th century normally show the fore-runners of Christ, occasionally with St. Peter and St. Paul. Not until the end of the century was any French doorway flanked by the apostles. Indeed the earlier doorways did not provide space for them since they only had three or four figures each side. The number of figures surviving at York—and there is no evidence that the whole series has been recovered— make it unlikely that they flanked a doorway of c. 1200. Although some late 12th-century stonework is reused in the foundations of the later church, there is no evidence for any major building work on the abbey church at that time. Only if rebuilding necessitated by the fire of 1137 was not completed till c. 1200 could the erection of a portal of this date be explained, but Mr. G. F. Willmot's excavations at the W. end of the abbey church have failed to find any foundations of sufficient width to carry a portal or portals of the necessary size.

An alternative solution to the problem of the site from which these figures came is suggested by a group of earlier figures from the Chapter House at St. Etienne in Toulouse, also including eight apostles. These have long been displayed in an arrangement based on a figured portal but Linda Seidel of Harvard University has now shown that these figures, standing in pairs, must have formed the bay divisions in the walls of the chapter house, from which sprang transverse arches under a barrel vault (The Art Bulletin, L (1968), 33–41). The Toulouse figures are carved in pairs with columns between the heads supporting arched canopies, but the Camara Santa at Oviedo, rebuilt during the second half of the 12th century, also has a barrel vault with transverse arches springing from capitals and these are supported by true column-figures of the French type. Earlier, English figures supporting vaulting were erected in the Chapter House at Durham (c. 1135), which owed their inspiration to Southern France, but in the late 12th century it may not have been necessary to go so far as Southern France or Spain for examples of chapter houses decorated with figure sculpture, as numerous chapter houses in Northern France have been destroyed and the small chapter house at St. Georges de Boscherville shows that column-figures were not necessarily part of a portal. Another column-figure not forming part of a portal, from the cloister of Saint-Père, Chartres, is illustrated by L. Pressouyre in Bulletin de la Société Nationale des Antiquaires de France (Séance du 15 Mai 1968, Plate 10) with a drawing from the Gaignières Collection. The figure represents St. Benedict.

The surviving fragments of the entrance to St. Mary's Chapter House are elaborately moulded and decorated and may be dated stylistically to the late 12th century. It is difficult to suppose therefore that the Chapter House itself was not built in the last years of the 12th century, despite the large projection of the buttresses shown on Ridsdale Tate's plan of 1912; but the irregularity of those buttresses suggests that they may not have been original. A date at the extreme end of the century, c. 1200, is suggested by the character of the abbots in the second half of the century; Abbot Clement (1161–84) was described as 'rapax lupus omnia vastans' and his successor Robert was deposed by the archbishop at his visitation of 1197. Robert Longchamp who succeeded him, a man of wealth and power and brother of the Chancellor, is the more likely builder both of the Chapter House and the Gatehouse.

We are left then with a series of statues of c. 1200 some of which were buried close to the Chapter House at a time when the Chapter House, of much the same date, was pulled down to make way for new buildings for the Palace of the Council of the North. Most of the figures appear to be Apostles but two are certainly not. It appears therefore that the twelve Apostles can have marked the bay divisions of the Chapter House; Moses, St. John the Baptist, and other unidentified figures would then have marked the bay divisions of the Vestibule, replaced by moulded vaulting shafts in the late 14th century. The whole series would then have led from the precursors of Christ in the Vestibule, through the Apostles on the side walls of the Chapter House to the Christ in Majesty recorded as occupying an elevated position at the E. end of the Chapter House. This theory is supported by the shape of the backs of the figures, most of which are flat to stand against a straight wall but others are rounded or angled to stand in a corner where two walls meet. At Toulouse the eight Apostles formed the bay divisions and four other figures stood in the four corners of the Chapter House.

2. A group of large-scale fragments appear to come from a Coronation of the Virgin (Plate 40); the Christ figure is complete except for the right arm but the hand appears placing the crown on the Virgin's head. This is a late interpretation of a theme in which earlier artists had shown Christ's hand raised in blessing, and the crown held by angels. The middle part of the figure of Christ was found built into some late mediaeval repair work of the nave of the abbey, suggesting that the sculpture may have been broken as a result of the fire of 1377. No evidence has been found to suggest its original position, but it is possible that it formed a reredos to the altar of the Virgin in the nave, and was damaged in the storm of 1377.

Other Mediaeval Sculpture

The Yorkshire Museum, built on the site of part of the cloister of St. Mary's Abbey, contains remains of the claustral buildings in situ and a collection of mediaeval architectural and sculptural stone carving. Most of the architectural fragments derive from the Abbey itself but among the decorative and figure sculptures there are more pieces from various other sources in York than there are examples in situ in the City outside the Minster. The principal items from St. Mary's Abbey (4) are listed on pages 23, 24; pieces associated with surviving buildings will be listed under those buildings; other pieces are listed here.

i. Anglian Cross-head (Plate 25b), probably found in York (YMC), of magnesian limestone, 6½ in. by 6½ in. Listed as No. 12 by W.G. Collingwood in 'Anglian and Anglo-Danish Sculpture in York' (YAJ xx (1909), 178, 181, 185). On one side, within a medallion 33/8 in. internal diameter, is a pentameter verse in fine lettering, which reads: 'Salve pro meritis, presbyter alme, tuis'. On the other side is a quatrefoil within a double circle.

ii. Cresset (Plate 25a), 9¼ in. high by 5¼ in. diameter at top (Collingwood, ibid, 200, 203, No. 22), of red gritstone. The shaft is plain up to a necking of two bands enclosing a two-strand twist. The bowl or cap has stylised leaf-forms growing from the necking in a chevron pattern, with a cable-moulded rim. This is not a reused baluster shaft, as the cable-mould forms a lip to the upper surface surrounding a hollowed-out bowl. Pre-Conquest.

iii. Fragment, of red sandstone, 9½ in. by 6 in. by 6 in., pattern on one side with interlaced double cable within a border of rectangular pellets; no provenance. Pre-Conquest.

iv. Top part of Grave-slab (Plate 25e), 23¾ in. by 17 in., 'found under the Mechanics' Institute in Clifford Street in July 1883'; the arms of the cross covered with tightly plaited interlace, the horizontal arms ending in animal masks; at the junctions of the arms are incised circles; the panels flanking the top of the cross each contain an animal with double outline, the hind leg extending as a double strap interlaced with the body; the panels are enclosed by a raised border treated, at the sides, as pilasters, one retaining a volute capital; pre-Conquest (Collingwood, ibid, 190, 193, No. 16).

v. Grave-slab (Plate 25c), of sandstone, 3 ft. by 1 ft., found in Parliament Street, with plain incised Latin cross with incised circles at the junctions of the arms; pre-Conquest (Collingwood, ibid, 162–3, No. 5a).

vi. Grave-slab (Plate 25f), of sandstone, broken, 2 ft. 9½ in. by 1 ft. 2 in., found in Parliament Street, with cross, cross-head with tapered arms in relief, cross-shaft incised only; the back similarly carved but unfinished; pre-Conquest (Collingwood, ibid, 162–3, No. 5b).

vii. Two Capitals (Plate 27e), carved with faces indicated by oval eyes and marked eyelids, found in a garden outside Bootham Bar; late 11th-century.

viii. Six Corbels (Plate 26), carved with grotesque or beasts' heads; 12th-century.

ix. Corbel (Plate 26b), of gritstone, carved with a complete animal, perhaps a wolf; 12th-century.

x. Head, damaged; late 12th-century.

xi. Two Label-stops (Plate 27f) carved with heads of a wolf and a bear respectively; late 12th-century.

xii. Fragments of an archway probably from All Saints', Pavement (Plate 28a–e): Nook-shaft richly carved with foliage; two Capitals, one with two-bodied lion with leaf-shaped tails, one with foliage and small leaf-tailed beasts; three Voussoirs with isolated roundels containing human figures and a bull; one Voussoir, from another order of the arch, with foliage on an undulating stem, and a roll-moulding; 12th-century. The nook-shaft is carved in a different style from the rest.

xiii. Tympanum (Plate 29a), carved with devils seizing the soul of a dead man as it emerges from his mouth, possibly the death of Dives, from the Hole in the Wall public house which stood on the N. side of Minster on the site of St. Sepulchre's chapel; late 12th-century.

xiv. Ten Voussoirs (Plate 28f) from an arch of at least three orders, one with beasts etc. in beaded roundels and other ornament, and a pattern of diagonal crosses on the soffit, a second order carved with formal foliage ornaments and a moulded soffit, a third order carved with beasts and a moulded soffit; all with roll mouldings; 12th-century.

xv. Capital to a nook-shaft (Plate 27b), with human head threatened by two dragons; 12th-century.

xvi. Virgin and Child (Plate 41b), headless torsos only, 15½ in. high; the Virgin wears a cloak held by a brooch secured with a cord, her hair falls in long plaits over her shoulders; late 12th-century.

xvii. Head of Cross carved with Christ in Majesty and, on reverse, Agnus Dei; 12th-century.

xviii. Corbel carved with human head; 13th-century.

xix. Virgin and Child (Plate 41a), both figures headless, 3 ft. high; the Virgin is seated and wears a simple dress with high belt, and cloak looped over left arm and draped across lap; the Child stands on her lap against her right arm; 14th-century.

xx. Figure of bishop (Plate 43a), head and legs missing, 20½ in. high, right arm broken, staff in left hand; 14th-century.

xxi. Head of bishop (Plate 42b), with low mitre; probably a label stop, 14th-century.

xxii. Small Head (Plate 42e), bearded, wearing a hood; found in Davygate; 15th-century.

xxiii. Figure, 14½ in. high, with name Maria Salome on base; c. 1500.

xxiv. Figure (Plate 42c), 27½ in. high, St. Margaret with dragon, perhaps from a tomb; the saint stands on dragon holding cross in right hand; early 16th-century.

xxv. Angle Bracket, 29 in. high, with half figure of angel, wings outspread, probably from the Carmelite Friary, Hungate; late mediaeval.

xxvi. Head of a man (Plate 43b), face badly damaged but carving of hair in good condition; late mediaeval.

xxvii. Figure of lady (Plate 43d), headless, 14½ in. high, with tight bodice above a full skirt; late mediaeval.

Monumental Effigies

xxviii. Mutilated recumbent effigy of a Knight in chainmail and surcoat, 4½ ft. long, formerly planted erect at the end of Clifton Village and known as Mother Shipton's stone; 14th-century.

xxix. Recumbent effigy of Knight with crossed legs, in chainmail and surcoat, 6½ ft. long, formerly used as a boundary stone for the parish of St. Margaret, Walmgate, on the E. side of Neutgate, now St. George's Street; the head rests on a pillow supported by angels; lion beneath feet; lizard-like creature by left leg biting shield; shield charged with cross flory and overall a bendlet, possibly for de Vescy (of the family of William de Vescy who gave the Carmelite Friary a site in Hungate in 1295); 14th-century.

Alabasters

xxx. Virgin and Child with bird (Plate 41c), headless fragment with traces of colour; found in the Ouse near St. Mary's Abbey; 14th-century.

xxxi. Six Panels from a sequence associated with St. William of York: (a) Birth of St. William in the presence of King Stephen; (b) Collapse of Ouse Bridge; (c) Edward I falling down a mountain, and the recovery of a fisherboy drowned in the Ouse; (d) Translation of St. William; (e) Virgin in Glory; (f) The Trinity with two donors; late 15th or early 16th-century. (G. F. Willmot, 'A Discovery at York' in The Museums Journal lvii no. 2 (May 1957)).

The bulk of pre-Conquest sculpture in York lies outside the scope of this volume; here, the most important item is the finely lettered crosshead fragment (i) (Plate 25b) which Collingwood ascribed to the early 8th century (op. cit. 178, 181, 185). The fragments of a grave-slab from St. Olave's church (Plate 25d) are of sufficiently high quality to suggest that they may have been from the tomb of a man of the importance of Earl Siward himself; they are similar to other slabs in York, one from St. Denys's church and others from the late Anglo-Danish cemetery under the S. transept of the Minster. The grave-slab (v) (Plate 25c) from Parliament Street is closely parallel to one from the same cemetery under the Minster.

Little is known of early Norman carving in York; capitals such as (vii) probably represent a local vernacular style much less sophisticated than contemporary quasi-Corinthian capitals in the Minster, which derive from Normandy. The collection includes a number of voussoirs from arches of 12th-century doorways which can be compared with the standing archways in various parts of the town, none of which is however in its original position. Those in the Museum are in better condition than most of those outside and the best picture of a complete doorway of this type is now to be derived from a drawing of the doorway of St. Margaret's church, Walmgate, made in 1791 and reproduced on Plate 44. This was an elaborate scheme with an archway in six orders. The outer order contains the Signs of the Zodiac and the Labours of the Months; to a similar series belong the voussoirs probably from All Saints' Pavement (xii). Two capitals from the same site are similar to capitals from St. Lawrence's and St. Maurice's. The foliage in a figure-of-eight pattern carved on other voussoirs resembles that on capitals in the crypt of the Minster.

Other Norman carvings include a number of corbels (viii–x), mostly of beasts' heads with open mouths; other heads probably formed the stops at the ends of hood-moulds.

Dragons appear in a number of carvings, either alone as at St. Lawrence's, where they terminate an order of the arch carved with foliage, and St. Margaret's, or in battle with men as on a capital probably from St. Mary's Abbey (Plate 29b, c).

The most ambitious figure composition is the damaged tympanum (xiii) from the cellar of a former public house which stood close to the N.W. tower of the Minster, found in 1817; the demons portrayed have their counterpart in a large scene with the mouth of Hell now in the Minster, found in the Deanery garden (John Bilson, 'On a Sculptured Representation of Hell Cauldron', in YAJ, xix (1907, 435–45). The scene probably portrays the death of Dives and may be compared with the death of Lazarus portrayed at Lincoln where Dives and his companions are already in Hell (G. Zarnecki, Romanesque Sculpture at Lincoln Cathedral, n.d., pl. 11).

The great figures from St. Mary's Abbey, of c. 1200, were discussed above (p. xlii). Of the same date, are a Virgin and Child from Cawood (Plate 41d), now in a fragmentary state, and a series of voussoirs from the abbey, carved with scenes from the Gospel story (Plates 38, 39), of a type unusual in England but in the tradition of the greater French cathedral doorways.

With the coming of the 13th century a gradual softening of features is noticeable. Hair is stylised but the hard edges of eyes, eyelids and eyebrows become more naturalistic. This is first seen in the St. John the Evangelist (Plates 1, 30) and is continued in a fragment of a head from the abbey (Plate 43c) and a corbel head probably from the abbey (Plate 42a).

Sculpture in the monumental tradition of the figures from the abbey is found in the fragmentary group of the Coronation of the Virgin (Plate 40) where the eyes of Christ have the hard lids of earlier carving but the robes have the jagged crinkly outline of fully-fledged Gothic.

The roof bosses from the abbey include some fine naturalistic carving of c. 1300. Of later sculpture there is little anywhere in York outside the Minster and the shrines associated with St. William from the Minster, which are at present in the Yorkshire Museum, but the simple flowing lines of 14th-century work are shown in the headless statue of a bishop (Plate 43a) and an alabaster Virgin and Child (Plate 41c).

The fragments of panelling in St. Olave's church, carved with angels playing musical instruments, must derive from a stone screen and most probably come from the abbey (Plate 52).

Churches

St. Olave's is the only complete church recorded; it is largely a building of the 18th century, retaining little mediaeval work undisturbed except for the tower, and it shows no trace of the church founded by Earl Siward in the 11th century. The chief interest lies in the way the church was integrated with the adjoining monastic structures, the parochial west tower being structurally one with the monastic chapel of St. Mary and the north wall of the church being built up on the base of the precinct wall of the abbey.

Of the other suburban churches only the tower of St. Lawrence's still stands; 12th-century doorways supposed to come from St. Nicholas's have been re-erected at St. Margaret's and St. Denys's, Walmgate, and from St. Maurice's at the church of St. James, Acomb Moor.

Monuments

Some of the monuments at St. Olave's are to men of importance. William Thornton, joiner and architect, who died in 1721, showed considerable engineering ability in the restoration of the north front of Beverley Minster under Hawksmoor; he also worked under Colen Campbell on a house in Beverley, at Castle Howard under Vanbrugh, at Wentworth Castle for the Earl of Strafford, and at Beningbrough, N. of York, where he may have been the architect. The Wolstenholmes were of local importance in the field of carving and decoration (see p. lvi). William Etty, R.A., was very distinguished in his day as a painter of the nude and of history pictures; it appears that he was not connected with the Etty family of carpenters and builders who practised in York in the 18th century.

Secular

The King's Manor

The King's Manor, developed from the 13th-century lodging of the abbots of St. Mary's Abbey, is a building of great historical and architectural importance. A separate house for the abbot in the 13th century is to be expected at an abbey of the importance of St. Mary's. Abbot Samson at Bury St. Edmunds built himself a house c. 1200 and the abbot's house at Westminster and the prior's house at Ely, both rebuilt in the 14th century, include the remains of structures going back to the late 12th century. The surviving remains giving the most complete plan of an abbot's house of the 13th century are to be found at Battle where the house erected for Ralph of Coventry, 1235–61, lie on the W. side of the cloister (Sir Harold Brakspear, 'The Abbot's House at Battle', in Archaeologia, lxxxiii (1933), 139–66). The house at St. Mary's, as rebuilt in the late 15th century, stands partly on 13th-century foundations but the complete layout of the 13th-century house has not been preserved.

The rebuilding in the last years of the 15th century was carried out in brick, a material that had been used in York for the Merchant Adventurers' Hall in the middle of the previous century and in Hull c. 1320 for the building of Holy Trinity church, and then for the town walls at Hull and the gates at Beverley. Brick-work was not new to the area in the late 15th century but the use of terracotta for the windows is exceptional and is as early a use of this material for structural work as any that has been recorded in England; other examples are to be found in Norfolk and Essex. The rectory at Great Snoring may be the earliest of the southern examples, probably c. 1500 but not exactly dated; the work at East Barsham followed c. 1515 and at Layer Marney c. 1520. The great hall on the first floor with a flat ceiling hiding the roof timbers is remarkable, though not the earliest in York. The construction of the roof itself, with king-posts, is not in the local tradition of houses in the City but is akin to work being done in the upland areas of the Pennines and the Lake District.

As the late 15th-century work has affinities with the brick and terracotta of East Anglia, so too the remodelling of the house in the 16th century as a palace for the Council of the North also shows affinities with contemporary work in Essex and the south-east. A particular connection with Essex may be attributed to Thomas Radcliffe, 3rd Earl of Sussex, President of the Council from 1568 to 1572, who was connected with the Fitz Walters of Essex and built himself a house at Boreham in Essex in 1573. The new wing begun in 1560 by the Earl of Rutland was mainly built of reused stone with stone-mullioned windows but the new windows inserted in the old building were made with brick jambs and mullions plastered to simulate stonework. This device was not uncommon in Essex and S.E. England but in the York area the only other example recorded is at Heslington Hall, just outside York, which was built by Thomas Eynnis, Secretary to the Council of the North in 1568. A plaster frieze at Heslington has been identified as coming from the same mould as one at Albyns in Essex (Jourdain, Fig. 10).

The use of plaster to simulate stone was a more reasonable economy in Essex where stone is not available locally. In York it appears to be less justifiable but the imitation of more expensive materials in cheaper substitutes is a regular feature of the royal buildings of Elizabeth I (E. Mercer, 'The Decoration of Royal Palaces 1553–1625' in Arch. J., cx (1954), 150).

Justice in a Triumphal Car beneath the Arms of the City. 1753.

Self Portrait, c. 1770. (13) City Art Gallery. Stained glass panels by William Peckitt.

The new range completed by Radcliffe was built without attics whereas Sheffield's range built against it some forty years later, c. 1610, had the roof space used for rooms from the start. Sheffield's range is contemporary with college buildings at Oxford and Cambridge which, for the first time, were being built with attic storeys, although attics had been contrived in the roof space of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, for instance, as early as Henry VIII's reign, and had been added to existing buildings at Oxford after c. 1570 (Exeter College, St. John's College and New College. VCH, County of Oxford, III (1954), 116–17, 261).

The decoration of the Huntingdon Room, carried out for Lord Huntingdon c. 1580, is among the most interesting features of the Manor, and the windows of this period are notable for the early use of the ovolo (quarter-round) moulding on jambs and mullions instead of a hollow chamfer. The earliest known uses of the ovolo form occur during the previous decade at Kirby Hall, Northants., and Leicester's buildings at Kenilworth Castle.

Among the early 17th-century features a number of surviving stone doorways are remarkable; the great semi-circular bay windows erected by Lord Sheffield are known only from drawings and a few fragments of stonework reused in various buildings. Later in the century the contemporary use of brickwork is illustrated on the pilastered upper storeys of the central N. block and in the S.E. gable added to the mediaeval building with oval bull's-eye windows and tumbled brickwork for the coping.

The development of the abbey site is completed by the former headmaster's house of 1899 and the City Art Gallery, monument (13), which contains a collection of topographical prints and drawings, important for the study of the buildings of York. It includes some three thousand items within the period c. 1680– c. 1900. The core of this collection was presented by Dr. W. A. Evelyn of York in 1934. Local artists who are represented include Francis Place, William Lodge, John Haynes, Joseph Halfpenny, Henry Cave and George Nicholson; visiting artists include Hollar, the Buck brothers, Rooker, Marlow, Girtin, Cox and John Varley. The gallery also owns works by several artists who worked in York c. 1727–78, such as Drake, Hauck, Doughty and William Etty. A self-portrait in the Art Gallery must be considered among the best work of William Peckitt, the York glass-painter, whose work is also to be seen in the church of St. Martin-cum-Gregory (York III, 24), in the Minster, at New College, Oxford, and at Stamford (Lincs.).

Other Public and Institutional Buildings

Ingram's Hospital (23) and Wandesford House (26) are two pleasing ranges of almshouses in simple brickwork of the 17th and 18th centuries respectively. The early mental hospitals of York are of considerable interest to the social historian but Bootham Park Hospital (21) is also of architectural importance, having been designed by the leading York architect, John Carr. In contrast to Carr's Palladianism, the Greek Revival of the early 19th century is represented by the Yorkshire Museum (12) with its Doric portico, designed by William Wilkins, R.A. This was followed ten years later by St. Peter's School (29) where John Harper dressed a building of classical symmetry in Tudor gothic with a multiplicity of turrets and pinnacles.

Domestic Buildings

The houses recorded are all of fairly late date: one (monument 76) retains a fragment of timber framing perhaps of the 16th century but there is no complete domestic structure earlier than the second half of the 17th century. In the Bootham and Monkgate areas this no doubt reflects the damage done in the siege of York in 1644. A few houses survive from the late 17th century, brick-built and mostly of two storeys; the arrangement of these houses on plan falls into two types: those with a main range parallel to the street giving two front rooms with subsidiary wings at the back, and those that are built end-on to the street with one front room and one back room and a massive chimney-stack between the two rooms. In No. 21 Bootham (37) there is an interesting survival of late 17th-century painted wall decoration.

There are a few 18th-century houses which are only one room deep; the great majority of house plans of this period are based on a through passage with a staircase, and front and back rooms either on one side only or on both sides, corresponding to the Class U plan identified in RCHM West Cambridgeshire (xlvii) and RCHM South-East Dorset (lxiii). The same plan types continued in use through the first half of the 19th century and the later houses in the Inventory, not described in detail, generally conform to them (see also York III, xciv–xcvi). The larger houses in Bootham show a considerable variety of layout developed from the basic four-square Class U plan, while a small 19th-century house in Clarence Street (monument 60) shows how an ingenious designer can introduce interest into the same basic plan in a very confined space. As in York III a number of houses have a staircase placed transversely between front and back rooms either as the only staircase in the house or as a secondary staircase for servants.

Kitchens seem generally to have been on the ground floor. Basements in Bootham were suitable only for storage; the basement kitchen at No. 56 (57) was replaced by a kitchen above ground very soon after the erection of the house. The same house has an important reception room on the first floor (in 1972 the Council Chamber of Flaxton Rural District Council) showing that the first-floor saloon had not been abandoned even after 1840. Some of the larger houses in Bootham were built with small projecting wings for closets but how these were fitted remains conjectural. The development of the indoor water closet is illustrated by Fishergate House (105) of 1837, where the plan is designed to accommodate original water closets, and the small houses in Penley's Grove Street where one has an original internal water closet for which the plan is not adapted, but others still rely on privies at the far end of a low back wing, beyond scullery, coalhouse, etc. The original names of rooms in these houses have been reproduced in Fig. 81 from the architects' plans.

The external appearance of the 18th-century houses depends on good red brick with stone bands, and timber cornices carrying concealed gutters at the eaves. Parapets hardly exist in this area. Stone is used in the form of plain string-courses or bands dividing the storeys and sometimes also joining the window sills. The combination of wide storey bands and narrower sill bands was a Palladian feature used frequently by John Carr and continued by other architects. In few houses do the corners receive emphasis: at Nos. 39 and 45 Bootham (41) appear the unusual rusticated quoins in which alternate stones project with long faces on both sides of the corner (see York III, fig. 14, p. lxxx); a more usual type of quoin appears on No. 49 Bootham (43). Windows are simply treated, without architraves; the window arches are usually of rubbed brick, only occasionally interrupted by stone keys. No. 47 (42) and Nos. 53, 55 (45) Bootham have stone cornices above the brick arches without the support of brackets, frieze or architrave, an idiosyncratic treatment used also at No. 56 Skeldergate (York III, (117) 103, pl. 189) which can probably be attributed to John Carr.

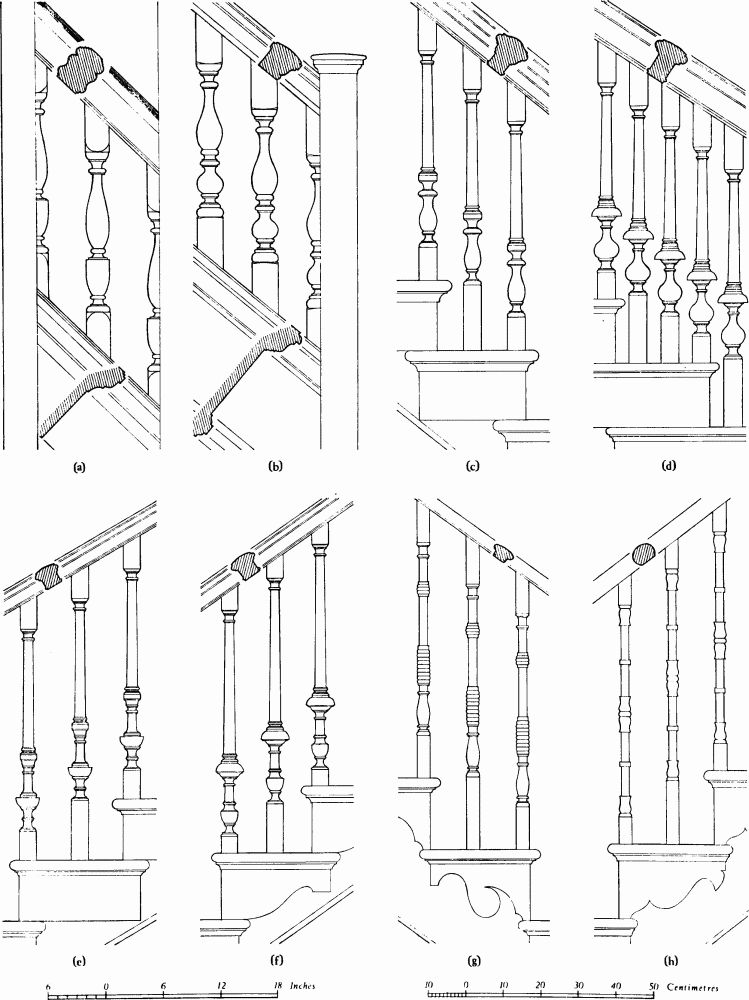

Fig. 8 (opp.). Staircases.

a. (40) No. 35 Bootham, late 17th-century.

b. (249) St. Olave's House, No. 48 Marygate, late 17th-century.

c. (41) No. 39 Bootham, 1748.

d. (39) No. 33 Bootham, 1754.

e. (38) No. 25 Bootham, 1766.

f. (128) No. 28 Gillygate, 1769.

g. (127) Nos. 16–20 Gillygate, early 19th-century.

h. (280) No. 42 Monkgate, early 19th-century.

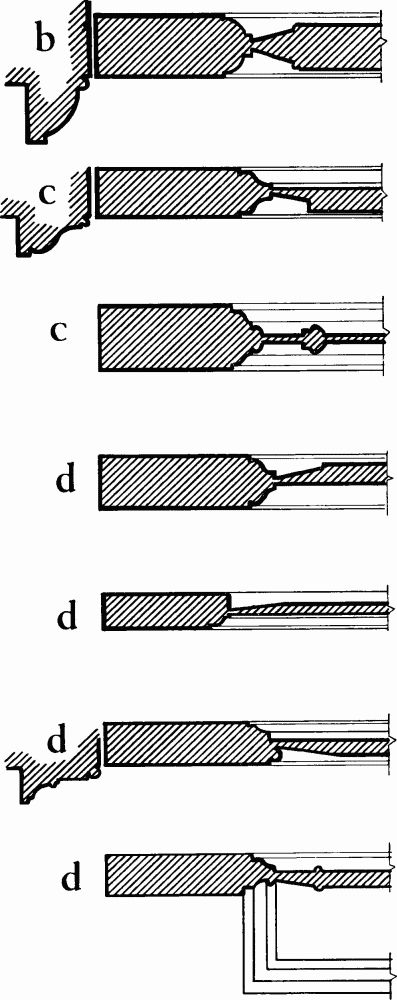

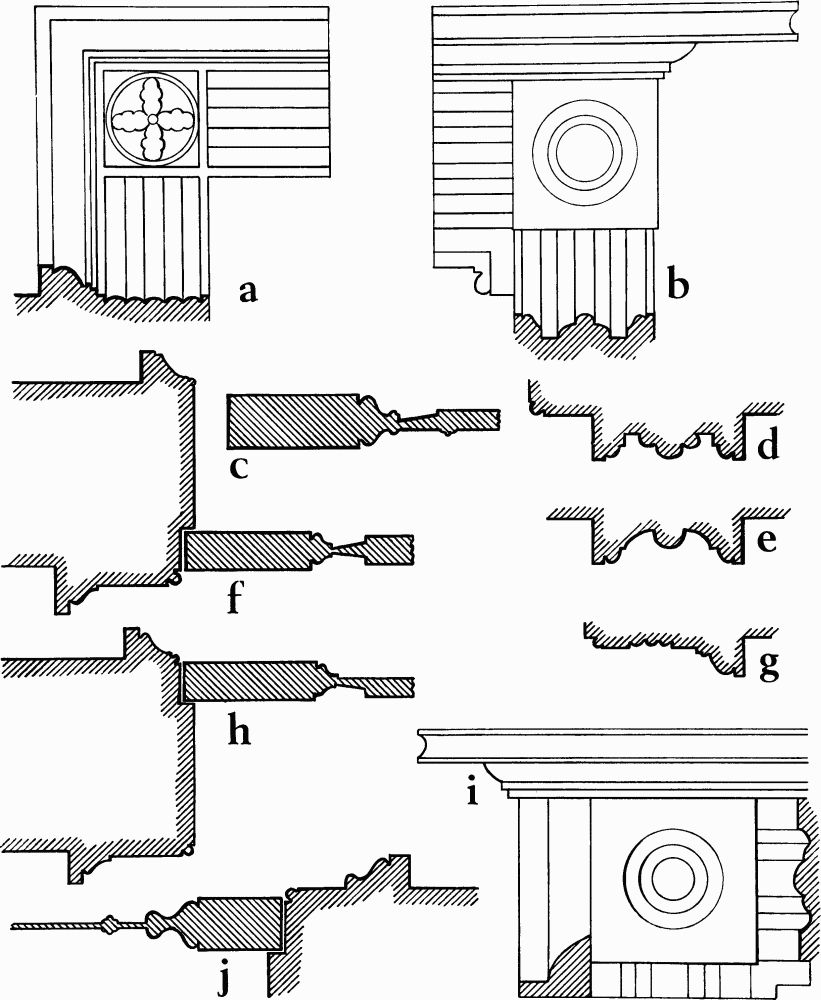

Fig. 9. Timber Mouldings, 18th-century.

a. (39) No. 33 Bootham, door architrave, 1754.

b. (128) Nos. 26, 28 Gillygate, door architrave and door, 1769.

c. (241) No. 29 Marygate, door architraves and door, c. 1780.

d. (117) Nos. 3, 5 Gillygate, door architraves and doors, 1797.

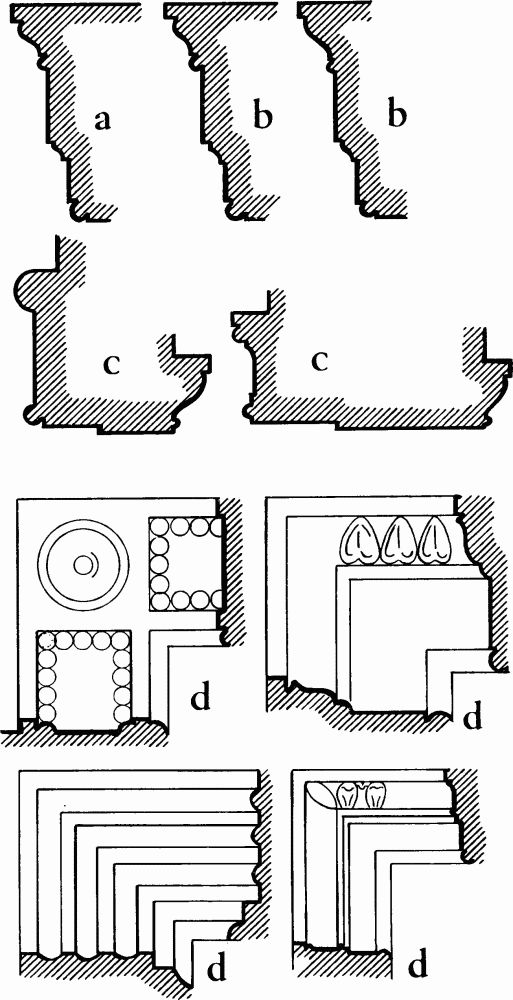

Fig. 10 (opp.). Timber Mouldings, early 19th-century.

a. (40) No. 35 Bootham, window architrave.

b. (263) No. 49 Monkgate, door architrave.

c. (263) No. 49 Monkgate, door.

d. and e. (109) Fulford Grange, door and window architraves.

f. (258) No. 15 Monkgate, door architrave and door.

g. (254) Almery Garth, Marygate Lane, door architrave.

h. (258) No. 15 Monkgate, door architrave and door.

i. (263) No. 49 Monkgate, fireplace surround.

j. (280) No. 42 Monkgate, door architrave and door.

Fig. 10.

House design of the later 18th century owes much to the influence of John Carr and his partner Peter Atkinson. Among the builders of the time whose work is represented in this area, Robert Clough stands out. His houses in Gillygate (Nos. 26 and 28, monument (128)) are rich in plasterwork, which was presumably executed by his son Robert who was a plasterer. Only one house in this area shows the use of decorative plasterwork around the staircase window; this is at No. 33 Bootham (39) also built by Robert Clough, but the plasterwork shows none of the profusion of decorative detail seen in the best houses in Micklegate described in York III. None of the Bootham houses have the richness of interior appointments found in some Micklegate houses; the most important features are generally the staircases which follow the same development discussed in York III, lxxxvii–xcii.

In 19th-century exteriors moulded architraves to windows make an occasional appearance (Nos. 51 Bootham (44) c. 1804 and 56 Bootham (57) c. 1840 and No. 44 Heworth Green (167)) but plain brickwork without dressings is more usual. The early years of the century produced little new building, but in the second quarter of the century there was extensive development of new streets of terrace houses, and the same period also saw the erection of a number of villa residences for the successful tradesmen and the professional class. The sale of the de Grey estate in Clifton in 1836 provided land for some of the larger residences but the biggest house to be erected at this time was Fishergate House (105), on the southern side of the City, built for a Mr. Laycock about whom no information has come to light apart from the bare record of his death. Fishergate House, designed by Messrs. J. B. & W. Atkinson, the grandsons of John Carr's partner Peter Atkinson, is a severe building of grey gault brick with brick pilasters at the angles. It is one of a number akin to the rather earlier grey gault brick houses of Cambridge, which have been noted for their originality, uncompromising severity, and bold articulation (RCHM, City of Cambridge, I, xcv). The pilastered treatment is also to be seen at No. 54 Bootham (56), No. 37 Monkgate (261) and Heworth Croft (164), and is repeated at Bootham Grange (80) where a certain grossness of scale makes it less acceptable. Internally Fishergate House owes much to the influence of Sir John Soane: the plan appears to derive from Tyringham and the elaborate three-dimensional design of the central arcaded light-well, with its interplay of arches without imposts, leaves little doubt as to the Atkinsons' source of inspiration. The arrangement of the staircase at Fishergate House is echoed on a smaller scale at No. 54 Bootham (56) where there is a similar lobby leading off the half landing to give access to a closet.

These severe houses carried out in gault brick show no detail which can be described as Greek, but the style may be derived from the ideas of simple architectural massing practised by such architects as Soane, Henry Holland and William Wilkins. Belle Vue House (145) seems to owe its gothic decoration to the trade of its owner as sculptor and monumental mason rather than to any general trend in architectural fashion. The only romantic house of any size, Glen Heworth (149), has been pulled down. Smaller buildings designed to be picturesque are illustrated in Plate 101.

In their interior fittings these 19th-century villas display an imaginative use of rather coarse modelling in ceiling cornices (Plate 122), while a number of doorcases and fireplaces are decorated with modelling from the moulds of Thomas Wolstenholme. Included in Wolstenholme's repertoire were a number of rectangular panels of mythological figure subjects and other decorative features which appear repeated in different houses (Plates 110–15). Throughout all the early 19th-century houses the most common form of architrave moulding is reeding butted against rectangular blocks at the angles, a motif used by Soane as early as 1790 (Stroud, 19) and incorporated into many of Wolstenholme's designs. Thomas Wolstenholme had achieved sufficient success by 1790 to purchase property at the junction of Gillygate and Bootham, on which he built houses. He died in 1812 and the business was carried on by his brother Francis who died in 1833 and his nephew John who died in 1865. They continued to use Thomas's moulds, with the same figure panels and the same idiosyncratic use of segmental shapes, after Thomas's death.

A striking feature of the larger 19th-century interiors is the number of staircases with decorative cast iron balustrades. Those at No. 37 Monkgate (261) were certainly supplied by the firm of John Walker of Walmgate (Design Bk. 1, YCM 365/41) and those at No. 61 Bootham (48) and Bootham Grange (80) are so close to one of Walker's designs as to leave little doubt that they too came from the same works. The firm specialised in railings, many of which are still to be seen in York, and their work went to many country estates, to Sandringham, Kew Palace and the British Museum, as well as overseas (VCH, York, 273). Cast iron was also used as ceiling decoration for the centrepieces from which gas chandeliers were suspended; one at Burton Cottage (82) has ventilation ducts behind the foliage (Plate 121).

Much of the 19th-century development comprises terraces of small houses. New Walk Terrace (290) is of a quality above the average both in the size of the houses and in the standard of finish. At Grove Terrace (202) the designer has used a central pediment and end pavilions to compose a row of houses into one architectural unit, now obscured by trees in the front gardens. Elsewhere the terrace houses show considerable uniformity in design, and the planning of a block of the humbler class of dwelling is shown in Fig. 71 illustrating Redeness Street and Bilton Street, both now demolished.

Industrial Building

The only surviving industrial building in the area erected before 1850 is the former flax mill in Lawrence Street (209). Advertised as of fireproof construction, it appears to have vaulted brick floors similar to those in Bootham Park Hospital (21). For the early history of fireproof construction see H. J. Johnson and S. W. Skempton, 'William Strutt's Cotton Mills 1793–1812' in Transactions of the Newcomen Society, xxx, for 1955–7.

Architects, Builders and Craftsmen mentioned in the Inventory.

John Carr, architect, born 1723, son of a mason and quarry owner, practised in York from 1754, served as Lord Mayor in 1770 and 1785, and died in retirement at Askham Richard, near York, in 1807 (Colvin, 122).

Peter Atkinson, senior, born 1735, trained as a carpenter, became assistant to John Carr and carried on the latter's practice after his retirement. Died 1805. (Colvin, 45.)

Peter Atkinson, junior, born c. 1776, son and pupil of the above, became his father's partner in 1801. Died 1842. (Colvin, 45.)

John Bownas Atkinson (1797–1875) and William Atkinson (1811–86) succeeded their father Peter in the architectural practice founded by John Carr. This practice is now carried on in York by Messrs. Brierley, Leckenby and Keighley.

Thomas Atkinson (c. 1729–98), architect, of York, was not connected with the above family (Colvin, 46).

John Harper, architect (1809–42), was born in Lancashire, became a pupil of Benjamin and Philip Wyatt, and practised in York (Colvin, 266).

Robert Clough, master builder, 1708–91, was the son of Robert Clough, bricklayer, who died in 1712. He owned the houses he built in Bootham and Gillygate (monuments 39, 128), as well as other properties. At the time of his death he was living in Low Petergate.

Robert Clough, plasterer, 1736–1800, son of the above, free of York 1758.

William Abbey Plows, sculptor and stonemason, 1789–1865, was the son of Benjamin Plows of Acaster Malbis (Gunnis, 308), who set up his own business in 1811 after 27 years as a journeyman (YC, 25/3/1811). William carried on his father's business at Foss Bridge after the latter's death in 1824, offering monuments, chimney-pieces and side tables in stone, marble, alabaster, Roman cement, etc., as well as copings, ridges, troughs, flaggings, etc. (YG, 1/5/1824). Designs for funeral monuments are preserved in YCL (Y718 Plows). He lived at Belle Vue House (145), decorated with gothic detail presumably from his own workshop, from c. 1834 till 1852. (See also York III, lvii, lviii.)

John Walker, ironfounder, apprenticed to the firm of Gibson of Walmgate 1815, became partner 1829 and sole proprietor 1838. Succeeded c. 1847 by his son William Thomlinson-Walker, who later owned Clifton Grove (monument 84).

Thomas Wolstenholme, joiner carver and maker of composition ornaments, born c. 1759, acquired property at the corner of Bootham and Gillygate 1790, died 1812 leaving his 'business in Composition ornaments ... with all the stock in hand, moulds ...' etc. to his brother Francis. Francis was succeeded in 1833 by his son John (1794–1865) who worked as a carver in the Minster. His signature appears on some of the bosses in the nave.

Fig. 11. (11) The King's Manor. Carving from 18th-century staircase.

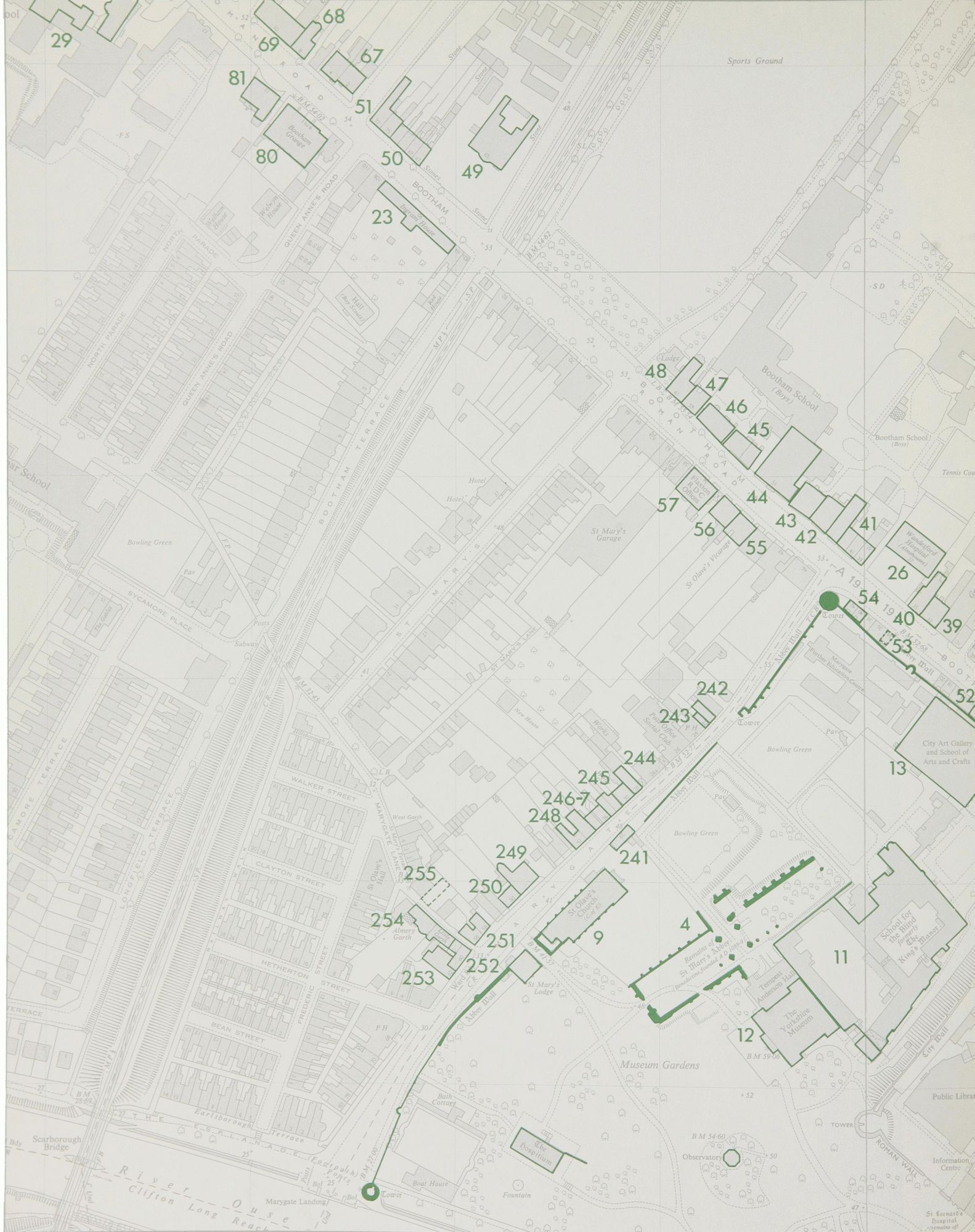

Map 2. Monuments in the Clifton area.

Map 3. Monuments in the Bootham area.

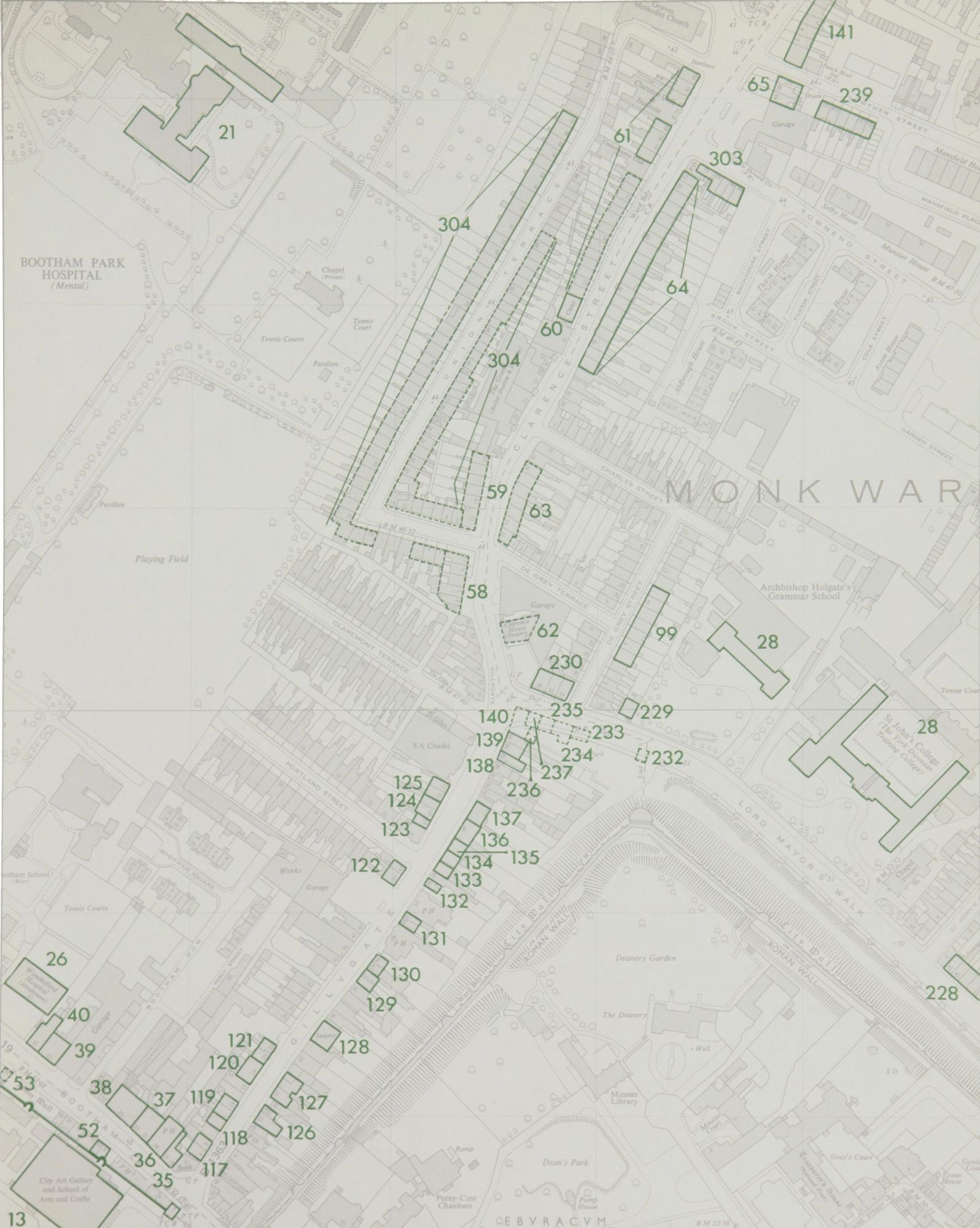

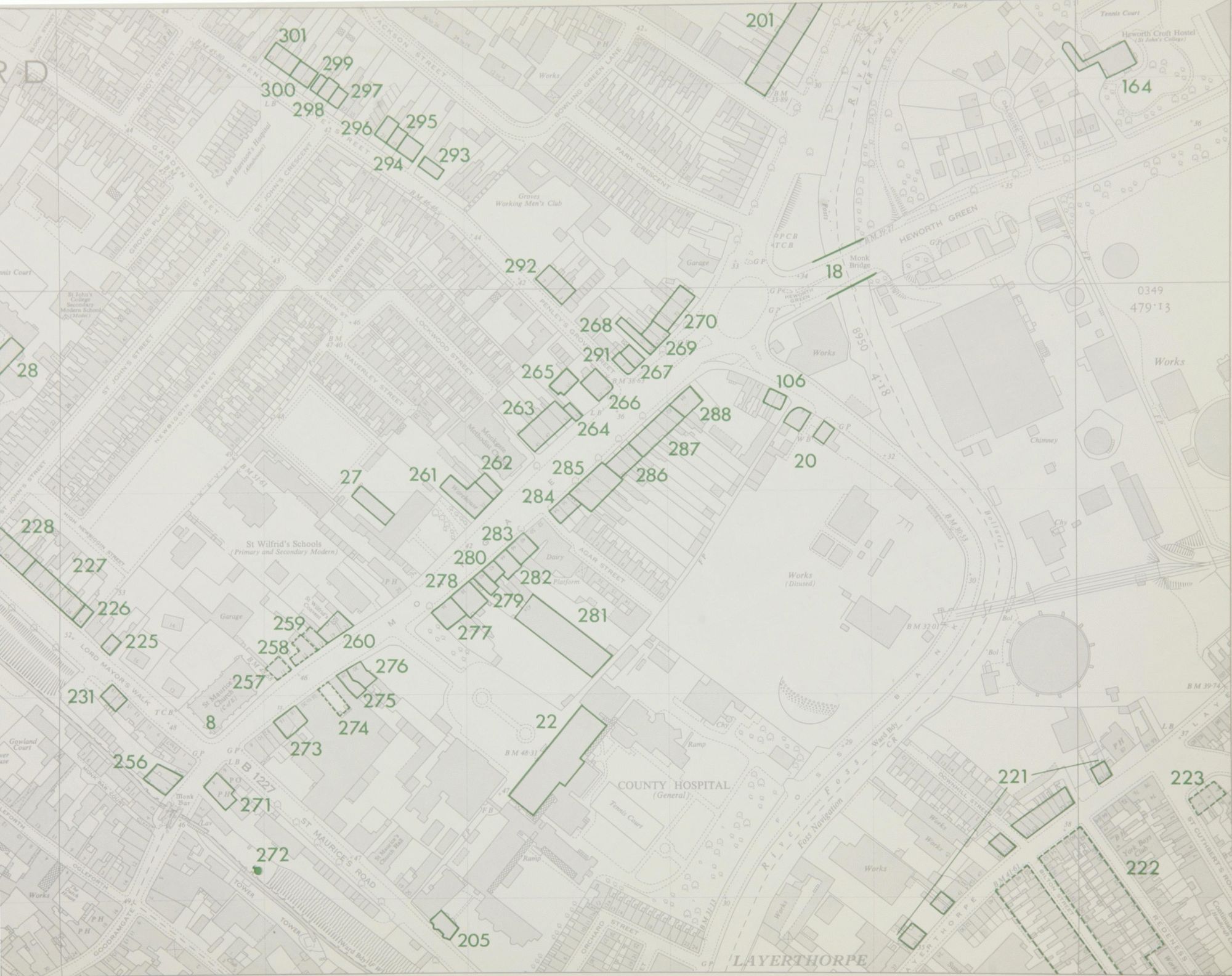

Map 4. Monuments in the Gillygate area.

Map 5. Monuments in the Monkgate area.