Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'King's Cross Road and Penton Rise area', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp298-321 [accessed 10 February 2025].

'King's Cross Road and Penton Rise area', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed February 10, 2025, https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp298-321.

"King's Cross Road and Penton Rise area". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 10 February 2025. https://prod.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp298-321.

In this section

CHAPTER XII. King's Cross Road and Penton Rise Area

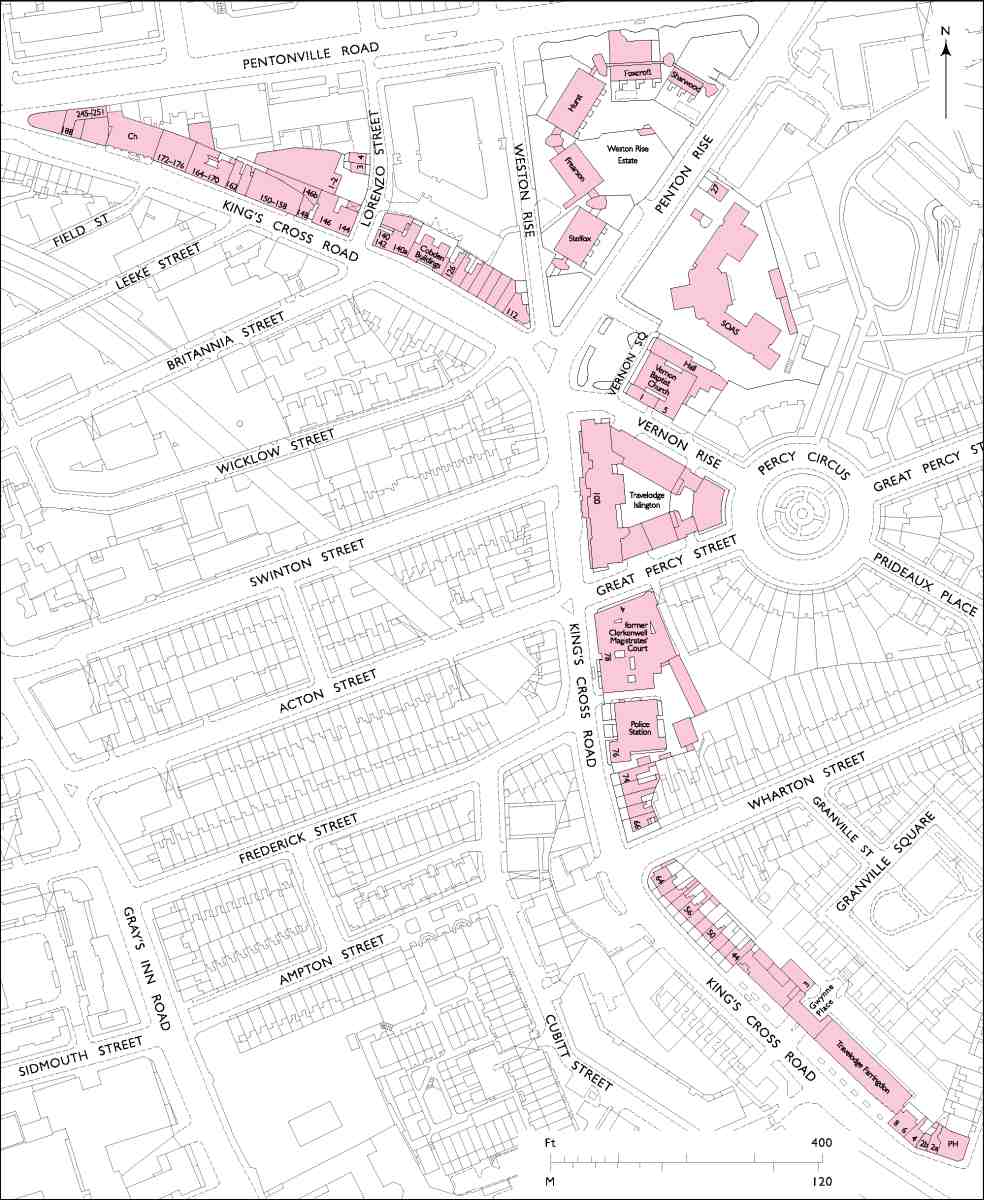

385. King's Cross Road and Penton Rise area

In terms of historical character, the area considered in this chapter can best be described as marginal, lying as it does at the edges of the old parish of Clerkenwell and of three important former Clerkenwell estates: Penton, Lloyd Baker and New River Company (Ills 3, 385). It consists in large part of a broad and shallow triangle, sloping steeply to the south from Pentonville Road—the southern ends of Henry Penton's fields, severed by the making of the road in the 1750s. From here King's Cross Road winds southward, following the line of the Fleet river, which, more or less, separated Clerkenwell from the parish of St Pancras. Only the Clerkenwell side of the road is discussed in detail here, together with the adjacent Vernon Square.

Although largely built up in the late eighteenth century, the area retains no building fabric to suggest this, the last original remnant having been erased as recently as 1995. Pentonville Road, Penton Rise and Weston Rise were formerly lined by good houses of the period, many of which, long déclassé, survived until after the Second World War. A large part of the ground is now occupied by public housing and later large blocks of building, chiefly residential or offices. Industry, an increasingly important presence from the mid-nineteenth century, has entirely disappeared over the past few decades, leaving little trace. The area of Lorenzo Street was always poorer, and more meanly built up. King's Cross Road itself acquired an increasingly dense and gritty urban character in the course of the nineteenth century, its hostels and lodging houses indicative of a poor and transient population. Today it presents an incoherent panorama of buildings dating variously from the early nineteenth century to the present, some preserving the original narrow plots, others on a larger scale.

The account opens with a chronological résumé of development and the area's changing character since the eighteenth century. This is followed by a topographically arranged inventory of existing buildings. The original development of the Pentonville Road frontage is sketched in Chapter XIV, where accounts of the present Pentonville Road buildings (excepting the Weston Rise Estate) are also given. The history and character of the Penton estate, which mostly lay on the north side of Pentonville Road, are discussed generally in the next chapter, while general accounts of the New River Company and Lloyd Baker estates are given in Chapters VII and XI.

The area before general development

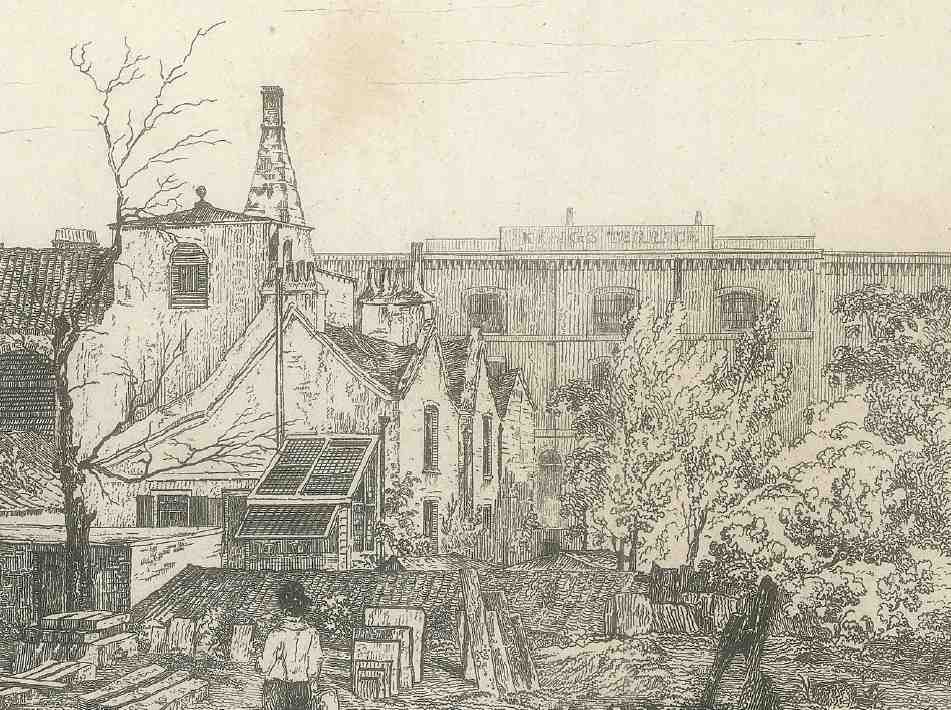

386. Bagnigge Place with Randell's tile kilns behind, c. 1800, from a watercolour of the mid-nineteenth century

Before the late eighteenth century there was little building, apart from nine houses present by 1746 at Battle Bridge, as King's Cross was then known. It was not in the main a desirable site, partly on account of the marshy nature of the ground close to the Fleet river, which ran along the western side of what is now King's Cross Road. This patch had been known since at least 1660 as Bagnall's Marsh, or Bagnall's Wash as the Fleet was called at this point. (fn. 1) Nevertheless, such was the demand for more building that many houses had been erected by 1825, when this part of the river was converted into a sewer. (fn. 2)

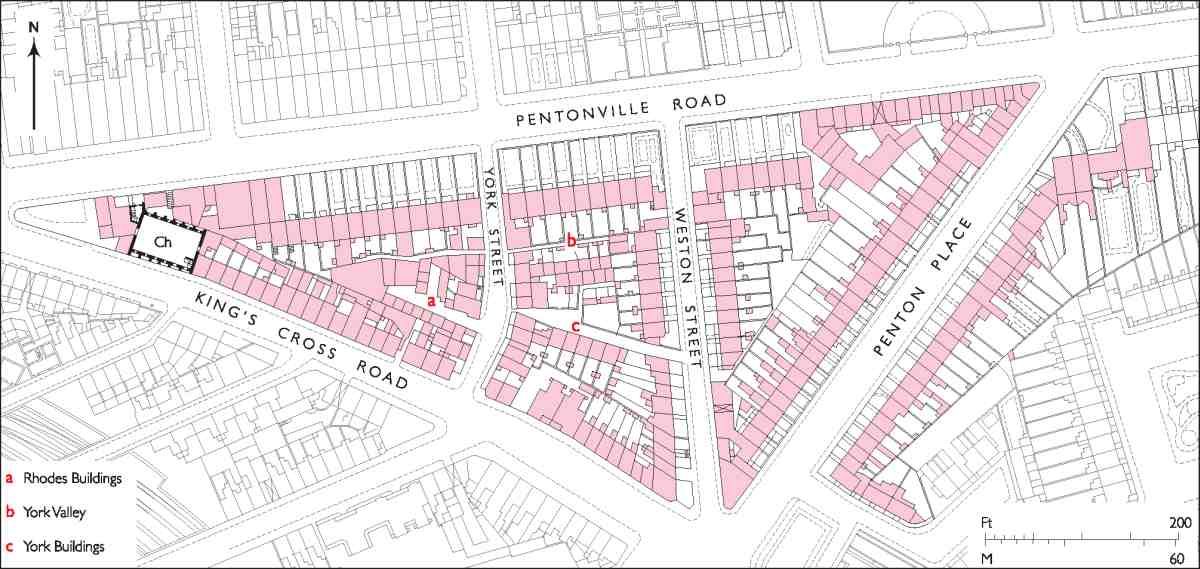

387. The Penton 'triangle', c. 1874

The pattern of land-ownership at the time of first development consisted of three large freehold estates on either side of what is now King's Cross Road, and three small patches of waste ground belonging to the manor of Cantlowes, a prebend of St Paul's Cathedral. On the east side of the road, though with almost no frontage to it, was part of the Penton estate, and south of that the New River Company and Lloyd Baker estates. On the west side were the Battle Bridge, Swinton and Calthorpe estates. (fn. 3) The waste ground consisted of a piece on the west side of the road, where the Holiday Inn now stands, and two narrow strips on the east side: one at the north end, developed as Hamilton Row, and a smaller one to the south, where Bagnigge Place was built, now the junction of Great Percy Street.

Though an ancient route, King's Cross Road acquired its name only in 1863. (King's Cross, the name given to the area around the intersection of the Euston—Pentonville Roads, Gray's Inn Road, and York Way, had been in use only since the late 1830s, after Stephen Geary's derided structure, surmounted by a statue of George IV, erected at the junction in 1836.) Until then it was Bagnigge Wells Road, this name applying to the way as far south as Coppice Row and so including part of what is now Farringdon Road. Cromwell and Pinks both identify Bagnigge Wells Road as part of 'the old and auncient high waie to High Bernet from Port Poole now Grayes Inn as also from Clerkenwell', mentioned in John Norden's Speculum Britanniae of 1598. (fn. 4) In the eighteenth century the northern part of the road was referred to variously as the road to Bagnall's (or Bagnigge) Marsh, the road to Battle Bridge or the turnpike road from Battle Bridge to Bagnigge Wells; the southern part is shown on Rocque's map of 1747 as Black Mary's Hole, the name of an old well or spring there (see page 23).

Bagnigge Wells, on the south-western side of the road (on the site of the present Holiday Inn), opened in 1758 at Bagnigge House, traditionally said to have been used as a retreat by Nell Gwynne and Charles II, and certainly in existence by 1680. One of the many resorts locally for entertainment and taking the waters, it remained famous and fashionable to the end of the eighteenth century, finally closing in 1841. (fn. 5) Already in existence by the 1740s on the Clerkenwell side was the Bull in the Pound public house, forerunner of the present Union Tavern.

A large brick- and tile-works grew up on the east side of the road in the late eighteenth century, on Lloyd Baker ground. It appears to have been started about 1769, and by the early nineteenth century was run by the Randell family. The original single 'bottle' kiln was joined by a second by about 1780 and by 1808 some twenty long buildings, most of them probably open-sided sheds, were clustered around them. A couple of small houses were built in 1807 in connection with the works. (fn. 6) The kilns' distinctive profiles were a prominent feature of the topography for the next fifty years or so (Ill. 386), until the 1820s when, on the expiry of the Lloyd Baker lease, the business moved to Maiden Lane in St Pancras.

Building under Alexander Cumming and John Weston, 1779–c. 1802

Development of the Penton triangle south of the New Road (Ill. 387) began in 1776–7 with the construction under Act of Parliament of Penton Place, linking the New Road with Bagnigge Wells Road. The line of the new street was an extension of Rodney Street on the north side of the New Road, thus giving some continuation of the main Pentonville street-grid. According to Pinks, Penton Place (present-day Penton Rise) was formerly lower-lying than in his day and prone to flooding when the Fleet sewer was unusually full due to rain or thaw. (fn. 7) Old photographs suggest that, if so, the increase in level cannot have been very great (Ills 388, 389). A problem with groundwater may have persisted, however, for a description of a house on the west side in the early twentieth century notes that cellars under the front garden were 'defective & swamped'. (fn. 8)

The eastern frontage of this 'new cut' was leased by Henry Penton in 1779 in three plots to the watchmaker and inventor Alexander Cumming, under whom it was mostly laid out with houses during the early to mid-1780s by a number of builders. The chief figures were the carpenters Thomas Vickers and John Symmonds, both of Clerkenwell, and Charles Douglas, of St Clement Danes. (fn. 9)

At the top end of the street a group of larger than usual houses were built facing north. Cumming himself occupied one of these until his death in 1814. He was also rated for an 'organ-shop' there for a few years in the mid-1790s, following his retirement from business in Clifford Street, Mayfair, and it was about this time that he bought and installed a machine organ he had made some years earlier for the Earl of Bute. Cumming's house, completed in 1781, seems to have been the westernmost house of this group, shown on Hornor's map of Clerkenwell as having several polygonal bays, but by the 1870s shorn of these and divided into two. It was originally detached, until neighbouring houses were built in 1792–3. (fn. 10) Cumming's lessees in Penton Place included an organ builder, John Wright, who took ground for several houses at the south end of the street. (For Cumming's musical connections locally, see also page 410.) Of the other houses on Cumming's side of the street, one, later numbered 25, was double fronted. This house, probably built in 1784 and originally of three storeys over the basement, was distinguished by a Classical door-surround in Coade stone (Ill. 390). (fn. 11)

In 1786 John Weston the elder, who had a large brickfield on Penton's estate north of the New Road, took a 99-year lease of all the Penton ground on the south side of the New Road west of Penton Place. (fn. 12) This extended nearly up to present-day King's Cross Road, the frontage to the road itself being in different ownership, held as copyhold of the Manor of Cantlowes.

The lease mentioned 'a new intended street' to bisect

the site from north to south with buildings set back 15 ft

on either side—this was to become Weston Street,

renamed Weston Rise in 1937. Over the next few years

Weston farmed out the development of the ground to a

number of undertakers, including his brickmaker son

William Weston; John Weston the younger, victualler;

Thomas Vickers; Thomas Stevens; and Thomas Hindle, a

stonemason who had built in St Pancras. Most of the

builders took plots for no more than three houses. (fn. 13) The

greater part of the New Road frontage was developed as

York Place and Clarence Place (see Chapter XIV). On the

west side of Penton Place, mostly built up between 1788

and 1793, the houses varied in size, more than half of them

being on frontages of 19 ft; others were as narrow as 13 ft

or 14 ft (Ill. 388). Two or three windows wide, they were

of three storeys over basements, some with an additional

mansard floor, and some with Coade stone decoration. (fn. 14)

The houses were of a good class and well appointed, as

expressed in an advertisement of 1796 for No. 42:

an excellent Dwelling, in good Repair, and elegantly fitted up

in the modern Stile … the Attick Story contains three good

Servants Rooms, with suitable Closets, and Trap Door to go

on to the Leads; Two Pair Story two Bed-Chambers, Closets,

and Marble Chimney Pieces—The Floor is completely and

elegantly furnished, and Register Stoves fixed … Ground

Floor two Parlours, with Closets, Marble Chimney Pieces, and

fixed stoves; Basement Story two boarded Kitchens, a Wine

Cellar … in the front Area are two arched Vaults and a

Pantry; a paved Yard back of Dwelling, and a Garden well

stocked with choice fruit trees about 38 yards long. (fn. 15)

The Weston Street houses, built between 1791 and 1802, were generally smaller, on 15 ft or 16 ft frontages, with two storeys over the basements and mansard floors (Ill. 391). (fn. 16)

More modest were the houses built along York (now Lorenzo) Street, a short, steep, slightly curving street laid out after 1786, between the New Road and what was then Bagnigge Wells Road. Building began in about 1795 and was largely complete by 1802. Still smaller were the houses in courts off Weston Street and York Street. (fn. 17)

Building in Bagnigge Wells Road, 1790s–1840s

While Weston's ground was being built up, development was also taking place on the manorial ground to the west under the builder Joshua Hodgkinson. The ground here, a piece of unenclosed manorial 'waste', had been assigned to three different tenants between the 1660s and 1740s. (fn. 18) But no tenant could be traced in the 1770s, and Hodgkinson was admitted as tenant in 1790. (fn. 19) The main portion of his ground was a strip about 600 ft long and 40 ft or so deep, running along the north-east side of the road from Battle Bridge to Bagnigge Wells (in modern terms, between the west end of the former Welsh Tabernacle, in Pentonville Road, and Penton Rise). Along with this there was a sliver 150 ft long and 20 ft wide at its greatest, where Great Percy Street now meets King's Cross Road.

Hodgkinson, described as a lime burner of Lewisham, had previously lived at Battle Bridge, working in the 1780s as a bricklayer for the Highgate and Hampstead Roads trustees. (fn. 20) He was very active as a developer, building in Winchester (now Killick) Street and elsewhere in Clerkenwell and St Pancras, including Somers Town. (fn. 21)

388. Penton Rise. West side in 1951

389. Nos 17–25 Penton Rise (left to right) in 1944. Vernon Square School in background, far right

390. No. 25 Penton Rise in 1951

391. Weston Rise. East side, looking south, 1943

The terms of Hodgkinson's copyhold allowed him to demise the ground for up to 63 years. In 1791–2 he filled most of the frontage to Bagnigge Wells Road west of Weston Street with Hamilton Row, a terrace of small houses on 16 ft frontages, sub-letting them typically for the full 63-year term (Ill. 406). (fn. 22) On the sliver to the southeast, adjoining the New River Company's ground, he oversaw the building of Bagnigge Place, a row of tiny houses (Ill. 386). (fn. 23)

St Pancras Vestry considered Hodgkinson's houses to be in their parish, and marked out their boundary in 1791 with a line of posts running behind, and in some cases through, the back gardens. (fn. 24) This led to a dispute with Clerkenwell Vestry, which came to a head in 1800–2 when Clerkenwell attempted to extract the poor rate from the residents, who took the matter to the quarter sessions and lost. The upshot was that the two parishes agreed a boundary running down the middle of Bagnigge Wells Road. (fn. 25) A ghost of the contested demarcation line survives in the uneven southern boundary of No. 146b King's Cross Road. Hamilton Row and Bagnigge Place soon passed out of the Hodgkinson family's hands. Joshua died in 1816 and his widow in 1823, following which Joshua Hodgkinson junior, scavenger, sold those houses he still owned. (fn. 26)

Always prone to flooding, the Fleet did so spectacularly in 1809 and 1818, when the whole area from the bottom of Penton Place to the Smallpox Hospital at Battle Bridge was flooded, and again in 1846. (fn. 27) The salubrity of the area was also compromised by a high concentration of activities such as bone-boiling, slaughtering and tanning, and poverty may be inferred from a high incidence of crime. In 1819 two residents of Hamilton Row were sentenced to death for sheep-stealing. (fn. 28)

When Bagnigge Place was put up for auction in 1827 it was snapped up by the New River Company, which already owned the adjacent land. But it was not until the early 1840s that the company was ready to develop this western portion of its extensive estate. The little houses were then demolished and the whole of the company's frontage to Bagnigge Wells Road built up with threestorey houses with shops, now all gone. (fn. 29)

By this time the frontage to the south, belonging to the Lloyd Baker family, had itself been built up. At the south end, the rebuilding of the Union Tavern in 1819–20 began the development of the Lloyd Baker estate generally. Within a couple of years the tile-maker George Randell, whose works still occupied part of the frontage as well as much of the immediate hinterland of Bagnigge Wells Road, entered into negotiations to build there. (fn. 30) Nothing came of this immediately because his lease had some years to run and he wanted an extension on part of the site. But between his ground and the Union Tavern work was already in progress by 1823 on a first group of houses, a terrace of four, extended to six by 1830, called Union Place. The builder was the pub's landlord, John Carr. (fn. 31) None of the houses survive—the present Albert House stands on the site of the southern two—but a seventh house which Carr added in the 1830s is still there (No. 4 King's Cross Road, see below and Ill. 397).

The only surviving plans to show what Lloyd Baker and his surveyor John Booth originally had in mind for Bagnigge Wells Road are for the central section—northwards of Union Place—which Randell was interested in developing. Dating from the early 1820s, they show seven houses in continuation of Union Place, and another seven (in one version ten) to the north, the two rows being separated by 'Lightfoot Street' leading into 'Sharp Square'. On the north and south sides of Lightfoot Street (subsequently Granville, now Gwynne, Place) are sites for two pairs of houses. (fn. 32) When the development of this central portion finally went ahead in the early 1830s, George and his partner John Randell elected to build only the southern terrace, and the two houses on the south side of Lightfoot Street. This three-storey terrace (eventually numbered 18–30 King's Cross Road) was a seven-house continuation of Union Place, and the building agreement, dated 1830, states that the houses should be in all respects similar to those already built by Carr. (fn. 33) Union Place was later renamed Union Terrace. None of these buildings survive.

Between Lightfoot Street and the northern boundary of the Lloyd Baker property two more terraces were built along the Bagnigge Wells Road frontage in 1831–2 (see Ill. 348 on page 266). These were King's Terrace, a row of seventeen houses later numbered 32–64 King's Cross Road, and, north of Wharton Street, Upper Terrace, later renamed King's Terrace North and from 1863 numbered 66–74 King's Cross Road. The greater part of King's Terrace survives (see Nos 44–64, below) but the original King's Terrace North was demolished in the 1860s for the Metropolitan Railway.

King's Cross Road and the Metropolitan Railway

From the early part of the nineteenth century Bagnigge Wells Road was sometimes referred to as Lower Road, Pentonville. In 1862 formal renaming was proposed by the Clerkenwell Vestry on the grounds that the old name was constantly misspelled on letters, leading to confusion. (fn. 34) With the completion of Farringdon Road then in prospect (see Survey of London, volume xlvi), there was a suggestion that its name should be applied to the whole of the way up to Pentonville Road. But in 1863 the Metropolitan Board of Works gave the new name King's Cross Road to Bagnigge Wells Road north of Lloyd Baker Street. The raft of subsidiary names, including on the Clerkenwell side Hamilton Row, Vernon Place, King's Terrace and Union Terrace, were abolished, and the whole street renumbered in odd and even sequences. (fn. 35)

In the early 1860s more than fifty houses on this side of the road were acquired for the construction, by cut-andcover, of the Metropolitan underground railway. (fn. 36) They included Nos 4–8 and 34–74, of which Nos 66–74 were demolished, to be rebuilt in 1874 following completion of the railway. The Lloyd Baker houses in Granville Place were among the other casualties. The railway has had a continuous adverse impact on King's Cross Road, for the inadequate backfilling over the lines—described in 1992 as 'spongey clay' (fn. 37) —has led to many houses having to be repaired or rebuilt.

Later history of Penton Rise and Weston Rise

In the early years, Penton Place had a number of artistic residents, including the clown Joseph Grimaldi in 1794–7, the watercolourist and engraver John Boyne in 1802–10, and from 1813 the artist and wood-engraver Luke Clennell. (fn. 38) Another artistic association was with a scenepainter at Covent Garden Theatre, Matthew Holligan, who as John Weston's son-in-law inherited the head leases on the Penton triangle between Penton Place (Penton Rise) and Bagnigge Wells (King's Cross) Road. He was, Penton's agent recorded in 1830, 'a wild fellow who has sold and squandered every thing leaving just enough to pay our ground rent and his agent's Commission of the Leases unsold'. Where he had sold leases, however, Holligan was apparently still collecting rent from the occupiers of the houses. He later died of apoplexy. (fn. 39) The social character of the street at this time is suggested by the fictional presence there in lodgings of William Guppy, the two-pounds-a-week law clerk in Bleak House, who boasts: 'It is lowly, but airy, open at the back, and considered one of the ealthiest outlets'.

392. King's Terrace, with the remains of Bagnigge House, Bagnigge Wells, in foreground, 1844

393. Nos 46–48 King's Cross Road (formerly part of King's Terrace), in 1952

As elsewhere on the Penton estate, industry was encroaching on the residential nature of the area by the later nineteenth century, and some of the long gardens of Penton Place and Weston Street were built over with workshops. One of the largest establishments was George Hopton & Co.'s timber works and mills, which spread behind Weston Street between the 1870s and the 1920s. This was a branch of their St Pancras Steam Wheel and Bent Timber Works in Manchester Street, Gray's Inn Road; the firm, founded in 1842, were contractors to the government and railways, and latterly supplied ash-wood for vehicle bodies. (fn. 40)

A number of leases eventually came into the hands of James Gordon Walls, a solicitor and developer, who built tenements on new leases in Pentonville Road and King's Cross Road. By 1887 Walls had been able to renew the leases of a substantial number of properties in and behind Weston Street, (fn. 41) but failed to advance all his plans for rebuilding. It was on Walls's sites there, and further Weston Street land, that a beer bottling and storage plant was built by Whitbreads about 1890. (fn. 42) This consisted of two large top-lit brick buildings of two storeys, running from York (Lorenzo) Street to Weston Street. (fn. 43) It swept away the whole of York Buildings and York Valley on the east side of York Street and so destroyed some wretched houses. But many of the larger houses in the area were in poor repair and multi-occupied by the late nineteenth century. In the 1890s Charles Booth's researchers found that No. 32 Penton Place was 'let to a thief' and the house used as a brothel. (fn. 44)

Both sides of Penton Rise were completely redeveloped in the twentieth century. On the east side, the south end was absorbed into the new Vernon Square School during the First World War, while the rest was overtaken in stages by the steel-stockholding depot of Macready's Metal Co. Ltd. In the mid-1930s Macready's built a warehouse at the corner of Pentonville Road and Penton Rise. A couple of the old houses to the south were destroyed by bombing in the war, and in 1955 work began on a large extension, which replaced those houses that remained. The new building, with a clock at the north end, where the wall was canted towards Pentonville Road, was faced in lightcoloured brick, artificial-stone render and matt blue tiling (Ill. 394). The architect was John K. Greed of Richmond. (fn. 45) This building and the rest of the works adjoining were demolished in 1993 and the site is now occupied by student residences. These and Macready's works generally are dealt with in Chapter XIV.

On the west side of Penton Rise a yet more drastic clearance took place in 1963, affecting the whole block between there and Weston Rise. The old houses, long in multi–occupation, were demolished by the London County Council for what was to become, under its successor the Greater London Council, the Weston Rise Estate.

King's Cross Road since the 1870s

King's Cross Road—a hell of noise and dust and dirt, with the County of London tramcars, and motor-lorries and heavy horse-drawn vans sweeping north and south in a vast clangour of iron thudding and grating on iron and granite, beneath the bedroom windows of a defenceless populace.

Though the details have changed, Arnold Bennett's evocation of King's Cross Road in the early 1920s (in Riceyman Steps) still strikes a chord today. The completion of Farringdon Road in the 1870s turned King's Cross Road into a major artery for City traffic. The horse-drawn trams of the London Street Tramways Co. arrived following the London Street Tramways (Extension) Act in 1885—albeit some locals protested that the way was, in places, too steep, too narrow, too sharply curved. (fn. 46) The London County Council's electric trams followed in 1909. (fn. 47)

The road's proximity to the great railway termini of King's Cross, Euston and St Pancras and its predominantly low-class character are reflected in the presence of hostels and model dwellings—Cobden Buildings (1865) and the former Mary Curzon Hostel (1913), both built on the site of Hamilton Row, and the huge now-demolished Rowton House on the St Pancras side (1894). A number of the older buildings survived as dingy shops and lodgings or business premises until after the Second World War, and something of this old character remains.

Air raids in the autumn of 1917 did much damage. The worst was on 24 September, when several houses were destroyed at the corner of King's Cross Road and Lorenzo Street (site of Nos 144–146), and others were damaged. (fn. 48) The Second World War, however, left the east side of the road almost unscathed. Long after the war, some of the housing here was still unmodernized and in poor repair. (fn. 49) An improvement in the street's commercial fortunes, at the expense of its old residential character, came with the building in 1970–3 of two large hotels—the London Ryan and the Royal Scot (now the Farringdon and Islington Travelodges).

King's Cross Road's shifting character since the war has, predictably, mirrored shifts in planning policy. In 1948 the screw manufacturers who owned Nos 144–146 were required to make use of a least one third of their premises as offices, light-industrial use not conforming with the London County Council's redevelopment plans. (fn. 50) By 1983, in contrast, proposals to convert warehouse and light-industrial buildings to offices were discouraged or refused, on the grounds that this was contrary to Islington's development plan not to lose commercial space and to the Greater London Council's policy to restrict office development. (fn. 51)

The 1970s and 1980s saw improvements in the remaining housing stock, much of it owned by Islington Council or housing associations, with the conversion of many multi-occupied houses to self-contained flats. (fn. 52) Although there has been a gradual shift, planning policy notwithstanding, away from light-industrial and warehouse to office use, there has been nothing like the degree of redevelopment seen further south in Clerkenwell from the 1980s. Nor, perhaps because of heavy traffic and proximity to King's Cross Station, long a locus for prostitution and latterly drug-dealing, has King's Cross Road undergone significant gentrification. There are, as yet, no 'loft apartments', and both Cobden Buildings and the former Mary Curzon Hostel are still used for almost exactly the same social-housing purposes for which they were built. But the insertion of a small but striking Deconstructionist office building at No. 178 in 2001–2, and the conversion of the magistrates' court to a hotel aimed at younger visitors in 2006–7 suggest that the avant garde of fashion may finally have arrived.

394. Warehouse and office extension, Penton Rise, for Macready's Metal Co. Ltd. John K. Greed, architect, 1955. Demolished

Individual streets and buildings: King's Cross Road

Union Tavern and Nos 2A and 2B

Rebuilt in 1877–8, the Union Tavern stands on a site occupied by licensed premises since the 1740s, when it was variously known as the Black Bull and the Bull in the Pound. Cromwell and Pinks describe it as a public house of 'vulgar fame' and 'low repute'. (fn. 53) Its name had been changed to the Union by 1807, presumably in response to the union of the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801. (fn. 54) The address, formerly No. 2 King's Cross Road, is now usually given as No. 52 Lloyd Baker Street.

In 1818, when William Lloyd Baker and his surveyor, John Booth, were planning the development of the Lloyd Baker estate, a publican called John Carr applied to take over and rebuild the tavern. Booth seized the opportunity both to set the building back, so as to improve the entrance to his intended new road there (Baker Street, later Lloyd Baker Street) and to provide a design which would make an impressive 'gateway' to the development, a foretaste of the fine architecture which Booth and his employer envisaged for the new streets and houses they were planning. Thus the rebuilding of the Union in 1819–20 effectively began the development of the Lloyd Baker estate. Carr spent about £2,000 on the building, more than he intended, but told Lloyd Baker's solicitor that he had no regrets. His confidence was seemingly well placed, for in 1821 the solicitor learned that Carr had been offered £5,000 for the premises, 'which is an enormous sum'. (fn. 55)

The new pub was basically L-shaped, two-storeys high, with a return to King's Cross Road and its main front on Lloyd Baker Street, where the central entrance was flanked by double-height bow windows (Ill. 395). The northern end of the King's Cross Road frontage comprised a brewhouse and a warehouse over stables and a coachhouse. In 1830 Carr leased some adjoining land to the east and north, where he laid out a yard and garden with a tea-room and a two-storey arcaded building, the upper storey of which is described in the lease as 'fitted up for a club room', and in the ratebooks as a 'music room' or 'assembly room'. (fn. 56) Later, probably in the 1840s, the Union was the venue for song-and-dance concerts, including black-faced minstrels. (fn. 57)

395. Union Tavern, Bagnigge Wells Road, c. 1850. Rebuilt

396. Union Tavern, and Nos 2a—b King's Cross Road, in 2006

397. Nos 2a and 2b, 4 and 6 King's Cross Road (right to left) in 2006

In 1865 the gardens and the various buildings there were destroyed for the Metropolitan Railway. It seems to have been because of damage caused by the railway works that the tavern itself was rebuilt, in 1877–8, for the landlord Frederick Guyer. (fn. 58) His architect was John Viney, a prolific pub specialist, and the builders were Atherton & Latta. Viney originally wanted to bring the front of the new building up to the edge of the freehold on Lloyd Baker Street, but this was at first refused. The revised design featured square bays which although wider than the earlier bows were allowed because Guyer gave part of the ground to be added to the public footpath. (fn. 59) The elevations are in the mixed Italianate and Gothic idiom common at that time, with a granite base giving way to brick upper storeys (Ill. 396). The present fittings, including etched- and cut-glass screens, and decorative wrought ironwork, probably date from 1891–2 when a saloon bar was created. (fn. 60)

398, 399. Travelodge Farringdon hotel, King's Cross Road, in 2006 (left), and view through hotel arch towards Gwynne Place and 'Riceyman Steps', in 2007. Michael Blampied & Partners, architects, 1971–3

As part of the 1870s rebuilding, the 1820s brewhouse and stables were replaced by shops, Nos 2a and 2b, in similar style to the tavern but plainer (Ill. 397). (fn. 61) The upper parts of both buildings were converted to flats in 1976, when a third floor was added to No. 2a. (fn. 62)

No. 4

Squeezed between later and taller buildings, this plain brick-fronted house is the only surviving vestige of John Carr's development (see above and Ill. 397). It was added by him to the south end of what was then Union Place (later part of Union Terrace), and first rated in 1838. A requirement of the lease was that the building should 'correspond to the houses already built adjoining northwest'. The shopfront is a later insertion. (fn. 63)

Nos 6–8, Albert House

Albert House was built as flats in 1913 for the Metropolitan Railway Surplus Lands Committee. (fn. 64) Of four storeys, with a shop either side of the central entrance and three pairs of windows on each of the upper floors, it is fronted in stock brick with red-brick dressings (Ill. 397). The doorway is of green glazed brick with a pedimented Classical surround, incorporating the building's name and date. The flats eventually came into the ownership of Islington Borough Council, whose Architect's Department updated them in 1987–8. (fn. 65)

Nos 10–42, Travelodge Farringdon hotel

Built in 1971–3 as the 209-room London Ryan Hotel, this occupies the sites of houses in the former Union Terrace and King's Terrace and of St Philip's Sunday School. It was designed by Michael Blampied & Partners. (fn. 66) The shallow site determined a simple plan of rooms leading off a spine corridor on the bedroom floors. The long frontage is broken by the double-height arch leading through to Gwynne Place and the steps up to Granville Square, famous as Arnold Bennett's 'Riceyman Steps' (Ills 398, 399). Regrettably the developer was allowed to extend the building over the roadway leading to the steps, spoiling the historic streetscape. Nonetheless the hotel's plain brown brickwork, multiple windows and shallow concrete arches in the manner of Basil Spence provide an impressive sweep of frontage to King's Cross Road.

Nos 44–64

These eleven houses are the surviving portion of King's Terrace, a row of seventeen erected in 1831–2 on Lloyd Baker leases by the building partnership of Edward Garland and Philip William Perkins (Ills 392, 393). Perkins was the lessee of Nos 56–64 and Garland (at Perkins's direction) of Nos 44–54. (fn. 67) Occupying the whole frontage between the former Granville Place and Wharton Street, King's Terrace was designed as a symmetrical range of three storeys over a basement and was topped with a bracketed cornice, which survives only at Nos 52–58 and 62. The three central houses broke forward slightly, and originally carried a raised parapet incised with the name King's Terrace. They had single, segmentheaded windows on the upper floors. (fn. 68) The ends were intended likewise to project and have different fenestration, but were not finished exactly to this plan. (fn. 69) All the houses, like many buildings adjacent to the Metropolitan Railway, have suffered structural damage and some have been completely rebuilt, No. 60 in a utilitarian neoGeorgian manner that pays little heed to the design of the rest. (fn. 70)

Nos 66–74

Between Wharton Street and the Lloyd Baker estate boundary the frontage was originally developed in 1831–2 by Philip William Perkins, who built a row of seven three–storey houses at first called Upper Terrace and then King's Terrace North. (fn. 71) Doubtless similar in appearance to Perkins' surviving houses in King's Terrace, they were all demolished for the Metropolitan Railway in 1865. The present five houses, of three storeys with steeply canted bays to the ground floors, were erected in 1874 under leases from the railway company, like the similar houses at the western ends of Wharton and Lloyd Baker Streets. The builders were Walter William Wheeler, Arthur Mazzini Wheeler and William Warren of Notting Hill; No. 66 may have been the work of John Ambrose of King's Cross Road. They seem to have been let in tenements from the beginning. (fn. 72)

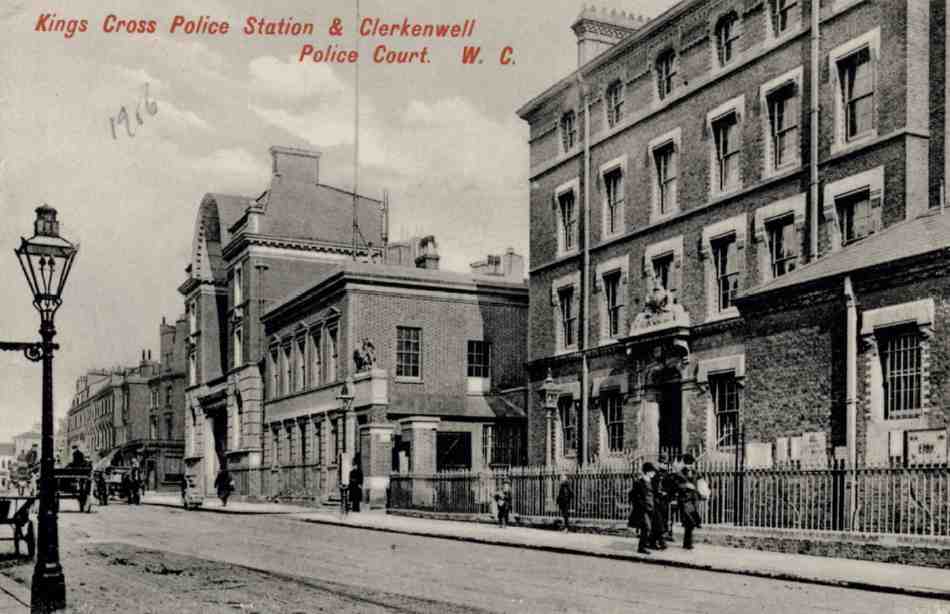

Nos 76 and 78, formerly King's Cross Police Station and Clerkenwell Magistrates' Court

Of the original early 1840s police station and police court on this site only the front portion of the court building survives. This is flanked by a replacement police station of the late 1860s, to the south, and a new court-house of 1903–6 (Ills 400, 401). Both court buildings were being converted into a hotel at the time of writing (2007), while the police station was still in use for operational work. (fn. 73)

'G' division of the Metropolitan Police, covering the parish of Clerkenwell, was created in 1830, its first station being in the old watch-house in Rosoman Street. (fn. 74) In October 1840 the Metropolitan Police Office acquired from the New River Company a building plot on Bagnigge Wells Road, backing on to Percy Yard, for a court and station house, to be enclosed by a high perimeter wall. Initial plans for constables' houses as well, facing Great Percy Street, were soon abandoned. (fn. 75) The station was under construction by February 1841, and the court, one of a number of magistrates' courts reconstituted as police courts in 1839, transferred to its new building here from Hatton Garden in December 1842. (fn. 76)

400. King's Cross Road looking north, c. 1906. King's Cross Police Station (right) and Clerkenwell Police Court (later magistrates' court)

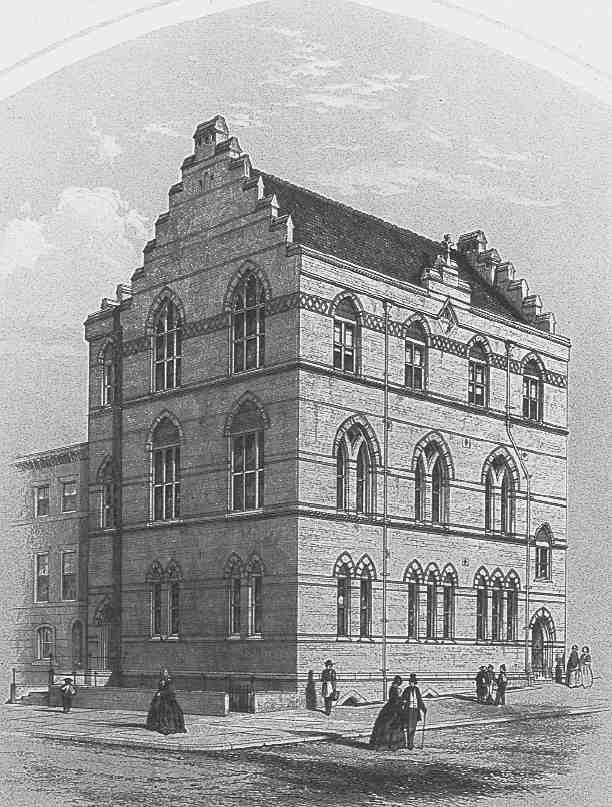

401. The former Clerkenwell Magistrates Court in 2007. John Dixon Butler, architect, 1903–6

It has been suggested that the architect of this ensemble was Charles Reeves, surveyor to the Metropolitan Police, but as he did not take up his position till 1842 that is questionable. (fn. 77) Both parts of the building, arranged either side of a severe-looking archway leading to a yard, were of two storeys over a basement, faced in stock brick with stuccoed ground and lower floors. The surviving court building, five windows wide, has pediments over alternate windows on the first floor. The right-hand doorway has been converted to a window and is surmounted by a carved stone coat of arms originally over the yard entrance. This change was probably made when the adjoining police station was rebuilt. The doorway originally opened into a passage leading to the public office at the back of the building and beyond that to the 'handsome, airy, wainscotted' court-room itself (Ill. 402). (fn. 78)

The police station lasted barely twenty-five years, the site being taken for the building of the Metropolitan Railway in the 1860s. With that complete, the site was bought back and a much larger station built in 1868–70 to the designs of the police surveyor T. C. Sorby, with Lathey Brothers as contractors. The cell block was taken into use in October 1869 and the whole station opened in January 1870. This housed 96 constables under two inspectors and two superintendents. (fn. 79)

Four storeys high over a basement, the building is of stock brick with Portland and Tilbury stone dressings. The austere Italianate front is of six bays, the main entrance with a heavy stone surround rising to a bracketed cornice and royal coat of arms with supporters. In its original form this entrance opened straight into a large room occupying half of the front. A larger room behind was reached from a central corridor leading straight through to the rear yard, which extended round both sides of the building to double gates either side, opening on to the street. The low block to the right (a condition of the sale of the land by the Metropolitan Railway was that buildings directly over their tunnel should only be of one storey) originally comprised eight cells. Its front section breaks forward and was added later, probably when alterations were made to the station in 1889. (fn. 80)

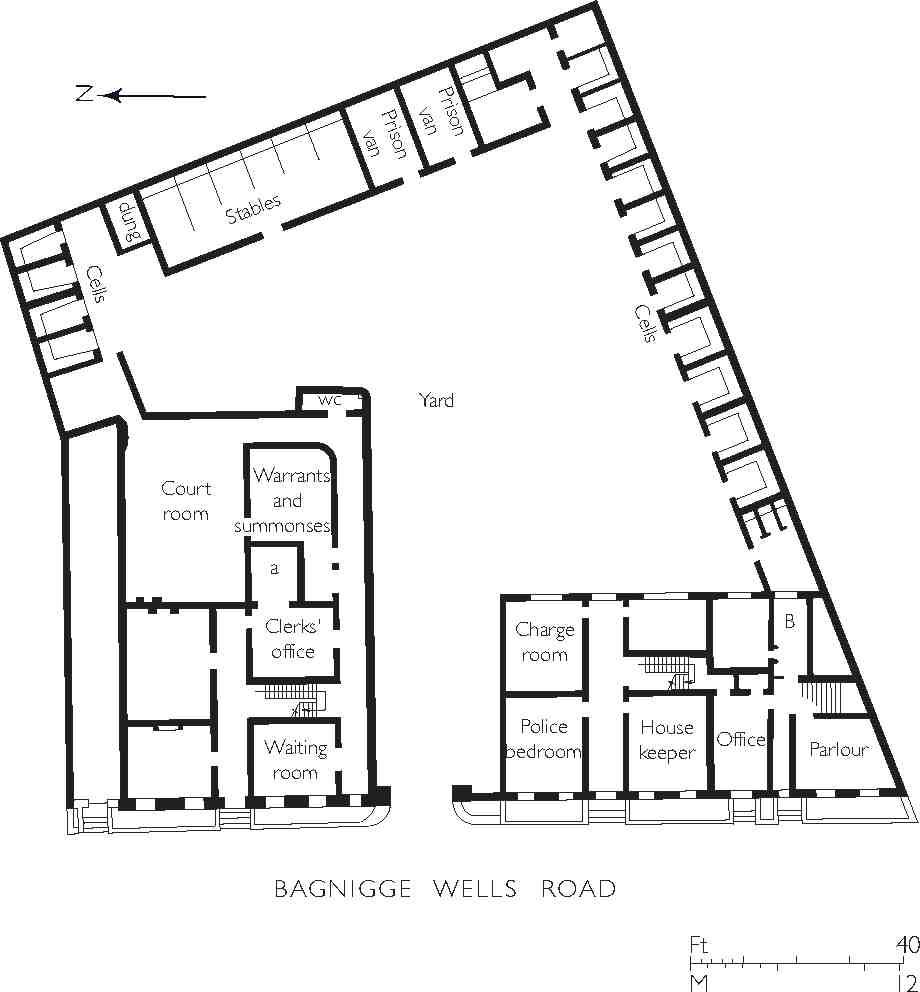

402. Clerkenwell Police Court and Police Station, Bagnigge Wells Road, ground plan, 1840s

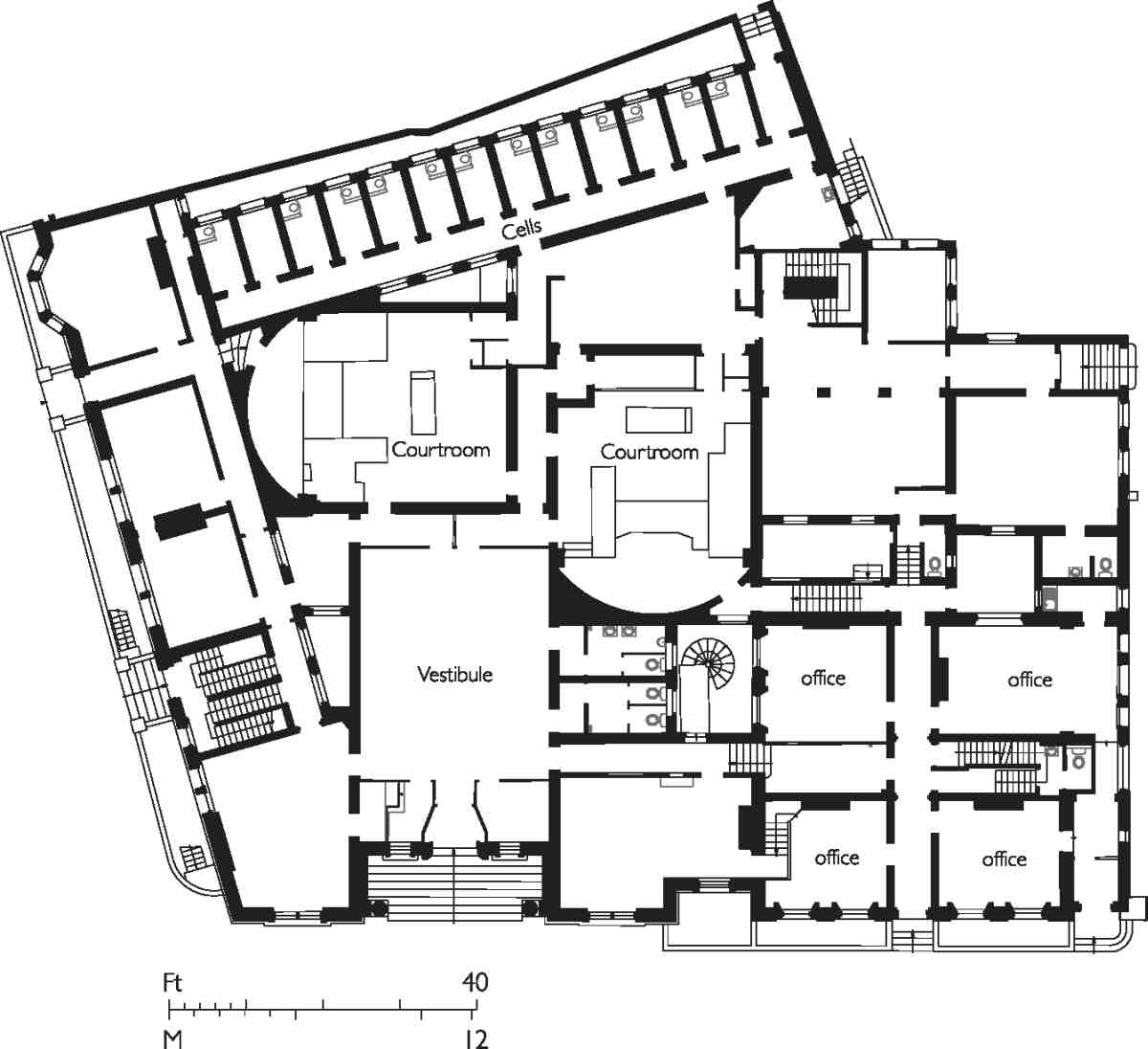

403. Clerkenwell Magistrates' Court, ground plan before conversion to hotel, 2001

The front of the old court, though not the rear, also survived the arrival of the new Clerkenwell police court alongside in 1903–6. (fn. 81) The architect of this was John Dixon Butler, surveyor to the Metropolitan Police since 1895. Butler admired Norman Shaw and worked with him on the extension of New Scotland Yard in 1904–6, at the same time as he was working here. His own manner has been described as 'a crisp austere version of the prevalent Free Classic or Anglo-Classic—the civic style doffing its regalia and donning a uniform'. (fn. 82) The Clerkenwell court is more formal and monumental than some of his work. The front has a giant semi-circular Portland-stone pediment supported by oversized brackets, above a shallow recessed bow flanked by bays of fine orange brickwork. The rising return along Great Percy Street is plainer and more domestic in scale, though with a touch of fin de siècle brio in the oversized swooping brackets of the two secondary entrances, a feature of several other Butler police courts.

The new building contained two court-rooms, and the old building, partially reconstructed, provided some of the ancillary accommodation (Ill. 403). There were two sets of magistrates' rooms, while the two upper floors facing King's Cross Road and Great Percy Street were taken up with offices. The quality of finish was high: the entrance hall had a decorative mosaic floor, featuring the Metropolitan Police crest, and stained-glass rooflights. (fn. 83)

In April 1939 Butler's successor G. Mackenzie Trench prepared plans to replace the 1870 station entirely with a new subdivisional police station on the site, but the war put paid to this scheme. (fn. 84) Other proposals for expanding the accommodation were abandoned because of cost, though Percy Yard was acquired. Entered via an archway on Great Percy Street through the 1906 court building, it was never used for much apart from parking. (fn. 85) Decades later, larger premises were obtained in the form of the new Islington police station in Tolpuddle Street of 1990–2 (see page 404). Since then, King's Cross police station has been used for stabling police horses and as a traffic-warden centre, and has in recent years been used in connection with the anti-vice, drugs and street-crime initiative, Operation Welwyn. (fn. 86)

The inadequacy of accommodation at the station was matched at the court-house. As early as the 1950s it had been suggested that two court-rooms were not enough, but apart from minor alterations in 1988 little was done. (fn. 87) By the late 1990s, with a staff of forty, the need for more space was overwhelming. (fn. 88) The courts last sat there in 1998, before transferring to Highbury Corner magistrates' court. In 2005 listed building consent was granted to Pebblevale Ltd for the conversion of the court to a 99-bedroom hotel, following the sale of the building as part of an estates rationalization by the newly created Greater London Magistrates Courts Authority. (fn. 89) The alterations have been designed by the architects ARP (Anthony Richardson & Partners). Boon Brown are the executive architects, and Kier Wallis the main contractors. The work includes the demolition of seven of the 14 holding cells to the rear, alongside Percy Lane (the approach to Percy Yard) and the building of a three-storey extension on their site. Two new stair towers are also to be erected at the rear. The two court-rooms are intended to be used as an internet room and residents' lounge. (fn. 90)

No. 100, Travelodge Islington hotel

The New River Company's frontage on Bagnigge Wells Road between Great Percy Street and Vernon Street (now Vernon Rise) was built up as Vernon Place in 1842–6. (fn. 91) Redevelopment schemes were drawn up in the 1960s for flats and shops, or a hall of residence, but in 1970–2 a hotel was built instead. Trevor Burfield's Centremoor Ltd were the developers, Trehearne & Norman, Preston & Partners the architects and John Laing the main contractors. Operated by Scottish and Newcastle Breweries, the 349-bed tourist hotel was called the Royal Scot. (fn. 92) It extended back along Vernon Rise and Great Percy Street to occupy the whole of the block up to Percy Circus, the frontage to which is in a half-hearted Georgian pastiche (see Chapter IX). The walls are of brown brick, supporting concrete slab floors, with four-storey projecting window-bays of brown and clear glass. There was a mezzanine bar and first-floor restaurant, while the fifth floor was largely given over to meeting rooms. The reception originally featured vinyl-faced panels and an illuminated ceiling, and the basement a hairdressing salon, with a shopfront and entrance at ground-floor level added in 1973. In 1987 the entrance front was altered and extended to the designs of Jeffrey Chappell, who subsequently designed a minor single-storey extension behind the front block. The building is now part of the Travelodge chain. (fn. 93)

Nos 112–126

These buildings occupy part of the large triangular site leased in 1786 by Henry Penton to the brickmaker John Weston. On the expiry of the old lease in 1885, a new 60-year building lease for ten houses was granted to Thomas Livesey Wardle. (fn. 94) In the event only eight houses were built, under a revised agreement, probably with the involvement of Wardle's mortgagee James Gordon Walls; they were completed (by Henry Ockenden, builder), in 1886. (fn. 95)

The buildings are each of three storeys over shop and basement, the first floor with round-headed windows, the second straight, and the third a mansard (Ill. 404). They were damaged in the air raids of 1917. (fn. 96) No. 112, on the corner of Weston Street, was extended in 1983–7 with a single-storey octagonal restaurant, built of wood and glass in the manner of a Victorian conservatory to the designs of Michael Businelli. At the same time the upper parts of Nos 112–120 were converted into bedsits with a threestorey brick entrance and extension fronting Weston Rise. The upper parts of Nos 124–126 were also converted to self-contained flats in 1996. (fn. 97)

404. Nos 112–126 King's Cross Road (right to left), in 2007

Nos 128–138, Cobden Buildings

Cobden Buildings were built in 1864–5 and named after the reformer Richard Cobden who died the year they were completed. This was one of the first blocks built by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Co., which developed a reputation for providing model dwellings which satisfied both tenants and investors. (fn. 98) It was probably designed by the builder Matthew Allen, with input from the first chairman, Sir Sydney Waterlow. (fn. 99)

405. Cobden Buildings, King's Cross Road, built by the Improved Industrial Dwellings Co., 1864–5. A contemporary view

The building is of five storeys with two window bays on either side of open access balconies and a central staircase, with (originally) exposed constructional ironwork (Ill. 405). The ground floor housed a shop to each side (Nos 128 and 132), the facias of which survive. (fn. 100) The plans followed the standard arrangement first used by the company at Langbourne Buildings, Finsbury, with four flats on each floor (two of three rooms and two of two), and well-ventilated wash-houses and sculleries at the back of each flat.

In 1870 the building was mortgaged to the Public Works Loan Commissioners (the legislation to enable such loans had been suggested by Waterlow) to finance the building of Derby Lodge in Britannia Street, on the St Pancras side of the road. (fn. 101) The shops were converted to living accommodation some time before 1913. (fn. 102) Among alterations made in 1979–81 for Circle 33 Housing, the iron columns on the balconies were encased in brickwork, and concrete beams were inserted in front of the iron joists. Further work for Circle 33 in 2000 included raising the balcony balustrades, the insertion of a lift and the creation of a glazed lobby on the ground floor. (fn. 103)

Nos 140–142

This five-storey office block is largely of 1991 but incorporates the front and side elevations of a tenement building of 1888. The site, together with that of old houses at Nos 112–126, was leased for redevelopment to Thomas Livesey Wardle of York in 1885. Wardle mortgaged the properties to the solicitor James Gordon Walls and others, and it seems to have been for Walls, who had acquired much property in the vicinity, that the building was erected. Stylistically it is very similar to Walls's tenements at Nos 233–239 Pentonville Road (q.v.), and so probably by the same architect, W. Youlle. It seems to have been built by the same contractor too, James Hunt of St John Street. (fn. 104) The building was faced in stock brick with rubbed red-brick dressings and some render, now painted white. The ground floor was occupied by two shops, the floors above each comprising four rooms and a WC. (fn. 105) The shopfronts had shallow canted bays, since removed. On the Lorenzo Street side are two terracotta panels spelling out 'AD 1888'.

Redevelopment as offices, by Raffoul Darrer Architects for Halkoutsi Overseas Ltd, was completed in 1991. This project included the redevelopment of No. 140a, where a workshop built about 1890 in connection with Cobden Buildings had been demolished some years before. (fn. 106) Of the 1888 building, only the front, side and a small portion of the rear elevation were retained, along with a singlestorey building behind used previously as an office and billiard hall. On the site of No. 140a the new façade follows the style of the main building. A vaguely postmodern triangular projection housing lifts and stairs, lit by a column of glass bricks and circular windows on each floor, was added to the rear.

Nos 144–146

Built in two stages in 1922–34, this is the third generation of buildings on the site. The two previous buildings, replacing the original houses of the 1790s, were largely destroyed in the air raids of 1917. (fn. 107) Of these, No. 144 was a substantial property, consisting of four floors of tenements over shops, erected by James Hunt in 1894, probably for James Gordon Walls. (fn. 108) The original No. 146 seems to have been rebuilt in the nineteenth century as a warehouse; behind it a two-storey warehouse had been inserted in the late 1880s. (fn. 109)

In September 1917 Nos 144 and 146 were wrecked in a raid by Gotha bombers. (fn. 110) They were reinstated in 1922 as premises for the sausage makers Palethorpes. Stanley Blount, the architect, was able to re-use the shopfront and part of the flooring of No. 144. As reconstructed, the building comprised a flat-roofed single-storey warehouse and office, with a garage on the site of No. 146. (fn. 111) Space was left for a staircase with a view to another floor, which was added in 1934. The architect for this was Frederick White, a pupil of A. Saxon Snell. (fn. 112) White's work is in red brick, with round-headed windows and a low, stepped pediment to King's Cross Road, where the date 1934 appears on a keystone. In 1949–50 the building was altered by T. Bedford, architect, who replaced the old shopfront with cream tiling and narrow strips of glazing, also adding a modish glass-brick surround (removed in the 1990s) to the new central main door. These works were done for Muller & Co. (England) Ltd, manufacturers of precision screws, who were there for more than 30 years. The building is currently known as Icis House. (fn. 113)

St Chad's Court, No 146

This unusual two-storey office building, approached by gates between Nos 144–146 and 148 and all but invisible from King's Cross Road, occupies a wedge-shaped site. Its southern edge follows the irregular northern boundary of Bagnigge Wash and of St Pancras parish, as defined by St Pancras Vestry in the late eighteenth century, while the forecourt perpetuates the entrance to Hamilton Court, a small court created here in the 1790s. (fn. 114) The present building stands on the site of a house in the court replaced by or incorporated into a two-storey workshop around 1890. From 1912 the premises were used by the Islington and North London Shoe Black Brigade, one of several such bodies founded in the 1850s that gave employment and accommodation to 'necessitous or crippled lads or men'. (fn. 115) It was later a metal-plating works. (fn. 116) The building was converted into offices in 1985–7 to the designs of CZWG Architects for the builder Mike di Marco. Red-painted steel gates now give access to the narrow forecourt and entrance door. A single-storey triangular entrance lobby opens into a double-height reception area, which was partially re-roofed. There are two open-plan floors joined by a spiral staircase in the reception. At the far end an art deco-style steel and glass door at first-floor level opens on to a small balcony, with steps down to the yard. (fn. 117)

No. 148

Another office building, this replaced what was probably the last surviving house of Joshua Hodgkinson's Hamilton Row (Ill. 406). (fn. 118) The old house was used by a rag and bone dealer and cat's-meat supplier in 1912, when it was described as 'dilapidated and almost derelict'. (fn. 119) In 1994 permission to demolish was given to Eddison Sadd, publishers, and by 1996 they had built in its place a four-storey office and studio building to the designs of Ken J. Humphries, architect, with Firmco as contractors. (fn. 120) A building in the postmodern manner, it has round-topped windows and a glazed double-height door surround, and red-brick walls toning in with Nos 150–156 adjacent. The top half of the façade is clad in light buff compositesteel-faced panels, originally intended to wrap round the side much further than they do; the hipped roof with round-topped dormers is clad in light-grey profiled metal sheeting.

406. No. 148 King's Cross Road in 1995. Demolished

Nos 150–162

Built in 1902–3, the building at Nos 150–156 was probably the speculation of J. J. Connelly, lessee of Nos 172–176. It originally comprised shops with rooms above, Nos 154 and 156 having goods hoists and winches. The façade is mildly ambitious, tricked out with shaped gables executed in rubbed brick with stone dressings. Large arched openings encompass both ground and first floors. It is now converted to offices and united with No. 158, one of a row of four houses with shops dating from the mid-nineteenth century, of which one (No. 164) has been demolished. (fn. 121)

Nos 164–70, formerly Mary Curzon Hostel for Women

The former Mary Curzon Hostel for Women was purpose-built in 1912–13 and is a rare survival of such a building still essentially fulfilling its original function (Ill. 407). It was built for a board of trustees—a diverse group that included Consuelo, Duchess of Marlborough, the Hon. Charles Russell and the Salvation Army's General Booth—at the expense of Lord Curzon, in memory of his wife Mary (d.1906). (fn. 122) The years immediately preceding the First World War saw a flurry of activity in building women's hostels, both for the outright poor and for the increased numbers of urban working-women since the turn of the century. A spur to this was the founding in 1909 of the National Association for Women's LodgingHomes, a principal figure in which was the social reformer Mary Higgs. Her personal account of passing as a tramp in order to assess the conditions faced by female vagrants in poor wards, published in 1906 as Glimpses into the Abyss, had drawn dramatic attention to the shortcomings of existing facilities.

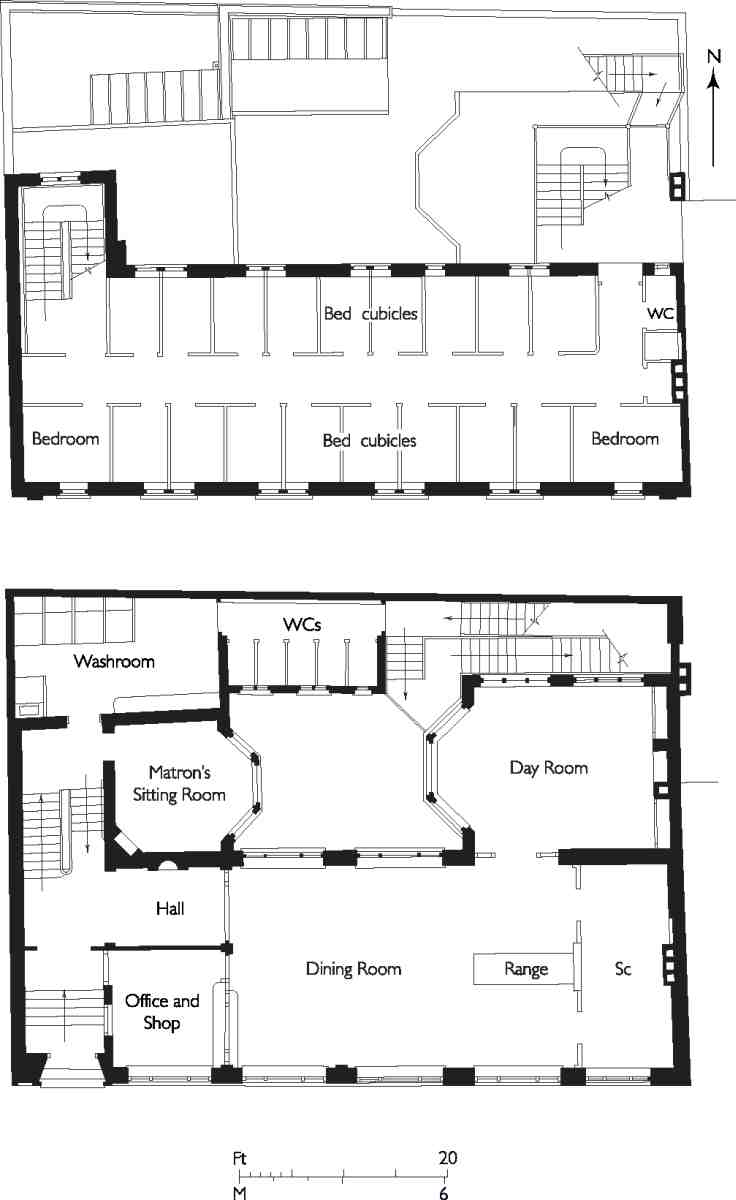

The architects of the new hostel were Lovegrove & Papworth, and the contractors J. Grover & Son. (fn. 123) Behind shops on the ground floor were an office, dining-room with range, and reading-room (Ill. 408). These were all lined in light-brown or deep-red tiles, while the main stair sported cream tiles. In the semi-basement were baths, a laundry, a pram store, and WCs in a top-lit rear annexe. Each upper floor contained narrow cubicles ranged on either side of a corridor, and two larger rooms for mothers with babies. It could accommodate 55 women 'of the respectable poor class'—49 single, plus six with babies. (fn. 124) Rates were 6d a night or 2s 6d a week, 2d for breakfast and 4d for dinner. (fn. 125)

407. King's Cross Road looking north in 2007. Right to left: former Mary Curzon Hostel for Women, Nos 172–176, and the former Welsh Tabernacle

At the formal opening by Queen Alexandra on 22 November 1913, Lord Curzon expressed the hope that it would be 'a haven at night, and a home of rest by day'. The Duchess of Marlborough saw it as the first of many the trust would build. This it was not, but in the following February the trustees licensed a second hostel at Green Street (now Roman Road), Bethnal Green. (fn. 126) Another opened at Hoxton in 1931. (fn. 127)

In 1932 the cubicles were substantially altered to form separate bedrooms as the lack of privacy was no longer acceptable. By then the residents were 'businesswomen' or 'girls employed in offices' rather than the homeless. It was probably at this time that an extra bathroom was added off the main staircase. (fn. 128) In 1941 the ground floor and basement were in use as a restaurant by the Londoners Meals Service. (fn. 129) In 1947 the London County Council took over the restaurant and leased the upper parts of the building, which had been empty for some time, as an emergency hostel for women made homeless during the war. (fn. 130) Having acquired the freehold in 1955, the LCC changed the name (a condition of sale made by the Curzon trustees) to the Susan Lawrence Hostel (after the socialist LCC member and MP). (fn. 131) More recently, the former dining-room has been converted into offices. (fn. 132) Since the abolition of the Greater London Council, the building has been run by Islington Council as the Susan Lawrence Reception Centre for women.

Nos 172–176

This two-storey building was erected as an office, workshops and stabling in 1899–1900, and was subsequently let on long lease to J. J. Connelly, who was probably the builder. It has a façade of blue engineering and red brick (all now painted over), with attenuated piers and moulded floral and other decorations (Ill. 407). (fn. 133) The left-hand bay originally had a door giving cart access to a horse ramp up to the first floor, replaced with steps and a lift in 1907. (fn. 134) The building was refurbished in 1987–90 as offices for the present occupiers, Community Service Volunteers. (fn. 135)

Nos 178–188 (and Nos 249–253 Pentonville Road)

408. Mary Curzon Hostel for Women, ground- and first-floor plans. Lovegrove & Papworth, architects, 1912–13

These numbers cover the triangular block west of the former Welsh Tabernacle (described in Chapter XIV), with frontages to Pentonville Road and King's Cross Road. Most of it consists of a building erected as shops, tenements and warehousing in 1883 by George Ell, his own development. (fn. 136) This is very plain, in stock brick with red-brick-headed windows. The shops in Pentonville Road were occupied for most of the first half of the twentieth century by the Dairy Outfit Co. Ltd, traces of whose painted sign remain on the King's Cross Road frontage. The easternmost part (No. 178), lower in height with a steeply sloping roof, comprised workshops or stores with hoists to the upper floors, and a lower timber shed. This was replaced in 2001–2 with a strenuously modish office building by Satellite Design Workshop, architects. (fn. 137) The adjoining buildings were altered and internally remodelled as part of the same project, called The Cross. On the King's Cross Road front the ground and first floors of the retained façade were partially reconstructed to replace two doors with windows. The new building, most obviously bringing to mind the work of Daniel Libeskind, is irregular in almost every plane, the front tilting in slightly above first-floor level, while the side elevation doglegs inwards, following the line of the demolished warehouse (Ill. 409). It is clad in stainless-steel sheeting which wraps round the front and roof. Through the structure runs a bright red service shaft, which emerges from a glazed box on the roof. In the retained building an irregularly faceted structure erupts at roof level in a simple glass-box boardroom.

409. The Cross, King's Cross Road. Entrance block at Nos 178–188 in 2007. Satellite Design Workshop, architects, 2001–2

Gwynne Place

Gwynne Place is named after Nell Gwynne, who was supposed to have lived on the site of Bagnigge Wells opposite. Until 1936 it was called Granville Place, and before that, in the 1830s, Lightfoot Street, both names being associated with the Lloyd Bakers, the freeholders. Today it is little more than a way through the Travelodge Farringdon to 'Riceyman Steps' and Granville Square; either side of its short length is taken up with entrances to car parks for the hotel. Only one building survives from previous developments (Ills 410, 411).

Gwynne Place first appears on John Booth's earliest plan of proposed building on the Lloyd Baker estate, of 1819, as the middle of three streets connecting Bagnigge Wells Road with what was to become Granville Square (see Chapter XI). The site was then still part of the Randell tile-works, and the excavations for clay and subsequent backfilling left their own legacy. When development did take place the square was larger than at first planned and Lightfoot Street correspondingly shorter, while the steep drop in ground level required the building of steps to link the two.

The first buildings in the new street were a pair of three-storey houses built on the south side in the 1830s by George and John Randell at the same time as their Union Terrace development; these became Nos 1 and 2 Granville Place. (fn. 138) The steps had not then been constructed. They were built, with vaults beneath, in the early 1840s by the builders of the western half of Granville Square, Benjamin Slipper and Joseph Cornick. Slipper and Cornick also found room for two low, flat-roofed tenements on either side of the steps, as adjuncts to Nos 32 and 33 in the square. (fn. 139)

The planning of this part of the Lloyd Baker estate, with the conjunction of Granville Square, Granville Place, Bagnigge Wells Road, Wharton Street and Baker Street, created spacious L-shaped backlands accessible from Granville Place. Over the years these have been used for stabling, crafts and light industry, garaging and parking. William Broder, a builder's merchant, arrived in 1843 and in 1848 built stables in Granville Place; at the same time he was building houses in Albion Street, Islington. (fn. 140) Residents in Granville Place in the 1840s and 1850s included a solicitor, and George and John Randell. By 1845 No. 4 Granville Place had been built on the north side and No. 5 next to it by 1860. (fn. 141)

All these buildings fronting or leading from Granville Place were demolished in 1865 for the Metropolitan Railway, and the site remained empty and neglected for more than 10 years. When rebuilding began in 1873, the open character of Granville Steps and Place was altered irrevocably by the building by Charles Ardon Kellond of Nos 33 and 34 Granville Square on the site of the tenements that had previously flanked the steps. (fn. 142)

In 1875 a new school for St Philip's Church was built on the north side of Granville Place, in connection with St Philip's, Granville Square. A modest Gothic-style building by Walter E. MacCarthy, architect, it fronted King's Cross Road. It was built in place of an intended larger National School building for the same site, designed by R. J. Withers in 1864 (Ill. 412). The school closed about 1924 and was demolished. (fn. 143) Opposite the school, on the site of the 1830s houses at Nos 1 and 2 Granville Place, two three-storey terraced houses were erected in 1876–7, with a yard and stabling adjoining (No. 1A). Nos 1 and 1A, and later No. 2 also, were occupied as a printer's joiner's workshop and from the 1920s as a haulier's, when most of the yard was covered over. Parts were let as workshops to shopfitters and flooring contractors. (fn. 144)

410, 411. Granville Place and St Philip's Church, Granville Square. Left: view c. 1860, showing flat-roofed tenements of 1841–2 flanking the steps. Above: view in 1924, after rebuilding. On the far left is St Philip's Sunday School, of 1875, and to the right Nos 1 and 2 Granville Place of 1876–7 and the double-fronted No. 30 King's Cross Road, c. 1830. Demolished

On the north side of Granville Place, the Metropolitan Railway had not entirely been covered over, leaving part of the cutting and a signal box. On the yard adjoining, a small factory was built between Nos 38 and 38a Granville Square, at No. 4 Granville Place. (fn. 145) No. 3 Granville Place, a four-storey tenement house, was built about 1880 to the west of the yard. (fn. 146) From about 1919 Nos 3 and 4 comprised the Granville Works, occupied for many years by businesses concerned with footwear or footcare. (fn. 147) In 1924–5 the premises were rebuilt following a fire, and it was probably then that the present two-storey structure at No. 3, a factory with a red-brick front and stone or cement cornice, was erected or adapted from the old house. (fn. 148) In 1927–8 the yard was roofed over for the Scholl Manufacturing Co. Ltd. (fn. 149) It has since been cleared and left as an open yard.

412. St Philip's National School, King's Cross Road. Unexecuted design by R. J. Withers, architect, 1864

413. Nos 20–22 Vernon Square (right to left) in 1912. Demolished

Vernon Square and Vernon Rise

Vernon Square, laid out in the early 1840s, is one of London's lesser squares, hardly a square at all. Its name derives from Robert Vernon (formerly Vernon Smith), a politician, the son of the New River Company Governor, Robert Percy Smith. (fn. 150) Facing a busy road junction it is easily missed, comprising essentially a paved forecourt to King's Cross Baptist Church. Though once railed and grassed as a public garden, it has never been much more than this. W. C. Mylne's incoherent layout of this corner of the New River Estate reads as what it was, residual tidying up at the tail end of a thirty-year development campaign (Ill. 385, and see Ill. 280 on page 219).

The area east of Vernon Square and north of Percy Circus, also part of the New River Company estate, was developed in 1844–50 as Percy Square. This was not a square at all, but a crooked cul-de-sac of variously grouped single- and double-fronted houses (Ill. 413). Building here was carried out by William Pilbeam, John Barnes and James Kent Vote, for James Rhodes who had taken over an agreement originally made by Pilbeam. (fn. 151) Percy Square was re-designated part of Vernon Square in 1906, only to be obliterated in 1913 for the construction of Vernon Square School.

Of Vernon Rise (Vernon Street until 1936) there is little to be said. On the north side three houses of 1844–6, built by William Watkins, were bombed in the Second World War. The present No. 9 is dealt with under Percy Circus in Chapter IX and No. 5 under King's Cross Baptist Church below. The south side was developed by William Greenwood in 1842–3, and is now occupied by one side of the former Royal Scot Hotel (see Travelodge Islington, above). (fn. 152)

King's Cross Baptist Church

This church, formerly called Vernon Baptist Chapel, was built in 1843–4 by the Rev. Owen Clarke, Secretary to the British and Foreign Temperance Society. The New River Company granted him the whole of the principal side of Vernon Square for it and flanking houses. Clarke undertook to make the houses like those already on Vernon Street (now Vernon Rise), and the chapel Gothic, 'so disposed as to harmonise as far as practicable with the buildings near it'. It is unclear to whom Clarke turned for his designs. It may have been to his builder, William Smith of White Lion Street, Pentonville—perhaps the same William Smith who had worked elsewhere on the New River estate in the 1820s calling himself a surveyor. Or James Harrison, the surveyor who in 1843–4 was active at Holford Square (see page 229), and had contact with Clarke, may have been involved. (fn. 153)

After Clarke's death in 1859 the predecessors of the present congregation took over the chapel, boosting attendances. In 1869–71 the pastor, Charles Burt Sawday, oversaw its enlargement on the east side, raising capacity to more than 1,300 worshippers. For this John Goodchild was the architect. In 1937 concerns about the roof prompted extensive reconstruction, accompanied by the addition of Sawday Hall at No. 5 Vernon Rise, a scheme devised and carried out by C. W. B. Simmonds, a builder and member of the congregation. (fn. 154)

The chapel is a simple brick building with a heavily buttressed stone-dressed Gothic front, conceived as a kind of screen between the associated houses (Ill. 414). The façade was cut down several feet and otherwise altered in 1937. Only the central window survives, those to either side having been bricked up. The nineteenth-century interior had three galleries of the later 1840s, and an open queenpost roof. In 1937 the east end of 1869–70 was reconfigured, the galleries were removed and a low shallow–vaulted ceiling was installed. A western screen was inserted in 1985. The basement hall, relatively unaltered, was first used as a school.

414. Vernon Baptist Chapel (now King's Cross Baptist Church), c. 1910

Clarke's flanking houses have gone. That to the north was replaced in 1933 by Vernon Hall, a low Gothic–fronted block built by J. Webb & Son. That to the south was bombed in 1941, and the site was redeveloped in 1962 with a low two-storey manse for which E. E. Swaine was the architect. This and Sawday Hall beyond are plain brick structures. (fn. 155)

School of Oriental and African Studies, Vernon Square Campus (formerly Vernon Square School)

Vernon Square School was built by the London County Council in 1913–16. In the previous decade the council had intended to build a school on Great Percy Street, between Amwell Street and Holford Street (see page 228), but the New River Company and Finsbury Borough Council together defeated this proposal through a public inquiry in 1907. The New River Company then suggested an alternative site at Vernon Square, around which lodging-houses were predominant and property values lower. This was not picked up until late 1911, when the LCC decided that it would build a large school at Vernon Square for 1,500 pupils. It was designed within the recently reformed Schools Division of the LCC Architect's Department under the leadership of Robert Robertson, the new Schools Architect. The land was transferred in 1912, and building contracts settled in 1913. Work on the project continued despite the outbreak of war, and the ground-floor Infants Department opened in 1915, the remainder of the school in 1916. The builders were Patman & Fotheringham. (fn. 156)

The school is a large, austere stock-brick building, the triple-decker massing of which shows the vestigial influence of the London School Board and its architect T. J. Bailey, who had retired in 1909 (Ill. 415). It has a butterfly or flying wedge plan, to fit the essentially triangular site, comprising two long wings arrayed so as to face Penton Rise and the Baptist Church. Small shaped gables above the staircases are almost the only ornamental features. The central hall block projects towards the Vernon Square corner with flanking semi-hexagonal towers. The accommodation was originally tiered by storey, with the infants below the boys, the girls above having use of a roof playground behind the parapets, which are pierced by openings with decorative cast-iron grilles.

Pressure on expenditure meant that the schoolkeeper's house at No. 27 Penton Rise was not built until 1926. (fn. 157) The main building was made a secondary school in 1949, and renamed Sir Philip Magnus School in 1952. This closed in 1979–80, and the site became part of Kingsway Princeton College in 1983. (fn. 158) In 1999 it was acquired by the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies to be its second campus. Under T. P. Bennett Architects there followed a conservative refurbishment that included the addition of brick-clad lift towers. The premises re-opened in 2001 to provide both teaching facilities and offices.

415. School of Oriental and African Studies, Vernon Square campus (former Vernon Square School), in 2007. Former schoolkeeper's house in foreground

416. (left). Weston Rise Estate, c. 1965, photographed (by Henk Snoek) from the south. Howell, Killick, Partridge & Amis, architects, 1965–8

Weston Rise Estate

Contained now behind high blue railings and with heavily used roads on two sides, the Weston Rise housing estate stands for a forlorn heroism in the transitional territory between King's Cross and Pentonville (Ills 416, 417). This testimony to the brutalist phase of English architecture was built for the Greater London Council in 1965–8 to the designs of Howell, Killick, Partridge & Amis (HKPA).

417. Weston Rise Estate, looking towards Penton Rise. Photographed by Tony Ray-Jones, 1970

The estate derived from a London County Council clearance scheme declared in 1959 for a small portion of the 2.3-acre triangle bounded by Pentonville Road, Weston Rise and Penton Rise; the rest of the site was purchased by the LCC. (fn. 159) The choice of HKPA to design the new housing followed in 1964. All four partners had worked as in-house architects for the LCC, notably on the Alton West Estate at Roehampton, before joining together in private practice. But the firm itself, which had just embarked on the LCC's Acland Burghley School in Tufnell Park, had not designed public housing before Weston Rise. John Partridge was the design partner for the scheme, which was shown at the Royal Academy in 1964. (fn. 160) By the time construction took place in 1965–8 the LCC had given way to the GLC, whose direct-labour force undertook the contract. Harris & Sutherland were the structural consultants. (fn. 161)

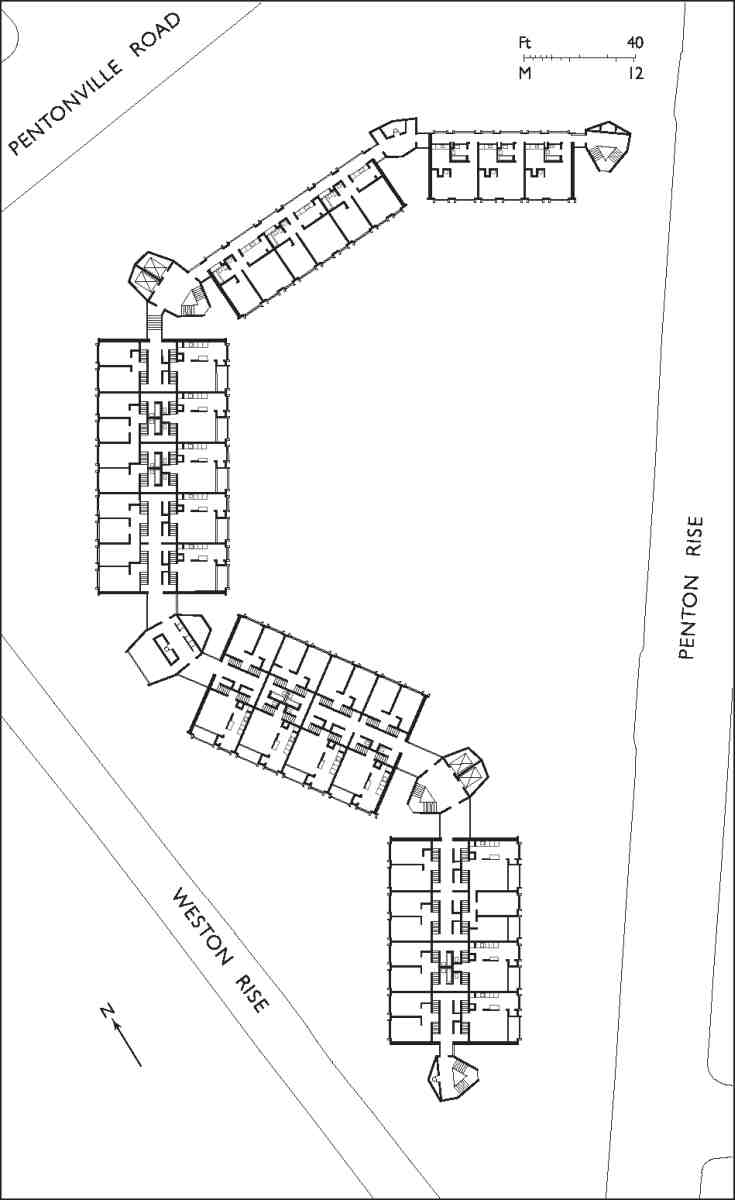

418. Weston Rise Estate, typical floor plans

Weston Rise consists of 147 dwellings arranged in five blocks, at a density of 195 persons per acre (Ill. 418). The two balcony-access blocks near the top of the site, Foxcroft and Sharwood Houses, of six and seven storeys, were destined for old people, whereas the larger blocks to their south and west, Hurst, Frearson and Stelfox Houses, varied from eight to ten storeys and contained maisonettes. Living rooms and bedrooms were mostly turned away from the noisy Pentonville Road, whose widening to a dual carriageway was anticipated. In the open court facing Penton Rise, then expected to become a backwater rather than a major through-route, was a 'kickabout' area with a garage beneath, while at the angle of Weston Rise and Penton Rise was sited a toddlers' playground, now a small gravelled garden with yuccas. Communal playspace was also provided in the access towers.

419. Lorenzo Street, looking north-west, in 2007: Nos 1–2 (former tramshed), to left, and Nos 3–4. York House, Pentonville Road, in background

In overall form Weston Rise shares characteristics with the Park Hill Estate, Sheffield, opened with much fanfare in 1961. These include the acute hillside site (dropping a full fifty feet), the obtuse angling-away of blocks at narrower pivotal points containing bridges and stairs, and the continuous level route starting on Pentonville Road and concluding high up in Stelfox House at the bottom of the hill. Nevertheless Park Hill was not a conscious model for the HKPA partners, who were more concerned with translating the plan-types of the LCC Architect's Department into the concrete language the firm had invented for the Churchill College, Cambridge competition and St Anne's College, Oxford. (fn. 162) From the LCC come the complex 'scissor' maisonette plans, whereby dwellings cross over the central access corridor, which occurs on every other floor. Devised by David Gregory-Jones and other in-house architects, the type was adopted in estates of the mid-1960s designed for the LCC both by its own architects and by private firms. Partridge and HKPA then clothed this and the other LCC dwelling-types with their architectural trademark of the time—storey-height panels and excrescences of prefabricated concrete, forcefully modelled and articulated, so that water would not run down the concrete and create unsightly stains. The precast panels were given an aggregate finish mixing granite, spar and marble. They contrast with the board-marked in situ concrete of the high stair towers at the pivot points. Surprisingly, the structure of the blocks consists not of a concrete frame but of loadbearing cross-wall construction in a special 'calculon' brick with in situ concrete floor slabs. The external panels are hung on projecting 'cladding support units' which do not carry the floors but help to stiffen the structure and give a heavy, staccato rhythm to the elevations.

Like other Pentonville housing estates, Weston Rise has not had an easy history. The monograph on HKPA's architecture published in 1981 alludes to it only briefly, the introduction merely commenting on the site as 'virtually a traffic roundabout and so quite unsuitable for housing'. (fn. 163) After the estate was transferred from the GLC to Islington Council, remedial and cosmetic works were undertaken in 1986–7 and again in 1990. (fn. 164) This did not shield the estate from a reputation as a 'haven for drug barons, junkies and prostitutes'. Following representations from a resourceful tenants' association, which urged upon Islington Council 'the concept of "defensible space"', a bigger initiative of refurbishment was undertaken in 1994–5 to raise the morale of the estate. (fn. 165) It included the reduction in the points of access from five to two, with the main entry being confined to No. 187 Pentonville Road, where a small new entrance block and community hall were added. To that campaign also belong the fence around the perimeter, the replacement of timber windows in plastic, the enclosing of outside stairs, and probably also the unhappy painting of the exposed concrete.

Lorenzo Street