An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 4, Outside the City Walls East of the Ouse. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1975.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Growth of the City to 1069', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 4, Outside the City Walls East of the Ouse(London, 1975), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol4/xxv-xxxvi [accessed 26 April 2025].

'Growth of the City to 1069', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 4, Outside the City Walls East of the Ouse(London, 1975), British History Online, accessed April 26, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol4/xxv-xxxvi.

"Growth of the City to 1069". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 4, Outside the City Walls East of the Ouse. (London, 1975), British History Online. Web. 26 April 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/york/vol4/xxv-xxxvi.

CITY OF YORK OUTSIDE THE CITY WALLS EAST OF THE OUSE: GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE CITY TO 1069

End of Roman York

The buildings, walls and streets of the Roman fortress and city were still in the generations preceding the Norman Conquest among the most prominent features of the townscape, and determined the town plan of both mediaeval and modern York. It is convenient to begin with a summary description of this legacy, already more fully described in the early volumes (York I, Roman York; York II for subsequent history of the defences).

The Roman settlement comprised three parts:

(i) The fortress, a defended enclosure of 50 acres, built on an elevated spur between Ouse and Foss, including what is now the Minster and central area of the town on the N.E. side of the Ouse. Most of the internal buildings were low structures of stone, or occasionally stone and timber, but the central administrative buildings partly under the Minster were of monumental proportions. A subsidiary military enclosure was attached to the N.W. side on a site occupied in part by the choir of St. Mary's Abbey and the King's Manor.

(ii) The canabae, a civil settlement extending along the N.E. bank of the Ouse from St. Mary's Abbey to Castlegate, between the fortress and that river, but with the greatest concentration of buildings S. of the fortress, including stone temples, and baths in the Ousegate-Castlegate area. There were quays along the river Foss.

(iii) The colonia or main civil town, on the S.W. bank of the Ouse, defended by walls, rising up the then steep slopes of Micklegate Hill and Bishophill in a series of revetted terraces. The area corresponded approximately but not exactly with the mediaeval walled city on this side of the river. It was laid out in a regular grid of streets with the main road from Tadcaster as its major axis. There were monumental buildings notably in the Old Station Yard, where they had a slightly divergent alignment, and in the area of George Hudson Street.

Colonia and fortress were connected by a bridge opposite the Guildhall, which was the focal point of a road system of which the main constituents were the Tadcaster road approaching from the S.W., crossed immediately N.E. of the bridge by a N.W. to S.E. road which by-passed the fortress along its S.W. side. Along these and other roads outside the settlement area were cemeteries which included tombs of considerable size, and suburban houses.

Major alterations from this plan within mediaeval York are the following:

(1) The movement of the main Ouse crossing downstream from the Guildhall site to the present Ouse Bridge, and consequent realignment of roads.

(2) The removal of the distinction between the military and civil areas on the N.E. side of the river. This had three main consequences:

(a) The S.W. and S.E. defences of the fortress became superfluous and were partly removed.

(b) There was no longer any need to by-pass the fortress. The main crossing of the Foss was moved from the Castle to Foss Bridge with a consequent realignment of the S.E. approach road and the development of the Walmgate suburb.

(c) There was a parallel development on the N.W. where St. Mary's Abbey was allowed to block the road by-passing the fortress, and Bootham became the main road.

(3) The development within the fortress of the building of York Minster on its own E.-W. axis athwart the alignments of the Roman layout.

(4) The various changes in the Foss. After the Conquest the Castle mills and the stagnum regis prevented the continued use of that river for commercial purposes. The wharves sited on the Foss for the convenience of serving the legionary fortress and the later Danish wharves were replaced by others on the Ouse more convenient for the later town.

Development from the Roman town plan to the mediaeval was seriously affected by drainage and the water table. Certainly Roman level is in places below what is now the average summer level of the Ouse, and at Hungate pollen analysis showed an orchard type vegetation on the banks of the Foss in Roman times in an area later known as in mariscis. Archaeological evidence for disastrous flooding exists (see below) in the period between the end of Roman York and the 7th century. Fluctuation in water level may have affected York at other times—for example the development of Newgate in 1336 (Raine, 171–2) where the 12th-century name of Patrick Pool suggests there had previously been a wet area. The Ouse was tidal above York before the building of Naburn Lock in 1757 and was confined between stone walls revetting gardens in the later mediaeval period.

Post-Roman York

Little is known of York between the end of the Roman administration at the beginning of the 5th century and the emergence of Northumbrian York in the 8th century. There are two major pieces of evidence for this period. First there is considerable evidence for severe flooding between the late 4th and late 6th centuries (Ramm, 'The End of Roman York' in Butler (ed.) Soldier and Civilian in Roman Yorkshire (1971), 181–3), which at its greatest extent rendered uninhabitable that area of the town below the then 35 ft. contour (Roman levels are on average 10 feet below the present surface). Although the fortress and a great part of the colonia were unaffected, the economic results on a town already weakened by the break-up of Roman administration would be considerable. The silting of harbour facilities such as those at Hungate illustrates the loss for a period of York's status as an international port. On the other hand the site of the town at the N. extremity of a vast area affected by flooding (28 miles wide E. to W. and 40 miles long from York to Bawtry in the S.—see Radley and Simms, Yorkshire Flooding (1971), fig. 1, which illustrates the comparable area flooded in 1625) will have emphasised some of the underlying factors which influenced the choice of the site in the first instance as far as land communication was concerned, and ensured continuation of the settlement as a local market and strategic centre. Some evidence for the continuation of the Roman building traditions into the 5th century comes from Bishophill Senior and under the Minster.

The loss of the Roman bridge can be attributed to these floods with a consequent division of the town into two parts linked by the more tenuous communication by ford or ferry. When the flooding stopped, the 'heather and ling shewing that the ground hereabouts must at one time have been open moor' (described by James Raine (YMH (1891), 216) under Anglian and Viking remains in Clifford Street within the Roman canabae) illustrates the aspect of the formerly flooded areas and explains why the Roman town plan disappeared within them.

The second main piece of evidence derives from the cremation cemeteries on The Mount and Heworth Moor, where burned bones enclosed in pottery vessels of Germanic type date from the 5th century but include at least one at Heworth which is certainly a 4th-century type (Myres, Anglo-Saxon Pottery and the Settlement of the English (1969), 73 ff.). The distribution of similar pottery in burials outside Roman towns in Eastern England has led to the hypothesis that they belonged to mercenaries employed by RomanoBritons rather than to hostile invaders. Both sites (NGR 59375109 and 61055292) are alongside main roads in close proximity to the late 4th and possibly 5th-century Roman burials, a possible confirmation of a 4th-century date for the commencement of their use for cremations. (fn. 1) The siting of the two cemeteries on either side of the city is important in that it implies occupation of the Roman fortress and town at this date. Unlike contemporary or near-contemporary Roman or sub-Roman burials with their mixture of different styles of burial, these cemeteries are compact and uniform and imply that even if the newcomers came as friends, they were unassimilated and un-Romanised.

Germanic mercenaries and levies were no new thing in York at the end of the 4th century. Indeed in 367–9, the Dux Britanniarum, whose seat was at York, himself had a name of Frankish origin. Earlier, in 306, there was an Alemannic King Crocus present at York (York I, xxxiv). The German officers, at least, in the 4th century became thoroughly Romanised and lost contact with their homes (A. H. M. Jones, Later Roman Empire (1964), II, 622), but less is known about the rank and file. A break in Roman tradition is implied, as noted in York I (xxxiv), by the rifling of tombs, and the re-use of sarcophagi for new burials. In some cases this re-use is associated with gypsum burial, a 4th-5th century rite, deriving from Africa, and with Christian associations (Ramm, 'End of Roman York' in R. M. Butler (ed.), Soldier and Civilian in Roman Yorkshire (1971), 188–9). One burial, probably but not necessarily in gypsum, in a stone coffin found near Micklegate Bar (YMH (1891), 138), had preserved with it a piece of cloth, now in the National Museum at Edinburgh, made by a technique of Germanic origin (YPSR (1951), 22). But although we have some evidence of social revolution, material from 4th-century burials at York is usually unmistakably Roman. Earlier levies would appear to have been assimilated: the people buried in the Anglo-Frisian urns on The Mount and at Heworth, so far as their burial customs were concerned, were not.

Slight hints of other Germanic burials exist: a well-known 5th-century glass bowl comes from an unspecified site on The Mount (YPSR (1927), 7; YAJ, xxxiv (1958), 430; Harden (ed.), Dark Age Britain (1956), 142, Pl. xvi g); a possible urn from a separate cemetery on Heworth Moor is recorded by J. Raine (MS. notes, YCL 16, under date May 1879); and two presumably pagan Saxon cremations in urns are recorded from the junction of Parliament Street and Market Street (Hargrove, New Guide (1838), 52–3).

Northumbrian York

Literary records reveal York's status in the 7th and 8th centuries as a cultural centre, the seat of an archbishopric, and the capital of the Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria, which stretched from the Humber to the Forth; the presence of a Frisian colony attested by Alcuin writing in the 8th century probably indicates a commercial centre too, but little is said of the topography or appearance of York at the time. Alcuin (De Pontificibus, 196. J. Raine (ed.), Historians of the Church of York, (Rolls Series), 1, 355) refers to York 'still below its lofty walls' (Euboricae celsis etiam sub moenibus urbis) and as built first by the Romans 'high with walls and towers' (hanc Romana manus muris et turribus altam fundavit primo). The Roman walls and towers must have been an impressive survival in the 8th century and not only the walls and towers, but also the great gatehouses. In 685 St. Cuthbert was consecrated bishop in St. Peter's church at York and was given a grant of land within the fortress in terms that are now ambiguous but certainly imply the survival of a 'great west gate' whether it be the N.W. or the S.W. gate (YAJ, xxxix (1958), 436 ff.), and it is possible that the later Danish Koningsgarthr (Egil's Saga, EHD, 1, 298–304) or Royal Palace used the S.E. gatehouse in King's Square. William of Malmesbury in the 12th century when the Roman walls were for the most part hidden beneath an earthen mound could still describe York as urbs ampla et metropolis elegantiae Romanae praeferens inditium (Gest. Pont. Prolog. iii), indicating the survival of other remains than the defences, and this is confirmed by the availability of Roman building material for re-use as late as the Norman period. A fortiori more survived in the 7th and 8th centuries, and when a 10th-century life of Archbishop Oswald describes York as a nobly built city then in decay through age, it is surely the Roman remains that inspire the comment.

Of Northumbrian buildings it is only the Minster that is described in any detail, although Alcuin says that St. Wilfrid adorned other churches with fine gifts and took care to increase congregations (ecclesias alias donis ornaverit opimis . . . curam . . . gerebat multiplicare greges. De Pont. (1227), loc. cit. 385) and he also refers to a church of St. Mary (Christi genetricis in aula. De Pont. (1605), loc. cit. 397). According to Bede, Edwin was baptised in 627 in a wooden oratory dedicated to St. Peter, around which he later built a square stone church which St. Oswald finished. This church fell into disuse and was repaired by St. Wilfrid c. 670. York suffered from fires in 741 and 761, the first of which burnt the Minster and the second devastated the city. Albert or Athelberht (Archbishop 767–80) first built a new altar over the place where Edwin had been baptised and provided it with fine ornaments. He then built a new basilica which he consecrated to God (Sophiae sacraverat almae) a few days before his death (Alcuin, De Pont. (1519), loc. cit. 394). Alcuin describes the church as a large one with arcades, numerous side chapels, galleries, splendid ceilings and windows. Archaeologically nothing is yet known of this building and its effect on York's topography is thus hard to assess. The excavations under the Minster (1966–9 and continuing) have not yet produced clear-cut evidence for the date at which the Minster assumed its present E.-W. alignment. Large parts of the cross-hall of the principia were standing and in use until the late 9th century, and other Roman buildings were repaired or adapted. Late Saxon (11th-century) graves under the N. half of the S. transept, and contemporary domestic structures under the E. end of the nave retain the Roman alignment. The place-names of York are Danish rather than Northumbrian. But if the name King's Square or Coney Garth reflects the palace of the Viking kings of York, then Coney Street may have reference to the palace of the earlier Northumbrian kings.

Evidence of Buildings, 400–866

Although the remains of structures are few, significant deductions can be made from them. S.W. of the river at Bishophill Senior there is evidence of Roman building traditions continuing into the 5th century. The hypocaust system of a house built in the late 4th century fell into disuse and small buildings were built in the service yard over the furnaces. These buildings had good solid masonry built in a thoroughly Roman tradition. N.E. of the river we have evidence of structures of a different kind, of timber on rough stone footings, rectangular but with rounded angles, crowding the S.W. side of the Roman fortress with a complete disregard for its defensive value. In Museum Gardens such a building overlay the filled-in fortress ditch outside tower S.W. 6; in St. Helen's Square, S.E. of the main fortress gate, rubbish pits have been dug into the berm between wall and ditch; in Davygate two separate fragments of building, 40 ft. apart, lay close inside the rampart behind the wall; and finally in Feasegate in front of the S. corner tower there were successively rubbish pits, an iron smelting hearth and a pit containing vegetable material and leather, of which the last is not later than the 10th century. In Museum Gardens the structure must date from a period when the fortress had gone out of use and, if a Danish rampart covered the fortress defences here as they did on the N.W. side, must precede this (i.e. date from the 5th-9th centuries). In Davygate beads of 9th-10th-century date came from just above the footings of the buildings. A stone tower, probably dating to the 7th-8th centuries, was built into a gap in the 4th-century fortress wall on the N.W. side (York II, The Defences, 112–15). The fortress walls even where they had become embedded in the expanding Northumbrian town still survived in an impressive condition as we know from Alcuin's poem and as indeed the surviving buried remains demonstrate. A burnt stone building on the N.W. side of Marygate in which was found a Saxon styca may indicate the spread of the town to the N.W. before the Danish occupation. Saxon sculpture of the 7th-8th centuries comes mainly from the Minster, but crosses from St. Leonard's Place, Bishophill Junior, and near the Old Station imply the existence of other churches. A hanging bowl from the Castle Yard (Haseloff, Med. Arch., II (1958), 82, 83; Cramp, Anglian and Viking York (1967), 5–6), and a bronze bowl with drop handles from Clifford Street (Arch., xcvii (1959), 60 fig. 1) might be part of the ecclesiastical equipment of a lost church or derive from 7th-century graves.

In the 7th-9th centuries the picture suggested is of a crowded town of timber houses, but with stonebuilt churches, expanding, on the N.E. bank of the Ouse at least, into areas kept clear in Roman times. Such a town would be liable to suffer from fire as indeed we are told it did, devastated (vastata) in 764 (Symeon Dunelmensis, Opera Omnia (Rolls Series), ii, 42. In 741 the Minster had been burnt, ibid., ii, 38). It was a sufficiently peaceful city to disregard the surviving Roman defences and to allow civil building to encroach on them. The structural evidence then indicates the survival of Roman building into the 5th century, but the Northumbrian town of the 7th-9th centuries is mainly of timber and the surviving masonry fragment differs in style, structure and material from the Roman buildings. This change may have been assisted by natural disaster, as well as by the settlement of the English, whose coming in the late 4th or early 5th century, as we have seen, seems to have been as allies rather than invaders.

Small Finds

The small finds, best illustrated by the map, are too few for firm deductions to be drawn from them. They occur on both sides of the river. In the S.W. they group in the Toft Green-Micklegate area, and N.E. of the river to the S. of the fortress and on the site of the later Earlsborough and St. Mary's Abbey. Some reoccupation of flooded land may have occurred before the Viking period: 9th-century finds occur within the flooded area in Tanner Row, and there is Anglian material as well as Viking from Clifford Street, including the bronze bowl perhaps of the 7th century (Arch., xcvii (1959), 60 fig. 1). The absence of finds from within the fortress area is probably fortuitous. At least two coin hoards come from near Bootham Bar. One containing 10,000 coins was deposited in a pot buried into the earth rampart behind the Roman wall near the De Grey Rooms in St. Leonard's where it was found in 1842. Its latest coins were of Osberht (deposed 866) and Archbishop Wulfhere. The second hoard, found in 1879, came from the site of the Art Gallery or its vicinity and consisted of 400 coins up to mid 9th-century in date. During the removal of the city wall, mound, and upper stages of the Roman wall to make St. Leonard's Place in 1833–4, 47 Northumbrian stycas as well as 46 Roman coins were found. These came from a much higher level than the first hoard and presumably represent strays from another hoard or hoards disturbed in heaping up the mound of the subsequent city defences—the quantity is much greater than is normally found within the city mound. These hoards were perhaps deposited by citizens fleeing from the approach of the Danes who occupied the city in 866, or as a result of the fighting in 867, or the revolt against the Danes in 872. They indicate not only the insecurity of the time but the route taken by the fleeing citizens and the part of the city from which the wealthier citizens came. Yet another hoard was found near or on the site of the Old Railway Station in 1840, providing further evidence for settlement S.W. of the river at this period.

Outside the central area evidence is even more tenuous. S. of the city the area subject to flooding will have widened out to include Hob Moor, the Knavesmire, most of the Fulford area, Low Moor and Walmgate Stray. Settlement is to be looked for on the higher ground, such as Holgate Hill, Acomb, along the Hull road, and at Heworth. Acomb and Heworth have produced 4th-century Roman pottery, and the latter 4th-century burials just without the city boundary; both have English rather than Scandinavian names, and the name of Heworth belongs to an early phase of English settlement. The early cremation cemetery on Heworth Moor is to be associated geographically with the city rather than any subsidiary settlement at Heworth and the same is also true of the inhumation cemetery at Lamel Hill, to the S.E. of the city, with burials in wooden coffins laid regularly E.-W., but without grave goods, probably Christian and English, and belonging to a date when the rule of extramural burial was still followed.

Viking and Late Saxon York, 876–1066

The Danes found a large and prosperous town, on both sides of the river, timber-built amongst the ruins of Roman fortress and colonia, with a cathedral symbolic of the leadership of the Church in the city's cultural life. The town did not entirely cover the area of Roman settlement and much of the formerly flooded areas must have been open land, dry but overlain with silt and covered with light vegetation, or still waterlogged and marshy, according to the drainage.

According to William of Malmesbury (Gesta Regum, II, 3) the city was burned in 866–7 (compare the evidence from Marygate above). Part of the Danish army settled in York, rebuilt the city (civitatem reaedificavit), and cultivated the neighbourhood (Surtees Soc., li (1867), 144), or, as a later work (loc. cit., 158) has it, rebuilt the walls of the city (Eboracae civitatis maenia, una ex his restauravit).

There is archaeological evidence for both forms of rebuilding. The Danes renewed three sides of the Roman fortress by covering the Roman wall and mound with an earth bank on which they erected a timber stockade, and, omitting the S.E. side, extended the enclosure to the river Foss where there was an open embankment to the river (York II, 8). This enclosure of 87 acres open-ended to a river compares with similar enclosures at Wareham, Dorset, of 80 acres, Hedeby in Schleswig-Holstein of 60 acres and at Birka in Sweden of 30 acres. But large as it was the side facing the Ouse was already abandoned by the later 10th or 11th century when tan pits were dug into the bank between Ousegate and Coppergate (YPSR (1902), 64), an industrial use of the site which had been replaced by stone houses in the 12th century (EYC, 1, 183–5). Tenth-century occupation debris occurs outside the S.W. defences in Clifford Street and Coppergate.

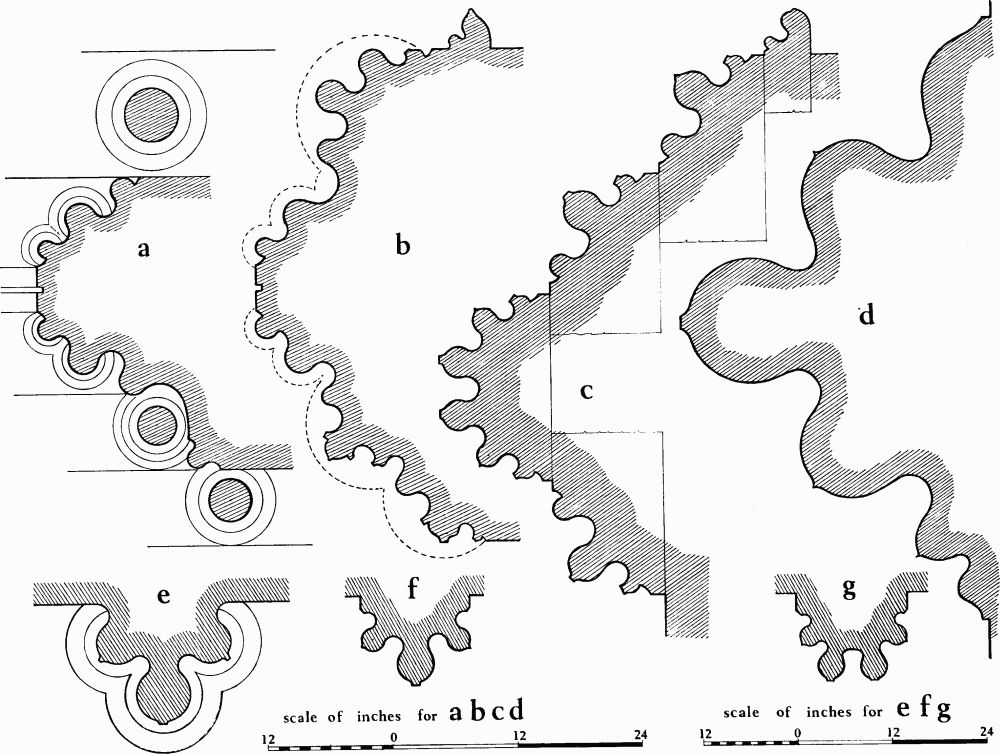

Fig. 4. York. 876–1066 a.d.

A large part of the area added to the Roman fortress was on the area previously flooded. The Hungate excavations revealed evidence of systematic reclamation and drainage (Arch. J., cxvi (1961), 59–61). Within the enclosure the distribution of finds shows the weight of occupation to have been within the S.E. third of the Roman fortress and in the S.W. half of the added enclosure. The most prominent feature within the Danish enclosure must have been the royal palace sited, on place-name evidence (Smith, EPNS, York and East Riding, 285), in King's Square, possibly in the Roman S.E. gatehouse. The Egil's Saga (EHD, 1, 299) described the house of Arinbjorn at York which had its court and a hall. In addition to the Minster and royal palace there were thus other large establishments, each presumably in its own enclosure. The picture in Egil's Saga is of a building of some size and sophistication.

Archaeological finds are more humdrum consisting, apart from occupation debris, of traces of timber buildings of 10th-11th century date from King's Square, Pavement, High Ousegate and Piccadilly (see Radley, 'Economic Aspects of Anglo-Danish York', in Med. Arch., xv, forthcoming). Radley suggests a commercial use for some of these buildings and there is evidence for crafts, particularly leather-working. The whole orientation of the new enclosure was to the river Foss; the weight of small finds illustrates this and the mediaeval street pattern confirms it. The later markets were in the enclosure: 14th-century documents refer to the Pavement area as 'marketshire' possibly implying one of the seven shires into which Domesday Book says late Saxon York was divided. The triangular street patterns of Ousegate-CoppergatePavement and King's Square-Colliergate-Shambles, the apex of the first towards Fossgate and of the latter towards King's Square, argue for roads able to converge over an open space to a natural focus rather than the grid of an artificially imposed pattern.

There need have been no great check on York's economic life as a result of the events of 866–7. York as a prosperous commercial centre had been to a considerable extent dependent on foreign merchants, particularly Frisians. Their position was decidedly insecure and they had to be ready to flee should enmity, aroused by envy of their wealth or by social prejudice, make this necessary. This is well illustrated by an episode described in Alcfrid's Life of St. Luidger (EHD, 1, 725) who had to leave York: 'For when the citizens went out to fight against their enemies, it happened that in the strife the son of a certain noble of that province was killed by a Frisian merchant, and therefore the Frisians hastened to leave the land of the English, fearing the wrath of the kindred of the slain young man.' That was in the 8th century. The Danish army, part of which under Halfdan eventually settled in York, is said to have been led by Halfdan, Inguar and Ubba, and the last-named is described in the life of St. Cuthbert (loc. cit.) as dux Fresconum or General of the Frisians. York already had commercial links with N.W. Europe and these were maintained by merchants accustomed to the dangers of political instability and ready also to take advantage of it. York's commercial position may indeed have been enhanced by the conquest, merchants following the Danish army, just as in Egil's Saga Egil's companions and shipmates are left behind in York under safe-keeping to sell their wares before moving south to find him. In the late 10th-century life of St. Oswald (Raine (ed.), Historians of the Church of York, 1, 154) York is said to be 'fantastically stocked and enriched with the treasures of merchants who come from all quarters particularly from the Danish people (ex Danorum gente)'.

Fig. 5. (4) St. Mary's Abbey. Vestibule to Chapter House. Pier base at W. entrance. c. 1200.

Fig. 6. (4) St. Mary's Abbey Church. Mouldings in stone.

a. N. aisle, jamb of window.

b. " " arch over window.

c. Nave arcade, arch.

d. " " W. respond.

e. N. aisle, vaulting shaft.

f. " transverse vaulting rib.

g. " " diagonal vaulting rib.

Within the added enclosure are two burial grounds—the one in Parliament Street is perhaps to be associated with a lost church of St. Swithin's and was probably never anything but Christian, the other in St. Saviourgate with rough wooden tree-trunk coffins may be pagan. One is reminded of the two cemeteries in the walls of Hedeby, the one Christian and the other, with wooden grave chambers, pagan. Of noble burials in 'hows' the only possible indication is the engraved bronze socket for an iron spearhead found at Howe Hill, between Holgate and Acomb (Arch. J., VI (1849), 402).

The abandonment of the S.W. Danish defences in the 10th and 11th centuries did not greatly affect York's topography except to remove an artificial barrier to expansion. Nor did the destruction of the Danish castrum by Athelstan (York II, 8) affect greatly the Danish element in the city dependent on commercial rather than military settlement. The city is still weighted towards a central area S.E. of the old Roman fortress involving new crossings of the Ouse and the Foss at the present Ouse Bridge and in Fossgate. Whether we look at the distribution of archaeological small finds or Anglo-Danish sculpture, Scandinavian street names or of churches, for the greater number of which a pre-Conquest date can be argued on a variety of grounds, the concentration S.E. and S. of the fortress is marked.

Beyond the Foss the street named Fishergate, attested as early as 1070–80 a.d., implies urban development by that date and presumably before 1066 a.d. The six mediaeval churches along the route from Fishergate to Foss Bridge can all except one (St. George) be shown to have existed before 1100, three of them outside the later walls. Four of the remaining six churches S.E. of the Foss lie outside the later city walls and all except one along the line of the Roman road approaching the city from the E., but only one of these has evidence for an early date. The siting of the churches indicates the importance of Fishergate and the road from Fulford (site of a battle in 1066 a.d.) and the survival of the Roman line from the E. which met Fishergate at or near the church of St. George. Walmgate is a short cut already existing by 1070–80 a.d. but which had then not yet attracted much urban development. The later defences centring on Walmgate and defending a compact arc of the town within a large loop of the Foss, and the loss of the road linking Foss Bridge and Fishergate have obscured the shape of earlier development straggling along the E. bank of the Foss to the Ouse and filling out the old city boundary in the area, a riverine settlement presumably served by wharves and moorings along the bank and suggesting commercial expansion from the main trading area N. of the Foss.

N.W. of the Minster area was the Earlsborough, the fortified residence of the Earls of Northumbria in the 11th century, occupying a site important in pre-Danish times. The name Bootham, Scandinavian in origin, implies some kind of temporary development of huts or shanties and does not suggest an important suburb.

On the S.W. bank of the river the simpler parochial pattern suggests later and less congested development. Micklegate had already before the Norman Conquest been diverted towards the new river crossing (Ouse Bridge). North Street and Skeldergate, following the line of the river bank, indicate the importance of riverborne commerce in the life of the town. An important excavation by Mr. Wenham, adjacent to St. Mary's Church, Bishophill Junior, has located an area separated by a wall from the 10th-century churchyard where fish had been cleaned and gutted in quantity. Fish formed an important item of commerce and a staple food. Documentary evidence exists that it was imported, presumably dried, from the Hebrides and sold at a market under the control of the Archbishop.

Downstream development took a different form from that in the Fishergate area, and was not considered as an extension of the town. Satellite harbour settlements are indicated by the -thorpe names of Clementhorpe, Bustardthorpe, Middlethorpe and Bishopthorpe, but the tolls from the ships which lay at Clementhorpe and beyond belonged by 1106 a.d. to the Archbishop. Satellite settlements on both sides of the river exist on the main E.-W. road line at Copmanthorpe, Dringthorpe and Layerthorpe and suggest that road traffic had its part, too, to play.

Outside the town a certain amount of arable was always included within the later city boundary, and the city had extensive rights of common. S.W. of the city the parishes of the city churches extend well beyond the city boundaries, and the -thorpe names suggest that many of the villages within them were satellite communities. E. of the Ouse some of the villages were also, in whole or part, within the city parishes, e.g. Naburn, Fulford, Heslington and Heworth. In Domesday there are 84 carucates which geld with York and are to be identified with the manors and vills listed immediately after the account of the city. These are all on the E. bank of the Ouse and their association may date back to the 9th century when a third of the Danish army settled in York and cultivated the land in circuitu (Surtees Soc., li (1867), 144). The absence of Danish place-names could imply existing communities where the inhabitants remained to work for the Danes living in York.

By 1066 a.d. the town of York was a large and important commercial centre. The greater part of the old Roman fortress was occupied by the Minster and its precinct; adjacent to the N.W. was the Earlsborough, the fortified palace of the Earls of Northumbria. Roman buildings still survived but the business heart of the town had moved to the S.E. of the fortress on to land where Roman remains had been erased by the floods of the 5th and 6th centuries. Trade which had originally centred on the Foss had been transferred to the Ouse with wharves and riverine settlement stretching far downstream. Indeed, the town was far less compact than when it had retreated within the later mediaeval walls. None the less the basic plan of the mediaeval town is now recognisable.